Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 12/181/07. The contractual start date was in September 2014. The final report began editorial review in January 2017 and was accepted for publication in July 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Dawn Skelton receives personal fees from Later Life Training Ltd outside the submitted work and is a Director of Later Life Training, a company that runs as a not-for-profit organisation delivering Falls Management Exercise (FaME) Postural Stability Instructor (PSI) training to health and fitness professionals across the UK.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by Adams et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background and study objectives

The literature search

To contextualise and evidence the Visually Impaired OLder people’s Exercise programme for falls prevenTion (VIOLET) study, a narrative review of the relevant literature was carried out. A literature review was undertaken in January 2016 to support the publication of the study protocol. The search terms ‘falls’, ‘fear of falling’, ‘visual impairment’, ‘sight loss’, ‘elderly’, ‘older people’, ‘older adult’ and their combinations were used to search the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Cochrane, MEDLINE (Medical Literature Analysis and Retrieval System Online, or MEDLARS Online) and PubMed databases. The grey literature was also searched to include significant government and other reports, such as work by the Royal National Institute for Blind People (RNIB) and reference lists of key studies provided a further literature source. The results are discussed below.

Falls and visual impairment

In the UK, one in eight people aged > 75 years and one in three aged > 90 years live with significant sight loss. 1 Visual impairment (VI) is associated with a loss of function in activities of daily living,2,3 and visually impaired older people (VIOP) are more likely than sighted peers to move into residential settings, be physically dependent and have poor quality of life (QoL). 4–6 Gleeson et al. 7 state that VI is an independent risk factor for falls. 5,8,9 Poor vision has been related to the recurrence of falls. 10 Waterman et al. 11 cite research identifying a number of falls risk factors associated with VIOP including muscle weakness, impaired balance and – specific to sight – poor visual acuity and contrast sensitivity, decreased depth perception and reduced visual field. 12,13 However, VI is not independently associated with a higher incidence of falls, despite being a risk factor. 14

Among the general population, falls in older people are common and can be life limiting and debilitating, and estimates suggest that, each year, between 30% and 62% of older people fall. 15,16 Falls are seldom due to a single cause6,12 and are associated with considerable morbidity and mortality,17 with approximately 10% of falls resulting in fractures. 18 The economic costs of falls are estimated at 0.07–0.20% of gross domestic product, with falls and their consequences accounting for 0.85–1.5% of Western economies’ total health-care expenditure. 19 In 2015 in the UK alone, falls in the over-65-year-olds were estimated to cost £4.6M per day. 20

Older people with VI have a (1.7-times) higher risk of falling than the general population, more hospital and nursing home admissions and report more contact with their general practitioner (GP) than those who do not have VI. 21,22 Although VI is not independently associated with a higher incidence of falls,14 Boyce22 suggests that in the UK 8% of falls-related hospital admissions are likely to occur in visually impaired people, accounting for 21% of the total cost of treating accidental falls. Such estimates are problematic in that costs to GPs may not be included in treatment costs, reasons for falling may not be known or recorded and aggregate estimates are likely to mask wide geographical variation.

Evidence suggests that multifactorial falls intervention programmes are effective in reducing falls among older people, often tackling underlying health problems, initiating strength and balance training and offering home modifications. 23–25 In 2004, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines on prevention and assessment of falls in older people25 suggested that by 2005 all NHS boards in the UK should provide a falls service. This echoed the earlier call in 2001 from the National Service Framework for Older People for specialist falls services in both hospital and community settings. 26 A 2008 survey noted that just half of participating falls clinics in the UK assessed for VI and there was little information about how to modify falls prevention programmes for VIOP. 27

Fear of falling and visual impairment

Fear of falling (FoF), with or without a fall, is also common in VIOP and can lead to a cycle of restricting daily activity and mobility, loss of confidence, diminishing physical and mental assets and reduced social participation and overall QoL. 28–30 A UK report by Visibility, a Glasgow-based vision charity, found that older people are highly likely to avoid activity because of VI. 31 Anxiety and depression are also common in those with VI and this may also lead to reduced activity. 1 In a recent randomised controlled trial (RCT) of a cognitive–behavioural therapy-based intervention to reduce FoF in older people, Parry et al. 17 suggest that FoF is likely to affect between 3% and 85% of community-dwelling older people who fall and up to 50% of those who have never fallen. The authors also cite research highlighting that FoF may lead to avoidance of activity, increasing frailty and risk of further falls independent of physical impairment. 32–36

Fear of falling is a significant predictor of a future fall. 37 Clinical and laboratory observations have shown that concerns about falling have a negative impact on older people’s gait patterns. For example, studies of gait and balance in older people’s use of elevated walkways showed both dysfunctional gait adjustments and disproportionately slow walking speeds38 as well as postural balance abnormalities39 when compared with younger subjects. It is also clear that there is a distinction between proper caution around activity and overcaution/a fear–avoidance cycle that perpetuates disability. 40,41 Indeed, a recent review suggests that FoF contributes to falls risk independent of actual gait or balance problems. 42

A recent Cochrane review investigating three-dimensional exercise – yoga, tai chi and strength and resistance training – in community-dwelling older people found that exercise can reduce FoF, but only in the short term, with evidence for long-term efficacy lacking. 43 The authors suggest that future exercise for older people intervention trials should have core outcomes that include FoF. Parry et al. 17 cite a systematic review that identified 12 high-quality RCTs, each with FoF as an outcome,35 but only one of these trials aimed to reduce FoF. 44 The interventions included a range of settings, from community tai chi to home-based multifactorial interventions, and all reported reduced FoF. However, Parry et al. 17 also highlight a more recent multifactorial intervention study, based in a geriatric outpatient setting, that did not find such a benefit. 45

There are also limited health economic data about FoF interventions. 40,42

Measuring the number of falls as a primary outcome does not take into account the more complex impact of an intervention that, by reducing FoF, may increase participants’ confidence in their ability to walk safely and continue to enjoy everyday activities. 46

In relation to VIOP, FoF can also be a barrier to uptake of exercise programmes. Research eliciting the views of VIOP28,31 suggests that perceived risk, stigma, lack of awareness among health professionals, lack of appropriate supporting materials and FoF may be barriers to exercise attendance. Enabling factors could include peer acceptability, appropriate supporting material with demonstration, sensitive explanation, carer involvement and individually tailored interventions.

Fear of falling is thus a vital outcome in falls intervention research, and there are important reasons for its inclusion in studies in VIOP. Any such intervention needs to include targeting of FoF, ameliorating its adverse outcomes and appropriate quantification, FoF being a key outcome measure.

Interventions for falls in visually impaired older people

Gleeson et al. 7 highlight well-designed exercise programmes that reduce falls in the general population44,47 but suggest that such programmes have not been successful in community-dwelling older adults with VI. For example, a recent Cochrane systematic review reports that home safety assessment and multicomponent home-based exercise programmes reduce the rate of falls and risk of falling in community-dwelling older people. 48 However, the New Zealand-based VIP trial49 did not demonstrate such results with VIOP. This study assessed the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of home safety and home exercise interventions for preventing falls and falls-related injuries in community-dwelling people aged ≥ 75 years with severe VI. The VIP trial included 391 participants with visual acuity of 6/24 or worse, of whom 361 (92%) completed 1 year of follow-up. The home safety assessment and modification programme was specifically designed for people with severe VIs and the 1-year home exercise intervention used the Otago exercise programme. 50 This programme includes specific muscle strengthening and balance retraining exercises that increase in difficulty and a walking plan, modified for those with severe visual acuity loss. The home safety modifications, delivered by an occupational therapist (OT), resulted in a significant reduction in the risk of falling while the group receiving home exercise, managed by a physiotherapist, showed a non-significant increase in the risk of falls. However, the authors highlighted that within the exercise programme stricter adherence to the prescription was associated with fewer falls.

Waterman et al. 11 suggest that the VIP study participants who received both home safety and home exercise interventions may have been unwittingly given confusing or conflicting messages from the OT and physiotherapist, this having a negative impact on intervention adherence and study outcome. 28 Adherence to the Otago programme was significantly lower in VIOP than in older people without significant VI in this study (only 18% of VIOP completed all home exercise sessions over a 1-year period)49 and this may have been due to lack of confidence in exercising at home without supervision.

The VIP2UK trial11 was adapted from the VIP Otago home-based programme to increase adherence in VIOP. This community-based feasibility study was carried out in north-west England and recruited 49 community-dwelling VIOP into a three-arm RCT with a control group receiving usual care and social visits, an experimental group receiving a home safety programme and another group receiving a home safety and home exercise programme. The social visits for the group comprised three social visits and two telephone calls and were designed to control for social contact that may reduce falls and influence lifestyle or QoL variables. 11

Falls primary outcome data were collected continuously over 6 months. Secondary outcomes on self-reported and instrumented physical activity and adherence were collected at baseline and at 3 and 6 months for home exercise and at 6 months for the home safety programme. All interventions were delivered by an OT. A total of 43 out of 49 participants (88%) completed the trial and 6-month follow-up. At follow-up, 100% reported partially or completely adhering to home safety recommendations but evidence for adherence to home exercise was equivocal. Whereas self-reported physical activity increased, instrumented monitoring [activPAL™ (PAL Technologies, Glasgow, UK)] showed a decrease in walking activity and there were no statistically significant differences in falls between the groups. However, the authors highlight that the study was not powered to detect a difference.

