Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 11/3005/40. The contractual start date was in September 2017. The final report began editorial review in October 2020 and was accepted for publication in May 2021. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2021 So et al. This work was produced by So et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2021 So et al.

Chapter 1 Context

The alcohol problem

Alcohol is increasingly acknowledged to be a global health problem. It is ranked as the ninth most common cause of death worldwide1 and is associated with over 200 medical conditions. Liver disease, including cirrhosis and liver cancer, is perhaps the most well-known harm, but other consequences of alcohol use include cardiovascular disease, unintended pregnancy, sexually transmitted infections, respiratory infections, some cancers, intentional and unintentional injuries, mental and behavioural disorders, diabetes mellitus and diseases of the nervous system. 2–5 The impact of alcohol use extends beyond the individual, with adverse effects on families, communities and the wider economy. As it is a major contributor to socioeconomic inequalities in health, both in the UK and elsewhere,6–9 alcohol consumption is a modifiable risk factor we can address to reduce health inequalities. 10–12

Scotland and the UK

The level of alcohol-related harm in the UK, in general, and Scotland, in particular, is high. 13,14 Scotland has a higher rate of hospital admissions due to mental and behavioural disorders caused by alcohol [International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) code F10] than any other UK country, except Northern Ireland. 15 Scotland also has a better ratio of diagnosed to treated cases (1.0 in 2017–18) for these disorders than any other UK country,15,16 suggesting that further treatment provision in Scotland is not a complete answer. Meanwhile, Scotland’s socioeconomic relative health inequalities are increasing and alcohol is a factor in this. 17,18 Relative inequalities in alcohol-related deaths in Scotland are currently higher than for other conditions monitored, but they are fluctuating and, ultimately, declining over the longer term. 19 The Scottish Government has been implementing a range of strategies to reduce alcohol consumption, alcohol-related harms and health inequalities. 20

In Scotland, in 2018, nearly two-thirds of alcohol-specific deaths were from alcohol-related liver disease. 21 The percentage of alcohol-related deaths caused by liver disease peaked in the mid-2000s and since then has been declining, but is still historically high, having doubled since 1982 (from 40% to 81%). 22 Alcohol-related deaths are highest in people aged 50–70 years and men are approximately twice as likely as women to die (or be hospitalised) because of an alcohol-attributable condition. 21 Up to 80% of alcohol-specific deaths in the UK are caused by liver disease. 23 The burden of severely ill patients admitted to hospital with liver disease in the UK continues to increase. 15

Minimum unit pricing legislation

In May 2012, Scotland became the first country to pass legislation to introduce minimum unit pricing (MUP) without reference to beverage type, a politically high-profile measure. 24–26 Introducing MUP to the Scottish Government’s agenda was challenging and resulted in valuable lessons about policy implementation27 now being applied in England, which has yet to legislate for MUP,28 although one was implemented in Wales in early March 2020. 29

The UK Government withdrew proposals to introduce MUP in England. Researchers have described how the industry used direct and indirect lobbying of politicians and policy-makers, attempted to ‘undermine’ scientific evidence, made legal challenges and sought ‘partnership’ with government agencies. 30,31 An account of the demise of one such partnership (the public health responsibility deal in England32) contrasts with the more ambitious Scottish approach,26,27,33–35 in which some parts of the alcohol industry worked closely, but not in a formal partnership, with the Scottish Government and others [e.g. the Scottish Licensed Trade Association (Edinburgh, UK) shared a platform with the Scottish Health Action on Alcohol Project (Edinburgh, UK) lobbying in the European Union for MUP]. Therefore, the Scottish Government actively sought to implement a measure to affect alcohol harm by manipulating price, despite the opposition of some elements of the alcohol industry.

This resulted in the implementation of MUP, although there was a delay of 6 years due to a legal challenge from some elements of the industry. The effectiveness and feasibility of partnerships, like the public health responsibility deal, between government agencies and the alcohol industry in reducing drinking to safe levels have come into question in a recent paper that showed that, in England, 38% of the industry’s profits are generated from people drinking more than the safe drinking guidelines of 14 units per week or less. 36 The loss of this revenue would clearly have serious and undesirable effects for the industry. As profit-led organisations, the claims of some parts of the alcohol industry freely to support safe drinking could be seen as disingenuous.

Following the legal challenges of the Scotch Whisky Association (Edinburgh, UK) and others in October 2016, a second ruling by the Scottish Court of Session ruled in favour of the legality of MUP. 37 In the final appeal, in November 2017, the UK Supreme Court ruled in favour of the Scottish Government. 38 Secondary legislation set the level at £0.50 per unit and MUP was implemented on 1 May 2018. To continue after April 2024, the Scottish Parliament must vote in its favour. The evaluation of the impact of MUP, including this study, will inform that vote.

Chapter 2 Research objectives

Text in this chapter is reproduced with permission from Katikireddi et al. 39 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Minimum unit pricing of alcohol represents a high-profile public health policy that has the potential to bring about myriad impacts. As the policy was implemented in a manner that was outside the control of the research team and introduced across the whole of Scotland on a single date, we consider the policy to be a natural experiment. 40,41 As randomisation is not possible under such circumstances, our study design involves making comparisons between our intervention area (i.e. Scotland) and a control area (i.e. the north of England).

For our quantitative analyses, we estimated the impact of the policy on health outcomes of interest by conducting a difference-in-difference (DiD) analysis, in which we compared trends in health outcomes in intervention areas with comparable control areas. 42 In doing so, we sought to identify comparable cities that had not been subject to MUP and could, therefore, provide an indication of what would have happened if the policy had not been introduced (i.e. the counterfactual for the trend in health outcomes). For this reason, we specifically selected cities in the north of England (rather than the whole of England) that are more comparable to Scottish cities in socioeconomic characteristics and drinking patterns. As the study design compares changes in health outcomes within intervention areas with changes in health outcomes in control areas, the study design does not assume similar levels of alcohol-related outcomes. However, we assume that trends in health outcomes would have been parallel in intervention and control areas if the policy had not been implemented.

For qualitative analyses, our primary interest was in understanding the perceptions, lived experiences and behavioural responses of those affected by MUP, both stakeholders and higher-risk drinkers. As our interest is in exploring potential mechanisms through which health outcomes may arise, rather than establishing causal effects, we did not collect equivalent data from control areas. Instead, we focused on achieving diversity in relation to socioeconomic position for higher-risk drinkers and professional background for stakeholders. For both sets of interviews, we were also interested in better understanding the potential role of geography (particularly urban–rural and socioeconomic differences) and, therefore, ensured that recruitment captured variation across these characteristics.

Reproduced from the published protocol (in accordance with the CC-BY license),39 this project focuses on both intended and possible unintended consequences of the intervention. 43 Although intended consequences included reduced alcohol consumption and harm, a number of potential risks arising from the introduction of MUP have been identified by policy-makers, the alcohol industry and public health professionals:27

1. Consumers may switch to alternative sources of alcohol not subject to MUP so that the price paid does not increase. Such sources include both legal (internet sales from outside Scotland, legitimate cross-border purchase for own use,44 and home fermentation) and illegal sources (counterfeit, or stolen alcohol). 45,46

2. Increased alcohol-related harm could occur through substitution (e.g. to counterfeit or industrial alcohol associated with greater toxicity) or changed drinking patterns (e.g. moving from regular drinking to binge drinking). People at higher intensities of dependence on alcohol are likely to be at risk in these ways owing to more severe withdrawal symptoms if they cannot obtain sufficient alcohol to meet their level of physical dependence. 47,48

3. Displacement effects with reductions in alcohol-related harms being accompanied by increases in harms related to other substance use could be observed,49–51 and

4. MUP could unfairly penalise deprived populations less able to absorb the additional financial cost52 and this may adversely affect access to other essentials such as food.

5. There may be adverse economic impacts on the Scottish alcohol industry retailers and/or manufacturers.

As per our published protocol,39 a broad programme of research is being co-ordinated by Public Health Scotland (previously NHS Health Scotland) that:

. . . will report to Scottish Ministers and the Scottish Parliament between five and six years after the start of the policy. This programme includes analyses of administrative data and alcohol sales data. 53 The [report] described here complements the NHS-led work and has been funded by the National Institute for Health Research Public Health Research programme to collect primary data in three associated studies.

The studies described in this report will address the first four of these potential risks, although analysis of existing data sets will further address the potential impact on access to essential goods. A study has been commissioned from the University of Sheffield (Sheffield, UK) by NHS Health Scotland to assess the effects on those drinking at harmful levels. The economic impact on the Scottish alcohol industry will not be addressed by our project, but is the subject of a study funded through the Monitoring and Evaluating Scotland’s Alcohol Strategy (MESAS) studies managed by Public Health Scotland.

The overall aim of our study is to investigate the impacts of MUP on health harms (including by deprivation, sex and age subgroups). This includes assessing the extent to which specific unintended consequences occur.

Our more specific research objectives (ROs) and how they are addressed by specific study components (C1–C3) are summarised below:

RO1: To determine the impact of MUP on alcohol-related harms and drinking patterns for the overall population and by subgroups of interest (age, sex and socioeconomic position).

Emergency Department (ED) survey of alcohol-related attendances (C1);

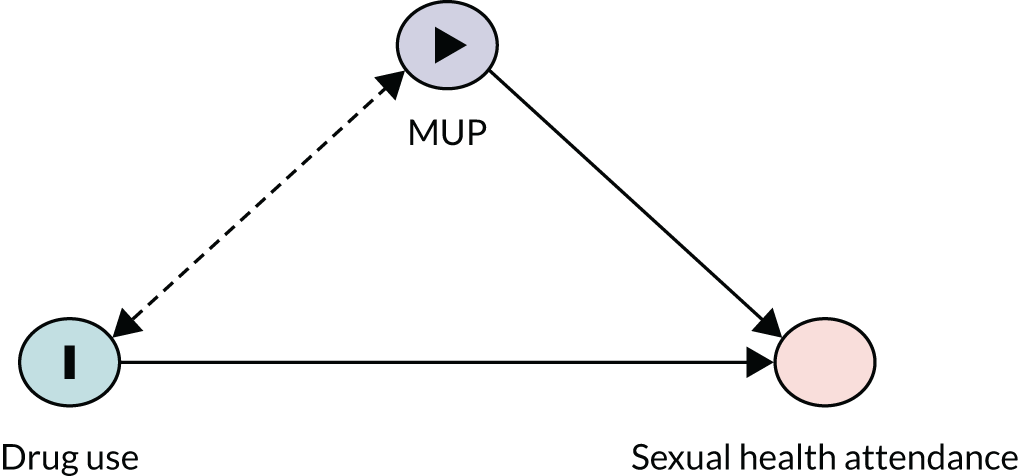

Survey of alcohol-related behaviours (consumption patterns, alcohol spend, source of alcohol, move to other substances) in SHCs (C2).

RO2: To determine the impact of MUP on non-alcohol substance use, and other unintended impacts, for the overall population and by subgroups of interest (age, sex and socioeconomic position).

Survey of alcohol-related behaviours in Sexual Health Clinics (SHCs) (C2);

Qualitative focus group study and stakeholders (C3).

RO3: To describe changes in experiences and norms towards MUP and alcohol use following the introduction of MUP by subgroups of interest (age, sex and socioeconomic position).

Qualitative focus groups with young people/heavy drinkers and interviews with stakeholders from public services (C3).

Chapter 3 Literature review

Minimum unit pricing

Minimum unit pricing of alcohol is a novel public health policy that aims to reduce alcohol-related harms across the population. In May 2012, Scotland became the first country to pass legislation to introduce MUP without reference to beverage type, a politically high-profile measure. 24–26 There is an inverse link between alcohol price and consumption and harm, although the strength of the association varies between studies. 10,54–60 The World Health Organization recommends pricing policies as an important method for reducing alcohol-associated health issues. 61–63 Alcohol MUP is an ‘upstream’ public health policy that aims to reduce alcohol-related harms across the population by setting a floor price for alcoholic drinks based on the amount of pure alcohol that they contain. Unlike tax increases, MUP must be passed on to the customer, reducing the opportunity for retailers to sell cheap alcohol as a ‘loss-leader’ to draw in custom. Under MUP, there are no cheaper ways of obtaining retail alcohol. As a structural intervention,64 MUP is an example of primary prevention and more likely than more ‘downstream’ approaches, such as policing, drink-driving legislation and treatment, to reduce health inequalities in alcohol-related harm. We know from recently improved estimates that there is higher consumption among the most deprived working age males in Scotland,65 which suggests that MUP is likely to reduce inequalities in alcohol consumption, as well as ameliorating inequalities in the health problems alcohol brings.

Evidence for minimum unit pricing

Reviews of alcohol control policies, in general,66 and evaluating the strategy of MUP,67 in particular,60 were limited before our study was started. Minimum pricing policies, in general, aim to set price levels below which alcohol should not be sold, but most previous policies of this type have implemented minimum prices that vary across different types of products (or apply to only certain products), rather than on the basis of alcohol content. Recently, a report from the Northern Territory in Australia studied a minimum unit price (which applies across all alcohol drinks) of AU$1.30 per 10 g of pure ethanol implemented on 1 October 2018 and found declines in alcohol-related harm across a range of key areas after its introduction. These include a 23% fall in alcohol-related assaults; a 17.3% reduction in alcohol-related emergency department (ED) presentations; reduced child protection notifications, protection orders and out-of-home care cases; fewer alcohol-related road traffic injuries and fatalities; and fewer alcohol-related ambulance attendances. 68 The evaluation reviewed routine data for varying numbers of years (i.e. before and for the year or part year after the intervention) on wholesale alcohol supply, police data, ambulance attendances, ED attendances and hospital admissions, sobering up shelter use, treatment centre sessions, road traffic crashes, child protection price monitoring, licensing, sales of substitution commodities, school attendances and tourism. The study used time series analyses. A year before implementing this MUP, a banned-drinker register was implemented in the Northern Territory (1 October 2017) and police auxiliary liquor inspectors were introduced from June 2018. Two additional interventions ran in parallel to the Northern Territory MUP intervention, making it impossible to determine effects attributable solely to MUP, and meaning that we cannot directly compare MUP in Australia and MUP in Scotland.

A version of minimum pricing referred to as ‘reference pricing’, which is not based purely on alcohol content, has been implemented in varying ways across Canadian provinces, with the minimum cost of alcoholic drinks determined by beverage type and strength. Evaluations in some Canadian provinces have found reference pricing to be effective, resulting in reductions in alcohol consumption, alcohol-attributable hospital admissions and crime. 69–77 Scotland implemented MUP in a competitive alcohol market at a national level, in contrast to the locally applied but government-owned monopolies where Canadian provinces introduced reference pricing. A more recent Canadian study showed that alcohol-related deaths increased when the price level for the reference pricing was allowed to effectively decrease because of price inflation. 78 Therefore, it may be important to link the MUP level to inflation. The evidence from Canada is not fully conclusive. One of the Canadian studies, which focused on ED visits, found no reduction in overall visits for alcohol-related injuries, although alcohol-related motor vehicle injuries did fall. 69 The introduction of minimum pricing for spirits (but not other alcoholic drinks) within The Russian Federation was associated with reductions in alcohol-related mortality, but this was, of course, beverage specific. 79

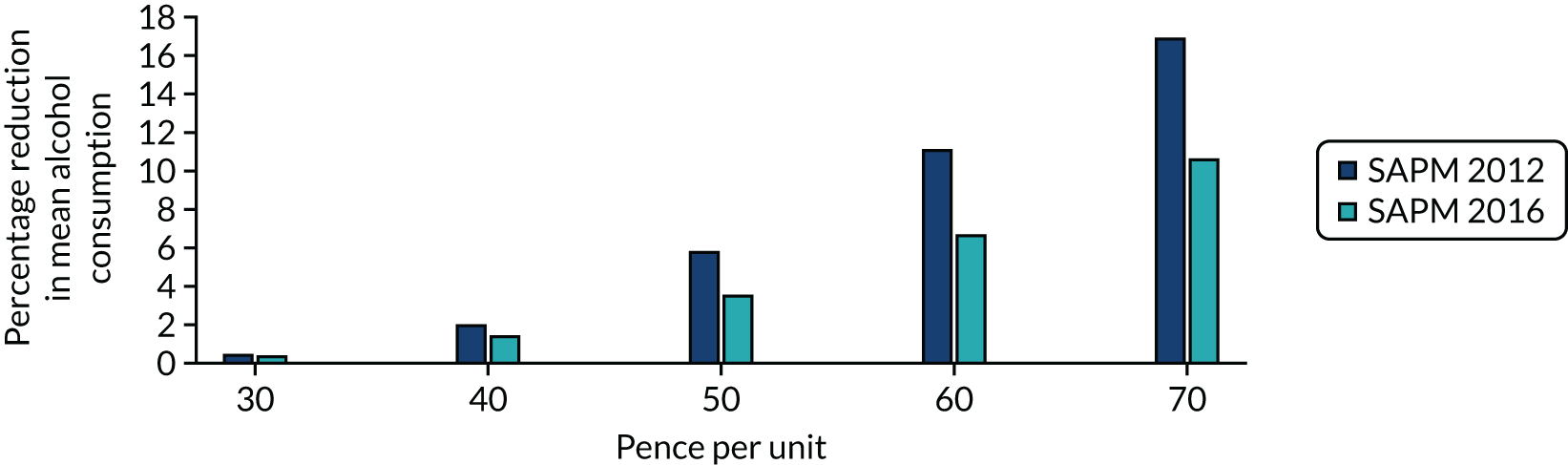

In 2018, the cost of alcohol had not risen in line with the rise in disposable income in the UK and alcohol was 61% more affordable than it was in 1987. 80 According to the Bank of England, the consumer price inflation-adjusted price would be £0.58 per unit in 2018 (from a £0.50 level in 2012). Modelling suggested that MUP would be more effective than a similar rise in UK taxation in reducing alcohol consumption, especially among the most vulnerable (i.e. heavy drinkers in poverty). 10,11,55,63,81–84 Currently, the UK tax on alcohol is beverage specific and much lower for cider than for other beverages of the same strength. 85 Early Scottish evidence from other studies has shown that alcohol sales (as a proxy for consumption) reduced post MUP86–90 and confirmed that there was good compliance with the policy. 91 As we wrote this report, the Lancet Commission into liver disease in the UK15 mentioned the fall in the volume of pure alcohol sold80,88,89 and good compliance91 in Scotland following MUP implementation. Putting pressure on the UK Government, the Lancet Commission criticised a lack of action in implementing MUP and other effective policies (e.g. alcohol duty escalator and extension of the sugar levy to alcoholic drinks) in England.

Minimum unit pricing is a logical way to prioritise public health in alcohol pricing policy because harm relates more to the amount of alcohol consumed than to beverage type. However, beverages do not contain alcohol alone and there have been suggestions that ‘white’ drinks (e.g. white cider, vodka) that contain low levels of antioxidants may be particularly damaging to the liver. 92 Emerging evidence suggests that beer or cider and spirits are associated with greater all-cause mortality and more cardiovascular events than wine and champagne, using Cox’s proportional hazards and a large population sample of 446,439 current drinkers from the UK Biobank, with adjustment for various confounders, including deprivation. 93 Angus et al. 94 reviewed taxation policies by beverage type in European Union countries and concluded that they do not primarily aim to improve public health.

Minimum unit pricing has widespread support within the public health community, which may be accused of taking a too narrowly health-focused perspective and ignoring wider social issues, such as effects on employment, the economy and crime. 2,61,95 A wider evaluation programme, MESAS, led by NHS Health Scotland (now Public Health Scotland) addresses this point. Scottish public opinion on MUP, assessed through Twitter (URL: www.twitter.com, Twitter, Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA), was divided, but more positive than negative,47 especially in tweets from Scottish public health and alcohol policy organisations. There is international interest in MUP and the results from the Scottish evaluation are likely to inform change in many countries. A small study96 showed that a minimum unit price at the Scottish level would increase prices in over half of alcohol sold from an off-license in the USA. Australia is planning a modelling study that includes the effects of MUP among other pricing policies. 97

Need for a wide real-world evaluation at the system level

Modelling alone is not always sufficient proof to implement government health policy. In a democracy, laws setting social policy must be justifiable through stronger evidence, as feasible, of a net benefit to the public or at least preventing net harm. 98 Therefore, the MUP policy needed to be evaluated once implemented. NHS Health Scotland (now Public Health Scotland) is leading the Scottish Government’s wider evaluation of Scotland’s alcohol strategy through the MESAS programme. 80 MESAS originally focused on evaluating licensing reforms, delivery of alcohol brief interventions and specialist treatment services. Public Health Scotland is building on MESAS to comprehensively evaluate MUP by using routinely collected data to assess changes in price, consumption and alcohol-related harms at a population level that occur as a result. In addition, Public Health Scotland has commissioned a number of studies to evaluate MUP,99 some of which have already reported,90,91,100–103 with others reporting later (including in 2023). These studies will cover effects on the alcohol industry, crime and those drinking at harmful levels, among a number of other topics.

Owing to the lack of real-world MUP evaluation studies covering areas inaccessible through these routine data, other studies, including our own,39 were independently funded to work alongside MESAS in an integrated programme of evaluation. We gathered primary data to measure changes in drinking and acute health harms, the possible unintended consequences of MUP and the hypothetical differential impact on young people who, in Scotland and across the world’s affluent countries, are reducing their alcohol consumption. 104,105 On average, for people living in deprived areas, there is evidence of higher levels of alcohol consumption and larger numbers of people drinking above the safe drinking guidelines; however, there is also a larger number of non-drinkers in the most deprived groups65 and so there are also likely to be different effects in deprived areas.

Scotland is the first country to implement a national MUP based on only alcohol content and so the evaluation programme will provide the first real-world evidence about the effectiveness of MUP at £0.50 per unit (one UK unit is circa 8 g or 10 cc of pure alcohol). Early evaluation work has reported reductions in the volume of pure alcohol purchased88 and sold90,103 since the introduction of MUP in Scotland.

Policy variation between England and Scotland and the natural experiment opportunity

We used the policy variation between England and Scotland to design our cross-sectional natural experiment using a DiD analysis for our two quantitative components. There was a pre-MUP baseline and two post-MUP follow-up waves in EDs at two Scottish and two northern English comparator hospitals, and at three Scottish and three comparator northern English sexual health clinics (SHCs). Natural experiments have been successful in other health research settings and there is now good knowledge about their design and validity. 40,41 Our evaluation of the natural experiment is based on a similar framework to the portfolio of studies investigating smoke-free legislation in Scotland. 106,107

Our third component was qualitative and set in Scottish communities only.

Effects on health (intended impacts)

Changes in ED attendances attributable to alcohol are likely to indicate some short- to medium-term effects of MUP, but are not available from routine data.

Estimates of the exact proportion of ED admissions attributable to alcohol range from 2% to 40% and may rise to 70% at peak times. 108 A recent paper covering England puts the mean alcohol-related attendances at 11.7% and admissions at 9.2%. 109 However, the data were for 2009–10. Alcohol-related attendances to EDs that do not result in admission are not routinely collected and so will not be included in MESAS. There was, therefore, a need for robust, prospective evaluation evidence to measure the effectiveness of MUP in preventing alcohol-related harm seen in ED attendees, and to monitor possible differential impacts and potential adverse consequences.

Our primary data collection methods and tools were based on previous studies used to quantify the national prevalence of alcohol-related attendances in EDs in England. 110 Our study was informed by the experience of the Scottish Emergency Department Alcohol Audit, which was carried out across 15–20 hospitals throughout mainland Scotland between October 2005 and June 2007. 111 We used the Fast Alcohol Screening Test (FAST), which is a reliable and validated tool that is a shortened form of the Alcohol use Disorders Identification Test Consumption (AUDIT-C) questionnaire designed for use in EDs. 112 Although the Single Alcohol Screening Questionnaire is quicker,113,114 the FAST tool was better for our purpose because it not only quantifies levels of harmful alcohol use, but also allows detection of changes in drinking patterns. 115 Such information is currently not adequately collected within routine health surveys, particularly for deprived populations that are most likely to be affected by the intervention. 116 Assessment of drinking patterns is crucial, as different patterns of consumption (e.g. binge drinking compared with chronic levels of use) are associated with different patterns of health, burden on EDs109 and other social harms. 3,117

Unintended consequences

Sexual health clinics are potentially a good setting to see both the unintended and the hoped-for effects of MUP, as attendees are younger118 and may be more open to experimentation with substances. 119,120 People at more risk of sexually transmitted infections are also more likely to have higher alcohol consumption levels, take greater sexual risks,121 drink in on-licensed (clubbing) premises122 and have more diverse sexual orientation. 120 They were, therefore, a relevant population potentially at risk of displacement effects.

Some possible unintended consequences from MUP are indicated from research and some can be theorised from other knowledge, as indicated in Chapter 2.

Communities

As stated in our protocol:39

. . . qualitative research has investigated the policy process through which MUP developed in Scotland, including assessing the role of commercial interests, and seeking to identify transferable lessons for public health advocacy. 26,27,35,123–127 The influence of econometric modelling has been specifically investigated. 128,129 The dominant media discourses and the roles of different policy stakeholders in articulating arguments to the public have been explored using content analysis of newspaper reporting and trends in newspaper coverage have been tracked over time. 33,130–132 The views of the public and heavy drinkers around MUP as planned have also been investigated. 63,133–135 There remained a need to investigate the views, experiences and norms of local service delivery stakeholders, the public, and heavy drinkers about the MUP [policy and its consequences] as implemented.

The focus of this component was on non-alcohol substance use and other unintended impacts in addition to alcohol use.

Chapter 4 Emergency department component

Component-specific research objectives

Emergency department attendances are likely to be sensitive to changes in alcohol-related harms, as they reflect both acute and chronic health problems in the target population. Therefore, we assessed the impact of MUP on alcohol-related ED attendances and drinking patterns among the ED attendees, and across age group, sex and different socioeconomic groups. Currently, alcohol-related attendances to EDs that do not result in admission are not routinely collected. Information collected through routine health surveys, meanwhile, is not adequate to understand the drinking patterns among young people and deprived populations who are most likely to be affected by MUP. 65,136 Therefore, we collected primary data to examine the changes in alcohol-related attendance and diagnosis and the trend in patterns of alcohol consumption that occur as a result of MUP. The component addresses RO1, that is to determine the impact of MUP on alcohol-related harms and drinking patterns for the overall population and by subgroups of interest (age, sex and socioeconomic position).

Methodology

Component design

We employed a repeated cross-sectional natural experiment design to study the impact of introducing MUP in Scotland. The natural experiment was the introduction of MUP in Scotland and we used the north of England as the comparison group. The component involved an audit of all alcohol-related attendances at ED, anonymised administrative data provided from hospitals and a face-to-face interviewer-administrated survey to ED patients. The component methods and tools were based on previous studies of alcohol-related attendances in EDs in England110 and experiences from the Scottish Emergency Department Alcohol Audit. 111

Setting

We recruited EDs from two hospitals in Scotland (Edinburgh and Glasgow) and two in the north of England (Liverpool and Sheffield). Table 1 shows the 2019 population137 across four cities that were chosen for this component. These cities had comparable population size and population composition. Table 1 also presents the proportion of data zone (Scotland)138/lower-layer super output areas (LSOAs) (England)139 in the most deprived 10% in Scotland/England. Edinburgh and Sheffield are the less deprived areas, whereas Glasgow and Liverpool are the more deprived areas. Northern England was chosen as the comparison group because it had the most similar drinking patterns to Scotland in terms of higher levels of hazardous drinking and binge drinking, economics and culture. 140–142

| Profile | City | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Edinburgh | Glasgow | Liverpool | Sheffield | |

| Total population (n) | 524,930 | 633,120 | 498,042 | 584,853 |

| Sex (%) | ||||

| Female | 51.2 | 51.0 | 50.1 | 50.2 |

| Male | 48.8 | 49.0 | 49.9 | 49.8 |

| Age group (years) (%) | ||||

| < 16 | 15.1 | 15.9 | 17.5 | 18.1 |

| 16–25 | 14.2 | 14.5 | 17.4 | 17.4 |

| 26–45 | 33.7 | 33.4 | 28.8 | 26.7 |

| 46–65 | 22.7 | 23.7 | 22.5 | 22.6 |

| ≥ 66 | 14.2 | 12.6 | 13.8 | 15.3 |

| Median age (years) | 36.5 | 35.6 | 34.8 | 35.4 |

| Deprivation | ||||

| Proportion (%) of data zone/LSOAs in the most deprived 10% nationally | 6.6 | 46.2 | 48.7 | 23.8 |

Data collection took place over three 3-week waves. The baseline wave was conducted in February 2018 before the implementation of MUP on 1 May 2018. There were two post-implementation follow-ups in September/October 2018 and February 2019. In each wave, data collection took place from 20.00 until 03.30 the following day from Thursday to Sunday, and from 09.00 to 16.30 on Monday to Wednesday.

We also requested anonymised information (i.e. sex, age group and diagnoses) collected routinely on all attendees over the 3-week collection periods for each wave.

Participant selection

The target population was all patients aged ≥ 16 years who attended an ED to receive acute treatment for a health condition. Trained research nurse interviewers considered all patients aged ≥ 16 years for approach and decided whether or not to approach them based on the following exclusion criteria:

-

patient too unwell

-

too distressed

-

grossly intoxicated (alcohol)

-

grossly intoxicated (drugs)

-

cognitive impairment

-

police in attendance

-

clear language barrier and no interpreter available

-

patient already participating

-

routine follow-up that has been instigated by ED staff

-

patient left department

-

patient admitted

-

staff safety issue

-

end of shift

-

dead on arrival

-

other.

Research nurse interviewers recorded reasons for not approaching, as well as the sex and age group of the patients who were not approached.

Potential interviewees were then given written information about the component and had up to 40 minutes to decide whether or not to take part. Face-to-face structured interviews were carried out by interviewers using iPads (Apple Inc., Cupertino, CA, USA). There was a formal screening where the potential interviewees were asked eligibility questions before consent was taken. The eligibility criteria were:

-

aged ≥ 16 years

-

able to speak English or interpreter available

-

a new ED presentation during the shift

-

conscious

-

physically and mentally well enough

-

sober enough (alcohol)

-

sober enough (drug)

-

still in the department (i.e. had not left or been admitted)

-

safe for staff to approach.

Eligible interviewees were asked to sign their consent on an iPad and whether or not they further consented to linkage of their hospital notes to the interview data. For interviewees who consented to data linkage, we requested demographic characteristics (i.e. date of birth, sex and postcode), attendance details, discharge status and diagnoses for attendances. More details about reasons for not being approached, interviews being terminated and failing the inclusion criteria can be found in Appendix 2, Tables 14–16.

Variables

Outcomes

The primary outcome of interest was the proportion of alcohol-related attendances among all ED patients we recorded through either observation or interview. We used a dichotomised score, where 1 indicated that the attendance was alcohol related and 0 indicated that the attendance was not alcohol related. Attendance was considered alcohol related if the attendee was not approached because of alcohol intoxication, if the potential interviewee was ineligible because of being not sober enough due to alcohol, if the interviewee had binged (≥ 6/8 units for women/men) in the last 24 hours or if the attendee self-reported that the attendance was alcohol related because of their own or another’s drinking.

We also analysed a range of secondary outcomes that were related to alcohol-related diagnosis, alcohol use and drinking patterns. Table 2 lists all the secondary outcomes and the corresponding analytic samples. Most of the secondary outcomes were binary, unless specify otherwise.

| Type of outcome | Sample | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Primary | All recorded attendees | Alcohol-related attendance |

| Secondary | All attendees | Alcohol-related diagnosis |

| All respondents | Current alcohol use | |

| Binge drinking in the past week | ||

| Binge drinking in the past 24 hours | ||

| Respondents who were current drinkers | FAST score | |

| Alcohol misuse (FAST score ≥ 3) | ||

| Increased alcohol use in the past year | ||

| Place of last drink (private location) | ||

| Place of last drink (on-licensed premise) |

Alcohol-related diagnosis

A diagnosis was alcohol related if attributable to alcohol consumption according to the definition used previously in a burden of disease study by NHS Health Scotland. 5 Appendix 2, Table 17, lists the alcohol-related conditions that are based on ICD-10 codes. 143 Conditions where alcohol is the sole clinical cause are considered as wholly alcohol-attributable conditions, whereas conditions where alcohol may be one of the causative factors are considered as partially attributable. 144 Based on this definition, we further categorised the alcohol-related conditions as wholly chronic, wholly acute, partially chronic and partially acute. A number of diagnoses are recorded in hospital data for attendees. We carried out analyses for both all diagnoses and for the primary (first in order) diagnosis only.

Current alcohol use

All respondents were asked whether or not they had ever had a drink of alcohol that was more than a sip in the past year. Those who answered ‘yes’ were classified as ‘current drinker’, whereas those who answered ‘no’ were considered as ‘not a current drinker’.

Binge drinking in the past week

Current drinkers were asked what was the largest number of drinks they had consumed on any 1 day in the last week. Those who answered > 6 or 8 units (for women or men) were classified as ‘binge drinker in the past week’, whereas those who had < 6 or 8 units (for women or men) were classified as ‘non-binge drinker in the past week’. As non-current drinkers did not have any drinks in the past week, they were also classified as ‘non-binge drinker in the past week’.

Binge drinking in the past 24 hours

Current drinkers were also asked how many drinks they had over the past 24 hours. Again, those who had > 6 or 8 units (for women or men) were classified as ‘binge drinker in the past 24 hours’, whereas those who had < 6 or 8 units (for women or men) and those who indicated that they were not current drinkers were classified as ‘non-binge drinker in the past 24 hours’.

Fast Alcohol Screening Test score

A reliable validated tool, the FAST, which is a shortened form of the AUDIT-C questionnaire designed for use in ED, was used to quantify levels of harmful alcohol use. 112,115 Current drinkers were asked to answer four questions related to their current drinking habits. The FAST score was the overall score created by summing up the answers of these questions. The score ranged from 0 to 16, with a higher score indicating more problematic drinking behaviours. We analysed FAST score as a continuous measure.

Alcohol misuse

Current drinkers who scored ≥ 3 on the FAST were classified as ‘alcohol misuse’, whereas those who scored < 3 were classified as ‘not alcohol misuse’.

Increased alcohol use in the past year

Current drinkers were asked if their alcohol consumption changed over the last 12 months. Those who answered ‘more than 12 months ago’ were classified as ‘increased alcohol use’, whereas those who answered ‘less than 12 months ago’ or ‘about the same’ were classified as ‘did not increase alcohol use’.

Place of last drink (private location)

Current drinkers were asked where they had their last drink. For those who answered ‘home’, ‘work’ or ‘friend/family home’ were classified as ‘private drinking’, and ‘no’ otherwise.

Place of last drink (on-licensed premise)

Current drinks who answered ‘pub’ or ‘club’ as their last drinking location were classified as ‘on-licensed premise’, and ‘no’ otherwise.

