Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 16/122/57. The contractual start date was in July 2018. The final report began editorial review in September 2020 and was accepted for publication in May 2021. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2021 Ali et al. This work was produced by Ali et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2021 Ali et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

Intellectual disability and health and social inequalities

Intellectual disability (ID) is a life-long condition characterised by an intelligence quotient (IQ) < 70 and impaired adaptive functioning arising before the age of 18 years. 1 The UK prevalence of ID is 1–2%. 2 People with ID have complex health needs, but experience substantial inequalities in health, including poorer access to health services, higher rates of physical heath disorders3,4 and higher mortality rates, and, on average, they die 20–25 years earlier than people in the general population. 3–5 They have higher rates of mental illness, with a point prevalence of 41%. 6,7 The prevalence of depression is the same as that in the general population, but people with an ID are more likely to experience chronic depression. 8,9 People with ID have greater exposure to adverse life events and social disadvantage,10 experience social exclusion because of stigma,11 have markedly smaller social networks12,13 and have a higher prevalence of loneliness than other people. 14 These factors may increase their vulnerability to depression. 14–18

People with ID may experience behavioural side effects from antidepressant treatment (e.g. aggression and agitation)19 and encounter inequalities in accessing psychological therapies. 20 There is a need to consider alternative, accessible interventions in the management of depression. One such intervention that has shown some promise is befriending. 21

Characteristics of befriending

Befriending is a one-to-one friendship-like relationship that is initiated, supported and monitored by an agency, usually a voluntary organisation in the community. 22 There are differences in the practice and implementation of befriending, which lies on a spectrum from being very similar to a friendship, whereby the relationship is reciprocal and equal, and is delivered by lay volunteers, to being a professional and therapeutic relationship with an emphasis on goal attainment, which resembles mentoring. 23 Most types of befriending relationships lie mid-way on this spectrum and may involve listening and providing emotional support, but may be prescriptive in terms of the length and duration of meetings. Those involved usually have a discussion about the boundaries of sharing personal information,23 from not sharing any personal details to introducing the befriendee to the befriender’s family or friends. Most schemes also offer training, supervision and ongoing support to volunteers.

Motivation and experience of befriending volunteers

Volunteers are important factors in the successful delivery of befriending and, therefore, it is important to understand the motivations of volunteers. Little is known about the motivations of volunteers who work with people with ID, although they are likely to be similar to those of volunteers who befriend people with other disabilities. Motivations can be categorised into ‘giving’, whereby volunteers have a desire to help others and contribute to society, and ‘getting’, where there is an expectation that they will gain valuable work experience or new skills. 24–26 Several studies that have explored the experiences of volunteers befriending individuals with mental illness have reported that volunteers feel empowered and rewarded by their efforts to support the befriendee’s recovery, and that befriending provides volunteers with a different perspective on how they view people with mental health problems, including improving attitudes towards such individuals. 25,27,28 Some volunteers with a history of mental illness also report gaining confidence and an increased sense of acceptance. 27 Negative experiences have also been described, for example, when there has been confusion about the role of volunteers and they have been regarded as counsellors or carers, or even as a ‘cab driver’, instead of as a friend. 25,29 Volunteers also report challenges in being non-judgemental towards their befriendee and difficulties with communication. 28,29 Other concerns included dissatisfaction in the recruitment process and limited reimbursement of expenses incurred during activities. 30

Experiences of people with intellectual disability

Only one published study has explored the experiences of befriending for people with ID. 30 Lack of service user empowerment and involvement was highlighted as a barrier. Befriendees commented that they had little choice over the selection of their befriender and little influence over how often pairs met and what activities they engaged in. Many described difficulties coping with the relationship coming to an end, including feelings of disappointment, anger and despair, and that they were provided with little information from the befriending service about the link ending. This highlighted the importance of managing endings and being clear about the time-limited nature of the intervention at the outset.

Mechanism of action of befriending

The causal mechanisms of befriending have not been fully elucidated, although social support is thought to be relevant. Social support has structural characteristics, such as the number and connectedness of social ties, and functional characteristics, such as providing instrumental or emotional support, information and advice. Social support may improve well-being by acting as a buffer to stress. There is evidence to suggest that it may mediate genetic and environmental vulnerabilities to depression through its effects on neurobiological factors and other psychosocial factors (e.g. coping strategies). 31 Perceived social support rather than received social support appears to be related to psychological well-being and, therefore, providing support where it is not needed can be unhelpful. 32 The main underlying assumption in befriending interventions is that providing an individual who is lonely and lacking in social networks with additional, enacted support through a befriender will lead to an increase in the individual’s level of perceived support, resulting in improved psychological well-being. Befriending may enhance social support by providing direct emotional and instrumental support, but the befriender can also help to link the befriendee to social activities, which may be sustainable outside and beyond the end of the befriending relationship; therefore, befriending may have longer-term benefits. Befriending may also improve health outcomes thorough its effects on social networks. 33

Effectiveness of befriending

Befriending (as an active control delivered by professionals) has been found to have similar effects to cognitive–behavioural therapy34 and acceptance and commitment therapy in schizophrenia. 35 There is evidence from a comprehensive systematic review21 that befriending in the general population may have a significant but modest effect on reducing symptoms of depression when compared with no treatment or treatment as usual in both the short term [standardised mean difference –0.27 depressive symptoms, 95% confidence interval (CI) –0.48 to –0.06 depressive symptoms] and the long term (standardised mean difference –0.18 depressive symptoms, 95% CI –0.32 to –0.05 depressive symptoms). The review included studies of paid and unpaid volunteers and befriending delivered in various ways, including face-to-face and telephone contact. A more recent review and meta-analysis36 of befriending by unpaid volunteers examined the effects of befriending on participants with physical and mental health disorders across a range of social and psychological outcome measures. Befriending was associated with better patient-reported outcomes across all primary outcomes, but the effect size was small (standardised mean difference 0.18, 95% CI –0.002 to 0.36). There was limited evidence for the effectiveness of befriending on individual outcomes, such as depression, loneliness or quality of life, when the studies were combined. 36 A randomised controlled trial (RCT) of befriending of people with psychosis by lay volunteers provides further evidence for the potential beneficial effects of befriending. 37 Participants in the intervention group had significantly more social contacts at the end of the 12-month intervention (adjusted difference 0.52 social contacts, 95% CI 0.04 to 0.99 social contacts) and at 6 months’ follow-up (adjusted difference 0.73 social contacts, 95% CI 0.05 to 1.40 social contacts; p = 0.04), suggesting that befriending may help to reduce social isolation in this group.

Benefits for volunteers and wider society

A systematic review and meta-analysis38 found that volunteering in general had beneficial effects on depression, psychological well-being and life satisfaction, and was associated with a lower risk of mortality in volunteers, although the causal mechanisms for these associations are unclear. The benefits to wider society include economic impacts, such as reduced burden on government spending and improved employability of volunteers; strengthening of social connections between different sectors and organisations within the community; and safer, stronger and more cohesive communities (e.g. inverse relationship between levels of volunteering and crime). 39

Rationale for proposed research

Although the benefits of befriending have been explored in a range of disorders, its effectiveness in people with ID has not been evaluated in a randomised trial. A single-arm feasibility study of one-to-one befriending by volunteers that was conducted by a voluntary organisation40 recruited 24 volunteers, of whom 15 were matched with an individual with ID. Overall, 60% of befriendees reported a positive change: 53% reported a decrease in isolation and 40% reported an increase in confidence. The study was limited by the lack of validated outcome measures, the lack of a control group and the lack of follow-up data. The study has not been published in a scientific journal.

One Australian study examined the feasibility of using active mentoring to improve the participation of older adults with ID in mainstream community groups. 41 The intervention comprised 29 individuals receiving the intervention and a matched comparison group. The participants in the intervention group reported better social satisfaction than those in the comparison group (effect size 0.78; p = 0.02). Symptoms of depression on the carer-reported version of the Glasgow Depression Scale for people with a Learning Disability (GDS-LD) were also reduced, but not significantly. The study found that the intervention was feasible and acceptable. However, this was a non-randomised study, the sample comprised older adults living in Australia and the intervention is not directly comparable to one-to-one befriending.

Given the dearth of studies examining befriending in people with ID and an insufficient number of data on feasibility, there is a clear rationale for conducting a pilot study prior to a full RCT.

Aims and objectives

The main aim of the study was to determine the feasibility and acceptability of a full-scale RCT to estimate the effectiveness of one-to-one befriending by volunteers for people with ID, compared with an active control group.

The objectives were to:

-

examine the recruitment and retention of individuals with ID and volunteers in the trial, and number of successfully matched pairs within the 6-month study recruitment period

-

record any negative consequences/adverse effects of befriending

-

measure the extent to which the intervention is delivered as intended by the volunteers and befriending schemes

-

examine the acceptability of the intervention and study procedures by exploring the views of individuals, volunteers, carers and befriending services

-

examine changes in health and social outcomes by carrying out exploratory analyses of the impact of befriending on depressive symptoms measured by the GDS-LD42 at 12 months and other outcomes (e.g. self-esteem, loneliness, quality of life and social participation) at 6 and 12 months post randomisation

-

carry out exploratory analyses of the impact of befriending on volunteers’ well-being, self-esteem, loneliness and attitudes towards people with ID at 6 and 12 months

-

estimate the sample size required and determine the final trial design for a full-scale RCT

-

assess the feasibility of collecting data that would inform a future analysis of cost-effectiveness.

