Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number NIHR135455. The contractual start date was in January 2022. The final report began editorial review in November 2022 and was accepted for publication in July 2023. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2023 Hock et al. This work was produced by Hock et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2023 Hock et al.

Background

The impacts of social class in childhood on adult health outcomes and mortality are well documented in quantitative analyses (e.g. Smith et al.). 1 Housing is one element that can impact on health via social and structural inequalities. 2 The impact of housing conditions on child health is well established. 3

Kohler4 presents the field of ‘child public health’, advocating for a move away from a narrow focus on clinical paediatric medicine, to place child health within its social, economic and political context, and uses the methods and tools of public health. This approach highlights the importance of children’s health and well-being within public health overall, due to the high proportion of children worldwide, their vulnerability and, in many cases, lack of agency, and the formative nature of childhood. 4 Cresswell5 argues that young people (and their families) who are homeless are a vulnerable group with particular difficulty in accessing healthcare and other services, and, as such, meeting their needs should be a priority.

There is an extensive and diverse evidence base on the relationships between housing and health, including both physical and mental health outcomes. Much of the evidence relates to the quality of housing and specific aspects of poor housing including cold and damp homes, poorly maintained housing stock or inadequate housing leading to overcrowding. There is also increasing concern about the health impacts of housing insecurity and concern that children may be particularly vulnerable to these effects of not having a secure and stable home environment. The current review was commissioned within the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Public Health Research (PHR) programme in response to concerns about the health inequalities related to the impact of housing insecurity on the health and well-being of children and young people (CYP).

Terminology and definitions related to housing insecurity

A wide variety of related terms and definitions are available to assess ‘unstable’ or ‘insecure’ housing and there is no standard definition or validated instrument.

Housing insecurity

The terminology and definitions used by the Children’s Society are based directly on research with children that explores the relationship between housing and well-being. 6 They use the term ‘housing insecurity’ for those experiencing and at risk of multiple moves that are (1) not through choice and (2) related to poverty. 6 This reflects their observation that multiple moves may be a positive experience if it is through choice and for positive reasons (e.g., employment opportunities; moves to better housing or areas with better amenities).

Housing instability

Housing instability is variably defined as having difficulty paying rent, spending more than 50% of household income on housing, having frequent moves, living in overcrowded conditions or doubling up with friends and relatives. 7

Unstable or precarious housing

Public Health England (PHE) [now the Office for Health Improvement and Disparities (OHID)] distinguish between ‘unhealthy’, ‘unsuitable’ and ‘unstable’ (or ‘precarious’) housing. The latter is defined as ‘a home that does not provide a sense of safety and security including precarious living circumstances and/or homelessness’. 8

Three-dimensional housing insecurity

Preece and Bimpson9 use a broad definition of ‘housing insecurity’ to explore the relationship with mental health. Their definition has three dimensions:

-

Financial insecurity includes issues such as the affordability of housing and its relationship with mental health, relationships with tenure, and the impact of housing-related debts and other financial stressors.

-

Spatial insecurity relates to the (in)ability of an individual or household to remain in a given dwelling or wider neighbourhood area. This includes issues such as eviction and forced moves and their relationship with mental health, tenure security and insecurity and rurality.

-

Relational insecurity draws out the ways in which individuals’ experiences of housing and home are bound up with relationships with others.

There are also specific and quantitative definitions used in research literature:

Residential mobility

This term may be defined in terms of frequency and/or number or distance of moves. 10

Residential transience

This term generally denotes a high frequency of moves and more specifically may be defined by a specific minimum number of moves before a specific age. For example, ‘moving three or more times before age 7 was associated with 36% greater likelihood of lifetime major depression and more than twice the likelihood of developing depression before age 14 compared with those who moved less’ (p. 683). 11

Homelessness/temporary housing

Regardless of housing tenure and the condition and suitability of housing for families, unstable or insecure housing circumstances are the most likely direct precursor to homelessness. This implies that evidence for the direct health effects of homelessness and/or living in temporary council-provided accommodation is directly relevant to understanding the impacts of unstable housing.

While acknowledging the lack of a standard definition or validated instrument for housing insecurity or instability, this review mobilises The Children’s Society definition of housing insecurity, which focuses on the actual experience of and risk of multiple moves that are (1) not through choice and (2) related to poverty. The rationale for this is that the definition goes some way towards acknowledging that the wider health and well-being impacts of housing insecurity may be experienced by families who may not have experienced frequent moves but for whom a forced move is a very real possibility. The definition allows for a range of precarious housing situations (e.g., private rental accommodation with short-term or insecure tenancy agreements; temporary or emergency housing and homelessness) and a range of reasons for insecurity, which link to poverty (e.g., domestic violence, recent migration). This is articulated in more detail in the inclusion criteria (see Methods).

Housing insecurity in the UK today – the extent of the problem

Recent policy and research reports from multiple organisations highlight a rise in housing insecurity among families with children. 7,9,12 Housing insecurity has grown as a result of a number of trends in the cost and availability of housing, reflecting in particular the rapid increase in the number of low-income families with children living in the private rental sector. 9,12,13 This is partly due to a lack of social housing and unaffordability of home ownership. 7 The nature of tenure in the private rented sector and gap between available benefits and housing costs means even low-income families that do not experience frequent moves may experience the impact of perceived housing insecurity. 14

The increase in homeless families, including ‘hidden homeless’ living with relatives or friends and those in temporary accommodation provided by local authorities, is a related consequence of the lack of suitable or affordable rental properties, which is particularly acute for lone parents and larger families. The numbers of children entering the care system or being referred to social services because of family homelessness contributes further evidence on the scale and severity of the issue. 15

COVID-19 has exacerbated housing insecurity in the UK. 13 This is related to increased financial pressures for families (due to loss of income and increased costs for families with children at home) meaning they are unable to keep up with mortgage/rent payments and compounded by a reduction in informal temporary accommodation being offered by friends and families due to social isolation precautions related to the virus itself. 13 Further, the COVID-19 pandemic has underscored the risks posed by poor housing quality (including overcrowding) and housing insecurity during a public health crisis. 13,16 Recent research with young people in underserved communities across the country has also highlighted their experience of the uneven impact of COVID-19 for people in contrasting housing situations. Young people described how lockdown measures keeping people at home more than usual had a more damaging effect on young people living in unsuitable accommodation. 17 The cost-of-living crisis is also likely to exacerbate housing insecurity among families in the UK, with private rental prices increasing steeply from December 2021 to December 2022. 18

While the temporary ban on bailiff-enforced evictions, initiated due to the pandemic, went some way towards acknowledging the pandemic’s impact on housing insecurity, housing organisations are lobbying for more long-term strategies to support people with pandemic-induced debt and rent arrears. 16 The Joseph Rowntree Foundation (JRF) has warned of the very real risk of a ‘two-tier recovery’ from the pandemic, highlighting the ‘disproportionate risks facing people who rent their homes’ (para. 1). 19 Their recent large-scale survey found that 1 million renting households ‘are worried about being evicted in the next 3 months’ and half of these are families with children. 19 The survey also found that households with children, renters from ethnic minority backgrounds and households on low incomes are disproportionately affected.

The cost-of-living crisis is now exacerbating the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, with many households experiencing or set to experience housing insecurity due to relative reductions in income accompanying increases in rent and mortgage repayments. 20 People experiencing or at risk of housing insecurity are disproportionately affected, due to higher food and utility costs. 21

Research evidence on relationships between housing in childhood and health

Housing is a key social determinant of health and there is a substantive evidence base of longitudinal cohort studies and intervention studies to support a causal relationship between the quality, affordability and stability of housing and child health. 22 This includes immediate impacts on mental and physical health outcomes and longer-term life course effects on wider determinants of health including education, employment and income as well as health outcomes. 23

The negative health impact of poor physical housing conditions (damp, mould, cold, overcrowding and safety issues) has been well documented. 24 A survey of 266 paediatricians in 2017 found that more than two-thirds reported homelessness or housing as contributing to ill health of the children they work with. 25 A variety of pathways have been implicated in the relationship between housing insecurity and child health and well-being, including ‘family processes such as maternal depression and psychological distress, material hardships, and parental nightly bedtime routines with children’ (p. 8). 22 Frequent moves are also associated with poorer access to preventive health services, reflected in lower vaccination rates. 26,27 Housing instability and low housing quality are associated with worse psychological health among young people and parents. 28,29 However, the ‘less tangible aspects of housing’ (p. 1) for low-income, vulnerable households are poorly understood. 24 The National Children’s Bureau12 draws attention to US-based research that has shown that policies that reduced housing insecurity for young children can help to improve their emotional health,30 and that successful strategies have the potential to reduce negative outcomes for children with lived experience of housing insecurity including the following: emotional and behavioural problems; lower academic attainment; and poor adult health and well-being. 31

Housing tenure, unstable housing situations and the quality or suitability of homes are inter-related. For example, if families are concerned that if they lost their home they would not be able to afford alternative accommodation, they may be more likely to stay in overcrowded or poor-quality accommodation or in a neighbourhood where they are further from work, school or family support. This may be an additional causal pathway whereby housing insecurity can lead to diverse housing and neighbourhood-related negative impacts for children, even if it is not reflected directly in experience of frequent moves or homelessness. Thus, the relationship between housing insecurity and child health is likely to be complicated by the frequent coexistence of poor housing conditions or unsuitable housing with housing insecurity. The relationship between unstable housing situations and health outcomes is further confounded by other major stressors, such as poverty and changes in employment and family structure, which may lead to frequent moves.

