Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 15/49/32. The contractual start date was in January 2017. The final report began editorial review in March 2021 and was accepted for publication in September 2021. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2023 Wright et al. This work was produced by Wright et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2023 Wright et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background and rationale

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a neurodevelopmental condition beginning in childhood characterised by atypical social communication, difficulties in creating and maintaining multiple social relationships, sensory reactivities or preferences, restrictive patterns of repetitive and stereotyped behaviour, and/or specific interests/preoccupations. 1 It is estimated to affect 1.1% of the UK population and up to 1.6% of children and young people (CYP) in the UK. 2–4 There are significant variations in the social, communicative and intellectual abilities of those with ASD, including increased rates of mental health problems such as anxiety, sleep problems, attention problems and behaviour problems. 5 Commonly experienced symptoms and problems can affect the individual into adulthood in areas such as social relationships, educational success and independent living. 6,7

Autistic CYP often experience difficulty with social and emotional skills and sometimes may not intuitively pick up on social rules or norms encountered in their daily lives. 8 Many autistic CYP attend mainstream school education environments, although this may expose them to difficulties in creating and maintaining relationships with their typically developing peers and, in turn, lead to increased feelings of isolation. 9,10 CYP learn and develop sociocognitive skills and gain language abilities through friendships and peer relationships, through which they also gain a sense of belonging to a peer group. 11 Autistic CYP often have smaller groups of friends than neurotypical peers and may face problems initiating/maintaining friendships,12,13 thereby potentially missing out on opportunities to develop their social and emotional competence, which can widen developmental differences between them and their typically developing peers.

Although it has been shown that many autistic CYP who struggle with social interactions find such situations anxiety-provoking,14 it has also been shown that they identify feelings of loneliness more frequently than their peers,13 suggesting an awareness of being excluded. Theories in this area suggest that autistic CYP may not be motivated by social interactions,15,16 but feelings of increased isolation perhaps indicate that they are simply differently motivated by such interactions. In addition, autistic CYP are at greater risk of being bullied by typically developing peers. 17 Evidence suggests that perceived exclusion from friendship groups can have negative effects on the quality of life, physical and mental health, emotional well-being and educational success of autistic and non-autistic CYP, creating concerns about appropriate education and health provisions. 18,19 Indeed, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) states in public health guidelines20 that the social and emotional well-being of CYP are significant factors in long-term outcomes, including educational attainment and physical and mental health.

Interventions to promote the development of social and emotional skills are a commonly used school-based approach both generally21 and for autistic CYP. 22–27 A Cochrane review28 showed some improvement in social competence following these interventions, although the published research was very limited, with only five studies meeting the inclusion criteria. 29–33 Different types of social skills interventions were assessed in these studies, including the following: a 20-week social adjustment enhancement curriculum for boys aged 8–12 years with high-functioning autism (HFA), Asperger syndrome and pervasive development disorders not otherwise specified;33 a manualised parent-assisted social skills intervention compared with a matched, delayed treatment control to improve friendship quality and social skills among autistic teenagers;31 12 weeks of a manualised intervention titled Children’s Friendship Training compared with a delayed treatment control group;29 a 16-week manualised social skills intervention designed to teach appropriate social behaviour compared with a waiting-list control group;30 and a manualised social intervention for CYP with HFA, including instruction and therapeutic activities, which focused on social skills, face–emotion recognition, interest expansion and interpretation of non-literal language. 32 A more recent review of school-based interventions that target social communication in autistic CYP found 22 studies, but only three of these reported significance or effect sizes,26 demonstrating a need for higher-quality future research methodologies. In this review26 many were adult-directed interventions.

Although social skills training interventions are commonly used and report moderate success with relatively low rates of attrition, studies to date have tended to use a skills deficit model, which potentially limits them. Common features include (1) being adult led and (2) focusing on skill building using various teaching methods. Participating CYP can also struggle to use learned skills outside the context of the interventions, a further limitation. 6,34

LEGO® (LEGO System A/S, Billund, Denmark) based therapy35 is a group-based social skills intervention specifically designed for autistic CYP that does not rely on adult-led teaching of skills. It has become popular in the UK, with many local authorities now recommending its use in schools. 36 The intervention focuses on collaborative building of LEGO sets in small groups of CYP, who are intrinsically motivated to play with this predictable and structured toy that has a wide range of alternative play sets appropriate for CYP of different chronological and developmental ages, genders, hobbies and interests. 37 The CYP’s own interests are used to motivate the learning and practising of social and emotional skills in a group context. Such naturalistic approaches used elsewhere have been shown to increase the likelihood that new skills will be used outside the context of the intervention, thus increasing overall effectiveness. 38

Although the use of LEGO® based therapy in schools across the UK is increasing, there is a lack of research evaluating the effectiveness of the intervention. A limited number of studies have been undertaken to assess LEGO® based therapy with autistic CYP, all of which had significant limitations in terms of research design, methodology and sample size. One of these was a small randomised controlled trial (RCT). 37

In 2004, Daniel LeGoff, the creator of LEGO® based therapy, used a repeated-measure waiting-list controlled trial to assess the impact of the intervention on the social competence of 47 autistic CYP aged 6 to 16 years. 39 He found that, compared with control participants, those receiving the intervention had greater motivation to initiate and greater ability to sustain social contact and decreased social impairment scores, as measured by the Gilliam Autism Rating Scale social interaction (GARS–SI) subscale. LeGoff and Sherman then undertook a retrospective cohort study to explore long-term outcomes associated with LEGO® based therapy. 40 Findings showed improvement on both the Vineland Adaptive Behaviour Scale socialisation domain (VABS–SD) and the GARS–SI in participants who had received LEGO® based therapy compared with control participants who had received similar, non-LEGO, therapies on a comparable timescale.

Owens et al. 37 undertook a small RCT of 31 CYP with Asperger syndrome and HFA aged 6–11 years, randomising between LEGO® based therapy and a Social Use of Language Programme (SULP). 41 A no-intervention control group was also followed up. The results showed some reduction in social difficulties in the LEGO® based therapy group compared with the SULP and control groups. The study had a number of limitations, including a lack of full randomisation: instead, one participant from each dyad matched on age, intelligence quotient (IQ), symptom severity and verbal IQ was allocated to either LEGO® based therapy or SULP. Intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis was not used and the sample size was small, with an attrition rate of 30% in each of the two groups. No measures were taken to assess the degree of delivery fidelity to the interventions.

The most recent UK study of LEGO® based therapy, and the first entirely school-based trial, used a single-case, non-concurrent, multiple-baseline-across-participants design to assess the impact of LEGO® based therapy on the social skills and the generalisability of those skills in autistic CYP. 42 This study had a very small number of participants (n = 6), who received a baseline phase consisting of between 2 and 13 sessions of free-play LEGO, each 15 minutes in length. Participants then received the intervention, which was delivered by trained school staff members 12 times (twice per week) for 45 minutes each. A maintenance phase followed the intervention in which observational data were collected from three 15-minute free-play LEGO sessions. The researchers reported significant improvements in social skills for five of the six participants and evidence that the improvements were maintained at follow-up.

Although the design of this study did allow for close examination of changes in behaviour of the participants, the sample size of six participants was very small, with only five receiving all 12 intervention sessions (one participant withdrew). The small sample size did not allow for varied participant demographics and characteristics, which may have affected the generalisability of, and conclusions to be drawn from, the study findings. There was no separate control arm for comparison or random allocation to treatment types. The authors also discuss their use of percentage of non-overlapping data analysis, which did not prove useful for effect size evaluation.

A scoping review of 15 studies investigating LEGO® based therapy was conducted in 2017. 43 Although the authors reported that LEGO® based therapy has the potential to improve various social skills, the consistently small sample sizes, together with the use of different study designs and outcome measures, makes drawing definite conclusions difficult. The review recommendations were for more rigorously designed trials of LEGO® based therapy using larger sample sizes. There is a need for a fully powered RCT to investigate the clinical effectiveness of LEGO® based therapy using a large sample size and standardised measures. Furthermore, as far as we are aware, no studies have examined the cost-effectiveness of LEGO® based therapy delivered in schools compared with other interventions or support services. This is a critical time to examine the effectiveness of LEGO® based therapy before it becomes a widely incorporated aspect of the school curriculum.

Research question, aims and objectives

The I-SOCIALISE (Investigating SOcial Competence and Isolation in children with Autism taking part in LEGO® based therapy clubs In School Environments) research team aimed to investigate the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of LEGO® based therapy on the social and emotional competence and perceived isolation of autistic CYP in mainstream school environments. The research design included cluster random allocation at the school level of CYP diagnosed with ASD to either LEGO® based therapy groups run in school environments in addition to usual support (i.e. the intervention arm) or usual support alone (i.e. the control arm).

Primary objective

-

To examine the clinical effectiveness of LEGO® based therapy groups on the social and emotional competence (specifically perceived social skills) of autistic CYP in schools, compared with usual support for autistic CYP, at 20 weeks after randomisation.

Secondary objectives

-

To examine the clinical effectiveness of LEGO® based therapy groups on the perceived social isolation of autistic CYP in schools, compared with usual support for autistic CYP, at 20 and 52 weeks.

-

To examine the clinical effectiveness of LEGO® based therapy groups on the academic competence of autistic CYP in schools, compared with usual support for autistic CYP, at 20 and 52 weeks.

-

To examine the clinical effectiveness of LEGO® based therapy groups on assertion, social control, externalising and internalising in autistic CYP in the school setting, compared with usual support for autistic CYP, at 20 and 52 weeks.

-

To examine the cost-effectiveness of LEGO® based therapy groups, compared with usual support for autistic CYP, at 52 weeks.

-

To examine the emotional and behavioural symptoms in those receiving LEGO® based therapy, compared with usual support for autistic CYP, at 20 and 52 weeks.

-

To determine if the impact of LEGO® based therapy is sustainable into the next academic year by comparing effectiveness on social and emotional competence (specifically perceived social skills) at 52 weeks after randomisation.

-

To examine the acceptability of the intervention at follow-up points using a purpose-designed questionnaire and telephone interviews at 20 weeks.

-

To examine treatment fidelity through independent observation of treatment sessions across schools and a self-report measure completed by the facilitator [i.e. a trained teacher or teaching assistant (TA)] after each session.

Chapter 2 Methods

This report is concordant with the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) statement44 and with the CONSORT extension for cluster RCTs. 45

