Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number NIHR130576. The contractual start date was in May 2021. The final report began editorial review in November 2022 and was accepted for publication in February 2023. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2023 Kinsey et al. This work was produced by Kinsey et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2023 Kinsey et al.

Chapter 1 Background

Pressure on hospitals and bed capacity

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, NHS hospitals were under pressure to maintain or improve their provision of care and ensure the cost-effective delivery of services. Between 2005/6 and 2015/16, there was a steady increase in the number and age of patients admitted to hospitals in England, with the number of combined elective and emergency admissions of 60–65-year-olds increasing by 57%. 1 The Office for National Statistics predicts that in England the proportion of people aged 65 years and over will increase further from 18.2% to 20.7% of the total population between mid-2018 and mid-2028. 2 In addition to the pressures of an ageing population, the COVID-19 pandemic has also had a considerable impact on waiting lists for elective procedures. The number of people waiting for elective treatment in the UK has increased from 4.24 million in March 2020 to 6.84 million in July 2022,3 and the number of patients facing delays in leaving hospital increased by 30% between December 2021 and August 2022, further contributing to increased waiting lists. 4

Compared to younger patients, older adults admitted to hospital for elective procedures face disrupted discharge trajectories out of hospital due to transport difficulties,5 are in poor physical health or living with frailty,6 are socially isolated7 or have living arrangements requiring additional support following discharge. 8 Older adult inpatients are also at increased risk of peri- or postoperative complications (e.g. delirium, falls, hospital-acquired infection, pressure sores and cognitive decline). 9–16 Such complications can impede patient recovery, increase length of stay (LOS) and influence discharge destination. 16

While hospitals are under increased pressure to speed recovery and manage capacity following elective procedures, particularly in the face of overwhelming urgent and emergency admissions, care is needed that this is not detrimental for older patients with more complex needs.

Existing literature

A recent systematic review examining the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of multicomponent interventions to enhance recovery and/or reduce LOS in older adults undergoing elective surgery found that across 73 studies containing data for 26,365 patients, such interventions were associated with either improved clinical outcomes (e.g. LOS, readmissions, complications, mortality, morbidity, clinical markers of recovery), or performed as well as standard care. 17 These findings confirmed the significant progress made in reducing hospital LOS for older adults after planned surgery in the last 20 years. Improvements in care inevitably now lead to diminishing returns on LOS, with patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) and patient-reported experience measures (PREMs) becoming increasingly valuable measures of service quality and thus improvement. 18,19

Recent research indicates that the transition home following discharge can be challenging and potentially unsafe for older adults, who may rely heavily on informal caregivers, emphasising the importance of examining and understanding patient outcomes and experience following this transition. 20 While there has been a drive to achieve earlier discharge from hospital, the subsequent impact on patient outcomes, such as quality of life, participation in meaningful occupations and engagement with health and social care services, is largely unknown. Given the ongoing crisis in hospital capacity in the UK, there is an urgent need to identify, appraise and synthesise the findings from studies that have considered the influence of multicomponent interventions to enhance recovery on longer-term patient recovery, PROMS and PREMS.

Our previous recent systematic review identified 208 studies evaluating the effectiveness of multi-component interventions aiming to enhance the recovery of older adult inpatients receiving planned surgery. 17 The review highlighted positive findings at the hospital level, but a striking lack of PROMS, PREMS or mid- to long-term outcomes. A narrative review of important markers of recovery following the use of enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) protocols further emphasised the need for studies to report such outcomes as part of their intervention evaluations. 21

Scoping searches were performed using MEDLINE in September 2019, looking for recent relevant primary qualitative evidence and systematic reviews regarding experiences of interventions to reduce LOS. 22 No systematic reviews were identified examining the experiences of patients, their carers and staff, across different types of multicomponent intervention aiming to enhance the recovery of older adults following any planned procedure, with existing reviews focusing on a narrow range of procedures, interventions and views. Jones et al. systematically reviewed evidence examining both quantitative and qualitative literature on PROMs and experiences of enhanced recovery but specific to orthopaedic surgery,23 while Sibbern et al. explored qualitative evidence about the views of adults receiving ERAS protocols specifically. 24 The latter review did not focus on older adults and excluded the views of carers, relatives and healthcare professionals. 24 Searches of the PROSPERO database for systematic reviews in February 2020 identified one systematic review examining staff experiences of implementing ERAS interventions. 25 However, this review focused on only one type of intervention and, because of this narrower focus, does not capture primary studies which we know through our scoping would be relevant for inclusion in our proposed review.

In summary, there is a dearth of systematic review evidence to inform decisions about the influence of multicomponent interventions to enhance recovery after surgery on mid- to long-term patient-reported outcomes, and to understand patient experiences of such interventions.

Why is this research important?

There is a strong evidence base supporting the effectiveness of multicomponent interventions in reducing LOS without detriment to hospital-recorded data and short-term outcomes. 17 However, it is increasingly important to look beyond what happens in the hospital. The NHS Long-Term Plan sets out a strategy that combines the desire to reduce time spent in hospital with better community care systems. 26 There is also planned investment to reduce waiting times for elective surgery, meaning that the turnover of patients undergoing such procedures will increase. Simultaneously, interventions such as ERP will become more widely implemented in hospitals, effectively minimising LOS. The utilisation of early community-led discharge pathways is also on the rise. This includes discharge to assess (or D2A) and HomeFirst initiatives, which were not included in our previous review. There will therefore be an increasing volume of older adults discharged back into the community or long-term care facilities a day or two after major surgery. After hospital discharge, older adults may require additional support from their family, carers and/or community services, including nurses, general practitioners (GPs), occupational therapists (OTs) and social workers. It is important to understand whether these demands are increased with enhanced recovery approaches or earlier discharge from hospital, particularly given the expected increase in patients meeting this profile in the coming years.

To understand the impact of multicomponent interventions intended to improve recovery of older adults, it is vital to seek the views of the patients themselves, their family/carers and professionals delivering the interventions, to identify aspects of care which can influence the quality and success of transition from hospital. This is best achieved through a combination of quantitative (e.g. PREMS, PROMS) and qualitative data.

Overall aims and objectives

To establish what is known about the impact of multicomponent interventions to enhance recovery after surgery on mid- to long-term patient outcomes and understand patient experiences of such interventions, we conducted a mixed-methods evidence synthesis which aims to:

-

understand the effect of multicomponent interventions which aim to enhance recovery and/or reduce length of stay on mid- to-long term patient-reported outcomes and health and social care utilisation

-

understand how different aspects of the content and delivery of interventions may influence patient outcomes.

This linked-evidence synthesis addressed the following research questions:

-

What is the impact of multicomponent interventions to enhance recovery and/or reduce LOS for older adults admitted for planned procedures on PROMs and service utilisation?

-

What are the experiences of patients receiving multicomponent interventions to enhance recovery and/or reduce LOS, their family and carers and staff involved with delivering care within these interventions?

-

Which aspects of multicomponent interventions to enhance recovery and/or reduce LOS are associated with better outcomes for older adults admitted to hospital for planned procedures?

Chapter 2 Impact of multicomponent interventions to enhance recovery and/or reduce hospital LOS for older adults admitted for planned procedures on patient-reported outcome measures and service utilisation

This chapter details the methods and findings from the systematic review of quantitative research, intended to answer research question 1: What is the impact of multicomponent interventions to enhance recovery and/or reduce LOS for older adults admitted for planned procedures on patient-reported outcome measures and service utilisation? The methods used to identify, appraise and synthesise evidence followed best-practice guidance. 27

Methods

Identification of evidence

Search strategy

For the systematic review of quantitative studies, the searches for our previous review were re-run with adaptations. 17 Search terms included terms for older people or interventions commonly undergone by older people, combined using the AND Boolean operator with terms for multicomponent interventions or terms that describe reducing length of stay, for example, ‘length’ adjacent to ‘stay’ adjacent to ‘reducing’. The full search strategy for MEDLINE ALL is included in Appendix 1. We adapted the search to include search terms for multicomponent interventions which were not relevant for our previous review, including supported discharge, and home or community rehabilitation. We also applied an adapted version of the study type filter used for our previous review, with an expanded set of search terms for non-randomised trials and controlled before-and-after (CBA) studies. 17 These terms were derived from the Cochrane EPOC study design filter (Paul Miller, EPOC, 23 August 2017, personal communication) and from inspecting the titles and abstracts of non-randomised and BA studies that were identified via supplementary searches for our previous review but which the bibliographic database searches failed to retrieve, thus ensuring that the bibliographic database searches had improved sensitivity. 17 In addition, we added search terms for quality-of-life studies.

The adapted search was developed by SB in conjunction with the review team and stakeholders in MEDLINE (via Ovid) and adapted for use in other databases. The full set of bibliographic databases searched included: MEDLINE ALL, Embase and the Health Management Information Consortium (HMIC) (all via Ovid), CENTRAL (via the Cochrane Library), and Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) and Allied and Complementary Medicine Database (AMED) (both via EBSCO). Searches were run in May 2021 and updated in April 2022. For the update searches, to improve the efficiency of the searching and screening process we used a Search Summary Table to identify the minimum set of bibliographic databases required to retrieve all included studies identified by the initial set of searches, and limited the search to these databases. 28 Thus, we ran the update searches in MEDLINE (via Ovid) and CENTRAL only.

Search results for both initial and update searches were exported to EndNote 20 (Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, PA, USA) and de-duplicated using manual checking and the EndNote de-duplication tool. To expedite the study selection process, the 218 articles included in our previous review and 282 articles we previously excluded due to population, country or language (and thus failing to meet inclusion for this review) were removed from the search results prior to screening.

We checked reference lists of all included studies and carried out forward citation searching of included studies from the initial search using the Science Citation Index (Web of Science, Clarivate Analytics) and Scopus (Elsevier) (DC). No citation searches were carried out on included studies identified by the updated searches. The results of forward citation searches were exported to EndNote 20, and reference-list checking was conducted using Microsoft Excel spreadsheets to document potentially useful studies thus identified.

Inclusion criteria

We sought studies of multicomponent interventions to improve and/or accelerate the recovery of older adults undergoing elective surgical procedures requiring an overnight stay in hospital. Additionally, studies had to assess at least one PROM relating to patient recovery. Specific inclusion/exclusion criteria were as follows.

Population

Studies were included if patients:

-

had a mean or median age of ≥ 60 years, as in our previous review, and based on the cut-off point agreed by the United Nations29

-

were undergoing planned hospital admission for surgical procedures, for example:

-

hip/knee replacement

-

cardiac surgery

-

colorectal surgery

-

-

were admitted to hospital for an overnight stay.

Studies were excluded if patients:

-

were undergoing an unplanned (i.e. non-elective or emergency) admission, as a result of an emergency or acute incident, for example following:

-

hip fracture

-

stroke

-

heart attack

-

acute injury

-

-

were receiving hospital treatment that did not require an overnight stay (e.g. day surgery)

-

had been admitted to psychiatric hospitals

-

had been admitted to hospital for a medical investigation that resulted in an unplanned inpatient stay.

Intervention

The intervention was any multicomponent hospital-based intervention or strategy for patients receiving planned care as an inpatient, which either explicitly aimed to reduce LOS or aimed to improve recovery.

Studies were included if:

-

the intervention had multiple components

-

the intervention aimed to enhance recovery such that patients were able to be discharged from hospital sooner

-

the intervention influenced the hospital stay, even if it was not strictly hospital-led.

Examples of potentially includable interventions were:

-

Enhanced recovery after surgery protocol, as described by the ERAS Society,30 which typically consist of elements delivered prior to, during and immediately after surgery. Depending on the type of surgery, this may include components such as: carbohydrate loading and no mechanical bowel preparation before surgery; goal-directed fluid management, catheter and drain protocols, modified anaesthesia and warming protocol during surgery; early mobilisation and early oral nutrition following surgery.

-

‘Fast-track’ recovery protocols. These usually feature elements seen in ERAS protocols, but are broader in nature as ‘fast track’ can have a variety of meanings.

-

The use of a comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) to inform a care pathway. This involves a multi-faceted and comprehensive assessment prior to surgery, and should lead to an adapted surgical pathway which involves measures to account for any identified vulnerability.

-

Prehabilitation programme consisting of a variety of exercises designed to prepare the patient physically and/or mentally for surgery. This might involve strength/fitness programmes or healthy lifestyle choices such as quitting smoking.

-

Early supported discharge interventions aim to put post-discharge measures in place to ease the transition from hospital to home and thus facilitate early discharge. Measures may include an assessment of the home environment and steps to make adaptations to negate mobility issues, home visits, provision of a healthcare contact, or education about how to change wound dressings.

Studies were excluded if:

-

the intervention focus was surgical technique

-

the intervention did not aim to enhance recovery from surgery

-

the intervention was not hospital-led or did not influence the hospital stay (e.g. a community care programme or an intervention based in a nursing home)

-

the intervention had only a single component, that is, it featured the administration of only a single dose or bout of an intervention, or it was delivered at a single time point and modality.

Examples of excludable interventions were:

-

early mobilisation in isolation

-

comprehensive geriatric assessment to identify odds of adverse events, without informing a care plan

-

minimally invasive surgery

-

an enhanced anaesthesia protocol

-

goal-directed fluid monitoring

-

home-based rehabilitation that did not influence duration of hospital stay.

