Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the EME programme as project number 10/90/04. The contractual start date was in April 2012. The final report began editorial review in February 2016 and was accepted for publication in August 2016. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The EME editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Ian M Anderson reports personal fees from Alkermes, Janssen, Lundbeck-Otsuka and Takeda, outside the submitted work. Rebecca Elliot reports grant support from Genzyme Therapeutics, Pfizer and Johnson & Johnson and personal fees from P1vital, all outside the submitted work. Colleen Loo reports lecture fees from MECTA Corporation, outside the submitted work. Rajesh Nair reports personal fees from Lundbeck and Sunovion, outside the submitted work. R Hamish McAllister-Williams reports personal fees from Roche, Ferro Group, Sunovion, Pulse, Janssen, My Tomorrows, Lundbeck, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cyberonics, Eli Lilly, Servier, Saudi Pharmaceutical Industries & Medical Appliances Corporation, Otsuka and Pfizer, outside the submitted work.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by Anderson et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background and objectives

Scientific background

Between 2000 and 2012 unipolar depressive disorders ranked ninth in the world, and third in Europe, among causes of health-related disability, making up 2.8% and 3.8%, respectively, of the total disease burden. 1 Bipolar disorder, in which time spent in a depressed state is at least three times greater than for mania,2 accounted for a further 0.5% of total disability both worldwide and in Europe during this period. 1 In the UK around 3% of the population meet the criteria for major depression at any one time3 and this high prevalence of depression is combined with a significant proportion of patients failing to respond adequately to treatment. In the largest study to date examining patient outcomes in major depression, the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) study, only one-quarter to one-third of patients remitted (i.e. had recovered or had minimal symptoms) after the first antidepressant and this fell to about one in seven in patients who had failed two or more treatments; overall, about one-third of patients failed to remit even after four sequential pharmacological treatments. 4

Clinical use of electroconvulsive therapy

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) as a treatment option for patients with severe depression that is life-threatening or for those with moderate or severe depression who have not responded to multiple drug treatments and psychological treatment. 5 ECT involves inducing a therapeutic generalised seizure by passing an electric current across the brain and predates the first antidepressant drugs by nearly two decades. 6 In modern practice ECT is given under a brief general anaesthetic with a muscle relaxant to minimise the physical seizure and potential harm from this. It is given two or three times a week for a typical course of about eight treatments over 3–4 weeks. ECT has been demonstrated to have greater acute treatment efficacy than pharmacotherapy [with a large effect size (ES) of –0.8]7 and it achieves acute remission rates of just under 50% in patients who have failed to respond to previous drug treatments. 8 The latest audit data from the Scottish ECT Accreditation Network (SEAN) reported that about 75% of depressed patients, most of whom have been resistant to previous treatment, had a good clinical response to ECT in 2014. 9 ECT has equal efficacy in both unipolar and bipolar depressed patients9,10 and in depression with and without psychosis. 9,11

Despite the robust evidence base demonstrating the efficacy of ECT, its use has fallen dramatically in recent decades. The number of patients receiving ECT in England and Wales was approximately 20,000 per year in the 1980s12 and this had fallen to < 5000 by 2006. 13 SEAN audit data show a small but continuing decrease in the number of people receiving ECT in Scotland between 2006 and 2014, from just over eight per 100,000 to just under seven per 100,000 of the population. 9 It is likely that there are a number of reasons for the reduction in ECT usage, including public and professional concerns about the nature of the treatment, negative perceptions of ECT, lack of consensus on its use and resource limitations. 14 A major contributing factor is concern, from both a professional15 and a patient16 perspective, about a poor risk–benefit balance because of adverse cognitive side effects following ECT.

Cognitive adverse effects of electroconvulsive therapy

Electroconvulsive therapy is incontrovertibly associated with significant acute objective impairments in cognitive function. A meta-analysis of 84 studies, involving 24 cognitive variables, found that ECT affected the majority of them when measured up to 3 days after the last treatment. 17 ESs ranged from –1.10 to –0.21; the largest effect was on verbal delayed recall, with significant impairment in all tests of anterograde memory, executive function and cognitive processing speed. However, as time passes after the last ECT treatment there is a rapid reversal of these deficits, and moderate to large improvements above baseline are seen in most measures after 1–2 weeks. 17 However, one study has shown deficits in spatial recognition memory enduring at 1 month after the end of treatment18 and retrograde amnesia or loss of autobiographical memories may also persist,19 although not all studies find this. 20,21 In addition, the methodology of the assessment of autobiographical memory impairment has been questioned, complicating interpretation of these data. 21,22 Nevertheless, a systematic review of seven studies assessing patient self-reports of memory effects following ECT found that 29–55% reported persistent, and often distressing, loss of important past memories,16 and an association has been reported between subjective memory impairment and objective autobiographical memory impairment both immediately after an ECT course and 6 months later. 23 Therefore, although the prevalence, severity and persistence of retrograde amnesia (including autobiographical memory loss) remains unclear, from a patient perspective it can be experienced as a distressing after-effect of ECT.

A survey across multiple hospitals suggested that the severity, incidence and persistence of memory and cognitive dysfunction after ECT are related to treatment approach and, in particular, to the use of a sine-wave stimulus to induce seizures. 24 Current practice is to use brief-pulse ECT (constant current delivery with square waves of 0.5- to 1.5-millisecond pulse width), which triggers seizures more efficiently than sine-wave stimulation. In addition, a number of studies have investigated whether or not differences in electrode placement, or ultra-brief pulses (< 0.5-millisecond pulse width), are associated with less cognitive impairment. There is consensus that both cognitive impairment and efficacy are related to stimulus dose, especially for right unilateral (RUL) ECT. 5,7,25 However, differences in cognitive impairment associated with different electrode placements for brief-pulse ECT when optimised for efficacy appear absent or modest. 26,27 There have been recent claims for marked cognitive benefit from RUL ultra-brief-pulse ECT compared with both bilateral ultra-brief-pulse ECT and all types of brief-pulse ECT without sacrificing efficacy;19,28 however, a recent meta-analysis of six studies, although confirming the cognitive advantage, found that it came at the price of lower efficacy than for bilateral brief-pulse ECT. 29

The role of glutamate in depression and the effects of electroconvulsive therapy

The precise mechanisms underlying the effects of ECT are not fully understood, but altered synaptic functioning in neural circuits involved in mood and cognition is thought to have a key role; these circuits include the hippocampus, amygdala, anterior cingulate cortex (ACC) and prefrontal cortex. 30,31 Neural circuits are dependent on the structure, function and connections of the neurones they contain. It is at this level that somatic treatments such as ECT are presumed to exert their effects, with evidence for alterations in neurotransmitter, neuromodulator and hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis function and in gene expression, neurogenesis and synaptic plasticity. 30 Of particular interest is evidence that ECT affects glutamate function. Glutamate is an amino acid neurotransmitter with a role in both neuroplasticity and excitotoxicity, which acts on a variety of receptors in the brain, the most widespread being N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) and α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methylisoxazole-4-propionic acid (AMPA) receptors. 32 Preclinical evidence supports a role for glutamate in mood regulation and in the action of antidepressant treatments;32,33 in particular, decreased NMDA-mediated and increased AMPA-mediated neurotransmission has been proposed. 33 Studies in depressed patients have found decreased frontal cortical measures of glutamate measured in vivo by magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS), which normalise with effective treatment. 32 In studies involving ECT, reduced pretreatment glutamate and glutamate-related concentrations have been found in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex34 and ACC35,36 and these either normalised after ECT34,36 or predicted treatment response. 35 Glutamate also has a central role in cognition, especially learning and memory, through its role in synaptic plasticity and the signalling pathway involved in long-term potentiation in the hippocampus. 37 It has been proposed that the memory impairment caused by ECT is a consequence of indiscriminate activation, or saturation, of glutamate receptors at the time of the seizure, leading to a disruption of hippocampal plasticity involved in memory. 38 Autobiographical memory impairment may occur through disruption of the reconsolidation of ‘fragile’ reactivated (i.e. recalled) memories. 39

Ketamine is a dissociative anaesthetic, analgesic and psychotomimetic that inhibits NMDA receptors but also stimulates glutamate release and potentiates activity at non-NMDA receptors such as AMPA receptors. 40 Recent studies have shown a rapid antidepressant effect after a single dose of intravenous ketamine alone, or as an adjunct to antidepressants, in both unipolar and bipolar depression. 41 Repeated administration maintains improvement but relapse occurs rapidly on stopping treatment. 42

Given acutely, ketamine can cause cognitive impairment,43 particularly in manipulating information in working memory (WM) and in encoding into episodic memory. However, preliminary human data from retrospective and non-randomised studies have suggested that anaesthesia with ketamine, compared with other anaesthetic agents, improves reorientation44,45 and word recall46 after ECT. This apparent contradiction is likely to be attributable to whether or not ketamine is present in the brain. Acute antagonism of glutamate receptors by ketamine will alter synaptic function, resulting in cognitive effects that disappear after ketamine is eliminated from the body; however, the same antagonism during ECT may protect neurones from excessive stimulation. Ketamine anaesthesia may also result in a more rapid clinical response to ECT. 47 Subsequent small randomised controlled trials (RCTs) have produced mixed results, including impaired reorientation48,49 and improved50 or unchanged48 Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) scores with ketamine. A further study found that ketamine augmentation produced no reduction in cognitive impairment after ultra-brief RUL stimulation on a range of tests;51 however, this technique is associated with less cognitive impairment than standard bilateral ECT (see Cognitive adverse effects of electroconvulsive therapy), which limits interpretation. Two recent meta-analyses looking at efficacy, and including the same four placebo-controlled RCTs in which ketamine has been combined with ECT, have reached different conclusions. When continuous measures were pooled a moderate to large advantage of ketamine was reported in one study,41 but no benefit was found for response, remission or continuous measures in another. 52 The latter meta-analysis also reported higher rates of confusion/disorientation/prolonged delirium with ketamine than with placebo. At present, the small heterogeneous studies of ketamine administered with ECT, either as the sole anaesthetic agent or alongside a conventional anaesthetic, emphasise the need for further, larger-scale trials.

Frontal cortical function in depression and after electroconvulsive therapy

Depressed patients have deficits in executive function, attention, psychomotor speed and memory,53 which may be associated with a poorer response to antidepressants. 54 Current neurobiological models of depression emphasise abnormalities in fronto-limbic and fronto-striatal neural circuits55,56 and it has been proposed that mood disorders involve altered reciprocal interactions between a ‘ventral circuit’, including ventral prefrontal and limbic areas (involved in affective cognition, mood and autonomic/neuroendocrine function), and a ‘dorsal circuit’, including dorsal prefrontal areas, dorsal ACC and parietal cortices (involved in executive, attentional and memory functions). 55,57 It has been suggested that unipolar depression is associated with underactivity of the dorsal circuit and overactivity of the ventral circuit, with recovery being dependent on ‘normalisation’ of these circuits through their modulation by the rostral ACC. 55 Broadly consistent with this, a meta-analysis of depression studies found significant decreases in resting cerebral blood flow/glucose metabolism in areas corresponding to the dorsal circuit and increases corresponding to the ventral circuit. 58 Effective treatment with antidepressants has been found to be associated with normalisation of pretreatment abnormalities. 58,59

Electroconvulsive therapy differs from antidepressants in that it improves mood but impairs cognition. Although limited by small sample sizes, imaging studies of the effects of ECT most consistently find a reduction in cerebral metabolism in the bilateral anterior and posterior frontal cortex. 60,61 Temporal lobe and dorsal frontal lobe decreases in cerebral blood flow have been associated with impairments in learning, attention, WM and autobiographical memory. 62 Although the picture is less clear for mood improvement, associations have been reported with a reduction in frontal blood flow,62,63 although also with increased subgenual ACC and hippocampal metabolism. 64 One hypothesis is that ECT, instead of reciprocally ‘rebalancing’ dorsal and ventral networks as is seen with antidepressants, produces a combined suppression of both networks, leading to the initial picture of mood improvement with impaired cognition. After the ECT course has ended the dorsal network recovers and cognition improves. If ketamine prevents cognitive deficits with ECT then a test of this hypothesis is whether or not ketamine prevents ECT-induced suppression of frontal cortical function.

