Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 17/44/29. The contractual start date was in October 2018. The final report began editorial review in May 2020 and was accepted for publication in December 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2021. This work was produced by Cox et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2021 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background

Smoking prevalence rates have continued to decline in the UK, with fewer young people starting to smoke and greater numbers of people quitting. 1 Smoking has also continued to decline across all socioeconomic groups. However, those from the most disadvantaged groups, such as those presenting with multiple and severe mental illness and substance use comorbidities, present smoking prevalence rates that far exceed those of other groups. 2–5

Smoking is extremely common among adults experiencing homelessness, with prevalence rates ranging from 57% to 82%;4 this is up to four times higher than the UK national average (15.1%). 1

Smoking is related to premature death and disease, and quitting can have a substantial positive impact on reducing harm and increasing life-years. 6 In smokers experiencing homelessness, tobacco-related disease has been cited as the second single cause of premature death and the single largest cause of death in those aged > 45 years. 7 Smoking is particularly fatal among this population because of a higher incidence of respiratory infection and disease. 8 These conditions are likely to be exacerbated because of a general likelihood of engaging in practices that increase the risk of developing respiratory infections, for example smoking discarded cigarettes and sharing cigarettes that act as a vessel for passing viral contaminants. 9,10 Poor respiratory health is also likely to be aggravated by smoking unfiltered and illicit tobacco, dragging harder on cigarettes and taking longer deeper puffs. 9 Beyond the health effects, smoking is also related to several social disadvantages; smokers experiencing homelessness are likely to engage in begging or ask strangers for cigarettes and are reported to spend up to one-third of their income on tobacco and cigarettes. 11

The types of lives that smokers experiencing homelessness have mean that quitting smoking is not a high priority and is also often overlooked by those who support them. 12 There is also some evidence that health and social care professionals are concerned that cessation will exacerbate mental illness and that taking something away, when many of these adults have so little, will be unfair or cruel. 13 Although these concerns are understandable, a survey we conducted in 2018 of 286 smokers accessing homeless services in England and Scotland showed that 75% of smokers have some desire to quit smoking and 75% have some history of quitting; however, quit attempts are often unsupported by behavioural support or licensed nicotine medication, and last less than 24 hours. 14

The UK has a clear goal of reducing the harms caused by tobacco smoking; central to this is the reduction in tobacco-related health inequalities by improving cessation rates. At present, however, smokers experiencing homelessness are not well represented in stop smoking services (SSSs) and cessation support is not mandatory in homeless centres. In the recent Tobacco Control Plan for England,15 the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) expresses its commitment to evidence-based innovations to support quitting and will seek to support smokers in adopting the use of less harmful nicotine products such as electronic cigarettes (ECs). Nevertheless, smoking cessation in the context of homelessness is underexplored in the UK. Our recent systematic review of 53 studies showed that only two cross-sectional studies had been conducted in the UK,4 of which one was conducted by our group. 14 Trial evidence from the US shows that there is potential to support cessation in this group. For example, Okuyemi et al. 16 measured the efficacy of motivational interviewing (MI) offered alongside licensed nicotine replacement therapies (NRTs) compared with NRTs alone. Using intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis, verified 7-day abstinence rates at week 26 were 9.3% for MI and NRTs, and 5.6% for NRTs alone (p = 0.15). To our knowledge, prior to the work presented here, there were no smoking cessation intervention studies in the UK. To reduce the burden of smoking among this population, more evidence of the efficacy of interventions is clearly required.

Our systematic review4 and public and patient involvement (PPI) work (conducted in 2017, with seven homeless centres, eight interviews from one major homeless charity and scoping data from 100 participants) helped to shape the design of this study. We were told that the multiple competing needs in this group meant that access to support needed to be made easy and appealing to provide the best chance of engagement. Thus, it was decided that the feasibility study should be embedded in centres that participants were already accessing. Our PPI work also suggested that ECs may be particularly appealing to smokers experiencing homelessness because (1) smokers in our scoping work were already experimenting with them, (2) they can be framed as a switch rather than a quit (which has connotations of loss), which has been highlighted as an issue of cessation, and (3) they can be offered at a location already being visited without a prescription, thus reducing the burden of making further appointments and removing a clinical approach. Taken together, the feedback was that ECs offer a pragmatic harm reduction approach to smoking cessation, and this is especially important when delivering interventions in the third sector, where substance harm reduction is already well established.

An individually randomised trial with allocation to one of two arms [ECs vs. usual care (UC)] was initially considered, but our PPI feedback (from staff and clients at homeless centres) strongly advised against this because of potential problems with compliance, contamination and issues of disharmony, for example resentment towards staff delivering the intervention in which one person had received an EC and another had not. Contamination, harmony and protection of staff were important; therefore, our decision was to opt for a feasibility cluster trial.

Here we present a pragmatic four-centre cluster feasibility study exploring the uptake and use of ECs by smokers accessing homeless support services. The overall purpose of this research was to evaluate the feasibility of supplying free EC starter kits for smoking cessation to smokers experiencing homelessness at a place that they were already accessing. The UC arm received standard existing treatment: advice to quit, an adapted NHS Choices fact sheet for smoking cessation and signposting to the local SSS, which offers weekly behavioural support and a choice of NRT or varenicline. The EC arm received a starter kit, a 4 weeks’ supply of e-liquid and a fact sheet.

Chapter 2 Objectives

To test the feasibility of future trial work, seven objectives were set. Table 1 presents the study objectives and associated outcome measures and whether the objective is specific to the cluster level or across levels.

| Objective | Outcome measure | Measured at |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Assess willingness of smokers to participate in the feasibility study to estimate recruitment rates and inform a future trial | In both arms, we will record the number of smokers asked to take part and the number of smokers who consent | Across arms |

| 2. Assess participant retention in the intervention and control arms | Record (1) how many participants complete assessment measures in each arm at each time point, and (2) how many participants still have, and are still using, ECs in the intervention arms | Across arms |

| 3. Examine the perceived value of the intervention, facilitators of and barriers to engagement, and influence of local context | Qualitative interviews with 4-week completers and non-completers, quitters and smokers (n = 24, approximately six per site) between weeks 4 and 8 across both arms | Across arms |

| 4. Assess service providers’ capacity to support the study and the type of information and training required | Qualitative interviews with keyworkers and front-line staff (n = 12, approximately three per site) across both arms | Across arms |

| 5. Assess the potential efficacy of supplying free EC starter kits | Measure breath CO levels, self-reported quit rates/cigarette consumption at each follow-up time point | Across arms |

| 6. Explore the feasibility of collecting data on contacts with health-care services among this population as an input to an economic evaluation in a full cRCT | Record participant utilisation of primary and secondary health-care services using a self-report service-use questionnaire at each time point and HRQoL using the EQ-5D-3L | Across arms |

| 7. Estimate the cost of providing the intervention and UC | Record all resources used in the delivery, including staff costs, ECs and other costs incurred. Staff will complete a pro forma to record contact time, non-contact time and other resources used in delivery | Across arms |

Chapter 3 Methods

Trial design

A four-centre cluster feasibility study with embedded qualitative process evaluation was conducted. A deviation from our protocol was made to the study design owing to the availability of centres. Centres were counterbalanced in each condition but not randomised (see Cluster allocation). However, participants joined after cluster allocation and allocation was concealed to participants until after the baseline assessment. Recruitment occurred during a discrete period starting from site initiation at each location (6 weeks).

Electronic cigarette sites offered an EC starter kit at baseline assessment. The EC arm is formed of two EC clusters.

