Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 14/185/13. The contractual start date was in May 2016. The final report began editorial review in December 2018 and was accepted for publication in May 2019. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Peymane Adab reports grants from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), Birmingham City Council and Zhejiang Yongning Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd (Taizhou, China) during the conduct of the study, and is a member of the NIHR Public Health Research (PHR) funding committee. Clare Collins reports being involved in the development of the original Healthy Dads, Healthy Kids (HDHK) intervention and previous evaluations. Furthermore, she is supported by an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council Senior Research Fellowship and a Faculty of Health and Medicine Gladys M Brawn Senior Research Fellowship at the University of Newcastle. Amanda Daley reports being a member of the NIHR Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Clinical Trials Committee, from July 2014 to July 2015. Emma Frew reports grants from NIHR and Birmingham City Council, outside the submitted work. Kate Jolly reports grants from NIHR and funding for the intervention from local authorities in the West Midlands and the South West during the conduct of the study; she is part funded by the NIHR Collaborations for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (CLAHRC) West Midlands and is a subpanel chairperson of the NIHR Programme Grants for Applied Research panel. Laura Jones reports grants from the NIHR PHR programme during the conduct of the study and personal fees from North 51Bionical (Willington, UK), outside the submitted work. Miranda Pallan reports grants from NIHR during the conduct of the study for HTA 12/137/05: cultural adaptation of an existing children’s weight management programme: the Child weigHt mANaGement for Ethnically diverse communities (CHANGE) intervention and feasibility randomised controlled trial. Philip Morgan reports that he developed the Healthy Dads, Healthy Kids programme.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Jolly et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

The epidemiology of overweight and obesity in men

Overweight and obesity are major public health challenges. Obesity is associated with an increased risk of diseases including type 2 diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, cancers (e.g. of the colon) and osteoarthritis. 1 It is also associated with higher rates of depression. 2 For each increase in body mass index (BMI) of 5 kg/m2, mortality increases by 30% and median survival reduces by 2–4 years for people with a BMI of 30–35 kg/m2 compared with those with a BMI of 22.5–25 kg/m2. 3 Owing to its associations with many long-term medical conditions, the cost of obesity is high. Public Health England estimated that obesity cost the NHS in England £6.1B in the year 2014–15 and the wider costs to society were estimated at £27B. 4

Men are at a higher risk of overweight and obesity than women. 5 Inequalities are evident, with a higher proportion of men in the lowest income quintile having a very raised waist circumference (> 102 cm) (38%, vs. 32% in the highest income quintile), which puts them at high risk of the long-term conditions associated with obesity. 6 In addition, compared with white Europeans, people of South Asian ethnicity living in England tend to have a higher percentage of body fat at the same BMI and more features of the metabolic syndrome at the same waist circumference. 7 The proportion of men who want to lose weight varies by age group, with the highest proportions among those aged 35–44 years (46%) compared with 39% of those aged 25–34 years and 44% of those aged 54–64 years. 6 Entrance into fatherhood is associated with an increase in BMI trajectory for both fathers who reside and fathers who do not reside with their children. 8 In the 2016 Health Survey for England,6 39% of men reported using some form of weight management aid: the most popular were gyms or another form of exercise (31%), 7% used websites or mobile phone applications, 6% used activity trackers or fitness monitors and only 2% attended dieting clubs. 6

In terms of dietary behaviours, men and women have suboptimal diets for long-term health. 9 Only 24% of men in England report eating at least the recommended five portions of fruit and vegetables each day5 and only 13% of men aged 19–64 years consume below the recommended amount of free sugars. 9

In conjunction with the high rates of overweight and obesity and poor dietary practices, men have become less physically active. Although 66% of men self-report meeting the UK government guidelines10 of achieving at least 150 minutes of moderate physical activity or 75 minutes of vigorous activity per week,11 objective measurement shows this to be an overestimate. 12 The most recent comparison of population-based objective measurement of physical activity by the Health Survey for England was in 2008,13 which found that only 5% of men aged 35–64 years achieved the recommended activity level. Overall, 26% of men in England are classified as inactive, namely undertaking < 30 minutes of physical activity each week. 11 People from Asian, black and Chinese ethnic groups were more likely to be inactive than those from white or mixed ethnic groups. 14 After having children, men’s physical activity levels generally reduce. 15–17

Evidence of the effectiveness of weight management programmes for men

In a series of systematic reviews, Robertson and colleagues collated the evidence for the management of obesity in men. 18 Fewer men than women joined weight management programmes, but, once they joined, they had higher retention rates and a similar or greater percentage weight loss than women. A meta-analysis of male-only weight loss interventions revealed a clinically significant difference in weight change favouring interventions over no-intervention controls at the last reported assessment [–5.66 kg, 95% confidence interval (CI) –6.35 to –4.97 kg]. 19 Successful men-only weight loss programmes have been run in football clubs20 and workplaces,21 tapping into a shared identity associated with their club or workplace. 18

Robertson et al.’s18 reviews identified no eligible studies that looked at how to increase the engagement of men in weight management interventions. However, many men said that a health concern motivated them to lose weight, rather than a concern about their appearance. 18 A qualitative synthesis of 22 studies18 identified that men felt an individual responsibility for their weight gain, and that men from socioeconomically disadvantaged communities were often constrained by economic circumstances from healthy eating and exercise. To date, few studies have explored the beliefs of men from minority ethnic groups in the UK. 22 The qualitative review18 also identified the features associated with successful weight loss programmes in men. These included group-based programmes and social support, promoting engagement with the use of humour, accountability and adherence, and goal setting. 18 Men also valued a personalised approach that took account of their individual needs, and individual tailoring of advice assisted weight loss.

The epidemiology of overweight and obesity and physical activity in children

Overweight and obesity in children (aged 2–15 years) has generally increased since the 1990s, with a rise from 1995 to 2005, but an overall levelling off in recent years, with a childhood obesity prevalence of 16% in 2016. 5 However, underlying this is a widening trend in inequalities, with overweight and obesity prevalence continuing to increase in more socioeconomically deprived communities. In 2017–18, 9.5% of children aged 4 or 5 years in England were classified as obese, with a further 12.8% classified as overweight. 23 The prevalence of overweight and obesity increases during the primary school years, with 20.1% of children aged 10 or 11 years classified as obese and a further 14.2% classified as overweight. 23 Ethnic differences in the prevalence of obesity have been shown in children aged 10 or 11 years, with 29.0% of black Caribbean and African children and 24.8% of South Asian children (originating from the Indian subcontinent) living with obesity, compared with 18.4% of white British children. There are socioeconomic differences in childhood obesity, with prevalence in the most socioeconomically deprived areas double that of the least deprived areas for children aged 4 or 5 years (5.7% of children in the least deprived decile were obese, compared with 12.8% of those in the most deprived decile) and 10 or 11 years (11.7% in the least deprived decile vs. 26.8% in the most deprived decile). 23

Engaging in adequate levels of physical activity is important for children in the short, medium and long term. 24 Apart from the increased risk of obesity with physical inactivity, there are many other negative physical and mental health consequences. 25,26 Active children are less likely to suffer the adverse health consequences of physical inactivity in adulthood, as habits formed in childhood track forward into adulthood. 26 In children, physical activity is essential for motor development, cognitive improvement, psychosocial health and cardiometabolic health; physical activity reduces body fat and can increase academic achievement. 25

Current UK recommendations27 for physical activity in children aged ≥ 5 years are that they should be at least moderately active for a minimum of 60 minutes every day. This is the minimum level, and there is a recommendation that children should engage in moderate to vigorous physical activity for up to several hours each day. It is also recommended that vigorous intensity activity, including muscle- and bone-strengthening activities, should be undertaken at least 3 days each week. 27

However, national objectively measured data using accelerometry shows that, in 2008, the proportion of boys and girls classified as meeting the minimum recommendations27 were 33% and 21%, respectively. 13 In children aged 4–10 years, 51% of boys and 34% of girls met the recommendations, compared with 7% of boys and no girls aged 11–15 years. Data from England’s 2016 Report Card on Physical Activity28 suggest that overall physical activity levels in children and young people has declined. Recent objective data on children’s physical activity come from regional studies. 29 A study from Bristol reported that boys and girls aged 5 or 6 years undertook a mean of 72.4 [standard deviation (SD) 20.7] and 62.3 (SD 16.2) minutes, respectively, of physical activity daily, and that there was a decrease in physical activity and increase in sedentary time in boys and girls between the ages of 5 or 6 and 8 or 9 years. 30 This demonstrates the importance of strategies to encourage and promote physical activity into later childhood and beyond.