Assessment of frontal cortex function: the use of near infrared spectroscopy

Verbal fluency (VF) and WM tasks consistently activate networks involving areas of the dorsal and lateral prefrontal cortex, but vary in the subcortical components involved. Using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), VF tasks activate predominantly left-sided areas including the inferior frontal gyrus (IFG) (Broca’s area), premotor and medial supplementary motor areas, dorsal ACC, anterior insula, temporal and parietal cortices, caudate nucleus and hippocampus, the last particularly in semantic tasks requiring associative memory. 65–67 In patients with depression, decreased responses have been found in the left lateral prefrontal cortex compared with control subjects in some studies using fMRI or single-photon emission tomography,68,69 with another study finding no difference70 and a further study reporting decreased responses only with recurrent, but not first-episode, depression. 71 Most studies also showed concurrent impaired performance. 68–70

Tests of WM, such as the n-back task, activate a network used in maintaining task-relevant information during a delay, involving rehearsal and goal-directed attention. This network includes the dorsolateral and ventrolateral prefrontal cortex, premotor area, dorsal ACC, parietal and temporal cortices and cerebellum. 72,73 Some imaging studies in depressed patients have found increased dorsolateral/ventrolateral prefrontal activation in the absence of impaired performance,74–76 but others have found no change77–79 or decreased activation. 77 One interpretation is that depressed patients recruit more brain regions in an attempt to maintain function. 74 A greater degree of improvement with antidepressant treatment has been associated with less dorsolateral prefrontal cortex hyperactivation before treatment,75 consistent with the dorsal–ventral network interaction theory of antidepressant response. 55

These two types of task, both activating the prefrontal cortex and dorsal ACC, offer the opportunity to investigate overlapping networks. The WM network is predominantly cortical, whereas the VF network includes the hippocampus and is involved in memory formation and recall. Encoding of memories activates the bilateral IFG and left hippocampus with the left IFG playing a pivotal co-ordinating part in associative encoding. 80 Autobiographical, episodic and semantic memory retrieval share a common functional network, which includes the left hippocampus, bilateral IFG, ACC and posterior cingulate cortex. 81 Therefore, although VF has traditionally been viewed as a ‘frontal’ function, it involves a memory network, and a recent fMRI study found hippocampal connectivity with a semantic network during semantic (category), but not phonetic (letter), fluency. 82 VF is strongly impaired by ECT, whereas WM is relatively unaffected by ECT. 17 Semantic VF is therefore a possible functional probe of the associative memory network, which includes the hippocampus, and is sensitive to the effects of ECT, whereas WM tasks appear more restricted to a cortical network that is less affected.

Functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS) is a portable brain imaging technique that can be used at the bedside or in a person’s home. It uses the differential light absorption properties of oxyhaemoglobin (HbO) and deoxyhaemoglobin (HbR) for near-infrared light when it passes through the scalp, skull and superficial layers of the cortex from a light source placed on the scalp. The change in the light absorption spectra, measured with detectors placed nearby on the scalp, can be converted into changes in concentrations of HbO and HbR. When these changes occur in response to a cognitive task, they can be used as a haemodynamic response to that task in the region being illuminated. 83 The neurovascular coupling principle links these haemodynamic changes with the underlying neural activity. 84 When a brain area is active, neuronal firing increases metabolic demand, which results in a localised increase in blood flow. The increase in blood flow is higher than the actual oxygen consumption by the firing neurones and, therefore, an increase in HbO and a decrease in HbR is expected in the active cortical areas. Hence, it is possible to use fNIRS as a measure of functional changes in cortical blood flow secondary to neuronal activation,85 analogous to fMRI using blood oxygen level-dependent (BOLD) changes. In addition, it is possible to use a spatially resolved spectroscopy technique, employing a modification of the diffusion equation of light transport, to provide an absolute measure of tissue oxygenation [the tissue oxygenation index (TOI)]. This index is the absolute percentage of total haemoglobin in the field of view that is oxygenated. 86 Its reliability and validity have yet to be established;87 however, it does provide a potential absolute measure with which to assess cerebral tissue metabolism across groups and within subjects. 88

Functional near-infrared spectroscopy has been extensively used to study frontal cortex activation using VF and WM tasks with a high degree of reliability with repeated administration. 83,89–93 Depressed subjects reliably demonstrate decreased lateral prefrontal cortex–anterior temporal cortex haemodynamic responses compared with control subjects during a VF task,94–106 including in bipolar depression. 107–109 There is some uncertainty over whether this is a state or trait abnormality, as some studies have found restored activation to a VF task following treatment110 and increased activation has been seen in hypomanic patients,108 whereas blunted responses have been found in remitted depressed patients111 and euthymic bipolar patients109 or failure to normalise after antidepressant treatment in depressed patients. 99 WM has been less investigated using fNIRS, but studies have also shown a decrease in lateral frontal haemodynamic responses in depression,112–114 which were associated with decreased performance in one study. 112 We hypothesised that severely ill depressed patients will have decreased lateral frontal activation to a VF task, which will correlate with clinical measures, and that ketamine will alleviate the further suppression of frontal activation by ECT, in line with its benefits in preserving cognitive function.

Objectives

The primary aim of the Ketamine-ECT study was to investigate, in a RCT, the effect of ketamine, given as an adjunct to conventional anaesthetics, on cognitive dysfunction caused by ECT in severely depressed patients who had consented to receive ECT as part of their usual care in NHS secondary care settings. The hypothesis was that adjunctive ketamine, compared with saline, would reduce ECT-induced cognitive impairment. Secondary aims were to (1) investigate the efficacy, tolerability and acceptability of adjunctive ketamine (we hypothesised that ketamine treatment would lead to a more rapid improvement in depressive symptoms with fewer ECT treatments needed to achieve remission) and (2) identify whether or not ketamine modified the effect of ECT on frontal cortical function using fNIRS during the performance of cognitive tasks (we hypothesised specifically that patients receiving ketamine, compared with saline, would show greater cognitive activation to a category VF task during an ECT treatment course).

Primary clinical objective

The primary objective was to determine whether or not intravenous ketamine (0.5 mg/kg), compared with placebo (saline), given immediately before the anaesthetic at each ECT treatment, would ameliorate impairment in anterograde amnesia caused by ECT. The primary outcome was delayed verbal recall in the Hopkins Verbal Learning Test – Revised (HVLT-R)115 at baseline and after four ECT treatments (mid-ECT), comparing patients randomised to ketamine with those randomised to saline who received at least one ECT treatment. This task was chosen given the evidence that delayed verbal memory is the most impaired cognitive function seen following ECT17 and because memory problems are a key complaint in patients receiving ECT.

Secondary objectives

Clinical objectives

-

To determine whether or not patients receiving ketamine, compared with saline, would show better/less impaired:

-

VF, autobiographical memory, visual memory and attention/WM at mid-ECT and at the end of treatment with ECT

-

anterograde memory at the end of treatment

-

autobiographical memory at 1 and 4 months after the last ECT.

-

-

To determine whether or not patients receiving ketamine, compared with saline, would show:

-

greater improvement in depression, anxiety and quality of life at mid-ECT

-

more rapid improvement in depression as shown by earlier time to remission and response and fewer ECT treatments needed to achieve remission.

-

-

To assess the safety and tolerability of ketamine augmentation of ECT as shown by:

-

adverse events (AEs) and adverse reactions (ARs)

-

reorientation after ECT treatments

-

psychotic and manic symptoms.

-

Mechanistic objectives

-

To determine whether or not patients receiving ketamine, compared with saline, would show, at mid-ECT and at the end of treatment, better/less impaired:

-

haemodynamic prefrontal cortex responses to a VF task using fNIRS, related to changes in VF performance

-

prefrontal cortex metabolism (TOI) using fNIRS, related to changes in VF performance.

-

-

In addition, although not in the original protocol, we wished to take the opportunity to compare patients and controls on:

-

measures of neuropsychological function

-

haemodynamic prefrontal cortex responses to VF and WM tasks using fNIRS

-

prefrontal cortex metabolism (TOI) using fNIRS.

-

(Note: in the original protocol mechanistic studies involving fMRI and MRS had been planned, but they were not able to be pursued because of insufficient recruitment.)

Chapter 2 Methods

Overview of the trial

The Ketamine-ECT study was a multicentre, two-arm (1 : 1 allocation), parallel-group, patient-randomised, placebo-controlled superiority trial of ketamine added to standard ECT during anaesthetic induction in severely ill depressed hospitalised patients or outpatients who have been referred for ECT by their psychiatrist. Assessment and ECT treatment was blind to treatment allocation but the anaesthetists administering the study medication were not blinded for reasons of safety. The primary outcome was neuropsychological function, with secondary efficacy outcomes and a mechanistic fNIRS substudy of prefrontal cortex function. ECT was administered twice a week until a patient’s depression had remitted, as determined by the patient’s treating clinical team, and patients were followed for 4 months after the end of ECT treatment.

All assessments were undertaken by trained research personnel under the supervision of the clinically trained principal investigators. There was no planned interim analysis and no ‘stopping rules’ for the study as a whole. Individual patients were withdrawn from the study medication if it appeared that to continue it would be deleterious to their mental health or safety. This was determined by the treating clinician and/or the research team in discussion with the patient. Withdrawal from study medication did not necessitate withdrawal from the study.

The study was registered on 27 December 2012 (ISRCTN14689382) under the public title ‘Ketamine-ECT study’. Clinical trial authorisation was given by the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) (EudraCT 2011–005476–41) on 18 May 2012. Ethical approval was granted by the North West – Liverpool East Research Ethics Committee (reference number 12/NW/0021) on 25 January 2012. Recruitment commenced in December 2012 and an extension to the study and to recruitment was granted by the funder in 2014, with the study finishing in August 2015. The trial protocol is available at www.nets.nihr.ac.uk/projects/eme/109004 (accessed 25 August 2016).

Patient and public involvement

There was patient and public involvement at all stages of the study, with regular meetings with a service user group throughout the study. Input was especially valuable in the design and content of all information sheets, with regard to issues related to informed consent, safety and patient experience and in response to challenges in the trial (see Chapter 3, Challenges to recruitment). There was service user representation on the trial management group, which met monthly to oversee the trial, and on the trial steering committee (TSC). The service user group took a central role in developing and delivering the survey of patient experiences in the trial (reported in Chapter 5).

Participants

Patients

Inclusion criteria

-

Consent given for ECT as part of standard clinical care.

-

Male or female aged ≥ 18 years.

-

Current Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fourth Edition (DSM-IV)116 diagnosis of a major depressive episode, moderate or severe as part of a unipolar or bipolar mood disorder, diagnosed by the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI). 117

-

American Society of Anesthesiologists score (excluding mental health considerations in the scoring) of 1, 2 or stable 3 and judged as suitable to receive ketamine by an anaesthetist.

-

Verbal intelligence quotient (IQ) equivalent to ≥ 85 and sufficiently fluent in English to validly complete neuropsychological testing.

-

Capacity to give informed consent.

-

Willingness to undertake neuropsychological testing as part of the study.

Exclusion criteria

-

DSM-IV diagnosis of a primary psychotic or schizoaffective disorder, current primary obsessive–compulsive disorder or anorexia nervosa.

-

History of drug or alcohol dependence (DSM-IV criteria116) within the past year.

-

Electroconvulsive therapy in the past 3 months (to avoid confounding the assessment of cognitive outcomes – this was 6 months in the initial protocol but was shortened to 3 months after the commencement of the trial; see Chapter 3, Challenges to recruitment) or previously received ECT in the current trial.

-

Known hypersensitivity or contraindication to ketamine or excipients in the injection, including significant cardiovascular disease, uncontrolled hypertension, glaucoma, cirrhosis or abnormal liver function or liver disease.

-

Known hypersensitivity or contraindication to concomitant medications used for ECT [propofol, thiopental (thiopental sodium) and suxamethonium (suxamethonium chloride) or excipients in the injections].

-

Evidence of organic brain disease including dementia, neurological illness or injury or medical illness that may significantly affect neuropsychological function.

-

Detained under the Mental Health Act (MHA) 1983 (as amended in 2007)118 or unable to give informed consent.

-

Pregnancy, or at risk of pregnancy and not taking adequate contraception, or breastfeeding.

-

Score of < 24 on the MMSE. 119

Healthy control subjects

Healthy control subjects (HCs) were prospectively sex- and age-group matched as far as possible with patients.

Inclusion criteria

-

Male or female aged ≥ 18 years.

-

Psychiatrically well, confirmed through the MINI,117 and on no current psychotropic medication.

-

Good physical health.

Exclusion criteria

-

Personal history of psychiatric disorder, as revealed by the MINI. 117

-

First-degree family history of major psychiatric illness requiring treatment.

-

Significant physical illness including organic brain disease, neurological illness or injury that could interfere with the interpretation of the results.

-

Psychotropic medication or other medication that could interfere with the interpretation of the results.

-

Score of < 24 on the MMSE. 119

Study withdrawal criteria

Patients withdrawing from study medication but continuing to receive ECT were encouraged to remain in the study and to complete assessments if possible, and consent remained valid. Reasons for study discontinuation were:

-

withdrawal of patient consent or decision to discontinue for any reason (e.g. AE) without having to give a reason

-

loss of capacity to provide continuing consent or detention under the MHA

-

local principal investigator or clinical team decision based on collaborative decision for safety reasons (e.g. serious AE or AR) or patient deterioration.