Comparator(s)

The comparator was any type of control group or comparator, for example ‘treatment as usual’, ‘usual hospital care’, ‘pre-pathway implementation’ or ‘usual best clinical practice’.

Outcomes

-

Studies need to include any metric of LOS, and any PROM, PREM or service utilisation measure.

-

Examples of PROMs/PREMs of interest include:

-

patient satisfaction survey

-

patient-reported physical assessments

-

quality of life measure

-

self-reported pain.

-

-

Examples of service utilisation measures include:

-

follow-up appointments

-

use of community services to support recovery/rehabilitation

-

home visits by nursing staff.

-

Other key outcomes that were of interest, but did not influence a study’s eligibility for inclusion, were:

-

readmission rates

-

complications

-

mortality.

Study design

Any of the following comparative study designs were included:

-

randomised controlled trials

-

non-randomised controlled clinical trials

-

controlled before-and-after studies

-

interrupted time series (ITS)

-

uncontrolled before-and-after (UBA) studies.

These study designs were chosen as the typical method of evaluating interventions in hospital settings. Patients are usually allocated to intervention and control groups prospectively, or the impact of interventions is judged by looking at outcomes before and since implementation.

Geographical context

Studies were included from any high-income country as defined by the World Bank list of economies. 31

Date of publication

The search was restricted to studies published since 2000. This date was selected in consultation with stakeholders in order to capture the most relevant types of intervention.

Study selection

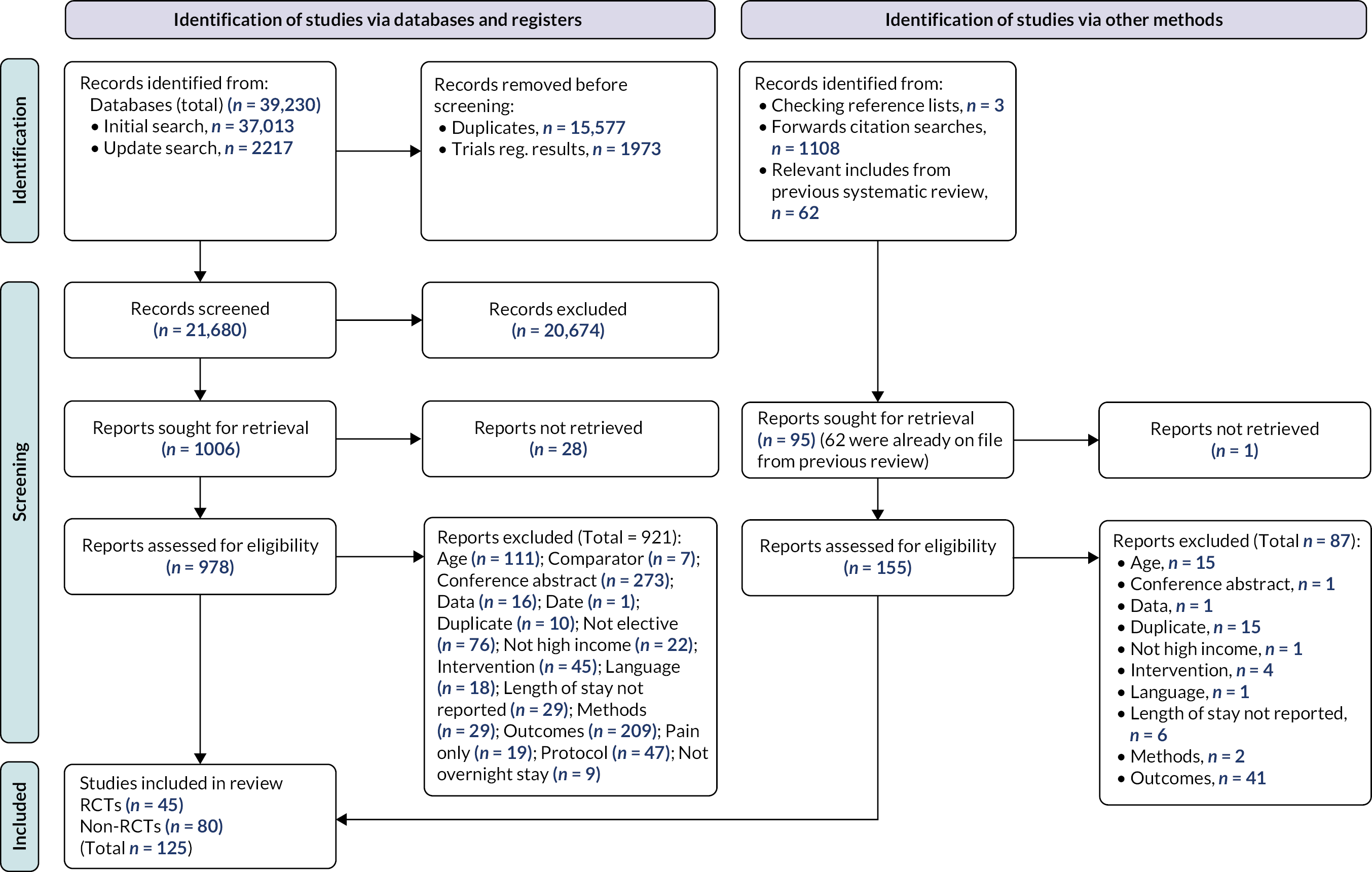

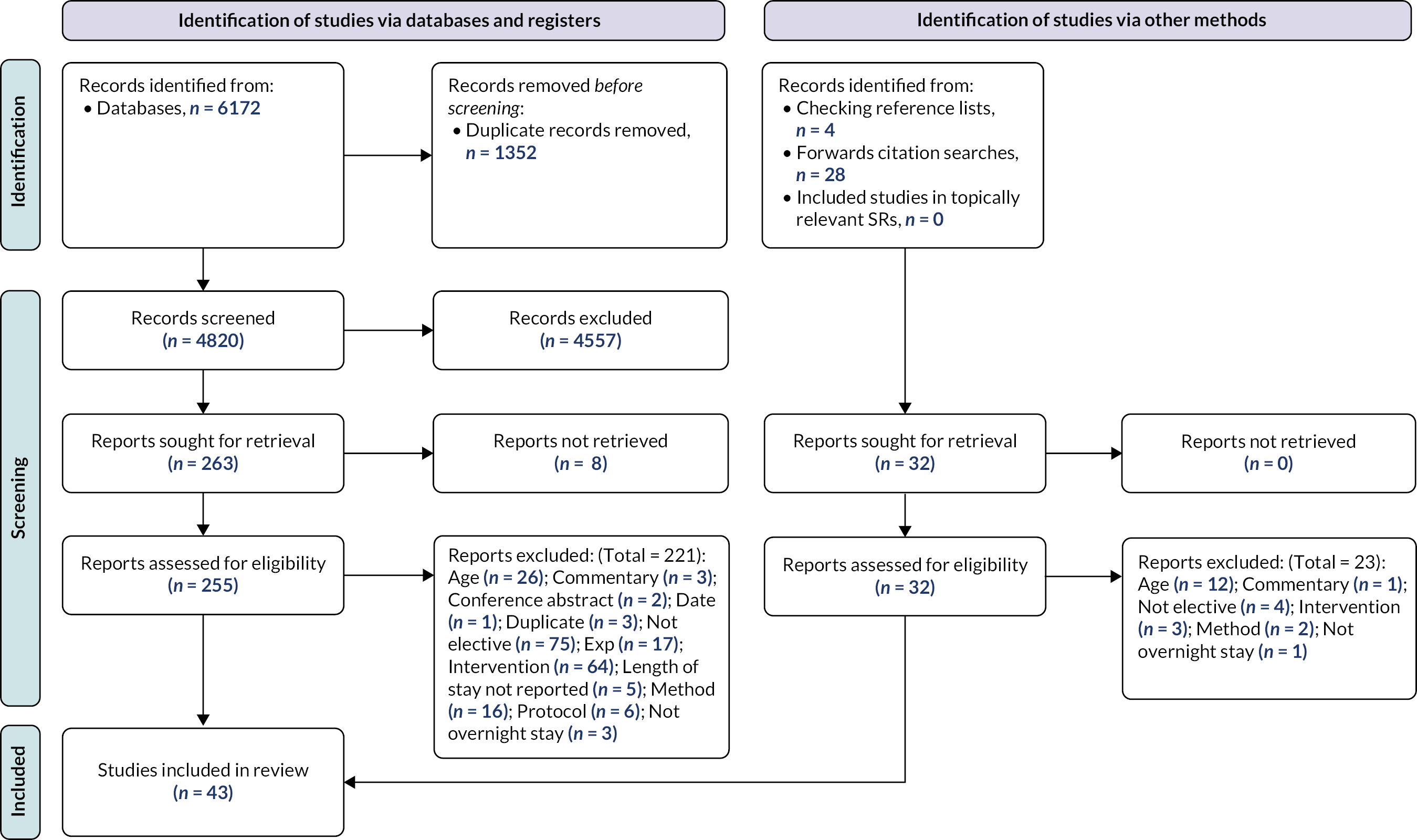

The inclusion and exclusion criteria were piloted on a sample of 100 records identified by the database searches by six reviewers (SF, DKi, DC, MN, LS, SB) independently. Following discussion, the criteria were refined and this process was repeated. After final refinement, the inclusion criteria, as detailed above, were applied to the title and abstract of each identified citation independently by two reviewers (SF, DKi, DC, MN, LS) with disagreements resolved through discussion. The full text of each potentially relevant paper was then obtained and assessed independently for inclusion by two reviewers (SF, DKi, DC, MN, LS) using the same approach. When necessary, the opinion of a third reviewer was sought. EndNote 20 software was used to support study selection. A Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta Analyses (PRISMA)-style flow chart was produced, detailing the study selection process.

In line with our approach in our previous work,17 upon identifying a potentially unmanageable number of studies, we opted to prioritise randomised controlled trials (RCTs) from any high-income country and UK-based non-RCTs. Studies which did not fall into this category (non-RCTs from high-income countries other than the UK) were subject to minimal data extraction (study details, design and location; sample size, age and reason for admission; intervention type and key features; comparator type; setting; stages of care affected by the intervention, outcomes of interest), tabulated and described separately. The prioritised studies were subject to full data extraction, quality appraisal and synthesis.

Data extraction

Through piloting and refinement, we developed a data-extraction template in Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) to be used for all prioritised studies. Data extraction was performed by one reviewer and checked by another (SF, MN, DC). The following information was extracted from each prioritised study:

-

study details (author, date, title, study design, country)

-

sample details (data collection period, number invited to participate, number commencing study, dropouts and details, data lost to follow-up, adverse events, age, sex, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, sampling method, place admitted to/from, discharge destination, inclusion criteria, reason for admission, coexisting conditions, ongoing treatment)

-

intervention details: name of intervention, category of intervention, aims, full description from paper, components which differed from the comparator condition, who delivered, training provided, who received, setting, target discharge day, discharge criteria, other treatments received during inpatient stay, adaptations made in response to patients’ needs, any modifications made during the study, whether fidelity or adherence were assessed

-

control details: as for intervention details

-

outcomes: for all relevant outcomes, describe the data collection method, construct being assessed, specific scores reported, the rater, whether blinded, any description of psychometric properties

-

outcome data: for all relevant outcomes, at post-intervention and longest follow-up, report the number completing the measure (n), the mean/median, standard deviation (SD)/range/interquartile range/standard error, assessment time. Repeat for intervention and control groups.

Quality appraisal

Quality appraisal was conducted for prioritised studies during the data-extraction phase, by one reviewer and checked by a second (SF, DC, MN). The Effective Public Health Practice Project (EPHPP) Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies was used, which is suitable for randomised and non-randomised studies. 32 We added an additional item, ‘Is it clear how LOS/PROM/PREM is defined/calculated?’, which did not affect the overall rating of the paper. After rating sections A–H a global rating was allocated based on sections A–F (selection bias, study design, confounders, blinding, data collection methods, withdrawals and dropouts) as follows:

-

strong (no weak ratings)

-

moderate (one weak rating)

-

weak (two or more weak ratings).

Quality appraisal was used to inform the interpretation of results, and not to inform inclusion in either the review or aspects of the synthesis.

Synthesis

We planned to perform three stages of synthesis for prioritised studies: first, a mix of meta-analyses and narrative synthesis to summarise the findings of all included effectiveness studies, second, a network meta-analysis and third a qualitative comparative analysis (QCA). As part of the process for assessing the feasibility of network meta-analyses, we considered evidence networks by outcome and type of surgery. All evidence networks included too few studies to generate meaningful comparisons, especially given the risk of imbalance of effect modifiers across sparse networks that could not be addressed through meta-regression. Evidence of the feasibility assessment is provided in Appendix 2, Tables 14 and 15. Therefore, this section describes the conduct of meta-analysis and narrative synthesis. The QCA is described in its entirety (methods, results and interpretation) in Chapter 4.

All studies were initially grouped by procedure and intervention category, as described previously. 17 Categories were informed by discussion with clinical stakeholders (JM, CL, AH). Briefly, interventions fell into the following categories:

-

enhanced recovery protocol – a broad category capturing interventions with components at multiple stages of the pathway

-

Prehab – focused on preparing the patient for surgery

-

Rehab – focused on postoperative exercise for recovery, whether in hospital or at home

-

discharge planning – an intervention focusing specifically on planning and supporting discharge from hospital (usually early discharge)

-

preoperative assessment with care plan (PACP) – an assessment prior to hospital admission, with a subsequent care plan for the patient.

