Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 14/185/09. The contractual start date was in June 2016. The final report began editorial review in December 2018 and was accepted for publication in September 2019. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Alison Avenell was chief investigator of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment (HTA)-funded REBALANCE project [Avenell A, Robertson C, Skea Z, Jacobsen E, Boyers D, Cooper D, et al. Bariatric surgery, lifestyle interventions and orlistat for severe obesity: the REBALANCE mixed-methods systematic review and economic evaluation. Health Technol Assess 2018;22(68)]. Andrew Elders reports a grant from NIHR during the conduct of the study. Mark Grindle reports that he is managing director of Eos Digital Health Ltd (Dunblane, UK), which is sole owner of the copyright of the Digital Narrative Approach. Frank Kee is a member of the Public Health Research (PHR) programme Research Funding Board and the PHR Prioritisation Group (board member 2009–2014 and chairperson 2014–2019). Pat Hoddinott was a member of the HTA Commissioning Board from March 2014 to March 2019.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Dombrowski et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK. Parts of this report have been reproduced with permission from Dombrowski et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Unported (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to copy, redistribute, remix, transform and build upon this work for any purpose, provided the original work is properly cited, a link to the licence is given, and indication of whether changes were made. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

2020 2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO Dombrowski et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Parts of this report have been reproduced with permission from Dombrowski et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Unported (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to copy, redistribute, remix, transform and build upon this work for any purpose, provided the original work is properly cited, a link to the licence is given, and indication of whether changes were made. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

This chapter introduces general background literature relevant to the study. Some of this evidence was published subsequent to the conduct of the study. Information on the specific intervention components and the evidence and approaches that underpin these are presented in the relevant chapters.

Obesity in men

In 2016, an estimated 26% of UK men were classified as obese. In the UK, men are less likely to be a healthy weight than women. 2,3 Obesity results in an increased risk of serious health conditions, such as cardiovascular disease, cancer and diabetes, and is a major public health priority. 4

Despite the growing problem of being overweight and obesity, men are a population underserved by current evidence-based weight management programmes. 5 Most interventions are designed for mixed-sex populations, but systematic review evidence5 suggests that men often require different interventions from women. Research on the most effective strategies for recruiting men to, and retaining men in, effective weight management programmes is required.

Innovative formats for delivering obesity interventions to men are needed, particularly to men in more disadvantaged circumstances. 5 Although some evidence of effective lifestyle interventions for obesity exists,6–8 little research to date has systematically consulted men on how to optimise engagement and make interventions acceptable and feasible. Rigorous feasibility studies and piloting with service user input at all stages is recommended. 5 Moreover, the evidence on the cost-effectiveness of interventions for men is limited. 5

Maintenance of initial weight loss is generally poor, even in interventions that focus specifically on maintenance. 9 Evidence suggests that ongoing and long-term support for weight loss maintenance is required,9,10 yet few weight management programmes are designed with maintenance in mind. 5 Gender-sensitised interventions that target weight loss as well as weight loss maintenance are required to support men in their weight management efforts. 11

The National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Public Health Research programme (call number 14/185) called for research into men’s weight loss services to answer the following research question: what are the effective interventions for weight management for men and how are men best engaged with effective weight management interventions?

This feasibility study examines two components of an intervention to support men to lose weight and maintain weight loss: (1) a narrative short message service (SMS) component and (2) a financial incentive component. The study builds on the evidence from NIHR-funded systematic reviews: the ROMEO (Review Of MEn and Obesity) systematic reviews5 of interventions to address obesity in men; the Benefits of Incentives for Breastfeeding and Smoking cessation in pregnancy (BIBS) study,12 which investigated the mechanisms of action of financial incentives aimed at changing behaviour in a different population (women around the time of childbirth); and SMS interventions aimed at supporting a reduction in alcohol intake. 13–15 The study sets out to deliver an intervention over a 12-month period to support self-directed initial weight loss, followed by a period of weight loss maintenance to sustain the clinical benefits of weight change.

To ensure that the intervention components were based on the latest evidence, the searches of three systematic reviews were updated to identify new evidence relevant to the feasibility study design. This update included a systematic review of the evidence for weight maintenance,9 a systematic review of incentives for weight loss,16 and the NIHR Health Technology Assessment systematic review of the evidence for the management of obesity in men. 5 Details of the updated searches and identified evidence can be found in Appendix 1. The findings of the updated reviews underlined the original review conclusions and did not provide further evidence that would require an amendment to or an extension of the planned protocol. The evidence underpinning the intervention design and approach we implemented is presented in the following two sections.

SMS interventions

Systematic reviews5,17–19 report no SMS-focused trials that target weight loss and weight loss maintenance in men with obesity. Mobile phone technologies are available anytime and anywhere, and are accessed by all sections of the population, including those from disadvantaged backgrounds. 20 The evidence for SMS interventions for all lifestyle behaviours, including weight loss, is promising. 17–19 Moreover, recent evidence that has emerged since this study was conducted suggests that narrative SMS delivery forms can engage hard-to-reach men in behaviour change interventions, for example moderating alcohol consumption, which could also help with weight loss. 13–15

Narrative SMS

Narrative SMS can be broadly defined as interactive life stories based around a group of characters with whom recipients can identify. In this study, the narrative format follows the characters’ attempts to achieve and maintain weight loss. This medium may provide an engaging vehicle through which to deliver theory- and evidence-based behaviour change techniques (BCTs). 21 The content, embedded in imaginable real-world scenarios and enabled by characters that are similar to participants, draws on established principles of engagement from the film and games industries. 22 For details of the specific approach used to develop the narrative SMS in the current study and how it used theory and evidence-based BCTs and storytelling elements, see Chapter 3.

Group-based weight management interventions are most promising for men. Although few men engage in weight loss groups compared with women, those who do so tend to have good outcomes. 5,7 SMS-delivered interventions using theory- and evidence-based BCTs and storytelling elements may overcome the limitations of real groups, such as low uptake, logistical challenges, dropouts and costs. 5 Narrative SMS in general have the potential to tap into some men’s weight management preferences by using humour, being fact based and flexible, and providing information that is simple to understand. 5

Narrative SMS have shown high levels of intervention engagement in recent trials. 14,15 The recently published TRAM (Texting to Reduce Alcohol Misuse) trial, which examined a narrative SMS intervention to reduce binge drinking in disadvantaged men, showed that almost all (92%) of the 411 men randomised to the narrative SMS condition replied to messages, with 67% replying more than 10 times. 15

SMS-based intervention delivery is scalable and can reach men across the socioeconomic spectrum. Tailored interventions and innovative means of delivering services, especially for men that are less likely to engage, are recommended. 5,23,24 Mobile technologies, using standard mobile phones, allow evidence-based strategies to be delivered anywhere and anytime, including information on reducing food intake and increasing physical activity, using BCTs and humour, tailoring to preference and providing other scientific facts. 5

Financial incentives interventions

A recent systematic review25 of financial incentives for habitual behaviour change highlighted the potential for incentives to change behaviours and help reduce health inequalities. The evidence for financial incentives for weight loss is growing26–29 and deposit contracts are effective while the incentives are in place. 5,30 Systematic reviews identified only one incentive trial targeting men with obesity. 5,31 This old US trial compared individual contracts with group monetary contracts, whereby men deposited US$30, US$150 or US$300 of their own money, and reported significantly greater weight loss with group contracts than with individual contracts at 1 and 2 years. 31 However, the impact on health inequalities and longer-term effectiveness is uncertain. 25 Workplace incentives were recommended in a Health Select Committee report;32 however, these will not reach unemployed people, self-employed people or students. A discrete choice experiment (DCE) found that paying people (£10–30 per week, varying by age and weight) to take part in diet and physical activity interventions is likely to improve the uptake of, adherence to and maintenance of behaviour change. 33

Endowment incentive contracts

Endowment incentive contracts are financial incentives whereby participants receive a hypothetical endowment, for example £400, at the start of a trial. They can ‘keep’ the money at certain time points if they achieve a weight loss target [e.g. 10% weight loss from baseline, the top-level target suggested by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)6] but will ‘lose’ money if targets are unmet. This is in line with the evidence for deposit contracts5,30 and insights from behavioural economics, including loss aversion and endowment effects. 34,35 Deposit contracts are not used in this study as they are likely to have a negative impact on the engagement of men from disadvantaged backgrounds. 5 However, an endowment incentive contract can mimic the effects of a deposit contract in terms of loss aversion: people are more motivated to avoid losses than they are to achieve similarly sized gains. 34 A randomised controlled trial (RCT) examining framing financial incentives as losses compared with framing them as gains among overweight and obese adults found that incentives framed as losses were more effective for achieving physical activity goals. 36

The endowment design used in this study draws on insights that people ascribe more value to something because it belongs to them. 34 A DCE12 combining incentives and SMS attributes showed promise for smoking cessation in women. Owing to the different active ingredients and mechanisms of action, the effects of SMS and incentive components could be synergistic.