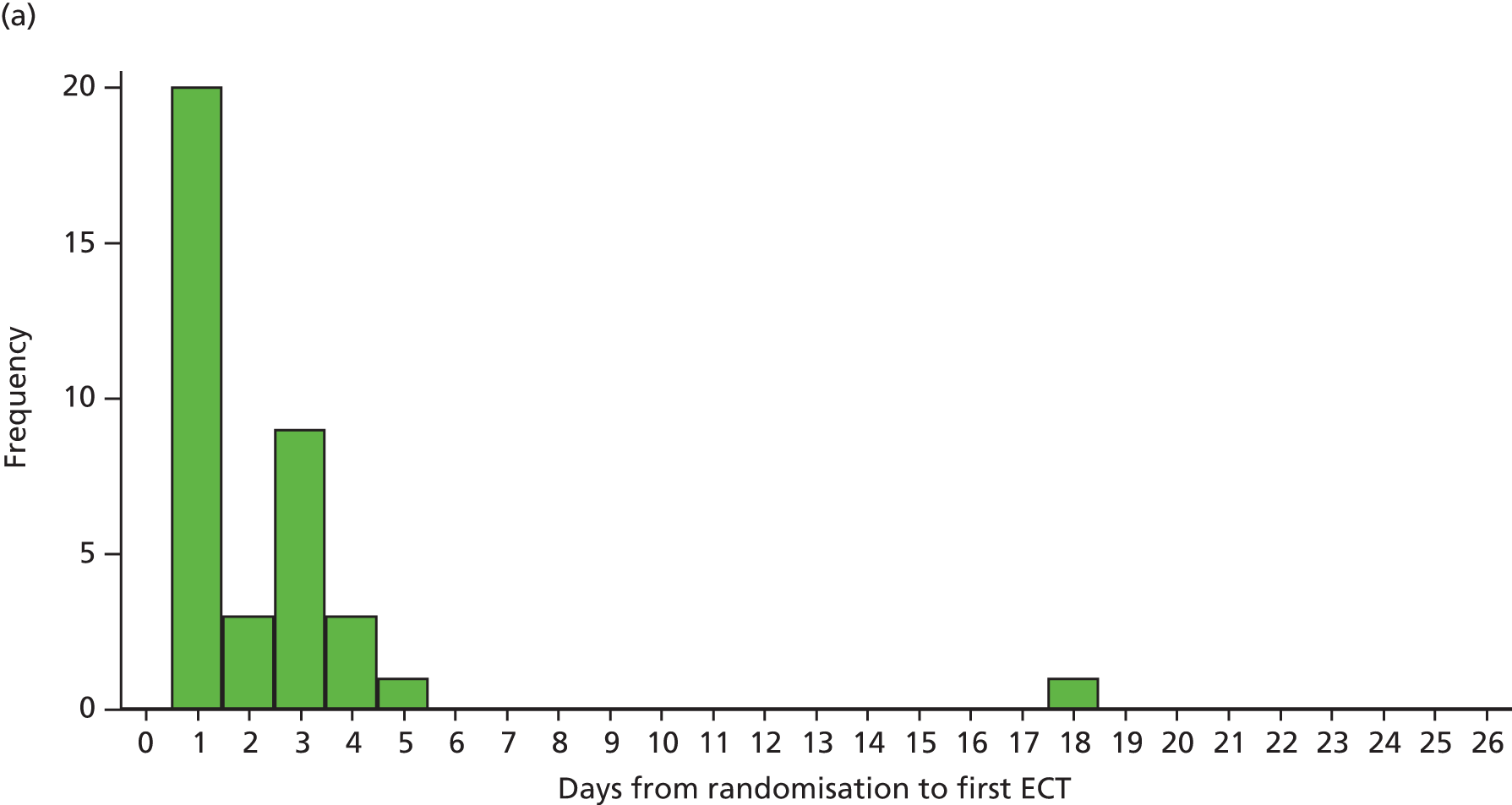

Recruitment

Recruitment was from secondary care settings, both inpatient and outpatient, in trusts in the north of England (see Table 2). Patients were identified through direct contact with inpatient wards and referrals to ECT suites. Potential eligibility was assessed through discussion with clinical teams and case note information obtained by authorised staff, and patients were invited to meet a member of the research team to have the study explained. HCs were recruited through advertisements in Manchester and the Volunteer Database in Newcastle, as well as by inviting relatives of participating patients.

Study design

Visits and assessment schedule

These are outlined in Table 1 and described further in the following sections.

| Assessments | Main study visits | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Screening and randomisation | Baseline | Week 0 | Visit 1, week 1 | Visit 2, mid-ECT week 2 | Visit 3a, 3b, etc. (weekly to end of treatment) | Visit 4, end of treatment | Visit 5, 4 weeks after end of treatment | Visit 6, 16 weeks after end of treatment | |||||

| Treatments | ECT 1 | ECT 2 | ECT 3 | ECT 4 | ECT 5 to final ECT | ||||||||

| Timing | 4 weeks–1 day pre ECT 1 | 2 weeks–1 day pre ECT 1 | 1–3 days after ECT 2 | 1–3 days after ECT 4 (± 1 ECT) | 1–3 days after even-numbered ECT | 1–5 days after final ECT | 3–5 weeks after final ECT | 12–20 weeks after final ECT | |||||

| Informed consent | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Pretreatment assessmentsa | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Safety measuresb | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Trial blinding assessment | ✓c | ✓c | |||||||||||

| Neuropsychological testsd | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Efficacy ratingse | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Near-infrared spectroscopyf,g | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

Screening visit

This occurred once a potentially eligible patient had consented to ECT and had agreed to see a member of the research team. Written informed consent was obtained after full explanation of the study. Eligibility was determined through a mixture of case note information and a semistructured interview to obtain demographic and background details and by using the MINI to determine diagnosis. Particular care was taken to determine potential physical reasons for exclusion from the study through the results of the standard clinical work-up for ECT including blood tests (full blood count, urea and electrolytes, liver function tests), an electrocardiogram (ECG) and physical examination. IQ and handedness were determined (see Assessments).

Baseline visit

At baseline the neuropsychological tests and efficacy assessments were carried out and, in those who consented to the mechanistic study, this was followed by near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) testing. This could be carried out over one or two visits according to patient wishes and practicality.

Randomisation

Randomisation occurred as close to the first ECT as possible to try to minimise dropout, as the modified intention-to-treat (mITT) population was based on patients starting ECT. In practice, this usually meant the day before ECT to allow for the study medication to be prepared and delivered to the ECT suite. Patients were randomised in a 1 : 1 ratio to ketamine or saline using permuted block randomisation (varying randomly from four to eight), stratified by NHS trust by the Christie Hospital Clinical Trials Unit (CTU). The relevant randomisation code was held by the CTU and also provided to the local site pharmacies. When a patient required randomisation the site research assistant (RA) contacted the CTU by telephone with the participant details; the CTU then contacted the local site pharmacy to prepare the drug in blinded, tamper-proof, secondary packaging according to the randomisation code.

Timing of neuropsychological and near-infrared spectroscopy assessments

Neuropsychological assessments were yoked to ECT sessions rather than to time from randomisation because of not-infrequent delays or missed ECT sessions as a result of patient (e.g. infections, failing to fast on the morning of ECT) or organisational (bank holidays, unavailability of staff) factors, as well as the need to carry out the tests within a specified time after the ECT session to capture cognitive impairment. Assessments were carried out at least 24 hours after an ECT session to avoid acute post-seizure and post-anaesthetic effects. The primary outcome assessment was carried out after four ECT sessions (usually just over 2 weeks after the first ECT session), when the effects of ECT should be apparent on cognition anterograde memory. 120 Given the individual variation seen in the number of ECT treatments administered, this time point was chosen to capture as many patients as possible before they stopped ECT, either because of dropout or improvement. Further assessments were carried out after the last ECT session (end of treatment) and at follow-up at 1 and 4 months after the last ECT session.

For those patients who had consented to the NIRS substudy, the imaging was carried out after the neuropsychological assessments.

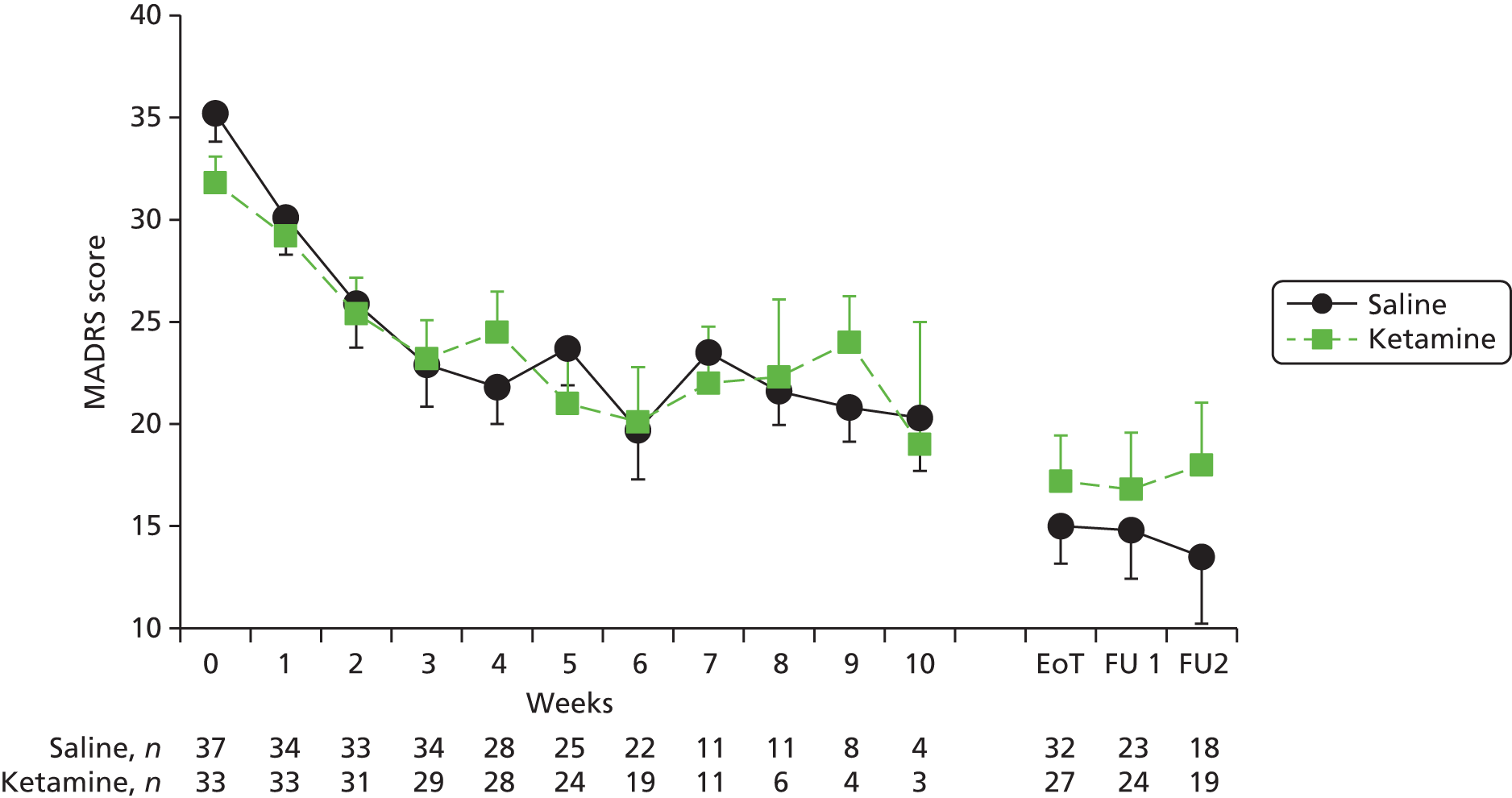

Timing of efficacy assessments

Efficacy assessments were carried out weekly until the end of treatment, with the week-2 assessment mostly coinciding with the mid-ECT neuropsychological assessment. The primary efficacy measure was improvement in the Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS),121 an observer-rated measure of depression severity.

Timing of safety assessments

Safety assessments were carried out during and after each ECT session in accordance with standard good practice in the administration of ECT and included monitoring of vital signs and pulse oximetry. Degree of reorientation 30 minutes after ECT was used to assess recovery after ECT and staff were instructed to record any problem during the recovery period as an AE or possible AR. Weekly mania and psychosis ratings were carried out as part of the efficacy assessments.

Interventions

Electroconvulsive therapy

Standard ECT protocols based on the Royal College of Psychiatrists’ (RCPsych) ECT Handbook122 were agreed between centres, with ECT treatments scheduled twice weekly. For each ECT treatment, after pre-oxygenation with 100% oxygen, anaesthesia consisted of propofol (or rarely thiopental if clinically indicated) combined with the muscle relaxant suxamethonium. Etomidate was not permitted as an induction agent because of its action in elevating blood pressure. Anaesthetic drugs remained the same for all ECT treatments unless change was required for clinical reasons. ECT treatment was given after motor end-plate depolarisation was determined by cessation of muscle fasciculation in the feet. Electrode placement was standard bifrontotemporal (bilateral) or RUL (D’Elia placement) and the treatment consisted of constant-current brief-pulse (0.5-millisecond pulse width) stimuli to induce seizure. The pulse width could be increased to 1.0-millisecond if clinically indicated. Treatment dose was determined by rapid stimulus titration to determine the seizure threshold in the first session treatment, based on that given in the RCPsych ECT Handbook. 122 Target treatment doses were 1.5 times threshold for bilateral and 4–6 times threshold for RUL electrode placement and the stimulus parameters remained the same until after the fourth treatment unless change was required for clinical reasons. Standard operating procedures were agreed between treatment centres to determine criteria for an adequate seizure, and for re-stimulation and dosage adjustments later in the course, based on the RCPsych ECT Handbook. 122

Oral psychotropic medication was continued by the clinical team and remained unchanged for the first four ECT treatments and, if possible, until the end of ECT, unless changes were required for safety or clinical reasons.

