Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the PHR programme as project number 15/181/01. The contractual start date was in January 2017. The final report began editorial review in September 2021 and was accepted for publication in May 2022. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PHR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2023 Lohan et al. This work was produced by Lohan et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2023 Lohan et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Structure of this report

This report presents the findings from a cluster randomised controlled trial (RCT) evaluation of the If I Were Jack programme. This chapter provides the background for the study and a description of the programme. Patient and public involvement (PPI) in the study is described in Chapter 2. The major focus of the PPI involvement was in relation to the optimisation of the programme that occurred within this study prior to the trial. The methodology for the trial and process evaluation is outlined in Chapter 3. The results of the recruitment and data collection processes are outlined in Chapter 4. The quantitative findings from the trial regarding the impact of the programme on student outcomes are reported in Chapter 5, and the findings from the accompanying qualitative process study are set out in Chapter 6. Chapter 7 details findings of the economic evaluation, and key issues and conclusions emerging from the findings are set out in Chapter 8.

The public health problem addressed: reducing unintended teenage pregnancy and promoting positive sexual health

Relationship and sexuality education (RSE) for young people is a challenging, complex, controversial and critical worldwide public health issue. High-quality comprehensive RSE for young people is not only essential to achieving better health and health care for adolescents, but is also key to ensuring women’s rights, gender equality, and sound demographic and economic development for future generations. As such, high-quality RSE addresses three 2030 sustainable development goals: to ensure quality education, gender equality, and good health and well-being. 1,2

Although teenage pregnancy is not universally negative,1 reducing teenage pregnancy has the potential to reduce a myriad of negative medical outcomes, such as low birthweight and undernutrition, as well as the negative consequences for educational and social well-being of young people and their babies over the life course globally. 2–6 Teenage pregnancy is widely understood as not just a cause, but also a consequence, of under-privilege, which is why addressing teenage pregnancy through developing young people’s agency to improve their own lives is so important.

The UK still has the highest rate of teenage pregnancy in Western Europe. 7–9 Despite the fact that conception rates for women aged < 18 years have been falling (halving in the last decade), the rate in England and Wales in 2018 was 16.8 per 1000 population. 10,11 Approximately 25,000 teenage women become pregnant in England and Wales annually, and approximately half of these pregnancies end in legal abortion. 12 The teenage pregnancy rate in Scotland was 30.2 per 1000 in 2017. 13 In Northern Ireland (NI), abortion was illegal until October 201914,15 and was considered lawful only in exceptional circumstances in which the life of the pregnant woman was at immediate risk, or if there was a risk of serious injury to her physical or mental health. Reflecting the different legal framework (pre October 2019), government targets around reducing teenage pregnancies in NI relate to births and not conceptions. In NI, the birth rate to teenage mothers per 1000 young women aged 13–19 years was 11.3 in 2013. 16 In the same year, the teenage birth rate in the most deprived areas was 23.0 per 1000, nearly six times that of the least deprived areas (3.9 per 1000). 17

Preventing unintended conceptions implies preventing unprotected sex. Drawing from robust representative epidemiological data of school-aged children across the UK18 and the Young Persons’ Behaviour and Attitudes Survey NI,19 it is known that between 25% and 33% of 15-year-olds are having sex, with an associated rate of 2.8% reporting unprotected sex. Changing practices of unprotected sex and unintended pregnancy is complex, and cannot be achieved through RSE alone. 20–26 However, high-quality comprehensive RSE is an essential component in the process of reducing unintended pregnancy rates, as well as being a vital aspect of improving holistic sexual health and well-being. 27–33 The UK governments emphasise the policy importance of the implementation of RSE in schools in decreasing conception rates for those aged < 18 years and the promotion of positive sexual health among teenagers. 34–36

Current status of relationships and sexuality education

The current status of RSE provision in schools in the UK is as follows: educational policy, including relationship and sexuality education, is devolved to the nations of the UK. Hence, the terminology to describe the education young people receive relating to sex and relationships varies in each nation as follows. RSE guidance in NI is predominantly structured under the personal development (PD) strand of the Learning for Life and Work curriculum. In England, sex and relationship education (SRE) is provided under the umbrella term personal, social, health and economic education (PSHE). Pupils in Scotland receive relationships, sexual health and parenthood education as part of their Curriculum for Excellence framework. In Wales, SRE forms one of the six Areas of Learning Experience. For the purposes of uniformity in this report, the appellation RSE is applied UK-wide. In England and Wales, RSE is currently undergoing significant reform. England introduced compulsory RSE in 2020, post data collection for this trial,37 and Wales is set to do so in 2022/3. 38 In England, however, parents will still be able to opt out their children when the topic of sex is being discussed. NI and Scotland have statutory guidance on what should be taught, although this is not compulsory, and many schools follow their own guidance or ethos concerning how the curriculum is delivered. 39,40 Therefore, throughout the UK there is no uniform guidance for the curriculum, and, where guidance exists, it is open to interpretation by schools in terms of how it should be implemented.

The If I Were Jack programme

Brief description

If I Were Jack is an evidence-based, theory-informed, user-endorsed intervention designed to engage especially with teenage boys and intended to increase both teenage boys’ and teenage girls’ intentions to avoid an unplanned pregnancy and to promote positive sexual health. In addition, it fits with a comprehensive approach to relationship and sexuality education. 41 If I Were Jack is a classroom-based RSE resource intended for use by teenagers aged 14–15 years. A specific aim of the intervention is to open up for scrutiny the gender norms that typically situate the issue of a teenage pregnancy as a woman’s problem, to also encourage males to share sexual and reproductive responsibility.

How it was developed

It has been designed, developed and piloted in Ireland, South Australia, NI and the remainder of the UK over 12 years by a team based at Queen’s University Belfast (QUB; Belfast, UK) led by Professor Maria Lohan and in consultation with pupils, teachers, sex education specialists and governments’ education and health promotion departments. 41 Further cultural adaptation initiatives are under way, one being led by Dr Sarah Skeen (Stellenbosch University; Stellenbosch, South Africa) and Dr Áine Aventin (QUB) in South Africa and Lesotho, and one being led by Professor Alejandra López Gómez (Universidad de la República; Montevideo, Uruguay).

Some key stages in the development of If I Were Jack as used in this study are as follows:

-

The development of an earlier version of the interactive video drama (IVD) of If I Were Jack, for the purposes of researching adolescent men’s views on teenage pregnancy and pregnancy resolution options in schools only. 42,43 The If I Were Jack IVD was directly inspired by, and closely based on, If I Were Ben – an original IVD used by Carolyn Corkindale and team at Flinders University (Adelaide, SA, Australia) for the purposes of similar research.

-

The development of the If I Were Jack RSE resource. In response to positive feedback and demand from schools that viewed the IVD, the QUB team redeveloped the IVD and developed an accompanying RSE programme (four to six classes) for NI and Ireland (two versions) through funding from the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) of the UK (RES-189-25-0300). Intervention development occurred in close consultation with young people, teachers, RSE experts and statutory policy stakeholders in Departments of Health and Education in Ireland and NI, in close examination of the evidence on the most acceptable and effective RSE components, and in line with Medical Research Council (MRC) guidelines for the development of complex interventions. 41

-

A feasibility trial, process evaluation and health economic evaluation (ISRCTN99459996) of the If I Were Jack RSE resource in NI and a transferability study in England, Scotland and Wales44,45 funded by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Public Health Research programme (15/181/01). The primary results of this stage were as follows –

-

Recruitment of schools was successful across a broad range of school types including faith-based schools (target 25%, achieved 38%).

-

No schools withdrew during the year-long trial, and pupil retention was good (target 85%, achieved 93%).

-

The process and transferability evaluations showed the intervention to be acceptable to schools, pupils and teachers, and that it could be feasibly implemented with some straightforward enhancements, including remaking a version of the IVD with English actors for an England/Wales audience and increasing the ethnic mix of actors.

-

The cost of delivery per pupil was calculated to be £13.66, and behavioural change effects showed promise.

-

The programme was also separately implemented and evaluated in Ireland through a qualitative mixed-methods study46 in a maximum variation sample of schools, where again the acceptability and feasibility of implementation were demonstrated –

-

Redevelopment of the parental component of the intervention. 47 The parental component was changed from a face-to-face to an online component, and student–parent homework exercises were retained in response to results of the above feasibility trial, in a separate study funded by the Public Health Agency of Northern Ireland.

-

The JACK trial – current study to include optimisation of intervention to update materials and make it more suitable for use in England, Scotland and Wales, and UK-wide effectiveness trial with process and health economic evaluation. 48

-

Underpinning research on parents and young people with highest needs. Alongside the above development of the intervention and the underpinning research with young people, the lead principal investigator (PI) has been involved in related studies49–51 researching parents’ experiences of talking to their pre-adolescent and adolescent children about relationships and sexuality, and researching RSE needs of especially vulnerable groups of young people, notably young people in care. 52,53

Intervention components

The intervention components available on the project webpage, www.ifiwerejack.com/ (accessed 20 October 2022), include:

-

A culturally sensitive computer-based IVD to immerse young people in a hypothetical scenario of a week in the life of Jack, a teenager who has just found out that his girlfriend is unexpectedly pregnant. The If I Were Jack interactive film asks pupils to put themselves in Jack’s situation and consider how they would feel and what they would do if they were Jack. (The film is interactive in the sense that it requires viewers to respond about how they would think or act as the narrative develops, but the film does not change in response to these choices.)