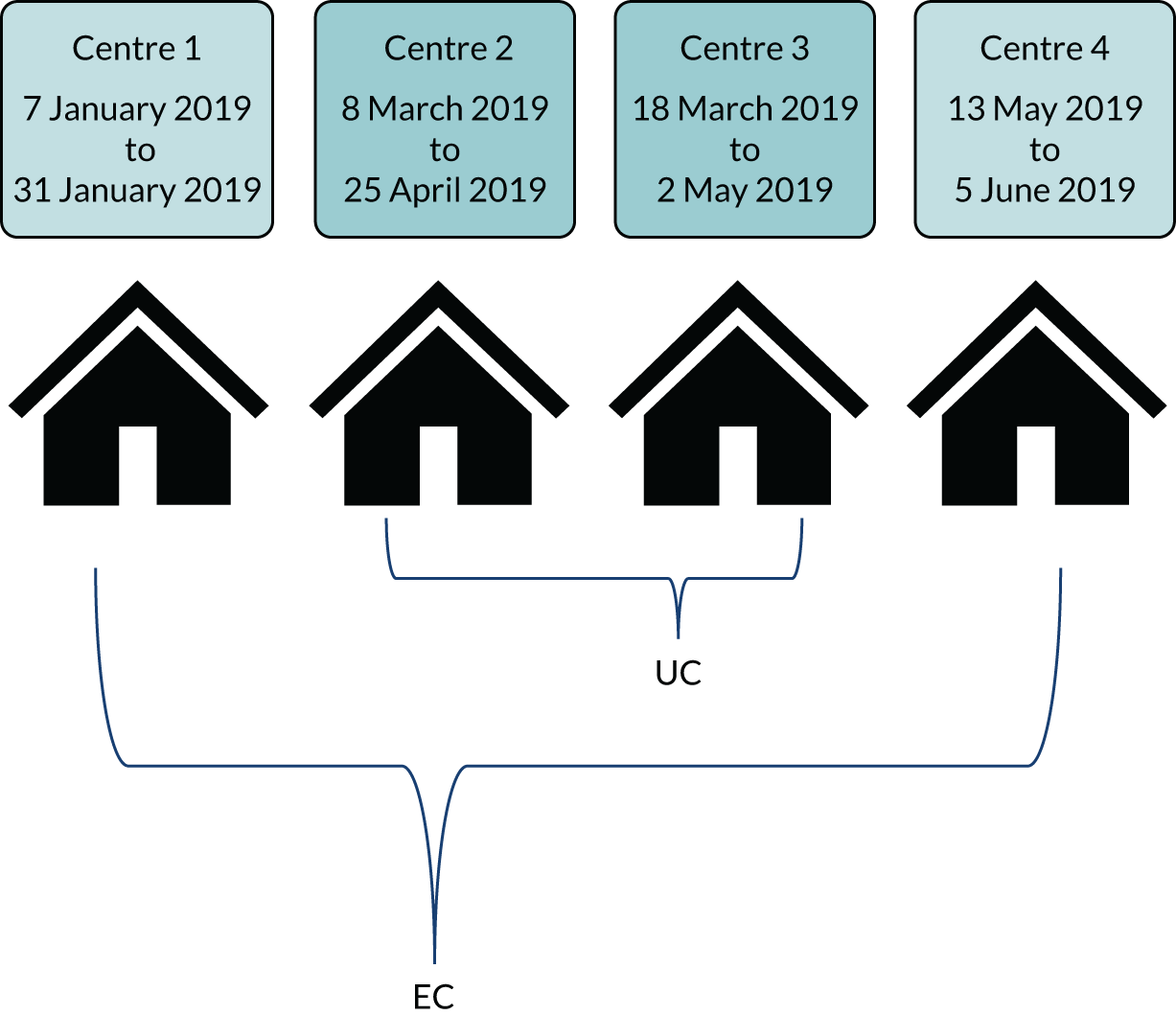

Usual care is defined as offering an adapted NHS Choices fact sheet for smoking cessation and signposting to the local SSS. The UC arm is formed of two UC clusters. The clusters are illustrated in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

The cluster sites. EC arm: Northampton (centre 1) and London (centre 4). UC arm: Edinburgh (centre 2) and London (centre 3).

Consent was taken at baseline by the research team. Follow-up data at 4, 12 and 24 weeks were also recorded by the research team. Keyworkers delivered the interventions (see Interventions).

Participants

Participants were selected by homeless centre staff based on the following inclusion criteria. Further eligibility checking was performed at baseline by the researcher. Eligibility criteria did not differ between clusters.

Inclusion criteria

-

Adult smokers (aged ≥ 18 years) accessing homeless support services on a regular basis and also known to staff.

-

Self-reported daily smokers only with smoking status also confirmed by support staff.

-

Smoking status also biochemically verified by exhaled carbon monoxide (CO) breath test at recruitment.

To gain wider representation, we did not exclude those who reported mental illness or substance dependence.

Exclusion criteria

-

Non-smokers or those reporting using another smoking cessation aid at the time of recruitment.

-

Anyone aged < 18 years, reporting pregnancy or unable to consent, for example they were currently intoxicated or unable to speak English.

-

All of those who were not well known to the centre staff were ineligible.

Description of settings

Centre 1 (electronic cigarette cluster)

This is a day centre (open Monday to Friday; 08.30–13.00) located within Northampton. Staff and volunteers, support workers, keyworkers, social workers and kitchen staff work to provide a range of facilities and programmes to serve the practical, physical and social needs of people experiencing or at risk of homelessness in the area. There is a breakfast and lunch service, training and employment skills programmes, and an emergency night shelter (run separately by the local council) for use during periods of inclement weather. The kitchen and day centre are open on Saturday mornings for people who are sleeping rough or in emergency accommodation.

Centre 2 (usual-care cluster)

This is a day centre (open Monday to Friday; 09.00–13.00) located within the city of Edinburgh. It offers breakfast, lunch and shower and clothing facilities, as well as spiritual support through chaplaincy and recreational facilities (TV, pool and day trips). Support staff provide crisis intervention advice and assistance with benefits, housing, accessing medical services for physical and mental health, and social and life skills emotional support.

Centre 3 (usual-care cluster)

This centre operates three linked sites of supported accommodation in London for people at risk of homelessness. Each site accommodates clients whose needs fall within the parameters of the level of care it is able to provide.

Site 1 has 21 bedsits in three adjoining three-and-a-half-storey houses with a shared garden and is staffed 24 hours for people with greater complex needs.

Site 2 has 12 bedsits for male residents who are semi-independent and benefit from the support of regular check-ins, health support, and help with advocacy and paperwork. The office staff are available Monday to Friday between 09.00 and 17.00.

Site 3 has seven units in one four-storey building. The residents are both men and women who are living mostly independently, with the support workers providing advocacy, signposting to services, and on-site management.

Centre 4 (electronic cigarette cluster)

Also located in London, centre 4 provides supported accommodation across four linked sites. Staff and volunteers include keyworkers, complex needs workers and kitchen and maintenance staff.

Site 1 is a 23-unit residential support service for men and women. Single accommodation units are set on two storeys and overlook an enclosed communal garden. There is a multipurpose meeting space in a small unit in the garden where staff run skills classes and social groups. Staff are on-site 24 hours for management and security. Residents have a range of abilities and needs, with the aim of returning to independent living. Staff aim to support people with complex needs through semi-independent living with keyworker support, advocacy and daily check-ins.

Site 2 is a 13-unit women-only supported accommodation, offering support to women who have been or are at risk of becoming homeless. The accommodation provides single-occupancy accommodation. There is a shared garden with chickens and a shared communal lounge and kitchen, but no private meeting spaces. Keyworkers provide support sessions within usual working hours: 09.00 to 17.00.

Site 3 is a short-stay house and site 4 provides first-night accommodation only (to provide emergency accommodation intended for people who are newly homeless or acutely at risk of rough sleeping).

The researchers routinely kept reflexive diaries to record observations and reflections about local contexts, as well as notes on the psychological impact of working in new and sometimes unpredictable environments where people are reacting to multiple, chronic and/or acute stressors and complex needs. These research notes formed the basis of debriefing meetings and discussions in the research team, in part to be informative of ecological differences between sites as well as to systematise the physical and psychological safety of the researchers.

