Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 13/117/02. The contractual start date was in September 2015. The final report began editorial review in April 2018 and was accepted for publication in August 2018. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Eileen Kaner reports grants from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Public Health Research Funding Board and grants from the NIHR Health Technology Assessment (HTA) programme. Denise Howel is a panel member for the NIHR Programme Grants for Applied Research (PGfAR) programme. Luke Vale is a member of the NIHR NTA Clinical Evaluation and Trials panel, was a panel member for NIHR PGfAR (2008–15), and is co-director of NIHR Research Design Service North East. Colin Drummond is part-funded by the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre at South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust, and the NIHR Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care South London, and is in receipt of a NIHR Senior Investigator Award. Elaine McColl was a member of the NIHR Journals Library Editorial Group (PGfAR) from 2013 to 2016 and a panel member for NIHR PGfAR from 2008 to 2016. Harry Sumnall reports grants from Diageo (Diageo plc, London, UK) outside the submitted work, and he is an unpaid trustee of a drug and alcohol prevention charity, Mentor UK (London, UK), which seeks funding to deliver evidence-based prevention programmes.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Giles et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Structure of the report and background to the research

Key points for Chapter 1

-

The Chief Medical Officer for England recommends that young people and children under the age of 15 years remain alcohol free. If young people aged 15–17 years drink alcohol it is recommended that they do so infrequently and no more than once per week. They should also not exceed adult daily limits.

-

Young people, however, continue to consume alcohol, although the proportion of those who do has been decreasing since 2003.

-

Young people are at increased risk of a range of communicable and non-communicable diseases and longer-term effects from consuming alcohol. Immediate risks include injury, unsafe sex and drug use.

-

Literature shows that alcohol screening and brief interventions (ASBIs) for young people are effective, although there is limited evidence within school settings.

-

There is currently insufficient evidence to be confident about the use of ASBIs to reduce risky drinking and alcohol-related harm in young people in a school setting.

Structure of the report

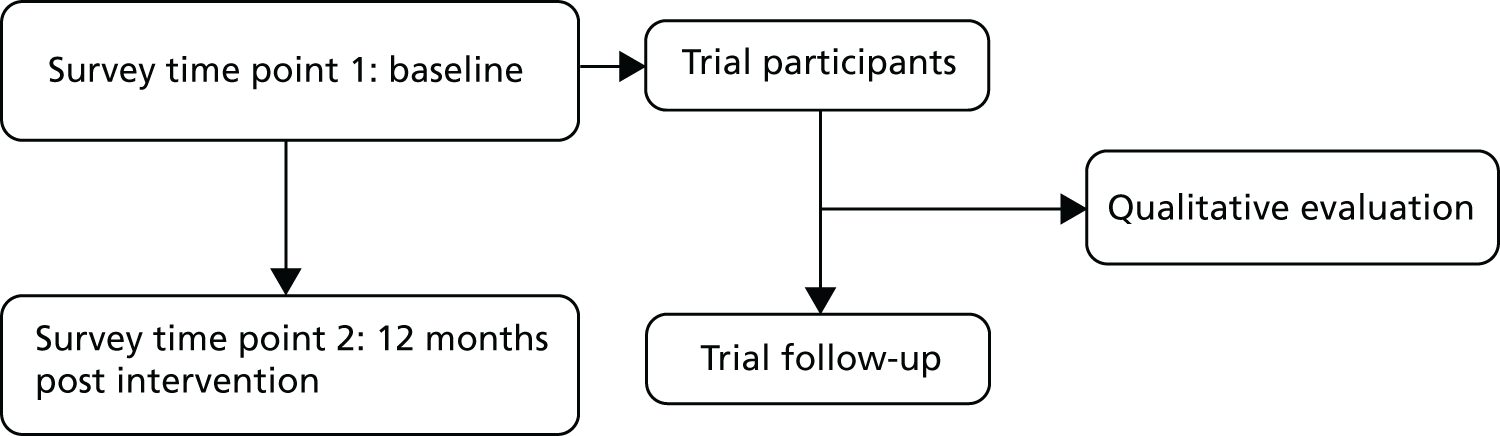

This study assessed the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of an ASBI (in a school setting) to reduce alcohol consumption in adolescents. This was achieved by way of a two-arm, parallel-group, individually randomised (with randomisation at the level of young person) trial in young people aged 14–15 years in Year 10 at 30 secondary schools across four geographical areas in England: north-east, north-west, Kent and London. The trial involved a baseline and a 12-month follow-up survey. The study included an integrated qualitative process evaluation (Figure 1) with key stakeholders. Young people allocated to the control arm of the trial received a healthy lifestyles information leaflet only; young people allocated to the intervention arm took part in a 30-minute one-to-one structured intervention session based on motivational interviewing (MI) principles with a member of trained school staff (learning mentor) and also received an alcohol information leaflet.

FIGURE 1.

Data time points of the study.

Research questions

This definitive trial builds on a pilot feasibility trial1 that explored the feasibility of offering an ASBI versus ‘standard care’ in this population; the focus of that preparatory study was on rates of eligibility, consent, participation in the intervention and retention for follow-up, as well as the feasibility and acceptability of the intervention for a range of stakeholders (teachers, learning mentors, young people and parents).

The aim of this definitive trial was to evaluate the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of ASBIs to reduce risky drinking in young people aged 14–15 years in the English school setting, with the primary outcome measure of the trial being total alcohol consumed in standard units in the previous 28 days using the Timeline Follow-Back (TLFB).

Chapters of the report

The report is structured as seven chapters detailing the design, management and outcomes of the main trial study. The report begins by providing the background to the research and outlines the key literature informing the design and conduct of the study. Following this, a chapter is dedicated to each core component of the study. Chapter 2 explores the design of intervention materials as well as the training and support provided to school staff in the delivery of the project. Chapter 3 reports the design, methods and results of the baseline and follow-up survey, as well as the findings in respect of the primary and secondary outcome measures. Chapter 4 provides the design, methods and results of the integrated qualitative evaluation. Chapter 5 details the design, methods and results of the health economic evaluation of the study. Chapter 6 presents a discussion of the key results. Finally, Chapter 7 provides the key conclusions.

Research ethics

The research study was granted ethics approval by Teesside University in September 2015 (reference number 164/15), with Newcastle University acting as the sponsor for the research. The trial is registered as ISRCTN45691494.

Changes to the original study protocol

The study protocol was published in 2016. 2

-

The TLFB was delivered by research co-ordinators, as detailed in the protocol, in all but one school. The remaining school indicated that it would only be willing for young people to complete the TLFB independently, because of staff time and resource constraints. An ethics amendment for this slightly revised procedure was submitted and approved (reference number R164/15, January 2017).

-

The sample size was originally calculated to provide 90% power to detect a standardised difference of 0.3 using a significance level of 5%. Given the difficulty in recruiting sufficient numbers the target for power was reduced from 90% to 80% after discussion with the Trial Steering Committee (TSC) and Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC).

-

The EuroQol-5 Dimensions, three-level version (EQ-5D-3L) was used instead of the EQ-5D-Y [EuroQol-5 Dimensions (Youth)]. The study used the EuroQol-5 Dimensions for lack of a better instrument and because it is used extensively in economic evaluations,3 making it a standard for comparing economic outcomes across different interventions.

Research management

The Trial Management Group (TMG) was responsible for ensuring the appropriate, effective and timely implementation of the trial. The TMG met once per month (more or less frequently depending on the needs of the project) and comprised the chief investigator, the project manager, co-applicants, named collaborators and researchers working on the project. A TSC and a DMEC were also appointed to provide an independent assessment of the trial procedures and data analysis. These groups met three times (joint meetings) and their remit was the progress of the trial against projected rates of recruitment and retention, adherence to the protocol, participant safety and the consideration of new information of relevance to the research question. Written terms of reference were agreed and used by the TMG, TSC and DMEC (see Appendix 1).

Research governance

The project complied with the requirements of the Data Protection Act 19984 and the Freedom of Information Act 2000,5 and other UK and European legislation relevant to the conduct of clinical research. The project was managed and conducted in accordance with the Medical Research Council’s Guidelines on Good Clinical Practice in Clinical Trials,6 which includes compliance with national and international regulations on the ethical involvement of patients in clinical research (including the Declaration of Helsinki, 2013). 7 All data were held in a secure environment with participants’ information identified by a unique participant identification number. Master registers containing the link between participant identifiable information and participant identification numbers were stored in a secure area separate from the majority of data. All staff employed on the project were employed by academic organisations and subject to the terms and conditions of service and contracts of employment of the employing organisations. When relevant, research staff were trained in good clinical practice and all staff worked to written codes of confidentiality. The project used standardised research and clinical protocols and adherence to the protocols was monitored by the TMG, TSC and DMEC. We also undertook patient and public involvement (PPI) work (see Appendix 2).

Background

Alcohol use as a public health priority

Consumption of alcohol is a risk factor for mortality and morbidity in adults, and is an important public health issue. Alcohol misuse leads to both societal and economic costs, as well as the burden of disease, yet it is preventable. 8 Although many adults in the UK consume alcohol in line with recommended guidelines, a proportion of adults drink above these recommendations and consume alcohol at harmful and hazardous levels. 9 It has been estimated that 10.8 million adults in the UK drink alcohol at levels that are harmful to their health. 10 Although young adults aged 16–24 years are less likely to drink than individuals in older age groups, when they do choose to drink they consume more alcohol. 11 As a result, this study focused on alcohol consumption in young people.

Prevalence of alcohol consumption in young people

In 2009 the Chief Medical Officer for England recommended that young people and children remain abstinent from alcohol until they are 18 years old. 12 This was accompanied by advice that young people and children should not consume alcohol before the age of 15 years, and, should they choose to consume it thereafter, that they should drink it no more than once per week and only under supervision. If young people aged 15–17 years drink alcohol, it is recommended that they do so on only 1 day per week and do not exceed adult daily limits, and ideally consumption should be below this level. 13

In the UK, the proportion of young people who drink alcohol has steadily decreased between 2003 and 2014. 12 As there was a change in the question around consumption of alcohol in the 2016 version of the ‘Smoking, Drinking, and Drug Use’ survey,14 it is not possible to calculate the change in alcohol consumption in 2016 relative to previous years; however, the direction of effect continues to show decreasing alcohol consumption.

The proportion of young people who have ever had an alcoholic drink in England increases with age, with data from 2016 suggesting that 11% of girls and 9% of boys aged 11–15 years had consumed alcohol in the 7 days preceding the survey. 12 Of these, 1% of 11-year-olds had consumed alcohol in the preceding week, increasing to 24% of 15-year-olds. In total, mean alcohol consumption in ‘the last week’ was lowest in those aged 11–13 years (6.9 units) and highest among 14-year-olds (11.1 units). 12 In terms of the amount of alcohol drunk by 11- to 15-year-olds, in 201712 the mean alcohol consumption in the preceding week was 10.3 units for boys and 8.9 units for girls. 12 For these reasons, this study focused on young people aged 14–15 years, given that the data indicate that more young people start to consume alcohol at this age.

