Notes

Article history

The contractual start date for this research was in April 2018. This article began editorial review in February 2023 and was accepted for publication in April 2024. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The Global Health Research editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ article and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Ul Haq et al. This work was produced by Ul Haq et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Ul Haq et al.

Background and introduction

Smoking is a key cause of the 10–25 years lower life expectancy observed among people with severe mental illness (SMI) (schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, other psychoses and severe depressive disorder) when compared to the general population. 1–3 Smoking prevalence estimates for people with SMI range from 40% to 60%4–6 and are even higher for all tobacco use (50–90%). 4,7 Our focus is South Asia, specifically India and Pakistan, where a small body of literature indicates a smoking prevalence of 50% among adults with SMI,4 which is significantly higher than in the general adult population (10% India,8 12.4% Pakistan9).

There is extensive evidence for smoking cessation interventions (pharmacotherapies alone or in combination with behavioural support) for the general population,10,11 particularly in high-income countries (HIC). Less and mixed evidence, again predominantly from HIC, is available for people with SMI. 12–15 Differences in cultural and contextual patterns of tobacco use, training of healthcare providers and available treatments, as well as regulatory approaches make it difficult to directly translate interventions from HIC settings to low- and middle-income country (LMIC) contexts.

In 2019, to address this important gap, we adapted three existing smoking cessation interventions5,16 (and personal communication by Sebastien M, January 2019) as part of the Improving Mental and Physical Health Together (IMPACT) programme, to create the Smoking cessation support for people with SMI in South Asia (IMPACT 4S) intervention. The IMPACT 4S intervention comprises (1) behavioural support (up to 10 one-on-one, face-to-face, counselling sessions of 30–40 minutes each), including exhaled carbon monoxide (CO) monitoring and feedback, and (2) pharmacotherapy (bupropion or nicotine gum alone or in combination).

The intention was to test the feasibility and acceptability of this intervention in a pilot trial (IMPACT 4S,17 ISRCTN34399445). However, in 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic meant that face-to-face delivery was not possible. We therefore considered remote delivery of the 4S smoking cessation sessions and pharmacotherapy; and consulted key stakeholders (people with SMI, their caregivers, relevant professionals) on the feasibility, and associated challenges and solutions. This paper presents this consultation and the subsequent adaptations made to the IMPACT 4S intervention.

Aims and objectives

The aim of the telephone consultation was to consult with key stakeholders on the feasibility, challenges and solutions for remote delivery of a smoking cessation intervention for people with SMI in India and Pakistan.

Methods

Study design and participants

This was a rapid mixed-methods consultation,18 conducted in September 2020 with Community Advisory Panels (CAP) constituted at the National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences (NIMHANS), Bengaluru, India, and the Institute of Psychiatry (IOP), Rawalpindi, Pakistan. CAP members had previously consented to be contacted for the IMPACT 4S study. Members were re-contacted to arrange a time for this telephone consultation. They received a payment of 1000 Indian Rupees or 500 Pakistani Rupees as a thank you for taking part. In India, all 16 CAP members participated. Of 20 CAP members in Pakistan, 16 took part (1 professional declined due to workload, 3 people with SMI declined as they were now well) (Table 1).

Data collection

Telephone consultations were conducted in English in India and Urdu in Pakistan. Before commencing, participants verbally re-confirmed their consent to take part and for the conversation to be audio-recorded. We sought general views on remote delivery of the IMPACT 4S intervention (is it possible, preferred delivery mode, session timing and duration), and specific views on feasibility (is it possible, challenges/solutions) of nine intervention components (one-way communication – providing information, advising; two-way communication – asking questions, discussion, assessing motivation; using resources – using a flipbook, recording activities in a booklet; practical tasks – measuring exhaled carbon monoxide, administering medication). Questions were a mix of quantitative and qualitative formats, and a question sheet was used to ensure consistency (see Report Supplementary Material 1). Consultations lasted between 35 and 45 minutes (India) and 25 and 50 minutes (Pakistan). They were audio-recorded.

Data analysis

The audio-recordings were transcribed verbatim. Urdu transcriptions were translated into English. Counts (N) were calculated for the quantitative data. Content analysis was used for the qualitative data. 19 Quantitative and qualitative data on general IMPACT 4S delivery and the nine intervention components were then triangulated in a matrix. 18

Agreeing adaptations to the intervention

The consultation findings were discussed among the wider IMPACT 4S intervention adaptation team and adaptations to delivery and content agreed.

Findings

We present below the quantitative findings supplemented with qualitative data including illustrative quotes, where available, to elucidate participants’ responses. Findings are presented by country and differences by participant group are highlighted. The subsequent adaptations to the IMPACT 4S smoking cessation intervention are summarised at the end.

General feedback on remote delivery

Delivering the smoking cessation programme remotely during the pandemic was seen as feasible by all (16/16) Indian participants and three quarters of Pakistani participants who responded (8/11). Considering the ongoing need for smoking cessation support, remote delivery was perceived as necessary, useful, better than nothing and innovative. Somewhat contradictory, when asked if it is better to deliver IMPACT 4S now remotely or wait to deliver it face to face, 6/10 of Pakistani participants who responded suggested to wait (just 2/16 Indian participants said this).

It is a great idea to deliver the smoking cessation programme remotely, it can help patients rather than not having anything. It is also an opportunity to test for innovative programmes remotely during pandemic situation. There are many successful programmes delivered remotely.

Professional, India

It is a very vulnerable time for people with a smoking addiction. Considering the current situation of COVID-19, we don’t know when this pandemic will end, hence people with SMI require smoking cessation support delivered remotely.

Caregiver, Pakistan

Several general reservations were raised by some people with SMI and professionals in both countries. Namely, that adults with SMI may find it hard to engage during a long telephone conversation would need their SMI to be well managed to focus on smoking cessation and require help from a caregiver for the sessions.

As I mentioned earlier clients with mental illness might have psychotic symptoms like hallucination and delusions, so telephone conversation won’t be feasible. We need to handle active symptoms before we start a smoking cessation intervention over the phone.

Professional, India

First, we need to manage the severe mental illness, after that you will be able to provide a smoking cessation intervention remotely with the support of family members.