Chapter 2 Methodology

The trial protocol was developed with input from the research team, collaborating partner organisations and the Priment Clinical Trials Unit (University College London, London, UK). A summary of the protocol has been published. 43

Design

The study design was a two-arm, parallel-group, researcher-blind pilot RCT with 1 : 1 allocation. Participants were randomly allocated to either the intervention group, where they received one-to-one befriending by a volunteer, or an active control group. Both groups had access to usual care and a booklet of local resources. A process evaluation, based on mixed methods, was conducted to examine the delivery and adherence to the intervention, and to explore stakeholder views on the acceptability of the intervention.

Eligibility criteria

To be enrolled to the study, participants with ID had to:

-

be aged ≥ 18 years

-

have mild or moderate ID (i.e. an IQ of 35–69) assessed using the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence™ (Second Edition) (WASI-II™)44

-

not be attending college/education or a day service for ≥ 3 days per week

-

have obtained a score of ≥ 5 on the GDS-LD,42 indicating the presence of depressive symptoms, but did not need to have a clinical diagnosis of depression

-

be able to speak English

-

be able to provide informed consent.

To take part in the study, volunteers had to be:

-

aged ≥ 18 years

-

available once per week for at least 1 hour, over a period of 6 months.

Volunteers did not need to have any prior experience of supporting people with ID.

Exclusion criteria

Individuals with ID were excluded if they:

-

had limited communication and comprehension that would prevent completion of the questionnaires.

Volunteers were excluded if they:

-

had a criminal record (any documented offence, owing to the vulnerability of the befriendee population) recorded on their Disclosure and Barring Service (DBS) check

-

were unable to provide two references or had unsuitable references.

Sample size

We did not have any estimates of the number of people with ID who were likely to be eligible and consent to taking part in the trial. If we approached 50 participants who were eligible to take part, this would allow us to estimate an expected recruitment rate of 80% (40 people), with a 95% CI of 68.9% to 91.1%. A sample size of 40 recruited people with ID would allow us to estimate a 30% dropout rate in the trial, with a 95% CI of 25.7% to 54.3%. The recruitment period was 6 months. There were two participating befriending services and, therefore, we needed to recruit 3.3 participants with ID per month at each site.

Recruitment

The recruitment period for the trial was from mid-April 2019 to mid-September 2019 (5 months). Recruitment issues are discussed in Chapter 3.

Two befriending services agreed to take part in the study. One was based in east London (Outward, based in Hackney) and the other was based in Suffolk (The Befriending Scheme). They were responsible for recruiting and training volunteers, matching volunteers to participants with ID, the provision of supervision to volunteers and monitoring of the befriending relationship. Both services had previous experience of supporting befriending relationships with people with ID.

Participants with intellectual disability

Participants with ID were recruited from existing and new referrals to the participating befriending services or were recruited from the caseload of clinicians working in four community ID services within the North East London NHS Foundation Trust (NELFT). Volunteer co-ordinators and clinicians screened referrals and caseloads for participants who were potentially eligible for the study and approached individuals to discuss the study. If the individual was interested in the study, they were given an information sheet and permission was sought for their details to be passed on to the research team. A referral form was then completed by the clinician or staff at the befriending service and e-mailed to the research team. The trial research assistant reviewed the information, contacted the potential participant to discuss the study and carried out the eligibility assessment, which comprised an assessment of IQ using the WASI-II (the two subset version was used). 44 The WASI-II was selected because it is a brief and reliable measure of cognitive ability and can be used to estimate the full-scale IQ across all population groups, including people with ID, which is useful in the context of research. The two-subset version consists of vocabulary and matrix reasoning and takes approximately 15 minutes to complete. The eligibility assessment also comprised an assessment of the presence of symptoms of depression using the GDS-LD. 42 If the individual was eligible, they were required to sign the consent form before completing the baseline assessment. If the research assistant was uncertain about whether or not a participant had met the eligibility criteria, the case was discussed with the chief investigator before the baseline assessment was carried out.

Volunteers

Volunteers were recruited by the befriending services through newspaper advertisements, befriending and job websites, social media, and recruitment events at colleges and universities. Information about the study was also available on the study website hosted by University College London, Division of Psychiatry (https://www.ucl.ac.uk/psychiatry/research/epidemiology-and-applied-clinical-research-department/bid-project), and study posters were circulated to psychology undergraduate students. Interested volunteers completed an application form and were invited to an informal interview to assess their suitability and motivation for becoming a volunteer. A DBS check was completed to ensure that they had no prior criminal record, and references were obtained. After completing training (see Training and supervision of volunteers), successful candidates were invited to take part in the study. They received an information sheet and were asked to sign a consent form before completing the baseline assessment.

Randomisation

Following the baseline assessment, details of the participant with ID were entered into a web-based randomisation system hosted by sealed envelope™ (Sealed Envelope Ltd, London, UK) by a non-blinded member of the research team. The randomisation procedure used randomly varying block sizes, stratified by befriending service. The randomisation protocol was created by the trial statistician and the set-up of the service was overseen by the Priment Clinical Trials Unit.

Participants were randomly allocated by the system to either the intervention group or the control group. The unblinded researcher informed the befriending service and participants with ID of the group to which they had been allocated. Owing to the nature of the intervention, it was not possible to blind participants to their assigned allocation group. However, outcome assessments were carried out by a research assistant who was blind to the participants’ allocation group.

Intervention group

Participants who were allocated to the intervention group were contacted by the volunteer co-ordinator, who arranged to meet them to discuss their hobbies, interests and activities that they would like support to participate in. Based on this information, participants were matched to a volunteer who could accommodate the person’s interests and availability.

