Notes

Article history

The contractual start date for this research was in April 2018. This article began editorial review in September 2022 and was accepted for publication in July 2023. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The Global Health Research editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ article and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Nava-Ruelas et al. This work was produced by Nava-Ruelas et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Nava-Ruelas et al.

Background

Depression is a common comorbidity in people with tuberculosis (TB) and it is significantly associated with poorer health outcomes. 1,2 Depression in TB can be treated, and it can potentially improve TB outcomes,3–5 as well as the mental health of people with TB. 6,7 This study is part of a larger grant that explores the comorbidities between mental health and physical health conditions.

There is strong support within global guidelines for patient-centred approaches to TB care,8–10 including addressing the psychosocial aspects of TB. Providing depression care in TB services would be an opportunity to deliver a more patient-centred approach to TB care and address the psychosocial and mental health needs of people with TB.

However, depression is not routinely diagnosed or treated as part of TB services in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). Despite global policy support for patient-centred approaches, there is little guidance on how to implement them into current practice. Understanding how to improve the management of comorbid depression as part of routine TB services is important, particularly for LMICs, where the provision of mental health services is already under significant constraints. 11 There have been some attempts in some LMICs to provide depression care for people with TB, but these have not been systematically documented or analysed.

Aims and objectives

In this review, we aimed to explore the approaches that had been used in LMICs to deliver depression care as part of TB services, and to understand the barriers and facilitators to implementation.

Review methods

We registered the protocol of this review with PROSPERO under registration number CRD42020201095.

Eligibility criteria

The inclusion criteria are described in Table 1. We included studies conducted in LMICs, according to the World Bank classification at the time of the searches, in primary, secondary or tertiary care, with the characteristics listed in Table 1.

| Population | We included studies addressing anxiety and depression (anxiety is a common comorbidity for depressive disorders and anxiety symptoms are commonly part of the presentation in depressive disorders) in people with TB, or attending TB services, in LMICs. Studies aimed at people attending TB services in a LMIC with pulmonary (latent, drug-susceptible or drug-resistant) TB and symptoms (or a diagnosis) of depressive disorder were included. For the purpose of this review, TB was defined as symptoms or signs suggestive of TB or a confirmed laboratory or clinical diagnosis of TB. |

| Intervention | We included studies describing approaches or arrangements for delivering services for depression as part of, alongside or co-ordinated or integrated with services (public and/or private) for pulmonary TB that have been implemented in LMICs. For the purpose of this review, these approaches can be defined as a process that brings together one or more of the funding, administrative, organisational, service delivery and clinical sectors to deliver benefits to people;12 or any management or operational changes implemented in health systems that bring together or co-ordinate the inputs, delivery, management or organisation of services and functions, with the goal of improving the quality, access, coverage, acceptability or cost-effectiveness of care.13 |

| Comparator | No studies were excluded based on the type, or absence, of comparator. |

| Outcome | No studies were excluded based on the type of outcome they measured. |

| Study design | We included any type of study that described or evaluated an attempt to implement or experience of implementing an approach to deliver depression care as part of existing TB services in LMICs. Studies consisting of primary research, secondary data analysis or reviews were eligible for inclusion. |

Search strategy

We designed and carried out the searches with advice from the librarian of the Health Sciences Department at the University of York. One reviewer (RNR) carried out the searches during June–July 2020 and covered all databases from inception. We searched 10 electronic databases for peer-reviewed and grey literature: MEDLINE, Scopus, PsycINFO, Web of Science, PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane Library, SciELO, LILACS and Health Management Information Consortium. We searched the websites of relevant organisations (World Bank, Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria and World Health Organization) using the Google Advanced Search feature. We considered these organisations important as they are major stakeholders in the delivery and funding of TB services in LMICs. 14 We also hand-searched the reference lists of the included studies to identify other relevant studies. An example of the search strategy used across databases is included in Appendix 1.

Quality assessment

We used the Mixed-Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) to appraise the quality of eligible studies. 15 We used this tool anticipating that the included studies would either be qualitative, quantitative or mixed methods studies. The advantage of the MMAT tool is that it provides a framework to assess qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods studies, following a minimum set of quality criteria for the methodological design. 16 This tool was developed in response to the inclusion of different types of evidence into systematic reviews for health services research. 17 This facilitates their integration into systematic reviews as it allows a comparison of overall quality between different methodological stances according to the quality criteria they have met.

Data extraction

Two reviewers (RNR, OT) participated in the screening and data extraction process. We used Rayyan software for the title and abstract screening phases. 18 We resolved disagreements through consensus and discussion before proceeding to the next stage. Two reviewers (RNR, OT) independently performed the full-text screening. One reviewer (RNR) extracted the data of the included studies, and a second reviewer (OT) cross-checked the data extracted against the original study to ensure consistency and reliability for two studies.

Data were extracted from the results and discussion sections of the included studies (see Appendix 2). We extracted the description of the study design, the type of intervention and the implementation process from the background and methods sections of the included studies (see Table 2; further descriptive information on the interventions and their implementation is described in Appendix 5).

| Study (author and numeric reference) | Year of study | Country | Intervention category | Type and no. of participants | Study design | Outcomes measured in the study | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TB-related outcomes | Mental health outcomes | Process outcomes | Other outcomes | |||||||

| Acha et al.25 | 1999–2004 | Peru | Psychological only | Multidrug-resistant TB | 285 | Qualitative | TB treatment success (treatment completion and cure) | None reported | Adherence to TB treatment | Participants’ experiences during implementation, all-cause mortality, quality of life for people with TB |

| Contreras et al.26 | 2015–6 | Peru | Combined, with socioeconomic support | Unspecified type of TB | 192 | Quantitative (cohort study) | None reported | None reported | Number of depression screenings, mental health treatment attendance, completed socioeconomic support evaluations for people with TB | None reported |

| Das et al.27 | 2012–4 | India | Combined | Multidrug-resistant TB comorbid with HIV | 45 | Quantitative (cohort study) | None reported | Changes in depression symptoms’ severity | Number of eligible patients screened for depression; number of referrals (to hospital care for TB) | None reported |

| Diez-Canseco et al.32 | 2015 | Peru | Screening only | Unspecified type of TB | 85 | Mixed methods | None reported | None reported | Number of depression screenings, number of referrals to mental health specialist services, appointment attendance after referral | Participants’ experiences pre, during and post implementation |

| Kaukab et al.29 | 2014 | Pakistan | Combined, with socioeconomic support | Multidrug-resistant TB | 70 | Quantitative (controlled-cohort study) | None reported | Changes in depression symptoms’ severity | None reported | None reported |

| Khachadourian et al.30a | 2014 | Armenia | Psychological only | Drug-susceptible TB | 385 | Quantitative (cluster randomised trial) | TB treatment success, loss to follow-up, treatment failure | Changes in depression symptoms’ severity | None reported | Changes in stigma score, changes in quality of life, all-cause mortality, changes in perceived social support |

| Li et al.31 | 2015–6 | China | Psychological only | Unspecified type of TB | 183 | Quantitative (cluster randomised trial) | None reported | Changes in depression symptoms’ severity | None reported | None reported |

| Lovero et al.33 | 2016–7 | South Africa | Combined | Unspecified type of TB | N/A | Mixed methods | None reported | None reported | Healthcare workers’ knowledge and adherence to mental health diagnosis, treatment and referral guidelines for people with TB | Non-patient participants’ experiences of the mental health intervention |

| Vega et al.28 | 1996–9 | Peru | Combined | Multidrug-resistant TB | 75 | Quantitative (cohort study) | None reported | Changes in depression symptoms’ severity | None reported | None reported |

| Walker et al.34 | 2015 | Nepal | Psychological only | Multidrug-resistant TB | 135 | Mixed methods | None reported | Changes in depression symptoms’ severity | Fidelity, feasibility, acceptability of the intervention | Participants’ experiences during implementation |

