Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 13/90/30. The contractual start date was in February 2015. The final report began editorial review in May 2017 and was accepted for publication in September 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Melanie J Davies and Kamlesh Khunti report personal fees from Novo Nordisk (Bagsværd, Denmark), Sanofi-Aventis (Paris, France), Eli Lilly and Company (Indianapolis, IN, USA), Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp. (Kenilworth, NJ, USA), Boehringer Ingelheim (Berkshire, UK), AstraZeneca (Cambridge, UK), Janssen Pharmaceutica (Beerse, Belgium), Servier (Suresnes, France), Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corporation (Osaka, Japan) and Takeda Pharmaceuticals International Inc. (Osaka, Japan), and grants from Novo Nordisk, Sanofi-Aventis, Eli Lilly and Company, Boehringer Ingelheim and Janssen Pharmaceutica. Melanie J Davies and Kamlesh Khunti are National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) senior investigators. Outside the submitted work, Joanna M Charles reports grants from Public Health Wales. Charlotte L Edwardson reports grants from NIHR Public Health Research during the conduct of the study.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Harrington et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction and background

Background and rationale

Physical activity levels of young people

It is well known that participation in regular physical activity (PA) has numerous short- and long-term physiological, psychological and social benefits for young people. 1–3 For example, reviews1,2 have shown that PA can improve blood pressure and bone mineral density, can lead to improvements in self-esteem and depression and, in the longer term, it can prevent chronic disease. Despite these benefits, a significant proportion of adolescents are not meeting the recommended guideline of participating in ≥ 60 minutes of moderate to vigorous intensity PA (MVPA) each day. 4 A recent review of pan-European studies5 found that, across all countries, less than 30% of adolescents achieved the recommended levels of MVPA. Furthermore, data from two of the most comprehensive surveys (the Global School-based Student Health Survey6 and the Health Behaviour in School-aged Children study7) showed that an even larger proportion of adolescents (80%) were not meeting the guideline levels of MVPA. 2 However, this proportion has been shown to be even higher when measured using accelerometers, with approximately 95% of 5- to 17-year-olds failing to meet the recommended level. 8 Data specific to the UK (collected in 2015) suggest that only 17% of 11- or 12-year-olds and 12% of 13- to 15-year-olds are sufficiently active. 9 Furthermore, it has been consistently shown that, as children get older, boys are more active than girls. 2,5,8,9 For example, data from the Health Survey for England 2015 showed that, while both boys and girls exhibit low levels of PA, only 16% and 9% of girls aged 11/12 years and 13–15 years, respectively, meet the guideline levels, compared with 15% of boys in each of the same age groups. 9 Worldwide data2 reinforce these findings, with the proportion of adolescents not achieving ≥ 60 minutes of MVPA per day being ≥ 80% in 56 out of 105 countries (53%) for boys and in 100 out of 105 countries (95%) for girls. Girls have therefore been identified as a key target for behaviour change in an effort to increase PA levels and improve current and future population health.

Physical activity interventions in adolescents

A plethora of PA interventions aimed at young people have been conducted over the past two decades. 10–13 These interventions have been varied in their approaches to increasing PA levels but they can be grouped into interventions targeting changes in the school cultural or physical environment, interventions targeting changes in the school curriculum, interventions incorporating extra PA within the school day, education-only interventions, after-school interventions, and interventions with a community or family component. Published reviews10,13 have found some evidence that interventions focused on increasing PA levels in adolescents can be effective, although only modest effects have been found. van Sluijs et al. 11 found that over half of the studies (n = 38, 67%) included in their review showed a positive intervention effect ranging from an increase of 2.6 minutes during physical education (PE) classes to a 42% increase in participation in regular PA and an increase of 83 minutes per week in MVPA, with multicomponent interventions providing the strongest evidence of an effect. A more recent review of interventions in older adolescents13 reported more promising results, with 7 out of 10 studies showing a significant difference in PA levels between intervention and control groups. Effects were generally small and short term (no longer than 1 month post intervention). Two reviews10,14 have been conducted that focus solely on the effectiveness of PA interventions aimed at adolescent girls. In a narrative review, Camacho-Miñano et al. 10 reported mixed results, with 10 out of 21 interventions showing a modest favourable intervention effect for PA levels. More recently, a meta-analysis quantifying the effectiveness of PA interventions among adolescent girls14 concluded that PA interventions had ‘small’ but significant effects. Compared with girls receiving the control conditions, those who received the intervention participated in 13.7% more PA than those who did not. Subgroup analyses showed that multicomponent interventions, those focusing on both PA and sedentary behaviour, theory-based interventions and intervention designs of high quality showed small trends in effecting the primary outcomes. 14 Furthermore, significant trends were found for interventions that were aimed at girls only, targeted at younger adolescent girls or delivered within school-based settings. 14

These reviews10–14 have consistently reported several major methodological limitations of previous research that have had an impact on the ability to draw robust conclusions. The vast majority of studies have suffered from weak methodological quality. This can be attributable to small sample sizes, which can lead to high rates of bias, and a reliance on PA outcomes that are assessed by self-report. 10,13,15 Furthermore, a high proportion of studies have been conducted in the USA. 10 For example, 18 of the 24 studies included in one review11 were conducted in the USA. This makes generalisability to other countries difficult, particularly because of differences in school infrastructure, curriculum, policies and practices and culture. These reviews10,13,15 have also noted a lack of long-term follow-up to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions in the longer term.

Importance of peers

Social support from parents, family and friends has been identified as a key determinant of young people’s PA level. 16,17 However, it has been observed that, as children move into adolescence and spend more time with their peers, support for PA from peers is reported to be more important than support from other sources. 18 Furthermore, numerous reviews have demonstrated a positive link between peer support and PA levels,19,20 and specifically for adolescent girls’ PA levels. 21 A 2014 review17 noted that peer support showed the greatest consistent association with PA level when compared with other sources of support. Greater social support from peers has also been associated with higher levels of self-efficacy, which, in turn, has been associated with higher PA levels. 16 Peers have been found to influence PA levels in a number of ways, including through the provision of encouragement and praise, joint participation in activity, the modelling of being active and by simply being present during PA. 17,19,20

This evidence from previous studies suggests that interventions that incorporate the influence of peers might be a useful avenue for increasing adolescent PA levels. Despite this, very few interventions have used peers as an intervention strategy. One review10 identified only two interventions that had focused on utilising the peer influence for promoting PA among adolescents and concluded that peer interventions showed promising evidence for being effective. More recently, further evidence has been published22 that supports the effectiveness of peer inclusion in interventions. Spencer et al. 22 reported that training peers to act as mentors by promoting PA during lunchtimes was successful in increasing PA levels during the school day. 22

The extensive amount of evidence highlighting the important role that peers play in adolescent PA and the limited intervention evidence conducted to date using the influence of peers highlights the need for future research to focus on the effectiveness of peer-focused interventions for increasing PA levels during adolescence.

Development of the Girls Active programme

The ‘Girls Active’ programme builds on more than 10 years of developmental work by the Youth Sport Trust (YST) (www.youthsporttrust.org; accessed 5 June 2018) on programmes specifically designed to engage girls in PA, sport and PE. The YST is the largest UK charity that is dedicated to the provision of school sport and high-quality PE for young people. Through partnerships and working with schools, the YST aims to create a brighter future for young people through programmes that increase opportunities for well-being, leadership and achievement. In 1998, Nike, Inc. (OR, USA) and the YST established the Nike Girls in Sport programme, which equipped PE teachers with the skills and ideas to develop girl-friendly PE. The Norwich Union Girls Active initiative (2006) built on this work, empowering teenage girls to enjoy PE and sport by having a stronger student voice and a greater choice of activities. However, despite the success of these initiatives and the excellent practices implemented in some schools, research23 found that, although PE and school sport met the needs of ‘sporty’ girls, they often remained unattractive to those who were less active. The YST then undertook more research to establish how to make PA, PE and sport relevant to all girls, to encourage them to participate more and to feel that being physically active is a positive part of who they are. As a result, and building on the earlier programmes, the YST worked with schools to create the Girls in PE and Sport initiative in 2012. This initiative underwent a pilot evaluation in 21 schools across England and Scotland. Questionnaires and interviews were conducted with a subsample of pupils and teachers (n = 189) at two time points during the initiative delivery period. The results demonstrated that the pilot was viewed very positively by school leads, pupils and peer leaders alike. 24 The school leads universally praised the training, support and resources for their clarity and usability and reported that this type of programme was sustainable in the long term. Suggestions for further support included school case studies, material to display in the schools and visits to schools to observe practice and share ideas. The girls involved in the pilot reported improvements in key determinants of behaviour change. For example, girls identified PA, sport and PE as fun, as an opportunity to be with friends, as feminine and as a part of who they are and what they do. Girls also reported feelings of confidence to take part and reported looking forward to PE, feeling positive about it and being more likely to want to take part in extracurricular PA. In addition, some important changes to self-reported PA participation were seen, including increases in the percentage of girls reporting walking to school and a decrease in the number reporting never achieving ≥ 60 minutes of PA. The peer leaders also reported positive experiences as a result of the pilot: they felt that the role had been fun and rewarding and they enjoyed having new responsibilities, encouraging other girls to be active and having an opportunity to influence PA delivery in the school. Following this successful pilot, the next logical step was for Girls Active to be formally evaluated through a cluster randomised controlled trial (RCT) with objective measures of PA levels. A cluster design was appropriate as the programme was delivered at the school, rather than at an individual, level.