-

Classroom materials for teachers containing detailed lesson plans with specific classroom-based and homework activities designed to build pupils’ skills to (1) obtain necessary information and (2) develop communication skills with peers and trusted adults. Teachers can deliver the intervention to pupils during four 50- to 60-minute or six 35- to 45-minute weekly classes.

-

Ninety-minute training session for teachers implementing the intervention.

-

Two short animated films to engage parents/guardians and help/encourage them to have a conversation with their teenager about avoiding unintended pregnancy.

-

Detailed information brochures, letters for schools, letters for parents about the intervention and factsheets and wallet cards about unintended teenage pregnancy (UTP) in general for schools, teachers, teacher trainers, young people and parents/guardians.

The Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) checklist54 is used to describe the intervention in more detail, and this longer description of the intervention is available in Report Supplementary Material 1.

Theory of change and how it is hypothesised to work

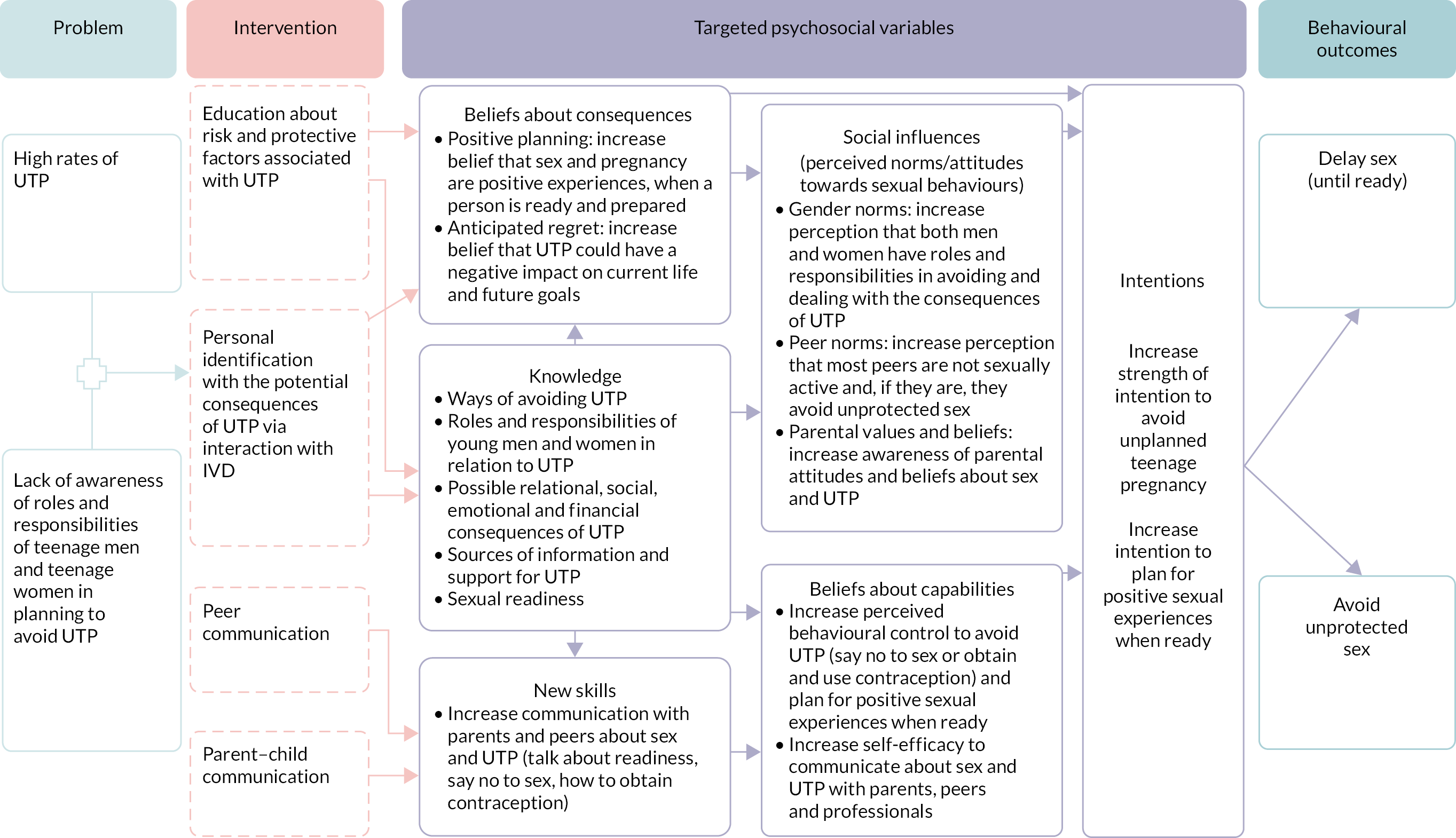

Presented in Figure 1 is the theory of change logic model of the intervention. Described on the left is the core public health problem: the relatively high rates of teenage pregnancy, as noted above. In addition, the public health need to engage young men as well as young women in addressing teenage pregnancy is stated. In brief, we hypothesise that by encouraging personal identification with the UTP scenario in the IVD, we engage pupils in an exercise of the imagination whereby they stop and think about the consequences that a UTP might have on their current life and future goals. This identification and reflection process is reinforced by providing knowledge about the risks and consequences of a UTP and ways to avoid it, and offering opportunities to practise communicating about UTP with peers and parents/guardians (activities that also increase awareness of peer norms, personal and familial values, and beliefs about sexual behaviour and unintended pregnancy). We hypothesise that by targeting these psychosocial factors, as well as inviting scrutiny and critical thinking in relation to wider social norms (gender norms and class norms), we can have an impact on teenagers’ sexual behaviour via pathways through their intention to avoid a UTP. The behavioural outcomes we seek to achieve are delaying sex until young people feel prepared and avoidance of unprotected sex.

FIGURE 1.

Theory of change logic model of the intervention.

Evidence supporting intervention components and theory of change

The characteristics of effective RSE programmes that help to increase their impact on sexual risk-taking behaviours have been précised in a number of systematic reviews. 25,55–62 These impactful characteristics include the use of theoretically based interventions targeting sexual and psychosocial mediating variables such as knowledge, attitudes, self-efficacy, intentions, perceptions of risk and perceptions of peer norms that are linked to sexual behaviour change; the use of culturally sensitive and gender-sensitive interventions; the use of interactive modalities that promote personal identification with the educational issues and engagement of young people; the use of skills-building components; the involvement of parents in the RSE process; and facilitating linkages with support services. The If I Were Jack intervention represents an innovative combination of all these different elements and is therefore predicted to decrease young people’s sexual risk-taking behaviour in relation to avoiding teenage pregnancy. The evidence for each of the components is further broken down below.

Evidence supporting a theory-based approach

Providing a theoretically informed foundation is considered key to the effectiveness of sexual health education programmes, ensuring that the most important determinants of young people’s sexual behaviour are targeted. 28,57,59,63–65 Early exploratory work for the design of the intervention is reported elsewhere. 41 The underpinning theoretical framework for this intervention combines the theory of planned behaviour,66,67 to address key psychosocial determinants of sexual behaviour, and gender-transformative programming, to address the broader context of promoting positive masculinities and addressing gender inequalities. 68,69

The use of theory of planned behaviour in If I Were Jack

The theory of planned behaviour largely focuses on individual-level behavioural antecedents of a particular behaviour of an unplanned pregnancy. The If I Were Jack intervention has been designed to increase teenagers’ intentions to avoid an unplanned pregnancy by delaying sexual intercourse until ready or avoiding unprotected sex by use of modern contraception. With these behaviours in mind, the intervention targets six psychosocial mechanisms, which research indicates are related to a reduction in risk-taking behaviour. These are: knowledge, skills, beliefs about consequences, social influences, beliefs about capabilities and intentions25,70,71 (see Figure 1). Each of the activities included in the intervention is designed to specifically target one or more of these psychosocial mechanisms, such as activities that provide pupils with educational information and opportunities for discussion, skills practise, reflection and anticipatory thinking.

Later critiques of the theory of planned behaviour bring an understanding of the broader socioenvironmental factors and underlying values that influence behaviours, such as religiosity and gender ideologies associated with teenage pregnancy. 24,67 Although these normative values are not addressed at a societal level in this intervention, they are addressed through young people’s agency. Through intervention activities, young people are invited to think critically about social class, religious and gender norms that may influence their thoughts and behaviours on this topic – hence especially the importance of gender-transformative theory.

If I Were Jack is also informed by gender-transformative programming

A gender-transformative approach was first developed by Geeta Rao Gupta68 in the context of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) epidemic, and has since gained traction as a means to improve health and well-being in sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) and health and development policy more generally. 69,72–75 The World Health Organization (WHO) defines gender-transformative approaches as those ‘that address the causes of gender-based health inequities through approaches that challenge and redress harmful and unequal gender norms, roles, and power relations that privilege men over women’69 (Gender Mainstreaming for Health Managers: A Practical Approach. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO).

