Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 15/82/01. The contractual start date was in April 2017. The final report began editorial review in March 2021 and was accepted for publication in August 2021. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2022 Whittaker et al. This work was produced by Whittaker et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2022 Whittaker et al.

Chapter 1 Context

The impact of parental drug use on children and families is a major public health problem. 1 In the UK, an estimated 350,000 children are affected by parental drug use. 2 Effects include the impact of in utero exposure to substances, as well as the adverse influence of the caregiving environment associated with a drug-using lifestyle. 3 Parental substance use is strongly associated with health and social inequalities,4 including intergenerational transmission of harm5,6 and child protection involvement, including repeat child removal. 7 Parental substance use is listed as a key concern in approximately one-third of serious child protection cases. 8 The estimated lifetime costs per victim of non-fatal child maltreatment in the UK is £89,390 and the cost per death from child maltreatment is £940,758. 9

In Scotland, there are between 55,800 and 58,900 problem drug users, and most (70%) are male. 10 In England, the number of opioid and crack users is estimated to be nearly 300,000, with 71% of users in treatment in any one year; of those in treatment, 79% are opioid users. 11 Most users have some parenting role and responsibility. For example, in Scotland, over 40% of new drug treatment attenders report living with dependent children. 12

Parental drug use is closely associated with compromised parenting, poor child development and increased rates of child maltreatment, particularly neglect. 3,13 As a consequence, improving outcomes for children and families affected by parental problem drug use is a key policy objective in the UK and elsewhere. 14–16

Despite policies, fathers and male carers tend to be excluded from parenting and family support services. 17 Evidence suggests that drug-using fathers have a parenting style that often involves physical and verbal aggression towards children and situational violence towards partners. 13,18 Furthermore, there have been ongoing concerns about fathers’ involvement in cases where there have been serious and catastrophic outcomes for children in families with paternal drug use. 19 This includes repeated commentary from child death inquiries20 and child protection reviews. 21,22

Literature review

Parenting programmes

Parenting programmes targeted at the general population have been successful in improving parents’ psychological functioning, including depression, anxiety, stress, anger, guilt, confidence and satisfaction with the partner relationship. 23 However, parenting studies rarely include fathers, and those that do rarely report outcomes for fathers. 24 Evidence suggests that fathers are reluctant to attend parenting programmes,25 which may relate to their perceptions regarding gendered parenting roles and mother-focused interventions. 26 Tully et al. 27 also found that lower levels of practitioner competencies, training and experience in engaging fathers in parenting programmes resulted in lower levels of father involvement. One concern is that there is some evidence that fathers benefit less from mainstream parenting programmes than mothers. 28,29 A meta-analysis of parenting intervention studies that included fathers compared with those that did not found significantly more positive changes in children’s behaviour, but fathers reported fewer desirable changes in parenting behaviours and beliefs than mothers did. 29 The authors concluded that fathers should be encouraged to engage in parenting programmes to maximise benefits for children, but that further research is needed on recruitment and retention of fathers, adjustments required to address the parenting needs of both fathers and mothers, and how mothers and fathers work together, or not, to implement the active components of the intervention.

Encouragingly, a small body of researchers have implemented and evaluated parenting programmes for marginalised fathers, such as young and low-income fathers, those engaged in intimate partner violence and those subject to child protection orders. 30–34 Findings indicate improvements in psychological functioning30,33 and father–child relationships. 31,34 However, poor engagement with fathers remains problematic. 32,35 In addition, it is not known how fathers affected by other forms of disadvantage and co-occurring problems might respond to parenting programmes, for example fathers who are drug dependent. Parents who use drugs are highly stigmatised and marginalised, and are often reluctant to engage with group-based parenting programmes. 36 Consequently, there has been growing recognition that targeted and more nuanced interventions are required for marginalised families, including fathers,23 especially when the father poses a risk of child maltreatment. 37

Parenting programmes for parents with a substance use disorder

A review of parenting programmes for those with problem drug use found that therapeutic interventions can be helpful in reducing drug use and improving parenting. 38 However, the review found that programmes commonly target parenting without taking into account the broader needs of substance-using parents. Although it is difficult to disentangle the negative impact of prenatal exposure and the postnatal environment that the child is raised in, it is clear that children need a family environment in which they feel safe and loved and are nurtured by reliable and affectionate carers. The multiple difficulties facing parents who use drugs can interfere with or lessen their ability to provide a child with this safe, loving and nurturing environment.

An innovative US intervention for fathers with problem drug use – ‘Fathers for Change’ (F4C) – was compared with ‘Dads “n” Kids’, which combines psychoeducational parenting with practical support for housing and welfare. 39 F4C addresses drug use, parenting skills and proximal psychological factors associated with intimate partner violence. Both intervention groups reduced affect dysregulation, anger and intimate partner violence. The reduction in affect dysregulation was significantly larger among participants receiving F4C, and participants were also less likely to use drugs (relapse) following the intervention. The authors suggest that F4C could be delivered in the community with fathers and their children (see also Stover40). However, the pilot randomised trial focused on fathers only, and those in abstinence-based residential drug treatment (a 12-step programme), with the majority of fathers mandated by the criminal justice system in return for reductions in their sentences.

The Parents under Pressure (PuP) programme,41 which was developed by members of the research team, is a parenting intervention that is specifically designed to address the needs of parents who use drugs. The PuP programme is underpinned by an integrated theoretical framework that draws on attachment theory,42 the concept of emotional availability,43 neurobiological models of stress and trauma44 and a socioecological developmental model of human development. 45 Each of these theoretical perspectives identifies the quality of the parent–child relationship as crucial for the healthy development of a child. Furthermore, the personal resourcefulness of parents (i.e. capacity to regulate their own emotional state, problem solve and engage social support) and the demands of the real world (e.g. housing and legal problems, financial strain and food insecurity) can have an negative impact on the parent–child relationship. Therefore, the PuP programme is based on the premise that responding to the needs of parents who use drugs requires a framework that can address problems across multiple domains of family functioning.

In the UK, the PuP programme has been subjected to a randomised controlled trial (RCT) and economic evaluation. 46 Parents were recruited from community-based drugs services in the UK and 115 primary caregivers (mostly mothers) were randomly allocated to the PuP programme or treatment as usual. The intervention was delivered by accredited PuP practitioners in the family home. Those participants receiving PuP demonstrated significantly reduced child abuse potential (primary outcome) compared with controls, and the intervention was cost-effective. 46 However, the small number of fathers in this UK study precluded an analysis of how the intervention might have affected them and their children.

Neger and Prinz38 recommended that more robust evaluations were required to assess efficacy and feasibility of these interventions. Evidence from the PuP programme and F4C studies present a compelling argument to involve fathers who use drugs in programmes that aim to improve fathering and father–child relationships within the context of family life. Greater emphasis should be given to reducing aggression towards children and partners and improving affect regulation. Given the context and target population [i.e. fathers mandated to attend residential abstinence-based drug treatment in F4C (USA) and mothers experiencing problem substance use and living in the community in PuP (UK)], difficulty with recruitment and retention46 and initial challenges embedding the intervention into existing services,39 it is efficacious to assess the feasibility of implementing an intervention for fathers into a new setting, such as the UK.

Rationale for the PuP4Dads feasibility study

We chose to focus on PuP in the current study because of our existing research collaboration with the originators of that programme. The proposed research also takes the vital next step of targeting men in parenting intervention research. It provides one of the first attempts to improve family functioning by addressing affect regulation as a key driver of parenting and couple-related behaviours among drug-dependent men receiving community-based opioid substitution therapy (OST). In addition, to the best of our knowledge, it is the first attempt to include opioid-dependent fathers, their partners/mothers, their children and their significant others in a ‘whole-family’ approach that is in line with the governmental policy priorities for this population in the UK. 14,16 In the UK, there are very few residential drug treatment units that can accommodate fathers and their children,47 and so demonstrating successful implementation within community-based settings in the UK is essential for future scale-up. As PuP has already been trialled in the UK, the research and intervention are highly relevant to the UK public health agenda, with implications for improving the quality of caregiving in families with complex needs, reducing child abuse and situational family violence, improving children’s developmental outcomes, and improving the trajectories of adults and families affected by drug use.

In addition, interventions need to include a focus on the broader ecological context of families’ lives, help families connect with a wider social environment and provide safety and some security around accommodation and financial issues. 38,48 Although relatively small in number, there is growing evidence that promotes such approaches when delivered across community settings, such as OST settings,49,50 and within the context of family drug courts. 51,52 Notably, these programmes address multiple domains in families’ lives and incorporate home visiting and a case management approach to address wider contextual factors.

