Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 12/180/20. The contractual start date was in April 2015. The final report began editorial review in May 2018 and was accepted for publication in February 2019. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Sharon Anne Simpson reports membership of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment programme, Clinical Evaluation and Trials funding committee from January 2017 to present. She also reports membership of the NIHR Policy Research Programme committee and the Chief Scientist Office Health Improvement, Protection and Services funding committee. Emma McIntosh reports membership of the NIHR Public Health Research funding board from January 2016 to present. There are no other competing interests in relation to personal, developer or institutional proprietorship of the current app or potential future product.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Simpson et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Obesity: a key public health problem

Obesity is typically defined as a condition of excess or abnormal accumulation of body fat at a level that impairs health. 1 Individuals with a body mass index (BMI) of ≥ 30 kg/m2 are considered obese. Obesity has been highlighted as one of the top 10 risk factors for global burden of disease. 2,3 In 2017, the UK prevalence of obesity was 24.9%, one of the highest rates in Europe. 4 In Scotland, where this study was undertaken, the prevalence of obesity increased from approximately 15% in the mid-1990s to 29% in 2017. 5 This high prevalence of obesity places a significant burden on health services, with individuals with increased BMI using greater health-care resources than those with healthy BMI. 6

Obesity, alongside poor diet and physical inactivity, is a significant contributor to diseases such as diabetes, cancer, heart disease, hypertension and stroke. 7 Preventative interventions that are accessible and engaging and successfully improve health behaviours are necessary to reverse current trends. Interventions to date have had limited impact and approaches that are known to work are not always adopted. 8 Therefore, novel interventions that incorporate effective approaches are needed.

To inform the background to this study, a literature search was completed on the MEDLINE and PsycINFO databases from inception to 2017 using keywords including obesity, overweight, weight loss, social support, social network, digital health, ehealth, mhealth, physical activity, exercise and diet. A summary of the findings is presented in Chapter 2, Overarching approach: 6SQuID to The HelpMeDoIt! intervention content.

Previous weight loss research

Although obesity has been a major public health issue for years, there is still no consensus on the most cost-effective approach to support individuals to lose weight. The obesity system map9 highlights the complex layers of influence acting to create and maintain current levels of obesity. This links with the multiple interacting domains of the socioecological model that contribute to the problem. 10 Research has demonstrated that tackling multiple health behaviours, such as diet and physical activity, can be effective. However, interventions to date have had mostly small or no effects, with longer-term maintenance remaining a key challenge. 11

Previous research has shown that theory-based interventions, which specifically link elements of an intervention to outcomes, generally have greater success. 12 Despite this, many interventions are not theory based and most do not attempt to take account of the complexity of influences contributing to the development and maintenance of obesity. 12 Evidence indicates that intervention effectiveness generally increases with the intensity or amount of intervention delivered (total contact time or number of contacts). 13,14 The challenge is how this can be achieved while keeping the intervention cost-effective, as successful interventions often employ intensive, high-cost, one-to-one approaches. 13 These interventions have low reach as the intervention is deliverable to only a small proportion of the population. Given the scale of the problem of lifestyle-related illness, it is clear that alternative, cost-effective approaches need to be developed and tested.

Behaviour change: goal–setting, self-monitoring and social support

Guidance from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)15 highlights the importance of developing interventions that are based on theory and identify specific intervention components. A refined taxonomy of 40 behaviour change techniques for physical activity and healthy eating, by Michie et al. ,16 highlighted the wide range of approaches used in studies aiming to change lifestyle behaviours. The NICE guidance identified three of these techniques as showing promise for behaviour change, including setting goals, monitoring progress and harnessing social support. Studies employing these techniques have been associated with better outcomes. 11,17 Goal-setting and self-monitoring are techniques associated with intrapersonal processes, whereas engaging social support is linked with interpersonal processes. These techniques derive, in the main, from social cognitive theory18 and control theory,19 two of the key theories on which the HelpMeDoIt! intervention is based (described further in Chapter 2).

Goal-setting and self-monitoring (intrapersonal processes)

The important role of goal-setting and self-monitoring is well established in behaviour change research. In a meta-analysis of behaviour change interventions for physical activity and healthy eating, more effective interventions were shown to combine self-monitoring with at least one other technique derived from control theory (e.g. intention formation, specific goal-setting). 17 Goal-setting and self-monitoring are two of the most commonly used behaviour change strategies in weight loss interventions, and are typically used in conjunction. 20,21 A recent meta-analysis of behaviour change techniques in 48 weight loss interventions found that goal-setting and self-monitoring were the most effective components of the interventions. 21 Other intrapersonal processes, which we planned to address within our intervention, included intrinsic motivation, self-efficacy, action-planning22 and implementation intentions23 (described further in Chapter 2).

Social support (interpersonal process)

Social support and its relation to health behaviour change is undertheorised. This is partly because social support is a broad and somewhat loosely used concept; for example, it is an element in the widely used terms of ‘social capital’ and ‘social networks’, which are used to frame ideas about social support. 24,25

Social support is multifaceted: there are various types of social support (e.g. emotional, instrumental, informational)26,27 and there are different kinds of support-giving/-receiving behaviours (e.g. reinforcement, encouragement, motivation, feedback, empathy, role-modelling). 28 Although it is generally used as a positive construct, social support may also have negative elements, such as bullying or co-dependency. 24,29 Minimising negative support, as well as promoting positive support, should be a consideration of behaviour change interventions. 29

Social support is also conceptualised in varied ways in terms of who provides the support. Family,30 friends and colleagues,31 influential people within existing social networks,32 and fellow members of groups with a shared behavioural goal (e.g. weight loss, exercise)33 have been found to be effective in supporting behaviour change in alcohol consumption, smoking prevention and cessation, physical activity, diet and sexual behaviour.

There is evidence that using a ‘buddy’ or ‘helper’ can be effective for weight loss. One trial31 found that when people came with a friend to a weight loss programme they were more likely to adhere to the programme, have greater weight loss and maintain weight loss than those who came alone. Another study34 exploring predictors of adherence to a weight loss programme found that having a buddy (family member or friend) led to an increase in programme adherence from 79.9% to 96.1%. In a study35 of 704 participants in a 15-week online weight loss programme, 54% of participants chose to use a buddy, and they lost more weight than those who did not have a buddy. The same level of effectiveness was found whether the buddies were romantic or non-romantic. A systematic review36 of 21 studies supported these findings, reporting that spousal support could be effective for weight loss. These findings identify the important role that a buddy, or helper, could have in supporting weight loss.

Individuals draw on different types of support from different people in their network. For example, they may derive emotional support from a close friend in their network but may choose to recruit a more distant friend for that person’s expertise in a particular area. Family and friends are significant social influences on health behaviour as a result of factors such as intimacy, influence and proximity to day-to-day health behaviours. They are also immediately accessible to participants because this type of support does not entail joining any kind of formal group.

Social support is important in the initiation and longer-term maintenance of behaviour change,13,31,37 and is typically employed and theorised as one of several elements of behaviour change interventions. 38 In reviews13,17 it has been identified as one contributing factor to effectiveness, alongside goal-setting and self-monitoring. Common intervention elements theorised to operate in conjunction with social support are self-efficacy,39 perceived control39,40 and social norms. 41 Ferranti et al. 42 found that social support is positively correlated with healthy diet. Social support is also associated with increased physical activity40,43 and can improve weight loss maintenance,31 encourage health-promoting behaviours and promote well-being. 44 There is also evidence that unhealthy lifestyle behaviours are correlated with less social support. 15 For many of us, a significant proportion of our social contact is now via digital technologies, and therefore an intervention using this medium to facilitate social support may be useful. In one study45 of an online intervention, despite social support not being specifically promoted as part of the intervention, findings demonstrated that perceived social support from existing social networks and the use of self-regulatory behaviours were strong predictors of improved physical activity and nutrition behaviour. Similarly, Neuhauser and Kreps46 argue that communication that is interpersonal, affective (not just rational), interactive, individually tailored and set within an individual’s social context is more likely than other forms of communication to be effective in changing health behaviour, and that this should be incorporated within new technology- and internet-based interventions. This type and quality of social support would be better facilitated through contact with family and existing friends, rather than anonymous online groups. However, social support from friends and families tends not to be incorporated into the formal design of online behaviour change interventions.

Using technology to influence lifestyle

Emerging evidence in this field suggests that technology-based interventions can be effective, for example texting to promote healthy behaviours. 47 A growing body of evidence on web-based interventions employing goal-setting and self-monitoring has demonstrated positive effects on programme engagement and health behaviours. 12,48 Mobile apps in particular could be a convenient, potentially cost-effective and wide-reaching weight management strategy. 49 There is also evidence that new technologies can be effective with both young and older people. 50,51 However, interventions have often been rather simplistic and not based on the best evidence or theory of effective behaviour change. 52 The effectiveness of these interventions could be enhanced by incorporating well-evidenced behaviour change techniques and promoting support from an individual’s social network to assist them to achieve health-related goals.

A key driving force behind digital health is the need to move to more cost-effective health-care delivery models. Reviews53,54 of digital health interventions have demonstrated that few evaluations have captured data that sufficiently allow for consideration of economic outcomes and the overall effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of interventions. NICE55 plans to develop a new evaluation system for digital health apps to respond to the recent growth in digital health.