Main trial methods

Trial design

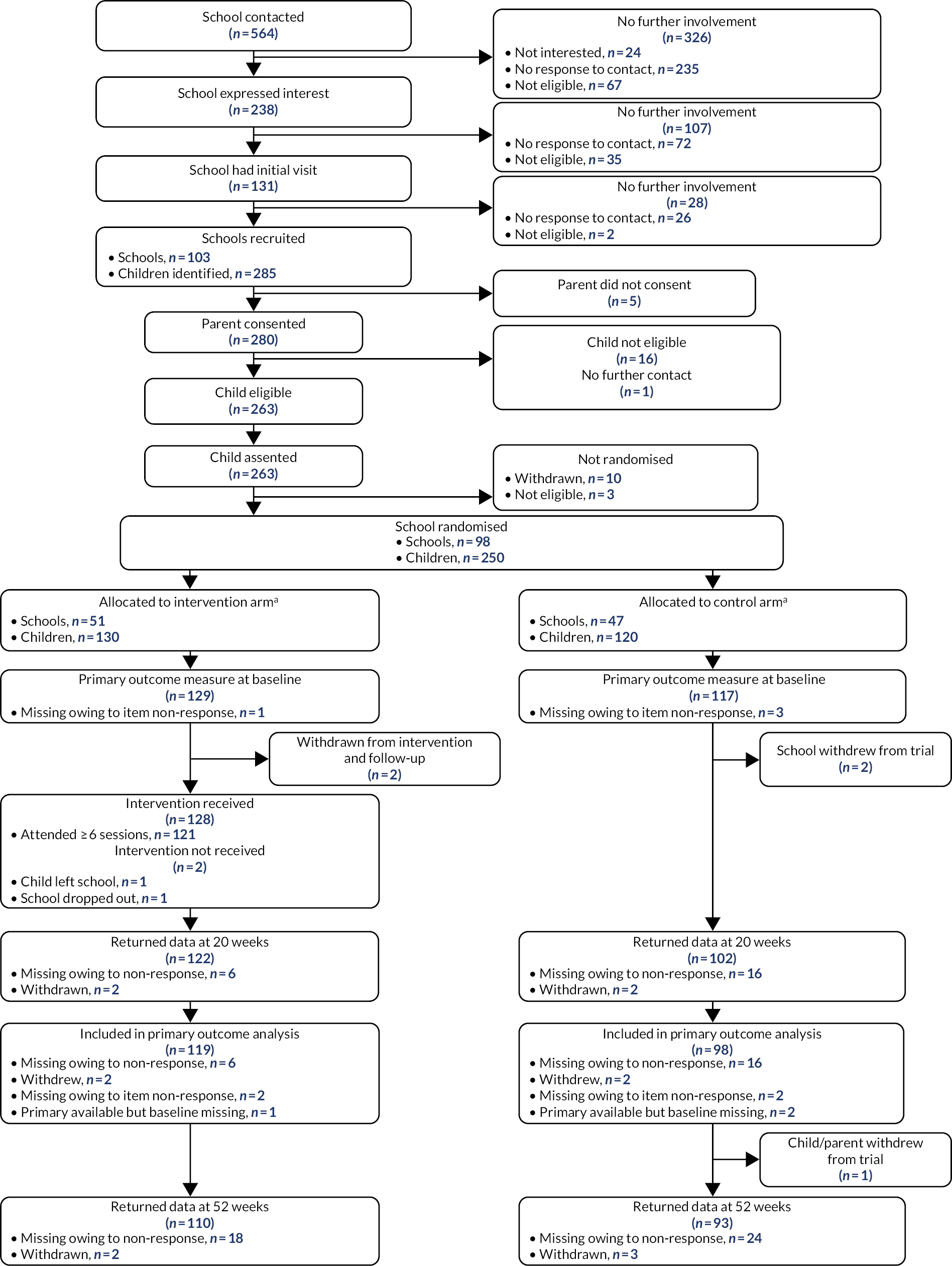

The I-SOCIALISE trial was a pragmatic, two-arm, cluster RCT at the school level with an internal pilot designed to examine the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of LEGO® based therapy groups for autistic CYP. The internal pilot study assessing recruitment feasibility was carried out over the first 10 months, for which a recruitment target of 120 CYP was set, one-third of whom (n = 40) were expected to have reached the primary end point of follow-up at 20 weeks after randomisation. Stop/go criteria were based on 75% of the recruitment target (n = 90) and 70% of the primary outcome target (n = 28) to assess the feasibility of continuing the trial. The trial also included an assessment of intervention fidelity and acceptability, a qualitative element and a nested economic evaluation.

Important changes to methods after trial commencement

August 2017

-

At this time the study protocol contained five objectives – the first five in the final list of objectives (see Chapter 1, Research question, aims and objectives). A sixth secondary objective was added to the existing five to enable the research team to examine the emotional and behavioural symptoms in CYP receiving the intervention compared with those in CYP in the control arm, using the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ). The objectives were then re-ordered; this objective is now number five in the final list of objectives (see Chapter 1, Research question, aims and objectives). Two further secondary objectives were added later (see September 2018).

March 2018

-

The first follow-up time point was changed from 16 weeks post randomisation to 20 weeks post randomisation. This was implemented following concerns in the study team that the 12 sessions of LEGO® based therapy would not have been completed by all schools when approached for their 16-week follow-up and that resulting data would not be balanced, with schools at different stages of the intervention. This change was approved and implemented following discussion with the trial Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC) and Trial Steering Committee (TSC). Prior to this change, one participant’s follow-up was collected at the 16-week time point. This participant’s school was allocated to the control arm of the study.

September 2018

-

The primary outcome measure used was clarified as being the social skills subscale of the Social Skills Improvement System (SSIS) (teacher), not the SSIS (teacher) total score.

-

The third secondary objective was amended to make it clear that the social skills subscale of the SSIS would be used at both follow-up time points to assess sustainability of the outcome.

-

Two additional secondary objectives were added, bringing the total to eight. These were (1) to examine the clinical effectiveness of the intervention on the academic competence of autistic CYP in the school setting, compared with usual support (measured using the academic competence scale of the SSIS), and (2) to examine the clinical effectiveness of the intervention on assertion, social control, externalising and internalising of autistic CYP in the school setting, compared with usual support (measured using the assertion, self-control and internalising subscales from the SSIS).

-

The per-protocol analysis was specified to include only those CYP who completed at least six sessions of the intervention.

-

The decision was made to offer training in LEGO® based therapy to schools in the trial allocated to the control arm directly following completion of the last participant follow-up (i.e. 52 weeks post randomisation) rather than at the end of the trial. This followed discussions in the study team and with the TSC around the ability of schools to access the training whether or not it was offered by the study team. It was hoped that this might also support continuing engagement, retention and compliance rates in control arm. This information was not known by the blinded research assistants (RAs) undertaking the research assessments or the families of autistic CYP; thus, there was no adverse impact on the trial and the blinding of RAs.

June 2019

January 2020

-

The study team implemented a prize draw for parents/guardians to increase participant retention and follow-up completion rates. This was approved by the University of York Research Ethics Committee (REC).

May 2020

-

An addendum to the SAP47 specified the addition of a sensitivity analysis to the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, different teachers completing the primary outcome at baseline and 20 weeks and outcomes being provided outside the ideal survey window (i.e. 20–26 weeks and 52–60 weeks for the 20- and 52-week follow-up, respectively). The amendment was approved by the study’s DMEC and TSC and by the funder. The addendum to the SAP is available online. 47

July 2020

-

The health economics analysis method was amended based on detailed discussions with the Trial Management Group (TMG) about the most appropriate perspective to take in the main analysis. The amendment, approved by the study’s DMEC, TSC and REC and by the funder, altered the perspective from NHS and education to NHS and Personal Social Services (PSS), with the education perspective included in a sensitivity analysis. The rationale of the change was that the NHS/PSS and education perspective would be problematic in terms of making decisions, because there is no accepted threshold value by which to judge cost-effectiveness, and because there is also an issue with regard to who finances such programmes. On the other hand, the NHS and PSS perspective is the standard perspective recommended by NICE. Using such a perspective allows the cost-effectiveness of interventions to be assessed by comparing incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) results with the national willingness-to-pay (WTP) threshold.

October 2020

-

Additional exploratory analysis was requested by the TMG to explore the potential for observational analysis of the trial data in a subsequent substudy.

No other changes were made to the methods during the trial.

Participants and eligibility criteria

Participants were CYP meeting the inclusion criteria, their parents/guardians, associated teachers/TAs in the CYP’s schools who knew them well and facilitator teachers/TAs who could run the study intervention if the school was allocated to the intervention arm. CYP were asked to provide informed assent and parents/guardians provided informed consent for themselves and their CYP to participate. Optional consent items were included on the consent form regarding video-recording of some of the intervention sessions and future contact about this or other research. Additional CYP were also recruited to the study when schools had fewer than three eligible CYP (i.e. the number needed for a LEGO® based therapy group). These additional CYP did not need to meet the inclusion/exclusion criteria and a minimal amount of information was collected about these additional CYP, including chronological age, gender, any documented diagnoses and details of any special educational needs (SEN) support. A parent/guardian was asked to provide this information and to complete a consent form for their child or young person’s participation, which also included two optional consent items regarding video-recording of some of the intervention sessions and future contact about this or other research.

Inclusion criteria

A child or young person was included if they:

-

were aged 7–15 years at the time of randomisation of the school

-

attended a mainstream school in or between Year 2 and Year 10

-

had a sufficient understanding of English to be able to provide informed assent and read the LEGO® based therapy instructions and their parent/guardian had a sufficient understanding of English to be able to provide informed consent

-

had an ASD clinical diagnosis from a qualified assessing clinician or team [based on best-practice guidance leading to an International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10)48 or Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-V),1 diagnosis as reported by the child or young person’s parent/guardian and in the child or young person’s school records, which may include the school’s SEN register, an individual education plan (IEP), an individual healthcare plan, a my support plan (MSP), an education healthcare plan (EHCP) and an individual learning plan (ILP) or equivalent]

-

had the ability to follow and understand simple instructions (as determined by the associated teacher/TA or parent/guardian)

-

scored ≥ 15 points on the Social Communication Questionnaire (SCQ).

A school was included if it:

-

was a mainstream school (i.e. not a specialist or independent school) located in Leeds, York, Sheffield or surrounding areas in the north of England

-

had not used LEGO® based therapy with CYP in the current or preceding school term (where LEGO® based therapy was defined, for research purposes, as meeting all of the main fidelity checklist criteria)

-

had at least one child or young person diagnosed with ASD (in line with the CYP inclusion criteria).

Exclusion criterion

A child or young person was not eligible to take part in the study if they:

-

had physical impairments that would prevent them participating in the activities (as assessed by the associated teacher/TA).

Settings and locations where the data were collected

Data were collected from participants in mainstream primary and secondary schools in York, Leeds, Sheffield and surrounding areas in the north of England. Data acquired from CYP and their parent/guardian were collected either in their home or at the child or young person’s school, depending on the family’s preference. Data from associated teachers/TAs and facilitator teachers/TAs were collected in school, via post or through a secure link sent via e-mail. Follow-up data were collected from CYP, parents/guardians and teachers through face-to-face visits at home (families only) or school, via post or through a secure link sent via e-mail.

Intervention

LEGO® based therapy

LEGO® based therapy is a social skills intervention designed to support CYP with social communication difficulties such as ASD by offering scaffolded, playful opportunities to practise social skills and develop social competence. It was first developed by Daniel LeGoff, a paediatric neuropsychologist who observed that autistic CYP may be particularly drawn to LEGO bricks, perhaps because of their interests and strengths in systemising. 37,39,40 LEGO® based therapy is a group-based intervention in which CYP build LEGO models together under the guidance and facilitation of a trained adult. By building with others, CYP can practise social skills that may enable them to develop more successful social interactions and gain a sense of connection and group belonging.

Collaborative building

Key to the intervention is building LEGO sets co-operatively rather than individually.

When building a set with instructions, each child or young person takes turns to play the role of an ‘engineer’, who communicates the instructions, a ‘supplier’, who locates the appropriate brick and passes it to the builder, and a ‘builder’, who fits the model together. They follow the instructions together to finish the model as a team and take turns by CYP agreement to rotate the roles. The CYP then progress to collaborative ‘freestyle’ building in which they build models of their own design together. Sessions aim to be CYP led, following their interests as far as possible. The targets of the intervention are multiple and flexible but include core skills required for successful social interaction and peer relationships, including social communication, turn-taking, joint attention, problem-solving, emotion regulation and compromise.

Learning through play

The aim of LEGO® based therapy is to provide a setting with playful and fun activities in which CYP can learn through play that promotes skills development. Learning through play happens when activities are experienced as joyful, actively engaging, meaningful, iterative (i.e. involving experimentation and testing out ideas) and socially interactive. 49 In LEGO® based therapy, CYP develop skills in a naturalistic play setting, meaning that they are learning how to collaborate with others through doing rather than by learning in the abstract. As their social learning is connected to a here-and-now activity, with the meaningful goal of getting a LEGO model finished, the skills they are practising have immediate impact and relevance in other, everyday, contexts.

Adult facilitation

Playful learning is most effective when play is guided by an adult in a CYP-led, exploratory style rather than being directed and prescriptive. 50 Adult facilitation in LEGO® based therapy aims to guide CYP rather than directing them explicitly, in terms of both the LEGO building and the social interactions and challenges that arise from working together. Adults are encouraged whenever possible to follow the CYP’s lead and to allow CYP to solve their own challenges, stepping in to prompt through open questions only when needed (as outlined in the training and in the manual). When challenges arise, adults may work their way towards direct instructions if CYP are unable to solve issues themselves or through guidance and prompting. CYP are encouraged to practise and role-play new social strategies that they have discovered in the sessions. The adult’s role is also to praise and highlight the positive things happening in a session, socially and otherwise, using rewards as motivation.

Group rules and rewards

In LEGO® based therapy the CYP, supported by adult facilitation, develop their own group rules for the behaviour expected during the sessions. CYP can earn points for prosocial behaviour, skill in LEGO building and attempting to overcome challenges. They can also receive certificates to acknowledge progression of skills. The overarching aim is to motivate CYP to participate, collaborate and practise social interaction skills.

Fostering connection and social identity

Autistic CYP can find it hard to make friends and may feel lonely or socially isolated. LEGO® based therapy provides CYP with an opportunity to interact with peers through collaborative play that has clear social expectations to promote positive interaction experiences and develop a sense of social identity. By offering CYP the opportunity to be with others in a way that feels safe, secure and enjoyable, LEGO® based therapy provides an opportunity for CYP to experience social success. autistic CYP often have limited play experiences with others, leading to a vicious cycle of social isolation and peer rejection. 51 Therefore, LEGO® based therapy may play a preventative role, offering CYP the chance to be with others and have fun. Because LEGO is a popular toy, participating in LEGO® based therapy may open up new opportunities to interact with peers, who might show a natural interest in what the autistic CYP have been doing in their LEGO sessions. By showing others what they have made, autistic CYP can develop confidence, have the chance to talk to others and have further positive social interactions outside the LEGO® based therapy sessions, thus providing opportunities for the use of social skills in other settings.