Details of the Girls Active programme

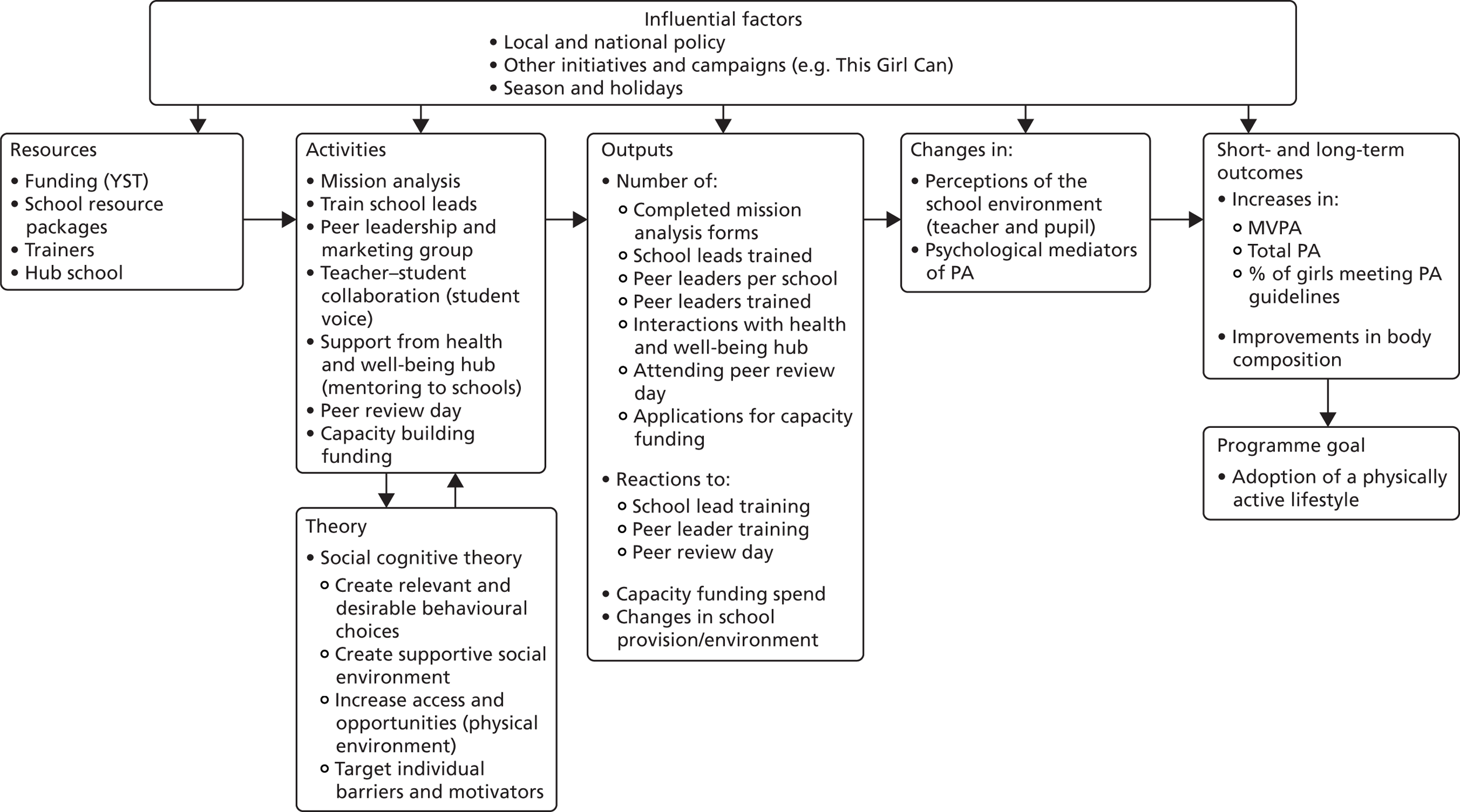

Girls Active is a school-based intervention aimed at girls in Key Stage 3 (KS3). KS3 is the first three years of secondary school for pupils aged 11–14 years and includes year groups 7, 8 and 9. It has been designed to provide a support framework for schools to review PE, sport and PA culture and practices to ensure that they are relevant and attractive to their 11- to 14-year-old female pupils. It has been designed to use leadership and peer marketing to empower girls to influence PE, sport and PA in their school, increase their own participation, develop as role models and promote and market PA, PE and school sport to other girls. The process was underpinned by teachers and girls working together to understand the preferences and motivations of girls with regard to PA participation. The research team undertook a post-hoc mapping of the programme elements and identified that the activities within the Girls Active programme are guided by social cognitive theory (SCT). 25 The proposed logic model is presented in Figure 1. The literature on PA in young people suggests that addressing multiple levels of influence on behaviour are key during adolescence. 10 Levels of influence can be from the individual level to the environmental level, and can mean creating choice for pupils through increasing access and opportunities to be active and fostering social support through positive peer relationships or friends. 10 These constructs are all embedded within SCT and have been incorporated into the Girls Active programme. Other core constructs of SCT, such as observational learning and self-regulation, have the potential to be undertaken as part of the Girls Active activities within schools. Although the intervention is multicomponent and designed to be flexible in delivery, it does have several key components that schools were encouraged to engage with and implement as described in Chapter 2, Intervention group: Girls Active programme.

FIGURE 1.

The proposed logic model for the Girls Active programme.

Aim and objectives

The main aim of the study was to evaluate the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the Girls Active programme in a multiethnic area of the UK.

Primary objective

To investigate whether or not the Girls Active programme leads to higher levels of objectively measured MVPA in adolescent girls compared with the control group at 14 months after the baseline assessment.

Secondary objectives

-

To investigate whether or not Girls Active results in changes in the following outcomes among adolescent girls in the intervention group compared with those in the control group at 7 and 14 months’ follow-up:

-

objectively measured overall PA level (mean acceleration)

-

the proportion of girls meeting the recommended PA target of 60 minutes per day of MVPA

-

time spent on MVPA (at 7 months)

-

time spent sedentary (assessed objectively and via self-report)

-

measures of body composition

-

psychological factors that may mediate PA participation (health-related quality of life; PA self-efficacy; PA motivation; social support from peers, family and teachers; PA enjoyment; perceived importance of PA; and physical self-perceptions).

-

-

To undertake a full economic analysis of the Girls Active programme, from a multiagency public sector perspective, at 14 months’ follow-up.

-

To conduct a mixed-methods process evaluation throughout the intervention implementation period (using qualitative and quantitative measures) with teachers, students and peer leaders and the YST to provide insights into the ways in which, and extent to which, the intervention was implemented and into participant experiences of the intervention.

Chapter 2 Study design and methods

Girls Active is a school-based cluster RCT. The trial was registered with the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number registry prior to recruitment of schools or data collection (www.isrctn.com/ISRCTN10688342; accessed 5 June 2018). The trial protocol was published in 2015,26 and is accessible online (www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/phr/139030; accessed 5 June 2018). A more detailed statistical analysis plan was subsequently signed off before any analysts had access to data. Documents related to the tools and methods described herein can be found at www.leicesterdiabetescentre.org.uk/Girls-Active (accessed 10 January 2019).

Ethics approval and research governance

Ethics approval for this research study was obtained from the University of Leicester College of Medicine and Biological Sciences research ethics representative prior to commencement of the study. The study was sponsored by the University of Leicester. All measurement team members were required to have a current enhanced Disclosure and Barring Service check. The measurement team leaders also completed the University Hospitals Leicester NHS Trust Safeguarding Children Policies and Procedures online training and were made familiar with the traffic light system for referrals to the University Hospitals Leicester safeguarding team.