Over the past decade in the RSE evidence base, the need for gender-sensitive interventions to address teenage pregnancy has been highlighted as a global health need by WHO76–78 and recommended in systematic reviews of RSE education. 25,79–81 By gender sensitive, it is meant that RSE should seek optimal ways to engage both young men and young women and to address gender norms, roles and relations that may lead to generating healthy and enjoyable relationships and positive sexual and reproductive health over their lifespan. In addition, the language of gender-transformative theory that explicitly challenges gender inequalities has been part of the WHO guideline82 on preventing adolescent pregnancy in developing counties since 2011, specifically in relation to the engagement of men and boys. More recently, the WHO83 recommendations on adolescent SRHR state that ‘building equitable gender norms through comprehensive sex education can contribute to preventing gender-based violence and to promoting joint decision making on contraception in couples’ (WHO Recommendations on Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.). The United Nations Population Fund also emphasises a focus on gender and empowerment outcomes consistent with a gender-transformative approach,84 as does the most recent agenda-setting document in the field: the Guttmacher–Lancet Commission on Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights. 85 A further term used in the scientific literature by Haberland and Rogow86 is an ‘empowerment approach to Comprehensive Sex Education (CSE)’, to refer to programmes that emphasise gender/power versus those that do not. Their review states that comprehensive sex education (CSE) is most effective when it highlights a gender/power perspective. 86 Finally, engaging men and boys in a gender-transformative approach is also embedded in an ‘enabling environment’: an ecological framework to improve adolescent sexual and reproductive health –

These approaches promote alternative norms and understandings of masculinity and behaviors in intimate relationships that involve mutual respect and equitable decision making, sharing responsibilities for reproductive health (e.g., condom use), and the greater involvement of men as fathers and caregivers. 87

Reproduced with permission from Svanemyr et al. 87 This article is available under the Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND license and permits non-commercial use of the work as published, without adaptation or alteration provided the work is fully attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

Hence, collectively across the literature with reference to a gender-sensitive, gender-transformative or empowerment approach to CSE, the need to develop RSE interventions that successfully engage adolescent women and adolescent men, and that address unequal gender dynamics in intimate relationships, has been expressed.

The If I Were Jack programme is designed to be both gender sensitive and gender transformative. It is gender sensitive as per the WHO definition, in that it is designed to include and engage young men on this topic alongside young women. It is gender transformative in that it addresses the negative gender norms and attitudes that place the burden of responsibility for preventing and dealing with the impacts of a teenage pregnancy on young women. It encourages communication and behavioural skills among young men and young women to enable them to prevent a teenage pregnancy and to know how to seek help. If I Were Jack acknowledges sexual pleasure and sexual intimacy in young people’s lives and asks young people to consider for themselves the balances between sexual pleasure and sexual responsibility in a gender-equitable manner. In addition, the programme seeks to address deficits in sex education for young men, particularly with respect to teenage pregnancy, that have been identified in the scientific literature, and that disadvantage adolescent men as well as adolescent women. 28,42,79,87–93

Evidence supporting the use of culturally relevant interventions

The resource includes an interactive computer-based modality incorporating drama and film. This is informed by research suggesting the need to engage with young people both empathetically and cognitively to convey the relevance of the issues being raised. 29,56,59,63,94 The feasibility trial and process evaluation44,45 demonstrated that the use of locally produced contemporary drama (in the IVD) made sex education more enjoyable and engaging for pupils. It is important to harness the potential for sex education to be enjoyed, especially by those who are less engaged in the wider school curriculum,30,95,96 a factor that was identified as a possible barrier to impact. 25 The feasibility trial44,45 also showed that the ability of users to identify with the key characters in the IVD, along with the overall tailored nature of the intervention in terms of linking in with local services, was central to its appeal and acceptability to pupils.

Evidence supporting the use of interactive computer-based interventions

The value of interactive computer-based interventions has been demonstrated in systematic reviews,59,60,97 particularly tailored, video-based interventions intended to elicit behaviour change. 98 A meta-analysis examining these reviews in relation to the theoretical mediators of safer sex61 concluded that they were successful in affecting knowledge, attitudes and self-efficacy relating to sexual health. Wearing headphones and sitting at individual computers, each participant is invited to answer questions on how he/she would feel and act as the drama unfolds.

Evidence supporting the use of skills-building components

Simply providing information does not lead to behaviour change; rather, young people must be supported to develop their own communication skills in relation to preventing risky sexual behaviours. 8,25,27–29,57,59,63,65,77,99,100 If I Were Jack emphasises the need for active participation and deliberation by the users so as to increase self-awareness and encourage ‘stop-and-think’ strategies in relationships. A further specific aim of the resource is to desensitise the discussion of sexual and reproductive topics through practising explicit ‘verbal scripts’63 for such conversations between young men and women.

Evidence supporting the involvement of parents in relationship and sexuality education

Although evidence suggests that schools are an important context for sex education,63,101,102 a number of systematic reviews have also shown that programmes that reach beyond the classroom can enhance effectiveness. 25,31,103 In particular, factors such as parental monitoring and supervision and familial communication have been associated with teenage sexual behaviours. 104,105 Parents are often a primary source of information about sex for adolescents,106 and teenagers who can recall a parent communicating with them about sex are more likely to report delaying sexual debut, and increased condom and contraceptive use. 107–109 One element of the If I Were Jack theory of change involves increasing self-efficacy in communicating about teenage pregnancy among parents and teens. This is built into the resource through home-based resources intended to generate communication and through short animated films for parents and guardians. This component informs parents of the resources and information about communicating about teenage pregnancy, including hints and tips about how to do so. Learning from the feasibility trial,44,45 in which parental attendance at information sessions was low (2.3%), the parental materials were redeveloped as animated films and provided online. Recent studies110–112 demonstrate the potential of embracing such ‘education entertainment’ or ‘edutainment’ modalities as engaging adjuncts to school-based education.

Importance of comprehensive relationship and sexuality education despite limitations of impact on health outcomes

Above, we have described the evidence for the programme characteristics of high-quality comprehensive RSE. Before we embark on describing the aims, objectives and results of this study, it is important to also sound a note of caution in terms of the limitations of comprehensive RSE alone in impacting on complex health behaviours, such as preventing unprotected sex and consequently preventing teenage pregnancy and reducing sexually transmitted infections (STIs). Another significant motivator for this study, however, was the importance of CSE as an international human right of young people and as an expressed need by young people.

By way of definition, CSE teaches about abstinence as part of the foundation for avoiding STIs and unintended pregnancy, and also teaches about condoms and contraception to reduce the risk of unintended pregnancy and of infection with STIs, including HIV. It also teaches interpersonal and communication skills and helps young people explore their own values, goals and options. 113 The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) specifies that CSE should be scientifically accurate, incremental, curriculum based, based on a human rights approach, based on gender equality, culturally relevant and contextually appropriate, transformative, and able to aid the development of life skills needed to support healthy choices. 33 This can be contrasted with the abstinence-only-until-marriage (AOUM) approach. The AOUM approach teaches abstinence as the only morally correct option of sexual expression for teenagers. It usually censors information about contraception and condoms for the prevention of STIs and unintended pregnancy. 113 If I Were Jack is part of CSE.

First, we acknowledge that two large cluster RCTs of CSE programmes24,114 in the UK did not show a significant effect on health outcomes. The SHARE (Sexual Health and Relationships Education) programme, trialled in Scotland, did not reduce conceptions or terminations by the age of 20 in comparison with conventional provision. 24 The Randomised Intervention of PuPil-Led sex Education (RIPPLE) trial was a peer-led sex education programme conducted in south-east England. The final results showed that the programme was not associated with change in teenage abortions but may have led to fewer teenage births. 114

Second, overall reviews of evidence have also detailed the limitations of CSE alone in affecting health outcomes, although they can have important impacts on knowledge, attitudes and skills. A NIHR-funded systematic review25 of the effect of interventions aiming to encourage young people to adopt safer sexual behaviour found that school-based interventions that provide information and teach young people sexual health negotiation skills can bring about improvements in behaviour-mediating outcomes such as knowledge, attitudes and self-efficacy but did not find significant effects on health outcomes. The review noted that these variables are, however, no less valuable than behavioural health outcome variables because they provide young people with a solid foundation on which to make sexual decisions. Similar findings have been noted in other reviews115–117> and meta-analyses, some of which are undertaken by organisations opposed to the implementation of CSE118,119 and favouring AOUM approaches. However, the AOUM approach not only has been found to be scientifically ineffective in helping adolescents to delay intercourse, but also is regarded as ethically flawed in terms of denying young people rights to information, endangering gender stereotypes and marginalising sexual minority youth. 120

Thus, despite some limitations noted in the scientific evidence for CSE alone in having an impact on ultimate health outcomes, such as teenage conceptions and teenage pregnancy terminations, the United Nations33 and WHO conclude from the evidence that ‘CSE can help adolescents to develop knowledge and understanding; positive values, including respect for gender equality, diversity and human rights; and attitudes and skills that contribute to safe, healthy and positive relationships’83 (WHO Recommendations on Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.). As the NIHR review also stated, these skills are no less important and reflect a holistic approach to RSE. 121–123

Moreover, young people have a right to high-quality comprehensive RSE. The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child,124 Articles 24 (health and health services) and 34 (sexual exploitation), stipulate that governments must provide education on health and well-being to enable children to protect their health, as well as implementing measures to protect children from sexual exploitation or violence. 124

Flowing from these fundamental rights, international human rights standards require that governments guarantee the rights of adolescents to health, life, education and non-discrimination by providing them with CSE in primary and secondary schools that is scientifically accurate and objective, and free of prejudice and discrimination. 125

The Committee on the Rights of the Child has further indicated that nation states should equip adolescents with relevant information in relation to contraception and avoidance of unintended pregnancy and STIs, including HIV/AIDS. 126

The right to sexual and reproductive health is also protected under the ‘right to the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health (https://www.refworld.org/docid/4538838d0.html; accessed 16 June 2020), enshrined in Article 12 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. 127 Finally, the right information and education to promote SRHR is also linked to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (targets 3.7 and 5.6). 128

However, few countries follow human rights standards129 and include CSE curricula to be part of the mandatory school curriculum, or implement and sustain large-scale CSE programmes. 83 Hence, the Guttmacher–Lancet Commission on Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights85 recognises the need for all countries to establish national curricula for comprehensive sexuality education based on evidence and drawing from international technical guidance such as that provided by the international policy community. 33 Furthermore, the Commission noted that, to be comprehensive, sex education must include strategies to increase gender equality and holistic health more broadly.