Engagement and motivation

Many CYP find LEGO engaging,52 thus allowing an initial level of engagement with the materials that might not necessarily be experienced in other types of social skills interventions. Autistic CYP might typically be reluctant to participate in group activities or may struggle to initiate and maintain interactions with peers. With LEGO as the focus of the intervention, motivation to participate in the groups might be increased. LEGO is also familiar to most CYP, meaning that they may have a better understanding of what to expect in sessions and, therefore, potentially feel less anxious about attending.

Materials and procedures

LEGO® based therapy is a relatively new social skills intervention in the UK. School staff who had not previously attended a training course were therefore expected to have limited knowledge of this intervention. A LEGO® based therapy intervention manual and treatment protocol were designed by the study team, based on the work of Daniel LeGoff and co-applicant Gina Gomez de la Cuesta. Training sessions in LEGO® based therapy were conducted by Gina Gomez de la Cuesta and expert colleagues for local authority members with expertise in education settings and ASD in each recruiting area and for study team members. These sessions provided training in both LEGO® based therapy principles and how to train other professionals in its implementation. Local authority members and study team members were then able to run training sessions for school staff members put forward as facilitator teachers/TAs to run the intervention sessions in schools randomly allocated to the intervention arm.

Training materials used for these training sessions included:

-

a LEGO® based therapy manual developed by the study team, based on work by LeGoff et al. 35 and co-authored by Gomez de la Cuesta, a co-applicant on the study (see Report Supplementary Material 1)

-

a training PowerPoint® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmont, WA, USA) presentation created by co-applicant Gina Gomez de la Cuesta for use in training sessions for professionals who would go on to train school staff members

-

a training PowerPoint presentation created by co-applicant Gina Gomez de la Cuesta for use in training sessions with school staff members who would run the intervention sessions.

Each school staff member who had been put forward to run the intervention attended one training session that lasted for approximately 3 hours. Between 1 and 15 staff members attended each session, depending on how many schools had been randomised to the intervention arm in time to attend a particular training date. Facilitator teachers/TAs were also trained in how to complete the two forms to be completed after delivery of each intervention session: (1) a bespoke session attendance and resource use form, used to capture resource implications of the intervention and details of any adverse events (AEs) that occurred, and (2) a fidelity checklist, used to monitor the fidelity of intervention delivery to the intended delivery method.

Each LEGO® based therapy group was run in a participating school randomised to the intervention arm of the trial, with three CYP and one adult facilitator in each group. Schools were given all the materials needed to run their sessions, including LEGO sets with instructions and freestyle bricks. The CYP took turns playing one of the three roles. Groups were given LEGO sets containing picture-based instructions to build collaboratively, along with a tray on which to sort the LEGO bricks, and some free-play LEGO bricks. Facilitators were also given ‘brick club’ materials, including an example of some potential group rules, role cards (i.e. for the supplier, builder and engineer), free-play building ideas and a points system chart, all of which they were encouraged to use in the group. These materials were provided to facilitators in the abridged LEGO® based therapy manual (see Report Supplementary Material 1).

Schools with fewer than three CYP who were eligible for the study were asked to invite ‘additional CYP’ who may benefit from the groups. Informed assent/consent was gained from these CYP and their parents/guardians but there were no inclusion/exclusion criteria in place. Groups were able to go ahead with fewer than three CYP if any were absent owing to illness or other circumstances, though most groups included three CYP at all times.

Intervention provider

The facilitators delivering the LEGO® based therapy groups were school staff members, typically teachers or TAs, but sometimes the school’s special educational needs co-ordinator (SENCO), a learning mentor (LM) or another education professional. Each facilitator was required to have some prior knowledge of ASD.

Facilitators were trained by members of the study team in how to deliver the LEGO® based therapy intervention. Each training session lasted a total of 3 hours, during which facilitators would learn the theory of LEGO® based therapy and how to run the groups. They were given both a paper and an electronic copy of the LEGO® based therapy manual.

Mode and locations of delivery

All sessions of LEGO® based therapy were delivered face to face in school with the participating CYP and the group’s facilitator.

All sessions of LEGO® based therapy were delivered in schools randomised to the intervention arm of the trial. A permanent room in school was recommended to maintain consistency for the CYP and for ease of storage; however, materials could be moved between rooms if necessary. A minimum requirement was that the LEGO® based therapy took place in a quiet room with few to no interruptions and with enough table or carpet space to build LEGO sets.

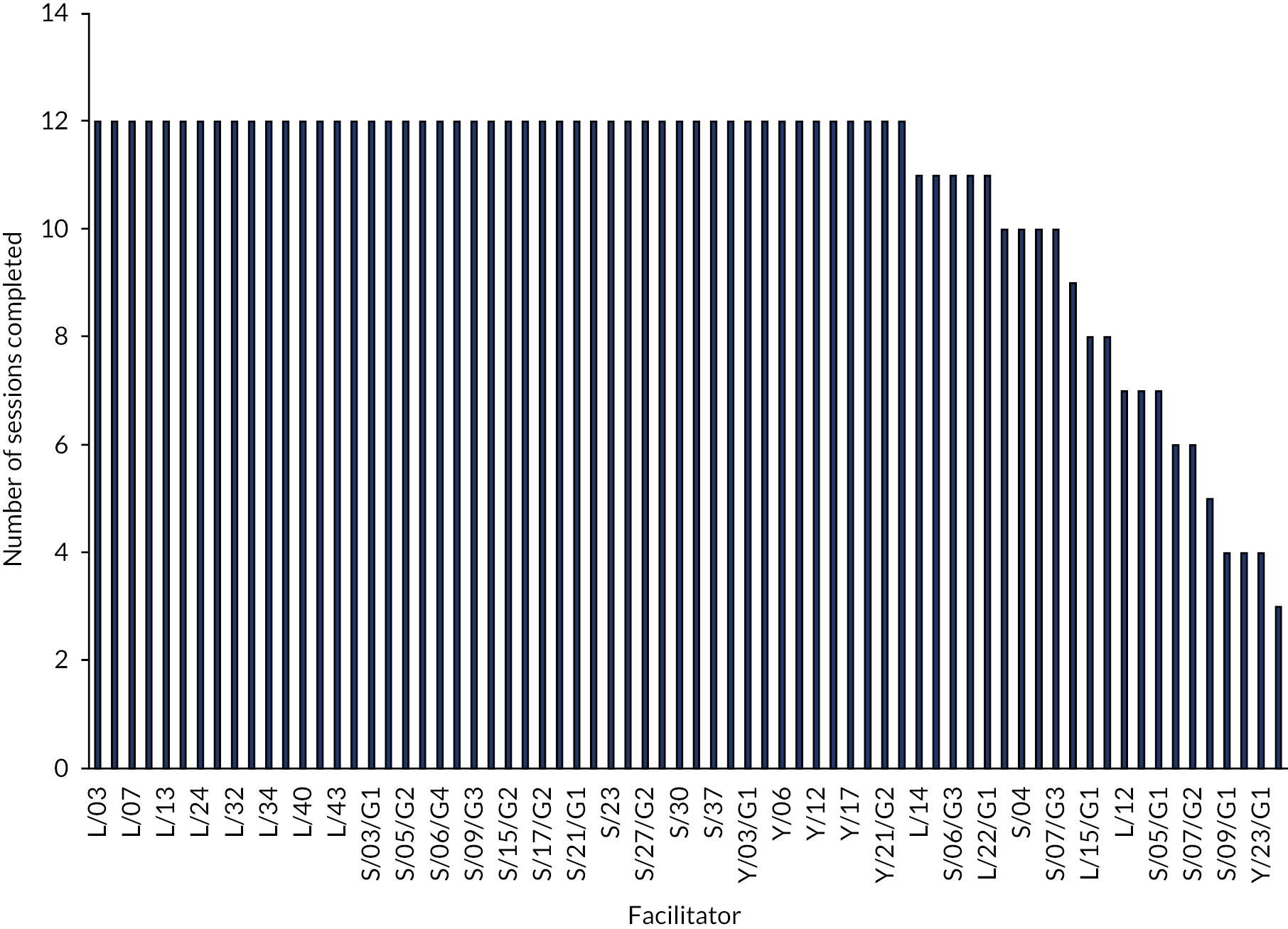

Frequency

Schools were asked to run 12 sessions of LEGO® based therapy over a period of 12 weeks. It was recommended that sessions were run for 1 hour once per week for the 12-week period. However, multiple sessions in 1 week owing to illness and time constraints were acceptable. Sessions shorter than 1 hour in duration were also acceptable, but facilitators were encouraged to run groups for at least 45 minutes.

Tailoring and modifications

During the training of the LEGO® based therapy facilitators, the trainers emphasised that, although the LEGO® based therapy intervention could not be modified during the course of the study, some features of the delivery of the intervention could be adapted to meet the needs of each group of CYP. These features included, for example, decisions about the choice of rules and reward systems, acknowledging that not all CYP will need the same rules or be motivated by the same things. Each group was encouraged to agree their own group rules based on what they thought was important for them, for example ‘be kind and polite’ or ‘remember to share’. Schools were encouraged to use existing reward systems if present. Some alternative reward systems were also suggested, such as the use of stickers, LEGO brick collection pots or LEGO figures.

It was also acknowledged that the amount of time during each session spent building the sets collaboratively was likely to change over the 12-week period depending on the group’s ability to use skills learned in the collaborative build activities and then move towards freestyle building.

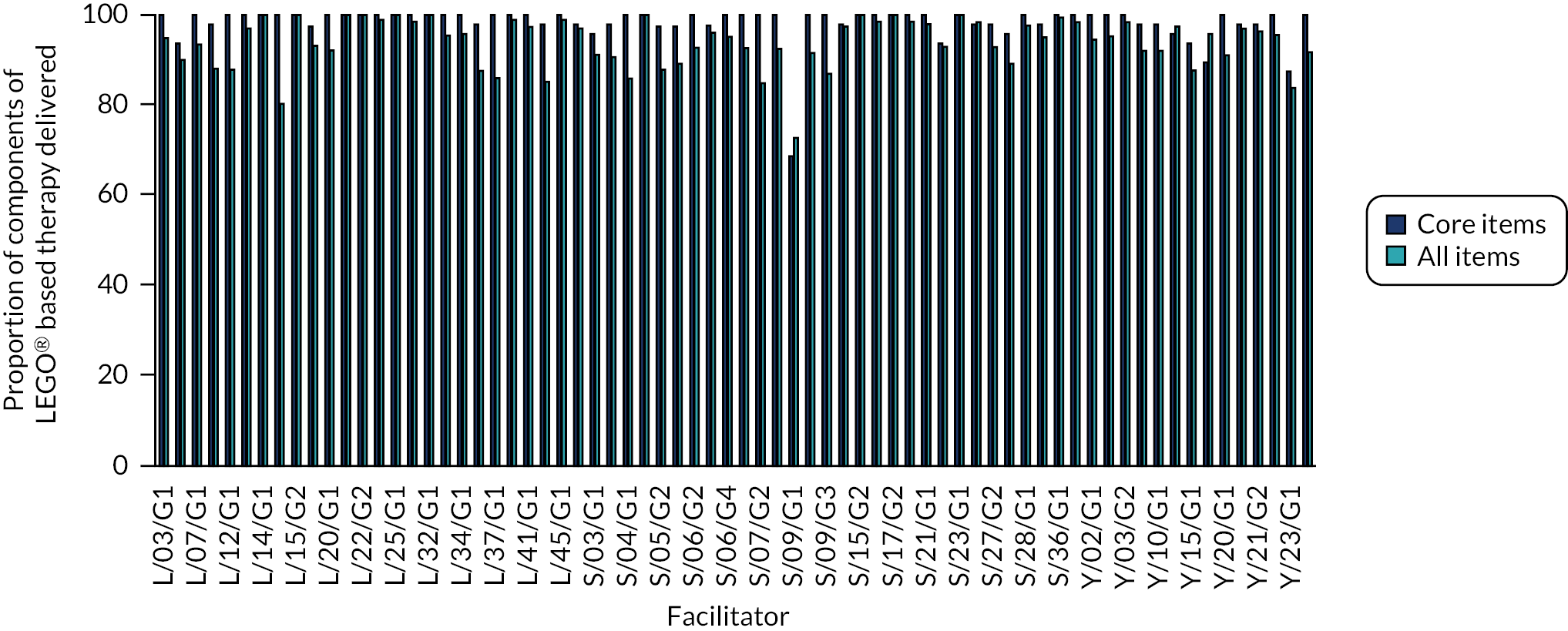

Fidelity

Intervention fidelity was assessed via two methods: (1) completion of the fidelity checklist after each session of LEGO® based therapy by all facilitators and (2) video-recording of a subset of sessions carried out. The self-report fidelity checklist is a 17-item questionnaire based on the main principles of LEGO® based therapy, which is designed to assess how closely the facilitator felt the session had followed the intended delivery method. These were completed after every session and were posted to the study team. Video-recordings were completed in schools where all participating CYP, their parents/guardians and the facilitator had consented to the recording. Recordings were then viewed by members of the study team and assessed for fidelity to the intended intervention delivery method and to the corresponding facilitator-completed fidelity checklist for each session.

