Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 15/01/19. The contractual start date was in September 2016. The final report began editorial review in May 2020 and was accepted for publication in December 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2021. This work was produced by van Sluijs et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2021 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Benefits of physical activity

Regular physical activity in children is positively associated with a wide range of health benefits. 1,2 This includes favourable associations with cardiovascular and metabolic,3–6 skeletal7 and mental8,9 health. Improved cognitive and academic performance has also been shown to be associated with regular physical activity engagement. 10 Furthermore, harmful effects have been reported of excessive or uninterrupted sedentary behaviour, especially screen time. 11,12 Given that children and adolescents have been reported to engage in sedentary behaviours for between 6–913,14 and 5–8 hours per day,15,16 respectively, this is a particularly concerning issue. Inactivity in childhood tracks into adulthood,17 increasing the risk of diabetes, cancer and mortality. 4 The development of interventions to promote and maintain children’s physical activity levels is, therefore, a public health priority.

Children’s levels of physical activity and interventions

The UK’s Chief Medical Officers recommend that children and adolescents engage in an average of 60 minutes of moderate to vigorous physical activity (MVPA) per day. 18 The number of children meeting this guideline dropped between 2008 and 2012,19 and the most recent reports suggest that that around one-fifth of English children and youth aged 5–17 years met the recommended physical activity guidelines. 20 Using device-measured physical activity, Steene-Johansen et al. 21 reported that, across Europe, only 29% of children and adolescents were sufficiently active. Observational data show that children are less active after school and at weekends than during school time,22–24 and that as children enter adolescence their levels of MVPA decline steeply,25 particularly at weekends. 24 Last, physical activity levels vary by children’s home location, with indications not only that rural 9- to 10-year-old children are less active than their suburban counterparts,26 but also that their 4-year decline in minutes per week spent in MVPA is higher than that among children living in suburban or urban environments. 24

The issue of declining levels of physical activity is even more concerning when young people’s physical activity levels are examined separately by sex. Girls are less active than boys throughout childhood21 and their participation in physical activity declines more precipitously than that of boys during the transition to adolescence. 27 Therefore, it is critical for young people to develop positive physical activity habits, as an active childhood can track into adulthood. 17,28

An effort to, at a minimum, maintain sufficient physical activity levels should be considered a public health priority. Therefore, intervening in children’s physical activity before they reach adolescence may be an important strategy. 29,30 To date, the majority of research on young people’s physical activity promotion has focused in and around school time. For instance, a considerable amount of attention has been given to general school-based interventions,31–34 active transport to and from school,35 activity at recess,36 physical activity during physical education lessons37,38 and activity generated through after-school programs. 39 Focusing in and around the school setting is understandable because of near-universal attendance rates and the large portion of young people’s waking hours that are spent at school, which makes school an ideal place to target physical activity interventions. However, the effectiveness of school-based physical activity promotion has been limited,31–34 and out-of-school approaches should be explored.

Parents, the family environment and children’s physical activity

The socioecological model (SEM) of health40 posits that individual behaviour is influenced by factors operating at different levels of influence, including individual, intrapersonal and institutional. Beyond individual-level variables, these include those related to the school, neighbourhood and family environment. For example, children’s activity is influenced by the encouragement they receive from their parents, and modelled on their parents’ own behaviour, which is in turn affected by, for example, the time that parents have available for such pursuits, and access to recreational facilities. 41 Indeed, family factors consistently exhibit positive associations with children’s physical activity, particularly parental support and parental modelling. 42,43

The importance of positive parental role-modelling and direct parental involvement in/support (e.g. transport, co-participation and encouragement) of young people’s physical activity is well known. 29,43–47 A recent cohort study by Abbott et al. 48 reinforced the importance of parental role modelling for both physical activity and sedentary behaviour, demonstrating significant associations between preschool children’s behaviours and their parents’ behaviours. In addition, the authors observed a potentially important role of same- and mixed-sex parent–child relationships. 48 Furthermore, family support has been shown to be associated with physical activity at weekends,23,46 when young people are known to be less physically active than on weekdays. 49,50

Parents may also influence their children’s health behaviours through a variety of other mechanisms, including their general parenting style, their parenting practices (e.g. rule-setting, behavioural consequences, establishing behavioural expectations) and their control of the home environment. 51,52 Interventions that target both the child and the family are particularly effective,29,53,54 and without the involvement of family members it is unlikely that a change in children’s physical activity levels will be maintained long term. 44,55,56 Thus, targeting whole families may create a more supportive, synergistic environment for the promotion of healthy behaviours,29,57 from which wider family members may also be able to benefit. 42

Together, this evidence highlights the need for the promotion of young people’s physical activity to target the family, where wider family members may also be able to benefit. 42 That said, little is known about how best to engage families. 29,44,52 This is highlighted by Tremblay et al. ,58 who state that ‘the role of peers and parents in creating supportive environments for physical activity is unequivocal’ but conceded that they could not draw any firm conclusions from their 38-country comparison.

Previous evidence on family-based physical activity promotion

Family-based physical activity promotion has received less attention than the promotion of young people’s physical activity in other settings. In 2016, investigators on the current project published a systematic review, including a meta-analysis and a realist synthesis, in which we included 40 family-based physical activity studies. 29 The meta-analysis showed moderate efficacy in changing children’s activity levels, but only one high-quality trial was identified. Using a realist synthesis approach, it showed the value of using combined goal-setting with reinforcement in the context of family constraints; focusing on changing the family psychosocial environment, for example through the child as agent of change; and drawing attention to additional (non-health) benefits of spending time, such as family time. In addition, this review highlighted the generally low quality of the evidence base (including self-reported physical activity, small sample sizes and limited blinding), lack of post-intervention follow-up, issues with selection bias, recruitment and retention, and the lack of knowledge on how and why interventions may or may not work.

The review also highlighted that most studies focus only on promoting child physical activity, rather than considering the family as a unit that may work as a team to change behaviour. 59 Intergenerational, family-based programmes targeting, for example, early literacy or prosocial development have shown positive effects, and highlight the potential benefit of including multiple family members in an intervention to improve child health outcomes. 60

Theoretical background

In conceptualising an intervention to improve physical activity in children and families, the investigator team used a socioecological approach. 40 Specifically, the SEM provided a framework for the intervention components. Within this framework, behaviour change strategies were guided by self-determination theory (SDT). 61 Brief descriptions of the theories guiding intervention development and evaluation are provided in the following sections.

Socioecological model

The SEM of health40 posits that individual behaviour is influenced by factors operating at different levels of influence, including individual, intrapersonal and institutional. Reviews of determinants corroborate this assertion,62 showing that a multitude of factors are associated with children’s physical activity levels. Family factors, in particular, consistently exhibit positive associations with children’s physical activity. 42,43,46 The family environment is most certainly an important influence on children’s physical activity;63 thus, efforts to increase children’s physical activity should target the whole family. 64 In fact, the involvement of family members may be crucial for long-term physical activity change. 55,56

Self-determination theory

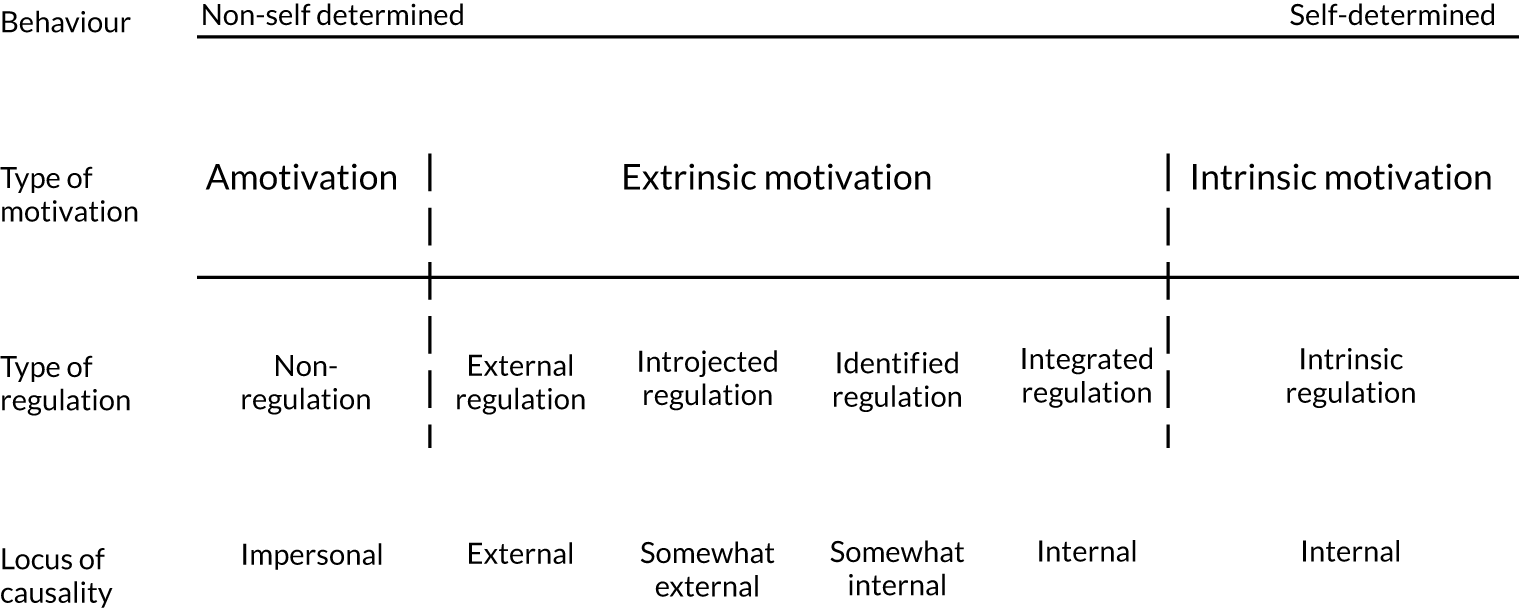

Self-determination theory is a motivational theory that has received significant empirical support in the context of health behaviour change61,65 and in the physical activity context specifically. 66–68 SDT makes a distinction between intrinsic and extrinsic forms of motivation. Intrinsically motivated individuals engage in a behaviour for its own sake (i.e. for the challenge or enjoyment). On the other hand, those motivated by extrinsic regulations engage in an activity to satisfy external demands that can be experienced as controlling or autonomous to varying degrees. 69 SDT posits that individuals move along a continuum as their extrinsic motives or reasons become more internalised they become more autonomous (or self-determined) to engage in behaviours over time (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

The self-determination continuum, showing the motivational, self-regulatory and perceived locus of causality from Deci and Ryan. 70 From ‘The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: human needs and the self-determination of behavior’, Deci EL, Ryan RM, Psychological Inquiry, 1 October 2000, Taylor & Francis, reprinted by permission of the publisher (Taylor & Francis Ltd, http://www.tandfonline.com).