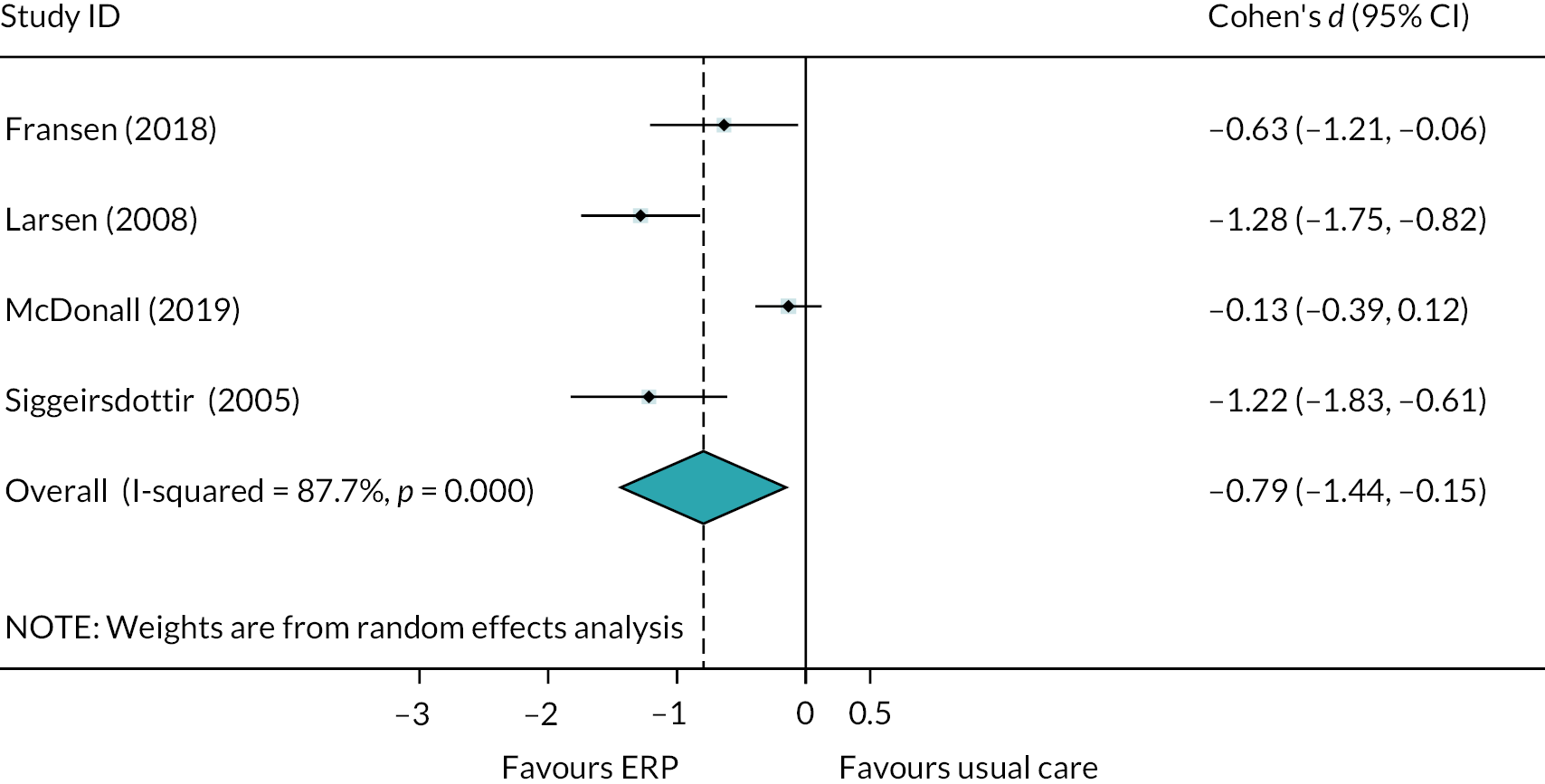

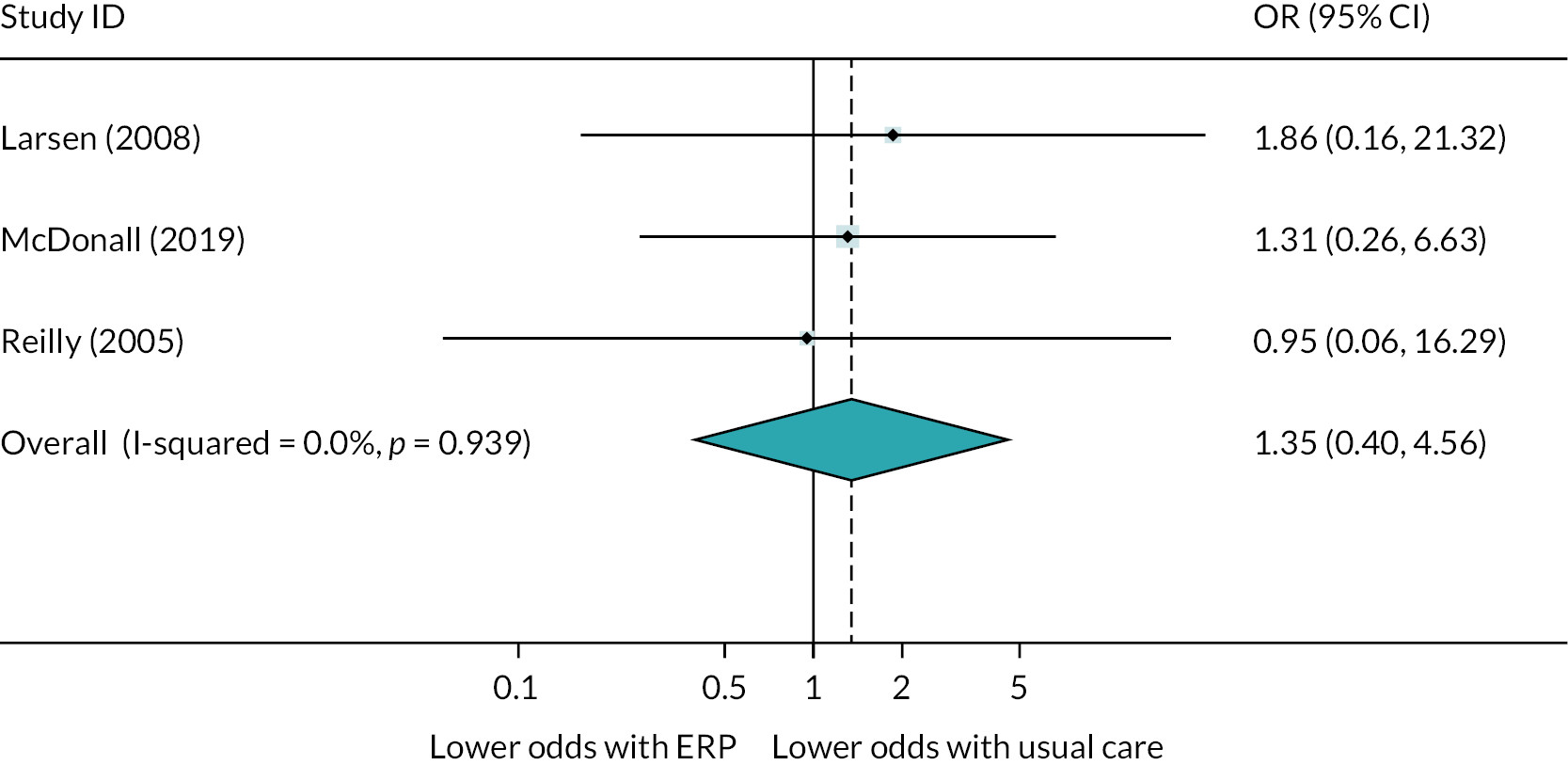

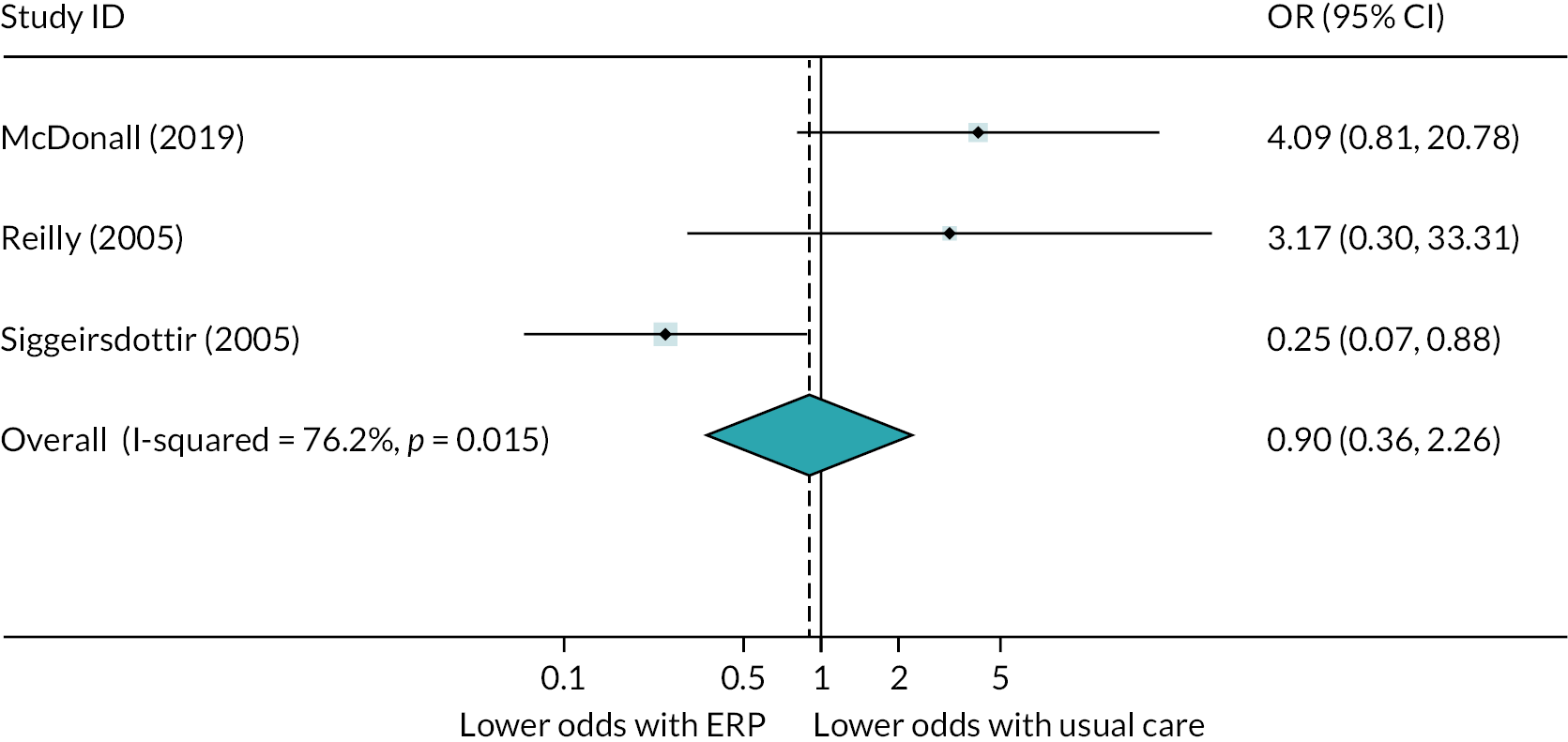

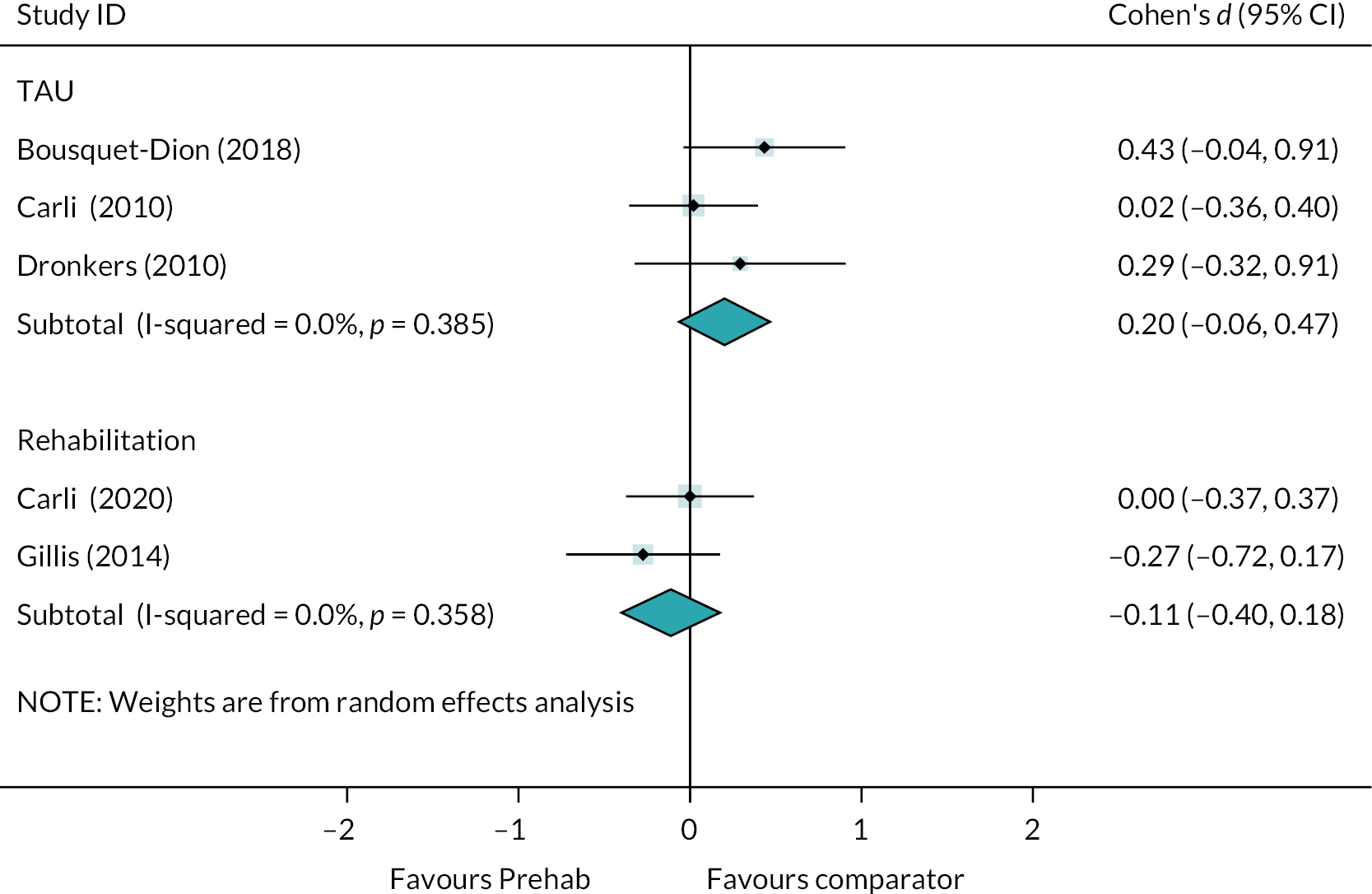

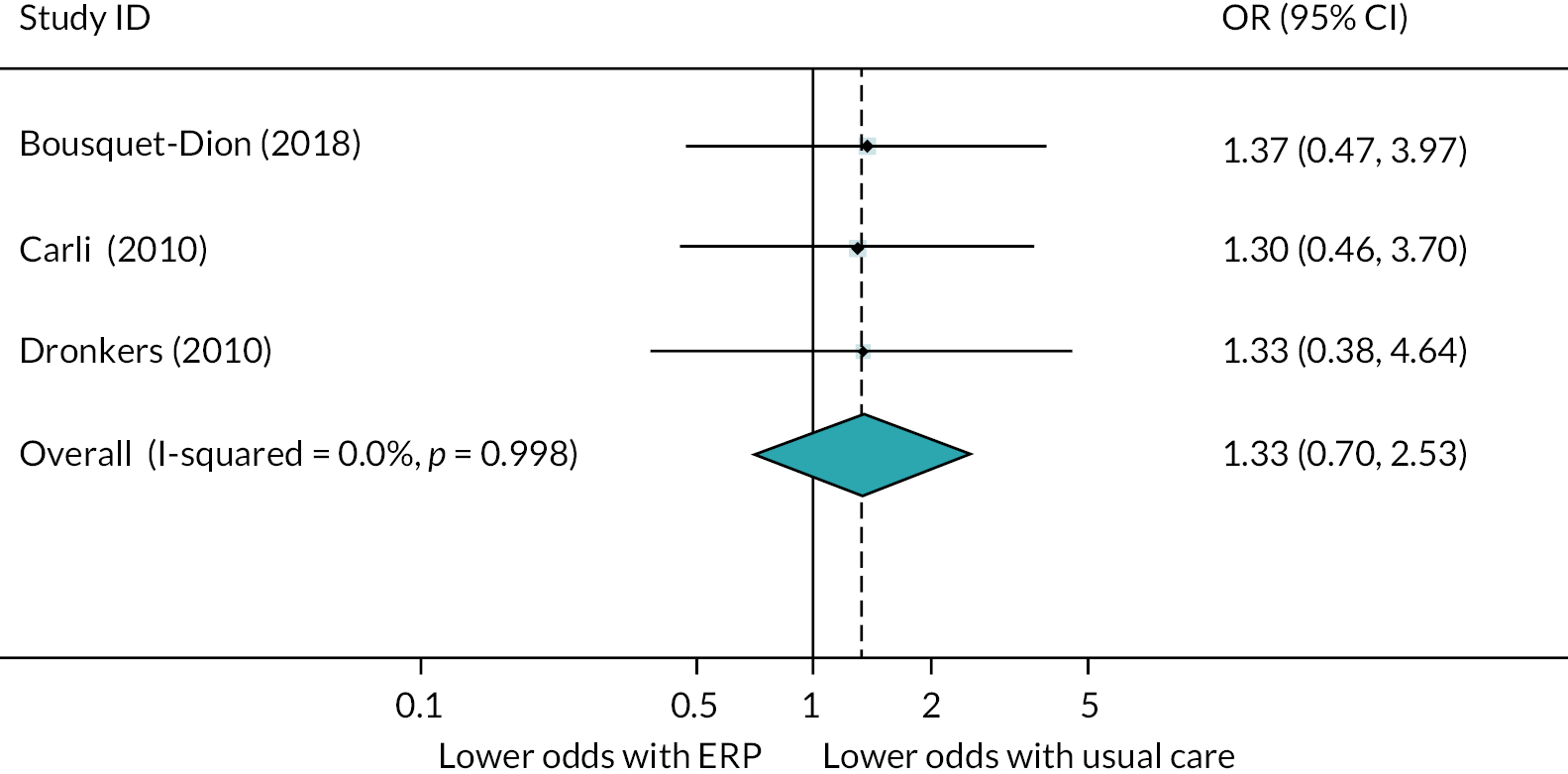

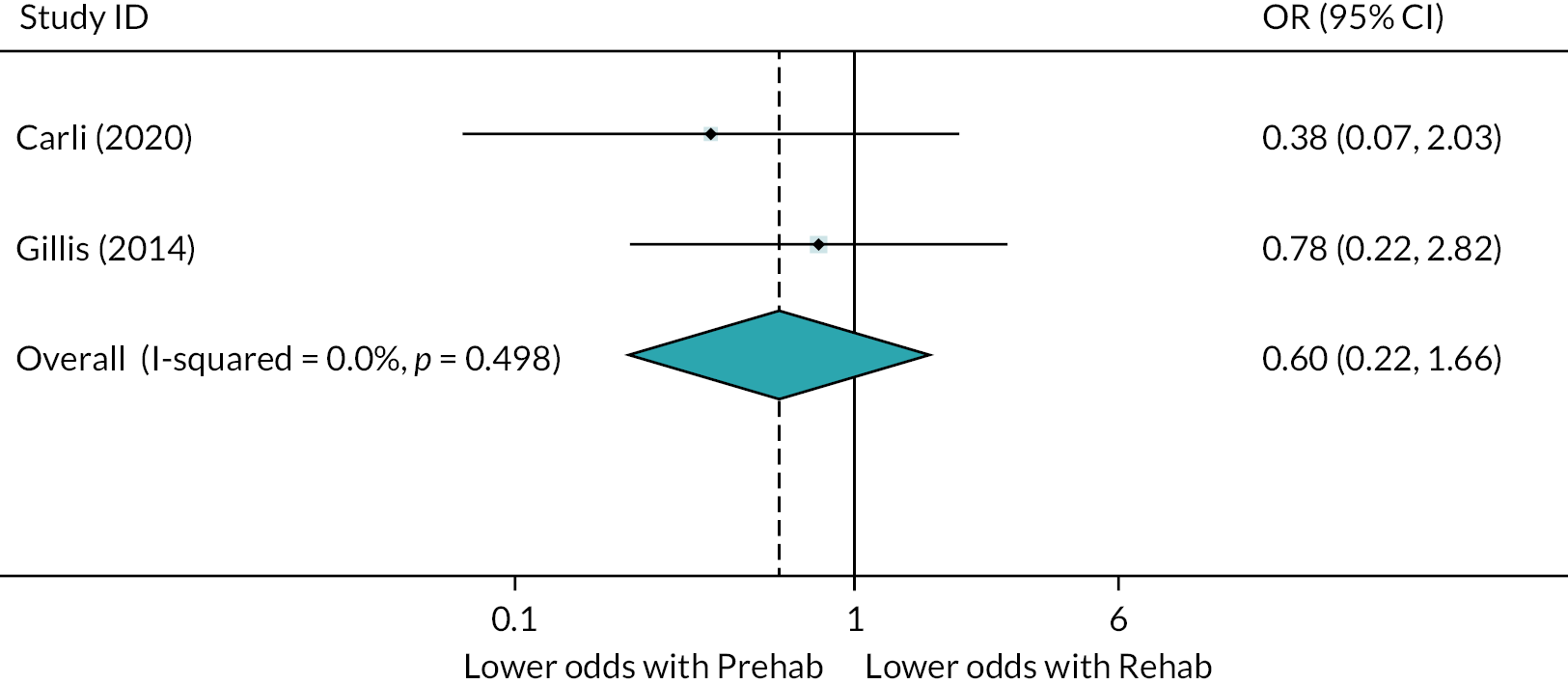

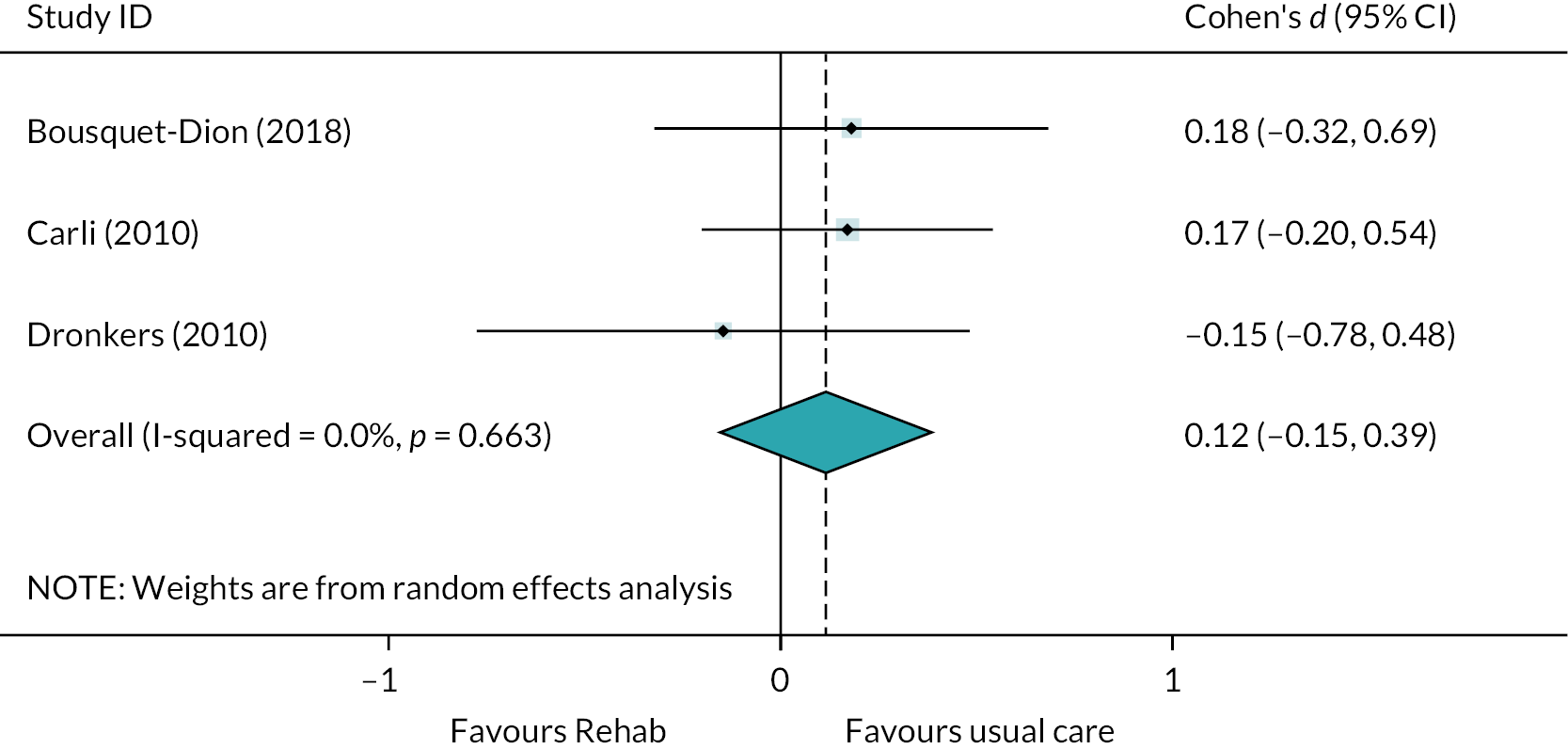

Procedure categories were defined based on surgical specialty, in consultation with clinical stakeholders (JM, CL, AH), as follows: colorectal, lower-limb arthroplasty (LLA), cardiac, pelvic, upper abdominal, abdominal, removal of tumours at various sites. Outcomes were then categorised as follows: LOS, readmissions, complications, mortality, quality of life, mental health, physical function, physical activity, patient satisfaction, pain, fatigue, social function, service utilisation. After categorisation, effectiveness findings were tabulated and summarised.