Refined logic model of the intervention

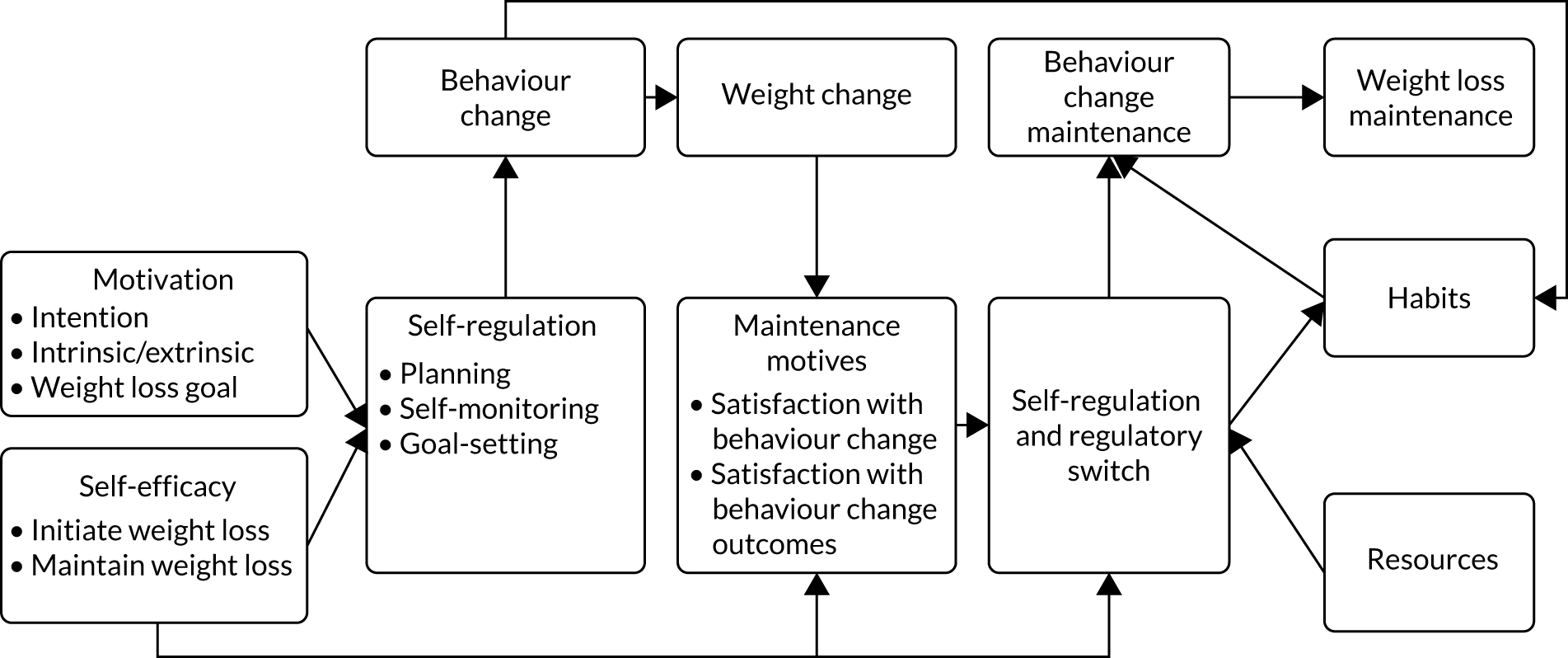

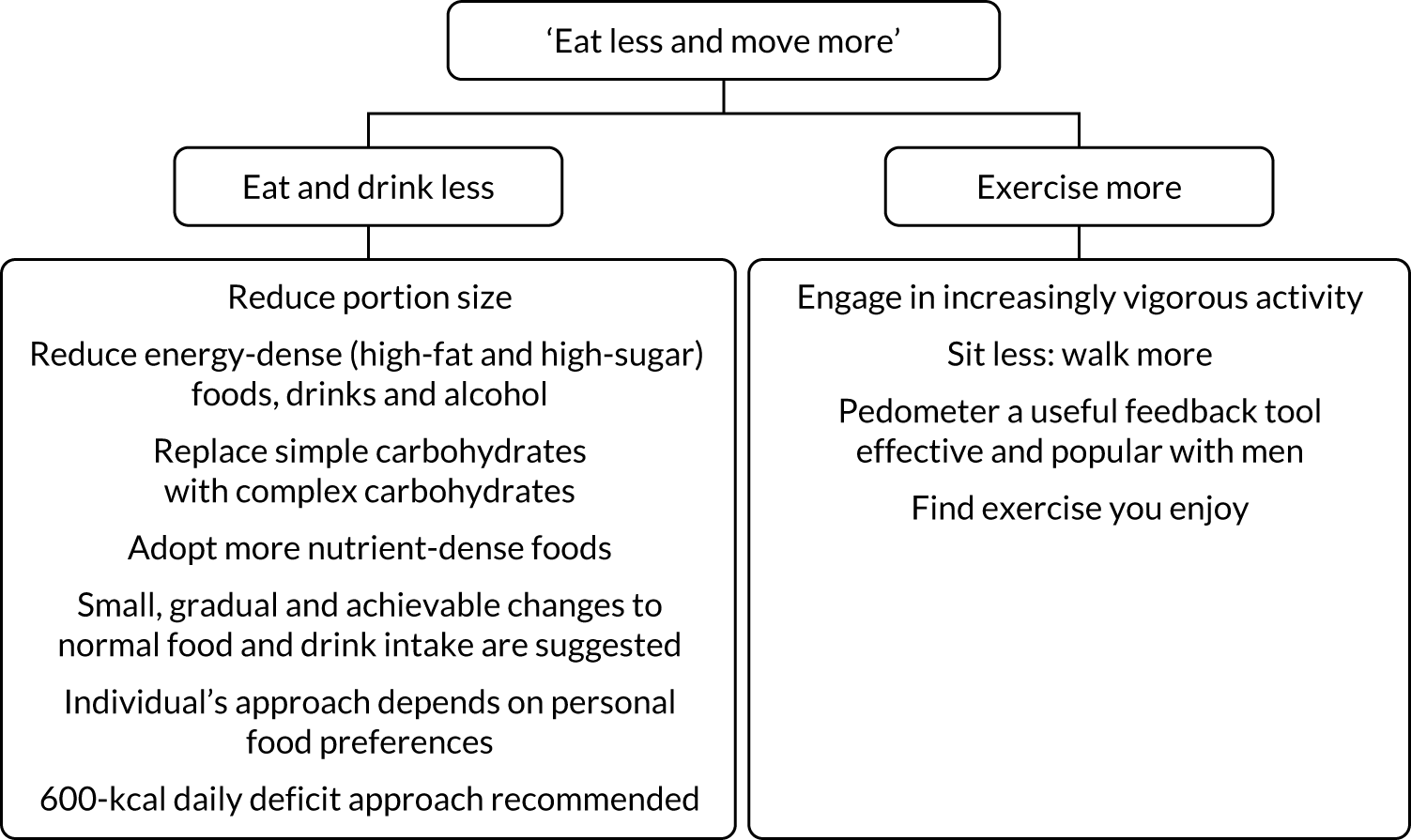

Figure 1 outlines the refined logic model based on the theory and evidence on which the behaviour change intervention components were based. (For details of how the logic model informed the development of the narrative SMS, see Chapter 3.) No single behavioural theory that fully explains the behaviour change process currently exists, and multiple theoretical approaches can inform complex behaviour change intervention design. The behavioural approach used in the current study draws on several psychological theories covering the three phases of behaviour change: (1) motivation, (2) action and (3) maintenance. The specific theories used are self-determination theory37 (motivation), health action process approach38 (motivation, action and maintenance) and Rothman’s maintenance theory39 (maintenance). These theories outline different complementary aspects across the change process and informed the study logic model. In addition, the logic model was updated to include the latest emerging evidence on theoretical maintenance of behaviour change. 40

FIGURE 1.

Refined logic model of the Game of Stones intervention.

The logic model combines the interactive psychological, behavioural and physiological processes that are hypothesised to underlie successful weight management interventions. The psychological processes include both motivational (e.g. intrinsic and extrinsic motivations) and action-related factors (e.g. self-regulation), as suggested by the underpinning theoretical frameworks. These processes cover both reflective (e.g. self-efficacy) and automatic (e.g. habits) factors, in line with Rothman’s maintenance theory. 39 The logic model further distinguished the initiation and maintenance of both behaviour change and weight change. The model specifies behaviour change influencing weight change, which in turn influences the psychological factors and processes theorised to facilitate long-term change. 40 The initiation of behaviour change and the resulting weight change influence maintenance motives. These in turn promote ongoing self-regulation of behaviour change, which is moderated through the formation of habits and availability of resources (i.e. the psychological and physical assets that can be drawn on during the process of behavioural regulation).

A key element of the logic model is the regulatory switch from a change and loss mindset to a maintenance mindset, whereby the maintenance of both behaviour change and weight change is perceived to be a successful outcome worthy of pursuit. The regulatory switch to a maintenance mindset, whereby weight maintenance rather than further weight loss is considered to be the goal of self-regulation, is hypothesised to be the main driver of ongoing maintenance.

