Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 16/57/01. The contractual start date was in February 2017. The final report began editorial review in December 2021 and was accepted for publication in June 2022. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2023 Moore et al. This work was produced by Moore et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2023 Moore et al.

Chapter 1 Background

According to the most recent Office for National Statistics data, around one in six adults in Great Britain smoke tobacco. 1 Much has been achieved in reducing smoking rates, with almost half of adults reporting being smokers in 1974, when Office for National Statistics data began. Nevertheless, smoking remains a major driver of ill health and health inequalities, and continues to be a major national and global cause of preventable death. 2 Many adult smokers first took up smoking in adolescence,3 and earlier initiation is associated with greater endurance into adulthood. 4 Hence, as well as effective intervention to support smokers to quit, reducing the prevalence of smoking requires prevention of new generations from taking up smoking.

Young people’s smoking peaked in UK nations in the mid to late 1990s, coinciding with publication of the government’s Smoking Kills: A White Paper on Tobacco. 5 Subsequent decades have seen increasing regulation of the marketing of tobacco,6 as well as regulation on age of sales and legislation prohibiting smoking in public places. 7 Declines seen for smoking uptake are mirrored internationally across other outcomes, such alcohol use,8 perhaps indicating that broader social trends beyond tobacco policy have contributed to wider changes in adolescent risk behaviour. Nevertheless, as a whole, tobacco regulation has likely contributed significantly to the prolonged downwards trajectory in young people’s smoking since the 1990s. Regular smoking among secondary school-aged young people is now estimated at around 2–4%,9 while experimentation with tobacco has become a minority behaviour of which most young people disapprove. 10 Nevertheless, a substantial number of young people, particularly young people from poorer backgrounds, still leave school as smokers. 9 As UK nations move towards ambitions to become smoke free by 2030,11,12 further action is needed to support cessation among smokers, while preventing the next generation from taking up smoking.

Recent years have seen increasing attention to potential (positive and negative) effects of e-cigarettes on smoking and smoking-related morbidity and mortality. Many people argue that e-cigarettes have potential to improve public health by offering smokers a less harmful alternative, or even make smoking obsolete. 13 However, concerns have centred around whether or not the appeal of e-cigarettes goes beyond smokers, creating new generations of young people addicted to nicotine. 14 In particular, there are concerns that e-cigarettes may lead to a reversal of successes in reducing the appeal of tobacco to young people.

The emergence of e-cigarettes in the UK

E-cigarettes and smoking cessation

Invented in China in 2003, e-cigarettes entered European Union (EU) markets around 200715 and began to gain significant traction as smoking-cessation aids around 2011, with rapid growth over the next couple of years. 16 The devices themselves are rapidly changing, with early products looking very much like cigarettes. More recent changes in product design have moved away from resemblance to cigarettes, with increased popularity of tank-based devices. Many people argue that public health communities should endorse e-cigarettes as a means of helping smokers to quit the more harmful behaviour of smoking. 17,18 Although long-term health effects are unlikely to be known for some time, some studies show important acute health benefits of switching to e-cigarettes. 19 Hence, e-cigarettes, where effective as cessation aids, may play an important role in reducing mortality and morbidity. 20

UK trials have found that e-cigarettes, accompanied with behavioural support, can be more effective than nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) in supporting cessation. 21 Nevertheless, in early 2020, the World Health Organization still described evidence for the effectiveness of e-cigarettes in cessation as inconclusive. 22 More recently, a Cochrane review concluded that there was moderate-certainty evidence that e-cigarettes are effective in helping smokers to quit and, indeed, appear to be more effective than NRT. 23 Public Health England’s recent evidence update argues that evidence is now increasingly strong that e-cigarettes make a significant positive contribution to public health via supporting cessation. 24 Indeed, reflecting this rapidly advancing evidence base, in 2021, regulators set out new guidance on how e-cigarettes might be offered on prescription as a smoking-cessation aid in England. 25

Although there is emerging consensus that e-cigarettes have a role to play in harm-reduction strategies,26 there is also consensus that e-cigarettes are not harmless. 27 Many people in the public health community continue to argue for caution until more is known about the potential harms of e-cigarettes. 28,29 However, although much has been written about a binary divide between ‘enthusiasts’ who wish to harness the potential of e-cigarettes for cessation and ‘opponents’ who see e-cigarettes as a threat to young people,30 in reality, positions are often more nuanced. Many people are both enthusiastic about the role of e-cigarettes in cessation, while taking seriously the need to prevent use by children and young people. 31 For people accepting a position that e-cigarettes have a role in supporting cessation, it remains important that use is restricted to smokers or ex-smokers as a means of quitting and preventing relapse back to smoking. 32

Young people’s use of e-cigarettes

Today’s young people have grown up in an environment of falling prevalence of tobacco use, among adults and peers. However, today’s young people are also the first generation to have grown up in a time when e-cigarettes have become a major presence in UK society. 33 The growing presence of e-cigarettes has led to some concerns that e-cigarettes might lead to a new generation of tobacco-naive young people addicted to nicotine. Some concerns were expressed early in the emergence of e-cigarettes that marketing for e-cigarettes used approaches that mirror those used by the tobacco industry, targeting young people as potential new consumers. 34 Indeed, as tobacco companies have bought e-cigarette companies or developed their own products, there is increasing overlap between actors responsible for these markets. 35 E-cigarettes commonly have features that many people argue might appeal to young people, such as their colourful and often sweetly flavoured nature. 36,37