To describe the interventions implemented, we used the description as it was stated in the included studies. After this, we classified the studies according to the main categories of interventions used for depression, according to the NICE guidelines19 and based on the descriptions provided in the studies. We created four intervention categories based on the descriptions provided: (1) psychological-only, (2) combined, (3) combined, with socioeconomic support and (4) screening-only. We defined psychological-only interventions as any type of group or individual therapy used to treat mental health conditions, such as depression, anxiety or psychosis (e.g. behavioural therapy, interpersonal therapy, cognitive–behavioural therapy, psychodynamic therapies, family therapy). We defined combined interventions as psychological and pharmacological interventions delivered simultaneously to the patient. We defined combined interventions with socioeconomic support as combined interventions provided alongside any form of support that aimed to address socioeconomic needs in people with TB. We defined screening-only interventions as screening for mental health conditions, followed by referral to mental health services outside of TB services, if needed.

In addition to the descriptive characteristics of the studies, we extracted qualitative and quantitative data, as appropriate, from the studies that described the interventions implemented for data analysis and synthesis. From the qualitative studies, or studies with qualitative components, we extracted the narrative descriptions of the intervention, such as the number and type of study participants, therapeutic strategies, the thematic content of sessions, narrative descriptions of participants’ responses to the interventions, interview responses and other excerpts verbatim from the articles. From the quantitative studies, or studies with quantitative components, we extracted narrative descriptions of the intervention and participants’ experiences (if available); numerical data on the type and number of participants, number of participants who received (or not) the intervention, number of participants who received training (if applicable), number of participants who adhered (or not) to the intervention, depression scores at baseline, depressions scores at the end of the intervention, number of death and descriptive statistics about the characteristics of participants, process outcomes (e.g. the number and type of interventions delivered, enrolment rate) and clinical outcomes (e.g. depression scores, TB treatment outcomes, lost-to-follow-up rates). From the mixed methods studies, we extracted both quantitative and qualitative data. A detailed description on the qualitative and quantitative data we extracted from each study is given in Appendix 2, where the qualitative data are described in Appendix 2, Table 5 and the quantitative data are described in Appendix 2, Table 6.

Data synthesis

We coded the quantitative and qualitative data from all studies according to the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR). This framework was chosen for analysis given its appropriateness to explore the facilitators and barriers to implementing diverse types of interventions. 20 This framework encompasses five main constructs (intervention characteristics, inner setting, outer setting, characteristics of individuals involved and process), divided into 26 subconstructs.

After extracting data from the eligible studies, we converted quantitative data [e.g. frequency tables, forest plots, ratios, number of participants who received (or not) the intervention] to qualitative data by creating narrative descriptions of the quantitative data and results. This process of qualitising data is used in mixed methods literature reviews to synthesise diverse types of evidence. 16 We coded the narrative descriptions of quantitative data along with the qualitative data. We used an analytical approach that was based on the framework method:21 we treated all data as primary qualitative data and coded this information in each study as barriers or facilitators. To create framework matrices, we used the CFIR constructs and subconstructs as an a priori coding framework, organised in columns while the different intervention categories were organised in rows. The data in each cell were verbatim extracts of qualitative data or narrative descriptions of quantitative results from the included studies. We defined the inner setting as the TB national services and/or where healthcare delivery for TB was routinely provided. We defined the outer setting as other governmental or private healthcare services provided within the country, or any other national and international institutions collaborating with TB national services.

The CFIR rating rules state that the coding process should consider the positive or negative influence that coded data have on implementation, and how weak or strong that influence is on implementation. 22 To determine valence, a rating of ‘X, ‘0’, ‘+’ or ‘− is assigned to the coded data. These symbols mean that the coded data had a mixed (positive and negative), null, positive or negative influence on implementation, respectively. To determine strength, a rating of ‘1’ or ‘2’ is assigned to the coded data. A notation of ‘1’ means that the coded data have a weak influence on implementation while ‘2’ means its influence is stronger. To determine the valence of the influence, we considered how many times the narrative data were mentioned in the study, the adjectives used to describe the influence of a construct (e.g. ‘very strong’, ‘very important’, ‘not strong’, ‘not important’), and whether the influence it had on implementation was negative, positive or mixed.

We adapted the CFIR construct definitions to the research objectives of the study. We used the definitions provided in the handbook and the website, and then re-interpreted them according to their relevance to TB services and mental health interventions (see Appendix 4).