School and participant recruitment

All state secondary schools in Leicester, Leicestershire and Rutland (LLR) with female pupils aged 11–14 years (n = 56 schools) were eligible and were invited to take part in the trial along with 26 other state secondary schools in Derbyshire, Nottinghamshire and Warwickshire. These schools were sent an initial letter outlining the Girls Active programme and evaluation and inviting them to a briefing event. At the briefing event, the school representatives received a detailed presentation about the Girls Active programme, the evaluation methods and the requirements of being involved. At the end of the briefing event, the school representative was given a written information pack for the head teacher, along with a school consent form. If schools were interested in being involved, they returned the consent form that had been signed by the head teacher. Following the recruitment of each school, a member of the research team contacted the designated lead teacher directly by e-mail. The school was then provided with an invitation pack for all eligible girls. Girls were eligible if they were in KS3 and between the ages of 11 and 14 years. The invitation pack contained an invitation letter to the parent(s)/guardian(s), a parent/guardian information sheet, an opt-out consent form for the parent(s)/guardian(s) (a signed opt-out consent form was required only if parents did not want their child to participate) and a participant information sheet for the girls. The parents/guardians had up to 2 weeks to return the opt-out consent form to the lead teacher. It was made clear to the parents/guardians and children that, even if they opted in at baseline, they were free to withdraw from the study at any time. At the end of the 2-week opt-out period, the lead teacher removed the names of any girl who returned the opt-out consent form or who told them that they did not want to participate from the list of participants. If > 90 girls were left as eligible (i.e. had not returned the opt-out consent or had not opted themselves out), 90 girls were randomly selected to take part using a computer-generated number system along with five back-up pupils. The lead teacher then invited these girls to attend the baseline measurement session.

At the beginning of the baseline measurement session, all methods were fully explained to the participants (girls aged 11–14 years) by a measurement team member who was suitably qualified and experienced and who was authorised to do so by the chief/principal investigator, as detailed on the delegation of authority and signature log for the study. Each participant then gave verbal assent if they were happy to participate. Verbal assent was requested again at the start of each follow-up measurement session. All schools received a £500 payment following the final measurement session at 14 months.

Stakeholder involvement

Key stakeholders were involved in the study through the Trial Steering Committee (TSC), cost diaries and school reports.

Trial steering committee

There were two lay members in the TSC to ensure that at least one would be available for each meeting. One was a former PE teacher (who attended one out of four meetings) and the other was a member of the public health team at the local government level (who attended two out of four meetings, with an in-person and e-mail debrief supplied for the missed meetings). The lay members contributed valuable insights on the school/education landscape and the local policy context in which this research sits. Certain questions for the lead teacher interviews were added or modified based on the input of the TSC, including a question on the impact of Girls Active on boys. A focus group with boys was also included on their recommendation.

Cost diaries

The feedback from the lead teachers was instrumental in refining our research methods in relation to the cost diaries. Feedback from lead teachers that came via the YST and direct from the teachers themselves was that the Microsoft Excel® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) cost diaries were difficult to manage. The research team took this feedback on board and, at the peer leader event, cocreated a simpler version of the cost diary with the help of all teachers in attendance. The lead teachers who found the original Microsoft Excel diary usable gave advice to the other lead teachers, meaning they supported the data collection process by helping their peers to understand and navigate the diaries.

School reports

At the 7-month interviews, lead teachers were asked which variables and measure would be of most interest to them and their school. This allowed the research team to create a personalised report to give to each school; this report contained the school’s baseline data, which was aggregated to school means (the reports were presented to schools in September 2016). Teachers felt that it was important to capitalise on the data and to use them within their schools to advocate for better or continuing provision of PA, PE and school sport.

Randomisation groups

Intervention group: Girls Active programme

Girls Active is a school-based programme aimed at girls in KS3. It has been designed to provide a support framework for schools to review their PE, sport and PA culture and practices to ensure that they are relevant and attractive to their 11- to 14-year-old female pupils. Although the intervention was multicomponent and designed to be flexible in delivery, it had several key components that were considered integral to the Girls Active process.

-

Self-evaluation and mission analysis. Schools completed a mission analysis document, which helped them to review their existing culture and practice for girls’ PA within the school and to set out an action plan tailored to their girls’ needs. This process drew on review, planning and evaluation frameworks used by UK sporting associations internally to generate sporting success at the 2012 London Olympic and Paralympic Games. This analysis was an exercise that was carried out twice by lead teachers at their schools: the first time as a ‘pre-course’ task ahead of the initial training and again after the peer review day.

-

Initial training for school leads. Lead teachers attended a 1-day face-to-face group training event at the hub school to introduce all school leads to the Girls Active programme. This event was facilitated by a YST national tutor. This training event had the following objectives:

-

to support teachers to explore their role and effectiveness in engaging girls in PE and sport in school

-

to challenge teachers to consider girls’ motivations in relation to PE and sport

-

to help teachers look at how a marketing approach can increase girls’ participation

-

to enable teachers to review a range of case studies and support resources

-

to provide teachers with the opportunity to share and develop practice with their peers

-

to challenge teachers to develop an action plan to support the Girls Active project with the support of other teachers and members of the senior leadership team.

-

The training objectives were covered in seven sessions during the training day, which involved a combination of presentations, discussions, practical activities and opportunities for teachers to share challenges, successes and ideas with each other and the tutors.

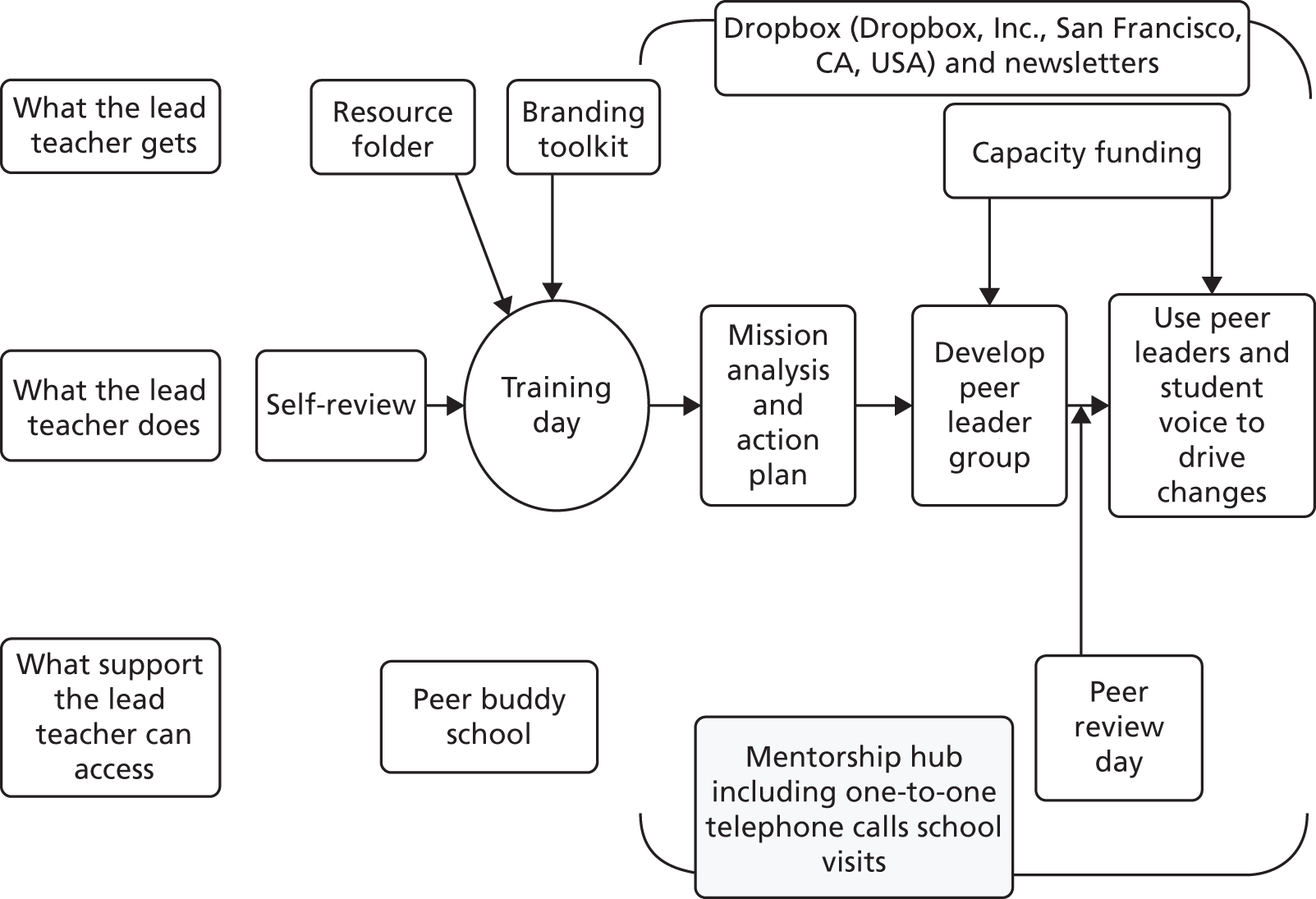

Figure 2 presents the Girls Active delivery model.

FIGURE 2.

The Girls Active delivery model.