Covariates

Our primary outcome focuses on all ED attendees who were recorded by research nurse interviewers. Information about attendees who were not interviewed was limited to reasons for not approaching/interviewing, as well as whether or not they were too intoxicated to participate. Interviewers also recorded sex and age group for unapproached attendees based on triage data or their observation. This information allowed us to adjust for sex and age group in the analysis of the primary outcome.

The anonymised data from the hospitals contained information about sex and age group of all attendees. Therefore, we adjusted for sex and age group in the analysis of alcohol-related diagnosis.

The questionnaire covered a range of sociodemographic data, including sex, age, ethnicity, first four digits of postcodes, employment status, marital status and housing ownership. Area-based deprivation scores were assigned to each respondent based on their postcodes. We used the 2011 Carstairs area deprivation scores calculated for wards in England and postcode sectors in Scotland. 145,146 This gave geographies with similarly sized populations and so a measure of deprivation comparable across all four cities and the two countries. In Scotland, postcode sectors were sometimes split between two Carstairs deciles when a postcode sector covered two councils. We used a population weighting method to assign a Carstairs score to the whole postcode dependent on the population split between the councils. These variables were used as covariates when we analysed the secondary outcomes.

Statistical considerations

Sample size

As stated in our published protocol:39

. . . based on the experience of the 24 hour survey of EDs in England,111 and the assumption that at least 50% of eligible ED attendees would be recruited, we anticipated that the four sites would result in 940 recruits per week. Recruiting over three three-week data collection – giving a total sample size of 5640 – would mean that we would be highly powered (> 80%) to detect an effect size of ± 5% in the proportion of alcohol-related attendances from an estimated 30% with 95% significance. We used a base rate of 30% informed by the 24 hours audit of EDs in England,111 and assumed a 5% decrease would be of public health importance and may be expected based on current evidence. For subgroup analyses, we would have good power (> 80%) to detect an effect size of 0.23 on the FAST score among those from the most deprived quintile (estimated to be 25% of attendances), and an effect size of 0.27 among those aged 18–24 (estimated to be 15% of attendances).

Statistical analysis

We evaluated the impact of the introduction of MUP by fitting fixed-effects multivariate regression models. For our main analysis, we fitted the following models:

in which y is the outcome variable, country is a dummy variable where 0 = England and 1 = Scotland, time is another dummy variable where 0 = before the introduction of MUP and 1 = after the introduction of MUP, hospital is a series of dummy variables (0 = Edinburgh, 1 = Glasgow, 2 = Liverpool and 3 = Sheffield), wave is a series of dummy variables (0 = wave 1, 1 = wave 2 and 3 = wave 3), MUP is the interaction term between country and time (i.e. a dichotomous indicator with the value 1 for patients who attended Scottish EDs after the implementation of MUP and 0 otherwise) and ε is the residuals. Our coefficient of interest is β1, the DiD estimate, which is defined as the difference in outcome between Scotland and England before and after the MUP was introduced in Scotland. We used logistic regression for binary outcomes and linear regression for continuous outcome.

Model 1 is the unadjusted model with the DiD estimate and fixed effects for country and time. The country fixed effects control for all unobserved country-specific factors that are time invariant, whereas the time fixed effects account for all seasonal effects over time. In model 2, we further adjusted for hospital and wave fixed effects. As the country and time fixed effects in the unadjusted model were confounded with the newly included hospital and wave fixed effects, we omitted them from model 2. In the final model, model 3, we further included a set of covariates (i.e. sex, age group, ethnicity, employment status, marital status, housing ownership and Carstairs deprivation score). We also performed stratified analysis to examine the primary and secondary outcomes by sex, age group, ethnicity, employment status, marital status and housing ownership.

Appendix 2 provides the percentage of missing data of each demographic (see Appendix 2, Tables 18–20) and outcome variable (see Appendix 2, Tables 21–25) by country and wave. We imputed all variables in the data set (except the anonymised data set requested from hospitals) using multiple imputation. A total of 20 imputed data sets were created and subsequently analysed in R using the MICE (multivariate imputation via chained equations) package (version 3.70) (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). 147 The parameters from the models were estimated in each imputed data set separately and combined using Rubin’s rules.

We included non-response weights in the imputation process and analysis regression models. Using the anonymised information for all attendees from the hospitals, we were able to calculate inverse probability weights to adjust for the differences in distribution of sex and age group between attendees and interviewees.

We undertook various sensitivity analyses to investigate whether or not our results were sensitive to the model specification and the selection bias of the sample. To examine whether or not our findings were sensitive to the FAST cut-off score, we analysed the effect of MUP against FAST cut-off points of ≥ 2 (hazardous drinker), ≥ 4 (harmful drinker) and ≥ 6 (dependent drinker). These cut-off points were validated using data from the Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey 2007. 148 We replicated the analyses on alcohol-related attendance (primary outcome) and alcohol-related diagnosis (secondary outcome) using the sample based on interviewees and by including ethnicity, employment status, marital status, housing ownership and Carstairs deprivation score as covariates. Finally, we performed the weighted and unweighted analyses on the complete cases, which included only cases with no missing data on both outcome variables and covariates.

Challenges for data collection

The inherent challenges for the ED data collection are consistent with challenges faced in other natural experiments, notably in minimising selection bias between waves. 149

Training

A single-site first pilot was carried out and each individual site had a further pilot. Each study site underwent a similar training session before each wave, and data collection times sites and methods were confirmed at baseline and reiterated in the training for subsequent waves. At the EDs, there was a 3- to 4-hour face-to-face training session. The nurses who had been recruited to conduct the data collection underwent the training. It was occasionally challenging to have all staff present for the training because of absence or if staff were required to keep the service running while the training was delivered. Where staff could not attend the face-to-face training, the lead nurse was given the training presentation to cascade to any staff who were unable to attend. Training was very interactive, consisting of a 15- to 20-minute presentation, outlining the aims of the research and an overview of the research tools, followed by a hands-on opportunity to use the iPads/paper questionnaires, followed by role play completion of the questionnaire, with certain scenarios presented by the trainers.

During the run up to baseline data collection, we held informal ‘huddles’ with ED sites by telephone conference to allow for the discussion of informal queries. These were useful both in resolving queries and keeping relationships with sites healthy.

Data collection times

The component protocol stipulated that all sites should collect data at the same time. ED data collection was from 09.00 to 16.30 Monday to Wednesday and from 20.00 until 03.30 from Thursday to Sunday over three 3-week periods. We could not go outside these times, but a 30-minute period after each shift was allowed for the completion of already started cases.

Research tools

Each site was given the same mechanism for data capture. This involved purchasing iPads for each ED site, making sure that all iPads were updated with the same version of iOS, that they were connected to the King’s College London (London, UK) server and that they had the same version of the data collection application (app) and all were able to access the internet through Wi-Fi within the site or through 4G mobile data. It was also imperative that each site updated the data collection software at the start of each wave of data collection to ensure that any data collection app updates were implemented and that all sites were working from the same version of the app. Sites were asked to manage the use of their iPads, ensuring that they were charged and data synchronised at the end of each shift. Although this was complex to administer across sites, we were able to synchronise the iPads successfully and this challenge was overcome.

Maintaining similar and adequate staffing levels

Given the busy nature of EDs, and we always seemed choose busy periods, it was difficult for the lead nurse at each site to schedule nurse shifts for the duration of the data collection. It was recommended that each shift had three members of staff allocated. Two research nurses would interview participants and one team member would provide administrative support. There were slightly differing models of utilising the staff, depending on the requirements of each ED. For example, in Edinburgh, one administrator was dedicated to monitoring which patients were eligible for interview, with two nurses conducting the interviews. In other sites, three nurses were used to conduct interviews. It was appropriate that each site was able to manage this individually, as the physical space and triage systems were different in each ED and it was felt that local sites were best placed to decide how to manage this aspect of data collection. However, consistency across waves was achieved by using a similar delivery model at each wave and regular weekly catch-ups with sites during each wave.

Confidentiality

The physical space in each ED was different, but a common issue reported by nurses was maintaining confidentiality during the interviews. Where possible, the interview was conducted in a private room; however, this was not always possible. Nurses were advised to respect patient confidentiality at all times, in line with their standard practice. This meant not conducting interviews within earshot of other patients or family members. This not only avoided breaches of confidentiality, but also encouraged interviewees to answer freely and honestly without fear of judgement from others.

Missing participants

On particularly busy shifts, there was potential to ‘miss’ patients who were in the ED for a short period of time. Nurses minimised this by monitoring patient flow on the ED computer system and approaching them at the earliest appropriate time.

Language barriers

It was difficult to ensure that there were always interpretation services available. Staff were trained to make use of interpretation services (i.e. a face-to-face or telephone-based interpreter) where possible; however, nurses informed the research team that this was often not possible as it could take time to connect with an interpreter, which would lead to missing other participants. Nurses were instructed not to make use of participants’ family members to translate, so as not to breach the participants’ confidentiality. There were very few cases recorded as not being able to participate because of language issues.

Avoiding disruption to regular workings of the emergency departments

Throughout the data collection process, it was essential to avoid disruption to the work of the ED for participants and other patients who were in attendance at the ED. Nurses reported that they were occasionally asked to contribute to non-research-related tasks and the principal investigator for each site was encouraged to instruct ED colleagues that the research nurses were not to be asked to complete non-research-related work unless it was completely necessary.

Obtaining sufficient recruitment numbers

Eligibility criteria meant that a number of staff could not be interviewed, but we collected observational data to measure our primary outcome. It was often a chaotic data collection environment; however, as a condition of ethics approval, we did not want to disrupt normal care for patients and so interviews were terminated while in process if a patient was to be urgently admitted.

Contextual issues

The ‘Beast from the East’ snowstorm closed data collection at most sites on 28 February 2018 and that day was excluded for all sites. There were also some staffing issues with, for example, staff off sick. Generally, the timeline for preparation for collecting data was short because of late announcement of the legality and then the relatively swift implementation date.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval had been obtained from the NHS through the Scotland A Research Ethics Committee, ED Research Ethics Committee (reference 12/SS/0120) and SHC Research Ethics Committee (reference 12/SS/0121). The Stirling Management School at the University of Stirling approved the qualitative studies for in-depth interviews with local stakeholders (application number 32) and focus group research with drinkers (application number 33). The paper meets the STROBE (Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology) checklist criteria for cross-sectional studies and the TREND (Transparent Reporting of Evaluations with Nonrandomized Designs) criteria for reporting evaluations with non-randomised designs. The trial registration number is ISRCTN16039407.

Changes to protocols

Changes to protocols were notified to the Ethics Committee. Version 1 was the original protocol from 1 June 2012.

The next version (v2.1, dated 13 February 2017) separated the protocols for the ED component and the sexual health component and entered this information into the new standard SPHSU (MRC/CSO Social and Public Health Sciences Unit, University of Glasgow) template. The mechanism of data collection was altered from paper and pen data collection to the use of iPads.

The following version (v2.2, dated 1 July 2017) added reviewer comments to v2.1, but there were no substantive changes.

The next change (v2.3, dated 1 August 2017) was as a result of the delay to the implementation of MUP. The chief investigator moved to Australia and a new chief investigator was appointed, and there were changes to the sponsor, local lead investigators, sites and timescales, and iPads were introduced for data collection. Our letter to the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) (dated 21 August 2017) gives further details (see Report Supplementary Material 1).

Protocol v2.4 (dated 20 August 2017) further updated the timescales.

The next change (v2.5, submitted in December 2017), covered the following points and included questionnaire changes arising from the pre pilot:

-

apply for the introduction of a fully electronic consent process

-

change the principal investigator name for Liverpool – should now be Dr Lynn Owens

-

ask if we can collect full postcode data rather than first four digits

-

reasons for did not complete

-

change in shift times

-

update posters to be more eye catching

-

update paper copy of MUP questionnaire to be more user friendly (see Appendix 4)

-

changes to questionnaire and new consent form (see Appendix 4)

-

include data linkage information on iPad

-

changes to information sheet (see Report Supplementary Material 2).

The next change (v2.6) was submitted to the Ethics Committee on 19 January 2018. In that submission, we introduced signed electronic consent (as this was considered more ethically acceptable than a tick box), an amendment to the poster to remove any mention of MUP and a new high-awareness banner poster.

The change in February 2018 was to the information sheet for Scotland (and consent form, by simply using the version number rather than date to cross-reference). The change provided a clearer explanation of the Community Health Index number and confidentiality, and did not require a change to the protocol:

This is a unique 10-digit number that includes your date of birth and a code for gender. We take confidentiality very seriously, and all records are de-identified and held on encrypted technology. Only trained staff have access to your information, and all information is stored securely.

Emergency department study patient information sheet (Scotland) v2 5 3

The final change (v2.7, in May 2018), was minor and concerned a change to a website address and a new member of the investigative team.

Results

Descriptive of sample

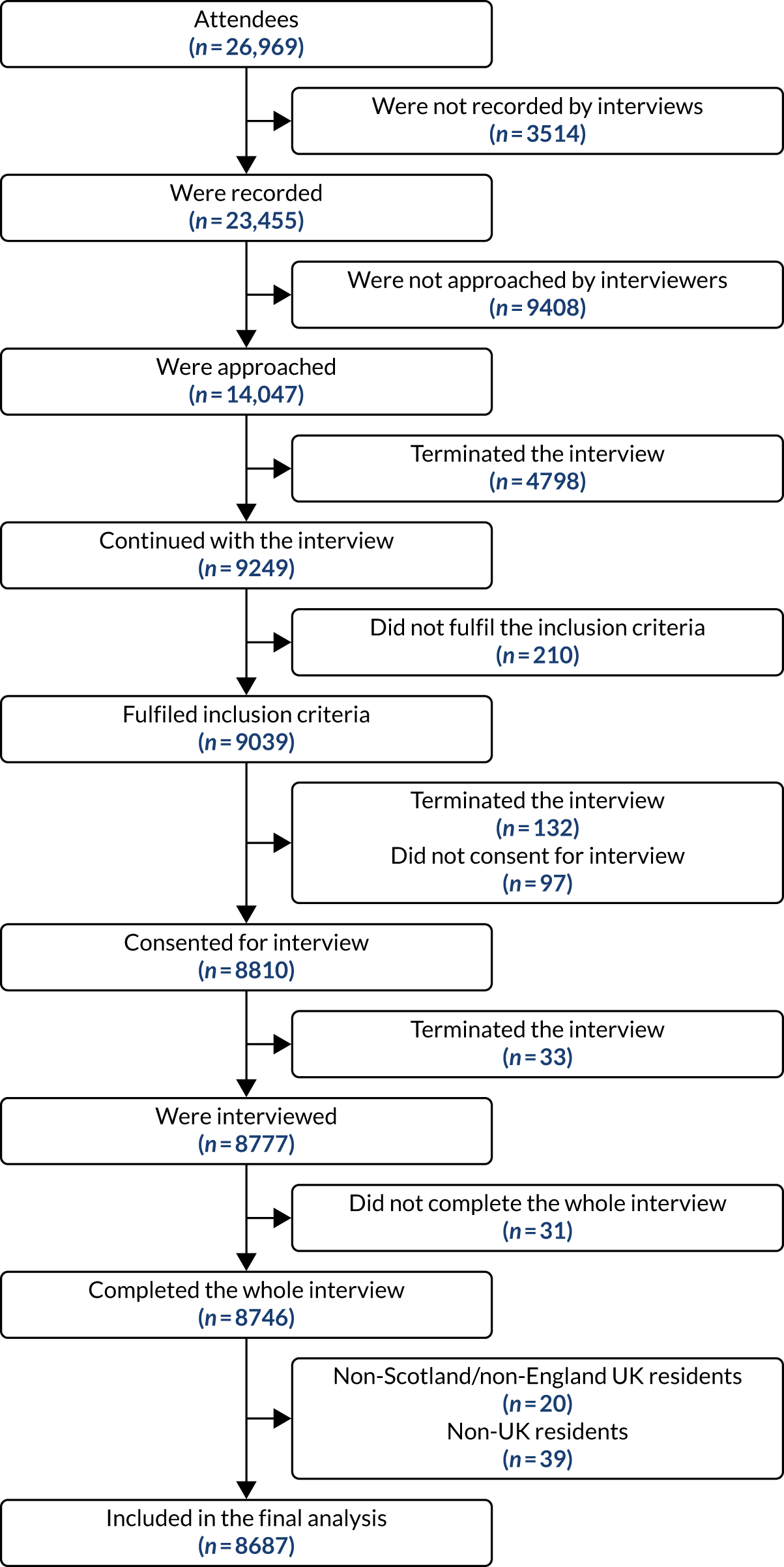

A total of 26,969 patients aged at least 16 years visited the EDs during the three study periods, and 23,455 (87.0%) of them were recorded for assessment of our primary outcome (not all interviewed) by research nurses. Among those who were recorded, 14,047 (59.9%) of them were approached and 12,249 were identified to be eligible to participate in the component, of whom 8746 (71.4%) completed the interview (Table 3). Figure 1 illustrates the flow chart that summarises the component participants in all four EDs and three waves.

| Site | Attendees | Wave 1 | Wave 2 | Wave 3 | Overall |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Edinburgh | Number of attendees | 2195 | 2381 | 2446 | 7022 |

| Number of recorded attendees | 2109 | 2357 | 2428 | 6894 | |

| Number of approached attendees | 1322 | 1662 | 1657 | 4641 | |

| Number of eligible attendees | 1149 | 1428 | 1496 | 4073 | |

| Number of completed interviews | 932 | 1041 | 1105 | 3078 | |

| Glasgow | Number of attendees | 2151 | 2351 | 2527 | 7029 |

| Number of recorded attendees | 1566 | 1787 | 1960 | 5313 | |

| Number of approached attendees | 874 | 1034 | 1049 | 2957 | |

| Number of eligible attendees | 776 | 879 | 910 | 2565 | |

| Number of completed interviews | 631 | 681 | 707 | 2019 | |

| Liverpool | Number of attendees | 1744 | 2023 | 1956 | 5723 |

| Number of recorded attendees | 1096 | 1575 | 1545 | 4216 | |

| Number of approached attendees | 640 | 1278 | 1257 | 3175 | |

| Number of eligible attendees | 556 | 1061 | 1152 | 2769 | |

| Number of completed interviews | 402 | 671 | 611 | 1684 | |

| Sheffield | Number of attendees | 2213 | 2465 | 2517 | 7195 |

| Number of recorded attendees | 2156 | 2394 | 2482 | 7032 | |

| Number of approached attendees | 903 | 1160 | 1211 | 3274 | |

| Number of eligible attendees | 805 | 984 | 1053 | 2842 | |

| Number of completed interviews | 599 | 724 | 642 | 1965 | |

| Overall | Number of attendees | 8303 | 9220 | 9446 | 26,969 |

| Number of recorded attendees | 6927 | 8113 | 8415 | 23,455 | |

| Number of approached attendees | 3739 | 5134 | 5174 | 14,047 | |

| Number of eligible attendees | 3286 | 4352 | 4611 | 12,249 | |

| Number of completed interviews | 2564 | 3117 | 3065 | 8746 |

FIGURE 1.

Flow chart of study participants. As described in Participant selection, people who were too drunk to be interviewed were classified as not approached or terminated and recorded as too drunk for inclusion as alcohol related.

We calculated two response rates: (1) the realistic response rate uses a denominator of all eligible attendees and (2) the absolute response rate uses all recorded attendees as the denominator. Table 4 presents both response rates by wave and hospital. The response rates in Scotland were generally higher than those in England. The overall realistic response rates decreased over the three waves from 78.0% in wave 1 to 71.6% in wave 2 and to 66.5% in wave 3. Across the three waves, Liverpool had the lowest realistic response rate (60.8%) among four hospitals. Meanwhile, Sheffield had the lowest absolute response rate (27.9%).

| Site | Response rate | Wave 1 (%) | Wave 2 (%) | Wave 3 (%) | Overall (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Edinburgh | Realistic | 81.1 | 72.9 | 73.9 | 75.6 |

| Absolute | 44.2 | 44.2 | 45.5 | 44.6 | |

| Glasgow | Realistic | 81.3 | 77.5 | 77.7 | 78.7 |

| Absolute | 40.3 | 38.1 | 36.1 | 38.0 | |

| Liverpool | Realistic | 72.3 | 63.2 | 53.0 | 60.8 |

| Absolute | 36.7 | 42.6 | 39.5 | 39.9 | |

| Sheffield | Realistic | 74.4 | 73.6 | 61.0 | 69.1 |

| Absolute | 27.8 | 30.2 | 25.9 | 27.9 | |

| Overall | Realistic | 78.0 | 71.6 | 66.5 | 71.4 |

| Absolute | 37.0 | 38.4 | 36.4 | 37.3 |

We performed Pearson’s chi-squared tests to compare the sex and age differences between respondents (those who completed the interview) and the sampling frame (Table 5). In wave 1, there were no significant differences on sex (except in Glasgow, which had fewer females than expected) and no differences on age group (except in Edinburgh and Glasgow, where respondents were younger than expected in both sites). In wave 2, ED respondents differed from the sampling frame on sex in Glasgow (fewer females than expected) and on age group in all sites (respondents were generally younger in all sites). For wave 3, we did not see any significant difference by sex in any of the sites. However, there were significant differences on age group in Edinburgh, Liverpool and Sheffield (respondents were younger than the sampling frame). The differences between waves were small for sex, but there were larger differences for age groups. Despite these differences, inverse probability weights were applied in all analysis models.

| Site | Difference | Wave 1 | Wave 2 | Wave 3 | Overall | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| χ2 | p-value | χ2 | p-value | χ2 | p-value | χ2 | p-value | ||

| Edinburgh | Sex | 4.8 | 0.028 | 6.6 | 0.010 | 1.0 | 0.315 | 11.0 | 0.001 |

| Age | 13.1 | 0.005 | 27.9 | 0.000 | 7.6 | 0.054 | 43.7 | 0.000 | |

| Glasgow | Sex | 1.2 | 0.267 | 0.0 | 0.992 | 0.7 | 0.419 | 1.3 | 0.251 |

| Age | 69.1 | 0.000 | 43.5 | 0.000 | 29.3 | 0.000 | 132.5 | 0.000 | |

| Liverpool | Sex | 1.1 | 0.295 | 1.1 | 0.298 | 0.0 | 0.945 | 1.2 | 0.267 |

| Age | 3.7 | 0.295 | 23.1 | 0.000 | 10.2 | 0.017 | 29.8 | 0.000 | |

| Sheffield | Sex | 0.7 | 0.390 | 1.2 | 0.277 | 1.9 | 0.168 | 0.1 | 0.724 |

| Age | 7.7 | 0.052 | 15.7 | 0.001 | 21.8 | 0.000 | 37.2 | 0.000 | |

| Overall | Sex | 3.5 | 0.060 | 2.1 | 0.143 | 0.0 | 0.847 | 4.2 | 0.041 |

| Age | 53.9 | 0.000 | 82.9 | 0.000 | 55.6 | 0.000 | 189.1 | 0.000 | |

Descriptive statistics

The demographic characteristics of all attendees, attendees who were recorded by nurse interviewers and those who completed the interview are shown in Tables 6 and 7. The analysis for the primary outcome focused on the sample of recorded attendees (n = 23,455). Meanwhile, the analytic sample for alcohol-related diagnosis was based on all attendees. As the diagnostic data from the Liverpool ED did not comply with ICD-10 codes, 5723 cases from Liverpool were excluded from the analysis and, hence, the total number of attendees in the analytic sample became 21,246.

| Characteristic | All attendees, n (%) | Attendees recorded by interviewers, n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scotland (N = 14,051) | England (N = 12,918) | Scotland (N = 12,207) | England (N = 11,248) | |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 7212 (51.3) | 6552 (50.7) | 6131 (50.2) | 5634 (50.1) |

| Male | 6837 (48.7) | 6366 (49.3) | 6015 (49.3) | 5499 (48.9) |

| Non-binary | 2 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Missing | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 59 (0.5) | 115 (1.0) |

| Age (years) | ||||

| 16–25 | 2509 (17.9) | 2725 (21.1) | 2450 (20.1) | 2210 (19.6) |

| 26–45 | 4211 (30.0) | 3830 (29.6) | 3769 (30.9) | 3119 (27.7) |

| 46–65 | 3832 (27.3) | 3081 (23.9) | 3155 (25.8) | 2571 (22.9) |

| ≥ 66 | 3499 (24.9) | 3251 (25.2) | 2762 (22.6) | 2846 (25.3) |

| Missing | 0 (0.0) | 31 (0.2) | 71 (0.6) | 502 (4.5) |

| Characteristic | Scotland (N = 5059) | England (N = 3628) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| Female | 2483 (49.1) | 1854 (51.1) |

| Male | 2574 (50.9) | 1774 (48.9) |

| Non-binary | 2 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Age (years), n (%) | ||

| 16–25 | 1137 (22.5) | 861 (23.7) |

| 26–45 | 1613 (31.9) | 1146 (31.6) |

| 46–65 | 1352 (26.7) | 901 (24.8) |

| ≥ 66 | 957 (18.9) | 720 (19.8) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||

| White | 4717 (93.2) | 3172 (87.4) |

| Non-white | 325 (6.4) | 438 (12.1) |

| Missing | 17 (0.3) | 18 (0.5) |

| Employment status, n (%) | ||

| Employed | 2590 (51.2) | 1690 (46.6) |

| Economically inactive | 1938 (38.3) | 1479 (40.8) |

| Unemployed | 498 (9.8) | 431 (11.9) |

| Missing | 33 (0.7) | 28 (0.8) |

| Marital status, n (%) | ||

| Married/co-habiting | 2116 (41.8) | 1453 (40.0) |

| Separated/divorced/widowed | 770 (15.2) | 547 (15.1) |

| Single | 2097 (41.5) | 1588 (43.8) |

| Missing | 76 (1.5) | 40 (1.1) |

| Housing ownership, n (%) | ||

| Owner occupied | 1917 (37.9) | 1285 (35.4) |

| Rented | 1306 (25.8) | 1207 (33.3) |

| Housing association/council | 888 (17.6) | 446 (12.3) |

| Other | 881 (17.4) | 627 (17.3) |

| Missing | 67 (1.3) | 63 (1.7) |

| Carstairs deprivation score | ||

| Mean (SD) | 7.06 (2.60) | 7.37 (2.54) |

| Median (minimum, maximum) | 8.00 (1.00, 10.0) | 8.00 (1.00, 10.0) |

| Missing, n (%) | 54 (1.1) | 166 (4.6) |

A total of 8746 attendees completed the interview (see Table 3). We excluded those who lived outside Scotland and England (n = 20) and non-UK residents (n = 39). As a result, 8687 respondents were included in the analytic sample for the following secondary outcomes: current alcohol use, binge drinking in the past week and binge drinking in the past 24 hours. The remaining six secondary outcomes [FAST score, alcohol misuse, binge drinking (at least) weekly, increased alcohol use in the past year, private location as place of last drink and on-licensed premise as place of last drink] were based on respondents who were current drinkers (n = 6991). Although there are some slight differences in the demographic distribution between the Scottish and English samples, we accounted for these in our DiD analysis.

