Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 14/54/19. The contractual start date was in January 2016. The final report began editorial review in October 2018 and was accepted for publication in March 2019. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Siobhan Creanor reports grants from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Public Health Research programme during the conduct of the study, and various other grants from NIHR and UK charities, outside the submitted work. She is also Director of the Peninsula Clinical Trials Unit, which is in receipt of NIHR Clinical Trials Unit Support Funding (current award ends 31 August 2021).

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Callaghan et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Some text in this chapter has been reproduced from Thompson et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Scientific background

Individuals in the criminal justice system (CJS) have a high prevalence of physical and mental health-care needs, have lower psychological well-being2 and experience significant problems in accessing health and social care services. 3 Services for those with multimorbidities who are under community supervision often appear fragmented. 4 Key barriers to access to health-care services include general practice registration, long waiting times for appointments and a perception of not being supported by services to make contact, such as probation. 5 Furthermore, a lack of trust in health services and health professionals (e.g. in primary care) causes many offenders to avoid medical help despite a high prevalence of emotional problems. 6

Unhealthy behaviours such as problematic alcohol use and smoking are much higher in the offender population than in the general population. 7 For example, 60–80% of the offender population report problematic alcohol use compared with 20–30% of the general population and ≈80% of offenders smoke compared with ≈20% of the general population. 8 In addition, prevalence data from a rapid systematic review showed that 53–69% of adults in the probation setting scored positively for an alcohol use disorder. 9 Both of these behaviours (which are often co-existing) lead to several health problems, and possibly low mental well-being, through a number of plausible processes (e.g. economic, social, psychological). 10 Likewise, substance misuse is particularly prevalent and is also linked to mental health problems. However, services in the substance misuse field are already very well developed for offenders. 11

In 2004, the government’s white paper Choosing Health: Making Healthy Choices Easier12 introduced a new workforce called health trainers, who are often drawn from the communities in which they operate. The introduction of health trainers signalled a shifting focus in the UK towards self-management of health, and on reducing the demands placed on formal care. 13 A health trainer’s main role is to provide one-to-one support to people in disadvantaged areas to facilitate health behaviour change and access health services. A handbook for health trainers was developed in 2008 outlining the approach and evidence-based techniques (e.g. goal-setting, self-monitoring, creating action plans) that health trainers can use to help people change their behaviour. 14 The core work of health trainers includes the support of behaviour changes such as healthy eating, stopping/reducing smoking, increasing physical activity, reducing alcohol consumption and improving mental well-being. Their work has been positively rated but there is still a lack of robust evaluation. 15,16

Our rapid review of published and grey literature, and contact with local probation service leads, revealed that the scope of health trainers has been extended to prison and probation settings, with promising findings,17 especially when the health trainer has experience of the CJS. Although health trainers have typically focused on supporting health behaviour change, there is increasing interest in their role being extended to facilitate improvements in mental well-being. Furthermore, when enhancing well-being has been the main focus, individuals are more likely to attain their planned goals. 17 In parallel work, a screening and brief intervention for reducing alcohol use in individuals in the criminal justice settings18–20 indicated no additional benefit in comparison with feedback on screening and a client information sheet,21 suggesting that a more client-centred intervention with longer engagement may be needed. A 2015 systematic review22 identified 95 studies working with offenders both in and out of prison (42 studies based in the community) on improving health outcomes, of which 59 led to improved mental health, substance use, infectious disease or health service utilisation outcomes, suggesting that interventions can be successful. However, 91 of the studies were judged as having an unclear or high risk of bias and the review highlighted the lack of high-quality rigorous research with a population that is comparatively under-researched. Further rigorous research is therefore needed to evaluate the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of a health trainer-led intervention aimed at improving mental well-being and health behaviour among people under community supervision, and to understand the change processes involved.

The recent reorganisation of community supervision, as part of the ‘Transforming Rehabilitation’ agenda, saw the split of services into Community Rehabilitation Companies (CRCs) and the National Probation Service (NPS). CRCs manage the majority of offenders, particularly those who are classified as being of low to medium risk, whereas the NPS supervises high-risk offenders. The reforms presented an opportunity to engage those released from prison with sentences of < 1 year (who previously would not have received supervision), as well as those serving community sentences. Providing health trainer support in this context could improve engagement with existing health promotion services23 and stimulate greater ownership and control over health behaviour change and involvement in activities to foster mental well-being. 24

There has been increasing interest in subjective well-being, distinct from lack of mental illness, as an important concept. The following five behaviours to increase mental capacity and well-being were recommended in the Foresight Report:24 (1) Connect with others, (2) keep Learning, (3) be physically Active, (4) take Notice of things around you and (5) Give (CLANG). Subjective well-being is an important outcome in its own right and has the potential to change relatively quickly.

Well-being potentially affects physical health (e.g. hypertension, heart disease) and mental health (e.g. depression, self-harm, substance misuse), health behaviours (e.g. smoking, alcohol use), employment and productivity, crime and society in other ways. 24 Although the role of exercise for improving well-being is clear, changing other specific health-related behaviours, such as smoking, can also improve subjective feelings of well-being for some individuals. 25,26 Individuals’ patterns of current behaviour, motivation to change and potential benefits will be idiosyncratic and require a personal analysis. Assessing the benefit of health promotion interventions is rarely easy and well-being poses particular problems. One method of assessing subjective well-being is through the Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (WEMWBS). 27 WEMWBS captures the two perspectives of mental well-being: (1) the subjective experience of happiness (affect) and life satisfaction (the hedonic perspective) and (2) positive psychological functioning, good relationships with others and self-realisation (the eudaimonic perspective). The latter, based on self-determination theory,28 includes the capacity for self-development, positive relations with others, autonomy, self-acceptance and competence; therefore, it has the potential to positively enhance further health-promoting behaviours.

The WEMWBS has been widely used at a population level to assess mental well-being, as well as with individuals in specific groups. 29–33 Original data we obtained from the Scottish Prisoner Service in 2014 (personal communication) showed a mean WEMWBS score of 43.2 [standard deviation (SD) 12.3, range 14–70], compared with a general population score of 51.6 (SD 8.71) for England31 and 49.9 (SD 8.5) for Scotland. 34 Lower scores are associated with smoking, lower consumption of fruit and vegetables, high alcohol use and lower socioeconomic status. 33 Although these associations are likely to involve reciprocal causal effects, this does highlight the need for interventions to improve the mental well-being among groups with the lowest scores.

People who receive community supervision from the new NPS and CRC services are particularly suitable for a high-intensity health promotion intervention for four reasons: (1) they are often excluded from ‘usual’ health care and health and well-being-promoting interventions as a result of a combination of access arrangements, lifestyle factors and distrust of authority; (2) they often have low levels of mental well-being and poor health-related behaviours; thus, the gains of the proposed intervention are potentially high; (3) while under supervision, and, therefore, in a period of sustained mandated contact with a service, there is an opportunity to both engage such individuals in an intervention and capture follow-up data in the context of a rigorous evaluation; and (4) being subject to justice supervision can often be a time when individuals wish to improve their life circumstances, particularly towards the start of sentences.

The current research aimed to develop and test the feasibility and acceptability of a client-centred intervention for individuals receiving community supervision, to support them to change one or more health-related behaviours, enhance their well-being and reduce the risk of long-term conditions. The health trainer role has been adapted for specific populations, including offenders17 and smokers,35 with early signs that the support is acceptable and feasible. However, further intervention development and piloting was required to integrate a focus on promoting well-being and multiple health behaviour changes in offenders in the new NPS/CRCs context, and to understand the interactions between well-being and health behaviour changes. These uncertainties were explored, and reduced, in a process evaluation, working with the peer researchers who have lived experience of the CJS. The pilot trial and process evaluation further tested our assumptions, the intervention and cost-effectiveness.

Aims and objectives of the pilot trial

The aim of this pilot randomised controlled trial (RCT) was to develop and implement a health trainer-led intervention to support health and well-being improvements for those under community supervision in the CJS. Furthermore, the pilot study sought to explore uncertainties about the acceptability and feasibility of the trial methods and intervention to inform the design of a full RCT.

The specific objectives were to:

-

assess the acceptability and feasibility of the STRENGTHEN intervention, alongside routine engagement with community supervision services, for the key stakeholders including participants receiving community supervision, CRCs, the NPS and health trainers themselves

-

assess the acceptability of recruitment, randomisation and assessment procedures in a pilot pragmatic RCT

-

determine, from the pilot RCT, completion rates for proposed outcome measurements to assess well-being (i.e. the WEMWBS), behavioural measures (e.g. self-reported alcohol consumption, smoking status, diet, physical activity, substance use) and quality of life [measured using the Short Form questionnaire-36 items (SF-36) and EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L)] at baseline and at the 3- and 6-month follow-ups

-

provide data to contribute to sample size calculations for a fully powered RCT to primarily assess subjective well-being (measured using the WEMWBS) and to ensure that the effect size (intervention vs. usual care) chosen for powering the definitive trial is plausible

-

use a mixed-methods process evaluation to further refine and understand the acceptability and feasibility of the intervention, its delivery and the trial procedures

-

estimate the resource use and costs associated with delivery of the intervention, and to pilot methods for the cost-effectiveness framework in a full trial.