Control arm: usual support

In addition to LEGO® based therapy, CYP in the intervention arm also received ‘usual support’, defined as the usual support they would receive from school, ASD specialist teachers, their general practitioners (GPs) and any other professionals. These data were collected using case report forms (CRFs) filled in independently by associated teachers and parents/guardians in both trial arms. Participating CYP in the control arm received usual support only.

Outcome measures

A range of outcome measures was used during the trial to assess the primary and secondary objectives.

Outcome measures were selected on the basis of (1) relevance for the study parameters and participant abilities, (2) brevity to reduce participant burden, (3) appropriate informant versions for those completing the measures and (4) acceptability to patient and public involvement (PPI) groups. The primary outcome measure, the SSIS, is a behaviour rating scale that can be completed by parents, teaching staff and appropriate students. It is widely used in national portfolio studies and has been shown to be sensitive to change resulting from interventions in autistic children. It has good levels of reliability and validity and is validated for use by teachers.

Measures were completed by CYP, parents/guardians, associated teachers/TAs who knew the CYP well and the facilitator teachers/TAs who delivered the intervention (if the child or young person’s school was allocated to the intervention arm). Data were collected face to face in family homes or at school, by post or online via a secure link sent via e-mail. All measures were completed by participants in both trial arms at baseline, 20 weeks after randomisation and 52 weeks after randomisation unless otherwise stated.

Associated teacher/teaching assistant questionnaires

-

The SSIS53 – three subscales:

-

Social skills subscale (primary outcome measure) – 46 items; higher scores indicate greater social competence. This measures social skills such as social communication, co-operation, social engagement, empathy, assertion, responsibility and self-control.

-

Problem behaviours subscale – 30 items; higher scores indicate fewer problem behaviours.

-

Academic competence subscale – seven items; higher scores indicate higher academic competence.

-

-

The SDQ54 – 25 items; higher scores indicate a higher chance of developing a mental health disorder.

-

Bespoke resource use questionnaires – used to capture the resource implications of usual support received by the CYP in both trial arms. Specific questions were included in the resource use form at 20 weeks to assess any AEs (at 20 weeks only).

Facilitator teacher/teaching assistant (intervention arm only)

-

A bespoke demographic information form collecting demographic information and information relating to training and experience of the facilitator teacher/TA (at baseline only).

-

A bespoke resource use questionnaire to capture the resource implications of running the LEGO® based therapy sessions at school (after each session):

-

Specific questions were included in the session resource use questionnaire to assess any AEs that might be attributable to the intervention (after each session).

-

-

A fidelity checklist based on the existing treatment manual35 (after each session) – 17 items; higher scores indicate higher treatment fidelity.

-

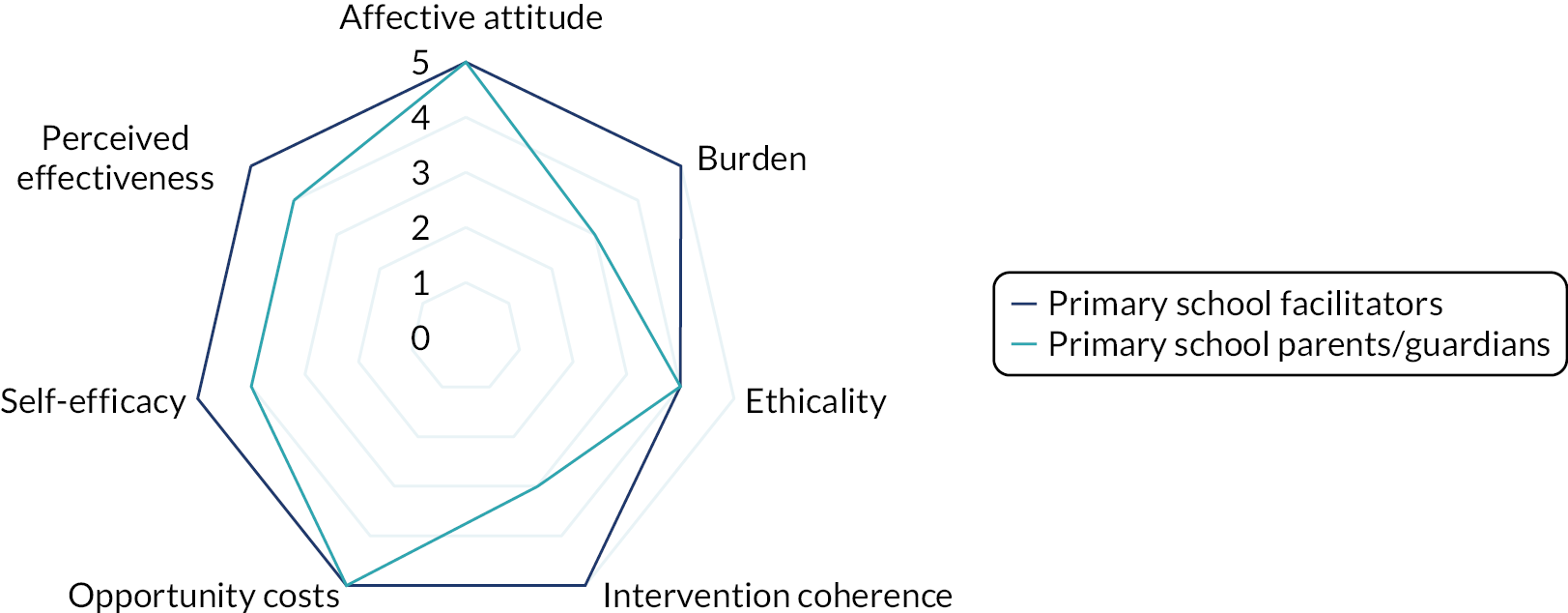

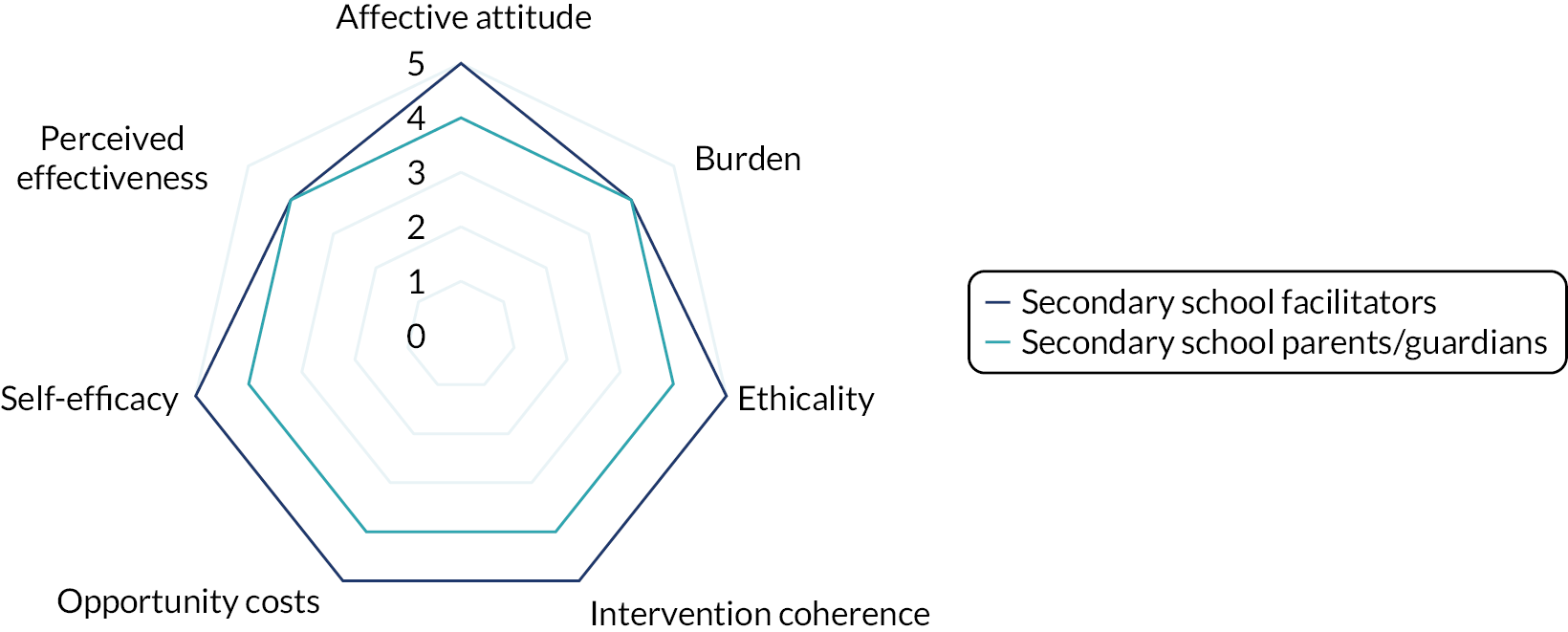

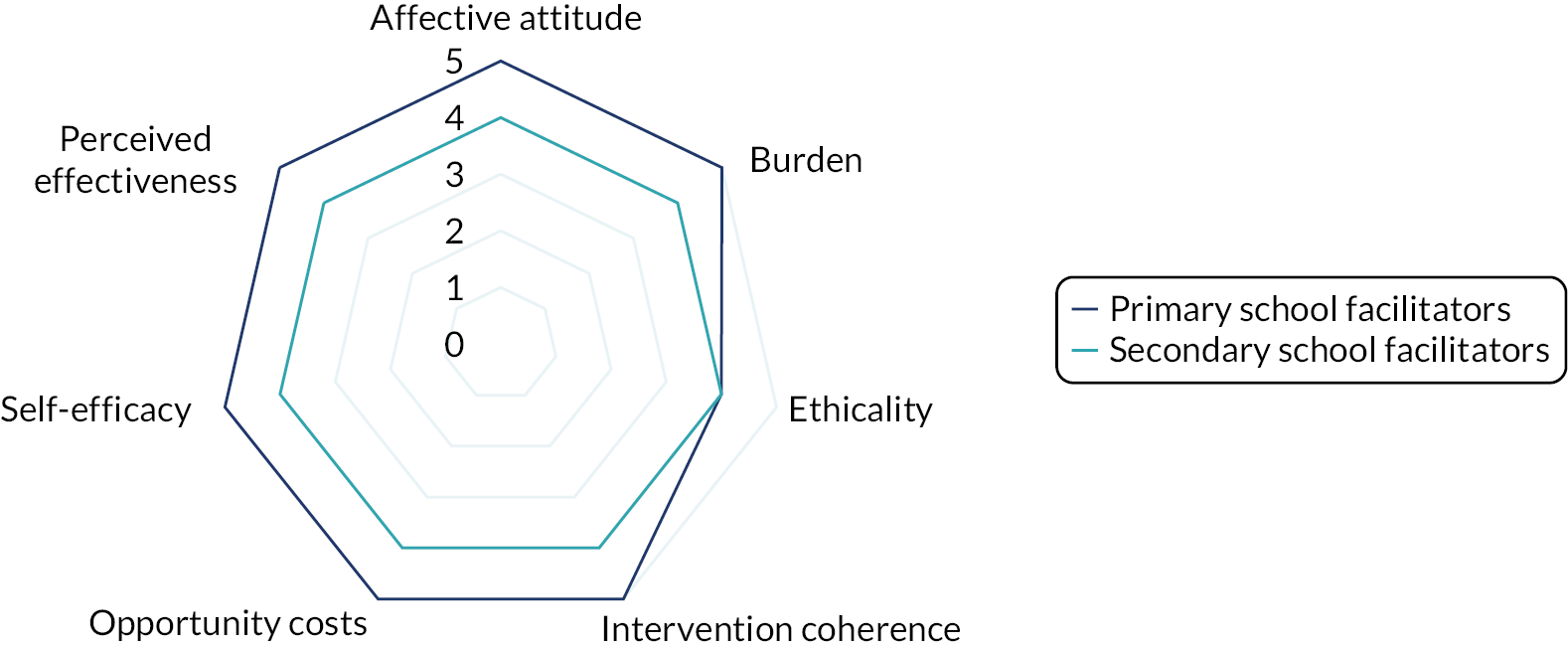

A bespoke questionnaire to assess acceptability of the intervention structured around the theoretical framework of acceptability (TFA)55 – 11 items; higher scores indicate greater acceptability (at 20 weeks only).