The growing accessibility of internet and smartphones

Technology offers opportunities to deliver behaviour change interventions that can reach a large proportion of the population at a low cost. 56 In particular, smartphone apps and web-based interventions can be effective in reaching large numbers of people. 47,57,58 In 2017, internet access was available in 88% of UK households. 59 Smartphones were owned by 85% of adults, of whom 55% reported checking their phone within 15 minutes of waking. 60 Interventions delivered via these technologies have the potential to reach large numbers of people, including ‘Silver Swipers’ (those aged 55–75 years), who were the fastest-growing adopters of smartphones in 2017;60 and those from lower socioeconomic groups, with 73% of people living in Scotland’s 20% most deprived areas having access to the internet. 61

Previous research

There are many smartphone apps (and accompanying websites) for weight loss available that incorporate some or all of the key behaviour change features of goal-setting, self-monitoring and social support [e.g. StickK (Brooklyn, NY, USA), www.stickk.com (accessed 1 June 2016);62 MyFitnessPal (Under Armour, Inc., Baltimore, MD, USA), www.myfitnesspal.com (accessed 1 June 2016)63]. However, a systematic review64 of the most popular apps for weight loss (n = 28) found that the majority were of inadequate quality, lacked evidence-based information on weight loss and lacked appropriate behaviour change techniques. Furthermore, although evidence from research-based interventions using new technologies suggested that they could be effective,47,57,58 the interventions were often simplistic and not based on the best evidence and theory of effective behaviour change. 52 The effectiveness of these interventions could be enhanced by incorporating well-evidenced behaviour change techniques and promoting support through an individual’s social network (family, friends and colleagues).

There is a need to improve our understanding of how interventions involving new technologies effectively facilitate changes, for example factors such as optimal website design, how to maximise exposure to websites or what type of prompting works best are areas that still require development. 65 Particular aspects of new technologies may enhance interventions, such as through higher intensity (e.g. more frequent contact with people in an individual’s social network). This may increase the success of an intervention13 but at a lower cost than traditional methods. Some applications may also allow for more personalisation or individual tailoring of an intervention to suit individual needs, which may also improve success rates. 66 However, the evidence base is limited and, to date, somewhat mixed. 67 Therefore, although there have been promising signs in this emerging field, such as the potential for high reach and for engaging hard-to-reach groups, there is a need to address research gaps in understanding how new technologies might support or enhance known health behaviour change mechanisms.

Currently available websites or apps for weight loss use various strategies for behaviour change, including elements such as monetary incentives or prizes, competing with others and behavioural goals. Some apps provide an element of social support, such as a chat forum. 63 There is some evidence to suggest that online social networks can have a positive impact on health behaviour change. 68 However, online users are typically not known to each other and the apps are not designed to harness the ‘offline world’ and the immediate support of family, friends and colleagues. Evidence indicates that support from key individuals in a person’s life is more effective than that provided by anonymous online contacts. 13

The perceived value of, and demand for, social support has resulted in many health behaviour change websites having chat forums or bulletin boards, which facilitate support from other users. These provide empathy and encouragement, but may not be able to build on evidence of the importance of who provides the social support and the many mechanisms through which social support can facilitate and sustain behaviour change. None of the resources we explored focused on the combination of elements that we used in our intervention, most importantly social support from key individuals within that person’s social network. These are individuals whom they know well, and who are part of their everyday lives and available to support them when needed, in a sustainable ongoing way.

The summary above has identified goal-setting, self-monitoring and social support as promising behaviour change techniques. 69 Although they have featured in a number of apps, for which there is mixed evidence, we have not identified any existing intervention that specifically aims to mobilise support from existing social networks using an application- (app) and web-based intervention. This is the unique aspect of the HelpMeDoIt! intervention, and this is the first study to our knowledge to explore the feasibility of engaging social support from existing social networks, in combination with goal-setting and self-monitoring, in a digital health intervention for weight loss. If brief engagement with an app could catalyse input from existing social connections to support longer-term change, then this could offer a sustainable approach to behaviour change.

Rationale for the current study

Policy

Improving health behaviours is a priority for government. However, current health behaviour change initiatives require improvements in their reach and effectiveness to have a significant impact on the population’s health. The House of Lords Science and Technology Select Committee report on behaviour change8 highlighted that no single approach is likely to be effective in tackling priority health behaviours and that complex interventions addressing multiple levels of behavioural determinants are likely to be needed to bring about sustained change. HelpMeDoIt! is a complex intervention addressing two of these levels: the intrapersonal and the interpersonal.

Economy

Lifestyle-related illness represents a significant cost to the NHS. One-to-one individualised lifestyle interventions are unlikely to yield substantial population-level improvements at a realistic cost to the public purse unless they are highly effective. In comparison, web- and app-based behaviour change interventions can reach substantial numbers at a lower cost. New technologies, such as smartphone apps, present opportunities to promote healthy lifestyles cost-effectively on a large scale. 70 Content, covering evidence-based behaviour change components with the engagement of community-based social support resources, can be delivered in an engaging and accessible way.

Evidence base

Although the intervention elements of goal-setting, monitoring and social support are well established, and although new technologies have shown promise, the evidence base is limited and theoretically underdeveloped. 50,52 Studies are often limited by small, short-term effects71 and high attrition. 12,72 There are significant gaps in understanding how these elements work together, for example how social support operates through personal networks mediated by new technologies, and what impact this has on mechanisms such as monitoring and goal-setting. There is a need to (1) explore the application and mechanisms of goal-setting, monitoring and social support via web and app-based interventions; (2) explore how they interact with each other: and (3) test this type of intervention in both a feasibility and a full-scale effectiveness trial. Feasibility trials of this nature are a necessary first step in developing public health improvement interventions, particularly where mechanisms, such as social support, are not well understood and where technological innovations present new possibilities.

Future impact

The proposed intervention has the potential to have both reach and effectiveness in all socioeconomic groups including those who are traditionally hard to reach. If the intervention were proven effective in a future powered trial, it could be applied to other behaviour change areas and would be universally available through a free-to-access website and/or promoted in specific NHS and community settings across the UK.

Study aims and objectives

The principal element of the HelpMeDoIt! intervention is social support from members of an individual’s close social network. This study explored the promising role of social support in successful health behaviour change, and developed theory concerning the types of social support that participants seek within their personal networks, which individuals they choose, the types of support provided in the context of a web- and app-based environment, the interaction with known behaviour change mechanisms such as goal-setting and monitoring, and the impact that this has on health behaviour change.

The aims of the study were to develop and test the feasibility of an intervention (HelpMeDoIt!) to promote health behaviour change for adults with obesity delivered via an app and website, which (1) incorporated evidence-based behaviour change techniques (goal-setting, self-monitoring and social support) and evidence-based information on weight loss strategies; and (2) delivered this information via a platform that was both usable for and acceptable to participants.