The befriending intervention

Frequency and types of activities

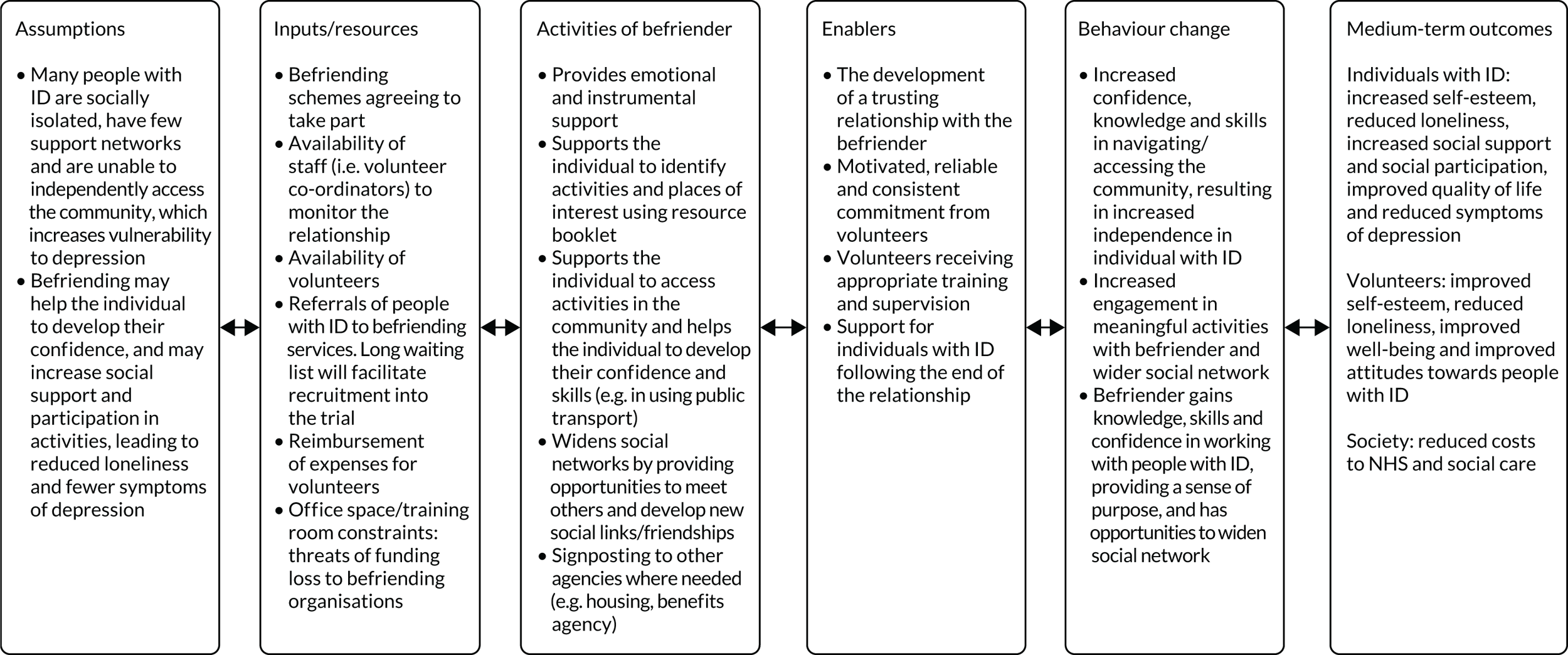

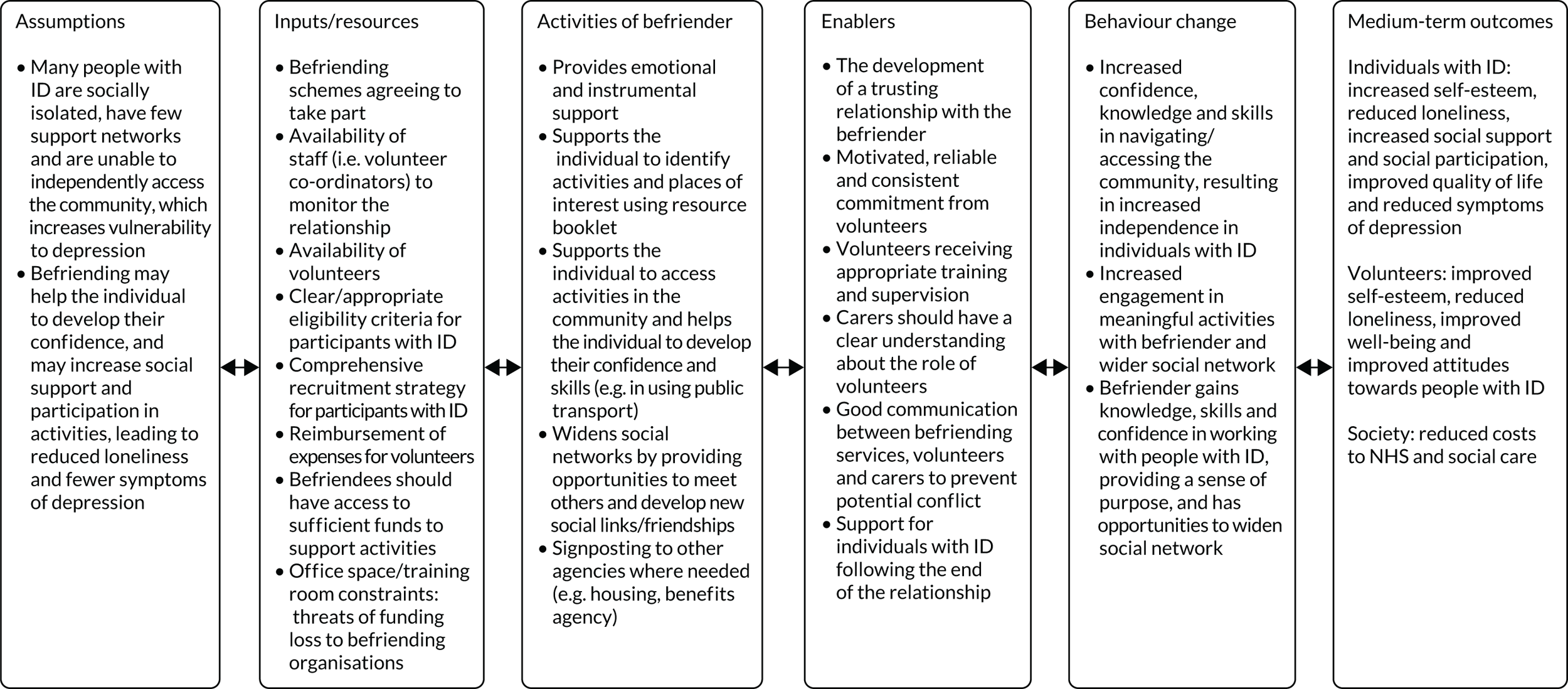

The befriending intervention was adapted from the existing models used by the two participating befriending services and from other studies of befriending. 37,40 The purpose of the befriending relationship was to provide friendship and emotional support, to facilitate community access, and to help the individual gain skills and confidence that would allow them to access activities in the community on their own (i.e. to promote sustained social activities beyond the befriending relationship). Figure 1 is a logic model of the intervention and describes the proposed mechanisms of action.

FIGURE 1.

Logic model of befriending in people with IDs.

The volunteer (befriender) and person with ID were expected to meet once per week for at least 1 hour, over a period of 6 months. However, it was anticipated that there may be breaks due to holidays or illness. The pair received a booklet with information about local activities and amenities, which was to be used as an aid to plan activities. The emphasis was on assisting the individual to make choices about the activities that they wished to pursue. The volunteer was not expected to carry out personal care, administer medication or accompany the individual to medical appointments. Contacts by telephone/social media were permitted in addition to face-to-face contact, and the pair were expected to spend at least 50% of the total number of meetings in the community. Meetings could take place during evenings/weekends, depending on the pair’s availability. Volunteers were asked to keep a record of their activities in a structured log, detailing whether or not they attended, reasons for cancellation, what they did at each visit, the duration of the activity and types of contact other than face to face. Volunteers’ travel expenses were reimbursed, but other expenses had to be agreed with the befriending service. Participants with ID were expected to pay for their travel and the other costs they incurred during outings.

Introduction and monitoring of the befriending relationship

A face-to-face meeting was arranged by the volunteer co-ordinator at the participant’s home to introduce the volunteer to the participant. If both parties were satisfied with the matching process, the pair then arranged to meet on their own. If the volunteer or individual with ID dropped out of the relationship once it had become established, they were offered the option of rematching. Volunteers were permitted to be matched to more than one participant with ID, although this did not occur in the trial.

Six weeks after matching, the volunteer co-ordinator contacted each person by telephone/face to face and then maintained contact every 4 weeks to monitor the progress of the relationship. A further meeting was held with the pair towards the end of the 6-month period to obtain general feedback about the befriending intervention, to discuss ending the relationship and to support the individual with ID in coming to terms with the ending. The pair could continue their relationship if they wished after the 6-month period was over, but arrangements for monitoring the relationship were outside the remit of the trial and varied according to the befriending service. Information was collected on any relationships that had continued beyond 6 months.

Training and supervision of volunteers

Volunteers completed face-to-face training and electronic learning prior to being matched. The training covered the following topics: benefits of befriending and issues related to confidentiality and lone working; advice on how to plan meetings effectively; health and safety; safeguarding; intellectual (learning) disability awareness, and professional boundaries, such as dealing with sensitive issues, ending relationships and expectations of the role of the volunteer. Volunteers received PowerPoint (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) slides and a manual developed by the research team, with information about the study and additional information relevant to working with people with ID, such as maximising communication, understanding the reasons for challenging behaviour, common mental health problems and what volunteers should do in an emergency.

Volunteers had access to individual supervision with the volunteer co-ordinator, which was delivered face to face or over the telephone once per month. The supervision sessions addressed issues related to the training needs of the volunteer and how to overcome issues that had arisen from the befriending relationship.

Training and support for befriending services

The two befriending services completed good clinical practice training and received training on the trial research processes and procedures as part of the site initiation visit. Volunteer co-ordinators received support from the research team through regular e-mail and telephone contact, and were members of the Trial Management Group.

Control group

To control for the effects of participants in the treatment group receiving more information about local activities than those in the control group, participants in the control group were also given a copy of the activities booklet, and met with a member of the research team who discussed the booklet with them (and their carer, if present) and encouraged them to engage with activities.

Both the control group and the intervention group had access to ‘usual care’. This included access to multidisciplinary input from community ID services, including appointments with their psychiatrist, psychologist and other members of the team. Participants continued to take their usual medication, which included antidepressants and antipsychotics. They had access to primary care and other community and hospital-based health services, as well as day services (e.g. day centres and colleges). Where it was possible, participants in the control group were asked if they wished to be matched with a volunteer after they completed their follow-up assessment.

Outcomes

Feasibility outcomes

Recruitment and retention of participants

We assessed the number of participants with ID recruited from those who were eligible; the number of volunteers who were recruited over a 6-month period; the number of participants who were successfully matched with a volunteer; the number of participants and volunteers who dropped out of the intervention; and the number of participants and volunteers who completed the follow-up assessment.

Adverse events

Adverse events were collected at each follow-up assessment using open-ended questions and were also reported directly to the chief investigator by the befriending services, including concerns about safeguarding. Adverse events were recorded in the medical records and case report forms (CRFs).

Adherence to the intervention

Adherence was assessed as part of the process evaluation (see Treatment adherence).

Acceptability of the intervention

This was informed by data on retention/dropout of volunteers and participants; the data from the process evaluation (see Process evaluation) that examined the extent of engagement with the intervention by participants and volunteers (based on number of sessions attended); and qualitative data obtained from volunteers, participants with ID, carers of people with ID and staff from the befriending service.

Outcome measures in participants with intellectual disability

Health and social outcome measures were assessed with the participant at baseline and at 6 months post randomisation. All the measures that were selected for use in the study have been validated and used in people with ID. A follow-up assessment at 12 months was planned as part of the original protocol but could not be conducted because of delays in setting up the study and poor recruitment (see Chapter 3). Face-to-face assessments were conducted by the research assistant, who was blind to group allocation, and these were carried out at the participants’ homes; where this was not possible, a telephone assessment was carried out. Participants were supported by the research assistant to complete the measures, which included reading out the questions and responses, and explaining and rephrasing items that were difficult to understand. The following health and social outcomes were assessed:

-

Depressive symptoms (main outcome of interest) were measured using the GDS-LD. 42 This 20-item scale has been developed and validated in people with ID and has been used in recent trials. 45 Participants were asked to rate their symptoms over the last week using a three-point response format scored 0 (‘no’), 1 (‘sometimes’) and 2 (‘a lot’). Scores on the scale range from 0 to 40, with higher scores indicating more symptoms. The scale is reported to have good test–retest reliability (r = 0.97) and internal consistency (with an alpha of 0.90).

-

Self-esteem was measured using the adapted Rosenberg self-esteem scale for people with intellectual disabilities. 46 This is a self-report scale with six items measured on a five-point response scale ranging from ‘never true’ to ‘always true’. Scores range from 6 to 30, with higher scores indicting greater self-esteem. The scale is reported to have an adequate internal consistency (with an alpha of 0.62).

-

Quality of life was measured using the 19-item Maslow Assessment of Needs Scale – Learning Disability (MANS-LD),47 and nine items from the adapted World Health Organization Quality of Life measure (WHOQOL-8). 48 Both measures are rated using a five-point response format (1–5), where higher scores indicate better quality of life.

