Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 15/82/12. The contractual start date was in March 2017. The final report began editorial review in March 2021 and was accepted for publication in February 2022. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Disclaimer

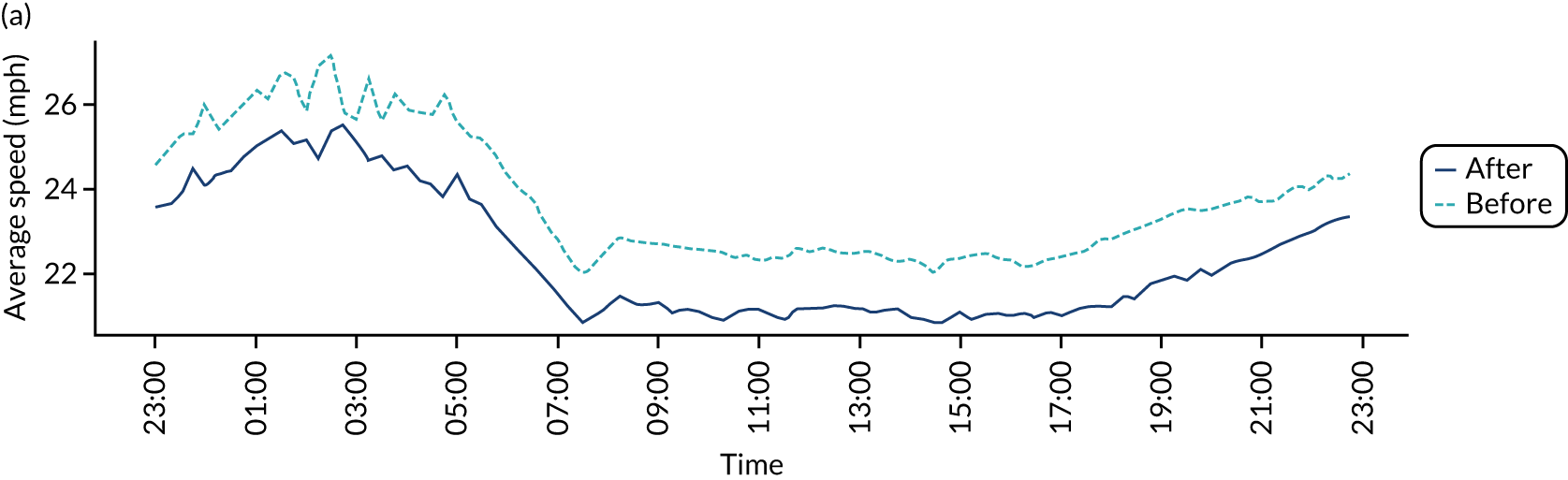

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2022 Jepson et al. This work was produced by Jepson et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2022 Jepson et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Context to the evaluation

In early 2015, Ruth Jepson and Paul Kelly were at a workshop where Eileen Hewitt from the City of Edinburgh Council was also present. Eileen was the Professional Officer for the 20-mph programme located in Strategic Planning, Services for Communities, City of Edinburgh Council. She talked about the plan for a citywide 20-mph intervention and the evaluation that the Council was planning. She also spoke about outcomes they would be interested in that might be outside the scope of the local evaluation. That short conversation led to the development of this research evaluation. Following the conversation, several further conversations took place between the developing research team and the 20-mph programme team in the City of Edinburgh Council. This led to the creation of an initial programme theory (see Developing an evaluation programme theory), the research questions that City of Edinburgh Council was interested in and the identification of the potential data sources that could be used to evidence the programme theory (see Table 6). At that time, connections were also being made with researchers in Belfast, another city that was planning to implement a pilot 20-mph scheme in its city centre. In November 2015 we submitted an outline application to the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR), and received final approval for starting in March 2017. This meant that, by the time we started the evaluation, despite some delays in implementation in Edinburgh, we had missed some of the initial implementation stages and were unable to collect baseline data. The implications of this for the evaluation are discussed in Chapters 4 and 6.

The 20-mph intervention and implementation

The intervention was the introduction of a 20-mph speed limit. However, within the intervention there were four components, as described in Table 1, namely legislation, signage and road markings, promotion and education, and enforcement.

| Component | Description | Organisations involved in delivery |

|---|---|---|

| Legislation | Traffic limit order or speed limit order | Edinburgh: CEC |

| Belfast: Roads Service, DRD NI | ||

| Signage and road markings | 20-mph road markings and traffic signs installed at the places where the speed limit changes. Smaller ‘20’ repeater signs placed at regular intervals | Edinburgh: CEC |

| Belfast: Roads Service, DRD NI | ||

| Promotion and education | In both sites a programme of awareness-raising and education would publicise and support the introduction of the 20-mph network, explain the benefits of lower speeds and ensure a smooth transition process | Edinburgh: CEC, Neighbourhood Partnerships, Police Scotland, schools, Sustrans |

| Belfast: DRD NI, Department of the Environment NI, Police Service of NI, Belfast City Council, Sustrans, schools | ||

| Enforcement | Warnings and issuing of speeding tickets. Speeding tickets were not used in the early implementation phases. Instead, warnings (community speed concern letters) were issued | Edinburgh: Police Scotland |

| Belfast: Police Service of NI |

Edinburgh and Belfast took different approaches to the shape and scale of the implementation of the 20-mph speed limits, and so are described separately.

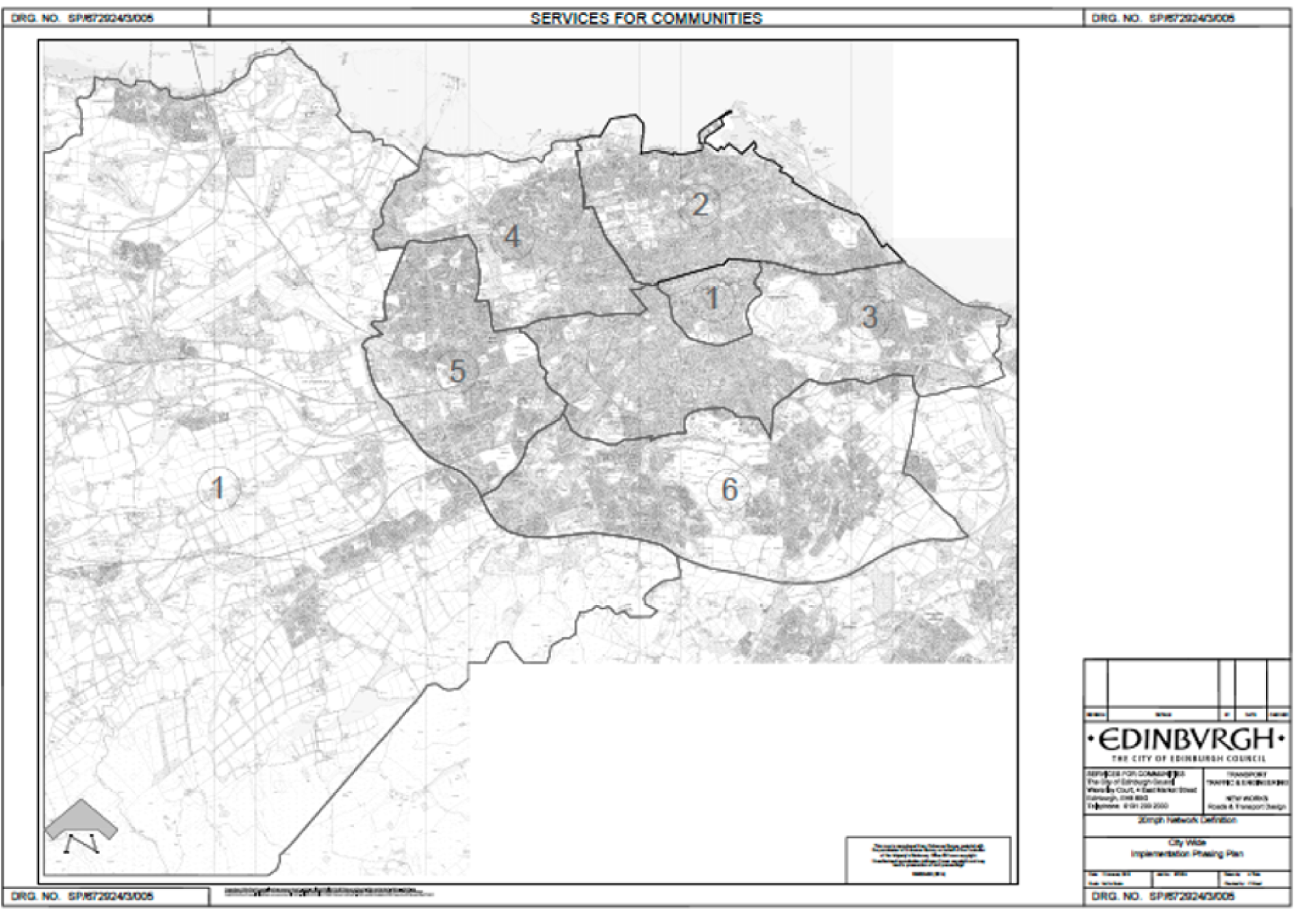

Edinburgh implementation

Edinburgh took a citywide approach to implementing the intervention, that is, streets that fell within the City of Edinburgh Council area. Prior to implementation, 50% of streets already had speed limits of 20 mph. Edinburgh implemented the 20-mph intervention in a further 30% of streets, which equated to an additional 1572 roads being reduced to 20 mph. This implementation resulted in 80% of streets in Edinburgh having speed limits of 20 mph (771 miles/1240.3 km), with a coherent network of 30-mph and 40-mph speed limits in the remaining 20% of streets. The 20-mph network was implemented under one citywide speed limit order. The city was split into seven implementation zones, and the intervention was implemented over three phases (Figure 1 and Table 2). Each implementation phase took approximately 16 weeks over a total period of 24 months (starting in July 2016 and finishing in March 2018).

FIGURE 1.

Map of the 20-mph implementation zones in Edinburgh. Copyright City of Edinburgh Council, contains Ordnance Survey data. © Crown copyright and database right (2021). All rights reserved. Ordnance Survey Licence Number 100023420.

| Zone | Zone name | Implementation phase | Implementation date |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1a | City Centre | 1 | 31 July 2016 |

| 1b | Rural West | 1 | 31 July 2016 |

| 2 | North | 2 | 28 February 2017 |

| 3 | South Central/East | 2 | 28 February 2017 |

| 4 | North West | 3 | 16 August 2017 |

| 5 | West | 3 | 16 August 2017 |

| 6 | South | 4 | 5 March 2018 |

Belfast implementation

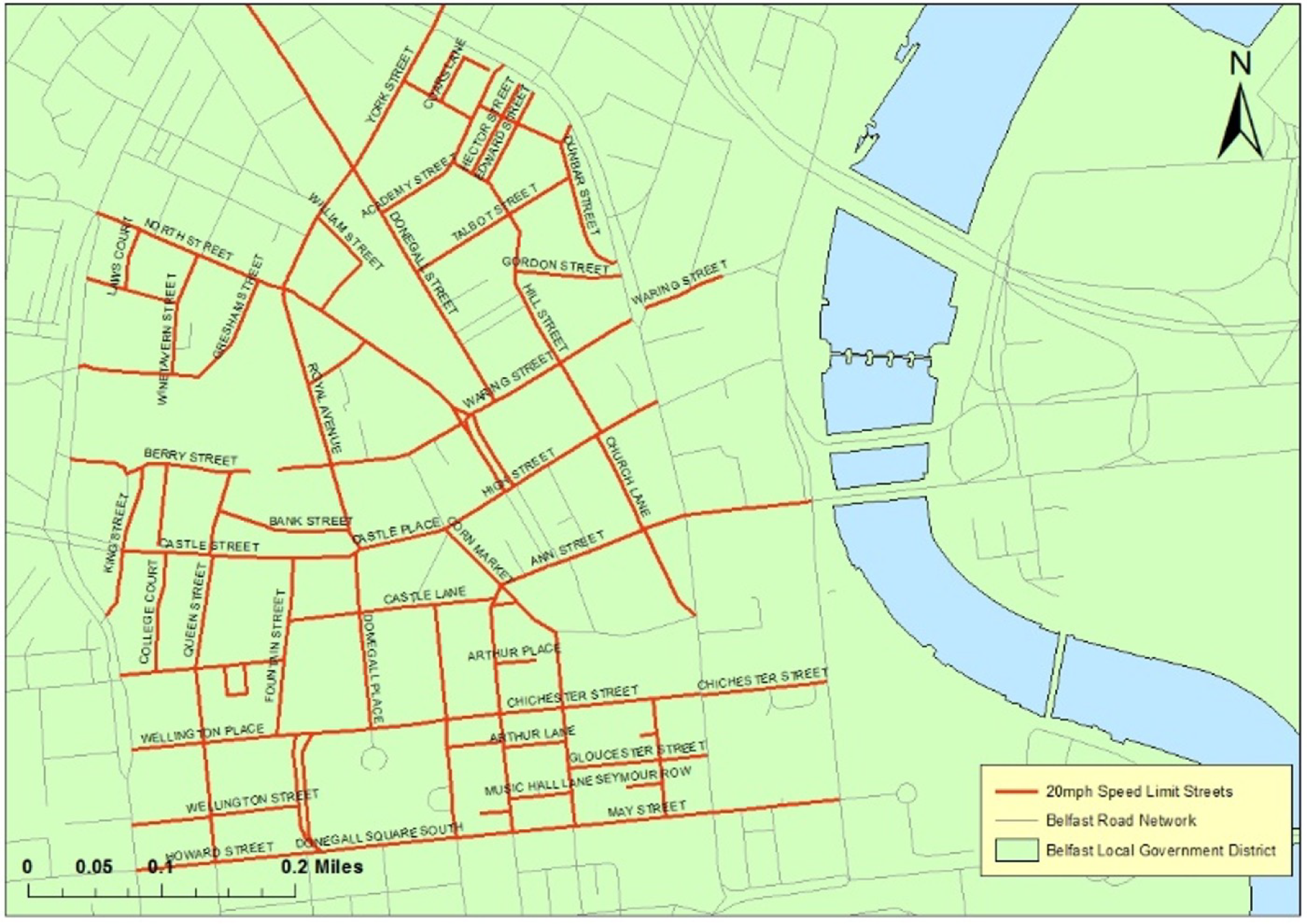

Belfast implemented the 20-mph speed limit as part of a wider pilot project. Five pilot 20-mph speed limit zones were implemented in Northern Ireland. Four were residential areas only; the fifth and largest site was in the central area of Belfast, encompassing a total of 76 streets. This is the part of the city centre with the highest levels of pedestrian movement, cycle activity and bus facilities. Twenty streets were subject to a Prohibition of Traffic Order (pedestrian zone) and seven were partially subject to a Prohibition of Traffic Order. Comparable with Edinburgh, the 20-mph streets in Belfast are surrounded by a coherent network of 30-mph and 40-mph streets in the city centre. In Belfast the intervention was implemented in a single phase in a similar geographical area (starting in February 2016) (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Map of the 20-mph implementation zones in Belfast. Provided by the Department for Infrastructure, Northern Ireland. Reproduced from Land and Property Services data with the permission of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, © Crown copyright and database rights MOU203.