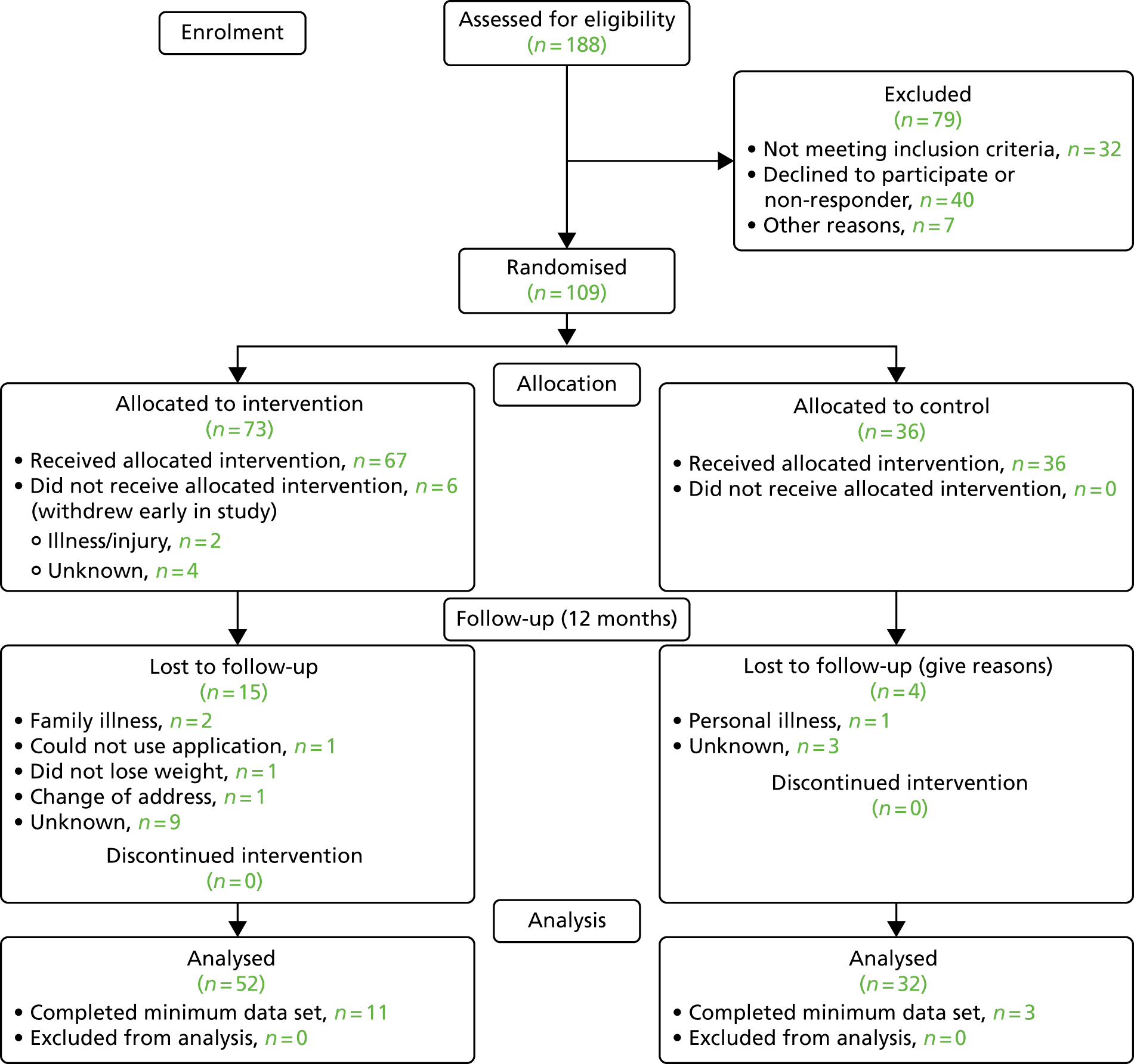

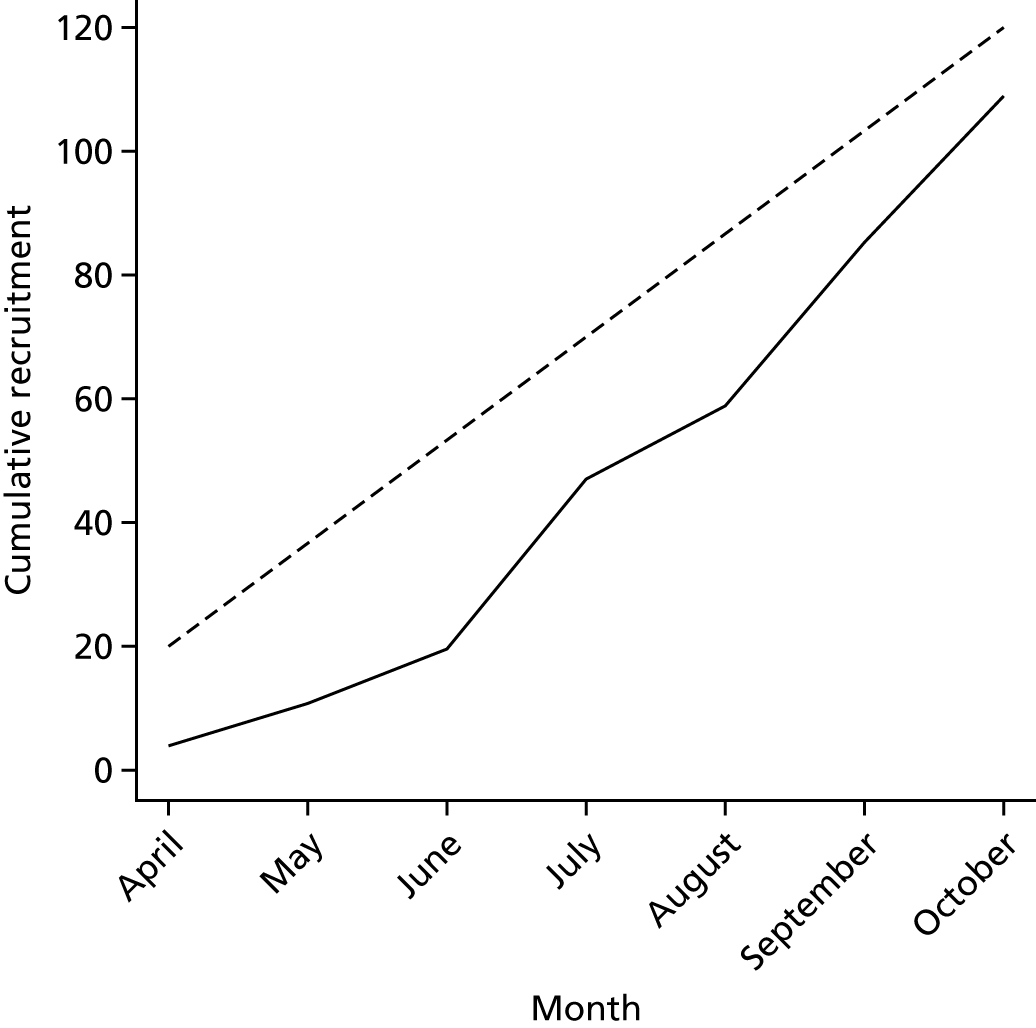

The study was completed in two stages (Figure 1):

-

In stage 1 the intervention was developed and piloted with the help of a panel of user representatives to address (1) the engagement and ease of use of the website and app and its success in promoting realistic goal-setting; (2) the acceptability of the social support content; (3) the functionality of the technology and its facilitation of social support from helpers; and (4) the views of the panel on how the intervention might attract and support helpers.

-

Stage 2 was a feasibility trial, with an accompanying process and economic evaluation, which aimed to examine reach, feasibility, acceptability and trial parameters for a future effectiveness trial. Findings from stage 2 will help to assess whether or not a larger randomised controlled trial (RCT) is warranted.

FIGURE 1.

The two stages of the HelpMeDoIt! study.

Key objectives of the study

-

To develop an app- and web-based intervention that enables participants to set and monitor goals and facilitate effective social support (see Chapter 2).

-

To investigate recruitment and retention as well as feasibility and acceptability of the intervention (see Chapters 4–6).

-

To explore the potential of the intervention to reach traditionally ‘hard-to-reach’ groups (e.g. lower socioeconomic groups) (see Chapters 4 and 6).

-

To explore the barriers to and facilitators of implementing the intervention (see Chapter 5).

-

To assess the feasibility and acceptability of different outcome measures for diet and physical activity in this population (see Chapters 4 and 5).

-

To use outcome data (diet, physical activity, BMI) to help decide on a primary outcome and to estimate the potential effect size of the intervention to facilitate the calculation of an appropriate sample size for a full trial (see Chapters 4 and 7).

-

To assess data collection tools and obtain estimates of key cost drivers to inform the design of a future cost-effectiveness analysis (see Chapter 4).

-

To investigate how participants and helpers engage with goal-setting, monitoring and social support using new technologies and how these elements interact within a behaviour change intervention (see Chapters 5 and 6).

-

To develop a conceptual model of how the key mechanisms of goal-setting, monitoring by self and others, social support and behaviour change are facilitated by the intervention (see Chapter 6).

-

To test the logic model and theoretical basis of the intervention in stages 1 and 2 (see Chapter 6).

-

To explore the characteristics of participants’ social networks and the influence social networks have on participant experiences and outcomes of the intervention (note that this was not part of the original funding application and will be published at a later date).

-

To assess whether or not an effectiveness trial is warranted (see Chapter 7).

Chapter 2 Stage 1: intervention development, methods and findings

An adapted version of the following methods was published open access in Matthews et al. 73 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

The HelpMeDoIt! study was undertaken in two stages: stage 1, an intervention development and formative evaluation phase; and stage 2, a feasibility RCT. This chapter describes stage 1, and is split into three key sections:

-

overarching approach to stage 1 intervention development

-

findings from stage 1

-

progression criteria from stage 1 to stage 2.

Multimethod approach to intervention development

The aim of stage 1 was to design the HelpMeDoIt! app and website with the help of users and to explore initial usability and acceptability. It was important that the development of the intervention was guided by the target audience, and was theory based built on the best available evidence for behaviour change. In addition to the app and website, the goal of stage 1 was to develop a comprehensive programme theory and logic model. This programme theory was tested and refined as part of both stage 1 and stage 2 of the study.

We took a novel approach to the design of the HelpMeDoIt! app and website by combining four approaches to intervention development. These were general intervention development methods in the form of the ‘6SQuID model’ (6 Steps in Quality Intervention Development);74 digital health-focused methods using the Person-Based Approach75 and the Behaviour Intervention Technology model;76 and identification of appropriate behaviour change theories and techniques using the behaviour change taxonomy16 and current theoretical evidence base.

A brief overview of each approach is provided below. The key components of each approach, and how they complement each other, are outlined in Appendix 1.

Approach 1: the 6 Steps in Quality Intervention Development (6SQuID) model

This model by Wight et al. 74 was developed to address gaps in current guidance for the development of interventions. For example, the Medical Research Council (MRC) guidance on developing and evaluating complex interventions77 is primarily devoted to evaluation and does not provide sufficient detail on actual intervention development. The 6SQuID method involved six steps:

(1) defining and understanding the problem and its causes; (2) identifying which causal or contextual factors are modifiable: which have the greatest scope for change and who would benefit most; (3) deciding on the mechanisms of change; (4) clarifying how these will be delivered; (5) testing and adapting the intervention; and (6) collecting sufficient evidence of effectiveness to proceed to a rigorous evaluation.

We adhered to this six-step process, and used it as the overarching approach throughout our intervention development from initial idea to testing in the feasibility trial.

Approach 2: the Person-Based Approach

The Person-Based Approach is a framework for developing digital interventions that are based on a comprehensive understanding of the social, psychological and environmental context of the target group. 75 This approach involves potential users in the development of the intervention and incorporates their perspectives. As well as focusing on the views of users about engagement, content and usability, crucially it also addresses the behaviour change techniques included in the intervention. We considered the Person-Based Approach complementary to the approaches we were already using to identify theory- and evidence-based approaches to changing weight-related behaviours. The Person-Based Approach provided a systematic approach to intervention development, relying on qualitative methods throughout the whole process to inform intervention design. This type of iterative, consultation approach, understanding user perspectives and incorporating key contextual influences, was key to developing an intervention that could be engaging and have a chance of being effective.

Approach 3: the Behaviour Intervention Technology model

Another digital health-related framework is the Behaviour Intervention Technology (BIT) model. 76 The BIT model was developed to fill a gap in the literature on the design of behavioural intervention technologies, such as lifestyle interventions using web-based technology and mobile phones. The BIT model helps answer the questions why, what, how and when. For example, ‘why’ was reflective of the intervention aims; ‘what’ includes the BIT elements such as app notifications and report logs; ‘how’ includes behaviour change strategies, such as goal-setting, and technical characteristics, such as personalisation of the app; and ‘when’ refers to the navigation through the app/website as determined by either the software or the user. This model was particularly helpful in guiding the development of software characteristics.

Approach 4: utilising theory and behaviour change techniques

Between 36% and 89% of interventions that seek to change health behaviours are not clearly theory based. 78 Interventions based on theories of behaviour change have been shown to be more effective, although reviews relating the impact of using theory to the success of interventions have shown mixed results, and theory is often poorly applied. 79 The use of behaviour change techniques and how they relate to theoretical concepts is also often inadequately reported. 80 We sought to address both of these issues by exploring multiple behaviour change theories and identifying the most appropriate candidate theories and associated behaviour change techniques that could be useful in the HelpMeDoIt! intervention. We used these theoretical underpinnings to develop a programme theory, identifying multiple causal mechanisms describing how the HelpMeDoIt! intervention could lead to positive outcomes for weight management in adults with obesity.