Although alcohol consumption among children and young people is declining, consumption among high-risk children and young people (e.g. those with intellectual disabilities) remains prevalent. 15 In comparison with other European countries, the UK has high levels of drinking among young people. 16 The north-east has one of the highest rates of young people who have ever drunk alcohol, with 49% of 11- to 15-year-olds reporting having ever drunk alcohol. 17 This compares with the lowest prevalence in London of 25% and the highest in the north-west of 50%, with an overall English average of 44%. 12

Consequences of drinking alcohol at a young age

Alcohol consumption at a young age is associated with a number of detrimental outcomes. These include physical and mental health issues, an impact on brain development, and an increased risk of accidents and injury. 12 Longer-term negative outcomes arise in particular from binge drinking, defined as the excessive consumption of alcohol in a limited time and often measured as consuming more than six units in a single session for both men and women. 18 These long-term effects have been observed in a large cohort study (the 1970 British Cohort Study) of > 16,000 babies born between 5 and 11 April 1970, and followed up at ages 5, 10, 16 and 30 years. 19 The findings showed that binge drinking in adolescence was associated with later (adulthood) negative consequences, such as alcohol dependence, homelessness, reduced educational attainment and convictions. In addition, there is evidence that alcohol use tracks over time, from adolescence into adulthood, and also is correlated with other risky behaviours, such as smoking. 20 That study therefore recommended that alcohol interventions target young people, even though the literature suggests that they do not always think that risky or harmful drinking is a concern for them. 21 More immediate consequences of alcohol consumption include school exclusions, with 9.5% of exclusions during 2015–16 in state-funded secondary schools being due to drugs and/or alcohol. 22

Other adverse effects of alcohol consumption in young people include an increased risk of mortality from accidents and suicide as a direct result of drinking alcohol. 23 Additional negative consequences include longer-term impact on brain development, liver damage, and changes in hormones vital for organ development and growth. 23,24 Short-term impacts can also arise from alcohol use in young people, including regretted sexual activity, self-harming, alcohol poisoning, drunk driving and criminal behaviour. 25 It can also lead to weight loss, appetite changes, sleep disturbance, depression and an impact on school performance. 26 In addition, the early consumption of alcohol has been shown to link with the amount of alcohol consumed in older adolescence and adulthood. 27 It is also the case that young people are more likely to binge drink alcohol when they do consume it, which in turn leads to increased risk from accidents. Alcohol use is also linked to non-communicable diseases, such as cancer, cardiovascular disease and gastrointestinal disorders. 28 In terms of short-term benefits, young people report similar reasons for drinking as adults, including for social confidence, for enjoyment26,29 and to celebrate special occasions. 26

Alcohol screening tools

A number of screening tools have been used with young people to identify those who are at risk from their drinking. A systematic review into the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of alcohol screening tools for adults and young people explored the use of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT),30 Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test – Consumption (AUDIT-C)31 and AUDIT-QF (first two questions of the AUDIT),32 FAST33 (Fast Alcohol Screening Test), CAGE,34 MAST (Michigan Alcohol Screening Test),35 Paddington Alcohol Test,36 SASSI (Substance Abuse Subtle Screening Inventory) for children and young people,37 ASSIST (Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test),38 SASQ (Single Alcohol Screening Question),39 TWEAK (Tolerance, Worried, Rye-opener, Amnesia, K/cut down)40 and T-ACE41 in prenatal screening, as well as laboratory and clinical markers. 42 The review found that alcohol screening tools were more effective at identifying young people drinking at a risky level than laboratory and clinical markers, with the AUDIT a particularly cost-effective measure. 43 The SIPS JR-HIGH pilot trial report discussed the evidence around screening measures in detail,2 although a review of existing reviews25 for ASBIs with young people found that the CRAFFT (Car, Relax, Alone, Forget, Family or Friends, Trouble) was used particularly for older adolescents (15–18 years old), and the AUDIT was found to have greater sensitivity and specificity than other screening tools in young people. In addition, the Adolescent Single Alcohol Question (A-SAQ) was shown to be a reliable single-screening question for drinking frequency44 in the SIPS (Screening and Intervention Programme for Sensible Drinking) research programme in adults. It is a modified version of the Single Alcohol Screening Question (M-SASQ),45 which is adapted for adolescent alcohol consumption. 39

Alcohol primary prevention in the school setting

Primary prevention is a treatment or intervention that seeks to prevent disease occurrence, whereas secondary prevention involves treating/intervening in a disease in its early stages. ASBIs are classified as a form of secondary prevention, in that they typically target individuals who have been identified as drinking alcohol in a pattern that is detrimental to their health. 46

There is limited literature published within the past 5 years that explores primary preventative school-based alcohol brief interventions in the secondary school setting in the UK. The majority of recently published literature focuses on college and university students in other countries, particularly US studies focusing on college students.

Of the previous studies that do exist, they have explored the use of classroom-based curricula and parental interventions as primary prevention with young people. 47 One such is the Steps Towards Alcohol Misuse Prevention Programme trial,47 which explored the effectiveness of a school and parent alcohol intervention. This trial found a significant reduction in heavy episodic drinking in 12- to 13-year-olds; the intervention was delivered at classroom level and not to individuals. 47 The Kids and Adults Together programme trial48 explored the acceptability of primary school classroom-based activities, family events and a digital versatile disc (DVD) to address the effects of alcohol in 9- to 11-year-olds in Wales as a primary preventative measure. The trial found mixed support from the nine primary schools, with two withdrawing from the study. One particular limitation highlighted was the inability to conduct follow-ups within secondary school settings once the young people progressed from primary school. In addition, members of the team conducted a systematic review of peer-led interventions with young people aged 11–21 years; they found 17 studies, of which six were school-based and showed a positive benefit on alcohol use. However, none of the six school-based studies was conducted in the UK and brief interventions were specifically excluded. A meta-analysis of school-based prevention for risky behaviours showed that school settings appear to be effective in reducing alcohol consumption,49 whereas a separate review50 of the prevention of multiple health risk behaviours in schools showed a small positive effect on alcohol consumption. The former review was, however, published in 2001 and the latter was not focused on individually targeted interventions and, therefore, the findings are of limited relevance in the context of the individualised ASBI considered here.

Alcohol screening and brief interventions

Interest in screening and brief interventions for risky drinking has developed since the 1970s. 51 ASBIs have been defined as ‘those practices that aim to identify a real or potential alcohol problem and motivate an individual to do something about it’. 52 Heather, in 1995, offered a more specific definition, stating that brief interventions are ‘a family of interventions varying in length, structure, targets of intervention, personnel responsible for their delivery, media of communication and several other ways, including their underpinning theory and intervention philosophy’. 53 In an early review of brief interventions, Bien54 found that brief interventions were more effective than no intervention or more extensive treatments, with six common elements of brief interventions discussed, based on the FRAMES (Feedback, Responsibility, Advice, Menu, Empathy and Self-efficacy) model. 54 More recent research has reported results of brief interventions in different settings and delivery modes, for example face to face or web based. 55 In terms of implementing a brief intervention, it is often used to provide simple advice for patients with an AUDIT score in the range of 8–15, who may be at risk of injury and chronic health conditions as a result of their alcohol consumption. 52 Given the heterogeneity of brief interventions and settings, it is therefore important to consider the context and components of brief interventions when assessing effectiveness, rather than focusing on general overall effectiveness. Heather53 in particular states the importance of clarifying the length of the intervention when assessing effectiveness, given that the length can range from 5 minutes to at least 3 hours. The same is true of the number of intervention sessions, which can be one or more, and the content of sessions (e.g. MI vs. self-help manual).

The pilot trial focused on the use of simple structured advice based on the FRAMES model, delivered by learning mentors as non-specialists, as opposed to behaviour change counsellors. 1 This approach was found to be acceptable in the school setting and hence was used again in this main trial.

In terms of secondary prevention, a previous review of reviews explored the use of ASBI with young people. 25 The review concluded that MI delivered in school settings is an effective way to reduce alcohol consumption. However, within this review, the definition of young people was wide, ranging from 10 to 21 years, even though the World Health Organization defines ‘young people’ as those aged 10–19 years. 56 An additional systematic review and meta-analysis of ASBIs for young people found that ASBIs led to a decrease in alcohol consumption and alcohol-related problems. However, this work included studies that focused on any level of (alcohol) risk, and also defined eligible participants as those aged 11–25 years. 57

There is some evidence to show school-based group ASBIs can be beneficial,58 but, even then, this has not always been found to be the case for high-risk drinkers. 59 Similarly, there is literature showing that family and school-based interventions can reduce adolescent alcohol use, but this evidence60 is not from a UK setting and does not involve personalised individual ASBIs. A separate systematic review57 of ASBIs with young people showed reductions in alcohol use as a result of ASBIs but included participants up to the age of 30 years, well outside secondary school age.

To focus on young people in particular, and also using recognised definitions for young people, a systematic review [Giles EL, McGeechan GJ, Ferguson J, Byrnes K, Newbury-Birch D. Teeside University. 2018. (In preparation)] was recently conducted to explore the evidence on the efficacy/effectiveness of ASBIs targeting risky drinking in young people (as defined by the World Health Organization) in randomised and non-randomised controlled designs, or quasi-experimental studies. The ASBI had to involve individual one-to-one advice delivered in one to four sessions to constitute a ‘brief’ intervention. Literature searches were conducted in June 2017 of the main databases including PsycInfo, Psycharticles, MEDLINE, Scopus and CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature). Searches combined key alcohol, brief intervention and young people search terms. Papers were eligible for inclusion if they were shown to meet the predefined inclusion criteria, and if their primary focus was around young people aged between 10 and 19 years, engaged in an alcohol brief intervention in any setting, in randomised or non-randomised controlled designs or quasi-experimental studies.

This review identified 16 papers that focused on risky drinking in young people. 61–76 The majority (n = 13) were studies conducted in the USA,61,64–67,69–76 with one in Germany,68 one in Mexico63 and one in Western Australia. 62 The setting was mainly emergency departments (n = 8),62,66,68,70–73,75 with three in universities,61,67,74 one with homeless adolescents,76 one with young people referred from not-for-profit agencies,65 one based in the community64 and two based in schools. 63,69 The ASBIs used largely followed a manual and/or used MI techniques. Findings showed that for the majority of the studies, the ASBI was effective at decreasing alcohol-related outcomes, including a reduction in binge/heavy drinking (n = 4), and/or a reduction in number of typical drinks/alcohol use (n = 10) and/or frequency of drinking (n = 5), and/or a reduction in negative consequences from drinking alcohol (n = 3). One study found no significant differences between the group receiving an ASBI and the control group. 75 Focusing on the two studies conducted in a school setting, one was conducted in Mexico. 63 In this study, the young people were moderate- to high-risk drinkers, mainly male (65%), with an average age of 16 years. The ASBI group received one 90-minute ASBI compared with a waiting list control. At the follow-up points of 3 and 6 months, the ASBI group showed a significant reduction in the amount of alcohol consumed compared with the control. The second study was conducted in the USA with young people who had an alcohol or drug use disorder. 69 The majority of participants were male (52%), with an average age of 16 years. The ASBI were two 60-minute sessions, with one group also receiving a parent session. Significant findings were reported for the number of days alcohol was consumed compared with the assessment-only control group. These two school-based studies therefore suggest that the use of a school setting to deliver ASBI to young people is effective (see Appendix 3).

