Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 13/164/10. The contractual start date was in June 2015. The final report began editorial review in June 2021 and was accepted for publication in May 2022. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2023 Dundas et al. This work was produced by Dundas et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2023 Dundas et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Sections of this report have been reproduced from this study’s protocol document, available at the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Funding and Awards website.

Background

Intervention in the early years is one of the most effective ways to prevent poor health and reduce inequalities. Health improvements during pregnancy, infancy and early childhood, and social patterning of any improvements, can track through life into adulthood and old age. Any health improvements that are made during pregnancy and the early years can reduce the prevalence of poor health and disease, and therefore increase life chances. For example, poor nutrition, tobacco exposure and pollution in pregnancy and infancy affect growth and lung development, in turn leading to respiratory illness in childhood and eventually lung disease in adulthood. 1 Poor nutrition in pregnancy and the early years of life have impacts on health. The developmental model of the origins of chronic disease proposes the causal influence of undernutrition in utero on coronary heart disease and stroke in adult life. 2 Maternal nutrition strongly influences child nutrition, which in turn tracks to adult eating patterns. 3–5 As poor nutrition is associated with lower socioeconomic status,6 these impacts may also perpetuate health inequalities. An intervention that modifies both maternal and infant diets thus has the potential to improve the health of the infant, and for these health gains to track into childhood and adulthood, thus reducing health inequalities.

The First 1000 Days7 initiative started at an international conference on global child undernutrition and has now influenced health policy in some high-income countries, including the United Kingdom (UK). 8 The premise is that the first 1000 days from conception to age 2 years is a period of rapid growth, and therefore what occurs during this time lays the foundations for future development. In 2010, the Fair Society, Healthy Lives report9 recommended giving every child the best start in life as a key policy intervention for a healthier society.

The principle of early life intervention has influenced government policy across the UK, ranging from high-level strategy documents such as Getting it Right for Every Child,10 Every Child Matters11 and Healthy Child Wales,12 through universal policies and interventions such as the Health in Pregnancy Grant13 and universal maternal and child health services to targeted interventions including the Family Nurse Partnership14 and Flying Start Wales. 15 Although these are in place across the UK countries, implementation and structure may differ. Therefore, there is a need to understand what strategies and policies improve health that so policy-makers can make better decisions about policies in the early years.

There have been some evaluations of early years policies. The Healthy Baby Program in Manitoba, Canada, was a programme for low-income pregnant women and then for their children. 16 This programme was associated with an increase in breastfeeding initiation (BI). In Sweden, the Salut Programme is a suite of interventions that combines health promotion and universal prevention interventions with the aim of improving health and well-being in children and families. 17 A positive impact on child and maternal health outcomes was found. However, there are other policies that have been introduced that have not been evaluated in terms of outcomes. In the UK these include enhanced provision of early years childcare,12,18,19 Healthy Start vouchers20 (HSVs) and the Baby Box in Scotland. 21 There have been process evaluations of some of these policies to understand acceptability and how they work in practice, but there is a need to evaluate interventions in pregnancy and childhood to determine which have an impact on health outcomes22 and which are cost-effective.

Intervention: Healthy Start vouchers

Healthy Start vouchers have the potential to improve the health of low-income families, who are likely to have poorer diets than more affluent families, and thereby reduce health inequalities. It is estimated that around 33,745 children and 10,551 women per annum across Scotland23 are entitled to HSVs and over 423,000 households in the UK claim HSVs. 24

Healthy Start vouchers, a means-tested voucher scheme, was introduced UK wide in 2006 as a replacement to the Welfare Food Scheme (WFS). The WFS started in 1940 as a universal benefit to ensure expectant and new mothers had a healthy diet during rationing. It subsequently became targeted to lower-income mothers and families. It provided tokens that could be exchanged for liquid and formula milk and vitamins to expectant and nursing mothers, and to children under the age of 4 years. The HSV scheme expands what the vouchers can be used for. The HSVs can be spent on milk, infant formula milk, fruit and vegetables. Between 2006 and 2021, vouchers worth £3.10 per week were given to eligible women; mothers with a child aged under 1 year received £6.20. The amounts were reviewed annually and have not changed since 2006. There are four main aims of the HSV scheme: to improve the nutrition of pregnant women, to increase fruit and vegetable intake, to initiate and maintain breastfeeding, and to introduce foods in addition to milk as part of a progressively varied diet when infants are 6 months old. 20

In 2002 it was estimated that it would cost the Exchequer £147M per annum to fund the HSV scheme. 25 In 2013/14, £93M was paid to retailers as reimbursement for vouchers. 24 This represented a substantial investment at a time when the UK government was trying to reduce the welfare bill.

Rationale

The effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the HSV scheme on a range of maternal and child health outcomes have not yet been demonstrated. A previous small (n = 336) comparison of the HSV scheme to the WFS found that mothers eligible for HSV had higher daily intakes of iron, calcium, folate and vitamin C than mothers eligible for WFS. 26 Three months postpartum, the HSV scheme mothers again reported higher iron, calcium, folate, and vitamin C intakes, as well as a higher consumption of fruit and vegetables than mothers eligible for the WFS. 27 A mixed-methods study28 of practitioners and low-income mothers found that recipients valued the vouchers but that there were substantial barriers to access, including low levels of awareness of the HSV scheme among both mothers and practitioners and uncertainty about the eligibility criteria among health professionals. A repeated cross-sectional analysis of the Health Survey for England29 found that fruit and vegetable intake in households eligible for the HSV scheme was similar to that of households in control groups.

A report on the operational aspects of the HSV scheme30 concluded that a comparative study is needed to assess the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the scheme. To determine the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of population-based feeding programmes including the HSV, such interventions need to be evaluated in larger studies using a wider range of outcomes with longer-term follow-up and methods appropriate for deriving causal inferences from observational data.

The evaluation of the effect of a means-tested voucher scheme can inform policies aiming to change behaviour, improve health outcomes and reduce health inequalities. It can inform public health decision-makers as to the benefits of vouchers for milk, fruit and vegetable intake during pregnancy and the postnatal/infancy period. Information on the characteristics of participants and non-participants and the reasons why women do and do not participate can also inform policy, so that if the vouchers are shown to be effective in improving vitamin use and breastfeeding rates, in addition to other health outcomes, take-up can be improved.

One criticism of the WFS was the potential to disincentivise breastfeeding because it offered tokens for formula milk. 31 The HSV scheme widened the scope of the vouchers to include fruit and vegetables and offered free vitamins to pregnant women. Therefore, the hypotheses for this study were that the HSV scheme would increase the use of vitamins in pregnancy, but that through the provision of vouchers for formula milk, it has the potential to decrease BI and duration (BD).

Aim and objectives

The overall aim is to evaluate the HSV scheme in relation to the extent to which HSV improves the nutrition of pregnant women and the health outcomes of their infants.

There are five objectives to investigate:

-

the effectiveness of the HSV scheme in relation to vitamin use in pregnancy, and BI and BD

-

the effectiveness of the HSV scheme in relation to infant and child weight and body size, child morbidity, infant and child feeding, and maternal health

-

how findings differ between different populations (Scotland and UK)

-

to establish actual voucher usage and determine the reasons for uptake and non-uptake of the HSV

-

to establish the cost-effectiveness of the HSV.

Chapter 2 Methods

Research design

The evaluation took a mixed-methods, natural experiment approach to investigate the effectiveness of the HSV scheme. The analysis used existing survey data and was enhanced with an embedded qualitative study, and the methods to conduct a health economic analysis alongside a natural experiment evaluation were established. Thus, there were three parts to this evaluation:

-

Secondary analysis of two existing data sets, including linking one to routinely collected health data (objectives 1, 2, 3).

-

Qualitative interview study of mothers, including a descriptive analysis of voucher usage (objective 4)

-

Establishing methods for a cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA), and conducting a preliminary analysis (objective 5).

As the intervention was not controlled by the researchers, we used multiple exposed and unexposed groups to assess the effectiveness of the HSV scheme. This follows Medical Research Council (MRC) guidelines for the evaluation of NEs. 32 The HSV ‘intervention’ is not randomly allocated to participants so it was difficult to have complete control for confounding; there were factors associated with both receiving HSV and the outcomes that needed to be taken into account. The use of multiple comparison/unexposed groups helped with the assessment of bias of the evaluation method.

Healthy Start voucher policy

The intervention being evaluated was the HSV scheme. There are four main aims of the scheme: to improve the nutrition of pregnant women, to increase fruit and vegetable intake, to initiate and maintain breastfeeding and to introduce foods in addition to milk as part of a progressively varied diet when infants are 6 months old. 20

It is a means-tested voucher scheme for pregnant women and families with children under the age of 4 years. If these women are in receipt of certain means-tested benefits then they are eligible for vouchers to be spent on milk, infant formula milk, fruit and vegetables. They also receive free vitamins. All mothers under the age of 18 years are eligible for the scheme. Between 2006 and 2021, vouchers worth £3.10 per week were given to eligible women; mothers with a child aged under 1 year receive £6.20. The amounts were reviewed annually and have not changed since 2006. As from April 2021, the monetary value of the voucher increased to £4.25 per week. These can be spent in neighbourhood shops and pharmacies. A health professional signs the application form confirming the pregnancy (or child under the age of 4 years) and that the applicants have received health advice. The voucher scheme was rolled out across the UK in 2006 as a replacement to the WFS.

The requirement for a health professional to countersign the application means that there is an opportunity for health promotion. The health professional who countersigns the application will have offered appropriate health, nutrition and lifestyle information to the mother.

Intervention and control groups

An issue identified from a scoping study of evaluating the HSV scheme in terms of outcomes was the lack of obvious control group. 33 There are different ways to assess the effectiveness of the HSV scheme on maternal and child outcomes. One would be to compare the WFS with the HSV scheme, but there are weaknesses in this comparison. It relies on a control group who is living at a different time period to the current HSV scheme and it would be difficult to identify and then subsequently obtain the necessary data on outcomes, exposures and confounders from existing data sets. This evaluation used contemporaneous control groups that can be identified in current existing data sources.

Guidance for the evaluation of a natural experiment advises the use of multiple comparison/unexposed groups to give multiple perspectives about sources of bias and therefore allow an assessment of these biases. 32 This evaluation used two unexposed groups.

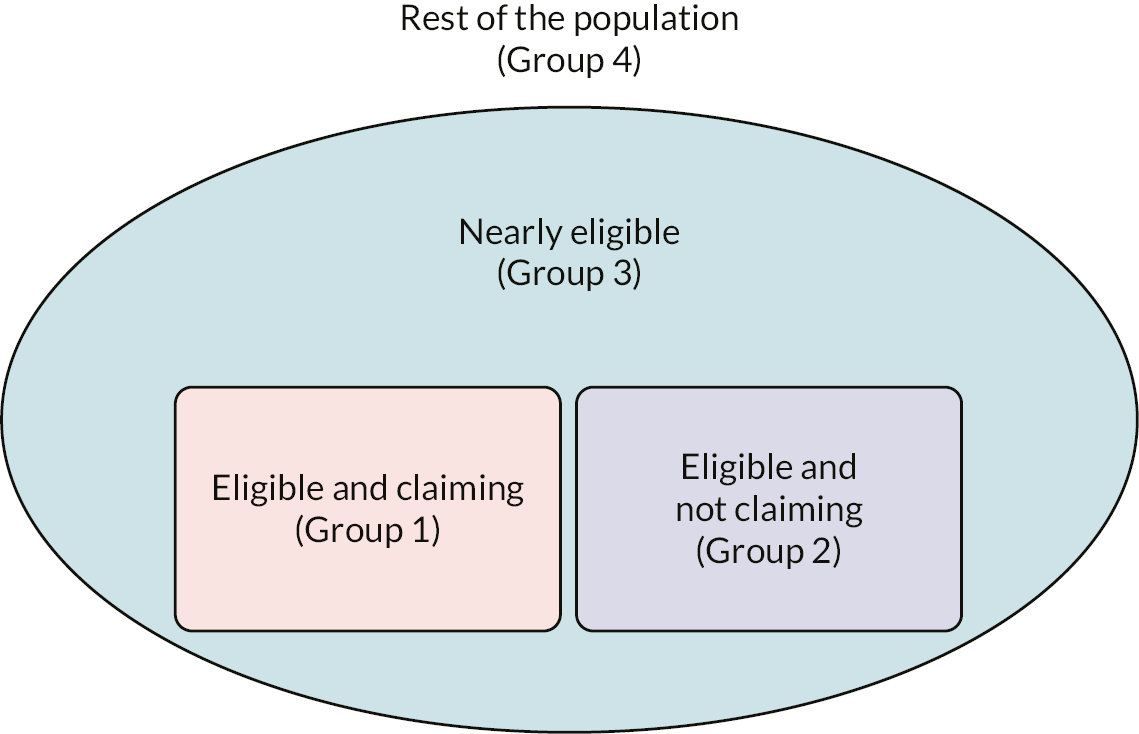

The population of mothers and their children can be divided into four mutually exclusive groups (Figure 1) according to their exposure to the intervention (HSV scheme). Group 1 is the exposed group, and they are eligible for HSV and claim the vouchers. Group 2 is the eligible but not exposed group: they are eligible for HSV but do not claim the vouchers. Group 3 is the nearly eligible group: they are those who just miss out on the eligibility criteria for HSV. Group 4 is the rest of the population: they are those who would never qualify for HSVs.