One of the main stages in the initial application to NIHR was to develop a programme theory to understand what change in outcomes were expected to occur as a result of the intervention, and the potential pathways. This programme theory was used to develop our research questions and frame the evaluation.

Developing an evaluation programme theory

This study used a theory-based approach to evaluation. Programme theory is ‘an explicit theory or model of how an intervention, such as a project, a program, a strategy, an initiative, or a policy, contributes to a chain of intermediate results and finally to the intended or observed outcomes’. 1 Proponents of this approach argue that evaluation should not be driven by methods, as all have their strengths and weaknesses. Rather, theories should be made explicit, and the evaluation steps (and design) should be built around them by elaborating assumptions, revealing causal chains and engaging all concerned stakeholders. To develop the programme theory, we also had to consider the systems in which the 20-mph intervention was being implemented. Following the Medical Research Council (MRC) guidance,2 considerable preliminary work was undertaken with stakeholders to develop an initial programme theory to inform, and be tested by, the outcome and process evaluations. 3 We also used a decision-theoretic approach (DTA), which is useful to inform recommendations about whether or not interventions are likely to be effective in the absence of trial evidence and/or when the evidence is unlikely to be strong enough to satisfy conventional levels of statistical significance. 4 It is also a useful way of framing an economic evaluation in which effectiveness is likely to remain uncertain.

The DTA has been described as a transparent way of using ‘relevant knowledge, theory and data from observational and experimental studies to [assess whether] an intervention is sufficiently unlikely to cause net harm [and if so, to] assess if the benefit relative to its cost is sufficient for the intervention to be recommended’. 5 The approach is particularly useful when ‘inappropriate adherence to underpowered randomised controlled trials’5 might undermine support for safe and cost-effective interventions with strong theoretical and observational support.

We also considered the role that systems play in modifying the effects of any intervention. Interventions, such as the introduction of 20-mph speed limits, are events in a system and they are best understood by employing systems theory. A system is a ‘set of actors, activities and settings that are directly or indirectly perceived to have influence in or be affected by a given problem situation’. 6 Within a system, an intervention exerts its influence by changing relationships, displacing existing activities and redistributing and transforming resources. 7 Systems theories are connected to both ontological and epistemological views. The ontological view implies that the world consists of integrative levels (systems). The epistemological view implies a holistic perspective emphasising the interplay between the systems and their elements in determining their respective functions. It is thus opposed to more atomistic approaches in which objects are investigated as individual phenomena.

Complex interventions take on the characteristics of complex systems: non-standardisation, interaction, multiplicity, emergent properties. Complexity is a scientific theory that asserts that some systems display behavioural phenomena that are completely inexplicable by any conventional analysis of the system’s constituent parts. 7 In other words, a complex system is one that is adaptive to changes in its local environment, is composed of other complex systems and behaves in a non-linear fashion (i.e. change in outcome is not proportional to change in input). A complex system approach helps to understand the wider implications of the intervention and the interactions that occur between components of interventions.

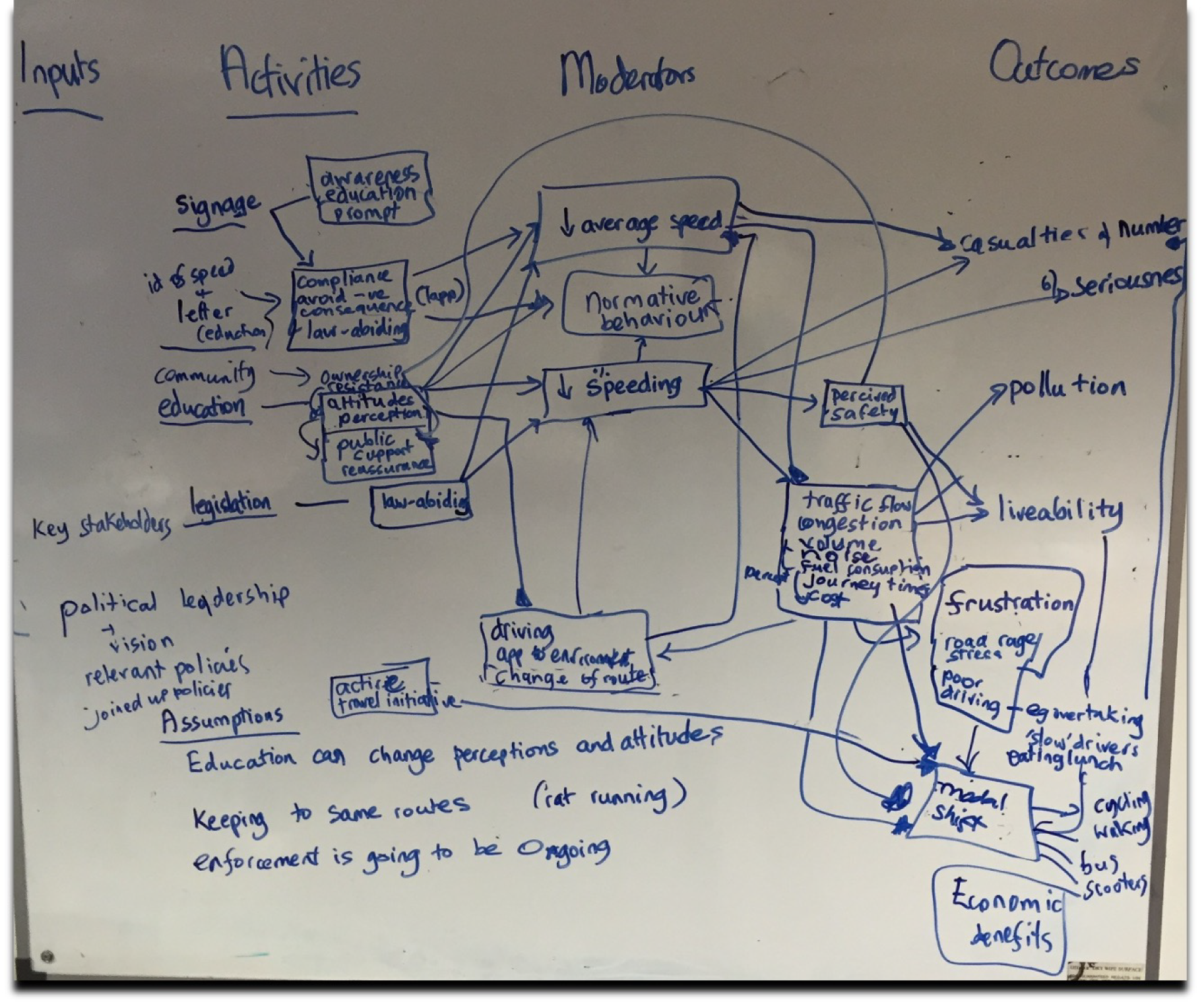

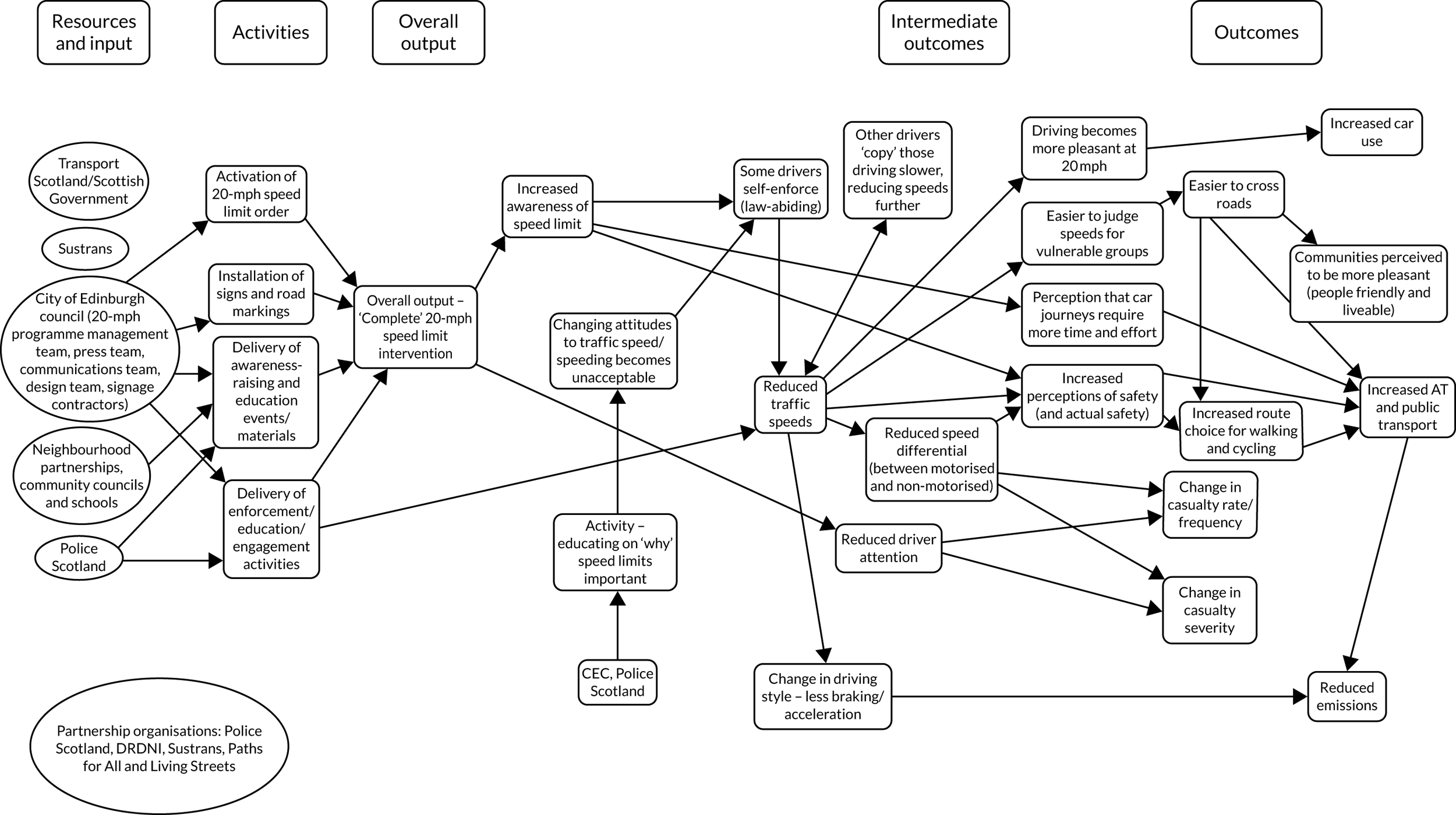

First iteration of the 20-mph programme theory

A very initial programme theory was developed (Figure 3) in discussion with the City of Edinburgh Council, but needed refinement. We therefore undertook a review of existing literature to refine the theory, and spoke to key stakeholders. This led to the programme theory that was used in the research bid to NIHR.

FIGURE 3.

First iteration of the programme theory.

Second iteration of the 20-mph programme theory (review of evidence)

The second iteration of the programme theory built on the first by drawing on the wider research evidence, complemented by discussions held with, and documents provided by, local authority officers delivering the 20-mph speed limit intervention in Edinburgh. There follows a summary of the evidence that we used to develop the theory.

Transport and health

The links between transport policy/infrastructure and health are well known. 8,9 Transport has the potential to promote health, through enabling greater access to work and social activities and encouraging physical activity, and also to have a negative impact on health through road traffic collisions and influencing exposure to noise and air pollution. 10 Transport interventions that are beneficial for public health include campaigns to prevent childhood injuries, increase bicycle and motorcycle helmet use, promote the wearing of seat belts and apply traffic-calming measures. 10

The recognition of these links to health has led to more integrated transport and health policies in the UK and internationally. For example, Scotland’s Transport Strategy in 2016 set out a vision for transport to play a significant role in enhancing health. 11 Furthermore, the importance of integration between public health and transport and planning policy was stressed by England’s public health White Paper, Healthy Lives, Healthy People. 12 At international policy level, the Toronto Charter13 discusses the importance of active travel in having a significant impact on sustainable development.

There are several transport-related issues that can negatively affect health, including a lack of infrastructure to support active travel; motorised vehicles being prioritised with regard to road space;14 and the direct and indirect health-related impacts of motorised traffic behaviour, for example collisions and perceived lack of safety. 15 Traffic speed, in particular, is a key risk factor in road traffic incidents, with regard to both the risk of a collision and injury severity. 16 For vulnerable road users such as pedestrians and cyclists, the relationship between speed and injury is even more severe. 16 Reductions in traffic speed can, therefore, offer multiple public health benefits. These include reducing the risk of traffic collisions and the resulting severity of injuries, encouraging greater uptake of physical activity (through increased walking and cycling), and improving pleasantness and social cohesion on streets. 17 Implementing 20-mph speed limits in the UK is becoming increasingly common. 18,19 For example, citywide 20-mph speed restrictions were introduced in Portsmouth20 and Bristol,21 and other local authorities have introduced 20-mph restrictions on a smaller, more localised scale on a pilot basis (see Cleland et al. 22 for a summary).

In both Bristol and Edinburgh, the success of pilot schemes led to the decision to roll out a 20-mph speed limit across the whole city. An umbrella review investigating the health implications of 20-mph (30-kph) zones and speed limits8 concluded that these schemes can reduce accidents, injuries, traffic speed and volume; improve perceptions of safety; and be cost-effective. Speed zones of 20 mph typically involve the use of physical traffic-calming measures such as speed humps or chicanes,23 whereas 20-mph speed limits generally rely on road signage and legislation, and less so on physical traffic-calming measures. 24 Of the 10 studies identified in the umbrella review, only two studies focused on speed limits specifically. Both studies provided evidence to support a reduction in injuries and casualties through a reduction in speed, although the effects on walking and cycling levels were unclear and need further investigation. Our more recent review22 also reported that 20-mph ‘zones’ were effective in reducing collisions and casualties. For 20-mph ‘limits’, the evidence was lacking, which is the primary reason why this evaluation was undertaken.

