Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 14/153/01. The contractual start date was in October 2015. The final report began editorial review in November 2017 and was accepted for publication in October 2018. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Mike Clarke is currently a member of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment General Board. Mark McCann has attended meetings and participated in activities with the Scottish Parliament Cross Party Group on Drugs and Alcohol, the Scottish Drugs Forum, Independence from Drugs and Alcohol Scotland and Addaction Springburn. He received grants from the Medical Research Council, Scottish Government Chief Scientist Office and the NIHR Public Health Research programme during the conduct of this study.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Higgins et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background and introduction

The purpose of this study was to provide public health-related research evidence on novel psychoactive substances (NPSs). This chapter sets out the background and rationale for the study and the research questions that guided it.

This report is presented in eight chapters. The methodology of the study is presented in Chapter 2, followed by five results chapters, each detailing substantive findings as set out by our guiding research questions. In Chapter 8, we synthesise essential learning from all aspects of the study and present implications for policy and practice.

Research questions

The research project had 11 research questions:

-

What are the types and patterns of NPS use?

-

What are the developmental pathways into NPS use and are they different across types of NPSs?

-

Is there an association between NPS use and health and social outcomes?

-

What are the patterns of NPS use as they relate to the patterns of other substance use?

-

Why do individuals with similar sociodemographic profiles and illicit substance use differ in their decision to use or not use NPSs? What are the emerging factors that contribute to this decision to use or not use NPSs?

-

Does the drug-taking profile of a NPS user differ according to age, sex and social class and across traditional drug-using groups?

-

What are the harms associated with NPS use and how are these different from those of conventional illicit substances?

-

What are the appeals of NPSs and how are these the same as or different from those of traditional illicit substances?

-

What are the risks associated with NPS use and how are these different from those of traditional illicit substances?

-

What knowledge and experiences do NPS users have of treatment services for NPSs and how do these differ from their knowledge and experiences of services for other substances (licit and illicit)?

-

How can the research findings be integrated into a framework to inform existing service provision/policy formation and educational initiatives UK wide?

Background

The public health impact of substance misuse is a global challenge. 1,2 Contemporary data reflect an increasingly graduated and fractured drug scene. The old dichotomy between a relatively small number of highly problematic drug users and a more significant number of recreational and experimental users is changing to a more complex and dynamic picture,1,3 with NPSs contributing to this fragmentation. NPSs are synthetic alternatives to traditional illegal drugs. Compared with traditional drugs, NPSs are inexpensive, relatively easy to source and frequently more potent. There is no universally accepted legal definition of NPSs. The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC)2 uses the term and defines NPSs as:

[S]ubstances of abuse, either in a pure form or a preparation, that are not controlled by the 1961 Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs or the 1971 Convention on Psychotropic Substances, but which may pose a public health threat.

UNODC2

UNODC highlights that ‘new’ does not necessarily mean original formulations (several NPSs were first synthesised many decades ago) but substances that have recently become available on the market. 2

In the UK, the Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs (ACMD) defines NPSs as:

[P]sychoactive drugs which are not prohibited by the United Nations Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs or by the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971 and which people in the UK are seeking for intoxicant use.

ACMD4

The European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA) adopts a similar definition, although some substances that are controlled in the UK fall outside international control mechanisms, for example methoxetamine. 5

Over the past decade, first-, second- and third-generation NPSs have been increasingly referred to in policy and research documents6,7 and these substances have been appearing on the drugs market at an exceptional rate. By 2012, the number of NPSs outnumbered the total number of substances falling under international control. The overarching legal term ‘NPS’, with numerous substances grouped under this single heading, is now out of date and is of limited use when investigating differential patterns of use and harm. 8 Recognising the need for a more refined definition of NPSs, the EMCDDA subdivided the market into five categories:

-

‘legal highs’ – marketed at recreational users; could be purchased online and in headshops until 2016

-

research chemicals – marketed as being for scientific research purposes; sold readily online

-

food supplements – aimed at individuals seeking to enhance themselves physically or cognitively; available to buy online

-

designer drugs – manufactured illegally in laboratories and sold under the guise of illicit drugs [e.g. 3,4-methylenedioxy-methamphetamine (MDMA) and heroin]

-

medicines – sourced from patients or illegally purchased via the black drug market.

Novel psychoactive substances have been broadly categorised5,9 as ‘synthetic cannabinoid receptor agonists’ [e.g. JWH-018 (‘spice’)], ‘aminoindanes’ [e.g. 5,6-methylenedioxy-2-aminoindane (MDAI)], ‘synthetic cathinones’ (e.g. mephedrone), ‘tryptamines’ (e.g. 5-Meo-DPT), ‘ketamine- and phencyclidine-type substances’ (e.g. 4-MeO-PCP), ‘plant-based substances’ (e.g. khat), ‘piperazines’ (e.g. benzylpiperazine), ‘phenethylamines’ (e.g. Bromo-DragonFLY) and ‘other substances’ [e.g. dimethylamylamine (DMAA)]. 10

For this research, we too attempted to disentangle where possible the various NPSs (see Adley’s drugs wheel11 for further information).

Legislative context

Novel psychoactive substances present challenges for legislation and monitoring, researching and developing interventions. For many years in the UK under the usual system of drug control, individual drugs, or groups of drugs with similar chemical structures (‘generic definitions’), were placed under the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971,12 based on the assessment of likely harms to individuals and society. That system of drug control is a lengthy process, which involves evidence gathering and reviews undertaken by the ACMD. Based on this review, the ACMD makes a recommendation regarding whether or not to classify or schedule the drug, and what other approaches could be used (e.g. specific prevention, treatment and harm-reduction advice). In 2010, changes to this process were signalled when mephedrone, possibly the most commonly known NPS, was banned in circumstances that caused the ACMD and others to question if this decision was based on the best available evidence. 13 Shops and online retailers selling the drug labelled as plant food cleared their shelves prior to the ban. Since then, and because of the large increase in the number of NPSs identified,2 the UK Government decided that it needed new laws and approaches to NPSs. This resulted in the temporary class drug orders (TCDOs). These drug orders put substances/groups of substances under temporary control for up to 1 year after a rapid review. In 2014, an expert review was published detailing a new legislative approach to dealing with NPSs. Subsequently, a complete ban on ‘psychoactive’ products was introduced in May 2016; this approach met criticism from many experts. Prior to this, NPSs had been controlled for under the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971;12 however, it was not possible to continually update the legislative approach for classifying drugs at a pace matching their emergence onto the market14,15 and, therefore, a new approach was needed.

The Psychoactive Substances Act 2016 (PSA)16 defines a psychoactive substance as any substance that:

(a) is capable of producing a psychoactive effect in a person who consumes it, and (b) is not an exempted substance.

The PSA goes on to define a psychoactive effect as when a substance depresses or stimulates a person’s central nervous system and has an impact on the individual’s mental functioning or emotional state.

In passing the PSA, the UK Government adopted the policy approach implemented by the Government of Ireland, which introduced comparable legislation in 2010 called the Criminal Justice Psychoactive Substances Act 201017 in a context relevant to the present research.

The PSA focuses on penalising suppliers rather than consumers; indeed, those caught supplying NPSs could face a prison term of up to 7 years, and those being found in possession of NPSs for personal use are not criminalised. Nevertheless, many NPS users were highly critical of the legislation,18 as were other groups. 15 Particular concern was expressed over how a psychoactive effect was defined by the Home Office in the PSA.

The PSA definition is problematic given that any number of substances can fall within it, including flowers and incense. The ACMD highlighted this concern and produced an alternative version. They also warned that some form of revision would be needed to make the law enforceable. Furthermore, the association between the closure of headshops and reduction in use of NPSs is not supported by data from Ireland,3 where similar legislation has been in place for some time. As is the case in a prohibition context, it is likely that continued demand for NPSs will result in driving the substances underground, thus resulting in even less potential for quality control than existed pre legislative ban. This may lead to riskier patterns of sale and consumption, as again has happened in Ireland. 15

The EMCDDA’s analysis of the situation was that current practices needed to be continually modified if they were to address a drugs problem that was in a state of constant change. 19 In some European locations, including the UK, Ireland, Poland, Portugal and Austria, approaches to NPS control have been constructed on the basis of broad definitions of ‘psychoactivity’, with harmful outcomes not always being taken into consideration. 1–3

Any benefits, harms and unintended consequences, both short and long term, from the PSA and similar legislation will be evident only over a more extended period.

Market context

The marketing approach to NPSs was qualitatively different from that of other illegal drugs owing to the greater use of attractive packaging and branding. 20 According to Wallis,20 the effects of media attention on the NPS market are often counterproductive, leading to spikes in use. Interviews with key stakeholders (e.g. retailers, NPS innovators, enforcement professionals, policy-makers) suggested that the PSA was unlikely to affect the supply of NPSs through the internet/fast courier system. Reports in Northern Ireland after the legislation suggested that mephedrone availability was relatively unaffected, although drug purity had decreased. 21

Novel psychoactive substances also produced other innovations in the drug market. Shapiro5 noted that, serendipitously, the parallel growth of the internet was, for some, a very effective aid for producing and selling NPSs. On a global scale, users were able to interact and exchange knowledge about NPSs and their effects. In addition, it was evident that enterprising individuals had performed searches for patents relating to compounds that had been investigated by pharmaceutical companies but were no longer being pursued.

To avoid detection, encryption technology is reported to have been used when purchasing NPS drugs or their raw chemicals from Asia. 5 Retail order and shipment occurred from websites with payment through third parties [e.g. PayPal Holdings, Inc. (San Jose, CA, USA)]. Finally, the ‘dark web’ grew to house online black markets such as ‘Silk Road’; a high level of technical expertise was needed to access NPSs via this route using virtual currency (e.g. bitcoin). Despite NPSs being more readily available online, some evidence suggested that only a small proportion of NPS users obtain their drugs via online retailers. 22 Rather, NPS users often sourced from friends, dealers and headshops. Although they may not use the internet to purchase NPSs, many habitual internet users availed of the internet to research NPSs. O’Brien et al. 18 investigated the experiences of ‘cybernauts’ using an online survey (n = 183). Around 3 in 10 participants reported using NPSs within the previous week. Participants considered themselves to be knowledgeable consumers owing to their internet use; for example, the internet was the medium through which they gathered information about NPSs and, in turn, passed on their own experiences (e.g. harms experienced) to others.