Professional, Pakistan

Telephone (mobile or landline) supplemented with video calls was the preferred mode of communication (12/16 India, 8/16 Pakistan), favoured particularly by Indian participants as the best way to facilitate two-way communication between the cessation advisor and the smoker. A quarter of Pakistani participants (4/16, no one from India) preferred telephone alone, seen as familiar, easy and affordable for people with SMI and caregivers alike. Potential problems with internet and phone connectivity were mentioned by a few participants in each country. An Indian professional and one person with SMI from Pakistan both observed that a remote programme would only be accessible to individuals with a mobile or landline telephone (ownership is not a given). Finally, the consensus was that a remote delivery cessation session should last between 25 and 30 minutes and be delivered between 10 a.m. and 12 midday to accommodate personal routines.

Delivering smoking cessation sessions remotely might have few issues with calls being interrupted by network issues and poor signal. It also depends on the length of the sessions because ensuring the patient’s attention and understanding is important.

Person with SMI, India

We can expect a few challenges for delivering this remote intervention such as people not having smart phones, internet connection issues, and supervising difficulties for the cessation advisor.

Professional, India

People with SMI might have side effects of psychiatric medication [drowsiness, trouble in sleeping], usually, they wake up a little late and completing morning ablutions will take time, hence, it would be suggested to have the calls between 10 am to 12 noon.

