Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 15/53/04. The contractual start date was in November 2016. The final report began editorial review in November 2018 and was accepted for publication in May 2019. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Kate Jolly reports grants from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR), local authority funding for the intervention and part-funding by NIHR Collaborative Leadership for Applied Health Research and Care West Midlands during the conduct of the study. Alongside her Cardiff University role, Heather Trickey worked part time as a senior researcher for NCT (London, UK) during the period in which the research was conducted. NCT provides breastfeeding peer support services. NCT volunteers were not included in this study. Pat Hoddinott is a member of the Health Technology Assessment Commissioning Board (March 2014 to present). She is working on a funding application to take forward the FEeding Support Team (FEST) feasibility trial that she led and that is cited in this report. The FEST feasibility trial informed parts of the design of the Assets-based feeding help Before and After birth study. Alice Sitch is supported by the NIHR Birmingham Biomedical Research Centre, University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust and University of Birmingham, UK.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Clarke et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

The benefits of breastfeeding for health and well-being

Breastfeeding (defined as the baby being put to the breast or receiving breast milk on at least one occasion) is associated with short- and long-term benefits to both the breastfed infant1–10 and the mother. 11 Internationally, the largest health gains are seen in low-income countries, as breastfeeding protects against infant mortality by reducing acute infections in infants. 1 However, considerable health gains from breastfeeding are also possible in high-income countries. Currently, only around 12% of babies in the UK are exclusively breastfed at 4 months. If this figure increased to 45% of women in the UK breastfeeding exclusively for 4 months, then at least £17M could be saved annually in NHS treatment costs for common acute illnesses in infants, with additional longer-term gains for mothers and children. 12,13

The benefits of breastfeeding are considerable. The evidence has been collated in systematic reviews1,9 and is consistent across cohort studies in a range of settings and from a randomised controlled trial (RCT) of a breastfeeding support intervention with long-term follow-up of the children. 14 For the infant and child, any breastfeeding is associated with reduced risk of gastrointestinal infection by 63% [95% confidence interval (CI) 50% to 94%],10 sudden infant death syndrome by 36% (95% CI 10% to 49%),15 otitis media by 33% (95% CI 28% to 38%),2 asthma when aged 5–18 years by 12% (95% CI 5% to 18%),3 being overweight in the future or obese by 26% (95% CI 22% to 30%),7 type 2 diabetes mellitus by 35% (95% CI 14% to 51%)7 and malocclusions by 68% (95% CI 60% to 75%). 5 Exclusive breastfeeding for > 4 months reduces the risk of hospital admission for lower respiratory tract infections in the first year by 72% [risk ratio (RR) 0.28, 95% CI 14 to 54]10 and for 3–4 months reduces the risk of eczema by 26% in children at < 2 years. 3 Exclusive breastfeeding for > 3 months is associated with a reduced risk of type 1 diabetes mellitus of up to 30%. 15 Meta-analyses show that being fed breast milk is associated with a 58% (95% CI 4% to 82%) reduced risk of necrotising enterocolitis in pre-term infants16 and with reduced mortality. It is also associated with improved performance in intelligence tests. 8 Mothers have a reduced risk of breast (26%, 95% CI 21% to 31%) and ovarian (37%, 95% CI 29% to 44%) cancers if they breastfeed for > 12 months11 and lower post-menopausal body mass index if they have ever breastfed. 17

Breastfeeding rates and duration in the UK

Breastfeeding duration in the UK is among the lowest worldwide, with routinely collected data and 5-yearly infant feeding surveys18–20 showing relatively small improvements over the past two decades, particularly for rates of exclusive breastfeeding. Although breastfeeding initiation increased from 76% in 2005 to 81% in 2010, exclusive breastfeeding at 6 weeks increased only from 21% to 23% during the same period. There are considerable health inequalities, despite government initiatives; breastfeeding initiation and duration rates are lowest in teenagers (58% initiated breastfeeding in 2010), women living in socioeconomically disadvantaged circumstances, women with lower educational outcomes and white women. 18 In 2010, 90% of UK mothers in managerial and professional occupations breastfed, compared with 74% of those in routine and manual occupations and 71% among those who had never worked. 18

The World Health Organization21 recommends exclusive breastfeeding for 6 months to optimise infant and maternal health, a recommendation endorsed by UK governments;22 however, < 1% of infants in the UK receive this. 18 Data from the Infant Feeding Survey 201018 show that the steepest decline in breastfeeding occurs soon after birth: 81% of women who give birth initiate breastfeeding but only 69% of babies are breastfed at 1 week, 66% at 2 weeks, 55% at 6 weeks and 34% at 6 months. Rates of exclusive breastfeeding are even lower: 46% at 1 week and 23% at 6 weeks. 18 More recent data collected from local authorities in England show that 44.4% of babies receive breast milk at 6–8 weeks, with the range being 19.3% to 75.6%. 23 Mothers express dissatisfaction with breastfeeding care,24,25 and 30% report feeding problems in the early weeks. 18 A 2017 survey by the National Federation of Women’s Institutes and the NCT (formerly known as the National Childbirth Trust) identified baby feeding as the greatest area of unmet need for support. 26 Women who reported that they did not receive support for breastfeeding difficulties in hospital or at home were more likely to discontinue breastfeeding within the first 2 weeks. 18

Effectiveness of peer support for breastfeeding initiation and continuation

In the UK, breastfeeding peer support has been widely recommended as a means of increasing breastfeeding initiation and continuation rates among women from disadvantaged communities. 27,28

Breastfeeding peer support has been defined as ‘support offered by women who have received appropriate training and either have themselves breastfed or have the same socio-economic background, ethnicity or locality as the women they are supporting’. 29 From a theoretical perspective, Dennis30 defines peer support as the provision of ‘emotional, appraisal and motivational assistance by a created social network member who possesses experiential knowledge of a specific behaviour or stressor, and has similar characteristics to the target population’. In comparison with health-care professionals, peer supporters may be considered more approachable and operate as positive role models to whom women can relate because of their direct experience of the challenges of breastfeeding, and in contexts where breastfeeding may not be the social norm. 31

A systematic review32 of breastfeeding peer support interventions reported a significant increase in breastfeeding initiation in three trials that targeted this support at pregnant women who had decided to breastfeed (relative risk for not initiating breastfeeding 0.64, 95% CI 0.41 to 0.99), but no difference in the three trials that offered universal peer support to all pregnant women (relative risk for not initiating breastfeeding 0.96, 95% CI 0.76 to 1.22). Heterogeneity in the meta-analysis of targeted breastfeeding peer support was high, which might be because of differences in the settings and context where the peer support was offered and the intensity of the interventions. 32

A systematic review29 to assess the impact of breastfeeding peer support on breastfeeding continuation rates reported significant effects on any breastfeeding rates and exclusive breastfeeding rates at the last study follow-up (relative risk of not breastfeeding at last follow-up 0.85, 95% CI 0.77 to 0.94, and 0.82, 95% CI 0.76 to 0.88, respectively). Heterogeneity was high and was explored using subgroup analyses and meta-regression. Peer support interventions were found to have a significantly greater effect on any breastfeeding and exclusive breastfeeding in low- or middle-income countries than in high-income countries. However, in high-income countries, peer support reduced the risk of not breastfeeding by 7% (0.93, 95% CI 0.87 to 1.00). The risk of non-exclusive breastfeeding decreased significantly, by 10% (0.90, 95% CI 0.85 to 0.97). No significant effect on any breastfeeding or exclusive breastfeeding was observed in the three UK-based studies. Peer support had a greater effect on any breastfeeding rates when given at higher intensity (five or more planned contacts; p = 0.02).

A 2017 Cochrane review33 of support for breastfeeding mothers found strong evidence that providing extra professional, lay or peer support for women who wish to breastfeed increases the duration of exclusive breastfeeding (cessation of exclusive breastfeeding at 6 months, average RR 0.88, 95% CI 0.85 to 0.92) and of babies receiving breast milk alongside other liquids or solids (cessation of any breastfeeding at 6 months, average RR 0.91, 95% CI 0.88 to 0.95). The review found that the effects of lay support were broadly similar to those of professional support. 33 Lay support is broader than peer support and does not require that the supporter and mother share experience or characteristics. Nine trials of lay support compared with usual care reported a RR of stopping breastfeeding before the last study assessment up to 6 months of 0.85 (95% CI 0.77 to 0.93), but with considerable heterogeneity, and 13 trials reported a reduced risk of stopping exclusive breastfeeding before the last study assessment (RR 0.76, 95% CI 0.65 to 0.87). However, the generalisability of these findings to the UK context is uncertain. Nine UK trials since 2000 providing additional support using a range of models, including peer, lay and professional support, have failed to improve breastfeeding outcomes significantly. 34

Similar systematic review results to those for peer support29 were reported by Renfrew et al. 35 in relation to frequency of planned contact for lay support. Interventions with four to eight contacts had a larger effect size than combined interventions with fewer than four planned contacts in trials with a usual care control group.

There is evidence that, to be effective, peer support should be offered proactively. In Canada, peer supporters with 2.5 hours’ training proactively telephoned women (n = 256) using a woman-centred format;36 the relative risk for any breastfeeding at 4 weeks was 1.10 (95% CI 1.01 to 2.72).

Preliminary research suggests that early proactive telephone support might suit a UK context. 37 In a pilot trial (69 women),37 intensive early proactive telephone support (not peer support) for women who initiated breastfeeding, delivered by a postnatal ward feeding team with personal breastfeeding experience, increased any breastfeeding by 22% (RR 1.49, 95% CI 0.92 to 2.40) at 6–8 weeks compared with the opportunity to access reactive telephone support from the team. A Cochrane review38 of telephone support for women during pregnancy and up to 6 weeks after the birth showed that women who had received a telephone support intervention were more likely to be exclusively breastfeeding (RR 1.51, 95% CI 1.19 to 1.93) at 3–6 months postpartum than those in the comparator group, but this included only three trials, and no difference was observed in the four trials that reported breastfeeding at 4–8 weeks postpartum. 38

A UK study39 applying a theory of constraints model to investigate the barriers to effective lay feeding help recommended that (1) to gain wider acceptability, interventions should be mother-centred (rather than breastfeeding-centred), both enabling breastfeeding and giving help with formula milk, (2) there should be a greater focus on the early weeks after the birth, as establishing breastfeeding can be difficult and mothers frequently stop feeding before they had planned, and (3) support should be offered proactively to improve the take-up of breastfeeding.