Interventions

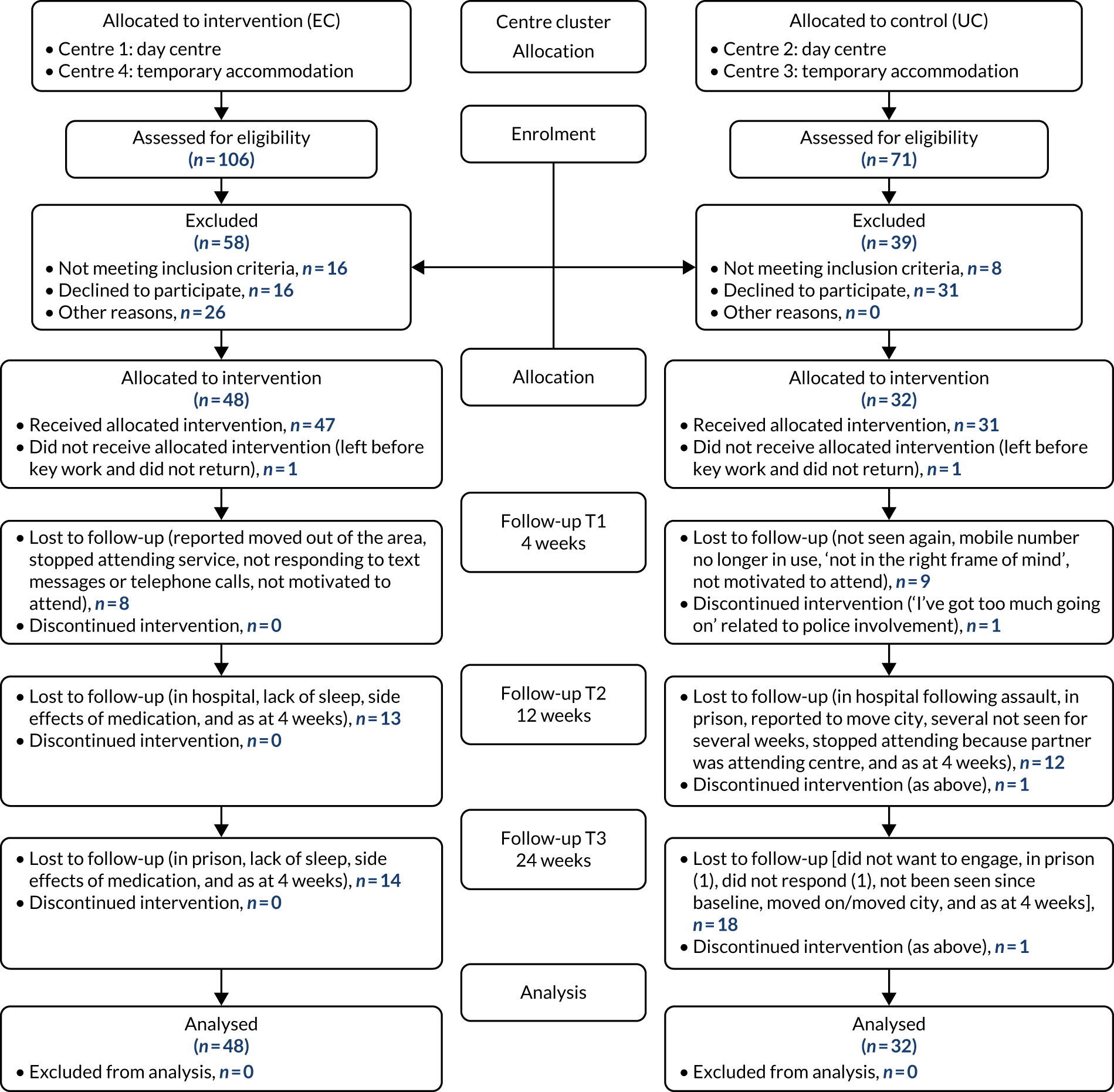

Interventions were delivered at cluster level. Appendix 1 presents the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram, which provides a summary of the stages of the study by intervention.

Pre-intervention staff training

The research team provided four education and training sessions to staff in each centre, 1–2 weeks before recruitment started. The educational content followed National Centre for Smoking Cessation and Training recommendations, to ensure that centre staff had a basic knowledge of the issues that surround smoking and smoking cessation and to optimise the delivery of the EC and UC interventions. The training was developed and led by Dr Deborah J Robson (King’s College London, London) with the support of the research team (LD, AT, SC, IU and AF); Table 2 presents an overview of the delivery of the staff education and training to 32 staff members across the centres. However, not all staff were able to attend the education and training sessions. In addition, new staff were employed in some centres during the intervention delivery phase of the study.

| Trial arm | Delivered by | Duration | Number of staff per training session | Materials provided |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EC | ||||

| Centre 1 | Deborah J Robson; Allan Tyler; Lynne Dawkins | 2 hours (plus individual coaching) | 12 | EC instruction pamphlet |

| Centre 4 | Deborah J Robson; Allan Tyler; Sharon Cox; Catherine Kimber | 2 hours (plus individual coaching) | 8 | EC instruction pamphlet |

| UC | ||||

| Centre 2 | Deborah J Robson; Sharon Cox; Allison Ford; Isabelle Uny | 1.15 hours | 7 | Help-to-quit leaflet |

| Centre 3 | Deborah J Robson; Allan Tyler; Lynne Dawkins | 1.15 hours | 5 | Help-to-quit leaflet |

Education and training content for both intervention arms included the following:

-

prevalence and patterns of smoking among the wider population and people experiencing homelessness

-

health effects of smoking

-

benefit of smoking cessation

-

common misperceptions around smoking cessation in the context of other addictions and mental illness

-

why this study was important and why it was needed now

-

how to complete the baseline and follow-up forms and what was expected from staff.

Additional electronic cigarette training

Staff were expected to deliver the intervention and were therefore provided with information on the evidence base of EC use, clinical effectiveness and safety among the wider population and a rationale behind why ECs may be useful for this group. In addition, in the training session, staff were provided with information about how to deliver correct advice about ECs to participants and given a practical hands-on demonstration relating to aspects of EC assembly, how to use the device, charge it, refill the tank and replace coils, and battery safety. Including the practical hands-on demonstration meant that the EC intervention training took up to 45 minutes longer than the UC training.

The research team in the EC arm provided additional coaching in preparation for each staff member’s first two keyworker sessions at baseline, and through shadowing and feedback at ongoing sessions. Ongoing informal training was provided, in the form of question-and-answer discussions with staff between keyworker sessions and before and after participants’ arrival.

Additional usual-care training

As in the EC arm, staff were asked to deliver the UC referral information and were therefore provided with detailed information on the role of SSSs, current licensed medications available to smokers in their local SSS and evidence for their clinical effectiveness. Staff were informed that, at the time of training, licensed stop smoking medicines alongside behavioural support offered at the SSS were the most effective way of quitting smoking. Details of the centre’s local SSS and how to make a referral were also included in the training.

Electronic cigarette intervention

All participants in the EC cluster (centres 1 and 4) received the same intervention.

Participants were provided with an unboxed Aspire PockeX kit (Aspire eCig UK, Peterborough, UK) starter kit comprising a tank-style refillable EC with a spare atomiser, charger and wall adapter plug. They were offered five 10-ml bottles of e-liquid, choosing from a combination of (1) e-liquid nicotine strengths (two options: 12 or 18 mg/ml) and (2) flavours (three options: tobacco, fruit or menthol). E-liquid nicotine strengths of 12 and 18 mg/ml were chosen based on previous reports from our group and others of high nicotine dependency among smokers experiencing homelessness. 14 The EC brand and e-liquid were decided on following our PPI work and advice from vapers. Vapers known to the research team who have engaged in other research suggested four of the top-selling, easy-to-use ECs. On purchasing these, smokers from one London homeless centre tried the four different ECs and provided feedback on ease of use, nicotine hit and likeability. The Aspire PockeX was consistently rated as the easiest and most satisfying to use. The flavours were recommended by a vape retailer because they are the most popular, that is best-selling, varieties.

At this time, the keyworker showed the participant how to use the device; this included how to (re)fill the liquid in the tank, how to charge the device, how to inhale and what to expect when first using the device. Participants were also provided with the device instructions, which in response to our PPI feedback had been retyped into a larger font, and a help sheet of ‘tricks and tips’ from experienced vapers. Participants were given time to try the device and experiment with the different flavours and nicotine strengths, and were permitted to switch between flavours. (Appendix 2 presents the selection of e-liquid flavours and concentrations that were given out by keyworkers.) The keyworker recorded the participants’ choices of e-liquid and the timing of the keyworker session in case report forms (CRFs) that were kept with the study equipment.

Once per week in the 3 weeks that followed the baseline meeting, participants met centre staff to report any concerns and collect up to five 10-ml bottles of e-liquid and a new atomiser. Ideally, participants met the staff member whom they had met at the baseline session and who had attended the staff training; however, because of staff turnover and time demands this was not always feasible. Staff recorded data on e-liquid and troubleshooting in the CRFs. With a larger number of participants attending follow-up appointments at centre 1, staff adopted a drop-in ‘surgery’ in which waiting participants also received peer advice and support.

Usual care intervention

All participants in the UC cluster (centres 2 and 3) received the same assessment measures, but UC differed across the two centres in this cluster.

At the end of the baseline assessment, and during the same session, participants were informed of their centre allocation. Participants were then referred to their keyworkers/other centre staff who advised them to consider quitting and provided them with the fact sheet and an adapted NHS Choices ‘help-to-quit’ leaflet; this included information about the location and opening hours of SSSs local to the centre. Paper copies of the help-to-quit leaflet (with SSSs’ contact details) were available as posters/flyers at homeless centres in the UC condition/cluster. Centre staff were asked to follow up with participants once per week for 4 weeks to record whether or not they had made contact with the SSS and to remind them to do so.

Process evaluation

All participants were asked after baseline CRF completion if they would be interested in taking part in the qualitative process evaluation. Individual interviews were conducted in a quiet, private space on homeless centre premises, between weeks 4 and 8 of the trial. A semistructured topic guide was used to ensure that all relevant topics were covered, and interviews were digitally recorded with participants’ consent.

The participants’ guide covered smoking history; awareness of local SSSs; experiences of trial processes; expectations and experiences of vaping (EC arm); and experiences of signposting to SSSs (UC arm).

The staff topic guide covered staff role and trial involvement; existing cessation support for clients; and views and experiences of the trial, processes, and the EC or UC interventions. Both guides covered unintended consequences and recommendations for improvements.

Incentives for retention

The wider literature on smoking and homelessness has shown that it is common practice to offer a financial incentive to participants and that this improves retention. 4 Regardless of cluster, all participants were compensated with a £15 high-street gift card (Love2Shop, Birkenhead, UK) for completing assessments at baseline and follow-up and the qualitative interview (totalling £75). Staff did not receive a gift card for taking part in the interviews. Participant payment was not contingent on quitting or cutting down and this was stressed to the individuals taking part.

Outcome measures

Some parts of the following text have been reproduced with permission from Dawkins et al. 17 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Table 1 presents the outcomes and associated measures, including the relationship to each intervention arm.