Professional, India

Feasibility and acceptability of intervention components

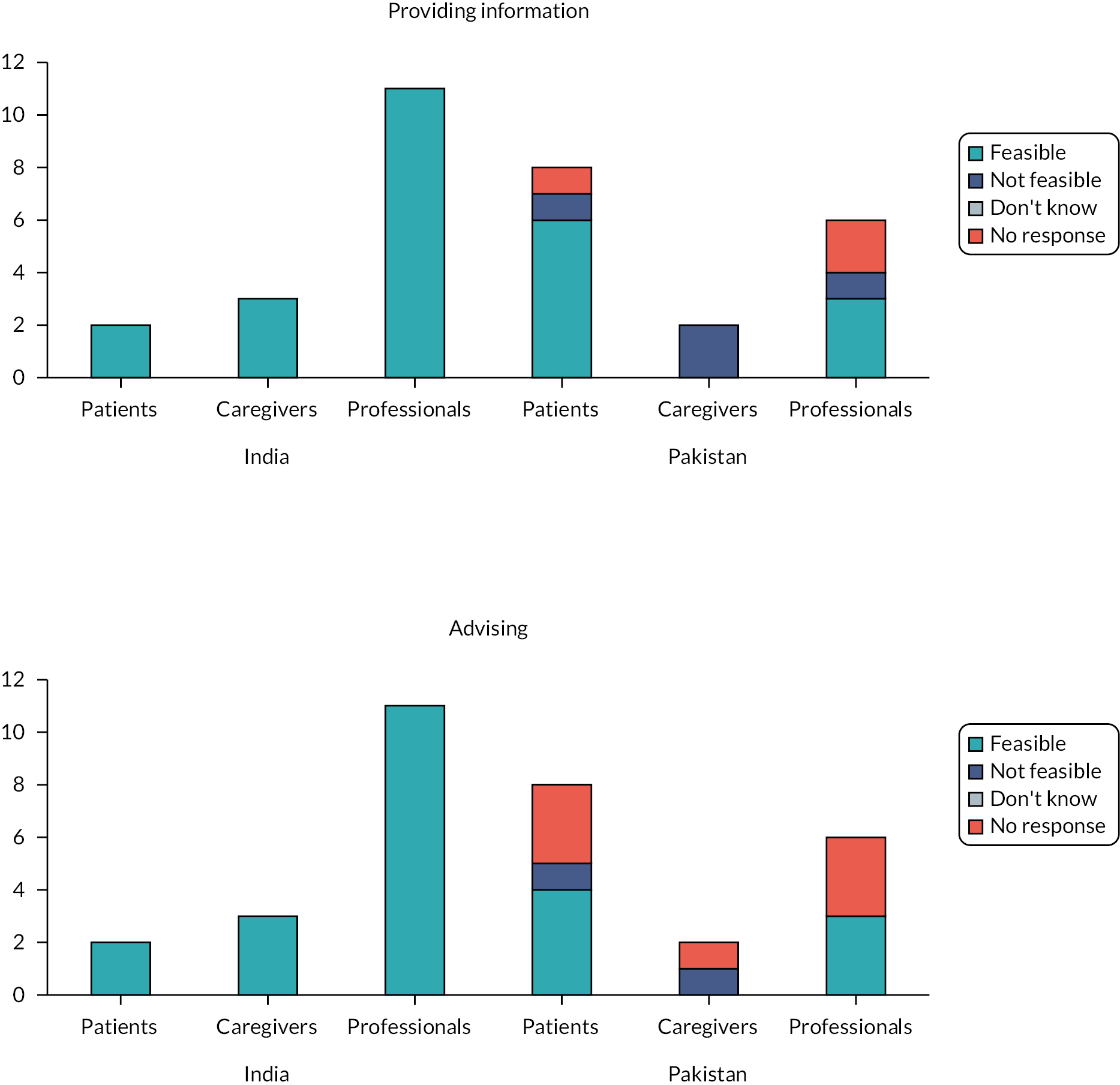

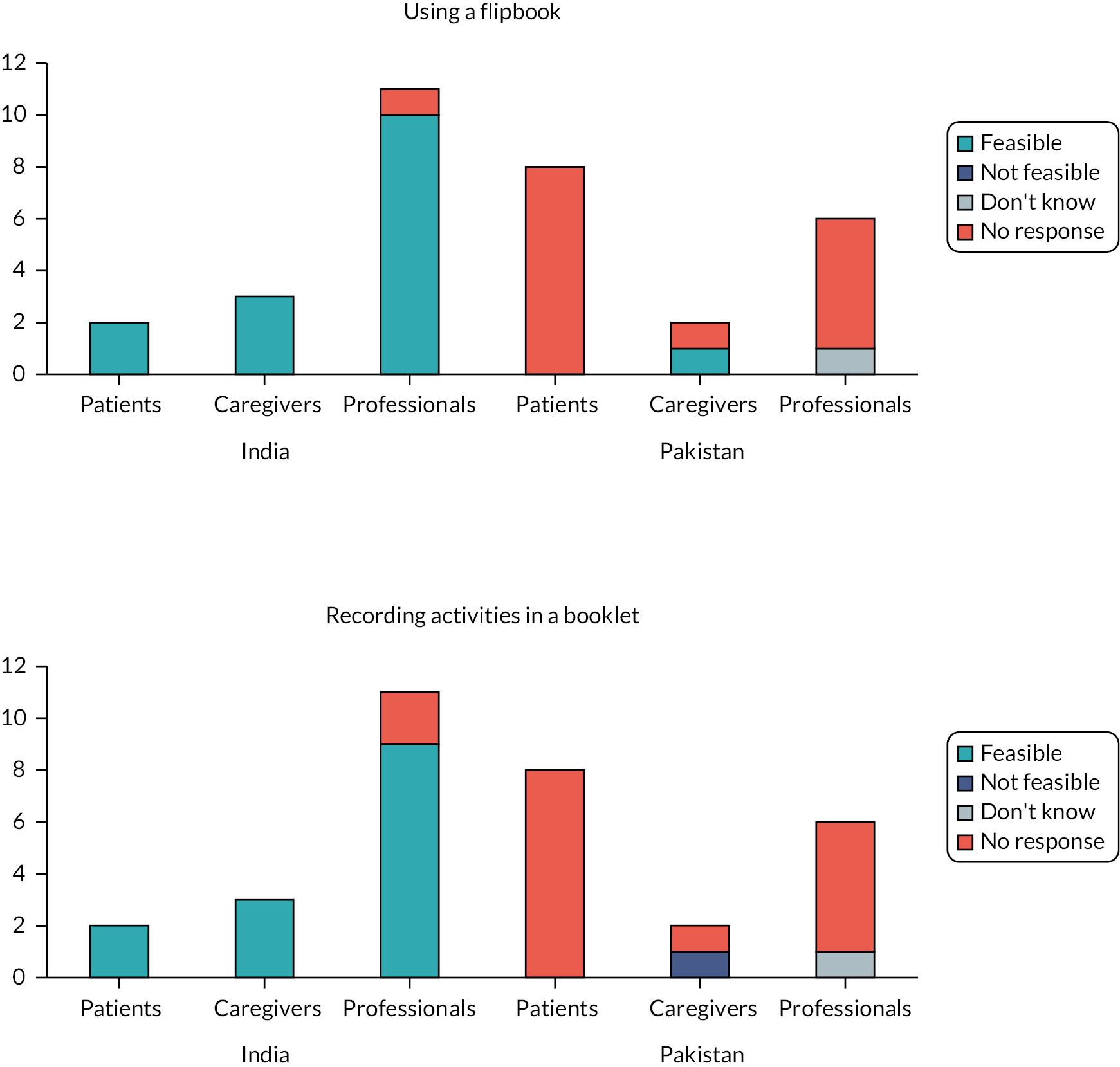

Quantitative feasibility data for the nine intervention components are presented in Figures 1–4. Except for ‘measuring exhaled carbon monoxide’, Indian CAP members consistently said that the IMPACT 4S intervention components could be delivered remotely, while also identifying challenges described below. The opinions were more mixed among Pakistani CAP members. Of note, there were significant missing quantitative data from Pakistan for some components.

There was general support, especially in India, for the feasibility of one-way communication from the cessation advisor to the patient: ‘Providing information’ (16/16 India, 9/13 Pakistan) and ‘advising’ (16/16 India, 7/9 Pakistan) (see Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Feasibility ratings for one-way communication.

The key challenge was seen to be the difficulty for people with SMI to concentrate, understand and retain information, particularly since the IMPACT 4S intervention is delivered over multiple sessions. Both caregivers in Pakistan offered this reason for remote delivery of information and advice not being possible. Several professionals in both countries emphasised the importance of using pictures and caregivers to support this one-way communication.

Yes, it would be possible, information can be provided on a phone call or WhatsApp call with family support. You can easily provide awareness and information from anywhere.

Person with SMI, Pakistan

These patients are already dealing with a mental illness so it would be difficult for them to concentrate on information said over the phone in these sessions.

Caregiver, Pakistan

We can ensure the usage of the flip books and activity booklet with pictures will help the client to understand easily during the remote sessions. You need to send hard copies to the clients before each session begins.