FIGURE 1.

Population of mothers and their children split by eligibility for the HSV scheme, identifying exposed and unexposed groups.

Comparison groups

With these exposure and control groups, there were three ways to compare these groups:

-

recipients versus eligible but not claiming (group 1 vs. group 2)

-

recipients versus nearly eligible (group 1 vs. group 3)

-

all eligible versus nearly eligible (group 1 and 2 combined vs. group 3).

The comparison groups represent different aspects of HSV effectiveness. Comparison groups 1 and 2 are analogous to evaluating the effectiveness of the ‘dose’ of HSV. Recipients of HSV (group 1) were compared with those who may be similar in many characteristics (group 2), especially in the eligibility criteria, but for whatever reason, they do not claim the HSV; recipients (group 1) were also compared with those who are close to the eligibility criteria but their income is just a bit too high to be eligible for HSV (group 3). Comparison 3 was effectively an intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis; this is how the HSV policy is working in practice.

Assessing effectiveness

This evaluation used a multiple analytical approach, using both propensity score matching (PSM) and regression discontinuity (RD). Using this combination of methods allowed control for both observed and unobserved confounders. In addition, the combination of methods allowed comparison of each method with their associated biases and therefore increased the robustness of the results. PSM is a technique used to limit the bias due to confounding in an observational study. The matching accounts for variables that are associated with receiving the intervention or control and therefore allows the estimation of the effect of the intervention. In RD designs, participants are assigned to an intervention or control based on a cut-off value of an assignment variable. Despite there being no random assignment, the RD design has comparable internal validity to randomised controlled trial (RCT) designs. 34

Table 1 details the method of evaluation for each of the comparison groups and notes, which method can be used for each of the data sets. The Infant Feeding Survey (IFS) does not have a suitable forcing variable for the RD method and so all comparisons were done using PSM.

| Comparison group | Data set | Evaluation method |

|---|---|---|

| 1: recipients vs. eligible but not claiming (group 1 vs. group 2) | GUS | Propensity score RD |

| 1: recipients vs. eligible but not claiming (group 1 vs. group 2) | IFS | Propensity score |

| 2: recipients vs. nearly eligible (group 1 vs. group 3) | GUS | Propensity score RD |

| 2: recipients vs. nearly eligible (group 1 vs. group 3) | IFS | Propensity score |

| 3: all eligible vs. nearly eligible (groups 1 and 2 combined vs. group 3) | GUS | Propensity score RD |

| 3: all eligible vs. nearly eligible (group 1 and 2 combined vs. group 3) | IFS | Propensity score |

All comparisons were important, but the main comparison of interest was between exposed (group 1) versus eligible but not exposed (group 2). This was a direct comparison of similar groups intended to be recipients of this targeted intervention and was the basis for the power calculation. The other two comparisons would determine the confidence in the results. The directions, sizes and significance of the effects would be indicative of the confidence in the effect of the HSV scheme. If the other two comparisons were in the same direction, significant and of the same magnitude then that would give us the most confidence that there is an effect of the HSV scheme. There would be reduced confidence if they were in the same direction but varied in size and/or significance and least confidence if the effects were in different directions, and significantly different from one another. Again, comparing effect sizes across the data sets and evaluation methods would also determine the confidence in the effect of HSVs.

Quantitative study: study population

The population was all women eligible for HSVs, that is, pregnant women and families with children under 4 years of age with low incomes or in receipt of certain means-tested benefits, all pregnant women aged < 18 years and all mothers aged < 18 years.

The Growing Up in Scotland (GUS) study was a stratified cluster random sample of the whole of Scotland and is available from the UK Data Archive. 35 Children were recruited to the second Birth Cohort in 2011 when they were about 10 months old; it had a sample size of 6127. Pre-project and preliminary inspections of the data determined that 1350 (22%) were from families that were identified as claiming HSVs and that 413 (7%) were from families that were identified as eligible but not claiming (Table 2).

| Data source | Group 1: recipients | Group 2: eligible not claiming | Group 3: nearly eligible (based on income between £15,600 and £20,799) |

|---|---|---|---|

| GUS – sweep 1 | 1320 | 413 | 507 |

The IFS23 is a random sample of births in the UK from August to October 2010. There were three stages of data collection; we used data from stage 3, when the infant is 8–10 months old. The sample size was 10,768 with 1906 (18%) were from families that were identified as claiming HSVs and 1535 (14%) were from families that were identified as eligible but not claiming (Table 3).

| Data source | Group 1 (recipients) | Group 2 (eligible not claiming) | Group 3 (nearly eligible) (IMD quintiles 1 and 2) |

|---|---|---|---|

| IFS | 1906 | 1535 | 4497 |

The IFS is available from the UK Data Archive and provides UK-wide data. It collected a wide range of detailed infant feeding patterns but does not have the range of other secondary outcomes available from the linked GUS data. The use of both complementary data sets would show the likely generalisability of the findings from GUS to the whole of the UK.

Quantitative: confounding variables

To enable greater comparability between the studies, identical/harmonised variables from IFS and GUS were used. The variables are described below.

The following groups have been identified as having more adverse birth outcomes and therefore were confounders for the analysis: those living in the most deprived areas, those in the lowest social classes, lone mothers, primiparous women, teen mothers and those in the lowest education group. The ethnic group of the mother was also an important factor for the outcomes. 36 We planned to include ethnicity as a covariate in the analyses. However, ethnicity in GUS reflects the ethnic composition of Scotland and is 95% white and 5% non-white; owing to the small sample sizes of non-white groups, it was not possible to break the non-white group into more refined ethnic groups. The ethnicity in IFS reflects the ethnic composition of Great Britain (England, Scotland and Wales) and is 82% white. Ethnicity was not asked in the Northern Irish sample.

Confounders in GUS were:

-

social class – national statistics socioeconomic classification (NS-SEC) of the mother, father and household

-

household income

-

educational status – education attainment of mother

-

family type – single mother/lone parent, couple family

-

primiparous – first born, other children

-

age of mother at birth of child – age < 20, 20–4, 25–9, 30–4, 35–9, ≥ 40 years

-

ethnic group – white, other ethnic background

-

urban/rural classification – large urban; other urban; small, accessible towns; small, remote towns; accessible rural; remote rural.

Confounders in IFS were:

-

social class – NS-SEC of the mother: 1, managerial and professional; 2, intermediate occupations; 3, routine and manual occupations; 4, never worked; 5, not classified

-

educational status – age mother left full-time education – ≤ 16, 17–8, > 18 years

-

single mother

-

primiparous – first birth, second or later birth

-

age of mother – age < 20, 20–4, 25–9, 30–4, ≥ 35 years.

When analysing GUS data and GUS/linked data, the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation (SIMD)37 was used. The SIMD combines information across six domains: income, employment, health, education, housing and geographical access. It provides a comprehensive picture of material deprivation in small areas within Scotland. The index ranks 6505 areas from the most deprived to the least deprived and measures the degree of deprivation of an area relative to that of other areas. The areas employed by the SIMD are data zones and are small: the 6505 data zones have a mean population of 780 people (approximately half the size of a lower super output area in England). The reason for employing small area geography at this scale is to permit identification of relatively small pockets of deprivation and minimise misclassification. Area-based deprivation was available for the IFS. It used an area deprivation measure appropriate for each country of the UK: the Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) for England,38 the Welsh IMD for Wales,39 the SIMD for Scotland37 and the Northern Ireland Multiple Deprivation Measure for Northern Ireland. 40

Sample size calculation

This was an analysis of existing data based on children in the GUS sample: as such the sample size was fixed. This calculation gave an indicative effect size that could be detected given the sample size. GUS has a sample size of 6127, with 1350 (22%) who were identified as being from families that were claiming HSVs and 2336 (38%) that were identified as being from families that were eligible but not claiming. GUS is a clustered sample of 199 data zones with approximately 30 respondents per cluster. Assuming an intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.01 and 63% BI, 80% power and 95% significance levels, the sample size of GUS would be able to detect a 5% difference (i.e. 68% BI).

Outcomes

Primary outcomes

There were two primary outcome measures: one relating to the mother during pregnancy and one relating to the child in early infancy. These are important periods of risk that measure different but important aspects of public health.

The aim of vitamin use during pregnancy is to create a healthy uterine environment, which is important for birth outcomes. An increase in vitamin use is one of the aims of the HSV scheme. In early infancy, breastfeeding is beneficial for many aspects of child health and morbidity. 41 An increase in breastfeeding rates and BD is one of the aims of the HSV scheme. Women from low-income families and low social class and teenage mothers have lower rates of breastfeeding and vitamin use in pregnancy than other women in the population. Providing health advice along with vouchers to use for a healthy diet (including milk and fruit and vegetables) should increase knowledge of the benefits of good maternal nutrition, reduce financial barriers to a more nutritious diet and, therefore, increase vitamin use.

The HSV scheme replaced the WFS, which provided only milk tokens for liquid and infant formula milk. There was therefore no incentive to breastfeed: if the mother was breastfeeding she could spend the vouchers on liquid milk only. The HSV scheme has broadened the scope of the vouchers to be used for fruit and vegetables as well as liquid and infant formula milk, so that mothers who choose to breastfeed are able to spend the vouchers on something other than milk. However, there is still a risk that the option of free formula milk will disincentivise breastfeeding. Conversely, the exposure to health advice associated with the HSVs could encourage higher rates of breastfeeding. Thus, comparing breastfeeding rates between those who do and those do not take up the vouchers is vital, mainly to exclude the possibility that the HSVs actually discourage breastfeeding.