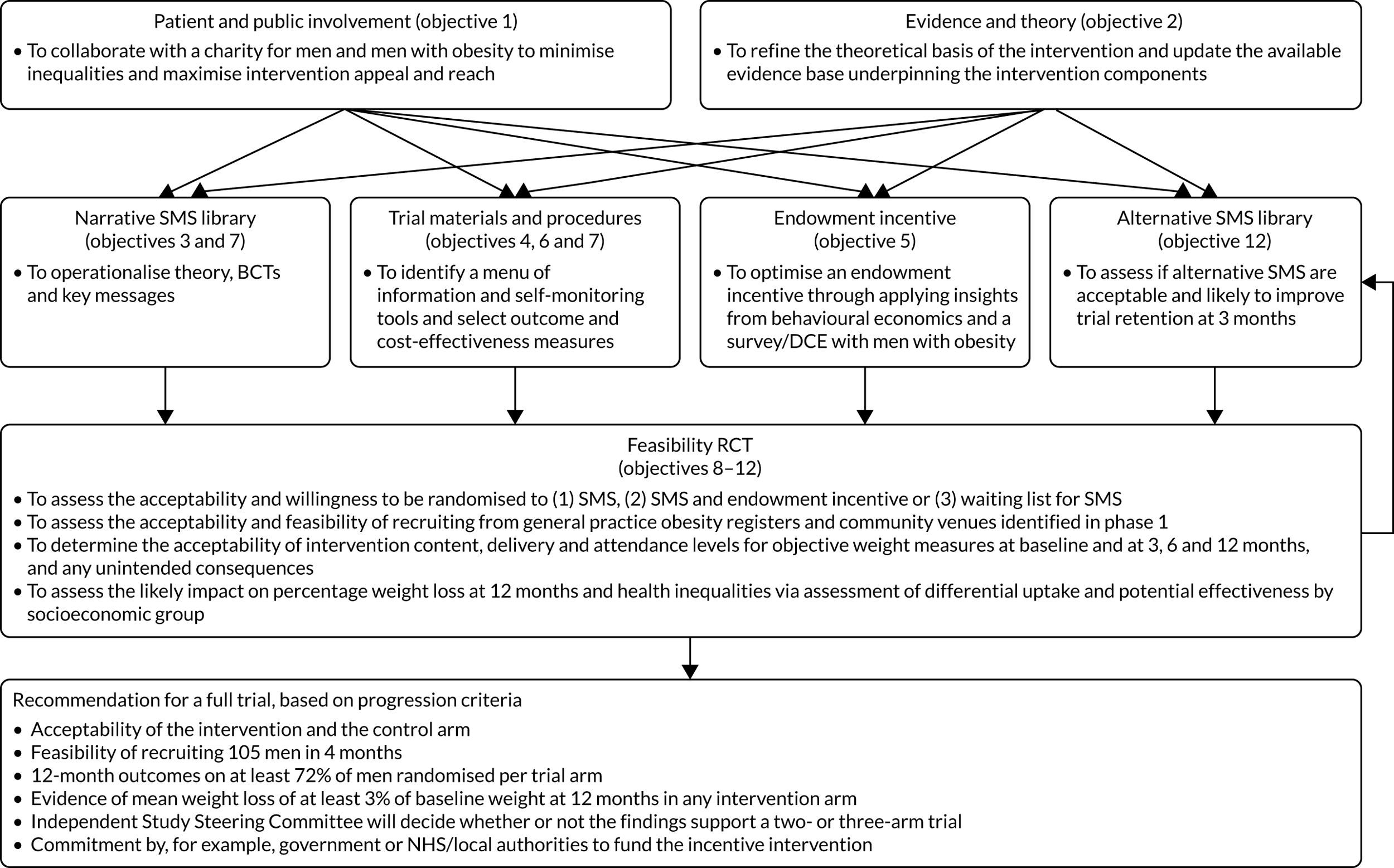

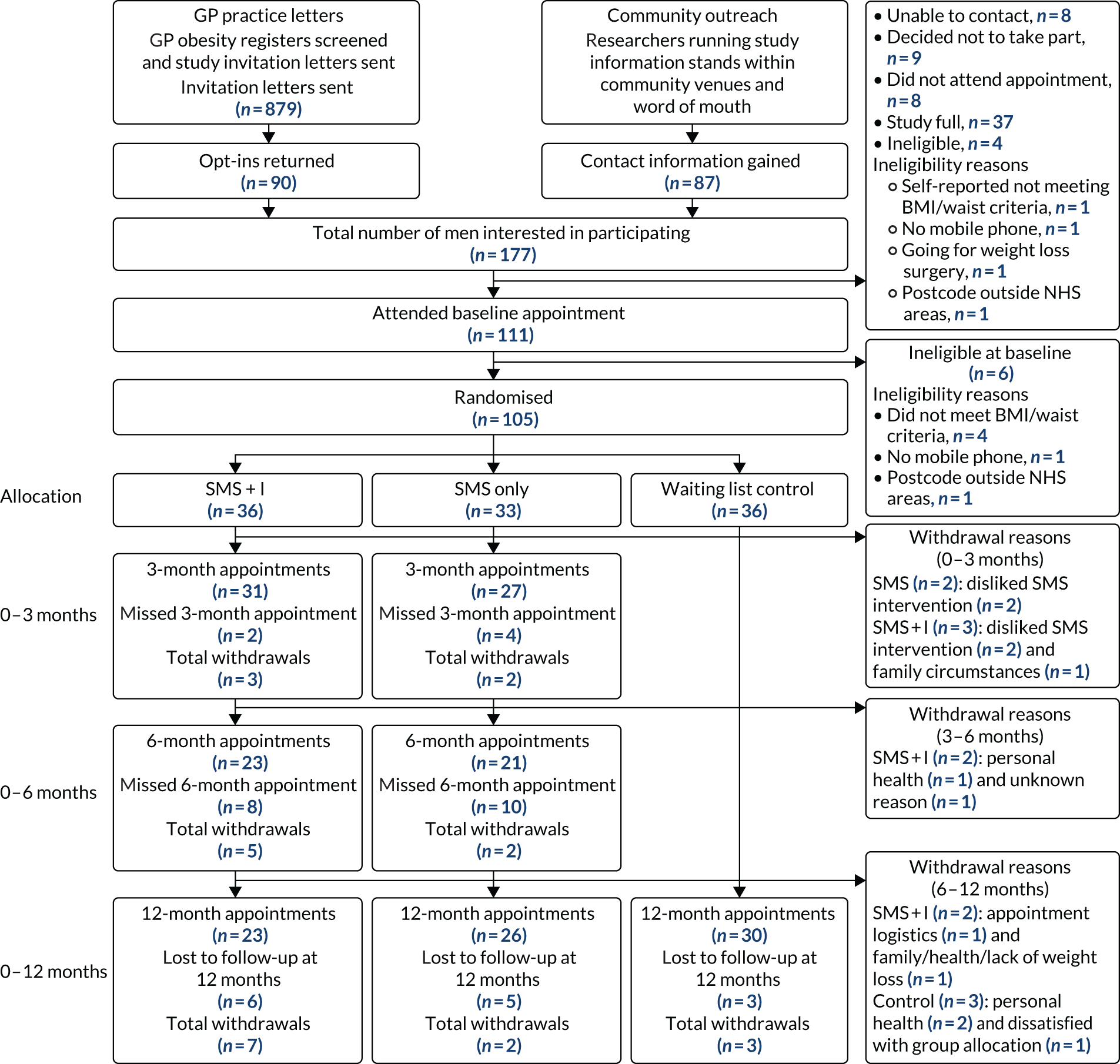

Game of Stones: a UK feasibility study

The current study aimed to test the acceptability and feasibility of engaging men with obesity with narrative SMS with or without incentives for weight loss in order to inform a future effectiveness and cost-effectiveness trial. The target population was obese adult men from disadvantaged areas who were recruited through either general practice obesity registers or community outreach. The study was divided into two phases; phase 1 focused on the adaptation and development of the intervention components and trial procedures and phase 2 focused on the feasibility trial to refine the approach, recruitment, randomisation, intervention delivery, engagement, retention and follow-up processes. A general overview of the study is shown in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2.

Schematic representation of the Game of Stones study.

Below are the aims and objectives as detailed in the study protocol.

Aim

To co-produce with patient and public involvement (PPI) an acceptable and feasible RCT design with broad reach to test a narrative, theory-based SMS intervention with embedded BCTs, with and without an endowment incentive, compared with waiting list control, to inform a future full trial.

Objectives

Phase 1: trial design

-

To collaborate with a charity for men and men with obesity to minimise inequalities and maximise intervention appeal and reach.

-

To refine the theoretical basis of the intervention by integrating systematic review findings and NICE evidence for reducing diets, physical activity, BCTs and theory to refine a logic model.

-

To operationalise acceptable and effective BCTs to embed in a novel narrative SMS delivery form, which builds on existing NIHR-funded narrative SMS alcohol interventions.

-

To identify acceptable ways to provide a menu of information resources on, for example, diet, physical activity, visual feedback of self-reported weight and waist circumference, and pedometer readings using our own or another available open-source website.

-

To optimise an endowment incentive to motivate behaviour change. This was to be achieved by applying insights from behavioural economics and a survey/DCE with men with obesity to define the frequency, constant or varying values and contingency of incentives on targets met for (1) initial weight loss and (2) weight loss maintenance.

-

To select acceptable and valid outcome and cost-effectiveness measures that have the potential for future long-term data linkage.

-

To produce a library of SMS content, recruitment materials and a phase 2 protocol.

Phase 2: feasibility trial to refine approach, recruitment, randomisation, intervention delivery, engagement, retention and follow-up processes

-

To assess the acceptability and willingness to be randomised to (1) SMS, (2) SMS and an endowment incentive or (3) a waiting list for SMS.

-

To assess the acceptability and feasibility of recruiting from general practice obesity registers and community venues, as identified in phase 1.

-

To determine the acceptability of intervention content and delivery and the attendance levels for objective weight measures at baseline and at 3, 6 and 12 months, and any unintended consequences.

-

To assess the likely impact on percentage weight loss at 12 months and health inequalities using an assessment of differential uptake and potential effectiveness by socioeconomic group.

-

To assess if alternative SMS based on mixed-methods data analysis are acceptable and more likely to improve trial retention at 3 months than the narrative SMS intervention. This objective was added to the protocol following an approved study extension request.

Progression criteria for a full trial

Progression criteria are based on systematic review evidence5 and NIHR studies. 13–15 These may or may not support a full trial with either two or three arms.

-

Acceptability of the intervention and the control arm (by the majority of the target group): willingness to be randomised. Evidenced by quantitative and qualitative data on satisfaction, recruitment and intervention engagement.

-

Feasibility of recruiting 105 men in 4 months.

-

Twelve-month outcomes on at least 72% of men randomised per arm, consistent with a recent UK weight management trial in men7 and systematic reviews of the literature on obesity in men. 5

-

Evidence of mean weight loss of at least 3% of baseline weight at 12 months in any intervention arm; NICE defines 3% as clinically significant. 6

-

An independent Study Steering Committee will decide whether or not the findings support a two- or three-arm trial.

-

Commitment by, for example, government or NHS/local authorities to fund the incentive intervention, if it shows positive indicative effects, to ensure translation and sustainability.

Main research question for a future full trial

Is a SMS intervention with embedded BCTs, with or without an endowment incentive, effective and cost-effective in supporting weight loss and weight loss maintenance at 12 months in men with obesity compared with a waiting list control?

Changes to original protocol

Two substantial changes were made to the original protocol: changes to the phase 1 qualitative interviews and the writing of alternative text messages.

Phase 1 qualitative interviews to inform narrative SMS

It was originally planned to carry out 20–30 qualitative interviews with men with obesity during phase 1 (months 0–7) to inform the intervention development. During phase 1, 10 qualitative interviews were carried out to inform the design of the incentive DCE and survey (see Chapter 4) and one focus group with the target population was held to inform the recruitment strategies (see Chapter 5). In addition, four audio-recorded small-group discussions took place about the narrative SMS, incentive intervention and recruitment strategies at a stakeholder workshop with 27 attendees (see Chapter 2). PPI to inform the narrative SMS text library is described in Chapter 3. The project management team considered that it would be more appropriate to assess the acceptability of the narrative SMS after men had received SMS for 3 months, rather than doing this hypothetically in phase 1 or waiting until the final 12-month assessments. This allowed the possibility of amending the SMS content and frequency based on participant experience and feedback. Men were keen to share their experiences at the assessments. The overall aim of the interviews was to seek overall feedback from men on their experiences of participating in the study, the acceptability of recruitment and the intervention components.

Writing of alternative SMS

The waiting list control participants were scheduled to receive SMS for 3 months after the 12-month final assessment. It was originally planned to use the first 3 months of the current 12-month narrative SMS intervention for this purpose. No assessment at 15 months was planned. Although many men found the narrative SMS acceptable, with some showing engagement in their content at that time, this view was not universal. A few expressed strong negative reactions that led to them withdrawing from the study or stopping or blocking the SMS. The aim of examining the acceptability and feasibility of an alternative style of SMS was to explore the potential for reducing strong negative reactions and dropout as a result of the SMS. (For details on how the alternative SMS were developed, see Chapter 5.) The waiting list control arm presented a unique opportunity to test the alternative SMS. Participants were followed up after 3 months and a further 12 qualitative interviews were undertaken to assess the acceptability of the alternative SMS. (For details on the analysis that informed the writing of alternative SMS, see Chapters 5 and 6.)

Report outline

This report has the following outline:

-

Chapter 1 has introduced the general background, study aims and objectives and has provided an overview of the study.

-

Chapter 2 outlines the PPI activities conducted throughout the study.

-

Chapter 3 provides details of the development of the narrative SMS.

-

Chapter 4 presents the results of the survey/DCE of 1045 men with obesity that was carried out to inform the development of the endowment incentive component.

-

Chapter 5 describes the methods of the feasibility RCT.

-

Chapter 6 presents the results of the feasibility RCT.

-

Chapter 7 discusses the findings.

Chapter 2 Patient and public involvement

Background

Systematic reviews of weight loss interventions for men with obesity have concluded that the target population is seldom involved in intervention development, study design or conduct. 5 In this feasibility study, PPI was integrated from study conception until study dissemination. PPI was informed using co-production approaches,41 the principles and practices recommended by INVOLVE42 and an overview of how PPI and mixed-methods research with the target population can complement each other and be synergistic. 43 The PPI undertaken is reported below using the GRIPP2-SF (Guidance for Reporting Involvement of Patients and the Public short form) guidance. 44

Aims

The aim was to involve members of the public and men with obesity from study inception to dissemination to (1) ensure that the interventions, study processes and community venues were acceptable and feasible, and (2) optimise recruitment, uptake, engagement and follow-up of men, particularly those from disadvantaged areas.

Methods

A continuous and responsive approach to PPI was adopted to prepare the grant application and throughout the study, as described by Gamble et al. 45 A summary is provided in Table 1.

| PPI | Number of individuals | Phase(s) of study | Type of PPI | PPI contributors | Description of PPI activities |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study name feedback | 75 | 1 | Responsive | Men from a range of backgrounds | Feedback detailing study name preferences and key considerations for name selection |

| Information material discussions | 6 | 1 | Responsive | Target group men | Individual face-to-face discussions with a researcher |

| Stakeholder workshop | 6 (and 2 PPI co-investigators) | 1 | Continuous and responsive | Target group men, and community engagement experts | Feedback on the narrative SMS, incentive strategy and study design |

| Narrative SMS | 20 | 1 and 2 | Continuous and responsive | Target group men | Story and narrative workshops, individual consultations with scriptwriter and researcher using drafts of the narrative SMS and script conferences |

| Alternative SMS | 10 | 2 | Responsive | Target group men | Individual consultations with researcher and e-mail feedback on a sample of the alternative SMS |

| Study team | 2 | 1 and 2 | Continuous |

Men’s Health Forum GB co-investigator Men’s Health Forum in Ireland co-investigator |

Team meetings, workshop, qualitative interpretation, SMS interventions, study materials and report writing |

| Study oversight | 2 | 1 and 2 | Continuous |

ManvFat director Alliance Scotland director |

Three Study Steering Committee meetings |

Continuous PPI was provided by a co-investigator partnership with the charities Men’s Health Forum GB and Men’s Health Forum in Ireland. The partnership commenced in 2011 with the ROMEO evidence syntheses5 of weight loss interventions for men with obesity. Men’s Health Forum GB, along with Public Health England, produced a guide, How to Make Weight-Loss Services Work for Men,46 to disseminate the ROMEO systematic review findings. These quantitative and qualitative reviews and the user guide informed this study protocol. Men’s Health Forum in Ireland contributed information from a physical activity study47 and website expertise for engaging men in lifestyle behaviours relevant to obesity.

During this study, co-investigators from each of the Men’s Health Forum charities attended trial management meetings to discuss decisions, data analysis, interpretation of findings and reporting. They provided feedback on the grant application, protocol, SMS libraries and information materials and engaged the wider involvement of men from their organisations to assist with appropriate language. 48 The Men’s Health Forum GB PPI co-investigator attended narrative SMS writing sessions and two qualitative data interpretation meetings.