Family physical activity and eating behaviours

Parental support, direct help from parents, support from significant others and perceived and actual physical competence have been shown to be positively associated with children’s physical activity levels, although the association with parental physical activity is inconsistent. 31 Promising strategies to involve parents in interventions to increase their children’s physical activity include engaging family members in a family physical activity programme, parent training, family counselling or preventative messages during family visits. 32 A systematic review of interventions to promote physical activity in children highlighted the limited evidence of the effect of interventions targeting low socioeconomic populations and interventions aimed at the home environment. 33

Family eating practices are associated with child eating behaviours. 34 Eating meals together as a family, parents role modelling healthy eating behaviours and having healthy foods available in the home have been shown to be positively related to the eating habits of children. 35–39 In addition, parents who have an involved and caring parenting style rather than a controlling style have children who eat healthier diets. 40,41 UK evidence from the National Diet and Nutrition Survey shows that whether or not families eat together is influenced by parents’ work schedules, children’s age and appetite for earlier eating than their parents, their child-care regimes, their extracurricular activities and the problem of co-ordinating different food preferences and tastes. 42

The health inequalities in obesity experienced by people from minority ethnic groups is likely to be, in part, affected by different dietary practices and beliefs about physical activity. 43,44 However, food practices of minority ethnic groups are heterogeneous and, although affected by ethnic background, they are also affected by age, religion, socioeconomic circumstances, geographical area and generation. 43 Factors that influence food practices in minority ethnic groups include sociocultural norms and affordability and accessibility of food; these need to be seen in the context of poverty and there have been calls for culturally sensitive interventions that build on positive food practices and adopt a family- and community-centred approach. 43 A systematic review44 of qualitative literature relating to the health beliefs of British South Asians on lifestyle diseases highlights the primacy of social and cultural norms over an individualised approach to lifestyle change, and many barriers to physical activity and exercise.

The Healthy Dads, Healthy Kids intervention

The Healthy Dads, Healthy Kids (HDHK) programme was developed by a team of researchers in Australia, including some of authors of this report (PM, CC and MY), and was established to address weight management in fathers, but in the context of their families, such that changes in their health behaviours would positively affect their children. A highly novel aspect to the intervention was that children also play a major role in motivating and helping their father to maintain his behaviour change.

The HDHK programme has been rigorously evaluated in two randomised controlled trials (RCTs) in Australia. 45,46 In the community RCT with trained facilitators in disadvantaged areas, the authors reported a mean difference in weight of the fathers of 3.4 kg (95% CI 2.1 to 4.7 kg) in favour of the intervention at 14 weeks, compared with a wait-list control. They also observed significant group-by-time reductions in children’s BMI z-scores (–0.10, 95% CI –0.21 to 0.00), physical activity levels and diet quality, favouring the intervention group. 45 A larger-scale community roll-out has demonstrated clinically meaningful weight loss sustained to 1 year in fathers (3.8 kg loss; 95% CI 3.1 to 4.6 kg), and a significant mean reduction in BMI z-scores (–0.12, 95% CI –0.17 to –0.07) in children. 47 Positive effects reported via qualitative research were improved family relationships and involvement of the fathers and children in joint activities. 47 In additional, the quantitative findings showed that participation in the HDHK programme positively affected fathers’ co-physical activity with their child and beliefs about healthy eating, which mediated changes in children’s diet and physical activity behaviours. 48 Although the intervention has been evaluated in Australia, its transferability to a multiethnic UK setting needs to be tested.

The existing Healthy Dads, Healthy Kids programme

Since the initial evaluation of the Australian HDHK programme, it has undergone a number of iterations, with changes to the number of sessions and the inclusion of mothers. At the time of commencing HDHK-UK, it had a format of nine sessions of 90 minutes’ duration, delivered at weekly intervals. Mothers/partners were invited to attend two sessions, fathers attended all nine and the children attended seven. In the joint sessions, the children and fathers separated for 20–25 minutes for a discussion session followed by a 1-hour joint physical activity session. The physical activity session aimed to be interactive, highly active and fun, focusing on elements associated with optimal child development outcomes across physical, cognitive and social–emotional domains. This included fundamental movement skills, health-related fitness-based activities and rough-and-tumble play.

The HDHK programme is based on social cognitive theory (SCT)49 and family systems theory (FST). 50 SCT constructs targeted in the HDHK programme are self-efficacy, goals/intention, outcome expectations, perceived facilitators of and barriers to changes, and social support. 49 The FST postulates a framework of reciprocal relationships between family members. 50 Thus, when a father changes his dietary behaviours and physical activity levels, this will be reflected in his child’s behaviour and the child will help to sustain their father’s behaviour change. 51

The HDHK programme aims to provide fathers with the knowledge and skills for long-term behaviour change. It teaches fathers about the importance of engaging with their children and uses healthy eating and physical activity as media to engage fathers with their children. The children’s engagement and enthusiasm for the HDHK programme’s father–child activity aims to reinforce the change in family lifestyle. During the programme, fathers come to understand the profound influence that their parenting, actions, behaviours and attitudes have on their children; this realisation becomes a driving force behind their motivation to get fit and become more engaged in their children’s lives.

The individual session content is summarised in Box 1. Resources include handbooks for fathers and children; a logbook for dads; and a website for self-monitoring, with an instruction guide for use.

Highlights the unique influence of dads in contributing to the physical and mental health of children.

Weight management for menExplores the challenges of healthy eating in the modern world, outlines the mathematics of weight loss and sets SMART goals to achieve activity and dietary ambitions.

Healthy eating for familiesProvides advice on appropriate portion sizes for the whole family, and discusses strategies for implementing the trust paradigm to encourage their children to eat healthily at home.

Being a healthy dad: strategies to enhance you and your family’s lifeHighlights the eight weight loss tips for men, tells dads how to ‘stay on track’ and provides advice on sustainable approaches to weight loss.

The unique and powerful influence of fathersExplains to dads why they have such a powerful influence over their children and the importance of being a good role model, and outlines the most effective parenting style.

Raising active kids in an inactive worldExplains the growing issues of childhood obesity and why physical activity is so important for children; highlights key strategies for dads to be physical activity leaders.

‘Switching on’ your child’s mind by ‘switching off’Highlights the physical and mental health issues created by excessive screen time and provides strategies for ‘switching off’.

‘Healthy’ fathering in a busy worldEncourages discussion of barriers to achieving SMART goals, and solutions for those barriers; highlights opportunities to create family traditions and maximise the time dads can spend with their children.

Continuing the ‘healthy dad’ journeyReviews the key messages of the programme, provides tips for staying on track after the programme, awards children with their certificates and awards dads with a card.

Children’s sessions Rough-and-tumble funChildren learn about their mission to ‘get dad fit and healthy’ and are taught about rough-and-tumble activities.

Turning dad into a healthy eaterThrough fun activities, children learn about ‘sometimes’ foods and ‘any time’ foods and how they can encourage dad to eat more healthily.

The Healthy Dads, Healthy Kids rainbow plateThrough fun activities, children learn about different fruits and vegetables and are challenged to make their plates ‘rainbows’ with a variety of healthy fruits and vegetables.

Quality time with dadChildren are given activities to help them think about games they can play with dad to spend quality time together.

Helping dad ‘switch off’Children think about activities they could enjoy with dad instead of playing on the computer or watching television.

Becoming dad’s personal trainerChildren develop an activity board with games and exercises the family can complete at home.

Helping dad stay on trackChildren review the programme and receive their HDHK certificate for achieving their mission to get dad fit and healthy. Dads receive a card from their children for their commitment to the programme.

SMART, specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, time-bound.

Rationale for the Healthy Dads, Healthy Kids UK study

This study addressed a commissioned call from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Public Health Research programme for research on weight loss services for men. The recruitment of fathers with their children, and the involvement of mothers/partners in the intervention, meant that meaningful health gains were possible for the whole family. There was the potential for sustained behaviour change as a result of family behaviour change, which would help to break the cycle of intergenerational obesity.

A patient and public involvement (PPI) group was consulted in the development of the research proposal and, through this group and the research team, it was identified that there would be a need to adapt the Australian version of the HDHK programme.

As a result of changes in migration patterns over the previous 20 years, urban populations, such as that of the West Midlands, have become more complex and ‘superdiverse’. Superdiversity is characterised by overlapping variables including country of origin, ethnicity, language, religion, regional/local identities, migration history and experience (influenced by sex, age, education, specific social networks and economic factors) and immigration status (encompassing a variety of entitlements and restrictions). 52,53 Such complexity in the population has created unique challenges with regard to how we identify and respond to the health needs of all members of a superdiverse society.

Cultural adaptations have been described by Resnicow et al. 54 with regard to different dimensions of cultural sensitivity: surface and deep structure. An intervention that addresses surface-structure adaptations would match intervention materials or messages to ‘fit’ within a specified culture – be it by matching on language, food, music or location, and including items of familiarity to the target population to help them engage with the intervention. Deep-structure adaptations would address the core cultural values or ethnic, cultural, historical, social or environmental factors that may influence specific health behaviours. 54

In relation to the delivery of the HDHK programme, a number of issues to be addressed in the adaptations were known to the research team from the outset, namely awareness of certain cultural barriers to engagement with behaviour change activities in some black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) groups. For example, participation in sports and physical activity outside the home may be discouraged among girls, and cultural dress codes can restrict physical activity.