Secondary outcomes

The secondary outcomes were in four categories: child weight and body size, child morbidity, infant and child feeding, and maternal health. Each secondary outcome related to at least one of the aims of the HSV and was available from up to three different data sources (Table 4).

| Outcome | HSV scheme aima | Data set |

|---|---|---|

| Primary outcome | ||

| Maternal: vitamin use in pregnancy | 1 | GUS, IFS |

| Child: BI and BD | 3 | GUS, IFS |

| Secondary outcomes | ||

| Child weight and body size | ||

| Birthweight | 1 | GUS, GUS-LK, IFS |

| Low birthweight | 1 | GUS, GUS-LK, IFS |

| Height at 3 years | 2 | GUS |

| Weight at 3 years | 2 | GUS |

| Mother’s perception of child weight at 3 years | 2 | GUS |

| Mother’s concerns about child weight at 3 years | 2 | GUS |

| Child morbidity | ||

| Pre-term birth | 1 | GUS-LK, IFS |

| Gestational age | 1 | GUS-LK, IFS |

| Morbidity in first year | 2, 3 | GUS, GUS-LK, IFS |

| Morbidity up to 3 years | 2, 3 | GUS, GUS-LK, IFS |

| Infant and child feeding | ||

| Use of formula milk | 3 | GUS, IFS |

| Use of cow’s milk before 1 year | 4 | IFS |

| Age at introduction of solids | 4 | GUS, IFS |

| Fruit intake at 3 years | 2 | GUS |

| Vegetable intake at 3 years | 2 | GUS |

| Mother’s perception of fruit/vegetable intake at 3 years | 2 | GUS |

| Vitamin intake at 3 years | 2 | GUS |

| Maternal health | ||

| Vitamin use during pregnancy | 1 | GUS, IFS |

| Current health | 2 | GUS |

| Smoking | 1 | GUS |

| Alcohol use | 1 | GUS |

| Financial strain | 1, 2 | GUS |

Data sources and numbers available for analysis

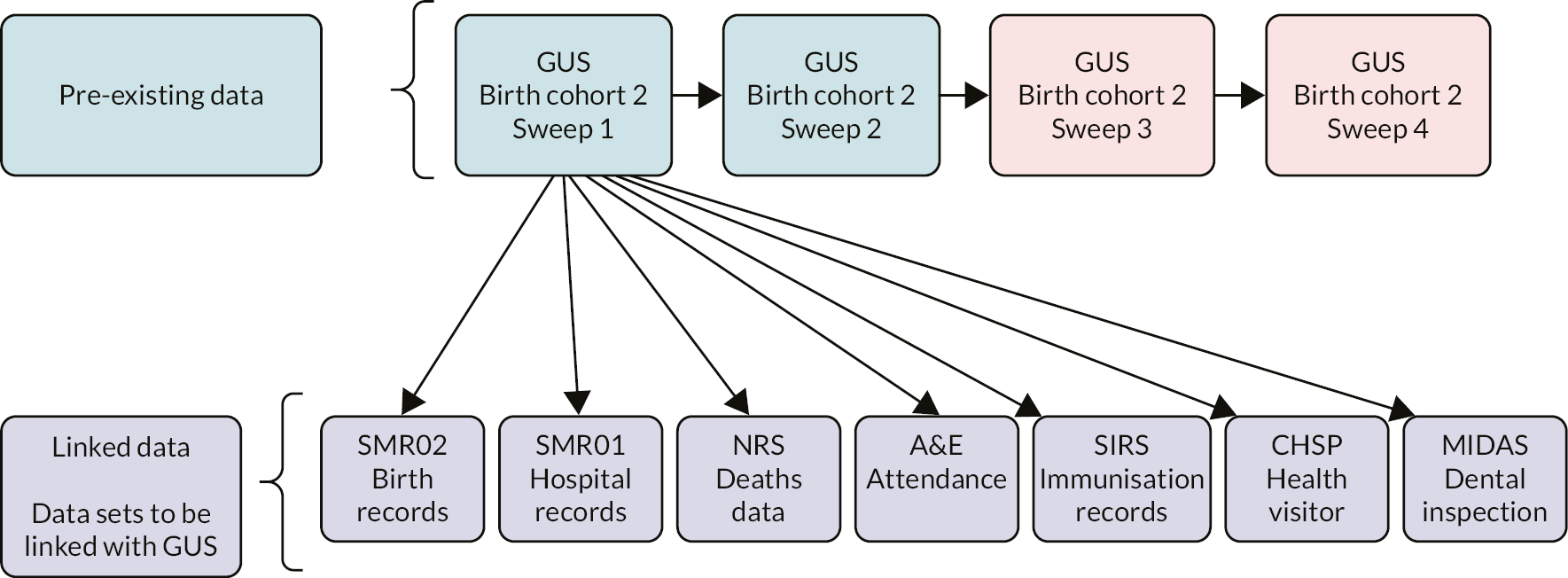

As part of the data collection process for GUS, the participants were asked if they consented to data linkage, which would allow for the individuals in GUS to have their survey data linked with routinely collected NHS data. Figure 2 displays the data sets to which we linked the GUS data. We linked the GUS data only for those participants who had consented to have their survey data linked to routinely collected NHS data. To do this, we applied to the NHS Information Services Division eDRIS service. An application was made to the Public Benefit and Privacy Panel for Health and Social Care. We provided information about the project, including why it was important and the methods and analysis, and noting the benefits it would bring to the public. We detailed the variables we required from each data set with justifications for them and also provided the variables we used from GUS. This was to ensure confidentiality. ScotCen (Edinburgh, UK) are the data owners of GUS and they provided the GUS data to eDRIS along with notices of consent. Note that this process has been superseded by a different, but similar, process since the Information Services Division became part of Public Health Scotland.

FIGURE 2.

Diagrammatic representation of the data linkage between GUS sweeps of data collection and routinely collected NHS data. Purple indicates data already collected and available; orange indicates future data collection. A&E, accident and emergency; CHSP, child health systems programme; MIDAS, Management Information and Dental Accounting System; SIRS, Scottish Immunisation and Recall System; SMR01, Scottish Morbidity Records general/acute inpatient and day case; SMR02, Scottish Morbidity Records maternity inpatient and day case.

There was consent from 91% of GUS participants to link their survey responses with the routinely collected NHS data. Sample sizes available in GUS and the routinely linked NHS data are shown in Table 6, with comparisons of demographic information. We also used the GUS birth cohort 2, sweep 2. The sweep 2 follow-up visits were conducted in 2013/2014, which made the children around 3 years of age. The number of GUS participants matched to the GUS birth cohort 2, sweep 1, are shown in Table 5. There were differences between the comparison groups in terms of follow-up, with higher follow-up among group 3 (nearly eligible) than among groups 1 (recipients) and 2 (eligible, not claiming). By the time of sweep 2, some of the group 2 and group 3 mothers were claiming HSVs. This could have been due to changes in financial or family circumstances that meant they now qualified for HSVs. We kept participants in the original groups.

| Data source | Group, n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (recipients) | 2 (eligible, not claiming) | 3 (nearly eligible) | |

| GUS birth cohort 2, sweep 1 | 1320 | 413 | 507 |

| GUS children 3 years of age (sweep 2) | 939 (71) | 307 (74) | 413 (81) |

| Receiving HSVs (sweep 2) | 441 (47) | 40 (13) | 17 (4) |

| Data source | Group, n | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (recipients) | 2 (eligible, not claiming) | 3 (nearly eligible) | |

| GUS birth cohort 2, sweep 1 | 1320 | 413 | 507 |

| Linked GUS, matched by mothers | 1235 | 394 | 460 |

| Linked GUS, matched by child | 1279 | 410 | 475 |

The number of GUS participants linked with routinely collected NHS health data is shown in Table 6. There were high rates of linkage across the three groups.

Statistical analysis

The socioeconomic data from GUS are more detailed than the IFS socioeconomic data and contain information to identify all three comparison groups, allowing a fuller evaluation. The data from IFS are from a larger sample and cover the whole of the UK. Both GUS and IFS allow for multiple comparison groups. Both PSM and RD can be used with the GUS data and comparison groups, but only PSM can be used for the IFS data.

The group of women who are eligible for HSVs are also those who are less likely to breastfeed and be at risk of more adverse outcomes; even within this eligible group, there will be variation in breastfeeding rates. One difficulty is how to control for these confounding characteristics and also be able to detect an effect of HSV given all these other influences on breastfeeding. There are many background characteristics that are related to both adverse outcomes and the likelihood of being low income and therefore eligible for HSV. In both GUS and IFS these can be adjusted for these influences in the analyses. The PSM gives the probability that an eligible person will have received HSV given the characteristics associated with uptake of HSV, and probabilities for the control group. Therefore the two comparison groups should be balanced in terms of the factors associated with uptake of HSV, and any effect of HSV should be unbiased.

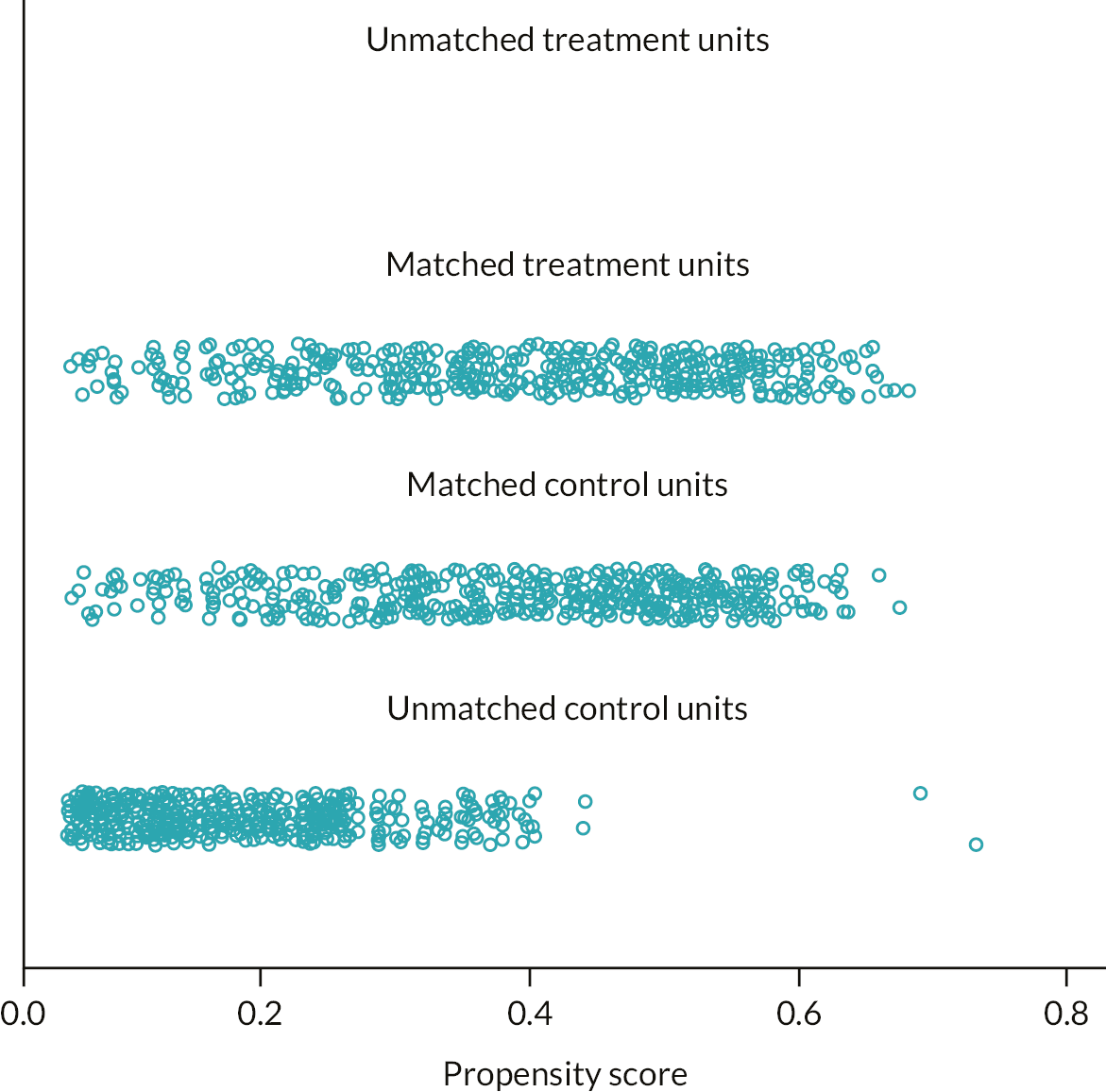

Propensity score matching

Propensity score matching is a technique used in case-control studies that enables direct comparison methods for assessing differences between groups to work more effectively through the selection of well-matched subsets of the original treated and control groups. 42–44 Theoretically, the function that produces the propensity score can be the logit, discriminate function or other functions that group treated and control units such that direct comparison becomes meaningful. 42 In PSM the number of controls has to be considerably more than the cases so that there can be a close match for each case. In current software for PSM, missing values are not allowed, and the definition of the groups is arbitrary, depending on number of subjects in each group. If the number of controls is fewer than the number of cases, as was the situation here, for a one-to-one matching for each control, a matching case would be chosen. Otherwise, there is the option of matching with a replacement, meaning that some individuals within the control group are replicated; however, there is still only one control group but in this situation the variances associated with measures would be considerably lower. The program MatchIt (version 4.5.2) package in R (version 3.0.3. The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria)43 provides sampling with replacements, but the number of matched controls does not exceed that of cases. 43,45 MatchIt also provides a weight measure when there is sampling with replacement; this weight measure can be used in subsequent regressions but is not applicable for direct comparisons, as is the case here. In situations in which the number of controls is fewer than the number of cases, there would be inevitable loss of power. For the present analyses one-to-one matching was deployed, as a direct comparison of primary and secondary outcome measures was used. It is also noted that the number of cases was more than controls for the GUS database. The following confounding variables, which define the characteristics associated with the uptake of HSVs, were used for the propensity matching process:

-

mother’s NS-SEC

-

mother’s education

-

family type

-

whether first-born child

-

mother’s age category

-

SIMD

-

urban–rural classification.