Continuous PPI at the study oversight level was provided by two independent lay members of the Study Steering Committee which met on three occasions. The director of the ManvFat website (www.manvfat.com; last accessed 25 June 2019) and author of the ManvFat self-help book (https://shop.manvfat.com/collections/tools; last accessed 25 June 2019) provided input both from the perspective of men accessing his organisation’s services and from his personal experiences of weight management. The director of The Health and Social Care Alliance (www.alliance-scotland.org.uk/; last accessed 25 June 2019), who has experience of promoting self-help interventions and addressing health inequalities, provided contact details of link workers (access to health and social care services) at ‘deep end’ general practices in disadvantaged areas to assist with study recruitment.

Responsive PPI occurred at the study funding application stage. Co-investigator Cindy Gray engaged men who had provided PPI input to the successful Football Fans in Training (FFIT) trial. 7 These men participated in two discussion groups. These groups disbanded before this study commenced, but two members continued to be involved and provided feedback as individuals.

During the study, members of the public from the target population or who had an interest in PPI and research activities relevant to men’s health were identified from several sources, including Men’s Health Forum GB, Men’s Health Forum in Ireland, Scottish Community Health Councils, Men’s Sheds, University of Stirling PPI group, Alliance Scotland and other co-investigator contacts. Effort was made to engage men living in more disadvantaged areas to be involved.

A total of 121 PPI contributors were involved during phase 1 and/or phase 2 of the study in a range of one-off or continuing activities (see Table 1).

Key PPI activities during the study included the following.

Study naming competition

The study name was selected by PPI during phase 1. A £20 voucher was offered for suggesting the winning name in the competition. An initial longlist of 91 potential study names was collated from suggestions by target group men, men’s health charities, co-investigators and University of Stirling staff. PPI partners, the Men’s Health Forum in Ireland, contacted individual men and asked partner organisations to request feedback on the longlist of names from their members by e-mail. This yielded feedback from 75 men from a range of ages and backgrounds, including members of Men’s Sheds; a young men’s project; a lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender support group; a rural farmers’ project; a separated fathers’ support group; sporting clubs; and users of the Men’s Health Forum in Ireland’s online resources. Key considerations for selecting the study name were suggested and the five most popular titles were nominated.

Based on the PPI feedback and in collaboration with the Men’s Health Forum in Ireland, the three most popular study name suggestions were anonymously voted on at the stakeholder workshop towards the end of phase 1.

Stakeholder workshop

A stakeholder workshop with 27 attendees was held to finalise study procedures, intervention components and the study name, and to make final decisions on the study protocol. Workshop attendees included a senior public health manager, co-investigators and study researchers (n = 10), dietitians (n = 3) and independent academics (n = 5) with a range of expertise in weight management, public health and financial incentives. PPI included Men’s Health Forum co-investigators (n = 2), men from the target group (n = 4) and individuals with expertise in the community engagement of men in areas of deprivation (n = 2).

Four structured small-group discussions were conducted about tabled documents that provided a sample of the narrative SMS, options for the incentive structure linked to different weight loss targets met and recruitment strategies. These discussions were audio-recorded to summarise the views expressed and to ensure accuracy. They were not transcribed verbatim, as this would introduce ethical implications for the PPI. 43 Stakeholder workshop attendees voted on the final three most acceptable and popular study names identified by PPI.

One-to-one patient and public involvement feedback on study materials

Researchers met men (n = 6) on a one-to-one basis to discuss the study materials (e.g. information leaflets and questionnaires) to ensure that these were appropriate and understandable. These individuals were Men’s Sheds group members (n = 2), former participants of the Football Fans in Training weight management programme (n = 2), a target group member and former weight management service participant (n = 1) and a community worker experienced in working with men from areas of disadvantage (n = 1). The researchers took notes during these meetings to capture the feedback gained, and, where appropriate, changes were made to the study materials.

Narrative SMS patient and public involvement

Responsive PPI consultations involved feedback from individual men from the target group (n = 20) who were identified through co-investigator connections and research networks. The methods and results of having responsive and continuous PPI in the development of the narrative SMS are described in Chapter 3.

Alternative SMS patient and public involvement

Responsive PPI consultations involved feedback from individual men (n = 10) recruited through three channels: the University of Stirling PPI group, PPI co-investigator connections and researcher networks.

The men involved agreed to provide feedback by e-mail (n = 9) or in person (n = 1) on the 12-week drafts of the alternative SMS. E-mail invitations were as follows:

These texts have been written to help men lose weight, based on men’s experience of weight loss and evidence of what helps people change their behaviour. Any comments on how these texts can be improved based on your experience would be very welcome!

These comments can be about anything: words used, individual texts, strategies suggested, overall themes, general style.

Thank you for your help.

Incentive strategy patient and public involvement

To inform the design of the novel endowment incentive strategy that aimed to invoke loss aversion theory, the PPI co-investigators were involved in the design and the interpretation of the findings from the DCE, which was completed by 1045 men with obesity, and think-aloud qualitative interviews. Men’s preferences for the incentive strategy were then presented at the stakeholder workshop to guide the final decisions about the feasibility trial protocol. Those attending the workshop were asked to discuss what should happen when men were found to fall short of their weight loss targets at appointments.

Results

Study naming competition

The five most popular study names from the feedback gained from 75 men in collaboration with the Men’s Health Forum in Ireland were ‘Game of Stones’, ‘Guts 2 Lose’, ‘Lean Mean Texting Machine’, ‘Lose It or Lose Out (LILO)’ and ‘tXt Men’. These men also put forward key considerations for the selection of the study name:

-

Avoid a name that uses the word ‘fat’ or similar (e.g. CHUBS) as this terminology carries too much baggage and reminders of personal circumstances.

-

Avoid a name with the word ‘fairies’ in it. This term was disliked regardless of sexual orientation.

-

Titles with ‘slim’ or ‘slimmer’ were seen as being aimed more at women.

-

Be cautious about being too smart; for example, younger men liked the name suggestion ‘W8M8’, but this name was poorly understood by older men.

-

Do not choose anything that seems to blame men for their situation, as many men feel that they are already blamed for all the ills of the world.

Based on the key considerations highlighted by PPI, of the five nominated names, the research team removed two (‘Lean Mean Texting Machine’ and ‘Lose It or Lose Out’) because of the words ‘lean’ and ‘lose’, which could be misinterpreted. The stakeholder workshop vote found that the most popular of the final three names, and therefore the one selected, was ‘Game of Stones’.

Stakeholder workshop

Appendix 2 provides a detailed summary of the discussions held between academics, clinicians and PPI members at the stakeholder workshop. The key issue unanimously raised by workshop attendees was recruitment. Two suggestions made by PPI members were to use workplaces and gyms as settings for community recruitment. Based on this feedback, researchers recruited men from two council work premises and the foyer of a gym. As recruitment had been raised as a key issue, a focus group was conducted at the end of phase 1 with men from the target population in a very disadvantaged urban area. This focus group is described in Chapter 5.

Summaries of feedback, suggestions and decisions made by PPI at the stakeholder workshop in relation to both recruitment and study procedures and the incentive strategy were documented (see Appendices 3 and 4).

One-to-one patient and public involvement feedback on study materials

A full summary of one-to-one PPI feedback and decisions or changes made to the information materials as a result can be found in Appendix 5. One example is a sentence in the initial draft of the post-randomisation leaflets that aimed to minimise contamination and disappointment bias between trial arms. The original sentence stated that we ‘ask that you are confidential about your participation in this study’. This was included as two newspaper articles about the study were published after the lay summary became publicly available on the NIHR website. The co-investigators wanted to avoid such media publicity, which could bias the study findings. However, PPI participants suggested that after losing weight they would want to share this success with friends and family, and that this confidentiality section should make clear that this would be OK. The section was then amended to state that ‘you can talk to close friends and family’ about the study.

Narrative SMS feedback

Chapter 3 provides details of the 20 PPI men who commented on the narrative SMS. All 20 men self-identified as belonging to the target group of those carrying excess weight.

Alternative SMS feedback

Appendix 6 provides details of the 10 PPI men who provided comments on the alternative SMS. The majority of men (n = 9) self-identified as belonging to the target group of those carrying excess weight. The group included the editorial and creative consultant at Men’s Health Forum GB, who has written award-winning health guides and online material for men on weight and other health issues. 46,48

Feedback received on the alternative SMS was both general (n = 7) and specific (n = 3). The volume of comments ranged from a few sentences (65 words) to a multipage reflective letter (2152 words). The face-to-face discussion on the alternative SMS lasted for 1.5 hours. Specific comments were provided as in-text comments in the circulated electronic document, and these ranged from 15 to 35 comments.

Substantial changes were made to the draft alternative SMS in response to feedback. Examples of specific PPI feedback and decisions about or changes made to the alternative SMS can be found in Appendix 7.

Incentive strategy feedback

Options for the incentive strategy based on the findings of the DCE were discussed at the stakeholder workshop. Key PPI issues that influenced decision-making are described in Chapter 4.

Discussion

The results demonstrate the considerable influence and impact that PPI had on the study name, the development and refinement of the interventions, the study materials, the approaches to recruitment and the overall design of the feasibility RCT. This is likely to have contributed to the overall acceptability and feasibility of the Game of Stones study and facilitated meeting the progression criteria for a full RCT.

Different views about the interventions, their delivery and the study processes became evident early on. This may reflect the diversity and the number of men providing PPI to the study, the pervasive health issue the study aimed to tackle and the novelty of the intervention components used. All viewpoints, together with evidence and theory, were considered by the research team. Final decisions were made by identifying options for the study protocol and materials and weighing up the pros and cons for each in relation to the study objectives. These options were triangulated with appraisal of the published evidence, behaviour change theory and study goals relating to the testing of incentive-based and SMS-delivered interventions that would have wide reach, address health inequalities, be scalable, be logistically and practically feasible and be sustainable in the future.

Humour was a key finding of the ROMEO qualitative synthesis of men’s experiences of weight loss. 49 Feedback from the diverse PPI in this study demonstrated how easy it is to use language that is disliked by men with obesity.

Reflections

The study team was fortunate to have excellent and continuing involvement with the Men’s Health Forum charities in Great Britain and Ireland; this involvement commenced in 2011 and these charities will continue to help with the dissemination of the findings and preparations for future research. The involvement and networking with key local community and charity stakeholder groups helped to involve men in the target population and men with an interest in PPI and research.

Feedback from PPI on the alternative SMS had to be collected swiftly following official approval of the study extension. E-mail consultations on the draft alternative SMS were efficient and allowed PPI input at various levels, including comments on individual SMS and at a more general and conceptual level. The written format ensured that all feedback was captured without information being lost or misinterpreted. However, e-mail necessitates internet or smartphone access, and less literate men might not have had the confidence to take up the offer of providing input. This potentially excluded some men from being able to contribute. Electronic PPI is efficient, precise and suitable when operating on a tight timeline, but would ideally be supplemented with substantial face-to-face input, as was done for the development of the narrative SMS.

For complex multicomponent interventions such as Game of Stones, the final decisions on the study protocol are crucial. Several plausible options for the development of the incentive (see Chapter 4) or narrative SMS intervention (see Chapter 5) components could have resulted in a different feasibility trial. Engaging and hearing the views of a large number of men with obesity through individual and group PPI and a workshop worked synergistically with data collection using phase 1 surveys and a recruitment focus group with men living in disadvantaged areas. The diversity of expertise, collaborative work and values of the co-investigator team that make the final decisions is therefore critical to intervention and trial design.

Chapter 3 The writing and development of a narrative SMS intervention component to help adult men with obesity lose weight and be more active

This chapter was written by the scriptwriter who developed the narrative SMS component. It is written based on his opinions, work and approaches.

Introduction

This chapter outlines the creative practice and process by which the narrative SMS intervention component was designed and written. It reports how published behavioural theory, evidence-based BCTs, input from behaviour change experts and co-production with the target demographic informed the narrative development process. A timeline represents how the narrative intervention component changed in content and format from the start of the intervention development process, how key stakeholders influenced the process, and the guiding principles, people and factors that were prioritised when making decisions. It outlines the behaviour change theory, the BCTs and the messages that were incorporated into the narrative, and how and when, during intervention development.