Professional, India

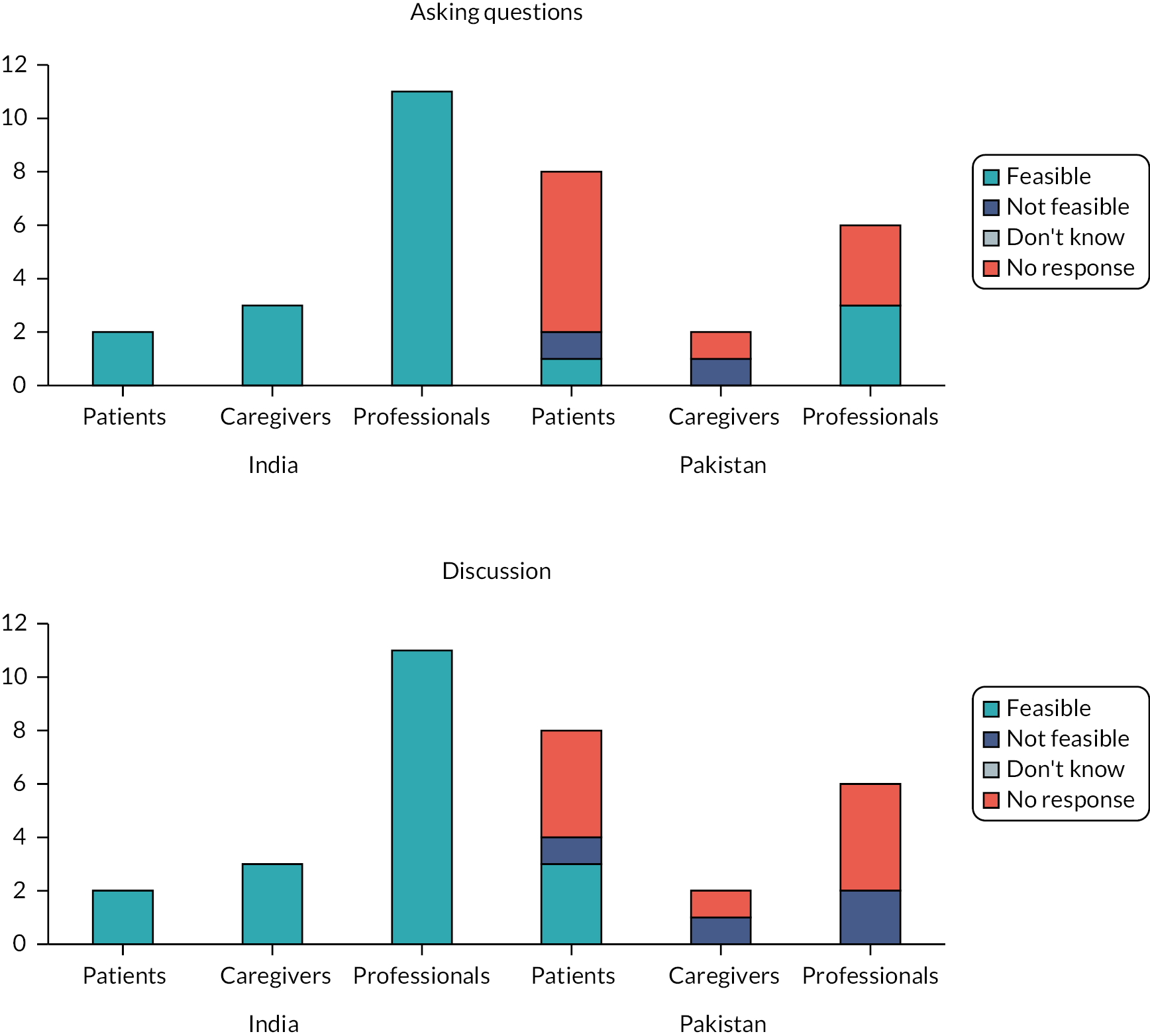

The feasibility of two-way communication was less supported in Pakistan than in India, particularly for the ‘discussion’ component: Asking questions (16/16 India, 4/6 Pakistan), ‘discussion’ (16/16 India, 3/7 Pakistan) and ‘assessing motivation’ (16/16 India, 2/5 Pakistan) (see Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Feasibility ratings for two-way communication.

Caregivers in Pakistan observed that people with SMI may have difficulty in understanding questions and retaining concentration for discussion, particularly if they were unwell with their SMI. Professionals in both countries mentioned that they may also struggle to articulate themselves without in-person contact and may not provide honest answers (instead wishing to please the advisor). They saw it as important for the smoking cessation advisor to be able to see the patients’ verbal expressions to check attention and understanding, preferring to use online visual platforms (in India) or face-to-face consultations (in Pakistan).

Patients will not understand or discuss easily, for this their full concentration is required which is not possible when they are ill.

Caregiver, Pakistan

With non-visual communication you do not know how the patient is responding, what is the environment around him, are you maintaining confidentiality, or if the person is speaking under the suggestions of others or taking decisions independently. If you use visuals, you can overcome these issues.

Professional, India

The patient may listen but how do you know if they are understanding or not, they may not be concentrating, you cannot see the facial expression of the patient. The best way of instructing any person with severe mental illness is face to face conversation in which you can use charts, visual guides, videos etc.

Professional, Pakistan

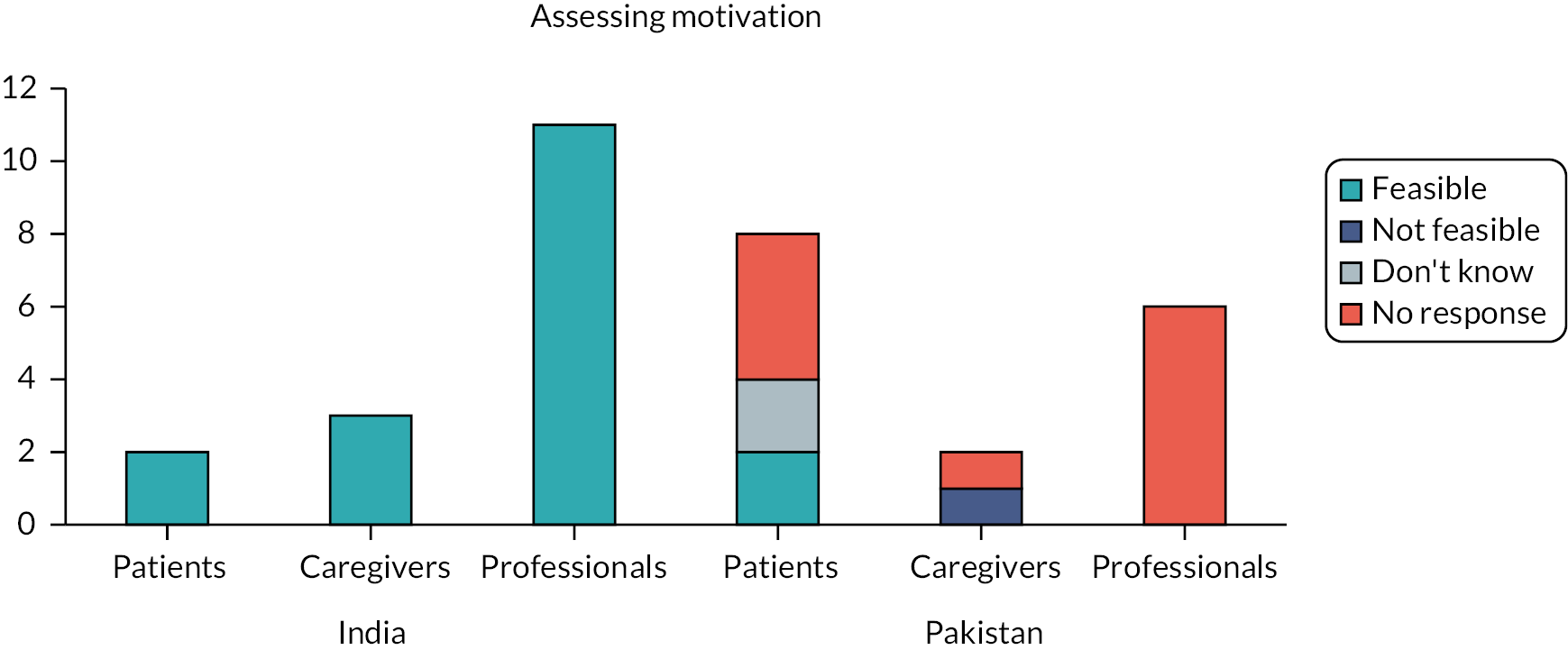

Feedback on the feasibility of using resources was very limited from Pakistan (just two participants provided quantitative data): ‘Using a flipbook’ (15/16 India, 1/2 Pakistan) and ‘recording activities in a booklet’ (14/16 India, 0/2 Pakistan) (see Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Feasibility ratings for using resources.

Participant comments from both countries across groups suggested it was feasible to send these resources to patients’ homes and for caregivers to provide support in using them during sessions. Professionals observed that their effective use would depend on patients’ and caregivers’ literacy.

You can send smoking cessation resource materials, send soft copies by email and if not possible to send online, then send hard copies through the post office or courier facilities.

Professional, India

Using these resources is possible but the patient’s level of education and understanding of using technology is important.