Package of resources for schools

At the face-to-face training day, schools received a package of resources from the YST, which was aimed at the teachers and the peer leadership and marketing group. This package contained resources such as marketing plans, an action planning guide, case studies, still and video images to stimulate discussion and a ‘Making it Yours’ branding toolkit for peer leaders, which included a CD (compact disc) with logos, graphics and designs that peer leaders and teachers could use in the campaign at their school.

Peer leadership and marketing group

At their schools, lead teachers agreed to establish a peer leadership and marketing group consisting of KS3 girls. It was suggested that these girls should be those who are not necessarily already engaged in sporting and physical activities or particularly enthusiastic about participation, but girls who would be seen as leaders for non-sporting reasons and, thus, could have a positive influence on their peers. The purpose of this group was to influence decision-making in the school, enable girls to develop as role models, promote PA to other girls and run peer-led PA sessions and events.

Using the student ‘voice’ to develop and market ideas for change

Schools were encouraged to consider the ‘voice’ of the adolescent when making important decisions about PA, PE and sport in the school, including the provision of changing facilities, kit, activity content, programming, inclusion and imagery. Schools were encouraged to facilitate teachers and girls working together to come up with innovative and alternative physical activities and sports that the girls would like to participate in and that could be incorporated into PE and extracurricular activities. Schools were challenged to consider a ‘different type’ of student voice: one that has probably not been used before as it involves students who would not traditionally be involved in this type of provision.

Ongoing support and mentorship from the health and well-being school and the Youth Sport Trust

Ongoing support and mentorship was available to schools through the local health and well-being school in Leicester and the YST. This ongoing support consisted of telephone and e-mail support and one-to-one in-person visits. This provided the opportunity for schools to seek advice on implementing their action plan and to discuss ideas and solutions to overcome any barriers and challenges as a result of the implementation of Girls Active.

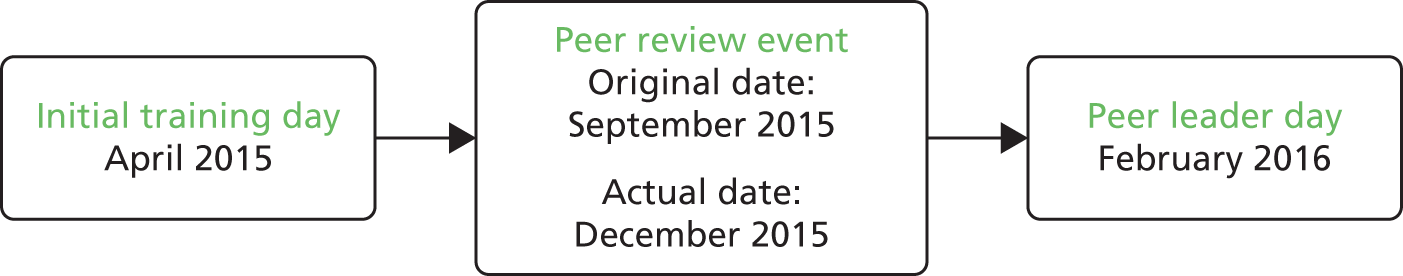

Peer review for teachers

All schools were invited to a face-to-face group peer review (half-day) event at the hub school to identify learning and share ideas. The peer review day was organised by the YST and run by a representative from the hub school (the school sport development manager) and a YST development coach. The objectives of the peer review event for teachers were to provide schools with the opportunity to learn about and share good practice, to share and celebrate success among the schools and for schools to receive peer-to-peer coaching. Following this review day, the schools were required to revise their mission analysis as necessary and submit it to the YST.

Funding for capacity building within schools

Schools were provided with a capacity payment of £1000, in two £500 instalments. These instalments were released on submission of the school’s mission analysis action plan documentation to the YST. The schools chose what to spend the money on.

Control group: usual practice

Schools randomised to the control arm were not given any specific guidance or advice and were assumed to continue with usual practice. A questionnaire was administered at each of the measurement time points to capture the school environment, including what the schools offered to girls in KS3 outside the typical PE and school sports clubs. Locally organised activity days available to girls in Leicestershire schools and the This Girl Can campaign were mentioned.

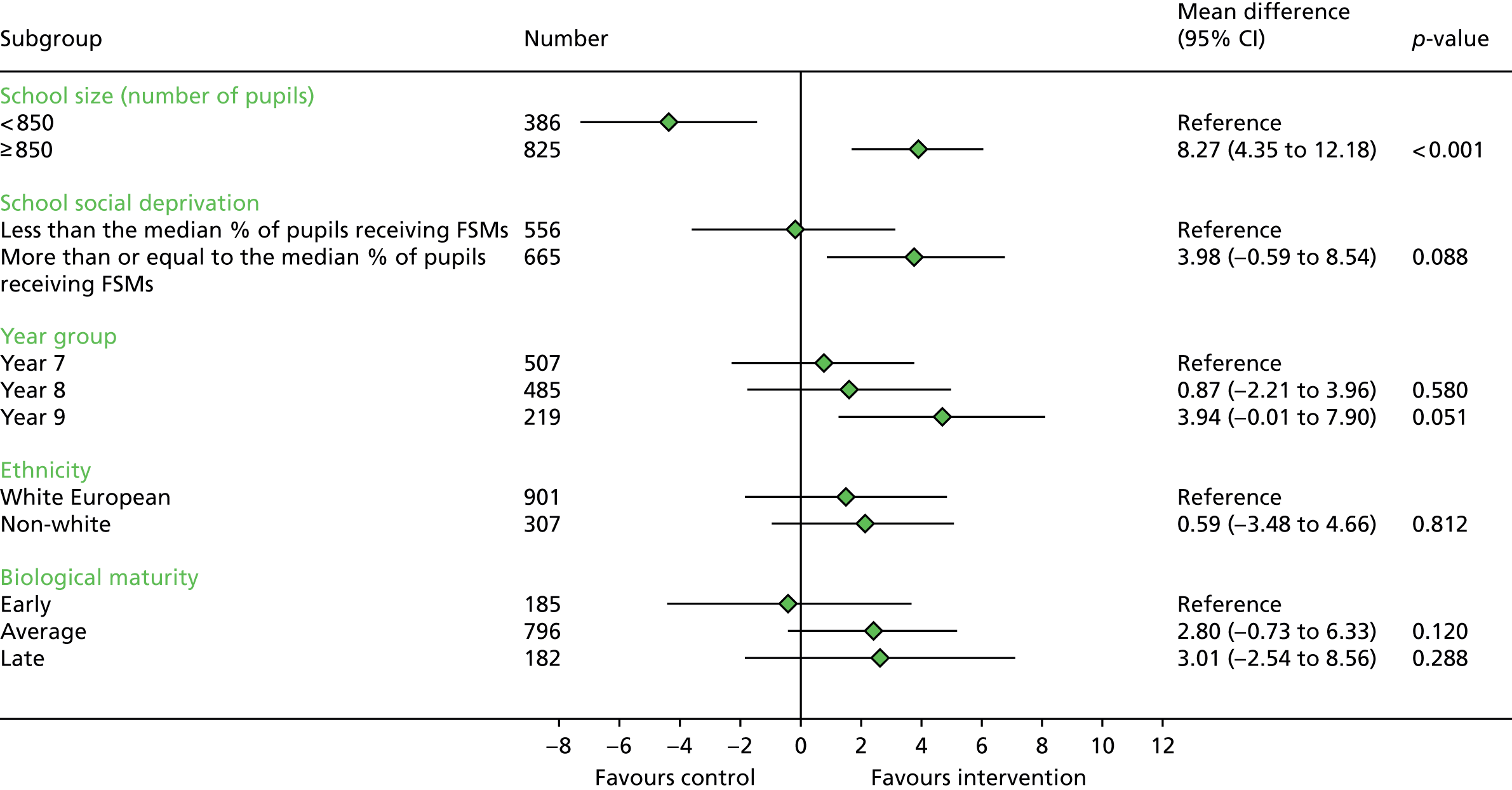

Randomisation

Once participants had completed the baseline measurements, the schools (clusters) were randomised to one of the two groups in equal proportions (1 : 1). An independent senior statistician within the Leicester Diabetes Research Centre generated the random allocation sequence and randomly assigned schools to their group. The randomisation of clusters was stratified by school size (median < 850 or ≥ 850 pupils) and percentage of black and minority ethnic (BME) pupils (median < 20% or ≥ 20% of pupils). A folder with sequentially numbered sections was used to implement the group allocations. The investigator team were not aware of the sequence until after the school was randomly assigned to a group. In order to reduce bias at the follow-up measurement sessions, the research team members conducting measurement sessions within the schools were blinded to randomisation. The team lead for the measurement sessions was not blinded. The named trial statistician was not blinded. However, the statistical analysis plan was published before data collection was completed. Any deviations from the statistical analysis plan are reported in Chapter 3, Changes to the planned analysis.