Finally, comprehensive RSE is also not just a right but a need, as expressed by young people themselves,41,45,96,130–133 and human rights standards state that the curricula should be developed with young people’s input, such as in the case of If I Were Jack (described more fully in the next chapter). With that balance of views on scientific evidence and children’s rights in mind, we now describe the aims and objectives of this study.

Aims and objectives of the JACK trial

The overall aim was to carry out the first UK-wide cluster RCT of a comprehensive relationship and sexuality education intervention using a gender-transformative approach to specifically engage with young men and young women to address teenage pregnancy and promote positive sexual health.

The objectives of the study were to:

-

assess the effectiveness of the intervention in preventing unprotected sex at 15 years of age among teenage boys and girls in a cluster RCT across the UK

-

assess the impact of the intervention on secondary outcome measures of knowledge, attitudes, skills and intentions to avoid teenage pregnancy, as well as additional behavioural outcomes of engagement in sexual intercourse, contraception use and STIs

-

examine any differential impacts for teenage boys and girls as well as for different socioeconomic groups and nations of the UK

-

conduct an economic evaluation of the intervention compared with current practice

-

conduct a process evaluation, examining reasons for participation and non-participation; intervention delivery and fidelity in intervention schools; RSE provision in all participating schools; and self-reported perceptions of effectiveness and moderating influences in intervention schools among a sample of pupils, teachers and school principals and parents.

The full protocol for this trial was published in June 2018,48 and the protocol and any updates to the protocol (described in Chapter 3, Deviations and rationale) can be found at the NIHR Evaluation, Trials and Studies website.

Chapter 2 Patient and public involvement

Introduction

Engagement of stakeholders, including policy-makers and commissioners, as well as teachers, young people and parents, has been central throughout this study. The purpose was to ensure that stakeholders’ views and opinions were used to inform key aspects of the intervention optimisation (stage 1 of this study), as well as study design processes, data collection procedures and dissemination. We begin this chapter with an overview of stakeholder involvement and then move to a fuller description of the process and results of stakeholder involvement as part of stage 1 of this study: intervention refinement and optimisation.

Overview of purpose and mechanisms of stakeholder engagement

The purpose and mechanisms of stakeholder engagement were as follows.

Intervention refinement and optimisation

-

During the intervention refinement and optimisation phase, (stage 1 of this study), we convened and consulted with a JACK trial Stakeholder Advisory Committee (SAC) (see Report Supplementary Material 2) consisting of senior representatives from key government departments and non-government organisations involved in RSE policy-making across the whole of the UK, including the Belfast Health and Social Care Trust (BHSCT; Belfast, UK), the Rainbow Project (Belfast, UK), Education Scotland (Livingston, UK), the Council for the Curriculum, Examinations and Assessment (Belfast, UK), the Personal, Social and Health Education Association (PSHEA; London, UK), NHS Glasgow (Glasgow, UK), Public Health Wales (Cardiff, UK), teachers and young people.

-

During the intervention refinement and optimisation phase, we also convened and consulted with a UK-wide Young Person’s Advisory Group (YPAG) (see below) on the refinement and acceptability of the intervention materials and processes.

Informing trial methodology

-

Throughout the study, consultations were held with the Trial Steering Committee (TSC) (see Report Supplementary Material 2). The TSC met four times: 13 March 2017, 22 February 2018, 16 May 2019 and 16 April 2021. The collective members of the international TSC included independent public members such as young people, parents, teachers and school principals; policy advisors to Public Health England (London, UK); experts in trial methodologies; and school-based RCT experts.

-

In addition, we engaged young people in the refinement of the trial outcome measure questionnaire. Representatives from the project YPAG, as well as young people who served on the TSC, provided feedback on the questionnaire that resulted in minor changes to the wording of some questions.

Implications of interim findings and dissemination

-

Members of the TSC, especially young person members, were consulted on the production of posters (see Report Supplementary Material 2) to thank schools for their involvement and provide an interim summary of findings.

-

The 2019 SAC meeting took the form of a ‘6 Nations’ Relationships and Sexuality Education Symposium held at QUB [with additional funding from QUB and EuroSocial (Madrid, Spain)]. In addition to members of the SAC, the event was attended by international experts from Departments of Health and Education across the four nations of the UK and from Ireland and delegates from the Ministry for Health in Uruguay. Dr Chandra Mouli from the WHO and Ineke van der Vlugt from Rutgers International, the Netherlands, also participated.

-

The symposium involved short presentations from each nation (including interim results of the JACK trial) and round table policy discussions on RSE and related sexual health policies.

-

The TSC met in April 2021 to consider the final findings of the study.

Stakeholder involvement in stage 1: intervention refinement and optimisation

Background and rationale

As reported in Chapter 1, in 2014/15 we conducted a cluster randomised controlled feasibility trial of the If I Were Jack intervention in eight schools in NI. In addition to the feasibility trial, and in preparation for the current UK-wide trial reported here, we also conducted a transferability study in nine schools in Wales, England and Scotland. The following research questions were addressed in the transferability study:

-

Was the intervention acceptable to schools and RSE curricula in other parts of the UK?

-

Would students and teachers in other parts of the UK find the intervention useful?

-

Could students in England, Wales or Scotland understand and relate to Jack and Emma as they appeared in the NI film?

-

Were there changes they would like to see to the classroom materials and film itself?

Together, the findings of the feasibility trial and transferability study indicated that, in all four UK nations, students, school staff and RSE experts welcomed and enjoyed the intervention. However, they also made some suggestions for improvements to the film, classroom materials, teacher training and parental components to make the resource materials relevant for use in their nations. We therefore sought to implement these and other changes in consultation with stakeholder groups, prior to commencing a full UK-wide trial. (Refinements to the parental components were conducted as part of a separate study in 2016, funded by the Public Health Agency for Northern Ireland.) This was achieved, as described below, during stage 1 of the current study.

Aim and objectives

Aim

-

To refine and optimise the If I Were Jack intervention for target populations in England, Scotland and Wales prior to a UK-wide RCT.

Objectives

Stage 1 of the current study involved a 12-month (January–December 2017) intervention refinement and optimisation process. This stage had the following objectives:

-

to convene a UK-wide SAC composed of RSE specialists and statutory stakeholders and YPAGs in each nation to inform refinement of the intervention and continue to build implementation capacity over the longer term

-

to produce updated and culturally refined versions of the If I Were Jack IVD – one for Scotland and NI using Northern Irish accents and one for Wales and England using English accents, both set in a UK urban setting and closely based on the original script and storyboarding

-

to refine classroom materials to match lesson-plan outcomes to learning outcomes of RSE curricula of the four nations where relevant (Scotland and Wales) and insert local information resources

-

to test the refined intervention in three schools based in England, Scotland and Wales judged against ‘stop/go’ criteria and deliver results to NIHR before progressing to stage 2.

Methods

Intervention refinement and optimisation was achieved via an iterative process involving consultation with stakeholders, including experts and YPAG members and a pilot study in England, Scotland and Wales. Table 1 summarises the key tasks and timeline of stage 1.

| Intervention refinement and optimisation tasks | Stage 1, year 1, January–December 2017 | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| January | February | March | April | May | June | July | August | September | October | November | December | |

| Tendering and procurement (films) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Recruit YPAG and SAC | ✓ | |||||||||||

| YPAG consultations | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Stakeholder group consultations | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Produce refined versions of interactive films | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Produce refined intervention materials | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Pilot study in England, Scotland and Wales | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Further minor refinements to intervention materials | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Phase 1: report to NIHR | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Phase 2: stop/go decision | ✓ | |||||||||||

Consultation on refinements to the interactive video drama

Our UK-wide YPAG was composed of 12 young people, aged 14–16 years, six male and six female, three from each of NI, Wales, Scotland and England. The young people were recruited via the project team’s network with pre-established community youth groups.