Results

Search results

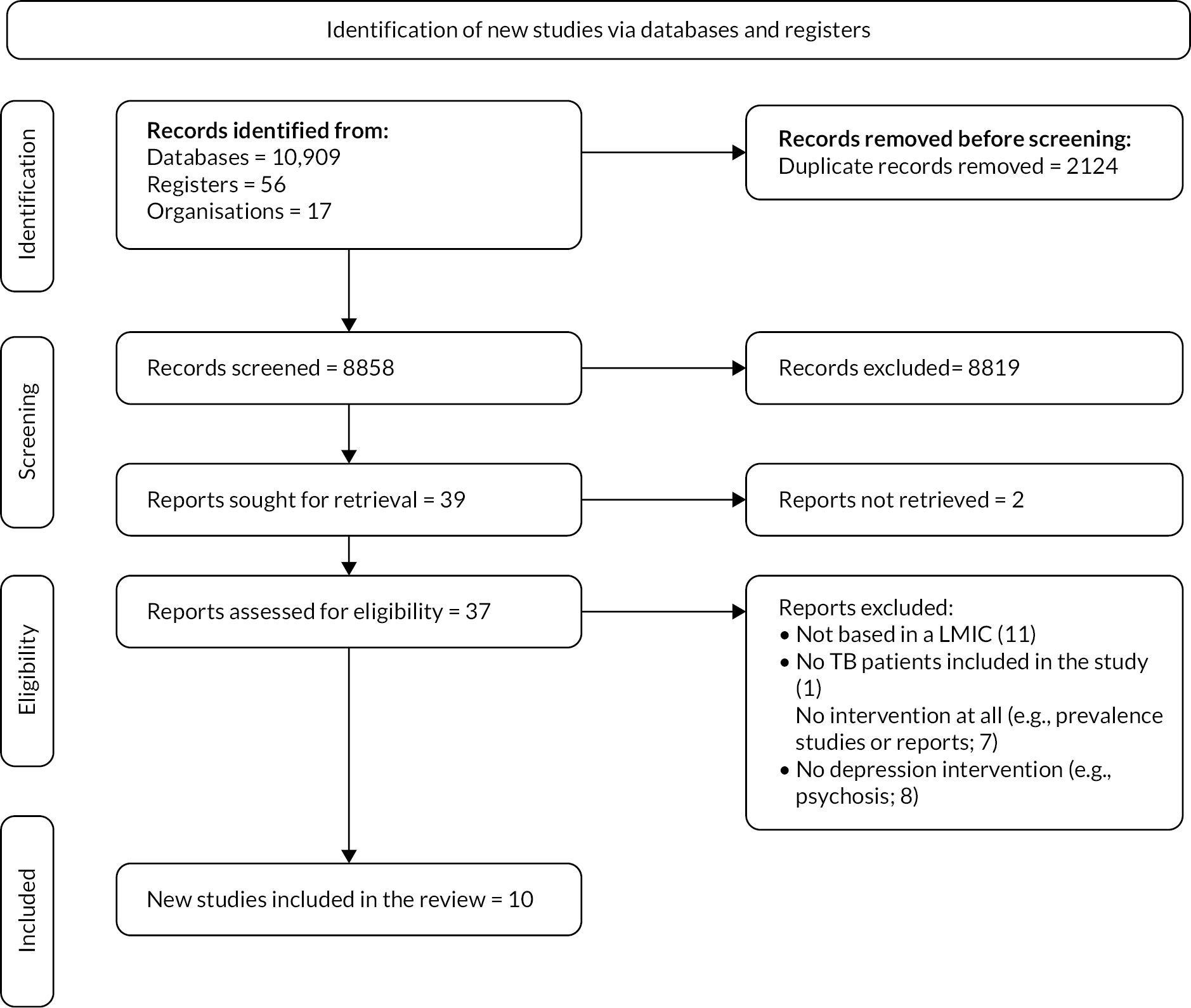

The total number of records retrieved from electronic databases was 10,982. After deduplication,23 two reviewers (RNR, OT) independently screened the titles and abstracts for 8858 records. We recorded our screening process using PRISMA guidelines (see Figure 1). 24

Thirty-nine articles were included in the full-text screening phase. At this stage, 11 articles were excluded because they were based in high-income countries, mostly the USA. One study was excluded because it did not include people with pulmonary TB. Two studies were excluded because they were prevalence studies. Five studies were excluded because they were discussion papers or reports. Eight studies were excluded because they did not describe interventions to treat depression – they focused on adherence or psychosis without depression as a comorbidity. Two articles were excluded because it was not possible to establish contact with the authors or national libraries in Brazil and Bolivia to access the full text. We give the full list of references for the excluded studies in Appendix 6.

Characteristics of the included studies

Ten articles met the inclusion criteria and were included in the analysis. They varied in terms of study design. One was a qualitative study, three were retrospective cohort studies, one was a controlled-cohort study, two were cluster randomised trials and three were mixed methods studies. 25–34 More details of the included studies are given in Table 2.

Four studies described a psychological intervention. 25,30,31,34 Three studies described interventions that combined psychological and pharmacological approaches. 27,28,33 Two studies described a pharmacological and psychological intervention that also included socioeconomic support (combined, with socioeconomic support). 26,29 One intervention consisted of screening only followed by referral to mental health services, when needed. 32

Quality assessment

Table 3 describes the results of a quality assessment using the MMAT tool. We assessed the included studies against the appropriate methodological quality criteria according to the study design. Given the research objectives of this review, we did not exclude any of the studies based on their methodological quality. The purpose of the quality assessment was to explore whether the findings from the included studies were of sufficient methodological quality. All the studies had appropriate study designs for their stated research questions, except for one. 29 In this study, we considered that the study design (quantitative non-randomised) was not appropriate for the research questions that the authors described in the study, which were to examine the effectiveness of a combined intervention, with socioeconomic support, delivered by pharmacists. 29

| Category of study designs | Methodological quality criteria | Studies | (25) | (26) | (27) | (32) | (29) | (30) | (31) | (33) | (28) | (34) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Screening questions (for all types) | Are there clear research questions? | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | ||

| Do the collected data allow the research questions to be addressed? | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | |||

| Qualitative | Is the qualitative approach appropriate to answer the research question? | Y | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | ||

| Are the qualitative data collection methods adequate to address the research question? | Y | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |||

| Are the findings adequately derived from the data? | Y | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |||

| Is the interpretation of results sufficiently substantiated by the data? | Y | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |||

| Is there coherence between qualitative data sources, collection, analysis and interpretation? | Y | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |||

| Quantitative randomised controlled trials | Is randomisation appropriately performed? | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Y | Y | N/A | N/A | N/A | ||

| Are the groups comparable at baseline? | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Y | Y | N/A | N/A | N/A | |||

| Are there complete outcome data? | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Y | N | N/A | N/A | N/A | |||

| Are outcome assessors blinded to the intervention provided? | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Y | N | N/A | N/A | N/A | |||

| Did the participants adhere to the assigned intervention? | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | Y | Y | N/A | N/A | N/A | |||

| Quantitative non-randomised | Are the participants representative of the target population? | N/A | N | N | N/A | N | N/A | N/A | N/A | Y | N/A | ||

| Are measurements appropriate regarding both the outcome and intervention (or exposure)? | N/A | Y | Y | N/A | Y | N/A | N/A | N/A | Y | N/A | |||

| Are there complete outcome data? | N/A | Y | N | N/A | Y | N/A | N/A | N/A | Y | N/A | |||

| Are the confounders accounted for in the design and analysis? | N/A | N | N | N/A | N | N/A | N/A | N/A | Y | N/A | |||

| During the study period, is the intervention administered (or did exposure occur) as intended? | N/A | Y | N | N/A | Y | N/A | N/A | N/A | Y | N/A | |||

| Quantitative descriptive | Is the sampling strategy relevant to address the research question? | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | ||

| Is the sample representative of the target population? | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |||

| Are the measurements appropriate? | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |||

| Is the risk of nonresponse bias low? | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |||

| Is the statistical analysis appropriate to answer the research question? | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | |||

| Mixed methods | Is there an adequate rationale for using a mixed methods design to address the research question? | N/A | N/A | N/A | Y | N/A | N/A | N/A | Y | N/A | Y | ||

| Are the different components of the study effectively integrated to answer the research question? | N/A | N/A | N/A | Y | N/A | N/A | N/A | Y | N/A | Y | |||

| Are the outputs of the integration of qualitative and quantitative components adequately interpreted? | N/A | N/A | N/A | Y | N/A | N/A | N/A | Y | N/A | Y | |||

| Are divergences and inconsistencies between quantitative and qualitative results adequately addressed? | N/A | N/A | N/A | Y | N/A | N/A | N/A | Y | N/A | Y | |||

| Do the different components of the study adhere to the quality criteria of each tradition of the methods involved? | N/A | N/A | N/A | Y | N/A | N/A | N/A | Y | N/A | Y | |||

| Total quality criteria met | 6/7 | 5/7 | 3/7 | 7/7 | 4/7 | 7/7 | 5/7 | 7/7 | 7/7 | 7/7 | |||

Description of approaches to deliver depression care as part of TB services

The 10 studies included in this analysis describe four main types of interventions that aim to provide depression diagnosis and/or treatment or referral to mental health services to people with TB in LMICs at the point of care for TB services. The four major approaches used to deliver depression care for people with TB in LMICs were psychological interventions, combined (pharmacological and psychological) interventions, combined interventions with socioeconomic support and screening-only interventions. See Appendix 5 for a detailed description of the interventions, components and resources required for implementation.