Results from the SIPS JR-HIGH pilot trial

The pilot trial of SIPS JR-HIGH1 was the first research in England to look at the acceptability and feasibility of a cluster randomised (at the school level) controlled trial of ASBIs in secondary schools with 14- to 15-year-olds. To the best of our knowledge, this current study is the first English research study to examine the effectiveness of ASBIs in young people in the secondary school setting who are identified as risky drinkers.

In the pilot feasibility study, young people who screened positive on a single alcohol screening question and who consented to take part (n = 229) were randomised, at the level of the school, to a control arm of an advice leaflet, to an intervention arm consisting of a 30-minute brief interactive session using structured advice delivered by the school learning mentor and an advice leaflet (intervention 1), or to the same 30-minute brief interactive session and advice leaflet combined with a 60-minute session including family members (intervention 2). Participants were followed up at 12 months (n = 202; 88%) and completed the same survey as at baseline.

Overall, the trial was able to recruit seven schools as originally planned, undertake intervention training with the learning mentors who themselves were able and willing to be trained, and undertake the screening survey with young people. In terms of the acceptability of intervention 1, this arm was found to be the most acceptable. In relation to intervention 2, it was not feasible to engage parents in the third arm of the trial, with qualitative interview findings suggesting that the school staff, the parents and the young people did not think that including parents was acceptable. As a result, intervention 2 was removed from the main trial.

Rationale for the present research

Overall, the pilot feasibility study showed that it was feasible and acceptable to undertake a trial of ASBIs in the school setting with young people, and with learning mentors delivering the intervention. 1 As stated above, given the lack of literature on the use of ASBIs with young people in the secondary school setting in the UK, this trial presented an important step in building the evidence base around the effectiveness of ASBIs with young people for reducing risky drinking.

Aim and objectives

Aim

The aim of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of ASBIs to reduce risky drinking in young people aged 14–15 years in the English secondary school setting.

Objectives

-

To conduct an individually randomised controlled trial to evaluate the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of an ASBI for risky drinkers compared with usual practice on alcohol issues conducted by learning mentors with young people aged 14–15 years in the school setting in four areas of England: the north-east, north-west, Kent and London.

-

To measure effectiveness in terms of percentage days abstinence over the last 28 days, risky drinking, smoking behaviour, alcohol-related problems, drunkenness during the last 30 days and emotional well-being.

-

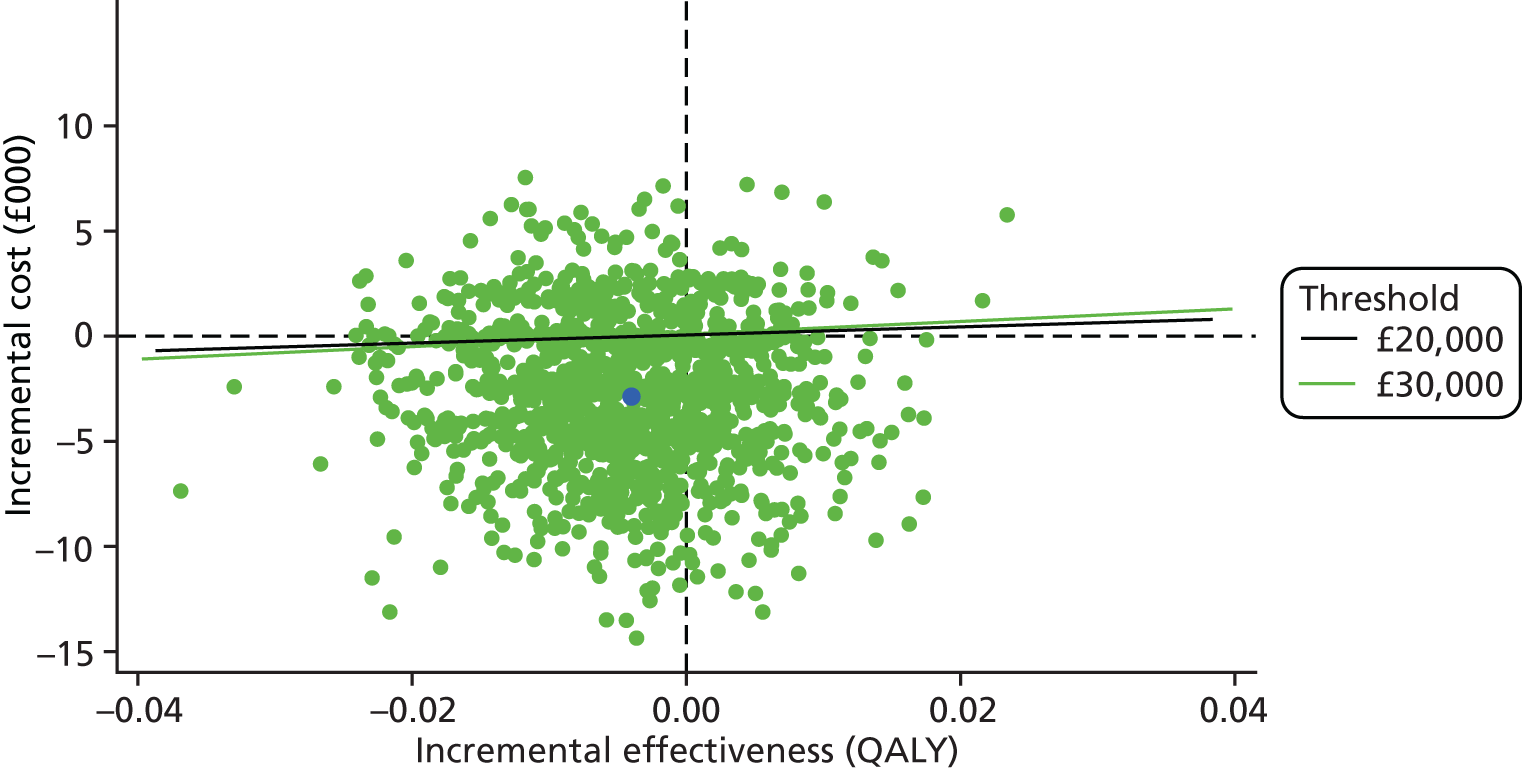

To measure the cost-effectiveness of the intervention in terms of quality of life and health state utility, quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs), service use costs and cost consequences at 12 months post intervention.

-

To monitor the fidelity of an ASBI delivered by learning mentors in the school setting.

-

To explore barriers to, and facilitators of, implementation with staff.

-

To explore young people’s experiences of the intervention and its impact on their alcohol use.

-

If the intervention is shown to be effective and efficient, to develop a manualised screening and brief intervention protocol to facilitate uptake/adoption in routine practice in secondary schools in England.

Outcomes and measurements of the SIPS JR-HIGH effectiveness trial

Validated tools were used in the study to capture the following primary and secondary outcomes measures. 2

Primary outcome

The primary outcome measure was the number of units of alcohol consumed over the previous 28 days, derived using the TLFB completed at 12-month follow-up77 (see documents on project page). The TLFB is designed to be completed retrospectively and employs periodic cues to obtain reliable estimates of daily drinking during a 28-day period.

Secondary outcome measurements

-

The Adolescent Single Alcohol Question (A-SAQ)78 was used to measure risky drinking (scoring ‘4 or more times but not every month’, ‘at least once a month but not every week’, ‘every week but not every day’, or ‘every day’). A score of three or above was considered positive for possible hazardous or harmful drinking. 2

-

Alcohol use frequency, quantity (on a typical occasion) and binge drinking (six or more drinks in one session for men and women)18 was assessed using the 10-question AUDIT. 79,80 Questions 1–8 each have five possible responses relating to how much or how often drinking behaviours occur, and these are scored from 0 to 4. Questions 9 and 10 have three responses and are scored 0, 2 or 4. Scores were summed to give a possible range from 0 to 40. A score of ≥ 4 was indicative of hazardous alcohol consumption in adolescent populations,81 and the adult cut-off point of 8 was also used. 2,30

-

The AUDIT-C was used to assess risky drinking, and comprises the first three questions of the AUDIT. All questions were scored from 0 to 4 and summed to give a range of scores from 0 to 12. An AUDIT-C score of ≥ 3 was indicative of hazardous alcohol consumption and ≥ 5 was indicative of possible dependence in adolescents. 2

-

Alcohol-related problems were assessed using the validated Rutgers Alcohol Problem Inventory (RAPI), which includes measures of aggression. 82 It consists of 23 questions about drinking behaviour, each with four possible responses, all of which are scored from 0 to 3. Responses were summed to give a total score ranging from 0 to 69. A higher RAPI score indicated more problematic drinking behaviour. 2

-

Drunkenness during the previous 30 days was dichotomised as ‘never’ and ‘once or more’. 2,83

-

Drinking motives were assessed using the 20-item Drinking Motives Questionnaire Revised (DMQ-R). 84 There were four sets of five questions designed to assess relative frequency of drinking within each of the subscales of coping, social, enhancement and conformity motives. All questions were on a Likert scale, for which one is ‘almost never/never’, two is ‘some of the time’, three is ‘half of the time’, four is ‘most of the time’ and five is ‘almost always/always’. Higher scores within each domain indicated stronger endorsement of positive reinforcement received through consumption of alcohol. 2,84

-

The percentage days of abstinence during the previous 28 days was calculated from the TLFB questionnaire by dividing the days on which no units were consumed by 28 and multiplying by 100. 2

-

Number of units of alcohol consumed per drinking day was derived by dividing the total number of units of alcohol consumed by the number of days on which > 0 units were consumed. Abstinent pupils were scored as 0. 2

-

Number of days when > 2 units of alcohol were consumed during the previous 28 days was calculated by counting the number of days on which > 2 units were recorded. 2

-

General psychological health was assessed using the 14-item Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (WEMWBS). 85 This tool used a five-point Likert scale that gives a score of 1–5 per question, giving a minimum score of 14 and maximum score of 70. A higher WEMWBS score indicated better mental well-being. 2,86,87

-

Two questions relating to sexual risk-taking were included. These were the same questions as in the pilot study:1 ‘After drinking alcohol, have you engaged in sexual intercourse that you regretted the next day?’ and ‘After drinking alcohol, have you ever engaged in sexual intercourse without a condom?’ Both questions could be answered with one of the three following options: ‘I have never engaged in sexual intercourse’, ‘yes’ or ‘no’. Information on changes in risky sexual behaviour for the two questions was derived from a cross-tabulation of baseline and follow-up responses to a given question and categorised as ‘never engaged in sexual intercourse’, ‘engaged in sexual intercourse that has been regretted during the last 12 months’ and ‘have engaged in sexual intercourse that has not been regretted’. 2

