Notes

Article history

The contractual start date for this research was in February 2022. This article began editorial review in July 2023 and was accepted for publication in June 2024. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The Public Health Research editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ article and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Combes et al. This work was produced by Combes et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Combes et al.

Background

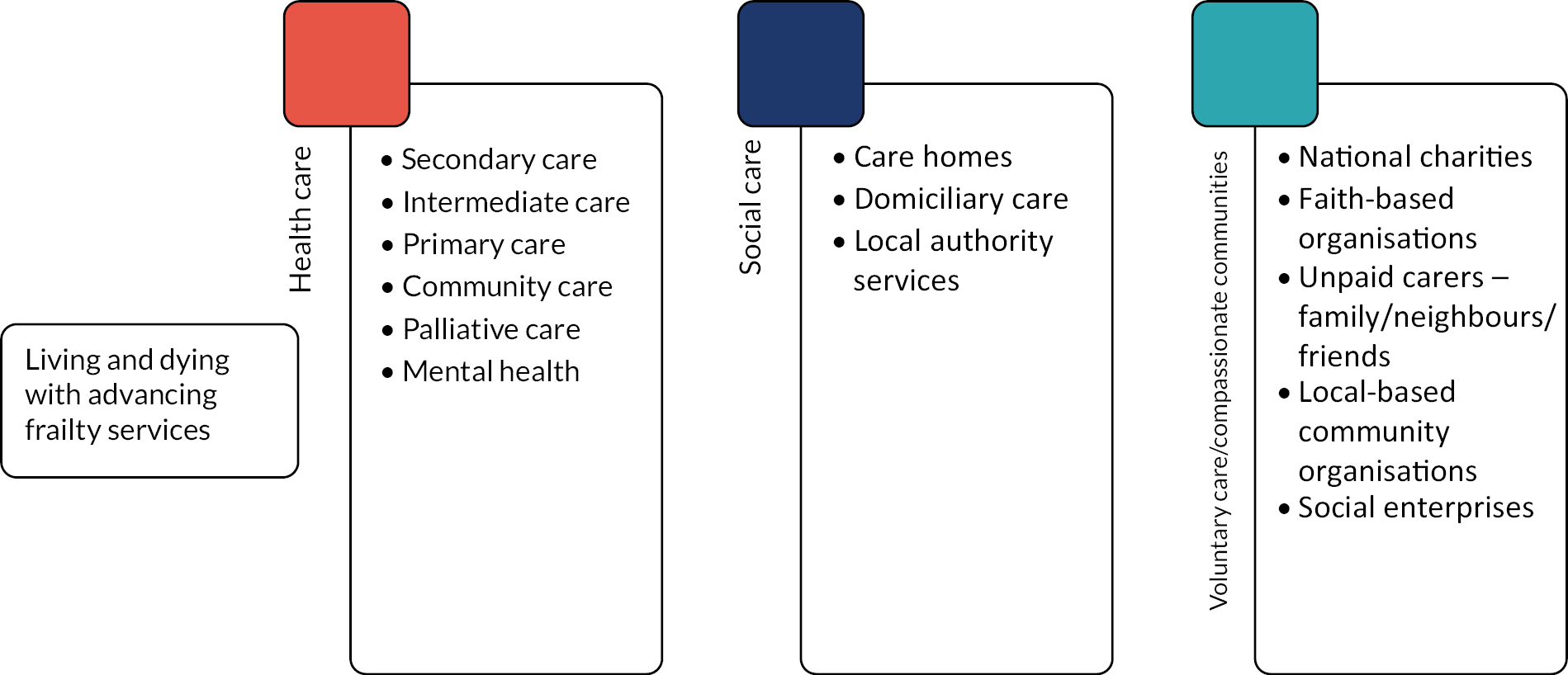

Frailty is ‘a complex medical syndrome, combining the effects of natural ageing with the outcomes of multiple long-term conditions, loss of fitness and reserve’. 1 Frailty affects around 10% of people aged over 65 years1 increasing to 65% of those aged over 90 years. 2 By 2040 the number of people dying each year is set to increase by over 25% and the number requiring palliative care is predicted to increase to between 25% and 42%,3 with many of these projected to be community-dwelling older people living with frailty. 4 As such it is predicted that community end-of-life care capacity will need to double by 2040, with care homes becoming the most common place of death in England and Wales. 3

Living with frailty makes people vulnerable to sudden deterioration, fluctuating ability, uncertain recovery and increases their risk of morbidity and mortality. 5 The frailty trajectory is uncertain and can be prolonged, and people living with moderate or severe frailty (known hereafter as advanced or advancing frailty) often have multiple, complex needs as they near the end of their life. This can include experiencing a variety of acute, functional, psychological and social problems, which require complex, multidomain health and social care services, orientated to support those living with, as well as dying from, advancing progressive illness. 6 Supporting the care of people with advancing frailty requires integrated care across the care continuum, including health, social and voluntary sector input. 7

Reviews of end-of-life care for this population describe the need for a continuum between specialist care of older people, emphasising physical function and rehabilitation, and palliative care which focuses on symptoms and concerns. 8 However, accessing palliative care in a timely manner can be difficult for older people living with advancing frailty for multiple reasons. These challenges include that this population are often not recognised as needing palliative care, because clinicians may not identify frailty as a complex, life-limiting syndrome,9 because older people and professionals regularly associate symptoms of frailty with normal ageing10 and clinicians,11,12 older people and their families13 often do not recognise when the person is starting to enter their final phase of life. Currently, if palliative care is accessed at all, it is often only in the last weeks of life,14 rather than being integrated into mainstream care provision,15 and thus is a barrier to appropriate care,16 impeding patient-centred decision-making,17 and choices around medical intervention and place of care. 18 Late recognition of palliative care needs can lead to inappropriate interventions,19 under-treatment of palliative symptoms20 and multiple transitions into hospital in the last year of life. 21 Hospital transitions may or may not be an appropriate crisis response; however, multiple inappropriate admissions contribute to avoidable healthcare system costs,19 and hospital deaths are common, although most older people state they would prefer to die at home. 22

Integrated care, care that enables care coordination and transitions across and between services, requires a shared understanding, language and practice, and is fundamental for older people with advancing frailty. Integrated care can be defined in many ways, but is commonly described as being at micro (person and provider level), meso (organisation level) or macro (system) levels of integration. 23 In England, there have been significant policy drivers for integration at a system level,24 with the creation of Integrated Care Boards and Integrated Care Systems seen as the structural mechanisms needed to support integrated care, and are focused on population health and wellbeing, including palliative care services. 25 Within systems, the vision is that health and care services are planned and delivered at place and neighbourhood levels. Place-based partnerships serve populations of around 30–50,000 and are commonly based on local authority footprints while neighbourhoods consist of groups of GPs working alongside other service providers as part of Primary Care Networks to deliver services. However, currently place and neighbourhood-based services for older people with advancing frailty are often poorly defined, reviewed and maintained. Additional challenges to integration include clinical tools that focus on what services can provide rather than what matters most to the older person, for example, addressing symptom control rather than social or practical needs26 and that the importance of relational networks, with domiciliary care workers as integral, are often overlooked. 27

To be effective, end-of-life care services need to respond to this contemporary landscape of dying in older age and configure services appropriately. 28 While service configurations should be evidence based, evidence is currently limited. There are several European Commission funded studies developing service models for older people at end of life such as PACE: Palliative Care for Older People29 and EU Navigate. 30 While these will add to the evidence base, their focus is specifically on people living in long-term care (PACE), or older people living with cancer (EU Navigate). Recent guidance from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence31 sets out expectations for services providing care to people in the last year of life, and was supported by a series of 13 evidence reviews citing a total of 2777 papers. However, many recommendations were poorly evidenced, and much of the evidence was of low quality, or not based on UK health and social care systems. Identifying care pathways that better support transitions for older people living with advancing frailty as they near the end of life is a key research priority. 32 Understanding who to involve and how to work together to enable coordinated, person-centred care is under-evidenced. ALLIANCE brought together partners across the integrated care sector to grow a research partnership to improve the delivery of integrated care and care transitions for older people living with advancing frailty as they near the end of life.

Methods

Partnership aims and objectives

Aim

To develop a sustainable, cross-sectoral partnership focused on (1) identifying priorities to improve the delivery of integrated care and care transitions for older people living with advancing frailty, (2) developing organisations in which to conduct this research and (3) submitting one or more study proposals for NIHR funding.

Objectives

-

To establish the Partnership infrastructure and identify key contacts within each region across the palliative and end-of-life continuum.

-

To understand the strengths, weaknesses, barriers and enablers of research readiness and current clinical services for people with advancing frailty.

-

To support provider services to become research ready.

-

To establish research questions across the Partnership and develop research proposals.

Objective 1: Establishing the partnership: working together

Plan

The ALLIANCE Partnership brought together people across the palliative and end-of-life care continuum who wanted to improve transitions for older people with advancing frailty as they near the end of life. The concept of transitions for older people living with advancing frailty is discussed throughout the literature, and in clinical practice, in multiple ways. These include personal biopsychosocial transitions, transitions in the focus of care or organisational responsibility for care, or transitions in the place of care. To add to this complexity, transitions are often not linear and require regular re-evaluation throughout the frailty and end-of-life trajectory. Within this Partnership, transitions across clinical and social care settings were the starting point. The importance of the biopsychosocial transitions of frailty and the attendant potential transitions in goals of care were also attended to.

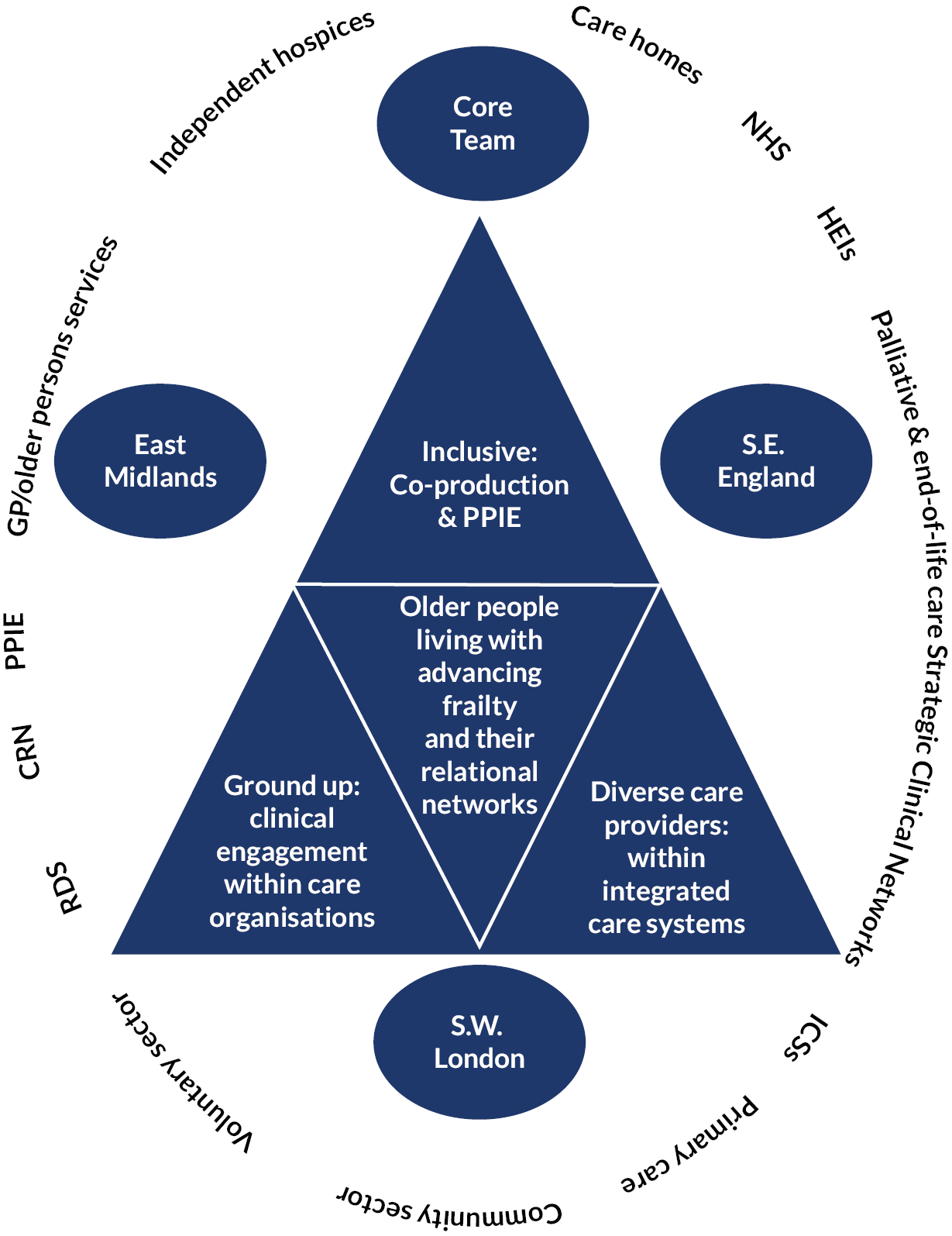

Figure 1 demonstrates the breadth of the Partnership across the regions and articulates its underpinning concepts of (1) inclusivity, (2) diversity in populations, people and care providers and (3) its aim to build from the ground up.

FIGURE 1.

The partnership.

The Partnership spanned three regions (see Table 1). The specific geographies were chosen as they have historically low levels of recruitment to NIHR palliative and end-of-life care Portfolio studies, with all areas, except Nottinghamshire, below the national average (ranging from 2 to 35 recruitments per 1000 cases). Nottinghamshire was included as an area of excellence to support development in the East Midlands.

| Geographic area | |

|---|---|

| East Midlands | Derbyshire, Lincolnshire, Nottinghamshire |

| South East England | Berkshire West, Isle of Wight, East Sussex |

| South West London | Kingston, Croydon, Richmond |

Infrastructure

The Partnership infrastructure adopted a hub and spoke approach. The hub comprised the Core group, a group of professionals in specialist palliative and geriatric care, paramedic practice, integrated care, patient and public involvement and clinical academic practice, with representatives across the clinical and academic spheres across the Partnership regions. The Core group met regularly to discuss partnership activities and share updates on key milestones, promoted ALLIANCE in their regions, identified potential ALLIANCE Partnership members, and supported the Partnership’s understanding of each region from the perspective of services supporting older people living with frailty. An Advisory group, with national-level representatives across specialist palliative and older people’s care, social care, integrated care systems, NIHR structures and patient and public involvement and engagement, provided additional support and governance. A list of Core and Advisory group members can be found in Appendix 1, Tables 10 and 11.

Spokes (known as key contacts) were key individuals within each region across the frailty pathway and end-of-life care continuum, across the integrated care system, throughout each of the three regions. Each key contact was identified for their knowledge, expertise or interest relevant to the Partnership, and links to other interested individuals in their area. Key contacts received no additional resources to fulfil this role. Appendix 2, Figure 8, illustrates the breadth of key contacts we attempted to establish and maintain throughout the Partnership.