In addition, the Australian programme was predominantly delivered by teachers, and this model was considered unlikely to be replicable in the UK owing to different incentives to deliver after-school activities in the two countries. In the Australian studies, the HDHK programme was delivered mainly in schools, often by a physical education teacher who was able to use the initial training towards their continuing professional development requirement. Our experience of working with UK schools suggested that teachers are overburdened and schools are regularly approached to take part in projects and initiatives. 55 There are similarities between Australia and the UK in the proportion of men who are overweight or living with obesity. 5,56 Australian guidance for adult fruit and vegetable intake is five or six portions each day, whereas the UK’s guidance is five portions. 57 About one in four men in the UK report adequate fruit and vegetable consumption,58 but < 5% of Australian men have an adequate intake. 59 Australian guidelines also separate fruit and vegetable portions, unlike the UK. 57 Guidance in relation to alcohol consumption is similar. Given these relatively modest differences, we considered that the intervention should be transferable with some adaptions.

However, it was also agreed that, as part of the study, cultural adaptation would need to be informed by the community and that changes would need to be made before implementing the HDHK programme in the UK setting.

Potential benefits of the adapted Healthy Dads, Health Kids UK programme

The potential benefits to the men of the adapted HDHK-UK programme are weight loss, improved physical activity levels and improved diet quality, which can result in a reduction in risk for a wide range of health conditions including type 2 diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, certain cancers, arthritis and other musculoskeletal symptoms. 60 Increased physical activity is also associated with mental well-being61 and joint activities with their children may result in closer relationships and bonding. 62 For the children, there are the benefits of healthier eating patterns and increased physical activity, resulting in a lowered risk of developing obesity,63 potentially improved attention and outcomes at school,64 improved social–emotional well-being and a shared activity with their father potentially leading to a closer relationship. 65

Chapter 2 Overview of study design and aims and objectives

Study aims

The overall aim of HDHK-UK study was to modify an existing weight management and healthy lifestyle programme for fathers and their children (aged 5–11 years) to be culturally acceptable in a UK multiethnic population and to assess the feasibility of conducting a RCT. The study was delivered in two phases.

Phase 1: adaptation of the existing programme

The aim of phase 1 was to modify an existing weight management and healthy lifestyle programme for fathers and their primary school-aged children45,46 so that it is culturally acceptable in a multiethnic population in the UK. The cultural adaptation (phase 1a) drew on the findings of qualitative interviews and focus groups from an ethnically diverse population in areas of socioeconomic disadvantage, as well as findings from a study that was culturally adapting a weight management programme for children in the same population. 53 The specific objectives for phase 1a were to:

-

explore the cultural (ethnic, religious and socioeconomic) acceptability of the programme elements and proposed questionnaires with fathers from a range of ethnic, religious and socioeconomic groups

-

increase the cultural acceptability of the programme using theoretically informed adaptations so that it is acceptable and accessible to a UK population with ethnic, religious and socioeconomic diversity.

In phase 1b, an uncontrolled feasibility trial was undertaken at two sites to explore the acceptability of the adapted programme and research methods. The specific objectives for phase 1b were to assess the:

-

feasibility of delivering the adapted intervention and the feasibility of recruitment and follow-up

-

acceptability of the HDHK-UK programme in an ethnically diverse population and make refinements to the programme based on the facilitators’ and participants’ feedback.

Phase 2: feasibility randomised controlled trial

The aim of phase 2 was to assess the feasibility of delivering the adapted intervention, the feasibility of recruitment and follow-up and the feasibility of a future definitive RCT. This was achieved using a two-arm RCT. Participants were randomised to the intervention or control arm in a ratio of 2 : 1, respectively. Data were collected from participants [fathers and their child(ren)] at baseline and at 3 and 6 months from the start of the intervention. Qualitative methods were also used as part of the evaluation. The specific objectives were to:

-

assess the acceptability of a UK-adapted weight management and healthy lifestyle programme for overweight/obese fathers of primary school-aged children in an ethnically diverse population and make refinements to the programme based on facilitator and participant feedback

-

determine levels of adherence to the programme

-

assess fidelity of intervention delivery and feedback from facilitators and modify the facilitator training programme if required

-

assess whether or not participants are willing to be randomised

-

assess whether or not the expected recruitment rate for a subsequent full-scale RCT is feasible and to identify successful recruitment strategies

-

explore the ability to obtain educational attainment data for children

-

explore participants’ and facilitators’ perceptions of the intervention, trial participation and processes

-

provide estimates of the variability in the primary outcome

-

test the components of the proposed RCT to determine the feasibility of the protocol.

Study partners

The feasibility study had two key study partners that were closely involved in the set-up and delivery of the trial.

University of Newcastle, NSW, Australia

Ranked in the top 1% of universities worldwide, the University of Newcastle (UoN) is a leading global institution that is distinguished by a commitment to equity and excellence.

Professor Philip Morgan is co-director of the Priority Research Centre for Physical Activity and Nutrition (PRC-PAN) at UoN, theme leader of the obesity research programme and founder of the original HDHK programme. The PRC-PAN investigates physical activity and nutrition for population health across the lifespan, with a particular emphasis on education and health promotion strategies for chronic disease prevention, treatment and well-being. Professor Morgan delivered training to the Fatherhood Institute, which later trained the HDHK programme facilitators. He also reviewed the UK cultural adaptations to the HDHK programme, ensuring that changes were in keeping with the original programme, and contributed to the intervention implementation, evaluation and research output.

Professor Clare Collins is co-director of UoN’s PRC-PAN, theme leader of the Nutrition and Dietetics research programme and a senior research fellow. In this study, Professor Collins advised on nutrition assessment and reviewed programme cultural adaptations to nutrition and dietary elements, ensuring consistency with the original programme.

Dr Myles Young is a post-doctoral researcher at UoN’s PRC-PAN who assisted on the original HDHK intervention. Dr Young assisted with training of the Fatherhood Institute, advised on practical aspects of the intervention implementation and contributed to research output.

The UoN team also provided support through the provision of resources and advice on all aspects of the trial, including recruitment, training, implementation and evaluation, for the duration of the project.

The Fatherhood Institute

The Fatherhood Institute (registered charity number 1075104) is a world leader in research, policy and practice with fathers. Activities include collating, undertaking and publicising research; lobbying for policy changes; and training and supporting public services, employers and others to approach families in a more father-inclusive manner. The Fatherhood Institute also works directly with fathers, mothers and children in a range of settings, including in health, education, the community and workplaces. The Fatherhood Institute’s mission is to give all children a strong and positive relationship with their father and any father figures, to support both mothers and fathers as earners and carers, and to prepare boys and girls for a future shared role in caring for children.

The Fatherhood Institute supported the adaptation of the HDHK programme materials to make them suitable for a UK audience and contributed to the father research materials. They also developed and delivered a number of training sessions for HDHK-UK facilitators. Report author Adrienne Burgess (Joint Chief Executive and Head of Research) was a member of the Study Management Group (SMG).

Study management

The study was overseen by two groups: the Study Steering Committee (SSC) and the SMG.

Study Steering Committee

The SSC included three independent academic members and an independent lay member. The committee convened at regular intervals throughout the study (October 2016, April and November 2017 and May and November 2018). The SSC monitored progress, recommended and agreed changes to protocol and monitored safety.

Study Management Group

The SMG consisted of the study co-investigators and research staff and met to oversee the research, to interpret findings and to agree the dissemination strategy. The SMG met at regular intervals (February and November 2016, April and October 2017 and March and September 2018).

Patient and public involvement

Patient and public involvement was integrated throughout the study and is described in detail in Chapter 7. The aim of PPI in the HDHK-UK study was to gain insight from fathers and their partners from the diverse communities where the study was to take place into issues that might affect the uptake and acceptability of the HDHK programme, methods of communication with fathers, participant-facing documents, data collection and how we might address the issue of an eligibility criterion of being ‘overweight or obese’. The PPI group was brought together by the Fatherhood Institute in one of the localities (site A) where the HDHK study was planned to take place. The first meeting took place during the development of the research proposal and seven fathers from diverse ethnic backgrounds were asked to comment on key features of the proposed protocol. This group agreed to support the study if funded. A male lay representative (AE) was invited to comment on the Plain English summary and was invited to be a member of the SMG. One male lay representative was recruited to be an independent member of the SSC.

Funding, ethics approval and study registration

Study funding was granted in October 2015 by the NIHR Public Health Research programme (reference number 14/185/13). The randomised trial was registered with the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number (ISRCTN) registry January 2017.