The evidence from cohort studies that shows a relationship between housing insecurity, homelessness or frequent moves in childhood and health-related outcomes can usefully quantify the proportion of children and families at risk of poorer health associated with housing instability. It can, however, only suggest plausible causal associations. Further, the ‘less tangible aspects of housing’ (p. 1) for low-income, vulnerable households are poorly understood. 24 Additional (and arguably stronger) evidence comes from the case studies and qualitative interviews with CYP that explore the direct and indirect impacts of housing insecurity on their everyday lives and their physical and mental well-being.

Aim and objectives

The current review aimed to identify, appraise and synthesise research evidence that explores the relationship between housing insecurity and the health and well-being of CYP. We aimed to highlight the relevant factors and causal mechanisms in order to make evidence-based recommendations for policy, practice and future research priorities.

The objectives in order to achieve this aim were as follows:

-

To produce a conceptual framework for exploring the relationship between insecure (or ‘unstable’) housing and the health and well-being of CYP.

-

To conduct a systematic review to identify, appraise and synthesise the most relevant research evidence on the relationship between housing insecurity and the health and well-being of CYP.

-

To identify evidence-based recommendations for housing policy and practice, and future research to address identified gaps in the literature.

Methods

Review methodology and approach

We undertook a systematic review synthesising qualitative data, employing elements of rapid review methodology,32–34 recognising that the review was time-constrained. Rapid review methods are described in the methods subsections below (e.g. limiting the number of papers that were double extracted, and not routinely contacting included authors for additional references). The protocol is registered on the PROSPERO registry, registration number CRD42022327506.

Search strategy

Database searches were conducted on 8 April 2022 of the following databases: MEDLINE, EMBASE and PsycINFO (via Ovid); Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ASSIA) and International Bibliography of the Social Sciences (IBSS) (via ProQuest) and Social Sciences Citation Index (via Web of Science).

Due to the short timescales for this project, searches aimed to balance sensitivity with specificity, and were conceptualised around the following concepts:

(housing insecurity) and (children or families) and (experiences)

including synonyms, and with the addition of a filter to limit results to the UK where available.

To expedite translation across different databases, searches consisted mainly of free-text search strings (including proximity operators), in order to retrieve these terms where they occurred in titles, abstracts or any other indexing field (including subject headings).

Since it was not possible to identify a UK geographic filter designed for PsycINFO (nor other reported procedures to limit results by geography), these results were screened separately from the others, with particular attention paid to study location.

The searches of ASSIA and IBSS (via ProQuest) and Social Sciences Citation Index (via Web of Science) used a simplified strategy based on those reproduced in Appendix 1.

Database searching was accompanied by scrutiny of reference lists of included papers and relevant systematic reviews (within search dates), and grey literature searching, which was conducted and documented using processes outlined by Stansfield et al. 35 (see Report Supplementary Material 1).

Inclusion criteria

Population

The population included families with children aged 0–16 experiencing or at risk of housing insecurity, living in a family unit, in the UK. This could include, but not be limited to, those on low incomes, lone parents and ethnic minority groups, including migrants, refugees and asylum seekers. Informants could include the children themselves, parents/close family members (e.g. grandparents, if the children live with them), or other informants with insight into the child’s/children’s experiences (e.g. teachers, clinicians). Children outside a family unit (i.e. who had left home or who were being looked after by the local authority) and traveller families were excluded, as their circumstances are likely to be very different from the target population.

Exposure

We defined ‘housing insecurity’ according to the Children’s Society6 definition: those experiencing and at risk of multiple moves that are (1) not through choice and (2) related to poverty. This included actual or perceived insecurity related to housing situations, which may include the following: private rental accommodation with short-term or insecure tenancy agreements; temporary emergency housing; homelessness (including ‘hidden’ homelessness). We also aimed to include research related to interventions that have the specific aim of reducing housing insecurity and/or mitigating the impact of housing insecurity on the health and well-being of children, where identified.

Context

The current UK policy context shows exacerbation of factors that can lead to housing insecurity. These include the following: trends in poverty and inequality exacerbated by the COVID pandemic; changes in the housing market (an increase in investment properties, loss of social housing); increased numbers of low-income families living in the private rental sector; insecure or short-term tenancies; increasing housing costs (and fuel/food costs) and lack of affordable properties (see Background).

Outcomes

Any reported immediate and short-term outcomes related to childhood mental and physical health and well-being (up to the age of 16) were included. Studies reporting on the long-term outcomes and impacts in adulthood of housing insecurity experienced in childhood were excluded, as were short-term outcomes reported by adults.

Studies

We included studies reporting qualitative data on the views of young people and/or parents with young children on how housing insecurity has impacted on their (or their children’s) well-being. This could include cross-sectional and longitudinal qualitative case studies, and mixed-methods studies that collected and analysed qualitative data. Books (with the exception of searchable e-books) and dissertations were excluded. Conference abstracts were only included if they contained relevant data unavailable elsewhere.

Study selection

Search results from electronic databases were downloaded to a reference management application (EndNote). The titles and abstracts of all records were screened against the inclusion criteria by one reviewer and checked for agreement by a second reviewer. A PDF version of each paper selected at the abstract screening stage by at least one of the two reviewers was downloaded and screened against the inclusion criteria by one reviewer. A proportion (10%) of papers excluded at the full text stage were checked by a second reviewer. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion.

Grey literature searches and screening were documented in a series of tables as recommended by Stansfield et al. 35 (see Report Supplementary Material 1). Titles of relevant data sources were screened against the inclusion criteria on each web platform searched, and the full documents of those with titles that suggested potential eligibility were downloaded in full for full text screening. The majority of grey literature sources were reports; however, briefings and web pages were also examined. One reviewer undertook full-text screening, and any queries were checked by another reviewer, with decisions discussed among the review team until a consensus was reached.

Reference lists of included studies and relevant reviews were screened for potentially relevant papers. The abstracts and full texts of relevant references were downloaded and examined for relevance by one reviewer.

Data extraction

A data extraction form was devised based on forms that the team has previously tested for similar reviews of public health topics. The extraction form was piloted by three reviewers and any suggested revisions were discussed and agreed.

We extracted and tabulated key data from the included papers. This included the study first author and year, location, population, study aims, whether housing insecurity was an aim of the study, study design and methods of analysis, informant/s, housing situation of family, reasons for homelessness/housing insecurity, conclusions, relevant policy/practice implications, any study limitations, and themes and qualitative data, including any relevant quotations, as reported in the findings of the study.

Data extraction was performed by one reviewer, with a 10% sample formally checked for accuracy and consistency by a second reviewer. Any qualitative data relating to housing insecurity together with some aspect of health or well-being in a child (or children) or young person (or young people) aged 0–16 were extracted in context (i.e., with relevant contextual data that aided the interpretation of the data in question). This included authors’ interpretations and verbatim quotations from participants. Authors’ themes relating to relevant data were also extracted to provide context and not for inclusion in the synthesis (see below in the Data synthesis subsection). Throughout the process of extraction, we sought to maintain fidelity to the authors’ and participants’ terminology and phrasing.

Quality appraisal

We assessed the quality of the included studies using appropriate checklists for the type of study and the type of literature source. Published literature was assessed using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) checklist for qualitative studies,36 and the quality of grey literature sources was appraised using the authority, accuracy, coverage, objectivity, date, significance (AACODS) checklist. 37 Quality assessment was performed by one reviewer, with a 10% sample checked for accuracy and consistency by a second reviewer.