Following the Medical Research Council guidance on the development and evaluation of complex interventions,53 there are five key reasons why a feasibility study was required in this instance. First, our proposed intervention is novel in that it involves an extremely high-risk group of fathers and is positioned in an area of research that is considerably under-researched. Second, given the well-known problems in engaging with parents who use drugs, we need to understand how these problems might affect the flow of participants in a research study (i.e. from recruitment to post-intervention follow-up). Third, we need to better understand the extent to which the intervention works as intended, including the facilitators of and barriers to adoption and implementation. Fourth, there is the need to establish a theoretical understanding of the mechanisms that may lead to improvement and thereby identify the most appropriate mediators, moderators and outcome variables and measures for a future evaluation. Finally, given the small number of evaluations, and drawing from guidance regarding the best use of resources,53 we need to consider the resource and methodological implications of conducting a larger evaluation, including the feasibility of an economic analysis.

Aim, research questions and objectives

Aim

Our aim was to implement and test the feasibility and acceptability of the PuP programme for opioid-dependent fathers and their families and to determine whether or not a future pilot RCT and full-scale evaluation, including an economic evaluation, could be conducted.

Research questions

For the intervention

-

How feasible is it to deliver PuP for opioid-dependent fathers in routine family-based local government and voluntary sector services?

-

How acceptable is PuP among staff and recipients, and what are the barriers to/facilitators of uptake and retention?

-

How acceptable and adequate is the training and supervision for staff?

-

To what extent can PuP be integrated into non-NHS settings across the UK?

For the study

-

What is the optimal level of recruitment, consent and retention for a future trial?

-

What are the best methods of collecting outcome data from fathers and mothers at baseline (pre-intervention), follow-up 1 (FU1), and follow-up 2 (FU2)?

-

How feasible is it to collect attendance, medical and cost data on participating families?

-

How acceptable and appropriate are the assessment methods?

-

Is the profile of change in fathers, mothers and children clinically significant?

-

What is the nature and extent of routine family support services for fathers receiving drug treatment?

-

Which study design would best suit a future evaluation, including an economic evaluation?

Objectives

-

To determine whether or not a pilot RCT and full evaluation, including an economic evaluation, could be undertaken on the PuP programme with drug-dependent fathers and their families.

-

To assess the recruitment and retention of drug-dependent fathers, as well as feasibility and acceptability of the intervention among fathers, mothers, practitioners, referrers and key services.

-

To assess the fidelity and reach of intervention delivery by PuP practitioners, including barriers to and facilitators of successful implementation.

-

To refine and test the logic model and theoretical basis of the intervention.

-

To enhance understanding of the parenting needs of drug-dependent fathers and what programme components work best with fathers.

-

To determine key trial design parameters for a possible future large-scale trial, including recruitment and retention rates and strategies, outcome measures, intracluster correlation and sample size.

-

To determine the key components of a future cost-effectiveness analysis and tested data collection methods.

-

To establish whether or not pre-set progression criteria are met and a larger-scale trial is warranted.

-

If yes, to design the protocol, including identification of required structures, resources and partnerships.

-

Structure of report

Chapter 2 includes an overview of the study methodology, providing detail of the design, setting, intervention, methods, analytic strategy, general management of the study and public engagement. The findings are then presented in two main chapters. Chapter 3 includes relevant quantitative data on recruitment, intervention delivery and engagement, retention in the study, a description of the study participants and quantitative results. Chapter 4 includes relevant qualitative and quantitative data reported for the main study research questions (RQs), and concludes with results on the progression criteria and feasibility assessment, using ADePT (A process for Decision-making after Pilot and Feasibility Trials). 54 In Chapter 5, the findings are then discussed in relation to the overall aim and objectives of the study, strengths and limitations of the study are noted, and conclusions and recommendations for a future evaluation of the PuP4Dads (Parents under Pressure programme for fathers) are provided.

Please note that our protocol (final version 5.0) for the PuP4Dads study is available via the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Journals Library [URL: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/phr/158201/#/ (accessed 6 September 2021)].

Chapter 2 Methods

Study design

A mixed-methods feasibility study was designed to test the implementation and acceptability of the PuP programme for opioid-dependent fathers and their families and the parameters for a future larger evaluation, including an economic evaluation.

The study included the following:

-

staff training, supervision and accreditation in the PuP intervention, alongside implementation support

-

delivery of the PuP intervention (over a period of approximately 6 months) by two non-NHS services [i.e. CIRCLE (Edinburgh, UK), a third-sector family support service, and PREPARE (Edinburgh, UK), a local authority-led specialist multidisciplinary pregnancy support service]

-

qualitative interviews with parent participants (i.e. opioid-dependent fathers and their partners/mothers) to explore their views and experiences of usual care for fathers, the acceptability of PuP, perceived benefits of the intervention and acceptability of the study measures and procedures

-

qualitative interviews with PuP practitioners, PuP supervisors and delivery site service managers to explore their views and experiences of staff training, implementation of PuP, acceptability of PuP, perceived benefits of the intervention and ‘fit’ with existing services and models of care, and the sustainability of PuP

-

focus groups with professional/potential referrers to explore barriers to and facilitators of recruitment, uptake and engagement, acceptability and ‘fit’ with drug treatment and other services using a multiagency partnership approach

-

collection of baseline (i.e. pre-treatment), FU1 (i.e. at end of treatment/dropout or 6 months after baseline) and FU2 (i.e. post-treatment or 6 months after FU1) measures from participating parents

-

completion rates and suitability of potential outcome measures for a future evaluation and feasibility of obtaining NHS, social services and economic data

-

feasibility of conducting a future large-scale evaluation of the PuP intervention with fathers receiving OST, including recruitment, uptake, retention and completion rates

-

convening an ‘expert event’ with stakeholders involved in the treatment and care of drug-dependent parents and their families to discuss preliminary study findings and potential scalability of the intervention for a larger evaluation.

Protocol changes and project extension

Eligibility criteria and new measures

Two changes were made to the eligibility criteria for the study, one on 6 June 2017 and one on 6 July 2018. The first change was made soon after the study began because PREPARE, one of the services delivering the intervention, identifies fathers during the antenatal period and normally provides parenting support in the lead-up to the birth. Therefore, the inclusion criteria needed to include expectant fathers to enable PuP to be delivered as part of routine practice in this implementation site. Including expectant fathers also meant that we needed to introduce a new measure of attachment because the Emotional Availability Scale (EAS) (i.e. a video observation measure of parent–child interaction)55 was not suitable for first-time parents at baseline. Therefore, the Paternal Antenatal Attachment Scale56 and the Maternal Antenatal Attachment Scale56 were added to the outcome measures administered by the researcher.

A second change in the eligibility criteria was made to include the normal range of children classed as ‘early years’ (i.e. 0–8 years of age), rather than limit this to pre-school children (i.e. 0–5 years). The research team received a number of referrals for families with children aged 6–8 years who were not, at the time, eligible to take part. Given that previous studies of PuP included parents with children aged 0–8 years and expectant parents,46,49 it was considered appropriate to extend the inclusion criteria for this study to match that in previous PuP studies.