Ethics approval for the two phases of the study was obtained from The University of Birmingham Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics Ethics Review Committee. Phase 1a was approved on 22 April 2016 (ethics reference number ERN_15–1287), phases 1b and 2 were approved on 16 January 2017 (ethics reference number ERN_16–1323). A number of amendments were submitted for review throughout the study, as detailed in Appendix 1. Important changes to the original protocol were (1) the widening of the eligibility criteria for phases 1b and 2 to include men categorised as overweight or with a waist circumference of ≥ 94 cm, (2) the inclusion of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire at follow-up for phase 2 and (3) stratification of the randomisation.

Chapter 3 Phase 1a: cultural adaptation methods and results

This phase of the study addressed the development stage of the UK Medical Research Council framework for the development and evaluation of complex health interventions. 66 Information from three main sources was used in the adaptation process:

-

data from a qualitative study with fathers and other family members from a range of ethnic, religious and socioeconomic groups

-

findings emerging from another NIHR-funded family-based weight management study designed for BAME communities in the UK, called CHild weight mAnaGement for Ethnically diverse communities (CHANGE),53 targeted at Bangladeshi and Pakistani children and their families, which was led by members of the HDHK-UK research team (MP and PA)

-

findings from the Dads And Daughters Exercising and Empowered (DADEE) programme67 for fathers and daughters, developed by the Australian HDHK team.

Qualitative study methods

Qualitative data collection with fathers and other family members

The qualitative study addressed the first of our aims, which was to explore the cultural acceptability of the programme elements and proposed questionnaires with fathers and other family members from a range of ethnic, religious and socioeconomic groups through qualitative interviews and focus groups.

We aimed to conduct up to five focus groups and 15 one-to-one interviews; focus groups were the preferred method of data collection as they use group interaction as a way to stimulate discussion. 68 However, individual interviews were also offered as a way to maximise participation.

Theoretical underpinning

We used Liu et al. ’s69 typology of cultural adaptations to make the programme culturally responsive and appropriate for multiethnic populations living in socioeconomically disadvantaged communities. The typology was the result of a comprehensive study69 that explored the adaptation of health promotion programmes that targeted diet, physical activity and smoking for minority ethnic groups. As part of this work, Liu et al. 69 undertook a systematic review of health promotion programmes that had been adapted for minority ethnic groups and included international literature, from which they developed a 46-item typology. Liu et al. 69 also highlighted the importance of taking a systematic approach to cultural adaptation and recommended that a generic theory of the health promotion cycle be used alongside the typology when adapting health promotion interventions. This programme cycle has eight stages: conception/planning, promotion, recruitment, implementation, retention, evaluation, outcome and dissemination. We started by considering each of the items in the typology, at which stage of the programme theory it might apply and how it might be relevant to our cultural adaptation. It was clear that the adaptations would apply both to the content and delivery of the intervention and to the research processes (see Appendix 2). The findings were used to inform the development of the topic guide for qualitative interviews and it supported the analysis of our qualitative interviews and focus groups (see Data analysis).

Finally, we used individual items in the typology to consider what adaptations to the intervention and to the research processes could and should be made, drawing on the findings from the qualitative interviews/focus groups, the findings from the CHANGE study70 and insights from the Australian HDHK programme team from the DADEE study. 67

Setting/context

Phase 1a was undertaken in three urban local authority areas in the West Midlands, UK. In these local authority areas, a high proportion of the populations are from BAME communities (32–48%) and > 50% live in the 20% most deprived neighbourhoods (lower-layer super output areas) in England; deprivation is measured by the Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD). 71 The West Midlands has the highest proportion of children aged < 16 years of all the English regions. 72

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

People were eligible to take part in phase 1a if they were a father/male guardian or family member from the Bangladeshi and Pakistani communities or from socioeconomically deprived communities (e.g. white British, African Caribbean and other ethnic groups). The focus on Bangladeshi/Pakistani ethnic groups was due to the particularly high rates of obesity in the adults and children from these communities,73 together with low attendance of members of these ethnic groups at weight management programmes for adults and children. 53

Sampling and recruitment

We used a purposeful sampling approach based on maximum variation. 74,75 The HDHK-UK intervention was to be evaluated in men with children of primary school age. Therefore, our intention was to recruit fathers and male guardians of primary school-aged children to phase 1a, as well as other family members who may act as gatekeepers to fathers/male guardians, namely mothers/significant female others (e.g. grandmothers). In relation to our recruitment strategies, we targeted socioeconomically disadvantaged locations and sampling was undertaken to include a range of ethnicities.

Multiple pathways were employed to identify suitable participants to take part and share their views in qualitative interviews or focus groups. We aimed to identify participants through community networks, including primary schools, and gatekeepers in local communities who acted as advocates on behalf of the research team. We approached a range of organisations for permission to canvas parents at their facilities or at the activities they ran. The following is a summary of the organisations approached and how the HDHK study was advertised via that organisation:

-

primary schools across the West Midlands – mail-out to pupils, canvassing parents at school gates during pick-up/drop-off, promotion via school media (website, text messages to parents)

-

after-school/youth organisations – approaching parents at after-school clubs and martial arts groups during pick-up/drop-off, and working with local Scouts organisations (district and local leaders were to identify interested parents)

-

parent and child classes – local child and parent groups at Sure Start centres

-

leisure and well-being centres – canvassing parents after popular child activity classes, for example swimming

-

charities and volunteer services – advertising the study on the Birmingham Volunteer Services website/e-newsletter sent to all members

-

research advocates in business districts – identifying prominent business people located in multiethnic business districts to approach customers on the research team’s behalf to share information about the study

-

contacts of the research team – e-mails to staff at the University of Birmingham.

At first approach, potential participants were given an invitation letter with details of how to contact the research team. People who expressed an interest in taking part in phase 1a were then sent a participant information leaflet and a time was booked for the interview/focus group.

Data collection

We conducted 18 one-to-one interviews with 14 fathers, two grandfathers and one mother, one paired interview with a couple (father and mother) and two focus groups consisting of 10 mothers overall. Overall, 30 participants took part. Eighteen interviews and one focus group were conducted in English, and one interview and one focus group were conducted in Urdu. Data collection was stopped when no new core themes were interpreted from the data. However, owing to difficulties in recruiting Bangladeshi and Pakistani fathers, we did not achieve saturation in the different ethnic groups.

All interviews were completed by Manbinder Sidhu (a male qualitative researcher in applied health sciences); focus groups and a single interview were completed in conjunction with a female qualitative researcher (Farina Kokab) from a South Asian background with the necessary language skills (Urdu). Prior to the start of each interview or focus group, participants were asked to provide written informed consent and complete a short demographic questionnaire to facilitate description of the sample. Participants were informed of their right to withdraw from the study at any time (although any data collected prior to withdrawal would be used in our analysis) and were assured that their personal details would be kept confidential.

We developed topic guides for the focus groups and interviews, which were informed by the typology of cultural adaptation,69 literature on facilitators of and potential barriers to men and children to attending weight management programmes, and discussions between the research team and PPI group. In addition, there was iterative development of topic guides, as certain topics that arose in earlier interviews were explored in greater depth in later interviews (i.e. gender considerations in an ethnocultural context).

The objectives of the interviews and focus groups were to explore a range of issues including but not limited to:

-

family- and community-embedded attitudes towards group participation in a physical activity programme with members from outside and within their own community

-

the cultural acceptability of girls and their fathers partaking in ‘rough and tumble’ and other physical activities together

-

acceptable locations and timing of sessions

-

any cultural issues related to fathers being more involved in food preparation

-

how fathers would like to be invited to take part, including the ‘hook’ that would encourage them to take part (e.g. personal weight loss, health, role modelling to improve children’s health, time with children)

-

any potential barriers to changes in diet and physical activity.

Our approach to interviewing, facilitating group discussions, topic guides and participant-facing material was developed with input from the study PPI group. Specifically, this group commented on the wording on the invitation flyers and raised issues about the HDHK programme and resources. We explored these issues further in the interviews and focus group discussions.

To provide context and facilitate discussions with our participants, we shared original resources from the intervention developed in Australia; these included presentation of information on PowerPoint® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) slides, printed images of physical activities with fathers and children, written resources to support the programme and details about the activities children and fathers would be expected to complete between the programme sessions. The intention of the researchers conducting data collection was to generate discussion, by providing a ‘space’ for participants to elaborate on points openly with the support of materials from the intervention. 76 Interviews lasted, on average, 50 minutes (range 35–67 minutes) and focus groups lasted, on average, 71 minutes (range 61–81 minutes). Interviews and focus groups were conducted in participant’s homes (n = 16), places of employment (n = 3) and recognised and trusted locations in their community (i.e. primary school and hair/beauty salon) (n = 2).

In carrying out interviews and focus groups, researchers emphasised and ensured that participants understood the overall purpose and why certain questions were being asked, while paying ongoing reflexive and critical attention to interpreting the social context behind accounts. 77,78 All participants received a £10 shopping voucher to cover their time/travel expenses and as a thank-you for taking part.