Developing a model to visualise the results

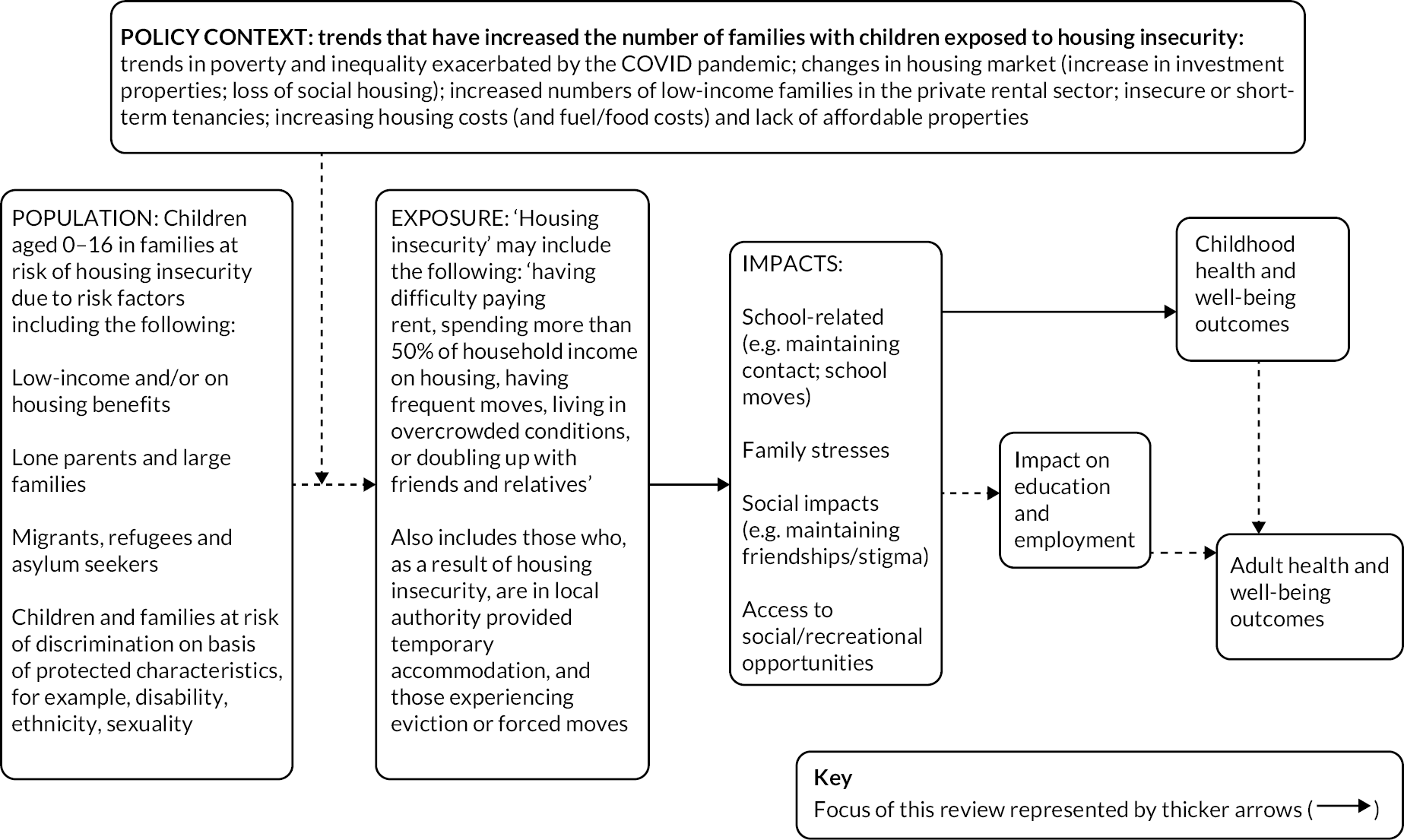

We undertook preliminary literature searches to identify an appropriate conceptual framework or logic model to guide the review and data synthesis process; however, we were not able to identify a framework that specifically focused on housing insecurity among CYP and was sufficiently broad to capture relevant contexts, exposures and impacts. We therefore developed an a priori conceptual framework, based on a consultation with key policy and practice stakeholders and topic experts and examination of key policy documents (Figure 1). This conceptual framework was used to guide data synthesis (see Data synthesis).

FIGURE 1.

A priori conceptual framework for relationship between housing insecurity and the health and well-being of CYP.

Data synthesis

The review question required that the synthesis be both deductive and inductive. Therefore, we adopted a dual approach whereby we synthesised data according to the a priori conceptual framework (see Figure 1) and sought additional themes, categories and nuance inductively from the data, in an approach consistent with the second stage of ‘best-fit framework synthesis’. 38,39 Inductive themes were analysed using the Thomas and Harden40 approach to thematic synthesis, but with coding of text extracts instead of coding line by line. 41,42

First, one reviewer (of two) coded text extracts inductively and within the structure of the conceptual framework (see Figure 1), simultaneously. Each relevant text extract (which reported on at least one element of the framework as it related to some aspect of the health/well-being of a child/young person experiencing housing insecurity) was linked to both an inductive code based on the content of the text extract and an element of the conceptual framework. Some extracts were assigned multiple codes and could be linked to any one individual element or to multiple elements of the conceptual framework. During the process of data extraction, we identified four distinct populations (see Results), and data were coded discretely for each population. We initially coded data against the ‘exposure’, ‘impacts’ and ‘outcomes’ elements of the conceptual framework (see Figure 1); however, we subsequently added a further element within the data; ‘protective factors’ (see Results).

Next, the data were synthesised according to each element of the logic model in turn. Where a text extract was coded against multiple elements, the data extract was synthesised for each one. Data relating to each population were synthesised separately. One reviewer examined the codes relating to each element of the logic model and grouped the codes according to conceptual similarity and broader meaning. The thematic structure and relationships between concepts apparent from the text extracts are reported in a logic model, as well as being reported narratively, in more detail.

Quotations from included papers have been used for illustrative purposes, including both authors’ interpretations and reporting, and verbatim quotations from study participants. All included studies used pseudonyms, and the same pseudonyms have been reported in the current synthesis.

Patient and public involvement and stakeholder involvement

During December 2021 key policy and practice stakeholders and topic experts were invited to comment on the potential focus of the review and the appropriate definitions and scope in terms of review questions and inclusion criteria. The list of stakeholders is in Appendix 2. We shared the protocol with the stakeholder advisory group, and sought their guidance on potentially relevant sources of grey literature (web platforms) to search. We searched all web platforms suggested by the stakeholders. We consulted stakeholders on the review findings and invited them to give general feedback and suggest additions or amendments to the implementations for policy and practice.

This review is based on the perspectives of those who have experienced housing insecurity (including children, young people and parents/carers) and people close to them (e.g. teachers, clinicians). Our whole approach therefore foregrounds the lived experiences of children, parents/carers and those working with them. We have also sought to work closely with youth organisations in the North with whom we have existing productive research collaborations. While the timing of the review (while the organisation was involved in another research project and then over the school summer holidays) has meant that we have been unable to seek advice and guidance early on in the review, we consulted with this group over the review findings. We sought to understand if the review resonated with their experiences, if they thought anything was missing and with whom they thought we should share the findings. We are also planning to work with them to produce accessible and engaging outputs for a public audience.

Results

Study selection

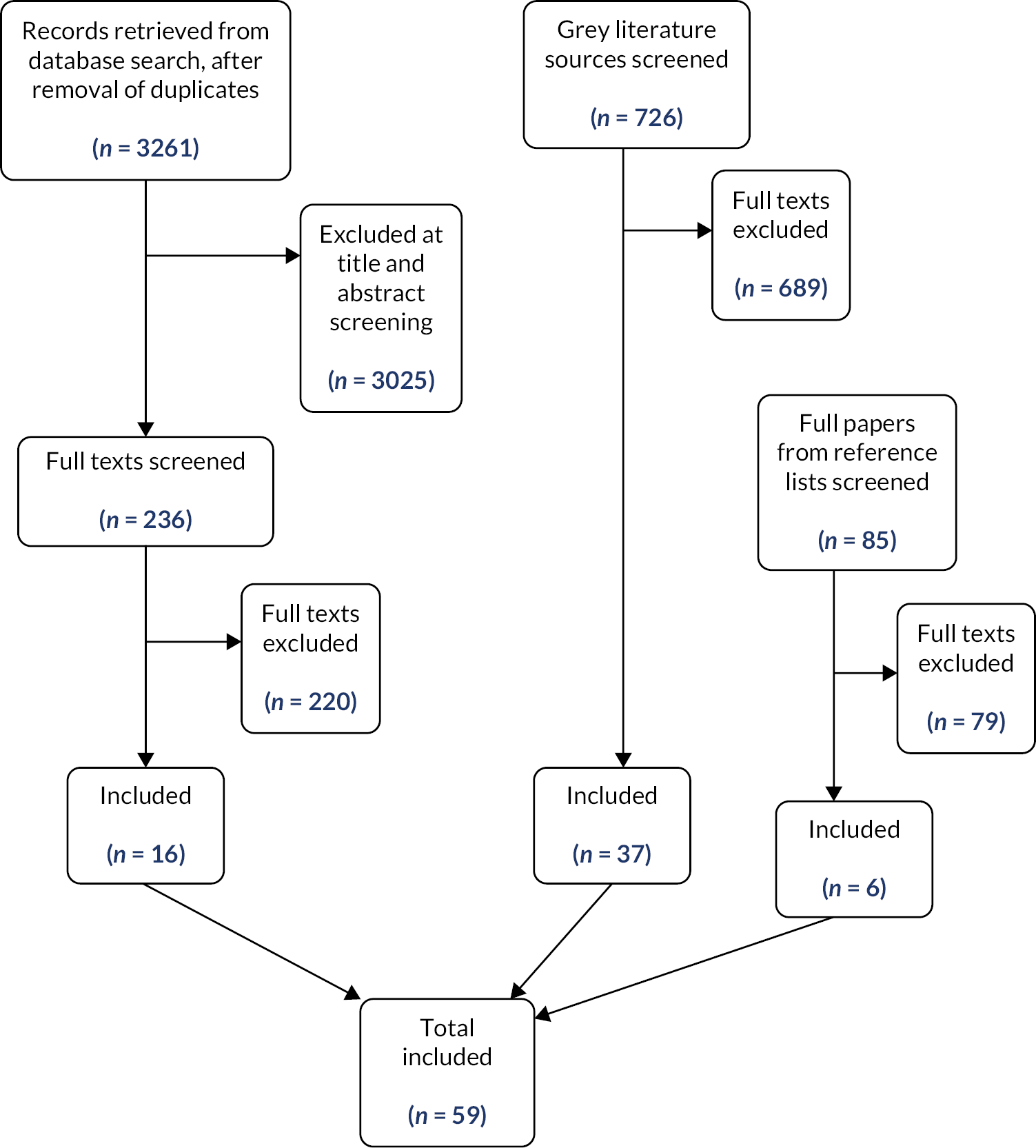

The database searches generated 3261 records after the removal of duplicates, of which 236 full texts were retrieved and 16 were included. Due to the large number of full texts excluded, the reasons for exclusion of each individual paper are provided in the Report Supplementary Material 1. Altogether, 726 grey literature sources were examined at full text, of which 37 were included. A further 85 papers were identified as potentially relevant from the references lists of included papers and relevant reviews and the full texts were examined, of which 6 were included in the review. The process of study selection is summarised in Figure 2 and a summary of study characteristics is presented in Table 1. Of the included studies, 16 took place across the UK as a whole, 1 was conducted in England and Scotland, 1 in England and Wales and 17 in England. In terms of specific locations, 13 were reported to have been conducted in London, a London Borough (Newham) or Greater London, 2 in Birmingham, 1 in Fife, 2 in Glasgow, 1 in Leicester, 1 in Rotherham and Doncaster, and 1 in Sheffield. The location of one study was not reported.