Baseline measures (across clusters)

-

Demographic information and homeless status/history.

-

Cigarettes smoked per day, smoking history (e.g. length of smoking, previous number of quit attempts, support used) and past and current EC use.

-

Severity of tobacco dependence, measured by the Fagerström Test of Cigarette Dependence (FTCD) (Fagerström18) and expired CO.

-

Motivation to stop smoking (MTSS), measured by the Motivation to Stop Scale, a seven-level single-item instrument that incorporates intention, desire and belief in quitting smoking. 19

-

Mental health status, measured using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 items (PHQ-9)20,21 for depression (total score ranging from 0 to 27, with a higher score indicating greater severity of depression) and Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) questionnaire (total score ranging from 0 to 21, with a higher score indicating greater severity of anxiety). 22

-

Alcohol use, measured using the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT), a 10-item screening instrument developed by the World Health Organization to screen for alcohol problems. Scores range from 0 to 40, with a score of > 8 indicating harmful or hazardous drinking and > 13 (females) or > 15 (males) indicating alcohol dependence. 23

-

Drug use measured using the Severity of Dependence Scale (SDS), a five-item screening measure of psychological aspects of dependence yielding a total possible score ranging from 0 (no/low dependence) to 15 (high dependence). 24

-

General health-care and service use measured using an adapted health-care and social service utilisation questionnaire relating to services accessed in the last 4 weeks.

-

Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) measured using the EuroQol-5 Dimensions, three-level version (EQ-5D-3L), a widely used measure that provides a single value for health status that can be used in the clinical and economic evaluation of an intervention. 25,26

All questionnaires and measures have good psychometric properties and have been used in previous research with vulnerable populations.

Follow-up data collection

Usual care

At weeks 4, 12 and 24, the following information was collected:

-

smoking information: self-reported smoking abstinence; number of cigarettes smoked in the past 7 days (to measure 7-day point prevalence abstinence); number smoked per day (to calculate smoking reduction from baseline)

-

exhaled CO breath test

-

engagement with the local SSS (appointments made and attended)

-

use of EC and other tobacco/nicotine-containing products

-

general health-care and service use; HRQoL; mental health status (GAD-7, PHQ-9)

-

other drug use/dependence (AUDIT, SDS)

-

direct and indirect staff contact time.

Electronic cigarettes

At weeks 4, 12 and 24, in addition to the aforementioned information, the following was collected:

-

Self-report information about 12 positive effects (e.g. throat hit, satisfaction, pleasant, craving reduction) and 21 negative effects (e.g. mouth/throat irritation, nausea, headache, heartburn) of EC use. This was reported using a visual analogue scale (VAS) and summed to create a percentage score (higher score = higher positive or negative effect) as used in our previous studies. 27

-

Information to further monitor risk and adverse effects (e.g. EC theft, exchanges, use for other substances), an unintended consequences checklist was developed specifically for this trial.

The research team collected all of the baseline and consent data and the 4-, 12- and 24-week follow-up data.

Feasibility study outcome measures

-

To assess willingness to take part in the study, we recorded (1) the number of people who were asked, (2) the number eligible to take part and (3) the number who consented to take part.

-

Retention and engagement were measured by recording (1) the proportion of participants who completed assessment measures in each arm at each time point, and (2) the proportion of participants still using ECs in the intervention arm and who had visited the SSS in the UC arm.

-

To estimate the parameters for future trial at each follow-up point, we recorded (1) CO-validated sustained abstinence (from 2 weeks post quit date allowing up to five slips); (2) CO-validated 7-day point prevalence abstinence (i.e. no smoking at all in the past 7 days); and (3) the proportion achieving 50% smoking reduction [calculated by subtracting cigarettes per day (CPD) at follow-up from baseline].

-

To explore the feasibility of collecting data on contacts with health-care services, we recorded participant utilisation of primary and secondary health-care services using a self-report questionnaire.

-

Data on staff contact time, non-contact time and other resources used in EC and UC delivery, including staff costs, ECs and other costs incurred, were collected to provide an indicative cost of the intervention.

The research team collected all of the baseline and consent data and the 4-, 12- and 24-week follow-up data.

Sample size

As this was a feasibility study for a main trial, no formal power calculation based on detecting evidence for efficacy was conducted; the outcomes of the study allowed us to calculate the required sample size [and an intracluster correlation coefficient (ICC)] for a possible future definitive cluster randomised controlled trial (cRCT).

As per our published protocol,28 a pragmatically chosen sample size (N = 120; n = 30 per centre, n = 60 per cluster) was based on our pre-feasibility PPI work and also taking information from published works in similar samples. This information allowed us to identify evidence of feasibility, recruitment rates and any problems with the intervention or research methods. Our pre-feasibility scoping work suggested that the centres had daily contact with between 25 and 120 individuals, of whom 70–90% were likely to be smokers. Other studies on homeless populations have reported follow-up rates ranging between 24% and 88% (depending on the location of visits, provision of incentives and use of prompts). 29 Therefore, we estimated that 50% of those who agree would drop out in the period between consenting to participate and the final follow-up at 24 weeks, leaving an estimated sample size at the final follow-up of 60.

In relation to the qualitative process evaluation, we planned to interview a subgroup of 24 homeless smokers (approximately six per centre) and 12 staff members (approximately three per centre). We also aimed to include continuing participants and those who did not complete their 4-week follow-up, and those in the EC and UC arms. This sample size is adequate for collection of qualitative data necessary to assess objectives 3 and 4.

Although there was no formal interim analysis or stopping guidelines, we did specify in our ‘project timetable and milestones’ that we would assess recruitment and 4-week retention at centre 1 after 2 months to determine whether or not to proceed with recruitment at centres 2, 3 and 4.

Cluster allocation

The centres in Northampton (centre 1) and Edinburgh (centre 2) are both day centres, whereas the two London centres (centres 3 and 4) are residential units. We planned to pair and match centres on accommodation provision; that is, each one of the residential centres would be paired with one of the day centres. We would then randomly allocate the two London centres, that is, one to the EC arm and the other to the control (UC) arm, with their accompanying pair (day centre) allocated to the other arm.

However, when we were ready to begin recruitment, the centres in London had not confirmed their availability for training and study start date. Thus, centre allocation could not be randomised and therefore deviated from protocol: we started with the centre that was ready to start training and recruitment, which was the centre in Northampton. We allocated this first centre to the EC condition so that we could explore recruitment, 4-week retention and any unintended consequences associated with the intervention to determine whether or not to proceed with recruitment at centres 2, 3 and 4. Centre 2 (Edinburgh) as the other day centre was therefore allocated to the UC condition. Centres 3 and 4 (London) were allocated to the UC and EC arms, respectively. Centre 3 was allocated to UC, as it was geographically closer to the researcher who was still collecting follow-up data from centre 1 and we expected lower uptake in the UC condition.

Thus, the actual allocation of centres to each arm was non-random; it was a pragmatic decision based on centre readiness and staff/researcher availability, though we balanced potential confounders and differences in environment by ensuring each cluster (EC and UC) contained one day centre and one residential unit.

Allocation concealment mechanism

As this represents feasibility work, a pragmatic approach to the concealment of the intervention was taken. Participants were told of the condition that they had been allocated to only after consent and baseline assessment; this was the same across the clusters. However, because of the nature of the conditions, namely that those in the EC clusters were provided with a starter pack and the social dynamics in the centres (particularly the day centres) were close-knit and interactive, the centre allocation was quickly revealed between participants and also to new participants.

Contamination

Contamination in the context of this design was defined as a participant receiving the intervention delivered by another participating centre, for example a participant in UC receiving a free EC starter pack from one of the EC clusters.

Implementation

This section is not applicable to this work.

Analytical method

This is a feasibility study for a trial in preparation for a future cRCT, and analyses of effect are not appropriate. Analyses were conducted to evaluate the feasibility study outcomes (see Table 1). Similarly, because this is a feasibility study for a trial, subgroup analyses are not appropriate.

Table 1 presents the objectives and associated outcome measure for each objective. Objectives 1, 2, 5, 6 and 7 were measured quantitatively, and objectives 3 and 4 were measured through the qualitative process evaluation. Each objective was measured across the whole sample, with the exception of objectives 5 and 7, which relate to efficacy and cost-effectiveness of the interventions. Chapter 4 (see Table 3) presents the descriptive data for participant characteristics for the trial. Appendix 3 also presents the data for the subset of participants in the process evaluation.

Baseline demographic data were summarised using frequencies and descriptive statistics, and the arms (EC vs. UC) were compared using a t-test/Mann–Whitney U-test or Fisher’s exact test for continuous and categorical variables, respectively. EC effects are summarised descriptively. Changes in mental health status and substance use were explored over time and between arms using repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA).

-

Objectives 1 and 2: participant willingness to take part and retention

Frequency information regarding the number of smokers who (1) were invited to take part, (2) were eligible to take part, (3) consented/completed the baseline assessment and (4) attended and completed each follow-up.