Data analysis

Interviews and focus groups were audio-recorded and transcribed clean verbatim for analysis by an external transcription company (The Transcription Company, Sutton Coldfield, UK). Transcripts of interviews conducted in Urdu were translated into English for conceptual equivalence, determined by FK and Manbinder Sidhu. 79

We used Braun and Clarke’s80 thematic analysis to inductively develop a coding framework informed by Liu et al. ’s69 typology, and surface and deep structural levels. We explored similarities and differences in narratives across the different groups of interest (e.g. gender, ethnicity and migration status). 81,82 Two members (MS and LJ) of the qualitative research team independently coded a batch of transcripts and then developed a descriptive framework to allow for inductive coding in each domain. 82,83 The Liu et al. 69 typology informed the coding and the development of a descriptive coding framework. Transcripts were coded using NVivo 10 (QSR International, Warrington, UK). The team met regularly to discuss themes identified in the data linked to adaptions that could influence the modified design of the programme. We then undertook further interrogation of the data81 to explore cultural adaption at (1) surface level and (2) deeper structural levels.

Findings of the qualitative component

Participant characteristics

Participant characteristics are presented in Table 1. We were able to achieve reasonable ethnic diversity, with over half of our sample comprising South Asian community members. Furthermore, aligning with the overall aim of the HDHK-UK trial, 20 participants (two-thirds of the sample) resided in locations in the highest quintile of socioeconomic deprivation nationally.

| Characteristic | Total sample (N = 30) |

|---|---|

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Male | 17 (56.7) |

| Female | 13 (43.3) |

| Age (years), n (%) | |

| 20–29 | 3 (10.0) |

| 30–39 | 10 (33.3) |

| 40–49 | 7 (23.3) |

| 50–59 | 5 (16.7) |

| ≥ 60 | 1 (3.3) |

| Missing | 4 (13.3) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |

| White | 7 (23.3) |

| Black Caribbean | 2 (6.7) |

| Indian | 9 (30.0) |

| Pakistani | 9 (30.0) |

| Bangladeshi | 3 (10.0) |

| Parental status, n (%) | |

| Father | 15 (50.0) |

| Grandfather | 2 (6.7) |

| Mother | 13 (43.3) |

| Marital status, n (%) | |

| Married | 29 (96.7) |

| Co-habiting | 1 (3.3) |

| Age (years) of childa | |

| < 4 | 1 |

| 4–11 (primary) | 52 |

| ≥ 11 | 15 |

| IMD, n (%) | |

| 1 and 2 (least deprived) | 2 (6.7) |

| 3 | 4 (13.3) |

| 4 | 4 (13.3) |

| 5 (most deprived) | 20 (66.7) |

All participants were recruited from inner-city locations. Participants were part of families with primary school-aged children, with some also having secondary school-aged children. Of our non-white sample, the majority were second-generation migrants, who were born in the UK. One participant, who used a wheelchair, discussed the potential for incapacitated adults to take part in a lifestyle programme with young children.

Relevance of the theory underpinning the Healthy Dads, Healthy Kids programme

As highlighted in Chapter 1, the HDHK programme has two underpinning theories: FST50 and SCT. 49 The relevance of FST to the lives of the families was confirmed by reports of the importance of the reciprocal relationships within families. Parents described the importance of being a good role model to their children, a key component of the theory [quotation sources include the work package number and the participants identifier (ID) number, followed by either ‘interview’ or ‘FG’ (focus group) and the participant’s ethnicity)]:

Just to be a good example to the children and to be a good role model and also to ensure that they’re to provide, first of all, and secondly to, er, like I said be a good role model, show them the rights and wrongs.

WP1a-06, interview, Pakistani mother

Parents described trying to ensure that they were setting good examples to their children around snacking behaviour, for example replacing high sugar treats like chocolate and crisps with healthier alternatives such as fruit and vegetables. Nevertheless, there were challenges in implementing and sustaining these behaviours. Mothers described a continuum of role models from a discordance between the dietary practices of fathers and the mothers’ desire for their children to eat healthily, to fathers being a positive influence:

I can eat fruit and veg and the kids can eat fruit and veg, but my husband will never touch fruit and veg. He just won’t touch it.

WP1a-FG1, Pakistani mother

So we look at the healthy options but my daughter now will reach for a yoghurt or carrots or grapes or strawberries, which are her favourite snacks. Whereas I, as a child, wouldn’t have done that so, and that’s my husband’s influence.

WP1a-06 interview, Pakistani mother

Family systems theory views the family as an emotional unit; therefore, the behaviours of one individual cannot be viewed in isolation. The importance of the family undertaking activities together was confirmed:

I think it’s a very good idea getting the kids and the parents to do activities together.

WP1a-59, interview, British Asian Indian father

If my little one pushes his dad, ‘You have to come, you have to come’, then he probably will.

WP1a-FG1, Pakistani mother

Lifestyle changes in people of Pakistani and Bangladeshi ethnicity needed to consider multiple family members living in a single household, that is grandparents (acting as matriarchs or patriarchs) who also influenced child behaviour:

. . . we’ll cap that time on the TV and we’ll cap their time [yeah] on the Xbox [Microsoft Corporation] so it will be half an hour, 20 minutes, 30 minutes, whatever it is that we’ve got [yeah]. Erm, so the grandparents, you know, they’re like, ‘No, we’ll just let them play’.

WP1a-064, interview, Bangladeshi father

The other theory underpinning HDHK was SCT. The relevance of the associated behaviour change techniques based on social cognitive constructs such as goal-setting and self-monitoring was not questioned by the fathers. There were examples of a lack of knowledge of important skills in weight management, such as calorie counting. Fathers reported setting goals in relation to exercise to manage their weight and acknowledged considerable barriers to behaviour change because of family constraints in relation to time for activity:

Well, I’d rather have somebody give me information face to face or in a group, then I know what to do, basically. How to do activities with the kids.

WP1a-03, interview, Bangladeshi father

I’ve never done calorie-counting, and it’s not, er, something I’ve ever pursued.

WP1a-37, interview, white British father

Logistical and pragmatic considerations of delivering the intervention

All participants reported that they would like the intervention to be delivered close to their homes for various reasons. For mothers, reasons were linked to familiarity, which was usually interlinked with issues of safety, that is knowing where their child would be for a given period of time even when attending with their father. The school was considered ideal for programme delivery, had ongoing relationships with parents and was a trusted location. Some mothers expressed concern about dropping their children back to school in the light of other commitments siblings may have, for example tutoring, scouts, religious readings or other physical activities. For fathers, attendance and likelihood of continuing to attend centred on working hours, travel time and the intervention having a degree of ‘in-built’ flexibility to account for traffic or unintended events:

I just think for me the school is the nub – is the nub, is the hub; it’s the place to start because that’s where you can engage with the families.

WP1a-23, interview, white British grandfather

Local, erm, and they have the space. You know, you open up the school hall, erm, school’s easy to get to. I don’t know if it’s gonna be linked to schools or, erm, but, you know, also if it does come from the school and the fathers are going along there, erm, then, you know, there might be less barriers to break down in terms of the – you know, they might know each other.

WP1a-37, interview, white British father

Although nearly all participants recognised the convenience and familiarity of delivering services in the school, some parents questioned whether or not young children would be happy returning to school in the evenings, having spent the majority of the day learning in the same location. Logistically, venues that accommodated travel by car were preferred, with availability of parking a key factor for many; otherwise, ease of access was important if travelling by public transport. The issue of parking was contextualised by expressing fears of having to travel to unfamiliar locations, or even known locations perceived to be areas with high rates of crime:

Somewhere close with, with, with somewhere you actually park. A, a busy road, you can do it by public transport or parking is hard to get to [OK].

WP1a-24, interview, white British father

Well, the place of where I live in, [place] to be specific, we don’t have much things going around. We just have, it’s, it’s more of a council estate area. Whenever you go out with your kids you have to watch your back, it’s not very safe . . .

WP1a-63, interview, Bangladeshi father

Views about the timing of the programme varied, largely because of child-related commitments with respect to child care or attending other extracurricular activities. Parents varied in their preferences for attending the programme on weekends or during evening weekdays, mornings or afternoons or evenings. For some, timing of the programme was strongly linked to continued attendance, with some suggesting that reminders would be helpful:

Because he [father] works in the morning. He goes at 8:30 and doesn’t come home until 7:00 in the evening. So he’s got no time to come.

WP1a-FG1, interview, Pakistani mother

They [children] go to school and they finish and they’ve got homework to do and I suppose one of the days in the evening wouldn’t be too bad. Weekend would be better . . .