Data processing

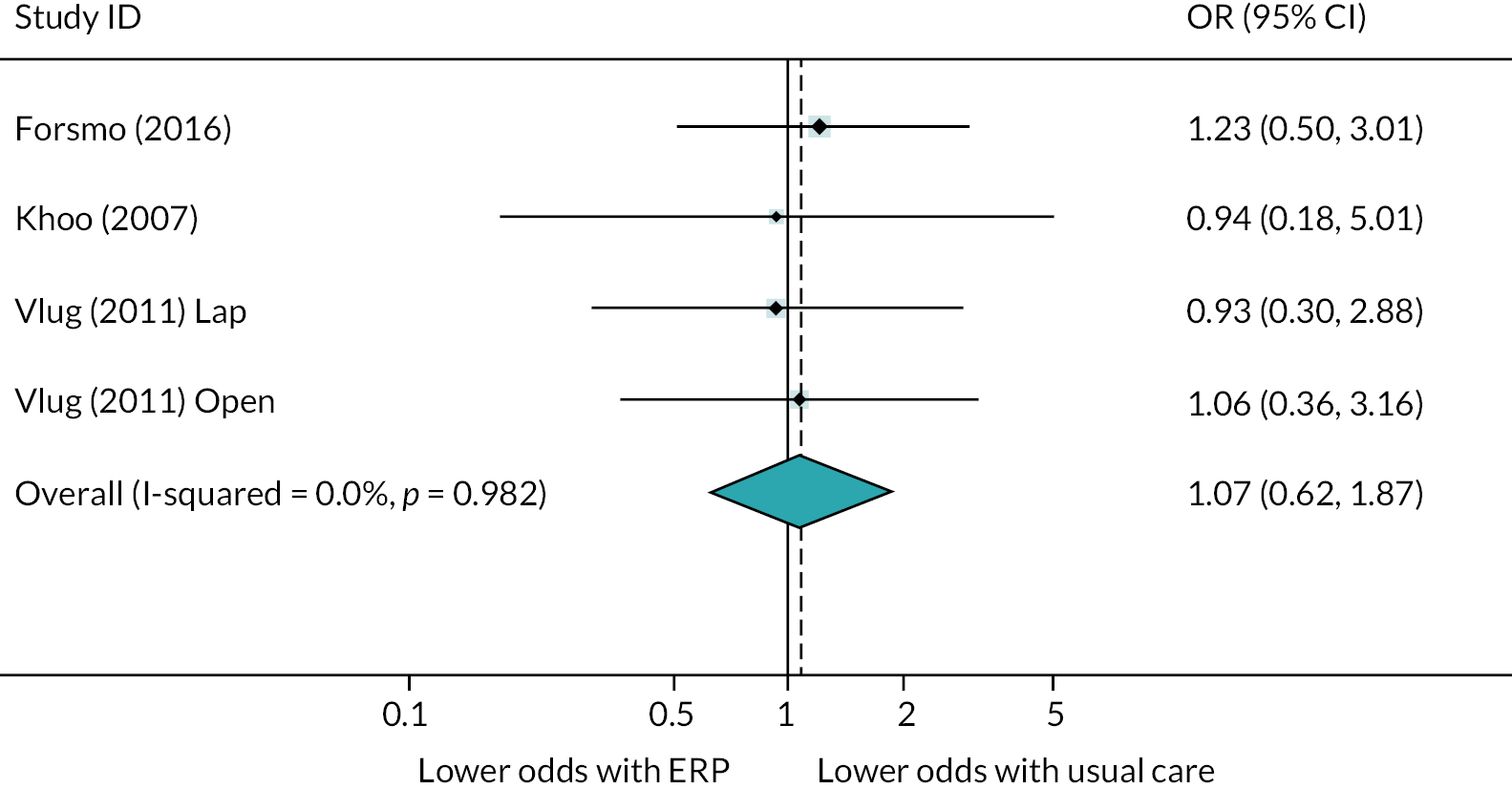

Between-group differences were evaluated at post-intervention and longest follow-up. For dichotomous outcomes (e.g. readmissions, complications) odds ratios (ORs) were calculated in Microsoft Excel using standard equations described in section 9.2.2 of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, version 6.3. 27 In addition, the statistical significance of the OR was assessed by calculating a p-value from the z-score for the difference and ascertaining 95% confidence intervals (CIs). 33

For continuous outcomes (e.g. scores on PROMs) Cohen’s d was calculated using the metan command in Stata (version 14.2, StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA). Effect sizes were interpreted in line with Cohen’s guidance (i.e. where d = 0.2 to 0.49, class as ‘small’; where d = 0.5 to 0.79, class as ‘medium’; and where d = 0.8 or above, class as ‘large’). 34 In addition, 95% CIs for the effect were calculated using the metan command in Stata. The p-value for the difference was obtained using the ttesti command in Stata, using data from the two-tailed analysis.

Where mean and standard deviation (SD) for an outcome were not provided, we used standard approaches to impute the required values27 (Cochrane ref section 7.7.3). Our approach to imputation is described elsewhere. 17 We did not impute data where studies only provided median and range for an outcome, due to high risk of skewness in the data.