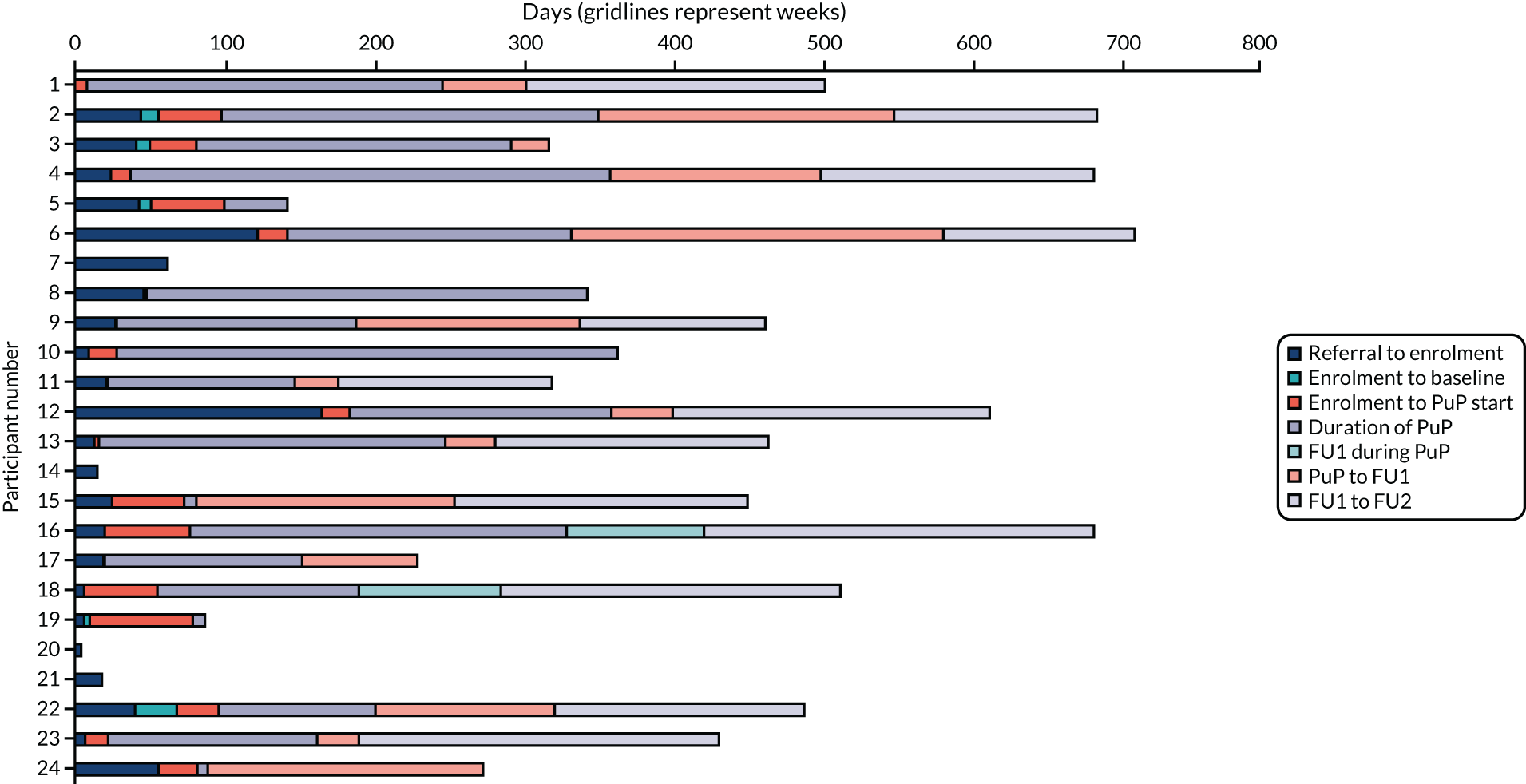

Data collection time points

During the course of the study, it became apparent that intervention delivery to a number of families was taking far longer than originally proposed in our study protocol (i.e. 4–6 months with an ‘end-of-treatment’ interview after completion). In some cases, families were taking up to 12 months to complete the programme. This was having knock-on effects on the FU1 (i.e. ‘end-of-treatment’) data collection time point and the FU2 (i.e. ‘6-month post-treatment’) data collection time point, making completion within the planned time frame impossible. With approval from NIHR and the NHS Research Ethics Committee (received on 6 August 2019), data collection time points were rescheduled for baseline and at 6 and 12 months, irrespective of intervention completion status.

Professional interviews

During the interviews with PuP practitioners, it became apparent that service/line managers would have their own opinions on the acceptability and suitability of PuP for their individual teams and staff, and would have views on the implementation of PuP from their own perspective. Therefore, we applied for an amendment so that we could invite them all into the study to take part in a qualitative interview and this was approved by the sponsor on 1 July 2019.

For a list of study protocol changes, substantial and non-substantial amendment and NHS Research Ethics Committee approvals, see Appendix 1, Table 9.

Research fellow absence

A period of research fellow (RF) sickness (approximately 6 weeks), followed shortly afterwards by a change of RF on the project, resulted in an extended period of time where recruitment into the study was curtailed, including a 3-month period when there was no RF in post (from 1 September 2018 to 30 November 2018). A no-cost extension was subsequently granted by NIHR for this 3-month time period when no RF was employed on the project (approved 25 June 2019).

Project extension

Owing to recruitment challenges and an inability to fully test the impact of additional strategies to improve recruitment, as well as prolonged intervention delivery time and associated delayed data collection, an application to extend the project for an 18-month period was submitted to NIHR. This funded extension, supported by the Study Steering Committee (SSC) and Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC), was approved on 25 June 2019. Therefore, the project timetable was revised from a 24-month project to a 45-month project, with a start date of 1 April 2017 and an end date of 31 December 2020.

Effects of the COVID-19 pandemic

COVID-19 affected the project from March 2020 onwards. Our final data collection (home visits) with some parents was suspended, although this affected only two final follow-up interviews and our sponsor agreed that we could conduct these over the telephone. The researcher administered the questionnaires over a number of telephone calls. Interviews with one practitioner and one manager were also conducted over the telephone. One focus group was cancelled. Data collection and analysis were also affected because response times to obtain NHS and Social Work Scotland (Edinburgh, UK) data were prolonged. Lockdown meant that researchers on the team were home schooling and so final analysis and write-up were difficult to achieve as planned. Our expert event in October 2020 was convened online rather than face to face, along with our dissemination and public engagement events at the end of the study. Nevertheless, we were able to complete the project on 31 December 2020.

Research pathway diagram: PuP4Dads study

A visual representation of the research pathway is outlined in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

The PuP4Dads research pathway diagram. R&D, research and development.

Setting

The study was conducted in two non-NHS community-based services for adults, children and families affected by parental substance use in the Lothian region in Scotland:

-

PREPARE, which is a local-authority social work-led specialist multidisciplinary service for pregnant women, substance users and their families

-

CIRCLE, which is a Scottish charity and early years family support service for disadvantaged children and families.

The Lothian region in Scotland includes one health board (NHS Lothian) and four local authorities (The City of Edinburgh Council, East Lothian Council, Midlothian Council and West Lothian Council). This study took place in the three local authority areas in Lothian where PREPARE and CIRCLE provide services [i.e. City of Edinburgh (PREPARE and CIRCLE), East Lothian (CIRCLE) and West Lothian (CIRCLE)].

The City of Edinburgh is a largely urban area with a population of 513,210 (as of December 2020), with 11.6% of the population living in the most-deprived category [Scottish Index of Multiple Deprivation (SIMD) category 1] and 43.5% of the population living in the least-deprived category (SIMD category 5). 57 East Lothian has a population of 104,840 that is distributed fairly equally across SIMD categories 1 to 5, with approximately half of the population living in urban (21.6%) or accessible rural (23%) areas. West Lothian has a population of 181,310 that is distributed fairly equally across SIMD categories 1 to 5, with the majority (82.5%) of the population living in accessible small towns. 57 Although Edinburgh and many surrounding small towns in East Lothian and West Lothian are considered affluent, approximately 22% of all children in Edinburgh live in poverty. 58 There are several areas of extreme deprivation, comprising large social housing ‘estates’ with a high prevalence of drug use. 59

Across Scotland, health and social care is now ‘integrated’ with social care, primary and community health-care services and some acute services managed by integration joint boards. Integration joint boards are made up of representatives from councils, NHS health boards, third-sector representatives, service users and carers. These integration joint boards, through their chief officer, have responsibility for the planning, resourcing and the operational oversight of a wide range of health and social care services. The delivery of adult services are the responsibility of Health and Social Care Partnerships. Within these partnerships, there are various services for adults with drug and alcohol problems and in each local authority there is an Alcohol and Drug Partnership (ADP) that is made up of local authority, NHS, third-sector, Police Scotland and prison representatives that’s primary aim is to co-ordinate the design, delivery and evaluation of drug and alcohol services.