-

Objectives 3 and 4: to examine the perceived value of the intervention, facilitators of and barriers to engagement, and influence of local context, and to assess service providers’ capacity to support the study and the type of information and training required

Interviews lasted between 16 and 65 minutes, were transcribed verbatim by professional transcribers, were checked for accuracy and were entered into NVivo 12 software (QSR International, Doncaster, UK) to facilitate coding and analysis. Data were analysed using thematic analysis. 30 Separate coding frameworks for both participants and staff, with themes initially formed deductively, were developed using the main objectives and interview topics. The qualitative team (AF, IU and AT) conducted a first round of coding with AF, checking all coding for consistency. Through discussion, inductive themes were identified and agreed, leading to a second round of coding. Using an iterative approach, coded themes were then used as the categories for analysis. Data were carefully examined to identify the range and diversity of responses and themes, and subthemes were created and/or refined as appropriate. Findings were interpreted and discussed among the wider team. Quotations were selected to illustrate findings. The study arm for each participant [EC or UC, centre code (01–04)] and whether or not the quotation was from a trial participant or a staff member are indicated alongside the quotations.

-

Objective 5: assess the potential efficacy of supplying free EC starter kits

The proportion of participants reporting sustained smoking abstinence, 7-day point prevalence abstinence (both CO verified) and a 50% reduction in smoking in each arm at each follow-up time point were recorded. These variables are presented with the denominator being the number of people who attended follow-up. Sustained abstinence is also presented and analysed using ITT analysis; that is, all those allocated are included in the analysis as belonging to the group to which they were originally allocated and those with missing outcome data were treated as smokers. The ICC was calculated by the Fleiss–Cuzick method. 31

-

Objectives 6 and 7: to explore the feasibility of collecting data on contacts with health-care services among this sample as an input to an economic evaluation in a full cRCT and to estimate the cost of providing the intervention and UC

The completeness of EQ-5D-3L and service use questionnaires was examined. We used the UK population tariff32 to convert the results of EQ-5D-3L to utility value. Quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) were then calculated in each arm using the area under the curve plotted from baseline and follow-up points. 33 A set of national weighted average unit costs were extracted from secondary or published sources (see Appendix 4 and Appendix 5). The quantities of services reported by participants were multiplied by the respective unit costs to present a preliminary cost profile. We also present the costs of the programme, including training and delivery, the details of which were recorded by the research team. Results from the health economics component will be used to refine the instruments for a full randomised controlled trial (RCT).

Recruitment

Recruitment and 4-week follow-ups ran sequentially across the three sites in England, with 12- and 24-week follow-ups overlapping. Recruitment and data collection in Edinburgh ran in parallel with the second centre in England.

The feasibility study was completed within the planned time frame. However, although we planned to recruit for 4 weeks at each centre, recruitment was extended to 6 weeks in the UC arm. This was a pragmatic decision taken with assistance from the Trial Steering Group, the research team and centre staff. Centre 1 saw high levels of interest in the study and extending the recruitment period to 6 weeks was not required. We did extend capacity in the 4-week window to recruit more participants who were interested in taking part, anticipating potentially lower uptake in smaller centres. Conversely, centre 2 proved to be particularly challenging for recruitment because of staff time and competing needs and resources. The research team had to adapt to the conditions of the centre, appointments had to be rescheduled, and staff were not always available to assist. Centre 3 was quieter and overlapped with data follow-up at centre 1. Residents also had daytime commitments that clashed with recruitment, so again the research team needed to be flexible and therefore recruitment was continued over 6 weeks until we reached saturation.

Sampling and recruitment for the qualitative process evaluation

All those enrolled in the trial were asked at baseline about their willingness to take part in the process evaluation interviews and whether or not they were willing to be contacted at a later date to arrange an interview. After the intervention phase, those who had consented to be contacted were approached by a researcher by telephone, or in person at the homeless centre, and invited to take part. At centre 1, staff identified participants whom they felt would be most willing to take part. Throughout the centres, staff who were supporting the participants and the project were also eligible to take part in an interview. Potential interviewees were provided with a participant information sheet and re-contacted several days later. An interview date and time were arranged for interested participants. Written consent was obtained at the start of the interview.

Purposive sampling was utilised with a pre-determined target to recruit approximately six trial participants and three staff members at each of the four homeless centres. Trial participants were also to be sampled according to (1) smoking status at week 4 of the trial and (2) whether or not they completed the week 4 follow-up.

Centre 1: electronic cigarettes

Recruitment/baseline: 7 January to 31 January 2019.

4-week follow-up: 4 February to 28 February 2019.

12-week follow-up: 1 April to 25 April 2019.

24-week follow-up: 24 June to 17 July 2019.

Centre 2: usual care

Recruitment/baseline: 8 March to 25 April 2019.

4-week follow-up: 8 April to 17 May 2019.

12-week follow-up: 4 June to 25 July 2019.

24-week follow-up: 23 August to 10 October 2019.

Centre 3: usual care

Recruitment/baseline: 18 March to 2 May 2019.

4-week follow-up: 18 April to 18 May 2019.

12-week follow-up: 18 June to 18 July 2019.

24-week follow-up: 10 September to 25 September 2019.

Centre 4: electronic cigarettes

Recruitment/baseline: 13 May to 5 June 2019.

4-week follow-up: 10 June to 4 July 2019.

12-week follow-up: 7 August to 28 August 2019.

24-week follow-up: 28 October to 20 November 2019.

Process evaluation

Interviews were conducted between February and July 2019 by one of a mixed-sex team of three full-time qualitative researchers experienced in interviewing vulnerable groups (AF, AT and IU).

Chapter 4 Results

Baseline data

Baseline data are presented in Table 3.

| Characteristic | Trial arm | Total (N = 80) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EC | UC | |||

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 42.75 (10.90) | 42.53 (10.78) | 42.66 (10.79) | 0.93 |

| Sex, n (%) | 0.34 | |||

| Female | 19 (40) | 9 (28.13) | 28 (35) | |

| Male | 29 (60) | 23 (71.88) | 52 (65) | |

| Employment status, n (%) | 0.11 | |||

| Full-time school or college | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| Paid employment/self-employed | 2 (4.16) | 0 (0) | 2 (2.50) | |

| Government training scheme | 1 (2.08) | 1 (3.13) | 2 (2.50) | |

| Unpaid or voluntary work | 9 (18.75) | 0 (0) | 9 (11.30) | |

| Waiting to work, already obtained | 1 (2.08) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.30) | |

| Looking for work/training scheme | 7 (14.58) | 5 (15.63) | 12 (15.00) | |

| Prevented by temporary sickness/injury | 2 (4.16) | 3 (9.38) | 5 (6.30) | |

| Permanently unable to work | 21 (43.75) | 17 (53.13) | 38 (47.50) | |

| Unemployed and not looking for work | 3 (6.25) | 2 (6.25) | 5 (6.30) | |

| Other | 2 (4.16) | 4 (12.5) | 6 (7.50) | |

| Current sleeping situation (past 7 days), n (%)a | ||||

| Sleeping rough on streets/in parks | 3 (6.25) | 4 (12.5) | 7 (8.80) | 0.42 |

| Hostel or supported accommodation | 31 (64.58) | 17 (53.13) | 48 (60) | 0.36 |

| Sleeping on somebody’s floor/sofa | 1 (2.08) | 2 (6.25) | 3 (3.80) | 0.56 |

| Emergency accommodation (refuge, shelter) | 8 (16.66) | 1 (3.13) | 9 (11.30) | 0.08 |

| B&B or temporary accommodation | 1 (2.08) | 1 (3.13) | 2 (2.50) | 1.00 |

| Housed: own tenancy | 8 (16.66) | 10 (31.25) | 18 (22.50) | 0.17 |

| Other | 2 (4.16) | 0 (0) | 2 (2.50) | 0.51 |

| Background, n (%)a | ||||

| Spent time in prison | 19 (40) | 21 (65.63) | 40 (50) | 0.04 |

| Spent time in secure/young offender unit | 9 (18.75) | 9 (28.13) | 18 (22.50) | 0.41 |

| Spent time in local authority care | 7 (14.58) | 10 (31.25) | 17 (21.30) | 0.10 |

| Spent time in the armed forces | 3 (6.25) | 4 (12.50) | 7 (8.80) | 0.43 |

| Admitted to hospital because of mental illness | 18 (37.50) | 13 (40.63) | 31 (38.80) | 1.00 |

| Been a victim of domestic violence | 18 (37.50) | 13 (40.63) | 31 (38.80) | 1.00 |

| Highest level of education, n (%) | 0.40 | |||

| School: stopped prior to GCSE/Standard Grade | 17 (35.42) | 7 (21.88) | 24 (30) | |

| School: GCSE/Standard Grade | 13 (27.08) | 13 (40.63) | 26 (32.50) | |

| College: A level/FE/Highers | 15 (31.25) | 10 (31.25) | 25 (31.30) | |

| University: degree level | 3 (6.25) | 1 (3.13) | 4 (5) | |

| University: postgraduate or higher level | 0 (0) | 1 (3.13) | 1 (1.30) | |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | 0.64 | |||