-

Loneliness and social satisfaction were measured using the Modified Worker Loneliness Questionnaire (MWLQ),49 which has 12 items and two subscales (aloneness and social dissatisfaction). Items are rated on a three-point scale (0–2), with a maximum score of 24. Higher scores indicate more loneliness. The test–retest reliability of the scale is reported to be between 0.76 and 0.89, and inter-rater reliability was 0.87 for aloneness and 0.85 for social dissatisfaction. The internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) was 0.65 for aloneness and 0.80 for social dissatisfaction.

-

Social support was measured using the Social Support Self Report for intellectually disabled adults (SSSR). 50 Participants are asked to rate support from family, staff, friends and their partner based on five items rated on a three-point scale (0–2) for each group. The maximum score is 40, with higher scores indicating receipt of more support. The scale has good internal consistency (with an alpha of 0.85).

-

Social participation was measured using the Guernsey Community Participation and Leisure Assessment (GCPLA). 51 Participants are asked to rate the frequency of their participation in five types of activities (i.e. services, vocational activities, leisure, social, and facilities and amenities) on a five-point scale ranging from never (0) to daily or more frequently (5). Higher scores indicate more social participation. It has good test–retest reliability (r = 0.87) and internal consistency (with an alpha of 0.93).

Outcome measures in volunteers

The following outcomes were assessed in volunteers at baseline (prior to matching) and 6 months after the baseline assessment:

-

Self-esteem was measured using the 10-item Rosenberg self-esteem scale. 52 Items are scored on a four-point Likert scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (4). The maximum score is 40. Higher scores indicate better self-esteem. Reported test–retest reliability ranges from 0.82 to 0.88 and internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) ranges from 0.77 to 0.88.

-

Psychological well-being and quality of life was measured using the widely used Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale (WEMWBS). 53 This is a 14-item scale that uses a five-point response format (1 = none of the time; 5 = all of the time). The maximum score is 70 , with higher scores indicating better well-being. It has a high internal consistency (with an alpha of 0.89) and a test–retest reliability value of 0.83.

-

Loneliness was measured using the revised University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) Loneliness Scale. 54 This is a 20-item scale that measures feelings of loneliness and isolation. Items are rated on a four-point scale (1 = never; 4 = often). The maximum score is 80 and higher scores indicate more loneliness. The measure has a high internal consistency (with an alpha of 0.96) and a test–retest reliability value of 0.73.

-

Attitudes of volunteers was assessed using the 67-item Attitudes Towards Intellectual Disability Questionnaire (ATTID). 55 This measure has five subscales (knowledge of causes of ID, knowledge of capacity and rights, discomfort, interaction, and sensibility or tenderness). Higher scores indicate more negative attitudes. Test–retest reliability ranges from 0.44 to 0.88, with an overall internal consistency of 0.92 and a subscale reliability ranging from 0.59 to 0.89.

Feasibility of carrying out a cost-effectiveness analysis

A preliminary health economic analysis was conducted to inform planning of future economic analyses, sources of data required and how best to collect these data. The following were recorded:

-

Health-related quality of life was measured using the EuroQol-5 Dimensions – Youth (EQ-5D-Y). 56,57 There are currently no EuroQol measures that have been developed specifically for adults with ID. The EQ-5D-Y was selected because it uses simple language and has been used in other studies of people with ID. 45 The EQ-5D-Y comprises the descriptive system (five dimensions relating to mobility; looking after myself; doing usual activities; having pain or discomfort; and feeling sad, worried or unhappy) that is rated by selecting the most appropriate statement that reflects the individual’s health state (‘no’, ‘some’ or ‘a lot’) for each dimension, and the EuroQol visual analogue scale (EQ VAS), where self-rated health is recorded on a vertical visual analogue scale between two end points labelled ‘the best health you can imagine’ and the ‘the worst health you can imagine’. The EQ VAS represents the participant’s own subjective view about their health, which may not be captured by the five dimensions, and is therefore considered to provide additional information in its own right. We assessed whether or not it would be feasible to collect self-reported data from individuals with ID on both the descriptive system and the EQ VAS. This was recorded at baseline and 6 months post randomisation.

-

The Client Services Receipt Inventory (CSRI)58 was used to assess the feasibility of collecting data on participant-reported health-care service use. Based on a review of the literature and input from the wider study team, we adapted the CSRI to people with ID. The adapted CSRI was completed with participants’ carers, where possible, or health professionals who knew the person well. If they did not have a carer, then information was collected from the participant. They were asked to recall health and social care service use during the last 6 months. This included contacts with primary care, community services, community ID services and hospitals, including outpatient and inpatient care. This was recorded at baseline and at 6 months post randomisation.

-

Concomitant medication was recorded on a CRF developed for the study. This information was obtained from carers and, where this was not possible, participants were asked to show medication boxes or blister packs to the research assistant. Information was recorded at baseline and at 6 months post randomisation for the previous 6 months.

-

For the befriending intervention, we recorded the resources used by befriending services. Volunteer co-ordinators at the befriending services kept a record of all their contacts with volunteers and participants and the duration of contacts (e.g. monitoring visits and supervision) and other expenses incurred during the intervention.

Process evaluation

A process evaluation using mixed methods59 was conducted to examine:

-

Adherence (fidelity) to the intervention: whether or not the different components of the intervention were consistently followed and the extent to which volunteers delivered the intervention as intended

-

Acceptability of the intervention and trial procedures. The aim was to understand the perceived value, benefits and unintended consequences of the intervention; to understand the contextual factors influencing how the intervention was delivered; and to develop an understanding of the likely mechanisms of action of the intervention and what modifications that would need to be made to the trial procedures and processes in a future randomised trial.

Treatment adherence

Data were collected on the uptake of volunteer training, supervision and the frequency of monitoring checks carried out by volunteer co-ordinators from routine records at each site to assess fidelity to the intervention by the befriending services. To understand how the befriending intervention was delivered, the location and content of the meetings and the range of activities undertaken were described based on an analysis of structured logbooks completed by volunteers. A framework was developed to categorise different types of activity to enable different types of befriending support to be distinguished and quantified.

We examined (1) how many sessions each volunteer attended and the average number of sessions attended by the volunteers, (2) how many pairs attended at least 10 meetings during the 6-month intervention period, (3) the average duration of sessions and (4) for how many participants the minimum threshold of at least 50% of meetings being outside the participant’s home was achieved.

Acceptability of the intervention

We invited all the participants with ID in both groups of the study, the volunteers who had been matched with a participant with ID, the volunteer co-ordinators at the two befriending services and carers of participants who had received the befriending (after seeking permission from the participant) to take part in semistructured interviews. A topic guide comprising questions and prompts was developed for each of the four groups (see Appendix 1, Boxes 1–4, for a list of questions). Interviews were conducted face to face, but during the COVID-19 pandemic modifications needed to be made to accommodate the lockdown restrictions. Interviews were therefore held by telephone or videoconferencing.

All the participants were asked about their views of the intervention (e.g. training, matching, supervision, support), what they perceived to be helpful and what aspects could be improved or required modification, as well as views about trial procedures (e.g. randomisation and completion of questionnaires). The interviews were audio-taped and transcribed.

Study expenses

Following completion of the baseline assessment and, again, after the 6-month follow-up assessment, all the participants and volunteers received a £15 gift voucher for their time and effort. Participants taking part in the qualitative interviews also received a £15 gift voucher.

Data management

Quantitative data were collected using the study CRFs, which were stored at the study sites. Data were entered into the secure and General Data Protection Regulation-compliant60 Red Pill (web-based) database hosted by Sealed Envelope Ltd and managed by Priment Clinical Trials Unit. A subsample of 5% of the CRFs was checked to ensure consistency in data entry. After completion of relevant data management processes, the data were exported from the database and analysed by the trial statistician.

Statistical analysis

Demographic and clinical characteristics of participants with ID and their mental health, quality of life and social outcomes were summarised by randomised group using mean [standard deviation (SD)] or count (percentage) for continuous and categorical data, respectively, at baseline and at the 6-month follow-up.

Demographic characteristics of befriending volunteers and their mental health and attitudinal outcomes were similarly summarised at baseline and at the 6-month follow-up.

The primary mental health outcome was depressive symptoms, measured using the GDS-LD. All participants were analysed in the groups to which they had been randomised. The effect of the befriending intervention was estimated using a linear regression model, with depressive symptoms at 6 months’ follow-up as the outcome and study group as the main explanatory variable, adjusting for depressive symptoms at baseline.

Owing to the small number of participants recruited to the study, we decided that it was inappropriate to explore the effect of the intervention on the secondary outcomes and further regression analyses were not conducted

Analysis of cost-effectiveness

The main aim of the economic evaluation was to determine the costs of delivering the intervention, and test the feasibility of collecting health-care resource use and health-related quality-of-life data to calculate the incremental mean cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) gained from the intervention, compared with the control (i.e. the cost-effectiveness), in people with ID for a full RCT. The detailed health economic analysis is described in Appendix 2.

We assessed the response rates from the CSRI, EQ-5D-Y and EQ VAS; and collected information on whether the CSRI was completed by carers, professionals or participants with ID. We noted any difficulties reported by participants in completing these measures.

The costs of the intervention were provided by the volunteer co-ordinators at the befriending services. They provided a breakdown of costs related to the intervention, such as costs of recruitment, DBS checks, and staff time in relation to training and supervision of volunteers and monitoring visits. Staffing costs were calculated using an hourly rate.