Although drug and alcohol services are not ‘integrated’ with children’s services, three local authority areas in Lothian commission CIRCLE (i.e. the third-sector organisation involved in this study) to provide services for families affected by parental substance use. 60 Uniquely, only the City of Edinburgh Health and Social Care Partnership provides a specialist service for pregnant women with problem substance use via PREPARE (i.e. the other service involved in this study). 61

PREPARE is a local government (City of Edinburgh Council)-led service that was established in 2006. It consists of an early intervention integrated multidisciplinary team that works with pregnant women and their partners who have significant substance use problems. The service aims to reduce substance use and related harms to mother and baby. The women and men who are allocated to PREPARE have multiple and complex needs related to poverty, substance use, poor mental health and domestic abuse. PREPARE receives approximately 50 referrals a year and normally has a caseload of up to 30 women plus their partners at any one time. Of PREPARE’s open cases, 90% will be involved in the child protection system, whereas the other 10% will be supported using the Getting It Right For Every Child (GIRFEC) model62 and Children Affected by Parental Substance Use (CAPSU) guidelines. 15 PREPARE comprises nine (full-time equivalent) staff, including a social work team leader, a senior early years officer, early years officers, community mental health (addiction) nurses, a health visitor and a midwife. The team is managed under social work children and families services and is supported by a named consultant obstetrician and consultant psychiatrist in addictions. At the start of the study, PREPARE also hosted a dedicated ‘fathers’ worker’ who was jointly funded and managed by both PREPARE and CIRCLE. The fathers’ worker is now based at CIRCLE.

CIRCLE, a Scottish charity founded in 2006, provides a range of family support services that aim to improve the lives of disadvantaged children and families. CIRCLE works in partnership with other organisations to provide whole-family support and delivers commissioned services specifically for CAPSU in the City of Edinburgh, East Lothian and West Lothian. These three services support approximately 240 families per year. In total, there are 14 (full-time equivalent) staff across the projects (Edinburgh, n = 7; West Lothian, n = 3.5; East Lothian, n = 2.5). These staff are assisted by a young person’s worker and a father’s worker in Edinburgh, and a pregnancy worker in East Lothian. Staff are qualified in social work, community development, health and social care and nursing. Funding for CIRCLE services and staff comes from a range of trusts and donations, as well as the ADPs in Edinburgh and West Lothian and a National Lottery Grant in East Lothian.

The intervention: Parents under Pressure

The PuP programme is a family support programme developed for families that may be experiencing difficult life circumstances that have an impact on family function, such as substance use, anxiety and depression, family conflict, homelessness and severe financial stress. In this study, PuP was delivered by non-NHS community-based family support services to fathers receiving OST and their families. The intervention is described here in line with TiDieR (Template for Intervention Description and Replication) reporting guidelines. 63

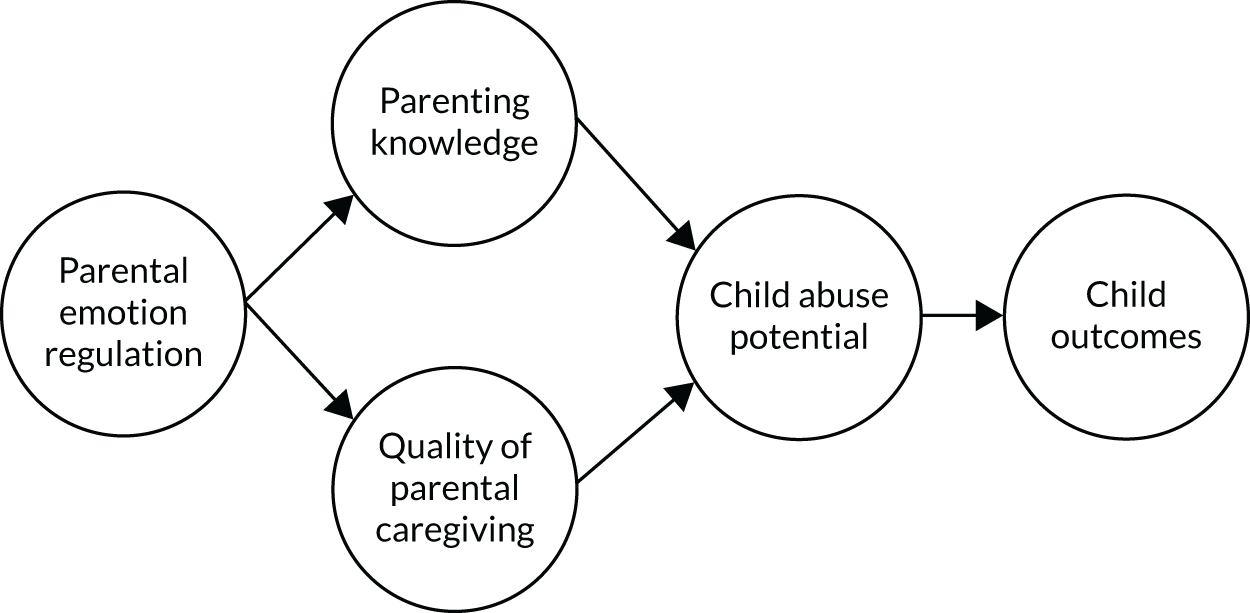

Parents under Pressure intervention theory of change

The PuP programme aims to enhance parents’ capacity to provide a safe and nurturing environment and sensitive and responsive caregiving for children. Sensitive and responsive caregiving, in combination with knowledge about appropriate parenting behaviours, can lead to improvement in child developmental outcome. However, to provide sensitive and responsive caregiving (including managing difficult behaviours and better limit setting), it is essential that parents are able to understand and manage their own emotions. Impulsivity and poor affect regulation are key features of substance use and can be viewed as a contributor to and a consequence of substance use. 64 Before parents, and in particular fathers/male caregivers, who have engaged in hostile and reactive behaviour patterns in the context of family life13 are able to respond sensitively to their children and partners, they need to be able to manage their own dysregulated affect.

Therefore, the PuP programme extends beyond instruction in traditional behavioural parenting strategies, such as managing non-compliance, better limit setting and rewarding good behaviour, to a focus on helping to develop a calmer, less reactive family environment in which both parents and children learn how to improve emotion regulation. There is extensive evidence supporting the direct relationship between the quality of caregiving, parenting knowledge and child outcome. 19,23 However, this is also mediated by parental emotion regulation: parental emotion dysregulation is associated with poor coping skills, poorer parental sensitivity and greater likelihood of harsh and abusive parenting. These, in turn, increase child abuse potential. For the families involved in the PuP programme, parental emotion dysregulation is a significant problem and is, therefore, directly addressed during programme delivery. This can be represented as a conceptual model in which the relationship between sensitive and responsive parenting (i.e. quality of caregiving), parenting skills (i.e. knowing what to do) and child outcome is influenced by the parent’s capacity to manage their emotions, which, in turn, influences child abuse potential (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Conceptual representation of the PuP integrated theoretical framework.

For the purposes of the PuP4Dads feasibility study, we proposed a logic model for the intervention that is specifically in relation to fathers with a substance use disorder (see Report Supplementary Material 1).

Parents under Pressure intervention material

To deliver the PuP programme, an individually tailored family support plan is developed in collaboration with the parent/carers. The underlying integrated theoretical framework (see Report Supplementary Material 2) for parents and practitioners provides an assessment framework in which to identify strengths and challenges across six domains of family functioning: (1) child outcome; (2) quality of the caregiving relationship; (3) parenting values, knowledge and skills; (4) parental emotion regulation; (5) connections to culture, community and family; and (6) the wider ecological context. Additional resources documenting exercises, discussion points and activities are contained in the PuP parent workbook and the PuP online toolkit, which can be used flexibly to help parents and children enhance family and child well-being. The parent workbook consists of 12 discrete modules [Table 1; see also the NIHR Journals Library URL: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/phr/158201/#/ (accessed 6 September 2021)]. 42 The order and sequencing of the family support plan is tailored to each family. Therefore, the order and focus of the modules delivered differs across families.