| White | 35 (72.92) | 26 (81.25) | 61 (76.30) | |

| Asian/Asian British | 6 (12.50) | 2 (6.25) | 2 (2.60) | |

| Black/black British | 2 (4.17) | 0 (0) | 9 (11.40) | |

| Mixed race/multiple ethnic groups | 5 (10.42) | 4 (12.50) | 8 (10.20) | |

| Sexual orientation, n (%) | 0.81 | |||

| Heterosexual or straight | 40 (83.33) | 28 (87.50) | 68 (85) | |

| Gay or lesbian | 1 (2.08) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.30) | |

| Bisexual | 2 (4.16) | 1 (3.13) | 3 (3.80) | |

| Prefer to self-define | 2 (4.16) | 1 (3.13) | 3 (3.80) | |

| Prefer not to say | 3 (6.25) | 0 (0) | 3 (3.80) | |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 2 (6.25) | 2 (2.50) | |

| Immigration status, n (%) | 0.68 | |||

| UK national | 45 (93.75) | 29 (90.63) | 74 (92.50) | |

| EEA national | 3 (6.25) | 3 (9.38) | 6 (7.50) | |

| Receiving public funds (benefits), n (%) | 0.16 | |||

| Yes | 48 (100) | 30 (93.75) | 78 (97.50) | |

| No | 0 (0) | 2 (6.25) | 2 (2.50) | |

| Long-standing illness, disability or infirmity, n (%) | 0.02 | |||

| Yes | 30 (62.50) | 29 (90.63) | 59 (73.80) | |

| No | 13 (27.08) | 3 (9.38) | 16 (20) | |

| Prefer to self-define | 4 (8.33) | 0 (0) | 4 (5) | |

| Prefer not to say | 1 (2.08) | 0 (0) | 1 (1.30) | |

| Number of CPD, mean (SD) | 20.5 (16.78) | 19.41 (13.07) | 20.07 (15.33) | 0.86 |

| Expired CO, mean (SD) | 19.60 (9.58) | 21.31 (10.77) | 20.29 (10.04) | 0.46 |

| Number of joints per day, mean (SD) | 0.29 (1.13) | 1.73 (2.69) | 0.7 (1.69) | 0.02 |

| FTCD, mean score (SD) | 5.24 (2.53) | 6.13 (2.35) | 5.51 (2.47) | 0.12 |

| Age (years) started smoking, mean (SD) | 16.02 (6.30) | 13.92 (3.72) | 15.17 (5.47) | 0.09 |

| Sharing cigarettes, n (%) | 0.10 | |||

| Not at all | 25 (52.08) | 9 (28.13) | 35 (43.80) | |

| Occasionally | 10 (20.83) | 7 (21.88) | 18 (22.50) | |

| Regularly | 3 (6.25) | 5 (15.63) | 7 (8.80) | |

| Daily | 9 (18.75) | 11 (34.38) | 19 (23.80) | |

| Smoking discarded cigarettes, n (%) | 0.43 | |||

| Not at all | 30 (62.50) | 15 (46.88) | 45 (56.30) | |

| Occasionally | 12 (25) | 10 (31.25) | 22 (27.50) | |

| Regularly | 3 (6.25) | 4 (12.50) | 7 (8.80) | |

| Daily | 2 (4.16) | 3 (9.38) | 5 (6.30) | |

| Asking strangers for cigarettes, n (%) | 0.35 | |||

| Not at all | 31 (64.58) | 16 (50) | 47 (58.80) | |

| Occasionally | 12 (25) | 9 (28.13) | 21 (26.30) | |

| Regularly | 2 (4.16) | 3 (9.38) | 5 (6.30) | |

| Daily | 2 (4.16) | 4 (12.50) | 6 (7.50) | |

| MTSS, n (%) | 0.04 | |||

| I do not want to stop smoking | 1 (2.08) | 4 (12.50) | 5 (6.30) | |

| I think I should stop but do not really want to | 4 (8.33) | 4 (12.50) | 8 (10) | |

| I want to stop but have not thought about when | 6 (12.50) | 4 (12.50) | 14 (17.50) | |

| I really want to stop but I do not know when I will | 3 (6.25) | 8 (25) | 11 (13.80) | |

| I want to stop smoking and hope to soon | 16 (33.33) | 5 (15.63) | 18 (22.50) | |

| I really want to stop and intend to within 3 months | 5 (10.42) | 3 (9.38) | 7 (8.80) | |

| I really want to stop and intend to within 1 month | 11 (22.92) | 3 (9.38) | 14 (17.50) | |

| Missing | 2 (4.16) | 1 (3.13) | 3 (3.80) | |

| Importance of quitting at this attempt, n (%) | 0.25 | |||

| Desperately important | 10 (20.83) | 3 (9.38) | 13 (16.30) | |

| Very important | 25 (52.08) | 15 (46.88) | 38 (47.50) | |

| Quite important | 7 (14.58) | 10 (31.25) | 19 (23.80) | |

| Not at all important | 5 (10.42) | 3 (9.38) | 8 (10) | |

| Determination to quit at this attempt, n (%) | 0.52 | |||

| Extremely determined | 13 (27.08) | 6 (18.75) | 19 (23.80) | |

| Very determined | 16 (33.33) | 10 (31.25) | 26 (32.50) | |

| Quite determined | 14 (29.16) | 10 (31.25) | 24 (30.50) | |

| Not at all determined | 3 (6.25) | 5 (15.63) | 8 (10.00) | |

| Missing | 3 (3.80) | |||

| Self-rated chance of quitting (1 = very low; 6 = extremely high), mean (SD) | 4.09 (1.21) | 3.81 (1.35) | 3.74 (1.53) | 0.34 |

| GAD-7, mean score (SD) | 9.87 (6.86) | 13.33 (7.04) | 11.22 (7.09) | 0.04 |

| PHQ-9, mean score (SD) | 12.46 (7.97) | 13.67 (8.50) | 12.93 (8.15) | 0.53 |

| AUDIT, mean score (SD) | 9.50 (10.46) | 8.80 (9.93) | 9.22 (10.20) | 0.77 |

| SDS, mean score (SD) | 3.49 (4.13) | 7.44 (4.90) | 5 (4.81) | < 0.01 |

The mean age of the sample was 42.66 years, and 65% of the participants were male. Participants were primarily white (76.3%) and heterosexual (85%).

Mental illness, health and substance use comorbidities

Seventy-four per cent of the sample self-reported a long-standing illness, 38.8% had been previously admitted to hospital owing to mental illness, 55% scored 10 or over on the GAD-7 indicating the presence of generalised anxiety disorder, and 60% of participants scored 10 or over on the PHQ-9 indicating the presence of major depression.

In relation to alcohol use, 33.8% of participants had an AUDIT score over 8, suggesting that they were drinking at harmful or hazardous levels. SDS scores were also high, indicating a high prevalence of substance dependence.

Half the participants reported having previously spent time in prison. A significant proportion (38.8%) of the participants, women and men, reported being a victim of domestic violence.

The arms also differed significantly on a number of baseline variables, namely GAD-7, SDS, cannabis joints per day, time spent in prison, physical illness and motivation to quit, with the UC arm scoring higher in all cases but having lower motivation to quit (see Table 3).

Education, employment and housing status

Overall, 37.6% were educated to A level/Highers (or equivalent) or above. Employment status varied: 2.5% reported being in current paid employment and 97.5% reported recourse to benefits (social security/benefits). Just over half of the sample (60%) were currently housed in supported accommodation or in a hostel, and 8.8% reported sleeping rough.

Cigarette dependence and smoking behaviour

The mean number of cigarettes smoked per day (including roll-ups) was 20 [standard deviation (SD) 15.33 cigarettes]; this is equal to a pack of cigarettes per day in the UK. The mean expired CO breath level was 20.29 parts per million (p.p.m.) (SD 10.04 p.p.m). The FTCD score was 5.51 (SD 2.47). In relation to smoking practices that increase the risk of respiratory infection, 55% reported that they shared cigarettes (24% reported doing this daily), and 43% reported that they had smoked discarded cigarettes (6% reported doing this daily).

Furthermore, MTSS varied considerably; although only 6% reported that they did not want to stop smoking, the large majority expressed a desire to quit smoking in the near future.