-

Energy drink consumption was assessed by asking young people how many times per week they consumed energy drinks. Young people could answer ‘never’, ‘less than once a week’, ‘2–4 days a week’, ‘5–6 days a week’, ‘every day once a day’ and ‘every day more than once a day’. Information on changes in the consumption of energy drinks was derived from a cross-tabulation of baseline and follow-up questions and categorised as ‘never consumes energy drinks’, ‘has stopped consuming energy drinks’, ‘has started consuming energy drinks’ and ‘consumes more/less energy drinks’. 2

-

Age of first smoking was asked, as was how many cigarettes had been smoked in the previous 30 days. 88 Information on changes in smoking behaviour was derived from a cross-tabulation of baseline and follow-up responses and categorised as ‘never smoked’, ‘still smoking’, ‘started smoking’ and ‘smoking more/less’. 2,89

-

Demographic information collected included gender, ethnicity and how free time is spent. The first part of the trial participants’ postcode was collected to facilitate calculation of Index of Multiple Deprivation. 2

-

Quality of life was measured using the EQ-5D-3L, which is a valid measure for those aged ≥ 12 years, and was used to measure health-related quality of life. 90 Responses to the five items were converted into utility scores using the UK population algorithm. This was administered at baseline and at 12 months post intervention. 2,90

-

Quality-adjusted life-years were estimated using general population tariffs from responses to the EQ-5D-3L administered and scored at baseline and 12 months; service use was assessed using the modified S-SUQ (Short Service Use Questionnaire) at baseline and 12 months. 2

-

Use of leisure time was assessed using a multiple-choice question that gave suggestions about how free time might be spent and the option to choose multiple answers. 2

-

Incremental cost per QALY gained at 12 months was calculated. 2

-

Modelled estimates of incremental cost per QALY and cost consequences in the longer term were calculated. 2

-

The NHS, educational, social and criminal services data were estimated using a modified S-SUQ91 and via a learning mentor case diary developed in the pilot study,1 measured at 12 months post intervention. 2

-

Cost consequences were presented in the form of a balance sheet for outcomes at 12 months. 2

Chapter 2 Trial process and development of intervention materials and training

Key points for Chapter 2

-

The study incorporated a control condition and a brief alcohol intervention. The brief alcohol intervention was manualised and designed to be delivered on a one-to-one basis to young people who screened positive for risky drinking and left their name on the questionnaire.

-

Young people in the control group were provided with a healthy lifestyle leaflet by the learning mentor.

-

Young people allocated to the intervention received feedback on their positive screen for risky drinking, immediately after which they took part in a 30-minute, six-step interactive intervention led by the learning mentor.

-

Learning mentors were asked to audio-record time spent with participants using a dictaphone. Audio-recorded control and intervention sessions were measured for fidelity using the Behaviour Change Counselling Index (BECCI),92 and control sessions were also assessed for differentiation from the brief alcohol intervention.

Introduction

All young people recruited into the trial, regardless of arm, continued to receive ‘standard alcohol advice’ delivered as part of the school curriculum. The first section of this chapter is concerned with defining what this consisted of in the study schools. In addition, young people allocated to the control condition received a healthy lifestyle information leaflet. No feedback was provided to them on their positive screen for risky drinking. Young people allocated to the brief alcohol intervention met with a trained learning mentor, received feedback on their alcohol screening result and took part in a 30-minute one-to-one structured intervention session. In addition, they received an alcohol advice leaflet. All young people recruited into the trial were followed up 12 months post intervention.

The rest of the chapter describes the design of intervention materials, as well as the training and support provided to learning mentors in the delivery of interventions. The rationale behind, and development of, both the control and the intervention is detailed, and the amendments that were made following the results of the pilot feasibility trial are outlined, with any resultant modifications to intervention materials reported.

Defining ‘standard alcohol advice’

All schools are required to provide Personal, Social, Health and Economic Education (PSHE) to ‘promote children and young people’s personal and economic well-being; offer sex and relationships education; prepare pupils for adult life and provide a broad and balanced curriculum’,93 delivered as part of a wider well-being remit through the National Healthy Schools Programme94 and the Social and Emotional Aspects of Learning strategy. 94 Classroom-based drug and alcohol education is delivered to pupils as part of PSHE classes, and is recognised as an important aspect of the secondary school curriculum (for those aged 11–16 years) in England, Scotland and Wales.

As there are no prescriptive guidelines on what PSHE should actually entail, schools have developed their own versions of PSHE education and different ways to deliver it, rather than following standardised frameworks of study. 93 We asked schools to report their usual practice and found that this varied from school to school, but included advice on drinking responsibly and ‘safe amount of units’, alcohol facts, provision of Addaction95 leaflets, assemblies on alcohol, advice on wider lifestyle choices, an alcohol awareness week, utilisation of Drinkaware96 resources and alcohol-awareness evenings for parents. Schools reported that this advice was delivered by a combination of teachers, pastoral leads, tutors, nurses, learning mentors and external speakers. One school said that it did not currently deliver advice on alcohol. Given the variability in alcohol advice across schools, standard alcohol advice is defined in this study as the regular provision of classroom-based alcohol education to Year 10 pupils as delivered at each particular school site. As a result, many of the young people may have received this standard alcohol advice as usual from their schools, in addition to the ASBI for those randomised to the intervention arm of the trial (see Appendix 4).

Trial process

Study setting and population

Young people aged 14–15 years in Year 10 at secondary schools/academies in four centres, north-east, north-west, Kent and London, were targeted.

In each of the four geographical centres, school performance league tables97 were reviewed and schools from the top, middle and bottom of the league tables were contacted. Efforts were made to recruit a cross-section of schools, including academy schools, schools in deprived areas, faith schools and private schools. Schools were included if they employed learning mentors (or equivalent members of pastoral staff).

In advance of screening, all parents/caregivers (hereafter referred to as ‘parents’) were sent a letter by the school informing them that young people would be screened for risky drinking as part of the study in their child’s school (see documents on project page). Parents had the choice to opt their child out of the study by completing an opt-out form and returning it to the school in a prepaid envelope. Opt-out consent by parents was chosen (instead of opt-in) as this was standard practice in schools (see documents on project page). They were provided with an information sheet to inform consent (see documents on project page). 2

At baseline, all participating schools showed an animation video to pupils who had not opted out of the study. This video detailed the study process. Young people then completed the baseline survey as part of the screening process (see documents on project page). This screening took place in the PSHE or registration class on an individual classroom basis.

Young people had the option to (1) not complete the questionnaire (indicative of lack of assent to screening from the young person), (2) complete the questionnaire anonymously or (3) complete the questionnaire, adding their name and class. 2

Those young people who screened positively on the A-SAQ and left their name were eligible for the trial.

Randomisation

Eligible pupils were individually randomised in a one-to-one ratio to the intervention or control arm of the trial. Randomisation occurred before consent to the trial because of timing constraints: it was not feasible for the learning mentor to access a real-time randomisation system during the session with the young person. Therefore, the randomisation was performed earlier on the list of eligible young people and the allocation was contained in a sealed envelope. Neither the learning mentor nor the young people knew the arm to which they had been allocated until they opened the envelope after consent had been given. Young people aged < 16 years provided assent and those aged 16 years provided consent, as per guidelines issued by the Research Governance and Ethics Committee in the School of Health and Social Care at Teesside University. 1 Hereafter, assent and consent is referred to as consent.

An independent statistician not otherwise involved with the study produced a computer-generated allocation list using random permuted blocks. This statistician was provided with a list of screening identification numbers (identifying the site, school and young person) for eligible participants, in the form of a Microsoft Excel® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) spreadsheet. This statistician also undertook randomisation, and an updated spreadsheet, including allocations to the study arms, was returned to an independent researcher (JF) at Teesside University, where the sealed envelopes containing the allocation were produced. Numbered envelopes containing a slip of paper indicating the arm to which each individual had been allocated were then prepared, sealed and sent to each school, to be opened only when consent had been attained.

School staff identified to deliver interventions

The pilot feasibility trial, which preceded the current trial, identified the learning mentor as the most appropriate role within the school structure to deliver an alcohol intervention. Learning mentors are specifically trained to provide a complementary service to teachers and other school staff, addressing the needs of young people who require assistance in overcoming barriers to learning in order to achieve their full potential. 98 They work with a range of pupils, but they focus on those pupils with multiple disadvantages that have an impact on their education. Within their established role, learning mentors address issues, such as punctuality, absence, bullying, challenging behaviour and abuse, disaffection, danger of exclusion, difficult family circumstances and low self-esteem, as well as underperformance against potential. 99 As part of this role, learning mentors are routinely required to provide advice and support to young people and, as such, are well placed within a school setting to deliver an intervention to young people about alcohol use. In this trial, interventions took place in the learning mentor’s classroom or office space.

Local areas vary in the essential qualifications they look for when appointing learning mentors. However, at a minimum, learning mentors need to have a good standard of general education, especially literacy and numeracy, as well as experience of working with young people. 100 In the present study, learning mentors were defined as the members of school staff trained in the delivery of the control condition/intervention to participating students. However, in practice, within each school, titles, roles and responsibilities varied and this did not constitute a homogenous professional group. Thus, for consistency, the school staff responsible for delivering interventions are referred to only as learning mentors throughout the rest of this report.

Control (healthy lifestyles leaflet)

Young people allocated to the control group met with the learning mentor in school during the week (Monday to Friday). The learning mentor explained the study to them and invited them to participate in the trial. Once a young person had consented to the trial, the learning mentor provided them with the healthy lifestyles leaflet (see documents on project page). This leaflet contained advice on eating less fat, sugar and salt; eating fruit, vegetables and fish; and the importance of breakfast. It also advised readers to ‘move more’. The healthy lifestyle leaflet was chosen as the minimally acceptable intervention that could be provided to young people without giving any alcohol advice. No feedback on the alcohol screening results was provided. The young people in the control group may also have received usual practice advice from the school.

Intervention (brief intervention and alcohol leaflet)

Appendix 5 reports further details on the intervention using the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) checklist. 101 The rest of this section details the intervention.