There are generally many matching methods that can be used. In general, it is recommended to use different matching methods and choose the one that works well with the data by giving the lowest mean differences between groups. For the current analyses the ‘nearest neighbour’ method was used, and three different matched groups were created. The first matched group consisted of subjects in group 2 (eligible group) to those of group 1 (receiving HSVs). The second matched group was subjects in group 3 (nearly eligible) matched to subjects in group 1 and the third matched group was subjects in groups 2 plus 3 matched to those in group 1. Therefore, a subject in group 1 could have been matched to a subject in groups 2 or 3 but as far as the group comparison was concerned the subjects in groups were unique.

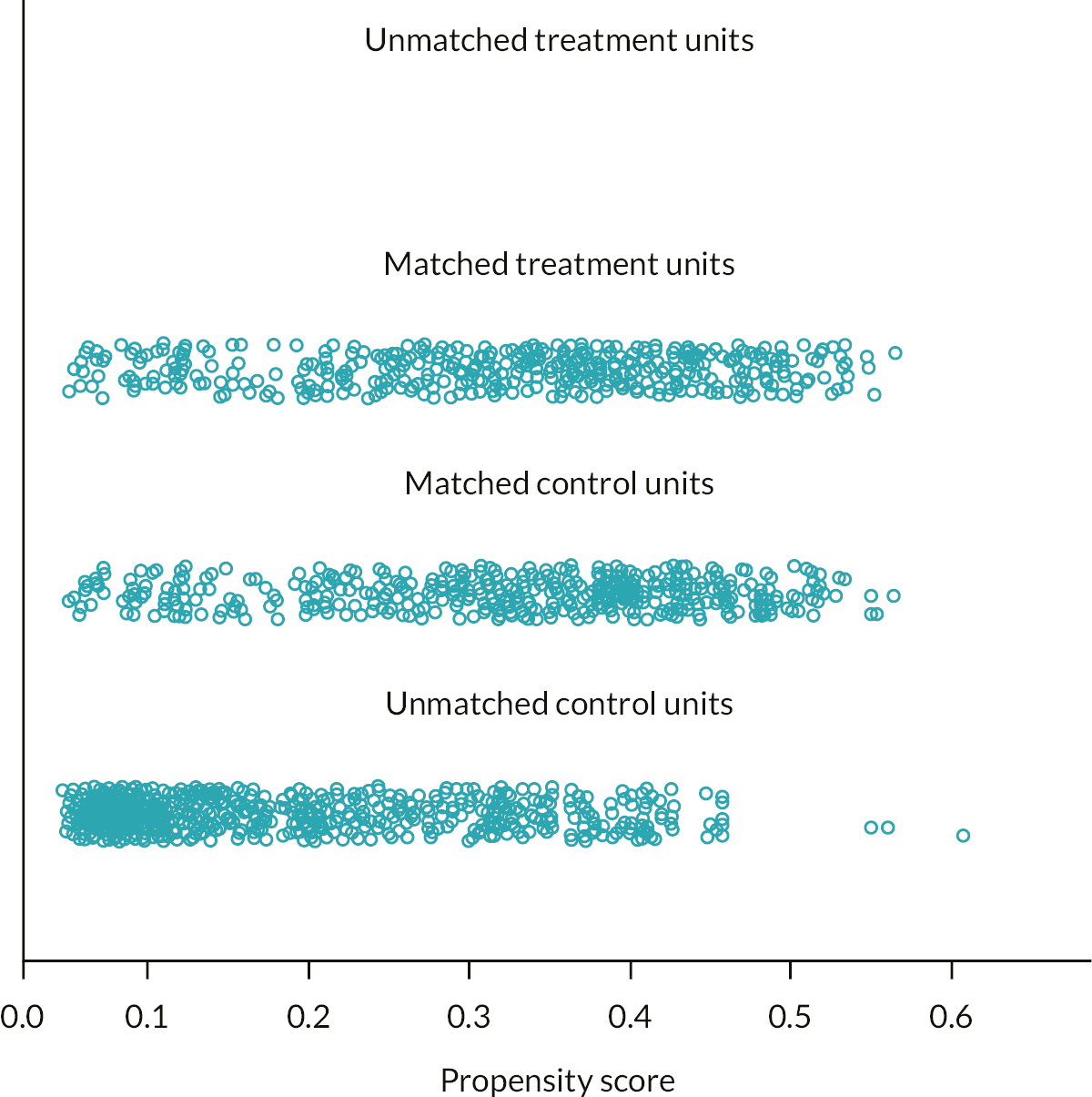

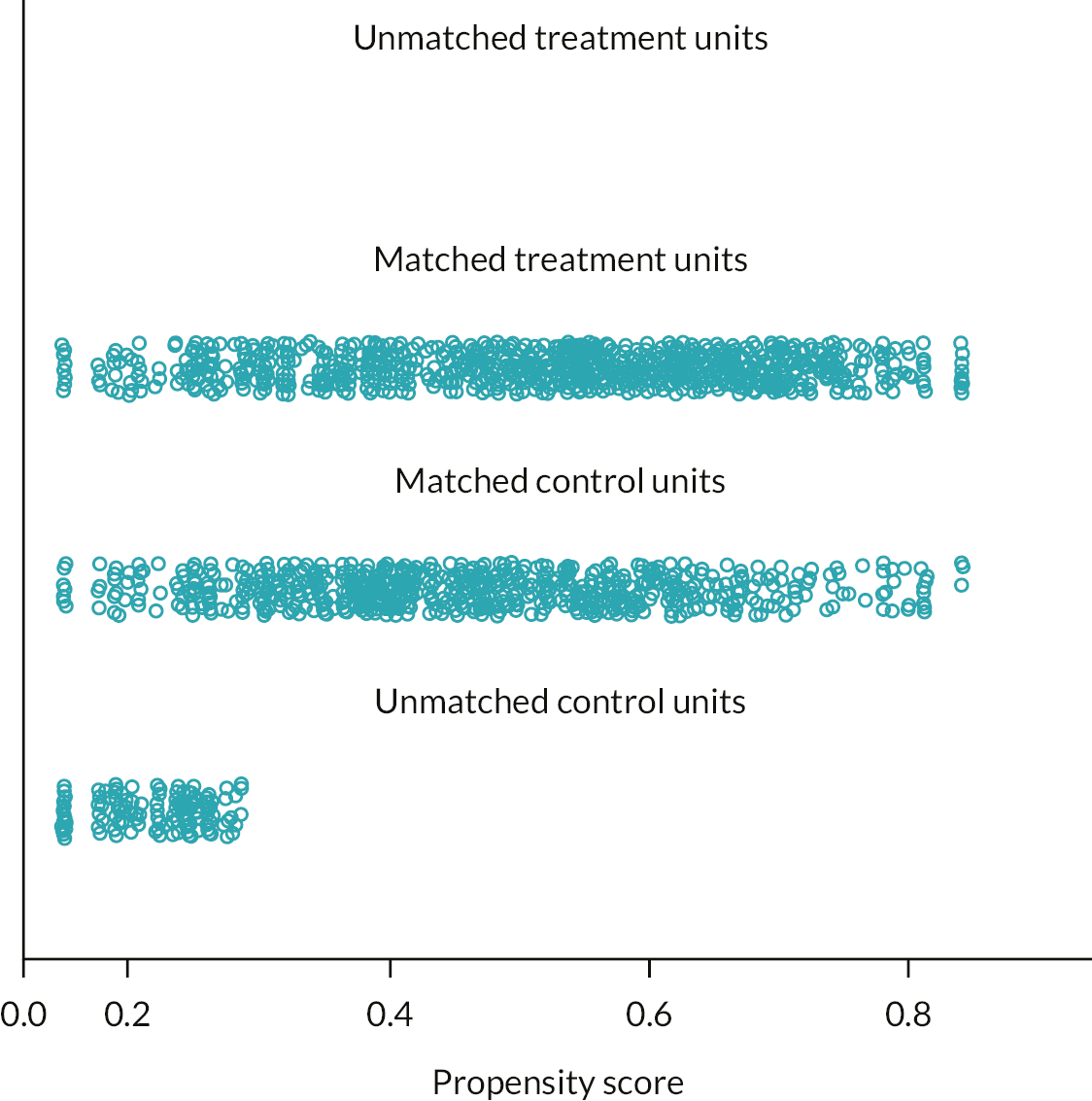

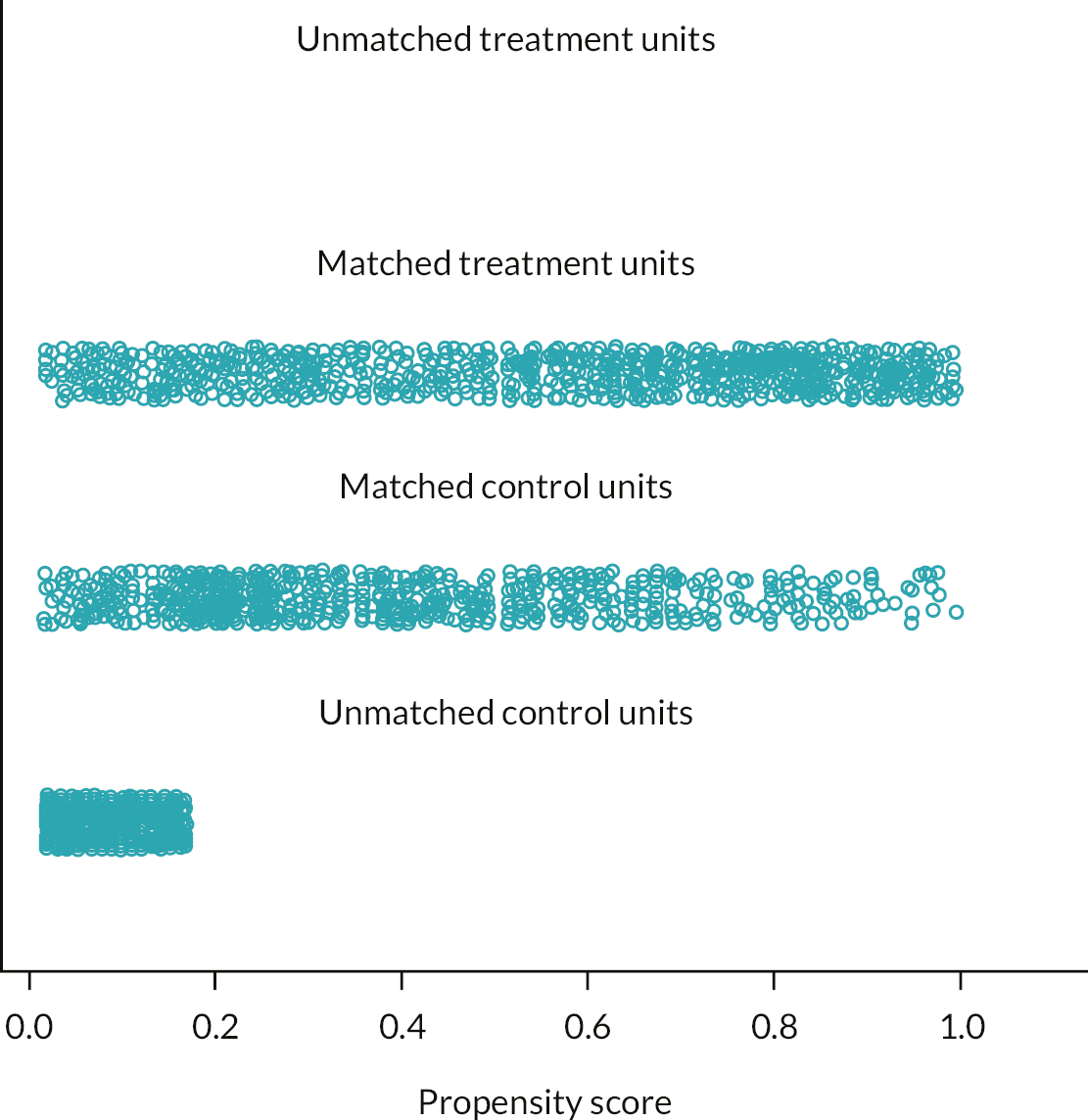

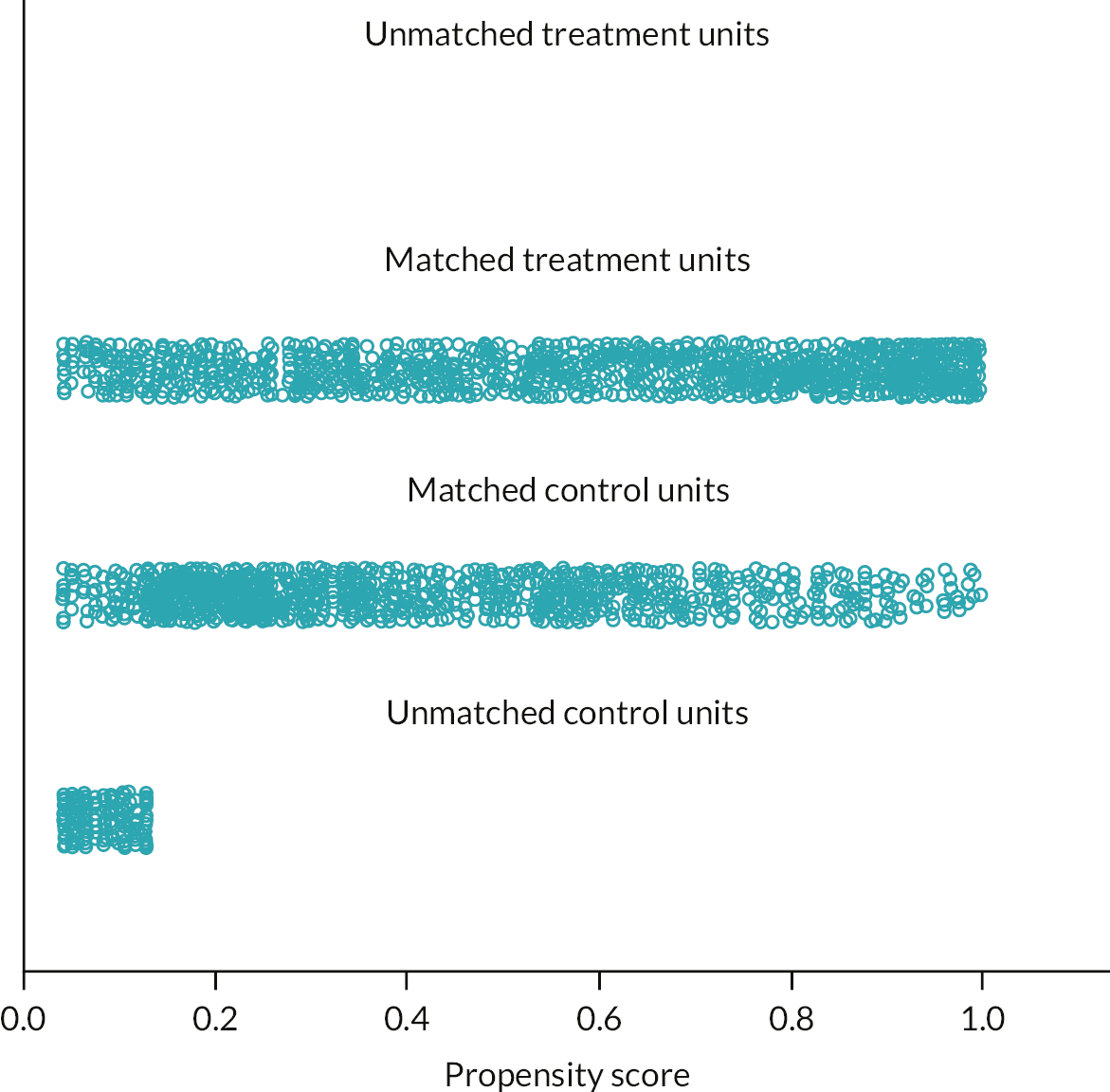

Having matched the subjects according to their propensity scores, the proportions of outcome variables (one proportion for the binary and all for the categorical variables) were compared between groups using two independent proportions or chi-squared tests. 46 The continuous variables were compared using a paired t-test. The comparison groups were 1 with 2, 1 with 3, and a combination of 1 and 2 with 3. The distributions of the scoring for the matched groups together with the distribution of confounder variables are shown in Appendix 1.

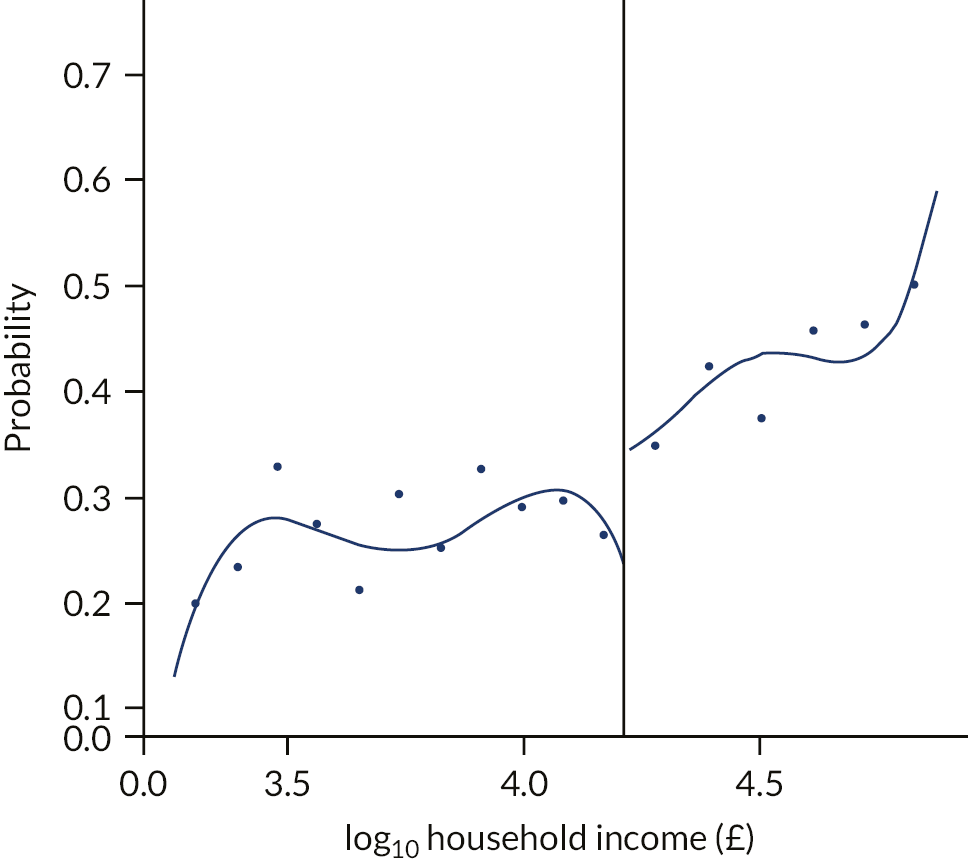

Regression discontinuity

For the RD analysis, we followed the approach outlined by Imbens and Lemieux. 34 Linear regression was used when the outcome was continuous and logistic regression was used when the outcome was dichotomous. All analyses were adjusted for appropriate confounders including maternal and family social status measures and area deprivation. Regressions with polynomials were used to assess the non-linearity of the relationship between outcomes and HSVs. Local regressions, therefore, were estimated for both the intervention and comparison groups and the difference between the two estimates is the effect of HSV.

The RD is a research design in natural experimental studies for the evaluation of an intervention in a population. 34 For each unit (i) in a RD design, a quadruple (Yi, Wi, Xi, Zi) is observed, in which Yi is the outcome measure, Wi is the assignment variable (0 or 1), and Xi and Zi are covariates with Xi as a scalar and Zi a vector. Both Xi and Zi are not known to be influenced by the outcome Yi and they may influence Yi. In this design the units (generally subjects) are either completely or at least partly (fuzzy design) assigned to treatment or in the current setting the probability of belonging to the HSV-receiving group for each outcome variable after correcting for the covariate vector (Zi). The function relating the outcome variable (Yi) and income level (Xi) remains unknown but the assumption is that there is a smooth relationship. In the GUS database there are nine income categories and in the IFS income is not ascertained. Because the predictor, Xi, is associated with the outcome variable, Yi, any discontinuity of the conditional distribution (or conditional expectation) of outcome with respect to Xi at cut-off may be interpreted as a causal effect of the treatment. 34 Because the HSV scheme is a means-tested benefit the income category or equalised income would not necessarily be primary criteria for entitlement. For example, entitlement is age dependent (< 18 years) or it can be triggered during or following unemployment, or it is assessed if employed but on certain state benefits such as child tax or working tax credits, which are tied to household income. In addition, in the GUS database the stated household income is not in any way verified. The HSV scheme agency uses the Department of Work and Pension systems for verification of entitlement but the actual income level remains confidential. 17