Figure 2 presents how these four approaches were combined. This involved the 6SQuID model being used as an overarching cradle-to-grave process, with the Person-Based Approach, the BIT model and behaviour theory approaches being incorporated to address more specific development issues. The other elements represented in Figure 2 will be described in detail throughout this chapter.

FIGURE 2.

The combined framework for the development of the HelpMeDoIt! intervention.

Overarching approach: 6SQuID

The remainder of this section is structured using the six steps of our overarching approach, the 6SQuID model. We describe under each step how and when we incorporated the other three approaches: the Person-Based Approach, the BIT model and behaviour change theories and techniques.

6SQuID step 1: ‘define and understand the problem and its cause’

The initial step of intervention development involved undertaking a literature review to identify up-to-date evidence on obesity. This involved gathering data on the prevalence, causes and associated risks. Obesity is a well-researched area, so there was extensive evidence providing insights into this public health problem. The causes of obesity are complex and multilayered, and the solutions are likely to involve intervening at multiple levels, including individual, interpersonal, organisational, community and policy. The HelpMeDoIt! intervention focused on the first two of these levels. An overview of our literature review findings was provided in Chapter 1. Further detail can be found in our study protocol (see Report Supplementary Material 1).

6SQuID step 2: ‘clarify which causal or contextual factors are malleable and have greatest scope for change’

As part of the above review, we explored causal and contextual factors that could be influenced as part of the intervention. The key influencing factors associated with weight loss are diet and physical activity. Harnessing positive social support was identified as an important factor, as were motivation and self-efficacy. These have already been discussed in Chapter 1.

6SQuID step 3: ‘identify how to bring about change: the change mechanism’

Identifying the potential mechanisms of change was a critical step in the development of the intervention. It was at this stage that we incorporated the first of our other intervention development approaches by identifying relevant behaviour change theories and techniques. We conducted a search to identify the intervention components most likely to contribute to successful weight loss, as well as components associated with successful and unsuccessful interventions. We also conducted a search for web-based and other technology-based interventions and those involving any kind of social support, whether from friends, family, colleagues or groups such as Weight Watchers. We also conducted an internet search for websites or apps aimed at changing health behaviours around diet and physical activity. We found many sites that utilised monetary incentives or prizes, competition with others, behavioural goals, and social support elements such as chat forums. However, we did not identify any that included family members and friends to encourage and promote weight-related behaviour change in the way we envisaged. Our review of the literature and 6SQuID steps 1 and 2 provided us with the rationale to develop an intervention for adults with obesity, using technology in the form of an app/website, to facilitate social support for weight loss. The resulting intervention is, thus, a combination of (1) individual behaviour change approaches, (2) social support and (3) the use of technology.