Young people allocated to the brief alcohol intervention met with the learning mentor face to face in school during the school week (Monday to Friday), in the learning mentor’s office or an alternative suitable space. The learning mentor provided feedback on their positive alcohol screen result and invited them to take part in the trial. Those who consented to the trial received one 30-minute one-to-one interactive session brief alcohol intervention. The session was developed within the pilot feasibility trial. The essential components of brief alcohol interventions were adapted for young people within a school setting after consulting with a PPI group and piloting the intervention. 1 The developed tool was a colourful A3 sheet detailing a six-step intervention, which was intended to lead to an interactive discussion between the young person and the learning mentor (see documents on project page). Based on the principles of MI,102 the intervention sought to increase the young person’s awareness of risks and enable them to consider their motivations for changing their alcohol use. It encompassed the elements of the FRAMES approach for eliciting behaviour change, as outlined in Chapter 1. 54 It was expected that young people would be taken out of class to attend the appointments with learning mentors. The intervention had been found to be feasible and largely acceptable within the pilot feasibility trial and linked qualitative study. The intervention used in the pilot trial, however, had included information about the calorie content of alcoholic drinks. Mixed views were expressed about this content in the pilot feasibility trial and, as such, this was removed from the intervention delivered in the present trial. Table 1 summarises the intervention and control arms.

| Component | Control condition | Brief alcohol intervention condition |

|---|---|---|

| Rationale, theory or goal | Comparison condition | MI to reduce alcohol use |

| Materials | Healthy lifestyle leaflet | Alcohol advice leaflet |

| Procedure | Provision of healthy lifestyle leaflet | Feedback on alcohol screening results, advice on recommended alcohol consumption levels and calculation of participants’ alcohol consumption, raise awareness of risks associated and delivery of behaviour change counselling |

| Intervention provider | Learning mentor | Learning mentor |

| Delivery mode | Information leaflet | Face to face and information leaflet |

| Location | School | School |

| Session duration and frequency | < 1 minute | Up to 30 minutes |

| Tailoring | None | Yes |

| Modifications | None | Adult recommended alcohol consumption reduced from 21 to 14 units per week during study period. The information on the intervention sheet was not changed; however, the learning mentor was advised to communicate this change to participants |

| Fidelity assessment plan | All sessions were to be audio-recorded and a random 20% sample were to be checked by an experienced and qualified alcohol counsellor to ensure differentiation from the brief alcohol intervention. Those in which no advice was given were considered to be at acceptable levels of differentiation | All sessions were to be audio-recorded and a random 20% sample were to be assessed by an experienced and qualified alcohol counsellor using the BECCI |

| Fidelity outcome | 18 sessions were recorded, of which seven were control, and were deemed to be at acceptable levels of differentiation | 11 intervention sessions were audio-recorded. The mean BECCI score was 1.6, indicating that behaviour change counselling was being delivered to ‘some extent’ |

Intervention worksheet

Section 1: how many units are in my drink?

This section sought to raise the young person’s awareness of the units of alcohol in drinks they often consumed. It was comparable with the information commonly provided in simple structured advice. 103 Young people were encouraged to calculate the number of units they drank during a typical drinking day. This calculation was then used as the basis for discussing the recommended levels for adults and the Chief Medical Officer’s recommendation that young people under the age of 15 years should not drink alcohol at all; it was also intended to enable personalised feedback about the risks associated with the young person’s drinking. The Chief Medical Officer’s recommendations on alcohol consumption changed part way through the trial, stating the alcohol guidelines for all adults and not differentiating between men and women, and so learning mentors were advised to verbally update the sheet when speaking with each young person. The young person was also asked how common they perceived alcohol use by young people aged 14–15 years to be. Learning mentors then advised the young people of the actual numbers before asking them to reflect on their thoughts about this. This component was informed by social learning theory. 104 This information was delivered in accordance with the elicit-provide-elicit approach to informing within MI.

Section 2: typical drinking day

In section 2, young people were asked to discuss their typical drinking day in more detail. This background description was intended to provide a useful context for the ensuing discussion about the young person’s drinking, and associated risk and change. The typical drinking day was informed by the SIPS Brief Lifestyle Counselling structure (www.sips.iop.kcl.ac.uk/blc.php). It was developed to provide greater structure and useful prompts about drinking behaviour (with, where, because) for both the young person and the learning mentor. In particular, the additional prompts were intended to provide information relevant to the identification of risk (e.g. the location where a young person consumes alcohol, which may increase or decrease risk) as well as to reinforce positive drinking behaviours (e.g. times when young people drink in ways that are not risky) and to identify the behaviours that may become the focus of change.

Section 3: are there any risks with my drinking?

Section 3 of the intervention built on section 2 and encouraged the young person to consider the risks associated with their alcohol use. The intention was that, by asking the young person to identify personally relevant risks, they would begin to identify motivation for change. It was expected that this would lead naturally on to how important it is for the young person to change their drinking. Young people were then advised of the common risks associated with drinking more than the Chief Medical Officer’s recommended levels before being asked to reflect on this in relation to their own drinking. As well as acting as a further prompt to identifying risks relating to their drinking, the delivery of this information was again in accordance with the elicit-provide-elicit approach to informing within MI.

Section 4: importance/confidence

Section 4 encouraged the young person to rate the importance of changing their drinking, and their confidence at their ability to change, using scaling questions. Importance scales are used in behaviour change counselling to elicit change talk and assess readiness to change. 105 By prompting the young person to consider what would need to happen for this number to increase, ratings may also be positively affected and motivation developed. Confidence scales are useful in identifying barriers to change. Exploration around this can enable the young person to find ways to overcome these barriers and assist in the development of a coping plan in section 6.

Section 5: what do I think about reducing my drinking?

Section 5 asked the young person to consider the ‘bad’ and the ‘good’ things about reducing their drinking. Beginning this section with the bad things before moving on to discussing the good things about reducing consumption enabled pro-change to be reinforced. This is comparable with the ‘Pros and cons of changing your drinking’, which is included in the extended brief intervention tool (www.sips.iop.kcl.ac.uk/blc.php) and discussed by Rollnick et al. 105 The terminology ‘pros and cons’ was changed to ‘good and bad’ to make the language more age-appropriate.

Section 6: what could I do about my drinking?

The final section of the intervention was concerned with developing an action and coping plan for change. It was acknowledged that not all young people would want to agree to such a plan. Those who did were expected to set their own goals, facilitated by the learning mentor, based on the content of the MI. The purpose of this section of the intervention was to elicit commitment talk from the young person,106 as well as to identify existing life skills and develop coping strategies to enable young people to achieve and maintain change. Learning mentors employed a strengths-based approach wherein self-efficacy was promoted. Young people who did not want to agree a plan to change their alcohol use at the present time were encouraged to consider a time when they might want to change their drinking and consider the strategies they would employ.

On completion of the brief alcohol intervention, the young people were provided with an alcohol leaflet, ‘Cheers! Your Health’, designed by the Comic Company (www.comiccompany.co.uk/). This leaflet was identified in the pilot feasibility trial as a suitable, age-appropriate resource that was acceptable to young people (see documents on project page).

Training and support

All learning mentors received training from November 2015 to January 2016 before commencing the study. The training was delivered to learning mentors in group sessions within the school environment by the trial co-ordinator in each study site. The trainers were themselves trained by Ruth McGovern, a senior interventionist. Outreach training has been found to be the most cost-effective implementation strategy for ASBI delivery in other settings. 107 Microsoft PowerPoint® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) slides were used to guide each training session. This was then followed by an audio-recorded role-play exercise wherein learning mentors practised delivering the intervention with each other to enable the development of skills. Learning mentors were required to record one role-play intervention delivery each. Learning mentors were also trained to issue the participant information leaflet, gather informed consent from the young person and deliver the alcohol information leaflet. Each training session lasted 2–3 hours. An intervention manual was provided to supplement the training (see documents on project page). Following the training session, an experienced alcohol interventionist (RM) listened to the audio-recorded role-plays, rated them using the BECCI and provided feedback on the content. This process was to ensure that learning mentors achieved a minimum standard of fidelity. All learning mentors were required to be rated at a minimum standard (a score of at least 1 on the BECCI) before they delivered the intervention to participating young people within the trial. A total of 80 learning mentors were trained from the four study sites. Four learning mentors were asked to repeat the role-play exercise after detailed feedback was given on their practice. All four learning mentors met the minimum standard following the second exercise. The number of learning mentors per school ranged from one to eight.

The research team provided regular support to the learning mentors, including ongoing guidance on intervention delivery. Co-ordinators made weekly visits/telephone calls and/or sent e-mails to each school throughout the study period to answer questions or concerns, collect materials from completed interventions (such as consent forms and hard copies of intervention tools) and encourage learning mentors to complete outstanding interventions. Finally, learning mentors were provided with a case diary sheet on which they were asked to record any interactions with the individual young people in the trial (see documents on project page). This information was used to calculate the time spent on intervention delivery and inform the cost-effectiveness analysis (see Chapter 5).

Fidelity of the interventions

Fidelity of an intervention within research refers to the extent to which the intervention is true to the therapeutic principles on which it is based. 108 Researchers need to be able to determine whether or not the intervention was delivered as intended; this requires the manualisation of the intervention wherein the philosophy, principles and procedures of the intervention are clearly described. Interventions delivered with high fidelity promote the ability to associate trial results with intervention effectiveness. A manualised intervention with verified fidelity enables the research to be replicated or the intervention to be implemented in practice, if it is shown to be effective.

Learning mentors were asked to audio-record all sessions with consenting participants that they delivered during the trial, from which a 20% sample from various time points would be rated to assess fidelity. However, only 18 recordings (from 11 schools) of the total 443 sessions (control interaction, n = 7, 3%; intervention delivery, n = 11, 5%) were made. Reasons for not recording sessions included the young person’s refusal, unavailable equipment and human error (i.e. forgetting to record the sessions). Because only a limited number of sessions were audio-recorded, all 18 recordings were rated. In this study the control condition was simply assessed as providing no alcohol advice (acceptable levels of differentiation from the alcohol brief intervention) versus providing any alcohol advice (unacceptable levels of differentiation). All seven recordings were free of any alcohol advice and, as such, this small selection of recordings were delivered to an acceptable level of differentiation. The BECCI was used to measure fidelity of the audio-recorded brief alcohol interventions delivered during the trial. BECCI is a tool developed specifically to measure the microskills of behaviour change counselling and MI (e.g. questions, empathic listening statements, summaries). 109 The instrument focuses on the practitioner’s consulting behaviour and attitude rather than the patient’s response. Sessions were rated by an experienced alcohol practitioner within the research team (RM), who is dual qualified in social work and counselling to master’s degree level. Scores were given on a range of 0–4 for 15 different items on a checklist, for which 0 = ’not at all’, 1 = ’minimally’, 2 = ’to some extent’, 3 = ’a good deal’ and 4 = ’a great extent’. A mean score was then calculated. Rating was completed in line with the BECCI Manual for Coding Behaviour Change92 for the purposes of measuring and reporting on the fidelity of intervention delivery within the trial. The mean BECCI scores for the 11 sessions ranged from 0.3 (behaviour change counselling delivered ‘not at all’) to 2.5 (behaviour change counselling skills delivered ‘a good deal’). The mean BECCI score for the 11 recorded interventions was 1.6 and the median BECCI score was 1.5; these scores suggested that overall the learning mentors were found to be delivering behaviour change counselling to ‘some extent’. This is similar to the BECCI scores reported in other studies110 of practitioner-delivered behaviour change counselling. Learning mentors typically performed well when discussing the risks associated with the young person’s alcohol use. Lower scores were observed in respect of microskills relating to discussing and exploring behaviour change.

The small number of interventions recorded is a significant weakness and limits our ability to assess threats to internal validity. 111 It is possible that the learning mentors who did not provide a recording differed in skill from those who did. Learning mentors may have selected recorded sessions in which they felt they performed better.