Young Person’s Advisory Group residential, Cardiff, April 2017

We held a 2-day residential workshop in Cardiff in April 2017, to discuss refinements to the If I Were Jack IVD. Three youth workers accompanied the Northern Irish, Scottish and English young people on the journey to Cardiff. Two film producers from Morrow Communications Ltd (Belfast, UK), which was commissioned to produce the new IVDs, also attended the workshop. The workshop was led by experienced youth advisory group facilitators from the Centre for Development, Evaluation, Complexity and Implementation in Public Health Improvement at Cardiff University (Cardiff, UK). It included six structured sessions over 2 days involving interactive focus groups, workshops and debates designed to promote discussion among, and feedback from, the young people. The sessions addressed the following: (1) identifying problems with the IVDs and film scripts, and (2) suggesting changes that would maximise the relevance and acceptability of the films for young people across the UK. YPAG members met again via videoconference in August 2020 to consult on draft versions of the films.

Consultation on refinements to intervention materials

In June 2017, members of the research team engaged in a 1-day workshop in London with the SAC from the four nations (see Aims and objectives of the JACK trial). This consultation focused on refinements to the non-film-based intervention inputs, activities and materials, including teacher training materials, student activities and materials, and proposed intervention delivery processes.

Stakeholders provided feedback, relevant to their representative nations, on the following:

-

sexual health services for young people including online information and local services

-

the RSE curriculum and potential positioning of the intervention within it and identification of existing similar interventions

-

delivery processes, including proposed length of sessions and identification of potential challenges

-

detailed comments on proposed teacher, student and parent activities.

Members of the SAC provided follow-up comments and feedback via e-mail on the refined versions of the intervention materials during July and August 2017. Draft digital and hard-copy versions of the intervention materials were prepared in October 2017 for use during the pilot study.

Feedback from the YPAG and SAC was collated and, along with findings from the feasibility and transferability studies, informed amendments to the script and film storyboard as outlined in the results section below.

Intervention optimisation: pilot study

In November and December 2017, the refined intervention was piloted in three schools, one each in Wales, Scotland and England. Teachers were trained to deliver the intervention by members of the research team, and students and teachers completed short surveys regarding their views on the intervention. Teachers who delivered the programme also took part in circa 30-minute semistructured interviews with members of the research team.

Results

Intervention refinements: films

The primary recommendations of the YPAG in relation to the IVD were (1) technology and music (e.g. add more generic background music and include texts on screen rather than on a particular mobile phone); (2) fashion (e.g. sportswear instead of jeans, updated hairstyles); (3) language (e.g. use of slang and occasional swear words to make interactions more informal and realistic); (4) filming locations and scenarios (e.g. pros and cons list at home not in a café); and (5) cultural representations (e.g. include more actors from ethnic minority/non-white backgrounds and include mixed-sex friendship groups). The young people also examined the film’s scripts in detail and recommended changes to the language used. A full report of the YPAG methods and outcomes is available in Report Supplementary Material 2.

The team worked with the film production company (Morrow Communications) to cast and produce two versions of the film (one for Scotland and NI casting actors with NI accents, and one for Wales and England casting actors with English accents). YPAG members met again via videoconference in August 2017 to consult on draft versions of the films and minor amendments were made at this stage following their recommendations. These minor amendments related to slight changes to the questions that appear in the IVD and inserting a space between the various parents’ reactions in the films. The young people were overwhelmingly positive about the revised versions.

Intervention refinements: materials

As well as the provision of nation-specific information noted above, the SAC offered the following key recommendations on refinements to the intervention materials:

-

Owing to the variability in relation to sexual health services, sexual health and RSE terminology and the provision of RSE across the nations, separate sets of materials would be required for each nation.

-

Stakeholders encouraged the use of more ‘sex-positive’ language in the materials, for example changing references to ‘abstinence’ to ‘sex when ready’.

-

Stakeholders encouraged the inclusion of activities and amendment of language that would make the materials more relevant to the lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning (or queer) (LGBTQ+) communities.

Pilot study results

In November and December 2017, the refined intervention was successfully piloted in three schools, one each in Wales, Scotland and England. Teachers were trained to deliver the intervention by members of the research team, and students and teachers completed short surveys regarding their views on the intervention. Teachers who delivered the programme also took part in circa 30-minute semistructured interviews with researchers. As outlined in Table 2, survey findings relating to the films were used to inform the stage 2 progression rules. Findings relating to the non-film intervention components (i.e. teacher resources and student activities) informed further minor refinements to the classroom activities and teacher training materials but were not part of the progression criteria.

| Progression rules | Pilot study findings | Stop/go decision | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| England | Scotland | Wales | ||

| At least 60% of students view the entire film | 93% of 43 participating students viewed the entire film | 100% of 34 participating students viewed the entire film | 100% of 56 participating students viewed the entire film | Go |

| At least 80% of students who view the entire film find the accents clear and understandable | 88% of 43 students found the accents ‘clear and understandable’ | 85% of 34 students found the accents ‘clear and understandable’ | 100% of 56 students found the accents ‘clear and understandable’ | Go |

| At least 80% of teachers report that they would be happy to use the If I Were Jack film again | 100% of two teachers said that they would use the film again | 100% of two teachers said that they would use the film again | 100% of two teachers said that they would use the film again | Go |

Conclusion

The involvement of stakeholders has been a key method of ensuring the quality and acceptability of the intervention and trial methods. Stakeholder voices and opinions informed intervention development and optimisation, study design processes and dissemination. The dedicated intervention refinement phase and pilot study allowed optimisation of the intervention materials prior to progressing to the stage 2 trial. Close consultation with stakeholders throughout was key to the success of stage 1 of the project and laid solid stakeholder-informed foundations on which to build and implement processes and procedures for stage 2 of the study. All resulting materials were made available on the If I Were Jack website post trial.

Chapter 3 Methodology

Study design

The JACK trial was a Phase III134 multicentre, parallel-group, cluster RCT with two treatment groups: the If I Were Jack intervention versus schools’ usual RSE provision. Schools were the unit of randomisation, with a 1 : 1 allocation. An embedded process evaluation and economic evaluation were conducted (economic evaluation methods are detailed in Chapter 7). The trial protocol was published. 48

Ethics approval and research governance

The trial was conducted in line with the ESRC Framework for Research Ethics and received a full ethics review by the School of Nursing and Midwifery (QUB) Research Ethics Committee in July 2017 (Ref: 11.MLohan.05.17.M6.V1), which independently assessed our compliance with the ESRC Framework. This approval covered data collection in each partner site. A trial steering group was convened to oversee the trial (see Report Supplementary Material 3). QUB acted as the main sponsor of the research and ensured that governance and indemnity procedures were in place. The project was registered on the Human Subject Projects database in QUB and prospectively registered in an international register of trials (ISRCTN99459996).

Participants

The study sought to recruit schools in the four nations of the UK, and to recruit teachers and pupils within these schools. Parents were also recruited but participated only in the process evaluation.

Inclusion criteria for schools

The whole of NI was included, but, for reasons of practicality, convenience and cost, geographical restrictions were put in place for England (Greater London area), Scotland (five specified local authority areas) and Wales (South Wales). All secondary schools with over 30 pupils in Year 11 (NI), Year 10 (England and Wales) and S3 (Scotland) were eligible to participate. The detailed recruitment strategy can be found in Report Supplementary Material 3.

Further inclusion criteria were as follows:

-

Schools had to be able to send e-mail or text messages containing a link to the video to parents of their pupils. Prior feasibility and transferability studies suggested that this would exclude a very small proportion of schools.

-

Faith-based schools were not excluded in any UK region.

The exclusion criteria were as follows:

-

Independent private, special and Irish/Welsh-medium and Scottish Gaelic schools were excluded. This exclusion criterion did not exclude schools that have an embedded Irish/Welsh-medium component.

-

Schools with < 30 pupils in the target year group (Year 11 in NI, S3 in Scotland and Year 10 in England and Wales) were excluded.

-

Schools that had already participated in the feasibility (n = 8, NI), transferability (n = 3, England; n = 3, Scotland; n = 3, Wales) and pilot studies (n = 1, England; n = 1, Scotland; n = 1, Wales) involving the If I Were Jack intervention in preparation for the Phase III study were also excluded.

Inclusion criteria for teachers

Teachers who were responsible for the delivery of RSE to pupils in Year 11 in NI, S3 in Scotland and Year 10 in England and Wales during the 2018/2019 academic year were eligible for the study.

Inclusion criteria for pupils

All pupils entering Year 11 in NI, S3 in Scotland and Year 10 in England and Wales (mean age 14 years across all nations) in 2018/19 in eligible schools were eligible for the study. Students with mild learning difficulties or poor English were supported to complete the questionnaire by trained fieldworkers.

Inclusion criteria for parents

All parents in intervention schools were eligible for inclusion in the study.