The most commonly implemented intervention was psychological. Nine out of 10 studies included in this review described the implementation of psychological interventions, or interventions with a psychological component, alone or in combination with other approaches; one study did not describe the implementation of a psychological intervention. 32 Psychological interventions were described as counselling or psychotherapy. The most common intervention for depression was counselling. 26–30,33,34 Counselling was delivered in interventions that implemented psychological interventions only, combined interventions or combined interventions with socioeconomic support. Counselling was defined as motivational and emotional counselling, patient counselling or psychological counselling. 27,30,34 It was also defined as TB counselling. 30 Most counselling sessions were individual, except when also conducted with family members and/or patient groups. 30,34 The content of counselling sessions was not described in most interventions. Only one study described the content of the counselling sessions as based on behavioural activation. 34

None of the interventions used pharmacological treatment alone; all pharmacological interventions were part of a combined strategy, incorporating psychological and socioeconomic support components.

Two interventions included socioeconomic support components combined with psychological and pharmacological interventions. 26,29 Socioeconomic support consisted of transport subsidies, food, fees for medical tests, school fees for family members and covered diagnostic tests’ fees for other comorbidities. Both studies justified the inclusion of socioeconomic support given the socioeconomic needs of people with TB. Both studies mentioned that the socioeconomic support was provided by non-governmental organisations (NGOs). 26,29

The interventions were described inconsistently. Information on treatments’ length, dose and end points was often missing from the published data in all the included studies. The studies that reported on psychological interventions, combined interventions and combined interventions with socioeconomic support did not report on treatment length or the number of psychological sessions received by participants. The frequency of psychological treatment sessions was mentioned in four studies. 25,29–31 Of the three combined interventions, one study provided detail about the combination of pharmacological therapy with psychotherapy given to patients, which were selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, tricyclic antidepressants or benzodiazepines;28 the dosages were not reported.

There was also variability in the instruments used to measure and diagnose depression; some studies described the use of more than one tool. 26,34 All studies reported measurements of depression scores at baseline. Baseline referred to the beginning of the intervention for depression in some studies, while in others it referred to the beginning of TB treatment. We found the same patterns in end point measurements. End-point measurements could refer to the end of the depression intervention or the end of the TB treatment. We extracted these data as reported in the studies (see Appendix 2). The follow-up measurements of depression scores were taken at different points in all the interventions; one study had no follow-up measurement. 32

All the interventions were implemented as part of routine public TB services and were often given at the same location and time as TB-service delivery, except in two interventions where patients received mental health services elsewhere. 32,33 Where applicable, the interventions used routine TB care as a control or comparator. 29–31 All the interventions relied on existing TB care pathways to incorporate screening and treatment for depression. All the interventions were provided free of charge for participants at the point of service delivery.

All the interventions relied on multidisciplinary teams to deliver the depression intervention. The teams comprised TB healthcare workers, primary healthcare workers with training in mental health or mental health specialists (i.e. psychologists or psychiatrists). In the studies that described the number and type of providers involved, there was a higher number of community or lay healthcare workers in comparison to the mental health specialists within the team. 25–27,33,34 When community or lay healthcare workers were involved in the intervention delivery, this was due to their role in the existing TB service-delivery structure, as they were often responsible for diagnosis and follow-up for people with TB and were often their first and only contact with TB services.

Most studies described how they required additional human or physical resources to those routinely used or available in the existing TB services. For example, most interventions described the requirement of additional human resources to deliver the intervention; the exceptions to this were combined and screening-only interventions where they used routinely available human resources. 27,28,32,33 Studies describing psychological interventions described the need for mental health specialists (psychologists, psychiatrists or both), social workers or additional community healthcare workers to deliver the intervention, working alongside routinely available TB healthcare workers. 25,30,31,34

All the interventions required community or lay healthcare workers to receive training for screening for depression and delivering the described intervention. The training components were described unevenly in all the studies. In some studies, it was not specified whether the training that the healthcare workers underwent was delivered as part of the intervention or before its implementation. 26–28,30 In some studies, training was only provided for the use of diagnostic tools. 31 In two studies, the training content or length was not described at all. 25,29 In the studies that described the training components, these usually covered the use of diagnostic tools and the provision of mental healthcare and were targeted to TB healthcare workers. 28,33,34 One study mentioned training the TB healthcare workers for a total period of 6 days. 34

All the interventions required the use of additional physical spaces to those routinely available in TB services in which to deliver the diagnosis or follow-up sessions for the intervention, for groups or individuals. Other requirements that were specific to the types of intervention were the use of IT infrastructure or mobile data plans to facilitate communication between patients and healthcare workers or between healthcare workers and the implementation team. 30,32 In the case of interventions that delivered antidepressants as part of the treatment, these were offered to patients at no cost. 27,28 Only one study provided in-kind incentives for community healthcare workers to participate in the intervention delivery. 32

Barriers and facilitators to delivering depression care as part of routine TB services

There was a lot of variability in terms of what represented barriers or facilitators to implementation across the intervention types and CFIR domains.

In Table 4, we describe an overview of the barriers and facilitators to the implementation of the interventions according to the CFIR framework, along with information on the constructs where there were no data available. The table includes a definition of the CFIR subconstructs and a summary of their role as barriers or facilitators to the implementation of each type of intervention for depression.

| Construct | Subconstruct | Definition of the CFIR subconstructs for the purposes of this review and in line with the CFIR handbooka | Psychological-only | Combined | Combined, with socioeconomic support | Screening-only |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention characteristics | Intervention source | Defined as the perception of healthcare workers or people with TB about whether the depression intervention is developed by local or national TB services or not | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| Evidence strength and quality | Defined as the authors’, healthcare workers’ or other participants’ perceptions on the evidence supporting the belief that the depression intervention will have the desired outcomes described in the study | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | |

| Relative advantage | Defined as the healthcare workers’ and/or people with TB’s perception about the advantage of delivering the depression intervention over the status quo or not delivering the intervention | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | |

| Adaptability | Defined as the degree to which a depression intervention was or can be adapted to meet local needs | 1 | X | 1 | −1 | |

| Trialability | Defined as the ability or possibility to test the depression intervention on a small scale in existing TB services. Previous experiences of piloting the depression intervention or one of its components was also considered in this subconstruct | X | ND | ND | 2 | |

| Complexity | Defined as healthcare workers’ and/or people with TB’s perception about the difficulty of implementing or delivering the depression intervention, which could also be reflected by the intricacy and number of steps required to deliver the depression intervention | −2 | −1 | X | X | |

| Design quality and package | Defined as the perceptions of the intervention participants about the presentation and quality of the materials needed for delivering the depression intervention | 2 | ND | ND | 2 | |

| Cost of intervention and or implementation | Defined as the costs of the depression intervention and costs associated with its implementation, including opportunity costs | −2 | −2 | −1 | −1 | |

| Outer setting | Needs of those served by the organisation | Defined as the extent to which the needs of people with TB are identified or met by the depression intervention | 2 | 1 | 1 | −1 |

| Cosmopolitanism | Defined as the degree to which TB services are linked with other organisations and its influence on the implementation of the depression intervention | 2 | 2 | 2 | ND | |

| Peer pressure | Defined as the perceived competitive pressure to implement the depression intervention in TB services | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| External policy and incentives | Defined as the local, regional or national public policies that support the implementation and delivery of depression care in TB services or for people with TB. Also defined as non-governmental organisations’ mandates and guidelines that support the implementation and delivery of the intervention | 1 | 2 | 2 | ND | |

| Inner setting | Structural characteristics of an organisation | Defined as the architecture, size and other organisational characteristics of TB services | ND | X | 1 | ND |

| Networks and communications | Defined as the quality of formal and informal social networks and communications within TB services | ND | −2 | 1 | ND | |

| Culture | Defined as the norms, values and basic assumptions of patients, communities and the healthcare workers employed by TB services or the organisation delivering the depression intervention | −1 | −2 | ND | −1 | |