A recent realist review40 of breastfeeding peer support interventions in high-income countries found that breastfeeding peer support appears to rely on a chain of mechanisms firing in sequence. The realist review found that intervention design should take account of needs as perceived by the target population; integration with health professional care can be critical, and so ensuring mutual respect and overcoming local barriers to integrated working practices, collaboration and feedback are important. Peers need to be accessible when mothers most need support; support around the time of the birth can help mothers who are unsure to firm up decisions to breastfeed. Peer support also needs to be proactive, as reactive support tends to be used by mothers who are motivated or confident, and is unlikely to be effective in improving rates overall. Mothers value friendly, competent and proactive peers, and these qualities may outweigh social similarity. Mothers who experience a warm and affirming relationship with their peer supporter often feel helped to overcome challenges and to meet their feeding goals. The review also found that peer supporters are motivated when they feel valued and are demotivated when their offers of help are rejected. As a result, peers tend to focus their energy on mothers who seek support and seem to be appreciative.

These findings from the realist review are in line with a meta-synthesis41 of women’s perceptions and experiences of breastfeeding support that recommended person-centred approaches and qualitative studies24,42 of women’s experiences of infant feeding support that found that structured approaches to support-giving are unpopular24 but flexible support is acceptable. 42 How breastfeeding interventions are delivered and the intervention-context fit are important determinants of outcomes. 43 The timing of support in the very early postnatal period may be an important feature of effective breastfeeding support. 40,44,45 Continuity of targeted peer support by having an antenatal visit and postnatal support from the same local supporter is associated with psychosocial benefits for mothers, health professionals and peer supporters. 42

Existing provision of breastfeeding support in the UK

In hospital, midwives deliver breastfeeding support, with breastfeeding counsellors and hospital peer supporters also available in some areas. However, length of stay following a singleton vaginal delivery in the UK is one of the shortest internationally (1.5 days). 46 Many women, including first-time mothers, go home 6 hours after giving birth; 19.8% of women in 2016/17 were discharged on the same day as the birth. 47 This gives insufficient time to establish breastfeeding. Reduced hospital stay following birth provides a suboptimal context to support establishing breastfeeding for many new mothers. Care is transferred from midwives to health visitors between 10 and 30 days postnatally. Much community breastfeeding support is provided by lay workers in children’s centres and by peer supporters. Breastfeeding peer support is offered by a range of organisations, including voluntary and charitable organisations, local authorities and the NHS. Peers may be paid or voluntary, and training and supervision are offered by a range of providers. The UNICEF UK (United Nations Children’s Fund, London, UK) Baby Friendly Initiative stage 1 accreditation48 requires a meaningful discussion about infant feeding in the antenatal period and identifies that this might be delivered by a peer supporter. Additionally, for accreditation, local maternity services are required to have mechanisms in place to enable mothers to access support for breastfeeding with basic problem-solving via their local maternity service or other local routes, for example breastfeeding support groups or peer support, and to ensure that mothers know about these services.

The characteristics of peer support provided for pregnant and breastfeeding women across the UK are not routinely collected. A survey in 2014 of all known infant feeding co-ordinators in the UK had a 19.5% response rate, and covered of 58% of NHS trust/health board areas. 49 This study identified wide availability of breastfeeding support across the UK, with peer support available in 78% of areas and breastfeeding support groups available in 90% of areas. However, these may not be representative of all areas and the support may be provided only in selected localities within trust/health board areas. The survey identified a lack of standardisation of the provision of breastfeeding peer support across the UK and the challenging context of limited financial support. Services were reduced and increased in line with funding availability. 49 The most common providers were third-sector organisations, such as the NCT and the Breastfeeding Network, and most peer supporters were volunteers. 49 In the 2010 Infant Feeding Survey,18 69% of women reported being given the details of a voluntary organisation or community group that helped new mothers to breastfeed, and 64% were aware of the National Breastfeeding Helpline. A report of breastfeeding support in London50 found that the proportion of new mothers receiving breastfeeding support from a peer supporter varied from < 5% to 52% in London boroughs.

Research into the role of UK fathers in supporting breastfeeding reported that they wanted to be able to support their partners, but they were often excluded from antenatal breastfeeding education or were considered unimportant in postnatal support. 51 Many fathers feel ignored throughout the whole journey of pregnancy and postnatal care. 52 Men want more information about how they can practically support their partner,51 and a survey of women with young children suggested that engaging the fathers in breastfeeding education was as a way of increasing breastfeeding support. 53

Apart from the father of the child, many other ‘significant others’ influence a woman’s decisions about breastfeeding,54 and the composition of a woman’s social network changes over time. 55 Women’s support needs can be mapped in an infant feeding genogram55 that records the feeding history of family and friends and the strength of relationships with these social network members. This genogram can be used as a tool to support discussion around breastfeeding and to identify support needs.

Information needs of and risks for mothers who feed their babies formula milk

Previous UK studies to promote breastfeeding have focused solely on breastfeeding, excluding any discussion of formula feeding with mothers. The evidence shows that, for infant-feeding interventions to be acceptable to women, it is important to address issues related to mixed feeding and formula feeding. 40,56 This need is now explicitly recognised by several UK key providers of peer support; for example, NCT (the UK’s largest charity for expectant and new parents) policy is to provide support to all women with their infant feeding decisions, regardless of how they are feeding their babies. 57 The 2010 Infant Feeding Survey showed that 54% of babies had received formula milk by the age of 1 week, 88% had received it by 6 months and 95% had received it by 9 months. 18 Furthermore, the survey highlighted that half of mothers who prepared powdered infant formula did not follow all three key NHS recommendations (making only one feed at a time, making feeds within 30 minutes of the water boiling and adding the water to the bottle before the powder), which are intended to reduce the risk of infection and overconcentration of feeds. Other studies have also highlighted a high frequency of errors in formula feed preparation. 58,59 Current guidance for mothers is available on the NHS website60 and includes a 13-point set of instructions for making up a bottle of formula. The evidence indicates that an intervention to increase breastfeeding rates that fails to address mothers’ needs in relation to formula feeding (particularly in a culture where mixed feeding is common) risks alienating potential beneficiaries, limiting intervention reach and retention, and decreasing the likelihood of achieving breastfeeding-related outcomes. 40,61 Improving the preparation of formula feeds will incur additional infant health benefits from reduced gastrointestinal infections. 59 Moreover, by focusing on the mothers’ needs, there may be less guilt associated with feeding decisions. 62

Assets-based approaches in public health

The use of peer support and encouragement to access community support for breastfeeding and social opportunities for new mothers is an exemplar of an assets-based approach to public health. An assets-based approach focuses on the positive capabilities of individuals and communities, rather than solely on their needs, deficits and problems. This approach is linked to the theory of salutogenesis (health origin),63,64 which conceptualises health as a continuum and focuses on what helps individuals retain positive health and well-being rather than on factors that cause disease. 63–65 It also has parallels with economic theories of capability and well-being, from a broad physical, psychological, social and community perspective. 66

Assets-based approaches are about recognising and making the most of people’s strengths to change the balance between meeting the needs of people and communities and nurturing their strengths and resources. 67 This is accompanied by a corresponding shift in focus from the determinants of ill health to the determinants of health and well-being. Although assets can include material resources,68,69 in public health more typically, the primary focus is on valuing individual and collective psychosocial attributes. These include confidence, optimism, self-esteem, knowledge and skills, as well as features of social capital such as social networks and reciprocity. 70–73

Longitudinal qualitative research with families living in disadvantaged areas suggests that family well-being rather than potential future health benefits is the outcome that matters most and that drives decisions to stop breastfeeding. 56 In the context of breastfeeding, assets may include intrinsic personal resources such as willingness to ask for and accept help, self-efficacy in relation to infant feeding,74 and motivation and drive to maintain feeding. 74–77 These assets also include extrinsic resources such as availability of social support from partner,78–80 family and friends, wider social networks of new mothers and women who have breastfed, and community assets such as children’s centres, mother-and-baby groups, breastfeeding groups or baby cafes. Local breastfeeding peer supporters are also community assets for breastfeeding. Hopkins and Rippon’s73 theory of change approach to assets-based working focuses on recognising and mobilising assets. An assets-based approach, by focusing on a woman’s priorities, is woman-centred.

Rationale for the ABA study

In 2015, the National Institute for Health Research Public Health Research programme called for studies to determine the effectiveness of community-based interventions that promote the uptake and maintenance of breastfeeding. Our study aimed to assess the feasibility of delivering a new Assets-based feeding help Before and After birth (ABA) infant feeding helper (IFH) intervention within a RCT. The ABA intervention was built on systematic review evidence,29,32,33,41 behaviour change theory,81 extensive qualitative research41,42,56,82 and learning from the FEST (FEeding Support Team) pilot trial about woman-centred feeding support after birth. 37,83

The study took place in geographical areas of socioeconomic disadvantage, as the largest potential public health gain is obtained from improving health outcomes for disadvantaged infants. 84

The ABA intervention used an assets-based approach, drawing on the community, social network, family and personal assets of each woman. This enabled the extent of support to be tailored to the assets a woman has available for infant feeding. This assets-based approach was enhanced with behavioural change theory. In addition, we developed a new feeding helper approach that is woman-centred, aims to establish a strong supportive relationship with continuity of care from pregnancy until after birth, respects a woman’s choices, is non-judgemental and discusses both breastfeeding and formula feeding issues, should a mother wish to. 56,62,82,83 This is because trials of breastfeeding peer support in the UK have had unexpected null results contrary to the worldwide systematic review evidence. 29 One hypothesis is that women who engage with breastfeeding-centred intervention research are those who are highly motivated to breastfeed. In taking a broader feeding approach, we were compliant with current UNICEF guidance,85 and at the same time aimed not to alienate women who were considering mixed or formula feeding43,56,62 by using the term ‘infant feeding’ in ABA information materials.