Delivery

Key contacts were identified through multiple routes including: palliative and end-of-life care strategic clinical networks; members of the Core and Advisory groups; professional societies, for example, the Royal College of Nursing, British Geriatric Society, and Hospice Social Workers palliative and end-of-life care and frailty sections; Integrated Care System (ICS) links; NHS England; and NIHR infrastructures including Research and Development Leads, Clinical Research Networks, Applied Research Collaborations; and targeted social media.

Key contacts were established through e-mail, telephone, Zoom (Zoom Video Communications, San Jose, CA, USA), video conferencing and speaking at regional meetings to introduce the Partnership. To support key contact identification and representation across regions, we developed and refined a sampling frame and ‘script’. To identify and connect with key contacts we found we needed to work across numerous micro, meso and macro organisational levels. Web-based searches were a helpful way to connect with voluntary and social care agencies, whereas social media was found to be an effective way to connect with clinicians.

Outputs and outcomes

-

Two hundred and forty-four contacts were made between 8 February 2022 and 26 May 2023 as follows:

-

East Midlands – 110

-

South East England – 76

-

South West London – 58

-

-

Seventy-six contacts agreed to key contact status. Regional areas were as follows:

-

East Midlands – 45

-

South East England – 22

-

South West London – 9

-

-

Coproduced ground rules for partnership working. To support collaborative working throughout the Partnership, the Core group collaboratively discussed and refined these ground rules, developed by Dr Nadia Brookes, for working together that could be developed and revised throughout the Partnership and beyond. A copy of these coproduced rules can be found in Appendix 3.

-

ALLIANCE website: www.surrey.ac.uk/research-projects/alliance-enhancing-quality-living-and-dying-advancing-frailty-through-integrated-care-partnerships. This website formed the central information repository for the Partnership, enabling cross-partnership communication and sharing of best practice. It was open access to enable Partnership members to share the resources with their organisations and networks. The website also linked to the Living and Dying Well programme at University of Surrey to enable users to access these wider frailty resources in addition to those curated for the Partnership. ALLIANCE resources include research capacity and capability development, patient and public involvement and engagement, and frailty resources.

Evaluation

This objective was more complex and labour-intensive than envisaged. Significant pre-study work was undertaken between June and September 2021 and contacts were made. However, due to organisational and staff changes within key contact organisations, much of this work was lost. Having lost these contacts, the top-down approach used with some organisations added additional time as managers suggested other managers, who suggested different managers, meaning multiple calls and emails were required before the relevant people were contacted. Additionally, many senior staff within palliative care and frailty were unable to signpost us to relevant individuals as staff were seen either as palliative care focused, where frailty was rarely recognised, or frailty focused, where end of life and palliative care was rarely recognised. Further, the nature of the Partnership was difficult for people to engage with as it was not research nor service improvement. For example, many potential key contacts were very keen to be involved in research but wanted to be research sites for established research proposals rather than being part of a research proposal development process. Hardest to find were General Practitioners, social care representatives and mental health professionals.

The voluntary sector was particularly hard to reach, both regionally (as key contacts) and nationally (within the Advisory group) despite multiple attempts. We believe this is due in part to the wide-ranging brief and geography of the Partnership, meaning the voluntary sector representatives approached often did not feel able to speak for the Partnership throughout all regions. Further, we found that for some voluntary organisations, the focus of the Partnership did not meet their current strategy, or often, they perceived becoming involved in research proposal development work to be too time consuming, and felt they lacked resources, time and funding to engage meaningfully. There were however, a few regional exceptions, and we hope to develop these over the next few months, and, once the research bid writing is underway, approach a national voluntary organisation for national, as well as local, support going forward. Of the original 244 contacts, 76 individuals agreed to key contact status. Their involvement in the Partnership is detailed within the relevant objectives below.

Objective 2: Mapping, scoping and analysing the current clinical services and research readiness: learning together

Plan

This objective sought to understand the Partnership’s strengths, weaknesses, barriers and enablers regarding (1) current clinical services for people living with advancing frailty and (2) research readiness across the Partnership. The outcome of this objective was to ensure future Partnership research proposals were focused on clinically relevant and impactful research, and to underpin research capacity development.

Understanding the Partnership’s current clinical services

To better understand current integrated care, its barriers and enablers, and establish unmet clinical need, we planned to map and scope clinical services relating to older people living with advancing frailty, focusing on pathways, transitions, and coordination of care. Data were to be analysed using the COM-B framework,32 a system of behaviour that suggests that behaviour change occurs when individuals, organisations or systems, have the Capability, Opportunity and Motivation to make and sustain the change. The COM-B framework was to be used to establish the barriers, enablers and priorities of each site and across the Partnership, with results used to inform research question generation (Objective 3).

Research readiness within the Partnership

Research readiness was defined as research capacity and capability, patient and public involvement and engagement, and links to regional and national research structures and opportunities. To better understand research readiness, we planned to map and scope research activity including: key people; organisational research infrastructures; skills and expertise; existing research collaborations; and patient and public involvement and engagement. A further scoping exercise of regional and national infrastructures, research training and other opportunities was planned to create an infrastructure map and database of regional and national research opportunities.

Delivery

Activity 1: Mapping and scoping the Partnership: services, patient and public involvement and engagement and research readiness

Key contacts, previously established, were sent an online survey to capture data on services, partnerships, patient and public involvement and engagement (PPIE) and research engagement. The survey was administered between 24 May 2022 and 10 June 2022 to 76 key contacts previously identified.

Activity 2: Mapping research infrastructures

National and regional research structures were searched along with Core and Advisory group, and key contacts’ local knowledge, alongside a web-based search of regions. A PPIE summary, based on the findings of the survey, alongside the PPIE conducted by the research team, was developed.

Outputs and outcomes

-

Analysis of barriers, enablers and priorities regarding research capacity building and delivering care within integrated care systems.

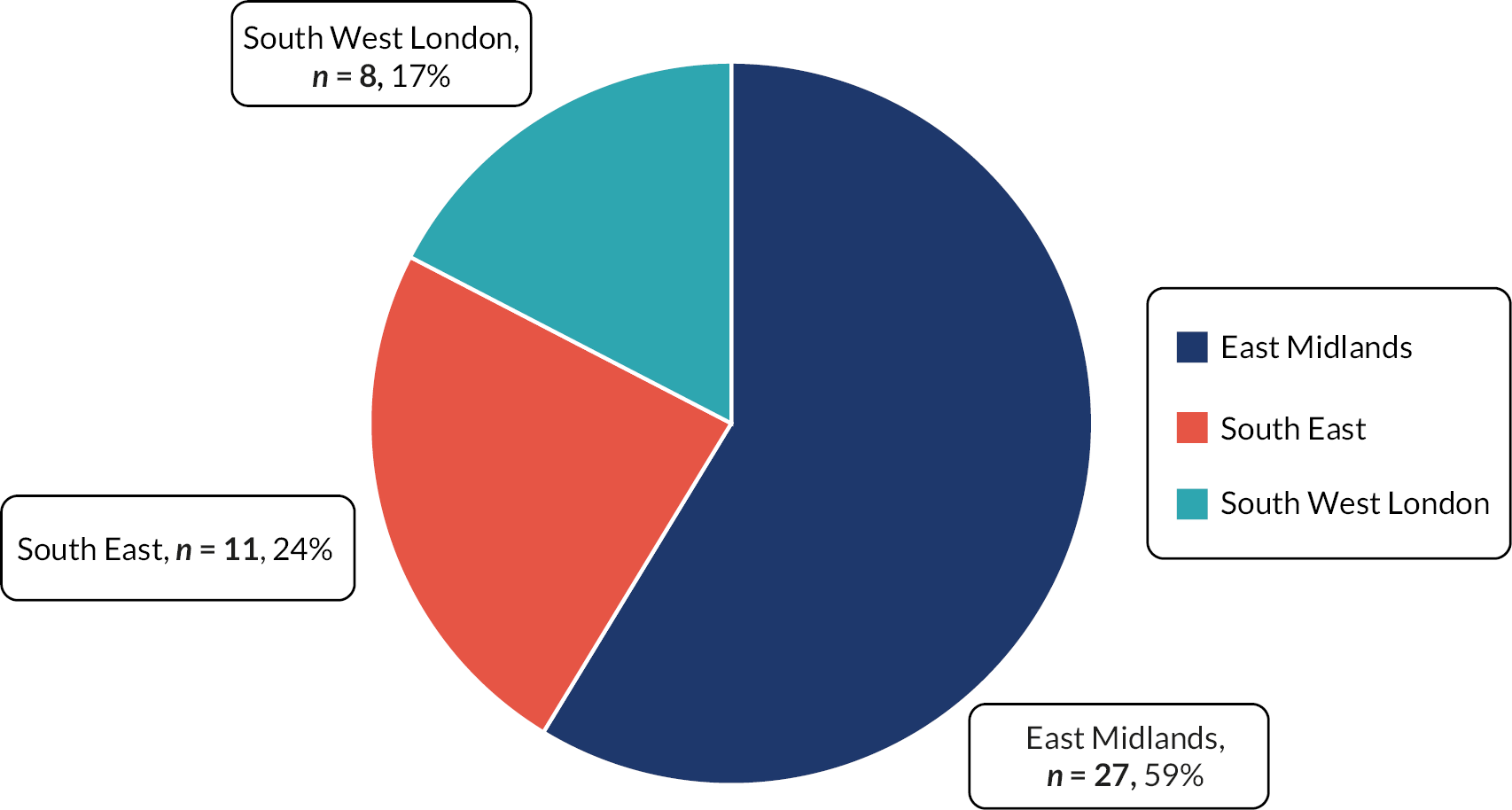

N = 46 people responded, 9 of which stated they worked for more than one service (see Tables 2–5 and Figure 2).

| Organisational leadership or governance | 18 |

| Service/patient-facing (either clinical or non-clinical) | 28 |

| Health care | 32 |

| Social care | 8 |

| Voluntary care | 5 |

| Voluntary sector (not care) | 1 |

| Acute | 3 |

| Ambulance service | 2 |

| Care home | 1 |

| Community | 18 |

| Intermediate | 1 |

| Palliative care across community, hospital and hospice | 1 |

| Primary | 5 |

| Area | Number of participants |

|---|---|

| East Midlands: Derbyshire | 1 |

| East Midlands: Lincolnshire | 8 |

| East Midlands: Nottinghamshire | 17 |

| Across East Midlandsa | 1 |

| South East: Berkshire West | 2 |

| South East: East Sussex | 7 |

| South East: Isle of Wight | 2 |

| South West London: Croydon | 3 |

| South West London: Kingston | 2 |

| South West London: Richmond | 2 |

| South West London: Wandsworthb | 1 |

FIGURE 2.

Geographic region (n = 46).

Demographics of key contacts (see Tables 2–4).

Demographics of service users: as estimated by key contacts (see Tables 6 and 7).

| N participants completing question | Minimum % | Maximum % | Mean % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | 33 | 0 | 71 | 43 |

| Black and minority ethnic backgrounds | 29 | 0 | 57 | 14 |

| Low-income households | 27 | 5 | 98 | 42 |

| Living alone | 32 | 0 | 86 | 51 |

| Minimum | 4% |

| Maximum | 100% |

| Mean | 48% |

Description of services

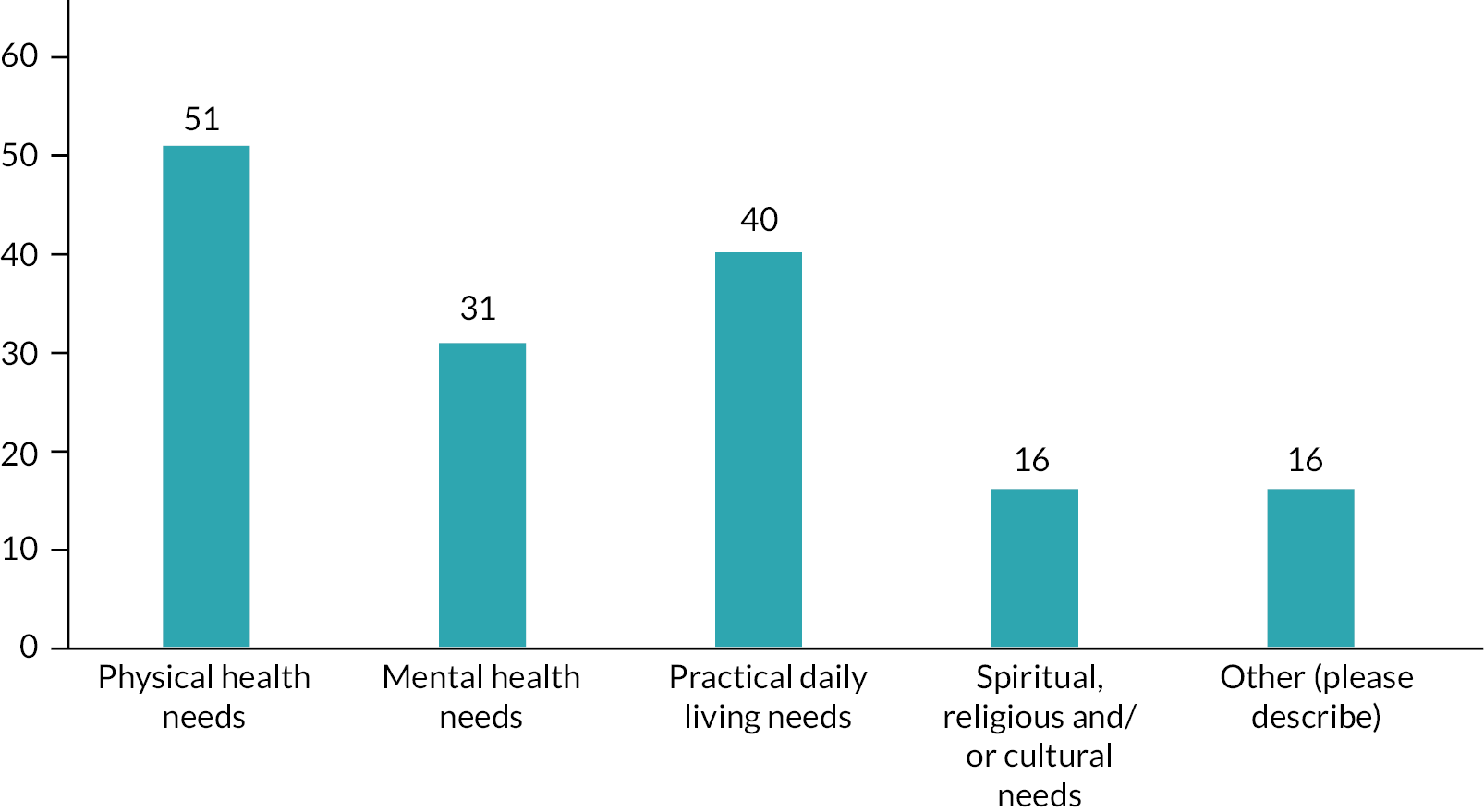

Most key contacts stated their services primarily supported physical health needs for older people living with advancing frailty as they neared the end of life. Practical daily living needs were secondary to this, followed by mental health needs, and equally spiritual, religious and cultural needs, alongside other needs. The details of the needs catered for within each domain are illustrated in Appendix 4, Figures 9–13.