Children and young people questionnaires

-

The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS)56 – 12 items; higher scores indicate a higher degree of perceived social support.

-

The Asher Loneliness Scale (ALS)57 – 24 items; higher scores indicate lower levels of loneliness and social dissatisfaction.

-

Child Health Utility-9 Dimensions (CHU-9D)58 – nine items; higher scores indicate higher health utility.

Parent/guardian questionnaires (one parent/guardian only)

-

The SCQ59 – 40 items; higher scores indicate more social communication difficulties (at baseline only).

-

The SSIS53 – two subscales:

-

The social skills subscale (primary outcome measure) – 46 items; higher scores indicate greater social competence. This measures social skills such as social communication, co-operation, social engagement, empathy, assertion, responsibility and self-control.

-

The problem behaviours subscale – 33 items; higher scores indicate fewer problem behaviours.

-

-

The SDQ54 – 25 items; higher scores indicate a higher chance of developing a mental health disorder.

-

The EuroQol-5 Dimensions-Youth (EQ-5D-Y) [based on the EuroQol-5 Dimensions, three-level version (EQ-5D-3L), proxy version]60 – five items; higher scores indicate higher health utility.

-

Bespoke resource use questionnaires to capture the health care and non-health resource implications attributable to the CYP’s ASD:

-

Specific questions were included in resource use form at 20 weeks to assess any AEs (at 20 weeks only).

-

-

Bespoke questionnaire to assess acceptability of the intervention structured around the TFA55 – 11 items; higher scores indicate greater acceptability (intervention arm only at 20 weeks only).

-

A bespoke demographic information form collecting demographic information pertaining to the CYP and the parent/guardian (at baseline only).

Adverse events and serious adverse events

Adverse events were reported at the 20-week follow-up point by parents/guardians and associated teachers in their CRFs and by facilitators in their session attendance and resource use form completed after each session of LEGO® based therapy. Reported AEs were assessed for seriousness and this information was reported to the trial manager, principal investigator and DMEC. An AE was classified as a serious adverse event (SAE) if it met the following criteria:

-

results in death

-

life-threatening

-

requires hospitalisation or prolongation of existing inpatient hospitalisation

-

results in persistent or significant disability or incapacity.

Three SAEs were reported during the trial: one in the intervention arm and two in the control arm. All were unrelated to the trial (see Table 21).

Changes to trial outcomes after the trial commenced (with reasons)

As discussed in Important changes to the methods after trial commencement, the study’s first follow-up time point was changed in March 2018 from 16 weeks post randomisation to 20 weeks post randomisation. This was implemented because of concerns in the study team that the 12 sessions of LEGO® based therapy would not have been completed by all schools when approached for their 16-week follow-up and that resulting data would not be balanced, with schools at different stages of the intervention. This change was approved and implemented following discussions with the trial DMEC and TSC. The primary outcome measure to be used in ITT analysis was clarified in September 2018 as the social skills subscale of the SSIS (as opposed to the entirety of the SSIS).

The fidelity checklist outcome measure completed by the facilitator teacher/TA after every session of LEGO® based therapy was altered in September 2018 after discussions around the ease of completion for participants. Question 14 originally included one question followed by a separate, second question. This was followed by an ‘or’ option leading to question 15. For clarity and ease of use by facilitators and study team members, the second question in question 14 was changed to become question 15a and question 15 became 15b.

During our study the country faced the consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic. UK schools closed multiple times over the course of the year (2020–1). However, for this study the impact was limited to the first ‘lockdown’ and school closures in March 2020. This coincided with the final months of data collection, meaning that for a small number of our 52-week follow-ups some CYP responses, for example in relation to levels of anxiety, may have been affected by the pandemic.

There was no impact on intervention delivery or the primary outcome measure because these had been completed by the summer of 2019.

Some additional analyses were conducted to assess the potential impact of the pandemic on the trial; these are discussed in Chapter 3, Recruitment and participant flow, Dates defining the periods of recruitment and follow-up.

Sample size calculations

The sample size used for the study was calculated based on a Cochrane review of five studies assessing the effects of social skills groups on the social competence of participants. 28 Four of the studies29–32 reported were RCTs that used standardised tools to measure social competence and could be synthesised via meta-analysis. When comparing group intervention receipt and usual support, the weighted mean standardised difference in social competence was found to be 0.47 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.16 to 0.78] and the review stated that this represented a clinically significant change in social competence. When using this standardised effect size to calculate sample size to give 90% power and at the 5% two-sided significance, a total of 194 participants would be needed (i.e. 97 per trial arm). This number was increased to 232 participants (i.e. 116 per trial arm) to allow for an attrition rate of 16%, the highest of the reported rates in the Cochrane review of social skills interventions. 28 The sample size was further inflated to 240 participants to allow for trainer/school effects, assuming equal clusters of size four (i.e. two LEGO® based therapy intervention groups per school and two CYP participants with a diagnosis of ASD per LEGO® based therapy group). The intraclass correlation (ICC) was assumed to be 0.01 based on findings from the ASSSIST (Autism Spectrum Social Stories In Schools Trial) feasibility study. 65 This gave a total recruitment target of 240 participants (i.e. 120 participants per trial arm) or 12 participants per month over all recruiting areas.

Explanation of any interim analyses and stopping guidelines

The study included a 10-month internal pilot to assess the feasibility of conducting the trial. The expected recruitment target was 120 participants, based on a recruitment rate of 12 participants per month, one-third (n = 40) of whom were expected to have reached the primary end point of 20 weeks post randomisation. Stop/go criteria were used to assess whether or not the study should continue. This was based on 75% of expected recruitment at 10 months (n = 90) and 70% of the primary outcome target (n = 28). In reality we had only 8 months for recruitment because of school holidays and delays with study approvals leading to recruitment start delays, meaning that the recruitment rate target became 15 participants per month.

Method used to generate the random allocation sequence

The unit of randomisation was school, each of which was randomised using stratified randomisation lists based on two strata: stage of education (i.e. primary or secondary) and number of eligible and participating CYP (i.e. ≤ 6 or > 6 CYP). All consented CYP were included in the intervention clusters. A blinded statistician from the Clinical Trials Research Unit (CTRU) at the School of Health and Related Research (ScHARR), University of Sheffield (Sheffield, UK), generated four randomisation lists (i.e. one for each combination of the two strata) using random blocks in the statistical package R (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Allocation to arms was undertaken remotely. The co-ordinating researcher telephoned the CTRU for the next entry on the appropriate list after establishing eligibility, obtaining consent and collecting baseline measures.

Type of randomisation and details of any restriction (such as blocking and block size)

Cluster randomisation was used at school level to avoid CYP in the same school receiving different interventions, thus limiting contamination. The allocation list was generated prior to recruitment using block randomisation, with each group of two or four recruited schools having a 1 : 1 balance between arms. Group membership was determined chronologically (by date of recruitment) in the four strata and the size of each subsequent group was selected at random.

Sequence generation, enrolment and assignation

Following random allocation, schools were informed of their allocation by the trial manager by post and by telephone or e-mail, and families were informed by post. Once schools allocated to the intervention had been informed of this, they were asked to select a member of staff to attend training in LEGO® based therapy and to run 12 sessions of the intervention before their 20-week follow-up. This method of enrolment was used successfully in a previous study of autistic CYP. 61

Blinding

All RAs in the study team were blind to treatment allocation to limit any potential bias at the two follow-up points (i.e. 20 and 52 weeks post randomisation). All forms were completed by participants themselves, and RAs had very little input, but, when instances of unblinding were reported, subsequent follow-ups were carried out by another blinded study team member, and these were recorded.

Trial statisticians were also blind to treatment allocation throughout the trial. The DMEC had access to unblinded data on request to enable it to investigate SAEs associated with the intervention.

Statistical methods

Intention-to-treat analysis was used to assess whether or not LEGO® based therapy had any effect on the social competence and perceived isolation of autistic CYP. This approach is appropriate for a pragmatic trial because of its focus on external validity despite dilution bias dangers when the regression slope may be biased towards zero. 62 Per-protocol analysis was also used based on a per-protocol definition of receiving six or more sessions of the LEGO® based therapy intervention. Comparability between baseline demographic and outcome measures was analysed and all data produced were assessed and reported based on RCT CONSORT guidelines44 and cluster RCT CONSORT guidelines. 45

The primary outcome measure was the social skills subscale of the SSIS completed by the associated teacher at 20 weeks post randomisation. This scale gives a summated score, treated as a continuous variable, with the significance level set at 5%.

As pre-specified in SAP version 2.0, the primary analysis of the primary outcome was performed using a multilevel mixed-effects model, with robust standard errors accounting for clustering within school. Covariates in the analysis were age, gender, baseline score on the social skills subscale of the SSIS, school (random effect), number of eligible and participating CYP (stratified by ≤ 6 or > 6 CYP), and school level (stratified by primary or secondary). The standardised mean difference, a two-sided 95% CI and p-values were presented. The primary analysis was performed on the ITT population.

Differences between arms were also summarised using unadjusted estimates with 95% CIs.

Secondary outcome variables were analysed using the same framework as the primary outcome. The sustainability analysis compared 20-week and 52-week estimates of differences between arms on the social skills subscale of the SSIS reported by the associated teacher.

Subgroup analysis of three levels of baseline symptom severity measured using the SCQ was undertaken in two ways. First, the interaction between subgroup and trial arm was added to the primary analysis model. Second, separate models were fitted for each of the three subgroups.

When data were missing from outcome measures because of withdrawals or attrition at follow-up points, multiple imputation (MI) methods were used in sensitivity analyses to reduce potential bias in the analyses resulting from the missing data.

All standardised effect sizes were calculated by rescaling the model estimated mean difference by the pooled standard deviation (SD) of the outcome at baseline, then multiplying by –1 for those outcomes in which a decrease in the score needs to be observed to find evidence in favour of the intervention arm.

Analysis populations

The following pre-planned analysis populations were studied for the primary outcome (analysis of secondary outcomes used the ITT population only):

-

ITT – those with data available for ≥ 42 of the 46 items in the primary outcome measure (social skills subscale at 20 weeks reported by associated teacher) and with recorded consent information

-

per protocol – the subset of the ITT population who received six or more of the 12 planned intervention sessions

-

complier average causal effect (CACE) – ITT analysis accounting for compliance (i.e. six or more sessions received)

-

MI population – imputation of missing social skills subscale scores using chained equations.

Additional analyses

Planned sensitivity analysis on the primary outcome

Sensitivity analyses were conducted for the primary outcome using the per-protocol, CACE and MI methods, and results were presented in a forest plot.

Additional sensitivity analyses accounted for the timeliness of follow-up data collection, associated teacher responses at the 20-week follow-up time point and the impact of UK lockdown measures resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic. The timelines analysis removed all responses submitted more than 26 weeks after randomisation (for the 20-week follow-up) and 60 weeks after randomisation (for the 52-week follow-up). The teacher analysis excluded all responses for which baseline and 20-week data had been provided by different teachers. The COVID-19 analysis removed all responses completed after 23 March 2020.

Unplanned sensitivity analysis on the primary outcome

Three unplanned analyses were undertaken to explore the potential for observational analysis of the trial data in a subsequent substudy.

First, two additional analysis populations were studied:

-

per protocol 2 – the subset of the ITT population for whom there was an average of two or more autistic CYP in therapy sessions

-

CACE 2 – ITT analysis accounting for compliance (i.e. CYP for whom there was an average of two or more autistic CYP in therapy sessions).

Second, subgroup analyses of the stratification variables used in the randomisation were undertaken using the same approach as the planned subgroup analysis.

Third, the three subgroup analyses undertaken for the primary outcome were repeated for six of the secondary outcomes: scores for the SDQ54 subscales peer problems and prosocial, ALS score,57 the MSPSS score and the parent-reported social score (all at 20 weeks) and the teacher-reported social score at 52 weeks. These were selected by clinical members of the team before they had knowledge of the results of the secondary outcome analysis.