Peer support is a behaviour change technique found to be effective in increasing breastfeeding initiation and continuation. 29,33,35,86 Peer support is recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE);87 many programmes are in existence in the NHS and are suggested by UNICEF as a potential mechanism for achieving effective onward community support. 85

This assets-based feeding intervention is a new approach to peer support that seeks to overcome some of the pitfalls identified in previous studies, while building in methods to enable women to identify and activate assets within their family and friendship networks and in the wider community.

Chapter 2 Methods

Aim and objectives

Aim

The overall aim of the ABA study was to investigate the feasibility of delivering the ABA intervention within a RCT.

Objectives

-

To adapt existing peer support services to provide a new IFH intervention underpinned by theory and evidence, and with service user and provider input.

-

To undertake a feasibility RCT of the new feeding helper role compared with usual care (control group) for women living in areas of low breastfeeding prevalence.

-

To determine levels of uptake of and engagement with the intervention and to describe socioeconomic/demographic profiles to ascertain intervention reach and explore health inequalities.

-

To describe care those in the usual care group received regardless of feeding method.

-

To assess fidelity of intervention delivery and any contamination, and to use feedback from feeding helpers to improve fidelity, if necessary.

-

To assess whether or not women are willing to be recruited and randomised, assess whether or not the expected recruitment rate for a subsequent full-scale effectiveness RCT is feasible and identify successful recruitment strategies.

-

To explore mothers’ and feeding helpers’ perceptions of the intervention, trial participation and processes.

-

To explore acceptability and fidelity of the intervention when it is delivered by paid and volunteer feeding helpers.

-

To assess the acceptability and integration of the intervention to other providers of maternity, postnatal care and social care.

-

To explore the relative value of the individual feeding support versus the community integration elements to inform the design of a future trial.

-

To provide estimates of the variability in the primary outcome to enable sample size calculation for a definitive trial.

-

To measure the features of the feeding helper provision and service use that would underpin the cost-effectiveness of the intervention and determine the feasibility of data collection.

-

To test components of the proposed RCT to determine its feasibility as outlined in the protocol.

Setting

The study was undertaken in two distinct geographical areas in England (site A and site B). Both areas had existing programmes of peer support, but these were provided reactively through, for example, midwife referral or self-referral. In site A paid peer supporters employed by a social enterprise organisation delivered the programme, whereas in site B peer supporters were volunteers managed by a national charity. The sites were selected from five that were initially identified as interested in participating in the study. Sites were chosen (1) to reflect the diversity of existing peer support services, but those with no proactive peer support offered antenatally, (2) as they had relatively high levels of socioeconomic disadvantage and low rates of breastfeeding initiation and continuation, and (3) because they were reasonably local to the investigators to enable oversight of the study.

Study design

We undertook a feasibility individually randomised controlled trial (1 : 1) in two UK sites with a mixed-methods process evaluation.

Study management

The ABA study was overseen by a Trial Steering Committee (TSC) made up of two subject experts, a statistician and a public representative. A study management group, comprising the principal investigator, the trial co-ordinator and the 10 co-investigators, met regularly to guide study conduct.

Ethics approval and study registration

Ethics approval was obtained on 28 November 2016 from South West – Cornwall and Plymouth Research Ethics Committee (16/SW/0336). The study was registered with the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Register Number ISRCTN14760978. During the course of the study, some minor revisions were made to the protocol (see Appendix 1). The final protocol was published as a journal article. 88