Recruitment procedure

Sampling frame

A sampling frame of Department of Education listed schools for each nation of the UK and defined the socioeconomic status of schools [based on eligibility for free school meals (FSM) as indicated by the School Meal Census] was used. In each nation, eligible schools were stratified into two levels according to FSM (schools above and below the median national percentage of FSM for all eligible schools, rank ordered randomly). In NI, 14 schools were randomly selected from the above-median stratum and 10 from the below-median stratum (total 24), and in England, Scotland and Wales eight schools were randomly selected from the above-median stratum and six from the below-median stratum (to give a total of 14). The decision to select slightly more schools from the above median national percentage of FSM stratum was to allow for even random allocation of schools to trial groups and to reflect research that indicates that public health need for addressing adolescent unintended pregnancy is greater in areas of higher social deprivation. 18,135

Recruitment of schools

Main study recruitment took place over a 6-month period (February–June and to end-September 2018), with a break during the summer period (July and August). Where possible, schools were approached via a relevant senior manager in the schools (e.g. senior teacher or deputy head in charge of pastoral care, identified with the help of the School Health Research Network in Wales, the School Health and Wellbeing Research Network in London, and local professional networks in Scotland and NI). In Scotland, permission was obtained from each local authority (typically by approaching the Director of Education) prior to commencing recruitment. Any school that declined to participate was replaced by a randomly selected school in the same stratum. A multifaceted approach to recruitment of schools was employed and consisted of an e-mail with attachments including a promotional leaflet, an invitation letter and an information sheet.

To promote school retention, schools were provided with £1000 on completion of baseline and follow-up measures. Schools that decided to participate were invited to consent by signing a memorandum of understanding (MoU), and were asked to nominate a main point of contact (a trial champion teacher, who was typically a teacher with responsibility for RSE delivery or governance) within the school to deal with future correspondence between the research team and the school. No stopping guidelines were put in place for this study; any and all schools and students who agreed to take part were included. The full school recruitment strategy is detailed in Report Supplementary Material 3.

Recruitment of teachers

Trial champion teachers then identified teachers responsible for RSE delivery to the relevant year groups during the 2018/2019 academic year, and researchers delivered an information session and provided the school letter and information sheet, MoU and consent form (see Report Supplementary Material 3 for examples of each).

Recruitment of pupils

Schools posted to parents/guardians an information sheet and an opt-out consent form for their child’s participation in the trial research (see Report Supplementary Material 3), with prepaid response envelopes and a return deadline. Researchers collated a list of parents/guardians who opted their child out of participation and returned this to teachers. At least 1 week prior to baseline data collection, pupils attended a short information session delivered by a member of the research team, which included an animated video. Pupils were provided with pupil information sheets (see Report Supplementary Material 3) and given an opportunity to ask questions prior to deciding whether or not to participate. Only eligible pupils whose parents/guardians did not opt out of providing consent for them to participate attended.

Recruitment of parents

Schools texted/e-mailed parents of all participating pupils in intervention schools a short online survey asking for their views on the parents’ videos and parent/pupil homework exercise. A maximum of two texts/e-mails were sent to parents (the original message and link to survey and one reminder). At the end of the survey, respondents were asked to provide their contact details if they would like to be approached to take part in a parents’ focus group discussion in the event that their school was selected as a case-study school.

Informed consent

Written, informed consent for random allocation was obtained from a member of the school senior leadership team, and from students, parents, teachers and intervention delivery staff for data collection. Parents were also informed about the trial and offered the opportunity to withdraw their child from the trial (although not the intervention).

Particular attention was paid to enhancing the process of informed consent for students within a school environment through the following measures:

-

Information and informed consent forms were administered and collected by the research team. Although teachers may have been present during this process, it was emphasised to pupils that their participation in the study was voluntary and that, should they decline to participate, they would have the opportunity to continue with independent study during data collection periods.

-

The research team also produced a short animation video informed by the pupil members of the TSG to convey what the study involved and their right to consent, as well as their right to withdraw their consent at any time without giving any reasons. This was shown to pupils in schools prior to asking for written informed consent.

Randomisation, concealment and blinding

When the recruitment quota for schools had been filled prior to baseline data collection, schools within each nation and socioeconomic stratum were randomly allocated (1 : 1 concealed allocation) to a trial group by an independent Northern Ireland Clinical Trials Unit (NICTU) statistician. The statistician produced eight randomisation schedules (using unique identifiers for schools), one for each FSM stratum for each nation, using random permuted blocks of mixed size, generated using Dotmatics nQuery Advisor 7.0 (San Diego, CA, USA). The NICTU was not involved with recruitment and released the randomisation code only when all schools were recruited and baseline data collection was completed, ensuring allocation concealment.

The statistician sent teacher trainers the allocation schedule for all schools. The teacher trainers were part of the intervention delivery team, and independent of the external research team. School allocation was communicated to each school by the nation-specific teacher trainer following baseline data collection within the school. Research teams were unaware of school allocation until after schools were informed of their allocation. (In a trial of this type, it was not possible to blind participants to allocation.) At randomisation, the NICTU Trial Statistician also randomly selected two intervention group schools from each nation as case-study schools for the process evaluation (see Process evaluation methods).

Treatment group allocation

Intervention

In schools that were randomly allocated to the intervention group, pupils in the relevant year group received the If I Were Jack programme.

Usual RSE provision

The schools in the control group did not receive the If I Were Jack programme but continued with the regular RSE curriculum and usual classroom activity. Schools in the control group were placed on a waiting list to receive the programme in 2020 following completion of the final follow-up survey.

Data collection and management

Data management

A Data Management Protocol (see Report Supplementary Material 3) was developed detailing the procedures to be followed in recording, storing and sharing project data. Survey data were provided to NICTU in the form of Microsoft Excel® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) documents, sent by password-protected e-mail by an external scanning company. Working files were created for each of the four locations: England, NI, Scotland and Wales. Validation checks were carried out on these data sets as per Data Management Guidelines and, when complete, four master data sets were created for analysis. Data sharing between sites was facilitated via a university-secure, password-protected Dropbox™ (Dropbox Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA) account.

Data retention/archiving

All data will be retained by QUB for a minimum of 5 years after completion of the final report (stored on a secure server, protected against unauthorised access by user authentication and a firewall). All hardcopy materials (other than pupil questionnaires) will also be stored by each partner institution for a minimum of 5 years after completion of the final report, in secure storage with restricted access, and accessible to the PI, if needed, on request. The data will be archived by year 10 in the UK Data Archive, located in the University of Essex (Colchester, UK).

Data collection

Baseline

At baseline (prior to commencement of intervention delivery), fieldworkers administered paper-based questionnaires to participating pupils, which they completed during the school day under exam conditions. Teachers were asked to stay at the front of the room to maintain order while also alleviating pupils’ concerns that teachers could see their answers. Fieldworkers supported pupils requiring extra help and ensured that questionnaires were completed confidentially.

Follow-up

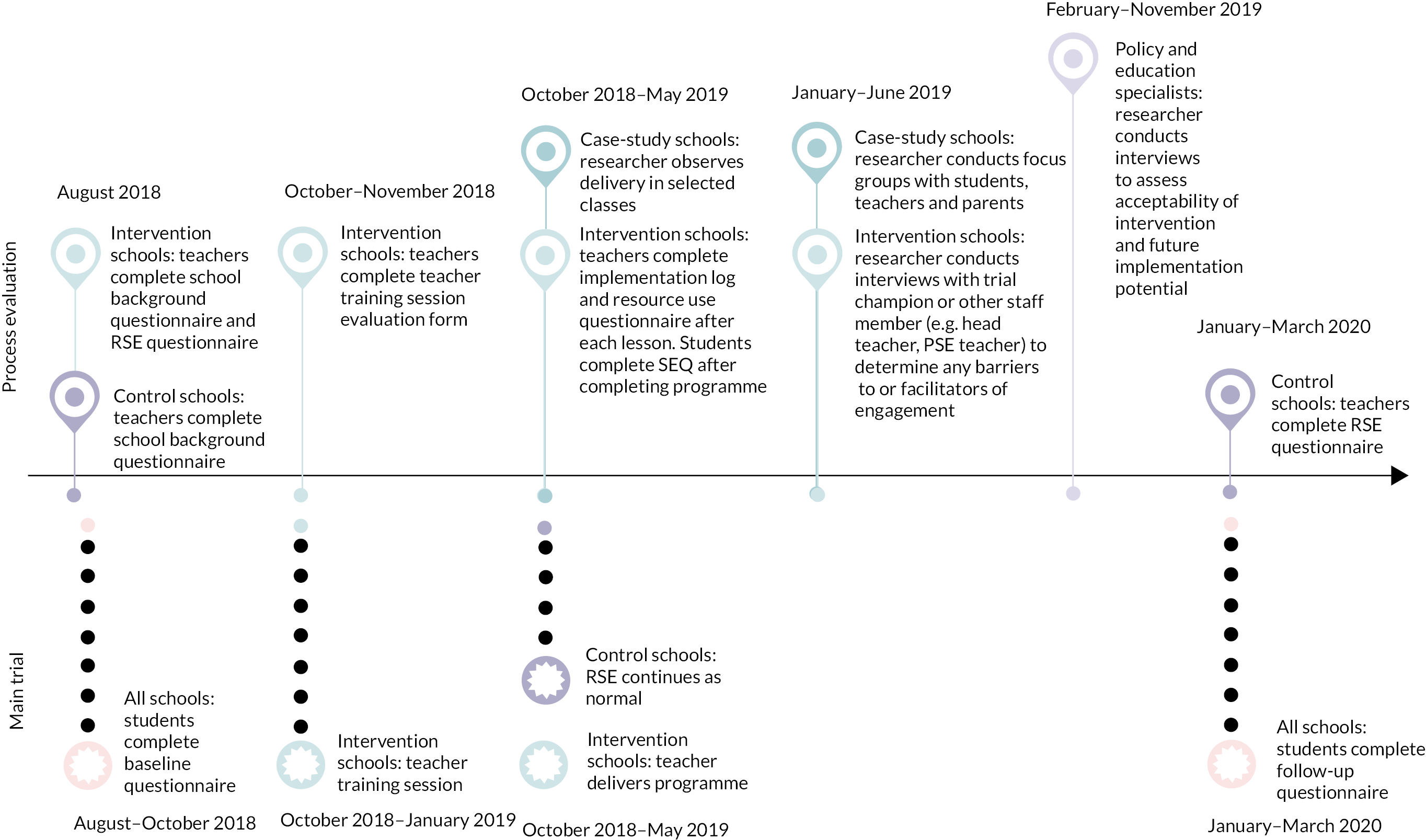

Participating pupils were in the study for approximately 18 months, and completed follow-up questionnaires between 12 and 14 months post intervention using procedures identical to those employed at baseline. The data collection timeline is shown in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2.