FIGURE 2.

Flow diagram of study selection.

| Study | Location | HI an aim?a (Y/N) | Population (numbers, where given) | Children (numbers, where given) | Informant/s (numbers, where given) | Study design analysis | Housing situation of family | Reasons for homelessness/HI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Backett-Milburn43 | Scotland | N | General N = 15 children/parent–child dyads |

15 children, aged 9–12 years. Only one reported on housing. | Children and their parents | Semistructured interviews using child-appropriate techniques Thematic analysis |

Vulnerably housed | Unemployment of parents |

| Bowyer44 | Unclear | Y | Domestic violence N = 5 children, girls aged 10–16 exposed to domestic violence |

5 children | Children | Semistructured interviews Interpretative phenomenological analysis |

Temporary accommodation, mostly refuges | Domestic violence |

| Bradley45 | London | N | General N = 13 parents, living in temporary accommodation |

Numbers not reported. Families had one to four children. Aged 2–9 years (mean 3.6 years). | Parents | Semistructured interviews Thematic analysis |

Temporary accommodation | Not reported |

| Coram Children’s Legal Centre46 | Greater London | N | Migrants No details |

Not reported | Parents | Case studies Methods of data collection and analysis are unclear |

Vulnerably housed | Immigration status |

| Dexter47 | London | N | Migrants Families seeking support under Section 17, as well as those who are already living on this support |

‘Destitute migrant children, whose parents have no recourse to public funds’ | N = 7 Children’s Society practitioners, N = 1 professional from Hackney Migrant Centre |

Semistructured interviews and a roundtable analysis of anonymised case files No analysis details |

Varied, usually temporary | Poverty, immigration status |

| Jolly48 | Birmingham | N | Migrants N = 15 immigrant families. Most from West Africa and Caribbean households |

24 children | Children | 17 semistructured interviews Qualitative: directive content analysis |

Mainly temporary, or relocated | Immigration status. Not in receipt of public funds |

| Karim49 | UK | N | General N = 35 families at follow-up. |

Mean number of children = 3 (range 1–7). | Main carer, usually mother | Semistructured interviews Thematic content coding |

Hostel (or other temporary accommodation) | Domestic violence (20%), neighbour harassment (23%), relationship breakdown (23%) and eviction (17%) |

| Lawson50 | Glasgow | Y | Gentrification 23 households, 21 of which ‘family households’ (≥ 1 adult + ≥ 1 child/young person) |

Gentrification Not described |

Parents | Longitudinal qualitative study (18 months) Semistructured interviews Grounded theory |

Being relocated due to regeneration | Regeneration (gentrification of local area) |

| Lawson51 | Glasgow | Y | Gentrification 20 family households (10 at follow-up) |

Gentrification 40 CYP |

Parents | Longitudinal qualitative study (18 months) Semistructured interviews Grounded theory |

Being relocated due to regeneration | Regeneration (gentrification of local area) |

| Minton52 | England and Scotland | Y | General ‘nearly 50 individuals’ | Not reported | Children, parents, doctors, teachers, religious leaders, housing and homelessness professionals | Study design not reported Analysis method unclear |

Various, including homeless, in temporary accommodation, and precariously housed/moved round a lot | Mainly eviction. Mostly poverty-related |

| Moffatt53 | North East England | N | General N = 38 tenants, all in receipt of welfare benefits |

11 children altogether – 9 households had 1 child aged < 18 years, 2 had 2, and 1 had 3 children. | Parents, service providers | Semistructured interviews Qualitative interpretive analysis |

Living in social rented properties | Poverty, bedroom tax |

| Nettleton54 | London | Y | General 20 families lived in London Boroughs |

17 children (including siblings), age 7–18 years | Children and their parents | Qualitative Semi structured interviews No reporting of analysis methods |

Mortgage repossession (implies currently in rented accommodation) | Mortgage repossession |

| Office of the Deputy Prime Minister55 | England | N | General N = 82 ethnic minority homeless households, 72 had a child, pregnancy, or children |

No details | One adult within each household interviewed, 73% female. Also, local authority service providers, charitable/voluntary sector service providers |

Interviews Thematic analysis |

Homeless | Various (domestic violence), relationship breakdowns, family disputes, eviction, social exclusion, pregnancy, severe poverty, losing accommodation tied to a job, loss of NASS accommodation, racial harassment |

| Oldman56 | UK | N | General 40 parents of children with physical disabilities or sensory impairments |

Physical disabilities or sensory impairments | Parents Children |

In-depth interviews Qualitative analysis |

Wide range of housing unsuitability and included those who had adapted or moved house in response to their housing needs | Disabled child |

| Price57 | England and Wales | N | Migrants N = 91 interviewees, including parents, local authority workers, and third sector workers/advocates |

Not reported | Parents, local authority workers, advocates, voluntary sector staff | Mixed methods – survey first, then in-depth interviews No detail on analysis |

Various, usually temporary | Poverty, immigration status, NRPF |

| Rowley58 | UK | N | Migrants 9 adults; 5 males, 4 females Refugees |

Not reported | Parents | Qualitative interviews Thematic analysis |

Homeless or temporarily housed | Refugee status |

| Thompson59 | Newham, East London | Y | General 20 families (N = 40) at wave 1, 15 families (N = 28) at wave 2 |

Age of children 11–16 |

Parents and children | Ethnography Described as narrative family interviews and narrative analysis with Bakhtinian interpretation |

Private renters, owned or were buying their own home. | Various including: overcrowding; joblessness; extremely poor quality of current housing; having ‘nowhere else to go’ (homelessness); and health problems |

| Tischler60 | Leicester | Y | Domestic violence 49 homeless families (couple or single mother with children) |

Families had a mean number of 3 children (range = 1–7) | Carer (usually mother) | Qualitative (semistructured) interviews Thematic analysis |

Large statutory hostel for homeless parents and children | Domestic violence |

| Tischler61 | Birmingham | Y | Domestic violence 28 homeless women with dependent children |

Children aged ≥ 3 years. The median number of children was 2, with a range of 1–6 | Mother | Semistructured interviews Thematic analysis |

Living in one of three local-authority-run hostels | Domestic violence |

| Tod62 | Rotherham and Doncaster | N | General 35 families – low-income households |

Not reported | 1 parent from each family and 25 health, education and social care staff | In-depth semistructured individual and group interviews Framework analysis | Mixture of privately owned, private rented and council rented | Low-income households at risk of instability |

| Warfa63 | London | Y | Migrants Somali refugees in the UK (21 families) |

School-age children | Adults Professionals in supporting roles |

In-depth group discussions | Refugees Frequent moves |

Migration – Somali refugees |

| Watt64 | East London | Y | General 5 young mothers (aged 18–24 years) and 12 female lone parents |

Not reported | Mothers | Interviews and participant observation | Hostel (homeless) | Family disputes, domestic violence and evictions |

| Wilcox65 | Sheffield | N | Domestic violence 20 white working class women |

Not reported | Mothers | In-depth interviews and participant observation Analysis not reported |

Council estate property | Fleeing domestic violence |

| Young Women’s Trust66 | London | N | General 4 young women living on low incomes |

Not reported | Mothers | Focus group Analysis not reported |

Unsuitable housing | Not reported |

| Children’s Commissioner67 | England | N | General N = 15 children N = 25 parents and carers |

No details | Children and parents | Observation ‘mosaic approach’ No analysis details |

In rented accommodation | Poverty (worry about being evicted) |

| Children’s Commissioner68 | England | Y | General Children and families living in temporary accommodation |

No details | Children, parents, specialist health visitor team | Described only as: ‘visiting and speaking with participants, and conducting analysis’ | In temporary accommodation, including B&Bs, converted office blocks and converted shipping containers | Various, not clearly described |

| Children’s Commissioner69 | England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland | N | General Described as ‘young people’ |

No details | Children | ‘Surveys, virtual visits to prisons, youth groups and children’s homes’ Analysis unclear |

Unclear | Unclear – reasons include poverty and migration |

| Children’s Commissioner70 | England | N | General N = 557,077 overall sample |

Aged 4–17 | Children | Online survey with focus groups and interviews Analysis unclear |

Unclear | Unclear |

| Children’s Society71 | England | N | Domestic violence Migrants N = 60 No details |

Not reported | Children | Longitudinal fieldwork – annual semistructured interviews Thematic analysis |

Temporary insecure housing | Various: to build a better life in the UK; to accommodate growing numbers of siblings; to live closer to extended family; parent with new partner; domestic violence, neighbourhood violence, family breakdown; eviction; poor-quality housing; health problems; current accommodation temporary |

| Pinter 2020 (Children’s Society)72 | England | N | Migrants N = 11 parents/carers |