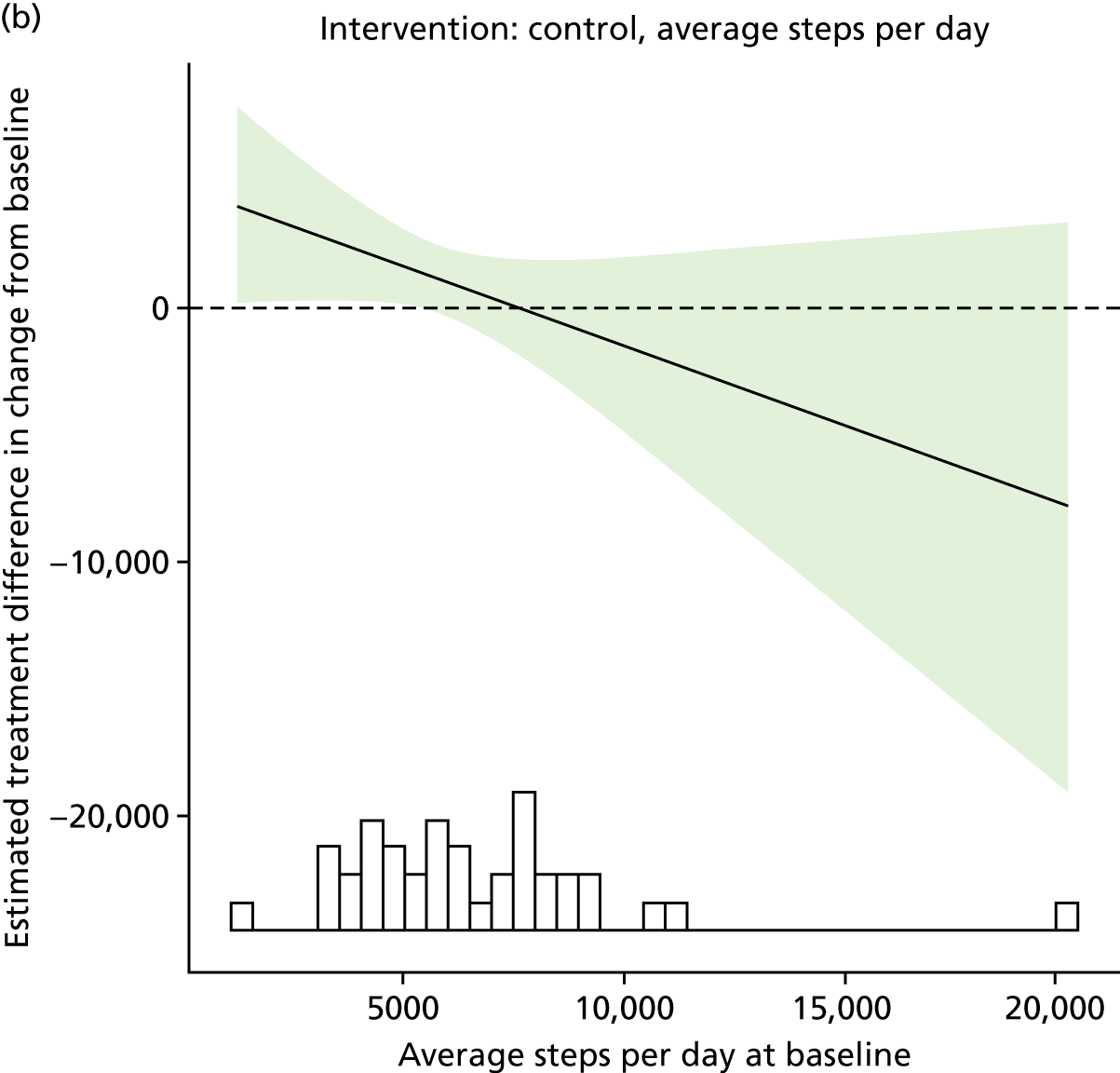

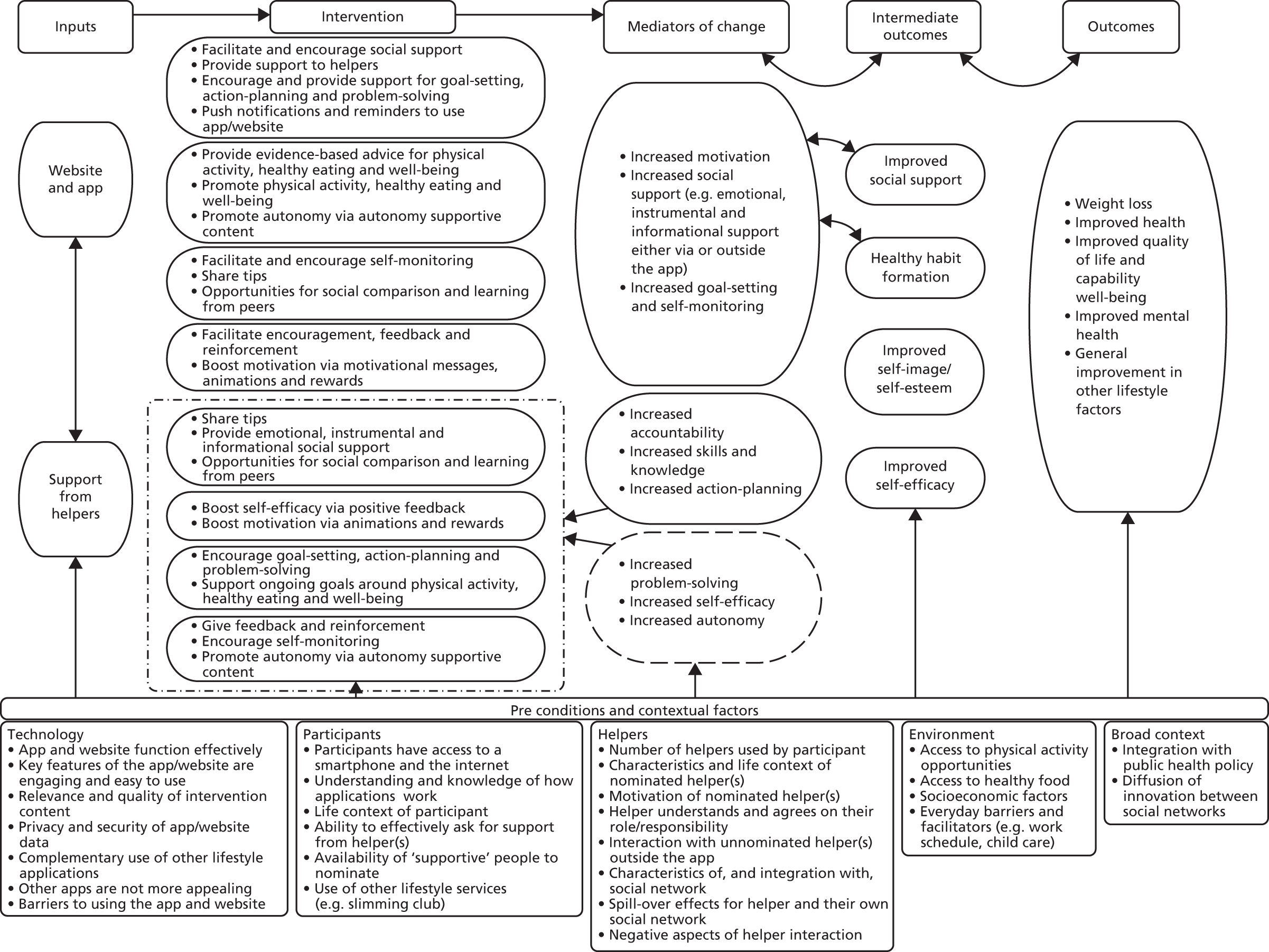

Behaviour change theories and techniques

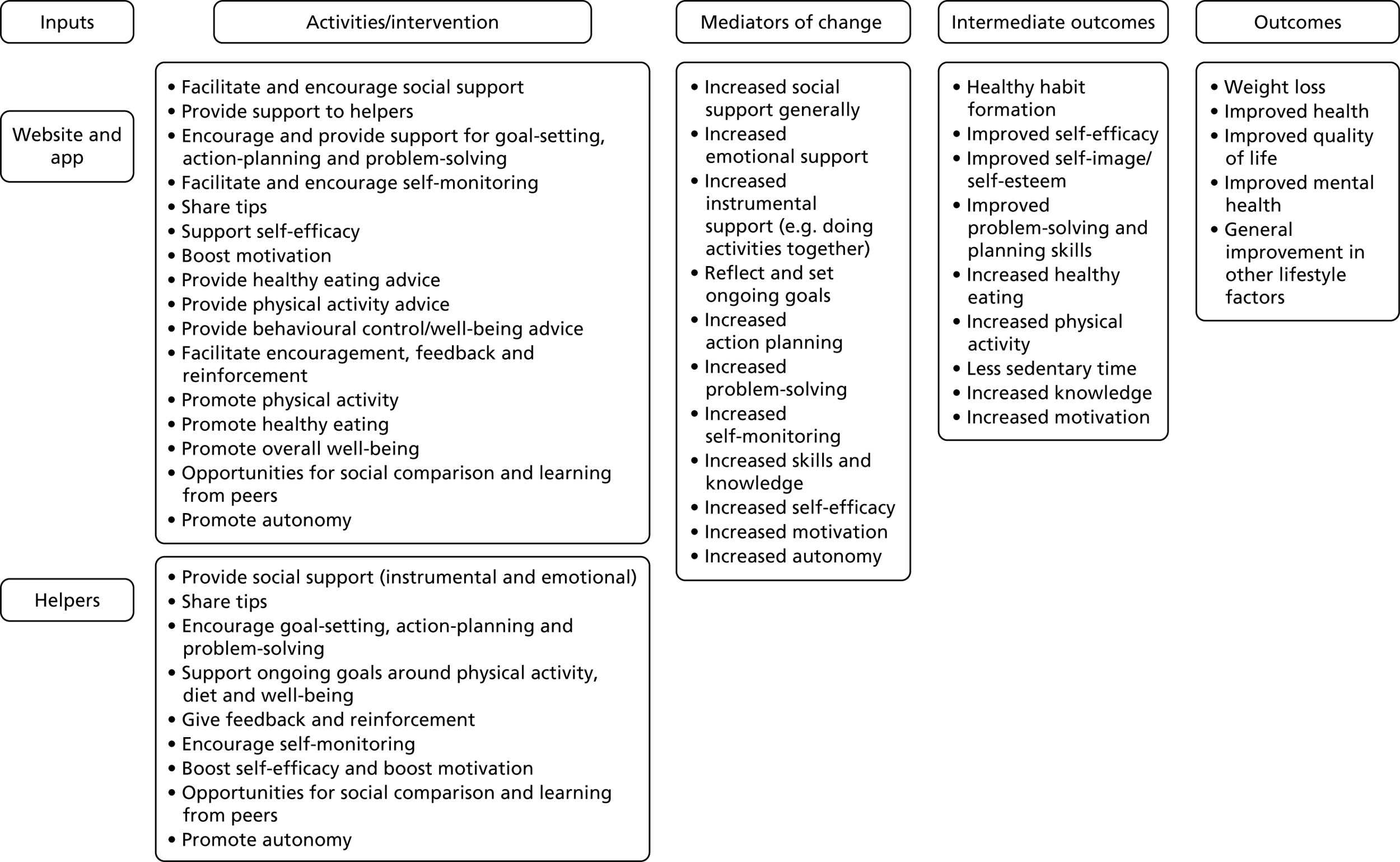

The literature review identified the most appropriate candidate theories and associated behaviour change techniques that could inform the early-stage development of the ‘version 1.0’ programme theory and logic model (Figure 3). This initial logic model broadly focused on goal-setting, self-monitoring and social support,as these techniques have been shown to be effective for weight loss. 11,81 It also included a number of other evidence-based techniques, such as boosting motivation and increasing autonomy. We mapped these behaviour change techniques to behaviour change theories relevant to our intervention. 82,83 These were Social Cognitive Theory,18 Self-Determination Theory,84 Control Theory19 and Social Support Theories. 27,85 Elements of the version 1.0 logic model that related to each of these theories are highlighted in Table 1.

FIGURE 3.

Version 1.0 of the HelpMeDoIt! programme theory and logic model.

| Source of input | Behaviour change technique | Behaviour change theory |

|---|---|---|

| HelpMeDoIt! website and app | Facilitate and encourage social support | Social support theories |

| Provide general encouragement and instruction (support) to helpers | Social cognitive theory | |

| Encourage and provide support for goal-setting, action-planning and problem-solving | Social cognitive theory | |

| Facilitate and encourage self-monitoring | Control theory/social cognitive theory | |

| Share tips | Social cognitive theory | |

| Support self-efficacy | Social cognitive theory | |

| Boost (intrinsic) motivation | Self-determination theory | |

| Provide healthy eating advice | Social cognitive theory | |

| Provide physical activity advice | Social cognitive theory | |

| Provide behavioural control/well-being advice | Social cognitive theory | |

| Facilitate encouragement, feedback and reinforcement | Social cognitive theory | |

| Promote physical activity | Social cognitive theory | |

| Promote healthy eating | Social cognitive theory | |

| Give feedback and reinforcement (app only) | Control theory/social cognitive theory | |

| Promote autonomy | Self-determination theory | |

| Opportunities for social comparison and learning from peers | Social cognitive theory | |

| Promote problem-solving | Social cognitive theory | |

| Support from helpers | Provide social support (instrumental and emotional) | Social cognitive theory/social support theories |

| Share tips | Social cognitive theory | |

| Encourage goal-setting, action-planning and problem-solving | Social cognitive theory | |

| Support ongoing goals around physical activity, diet, etc. | Social support theories | |

| Give feedback and reinforcement | Social cognitive theory | |

| Encourage self-monitoring | Control theory/social cognitive theory | |

| Boost self-efficacy | Social cognitive theory | |

| Boost (intrinsic) motivation | Self-determination theory | |

| Opportunities for social comparison and learning from peers | Social cognitive theory |

Table 1 presents the mapping of individual behaviour change techniques used in the intervention to these four behaviour change theories.

6SQuID step 4: ‘identify how to deliver the change mechanism’

Version 1.0 of the logic model was based on the research evidence, using 6SQuID steps 1–3. The logic model was used as a starting point for then engaging with stakeholders, with a view to further refining the mechanisms of change and intervention content. At this point we began developing the intervention alongside potential users and technical experts from a software company. This was a critical stage in our intervention development and involved the use of the two other approaches: (1) the Person-Based Approach75 and (2) the BIT model. 76 Each of these explored how to effectively deliver the mechanisms of change and specific content of the interventions.

The Person-Based Approach

We adopted the Person-Based Approach as an appropriate method of involving key stakeholders in the development of the intervention, allowing us to iteratively explore usability, engagement and content, including relevant behaviour change techniques. The first step of the Person-Based Approach was to develop guiding principles on which to base the intervention. Our HelpMeDoIt! guiding principles are outlined in Appendix 2. The second step was to gather insights from key stakeholders, namely potential users of the app/website and members of the software company (described below). The Person-Based Approach helped identify which key components should be included, taking into account context and implementation, in a way that was acceptable and convincing to the target group.

The Behaviour Intervention Technology model

The purpose of using the BIT model was to guide the practical build of the intervention in relation to its conceptual aim of weight loss using social support. The BIT model was crucial in providing us with a digital health-focused framework for ensuring that the intervention’s technical aspects aligned with its objectives of goal-setting, self-monitoring and social support via helper interaction. The model is based on five elements: (1) why the software is being developed, for example to promote weight loss; (2) how the software is conceptually considered to achieve the overall goal of weight loss, for example via goal-setting, self-monitoring and social support; (3) what elements the software requires to ensure that these aspects of the intervention are achieved, for example use of notifications and reminders to use the app; (4) how these features will technically be delivered by the software to meet the needs of the participant, for example specific requirements, such as choosing days of the week, for the goal-setting feature; and (5) when the various elements of the intervention are delivered; for example, the timing of some features will be led by participants, compared with other features that will be time-based and set by the software, such as push notifications. Table 2 provides examples of how the BIT model helped develop the technical build of the app and website. For this phase, we worked alongside a software company, ensuring that we captured their expertise in and insights into developing the intervention into an app and website.

| BIT component | Examples | |

|---|---|---|

| Why | Intervention aims (informed by our previous scoping work under 6SQuID step 1) | Weight loss:

|

| How (conceptual) | Behaviour change strategies (informed by our previous scoping work under 6SQuID steps 2 and 3) |