Chapter 2 Intervention development

Development of the STRENGTHEN intervention

Through original research and literature reviews, we developed an extensive understanding of what are likely to be the effective components of an intervention targeted at health behaviours and improvement of health and mental well-being in this population. A clear starting point logic model of intervention components and aims underpins the intervention, based on the health trainer role in a previous trial of smoking cessation in disadvantaged groups35 and the development of a collaborative care model for prison leavers with multiple health problems. 36

The health trainer role has been adapted for specific populations, including offenders17 and smokers,35 with early signs that the support is acceptable and feasible. However, further intervention development and piloting was required to integrate a focus on promoting mental well-being and multiple health behaviours and to understand the interactions between mental well-being and health behaviour changes. As with our previous research, we used the original health trainer manual with its focus on smoking, alcohol consumption, physical activity and diet as a starting point for possible content and structure, adapting and developing when necessary to meet our specific aims (i.e. a stronger focus on mental well-being).

Through engaging with patient and public involvement (PPI) groups to understand what and how ‘mental well-being’ may be interpreted and understood alongside the target behaviours, we integrated mental well-being and the four target behaviours in the logic model in such a way that they exist independently from, and are interwoven with, each other. It was felt that, for some people, their mental well-being may be so low that it would need to be addressed directly before other changes could be considered. For others, addressing the four behaviours could implicitly lead to improvements in mental well-being. Therefore, the training manual was developed in such a way that health trainers were trained to support people with improving their well-being as a target in and of itself, as well as being able to support change in the four behaviours. In creating the STRENGTHEN training manual [see the project web page: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/phr/145419/#/ (accessed 30 August 2019)], extensive work was given to adapting the way the behaviours can be supported in such a way to implicitly and explicitly maximise the benefit for people’s mental well-being.

Incorporating the Five Ways to Well-being

The framework chosen for promoting mental well-being was the Five Ways to Well-being (5WWB) [see the project web page: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/phr/145419/#/ (accessed 30 August 2019)]. The 5WWB were developed as an accessible public health message based on evidence-based practices people can perform easily every day, which could lead to improvements in mental well-being. 23 PPI work supported the 5WWB as being an acceptable and useful framework that could be applied to the target population.

To incorporate the 5WWB, members of the research team took part in a 1-hour training session during which they were trained to understand and focus on their own well-being to ensure familiarity and understanding of the framework. Following this, the 5WWB were incorporated into the training manual as a stand-alone section for supporting people who want to improve their well-being. A section was also developed that embedded ways to promote the four health behaviours of the original health trainer manual in ways that would maximise their impact on well-being. For example, supporting a reduction in alcohol use could also link to exploring how this might help a client to connect with others (who may be trying to do likewise), learn about the physical and mental health consequences of alcohol use and guidance on safer levels of use, discover how physical activity can help deal with alcohol cravings, notice the effects of alcohol on financial, social, emotional and cognitive functioning, and give support to others to manage their alcohol consumption. A similar set of examples can be developed for each of the health behaviours.

Adapting the health trainer role and intervention

Content from the original health trainer manual that was considered appropriate was adapted for the STRENGTHEN intervention; the central ethos of being client-centred and embedded in the community was carried forward into the STRENGTHEN intervention, as were components such as action-planning, problem-solving, self-monitoring and signposting. The intervention included:

-

a heavy focus on engagement, trust/rapport building

-

a focus on reduction rather than stopping smoking, or pushing guidelines (five a day, 14 units, etc.), as this would be seen as threatening

-

flexibility of timing, frequency and duration.

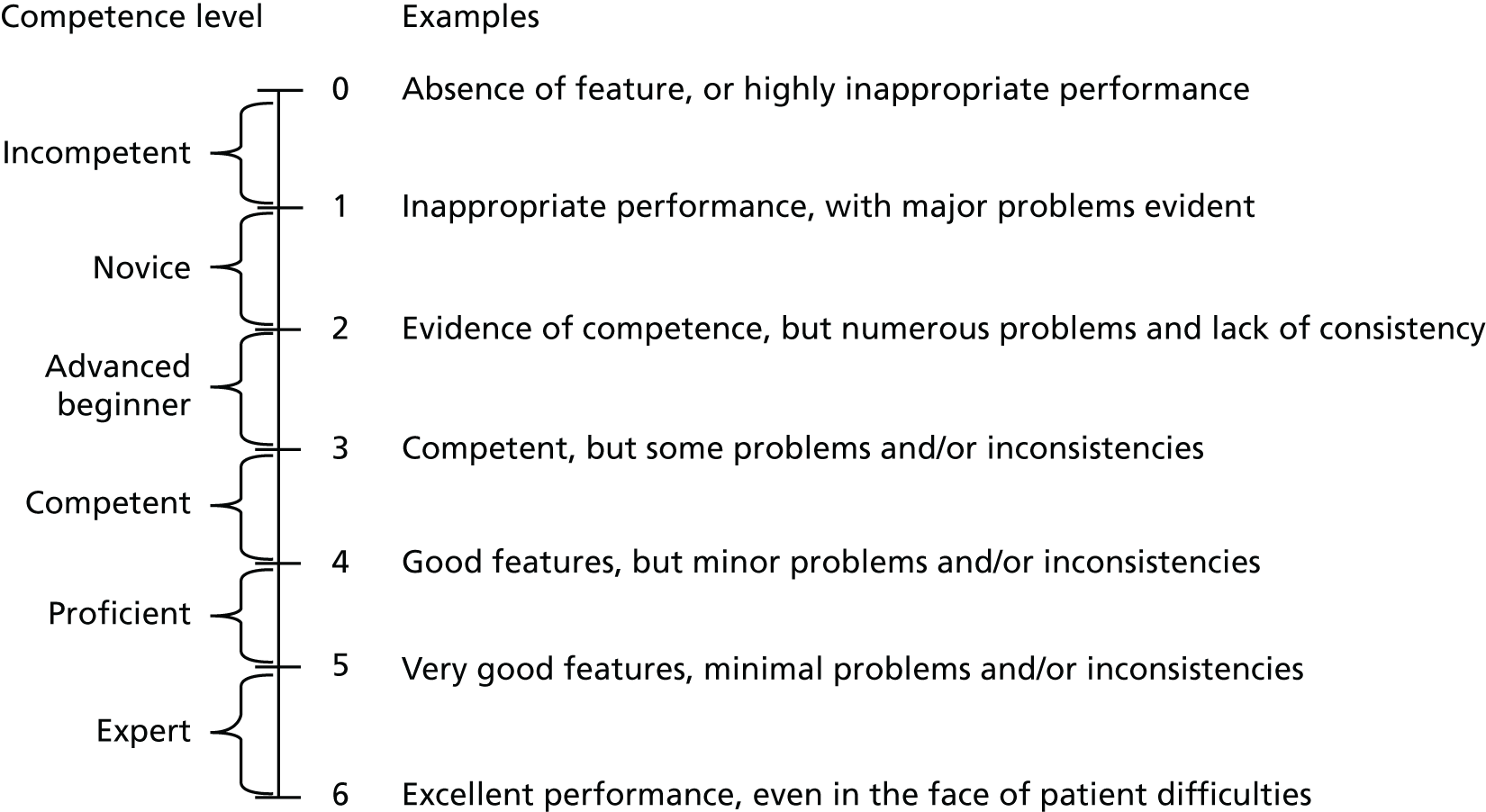

The core competencies

As with our previous work adapting the health trainer role,35 a set of six core competencies were developed, which were designed to underpin the work of the health trainer (see Appendix 1). They reflected elements that were considered to be crucial to successful delivery of the intervention, and were reinforced throughout the manual, health trainer training and the supervision process. They were (1) active participant involvement, (2) motivation-building for changing a behaviour and improving well-being, (3) set goals and discuss strategies to make changes, (4) review efforts to make changes/problem-solving, (5) integration of concepts: building an association between well-being and behaviour and (6) engage social support and manage social influence. These competencies not only served as a guide for what the health trainers should be mindful of in their delivery, but also for assessing intervention delivery fidelity (as discussed in Chapter 6).

Patient and public involvement and stakeholder input to intervention development

In order to ensure that the intervention was acceptable and tailored to the needs of the target population, intervention development work was undertaken in the form of the establishment of PPI groups and a stakeholder consultation. A summary of the findings that were used to shape the intervention manual and health trainer training is provided in the following sections.