This chapter aims to provide a direct analytical link between the intervention aim to help adult men with obesity, particularly those from more disadvantaged areas to lose weight by eating fewer high calorific foods and moving more. It also outlines the narrative SMS approach used to achieve this. Overall, this chapter presents a theory- and evidence-based methodology that may be replicated in further behaviour change interventions and studies across health outcomes: a ‘how-to’ guide to developing an evidence- and theory-based narrative text intervention.

What is a narrative SMS intervention?

Narrative SMS are story-based text messages sent from a computer and received by study participants on their mobile phones. Published studies suggest that ‘narrative’ can simulate the processes that make group-based interventions successful: humour, banter, peer support, facts about diet and physical activity, personal tailoring and evidence-based BCTs. 5 By creating an empathic bond with the characters, users pay more attention to and become engaged with and immersed50,51 in the story. This leads to optimal learning and conceptualisation of the target information. Narrative SMS are defined as interactive life stories based around a range of characters that can simulate the processes that make group-based interventions successful, and are used to embed how-to-do-it, diet and physical activity tips, friendly humour and support. 13–15

Narrative was defined in this intervention as the audio-visual and digital representation of how a character (or characters) interacts with the environment, objects and others and how he or she feels about it and changes over time. 22 Narrative texts in this study represented how a character reflected and acted on his need to lose weight, the familial, social, economic and environmental pressures acting against him, and how he felt about changing his established lifestyle incrementally over 12 months and overcoming his low self-esteem as a result. This specific population, the nature of the SMS channel and the term (12 months) of engagement required a coherent theory- and evidence-based, practical approach to health behaviour change, an approach designed to engage men in long-term behaviour change.

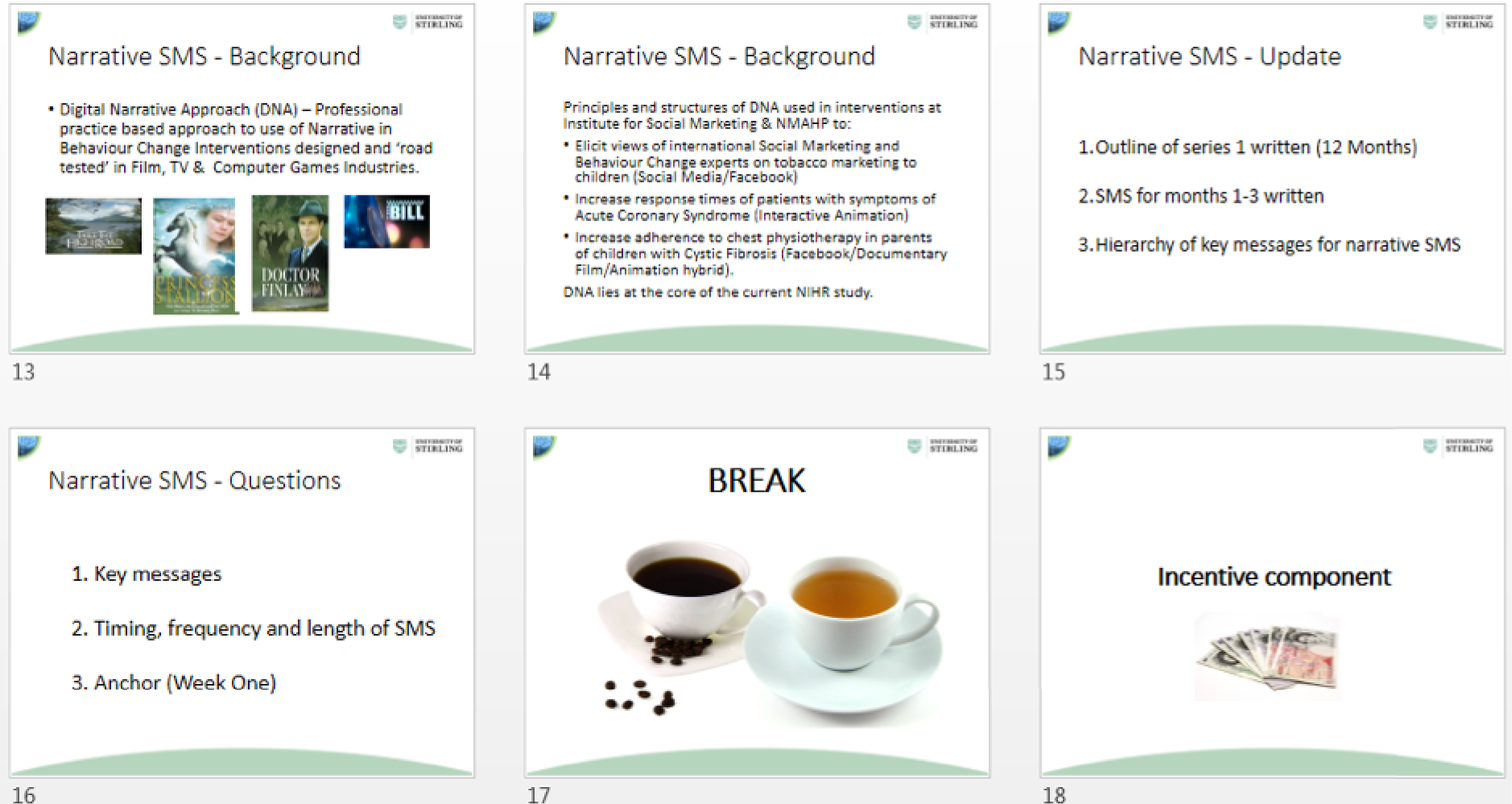

The digital narrative approach to health behaviour change (formerly the digital narrative transformation framework22) is a theory- and evidence-based practical approach to designing, writing and evaluating digital narrative health behaviour change interventions. It represents an approach to enhancing user engagement for health behaviour change in the short and longer term. The approach is interdisciplinary and draws from diverse fields: neuroscience, evolutionary psychology, human–computer interaction, philosophy, history, politics, commercial marketing and social marketing. 22 Digital narrative approach was developed in broadcasting, film and computer games by a professional scriptwriter, developer and executive producer who was engaged in this study as scriptwriter and co-investigator.

Digital narrative approach has been deployed in a number of health behaviour change studies and interventions, and has shifted the focus of health behaviour change research from ‘top down’, cognitive approaches to an emphasis on the need to engage emotionally. It adopts the theoretical stance that, by relying less on information exchange and engaging non-consciously and emotionally, digital narrative enables characters represented digitally – avatars – to convey and model the key messages and behaviours of an intervention and facilitate the viewer’s empathy. Digital narrative approach has, therefore, the potential for participants to internalise key messages and BCTs through their emotional involvement with the development of the narrative, the characters and their stories.

Digital narrative approach blends five core components at the level of the narrative: behaviour change theories, BCTs, key messages relevant to the desired outcomes, commercial digital narrative strategies and evidence from previous studies using digital narrative approach. It also incorporates PPI (see Chapter 2 and below) and input from health behaviour change experts. These core principles and structures have been used across a range of health outcomes. Examples include promoting smoking cessation among pregnant young women,52 reducing binge drinking among adult men,13,15 improving response times to symptoms of acute coronary syndrome53 and improving adherence to physiotherapy among parents of children with cystic fibrosis. 54 Levels of engagement have been encouraging, particularly the extent to which participants engage emotionally as well as rationally and behaviourally. The core narrative principles and structures apply equally to fiction and to documentary styles. They can be delivered over many digital media platforms and are applicable to a range of health outcomes. Digital narrative approach was deployed in the current study to enhance this particular intervention to have an impact on the quality of participants’ motivation (intrinsic and/or extrinsic), and to impart key messages and behaviours around the intention to lose weight and become more active in a specific demographic group (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

The digital narrative approach to health behaviour change.

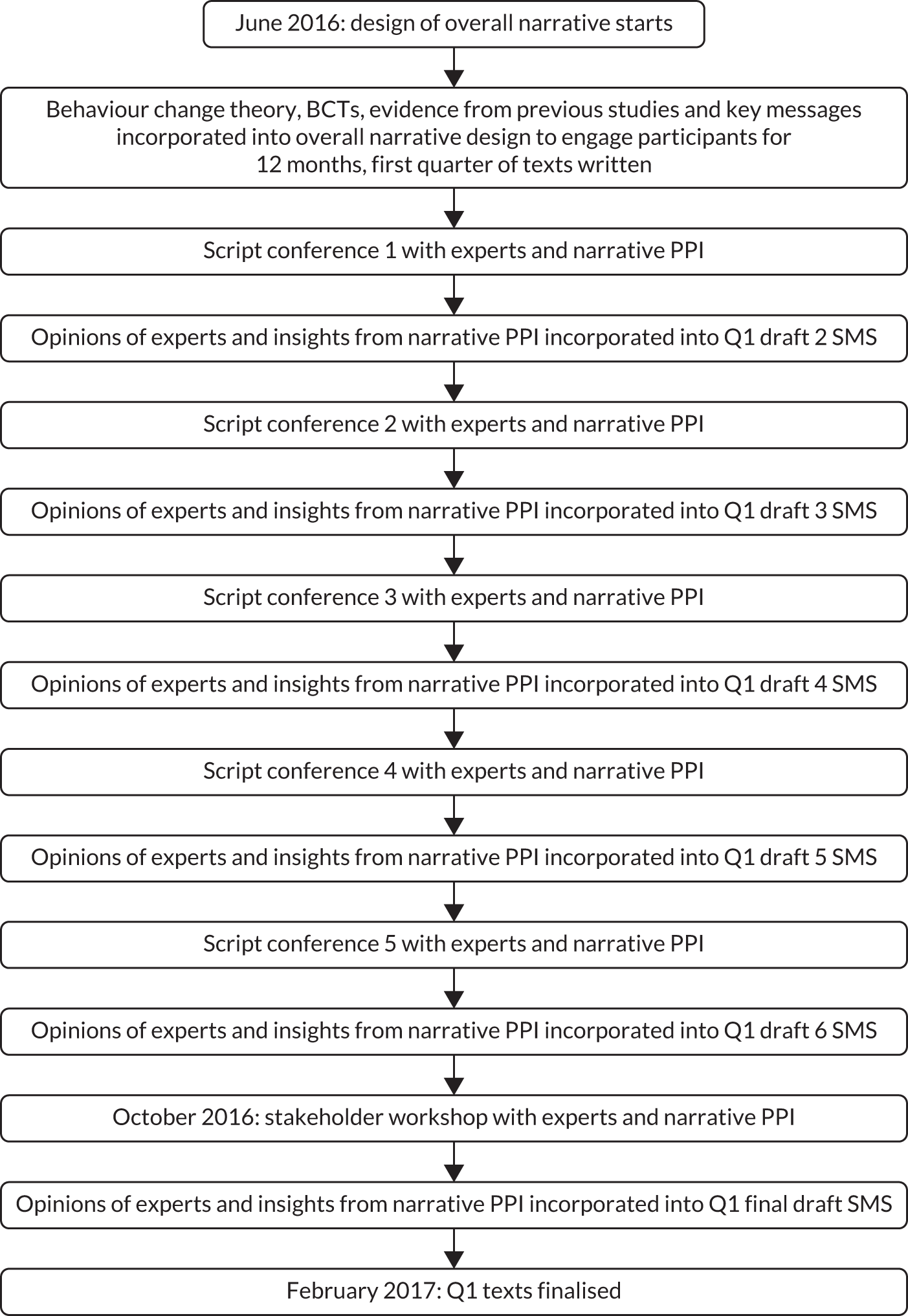

The narrative SMS design

The narrative SMS library was designed and written systematically and iteratively using professional writing and development practices as well as co-production with the target demographic. This process was broken down into two key phases: phase 1, the narrative text intervention design using PPI with the target demographic, and phase 2, the narrative text writing and intervention using live feedback from the study participants as they responded by text to the main character of the story. Figure 4 depicts phase 1. For details on the PPI participants and how PPI influenced the narrative component, see Appendices 8 and 9.