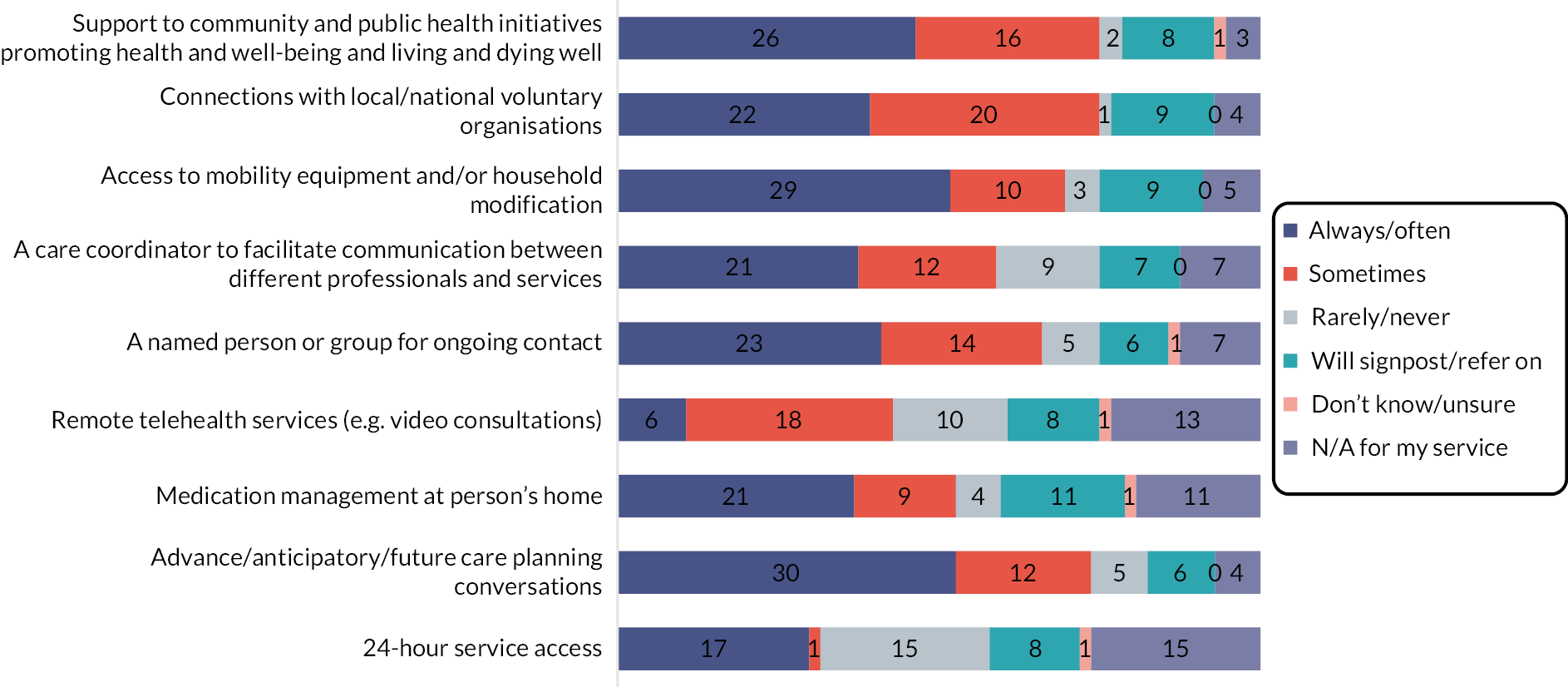

In addition to needs, participants were asked to specify the wider elements their service provided. More than half of all respondents said their services always addressed some form of advance or anticipatory care planning and access to mobility equipment or household modifications. The element that was least supported by all services as standard was remote telehealth services such as video consultation, although many more services stated they were able to offer this sometimes (see Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Which of the following elements does your service provide? (n = 49) (multiple choice).

The details of the above elements can be found in Appendix 5, Tables 12 and 13, and Figures 14–16. Details of who the services received referrals from and referred older people and carers on to can be found in Appendix 6, Figures 17–19.

Demographics of service

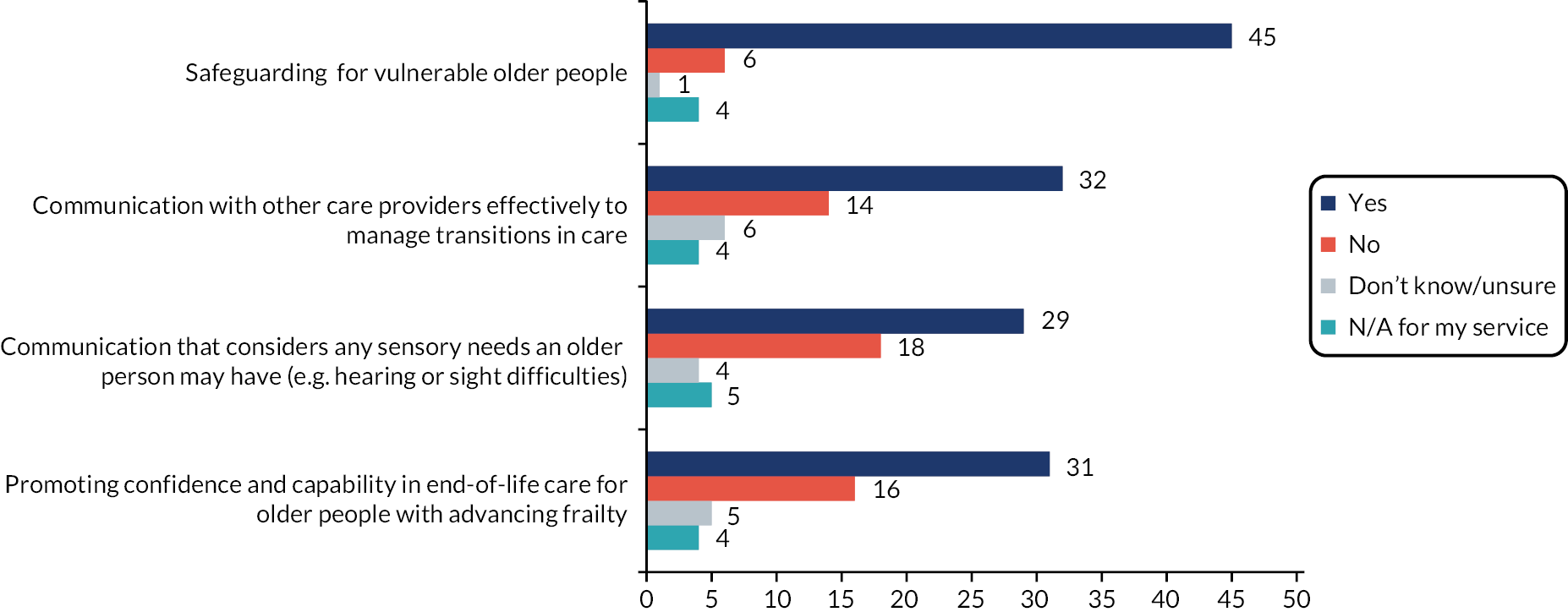

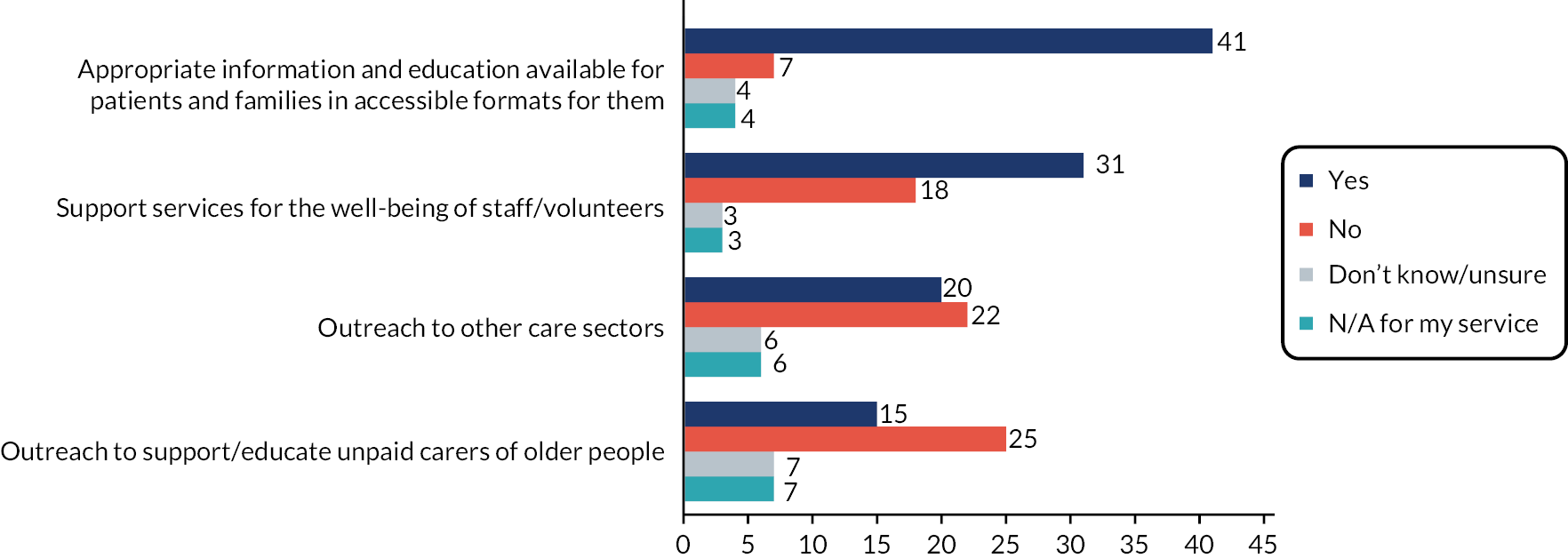

Key contacts were also asked if their services or organisations were involved in workforce development, and which areas of workforce development they provided (see Figures 4 and 5):

FIGURE 4.

Does your service/organisation provide education/training for … n = 56 (multiple choice).

FIGURE 5.

Does your service/organisation provide … n = 54–56 (multiple choice). N = 54 for both outreach categories, n = 55 for support of staff/volunteers, n = 56 for appropriate information.

Barriers and facilitators to supporting people living with advancing frailty

Participants were also given the option to submit additional free text regarding barriers and enablers to support people with advancing frailty to move between services as they near the end of life. Nineteen participants chose to provide additional information, and a brief analysis of the free text data showed the following barriers and enablers (see Table 8).

| Barriers | Enablers |

|---|---|

| Lack of funding | Joined up services |

|

|

| Understanding | Funding |

|

|

| Stretched services | Recognising palliative care needs |

|

|

| Geography | Relationships |

|

|

| Relationships | Environment |

|

|

Analysis of current PPIE representation

Participants were asked if they had a PPI group in their service or organisation. Of n = 53 responses (due to some participants working for multiple services), 39% had a PPI group, 35% did not, and 26% were unsure. Those who answered ‘Yes’ to having a PPI group were asked whether older people living with advancing frailty, or their carers, were part of the PPI group. Nineteen per cent said yes, 10% no, and 71% were unsure. It is unclear from the findings whether some services had established PPIE groups, but service staff were not aware of them, or PPIE groups themselves did not exist within the service or organisation. These findings spoke to the need for services to establish and embed PPIE within their organisations more robustly, and to include older people with frailty, and those important to them, as representatives in these PPIE groups. For the Partnership, these findings meant that rather than our aim to support Partnership members to further embed PPIE, a step back was required. Instead, we needed to establish an understanding of the importance of, and need for PPIE representation, and to find and signpost services to relevant potential PPIE regionally and nationally.

Database of aspiring researchers to benefit from, and contribute to, ALLIANCE activity

Participants were asked whether they, or any named colleagues, were already involved, or were interested in being involved in research or evidence building. Twenty-five names of key contacts and others were put forward across the integrated care network: voluntary sector (n = 2), social care (n = 4) and health care (n = 19), with most responses from the East Midlands (n = 15), and n = 5 each in South East England and South West London.

Mapping research infrastructures; Database of regional and national training and other opportunities to support capability and capacity building

The research team contacted the following:

-

Core group and specific members of the Advisory group

-

NIHR departments across the Partnership, for example CRNs, ARC, AHSN

-

NHS research departments across the Partnership

-

Networks such as CHAIN, PCRS, CHART, Palliative Care ARC

-

searched Twitter contacts of key geriatric and palliative care professionals and advertised on Twitter for contacts

-

searched the original 244 contacts for professionals who had links to research and asked for their help

-

spoke at multiple regional meetings to promote the Partnership and request contact

-

conducted web searches.

This work, while time consuming, surfaced few connections outside of those of the Core and Advisory group and key contacts, and minimal information regarding regional or national research infrastructure. The best results were found through searching NIHR funded-research, then title and abstract checking for anything that might be relevant. Two potential researchers were found through this route, however, neither returned our contact.