The STRENGTHEN peer researcher input to intervention development

The research team have established a collaborative relationship with a local day service for substance use and alcohol rehabilitation that supports people with multiple and complex needs. The service had recently collaborated in extensive PPI activities for a trial of an intervention to support prison-leavers with common mental health problems to achieve their goals (ENGAGER 2). 36 The research team attended the regular Monday morning group session in order to provide service users with information about the STRENGTHEN pilot trial and invite them to an introductory session to help them decide if they would like to be involved in advising about the development of both the intervention and the trial. It was at this stage that service users advised the research team that, due to the potentially sensitive nature of the topic, there should be separate groups for men and women. It was also seen as beneficial to the development of the intervention, as potential gender-specific aspects of content, implementation and delivery could be teased out in order to maximise acceptability to both women and men.

Group members were keen to adopt the title of ‘peer researcher’ that was used in the ENGAGER 2 PPI groups. 37 This both helped them to define their role in the project and put them on an equal footing in the team, with their expertise being their lived experience and understanding of the context in which the intervention would be delivered. The groups met on a bi-weekly basis for 4 months (with two or three missed sessions to take account of school holidays as a result of parenting responsibilities of some group members). Although there was some fluctuation in the attendance of both the men’s and women’s groups, a ‘core group’ of attendees emerged who attended the majority of peer researcher meetings (approximately five in the men’s group and six in the women’s group). This continuity allowed peer researchers to follow the development of the study and to witness how the outcomes of the previous meeting were implemented. Each meeting was 2 hours long, with a 15-minute mid-point break, and was facilitated by two members of the research team. Each meeting followed a schedule of activities to address issues regarding the design of the intervention and/or the research, with flexibility to discuss other topics that peer researchers raised as relevant to the intervention/research. The start of each group involved a catch-up on progress with the pilot trial and, as the groups progressed, how the advice that the group had provided during the previous meeting had been used and implemented. It was clear that these updates of how the work of the group had been utilised were key to maintaining engagement by showing the changes to and progress with the study to which the peer researchers contributed.

The PPI groups contributed to the intervention in terms of its conceptualisation, content and practicalities of delivery. Each of these will be dealt with in turn, with reference to the contribution and changes made by the groups and illustrative quotes from group meetings, when appropriate.

Conceptualisation

Title and logo

Peer researchers saw it as important that the title of the intervention was one that both attracted potential participants and encapsulated the meaning of the intervention. Both the men’s and women’s groups discussed the aims of the intervention and what these meant to them. Both the men’s and women’s groups were keen to capture the notion of building futures on firm foundations. The men’s group generally used building analogies (‘firm foundations’, ‘scaffolding’) and the women’s group used more analogies from the natural world (‘trees’, ‘strong roots’). Both groups posited that the intervention title should provide the feeling that it would support participants to build their own strength, laying down firm foundations for a healthier future:

It’s about strengthening people so they can take control.

For some reason in my mind I’ve got a picture of a tree. You’ve gotta start with your roots, haven’t you? So you get your group going, your roots. Then a few sessions, the trunk will get stronger and stronger and stronger and then the ideas come and branch out and hopefully, if it works, it will bear fruit.

The outcomes of the peer researcher discussions were delivered to the wider team and an art and photography student from a local school who was on work experience in the Community and Primary Care research team. A range of title options were developed and presented to the peer researchers, who decided that the intervention would be best represented by the word ‘strengthen’, with the tagline, ‘Firm foundations for health and well-being’. The work experience student was provided with anonymised quotations from the peer researcher discussions and provided two draft logos: the first, an outline of a human head with a tree-like structure formed of dendrites within the head, with roots at what would be the brain stem, representing growth and change, and the second, a version of a human figure in the yoga ‘tree’ pose, to represent strength and well-being. Both the peer researcher groups and the research team chose the former logo as that to be used on all trial, intervention and promotional/dissemination materials for the course of the pilot trial.

Practicalities of delivery

Peer researchers discussed a range of practical issues and potential solutions that could encourage both initial participation and intervention engagement that were included in the health trainer training.

Location

It was put to the groups that, when risk assessment outcomes allowed and at the preference of intervention participants, health trainer sessions could be held in locations other than the NPS or CRC offices where participants were initially recruited. Peer researchers provided a range of options for suitable locations in the Plymouth area, which provided a starting point for Plymouth health trainers, and categories of location types (cafes, rooms linked to key services, etc.) for Manchester health trainers to identify during intervention set-up. Both groups considered that the option of attending sessions at a location that was local to participants or somewhere ‘friendlier’ than the probation offices may remove a potential barrier to participation and engagement. It was therefore decided that, following the initial health trainer session in the probation offices and confirmation of risk level with the offender manager, participants would be given the option of meeting at another agreed location. The women’s group also stated the importance of provision for children at session locations. One woman who had experience of prison sentences advised that some women who have recently been released from prison could be subject to orders stating that other people are unable to take care of their children, which would necessitate children being present during sessions.

Mode of delivery

Peer researchers felt that in-person sessions would be more personal than sessions delivered over the telephone, emphasising the more personal aspect of meeting face to face, including developing empathy and picking up on body language. They also saw it as important for participants to have human contact and not, as they put it, ‘talking to another machine’. Peer researchers were clear that all first intervention sessions should be in person, with participants being able to choose if subsequent sessions were delivered in person or by telephone.

Contact

Peer researchers agreed that telephone was generally the best way to contact people. Peer researchers suggested informal, between-session contact via telephone call or text, for example providing information linked to a goal or enquiring after them following an appointment/event, to be important in terms of developing trust. Members of the women’s group said that they would not answer a telephone call if it was from a number that they did not know and so suggested that health trainers and researchers should send a text first saying who they are. Female peer researchers also suggested that some women in abusive relationships would have their text messages read and telephone calls monitored and that health trainers should be mindful of this when sending messages and making telephone calls (i.e. not to leave messages with anyone else answering the telephone/ask if they can talk when making calls).

Building trust

Building trust and rapport with participants was seen by peer researchers as essential in ensuring effective delivery of the intervention. Peer researchers discussed their own and others’ negative interactions with a range of services and also the type and impact of positive interactions with services with which they had worked well. The groups were clear that health trainers should make building trust a priority and not launch straight in to supporting participants to identify target health behaviour(s). It was viewed as important that health trainers be non-judgemental and understand the difficulties and barriers faced by participants in their interactions with other services. The groups described balancing being professional with being a friend. The women’s group in particular talked at length about the importance of health trainers showing that they care and provided a range of ways in which they could do this, for example by taking the time to listen, following participants up in a non-judgemental way if they do not attend an appointment, sending between-session texts during difficult periods/trigger times. They also suggested that, rather than immediately asking how participants had got on with their goals at the start of a session, the health trainer should ensure that they spend some time asking how the participant has been, to ensure that it is clear that the session is focused on them as a person.

The importance of trust and ways in which health trainers could achieve this was included in both the intervention manual and the training. It was made clear that the first two or three sessions should be focused on developing trust and getting to know the participant before moving on to focus on identifying and working towards goals.

Stakeholder input to intervention development

Lynne Callaghan interviewed eight stakeholders from a range of related health trainers and CJSs in order to identify any changes/adaptations that needed to be made to the intervention to meet the needs of the population and deliver the intervention in the current context. Roles included management and delivery of a similar health trainer intervention in probation services; practitioners with a remit of providing well-being and housing services, with a particular focus on women; a court advice and support service; a community-based support worker working alongside custody liaison and diversion workers; and a signposting and support service that worked in collaboration with the CRC and other key services. Most of these services were located in the south-west of England, with two participants located in the south central region. As the second site had not yet been identified and secured at this stage, it was not possible to include services from this area. Interviews had a focus on understanding the facilitators of and barriers to working with men and women in the CJS, in particular those under community supervision; the experiences of supporting clients to change health behaviours and mental well-being; the process of goal-setting used with clients; the mode and frequency of contact and how they worked with clients to support initial and ongoing engagement; and what works well and what does not work so well in supporting clients to change their health behaviours and improve mental well-being.

Interviews were transcribed verbatim and analysed using thematic analysis. A summary of emergent themes is included in the following sections.

Challenges to behaviour change

Some of the challenges to health behaviour change included managing concurrent mental health needs of clients with little support available, low confidence to make changes and difficulties of taking ownership. A large proportion of services to which health trainers can signpost a client in order to support behaviour change are delivered in a group format, which, it was perceived, is often not acceptable to clients. It was also viewed that clients perceive activities to support behaviour change as expensive. Returning to prison was seen as a particular challenge with working with this client group, as well as returning to old patterns of behaviour.

Behaviour change facilitators

-

Trust and rapport with clients was seen as key to effectively supporting behaviour change, achieving something for the client (no matter how small) so ‘they feel quite positive about what you can do’.