The VIP2UK authors suggest that further research is needed to explore the differences between the subjective and objective measures of activity and adherence issues. Whereas home safety modifications required a ‘one-off’ input from participants, ongoing adherence to the physical exercise programme (the Otago programme) might have been particularly challenging for the VIOP, some of whom lived alone. Despite the use of mentors, extra telephone calls and audio exercise clips and embedding exercises into daily living, it might have required a lot of effort to follow instructions via large print or audio and continue to be motivated to complete home exercises. The authors conclude that perhaps weekly home visits from an exercise trainer may improve adherence for VIOP or that group exercise with tailored support dependent on VI may lead to better progression in relation to strength and balance and, relatedly, to falls.

Finally, Gleeson et al. 7 highlight three small studies demonstrating that multimodal exercise and tai chi may improve physical functioning in VIOP51–53 in controlled environments when physical and verbal guidance is provided. These were carried out in residential settings and cannot be generalised to community-dwelling adults, who are likely to encounter more environmental hazards and who are more mobile. Gleeson et al. ’s randomised control trial7 with 120 community-dwelling people aged ≥ 50 years investigated the impact of 12 weeks of Alexander Technique lessons on balance and mobility with VIs compared with usual care. There was no impact on the primary outcome: the Short Physical Performance Battery score. However, there were greater intervention effects in the subgroup of multiple fallers, who are at an increased risk of injury compared with non-multiple fallers. Although the study was not powered for falls within the intervention group, trends towards a lower rate of falls and injurious falls were noted. 7 The Alexander Technique uses verbal feedback and manual guidance to teach awareness of previously unnoticed tension and, the authors suggest, may be a suitable intervention for people with VI as it does not require vision or the performance of regular exercises.

Falls Management Exercise and the VIOLET study

With an ageing population, the number of VIOP is predicted to rise. 54 Increasing incidences of key underlying causes such as macular degeneration and diabetes suggest that, without intervention, the number of people with VI in the UK could dramatically increase over the next 25 years. 54 This has implications for the need for falls prevention programmes that are tailored to VIOP. As outlined in The literature search and Falls and visual impairment, falls and FoF in later life are common, falls can be recurring and costs of care for those who fall are a disproportionate drain on local inpatient and adult social care budgets. 55,56 In the UK, falls are a major cause of disability;57 in Scotland, in 2010, three-quarters of people registered as blind or partially sighted (25,609; 74.2%) were aged ≥ 65 years and about one-third (11,158; 32.3%) had additional disabilities. Of the latter, over one-fifth (2476; 22.2%) were also deaf. 58

Our feasibility study draws on the learning from a number of previous studies, including the Falls Management Exercise (FaME)59 programme, the VIP trial49 and the recently completed VIP2UK pilot. 11 A recent Royal College of Physicians report60 demonstrated that 54% of falls exercise services have trained Postural Stability Instructors (PSIs) delivering the FaME programme in groups. A 6-month programme of FaME exercises has also been shown to significantly increase habitual physical activity (i.e. by 15 minutes of moderate to vigorous activity per day) in older people recruited through primary care even at 12 months post intervention, as well as reducing falls. 61 The FaME programme also has significant reach across the UK with a pool of qualified instructors.

A systematic review of falls prevention exercise62 suggested that at least a total of 40 hours of challenging balance and strength work is necessary to reduce falls. In the current study, 12 weeks (with a weekly group session and twice-weekly 1-hour home exercises) equates to 36 hours. We have therefore taken a pragmatic approach to what is achievable when considering roll-outs through NHS- or council-led services using the FaME approach. Indeed, both a scoping report for the Service Development Office27 and the Royal College of Physicians Audit60 suggested that, on average, falls services across the UK should deliver groups or sessions once a week for 8–12 weeks.

There are potential risks and benefits to introducing exercises to this population. As noted in Falls and visual impairment, FoF in VIOP may exacerbate existing gait and balance difficulties, further increasing the risk of falls. Recent research has identified that older people are at increased risk of falling following intensive endurance exercise bouts63 owing to exercise-induced alterations in respiration and muscular fatigue. It was also noted that VI could increase exercise-induced changes to postural control and consequently the risk of falling.

The feasibility study will provide an opportunity for VIOP to contribute to the adaptation and design of an acceptable community-based group exercise programme that could be incorporated into a general health promotion exercise programme. This study will enable VIOP to collaborate with researchers and instructors, and to draw on their expertise and experience to adapt a commonly adopted exercise programme (that is known to reduce falls risk in high-risk frequent fallers59 and low-risk older adults61) to their specific VI needs. This in turn may have a positive impact on gait and balance, increase confidence and lessen FoF. This study will add to an emerging body of work that is using FoF, as assessed by a widely validated cross-cultural tool [Falls Efficacy Scale – International (FES-I)], to address the gap in knowledge of how to successfully manage FoF.

Research aims

The rationale for the study is to provide an opportunity for VIOP to contribute to the adaptation of a group-based falls prevention programme that is prevalent in falls services across the UK. This should facilitate an acceptable, feasible and appealing intervention that will improve uptake and adherence to an intervention known to be effective. The aim of the study is to conduct a mixed-methods feasibility pilot study to inform the design and conduct of a future definitive multicentre RCT and economic evaluation of an adapted group-based exercise programme to prevent falls and reduce FoF among VIOP.

The research questions were:

-

Can an existing exercise programme be adapted for VIOP and successfully delivered in the community?

-

Is it feasible to conduct a RCT of this adapted exercise intervention and what would be the features of a future definitive trial?

Study objectives

The specific objectives were to:

-

explore participants’ ability to act as lay partners in a study to develop a condition-appropriate intervention and what methods enabled them to contribute to research as active partners

-

assess recruitment of VIOP and their willingness to be randomised

-

choose candidate outcome measures for a future RCT from FoF (confidence), activity avoidance, well-being/QoL, anxiety, depression, loneliness and number of falls

-

test the trial methodology and provide outcome data to inform sample size calculations for a definitive RCT

-

explore the capacity to deliver the adapted exercise programme

-

examine delivery of (fidelity) and compliance with the exercise intervention

-

explore participants’ reasons for participating in the exercise programme and acceptability of the exercise programme and trial procedures

-

develop a manualised intervention protocol and training package for a definitive RCT

-

assess the feasibility of collecting service use data for an economic evaluation of the intervention in a future RCT.

Prior to the completion of the feasibility study, the plan was to use the findings of this work to seek funding to conduct a definitive multicentre RCT to evaluate the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of an adapted group-based exercise programme to prevent falls in VIOP by decreasing their FoF.

Chapter 2 Stakeholder involvement in the adaptation of the Falls Management Exercise programme: conduct and results of focus groups

Introduction

A number of issues have been identified in the literature (see Chapter 1) regarding risk of falling and FoF in those both with and without VI. Despite evidence of the effectiveness of exercise programmes, poor adherence and compliance remain problems and have been found to reduce the effectiveness of any exercise programme. In a RCT carried out in New Zealand with VIOP,49 home safety modifications delivered by an OT resulted in a significant reduction in risk of falling, but the group receiving a home exercise programme (which had already been shown to be highly effective in reducing falls in older people without VI) showed a non-significant increase in risk of falls. On a planned subanalysis, the authors found that adherence to the home exercise component was poor and that those who did adhere to the home exercise programme did see a reduction in falls. 49 A UK study has sought the views of VIOP to help increase adherence to a home exercise programme. 28

In another, smaller, exercise study in people with VI aged ≥ 50 years,7 there was a trend for fewer falls overall, but the rate of falls was not significantly different between those who received 12 lessons on the Alexander Technique and those who did not. Levels of adherence to this programme were high as an instructor visited participants weekly at home. A recent systematic review of exercise in the prevention of falls in VIOP has highlighted the lack of studies in community-dwelling older people, particularly group-based as opposed to home-based exercise. 64

In the UK, two main programmes of exercise are offered as part of falls prevention services: the Otago home exercise programme49,65 and the FaME group exercise programme delivered by PSIs. 59 A Royal College of Physicians report66 showed that 54% of falls exercise services in the UK have trained PSIs delivering the FaME programme. FaME exercise classes are balance-specific, individually tailored and include backward chaining, functional floor exercises and targeted training for dynamic balance, strength, endurance, flexibility, functional skills, gait and ‘righting’ or ‘correcting’ skills to avoid a fall. A full description of the exercise programming and progression has been published. 67

Given the prevalence of both falls and FoF in VIOP, there has been relatively little research into adapting existing falls prevention interventions for this population. This formed the aim of this phase of the VIOLET study.

Aim

The aim of this phase was to recruit and run VIOP stakeholder groups to act as consultants on adapting an existing evidence-based falls prevention programme (FaME) for this population. The findings from this phase were to inform the adaptation of the FaME programme for the subsequent feasibility study.

This chapter reports on the findings of four stakeholder focus groups with VIOP. It explores their main concerns surrounding falls and details their recommendations on adapting a falls prevention programme.

Method

Stakeholder panels were conducted in the two geographical locations of the intervention sites: Newcastle upon Tyne and Glasgow. They took the form of focus groups facilitated by research staff. Two focus groups were completed in each area: the first covered views on falls and falls prevention; the second covered proposed tools to measure the outcomes.

Focus groups were used in this study to explore experiences, views and concerns, to clarify why particular views were held and to facilitate discussion among focus group participants. 68 Ethics approval was gained from both universities’ ethics committees. All participants gave recorded verbal consent.