Evaluation

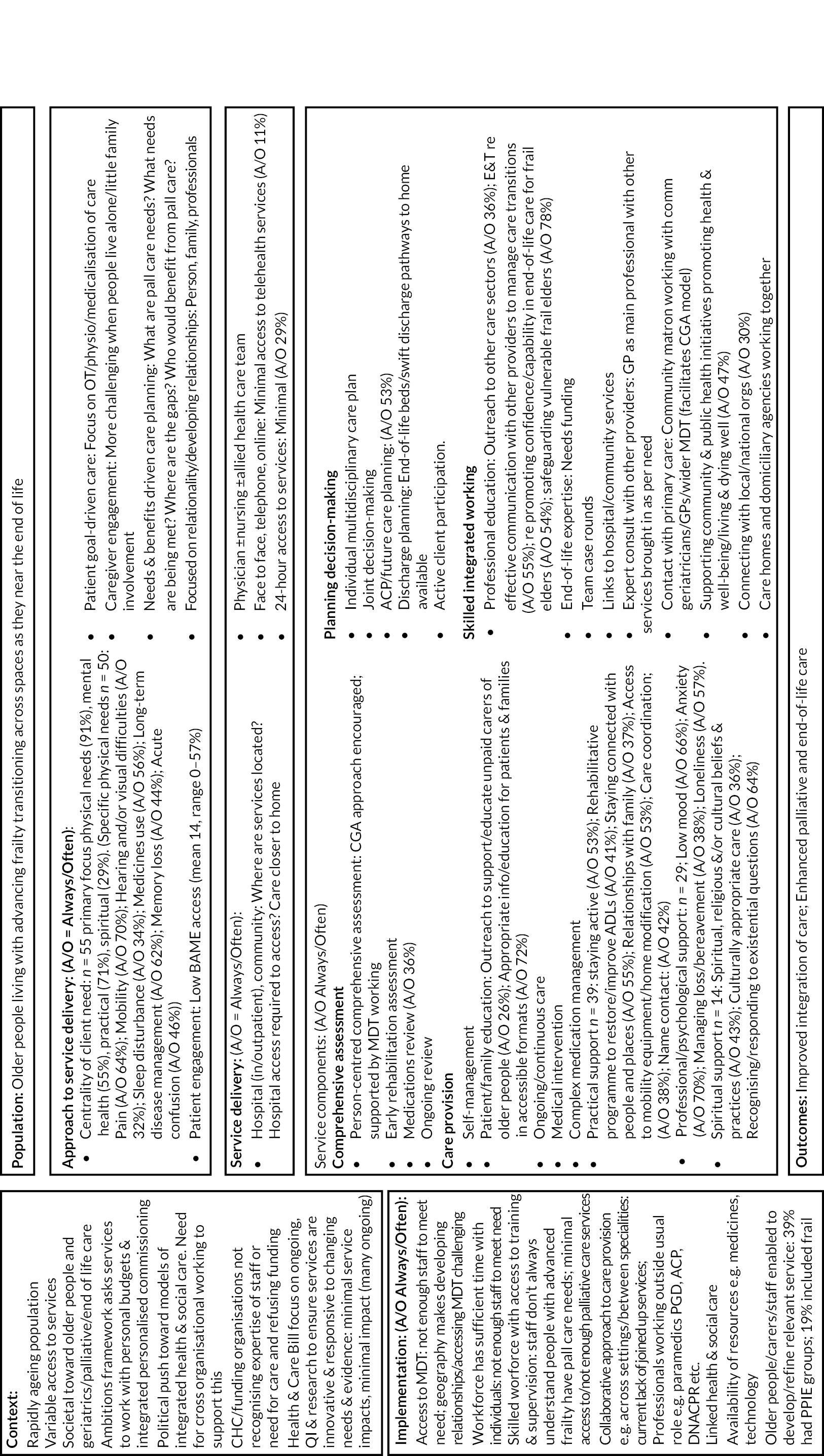

As with Objective 1, this objective was more complex and labour intense than envisaged, particularly regarding mapping the research infrastructure. Mapping and scoping current clinical service, PPIE involvement and research interest within the Partnership, was conducted using the extensive Phase 2 survey. The initial plan had been to use COM-B32 as a framework. However, the collected data spoke far more to the organisation of systems, components of services and perspectives on the enablers and barriers to delivering better care for older people with advancing frailty towards the end of life. Thus Bayley et al. ’s common components logic model,33 which details effective service delivery models for older people with advanced progressive conditions, such as advancing frailty, was used as a framework (see Figure 6).

FIGURE 6.

Service framework for older people living and dying with advancing frailty.

The mapping and scoping of national and regional research activity was time and resource heavy. We attempted to map researchers, research and infrastructure through multiple sources as noted above. However, while we connected with CRN, RDS and other infrastructure within all regions, as far as possible, existing intelligence was hard to find, and it was agreed by the Core group that this objective was not possible within the remit of the Partnership. As such, we reframed our aim and instead focused on support and, using the knowledge of Core group members, we created webinars to support Partnership members’ research development. This is discussed under Objective 3.

Objective 3: Establishing research questions across the partnership and supporting provider services to become research ready: growing together

Plan

This objective sought to enable the Partnership both to generate research questions for Part 2 of the NIHR call, and to support Partnership members to become research ready. Research readiness was understood as a continuum from being ready to recruit participants into research studies external to the service, to services wishing to develop towards research generation.

Delivery

Activity 1: Generating research questions for prioritisation

A long list of up to 15 important, unanswered research questions was to be established using a partnership-wide survey and ongoing group discussions supported by data from Objective 2. PPIE engagement was to be used to ensure the inclusion of older people living with frailty and informal carers, including people with communication or other accessibility issues, for example, using differing formats to gain views. The survey was administered between 11 October 2022 and 4 November 2022.

Activity 2: Supporting provider services to become research ready

Following the coproduction principle of reciprocity,34 knowledge exchange was to be fostered by buddying sites with research capacity and expertise with research-naïve sites to optimise skill-sharing, efficiency and development of research strategies and guidelines. Knowledge gained in Objective 2 was to be used to support and embed PPIE to ensure representation of local needs and demographic diversity, where possible drawing on established PPIE training for staff and for PPIE representatives.

Outputs and outcomes

Generation of research questions for prioritisation

Objective 2 data, ongoing conversations with Partnership members, the Core group and PPIE, and knowledge of the literature and clinical practice, was used to create four broad topic areas and research questions. These were as follows: (1) Transitions in the last years of life (transitions towards the end of life, and across care settings); (2) Decision-making and parallel planning; (3) Person-centred care across the continuum of living and dying; and (4) Integrated Care Workforce. These broad topic areas recognised (1) the complexity of person-centred end-of-life care for older people living and dying with advancing frailty, (2) the need to move away from a solely clinical focus to encompass integrated care and (3) the importance of the role of family, social networks and care closer to home as underpinning themes.

Established skills sharing/knowledge exchange infrastructure; Research-ready organisations and individuals; Established buddying system/bespoke training network

Following the results of the Objective 2 mapping and scoping, the skills sharing, knowledge exchange and development of research-ready individuals were provided in the form of two free webinars open to research-orientated health and social care professionals throughout the ALLIANCE Partnership, and promoted to a wider audience of these professionals provided they worked with older people living with advancing frailty in the community. The aim of the webinars was to provide educational content with a focus on networking research-orientated individuals within the group of attendees, and signposting to resources and local and national support, for example ARC, CRN, RDS and PPIE representatives and resources. All resources are hosted on the ALLIANCE website. A secondary aim for the webinars was to support the development of a network of research-orientated individuals who would support Partnership sustainability by supporting bid writing and potentially conducting research in the future.

Potential attendees were asked to complete pre- and post-webinar questionnaires. Thirty-four research-orientated individuals completed the pre-webinar questionnaire, n = 19 from the ALLIANCE Partnership areas, and n = 15 from outside Partnership areas. Eighty-two per cent had previously taken part in evidence-building activities, 94% had plans for future evidence-building activities, 70% said they, or their service, had plans to involve older people in evidence building in the future and 68% gave examples of what they would like to include or achieve in a 30-minute career development session focused on supporting them to evidence build.

Webinar 1 focused on capacity building research-orientated individuals to better understand how they can personally (or as a service or organisation) become more engaged in evidence building, whether that is engaging in research or service development, and included signposting aspiring researchers to established regional and national opportunities such as the NIHR ICA scheme and linking them to their most relevant RDS or CRN. Twenty-six individuals attended, n = 12 from ALLIANCE areas, and n = 14 from non-ALLIANCE areas. Two attendees completed the post-webinar evaluation form. Webinar 2 is discussed under Active frailty/Palliative and end-of-life-care PPIE in each region below.

Coproduced guidelines/strategies

Due to issues around developing and maintaining key contacts and links with research-orientated individuals, buy-in from the sector, and changing staff and services, it was not possible to develop ALLIANCE areas as we had wished and therefore coproduced guidelines and strategies were not relevant. These will now be developed, as relevant, as part of the future bid.

Active frailty/Palliative and end-of-life-care PPIE in each region

As mentioned in Objective 2, the survey findings demonstrated that few services had established PPIE groups, and fewer still had older people living with frailty represented within them. This output was therefore reframed to support services around understanding the importance of PPIE and supporting them to create meaningful PPIE groups. To do this we created a PPIE webinar (webinar 2) that focused on how attendees could better engage PPIE within their evidence building or service development and included guidance on how to support meaningful PPIE engagement with older people living with frailty and signposting to local and national PPIE services as well as services through the local and national RDS and CRNs. Fifteen people attended, n = 9 from ALLIANCE areas, and n = 6 non-ALLIANCE areas. Three completed the post-webinar evaluation form. All resources are available on the ALLIANCE website.

Evaluation

Regarding the generation of research questions, the initial plan was to create and administer a survey to generate the long list of questions. However, this was not required as data collected in Objective 2 was extensive and covered mapping and scoping the services, barriers, enablers and priorities regarding research, PPIE and care delivery within integrated care systems. This change to the plan was based on feedback from multiple key contacts as the best use of their time.

Regarding the database of aspiring researchers, throughout the timeline of the Partnership we lost contact with several of these research-interested individuals. We are unable to report with certainty why this was, but it is likely due to reasons such as people changing roles, clinical priorities and lack of infrastructure and resources to buy out time from clinical practice. From a Partnership perspective, it was difficult to keep interest intact throughout the three diverse regions, and the interest in the East Midlands perhaps speaks to its investment in Clinical Academic Careers and a strong, established research infrastructure. To reinvigorate interest, as discussed above, we promoted the webinars widely, for example through the British Geriatric Society and Palliative Care Research Society and established and promoted the repository.

In regard to PPIE engagement, as well as supporting services within the Partnership to embed PPIE, ALLIANCE also sought to establish engaged and meaningful PPIE throughout the Partnership on a regional and national level. There were multiple challenges, many of which are mentioned in Evaluation, Objective 1. However, while this engagement took time to grow momentum, meaningful engagement was established, specifically with regional carer organisations and, as discussed in Objective 4, by holding two PPIE events at lunch clubs. A report of PPIE representation and learning around engaging PPIE in this population at the interface between frailty and end-of-life care is included in Appendix 7. Future overarching engagement will come through using the remaining PPIE funds to support further and ongoing engagement with bid writing and growing sustained PPIE involvement within the Partnership, particularly around developing and embedding PPIE within each region and supporting ethnicity, diversity and inclusion.

Objective 4: Establishing research questions across the Partnership and developing research proposals: building together

Plan

This objective sought to explore and finalise the coproduced research priorities and establish the research question(s) the Partnership would develop into the bid for the Part 2 call. The outcome of this objective was coproduced, clinically applied, translational research proposals focused on enhancing palliative and end-of-life care for older people living with advancing frailty. Learning regarding the research engagement process, working across integrated care and establishing research partnerships were also to be disseminated to support ongoing research capacity development.

Delivery

A virtual nominal group technique35 was to rank and finalise the selection of research topics identified in Objective 2. A facilitated online workshop with up to 25 participants, from across ALLIANCE, including PPIE and informal carers, would use plenary and small group work to: (1) prioritise research questions and identify any omissions; (2) discuss each one to determine clarity, importance and feasibility using the FINER criteria;36 and (3) vote to prioritise the top five research questions. Proposal-writing around these top five research questions was to take place in smaller Partnership teams defined by interest and expertise, and be supported by organisational and national infrastructures, for example, Clinical Research Networks, Clinical Trials Units and the Research Design Service. Processes for disseminating and translating research into commissioning and practice were established as relevant.

Outputs and outcomes

Agreed priority questions

Rather than using the virtual nominal group technique,35 three different prioritisation methods were used. The rationale for this change is discussed in Evaluation. These methods were as follows:

-

Research-orientated key contacts focused – A survey was created for professionals working within services across the integrated care system. These contacts were asked to gain feedback from their PPIE groups, if established, to support completion of the survey.

-

PPIE representative focused – The above survey was refined by Dr Nadia Brookes to create a short prioritisation exercise to enable meaningful engagement by PPIE representatives.

-

PPIE focused – To support the engagement of older people living with frailty and those important to them, two PPIE events were held at two lunch clubs for older people, where the short prioritisation survey (point 2 above) was used to engage with older people one-to-one. A report of these exercises is included in the PPIE summary in Appendix 7.

The engagement is detailed in Table 9.

| Research-orientated individuals | Representatives of carers and older people | Older people | Care homes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sent to: 25 | Sent to: 24 | 21 older people | Sent to: 8 |

| Responded: 11 | Responded: 7 | aged 75–97 years | Responded: 3 |

| Responses from: | Responses from: | Responses from: All South West London | Responses from: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

|

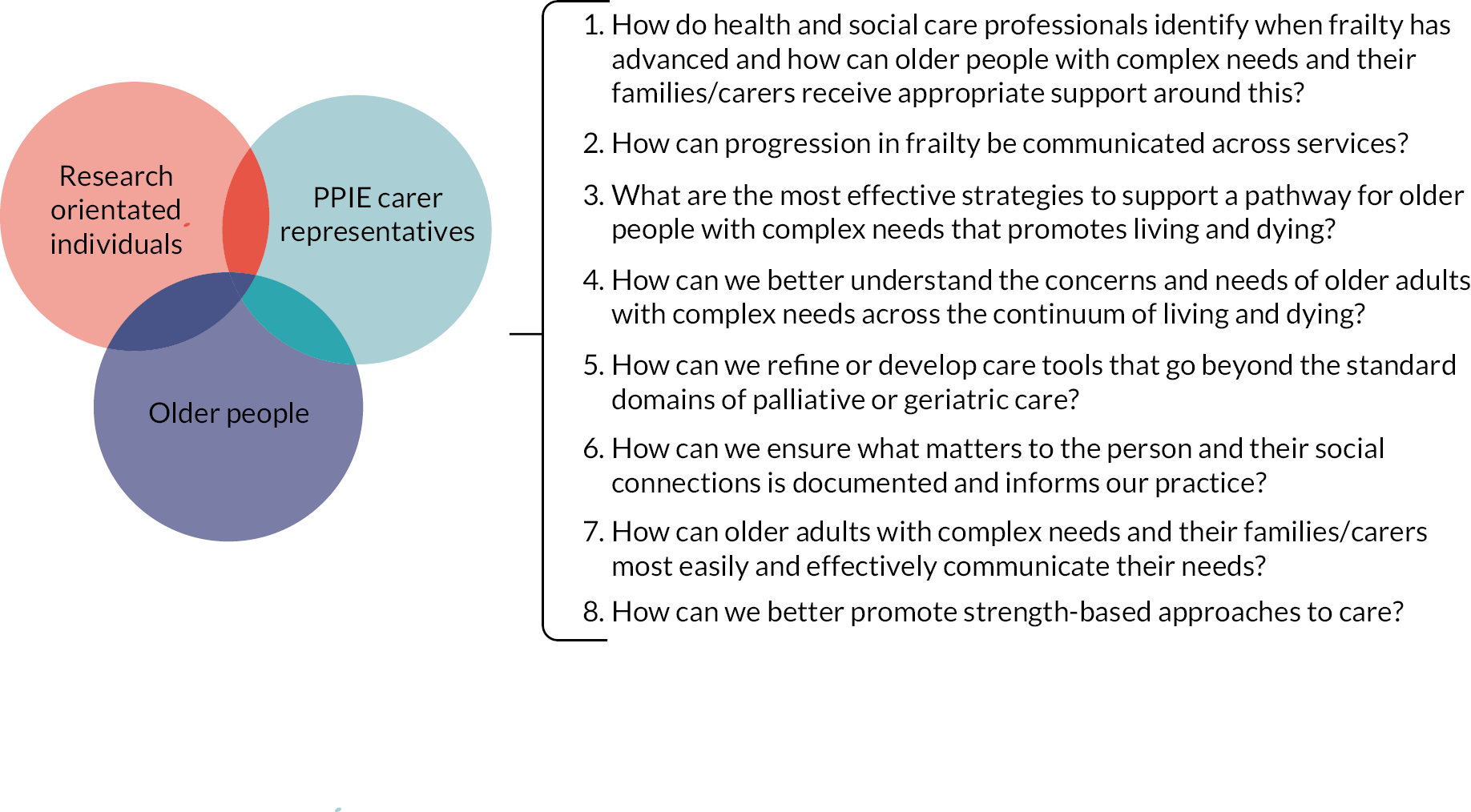

The results of the three prioritisation exercises were then combined, as shown in Figure 7.