Professional, India

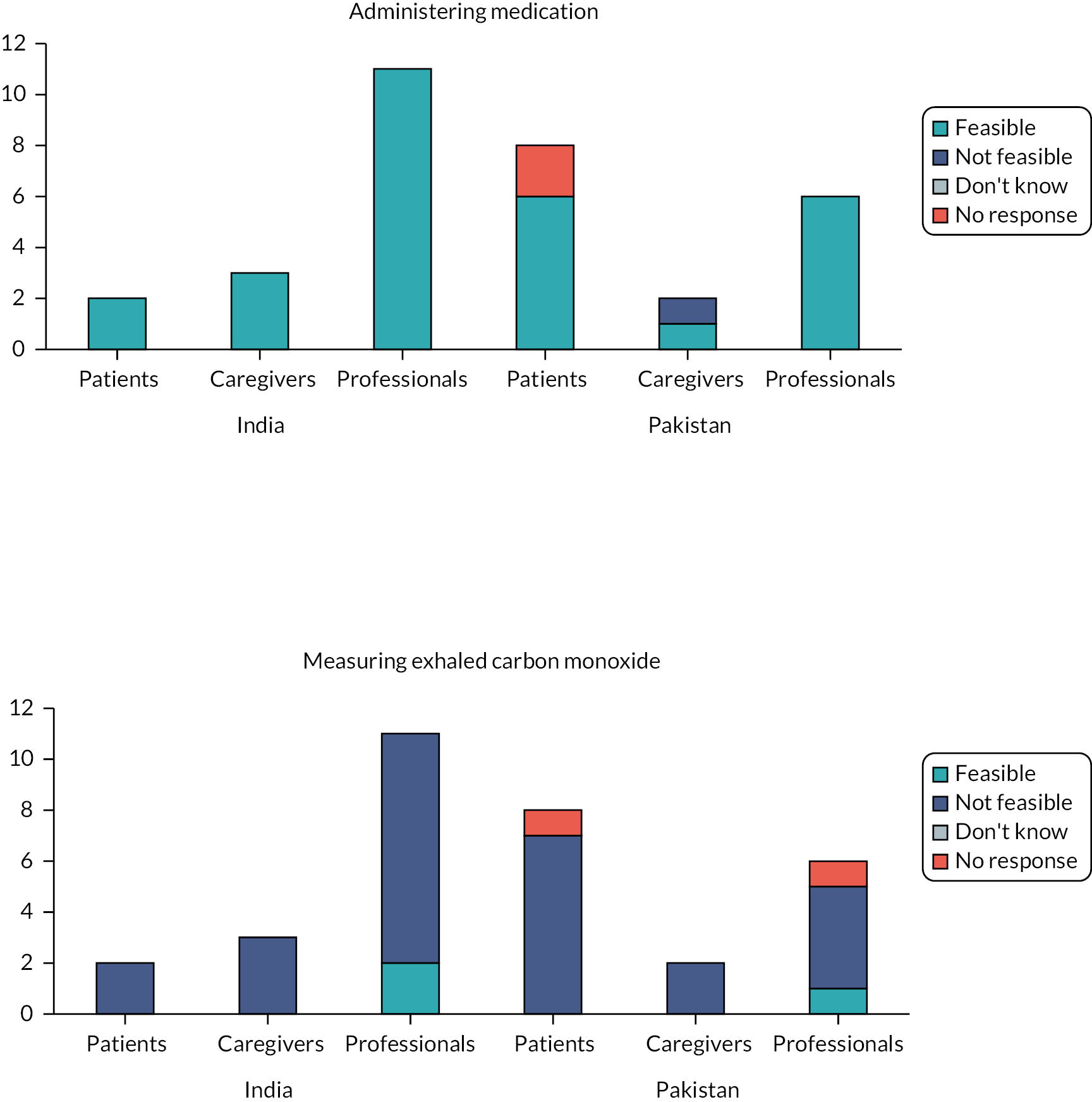

Finally, CAP members considered two practical tasks (see Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

Feasibility ratings for practical tasks.

In both countries and across participant groups (16/16 India, 13/14 Pakistan), it was seen as possible to deliver both types of medication [nicotine replacement gum (NRT), bupropion] by post, courier, community health workers or picked up by patients from a collection point. Caregivers’ and professionals’ concerns were how to ensure patients take the medication correctly and to monitor side effects. The solutions were seen as cessation advisors providing clear instructions and regular reminders/follow-ups alongside caregiver support.

It’s not a big deal to send medication and NRT through the post or by courier; you can collect the postal address over the telephone.

Professional, India

The side effects cannot be managed through instructions on call as the doctor will not be able to assess the real condition of the patient if he/she is not physically present.

Caregiver, Pakistan

Taking NRTs can be guided remotely. The advisor can prescribe and explain when to take the medication and how to take it. Family support will be required. You can also send reminder messages. You can deliver the medication or post it.

Professional, Pakistan

In stark contrast to the views on administering medication, the consensus (14/16 India, 13/14 Pakistan) (see Figure 4) was that measuring exhaled carbon monoxide could not be done remotely. Just two professionals in India and one in Pakistan proposed that the measurement device could be delivered, and caregivers trained up to do the test. Most professionals in both countries considered remote assessment to be ‘risky’ with patients attending in-person for these tests seen as the better option when possible within COVID-19 protocols.

Assessing and monitoring carbon monoxide levels is expensive and risky. It is not possible or is difficult [to do remotely] as patients and caregivers won’t know how to measure this properly.

Professional, India

This is not possible because the physical presence of the patient is necessary. You cannot send the monitor to their home. The patient cannot read his own reading as the patients visiting government hospitals are mostly not educated according to my experience in working in government hospitals. So, I don’t think that the patient will be able to operate any device on his own.