Representing 21 children | Parents/carers | Mixed methods – analysis of database and case notes, semistructured interviews No detail on analysis |

Temporarily housed, mainly | Immigration status and having NRPF |

| Children’s Society6 | UK | Y | General N = 24 participants recruited through schools |

No details | Children | In-depth interviews, conducted annually over 3 years Thematic analysis |

Various, mainly temporarily housed, or in ‘permanent’ or indefinite housing but with threat of moving | Evicted for non-payment of rent, DV, being housed in temporary housing, unsuitability of housing |

| CPAG and CoE73 | UK | N | General 21 parents (some lone parents/some part of couples) on low income |

1–5 children | Parents | Interviews Thematic analysis |

No details | Low income |

| CPAG74 | UK | N | General N = 129 professional informants |

Not reported | 117 social workers and 12 other professionals |

Survey No details on analysis |

Homeless | Low income |

| Hardy and Gillespie75 | London | Y | General No details |

No details | Parents | 64 structured interviews (32 recorded) No details on analysis |

Approached Newham Council to address a housing or homelessness need within the last year | Rent rises, cuts to benefits leading to rent arrears and family breakdown |

| Jones76 | England | N | Domestic violence Adult and child sanctuary service users |

2 children, no details | Parents, children, professionals | Telephone interviews (semistructured). Thematic analysis. |

In own home | DV |

| Joshi77 | England | N | General Family participation events: N = 16 parents; N = 15 children, Interviews: N = 9 parents |

Children aged 0–4 years | Children, parents | Conversations ‘mosaic approach’ Thematic analysis |

Renting | Poverty, high rents |

| JRF78 | England | Y | General 145 tenants experiencing forced moves and evictions Age 18+, 84 females, 61 males. 67 Families |

Not reported | Parents | Qualitative interviews Thematic analysis |

Facing forced move or eviction | Facing a forced move or eviction, or who had experienced a forced move or eviction within the recent past |

| JRF79 | UK | N | General 72 participants in 6 case study areas |

Not reported | Parents | Qualitative longitudinal panel study Analysis not reported |

Home owners, private renters, social renters | Not defined |

| JRF80 | UK | N | General In poverty |

Not reported | Insights from the JRF GPAG | Charity annual report | Social housing | Not reported |

| Maternity Action81 | England | N | Migrants N = 10 women with recent experience of pregnancy and asylum support |

No details | Mothers | Online group discussion No analysis details |

Temporary accommodation | Asylum seeking |

| Project 1782 | London | N | Migrants N = 2 families |

Children aged 6–12 | Parents and children | ‘Informal qualitative research’ | Homeless | Refusal of Section 17 support (for migrant children or children of adult migrants with no recourse to public funds) |

| Project 1783 | London | N | Migrants 11 families being supported under Section 17 |

N = 17 children aged 7–17 | Children | Mixed-methods approach No analysis details |

Temporary, transient, some were street homeless for periods of time | Immigration status, no recourse to public funds |

| RCPCH84 | London | Y | General No details |

No details | Parents, carers and young people | Workshop No analysis details |

Living in temporary accommodation | Poverty |

| RCPCH25 | London | N | General N = 266 professionals |

No details | Professionals | Survey No analysis details |

Living in poverty | Not reported |

| Renters’ Reform Coalition85 | UK | Y | General No details |

Not reported | Parents | Not reported | Private renters | Eviction and increasing costs |

| Scottish Women’s Aid86 | Fife | Y | Domestic violence N = 4 (interviews), women who had experienced or been at risk of homelessness as a result of domestic abuse |

3 had dependent children | Parents | Participatory action research Mixed-methods survey/interviews No analysis details |

Homeless/temporary accommodation | Domestic abuse |

| Mustafa Z87 | UK | Y | General Homeless children |

N = 29 children 17 males, 12 females Age 4–16 |

Children | Writing and drawing in activity books, completing a questionnaire and participating in drama exercises Follow-up interviews No analysis details |

All of the children were, or had recently been, homeless. Rehoused in private/social rented or hostels | Relationship breakdown or eviction, or the need to escape violence or racist abuse |

| Mustafa Z88 | England | N | Domestic violence No details |

Not reported | Parents | Not reported | Temporary accommodation | Fleeing domestic violence |

| Mustafa Z89 | England | Y | General No details |

Not reported | Parents | Policy briefing. No analysis methods reported | Private rental | Private rental insecurity |

| Mustafa Z90 | UK | Y | General 171 adults at baseline (within 1 month of moving in) 71 women and 57 men at 19 months (final visit), ‘with a fairly even split of single households and households with children’ |

No details on children | Parents | Qualitative semistructured and unstructured interviews. 19-month follow-up No analysis details |

Homeless – recently been resettled into private rented accommodation | Not stated |

| Mustafa Z91 | England | Y | General 194 families: 72% lone parents, 28% couples |

62% had a child/children under the age of 4 living with them, 38% had a child/children aged 5–10 years living with them, 26% had a child/children aged 11–16 living with them, 9% had a child/children aged 17–18 living with them | Parents | Questionnaires In-depth case history interviews No analysis details |

Temporary accommodation | Not reported |

| Mustafa Z92 | England | Y | General 20 families 6 teachers/learning mentors |

14 families had children under 10 years | Parents/teachers | Qualitative interviews Thematic framework analysis |

Families in non-self-contained accommodation, such as B&Bs and hostels | Not reported |

| Mustafa Z93 | UK | Y | General 25 parents living in emergency accommodation |

Not reported | Parents | Qualitative interviews. Thematic framework analysis | Living in emergency accommodation (some for 6 months or more) | Not clear |

| Mustafa Z94 | UK | N | General N = 19, including 11 families with dependent children, 3 couples and 4 single people |

11 families with dependent children (no details) | Parents | In-depth interviews Qualitative Thematic analysis |

Currently, or have previously been at risk of becoming homeless | Debt |

| Mustafa Z95 | England | Y | General 23 families currently living in emergency accommodation, or who had left within the last 3 months |

10 children aged 6–16 years | Parents and children | Qualitative interviews. Thematic framework analysis | Emergency accommodation | Not reported |

| Mustafa Z96 | England | Y | General Primary and secondary schools’ populations |

No details | 8 teachers and 3 education professionals 10 different primary and secondary schools |

Qualitative interviews Thematic analysis |

Homeless | Not reported |

| Mustafa Z97 | UK | N | General Social housing tenants and private rented (no details on individual children) |

Not reported | Mixed-methods study. Qualitative data presented as case studies No analysis details. |

Social housing tenants plus struggling private renters | Varied – most at risk rather than homeless | |

| Mustafa Z98 | UK | N | General No details |

Not reported | Professionals (no details) | Website with case study quotations | Evicted from private rented accommodation | Eviction |

| White99 | England | N | General 9 family case studies (with 18 families, 2 per case study), based on 9 (9-day) site visits |

No details | Families (any family member aged ≥ 5 years), FIP staff, local agencies and services that work with a FIP | Mixed-methods evaluation: 9 case studies, 44 telephone interviews No analysis details |

Housed, mostly local authority renting, most families had housing enforcement actions (threat of removing tenants) | Antisocial behaviour |