FIGURE 7.

Overarching research priorities. Key: blue – prioritised by older people living with frailty; green – prioritised by older people and PPIE carer representatives; orange – prioritised by research-orientated staff.

Proposal(s) written for Part 2 (and other) call(s)

The overarching research priorities (see Figure 6) and PPIE feedback from the prioritisation exercises were used by the Core group alongside advice from the Advisory group to finalise the research question to develop into the bid for the Part 2 call. Multiple research questions were considered under these priorities, and many may be worked up in the future as research bids. However, for the Part 2 call, the ALLIANCE Partnership chose to play to its strengths: its underpinning coproduction and PPIE focus, its desire to prioritise the voices of older people living with advancing frailty and those important to them, and the strengths of the integrated care system across the Partnership regions. As such, the ALLIANCE research question combines the priorities selected by the older people and PPIE representatives and focuses on supporting services as they currently are to be better at involving older people living with advancing frailty, and those important to them, to ensure what matters most to the older person informs professional practice. Following the prioritisation and choice of research question, a virtual Discussion group was held. This was led by experienced facilitators who supported the participants, health and social care professionals and PPIE representatives to meaningfully engage with the research question in regard to what they felt was required to support services to better include older people and those important to them in professional practice.

Disseminate learning

Multiple dissemination activities have taken place and are planned for the future. These include:

-

The development of multiple resources and curation of key documents which are held in the website repository www.surrey.ac.uk/living-and-dying-well-research and promoted through the Twitter account @ALLIANCE_Collab under the @LDW_Research banner.

-

Presentations including at the Royal Society of Medicine PPIE webinar (18 April 2023), NIHR Research Active Hospices conference (20 June 2023) and NIHR ARC Wessex CRED talk (Care and Research Education and Debate) (23 March 2023).

-

Publications including on Open Access Government37 and conference proceedings. 38

-

Development of multimedia, for example the creation of films on how to support older people living with frailty to meaningfully engage with PPIE.

PPIE

While the Partnership has finished, we continue to work with PPIE representatives to understand what matters most to older people with frailty, unpaid carers and unpaid carer representatives. Most recently, building on the findings of ALLIANCE, an online workshop was held to understand and explore the knowledge and experiences of PPIE regarding holistic assessments; what matters most, what works well, and what needs to change in order to develop a research bid. A visual minute of this discussion group can be accessed here: www.surrey.ac.uk/living-and-dying-well-research/resources.

Evaluation

While the Partnership planned to use the virtual nominal group technique35 to prioritise the final research questions, this was amended to three specific prioritisation exercises. This was for several reasons. The extensive survey in Objective 2 had enabled the development of the Generation of Research Questions for Prioritisation (within Objective 3), which had allowed the Partnership to thematise the potential research questions into four broad topic areas and prioritise them. Further, on reflection with the Core group and Advisory group, it was felt that the nominal group technique would not enable the meaningful engagement of all participants across the different stakeholders. The three different prioritisation methods were used to enable different stakeholder to engage in ways that played to their strengths, and methods were altered accordingly. For example, the PPIE sessions with older people were to be a face-to-face group exercise, but when the researchers attended, they found individual conversations, that supported the person to engage, worked far better. This is discussed further in Appendix 7.

The Partnership originally planned to develop writing groups to write proposals for the top five research questions to be submitted in the round 3 funding. However, due to challenges including the labour intensity of previous objectives, the Partnership member’s research readiness, the desire to submit a bid that considers the learnings from, and plays to the strengths of ALLIANCE, and to allow time for meaningful PPIE engagement, the Partnership is instead currently writing a bid that is likely to be submitted to the Health and Social Care Delivery Research Programme funding stream. There is also the potential to work up and submit further proposals under other bid streams in the future. In regard to disseminating the findings into practice, this has already started, some examples of which have been detailed above, and will be addressed in more detail in the Part 2 call bid going forward.

Reflections on the partnership

The Partnership brought together experts, by profession or experience, across specialist palliative and older people’s care from three diverse areas of England. This included older people living with frailty, those important to them, those working in health and social care and the voluntary sector, and those from the academic arena. Each brought their experience and expertise, and supported the development of new knowledge regarding the current state of service provision and research for older people living with advancing frailty as they transition across spaces. The Partnership has developed and curated multiple resources to support professionals in how to support people with frailty better, how to engage them in research, and how to become more research ready. The webinars were considered to be particularly successful, and, with more attendees from outside the Partnership’s established key contacts, demonstrated a desire within the sector to learn more about supporting frail older people to engage in research and developing as a clinical academic.

Challenges were experienced with key contacts leaving the Partnership due to multiple reasons documented previously, and issues around the nature of the Partnership as there was no immediate clinical output or funding benefits related to the work. This led to us developing particular ways to talk about ALLIANCE depending upon which part of the integrated care system we engaged with. Issues were experienced when working across the interface of health, social and voluntary care, where there is little shared language or care pathways, and with many staff siloed into palliative or frailty care. This has been compounded by a system in flux as integrated care systems evolve and staff move roles. The findings also speak to the challenge of including older people living with advancing frailty in this kind of work. Within this project only 39% of respondents had a PPIE group within their service or organisation, and of these, only four had older people living with advancing frailty or their carers as part of that group. This demonstrates the minimal understanding of PPIE, and lack of evidence of engagement with older people living with frailty, by many organisations, alongside the need for further support and education in this area. We will support these existing groups and identify where there may be interest in developing these across organisations.

The Partnership has therefore grown and changed over the 15-month period, and now has an established quorum of interested individuals across the integrated care system across the Partnership regions. Our next steps are to move forward to support research bid writing, and the Partnership will continue to support research readiness and PPIE engagement through the Partnership regions and beyond.

Conclusion

The Partnership has highlighted the challenges with working in this area. That despite recognition of the importance of integrated care for older people living with advancing frailty, there remain serious challenges in improving services, implementing research, and promoting research capacity in health, social and voluntary care sector organisations. In 2001, Seymour et al. ,39 called for a closer partnership between palliative and geriatric care to ensure older people did not remain ‘systematically disadvantaged’, particularly regarding specialist service access. Over 20 years later, we have a greater understanding of the needs of older people with advancing frailty, and yet service development and configuration, and the research to support this, remains poor. However, over a 15-month period, the ALLIANCE Partnership established its infrastructure and identified key contacts within each region across the palliative and end-of-life continuum. We mapped, scoped and analysed the strengths, weaknesses, barriers and enablers of current clinical services for people with advancing frailty and research readiness among Partnership services. We supported Partnership services, and staff outside the Partnership, to become research ready. We also established research questions across the Partnership to develop into a Part 2 research proposal. As a result, the Partnership has developed a service framework for older people living and dying with advancing frailty (see Figure 6). Further, the partnership has a quorum of members who will continue to collaborate, and coproduce clinically applied, translational research proposals focused on enhancing palliative and end-of-life care for older people living with advancing frailty.

Reporting equality, diversity and inclusion/patient and public involvement and engagement

Equality, diversity and inclusion (EDI) are underlying principles of the partnership. Sites incorporated geographical and socio-economic diversity. The guiding tenant of the work has been to raise the voice, concerns, and care needs of older people with frailty and their unpaid carers at end of life; currently an underserved majority in relation to receiving palliative care. ALLIANCE aspired to coproduce activities as much as possible and developed a core set of values for how the different Partnership stakeholders worked together (see Appendix 3). These values have been adapted from the coproduction principles34 and the UK standards for Public Involvement,40 and include inclusivity, empathy, reciprocity, equality and investment in relationships. Values were key to facilitating and enabling collaboration among the different groups involved in the partnership, which was underpinned by an assets-based approach, supporting the partnership to think positively and identify collective strengths and opportunities, rather than focus on problems and deficits.

The understanding of EDI and involvement of PPIE was embedded throughout ALLIANCE. Pre-Partnership, PPIE contributed to the bid in multiple ways, including articulating the need for research focused explicitly on the care of people with advancing frailty,41 and the need to improve the delivery of integrated care with particular attention to care transitions at the end of life. 27 During the Partnership activities included building and strengthening relationships, understanding barriers and facilitators to excellent care, refining the Phase 2 survey, hearing the stories of older people and those important to them in regards to the lived experience of advancing frailty, prioritising the potential research questions, and refining the final chosen research question. As part of the PPIE work to support Partnership members, but also the care of older people living with advancing frailty more generally, multiple resources were created including those now used by Hospice UK to support work with older people living with advancing frailty, a film of an unpaid carer articulating how she supported her mother living with advancing frailty to take part as a PPIE member, and a summary written on PPIE engagement within the Partnership, including two case studies from PPIE involvement work with two separate lunch clubs in South West London. Two Core group members presented at the Royal Society of Medicine’s Innovations in patient and public involvement in palliative care research event (April 2023), and going forward, PPIE representatives from carer support groups have agreed to work further with the Partnership to shape the Part 2 bid. The principle of PPIE involvement continues as we work with multiple PPIE representatives to understand what matters most to older people with frailty and unpaid carers, and develop the ALLIANCE bid.

Additional information

CRediT contribution statement

Sarah Combes (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9708-4495): Conceptualisation (equal), Funding acquisition (equal), Methodology (equal), Investigation (equal), Data curation (lead), Formal analysis (lead), Writing – original draft (lead), Writing – editing and reviewing (lead), Project administration (lead), Visualisation (lead).

Rowan H Harwood (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4920-6718): Conceptualisation (equal), Funding acquisition (supporting), Methodology (supporting), Supervision (equal), Writing – original draft (supporting), Writing – editing and reviewing (supporting).

Louise Bramley (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0425-1734): Conceptualisation (supporting), Methodology (supporting), Writing – original draft (supporting), Writing – editing and reviewing (supporting).

Nadia Brookes (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6661-2814): Conceptualisation (supporting), Methodology (supporting), Investigation (supporting), Writing – original draft (supporting), Writing – editing and reviewing (supporting).

Adam L Gordon (https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1676-9853): Conceptualisation (supporting), Writing – original draft (supporting), Writing – editing and reviewing (supporting).

Diane Laverty (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1082-3727): Conceptualisation (supporting), Writing – original draft (supporting), Writing – editing and reviewing (supporting).

Julie MacInnes (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9220-1007): Conceptualisation (supporting), Supervision (supporting), Writing – original draft (supporting), Writing – editing and reviewing (supporting).

Emily McKean (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3045-296X): Project administration (supporting), Data curation (supporting), Investigation (supporting), Formal analysis (supporting), Writing – original draft (supporting), Writing – editing and reviewing (supporting), Visualisation (supporting).

Shannon Milne (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5202-4237): Conceptualisation (supporting), Writing – original draft (supporting), Writing – editing and reviewing (supporting).

Heather Richardson: Conceptualisation (supporting), Writing – original draft (supporting), Writing – editing and reviewing (supporting).

Joy Ross (https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1894-5953): Conceptualisation (supporting), Writing – original draft (supporting), Writing – editing and reviewing (supporting).

Emily Sills (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7371-0113): Conceptualisation (supporting), Writing – original draft (supporting), Writing – editing and reviewing (supporting).

Caroline J Nicholson (https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4422-413X): Conceptualisation (equal), Funding acquisition (equal), Methodology (equal), Supervision (lead), Formal analysis (supporting), Writing – original draft (lead), Writing – editing and reviewing (supporting).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all potential and actual Partnership members, collaborators and gatekeepers for their time, knowledge and engagement. Further thanks to the patient and public involvement and engagement representatives including Colin Hopkirk, EveryOne; Mark Turton, LinCA; Nicola Wilson, Crossroads Care; Sue McVicker, Croydon Neighbourhood Care Association; Steve Castellari, The Carers Centre; Age UK; and Carers UK. Particular thanks to the Core group: Dr Louise Bramley (Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust), Dr Nadia Brookes (University of Kent), Professor Adam Gordon (University of Nottingham), Dr Diane Laverty (London Ambulance Service NHS Trust), Dr Julie MacInnes (University of Kent), Dr Shannon Milne (Princess Alice Hospice), Professor Heather Richardson (St Christopher’s Hospice), Dr Joy Ross (St Christopher’s Hospice) and Emily Sills (Princess Alice Hospice). Thanks also to our Advisory group: Professor Barbara Hanratty, Professor Martin Vernon, Professor Julienne Meyer CBE, Dr Jo Zamani, Dr Caroline Chill and the Venerable Dr Justine Allain Chapman.

Data-sharing statement

All data requests should be submitted to the corresponding author for consideration. Access to anonymised data may be granted following review.

Ethics statement

As this was not a research study, it did not require ethics approval.

Information governance statement

The study did not handle any personal information.

Disclosure of interests

Full disclosure of interests: Completed ICMJE forms for all authors, including all related interests, are available in the toolkit on the NIHR Journals Library report publication page at https://doi.org/10.3310/ACMW2401

Primary conflicts of interest: None declared.

Department of Health and Social Care disclaimer

This publication presents independent research commissioned by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR). The views and opinions expressed by authors in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the NHS, the NIHR, MRC, NIHR Coordinating Centre, the Public Health Research programme or the Department of Health and Social Care.

This article was published based on current knowledge at the time and date of publication. NIHR is committed to being inclusive and will continually monitor best practice and guidance in relation to terminology and language to ensure that we remain relevant to our stakeholders.

Funding

This article presents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Public Health Research programme as award number NIHR135262.

This article reports on one component of the research award ALLIANCE: Enhancing the quality of living and dying with advancing frailty through integrated care partnerships: Building research capacity and capability. For more information about this research please view the award page (https://fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/NIHR135262).

About this article

The contractual start date for this research was in February 2022. This article began editorial review in July 2023 and was accepted for publication in June 2024. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The Public Health Research editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ article and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Copyright

Copyright © 2024 Combes et al. This work was produced by Combes et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

Glossary

ALLIANCE Enhancing the quality of living and dying with advancing frailty through integrated care partnerships: Building research capacity and capability.

List of abbreviations

- EDI

- equality, diversity and inclusion

- NIHR

- National Institute for Health and Social Care

- PPIE

- patient and public involvement and engagement

References

- Clegg A, Young J, Iliffe S, Rikkert MO, Rockwood K. Frailty in elderly people. Lancet (London, England) 2013;381:752-62.

- Gale CR, Cooper C, Aihie Sayer A. Prevalence of frailty and disability: findings from the English Longitudinal Study of Ageing. Age Ageing 2014;44:162-5.

- Etkind SN, Bone AE, Gomes B, Lovell N, Evans CJ, Higginson IJ, et al. How many people will need palliative care in 2040? Past trends, future projections and implications for services. BMC Med 2017;15:1-10.

- Bone AE, Gomes B, Etkind SN, Verne J, Murtagh FE, Evans CJ, et al. What is the impact of population ageing on the future provision of end-of-life care? Population-based projections of place of death. Palliat Med 2018;32:329-36.