FIGURE 4.

Phase 1: narrative SMS intervention development timeline and key influences on narrative texts.

The overall narrative

The overall narrative and the first 3 months of texts were designed and written during the narrative SMS intervention design phase 1. The narrative was designed to be intimate, taking advantage of the one-to-one conversational style of the texts. It was written from the point of view of Jimmy Nesbit, a character who reports, in the first person, his experience of trying to lose weight, maintain his weight loss and overcome the threat of type 2 diabetes over a period of 12 months. The narrative draws on fictional and real-world (documentary) characters’ experiences of overcoming low self-esteem and losing weight. It characterises how Jimmy’s obesogenic environment, his home, family and social context, and the corporate determinants of obesity can influence his eating and exercise behaviours negatively, thereby throwing into relief the behaviours, lifestyle changes, attitude and beliefs he needs to adopt, and the barriers that he must overcome, if he is to lose weight, exercise more and be healthier.

The characters

Seven characters (Table 2) and their stories were written by the scriptwriter/researcher who wove together their individual storylines using commercial narrative strategies, humour, behaviour change theories, BCTs and key messages. The characters and their backgrounds were designed to reflect the lives and circumstances of, and to appeal and be credible to, the target audience. This involved extensive fieldwork and PPI with the target group in their environment.

| Character | Description |

|---|---|

| Jimmy Nesbit | Aged 39 years. Jimmy weighs 19.5 stones and is clinically obese. His friends call him ‘Slim’. Jimmy suffers from low self-esteem |

| Wilma Nesbit, Slim’s wife | Aged 35 years. Wilma wishes Slim would get a job. She enjoys the food they eat and going out to drink. But she misses their physical relationship |

| Budge, Slim’s best friend | Budge also weighs 19.5 stones. But for Budge, fat is the new black and life is for living |

| Mikey | Aged 32 years. Maintenance Mikey maintains his weight at a steady 76.2 kg. He provides Slim with help, support and guidance. He teaches him to ‘surf the urge’ when faced by triggers in the environment and helps him improve his lifestyle over 12 months |

| Dr Sharpe | Aged 56 years. Although she means for the best, Slim’s general practitioner is somewhat condescending. She tells Slim to ‘just choose a diet and stick to it’. She sees Slim as ‘hard to reach’ – rather than as a whole human who suffers from low self-esteem and is vulnerable to comfort eating |

| Claire, district nurse | Claire is 27 years old and genuinely cares for Slim’s welfare. She helps him improve his self-esteem over 12 months |

| Colin | Colin is owner of The Head, the local pub. At 24 years old he has inherited money made from importing sugar. Colin’s new ‘Power Up Super Juice’ range proves irresistible to Slim |

The scriptwriter further developed and wrote the characters by working closely with a graphic artist. This process helped to define the characters, their relationships and their stories and provided visual prompts in character and story workshops with the target demographic to assess the characters’ likeability and credibility, their stories and the real-world barriers to and facilitators of behaviour and lifestyle change. The biographies and images of the characters were published on the study website to allow participants to visualise the characters, including the main character, Slim, from whom they would receive the texts regularly.

The overall narrative synopsis

Jimmy Nesbit is 39 years old and unemployed and suffers from low self-esteem. He weighs 19.5 stones and his friends call him ‘Slim’. Dr Sharpe, Slim’s general practitioner (GP), warns him that he is at risk of developing type 2 diabetes, various forms of cancer and coronary heart disease, including the risk of having a stroke. She recommends that he needs to keep a food and exercise diary. She tells him that he must ‘choose a diet and stick to it’.

Slim reflects on his poor health and monitors his food intake and physical activity using a diary, but he is confused by the range of diets and conflicting advice available to him and remains unmotivated. His cycles of low mood leave him vulnerable to comfort eating in response to triggers in his environment (i.e. the marketing of high-fat, high-salt and high-sugar foods). Slim’s closest friend and drinking buddy is Budge, who also weighs 19.5 stones. He advises Slim that ‘fat is the new black’ and ‘life is for living’. Unlike Slim, Budge is in complete denial about the threats to his own health from poor diet and lack of physical activity.

A stranger appears in the community, Mikey, who has has embraced weight loss and maintenance for his own personal reasons. He sets up a weight loss competition between Slim and Budge. He introduces Slim to a method of ‘surfing the urge’. This is a way to control responses to the triggers in the environment that usually result in comfort eating. Slim makes an effort to take control at home. Unfortunately, the poor eating habits and the sedentary lifestyle that he has established over the past 10 years all prove to be barriers to the changes that he needs to make. Frustrated at his apparent inability to change, Wilma leaves Slim. Slim remains hopeful that Wilma will come back, even if it means building her that summer house that she has always wanted in the back garden. Claire, the district nurse, sees clearly that Slim needs not just an improved diet and exercise, but also a better sense of his own worth.

When Slim discovers that Wilma is pregnant he takes to the weight loss competition with a vengeance. He wants to be able to play football and be a good father to his son. He finds that by drinking a new brand of energy drink, ‘Power Up Super Juice’, he can eat less and exercise more, but, as Claire points out, Slim is gaining weight because of the sugar content of the drinks. The news that Wilma has given birth to a child possibly fathered by another man sends Slim back into cycles of comfort eating. He vows to be a good father regardless. Motivated, he renews his weight loss and maintenance routine. During all of this, his estranged friend and competitor Budge has a stroke.

The news that Budge is in a coma helps Slim finally see himself and his unhealthy lifestyle fully ‘in the mirror’. He manages to lose weight and maintain that loss through action. He wins the weight loss competition as well as reducing his risk of type 2 diabetes, bowel cancer, heart disease and stroke. Slim finds he has confidence in his strategies to lose weight and maintain weight loss. Most importantly, he discovers improved self-esteem, motivation and resilience.

The approach to the design of the narrative

When Slim first texts participants, he is unemployed, his marriage is on the rocks and he is suffering from low self-esteem. It was critical that Slim have significant and credible setbacks so that the narrative could be sustained in a long-term intervention.

Slim’s thoughts, perceptions, emotions and imagination, the influence of significant others and the impact of stimuli in the environment were plotted to ensure that his levels of motivation and ability to self-regulate were plausible and realistic over 12 months and also that Slim took control of his lifestyle in an engaging manner. Dramatically, this necessitated that Slim suffer relapses and setbacks along the way.

In the second quarter (months 4–6), Slim attempts to change his home environment, for instance so that he can resist the triggers of eating foods high in fats and calories. His attempts are thwarted by his wife, Wilma, as, although she wants him to be physically fit again, ironically she is unable to respect his needs and to change the habits and routines of their marriage and home life. Mikey teaches Slim how to ‘surf the urge’ to control the stimuli in his home and the external environment. In story terms, Slim’s desire to eat when he is down is continually triggered by marketing promotions for high-fat, high-salt and high-sugar foods in the supermarket and on advertising billboards. Slim is continually able to deal with relapses and plan ahead to avoid temptation when he is socialising and eating out. In the third quarter, Slim uses his new knowledge to fight against all odds to lose weight. In the final quarter, Slim develops the habits that will begin to sustain his weight loss. He learns to reflect on and enjoy his achievements and the physical, social and psychological benefits of being healthier.

The setting

The setting for the narrative overall was a secret location in Scotland with the same socioeconomic status as the target demographic. The emphasis was placed on blending comedic and dramatic storylines to maximise emotional engagement throughout. This is a potential limitation as using a real location might lead people to identify more or less with the story depending on where they come from. It is also a potential limitation if during recruitment the target group changes and represents a different demographic from that originally intended and for which the narrative was originally designed.

The theories of change embedded in the narrative intervention

Three key phases of behaviour change – motivation, action and maintenance – were merged at the core of the overall narrative according to the principles and structures of digital narrative approach: Ryan and Deci’s self-determination theory,37 which focuses on the quality of participant motivation; Schwarzer’s health action process approach, which emphasises the need for motivation, action and maintenance of behaviours;38 and Rothman et al. ’s maintenance theory,39 which focuses on the need for maintaining weight loss maintenance over time. These theories are described in detail in Chapter 2. What concerns us here is how these theories, BCTs and key messages were operationalised at the level of the narrative and in the individual texts transmitted to participants over 12 months.

Ryan and Deci’s self-determination theory37 was incorporated into the overall narrative, which sees the quality of Slim’s motivation increase incrementally over the 12-month period as his self-esteem improves. Slim’s health improves as he develops the intrinsic motivation to engage in more vigorous activity tailored to his preferences, for example his goal to walk longer and longer distances without his stick and his increased sense of control over his diet, alcohol consumption and portion sizes. Slim secures intrinsic motivation through the feedback he receives around the success in his hobby, which is writing a computer game he calls Game of Stones. It is through this game that the desired behaviours and key messages are repeated and reinforced. As he learns from Mikey the need for regular goals, rules, feedback, rewards and self-regulation, so Slim develops his game to help people like him lose weight online. This helps Slim, with Claire’s support, to overcome his low self-esteem and take full control of his marriage and lifestyle, not just his diet and physical activity regimens. By taking control over his own destiny Slim enjoys acceptance back into the local community.

The intervention overall was designed to encourage participants to lose 10% of their body weight over 12 months. It was decided that the main character, Slim, would also set this goal and achieve 10% reduction in his body weight over 12 months. If Slim had learned to lose and maintain 10% of his weight over 3 months, the story would have been resolved and it would not have been possible to sustain the intervention over 12 months in a credible and engaging manner. This meant that the actions Slim took to achieve that weight loss had to be introduced incrementally and credibly, and this progression had to be consistent with the key concepts taken from the underlying theories, such as the need for motivation, action and maintenance.