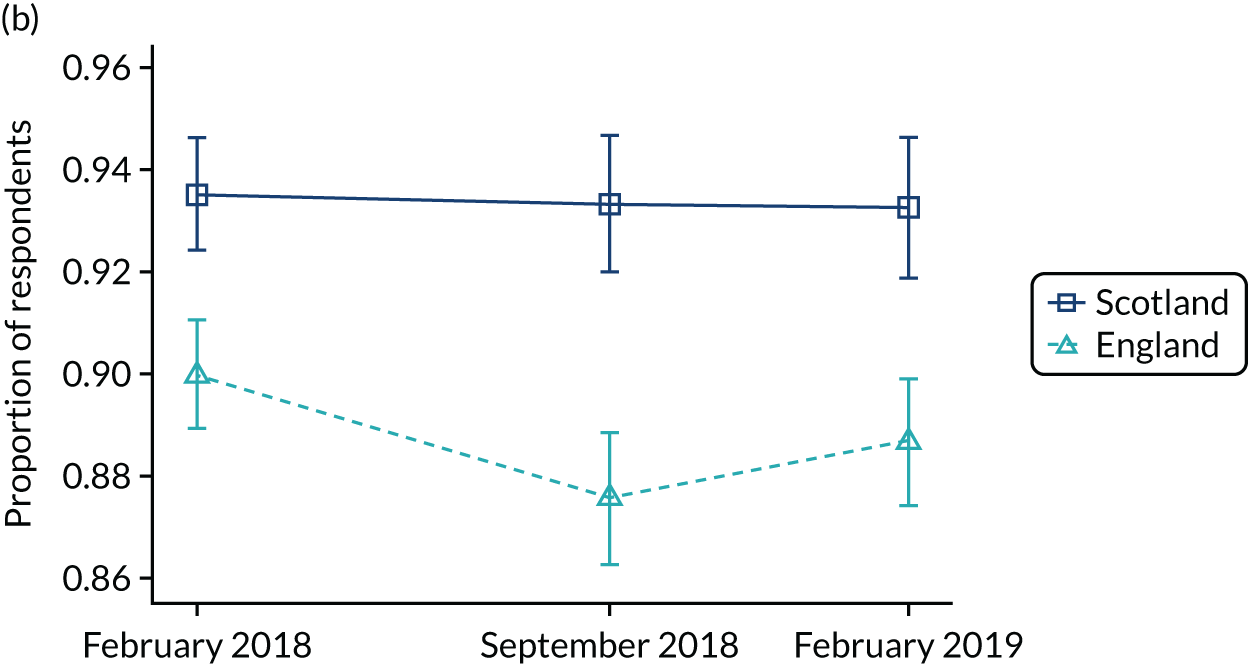

Main analysis

Primary outcome

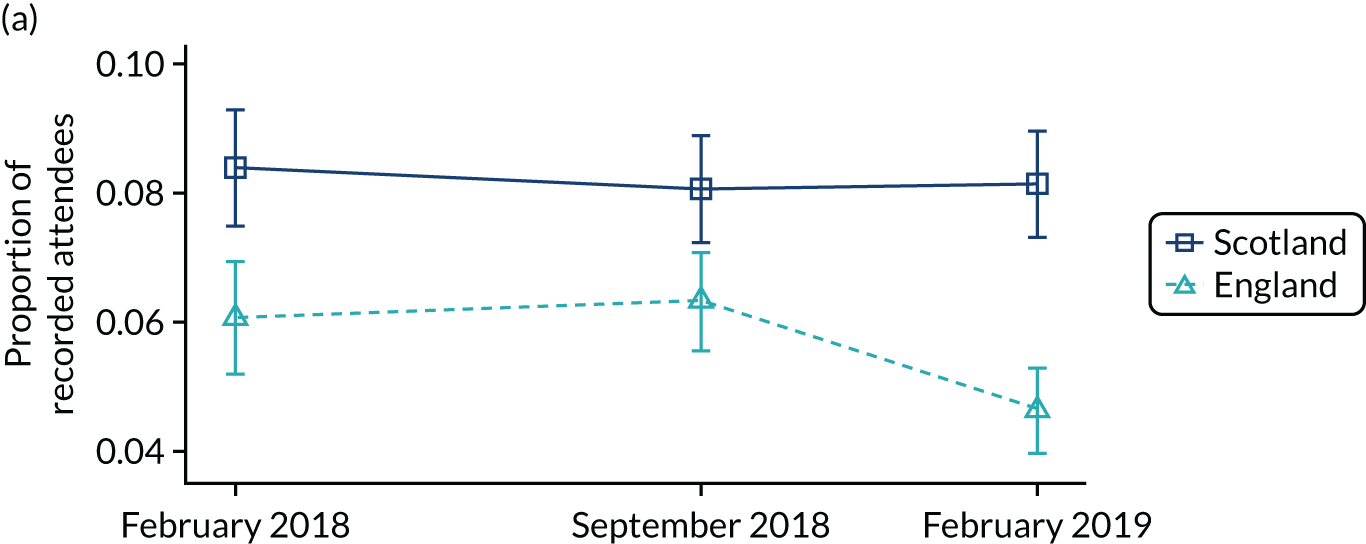

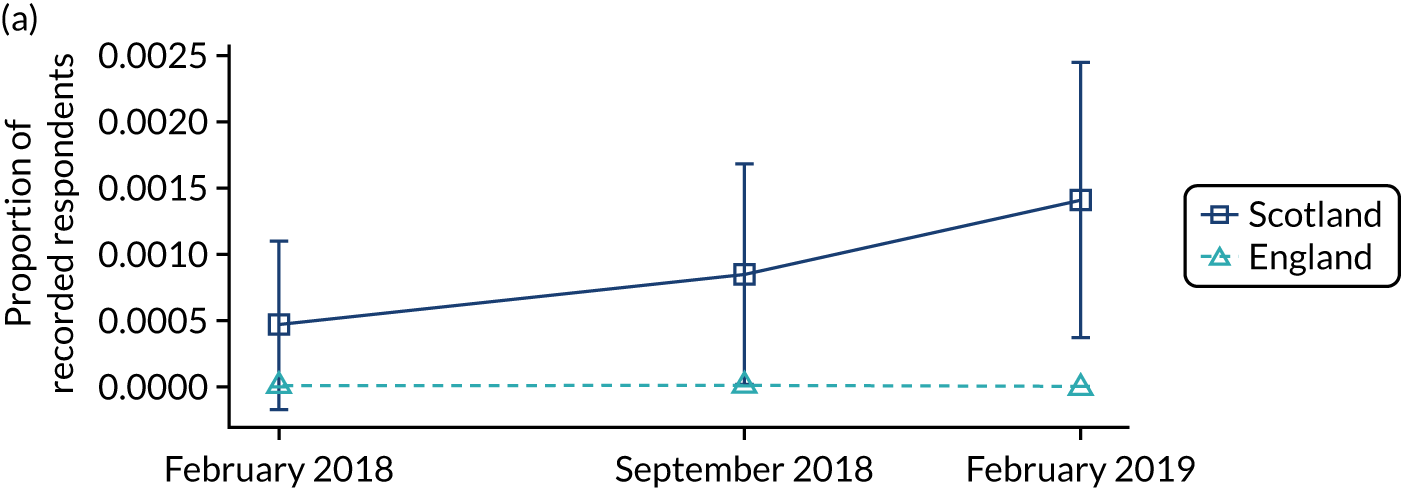

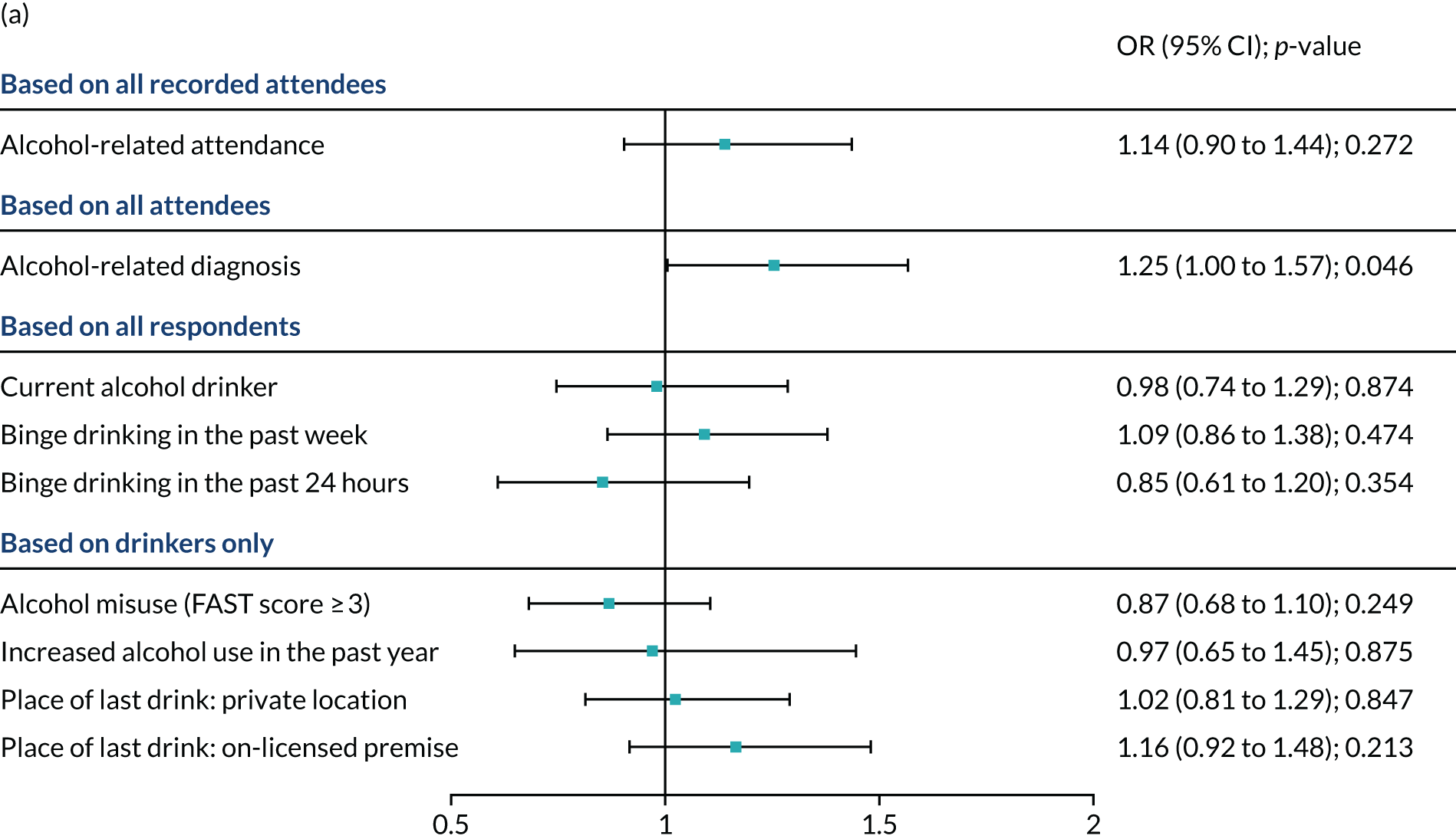

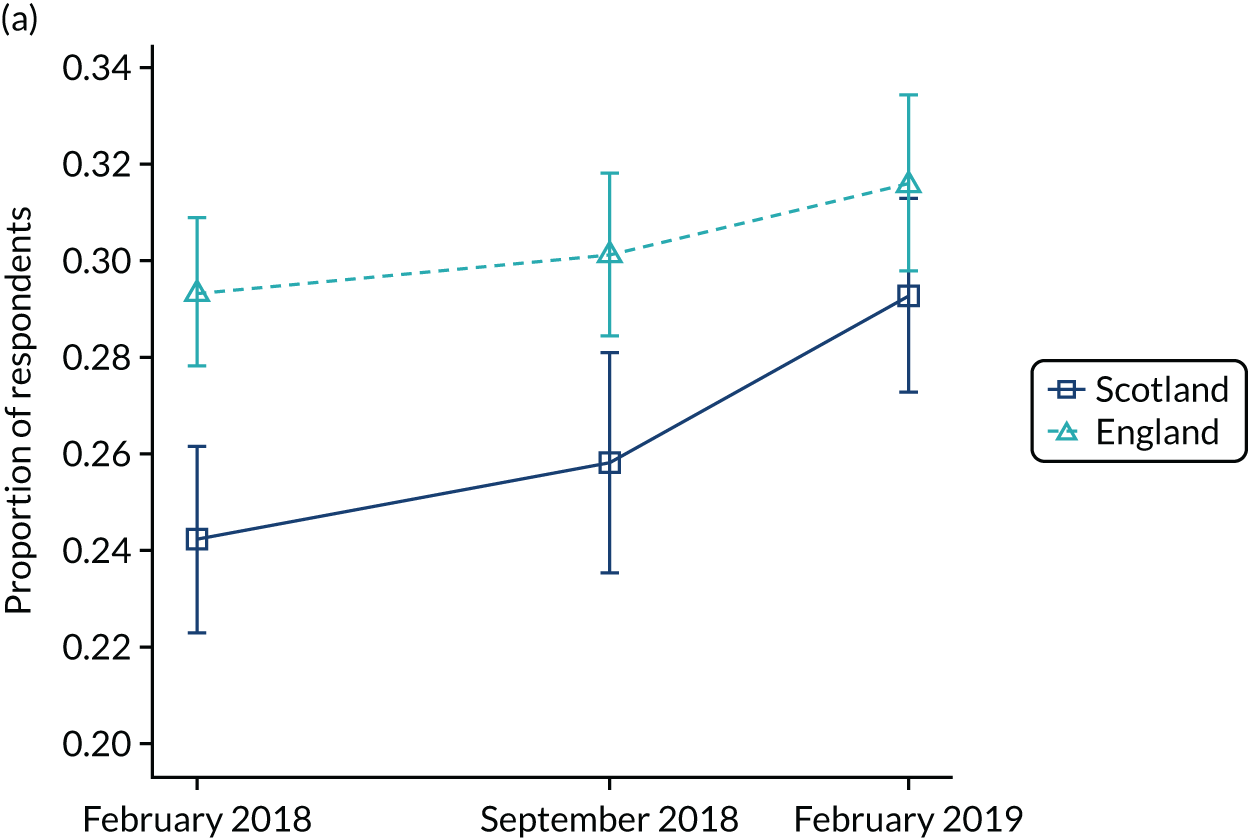

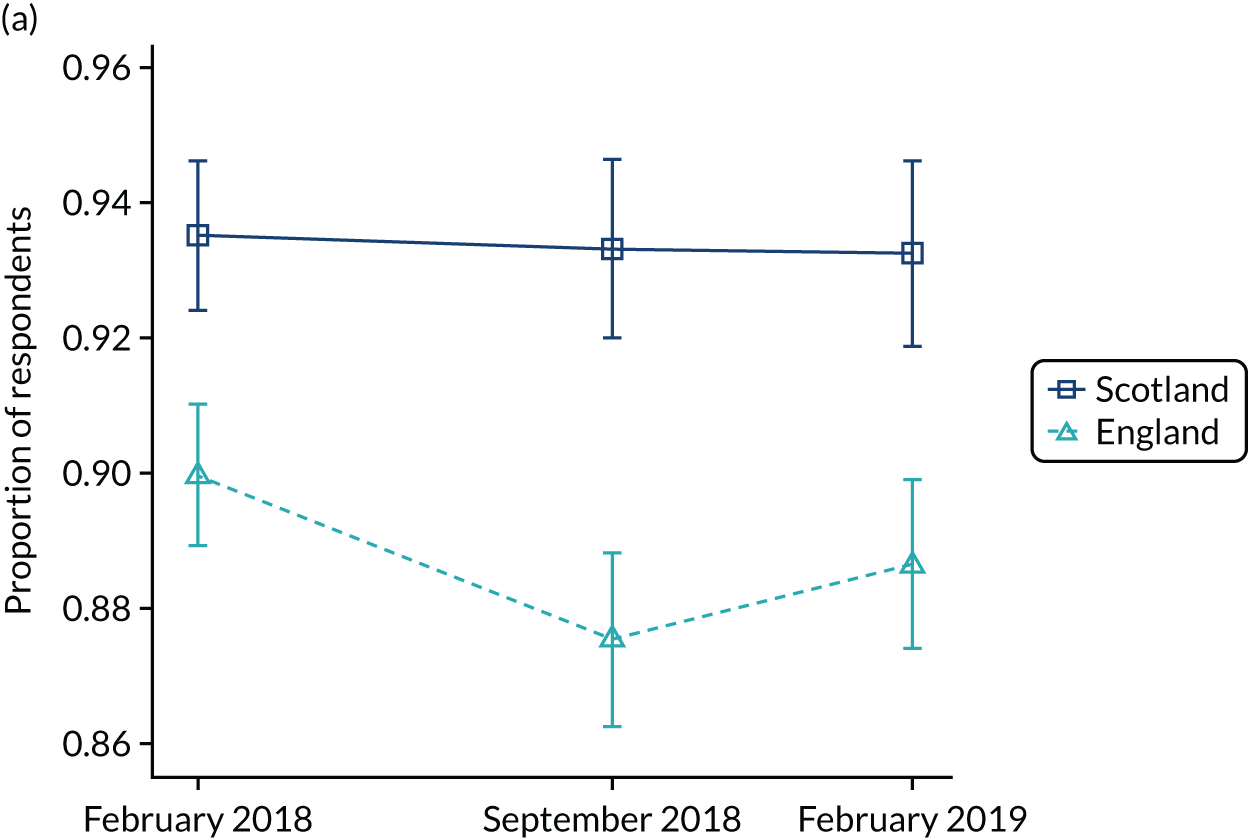

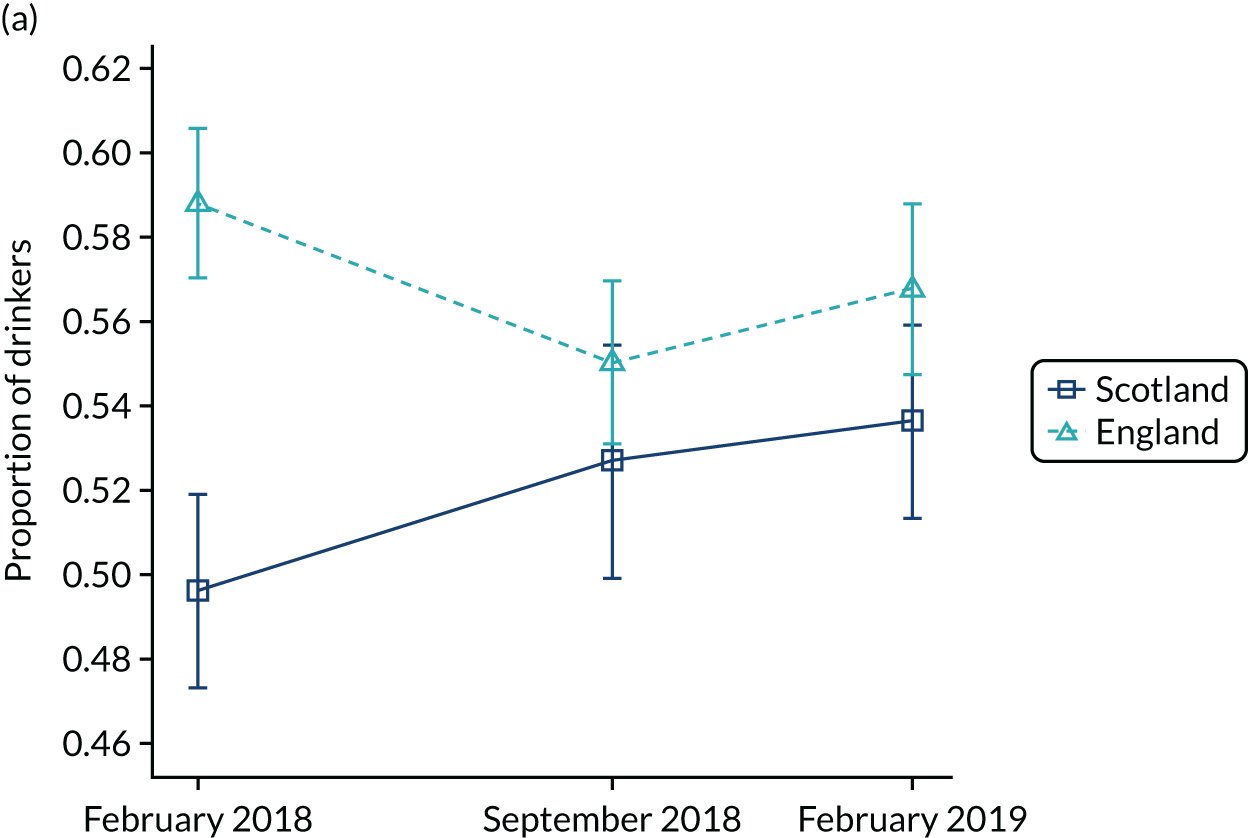

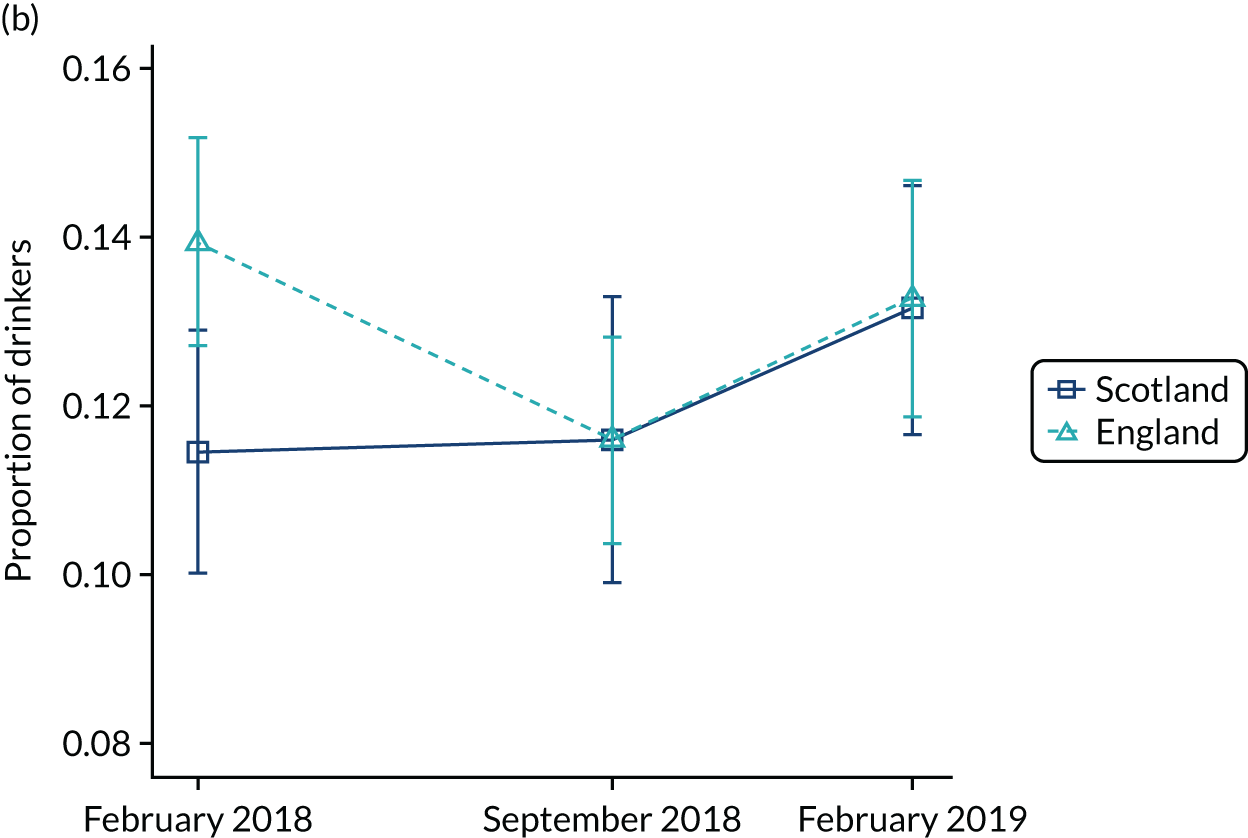

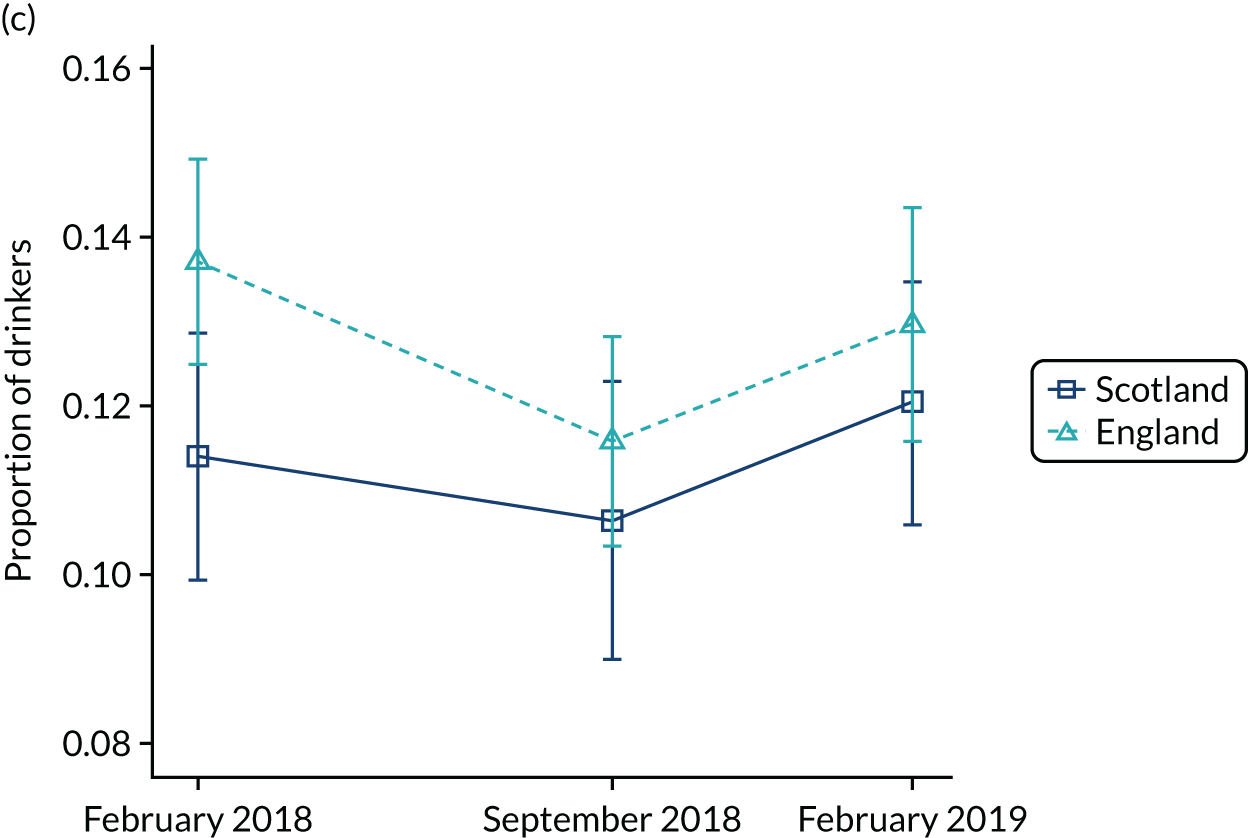

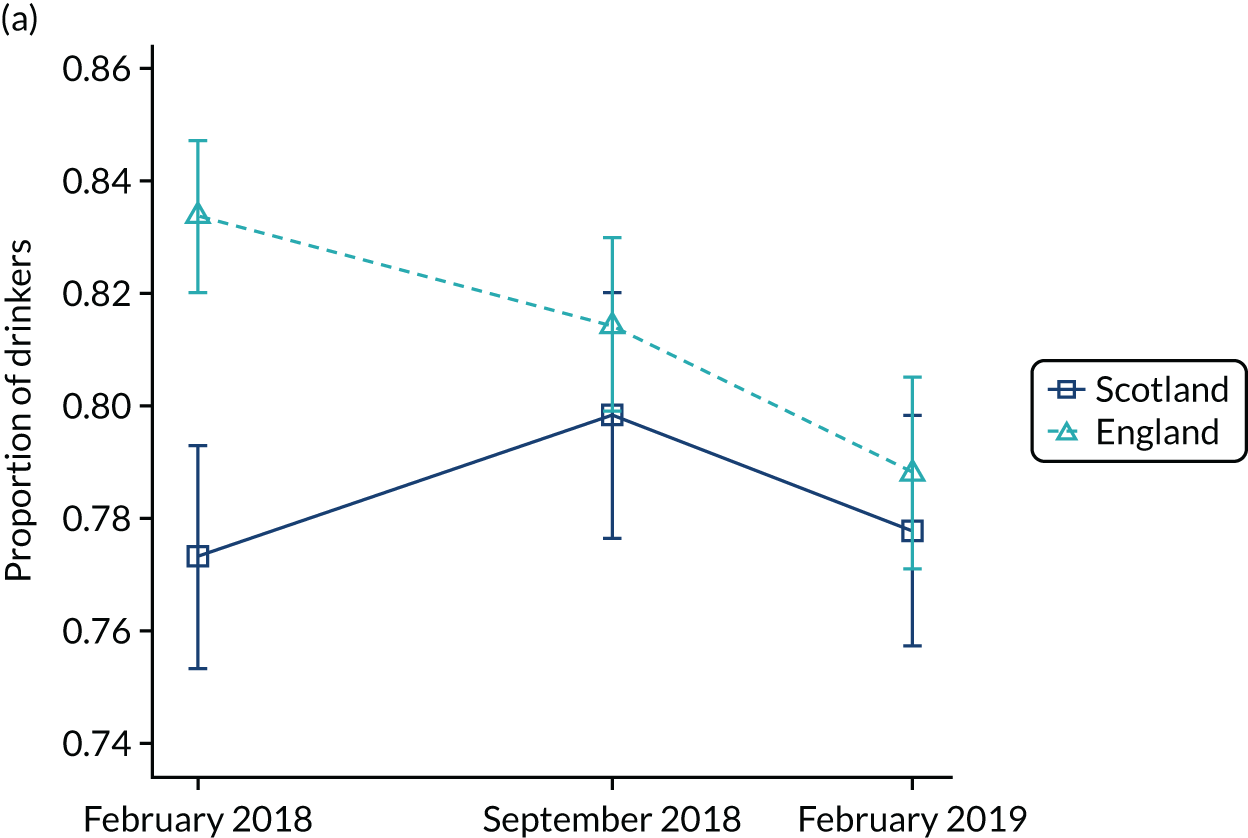

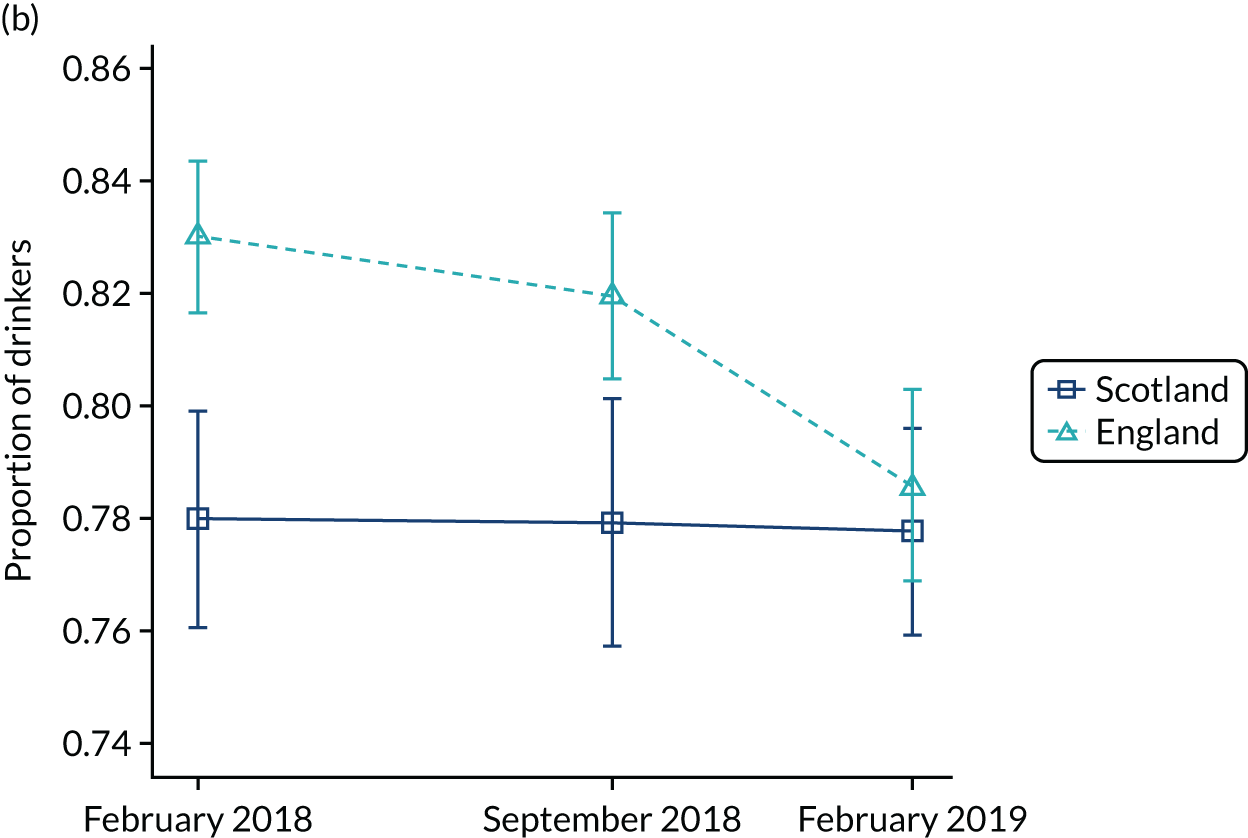

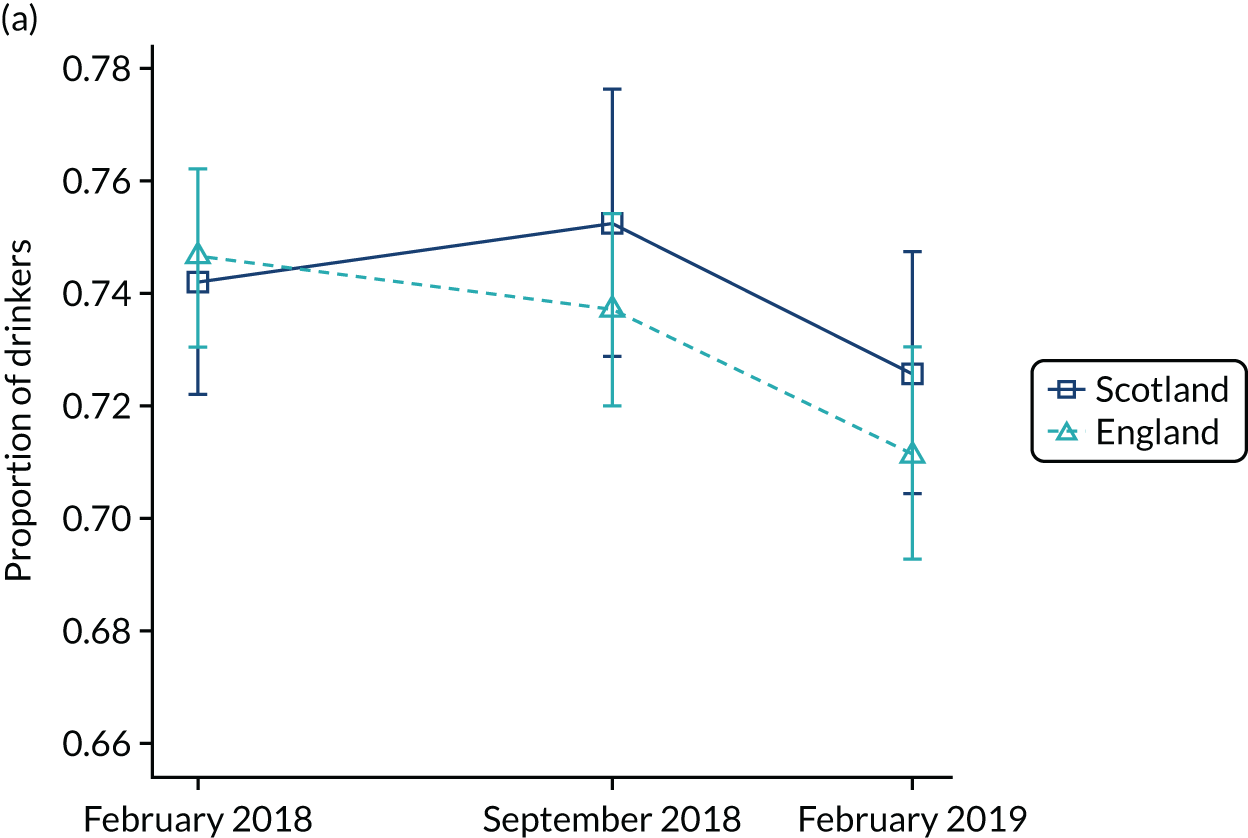

Figure 2a shows the changes in the proportion of recorded attendees with alcohol-related attendance in Scotland and England before and after the introduction of the MUP. On average, Scotland had a higher proportion of attendances that were alcohol related than England. Scotland had a stable trend, whereas there was a decreasing trend in England. There was no evidence of statistically significant differences in the primary outcome after the introduction of MUP in Scotland. The odds ratio (OR) of having an alcohol-related attendance before and after implementation of the MUP was 1.14 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.90 to 1.44; p = 0.272] in Scotland compared with England (see Figure 4 and Appendix 2, Table 26, for the summary of DiD estimates from full regression models).