Participants and recruitment

Participants were accessed through vision-related charitable organisations who were partners in the research project: Visibility in Glasgow and the Newcastle Society for Blind People (NSBP) in Newcastle. The dissemination of the information regarding the project and the focus groups was facilitated locally by the charitable organisations. Inclusion criteria were being aged ≥ 60 years with or without experience of falling and having a VI.

Participants were not excluded from the feasibility study if they had participated in the focus groups.

Focus group structure and prompts

The groups were co-facilitated by two members of the research staff (VD and DS). Also present were representatives of the charitable organisations and observers from within the research team. In a deliberate attempt to make the focus groups accessible, they were held in venues familiar to the VIOP and hosted by the charitable partners. As an aid to participation, the focus groups were held from late morning to early afternoon – that is, during accessible daylight hours. Participant transport costs were covered by the research budget.

Four sessions were held in total, two focus groups at each site, with the same participants in each site being invited to both groups. The groups were scheduled to last for a maximum of 2 hours with a 15- to 30-minute break for refreshments; actual duration was 110–124 minutes. Across the sites, both focus groups opened with a statement of their aims and purposes.

The aim of the first group meeting at each site was to explore how the existing FaME programme should be adapted so that VIOP might best be enabled to participate. The aim of the second set of group meetings was to ascertain the most suitable set of trial outcome measures important to the VIOP and to adapt data collection procedures to maximise participation and minimise participant burden.

The first groups opened with a general discussion in which participants were invited to talk about their experiences of, and opinions around, falls and falling. A member of the research team (DS) then introduced the FaME intervention and verbally described the exercise programme. Large-print excerpts of the home exercise programme booklet that accompanies the group sessions were made available, although most participants were happy with the verbal descriptions. Finally, the participants were invited to try some of the exercises and feedback was sought on acceptability and potential adaptations.

The second groups covered a précis of the information gained in the first focus groups, for member checking, then focused on the outcome measures and trial data collection procedures. Some candidate outcome measures had previously been chosen by the research team. Large-print versions of each tool/questionnaire were available; however, as with the first groups, most participants preferred a verbal description. Each tool was described in detail, including introductions to questionnaires, instructions on how they were completed and questionnaire content. Views were then sought on how participants could best access and complete these measures and preferred modes of interacting with the research team. The second focus groups concluded with a discussion of areas of life that are affected by falls and FoF that were not captured by these candidate measures. Suggestions were sought on how these areas of life could best be captured to allow patient-centred outcome measures to be used in the future feasibility RCT.

The groups were lively and interactive. The facilitators aimed to ensure that every participant had an opportunity to have their opinion heard. Facilitators needed to do little more than present the focus group prompts and discussion followed. A ‘one-at-a-time’ conversational rule was encouraged and on every major topic a group round was conducted to ensure that all opinions were collected.

Analysis

Notes were made during the focus groups and the opinions in the room were précised by the facilitator and checked for accuracy with the group. At the beginning of the second group we member-checked with the participants about the main themes that had come out of the first group. During the second group we discussed, summarised and fact checked throughout, as in the first group. Following this, notes were analysed to both check for accuracy and draw out information on how the intervention should be adapted.

Results

Across both areas, a total of 14 VIOP took part in the four focus groups. The maximum attendance was nine, the minimum five. All but one person at each site attended both focus groups. Participants had a range of VIs including macular degeneration, VIs following stroke and complete blindness. Some had been visually impaired for their whole life and some had started losing their sight more recently. Two people had guide dogs.

Views on falls and falling

As one participant put it, daily life ‘is a pilgrimage into the unknown’ for people with VI. There was a general agreement that falls and FoF were significant issues for this group. FoF was particularly an issue when people were outside their home and in unfamiliar environments. Main areas of concern were street furniture, the state of repair of roads and pavements, steps (on and off, up and down) and unclear or confusing signposting of step edges (leading edges demarcated, last/first step identified). Public transport was a significant issue for all participants, particularly getting on and off, and the wheelchair/pushchair-friendly but VIOP-‘unfriendly’ expanded atriums of newer buses (too large an open space with fewer handholds). People also remarked on the often unhelpful behaviour of drivers (accelerating before VIOP were seated, not informing them of stops). It was also remarked that VI is often ‘invisible’ and not readily apparent to members of the public (i.e. in the absence of a cane or guide dog) and, as a result, other pedestrians/pavement users can cause problems for VIOP. Pain, distraction, overcaution and poor lighting were other issues people mentioned as increasing the likelihood of falls and trips and fear of these.

Most participants reported that they had fallen. On closer questioning, and having agreed on a definition of a fall as ‘an involuntary ending up on the ground or lower level’, it was clear that most participants had not fallen directly to the ground but had experiences that were described as a ‘near miss’. These were slips and trips where the individual had been prevented from falling by either saving themselves or being assisted by another person. However, near misses were thought to affect confidence and curtail activity as much as a fall. So common were trips and slips that the groups talked about them as if they were to be expected, as were minor injuries, bruises and grazes. Most falls, trips and slips had occurred outside the home, though one participant had a significant fall in their own bathroom.

Differing views were expressed regarding the effect the degree of VI would have on FoF and falling. It was felt that this was a complex issue and that it was often influenced by what was referred to as ‘the nature of the person’ – that is, certain people would be more affected by these issues than others depending on their personality. It was also suggested that duration of VI (i.e. from birth or in later life), personal coping strategies, degree of local knowledge of the environment and a desire to be independent would all have an impact on susceptibility to falls and FoF. The views of VIOP in this study resonate with the views of VIOP in the VIP2UK study. 28

Adapting the FaME programme

There was almost universal enthusiasm for the proposed exercises and their perceived potential to increase strength, balance and confidence. Participants were very positive about not just falls prevention but the concept of ‘falling better’ and being enabled to get up off the floor should a fall occur.

Group venue and environment

It was generally thought that somewhere familiar would be less problematic, but if this was not possible then time to become familiar with the venue layout would be appreciated. There was agreement that no music should be played during the exercise sessions in order to hear well and concentrate. There was less consensus around lighting, with some preferring dim and others preferring bright light depending on their particular VI. It was suggested that aids such as ‘anti-glare glasses’ could be utilised by participants who may have a sensitivity to light at certain times.

Group size and personalised support

Specific suggestions regarding modification of FaME were made around group size, for which it was suggested that 6–8 people was the most appropriate number per exercise session. This was mostly to do with feeling confident that the instructor was able to keep an eye on the participants and in order to get to know everyone well, by voice if necessary. During the FaME ‘taster’ exercises, it became apparent that some participants would need one-to-one support depending on their degree of VI and any additional impairment such as deafness. In addition, the participants suggested they should be given the choice to bring another person (friend/relative/carer) with them to give assistance or that another person should be present to assist the VIOP.

Group exercise delivery and instruction

It was also apparent that the pace and content of the class needed to be adjusted to allow for a more detailed verbal instruction, with reinforcement from additional facilitators working with some individuals. There was a consensus on the need for instructors to understand the impact of specific VIs and associated limitations and the need for instructions to be given clearly and at an appropriate pace.

At the Newcastle site, greater anxiety was expressed about learning to get up off the floor, as participants were worried about getting down onto the floor during the exercise classes. They expressed the opinion that once you are down it is hard to get up. Once it was explained that this was precisely why floor exercises were practised and that this was done in a graded manner at their own pace, their anxieties were allayed.

There was a universal preference for the inclusion of a social element, which included the exercise instructor. One of the groups felt that it would be better to have the social element after the exercise class and to ‘get the business out the way first’. Other suggestions centred on multiple classes per week as a catch-up if someone could not attend their usual class and that a peer-support group may develop from the exercise classes in addition to the social aspect that occurred at the end of the classes.

There was no consensus on how instructions were preferred; each individual had their own preference, with some wanting verbal instruction, some hands-on guidance and others retaining enough sight to copy the instructor’s demonstration.

Home exercise programme

It was initially suggested by the research team that each person would complete two 1-hour sessions of exercise at home. Most felt that this was unattainable but that the total of 2 hours per week could be met if it was broken down into 10–20 minutes per session. Some preferred a prompt of some kind, either a booklet or audio disc detailing exercises to follow in ‘chunks’, whereas others preferred incorporating exercises into usual daily activities, such as standing on toes while waiting for the kettle to boil or other exercises while preparing a meal. Again, the consensus was that individual choice and discussion with the instructor about what was best for the individual should determine the home exercise programme.

Measuring meaningful outcomes

Measurement/form of outcome assessment

The key finding that emerged regarding how outcome measures were presented, completed and returned concerned choice. A range of preferences were expressed. Some participants wanted assessment tools to be read to them and to reply (face to face or over the telephone), others wanted large print, some could see large print but not their own writing, and some were happy to receive materials by e-mail as they had screen readers on their computer. Although most participants thought outcome measures would need to be read aloud to them and their responses documented, they also thought that doing this over the telephone would also be acceptable; again, the consensus was that people should be given choice.

In both groups, a considerable amount of time was spent discussing how best to keep a falls diary and how to interpret its contents. This was considered the most ‘heavy’ participant burden, as it needed to be completed every day and submitted weekly. Although there was no overall consensus, most participants, after discussion with the research team, were happy to do this by way of a weekly telephone call.

Content of outcome measures

With a few minor caveats, most participants found all candidate outcome measures acceptable. There was some general discussion about adapting some questionnaires to Likert scales, as this was the group preference for response options. Once it was explained that outcome measures are valid as such only in their existing form, they understood and accepted the difficulty in adapting such questionnaires. However, several participants did express the worry that the questionnaires that focus on limitation and reduced QoL could adversely affect people’s mood, and that this should be highlighted by the interviewer prior to administration.