Chapter 3 Trial methods and results

Key points for Chapter 3

-

A total of 1064 (23.5%) young people screened positive on the A-SAQ.

-

Of those, 443 young people were recruited to the trial from 30 schools in four areas.

-

Follow-up data at 12 months were collected from 84.4% of those recruited.

-

There was evidence of a reduction in drinking across the trial, as reflected in a change in AUDIT score over the 12-month period.

-

Thirty-eight (21%) young people in the intervention arm and 55 (28%) in the control arm reported drinking no alcohol in the previous 28 days on the TLFB.

-

There were few or no differences between the trial arms in the distribution of variables summarising alcohol consumed in the previous 28 days from the TLFB.

-

There were few or no differences between the trial arms in the distribution of survey variables summarising other drinking-related aspects, smoking, psychological well-being and sexual behaviour at 12 months.

Trial summary

Inclusion criteria

-

Young people aged 14–15 years, inclusive.

-

Parents had not opted them out of the study.

-

Scored positive on the A-SAQ and left their names.

-

Were willing and able to provide informed written consent for intervention and follow-up.

Exclusion criteria

-

Were already seeking or receiving help for an alcohol use disorder.

-

Had recognised mental health or challenging behaviour issues, identified by school staff.

Sample size and power

The sample size was calculated to have a 90% power to detect a standardised difference of 0.3 (which equated to a ratio of 1.5 in geometric means) in total alcohol units consumed in 28 days, using a significance level of 5%. Parameter estimates came from the pilot trial1 (mean year group size = 210, 87% completing baseline questionnaire, 80% recruited to trial and 88% providing data at the 12-month follow-up). In the pilot trial we found that 18% of young people had screened positive and left their names. However, given that the numbers screening positive were anticipated to be lower in the south of England, and the extra efforts put in place in the current trial to encourage young people to leave their names on the questionnaires, it was estimated that this figure would be 20% in the full trial. Using these estimates, follow-up data would be required from 235 young people per arm. The number required to have follow-up data if the power was reduced to 80% was 176. Given the difficulty in recruiting sufficient numbers, the target for power was later reduced from 90% to 80%, after discussion with the TSC and DMEC.

Statistical analysis plan

Individual site staff input the trial data into a MACRO™ (Elsevier Limited, London, UK) database held and maintained by the Newcastle Clinical Trials Unit. Data were extracted from MACRO into statistical software package Stata® version 14 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). 1 A complete statistical analysis plan providing full details of all statistical analyses, variables and outcomes was finalised and signed before the final database download. Scoring systems for numerical scales are shown in Appendix 6. All analyses were carried out on an intention-to-treat basis, retaining patients in the analysis group to which they had been randomised and including any protocol violator and ineligible participants.

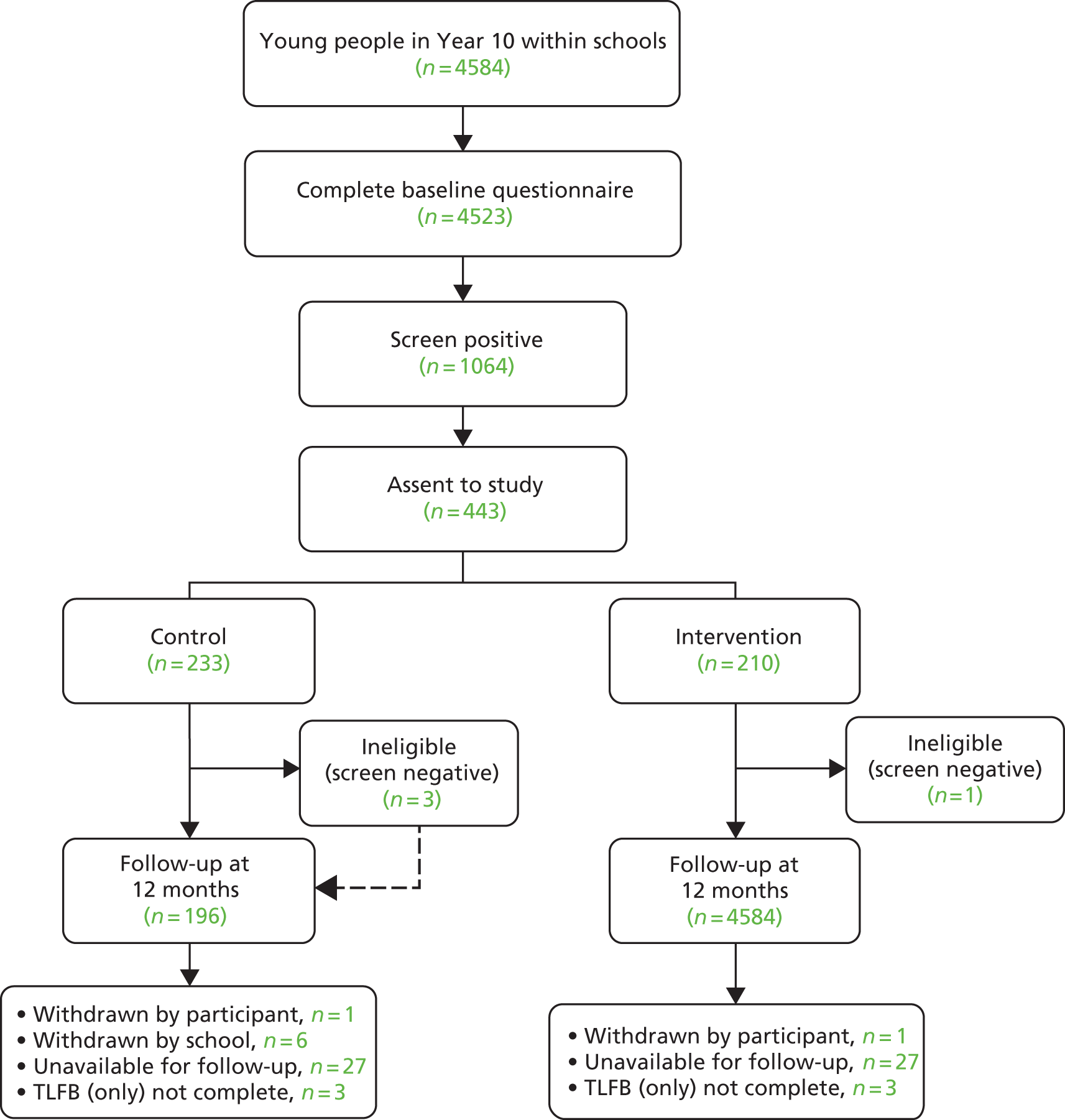

Descriptive analyses

After the recruitment of schools, the flow of young people through the study was presented using a Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT)2 flow diagram (Figure 2). The number of young people in the age group, how many completed baseline questionnaires, how many screened positive, how many assented and how many completed the 12-month follow-up were reported by region and by school. Any reasons for not completing follow-up were reported when known. Descriptive statistics were used to report the pupil-level baseline data, by arm. These included all measures reported in the baseline questionnaires, reported as comparisons of percentages and means or medians as appropriate.

FIGURE 2.

The CONSORT flow diagram.

Inferential analyses

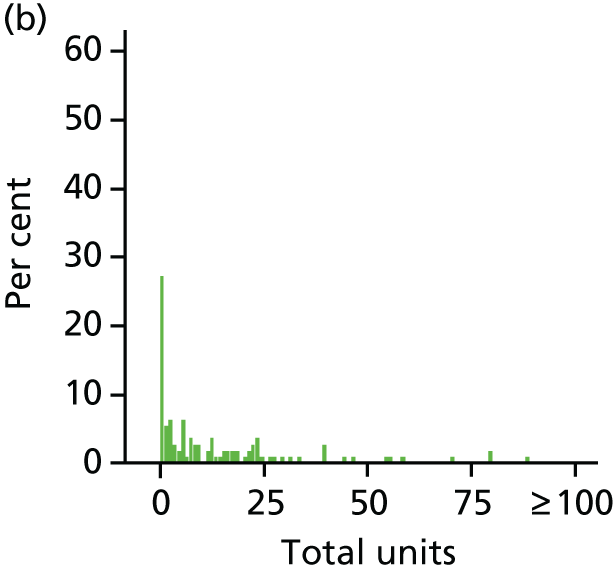

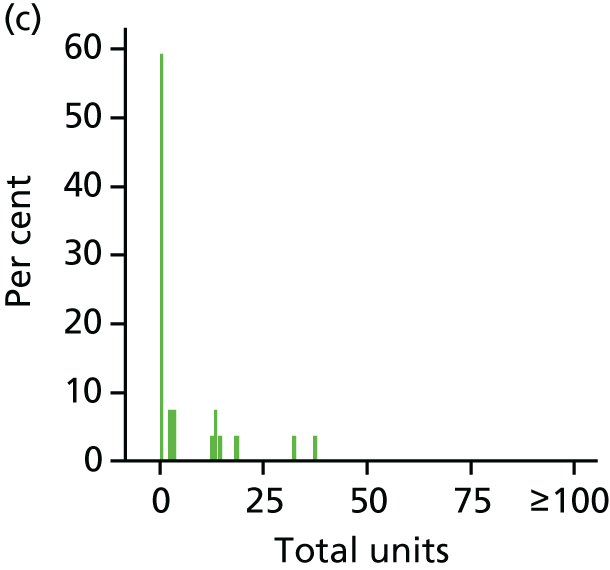

It was planned to use multiple linear regression to compare the primary outcome (mean number of units consumed in the previous 28 days) between the two trial arms at 12 months, estimating the difference between mean scores and adjusting for any imbalance in key covariates, namely gender, region (north-east, north-west and south), level of deprivation (percentage of free school meals) and baseline AUDIT score. Data from the London and Kent areas were combined as the ‘south’ region as there were very few young people providing responses at baseline and 12 months in London schools. If, as was considered likely, the primary outcome was skewed, the statistical analysis plan stated that there would be a logarithmic transformation and results would be presented as ratios of geometric means. Alternatively, other root transformations could be considered and confidence intervals (CIs) around differences in means would be obtained by bootstrapping. However, at 12 months a substantial minority of participants reported consuming 0 units of alcohol. This made it impossible to use a logarithmic transformation, and root transformations did not deal with the skewness. Hurdle models3 were considered to deal with the zero inflation, but convergence was not achieved for all variables. It was therefore decided to use quantile regression to model the median number of units consumed in the previous 28 days using the same covariates: the results were very similar to those of the Hurdle models when results were available. The majority of secondary outcomes were analysed similarly. The only exception was the comparison of the proportions who had reduced their drinking below hazardous (or dependent) levels between baseline and 12 months; this was done by logistic regression, adjusting for the same covariates as for other outcome variables.

In a post hoc analysis, Bayes factors were calculated to determine the strength of support for the alternative hypothesis (HA: the intervention shows some difference in alcohol consumption between trial arms) versus the null hypothesis (H0: no effect). Bayes factors can determine whether there is simply a lack of evidence for the alternative hypothesis or whether the evidence supports the null hypothesis. A Bayes factor of > 1 indicates support for HA, whereas one of < 1 indicates support for H0. Values of Bayes factors of > 3 or < 1/3 are regarded as substantial evidence for the alternative or null hypothesis, respectively.