In RD design the choice of the forcing variable (x axis) is such that for a value above or below a cut-off point (depending on the context) the unit (individual) is assigned to the intervention. The household income could be regarded as a forcing variable and the cut-off point could be set as the HSV eligibility criteria, which is a family income of ≤ £16,190 per year. The use of equivalised income as forcing variable was in keeping with RD design in that this predictor may itself be associated with potential outcome (the probability of being in the HSV group). The use of household income would entail the use of fuzzy RD design, in which the probability of exposure increases sharply at the cut-off point, but not from 0 to 1.

There were 447 out of 1320 (34%) subjects in the HSV cohort with a family income of more than the third category (£15,600–20,799). The outcome variable in RD is generally a measure with a ratio scale of measurement, such as a test score, or it can be a probability for binary outcomes, for example the odds ratio of taking vitamin D or folic acid before or during pregnancy. The odds ratios of taking vitamin D or folic acid for the HSV group were computed using logistic regression. In this logistic regression the outcome was taking vitamin D or folic acid before pregnancy, with the group assignment and optimum confounders as explanatory variables. In such a setting it was possible to obtain discontinuity at the income threshold using the ‘rdrobust’ package in R. 47

Missing data

The missing values for the confounder variables were imputed using multiple imputation with chain equations48 implemented in R. 49 The imputations were carried out for each comparison group separately. For example, for the GUS database, group 1 (recipients of HSV) with group 2 (eligible but not claiming group), similarly for group 1 with group 3 and groups 1 and 2 with 3. For each grouping 20 imputations were generated. The Stata® (Stata SE 14, StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) software using Rubin’s Rule was used to estimate the coefficients of logistic regressions for comparison groups. The results were almost identical to those without imputation of the missing values. The imputations were not repeated for the IFS database because of the very low level of missing values.

Generalisability

The data used for this project came from different existing sources using different methods for collection and different questions. IFS is a questionnaire that subjects complete. Mothers are invited to take part via a letter and can complete the questionnaire either online or on paper and then post it back. GUS is a face-to-face interview with a researcher. Mothers are invited to take part via a letter and an interview time is agreed. The questionnaire is completed using computer-assisted personal interviewing; some parts of the questionnaire may be self-completed during the interview process. These different methods of data collection and differences in questions may cause bias in the results. To make statements about the generalisability of the broader range of outcomes available in GUS, we compared the propensity score-matched results from GUS and IFS for all comparison groups, for the primary outcomes of vitamin use in mothers and breastfeeding for infants.

Reporting of the quantitative results

We have reported the results of all pre-specified primary and secondary outcomes, and not just those that reached statistical significance. The analysis involved conducting many tests, which were not independent of each other. Rather than adjusting confidence intervals or p-values to account for this we have presented the results of all analyses and caution the reader regarding the interpretation of the results.