Retailers have capitalised on the knowledge shared by these online communities and have even reported monitoring internet forums to gauge demand for different NPS types, adjusting their stock accordingly. 20 The relationship between NPSs and existing traditional markets is a highly complex one, and a temporal relationship between variations in the purity of traditional substances can be observed. 23 Other authors have documented the displacement effect of the various forms of NPSs. 24

Pharmacological context

From the pharmacological perspective, the level of innovation in the production of NPSs limits the knowledge of both the pharmacodynamics and the acute and chronic toxicity of these continually evolving substances. 25 Identifying individual substances bought via the internet or on the street is difficult. 26 Even when a new chemical is clearly and accurately identified, all too often there is little or no information on associated harms and suitable treatments. There is progress in studies aimed at assessing their pharmacology: individual pharmacodynamics and kinetics, toxicity profile, dependency risk and short- and longer-term threats to physical and mental well-being. 27,28

Furthermore, various NPSs are often ingested together or in conjunction with alcohol and/or other substances in an idiosyncratic way, adding uncertainties about the consequences of combined intake. 29 Synthetic cannabinoids (SCs) have also been examined in detail. 30

To assist in the identification of emergent NPSs, the Welsh Emerging Drugs and Identification of Novel Substances (WEDINOS) project was set up in September 2013. Prior to the blanket ban, results posted on submitted NPS samples have generated a reactive response, for example the invocation of procedures to also ban the next substance emerging from laboratories. Results from WEDINOS31 indicate how complicated the picture is, in that there is a cross-fertilisation between NPSs and other drugs leading to a more difficult screening and assessment process.

Against this backdrop of legislative, market and pharmacological challenges, we now examine the existing evidence base on the various NPSs as they relate to traditional drug use. This introduction is followed by a summary of available information on the assessment of NPS use in the light of potential interventions. Before we consider the extant literature, NPS contextual data (e.g. prevalence and death rates) are briefly summarised. A more detailed summary of NPS and other drug contextual data in UK regions is presented in Report Supplementary Material 1, Tables 31–38 and Figure 9.

Key messages from prevalence data

There is an incomplete picture of NPS use prevalence; nevertheless, available data indicate that NPS use is relatively low when compared with more frequently used illicit drugs (e.g. cannabis, powder cocaine, ecstasy), with NPS use tending to be higher in specific subgroups (SGs).

Data on general NPS use from nationally representative surveys are of course limited to recent years. In 2014/15, the prevalence of lifetime NPS use (mephedrone excluded) was 2% in Northern Ireland (Department of Health Northern Ireland)32 and Scotland (National Statistics Scotland)33 and 3% in England and Wales (Office for National Statistics). 34 There was a statistically significant reduction in the prevalence of NPS use in the previous year between 2010/11 and 2014/15 in two regions of Northern Ireland: South Eastern and Western Trusts (down by 1.4% and 1.1%, respectively, since 2010/11). 32 The estimate of the prevalence of lifetime NPS use for the UK from the European Commission22 survey was higher (10%) than in other UK national surveys, and was above the average prevalence rate for European countries (8%).

Data from UK misuse databases

The UK regional drug misuse databases provide an indication of recent drug use by problem users. Drug misuse databases in Northern Ireland and England/Wales report on a NPS category. In 2015/16 in Northern Ireland, 7% of service users with drug use problems reported NPS use [Northern Ireland Drug Misuse Database (NIDMD)]35 compared with 1.3% in England/Wales [National Drug Treatment Monitoring System (NDTMS)]. 36 A specific NPS category was not reported in Scotland [Scottish Drug Misuse Database (SDMD)]. In Northern Ireland, NPS use was much more frequently reported in the Western services than in any other areas. Weekly use was the most frequent form of use for those using NPSs, mephedrone, cocaine, speed, ecstasy and other stimulant drugs. The vast majority of users reported trying NPSs before the age of 25 years in Northern Ireland.

Deaths

In Northern Ireland, death by substances on death certificate statistics suggest that although deaths in which NPSs are implicated, are rare, they have become more common in recent years. 37 In 2015, deaths implicating NPSs were most frequent in Scotland (1.4 per 100,000),38 followed by Northern Ireland (0.9 per 100,000) and England/Wales (0.2 per 100,000). 39 In Scotland in 2015, the majority (77%) of the 74 deaths in which NPSs were implicated involved benzodiazepine NPS (e.g. etizolam). In research studies, deaths in which SCs, mephedrone and phenethylamines have been implicated have been reported. 40–44

Existing empirical evidence on novel psychoactive substances

Synchronous with the present study, Mdege et al. 45 were commissioned by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) to undertake an empirical and conceptual review of NPS to provide research recommendations. Focusing on the UK, their principal objective was to provide review evidence to be used in developing public health interventions targeting NPSs.

The study comprised a scoping review and narrative synthesis of evidence focusing on NPS use, associated harms and responses. Spanning the decade 2006–16, the authors examined Google (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA) and relevant websites and online drug forums, and contacted experts on NPSs. Their research included primary and secondary studies detailing relevant research or discussion of key research. They also developed a UK-focused conceptual framework detailing an evidence-based public health approach to NPS use.

Using a scoping review, Mdege et al. 45 identified 995 articles, the majority of which examined the health-related adverse effects of NPS use at the individual level. They highlighted that the expanding literature on the NPS phenomenon is primarily clustered around four key areas:

-

Surveys and surveillance studies.

-

Qualitative work that focuses on the harms associated with use.

-

A limited number of systematic reviews centred on harms.

-

Literature that seeks to evaluate policy responses to the NPS phenomenon. There are also clinical guidelines based on the evidence, such as those of the Novel Psychoactive Treatment UK Network (NEPTUNE). 46 They conclude that the literature is characterised by being early in its stage of development and lacking in data to directly inform an evidence-informed public health response to NPSs. 45

Regarding survey data, there are 29 identified studies that assessed NPS use prevalence in the UK. The authors usefully summarised the findings of the prevalence studies in tabular form. These included results from the Crime Survey England and Wales (CSEW), the Scottish Crime and Justice Survey (SCJS), the All Ireland Prevalence Study (AIPS) and a range of additional European surveys and school-based surveys. They also included a useful summary of systematic reviews uncovered by study name, study population, NPS type and methodological characteristics. In the UK, nationally representative prevalence surveys have focused largely on mephedrone, with data on other NPSs much less developed. More detailed data covering motivations and patterns of use tend to be restricted to a small number of qualitative studies.

Age and sex trends

The prevalences of lifetime NPS use in young people [defined as people aged 11–15 years (in England and Wales) and 13–15 years (in Scotland)] in England and Wales (2.5%)47 and Scotland (2.0%)48 are comparable. In England, NPS prevalence was 10 times higher among 15-year-olds than among 11-year-olds (5.0% vs. 0.5%, respectively). 47 Similarly, in Scotland, 1% of 13-year-olds and 4% of 15-year-olds reported NPS use. 48 Although NPS use was marginally higher among males than among females in the Scottish Schools and Adolescent Lifestyle and Substance Use Survey (SALSUS) (2% vs. 1%, respectively),48 this pattern was not evident in the NHS Digital survey47 nor in the survey by the European Commission. 22 With a broader definition of young people (e.g. people aged 16–24 or 15–34 years), NPS use was around two to three times (4–7%) higher in younger than older adults across all UK regions. Some variations were possibly attributable to the use of different definitions of young people. 32–34

At-risk populations

Studies specifically designed to measure NPS prevalence have not examined SGs other than in standard demographic groups (e.g. age, sex). Research has highlighted higher prevalence rates among specific populations than at the wider population level, including people with eating disorders,49 mental health inpatients,50,51 men who have sex with men (MSM),52 prisoners,53 the homeless54 and club attendees. 55 Although these prevalence rates may not give precise prevalence estimates for these specific groups, they do indicate that these groups are more likely to use NPSs. Among those with eating disorders, patients with a history of self-harm and bingeing/purging were more likely to report NPS use. 49 Given the high prevalence of eating disorders in females, this factor may play more of a role in female NPS use initiation. A study of mental health patients – individuals who were younger, male and had a criminal record – reported higher rates of use. 50 Evidence suggests that mephedrone (41%) is the most popular NPS among club attendees, whereas lifetime prevalence for the use of other substances was less frequent [e.g. methylone, 11%; methylenedioxypyrovalerone (MDPV), 2%]. 55 Almost all mephedrone users (94%) reported use in the previous year and most (80%) reported using NPSs within the previous month. In a sample of patients at two sexual health clinics, Thurtle et al. ’s52 study revealed that monthly use was low (1.6%) in the total sample and particularly low in 16- to 24-year-olds (0.3%). However, among HIV-positive MSM, Chung et al. ’s56 case review found that 24% reported lifetime mephedrone use. Bourne et al. 57 describe reports of MSM in London using mephedrone in combination with gamma-hydroxybutyrate (GHB)/gamma-butyrolactone (GBL), using these ‘chemsex’ drugs during sex, often involving groups and adventurous sexual activity (e.g. ano-brachial intercourse).

Motivations for use

A systematic review focusing on international surveys of SC use found that motives for use are often centred around perceptions that SCs are safer than other non-cannabinoid illicit drugs and that it is easier to avoid detection in drug tests while still enjoying a ‘cannabis-like’ high. 40 Within the UK portion of the Global Drug Survey sample, Winstock et al. 55 found that motivations for the use of methoxetamine, relative to those for ketamine, were centred around easier access, less damage to kidneys or bladder and a preference for the drug’s effects. Users of mephedrone often report pleasant effects of the drug, such as euphoria and a sense of well-being. 21,58 Another study focused on salvia; users of this NPS sometimes experienced pleasant hallucinogenic effects. 59 Motives for use do appear to vary by population; for example, among prisoners, the main reasons for using SCs were to evade drug detection, to help pass time and for relaxation. 53 Among the homeless, NPSs are often viewed as being a less costly substitute for alcohol and other illicit drugs. 54

Adverse effects

In contrast to the limited body of research on motivations for NPS use, there has been more focus on the harmful impact of NPS use, as revealed in the recent review by Mdege et al. 45 Systematic review evidence suggests that frequent side effects of NPS include psychotic symptoms, behavioural changes (e.g. aggression) and physiological effects such as changes in blood pressure, pulse and temperature. 60

The adverse effects are further summarised here according to substance type.