According to SDT, social environments that support individuals’ basic psychological needs (i.e. autonomy, relatedness and competence) are assumed to foster more autonomous motivational patterns. 71 When individuals are more autonomously motivated or self-determined, ‘they experience volition, or a self-endorsement of their actions’. 69 The highest level of self-determination is intrinsic motivation, whereby behaviours, such as physical activity, are performed for their own inherent rewards, such as enjoyment or challenge. 70

Specifically, SDT argues that there are basic psychological needs for autonomy, competence and relatedness, all of which are critical and universal among individuals for psychological health and to move towards autonomous motivation. 70 Satisfaction of these basic needs results in increased feelings of vitality and well-being. 72 Thus, Deci and Ryan’s concept of need support is what is thought to explain individual differences in the development of motivation across the lifespan. 70 Consequently, behaviour change interventions, including those in the area of physical activity, that enhance the satisfaction of participants’ basic needs may be particularly effective. 73,74

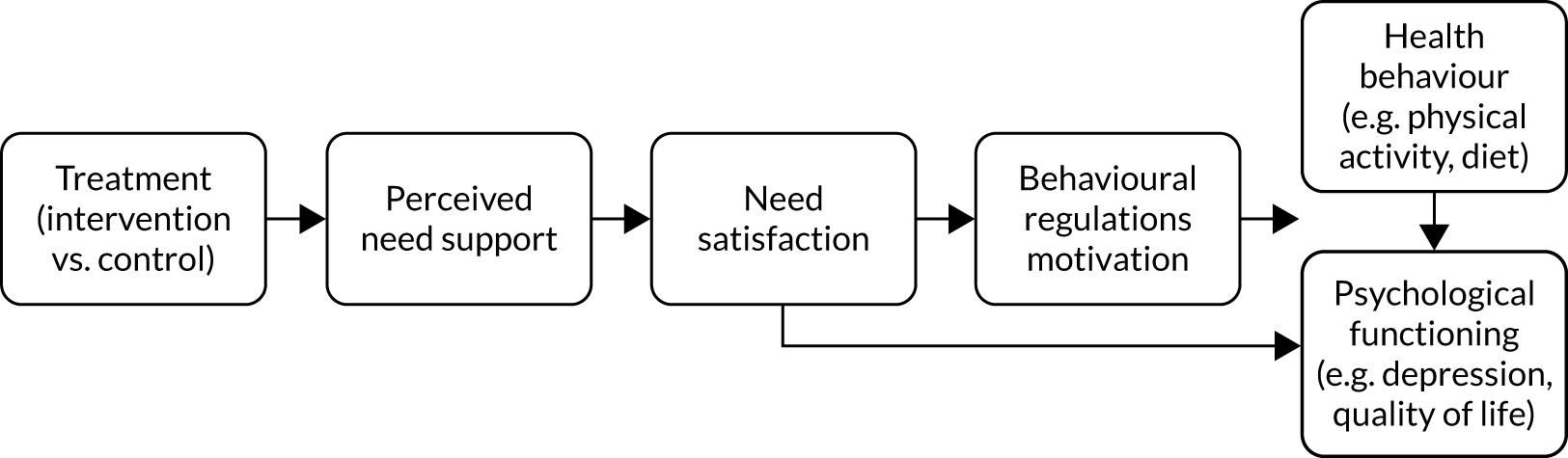

In summary, the broad purpose of SDT interventions is to assist individuals’ progress on the continuum towards more autonomous forms of motivation. Overall, when the complete SDT causal sequence (Figure 2) is used, it creates an intervention outline that has the potential to be quite powerful. 71

FIGURE 2.

The SDT process model for health behaviour change in intervention research from Fortier et al. 71 Reproduced with permission. This article is published under license to BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Summary and rationale for the FRESH project

The above literature highlights the importance of physical activity promotion in young people. This was echoed by an international expert panel, who concluded that developing effective and sustainable interventions to increase physical activity among young people is a key research priority in children’s physical activity. 75 In addition, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence76 in the UK has identified ‘The effect of community and family interventions on young people’s physical activity levels’ (p. 28) as an evidence uncertainty requiring further primary research.

Much of youth physical activity promotion has been predominantly targeted in and around the school setting; however, this project focuses on the important intrapersonal domain of the SEM. Moreover, most studies focus only on promoting child physical activity, instead of considering the family as a unit that may work together to change behaviour,59 despite the known potential benefit of including multiple family members in an intervention to improve child health outcomes. 60 The Families Reporting Every Step to Health (FRESH) intervention, based on extensive prior work, including input from families themselves, will target the whole family and will be able to investigate whether or not this approach is more effective than solely targeting the child. The project was proposed to show whether this approach is feasible and acceptable and potentially effective in changing whole-day physical activity levels of the child and their family members, informing a potential definitive evaluation.

The FRESH project received funding from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Public Health Research programme in 2015 and commenced in late 2016. FRESH consisted of two phases: (1) intervention optimisation and feasibility testing, and (2) pilot testing. Both phases are described in this report, as is an additional project aimed at optimising family recruitment. As per NIHR definitions,77 ‘a feasibility study asks whether something can be done, should we proceed with it, and if so, how’. Feasibility studies are used to estimate important parameters that are needed to design the main study, but do not evaluate the outcome of interest. ‘A pilot study asks the same questions but also has a specific design feature: in a pilot study a future study, or part of a future study, is conducted on a smaller scale’. 77

Study aims and objectives of FRESH feasibility and pilot project

The investigator team identified several strategic and practical uncertainties that needed to be dealt with before a definitive evaluation of the FRESH intervention could commence. The project reported on here consisted of the feasibility and pilot phases of the FRESH trial to reduce these uncertainties. The results of this project were to inform the decision whether or not to proceed with a definitive trial. As stated in the original funding application, the overall aim of a future definitive trial would be ‘to establish the long-term effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the family-based FRESH interventions to promote MVPA in 8-10 year-old children and their families living in rural Norfolk’.

The aim of the FRESH feasibility and pilot project was to assess the feasibility of delivering the FRESH intervention and its accompanying evaluation. The specific objectives are listed in Box 1.

-

To further develop and optimise the content and delivery of the FRESH interventions (child-only, family) in collaboration with families and stakeholders.

-

To demonstrate feasibility and acceptability of delivery of the FRESH interventions in a short-term feasibility study.

-

To examine the feasibility and relative efficacy of different recruitment strategies and to identify optimal recruitment strategies.

-

To describe the characteristics of families and individual participants recruited in the context of the eligible population.

-

To examine intervention uptake, adherence and maintenance in both intervention groups.

-

To estimate the recruitment and retention rate in a long-term pilot evaluation.

-

To demonstrate the feasibility and acceptability of measurement procedures.

-

To assess the effect size and 95% confidence interval for the proposed primary outcome measure.

-

To test methods of assessing family physical activity and establish an intraclass correlation coefficient.

-

To examine participants’ experience of the intervention and trial participation through questionnaires and interviews.

-

To develop and pilot a family physical activity-related expenditure questionnaire.

-

To model the long-term intervention costs and outcomes to inform discussions with potential funders of the intervention, and to inform the likely efficiency of a future definitive trial.

-

To decide on the feasibility of a definitive FRESH trial and prepare a grant application, if relevant.

The four main research questions addressed were:

-

In what ways does the FRESH intervention(s) need to be optimised prior to a definitive trial?

-

What is the feasibility and acceptability of the FRESH family-based physical activity promotion intervention and accompanying evaluation?

-

Which methods are valid and acceptable for measuring family physical activity?

-

What are the most effective and resource-efficient methods for recruiting families into obesity prevention programmes?

Progression criteria

The FRESH progression criteria were pre-defined at the grant application stage. The following parameters were to be used to inform progression to a definitive trial, taking into account qualitative findings on the acceptability of trial procedures:

-

intervention adherence (> 75% of families uploading steps at least six times in the first 3 months of the pilot study)

-

demonstrable feasibility of recruiting 20 families per month (based on pilot and accounting for increased staffing in a future definitive trial) and retaining 75% of index children at 1 year

-

intervention optimisation feasible (identified adaptations are practical, affordable and acceptable)

-

evidence to suggest that an adequately powered trial would require a feasible number of participants (n = 250 is considered logistically feasible and to provide sufficient power)

-

discontinuation of trial arm based on evidence of harm or limited acceptability/feasibility

-

positive expected net gain of sampling from definitive trial.

FRESH project study management

The overall FRESH project was managed by the FRESH project group, which was chaired by the principal investigator and consisted of all applicants, research associates working on the project, the study co-ordinator and a local stakeholder. Depending on the project phase, the project group met once every 1–3 months. Operational management was led by the FRESH operational group, consisting of the principal investigator, the study co-ordinator and the main research associate appointed on the grant.

At the start of the project, the FRESH Study Steering Committee (SSC) was established, consisting of seven independent members and the principal investigator. The independent members represented various scientific disciplines (young people’s physical activity promotion, public health, family-based interventions, health economics, physical activity measurement, feasibility and pilot trials) and included stakeholders (public health) and members of the public (including with expertise in web-design). The FRESH SSC met once or twice each year. Its stated role was to:

-

oversee the development and co-ordination of research activities

-

act as a sounding board and provide advice on research matters to ensure the long-term health, development and scientific value of the project

-

advise on the continuation of the project after the completion of a pilot study.