Sample size

This trial was designed to provide adequate power to detect a difference in objectively measured MVPA of 10 minutes per day between groups, a magnitude that has been associated with a meaningful difference in cardiometabolic risk factors for young people. 27 In order to detect a difference of 10 minutes per day between groups, assuming a standard deviation (SD) of 18 minutes of MVPA,28 a power of 90%, a 0.05 level of statistical significance, a cluster size of 56 girls and an intraclass correlation of 0.1, the targeted sample size was 18 schools, increasing to 20 schools (10 schools per group) to allow for cluster attrition. To allow for 30% loss to follow-up and non-compliance with accelerometer wear, a random sample of 80 girls per cluster (1600 girls in total) was needed. This sample size was independently validated.

Incomplete follow-up

For each school, follow-up sessions were scheduled at 7 and 14 months post study baseline. If > 10% of pupils were absent from the school during the follow-up sessions, then a bespoke return visit was undertaken in order to obtain complete data for the evaluation of the primary and secondary end points. Follow-up was terminated only for any one of the following reasons:

-

no assent was given

-

the participant opted out at 7 months

-

the participant opted out at 14 months

-

the participant left school between baseline and 7 months

-

the participant left school between 7 and 14 months

-

the participant was absent or unavailable at 14 months

-

we were unable to collect any data from the school.

Summary of outcome measures

The primary and secondary outcome measures detailed in the following sections were collected during the trial (Table 1). All data were collected in the participating schools during school hours by the measurement team that travelled to the schools. Each participant was assigned a unique participant identification (PID) number that was used throughout the trial.

| Assessment | Time frame | Processes and assessments undertaken |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline | February 2015 to April 2015 |

|

| 7-month follow-up | September 2015 to November 2015 |

|

| 14-month follow-up | April 2016 to June 2016 |

|

Primary outcome measure

The primary outcome measure was accelerometer-assessed mean number of minutes per day of MVPA at 14 months for participants.

Secondary outcome measures

Data for the following secondary outcome measures were collected from participants at 7 and 14 months:

-

accelerometer-assessed overall PA level represented by mean acceleration per day (overall and split by weekday and weekend day, and during school hours and after school hours)

-

accelerometer-assessed mean minutes per day of MVPA on weekdays and weekend days split, and during the school hours and during the after-school hours split

-

the proportion of girls meeting the recommended PA guideline level of 60 minutes per day of MVPA

-

time spent on MVPA at 7 months

-

accelerometer-assessed mean number of minutes per day of sedentary behaviour (overall and split by weekday and weekend day, and during school hours and after school hours)

-

self-reported (via a validated questionnaire) mean time spent in different types of sedentary behaviours

-

measures of body composition [i.e. body mass index (BMI) z-score and percentage of body fat]

-

psychological factors that may mediate PA participation (health-related quality of life; PA self-efficacy; PA motivation; social support from peers, family and teachers; enjoyment of PA; perceived importance of PA; and physical self-perceptions).

Detailed description of measures

Accelerometer measurements

Participants were asked by the measurement team to wear the wrist-worn GENEActiv™ (Activinsights Ltd, Kimbolton, UK) accelerometer on their non-dominant wrist continuously (i.e. 24 hours/day) for 7 days to assess PA and sedentary time. This lightweight research-grade device resembles a sports watch and is waterproof. Published cut-points are available to classify sedentary time and MVPA based on children’s observations and indirect calorimeter data. 29,30 The GENEActiv accelerometer was selected for these advantages and, based on the team’s previous experience and feedback from secondary school pupils at a patient and public involvement event, continuous wrist wear helps maximise compliance and reduce missing data in this age group. The GENEActiv devices were initialised with a sampling frequency of 100 Hz and were set to start recording at midnight on the first day of data collection and stop recording at midnight 7 days later. The accelerometers were distributed at the school measurement visit and collected from the school between 8 days and 3 weeks after the measurement visit. GENEActiv data were downloaded using GENEActiv software version 2.2 (Activinsights Ltd, Kimbolton, UK) and saved in a raw format as binary (.bin) files. Participants were given a £5 gift voucher as a thank you for providing full data. Data were included if participants had over 16 hours of wear time recorded during each 24-hour day.

Accelerometer data processing and analysis

The GENEActiv .bin files were analysed with GGIR version 1.2-11 [R Project; The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria; http://cran.r-project.org (accessed 5 June 2018)]. 31,32 Signal processing in GGIR includes the following steps:

-

autocalibration using local gravity as a reference31

-

detection of sustained abnormally high values

-

detection of non-wear

-

calculation of the average magnitude of dynamic acceleration {i.e. the vector magnitude of acceleration corrected for gravity [Euclidean norm minus one (ENMO) g]} over 5-second epochs with negative values rounded up to zero as:

Files were excluded from all analyses if post-calibration error was greater than 0.02 g33 or if less than 16 hours of wear time was recorded by either monitor during the 24-hour day of interest. Detection of non-wear has been described in detail in ‘procedure for non-wear detection’ in the supplementary document in van Hees et al. 32 In brief, non-wear is estimated based on the SD and value range of each axis, calculated for 60-minute windows with 15-minute moving increments. If, for at least two out of the three axes, the SD is less than 13 mg or the value range is less than 50 mg, the time window is classified as non-wear.

The average magnitude of dynamic wrist acceleration (ENMO), time accumulated in sedentary behaviour, light-intensity PA, MVPA and time spent sleeping were calculated over the entire 24-hour day. Thresholds for determining PA intensity categories were as follows: 0–40 mg for sedentary behaviour (minus sleep), 41–199 mg for light activity and ≥ 200 mg for MVPA. 29,30 Each school reported the start and end times of each school day. These times were then used to extract activity variables (sedentary time, light activity and MVPA) during and after school hours. The after-school period was until 21.00 hours.

In order to partition sleep from total daily sedentary time, sleep was determined using the nocturnal sleep detection algorithm incorporated in GGIR. 34 Periods of sustained inactivity are defined as no changes in arm angle of greater than 5° for ≥ 5 minutes during the 12-hour window, centred at the least active 5 hours of the 24-hour period. Individual nights were excluded from the sleep analyses if the sleep duration recorded for a night was < 6 hours or > 12 hours and if visual examination suggested non-wear or erroneous data. Variables extracted were time of sleep onset to wake (called ‘time in bed’ in the software output but actually time from sleep onset to wake and waking time determined from accelerometer data), sleep duration (total sleep duration determined from accelerometer data excluding detected waking episodes during the night) and sleep efficiency (sleep duration/time in bed × 100). Sleep variables were averaged for weekday nights (Sunday to Thursday) and weekend nights (Friday and Saturday).

The following accelerometer variables were calculated:

-

average time spent in MVPA (overall and split by weekday and weekend day, and during school hours and after school hours)

-

average time spent in sedentary and light PA (overall and split by weekday and weekend day, and during school hours and after school hours)

-

overall PA level (average acceleration) for the whole measurement period and split by school days and weekend days.

School (cluster) characteristics

Free school meals eligibility

The proportion of full-time pupils eligible for free school meals was collected as a proxy indicator of school-level deprivation. These data were obtained from the January 2015 Department of Education census. 35 These data were used as a confounder in the primary and secondary analyses.

School size

Pupil numbers were reported by the teacher and these were verified by 2015 school census data. 35 This variable was used as a randomisation stratification factor and also included as a confounder in the primary and secondary outcome analyses.

School environment

Lead teachers completed a school environment questionnaire at the baseline, 7-month and 14-month follow-ups. Although this questionnaire was put together specifically for the study, it contained questions used in previous international school-based studies. 36 Lead teachers provided data on school PE, PA and sport staff (both full-time and part-time staff). Teachers provided an inventory of the PA opportunities at the school, both generally and specific to girls in KS3, which was adapted from the PE and Sport Survey. 37 The questionnaire also queried school provision for PA, including the availability of, opportunities for and access to PA and recreation facilities; whether or not PA, PE and sport policies and practices existed; and the structure of PE classes and clubs (e.g. split sex) similar to those in the International Study of Childhood Obesity, Lifestyle and the Environment school administrator questionnaire. 36 The questions had multiple-choice answers with free text space to allow the teachers to expand on their answers.

Participant demographic characteristics

Age

Participant age at each measurement visit (in months) was calculated from participants’ self-reported date of birth.

Ethnic background

Participants self-reported their ethnic background in response to a question asked by the researcher. The participant was shown a list of 16 categories that aligned with the categories used in the 2011 UK census. Participants chose one category that best represented their ethnic background without assistance from the measurement staff member.