Goal-setting Self-monitoring Social support Action-planning Problem-solving |

| What | Elements |

Information delivery Messaging Notifications Rewards Passive data collection Reports App-to-app contact |

| How (technical) | Characteristics |

Medium – app and website Complexity – option to use free text or templated goals Aesthetics – friendly-looking, bright Personalisation |

| When | Workflow |

User defined Frequency – reminders Conditions |

Methods for involving users in the development phase

We recruited a development panel of 10 users. An overview of the methods used with the development panel is provided in Table 3. The development panel was instrumental in helping us develop features of the app and website that were evidence based but user led. It allowed the study team to gather critical insights into the psychosocial context as well as the perspectives of potential users. It enabled us to explore ideas for engagement, and helped refine the key elements and delivery mechanism of the app and website. Findings are presented in Results of stage 1 intervention development.

| Study aspect | Methods used |

|---|---|

| Sample | 10 user representatives who were adults aged ≥ 18 years, owned a smartphone and were interested in losing weight |

| Recruitment | Posters in large organisations; adverts via Gumtree; frequent tweets using our HelpMeDoIt! Twitter account (Twitter, Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA; www.twitter.com); and frequent posts on our HelpMeDoIt! Facebook page (Facebook, Inc., Menlo Park, CA, USA; www.facebook.com) |

| Sampling frame | Based on age, gender, postcode and current experience of using apps |

| Role | To contribute to the concept, design and development of the intervention, and to test the beta version of the app and website |

| Method |

Invited to three evening focus groups Focus group 1 was held in June 2015 and involved participants discussing potential key features of the intervention. The study team and the software company subsequently worked on developing initial plans for the intervention based on these findings Focus group 2 was held in September 2015 and involved participants sharing their feedback on the initial designs and key features Focus group 3 was held in December 2015 and involved participants giving feedback after having had the opportunity to test the app and website on their telephone/PC for 1 week. At this point they also completed the USE questionnaire, which collects data on acceptability. 86 The study team and the software company subsequently used the findings from this group to refine and strengthen the software ready for implementation in stage 2 |

| Analysis |

Focus groups were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Although a full thematic analysis was not carried out at this stage, two members of the study team analysed the transcripts for key data to inform the software development, including the scope, intervention content and design. This involved separately extracting key points from the transcripts related to potential key elements of the intervention. These data were tabulated and discussed in detail both among the study team and with the software company. Further analysis and discussion included comparing key points with evidence from the literature and current software capabilities This analysis categorised potential software features into three groups: (1) definitely to be included (i.e. evidence based, feasible to implement and welcomed by participants); (2) maybe to be included (i.e. some evidence base, feasible to implement but with challenges and disadvantages, and welcomed by majority of participants); or (3) not to be included (i.e. limited evidence base, challenging to implement, welcomed by some participants). Decisions on software development were presented and discussed with the development panel at each focus group, following which the key elements of the intervention were developed further |

| Software development | Software was refined based on these findings |

6SQuID step 5: ‘test and refine on a small scale’

In addition to our development panel, we used a separate testing group to gather feedback at various points throughout the development process.

Methods for involving users in the testing phase

An overview of the methods used with our testing group is provided in Table 4. In addition to gathering feedback on the content, look and navigation of the app and website, this testing stage helped identify technical bugs, software issues such as navigation errors, and areas of the app/website that could be strengthened further. Findings are presented in Results of stage 1 intervention development.

| Study aspect | Methods used |

|---|---|

| Sample | 28 user representatives who were adults aged ≥ 18 years. Unlike the development panel, it was not necessary for this group to own a smartphone or have an interest in losing weight. This phase of testing focused on operational aspects of the app and website, and not on the behaviour change content |

| Recruitment | The methods were the same as for the development panel, with the addition of (1) inviting individuals who were not selected for the development panel to join our testing group and (2) word of mouth (by members of the original development panel to people in their social network) |

| Sampling frame | Based on age, gender and socioeconomic status |

| Role | To test the app and website prior to their delivery in the trial |

| Method | Conducted over a 4-month period using two methods. (1) Individual semistructured interviews between August and November 2015. Users were presented with initial software designs for the app and website (either printed as a hard copy on A4 paper or presented as a digital copy on a PC/television screen) and asked to provide feedback in relation to the look, feel, key features, wording and content. (2) Think-aloud interviews87 were undertaken about the prototype version of the app and website in late November–December 2015. During these interviews, users were asked to work their way through the software and share their immediate feedback by speaking out loud their thoughts while using it, and with the interviewer present. The interviewer asked questions throughout the process to probe further into the thought process of participants (e.g. ‘You’ve been quiet for a few moments. Can you tell me what you are thinking?’). This helped to assess the clarity and ease of use of the app and website interface and also to identify ‘sticking points’ |

| Analysis | All sessions were audio-recorded and analysed by two members of the study team. Analysis included collating (1) a list of positive and negative feedback on participants’ test runs of the app; (2) feedback on the look, feel, key features, wording and content; and (3) insights from participants on using the intervention in the context of their daily lives. Data from these interviews and think-aloud sessions were fed back to the software company and this led to further refinement of the app, website and programme theory |

Heuristic evaluation

Further testing was performed via a heuristic evaluation. This standardised process involved the app and website being assessed by two independent technology experts. 88 Each expert applied and assessed set heuristic criteria to both the app and the website (see Appendix 3). The aim of the heuristic evaluation was to identify strengths and limitations of the software and highlight areas for further refinement.

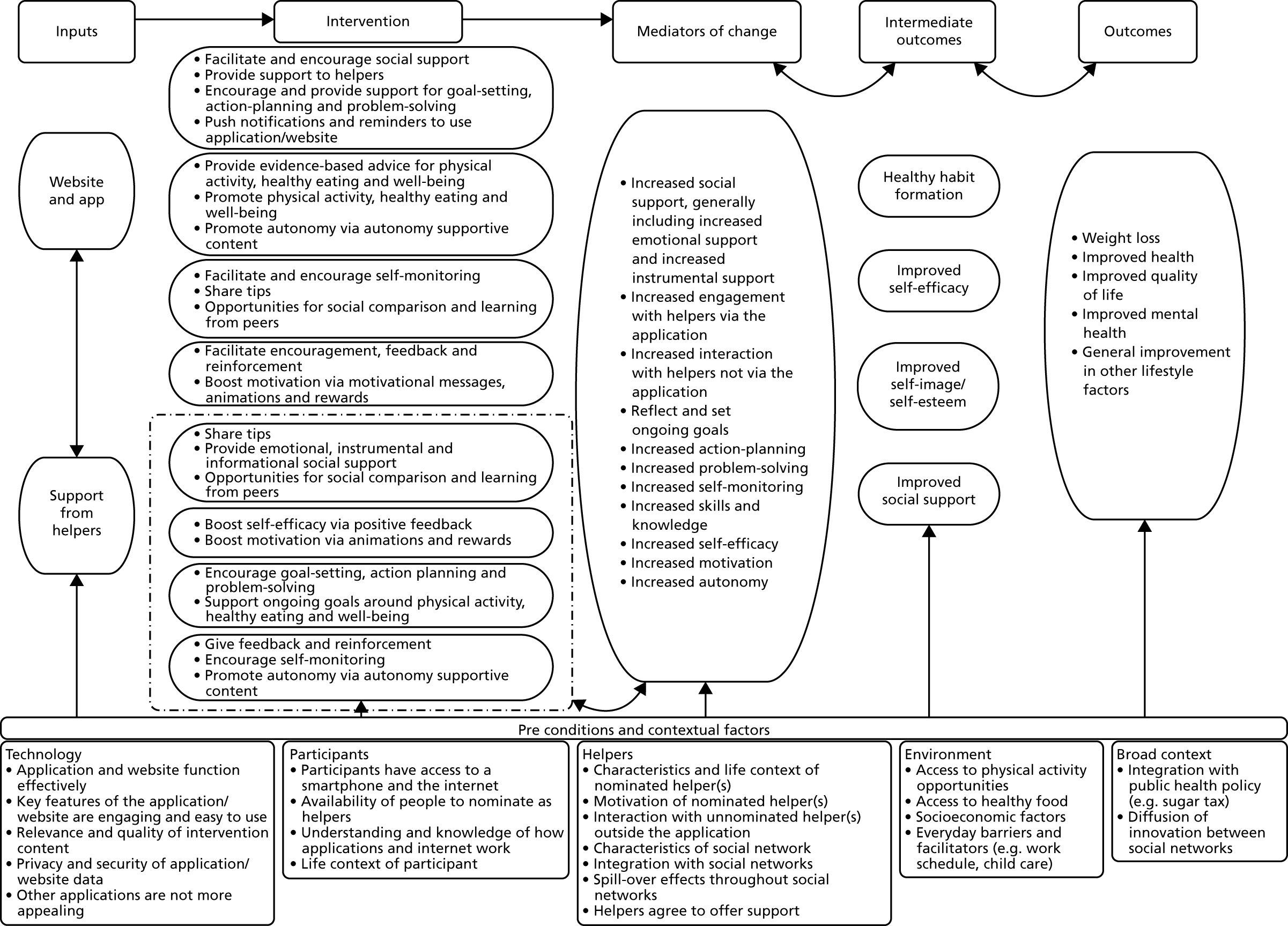

Logic model and programme theory development

The valuable insights gathered by 6SQuID steps 1–5, incorporating the Person-Based Approach, BIT model and behaviour theory/technique exploration, helped refine and strengthen the HelpMeDoIt! programme theory and logic model. We developed and continually updated the programme theory used to design our intervention and plan the evaluation, and this is represented in the logic model. The original version 1.0 of the programme theory logic model (see Figure 3) identified general links between the software elements of the intervention and the proposed outcomes. The ongoing user involvement and feedback throughout stage 1 allowed us to consider additional contextual factors and further refine ‘version 2.0’ of the programme theory and logic model. The revised logic model now included (1) further mechanisms of action (e.g. increased motivation and increased autonomy); (2) a reduced number of intermediate outcomes (e.g. less sedentary time and increased physical activity and healthy eating were condensed into healthy habit formation); and (3) multiple contextual factors (e.g. availability of people in participants’ social network to act as helpers) (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

Version 2.0 of the HelpMeDoIt! programme theory and logic model.