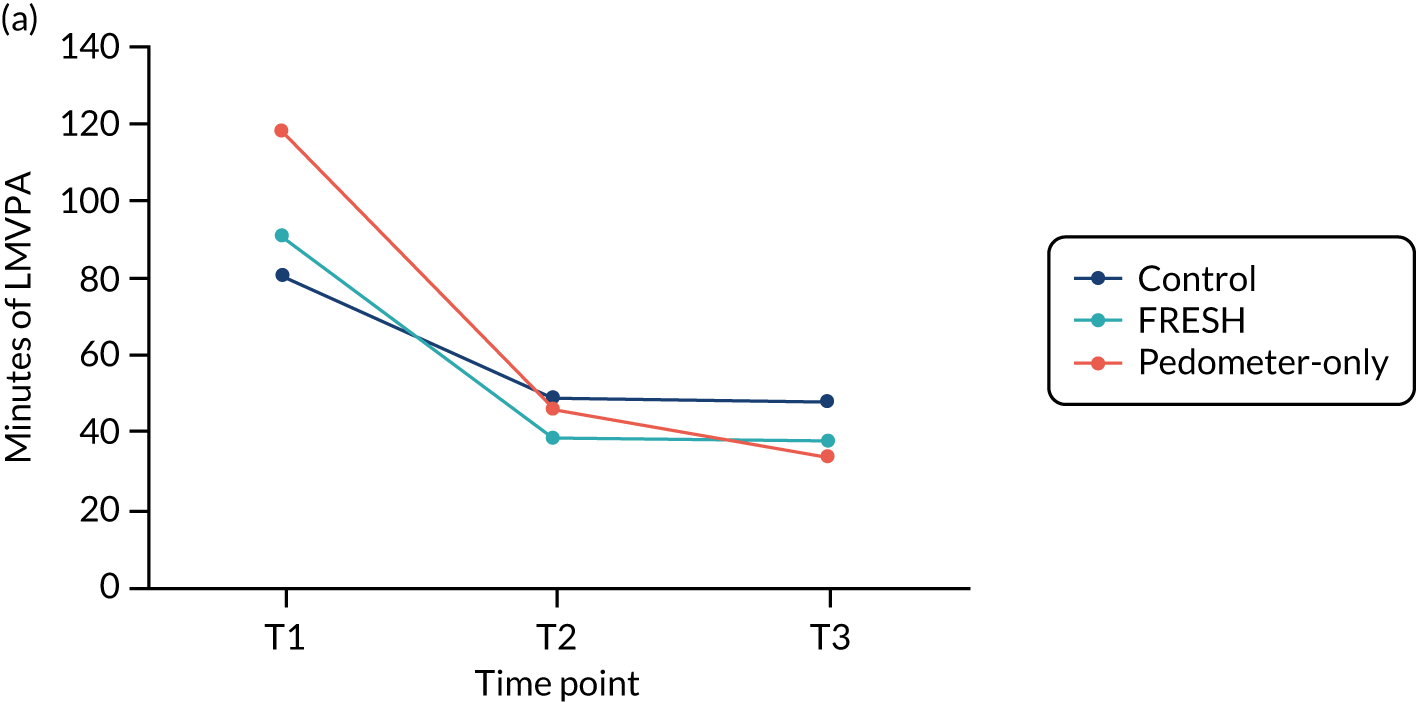

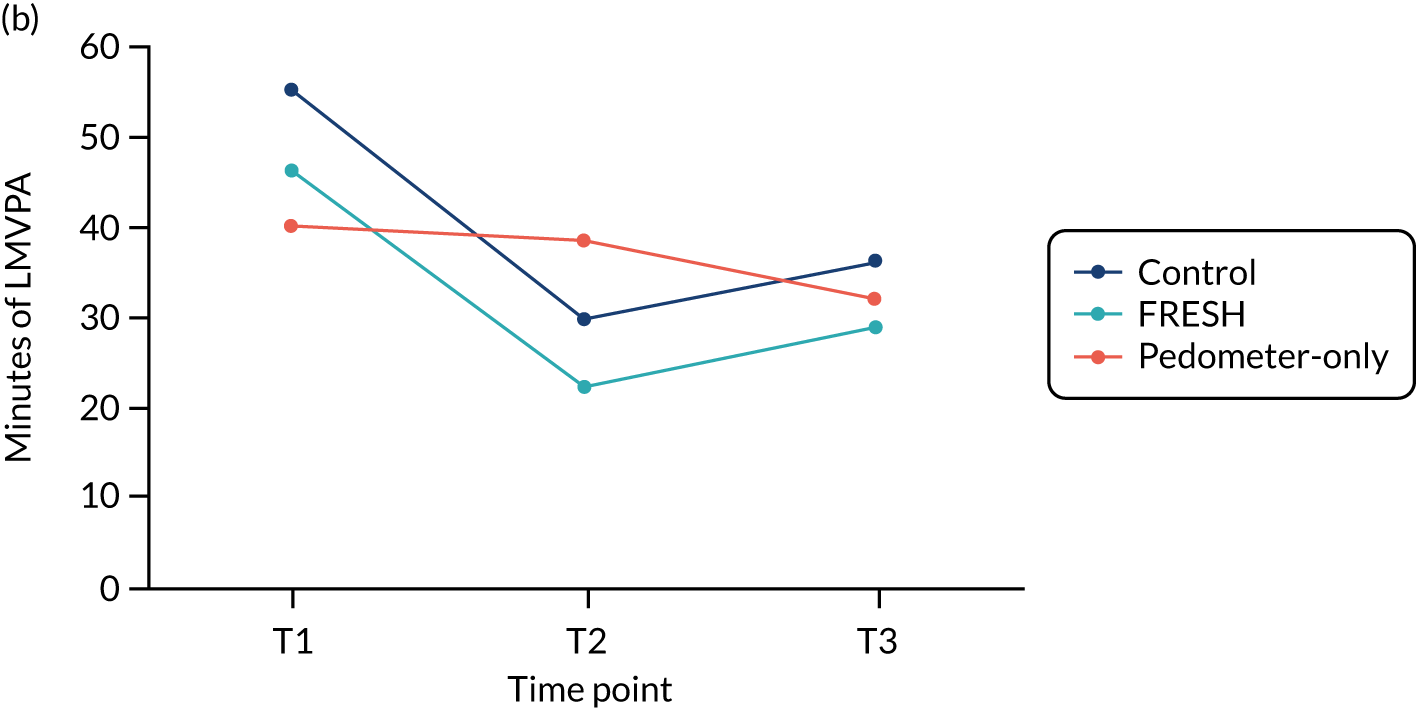

At its first meeting, the SSC agreed that, in addition to the pre-established progression criteria, it would consider ‘changes in MVPA’ as ‘evidence of promise’ to inform progression to a full trial.

Chapter 2 The development, trial design and methods of the FRESH feasibility trial

Parts of this chapter are reproduced with permission from Guagliano et al. 78 © The Author(s). 2019 Open Access. This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Introduction

Previous evidence indicates that home-based physical activity interventions are potentially more effective than those that require the family to travel to community or other intervention locations. 63,79 Furthermore, it is unlikely that any change in children’s physical activity levels will be sustained long term without the active involvement of wider family members. 44,55,56 Many previous studies, however, focus only on promoting children’s physical activity instead of considering the family as a unit that may work together to change behaviour. 59 Calls for physical activity research in young people and families highlight the dearth of research in this area76 and the need to develop and evaluate innovative interventions targeting children and families.

Responding to this challenge, we sought to identify and develop a family-based physical activity intervention and evaluation. In this chapter, we describe the development of the FRESH intervention and recruitment strategy, and the protocol of the FRESH feasibility study. The aims of this study were to (1) assess the feasibility and acceptability of the FRESH recruitment strategy, intervention (including intervention fidelity) and accompanying outcome evaluation; and (2) explore how FRESH could be optimised through a mixed-methods process evaluation.

Methods

Overview of study design

The reporting of this study was guided by the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) extension to randomised pilot and feasibility trials guidelines80 and the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR). 81 This feasibility study received ethics approval from the Ethics Committee for the School of the Humanities and Social Sciences at the University of Cambridge and was prospectively registered (ISRCTN12789422).

We conducted a 6-week, two-arm, parallel-group, randomised feasibility study, using a 1 : 1 allocation ratio, aiming to recruit 20 families with an ‘index child’ aged 8–10 years. The study focused on this age group, as these are the ages when physical activity starts to decline more steeply,25 and it was anticipated that children of in this age group could be engaged effectively with intervention implementation. After measurements were completed at baseline, families were randomly assigned to one of two intervention arms. In the ‘child-only’ arm, the index child was the focus of the intervention, with family members simply providing support. By contrast, in the ‘family’ arm, all participating family members received the FRESH intervention (described in Description of the FRESH feasibility study intervention).

An independent statistician performed the randomisation procedure in Stata® (version 14; Stata Corp LP, College Station, TX, USA) using a computer-generated algorithm and a randomised block design (blocks of four) to ensure equal numbers in each condition and enrolment in both conditions at similar time points and rates.

Eligible participants

Families were eligible to participate when at least one child aged 8–10 years (hereafter referred to as index children) and at least one adult responsible for their care and living in their main household provided consent. Participants also needed to be able to take part in light-intensity physical activity (e.g. walking), have access to the internet and have a sufficient understanding of the English language. No restrictions were placed on family type (e.g. single parent, inclusion of grandparents, siblings). All other family members living in the index child’s main household were invited to participate, but their participation was not required. In addition, intervention and evaluation participation were separate; family members could take part in the intervention irrespective of whether they participated in the accompanying evaluation, and vice versa. Specific exclusion criteria applied only to the evaluation of this study, and these are outlined below.

Study setting

Families were recruited from rural Norfolk, a county in East Anglia, UK (Figure 3). Norfolk has an area of 2074 square miles and an estimated population of 898,400. 82 About half of the population live rurally;83 rural–urban disparities in physical activity have been reported. 24,26 In accordance with the Office for National Statistics84 classification, ‘rural’ was defined as having a postcode falling in a small town, village, hamlet or dispersed settlement.

FIGURE 3.

Map of England showing study location of FRESH feasibility and pilot studies (note that the feasibility study was conducted in Norfolk only).