Synthetic cannabinoids

Several systematic reviews have explicitly focused on the adverse effects of artificial cathinones. 40,61–64 Numerous side effects of SCs have been reported by these reviews, including physical (e.g. hypertension, seizures, palpitations, chest pain, tremors) and neuropsychiatric (e.g. aggression, suicidal thoughts, anxiety and psychosis) effects. Although SC use can lead to hospitalisation, people hospitalised because of SC use are usually released within 24 hours,40 with typical treatment including intravenous fluids, benzodiazepines and oxygen. 40,41

However, for patients who have more severe side effects of SCs (e.g. acute kidney injury, psychosis), hospitalisation can be as long as 2 weeks. Interestingly, more than half of prisoners in a study53 reported that they thought that spice was a more hazardous substance than cannabis, and that it was ‘fairly’ or ‘very’ addictive; they also mentioned that high prices in prison had got them into debt.

Mephedrone

Two studies21,58 examining the effects of mephedrone reported side effects similar to those of SCs, such as nasal damage associated with snorting, and challenging ‘comedowns’. In the study by Brookman,58 a cyclical association between crime and mephedrone was evident; specifically, violence often happened during the ‘buzz’ or comedown phase, after which they had to resort to crime to further fund their habit. Concerningly, many mephedrone users reported becoming violent when using the substance,58 and having to use other drugs, such as diazepam or cannabis, to deal with the comedown effects. Those using mephedrone in conjunction with GHB/GBL for sexual purposes regularly reported a negative impact on their relationship. Other issues included concerns over sexual selfishness and damage to employment and career prospects. 57

Salvia

One study59 focused on the effects of salvia; interestingly, not all users reported feeling any effects or even inconsistent effects. Lack of impact may be due to the short half-life of the drug.

Phenethylamines

Two systematic reviews42,43 have synthesised the research on phenethylamines effects; common side effects included agitation, tachycardia and hypertension. In the Suzuki et al. 43 review of patient case reports, as many as 4 in 10 patients required admission to an intensive care unit.

Bath salts

For bath salts, systematic review evidence suggests that the comedown effects can be similar to and, in some cases, more intense than those of other stimulants. 61

Evidence on prevention and intervention

The literature provides a useful summary of the research on, among other things, prevalence, motivations for use and adverse effects. Notable, however, is the absence of a knowledge base for the efficacy of any prevention/interventions for NPS use. To date, evidence has focused on providing guidance and advice on possible referral pathways and highlighting probable interventions. This is framed according to the symptomology, identified patterns of use, NPS class and specialist groups, including MSM and young people. To our knowledge, there are at present no completed or ongoing methodologically rigorous experiential trials or structured research evaluations of the effectiveness of pharmacological and/or psychosocial interventions for NPS use, either as a standalone drug of choice or within the unplanned or adjunctive drug context. 65

Chapter summary

This chapter set out the research questions of the present study in the context of existing evidence on NPSs. To accomplish that goal, we provided definitions of NPSs and summarised the legislative, market and pharmacological contexts of our work. Existing literature on a range of areas as they relate to the NPS phenomena was reviewed. This included reflections on current responses concerning interventions for the various NPSs as well as NPS vis-à-vis other substance use. Related to that effort, it became evident that there is a resounding need for more evidence within this area, which will help to articulate a clearer understanding of the complex nature of NPSs. The umbrella term ‘NPS’, used for legal purposes with multiple drugs grouped under this single heading, lacks utility for the practical purpose of exploring the markedly differential trajectories of use and harm. We seek in our findings to draw out a level of nuance that contributes to our grasp of the different categories of NPSs and their use by participants. In the research presented in the following chapters, we posit findings that can substantially contribute to the knowledge base on the use of NPSs, which constitute an ongoing public health challenge. We now present the methodology for the study, followed by our four substantive findings chapters.

Chapter 2 Methods

Design

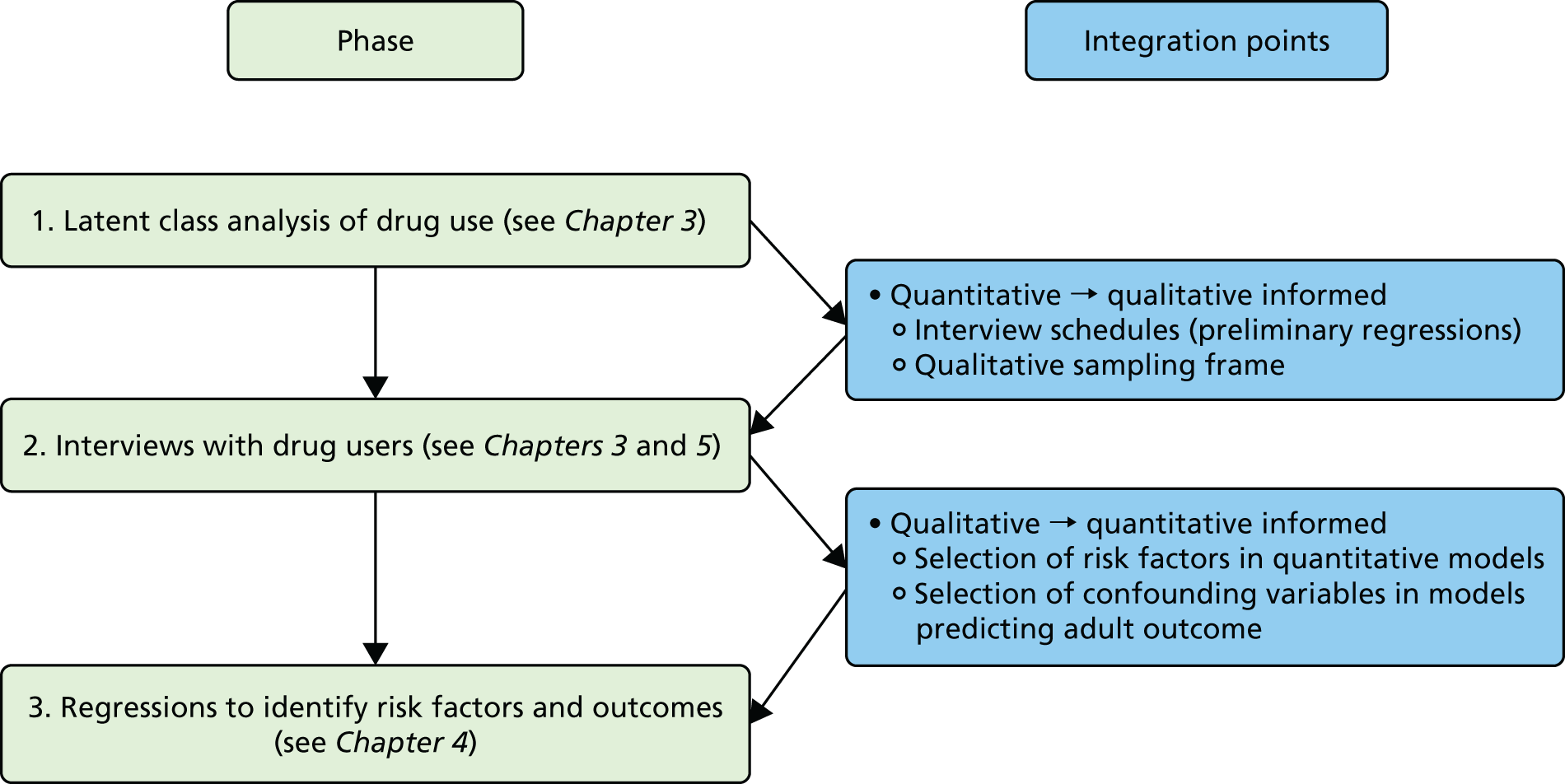

The study used a three-phase mixed-methods design, as summarised in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Study design.

Phase 1 was a quantitative phase involving secondary data analysis of the Belfast Youth Development Study (BYDS) (see Secondary data source: Belfast Youth Development Study). A latent class analysis (LCA) using the 2039 BYDS participants who completed the ‘ever used’ drug questions at wave 7 (participants aged 21 years) was conducted to identify categories of drug use (including NPS use).

Phase 2 involved extensive qualitative analysis via narrative interviews of participants – sampled from BYDS, drug and alcohol service settings and prison – to explore trajectories of NPS use. NPS use did not emerge as a specific isolated class of drug use in phase 1 (see Chapter 3), which meant that robust conclusions could not be drawn about NPS use as distinct from other substance use through the quantitative analysis. By contrast, in phase 2 the narrative approach allowed rich data related specifically to NPS use to be obtained, allowing for highly detailed analysis of NPS use types. In addition, general risk factors related to polydrug use were identified.

In phase 3, the final quantitative phase, using the BYDS data set, the generalisability of the shared risk factor part of the model was tested, using the manual three-step approach66 to examine risk factors associated with latent class membership. In addition, adult outcomes (e.g. education, employment, health) associated with drug use were examined using weighted regressions. All analyses in this phase used multiple imputation to deal with missing data; extensive sensitivity tests were used to assess the quality of the multiple imputation models. Several integration analyses were built into the design to maximise the utility of the sequential mixed-methods design. Specifically, by integrating quantitative material with qualitative information, this allowed emerging findings to be further explored and cross-validated and later-phase methodologies to be refined.

Integration point 1

Following the completion of phase 1, the derived latent classes were used to inform a sampling frame for the qualitative analysis. This sampling frame was designed to allow the selection of participants from four groups who varied in terms of their NPS use pattern. The four sampling groups were (1) alcohol, (2) alcohol and tobacco (AT), (3) alcohol, tobacco and cannabis (ATC) and (4) polydrug. These specific groups were designed to help distinguish between factors related to NPS use and other drug use. In addition, preliminary regression analyses ran concurrent to qualitative data collection and identified key risk factors of drug use to be focused on in the phase 2 narrative interviews.