Road casualties

The term ‘casualties’ in this context refers to a person killed or injured in a road accident, and can be subdivided into killed, seriously injured and slightly injured. 25 Motorised transport is responsible for about 120,000 deaths and 2.4 million casualties each year in the European region. 26 In Great Britain in 2014, nearly 25,000 people were killed or seriously injured as a result of road accidents, with the proportions of fatalities of pedestrians and cyclists similar to those for the European region, at 25% and 6%, respectively. 25 Casualties were socially patterned, with levels of casualties higher in areas of socioeconomic disadvantage. 27

Pedestrians and cyclists are at a disproportionately higher risk of death and serious injury than those using motorised vehicles. 26 Data from 1997 for the European region indicated that pedestrians and cyclists accounted for 22% of people involved in serious car crashes for that year, but 33% of those killed,28 showing their increased risk of death if involved in a collision. Vehicle speed is related to the likelihood of a crash occurring in the first instance; at higher speeds, a driver’s time to react is shorter, stopping distance is greater and manoeuvrability is compromised. 29 Vehicle speed is also a significant factor in determining the severity of road traffic casualties. It is suggested that the fatality risk for a pedestrian struck by a vehicle travelling at 31 mph is twice that of being struck by a vehicle travelling at 25 mph, and five times that of being struck by a vehicle travelling at 19 mph. 30 These data align with those from other studies; one study suggested that pedestrian risk of death reaches 10% at 24 mph, 25% at 32 mph, and 50% at 41 mph. 31 One modelled estimation is that a reduction in average speed of 1 mph is associated with a reduction in casualties of 5%, rising to 6% when applied to urban areas. 32

Previous signage-only 20-mph schemes have provided encouraging results with regard to speed reduction. Results from the pilot scheme in Edinburgh indicated an overall reduction in speed of 1.9 mph on roads where 20-mph limits were implemented. 33 In Portsmouth this figure was 1.3 mph,20 and the figures for two pilot areas in Bristol were 1.4 mph and 0.9 mph. 34 If these speed reductions were observed in future 20-mph speed limit implementation areas, it would be reasonable to assume a potential decrease in casualties of between 6% and 12%. Furthermore, on roads that were characterised by speeds of > 24 mph before 20-mph speed limits were introduced, an average reduction of 6.3 mph was observed in Portsmouth, and of 3.3 mph in Edinburgh. 20,33 These figures indicate potentially even greater positive implications for casualty rates and severity. In Portsmouth, a reduction of 22% in reported road casualties was observed when comparing the 3 years prior to implementation with the 2 years post implementation. 20 However, there is little evidence to suggest that such schemes will substantially reduce health inequalities in relation to traffic casualties. 8 It is unclear at present whether this is an absence of effect, or an absence of evidence. Some evidence suggests that the greatest beneficial impact in the future will be evident in the least deprived areas,27 a not uncommon problem with some public health interventions. 35

Perceived safety

Preliminary findings from our developmental, preparatory, qualitative work with key stakeholders of the 20-mph scheme in Edinburgh identified perceived lack of safety as a substantial factor in deterring greater levels of walking and cycling. 3 Where pedestrians and cyclists are safer, levels of walking and cycling tend to be higher. 15 A literature review reported that 20-mph limits without traffic calming significantly increased walking and cycling by increasing actual, and perceived, road safety. 36,37 One potential mechanism for this action may be in reducing the speed differential between motorised vehicles and cyclists on the roads, thus increasing cyclists’ perceived and actual safety.

Physical (in)activity

Physical inactivity, as characterised by a lack of sufficient physical activity (< 150 minutes/week), is in the top 10 leading behavioural risk factors for global mortality. 38,39 In highly physically active cohorts, reductions as high as 41% in all-cause mortality have been observed. 40 Physical inactivity is responsible for at least 6% of coronary heart disease, 7% of type 2 diabetes and 10% of both breast cancer and colon cancer cases worldwide. 38 The global prevalence of physical inactivity is 31%41 and the World Health Organization (WHO) has targeted a reduction in physical inactivity of 15% by the year 2030. 42 Research is needed to develop and evaluate large-scale interventions with the potential to increase population levels of physical activity.

Walking and cycling have been shown to reduce the risk of all-cause mortality by 11% and 10%, respectively,43 and it is estimated that up to 50% of short trips could be easily walked or cycled. 15 Active travel (physical activity primarily through walking and cycling for commuting and utility purposes) has been suggested to be ‘the most practical and sustainable way to increase physical activity on a daily basis’. 44,45 There is evidence that active travel can be a major contributor to meeting physical activity guidelines,44 and is associated with a healthy body weight and composition. 46 Guidance from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends that environmental- and policy-level actions will be required to support walking and cycling, such as reducing the actual and perceived dangers associated with travel on roads. 47 Findings from the 20-mph pilot project in Edinburgh showed an increase of 7% in journeys made on foot, and an increase of 5% in journeys made by bike. 33 Similarly, increases of at least 10% in walking and at least 4% in cycling were found in the Bristol pilot project. 34

A 20-mph speed limit and social cohesion/connectedness and liveability

There is evidence that walkable streets, as well as encouraging physical activity, also strengthen social support networks, which is of great public health relevance. 45 The impact of traffic behaviour on communities has long been demonstrated. For example, in Bristol,48 it was found that residents living on streets characterised by heavy traffic volumes had significantly fewer friends and acquaintances on their street in comparison to those residing on streets with light traffic volumes. In discussing the implications for their findings,48 it was suggested that similar findings of low social connectedness were likely to be found on most UK cities’ streets with high traffic flow. In Bristol, on streets with light traffic, occasional speeding was sufficient to create the perception of a dangerous environment; speeding traffic was the most frequently cited cause of stress among residents. 48

Speeding behaviour by traffic has been identified as the greatest antisocial behaviour problem in local communities, based on data from the British Crime Survey (now the Crime Survey for England and Wales). 49 Traffic behaviour, in particular aggressive and speeding-type driving styles, provide unnecessary noise and can contribute to stress-related illness in residents,50 indicating that lowering speed limits to 20 mph would result in increased liveability in cities. Dorling51 proposed that traffic travelling at lower speeds requires less space to move safely, allowing more space and scope to enhance the pleasantness of residential environments, and more space for pedestrians, planting, seating and other street furniture. 10

Edinburgh pilot implementation

An area-wide 20-mph limit was implemented across south-central Edinburgh, with the scheme launched in March 2012. The speed limit was changed to 20 mph on 28 streets; these streets, along with 20 streets that retained a 30-mph limit, were monitored before (May and June 2011) and after implementation (May and June 2013) for traffic speeds. In the 20-mph streets, average speeds fell by 1.9 mph (from 22.8 to 20.9 mph); in 12 streets where average speeds exceeded 24 mph before implementation, a greater average reduction of 3.3 mph was found. Four streets saw slight increases in average speed after implementation, and four streets had average speeds of > 24 mph. Speeds also reduced on the roads that were maintained at 30 mph, by a smaller magnitude of 0.9 mph (from 26.3 to 25.4 mph). More than 1000 household surveys were carried out before and after implementation. Before implementation, 68% supported 20-mph speed limits; after implementation, this figure rose to 79%. Strong support increased from 14% to 37%. Opposition to the limits reduced from 6% to 4% after implementation. There was a net increase of 7% for journeys on foot, an increase of 5% for journeys by bike and a decrease of 3% for car journeys. This evaluation was small scale and did not utilise the robust methods that were used in the evaluation reported here.

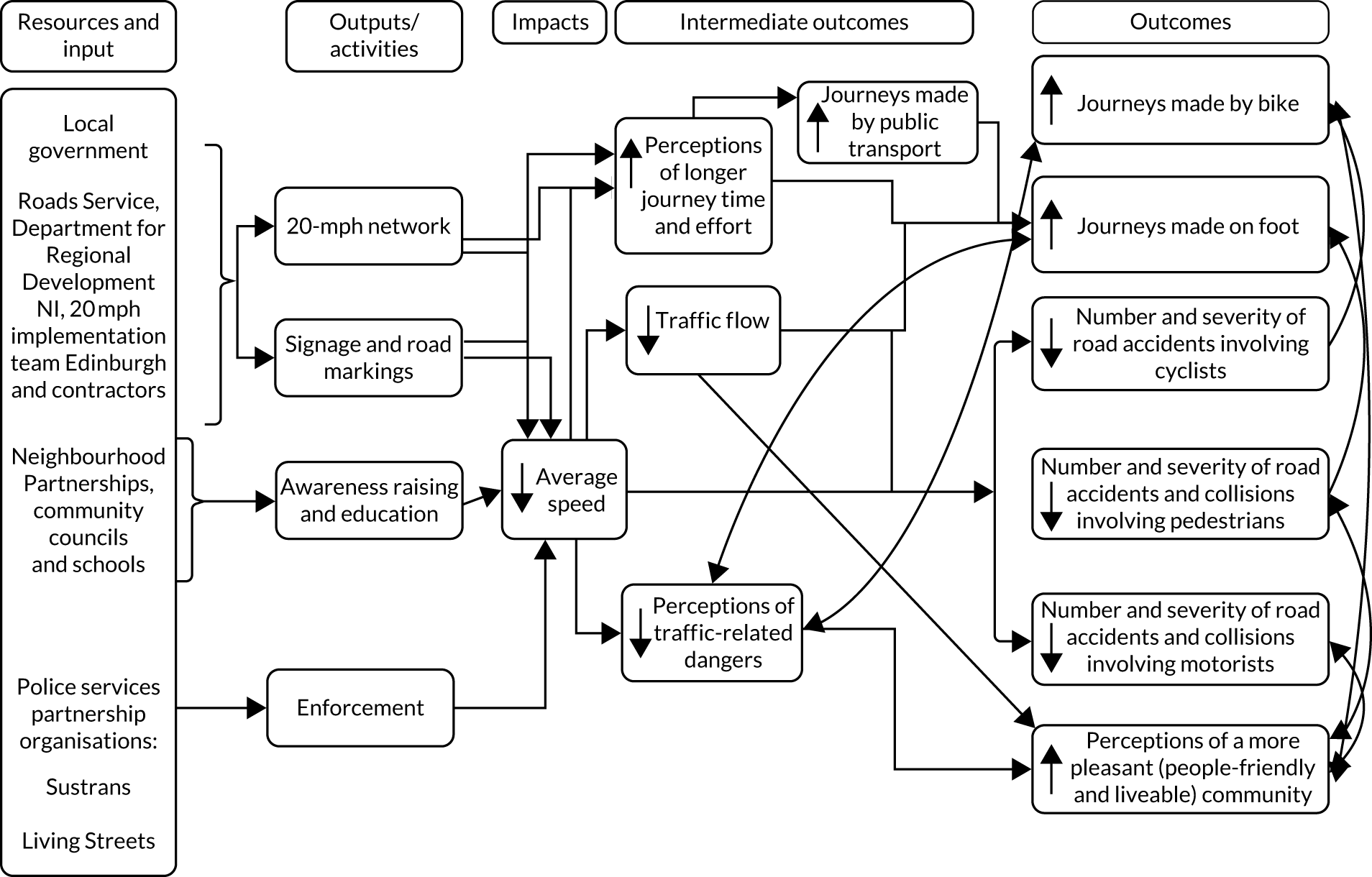

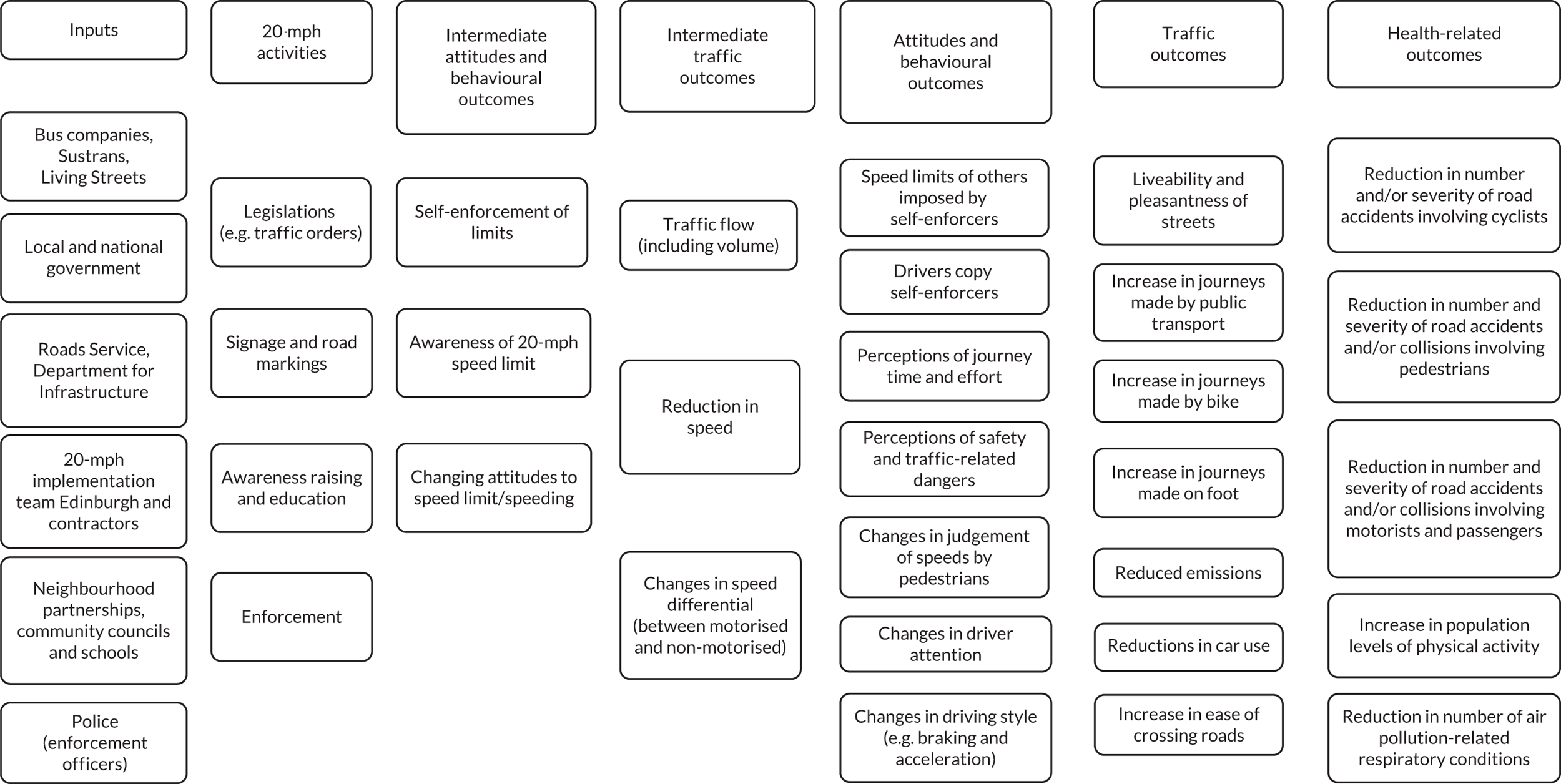

The second iteration of the programme theory was based on the existing evidence base, and hypothesised theories of the effect of the intervention on the outcomes. Although we knew what had happened in other cities, we did not know what would happen in Edinburgh and Belfast.