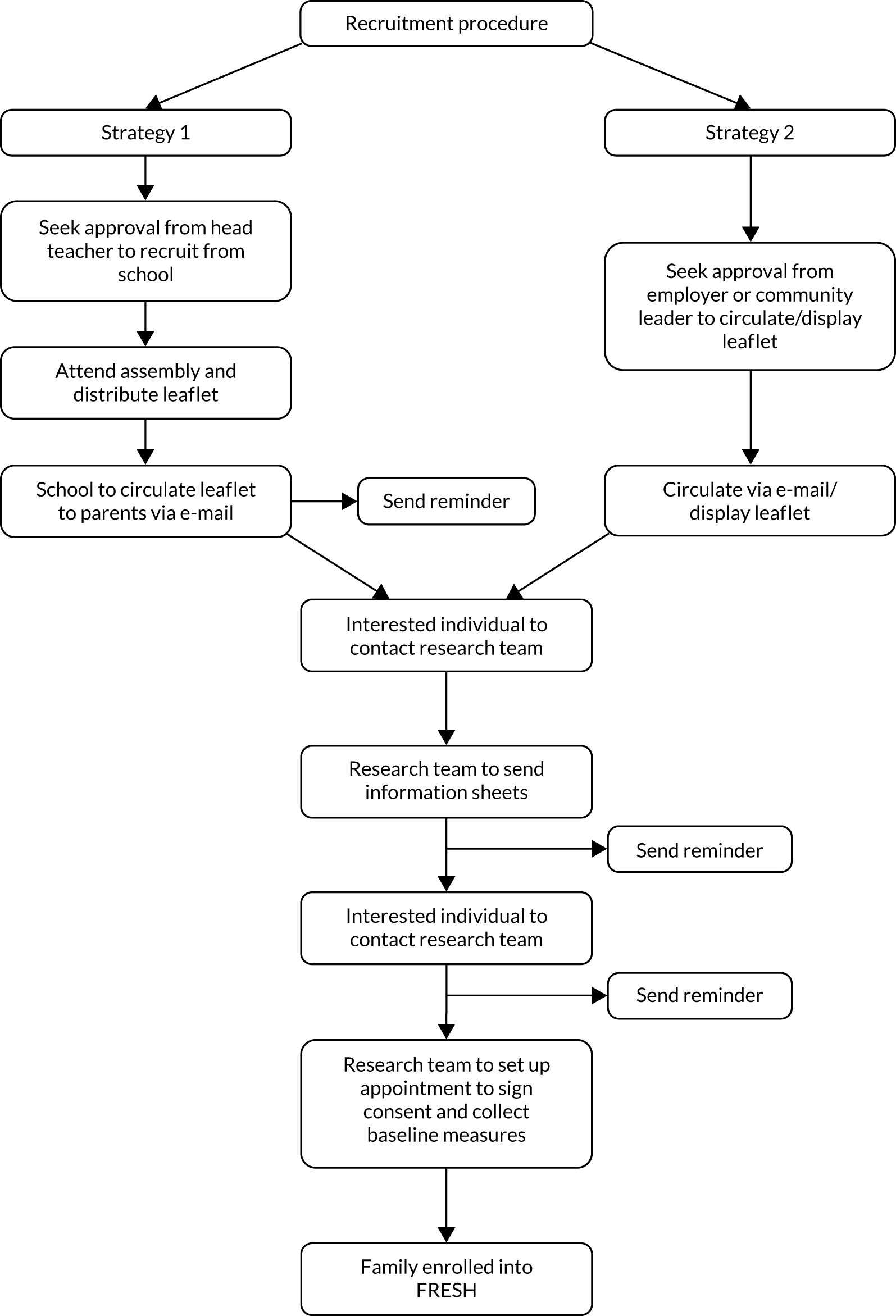

Recruitment method

Formative work informing the development of the FRESH recruitment strategy

The recruitment of families is known to be particularly challenging and there is little evidence to suggest how best to engage families in physical activity research. 44,52 To inform recruitment and retention, prior to the start of the FRESH project, we conducted focus groups with 17 families (82 participants, consisting of 2–6 family members). 30 The findings of these led to the following recommendations for effective recruitment: (1) using a multifaceted recruitment strategy (i.e. through different setting and different methods) and (2) highlighting the wide range of benefits of research and physical activity participation (particularly social, health and educational outcomes). The findings explicitly contributed to the planned recruitment strategies for the current study, where we planned school- and community-based (e.g. Brownies/Cubs, community centres, general practitioner clinics) recruitment, and highlighted the benefits of spending time together as a family in our recruitment material.

Recruitment protocol

To recruit schools and community-based organisations, we first contacted lead personnel (e.g. head teachers, physical education co-ordinators and heads of community-based organisations) by sending an information pack that included information sheets and a leaflet describing the purpose of the study and what it would involve for schools, parents and children. We followed this up with a telephone call if no response was received. Verbal or written approval was sought from the gatekeeper (e.g. Brownies leader, head teacher) prior to family recruitment. Gatekeepers were asked to send home study leaflets with children, circulate our leaflet to parents online (i.e. via Parentmail or an equivalent system) and send an online reminder to parents approximately 2 weeks later. From schools, we also sought permission to present the study to Year 3–5 students at a scheduled assembly.

Interested parents were asked to contact the study team by e-mail or Freephone, after which their eligibility was assessed and they were e-mailed the study information. Following this, a baseline assessment appointment was made with those families still interested in participating. At the start of the visit, written informed consent was obtained for participating adults, and written parental consent and child assent for each participating child.

Intervention selection and development

Building on previous evidence

As described in Chapter 1, we previously conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to study the effectiveness of family-based physical activity promotion on children’s levels of physical activity. 29 The meta-analysis showed a small, but significant, effect favouring the experimental groups of family-based interventions compared with controls [Cohen’s d = 0.41, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.15 to 0.67]. However, it also highlighted the scarcity of family-based intervention studies that (1) clearly indicated intended behaviour change mechanisms, (2) employed objective measures of physical activity, (3) engaged with/assessed intervention effects on wider family members and (4) were theory-based. The development of the FRESH intervention was informed by a programme theory for family-based physical activity interventions, developed as part of this review. 29 This programme theory highlighted the value of (1) using goal-setting combined with reinforcement in the context of family constraints (e.g. lack of time or scheduling difficulties), (2) focusing on changing the family psychosocial environment (e.g. using the child as agent/instigator of change) and (3) focusing on something other than the health benefits of physical activity (e.g. spending time together as a family). These collective findings were considered in the development of the FRESH intervention.

Intervention selection through public involvement

The research team developed four potential intervention concepts based on their previous work. 29,30 The four concepts were:

-

Buddy scheme – families would be paired or grouped to facilitate peer support for physical activity.

-

Small changes – providing a resources toolkit to each family, containing information on making small changes to increase physical activity (e.g. active travel suggestions, such as getting off the bus a stop early).

-

Sports equipment library – a ‘travelling library’ of a large range of sporting equipment would move through a community once per week, allowing families to borrow equipment.

-

Family challenge – families would be framed as a ‘team’ working towards a common goal (e.g. an overall step count to ‘walk around the world’).

These four concepts were then brought to families during a university-run community engagement event. At this event, children acted as researchers to identify which intervention concept their family would enjoy most. Based on the feedback, the most popular concepts were further refined during meetings with stakeholders (i.e. parents, teachers, family health practitioner). This led to the selection of an intervention that allowed families to work as a ‘team’, tracking their efforts towards a common goal and receiving small rewards for progress (the family challenge described above). This initial input from families and stakeholders was used as a starting point from which develop FRESH in its current form.

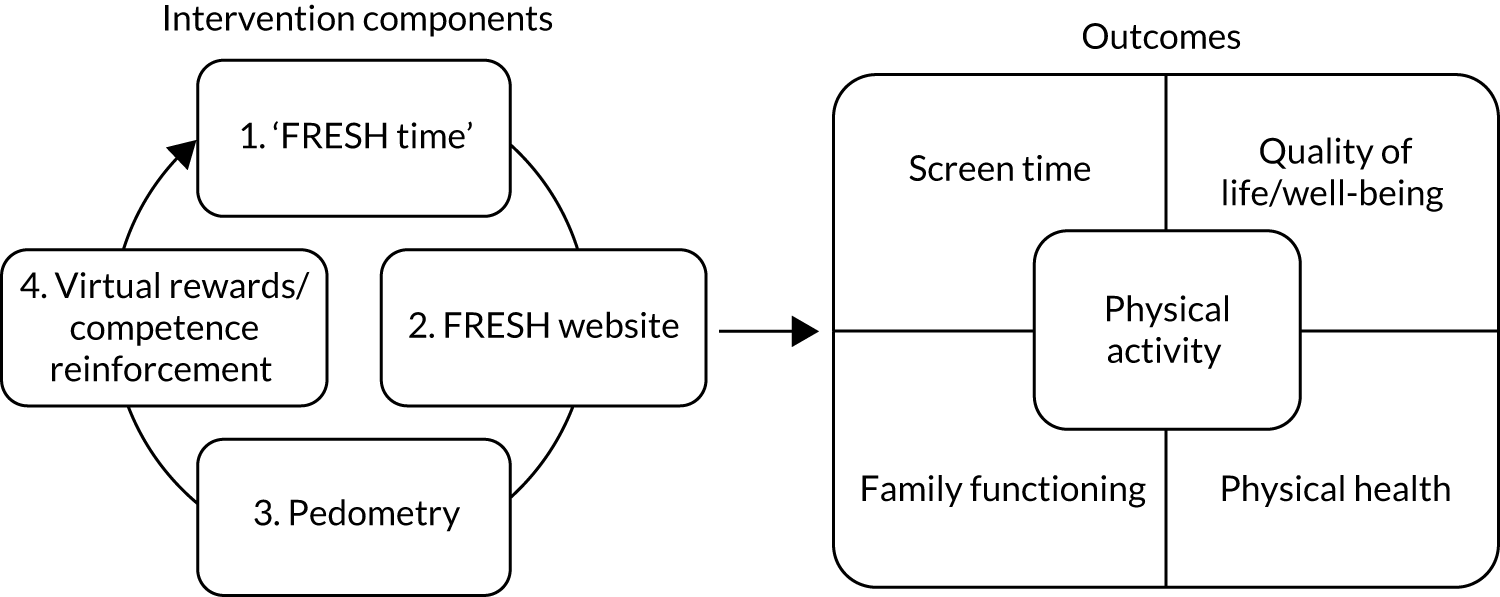

Description of the FRESH feasibility study intervention

In brief, FRESH was primarily a goal-setting and self-monitoring intervention aimed at increasing physical activity in whole families. The SEM (individual and interpersonal levels)40 and family systems theory85 provided a framework for the intervention components. Within this framework, behaviour change strategies were guided by SDT. 61 A detailed description of the FRESH intervention components and associated behaviour change techniques,86 targeted SDT constructs and hypothesised mediators is provided in Table 1. In addition, the FRESH feasibility study logic model can be found in Figure 4.

| Intervention components | Dose | Description | Behaviour change techniques | Targeted SDT constructs | Hypothesised mediators |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. ‘Family time’ | Minimum once per week, 10–20 minutes | ‘Family time’ provided an opportunity for index childrena and family members to plan PA, monitor their week’s steps, discuss any potential PA barriers and strategies to overcome them by logging in their family action planners.27 Regular ‘family time’ was hypothesised to provide index children with:

|

Goal-setting Self-monitoring Positive feedback on progress Social support Praise Positive reinforcement |