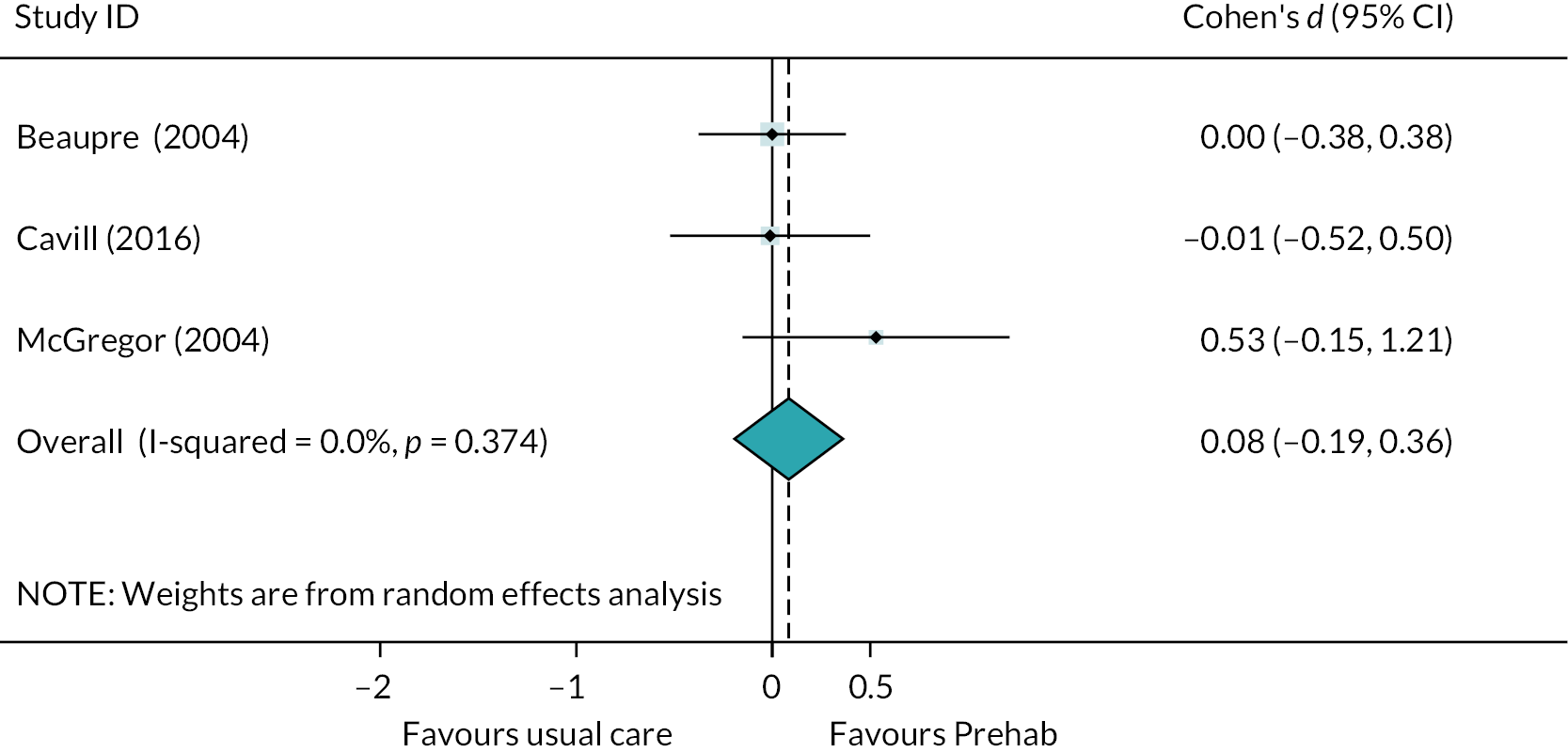

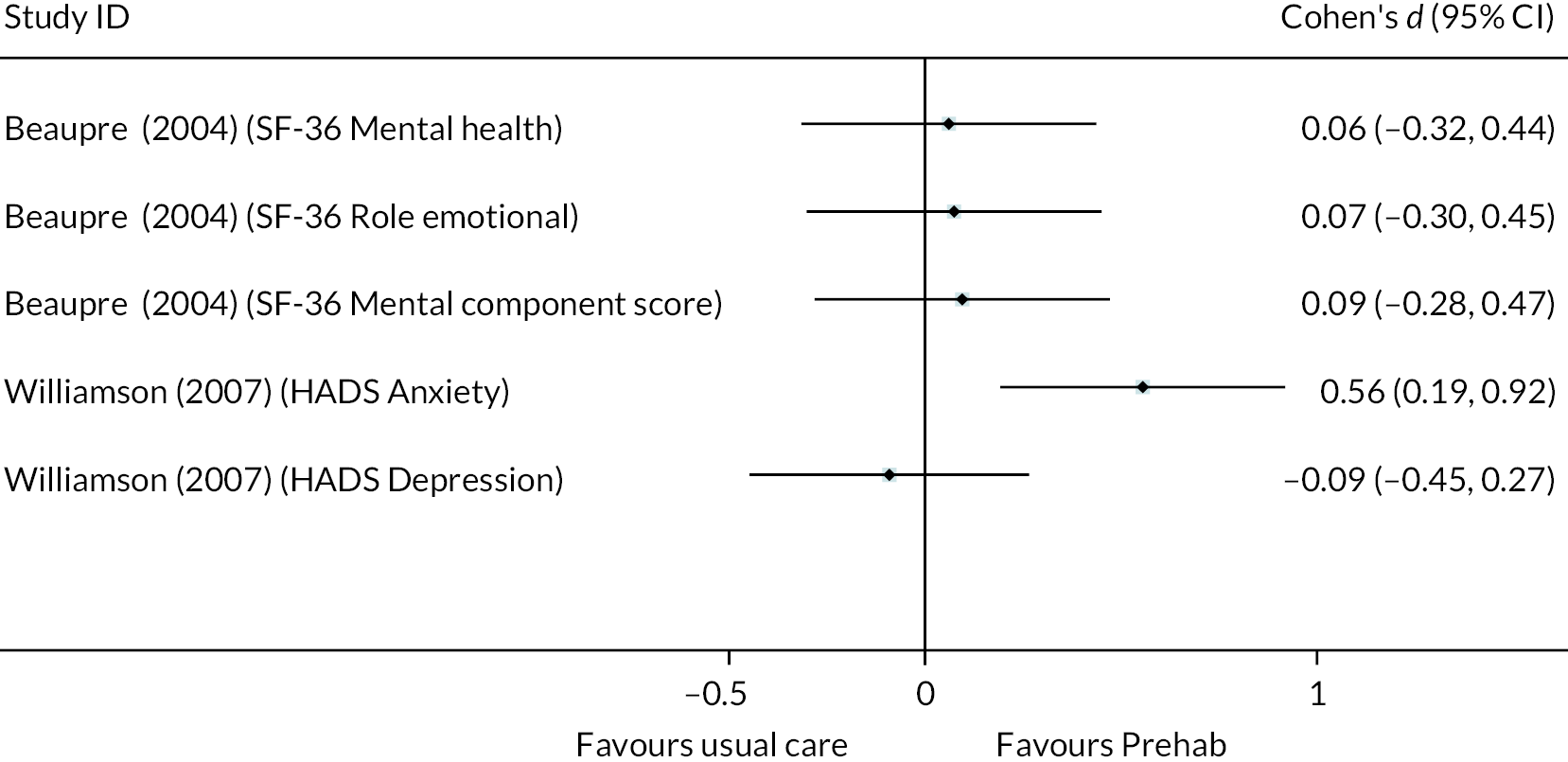

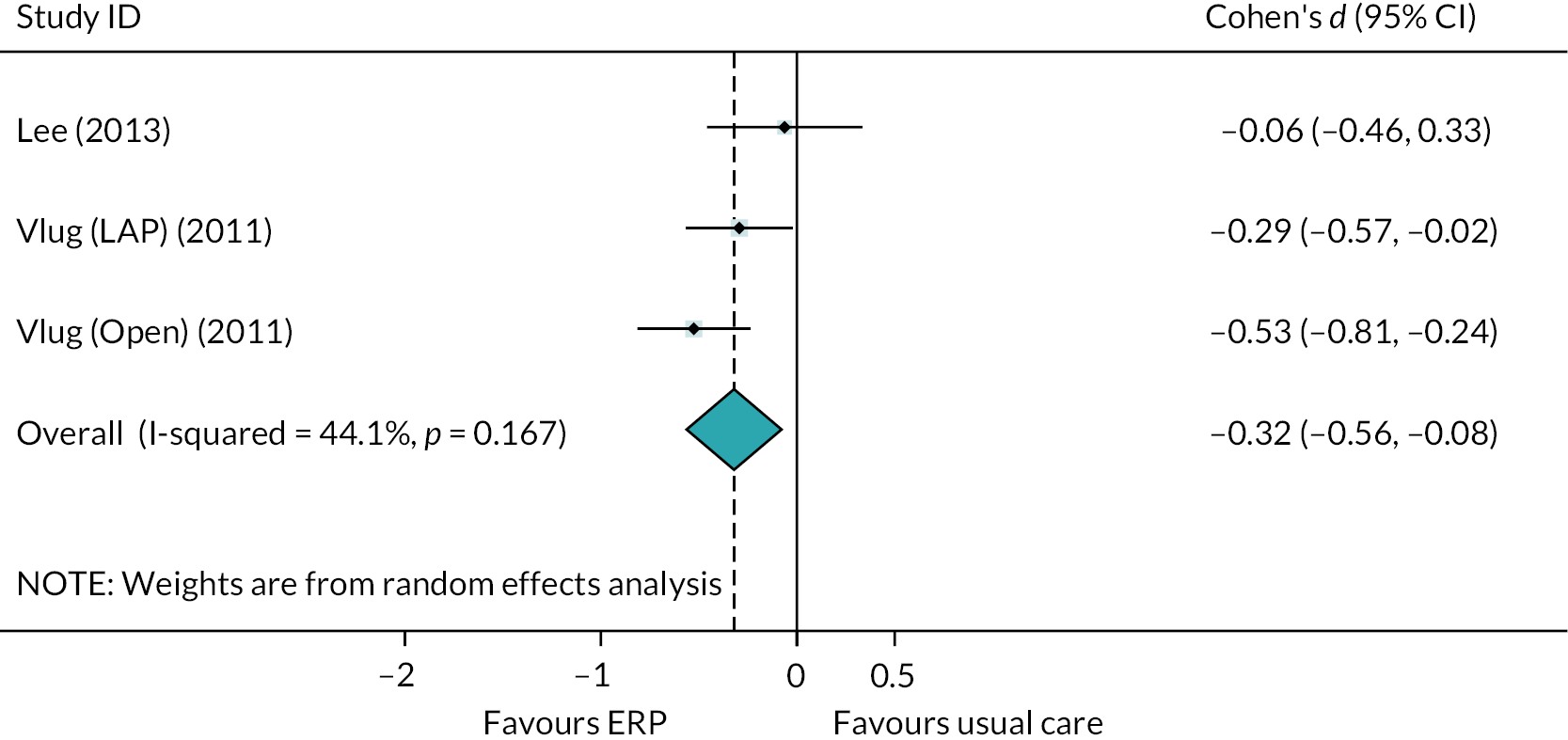

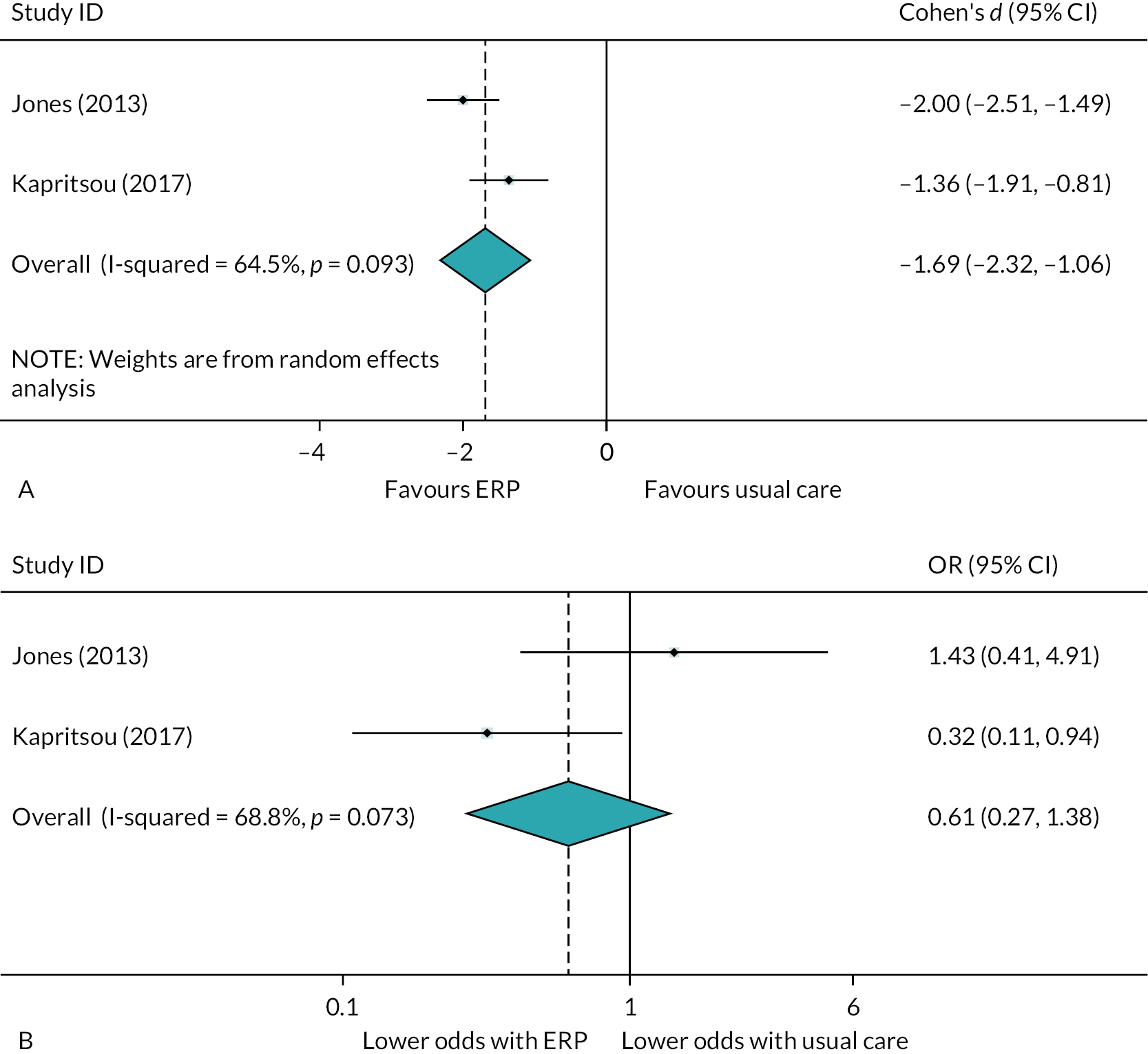

Where similar procedure, intervention, comparator and outcome categories were present for two or more RCTs, random-effects meta-analysis was conducted. Forest plots were produced as part of the metan command in Stata. Pooled effects with 95% CIs and p-values were reported. Statistical heterogeneity was assessed using the I2-statistic, with greater a percentage indicating a greater proportion of total variance due to between-study variance as opposed to sampling error. 35 Meta-analysis of ORs was performed using log-transformed data.

When multiple measures of LOS or complications were presented within the same outcome category for a study included in the meta-analysis, one measure was chosen as the ‘best representative’. In the case of LOS, this meant the outcome that most closely accounted for the longest portion of the hospital stay, without consideration of readmissions. For example, ‘total LOS’ would be chosen ahead of ‘postoperative LOS’. For complication data, summary or composite outcomes were preferred, rather than incidences of specific complications. When only incidences of individual complications were presented, they were summed and the total number was used in meta-analysis.

Where multiple PROMs were available within the same outcome category, for example multiple mental health measures, we sought to calculate a composite score using standard approaches. 36

Studies that were not eligible for meta-analysis were described narratively. This included a description of the main characteristics and findings of each study.

Results

This section is structured as follows:

-

Description of study selection process and characteristics of included studies.

-

Description of study outcomes and meta-analysis, arranged by procedural category.

Study selection

The PRISMA flow diagram in Figure 1 summarises the study selection process. Database searches identified 37,013 records initially, and a further 2217 through the update search, which reduced to 21,680 following de-duplication. After excluding 20,674 records at the title and abstract screening stage, 978 full texts were reviewed. We excluded 921 papers for reasons listed in Figure 1. The most common reasons for exclusion were being conference abstracts only (n = 273), no relevant outcomes (n = 209) and the mean/median sample age being below 60 (n = 111). Supplementary search methods yielded a further 1111 studies to review at title and abstract, of which 155 were reviewed at full text. The most common reason for exclusion at this stage was outcomes (n = 41). Reasons for exclusion for each paper excluded at full text are provided in Report Supplementary Material 1, Table 1. Following full text screening, 125 papers were included in the review, of which 45 were reports on 42 RCTs, eight were reports on 7 UK-based non-RCTs, and 72 were reports of non-UK-based non-RCTs. The eight papers reporting on seven UK-based non-RCTs and the 45 papers reporting on 42 RCTs were prioritised for full extraction and synthesis. The remaining 72 non-RCTs are described in Report Supplementary Material 2, Tables 1 and 2.

FIGURE 1.

PRISMA diagram – review of quantitative evidence.

Sample characteristics

Table 1 displays information about the prioritised studies, and the patients sampled within. Of the 49 prioritised studies (53 articles), 14 (15 articles) were conducted in the UK,37–51 7 of which were RCTs, 3 were uncontrolled before-and-after UBA trials,41,46,47 2 ITS studies,39,40 1 controlled trial42,43 and 1 CBA study. 48

| Study, country | Study design | Sample size | % female | Mean age (SD) (range) | Place of admission | Comorbidities (intervention vs. comparator) | Inclusion criteria |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Broad procedural category: abdominal surgery | |||||||

| Kapritsou 2020,81 GRE | RCT | 85 | 62.6% | 62.6 (11.8) (NR) | Oncology hospital | NR | Pancreatoduodenectomy, age 30–82 years, ASA I–III, normal level of consciousness, ability to communicate verbally. Excluded if: chronic pain (long-term use of analgesics), kidney disease, neuropathy, and systemic/chronic treatment with analgesics |

| Takagi 2019,87 JAP | RCT | 80 | 45.9% | 67.3 (9.5) (NR) | Hospital | ASA 1: 8% vs. 16%, 2: 62% vs. 70%, 3: 30% vs. 14%, HTN: 49% vs. 38%, diabetes: 38% vs. 41% | Pancreatoduodenectomy, 20–80 years. Excluded if: unable to obtain consent; severe respiratory dysfunction (arterial PaO2 < 70 mmHg), severe cardiac dysfunction (New York Heart Association 3), severe hepatic dysfunction (Child Pugh classification C), severe renal dysfunction (hemodialysis), pregnancy, preoperative chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy, acute bacterial infection, severe psychiatric disorder, advanced malignancy, palliative surgery, emergency surgery |

| Broad procedural category: cardiac surgery | |||||||

| Arthur 2000,52 CAN | RCT | 249 | 15.0%a | 62.8 (8.15) (NR) | General hospital | Previous myocardial infarction: 52.6% vs. 52.1%, diabetes: 16.4% vs. 25.6%, current smoker: 20.3% vs. 13%, aortocoronary bypasses (mean/median): 2.6/3 vs. 2.6/3 | First CABG, low risk, surgery date > 10 weeks away. Excluded if combined CABG and valve surgery, if ejection fractions < 0.40, if could not attend exercise classes, unable to participate because of physical limitations |

| Bennett 2020,37 | RCT | 182 | 24.0% | N = 38 aged 60 or below; n = 104 aged 61 to 75; n = 40 aged 76 or over | Hospital | Diabetes: 33.3% vs. 66.7%, HTN: 49.6% vs. 50.4%, Neurological history: 50% vs. 50%, Arrhythmias: 50% vs. 50% | Elective and stable-urgent, inpatients undergoing cardiac surgery with cardiopulmonary bypass who were capable and willing to complete the pre-operative neurocognitive tests |

| King 2008,76 USA | RCT | 146 | 47.9% | 73.5 (9.67) (47–79) | Hospital | NR | Short-stay cardiac implant placement over 18 years, suitable for elective resection and no pre-operative radiological or clinical evidence of metastases. Patients with transverse colon cancers or who had had a malignancy within the last five years were included |

| Rief 2017,72 Auer 2017,71 GER | RCT | 83 (SMC and EXPECT) | 12.8% | 66.5 (8.3) (NR) | University hospital | Smoker: 16.2 vs. 14.6%, EuroSCORE II [median (SD)] 1.25 (0.8) vs. 1.53 (0.8); NYHA I: 0% vs. 2.4%, II: 32.4% vs. 22.0%, III: 45.9% vs. 68.3%, IV 8.1% vs. 2.4%, LVEF ≥ 50: 78.4% vs. 48.8%, LVEF 49-30: 10.8% vs. 31.7%, LVEF < 30: 0% vs. 4.9%, Previous myocardial infarction: 16.7% vs. 23.1%, Current mental disorder: 21.6% vs. 9.8% | Elective on pump CABG or CABG combined with valve surgery over 18 years, able to give informed consent, sufficient fluency in German. Excluded if presence of a serious non-cardiac medical condition or psychiatric condition that substantially affected disability |

| Sadlonova 2022,73 GER | RCT | 64 (SMC and IB) | 20.7% | 64.87 (11.22) (NR) | University hospital | Angina pectoris: 27.6% vs. 27.6%, chest pain: 24.1% vs. 27.6%, dyspnoea: 34.5% vs. 69%, syncope: 6.9% vs. 6.9%, NYHA I:13.8% vs. 10.7, II: 48.3% vs. 60.7%, III or IV: 37.9% vs. 28.6%, hypertension: 89.7% vs. 86.2%, Dyslipidaemia: 62.1% vs. 48.3%, Diabetes: 34.5% vs. 37.9%, Smoker: 13.8% vs. 17.2% | Elective CABG surgery, German fluency, able to provide informed consent. Excluded if: previous open-heart surgery, unable to complete self-assessment questionnaires or study procedures, serious comorbid psychiatric condition (i.e., psychotic disorder, substance use disorder other than tobacco use disorder, dementia, severe depressive disorder, recent suicidal ideation), malignant tumour (except curative with treatment or relapse free), inability to use VR glasses or headphones (i.e. blindness or disease of the eye or ears) |

| van der Peijl 2004,64 NED | RCT | 309 | 21.1% | 62.65 (10.2) (NR) | University medical centre | Diabetes mellitus: 19% vs. 19%, COPD 12% vs. 6%, peripheral or CVD: 9% vs. 5%, HTN: 47% vs. 33%, main stem lesion (> 50%): 20% vs. 21% |