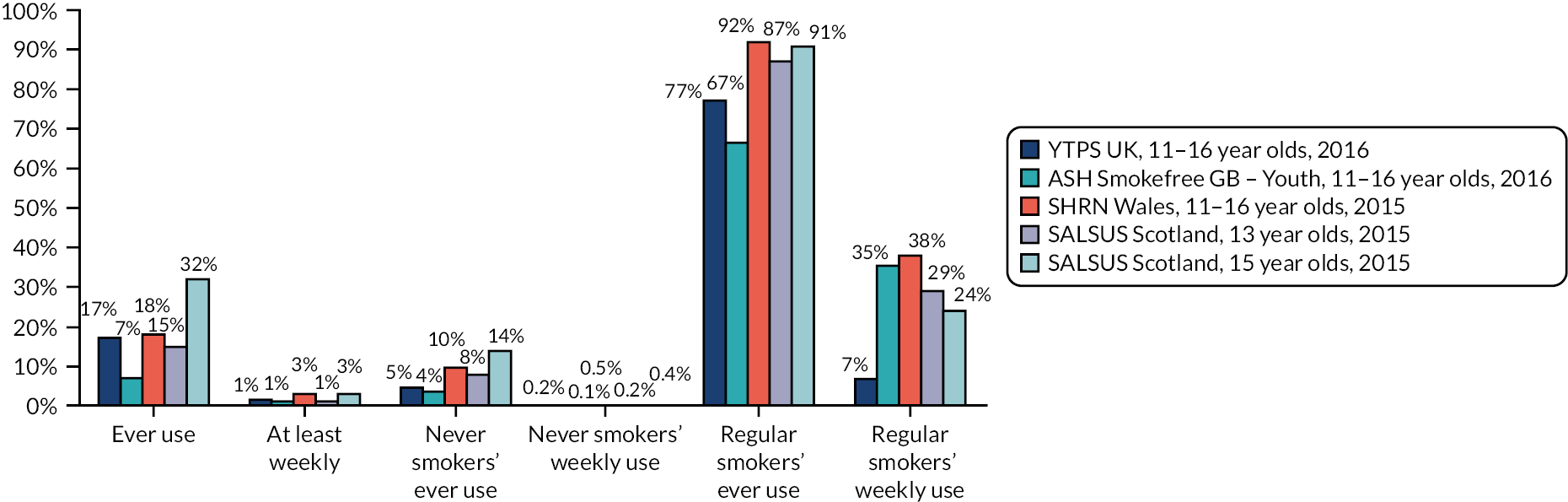

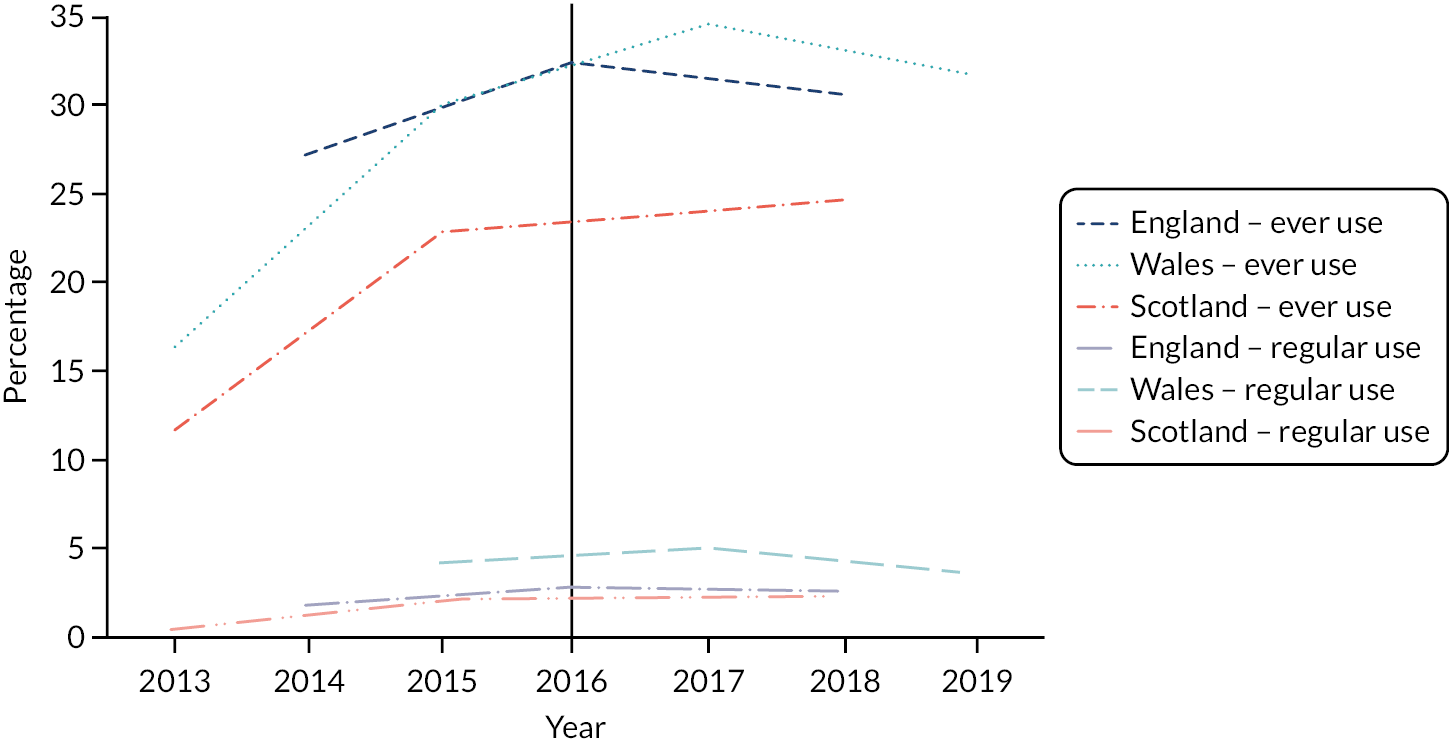

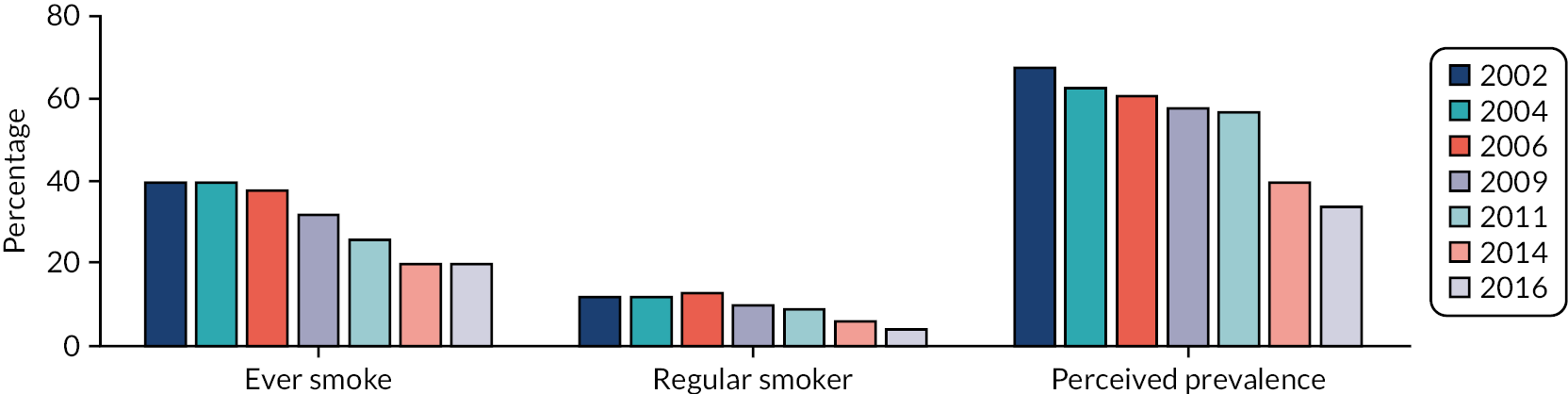

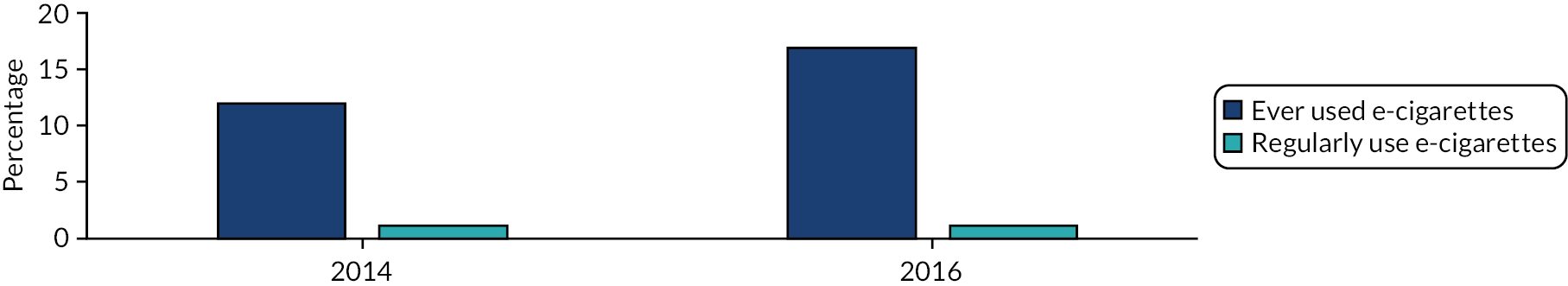

Young people’s use of e-cigarettes did not begin to be measured in UK social surveys until around 2013. Early estimates from Wales indicated that ever use of e-cigarettes was approximately equal to ever use of tobacco cigarettes, as 12% of young people had tried vaping and 12% had also tried smoking. 38 However, the proportion of young people reporting more regular use was small. Over the next 2–3 years, data accumulated from surveys across UK nations (see Figure 1), reinforcing this picture of sharp increase in experimentation with e-cigarette use, but with regular use remaining low and concentrated among smokers. 24,39

FIGURE 1.

Percentages of young people who have ever used an e-cigarette or who use an e-cigarette at least weekly, by smoking status. Reproduced with permission from Bauld et al. 39 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Nevertheless, rapid growth of experimentation in the early years of the emergence of e-cigarettes in the UK signalled a need for careful ongoing monitoring. Concerns that e-cigarettes may become harmful for young people centred both on potential indirect harms, via their perceived potential role in reversing successes in reducing smoking uptake, but also direct harms of use by young people who would not otherwise be smoking.

Effects of e-cigarettes on young people’s smoking uptake

There are two major hypothesis surrounding potential mechanisms through which e-cigarettes may lead to increases in young people’s smoking uptake: (1) the gateway hypothesis and (2) the renormalisation hypothesis.

The gateway hypothesis

The gateway hypothesis has a long history in drug research. The gateway hypothesis has long been debated, for example whether or not cannabis acts as a gateway into harder drug use. 40 Applying the gateway hypothesis to e-cigarette use, it is assumed that e-cigarettes might appeal to young people who would not have otherwise smoked. Therefore, these young people may then become addicted to nicotine via use of e-cigarettes, increasing vulnerability to subsequent tobacco use. 41 There is, indeed, now a very large and consistent body of systematic review-level evidence, much of which is from the UK, which finds that young people who try an e-cigarette are more likely to go onto smoke than young people who do not. 42,43 The evidence is limited by issues such as publication bias, high sample attrition and inadequate adjustment for potential confounders. Hence, it remains unclear if using e-cigarettes causally increases risk of future smoking or if this association is explained by common liability, or if both offer a partial explanation. Recent studies find that although unadjusted associations of ever e-cigarette use with subsequent smoking are large, the associations become smaller or non-significant the more common causes are adjusted for. 44 One large study in France found that among 17- to 19-year-olds, having tried an e-cigarette was associated with reduced likelihood of daily smoking, but this was moderated by age of first use, and very early experimenters who had used an e-cigarette by age 9 were more likely to become smokers. 45 Given that few non-smokers were becoming regular users of e-cigarettes while experimentation was becoming widespread, it is likely that any gateway effects which are occurring may have to date occurred on a small scale, unlikely to reverse population trends in tobacco use.

The renormalisation hypothesis

The renormalisation hypothesis, although often conflated with the gateway hypothesis, differs from the gateway hypothesis in its focuses on sociological processes around norms for tobacco use. Several decades ago, smoking was a highly normalised behaviour. 1 Smoking was a social practice adopted widely across socioeconomic groups, with non-smokers tolerant and accepting of others’ smoking. Although controversial in creation of stigma for those who continue to smoke, with this stigma falling mostly on already marginalised groups,46 much success in reducing population-level uptake of tobacco has been achieved via denormalising smoking. This denormalising has increasingly been achieved through excluding smoking from the rhythms and activities of daily life, restricting when and where smoking can take place to make tobacco an unattractive and unappealing product for non-smokers. Actions have included mandating health warnings on cigarette packs, with international evidence suggesting that these warnings can have important impacts on both cessation and uptake. 47 Smoking in enclosed workplaces was prohibited in Scotland in 2006, and elsewhere in the UK in 2007. Although implemented largely to protect hospitality workers,48 impacts on children received much attention. Plans were met with arguments that this would harm children by displacing smoking into the home, but UK and international evidence found that this was not the case, as second-hand smoke exposure and smoking in the home declined following legislation. 49,50 This legislation, recently selected by the Royal Society for Public Health (London, UK) as the greatest achievement of the twenty-first century,51 played a major role in communicating that smoking in front of non-smokers, including children, was unacceptable. It was followed by other moves, including increases in age of sales to 18 years and point of sale restrictions. Laws prohibiting proxy purchasing of tobacco sought to further restrict young people’s access to tobacco, with current arguments for increasing age of sales further to 21 years centred partly around further inhibiting the ability of young people to obtain cigarettes via older friends. 52 From 2015, bans on smoking in cars carrying children were introduced. 11

The hypothesis that e-cigarettes renormalise smoking is based around assumptions that because e-cigarettes mimic the act of smoking, their growing presence will reverse successes in denormalising smoking. 53 In support of this notion, one recent USA-based study found that greater exposure to second-hand e-cigarette aerosol in public places was associated with increased tolerance of, and susceptibility to, future smoking. 54 However, an increasing number of studies focused on whether or not smoking rates among young people increase in parallel with growing population prevalence of e-cigarettes have offered limited support for this notion. Recent international studies from Taiwan55 and New Zealand56 find that smoking rates fell as fast, or faster, during the emergence of e-cigarettes than in the preceding years. Analysis of data from the National Youth Tobacco Survey (NYTS) in the USA also indicate continuing decline in tobacco use during this period, with ever smoking declining at a faster rate post 2011, although the rate of decline in current smoking began to plateau in 2014. 57 Also using NYTS data, Foxon and Selya58 found that a counterfactual trend projected from data up to 2009 overestimated observed smoking rates from 2010 to 2018. Sokol and Feldman59 similarly found that projections of smoking rates for US 12th graders (i.e. aged 17/18 years) from Monitoring the Futures data prior to 2014 overestimated prevalence to 2018, concluding that many adolescent e-cigarette users would likely otherwise have become smokers. 59

Notions that e-cigarettes renormalise the different, but related, behaviour of tobacco smoking centre around the assumption that the behaviours are viewed by young people as sufficiently related that growth in one will renormalise the other. The extent to which this assumption is upheld may vary across contexts and may be influenced, in part, by how products are positioned in public policy and discourse. In the USA, the Food and Drug Administration include e-cigarettes as ‘tobacco products’. 60 However, given that e-cigarettes do not use tobacco, this labelling has been described as a particularly US phenomenon. 61 There is some evidence from the UK that finds that children see tobacco and e-cigarettes as distinct products. 62,63 In one study, for example, young people whose parents used e-cigarettes were most likely to perceive them as things adults use to stop smoking, with this perception of e-cigarettes as cessation aids associated with lower smoking susceptibility. 64 Hence, where perceived as stop smoking aids, others’ use of e-cigarettes might be interpreted by young people as a social display of efforts to give up smoking, rather than as an endorsement of a smoking-like behaviour.