Differences between the intervention arms

The proportion of participants who had previously spent time in prison or who had a long-standing illness, disability or infirmity was significantly higher in the UC arm than in the EC arm. UC arm participants also scored higher on anxiety and substance dependence, smoked more cannabis joints per day and were less motivated to quit smoking. Given these differences and the differences between centres (see Description of settings), we conducted sensitivity analyses (one-way ANOVA with post hoc tests for continuous variables and Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables; not per protocol) to explore differences between the four centres regarding variables in which there was a significant difference between arms. Cannabis smoking and substance dependence scores were significantly higher at the day centre in Edinburgh (centre 2; UC) than at all other centres (all p-values for cannabis smoking were < 0.01 and all p-values for SDS were < 0.05), which did not differ from each other. Similarly, anxiety (GAD-7) scores were also highest at centre 2, and these differed significantly from centre 1 (day centre, Northampton, EC) and centre 4 (residential centre, London; EC) (p < 0.05) but not from centre 3 (residential centre, London, UC). In addition, MTSS was significantly higher at centre 1 than at all other centres (p < 0.01), which did not differ from each other. A higher proportion of participants from centre 2 had spent time in prison (73% compared with 36%, 50% and 56% in centres 1, 3 and 4, respectively). The difference between centre 1 and centre 2 was statistically significant (p < 0.01). A higher proportion of participants from centres 2 (91%) and 3 (90%) (both UC) reported a long-standing illness than participants from centres 1 (67%) and 4 (44%). Significant differences were observed between centres 2 and 4 and 3 and 4 (p < 0.05).

Numbers analysed

Appendix 1 presents the CONSORT flow diagram showing the numbers for each intervention arm.

Objective 1: assess willingness of smokers to participate in the feasibility study to estimate recruitment rates and inform a future trial

Outcome: record the number of smokers asked to take part and the number of smokers who consent

Across the four centres, 177 participants were initially invited to take part. Of these, 24 were not eligible (16 in the EC arm and eight in the UC arm). Of the remaining 153 eligible individuals (90 in the EC arm and 63 in the UC arm), 80 consented to take part in the study: 48 (56%) in the EC arm and 32 (50.5%) in the UC arm. Although we did not reach the recruitment goal of 120 that we set ourselves (based on our preliminary scoping work), we did recruit these 80 participants during the originally specified 5-month period. Recruitment also differed between centres; the two day centres were most successful in terms of recruitment (39 consented at centre 1 and 22 at centre 2), together accounting for 77.5% of the total sample, and there was a waiting list of participants who could not be recruited at centre 1 as the researcher had to move on to the next centre. The residential units had fewer eligible individuals, including fewer smokers, and potential participants were less available because of work or other appointments and less interested in the study. Furthermore, there was less opportunity to recruit in the residential centres because of centre space and room availability, and issues around disturbing residents (see Discussion for more information).

Summary of learning points for a future trial

Ensure sufficient researchers are employed on the project to deal with recruitment and limit sites to day centres only.

Objective 2: assess participant retention in the intervention and control arms

Outcome: record (1) how many participants complete assessment measures in each arm at each time point, and (2) how many participants are still using electronic cigarettes in the intervention arm

The CONSORT flow diagram presents the participant numbers at recruitment, and follow-up data by intervention (Appendix 1). In the EC cluster, retention rates were 81%, 69% and 73% at 4, 12 and 24 weeks, respectively. In the UC cluster, retention rates were 66%, 53% and 38% at 4, 12 and 24 weeks, respectively.

There was a lower rate of attendance in the UC intervention at the 12- and 24-week follow-ups. The most common reason for not following up was that participants were no longer attending the services; although exact reasons were not formally documented by the research team, these reasons were highlighted informally by conversations with centre staff.

This difference in retention between arms did not appear to be due to the UC condition per se but, rather, due to baseline differences that might influence the ability to attend follow-ups. The UC arm was associated with a higher incidence of criminal background, illness, disability, substance abuse, anxiety and lower motivation to quit (see Table 3). This was particularly the case for centre 2 (day centre in Edinburgh; see Differences between the intervention arms), which was also associated with a far lower 24-week retention rate (26%) than centre 3 (residential centre in London; 67%).

We asked all participants in the EC intervention if they were still in possession of the EC that we had provided (although they did not have to present it at the appointment), and whether or not they were still using the EC. Assuming that all those who did not attend follow-up sessions did not still have, or were not still using, the EC, at 24 weeks 46% (22/48) still had the EC that we had provided and 56% (27/48) were still using it. Table 4 presents the data based on the number of participants who attended and answered the question at each follow-up. The greatest fall in use was between the 12-week and the 24-week follow-ups; however, 63% of those asked self-reported that they were still in possession of the device. Similarly, in relation to still using an EC, the greatest fall was between the 12-week and the 24-week follow-ups; however, of those in attendance at 24 weeks, 79% reported that they were still using an EC, either the device that was provided at baseline or a different one.

| EC intervention | Time point, n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 4-week follow-up | 12-week follow-up | 24-week follow-up | |

| Still have the EC? | |||

| Yes | 33 (85) | 28 (82) | 22 (63) |

| No | 6 (15) | 6 (18) | 13 (37) |

| Still using an EC? | |||

| Yes | 37 (95) | 30 (91) | 27 (79) |

| No | 2 (5) | 3 (9) | 7 (21) |

Summary of learning points for a future trial

Larger numbers, more clusters and official randomisation should reduce baseline differences between arms. Randomisation with stratification by region should also ensure that variables that predict dropout are equally distributed between arms, thus reducing the difference in retention across arms. In the event of a future trial, it would be important to consider ways in which retention could be maximised, including other ways of maintaining more regular contact with participants, for example increasing text and verbal contact between appointments. 29

Objective 3: examine the perceived value of the intervention, facilitators of and barriers to engagement, and influence of local context

Outcome: qualitative interviews with 4-week completers and non-completers, quitters and smokers (N = 24, approximately six per site) between weeks 4 and 8 across both arms

This section presents the findings of 22 in-depth qualitative interviews with a subsample of study participants. Given the difficulty in contacting most of those participants who had not completed their 4-week follow-up, and with the majority of study participants smoking at week 4, it was not possible to conduct interviews with a good range of completers and non-completers, quitters and smokers as intended. However, there is a good spread of qualitative participants across the four homeless centres and both study arms (see Appendix 3 for the qualitative sample characteristics). Nineteen interviewees (86.4%) had completed their 4-week follow-up and three (13.6%) had not completed this follow-up. At the 4-week follow-up, 18 of the 22 interview participants (81.8%) were smoking, one was abstinent and three did not provide smoking information.

We explored participants’ experiences of the study in line with research objective 3. The findings present six topic summary themes: barriers to and facilitators of the study and intervention engagement; experiences of the EC intervention; experiences of UC; perceptions of study processes; unintended consequences; and perceived value. Local differences, if they exist, are highlighted in the text. The section ends with a summary of key learning points for a future trial.

Barriers to study and intervention engagement

Participants’ personal barriers

Interview narratives highlighted the psychological and emotional vulnerability of many of our participants. Some explained that their mental state, attention difficulties, anxiety around social interaction and difficulties with appointments made engaging in treatment programmes challenging:

It is partly my mental health . . . I do panic about talking to people . . . It’s very hard sometimes, just to sit and explain yourself.

Participant 16, C03, UC

Several displayed mistrust in authorities and research:

I thought ‘oh this definitely a government initiative. They’re going to run a test on the homeless . . . maybe they’ve got a dodgy batch of [e-liquid] and they just want to see if it takes anyone out before they put them up for sale.

Participant 02, C01, EC

Although some reported being comfortable providing personal data as part of the study, this was a major concern for others, with particular anxiety around whether or not data would be shared:

. . . if I thought my information was being shared, then I wouldn’t take part.

Participant 11, C02, UC

Participants also lacked confidence in their ability to stop smoking, and many reported that their ideal outcome would be to cut down first, rather than stop straight away: ‘if you can cut down, then you can go that further field’ (Participant 09 C02, UC). This was due to their reported reliance on smoking to deal with stress, isolation or boredom. Traditional stop smoking approaches, particularly NRT, which was reported to have interacted unpleasantly with substance use or mental health in previous quit attempts, were unappealing to participants. This presented a significant barrier to engagement with local SSSs for those in the UC arm.

Cannabis smoking

For participants regularly smoking cannabis mixed with tobacco, most reported wanting to reduce or stop their cannabis consumption, although this presented concerns and was highlighted as especially difficult given the associated pleasure: ‘I feel relaxed [smoking cannabis when] I’ve been wound up all day’ (Participant 11, C02, UC). Some noted how cannabis use had drawn them back to smoking in previous quit attempts:

I’ve quit smoking a couple of times and the thing that always brought me back was smoking weed with the tobacco.

Participant 04, C01, EC

Two participants, previously dependent on heroin, described reliance on cannabis as a protective factor in abstaining from other substances:

I’m an ex-addict, I used to inject heroin etcetera, now I stopped all that and started smoking cannabis and that stopped me taking any other drug.

Participant 13, C02, UC

Participants experiencing mental health distress explained that cannabis helped them to cope and were anxious that stopping cannabis use would exacerbate their symptoms:

I suffer from a lot of anxiety and depression, so it’s just heightened it. It made it worse, trying to stop.