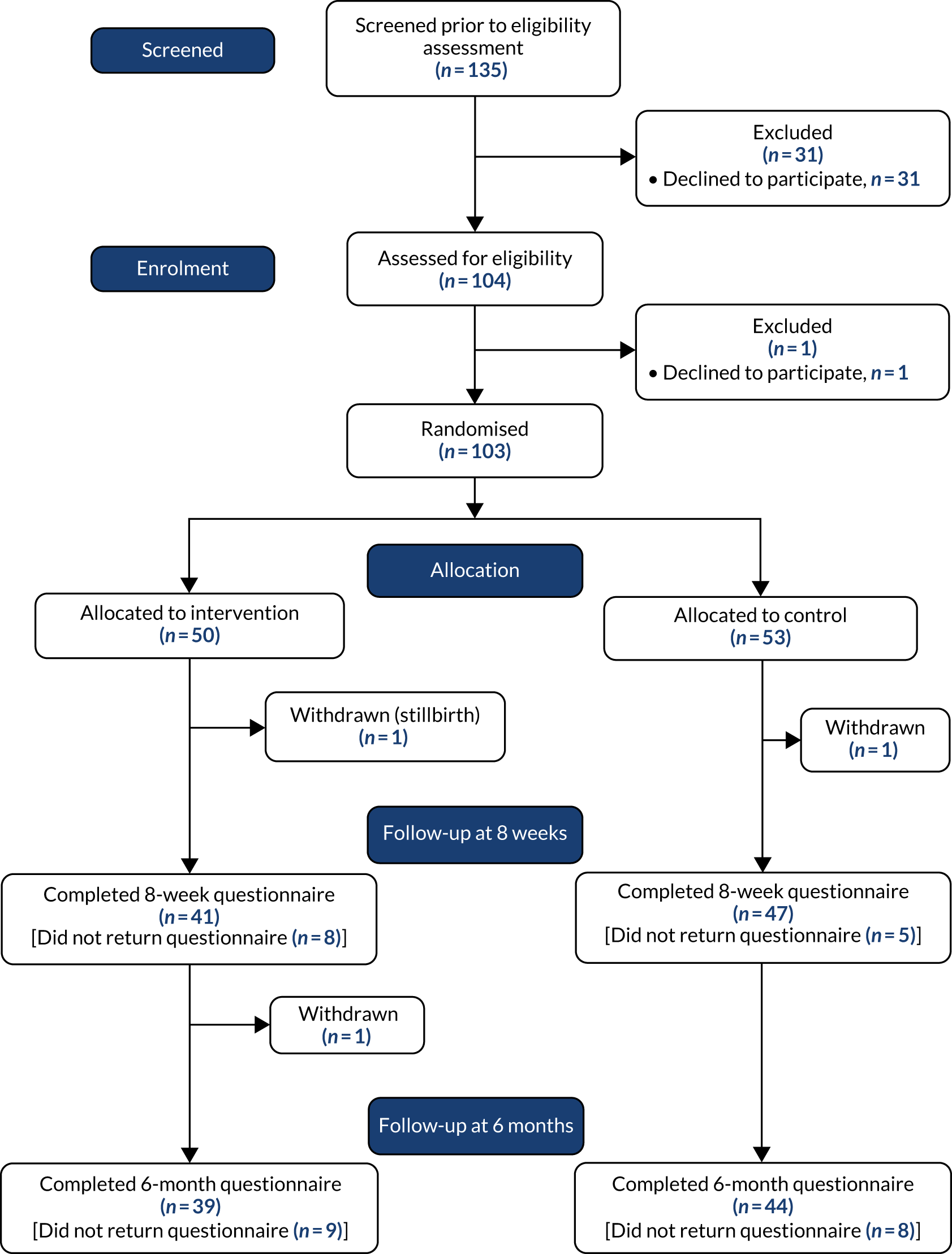

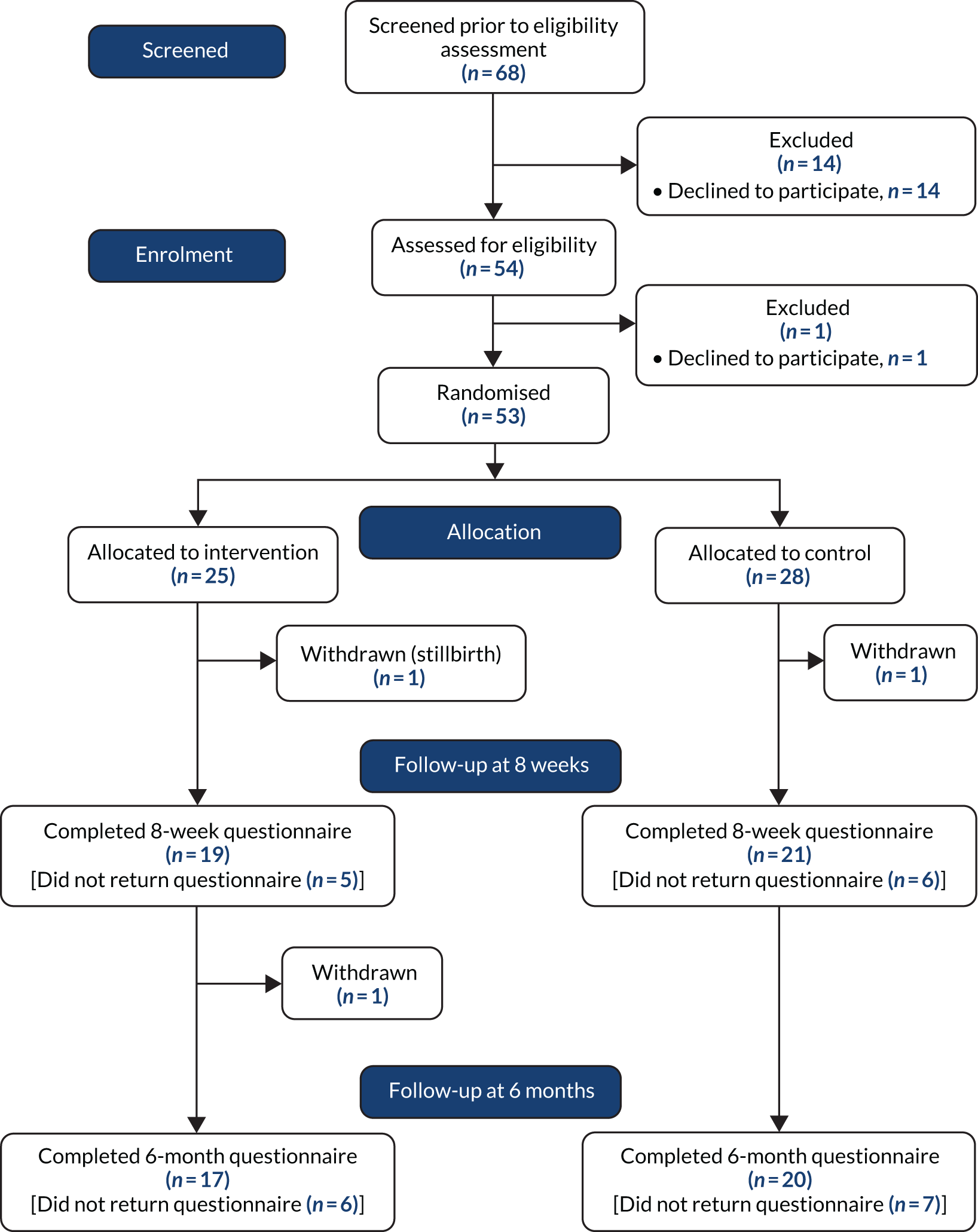

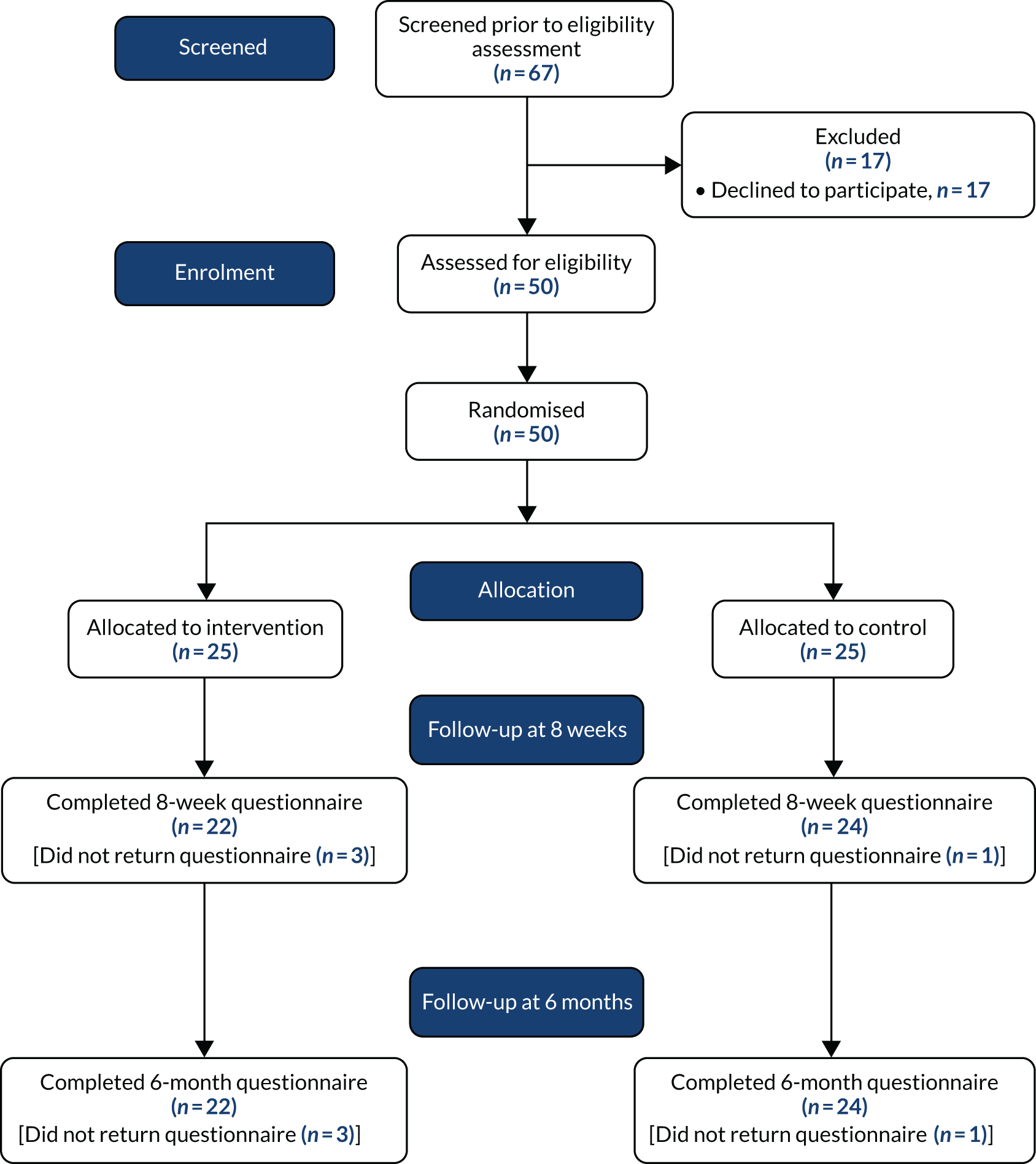

Participant identification

We aimed to recruit 100 women to the study (at least 50 from each site), with half randomly allocated either to the intervention group or to the usual care group. We hoped to recruit sufficient numbers of teenagers, women of low socioeconomic status and women with limited social network breastfeeding exposure to allow us to investigate their experiences of the intervention. The two study sites were selected to reflect our target population.

Community midwives in the study areas were asked to hand out a summary participant information leaflet (PIL) to women who were pregnant with their first child at their 25-week antenatal appointment. At their 28-week antenatal appointment, women were approached in clinic by a researcher. The researcher provided the woman with further information about the study, including a full PIL (see Appendix 2), and gave her an opportunity to ask any questions. The woman was then asked if she would like to take part in the study. Women were given the option of signing up to the study there and then, or having time to think about it and/or discussing with others before contacting the researcher to arrange a time and place to sign up. Women were able to enrol in the study only up until 32 weeks’ gestation; this was to allow sufficient time for intervention participants to meet with their IFH before the birth. Researchers completed screening logs to record the number of women who were approached. At recruitment, women were told that if they completed and returned follow-up questionnaires at both 8 weeks and 6 months, they would receive a £25 shopping voucher at the end of the study to thank them for their time.

Recruitment ran from 28 February 2017 until 23 May 2017 in site A and from 21 April 2017 until 31 August 2017 in site B. Follow-up took place between 24 April 2017 and 12 March 2018 in site A and between 21 June 2017 and 23 May 2018 in site B. Recruitment ended when at least 50 participants had been recruited from each site.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Women were eligible to take part in the study if they were:

-

pregnant with their first child (excluding previous stillbirth)

-

aged ≥ 16 years.

Women were excluded if they had had a previous live birth or were aged < 16 years.

We decided to include only first-time mothers as they would have had no experience of infant feeding and might have been more likely to be influenced by the intervention. This is because mothers often repeat the infant feeding method they used for their first baby with their second baby. 89

Consent-taking process

The researcher checked the woman’s eligibility to participate in the study before asking her to complete, sign and date three copies of the consent form (see Appendix 3). The consent form was also signed and dated by the researcher. One copy of the consent form was given to the participant, one was kept by the research team and the third was stapled into the woman’s maternity notes. Details of the discussion about informed consent were recorded in the woman’s maternity notes (including date, name of study, discussion summary, PIL and consent form version numbers). Participants’ contact details were recorded and a baseline questionnaire was completed at the time of recruitment. Women were given a fridge magnet with the ABA study team contact number and were asked to notify the team as soon as their baby was born.

Randomisation

Women were randomised to intervention or usual care in a 1 : 1 ratio. The randomisation process differed by site.

In site A, a randomisation list was developed by the clinical trials unit, minimised by age group (< 25 years and ≥ 25 years). The list was stored securely and was not available to the researcher enrolling participants. After the participant had signed the consent form, the researcher telephoned the randomisation service who checked the participant’s eligibility and assigned her to the intervention or usual care. The researcher informed the participant there and then of her allocation. If the telephone randomisation service was unavailable, the researcher contacted the woman later, by letter, to inform her of her allocation.

In site B, a different method of randomisation was required to be able to match the number of IFHs available in the different areas of the study site (in site A, all IFHs were available to cover the whole study site). Therefore, block randomisation was used to randomise multiple women from each area of the site. Each block of women was randomised simultaneously by a researcher who was not undertaking recruitment; the recruiting researcher was then informed of allocation and notified women in writing.