It was the content of the falls diary that received most discussion. It was felt that falls should be distinguished from ‘near misses’ – trips (tripping on an obstacle) and slips (losing footing) – and that all three should be recorded. The terminology of the falls diary was considered unclear. Most participants were not sure what a soft tissue injury was and they wanted to add ‘graze’ and have a chance to tell someone rather than try to explain it on a form that they could not see well (or at all). Participants also wanted a question on whether or not they were physically or psychologically affected by a fall that, subsequently, reduced their activities or substantially changed their routines, and they wanted to be able to record changing and limiting activity (as opposed to ‘immobilisation’ as currently recorded in the diary). Similarly, the ‘costs’ of a fall were unclear to participants. Again, after discussion with the research team, participants were happy for the falls diary to be a ‘daily yes or no’ document and for all other details to be elicited within a weekly telephone call. Finally, for the Timed Up and Go (TUG) tests, participants wanted to know that they could use the standard aids (or dog) that they normally used to walk.

The groups were asked to reflect on any important outcome measures that they thought were missing and what would be a good outcome for them and important to measure (patient-specific outcome measures). There was a strong feeling among some members that we needed more VI-specific demographics – such as nature of VI; duration of VI (or lifelong); stable, progressive or changeable VI; recent change in VI; personal adaptation and confidence related to VI; and impact of VI on daily activity – in order to fully understand whether or not some people respond better to training than others and what support they would need in the exercise programme. The level of VI (and a person’s ability to cope and function with it) appeared to be an important consideration that they felt was vital for the instructor to understand.

One area that was discussed at some length was the specific impact the intervention could have on QoL, confidence and daily activity as determined by VI. There were various suggestions for capturing this in the form of ‘before and after’ data such as asking specific additional questions, for instance ‘are you impaired in everyday activities as a result of your VI?’. From these discussions, other validated outcome measures were suggested by the research team [e.g. the ConfBal69 scale or the Work and Social Adjustment Scale (WSAS)70], but the groups also felt that it was important to ask about confidence and ability to orientate in new environments and to assess amount of physical activity, degree of general happiness and amount of pain. Finally, several members of the group suggested targets that were meaningful to them and that these could be measured by degree of achievement before and after the groups. From these additional comments, outcome measures were identified to capture these aspects in the feasibility study.

Focus group summary

The opening discussions in both groups highlighted how significant an issue falls and FoF are for this group and the extent to which these concern individuals on a daily basis.

The participants were volunteers recruited from third-sector organisations and thus enthusiastic about the exercise programme. Although some expressed anxieties about practising new skills, they appreciated without exception the usefulness of doing so. Similarly, participants engaged enthusiastically with the process of research and appreciated the necessity of measuring change.

Overall, participants strongly recommended having individual choice and autonomy throughout the proposed intervention, whether this was related to how they participated in the exercise class, completed the outcome measure assessment tools or reported their falls and ‘near misses’. In terms of incidentals, participants gave clear indications of preferring smaller group exercise classes, no music during classes, venue familiarisation, more than one weekly class to choose from, flexibility to bring someone with them, a social element and working with instructors who had an understanding of the impact of living with VI. Thus, many of the recommendations related to the facilitation of the intervention rather than to the actual content of the exercise programme.

Adaptations made to the feasibility randomised controlled trial design

All stakeholder requests were incorporated into the planning and delivery of the classes with the exception of smaller class size and a choice of classes each week. Owing to study resource constraints, class sizes were planned at 10 and offered only once per week. However, this feedback will inform future interventions.

The request for instructor VI training was met. This training was expertly managed by Visibility in Glasgow and incorporated the use of blindfolds and adapted spectacles. All actors from both locations were included. Both exercise instructors and the research team simulated being both a person with VI and a guide and learned invaluable communication and guiding techniques. This training also covered the need for weekly discussions with participants about any changing needs regarding support, aids, position in the class (lighting/hearing) and the importance of social contact and peer support within the group.

An induction session, for introducing the venue and getting to know everyone, formed part of the first session. Participants were encouraged to bring along any carer/family member to the class and extra support personnel were available to help individuals who needed more personalised instruction in the group. The proposed home exercise content was also modified in accordance with the stakeholder panel’s overall feedback. This included adapting the 60-minute FaME home exercise element to graded exercise components of 10 minutes, 15 minutes and 20 minutes. The home exercise booklet used by PSIs71 was adapted to include a series of prompts, particularly focusing on incorporating some of the exercises into everyday activities, and split into smaller ‘chunks’ of exercise that lasted approximately 10 minutes and progressed in duration and intensity/difficulty over time (to a maximum 20-minute session). Audio clips were made available for those who wanted their home exercise programme to be verbal. These could be played on either a compact disc (CD) player or an MP3 player. A digital versatile disc (DVD) was also available to use.

In relation to VIOP’s views on completing the related assessment tools, participants were asked about their preferred mode of assessment tool delivery, such as large print or being read aloud. The preferred solution to the fall diary was implemented in the form of a weekly telephone call between a member of the research team and the participant. This protocol captured falls and ‘near misses’ and allowed a reporting of the financial costs of any such event.

Probably the single biggest impact on the conduct of the feasibility RCT has been a shift in emphasis to interpersonal communication. In trials, the mediating agent between triallists and participants is often the written word. In the case of the VIOLET study we endeavoured to make both the initial and ongoing collection of data based on interpersonal communication. Although this is more burdensome for the research team, we believe it gave the feasibility study a much higher chance of maximising retention and also provided a means of monitoring the impact of the intervention on participants. It also allowed us to address some of the issues that would otherwise be hard to address via written communication. For instance, given the feedback from the stakeholder groups that some of the QoL questions might be upsetting, we were now in a position to highlight and discuss this, both before and after administration of the outcome measures.

Limitations

The participants lived in cities and so would not necessarily represent the experiences of people living in rural areas, who might have different experiences of the accessibility of group classes or external environmental concerns (street furniture, lighting). Participants were recruited from low-vision charities and so were already engaged with external organisations and were less likely to be isolated. Although there was a range of ages, a mix of males and females, people with a history of falls and without, and a range of VIs and histories of sight loss, there was an absence of ethnic minorities and only one person had dual sensory loss. This limits the findings.

One of the focus group facilitators (DS) was the author of the FaME programme, delivers training to specialist exercise instructors and has extensive experience in presenting the exercise programme in a motivating manner. This may have influenced the participants’ enthusiasm for the programme and willingness to try floor-based exercises.

Summary of recommendations from the stakeholder group

These recommendations related to the content of the FaME programme, the way in which it was delivered, the logistics of attending the programme and the design of the subsequent feasibility study. The main recommendation was that personal choice and individual adaptation should be maximised in both the conduct and measurement of the intervention. Specific recommendations centred on venue familiarity, group dynamics and training of facilitators on VI. Additional recommendations were made regarding individual goal setting and choice regarding the methods by which study materials were received and administered.

It was the adaptation of the environment to the needs of a visually impaired person rather than the adaptation of the actual exercises that received most attention from the stakeholder group. Each point was considered in the design and delivery of the subsequent intervention. Recommendations were as follows.

Recommendations for adapting FaME:

-

a fully accessible, familiar venue or the option to get to know an unfamiliar venue before sessions

-

aid getting to and from the venue (e.g. by taxi)

-

a maximum group size of eight persons

-

no music

-

individual adaptation regarding lighting and glare

-

the option to bring another person (or guide dog)

-

a social element (e.g. tea and a chat) after exercise sessions

-

run more than one class (flexibility regarding class time) at the beginning for group bonding

-

home exercises – reduce the length of home exercise sessions to 10–20 minutes; provide a variety of exercises; provide prompts (e.g. in large print, on DVD or audio); integrate exercises with daily living activities

-

train PSIs on (1) the impact of VI, (2) adaptations (aids) that can be used for specific VIs and (3) communication (verbal clarity)

-

more than one instructor or additional person to help VIOP

-

provide the PSI with information regarding individual participants and time to fully understand the nature of the VI, how it may affect the individual and how it may vary across timeframes

-

tailor content to the individual (e.g. floor work).

Recommendations for outcome measures and trial procedures:

-

the possibility to choose how outcome measures are received and administered (e-mail, post, verbal)

-

reduce the content of the falls dairy

-

remove the resources/expenses form so that the researcher administers this

-

incorporate a weekly telephone call to capture data concerning the nature of slips/trips/falls and the impact of these (to ensure capture of ‘near misses’)

-

define ‘slip’, ‘trip’ and ‘fall’

-

patient-centred outcome measures (personal goals)

-

use a tool to capture the impact of VI on an individual and their activities.

Conclusion

Participants expressed very individual preferences and needs regarding the attendance of group exercise to prevent falls. They voiced a strong desire for instructors to be specifically trained in how to tailor instruction and delivery to each individual’s very different functional or visual limitations, which may change week to week. There was an equally strong preference for alternatives and choice in methods of engaging with home exercise and completion of outcome measures. These stakeholders gave clear and useful guidance on ways to adapt an existing falls prevention exercise intervention to maximise both uptake and adherence for VIOP. No matter how good an intervention is, if participants cannot or do not want to engage with it, it is effectively useless. Actively involving stakeholders in the modification of this intervention maximised the possibility that the intervention would be useful for the VIOP population.