Index of Multiple Deprivation

The English Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) 201538 is the official measure of relative deprivation for English neighbourhoods. IMD scores based on participant postcode were used as an indicator of relative deprivation and participant socioeconomic status. IMD scores are publicly available continuous measures of compound social and material deprivation that are calculated using a variety of data including current income, employment, health, education and housing. As a postcode could be deemed a sensitive piece of information, a full description of why postcodes were being collected was given to participants, in addition to reassurance that postcodes would not be recorded or stored with any of their health-related information. These postcodes were uploaded to an online ‘postcode lookup’ tool (URL: http://imd-by-postcode.opendatacommunities.org/ accessed 29 August 2018), which outputted the corresponding IMD rank and decile. The IMD ranks every small area in England from 1 (the most deprived area) to 32,844 (the least deprived area), and the decile represents where the neighbourhood is positioned when IMD ranks are divided into 10 equal groups.

Anthropometric measurements

Owing to the relationship that PA has with adiposity, and the potential for school-based programmes to have an impact on the prevention of obesity,39 assessment of height and weight was undertaken by the measurement team for the calculation of BMI. Sitting height was measured as it is used, in addition to height and weight, to predict age at peak height velocity (APHV) using a sex-specific multiple regression equation. 40 APHV is an indicator of physical maturity, reflecting the maximum growth rate in stature during adolescence. All anthropometric measurements were taken in a private, screened-off area, and only female research team members took the measurements. Weight was measured using scales with a covered remote display so that the participants did not see their own weight. The girls were reassured that all measurements were confidential and that research data would be linked only using a non-identifiable participant number. Participants removed their shoes, any large items of clothing, such as jumpers and any items from their pockets. In order to assess body composition via impedance, participants were asked to also remove socks or tights.

Standing height

Standing height was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm using a portable stadiometer (Seca 213; Seca, Birmingham, UK), with the participants standing fully erect with their arms by their sides and their head in the Frankfort plane. Measurements were taken twice, and an average of the two measurements was used.

Sitting height

Sitting height was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm using the portable stadiometer, with the participant sitting fully erect with their legs hanging freely while sitting on a high stool. Measurements were taken twice, and an average of the two measurements was used.

Body mass

Body mass was measured to the nearest 0.1 kg using an electronic scale with a remote display (Tanita SC-330ST; Tanita Europe BV, Middlesex, UK).

Body fat percentage

Body fat percentage was estimated via bioelectrical impedance using a body composition analyser specifically designed for young people (Tanita SC-330ST). Participants were asked whether or not they had a pacemaker or another implanted medical device prior to the measurement. If they reported that they did, then the basic weight function was chosen instead of the impedance function.

Body mass index z-score calculation and categorisation

Body mass index was calculated and converted to a BMI z-score based on UK reference data. 41 To calculate the BMI z-scores, the zanthro function in Stata® version 14.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) was used42 and z-scores were based on British 1990 growth reference data. 41 This is the same UK reference population as that used by Public Health England for the National Child Measurement Programme. 43 The variables required for the function are the participant’s BMI [weight (kg)/height (metres)2], age (in years) and sex (female was indicated as 1 using dummy variables). BMI z-scores were then categorised: scores of < –2 were categorised as underweight, scores ≥ –2 but < 1 were categorised as normal weight, scores > 1 but ≤ 2 were categorised as overweight and scores > 2 were categorised as obese.

Age at peak height velocity calculation and categorisation

A sex-specific multiple regression equation40 was used. This technique estimates maturity status to within an error of +1.14 years for 95% of the time in girls40 and has been utilised successfully in a number of studies. 44–46 Four variables were required: (1) chronological age (years), (2) standing height (cm), (3) sitting height (cm) and (4) body weight (kg). The leg length was estimated by subtracting the final sitting height from the final standing height. Interaction variables in the multiple regression equation included leg length and sitting height, age and leg length interaction, age and sitting height and age and weight. The ratio variable included weight divided by height multiplied by 100. The equation used to calculate years from APHV was:

Subtracting the years from APHV from the participant’s chronological decimal age provides a predicted APHV. Biological maturity categories were computed using the equation APHV ± 1 SD. 47 Girls with an APHV of < –1 SD were categorised as ‘early maturing’, whereas girls with an APHV of > 1 SD were categorised as ‘late maturing’. Girls with an APHV that was within ± 1 SD were categorised as ‘average maturing’ or ‘on time’.

Self-reported behaviours

A number of questionnaires were used to assess physical activities and sedentary behaviours that have proven relationships with current and future health outcomes and that may be affected by the Girls Active programme. These questionnaires were administered by the measurement team.

Sports and physical education participation

The Physical Activity Questionnaire for Adolescents (PAQ-A)48 contains a set of questions that query individual activity participation. Participants were given a list of 27 common sports and activities and were asked whether or not they had participated in any of them within the previous 7 days. Five response options were available, ranging from ‘none’ to ‘7 times or more’. Participants were also asked how active they were in their PE classes over the previous 7 days, with five possible responses ranging from ‘I don’t do PE’ to ‘always’.

Psychosocial measures

A variety of psychosocial outcomes were assessed using existing questionnaires that have demonstrated reliability and validity for use with this age group, which were administered by the measurement team. A measure of internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) for these questionnaires is reported for the Girls Active baseline questionnaire results, calculated using IBM SPSS Statistics version 20.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). Psychosocial outcomes were chosen as they could be included in a SCT-grounded logic model describing variables that could mediate any effects on the primary outcome. The words or terms in some of the questionnaires originating in the USA were adapted, when necessary, to make the wording more applicable in a UK setting. At each measurement visit, participants were given specific guidance on certain questions, words or phrases that had been identified in the pilot testing as being potential causes of difficulty for participants. A questionnaire standard operating procedure (SOP) was developed and each measurement team member was required to read it before the measurement session. This SOP contained a ‘live’ list of frequently asked questions, which came from the participants, and a set of standardised answers that the measurement team were instructed to give in order to avoid the measurement staff interpreting the questions in their own way.

Intention to be active

Participants were asked about their intention to be active for ≥ 60 minutes every day during the next month (three items on a seven-point Likert scale, with responses ranging from ‘very unlikely’ to ‘very likely’), using statements that were used in a previous study49 and rephrased so that the term ‘physical activity’ was used in place of ‘sport or vigorous physical activities’. Reliability was good, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.88. For the analysis, a mean score of the three statements was used.

Importance of physical activity

Participants were asked to rate how important it was for them to be physically active regularly. They marked one number on a scale from 1 to 10, with 1 being ‘very unimportant’ and 10 being ‘very important’.

Attitudes to being active

The participants responded to six positive and eight negative statements regarding how they felt about being physically active. 50 The responses were on a five-point scale, ranging from ‘disagree a lot’ to ‘agree a lot’. For the analysis, the mean of both the positive statements (α = 0.57) and the negative statements (α = 0.81) was used as two individual variables. In an effort to create one variable that represents attitudes, the negative scores were reversed and a mean of all 14 statements was used [listed as ‘whole attitudes’ in the results (see Table 15)]. Reliability for the ‘whole attitude’ score was questionable, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.65.

Perceived physical activity social support from family

Participants responded to three statements on their perception of their family’s support for PA. 51 Responses were on a four-point scale, ranging from ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree’ (α = 0.69). A mean of the three statements was used in the analysis.

Perceived physical activity social support from peers

Participants responded to five statements on their perception of their peers’ PA. These five statements reflected peers being active together and participants’ perceptions of their peers activity levels. 51 Responses were on a four-point scale, ranging from ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree’ (α = 0.73). A mean of the five statements was used in the analysis.

Perceptions of the school environment

Participants reported on their perceptions of the school PA social (eight items including teacher encouragement and feelings of safety) and physical (eight items including equipment, facility quality and programming) environment. The shortened version52 of the Questionnaire Assessing School Physical Activity Environment was used. Answers were given on a five-point scale, ranging from ‘strongly agree’ to ‘strongly disagree’. Reliability was good, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.86. A mean for both the physical environment and the social environment was used in the analysis.

Perceived physical education teacher autonomy support

Participants responded to six items on the Sport Climate Questionnaire that was previously modified to specify PE for use with adolescents. 53 The items query whether or not participants feel that their PE teacher is supportive of their autonomy and choice. Responses were given on a seven-point scale, ranging from ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree’ (α = 0.89). A mean of all statements was used for the analysis.

Physical activity confidence (self-efficacy)

Participants responded to eight statements about their confidence in taking part in PA under a range of situations, for example ‘even if I could watch TV or play video games instead’ and ‘I can ask a parent or other adult to do physically active things with me’. 54 Responses were given on a five-point scale, ranging from ‘disagree a lot’ to ‘agree a lot’ (α = 0.83). A mean of all statements was used for the analysis.