The goal was to treat patients to remission (MADRS score of ≤ 10) in accordance with NICE guidance5 but the final decision to finish ECT treatment rested with the clinical team in consultation with the patient and the ECT team.

Study medication and blinding

The experimental intervention was 0.5 mg/kg of intravenous ketamine or an equal volume of normal saline (0.9% sodium chloride solution), given in accordance with the randomisation schedule by the anaesthetist as a slow bolus directly before the anaesthetic induction agent and before suxamethonium at each ECT treatment. Ketamine (at a concentration of 10 mg/ml) or saline was provided as a clear solution in ampoules retaining their original labelling, provided in secondary tamper-proof trial packaging by the local clinical trials pharmacy. The anaesthetic team broke the seal away from the psychiatric ECT team, drew up the trial medication into a syringe and disposed of the ampoule without revealing which drug was being administered. Members of the research team responsible for outcome assessment did not attend ECT sessions to minimise the risk of treatment allocation being inadvertently revealed.

Assessments

Screening and baseline tests

Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview

The MINI is a brief structured interview for the major axis I psychiatric disorders in the DSM-IV,116 with good concordance with more comprehensive diagnostic interviews for mood disorders. It can be used with little training by clinicians but can be used by lay interviewers after training (provided in this study by IMA) and takes approximately 22 minutes to administer. 117

Mini Mental State Examination

The MMSE is a 30-item screening tool for dementia with scores of < 24 being considered abnormal. 119

Wechsler Test of Adult Reading

The Wechsler Test of Adult Reading123 is a language test to assess premorbid intellectual functioning and is thought to be relatively insensitive to cognitive deterioration. It uses vocabulary level as a correlate of IQ with the patient being presented with irregularly spelled words and prompted to pronounce each one. It consists of 50 irregularly spelled words of progressive difficulty and is discontinued after 12 consecutive incorrect pronunciations. Each correct pronunciation is given a score of 1 and the raw score is then standardised by age and compared with the scores predicted for the patient’s demographic classification to provide an estimate of premorbid IQ.

Modified Edinburgh Handedness Questionnaire

The modified Edinburgh Handedness Questionnaire124 asks participants to indicate which hand they use for eight common tasks, with responses ranging from ‘always left’ to ‘always right’ on a five-point scale. This is scored to determine right-, left- or mixed-handedness.

Massachusetts General Hospital Scale

The Massachusetts General Hospital Scale (MGHS)125 is a method for staging pharmacological treatment of depression that generates a continuous variable representing the degree of treatment resistance, taking into account the intensity and optimisation of each previous treatment. Non-response to an adequate trial of a marketed antidepressant (≥ 6 weeks at an adequate dose) scores 1 point per trial, with 0.5 points per trial added for each optimisation strategy. ECT increases the score by 3 points. In one study a score of 3 was found to confer a < 20% chance of remission with the next treatment, which diminished as the score increased further. 126

Other assessments

Other assessments consisted of those carried out by the clinical team as work-up for ECT and included a physical examination, including height and weight, cardiovascular system and blood pressure, an ECG and blood tests, including liver function tests.

Safety assessments

Monitoring before, during and after anaesthesia and electroconvulsive therapy treatment

Safety measures were those applied in standard practice, consisting of monitoring heart rate, blood pressure and peripheral oxygen saturation using pulse oximetry and, if indicated, capnography.

Reorientation

Reorientation was used as a measure of recovery from ECT and is a routine clinical assessment. To provide a standardised measure, reorientation 30 minutes and 60 minutes after eye opening was recorded, defined as being correct in four out of five orientation items (name, place, day of the week, age and birthday). 127 In addition, the number of correct orientation items at these time points was recorded. Reorientation usually occurs before 30 minutes49 and a delay beyond 60 minutes is extremely rare. The 30-minute time point was used to compare treatment arms.

Agitation and psychosis

This was not formally assessed during the recovery period but ECT staff were asked to record events that were unusual or more severe than expected as AEs, as well as any suspected ARs. The 18-item Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS),128 with an additional 19th item for elevated mood, was used to assess symptoms of psychosis (sum of items 3, 4, 7, 8, 11, 12, 15 and 16) and mania (sum of items 8, 10, 17 and 19) outside the ECT sessions, at the same time as efficacy assessments.

Neuropsychological tests

The neuropsychological tests were chosen to be sensitive to the effects of ECT27,129,130 and to have a duration short enough to be acceptable to patients (total of 35–40 minutes).

Hopkins Verbal Learning Test – Revised

The HVLT-R115 is a word-list learning task in which the participant is asked to listen as a word list consisting of 12 words is read out to them and then to recall as many words as possible; this is carried out three times. Following an interval of 30 minutes the participant is given an unannounced recall task for the words previously learnt and a forced-choice recognition task in which the previously presented words are mixed with 12 words not heard before. Although repeated administration means that the delayed recall is no longer a surprise, this does not appear to affect performance. 131 The sum of the number of words recalled after the three presentations is used as a measure of learning and the number of words recalled after the delay is used as a measure of delayed recall (the primary outcome in this study). In addition, a retention score is calculated (the number of words on trial 4 divided by the highest score on trials 2 and 3 expressed as a percentage), as well as a recognition discrimination index (the number of true positives minus the number of false positives).

It is available in six alternative forms, which were used at the different time points in the study, with two different orders of presentation assigned according to even or odd participant numbers.

Controlled Oral Word Association Test

The Controlled Oral Word Association Test (COWAT)132 tests letter and category fluency, with participants asked to generate as many words as they can in 1 minute starting with the letters F, A or S and in a given category (animals or fruit and vegetables), with rules excluding proper names or variations of a word. The same letters were presented on subsequent tests and the two categories were alternated with a different order of presentation assigned according to even or odd participant numbers.

Autobiographical Memory Interview – Short Form

The Autobiographical Memory Interview – Short Form (AMI-SF)133 tests memory for personal events in the past with reference to an initial interview eliciting personal memories. This covers six areas with a score given to any events remembered with sufficient detail to be questioned about them again on subsequent occasions. On retesting, only items that had been mentioned the first time can be scored, with points deducted for missing items, so it is possible for scores to decrease even if a richer memory overall is recalled. The AMI-SF has been criticised as it does not allow for improvements to be detected, for its lack of normative data for the normal loss of consistency over time and for a lack of information about the independent effect of mood,22 although it has been defended against these criticisms. 19 An alternative extended scoring method has been recently proposed that allows more details to be scored at baseline, with points given for all items recalled. 134 A decrease in the consistency of memory of about 20% over 6 months in healthy volunteers has been found with the extended scoring method. 134 In this study we used both the standard and the extended scoring method to assess autobiographical memory. We did not administer the AMI-SF to HCs as we were not retesting them, and the baseline scores have little comparative value, although depressed patients do produce fewer episode-specific memories than healthy volunteers. 134

Medical College of Georgia Complex Figure Test

The Medical College of Georgia Complex Figure Test (MCGCFT)135 consists of first copying, and then reproducing from memory (immediately and after a delay), a complex line drawing with multiple elements, which tests not only visuospatial abilities but also memory, attention and planning. It is available in four alternative forms and different forms were used for the first four time points in the study, with two different orders of presentation assigned according to even or odd participant numbers.

Digit span

For the digit span task, strings of numbers of increasing length are read out slowly and in an even rhythm and participants are asked to repeat them back. 136 In the forward condition they are repeated in the same order as presented and in the backward condition they are repeated in reverse order. This task is a test of attention and being able to hold the numbers in WM to reproduce them, particularly for the backward condition. The number of digits remembered is reported (the ‘clinical’ digit span).

Self-reported Global Self-Evaluation of Memory

One of the problems in research into memory problems following ECT is the lack of agreement between the impact on subjective memory and objective memory measures. The self-rated Global Self-Evaluation of Memory (GSE-My)137 has been reported to correlate with AMI-SF scores after ECT. Patients are asked to rate their global memory and the effect of ECT on their memory on a 7-point scale.

Efficacy measures

Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale

The MADRS is a 10-item observer-rated depression scale, which is sensitive to change and has internal consistency. 138 Each item is scored from 0 to 6 on the basis of defined anchor points; a score of ≤ 10 was taken as the cut-off for remission. 139 In addition to the standard MADRS, an alternative bespoke form was scored that included atypical depressive symptoms of increased appetite and sleep (MADRS atypical).

Clinical Anxiety Scale

The Clinical Anxiety Scale (CAS)140 is a 7-item observer-rated scale derived from the Hamilton Anxiety Scale for measuring the severity of anxiety. The seventh item is meant to be scored separately. Each item is scored from 0 to 4 on the basis of defined anchor points, and we calculated the total score and the total score of the first six items for this study.

Clinical Global Impression-Severity and Clinical Global Impression-Improvement

The Clinical Global Impression scale is a widely used 7-point observer-rated scale that is used to measure global severity [Clinical Global Impression-Severity (CGI-S)] judged in comparison to the overall range of depression seen in patients in clinical practice (1 = ‘normal, not at all ill’ to 7 = ‘among the most extremely ill patients’) and overall global improvement [Clinical Global Impression-Improvement (CGI-I)] compared with baseline (1 = ‘very much improved’ to 7 = ‘very much worse’). 141

Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale

The BPRS is an observer-rated instrument used to measure the overall range of psychiatric symptomatology. We used the 18-item version with an additional 19th item for elevated mood. Each item is scored from 1 to 7 on the basis of defined anchor points. Subscales were used to assess psychosis and mania as described under Safety assessments.

Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology – Self Report

The Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology – Self Report (QIDS-SR)142 is a 16-item self-rated depression scale that was used in the STAR*D study4 and rates the nine DSM-IV depression items, each on a scale of 0–3.

European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions three-level version

The European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions three-level version (EQ-5D-3L)143 is a self-rated quality-of-life instrument, with participants rating their degree of impairment or experience on five dimensions (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression) on a scale from 1 to 3. Based on standardised population studies, each item is weighted and an overall quality-of-life ‘index’ score is calculated to give a utility score ranging from 0 (death) to 1 (perfect quality of life); the lowest score is –0.59, that is, worse than death. In addition, a visual analogue scale (VAS) is scored from 0 (worst imaginable health state) to 100 (best imaginable health state).

Trial blinding assessment

A treatment allocation questionnaire was developed for the trial in which patients and research staff were asked to ‘guess’ their treatment allocation, indicate how certain they were on a 4-point Likert scale and identify the reason for their choice. The ratings were put in a sealed envelope and sent directly to the CTU for data entry to minimise the risk of those involved in study ratings being influenced by others’ beliefs.

Sample size

Original sample size and power calculations

Across the six NHS trusts originally involved in the study, 355 patients had received ECT over a 12-month period in 2009/10 (the most recent period available when planning the study). The most comparable recent study in the UK, using similar inclusion/exclusion criteria to ours,144 found that 41% of patients receiving ECT were eligible and 18% were randomised (to either ECT or transcranial magnetic stimulation). Given that the current study offered adjunctive rather than alternative treatment, a 22.5% recruitment rate was predicted. Based on these figures, recruiting 160 patients over a 24-month period was forecast as feasible, providing 152 patients for the primary end point assuming that 95% of patients could be assessed after four treatments.

The power calculation was based on a clinically useful benefit of a moderate standardised ES for the ketamine–saline difference (0.5–0.6). With 90% power, and a two-sided p = 0.05, based on independent t-tests, we would have been able to detect a standardised ES of 0.51 for the full intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis and 0.54 for a single primary cognitive outcome based on completer assessments. Using a Bonferroni correction for the originally proposed three interdependent measures for the primary cognitive outcome, HVLT-R delayed recall, COWAT category fluency and AMI-SF (i.e. assuming independence), gives 80% power to detect a standardised ES of 0.51 given a two-sided, corrected p = 0.05 for each measure.

The study aimed to recruit 100 patients (50 per treatment group) and 50 matched HCs to the mechanistic studies. This would have had 80% power to detect an ES of 0.5 with a two-sided alpha level of 0.05 between groups and an ES of 0.57 with a two-sided alpha level of 0.05 between groups. A meta-analysis of fNIRS studies in depressed patients145 found an ES difference compared with control subjects of 0.74 in frontal cortex HbO response to cognitive tasks activating the frontal cortex.

Revised power calculations

Following initial slow recruitment, the revised recruitment target for the clinical trial was adjusted to 100 patients, with 95 reaching the primary outcome time point, and the primary outcome was changed to the HVLT-R delayed recall alone. This sample size provided 80% power to detect an ES of 0.57 (ITT analysis) and 0.58 (completer assessments) with a two-sided p = 0.05.