| Module | Description |

|---|---|

| 1: starting the PuP journey | This module aims to assist parents to identify the strengths and challenges that they may be facing. A shared understanding of a family’s current concerns, strengths and challenges is the basis for working together to make family life better and support the development of children |

| 2: planning my PuP journey | This module provides feedback on the assessment and arrives at shared views and ways of working towards these goals. This module also helps identify involvement of partners or other carers in the PuP journey |

| 3: view of self as a parent | This module aims to help parents reflect on their view of themselves as parents |

| 4: connecting with your child to help them feel loved and safe | This module is aimed at promoting a positive parent–child relationship. This involves encouraging sensitive and responsive parenting to provide the maximum opportunity for the development of a nurturing and loving relationship |

| 5: understanding what may happen when children are exposed to trauma or loss | This module supports parents to understand the impact of children’s exposure to trauma, loss or grief. It provides information on the effects of these events to help understand children’s behaviour and strategies to support recovery |

| 6: health check your child | This module is designed to open up a discussion on health, hygiene and nutrition |

| 7: how to manage emotions when under pressure – increasing mindful awareness | The aim of this module is to teach and encourage the use of emotion regulation and self-soothing skills. There is an emphasis on mindfulness-based strategies to support both the parent and the child |

| 8: supporting your child to develop self-regulation | This module helps the parent to teach their own children how to increase self-regulation. Child-focused mindfulness activities are included, plus a range of activities that help parents support the development of overarching executive functioning |

| 9: managing substance use problems | This module aims to support parents in managing substance use problems. There is a focus on identifying potential substance use problems and/or relapse using established strategies informed by models of addiction treatment including relapse prevention |

| 10: connecting with family, community and culture | This module aims to support connection with family, community and culture. This may be around extending social supports, establishing community links (e.g. with schools) and supporting connection and/or reconnection with culture and faith |

| 11: life skills | This module addresses the day-to-day business of parenting and family life. Stressors relating to budgeting, housing and schooling can be addressed using problem-solving and supporting emotion regulation. These are considered therapeutic opportunities to test out new skills around emotion regulation |

| 12: relationships | This module addresses issues around communication skills and other problems in adult relationships. The module is used when the parent would benefit from knowing how to communicate effectively with their partner or when their relationship is experiencing difficulties (e.g. domestic violence) |

The PuP therapist manual provides the theoretical overview underpinning the programme and was provided to PuP practitioners as part of the training process. Materials are copyrighted to Griffith University (Nathan, QLD, Australia). Practitioners undergoing training and accredited practitioners in the PuP programme have access to the PuP resources, including online exercises from the parent workbook, access to standardised measures, scoring and an interpretation report. These measures (e.g. the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale) reflect the domains of family functioning contained in the integrated theoretical framework. Each practitioner has their own username and password used to access the PuP online toolkit.

Parents under Pressure intervention procedures

The PuP programme is individualised for each family. An assessment model allows for an individualised case plan to be developed, which is guided by a model of case conceptualisation. Immediate priority areas and goals for change are identified by the practitioner and parent, and are worked towards collaboratively. Modules are then selected and ordered according to the needs of the family and the immediate presenting issues. This approach allows for flexibility, as immediate problems may include, for example, potential homelessness and high risk of relapse to drug use, which need to be addressed to introduce both stability in the family environment and engage high-risk families. Integral to these processes is engagement of the parent(s) in the process of developing confidence in their parenting capacity, nurturance of their children and skills to identify and manage their emotions. These three ‘threads’ runs through all PuP sessions regardless of the task at hand or even the location of the session. Practitioners are encouraged to engage with the three ‘threads’ at all times (e.g. supporting a parent during a visit to the housing association provides a therapeutic opportunity to comment on and support each of the three threads).

The quality of the parent–child relationship is intrinsically linked with the capacity of parents to provide nurturing, sensitive and responsive caregiving,50 and the capacity of parents to regulate their own emotional state in the face of parenting challenges can fundamentally impact this capacity. 65,66 Therefore, many of the PuP treatment modules focus on improving parents’ emotional state and fostering a positive parent–child relationship. For example, the ‘connecting with your child to help them feel loved and safe’ and ‘supporting your child to develop self-regulation’ modules focus on helping parents to develop a range of appropriate and non-punitive child management techniques, strategies for ‘mindful play’, skills for understanding their children’s cognitive and emotional states, and mindfulness techniques to promote sensitive caregiving in stressful parenting contexts (e.g. tantrums or prolonged infant crying). Being in the ‘right state of mind’ to manage difficult parenting situations, helping parents to develop coping skills and mindfulness strategies to reduce dysregulated affect aims to reduce coercive hostile parenting behaviours, make caregiving more nurturing and child focused, and enable a reduction in situational aggression between partners. 66

With regard to parental emotion regulation, the PuP parent workbook contains several treatment modules that aim to reduce dysregulation and psychopathology through the use of mindfulness exercises (e.g. the ‘how to manage emotions when under pressure: increasing mindful awareness’ module) and urge-surfing techniques for substance use issues (e.g. the ‘managing substance use problems’ module). In addition, this study provided an opportunity for fathers and their partners to develop communication skills and to co-regulate by identifying high-risk situations for situational verbal and physical aggression, drawing from the ‘relationships’ module. This component of PuP was initially undertaken with fathers alone and then extended to couples’ sessions. Although relationship work needs to be undertaken with great sensitivity and awareness of safety issues for both partners, the work of Stover40 indicates that this approach is acceptable for both partners. PuP includes exercises on ‘communication in intimate relationships’, and these were combined with modules on managing emotions to address interpersonal aggression between partners and, potentially, towards children.

Finally, self-regulatory skills are developed with children through combined sessions with the caregivers and child/children. These self-regulatory skills, again, draw from mindfulness constructs, with a growing body of evidence supporting the relationship between mindfulness and adaptive emotion regulation,67 particularly for young children with difficulties with emotion regulation. These skills are appropriate for children aged 3–5 years. As parents become more emotionally regulated, they are able to provide more sensitive caregiving. This, in turn, is associated with the development of emotion regulation in young children. 68 Therefore, the parent workbook supports the parent by allowing for documentation of their personal journey through the programme.

Parents under Pressure intervention delivery

The PuP programme is designed to be delivered face to face by the PuP practitioner in families’ homes. When there are concerns regarding practitioner safety, it can be delivered in community-based clinical settings. It has also been delivered in residential therapeutic communities and prison settings.

The PuP programme was delivered to fathers, resident or non-resident, with or without partners/mothers. Depending on the individual needs and circumstances of the parents, some modules were delivered by the PuP practitioner to the couple, whereas other modules were delivered individually to one or both parents. If the parents were not cohabiting, then the programme was delivered individually to each parent or just to the father if the mother did not wish to participate. Participation of the partner/mother in the programme was not dependent on whether or not they enrolled in the study. One mother chose to engage in the programme with the father, but declined to enrol in the study.

The time allocated to the family support plan varied and was dependent on the family’s needs and family support remit of the agency delivering the PuP programme. Appointments were generally held on a weekly or fortnightly basis for 1–2 hours. The PuP programme has been delivered over 646,49 and 12 months. 69

Parents under Pressure intervention providers

To use the PuP programme, the intervention provider is required to have undertaken an 8-month training course, which comprised an initial 2-day training in the overall model and programme followed by implementation support provided at 2, 4 and 8 months (see Parents under Pressure training programme). (Note that COVID-19 restrictions resulted in a 2020 online adaption of the PuP training.) Completion of this training leads to accreditation as a PuP practitioner. Practitioners are not required to have a professional qualification (e.g. social work or psychology) to become an accredited PuP practitioner. However, commitment to working with complex-needs families using intensive case management and an approach that encompasses therapeutic family support is essential. The intervention in this study was delivered by accredited PuP practitioners from two organisations (CIRCLE and PREPARE) who were experienced family support workers from a variety of backgrounds, including social work, early years practice and community education.

Practitioner training and accreditation in Parents under Pressure

Underlying philosophy

A key issue with implementation of parenting and family support interventions has been the way in which training is delivered. The traditional model of training usually involves bringing together professionals for a one-time training workshop delivered across consecutive days, with the assumption that the knowledge and skills obtained will be translated into change in front-line practice. This ‘train and hope’ model has been the standard approach to delivering training and there is little to show that practice has changed as a result. 70

Training is most effective when the participants are actively involved in the training process and requires effort on the part of the participants. Training needs to include opportunities to practise the skills taught through either role playing or reviewing content via video/film to actively engage in the training process. 71 Furthermore, participants need to be provided with training aids and exercises that help them organise, apply and embed new learning knowledge across several months, with ongoing consultation and coaching to ensure uptake and quality implementation. This approach has been linked to both better training outcomes and better client outcomes. 72,73 Sustainability is enhanced by supporting or identifying champions of the programme within the organisation. PuP training has, therefore, drawn from this extensive literature and developed a training route that embeds these principles in an 8- to 12-month training process.

Parents under Pressure training programme

The PuP training programme comprises a range of training events and assessments that lead to accreditation as a PuP therapist. To achieve accreditation, practitioners are required to complete the following three tasks:

-

attendance at all PuP training events

-

assessment of three families using the PuP online toolkit

-

completion of a case study using a purpose-designed template reflecting the domains underpinning the PuP integrated theoretical framework.