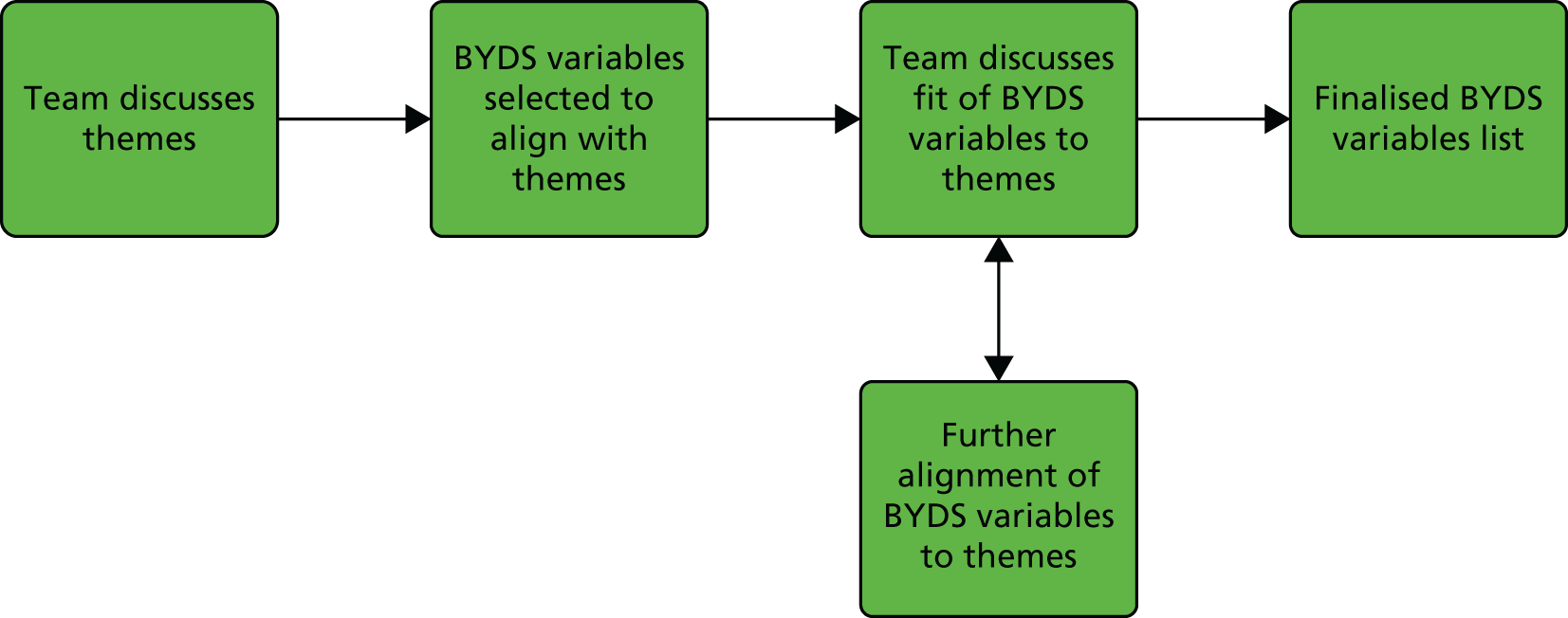

Integration point 2

The qualitative and quantitative team members selected variables from the BYDS longitudinal data sets to use in the phase 3 quantitative models assessing general risk factors and outcomes associated with drug use. Potential risk factors with the highest node frequencies were selected to be included in the quantitative models; subsequently, a process of aligning these risk factors with the BYDS variables was initiated. This was a dynamic and iterative process that continued until the team were content that optimal alignment between the risk factors and BYDS variables had been achieved.

Specific methodological details of each study phase are detailed in their respective results chapters.

Patient and public involvement

A professional liaison group (PLG) comprising key individuals from government, statutory sectors and community sectors and service users was formed. In addition, an international scientific advisory group (SAG) with membership from a range of key institutions in academia was set up. These groups were consulted at strategic points throughout the project and played an active role in the development of the project and interpretation of findings. For membership, see Acknowledgements. The research team also had regular contact with a local drug advocacy group [Belfast Experts by Experience (BEBE)]. This group provided valuable input at various stages throughout the study.

Secondary data source: Belfast Youth Development Study

This study used data from the BYDS, a longitudinal study of substance use during adolescence. The participants were young people who attended the target school year in post-primary schools in three locations across Northern Ireland. Schools were located in the Belfast conurbation, Ballymena and Downpatrick. The two townlands, Ballymena and Downpatrick, included rural catchment areas. The first data-collection wave took place in spring 2001, during the second part of the 2000–1 academic year; all pupils attending school year 8 in the schools that were taking part were invited to participate in the study. Parental consent was obtained by sending opt-out letters detailing the study for parents to return if they did not want their child to take part. In the following year (2002), data collection was repeated with the same methods for all pupils attending the successive school year 9 in participating schools. Data collection was repeated yearly until 2005 or school year 12 (participants aged 15–16 years).

The sampling strategy involved surveying all pupils in participating institutions from the targeted year group; therefore, cohort members entered and departed the study as they moved to or from participating schools. A number of schools participated in industrial action in years 4 and 5, and this led to lower completion rates in those years. Two further sweeps were carried out, one between the years 2006 and 2007; at this stage, some cohort members had left school, therefore the sampling strategy was adjusted to survey all participants for whom valid contact details had been provided. In addition, a number of schools and other educational institutions (including further education colleges and government training programmes, which were anticipated as destinations for school leavers from the original BYDS cohort) were invited to take part, and all pupils in these institutions were also surveyed. A seventh sweep of data collection was conducted between 2010 and 2011: all cohort members for whom contact details were available (n > 4000) were invited to participate through letters, e-mails, text messages or face-to-face contact. Cohort members were aged about 21 years at this stage. For more information on the BYDS, see Higgins et al. 67 and the Queen’s University Belfast (QUB) project webpage [www.qub.ac.uk/research-centres/darn/Projects (accessed 14 May 2019)].

The sample was further supplemented to include substance users recruited from carefully chosen sites (prisons, sexual health clinics and statutory and voluntary drug and alcohol services). The rationale for generating a further supplementary qualitative sample was threefold:

-

Elicit the most contemporary data available on the NPS phenomena (post PSA) and in the light of its fast-paced nature.

-

Maximise geographical coverage.

-

Seek locations with the potential for broad categories of user (e.g. prison, high-risk/complex users). This approach allowed us to capture a number of BYDS participants who were recorded in our data set as serving time in prison. We considered this expansion to cover prisons necessary as (1) our ongoing secondary data analysis showed a link between delinquency/criminality and polydrug use, (2) those in prison are a marginalised group who may not have engaged well with traditional drug and alcohol services, (3) the drivers of NPS use in prison are often unique to that environment (e.g. to avoid failing mandatory drug tests) and (4) our patient and public involvement (PPI) group discussions had indicated that the prison estate transcends geographical variation, thus maximising the opportunity to investigate the range in variations in types of NPSs. 40 Expanding our sample to include statutory and voluntary drug and alcohol services/sexual health clinics allowed us to broaden coverage to include high-risk, complex current users, who were uncommon in the BYDS sample.

The nature and extent of NPS use within the community derived from the BYDS sample, when complemented by knowledge gained from the prison estate, sexual health clinics and drug and alcohol services, provides a more robust and detailed evidence base to inform public health interventions. For this reason, the achieved sample was treated in a composite way. However, where relevant, our use of ‘setting codes’ in our analysis (see Analysis framework) was utilised to allow us to differentiate where experience was different according to site/setting.

Sample recruitment for the qualitative phase

The BYDS and supplementary sample participants were invited to take part in a narrative interview (see Belfast Youth Development Study sample and Supplementary sample for more detail on method) with two members of the research team, either on QUB premises or at a location more convenient to the participant (e.g. at a local community centre). The recruitment strategies for the BYDS, supplementary and prison samples were as follows.

Belfast Youth Development Study sample

Recruitment of BYDS participants commenced in March 2016. The sampling framework for the recruitment of BYDS participants was informed by the LCA of the BYDS data. Specifically, four groups were derived to take account of patterns of drug use as revealed by the LCA and to allow for detailed and controlled exploration of NPS use experiences. The four sampling groups were (1) alcohol; (2) alcohol, tobacco; (3) alcohol, tobacco, cannabis; and (4) polydrug. These groups were recontacted for their participation by two members of the team. Names and contact details of potential participants were provided by the study statistician in batches of 80 (20 from each of the four groups). Those responsible for recontacting were blinded to group status until each interview was completed. In previous BYDS surveys, young people were asked to provide their address, mobile phone number, house number and e-mail address. For some participants, all of this information was available; for others, partial information was available; and, for some, no information was provided from the last sweep. In the first instance, participant information sheets were posted to their home address and a week later each person was contacted by telephone. The recruitment process was designed to be as thorough as possible. Attempts were made to contact each potential participant by telephone on up to three occasions, over three different days and at three different times (i.e. morning, afternoon and evening). All details from call attempts and the result of any contact were recorded. For example, some phone numbers no longer worked, some young people were living abroad and some young people had moved house. On occasion, we were able to obtain new contact details from family members. In total, 25 participants were recruited from the BYDS.

The 25 participants recruited from the BYDS comprised 14 females and 11 males and all were aged 27–28 years at the time of interview. The majority were from the Greater Belfast area.

Supplementary sample

The process of recruiting individuals from the supplementary sample began in May 2016. With the help and guidance of local collaborators from the five Health and Social Care Trust areas, the research team compiled a database of statutory and voluntary drug and alcohol services as well as sexual health clinics across Northern Ireland. Contact with stakeholders was initiated with a phone call and followed up with an e-mail as well as postal delivery of study documentation (e.g. study leaflets/posters and information sheets). All but one service agreed to display posters to facilitate recruitment to the study. At this time, a study mobile phone was in use, and this proved beneficial in terms of recruitment for those in contact with drug and alcohol services, particularly in relation to the timing of calls but also in terms of flexibility regarding method of communication. We found that some respondents did not answer the phone to confirm interview attendance the day before the interview but did respond to a text message. The research team aimed to be as flexible as possible in relation to accommodating interviews for those in contact with drug and alcohol services while ensuring the safety of participants and the research team. The majority of interviews, particularly for those participants living in the Greater Belfast area, took place in an office at QUB; however, the research team did travel to community centres/public spaces closer to participants on request. It was necessary to monitor the number of interviews with participants recruited from specific services and also pay attention to demographics of the supplementary sample. Participants from this sample reported seeing the poster advertised in general practice surgeries, sheltered accommodation, hostels and youth drug and alcohol services and receiving information passed on by drug outreach workers. Follow-up contact was made with each service from which there was no uptake to ensure that posters were visibly displayed and confirm that lack of uptake was attributed to lack of interest as opposed to absent study information. Despite continued efforts, there was no uptake from sexual health clinics. The supplementary sample included a total of 36 participants (two participants participated in the interviews but were withdrawn and the interviews terminated once it became apparent that each was intoxicated). The majority of those recruited through services were male (n = 26). Participants’ ages ranged from 16 to 56 years, with the majority aged between 16 and 20 years.