In addition to the slow recruitment, there were practical difficulties with patients being offered fNIRS over a large geographical area, resulting in the target for recruitment to the mechanistic studies being decreased to a sample size of 20 patients (10 per treatment arm) and 50 control subjects. This has only a 21% power to detect an ES of 0.6 (with a two-sided p = 0.05) between the two treatment arms (i.e. 10 per arm) but a 70% power to detect the same size of effect of ECT itself (two-sided p = 0.05). Recruitment of 20 patients and 50 control subjects enables detection of an ES of 0.6 between groups with 60% power.

Analysis

Clinical trial

The full statistical analysis plan (SAP) (see Appendix 1) was agreed before the blind was broken by the data monitoring and ethics committee (DMEC) and signed off by the TSC. When there have been minor modifications to the SAP in the course of the analysis this is indicated with the reasons given.

Data analytical strategy

Statistical analysis of the randomised treatment groups was based on the mITT population subject to the availability of data; to be included a subject must have received electrical stimulus. Statistical analyses were carried out using Stata 13 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) and IBM Statistical Product and Service Solutions (SPSS) Statistics version 22.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA).

Pro-rating was used to calculate total scores when there were missing items for the efficacy scales. Values for the missing items were calculated by replacing the missing item with the mean of the other available items for that occasion provided at least 70% (75% for the BPRS mania subscale) of items had been completed. Pro-rating was not undertaken for the neuropsychological outcomes.

Analysis of the primary outcome measure and other neuropsychological secondary outcome measures

The SAP states that cross-sectional analysis of covariance (ANCOVA, i.e. linear regression) models would be fitted to the primary and secondary neuropsychological outcomes at the mid-ECT, end of treatment, follow-up 1 (1 month post ECT) and follow-up 2 (4 months post ECT) assessment times. However, with 15 outcomes this would mean fitting 60 separate models. Therefore, it was decided instead to fit a Gaussian repeated measures model to each of the 15 continuous neuropsychological outcomes using all of the available data and taking account of the correlation between measures on the same subject. These models were fitted using the ‘mixed’ procedure in which dropouts are assumed to be ‘missing at random’ (i.e. missing outcome data are conditional on observed data). This assumes that future behaviour, given the past, is the same for all, whether or not a subject drops out. This allows distributional information to be ‘borrowed’ from those who remain on the trial and applied to those who drop out, given that they have the same covariate set-up until the time of dropout. Therefore, the estimand of the treatment effect is what would be seen if all subjects had remained on the study until the end.

Before fitting the repeated measures models we examined the summary statistics for time from first ECT to each neuropsychological assessment (see Table 5). From this, the overall means of 2, 6, 10 and 22 weeks were used as the values for the discrete time variable in the repeated measures models. A time × treatment interaction was included to assess the treatment effect at each time point, adjusting for the covariates specified in the SAP, that is, age at randomisation, sex, baseline degree of treatment resistance, electrode placement (bilateral or unilateral) and baseline value of the outcome being evaluated.

The programmatic rules in the appendix to the SAP (see Appendix 1) were used to assign valid mid-ECT and end-of-treatment neuropsychological assessments. If the rules were not met then data for that assessment were set to missing, the only exception being that one patient who received six ECT treatments prior to the mid-ECT neuropsychology assessment was included, as one extra treatment would not be expected to have a major effect on the scores.

The use of the repeated measures analysis meant that no assessments could be carried forwards or backwards if there were missing data at critical time points, as stated in the appendix to the SAP. One exception was for a subject who responded to treatment after four ECTS [rule (e) of the appendix to the SAP], so that their end-of-treatment neuropsychology assessment was repeated for their mid-ECT value. All repeated measures model analyses involved the use of robust standard errors and associated confidence intervals (CIs) and p-values (allowing for non-normality and constraints in the ranges of some of the cognitive outcomes).

As this main outcome analysis did not assess whether or not there was a significant change in neuropsychological test scores during treatment (i.e. the presumed effect of ECT), post hoc exploratory univariate repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) was carried out separately for the treatment-related assessments (baseline, mid-ECT and end of treatment) and during follow-up (end of treatment, follow-up 1 and follow-up 2) to describe the change over time.

Efficacy analyses

Continuous outcomes

The weekly efficacy data were analysed using a random-effects (random intercepts and slopes) ANCOVA model with time (in weeks) since the first ECT as a quantitative explanatory variable. To prevent bias from efficacy assessments being delayed, time from first ECT to assessment was included as a continuous variable in a longitudinal mixed-effect model rather than the notional assessment week recorded by the RA (RA week). Only data until the end-of-treatment assessment were included (i.e. excluding follow-up data). The fixed covariates included in each model were treatment, the time × treatment interaction and the same prespecified baseline participant characteristics as used for the neuropsychology repeated measures analyses. For each model, two correlated random-effects terms were included to capture between-subject variation in the intercept and slopes, assuming that people might have different rates of improvement with treatment. All models involved the use of robust standard errors and associated CIs and p-values.

A sensitivity analysis was performed on the primary efficacy outcome, the MADRS score, by fitting a longitudinal mixed-effect model using time since randomisation instead of time from first ECT.

Binary outcomes

To assess efficacy data up to the end of acute treatment for the remission and response binary variables, the frequency and cumulative frequency of first occurrence according to the week recorded by the RA (RA week) up to the end of treatment were tabulated. When the end of treatment occurred < 13 days after the previous week’s assessment it was designated as being 1 week after the last assessment; when it was ≥ 13 days then a gap of 2 weeks was assigned instead.

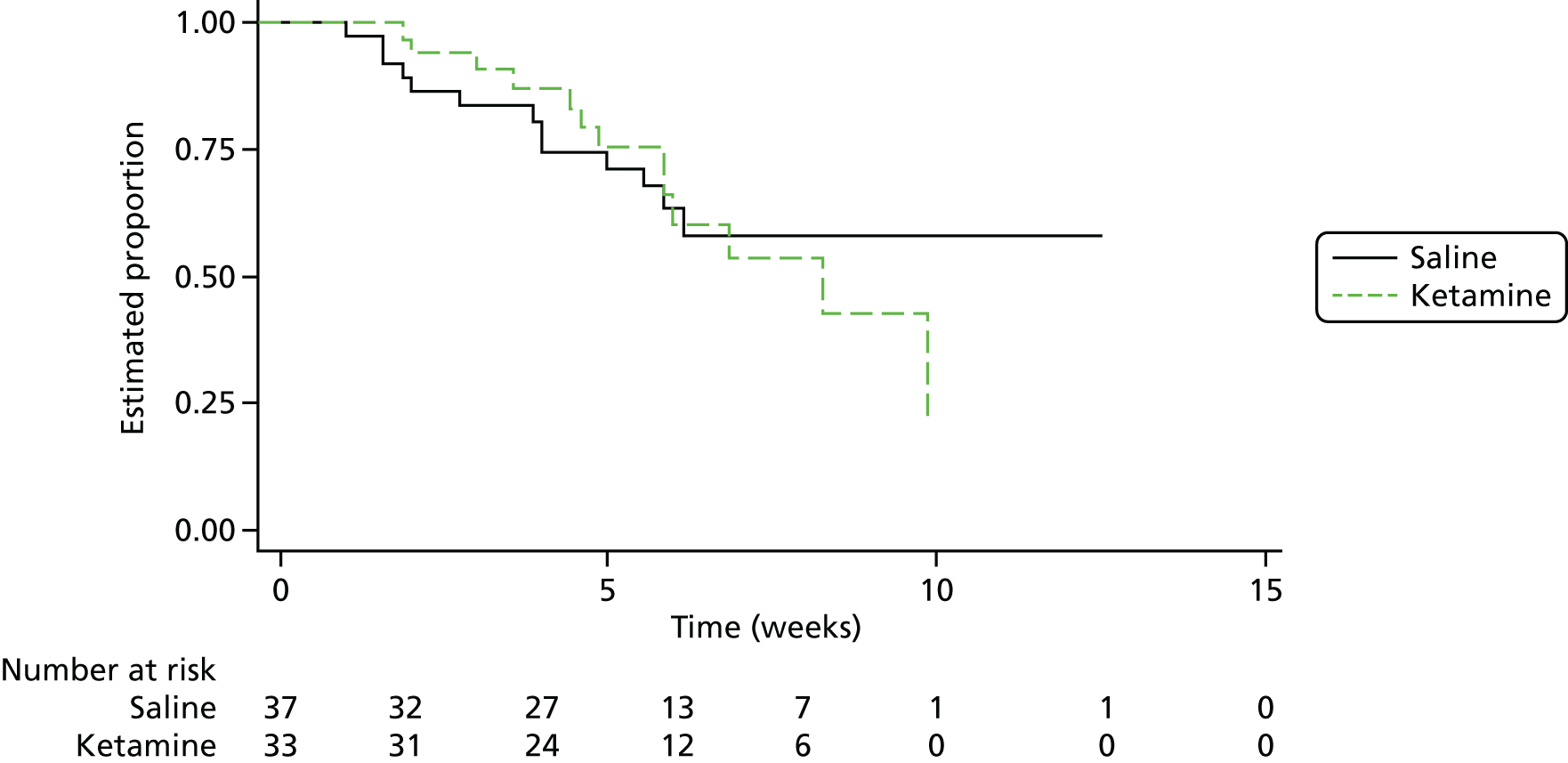

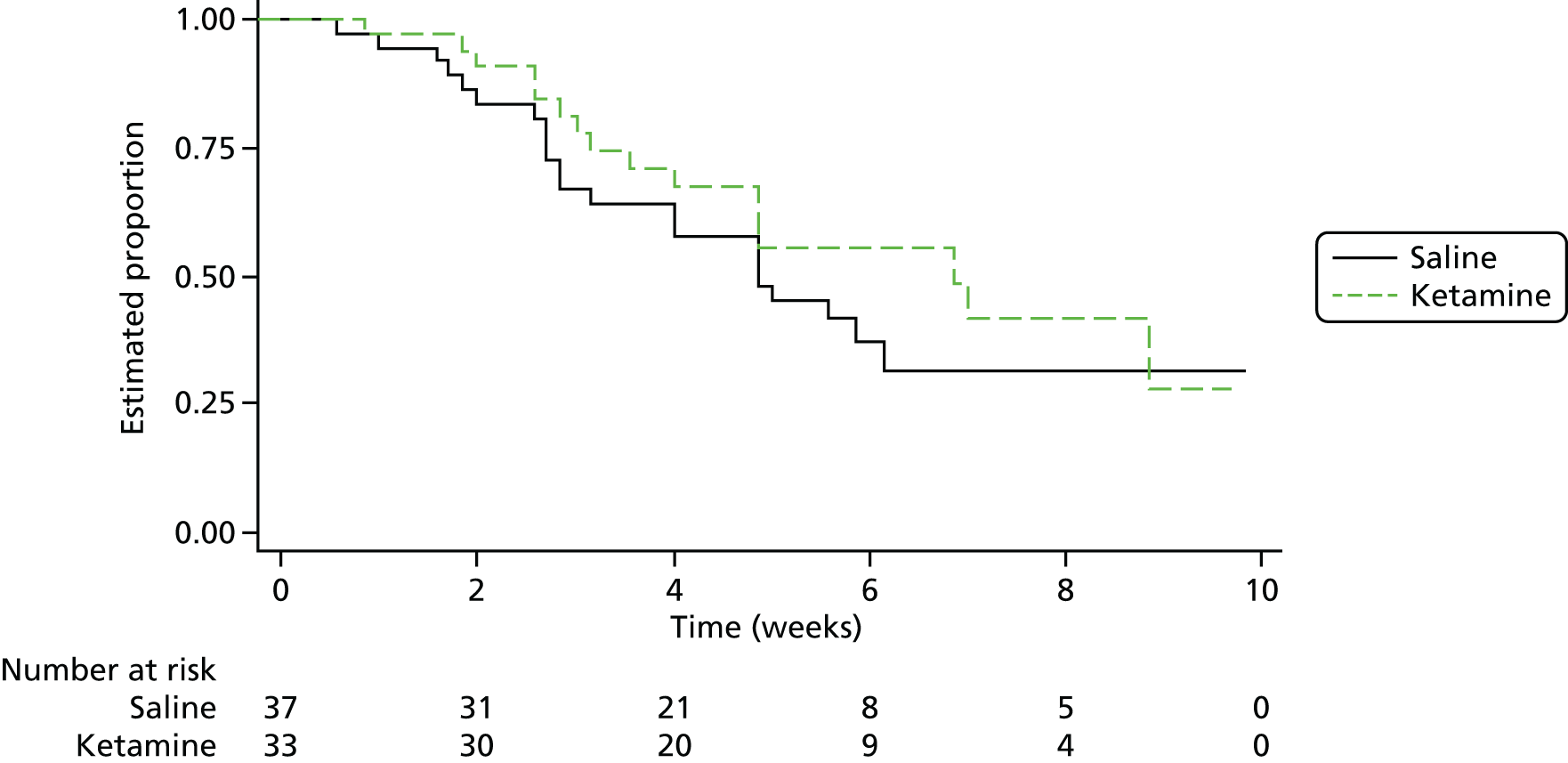

Kaplan–Meier plots and Cox analyses (adjusting for the same baseline variables as used for the repeated measures and longitudinal mixed-effect models, including baseline MADRS score) were undertaken. For these analyses the time to ‘event’ was defined as the difference between the first ECT date and the date of assessment. For censored subjects, their last known efficacy assessment date while on acute treatment relative to their first ECT date was used.