6SQuID step 6: ‘collect sufficient evidence of effectiveness to justify rigorous evaluation/implementation’

In step 6 of the 6SQuID process, the resulting version 2.0 logic model and intervention were ready for implementation and testing in a feasibility RCT with accompanying process and health economic evaluation (stage 2). The methods and findings for this stage are presented in Chapters 3–6.

Results of stage 1 intervention development

As described above, the intervention was developed in collaboration with a development panel of users, a testing group of users and a software company and used evaluation feedback from software experts. Details of how this input helped inform the development of the HelpMeDoIt! intervention are presented below in the following order:

-

findings from the development panel

-

findings from the testing group

-

usage statistics for the app and website

-

findings from the heuristic evaluation

-

findings from the USE questionnaire.

Findings from the development panel

We recruited 10 individuals with a range of characteristics to our development panel. We had a good gender balance (female, n = 6; male, n = 4) and spread of ages (18–70 years). All participants were interested in losing weight. We also attempted to include individuals with characteristics associated with a higher likelihood of obesity, and thus included participants of non-white ethnicity (n = 2) and a greater number of individuals from areas of lower socioeconomic status (n = 7). We included two individuals with limited experience of using smartphone apps (the majority of people who responded to the study advert were experienced in this). When participants were unable to attend one of the focus groups, their feedback was collected via a one-to-one interview (n = 1) or by e-mail (n = 2).

Insights and feedback from the development panel were useful and informative at all data collection time points. Participants were engaged, motivated and creative in their approach to the software development and many of their ideas and suggestions were incorporated into the prototype of the app and website. Some suggestions were not included as they were beyond the scope of the app, such as taking photographs of a meal and the app providing an accurate nutritional analysis.

Thematic analyses of the focus groups identified three main themes and related subthemes. These are detailed in Table 5 along with examples of how the different themes were addressed within the app and website.

| Theme | Subtheme | Description | Examples of how theme was addressed |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Software design | Avoiding non-adherence | Barriers to and facilitators of using the app and website, and ongoing engagement using various methods (e.g. autonomous wording and gamification) | Participants can earn medals and trophies for engaging with the app |

| Adaptability of the app | Issues related to flexibility and individual tailoring of the app | Options for setting unit of measurement for inputting weight (e.g. kg or lb) | |

| Usability of the app | Technical-related factors, such as the app interface, colour and font, and software issues | Colour palette was chosen to be unintimidating, friendly and fun | |

| 2. Intervention content and features | Key features of the app | Insight related to the three key features of the app: (1) goal-setting, (2) self-monitoring and (3) helper interaction | Animated smileys created for participants and their helpers to interact via the app |

| Feedback from the app | Issues related to app engagement around progress graphs, reminders, prompts and rewards | Weight change graph included in the app so participants could see progress | |

| Key features of the website | Issues related to the purpose and content of the website compared with the app | Website information provided on the emotional benefits of weight loss | |

| 3. People and context | Characteristics of social support for lifestyle change | Issues related to peer modelling, characteristics of helpers, types of social support offered, and barriers to and facilitators of being a helper | Website offered examples of what type of person might make a good helper |

| Person-centred motivations | Motivations for using the app, making and sustaining lifestyle change, and types of motivations (e.g. intrinsic vs. extrinsic) | Promotion of intrinsic motivation via app (e.g. template well-being goals and well-being messages) | |

| Context of using the app and website | Insight into how participants might fit the intervention into their everyday life, including working patterns; child care; memory problems; comparison with other apps; and previous experiences of app use | Appropriate font size used for both app and website |

Theme 1: software design

This theme included discussion around how the design of the app and website could influence whether or not it was adopted and used successfully.

Subtheme 1.1: avoiding non-adherence

This included discussion on barriers to and facilitators of using the app and website, and how to facilitate ongoing engagement. Our review of the literature had highlighted that ongoing engagement with apps was a significant challenge for software designers. Therefore, the development panel were asked for their insights on what features might help maintain their engagement with the app. Various methods were discussed, such as wording that boosted intrinsic motivation, as well as gamification, daily messages/tips from the app, and a method of receiving instant feedback from their helper(s). These ideas were explored further in the three focus groups. The agreed features were (1) gamification, where participants and helpers could earn points (which would convert to medals and trophies); (2) regular tips via the app or e-mail, which included tips for weight loss, physical activity, well-being, SMART (specific, measurable, attainable, relevant and time-bound) goal-setting, self-monitoring and social support; (3) daily messages via the app or e-mail, which provided motivation, inspiration and encouragement; and (4) instant feedback between participants and helpers via fun animations, for example an animated ‘high five’ from helpers to participants when the latter achieved a goal.

The development panel also discussed likely barriers to and facilitators of using the app. For example, when they were asked to identify reasons they might not use the app, their responses included having trouble with the login process; not having in-app rewards; if the app shows adverts or asks for money; a lack of engagement from the nominated helper; difficulties with using the interface; or if they found another app that performed better.

Subtheme 1.2: adaptability of the app

Here, issues about flexibility and the individual’s ability to tailor certain aspects of the app to suit their routine were discussed. Participants provided useful insights into contextual factors that might encourage use, for example being able to personalise the time and frequency of notifications to match their work schedule:

You could also change it, like if you do get a reminder, you can set snooze for 1 hour, 2 hours. I don’t know if that’s possible. I don’t know, but it’s an option. Because you may think, ‘I am at work just now, but maybe when I get in I want to be reminded’ and you can upload that information.

DP02, male, 40 years

Not all members of the development panel viewed the use of short message service (SMS) text messaging positively. Although some participants did not mind receiving text messages, others felt that this was ‘intrusive’:

I don’t like that [receiving messages via text]. The same as you get text messages from all these companies, stuff like that . . . I feel like junk spam kinda text messages.

DP01, male, 40 years

It was agreed that the main method of communication from HelpMeDoIt! would be set as a preference by the participant (i.e. they would have the choice of receiving push notifications via the app or by e-mail). Several participants indicated they would choose to receive notifications via the app, with some stating that they enjoyed logging into an app each day and seeing a different message. This provided variety and helped with ongoing engagement. However, SMS text messaging was not considered intrusive in the context of helper interaction. Participants liked the idea of receiving supportive text messages from their helper(s). It was agreed that a ‘quick access’ icon would be included in the app to allow participants and helpers to send text messages to each other.

Subtheme 1.3: usability of the app

This related to technical issues such as the app interface, colour and font, and the software itself. The development panel provided feedback on the initial designs and then finally on the prototype of the app and website. Overall, their feedback was positive. The majority of participants liked the layout, colour scheme, design and key features. The development panel also shared critical feedback of the app and website that identified areas for further consideration and refinement. Criticisms of the intervention included difficulties with the initial login via the third-party test app; numerous software bugs affecting their ability to test run the app (e.g. absence of screen animations, buttons obscured by text); not having enough guidance on how to initially use the app or earn rewards; and not having the ability to earn points, and, thus, rewards, during the early stages of testing.

Theme 2: intervention content and features

This theme included the actual intervention elements, what they might look like within the app and website, and how they could help or hinder the process of adopting a healthy lifestyle change.

Subtheme 2.1: key features of the app

This consisted of insights related to goal-setting, self-monitoring and helper interaction.

Participants agreed that having template goals developed by the research team would be useful to help them understand what an appropriate and manageable goal was. They felt that it was important that the template goal could be edited so that they could tailor it to their own circumstances. They also suggested that focusing on a small number of goals would be beneficial, and that goals should focus on sustainable lifestyle change rather than simply weight loss:

It was good that it [the app] gave you the option of already made goals, if that makes sense. Something you struggle to think of. Having one there and being able to work on it gives you more ideas. It’s a good idea.

DP05, female, 70 years

Graphs were unanimously participants’ preferred method of viewing and monitoring progress. Participants shared positive experiences of using graphs on other apps and requested that the HelpMeDoIt! app use a simple yet informative style similar to that of apps they had previously used. They understood that monitoring their progress could help them ‘learn to succeed’:

. . . you are proving to the app like I can do this. Not saying something like ‘I am going to change the world’ but at least like ‘to walk more’, ‘take one bus stop less’. Yes, more like lifestyle changes.

DP08, male, 51 years

Early discussion highlighted that participants were engaged with the concept of helpers, and in particular with helpers interacting via an app. They felt that the intervention could be helpful and effective but they spoke about other lifestyle apps that they used (e.g. MyFitnessPal) and emphasised that HelpMeDoIt! needed to identify its uniqueness in relation to the helper interaction. They shared numerous ideas in relation to interaction with their helper(s). This included insight into the motivation of helpers, who potentially would be more willing to log on to the app and support their friend initially for the fun and novelty. Some shared thoughts on how they imagined the helper would use the app for instant feedback (e.g. a husband or wife messaging their partner from across the room). Participants agreed that having a ‘pat on the back’ from their helper would be encouraging and motivating, and they thought they would enjoy receiving motivating messages from their helper(s). To maximise the support that helpers provide, it was recommended that as much information as possible was shared with them, with helpers basically seeing the same version of the app as the participant. This would allow helpers to see the achievement of small goals, as well as larger weight loss goals. Helpers should therefore receive notifications of new goals, goal progress and goal lapses; however, participants recognised that the frequency of notifications should be limited to avoid their helper(s) becoming annoyed and disengaged with the app:

[I like] having other people helping you. No one pats you on your back unless you go around [saying] ‘I reached my target weight’. All right there are no like celebrations, no cake, no anything like that.