Data collection timeline. PSE, Personal and Social Education.

Outcomes and measures

The outcomes measured in this trial are based on the logic model (see Figure 1) and described in Table 3. A full copy of the baseline questionnaire is available in Report Supplementary Material 3.

| Component | Aim | Measurement |

|---|---|---|

| Knowledge | Increase knowledge about ways of avoiding unintended pregnancy; roles and responsibilities of young men in relation to unintended pregnancy; possible negative relational, social, emotional and financial consequences of unintended pregnancy; and sources of information and support for unintended pregnancy | Individual assessment. Selected items from the Mathtech Knowledge Inventory136,137 |

| Communication skills | Increase skills for communicating with parents and peers about avoiding unintended pregnancy | Comfort communicating about pregnancy scale (parents, peers and professionals). Selected items from the Mathtech Behaviour Inventory136,137 |

| Attitudes about unintended pregnancy | Increase anticipated regret about the consequences of unintended pregnancy on current life and future goals | Items from the intentions to avoid teenage unintended pregnancy scale developed and psychometrically tested in our feasibility trial44 |

| Social influences | Increase awareness of peer norms, stereotypical gender norms and parental attitudes and beliefs about teenage pregnancy Gender norms: increase perception that both men and women have roles and responsibilities in avoiding and dealing with the consequences of unintended pregnancy Peer norms: increase perception that most peers are not sexually active and use contraception when they are Parental values and beliefs: increase awareness of parental attitudes and beliefs about unintended pregnancy |

Male role gender norms: Male Role Attitudes Scale139 and knowledge items relating to responsibility for avoiding pregnancy Peer norms: knowledge items about sexual behaviour/contraceptive use among peers and sexual socialisation instrument (peer subscale)140 Parental values and beliefs: sexual socialisation instrument (parent subscale)140 |

| Beliefs about capabilities | Increase perceived behavioural control to avoid unintended pregnancy (say no to sex or obtain and use contraception correctly) and increase self-efficacy to communicate about avoiding unintended pregnancy with parents, peers and professionals | Sexual Self-efficacy Scale using an adapted version of the Sexual Self-efficacy Scale141,142 |

| Intentions | Increase strength of intention to avoid unintended pregnancy | Teenage unintended pregnancy scale44 |

| Sexual behaviour | Abstinence from sexual intercourse (delay initiation of sex or return to abstinence) or avoidance of unprotected sexual intercourse (consistent correct use of contraception) | Sexual behaviour items (ever had sexual intercourse, frequency of sexual intercourse, contraception use ever/at last intercourse). Items adapted from previous sexual health surveys143,144 |

| Pregnancy | Avoidance of unintended pregnancy | Ever pregnant |

Primary outcome

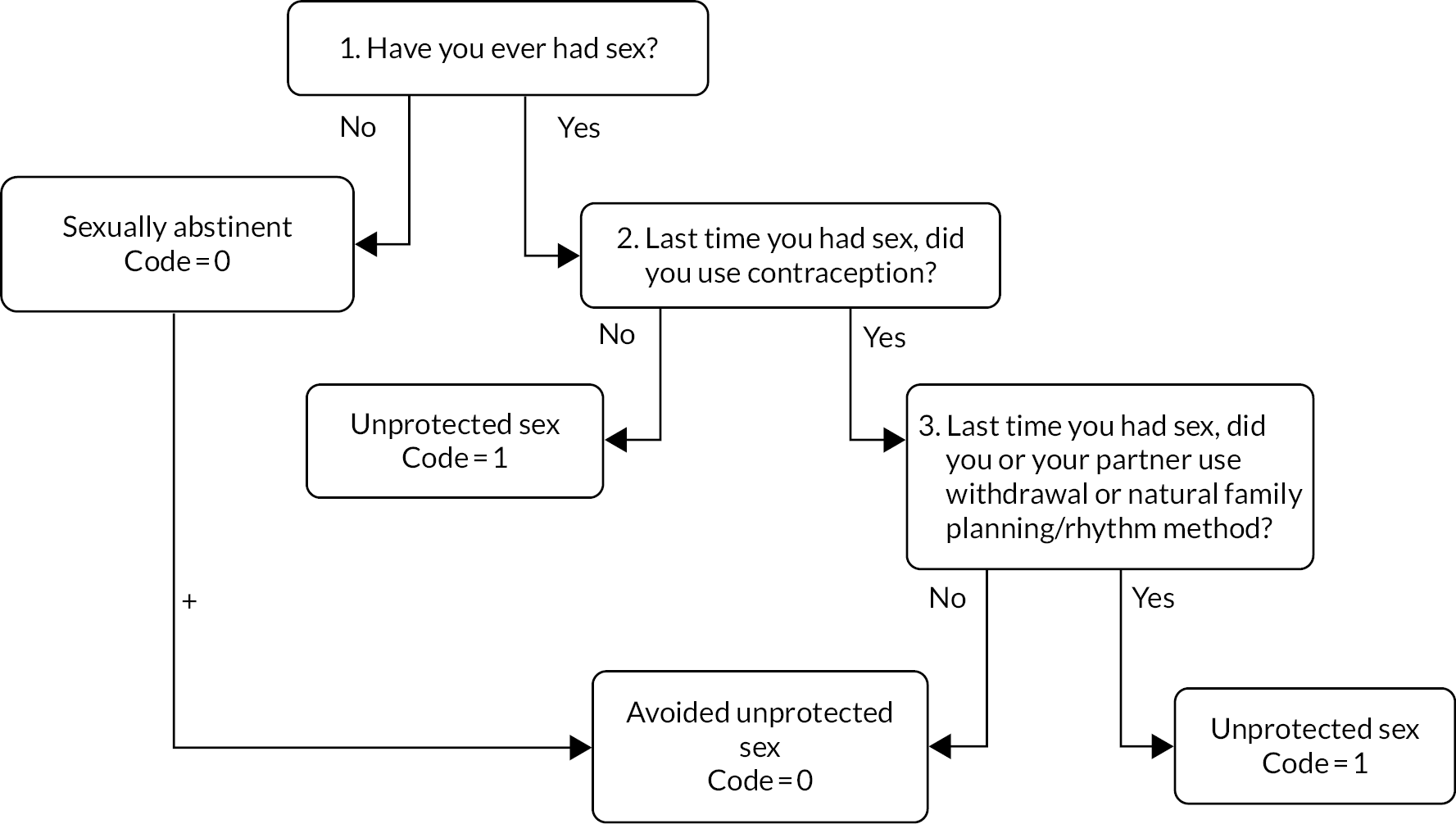

The primary outcome was self-reported avoidance of unprotected sex at last sexual encounter, defined as sexual abstinence or use of contraception (barrier or hormonal) at last sex, as measured by items on a paper-based questionnaire at baseline and again between 12 and 14 months later.

Analysis of the primary outcome, avoidance of unprotected sex, was undertaken with the whole study analysis population and included those not yet sexually active, alongside those who were. The unprotected sex category combined respondents who reported no contraception or unreliable contraception at last sex. Avoidance of unprotected sex combined all those who remained sexually abstinent and those who used reliable contraception at last sex.

Figure 3 shows how the primary outcome was determined. Three questions were used to determine if students were sexually active, The first question was ‘Have you ever had sex (penis-in-vagina)?’ If the answer was ‘no’, this was coded ‘0’ (no unprotected sex). If the answer was ‘yes’, the student was directed to the next question: ‘Last time you had sex did you use contraception?’. If the answer to this question was ‘no’, the response was coded 1. If the answer was ‘yes’, the student’s response to a third question was used as a check on use of reliable (barrier or hormonal) contraception. If participants answered ‘yes’ to the question ‘[l]ast time you had sex, did you or your partner use withdrawal (pulling out before ejaculating/cuming) or natural family planning/rhythm method (only having sex at certain times of the month)?’, their response was coded 1. If they answered, ‘no’, their response was coded ‘0’. A binary outcome was derived, with a score of 0 indicating not having had unprotected sex or never having had sex and a score of 1 indicating having unprotected sex.