Use of e-cigarettes among young people as an emerging public health risk in its own right

Although links between e-cigarettes and smoking have dominated debates regarding potential harms of e-cigarettes to young people, e-cigarettes themselves are unlikely to be harmless. Hence, although switching from tobacco to e-cigarettes is likely to reduce harm, taking up e-cigarette use without prior smoking introduces new potential for, as yet, unknown harms. In one recent study,65 estimates of the extent to which risk-adjusted nicotine product days decreased over time as tobacco use fell but e-cigarette use grew were described as highly dependent on assumptions regarding risks of e-cigarettes relative to tobacco. Although commonly based on animal models and, therefore, with questionable transferability, common arguments for regulating e-cigarettes to prevent young people from using them have included potential impacts of nicotine on brain development among young people. 66

As described, few young people in the UK have historically used e-cigarettes regularly, unless they are also smokers. However, in the USA, the 2018 NYTS indicated that in the space of a year the percentage of high school students reporting past 30-day use of e-cigarettes doubled to almost one in five, with more than one in four young people reporting past 30-day vaping in 2019. 67 This growth was framed widely as an epidemic of young people’s vaping,68 triggering international calls for regulation. In 2019, Hammond et al. published an influential analysis of change in young people’s smoking and e-cigarette use from 2017 to 2018, finding increases in vaping in the USA and Canada, although no growth in England. In Canada, analyses indicated that this increase in vaping was accompanied by growth in smoking. 69 In 2020, the authors published an update in which data were calibrated with external data sources, with the consequence that the previously reported increase in smoking in Canada was attenuated. Hence, although revised analysis weakened common interpretations that e-cigarettes were acting as a pathway into smoking, the analysis did signal rapid growth in young people’s use of e-cigarettes as a potential problem in its own right. Newer data from the 2020 and 2021 NYTSs indicate that rapid growth in vaping from 2017 to 2019 did quickly begin to subside. 70,71

In the context of these rising international concerns about the growth of young people’s use of e-cigarettes, concerns regarding the safety of e-cigarettes, particularly for young people, were further raised by the EVALI (e-cigarette or vaping use-associated lung injury) outbreak. 67 This was an outbreak of vaping-related lung injury, which led to a number of deaths, predominantly in the USA in 2019, attributed to the specific chemicals tetrahydrocannabinol and vitamin E acetate,72 in unregulated devices. The outbreak received intense media coverage, and one study73 found the outbreak to be associated with increased risk perceptions for e-cigarettes among English adult smokers. Following this outbreak, debate regarding potential for an epidemic of young people’s smoking in the UK intensified. 74 One group of paediatric health-care professionals, for example, wrote that with 30% of high school children in America using e-cigarettes, most of whom had never smoked tobacco, similar rates were inevitable in the UK. 75 The claim that most use was occurring among tobacco-naive young people is not borne out by reanalysis of the NYTS data, which finds that most use, particularly regular use, occurred among young people who had smoked. 76 However, this reflected growing concerns that the US epidemic would cross the Atlantic and that e-cigarette use in itself might become a commonly adopted risk behaviour among young people who would not otherwise be smokers.

E-cigarette regulation in the UK

Divergence in positions on e-cigarettes among the public health community is reflected in international approaches to regulation,77 which have ranged from highly restrictive regulation in countries such as Australia78 to more liberal approaches in countries such as the UK, where no specific regulation existed prior to 2015. Age of sales regulations for e-cigarettes were implemented in England and Wales in late 2015 and in Scotland in early 2017. In Wales, the Welsh Government’s 2015 Public Health Bill attempted to introduce legislation that would have prohibited the use of e-cigarettes in any place where tobacco cigarettes are currently prohibited. 79 This failed to pass into law after a last-minute loss of cross-party support led to a minority Labour government losing at the final stage of the legislative process. The bill returned in 2017, re-introduced by a minority Labour Government, with provisions relating to e-cigarettes removed. 80 Key arguments against including e-cigarettes alongside bans on smoking in public places have included that this may undermine quit attempts by reducing relative advantage of e-cigarettes over tobacco. 81

In the meantime, in May 2016, Tobacco Products Directive (TPD) regulations were introduced in EU member states. The TPD regulations included a broad suite of regulations for tobacco, many of which reflected tobacco control actions already implemented in the UK, with exceptions including a ban on sales of smaller packs of tobacco cigarettes and (later) bans on sale of menthol-flavoured cigarettes. 82 Article 20 was specific to e-cigarettes, and represented the first major supra-national regulation of e-cigarettes. TPD regulations prohibited cross-border advertising of e-cigarettes, with immediate effect from May 2016. Recent market liberalisation in Canada has been associated with increased marketing exposure and use of e-cigarettes among young people, with comprehensive provincial restrictions associated with lower exposure and use. 83 Hence, it is plausible that marketing restriction within TPD may act to reduce young people’s exposure and use. TPD also included a suite of regulations on the products themselves, which were to be more gradually introduced, with full implementation to be achieved by May 2017. These regulations included a mandatory warning across 30% of the packet indicating that the products contain nicotine, which is a highly addictive substance. Manufacturers are mandated to notify the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency of intention to launch new products 6 months in advance, including notification of all product ingredients. e-cigarettes and liquids are to be sold in tamper-proof containers to include an information leaflet listing all ingredients, with nicotine strength limited to 20 mg/ml. Device refills were restricted in size. TPD regulations aligned e-cigarettes with tobacco in so far as they involve regulation under the banner of a ‘Tobacco Products Directive’, but e-cigarettes themselves are not referred to as tobacco products. There is some limited evidence that first use of flavoured e-cigarettes is associated with more persistent use among young people. 84 Hence, some EU member states went beyond mandatory requirements of TPD regulations, through introduction of flavour regulations left within TPD for individual member states to determine,77 although the UK has not to date.

The regulations were a cause of concern for the vaping community and some scientists who argued, in particular, that a reduction in nicotine strength might inhibit the usefulness of e-cigarettes as cessation devices or cause users to relapse to smoking, as the lower strength may not satisfy cravings. 85 The warning focused on the addictiveness of nicotine was found in one study86 to likely put smokers off using e-cigarettes as cessation devices. However, surveys of adult smokers, ex-smokers and vapers indicate that, after implementation, the regulations went largely unnoticed by many, with most using compliant devices while unaware that these had changed. 87 E-cigarettes remain the most popular smoking-cessation devices used by smokers and recent ex-smokers in the UK. 16 Part of the rationale for introduction of these regulations include assumptions that e-cigarettes can develop into a gateway to nicotine addiction and tobacco consumption, and that e-cigarettes mimic and normalise the act of smoking. 82 To date, however, there has been limited evaluation in the UK of (1) the role of e-cigarettes in renormalising smoking and (2) the impacts of this regulation on children and young people’s use of e-cigarettes (and tobacco).

Objectives

This report describes findings from a mixed-method natural experimental evaluation of the impacts of TPD regulations in the UK. Theoretically, we view e-cigarette regulation as an ‘event’ within a complex system88,89 that has the potential to bring about (intended and unintended) change through altering the behaviours and interactions of a diverse range of actors, including regulators, retailers, consumers and, ultimately, young people. Hence, the research first explores system history and starting points prior to regulations through examining trends in young people’s tobacco use in the lead up to regulation, addressing questions of whether or not e-cigarettes were re-normalising smoking in the lead up to implementation of TPD and exploring normative perceptions for e-cigarettes as a product in their own right. The study does this through combining quantitative analyses of trends in secondary school-based survey data in the lead up to regulation with qualitative pupil interviews, exploring perceived norms in relation to tobacco and e-cigarettes. Subsequently, interviews with policy stakeholders, trading standards officers (TSOs) and retailers are used to understand implementation processes, whereas retailer audits examine implementation fidelity. Mechanisms through which TPD regulations might achieve impact on young people’s use of e-cigarettes, and smoking, are investigated using repeated qualitative pupil interviews prior to use of before-and-after survey data to evaluate change in trend for e-cigarette use, and smoking, following TPD implementation.

Chapter 2 Methods

Material throughout the report has been adapted from the study protocol [see NIHR Journals Library www.fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/16/57/01 (accessed 19 December 2022)].

Research questions

Our primary aim was to investigate the role of e-cigarette regulation, via the TPD, in influencing trajectories in young people’s use of e-cigarettes. We address the following research questions in relation to this aim:

-

Did increased regulation of e-cigarettes interrupt prior growth of young people’s e-cigarette use?

-

How did young people perceive risks and social norms surrounding e-cigarettes (and how did perceptions change over time as products become TPD compliant):

-

as a product in their own right?

-

relative to tobacco?

-

-

How did young people interpret and respond to the presence or absence of health warnings on e-cigarette packets?

-

To what extent, and in what ways, did young people continue to interact with e-cigarette marketing after the prohibition of cross-border advertising?

As a secondary aim, we also examine trends in young people’s smoking behaviour over time. This allows us to test the theoretical basis for much e-cigarette regulation, including that via the TPD, which centres on assumptions that e-cigarettes renormalise smoking. In addition, it enables us to estimate if the suite of regulation introduced in 2016 has maintained or increased the downwards trend in young people’s smoking uptake. We will address the following questions:

-

Have trajectories in young people’s ever and current smoking been significantly interrupted (positively or negatively) by growing prevalence of e-cigarettes?

-

Did the rate of decline in young people’s smoking change after additional regulation of tobacco and e-cigarettes in May 2016 (including TPD and plain packaging)?

Finally, as additional secondary aims, we explore the implementation and context of TPD regulation, including:

-

To what extent was compliance with TPD in product sales achieved, and what are the barriers to and facilitators and unintended consequences of implementation?

-

To what extent, and in what ways, did variations between UK countries in e-cigarette policy emerge during the study period?

-

What other changes to the regulatory context of tobacco and e-cigarettes occur during the study period in the UK and across individual UK countries?