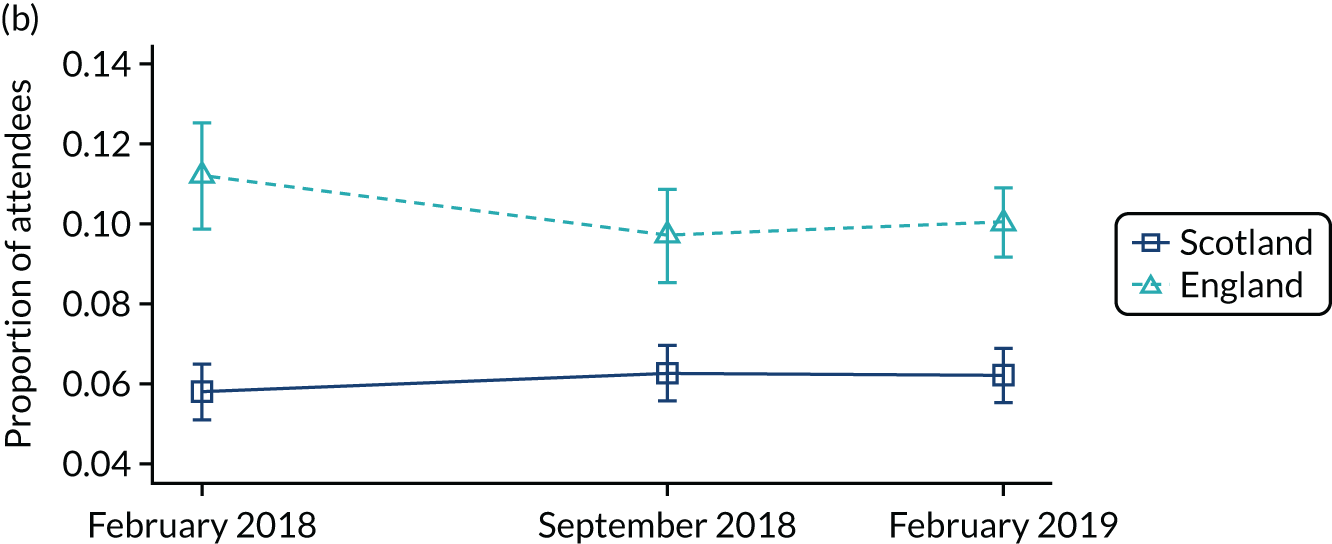

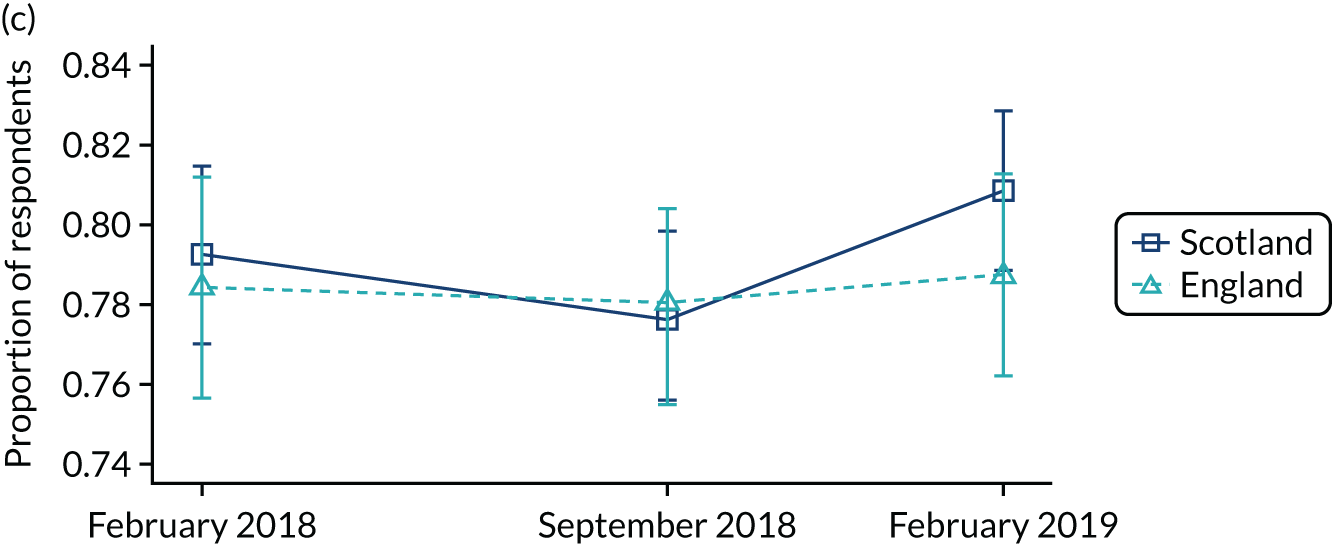

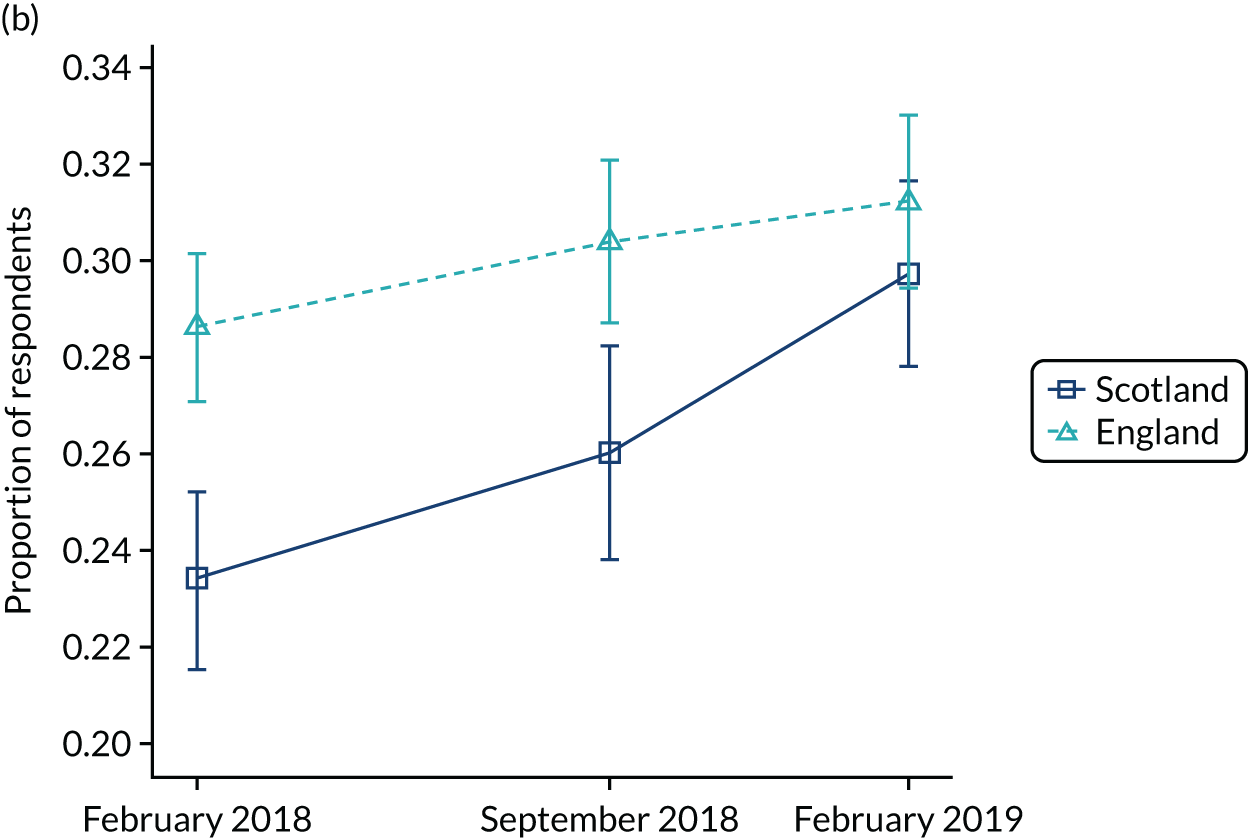

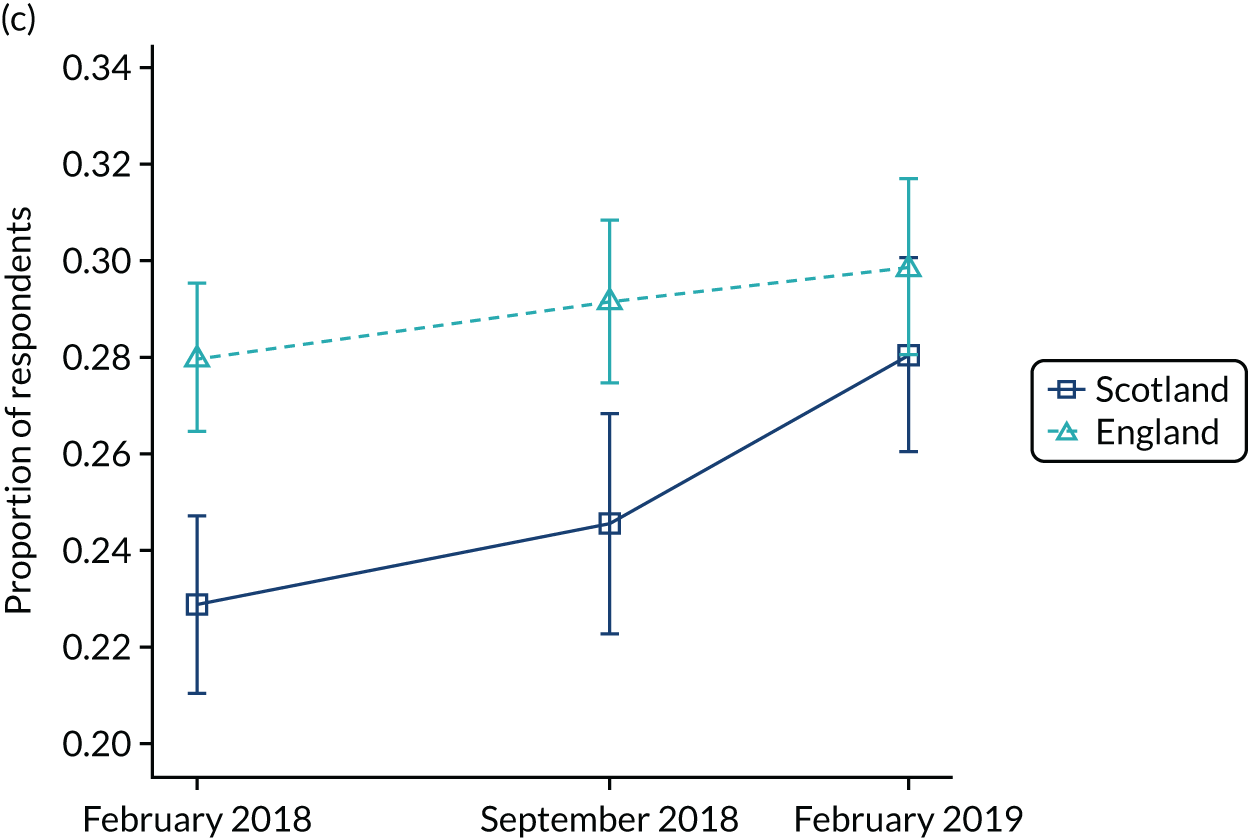

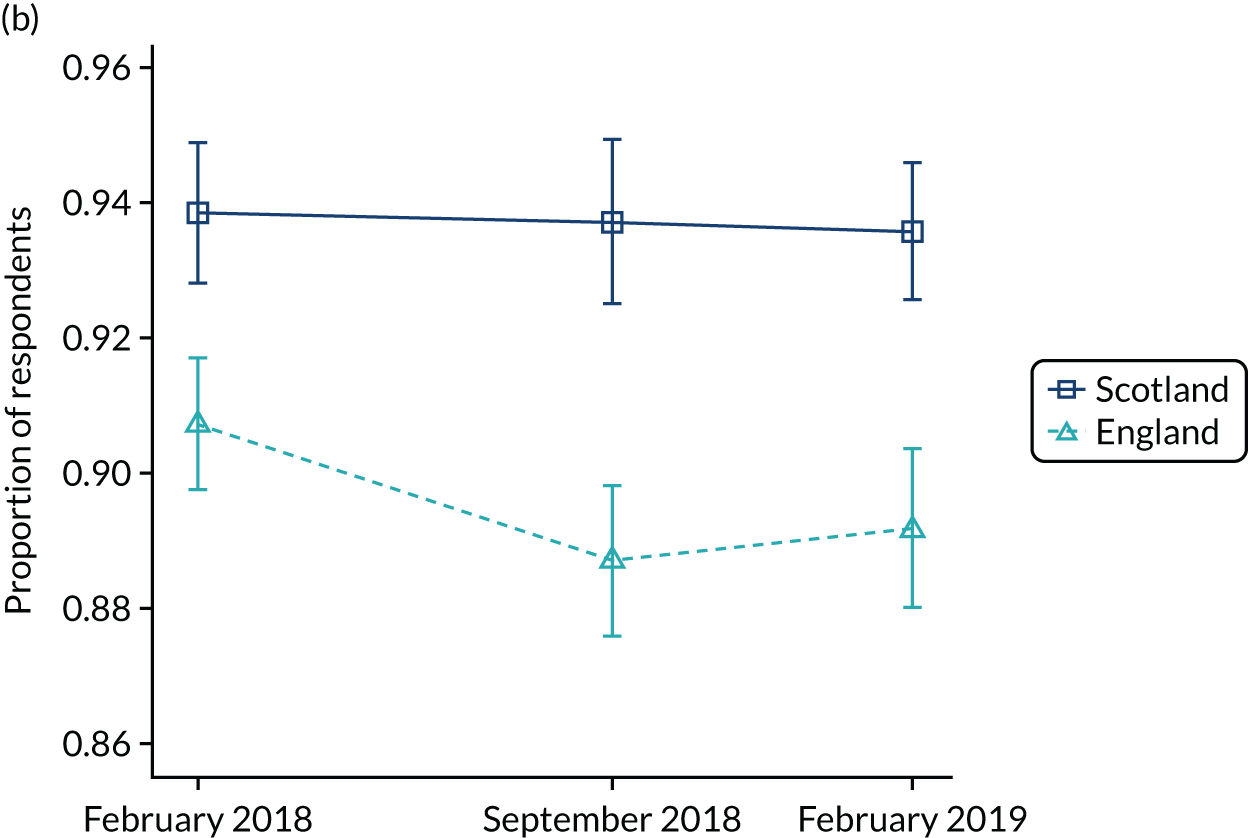

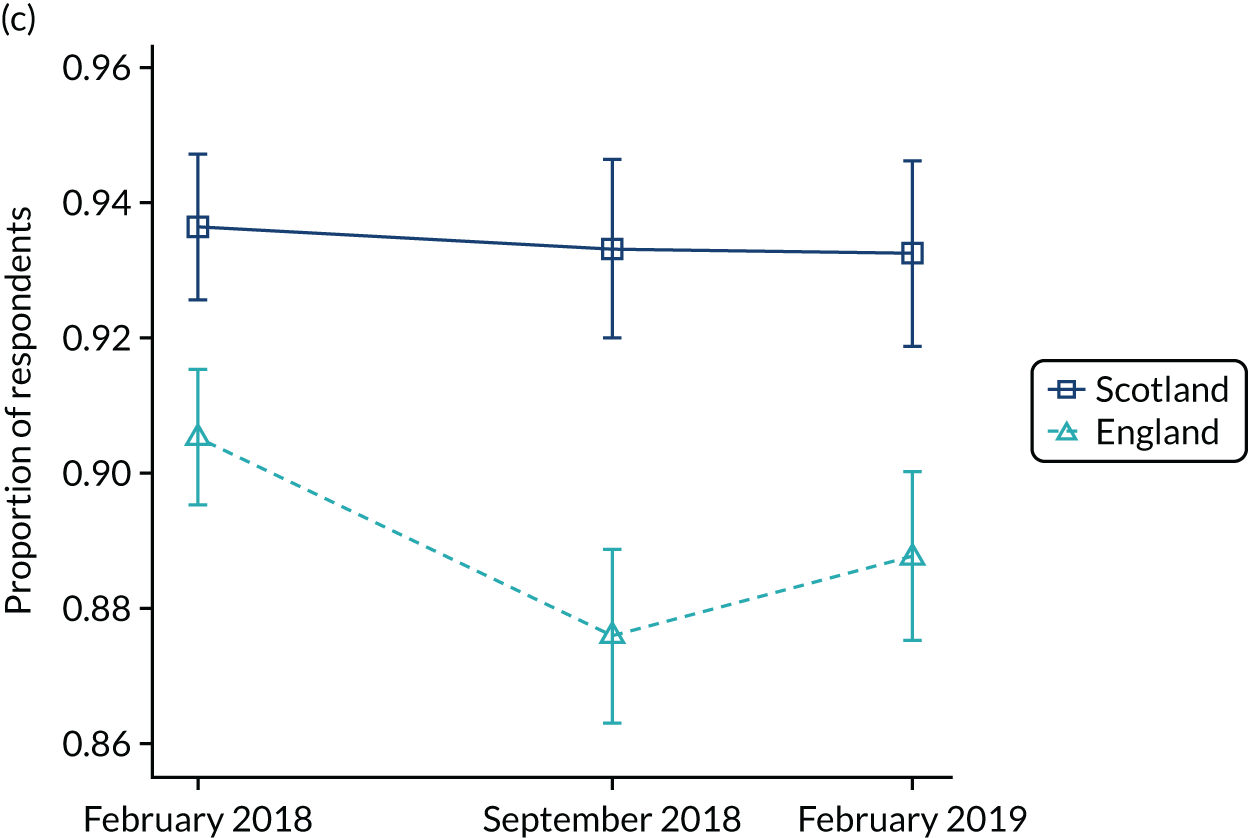

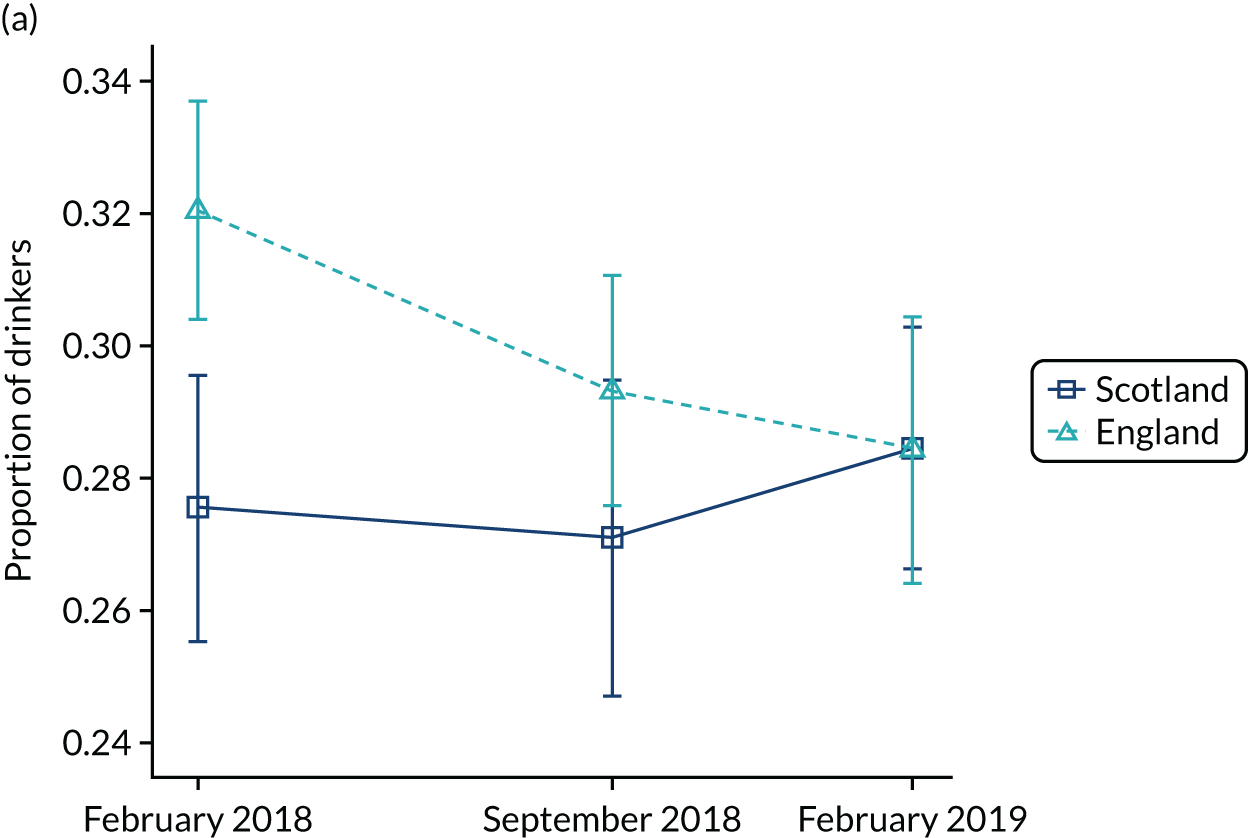

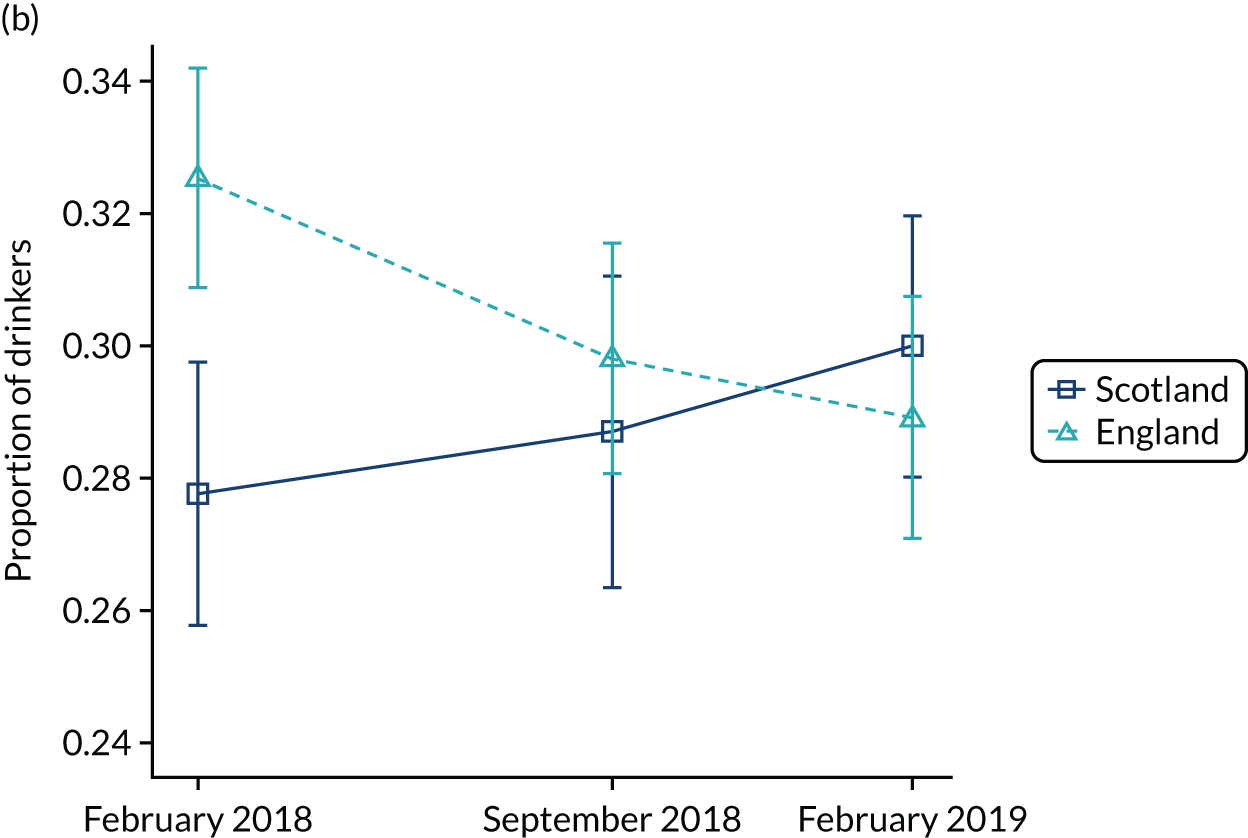

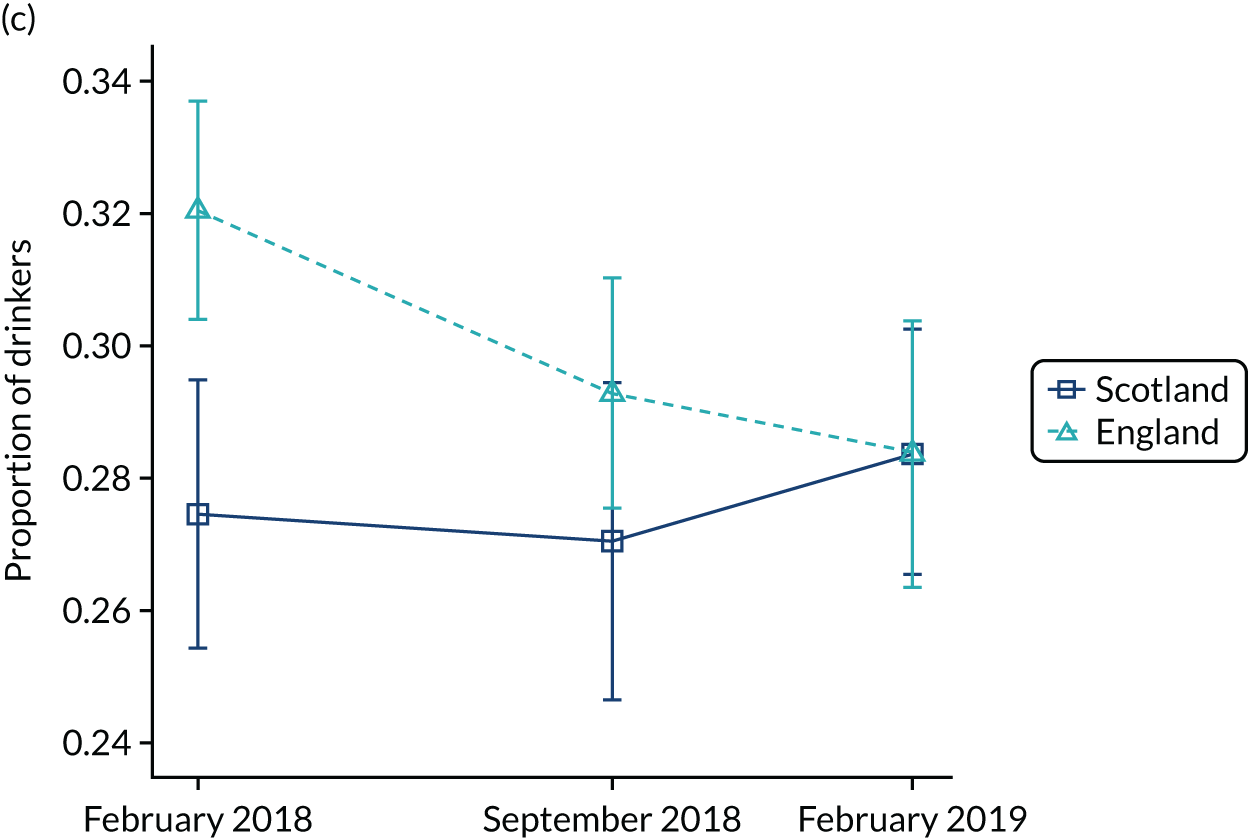

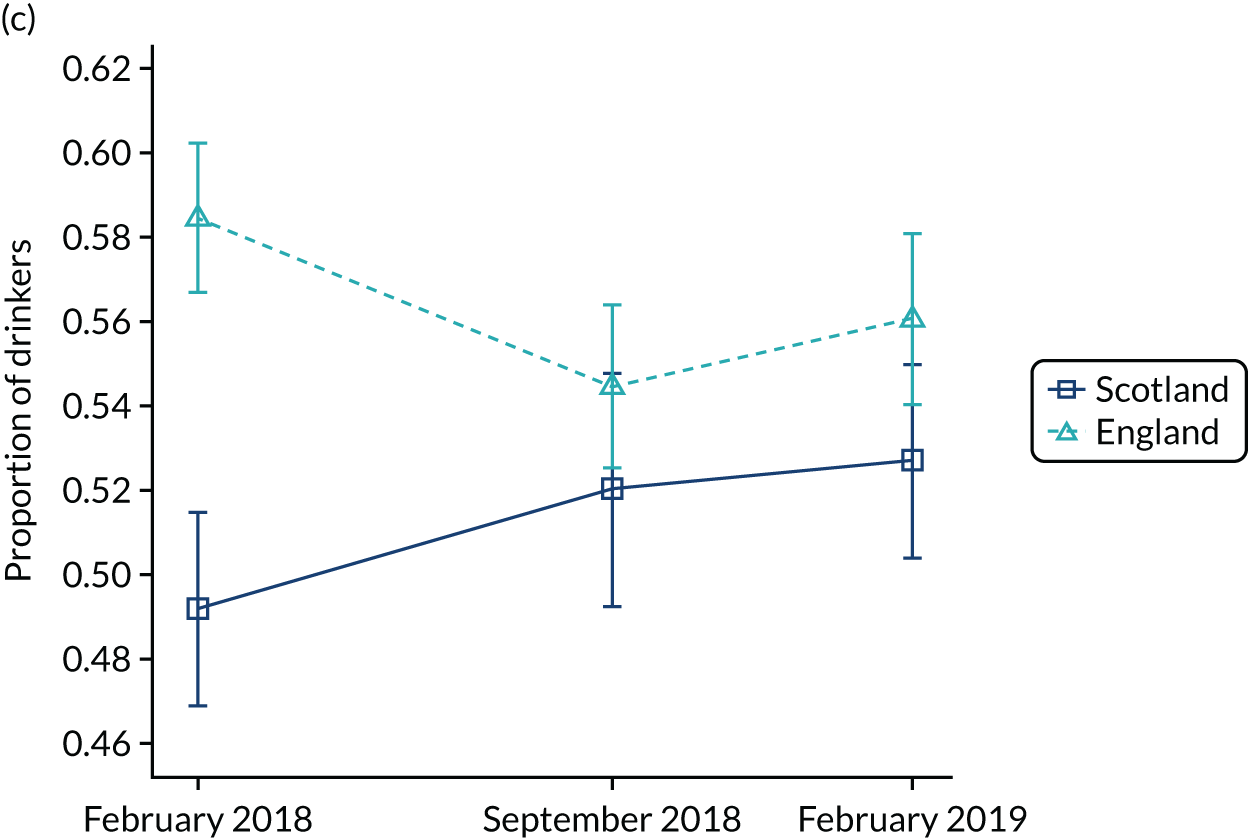

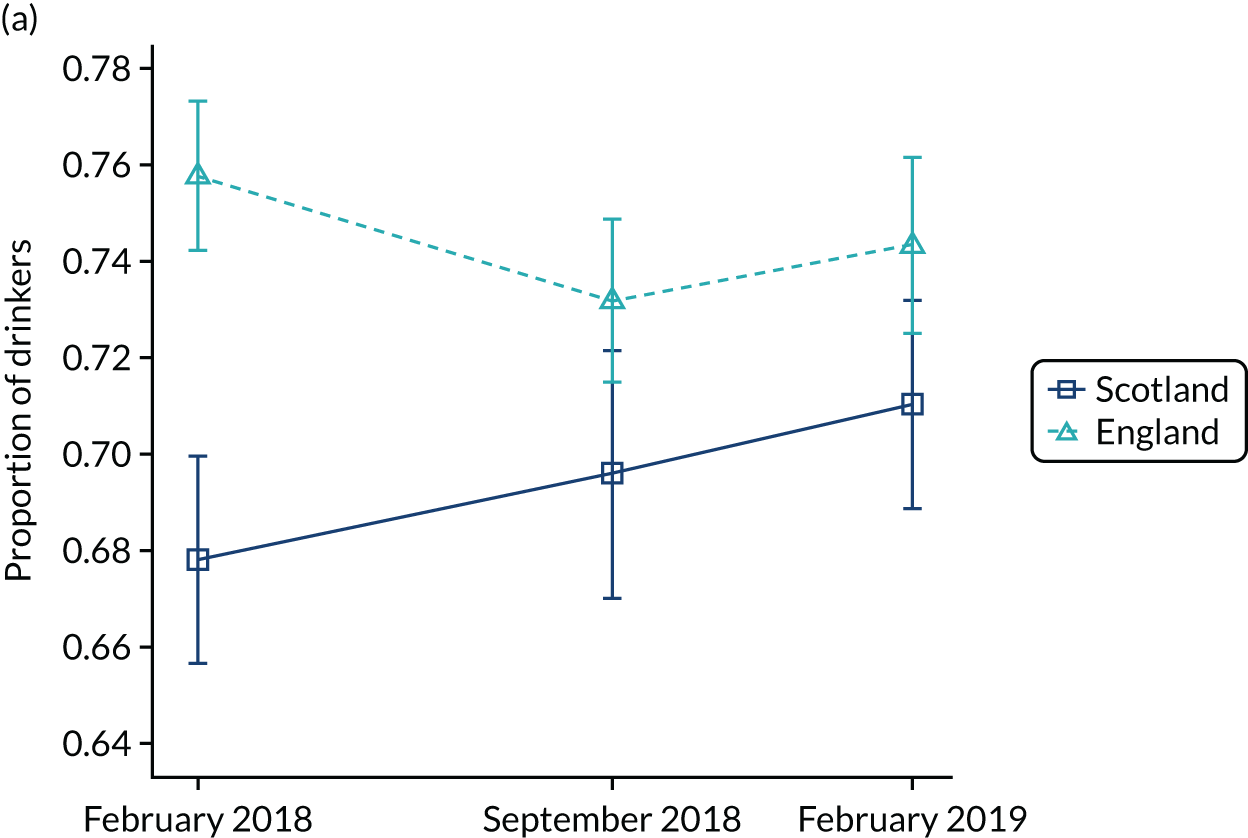