WP1a-45, interview, British black Caribbean father

Programme structure and delivery

Programme length and commitment

Parents shared concerns that the programme might be too long in duration for their children to maintain concentration and interest, and fathers (particularly those with alternating working patterns) expressed concerns about the time commitment. With travel time and completing weekly tasks as part of the programme, as well as remembering to bring resources, the programme would take up a significant amount of time in a single day. Therefore, a shorter intervention (time allocated per session) was preferred by some:

I think the length of time will cause a problem to people because 90 minutes is an hour and a half. You’ve got to realise that you’ve got time to get there and time to get back. If it’s a weekday, then you’ve also got – depending on the child’s age, you’ve got to take into account homework and things like that as well. So, that might cause an issue.

WP1a-59, interview, British Asian Indian father

If it’s in the weekday, then 90 minutes is too long . . . activities that they have, they don’t last more than 45 minutes anywhere, so say 45 minutes, 1 hour on a weekday is maximum that somebody would, er, tend to give.

WP1a-61, interview, Indian father

Session delivery

Fathers questioned elements of the programme. Although the 90 minutes was broken into three subsessions, the fathers’ session in particular drew the greatest criticism; criticism highlighted the drawbacks of using PowerPoint and, therefore, the perception that speakers would be lecturing rather than teaching. As the majority of our participants in this study were British-born, discussion of language issues as a barrier to attending or understanding content was limited (note that ‘school mothers’ indicates mothers who attended a focus group at a school and ‘salon mothers’ indicates mothers who took part in a focus group in a hairdressing salon):

I think, personally, it’s too long. I would switch off. 20 minutes for me, I’d think, ‘What am I doing here?’ That is too long for me. If they can break it down.

WP1a-FG1, Pakistani school mothers

I always find, honestly, in my educational as well experience, I hated lectures with a passion. That lecturer standing in the front with that PowerPoint presentation, I actually wanted to die. Really I did.

WP1a-FG1, Pakistani mother

The visual presentation of material was welcomed, with appreciation of novel methods to convey well-known public health messages, although the method of using PowerPoint so extensively was a deterrent; instead, there was a desire for more demonstration-based learning.

The programme materials

The programme resources (manuals for the fathers, children and mothers; activity cards and homework slips) were welcomed and considered a useful addition to the programme, potentially enhancing the take-home messages from each session. Nevertheless, parents felt cautious and some overwhelmed with the quantity of information and concepts used in it. Many struggled to understand certain terminology without initial explanation; this could be interpreted as a barrier to engagement. As this was highlighted by British-born participants, this was not an issue of a language barrier due to having English as a second language, but an issue of plain English at an appropriate reading level. This further coincided with the use of terms such as ‘manual’, with some finding this slightly condescending and others suggesting they would be unlikely to read such a document:

How many times have you, man, read a manual?

WP1A-61, interview, Indian father

Nevertheless, the fathers welcomed the extensive use of visual representation in the Dad’s manual to present ideas and information to help challenge established parental messages/habits/practices common among families that are culturally ingrained and to convey new ones, for example praising a child for finishing all the food on a plate:

See, the thing is, the language is quite complicated in general. Family strategies I’ll understanding, ‘To make the Trust paradigm work’, what do they mean by, ‘paradigm work’? [Mmm]. So, I would personally say it’s too complicated for the Bangladeshi community [OK] to understand that.

WP1a-63, interview, Bangladeshi father

It’s like a manual made for people who like reading [yeah] and look how big it is – erm, who like reading, who’ve got time, who are keen . . . it’s way too much, too much information [yeah] – I would switch off, I would switch off. I wouldn’t read this.

WP1a-39, interview, British Asian Indian father

Manual for Dads. Erm it may be a bit sort of – not patronising’s the word, may be a bit for suggesting, ‘Oh, I know how to be a dad. You’re telling me how to be a dad!’

WP1a-41, interview, British Asian Indian father

Notably, when shown the Australian materials, nearly all non-white participants (as well as some white participants) identified the lack of ethnic representation in materials, namely images of non-white families taking part in the programme were missing throughout. Hence, many felt that it was important that images of ethnic minority families were embedded in the materials to help them relate to the content and imagine their own families performing tasks and activities promoted as part of the programme:

What is noticeable is the ethnicity of the, err, the males in the pictures. Erm yeah. And I just think it would definitely have to be relevant for me.

WP1a-45, interview, black British Caribbean father

Right, the images aren’t multicultural; I’ll tell you that straightaway at the start off. They are – if you’re gonna aim at a broad range of people within the community, these are just aiming at the European ones, so you need to have more multicultural images. That will then help people associate with it and recognise – say that they can recognise that lifestyle and go from there.

WP1a-59, interview, British Asian Indian father

Facilitator characteristics

Overall, men welcomed the group nature of the fathers’ session, which was then followed by physical activity play with children. Some mothers expressed the desire for more information about the activities that their children would be taking part in and in the presence of whom:

The person delivering the programme would never be one-to-one interacting with my child anyway. If that did happen, that would concern me quite a bit. I’m assuming that they are CRB [Criminal Records Bureau] checked and all that. So as long as you’ve done all your background checks, that person’s safe to work with children and things like that.

WP1a-FG1, interview, Pakistani school mothers

For non-white men, some stated the preference for cultural and gender-based concordance, whereas others stated that they would feel more comfortable if the intervention was delivered by a fellow father. Notably, there was little importance placed on ethnic concordance between facilitator and fathers:

The big no-no is if you give an Asian lady, a Bangladeshi lady with a bunch of Bangladeshi guys . . . So you need probably a male with a male and definitely a female with a female.

WP1a-63, interview, Bangladeshi father

I’d say another father, certainly somebody that you can say ‘well at least they know what they’re talking about’ because, you know, they’ve been in those shoes that I’m in so they’d understand it.

WP1a-06, interview, Pakistani mother

People have issues with it, if they’re obviously from a nationality [mmm], possibly or especially a different religion [mmm], I don’t know. But that, to me, that wouldn’t make a difference at all with that [mmm]. It’s, it, the same things would work whichever way you go [yeah]. The same things apply to anybody no matter where they’re from.

WP1a-24, interview, white British father

Group delivery

In general, fathers welcomed the face-to-face nature of their specific sessions, but shared concerns about the nature of group and how supportive the interactions would be, not only with the facilitator but other fathers in the group, and whether or not they would be confident sharing personal anecdotes from their family experiences. Furthermore, many of the older fathers questioned whether or not their experiences would be relatable to younger fathers present in the group. Some shared concerns about being stigmatised for being obese, even when in a group where all participants are overweight:

I think it would depend on the makeup of the group. Erm, if I felt – if I felt there were similar to me then I’d be comfortable, obviously, but I’m probably – I’m on the older side for parenting, really. I was fairly old when the children came into my life, compared with most, so if I felt I was way older than everybody there, I’d be uncomfortable with it. If I felt I was from a different kind of social background, I’d be uncomfortable with it.

WP1a-36, interview, white British father

There were mixed feelings about taking part with a group of men of different weights, sizes and body image, some of whom were perceived as potentially being ‘competitive’ men:

I don’t want to be there with the rest of the dads and they’re going to be . . . because, you know, the competitive dads and they’ll be, ‘Oh, I’ve lost weight.’ Then it turns into them rather than them and the kids.

WP1a-41, interview, British Asian Indian father

I think it would depend on the makeup of the group. Erm, if I felt – if I felt there were similar [size] to me then I’d be comfortable.

WP1a-36, interview, white British father

Content of the programme

Weight

Mothers welcomed the nature of focusing on calories; South Asian mothers, who predominantly prepared meals, stated that they would like to know more about how health promotion information, such as calories and portion control, could be applied to South Asian cuisine, inclusive of halal practices for Muslims. Men also recognised the need to know more about calories, portion control and healthier alternative foods/drinks, yet the greatest concern was how best to incorporate these changes in their family routines. If this could be achieved over the long term, it was clear to many that there would be benefits to their health and well-being, as well as financial benefits:

It doesn’t say anywhere how many calories are in a chapatti or how many calories are in a curry. Maybe because to know the calorie of a curry you’d have to make it word by word from a recipe.

WP1a-FG1, Pakistani school mothers

. . . never been interested, really, in counting calories. I’m more interested in my own weight issues, if you like. I know I’m overweight a bit, but I don’t focus on what I’m eating and drinking. I would rather focus on increasing the time I spend at the gym and trying to work it out that way.

WP1a-36, interview, white British father

Nutrition

There was an awareness that family nutrition was often not as good as it could be. All participants reported that their families consumed a varied diet where traditional staples, regardless of heritage, were being replaced by more unhealthy Western foods, combined with dining out, as well as regularly purchasing takeaway either as snacks or to replace cooked evening meals:

My daughter, she’s very fussy. She only likes chicken nuggets and pizza, and it has to be a particular pizza.

WP1a-FG1, Pakistani school mothers

Men described the challenges they faced in keeping to a healthy lifestyle:

You start having a few beers, you start having the odd takeaway.