Study design

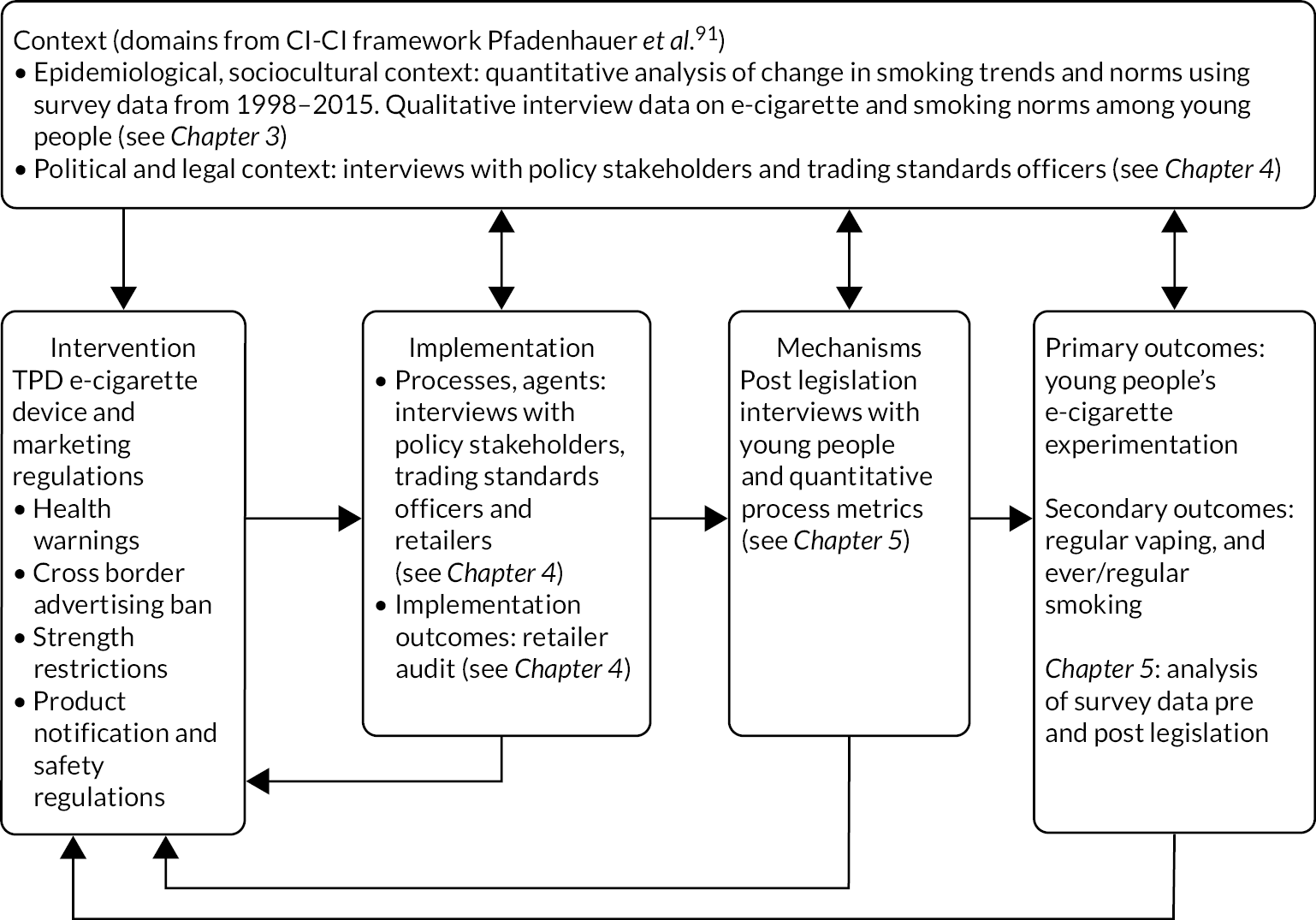

This study used a mixed-method natural experimental evaluation design to address the above research questions. The quantitative study elements drew on repeated cross-sectional secondary data from routinely undertaken surveys in Wales, Scotland and England. Study populations were nationally representative samples of secondary school-aged young people aged 13/15 years (or equivalent school years, i.e. years 9 and 11 in Wales and England and S2 and S4 in Scotland). These data were analysed alongside qualitative data from young people, policy representatives, TSOs and retailers of e-cigarettes, and retailer audits. Our overall evaluation and integration framework is presented in Figure 2, which provides an overview of how data sources are mapped onto subsequent findings chapters. Our evaluation and integration framework draws on the Medical Research Council (MRC) guidance for process evaluation90 and on the more recent context and implementation of complex interventions framework91 in framing context and implementation processes.

FIGURE 2.

Evaluation and integration framework for TPD evaluation. CI-CI, content and implementation of complex interventions. Adapted with permission from Moore et al. 90 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Secondary data analysis

Data sources, collection and handling

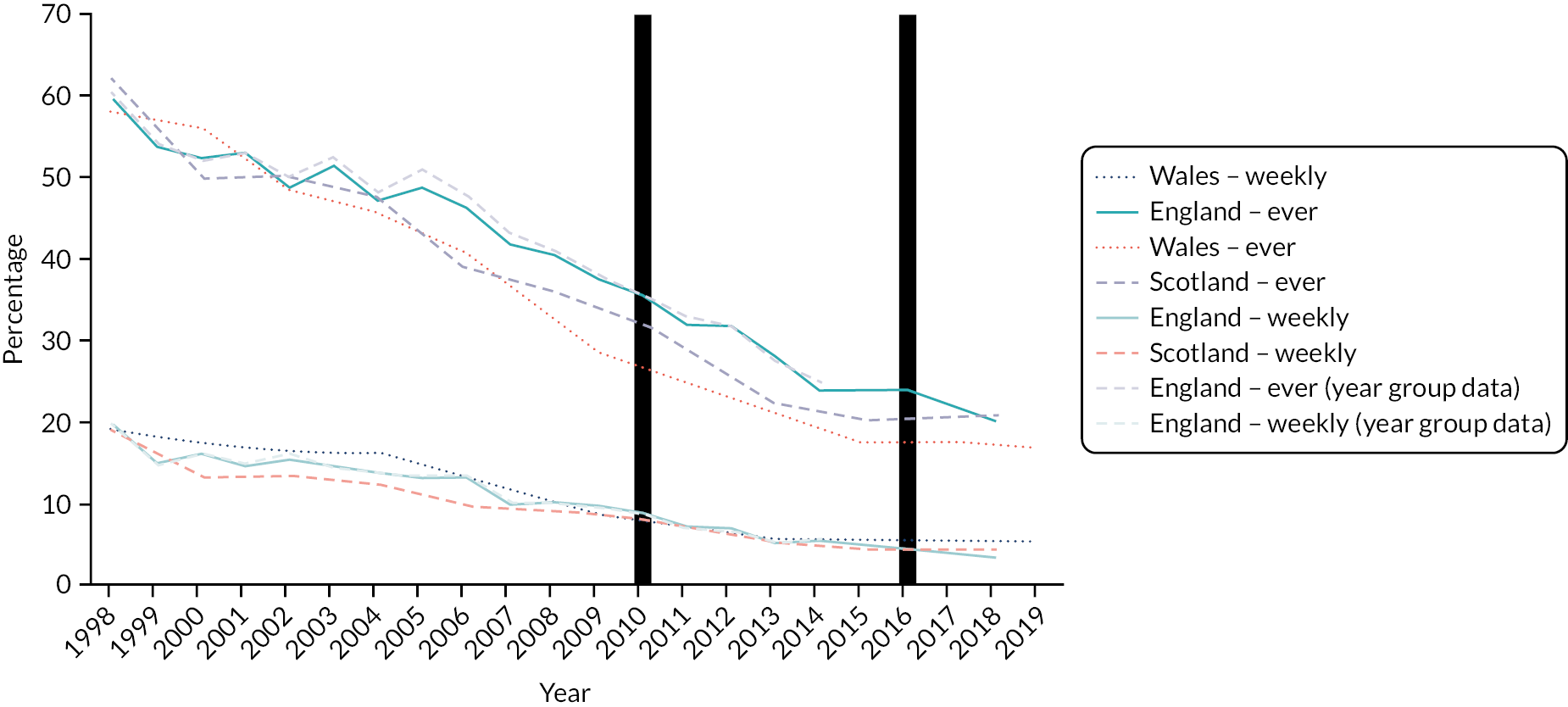

We obtained data from routinely collected school-based surveys in each UK nation. Although some of these surveys go back to the 1980s, we made an a priori decision to restrict our analyses to data sets from 1998 to 2019 because published estimates indicate that smoking rates climbed up to this point, but have followed a prolonged period of decline ever since.

Data from Wales were obtained from the Welsh Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) survey, conducted as part of an international World Health Organization collaboration every 2–4 years,92 and the biennial School Health Research Network (SHRN) survey. 93 The SHRN survey was introduced in 2015 and was modelled on the HBSC survey, and from 2017 the SHRN survey incorporated the smaller HBSC survey as a component of it. Hence, HBSC survey data were obtained from 1998 to 2013, with SHRN survey data from 2015 to 2019. Data for Wales before 2013 were provided by the Welsh Government. SHRN and HBSC data from 2013 onwards are held by the principal investigator’s research group.

Although HBSC surveys are also conducted in England and Scotland, neither country included measures of e-cigarette use prior to TPD implementation, and these surveys are conducted only once every 4 years. Hence, in Scotland and England, we used the larger and more frequent Scottish Schools Adolescent Lifestyle and Substance Use Survey (SALSUS)94 and Smoking, Drinking and Drug Use (SDDU) survey in England. 95 In Scotland, the SALSUS is a bi-ennial, school-based survey undertaken in local authority and independent schools. E-cigarette use questions were first incorporated into the SALSUS in 2013. The UK data service includes a time series data set that provides ready-pooled data through to 2013. Our original intention was to use the SALSUS planned for 2017 and 2019 as post-TPD data sets in Scotland; however, SALSUS 2017 was postponed to 2018,and no data were collected in 2019. Hence, we integrated measures from the 2015 and 2018 data sets into the time series data set, providing only one post-TPD survey for Scotland. In England, the SDDU survey was conducted annually until 2014, but then moved to a bi-ennial cycle. Measures of e-cigarette use were included in the SDDU survey from 2014. The SDDU survey shares substantial overlap with the SALSUS, including use of similar measures of smoking and e-cigarette use. Data sets from 1998 to 2018 were obtained via the UK data service. Data files were combined into a single data set and stored on a secured network at Cardiff University. The Cardiff University-owned Welsh data will be retained, and models updated with newer data following completion of this study. Terms of use for the third party-owned data sets require these data to be deleted following completion of the use period, currently the end of 2022.