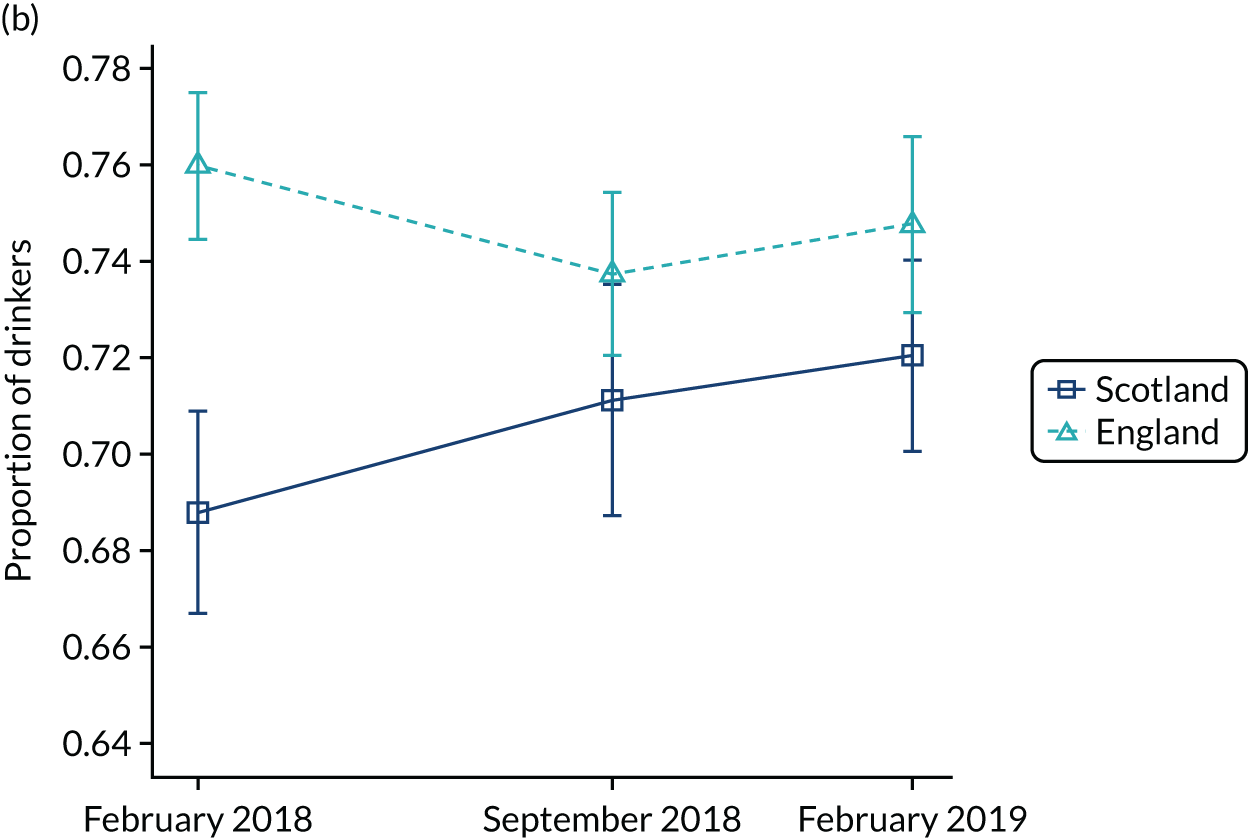

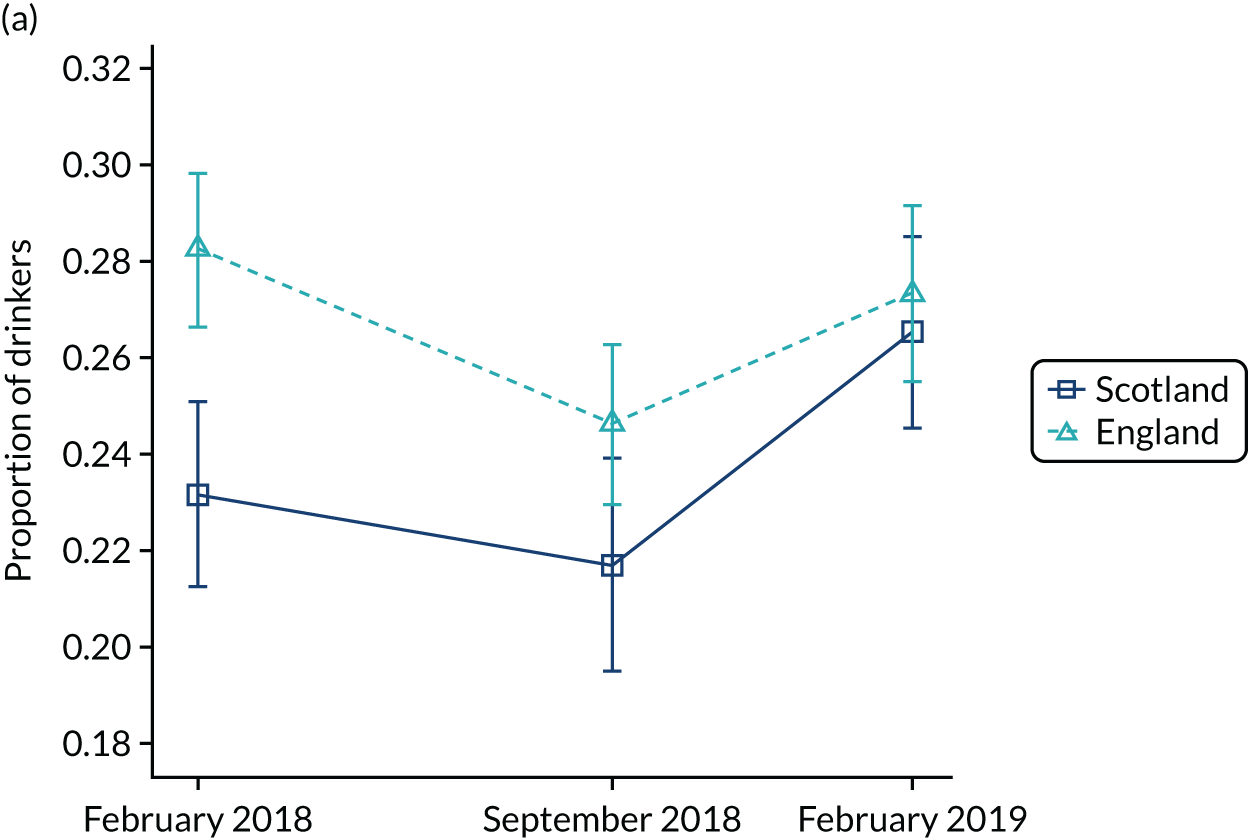

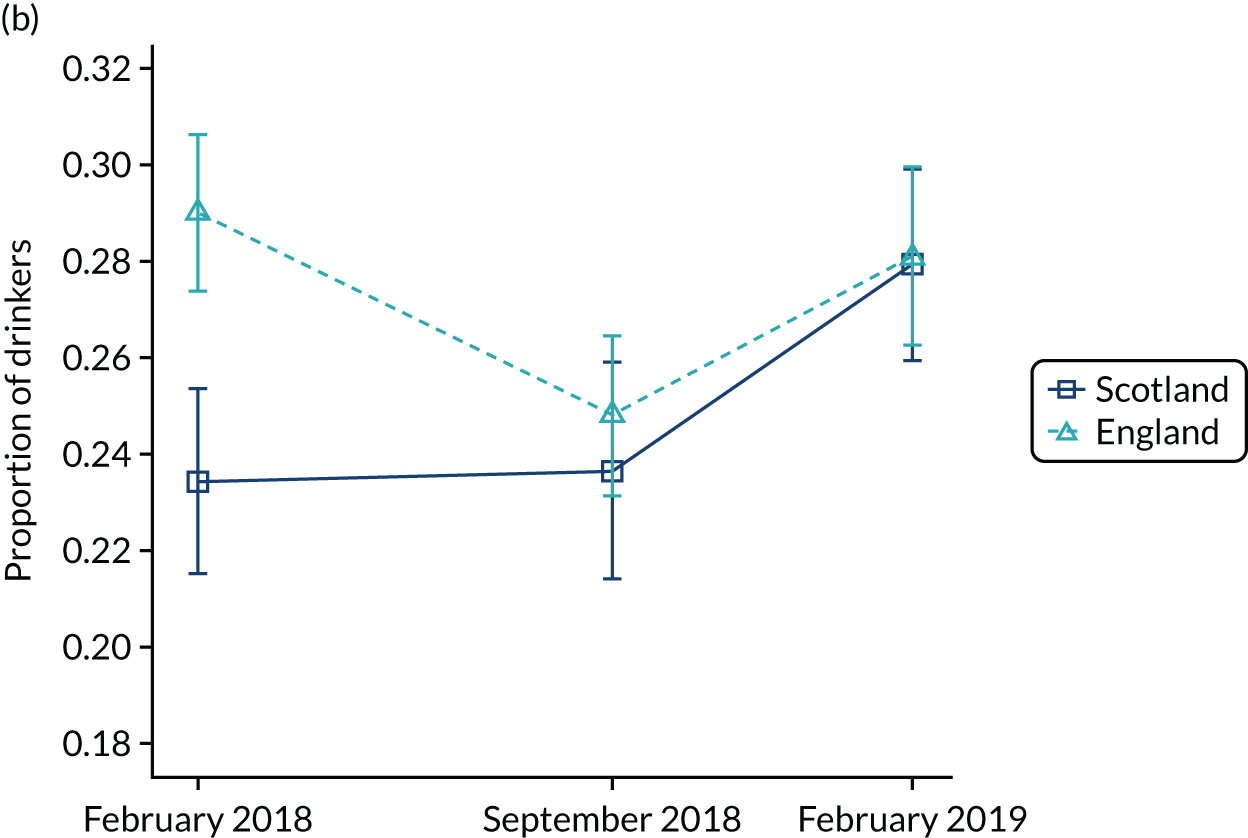

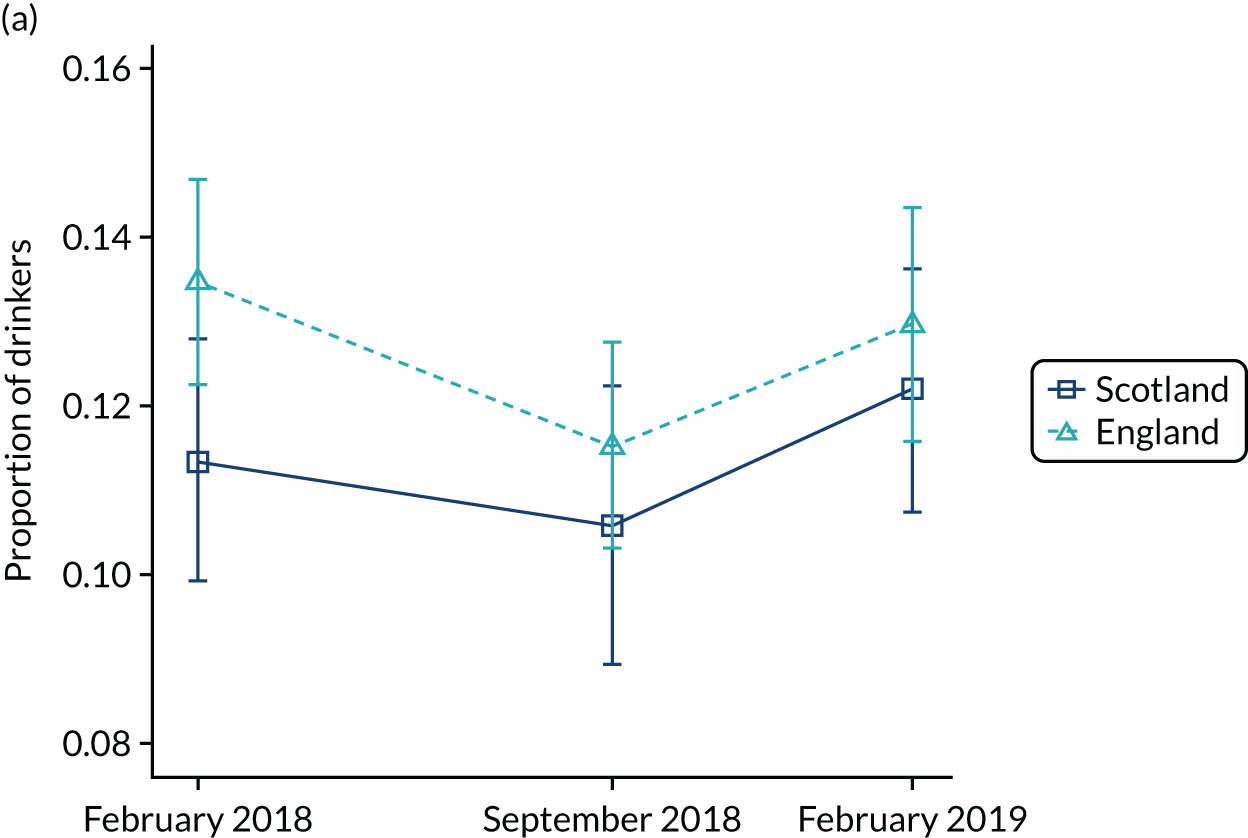

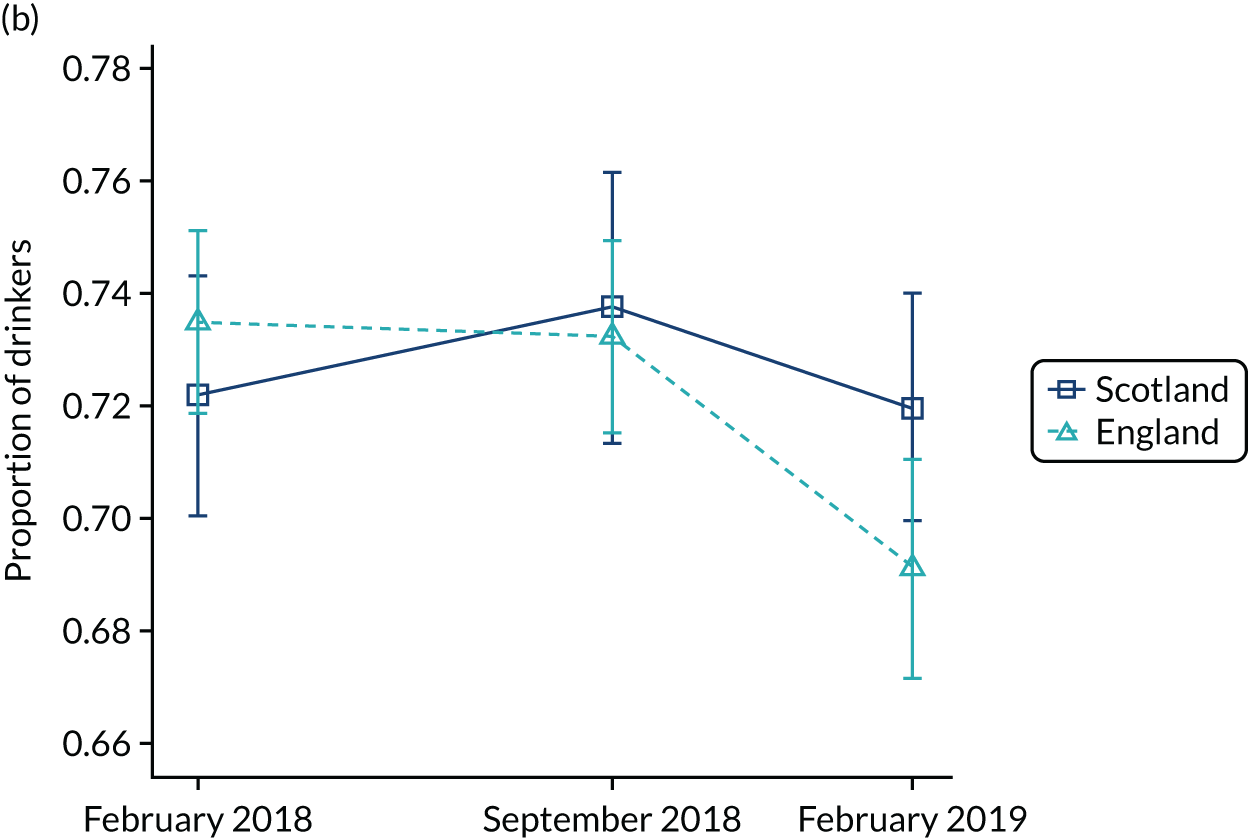

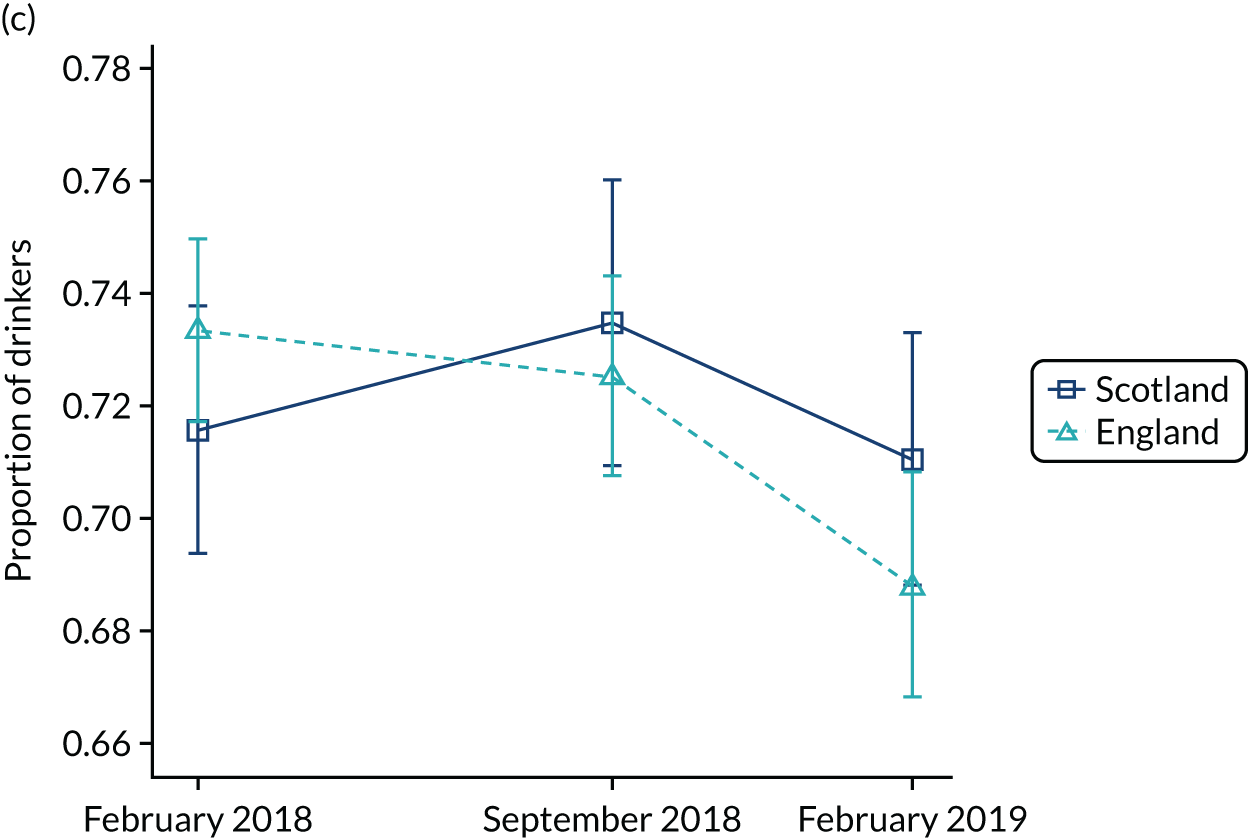

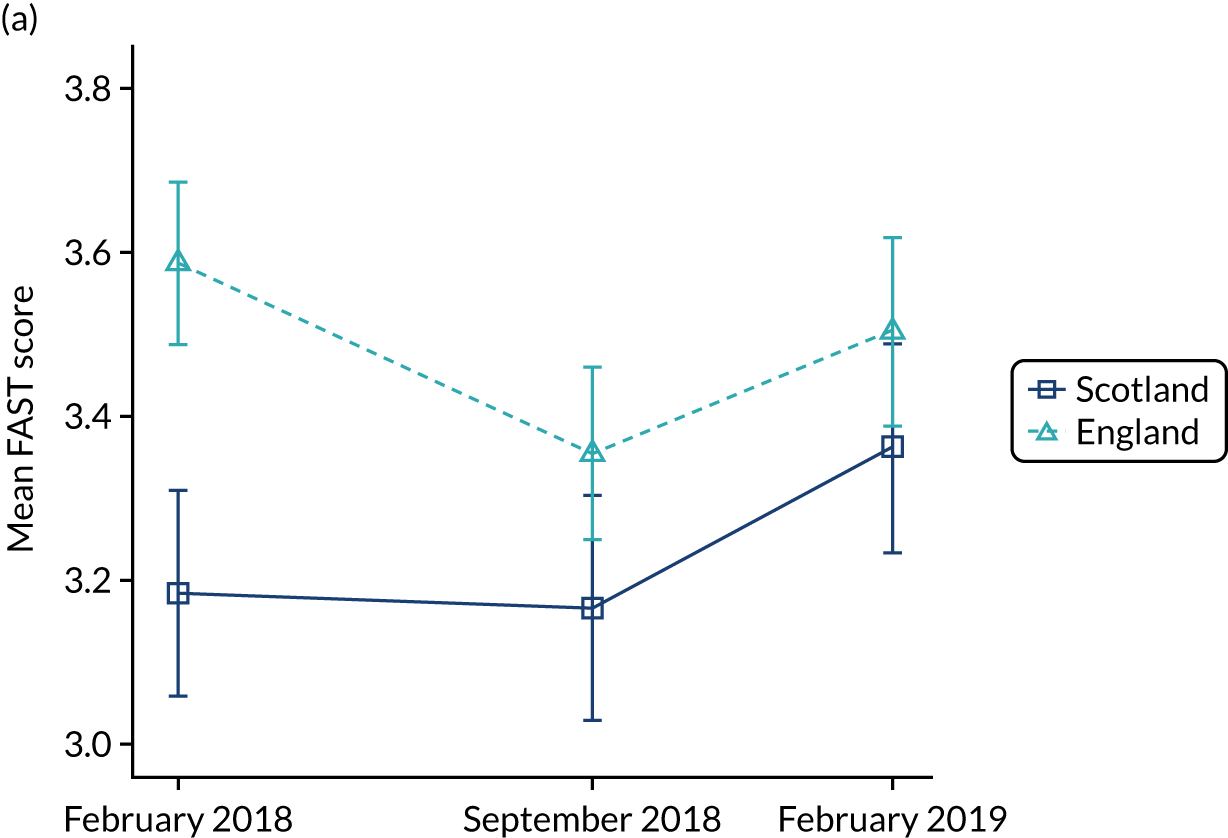

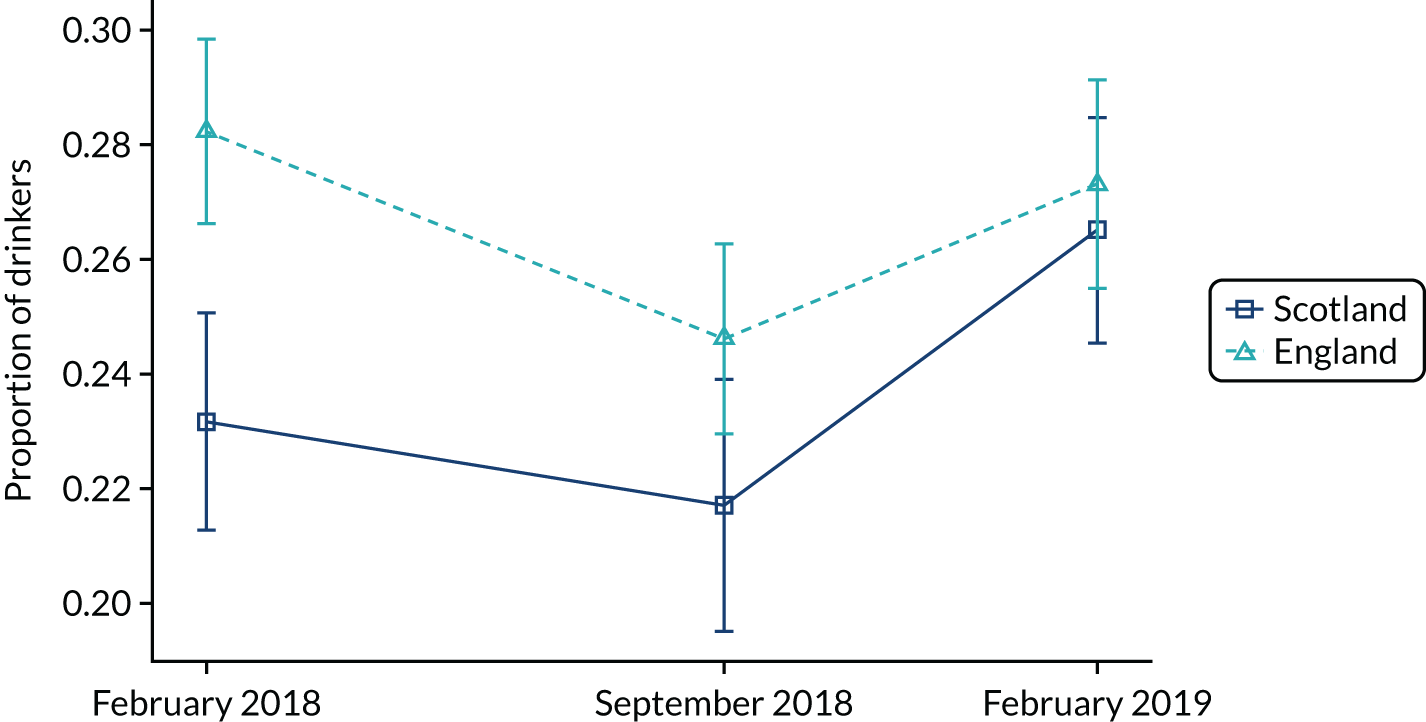

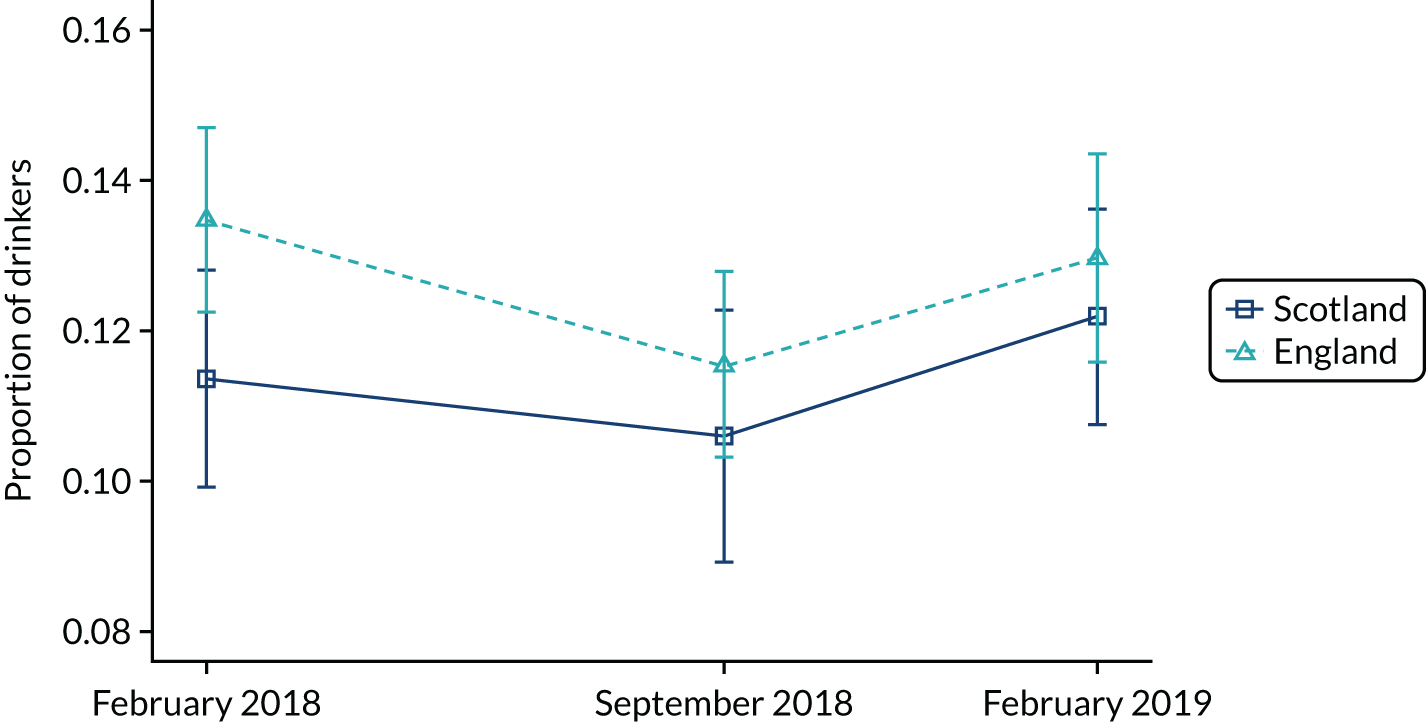

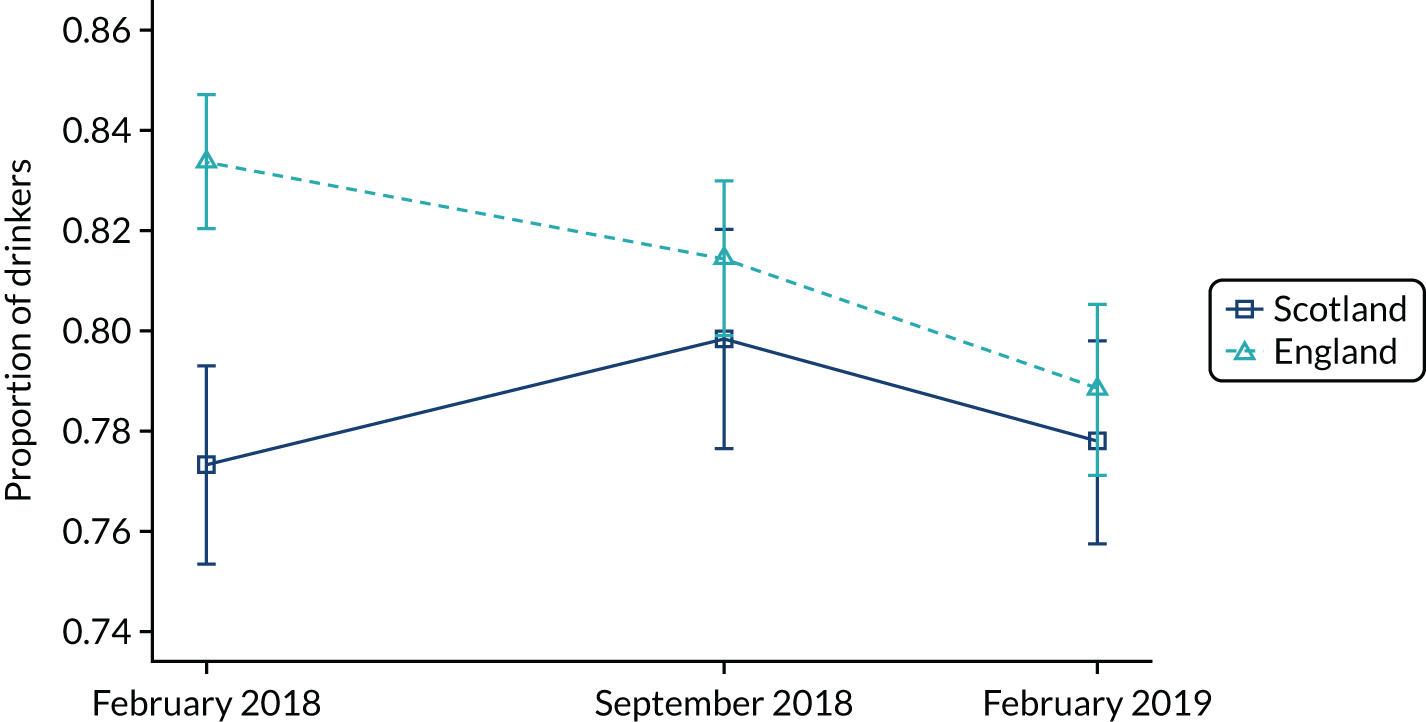

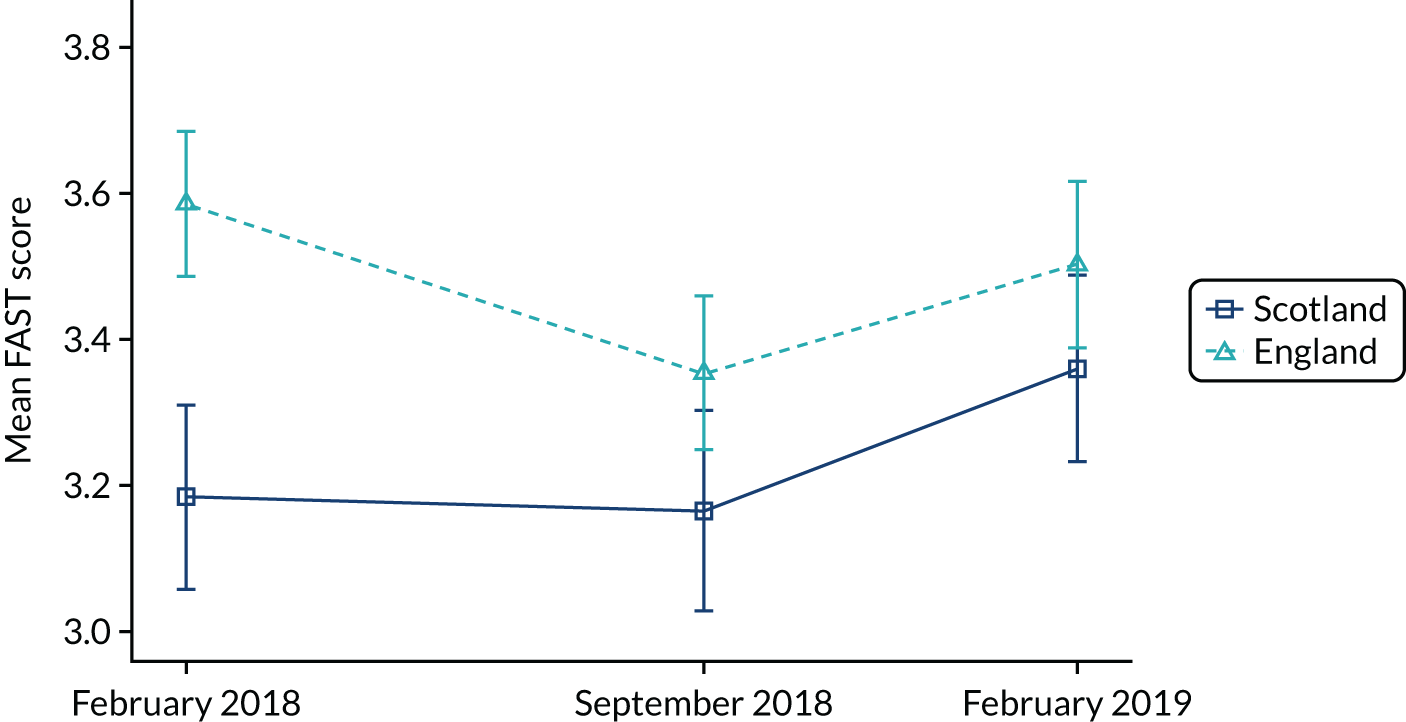

FIGURE 2.