To calculate the costs of using health and social care services, we adopted the perspectives of the NHS and Personal Social Services. The horizon of the study was 6 months; therefore, discounting was not performed.

The mean (SD) health and social care resource use and costs of medication were calculated and costed using nationally recognised, published unit costs61–63 to estimate the mean (95% CI) costs per participant. Costs were in Great British pounds at 2019 values or adjusted for inflation if costs for 2019 were not available (see Appendix 2, Tables 10 and 11, for unit costs and prescription costs).

Responses from the EQ-5D-Y were converted into a single value (index number). The collection of index values for possible EQ-5D states is referred to as the value set. Research is currently ongoing to produce EQ-5D-Y value sets and, therefore, although not recommended, the regular EuroQol-5 Dimensions, three-level version (EQ-5D-3L), value sets were used to obtain utility values. Utility values range from 0 to 1, with scores close to 1 indicating ‘full health’ (with a score of 0 indicating ‘death’). The EQ VAS was used as a quantitative measure of health outcome that reflects the participant’s own judgement about their health status. We examined whether or not scores on the EQ VAS were consistent with the EQ-5D-Y utility values, as this would help us to determine if the EQ-5D-Y is a suitable measure of health status in people with ID.

Incremental cost per change in the primary health outcome (depression scores on the GDS-LD) between the intervention group and the control group was estimated. The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) was calculated by dividing the difference in total costs (incremental cost) by the difference in the health outcome (incremental effect) to provide a ratio of ‘extra cost per extra unit of health effect’ for the more expensive intervention compared with the alternative. ICERs reported by economic evaluations are compared with a predetermined threshold to decide whether or not choosing the new intervention is an efficient use of resources.

Analyses followed the Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS) Good Reporting Practices. 64

Qualitative data analysis

Transcripts from the interviews with participants with ID, staff at befriending services, volunteers and carers were transcribed and analysed using thematic analysis65 supported by computer software (NVivo 9; QSR International, Warrington, UK). Thematic analysis aims to identify themes or patterns in the data set through a rigorous process of data familiarisation, coding of data, and the development and refinement of themes. It was selected because of its flexibility in incorporating a range of different approaches and its use in a wide range of contexts. Data were coded by two members of the research team, using both deductive (i.e. coding guided by existing concepts and ideas) and deductive (i.e. coding guided by the content of the data) approaches. The codes and initial themes were discussed with the research team, followed by further revision of themes. The analytic strategy aimed to identify themes related to the barriers and facilitators affecting the implementation of the intervention, potential benefits to participants and volunteers, and possible mechanisms of action. Analysis also allowed for the consideration of themes that arose more inductively from the data. The reliability of the coding frame was not assessed.

Progression criteria

The following criteria were used to evaluate whether or not the pilot trial had been successful:

-

At least 70% (35) of participants are recruited from the 50 potentially eligible individuals who are approached.

-

At least 70% of participants with ID in the intervention group are successfully matched to a volunteer (befriender) and they meet on a minimum of 10 occasions.

-

The dropout rate of participants with ID in both groups, post randomisation, is < 30% at 6 months’ follow-up.

-

The intervention and trial procedures are considered to be acceptable by volunteers and individuals with ID.

-

If the target recruitment rate and number of matched pairs is between 50% and 69%, or the dropout rate is between 31% and 50%, we would consider if these could be rectified by modifying the protocol. If this was the case, a full study could still be considered. If the recruitment rates were < 50% and the dropout rates were > 50%, then a full trial would not be considered feasible.

Management of the study

The study was sponsored by University College London. The study research assistant was supervised by the chief investigator and they met weekly. The Trial Management Group, comprising the research team, co-applicants, and staff from the two befriending schemes and Priment Clinical Trials Unit, met every 3 months. An independent Trial Steering Committee, comprising five members [an academic clinician, clinician in ID, statistician, health economist and patient and public involvement (PPI) representative] was appointed and approved by the funders. Meetings were held annually and minutes were made available to the funders.

Patient and public involvement

Proposal development

In developing the proposal, three befriending services for people with ID were consulted. They agreed that it was important to carry out a trial on befriending that captured a range of outcomes for individuals with ID and volunteers. Two of these services subsequently agreed to take part in the study and contributed to the design of the study. In addition, a consultation group meeting was held in July 2017 with volunteers, befriendees and volunteer co-ordinators at the Suffolk service. We discussed the nature of the befriending intervention, its impact on both befriendees and volunteers and the best choice of outcomes for the study. Feedback was obtained from an advisory group of carers and service users linked One Westminster (London, UK) befriending service who thought that the study was very important. They highlighted areas that they felt should be addressed carefully, such as ensuring participants with ID were safeguarded, that they had opportunities to voice concerns if they were dissatisfied, and that adequate training and supervision were available for volunteers. These suggestions were incorporated into the proposal.

Patient and public involvement during the trial

We advertised for people with ID who had experience of befriending to become members of an advisory group. Unfortunately, despite some initial interest, we were unable to recruit enough members during the initial stages of the trial. Following the closure of recruitment and to understand the reasons for the poor recruitment, we consulted with three people with ID and a volunteer co-ordinator who were members of Gig Buddies, a befriending service provided by My Life My Choice (Oxford, UK), a voluntary organisation. These individuals had experience of befriending as a peer befriender, which meant that they were befrienders to other people with ID. They had a unique perspective on the befriending experience. They suggested some reasons for the poor recruitment, but were largely positive about the study. These suggestions are discussed in Chapter 5.

Ethics issues

The study received ethics approval from the London – City and East Research Ethics Committee (reference 18/LO/2188) and from the Health Research Authority (HRA) on 8 January 2019. All substantial amendments to the study were approved by the sponsor and were submitted for ethics approval. Participants with ID were provided with an accessible information sheet and were required to provide written consent prior to taking part in the study. Volunteers, volunteer co-ordinators and carers were also provided with an information sheet and were required to give written consent. Data confidentiality was maintained by assigning participants study identification numbers. One of the main concerns about the study was the potentially negative impact on the participant with ID of relationships ending, particularly if they had limited access to other forms of support. Unfortunately, it was not possible to explore these issues in detail as we were unable to complete the 12-month follow-up (reasons for which are explained in Chapter 3).

Several ethics issues arose during the study. First, the Suffolk befriending service raised concerns about the randomisation of participants and expressed the view that it was unacceptable to assign participants to the control group. To manage this issue, it was agreed that individuals referred to the service would have the option of taking part in the study or remaining on the waiting list. This had significant consequences for recruitment (discussed further in Chapter 3). Second, carers were occasionally found to obstruct relationships and, on two occasions, appeared to be responsible for the breakdown of the befriending relationships. This situation was distressing for the volunteers. In both cases, the participant with ID did not express dissatisfaction with the relationship. This raises questions about the lack of autonomy that some people with ID may have in making decisions. Finally, one safeguarding alert was raised by a volunteer when their befriendee reported being bullied by a paid carer (discussed further in Chapter 3).

Chapter 3 Results

In this chapter, we report on the following feasibility outcomes:

-

recruitment of participants with ID and volunteers

-

the number of participants with ID who were successfully matched

-

the number of participants who completed the follow-up assessment at 6 months and withdrew from the trial

-

exploratory analysis of the health and social outcomes

-

exploratory data on the analysis of cost-effectiveness.

Overview of issues encountered in recruitment

The study began in July 2018 and was funded for a 2-year period. In the original study Gantt chart, we had aimed to obtain all the necessary approvals (i.e. approval of the protocol by Priment Clinical Trials Unit, sponsorship and ethics approval, exchange of site contracts and approval of the study database) and start recruitment within 4 months of the trial start date. This target proved to be unrealistic and, as a result of delays in obtaining the necessary approvals, recruitment did not begin until April 2019, 6 months later than intended. Recruitment was slow, and the number of participants with ID who were eligible or willing to take part was smaller than anticipated, as was the number of volunteers expressing an interest in taking part in the study. One issue that we encountered with recruitment through the Suffolk scheme was that it was not considered to be appropriate (or acceptable) by the scheme to change the current standard of practice, because of concerns over randomisation and the potential allocation of participants to the control group. This issue was raised after the protocol was approved and sponsorship approval had been given. It was agreed that the scheme could offer individuals the option of entering the study or remaining on the waiting list for a befriender. Owing to the uncertainty of whether service users would be allocated a befriender or be in the control group, those who were approached chose to remain on the waiting list until a volunteer was allocated through the usual route, even if it meant waiting for a longer period. Staff at the service also expressed their discomfort at the possibility of participants being left in the control group without a befriender for a year. To manage this situation, we agreed to make changes to the protocol to permit participants in the control group to be allocated a befriender after they completed their 6-month follow-up. It was not possible to change the design of the study (e.g. to a waiting list control group) because of the time frame and delays to the study, as this would have required significant changes to the protocol and approval from the funders.

A number of changes to the protocol were made to improve recruitment (see Protocol changes and amendments), such as recruiting student and staff volunteers directly through University College London and the study website, and recruiting participants through advertising on posters, but these strategies did not contribute to an overall improvement in recruitment. Further changes to the study protocol were also considered, such as expanding the number of befriending services taking part in the study and introducing patient identification sites, but these changes were not implemented as the study funders did not approve extending the recruitment period, which would have also required a costed extension to the trial duration and study end date. In September 2019, the funders communicated to the chief investigator that recruitment should close and that preparations should be made to end the study in June 2020, which was the expected end date. The chairperson of the Trial Steering Committee was consulted for advice. With this time frame, it was not possible to complete the 12-month post-randomisation follow-up outcome assessments, and the protocol was updated to reflect this change. Owing to the COVID-19 pandemic, there were some delays in conducting the qualitative interviews and, therefore, a no-cost extension of 2 months was granted.