Professional, Pakistan

Adaptations to the 4S smoking cessation intervention

Table 2 presents the adaptations that were made to the delivery and content of 4S intervention following the stakeholder consultation, with the rationale for the change. In short, the resultant intervention was for hybrid delivery, using shorter cessation sessions attended by caregivers, with a focus on simplifying components and resources.

| Adaptation | Rationale | |

|---|---|---|

| DELIVERY | Moved to hybrid delivery where possible, employing a combination of in-person and remote sessions Patients’ existing appointments at the mental health facilities were used for face-to-face sessions. Remote sessions were via voice or video calls depending on person with SMI’s preference. | Face-to-face appointments are seen as preferable. CO monitoring cannot be done remotely. |

| Increased the number of remotely delivered cessation sessions (from 10 to 15) and reduced the duration from 30–40 minutes to 15–30 minutes maximum. | Recommendation to keep remote sessions at < 30 minutes. The number of sessions was increased to accommodate the shorter duration. | |

| Requested caregivers to attend a preparation session to discuss family support for smoking cessation. Invited caregivers to attend all cessation sessions. | Caregiver attendance at remote sessions was seen as important to facilitate the person with SMI’s engagement with the activities. | |

| Posted resources (flipbook, booklet) to the person with SMI’s home. | Having the resources ‘in-person’ was seen as important. | |

| Delivered NRT medication by courier. Adherence and side effects checked via telephone call. | Delivery seen as acceptable as long as advisor monitoring was in place. | |

| CONTENT | Tasks (e.g. assessing motivation for quitting) and resources were simplified (e.g. more use of pictures) to ensure they were appropriate for people with SMI including those with low literacy. | Short concentration span and low literacy of some people with SMI and caregivers were seen as potential challenges of remote delivery. |

| Cessation advisor’s script was modified to ensure discussion of whether the person with SMI was in a suitable place for session delivery, that is without distractions. | Short concentration span of some people with SMI and caregivers were seen as a potential challenge of remote delivery. |

Discussion

Overall remote delivery was considered feasible with a preference for telephone sessions, supplemented with video, delivered for 30 minutes in the morning. Except for ‘measuring exhaled carbon monoxide’, all components were seen to be feasible, with more positive opinions evident in India. All three participant groups identified challenges and solutions. The key challenge related to achieving effective communication over the phone, especially for people with SMI or low literacy. Access (connectivity and phone ownership) and monitoring medication use were other challenges. Popular solutions were to involve caregivers in all intervention components and to ensure these components and associated resources were appropriate for this patient group including those with low literacy. Based on this valuable feedback, the IMPACT 4S smoking cessation intervention was adapted for hybrid instead of exclusively remote delivery with significant changes made to its delivery and content.

The COVID-19 pandemic forced health service providers to move away from traditional face-to face delivery to remote, technology-supported services. 20,21 A consequence is the proliferation in published work reviewing the implementation of telehealth,22 telemedicine,23 telemental health24 and telebehavioural health25 interventions. For people with SMI, this recent literature focuses mainly on adapting mental health services for remote delivery,20,26–28 rather than smoking cessation programmes per se. 29 It also offers a predominantly HIC perspective24–27,29 with limited insight from LMICs, including countries in South Asia. 23,30,31 Nevertheless, it provides a useful backdrop to discuss our findings.

We found general CAP support for the feasibility of delivering the IMPACT 4S smoking cessation intervention remotely. Indeed, remote delivery offers several advantages to the patient: eliminating travel costs and time, offering scheduling flexibility20,32 and the opportunity for additional anonymity in a familiar setting, potentially reducing social anxiety for those affected by this. 20 Some authors suggest it may be less well suited to people with SMI. 24,25,32 Others see this ‘paradigm shift’, (p. 49)20 as an opportunity for improving access and quality of services,23,28 thus reducing the ‘treatment gap’23 for people with SMI, including those in countries with scarce mental health resources. 23,28

The challenges of communication, access and monitoring medication adherence and side effects voiced by the CAPs mirror those reported elsewhere for general patients24,25 and people with SMI. 20,23,28,32,33

Achieving effective provider–patient communication is often framed in the context of the ‘therapeutic alliance’28 and viewed as more difficult in remote consultations where visual cues are absent24,28 and for people with SMI. 20,32,33 Recommended approaches20,26,32–34 include focusing the first session on building rapport and reducing anxiety, pacing sessions according to the patient’s needs (for smoking cessation and in the context of their SMI), paying close attention to concentration levels, emotion, tone of voice etc. and asking more questions than normal to check understanding. Social support from caretakers is seen as paramount to people’s confidence and motivation. 26,35 Tailoring content to patients’ reading and cognitive levels and simplifying messages using symbols or pictures are perhaps even more important in remote delivery. 26,32 Our adaptations to the 4S smoking cessation incorporate these recommended approaches alongside more detailed CAP suggestions. We also updated the cessation advisors’ script and trained them in strategies for engagement and rapport building via video-conference and phone. 20

In a review of telehealth for SMI patients, telephone support was found to be effective in improving medication adherence. 36 Indeed, NIMHANS (the site of the Indian CAP) successfully delivered telemental health services during the pandemic that included access (e-prescriptions, home delivery) and telephone monitoring of medications and side effects. 23 Both these examples are focused on drugs for SMI; however, there seems no reason why this should not be possible for NRTs.

Finally, inequitable access to phone/internet services and connectivity challenges are a concern in South Asia. 37 Women,37,38 rural populations,37 older37 and less educated37 people are less likely to have access to a mobile phone or the internet, as are people with SMI. 20,23 Participants for the IMPACT 4S pilot trial may well face these challenges, reconfirming the importance of feasibility and acceptability testing of the modified IMPACT 4S intervention.

Future research

Following this consultation and the subsequent adaptations to the content and delivery of the IMPACT 4S smoking cessation intervention, the randomised controlled feasibility trial was completed. This work is currently being prepared for publication. A fully powered randomised controlled trial [Smoking Cessation Intervention for Mental Ill Health – South Asia (SCIMITAR-SA)] will commence in July 2024.

Lessons learnt

Valuable insights were captured from the CAP members using this telephone consultation methodology, with helpful ideas for adapting the IMPACT 4S intervention.

Limitations

This was a rapid consultation with a small sample of stakeholders who may have expressed different views to other groups of people with SMI, caregivers and professionals. There were missing quantitative data in Pakistan, particularly for the using resources questions. Nevertheless, we captured general support for remote delivery with wide-ranging views on challenges and ideas for solutions. Triangulating the quantitative and qualitative data sets enabled us to interpret participants’ quantitative ratings of feasibility.

Conclusions

Key stakeholders viewed remote delivery of the IMPACT 4S intervention among people with SMI as feasible and particularly important when face-to-face delivery is not possible. Studies evaluating the feasibility and acceptability of the actual delivery of smoking cessation interventions among people with SMI this way are warranted.

What this study adds

This study adds to the evidence base exploring alternative ways to deliver health services to people with SMI, with a specific focus on smoking cessation programmes in LMICs that is lacking in the literature.

Additional information

CRediT contribution statement

Baha Ul Haq (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9665-3609): Methodology (equal), Investigation (equal), Formal analysis (equal), Writing – original draft (equal).

Faiza Aslam (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7847-7250): Methodology (equal), Supervision (equal), Writing – reviewing and editing (equal).

Papiya Mazumdar (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7847-7250): Methodology (equal), Supervision (equal), Writing – reviewing and editing (equal).