Study oversight and management

The study was managed throughout by two trial managers, one at the ScHARR CTRU and one in the Leeds and York Partnership NHS Foundation Trust (LYPFT), with support from the Chief Investigator and CTRU Director. Oversight took the form of four groups: the TMG, the Operations Group, the TSC and the DMEC. TMG meetings, involving study team members and co-applicants, were held monthly for the majority of the study period until January 2019, when their frequency was changed to quarterly, with Operations Group meetings (involving core study team members) occurring monthly in their place. TSC and DMEC meetings occurred every 6 months for the duration of the study period and involved independent members and stakeholders with relevant expertise. In addition, a 6-monthly study report was submitted to the funder, the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Public Health Research (PHR) programme, and regular communication occurred between all members of the study team.

Internal monitoring of the study was carried out in October 2018. At this time, each of the two sites [the Child Oriented Mental Health Intervention Centre (COMIC), University of York (York, UK), and the University of Sheffield CTRU] visited the other to check the study site files for completeness and accuracy. Findings were logged and any errors amended by the study team. In addition, in January 2019, the trial master file kept at the Sheffield CTRU was checked along with a randomly selected 10% sample of the completed CRFs at each site (COMIC, n = 9; Sheffield CRTU, n = 10). These were checked for accuracy of entry onto the bespoke clinical data management system. Data entry accuracy was relatively high.

External monitoring was then conducted at the COMIC research site in June 2019 by a member of the Harrogate and District NHS Foundation Trust’s research and development team. This included checking the site file for completeness and accuracy, assessing the trial’s Good Clinical Practice compliance, and source data verification (SDV) checking 10% of the completed CRFs at the site (n = 14). All errors noted in the monitoring report were amended by August 2019. This monitoring session confirmed the findings of the initial site monitoring in that there was a very small number of data entry errors. Therefore, the study team decided to carry out full SDV checks of all critical data (see Appendix 1, Table 29). Overall SDV error percentages were very low, with a total of eight forms out of 48 exceeding the 1% error rate. All identified errors were corrected on discovery.

Ethics arrangements and regulatory approvals

Positive ethics opinions for the study were obtained from the Health Research Authority (HRA) (18/HRA/0101) and from the University of York’s REC. Approvals for any changes to study documents or other required approvals were sought prior to implementation from the REC, the NIHR PHR programme, the sponsor and the HRA when necessary. The trial was not conducted in, and did not recruit from, the NHS, nor did it involve or identify participants based on their use of the NHS; thus, NHS ethics approval was not required. In addition, clinical trials authorisation was not required, as no medical devices or pharmaceutical elements were used.

Patient and public involvement

Study design

The study team worked closely with PPI members from different groups representing the target population to develop the original research proposal and in the early stages of study set-up. The PPI representatives included a parent/guardian of a child or young person with ASD and individuals from the Young Dynamos research advisory group (Bradford District Care NHS Foundation Trust, Shipley, UK) and the National Autistic Society (NAS) (London, UK). The Young Dynamos, a research advisory group from the Bradford District Care NHS Foundation Trust, is made up of young people of varying ages. The project was presented to the group, which comprised around 10 young people (the number differed at each meeting) and the two adult group leaders, at multiple time points throughout the study. Two members of the NAS gave valuable feedback regarding initial study design early in the project. A parent of a child with ASD helpfully agreed to be a member of our TSC and was able to provide input on discussion points throughout the study. We also gained input from a specialist teacher for autism from the York local authority (York, UK) during the study, which aided discussions. The recommendations provided by PPI representatives were implemented and contributed towards the smooth running and high recruitment rates of the trial.

Study oversight

The TSC included a parent/guardian of an autistic child. This representative was present at TSC meetings, which meant that the parent/guardian’s perspective was present when discussing the general running of the trial and any current problems faced by the study team. This type of PPI aided decision-making, and valuable insights were gained over the course of the trial. Ideally, a child or young person and a teacher would also have been involved, but this was not possible because TSC meetings often took place during school time.

The PPI representatives also provided helpful input for the plain English summary used in this report. In addition, a discussion was set up with PPI group members, clinicians and the TSC around the language to be used in this report to refer to the CYP participants with a diagnosis of ASD. It was noted that there are many terms that are used to refer to ASD, and some people with this diagnosis have a specific preference. The group concluded that it would be best to use the clinical terminology of ASD but to include an explanation of this along with acknowledgement of the many other terms preferred by this population.

The trial was presented in January 2020 at the NIHR Clinical Research Network Yorkshire and Humber’s Vision 2021: PPIE – Working Together in Research conference (York, UK, 28 January 2020) by the York trial co-ordinator and a young person from the Young Dynamos PPI group. The group’s involvement in the trial was described by the young person, and the involvement of other PPI members was also presented.

Health economic methods

Background

The trial design was a cluster RCT to investigate the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the LEGO® based therapy intervention on the social and emotional skills of autistic CYP compared with usual support only. In this design, the health economics component was a cost–utility analysis, measuring the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of the LEGO® based therapy intervention over the control arm.

Effectiveness

Effectiveness for the health economics analysis was measured using the EQ-5D-Y and the CHU-9D.

EuroQol-5 Dimensions-Youth

The EQ-5D-Y60 is a five-item, generic, preference-based measure of health-related quality of life (HRQoL) that can be completed by proxy person (i.e. parent/guardian) on behalf of the participant. The EQ-5D-Y comprises five dimensions: mobility, looking after oneself, doing usual activities, having any pain or discomfort and feeling worried. Each dimension presents three levels of problems: ‘no problems’ (level 1), ‘some problems’ (level 2) and ‘a lot of problems’ (level 3). There is also a visual scale of the child or young person’s overall health status from 0 (worst health imaginable) to 100 (best health imaginable). All questions refer to the child or young person’s health state ‘today’. The EQ-5D-Y has been shown to be a reliable and valid HRQoL instrument for use in CYP and adolescents,63 and it can be used for a cost–utility analysis.

Child Health Utility-9 Dimensions

The CHU-9D58 is a CYP-completed nine-item questionnaire that measures HRQoL. CYP are required to select one of five sentences for each question that describes how they feel in relation to the construct listed in that question. The constructs are ‘worried’, ‘sad’, ‘pain’, ‘tired’, ‘annoyed’, ‘schoolwork/homework’, ‘sleep’, ‘daily routine’ and ‘able to join in activities’. The CHU-9D also provides utility values, allowing the calculation of quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) for use in a cost–utility analysis.

Cost

Cost of the intervention

The cost of the intervention included the cost of training and the cost of delivering LEGO® based therapy. Training costs were calculated using the time spent by the trainer and included travel costs and the costs of materials and consumables (e.g. pens, paper, file folders, sticky notes, manuals used to deliver the intervention) used in the training. Costs associated with delivering the LEGO® based therapy intervention were calculated using the time spent by facilitator teachers/TAs in planning and conducting sessions and undertaking any additional work. A bespoke questionnaire developed by the research team was used for collecting data on the costs of training and delivering LEGO® based therapy.

Cost of the service use

Service use data were collected using bespoke questionnaires (completed by the parent/guardian and associated teacher of each CYP in the study) on the use of the following services:

-

community-based health services, including appointments with GPs, nurses, walk-in centre staff, social workers, family support workers, educational psychologists, educational welfare officers, and school and college nurses

-

mental-health-related services, including appointments with psychiatrists, psychotherapists, psychologists, Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) therapists, mental health nurses, family therapists, GPs, school counsellors and privately paid mental health service staff

-

hospital-based services, including outpatient visits, inpatient admissions, accident and emergency department visits, and urgent care centre visits

-

school-based interventions/support provided by teachers

-

other services, including medication, privately paid services and productivity costs.

Parent-/guardian-completed resource use questionnaires informed individual-level use of the above-listed services, specifically primary and secondary healthcare and social care services. The tailored questionnaire was based on a previous questionnaire by Barrett et al. ,64 which has since been adapted for use in school-based trials. 65,66 Teacher-completed questionnaires captured any school-based interventions/support and the implications of a child or young person’s behaviour on school resources.

Service use was multiplied by unit costs to arrive at total cost in each arm. Unit costs of health and social service use were obtained from the UK national database of reference costs (2016–17)67 and the Personal Social Services Research Unit (PSSRU)’s Unit Costs of Health and Social Care 2015. 68 Medication costs were based on Prescription Cost Analysis, England 2017. 69 Data reported by the Department for Education70 were used to estimate the cost of teacher time, with any privately paid services being separately estimated using market prices. In cases in which funding sources for a member of staff were unclear, assumptions were made based on service location and published guidelines (such as PSSRU guidelines). 69

Economic analysis

The health economics analysis was conducted from a UK NHS and PSS perspective. This took the form of a within-trial cost–utility analysis to compare the LEGO® based therapy intervention with usual support for autistic CYP. Costs were measured using tailored service use questionnaires. Health outcomes were measured using QALYs based on the parent-/guardian-completed EQ-5D-Y as a health descriptor measure. QALYs were estimated using the area-under-the-curve approach between baseline and each follow-up.

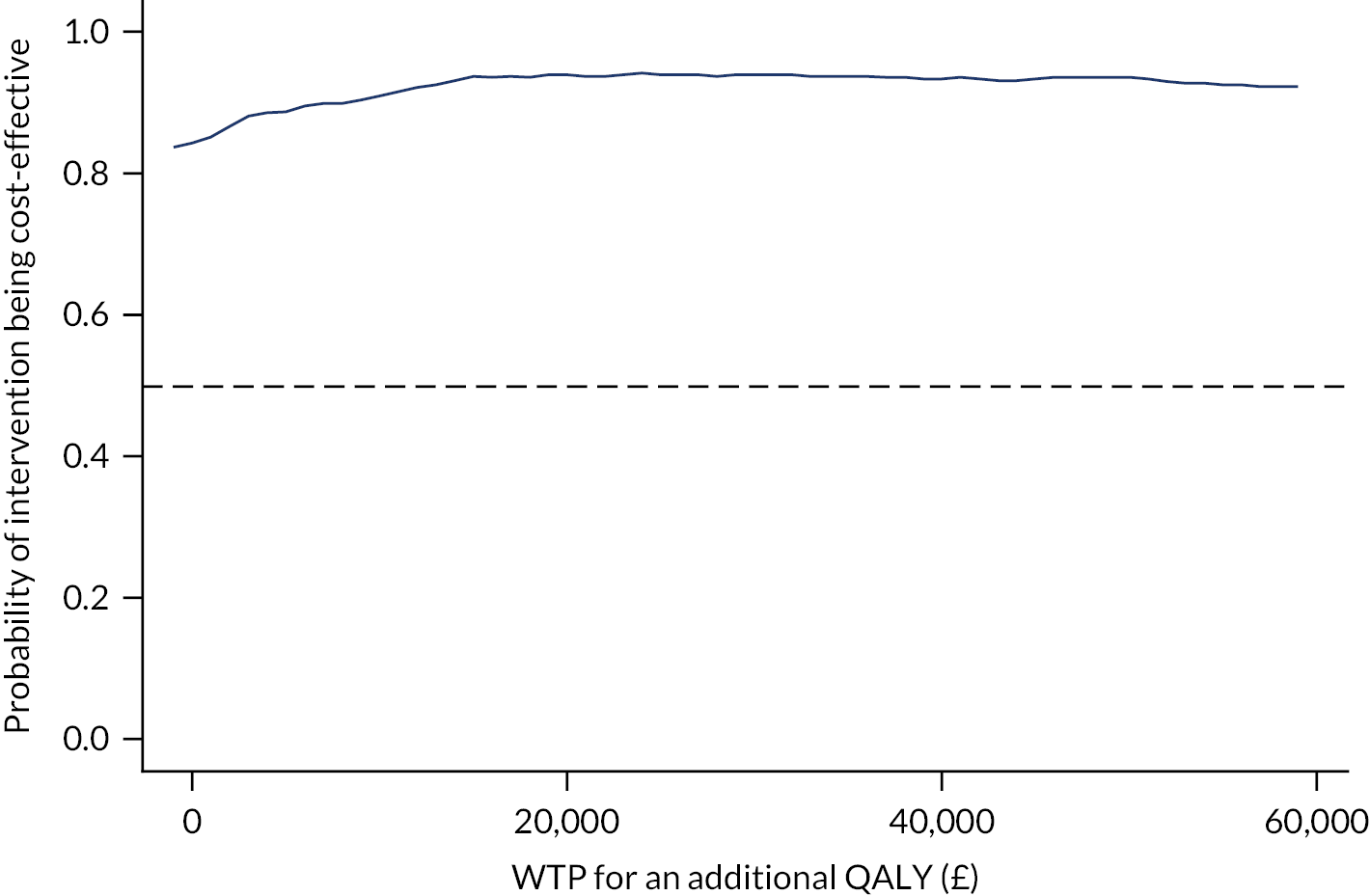

Combining costs and QALYs, an ICER of cost per QALY gained was calculated and then compared with the national WTP threshold of £20,000–30,000 per QALY gained71 to assess the cost-effectiveness of the intervention.