Physical activity enjoyment

Participants responded to 16 statements, seven of which were negative statements about their feelings when they are being active. 55 Participants provided responses on a five-point scale, ranging from ‘no, not at all’ to ‘yes, a lot’, to items including ‘I enjoy it’ and ‘it’s no fun at all’ (α = 0.89). Scores for negative statements were reversed and a mean of all 16 statements was used for the analysis.

Physical activity motivation

The participants responded to 20 items about why they take part in PA, which were taken from work by Goudas et al. 56 This whole questionnaire consisted of five motivation subthemes. These were (1) extrinsic (motivated by external goals; α = 0.80), (2) introjected (motivated by external pressures that need to be accepted; α = 0.73), (3) identified (motivated by engaging in activities that are a means to an end; α = 0.82), (4) intrinsic (motivated by engaging in autonomous activities for pleasure and fun; α = 0.86) and (5) amotivation (neither intrinsically nor extrinsically motivated and may not value the activity; α = 0.78). 57 The reliability score for all of the constructs together was acceptable, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.73. Responses were on a five-point scale ranging from ‘no, not at all’ to ‘yes, a lot’. The mean of each subtheme was used in the analysis.

Physical self-perception

Participants responded to a range of statements on physical self-perception subthemes: self-esteem, physical self-worth and body attractiveness (six statements each). The items from the physical self-perception profile questionnaire included two opposing statements58 that were difficult to answer, and so these were adapted, similar to previous work in adults,59 to represent a simple statement that participants responded to on a five-point Likert scale, with responses ranging from ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree’. Negative statements were reversed. Reliability was good, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.92. A mean for each subtheme was used for the analysis.

Other health behaviours

Data on potential negative health behaviours that might develop over time were also collected by the measurement team in an effort to assess any potential unintended consequences of the Girls Active programme.

Smoking

Whether or not the participant had ever smoked traditional cigarettes was queried using two simple questions from the Health Survey for England. 60 Participants self-reported whether or not they had ever tried a cigarette and, if they responded ‘yes’, chose one of five options ranging from ‘I have only smoked once or twice’ to ‘I smoke more than six cigarettes a week’. Electronic cigarettes were not included in these questions.

Alcoholic beverage consumption

Whether or not the participant had ever drunk an alcoholic beverage was queried using two simple questions that were also from the Health Survey for England. 60 Participants self-reported whether or not they had had a ‘proper alcohol drink – a whole drink and not just a sip’. If they responded ‘yes’, they chose one of seven options ranging from ‘almost every day’ to ‘I never drink alcohol’.

Health economics methods

The health economics research questions were:

-

What is the cost of delivering the Girls Active programme in the intervention schools taking part in the trial?

-

What was the effect of the programme on the primary outcome measure (minutes/day of MVPA at 14 months) in the sample of participants included in the economic analysis (i.e. in participants who had both MVPA data and service use data)? (This was conducted as confirmatory analysis using the subset of the main sample for economic purposes as per standard economic practice. 61,62)

-

What was the effect of the programme on the secondary economic outcome measures of frequencies and costs of general practitioners (GPs), school nurse and school counsellor contact, and on health-related quality of life measured by the Child Health Utility – 9D (CHU-9D) at 14 months?63

-

Were there any statistically significant differences between the intervention group and the control group for marginal mean number of minutes per day of MVPA, CHU-9D63 utility index scores and frequencies and costs of service use at 14 months?

-

Did year group and level of implementation affect the results (to be done as part of exploratory subgroup analysis)?

Microcosting methods

Microcosting methodology64 was applied to calculate the costs of delivering the programme over one school year for the intervention schools taking part in the trial and to provide a mean cost per school and per pupil. In this economic analysis, we fully costed the delivery of the Girls Active programme and its constituent costs, such as teacher time, and the cost of other consumables and materials used. Costs were collected from a local authority (school) perspective, accounting for oncosts, and using the cost year 2015/16. Costs were measured in Great British pounds sterling (GBP).

A cost diary was administered by one member of the research team (JMC) to the school leads responsible for delivering Girls Active. The diary asked school leads to complete a record of the additional time, or displaced time, taken to offer the Girls Active programme, and they described activities undertaken and items purchased (e.g. sports equipment or sports clothing such as hoodies). The diary was developed with input from the wider Girls Active research team and the YST, which was responsible for training and supporting teachers to deliver the trial. Three versions of the diary were used throughout the programme implementation. The diary was originally sent to teachers by e-mail as a Microsoft Excel file, with rows for each activity and a space for ‘other’ activity and costs that were not covered by the other rows. The diary was sent with instructions and an example of a completed sheet to provide the respondents with the information and level of detail required when competing the diary. We asked the teachers to complete the diary weekly. A member of the research team requested the Microsoft Excel diary at 2-month intervals while the intervention was being implemented (April 2015 until May 2016). Any queries regarding the information that was provided were e-mailed to staff, and researcher contact details were provided in e-mails. After receiving the final Microsoft Excel diary, any final queries were sent by e-mail.

The research team received feedback that some teachers were struggling to keep the Microsoft Excel diary and were not comfortable with the format. In response, we created a paper logbook with sections to complete for activities and costs. These logbooks were printed and administered by the Girls Active research team. It was requested that teachers keep these logbooks with them in their own diaries and that they note activity and costs related to Girls Active as and when they happened. As a final method to ensure that we had information from Girls Active lead teachers, a survey was produced and administered during a peer review day that was organised by the research team and the YST. The survey used fields from the Microsoft Excel diary and the logbook and was followed up with a telephone call from the researcher responsible for the microcosting to provide context for the responses. Each of the three methods (Microsoft Excel diary, survey and logbook) requested demographic information about the teacher completing the diary, such as school name, job title and salary band.

The salary band information was used to calculate teacher costs in the microcosting, using the National Union of Teachers pay structure for qualified classroom teachers in England and Wales (from 1 September 2015 for cost year 2015/16). 65 A school year consisting of 39 weeks was used to calculate the teacher costs per hour, taking into account sickness, continuing professional development and annual leave. Salary calculations were inclusive of employers’ oncosts. Oncosts include National Insurance and pension charges, as well as costs for annual increments and allowances.

When collating information from the diaries, any costs relating to research (e.g. time to complete diary or measurements or to undertake interviews) were not included in the final microcosting calculations. These were considered as research costs. This decision was made in order to provide local authorities with information pertinent for future rollout (training and delivery costs), rather than costs specific to conducting a research trial.

Cost–consequences methods

Perspective

Cost–consequences analysis is a form of health economic evaluation in which all costs and outcomes are listed in a disaggregated format. From a public sector multiagency perspective (community care, GP, local authority and school), we conducted a cost–consequences analysis of the Girls Active programme, using minutes of MVPA and health-related quality of life (CHU-9D),63 as the outcome effects, and primary care (GP) and school-based services (school nurse and school counsellor), as the measure of costs.

Time horizon

Data were gathered at baseline, 7 months post baseline and 14 months post baseline. As the intervention follow-up period was more than 1 year, costs at 14 months post baseline were discounted at the base rate of 3.5% [National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) 201366] as part of the sensitivity analyses.

Costs

The costs of the programme were calculated from a local authority (school) perspective using microcosting techniques. 64 As variation was found in the implementation of the programme across the schools, three costing scenarios were produced to reflect the different levels or dose of delivery activity.

Client service receipt inventory

The client service receipt inventory (CSRI)67 is a questionnaire for collecting retrospective information about trial participants’ use of health and social care services. The CSRI was administered at baseline, 7-month follow-up and 14-month follow-up, each time asking the participant to recall service use over the previous 7 months. This information was combined with national sources of reference unit costs68 in order to calculate a mean cost of service use per participant per arm for the cost–consequences analysis. Table 2 outlines the published unit costs, and their sources, used in this cost–consequences analysis. The cost year of 2015/16 was applied for all costs, and costs were given in GBP.

| Health-care resource | Unit | Unit cost (£) | Details and sourcea |

|---|---|---|---|

| GP (clinic) | Visit | 36 | Per surgery consultation lasting 9.22 minutes, including direct care staff costs and with qualificationsb |

| School nurse or specialist nurse | Visit | 44 | Per consultation lasting 30 minutesc |

| District nurse | Visit | 42 | Per 1 working hour with qualifications (band 6 Counsellor)b |

Consequences

The CHU-9D is a paediatric generic preference-based measure of health-related quality of life. It consists of nine dimensions (worried, sad, pain, tired, annoyed, school work/homework, sleep, daily routine and ability to join in activities) that take physiological, psychological and daily routine aspects into account. Participants have the choice of five responses for each dimension, ranging from ‘I have no problems with [given dimension] today’ to ‘I can’t do [given dimension] today’. The tool has been validated with children aged 11–17 years as a self-report measure. 63 The scores from each domain have a weighting applied and all domain weightings are summed together to produce a utility index.