Studies included in the review

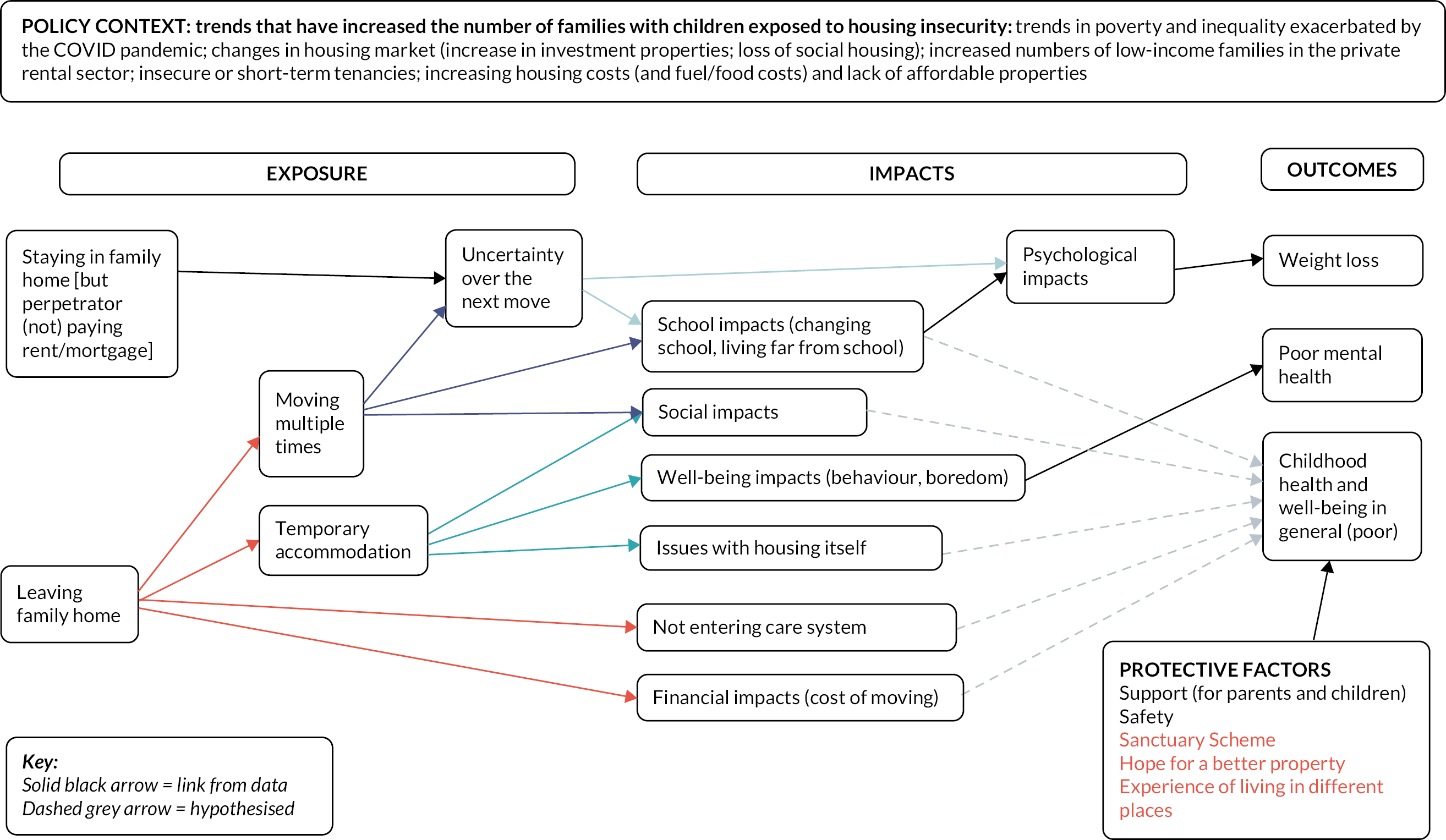

We identified four distinct populations for which research evidence was available during the process of study selection and data extraction:

-

general population (evidence relating to housing insecurity in general) (reported in 40 papers)

-

domestic violence population (evidence relating to those experiencing housing insecurity associated with domestic violence) (reported in nine papers)

-

migrant, refugee and asylum seeker population [evidence relating to those experiencing housing insecurity associated with migration status – this included children who had migrated or arrived in the UK as a refugee or asylum seeker with their family and children born in the UK to one or more parents who had migrated to the UK under any of those circumstances, including those with no recourse to public funds (NRPF)] (reported in 13 papers)

-

relocation population (evidence relating to families forced to relocate due to planned demolition) (reported in two papers).

Evidence relating to each of these populations has been synthesised separately, because the specific circumstances relating to their housing insecurity may impact differently on health and well-being and we anticipated that specific considerations would relate to each population. Some studies reported evidence for more than one population.

Quality of evidence

The quality of evidence varied somewhat between studies, with the published literature generally being of higher quality than the grey literature with methods that were generally more transparent, although reporting of methods of data collection and analysis varied considerably within the grey literature. From the 18 published studies all reported an appropriated methodology, addressing the aim of the study with an adequate design. Eleven of the 18 studies reported ethical considerations, and only 2 reported reflexivity. Most studies had an overall assessment of moderate-high quality, with approximately 13 of the 18 studies providing relevant data for the review. However, given the qualitative nature of the review, no studies were excluded based on quality. Most of the grey literature included originated from known and valued sources (e.g. high-profile charities specialising in poverty and housing). Although methodologies and methods were often poorly described (or not at all), primary data in the form of quotations were usually available and suitable to contribute to the development of themes within the evidence base as a whole. Quality appraisals of included studies are presented in Appendix 3, Tables 2 and 3.

Housing insecurity and the health and well-being of children and young people

General population

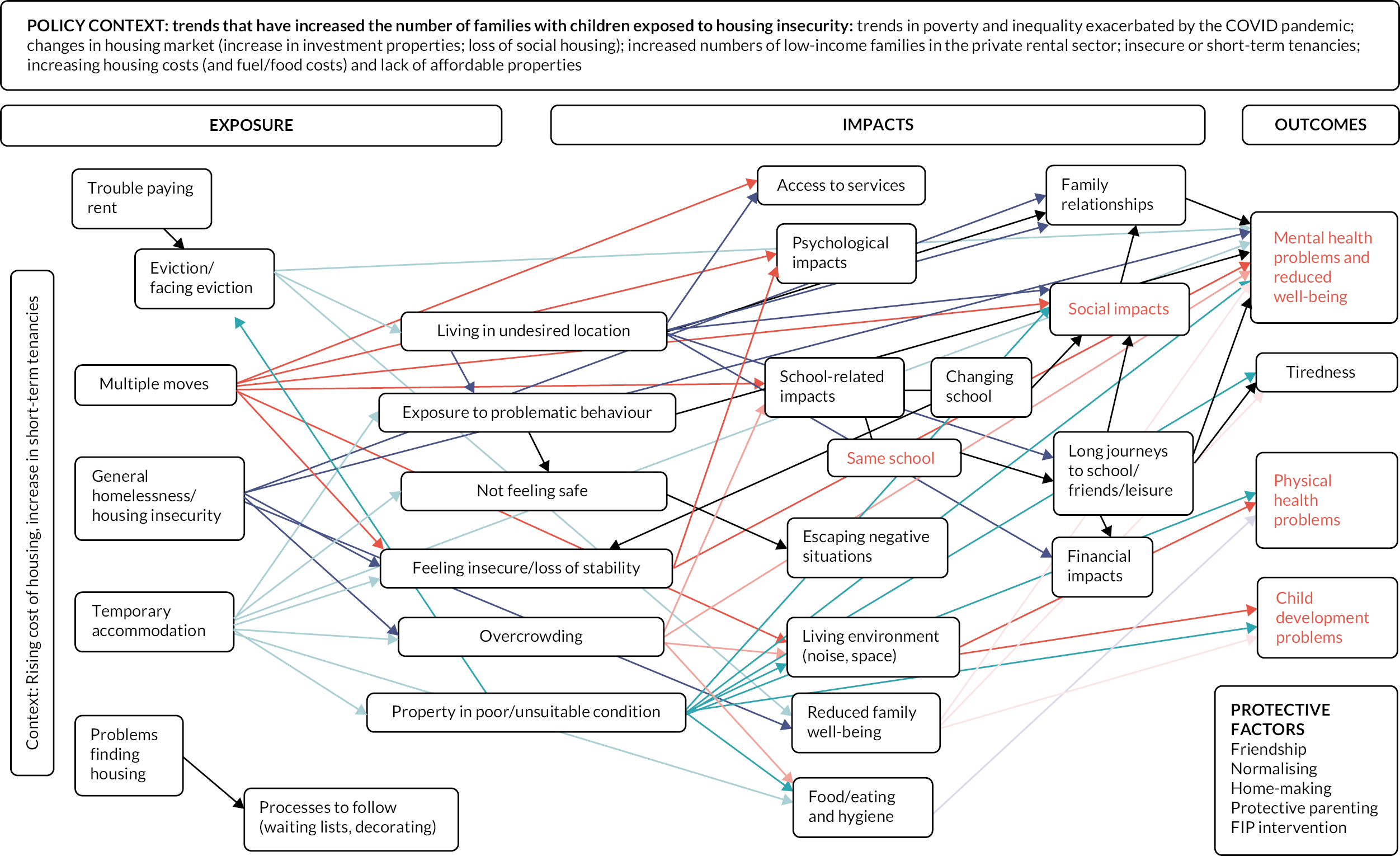

The final logic model for the impact of housing insecurity on the health and well-being of children aged 0–16 in family units is presented in Figure 3 (coloured arrows are used to distinguish links relating to each element of the model). There were no gaps in the evidence in terms of elements identified in the a priori conceptual framework (see Figure 1).

FIGURE 3.

Logic model for the relationship between housing insecurity and the health and well-being of CYP in the general population.

Population

The general population covers families experiencing housing insecurity (as per the definition outlined in the Background section) in general. 6

Exposure

Cost of rent and eviction

Fundamentally, a key driver of housing insecurity is poverty. The high cost of housing (relative to the income of the family) could render their living situation precarious, with housing benefit not fully covering the rent amount. 97 Similarly, having difficulty paying the rent and falling into rent arrears were sources of housing insecurity,6,73,78 due to a parent’s change in circumstances78 and a parent’s difficulty finding suitable employment. 6 Sometimes, families were evicted for non-payment of rent,6 and this could be linked to the rising cost of housing. 90 Some children reported being evicted but for a reason not known to them,71 and the prospect of facing eviction from private rented property (for reasons not explained) was also a source of housing insecurity. 97

Multiple moves

The cost of rent could lead to families having to move multiple times, as they repeatedly sought somewhere affordable to live. 97 The use of short-term tenancies by local authorities and private rental landlords can require multiple moves. 90,97 In two of the case study families from the seminal Children’s Society report Moving, Always Moving, children discussed moving multiple times as a source of housing insecurity, but they were unaware of the reasons for some or all of the moves, or did not want to talk about the reasons. 6

They moved all the time, he couldn’t even say how many times, and he didn’t understand why they weren’t allowed to just live in one place instead of having to pack, leave, unpack, pack again, leave, unpack and on and on like that. 6 (p. 35)