Visually impaired older people stakeholder involvement in the adaptation of the FaME programme produced the first health promotion and falls prevention exercise intervention protocol developed collaboratively with older people for community-living VIOP. 46 As detailed in Appendix 1, the intervention protocol manual will enable accurate replication of the feasibility study intervention in a larger multisite study in the future, and can be used to ensure that adaptations of the original FaME intervention for VIOP can be replicated in practice in falls prevention programmes.

Chapter 3 Randomised controlled feasibility trial of the adapted Falls Management Exercise intervention versus usual activities: research process and conduct

Introduction

This chapter describes the methods employed for the research process and conduct of the feasibility study, including identification, screening, consent and recruitment strategy, inclusion/exclusion criteria, flow of participants through the study, design and delivery of the intervention and the outcome measures used for data collection.

The overall aim of this phase was to conduct a feasibility study in order to inform the design and conduct of a future definitive multicentre RCT of an adapted community-based group exercise programme to prevent falls and reduce FoF in VIOP. This was in order to facilitate the development of a feasible and acceptable intervention to improve uptake of, compliance with and adherence to an intervention known to be effective.

The research questions were:

-

Can an existing exercise programme be adapted for VIOP and delivered successfully in the community?

-

Is it feasible to conduct a RCT of this adapted exercise intervention and what are the features of a future definitive trial?

The objectives are presented in Chapter 1.

Study design

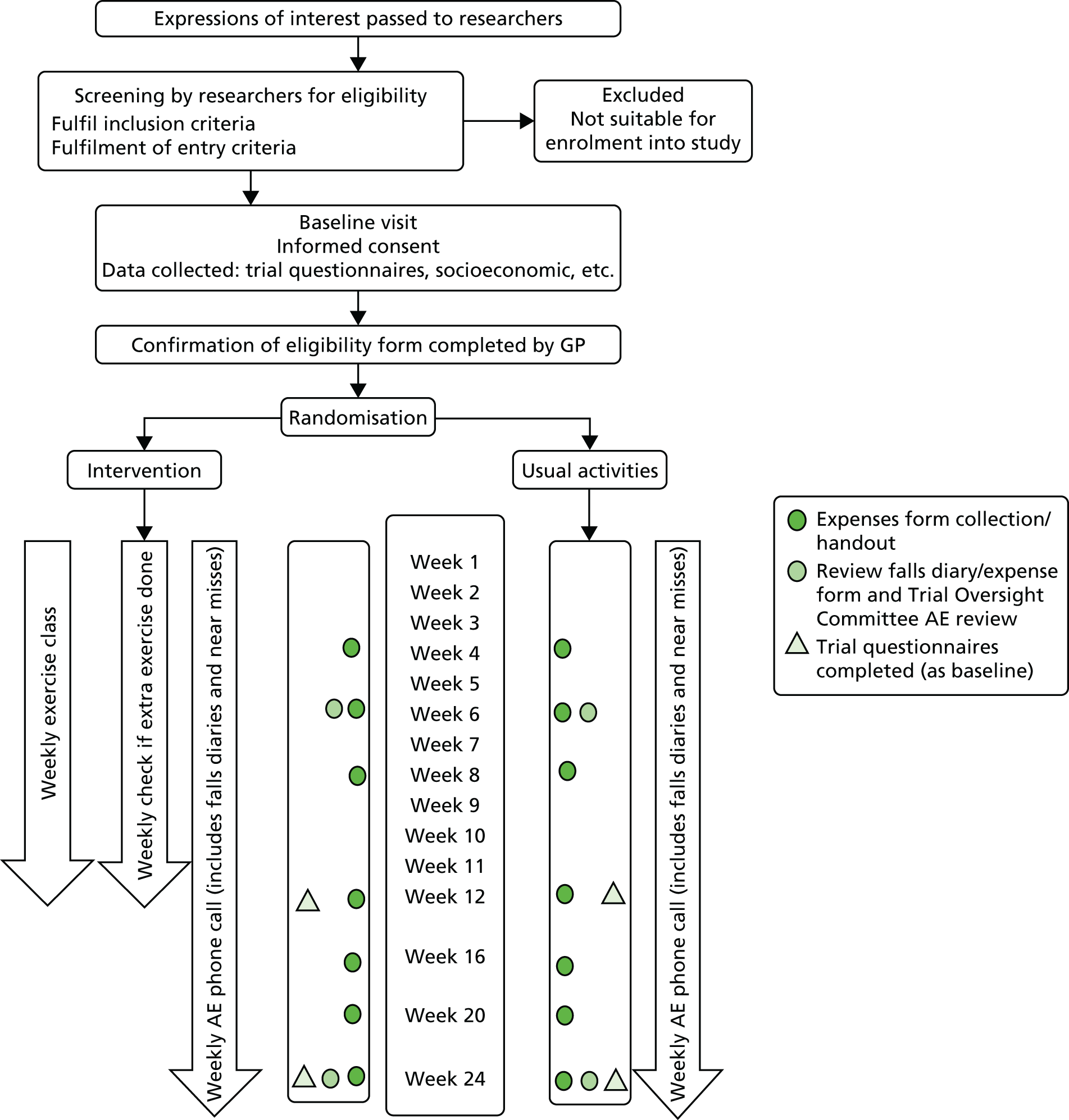

This study adapted an existing, effective group-based health promotion intervention for older people (FaME) to reduce falls, with VIOP as experts. Because of the lack of relevant information for a full RCT on this topic, a randomised mixed-methods feasibility study was designed to inform the design and conduct of a future definitive multicentre RCT on an adapted version of FaME. The feasibility study addressed issues relating to the generalisability and transferability of the proposed intervention and investigated the viability of a future definitive RCT.

This was a two-centre randomised pilot trial of an adapted exercise programme for VIOP versus no intervention with embedded qualitative evaluation. An economic evaluation was also carried out (see Chapter 6). Older people with VI were recruited from two study sites (Newcastle and Glasgow) and randomised into one of two groups:

-

group 1 – 12-week exercise programme (1-hour session per week)

-

group 2 – usual activities.

Assessment of the feasibility to progress to a full trial

The criteria to judge the feasibility of progressing to a full trial at 6-month follow-up were as follows:

-

Fifty per cent or more of VIOP eligible for the study were willing to be recruited into the feasibility study.

-

Seventy per cent or more of the participants in the intervention arm have completed 9 to 12 group sessions in the exercise programme (compliance).

-

Data on key outcomes was collected at 6-month follow-up for ≥ 70% of those recruited.

-

Less than 10% of serious adverse events (SAEs) were deemed to be caused by the intervention.

Study population

The study population were drawn from community-living VIOP in Newcastle and Glasgow.

Inclusion criteria

-

Aged ≥ 60 years.

-

Attend a low vision clinic and/or are a member of organisation(s) for the visually impaired such as NSBP in Newcastle or Visibility in Glasgow.

-

Live in own home.

-

Able to walk indoors without the help of another person but may use the assistance of a walking aid.

-

Able to walk outdoors but may need the help of another person and/or walking aid.

-

Have the physical ability to take part in a group exercise class.

-

Have provided informed consent (as appropriate to each older person with VI) to participate in the study prior to any study-specific procedures.

Exclusion criteria

-

Inability to comprehend or follow simple movement instructions in English.

-

Presence of acute or uncontrolled medical problems in addition to VI that the participant’s GP considers would exclude them from undertaking the exercise programme [e.g. uncontrolled heart disease, poorly controlled diabetes, acute systemic illness, neurological problems, severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)].

-

Medical conditions that would necessitate a specialist exercise programme or prevent participants from maintaining an upright seated position or moving around indoors independently (e.g. uncontrolled epilepsy, severe neurological disease or impairment).

-

Current involvement in other falls prevention exercise programmes (with the exception of walking programmes), investigational studies or trials.

Ethics and regulatory issues

The conduct of this study was in accordance with the recommendations for physicians involved in research on human subjects adopted by the 18th World Medical Assembly, Helsinki, 1964, and later revisions.

Ethics approval from the Newcastle and North Tyneside Research Ethics Committee (REC) was sought prior to the commencement of the intervention, as was research and development approval. The REC reference was 15/NE/0057 and the UNN reference was RE-HLS-13-140707-53bb0a7806e37.

Local approvals were sought before recruitment commenced at each site. Newcastle Clinical Trials Unit received a written copy of local approval documentation before initiating each centre and accepting participants into the study. The study was registered as Current Controlled Trials ISRCTN16949845.

Information sheets were provided to all eligible subjects and written informed consent obtained prior to any study procedures. If subjects were unable to sign the consent form, verbal consent was witnessed by a third party, who signed the witness section of the consent form.

Confidentiality

Personal data were regarded as strictly confidential. To preserve anonymity, any data leaving the site identified participants by their initials and a unique study identification code only. The study complied with the Data Protection Act 1998. 72 All study records and investigator site files were kept in offices with restricted access.