Initial training comprises 2 days in which participants are provided with an overview of the PuP integrated theoretical framework (see Report Supplementary Material 3), a review of programme focus and content, and an introduction to the assessment of quality of caregiving.

In month 2, participants are invited to their first ‘case review day’, during which they revisit the PuP integrated theoretical framework and use this to develop a case conceptualisation and a family support plan. Goals are identified in discussion with the family, and practitioners are supported to develop action plans that help with goal achievement. Resources to support this are drawn from the parent workbook and the PuP online toolkit. There is an emphasis on using the PuP programme and resources as a toolkit, with the metaphor of ‘use the right tool for the right job’ embedded in the case review process.

In month 4, a second case review day provides practitioners with the opportunity to revisit the PuP integrated theoretical framework with direct application to families with whom they are working. There is an emphasis on the process of case conceptualisation. Practitioners are introduced to the case study pro forma and provided with an opportunity to begin populating the template.

In month 8, a third case review day gives practitioners the opportunity to present a case study, review cases and family support plans.

In month 12, an optional development day is offered to enhance ongoing use of the PuP programme. Specific topics are selected from a suite of topics. Example topics include (1) ‘understanding fetal alcohol spectrum disorder: a PuP programme perspective’, (2) ‘trauma-informed practice: how this is achieved within the PuP programme’ and (3) ‘enhancing the development of self-regulation and executive functioning in vulnerable children: integration with the PuP programme’.

Parents under Pressure supervision and implementation support

Expert staff supervision for practitioners in the study was provided initially by an accredited PuP supervisor and trainer. To ensure sustainability, the PuP programme training process includes the identification of senior practitioners or team managers who are able to take on additional training as an accredited PuP supervisor. Identified individuals undertake an additional 20 hours of training and support, working through a series of guided exercises and tasks. The purpose of this training programme is to provide an advanced understanding of the underlying conceptual framework of the PuP programme. A series of readings are provided and practitioners are asked to a complete set of exercises to practise the skills and demonstrate competency. This includes additional training in case conceptualisation, an understanding of the presenting issues for children with a range of developmental disorders, advanced readings and practice in mindfulness, and a comparison of the PuP programme with another parenting programme. Training is also provided in implementation support, including helping trainees to provide constructive feedback on case study requirements for accreditation as a PuP practitioner.

Project management and oversight

The chief investigator led the study and provided support to the RF employed on the study. After NHS Research Ethics Committee and research and development (R&D) approvals, the project started on 1 April 2017. With the 21-month extension, the project was 45 months in total and completed on 31 December 2020. COVID-19 affected the final phase of data collection, data analysis and write-up (from March to December 2020). However, participant recruitment had ended before the pandemic began and, therefore, most parents had completed the intervention and the final data collection and research activities could be conducted by telephone or via online video-conferencing (including the ‘expert event’ with key stakeholders), allowing the study to complete on time.

Oversight and management of the PuP4Dads study was undertaken by the following groups and committees: the Study Research Group, including service delivery collaborators, the SSC and the DMEC. The membership, role and remit of each group, as well as meeting dates, are detailed in the appendices (see Appendices 2–4).

Patient and public involvement and engagement

Our public engagement strategy at the beginning of the study included:

-

involving fathers and mothers with lived experience of opioid dependence as advisors on the study

-

including clinicians with experience of working with this population on the SSC

-

conducting an expert event towards the end of the study to present and discuss the preliminary findings with a wider stakeholder group

-

involving study participants in dissemination events.

A father and mother with a history of drug use [identified via the Scottish Drugs Forum’s Addiction Worker Training Project (Glasgow, UK)] were invited to join the SSC before the start of the study and their appointment was approved by NIHR. The first RF (KK) met with the parents individually and then together at the beginning of the study to pilot the participant information sheet, consent form and interview schedules designed for parents. The parents also commented on the ‘participant details sheet’, planned questionnaires (e.g. in what order they should be administered) and the qualitative interview schedules. The parents’ input helped to ensure that these materials were suitable and understandable for participants and could be sensitively administered to parents to maximise completion rates. The parent representatives declined our invitation to attend SSC meetings, citing difficulty in taking time off work [i.e. they would have needed to take a whole day off to travel to the University of Stirling (Stirling, UK) from Glasgow and both parent representatives were new into employment]. The research team also felt that the parents were more relaxed and comfortable in one-to-one meetings and could contribute more meaningfully this way.

Around the time of the next SSC meeting, the researcher contacted the parents by telephone to discuss recruitment strategies and then again 6 months later to discuss plans for a project extension. Parents provided input into the decision-making process, including the time frame for extending the recruitment period and intervention delivery times. In addition, parents were of the opinion that intervention timelines should be tailored to individual families (according to what the parents and family needed) and they supported the idea of changing the data collection time points to fixed time points (i.e. baseline and at 6 and 12 months) to enable the study to complete on time. Therefore, parents were against the idea that families should be pressurised into completing the programme within a certain time frame.

The research team were unable to contact the two parents towards the end of the study, as both were in full-time employment and did not respond to messages. We contacted the Scottish Drugs Forum to see if we could re-establish contact, but were unsuccessful. In preparation for the expert event in October 2020, the research team decided to invite a number of fathers who had taken part in the study to attend the event. Two fathers (FA22 and FA23) who had participated in the PuP programme and study agreed to attend. Both fathers joined the online sessions on the day [via Microsoft Teams video-conferencing (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA)] and contributed well to the discussion. Feedback from other participants at the event confirmed the value of the fathers’ input as recipients of the programme and participants of the study. FA22 and FA23 also provided assistance with the Plain English summary for this report and both engaged in discussions on the study design for a future evaluation of PuP4Dads. This input helped confirm the fathers’ support for research on the effectiveness of the programme and their views on maintaining an ‘inclusive’ approach to the eligibility criteria for a main study (they were both keen that non-resident fathers should be included and that all fathers should ‘be given the chance’ to receive the programme).

For a full description of the expert event and results from this public engagement activity, see Chapter 4, Expert event (public engagement).

Reflections on our experience of patient and public involvement and engagement for this study

Engaging parents who are drug dependent in patient and public involvement and engagement (PPIE) presents a number of challenges, as they are a stigmatised and marginalised group of parents who often lack the confidence to participate in groups or committee meetings, and the families have child care responsibilities, but often do not have child care or the spare time to engage in PPIE activities. Engagement often needs to be on a one-to-one basis and in settings that are comfortable and non-threatening (e.g. home visits, coffee shops or over the telephone). Families are often engaged with multiple services and can be working in jobs with irregular hours, and so achieving contact within usual ‘office hours’ can be challenging. Therefore, extreme flexibility is required by the RFs. In addition, parents need to be reasonably ‘stable’ drug users (not intoxicated) to be able to contribute to discussions and to maintain contact with the study team. Even when they are stable and motivated to be involved in research, this population often lack the resources to contribute (e.g. time, effort, equipment and money, including sufficient credit to return missed calls and enough data to attend video-conferencing meetings). Therefore, considerable research resource is needed to engage this population in the research process in a meaningful and consistent way. Despite these difficulties, the involvement of parents in this study who were active drug users (prescribed OST and involved in drug treatment services) was really valuable, as they were able to provide up-to-date accounts of some of the challenges that fathers who use drugs face.

Study procedures

This section of the report describes the study procedures, including data collection methods, for each participant sample that took part in the study, beginning with the fathers and their families and followed by PuP practitioners, supervisors, service managers and referring professionals.

Participants: fathers and families

The target population for this study were families living in Lothian with children (aged 0–8 years) affected by paternal drug use, namely families with fathers/male caregivers diagnosed with opioid dependence and currently prescribed OST. We anticipated that most fathers who enrolled in the study would reflect the population of men normally engaged in OST (i.e. the majority were aged between 18 and 55 years, on a low income or unemployed and in receipt of welfare benefits, living in social housing in areas of deprivation and had a history of polydrug use and criminal justice involvement, including imprisonment).

Sample size

The target was to recruit 24 families with a father/male caregiver receiving OST. This number was expected to be sufficient to allow the qualitative and quantitative progression criteria to be assessed and to provide information on key parameters for the design of a future evaluation, allowing for expected attrition of one-third [see sample size justification in study protocol v5.0, NIHR Journals Library URL: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/phr/158201/#/ (accessed 6 September 2021)].