Exposure to problematic behaviour

Some phenomena were found to be both exposures and impacts of housing insecurity, in that some impacts of housing insecurity further exacerbated the living situation, causing further insecurity. One such situation included exposure of the family to the problematic behaviours of others, for instance, criminal behaviour, people taking and selling drugs. 93 Another related to where the location of the new housing or temporary housing left the family and child(ren) isolated and far away from family, friends, other support networks, work, shops, school and leisure pursuits. 6,64,68,78,85,90 Not feeling safe in a particular locality or neighbourhood was another situation that could exacerbate the original situation, leading to families needing or wanting to move again. 6

Feeling insecure

Feeling insecure (including uncertainty over when and where the next move will be, or if another move is happening) is a further impact of living in insecure housing situations (including temporary housing, making multiple moves, being evicted) but also part of the experience of housing insecurity for CYP,6,68,71,95,97 potentially leading to stress and worry. 6,95

One of the major issues that Hannah says affects her mental health is the uncertainty of their situation. She says it is hard to not know where they will be staying one night to the next. It is also difficult to adjust to living without her furniture and clothes. 95 (p. 17)

Overcrowding

Overcrowding was another issue that was both an impact of housing insecurity (often a feature of living in temporary accommodation or needing to accept whatever accommodation was on offer) and a contributory factor to families’ need to move to escape being overcrowded. Overcrowding could take the form of siblings sharing a room and/or bed,6,25,52,59,90,92–95 family members sleeping on the floor or sofa,6,52 children sharing a room with parents,52,75,90,92–95 a room being too small to carry out day-to-day tasks,93–95 a lack of privacy in general,92,93 living in close proximity to other families95 and cramped conditions when too many people and possessions had to share a small space. 6,90,95

No. It’s a box. Because, with it being so small we’ve had to buy [daughter 1] a camp bed, like just a small 3ft one and [daughter 2] is in [daughter 1]’s old cot bed and it’s literally right next to the radiator, under the window. 90 (p. 28)

His mum had slept in the living room while he had shared a small bedroom and one bed with two of his siblings, lots of furniture and everyone’s belongings piled up wherever there was space. 6 (p. 53)

Poor condition or unsuitable property

Similarly, living in a property in poor condition could exacerbate initial exposure to housing insecurity, both because families wanted to move into a better property and because they were reluctant to complain and ask for repairs on their current property in case the landlord increased the rent or evicted them. 67,77 One study reported a family being evicted after requesting environmental health issues be addressed,55 and another study reported a family being evicted because they withheld rent as their landlord had not addressed several health and safety issues. 97 Such issues included accommodation being in a poor state of decoration,79 broken or barely useable fixtures and fittings,67,77 broken appliances or fixtures,52,77,78 structural failings78 and mould. 52,77,78,85,90 Likewise, living in an unsuitable property may represent a lack of choice and a need to move, but could also precipitate a need to move again. Many families with young children found themselves living in upper floor flats, having to navigate stairs with pushchairs and small children. 52,55,59,64,68,73,90 One study reported how a family had to join the transfer list, as their council refused to install central heating in their current home. This was particularly relevant for their child’s health and well-being as the child had cerebral palsy and suffered from asthma. 56

Additional constraints

Sometimes, when a family desired a move, they may have to fulfil certain requirements. One family reported having to decorate their three-bedroom accommodation in order to be eligible for a four-bedroom house. 6 Sometimes a family could encounter problems finding appropriate housing, for instance due to landlords not accepting people on benefits. 6,66,98 Waiting lists for social housing could be prohibitively long. 78,79,97

Then it took us 13 years to get this house. I went through a lot, 13 years of bidding, fighting up against it, letters from everywhere, from the school, my boy’s school, doctors, psychiatrists, mental health unit, the hospitals …79 (p. 28)

Impacts

Impact on friendships

A particularly large and disruptive impact, positive or negative, of housing insecurity was the effect it had on children’s friendships and social networks. This social impact could be experienced in multiple ways. Multiple moves could lead to a young person having the challenge of building new social networks and build up a reputation each time they moved,6,87 and worries about maintaining friendships. 71 One young person spoke of the beneficial side to this, in that she had friends all over town, although she also reported difficulty in forming close friendships with anyone due to constantly moving. 6 Children living in temporary, overcrowded or poor condition accommodation often felt ashamed of their housing and concealed it from their friends. 6,59,92,93,95,96 In some cases, renting led to shame among those whose parents had previously owned a house and had it repossessed. 54 Not feeling able to invite friends over caused sadness,92,95 and increased distance from friends due to moving made it difficult to maintain friendships and a social life, leading to boredom and social isolation. 95 Likewise, the threat of an impending move at a distance from friends could cause sadness and worry,95 and many young people missed the friends they had left behind. 6,71

I was quite upset because I missed all my friends…I really miss my friends…I can’t really like chat to them or Skype them because I’m trying to get the numbers from my old phone. (Girl, 12)71 (p. 15)

Some young people felt compelled to turn down invitations to go out with friends to avoid leaving a parent alone with younger sibling/s,95 or because the family could not afford the activity. 96 Another barrier to friendships was feeling different from their peers, either because of looking messy and unkempt or because of lacking in confidence. 96 While these issues are not a specific feature of housing insecurity per se, they highlight that often the issues caused by housing insecurity are compounded by other causes of stigma related to their appearance or by practical issues such as lack of money.

School-related impacts

Another key impact of housing insecurity was the impact on education, and this was closely intertwined with the impact on friendships. Faced with moving, often multiple times, sometimes to uncertain locations, families were faced with the decision to keep the child(ren) in the same school/s, or to change schools. Both scenarios had different, but in each case negative, impacts. Several papers and reports described CYP changing schools, often due to multiple moves, and an unfeasibly long journey to school, or facing the likely prospect of having to change schools. 6,71,87,89,92,97 This could in turn impact on the child’s sense of stability, academic performance and also on maintaining friendships and concerns about forging new friendships. 71,92,96,97

My 12-year-old daughter has gone to eight different schools and has really struggled with constantly making friends and losing friends because of all our moves. All the upheaval makes her so unhappy. 97 (p. 29)

Meanwhile, staying at the same school created some stability in the child’s life,6 and allowed for friendships in school to be maintained, and for being known by the teachers and the school. 6 Staying at the same school, however, was quite often the only option, due to not knowing their next location,6,94 and was not without issues. Those who were unhappy with school were effectively prevented from changing schools due to the family’s precarious housing situation; there was no point in changing schools if they did not know where their next location would be. 6,71 It was not unusual for families to be rehoused at a considerable distance from the school. 6,74,75,94 This often meant having to get up very early to travel a long distance to and from school by bus (often more than one), sometimes train, or taxi,6,71,75,87,92,94 which in turn led to difficulty maintaining friendships and participating in social activities. 96 This also led to increased tiredness,6,92,94–96 and left little time for homework and extracurricular activities. 94–96

I wake up about five in the morning […] walk from our house to the shopping centre […] through there to [the train station] and we go from there until [two stops away] and then…I’m going to [one] bus […] and then we…pick [another bus] […] and we walk from Tesco to school. (Girl, 11)6 (pp. 17–8)

Another option was to stay with friends or relatives closer to school on school nights, which some secondary school children in one study reported doing, although these arrangements did not seem to persist for long. 6,71

Tiffany had taken to staying with her eldest sister on school nights so she wouldn’t be late in the mornings and have her attendance record adversely effected. Her sister lived closer to Tiffany’s school, and sometimes their mum would stay over too. 6 (pp. 38–9)

Regardless of whether the child moved schools or stayed at the same school, living in temporary housing was associated with several practical challenges in relation to schooling, for instance, keeping track of uniform and other possessions, limited laundry facilities, limited washing facilities and a suitable space to do homework. 93,96 Parents noted academic performance worsened following the onset of housing problems. 92,94,97 Limited space and time to work,92–95 tiredness and poor sleep,92,94 travelling and disrupted routines,95 disruptions from other families (e.g., in a hostel),95 a lack of internet connection,95 and the general impact of the disruption and upheaval caused by their housing situation,92,94,97 made it challenging for CYP experiencing housing insecurity to do well at school. Families living in shared emergency accommodation (e.g., hostels) often had to wake up early to access shared facilities before school. 94,95 Some children missed school altogether during periods of transience, because the family were moving so often (and/or staying in temporary accommodation) that school attendance was not viable,52,87,92 the family were not able to secure a school place in the new area,90 or they could not afford the bus fares and money for lunch to send the children to school. 62 Predictably, this non-attendance affected academic performance. 87,92

Nineteen months later, one mother was still unable to have her child in school. ‘She cries when you drive past the school and see all the kids in the playground, like she wants to go. She’ll be one of them kids that skips to school.’90 (p. 33)

Their education was put on hold. My daughter was ahead on everything in her class and she just went behind during those two weeks. S, 30, Mum92 (p. 15)

Family relationships

In addition to the social impact on friendships, young people experienced an impact on family relationships, particularly within the immediate household. One study reported on how family relationships had become more strained since the family started experiencing housing insecurity. 6 In particular, some children described improved relationships with friends (who did not live nearby) at the expense of worsening relationships with family members. 6

[…] he had started to stay over with friends not only on the two football nights each week, but on other nights as well. And […] his relationships at home had become strained. In particular, Sean was finding things really difficult with his mum and one of his sisters. 6 (pp. 73–4)

In some cases, however, housing insecurity led to improved family relationships. For instance, one study reported on a non-resident father who became more involved,6 and another reported how all children felt closer to their parents. 87