Recruitment and retention of participants

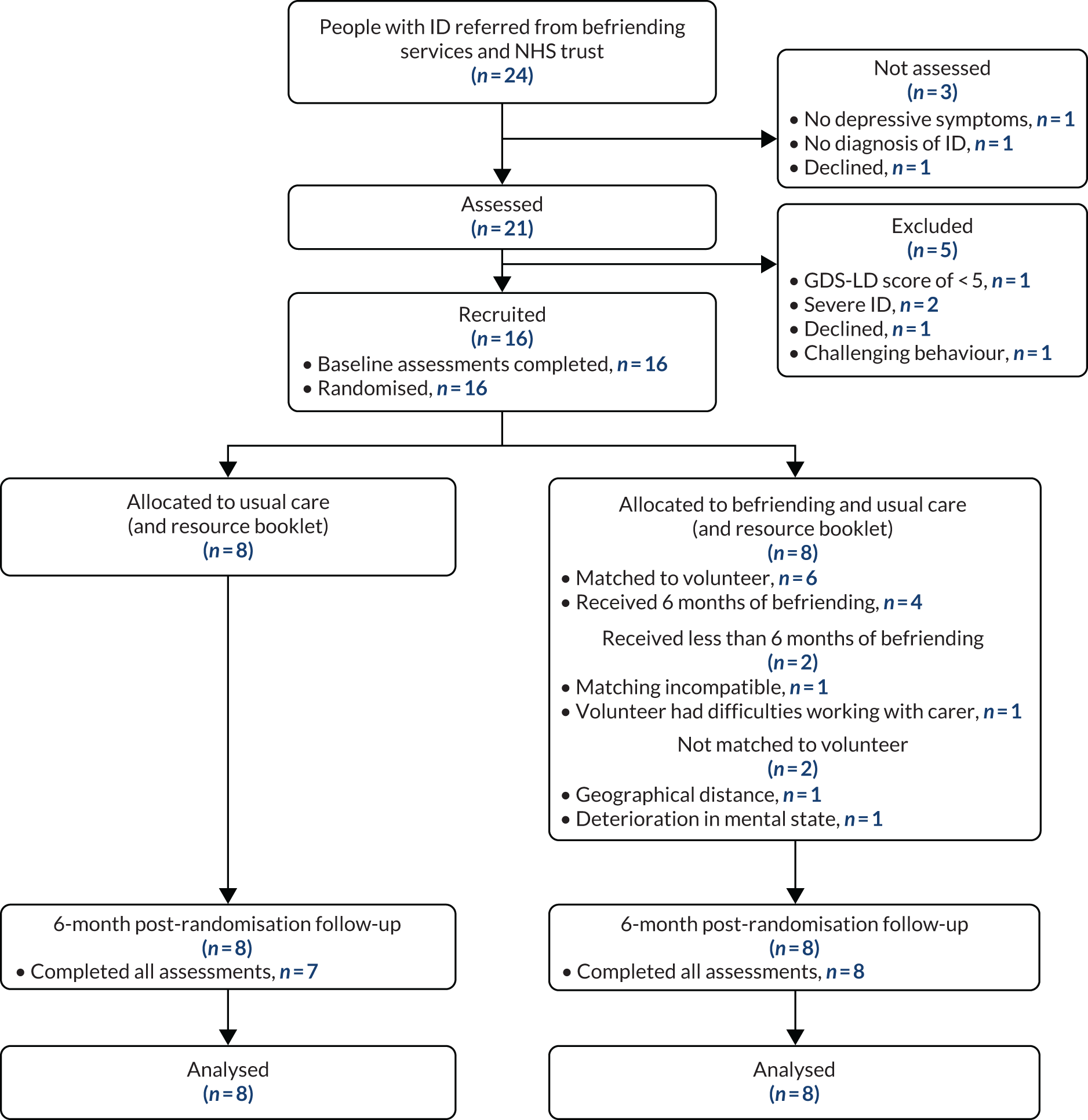

The flow of participants with ID in the pilot trial is shown in the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram (Figure 2). Twenty-four potential participants were referred to the study team. Fifteen referrals were from NELFT clinicians, six were from Outward (Hackney) and three were from The Befriending Scheme (Suffolk) (Table 1). The number of participants with ID and volunteers who were recruited each month is shown in Table 2. On average, just under three participants (2.7) and two (1.7) volunteers were recruited each month into the study. Of the 24 participants with ID referred to the study, 21 were assessed and five were excluded (1) because they did not meet the inclusion criteria (n = 3), (2) because they declined to take part (n = 1) or (3) because of challenging behaviour that may have put the safety of volunteers at risk (n = 1). Sixteen participants agreed to take part in the trial and were randomised to either the intervention group (befriending, resource booklet and usual care; n = 8) or the control group (resource booklet and usual care; n = 8).

FIGURE 2.

The CONSORT flow diagram for participants with ID.

| Referral | Referral source | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| NELFT | Hackney scheme (Outward) | Suffolk scheme (The Befriending Scheme) | |

| Participants with ID | |||

| Total number of referrals | 15 | 6 | 3 |

| Number eligible | 14 | 3 | 1 |

| Number randomised | 13 | 2 | 1 |

| Volunteers | |||

| Total number of referrals | N/A | 9 | 3 |

| Total number enrolled into study | N/A | 8 | 2 |

| Month | Number of participants recruited | |

|---|---|---|

| People with ID | Volunteers | |

| April | 2 | 3 |

| May | 2 | 2 |

| June | 2 | 1 |

| July | 6 | 0 |

| August | 1 | 1 |

| September | 3 | 1 |

| October | 0 | 2a |

Of the eight participants who were randomised to the intervention group, six received the befriending intervention. It was not possible to match two of the participants with a volunteer; the reasons for this were geographical distance (no local volunteer could be identified) and, in one case, deterioration in the mental state of the participant prior to matching.

Of the six participants who were matched, only four had a volunteer for the whole 6-month period. One participant was matched with another volunteer after the first volunteer dropped out because of work commitments. Of the two participants who did not have a volunteer for the 6-month period, in one case the family carer was not satisfied with the match, as they felt that the interests of the participant and the volunteer were not compatible, and in the other case the volunteer experienced difficulties working with the participant because of interference from the participant’s paid carers, who were based in the participant’s supported living accommodation.

All 16 trial participants completed the 6-month follow-up, but one participant in the control group only partially completed the outcome measures owing to a deterioration in their mental state and refusal to continue the assessment.

The flow of volunteers recruited to the study is shown in Figure 3. Twelve volunteers expressed an interest in taking part in the study (nine from the Hackney site and three from the Suffolk site). Two dropped out before being enrolled in the study (one did not complete the training and one could not be contacted for their baseline assessment). Ten volunteers completed the baseline assessment, but one dropped out shortly afterwards (no reason given). Of the nine remaining volunteers, seven were matched with a participant with ID; however, one volunteer who had been matched dropped out of the study because of work commitments. Two volunteers in Suffolk were not matched, as no participants with ID were allocated to the intervention group (the only participant to be randomised was allocated to the control group). All eight remaining volunteers completed the 6-month follow-up assessments.

FIGURE 3.

Volunteer flow chart.

Baseline characteristics of participants

The average age of the 16 participants who took part in the trial was 41.6 (SD 16.7) years; nine were female (56%), eight were of white ethnicity (50%) and nine (56%) were living in supported living accommodation. The majority of the participants had a mild ID (81%), and the average IQ was 55.3 (SD 7.6). Ten participants (63%) had a clinical diagnosis of depression and five (31%) had a diagnosis of anxiety disorder. Nine participants (56%) were taking an antidepressant.

Table 3 displays the participants’ demographic characteristics according to allocated group. The participants in the intervention group were older than those in the control group [average age 48.9 (SD 17.2) years, compared with 34.3 (SD 13.4) years, respectively], were mainly female [6 (75%) compared with 3 (38%), respectively], were less likely to have a diagnosis of depression [4 (50%) compared with 6 (75%), respectively] and there were fewer multiple mental health diagnoses [2 (25%) compared with 5 (62.5%), respectively].

| Demographic | Group | |

|---|---|---|

| Control (N = 8) | Intervention (N = 8) | |

| Age at randomisation (years), mean (SD) | 34.4 (13.4) | 48.9 (17.2) |

| Gender, n (%) | ||

| Male | 5 (63) | 2 (25) |

| Female | 3 (38) | 6 (75) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||

| White | 4 (50) | 4 (50) |

| Asian | 1 (13) | 3 (38) |

| Black | 0 (0) | 1 (13) |

| Mixed | 3 (38) | 0 (0) |

| Living arrangements, n (%) | ||

| Alone | 1 (13) | 3 (38) |

| With family | 1 (13) | 1 (13) |

| Supported living (< 24 hours) | 0 (0) | 1 (13) |

| Supported living (24 hours) | 5 (63) | 3 (38) |

| Residential care | 1 (13) | 0 (0) |

| IQ score: mean (SD) | 55.6 (10.3) | 54.9 (4.1) |

| Degree of ID, n (%) | ||

| Mild | 6 (75) | 7 (88) |

| Moderate | 2 (25) | 1 (13) |

| Mental health diagnoses, n (%) | ||

| Depression | 6 (75) | 4 (50) |

| Psychosis/schizophrenia | 1 (13) | 2 (25) |

| Bipolar affective disorder | 1 (13) | 0 (0) |

| Anxiety disorder | 3 (38) | 2 (25) |

| Autism | 2 (25) | 0 (0) |

| ADHD | 2 (25) | 0 (0) |

| Other | 1 (13) | 1 (13) |

| Two or more mental health diagnoses, n (%) | 5 (62.5) | 2 (25.0) |

| Taking antidepressants: yes, n (%) | 5 (63) | 6 (75) |

| Concomitant epilepsy: yes, n (%) | 1 (13) | 0 (0) |

| Mobility, n (%) | ||

| Mobilises independently | 8 (100) | 5 (63) |

| Mobilises with walking stick or frame | 0 (0) | 3 (38) |

| Travels independently: yes, n (%) | 8 (100) | 6 (75) |

Table 4 summarises the outcome measures at baseline according to group allocation. Depressive symptoms at baseline were lower in the intervention group than in the control group, with mean GDS-LD scores of 18.6 (SD 5.7) and 21.4 (SD 9.8), respectively.