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes were 12- to 14-month impacts on knowledge, attitudes, skills and intentions to avoid teenage pregnancy, as well as sexual behaviours. Table 3 outlines the questionnaire components of the key secondary outcomes we were assessing, consistent with our logic model, provided in Chapter 1 (see also an early design paper). 41 Secondary outcomes were assessed using a number of standardised measures as follows. Knowledge was measured by items selected from the Mathtech Knowledge Inventory and Sexual Knowledge and Attitudes Test for Adolescents. 136–138 This measure included items relating to knowledge of safe contraceptive methods, how to access contraception and the age of sexual consent. Attitudes were measured by the male-role attitudes scale. 139 This scale was included to examine change in gender attitudes (masculinities) more generally in society and was not specifically related to teenage pregnancy. Higher scores indicate endorsement of traditional male-role stereotypes. Skills were measured through the Comfort Communicating Scale137 and the Sexual Self-efficacy Scale. 141 The Comfort Communicating Scale specifically looked at communication between peers, parents and health professionals around avoiding pregnancy. The Sexual Self-efficacy Scale measured one’s perceived ability to have protected consensual sex when ready. It included items relating to communicating consent, sexual preferences and sexual readiness. Intentions to avoid an unintended pregnancy were assessed using an ‘intentions to avoid a teenage pregnancy scale’, developed and psychometrically tested in the Phase II feasibility trial. 44 This measure was based on the concepts of sexual competence145 to include subscores on contraception (intentions to know about, discuss and use contraception effectively); willingness (intentions to have sex when both partners have communicated willingness and consent); readiness (intentions to weigh up when they are ready to begin a sexual relationship); norms (intentions to avoid peer pressure to have sex); and attitudes (intentions to be prepared and share responsibility for contraception with a partner). The items that make up each scale, as well as the internal validity of the scales used as part of the questionnaire, are described in Report Supplementary Material 3.

Secondary behavioural outcomes were assessed using the following questions:

-

Have you ever had sex without using any contraception?

-

The last time you had sex, was any form of contraception used?

Subgroup analyses

Informed by the intervention theory of change model and research design (see Figure 1), the effect of the intervention on the primary outcome for the following prespecified subgroups was examined: those reporting having had unprotected sex at baseline or not (as an especially high-risk group), nation (Wales, England, Scotland, NI), sex and socioeconomic status as measured by the Family Affluence Scale. 157 Finally, we also looked at subgroup variation by ethnic group.

Post hoc exploratory analyses

Three exploratory post hoc analyses were conducted after reviewing the primary outcome analyses. These were conducted to separately analyse the component questions used to identify the primary outcome of avoidance of unprotected sex: sexual abstinence (Have you ever had sex with another person?) and use of reliable contraception at last sex (Last time you had sex, did you use contraception? Last time you had sex, did you or your partner use withdrawal or natural family planning/rhythm method?). We also examined sex differences in use of reliable contraception.

Sample size

This trial was powered to detect a 50% reduction in the incidence of unprotected sex (from an expected rate of 2.8% to 1.4%) by 15 years of age. A difference of 1.3% in unprotected sex has been shown to have a meaningful impact on pregnancy rates. 24,146–148 The between-group difference in the incidence of unprotected sex of 1.3% [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.5% to 2.2%] by 9 months in our feasibility trial149 demonstrated that such an effect size is plausible and is consistent with effect sizes seen in the literature. 146 This study was designed to also take account of clustering. In the feasibility trial data, the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was 0.01. 44 As pilot studies can provide imprecise estimates of ICCs,150 we re-estimated using ICCs from three sources: (1) the RIPPLE cluster RCT,148 (2) the WHO Health Behaviour in School-aged Children Survey (HBSC) GB18 and (3) the Young Persons’ Behaviour and Attitudes Survey 2011. 151 The data from the WHO and Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency (NISRA) studies were combined. Both the RIPPLE and combined WHO and NISRA studies found an ICC of 0.004. Based on (1) the ICC of 0.01 (95% CI 0.01 to 0.04), and assuming 120 students per year group in school, and (2) a 7% rate of attrition (based on the conservative attrition rate found in the feasibility study plus two additional schools), the sample size calculation showed that a trial involving 33 schools per group would provide 80% power at a 5% significance level. The alternative ICC of 0.004 was calculated to provide 93% power.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis (primary and secondary outcomes)

Primary analysis (at 12–14-months’ follow-up)

The primary effectiveness analysis was on an intention-to-treat basis, using a multilevel logistic regression model (two levels: pupils nested within schools) adjusting for the baseline outcome and stratification variables. 152

Subgroup analysis (at 12–14 months’ follow-up)

Multilevel logistic regression was used with interaction terms (treatment group by subgroup) for each of the above pre-specified subgroups. Owing to the low power and number of interactions being tested, the results of the subgroup analysis are reported using 99% CIs.

Missing data

Sensitivity analyses including imputed follow-up data based on the worst-performing school (in relation to detected incidence of unprotected sex) and best-performing school (where students did not have unprotected sex) at baseline were conducted for schools that did not collect follow-up data.

The scales captured as secondary outcomes for this trial generally had two types of missing data: (1) complete missing data (i.e. because the student was not present in school when the data were collected); and (2) partial missing data, where the student had completed some but not all items of the questionnaire. N is reported for each outcome to show the level of complete missing data for each outcome. The analysis population includes those for whom complete data at both baseline and follow-up were available. Partial missing data for the Male Role Attitudes Scale,139 Comfort Communicating136,137 and Intentions Scale44 was dealt with by averaging the responses of the questions answered, standardised on a scale of 0 to 1 then multiplying by 100 to derive a score for all students who completed some of the questionnaire.

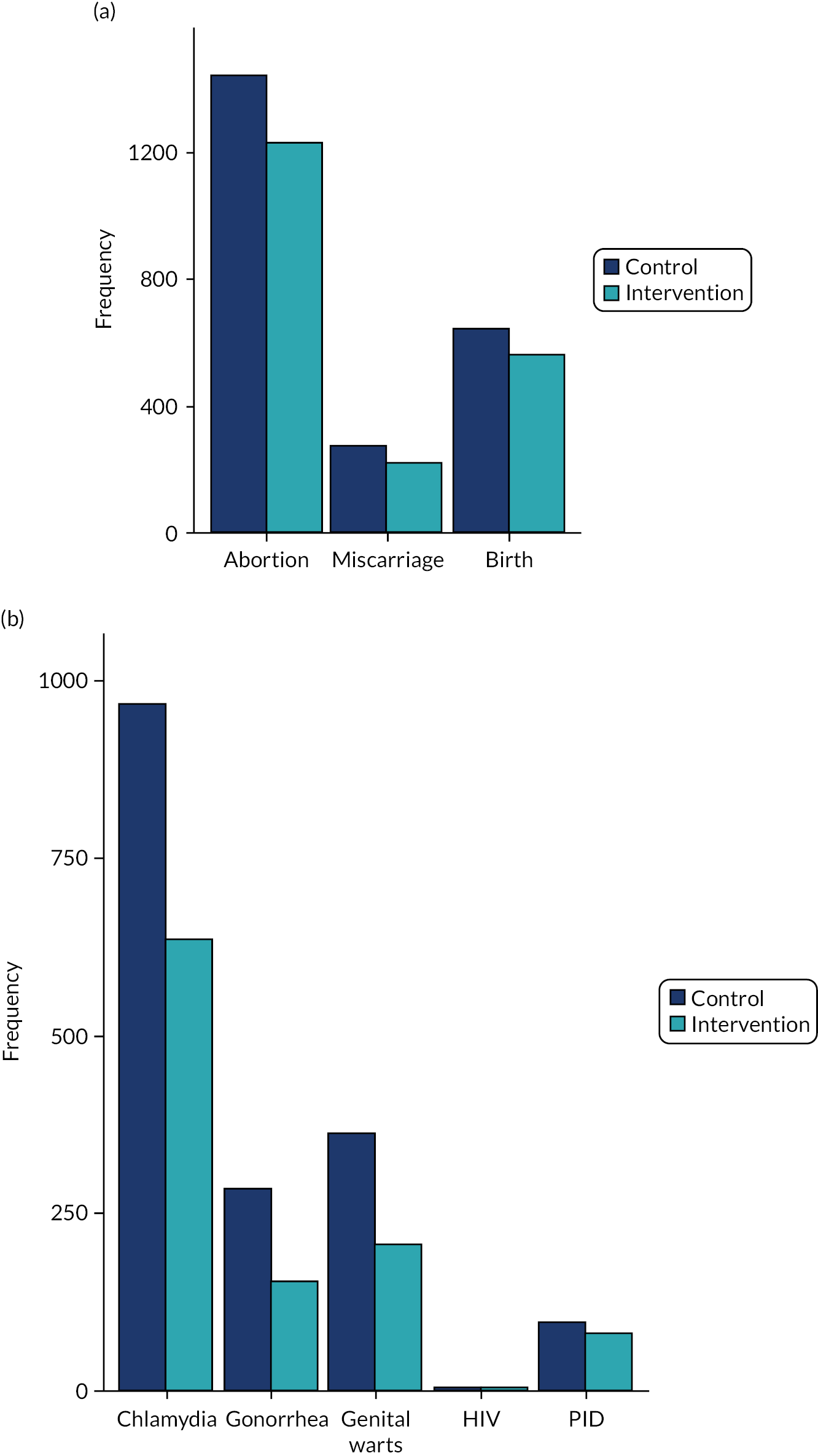

Data linkage