Intervention design

Intervention design was informed by the Medical Research Council Complex Interventions and RE-AIM (Reach, Efficacy, Adoption, Implementation, Maintenance) frameworks. 90,91 We also used information from systematic reviews, surveys and qualitative studies and discussions with our patient and public involvement (PPI) group to ascertain barriers to both breastfeeding initiation and breastfeeding continuation. We used the behaviour change wheel framework [in which behaviour is analysed in context with respect to capability, opportunity, motivation and behaviour (COM-B)] alongside the theoretical domains framework to identify a number of behaviour change functions and behaviour change techniques (BCTs) from the behaviour change taxonomy. 81,92 Following this, we considered possible BCTs using the APEASE (Affordability, Practicality, Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness, Acceptability, Side-effects/safety, Equity) criteria. Components of the intervention were identified that were simple, low cost, practical and acceptable. A review of multicomponent incentive interventions to support breastfeeding had mapped BCTs and discovered social support to be predominant. 93 Social support is fundamental to peer support. 30

The chosen BCTs, with definitions and prespecified examples based on the ABA intervention, are shown in Table 1. Core and non-core BCTs for the antenatal part of the ABA intervention were agreed by the research team (core BCTs were social support and restructuring the social environment; non-core BCTs were emotional social support and instruction of how to perform behaviour). Some of these BCTs overlapped with the social support and use of social networks within the assets-based approach.

| BCT number | Label | Definition | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1: goals and planning | |||

| 1.2 | Problem-solving | Analyse, or prompt the person to analyse, factors influencing the behaviour and generate or select strategies that include overcoming barriers and/or increasing facilitators | Prompt the woman to consider what may encourage or prevent her from successful breastfeeding. Help the woman to identify strategies, solutions and support she can access to help overcome any difficulties |

| 1.3 | Goal-setting (outcome) | Set or agree on a goal defined in terms of a positive outcome of wanted behaviour | To discuss the woman’s (postnatal only) goals for breastfeeding |

| 1.7 | Review outcome goal(s) | Review outcome goal(s) jointly with the person and consider modifying goal(s) in light of achievement. This may lead to resetting the same goal, a small change in that goal or setting a new goal instead of or in addition to the first | To have ongoing discussions about the woman’s breastfeeding achievements, and to provide support for alternatives (i.e. mixed feeding, breastfeeding cessation) as appropriate |

| 2: feedback and monitoring | |||

| 2.7 | Feedback on outcome(s) of behaviour | Monitor and provide feedback on the outcome of performance of the behaviour | Inform the woman about ongoing health benefits of breastfeeding at different stages |

| 3: social support | |||

| 3.1 | Social support (unspecified) | Advise on, arrange or provide social support (e.g. from friends, relatives, colleagues, ’buddies’ or staff) or non-contingent praise or reward for performance of the behaviour. It includes encouragement and counselling, but only when it is directed at the behaviour |

Suggest that the woman calls a ‘buddy’ if she feels that she is struggling with feeding or needs some support Provide positive feedback on the woman’s progress with breastfeeding Arrange for a family member or friend to encourage continuation with breastfeeding |

| 3.2 | Social support (practical) | Advise on, arrange or provide practical help (e.g. from friends, relatives, colleagues, ‘buddies’ or staff) for performance of the behaviour |

Suggest that the woman call an IFH, health professional, helpline or ‘buddy’ if she feels that she is struggling with feeding or needs some support Ask the partner/family members of the woman to bring her the baby when the baby is ready to feed, bring a drink for the mother Ask the partner/family members to help with other activities in the home while the mother is feeding the baby (meal preparation, washing) Encourage the woman to access a breastfeeding support group or to call a helpline during times when other people are not available to help |

| 3.3 | Social support (emotional) | Advise on, arrange or provide emotional social support (e.g. from friends, relatives, colleagues, ‘buddies’ or staff) for performance of the behaviour | Ask the woman to take a friend to the breastfeeding group, or ask the feeding helper to meet her there |

| 4: shaping knowledge | |||

| 4.1 | Instruction on how to perform a behaviour | Advise or agree how to perform the behaviour (includes ‘skills training’) |

Provide information (visual images, DVD) and model demonstrations to show the woman how to position her baby to facilitate good latching on Show a woman how to prepare a bottle of formula correctly |

| 5: natural consequences | |||

| 5.1 | Information about health consequences | Provide information (e.g. written, verbal, visual) about health consequences of performing the behaviour | Explain the health benefits of breastfeeding for both the woman and the baby |

| 6: comparison of behaviour | |||

| 6.1 | Demonstration of the behaviour | Provide an observable sample of the performance of the behaviour, directly in person or indirectly (e.g. via film or pictures) for the person to aspire to or imitate |

Demonstrate breastfeeding in a film clip or via the use of aids (e.g. breastfeeding doll). Pictures of ‘good’ positioning and attachment to be shared with women Encourage attendance at breastfeeding group to observe other women breastfeeding |

| 8: repetition and substitution | |||

| 8.1 | Behavioural practice/rehearsal | Prompt practice or rehearsal of the performance of the behaviour one or more times in a context or at a time when the performance may not be necessary to increase habit or skill | Show and ask women to practice behaviours (i.e. hand expressing or breastfeeding) using aids such as a breastfeeding doll or knitted breast |

| 12: antecedents | |||

| 12.2 | Restructuring the social environment | Change or advise to change the social environment to facilitate performance of the wanted behaviour | Encourage the woman to attend social gatherings where other mothers are breastfeeding |

| 13: identity | |||

| 13.1 | Identification of self as role model | Inform that one’s own behaviour may be an example to others | Inform the woman that if she breastfeeds she will be a role model within her community and to her child, who will be influenced by her feeding choice |

| 15: self-belief | |||

| 15.1 | Verbal persuasion about capability | Tell the person that they can successfully perform the wanted behaviour, arguing against self-doubts and asserting that they can and will succeed |

Inform the woman that she can successfully breastfeed despite initial difficulties Encourage women to talk to friends/family members as well other mothers at breastfeeding groups to hear stories of how others have managed to breastfeed successfully |

| 15.2 | Mental rehearsal of successful performance | Advise to practice imagining performing the behaviour successfully in relevant contexts | Ask and encourage women to imagine breastfeeding in public locations and plan how this can be undertaken discreetly |

Table 2 provides details of the rationale for including the intervention components drawing on behaviour change theory and assets-based approaches.

| Behaviour change item | COM-B component | BCT | Assets-based approach | Mode of delivery | Intervention function |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Discuss benefits of breastfeeding | Motivation |

Information about health consequences (individual) Goal-setting (outcome) |

– | Face to face | Education |

| Video clip about breastfeeding | Motivation |

Information about health consequences (general) Mental rehearsal of behaviour Instruction on how to perform the behaviour |

– | Internet link from phone |

Education, persuasion Enablement |

| Breastfeeding support groups/social groups |

Social opportunity Capability Motivation |

Social support Rehearsal (mental or actual) of behaviour Verbal persuasion about capability Demonstration of behaviour Instruction on how to perform the behaviour Restructuring the social environment |

✓ |

Face to face Social media |

Education, persuasion Enablement |

| Written and website materials about feeding | Motivation |

Information about health consequences Instruction on how to perform the behaviour |

– |

Leaflet Study website |

Education, persuasion Enablement |

| Identification of social network, social comparison, other facilitators of and barriers to breastfeeding/support to overcome them |

Capability Social opportunity |

Social support Problem-solving |

✓ | Face to face | Enablement |

| Further telephone contact |

Capability Motivation |

Social support Feedback on outcome(s) of behaviour Verbal persuasion about capability Problem-solving Review outcome goal(s) Identification of self as role model |

✓ | Telephone |

Enablement Persuasion Education |

The ABA intervention consisted of proactive peer support underpinned by behaviour change theory and an assets-based approach. The intervention delivered person-centred care41 and used best evidence in terms of setting and frequency, duration and manner of support provision from the ABA IFH. The ABA intervention aimed to be inclusive of all feeding methods (i.e. breastfeeding, formula or mixed feeding) and to provide support to all women.

Before the intervention commenced, researchers developed an ‘assets leaflet’ at each study site that was designed by a graphic designer. This leaflet (developed with the assistance of local contacts and using internet searches) was specific to the study areas and included information on local community ‘assets’ (e.g. antenatal or postnatal groups, breastfeeding drop-in centres, details of local breastfeeding counsellors and baby groups), as well as details of national helplines and internet resources. The leaflet, entitled ‘What’s available locally for you and your baby?’, had input from two PPI groups (mothers of young babies attending children’s centre groups) that provided constructive feedback on making the leaflet more user-friendly. Quotations from previous qualitative work were included in the leaflet (e.g. concerning the usefulness of breastfeeding drop-in centres), as well as tips on what to do when feeling uncomfortable about going along to a new group. Contact details for the ABA study were included on the leaflet, along with a space for the IFH to put their name and contact details. All details were checked prior to the start of the intervention to make sure they were up to date. For an anonymised example of the leaflet, see Appendix 4.

The two PPI groups were also asked for their opinions on a library of text messages produced by the research team, intended to be used by IFHs to engage with and support women in the intervention group. These texts aimed to take a woman-centred approach, to be infant feeding rather than breastfeeding centred and to draw on BCTs and an assets-based approach. The PPI groups were given cards with the various text messages and were asked to put them into one of three piles (yes, no or maybe). A group discussion was then facilitated by a researcher, and feedback on and suggestions about the various messages were noted. The PPI feedback was then used to finalise the library of suggested text messages available for use by the IFHs (see Appendix 5).