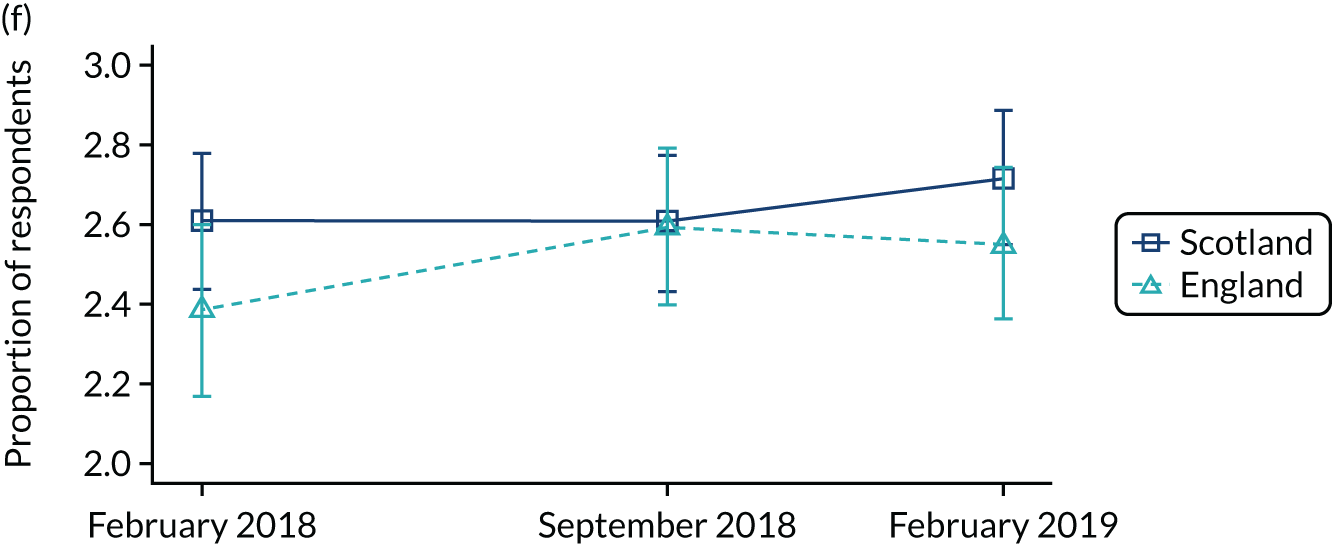

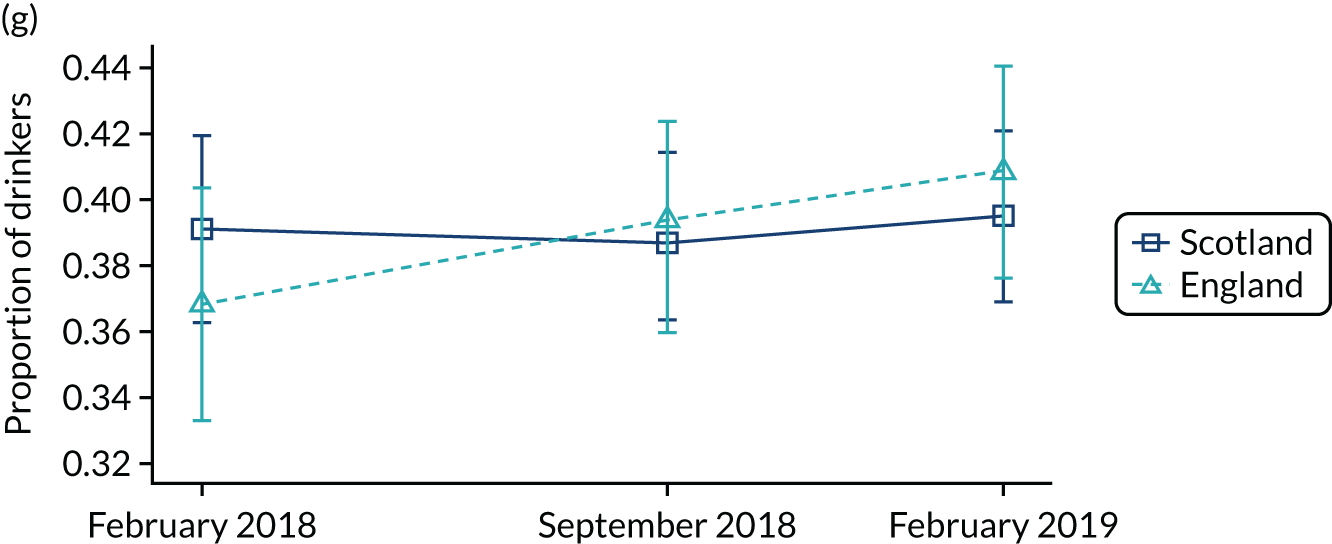

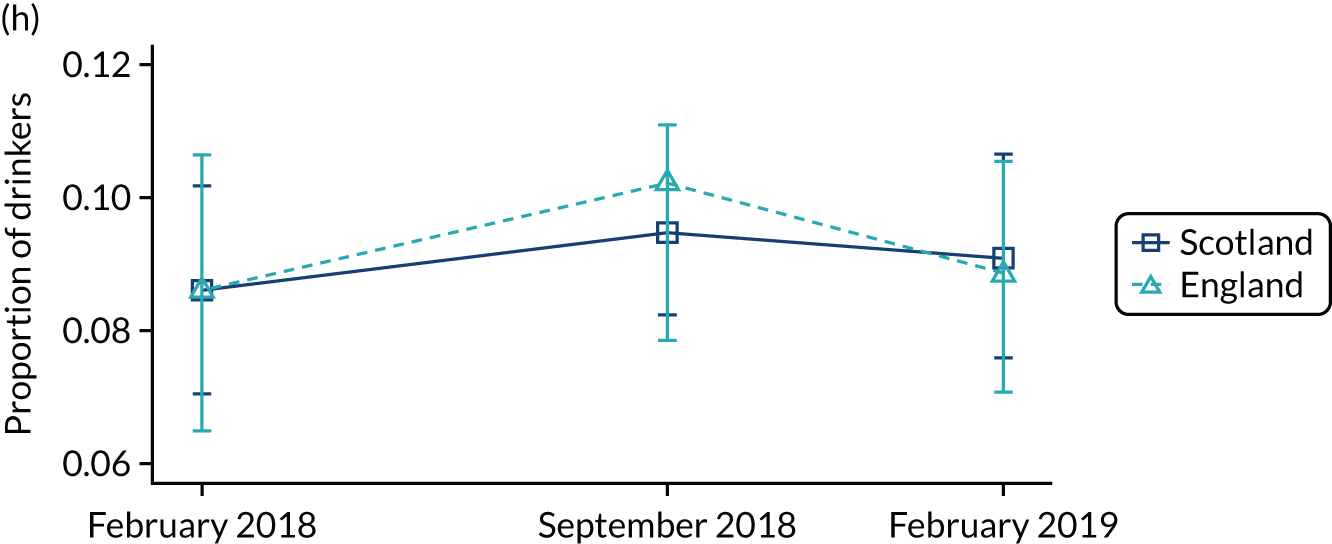

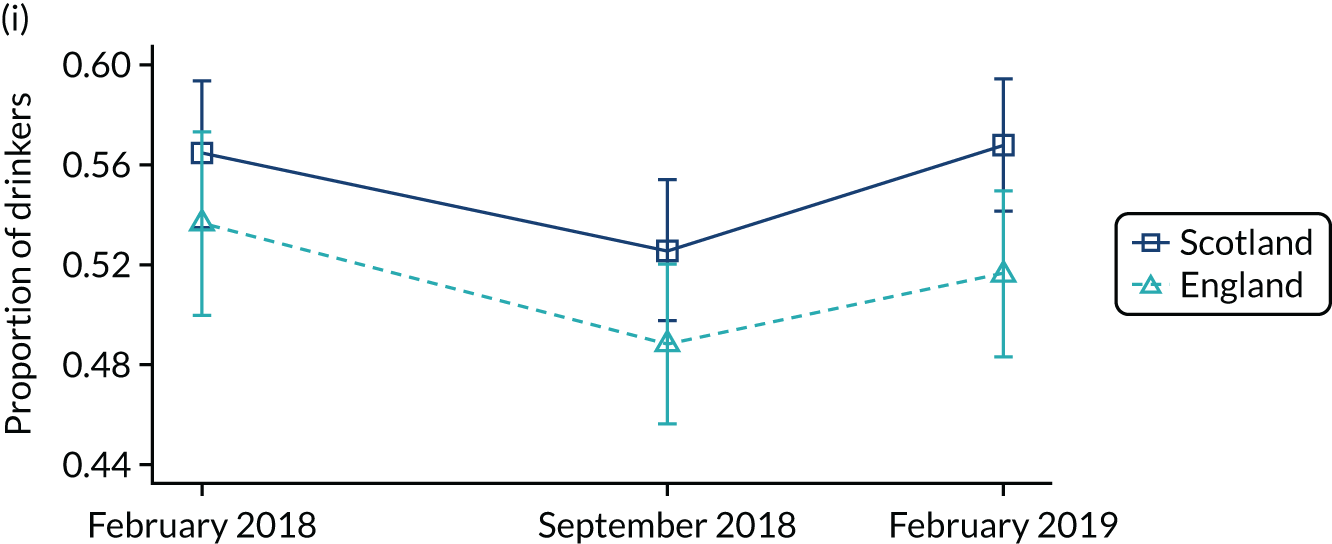

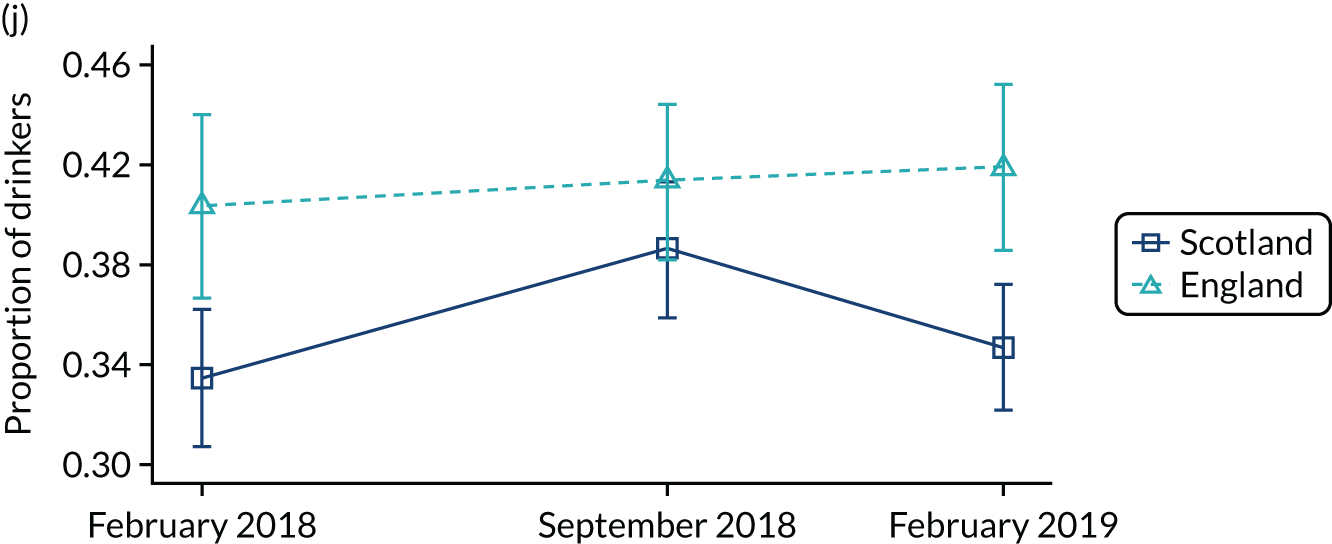

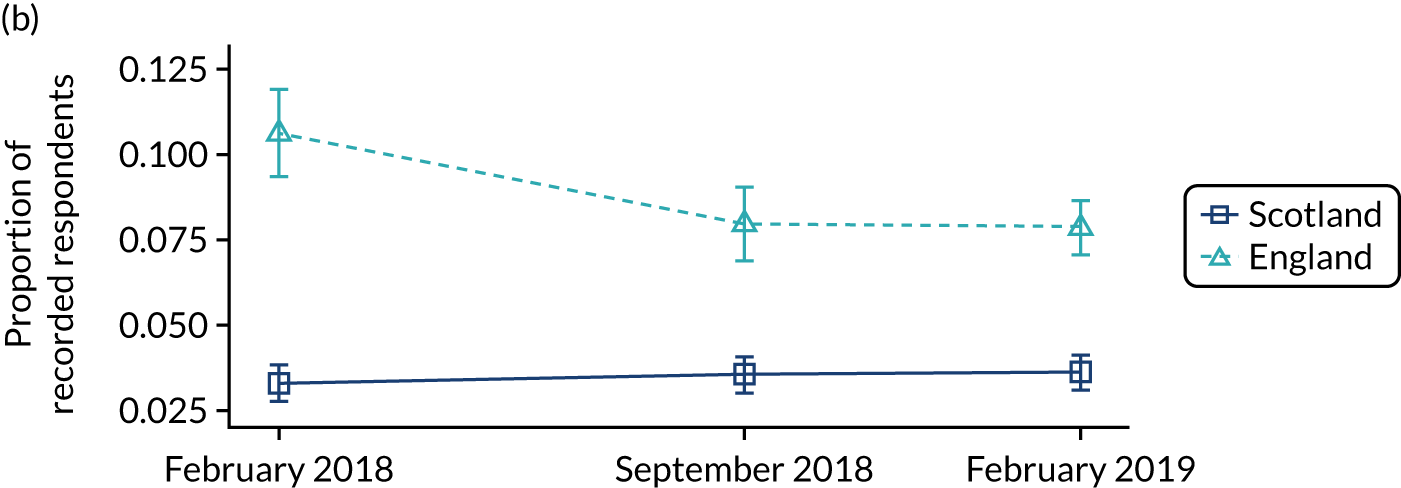

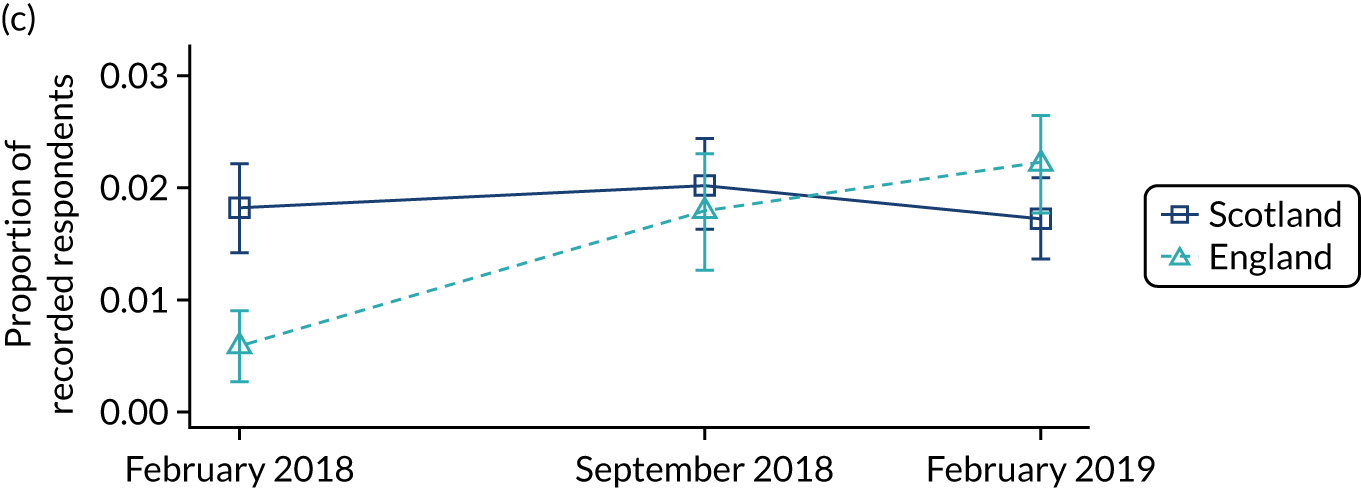

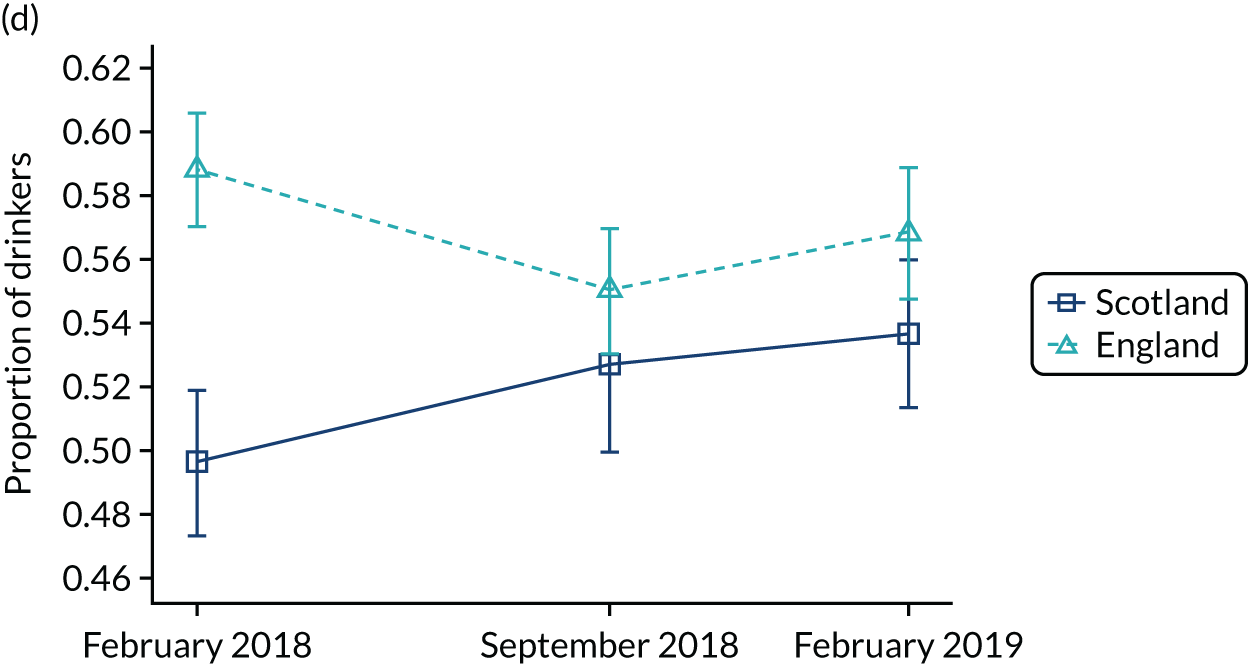

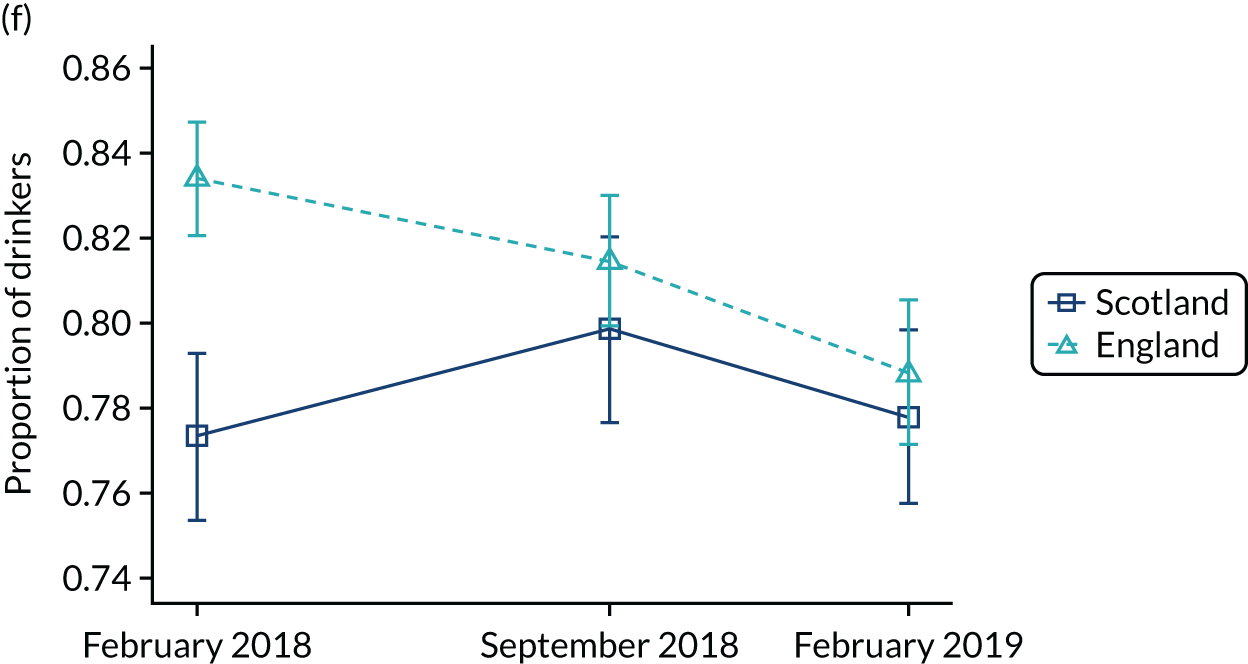

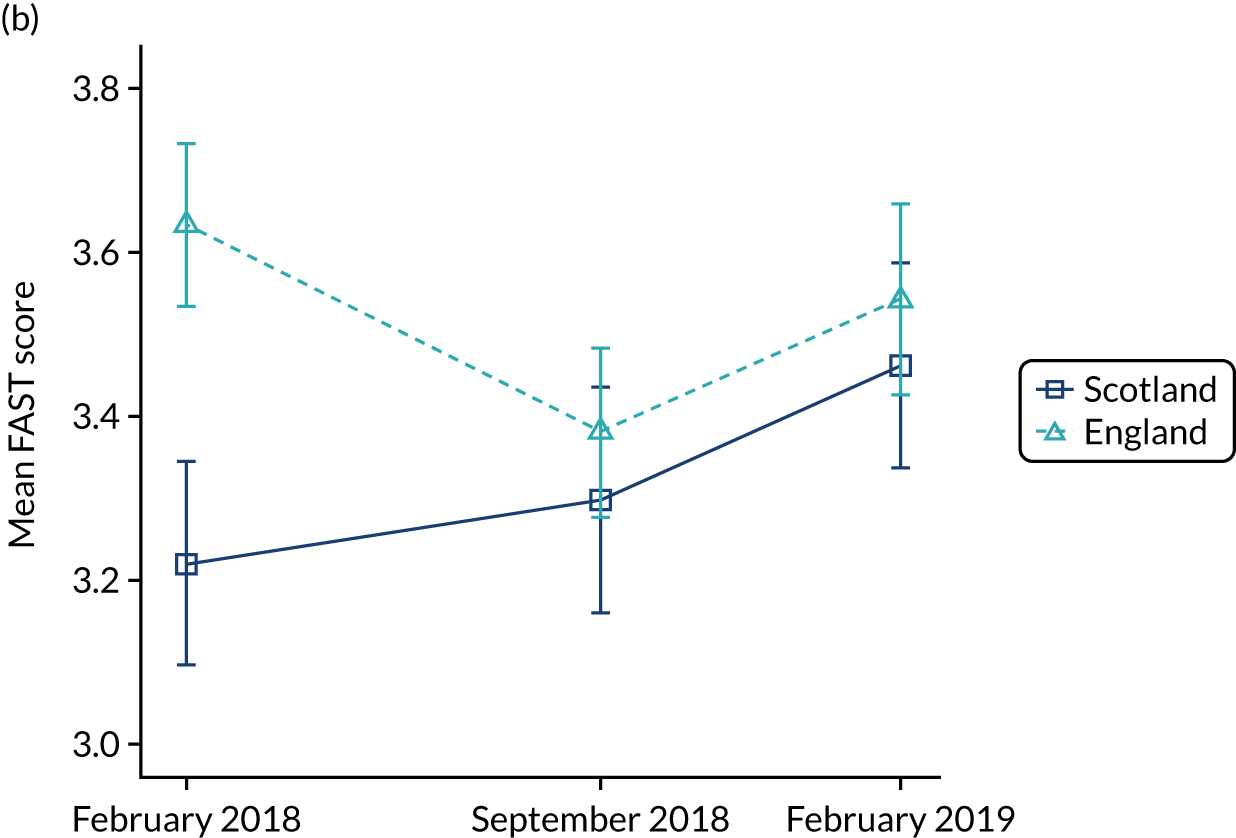

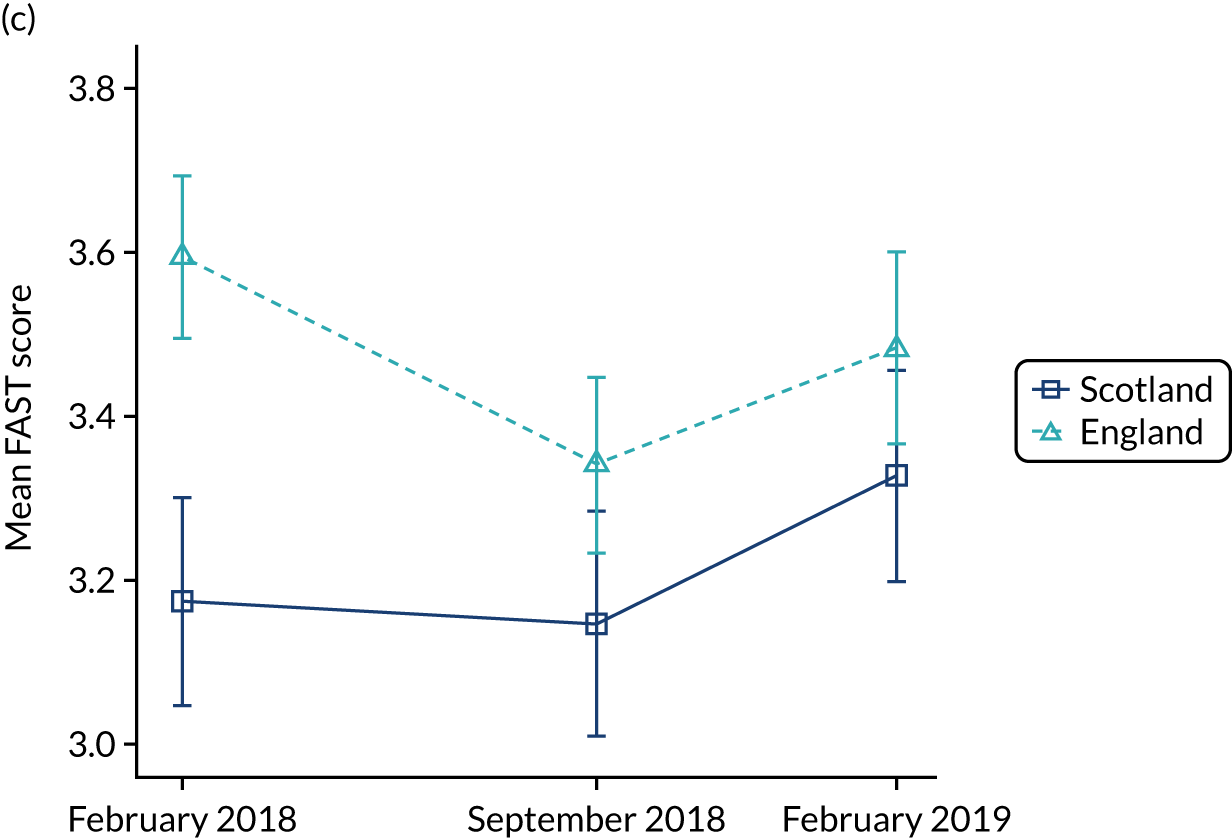

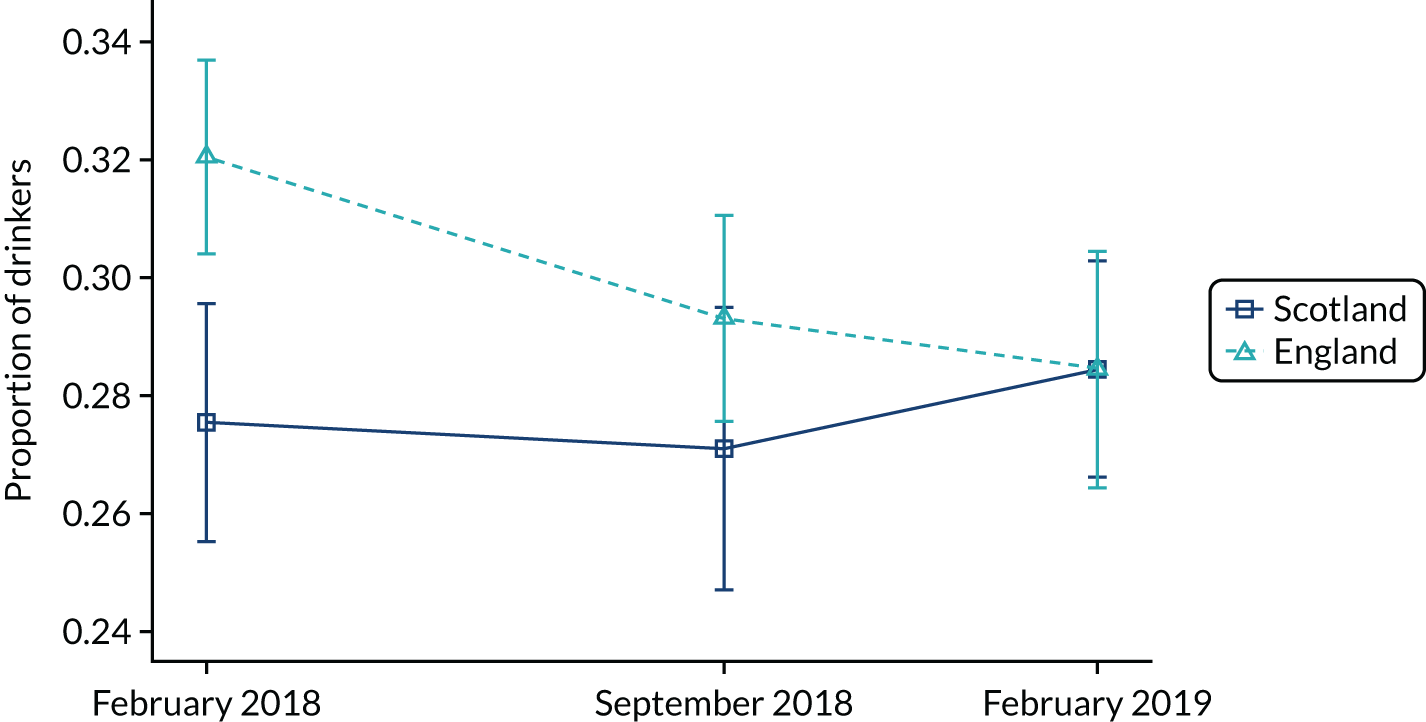

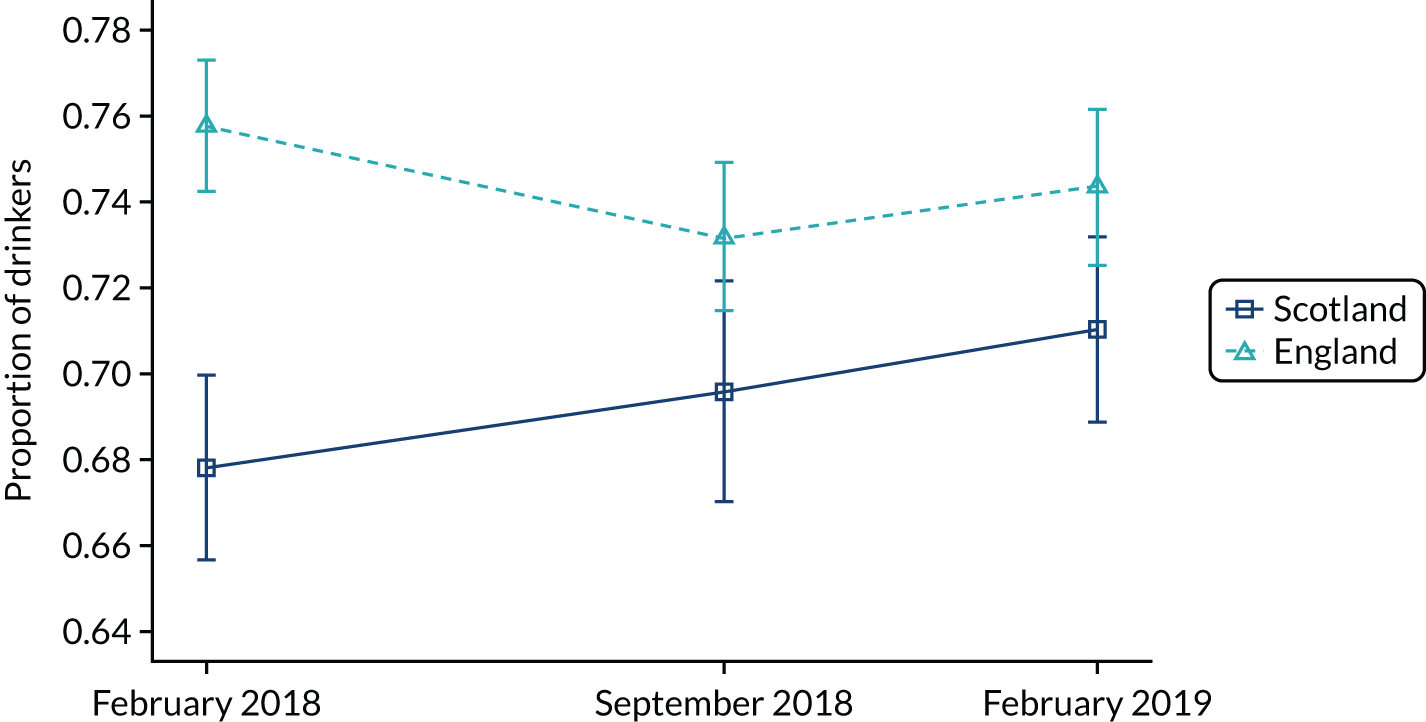

Outcome trend across three waves compared between Scotland and England. (a) Alcohol-related attendance; (b) alcohol-related diagnosis; (c) current alcohol drinker; (d) binge drinking in past week; (e) binge drinking in past 24 hours; (f) FAST score; (g) alcohol misuse (FAST score ≥ 3); (h) increased alcohol use in past year; (i) place of last drink (private location); and (j) place of last drink (on-licensed premise).

Secondary outcome

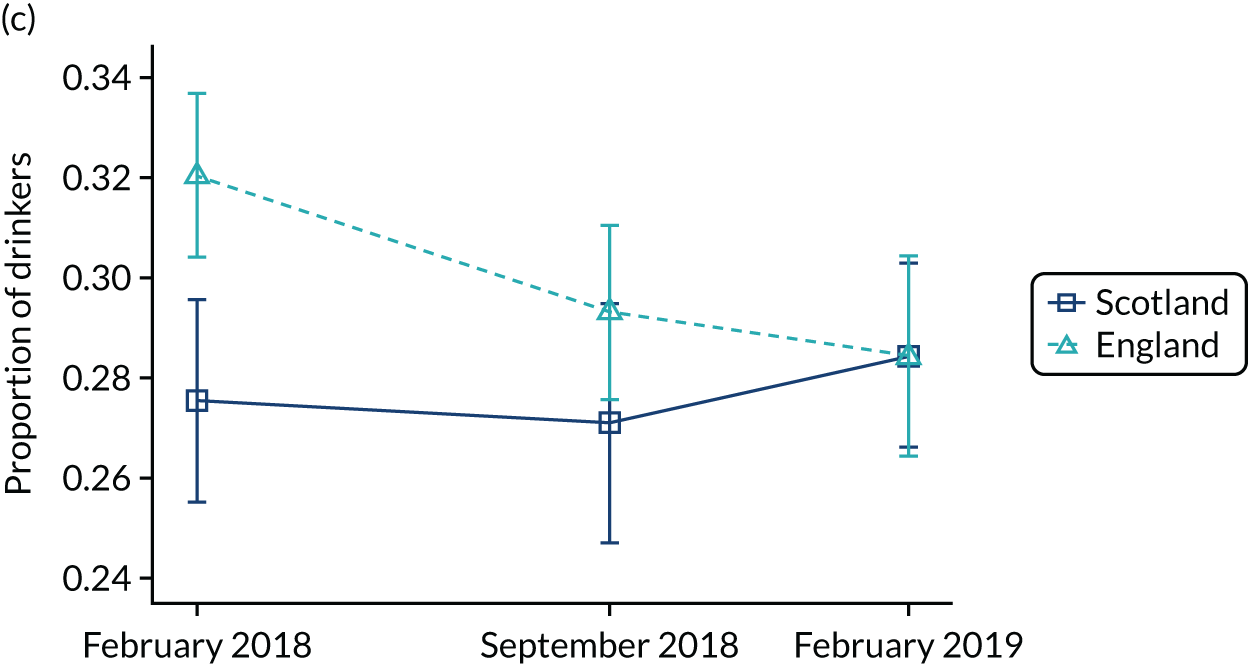

In contrast to alcohol-related attendance, which was lower in England, England had a higher prevalence of alcohol-related diagnosis than Scotland (see Figure 2b). Note that our comparison was with hospitals in the north of England. The proportion of attendees with at least one alcohol-related condition rose slightly in Scotland, but fell in England. Figure 3 shows the changes in proportion of different alcohol-related diagnosis across waves. There were more attendees diagnosed with partially chronic alcohol-related diagnoses among all alcohol-related diagnoses, followed by wholly acute, partially acute and wholly chronic alcohol-related diagnoses. As the prevalence of partially acute and wholly chronic conditions was very low, we combined all alcohol-related diagnoses as one outcome in the analysis.

FIGURE 3.

Trend for alcohol-related diagnosis by conditions across three waves. (a) Wholly chronic alcohol-related diagnosis; (b) partially chronic alcohol-related diagnosis; (c) wholly acute alcohol-related diagnosis; and (d) partially acute alcohol-related diagnosis.

Across waves, there was a slightly increased trend in being a current alcohol drinker in both countries (see Figure 2c). Binge drinking in the past week among all respondents increased slightly in Scotland, but decreased in England (see Figure 2d). However, both countries showed a slight increase in binge drinking in the past 24 hours across waves (see Figure 2e). The mean FAST score among drinkers increased in both Scotland and England (see Figure 2f). The proportion of alcohol misuse (i.e. a FAST score ≥ 3) increased in England, whereas Scotland had a relatively stable trend (see Figure 2g). Meanwhile, the proportion of drinkers who reported an increase in alcohol use in the past 12 months also had a stable trend in both countries (see Figure 2h). Figures 2i and 2j show that the proportion of drinkers who had their last drink in a private location was higher than those in on-licensed premise. However, the trends were stable for both private location and on-licensed premise across waves.