Sample sizes and response rates

Table 1 provides sample sizes by country and survey year, overall and for the target age group. Survey response rates, where available, are presented in Appendix 1, Table 19. These data indicate a gradual decline in response rates over time in Scotland (from 70% in 1998 to 52% in 2018), and a much larger decline in England (from 70% to 22%). However, there was recent growth in response rates in Wales, with the 2019 SHRN survey achieving a response rate of 77%.

| Years | Wales: HBSC/SHRN | Scotland: SALSUS | England: SDDU | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Target year groups sample (school year) | Target age groups sample (age) | |||

| 1998 | 2716 | 1737 | 1975 | 2174 |

| 1999 | 3629 | 3856 | ||

| 2000 | 2321 | 2376 | 2764 | 3003 |

| 2001 | 3600 | 3917 | ||

| 2002 | 2641 | 23,090 | 3758 | 4162 |

| 2003 | 4040 | 4443 | ||

| 2004 | 2755 | 7062 | 3701 | 4102 |

| 2005 | 3592 | 3916 | ||

| 2006 | 2882 | 23,180 | 3193 | 3587 |

| 2007 | 3079 | 3458 | ||

| 2008 | 10,063 | 3019 | 3381 | |

| 2009 | 3558 | 3010 | 3365 | |

| 2010 | 37,307 | 2877 | 3172 | |

| 2011 | 2549 | 2869 | ||

| 2012 | 3029 | 3364 | ||

| 2013 | 3505 | 33,685 | 2067 | 2282 |

| 2014 | 2443 | 2782 | ||

| 2015 | 11,817 | 25,304 | ||

| 2016 | 5523 | |||

| 2017 | 39,212 | |||

| 2018 | 23,365 | 5942 | ||

| 2019 | 43,404 | |||

Study measures

E-cigarette use

In Wales, young people were asked if they had ever tried e-cigarettes, with options of never, once or more than once. Young people who selected ‘more than once’ were asked how often they currently use e-cigarettes (with options of, I don’t, less than weekly, at least weekly or daily). In Scotland and England, young people were asked to select a single option from a list of statements, which included they had never tried e-cigarettes, had used e-cigarettes once or twice, have used them in the past but don’t now, use e-cigarettes now but less than once a week, or use e-cigarettes now at least once a week. In all cases, a binary variable of ever use was created, which compared ‘never’ responses with all others. A regular (at least weekly) use measure was derived by classing all young people who selected options of weekly or more as regular users.

Smoking

In Wales, young people were asked at what age they first engaged in a range of risk behaviours (including smoke a cigarette) and were instructed to select the never option if there was something they had never done. Options included ‘never’ and ages from 11 to 16 years. A second question asked young people how often they currently smoked (with options of I don’t, less than weekly, at least weekly or daily). In Scotland and England, young people were asked to select a single option from a list of statements, which included they had never tried smoking, had tried smoking only once, used to smoke but don’t now, smoke but less than once a week, smoke between one and six cigarettes a week or smoke more than six cigarettes a week. In all cases, a binary variable of ever use compared ‘never’ responses with all others. A regular (at least weekly) use measure was derived by classing all young people who selected options of at least weekly or more as regular users.

Smoking attitudes

The acceptability of smoking is measured in both the SALSUS and SDDU survey via a question asking young people whether or not they think it is OK for someone their age to try smoking a cigarette to see what it is like. In the SDDU survey, young people were also asked whether or not it was OK for someone their age to smoke cigarettes once a week. Response options for both questions were: ‘it’s OK’, ‘it’s not OK’ and ‘I don’t know’. Responses of ‘I don’t know’ were combined with ‘it’s not OK’ to create a binary variable (sensitivity analyses combining ‘don’t know’ with ‘it’s OK’ showed similar trends over time). This item was used as an indicator of the plausibility of change in trend for smoking being caused by the mechanism of smoking renormalisation (see Statistical analysis of survey data).

Cannabis use

In SALSUS, young people were presented with a grid listing a range of drugs, including cannabis, and were asked which, if any, they have ever used. In the HBSC survey, young people were asked how many times they have used cannabis in their lifetime (response options: never, once or twice, three to five times, six to nine times, 10–19 times, 20–39 times and ≥40 times). In the SDDU survey, young people were asked if they had ever tried cannabis, with response options of yes or no. A binary variable indicating whether or not young people had tried cannabis was derived, with any response other than never (or no) classed as ever use. This item is used to examine whether or not any change in trend observed for tobacco use is specific to tobacco use (see Statistical analysis of survey data).

Alcohol use

Both the SALSUS and SDDU survey asked young people whether or not they had ever had a proper alcoholic drink. Since 2002, the HBSC/SHRN surveys asked young people at what age they first did a list of things, including drinking alcohol, with response options of never, and ages from 11 to 16 years. All responses other than never were classed as indicative of ever drinking. A binary variable was derived to distinguish between ever and never use of alcohol. This item is used to examine whether or not any change in trend observed for tobacco use is specific to tobacco use (see Statistical analysis of survey data).

Energy drinks

From 2013, in the HBSC survey, students in Wales were asked how often they drank energy drinks (response options: ‘never’, ‘less once a week’, ‘once a week’, ‘2–4 days a week’, ‘5–6 days a week’, ‘once daily’ or ‘more than once daily’). A binary variable was created to distinguish students who ever used energy drinks from students who never used energy drinks. This item is used to examine whether or not any change in trend observed for e-cigarette use is specific to e-cigarette use (see Statistical analysis of survey data).

Time and intervention variables

Time and intervention variables differed across analyses because of differences in data availability and granularity. In each case, time was coded as a continuous variable, starting at 0 at the start of the time series and increasing by 1 point per unit of time (using ‘month’ as unit of time in our primary statistical analysis of e-cigarette use in Wales, and ‘year’ as unit of time in three country analyses of smoking trends over time). Quadratic terms were generated by squaring time variables. For analyses of change in smoking outcomes following the emergence of e-cigarettes, we use a ‘level’ variable coded 0 for the baseline period 1998–2010, and 1 within the period from 2011 to 2015. Although not an ‘intervention’, the analytical approach of examining change in level and trend following the emergence of e-cigarettes follows a similar format to the evaluation of our intervention of interest (i.e. TPD). The period of 2011–15 was chosen because survey measures in the UK began to identify e-cigarette use among adult smokers from 2011, which grew rapidly from 2011 onward. 16 We used a ‘post-slope’ variable coded 0 through the baseline period and sequentially from 1 to 5 through the period 2011–15. For our analysis of e-cigarette use, using Welsh data that were broken down by month, we used a ‘level’ term coded 0 prior to May 2016, coded 1 from May 2016 onwards and a ‘post-slope’ term coded 0 prior to May 2016, increasing by 1 point per month from the intervention point onwards. For analyses of post-TPD changes in tobacco smoking, level and post-slope variables were coded 0 prior to 2016 and 1 thereafter, and sequentially coded 1 onwards from 2016 to 2019. In simpler analyses of data for which few time points were available, time is analysed as a categorical variable (see Statistical analysis of survey data).

Sociodemographic information

In all surveys, young people were asked to indicate their gender. Historically, this question has been asked as a binary variable, which asks young people to indicate whether they consider themselves to be a boy or a girl. In SHRN in 2019, following consultations with policy and practice stakeholders and young people, a response option of ‘neither option describes me’ was provided. However, as data on young people identifying as neither male nor female are available only at one time point, our analysis of change over time is limited to young people identifying as a boy or girl. The percentage of students selecting ‘I do not want to answer’ to the question on gender was reduced (relative to 2017) by an amount equivalent to the percentage of young people selecting the new ‘neither option describes me’, suggesting that young people selecting this option were more likely to previously have declined to answer. 96

School year was used as a proxy for age, with years 9 and 11 in England and Wales and S2 and S4 in Scotland used to represent young people aged 13 and 15 years, respectively. However, from 2016, the SDDU data set removed pupil year group because of concerns regarding potential deductive identification of individual children outside the expected school year for their age. Pre-legislation analyses were complete prior to this data set being obtained. Hence, in analyses using data from 2016 onward only, a variable for age rather than school year is used throughout the time series in England (i.e. ages 13 and 15 years).

For Wales, socioeconomic status (SES) was measured using the Family Affluence Scale (FAS),97 which, from 2013, comprised six items measuring car, computer and dishwasher ownership, bedroom occupancy, number of household bathrooms and prevalence of family holidays. An overall measure of family affluence is computed via summation of individual item scores (with higher scores reflecting greater material affluence). However, although consistent from 2013 to 2019 (i.e. the time period for our primary statistical analysis of change in e-cigarette use), this scale has changed over time as material products lose their ability to differentiate between socioeconomic groups and is problematic as an indicator of affluence over time for the period 1998–2019. To help assess inequality over time with HBSC/SHRN data in analyses beginning prior to 2013, a relative measure of SES was used, whereby the sample was divided into ‘high’ and ‘low’ affluence, regardless of the content of the FAS in any given year. SES was measured by free school meals entitlement in England from 1999 to 2014 (the SDDU survey also switched to use of FAS from 2016 onward) and in Scotland from 2006 to 2013. For Scotland, a measure of SES indicated by the Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation (reported in quintiles) was available between 2006 and 2018. Items on ethnicity were introduced into HBSC from 2009/10. The SDDU survey provided data on ethnicity for most survey years, although no measures of ethnicity were included in most SALSUS data sets.

Statistical analysis of survey data

Analyses were based on a statistical analysis plan agreed with our Study Steering Committee in advance of data sets being combined for analysis. Analyses completed at each stage of the study were presented to the committee prior to submission for publication. Although our primary aim was to evaluate impacts of TPD, analyses are described (and presented) in the order in which they were undertaken, in line with our overall evaluation and integration framework (see Figure 2), including analyses of:

-

trajectories in young people’s smoking before and after the emergence of e-cigarettes (but prior to TPD)

-

change in young people’s e-cigarette use following the implementation of TPD

-

change in trend for young people’s smoking following the 2016 suite of tobacco control legislation.

As described in our evaluation and integration framework in Figure 2, our analysis of trends in young people’s smoking prior to TPD is conceived as an element of our process evaluation, in that this provides an understanding of the epidemiological context into which intervention was introduced. This analysis is, however, described in this section to limit repetition due to methodological similarity with our primary statistical analysis.