| Implementation climate: | Defined as the general receptivity to change within TB services shown by healthcare workers or other participants which cannot be coded to any of the subconstructs below: | − | − | − | − | |

| a. Tension for change | Defined as the authors’, healthcare workers’ or other participants’ perceptions about the need for change in the current service provided to people with TB | 2 | ND | ND | ND | |

| b. Compatibility | Defined as the authors’, healthcare workers’ or other participants’ perceptions about the compatibility or fit of the depression intervention with their current practices, values and/or systems | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| c. Relative priority | Defined as the authors’, healthcare workers’ or other participants’ perceptions about the importance of the implementation and delivery of depression care in existing TB services | ND | −2 | ND | ND | |

| d. Organisational incentives and rewards | Defined as the incentives and rewards provided by study leads, TB services or other organisations involved in the implementation of the intervention that have a goal to increase or improve the uptake of the depression intervention | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| e. Goals and feedback | Defined as the communication of goals and feedback to health-care workers delivering the depression intervention | ND | −1 | ND | 2 | |

| f. Learning climate | Defined as the presence or absence of a learning climate in TB services. A learning climate is defined as a climate in which leaders express their own fallibility and need for team members’ assistance and input; team members feel that they are essential, valued and knowledgeable partners in the change process; individuals feel psychologically safe to try new methods and there is sufficient time and space for reflective thinking and evaluation (CFIR, 2021) | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| Readiness for implementation: | Defined as the tangible indicators of a TB service’s commitment to the implementation of depression in its routine services, and which cannot be coded in the subconstructs below: | − | − | − | − | |

| a. Leadership engagement | Defined as the involvement of TB services or other relevant organisational leaders in the implementation and delivery of the depression intervention | ND | 1 | ND | ND | |

| b. Available resources | Defined as the availability of resources (i.e. physical, human, financial) dedicated to the implementation and delivery of the depression intervention | −2 | −2 | 1 | X | |

| c. Access to knowledge and information | Defined as the provision of knowledge and information to healthcare workers (e.g. training) and people with TB (e.g. educational materials or sessions) about the depression intervention and/or TB | 2 | 2 | ND | 2 | |

| Characteristics of individuals | Knowledge and beliefs about the intervention | Defined as the authors’, healthcare workers’ or other participants’ (i.e. patients) attitudes and beliefs about the depression intervention | 1 | X | ND | 2 |

| Self-efficacy | Defined as the healthcare worker’s belief in their capacity to implement and deliver the depression intervention | 2 | −2 | ND | 2 | |

| Individual stage of change | Defined as the individual stages through which healthcare workers move towards the sustained and skilled delivery of the depression intervention | 1 | 2 | ND | 2 | |

| Individual identification with organisation | Defined as healthcare workers’ and people with TB’s perceptions of TB services and their commitment to them | ND | ND | ND | ND | |

| Other individual characteristics | Defined as healthcare workers’ personality traits, such as their tolerance of ambiguity, intellectual ability, motivation, values, competence, capacity and learning style (CFIR, 2021) | 2 | ND | ND | ND | |

| Process | Planning | Defined as the development of plans and strategies for the implementation and delivery of depression care before its implementation | X | ND | ND | 2 |

| Engaging: | Defined as the strategies and outcomes of activities to engage different individuals in the implementation and use of the depression intervention, and which cannot be coded in the subconstructs below: | − | − | − | − | |

| a. Opinion leaders | Defined as individuals or groups of individuals (e.g. family, community members) that have a formal or informal influence on the attitudes or beliefs of others towards the intervention and its implementation | 2 | ND | ND | 2 | |

| b. Formally appointed internal implementation leaders | Defined as healthcare workers or individuals from within TB services who have been formally appointed as implementers, co-ordinators, project managers, team leaders or other similar roles. | ND | 0 | ND | ND | |

| c. Champions | Defined as individuals who help overcome indifference or resistance to the depression intervention within TB services or by other participants | 2 | ND | ND | ND | |

| d. External change agents | Defined as individuals affiliated with other organisations outside TB services that facilitate the implementation of the intervention | 1 | 1 | 1 | ND | |

| e. Key stakeholders | Defined as the healthcare workers within TB services or organisations involved in delivering the intervention | 2 | 2 | X | 2 | |

| f. Innovation participants | Defined as people with TB, their families and/or caregivers | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | |

| Executing | Defined as the implementation of the depression intervention according to what was planned (i.e. fidelity) | −1 | −2 | ND | 2 | |

| Reflection and evaluation | Defined as the feedback about the process of implementation and/or the intervention from healthcare workers and people with TB towards study leads or implementation leaders | 2 | 0 | ND | 2 |

Barriers

The construct, cost of intervention and/or implementation, is contained within the intervention characteristics domain in the CFIR framework. Most studies discussed the spill-over effects of this barrier in the context of implementation. This was a major barrier to implementation for all intervention types. There were different types of costs referenced in the studies, associated with additional human resources, lack of physical spaces and lack of funding for the mental health intervention.

All the interventions required the use of additional physical and/or human resources to those routinely available and required additional resources for training activities. Examples of additional human resources were the recruitment of specialist mental health workers (i.e. psychiatrists or psychologists) and additional community health workers. 25,34

The lack of physical spaces to deliver the interventions for depression was also a recurring barrier in most studies. Only the screening-only intervention did not mention lack of physical space as a barrier, since patients were referred to spaces outside the TB clinic to receive mental health care. 32

One study describing a combined intervention mentions the lack of funding as a worsening factor that negatively impacts on implementing mental healthcare interventions in routine primary care services: ‘the problem is human resources, material resources, and funding all combined … ’ (p. 7). 33

Other barriers across interventions

Complexity is part of the intervention characteristics construct. This was a barrier for psychological and combined interventions, but it had a mixed impact on interventions combined with socioeconomic support and screening-only interventions. For a detailed description of the role of this construct as a barrier, see Appendix 3.

Culture was referred to as a barrier when the organisational or patients’ culture clashed with the goals of the intervention. Culture was a barrier for all types of interventions, except for combined interventions with socioeconomic support, where there were no data available. For a detailed description of the role of this construct as a barrier, see Appendix 3.

Facilitators across intervention types

Relative advantage

Participants perceived that it was advantageous to implement the depression intervention since it improved the TB care provided at the time of implementation. All the studies reported statements referring to the participants’ belief in the advantage and benefit of delivering mental health care to people with TB as opposed to routine care or no mental health intervention at all. In most studies it was recognised that people with TB have complex care needs that cannot be addressed by focusing on TB treatment alone. One study explicitly stated that the intervention improved and complemented the current services provided for TB patients and improved their access to integrated care.

[The intervention] offered additional evaluations to supplement those covered by the TB services at the health facilities … [the intervention’s] strategy of having a field team who function as case managers and patient advocates is one method for offering co-ordinated care in a system where care is not integrated at the provider level. (p. 509)26

The favourable opinion about the relative advantage of the intervention was shared by patients, TB healthcare workers and policy-makers. ‘Some [patients] also stated that the intervention should be available in all multi-drug-resistant (MDR)-TB centres’ (p. 9). 34 Healthcare workers felt that the intervention helped them to provide better care to their patients.