- Clegg A, Bates C, Young J, Ryan R, Nichols L, Ann Teale E, et al. Development and validation of an electronic frailty index using routine primary care electronic health record data. Age Ageing 2016;45:353-60.

- National Health Service . The NHS Long Term Plan 2019. www.longtermplan.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/nhs-long-term-plan-version-1.2.pdf (accessed 12 July 2023).

- Department of Health and Social Care . Integration and Innovation: Working Together to Improve Health and Social Care for All: The Department of Health and Social Care’s Legislative Proposals for a Health and Care Bill 2021.

- Evans CJ, Ison L, Ellis‐smith C, Nicholson C, Costa A, Oluyase AO, et al. Service delivery models to maximize quality of life for older people at the end of life: a rapid review. Milbank Q 2019;97:113-75.

- Pialoux T, Goyard J, Hermet R. When frailty should mean palliative care. J Nurs Educ Pract 2013;3.

- Teunissen SC, de Haes HC, Voest EE, de Graeff A. Does age matter in palliative care?. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2006;60:152-8.

- Gill TM, Gahbauer EA, Han L, Allore HG. Trajectories of disability in the last year of life. N Engl J Med 2010;362:1173-80.

- Sharp T, Malyon A, Barclay S. GPs’ perceptions of advance care planning with frail and older people: a qualitative study. Br J Gener Pract 2018;68:e44-53.

- Mathie E, Goodman C, Crang C, Froggatt K, Iliffe S, Manthorpe J, et al. An uncertain future: the unchanging views of care home residents about living and dying. Palliat Med 2012;26:734-43.

- Bennett MI, Ziegler L, Allsop M, Daniel S, Hurlow A. What determines duration of palliative care before death for patients with advanced disease? A retrospective cohort study of community and hospital palliative care provision in a large UK city. BMJ Open 2016;6.

- Care Quality Commission . A Different Ending: Addressing Inequalities in End of Life Care. Overview Report 2016. www.cqc.org.uk/sites/default/files/20160505%20CQC_EOLC_OVERVIEW_FINAL_3.pdf (accessed 12 July 2023).

- Polak L, Hopkins S, Barclay S, Hoare S. The difference an end-of-life diagnosis makes: qualitative interviews with providers of community health care for frail older people. Br J Gener Pract 2020;70:e757-64.

- Zheng L, Finucane A, Oxenham D, McLoughlin P, McCutcheon H, Murray S. How good is UK primary care at identifying patients for generalist and specialist palliative care: a mixed methods study. Eur J Pallat Care 2013;20:216-22.

- Perrels AJ, Fleming J, Zhao J, Barclay S, Farquhar M, Buiting HM, et al. Cambridge City over-75s Cohort (CC75C) Study Collaboration . Place of death and end-of-life transitions experienced by very old people with differing cognitive status: retrospective analysis of a prospective population-based cohort aged 85 and over. Palliat Med 2014;28:220-33.

- Cardona-Morrell M, Kim JC, Turner RM, Anstey M, Mitchell IA, Hillman K. Non-beneficial treatments in hospital at the end of life: a systematic review on extent of the problem. Int J Qual Health Care 2016;28:456-69.

- Murray SA, Kendall M, Mitchell G, Moine S, Amblas-Novellas J, Boyd K. Palliative care from diagnosis to death. BMJ 2017;356.

- Hanratty B, Holmes L, Lowson E, Grande G, Addington-Hall J, Payne S, et al. Older adults’ experiences of transitions between care settings at the end of life in England: a qualitative interview study. J Pain Symptom Manage 2012;44:74-83.

- Gomes B, Calanzani N, Curiale V, McCrone P, Higginson IJ, de Brito M. Effectiveness and cost‐effectiveness of home palliative care services for adults with advanced illness and their caregivers. Cochr Datab Syst Rev 2013;2013.

- Shaw S, Rosen R, Rumbold B. What Is Integrated Care. London: Nuffield Trust; 2011.

- NHS England . Five Year Forward View 2014.

- Goodwin N. Understanding integrated care. Int J Integr Care 2016;16.

- Nicholson CJ, Combes S, Mold F, King H, Green R. Addressing inequity in palliative care provision for older people living with multimorbidity. Perspectives of community-dwelling older people on their palliative care needs: a scoping review. Palliat Med 2023;37:475-97.

- Green R, Nicholson C. Older people with severe frailty talking about their palliative care needs: an interview and survey study during the COVID-19 pandemic. Palliat Med 2021;35.

- National Institute for Health Research . Better Endings: Right Care, Right Place, Right Time 2015.

- European Commission . Comparing the Effectiveness of Palliative Care for Elderly People in Long Term Care Facilities in Europe 2018. https://cordis.europa.eu/project/id/603111 (accessed 9 April 2024).

- EU Navigate . EU Navigate, Supporting Older People With Cancer: A European Project Investigating Navigation Programmes in Different EU Countries 2024. https://eunavigate.com/ (accessed 9 April 2024).

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . End of Life Care for Adults: Service Delivery [NG142] 2019. www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng142 (accessed 12 July 2023).

- Michie S, Van Stralen MM, West R. The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci 2011;6:1-12.

- Bayly J, Bone AE, Ellis-Smith C, Yaqub S, Yi D, Nkhoma KB, et al. Common elements of service delivery models that optimise quality of life and health service use among older people with advanced progressive conditions: a tertiary systematic review. BMJ Open 2021;11.

- National Institute for Health Research . Guidance on Co-Producing a Research Project 2021. www.learningforinvolvement.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/NIHR-Guidance-on-co-producing-a-research-project-April-2021.pdf (accessed 12 July 2023).

- James Lind Alliance (JLA) . Lab Activity 1: Development of Online Priority Setting Workshop – Lessons Learned Report 2021. www.jla.nihr.ac.uk/jla-lab/Report-on-JLA-PSP-online-priority-setting-workshops.pdf (accessed 12 July 2023).

- Cummings SR, Browner WS, Hulley SB. Conceiving the research question and developing the study plan. Design Clin Res 2013;4:14-22.

- Nicholson CA. New approach to older people’s end of life care: living and dying well. Open Access Govern 2023;37:28-9.

- Combes S, Harwood R, McKean E, Nicholson C. P-31 ALLIANCE: enhancing the quality of living and dying with advancing frailty through integrated care partnerships. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2022;12.

- Seymour J, Clark D, Philp I. Palliative care and geriatric medicine: shared concerns, shared challenges. Palliat Med 2001;15:269-70. https://doi.org/10.1191/026921601678320241.

- National Institute for Health Research . UK Standards for Better Involvement in Research: Better Public Involvement for Better Health and Social Care Research 2019. www.invo.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/11/UK-standards-for-public-involvement-v6.pdf (accessed 12 July 2023).

- Combes S. Conversations on Living and Dying: Facilitating Advance Care Planning for Community-Dwelling Older People With Frailty 2018. https://fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/ICA-CDRF-2017-03-012 (accessed 12 July 2023).

Appendix 1

| Name | Region | Position held | Role | Organisation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Professor Caroline Nicholson | N/A | Professor of Palliative Care and Ageing/Honorary Consultant Nurse | Leading direction and interface with integrated care. Co-leading governance and reporting. Leading ECR managerial and research support. Expertise in intervention design, clinical academic praxis and PPIE | University of Surrey/St Christopher’s Hospice |

| Professor Dr Rowan Harwood | East Midlands | Professor of End of Life Care, Honorary Consultant Geriatrician | Co-lead; mentorship and support for joint-lead applicant. Co-lead governance, reporting and strategic direction | The University of Nottingham |

| Dr Sarah Combes | N/A | Research Fellow in Palliative Care and Ageing/NIHR Senior Research Leader Nursing and Midwifery | Leading day-to-day management, Partnership and site research support | University of Surrey/St Christopher’s Hospice |

| Professor Heather Richardson | South West London | Director of Education, Research and End of Life Policy | South West London research capacity and capability building co-lead, strategic and clinical guidance | St Christopher’s Hospice |

| Dr Joy Ross | South West London | Consultant in Palliative Medicine | South West London research capacity and capability building co-lead, clinical academic guidance | St Christopher’s Hospice |

| Professor Adam Gordon | East Midlands | Professor of the Care of Older People | Lead for meaningful inclusion of long-term care, clinical academic research capacity building | The University of Nottingham |

| Dr Diane Laverty | South West London | Macmillan Nurse Consultant Palliative Care | Representative for Ambulance Clinicians and lead for meaningful inclusion of ambulance clinicians | London Ambulance Service NHS Trust |

| Dr Louise Bramley | East Midlands | Head of Nursing and Midwifery Research | East Midlands research capacity and capability building lead and clinical academic guidance | Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust |

| Dr Julie MacInnes | N/A | Senior Research Fellow, Applied Health and Social Care | Lead for integrated health and social care systems, and meaningful inclusion of voluntary and social care | University of Kent |

| Dr Shannon Milne | South East England | Research Lead | South East England research capacity and capability building lead and clinical guidance | Princess Alice Hospice |

| Dr Emily Sills | South East England | Consultant in Palliative Medicine | South East England research capacity and capability building lead and clinical guidance | Princess Alice Hospice |

| Dr Nadia Brookes | N/A | ARC KSS Coproduction theme lead/Senior Research Fellow | Lead to facilitate a coordinated approach to coproduction and PPIE across the Partnership | University of Kent |

| Dr Emily McKean | N/A | Research Assistant | Research Assistant for project and PPIE support | University of Kent |

| Name | Specialist area | Role/speciality | Institution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Professor Barbara Hanratty | Palliative care | Professor of Primary Care and Public Health, and GP with speciality in frailty | Newcastle University |

| Professor Martin Vernon | Older people | Consultant Geriatrician and Clinical Director, Community Adults and Specialist Services Directorate | NHS England; Greater Manchester Strategic Clinical Network; North West Clinical Senate |

| Professor Julienne Meyer CBE | Social care | Emeritus Professor and nurse, with speciality in care homes and social care | City, University of London |

| Dr Jo Zamani | NIHR links | CEO NIHR Clinical Research Network for Kent, Surrey and Sussex | CRN KSS |

| Dr Caroline Chill | Integrated Care Systems | GP and Clinical Director for Healthy Ageing | Health Innovation Network |

| The Venerable Dr Justine Allain Chapman | PPIE | Archdeacon of Boston, Lincolnshire, pastoral care for ageing parishioners and carer for ageing parents | Archdeacon of Boston, Lincolnshire |

Appendix 2

FIGURE 8.

Key contacts we attempted to establish and maintain across the integrated care system throughout each of the three regions.

Appendix 3

ALLIANCE core values to support coproduction and working together

A number of values will guide ALLIANCE and the ways in which participants work together: inclusivity, empathy, reciprocity, equality and investment in relationships. These values will be key to facilitating participation, establishing trust and enabling collaboration amongst the different groups involved in the partnership. Underpinning this will be an assets-based approach to support the partnership to think positively, identifying collective strengths and opportunities rather than problems and deficits.

Inclusivity: including all perspectives

Different voices need to be heard in the research process. ALLIANCE will ensure that all partners feel able to engage and contribute through an open and inclusive process. Activities, methods and tools will be designed to ensure inclusivity.

Empathy: respecting and valuing others

Empathy is central to achieving a high level of engagement and collaboration. ALLIANCE will ensure that as well as shared experiences, diversity in knowledge and experiences are recognised to allow for mutual learning and appreciation of each other’s opinions.

Reciprocity: learning from each other

The ability to create and sustain reciprocal relationships will have an impact on the level of engagement and in establishing the nature of collaborations. ALLIANCE will facilitate creative, enjoyable and reflective experiences of participation that will help the exchange of ideas.

Working towards greater equality

Establishing greater equality across stakeholders is key for establishing shared understanding and collective decision-making. ALLIANCE will promote equality by attending explicitly to barriers that reduce the opportunity to participate and shape the thinking and work of ALLIANCE. All members will be mindful of the power they have, and ways in which they could reduce the power of others – actively working to avoid the latter by choosing neutral spaces, ways of communicating, and creating an atmosphere where all partners feel welcome to share their views with each other.

Investment in relationships: getting to know each other

To enable coproduction to happen it is essential to build relationships and trust. ALLIANCE will create conditions that facilitate this, allowing the time, opportunities and the flexibility necessary.

Agreed on 16 May 2022 Version 1

Appendix 4 Objective 2: Description of the services

FIGURE 9.

Which of the following does your service primarily provide support for? Note: Completed by n = 47, n = 9 listed an additional service. Multiple choices were selected. (Support can be addressing a need or signposting/referring to another service.) Of the 16 ‘other’ focus, most fitted within a listed survey category for example polypharmacy within medications management, said ‘All’, specified EoL or palliative care approaches, or specified services for people living with learning disabilities. Needs not mentioned include social care needs such as loneliness and isolation (n = 3) and self-advocacy and influencing (n = 1).

FIGURE 10.

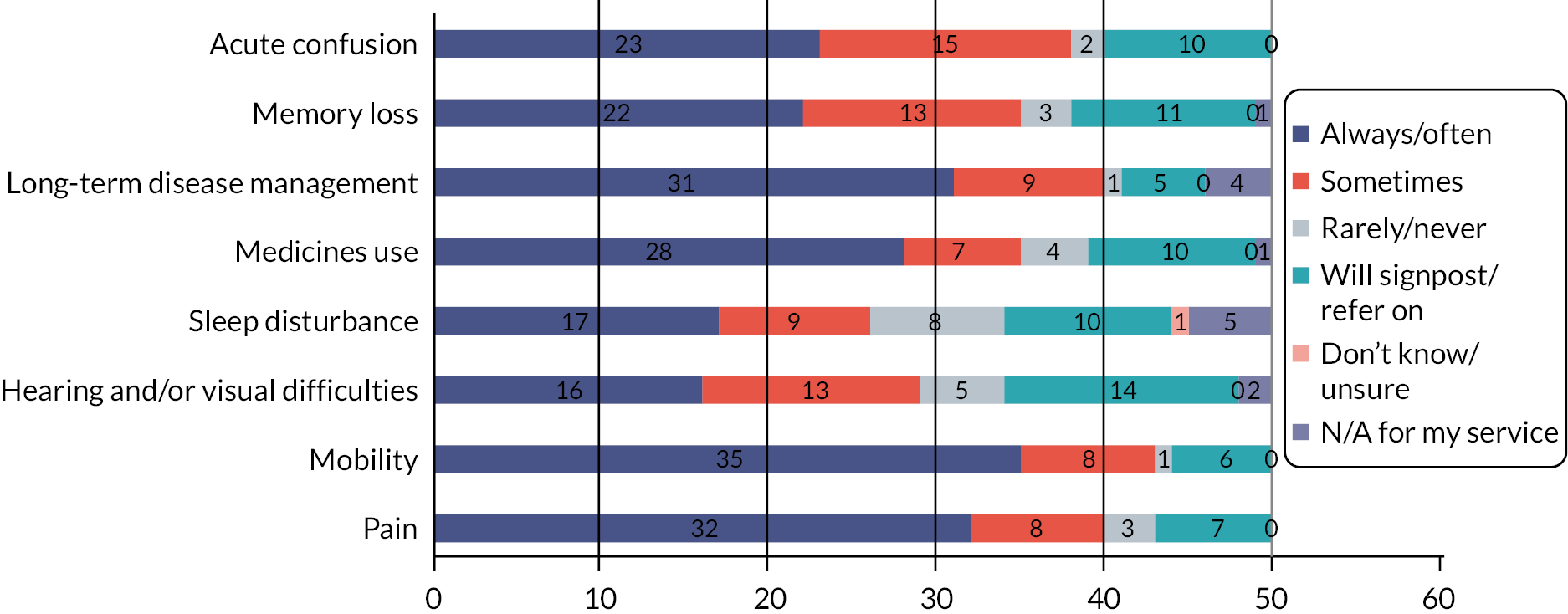

Which physical needs does your service support? Note: Completed by n = 44, n = 6 listed an additional service (n = 50 combined).