Qualitative interview study

To inform the understanding of the results of the quantitative study, and to understand the process of claiming and using the vouchers, we gathered qualitative data on the lived experiences of women, ascertaining reasons for uptake and non-uptake of HSVs and what the vouchers are spent on.

We carried out 40 in-depth interviews, spread across each of the following groups, mirroring the comparison groups identified in Figure 1:

-

GUS mothers who received HSVs

-

GUS mothers eligible for HSVs but who did not claim

-

mothers who were receiving HSVs

-

mothers who were eligible for HSVs but who did not claim

-

mothers who were nearly eligible for HSV, but did not meet the criteria.

This study started in 2015, when children in GUS were 5 years old. The HSV scheme is in place until the children are 4 years old. Mothers from GUS may have had difficulty recalling their thought processes from up to 5 years previously. We therefore complemented interviews with GUS mothers with interviews with mothers who were current claimers of HSVs and also those currently eligible for HSVs but who did not claim. We identified them from community groups that support families on low incomes. Those mothers nearly eligible for HSVs were also identified by this method. The mothers were selected to ensure that the sample contained women with a range of characteristics including age, number of children, ethnicity and education level.

The interviews were semistructured, face to face, approximately 1 hour in length and covered a range of topics, including what mothers knew about the scheme; how they found out about it; reservations about using it; and, if relevant, main reasons for not using it. If they were currently using the scheme or had used it previously, we asked about when they started using it, who knew they were using it, perceived extra monetary benefits, how conscious they were of extra money and how they used this extra money.

The interviews were recorded on an encrypted recorder, anonymised and transcribed verbatim. Recordings were anonymised before transferring to the transcribing service. The transcribing agency involved was subject to MRC/Chief Scientist Office (CSO) Social and Public Health Sciences Unit data confidentiality policies. Data were transferred and held in a secure environment subject to MRC/CSO Social and Public Health Sciences Unit data-sharing policies.

The transcripts were checked against the original recording before analysis started. They were coded according to prior and emergent themes using NVivo (QSR International, Warrington, UK) and summarised systematically by charting according to key themes, and emerging hypotheses were tested according to all the relevant data. Particular foci were the processes involved in the take-up, non-take-up or discontinuation of the HSV scheme, the experience of using HSVs and how the vouchers were used. Responses were compared between the five groups of women.

The 20 women sampled from GUS were sent an information leaflet and letter inviting them to take part in the semistructured interviews. A follow-up telephone call was made to get their response. For those who declined, they were replaced by other GUS participants with similar characteristics. The 20 women currently claiming/not claiming HSV were sampled from parent groups in deprived areas of Glasgow. Information leaflets were given to these groups inviting them to take part in the semistructured interviews. The participants were fully informed of the study before agreeing to participate. Once the women agreed to participate, an appointment for interview was made, with a reminder telephone call made in the week prior to the interview. The participating women were offered a £20 voucher in recognition of their time spent being interviewed.

Full details of the design, methods, analysis and results are in Chapter 5.

Health economics and assessment of the cost-effectiveness

Conducting health economic evaluations alongside NEs is relatively new. Therefore, the methodology for doing this is not well established. As part of this project, we developed and proposed methods and guidance for conducting such economic evaluations in population health using observation data from NEs. Such evaluations are subject to the inherent biases that affect analyses using observational data.

Our methodology drew on economic methods guidance50–53 and on evidence from economic evaluations carried out in similar early years contexts. 54,55 In addition, methods from previous studies incorporating economics into NEs in education and microeconomics,56–58 including a recent review on health economic evaluations and observational data,59 were used. Current guidance for economic evaluation focusses on RCT designs and therefore does not address the specific challenges for natural experiment designs. Using such guidance can lead to suboptimal design, data collection and analysis for NEs, leading to bias in the estimated effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the intervention or policy. Fuller descriptions of the methods to develop the guidance and the health economics plan are reported in Chapter 6. The full economic evaluation is out with the scope of this report; it is subject to ongoing work and will be reported separately.

Patient and public involvement

When conducting patient and public involvement (PPI) for this project, we first defined our ‘population’ group. We identified low-income women as our PPI target group; their experiences reflected the population with the potential to be affected by the HSV scheme and the results of this project. The aim of PPI was to inform the qualitative interview schedule and refine and reflect initial analysis. As part of the PPI work, we undertook a focus group with 11 women to share our initial findings from the qualitative study and quantitative analysis. These women were recruited from third-sector organisations that support low-income families. During this process the women suggested adding the financial strain and challenges to the list of secondary outcomes, as they felt that, although HSVs represent a relatively small cash amount of £3.10, they do contribute some money to the family budget.

As part of the application process to link the GUS data to the routinely collected NHS data, lay members were part of the Public Benefit and Privacy Panel. Their opinions were fed into the decision to allow permission to use routine data for research and offer comment as to the public benefit of the research.

Ethics statement

Secondary analysis of existing data

Ethics approval was not required as there was no primary data collection. The data for both the IFS and GUS had already been collected and were available for use for research purposes. The linkage and release of the GUS data with the routinely collected NHS data for research purposes were subject to agreement from the Privacy Advisory Committee (and superseded by the Public Benefit and Privacy Panel) at NHS National Services Scotland. The data collection, storage and release for research purposes are subject to strict protocols governing privacy, confidentiality and disclosure of data. The project was approved subject to Public Benefit and Privacy Panel for Health and Social Care project number 1516-0614.

We used the GUS and IFS data from the UK Data Archive, subject to their end-user licence agreement. Note current arrangements for accessing GUS data may differ.

Qualitative interview study

Participants in GUS had already given consent to be contacted for research purposes. Only those who agreed to further contact for research purposes were approached to be interviewed. This qualitative study was reviewed and fully approved by the University of Glasgow, College of Social Science Ethics Committee in October 2015 (reference number 400150028). This Committee complies with the Economic and Social Research Council’s research ethics framework.

Chapter 3 Effect of Healthy Start vouchers on infant and child health

This chapter reports the results of the quantitative analysis of GUS and IFS linked to routinely collected health data sets for child outcomes. The range of outcomes covers aspects that are important for infant and child health, and they could be expected to be influenced by HSV. There are 1320 in group 1 (recipients of HSVs), 413 in group 2 (eligible but not claiming HSVs) and 507 in group 3 (those women who are nearly eligible for HSVs but their income means that they do not qualify for the HSV scheme).

Descriptive statistics for Growing Up in Scotland

Tables 7 and 8 show the descriptive statistics for the confounders contained in the GUS data set for each of the exposed and control groups. Group 2 had more mothers under the age of 20 years at the birth of their child than those in group 1, but fewer aged 20–4 years old. Apart from these differences the age groups were fairly similar for these two groups. Group 1 mothers were younger at the birth of their child than those in group 3 (see Table 7). For maternal social class, group 1 had more mothers who had never worked. Across all groups, the biggest proportion of mothers was in semi-routine or routine occupations. There was a large proportion (21%) of group 3 mothers in the intermediate occupation group. For group 1, the proportions for household social class were similar as for maternal social class, but groups 2 and 3 had different social class proportions for household and maternal social class. Group 3 had a large proportion (26.8%) in the managerial category. Groups 2 and 3 had similar profiles for mother’s education, but group 1 had more women in lower education categories than groups 2 and 3 (see Table 8). There was a gradient across the groups for lone parent families, with the highest proportion of lone parents in group 1 and the lowest in group 3. There were more women classified as living in the most deprived areas using both Carstairs Index and SIMD in group 1 than in groups 2 and 3. In terms of urban–rural, most women lived in urban areas across all three groups, but fewer group 1 mothers lived in accessible rural areas and more lived in small remote towns than those in groups 2 and 3.

| Confounder | Group 1 (recipients) (N = 1320), n (%) | Group 2 (eligible, not claiming) (N = 413), n (%) | Group 3 (nearly eligible) (N = 507), n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mother’s age at birth (years) | |||

| < 20 | 235 (17.8) | 45 (10.9) | 41 (8.1) |

| 20–4 | 358 (27.1) | 140 (33.9) | 113 (22.3) |

| 25–9 | 309 (23.4) | 115 (27.8) | 154 (30.4) |

| 30–4 | 254 (19.2) | 67 (16.2) | 123 (24.3) |

| 35–9 | 137 (10.4) | 37 (9.0) | 58 (11.4) |

| ≥ 40 | 27 (2.1) | 9 (2.2) | 18 (3.6) |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Family type | |||

| Not lone parent | 679 (51.4) | 254 (61.5) | 378 (74.6) |

| Lone parent | 607 (46.0) | 152 (36.8) | 119 (23.5) |

| Missing | 34 (2.6) | 7 (1.7) | 10 (2.0) |

| Index child mother’s first born | |||

| Yes | 698 (52.9) | 175 (42.4) | 239 (47.1) |

| No | 622 (47.1) | 238 (57.6) | 268 (52.9) |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Ethnicity of respondent | |||

| White | 1257 (95.2) | 395 (95.6) | 469 (92.5) |

| Non-white | 58 (4.4) | 18 (4.4) | 37 (7.3) |

| Missing | 5 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) |

| Confounder | Group 1 (recipients) (N = 1320), n (%) | Group 2 (eligible, not claiming) (N = 413), n (%) | Group 3 (nearly eligible) (N = 507), n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal social class (NS-SEC) | |||

| Intermediate occupation | 147 (11.1) | 69 (16.7) | 106 (20.9) |

| Lower supervisory | 63 (4.8) | 34 (8.2) | 46 (9.1) |

| Managerial | 175 (13.3) | 54 (13.1) | 90 (17.8) |

| Never worked | 233 (17.7) | 27 (6.5) | 24 (4.7) |

| Semi-routine and routine occupation | 663 (50.2) | 206 (49.9) | 212 (41.8) |

| Small employers and own account workers | 36 (2.7) | 22 (5.3) | 28 (5.5) |

| Missing | 3 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) |

| Household social class (NS-SEC) | |||

| Intermediate occupation | 148 (11.2) | 70 (16.9) | 102 (20.1) |

| Lower supervisory | 114 (8.6) | 44 (10.7) | 71 (14.0) |

| Managerial | 223 (16.9) | 70 (16.9) | 136 (26.8) |

| Never worked | 169 (12.8) | 16 (3.9) | 5 (1.0) |

| Semi-routine and routine occupation | 597 (45.2) | 173 (41.9) | 142 (28.0) |

| Small employers and own account workers | 66 (5.0) | 39 (9.4) | 50 (9.9) |

| Missing | 3 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.2) |

| Mother’s highest education level (SCQF) | |||

| No qualification | 216 (16.4) | 26 (6.3) | 31 (6.1) |

| Lower level standard grades | 187 (14.2) | 40 (9.7) | 28 (5.5) |

| Upper level standard grades | 433 (32.8) | 133 (32.2) | 131 (25.8) |

| Higher grades and upper level vocational | 287 (21.7) | 146 (35.4) | 180 (35.5) |

| Degree level | 162 (12.3) | 55 (13.3) | 109 (21.5) |

| Other | 29 (2.2) | 13 (3.1) | 27 (5.3) |

| Missing | 6 (0.5) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) |

| SIMD 2009 quintiles | |||

| 1 (least deprived) | 95 (7.2) | 37 (9.0) | 45 (8.9) |

| 2 | 143 (10.8) | 54 (13.1) | 85 (16.8) |

| 3 | 232 (17.6) | 98 (23.7) | 93 (18.3) |

| 4 | 327 (24.8) | 101 (24.5) | 145 (28.6) |

| 5 (most deprived) | 522 (39.5) | 123 (29.8) | 139 (27.4) |

| Carstairs deciles | |||

| 1 (least deprived) | 43 (3.3) | 19 (4.6) | 23 (4.5) |

| 2 | 67 (5.1) | 28 (6.8) | 36 (7.1) |

| 3 | 92 (7.0) | 39 (9.4) | 48 (9.5) |

| 4 | 73 (5.5) | 31 (7.5) | 48 (9.5) |

| 5 | 116 (8.8) | 31 (7.5) | 47 (9.3) |

| 6 | 164 (12.4) | 46 (11.1) | 53 (10.5) |

| 7 | 140 (10.6) | 57 (13.8) | 66 (13.0) |

| 8 | 188 (14.2) | 42 (10.2) | 59 (11.6) |

| 9 | 192 (14.5) | 55 (13.3) | 53 (10.5) |

| 10 (most deprived) | 245 (18.6) | 65 (15.7) | 74 (14.6) |

| Urban–rural classification | |||

| Remote rural | 71 (5.4) | 18 (4.4) | 28 (5.5) |

| Accessible rural | 127 (9.6) | 56 (13.6) | 70 (13.8) |

| Large urban | 546 (41.3) | 162 (39.2) | 189 (37.3) |

| Other urban | 416 (31.5) | 128 (31.0) | 153 (30.2) |

| Small remote towns | 70 (5.3) | 10 (2.4) | 22 (4.3) |

| Accessible towns | 90 (6.8) | 39 (9.4) | 45 (8.9) |

Tables 9 and 10 show the descriptive statistics for the exposed (group 1) and control (groups 2 and 3) for the outcomes at age 10 months (see Table 9) and 3 years (see Table 10). There is a breastfeeding gradient, with the lowest proportion breastfeeding in group 1 and highest in group 3. There is also a gradient with BD: those in group 1 breastfed for a shorter time period than those in groups 2 and 3. Other outcomes in GUS sweep 1 are similar across the groups. For sweep 2, when the children were about 3 years of age, the outcomes were similar across the groups. There was a lower proportion of children who received vitamins at 3 years of age in group 1 than in groups 2 and 3.