Young people’s tobacco cigarette smoking before and after the emergence of e-cigarettes

Percentages and confidence intervals (CIs) of ever and regular smoking are presented for each outcome by year, country, age and sex. Binary logistic segmented regression analyses98 were then used to estimate change in smoking level and trends (post slope) during the emergence of e-cigarettes, relative to secular baseline trends, using the time, level and post-slope terms described in Study measures. The analysis was modelled on a similar approach used by Katikireddi et al. 99 to examine change in trend for young people’s smoking following smoke-free legislation (using many of the same data sets), with two main differences. Although Katikireddi et al. 99 conducted linear regression analyses of aggregated estimates, we had access to, and hence analysed, individual participant survey data. Furthermore, although Katikireddi et al. 99 used estimates dating back to the 1980s (see Katikireddi et al. 99 for a full list of historical data sets earlier than the cut-off point selected for this study), including a quadratic term to account for non-linearity, given that smoking rose until the mid-1990s, we limited our analyses to 1998 onward because of the continued decline in young people’s smoking from this date. Individual survey data on smoking from 1998 to 2015 for each of the three countries were used, with 2010 treated as the end of the baseline period and compared with the period 2011–15 (see Study measures). Country was included as a covariate, modelled as a set of dummy variables, and analyses were adjusted for gender and age. These analyses were conducted, presented to our Study Steering Committee and submitted for publication10 prior to obtaining post-legislation data sets.

Models were repeated for a secondary outcome of attitudes towards smoking (available from Scotland and England only). According to theories of renormalisation, e-cigarettes drive re-growth in young people’s smoking by increasing the extent to which young people see smoking as a normative behaviour. Analyses of attitudes towards smoking (i.e. the extent to which young people thought it was ‘OK’ for young people to smoke) provided evidence on plausibility of any change in trend (post slope) for smoking being causally driven by this hypothesised mechanism. For our primary statistical analysis, we were asked by the Public Health Research (PHR) Funding Committee to include falsifiability analyses, in line with the Bradford Hill criterion for causal inference of ‘specificity’. 100 The falsifiability analyses involve modelling the same time series for related variables, which would not be expected to be altered by the exposure. Hence, following discussions with our Study Steering Committee prior to undertaking analyses, changes in trend for ever alcohol and cannabis use were also modelled to test whether any break in trend observed for tobacco use was unique to smoking or reflective of wider trends in young people’s substance use behaviours.

Although our a priori analysis plans for trends in smoking assumed linearity in the relationship between time and smoking behaviours, visual inspection indicated some evidence of a quadratic trend. Hence, consistent with similar analyses on change in young people’s smoking following smoke-free legislation,99 a quadratic time variable was included to account for non-linearity in the data. Both linear and quadratic models are presented, and models including the term treated as the final model. We also handled non-linearity through a post-hoc sensitivity analysis, which limited the baseline period to 2001–10, a period during which there was no statistical evidence of departure from a linear trend for smoking outcomes, for our main models. As additional sensitivity analyses, we ran our pre-legislation models (1) for England only (the country with the largest number of data points for pre-legislation analysis) and (2) excluding SALSUS rounds conducted at a different time of year to the rest of the data series (i.e. 2002–6). Given that later analyses also switched to use of age rather than year group for England, as described, we also re-ran our main pre-legislation models using this new age classification.

To estimate change in young people’s e-cigarette use following Tobacco Products Directive regulations

Percentages and 95% CIs for ever and regular e-cigarette use are presented by year, school year/age, gender and country. Trends are presented graphically, with estimates for each country plotted on a single graph to enable comparison of trends over time by nation. Segmented regression analyses were then used to formally test changes in the prevalence of ever e-cigarette following TPD implementation, using monthly measures of time, level and post slope (see Study measures). Models were adjusted for age and gender. Quadratic terms were not significant in models for e-cigarette use and so were not included. As TPD regulations were brought in gradually with a 1-year transitional phase, we anticipated that change in trend is more likely than immediate change in level. Indeed, for a public health problem with a rising baseline trajectory, whether or not an intervention is able to reverse, or at least slow, growth in young people’s e-cigarette use is of greater interest than whether or not an intervention causes a stepped disruption followed by a return to growth. Hence, we present changes in level and trend (post slope), focusing primarily on the latter.

In segmented regression analyses, there are trade-offs between long- and short-term analyses, in that longer-term analyses will have more power, but passage of time also increases the likelihood of changes being caused by other events. 98 Hence, we model both short- (to 2017) and long-term (to 2019) changes in level and trend, and attend to similarities and differences between short- and long-term models. Models were implemented for the short-term post-implementation data (2013–17), presented to our Study Steering Committee in June 2019 and were submitted for publication before long-term data were available. Following peer review and publication of short-term effect models,101 these models were replicated and extended using the same syntax once longer-term data were available, and were presented to our Study Steering Committee in November 2020. Short-term models were constructed by a second analyst who covered a period of maternity leave for the study’s lead analyst and, hence, the lead analyst fully reproduced short-term models prior to extending them.

This analytical procedure was replicated for energy drink use in Wales to evaluate whether or not any change in level or trend was specific to e-cigarettes or replicated on an unrelated outcome. Energy drink use was selected as an example of another psychoactive substance that, like e-cigarette use, was relatively new and not following the secular decline observed among other substances, such as tobacco and alcohol use.

Although data sets in Scotland and England provided insufficient data points for more fine-grained segmented regression analyses, we use the data sets to evaluate whether trends observed within our primary statistical analyses are specific to the Welsh data or are mirrored in the data from other nations. Data from England provided one pre-TPD time point (2014) and two post-implementation time points (2016 and 2018), whereas Scottish data provided two pre-implementation time points (2013 and 2015) and one post-implementation time point (2018). Binary logistic regression models were constructed in each nation examining change over time in ever use of e-cigarettes, using the time point closest to TPD implementation as the reference category. These analyses were also conducted for our secondary outcome of regular e-cigarette use (including in Wales, where regular use was not measured until 2015).

Models using only Welsh data were adjusted for school-level clustering, but this was not possible in other data sets, as most data sets did not include school identifiers.

For our primary statistical analyses of ever e-cigarette use in Wales, we observed that in models stratified by ever smoking status, changes in trend were both of greater magnitude than for the whole group models (i.e. models including all eligible participants). We hypothesised that this may have been because ever smoking acted as a time-varying confounder. Hence, as an additional data-led post-hoc analysis, we included a term for ever smoking in whole group models, which increased the estimate of change in trend. As this was an unplanned post-hoc analysis, we refer to models without this term as our primary statistical analyses, but report the model with additional adjustment. Although our analyses were limited to 13- and 15-year-olds for comparability with nations where only these year groups are surveyed, we also ran our analysis of ever e-cigarette use for the whole Welsh sample (i.e. for 11- to 16-year-olds) as a sensitivity analysis.

To estimate post-intervention change in young people’s smoking uptake

Given the longer time series available for the secondary outcomes of ever and regular tobacco smoking, analyses involved repeating and extending models constructed to estimate pre-legislation changes in trend, with additional level and post-slope terms with 2016 as the intervention point (see Study measures). Although we aimed to analyse the same outcomes as included in pre-legislation analysis, changes in data collection schedules for some surveys and changes to question wording for some outcomes meant that fewer data were available for this analysis than had been hoped. Analyses are, therefore, limited to outcomes present in all five post-legislation data sets.

Additional analyses

Whole sample models were visually represented to aid interpretation, using plots of predicted probabilities over time, estimated following model execution in Stata® (see Report Supplementary Material 1, Figures 1 and 2). For each objective where data were available across data sets, subgroup effects were examined for gender, age/school year, SES, ethnicity and smoking status. The subgroup effects differ between analyses because of data availability. An additional data source held by the research team was the Youth Tobacco Policy Survey (YTPS) (principal investigator: AMM). These data were not integrated into our main analyses because of small numbers in the target age groups and the limited number of data points. However, the YTPS data provide an additional source of external data for triangulation of our findings. Time trends in the prevalence of our main study outcomes in the YTPS from 2002 to 2016 are presented in Appendix 2, Figures 10 and 11.

Procedure for dealing with missing data

The main outcomes for each of our objectives were available for ≥95% of respondents. For our overall primary outcome (i.e. ever e-cigarette use), data were available for 95% of young people, whereas 97–98% of young people were included in the final analytical samples for tobacco use. Hence, no imputation was undertaken, and analyses are based on complete cases.

Weighting

There is inconsistency within surveys over time in whether or not weighting is used to ensure national representativeness. Weights were included in data sets from 2006 in Scotland, 2009 in Wales and 2010 in England. In Wales, following movement from a sample to a whole population survey, weights were no longer used after 2013. Weights are calculated on the basis of the composition of the samples as a whole; however, in England and Wales, our analyses focuses on subsets of available data to harmonise age groups across countries. In plots of smoking prevalence trends over time using weighted (where available) and unweighted data, differences between these were barely discernible. Hence, for tobacco use models, we ran analyses using unweighted data, re-running whole group models with weights applied where available, as a sensitivity analyses. Survey weights were available in Scotland and England (but not Wales) for all surveys since first measurement of e-cigarette use. Hence, whole group and subgroup analyses for e-cigarette use in England and Scotland are presented with and without weights.

Software

All statistical analyses were undertaken in Stata/SE 15.0.

Process evaluation

Drawing on MRC guidance for process evaluation,90 we conducted an in-depth process evaluation focused on key uncertainties in causal logic for the TPD regulations, in relation to implementation, mechanisms and context. The evaluation included (1) qualitative interviews with young people aged 14–15 years, during the transitional phase and after full implementation of TPD regulations; (2) observation of compliance with TPD regulations in e-cigarette retailers, conducted at the same time as pupil interviews; and (3) interviews with policy stakeholders, TSOs and retailers on the context, implementation and perceived unintended consequences of the TPD regulations. In consultation with our patient and public involvement group Advice Leading to Public Health Action (ALPHA), a small number of items on potential mechanisms through which TPD might impact young people’s e-cigarette use were developed for inclusion in 2017 and 2019 SHRN surveys to enable triangulation of qualitative data on post-legislation change in these mechanisms. Process evaluation data collection materials are provided in Appendix 3.