Perceived competence Perceived relatedness Perceived autonomy |

Family social norms for PA PA awareness Basic needs satisfaction PA motivation |

| 2. FRESH website | Minimum once per week, 5–20 minutes | The FRESH website facilitated self-monitoring of step counts, and goal-setting through selecting challenges. Specifically, the FRESH website allowed families to choose one of three target cities to ‘walk to’ weekly, with the aim to eventually ‘walk’ around the world. Each week, families chose an easy, moderate or difficult challenge, which represented a 0%, 5% or 10% increase, respectively, relative to the average steps they had taken in preceding weeks. Increases were adjusted to 0%, 2.5% and 5% once adults and children accumulated an average of 10,000 and 12,000 steps per day, respectively. Families also had access to a general resources area that provided suggestions of activities that families could do together and a map to give a visual representation of the locations families had travelled to |

Goal-setting Self-monitoring Positive feedback on progress Rewards |

Perceived competence Perceived relatedness Perceived autonomy |

Social support Family social norms for PA PA awareness Basic needs satisfaction PA motivation |

| 3. Pedometry | Throughout intervention (6 weeks) | Participants were provided with pedometers for self-monitoring and immediate feedback. Pedometers are simple to use and convenient and are associated with effective interventions for increasing parent–child physical activity.35 Index children logged their steps (and their family members’ steps) into the FRESH website and/or onto the family action planners, which allowed participants to view their progress towards their proximal and distal step goals |

Self-monitoring Immediate feedback |

Perceived competence Perceived autonomy |

Social support Family social norms for PA PA awareness Basic needs satisfaction PA motivation |

| 4. Virtual rewards/competence reinforcement | Approximately once per week (6 weeks) | To praise effort (i.e. competence reinforcement), participants received supportive messages, virtual passport stamps (i.e. virtual rewards) and access reinforcement materials (i.e. interactive multimedia information about the cities they have visited) on the FRESH website as they completed challenges to various cities around the world. Participants received 2–4 passport stamps for completed challenges (i.e. as difficulty increased, more stamps were awarded) and one passport stamp for an incomplete challenge |

Feedback on progress Rewards |

Perceived competence |

Basic needs satisfaction PA awareness |

FIGURE 4.

The FRESH feasibility study logic model.

To initiate intervention participation, a facilitator visited all families a week after baseline assessments for a ‘kick-off’ meeting to introduce the families to the intervention components and accompanying materials (e.g. family action planner). The main purpose of this meeting was to familiarise families with the website and prompt them to schedule regular ‘family time’ meetings (a suggested minimum of one per week) during which they would review and update their family action planner. All meetings occurred in participating families’ homes and lasted approximately 1 hour. Participant-initiated distant support was available for the duration of the intervention.

A detailed description of the FRESH intervention components can be found in Table 1. At the start of each new weekly challenge, families had ‘family time’, during which they selected a challenge on the FRESH website and filled in their action planners. The FRESH website allowed families to choose one of three target cities to ‘walk to’ each week, with the aim of eventually ‘walking’ around the world. The FRESH website primarily facilitated the self-monitoring of step counts and goal-setting through selecting challenges of varying difficulty. In both study conditions, children were allocated the role of ‘team captain’, leading on destination selection and uploading steps online. Families were to wear their pedometers for as long as possible daily to capture their steps and were asked to upload their step counts at least once weekly. After completing a challenge, families received effort-praising messages and virtual rewards (i.e. virtual passport stamps) and were able to track their progress around the world and access reinforcement materials on the FRESH website (i.e. interactive information about the cities they had walked past and reached during their challenge). If a family did not complete a challenge, to praise their effort, they progressed to a hidden city along their challenge route and still received a supportive message, a virtual passport stamp and access to reinforcement materials. Completing a challenge (or the week coming to an end) initiated the next ‘family time’ meeting, when the above cycle was repeated (see the cycle in Figure 4).

FRESH child-only condition

The child-only condition was essentially the same as described above, but in this condition only the index child received a pedometer and was able to record their steps on the FRESH website. All other components were kept the same.

Refining the prototype FRESH intervention

The initial FRESH intervention was developed further through public involvement activities. We sought input from children (n = 7) through a talk-aloud session regarding the layout and design of the FRESH website and also from families (n = 2) who pilot-tested the intervention protocol described above. Overall, the FRESH intervention was well received, children found the website easy to navigate, and no changes were made to the protocol. However, based on participants’ suggestions, minor changes were made to the intervention website. For example, participants found it discouraging when they participated in activities that could not be captured by their pedometers (e.g. swimming). Therefore, we added a ‘step calculator’ to the website that enabled participants to estimate the number of steps that various activities, such as swimming, would give them, using data from a readily available online activity-to-step converter. 87

Outcome evaluation measures

As part of this feasibility study, we aimed to assess the feasibility and acceptability (i.e. not the effectiveness) of the planned outcome evaluation. Therefore, here we briefly describe the measures included to provide an overview of what the outcome evaluation entailed. Table 2 outlines the measures taken, including the order of assessments and the estimated duration of each. Data collection was carried out by two trained research staff in participating families’ homes. Outcomes were assessed at baseline (prior to randomisation) and at follow-up (at 6 weeks) for all participating family members (excluding children aged ≤ 2 years). All consenting family members took part in measurements, irrespective of their intervention allocation and participation.

| Measure | Duration |

|---|---|

| 1. Anthropometric measures (height, weight, waist circumference) | 5 minutes per person |

| 2. Questionnairesb | 20 minutes per family |

| 3. Blood pressure | 10 minutes per person |

| 4. Step test (aerobic fitness) | Preparation: 5 minutes per person |

| Test: 8 minutes per family | |

| 5. Accelerometer and GPS explanation | 5 minutes per family |

| 6. Fictional Family Holiday (family functioning) | 10 minutes per family |

| Total duration of measurements | Minimum of 73 minutes |

| Total duration of visit (including consent process) | Minimum of 88 minutes |

Physical activity assessment

To assess individual physical activity, and family co-participation in physical activity, participants were asked to simultaneously wear an ActiGraph GT3X+ triaxial accelerometer (ActiGraph LLC; Pensacola, FL, USA) and QStarz Travel Recorder BT1000X Global Positioning System (GPS) monitor (QStarz; Taipei, Taiwan). Participants wore the monitors affixed at each hip on an elastic belt during waking hours for 7 consecutive days. The monitors where then picked up by a member of the study team, or participants were asked to return the monitors to the study office in a prepaid enveloped. Accelerometer data were downloaded and processed. A valid week was defined as ≥ 600 minutes per day from 3 weekdays and 1 weekend day during the 7-day measurement period. 88 Non-wear was defined as ≥ 90 minutes’ consecutive zeros using vector magnitude. ActiGraph accelerometers have been shown to be valid and reliable devices for the measurement of physical activity levels in children and adults;89–91 the GPS monitor used has been shown to have high static and dynamic validity in a variety of settings. 92

Combined GPS and accelerometer data were collected to enable the assessment of family co-participation in physical activity (i.e. family members being active in proximity to each other). Accelerometer and GPS data were matched using Java; after this, data points that had a time difference of ≤ 30 seconds between the accelerometer timestamp and that of its matched GPS location were considered valid for inclusion. Matched data points with a time difference greater than this, for example when the GPS had been switched off or had lost signal, were considered as missing location information because the participant might have moved to a new, unrecorded, location. From the matched data, we computed the minutes per day for which the GPS had maintained a signal, and had therefore recorded the participants’ location, as an indicator of data completeness. Only wear time data will be presented as part of the feasibility study; therefore, we have only provided information relevant to estimating wear time using both monitors.

Health outcomes

Aerobic fitness was measured using an 8-minute submaximal step test. 93 Children aged < 8 years were excluded from the aerobic fitness test because of the height of the step. Older children and adults were all asked to complete the step test. Height, weight, waist circumference and blood pressure [using an OMRON 705IT digital blood pressure monitor (OMRON Healthcare UK Ltd, Milton Keynes, UK)] were measured in accordance with standardised operating procedures. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated and was converted into age- and sex-specific percentiles using standard growth charts for children using LMSgrowth Program version 2.77 (Child Growth Foundation, London, UK). 94

Behavioural and psychosocial measures

Questionnaires assessed behavioural and psychosocial measures: adult and child screen-use time;95–98 quality of life;99–102 family co-participation in physical activity;98 physical activity awareness;103,104 family social norms for physical activity;105,106 family support;105 children’s and adult’s motivation for physical activity;107,108 and children’s perceived autonomy, competence, and relatednesss. 108 Table 3 provides an overview of the measures used with children and adults. Children aged ≤ 4 years did not complete this questionnaire. Research assistants were available to answer questions during completion.

| Measure | Assessment method§ |

|---|---|

| Screen time | Adult: two items from the Recent Physical Activity Questionnaire95 |

| Child: parent proxy using one item from the Children’s Physical Activity Questionnaire96 | |

| Family co-participation in screen time | Four items derived from the SPEEDY study questionnaire |

| Screen-based restriction | Restricting access to screen-based activities was measured with two versions (parent-report and child-report versions) of the Activity Support Scale for Multiple Groups97 |

| Quality of life | Adult: EQ-5D-5L99,100 The EQ-5D-5L asks respondents to describe their health today using five dimensions, each at five levels. The dimensions are mobility, self-care usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression |

| Child: CHU-9D.101,102 The CHU-9D asks respondents to rate their health today using nine dimensions, for example pain and usual activities, school work/homework, tired and sleep. Algorithms exist based on population preferences for both scales to be converted into a ‘health state utility’, an index relative to two anchor points of 0 (dead) and 1 (perfect health). Integrating these over time allows the calculation of QALYs | |

| Physical activity awareness | Adult: self-report whether or not they achieve enough MVPA to meet national guidelines, as used previously104 |

| Child: one item on the child and parent questionnaire from Corder et al.103 | |

| Family social norms for PA | Adult: single item using previously used question105 |

| Child: four items from previously used questionnaires106 | |

| Family support | Adult and child: six items using previously used questionnaires105 |

| Motivation for PA | Adult: BREQ-2, developed by Markland and Tobin107 |

| Child: questionnaire developed by Sebire et al.108 | |

| Basic psychological needs satisfaction | Children’s perceived autonomy, competence, and relatedness will be assessed in child participants only, using a questionnaire developed by Sebire et al.108 |

Fictional Family Holiday

The Fictional Family Holiday paradigm, a 10-minute video-recorded activity where families were asked write out a week-long holiday itinerary with unlimited budget, was used to assess family functioning via family relationships109 and connectedness. 110 This is because the activity requires ‘power sharing’ (i.e. taking turns) and prompts the viewpoints of all family members on the topic, eliciting both individuality (through suggestions for destinations/activities or disagreements) and connectedness (through agreements, questions, or initiating compromise), contributing to the family’s final plan. 109

Family out-of-pocket expenditure for physical activity

Information on family expenditure related to physical activity was collected using a questionnaire that was developed and tested for the current study. This was completed by one adult for their whole family. The questionnaire consisted of two questions about expenditure related to membership fees and subscriptions (e.g. for sports clubs, fitness centres) and sports equipment (e.g. sportswear, gadgets).