Prison sample

In August 2016, the team was awarded additional resources to extend the study to include a sample from the three Her Majesty’s Prison (HMP) sites in Northern Ireland. This extension added value to the study and enabled us to learn more about NPS phenomena. Those in prison present as an even more marginalised group, some of whom will not have accessed/engaged well with traditional drug and alcohol services. Access to the three locations in the prison estate was granted separately by the governor in each setting. We secured the co-operation of the local drug and alcohol support service Alcohol and Drugs: Empowering People through Therapy (AD:EPT), which operates throughout all locations, to assist with study recruitment and arrangements for interviews. Recruitment strategies operated in broadly similar ways as the current study. Study recruitment posters were placed in communal areas of the prison and potential participants expressed their interest in taking part to the AD:EPT team. Recruitment posters outlined that researchers would be speaking to individuals who had ever used NPSs, thereby alleviating concerns around disclosure of present use by virtue of participation. AD:EPT staff would issue the study participant information sheet and co-ordinate arrangements with those who agreed to participate.

Total

In total, we completed 84 highly detailed life course narrative interviews across the sample sites:

-

BYDS sample (n = 25)

-

service sample (n = 34)

-

prison sample (n = 25)

-

site 1 (n = 15)

-

site 2 (n = 8)

-

site 3 (n = 2)

-

-

total (n = 84).

Life course perspective

The life course perspective, an effective methodological approach, was used to examine the trajectory of each participant’s drug taking. This affords the opportunity to understand the individual circumstances of respondents, as their trajectories can often be non-linear and highly varied. Importantly, it permits the location of drug use within the overall context of the participant’s life, that is, their experiences are about much more than the drugs they use. Risk and protective factors were used as a shared theoretical lens for the quantitative and qualitative data.

Loeber et al. 68 proposed that the presence of protective factors can predict low probability of substance use and other adverse outcomes. Longitudinal and other studies have identified a number of well-established individual, family, school and community risk factors that are associated with alcohol and drug use throughout the life course. 69–73 At an individual level, risk factors include attitudinal, biological, cognitive, developmental, personality, pharmacological and social factors. 74 For example, cognitive risk factors for substance use include a lack of knowledge about the risks of substance use as well as the viewpoint that substance use is ‘normal’ and that most people are substance users. Resilience may interact with such risk factors in a positive way by minimising their effects. 71 According to the self-medication hypothesis, effective regulation performs a key role in development of substance use. 75 Psychological characteristics related to substance use include low self-esteem, lack of assertiveness and poor self-control of behaviour. In addition, it is clear that there is a positive relationship between the importance of pharmacological risk factors and the frequency and quantity of substance use by an individual. As with the effects of traditional licit drugs use, the effects of NPS use are likely to vary owing to individuals’ neurochemical reactivity to drugs, putting some individuals at a considerably greater risk.

A number of factors at the level of the family are important in relation to attitudes towards substance use and behaviour. Genetics have a part to play in terms of the development of substance use disorders, social learning is crucial in terms of modelling behaviour and attitudes towards substance use, and parenting practices can be influential in terms of parenting style and family environment. In the same vein, family-level factors can serve in a protective capacity in preventing adolescent substance use, particularly through the use of parenting practices that centre round open communication, boundary setting, monitoring and nurturing. 73,76–78 Finally, at the school and community level, the degree to which an adolescent bonds with school and community are associated with substance use. 78–80 Students who are not engaged with school, and perform poorly academically, are more likely to use substances. Adolescents who feel isolated from or unsafe in their communities are more likely to use substances.

This was the perspective taken within the BYDS, and statistical data were utilised to model pathways in and out of substance use within the context of a wide range of variables at individual, family, school and community levels (see Higgins et al. 67), all underpinned by an integrated theoretical framework based on the risk and protective factors noted. So, too, is this conceptualisation evident in the life course perspective central to the qualitative narrative interviews conducted. In these interviews, we were able to focus on the individual’s substance use and their individual characteristics and agency not only at a single point in time but in the broader contexts of their family, school life and the community in which they lived. This life course approach allows for consideration of past episodes and future projections. In using this technique, we had capacity to identify moments of disruption, critical events or turning points that were important to individual’s drug careers. The ideas of a crossroads, bifurcation or ‘point of no return’ are constant in these biographical narratives, which are detailed further in subsequent chapters.

Narrative interviews

A narrative interview format was selected as optimal for accommodating a life course perspective to a participants’ substance use trajectory. The narrative interview is designed to encourage the participant to recount a significant event or period, in the wider context of their life history, and reconstruct the story from their own perspective. 81 The four stages of the narrative interview that we adopted were (1) substance use initiation, (2) main narration, (3) questioning phase and (4) concluding talk. 81

Interviews were completed with 84 participants and these were conducted in a dyad format (two interviewers per subject). The two-interviewer format has been utilised in circumstances where an interpreter is required or a cultural need is identified. In our case the rationale was twofold; from a pragmatic perspective the narrative method elicits significant amounts of information. Some narrative and/or non-narrative questions arose from what was said in the first interview. Given (1) the characteristics of the participants in the current study – a vulnerable population harder to reach and engage – and (2) the restrictions around access to some of the interview venues (e.g. prison), a decision was taken that in one sitting both interviewers could perform this ‘subsession’ function and gather as much detailed information as possible. This method was first trialled in our pilot and feedback was provided. The highly positive and detailed responses from participants, accompanied by endorsements of the method by our various gatekeepers, resulted in us adopting this method for all interviews. The method also successfully mitigated many of the issues that are presented by a lone-researcher format. The narrative interview was supplemented by a structured set of questions specifically relating to NPSs (see Appendix 1).

We were aware that ‘narratives are interactional accomplishments, not communicatively neutral artefacts’. 82 In recognition of this, we ensured rigour in analysing the data generated, attended to important issues of reflexivity and clearly explicated our overall method as detailed throughout. Shortly after conducting the interviews, the audio recordings and interview notes were reviewed. This information was used to document a basic memo for each participant. The accuracy of all transcripts was assessed against the audio recording and corrections were made where appropriate. Transcripts were analysed manually, as well as using NVivo 11 (QSR International, Warrington, UK) to support data organisation, coding, memo recording, notation of emerging themes, query running, etc. Structure was provided to the narratives by considering the data within the framework of risk and protective factors at individual, family, school and community levels (see Chapter 3 for further details).

Analysis framework

Our work required an integrated analytic approach, which necessitated both a deductive organising framework for code types (informed by our research questions and the quantitative findings) and a means to inductively develop codes. Previous researchers identified various code types. 83,84 Bradley et al. 85 documented an approach to data analysis that applied the principles of inductive reasoning while also employing predetermined code types to guide their data analysis and interpretation. These included (1) identifying key concept domains and essential dimensions of these concept domains, (2) relationship codes (identifying links between other concepts coded with conceptual codes), (3) participant perspective codes, which identify if the participant is positive, negative or indifferent about a particular experience or elements of an experience (e.g. a certain drug), (4) basic participant characteristic codes and (5) setting codes (basic information on specific sites).

In summary, Bradley et al. 85 posit that conceptual, relationship, perspective, participant characteristic and setting codes collectively express a structure appropriate for generation of three things: (1) taxonomy, (2) themes and (3) theory. They suggest that conceptual codes and subcodes facilitate the development of broad taxonomies. Relationship and perspective codes facilitate the development of themes and theory. Intersectional analyses with data coded for participant characteristics and setting codes can facilitate comparative analyses. We utilised a similar approach, which allowed us to generate the four-group taxonomy while also teasing out important themes and theory through our analysis.

Taxonomy development

The team utilised the five-code-type framework outlined in Analysis framework. Using the concurrent coding process across four team members, basic participant characteristic codes and setting codes (basic information on specific sites) were constructed and cross-checked across the team members. Characteristic codes included participants’ age, sex, relationship status, basic profile of drug use (ever use of traditional substances) and ever use of NPSs. Setting codes differentiated between samples (e.g. BYDS participants, those recruited from drug and alcohol services and those in prison). Setting codes also served to contextualise participants’ past and present environments and physical (e.g. growing up in care/varied familial structure), geographical (e.g. urban/rural and areas of social deprivation) and cultural (e.g. attitudes towards drug taking, normalised behaviour within peer and community setting) contexts.