| Outcome | Group 1 (recipients) (N = 1320) | Group 2 (eligible, not claiming) (N = 413) | Group 3 (nearly eligible) (N = 507) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary outcome | |||

| Child ever breastfed: yes, n (percentages) | 549 (0.45) | 219 (0.53) | 314 (0.62) |

| Duration of breastfeeding (months), mean (SD) | 1.18 (1.99) | 1.46 (2.16) | 1.88 (2.34) |

| Child weight and body size | |||

| Birthweight (g), mean (SD) | 3295 (629) | 3376 (625) | 3418 (507) |

| Low birthweight (< 2500 g), n (proportion) | 121 (0.092) | 27 (0.065) | 28 (0.055) |

| Child morbidity, n (percentages) | |||

| Birth timing: early | 568 (0.43) | 161 (0.39) | 233 (0.46) |

| Birth timing: on time | 145 (0.11) | 62 (0.15) | 71 (0.14) |

| Birth timing: late | 594 (0.45) | 190 (0.46) | 198 (0.39) |

| Premature birth: yes | 94 (0.071) | 28 (0.067) | 25 (0.05) |

| Infant and child feeding | |||

| Age at introduction of solid food (weeks), mean (SD) | 18.7 (5.9) | 19.4 (5.7) | 19.4 (5.5) |

| Outcome | Group 1 (recipients) (N = 939) | Group 2 (eligible, not claiming) (N = 307) | Group 3 (nearly eligible) (N = 413) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Child weight and body size, mean (SD) | |||

| Child weight (kg) | 11.71 (1.96) | 11.80 (2.23) | 11.64 (1.99) |

| Child height (cm) | 93.8 (4.6) | 94.4 (4.6) | 94.5 (3.9) |

| Mother’s perceptions of child’s weight age 3 years, n (percentages) | |||

| Normal weight | 883 (0.94) | 286 (0.93) | 384 (0.93) |

| Underweight | 38 (0.04) | 18 (0.06) | 21 (0.05) |

| Somewhat and very overweight | 19 (0.02) | 6 (0.02) | 8 (0.02) |

| Mother’s concerns about child’s weight age 3 years, n (percentages) | |||

| A little concerned | 85 (0.09) | 28 (0.09) | 41 (0.1) |

| Not concerned | 845 (0.9) | 273 (0.89) | 363 (0.88) |

| Quite and very concerned | 9 (0.01) | 6 (0.02) | 8 (0.02) |

| Infant and child feeding, n (percentages) | |||

| Daily fruit consumption | |||

| None | 85 (0.09) | 6 (0.02) | 8 (0.02) |

| 1 | 103 (0.11) | 9 (0.03) | 17 (0.04) |

| 2 or 3 | 282 (0.3) | 31 (0.1) | 66 (0.16) |

| 4 or 5 | 56 (0.06) | 9 (0.03) | 12 (0.03) |

| > 5 | 9 (0.01) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Mother’s perception of fruit consumption | |||

| Less than usual | 150 (0.16) | 12 (0.04) | 21 (0.05) |

| Same as usual | 357 (0.38) | 43 (0.14) | 78 (0.19) |

| More than usual | 19 (0.02) | 0 (0) | 4 (0.01) |

| HSV vitamin use, n (percentages) | |||

| Yes | 178 (0.19) | 95 (0.31) | 182 (0.44) |

| No | 761 (0.81) | 212 (0.69) | 231 (0.56) |

Descriptive statistics for Growing Up in Scotland data linked to routinely collected NHS data

Descriptive statistics for outcomes available in the GUS data linked to NHS routinely collected NHS data are shown in Table 11. In groups 1 and 2 the descriptive statistics were similar across all outcomes. There were differences between groups 1 and 2 and group 3, with group 3 tending to have slightly better outcomes across the range of outcomes. There were gradients for both the number of hospital stays and the average length of stay in hospital, with group 1 subjects having more stays with longer lengths of stay and group 3 subjects having fewer stays and shorter durations of stay. The exception was the proportion of children registered with a dentist. For all groups there was an increase across all years in the proportion of children registered with a dentist. By 2016, 90% of all children were registered with a dentist.

| Outcome | Database | Group 1 (recipients) | Group 2 (eligible, not claiming) | Group 3 (nearly eligible) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Birthweight (g) from birth records | SMR02 | N = 1204 | N = 382 | N = 454 | |

| Mean (SD) | 3365 (594) | 3389 (625) | 3486 (542) | ||

| Feeding status at health visitor first visit | Health visiting | N = 1190 | N = 388 | N = 461 | |

| Breast, n (percentages) | 274 (0.23) | 97 (0.25) | 180 (0.39) | ||

| Formula, n (percentages) | 821 (0.69) | 252 (0.65) | 235 (0.51) | ||

| Mixed, n (percentages) | 71 (0.06) | 35 (0.09) | 41 (0.09) | ||

| Unknown, n (percentages) | 24 (0.02) | 4 (0.01) | 5 (0.01) | ||

| Morbidity | |||||

| Hospital stays in 5 years (number of children with event), n (percentages) | SMR01 | 675 (0.53) | 191 (0.47) | 212 (0.44) | |

| Length of hospital stays in 5 years (days), mean (SD) | 1.15 (2.98) | 1.06 (1.92) | 0.85 (1.3) | ||

| Number of visits to A&E (number of children with event), n (percentages) | A&E | 293 (0.23) | 78 (0.20) | 64 (0.14) | |

| Number of visits to A&E (number of occasions), n (SD) | 1.5 (1.1) | 1.3 (0.7) | 1.2 (0.6) | ||

| Proportion registered with dentist, by year, n (percentages) | Dental records | N = 1246 | N = 405 | N = 417 | |

| 2010 | 78 (0.06) | 25 (0.06) | 32 (0.07) | ||

| 2011 | 465 (0.37) | 140 (0.35) | 184 (0.39) | ||

| 2012 | 759 (0.61) | 248 (0.61) | 302 (0.63) | ||

| 2013 | 942 (0.76) | 299 (0.74) | 378 (0.79) | ||

| 2014 | 1035 (0.83) | 326 (0.81) | 409 (0.86) | ||

| 2015 | 1088 (0.87) | 346 (0.85) | 434 (0.91) | ||

| 2016 | 1120 (0.90) | 361 (0.89) | 439 (0.92) | ||

| Vision test, na | Vision | 1007 | 338 | 409 | |

| Hearing test, nb | Hearing | 1132 | 366 | 441 | |

| Immunisations, nc | SIRS | 1246 | 405 | 477 | |

Mothers were seen to be engaging with health services for routine tests and immunisations. This was demonstrated by 98% of children in each exposure and control group having a vision test, 100% of children in each exposure and control group having a hearing test, and 100% of children in each exposure and control group having the specified immunisations.

Descriptive statistics for the Infant Feeding Survey

Tables 12 and 13 show the descriptive statistics of confounders and outcomes across the exposure and control groups for IFS. Group 3 had consistently better levels of all confounders than groups 1 and 2. This was different from the GUS sample. There was a higher proportion of mothers in managerial and professional NS-SEC (34.4%) in group 3 than in groups 1 (6.6%) and 2 (15.8%). Group 3 had a much lower proportion of women who were aged ≤ 16 years old when they left full-time education (16.8%) than groups 1 (40.0%) and 2 (25.7%).

| Confounder | Group, n % | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Group 1 (recipients), N = 1906 | Group 2 (eligible, not claiming), N = 1535 | Group 3 (nearly eligible), N = 4624 | |

| Mother’s age at birth (years) | |||

| < 20 | 319 (16.7) | 153 (10.0) | 127 (2.7) |

| 20–4 | 587 (30.8) | 442 (28.8) | 717 (15.5) |

| 25–9 | 478 (25.1) | 421 (27.4) | 1521 (32.9) |

| 30–4 | 305 (16.0) | 310 (20.2) | 1408 (30.4) |

| ≥ 35 | 202 (10.6) | 198 (12.9) | 830 (17.9) |

| Missing | 15 (0.8) | 11 (0.7) | 21 (0.5) |

| Maternal social class (NS-SEC) | |||

| Never worked | 564 (29.6) | 194 (12.6) | 309 (6.7) |

| Not classified | 205 (10.8) | 130 (8.5) | 356 (7.7) |

| Routine and manual occupation | 801 (42.0) | 655 (42.7) | 1344 (29.1) |

| Intermediate | 211 (11.1) | 314 (20.5) | 1025 (22.2) |

| Managerial and professional | 125 (6.6) | 242 (15.8) | 1590 (34.4) |

| Missing | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Mother’s age when finished full-time education (years) | |||

| ≤ 16 | 763 (40.0) | 395 (25.7) | 775 (16.8) |

| 17 | 351 (18.4) | 245 (16.0) | 552 (11.9) |

| 18 | 304 (15.9) | 332 (21.6) | 775 (16.8) |

| ≥ 19 | 454 (23.8) | 546 (35.6) | 2457 (53.1) |

| Missing | 34 (1.8) | 17 (1.1) | 65 (1.4) |

| Marital status | |||

| Partnership | 441 (23.1) | 568 (37.0) | 2696 (58.3) |

| Living together | 453 (23.8) | 435 (28.3) | 1378 (29.8) |

| Widow/separated | 60 (3.1) | 41 (2.7) | 40 (0.9) |

| Single | 916 (48.1) | 472 (30.7) | 445 (9.6) |

| Missing | 36 (1.9) | 19 (1.2) | 65 (1.4) |

| Mother’s first baby | |||

| Yes | 719 (37.7) | 848 (55.2) | 2425 (52.4) |

| No | 1187 (62.3) | 687 (44.8) | 2199 (47.6) |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| IMD quintilesa | |||

| 1 (most deprived) | 898 (47.1) | 516 (33.6) | 2240 (48.4) |

| 2 | 476 (25.0) | 353 (23.0) | 2327 (50.3) |

| 3 | 286 (15.0) | 293 (19.1) | 27 (0.6) |

| 4 | 163 (8.6) | 230 (15.0) | 21 (0.5) |

| 5 (least deprived) | 83 (4.4) | 143 (9.3) | 9 (0.2) |

| Outcome | Group 1 (recipients), N = 1906 | Group 2 (eligible, not claiming), N = 1535 | Group 3 (nearly eligible), N = 4624 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary outcome | |||

| Child ever breastfed: yes, n (percentages) | 1011 (0.53) | 1059 (0.69) | 3560 (0.77) |

| Duration of breastfeeding (months), mean (SD) | 1.24 (2.47) | 1.94 (2.96) | 2.97 (3.50) |

| Child weight and body size | |||

| Birthweight (g), mean (SD) | 3334 (589) | 3383 (621) | 3424 (566) |

| Low birthweight (< 2500 g), n (percentages) | 134 (0.07) | 106 (0.069) | 222 (0.048) |

| Child morbidity, n (percentages) | |||

| Full term | 1726 (0.9) | 1397 (0.91) | 4300 (0.93) |

| Premature | 128 (0.067) | 107 (0.072) | 254 (0.054) |

| Missing | 52 (0.03) | 31 (0.02) | 70 (0.014) |

| Infant and child feeding, mean (SD) | |||

| Age at introduction of solid food (months) | 4.78 (1.54) | 4.89 (1.47) | 5.06 (1.32) |

| Baby given cow’s milk (months) | 7.39 (1.61) | 7.00 (1.76) | 6.87 (1.44) |

For the outcomes (see Table 13), there were gradients across the groups for BI and BD with group 1 having the lowest proportion and shortest duration, then group 2 and group 3 having the highest proportion breastfeeding and the longest duration. For child body weight and size outcomes, groups 1 and 2 were similar to each other. In terms of infant feeding, group 1 infants were introduced to solid food earlier than those in groups 2 and 3, but this was only by a couple of weeks.