Excluded if: concomitant surgical procedures, severe comorbidity interfering with daily life, insufficient Dutch language, mental disorders, PO complications jeopardising standardised exercise programme |

| Broad procedural category: colorectal surgery | |||||||

| Bousquet-Dion 2018,54 CAN | RCT | 80 | 27.0% | Prehab median 74 (67.5–78), Rehab median 71 (54.5–74.5) | Hospital | ASA status 1: 3% vs. 12%, 2: 62% vs. 42%, 3+: 35% vs. 46%, diabetes: 27% vs. 15%, COPD: 5% vs. 15%, CAD: 5% vs. 15%, HTN 62% vs. 42%, PVD: 5% vs. 4%, AF: 11% vs. 4%, tumour stage 0: 11% vs. 15%, 1 and 2: 59% vs. 42%, 3 and 4: 30% vs. 42% | Non-metastatic colon cancer resection, excluded if: presence of metastatic cancer, did not speak English or French or had concurrent medical conditions that contraindicated exercise |

| Carli 2010,56 CAN | RCT | 133 | 42.0% | 60.5 (15.5) (NR) | University health centre | NR | Resection of benign or malignant colorectal lesions, or for colonic reconstruction of non-active inflammatory bowel disease, ≥ 18 years old, receiving pre-op chemo/radiotherapy. Excluded if: health conditions prohibiting participation in exercise programmes/testing procedures |

| Carli 2020,55 CAN | RCT | 110 | 28.2% | 78 (7) (NR) | 2 × hospitals | Prehab: Rehab; DM2: 35% vs. 38%, hypertension: 53% vs. 76%, CVD: 27% vs. 35%, AF: 16% vs. 9%, OSA: 9% vs. 9%, COPD: 15% vs. 5%, arthritis/connective tissue disease: 27% vs. 43%, Dyslipidaemia: 49% vs. 48%, hypothyroidism: 22% vs. 20%, Asthma: 13% vs. 2%, Frailty scores (2, 3, 4, 5): score 2: 45% vs. 31%, score 3: 29% vs. 40%, score 4: 13% vs. 18%, score 5: 13% vs. 11% | Surgical treatment of non-metastatic colorectal cancer, > 65 years, scheduled for surgical treatment of non-metastatic colorectal cancer. Excluded if: Fried Frailty Index of 1, did not speak English or French, presence of metastatic cancer or premorbid conditions (i.e. cardiorespiratory, musculoskeletal, and/or neurological) that contraindicated exercise and fitness assessments |

| Dronkers 2010,67 NED | RCT | 42 | 25.0%b | 70 (6.73) (NR) | General hospital | COPD: 3/21 vs. 3/17, coughing: 2/20 vs. 2/18, diabetes: 8/14 vs. 1/19c | First elective colon surgery for gastric cancer, minimum waiting period of 2 weeks, age 60 years, adequate cognitive functioning (good understanding and accurate execution of instructions). Excluded if: heart disease/orthopaedic conditions which impede exercise, severe systemic illness, recent embolism, thrombophlebitis, uncontrolled diabetes,d wheelchair dependent |

| Forsmo 2016,88 NOR | RCT | 324 | 46.3% | Median: 65.5 (NR) (19–93) | University hospital | NR | Elective open or laparoscopic colorectal surgery, (including patients with rectal cancer previously treated with pelvic radiation) for malignant or benign disease, older than 18 years. Excluded if: multivisceral resection planned/ASA grade IV, pregnant, emergency operations, difficulty providing informed consent due to impaired mental capacity, inability to adapt to ERAS criteria. Randomised patients excluded if intended colonic or rectal surgery not performed |

| Frontera 2014,82 ITA | RCT | 74 | 30.0% | 72 (NR) (40–95) | Rural hospital | ASA I: 26.3% vs. 30.6%, II: 65.8% vs. 52,8%, III: 7.9% vs. 16.7% | Elective surgical colon-rectal resection for benign or malignant disease, over 18 years. Excluded if: unable to consent, ASA IV, patients with serious cardiovascular dysfunction (NYHA class > 3), respiratory dysfunction (arterial pO2 value < 70 mmHg) or hepatic dysfunction (Child C), extensive metastases, other pathologies requiring relevant surgery treatment, neoplasm of the lower rectum |

| Gillis 2014,59 CAN | RCT | 89 | 37.7% | 65.9 (11.3) (NR) | University-affiliated tertiary centre | Ischaemic heart disease: n = 3 (7.5%) vs. 2 (5%), HTN: n = 8 (21%) vs. 12 (31%), Diabetes: n = 3 (7.5%) vs. 5 (13%) | Curative resection of non-metastatic colorectal cancer, excluded if: did not speak English/French, premorbid conditions that contraindicated exercise |

| Khoo 2007,45 UK | RCT | 81 | 61.0% | Median: intervention: 69.3, comparator: 73.0 (overall range = 46.3–87.7) | Hospital | NR | Colorectal resection for cancer, no upper age limit. Excluded if: unable to mobilise independently over 100 m at pre-op assessment, contraindications to thoracic epidurals, pre-existing clinical depression, palliative care only, undergoing joint operation involving another surgical specialty |

| Lee 2011,85 KOR | RCT | 100 | 44.0% | 61.2 (7.62) (NR) | University hospital | NR | Laparoscopic resection for colonic tumour, suitable for laparoscopic colonic resection, between 20 and 80 years old. Excluded if: synchronous distant metastasis, intestinal obstruction/perforation, previous MAS, severe pulmonary disease/cardiovascular disease |

| Lee 2013,84 KOR | RCT | 98 | 34.7% | 61.4 (10.8) (NR) | Hospital | NR | Laparoscopic resection for colonic tumour, suitable for laparoscopic colonic resection, between 20 and 80 years old. Excluded if: synchronous distant metastasis, intestinal, obstruction/perforation, previous MAS, severe pulmonary disease/cardiovascular |

| Pappalardo 2016,83 ITA | RCT | 50 | 48.0% | 66.65 (NR) (45–83) | NR | Pulmonary: 48% vs. 56%, cardiovascular/hypertension: 64% vs. 60%, diabetes: 24% vs. 20% | Open extra-peritoneal rectal cancer surgery, without a primary derivative stoma (DS) with or without a secondary DS, extra-peritoneal tumour location,e cT2–T4 tumours, with or without positive lymph nodes, use of modified FTP, neoadjuvant therapy where indicated (T3–T4 or N+). Excluded if: tumours located over 12 cm above the anal verge, cT1 or M1, urgent procedures; patients ASA > 3, operated on with abdominoperineal resection or Hartmann’s procedure, refusing neoadjuvant therapy, refusing or unable to follow FTP, coagulation disorders contraindicating epidural catheter insertion |

| Vlug 2011,65 2011 NED | RCT | 427 | 41.5% | 66.5 (8.68) (NR) | Three university hospitals and 6 general hospitals | % with comorbidities per group: Lap+FT = 71%; Open+FT = 59%; Lap+standard = 68%; Open+standard = 68% | Elective segmental colectomy for histologically confirmed adenocarcinoma or adenoma, and without evidence of metastatic disease, between 40 and 80 years of age, had an American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) grade of I, II or III. Excluded if: previous midline laparotomy, unavailability of a laparoscopic surgeon, emergency surgery, or a planned stoma |

| Broad procedural category: lower-limb arthroplasty | |||||||

| Beaupre 2004,53 CAN | RCT | 131 | 55.0% | 67 (6.5) (NR) | University hospital | % with no morbid condition: 70% vs. 55% | TKA, between 40 and 75 years with diagnosis of non-inflammatory arthritis, were able to understand and comprehend verbal and written English or have a translator |

| Borgwardt 2009,66 DEN | RCT | 50 | 55.0%f | 65.6 (NR) (44–86) | University hospital | NR | UKR, resident in the county of Copenhagen, ASA I or II, no medical history of GI bleeding, someone to look after following discharge. Excluded if: major psychiatric disease, incapable of managing own affairs, inflammatory joint disease, neurological/other disease(s) affecting lower limbs, previous major surgery of the knee |

| Cavill 2016,79 AUS | RCT | 64 | 52.0% | 66.15 (9.5) (NR) | Hospital | NR | Hip or knee arthroplasty, Risk Assessment and Prediction Tool (RAPT) score ≥ 6. Excluded if: lived outside the catchment areas; having surgery < 4 weeks from surgical review; unable to follow commands; having revision surgery; unable to mobilise without a wheelchair; corticosteroid injection within last 6 months |

| den Hertog 2012,75 GER | RCT | 160 | 70.8% | 67.41 (8.11) (40–85) | Non-academic hospital specializing in orthopaedic surgery | Diagnoses (n): degenerative arthritis: 72 vs. 72, posttraumatic arthritis: 0 vs. 1, Ahlback’s disease: 2 vs. 0, arthritis in knee without surgical procedure: 38 vs. 34, secondary disorders/concomitant diseases (n): cardiac: 50 vs. 39 gastrointestinal: 16 vs. 14, allergies: 4 vs. 5, kidney/urinary tract: 2 vs. 4 | TKA, male and female (age range 40–85 years). Excluded if: missing informed consent, lack of cooperation capability, ASA score > 3, RA, cancer, substance abuse, previous major surgery on affected joint, neurological or psychiatric disease, pregnant, participation in other clinical studies |

| Fransen 2018,60 NED | RCT | 49 | 59.0% | 62.5 (8) (NR) | Teaching hospital | NR | TKA, ASA status I or II and were willing and able with the rehabilitation programme. Excluded if: other lower-limb problems, insulin-dependent diabetes, severe osteoporosis, rheumatoid arthritis, or a different inflammatory cause for osteoarthritis |

| Garriga 2019,40 UK | ITS | 486,579 | 57.0% | 70 (9) (NR) | Hospitals | NR | TKA, between 1 April 2008, and 31 December 2016. Excluded if: without a concordant date of surgery between the UK National Joint Registry (NJR) and Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) databases. Further exclusions were made specific to the outcome being analysed. Excluded patients with a hospital stay beyond 15 days |

| Garriga 2019,39 UK | ITS | 438,921 | 60.0% | 69 (11) (NR) | Hospitals | NR | THA, between 1 April 2008, and 31 December 2016. Excluded if: without a concordant date of surgery between the UK National Joint Registry (NJR) and Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) databases. Further exclusions were made specific to the outcome being analysed. Excluded patients with a hospital stay beyond 15 days |

| Higgins 2020,41 UK | UBA | 1256 | 58.0% | 68.8 (9.8) (NR) | University teaching hospital | Adjusted Charlson Comorbidity Index, class 0: 115 (33.6) vs. 277 (35.4), class 1: 131 (38.3) vs. 293 (37.4), class 2: 50 (14.6) vs. 141 (18.0), class 3: 29 (8.5) vs. 54 (6.8), class 4+: 17 (5) vs. 19 (2.4); ASA classification, class 0 8 (1.7) vs. 0 (0), class 1: 24 (5.1) vs. 31 (4.0), class 2: 352 (75) vs. 592 (76), class 3: 17.2 (7.8) vs. 18.4 (7.7) | TKA, The Pre-PES cohort was made up of TKA patients from 1 April 2014 to 31 March 2015. All data were assessed retrospectively from within the institutional databases. The PES cohort included all patients planned for TKA surgery from 1 April 2015 to 1 December 2015 with each patient being invited to participate in the study and providing informed consent. All patients experiencing PES were assessed prospectively |

| Hoogeboom 2010,63 NED | RCT | 21 | 67.0% | 76 (4.1) (69–90) | Hospital | Mean n = 1.5 and 1 in Experimental and Comparator groups, range 0–4 | Primary THA, 70+ years, OA of the hip, minimum waiting time of 3 weeks, score of ≥ 2 on Clinical Frailty Scale. Excluded if: unable to communicate, severe heart disease |