They [the healthcare workers] believed the training made them more aware of the importance of caring for people’s mental health, provided them with knowledge and skills in mental health – an understudied topic in their professional education – taught them how to use a screening tool to assess their patients’ mental health, and offered them necessary skills to help their patients. (p. 14)32

TB programme leaders at district level mentioned that mental health delivery programmes had achieved some improvements on routinely provided TB care. 33

Compatibility of the intervention

This construct is part of the inner setting. The studies reported positive statements about the compatibility of the intervention components (i.e. screening, treatment) with the values of the TB services and current practices. In two studies, describing a psychological and a screening-only intervention, components were designed with the input from the healthcare workers delivering the intervention and adapted according to their feedback as the implementation progressed. 32,34 The studies describing combined interventions for depression also described how the screening and treatment components were compatible with their programmes and were included in their operational manuals or supported by national TB policies. 26–28,33

Innovation participants

The people who received the intervention, that is people with TB (and, in some psychological interventions, their families), were facilitators for implementation. In all the interventions, there were comprehensive measures taken to involve the people with TB and their families in the implementation of the intervention. In some interventions, this included providing home visits to people with TB. 25,26,28,31 In some interventions, family members and friends were included in the psychological component of the intervention. 25,30,31,34 In one intervention, patients were given an option of where to receive care, depending on their situation at home. 26,33 In all the interventions, the active participation of the people with TB, their families or their communities was a facilitator for the implementation of the intervention for depression, regardless of the type of intervention.

Other facilitators across intervention types

There were other facilitators across most, but not all, intervention types.

Evidence strength and quality was defined as the belief, sustained by evidence, that the intervention would have the desired outcome. This was a facilitator in psychological, combined and combined with socioeconomic support interventions. For a detailed description of the role of this construct, see Appendix 3.

Cosmopolitanism, part of the outer setting, seemed to be a facilitator for all types of interventions, except for screening-only, where there were no data to assess this. Cosmopolitanism was defined as the linkages between TB services and other public or private services. For a detailed description of the role of this construct, see Appendix 3.

External policy and incentives, part of the outer setting, seemed to be facilitators for all types of interventions, except for screening-only, for which there were no data to assess this. For a detailed description of the role of this construct, see Appendix 3.

Access to knowledge and information, part of the inner setting, acted as a facilitator for all types of interventions, except for combined interventions with socioeconomic support, where there were no data available to assess this. More details of the role of this construct are included in Appendix 3.

Individual stage of change, part of the characteristics of individuals domain, seemed to be a facilitator for all types of interventions, except for combined interventions with socioeconomic support, where there were no data to assess this. This construct refers to the stages that healthcare workers go through towards the sustained and skilled delivery of the intervention, in terms of the change in their confidence and knowledge to implement the intervention. See Appendix 3 for a detailed description of the role of this construct.

The influence of external change agents as facilitators of implementation was present in all interventions, except for the screening-only intervention, where there were no data available to assess this. External change agents were defined as individuals affiliated to other organisations that are not governmental or public TB services. See Appendix 3 for a detailed description of the role of this construct.

Discrepancies in barriers and facilitators across intervention types

There were some discrepancies in the roles that some constructs had across interventions. This section describes the constructs that were facilitators for some interventions and barriers to implementation in others, based on the data available in the included studies.

Adaptability, part of the domain of the intervention characteristics, had a different role in the implementation of different types of intervention. It acted as a facilitator in the implementation of psychological-only and combined interventions with socioeconomic support; it was a barrier to the implementation of the screening-only intervention and it had a mixed impact in the implementation of combined interventions (without socioeconomic support). As a facilitator, the construct of availability included statements from the included studies that referred to how screening and treatment components were adapted to meet the local cultural needs. In one psychological intervention, this involved a change of screening tool from the less compatible PHQ-9 to the more compatible PHQ-2 with healthcare workers’ routine activities. 34 In another psychological intervention, this involved the use of culturally adapted treatments for depression according to patients’ needs. 31 However, in the implementation of combined interventions, one of the studies described how the adaptability of the intervention led to its uneven implementation in different primary care settings. 33 The characteristics of the screening-only intervention meant that it was not possible to fully adapt the intervention to local practices and workflows, even if it was designed to be compatible. 32

The construct, needs of those served by the organisation (i.e. people with TB needs), part of the outer setting domain, was a facilitator in psychological, combined and combined interventions with socioeconomic support. However, it was a barrier in the screening-only intervention. For a detailed description of the role of this construct as a barrier and facilitator, see Appendix 3.

The role of the available resources construct, part of the inner setting domain, was a facilitator for implementation in combined interventions with socioeconomic support. However, this construct was described in the context of barriers to implementation in psychological and combined interventions. Additionally, this construct was one of the few to have a mixed impact, as a barrier and facilitator, in the implementation of screening-only interventions. For a detailed description of the role of this construct as a barrier and facilitator, see Appendix 3.

Self-efficacy, part of the characteristics of individuals domain, was a facilitator for the implementation of psychological-only and screening-only interventions, but it was a barrier to implementation for combined interventions. For a detailed description of the role of this construct as a barrier and facilitator, see Appendix 3.

In psychological, combined and screening-only interventions, the role of key stakeholders was as a facilitator for implementation. However, the same construct had a mixed impact in the implementation of combined interventions with socioeconomic support. Key stakeholders were defined as healthcare workers who were part of TB services and involved in TB service delivery. Key stakeholders were multidisciplinary: the teams involved in the implementation of screening and treatment interventions were social workers, counsellors and psychologists or psychiatrists, nurses with mental health training, community healthcare workers or TB healthcare workers. In interventions that involved mental health specialists, such as psychologists or psychiatrists, these would often be involved in the training and supervision of community health workers or data collectors implementing the screening and treatment. 25,27,32 In these interventions, the role of specialists was also to provide ongoing support and sometimes feedback to the community health workers providing the intervention. However, in one combined intervention with socioeconomic support, the role of psychologists or mental health specialists was unclear in terms of their role in providing support or training to the healthcare workers delivering the intervention. 29 In this intervention, the role of TB healthcare workers was also unclear, as it was stated that pharmacists delivered the intervention, and their affiliation was unclear at the time of implementation.

Executing, part of the process domain, was a facilitator for the implementation of the screening-only intervention, while it was a barrier to implementation in psychological and combined interventions. In the screening-only intervention, its technological characteristics (i.e. being app-based) allowed for the consistent implementation of the intervention, and the intervention implementation process was designed so that researchers could provide support to healthcare workers quickly if they noticed that the intervention was not being implemented adequately. 32 However, for the implementation of psychological interventions, the studies described issues with the adequate execution of the intervention. These were attributed in part to the insufficient resources or the unsustainability of the interventions when healthcare workers aimed to include it in their day-to-day practice. ‘Although it only took 5–10 minutes to go through, this seemed to become a barrier to them using the flipbook. They stated that they gave the same messages but more briefly’ (p. 9). 34 In combined interventions, two studies described issues with uneven implementation. They described deficiencies associated with the adequate, sustained and consistent implementation of the intervention across settings. 33 One study mentioned that the mental health intervention components (i.e. routine screening, the use of the designated screening tool, referral and treatment) were unevenly implemented according to healthcare workers’ self-reported performance. 27

Constructs with no data

For the rest of the interventions implemented, there were some constructs that had no data available across all intervention types. Most of the data coded in the studies were attributed to the subconstructs included in the larger intervention characteristics and characteristics of individuals constructs. However, there were evident gaps in information in other domains. The most evident gap in evidence was in the inner setting construct. In this construct, few studies described data that could be used to reveal patterns about the influence of the constructs in this domain as barriers or facilitators. The lack of data was evident also in the process construct of the framework, where there was little information available on the role of planning and engaging different actors in the implementation of the intervention. See Table 4 for more details.