Impacts relating to well-being (diet and hygiene)

Some impacts related to the child’s health and well-being. For instance, an impact on diet; one 3-year-old child stopped eating solid food (which affected their growth). 94 Other impacts on diet included insufficient money for the child(ren) to eat properly,6,80,87 a lack of food storage and preparation space in the accommodation (including sometimes a lack of refrigeration)84,93 and a hazardous food preparation environment unsuitable for small children. 93 Two families spoke about a lack of control over the heating in a hotel, leading to excessive heat at times. 87 Hygiene issues relating to dripping water, overcrowding, damp, dirt, electrical hazards, vermin, flooding and a lack of washing and laundry facilities were reported as a result of unsuitable temporary accommodation, including converted shipping containers, hostels, bed and breakfast (B&B) accommodation and houses. 25,52,55,62,68,69,85,87,90,93,97

When we sleep water drips on us which we don’t like. (Daisy, 11) [living in a shipping container]68 (p. 14)

Psychological impacts

Psychological impacts of housing insecurity, which have the potential to affect health and well-being outcomes, were also reported. Teachers in one study reported that children experiencing homelessness saw themselves as being different from their peers, and were less able to ‘blend in’, which could then impact on their mental health (see Outcomes). 96 Sometimes, multiple moves could result in children having high hopes that the next property would be better in some way than the current one, only to be disappointed each time. 6 One study reported that when a family moved to a quieter area, the children felt that it was difficult to fit in. 6 Not feeling safe was a frequent concern, reported by children, and by parents in relation to their children. This included living in neighbourhoods or localities that did not feel safe,6,68,71,84 and accommodation that did not feel safe (due to the other people there and/or a lack of security provision). 68,78,90,93–95 In one case, a young person’s perception of safety improved over time, with them reporting that they had grown to like the neighbours and area. 6

Often, this experience of being unsafe was due to the children being exposed to problematic behaviour in or around their accommodation. This included hearing other children being treated badly,93 being exposed to violence,95 including seeing their parents being attacked,92,93,95 witnessing people drinking and taking drugs,64,71,92,93,95 finding drug paraphernalia in communal areas,93,95 hearing threats of violence,92 hearing shouting and screaming coming from other rooms in shared accommodation,95 hearing their parents being sworn at,64 witnessing people breaking into their room64 and witnessing their parent(s) receiving racist abuse. 64

There’s a lot [of] drugs and I don’t want my kids seeing that…One time he said ‘mummy I heard a woman on the phone saying ‘I’m going to set fire to your face’.’ She was saying these things and my son was hearing it. […] He was scared. H, 35, Mum. 92 (p. 15)

Noise

Noise was another disruption that children experienced in connection with their housing situation. This could relate to the location of the property, for instance, noise disturbance from traffic on a main road,6 or a factory nearby,91 or noise disturbance from other people in a B&B, hotel or hostel banging and shouting or just moving around and going about their day,87,93 or people in neighbouring properties shouting and banging doors. 6

Several of the children from Bayswater Family Centre mentioned noise going on 24 hours of the day. One child, who had stayed in bed and breakfast accommodation for two years, said she had not been able to sleep until they moved from that particular hotel. 87 (p. 19)

Loss of security and stability

Multiple moves, or the fear of having to move, disrupted children’s sense of continuity and they experienced a loss of security and stability in their lives (see Exposure). 66,68 One (seminal) report identified that young people experiencing housing insecurity experienced instability in many other spheres of life as well. 6 A loss of security and stability led children to feel responsible for helping and providing support to their parents, including putting on a brave face and hiding their feelings in relation to the housing situation so as not to further upset them. 92,95 Some children stopped asking their parents for things they wanted. 6,94 Children also felt a sense of displacement and a feeling of not belonging anywhere as a result of the loss of safety and security, with no place that felt like home. 6,96

[…] a sense of place formed a crucial component in their experiences, and something appeared to be lost for those who were forced to move repeatedly and continually navigate their place attachments amidst the dislocations. For Tiffany it meant a loss of belonging and a longing to be back home. 6 (pp. 40–1)

Even when a family is provided with decent temporary housing in the right location, the threat of being moved on somewhere else always hangs over their heads, depriving children of a sense of stability and security. 68 (p. 15)

Loss of stability and security triggered a desire for stability, for the family to be able to settle, having friends over, and not having to constantly worry about having to move. 90

Parental and family well-being

Often, CYP were aware of the impact of their precarious housing situation on their parents,6,87 which would then impact their own well-being. In other cases, CYP were not directly aware, but would experience other negative impacts of reduced parental well-being, such as increased arguments and increased family stress. 6,74 Reduced parental well-being due to housing insecurity can further impact on child development,25 and reduced their ability to care for children with chronic conditions. 25

Overcrowding and lack of space

Families felt pressured by the need for emergency accommodation to take whatever was on offer, even when emergency temporary housing or another rental property was unsuitable in some way. The condition of the property, distance from school, friends and relatives, and overcrowded conditions not only contributed to the experience of housing insecurity in their own right, but could also, in turn, lead to additional impacts. Many accounts described overcrowding in housing that was intended to be temporary, resulting from the need to be housed quickly (and a lack of available, suitable properties). In turn, overcrowding could mean that siblings, and parents and children, had to sleep in the same room,45 and sometimes the same bed as each other,97 which could lead to disturbed sleep. 6 In some cases, family members (usually one or both parents) had to sleep in a living room. 6,91 Families would also lack privacy, for instance, they would have to change clothes in front of each other. 95 Small, overcrowded accommodation meant little space for possessions, so children would experience cramped conditions. 45,71 In some cases, whole families and their possessions would inhabit one room, reducing their freedom to move around. 78,84,95

It’s all of us in one room, you can imagine the tension…everyone’s snapping because they don’t have their own personal space…it’s just a room with two beds. My little brother has to do his homework on the floor. 78 (p. 43)

This meant it was difficult for each child or young person to have their own space, even for a short time. 79 Older children lacked the space to do schoolwork,95 and to invite friends over, directly because of the lack of space, and indirectly because they felt ashamed (see earlier in the section). 84 Families sometimes had to cohabit with extended family, which could lead to overcrowding due to a large amount of people inhabiting a modest-sized property. 91 Others were initially living in a property of the right size, but ended up outgrowing it, or anticipated they would outgrow it in the future, when children were older. 97 In some cases, overcrowding took the form of multiple families and single people being crammed into a single building, for instance a hostel or shelter, which presented difficulties for single parents when using shared bathroom facilities, as they did not want to leave their child(ren) alone in the room. Living in overcrowded conditions could lead to, or exacerbate, aggressive behaviour and mental health problems among CYP (see Outcomes). 53 Overcrowded conditions caused a ‘relentless daily struggle’ for families (p. 48). 64

Poor condition or unsuitable property

Similarly, the need to take whatever property was on offer led to families living in properties in poor condition (also see Exposure). This included properties with damp and mould, unsafe gardens, broken appliances, fixtures and fittings. 71 This created a vicious cycle, whereby families would either try to endure these poor conditions, or else would attempt to move to a more suitable property. Requesting a repair or resolution from the landlord could lead to further housing insecurity. These latter two exposures are discussed in detail in the Exposure subsection.

Another impact of being moved to an unsuitable property (in particular, temporary accommodation) was a lack of space for children to play. Often this was due to the family inhabiting a small space such as studio flat or room in a hostel or refuge. 68 For small children, this could present a health and safety hazard,68 and parents reported injuries in very young children. 93 Keeping small children occupied in just one room was a further challenge. 93 Sometimes the lack of space to play was due to poor housing conditions making the space unsuitable, for instance, a vermin infestation. 68 For older children and adolescents, a lack of space meant a lack of privacy. 93 School holidays could be particularly challenging for families of school-aged children, particularly when outside play spaces were not deemed suitable due to safety concerns (e.g., people selling drugs, broken glass). 68,87

School holidays are very tight. It’s very scary allowing the children to play downstairs in the communal playground – it is risky because of drug dealers, it is very hard to let my children out. (Sophia, mother of children aged 14, 11 and 8)87 (p. 15)

Some temporary accommodation restricted access during the daytime, making it difficult to entertain and occupy children without spending money. 93

Financial impact

Moving house also had a financial impact on families. Moving into temporary accommodation meant that possessions had to be left behind, particularly if the temporary accommodation was small and overcrowded, with the cost of decorating, carpets, curtains and furniture to be covered each time a family moved. 6,79 This could incur considerable debt among families. 79 One family reported having to sign up to rent a larger house than they could reasonably afford, and purchase white goods and curtains, due to being served insufficient notice on their previous tenancy. 85 If the new location was far away from school, family, friends and, in some cases, shops, then the family incurred further costs travelling on buses and in taxis for day-to-day business. 6,68,75,93,95 Other financial aspects of housing insecurity could also have an impact. The threat of sanctions for missed payment of rent could lead to reduced family well-being, characterised by feelings of despair, failure and a loss of hope. 74 Another knock-on effect of the financial impact of housing insecurity was that parents had to refuse children’s requests for possessions or experiences. 94

Access to services

Multiple moves, particularly across local authority boundaries, could impact on the ability of either family or children to access services, particularly those aimed at vulnerable families. 25,52 Living far away could lead to problems accessing health services,71 including specialist healthcare that is required to manage children’s health conditions. 64