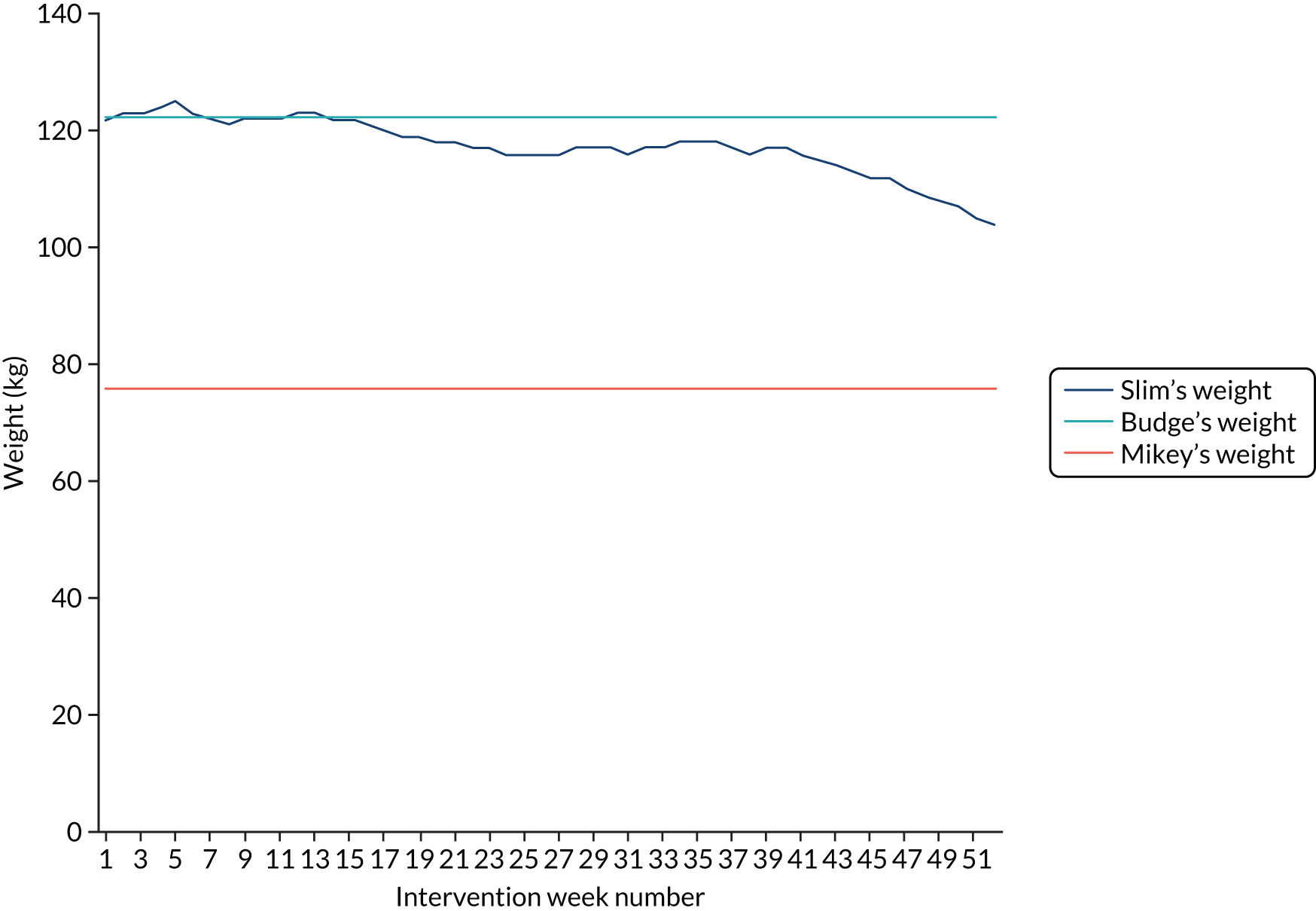

The narrative was designed to incorporate the diet component options recommended as part of the 600-calorie daily deficit approach. 6 Slim’s weight was plotted over 12 months to ensure that the cycles of weight loss, weight gain and maintenance were feasible – given his intentions, motivation, emotional state and actions – and enabled him to lose 10% of his body weight over 12 months credibly. Slim gradually started to eat more nutrient-dense foods, reduce his portion sizes of energy-dense foods and reduce his intake of snacks, sugar and alcohol over the 12-month period. How Slim put this into action depended on his initial personal food preferences, and small, gradual and achievable changes to his normal diet were incorporated in line with recommendations. 6 In narrative terms, Slim’s weight loss objective was conveyed using the story of an ongoing weight competition between Slim and his friend Budge and refereed by ‘Maintenance Mikey’, who becomes Slim’s coach. Throughout, Mikey’s advice and guidance remain consistent with his own ability to maintain a steady weight through resilience and self-regulation to control his diet and physical activity regimens. It is as a result of Mikey’s information advice, guidance and emotional support that Slim learns to recognise the environmental triggers of his eating behaviours and the barriers to changes in his lifestyle. Slim’s weight loss trajectory was then plotted against that of his friend and opponent Budge, whose attitude, intentions, levels of motivation and lack of action mean that he maintains a weight of 122.5 kg, and that of his mentor, Mikey, who maintains his weight at a mean of 76.2 kg. Figure 5 charts Slim and Budge’s weight loss trajectory, merging theory, BCTs and narrative to represent credible weight loss and behaviour change over 12 months.

FIGURE 5.

Slim’s, Budge’s and Mikey’s weight loss trajectories.

The behaviour change techniques embedded

This section shows how the main evidence-based BCTs were implemented in the narrative using digital narrative approach. The aim was to operationalise techniques at the level of the text intervention component that could be acceptable and effective in a weight loss intervention. BCTs that are most likely to be successful in sustaining behaviour change in weight loss and maintenance have been identified in systematic reviews,5 theory34,35,37–39 and NICE guidelines. 6,55 Table 3 represents the BCTs that the scriptwriter identified had been embedded in the narrative intervention.

| BCT cluster | BCT |

|---|---|

| Reward and threat | Social reward; anticipation of future rewards; incentive |

| Repetition and substitution | Behaviour substitution; habit reversal; habit formation; restructuring the social environment; avoidance of/changing exposure to cues for the behaviour |

| Antecedents | Restructuring the physical environment; restructuring the social environment; avoidance of/changing exposure to cues for the behaviour; distraction |

| Associations | Discriminative (learned) cue; prompts/cues |

| Natural consequences | Health consequences; social and environmental consequences; emotional consequences; self-assessment of affective consequences; anticipated regret |

| Feedback and monitoring | Feedback on behaviour; self-monitoring of behaviour |

| Goals and planning |

Action-planning (including implementation intentions); problem-solving/coping-planning; commitment; goal-setting (outcome); behavioural contract Discrepancy between current behaviour and goal standard; goal-setting (behaviour) Review behaviour goal(s); review of outcome goal(s) |

| Social support | Social support (practical); social support (general); social support (emotional) |

| Comparison of behaviour | Modelling the behaviour; information about others; approval; social comparison |

| Self-belief | Mental rehearsal of successful performance; focus on past success; verbal persuasion to boost self-efficacy |

| Identity | Identification of self as role model; self-affirmation; identity associated with changed behaviour; reframing; cognitive dissonance |

| Shaping knowledge | Reattribution; antecedents |

| Behavioural experiments | Instruction on how to perform a behaviour |

| Regulation | Regulate negative emotions; conserving mental resources; paradoxical instructions |

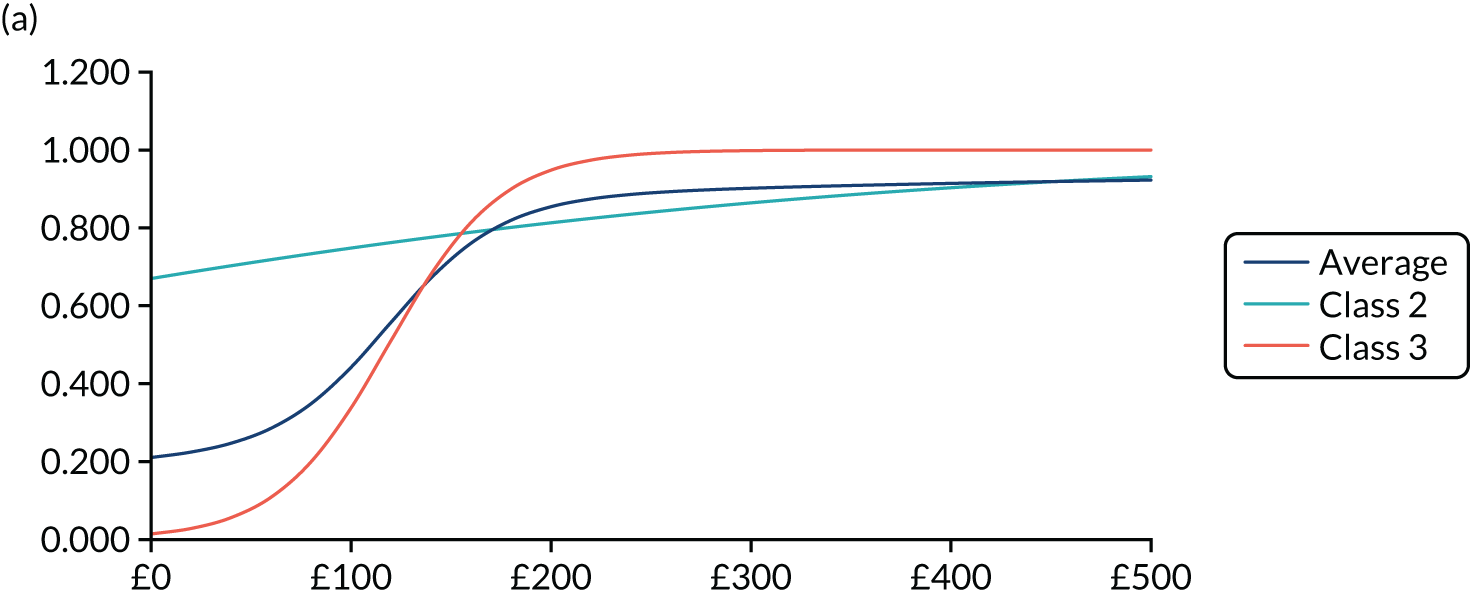

The key messages embedded

Patient and public involvement in the development of the narrative proved critical in assimilating key messages. Opinions varied; some thought that the message should be ‘just choose a diet and stick to it’, whereas others cited a wide range of diet and physical activity advice and tips available on official NHS advice websites. The PPI consultants mentioned that there was a confusing array of messages pertaining to the ideal diet and physical activity approaches ‘out there’. This issue was taken back to the narrative design team in subsequent script conferences, where it was decided that a hierarchy of key messages should be drawn up (Figure 6). This was then returned for consultation with 20 narrative patient and public participants. Through individual consultations and story and character workshops with the target demographic, it became apparent that only one message was meaningful: ‘eat less and be more active’. The rest of the messages were seen as confusing and often contradictory. ‘Eat less, move more’ then became the central key message to the thrust of the narrative and was embedded in the individual storylines.

FIGURE 6.

The hierarchy of key messages embedded in the narrative SMS.

The final key messages were consistent with current recommendations for weight management that focus on adhering to this message rather than on specific diets. 56

A total of 604 texts were sent by Slim over the 12 months. The overall narrative was first designed with enough interlinked stories to engage participants over 12 months, taking into account the number and frequency of texts used in previous studies that showed strong levels of engagement. 13,15,21,57 The number of interwoven stories was therefore increased to create an engaging narrative using no more than five texts per day over the 12 months.

Phase 2: intervention and narrative text writing

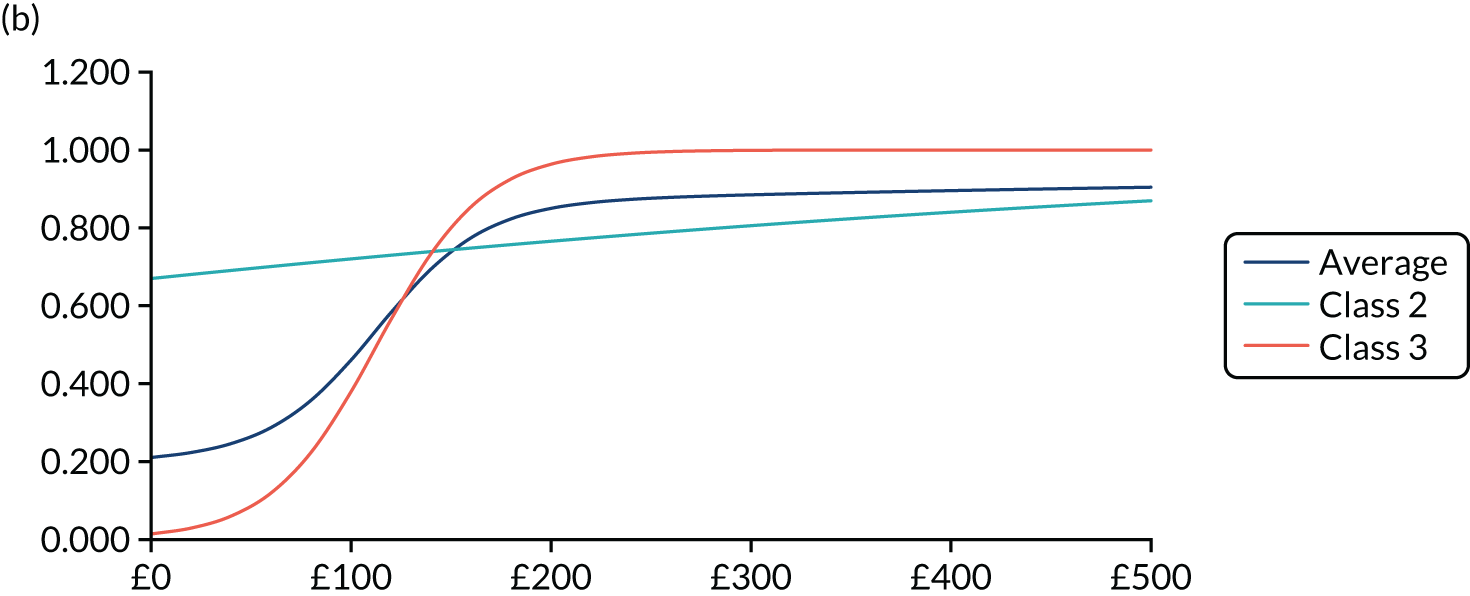

The first quarter of texts were written 12 weeks prior to the intervention start date. The scriptwriter wrote the texts and then elicited comments from health behaviour change psychologists, medics, experts in dietary control and members of the target demographic. Evidence from feedback was incorporated, as were the participants’ text responses to Slim. This feedback informed the writing and development of the texts transmitted in subsequent quarters in an iterative manner. Figure 7 represents phase 2: intervention and narrative text writing.