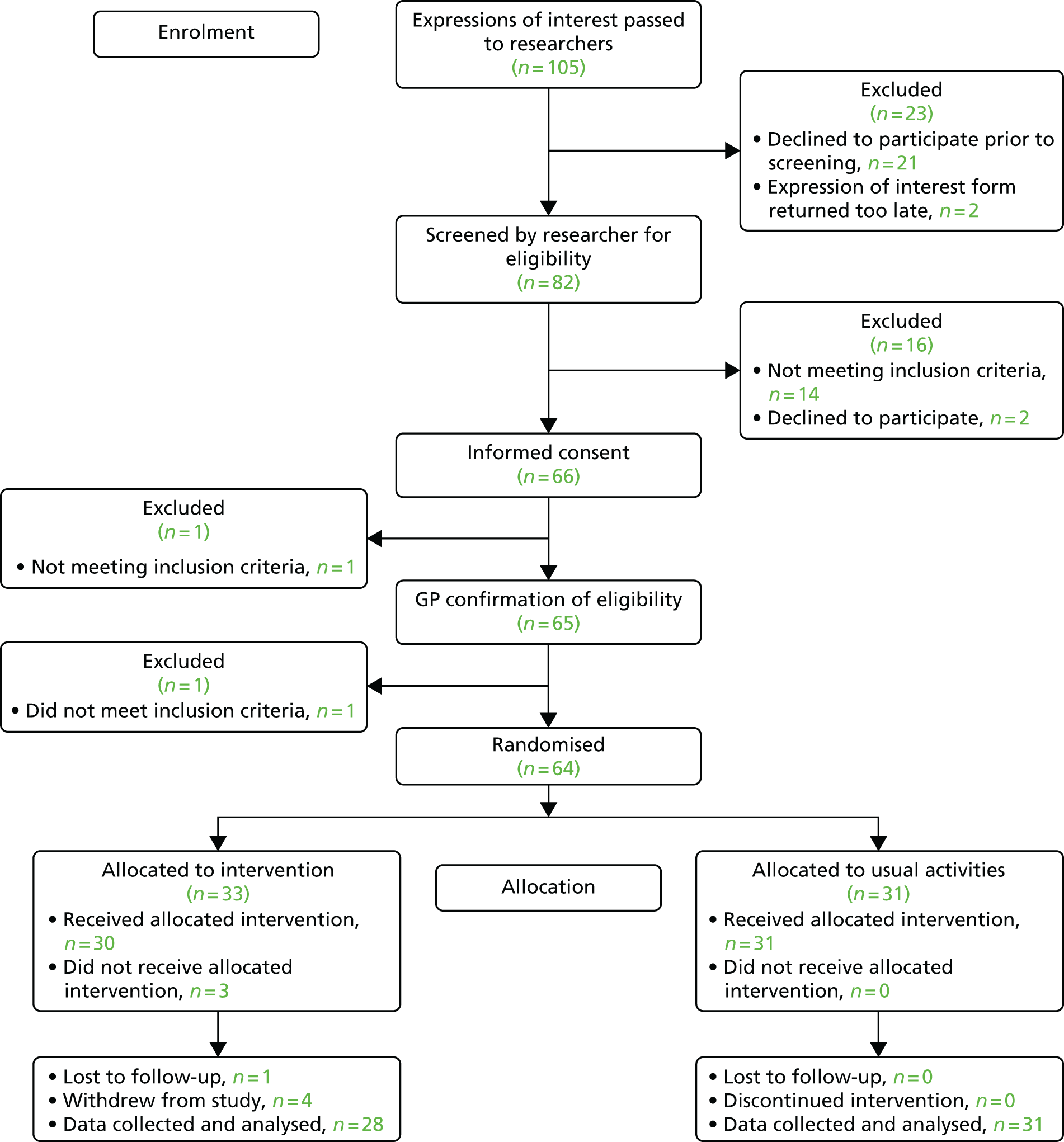

Identification, screening, recruitment and consent of participants

The Ophthalmology Department at the Royal Victoria Infirmary (RVI) in Newcastle sees an average of 3138 patients per month aged ≥ 65 years, with approximately 45 patients per month aged ≥ 65 years attending the low-vision clinic. NSBP has approximately 1500 members. NHS Greater Glasgow & Clyde saw approximately 500 patients per month in the general eye clinic, with 20–25 VIOP attending the Glasgow Caledonian University low-vision clinic per month. Visibility ran both a patient support service and an information line and across both they had contact with around 1500 people per year. These organisations identified potential participants and passed on expressions of interest to the research team.

It is known from previous studies that recruitment and adherence in frail older people can be difficult, although data for recruitment and retention rates in VIOP were relatively unknown. In the VIP2UK study,11 only 51% of eligible participants and 10% of those who were originally screened agreed to take part. However, the inclusion/exclusion criteria meant that the study excluded participants who would have been eligible for the VIOLET study.

Visually impaired older people who expressed an interest in participating in the VIOLET study received further information. This information was available in large-print and audio formats. These materials had been designed in consultation with the stakeholder panel and checked to ensure that they met RNIB standards in terms of suitability for those with VI.

The researcher then invited eligible VIOP to participate and answered any questions raised. Signed consent to participate in the feasibility study was sought only when the researcher had ensured that the participant had accessed and understood the information. Once consent had been gained, a letter was sent to the participant’s GP explaining the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the study. This allowed the GP to make a judgement regarding the medical fitness of the participant to take part in the study based on these criteria. Once a participant’s GP confirmation of eligibility had been received, the participant was randomised.

Identification of potential participants

The primary recruiting source at the Newcastle site was NSBP. The organisation raised awareness of the study in its newsletter, which is sent to all members. In addition, members of the research team visited member meetings to discuss the study and how to receive further information. When recruitment began, a dedicated member of NSBP rang the members aged ≥ 60 years to discuss the study and gain permission to forward their contact details to the research team.

Identification of participants from the RVI low-vision clinic proved problematic. The physical space of the clinic area was unsuitable for the research team to approach potential participants. The responsibility for raising awareness of the study was then transferred wholly to the medical and paramedical staff in both the eye clinics and low-vision clinics. Although the managers of these departments and the lead consultant were aware of the study, very few of the staff referred potential participants to the researchers. In an effort to increase recruitment from the NHS site, a minor amendment was made to allow Eye Clinic Liaison Officers (ECLOs) to approach potential participants. They were able to identify potential participants who had recently been seen in their service and, with their permission, forwarded expressions of interest to the research team. These potential participants were then contacted by the research team and assessed for eligibility in the same manner as participants identified through the low-vision clinic and NSBP.

The primary recruiting source at the Glasgow site was Visibility. It raised awareness of the study in its newsletter to members, with expressions of interest being forwarded to the study team. As recruitment via this mode was felt to be slow, Visibility contacted potential participants directly. Expressions of interest were again forwarded to the research staff.

It had been planned to recruit participants from the low-vision clinics held in Glasgow Caledonian University. Unfortunately, recruitment coincided with the summer period when the clinics in the academic setting were not running. Therefore, no recruitment took place from this source.

Screening procedures

Visually impaired older people who expressed a continued interest in participating in the study were screened for eligibility by a researcher over the telephone or at a site mutually convenient to the researcher and the potential participant. Screening was based on the inclusion/exclusion criteria. Eligibility was confirmed by the GP.