Sadananda Reddy (https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6111-750X): Methodology (equal), Investigation (equal), Formal analysis (equal), Writing – reviewing and editing (equal).

Mariyam Sarfraz (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0817-4879): Formal analysis (equal), Writing – original draft (equal).

Nithyananda Srinivasa Murthy (https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9087-8180): Methodology (equal), Investigation (equal), Formal analysis (equal), Writing – reviewing and editing (equal).

Cath Jackson (https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3181-7091): Methodology (equal), Supervision (lead), Writing – original draft (lead).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the CAP members for their participation in this telephone consultation. Thanks also to Dr Noreen Mdege and Professor Pratima Murphy for their helpful feedback on an earlier draft of the manuscript.

Confidentiality and anonymity

All CAP members were assigned an ID number and their consultation data were stored using this ID number. Their name and contact details were stored on secure, password-protected computers at NIMHANS and IOP and not linked to any consultation data. All CAP members signed a consent form prior to joining the CAP.

Data-sharing statement

All data requests should be submitted to the corresponding author for consideration. Access to anonymised data may be granted following review.

Ethics statement

This research was conducted in accordance with the World Medical Association’s Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval was secured from: University of York, Health Sciences Research Governance Committee (Ref. HSRGC/2019/346/D, approved 5 July 2019); NIMHANS Ethics Committee, Behavioural Sciences Division (Ref. 2019-7975, approved 20 August 2019); National Bioethics Committee, Pakistan (Ref. 4-87/NBC-434-Amend/21/1508, approved 10 December 2019); and the Institutional Research Forum of Rawalpindi Medical University (Ref. R-48/RMU, approved 24 August 2019).

Information governance statement

The IMPACT collaboration is committed to handling all personal information in line with the UK Data Protection Act (2018) and the General Data Protection Regulation (EU GDPR) 2016/679. Under Data Protection legislation the NIMHANS and the IOP are the Data Processors; the Core (Management) Group of the IMPACT Collaboration is the Data Controller, and we process personal data in accordance with their instructions. You can find out more about how we handle personal data, including how to exercise your individual rights and the contact details for the IMPACT Collaboration’s Data Protection Officer here: https://www.impactsouthasia.com

Disclosure of interests

Full disclosure of interests: Completed ICMJE forms for all authors, including all related interests, are available in the toolkit on the NIHR Journals Library report publication page at https://doi.org/10.3310/MWRX6801.

Primary conflicts of interest: Baha Ul Haq, Faiza Aslam, Papiya Mazumdar, Sadananda Reddy, Mariyam Sarfraz and Nithyananda Srinivasa Murthy: None declared.

Cath Jackson was part of Grant 17/63/130 NIHR Global Health, Research Group: Improving Outcomes in Mental and Physical Multimorbidity and Developing Research Capacity (IMPACT) in South Asia at the University of York.

Department of Health and Social Care disclaimer

This publication presents independent research commissioned by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR). The views and opinions expressed by the interviewees in this publication are those of the interviewees and do not necessarily reflect those of the authors, those of the NHS, the NIHR, MRC, NIHR Coordinating Centre, the Global Health Research programme or the Department of Health and Social Care.

This article was published based on current knowledge at the time and date of publication. NIHR is committed to being inclusive and will continually monitor best practice and guidance in relation to terminology and language to ensure that we remain relevant to our stakeholders.

Funding

This article presents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Global Health Research programme as award number 17/63/130 using UK aid from the UK Government to support global health research. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the UK government. Research is published in the NIHR Global Health Research Journal. See the NIHR Funding and Awards website for further award information.

Study registration

This study is registered as ISRCTN34399445.

This article reports on one component of the research award Improving Outcomes in Mental and Physical Multimorbidity and Developing Research Capacity (IMPACT) in South Asia at the University of York. For more information about this research please view the award page (https://www.fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/17/63/130)

About this article

The contractual start date for this research was in April 2018. This article began editorial review in February 2023 and was accepted for publication in April 2024. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The Global Health Research editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ article and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Copyright

Copyright © 2024 Ul Haq et al. This work was produced by Ul Haq et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

List of abbreviations

- 4S

- Smoking cessation support for people with severe mental illness in South Asia

- CAP

- Community Advisory Panel

- HIC

- high-income countries

- IMPACT

- Improving Outcomes in Mental and Physical Multimorbidity and Developing Research Capacity in South Asia

- LMIC

- low- and middle-income countries

- NRT

- nicotine replacement therapy

- SMI

- severe mental illness

Notes

Supplementary material can be found on the NIHR Journals Library report page (https://doi.org/10.3310/MWRX6801).

Supplementary material has been provided by the authors to support the report and any files provided at submission will have been seen by peer reviewers, but not extensively reviewed. Any supplementary material provided at a later stage in the process may not have been peer reviewed.

References

- Walker ER, McGee RE, Druss BG. Mortality in mental disorders and global disease burden implications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 2015;72:334-41. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.2502.

- de Mooij LD, Kikkert M, Theunissen J, Beekman ATF, de Haan L, Duurkoop PWRA, et al. Dying too soon: excess mortality in severe mental illness. Front Psychiatry 2019;10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00855.

- Dregan A, McNeill A, Gaughran F, Jones PB, Bazley A, Cross S, et al. Potential gains in life expectancy from reducing amenable mortality among people diagnosed with serious mental illness in the United Kingdom. PLOS ONE 2020;15. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0230674.

- Szatkowski L, McNeill A. Diverging trends in smoking behaviors according to mental health status. Nicotine Tob Res 2015;17:356-60. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntu173.

- Gilbody S, Peckham E, Bailey D, Arundel C, Heron P, Crosland S, et al. Smoking cessation for people with severe mental illness (SCIMITAR+): a pragmatic randomised controlled trial. Lancet Psychiatry 2019;6:379-90. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30047-1.

- de Leon J, Diaz FJ. A meta-analysis of worldwide studies demonstrates an association between schizophrenia and tobacco smoking behaviors. Schizophr Res 2005;76:135-57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2005.02.010.

- World Health Organization Regional Office Europe . Tobacco Use and Mental Health n.d. www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0011/516593/fs-tobacco-use-and-mental-health-eng.pdf (accessed 12 August 2022).

- Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai and Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India . GATS 2 Global Adult Tobacco Survey Fact Sheet India 2016–17 n.d. https://tiss.edu/uploads/files/National_FactsheeIndia.pdf (accessed 12 August 2022).