Qualitative interviews with young people

School sampling

Although it was not possible to interview young people prior to legislation, which came into force before the study began, we aimed to interview young people as early as possible before the date of full compliance and then again 1 year later. Collecting data both during the transitional period and after full implementation of the TPD regulations enabled us to understand perceptions in relation to a context where unregulated e-cigarettes were, or were not, legally available for sale on the UK market. Our aim was to recruit 12 schools overall to provide representation of (1) schools in each of the three countries, (2) high, low and medium SES schools (as indicated by free school meal entitlement) and (3) urban and rural locations (which was a larger number than the six we had originally proposed, but followed a request from the PHR Funding Committee to expand this). However, contracting and ethics approval were not in place until March 2017, limiting time for recruitment. Hence, nine schools agreed to participate and data collection was completed within seven schools, including a total of 76 young people. The risk of low recruitment was anticipated in our protocol, given the time frame in which these were undertaken, and we indicated that should our intended level of recruitment not be achieved in the first round of data collection, then further schools would be recruited for post-legislation interviews in 2018 to provide a broader set of perspectives. Hence, in 2018, we returned to schools that participated in the first round and recruited a number of additional schools for post-implementation interviews only to provide a broader range of perspectives. We conducted post-implementation interviews in 11 schools. One original school was unable to take part in phase 2, with 62 of the same young people within six of these schools completing follow-up interviews in 2018. A further 86 young people participated in interviews at phase 2 only. Our intention was to complete follow-up interviews by Easter 2018 to reduce conflict with exams, but our planned data collection period coincided with university strikes and a period of extreme weather, including closures of schools (and in some cases universities) due to snow occurring in all three sites simultaneously, leading to challenges rescheduling school visits. Hence, data were collected between February and May 2018. Schools received a payment of £100 per data collection as compensation for administrative time supporting data collection.

Pupil sampling

We aimed to conduct four group interviews in each participating school, with three to five young people (aged 14–15 years when recruited, corresponding to Year 10 in England and Wales, and S3 in Scotland) in each group. To maximise rapport and interaction between young people within groups, we worked with school staff to identify groups of friends for interviews. Although smoking rates have historically been higher among girls, with convergence in genders in recent years, the opposite was true of e-cigarettes, which were becoming more popular among boys. Hence, we conducted single-gender group interviews, and sampled young people from higher- and lower-ability classes within secondary schools. Given that normalisation processes are driven as much by the reactions and behaviours of the majority who do not engage in a given behaviour as by the minority who do, we did not explicitly attempt to recruit young people who did smoke, or who were at high risk of smoking, or used e-cigarettes. We advised teachers of this in advance so that they did not use pupil smoking and vaping behaviours as criteria for selection.

Interview schedules

Semistructured interview schedules explored young people’s perceptions of e-cigarettes, tobacco and the inter-relationship between the two, with an emphasis on normalisation and elements of TPD theorised as likely to influence young people’s perceptions, including marketing and product-labelling. Interviews focused primarily on perceptions of tobacco and e-cigarettes among their peer group, rather than young people’s own use of e-cigarette and tobacco use. Topics included perceptions of social norms for e-cigarettes and tobacco use, including norms among their peer group and perceived parental reactions to tobacco and e-cigarettes, exposure to and perceived responses to advertising for e-cigarettes, and risk perceptions for tobacco and e-cigarettes, including views on elements of the TPD regulations, such as warnings about nicotine.

Data collection

Interviews were held on school premises during school time. Data collection was undertaken by research staff with prior experience of data collection with young people in education contexts. Researchers without this prior experience were accompanied by experienced staff in initial data collections. Interviews were recorded on a handheld digital recorder and uploaded to a secure university server at the earliest opportunity before being deleted from the recorder.

Retailer audits and interviews with professional groups

Retailer audits

We audited approximately 10 e-cigarette retailers in each country on two occasions to assess the availability of TPD-compliant/non-compliant products during and after the transitional phase. Audits were conducted at times coinciding with qualitative pupil interviews to put in context the extent to which unregulated products remain available during initial interviews conducted during the transitional phase, where non-compliant products could still legally be sold, and the extent to which fuller compliance was achieved by follow-up interviews after full compliance is expected. Our intention was that two observers independently estimate the proportion of e-cigarettes on sale in each location that have compliant labelling at each time point to enable assessment of interobserver agreement; however, because of a miscommunication in one nation, only one observer undertook each observation. Hence, estimates of interobserver agreement are based on the remaining two nations. Locations were sampled purposively to include large and small mixed retailers (e.g. supermarkets and newsagents), specialist e-cigarette shops and street vendors. Retailers sampled included any near the schools in which qualitative interviews were undertaken, and included supermarkets, specialist e-cigarette vendors, convenience store/newsagents and garages. Observations were ‘covert’ in so far as researchers did not voluntarily identify themselves as researchers to the store staff. However, researchers carried an information sheet with contact details for the study team, which was made available to any staff who asked the researchers what they were doing. Researchers were to leave the store if asked to do so.

Interviews with retailers, policy stakeholders and trading standards officers

We conducted interviews with 27 e-cigarette retailers after the final date for full compliance. Although audits included an approximately even split of retailer types, we anticipated that specialist e-cigarette retailers would provide more rich information on the implementation of TPD and regulation of e-cigarettes. Hence, two-thirds of interviewees were specialist retailers and one-third were non-specialist retailers. Interviews were conducted either by telephone or at the interviewee’s place of work. Interviews were conducted between June and November 2018, approximately 2 years after the initial implementation date for the TPD regulations (and 1 year after the date for full compliance).

We conducted interviews with 12 policy representatives and 13 TSOs across the three nations to explore perspectives on e-cigarettes, as well as barriers to and facilitators of implementing the legislation. Policy representatives were recruited through the team’s existing links with UK governments, public health agencies, non-governmental organisations and other organisations involved in the policy-making process. Interviews focused on perceived roles of e-cigarettes in movement into and out of smoking, policy implementation and compliance, local contextual factors and variations in e-cigarette policy, and theorised mechanisms of the TPD legislation in relation to e-cigarettes. Topic guides allowed flexibility in response to the roles of interviewees, for example with less emphasis on policy development and more emphasis on enforcement activity when speaking with TSOs. Interviews were conducted between June and November 2018. Interviews with policy representatives included a focus on perspectives regarding the renormalisation of smoking and were completed before our own findings relating to this were in the public domain.

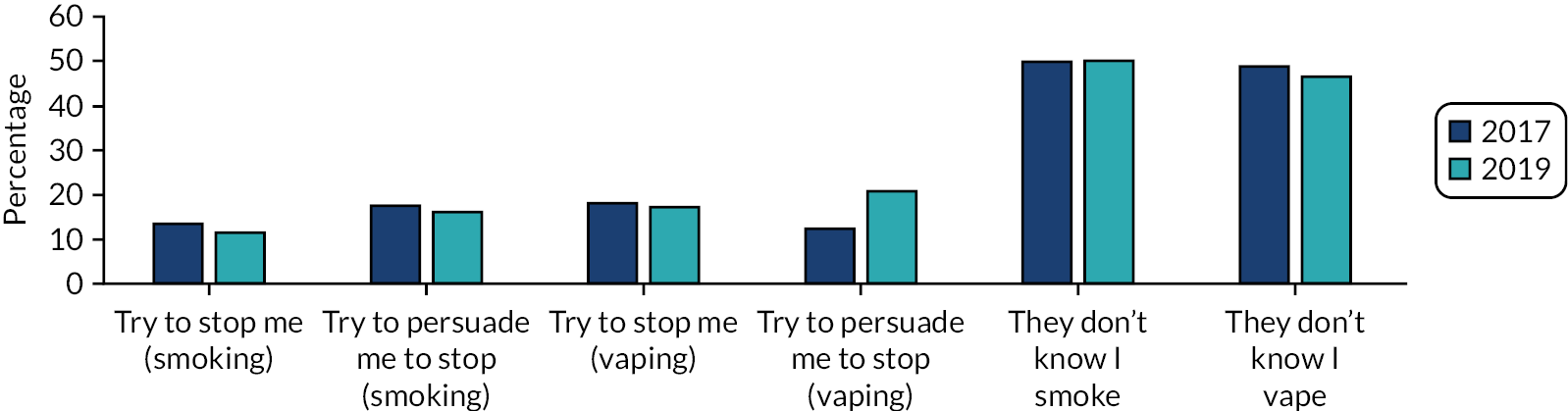

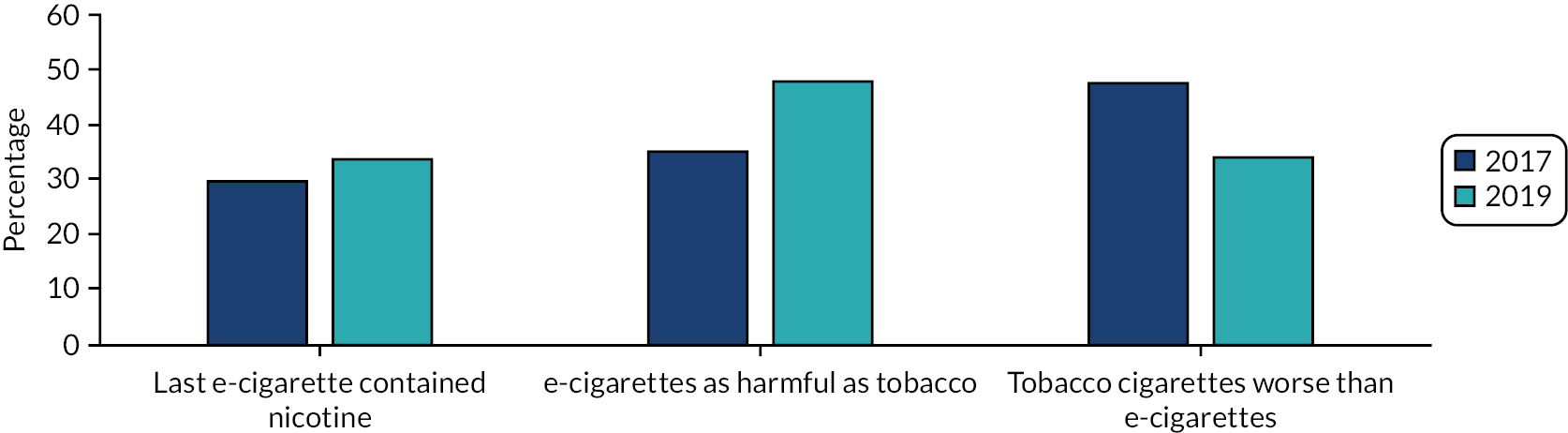

Quantitative process indicators

For the 2017 SHRN survey, a number of questions were added in consultation with our patient and public involvement group to provide a snapshot of the prevalence of potential mechanisms through which TPD may impact pupil’s use of e-cigarettes, and were linked to research questions on young people’s perceptions of risks and norms for e-cigarette use and tobacco (see Table 2). In our protocol, in response to PHR programme feedback, we indicated that we would request to add questions on where young people obtained e-cigarettes from and whether or not e-cigarettes used by young people contained nicotine. In addition, we included measures of risk perceptions for e-cigarettes compare with tobacco, exposure to marketing and perceived parental attitudes, mapping onto themes arising from our qualitative analysis. Most items were repeated in 2019, allowing examination of post-legislation change over time. In both cases, owing to pressures on the survey, items were asked of a random subsample of participants, rather than all survey participants.