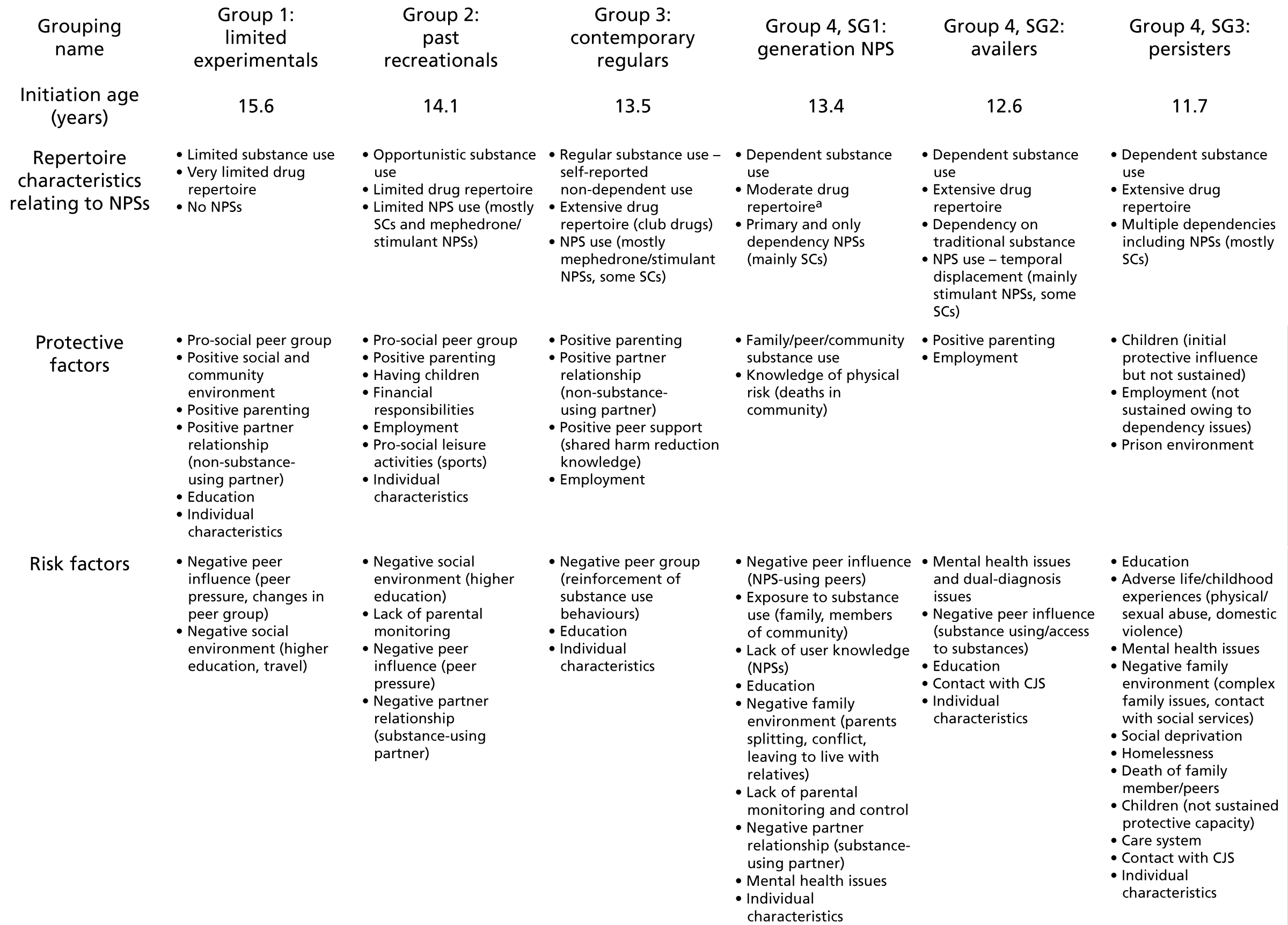

After several checks and refinements, it was evident that in terms of ‘conceptual codes’ there was a range of factors driving groupings of certain respondents together. These broad groupings clearly dominated the data and affected how other subcodes and types of codes (e.g. relationship and perspective codes) operated in these groupings. After several team-wide assessments of the codes, we used them to construct a four-group taxonomy. A taxonomy is a system for classifying multifaceted, complex phenomena according to common conceptual domains and dimensions. A common language or taxonomy that distils complex information about groups of individuals into key components is paramount.

Our taxonomy identified key domains that were broad in nature. These included broad-based risk and protective factors at individual, family and community levels (guided also by quantitative analysis), detailed substance use repertoire and location of NPS in that context, patterns of use, primary motivations for substances used and critical incidents that resulted in either desistance or increased use. These conceptual codes defined key domains that characterised, for example, how the phenomenon of use in a ‘limited experimental’ way/‘contemporary regular’ way took shape, and differentiated them from one another. Conceptual subcodes helped to further define common dimensions in those key domains. One example was age as it interacted with market trends and availability; younger participants obviously reported greater exposure and access to NPSs during adolescence (with some initiating with NPSs), whereas older participants recounted early experiences with traditional drugs.

Key domains were also examined alongside multiple code types. For example, participant perspective was explored in conjunction with reported risk and protective factors from early years to present day (participant characteristics and setting codes) and relationships between exposure to risk, perception of risk and patterns of drug use/risk behaviour were noted. Participant perspective codes were also used, in terms of pleasure seeking as linked with certain taxonomy grouping (i.e. past recreationals and contemporary regulars). Furthermore, although persisters viewed severe intoxication from SCs as a positive side effect, contemporary regulars perceived these effects as highly negative.

Bradley et al. 85 noted that within each dimension there may be further subdimensions depending on the complexity of the inquiry. In our case, this meant further subdividing group 4, as detailed below. In essence, our taxonomy set out to describe a discrete set of axes or domains that characterised the multifaceted phenomena of NPS use. This was based on a conceptualisation that, over and above repertoire of drugs used, sex and so on, there was an overriding conceptual basis to why these taxonomy groupings were distinctive.

Intersectional analyses with data coded for participant characteristics and setting codes facilitated our comparative analyses as we finalised our coding framework. Biographical information on participants was reinforced by the use of our quantitative and qualitative data.

In the current study, we were keen to avoid simply pasting together data of two types; rather, we aimed to devise a system of data collection and analysis that followed a certain methodological logic, and one that met theoretical requirements, as dictated by the BYDS analysis, as outlined in Figure 1. A comparison of preliminary and emergent codes was back-coded to early transcripts to ensure coding consistency. This process was of considerable duration and the coding structure was considered finalised only at the point of theoretical saturation. 86–88 This is the point at which no new concepts emerge from reviewing of successive data from participants. Theoretical saturation took time to accomplish owing to diversity in our sample in terms of participant characteristics, perspectives and settings. Interviews ceased only when we were confident that data represented various NPSs from the perspective of the individual and reflected the multifaceted role that certain NPSs, and other substances, played in participants’ lives at different points in time.

The finalised code structure was then applied to the data delineated by taxonomy group and this approach (i.e. the five types of code) allowed us to generate themes by which to further analyse and facilitate theory development. The team met as a group to review any discrepancies (quantitative and qualitative) and resolved minor differences by negotiated consensus.

Themes evolved not only from the conceptual codes and subcodes, as in the case of our taxonomy group, but also from the relationship codes, which tagged data that linked concepts to each other. We recorded such linkages carefully within NVivo. We were able to conduct a comparative analysis of concepts coded in different taxonomy groups that were related to some extent by our basic setting codes. Through this comparison we attempted to assess whether or not certain concepts, relationships among concepts, or positive/negative perspectives were more apparent (as noted in the examples above) or were experienced/reported differently between taxonomy groups. This is evident in Chapters 3–7, where there is some exploration of setting codes, notably those in homeless accommodation or in prison settings.

Theory emphasises the nature of correlative or causal relationships and is used to explain phenomena. 89 We both deductively and inductively used theory within our study. For example, in our data, early-onset substance use was not linked to polydrug use trajectories after controlling for other influential variables. We attempted to be highly consistent in cataloguing relationships among concepts, using the constant comparison method to generate inductively conceptual codes and subcodes as well as relationship codes. Through its theoretical development, our study confirms much existing theoretical and empirical research but also suggests some new paradigms for understanding NPS as a deconstructed phenomenon.