-

Focusing on the positive during sessions: ‘I mean, the more that we turn things into a positive the better with this client group . . . because they’re always, you know, talked at in a condescending way’.

-

Helping clients to see the relationship between their goals, ‘allowing them to see how kind of they can build a pathway really for themselves’.

-

Setting simple, achievable goals: ‘and we do a lot around making sure that people achieve and that actually something that seems really, really simple is actually quite a challenge to some people. So they have very simple goals’.

-

Support to access free/inexpensive activities to support behaviour change, for example: ‘I used to try and promote the outdoor gym . . . which is the cheapest gym I know, if you’ve got a dog, go for a walk, if you’ve got a pushbike, go and ride your pushbike . . . you know, it’s cheaper than the gym. ‘Cause a lot of people I worked with were on a very low income’.

-

Clients supported to set their own goals, not goals decided by the health trainer: ‘It’s better to get people to set their own goals . . . because they’re more powerful if it’s your own goal’.

Challenges to conducting the role

-

Location of the service and perceived oppressive environment of CJS premises: ‘But a lot of people say “oh, I’m not going in there, I’m not . . . you know, yeah, you might be lovely and all the rest of it, and give me what I want, but I’m not walking through that door” ’.

-

Limited time in sessions to build trust and rapport: ‘just everything from really getting to know people well. Erm, and that takes time. Erm, and that suffers when we have, you know, a very busy session’.

-

Being seen as part of the probation service: ‘So working for a charity we’ve worked alongside probation very closely and then we get seen as probation by the client, and so we get kind of lumped as “oh yeah, just part of the authorities” . . . I’ve been told, you know, “you’re just one of them”’.

-

Difficulties in keeping in contact via mobile phone: ‘even the ones I work with now, um, don’t have mobile phones cause they’ve probably sold it to buy drugs or more alcohol’.

Facilitators of conducting the role

-

Getting to know the client: ‘so before we did anything about what they actually wanted me to help them with, we’ll have a chat about the footy at the weekend . . . but then you, you get to meet people . . . and people come in just for a chat . . . and then I think you’ve broken most of the barriers then . . .’.

-

Networking with other services for effective signposting/advice: ‘and they’re much more likely to help you, I think, than if it’s sort of, someone random that they don’t know’.

-

In-person contact is important for the client: ‘I just think when you’ve met somebody and you’ve seen their face and you kind of, I meant they’re quite short visits, you know, those initial ones, but you get, probably get a sense, a better sense of what the person can support you with’.

-

Sharing with colleagues and team problem-solving: ‘but it’s also good to throw things around with people. People give you ideas, and people give you sort of advice and, and it’s always good to have those conversations’.

-

Reimbursement of travel expenses.

-

Building and maintaining a directory of organisations and resources.

Findings from the thematic analysis supported writing of the manual and preparation of the training materials and structure. Direct quotations from both stakeholder interviews and PPI sessions were used as reflection points and to exemplify specific points throughout the manual; by doing so, they were ‘bringing the manual to life’ by showing the practical application of key points.

The STRENGTHEN intervention

The STRENGTHEN training manual [see the project web page: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/phr/145419/#/ (accessed 30 August 2019)] provides a detailed insight into the structure, delivery style, components and content of the intervention.

The key components of the piloted intervention were as follows:

-

A health trainer was available for one-to-one sessions over 14 weeks, by either face to face or telephone (the frequency and length of sessions was negotiated with each participant). The face-to-face intervention sessions took place in a variety of settings, including probation services and other local community locations.

-

An initial invitation to engage with the health trainer was described as an ‘open and flexible’ opportunity to receive support for one or more of the target health behaviours and/or improving overall health and mental well-being through other activities, including CLANG (as part of the 5WWB).

-

Health trainers were trained to help participants understand the inter-relationship between health behaviours, such as smoking, alcohol use, diet, physical activity and their relationship to mental well-being, and other positive and negative behaviours, including substance use. Each participant was encouraged to develop a personal plan based on individual behaviour-change goals and motivation to improve mental well-being. Some participants had positive perceived mental well-being but engaged in risky behaviours; others were concerned about emotional distress. The intervention was intended to be flexible enough to support both these extremes.

-

The support was described as ‘open’ to reflect the planned underpinning and overlapping influence of self-determination theory and the client-centred principles of motivational interviewing,38 which were central to the intervention. Health trainers avoided giving ‘advice’ and empowered clients to confirm the desire for change and develop self-regulatory skills such as self-monitoring, setting action plans and reviewing progress. The intervention was tailored to and led by the participants’ needs.

-

The health trainer, informed by the 5WWB, helped clients to build positive behaviours [e.g. initiating and maintaining activities (physical, creative, etc.)] and find opportunities for gaining core human needs (i.e. sense of competence, autonomy and relatedness), as well as to learn and notice, to enhance mental well-being.

-

Any reductions in alcohol consumption (as units per week, alcohol-free days or avoidance of trigger events) or smoking (using different strategies)35,39,40 and increases in physical activity and healthy eating were supported, with the underlying aim (not necessarily explicitly discussed with the participant) to build confidence to meet guidelines for safe alcohol consumption, to quit/reduce smoking, to engage in daily/weekly physical activity and eat healthily.

-

Participants were actively supported to gain help from friends and family, link with other community resources (parks, leisure centres) and services (e.g. Stop Smoking Services, Drug and Alcohol Treatment Service) as a part of achieving their personal plan, and explore options for continued support after the intervention as appropriate.

Training the health trainers

Following the development of the health trainer manual, a training plan was developed, which the training manual supported. The training consisted of various sections covering the key components of the intervention (see Appendix 1). The training was delivered over 3 days at both sites, led by the intervention lead (TPT) with input from key members of staff (LCal, AHT) to support delivery. The training included multiple opportunities for feedback and discussion, as well as skills practice with staff and PPI representatives. Following the training, health trainers were allocated up to three practice participants, who were recruited from the peer researcher groups as a way to develop real-world experience of delivering the intervention.

Supervision of the health trainers

A supervision contract was drawn up [see the project web page: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/phr/145419/#/ (accessed 30 August 2019)] outlining expectations of supervision sessions. Supervision sessions were led by the intervention lead (TPT) and took place bi-weekly with both sites simultaneously via Skype™ (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). The supervision sessions began following the delivery of the intervention with practice participants. Supervision sessions followed a standing agenda, which allowed for discussion and feedback on specific cases and resolution of any difficulties health trainers may have been facing, and allowed health trainers to feed back any issues that they felt needed to be resolved. Issues included elements that they felt were not working, or elements they felt would be a useful addition; these were fed back by the intervention lead to the project management group who would decide if any changes were necessary as part of the formative process evaluation. Audio-recordings of sessions were also reviewed in some supervision sessions and linked back to the core competencies.

Chapter 3 Trial design and methods

Trial design

The STRENGTHEN pilot trial was a parallel two-group randomised pilot trial with 1 : 1 individual participant randomisation to either the intervention plus standard care (intervention) or standard care alone (control), with a parallel process evaluation. Participants were recruited through CRCs in the south-west and north-west of England, and through the NPS in the south-west only. Participants were recruited through the NPS at only one site to test the feasibility and acceptability of recruitment and engagement of those classified as presenting a high risk of serious harm to researchers or health trainers. Follow-up assessments were carried out at 3 and 6 months post baseline data collection. Ethics approval for the trial was granted by the Health and Care Research Wales Ethics Committee and the former National Offender Management Service, now Her Majesty’s Prison and Probation Service (Research Ethics Committee reference number: 16/WA/0171; National Offender Management Service reference number: 2016-192).

Eligibility criteria

Participants had to satisfy the following criteria to be enrolled in the trial:

-

male or female and aged ≥ 18 years

-

currently receiving community supervision

-

having a minimum of 7 months left of community sentence/supervision

-

having been in the community for at least 2 months following any custodial sentence

-

willing and able to receive support to improve one or more of the four target health behaviours and/or mental well-being

-

willing and able to take part in a pilot randomised controlled trial with follow-up assessments at 3 and 6 months

-

residing in the geographical areas of the study.

Exclusion criteria were as follows:

-

presenting a serious risk of harm to the researchers or health trainers

-

unable to provide informed consent

-

having disrupted/chaotic lifestyles that may have made engagement in the intervention too difficult.

Sample size

A recruitment target of 120 participants was set across the two geographical regions (with the aim of recruiting 60 participants per region). Following consultation with the Trial Steering Committee, the decision was made for a 60 : 40 men-to-women purposive sample to inform understanding of the experience of women in the CJS. Women make up a smaller proportion of those under community supervision, and represent a small number of the total prison population. 41 However, the aim was to over-recruit for women in an attempt to avoid losing that understanding of experience through proportional sampling.