FIGURE 7.

Phase 2: narrative SMS intervention and key influences on final narrative texts.

Mode of narrative SMS delivery

The narrative SMS intervention was delivered using technology used in other RCTs linked to Tayside Clinical Trials Unit. 13–15 Although participants could interact by responding to the texts sent to them, there was no requirement for them to do so. This design provided the opportunity to gauge participants’ feelings about the texts. The scriptwriter received participants’ responses, which suggested how participants were feeling and acting in response to the texts sent to them in real time. The scriptwriter was then able to adjust the texts for the following quarter accordingly and in an iterative manner. For example, the scriptwriter received feedback about Slim and Wilma during character and story workshops conducted with representatives from the target demographic about the critical role a partner plays in helping to make or resisting changes in the home environment if new diet and exercise behaviours are to be adopted and triggers of old habits removed. However, Slim and Wilma’s marriage story appeared to resonate negatively with one participant during the actual intervention, who ‘had his own problems’ and felt that the story was ‘too close to home’. It was clear that the emotional power of this story was too resonant for some. The scriptwriter then reduced the number of texts featuring the marriage story. For examples of interpretations of the SMS replies and how these influenced the narrative, see Appendix 10.

Chapter 4 Phase 1 survey to inform the endowment incentive and trial processes

Background

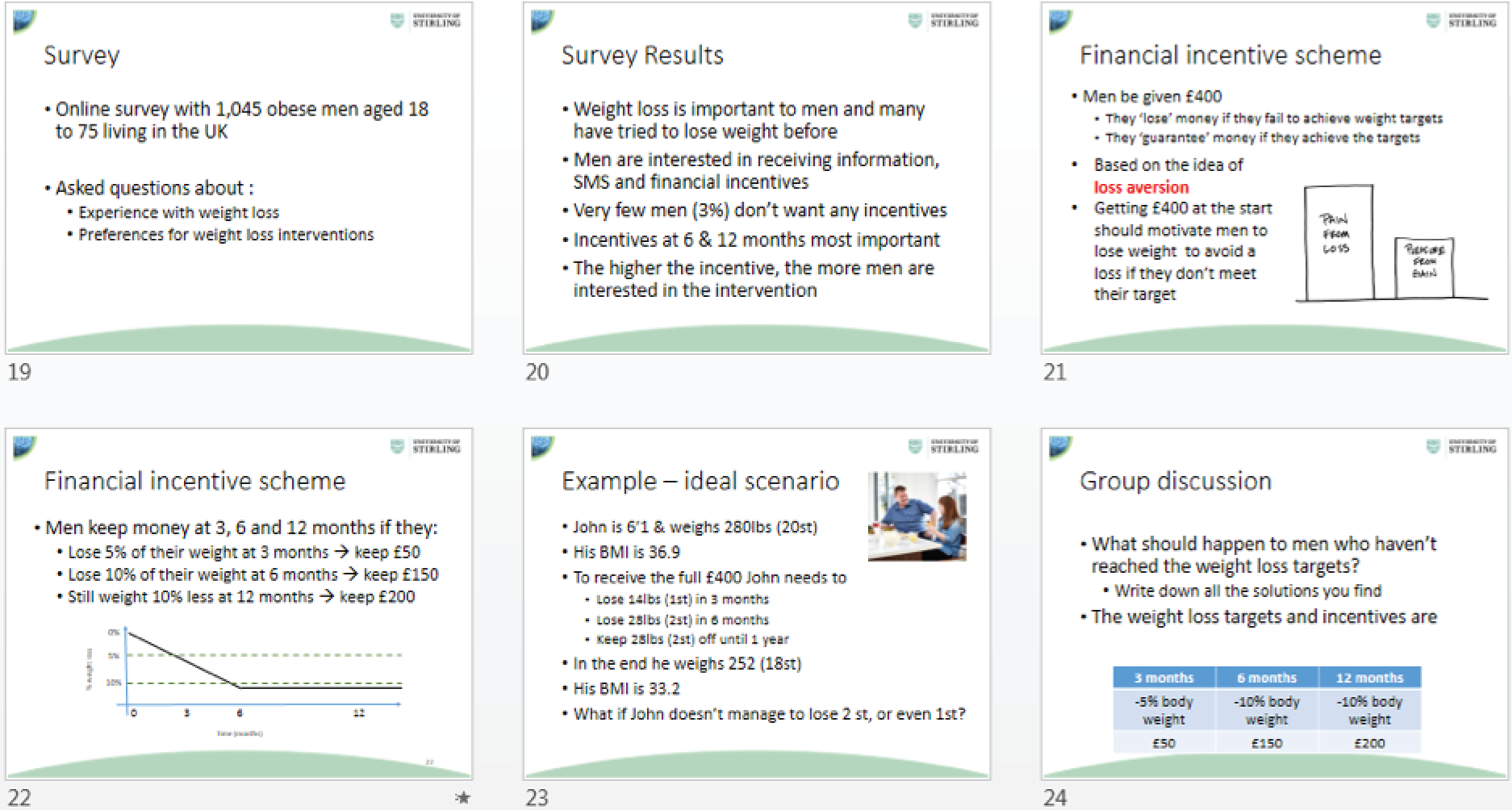

The use of financial incentive schemes to encourage health behaviours such as smoking cessation, weight loss and physical activity has become increasingly popular. 27,29,58 However, the design of incentive schemes does not always receive sufficient attention, even though this can vary in several dimensions, including value, frequency and direction (gain or loss). Researchers argue for more thought when designing financial incentive schemes, as the evidence for the optimal configuration is currently limited. 59,60 This study optimises the design of financial incentives by drawing on insights from behavioural economics, incorporating individuals’ preferences for different incentive designs and incorporating PPI (see Chapter 2). Designing interventions in line with participants’ preferences is argued to increase uptake and engagement.

A survey of men’s preferences was conducted to inform the incentive design, as little is known about these. The survey was also used to inform all components of the intervention (including SMS) and trial processes. Preferences for the incentive design were elicited using a DCE. The usefulness of DCEs in this context was first suggested by Purnell et al. 28 Hashemi et al. 61 undertook the only study to have used a DCE to elicit preferences for three dimensions of a financial incentive scheme for weight loss: the value of the monetary incentive, the form of the incentive and the timing of the payment. The results showed that individuals preferred larger incentives, more flexible forms of incentives and more immediate payments. Our study adds to this evidence and demonstrates the usefulness of DCEs in this context.

Methods

The survey included a DCE to inform the financial incentive design, questions to inform overall intervention design and sociodemographic questions. Validated questions were used when possible. The data were collected using an online survey administered by Ipsos MORI (London, UK; www.ipsos.com/ipsos-mori-en-uk). The sample size for the survey was calculated using an estimate of the population of interest (i.e. adult men with obesity in the UK: ≈6 million), a conservative estimate of variation in answers to the question of interest of 0.25, and an assumed margin of error of 3% in line with public opinion research. The sample consisted of 1045 UK men with obesity aged 18–75 years (quotas were imposed for age and UK regions to ensure that the sample was representative of the UK population in terms of these characteristics). Men were eligible if their reported height and weight placed them in the upper body mass index (BMI) quartile (i.e. ≥ 30 kg/m2). Ethics approval was obtained from the University of Stirling Research Ethics Committee.

A discrete choice experiment to inform financial incentive design

A DCE was used to elicit men’s preferences for different configurations of the financial incentive scheme in terms of scheduling, frequency and magnitude to optimise uptake and engagement. A DCE is a survey method that presents participants with a series of choices between two configurations of services, in this case configurations of weight loss programmes. Using regression modelling, the relative importance of the different dimensions (or attributes) of the programme can be estimated. This information can be used to decide on the optimal configuration of the financial incentive scheme.

The relevant attributes of the DCE were largely predetermined. The Adams et al. 59 framework was used to identify the different domains (or attributes) of a financial incentive scheme. The attributes included direction, form, magnitude, certainty, target, frequency, immediacy, schedule and recipient. Choices for several dimensions were predetermined based on existing evidence, trial logistics, feasibility if rolled out, and perceived acceptability to the public and to service providers (Table 4). These included cash, based on evidence for the preference of cash;31 certainty, based on trial logistics; target weight as a proxy measure for behaviour (i.e. weight loss); delivery at 12 months, based on trial logistics, and individual recipients based on trial logistics. The detailed justification for the a priori £400 ceiling level of the financial incentive is provided in Appendix 11.

| Domain | Dimension | This study |

|---|---|---|

| Direction | Positive reward; avoidance of penalty | Evidence: avoidance of penalty |

| Form | Cash; vouchers for range of goods or services; specific good/service | Evidence: cash |

| Magnitude | Continuous |

Unclear Acceptability and evidence: £400 (equal to annual cost of the drug orlistat, excluding monitoring costs) |

| Certainty | Certain; certain chance; uncertain chance | Trial logistics: certain |

| Target | Process; intermediate; outcome; proxy measure of behaviour | Trial logistics and acceptability: proxy measure for behaviour – weight loss |

| Frequency | All instances incentivised; some instances incentivised |

Unclear Trial logistics: maximum number of three instances (3, 6 and 12 months) |

| Immediacy | Continuous | Trial logistics: incentive paid out at 12 months only |

| Schedule | Fixed; variable | Unclear |

| Recipient | Individual; group; significant other; clinician, parent | Trial logistics: individual |

The choice of direction of the reward was based on insights from behavioural economics. The majority of previous studies using financial incentives at part of weight loss programmes used deposit contracts,62,63 which have been shown to be effective. 58 With deposit contracts, individuals deposit their own money into an account, and the money is returned if they follow through with a predetermined goal (e.g. achieving a certain amount of weight loss). However, individuals lose the money if they do not achieve the goal. Deposit contracts focus on losses rather than gains, which in theory improves effectiveness, as individuals tend to be loss averse, that is they value losses at a higher rate than equivalent gains. 64 The preferred direction of the current financial incentive scheme was, therefore, avoidance of losses.

This study targeted men with obesity living in areas of deprivation, where men may face financial constraints likely to have a negative impact on uptake and engagement. Therefore, it was decided to use a hypothetical endowment to try to invoke loss aversion. A hypothetical endowment is pledged at the start of the scheme. Participants can then secure set values of the money at certain time points if they achieve a weight loss, but will ‘lose’ money if targets are unmet. This scheme is similar to a deposit contract, the difference being that a hypothetical amount is pledged at the start rather than participants depositing their own money. Pledging the money at the start is likely to invoke an endowment effect, with individuals ascribing a (higher) value to the money because they believe that they ‘own’ it.