Process evaluation

A mixed-methods process evaluation was conducted at the end of the 6-week intervention. In questionnaires, adults self-reported their overall opinion of FRESH, their opinion of the intervention components and measurements, and suggestions for improvement using open-ended and 5-point Likert-scale questions (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree). Children also self-reported on the above topics, responding to dichotomous ‘yes/no’ questions. In addition, we conducted semistructured focus groups with 11 out of 12 families (one family declined to participate), focusing on families’ perceived acceptability of the individual FRESH intervention components, intervention fidelity, challenges/barriers to engaging with FRESH, and suggested improvements. The mean duration of focus groups was 34 minutes [standard deviation (SD) 10 minutes; range 17–50 minutes]. All focus groups were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Data analysis

Quantitative data

Frequencies, percentages, means and SDs were calculated to describe the data related to recruitment, retention, fidelity, intervention optimisation, website engagement and outcome measures.

Qualitative data

Using a long-table approach, a content analysis was conducted using existing guidelines. 111 Specifically, the analysis was conducted in two separate phases. During the data organisation phase, text from each transcript was divided into segments (i.e. meaning units) to produce a set of concepts that reflected meaningful pieces of information. 111 Tags were then assigned to each meaning unit. Tagging was performed by one researcher, with a second double-tagging approximately 25% of the transcripts. In the data interpretation phase, the inventory of tags from all transcripts was examined by two researchers, which led to the emergence of themes and subthemes within each overarching category.

Chapter 3 FRESH feasibility trial findings

Parts of this chapter are reproduced with permission from Guagliano et al. 78 © The Author(s). 2019 Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

The FRESH feasibility study was conducted in May–August 2017, in accordance with the protocol described in Chapter 2. This chapter describes the findings of this study, which had the following aims: (1) to assess the feasibility and acceptability of the FRESH recruitment strategy, intervention (including intervention fidelity) and accompanying outcome evaluation; and (2) to explore how FRESH could be optimised through a mixed-methods process evaluation.

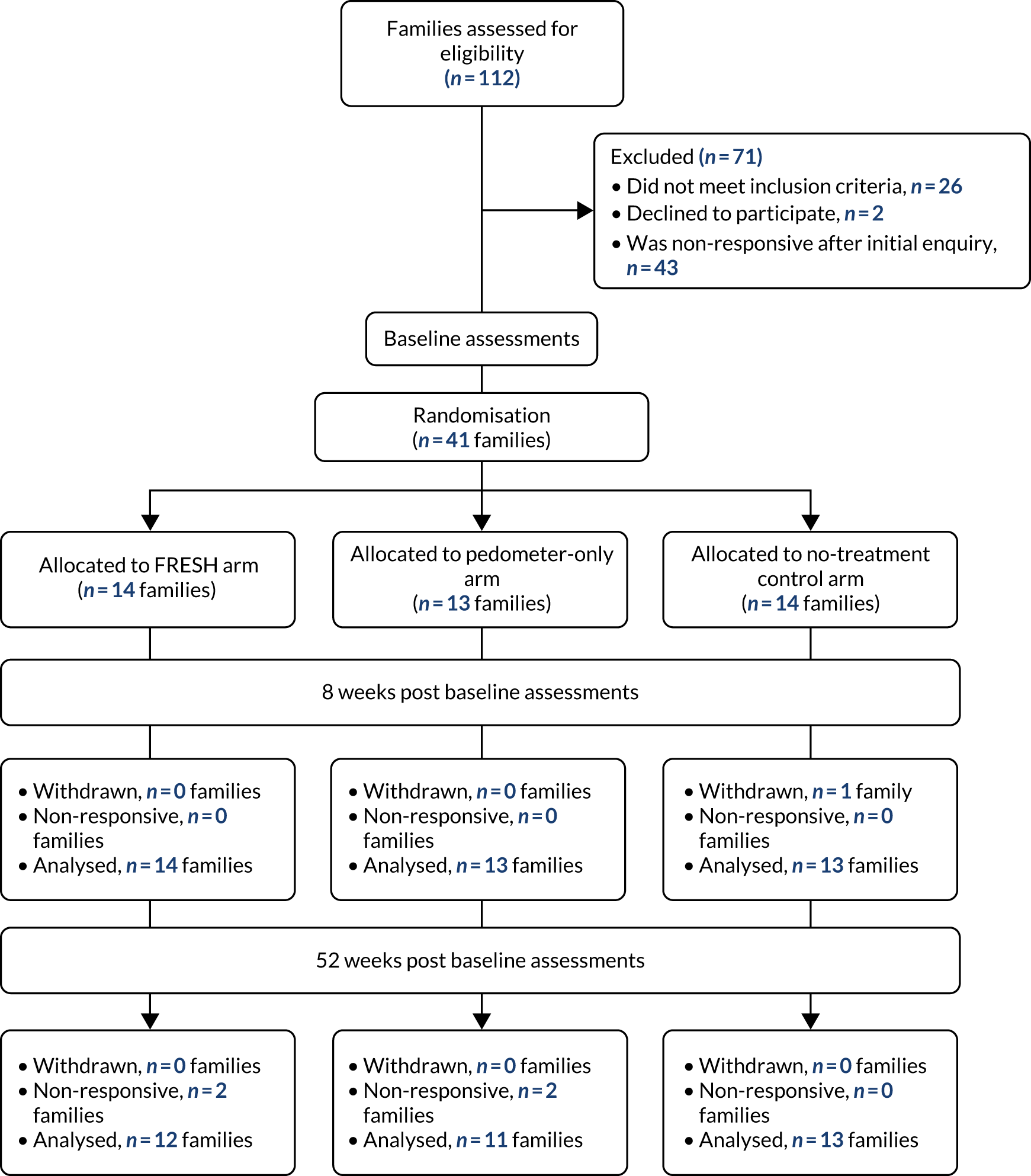

Recruitment and retention

Owing to intervention development delays, we were only able to deploy school recruitment strategies. Of 11 schools approached, three declined (too busy, n = 2; doing enough physical activity promotion already, n = 1), and three did not respond. Five schools with an estimated 437 eligible students in Years 3–5 agreed to disseminate the FRESH recruitment material (reach).

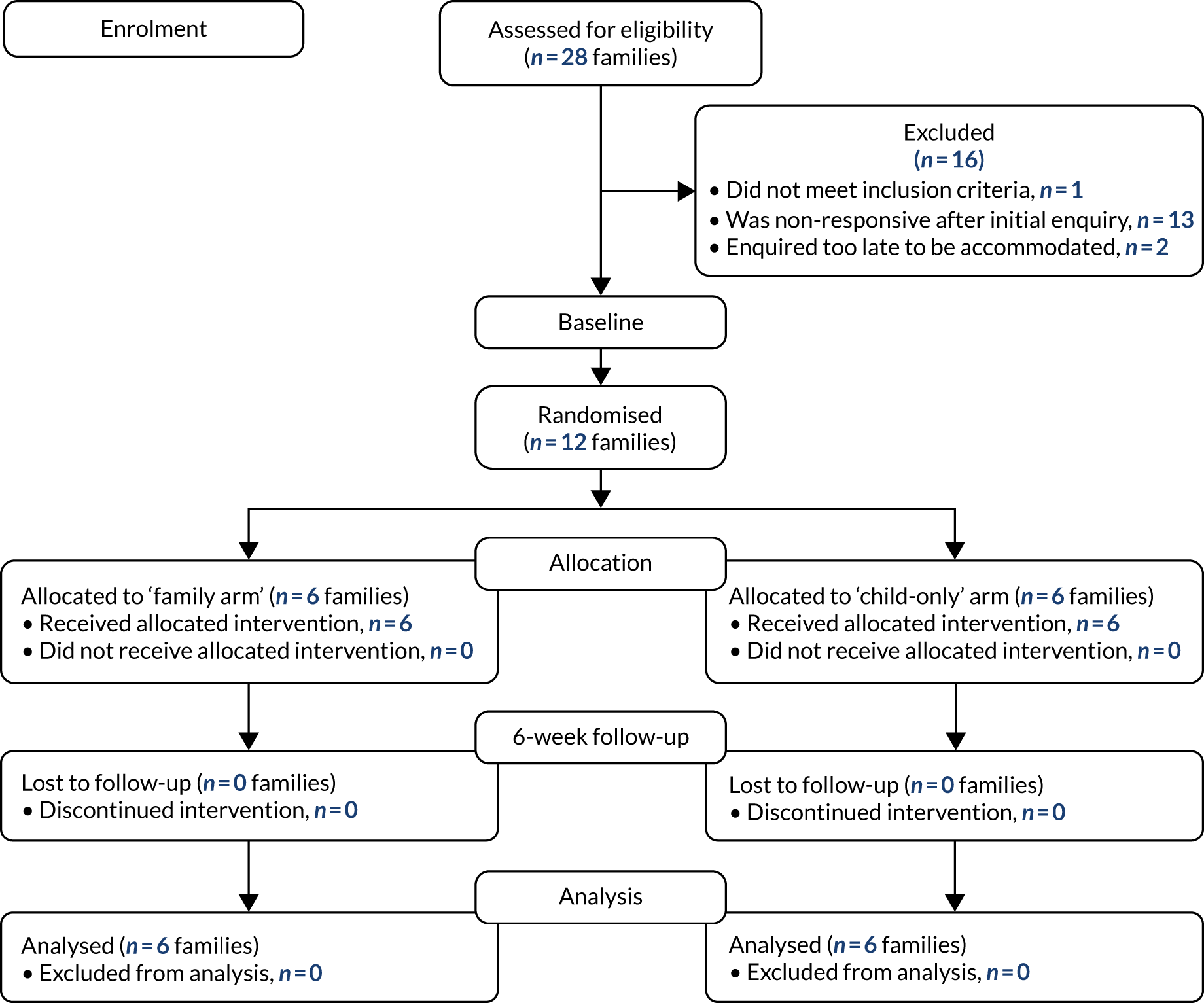

Figure 5 shows the flow of participants from the number of families assessed for eligibility through to the number analysed. Of those families reached, 6.4% (i.e. 28 families) expressed interest; initial interest came from 23 mothers and 5 fathers. Expressions of interest occurred at a rate of three or four families per week or five or six families per school assembly conducted. Fewer than half of the families expressing interest in participation subsequently signed up to participate in FRESH (n = 12 families), and these were enrolled at a rate of one or two families per week. All families were retained at the 6-week follow-up.