FIGURE 11.

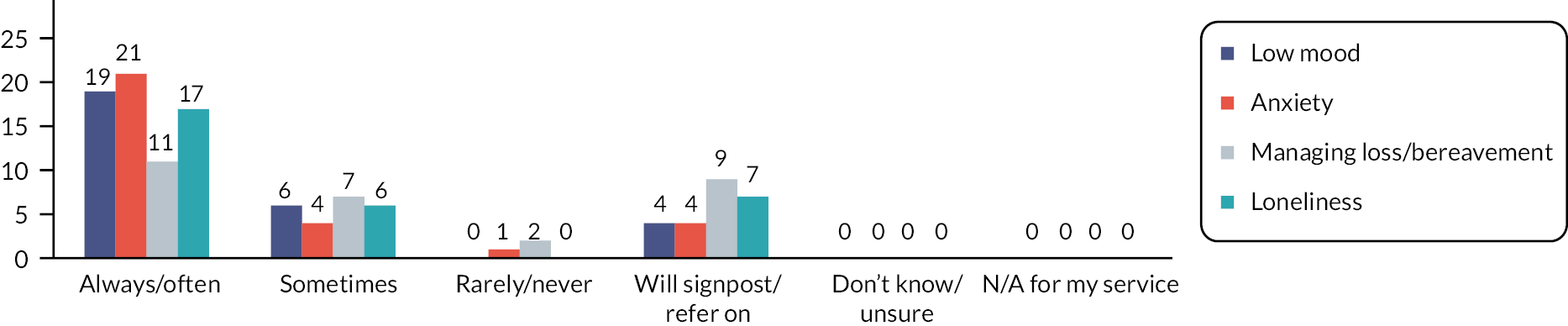

Which psychological/mental health needs does your service support? Note: Completed by n = 25, n = 5 listed an additional service (n = 30 combined). One respondent missed scoring for low mood, one for managing loss, hence n = 29 for these questions.

FIGURE 12.

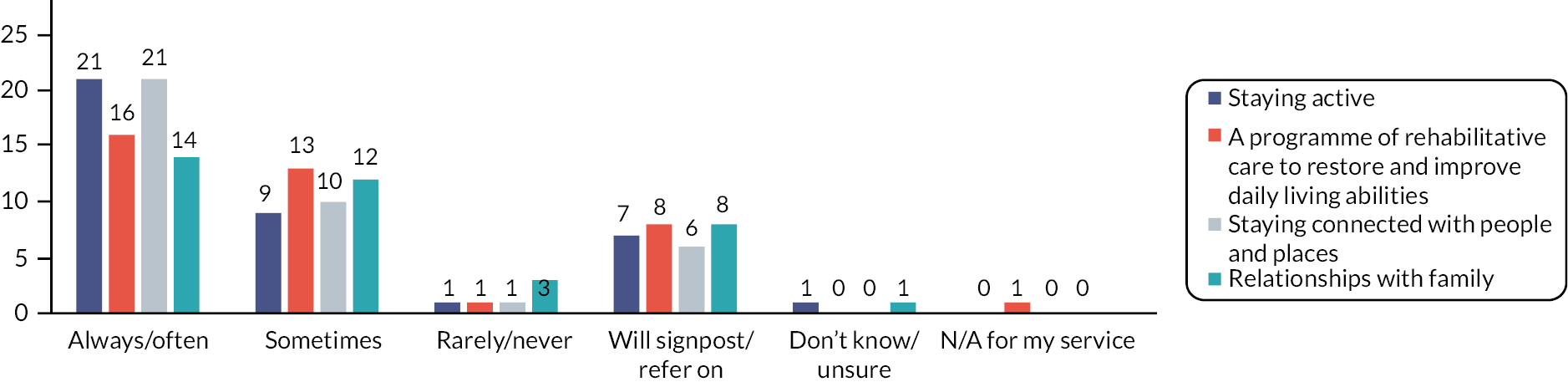

Which practical needs does your service support? Note: Completed by n = 34, n = 5 listed an additional service (n = 39 combined). One respondent missed scoring for Staying connected and one for Relationships with family, hence n = 38 for these questions.

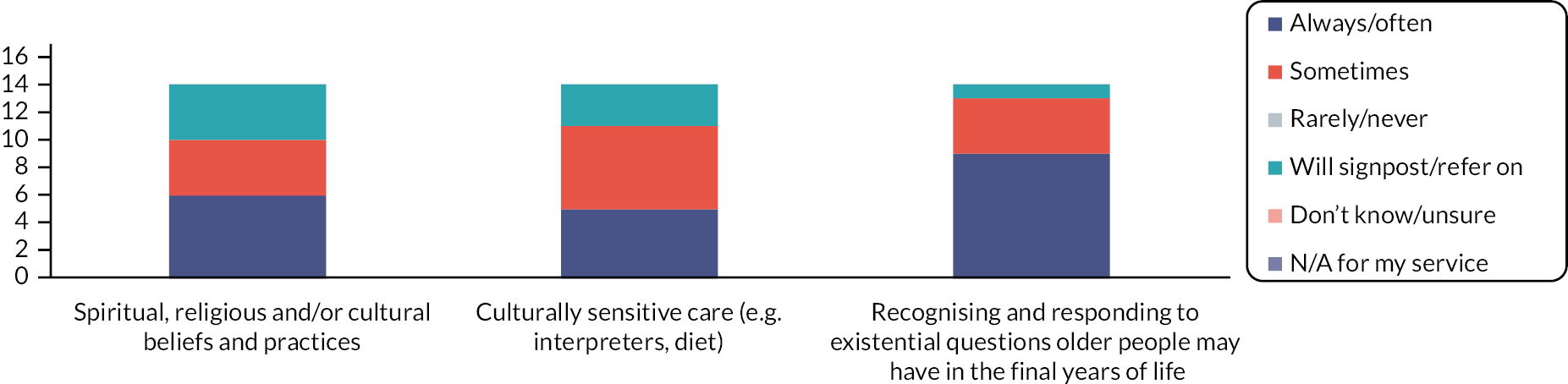

FIGURE 13.

Which spiritual needs does your service support? Note: Completed by n = 13, n = 1 listed an additional service (n = 14 combined).

Appendix 5 Objective 2: Details of what each service provides

| Having an organisational single point of contact that is always available | 12 |

| Providing some cover and then signposting to other services at other times | 6 |

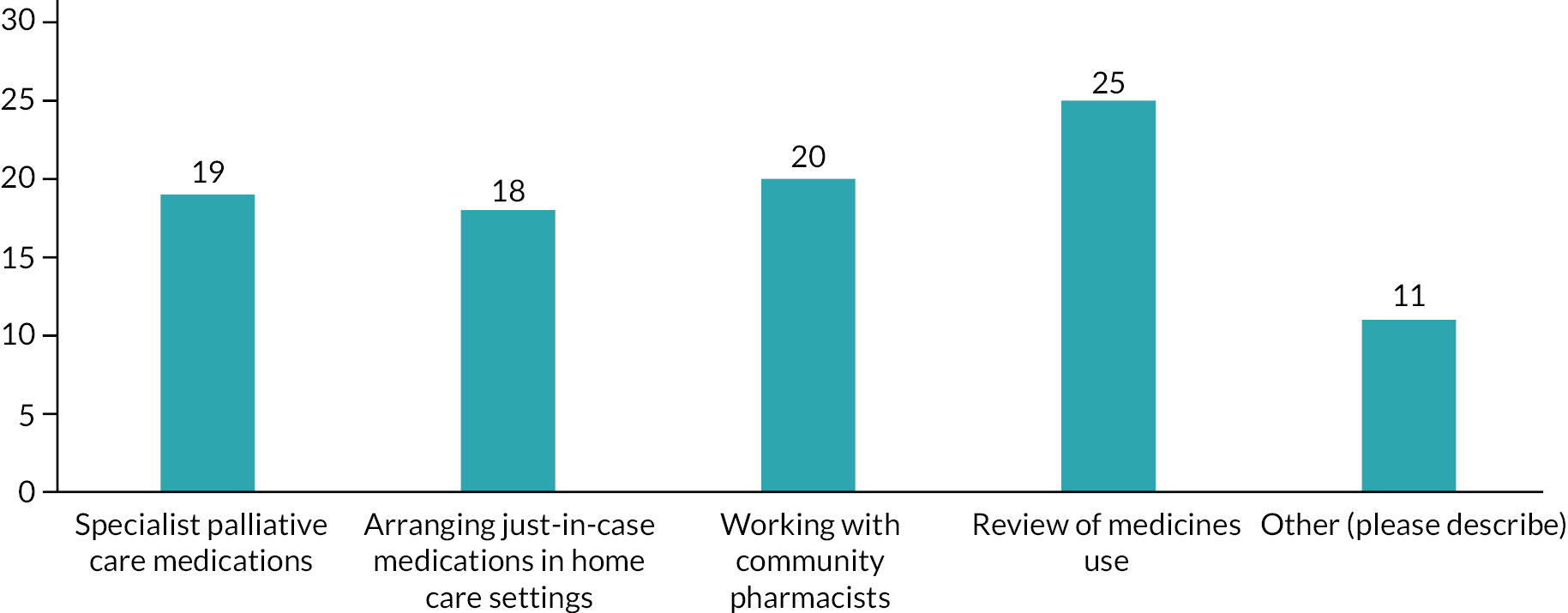

FIGURE 14.

How does your service provide medications management at home? Note: (n = 93 answers).

| General theme/topic | N = 10 |

|---|---|

| Administer/train carers/support administration of medications | 4 |

| Emergency provision of medications (e.g. crisis OOH) | 1 |

| Medications to manage dementia | 1 |

| Nurse prescribers within service | 1 |

| Pharmacist within service for SMRs and support | 1 |

| Signpost to GP for review/provide JIC medications | 2 |

FIGURE 15.

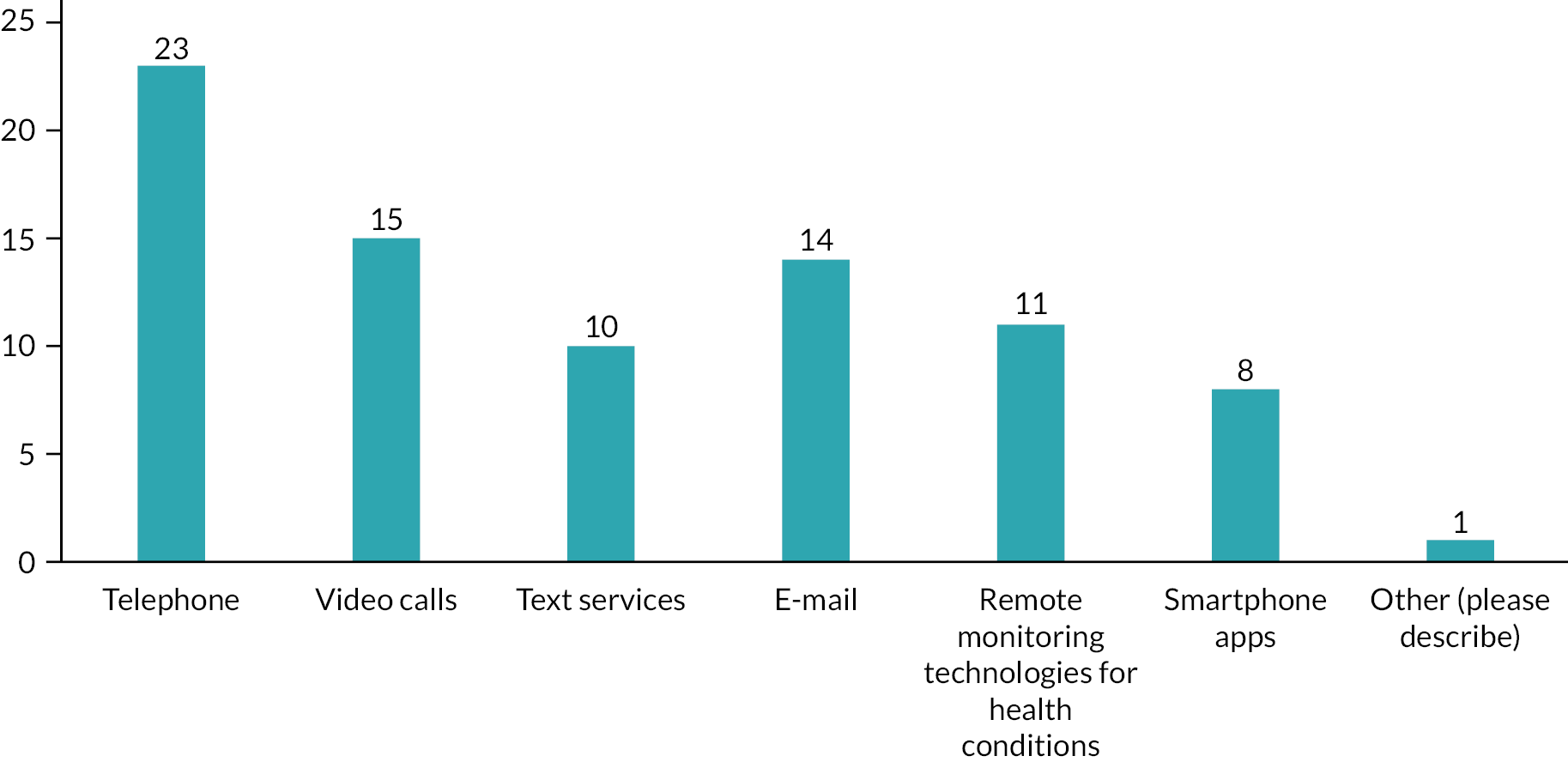

Which technology-facilitated communication methods does your service use for the facilitation and delivery of care remotely? Note: (Please select all that apply) n = 82 answers. Other n = 1 ISLA photos.

FIGURE 16.