| Process indicator | Asked of | Question | Response options |

|---|---|---|---|

| Risk perceptions | All participants | Which of the following statements do you agree with the most? | Tobacco cigarettes are worse for your health than e-cigarettes E-cigarettes are worse for your health than tobacco cigarettes Tobacco and e-cigarettes are equally bad for you I don’t know |

| Nicotine content of last device used | Ever users of e-cigarettes | The last time you used an e-cigarette, what was in the vapour you inhaled? | Nicotine Just flavouring/water vapour (no nicotine) Cannabis or cannabis oil Something else I don’t know |

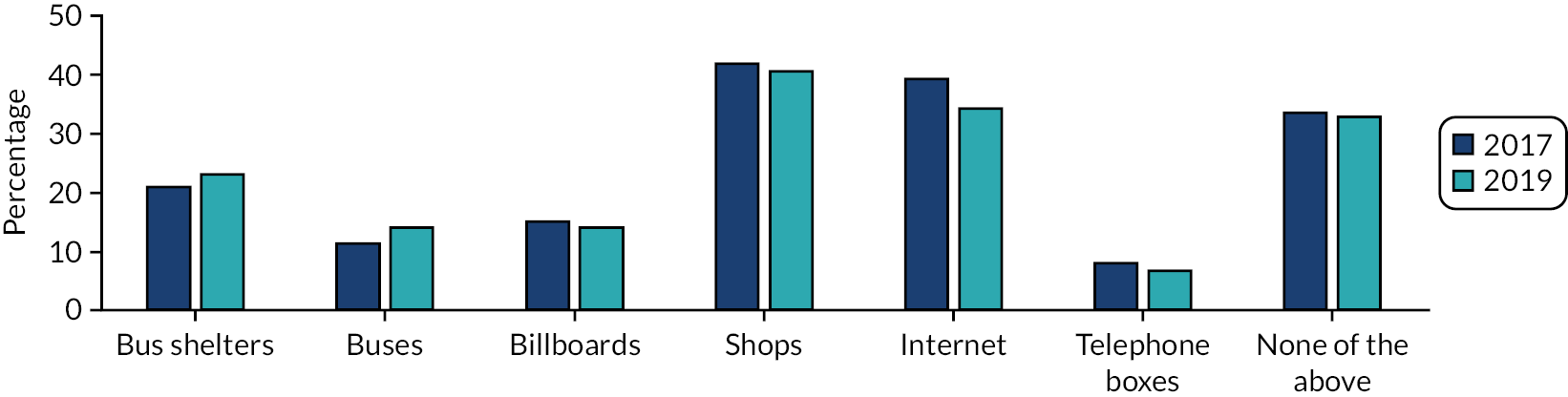

| Exposure to advertising | All participants | In the past month, have you seen advertising for e-cigarettes in any of the following places? | In bus shelters On the sides of buses On billboards In supermarkets, petrol stations, newsagents, vape shops On the internet On phone boxes Other I haven’t seen any advertising |

| Perceived parental reactions | Non-smokers/non-vapers | If you were to start smoking/using e-cigarettes, what do you think your parents/carers would do? | Try to stop me Try to persuade me to stop Do nothing They would encourage me to smoke/use e-cigarettes |

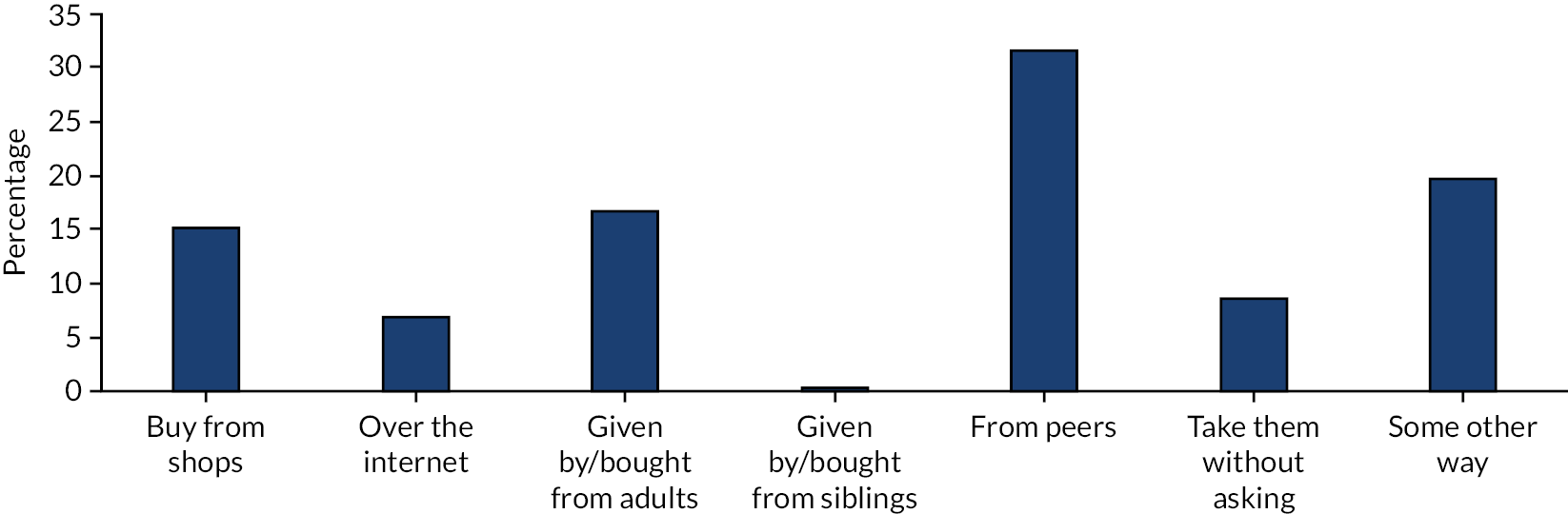

| Where e-cigarettes obtained from | Current users only | Where do you often get your e-cigarettes and/or e-liquids from? | I buy them myself I get someone else to buy them for me Someone gives them to me I take them without asking I get them in some other way I do not want to answer |

Analysis of process evaluation data

All qualitative interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim, with identifiable details (e.g. names of individuals and organisations) removed during and following transcription. The transcribed data were subjected to thematic analyses using Braun and Clarke’s102 six-step approach, which included (1) data familiarisation, (2) generating initial codes, (3) searching for themes, (4) reviewing themes, (5) defining themes and (6) writing up the account. Data analysis and data collection were conducted in parallel. Philosophically, the analyses were conducted through an abductive critical realist lens, beginning with exploration of predefined themes derived from the intervention logic model, and pursuing themes that emerged inductively from earlier interviews in later ones. A first researcher developed draft coding frames, with a sample of interviews second coded by a second researcher. Inconsistencies and disagreements were resolved through discussion with other members of the process evaluation subteam where necessary. For pupil interviews, which included a longitudinal cohort of young people and a cross-sectional sample of pupils recruited at follow-up only, the longitudinal and cross-sectional data were analysed as separate data sets prior to synthesis of themes across data sets. For structured observations, percentage interobserver agreement is presented for each item. One observer was a priori assigned as the primary observer, with percentages of retailers selling TPD-compliant products at each wave presented by retailer type, according to the primary coder. For quantitative process indicators, simple descriptive statistics are presented graphically by year the questions were asked (i.e. 2017 and 2019). These statistics are presented alongside the themes from the qualitative analyses of pupil data to examine the extent to which views expressed in qualitative interviews concur with, or contradict, views expressed in the national surveys.

Triangulation and integration

Combining data sources

Our sampling methods for qualitative process evaluation components were directed towards obtaining views from a diverse range of participants, rather than representativeness. By contrast, quantitative surveys aimed for representative of participants’ respective countries. This combination enables us to advance nuanced explanations for quantitative trends, and examine the extent to which views expressed within our qualitative interviews concur with, contradict or build on survey fundings. At each phase, quantitative and qualitative data analyses were conducted in parallel, but converged following analysis. Qualitative and quantitative analyses were undertaken by different subgroups, with integration of quantitative and qualitative data subsequently focused on areas in which data sources aligned, challenged one another’s conclusions or added further nuance and explanation. Study components were synthesised into a whole using an evaluation and integration framework based on MRC guidance for process evaluation90 (see Figure 2), with data sources organised and presented chronologically rather than by method. Although we considered a more traditional presentation by method, with effects data followed by process evaluation data, this would involve a potentially confusing rotation between a range of different time frames. Hence, the most coherent means of narrating the current study as a whole was to position the impact of TPD as the ending of the story. Hence, Chapter 3 presents data on the context into which TPD was introduced (i.e. pre-implementation trends in smoking and young people’s perceptions of vaping), Chapter 4 presents data from policy stakeholders, TSOs and retailers on implementation of legislation, before Chapter 5 presents data on mechanisms of change and post-legislation vaping and smoking outcomes.

Owing to significant policy interest in findings and the fast-moving nature of this evidence base, we chose to conduct analyses in a sequential manner and publish these as they were completed, rather than waiting for the final report. Our analyses of smoking trends during the emergence of e-cigarettes was, for example, one of the first of its type (and formed part of an evidence review on e-cigarettes and smoking uptake within National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guideline development immediately after publication);103 however, a number of similar analyses have since been published internationally, as described in Chapter 1. All findings have been published under Creative Commons Attribution licenses that allow adaptation and re-use of material for any purpose so long as the original work is properly cited. The original contribution of this report relates to the synthesis of previously published components, and additional unpublished data, to tell the story of the study as a whole. We indicate at the beginning of each chapter which elements draw on previously published sources, and which are new.

Cross-country integration

The quantitative elements of the study involve pooling of data sets collected at differing time points, using slightly different questions in each nation. The most robust analysis available to test the impact of TPD on vaping rates is the Welsh data, which (1) is available in a monthly format, therefore, providing multiple time points within the same survey year, and (2) includes data on ever e-cigarette use since 2013, enabling a segmented regression approach. However, this is supplemented by more crude before-and-after analyses of e-cigarette and tobacco use rates across all three countries, using an integrated three-country data set to examine the transferability or context specificity of findings relating to change in trend in our primary statistical analysis in Wales to other nations in Great Britain. Analyses of tobacco use draw on an integrated three-country data set, with adjustment for country. The process evaluation is conducted using harmonised methods across countries and was analysed as a single data set.

Management and governance

Ethics and consent