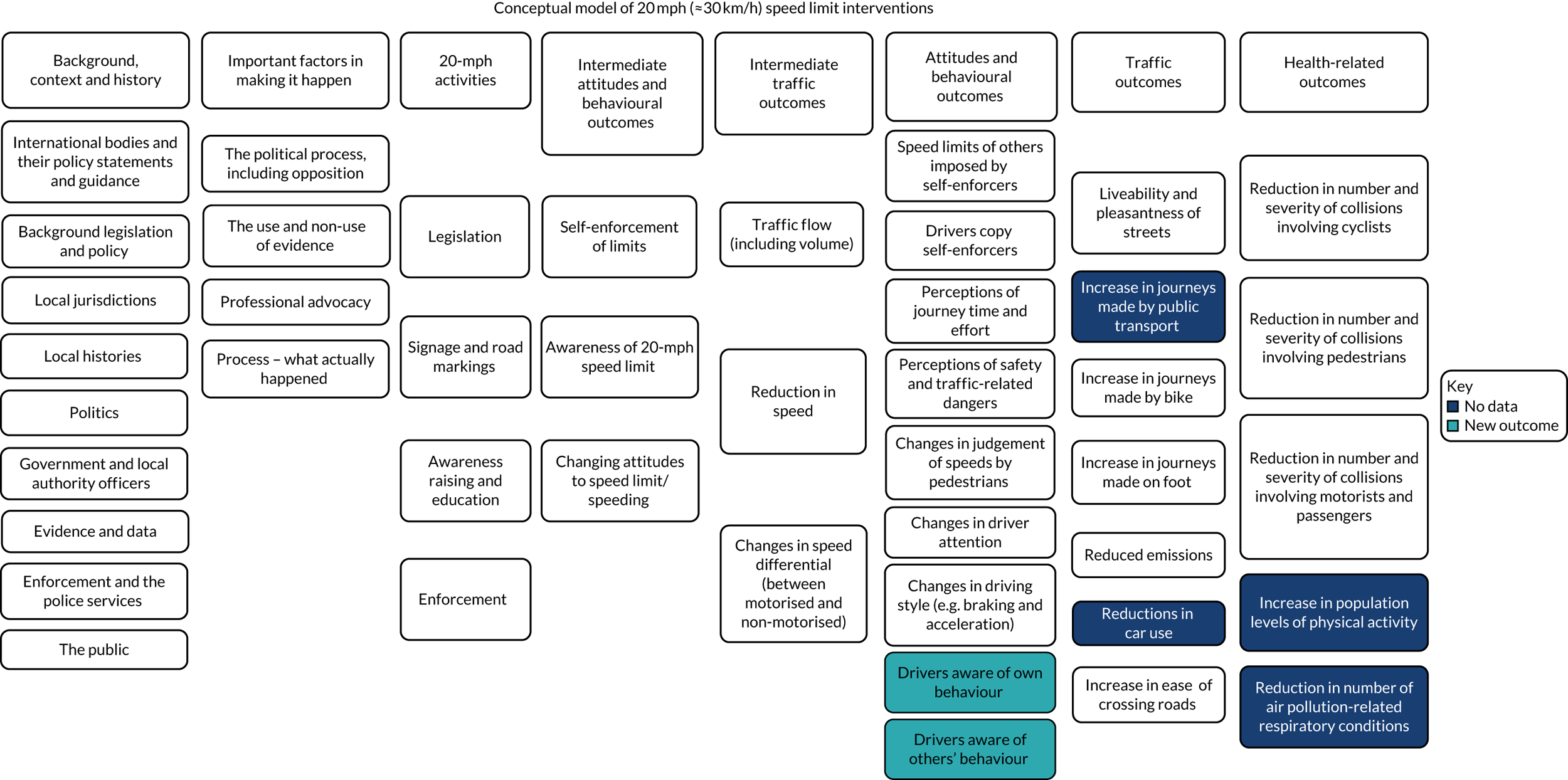

Figure 4 shows the programme theory we used in the application for funding.

FIGURE 4.

Second iteration of the programme theory. Reproduced with permission from Turner et al. 4 © 2018 The Authors. Published by Elsevier Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/BY-NC-ND/4.0/).

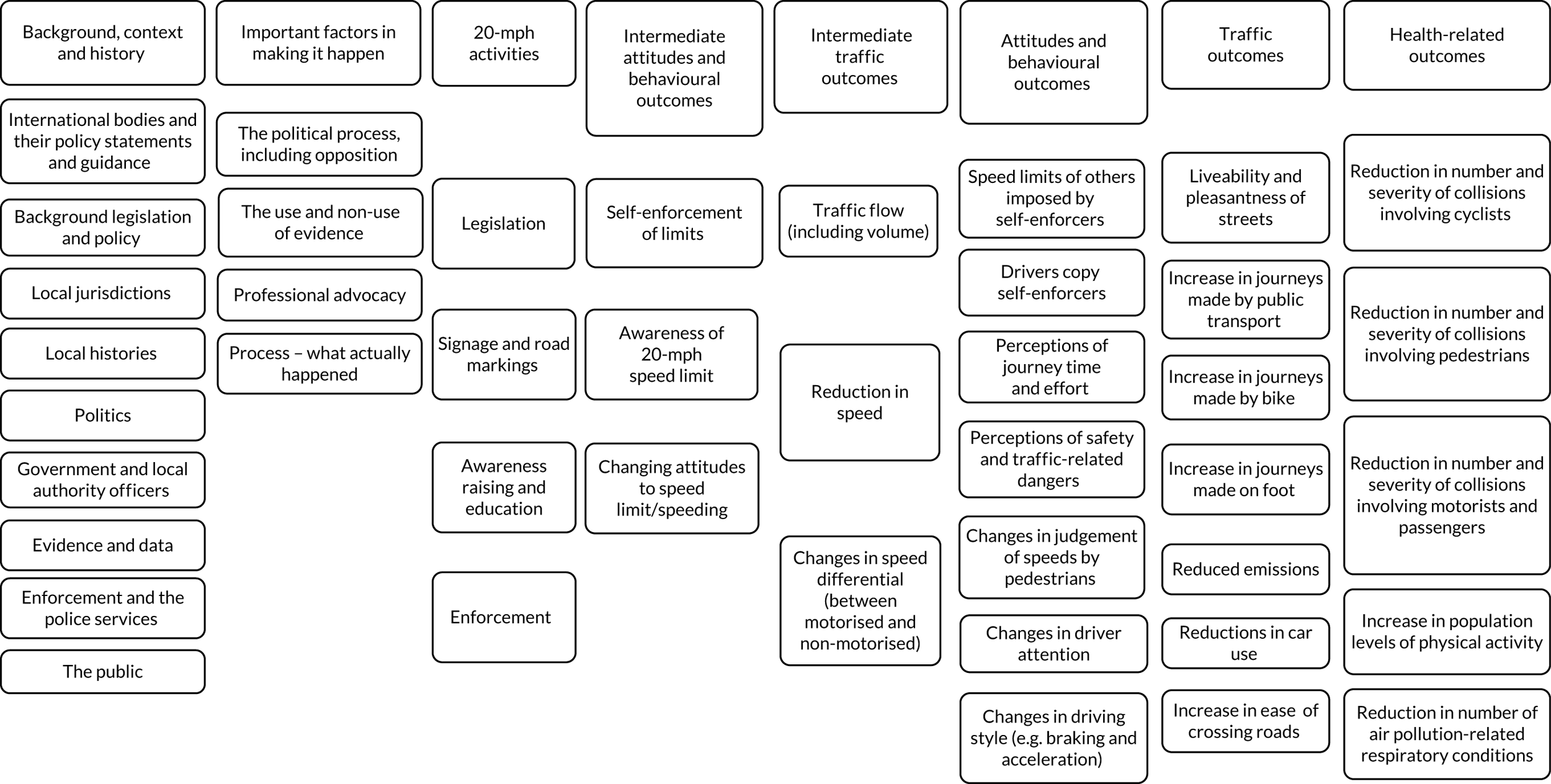

Third iteration of the programme theory

The research team undertook a qualitative study that involved engagement with a range of stakeholders, including the general public. 3 The inclusion of stakeholders in theory development is considered good practice. 52 In the third iteration, the previous (second) iteration was further informed and refined through two streams of activity: semistructured interviews with key stakeholders involved with, or who had a vested interest in, Edinburgh’s scheme, and focus groups and interviews with members of the general public covering a range of demographics. Data collected were used to help identify mechanisms of change explaining how intervention activities were proposed to lead to purported changes in health outcomes (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5.

Third iteration of the programme theory. AT, active travel; CEC, City of Edinburgh Council; DRDNI, Department for Regional Development Northern Ireland.

The programme theory outlined in this version demonstrates the complexity of the pathways (i.e. perceptions, behaviours) through which the reduced peak and average speed is purported to lead to more objective health-related outcomes such as active travel. Consequently, this study was designed to address not only the question of the effects, impacts and costs of the intervention, but also the question of how and why the intervention and effects/impacts occurred or did not occur.

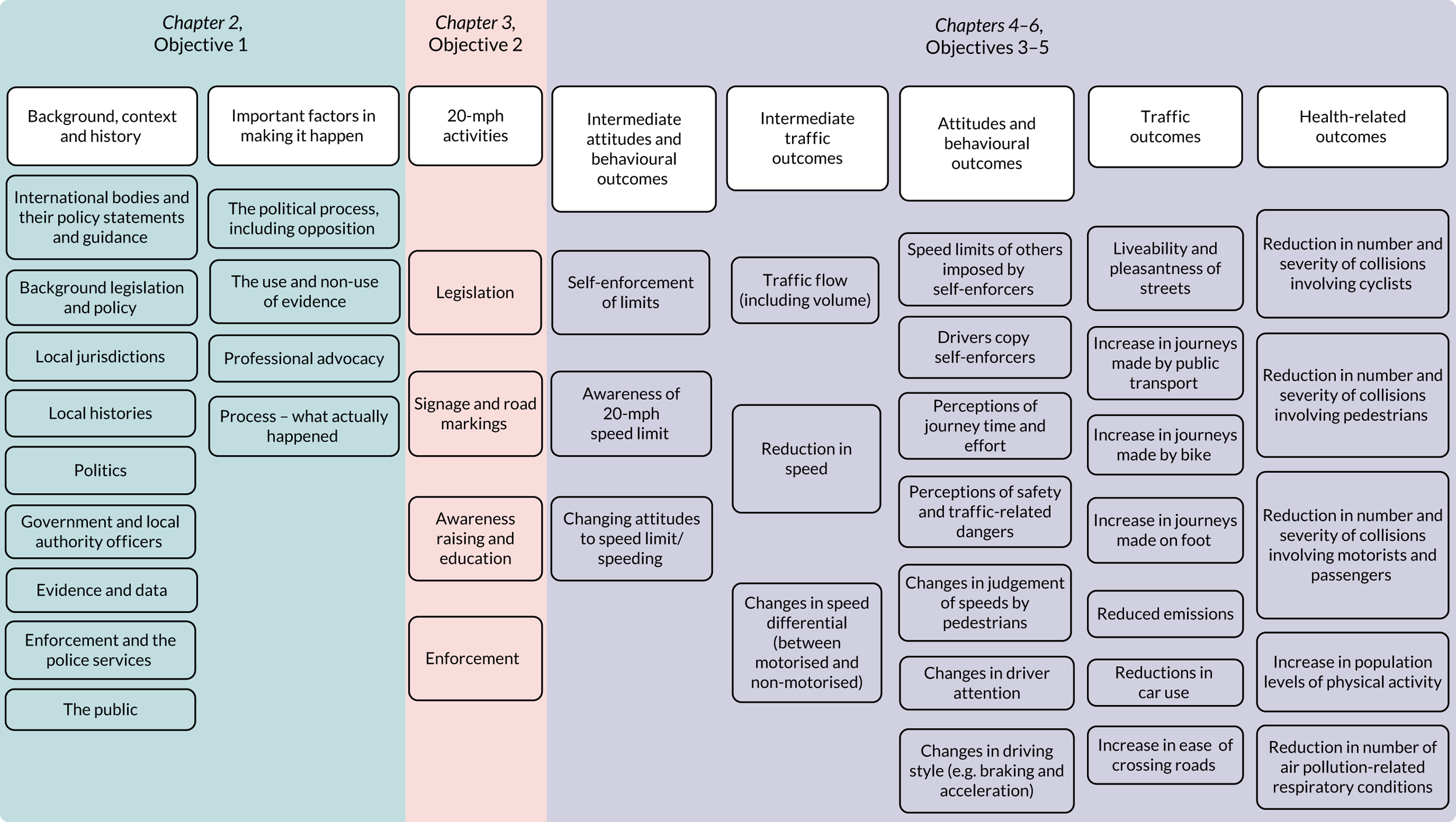

The fourth iteration (Figure 6) provided us with an outcomes framework, which we used to facilitate our appraisal of the various data sources to be used. We organised the outcomes into useful categories by theme and time. Once the data sources were appraised, the outcomes framework further helped us plan and conduct the analysis and reporting of some of the outcomes we observed.

FIGURE 6.

Fourth iteration of the programme theory.

The final project used a range of theoretical frameworks to assist in the interpretation of the results. These theories provide different ‘lenses’ through which to analyse the policy process, and provide a theoretically grounded underpinning to the analysis. A theory-based evaluation enables the use of a realist perspective to understand what worked, for whom, in what circumstances and why. 53 During the initial period of the grant development, we developed our programme theory further. However, as described in previous sections, this was a hypothesised model. We did not have any evidence to suggest that the intended inputs or activities would be available and/or implemented in the two cities, nor did we have evidence that the input, activities and implementation strategies would result in the desired change in outcomes. The process of developing this model was iterative, and involved important contributions from the Study Steering Committee (SSC) when we presented early drafts of the findings and our explanations. During the evaluation, other smaller side projects were undertaken to contribute to the evidence base, and to help answer some of the questions raised by the SSC; for example, a small-scale master’s dissertation looking at the impact on air pollution was undertaken, supervised by a member of the SSC (Dr Stefan Reis) (see Chapter 4, Air pollution).

At the end of the project, based on the findings from all work packages (WPs), our programme model was further refined to create our final model, as shown in Figure 7. A description of each box on the final model is included in Appendix 1.

FIGURE 7.

Final programme model.

Overall research aim and objectives

Aim

The overall aim of this research was to evaluate and understand the processes and effects of citywide 20-mph legislation in Edinburgh and Belfast. The focus was on health-related outcomes (active travel and casualties) and the pathways and processes that cause this transport policy to have public health benefits. Alongside this was research into the political, historical and policy factors (conditions) that led to the decision to implement the new speed limit, with a view to understanding possible transferability and national impact.

Objectives and research questions

The objectives and research questions were developed to link in broadly with the programme theory.

Objective 1

Objective 1 was to explore the decision-making processes that made 20-mph speed limits possible in Edinburgh and Belfast.

Objective 1 research questions:

-

What factors led to the rise of 20-mph limits on the political and policy agenda?

-

What processes hindered and enabled agreement to implement the 20-mph policy?

-

What are the likely facilitators of and barriers to long-term successful implementation of the 20-mph policy in these cities?

Objective 2

Objective 2 was to describe and understand the what and how of implementation (i.e. the implementation processes) of the two 20-mph speed limit interventions.

Objective 2 research questions:

-

How was the 20-mph speed limit intervention implemented in each city?

-

To what extent was the intervention delivered as intended in each city, and what adaptations were made to how the interventions were delivered?

-

What were the barriers to and enablers of implementation in the two cities?