Descriptive analysis

Total costs, including intervention and service utilisation costs and QALYs, were compared between intervention and control arms using appropriate descriptive analyses.

Handling missing data

Missing data existed in both service use and health outcome data. For service use, data were deemed missing when all questions under a particular section were left blank. If one of these questions was answered, the other answers were assumed to be 0. For the EQ-5D-Y, a section was considered missing if any of its five questions was not answered. Missing data were further imputed using Rubin’s MI method. 72

Regression analysis and bootstrapping

A regression model was used to compare mean costs and QALYs based on an ITT approach. The regression analyses were controlled for baseline differences in utility,73 costs and other baseline characteristics of autistic CYP, such as age, gender and SCQ score. The model specification followed the approach recommended by Glick et al. ,74 which considers the distribution of the dependent variable and any correlation found between cost and QALY outcomes. The ICER was then calculated based on the regression coefficients on intervention, because they represent the difference in mean cost and mean QALYs between the two groups. To take uncertainty into consideration, a non-parametric bootstrap resampling method was used to produce the CI for the ICER. This was carried out because the distribution of regression residuals was likely to be skewed. 75

The bootstrapped results were presented in the conventional form of a cost-effectiveness plane and a cost-effectiveness acceptability curve (CEAC). The uncertainty based on the outcomes of the 5000 bootstrap iterations was represented graphically on the cost-effectiveness plane, and the CEAC presented the probability of the intervention being cost-effective over a range of WTP thresholds per QALY gained. 76

Sensitivity analysis

A set of sensitivity analyses was conducted, as follows:

-

To assess the impact of the missing data, a sensitivity analysis using complete cases was conducted.

-

To account for the economic impact on the stakeholders, a sensitivity analysis adopting a NHS/PSS and education perspective was conducted.

-

To account for the economic impact outside the NHS/PSS perspective, a sensitivity analysis was conducted using a societal perspective to cover service costs from healthcare and education sectors, private expenses and costs of parental productivity loss.

-

A sensitivity analysis that used the CHU-9D instead of the EQ-5D-Y to estimate QALYs based on the UK population tariff58 was also conducted.

Qualitative methods

Qualitative methods

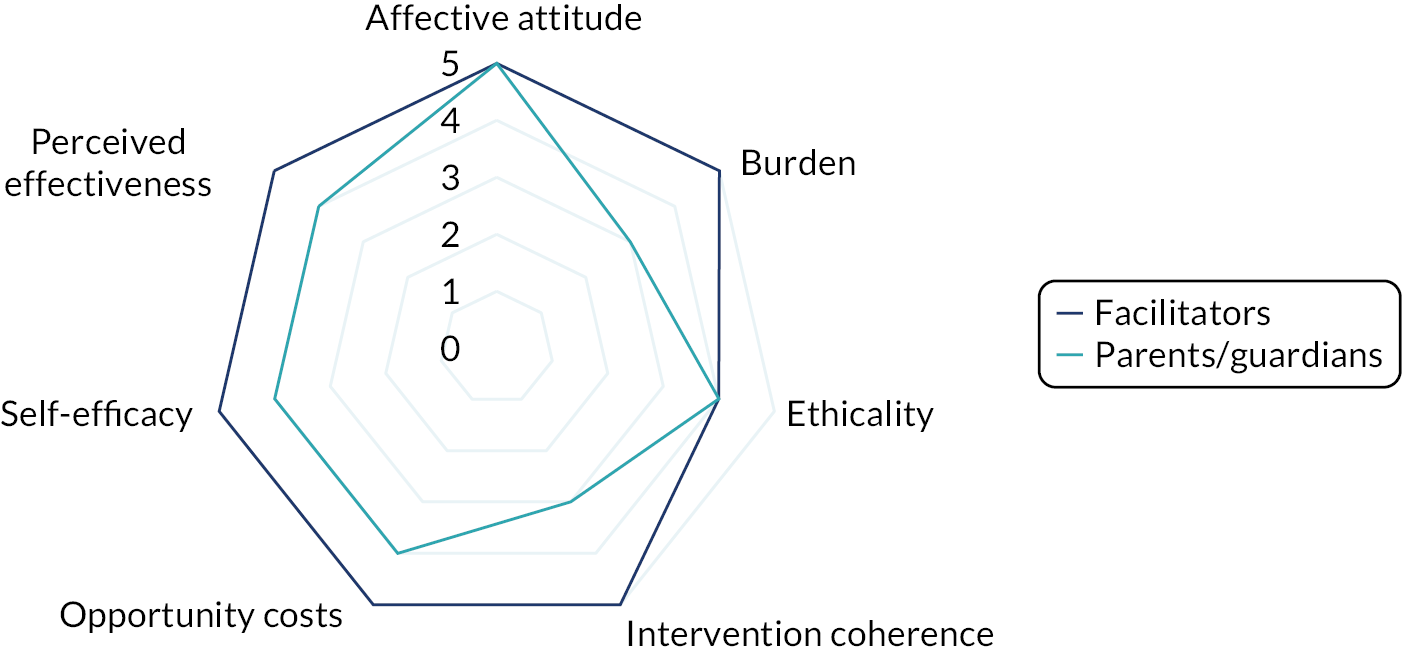

Interviews were conducted following the completion of the intervention with a subsample of facilitator teachers/TAs across school types (primary or secondary) who provided consent to be invited to participate in the qualitative substudy. The TFA55 and normalisation process theory77 were used to guide the design of the interview schedule and help frame the data analysis to aid our understanding of acceptability and implementation issues related to the intervention. Sekhon et al. 55 define acceptability as ‘a multi-faceted construct that reflects the extent to which people delivering or receiving a healthcare intervention consider it to be appropriate, based on anticipated or experienced cognitive and emotional responses to the intervention’. Sekhon et al. 55 outline seven component constructs of acceptability. Given that we have used the TFA to structure the measurement of intervention acceptability, the definitions of each construct have been included as a direct quotation for transparency as follows:

-

affective attitude – ‘How an individual feels about the intervention’55

-

burden – ‘The perceived amount of effort that is required to participate in the intervention’55

-

ethicality – ‘The extent to which the intervention has a good fit with an individual’s value system’55

-

intervention coherence – ‘The extent to which the participant understands the intervention and how it works’55

-

opportunity costs – ‘The extent to which benefits, profits or values must be given up to engage in the intervention’55

-

perceived effectiveness – ‘The extent to which the intervention is perceived as likely to achieve its purpose’55

-

self-efficacy – ‘The participant’s confidence that they can perform the behaviour(s) required to participate in the intervention’. 55

Normalisation process theory has been proposed as a way of identifying whether or not an intervention is likely to become part of routine practice. 78 It offers an explanatory model for the adoption and embedding of new practices into pre-existing routines based on the concept that changing such established routines is a complex process for individuals. The interview schedule was piloted with two teaching staff with experience of delivering LEGO® based therapy prior to commencing data collection as part of the trial.

Invitation e-mails were sent to all eligible facilitators who had given prior consent to participate in an interview, which included a short reminder of the interview purpose, and those who were still interested and available to participate responded accordingly.

All interviews were conducted by telephone by a member of the research team (AB, a postgraduate non-clinical RA at the time of study). Facilitators were asked to position themselves in a private location (e.g. work offices/private rooms on school premises) during the interview. All interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim. Interview data were analysed using the framework analysis approach,79 supported by NVivo version 12 (QSR International, Warrington, UK) software.

Interview data were coded by two independently trained researchers in the research team. The coders met regularly to develop a coding manual and to ensure the grounding in original data of all developed codes. The framework used was amended to allow for new codes and the deletion of unnecessary codes, leading to a final framework representative of the whole data set. The final versions of the coding manuals were presented to the TMG and TSC to confirm validity, coherence and relevance.

Acceptability study

The acceptability of the intervention to CYP was assessed using the number of sessions attended and data collected from the facilitator and parent/guardian, because we did not want to overburden the CYP participants at each session. We designed a bespoke questionnaire based around the TFA55 to assess acceptability of the intervention to parents/guardians and facilitators at the 20-week time point. This questionnaire was piloted with two members of teaching staff with experience of delivering LEGO® based therapy and with the PPI members of the TMG prior to finalising content and design. All data were summarised descriptively. Results from the survey are presented using descriptive statistics.

Fidelity methods

Intervention fidelity was monitored and assessed using the following mechanisms throughout the study:

-

An abridged training manual created by the study team based on the LEGO® based therapy manual. 35

-

A training programme developed with the training manual and delivered by co-applicant and co-author of the LEGO® based therapy manual, Gina Gomez de la Cuesta.

-

Video-recording of a subsample of intervention sessions in schools; full written consent for this was obtained from the parents/guardians of all group members (and assent from group members themselves where possible) and the facilitator teacher/TA. Details are as follows:

-

A fidelity checklist developed from work by Gina Gomez de la Cuesta was used to monitor the content of the intervention sessions. This was also completed by facilitators after each session.

-

The aim was to record 10% (i.e. 72) of all intervention sessions in the study. These were sampled at school level (primary or secondary), with the aim of three session recordings per school, ideally one of the first four sessions, one of the second four sessions and one of the final four sessions.

-

Videos of the intervention sessions were reviewed by two independent observers to assess fidelity to the checklist, and inter-rater reliability was analysed.