| Outcome | Group | |

|---|---|---|

| Control (N = 8) | Intervention (N = 8) | |

| Depressive symptoms (GDS-LD), mean (SD) | 21.4 (9.8) | 18.6 (5.7) |

| Self-esteem (adapted Rosenberg self-esteem scale), mean (SD) | 20.8 (4.5) | 22.4 (4.1) |

| Quality of life, mean (SD) | ||

| MANS-LD | 64.1 (10.3) | 73.0 (9.4) |

| WHOQOL-8 | 23.8 (4.7) | 30.0 (4.4) |

| Loneliness and social satisfaction (MWLQ), mean (SD) | ||

| Aloneness | 7.6 (2.8) | 8.4 (2.3) |

| Social dissatisfaction | 6.8 (3.4) | 7.9 (3.5) |

| Social support (SSSR), median (IQR) | ||

| Family | 5.0 (0.5–6.5) | 5.5 (2.5–6.5) |

| Staff | 5.5 (5.0–7.0) | 5.5 (3.5–7.5) |

| Friends | 5.5 (3.5–7.5) | 3.5 (1.5–6.0) |

| Partner | 0 (0–7.5) | 0 (0–3.5) |

| Social participation (GCPLA), mean (SD) | 73.9 (25.9) | 57.5 (23.4) |

Self-esteem, as measured by the adapted Rosenberg scale, was higher in the intervention group (mean 22.4; SD 4.1) than in the control group (mean 20.8; SD 4.5), as was quality of life, as measured by the MANS-LD [mean 73.0 (SD 9.4) and mean 64.1 (SD 10.3), respectively] and the WHOQOL-8 [mean 30.0 (SD 4.4) and mean 23.8 (SD 4.7), respectively]. Social support, as measured by the SSSR, was similar across both groups, although the control group reported more contacts with friends [median 5.5 contacts, interquartile range (IQR) 3.5–7.5 contacts] than the intervention group (median 3.5 contacts, IQR 1.5–6.0 contacts). Social participation, as measured by the GCPLA, was 16.4 units higher in the control group (mean 73.9 units, SD 25.9 units) than in the intervention group (mean 57.5 units, SD 23.4 units).

The baseline characteristics of the volunteers are summarised in Table 5. The average age of volunteers was 33.2 (SD 11.2) years. Seven (70%) volunteers were female and seven (70%) volunteers were of white ethnicity. Six (60%) volunteers were single, seven (70%) were employed and the majority had A Level (Advanced Level) qualifications or a higher level of educational qualification (n = 7; 70%). Four (30%) volunteers had prior experience of working with someone with ID and three (30%) had experience of working with someone with mental health problems. The baseline scores on the outcome measures of self-esteem, psychological well-being, loneliness and attitudes towards people with ID are shown in Table 6.

| Demographic | Befriending volunteers (N = 10) |

|---|---|

| Age at entry (years), mean (SD) | 33.2 (11.2) |

| Gender, n (%) | |

| Male | 3 (30) |

| Female | 7 (70) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |

| White | 7 (70) |

| Asian | 2 (20) |

| Other | 1 (10) |

| Marital status, n (%) | |

| Married or cohabiting | 4 (40) |

| Single | 6 (60) |

| Highest completed level of education, n (%) | |

| No qualification | 1 (10) |

| GCSE or equivalent | 1 (10) |

| NVQ or equivalent | 1 (10) |

| A Level or equivalent | 2 (20) |

| Degree or higher degree | 5 (50) |

| Employment status, n (%) | |

| Employed | 7 (70) |

| Unemployed, not seeking work | 1 (10) |

| Student | 2 (20) |

| Previous experience of working with, n (%) | |

| People with ID | 4 (40) |

| People with mental health problems | 3 (30) |

| Outcome | Time point, mean (SD) score | |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline (n = 10) | Follow-up (n = 8) | |

| Self-esteem (Rosenberg self-esteem scale) | 28.3 (2.3) | 32.0 (4.6) |

| Psychological well-being (WEMWBS) | 50.6 (6.9) | 53.0 (6.0) |

| Loneliness (UCLA Loneliness Scale) | 55.5 (3.9) | 56.0 (4.0) |

| Attitudes (ATTID) | ||

| Discomfort | 30.5 (10.6) | 29.9 (9.3) |

| Knowledge of capacity and rights | 46.6 (6.6) | 42.9 (6.9) |

| Interaction | 26.6 (8.7) | 24.4 (8.6) |

| Sensibility or tenderness | 16.5 (2.9) | 16.6 (3.5) |

| Knowledge of causes of ID | 18.8 (6.4) | 19.4 (7.0) |

Adverse events

There were no serious adverse events associated with the intervention for participants with ID. In the case of volunteers, there was one incident involving a disagreement between a paid carer at a supported living placement and a volunteer. The volunteer was unfairly accused of buying the participant an unhealthy meal and disregarding his care plan. This disagreement led to a breakdown in the befriending relationship and was upsetting for the volunteer. The volunteer reported this incident to the volunteer co-ordinator, who raised the issue with the manager of the placement. The manager acknowledged that there was a misunderstanding between the paid carer and volunteer.

Other incidents

A volunteer raised a safeguarding alert after their befriendee reported feeling bullied by a member of staff at their supported living placement. The volunteer supported the individual to report the incident. The incident was investigated by the local authority and the situation was satisfactorily resolved.

Outcome assessments at 6 months’ follow-up

Table 7 shows the scores on the outcome measures for participants with ID at 6 months’ follow-up. Depressive symptoms at 6 months’ follow-up were lower in the intervention group than in the control group, with mean GDS-LD scores of 12.9 (SD 6.7) and 17.5 (SD 6.5), respectively. Compared with baseline scores, there was a reduction in the GDS-LD score in both groups (3.9 units in the control group and 5.7 units in the intervention group). There was a slight increase in mean self-esteem scores in both groups: an increase of 0.6 units in the control group, to 21.4 units (SD 3.5 units), and an increase of 1.5 units in the intervention group, to 23.9 units (SD 3.4 units). Mean quality-of-life scores on the MANS-LD also increased in both groups: an increase of 7.9 units in the control group, to 72 (SD 5.5) units, and an increase of 7.0 units for the intervention group, to 80.0 (SD 9.9) units. The mean WHOQOL-8 scores in the control group increased by 4.6 units, to 28.4 (SD 3.5) units, but the scores in the intervention group decreased by 0.6 units, to 29.4 (SD 5.3) units. There were only small changes in the scores for loneliness and social dissatisfaction on the MWLQ. The median social support scores increased slightly in the control group in relation to family (an increase of 2 units, to 7.0 units, IQR 4.0–9.0 units), compared with no change in the intervention group, and in relation to friends (an increase of 1.5 units to 7.0 units, IQR 4.0–9.0 units), compared with an increase of 0.5 units in the intervention group (4.0 units, IQR 3–6.5 units). Between baseline and follow-up, the social participation score increased by 3.8 units in the intervention group (to a mean of 61.8; SD 22.5) and by 0.5 units in the control group (to a mean of 74.4; SD 20.4).

| Outcome | Group | |

|---|---|---|

| Control (n = 8) | Intervention (n = 8) | |

| Depressive symptoms (GDS-LD), mean (SD) | 17.5 (6.5) | 12.9 (6.7) |

| Self-esteem (adapted Rosenberg self-esteem scale), mean (SD) | 21.4 (3.5) | 23.9 (3.4) |

| Quality of life, mean (SD) | ||

| MANS-LD | 72.0 (5.5) | 80.0 (9.9) |

| WHOQOL-8 | 28.4 (3.5) | 29.4 (5.3) |

| Loneliness and social satisfaction (MWLQ), mean (SD) | ||

| Aloneness | 7.0 (3.7) | 8.6 (3.5) |

| Social dissatisfaction | 8.3 (2.7) | 7.6 (2.1) |

| Social support (SSSR), median (IQR) | ||

| Family | 7.0 (4.0–9.0) | 5.5 (1.5–7.0) |

| Staff | 6.0 (5.0–8.0) | 6.0 (2.5–7.5) |

| Friends | 7.0 (4.0–9.0) | 4.0 (3.0–6.5) |

| Partner | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–5.0) |

| Social participation (GCPLA), mean (SD) | 74.4 (20.4) | 61.3 (22.5) |

Regression analysis of main outcome (depression)

After adjustment for depressive symptoms at baseline, depressive symptoms were lower in the intervention group. We estimated a four-point difference in the GDS-LD depressive symptoms score in the intervention group compared with the control group (adjusted mean difference –4.0, 95% CI –11.2 to 3.2). This difference was equivalent to a standardised effect size of 0.5 SDs.