This pilot trial was not powered to detect between-group clinically meaningful differences in the proposed primary outcome. Therefore, the target sample size was primarily set to assess the feasibility objectives of the trial and to inform sample size calculations for a planned definitive trial. When data from a pilot trial are required to estimate the SD of a continuous outcome, to maximise efficiency in terms of the total sample size across pilot and main trials, the recommendation is that a two-group pilot trial should have follow-up data from at least 70 participants (i.e. 35 per group). 42 As most participants would remain engaged with the probation service for the length of the trial, it was anticipated that retention would be reasonably high. A recruitment target of 120 participants, based on an assumed non-differential retention rate of 75% at 6 months, in an aim to obtain follow-up outcome data on a minimum of 45 participants in each of the allocated groups, across both regions. A retention rate of 60% would still provide sufficient data for planning the future trial. 42 Local services suggested that, over a 3-month window, there may be 20–30 ex-offenders entering each of the two local community supervision systems per week. It was estimated that around 10% would decline to participate in a baseline assessment11,17,43 and a further 20% would be found to be ineligible following the baseline assessment. Based on recruitment rates from other probation trials,11 it was estimated that around 50% of eligible subjects would consent to participate.

Recruitment

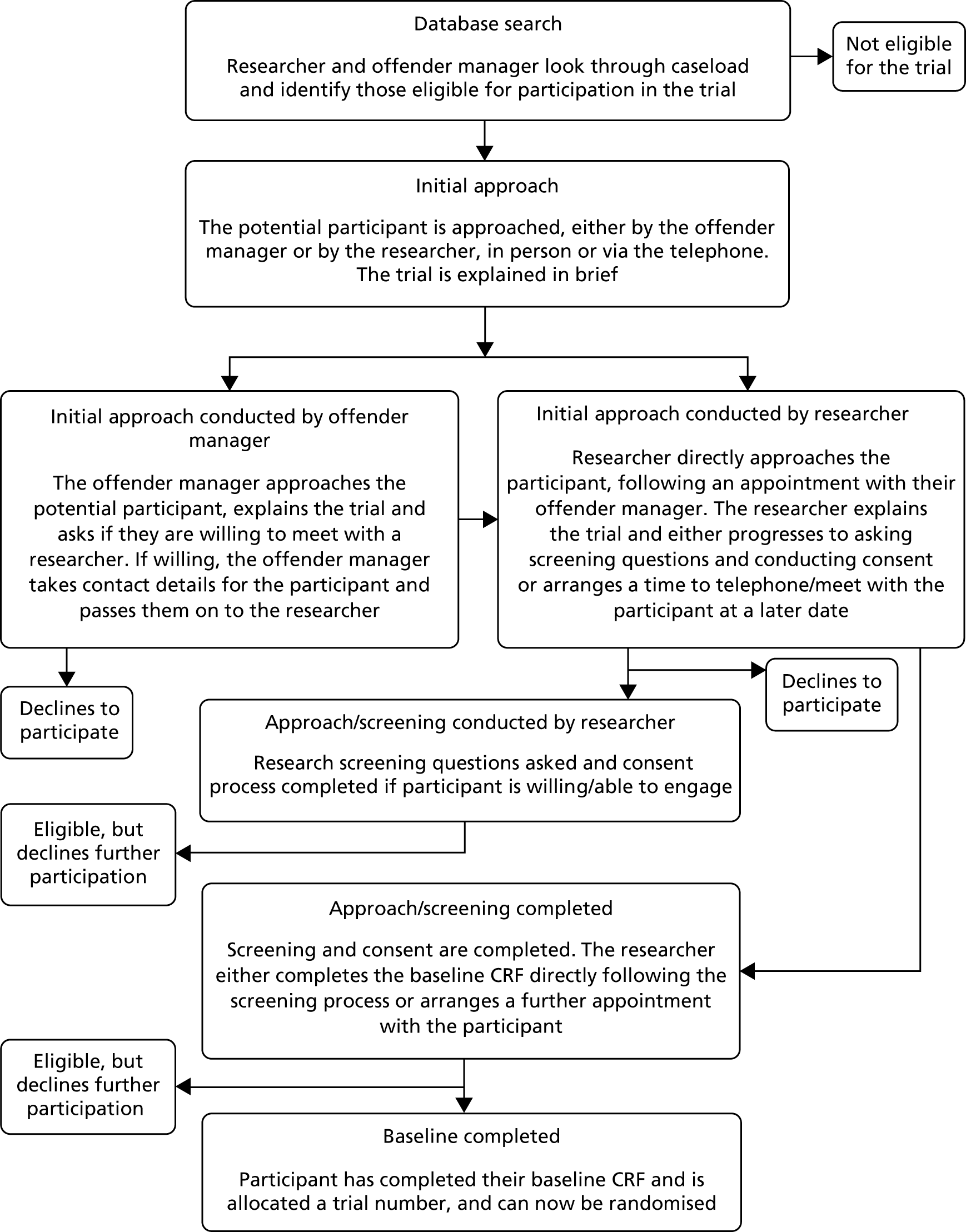

Recruitment for the trial was over a 14-month period between October 2016 and December 2017; initially, the planned recruitment period was a 3-month period from October to December 2016. This is discussed in more depth in Chapter 4. There were two pathways to participant recruitment: (1) via the CRCs and NPS and (2) via community organisations, including drug and alcohol rehabilitation centres, homeless hostels and day centres (in the Plymouth site only) (Figure 1). Recruitment via community organisations was introduced as an attempt to reach those not engaging regularly with the CRC or NPS services.

FIGURE 1.

Participant pathway to recruitment. CRF, case report form.

Initially, a single point of access administrator was identified for both the CRC and NPS. The single point of access administrator identified potential participants using the nDelius record system (Beaumont Colson Ltd, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK) for both services. The offender managers of identified individuals were then consulted by the researchers for screening for inclusion/exclusion criteria and assessment of risk. Further into the trial, a decision was made to alter this process, with researchers helping the offender managers to screen caseloads (i.e. sitting alongside them, but without visibility of personal information) to maximise efficiency and reduce overall staff demand [see the project web page: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/phr/145419/#/ (accessed 30 August 2019) for documents related to the screening process].

Those individuals who were assessed as eligible for participation in the research were initially approached by their offender manager, who explained the trial and asked if clients would be interested in speaking to the researcher directly after their appointment (if researchers were available), at their next scheduled appointment or via the telephone. On receiving verbal agreement to approach the client, the offender manager facilitated this meeting, providing an introduction. All participants were given the opportunity to meet the researchers for the initial appointment at the CRC/NPS offices.

Recruitment via community organisations

Identification of participants through community organisations involved key staff (e.g. day centre managers) initially approaching potential participants and inviting them to talk to a researcher about the trial. On receiving verbal agreement to approach, the researcher made a time and date for a meeting, to explain the project in more detail. The consent form [see the project web page: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/phr/145419/#/ (accessed 30 August 2019)] for potential participants who were identified through the community organisations requested consent for the researcher to make contact with their offender manager, to establish whether or not the individual met the criteria for participation in the trial. Following positive assessment by the offender manager, the researcher made contact with potential participants to arrange a time to conduct baseline data collection. If the offender manager assessed the potential participant as not meeting the inclusion criteria, the researcher made a time to explain to the individual why they were not eligible for participation in the trial.

Participant approach by researcher

During approaches, at both the CRC/NPS and community organisations, the researcher explained the trial, presenting information from the participant information sheet [see the project web page: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/phr/145419/#/ (accessed 30 August 2019)], including the potential time burden for the participant. Emphasis was placed on ensuring that the potential participant understood fully the concept and implications of randomisation, the voluntary nature of the research and their right to withdraw without detriment to their care or legal rights. Confidentiality (including reasons for a breach of confidentiality) and data protection were also presented at this stage. Potential participants were given the opportunity to ask questions and discuss their involvement in the trial. All participants were asked if they were willing and able to:

-

receive support to improve one or more of the target health behaviours and/or improve mental well-being if randomised to the intervention

-

take part in a pilot RCT with follow-up assessments at 3 and 6 months.

If the individual expressed further interest in taking part in the trial, the researcher progressed with the informed consent process, in which both the participant and researcher signed two copies of the consent form [see the project web page: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/phr/145419/#/ (accessed 30 August 2019)] (one retained by the participant and one by the researcher). If the participant expressed a need for time to think about their involvement, the researcher arranged a later date and time to contact the individual to discuss whether or not they wanted to continue with the trial. Individuals who were unwilling or unable to proceed were thanked for their time and reminded that there were no negative consequences of not taking part.

When the consent form was completed, the researcher continued with the baseline data collection during the same appointment if the participant was happy to proceed, or made a further appointment for baseline data collection if not. In addition to the baseline data assessment, the researcher completed a contact form [see the project web page: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/phr/145419/#/ (accessed 30 August 2019)] for each participant, noting contact numbers and addresses, as well as any key services with which they were engaging. The participant signed this form to confirm their permission for the research team to contact them via relevant services.