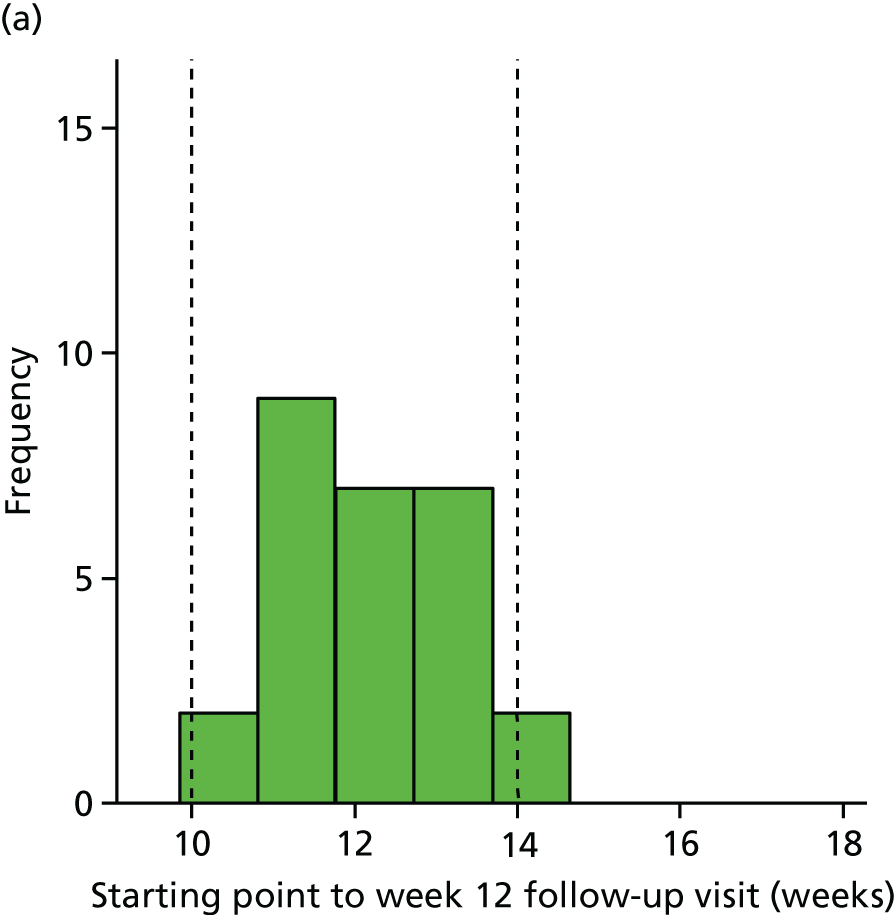

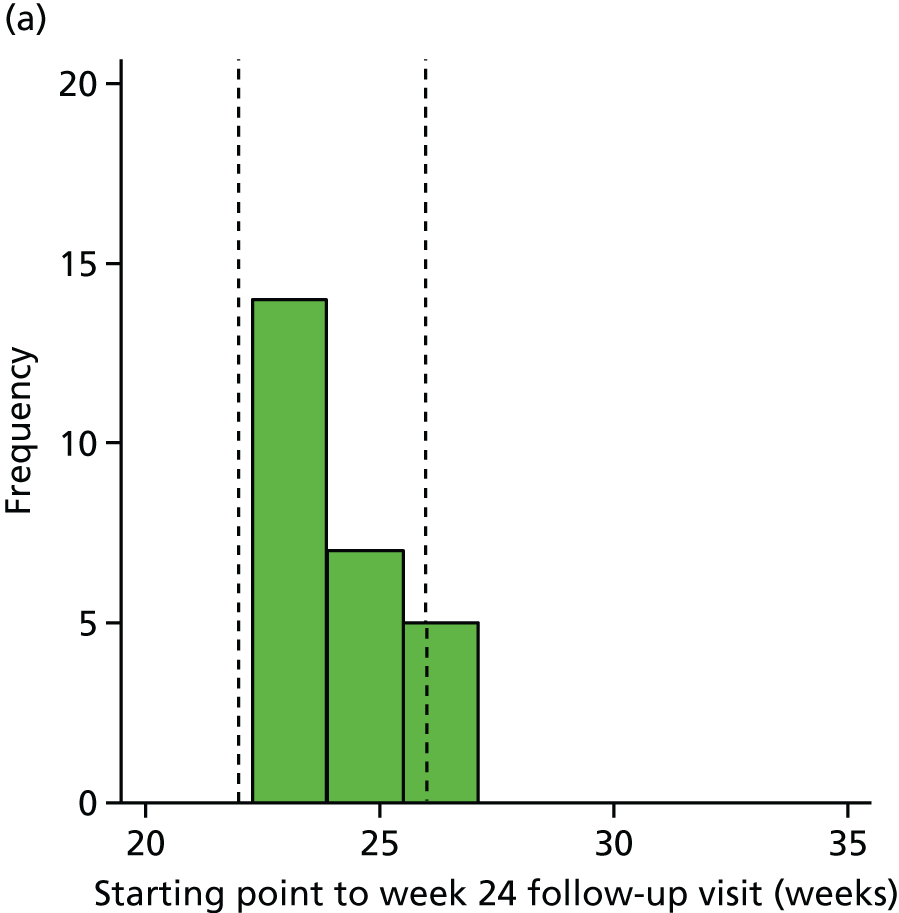

To facilitate the first running of the first cohorts in both Newcastle and Glasgow, a staggered start was employed at both sites. This enabled those for whom GP confirmation of eligibility had not been returned promptly to start at any time within the first 3 weeks and continue to complete the 12 sessions. More than 12 weeks of sessions were offered so that each participant was able to attend 12 sessions even with a delayed start.

Consent procedures

Once screening for eligibility had been completed, the researcher invited the VIOP to participate and answered any questions they raised. Following receipt of information about the study, participants were given reasonable time (a minimum of 24 hours) to decide whether or not they wanted to participate. As previously stated, signed or recorded verbal consent to participate in the feasibility study (as appropriate for each VIOP participant) was sought only when the researcher had ensured that the participant had accessed and understood the information provided. If the VIOP was unable to sign the consent form, verbal consent was witnessed by a third party, who signed the witness section of the consent form.

The original signed consent form was retained in the investigator site file, a copy added to the clinical notes (for participants recruited from the NHS) and a copy provided to the participant. The participant specifically consented to their GP being contacted regarding their medical fitness and being informed of their participation in the study.

The right to refuse to participate without giving reasons was respected.

The information sheet and consent form for the study was available in English only. It was decided to exclude participants who were unable to understand simple instructions in English as they would not be able to understand the movement instructions given during the exercise sessions if randomised to the intervention arm of the study.

Randomisation

A computer-based system allocated participants to the intervention and control groups in a 1 : 1 ratio using permuted random blocks of variable length and stratification by centre. This was administered centrally via Newcastle Clinical Trials Unit using a secure web-based system. The principal investigator (PI) at the site, or an individual with delegate authority, accessed the web-based system. Random allocation was determined after a participant screening identification number and initials were entered into the web-based system; participants could then be informed.

Study intervention

The proposed intervention was adapted from the group-based FaME programme, which is widely used as a health-promoting activity in the UK with community-dwelling older people.

For the intervention arm, local qualified FaME PSIs working on each site were trained by a research team member (DS) on adapting the exercises for people with VI following recommendations from the stakeholder panels. The PSIs also received VI training from Visibility.

The exercise programme (the intervention) ran weekly over 12 weeks, with each session lasting up to 1 hour. Two exercise groups were held at each site. In order to maximise recruitment, a further exercise group was held at the Newcastle site. All groups were held in a community venue. In Glasgow, the exercise groups were run at Visibility because this venue was known to the participants. In Newcastle, classes were run at the Trinity Centre. These were city centre venues and required participants to travel into the city centre.

None of the groups had more than 10 participants. The exercises consisted of balance-specific, individually tailored and targeted training for dynamic balance, strength, endurance, flexibility, gait and functional skills and ‘righting’ or ‘correcting’ skills to avoid a fall, as well as backward chaining, that is, retraining of the ability to get down to and up from the floor. The exercises also included functional floor exercises and adapted tai chi exercises. The intervention increased in difficulty over the 12 weeks. Resistance bands and mats were used throughout the study. The details of the methods of delivery, group size, support and timing were decided by the stakeholder panels. A full description of the original exercise programming and progression has been published and an adapted manualised intervention is included as Appendix 1, as this was an important objective of the study.

Prior to commencing the exercise sessions, all participants completed a health screening tool that is normally administered by the exercise instructors prior to delivery of the FaME programme.

The first session was used as an induction to familiarise VIOP with the venue and instructor. Any time remaining after this induction was used for a short exercise session. All following sessions lasted 1 hour and comprised:

-

a 10- to 15-minute warm-up focusing on circulation exercises

-

targeted full-range joint mobilisation and light stretches

-

a standing cardiovascular endurance section lasting 5 minutes in week 2 and increasing to 10 minutes by week 12

-

a balance retraining section of 10 minutes starting with static exercises (such as one-leg stands) and progressing to highly challenging dynamic exercises (such as heel walking and backwards walking)

-

a 10-minute seated resistance component using progressively more challenging resistance bands

-

a 10-minute cool-down including developmental stretches for both the upper and lower limb muscles and one form of adapted tai chi that progressed in difficulty.

The introduction of the backward chaining approach for getting down to and up from the floor was not planned for a specific week of the intervention, given that the VIOP stakeholders had expressed some concern about the ability of the target population to perform this safely. The PSIs were advised to introduce the floor-based exercises at a stage appropriate to the group and no sooner than week 4.

Participants were also advised to exercise at home for up to 2 hours per week using an adapted standardised home exercise programme that has been developed by DS and used in other related studies. Exercises were provided in large-text or audio format and consisted of specific chair and standing exercises to improve balance, bone and muscle strength and flexibility, similar to the exercises carried out in the exercise classes. The home exercises were designed to be completed in 10- to 20-minute blocks, commencing with 10-minute blocks in the first 4 weeks, increasing to 15-minute blocks for a further 4 weeks and increasing again to 20-minute blocks in the last 4 weeks. A greater number of exercises and more challenging balance exercises were included as the duration of the sessions gradually increased. This progressive approach was implemented following VIOP stakeholder advice that 30-minute blocks of home exercise would not be realistic. The exercises were to be performed 6 days per week – that is, every day excluding the day of the exercise class. All home programmes contained ‘prompts’ that linked exercises to daily tasks (e.g. performing heel raises while waiting for the kettle to boil). The prompts were included to increase compliance, following VIOP stakeholder advice. The PSIs supplied participants with the home exercise programmes and were responsible for encouraging participants to adhere to and progress through the programmes. PSIs were asked to ensure that the content of the home exercise programmes had been taught in the group sessions and to help participants with the specific exercise techniques to reduce the risk of any adverse events (AEs) from the home exercises.

Participants were provided with transport by taxi to and from the classes, if required, and invited to bring along someone for support if they wished.

The description of this adapted exercise programme is provided in the manualised intervention, which is available on the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) website.

Those participants who were randomised to the usual activities group received no intervention. However, they were offered an equivalent exercise programme after the week 24 follow-up data collection at both sites.

Fidelity of the intervention

Postural Stability Instructors were given a flexible framework of lesson plans for the 12-week programme prior to the start of the intervention.

A standardised quality assurance checklist was used to ensure effective and safe delivery of the programme, including progression, adherence to the protocol (i.e. providing home exercise programme, checking on adherence to home exercise and recording any falls mentioned) and completion of all paperwork.

The PSIs compliance with the course content (fidelity) was assessed by videoing two sessions at each site at weeks 3 and/or 4 and weeks 9 and/or 10 respectively.

These videos were examined by a research team member to check that the main components of fitness were covered and progressed sufficiently. Their delivery was signed off by checking against the videos provided.

The quality assurance checklist can be found appended to the manual of the adapted FaME intervention (a copy of this is available from the VIOLET project page on the NIHR website).