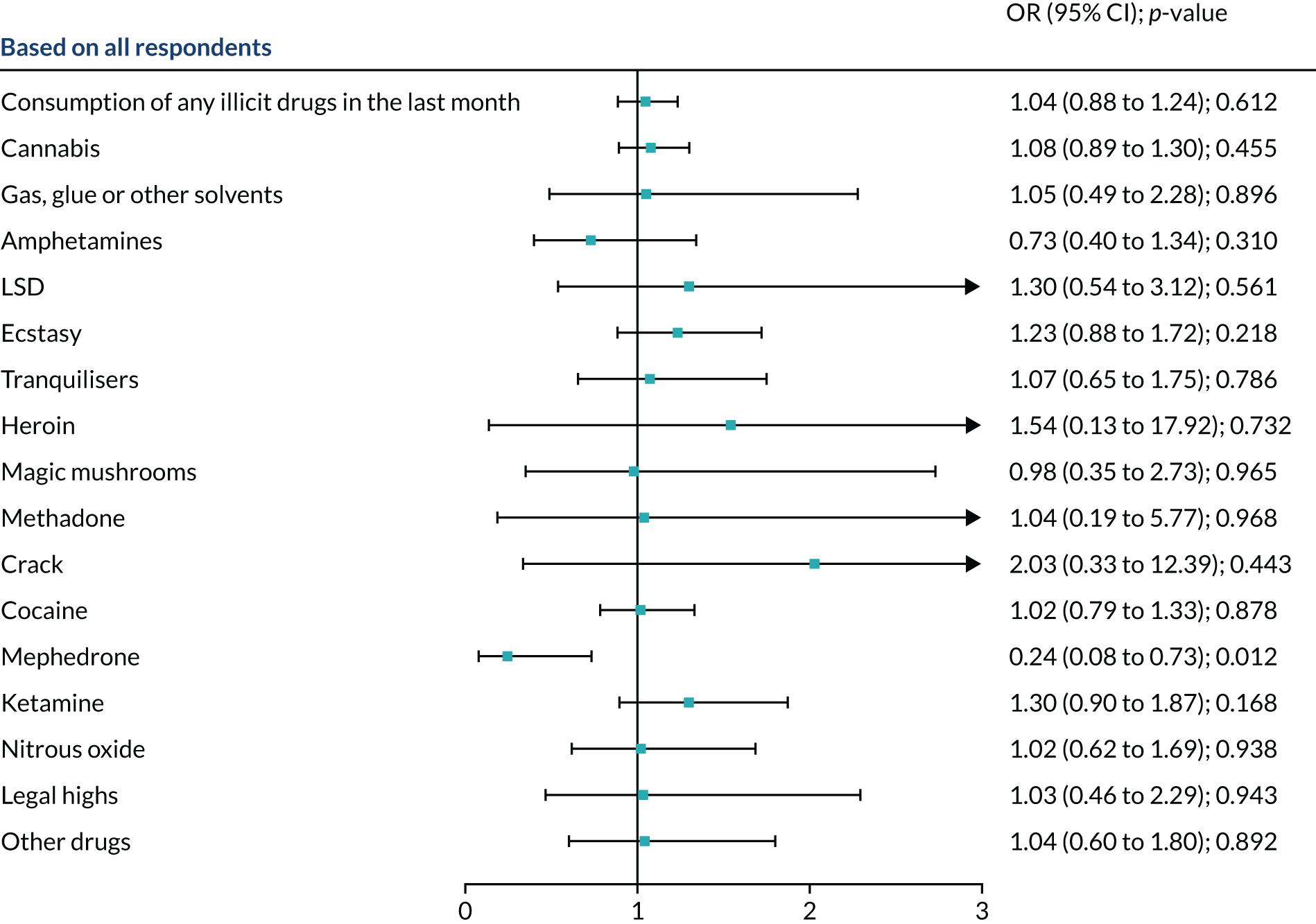

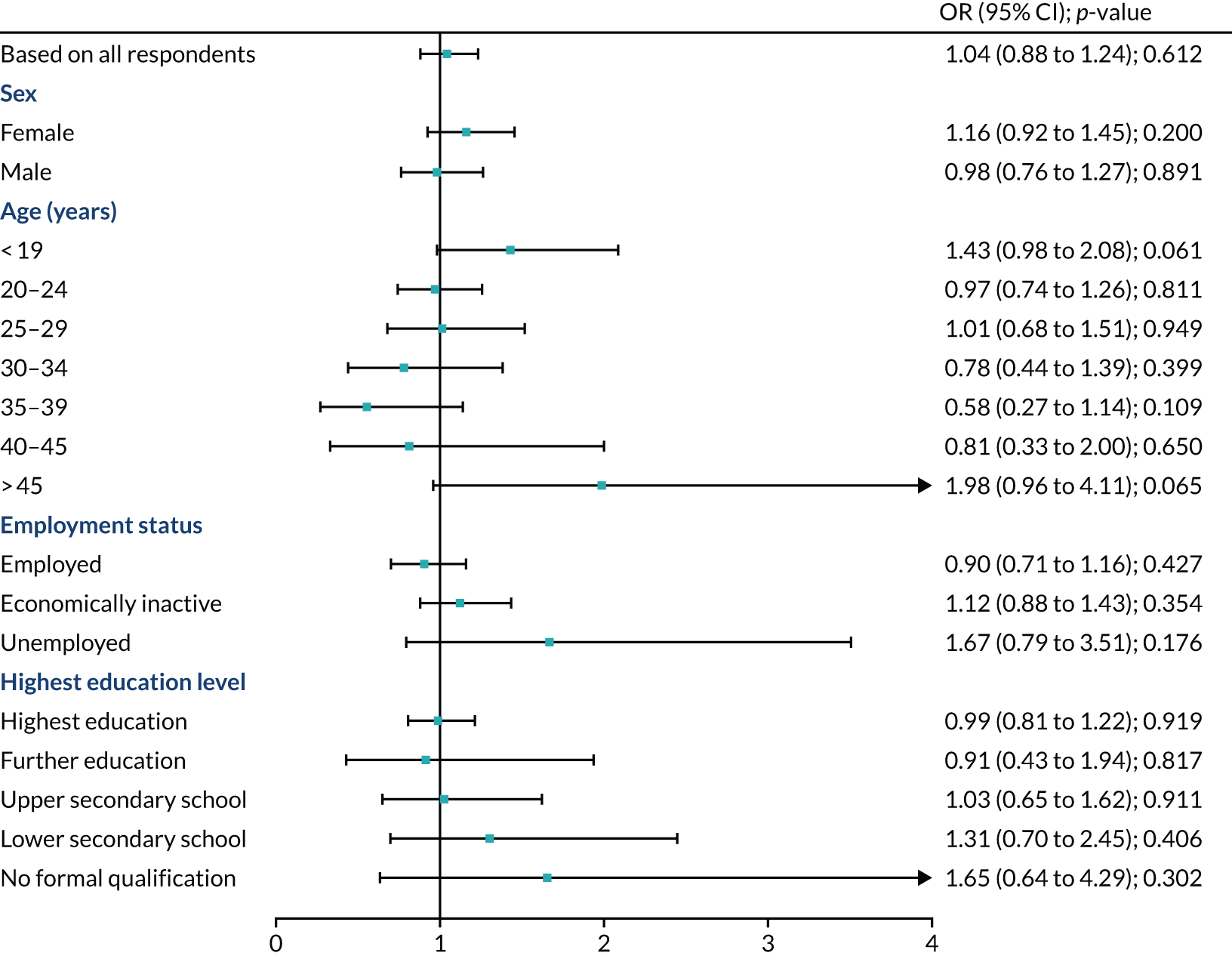

Figure 4 shows the DiD estimates from the final regression models for our secondary outcomes (see Appendix 2, Table 26, for the summary of DiD estimates from full regression models). There was no evidence of significant differences in most outcomes after the introduction of MUP in Scotland. The DiD estimates show that among all attendees the odds for an attendee having at least one alcohol-related diagnosis increased by 25% relative to change observed in England after MUP (OR 1.25, 95% CI 1.00 to 1.57; p = 0.046). Nevertheless, there was no effect on other secondary outcomes, suggesting that the introduction of MUP in Scotland did not substantially alter these outcomes in the population studied.

FIGURE 4.

Difference-in-difference estimates of the overall effects of MUP (a) based on all recorded attendees; and (b) based on drinkers only.

Stratified analysis

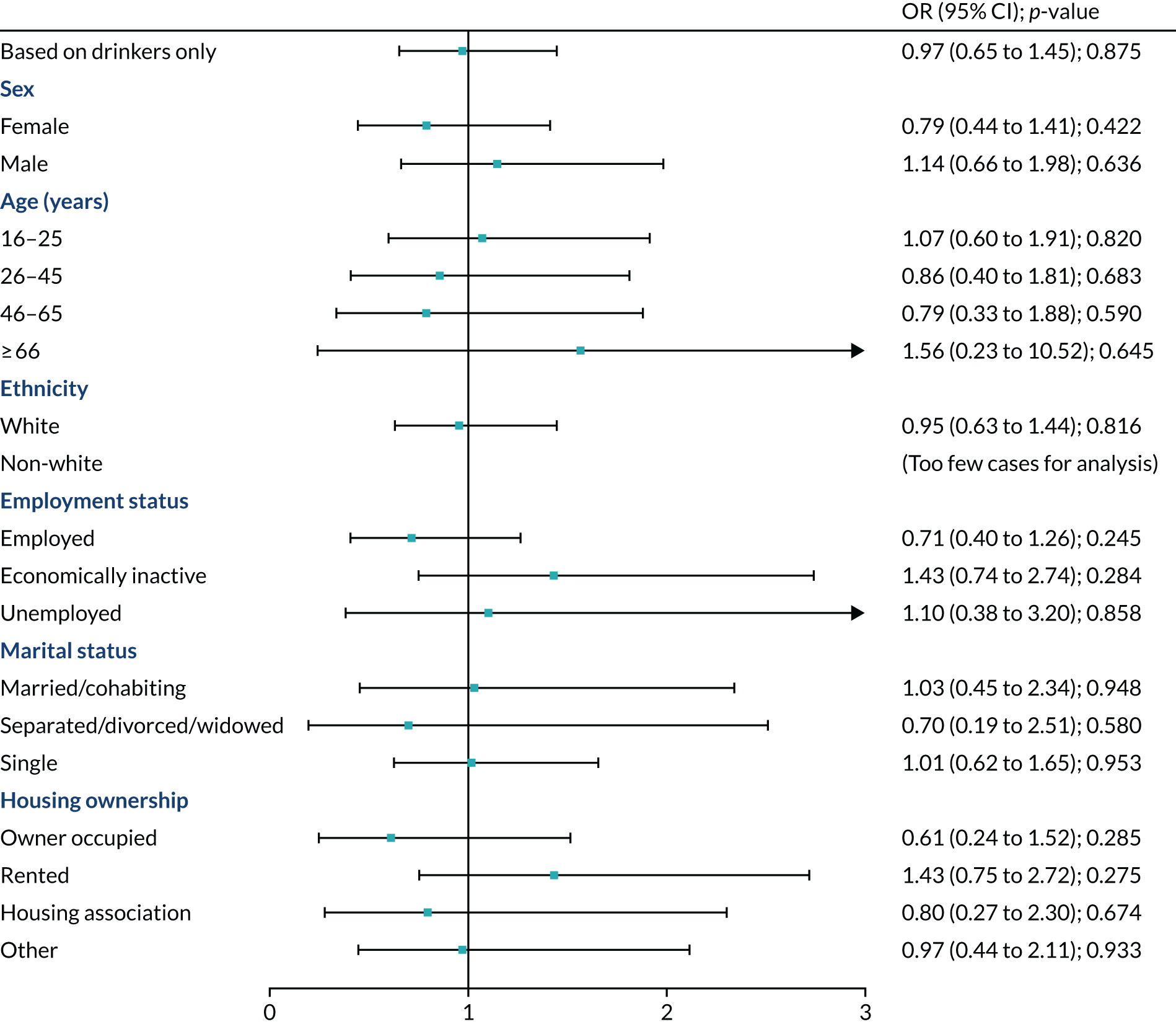

We further investigated the outcomes by sex, age group, ethnicity, employment status, marital status and housing ownership. A Bonferroni correction was used to adjust the p-values for multiple comparison. The p-values reported in Figures 5–14 were uncorrected. We indicated where the corrected p-values remain significant after adjustment.

Primary outcome

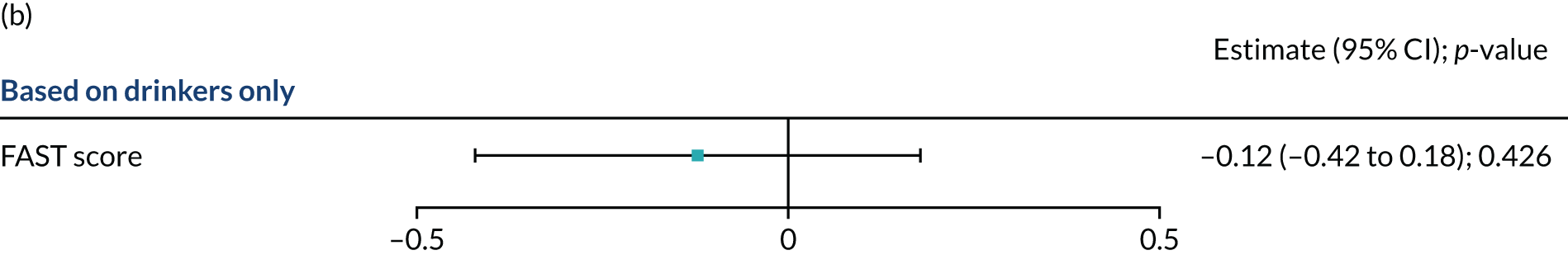

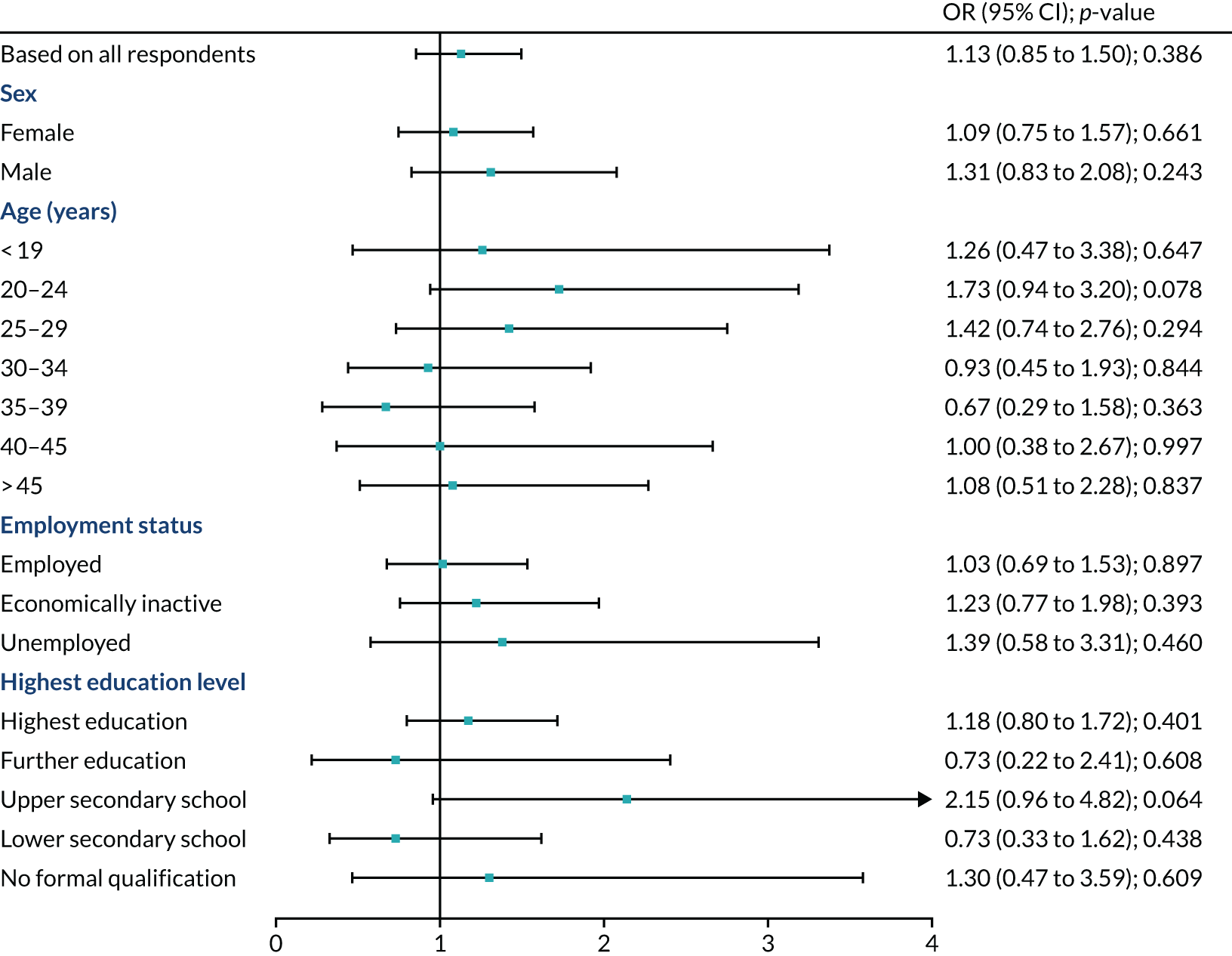

Figure 5 shows the stratified results for the primary outcome. There was no evidence to show that MUP had any differential effect across sex and age group. The summary of DiD estimates from the full regression models were presented in Appendix 2, Tables 27–39).

FIGURE 5.

Stratified analysis for primary outcome: alcohol-related attendance. Note that the p-values in the forest plot were uncorrected.

Secondary outcome

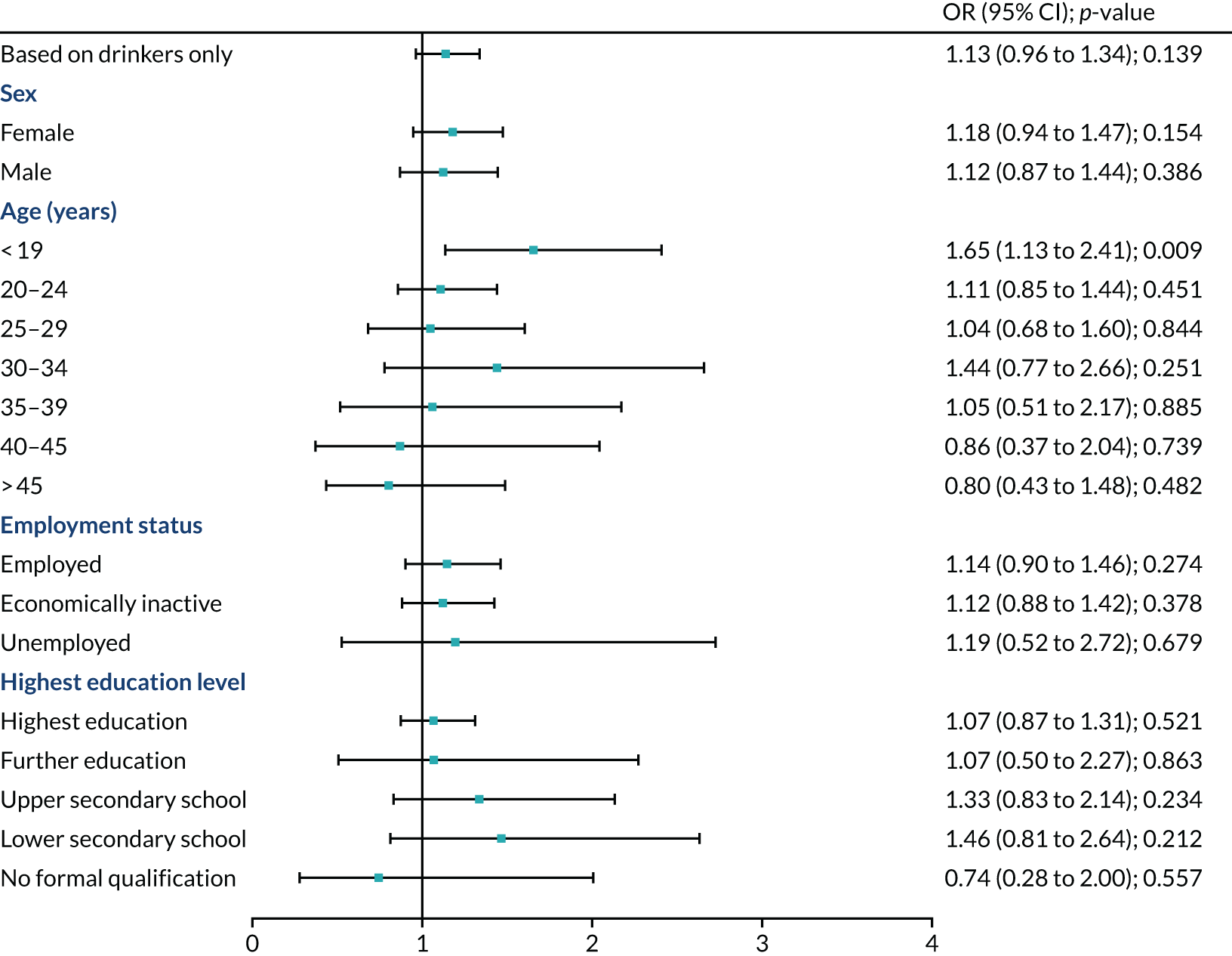

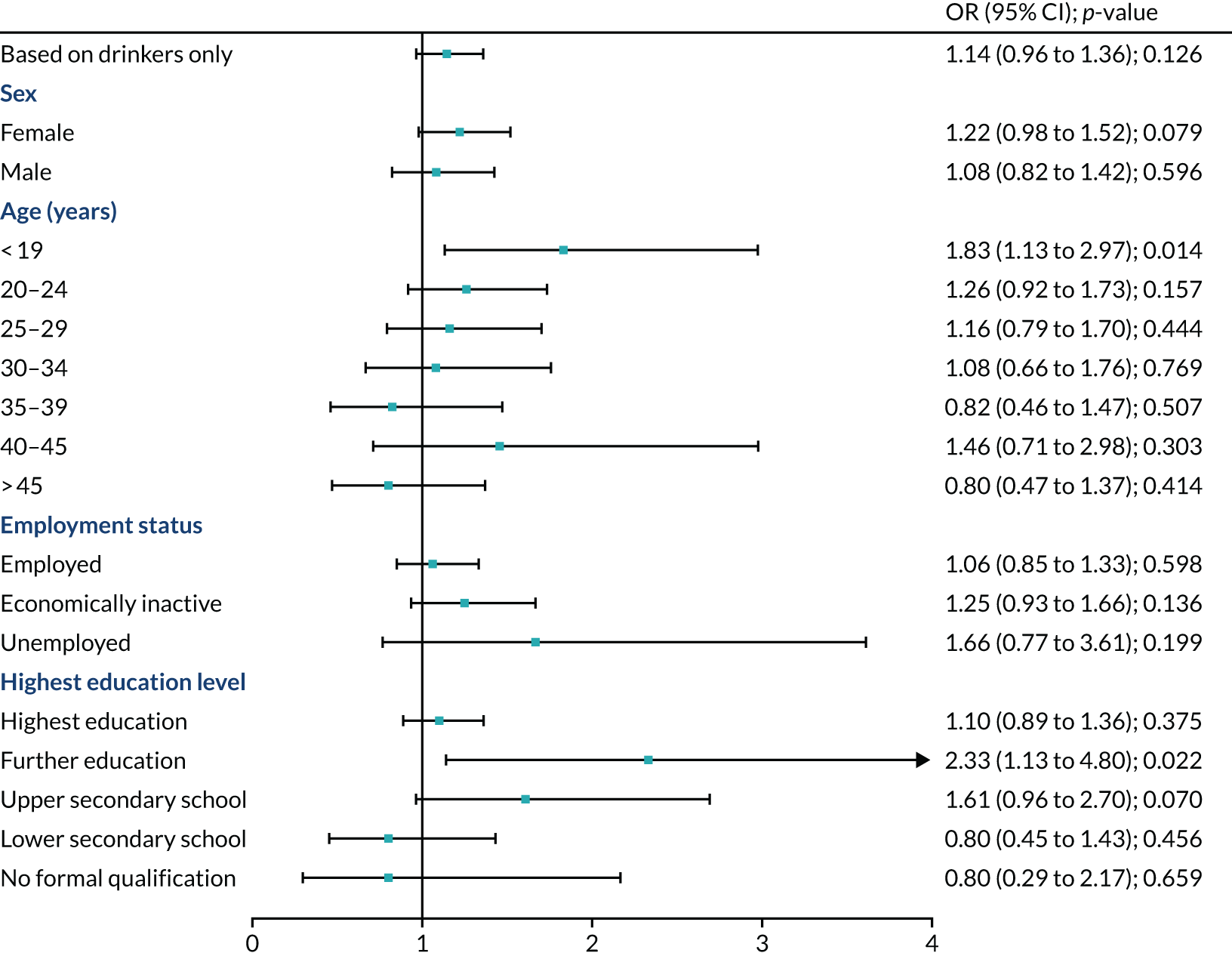

Alcohol-related diagnosis

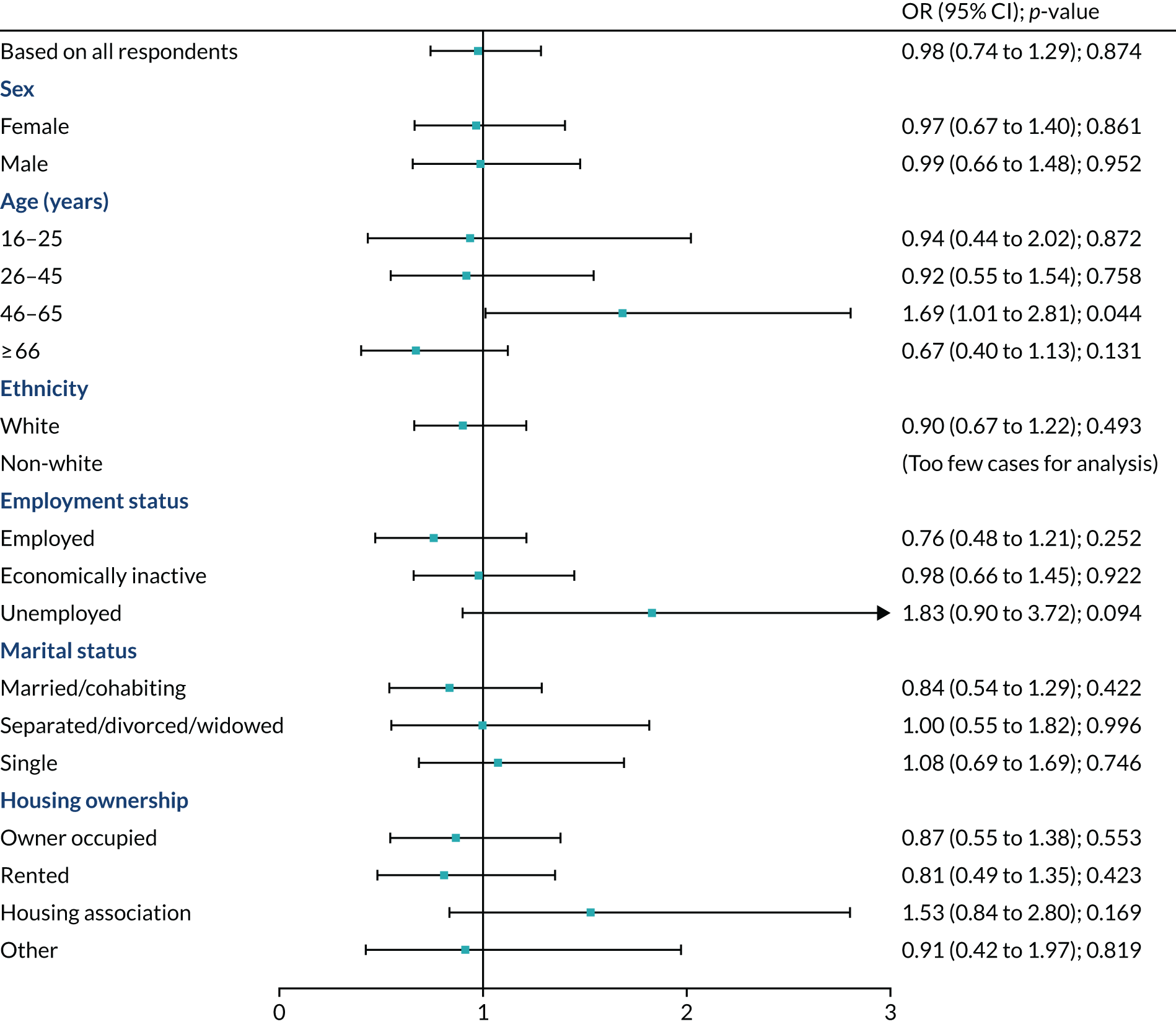

The stratified analysis in Figure 6 shows that the introduction of MUP in Scotland was associated with increased odds of alcohol-related diagnosis among men who attended the EDs (OR 1.56, 95% CI 1.16 to 2.11; p = 0.004). Meanwhile, MUP was associated with significantly reduced odds of alcohol-related diagnosis for those aged 16–25 years (OR 0.47, 95% CI 0.23 to 0.95; p = 0.035), but increased for those aged ≥ 66 years (OR 1.65, 95% CI 1.11 to 2.44; p = 0.013). After adjusting for multiple comparison, the impacts remained significant for men (corrected p = 0.022), but became non-significant for those aged 16–25 years (corrected p = 0.212) and ≥ 66 years (corrected p = 0.076).

FIGURE 6.

Stratified analysis for secondary outcome: alcohol-related diagnosis. Note that the p-values in the forest plot were uncorrected. a, Corrected p < 0.05 after Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons.

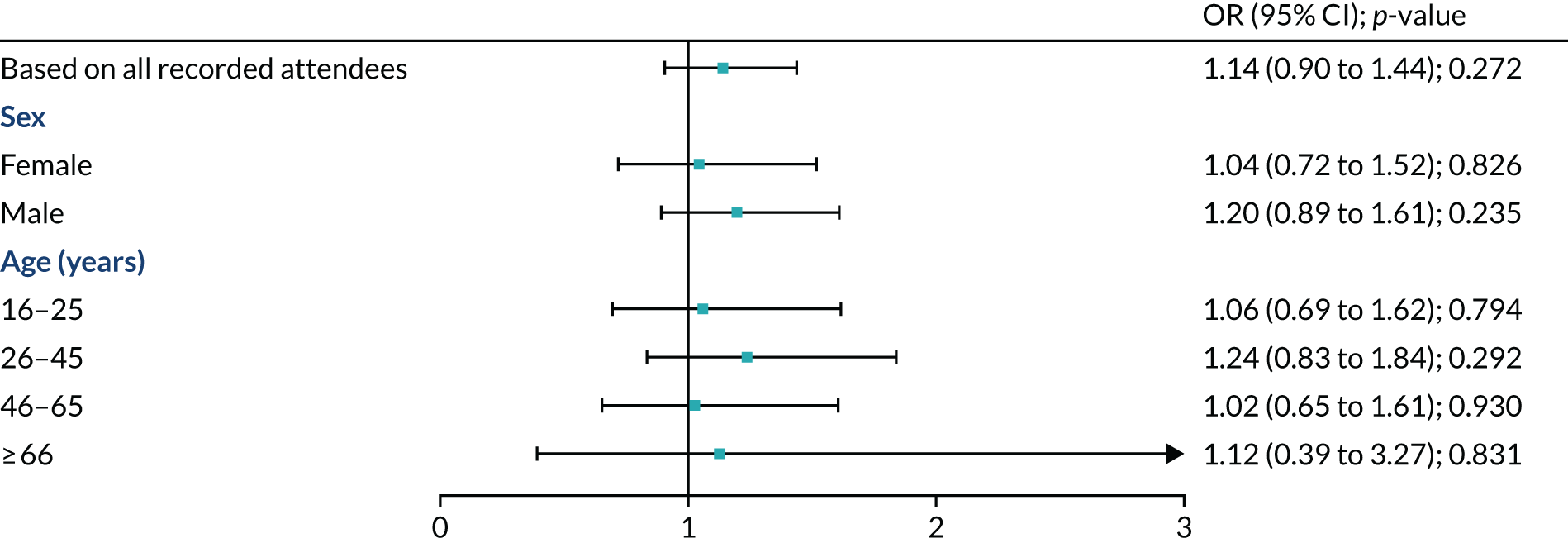

Current alcohol drinker

Results from the stratified analysis suggested that only those who were aged between 46 and 65 years were more likely to become an alcohol drinker in Scotland after the implementation of MUP (OR 1.69, 95% CI 1.69 to 2.81; p = 0.044) (Figure 7). However, after corrected for multiple comparison using Bonferroni correction, the impact of MUP on this group of population became insignificant (corrected p = 0.799).

FIGURE 7.

Stratified analysis for secondary outcome: current alcohol drinker. Note that the p-values in the forest plot were uncorrected.