In regards to the consent process and data collection, individuals who lacked capacity on a particular day (potentially through intoxication) were given additional opportunities to complete assessments before being deemed to be ineligible to proceed. Given the often challenging and chaotic lives that this population can present with, this flexibility was particularly important.

Randomisation and concealment

Allocation to the intervention or control group was 1 : 1 and used a minimisation algorithm with a random element, to ensure balance between allocated groups with respect to age, gender and recruitment region.

On completion of the screening interview and baseline data collection, the researcher entered the participant details into a password-protected web-based randomisation system set up and managed by the Peninsula Clinical Trials Unit (PenCTU), and confirmed that the participant had completed the baseline case report form (CRF). The participant would then be allocated a unique randomisation number, and the participant’s allocated group (STRENGTHEN intervention or control) was then sent to the trial administrator via e-mail. To maintain blinding of the research assistants (RAs), the website would confirm that the allocation process had been successful, but would not display the participant’s allocated group. Health trainers would contact participants (via telephone) who had been allocated to the intervention arm of the trial and arrange an initial date/time to meet. Participants allocated to the control group were contacted by telephone or in person at CRC/NPS offices by either a health trainer or a research administrator, to maintain RA blinding. The conversation included a discussion of the randomisation process, to ensure that the participant had understood which group they had been allocated to.

Blinding of the researchers was tested for feasibility, to see whether it would be possible in a definitive trial. Researchers were asked to record instances when they believed they had been unblinded in the baseline, 3- and 6-month CRFs. We recognised from pilot work in our ENGAGER37 trial that concealment of trial arm may be very difficult because the RA mostly conducted the follow-up assessments in the offender management service, and offender managers or participants themselves may mention their involvement in the intervention in passing.

Data collection

Proposed outcome measures were collected at baseline (at or shortly following recruitment) and 3 and 6 months post baseline. Six months is the proposed primary assessment point for the future definitive trial [see the project web page: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/phr/145419/#/ (accessed 30 August 2019) for documents related to data collection].

Baseline data collection

The researcher typically continued with the baseline data collection following screening; however, additional sessions were arranged to meet the needs of individual participants. Detail of demographic data, as well as primary and secondary outcome measures collected at baseline, is in Proposed primary and secondary outcomes. Baseline data collection was delivered using a narrative conversational format developed in previous studies. 11 For the proposed primary outcome, the WEMWBS, participants were given the option to complete it themselves or have the researcher read responses aloud (method of completion was recorded). Questions from other measures were incorporated into a constructed, flexible script that avoids duplication to minimise disengagement.

On completion of the baseline assessment, the researchers discussed the 3- and 6-month follow-ups with participants, and agreed the best way to contact the participant for that appointment, depending on a range of scenarios, and changes to modes of follow-up, including any new mobile telephone numbers.

Three- and six-month data collection

Researchers contacted participants to arrange a time and date to complete the 3- and 6-month follow-ups. Contact ranged from initial text messages, to telephone calls and letters (if consent had been given). When researchers struggled to re-contact participants, offender managers were approached for information and to engage participants at appointments by asking if they were willing to meet with the researcher. Researchers arranged to meet with participants either in the CRC/NPS offices or at a suitable location in the community. When possible, assessments were conducted on the premises of services that participants were engaging with, in order to minimise risk to the researcher. When this was not possible, researchers adhered to the project’s lone-working policy [see the project web page: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/phr/145419/#/ (accessed 30 August 2019)] and used buddies as an additional safeguard if required. Data collection could be completed via a telephone call, but the preference was for face-to-face appointments to support continued engagement with the study.

Prior to the follow-up assessment being conducted, the researcher reminded the participant of the contents of the information sheet and consent process, drawing attention to data confidentiality and instances of disclosure for which the researcher would need to breach confidentiality. Identical measures to those collected at baseline were collected for the 3- and 6-month assessments, with the exception of ethnicity, to avoid unnecessary duplication/participant burden.

Feasibility and acceptability questions

A key aim of this trial was to collect data on the following acceptability and feasibility outcomes:

-

proportion of eligible participants

-

recruitment rates

-

rates of attrition and loss to follow-up

-

completion and completeness of data collection

-

estimates of the distribution of outcome measures

-

acceptability of intervention to participants

-

acceptability of trial procedures (e.g. blinding, randomisation) to participants.

Proposed primary and secondary outcomes

The proposed primary outcome for the definitive trial was the WEMWBS, to measure subjective mental well-being, which has good psychometric properties. 27,44 The short Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (SWEMWBS) was subsequently calculated for the purposes of possible future interest. 44

Secondary outcomes were:

-

self-reported smoking (number of cigarettes smoked per day)

-

Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence

-

alcohol use (measured using the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test)

-

diet (measured using the Dietary Instrument for Nutrition Education)

-

physical activity (measured using the 7-day Physical Activity Recall questionnaire)

-

substance use (measured using the Treatment Outcomes Profile)

-

confidence, importance (i.e. an individual’s perception of the importance of changing the target behaviour), access to social support, action-planning and self-monitoring measures relating to health behaviours

-

health-related quality-of-life [measured using the EQ-5D-5L and Short Form questionnaire-6 Dimensions (SF-6D) (derived from the SF-36)]

-

intervention costs (related to health trainer time, training, supervision, travel, consumables)

-

health care use, social care use and other resource use data were collected using a participant self-report resource use questionnaire.

The secondary outcome measures were selected as they link on to the four health behaviours and were rated as acceptable to participants during the PPI consultation stage.

Summary of process evaluation methods

The aims of the process evaluation were to:

-

assess whether or not the intervention was delivered as per the manual and training

-

ascertain components of the intervention that are critical to delivery

-

explore reasons for divergence from delivery of the intervention as manualised

-

understand when context is moderating delivery

-

understand the experience and motivation of participants in the control arm of the pilot trial to maximise retention in a full trial

-

explore reasons for declining to participate in the trial

-

explore reasons for disengaging in the intervention before an agreed end

-

understand, from a participant perspective, the benefits and disadvantages of taking part in the intervention.

Data collection

Semistructured one-to-one interviews

One-to-one semistructured interviews were conducted with the following participant groups:

-

participants randomised to the intervention arm of the pilot (n = 11)

-

participants randomised to the control arm of the pilot (n = 5)

-

health trainers across both geographic regions (n = 6)

-

offender managers/probation workers across both geographic regions (n = 6).

Interviews were guided by semistructured interviews schedule [see the project web page: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/phr/145419/#/ (accessed 30 August 2019)]. All interviews were digitally audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Discussions with decliners

Researchers asked up to four potential participants who declined to take part following screening for their reasons for not continuing with participation. The researcher was sensitive to the right to withdraw from the trial without providing a reason and did not question the potential participant further should they decline to divulge their reason for discontinuation. These discussions were not recorded, but notes were taken to inform the process evaluation.

Digital audio-recordings of health trainer sessions (n = 20)

Health trainers were asked to record sessions with participants. The choice of sessions to record was a collaborative decision between the health trainer and the research team based on appropriateness (assessed by the health trainer) and data required (assessed by the research team and guided by their knowledge of each case via the health trainer session report forms). All participants were asked for their consent for sessions to be recorded at the start of the intervention. However, health trainers were requested to seek verbal consent to record each session prior to recording.

Health trainer session report forms

Health trainers kept an electronic record of each session on the bespoke intervention section of the data management system. Each contact and session was recorded, including information on date, location, duration, type (face to face or by telephone), subsidies taken up by participant, primary and secondary goals of participant, goals met (if applicable) and any particular difficulties encountered, for discussion in supervision.