WP1a-23, interview, white British grandfather

Physical activity

Fathers understood physical activity as an important element of building a closer bond with their children, rather than as a method for them to lose weight or become healthier. Working fathers questioned how easy it would be for them to engage in physical activity with their children if they did not already have some form of close relationship prior to beginning the programme. Furthermore, owing to gender–cultural considerations, the programme was considered more appropriate for younger children in the eligible bracket (4–8 years), as opposed to children aged 9–11 years:

It’s nice to have that time with your kids and there’s – they know it’s – I know it’s for me and I also know they know it’s for them too and it’s for us together, you know, an activity together or time together.

WP1a-45, interview, British black Caribbean father

Gender considerations

Gender considerations in both delivery and within-programme active play was a focal theme among parent narratives. In particular, South Asian participants who took part in the earlier interviews raised the issue, and the remainder of participants were directly questioned on this topic.

Through analysis of subgroups, there were notable differences between participants who were either migrants or married to migrant partners from South Asia. First, these participants felt that sport or engaging in physical activity, particularly outdoors or away from home, were activities exclusive to boys or men. This was particularly acute when girls reached the end of primary school. 84

For Pakistani and Bangladeshi Muslim participants, there were clear distinctions between female and male obligations: certain practices, in particular household tasks, needed to be encouraged in girls from a young age. In conjunction, migrant parents recognised the lack of sporting/physical activity role models for both girls and boys, while parents also recognised that they too were poor role models. Notably, some migrant Pakistani mothers felt that it was culturally appropriate to prepare their daughters to be Pakistani women. There was the perception of greater stigma attached to girls’ behaviour in comparison with that of boys:

I mean, being from an Asian background, you know, we have certain cultures and traditions and everything, so up to the age of probably, of probably like, 7, 8 I’d say, would be OK with [mmm] their daughters [mmm]. Anything more than that, I don’t think a lot of dads would be comfortable [OK] so I, personally, I wouldn’t be comfortable [mmm]. So, I mean, with boys it’s OK, I mean, you know.

WP1a-03, interview, Bangladeshi father

I have seen that there is so many burdens on women, that even if the men aren’t doing anything, their mothers say nothing, it’s their son, but if it comes to their daughter, yes it is important . . . some kids say ‘daddy doesn’t do it, so why should I do it?’

WP1a-FG2, Pakistani salon mothers

South Asian migrant mothers and fathers were very clear that, from a certain age (ranging from approximately 7 years to the start of menstruation), there should be a culturally determined distance between fathers and their daughters, based largely on limiting tactile contact:

We have certain cultures and traditions and everything, so up to the age of probably, of probably like 7, 8 I’d say, would be OK with [mmm] their daughters. Anything more than that, I don’t think a lot of dads would be comfortable. So I, personally, I wouldn’t be comfortable.

WP1a-03, Bangladeshi father

There are a lot of problems; we watch the news, and so, as a Muslim, Islam teaches us about the gap, when the daughter starts her periods, keep a gap [in contact between the daughter and her father].

WP1a-04, Pakistani mother

Some parents expressed concern about children engaging in inappropriate rough-and-tumble play outside the intervention; hence, there was an implicit need to establish ground rules for both children and adults to adhere to about when and with whom rough-and-tumble play was acceptable:

With my daughter, she’s very smart. She’ll understand that we’re doing this here. It’s a little activity. We’re not going to continue to do it at home or maybe I’m not going to continue to do this with my friend, male friend at school.

WP1a-FG1, Pakistani school mothers

In addition, one mother raised the issue of girls mixing with boys, once they had reached the age of 11 years:

You know, you said 4- to 11-year-old kids as well, didn’t you? And I think there’s some barriers around– sometimes don’t want their daughters of 11 to mix with boys of 11. I mean, I think that might be an issue as well . . .

P1a-06, interview, Pakistani mother

Alcohol

Pakistani and Bangladeshi participants acknowledged that some members of their community may drink alcohol, but still felt that it would be awkward for those who drink privately:

It wouldn’t mean much because I don’t drink, I’m, I’ve come from a Muslim background, so that wouldn’t mean anything, but then again, a lot of Bangladeshi people do drink [yeah] and they probably drink heavier than the people that are allowed to drink [yeah].

WP1a-63, interview, Bangladeshi father

Screen time

A topic covered in the HDHK programme is the amount and nature of screen time that children spend on electronic gadgets. This resonated with the parents who were concerned about the amount of time their children spent playing computer games and looking at their phones and electronic tablets. Fathers also expressed concern about not knowing what their children were reading/watching and the nature of the activity itself, which is often in isolation away from the family:

Our kids are coming to a teenage time, we didn’t know they know how to play iPad [Apple Inc., Cupertino, CA, USA] and PlayStation [Sony Corporation, Tokyo, Japan], we had the proper childhood, we could run around and play games.

The electronic media that our children have, we never sat still or indoors.

Electronics have stolen their childhood. They sit on their phones all day now.

WP1a-FG2, Pakistani salon mothers

My son came back, my oldest son, well, middle son, came back from school and he was supposed to sit down and do some reading and he wasn’t interested at all. All he wanted to do was sit on his iPad . . . it’s when they seem more interested in what’s going on on YouTube [YouTube, LLC, San Bruno, CA, USA] and whatever else then actually their own development, that’s when I think it’s a problem.

WP1a-45, interview, British black Caribbean father

Nowadays, what the kids are doing, especially my one, they’ve got this, erm, iPad in front of them, they’ve got a TV in front of them, hardly any exercise, hardly any running around.

WP1a-63, interview, Bangladeshi father

Parenting

South Asian mothers felt that their husbands took a laissez-faire attitude to fatherhood, conforming to traditional working-class masculine ideals of male breadwinner and provider. Nevertheless, there were notable exceptions in the accounts between Indian and Pakistani/Bangladeshi mothers, with the former sharing accounts of men playing a greater role in household duties. However, all recognised and understood the value of men as fathers and the importance of being good role models for their children. South Asian fathers, in particular, were less likely to narrate experiences of spending significant periods engaging with their children in either home-based or outdoor activity without the supervision of their partner. For South Asian mothers, particularly Muslim Pakistani mothers, it was imperative that there was a bond between fathers and their children:

Nothing, praise be to Allah; my husband is very friendly, he’s very attached to my kids. I have nothing to worry about nor do I desire anything else; he is ready to do something before I am.

WP1a-FG2, Pakistani salon mothers

We want equal bonding that mother and father should play an equal role.