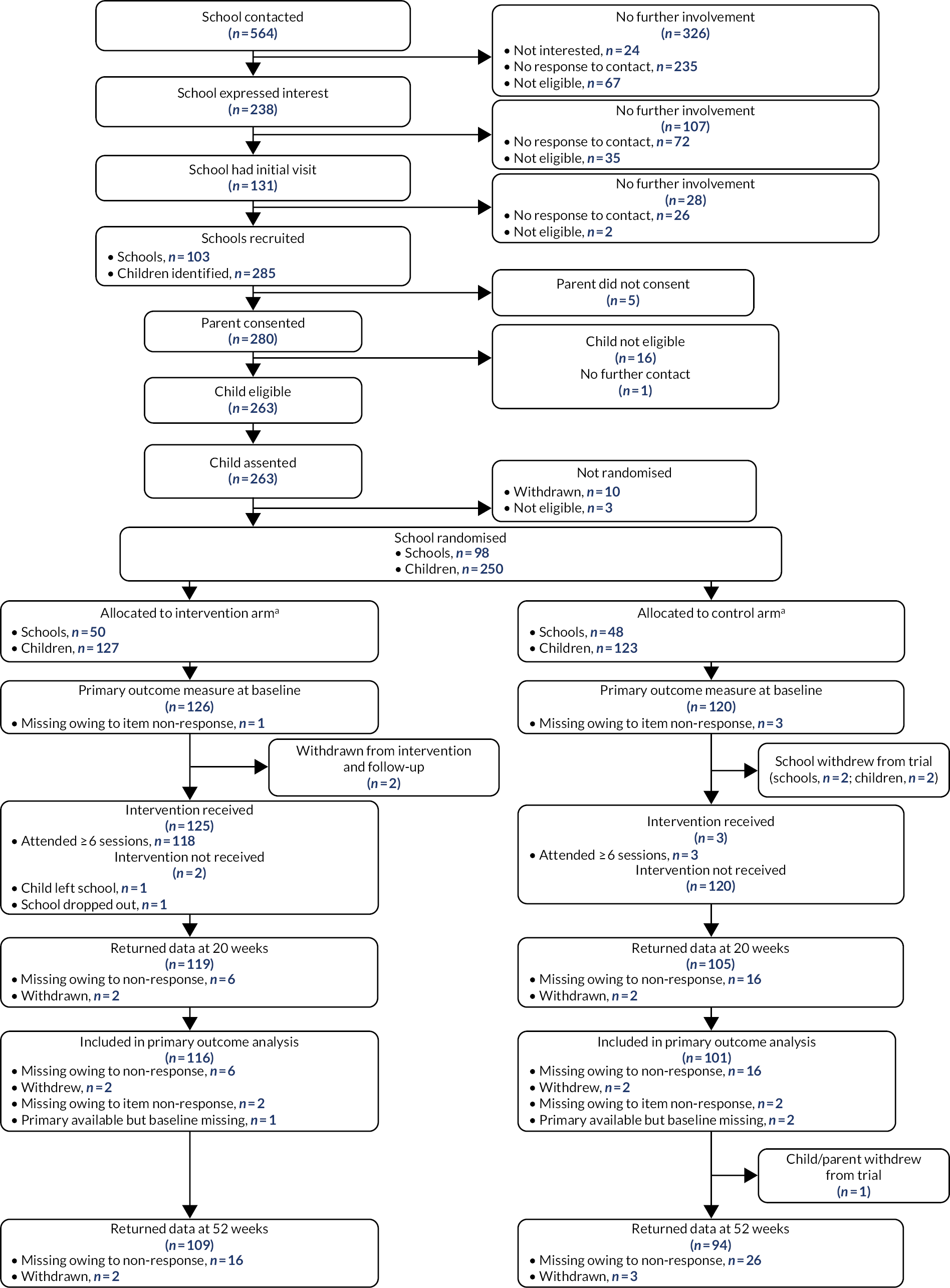

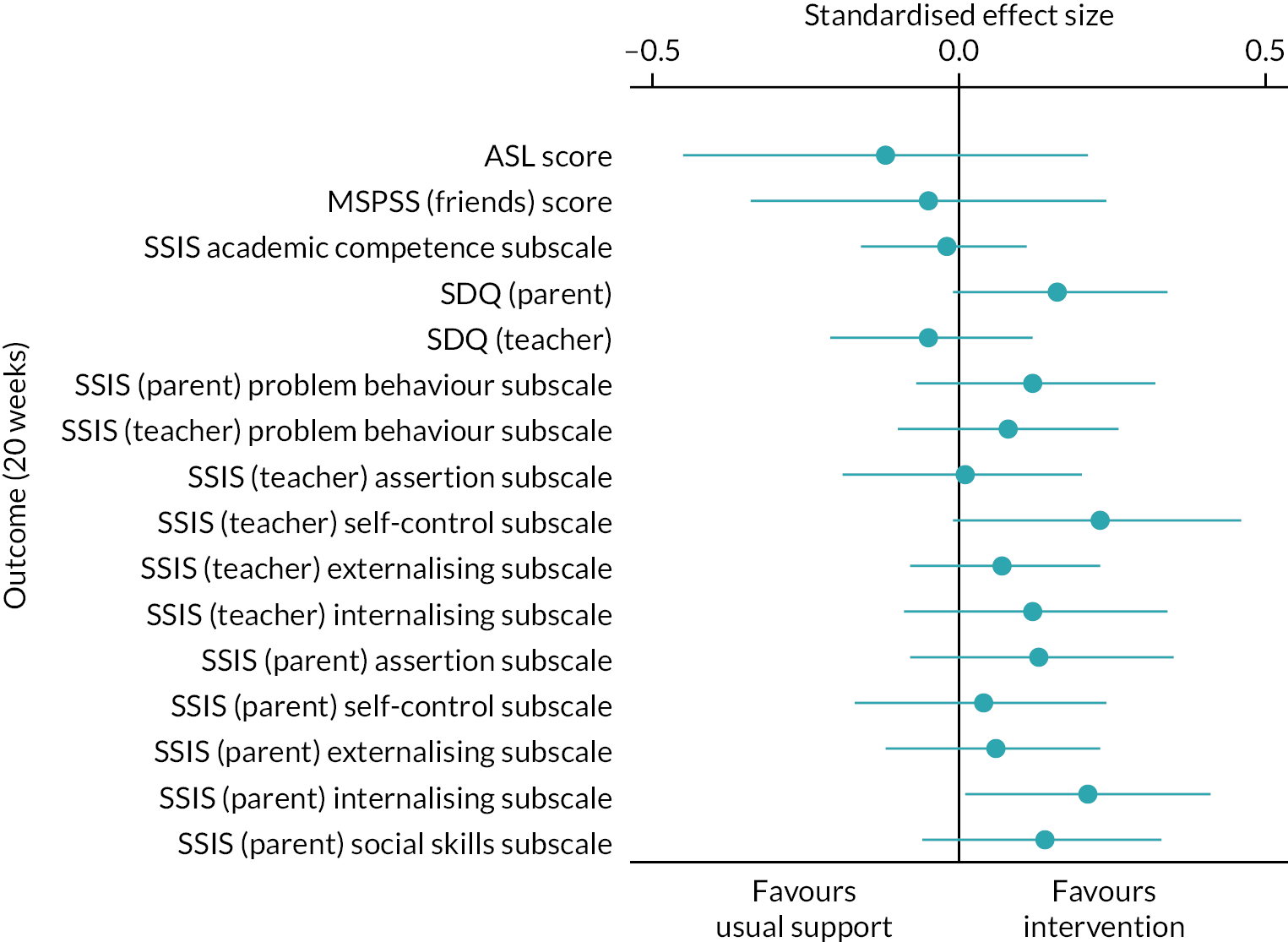

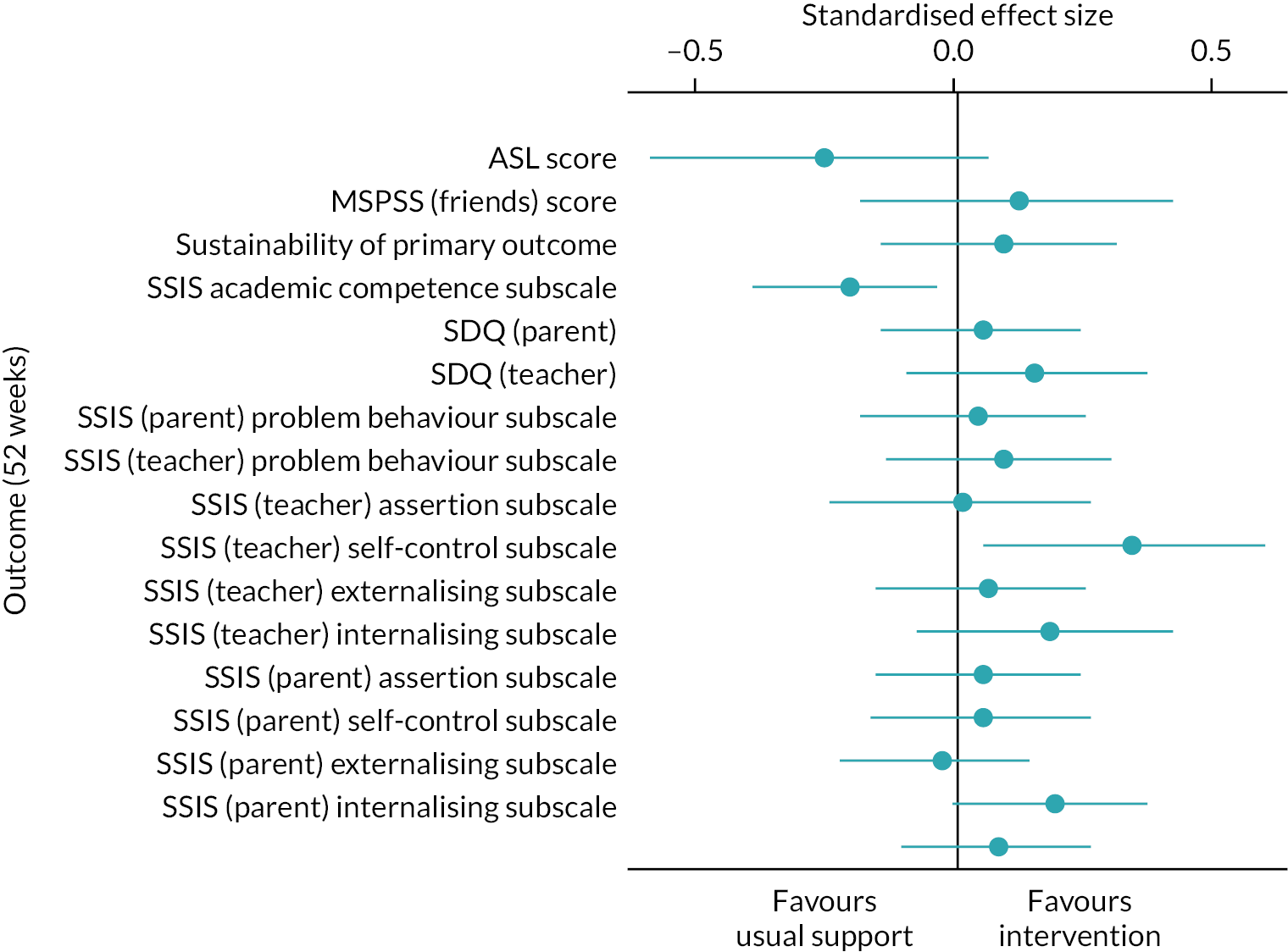

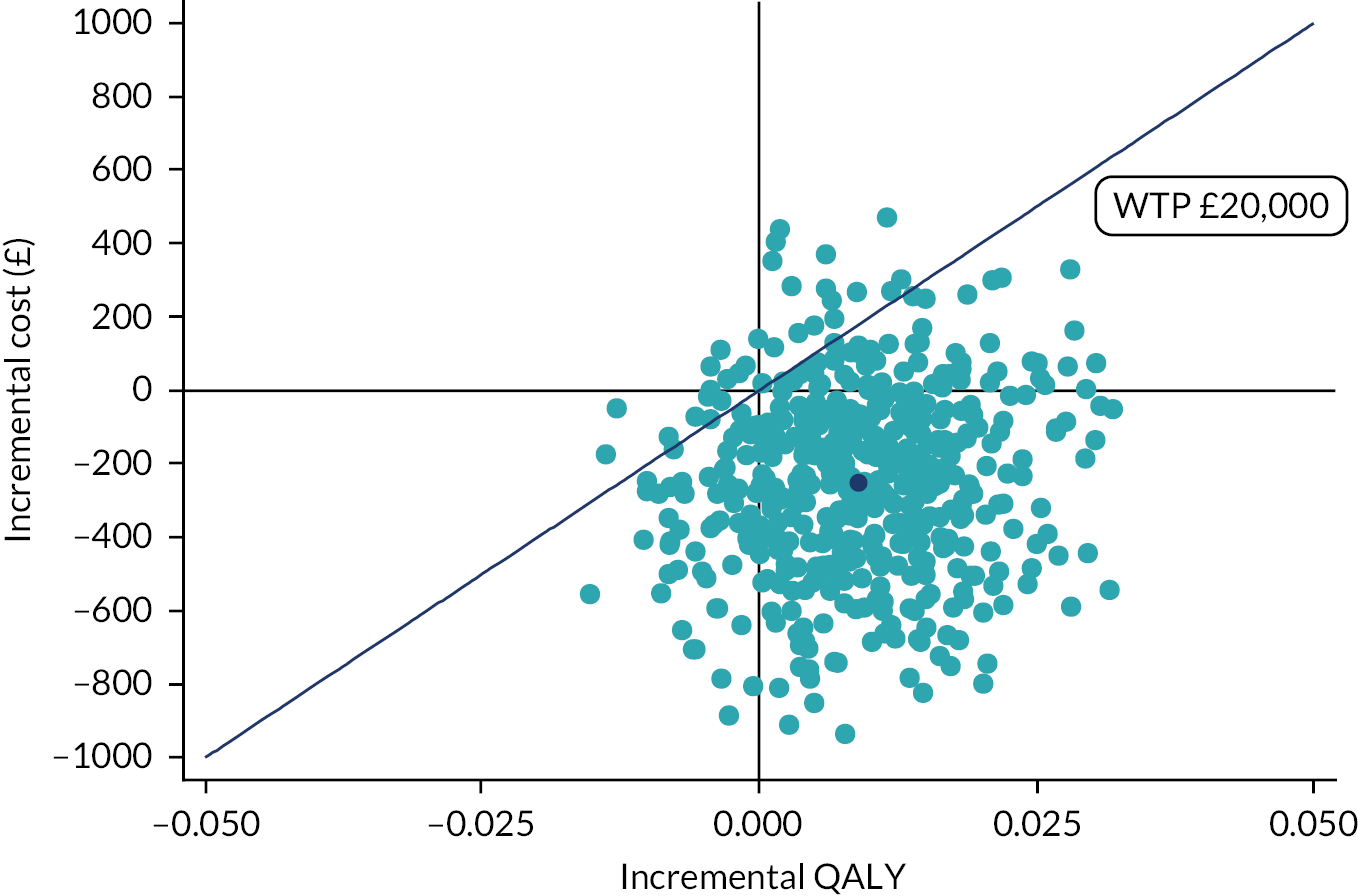

-