Outcome assessments in volunteers

At 6 months’ follow-up, there was an increase in the mean scores for self-esteem (an increase of 3.7 units to 32.0 units; SD 4.6 units) and psychological well-being for volunteers (an increase of 2.4 units to 53.0 units; SD 6.0 units; see Table 6) from baseline. There was a slight increase in mean loneliness scores at 6 months’ follow-up (a 0.5-unit increase to 56.0 units; SD 4.0 units). Scores on the measure of attitudes towards ID changed very little, apart from a slight improvement in the mean scores for knowledge of capacity and rights (a decrease in score of 3.7 units to 42.9 units; SD 6.9 units).

Health economic data

The total cost of intervention implementation was £5647.38 (see Appendix 2, Table 12), which includes the cost of recruitment (staff time); DBS and reference checks; the cost of staff time and resources to deliver training, supervision, monitoring calls and visits; and volunteer expenses. The mean cost per participant was £701.00.

It was possible to obtain NHS resource data from carers or from health professionals in the majority of cases, but three participants (who lived independently and had minimal support) provided self-report data. Data were available for all 16 participants at baseline and follow-up. No significant difficulties were reported by carers or participants with ID, although participants with ID may have had difficulty recalling the number of contacts with health services over the previous 6 months. Participants were encouraged to use their diaries to record this information.

The costs of NHS resource use and EQ-5D-Y health state values at baseline and at 6 months post randomisation are provided in Appendix 2, Tables 13 and 14. Health-care resource use costs at baseline were substantially lower in the intervention group (mean £1387; 95% CI £359 to £2415) than in the control group (mean £4949; 95% CI £351 to £9548). In both groups, resource use costs at 6 months’ follow-up were lower than those at baseline (mean £855 in the intervention group and mean £4014 in the control group). The mean difference in resource use costs between the two groups was –£3159 (95% CI –£6250 to –£73), but this difference does not take into account baseline cost differences. After including the intervention cost, the mean difference was –£2458 (95% CI –£5549 to £628), but was not statistically significant.

The EQ-5D-Y and EQ VAS were completed by individuals with ID. The EQ-5D-Y was completed by all participants at baseline, but data were missing for one participant at 6-month follow-up. The EQ VAS was completed by almost all of the participants (data were missing for one participant at baseline and follow-up). No issues were reported in the completion of the EQ-5D-Y descriptive system, but some participants found the instructions for the EQ VAS difficult to understand, which may explain the discrepancies in the scores between the EQ-5D-Y and EQ VAS (see below).

At baseline, the EQ-5D-Y utility value was slightly higher in the intervention group (0.90; SD 0.10) than in the control group (0.88; SD 0.08). At 6 months, it was slightly higher in the control group (0.90; SD 0.13) than in the intervention group (0.88; SD 0.11). At baseline, the EQ VAS score was substantially higher in the intervention group (75.0; SD 23.2) than in the control group (45,6; SD 31.5), but, at 6 months’ follow-up, the EQ VAS score appeared to decrease in the intervention group (62.3; SD 40.8) and increased slightly in the control group (50.7; SD 27.6). The CIs for the EQ VAS were large, and the scores did not appear to correspond well to the EQ-5D-Y utility values, suggesting that the EQ VAS may be difficult for people with ID to complete.

We have explored further the responses to the EQ-5D-Y questionnaires that are displayed in Appendix 2, Tables 15 and 16, splitting the EQ-5D-Y levels into ‘no problem’ (level 1) and ‘any problems’ (levels 2 and 3), changing the profile into frequencies of reported problems. This is helpful, as it describes the changes in health over time. Although an overall summary is preferred, this approach shows that there were improvements in usual activities; pain and discomfort; and feeling worried, sad or unhappy in the control group; and improvements in participants looking after themselves in the intervention group.

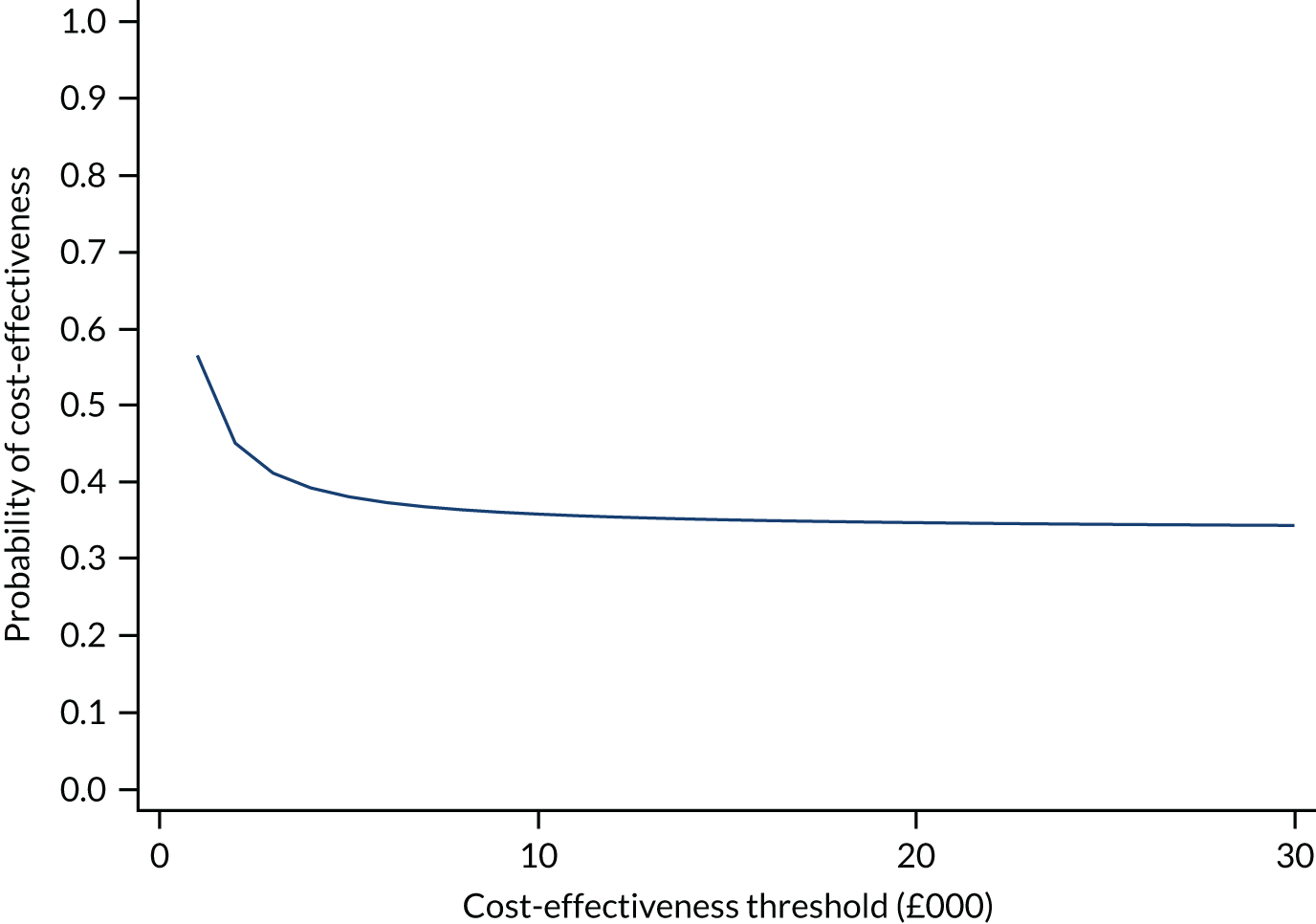

Owing to the small sample size and discrepancies in the scores, QALYs were not calculated. Therefore, the incremental cost per change in the primary health outcome (depression scores on the GDS-LD) between the intervention group and control group was estimated. After adjustment for baseline values, the ICER was –£1810 per 1-point change in GDS-LD score.

The befriending intervention has a 35% probability of being cost-effective at a willingness to pay of £20,000 (see Appendix 5, Figure 5). These results are illustrative only and should be interpreted with caution because of the small sample size.

Protocol changes and amendments

Protocol changes and amendments were approved by the Public Health Research programme manager and submitted for sponsorship and ethics approval. The main changes were as follows:

-

Amendment 1 (approved on 21 June 2019): changes to recruitment to include recruitment of volunteers via the trial website, recruitment of undergraduate students at University College London and use of posters to recruit participants with ID from ID services in NELFT. Changes to the matching process were also introduced, following recommendations from the Trial Steering Committee, enabling participants to be rematched if a volunteer dropped out, and for more than one volunteer to be matched to a participant.

-

Amendment 2 (approved on 25 March 2020): the 12-month follow-up was removed because of significant delays to the study. Focus groups with volunteers, carers and volunteer co-ordinators were changed to interviews to assist data collection.

Chapter 4 Process evaluation results

In this chapter we will discuss:

-

adherence to the intervention by volunteers and the befriending services

-

acceptability of the intervention and trial procedures and processes.

Intervention adherence

Intervention adherence by volunteers

Volunteers were asked to meet their befriendee once per week for 1 hour, over a period of 6 months (24 visits). Volunteers were required to document their activities with their befriendee in a structured logbook following each session. They were required to record whether or not they had had a meeting and reasons for cancellation, what activities they did with their befriendee, where they spent their time together (e.g. at the person’s home or in the community), the duration of the meetings and their reflections on the visit in terms of aspects that did or did not go well.