Quantitative procedures

Latent class analysis

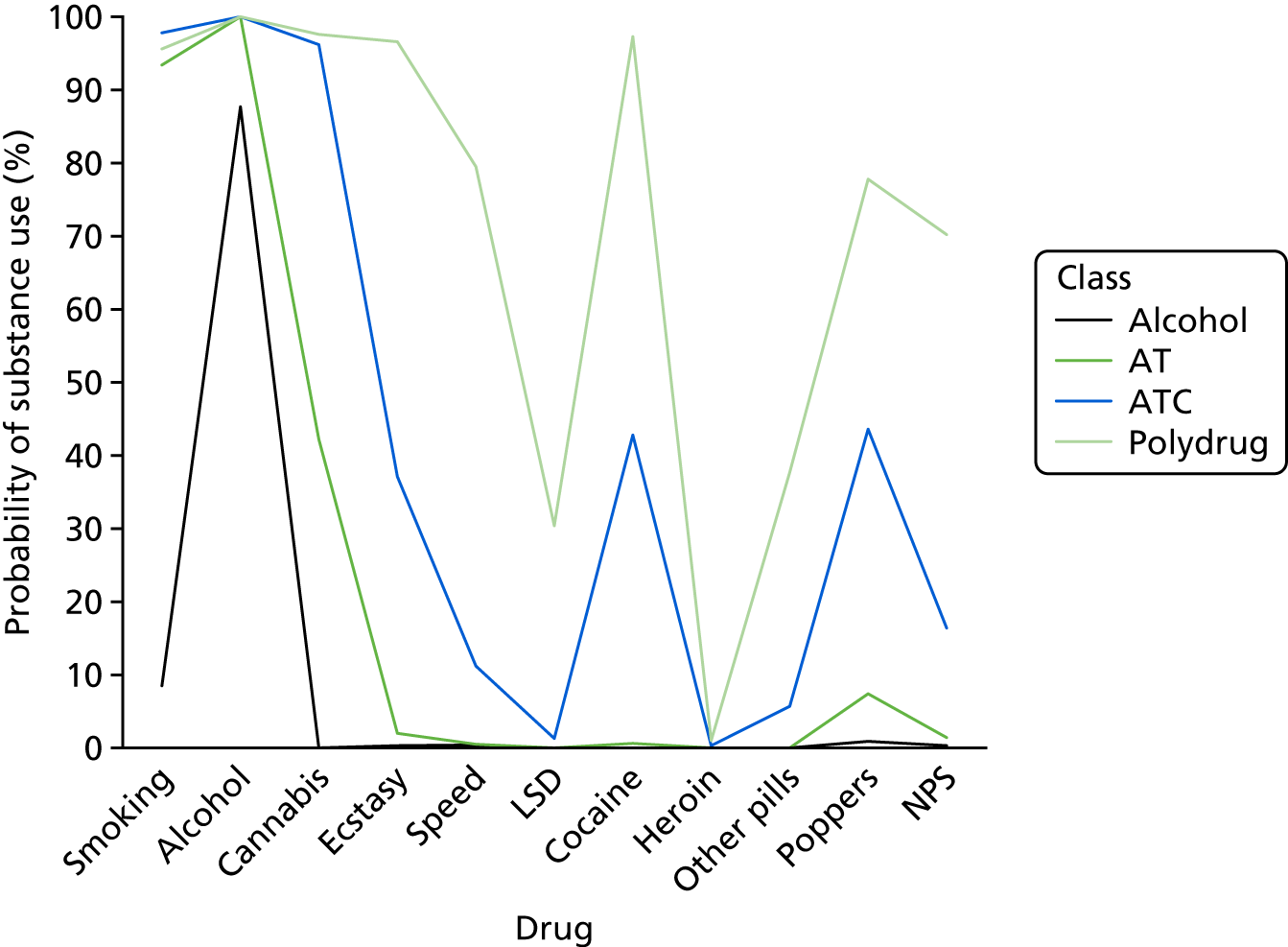

We conducted a LCA using data from the BYDS to identify the underlying patterns (or classes) of substance use based on student responses to questions on ‘ever use’ of the drug variables included in our data. These included alcohol, tobacco, cannabis, ecstasy, speed, lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), cocaine, heroin, other pills, poppers and NPSs. The models were run in Mplus version 7 (Muthén & Muthén, Los Angeles, CA, USA) using maximum likelihood with 100 iterations and randomly generated start values. Model fit was assessed using Akaike information criterion (AIC), Bayesian information criterion (BIC), sample-size-adjusted Bayesian information criterion (ssaBIC), entropy, the Lo–Mendell–Rubin likelihood ratio test (LMR) and bootstrapped Lo–Mendell–Rubin likelihood ratio test (BLMR). Models with two to six classes were run and fit statistics for these models were compared. Subsequently, model estimates for both three- and four-class models were inspected, and the four-class solution was chosen as this provided more clearly distinguishable classes. A polydrug class emerged that was also characterised by NPS use (n = 214). The other three classes were ATC (n = 367), AT (n = 926) and alcohol (n = 532).

Examining risk factors and outcomes associated with drug use

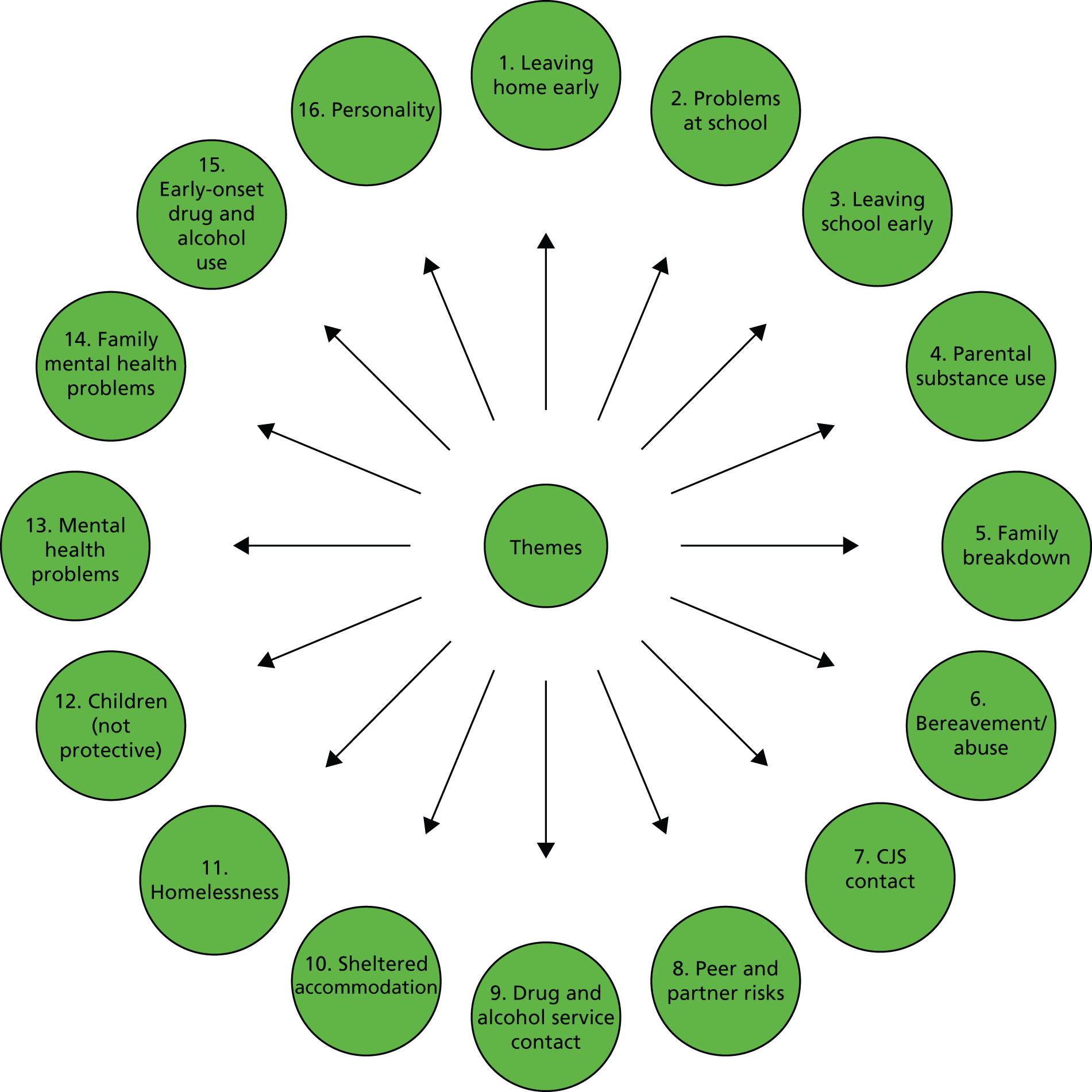

The qualitative analysis, in conjunction with the professional advisory group (PAG) discussions, identified 16 risk factor themes associated with more problematic drug use. These themes were leaving home early, problems at school, leaving school early, parental substance use, family breakdown, bereavement/abuse, criminal justice system (CJS) contact, peer and partner risks, drug and alcohol service contact, sheltered accommodation, homelessness, kids, mental health problems, family mental health problems, early-onset drug and alcohol use, and personality. The themes identified from the qualitative analysis were mapped onto the BYDS variables using an alignment process. During this alignment process, the team identified BYDS variables that mapped onto the risk factor themes, checked the quality of alignment with the qualitative researchers and revised where appropriate.

Next, a series of models were run that looked at risk factors and outcomes associated with drug class. In these models, multiple imputation was used to handle missing data and extensive sensitivity testing was used to assess the extent to which our results change if the missing at random (MAR) assumption is incorrect by adjusting imputed data set estimates for the outcome variables upwards by 1–20% above that predicted by the imputation model. In the risk factors models, BYDS risk factor variables, as identified in the alignment process, were entered into LCAs at stage three of the manual three-step approach;66 in these models, polydrug was the reference class. Longitudinal risk factor variables were first modelled via growth curve analysis using robust maximum likelihood (MLR) estimation to derive initial status and slope parameters. Fit indices for all models indicated good fit. These intercept and slope parameters, instead of the original variables, were used in the analyses.

Subsequently, in the outcome models, adult outcomes associated with latent class membership were examined via weighted regression models. The outcomes examined included key domains such as mental health, drug and alcohol use, delinquency, education and employment. In these models, the risk factors that emerged as significant in the previous analyses were entered into the models as confounding variables. A full and detailed description of methods used in the quantitative models is included in Chapter 4.

Ethics and governance

Ethics approval for the quantitative component of the study (i.e. secondary analysis of BYDS data) was granted by the Research Ethics Committee, School of Social Sciences, Education and Social Work, QUB, in November 2015. Approval for the qualitative component with non-BYDS participants was granted from the Office for Research Ethics Committees Northern Ireland (ORECNI) in December 2015. Owing to using health and social care premises as participant identification centres, global governance was applied for and attained in March 2016. The extension for the study to include the three prisons in Northern Ireland as recruitment sites was approved by the NIHR in August 2016. Ethics approval and governance as well as security clearance were all in place by March 2017.

Quality control and qualitative research

The inclusion of the BYDS sample as well as a range of recruitment sites reduced selection bias inherent to recruitment from clinic populations alone. A purposive sampling strategy allowed for the inclusion of outliers and discovery of deviant cases. Data were then interrogated on the basis of corroboration while paying attention to negative cases. Secondary analysis of BYDS data, coupled with the collection and analysis of empirical data, allowed for triangulation in terms of answering the research questions.

Interview data were first coded by the same two researchers responsible for conducting the interviews, thus ensuring familiarity with the data and maximising efficiency in terms of time and cost. Both researchers read and independently coded the first five interviews using the coding framework generated from the research questions, adding new codes where necessary. Following independent coding, the two researchers collectively discussed and agreed decision-making around codes. Coding was then discussed among the wider team, as noted previously, and the coding frame was developed with continuous cross-checking of data among the researchers and the wider team, facilitating refinement throughout analysis and prior to interrogation of data during interpretation.

The involvement of the wider team in discussions around coding, refinement and development of themes ensured that the two researchers responsible for conducting the interviews and coding data were not hindered by familiarity and proximity to the data.

Detailed memo-keeping, from data collection through to interpretation, provided a visual audit trail of thought processes as the study progressed and facilitated researcher reflexivity.

Reflexivity emerges from the position that social researchers are part of the world they study90 and relates to the ways in which data might be shaped by researchers and the research process. The majority of the interviews were conducted by two female members of the research team. Both researchers were white, heterosexual, aged 30–35 years, had backgrounds in academia and had experience of working in the area of drug use and with vulnerable populations in non-clinical settings. At the beginning of each interview, researchers took time to offer refreshments and informally talk to participants in an attempt to put them at ease. The researchers introduced themselves and talked briefly about their job and research interests. Participants were given the opportunity to ask questions and raise any concerns about the interview. Post-interview feedback indicated that almost all participants reflected positively on the interview, stating that they felt comfortable and that researchers were non-judgemental about information divulged. In addition, younger participants mentioned that they expected the interview to be much more formal, but the fact that the researchers were informally dressed, friendly and relatively young put them at ease.