DP04, female, 34 years

Subtheme 2.2: feedback from the app

This related to app engagement around progress graphs, reminders, prompts and rewards. Participants were aware that receiving too many push notifications and e-mails could be a potential barrier to engagement. The majority agreed that either a weekly or a fortnightly summary e-mail of their progress would be useful and non-intrusive. They also agreed that push notifications were a good method of receiving feedback, as these reminded them to use the apps on their phone:

I think in Fitbit [Fitbit, Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA] every week you get an e-mail to see how many steps you’ve done and your overall progress or whatever, which is I suppose it saves you being bombarded.

DP01, male, 40 years

Subtheme 2.3: key features of the website

This addressed content that participants considered useful and informative to have on the accompanying website. The majority considered that they would use the website as a source of information, but would use the app as the main source of the intervention. They did not want all of the information on the app, a suggestion that was also supported by the software company, which also suggested trying to keep the app simple and develop any extra detail for inclusion on the website. Ongoing discussion with the development panel identified that the website should provide guidance (1) for participants on how to safely and effectively lose weight and get the most out of their social support; and (2) for helpers on how to be a good helper and how to support their friend when they experience setbacks, etc.:

. . . maybe for some web page maybe some particular advice, I don’t know . . . What to eat? Or . . . I don’t know. Because that would . . . for me reinforcement is you would go to a web page for reinforcement. For me it’s some sort of psychological reinforcement.

DP08, male, 35 years

Theme 3: people and context

This theme covered social support and contextual factors in the participant’s life that could affect the likelihood that they would be able to make lifestyle changes. This theme included how people in the participants’ social network could help them achieve their goals and what that their social network looked like in terms of supportive and less supportive individuals. It also touched on factors related to the motivation needed to effect change. Finally, this theme included discussion of contextual factors in terms of work obligations, family responsibilities and friends, and the participants’ own histories of health and attempts to lose weight.

Subtheme 3.1: social support for lifestyle change

This related to peer modelling, characteristics of helpers, types of social support offered, and barriers to and facilitators of being a helper. Participants discussed the different people they had in their social network and how some of them might be good helpers because they would be good at motivating them, while others might be supportive because they too were embarking on lifestyle change. Some were reluctant to choose helpers who had an active healthy lifestyle, feeling that these helpers might lack empathy and understanding of a weight loss journey. Most participants liked the idea of nominating helpers from their social network rather than strangers:

I think having someone who can push me would be very good because I lack motivation on my own. But I think it is better to have one single person than different persons.

DP05, female, 65 years

Subtheme 3.2: motivation

This encompassed participants’ motivations for using the app, lifestyle change, sustaining lifestyle changes, and whether motivation was intrinsic or extrinsic. Some participants were motivated by recently diagnosed health problems, for which their lifestyle change was a form of disease management. Others described how they were motivated by the change in lifestyle rather than setting goals, and therefore sustained lifestyle change was the ultimate goal. They also shared important insight into their motivation for continuing to use the app, which typically involved the app being simple, engaging and fun to use:

. . . from my perspective, I am not looking to achieve my target weight. I am looking to generally improve my lifestyle [. . .] drinking water rather than Irn Bru [AG Barr, Cumbernauld, UK]. Rather than actual 18, 15, 10 stone. The rest of it is no target for me [. . .] ideally I would like it to be sustainable for the rest of my life.

DP08, male, 35 years

Subtheme 3.3: context

This included insights into how participants might fit the intervention into their everyday life, including working patterns, childcare, problems with their short-term memory, comparison with other apps and previous experiences of app use. Participants described how they used apps on their phone daily, and typically checked their phone when they woke up in the morning. Others noted how their busy work day made it difficult to manage apps during the day; however, they used their evenings to ‘catch up’ on notifications. Some participants described the challenges of sustaining lifestyle change around shift work, and how weekly rather than daily goals were likely to have greater chance of success:

I don’t have some apps on my phone, because I don’t have time during the day. I only do it on my iPad [Apple Inc., Cupertino, CA, USA] at night-time so I am not harassed by notifications. But I like to be harassed at night. That’s when I fill everything in.

DP04, female, 34 years

First thing I do is check my phone when I get up.

DP03, female, 26 years

Table 6 presents a summary of the key features agreed by the development panel for inclusion in the app and/or website.

| Intervention component | Specific intervention strategies |

|---|---|

| Goal-setting |

|

| Self-monitoring |

|

| Helper interaction |

|

| Settings |

|

Findings from the testing group

Feasibility of the app and website was also evaluated by the 28 participants recruited to the testing group. We purposely aimed to recruit participants with a range of characteristics: 19 were women and 9 were men; age range was 18–64 years; nine participants were from the top two quintiles of socioeconomic deprivation; two participants were from minority ethnic backgrounds; and two individuals had limited experience of using apps (the majority of people who responded to the study advert were experienced in the use of smartphone apps). Participants were recruited via word of mouth (n = 15) (e.g. by members of the original developmental panel to people in their social network), study adverts on Gumtree (www.gumtree.com) or Facebook (Facebook, Inc., Menlo Park, CA, USA) (n = 8), and a university-wide staff e-mail announcement (n = 4). Although feedback was collected on an ongoing basis between August and December 2015, participants provided feedback on only one occasion as a ‘user’ (n = 11), a ‘helper’ (n = 11) or both (n = 6). Detailed feedback from the testing group is presented in Appendix 4. A brief overview is provided below. Overall, feedback from the testing group was constructively critical.

Early feedback at the first time point (August and September 2015) focused on gathering feedback on the initial ideas and designs for the app and website. Feedback was positive, with participants in agreement about the proposed key features of goal-setting, self-monitoring and helper interaction, as well as how these would be delivered. They provided feedback on the initial design, look and feel of the app, and the majority of responses were positive comments on the simple design and colour scheme. Helpful suggestions related to grammar were received to help make the app more engaging. They also provided insights to help the team refine the initial design, for example guidance to choose from more than one goal category.

Feedback collected at time point 2 (October and November 2015) focused on participant insights on our refined app and website ideas. Feedback highlighted that some guidance was required to help participants choose and set goals using the app. This phase of testing also identified useful content to support helpers in their supportive role. Ideas participants provided for the helper section of the website included (1) example conversations between the helper and their friend; (2) guidance on what a helper could do if their friend was struggling to meet their goals; (3) things not to say to their friend; and (4) an online quiz to engage and motivate helpers:

When mentoring at my work it’s about trying to be encouraging so maybe some examples of encouraging dialogue.

TG08, female, 33 years

At the final time point (December 2015), participants were presented with the prototype version of the app. This was accessed using a third-party testing platform. This enabled participants to access and use the app in its beta version and sync to the latest version as features were updated and errors were rectified.

Feedback was gathered via the ‘think-aloud’ approach. 87 This approach facilitated identification of software bugs and errors, which the software company worked on rectifying immediately (e.g. icons obscured by text, inconsistent display of progress graphs). Many of the software bugs were caused by the interaction of our software with a third-party testing platform. Some of these were addressed when the third-party testing platform released an update near the end of our testing phase. In addition to software issues, the feedback helped highlight navigation issues, things that were not intuitive in the design and areas of the app that could be strengthened further. One key suggestion was the need for tutorial guidance to help first-time users understand the process of choosing template versus custom goals:

I’m not sure what I’m meant to do here [on goal-setting screen]. Do I press this button? How do I go back and see the list of goals again?

TG18, female, 39 years

When time allowed, some participants in the testing group also provided feedback on the website (n = 8). Feedback for the website was very positive, with the majority of participants commenting on the simple layout, easy navigation, clear display of information and fun animations. Several suggestions were made to strengthen the website further, for example embedding hyperlinks within the text and simplifying some of the grammar.

Usage statistics for the app and website

There were 498 individual logins recorded for the app, showing that the development panel accessed the software regularly during the testing period. All key features of the app were used. The website was accessed by the development panel on 70 occasions, with 687 web page views in total. The average login for each member of the development panel was four sessions of around 10 minutes’ duration. During this initial testing phase, a number of software issues and bugs were identified and several participants had difficulty logging in. This is normal and expected when beta-testing software.

Findings from the heuristic evaluation

A heuristic evaluation was undertaken by two independent technical experts. The aim of the evaluation was to identify strengths and limitations of the software and to highlight areas for further refinement. This involved applying and assessing set heuristic criteria to both the app and the website. The heuristic criteria were scored on a scale of 1–5 (1, very poor; 5, excellent).

Overall, the findings of the heuristic evaluation were positive. The full heuristic report is presented in Appendix 3. The majority of criteria for the website (71%; n = 35 of 49 criteria) and the app (71%; n = 24 of 34 criteria) were assessed as either ‘good’ or ‘excellent’. Eleven issues were identified as needing improvement. Most of these were minor, for example slowing down the images on the website homepage, and clarifying the goal template headings in the app. Two issues with the app were rated as ‘poor’ and related to a lack of a clear method of returning to (1) the main navigation menu and (2) the main dashboard. All issues highlighted by the heuristic evaluation were addressed by the study team and the software company.

Findings from the Usefulness, Satisfaction, and Ease of Use questionnaire

During the final focus group, participants were asked to complete the Usefulness, Satisfaction, and Ease of Use (USE) questionnaire. 86 This explored the acceptability of the software and also allowed the study team to assess the feasibility of using this questionnaire as a process measure in the trial. Overall, the questionnaire was quick and simple to complete and it was identified as useful for stage 2. Participants responded to 30 individual statements on a scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). The results are presented in Appendix 5. Despite the app being a prototype, all of the mean responses (with the exception of question 29) had a score of ≥ 4 [i.e. all mean participant responses were greater than or equal to a score of 4 (neutral)]. However, it should be noted that in this initial test run some of the USE questions were difficult to answer as participants did not have access to the software over a longer period of time to be able to assess items such as ‘the software helps me be more effective’. In addition, some participants had access to the software for less than 1 week (owing to difficulties with the login process caused by third-party software), which affected their ability to answer all of the USE questions, as some were not applicable because they referred to longer-term use. The USE questionnaire would therefore benefit from a ‘not applicable’ response option.

The HelpMeDoIt! intervention content