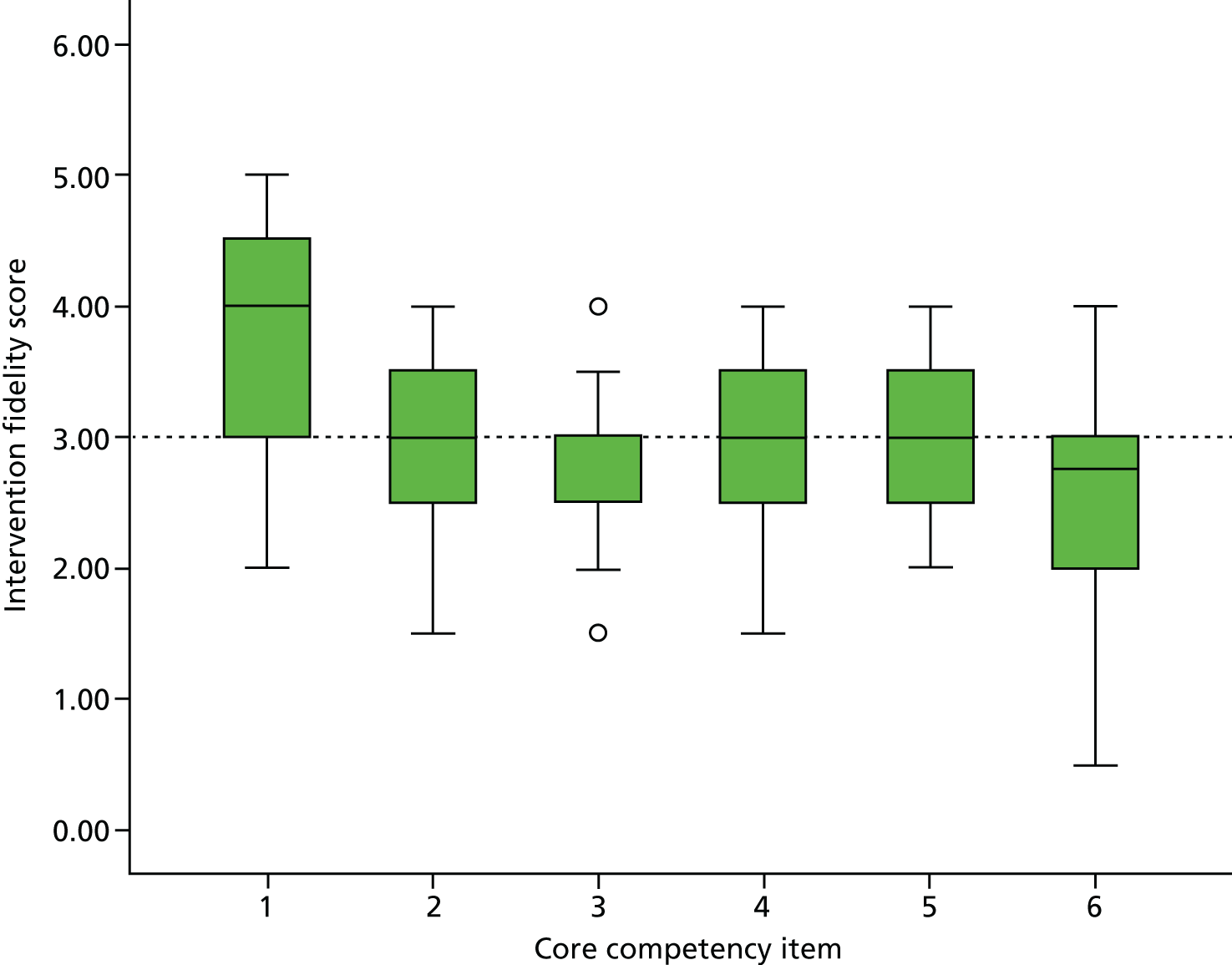

Analysis

Intervention fidelity was assessed through the scoring of audio-recordings of health trainer sessions against a developed list of key intervention processes, or the six core competencies detailed in Chapter 1 [(1) active participant involvement, (2) motivation-building, (3) goal-setting, (4) reviewing efforts to make changes and problem-solving, (5) integration of concepts and (6) engaging social support and managing social influences]. These were scored on two domains: (1) practitioner adherence to the core competencies outlined in the intervention manual and (2) competence of delivery. Recordings were scored independently by two researchers.

Quantitative data were summarised descriptively, with confidence intervals (CIs) as appropriate.

Any factors that were identified as possibly contributing to participants’ intervention engagement, and trial recruitment and retention will be explored in more detail in Chapter 6. All data were organised using NVivo version 11 (QSR International, Warrington, UK). 45 Data related to feasibility and acceptability of trial method and the intervention were analysed using thematic analysis. Interview data and session notes were synthesised into a framework analysis grid to understand the experience of participants in receiving the intervention in order to understand how the intervention works in practice and the components of the intervention that are critical to delivery. This allowed the feasibility and acceptability of the intervention, the intervention delivery and the research data collection to be assessed. Any procedures that needed to be adapted were identified and potential improvements and solutions were suggested.

Statistical analysis

A detailed statistical analysis plan was written by the trial statisticians and approved by the chairperson/independent statistician on the Trial Steering Committee (statistical analysis plan version 1.0, dated 8 June 2018) prior to trial database lock.

Analytical approach

Analyses were undertaken in accordance with the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) extension for randomised pilot and feasibility trials. 46 The primary analysis (in the form of summary statistics, not formal/inferential analysis) was undertaken on an intention-to-treat basis, in which participants are analysed according to their allocated group, regardless of adherence to the protocol or lack of participation/engagement, if allocated to the intervention group.

Statistical significance levels

As this was a feasibility trial, no inferential between-group comparisons were undertaken (i.e. there was no between-group hypothesis testing). Where presented, confidence intervals are at the 95% level, unless otherwise stated.

Interim analysis

There was no planned interim analysis for this trial.

Time points of statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was undertaken once the final group of participants completed the final assessment and the database was locked following final approval and sign-off of the statistical analysis plan by the Trial Steering Committee.

Missing data

One of the objectives of this feasibility trial was to assess the completeness of potential outcome measures for the definitive trial, at the level of both item and outcome measure. Missing outcome data were noted and used to inform the probable pattern of missing data in a full-scale trial.

Imputation methods

No imputation of missing values was undertaken, with the exception of missing values in the proposed primary outcome, WEMWBS. The established method for imputing missing item-level data was implemented when participants were missing between one and three items on the WEMWBS. 44

Statistical software

The statistical analyses were undertaken using Stata® version 14 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA), supplemented when required by R (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

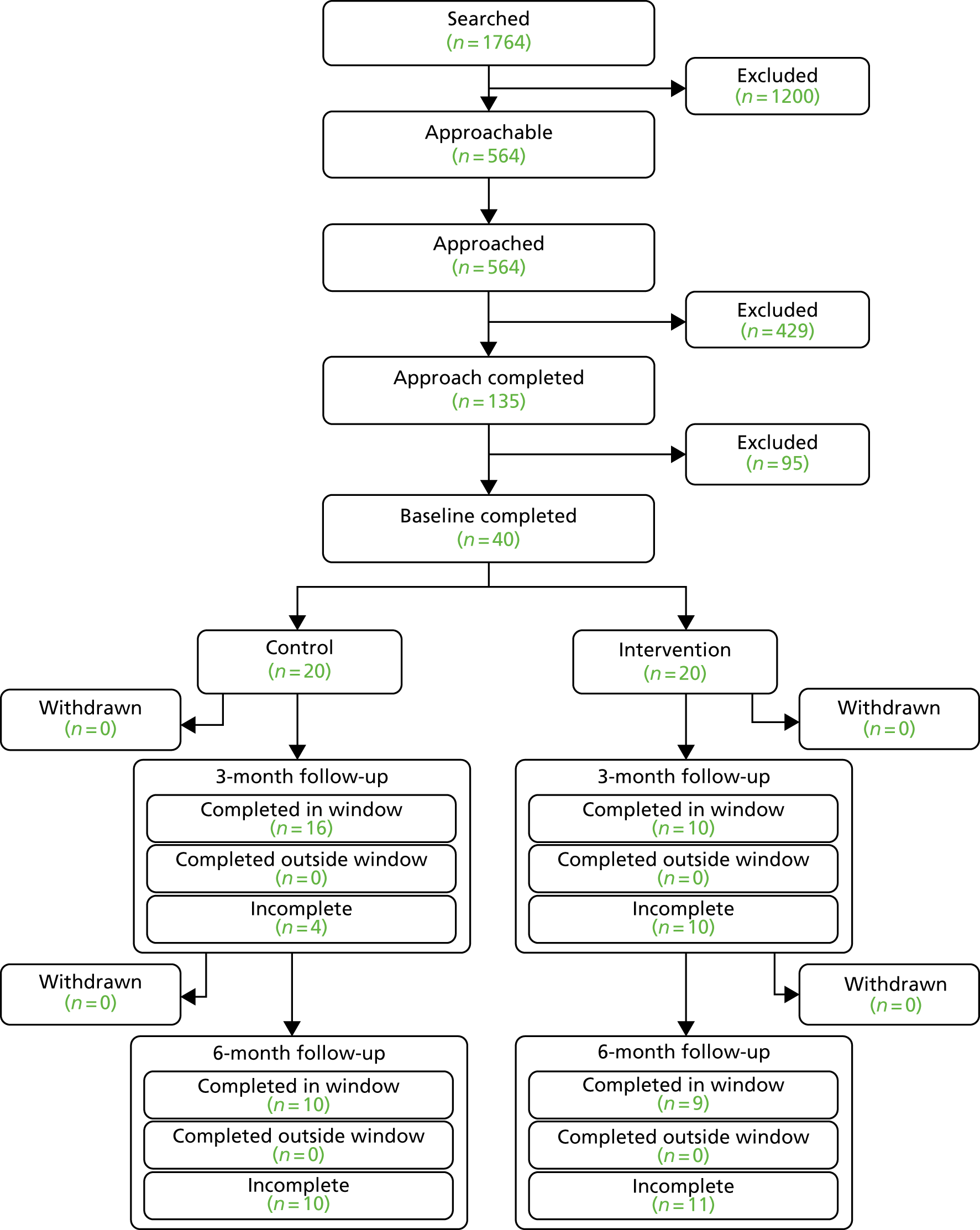

Trial population

Data from the screening process through to the completion of the trial were recorded and presented in a CONSORT-style flow diagram (see Figure 2).