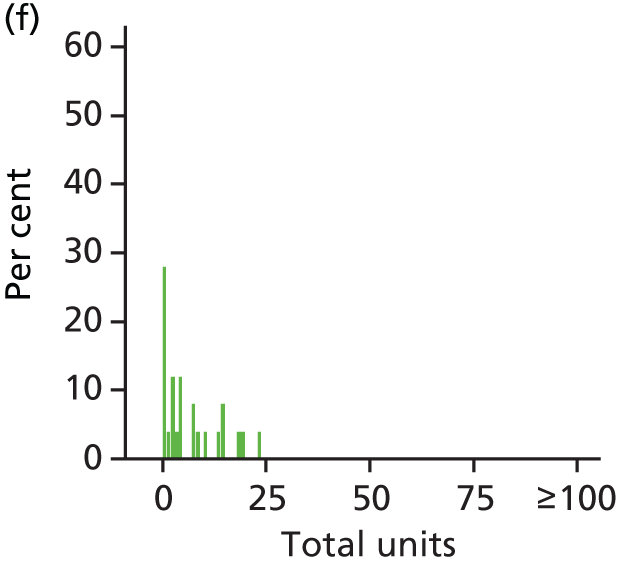

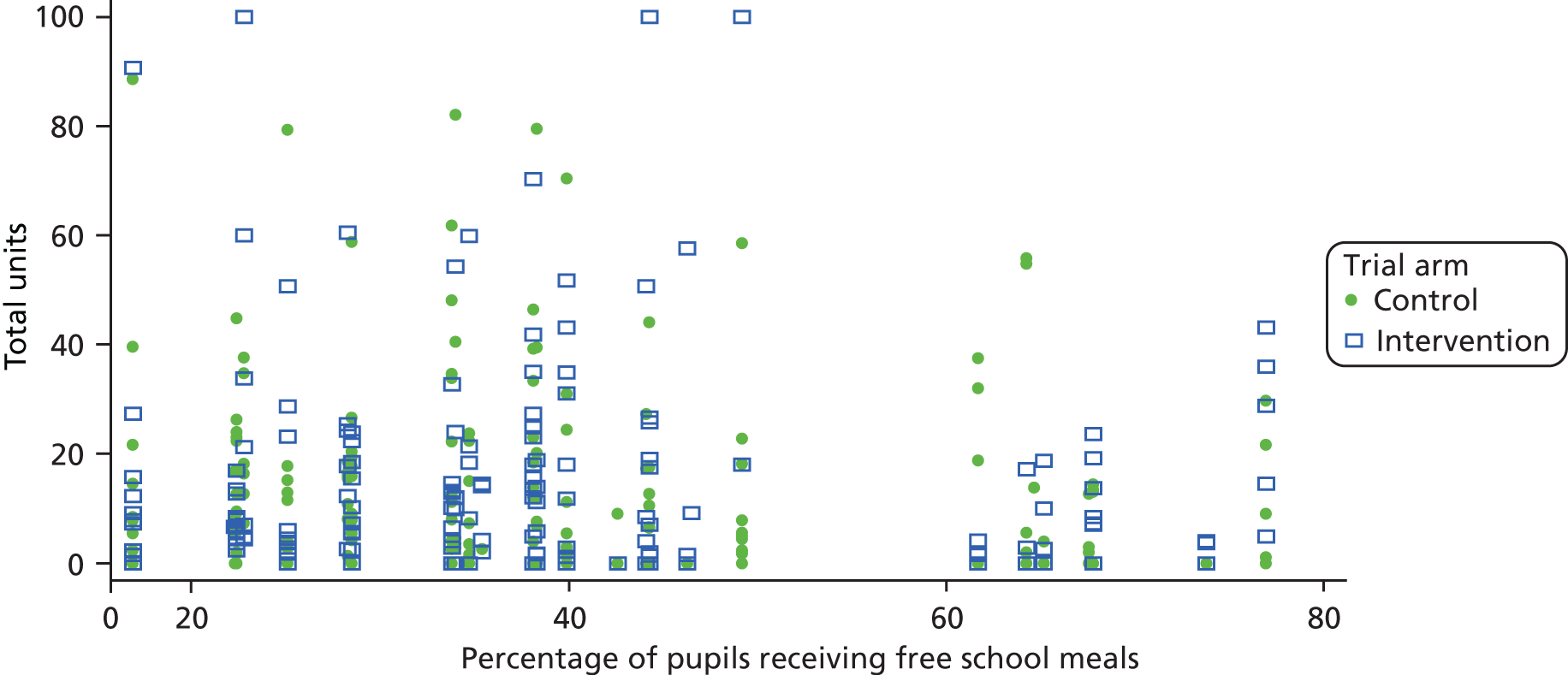

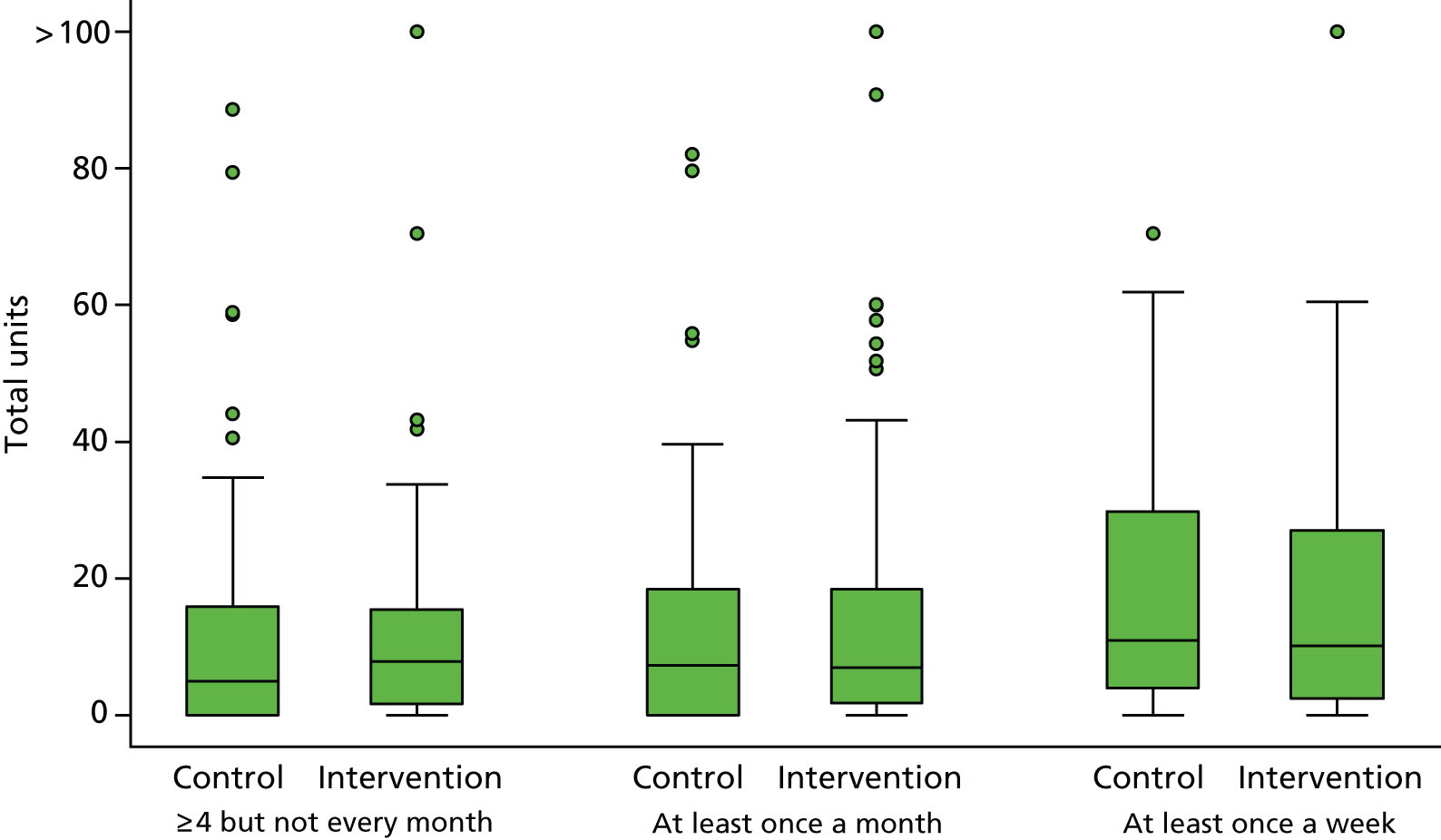

Exploratory analyses

Exploratory analysis included investigating differences in the primary outcome by gender, deprivation (percentage of free school meals) and levels of drinking at baseline (A-SAQ). Gender and A-SAQ differences were illustrated by box plots, and associations with deprivation were illustrated by a scatter plot. The levels of drinking according to the A-SAQ at baseline were categorised as those drinking ‘more than 3 units on four or more times in the last 6 months but not every month’, those drinking ‘at least once a month’ and those drinking ‘at least once a week (including those drinking daily)’. It had been planned to look at the extent of the intervention received, but as all of the young people allocated to the brief intervention received it, no such analysis was necessary.

Recruitment and follow-up

The recruitment of schools took place between November 2015 and June 2016. During this period, 154 schools were invited to take part (north-east, n = 44; north-west, n = 35; London, n = 36; and Kent, n = 39). Thirty-three schools were recruited (north-east, n = 13; north-west, n = 7; London, n = 5; and Kent, n = 8); few of the non-participating schools gave reasons for not taking part, but those that did mentioned impending school closure (n = 1), lacking time or staff availability (n = 7), having a policy not to take part in surveys (n = 1) and lacking agreement with elements of the research (n = 2). Two schools that initially agreed to take part subsequently withdrew shortly after recruitment: one in the north-west did not like the sexual health questions, whereas the other, in Kent, withdrew because of school closure. A third school in London later withdrew because of issues with the trial; this was after the young people had been screened but before the meetings to obtain consent had taken place. The number of schools recruited had to be increased from the 20 planned, partly because the average year-group size was much smaller than anticipated from our experiences in the pilot trial.