The sampling strategy aimed to include a diverse range of fathers and families who broadly reflect the diversity of family constellations that are commonplace among this population, for example:

-

biological and non-biological (‘social’ or ‘step’) fathers

-

resident and non-resident fathers (living with or apart from the children)

-

concordant couples (where both the father and the mother are drug dependent)

-

discordant couples (where only one adult – the father – is drug dependent).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria

-

Fathers with an International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision,74 diagnostic criterion for opioid dependence and prescribed OST {e.g. methadone [methadone hydrochloride, Alliance Healthcare (Distribution) Ltd] or buprenorphine [subutex, Indivios UK Ltd]}.

-

Mothers/partners of fathers recruited into the study (regardless of whether or not they had a diagnosis of substance dependence themselves).

-

Families that have at least one ‘index’ child aged 0–8 years or are expectant parents (revised in June 2017 from pre-school children only).

-

Biological or non-biological fathers.

-

Fathers/male carers involved in the day-to-day care of the index child.

-

Fathers in a relationship with the mother/partner for at least 6 months.

Exclusion criteria

-

Either parent had a serious mental illness (e.g. active psychosis) that prevented them from fully participating in the programme.

-

Families in which domestic abuse or child abuse resulted in the father being prohibited from contact with the target child or family.

-

Families in which the father was facing an imminent prison sentence of > 6 months or a criminal justice order of > 6 months that would prohibit their active involvement in the programme.

-

Either parent was aged < 16 years.

-

Either parent was not officially resident in the Lothian region.

Recruitment process

Treating clinicians were contacted, informed about the study and encouraged to invite eligible fathers to take part. Recruitment sites included NHS Lothian substance misuse directorate and partner drug agencies (third sector), selected primary care teams in areas of deprivation in Edinburgh [with general practitioners (GPs) who prescribed OST to drug users], health visiting teams throughout Lothian and the two implementation site services (PREPARE and CIRCLE). A study invitation letter was sent to all recruitment sites, which included information on the study, participant eligibility criteria and clear instructions on how to refer into the study. Meetings were arranged with potential referrers working in community-based teams across Lothian (n = 8) to answer questions about the study and the intervention. Staff were asked to approach eligible fathers when they attended for routine appointments. If fathers showed an interest in taking part in the study, the clinician passed the contact details of the father (i.e. name, address and telephone number) onto the research team. Potential participants were then contacted by the research team by telephone to discuss the study. If the father was interested, arrangements were made to meet the father and family in their home to discuss participation in full and to provide a participant information sheet. Informed written consent was obtained if the father agreed to take part [see NIHR Journals Library URL: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/phr/158201/#/ (accessed 7 September 2021)].

The consent process involved agreement regarding confidentiality (including the limits of confidentiality in respect of child and adult protection and legal issues), permissions regarding data collection (including audio- and video-recording and follow-up), data management and anonymity, GP notification, payment of expenses, consent to access NHS prescribing data and social work child protection data, and freedom to withdraw from the study. When the father had an eligible partner, mother or co-parent, they were invited to take part in the study. Children in the family who were deemed to have the capacity to consent and who wished to participate in the intervention were eligible to take part. Similarly, kinship carers or other family members (e.g. grandparents) who wished to take part in the programme were invited to enrol in the study. However, neither young people nor kinship carers were enrolled in this study.

For safety reasons, and in accordance with lone-worker and home-visiting policies, two researchers attended the first home visit with participants or, where appropriate, the researcher arranged a joint visit with the practitioner from PREPARE or CIRCLE. When it was assessed as safe to do so, subsequent appointments were conducted by a lone researcher, unless the EAS (video observational measure) was administered, in which case the principal investigator (AW) attended the visit to administer this measure using an NHS laptop (a requirement to ensure security of personal identifiable video data).

Strategies to promote retention

The following strategies were used to enhance engagement and retention of fathers in the study:

-

On enrolment, seeking permission from the parents to document the name, address and mobile telephone number of significant others who may know the whereabouts of the family if the study team could not contact or locate them. This involved completing an ‘alternative contacts form’ with a list of professionals, family members and others who the parents agreed could be contacted if required. This allowed the research team to locate several fathers and families, for example, after they had moved address, changed their telephone number or had separated from their partners.

-

Mobile telephone text messaging was used to arrange appointments, send appointment reminders and to generally communicate and ‘check-in’ with families. A lot of families had very limited finances and so would not make audio calls or listen to voicemail, as these cost more. However, mobile telephone communications could be unreliable, as many parents ‘ran out of credit’ and their telephones were switched off, so appointment letters were also posted to participants.

-

Researcher interview appointments were also arranged at a convenient time to suit participants, and appointments were flexible and could be rearranged at short notice to accommodate the changing availability of the parents.

-

When participants failed to attend research appointments or cancelled appointments, repeat offers were made and there was no limit placed on the number of appointments missed or cancelled (which were numerous).

-

Parents who had children in out-of-home placements were also interviewed with their children where this was possible to arrange. This often involved seeking permission from the ‘corporate parent’ (i.e. via the allocated social worker) to accompany the parent to a supervised contact visit. Assent from the child was then sought and the researcher attended the contact visit site with the parent.

-

Maintaining contact with the parents was also undertaken by sending Christmas, birthday and Father’s Day/Mother’s Day cards to participants.

-

The researcher maintained contact with the PuP practitioner to ensure that any parents who dropped out of the intervention could be approached for a follow-up interview.

-

Participants were offered gift vouchers for taking part in each research interviews as a thank you and to cover any out-of-pocket expenses (e.g. child care costs, travel costs and subsistence costs). The voucher payment schedule was escalated so that follow-up interviews were worth more for the participants (i.e. £15 at baseline, £20 at FU1 and £25 at FU2).

Data collection

Data were collected at three time points with parents:

-

baseline (pre-treatment interview)

-

FU1 (end of treatment/dropout or 6 months after baseline)

-

FU2 (post treatment or 12 months after baseline).

Once consent was given, arrangements were made to collect baseline data at a time convenient for the father (and mother). The researcher administered the questionnaires separately to fathers and mothers, often on different days over two, sometimes three, visits. The researcher also then referred the family to a PuP practitioner in one of the implementation sites (if the referral was not from an implementation site practitioner).

Measures

The measures taken at each time point are listed in Table 2 and described in more detailed below.

| Measure | Time point | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | FU1 | FU2 | After FU2 | |

| Sociodemographic data | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| BCAPI | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| PSCS | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| DERS | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| CTS2 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| TOP | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| EQ-5D-5L (quality-of-life measure) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| EAS | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| PAAS/MAAS | ✓ | |||

| BITSEA or SDQ (dependent on age of child) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| PuP fidelity bespoke questionnaire (on one occasion only, when the PuP programme is completed) | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Short qualitative interview exploring previous experience of parenting and family support services | ✓ | |||

| Longer qualitative interview exploring experiences of PuP and study measures and procedures | ✓ | |||

| PuP session attendance data from PuP practitioners (requested at the end of treatment) | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Service use survey (health economics) | Participants requested to complete this after each PuP session throughout the intervention period | |||

| OST prescription data requested from NHS (health service) prescriber | ✓ | |||

| Details of child protection status requested from Social Work Scotland records | ✓ | |||

Baseline

At the pre-treatment assessment (i.e. baseline interview), sociodemographic data were collected on a ‘participant details sheet’ and both fathers and mothers were asked to take part in a brief semistructured qualitative interview to explore their views on ‘usual’ parenting/family support services for fathers and previous experiences of parenting interventions [see NIHR Journals Library URL: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/phr/158201/#/ (accessed 7 September 2021)]. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. In addition, the following measures were administered, as appropriate, to both fathers and mothers.

-

The Brief Infant Toddler Social and Emotional Assessment (BITSEA)75 has 42 items, is widely used, is sensitive to change and is used for infants aged 12–36 months.

-

The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ)76 has 25 items (including subscales of attention and concentration, conduct problems and emotional problems) and is used for children aged 2–16 years. The SDQ is widely used across diverse groups and showed sensitivity to change in the PuP RCT. 46

-

The EAS55 assesses emotional availability using a 10-minute video-recording of a parent and a child engaging in an age-appropriate game or activity. The EAS55 draws from attachment theory and emotional availability constructs and has good convergent validity with attachment style as assessed by the Strange Situation procedure. 78 The EAS is suitable from infancy to late childhood.