There were initial concerns that the presence of two researchers during each interview might tip the power balance and result in participants’ discomfort or unwillingness to open up. This was mitigated by ensuring that one researcher led the interview while the other asked questions only intermittently and on invitation from the lead interviewer so as not to disrupt the flow of the interview. Furthermore, two researchers present at each interview was beneficial to the data collection process for a number of reasons: first, in terms of rigour, having two people conduct the interview ensured exhaustive probing of the participant narrative (i.e. no relevant information was missed during the interview); second, in terms of researcher safety on campus, at community venues and in prisons; third, in terms of emotionality – biographical accounts regularly included sensitive information on adverse life experiences, for example abuse (physical, sexual, domestic), loss of family members/friends and experiences of homelessness. On occasion, participants became emotional during their narrative interview; for some this was the first time they had recounted these experiences. In a similar vein, emotionality was an issue for the researchers listening to an individual’s story. Researchers were very much in tune with how the other was dealing with the interview, and were on standby to take over questioning if necessary.

In terms of the research environment, interviews were conducted in a range of settings, including a private office on university premises, private offices in community centres (for participants that did not reside local to the university) and private rooms at each of the prison sites. The potential for the physical setting to have an impact on the data is acknowledged in each space. The university, as an institution, may have been perceived by some as oppressive, despite our intent and efforts to make participants feel as comfortable and at ease as possible. During the informal chat with participants (after the recording device was switched off), no participant expressed concerns about the interview venue. Community centres were generally chosen by participants for ease of access and so posed few issues in terms of interview dynamic and physical space. The prisons as venues for data collection might be considered to be the most problematic venues. One might imagine that prison itself is an oppressive environment wherein issues around substance use could not be discussed freely. A pilot interview was conducted in the prison prior to data collection. Following the interview, the participant was asked about his experience and his opinion on the content of the interview. Researchers received positive feedback and the participant highlighted that the prisoner development unit, where interviews were taking place, was a regular venue for individuals to work with the AD:EPT team and other teams in the prison, therefore discussing substance use in this environment was not an issue.

The strengths and limitations of the study are discussed in Chapter 8.

Chapter 3 Patterns of drug use

To map the patterns of drug use generally and as they relate to NPSs, we devised a twofold process.

First, we present a LCA and regression modelling of the BYDS data. These were used to classify different patterns of drug-taking behaviour in BYDS participants. Additional analyses using the latent class data to inform the subsequent qualitative analyses are also summarised. These additional analyses included provisional regression models to identify risk factors associated with types of drug-taking behaviour. The way in which the LCA informed the sampling frame for qualitative data collection and the integration of regression analyses to the qualitative component is also presented.

Second, using the narrative data we develop a taxonomy of use and discuss how four distinctive drug use typologies emerged. Characteristics of these groups and how they relate to the various NPSs used are presented, with a discussion of how the qualitative analysis informed the next stage of quantitative modelling. Specifically, the themes identified in the qualitative analysis were aligned with BYDS quantitative variables. These BYDS variables were then used as predictors of substance use in the quantitative models and are presented in Chapter 4.

Latent class analysis of the Belfast Youth Development Study

Determining the number of drug classes

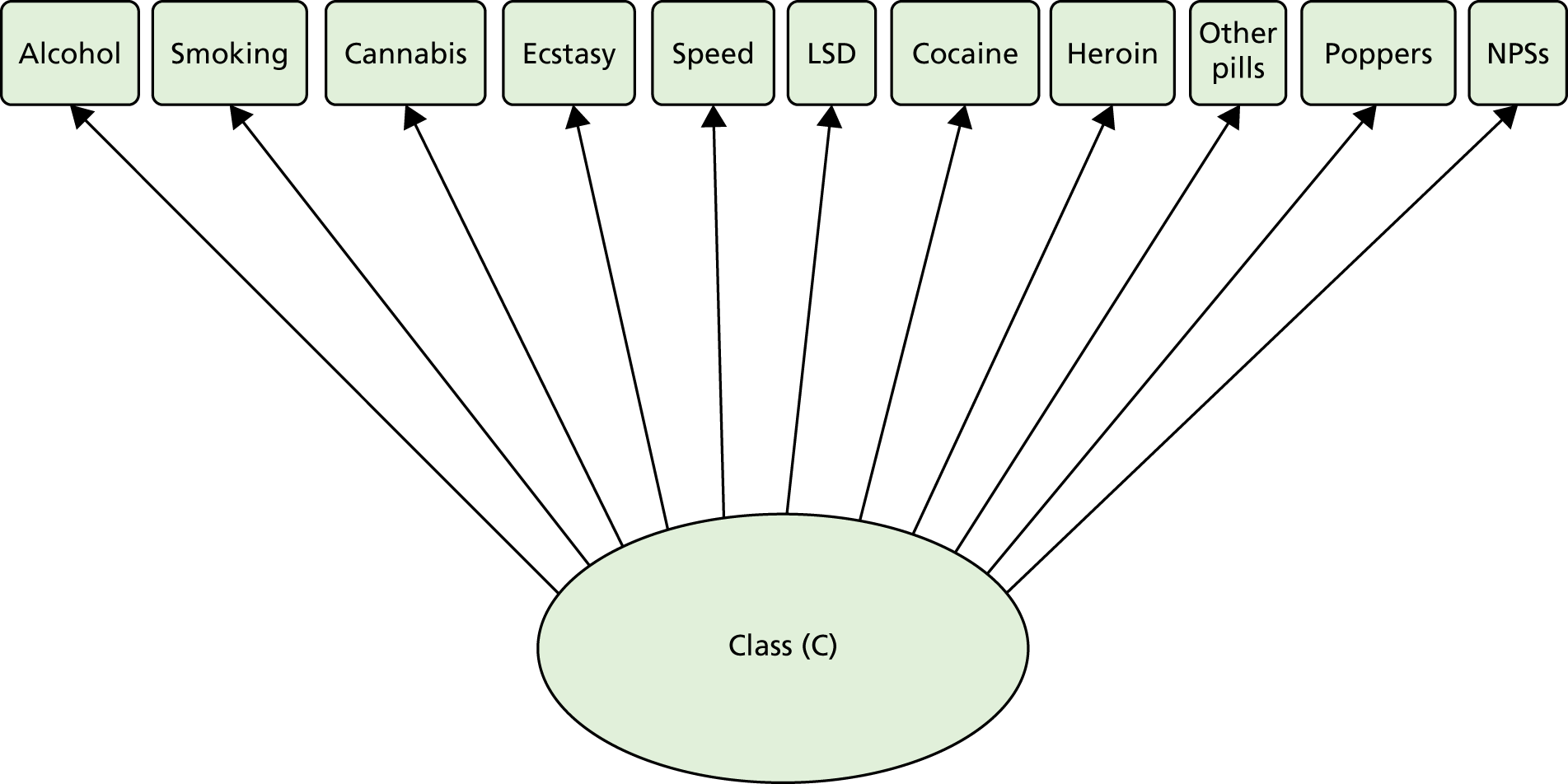

This study was a secondary analysis of data from the BYDS, a longitudinal study of substance use during adolescence (see Chapter 1 for more information). The data extraction plan was prepared and confirmed between October 2015 and November 2015 and then finalised in December 2015 through consultation with the knowledge exchange (KE) group. A draft analysis plan that addressed each of the research components was negotiated and completed by the team in January 2016 and a number of strategies were implemented over the next month to prepare the groundwork and data for the first stage of the analytical plan. We hypothesised in our application and follow-up responses that a number of homogeneous subpopulations would emerge in the data and would include a class of NPS users given the adequate numbers of NPS use in the sample. As depicted in Figure 2, the first stage of this strategy was to apply LCA to the data to identify the number and nature of classes based on ‘ever use’ of the drug variables included in our data. These included alcohol, tobacco, cannabis, ecstasy, speed, LSD, cocaine, heroin, other pills, poppers and NPSs. The actual questions used to assess drug-taking behaviour are shown in Appendix 2, Table 13.

FIGURE 2.

Representation of basic latent class structure: traditional and NPS drug use.

As is standard in LCA, models with two to six classes were estimated using MLR. 91 To help prevent solutions based on local maxima and reduce the risk of missing the model with the best fit, initially 100 random sets of starting values were specified, with 20 final-stage optimisations. The models were then compared in terms of relative fit by using information theory-based fit statistics (Table 1), namely the AIC, BIC and ssaBIC. For these three fit measures, lower values are representative of better model fit.

| Number of classes | Log-likelihood | Best H0 replicated | Number of parameters | AIC | BIC | ssaBIC | LMR (p-value) | BS-LRT (p-value) | Entropy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | –7793.80 | N/A | 11 | 15,609.59 | 15,671.41 | 15,636.46 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| 2 | –6039.21 | Yes | 23 | 12,124.41 | 12,253.68 | 12,180.60 | 3471.22 (< 0.001) | 3509.18 (< 0.001) | 0.89 |

| 3 | –5674.01 | Yes | 35 | 11,418.02 | 11,614.72 | 11,503.53 | 722.49 (< 0.001) | 730.39 (< 0.001) | 0.83 |

| 4 | –5612.82 | Yes | 47 | 11,319.64 | 11,583.79 | 11,434.47 | 121.05 (< 0.001) | 122.37 (< 0.001) | 0.77 |

| 5 | –5588.16 | Yes | 59 | 11,294.32 | 11,625.91 | 11,438.46 | 48.79 (0.010) | 49.33 (< 0.001) | 0.74 |

| 6 | –5576.52 | Yes | 71 | 11,295.03 | 11,694.07 | 11,468.49 | 23.04 (0.169) | 23.29 (0.143) | 0.76 |

The LMR and bootstrap likelihood ratio test were also used to compare models with increasing numbers of latent classes. Model estimates for both three- and four-class models were examined and the four-class solution was subsequently selected based on the interpretability of the results. After extensive exploratory modelling work we were able to determine that a four-class model was the best-fitting model according to the fit indices and information criteria; this provided us with unique and interpretable clusters of individuals with similar profiles within the latent SGs. Average latent class probabilities for most likely latent class membership are shown in Appendix 3, Table 14. Figure 3 shows that a four-class solution provides good cluster delineation (see Appendix 3, Table 15).

FIGURE 3.