Objective 3

Objective 3 was to assess the impact of introducing 20-mph speed limits (primarily signage) on a range of health outcomes.

Objective 3 research questions:

-

Does introducing 20-mph speed limits result in reductions in the speeds of motorised vehicles?

-

What is the impact on the number and type of road collisions?

-

What is the impact on participants’ perceptions of the safety and pleasantness of their home and work environments?

-

What is the impact on the number of people (journeys) cycling or walking to work or study?

Objective 4

Objective 4 was to investigate peoples’ experiences of, and interactions with, the multiple intervention activities, examining how and why behaviour change occurred or did not occur.

Objective 4 research questions:

-

How are the effects (or lack of effects) experienced by various population subgroups?

-

Do the qualitative and quantitative data support the causal pathways and mechanisms outlined in the programme theory?

-

Are there any unintended/unexpected pathways and consequences that need to be incorporated in the model?

Objective 5

Objective 5 was to carry out an economic evaluation of the 20-mph speed limit policies.

Objective 5 research questions:

-

How do the public health benefits compare with the costs (potentially including opportunity costs) of implementation?

-

What additional benefits or consequences are there that would make implementing 20-mph speed limits more or less cost-effective?

Objective 6

Objective 6 was to assess the transferability of 20-mph speed limit networks to other cities, towns or districts in the UK.

Objective 6 research question:

-

What is the potential for implementing the 20-mph speed limit in other parts of the UK?

Overall methods and approaches to the evaluation

This was a mixed-methods evaluation, comprising several studies that, between them, aimed to gather comprehensive data on the 20-mph interventions. The number and variety of individuals, groups and systems likely to be affected by the 20-mph limits, and the importance of their behaviour and the interactions between them, required an evaluation appropriate for the complexity of the intervention. 2 Guided by our programme theory, we undertook a pragmatic, theory-based, mixed-methods evaluation. It combined routinely and locally collected quantitative data with primary quantitative and qualitative data. No single study, or methodological approach, can provide answers to all the research questions related to the overall and differential impacts of the intervention. Similar mixed-methods approaches have been used in other transport-related natural experiments. 50,54 This research commenced in September 2017, approximately 14 months after implementation began in Edinburgh and 19 months after implementation in Belfast. The draft project report was submitted in March 2021. In summary, we used the following methods.

The outcome evaluation was a natural experiment, comprising before-and-after (controlled when possible) studies in Edinburgh and Belfast,55 using matched geographic control zones whenever possible. Natural experimental approaches are specifically advocated when ‘[i]t is possible to obtain the relevant data from an appropriate study population, comprising groups with different levels of exposure to the intervention’. 55 In Belfast and Edinburgh, a number of stakeholders were already collecting data; it is more efficient to make use of available data, supplementing when necessary, than to replicate costly data collection. We explored and took account of the biases that are known to affect observational methods, particularly before-and-after studies, using appropriate methods. 55 Specifically, the implementation of the interventions and the data that were collected were decided and controlled by the local jurisdictions and the difficulties (ethical and logistical) of maintaining a rigorous experimental study (such as a randomised controlled trial) across urban areas meant that observational and natural experimental methods were employed. 2

To understand the context and transferability, we used key informant interviews, documentary analysis and media analysis. These are described in more detail in the following sections.

The economic evaluation team used the DTA, using relevant knowledge, theory and data from empirical studies (observational and, if available, experimental) to form a view on:

-

whether or not the intervention is likely to cause harm

-

if not, whether or not, in the light of the (low) cost of an intervention, it is likely to be effective enough to be cost-effective, even if effect sizes do not reach conventional levels of statistical confidence.

A substantial part of this study was a process evaluation following the MRC guidance on process evaluations of complex interventions56 to provide lessons and recommendations that could be applied to other urban areas wanting to implement new speed limits for motorised vehicles.

Changes to the original protocol

Over the 3.5 years of the evaluation, we had to make some changes to the study protocol. The main change was the adjustment of our analyses of active travel. We had originally anticipated that the data that we received from the local jurisdictions and Sustrans would be suitable to be able to undertake longitudinal analyses and to measure the effects of the intervention on cycling and walking. However, this proved to be impossible for a number of reasons, linked to how, when and where the data were collected (see Chapter 4, Active travel). This affected not only the outcome evaluation, but also our ability to do an economic evaluation (see Chapter 6). This meant that the cost–utility analysis based on the relationship between changes in active travel and physical activity-related health improvements, with associated changes in length and quality of life, could not be estimated. In addition, emissions data were not available and the data gathered in the study suggested that perceptions of safety had not changed much following the introduction of 20-mph speed limits. In practice, the final analyses planned were not possible owing to changes in the role of the health economist co-leading the economic evaluation (NC). He is a government economist and was moved full time to COVID-19-related work.

Therefore, in the report, we present the findings from the analyses carried out to inform the progression decision, update these where we can with the data we have, reflect briefly on how these updated findings may affect the overall conclusions from the economic evaluation and give pointers to the further work that would be required to complete the planned analysis.

In our investigation of implementation (see Chapter 3), the original aim was to conduct interviews with 20 implementation agents: six in Belfast and 14 in Edinburgh. In Edinburgh, we originally intended to investigate implementation processes at both the citywide level (six interviews) and the local level, following implementation at each geographical phase (totalling eight interviews). Through the early interviews, it became apparent that there was less of a direct implementation role at the local level and the role of individuals/organisations previously identified as potential implementation agents was minimal. Therefore, no interviews took place at the local level; instead, we increased the number of interviews held with agents involved at the citywide level.

We had originally anticipated recruiting members of the general public to focus groups (see Chapter 5) via sampling based on responses to routinely collected quantitative surveys (e.g. the Edinburgh People Survey conducted by City of Edinburgh Council). However, only anonymised data sets were provided to the research team, meaning that this was not possible. We instead maximised the recruitment of participants via other means.

We had intended to evaluate the impact on health inequalities, but the data were not suitable. We had wanted to use rates by Index of Multiple Deprivation to investigate casualties by area of deprivation. We examined the multiple deprivation profiles of the implementation areas in Edinburgh and Belfast for the control site selection process. The difficulty was that these areas range in size from 11 to 170 Data zones or small areas, which are the geographic units at which the multiple deprivation measures are allocated. However, the distributions were mostly heavily skewed. Although we sampled the focus groups to reflect low-income areas, and people from different ethnicities, we found no data suggesting that there were differences in impact perceived by the different populations.

Finally, we had expected to conduct workshops to discuss the implementation and transferability of the intervention, but we were not able to because of the COVID-19 pandemic. We have, however, gained additional funding from the Wellcome Trust to undertake other forms of dissemination activities (see Chapter 7, Maximising the impact of the findings: dissemination).

The idea that complexity is paramount in public health and other policy arenas has gained widespread traction in recent years. 57–59 The MRC has published a series of guidelines over the years2,60 to help researchers manage the tricky issues that need to be grappled with when doing research on matters defined as complex. Various guidelines have been developed and the problems with doing evidence synthesis when complexity is involved are widely discussed (e.g. Noyes et al. 61). The current project sits firmly within the complexity arena: the actual intervention was multiplex, and variable things were done at different times, in different places, in different ways, in environments with varying histories, politics, organisations and personnel. The initial programme theory was the first opportunity to describe the complexities involved. Through subsequent iterations, we elaborated the theory to take account of local political and organisational dynamics and to identify some of the uncertainties involved. The interventions were not under the control of the researchers, and the fidelity of the individual components was pretty well impossible to assure. Although we framed our work in terms of being theory based, we have not overtheorised our work; instead, we have tried to disentangle the component parts of the activities in both cities and empirically get as much purchase as possible on what was going on. Our report reflects this approach, and, we hope, provides insights into the effectiveness of this type of intervention, as well as the difficulties in doing research in real-world settings and with the constraints described here.

Ethics arrangements and data management

This was a complex evaluation comprising several studies. Different types of data were being utilised, which required different levels of ethics approval. The study was conducted in line with MRC guidelines62 and the Economic and Social Research Council ethics framework. 63 Ethics approval was sought from the Moray House School of Education Ethics Committee, University of Edinburgh (see Chapters 3 and 4 for details). The committee has three levels of approval:

-

level one – study that includes only anonymised data (e.g. large data sets)

-

level two – study that includes primary data collection (qualitative and quantitative)

-

level three – study that includes primary data collection from vulnerable groups (e.g. children, those who do not have capacity to consent).

The evaluation required level one and level two, but not level three, approval. When there were minor changes in research instruments, further ethics committee advice was sought.

The evaluation utilised a mixture of routinely collected and primary data:

-

Routinely collected data – many of the data were collected by other parties (e.g. local councils and Sustrans) as part of routine monitoring and evaluation. We received data from these sources only after they had been fully anonymised.

-

Primary data – the main primary data collected by the evaluation team were qualitative and survey data. For these types of data, we sought informed consent to participate. All data will be held for 5 years on university password-protected computers. Paper documents such as consent forms were stored in locked filing cabinets.

Patient and public involvement

For a project such as this (evaluating a natural experiment/an intervention that we were not delivering), our approach to patient and public involvement was about engaging the public and various public bodies. Considerable impetus for getting the 20-mph limit to the stage of implementation in Edinburgh and Belfast originally came from public opinion and public interest groups such as Sustrans and Living Streets. Both organisations worked closely with the team as the original research proposal was developed. They were particularly helpful concerning the collection of process and outcomes data. Sustrans also partly funded the intervention in Edinburgh and a senior member of Sustrans was a co-applicant on the grant. Sustrans has significant experience in collecting data on active travel and collected many of the data in Edinburgh and Belfast. Living Streets also advised on data collection methods for the liveability assessments. Both organisations were represented on the SSC and were involved in dissemination.

We conducted qualitative work (focus groups and interviews) with members of the public, which informed the development of the original research proposal and objectives. The data collected from this work allowed us to produce the original programme theory that framed what (and how) we evaluated in the project, an example being the development of questions for the perceptions survey. This qualitative work involved 37 members of the public from various professions and public groups: teachers, NHS workers, young professionals, older adults, school parent councils, students and residents. Stakeholders were also involved with the evaluation strategy and the planning and design of the research. We conducted 17 stakeholder interviews from a broad range of public service organisations: the council, charitable organisations (Sustrans, Living Streets), public transport companies (bus and taxi), driver groups (Institute for Advanced Motorists, Motorcycle Action Group), the local health board, Transport Scotland and the Scottish Fire and Rescue Service.

The SSC had representatives from public transport (Lothian Buses); driver groups (Institute for Advanced Motorists); charitable organisations (Living Streets, Sustrans, Belfast Healthy Cities); the local health board; Transport Scotland; the Department for Infrastructure, Northern Ireland; Police Scotland; and the City of Edinburgh Council.

During the project we engaged with 29 stakeholders from a broad range of public service organisations [the council, charitable organisations (Sustrans), the local health board, government agencies (Transport Scotland; Department for Infrastructure, Northern Ireland), police], 159 members of the public (across 24 focus groups in the two cities), the parents of young/school-aged children, older adults, pedestrians, cyclists, motorised transport users, young drivers, residents/community councillors, public transport companies (bus and taxi) and driver groups (Institute for Advanced Motorists, advanced motorcyclists).

Other groups, such as Belfast Healthy Cities; the Department for Infrastructure, Northern Ireland; the Police Service of Northern Ireland; Belfast City Council; and the City of Edinburgh Council 20-mph implementation team, also sat on the SSC and assisted with providing access to data and with dissemination.

Structure of the report

Rather than have a single methods section followed by results, each of the consequent chapters focuses on a different research objective (Table 3) that relates to our initial programme theory. We undertook the work in different WPs.

| Research objectives and related WPs | Summary of methods and approach | Chapter in report |

|---|---|---|

| To study the factors that led to the eventual implementation of the schemes (pre implementation), including the historical and political contexts in both cities. WPs 2 and 3 |

|

Chapter 2 |

| To understand barriers to and facilitators of successful implementation in Edinburgh and Belfast. WPs 2 and 3 | Stakeholder interviews | Chapter 2, Chapter 3 |

| To assess the impact of introducing 20-mph speed limits (primarily signage) on a range of health outcomes. WP1 | Before-and-after (controlled when possible) studies in Edinburgh and Belfast | Chapter 4 |

| To explore and refine the causal pathways and mechanisms in the conceptual model. WP2 |

|

Chapter 2 , Chapter 5 |

| To carry out an economic evaluation of the 20-mph speed limit policies. WP4 | Cost–utility analysis supplemented with partial cost–benefit and cost–consequences analyses | Chapter 6 |

| To assess the transferability of 20-mph speed limit networks to other cities, towns or districts in the UK | Key informant interviews | Chapter 1 , Chapter 7 |

Each of these chapters focuses on explaining and/or evidencing the programme theory, which continued to evolve during the evaluation period. The final programme theory is described step by step in the next chapters. Each chapter focuses on specific objectives and sections of the programme theory, highlighting where effects were found or not found (Figure 8).

FIGURE 8.

Programme theory and relationship to chapters and objectives.

Chapter 2 How did 20 mph become a reality in Edinburgh and Belfast?

Introduction

Given that most public health interventions are implemented in complex systems, we explored and explained the political, historical, policy and cultural factors involved in implementation in both sites. As both Northern Ireland and Scotland have legislative powers for transport, this part of the evaluation provides useful learning across jurisdictions and may help inform transferability UK wide and development of implementation guidance.

Objective and research questions

The objective was to explore the processes that led to the development and implementation of 20-mph speed limit policies in Edinburgh and Belfast.

The research questions were as follows:

-

What factors led to the recent rise of 20-mph limits on the political/policy agenda in the UK?

-

What processes hindered and enabled agreement and implementation of the 20-mph policy in different cities?

-

What are likely to be the facilitators of and barriers to long-term successful implementation of the 20-mph policy in the two cities?