Recruitment at the young person level is summarised in the CONSORT flow diagram (see Figure 2). Table 2 shows the figures on recruitment, screening, consent and randomisation, by area. Among the schools recruited, 4523 (98.7% of the year groups) pupils completed the baseline questionnaire and 1064 (23.5% of those completing the questionnaire) screened positive. Of those screening positive, 443 (41.6%) consented to take part in the study by providing their names. Using the pilot study data,1 we had expected that 14% of those surveyed would screen positive and consent to take part in the trial, whereas we managed to recruit only 443 out of 4584 (9.7%). The lower than anticipated numbers eligible and willing to take part was largely explained by fewer than expected screening positive on the A-SAQ. Four young people scored negative on the A-SAQ and were incorrectly included, even though they were ineligible, through human error. Three of these were randomised to the control group and completed the 12-month follow-up, but the one randomised to the intervention group withdrew before the intervention. It can be seen that the screen-positive rate varied by area (north-east, 27.4%; north-west, 19.4%; London, 14.6%; and Kent, 24.2%). Table 2 also shows the trial arm to which each young person was randomised. All 210 young people randomised to intervention received the brief intervention. The numbers screening positive and assenting to the study broken down by area and school are shown in Appendix 7. Table 3 summarises the numbers of young people ineligible, withdrawn and lost to follow-up.

| Area | Number of | Consent to study (% of positive) | Randomised to (n) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Young people in year | Surveys completed (% of young people in year) | Surveys positive (% of surveys completed) | Intervention | Control | ||

| North-east | 2132 | 2115 (99.2) | 579 (27.4) | 241 (41.6) | 116 | 125 |

| North-west | 734 | 715 (97.4) | 139 (19.4) | 59 (42.4) | 27 | 32 |

| London | 677 | 665 (98.2) | 97 (14.6) | 5 (5.2) | 2 | 3 |

| Kent | 1041 | 1028 (98.8) | 249 (24.2) | 138 (55.4) | 65 | 73 |

| Total | 4584 | 4523 (98.7) | 1064 (23.5) | 443 (41.6) | 210 | 233 |

| Reason | Trial arm (n) | |

|---|---|---|

| Intervention | Control | |

| Ineligible | ||

| Enrolled in trial but had not screened positive on A-SAQ | 1 | 3 |

| Total | 1 | 3 |

| Withdrawal | ||

| Withdrawn: student no longer wished to participate | 2 | 1 |

| Withdrawn by school: poor attendance/disciplinary issues | 0 | 4 |

| Withdrawn by school: health reasons | 0 | 2 |

| Total | 2 | 7 |

| Lost to follow-up/unavailable for follow-up | ||

| Lost to follow-up: participant left school | 10 | 14 |

| Lost to follow-up: reason unknown | 1 | 2 |

| In exam/absent on day of scheduled follow-up | 3 | 6 |

| Lost to follow-up: not contacted within 30 days | 13 | 5 |

| Total | 27 | 27 |

Appendices 8 and 9 show the distribution of the baseline characteristics (categorical and questionnaire responses) of three groups of young people: those screening positive and consenting to the trial, those screening positive and not assenting and those who screened negative. There are similar baseline characteristics between the two subgroups who screened positive, but those who screened negative differed from the screen-positive subgroups in terms of smoking, drinking and sexual behaviour.

Follow-up data at 12 months were collected on 374 young people (84.4% of those recruited to the trial). A few young people did not complete the TLFB, but that information was available for 368 participants (83.0% of those recruited). The numbers providing data on the TLFB and other questionnaires at 12 months in each area are shown in Table 4. Numbers by area and by school can be found in Appendix 10.

| Region | Trial arm | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention | Control | |||||

| Randomised (n) | TLFB complete, n (%) | 12-month questionnaire complete, n (%) | Randomised (n) | TLFB complete, n (%) | 12-month questionnaire complete, n (%) | |

| North-east | 116 | 98 (84.5) | 98 (84.5) | 125 | 110 (88.0) | 110 (88.0) |

| North-west | 27 | 25 (92.3) | 25 (92.3) | 32 | 27 (84.4) | 26 (81.3) |

| London | 2 | 1 (50.0) | 1 (50.0) | 3 | 3 (100.0) | 3 (100.0) |

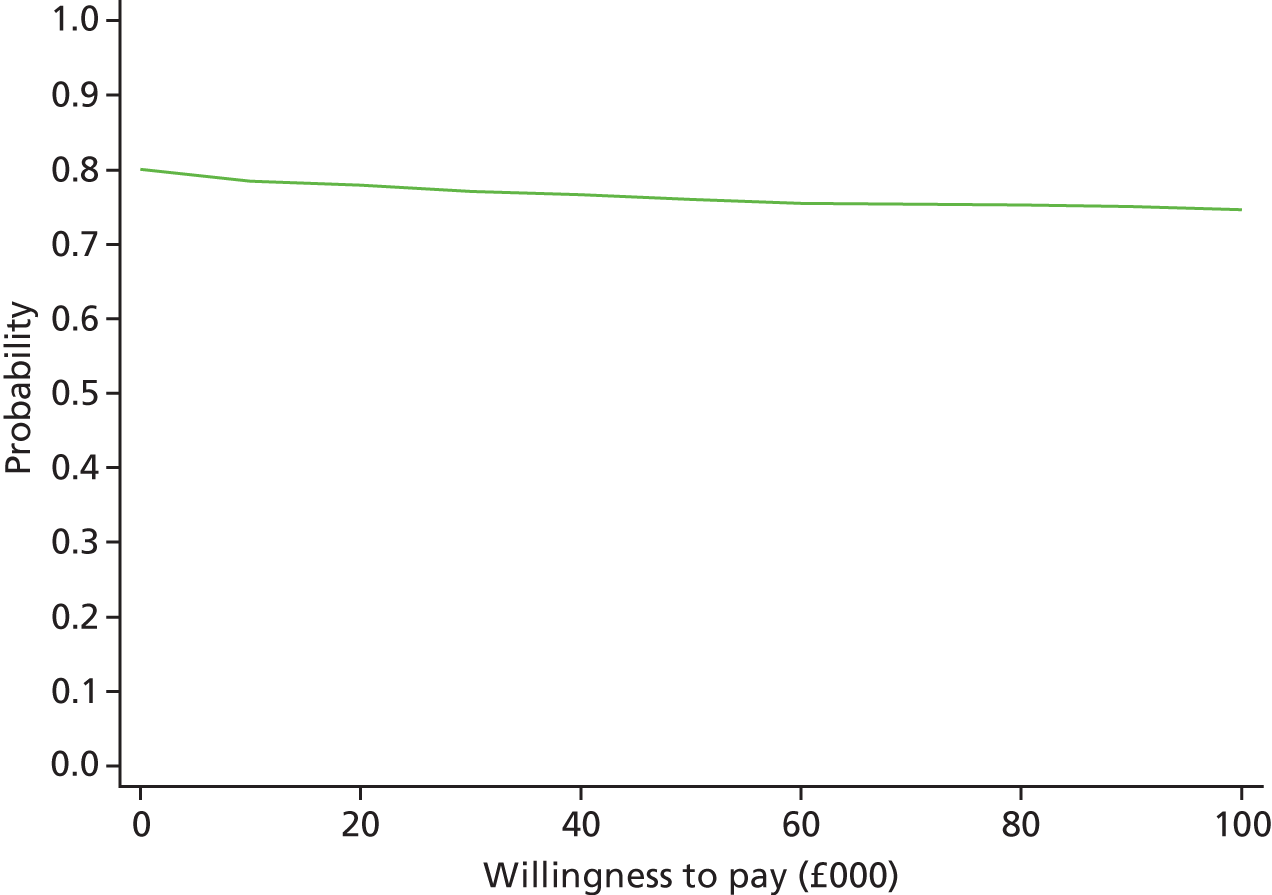

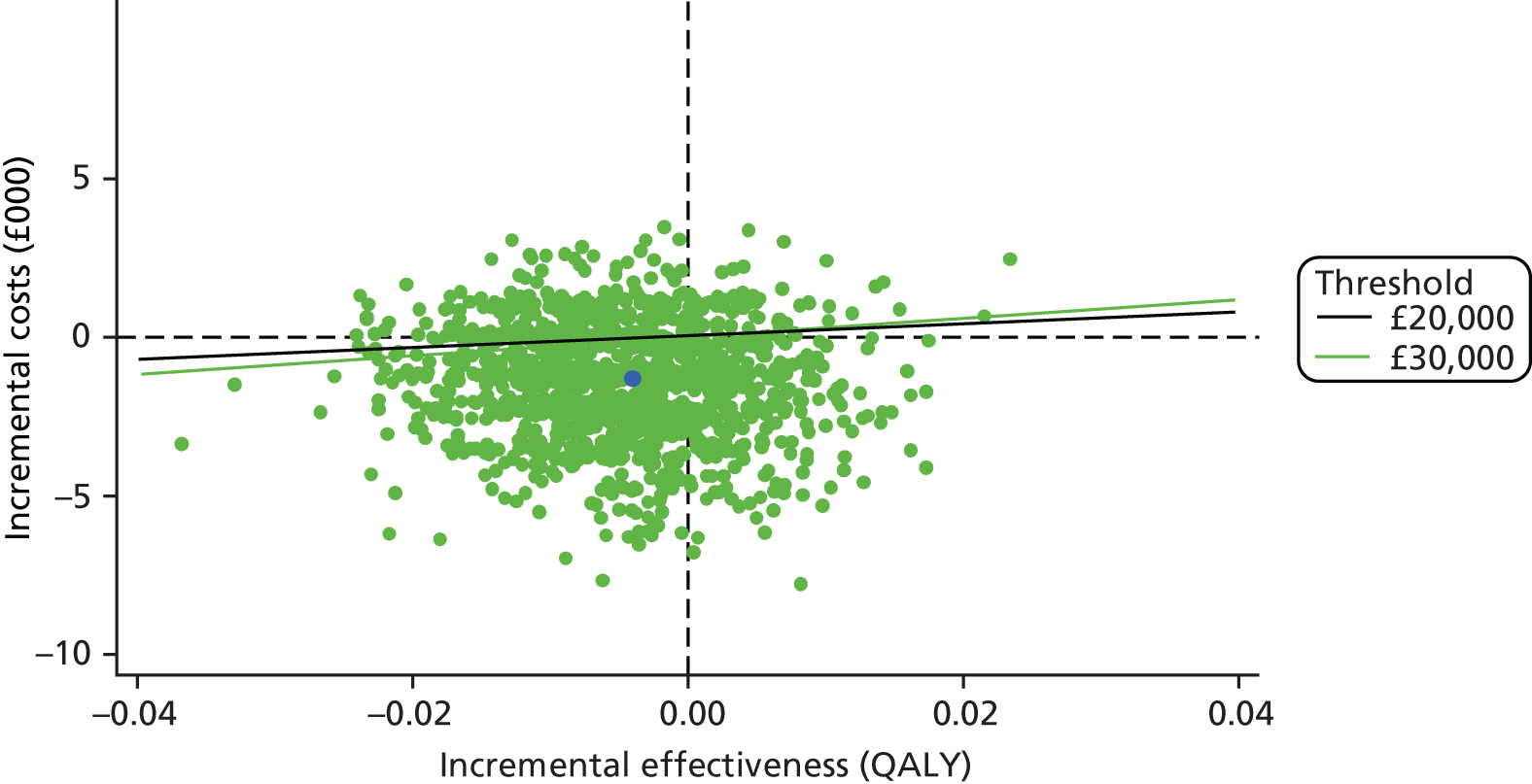

| Kent | 65 | 54 (83.1) | 57 (87.7) | 73 | 56 (76.7) | 58 (79.5) |