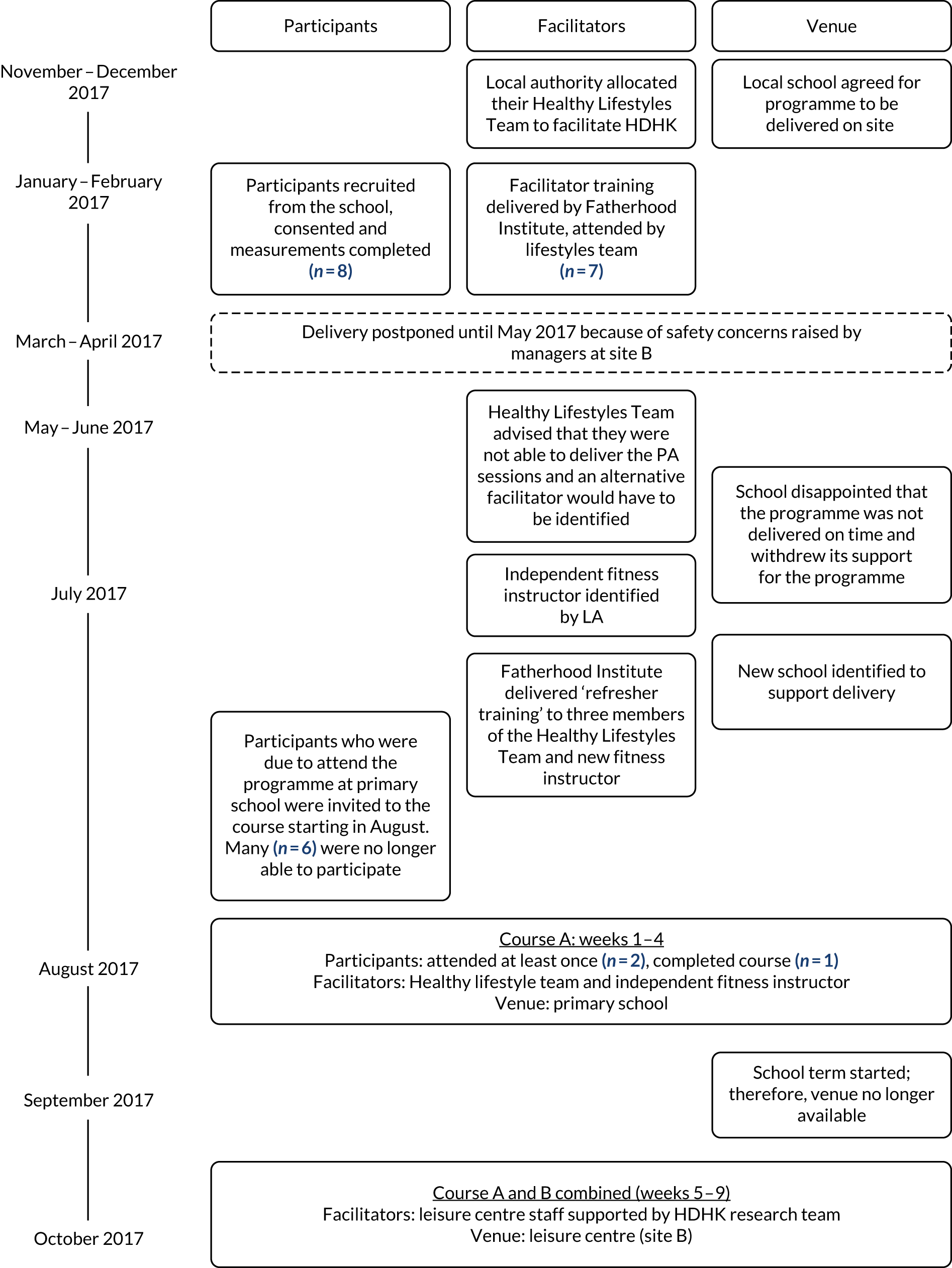

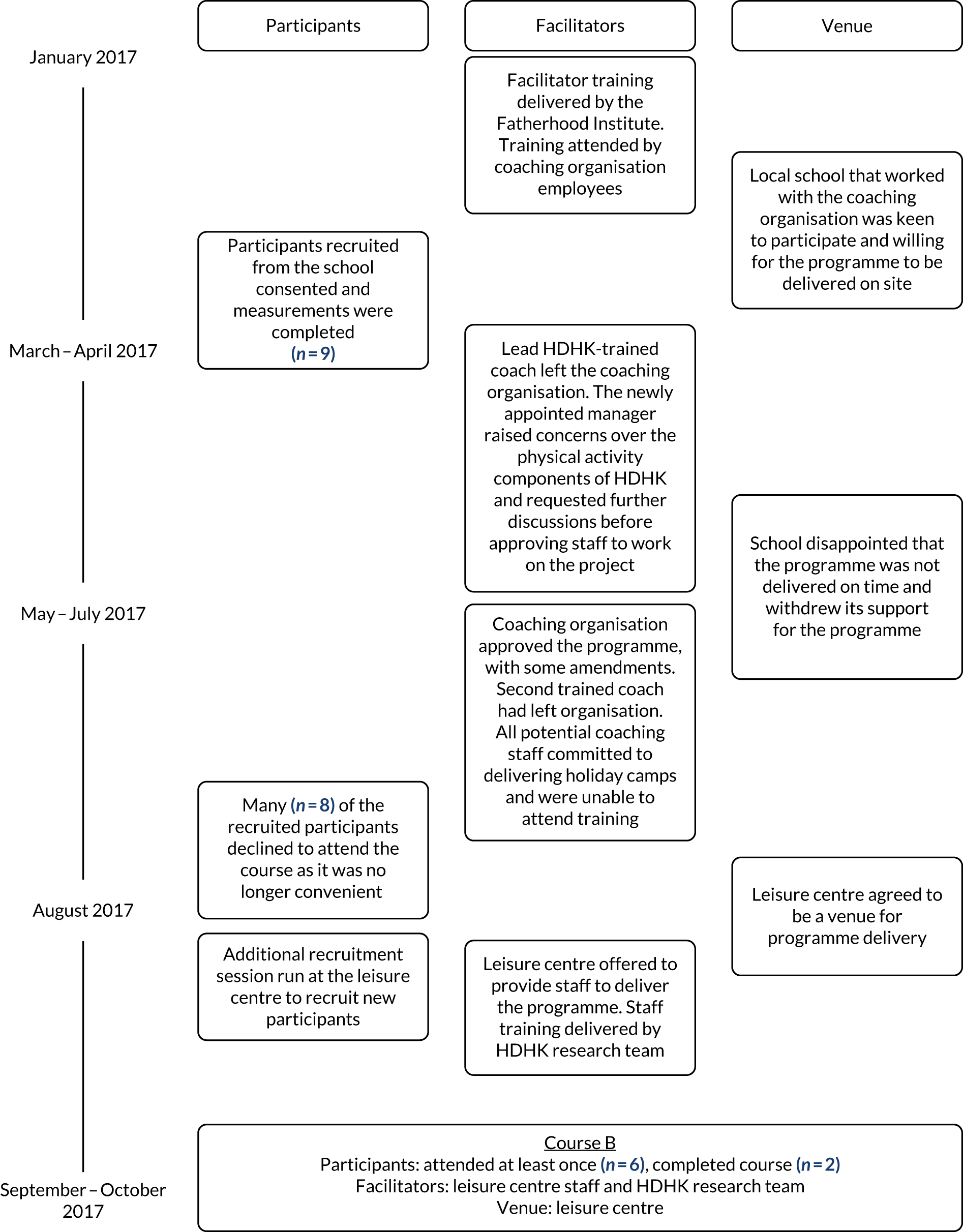

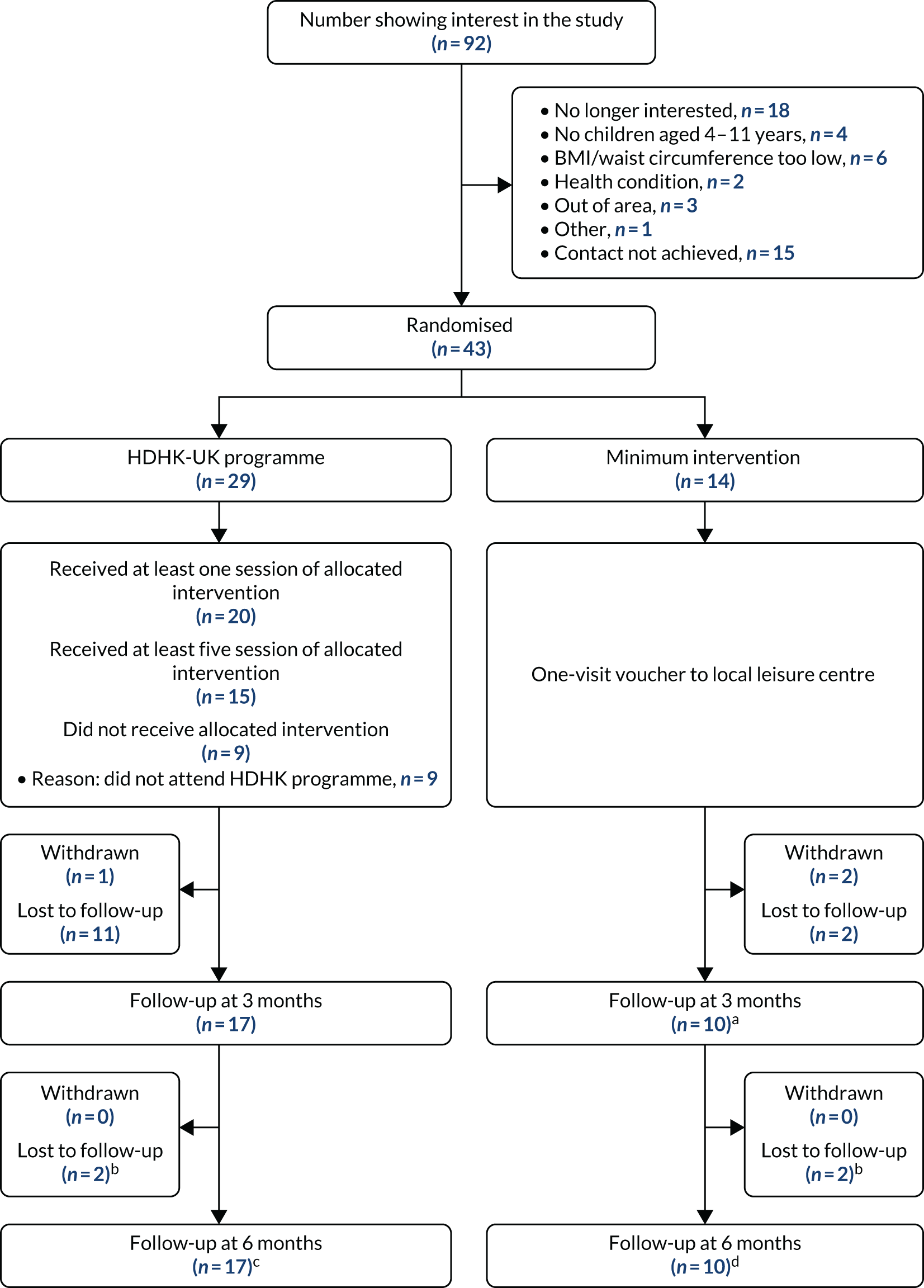

WP1a-FG2, Pakistani salon mothers