Analysis

In order to analyse clustered data appropriately and in line with the main outcomes analysis, the main statistical analysis plan and methods as described in Chapter 3, Analysis of the primary outcome, were used for this cost-consequences analysis’. The generalised estimating equation (GEE) model was used to determine the difference in mean number of minutes per day of MVPA, CHU-9D utility index scores and service use frequencies and costs between pupils from schools allocated to the intervention group and those from schools allocated to the control group, taking account of clustering in the trial design. The variables included in the analysis and the GEE model specification were the same as those outlined in Chapter 3, Analysis of the primary outcome. For service use frequency and cost models, generalised linear model diagnostic tests were conducted because the models failed to converge using the GEE model structure. From the results of the diagnostic tests, the family was amended from Gaussian to gamma and the link was amended from identity to power –1. After changing these specific parameters, the models achieved convergence and these models were used for the variables of service use frequencies and costs in the xtgee models.

For the analysis of the CHU-9D, the utility index score was calculated using the syntax provided by the questionnaire developers. 70 We calculated the differences in marginal mean CHU-9D utility index scores between the groups and produced 95% confidence intervals (CIs) around these differences with 1000 bootstrapped replications. The change in marginal mean number of minutes per day of MVPA for the intervention group and the control group and the differences between the groups were calculated and 95% CIs around these differences with 1000 bootstrapped replications were produced.

Sensitivity analysis

As the intervention follow-up period was > 1 year, as part of the sensitivity analysis service use costs at 14 months post baseline were discounted at 3.5% (the base rate recommended by NICE, 201366), and the model was re-run with these discounted costs.

Missing data for mean number of minutes per day of MVPA, total frequencies of service use and total costs of service use were imputed as part of the sensitivity analysis, following the methods employed in the main analysis. The CHU-9D utility index scores were not imputed as the developers of the measure state that utility values cannot be calculated when questions have missing answers. 63 The developers advise that only observations with complete data should be included; therefore, in line with these recommendations, imputation was not conducted on the CHU-9D scores.

Exploratory subgroup analysis

As part of an exploratory subgroup analysis, the effects of year group and level of implementation, which were based on the levels described in the microcosting, were tested on mean number of minutes per day of MVPA, CHU-9D utility index scores and frequencies and costs of service use for the complete-case sample, by including them in the xtgee model run in the main analysis.

Analysis of costs

We compared the frequencies and costs of health care and school-based service use over 14 months between the intervention group and the control group. We calculated the marginal mean total service use for the intervention group and the control group. We went on to calculate the differences in marginal mean total service use between the groups, and produced 95% CIs around these differences with 1000 bootstrapped replications. Marginal means are presented throughout; this reports the mean following the xtgee model and takes account of clustering in the trial design.

Process evaluation methods

The process evaluation for Girls Active involved collecting data and information from a variety of sources over the course of the evaluation time frame. Information on process evaluation, data collection and timings is outlined in Table 3, based on the published plan around the level of implementation, reach, impact and sustainability. Although prespecified themes were included in the original process evaluation plan, other themes were added to the teacher and focus group question schedule (see Appendices 1–3) based on advice from the lay members of the TSC. Data were anonymised and any comments on observations that could allow individuals or schools to be recognised were removed.

| Type of data | Collected from | Timing |

|---|---|---|

| School details | Self-reported by teacher, from school’s own records and from the Department of Education’s school census | School details reported at baseline, 7 months and 14 months; data from the 2015 census71 are used herein |

| Training event resources | Documents used at the training (i.e. timetable, presentation and handouts) | During the training event |

| Training attendance and evaluation forms | Lead teachers at training | Following the initial training day and peer review day |

| Peer leaders | After the peer leader event | |

| Notes from training events | Observer | During the training event |

| Interviews | Lead teachers | 7 and 14 months |

| YST staff members | 7 and 14 months | |

| The hub and development coach | 7 and 14 months | |

| Focus groups | Peer leaders | 14 months |

| Subgroups of evaluation sample | 14 months | |

| A sample of boys | 14 months | |

| Exit survey | Girls in original sample in all intervention schools | 14 months |

Training resources

All resources used at the training events were collected. These included tutor notes, Microsoft PowerPoint® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) presentations, the event schedule and any sessional or post-training resources that were circulated. This was to help understand what training was delivered to lead teachers. An observer from the research team attended the peer review day and took notes in an effort to explore what was delivered to teachers compared with what was planned and how the teachers responded to what was delivered. A copy of the resource folder given to each intervention school was also obtained.

Feedback forms

At the end of the initial training day, peer review day and peer leaders event, participants completed evaluation forms that included questions on content, perceived learning, delivery and venue. These forms were designed and utilised by the YST for these types of programmes. Attendance records and feedback forms from the lead teachers and peer leaders were also collected.

Exit survey

All participants in the intervention schools were asked to complete an exit survey at the end of the 14-month measurement visit. This survey queried what the participants understood about Girls Active, whether or not they took part in any Girls Active activities, what their most and least favourite parts of Girls Active were and what their feelings and views were on a number of statements related to the programme.

School environment

Lead teachers completed a school environment questionnaire at baseline and the 7-month and 14-month follow-ups, as described in School (cluster) characteristics. This questionnaire captured any changes in the school physical and social environment that may have an impact on the delivery of Girls Active.

Lead teacher interviews

Interviews with all teachers were undertaken at the 7-month and 14-month follow-ups. Appendices 1 and 3 provide the questions for the intervention school teacher interviews at 7 months and 14 months, respectively. A series of questions was mapped out to serve as an opening question. Probes were provided to the interviewer to help allow the participant to expand on the topic. The aim of these interviews was to understand what was delivered, whether or not there were any changes in the school and PE department that might have had an impact on delivery and to understand the barriers, facilitators, challenges and opportunities that the teachers encountered throughout their Girls Active programme journey. These interviews also provided an opportunity to get further feedback about training days, resources and support. Appendix 3 contains the questions for the control school lead teacher interviews. The aim of these interviews was to get a brief understanding of what had been going on at the school and to see whether or not anything had changed in terms of PA, PE and sport provision for girls. Teachers were given a participant information sheet ahead of the interview and they signed a consent form.

Youth Sport Trust and hub school staff interviews

Interviews with intervention delivery staff (i.e. staff from the YST and the hub school and the development coach) were undertaken at 7 and 14 months. The aim of these interviews was to understand what was delivered to teachers by the YST and what support was given to schools by the hub school and by the development coach. We were interested in understanding what support was given, in knowing whether the school lead initiated the request for support and how the interactions between the teachers and the available support worked in practice. It was relevant to understand the barriers, facilitators, challenges and opportunities that were faced by the intervention delivery staff. Staff were given a participant information sheet ahead of the interviews and signed a consent form. The questions used in these interviews can be found in Appendix 4. The opening questions were followed by probes to prompt the participant to expand on the topic, if necessary. All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Focus groups

Peer leaders

One focus group session per school was undertaken with the peer leaders at 14 months. The aim of these focus groups was to explore what the peer leaders understood about Girls Active, to explore their feelings about being a peer leader, to understand what went on at their school from their perspective (including recruitment of peer leaders and activities undertaken) and to understand any barriers, facilitators, challenges and opportunities from the peer leader perspective. As these girls may not necessarily have been among the 90 girls included in the RCT, peer leaders were given a participant information sheet and a parent/guardian information sheet 2 weeks prior to the focus groups by the lead teacher. They were asked to return the signed parent/guardian opt-out consent form only if they did not want to take part. Participants then signed an assent form prior to the focus group. Focus groups lasted between 30 and 60 minutes, and timings were often constrained by the duration of the class that they were excused from. The questions used in these focus groups can be found in Appendix 5. The opening questions were followed by probes to allow participants to expand on the topic. Some of the questions were explored using flipcharts and sticky notes. For example, when asking the peer leaders what they did, each peer leader wrote every activity they could think of on single sticky notes and then all peer leaders plotted the activities (everything from peer leader group inception up to the present day) along a timeline. Questions to explore likes, dislikes, barriers and facilitators were then asked based on the timeline. The non-written portions of the focus groups were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Subgroup of intervention school girls

One focus group session per school was undertaken with a subgroup of girls from the evaluation at 14 months (see Appendix 6). Each lead teacher chose a group of girls (between five and eight girls) from the pupils who were already part of the evaluation cohort to be part of the focus group. For practical reasons, the lead teacher was told that the girls chosen should exhibit a range of activity from ‘inactive’ to ‘active’, but all should be willing to speak up on behalf of their class. As these girls were already consented as part of the main programme, only verbal assent was obtained before the focus groups began. The aim of these focus groups was to see whether or not the girls knew about the Girls Active programme at their school (i.e. if they had they heard about it and, if they had, what had they heard and seen), to explore what they understood about the aims of Girls Active and what went on at their school and to explore their feelings about what was delivered (e.g. the peer leaders and any activities).

Group of intervention school boys