The proportion worsening at follow-up after acute treatment (MADRS increase of ≥ 4 points + CGI-S increase of ≥ 1 point to CGI-S ≥ 3 from the end-of-treatment assessment or, if not available, the last RA week assessment) was determined provided that there was a MADRS and CGI-S score at the end of treatment and at least one follow-up time point. The proportions worsening in each group were compared using Fisher’s exact test.

Near-infrared spectroscopy

Patients who consented to NIRS in addition to the main study neuropsychological tests were tested after they had undertaken the main tests. The intention had been to administer NIRS at the same time points as neuropsychological testing, but because of the low numbers recruited and dropouts, there were sufficient participants for analysis only at baseline and mid-ECT.

Data acquisition

Two purpose-built optical topography systems (NTS Optical Imaging System, Biomedical Optics Research Laboratory, Department of Medical Physics and Bioengineering, University College London, London, UK), each providing a 24-channel array for topographical coverage of the bilateral dorsolateral and ventrolateral prefrontal cortices, were deployed in Manchester and Newcastle.

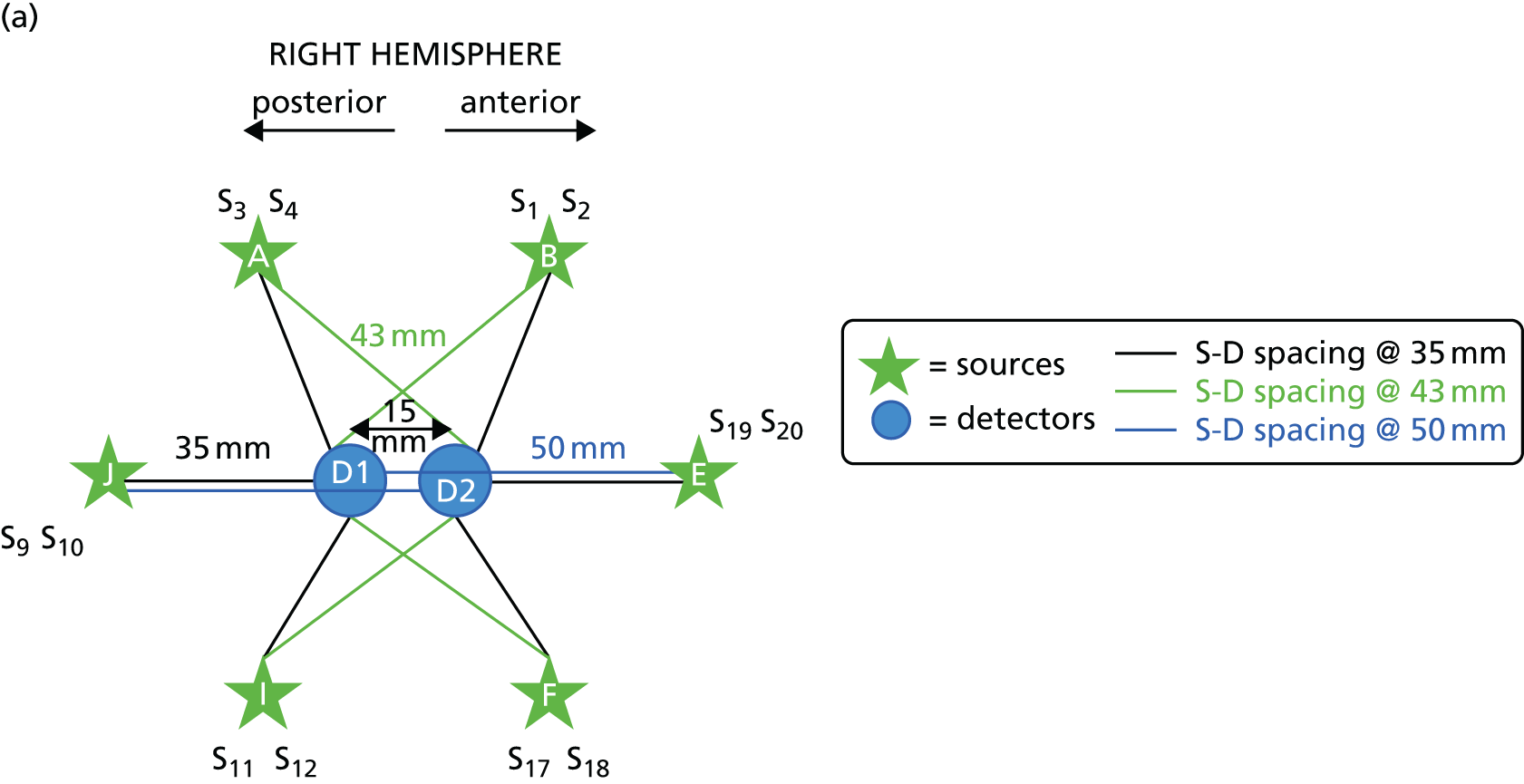

The optode array utilised six light sources and two light detectors for each hemisphere, arranged in a star-like configuration to optimise the overlap between source–detector pairs (channels) and to provide adequate spatial coverage (Figure 1). Each light source emitted light at two wavelengths (780 and 850 nm) so that it is possible to recover, and differentiate between, HbO and HbR given their different absorption spectra at these wavelengths.

FIGURE 1.

The NIRS array layout used in the study. (a) Right hemisphere; and (b) left hemisphere. S, source; D, detector.

Near-infrared spectroscopy presents more challenges in adults than in its more widespread use in infants because of the light absorption properties of hair and the greater distance to the cerebral cortex from the skin surface. The distance between source and detector pairs can be varied to achieve an optimal signal for different depths below the skin. The shorter channel lengths offer the greatest signal-to-noise ratios but are less penetrating and, conversely, longer path lengths provide the greatest depth penetration but a poorer signal. In adults a channel distance of > 30 mm is typical. The array utilised in this study used a combination of 35-, 43- and 50-mm channels to try to optimise both penetration and signal quality (see Figure 1). The in-line arrangement of two sources and two detectors (including the two 50-mm channels) was designed to allow calculation of the TOI.

The bilateral arrays were built into left and right VELCRO® (Velcro Limited, Middlewich, UK) pads with fixed optode distances and configuration. The pads were attached to an optode placeholder (Figure 2a), which was positioned first on the head of participants in a consistent and reproducible way using reference points related to the 10/20 positioning system used in electroencephalogram (EEG) research. Participants were measured from each pre-auricular point, using the zygomatic notch as a reference, to ascertain the 10/20 position of Fpz above the nasion. The optode placeholder was adjusted according to the size of head to ensure that the detectors were in a standard position just below the F3/F4 EEG placement, with the lowest sources lying on the Fp1–T3 and Fp2–T4 lines. After moving hair obstructing the contact of the optodes with the skin, the array pads were attached (Figure 2b) and secured with further VELCRO straps to ensure contact with skin, prevent movement and exclude ambient light. To check the signal quality in each channel a read-out of each source–detector pair was checked using built-in software (mini NTS 24s 4d version 2.2, © UCL Medical Biophysics 2013, UCL, London, UK) and adjustments were made to the array if necessary to maximise the signal quality.

FIGURE 2.

Placement of NIRS array. Illustrated are (a) the array placeholder; (b) the array attached to the placeholder; and (c) fiducial markers used for magnetic resonance imaging co-registration. Photographs © Darragh Downey. Reproduced with permission.

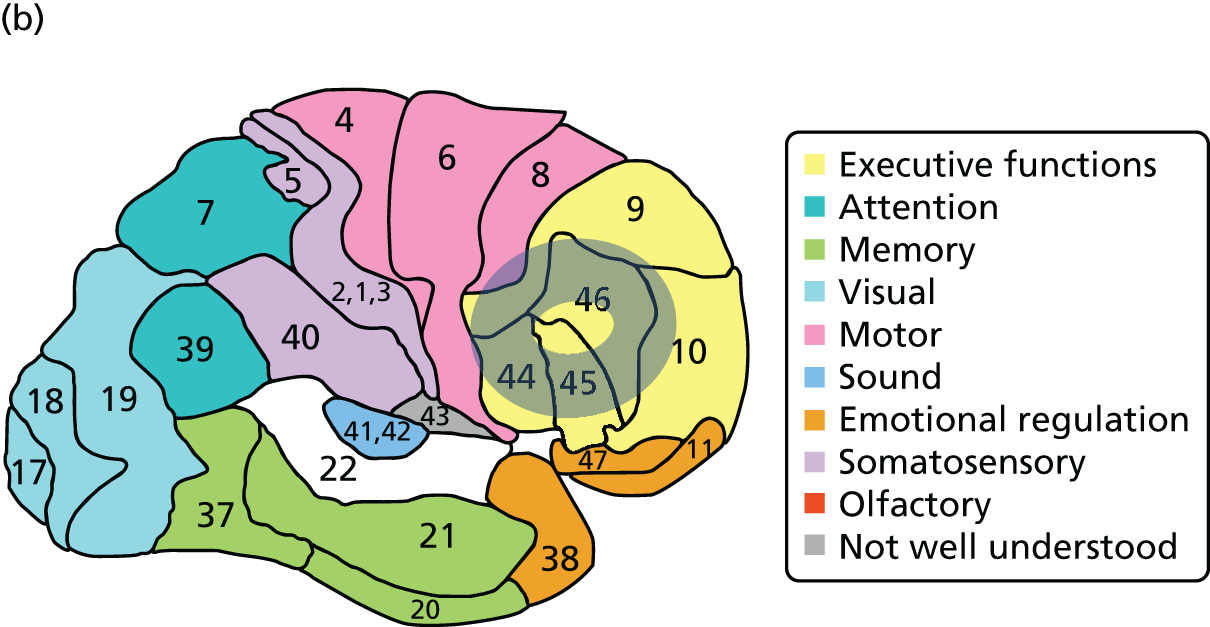

To confirm the location of the array with respect to the underlying cortex, a co-registered structural magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scan was undertaken using cod liver oil capsules in the array pads as fiducial markers (Figure 2c) in a single participant on two occasions. Magnetic resonance T1-weighted structural images were acquired on a Philips 3T Achieva MRI scanner (Amsterdam, Netherlands) based at the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR)/Wellcome Trust Clinical Research Facility, Manchester [repetition time (TR) 9 milliseconds, echo time (TE) 4 milliseconds, voxel size 0.8 × 0.8 × 1.0 mm]. The fiducial markers were rendered using SPM12 [see www.fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/software/spm12/ (accessed 28 August 2016)] and MRIcroGL [see www.cabiatl.com/mricrogl/ (accessed 28 August 2016)]. The areas below the array correspond to Brodmann areas (BAs) 44, 45 and 46 and parts of BA 9 and BA 10 in the ventrolateral and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (Figure 3). The within-subject reproducibility of the cortical area covered by the array was within a few millimetres. Data were acquired from all 24 channels at a rate of 10 Hz and manually synchronised with the onset of behavioural tasks using an event marker at the start of the task, triggered by the researcher.

FIGURE 3.

The areas of prefrontal cortex covered by the array. (a) A surface render of the fiducial markers on the right side with a shaded ‘doughnut ring’ indicating where the fNIRS signal was recorded; and (b) the shaded ring indicates the approximate BAs corresponding to the area of signal acquisition [BAs map reproduced with permission from BrainMaster Technologies, Inc. (see www.brainm.com/software/pubs/dg/BA_10-20_ROI_Talairach/functions.htm; accessed 28 August 2016), Brodmann Atlas].

Imaging tasks

The fNIRS tasks were administered after the main study neuropsychological tasks and, mindful of this, were designed to be as short and as straightforward as possible. The total time for testing was about 40–50 minutes (21 minutes performing the tasks).

Verbal fluency task

In the VF task participants were shown a category on a computer screen and asked to name out loud a word that matched that category (e.g. boys’ names, jobs, games and sports, vegetables). To minimise movement of the array caused by speaking, participants were instructed to verbalise through a fixed, or lightly locked, jaw, speak softly and remain as still as possible. The task was paced and consisted of prompts to produce the next word being given every 3 seconds in a block lasting 30 seconds (i.e. nine prompts per block). Pacing of the task was carried out to standardise, and to try and sustain, effort during the block, in an attempt to minimise expected performance differences between individuals, especially between patients and HCs. The category conditions were contrasted with rest blocks also lasting 30 seconds. A control naming task was not used so that the task was as short as possible while capturing the maximum signal–control difference in the haemodynamic response. The task consisted of an initial 30-second rest followed by 10 category naming blocks each separated by 10 rest periods. The total task duration was 10.5 minutes.