FIGURE 5.

Flow of participants in the FRESH feasibility study.

Of the 12 families enrolled, four were whole families and six were dyads (i.e. one parent and one index child); 32 family members participated overall. About two or three family members took part per family (range 2–4 family members); four families had an additional eligible adult, three families had an additional eligible child and one family had both. Table 4 describes the participant characteristics.

| Variable | Adults (n = 18) | Children (n = 14) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex (% male) | 38.9 | 50.0 |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 39.8 (8.2) | 8.3 (1.7) |

| Height (cm), mean (SD) | 168.6 (8.6) | 133.6 (12.7) |

| Weight (kg), mean (SD) | 74.7 (15.9) | 32.5 (10.8) |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 26.3 (5.8) | N/A |

| BMI z-score, mean (SD) | N/A | 0.5 (1.1) |

| Waist circumference (cm), mean (SD) | 92.0 (12.7) | 66.6 (12.3) |

| Blood pressure (mmHg), mean (SD) | ||

| Systolic | 127.8 (16.2) | 110.0 (105) |

| Diastolic | 72.6 (9.1) | 64.6 (7.2) |

| Pulse rate | 68.3 (7.1) | 81.0 (7.8) |

In focus groups, families were asked about the perceived challenges to recruitment, which revealed four challenges to be considered for optimising future recruitment. A brief description of the challenges is provided below, with supporting quotations in the first part of Table 5.

| Subheading | Supporting quotations |

|---|---|

| Findings related to recruitment and retention | |

| Children trying to convey what FRESH was to parents | I guess because you did it in assemblies, I wasn’t sure what he was going on about. It wasn’t till [a mother of a participating family] had obviously been in touch with you that we found out more. But going back to the whole thing of trying to then explain [FRESH], if the kids can’t do it, it becomes sort of Chinese whispers between the parents, doesn’t it?Mother 7, family arm |

| Participation would be time-consuming | I think people have misconceptions . . . I think they just heard the words research project and thought, ‘oh no, we’re going to have to do a load of stuff’ ’. . . but you don’t have to do anything, just wearing this [pedometer] and going about what I do normally and log on the website every night or a couple of times a week and have a look at how we’re doing. I didn’t think it was a hassle at allFather 5, child-only arm |

| Lack of confidence for physical activity | Exercise is a funny thing, you know . . . Like if they’re overweight or they don’t eat healthy . . . they may think they’re being judged by it and actually they’re not being judged by it at all. That’s not what this was about . . . but there’s a fear factor when it comes to exercise for some people . . . And given that I think obesity levels are pretty high around here for the national average, I think West Norfolk’s one of the fatter areas, people may be a bit . . . I don’t know, possibly there was lack of confidence about signing up to something like thisMother 5, child-only arm |

| Reluctance to be measured | It was the measurements, I would’ve done the other stuff . . . I think with some people that just puts you off straightaway. I think it did for me . . . I was like ‘no, I don’t want to do that’ and I’m sure others felt the same. Luckily [father] didn’t mind because she really wanted to do thisMother 12, family arm |

| Findings related to intervention feasibility, acceptability, fidelity and optimisation | |

| Feasibility and acceptability of FRESH | Definitely more aware, I underlined that [on the process evaluation questionnaire] because I think in terms of our awareness, it has made us a lot more aware of the steps that we are doing. I really, really liked that, for me that has been the best thingFather 6, family arm |

| . . . you [speaking about index child] wanted to walk more didn’t you, like if we were going to nursery you were like, ‘can I walk because I want to get more steps’. I noticed that on a few things, whereas before she would have been like, ‘oh, can we go in the car?’Mother 12, family arm | |

| I do think if you’d given step counters to everyone in the family it gives us more onus to do it. Once you’d gone, it was all about him and no one else in the family, I felt like I’d done my bit and it was all down to just him and his step counter; whereas, if I’d have had a step counter . . . for the 6 weeks I probably would have been more aware about how active I was, and not necessarily competed with you, but just the fact that I had my own one to keep an eye on how active I’d been, then I’d have probably felt more involvedFather 8, child-only arm | |

| ‘Family time’ | We would actually compare on a daily basis . . . we’d be like ‘who’s done the most steps today?’ and you know, ‘oh, you’ve done more than you normally do, [index child]’ or ‘you have done less then you normally do’. So, we were able gauge, ‘oh, it’s been a slow day, why has been it slow day? What have you been doing at school today?’Father 6, family arm |

| We had the planner out the whole time in the kitchen, so it was easier to fill in. [Index child] was involved with it because, at the end of the day, I would say,’ have you written your log?’ And before bed she would have a look and she would write her number down and [father] and I would shout our numbers to her and say, ‘oh this is mine, put mine in’Mother 6, family arm | |

| FRESH website | We pretty much just went on [the website] to log [steps] . . . I think we found that hardest thing, we would fall out over whose going to log [on the website] . . . so that wasn’t that helpful for the family dynamic [laughs]Father 6, family arm |

| Well I’d like to have a leaderboard, that shows everyone doing it and it says, ‘you’ve got to beat this person and their name’, like it says on my football gameBoy 5, child-only armYeah, a family one would be good. That would spur us all on wouldn’t it! It would spur us all on massively, yeahFather 5, child-only arm | |

| Rewards | He enjoyed that [virtual badges], but . . . maybe do a certificate or stickers or something, you know, even if you posted one to them, so they receive the post and we could be like ‘oh yeah, look what you’ve done!’ and . . . especially if you named it to them personally, so they actually got the physical post . . . ‘I’ve got a letter, I get to open that, wow, got my certificate in it!Mother 3, family arm |

Children trying to convey what FRESH was to parents

Delivering school assemblies emerged as an effective strategy for captivating children’s interest in FRESH. The children’s interest in FRESH following assemblies appeared to be the main reason parents expressed interested in participating. However, children struggled, or were unable, to explain to their parents what FRESH involved, which is likely to have had an impact on the likelihood of recruiting the family unit.

Participation would be time-consuming

Parents suggested that one of the main barriers was the perception that participation in FRESH would be burdensome and time-consuming. However, participating parents reported that FRESH participation did not impede their normal daily activities.

Lack of confidence about physical activity

One family said that a major challenge in recruiting families in their county might be a high prevalence of obesity, and they suggested that families would be reluctant to register for a physical activity intervention owing to a lack of confidence.

Reluctance to be measured

It was also confirmed that some family members chose not to participate in FRESH at all because they did want to participate in measurement sessions.

Family focus groups also revealed suggested strategies for improved recruitment. This included a return visit to schools to give parents an opportunity to hear about FRESH and ask questions; exploring recruitment strategies that targeted adults through formal (e.g. employers) or informal settings (e.g. clubs, local fetes, shopping centres); using social media, such as Facebook or Twitter; and providing endorsements from previous participants or familiar organisations.

Intervention feasibility, acceptability, fidelity and optimisation

Feasibility and acceptability of FRESH

All children reported that they liked taking part in FRESH and thought that it was fun. Table 6 shows adults’ overall perceptions of FRESH. Scores were generally positive. In particular, adults agreed that FRESH was fun, encouraged their family to do more physical activity, and made their family more aware of the amount of physical activity they did, which was confirmed in focus groups (see Table 5). Goal-setting also emerged as a major theme, particularly in those randomised to the ‘family’ arm. Participants (adults and children) were aware of the daily step counts required to complete their weekly challenge and were able to identify ways to accumulate additional steps to meet the daily targets (e.g. active travel; see Table 5). Participants also reported receiving socioemotional (e.g. feeling ‘closer’ as a family) and perceived cognitive benefits (e.g. to the index child’s maths ability) as a result of their participation. Last, all six families allocated to the child-only arm demonstrated a clear preference for the whole family to be involved in FRESH. This finding was particularly evident among fathers (see Table 5).

| Overall | Family arm (n = 8 adults) | Child-only arm (n = 6 adults) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| The FRESH study . . . | |||

| . . . was fun for my family and me | 4.2 (0.8) | 4.3 (0.7) | 4.2 (1.0) |

| . . . encouraged my family and me to do more physical activity | 3.9 (0.8) | 4.0 (0.6) | 3.8 (1.0) |

| . . . has led my family and me to do more physical activity than we did before FRESH | 3.5 (1.0) | 3.6 (0.7) | 3.2 (1.3) |

| . . . has led my family and me to do more activities (other than physical activity) together than we did before FRESH | 3.4 (0.7) | 3.3 (0.7) | 3.5 (0.8) |

| . . . has made my family and me more aware of the amount of physical activity we do | 4.6 (0.5) | 4.7 (0.5) | 4.6 (0.5) |

| . . . is something my family and I would like to continue to be part of | 3.8 (1.3) | 4.3 (0.8) | 3.4 (1.5) |

| Regarding ‘family time’, to what extent do you agree or disagree with the following? | |||

| It was easy to schedule ‘family time’ | 3.1 (1.1) | 3.1 (1.4) | 3.1 (0.8) |

| My family consistently scheduled ‘family time’ | 3.1 (1.2) | 3.1 (1.4) | 3.2 (1.0) |

| My child reminded us about ‘family time’ | 2.9 (1.6) | 3.0 (1.7) | 2.7 (1.5) |

| My child led/initiated ‘family time’ | 2.6 (1.4) | 2.7 (1.5) | 3.0 (1.5) |

| Regarding the FRESH website, to what extent do you agree or disagree with the following? | |||

| It was easy to use | 3.6 (1.3) | 3.6 (1.4) | 3.5 (1.4) |

| I enjoyed using it | 3.6 (0.9) | 3.6 (1.1) | 3.7 (0.8) |

| My child/children enjoyed using it | 4.0 (1.2) | 3.9 (1.3) | 4.2 (1.0) |

| I thought the website was appealing | 3.7 (0.9) | 3.6 (0.8) | 3.8 (1.0) |

| I liked that there were varying degrees of difficulty with the challenges | 4.3 (0.9) | 4.3 (1.1) | 4.3 (0.8) |

| I enjoyed the information about the cities | 3.9 (1.1) | 3.6 (1.3) | 4.3 (0.8) |

| My child/children enjoyed the information about the cities | 3.8 (1.1) | 3.4 (1.3) | 4.3 (0.8) |

| The step converter was useful (e.g. converting swimming to steps) | 3.3 (1.3) | 2.8 (1.2) | 4.0 (1.2) |

| The resources page was useful | 3.2 (1.1) | 3.0 (1.2) | 3.5 (1.0) |

| I enjoyed the recipes | 3.3 (0.9) | 3.1 (1.1) | 3.5 (0.8) |

| My child/children enjoyed the recipes | 3.4 (1.0) | 3.1 (1.1) | 3.7 (1.0) |

| Logging our steps was easy | 3.7 (1.5) | 3.9 (1.7) | 3.5 (1.4) |

| Regarding the step counter we gave out to log your steps, to what extent do you agree or disagree with the following? | |||

| I didn’t mind wearing it | 4.0 (1.2) | 4.0 (1.2) | N/A |

| My child/children didn’t mind wearing it | 3.9 (0.9) | 3.9 (1.1) | 4.0 (0.6) |

| It was easy to use | 4.5 (0.7) | 4.6 (0.5) | 4.3 (0.8) |

| I thought it was reasonably reliable at counting steps | 4.3 (0.7) | 4.6 (0.5) | 3.8 (0.8) |

| I used the memory feature to go back and look at the number steps my family and/or I took | 4.6 (0.5) | 4.6 (0.5) | 4.5 (0.5) |