Discussion

In this systematic review, we aimed to explore the approaches that have been used to deliver depression care as part of TB services in LMICs. This review also aimed to describe the barriers and facilitators to their implementation using the CFIR framework as an analytical framework. While the goal of this review was not to assess effectiveness, two studies that used cluster randomised controlled trial design reported improved TB and/or mental health outcomes compared to baseline assessments. This is consistent with findings about the efficacy of delivering pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions for common mental disorders in people with TB. 35 This potential effectiveness makes it important to identify how to best deliver mental healthcare interventions for people with TB and implement them within routine TB services.

Most studies met the criteria for quality of reporting according to their study design. However, the studies described the implemented interventions inconsistently, and some of them did not report dosage, length of treatment or follow-up information about the interventions, which are factors that can mediate the efficacy of the interventions. This is consistent with other reviews carried out to evaluate the effectiveness of pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions for common mental disorders in people with TB where meta-analyses were not possible due to the sparse data reported in studies and the methodological variation in study designs. 35

Approaches to deliver depression care as part of TB services

There were different approaches to deliver depression care for people with TB in LMICs. The most common approach was the implementation of psychological components, alone or in combination with pharmacological components and with socioeconomic support. This is consistent with the findings of other systematic reviews for interventions that integrate mental health into primary care in LMICs. 36 Psychological and pharmacological interventions for depression have the potential to be delivered in resource-constrained settings by providing training to non-specialist mental healthcare providers and using task-shifting approaches, achieving highly effective results when delivered by non-specialists alone or supervised by mental health specialists. 37 However, the implementation process will inevitably require additional physical and training-related resources.

Barriers and facilitators to implementation

The provision of mental health training to lay or community healthcare workers was an important facilitator for implementation. This finding is in line with the results of other systematic reviews: it is essential to provide training to lay healthcare workers or community healthcare workers to provide mental health care. 38 The type of training and the number of sessions required will vary according to the healthcare workers’ baseline characteristics and their previous knowledge of mental health and mental health interventions. There is some preliminary research on the activities within training that are necessary to implement sustained change, such as the formal appointment of supervisors and self-reflection or evaluation of fidelity to the intervention, to name a few. 39 Training content should cover basic information about mental health conditions, interventions, terminology and diagnostic and referral criteria. Also, the provision of mental health and TB knowledge to patients, families and communities facilitates implementation. Other studies have similar findings: when mental health interventions facilitate interaction between providers, beneficiaries and their families, in culturally appropriate ways, it facilitates the implementation process and creates a positive experience for those involved. 40 When healthcare workers felt they lacked the skills to address mental health in their patients, they regarded this as a barrier to integrating mental health assessments or related activities in their practice. 41

All interventions and their implementation processes incurred costs, mainly related to the use of human resources, training and physical spaces. This finding is consistent with the results of a systematic review that analysed the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of integrating mental health care in LMICs, where the findings of the study show that all intervention arms increased the effectiveness of depression treatment and costs. 36 The cost of the intervention and its implementation can be attributed to the legacy of insufficient funds allocated to mental health care. 11 ‘Given the low levels of spending on mental healthcare … the finding that increasing the availability of mental health services increases direct costs should not surprise’ (p. 48). 36 Based on evidence from 42 studies, the integration of mental health services for depression in primary care can result in an immediate increase in health costs at a service level, mainly due to the increased use of human resources and the cost of treatment but is cost-effective from a healthcare perspective or reduces costs from a societal perspective. 36

To date, there is not a systematic review that analyses the costs of implementation of depression interventions in LMICs, which makes it hard to assess what resources are needed for implementation. In all the included studies, it was mentioned that there were not enough resources available for TB services, which will impact the feasibility of the implementation of mental health interventions in routine TB services. This tension overlaps with the availability of human resources for the delivery of mental health services. It is often not enough to train existing healthcare workers to deliver mental health care in the context of a poorly resourced workforce. 40 Further resources should be created and earmarked to facilitate the training of healthcare professionals in mental health care, add dedicated healthcare workers to provide mental health care, add specific mental healthcare tasks to existing care pathways or use a care co-ordinator. 36 The findings of this review suggest that the additional workload related to mental health care for existing healthcare workers is likely to be unfeasible and unsustainable within existing TB programmes. TB services in LMICs are well-established and have dedicated resources apart from wider health systems’ structures. 42 Thus, in this context, it would be more effective to earmark existing resources to train TB healthcare workers on mental health care delivery or use care co-ordinators to integrate mental health care into people with TB’s care. Mental health interventions in LMICs can be more effectively implemented if they adhere to existing care pathways and service delivery networks. 40

The provision of training alone is not sufficient if this is not accompanied by earmarked resources that create the space to deliver these interventions in existing service delivery structures, including considerations to increase the number of providers. TB services, as part of their aim to provide patient-centred care,10 could frame that as a window of opportunity to create said space and use existing resources to deliver mental health interventions for people with TB as part of their routine care.

Greater understanding and information on the organisational characteristics of TB services, such as internal incentives and rewards, the role of peer pressure, the learning climate or individuals’ identification with the organisation, can help to inform how to integrate care for mental health into TB services so that they can be feasibly and sustainably delivered. Understanding organisational characteristics can help with planning adequate interventions and implementation strategies. For example, interventions for depression that include financial incentives can help to alleviate the economic vulnerability of people with TB in LMICs. 43,44 This is important to explore because of the way that TB care is financed and provided in LMICs, including a range of organisations and collaborations. 14 Published peer-reviewed systematic reviews hint that health system characteristics, such as funding structures and available human resources, can become important barriers to implementation if they are not addressed before implementation stages, or if there are not discrete resources allocated to the integration of mental health care in existing health services. 41

Future research

This review includes studies that were published or carried out before the COVID-19 pandemic. Thus, the results presented here are likely to not be reflective of the current status of mental health and TB services in the countries reflected in the studies included in this review. A feasible way to improve this review would be to include an analysis of how the TB and mental health services of the countries represented have been affected by the pandemic.

Lessons learnt

The availability and reliability of the information on implementation efforts depend more on the study design (e.g. feasibility and acceptability) rather than on the intervention type being implemented (e.g. psychological, combined). Because the nature of the majority of the studies was not focused on implementation, that meant that a lot of cells within the framework matrix were empty (no data) for most intervention types and studies, except for two which had implementation-focused study designs. 32,45 This is consistent with other implementation reviews that focus on depression interventions in LMICs. 46,47 Future studies should be based on implementation-based questions such as the feasibility, acceptability and sustainability of the intervention. Future research should focus on assessing the interventions’ effectiveness and their implementation in resource-constrained settings, which would focus on the later implementation stages’ outcomes, such as cost, penetration and sustainability. 46

Community engagement involvement

There was no patient and public involvement in this study. We considered this to be inappropriate given the objective of the study, which was to synthesise the available evidence.

Limitations

The CFIR framework may not be able to capture the full complexity of TB services and their impact on mental healthcare delivery in LMICs. Although this framework was useful in identifying barriers and facilitators, there were characteristics from local health systems that could not be coded to the existing constructs in the framework. For example, national and international donors for TB and mental health programmes can influence the interventions that are implemented, based on their preferences and agendas. 40 Adaptations that make the CFIR framework more relevant to LMICs’ contexts are possible and should be explored as they can help assess barriers and facilitators that are prevalent in resource-constrained settings. 47 In line with the findings from other reviews,46,47 the next research priorities should move away from trying to test the effectiveness of interventions and rather focus on the implementation strategies and outcomes that can lead to successful implementation efforts for depression interventions in LMICs.