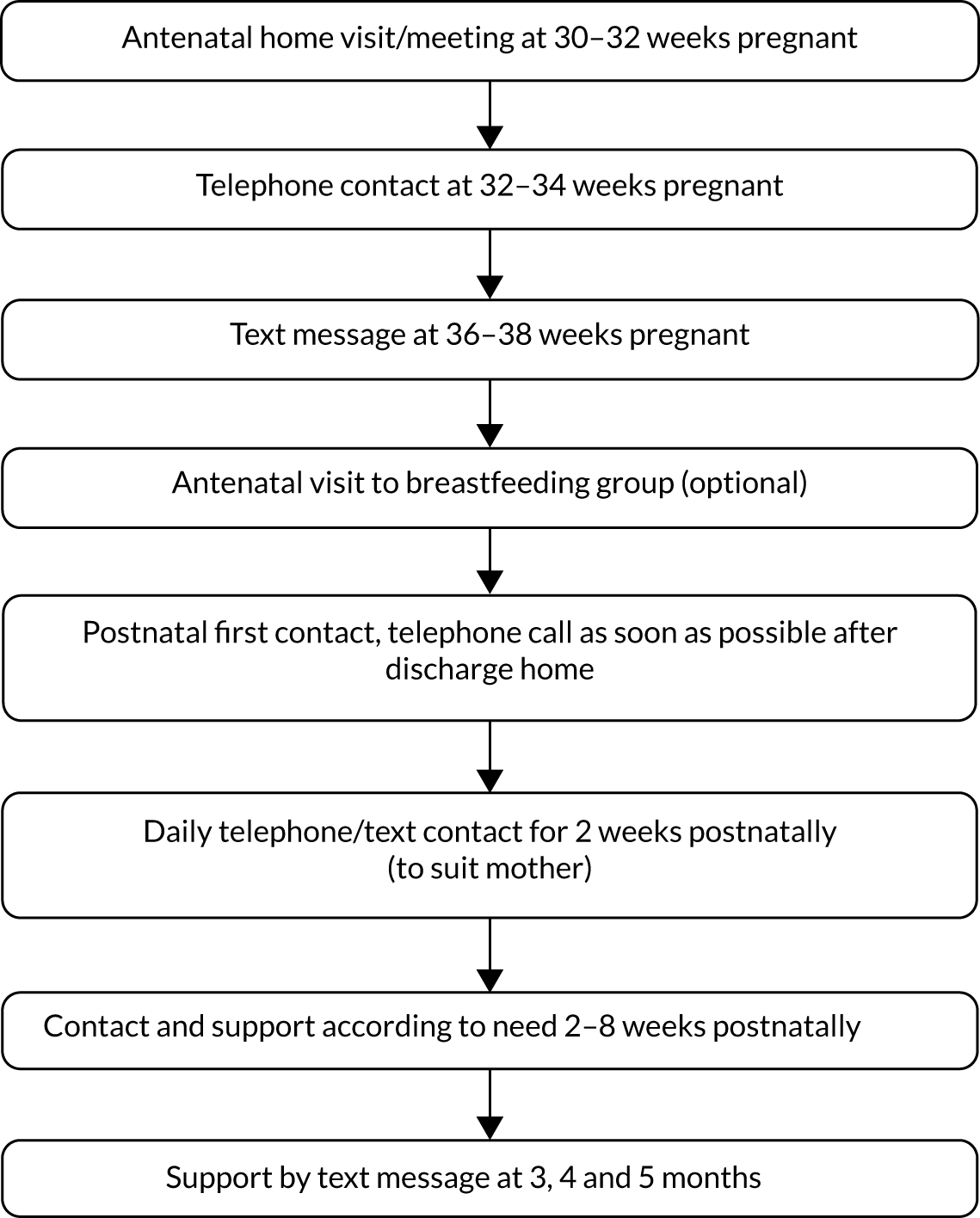

The ABA intervention outline is shown in Table 3. The intervention started at around 30 weeks’ gestation and could continue up until 5 months postnatally. At around 30 weeks’ gestation, the IFHs contacted women by telephone to arrange a face-to-face meeting, either at home (site A only) or at a suitable location, such as a café or children’s centre. The IFHs in site B (volunteer peer supporters) were not able to offer home visits because of local policies, unlike the paid peer supporters working in site A. Women were welcome to include partners or family members in this and subsequent meetings. The purpose of this face-to-face meeting was to talk about infant feeding and investigate the woman’s personal, family and social network assets for infant feeding. An approach of ‘narrative storytelling’ was used to produce a simple family tree diagram (‘genogram’) of experiences with infant feeding,55 incorporating the woman’s social network, to allow her to reflect on future feeding relationships and sources of support. 54 [See Appendix 6 for an example genogram from the training session (real names are not used).] At the antenatal visit, IFHs gave the woman the assets leaflets and explained the range of support available for infant feeding. In addition, contact details were swapped and a ‘Let us know when you’ve had your baby’ fridge magnet was given to the woman to encourage her to include the IFH on the list of people she would notify of the birth of the baby.

| Timing | Objectives and tasks |

|---|---|

| Antenatal face-to-face meeting (plus partner/family if woman would like this) at 30–32 weeks (duration 1 hour) |

|

| Telephone call after 2 weeks (text if no response) (approximately 32–34 weeks) |

|

| Text after 4 weeks (approximately 36–38 weeks) |

|

| Postnatal first contact | To commence contact via text or telephone calls within 24 hours of the woman’s discharge from hospital, and to offer face-to-face contact (site A only) |

| Postnatal visit/Skype™ (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) (site A only) |

Practical feeding issues: observe feed if possible, advise about any difficulties experienced, encourage to take it a day at a time Find out whether or not the mother feels that she is receiving sufficient help from others Discuss practical help that the mother could ask for |

| Daily telephone calls or texts for 2 weeks |

Focus: person centred, well-being and feeding Arranged to suit mother/frequency determined by mother Encourage mother to start thinking about attending local feeding group |

| 2–8 weeks: contact and support as needed |

Encouragement to continue breastfeeding – taking it a day or a week at a time Troubleshoot any problems Advise mother of option to pull in people who will help and develop a strategy for those who do not help Encouragement to attend mother and baby groups/breastfeeding groups Planning for getting out and about Advise mother to call IFH if considering changing how she feeds her baby If formula feeding established, negotiate end of support |

| 3, 4 and 5 months – standard texts | For those still breastfeeding:

|

Following the face-to-face antenatal visit, the IFHs were asked to call and/or text the women fortnightly during the pregnancy. The aim was to encourage a strong rapport between the IFHs and the women that would facilitate successful immediate engagement after birth. In addition, IFHs were encouraged to facilitate a visit (antenatally) by the woman to a local breastfeeding group. The aim of this was so that the woman would know how and where to access support for infant feeding once her baby was born.

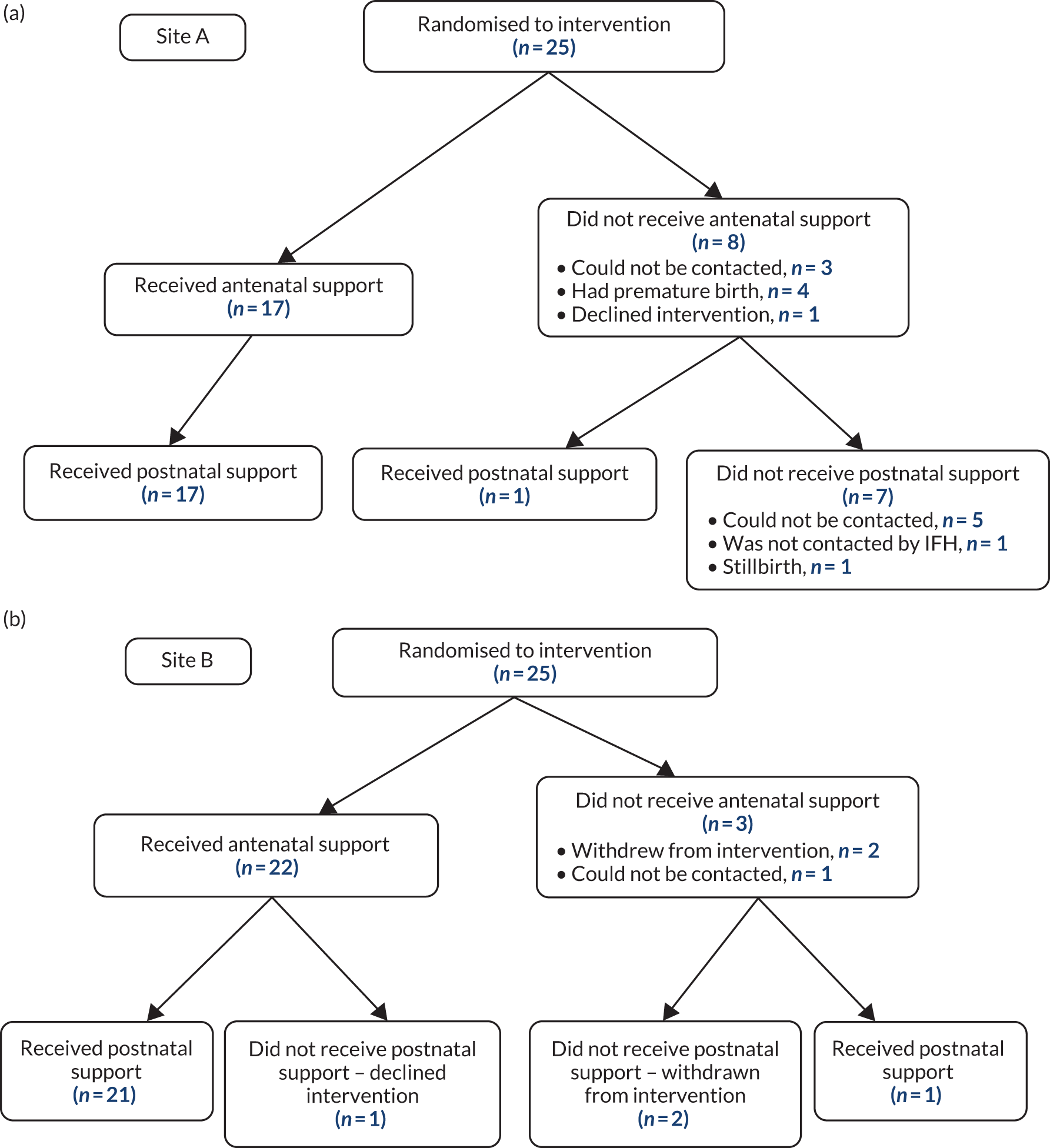

Postnatally, support from IFHs in both sites was by telephone calls or text messages every day until the baby was 2 weeks old. Additionally, at site A, IFHs were asked to arrange a postnatal home visit/Skype call as soon as possible after the mother and baby were discharged home.

From 2 to 8 weeks, frequency of contact was reduced based on the preferences of the mother. Text messages were sent to those still breastfeeding (or mixed feeding) at 3, 4 and 5 months. Women were able to ask for telephone calls or text messages to stop at any point. At site A, IFHs were unable to support women from 8 weeks postnatally because of their working practices. Therefore, in site A, a researcher sent out the 3-, 4- and 5-month texts and provided signposting support for women if required.