Intervention acceptability and fidelity

Kick-off meeting

Using a five-point Likert-scale (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree), all families felt that the ‘kick-off’ meeting was useful (family vs. child only: mean 4.4, SD 0.8, vs. mean 4.5, SD 0.8) and appreciated the fact that it was a face-to-face meeting as opposed to a telephone or video meeting. Most families felt that they had enough technical support (mean 3.9, SD 1.5; mean 4.2, SD 1.0), and the majority of families stated that a single meeting was enough for them to understand the protocol and how to use the intervention website and materials. However, two families would have liked a follow-up meeting the following week.

‘Family time’

Overall, adults disagreed that children led or reminded them of ‘family time’ (see Table 6). In line with the adult data, the majority of children did not view themselves as their family’s team captain to lead on ‘family time’. Several children said that they forgot they were team captain or they could not be bothered to be the team captain. There was also evidence to suggest that some parents took over the team captain role.

Overall, adults reported that it was not particularly easy for their family to schedule ‘family time’ or to have it consistently. Most families claimed they either rarely or never had ‘family time’. A lack of time was the most commonly cited challenge to having ‘family time’. In addition, some parents’ work schedules (i.e. shift work) made it difficult to organise ‘family time’ with all family members present. However, focus group evidence shows that some families were discussing physical activity in a manner that would have been unlikely prior to FRESH (see Table 5).

Generally, families used their action planners only to log daily step counts and not to plan weekly activities or anticipate barriers to meeting step goals. Most families preferred to write their step counts out on their paper-based action planners and transfer them to the FRESH website once, near the end of their weekly challenge (see Table 5).

FRESH website

Compared with the child-only arm, the family arm exhibited greater website engagement, as they travelled to more cities (mean 36, SD 11, vs. mean 13, SD 8) and failed fewer challenges (mean 1.5, SD 1, vs. mean 3, SD 1). All children in the family arm and most (≈ 80%) children in the child-only arm wanted to continue using the FRESH website. Children in the family arm also found it easier to use the website than those in the child-only arm (83% vs. 60%). Overall, adults’ mean scores were generally positive in relation to the FRESH website (see Table 6), although more critical opinions were voiced during the focus groups. For the majority of families, the extent of their website engagement entailed selecting challenges and logging steps, which was normally a task performed reluctantly by parents (see Table 5). Many adults and children were unaware of or had not used several of the website elements (e.g. step calculator, parent resources, virtual rewards). Others stated that children had been interested in the website (e.g. information about cities) but that their interest wore off and only an interest in accumulating steps remained.

Technical issues arose with the website, particularly with the algorithm that calculated the number of steps that families needed to accumulate to complete their challenge. This might have negatively affected some participants’ experiences. Aside from technical bugs that needed resolving, families provided input on other potential improvements that could be made to the website. Almost unanimously, families wanted an element of competition on the website. It was evident from numerous focus groups that within-family competition occurred throughout the intervention period. However, the ability to compete against other families was also suggested in several focus groups (see Table 5). Other suggested website improvements included (1) adding a step history page to enable families to view progression over the intervention period; (2) providing more feedback/praise from the research team; (3) providing more flexibility in challenge destinations; (4) sending a text or e-mail reminder to log steps, and (5) improving the website design.

Pedometers

Overall acceptability of the pedometers was high among adults in both arms (see Table 6). Generally, adults stated that it became ‘routine’ or ‘second nature’ to wear pedometers, although some would have preferred wrist-worn pedometers. The most frequently cited reason children gave for wanting to participate in FRESH was to receive a pedometer. Families reported that there were few settings where children were not allowed to wear their pedometers, with the most cited setting being during physical education. Wearing the pedometer was more acceptable to children in the family arm than to those in the child-only arm (≈ 80% vs. 60%).

Rewards

Overall, parents moderately agreed that their child enjoyed receiving virtual rewards (mean 3.5, SD 1.2), with slightly higher scores in the child-only arm than in the family arm (mean 3.8, SD 1.0 vs. mean 3.1, SD 1.3). Children’s responses in the focus group generally supported parents’ perceptions that the virtual rewards were not particularly of long-term interest to them. Most parents suggested that a small, tangible reward, such as a posted certificate or stickers, would appeal to their child more than a virtual reward. Other suggestions included vouchers, clothing or equipment that encouraged physical activity (see Table 5).

Risk of contamination

Focus groups revealed that children were aware of other FRESH participants in their school and that some families did indeed communicate among each other about FRESH, with some even revealing their allocated condition. One family allocated to the child-only arm disclosed that they had purchased a set of pedometers.

Findings related to feasibility of outcome evaluation

Data collection took a mean of 91.1 (SD 27.7) minutes per family at baseline and 77.1 (SD 24.5) minutes per family at follow-up. Overall, adults disagreed that there were too many measures and that data collection took too long. All children self-reported that they ‘liked’ being measured. With the exception of accelerometer/GPS and step test assessment (one refusal each), all participants completed all measures at baseline. At follow-up, 91% of participants accepted an accelerometer/GPS and completed the step test; 94% of participants completed all other measures.

At baseline, mean valid accelerometer wear time was 851.5 (SD 54.1) minutes for adults and 755.7 (SD 29.7) minutes for children. At follow-up, mean wear time was 843.1 (SD 78.6) for adults and 742.3 (SD 56.4) for children. The GPS provided a location for a mean of 750.6 (SD 191.4) (adults) and 646.2 (SD 189.0) (children) minutes at baseline and for a mean of 720.0 (SD 237.6) (adults) and 586.8 (SD 262.8) (children) at follow-up. Valid data (600 minutes) on ≥ 4 days (including one weekend day) was available for 83% of adults at both baseline and follow-up; this was slightly lower for children, at 75% and 67%, respectively. A visual inspection of wear-time data revealed a tendency for children to remove their devices at around dinner time, for parents to remove their devices after their child had gone to bed, and for families to put on their devices much later in the day at the weekend than on weekdays.

An initial assessment of family functioning via the video-recorded Fictional Family Holiday activity showed poor to moderate data quality, as discussions were limited and cursory. Three factors may have affected data quality: (1) most families enrolled were dyads, limiting opportunities for whole-family discussion; (2) providing families with a planner to write out their itinerary may have shifted the emphasis away from open-ended discussion; and (3) the activity was completed at the end of the visit, when participants may have been fatigued from data collection.

The physical activity-related expenditure questionnaire developed for this study appeared to have appropriate face validity and was capable of providing rich data related to membership fees and subscriptions (e.g. for sports clubs, fitness centres, after-school clubs) and sports equipment (e.g. sportswear, gadgets).

Chapter 4 Lessons learned from the FRESH feasibility study

Parts of this chapter are reproduced with permission from Guagliano et al. 78 © The Author(s). 2019 Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

The FRESH feasibility study described in Chapters 2 and 3 provides a response to calls for the need for innovative interventions targeting young people and families. 76 To our knowledge, FRESH is among the first physical activity interventions to specifically target whole family engagement, helping to create supportive, synergistic environments for the promotion of healthy behaviours and long-term change. 29,57,59 We assessed the feasibility and acceptability of the FRESH intervention and accompanying evaluation to inform future research. Our findings showed that it was feasible and acceptable to deliver and evaluate a family-targeted physical activity promotion intervention with generally high acceptability from participating families. This feasibility study, however, also revealed areas for improvement.

Optimising recruitment

Previous literature has identified family-based recruitment as being particularly difficult. 44,112 Our formative work30 and other studies (see a review by Morgan et al. 52) recommend a multifaceted recruitment strategy in family-based research. Owing to unforeseen delays, we were unable to employ our planned multifaceted recruitment strategy, which likely contributed to our under-recruitment of families (60% of targeted 20). Of the families enrolled, only one-third included all family members. There was some suggestion that this may have been because of either a lack of confidence in physical activity or a reluctance to be measured. Improved messaging is, therefore, required early in the recruitment process to reassure low-active families, and individual family members, that FRESH is tailored to their activity levels and to highlight that they have the option of opting out of (parts of) the measurements. Allowing family members to be involved in the intervention, regardless of their participation in the evaluation, as was done in FRESH, may improve effectiveness and long-term behaviour change. 44,55,56,59

Interestingly, our findings showed that fathers appeared to be interested in participating in FRESH, but only 5 out of 28 expressions of interest were initiated by fathers. This may be because, among heterosexual parents, tasks such as making telephone calls (e.g. to express interest) or family event preparation (e.g. study participation) are more likely to be performed by mothers than fathers. 113 Therefore, recruiting whole families, whereby any parent can initiate an expression of interest, may be an important catalyst for the inclusion of more fathers in family-based research.

Other key areas of improvement to recruitment include optimising the conversion from children reached to families expressing an interest (e.g. extending the age range of index children to cover the whole of UK Key Stage 2 (Years 3–6, covering ages 7–11 years); reducing the burden on children to explain FRESH to their parents (e.g. by directing parents to a video); targeting adults directly via community- and employer-based recruitment or social media; and obtaining recruitment support from local organisations.

Optimising the FRESH intervention

FRESH was designed as a goal-setting and self-monitoring intervention, aimed at increasing family physical activity. Encouragingly, these behaviour change techniques resonated with most families and align with recommendations to increase family physical activity. 29 Participants reported being aware of what their daily step goals needed to be in order to complete their weekly challenges. Interestingly, the challenge context did not seem to be important to participating families (i.e. choosing challenge cities to walk to virtually). Instead, focus group interviews revealed that meeting daily step goals, completing weekly challenges and intrafamily competition appeared to be the key drivers motivating families throughout the intervention period.