Due to the objectives of this study, the information analysed corresponds only to that reported in the published studies and is, therefore, subjected to reporting bias in the individual studies. Although a quality assessment was made according to each study type, this did not influence the weighting of how findings were represented in this review, as this study was concerned with providing a narrative synthesis of the approaches to depression care in TB services. Thus, this study should not be interpreted as evaluating the effectiveness of the interventions included in the analysis. Nonetheless, we are confident that we were able to identify and describe the various approaches that have been implemented to provide depression care in TB services in LMIC.

Conclusion

In this review, we aimed to identify the approaches used in LMICs to provide depression care for people with TB. We also aimed to explore the barriers and facilitators to their implementation.

What this study adds

We identified psychological interventions as the most common approach used to deliver depression care for people with TB in LMICs. The findings from this review suggest that the implementation of interventions for depression is facilitated by the belief that the intervention is advantageous to the status quo (i.e. no provision of mental health care) (relative advantage), the compatibility of the intervention with existing workflows and the positive attitude that patients, families and communities display towards the intervention (innovation participants). All the interventions faced barriers to implementation related to the costs of the intervention and/or its implementation, which were expressed in terms of costs associated with insufficient human resources, lack of physical resources and lack of financial resources altogether for the provision of mental health care to people with TB. The choice of the best intervention to implement will depend on the available resources and the attitude of stakeholders to the intervention. From the evidence reported in the included evidence in this study, it appears that psychological interventions with some form of community engagement are the most compatible with local attitudes towards mental health interventions and can be delivered with existing or few additional resources, if training is provided. These are important factors that will facilitate the implementation of these types of interventions.

Key learning points

-

There are barriers and facilitators faced by all types of interventions for depression implemented into existing TB services. However, different barriers and facilitators can arise according to the types of intervention implemented.

-

Interventions to treat depression among TB patients are unlikely to be feasible without investment in human resources to deliver care.

-

The implementation of any mental health intervention in TB services will require some degree of training. However, for the sustainable delivery of the intervention, mental health tasks and activities could be included in routine TB care or there could be a designated workforce for the delivery of this intervention.

Deviations from protocol

Outcomes of interest as stated in the protocol were defined as

those described in eligible studies, which could be process or clinical outcomes, for example: process outcomes (e.g. number of diagnostic tests performed, number of patients with access to the intervention to treat depression) or clinical outcomes (e.g. patients with negative sputum smear test, mortality, patients with reduced depression severity).

In practice, none of these data were extracted as they were not consistently reported across studies, and they were not required for the main analysis of barriers and facilit

Additional information

Contributions of authors

Rocio Nava-Ruelas (https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5890-7519) (PhD Candidate, Health Sciences, University of York) contributed to the design of the study and conducted the literature searches, screening, analysis and writing of the report.

Olamide Todowede (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5785-1426) (Research Fellow, Health Sciences, University of Nottingham) conducted the screening and collaborated with writing the report.

Najma Siddiqi (https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1794-2152) (Professor of Psychiatry, Health Sciences, University of York) contributed to the design of the study and the writing of the report.

Helen Elsey (https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4724-0581) (Senior Lecturer in Global Health, Health Sciences, University of York) contributed to the design of the study and the writing of the report.

Disclosure of interests

Full disclosure of interests: Completed ICMJE forms for all authors, including all related interests, are available in the toolkit on the NIHR Journals Library report publication page at https://doi.org/10.3310/GRWH1425.

Primary conflicts of interest: Rocio Nava-Ruelas received grant support from Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnologia for her doctoral studies. Olamide Todowede declares no competing interest. Najma Siddiqi was part of Grant 17/63/130 NIHR Global Health Research Group: Improving Outcomes in Mental and Physical Multimorbidity and Developing Research Capacity (IMPACT) in South Asia at the University of York. Helen Elsey declares no competing interest.

Data-sharing statement

Data can be obtained from the corresponding author upon request.

Ethics statement

This study did not require ethical approval as it did not involve human participants as data subjects.

Equality, diversity and inclusion

We designed our study to be of relevance to the population of interest (people with TB), regardless of their socioeconomic status, gender, ethnicity, religion or age. We believe that the study population from the included studies is reflective of the population of interest. We believe we have addressed EDI concerns pertaining to the study design, which is an evidence synthesis, in that we did not exclude any study based on the type of population as long as they met the principal inclusion criteria.

Department of Health and Social Care disclaimer

This report presents independent research commissioned by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). The views and opinions expressed by authors in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the NHS, the NIHR, MRC, CCF, NETSCC, the GHR programme or the Department of Health and Social Care.

Study registration

The protocol of this review is registered with PROSPERO under registration number CRD42020201095.

Funding

This article presents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Global Health Research programme as award number 17/63/130 using UK aid from the UK Government to support global health research. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the UK government. Research is published in the NIHR Global Health Research Journal. See the NIHR Funding and Awards website for further award information.

About this article

The contractual start date for this research was in April 2018. This article began editorial review in September 2022 and was accepted for publication in July 2023. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The Global Health Research editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ article and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

This article was published based on current knowledge at the time and date of publication. NIHR is committed to being inclusive and will continually monitor best practice and guidance in relation to terminology and language to ensure that we remain relevant to our stakeholders.

Copyright

Copyright © 2024 Nava-Ruelas et al. This work was produced by Nava-Ruelas et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

This article reports on one component of the research award Approaches used to deliver depression care in TB services in LMICs and barriers and facilitators to implementation: a systematic review. For more information about this research please view the award page (https://www.fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/17/63/130)

List of abbreviations

- CFIR

- Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research

- LMICs

- low- and middle-income countries

- MMAT

- Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool

- NGO

- non-governmental organisation or not-for-profit organisations

- TB

- tuberculosis; for the purposes of this article, this encompasses only pulmonary TB, in drug-resistant and drug-susceptible variants

References

- Alene KA, Clements ACA, McBryde ES, Jaramillo E, Lonnroth K, Shaweno D, et al. Mental health disorders, social stressors, and health-related quality of life in patients with multidrug-resistant tuberculosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Infect 2018;77:357-67.

- Koyanagi A, Vancampfort D, Carvalho AF, DeVylder JE, Haro JM, Pizzol D, et al. Depression comorbid with tuberculosis and its impact on health status: cross-sectional analysis of community-based data from 48 low- and middle-income countries. BMC Med 2017;15.

- Janmeja AK, Das SK, Bhargava R, Chavan BS. Psychotherapy improves compliance with tuberculosis treatment. Respiration 2005;72:375-80.

- Morisky DE, Malotte CK, Choi P, Davidson P, Rigler S, Sugland B, et al. A patient education program to improve adherence rates with antituberculosis drug regimens. Health Educ Q 1990;17:253-67.

- M’Imunya JM, Kredo T, Volmink J. Patient education and counselling for promoting adherence to treatment for tuberculosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;2012.

- Baral SC, Aryal Y, Bhattrai R, King R, Newell JN. The importance of providing counselling and financial support to patients receiving treatment for multi-drug resistant TB: mixed method qualitative and pilot intervention studies. BMC Public Health 2014;14.