The intervention timeline is presented in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

The ABA intervention timeline.

Recruitment of ABA infant-feeding helpers

At site A, a paid peer support service providing reactive postnatal support (and no antenatal support) already existed. Although the service was available across the entire local authority area, peer supporters had traditionally worked within certain inner-city areas. Within the local authority, community midwives were split into three teams, each serving a distinct geographical area. For the ABA study, site A was selected as it was the area with the lowest rate of breastfeeding and highest rate of teenage pregnancy within the local authority. This area had traditionally not been served by the peer support service. The peer support service manager was willing to support the ABA study following discussions with the research team.

In site A, researchers attended part of the peer supporters’ regular team meeting on two occasions prior to the ABA training day. The purpose of these meetings was to introduce the ABA study, to encourage the peer supporters to take part in the study and to provide background information that would facilitate the smooth running of the ABA training day. Researchers also attended a team meeting after the training day to answer any questions arising from the session.

At site B, a volunteer peer support service was already in existence, which was overseen by a national charity. Again, this service provided reactive postnatal support, based around breastfeeding support groups, and no antenatal support. The geographical areas chosen within site B were those with the lowest breastfeeding rates within the local authority and with active peer supporters. Researchers met the charity manager and the peer supporter co-ordinator to discuss details of the study and recruitment of peer supporters.

Within the two sites, existing peer supporters were asked if they would like to support the ABA study. At site A, six of the seven existing peer supporters agreed to participate. At site B, seven of 11 peer supporters volunteered to be involved.

Training for ABA infant-feeding helpers

Infant feeding helpers were provided with 6 hours of training plus a study folder. The folder included details of all aspects covered in the training day. The intervention training was delivered face to face on 1 day in site A and over 2 half-days in site B. Heather Trickey led on the development of the training materials and led the training days, with input from Dr Kirsty Darwent (Programme Director, Family Therapy Training Network Ltd).

The aims of the training were (1) to promote competence and confidence in delivering the ABA intervention and (2) to facilitate understanding of the ABA study (to enhance fidelity to the intervention delivery). The training was designed to enable IFHs to learn about how to deliver the ABA intervention and to practise the skills required to deliver the intervention effectively. The training was interactive and involved simulations and role-play of contact with women as well as group-based learning activities.

Although the training did not explicitly present the BCTs to IFHs, it specifically focused on the delivery of the prespecified core BCTs (social support and restructuring the social environment) via the genogram and assets leaflet.

The training included the following.

-

Study information

Kate Jolly gave an overview of the study. She explained that the aim of the ABA study was to compare two ways of delivering feeding help to first-time mothers in areas where breastfeeding rates were low. Half of the mothers recruited to the study would have the usual feeding support from midwives, health visitors and any voluntary agencies or peer support that they choose to access; the other half would, in addition, receive the new ABA intervention.

-

Overview of the intervention

The ‘assets-based’ approach was outlined as an approach that encourages women to draw on support and help from their family, social and community networks. It was explained that the intervention was more intensive than usual peer support, and that is was peer supporter initiated rather than mother initiated. Every woman in the intervention would be offered antenatal contact, and continuity of care would be given wherever possible by women having the same IFH throughout the intervention. Trainees were informed that the intervention would end when the baby was 5 months old (if still being breastfed), or at a time when formula feeding had been established. Key principles of the ABA intervention were presented: the importance of a woman-centred approach and building a strong rapport, the use of open questions and active listening, seeing the woman (not the IFH) as the solution and viewing relationships as assets. The intervention timeline (see Figure 1) was presented to the IFHs, with opportunities given for discussion and clarification of any uncertainties.

-

Antenatal contact

In this part of the training, expectations for the antenatal visit were detailed. The trainers simulated the visit to facilitate good practice. Role-play techniques were then used to allow the IFHs to try out the approach. This session included:

-

Introducing themselves as an ABA IFH and explaining the purpose of the antenatal visit.

-

Learning how to explain the ABA timeline so the woman knows what to expect.

-

Learning how to open a conversation on infant feeding, and being led by the woman. The importance of good listening skills and using open questions was emphasised.

-

Discussing support from family and friends, including completion of a simple genogram.

-

Discussing support available in the community, and introducing the ‘assets leaflet’.

-

Offering to accompany the woman on an antenatal visit to a local breastfeeding support group and encouraging the use of the group after the baby is born.

-

Swapping telephone numbers, encouraging the women to let the IFH know when they have given birth, and discussing plans for keeping in touch.

-

The role plays were also used as an opportunity for IFHs to practise person-centred listening skills, with IFHs working in groups of three to give feedback to each other on the use of verbal and non-verbal active listening techniques.

-

Supporting mothers who use formula milk

The importance of being inclusive of all feeding types was stressed. A group discussion on supporting mothers who formula feed was facilitated, with the aid of a ‘myths and truths about formula feeding’ exercise. Key information about different kinds of formula milk and preparation of feeds, and up-to-date advice on formula feeding in response to the baby’s cues was delivered to IFHs during the session and supplemented with a key messages information leaflet and links to further information.

-

Postnatal contact

In this session, scenarios and group work were used to facilitate understanding. Groups worked together to decide how they would support women in the different scenarios. The ‘assets-based approach’ was underlined in the support provided, for example by encouraging women to use their personal and community-level assets for infant feeding.

Comparator group

Women allocated to the comparator (or ‘usual care’) group received usual care for infant feeding available in the study areas; this included routine support from midwives and health visitors. We describe the support for infant feeding that was available and accessed by women, which included local services, such as breastfeeding support groups and peer support, and national breastfeeding helplines. This usual care was available only reactively to women (i.e. the woman had to ask for support or the midwife asked for support on behalf of the woman).

In site A, peer supporters who did not volunteer to participate in the study were available to cover any requests for support received from the usual care women (as per usual care). In site B, breastfeeding support was available at any of the breastfeeding groups in the area.

Outcome assessment

All women were asked to notify the ABA study team about their baby’s birth by text message, e-mail or telephone call. To ensure that we found out about as many births as soon as possible, researchers from the ABA study team in site A also maintained daily telephone contact with the community midwives to find out if any of the women had given birth. On notification of an intervention participant giving birth, researchers contacted the IFHs to let them know. In site B, we relied on women notifying the research team or their IFH directly. Details of those who did not use either method in site B were obtained from midwives.

Feasibility outcomes

The feasibility of intervention delivery and the research methods were determined by:

-

Reach of recruitment of women to reflect required sociodemographic profile.

-

Ability to recruit, train and engage current peer supporters to the new ABA IFH role.

-

Ability to deliver planned number of contacts at a time and location convenient to participants.

-

Acceptability to women.

-

Fidelity of delivery and whether or not woman-centred care was provided.

-

Unintended consequences of the intervention.

-

The feasibility of a future definitive trial assessed by recruitment rates, willingness to be randomised, follow-up rates at 3 days, 8 weeks and 6 months and level of completion of assessments by text94 (see Criteria for progression to main trial).

-

Potential cases of intervention contamination in the usual care group; at 8 weeks’ follow-up, all women were asked if they had used national breastfeeding helplines or any breastfeeding support, whether or not there was a home visit or one-to-one meeting at a children’s centre and number of contacts by the IFHs. They were asked in interviews whether or not they had met other women taking part in the study and whether or not they had discussed the study.

Assessment of feasibility outcomes

A number of methods were used to assess feasibility outcomes. Table 4 summarises these.

| Feasibility outcome | Method of assessment |

|---|---|

| Reach of recruitment of women to reflect required sociodemographic profile |

|

| Ability to recruit, train and engage current peer supporters to the new ABA IFH role |

|

| Ability to deliver planned number of contacts at a time and location convenient to participants |

|

| Acceptability to women |

|

| Fidelity of delivery and whether or not woman-centred care was provided |

|

| Unintended consequences of the intervention |

|

| The feasibility of a future definitive trial assessed by recruitment rates, willingness to be randomised, follow-up rates at 3 days, 8 weeks and 6 months, and level of completion of assessments |

|

| Potential cases of intervention contamination in the usual care group |

|

| Presence of social desirability bias |

|

Researcher notes of meetings with peer supporters, including training sessions

Researchers kept reflective notes of all meetings with peer supporters and their organisations, including the training sessions. These notes included documentation and reflections on the number of peer supporters recruited, the ease of recruiting peer supporters to the role, and the engagement of peer supporters with the new ABA intervention.

ABA infant feeding helper electronic database (site A only)

At site A, there was an existing electronic database in place to capture details of peer supporter contact with women, including date of contact, mode of contact and notes of discussions. We secured agreement for this data set to be shared with the study.

ABA infant feeding helper case notes

At site A, case notes were already used by peer supporters to record details of home visits and ongoing support. At site A, these case notes were amended for the purposes of the ABA intervention to include the ABA logo and approach, the intervention timeline and space for notes from the antenatal visit (including whether or not the genogram was completed, the assets leaflet was handed out and telephone numbers were exchanged).

At site B, logs were developed to include similar items to the amended site A case notes to record text messages, telephone calls and other contacts, such as visits to breastfeeding groups.

Recordings of antenatal visits

The IFHs were asked to audio-record their discussions with women during the antenatal visit. IFHs were provided with encrypted voice recorders and asked to seek permission from women to record the discussion. Researchers devised a fidelity checklist (see Appendix 7) for use when listening to recordings to record:

-

the feeding intention of the mother (based on categorisation by spontaneous statements developed by Hoddinott and Pill95)

-

whether or not the IFH described the intervention as intended, including the purpose of the visit, the support she would provide as an IFH, the timeline of the intervention, and the requirement for the mother to contact the IFH once the baby was born

-

whether or not the IFH introduced local assets, including taking the mother through the local community assets leaflet and introducing specific local assets to the mother

-

whether or not the IFH used the genogram as intended, including whether or not the genogram was used to stimulate a conversation about feeding and whether or not a photograph of the genogram was taken

-

whether or not the IFH used BCTs as part of the conversation, including the use of specified core techniques – ‘social support’ and ‘restructuring the environment’ – as well as non-core techniques such as ‘emotional support’, ‘instruction to perform a behaviour’, ‘information about health consequences’, ‘verbal persuasion about capability’ and ‘mental rehearsal for successful performance’

-

whether or not the IFH achieved fidelity in terms of the overall intended tone of the encounter, including achieving rapport, demonstrating inclusivity (about intended feeding method), using active listening skills and delivering a mother-centred rather than breastfeeding-centred conversation.