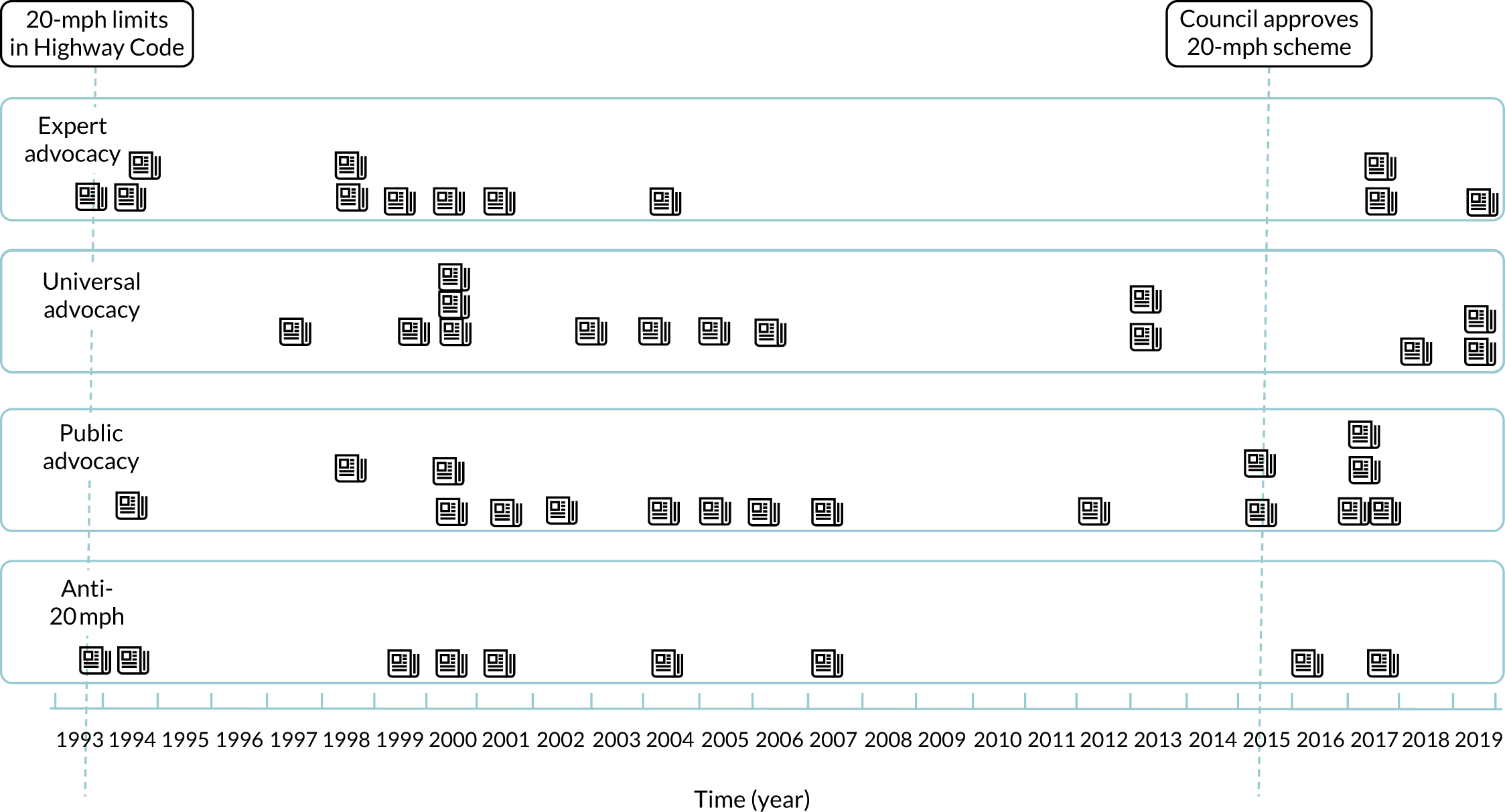

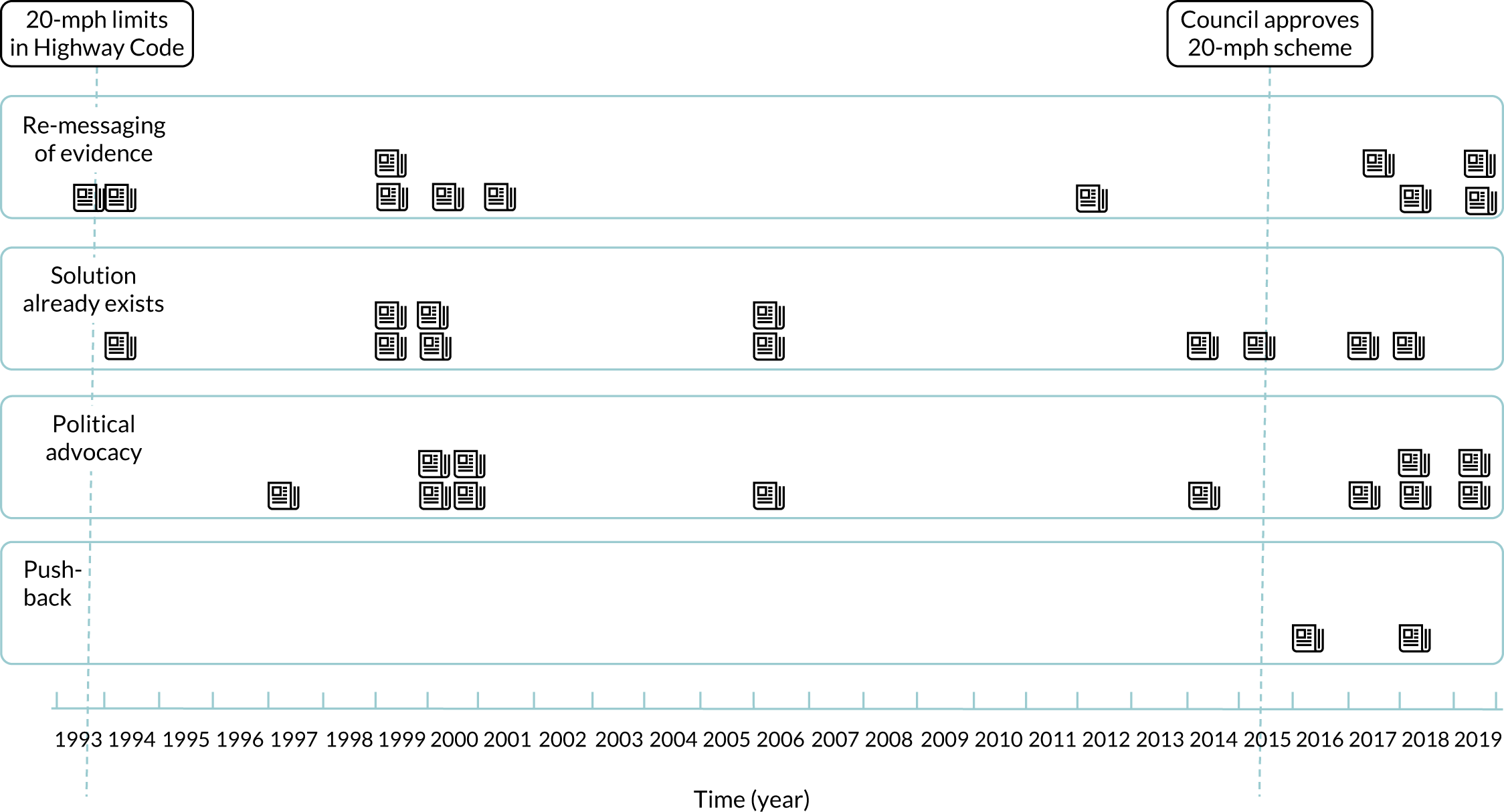

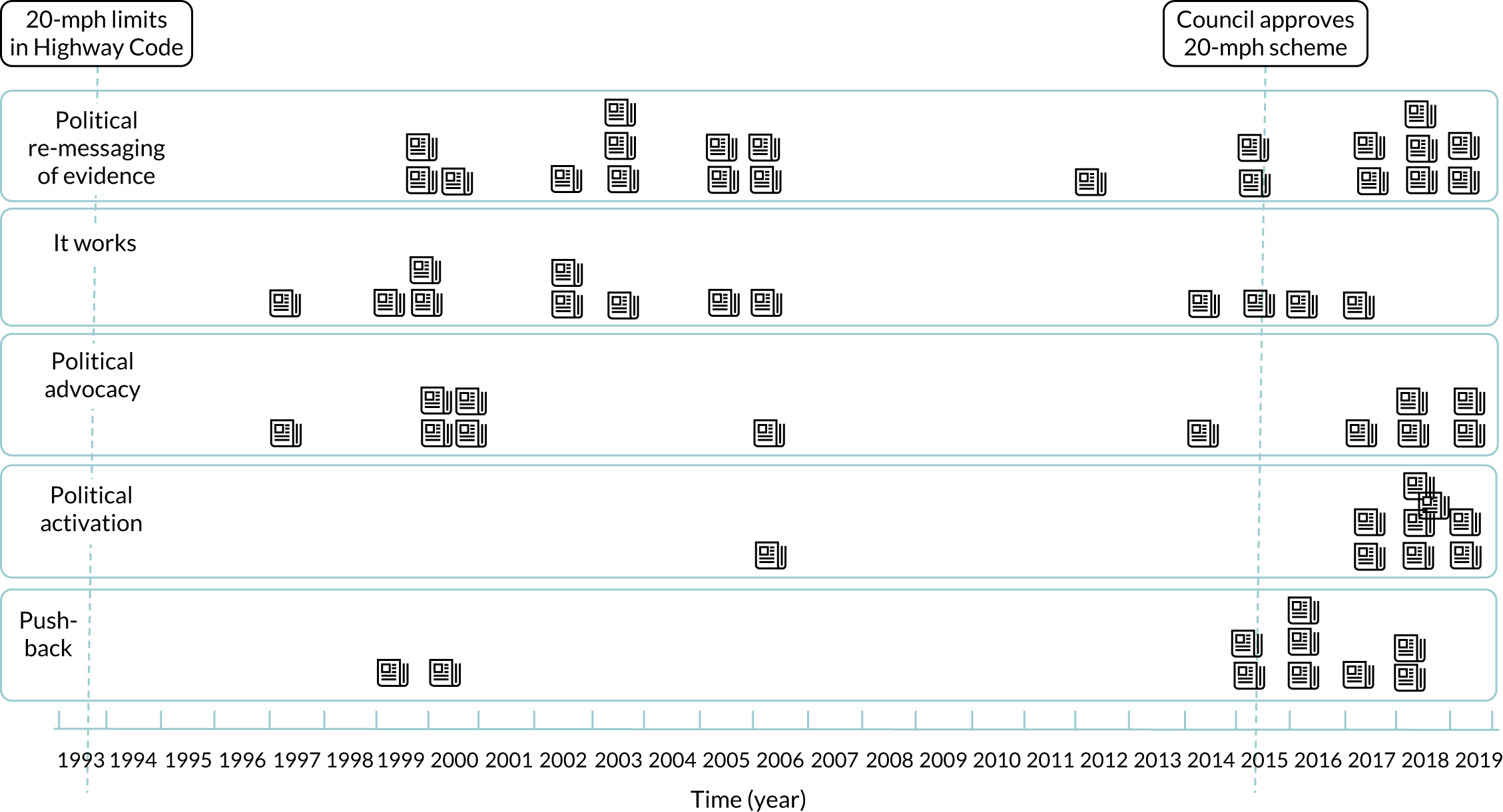

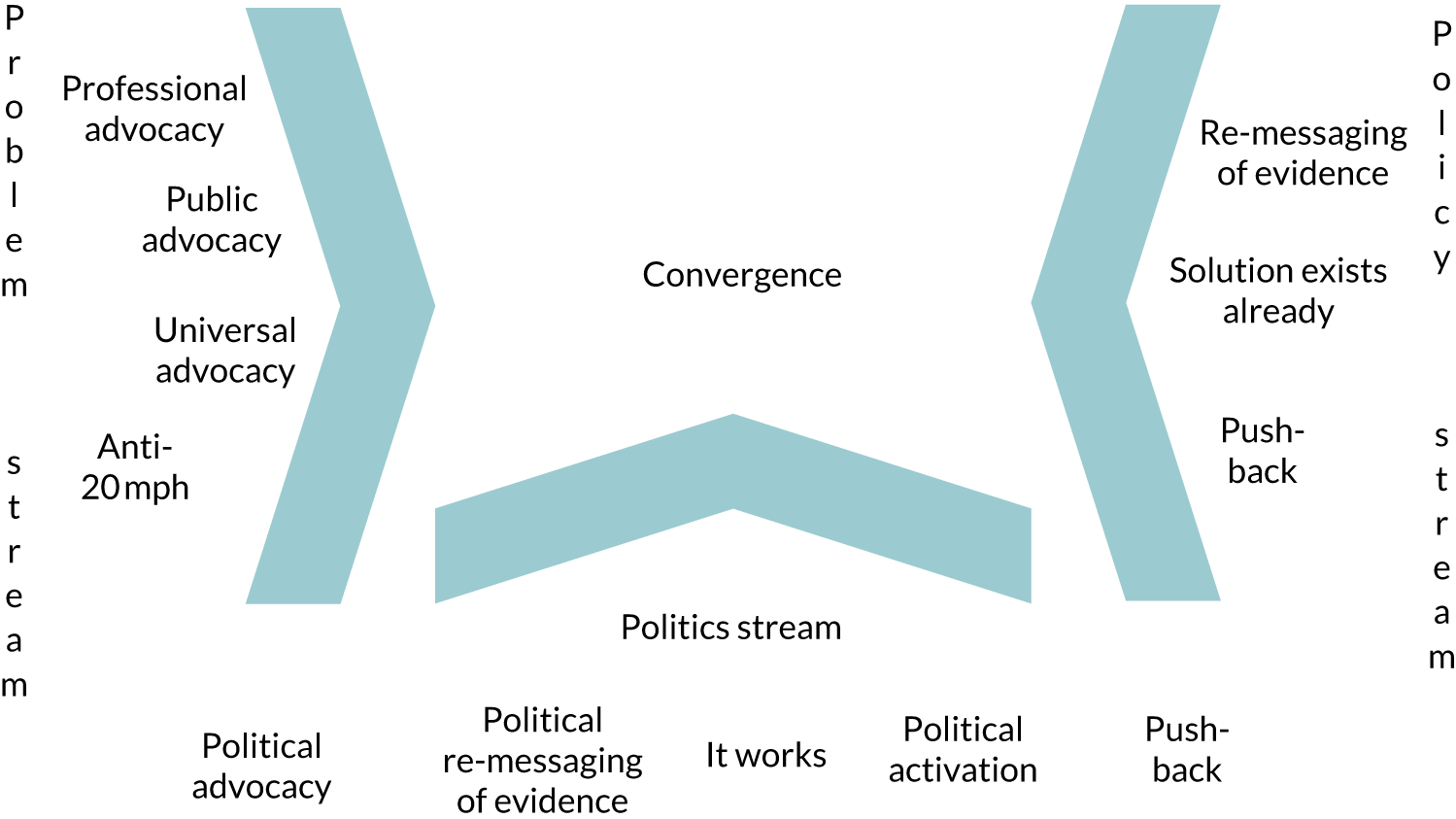

This chapter focuses on the first two columns (‘background, context and history’, and ‘important factors in making it happen’) of the explanatory model outlined in Figure 7. We explored the processes involved in 20 mph becoming a political reality in the two cities using three data collection methods: (1) document analysis, (2) stakeholder interviews and (3) print media analysis. The methods and analysis and results of the documentary analysis and stakeholder interviews are reported in Documentary analysis and stakeholder interviews, with Print media methods and analysis focusing on the methods and analysis of the print media.

Documentary analysis and stakeholder interviews

Documentary analysis

We conducted searches of key websites to identify documents relevant to 20-mph speed limits, including UK-wide developments, as well as national and local activity. We were interested in identifying any legislation, policy documents, research reports and official statistics, as well as other written records of events including political speeches, official announcements, committee reports and debates. The websites searched included those of the national governments (Scotland and Northern Ireland) and the City of Edinburgh Council. We did not look for local council documents in Belfast as the scheme was led and managed by the government of Northern Ireland (through the Department for Regional Development, which is now the Department for Infrastructure).