Propensity score matching results for Growing Up in Scotland and Infant Feeding Survey

Tables 14–16 show the results for the propensity score analysis. Children were not randomly assigned to the comparison groups. Therefore, to ensure we were making fair comparisons across the groups in evaluating the effectiveness of HSVs, we used PSM. PSM is the probability of being assigned to a treatment being conditional on the observed baseline characteristics. This method tries to mimic the characteristics of a RCT when a RCT is not possible (or desirable) but there are other observational data that can be used. The propensity score is a balancing score, which means that if you condition on the propensity score, the distribution of observed baseline covariates will be similar between exposed and control subjects. In other words, this matching on key characteristics can allow for the groups to be more balanced on covariates. It is a technique that can minimise selection bias and is better at getting to the causal effect than simple covariate adjustment in models. Children were matched using propensity scores to balance the groups according to confounders (see Chapter 2, Methods). The distribution of propensity scores for matching for both the GUS and the IFS databases are shown in Appendix 1, Figures 5–10. These figures show the distributions for matching group 2 to group 1 (see Appendix 1, Figures 5 and 8), group 3 to group 1 (see Appendix 1, Figures 6 and 9), and groups 1 and 2 to group 3 (see Appendix 1, Figures 7 and 10).

| Outcome | Group 1 (recipients), N = 412 | Group 2 (eligible, not claiming), N = 412 | p-value | Group 1, N = 505 | Group 3 (nearly eligible), N = 505 | p-value | Groups 1 and 2, N = 505 | Group 3 | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary outcome | |||||||||

| Child ever breastfed: yes, percentages | 0.49 | 0.53 | 0.255 | 0.58 | 0.62 | 0.189 | 0.58 | 0.62 | 0.168 |

| Duration of breastfeeding (months), mean (SD) | 1.32 (2.1) | 1.46 (2.2) | 0.374 | 1.73 (2.3) | 1.88 (2.3) | 0.315 | 1.84 (2.4) | 1.88 (2.3) | 0.803 |

| Child weight and body size | |||||||||

| Birthweight (g), mean (SD) | 3313 (614) | 3377 (626) | 0.162 | 3357 (616) | 318 (628) | 0.117 | 3345 (620) | 3418 (628) | 0.062 |

| Low birthweight (< 2500 g), percentages | 0.085 | 0.066 | 0.358 | 0.083 | 0.056 | 0.08 | 0.081 | 0.055 | 0.13 |

| Child morbidity | |||||||||

| Premature birth: yes, percentages | 0.061 | 0.067 | 0.779 | 0.075 | 0.049 | 0.118 | 0.059 | 0.049 | 0.579 |

| Infant and child feeding | |||||||||

| Age at introduction of solid food (weeks), mean (SD) | 18.7 (6.0) | 19.4 (5.7) | 0.11 | 19.4 (5.7) | 19.4 (5.5) | 0.91 | 19.5 (5.6) | 19.4 (5.5) | 0.726 |

| Outcome | Group 1 (recipients) | Group 2 (eligible, not claiming) | p-value | Group 1 | Group 3 (nearly eligible) | p-value | Groups 1 and 2 | Group 3 | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Birthweight (g) from birth records, n | 262 | 305 | 305 | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 3394 (627) | 3414 (560) | 0.768 | 3376 (605) | 3395 (570) | 0.683 | 3427 (618) | 3395 (570) | 0.654 |

| Morbidity | |||||||||

| Hospital stays in 5 years (number of children with event), n | 182 | 205 | 205 | ||||||

| Length of hospital stays in 5 years (days), mean (SD) | 3.6 (8.1) | 3.4 (5.4) | 0.086 | 4.4 (13.7) | 4.1 (9.5) | 0.11 | 4.3 (9.8) | 4.1 (9.5) | 0.11 |

| Number of visits to A&E (number of children with event), n | 74 | 60 | 60 | ||||||

| Number of visits to A&E (number of occasions), mean (SD) | 1.4 (0.9) | 1.3 (0.7) | 0.777 | 1.5 (1.3) | 1.2 (0.6) | 0.343 | 1.4 (0.8) | 1.2 (0.6) | 0.112 |

For outcomes in GUS sweep 1, across all comparison groups (group 1 vs. group 2, group 1 vs. group 3, and groups 1 and 2 vs. group 3), the outcomes did not differ. There was a slight difference in birthweight for the comparison groups 1 and 2 versus group 3 (p = 0.062), but the difference was only 73 g.

For outcomes in GUS linked to routinely collected NHS health data, across all comparison groups (group 1 vs. group 2, group 1 vs. group 3, and groups 1 and 2 vs. group 3), the outcomes did not differ. There was a slight difference in average length of hospital stay for the comparison group versus group 2 (p = 0.086), but the difference was only 0.2 days.

For outcomes in IFS, outcomes differed across the different comparison groups. For group 1 versus group 2, the children in group 1 were less likely to have been breastfed than those in group 2: 57% ever breastfed in group 1 compared with 69% in group 2. Those in group 1 were also breastfed for a shorter duration than those in group 2. There was a difference in ever breastfeeding and duration of breastfeeding across all the comparison groups. Birthweight differed between groups 1 and 3, and groups 1 and 2 and group 3. All outcomes differed between groups 1 and 2 and group 3 (see Table 16).

| Outcome | Group 1, (recipients), N = 1513 | Group 2 (eligible, not claiming), N = 1513 | p-value | Group 1, N = 1862 | Group 3 (nearly eligible), N = 1862 | p-value | Groups 1 and 2, N = 3375 | Group 3 N = 3375 | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary outcome | |||||||||

| Child ever breastfed: yes, percentages | 0.57 | 0.69 | < 0.0001 | 0.53 | 0.7 | < 0.0001 | 0.6 | 0.74 | < 0.0001 |

| Duration of breastfeeding (months), mean (SD) | 1.37 (2.58) | 1.94 (2.96) | < 0.0001 | 1.23 (2.45) | 2.09 (3.11) | < 0.0001 | 1.53 (2.70) | 2.51 (3.30) | < 0.0001 |

| Child weight and body size | |||||||||

| Birthweight (g), mean (SD) | 3350 (584) | 3381 (622) | 0.156 | 3334 (589) | 3398 (569) | 0.0007 | 3355 (604) | 3421 (560) | < 0.0001 |

| Low birthweight (< 2500 g), percentages | 0.065 | 0.071 | 0.607 | 0.071 | 0.052 | 0.025 | 0.071 | 0.048 | < 0.0001 |

| Child morbidity, percentages | |||||||||

| Full term | 0.91 | 0.9 | 0.341 | 0.9 | 0.92 | 0.186 | 0.93 | 0.91 | 0.0047 |

| Premature | 0.065 | 0.073 | 0.066 | 0.06 | 0.05 | 0.07 | |||

| Missing | 0.024 | 0.021 | 0.025 | 0.02 | 0.01 | 0.02 | |||

| Infant and child feeding, mean (SD) | |||||||||

| Age at introduction of solid food (months) | 4.78 (1.52) | 4.89 (1.47) | 0.161 | 4.78 (1.52) | 4.89 (1.50) | 0.108 | 4.83 (1.5) | 4.97 (1.37) | 0.0037 |

| Baby given cow’s milk (months) | 7.39 (1.58) |

7.00 (1.76) |

0.02 | 7.38 (1.59) |

6.96 (1.58) |

0.003 | 7.2 (1.68) |

6.93 (1.47) |

0.0069 |

Regression discontinuity results for Growing Up in Scotland

The forcing variable for the regression discontinuity method was household income. Categorical income was transformed into equivalised household income to make the forcing variable (see Chapter 2, Methods). It was not possible to use RD methods for most of the outcome variables as assumptions were not met. We present the results for the primary outcome of BI and BD, and the secondary outcomes of birthweight and low birthweight.

Table 17 gives the coefficients and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the RD analyses. There were no differences in the outcomes between those in group 1 (recipients) and those in group 2 (eligible). For group 1 versus group 3 (nearly eligible), children in the recipient group were less likely to be breastfed than those in the nearly eligible group. If they were breastfed, it was for a shorter duration (0.45 months shorter on average). Those in group 1 had a lower birthweight and were more likely to be in the low birthweight category than those in group 3. Those in groups 1 and 2 were breastfed for a shorter duration (0.33 months shorter on average) and had lower birthweight (0.018 g lighter on average) than those in group 3.

| Outcome | Group 1 (recipients) vs. group 2 (eligible, not claiming), coefficient of RD (95% CI) | p-value | Group 1 vs. group 3 (nearly eligible), coefficient of RD (95% CI) | p-value | Groups 1 and 2 vs. group 3, coefficient of RD (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary outcome | ||||||

| Child ever breastfed: yes | 0.036 (–0.047 to 0.121) | 0.394 | –0.068 (–0.138 to 0.0010) | 0.053 | –0.062 (–0.135 to 0.018) | 0.135 |

| Duration of breastfeeding (months) | 0.457 (–0.179 to 0.963) | 0.179 | –0.45 (–0.7938 to –0.109) |

0.0097 | –0.332 (–0.626 to 0.011) | 0.058 |

| Child weight and body size | ||||||

| Birthweight (g) | –26.75 (–109 to 40.71) | 0.368 | –49.50 (–84.0 to –17.0) | 0.0025 | 0.018 (0.005 to 0.035) | 0.0073 |

| Low birthweight (< 2500 g) | –0.0028 (–0.0183 to 0.0120) | 0.674 | 0.024 (0.011 to 0.040) | 0.0117 | –3.22 (–30.5 to 60.05) | 0.523 |

Table 18 summarises the comparisons across the two methods (propensity score with RD) and the two data sets (GUS and IFS) for outcomes available in both data sets. The main comparison group is group 1 versus group 2. For nearly all the outcomes, apart from ever BI and BD in IFS, the results indicated that there is no effect of HSV on the outcomes. For ever breastfed and duration of breastfeeding, there are differences between propensity score results from GUS and IFS, with the IFS indicating a negative effect of HSV on breastfeeding.

| Outcome | Group 1 (recipients) vs. group 2 (eligible, not claiming) | Group 1 vs. group 3 (nearly eligible) | Groups 1 and 2 vs. group 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Child ever breastfed: yes | |||

| GUS (RD) | R > E | R < NE | AE < NE |

| GUS (PS) | R < E | R < NE | AE < NE |

| IFS (PS) | R < E | R < NE | AE < NE |

| Duration of breastfeeding (months) | |||

| GUS (RD) | R > E | R < NE | AE < NE |

| GUS (PS) | R < E | R < NE | AE < NE |

| IFS (PS) | R < E | R < NE | AE < NE |

| Birthweight (g) | |||

| GUS (RD) | R < E | R < NE | AE > NE |

| GUS (PS) | R < E | R < NE | AE < NE |

| IFS (PS) | R < E | R < NE | AE < NE |

| Low birthweight (< 2500 g) | |||

| GUS (RD) | R < E | R > NE | AE < NE |

| GUS (PS) | R < E | R < NE | AE < NE |

| IFS (PS) | R < E | R < NE | AE < NE |

| Premature | |||

| GUS | R < E | R > NE | AE > NE |

| IFS | R < E | R – NE | AE < NE |

| Age at introduction of solid food (months) | |||

| GUS | R < E | R – NE | AE – NE |

| IFS | R < E | R < NE | AE < NE |