N-back task

The WM task was a shortened, adapted version of a standard blocked fMRI n-back task in which a series of letters were presented on a computer screen and participants were asked to respond to letters that matched ones that had appeared previously (in 1-back the letter matches the previous letter, in 2-back the letter matches the letter before last, etc.). This requires continuous updating of information held in WM. To maximise the signal, and to shorten the task, only the 2-back condition and rest were used. Participants were asked to attend to the letters and, if they saw a letter that was the same as one shown two letters previously, they were to press the keypad. They received a practice task to ensure that they understood the instructions. A total of 17 letters were displayed in a 30-second block, with four repeated (target) letters per block, followed by a 30-second rest block. Following an initial 30-second rest block, there were 10 2-back blocks each separated by 10 rest blocks, resulting in a task lasting 10.5 minutes.

Near-infrared spectroscopy analysis

Poor signal seen in the 50-mm channels meant that these data could not be used and the planned TOI analysis was not possible; the analysis method for this is therefore not described.

Functional near-infrared spectroscopy data were analysed with the Homer2 NIRS processing package146 based in MATLAB [see uk.mathworks.com (accessed 30 August 2016)]. For each participant, channels that measured a very low optical intensity (below the noise level of the device, e.g. because of poor optode–skin contact) were discarded from the analysis. Intensity data were then converted into optical attenuation data. For this preliminary analysis motion artefacts, that is, time points for which data exceeded selected changes in amplitude (AmpThresh) or standard deviation (SD) (StdThresh) over a period of 0.5 seconds, were identified in each channel. The choice of these parameters is data dependent, and a compromise between the number of motion artefacts identified in noisy channels and the number identified in less noisy channels is needed. In this study, AmpThresh = 10, StdThresh = 0.5 for all of the HC data and the patient mid-ECT data for the n-back task and AmpThresh = 8, StdThresh = 0.5 for all of the other patient data. The identified motion artefacts were corrected by applying a spline interpolation algorithm,147 which models the artefact with a cubic spline interpolation, subtracts it from the original signal and then corrects for the baseline shift caused by the subtraction. As some of the motion artefacts might still be present in the data even after this correction step, trials with remaining motion artefacts were rejected. A band-pass filter (third-order Butterworth filter) with cut-off frequencies of 0–0.5 Hz was applied to the data to reduce high-frequency noise. The filtered optical attenuation data were finally converted into concentration changes by applying the modified Beer–Lambert law,148 assuming a differential pathlength factor of 6.26. 149 Mean haemodynamic responses were calculated by block averaging all trials in an interval from 5 seconds before stimulus presentation to 60 seconds after stimulus presentation (hence containing both the 30-second task period and the 30-second rest period). Mean haemodynamic responses were baseline corrected by subtracting the mean value in the interval from –5 seconds to 0 seconds.