We compiled a timeline of the publication of relevant documents for each of the two cities. These were shared with a range of stakeholders in each city to confirm their comprehensiveness. Any additional documents that were identified by the stakeholders were added to the list. Each interviewee (see Stakeholder interviews for details) was also asked to verify the completeness of the list. In total we identified 19 documents for Edinburgh, published between 2000 and 2016, and 20 documents for Belfast, published between 2001 and 2016. These documents consisted of policy statements, reports of council decisions and reports of responses to public consultations. We obtained a copy of all documents and conducted thematic content analysis using NVivo 12 software (QSR International, Warrington, UK). An inductive approach was used, whereby no themes were proposed a priori. Documents relevant to Edinburgh and Belfast were analysed separately. Data were extracted independently by two members of the research team (KM and MPK), and the final coding framework for each city was agreed through discussion.

Stakeholder interviews

Interviews were conducted with 16 stakeholders: eight in Edinburgh and eight in Belfast. These were the same stakeholders as discussed in Chapter 3, Stakeholder interviews (more details of the methods can be found there). The Edinburgh-based participants consisted of council officers (n = 2), elected members of the council (n = 3), Sustrans officers (n = 2) and a civil servant. In Belfast, seven interviews took place with eight interviewees including representatives from government departments (n = 6), the Police Service of Northern Ireland (n = 2), a public transport organisation (n = 1) and a third-sector organisation (n = 1). Interviewees could represent more than one department. Interviews took place in November 2017: 25 months after the legislation went live, and 22 months after the signage was implemented. An additional interview (interview 8) took place with two representatives from the Department for Infrastructure (responsible for implementing the intervention) in March 2019 (38 months post implementation of signage) following completion of the initial ‘3-year pilot’ phase.

Briefly, a semistructured interview guide was used to discuss topics such as involvement in the scheme, the main drivers for getting it onto the policy agenda, barriers to and facilitators of moving it forward and key individuals or groups. The audio files were transcribed verbatim and uploaded to NVivo 12 for analysis. As with the document analysis, the analysis of the interviews was approached inductively using thematic content analysis and conducted separately for each city. Data were independently coded by two members of the research team (KM and MPK), and the final coding framework for each city was agreed through discussion. The findings from the documents and interviews for each city were triangulated to provide a more complete picture of the political processes and events in each city.

Results from the document analysis and interviews

The findings from the documents and interviews from the two cities are presented together under 11 key themes that emerged from the analysis (Table 4).

| Theme | Brief description |

|---|---|

| The political context of the two cities | Local and national government responsibilities for 20-mph speed limits |

| Agenda-setting and key policy drivers | How 20 mph reached the policy agenda |

| Leadership for 20 mph | Importance of leadership |

| The gradualist political–bureaucratic process | How 20 mph moved up the policy agenda |

| The role of evidence | How scientific evidence affected decision-making |

| Facilitators of and influences on momentum | How momentum was maintained |

| Support for 20 mph | Levels of support for 20-mph speed limits |

| Opposition to 20-mph speed limits | The main opposition groups |

| The role of ‘pilot’ schemes | How pilot schemes influence decision-making |

| Implementation | Factors involved in implementation decisions |

| Sustainability | Factors influencing sustainability |

The political context of the two cities

Although the Scottish Government sets policies and targets for the design of streets, road safety and other related issues, responsibility for implementation of these policies lies with local authorities. In 2014 the Scottish Government published its Good Practice Guide for 20 mph Speed Restrictions;64 however it was left to local authorities to set appropriate speed limits on local roads to meet local circumstances. According to interviewees from Edinburgh, the Scottish Government officials in transport were passively supportive of Edinburgh taking 20-mph speed limits forward, but they remained distant from implementation of the scheme.

In contrast, Northern Ireland operates differently to the rest of the UK, in that decision-making about traffic regulation takes place centrally by the devolved government. The Department for Infrastructure is responsible for all aspects of the road network, including speed limits, bus lanes and changes to infrastructure. The local authority plays no role in decision-making nor implementation of speed limits or other traffic regulation measures.

Agenda-setting

In relation to the 20-mph initiatives, there was a long process in both cities, with many years of thinking, planning and discussion. In Edinburgh this began in 2000 when the council adopted its first Local Transport Strategy, which included the installation of 20-mph ‘zones’ in residential areas, outside schools, and in shopping areas, as one measure to ‘eliminate deaths on the City’s roads’. 65 In Belfast, discussions began about the same time, with the publication of New Directions in Speed Management,66 which set out the evidence from speed-related research in the UK and concluded that a framework was needed in Northern Ireland for determining speeds on all roads with limits that were rational, consistent, readily understood and appropriate for the circumstances.

A key driver for 20-mph speed limits in both cities was road safety, particularly near schools, and both cities initially introduced full-time or part-time 20-mph schemes close to schools. Road safety seems to have been a key driver for scaled-up action beyond schools, although this was not explicit in Belfast and there was no apparent problem with safety or collisions in the city centre. There was, however, significant regeneration taking place across the city to create a more welcoming environment, particularly for tourists, and it was intended that 20-mph speed limits would contribute to this through reductions in traffic in the city centre. Increasing walking and cycling levels was also a driver in both cities, although it was noted, particularly among stakeholders in Belfast, that there was limited empirical evidence to support the notion that reducing speed limits would increase the number of people walking and cycling.

Leadership for 20 mph

There was political leadership for 20 mph in Edinburgh from the Scottish Labour Party councillor, and then convener of Edinburgh’s Transport, Infrastructure and Environment Committee, Lesley Hinds, and broad political buy-in across the Scottish National Party and Scottish Labour administrations. There was not a clear political divide in terms of support and opposition, but key individuals across parties and other stakeholder groups were in support of the initiative:

There wasn’t widespread party-political support. It was much more about individuals in different political parties, council officers in the active travel and activists within the local community not necessarily aligned with any party, just community council activists and other community groups, schools, parents, boards and stuff like that that were pushing for this.

Elected member

The Scottish Conservatives did not see it as one of their priority areas but did not express strong opposition. Community councils showed active support and were considered to have been critical in giving the politicians sufficient ‘weight’ to drive the initiative forward:

I don’t think politically there was the strength of feeling to drive this forward without the active participation, the active support of the community councils . . . I don’t think it would have been possible to get it through. In fact, I’m sure it wouldn’t have been possible to get it through the committee if there hadn’t been active support from the community councils that were affected . . . It was the community support for this that made it possible.

Elected member

In Belfast there were key politicians who were important in moving the idea forward. One Social Democratic and Labour Party member introduced a private member’s bill:

Conall McDevitt’s private member’s bill, which was 2012 when he first introduced that to the Northern Ireland assembly, and that was the Road Traffic (Speed Limits) Bill and that was to make the 20 mph the default speed limit on residential roads across Northern Ireland.

Translink

The bill took some time to go through the legislative process and eventually fell owing to the cost of signage to implement it. As a way to reduce costs it was suggested that 20mph should be made the default limit, meaning only a few remaining 30mph would need to have signs, but it seems there was insufficient support for 20mph and cost continued to be cited as a barrier to their implementation.

As with Edinburgh there was not a clear party-political divide between those who supported 20-mph speed limits and those who did not; rather, across all parties, there were individuals who were for and individuals against. In Belfast, all parties were supportive of the intended outcomes – safer streets and more walking and cycling – but there were mixed views on whether 20-mph speed limits was the best intervention for achieving those outcomes.

The gradualist political–bureaucratic process

In both cities the approach was gradualist, with a range of reasons to implement 20-mph speed limits building over time, creating a progressive move towards gaining support and, ultimately, the scheme being implemented. In both cities, discussions about 20-mph speed limits started to emerge around the year 2000; however, clear decisions to implement, subject to public and stakeholder consultations, did not happen till 14 or 15 years later. Neither city had major landmark events that caused a radical shift in policy. Rather ‘baby steps’ were taken to nudge closer and closer to the idea and the eventual reality over a sustained period of time, such that what eventually unfolded was seemingly inevitable.

Over the long lead-in time, the narrative shifted from a specific intent to reduce collisions and casualties to 20-mph speed limits contributing to a wider range of aspirations. This was particularly the case for Edinburgh. For example, in the 2011 report on the consultation on the 20-mph South Edinburgh pilot proposal, the council argued that its approach would contribute to living longer, healthier lives, free from crime and disorder, in well-designed, sustainable places with access to amenities and services, where it is possible to value and enjoy the built and natural environments, protect and enhance them for future generations and reduce the local and global impact of consumption and production. 67 The subsequent Local Transport Strategy, published in 2014, emphasised the contribution of speed restrictions to enhancing ‘the Council’s reputation for excellence, inclusivity and responsiveness to Edinburgh’s communities’. 68 In Belfast, the narrative was less aspirational, although the proclaimed benefits of 20-mph speed limits also broadened over time. For example, 20 mph was linked to overcoming social exclusion and strengthening rural communities, as well as aiding wider economic and environmental objectives.

The role of evidence

In Edinburgh there were references to evidence throughout the various documents. In 2010, the City of Edinburgh Council explored the relationship between speed and risk. The evidence was interpreted to mean that risk increases slowly until impact speeds of around 30 mph. They noted that even though the risk of pedestrians being killed at 30 mph is relatively low, approximately half of pedestrian fatalities occur at or below this impact speed. The council argued that vehicle speed was the single most important factor in the severity of road collisions, with the risk of fatal injury to pedestrians being more than eight times higher at 30 mph than at 20 mph. They noted that the chance of survival halves again between speeds of 30 mph and 40 mph. They also observed that streets with slower traffic are more attractive to residents, pedestrians, cyclists and children, and can improve the environment for business and social interaction. They argued that cars travelling at 20 mph generate less noise. An emphasis was put on the fact that a high proportion of pedestrian and cyclist casualties occur on the busiest streets in the inner areas of the city. In many of these streets, average speeds were already fairly low, but a 20-mph limit had potential to help rebalance them in favour of pedestrians and cyclists. Although evidence on speed and risk was referenced in Edinburgh, there was little mention of any evidence on the effectiveness of 20-mph speed limits. There seemed to be an assumption that 20 mph ‘works’ despite very little reference to any empirical evidence.

In Belfast, a range of evidence was presented to support the 20-mph initiative from 2010. A 1996 document on setting local speed limits presented a range of data. 69 It argued that 20-mph zones are very effective at reducing collisions and injuries. It noted that 20-mph speed limits may reduce overall average annual collision frequency by around 60%, and the number of collisions involving injury to children may be reduced by up to two-thirds. Twenty-miles-per-hour zones, it observed, help reduce traffic flow, where research has shown a reduction in injuries by over one-quarter as well as a modal shift towards more walking and cycling. 69 The authors pointed out that signed-only 20-mph speed limits generally led to only small reductions in traffic speeds, and that therefore 20-mph speed limits are most appropriate for areas where vehicle speeds are already low. 69

The same document pointed out that there was clear evidence of the impact of reducing traffic speeds on reducing collisions and casualties, as collision frequency is lower at lower speeds, and when crashes do occur, there is a lower risk of fatal injury at lower speeds. It noted that, on urban roads with low average traffic speeds, any 1-mph reduction in average speed can reduce the collision frequency by around 6%. 69 It suggested that there may also be environmental benefits, as, generally, driving more slowly at a steady pace will save fuel and carbon dioxide emissions, unless an unnecessarily low gear is used. Later documents made reference to the economic benefit of preventing collisions and casualties. For example, a document published in 2014 stated that the average value of preventing a collision is approximately £72,700. 70

Facilitators of and influences on momentum

Lower speed limits were seemingly consistently viewed as a good idea by City of Edinburgh Council. Scottish Government guidance at the time of the South Edinburgh pilot was that 20-mph interventions had to involve physical traffic-calming infrastructure, but the Scottish Government allowed the South Edinburgh pilot to go ahead as a trial of a ‘signs-only’ approach. Following the pilot, the Scottish Government relaxed its guidance on 20 mph such that 20-mph ‘zones’ with physical infrastructure were no longer necessary and ‘limits’ using only signs was an option. This meant that citywide implementation would be more feasible and would cost substantially less. This seems to have been the most significant factor in the council increasing momentum for large-scale roll-out.

Subsequently, NICE recommended the introduction of 20-mph speed limits without physical measures to avoid unnecessary accelerations and decelerations in a bid to promote smooth driving and speed reduction and to improve air quality. 71 Then Northern Ireland’s Road Safety Strategy to 202072 outlined a commitment for Transport Northern Ireland to pilot a number of 20-mph speed limits without additional self-enforcing engineering measures, the most substantial of which became the Belfast city-centre intervention.

Support for 20-mph speed limits

The public were supportive of 20-mph speed limits in Edinburgh, and this support was thought to stem from accident statistics and concerns about road safety:

But also because there was demand from the local residential groups who wanted to bring 20 miles an hour in. So, we would continually be getting letters and deputations, etc. to bring it in.

Elected member

Other lobbying groups were equally important, including Sustrans, Living Streets and cycling organisations:

I think the most coherent lobby in favour, I would say, was the cycling lobby. Yeah, there was, I mean, Living Streets were also in there in favour, but the strongest and most coherent component was the cycle lobby.

Council officer

Views among the public were mixed in Belfast. Although there was relatively wide support for limits in residential areas and near schools, the city-centre scheme elicited mixed reactions. Those who expressed objections had concerns over traffic flow and the potential economic impact. There were also concerns that 20 mph may conflict with other government commitments to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and improve air quality. If speed restriction measures were to be put in place, drivers favoured the signs-only approach over the physical traffic-calming measures owing to the ‘wear and tear’ on cars caused by physical infrastructure. Some people felt, however, that the physical infrastructure was necessary to change behaviour. Physical infrastructure was felt to be inappropriate in rural areas because it presents challenges for modern agricultural and heavy goods vehicles. Lobby groups were also perceived to play a significant role in Belfast:

. . . it was probably pressure from the Twenty’s Plenty lobby groups and the people who thought this is the answer to our . . . be it antisocial driving or be it . . . this is something that would help our quality of life, and there was the 20 mph, that lobby group are powerful, they know how to get their message out there and so on . . . it’s hard to resist if you haven’t got empirical evidence that demonstrates your argument is flawed. So you’ve got to try it and you’ve got to give it a go.

Police Service of Northern Ireland

Opposition to 20-mph speed limits

In Edinburgh, the main opposition to 20-mph speed limits came from bus operators and taxi drivers, although opposition was also expressed in the local evening newspaper and by the Institute of Advanced Motorists. Bus operators were worried about the impact of 20-mph speed limits on their operations. The council responded to these concerns with assurances that research in other cities had shown that journey times would not significantly increase, and that by easing traffic flow during busy periods, 20 mph may actually reduce some journey times. The council agreed to work with the bus operators to ensure that remaining uncertainties regarding impact on the bus network could be satisfied, or that solutions could be developed to mitigate any impact. 68

According to one of the interviewees:

The thing that changed for Lothian Buses was they installed Wi-Fi on the buses after they were consulted on the pilot in South Edinburgh. That gave them the opportunity to monitor in real time how fast the buses were going and where they were on the route. When they modelled that based on real information, they found that the cumulative effect of all buses going through the total area of the pilot area, was 30 seconds, that was the impact on their selves.