- Saqib MAN, Rafique I, Qureshi H, Munir MA, Bashir R, Arif BW, et al. Burden of tobacco in Pakistan: findings from global adult tobacco survey 2014. Nicotine Tob Res 2018;20:1138-43. https://doi.org/10.1093/ntr/ntx179.

- Lancaster T, Stead LF. Individual behavioural counselling for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;3. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD001292.pub3.

- Stead LF, Carroll AJ, Lancaster T. Group behaviour therapy programmes for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;3. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD001007.pub3.

- Khanna P, Clifton AV, Banks D, Tosh GE. Smoking cessation advice for people with serious mental illness. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016;1. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD009704.pub2.

- McGinty EE, Baller J, Azrin ST, Juliano-Bult D, Daumit GL. Interventions to address medical conditions and health-risk behaviors among persons with serious mental illness: a comprehensive review. Schizophr Bull 2016;42:96-124. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbv101.

- Peckham E, Brabyn S, Cook L, Tew G, Gilbody S. Smoking cessation in severe mental ill health: what works? An updated systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry 2017;17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-017-1419-7.

- Roberts E, Eden Evins A, McNeill A, Robson D. Efficacy and tolerability of pharmacotherapy for smoking cessation in adults with serious mental illness: a systematic review and network meta‐analysis. Addiction 2016;111:599-612. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.13236.

- Boeckmann M, Nohavova I, Dogar O, Kralikova E, Pankova A, Zvolska K, et al. TB & Tobacco Project Consortium . Protocol for the mixed-methods process and context evaluation of the TB & Tobacco randomised controlled trial in Bangladesh and Pakistan: a hybrid effectiveness-implementation study. BMJ Open 2018;8. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019878.

- Mazumdar P, Zavala G, Aslam F, Muliyala KP, Chaturvedi SK, Kandasamy A, et al. IMPACT smoking cessation support for people with severe mental illness in South Asia (IMPACT 4S): a protocol for a randomised controlled feasibility trial of a combined behavioural and pharmacological support intervention. MedRxiv 2021. https://doi.org/10.1101/2021.11.03.21265856.

- Cresswell JW, Plano Clark VL. Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research. Thousand Oaks, US: Sage Publications; 2007.

- Elo S, Kyngas H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs 2008;62:107-15. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x.

- Talley RM, Brunette MF, Adler DA, Dixon LB, Berlant J, Erlich MD, et al. Telehealth and the community SMI population: reflections on the disrupter experience of COVID-19. J Nerv Ment Dis 2021;209:49-53. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0000000000001254.

- Kelly JT, Campbell KL, Gong E, Scuffham P. The internet of things: impact and implications for health care delivery. J Med Internet Res 2020;22. https://doi.org/10.2196/20135.

- Torous J, Jän Myrick K, Rauseo-Ricupero N, Firth J. Digital mental health and COVID-19: using technology today to accelerate the curve on access and quality tomorrow. JMIR Ment Health 2020;7. https://doi.org/10.2196/18848.

- Jayarajan D, Sivakumar T, Torous JB, Thirthalli J. Telerehabilitation in psychiatry. Indian J Psychol Med 2020;42:57S-62S. https://doi.org/10.1177/0253717620963202.

- Madigan S, Racine N, Cooke JE, Korczak DJ. COVID-19 and telemental health: benefits, challenges, and future directions. Can Psychol 2021;62:5-11. https://doi.org/10.1037/cap0000259.

- Schoebel V, Wayment C, Gaiser M, Page C, Buche J, Beck AJ. Telebehavioral health during the COVID-19 pandemic: a qualitative analysis of provider experiences and perspectives. Telemed J E Health 2021;27:947-54. https://doi.org/10.1089/tmj.2021.0121.

- NHS . IAPT Guide for Delivering Treatment Remotely During the Coronavirus Pandemic. 25 March 2020, Version 1 n.d. https://amhp.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/IAPT-Guidance-for-Covid.pdf (accessed 5 June 2024).

- Ojha R, Syed S. Challenges faced by mental health providers and patients during the coronavirus 2019 pandemic due to technological barriers. Internet Interv 2020;21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.invent.2020.100330.

- Wind TR, Rijkeboer M, Andersson G, Riper H. The COVID-19 pandemic: the ‘black swan’ for mental health care and a turning point for e-health. Internet Interv 2020;20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.invent.2020.100317.

- Leutwyler H, Hubbard E. Telephone based smoking cessation intervention for adults with serious mental illness during the COVID-19 pandemic. Tob Use Insights 2021;14:1179173X2110659-211065989. https://doi.org/10.1177/1179173X211065989.

- Junaid K, Ali H, Nazim R. The psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic on Pakistani population: managing challenges through mental health services. Ann King Edw Med Univ 2020;26:291-3. https://doi.org/10.15761/CCRR.1000482.

- Mumtaz M. COVID-19 and mental health challenges in Pakistan. Int J Soc Psychiatry 2021;67:303-4.

- Early Intervention Foundation . COVID-19 and Early Intervention: Evidence, Challenges and Risks Relating to Virtual and Digital Delivery 2020. www.eif.org.uk/report/covid-19-and-early-intervention-evidence-challenges-and-risks-relating-to-virtual-and-digital-delivery (accessed 30 August 2022).

- Knowles S, Planner C, Bradshaw T, Peckham E, Man MS, Gilbody S. Making the journey with me: a qualitative study of experiences of a bespoke mental health smoking cessation intervention for service users with serious mental illness. BMC Psychiatry 2016;16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-016-0901-y.

- Rüther T, Bobes J, De Hert M, Svensson TH, Mann K, Batra A, et al. European Psychiatric Association . EPA guidance on tobacco dependence and strategies for smoking cessation in people with mental illness. Eur Psychiatry 2014;29:65-82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpsy.2013.11.002.

- Carswell C, Brown J, Balogun A, Taylor J, Coventry P, Kitchen C, et al. Exploring determinants of self-management in adults with severe mental illness: a qualitative evidence synthesis. BJPsych Open 2021;7 Supplement S1. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2021.93.

- Lawes-Wickwar S, McBain H, Mulligan K. Application and effectiveness of telehealth to support severe mental illness management: systematic review. JMIR Ment Health 2018;5. https://doi.org/10.2196/mental.8816.

- ITU Publications . Global Connectivity Report 2022. www.itu.int/hub/publication/d-ind-global-01-2022/ (accessed 30 August 2022).

- GSMA . Mobile Gender Gap Report 2019. https://www.gsma.com/solutions-and-impact/connectivity-for-good/mobile-for-development/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/GSMA-The-Mobile-Gender-Gap-Report-2019.pdf (accessed 5 June 2024).