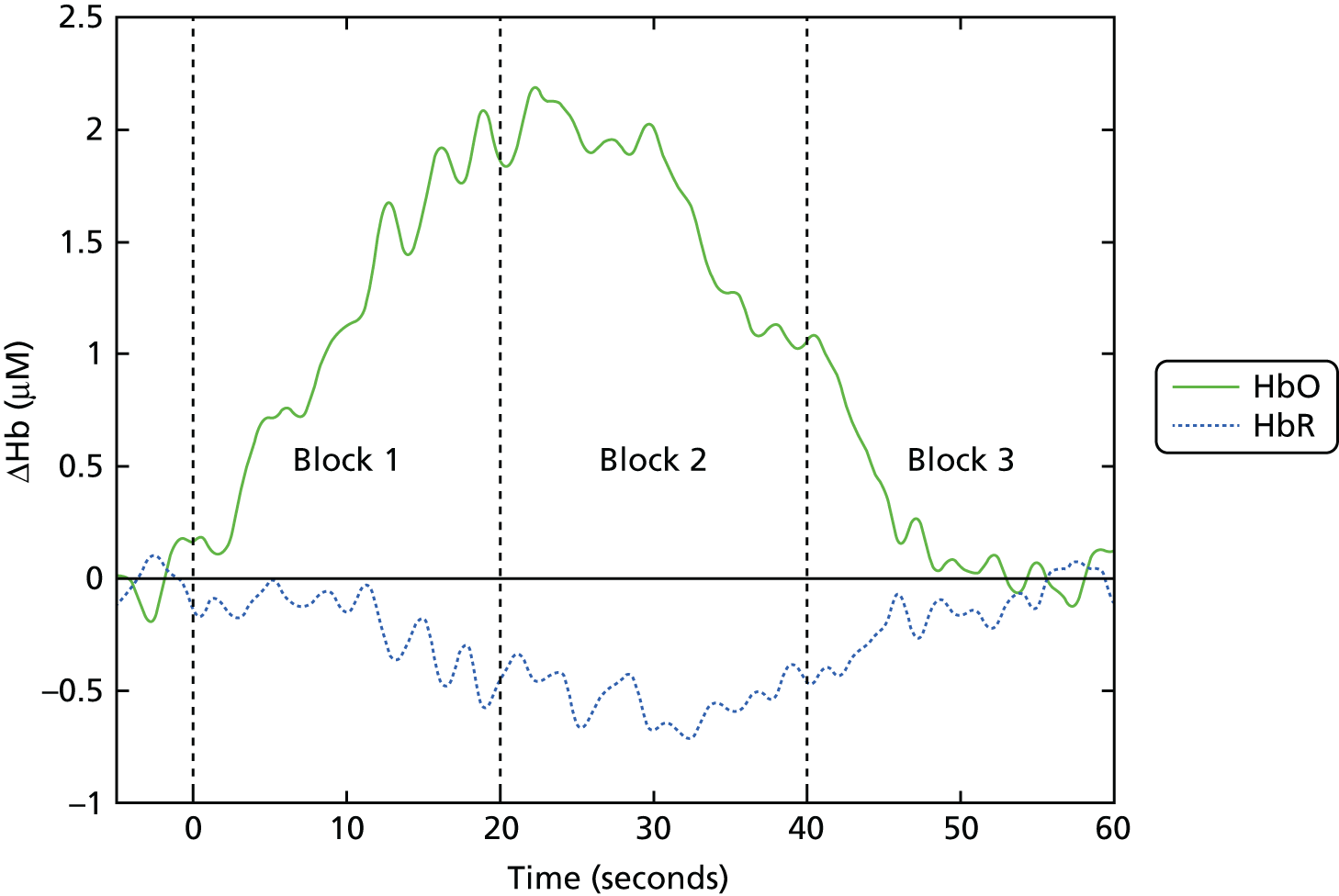

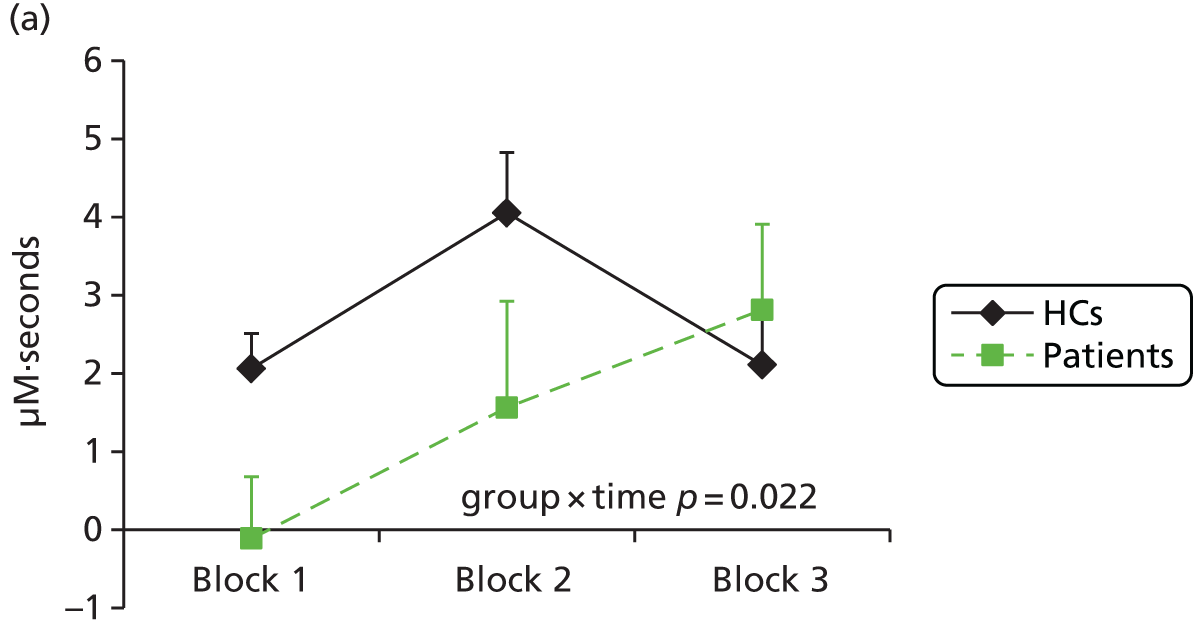

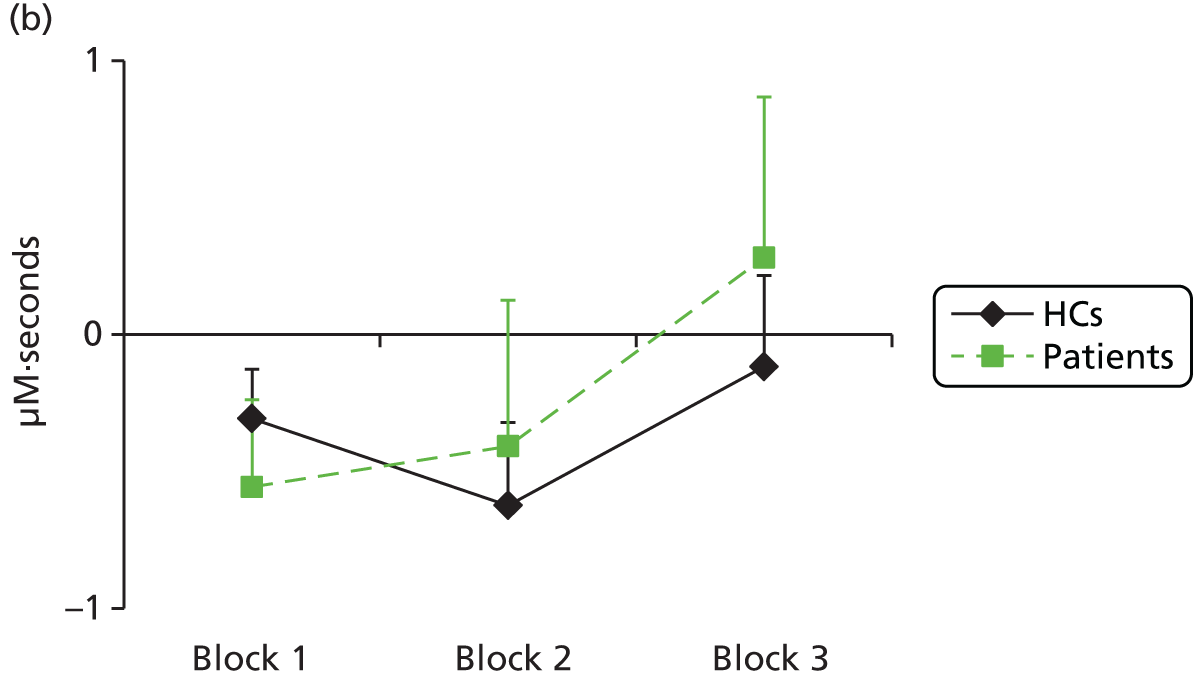

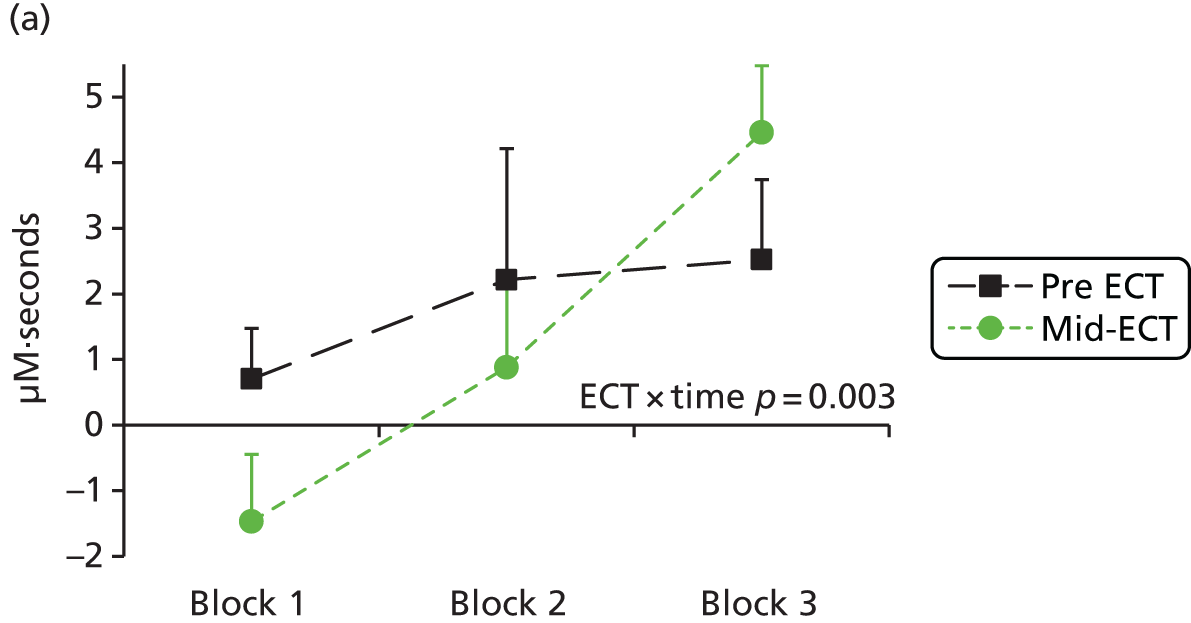

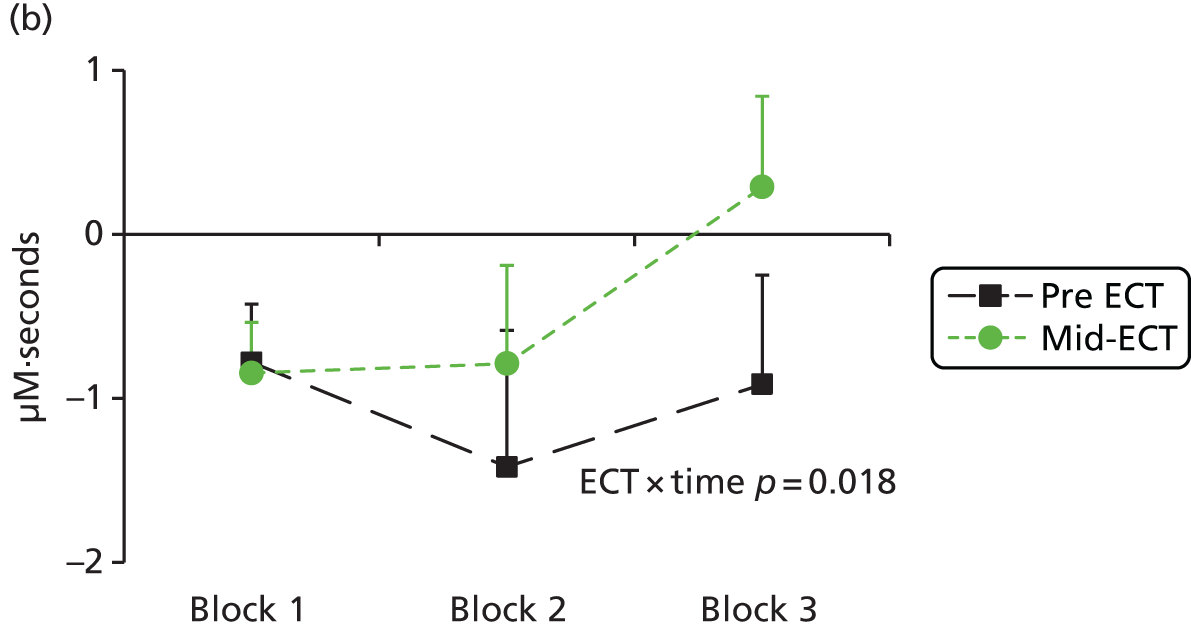

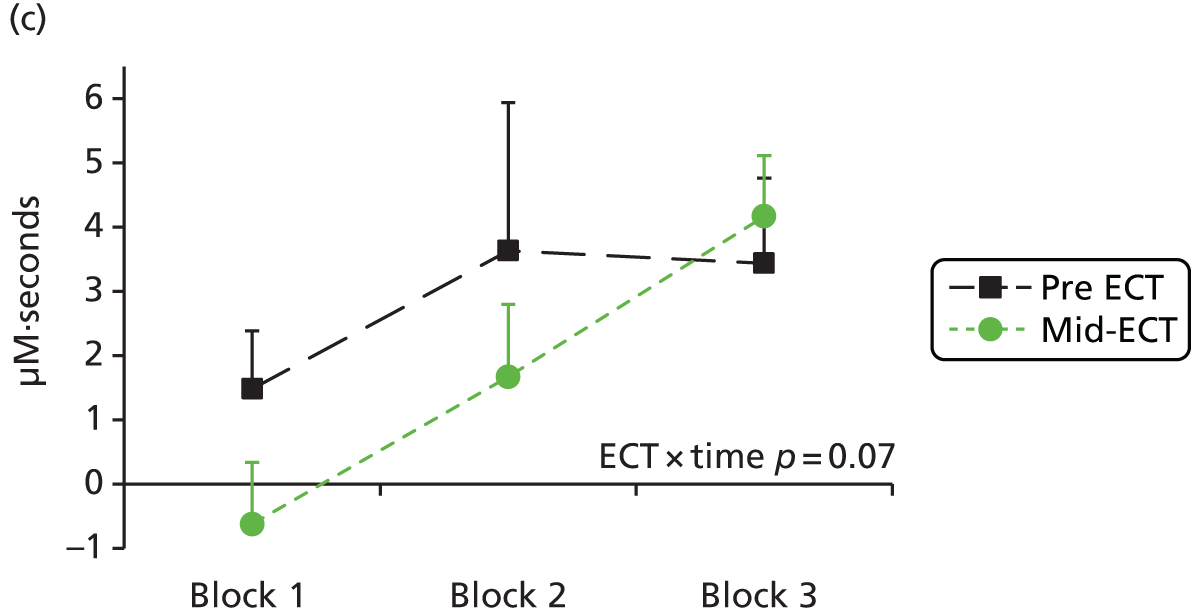

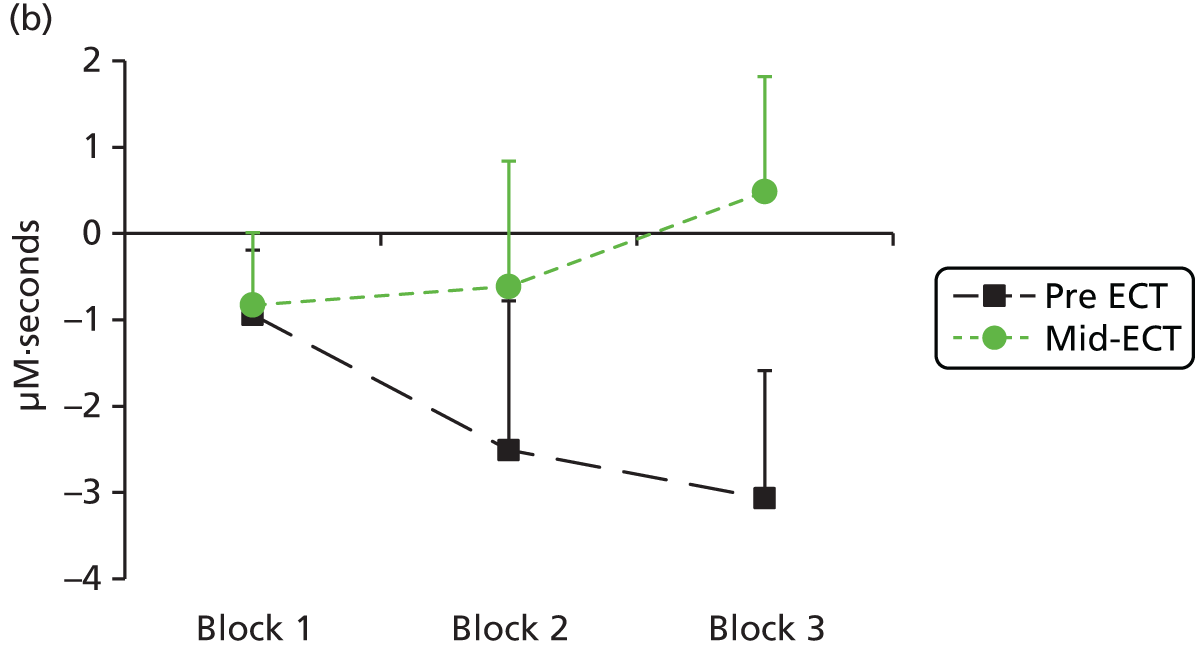

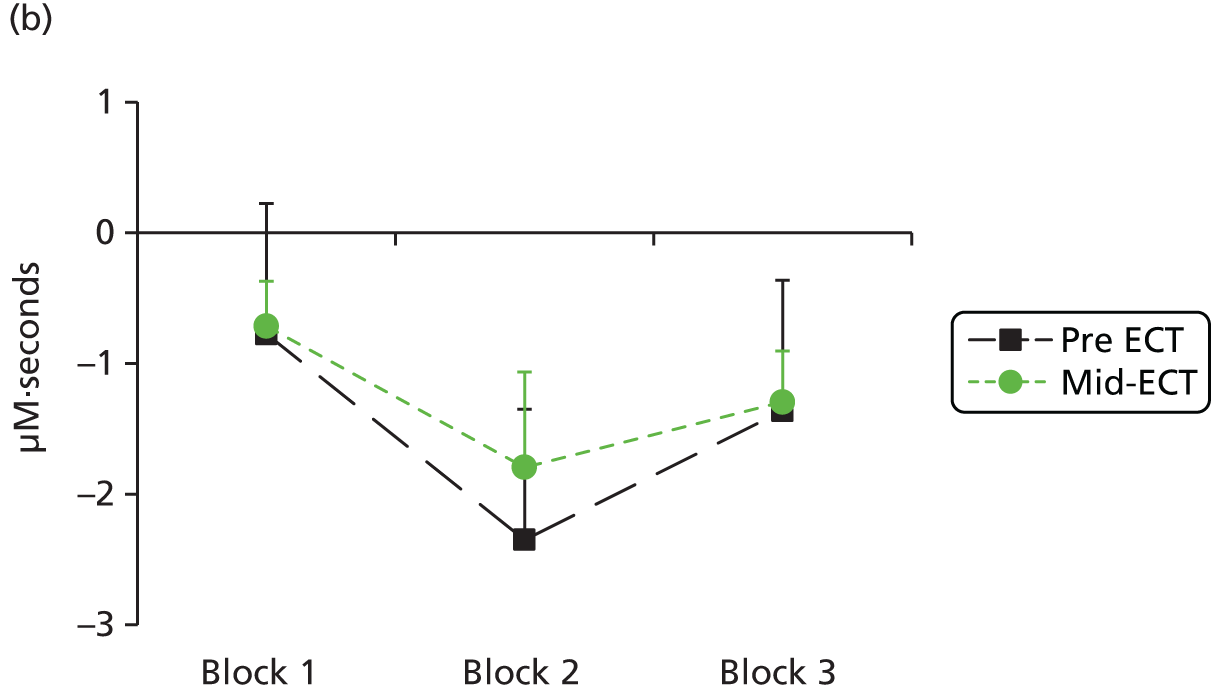

This produced one mean haemodynamic response for each channel in each participant, which was divided into three blocks of 20 seconds (0–20 seconds, 20–40 seconds and 40–60 seconds) (Figure 4). The integral of the mean haemodynamic response in each of these blocks was computed [area under the curve (AUC) for blocks 1, 2 and 3] for analysis.

FIGURE 4.

Example of mean haemodynamic response and block timing. The timings of the three 20-second blocks used in the analysis are shown (block 1: 0–20 seconds; block 2: 20–40 seconds; block 3: 40–60 seconds). The value of the integral in these blocks was used for fNIRS analysis. Hb, haemoglobin.

Given that the haemodynamic response typically lags behind neuronal activation by about 6 seconds, block 1 includes the onset of the haemodynamic response during the active task, block 2 includes the period of greatest sustained response during the task and block 3 includes the return of blood flow to rest level. As displayed in Figure 3, the areas of cortex in which HbO and HbR are measured by the array form a ring around the detectors. The data were collapsed to cover four regions, two on each side, an inferior and more posterior region consisting of BA 44, BA 45 and the inferior part of BA 9 [left ventrolateral prefrontal (LVF) and right ventrolateral prefrontal (RVF) regions] and a superior and more anterior region consisting of BA 46 and parts of BA 9 and BA 10 [left dorsolateral prefrontal (LDF) and right dorsolateral prefrontal (RDF) regions] (see Figure 3). This was carried out by calculating the mean of the channel values for that region [LVF: mean(D, C, L); LDF: mean(K, H, G); RVF: mean(F, I, J); RDF: mean(E, A, B); letters refer to channel sources shown in Figure 1] (see Figure 3). The long 50-mm channels had a poor signal and were excluded from the analysis, so that each region consisted of the mean of up to five channels (three 35-mm channels and two 43-mm channels).

The optimal haemoglobin factor for detecting cortical activation remains unclear: HbO is regarded as the most sensitive and has been most commonly reported in tasks of cortical activation, HbR changes less and appears minimally influenced by motion-induced changes and the difference between HbO and HbR values (Hbdiff) may provide an overall ‘oxygenation index’. 150 Analysis was carried out using all three measures.