Participant 11, C02, UC

Facilitators of the study and intervention engagement

Opportunity: right time and place

All our interviewees reported a desire to stop or reduce their smoking, expressing concerns about finances or health. Although most had tried to quit previously, negative experiences with NRT and mainstream routes of support [e.g. general practitioner (GP) appointments] meant that these approaches were unattractive. This made opting in to an incentivised, on-site smoking treatment programme appealing. Many illustrated their receptivity to engaging with support at a place they already attended. Bringing smoking cessation aids and services to participants in their own environments was therefore a key facilitator of engagement:

I just thought if you were coming here and Tuesday is my day off, I’d definitely benefit by taking part . . . So why not?

Participant 15, C03, UC

So I’m glad that this has come along because I don’t think, if this hadn’t have happened, I would have bothered to give up. I had no plans of giving up, until that day, none.

Participant 19, C04, EC

Free electronic cigarette starter kit and gift cards

The incentive of receiving a free EC starter kit and/or Love2Shop follow-up gift cards played an important role in study engagement. Although the gift cards received for attending follow-up appointments were valued by all participants, they were especially important for facilitating study recruitment for the UC arm:

My main incentive – I can’t tell lies – is the £15 voucher aye. Why not? If you can come to the centre and make £15 pounds, well then that is fine. Happy days.

Participant 11, C02, UC

In the EC arm, the offer of a starter kit capitalised on participants’ desire to quit and perceived lack of existing cessation options. Despite some participants’ lack of initial enthusiasm for vaping, participants said it prevailed as worth trying, given the availability and offer of the device and e-liquid, especially at a time of financial hardship:

[I] didn’t have to go out and buy it you see, you know, ‘here it is, just try it’.

Participant 07, C01, EC

. . . the thought of maybe it might work and there’s nothing to be lost, there’s only something to be gained, you don’t have to pay for the device . . .

Participant 02, C01, EC

Providing free starter kits also overcame start-up cost barriers for those who had expressed previous interest in vaping:

I have wanted to do it before but thought it was going to be really costly to start up. I haven’t got a spare 30 quid to lay down, ever.

Participant 19, C04, EC

Social context

Social dynamics facilitated EC intervention engagement. Some participants described becoming strong study and vaping advocates. EC intervention buy-in, particularly from individuals with social status among peers, helped raise awareness and interest. Word-of-mouth communication quickly relayed vaping benefits to potential participants:

Everyone I see who smokes I tell them you’ve got to try it, and I really try and talk them into it. But I’m worried I’m becoming one of those [laughs] people that gives up smoking and just like is a pest. But I want to pester them because it’s – I know it’s good.

Particioant 19, C04, EC

. . . now four or five key people have done it and no one, there was no ‘oh are you vaping?’

Participant 02, C01, EC

Positive peer influence was especially prevalent at the day drop-in centre (centre 1), with high demand for the intervention and the creation of a vaping community, characterised by peer advice on equipment and technique, and social vaping norms:

I’ll go out, still socially . . . six or seven of us are vaping away . . . there’s no stigma attached to it anymore. You can just vape happily.

Participant 02, C01, EC

. . . they encourage you to stop smoking, you encourage them. So it’s a bit of like support in a way. Moral support to try and cut down.

Participant 03, C1, EC

A vaping community was not as evident in the residential centre (centre 4). Generally, in these residential units, the service users we met tended not to mix as much and reported more solitary activity, often staying in their rooms:

I don’t [notice others vaping] . . . I don’t pay any attention to them. I just come in and go out.

Participant 21, C04, EC

Participants’ experiences of the electronic cigarette intervention

Participants in the EC arm provided detailed descriptions of their initial expectations, the information and instructions they received, the EC and e-liquids, and their experiences with vaping.

Initial expectations

Most participants had not tried vaping before, reporting little knowledge of ECs. Many described their initial scepticism and low expectation that ECs would help them to reduce or stop smoking. It was common for participants to think the intervention would not be suited to them. For others, engagement in the study meant going against their negative view on vaping:

I was anti-vape.

Participant 02, C01, EC

I did not think for a minute it would fit for me, and work with me at all. I had no hope . . . hugely low expectations . . . I didn’t give myself a hope in hell.

Participant 05, C01, EC

Electronic cigarette information and instructions

Most participants reported satisfaction with the information provided. Instructions were considered thorough and participants particularly valued the practical demonstration, which included advice on device set-up, maintenance and use. Some said the practical help leaflets were useful to refer back to:

They basically showed me how to use the vape and how to change the liquid . . . how to charge it . . . change my coil . . . what to do when I need to clean the vape out. So it was just a really big help because I didn’t really understand anything about vaping and vape pens before.

Participant 03, C01, EC

Electronic cigarette device

Perceptions of the device were mixed. Some found it easy to use and liked its compact size, light weight and long-lasting battery. Although there were several reports of batteries overheating, this issue was a suspected manufacturer fault. Others reported problems with durability, reporting that the device broke easily when dropped (a common occurrence), resulting in cracks and leak of e-liquid:

I mean I’ve dropped mine several times . . . I’ve sort of repaired it . . . it’s still leaking juice.

Participant 02, C01, EC

With no money readily available to replace devices or replacement parts, some had used tape to repair their devices. One highlighted the importance of accessible and affordable replacement parts:

If you are going to use a vape on a study with vulnerable and homeless people, I would suggest you pick a vape that the parts are more accessible. Because, most of these things you have to go online to get them. And most of these people don’t have a bank account, let alone be able to go online.

Participant 01, C01, EC

E-liquid

Finding a preferred e-liquid was important for continued use and participants had differing preferences. Perceptions of the e-liquid provided were generally positive. Many interviewees said that they were satisfied with the variety of flavours and amount and nicotine content of the e-liquid. Experimentation was important for participants to find what suited them best. The flavour options were not liked by all, however, and several suggested the study should provide a greater variety. Some described mixing flavours, exchanging flavours with others and purchasing different flavours:

I think [the variety] covered all bases . . . I was telling everyone three quarters blueberry or half blueberry and half polar bear and seems to have gone down rather well.

Participant 02, C01, EC

Some also commented that the available strengths were too high, leading to initial adverse effects such as coughing and feeling sick, which could put them off continued use:

I shouldn’t have started on 18 [mg] straight away . . . I think I went full out too strong . . . I didn’t give myself a chance.

Participant 06, C01, EC

. . . the 12 [mg]s and 18 [mg]s are very high. A lot of people get head rushes and things . . . I can hit it about twice before nearly passing out. I have to mix mine down.

Participant 04, C01, EC

Vaping experience

Many interviewees noted that their vaping frequency increased over time, with the reported realisation that vaping was helping with smoking reduction and was more useful than NRT. Many were pleasantly surprised with these changes and intended to continue:

It surprised me . . . I know 65% [smoking reduction] isn’t massive but I’ve been smoking 30 years. It’s a dramatic amount in the short space of time . . .

Participant 01, C01, EC

Well at first . . . I thought maybe it’s just going to be a couple of days thing and then just put it on the side but no I use it every single day . . . it’s helped.

Participant 18, C04, EC

For some, vaping easily fitted in with existing routines and habits; it was easy to vape and more convenient than rolling a cigarette, especially when outdoors. One noted that vaping helped them to relax. Others found it more difficult to replace certain cigarettes with vaping, for example the first one in the morning or after dinner, and some described quickly choosing to smoke if their EC was unavailable or they were experiencing stress:

I probably smoke about 35% cigarettes and 65% vape . . . It changed for a little bit where I was doing about 50/50, but I was having a well stressful time . . . if I have a stressful day like I know I’m going to have today, I will have about five [cigarettes].

Participant 01, C01, EC

Participants’ usual-care experiences

There was little evidence of engagement with UC among our interviewees. Although some said that they appreciated the information provided in the help-quit leaflet, many acknowledged that they had not looked at it since the baseline appointment: ‘I’m sorry to say that I didn’t actually read through it’ (Participant 12, C02, UC).

Only three of our interviewees made contact with local cessation support. When accessing support, participants emphasised that making contact with, or contact being facilitated by, someone they trust was important. At centre 2, participants with a methadone prescription reported good relationships with the local pharmacist. Although one participant obtained a nicotine inhalator this way, another did not obtain support as he was reluctant to speak with anyone else:

Have you managed to go to the pharmacy to get some advice on reducing your smoking?

No because every time I go [pharmacist] is not there.

OK. But they must have someone else who can do it?

Aye but I get on well with [pharmacist] so I would rather talk to people that I know.

Participant 13, C02, UC

At centre 3, two of our interviewees attended the local SSS accompanied by their keyworker. Without this keyworker support, one participant noted: ‘I wouldn’t have gone on my own’ (Participant 15, C03, UC). Participants who had tried the UC approach were ambivalent about their experiences. The participant who used an inhalator complained of a sore head and nausea, had not found the nicotine delivery satisfying, and had not returned for further advice or support. At centre 3, participants received a combination of patches and lozenges; however, they were critical of the advice provided and lack of availability of appropriate products:

. . . they didn’t have the appropriate strength to my taste and they gave me a weaker one. But I’ve tried it maybe 4 or 5 days . . . I didn’t quit smoking completely, but I reduced it like notably.

Participant 15, C03, UC