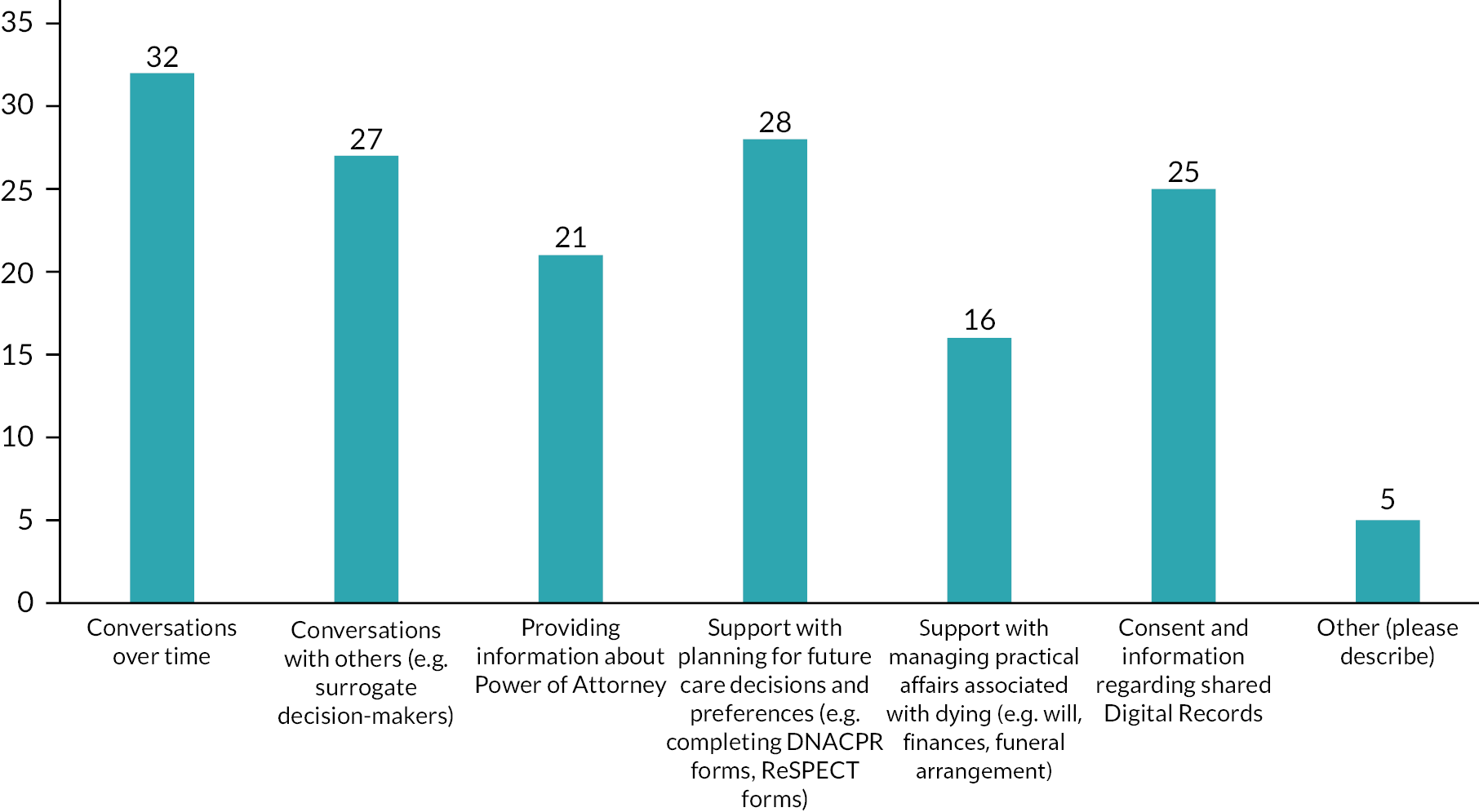

How does your service provide advance/anticipatory/future care planning? Note: (Please select all that apply). Other n = 4 responses provided: Information about/referral to specialist palliative care n = 2. Proactive ACP programme for people with rising need n = 1. Personalised care and support plans n = 1.

Appendix 6 Objective 2: Referrals: who the service refers to, and who refers to the service

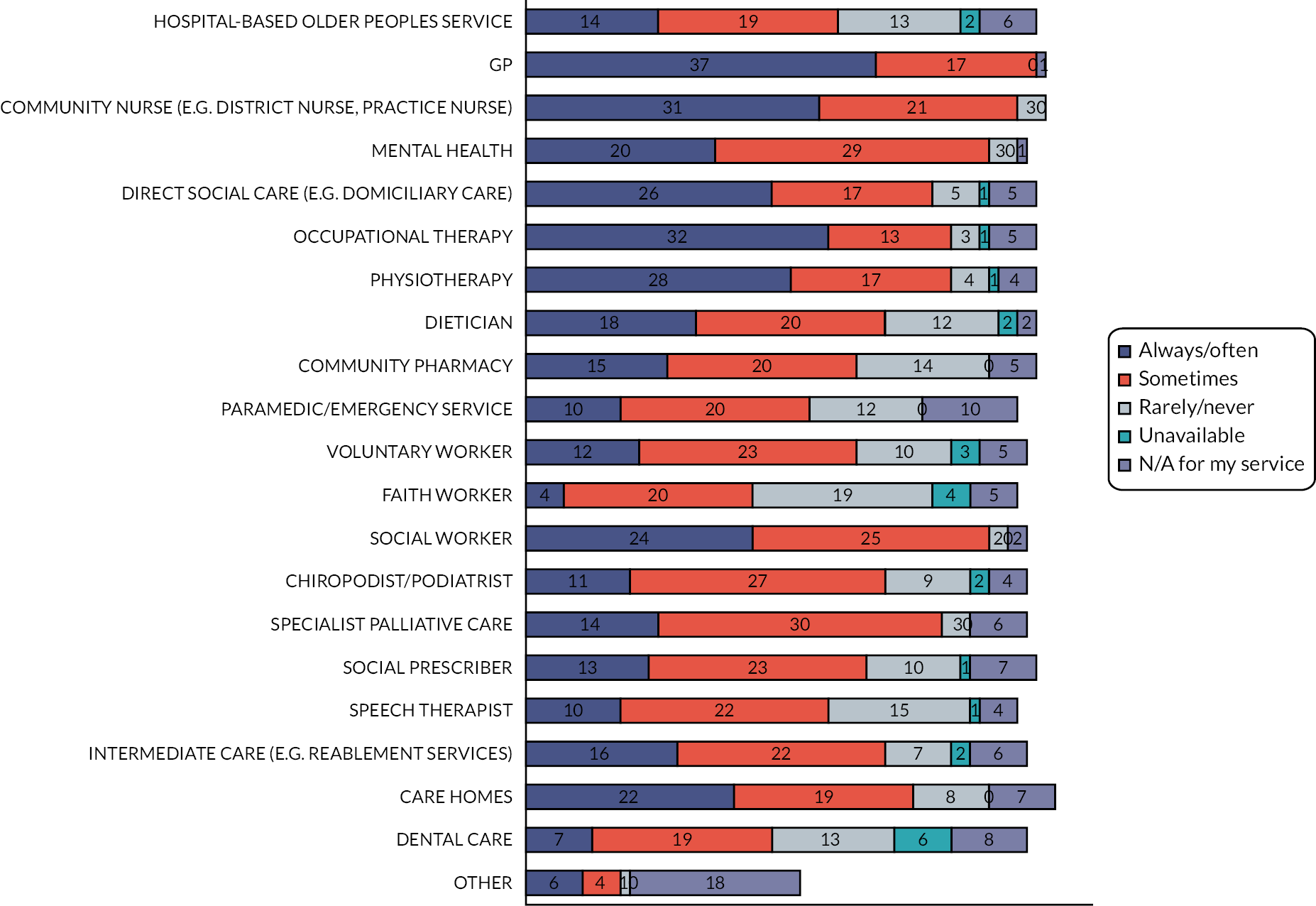

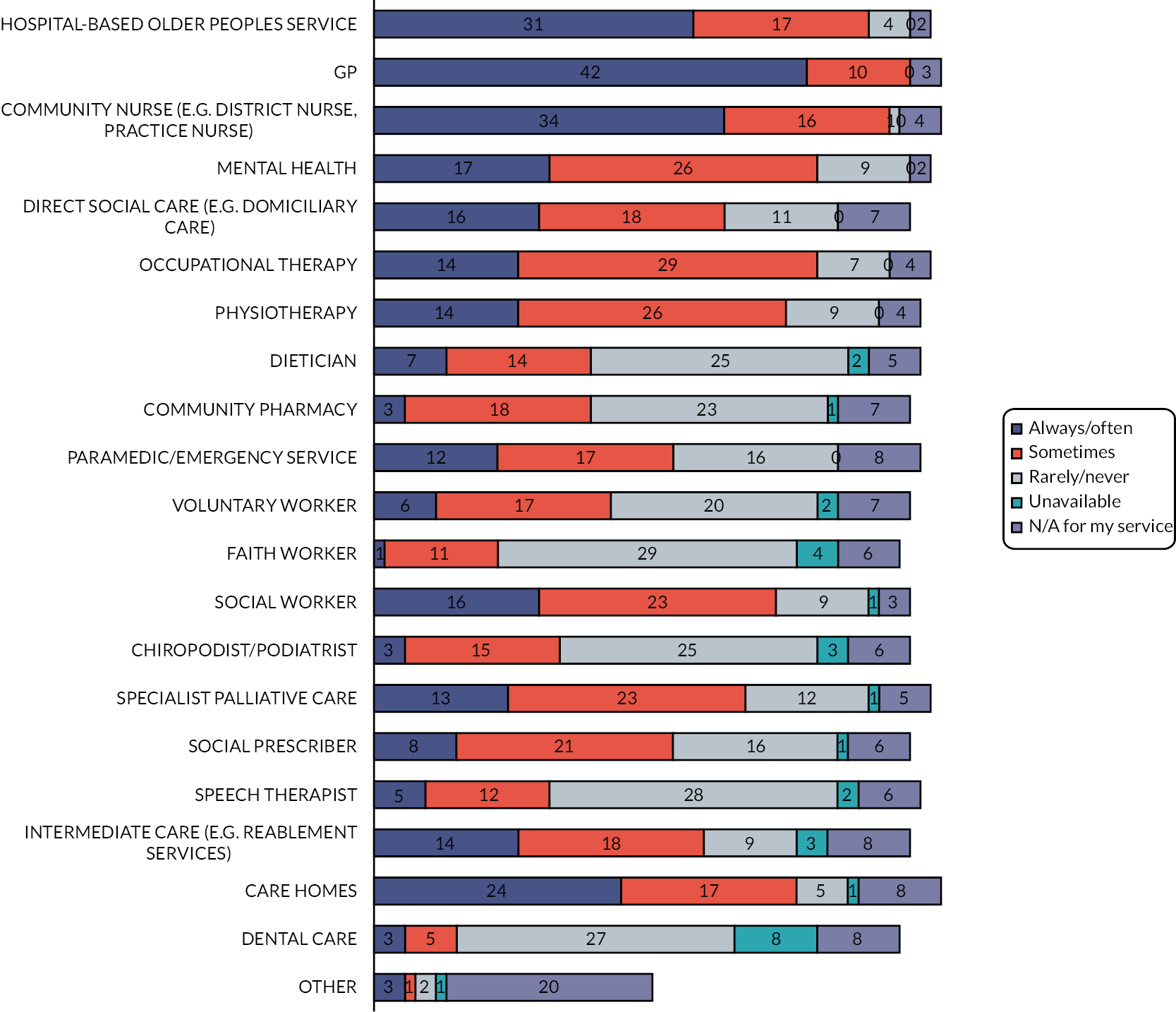

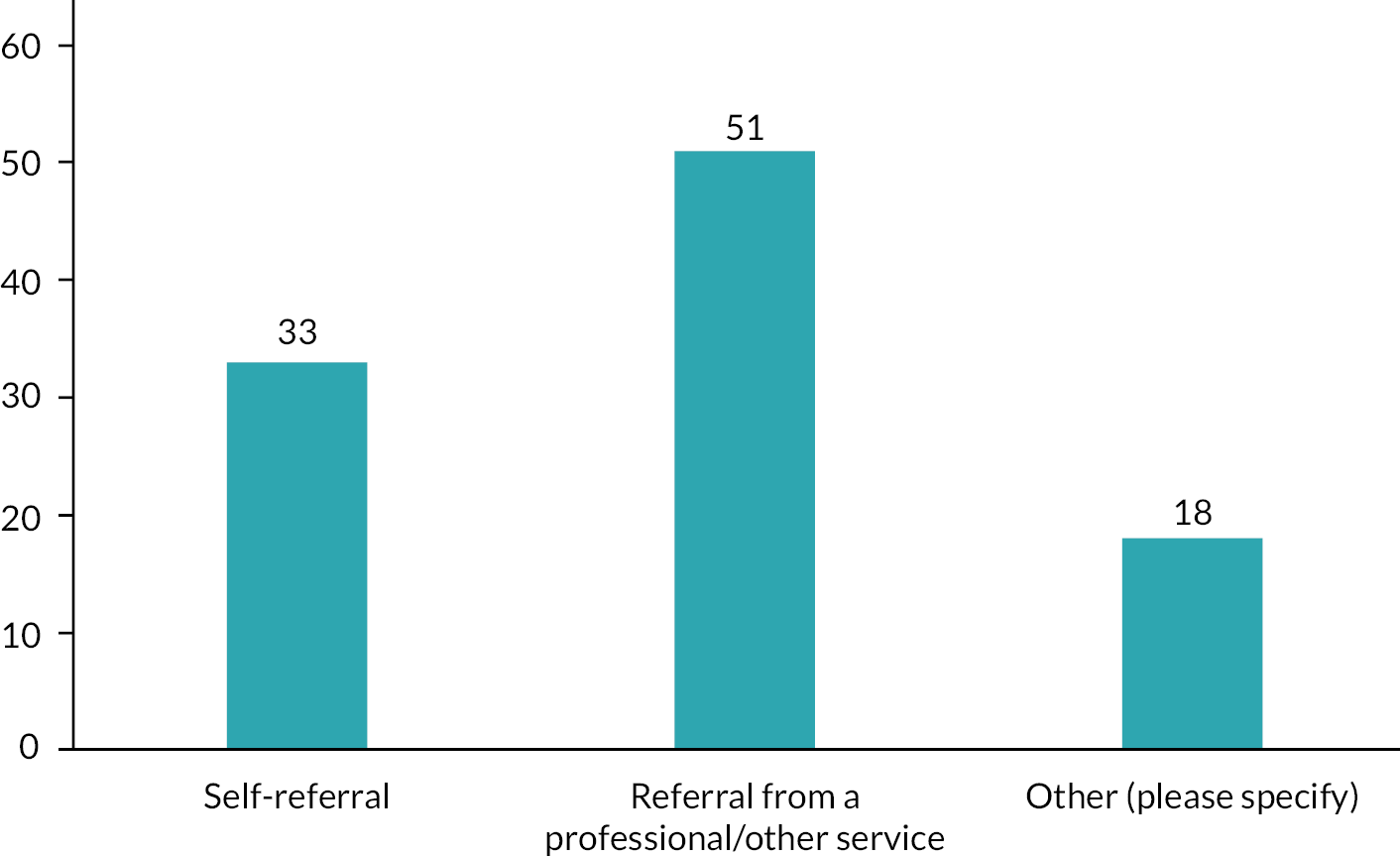

FIGURE 17.