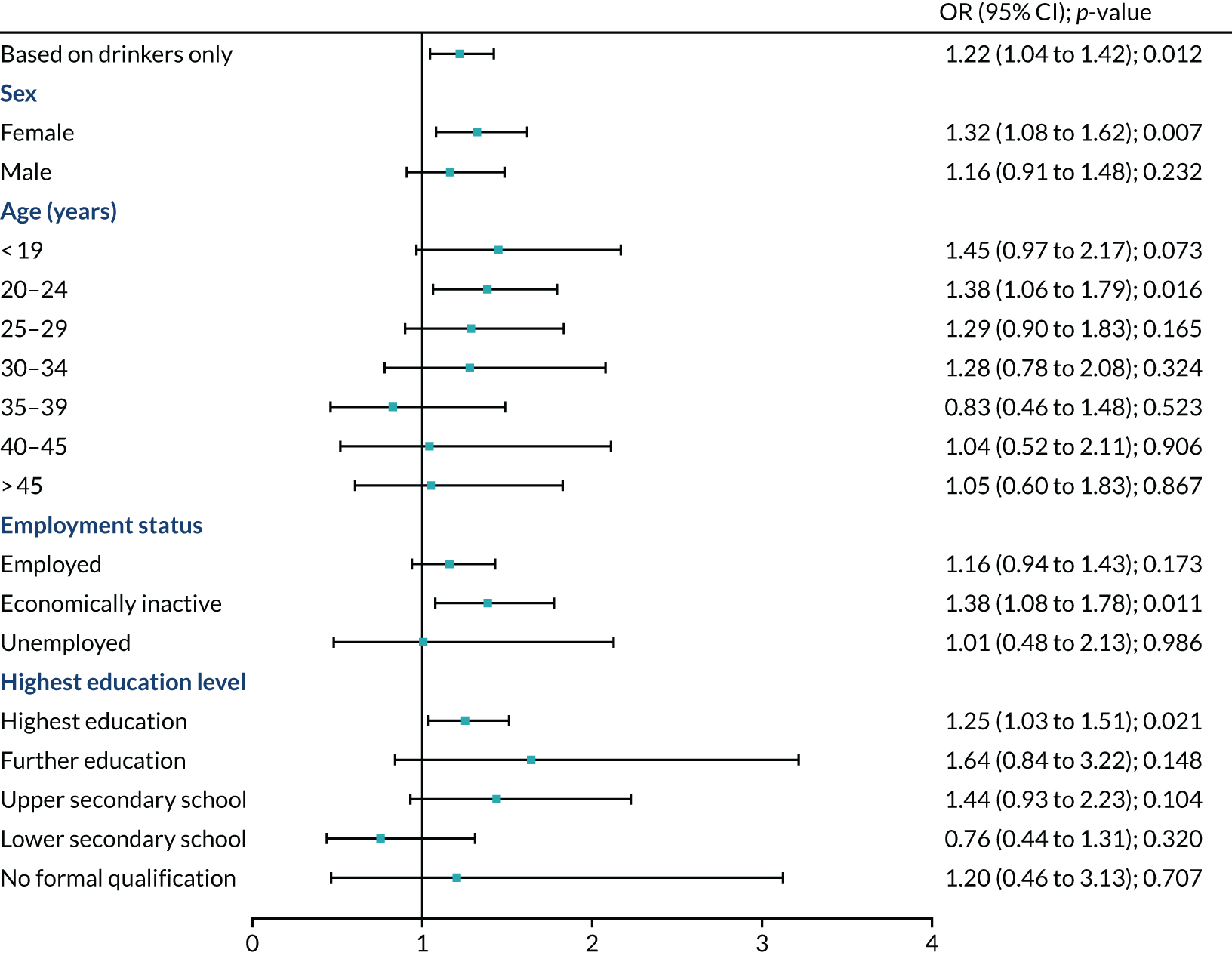

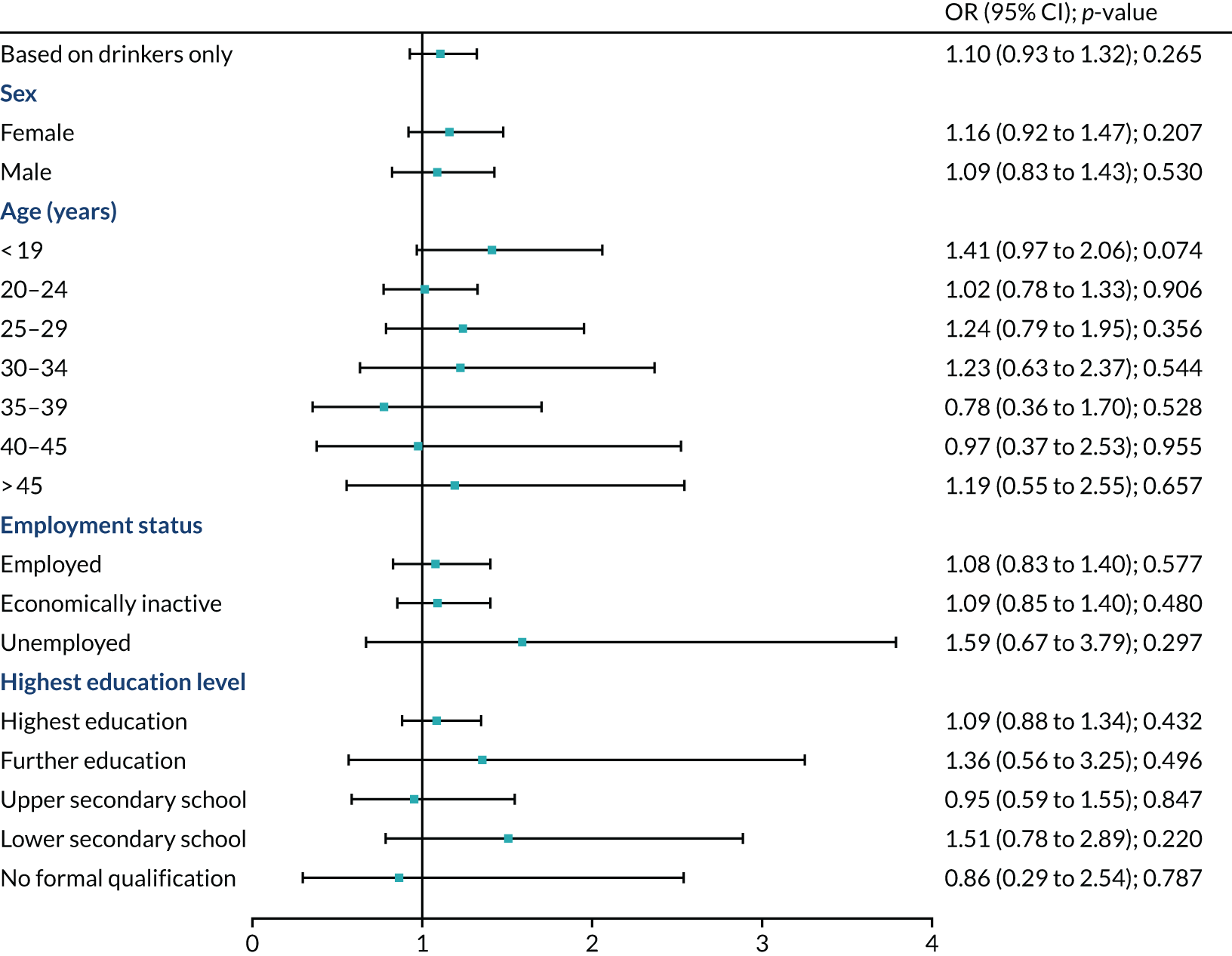

Binge drinking in the past week

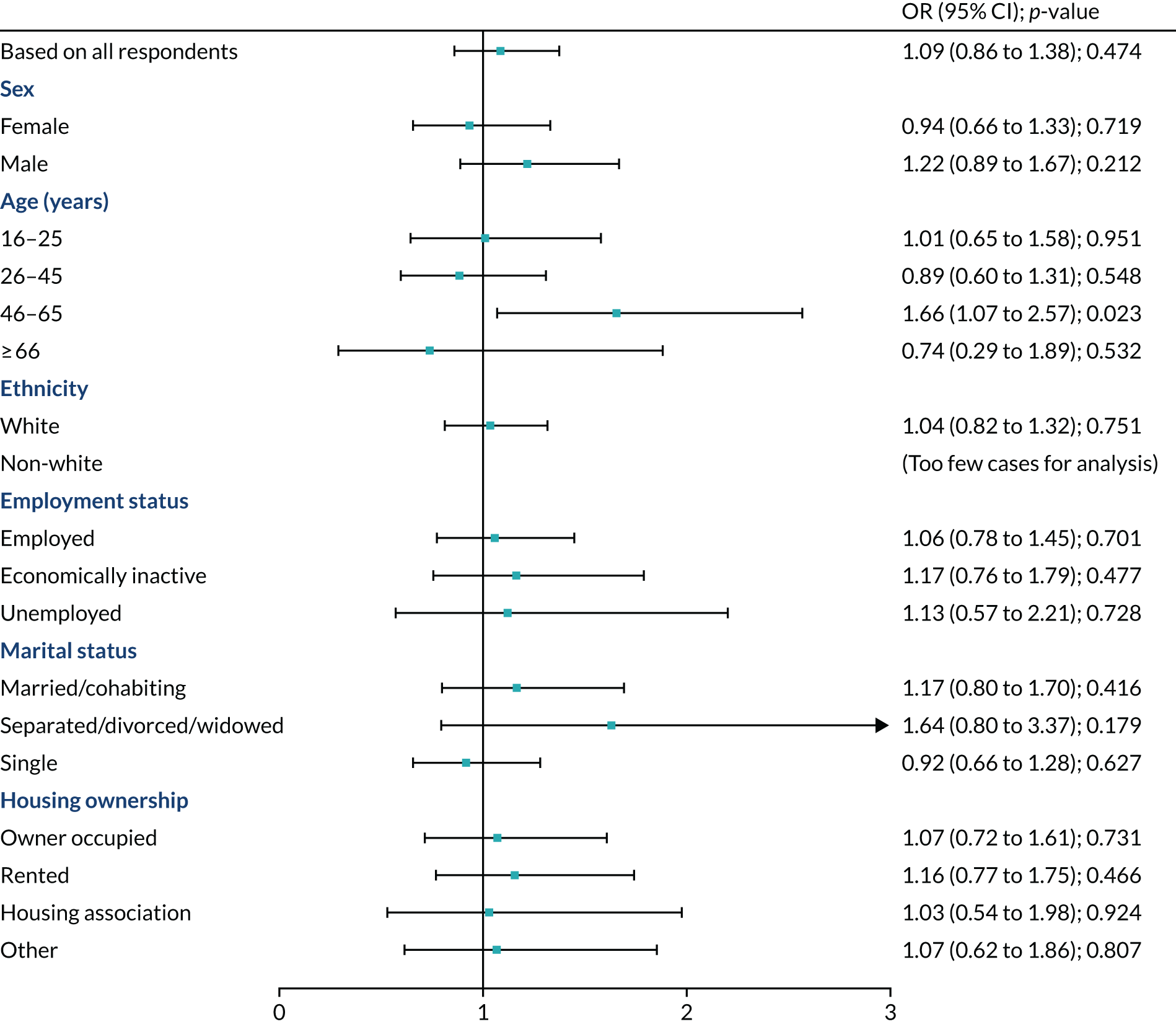

Figure 8 suggests possible increases in binge drinking in the past week in those aged 46–65 years in Scotland, relative to the comparison group (OR 1.66, 95% CI 1.07 to 2.57; p = 0.023). After adjusting for multiple comparison, the effect became insignificant (corrected p = 0.417).

FIGURE 8.

Stratified analysis for secondary outcome: binge drinking in the past week. Note that the p-values in the forest plot were uncorrected.

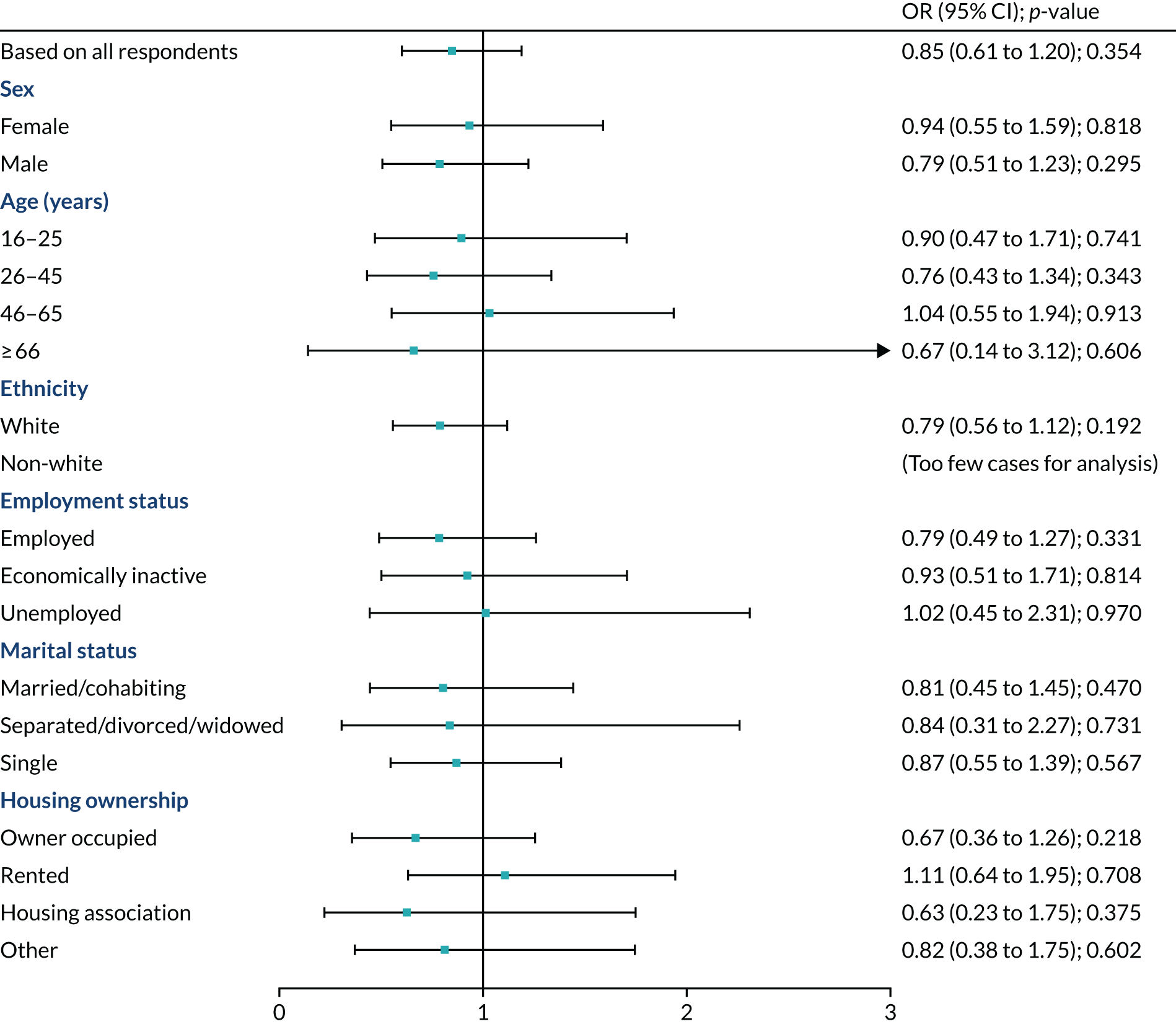

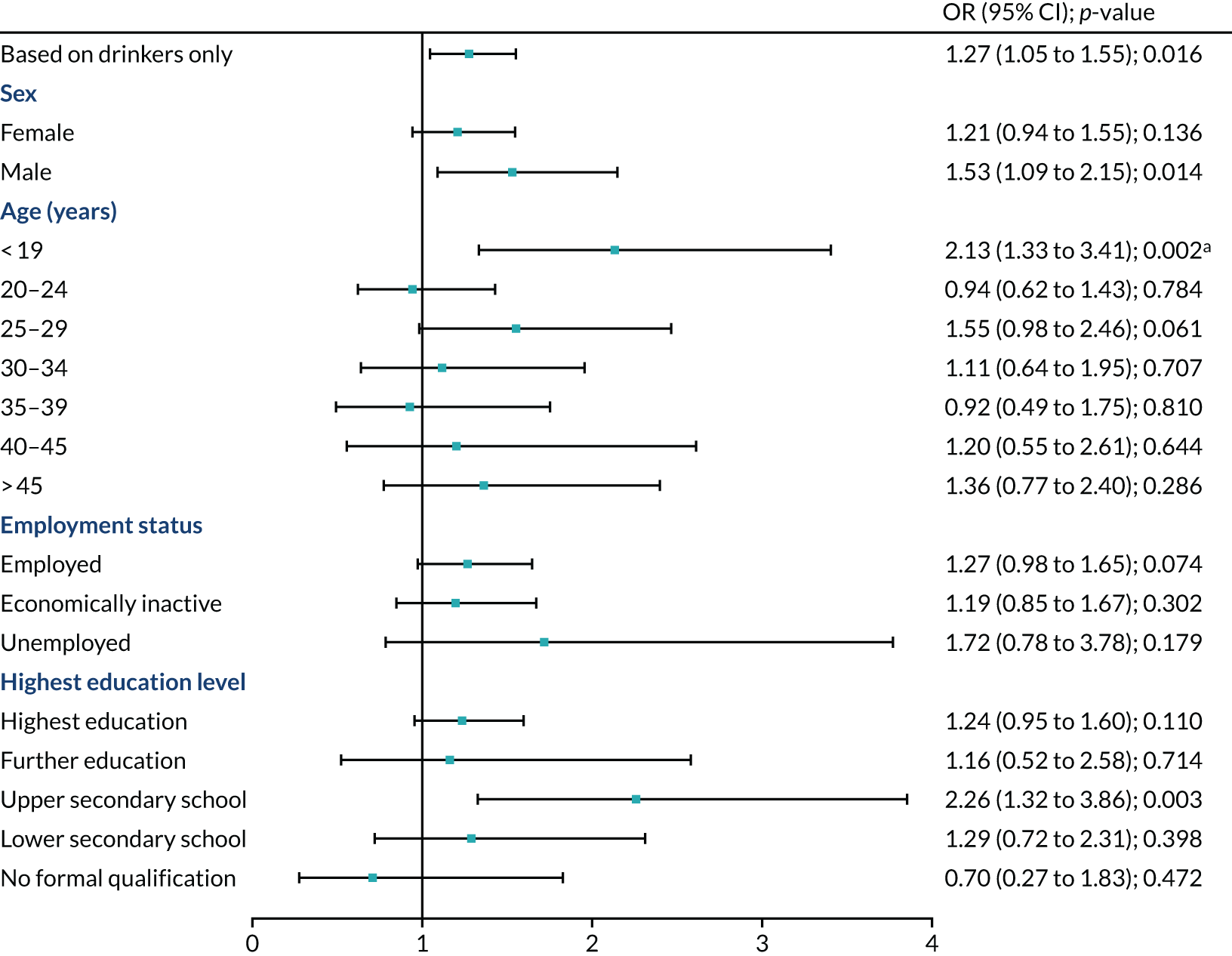

Binge drinking in the past 24 hours

The introduction of MUP did not have any differential effect on any of the subgroup for binge drinking in the past 24 hours (Figure 9).

FIGURE 9.

Stratified analysis for secondary outcome: binge drinking in the past 24 hours. Note that the p-values in the forest plot were uncorrected.

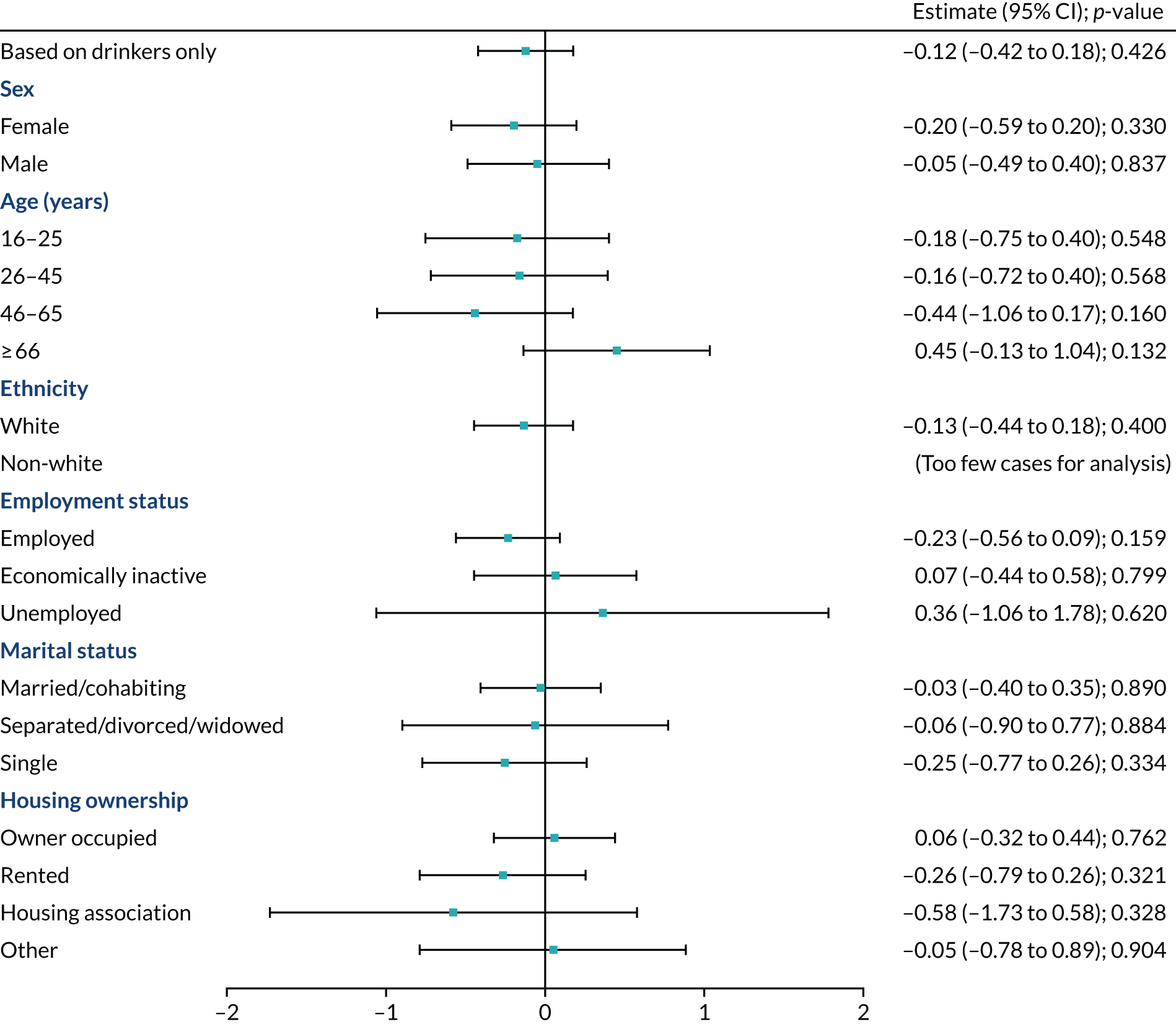

Fast Alcohol Screening Test score

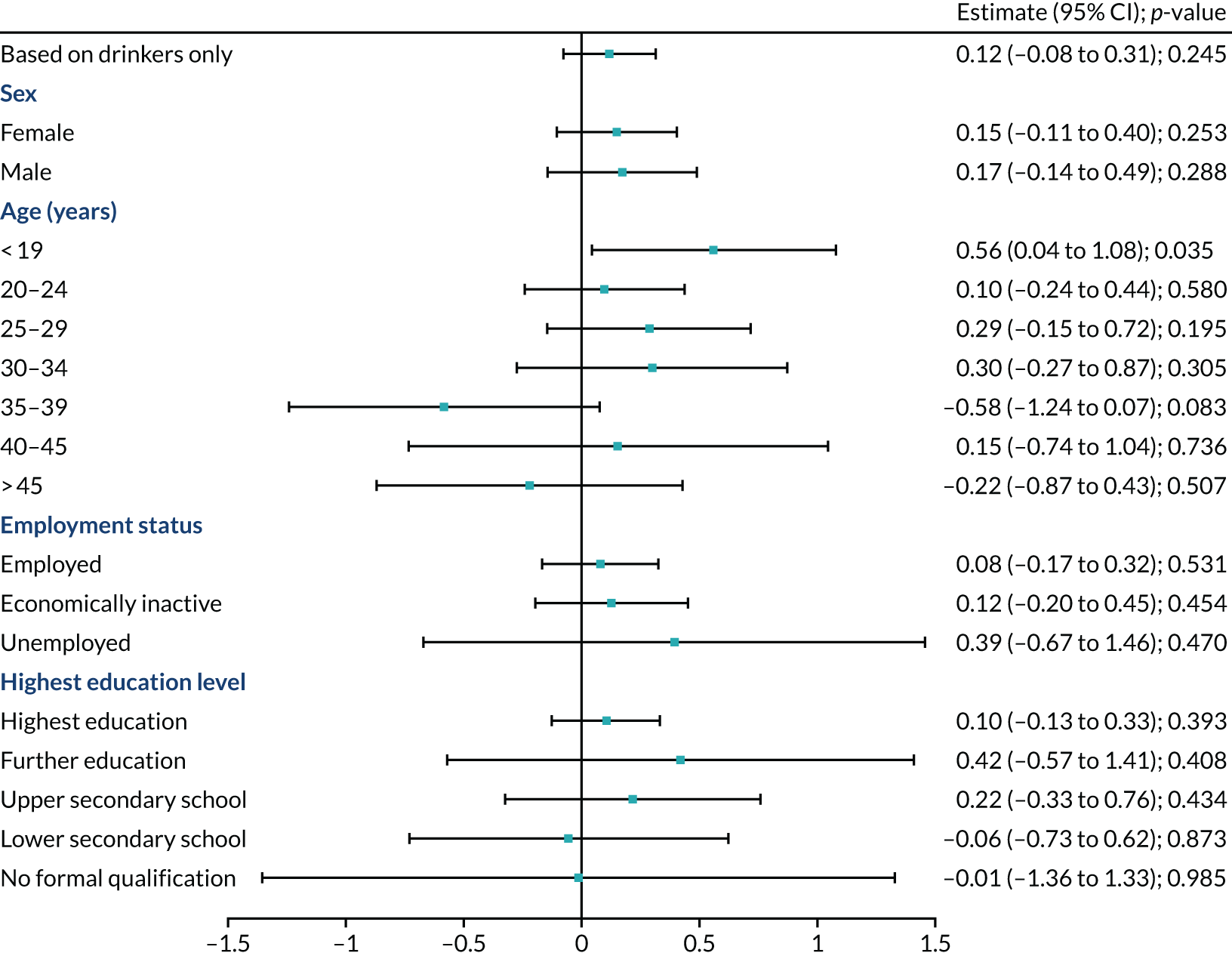

Again, there was no evidence that MUP had any effect across sex, age, ethnicity, employment status, marital status and housing ownership for overall FAST score (Figure 10).

FIGURE 10.

Stratified analysis for secondary outcome: FAST score. Note that the p-values in the forest plot were uncorrected.

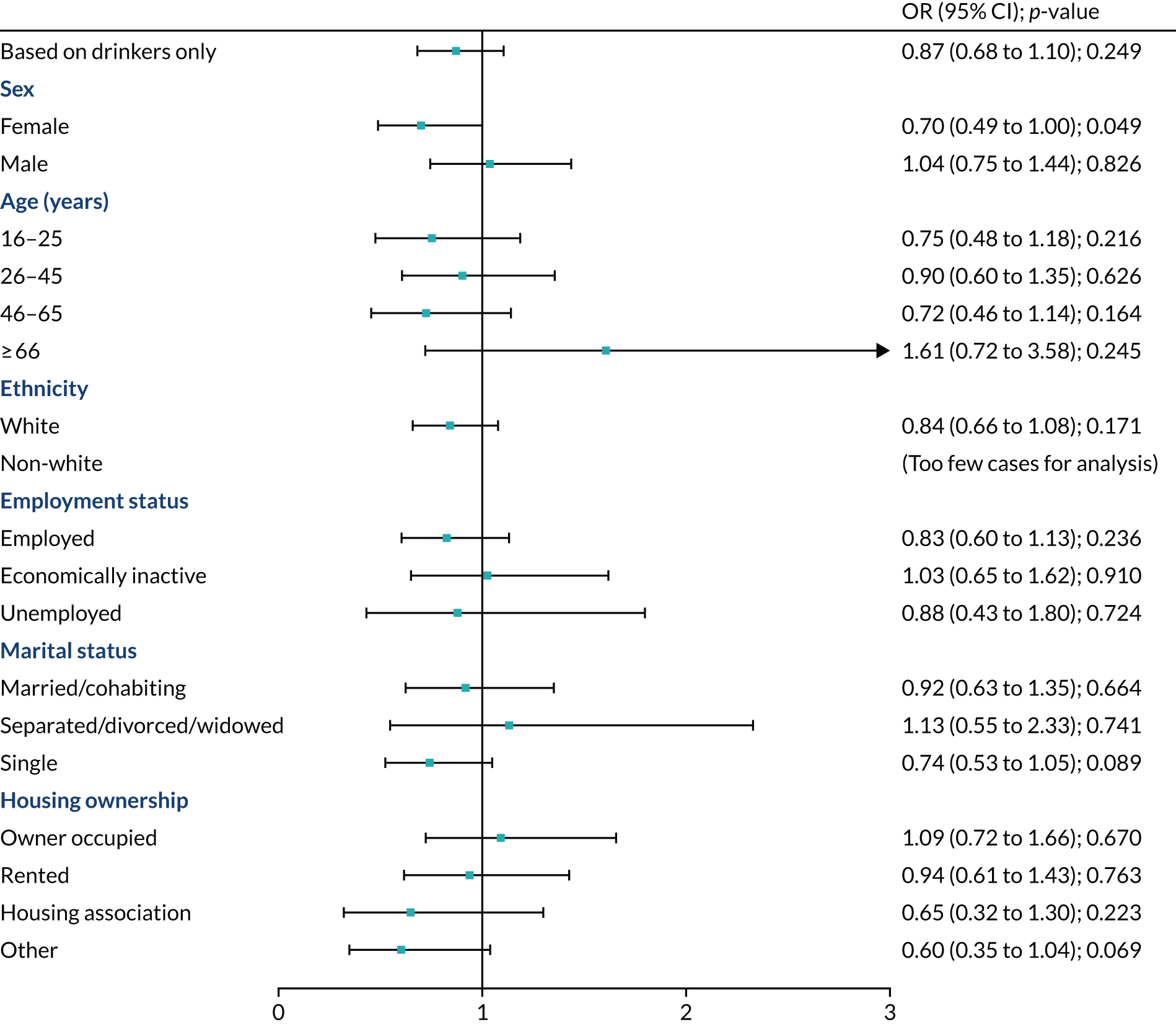

Alcohol misuse

Women’s odds for alcohol misuse decreased in Scotland after MUP was implemented (OR 0.70, 95% CI 0.49 to 1.00; p = 0.049) (Figure 11). The effect diminished after corrected for multiple testing using Bonferroni correction (corrected p = 0.884).

FIGURE 11.

Stratified analysis for secondary outcome: alcohol misuse (FAST score ≥ 3). Note that the p-values in the forest plot were uncorrected.

Increased alcohol use in the past year

Figure 12 shows that there was no evidence that the proportion of drinkers who increased their alcohol use in the past year had changed in Scotland relative to England since the MUP was introduced.

FIGURE 12.

Stratified analysis for secondary outcome: increased alcohol use in the past year. Note that the p-values in the forest plot were uncorrected.

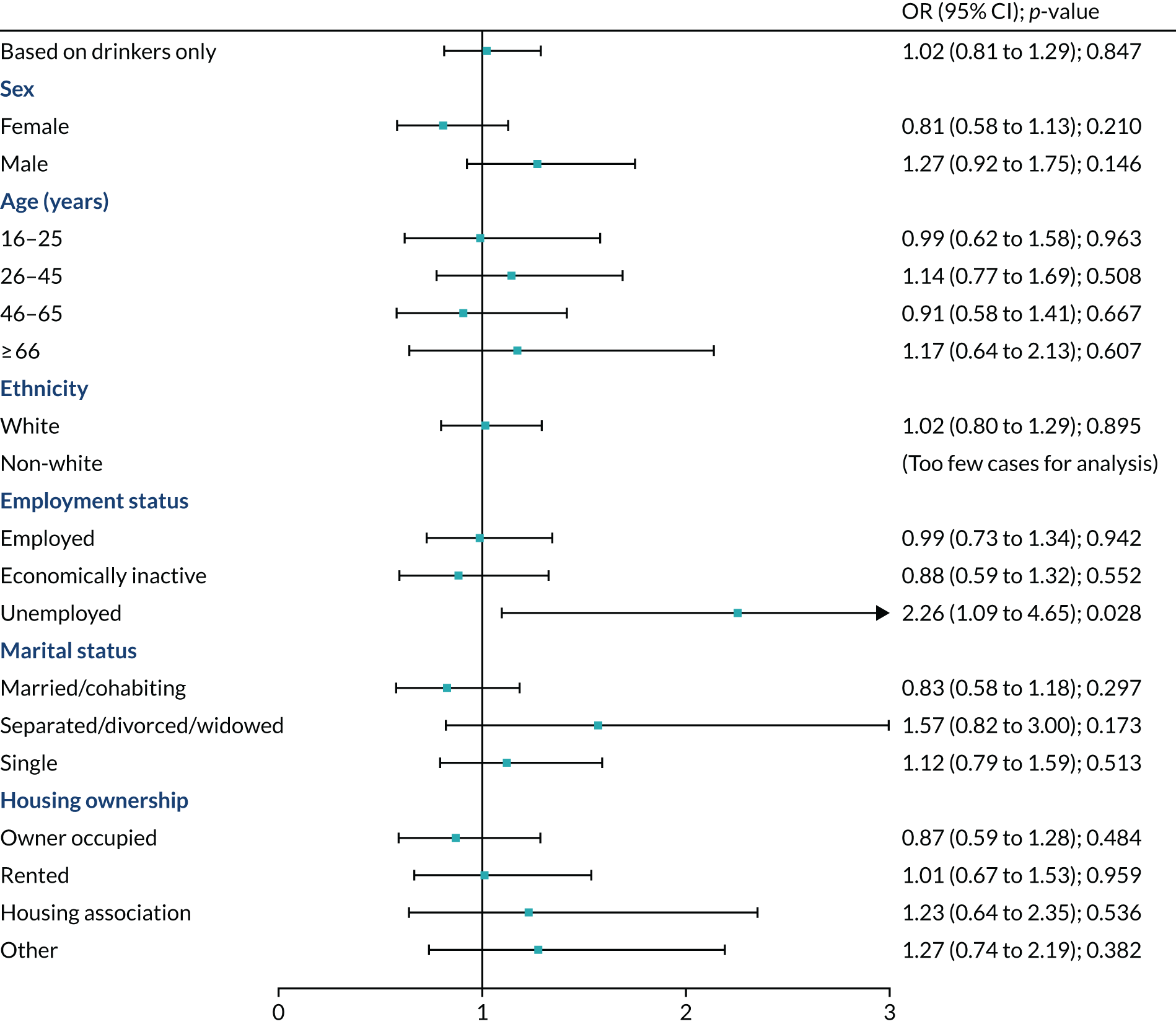

Place of last drink: private location

Those who were unemployed were more likely to have their last drink in a private location in Scotland (OR 2.26, 95% CI 1.09 to 4.65; p = 0.028) (Figure 13). After adjusting for multiple comparison using Bonferroni correction, the impact became insignificant (corrected p = 0.501).

FIGURE 13.

Stratified analysis for secondary outcome: private location as place of last drink. Note that the p-values in the forest plot were uncorrected.

The stratified analysis shows that women (OR 1.56, 95% CI 1.10 to 2.21; p = 0.014) and those who were married (OR 1.53, 95% CI 1.05 to 2.23; p = 0.028) were more likely to have their last drink in on-licensed premises (Figure 14). However, the unemployed in Scotland had smaller odds to have their last drink in on-licensed premise (OR 0.46, 95% CI 0.21 to 0.99; p = 0.048). However, after adjusting for multiple comparison, these differential effects became insignificant (corrected p-value for females = 0.245, corrected p-value for those married = 0.505 and corrected p-value for those who were unemployed = 0.863).

FIGURE 14.

Stratified analysis for secondary outcome: on-licensed premise as place of last drink. Note that the p-values in the forest plot were uncorrected.

Sensitivity analysis

Testing the robustness of our analysis, we analysed the effect of MUP against FAST cut-off points of ≥ 2, ≥ 4 and ≥ 6, repeated the analysis on primary outcome using the sample based on survey respondents and replicated the analysis using unweighted and weighted complete cases. All these analyses produced similar results (see Appendix 2, Tables 40–43). We also performed a sensitivity analysis on alcohol-related diagnosis based on survey respondents who consented to data linkage. Results from the sensitivity analysis showed that the DiD estimate was not significant at a 5% level, whereas the main analysis showed a significant difference. As the sensitivity analysis was based on respondents who consented to data linkage, which may be subject to selection bias, we were more confident that results from the main analysis were more robust.

Discussion