All recordings were analysed by Heather Trickey using the checklist. The task of double-assessing the recordings was shared among seven other members of the research team (GT, JI, JLC, DJ, SD, KD and KJ) to ensure inter-rater reliability in fidelity testing.

Qualitative study

Semistructured interviews were undertaken with women, and focus groups (FGs)/interviews were undertaken with IFHs and midwives and other health-care providers. Further details are provided in Qualitative research.

Qualitative research

Semistructured interviews with women were carried out in the woman’s own home or in another convenient location. Sampling was purposive, aiming for a diverse range of experiences, and included teenagers, unemployed women (as indicated on the baseline questionnaire), women in socioeconomically disadvantaged areas, women with disparate feeding methods, women with different levels of contact with the IFH and women in the usual care group where intervention contamination was suspected (based on responses to the 8-week questionnaire).

With the exception of the first four, interviews took place after return of the 8-week questionnaire. After the first four interviews (all at site A), we decided to wait until after the 8-week questionnaire had been completed to avoid any possible interference with the primary outcome of a future definitive trial (any breastfeeding at 8 weeks). We aimed to interview around 15 women at each site (10 intervention, 5 usual care). Women were able to have a person of their choice present for the interview (research team experience has been that this can boost participation among socioeconomically disadvantaged groups). Interviews with women were conducted by Joanne L Clarke (site A) or Debbie Johnson (site B), both experienced qualitative researchers.

Interviews with women allocated to the intervention group explored the acceptability of the ABA intervention, as well as investigating the interaction of the intervention with other sources of support that are available, particularly with respect to existing community assets (e.g. breastfeeding support groups and baby groups). Interviews with women in the usual care group looked at their experiences of ‘usual care’ for infant feeding, and investigated possible cases of contamination. In addition, all women were asked about their experiences of being part of the ABA study, including the acceptability of the recruitment and randomisation process and follow-up methods.

We conducted FGs or interviews with all IFHs (n = 13), with the IFH manager at site B and with health-care providers (midwives and other providers of infant feeding support) working in the study areas (n = 17). FGs and interviews with IFHs investigated intervention acceptability, satisfaction with the ABA training, experiences of delivering the intervention and any barriers to or facilitators of intervention implementation. We also explored any additional training or supervision requirements.

Focus groups and interviews with health-care providers investigated how the ABA intervention fitted with existing support and whether or not the intervention had in any way changed ‘usual care’, as well as issues concerning referral or delivery. Possible cases of contamination were investigated with both IFHs and health-care providers.

Focus groups took place in a convenient location, and interviews with those unable to attend the FGs were conducted over the telephone. At the FGs with the IFHs, there was a lead facilitator (GT) who had no prior interactions with the IFHs, and at least one other member of the project team (JLC, DJ or JI) to record notes, interpersonal issues and ask follow-up questions, as appropriate. The FGs with health-care providers were conducted by Joanne L Clarke at site A and by Debbie Johnson and Jenny Ingram at site B. At the start of the FGs, all participants were asked to be mindful of confidentiality issues, whereby they should refrain from providing personal information about individual cases, and not to share what was discussed outside the FG. During the FGs, the lead facilitator encouraged all individuals to share their views, such as through seeking confirmatory or disconfirming views, and questions were directed to different individuals. At the end of the FGs, a summary of all key issues discussed was provided, with participants invited to offer any final comments.

Semistructured interview schedules were developed (see Appendix 8) based on research literature, team discussions, our logic model, PPI input and the ‘stages of breastfeeding peer support intervention design model’ constructed from a realist review of peer support intervention studies. 40

All interviews and FGs were audio-recorded. An external transcription company was employed to transcribe the recordings verbatim, including pauses and laughter, and anonymise them (by removing names of people and places). Transcriptions were checked for accuracy by researchers and reflective notes were made after every interview.

Qualitative analysis

For the qualitative analysis, we undertook thematic analysis using Braun and Clarke’s96 thematic approach supported by NVivo version 11 (QSR International, Warrington, UK). First, in line with the adopted approach, three researchers (JLC, DJ and GT) listened to the recordings and read and reread the transcripts of four participant interviews (one usual care and one intervention from each study site) before independently performing line-by-line inductive coding. Codes were discussed and developed into an initial and tentative coding framework of themes and subthemes. The remaining transcripts from all participant groups were then coded by Joanne L Clarke and Debbie Johnson using the coding framework that was iteratively refined (i.e. new codes added and/or refined), as appropriate. A number of external checks were undertaken to ensure that all data were represented within the coding framework. This involved the coding framework and NVivo files being reviewed by Gill Thomson, followed by discussions with Joanne L Clarke and Debbie Johnson, and amendments made as appropriate. The final coding framework was agreed by all researchers. In this report, we describe the qualitative results relevant to the feasibility outcomes. The full qualitative findings will be published in Health Expectations.

For each of the participant interviews, BCTs delivered by IFHs were coded as standalone themes. Coding of BCTs was based on reports of the behaviour of the IFH, regardless of the participant’s response. BCTs delivered by people other than the IFHs (e.g. midwives) were not coded for the purpose of this analysis.

Outcome measures for a future trial

The primary outcome for a future trial was any breastfeeding at 8 weeks.

Secondary outcomes for a future trial were:

-

breastfeeding initiation (at 2–3 days, as defined by the UK Infant Feeding Survey 2010,18 even if on one occasion only; includes giving expressed breastmilk)

-

exclusive breastfeeding at 6–8 weeks (exclusive breastfeeding defined in accordance with the WHO definition of infants who received only breastmilk during the previous 24 hours)97

-

any/exclusive breastfeeding at 6 months

-

duration of any and exclusive breastfeeding, if ceased breastfeeding

-

maternal well-being [Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (WEMWBS)]98

-

maternal satisfaction with feeding experience and support provided at 8 weeks and 6 months (using a single-item question used in a previous trial37 and coproduced with PPI).

Outcomes for a future economic evaluation included in the feasibility trial were:

-

self-reported use of health and feeding support services

-

overall feeding support activity during the intervention

-

use of child care.

Assessment of outcomes

Table 5 presents a summary of the data items collected. At baseline (around 28 weeks’ gestation), women were asked to complete a baseline questionnaire. This included questions on demographic characteristics, feeding intentions, how they were fed as a baby, whether or not they knew anyone who had breastfed a baby, maternal well-being (WEMWBS) and use of health services. A researcher was present during questionnaire completion to answer any queries or clarify any points on the questionnaire.

| Type of data | Time point | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (antenatal) | 2–3 days postnatally | 8 weeks postnatally | 6 months postnatally | |

| Demographics [date of birth, ethnicity, highest level of qualification, relationship status, postcode (for calculation of Index of Multiple Deprivation quintile), work status] | ✓ | |||

| Feeding intentions | ✓ | |||

| How participant was fed as a baby | ✓ | |||

| Knowledge of contacts who have breastfed | ✓ | |||

| Receipt of benefits | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| WEMWBS98 (score ranges from 14 to 70; 70 indicates highest level of well-being; minimum clinically important difference varies between 3 and 8 points)100 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Use of health services | ✓ | |||

| Feeding status | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Delivery details and length of hospital stay | ✓ | |||

| Feeding history | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Satisfaction with feeding support (hospital and community) | ✓ | |||

| Requests for support (frequency and location) | ✓ | |||

| Feeding experiences | ✓ | |||

| Adverse events | ✓ | |||

| Medical Outcomes Study Social Support Survey99 (score ranges from 0 to 40; 40 indicates highest level of social support) | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Use of child care | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Work status | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Weaning status | ✓ | |||

At 2–3 days postnatally, women were sent a text message by the study team asking them how they had fed their baby since the birth. They were asked to text back a response: 1 for formula milk, 2 for breastmilk or 3 for formula milk and breastmilk (see Appendix 9).

At 8 weeks and at 6 months postnatally, women were sent a brief questionnaire in the post (with a prepaid return envelope). These included questions on the delivery of their baby, the length of hospital stay, feeding methods, feeding support received and satisfaction with feeding support, maternal well-being (WEMWBS) and social support. 99 Women who did not return their questionnaire within 2 weeks received a text-message reminder followed by a telephone call giving them the option of completing the questionnaire over the telephone. If women were reluctant to complete a questionnaire, attempts were made to secure the primary outcome (feeding status at 8 weeks) over the telephone.

See Putz et al. 100 for copies of the questionnaires.

For women who did not return their 8-week questionnaire, and who could not be contacted by telephone to secure data on the primary outcome of a definitive trial (feeding status at 8 weeks), local health visiting teams were contacted to request this information.

Assessment of adverse events

Information on possible adverse events was collected at 8 weeks using an open question asking about any difficulties experienced in feeding their baby and any hospital admissions related to infant feeding for mother or baby. The research team contacted the woman for more information, as required. The chief investigator reviewed adverse events to define their severity and causality. Only serious adverse events that could be related to the intervention were to be reported to the Research Ethics Committee.

Sample size

The selected sample size (n = 100) allowed us to estimate feasibility outcomes with reasonable precision, allowing us to estimate recruitment, follow-up and questionnaire completion rates to within ± 15% with 95% confidence. This was based on a worst-case (in terms of precision) estimate of 50% for each outcome, the targets being 75% for recruitment, 75% for follow-up and 70% for questionnaire completion.