Participants who discontinued, withdrew or were lost to follow-up

It was possible that participants would withdraw consent part-way through the trial. Participants who discontinued were categorised as follows:

-

continued to consent for follow-up and data collection

-

consented to use pre-collected data only.

Reasons for withdrawal or loss to follow-up were summarised, when reported, both prior to and after randomisation.

Participants who withdrew from the trial were not replaced. The extent of discontinuation, withdrawal and loss to follow-up will be used to inform the design of the anticipated fully powered trial, predominantly to ensure a sufficiently powered trial after allowing for losses to follow-up.

Statistical analyses

As this was a pilot trial, it was not powered to be able to support or justify any conclusions regarding intervention effectiveness realised from hypothesis testing;47 indeed, that was not the purpose of the trial. As a result, the analysis of the results did not involve formal/inferential statistical comparisons between groups, but rather was descriptive, with the view to informing the design of a fully powered definitive trial.

Continuous measures were summarised as means, SDs, ranges, medians and interquartile ranges. Categorical data were summarised by frequencies and percentages. When appropriate, parameter estimates (e.g. between-group differences) are presented with 95% confidence intervals.

Baseline characteristics and measures, collected prior to randomisation, were summarised by allocated group to informally check for balance between groups and provide an exploratory overview of the trial sample. An analysis of randomised groups at baseline is not good practice47 and so was not undertaken, but we considered imbalances to assess the efficiency of the randomisation procedures.

Analyses of quantitative data were conducted to summarise feasibility outcomes and to evaluate engagement with the STRENGTHEN intervention and the completion of the planned primary and secondary outcome measures. Summary statistics were calculated for each of the outcome measures at each time point. Between-group differences in WEMWBS scores at the 3- and 6-month follow-ups were calculated, together with 95% confidence intervals (no p-values are presented). The correlation between baseline and follow-up WEMWBS scores was calculated across all participants with available data, with corresponding confidence intervals, together with upper confidence limits for the SD of WEMWBS, to inform sample size calculations for future trials.

Cost-effectiveness and data collection

The pilot trial aimed to estimate the resource use and costs associated with the delivery of the intervention, and develop a framework for estimating the cost-effectiveness of the STRENGTHEN intervention plus usual care, versus usual care alone, in a future economic evaluation alongside a fully powered RCT. We aimed to develop and test economic evaluation methods for the collection of resource use data, for estimating related costs, and also the collection of outcome data appropriate for economic evaluation. Full details of the methods used are presented in Chapter 5.

Patient and public input to trial methods

The peer researcher groups introduced in Chapter 2 reviewed and discussed trial methods, including the following:

-

participant information sheets and consent forms

-

semistructured interview schedules

-

CRFs and associated data collection.

Both peer researcher groups reviewed the information sheets and consent forms for the pilot trial and the process evaluation. The first drafts reviewed were adapted from ENGAGER 2 information sheets and consent forms that themselves had been reviewed by the ENGAGER 2 peer researchers. Peer researchers provided guidance to adapt wording and order of text to aid comprehension and to ensure that the main points of the trial and requirements for participation were clear.

The first draft of the CRF was given to each of the peer researchers (literacy levels had already been assessed by researchers). Over 3 weeks, peer and trial researchers role-played each of the measures in pairs or threes, as appropriate. It was made clear that peer researchers did not need to answer honestly but could play a role in order that they did not have to disclose any confidential or sensitive information. Peer researchers discussed the measures in turn and/or annotated drafts and gave them to the trial researchers. Each of the issues raised by the peer researchers in relation to the CRF are detailed in the following list, with reference to the changes made, when applicable:

-

Removal of the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 items (PHQ-9)

The original STRENGTHEN CRF contained the PHQ-9 (a measure of depression). Peer researchers questioned the use of the PHQ-9 for a trial in which the primary outcome was mental well-being, as opposed to mental illness. They were particularly concerned about the impact that some of the items may have on participants who may be experiencing challenging life circumstances, and potentially have mental health needs, when it was not in a therapeutic context. As one of the peer researchers stated, ‘if someone was just starting a recovery journey, they may not be in a stable headspace and question 6 could be triggering.’ The trial researchers took this issue back to the project team, which supported the PHQ-9’s removal from the CRF as the collection of this outcome was not critical to the aims of the pilot trial.

-

Simplification of response format

There was some concern among peer researchers that some of the formats by which participants could respond to items were complex and in some instances provided too nuanced a set of choices. It was explained to the peer researchers that, in the case of validated measures, the responses could not be amended. However, for the measures included to capture confidence, control and connectedness in relation to changing each of the target health behaviours, where there was originally a 9-point scale, this was amended to a 7-point scale on the advice of the peer researchers. Furthermore, also on the advice of the peer researchers, to assist participants in making the appropriate response to the items contained in the validated measures, the researchers produced laminated A4 ‘answer cards’ that contained the options required for each item.

-

Understanding of item choice

Peer researchers noted that some of the items could be perceived as sensitive by participants and that it was not always clear as to the rationale for including all of the measures. Therefore, it was agreed that the research team would add a short paragraph or script for researchers at the start of each measure to explain why they were asking the items contained in each measure.

-

Wording of items

Similar to response format, peer researchers were aware that the wording of validated measures could not be amended. Concerns were raised about what were considered ‘Americanisms’ in the SF-36, for example ‘blocks’ and ‘pep’. For items such as this, the peer researchers provided alternatives that researchers could use to aid participants’ comprehension.

-

Order of measures

In the first draft of the CRF, the WEMWBS and the items related to offence history were at the start of the booklet. Peer researchers felt that it would be best to start with generic questions before asking those that could be considered more personal. They understood the need to order the WEMWBS near to the start of the CRF to ensure that this was collected if a follow-up appointment was unexpectedly cut short. It was therefore agreed between the peer researchers and the research team that this would be presented after demographic measures and that offence data (considered particularly sensitive) would be collected after measures of target health behaviours.

Chapter 4 Results

This chapter reports on:

-

participant recruitment

-

trial attrition and associated factors

-

baseline participant characteristics for the total sample and by allocated group

-

outcomes (e.g. WEMWBS, health behaviours) over time, by allocated group

-

WEMWBS descriptive data at follow-up, by allocated arm and CRC/NPS

-

intervention engagement

-

the association between intervention engagement and WEMWBS at follow-up

-

factors associated with intervention engagement

-

other methodological considerations

-

the indicative sample size calculation for definitive trial.

Brief overview

A number of barriers to recruitment were overcome, for example by taking on Manchester instead of Southampton as a second site at a late stage (and putting the resources and governance processes in place), and working with offender management services (OMSs) while they were becoming established and overcoming their own challenges. A great deal was learnt about participant flow into the trial and the reasons for excluding those in the service and after having been approached. Having recruited our target of 120 participants, we are now in a strong position to estimate the resources required to recruit participants.

Trial attrition was initially around 50%, but with improved processes throughout the pilot trial this was improved to 60% overall, which partly met our progression criteria. There was no clear influence of trial arm or recruitment service on retention. An acceptable level of retention was achieved without financial incentives.

The characteristics of the sample were described; overall, they had low levels of well-being; unhealthy lifestyles, particularly with respect to diet, alcohol and smoking; and were from low socioeconomic backgrounds.

It was not an aim of the trial to detect statistical significance between group differences, but the reported values for the main outcome variable, WEMWBS, at the 3- and 6-month follow-ups indicated some differences in favour of the intervention arm, from which to provide estimates for a sample size calculation for a definitive trial. There were also some encouraging signs that there was lower tobacco and alcohol consumption at follow-up in the intervention arm than in the control arm. Data for all measures were generally complete because assessments were mainly conducted face to face. Those who had moderate (2–5) intervention sessions appeared to have higher WEMWBS scores at follow-up than those who had lower and higher engagement.

Overall, 28% of participants did not attend any sessions, and 62% attended at least two sessions, which partly met our progression criteria. The overall mean number of sessions attended was 3.7 (SD 3.4), with a median of 3.

Recruitment and retention of participants

The flow of participants through the pilot trial is shown in the CONSORT flow chart (Figure 2) for the whole sample recruited (i.e. n = 120) from identification to recruitment and randomisation, through to completion of follow-ups at 3 and 6 months. Additional data on participant flow through the trial for each OMS are shown in Appendix 2, Figures 5–7.