-

The Maternal Antenatal Attachment Scale (MAAS) or Paternal Antenatal Attachment Scale (PAAS)56 were used when parents were expecting a baby and were not caring for another child. The PAAS56 is the corresponding measure to the MAAS and is a 16-item self-report scale used to measure paternal antenatal attachment. It is an accurate predictor of post-birth father–child attachment. The PAAS was conducted at baseline and before the estimated date of delivery. The MAAS56 is a 19-item self-report scale used to measure antenatal maternal attachment and is widely used. The MAAS is suitable for first-time parents or those without current child care responsibilities during the antenatal period. The MAAS was conducted once at baseline and before the estimated date of delivery.

-

The Parenting Sense of Competence Scale (PSCS)79 is a 17-item self-report scale used to measure satisfaction/comfort with being a parent, parental self-efficacy (i.e. perception of knowledge and skills) and interest in parenting. The PSCS is widely used in parenting literature and is sensitive to change.

-

The Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS)80 is a 36-item scale that measures six dimensions of emotion dysregulation (e.g. lack of awareness of emotional responses, limited access to emotion regulation strategies and difficulties controlling impulses when experiencing negative emotions). The DERS is well validated psychometrically and widely used in intervention studies that focus on mindfulness.

-

The Revised Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS2)81 is a 39-item scale that is used to assess the presence and severity of intimate partner violence, including psychological and physical abuse subscales, and is sensitive to change. The CTS2 has been used by Stover et al. 18 in studies of intimate partner violence prevention in substance-using men.

-

The Treatment Outcomes Profile (TOP)82,83 has 20 items measuring domains of drug-related harm, including daily illicit drug use and alcohol use in last 28 days (drug type and amount), and is based on the Timeline Followback questionnaire. 84 The TOP also includes items on injecting risk behaviour, crime, physical and psychological health, and quality of life. The TOP is widely used in clinical practice in the UK to measure change and progress during drug treatment.

-

The EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L),85 is a five-item health-related quality-of-life survey that is used in the generation of quality-adjusted life-years.

-

At baseline, parents were provided with the ‘service use survey’ and were shown how to self-complete the forms. Parents were asked to complete one survey form each after every PuP session (assumed to be weekly or fortnightly). This form included a simple record of their health, social care and criminal justice service use since the last PuP session. Completed forms were collected by the researcher at the FU2 interview.

Follow-up 1

At 6 months after baseline or at end of treatment/dropout, a follow-up interview was arranged. A longer qualitative interview was conducted with all participants, exploring the acceptability of the PuP programme, perceived benefits of engaging in the PuP programme and acceptability of the study measures and procedures [see NIHR Journals Library URL: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/phr/158201/#/ (accessed 7 September 2021)]. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Once the interview was complete, all the measures taken at baseline were repeated, except for the MAAS and PAAS,56 which were not applicable because all participants’ babies had been born by FU1.

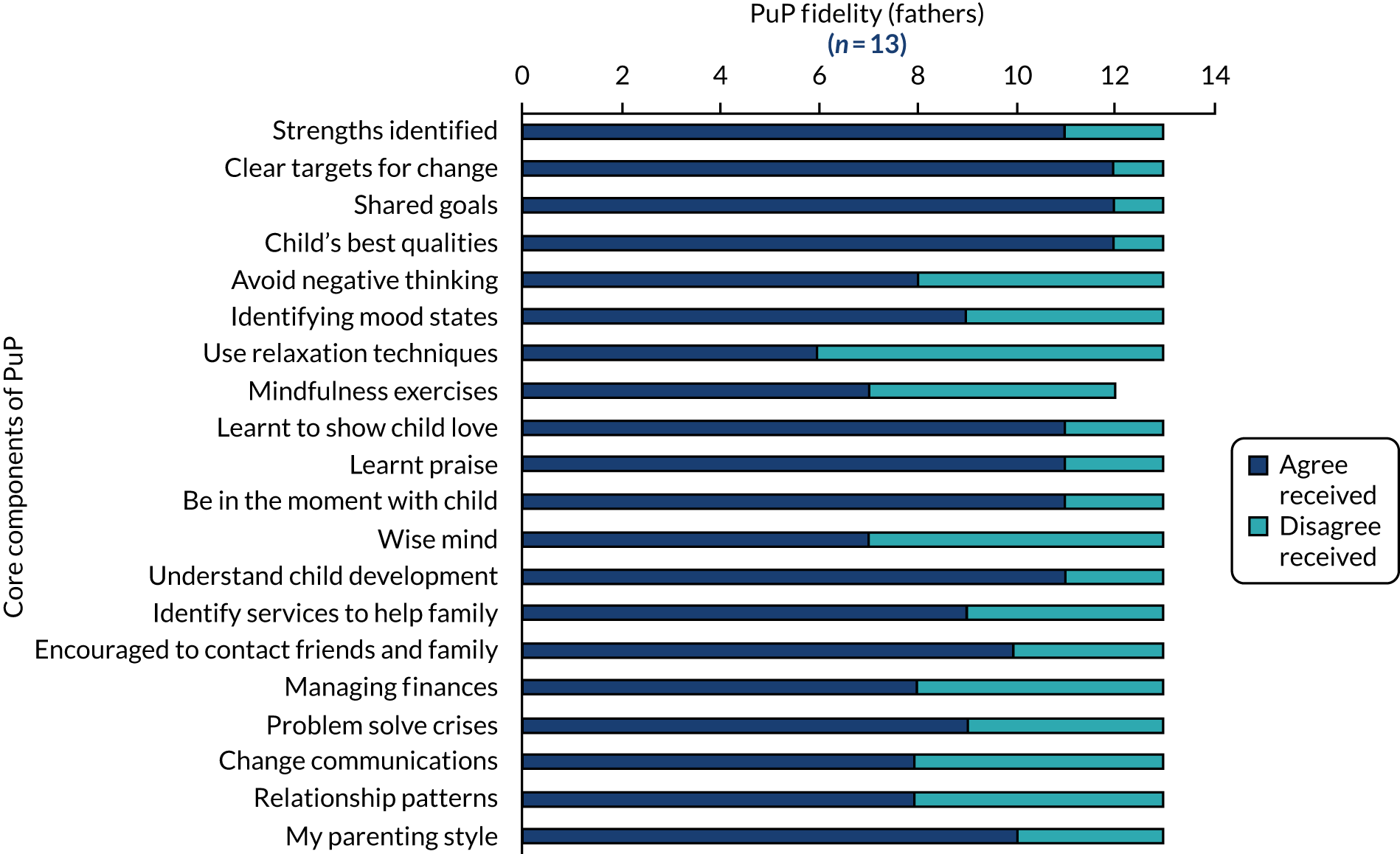

The PuP fidelity measure (a bespoke 20-item scale used to assess which components of the PuP programme were received, according to each parent) was administered if the participant had finished undertaking the programme.

On completion of the programme or dropout/discharge from the service, PuP session attendance data for fathers and mothers were recorded by the PuP practitioner on an attendance sheet provided by the researcher. This recording sheet included the participant’s unique identification code, dates of appointments ‘attended’ and dates of appointments ‘not attended’ (fathers and mothers recorded separately) so that the length of programme delivery could be calculated along with attendance rates.

Follow-up 2

Follow-up 2 (i.e. the third interview with parent participants) was scheduled for 12 months after baseline (or 6 months post completion of treatment /dropout). At FU2, all questionnaire measures completed in FU1 were administered by the researcher.

After follow-up 2

The following data were collected retrospectively for all consenting participants for the study period.

-

Data about child protection registrations and de-registrations and out-of-home placements were obtained from Social Work Scotland records (with participants’ permission) for the period from enrolment to FU2. The research team wrote to the chief social work officer in each local authority area to request these data.

-

Data about medications prescribed for the treatment of opioid dependence (i.e. OST) were obtained from prescribers (i.e. GPs) or from the addiction service prescription database (with participants’ permission) to show changes in drug type and daily dosage for the period from enrolment to FU2. The research team wrote to GP prescribers and contacted the NHS addiction team to request these data and a payment was provided to reimburse clinicians for the time required to obtain and report these data.

Participants: Parents under Pressure practitioners, supervisors and service managers

Sample

Parents under Pressure practitioners (n = 8) who delivered the intervention to study participants were invited to join the study and take part in a qualitative interview. Two PuP practitioners (one in PREPARE and one in CIRCLE who later trained to become an accredited PuP supervisor) were also invited to take part in a second interview after they qualified. In addition, all line managers and senior managers in PREPARE and CIRCLE (n = 7) were invited to join the study and take part in a qualitative interview towards the end of the intervention delivery phase.

Recruitment