Elected member

Taxi drivers proved the hardest group to convince and were described as the ‘last man standing in terms of opponents’ (elected member). Even after implementation of the intervention, taxi drivers felt that the speed limit should not apply to them as they drive according to ‘common sense’.

In terms of stakeholder groups in Belfast, the main opposition was from the Federation of Small Businesses in the Belfast Chamber of Trade and Commerce, which was concerned that the scheme would slow down business. This included pizza deliveries being delayed because the city would be ‘grinding to a halt’, but also people being deterred from coming into the city, thereby causing a reduction in footfall for local businesses.

In both cities the police expressed concerns. Because the intervention would consist of signs only, without traffic-calming measures, extra police enforcement would be needed and the police in both cities expressed concern over the additional burden this would place on their workload. Civil servants were of the opinion that enforcing 20-mph speed limits should not be a police priority:

There’s a bigger question, really. If police resources are stretched, is that really the best use of police resources? If people aren’t being killed or seriously injured because somebody goes 5 miles over a 20-mph speed limit . . . I think you have to put it into context, and to have police sitting around Belfast city centre just trying to catch people breaking the speed limit doesn’t seem to be great use of their time.

Civil servant

The role of ‘pilot’ schemes

As part of the gradualist approach in Edinburgh, and to ‘test the water’, the council decided to implement a pilot 20-mph scheme in South Edinburgh. The south of Edinburgh was purposefully selected as the pilot site owing to the demographic mix in the area (students, young families, cyclists) and local activism for safer streets. The pilot scheme was launched on 23 March 2012. The evaluation report33 drew on information from elsewhere in the UK (Portsmouth, Oxford, Bristol, Warrington, Islington, Hackney, Norwich and Birmingham). The way this information (not evidence) was presented in the report was that, in some of the towns, such a scheme had been introduced successfully; it was not stated that it worked, although the assumption clearly is that it had.

Evidence on the impact of the pilot on a range of outcomes was equivocal. Four locations across the pilot saw slight increases in average vehicle speeds from the ‘before’ to the ‘after’ survey; four locations continued to have average speeds of ≥ 24 mph; and there was an overall increase in the number of vehicles on most (34 from the 48 locations measured) 20-mph and 30-mph streets from the ‘before’ to the ‘after’ period, although in no location was this deemed ‘notable’. 33 However, the pilot was reported to have had a significant positive impact on attitudes towards 20 mph:

The figures were startling, because the pilot was in Edinburgh south, when we asked people initially, ‘do you support it?’, two-thirds said no. The numbers for cycling, walking, playing outside for kids and all that kind of stuff was quite low. When we asked people after the pilot, ‘do you support it?’, the figures completely inversed. So, when people were living with it, support just skyrocketed and opposition just crumbled. So, it was then about two-thirds support and one-third opposition. The stats on ‘would you let your kid cycle to school? Would you let your kid play outside unattended?’, were much higher . . .

Elected member

In reporting the attitudes of residents, the main benefits of the pilot, as viewed by residents, were (in priority order): safety for children walking about the area, safety for children to play in the street, better conditions for walking, fewer traffic incidents and better cycling conditions. 67 The report concluded that there had been a net increase in levels of walking and cycling during the pilot, levels of car use during the pilot reduced overall and there had been a general fall in overall speed. 33

Belfast had not conducted a pilot, but the city-centre scheme was itself viewed as a pilot. There was an intention to implement the scheme on a ‘trial basis’ and determine the impact. This would inform decisions on whether or not to implement similar initiatives in other cities and towns. Although the Belfast scheme was termed a ‘pilot’ that would run on a ‘trial basis’, there was no explicit intent to restore the streets to their former 30-mph limits if the impact of the intervention was found to be non-significant.

Implementation

At the time that the decision was made to roll out 20-mph speed limits citywide, parts of Edinburgh had already had 20-mph limits for a number of years; this was thought to have helped, in that 20 mph was already starting to feel like ‘the norm’. The scheme in Edinburgh was rolled out in stages. Phasing it in area by area had many advantages in terms of staff capacity for putting up signage and ensuring that only sections of the transport network were disrupted at one time. Interviewees reported that some council officers felt under pressure to ensure that gridlock was not caused in the city, as this would have had a negative impact on support for the initiative. Implementation was done in six phases over 2 years, allowing 16 weeks for each phase. The localities that had the greatest number of road collisions and the highest levels of pedestrian and cycling activity would be phased in earliest. This plan was itself subject to consultation in individual areas.

At the time of implementation in Belfast, there were no permanent 20-mph limits in Northern Ireland. The area to be covered by the 20-mph scheme in Belfast was the city centre, and thus was a much smaller geographical area than the Edinburgh scheme. A decision was made to introduce the change across the whole city centre on a specific date; therefore, implementation happened ‘overnight’ across the whole area.

Sustainability

Once the 20-mph scheme was in place in Edinburgh, there was a sense that the political landscape changed, and that it would now be politically contentious to take the scheme away and restore the streets to their former limit of mostly 30 mph:

Yes, opposition has reduced. So, I mean I said at the time if we get to a point of implementation it will be really difficult for anyone to go to someone on a street and say ‘we’re taking away your 20 miles an hour and make it 30 miles’. It’s quite easy to oppose something that’s unknown, so if it’s quite easy for a street to say ‘we don’t want to be 20 miles an hour, we want to be 30 miles an hour’, and it would have been easy politically to respond to that or it was also easy politically to say, well actually for other reasons we’re going to impose it. To take it away you only need one, realistically, mother with a child saying ‘wee Johnny now cycles to school because of this policy, do not take this away’. It takes one now to make it almost politically impossible to change, which is great.

Elected member

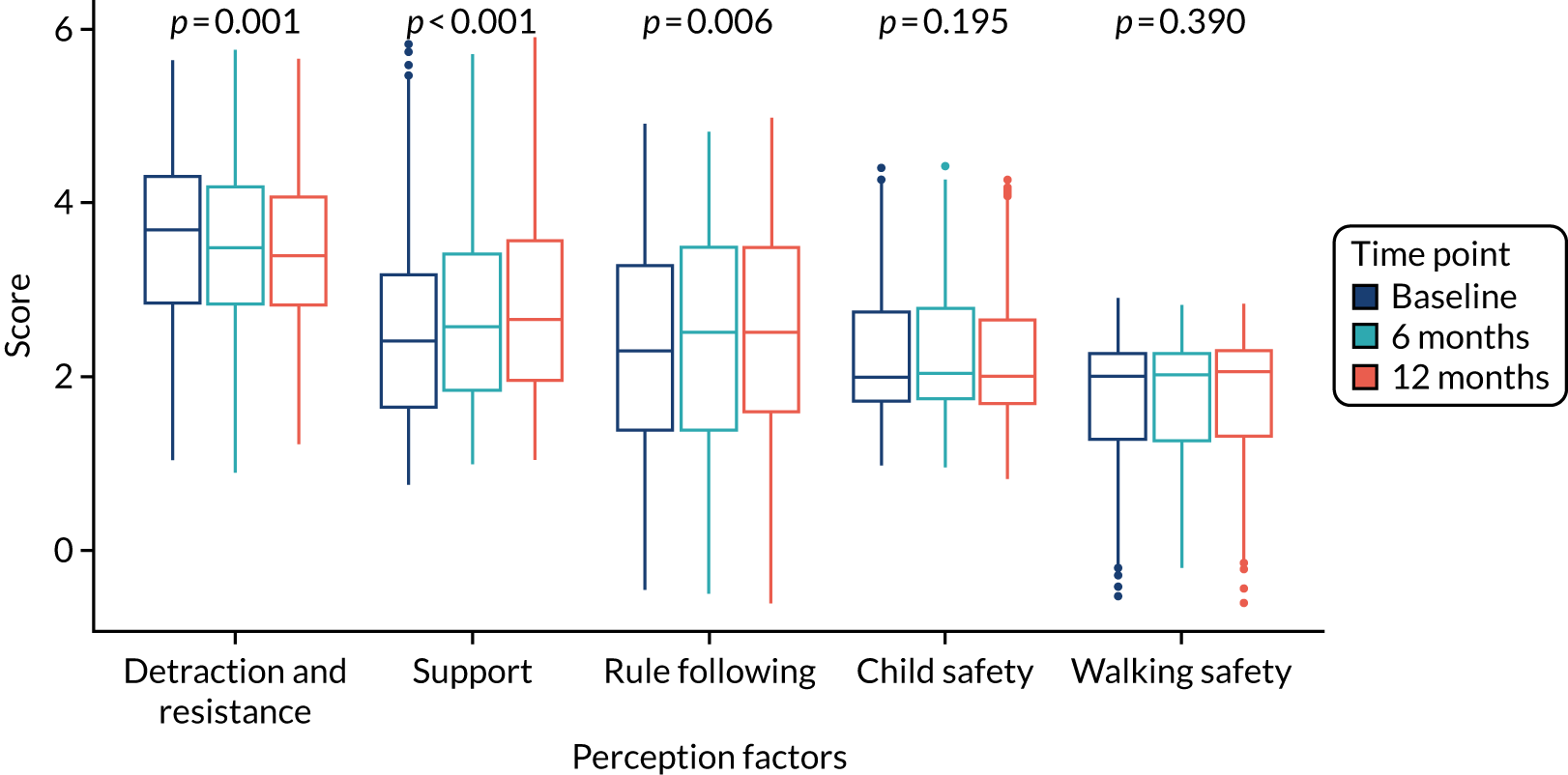

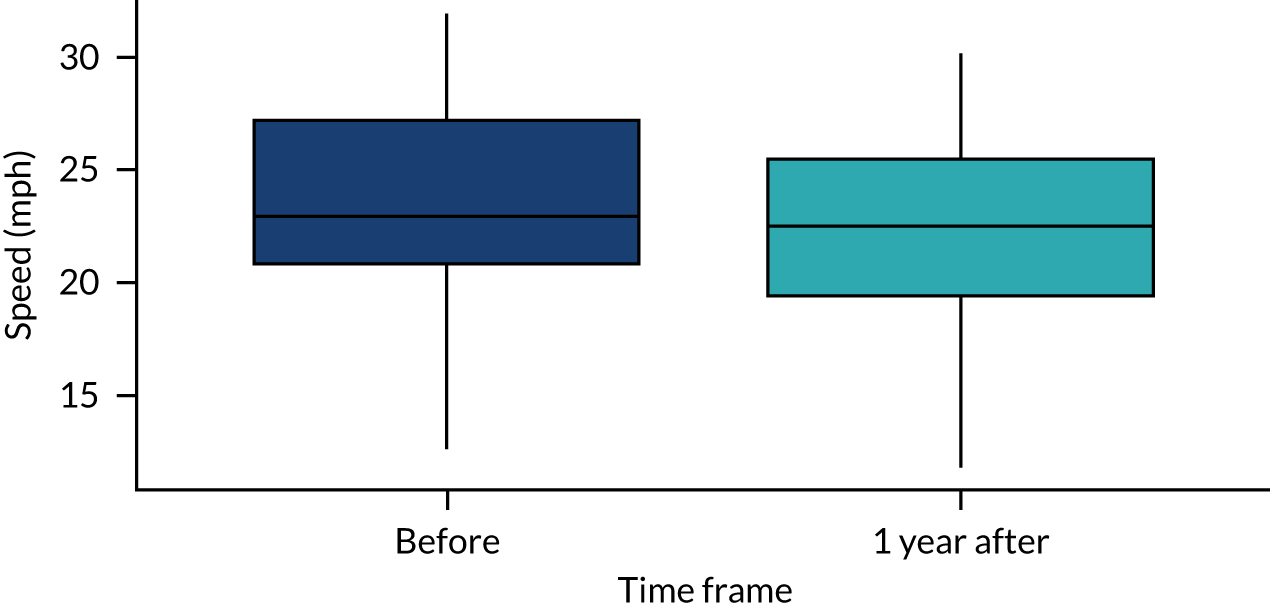

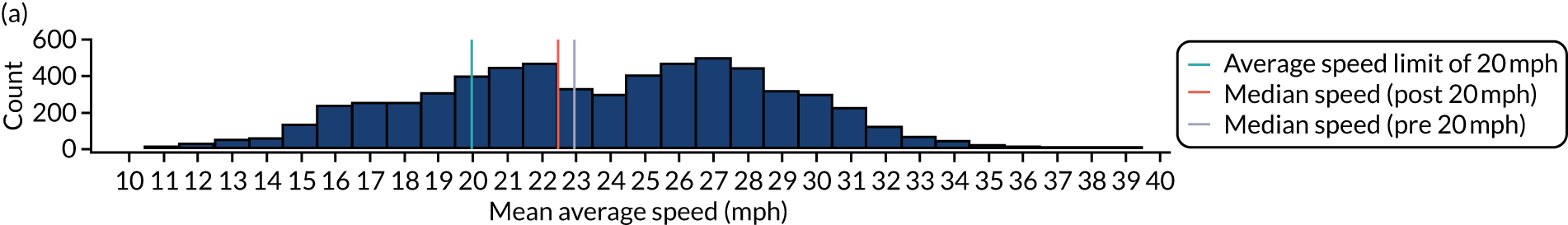

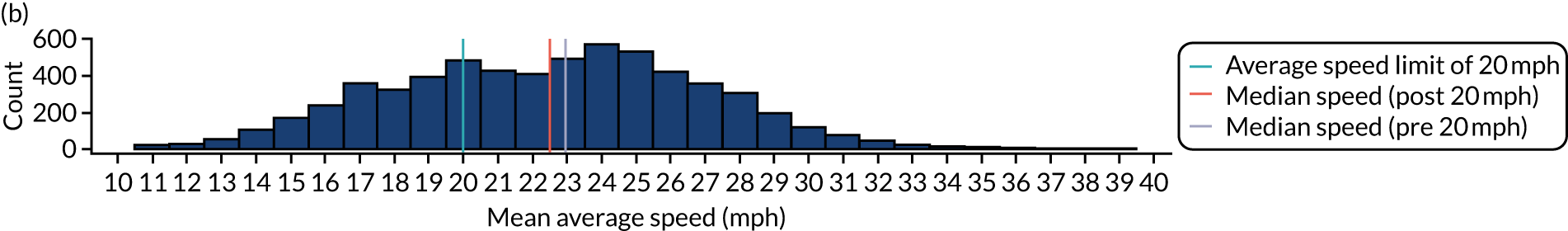

Belfast was always presented as a ‘pilot’ scheme; there does not seem to have ever been an intention to withdraw the scheme if it had no or minor impact. It seems likely that the intervention will be sustained in both cities.