Qualitative interviews

As this was a feasibility study, qualitative interviews were conducted to explore acceptability and applicability of the intervention, the research methods and the outcome measures. These interviews are reported in Chapter 5. Structured interviews were also conducted with a purposive sample of the exercise practitioners at two points (before training and at the end of the intervention) to explore their (changing) perspectives on the provision of the intervention over the duration of the intervention (see Chapter 5).

Outcome measures and assessment

A key aim of the feasibility study was to determine whether or not the primary and secondary outcomes for a proposed full trial could be measured for all participants. The feasibility study was not powered to detect significant differences in these measures but was able to describe observed changes between time points and their direction.

The selected candidate outcome measures were standardised assessment instruments that have been used previously in comparable studies. These measures were selected in consultation with the stakeholder panels. The main reasons for this selection were the relevance of the questions to the participants and that the questionnaires were short and, therefore, easier for a person with VI to manage. The proposed measurement tools were reviewed by the stakeholder panels at both sites to ensure that the most appropriate and most acceptable outcome measurement tools were selected and used in the pilot trial. FoF was selected as the primary outcome because, although FoF is common, debilitating and a significant predictor of a future fall particularly among older people, successful management of FoF is limited. Recent reviews show that there is a lack of high-quality research that has FoF as a primary health outcome. There are also limited health economic data about FoF interventions.

Measuring the number of falls as a primary outcome does not take into account the more complex impact of an intervention. Reducing FoF may increase participants’ confidence in their ability to walk safely and continue with everyday activities. Assessing FoF before and after the proposed intervention captures participants’ self-reported change in confidence to continue with physical and social activities. This provides an indication of their perceived QoL and whether or not the negative impacts of FoF, such as social isolation and risk of further falls, have been reduced.

Primary outcome measure

The measures were selected together with VIOP and were modified following the stakeholder panel (see Chapter 2). The final primary outcome of the future RCT would be decided by responsiveness to change, participant burden and participant feedback in this study. A potential candidate outcome was FoF (FES-I). 73

Fear of falling was assessed at baseline and at weeks 12 and 24 by the Short Form FES-I. It captured participants’ self-reported change in confidence to continue with physical and social activities. This in turn gave an indication of their perceived QoL and whether or not the negative impact of FoF, such as social isolation and risk of further falls, had been reduced.

The Short Form FES-I uses seven items – each scored from 1 (not concerned) to 4 (very concerned) – to assess selected activities and provide an indication of how afraid of falling the responder is while doing these activities. The total score for all seven items (range 7–28) is categorised as low (range 7–8), moderate (range 9–13) or high (range 14–28) concern.

Secondary outcome measures

Activity avoidance (two questions)

Activity avoidance can be a consequence of FoF. The degree of activity avoidance was captured using two questions. 34 It was recorded at baseline and at weeks 12 and 24.

There are two stand-alone questions – ‘Are you afraid of falling?’ and ‘Do you avoid certain activities due to fear of falling?’ – scored on a Likert scale with five options: ‘never’, ‘almost never’, ‘sometimes’, ‘often’ or ‘very often’.

Balance/falls risk

Balance/falls risk was assessed by two methods: the TUG test74 and a self-assessment – the Falls Risk Assessment Tool (FRAT),75 which has been used in previous studies in ageing populations. These were assessed at baseline, week 12 and week 24.

The purpose of the TUG test is to assess mobility. Participants can wear their usual footwear and use walking aids if needed. The time taken (in seconds) for them to stand up from the chair, walk to a line 3 metres away at their normal pace, turn around, walk back to the chair and sit down again is recorded using a stop watch.

An older adult who takes ≥ 12 seconds to complete the TUG test can be considered at high risk of falling.

The self-assessment FRAT, developed from the Peninsula FRAT,75 was used. It is a five-item questionnaire (with yes/no responses). Scores of > 3 (yes) indicate that further assessment is required.

Number of falls (falls diary and weekly telephone call)

As well as answering the study questionnaires at the specified time points of baseline, week 12 and week 24, each participant completed a falls diary each week, with assistance from a researcher, during their weekly telephone call. Data were collected for each day, Monday to Sunday, as yes/no responses to the question ‘did you fall’? If a response was ‘yes’, it was coded as follows:

-

0 – no injury

-

1 – bruise and/or cut

-

2 – bruise and/or cut and immobilisation

-

3 – soft tissue injury

-

4 – broken bone

-

5 – other.

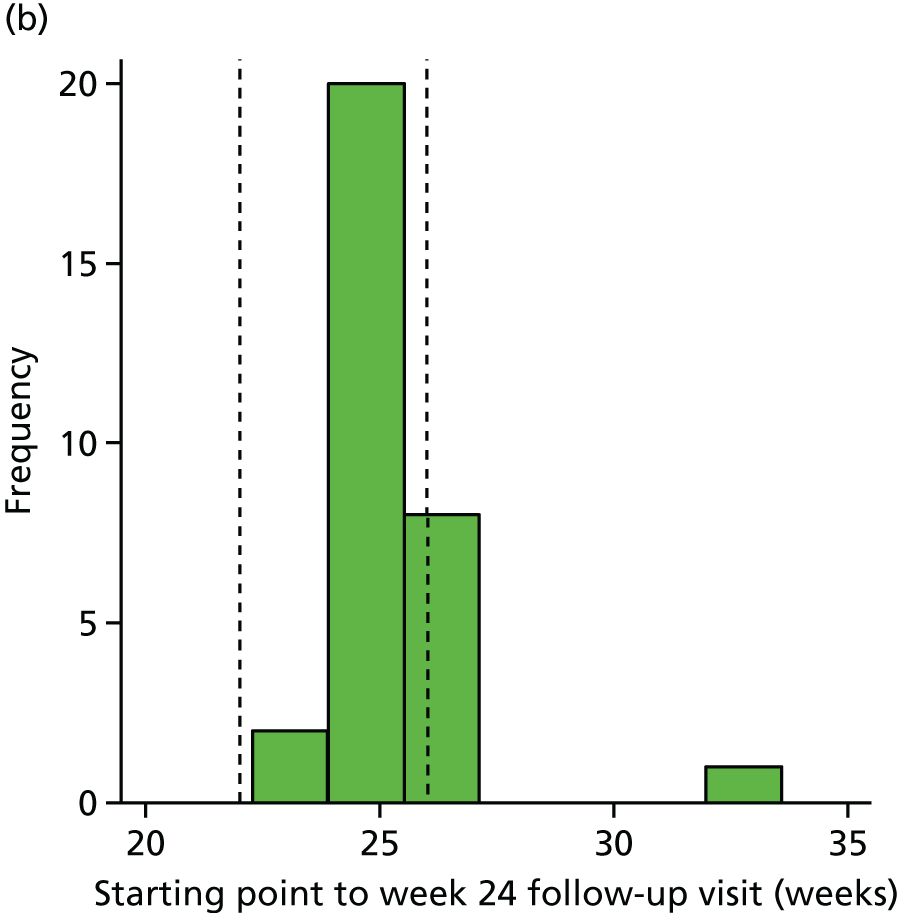

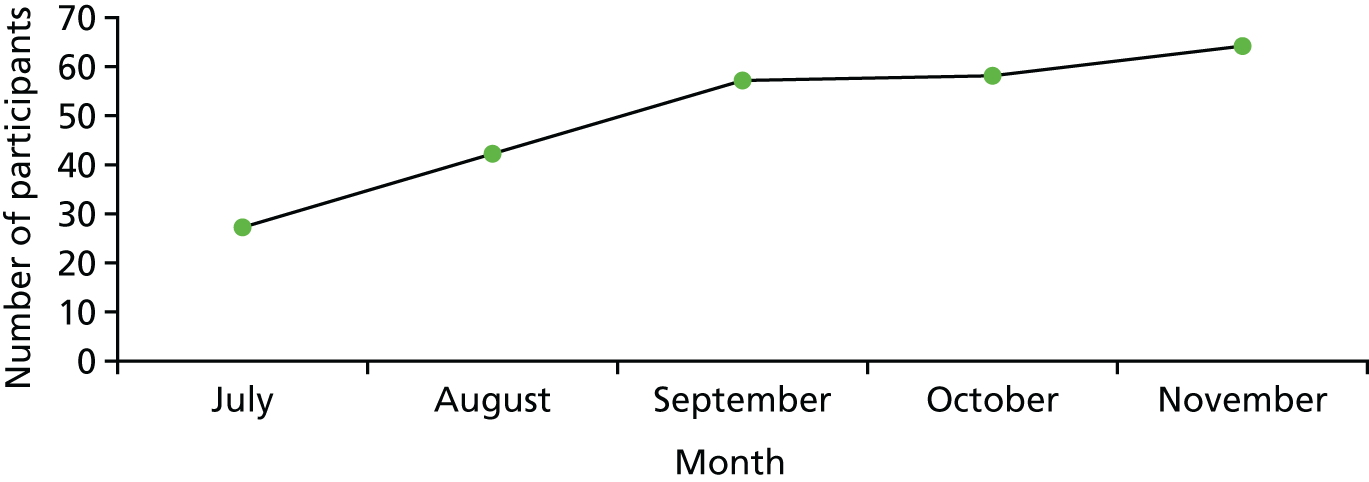

Each participant was telephoned 7 ± 2 days from date of previous contact. A suitable time was arranged for each participant and recorded in the trial documentation along with ongoing consent. Details of any AEs and near misses were also recorded at this time and described in the safety analysis.