| Hunt 2009,42 2009, Salmon 2013,43 UK | CT | 579; 599 | 54.3%; 58.4% | 67.4 (NR) (23–93);g 67.8 (10.5) (NR) | One of three sites: General Hospital. South-West London Elective Orthopaedic Centre (SWLEOC), University Hospital | Comorbidities (%) in Intervention vs. Comparator 1 vs. Comparator 2: hypertension: 47 vs. 45 vs. 51, CAD: 14 vs. 12 vs. 5, COPD: 16 vs. 12 vs. 20, diabetes: 9 vs. 10 vs. 13, thyroid disorders: 10 vs. 4 vs. 3, CVD: 7 vs. 3 vs. 2, GI disease: 14 vs. 14 vs. 10, psychiatric disorders: 6 vs. 3 vs. 7 | Unilateral primary hip arthroplasty |

| Larsen 2008,69 Larsen 2008 (Thesis),68 DEN | RCT | 90 | 50.6% | 65 (10) (NR) | Regional hospital | NR | Primary THA, TKA or UKA. Excluded if: mental disability or (2) severe neurological disease |

| Maempel 2015,47 UK | UBA | 165 | 52.1% | 69.9 (9.7) (NR) | Hospital | NR | Prosthetic total knee replacement. Excluded if: unicompartmental knee replacements, patellofemoral replacements and revision TKRs |

| Maempel 2016,46 UK | UBA | 1161 | 60.9% | Median age: 65 (NR) (IQR 25–94) | General hospital | NR | Primary THA. Excluded if: patients undergoing THA between April and December 2010, simultaneous bilateral THA, transferred from a medical ward for planned semi urgent THA and returned to the medical ward PO, sustained a per prosthetic femoral fracture, requiring further surgery and prolonged rehabilitation |

| McDonald 2012,48 UK | CBA | 1816 | 68.9% | 69.4 (11.8) (NR) | Hospital | NR | UKA. Excluded if: revision knee surgery, unicompartmental knee replacement, bilateral knee replacement or patients requiring general anaesthesia, planned postoperative epidural analgesia or peripheral nerve blockade |

| McDonnall 2019,89 UK | RCT | 241 | 55.1% | 66.5 (9.2) (NR) | Private (not-for-profit) teaching hospital | NR | TKR, aged > 18 years, elective admission for primary, unilateral, TKR surgery. Excluded if: cognitively impaired or difficulties with informed consent or ability to complete questionnaires |

| McGregor 2004,49 UK | RCT | 39 | 71.4% | 71.9 (9.3) (51–92)h | Hospital | NR | THA. Excluded if: revision or bilateral arthroplasty, previous hip arthroplasty, coexisting morbidity, e.g. history of severe cardiovascular, respiratory, neuromuscular disease, RA, mentally confused, inadequate comprehension of English |

| Pour 2007,78 USA | RCT | 100 | 46.9%i | 60.8 (8.9) (NR)j |

University hospital | NR | Unilateral THA, 18–75 years, any gender/race, underlying diagnosis of OA, consent to participate in the study. Excluded if: BMI > 30 kg/m2, cognitive impairment/severe psychiatric illness precluding participation in the protocol procedures |

| Reilly 2005,50 UK | RCT | 41 | 41.5% | 63 (NR) | Nuffield Orthopaedic Centre | NR | UKA, diagnosed with anteromedial OA,k good understanding of procedure, tolerance of large doses of NSAIDs, suitable home situation within 25 mile radius, upper age limit of 75 years. Excluded if: diagnosis of diabetes/severe respiratory disease/DVT, previous heart surgery, diagnosed with tri-compartmental arthritis at Pre Admission Clinic |

| Siggeirsdottir 2005,86 ICE | RCT | 50 | 52.0% | Overall mean: 68 (NR) (28–86) | University hospital or general hospital | Diagnosis: 24 patients had osteoarthrosis: 24 vs. 21, RA: 1 vs. 1, previous fractures: 2 vs. 0, deformity after Perthes disease: 0 vs. 1 | Primary hip replacement, diagnosed with OA of the hip, RA, primary segmental collapse of femoral head, and sequelae after developmental diseases and hip trauma, living in their own home. Excluded if: primary hip fracture, metastastatic tumours, dementia |

| Soeters 2018,77 USA | RCT | 126 | 63.5% | 61 (9) (37–85) | Hospital | NR | TJA, 18–85 years old, ambulate independently half a block or more and perform nonreciprocal stairs with/without an assistive device, planned to be discharged home after surgery |

| Vesterby 2017,70 DEN | RCT | 73 | 46.6% | Medians: Intervention: 63 (NR) (43–80), Comparator: 64 (NR) (45–84) | Urban teaching hospital | NR | Primary fast-track elective THR. Excluded if: distance to hospital > 60 km, previous hip surgery, mental disability, inability to communicate in Danish, no support person, no internet connection |

| Williamson 2007,51 UK | RCT | 181 | 54.0% | 70.7 (8.8) (NR) | General hospital | NR | Knee-replacement surgery, (total, unicondylar, unilateral, bilateral). Excluded if: taking anticoagulants; within 2 months after receiving an intra-articular steroid injection: experiencing back pain associated with referred leg pain; suffering from ipsilateral OA of the hip; psoriasis or other skin disease in the region of knee; RA, received acupuncture or PT within last year |

| Broad procedural category: pelvic surgery | |||||||

| Frees 2018,58 CAN | RCT | 23 | 22.0% | 68.33 (NR) (49–86) | General hospital | ASA I: 10% vs. 0%, 2: 10% vs. 54%, 3: 10% vs. 46% | Radical cystectomy, diagnosis of BC with an indication for RC, able to complete a QoL questionnaire, study subject diary, and subject experience and satisfaction questionnaires. Excluded if: diagnosis of insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus, Parkinson’s disease, and other neurological co-morbidities |

| Broad procedural category: thoracic | |||||||

| Ferriera 2021,57 CAN | RCT | 124 | 46.0% | 67.0 (9.4) (NR) | General hospital | Prehab vs. Rehab – ASA I: 2% vs. 2%, II: 64% vs. 54%, ≥ III: 35% vs. 44%, diabetes: 14% vs. 16%, HTN: 48% vs. 26%, CVD: 10% vs. 16%, COPD: 10% vs. 16%, tumour stage 0: 19% vs. 14%, IA1: 4% vs. 5%, IA2: 19% vs. 23%, IA3: 21% vs. 14%, IB: 6% vs. 14%, IIA: 4% vs. 0%, IIB: 13% vs. vs. 5%, IIIA: 10% vs. 23%, IV: 4% vs. 2%, current smoker: 19% vs. 26% | Non-small cell lung cancer resection. Excluded if: metastatic cancer, did not speak English or French, concurrent medical conditions that contraindicated exercise |

| Broad procedural category: surgery to remove tumours (various locations) | |||||||

| Hempenius 2013,61 Hempenius 2016,62 NED | RCT | 297; 260 | 64.0%; 62.0% | 77.54 (7.21) (NR); 77.4 (7.3) (NR) | University medical centre, medical centre, community hospital | Comorbidities: 2013: ≤ 2: 39.6% vs. 40.4%, > 2: 60.4% vs. 59.6%. 2016: ≤ 40.2% vs. 41.4%, > 2: 59.8% vs. 58.6% | Surgery for solid tumour, over 65 years of age |

| Schmidt 2015,74 GER | RCT | 652 | 31.5% | 71.8 (4.85) (NR) | Two tertiary medical centres | ASA I/II: 67.2% vs. 63.2%, ASA III/IV 32.8% vs. 36.8%, ECOG 0: 99.6% vs. 95.4%. 1: 2.5% vs. 3.7%, 2/3: 0.9% vs. 0.9%, comorbidities (POSSUM) both groups 2 (2–4) (median, IQR) | Surgery for gastro-intestinal, genitourinary, gynaecological, or thoracic cancer age > 65 years, for major onco-surgery, proficient in German language, a Mini Mental Score (MMSE) of ≥ 24 points, able to consent. Excluded if: 2 or > concurrent carcinomas, emergency surgery, life expectancy of > 2 months, as well as current participation in another trial, living in a closed institution due to an official or judicial ruling |

| Broad procedural category: upper abdominal surgery | |||||||

| Dunne 2016,38 UK | RCT | 38 | 31.6% | Median: 62 (NR) (IQR 54–69) | University hospital | Comorbidity (n): cardiovascular: 10 vs. 8, respiratory: 3 vs. 4, diabetes: 2 vs. 2, renal disease: 1 vs. 0, none: 1 vs. 3, primary tumour: node-positive; 12 vs. 10, adjuvant or neoadjuvant treatment: 11 vs. 7, metastatic presentation; synchronous presentation: 8 vs. 10, extrahepatic metastatic disease: 3 vs. 4, > 3 hepatic metastases; 5 vs. 7, metastasis > 5 cm in diameter; 7 vs. 6 | Liver resection, aged > 18 years and able to: give informed consent, partake in cycle-based exercise, and complete the exercise programme before proposed surgery date, metastases deemed surgically treatable with curative intent. Excluded if: known pre-existing chronic liver disease |

| Jones 2013,44 UK | RCT | 104 | 41.0% | 65.5 (NR) (27–84) | Hospital | NR | Open liver resection, all adult patients presenting for procedure eligible. Excluded if: patients entirely laparoscopic operation, needed a second concomitant procedure, inoperable at the time of surgery, unable to consent |

| Kapritsou 2017,80 GRE | RCT | 63 | 39.7% | 60.9 (11.7) (NR) | Oncology hospital | NR | Hepatectomy or pancreatectomy, up to 2 months after cancer diagnosis, ASA classification of I–III, age > 18 years, normal level of consciousness and communication. Excluded if: presence of chronic pain, kidney disease, neuropathy, systemic or chronic treatment with analgesics |

Thirty-five (38 articles) were RCTs conducted in 1 of 12 other high-income countries, the most common of which was Canada (n = 8), studies. 52–59 Five studies were from the Netherlands,60–65 four each from Denmark66–70 and Germany,71–75 three from the USA,76–78 two each from Australia,48,79 Greece,80,81 Italy82,83 and Korea84,85 and one each from Iceland,86 Japan87 and Norway. 88

All the prioritised articles were published in peer-reviewed journals, apart from two which were PhD theses. 68,76 Most articles (83.1%) were published from 2008 onwards, with 28 published since 2014 (52.8%). 37–41,46,47,54,55,57–62,70–74,77,79–83,87–89 Data were collected from 936,859 patients across 49 studies, with a mean number of 19,119 patients per study, ranging from 21 in an RCT63 to 486,579 within an ITS40 utilising database sampling. With the large database studies by Garriga and colleagues removed,39,40 the mean number of patients per study was 242, with a median of 100 and a range of 1795. The proportion of female participants across all studies was 58.3%.

Ten studies had an upper age limit for inclusion: 75 years,50,53,78 80 years,65,84,85,87 85 years,75,77 82 years. Kapritsou and colleagues81 and Dronkers et al. 67 exclusively recruited patients aged ≥ 60 years, whilst patients in four studies:55,61,62,74 had to be > 65 years for inclusion and 70+ years in the study by Hoogeboom and colleagues. 63

Studies explicitly excluded patients who lived with cognitive impairment (n = 5)67,73,74,78,89 had ‘psychiatric illness’ (n = 6),66,69,71–73,75,78 had mental disability (n = 6),45,64,68–70,73,88 had periods of confusion (n = 3),49,80,81 or were unable to consent (n = 7). 38,44,74,78,87–89 In contrast two studies55,63 selected more frail patients.

The reasons for admission, according to our broad procedural categories, were LLA (n = 22)39–41,43,46–51,53,60,63,68–70,75,77–79,86,89,90 colorectal surgery (n = 12),45,54–56,59,65,67,82–85,88 cardiac surgery (n = 6),37,52,64,71–73,76 upper abdominal surgery (n = 3),38,44,80 abdominal surgery (n = 2),81,87 tumour removal (various locations) (n = 2),61,62,74 pelvic surgery (n = 1)58 and thoracic surgery (n = 1). 57

Intervention characteristics

Intervention characteristics are summarised in Table 2. The most common category of intervention was ERP (n = 28 studies),37,39–42,44–48,50,58,60,65,66,69,73,78,80–89 followed by Prehab (n = 16 studies),38,49,51–57,59,63,67,71,72,74,77,79 with Rehab (n = 3 studies),64,70,75 and single studies evaluating discharge planning76 and a preoperative assessment and care plan61,62 populating the remaining intervention categories.

| First author, country | Intervention name in study (category) | Stated aims of intervention | Comparator name in study (category) | Stages of the care pathway at which intervention elements were delivered | Site | Who was involved in delivery? | Relevant outcomes reported (other than LOS) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-admission | Pre-operative | Perioperative | Post-operative | Post discharge | |||||||

| Abdominal surgery ( n = 2) | |||||||||||

| Kapritsou 2020,81 Greece | ERAS (ERP) | Improve recovery in terms of pain intensity, emotional response and stress biomarkers | Control (TAU) | EON EMOB |

Oncological hospital | NR | Complications, pain, emotional response | ||||

| Takagi 2019,87 Japan | ERAS (ERP) | Accelerate postoperative recovery and reduce LOS without increasing morbidity | Standard Care (TAU) | AEI | nMBP; NUT |

FM | nNGT; EON; CATH; NUT; DRA; TP; ANA; EMOB |

TEL | University hospital | NR | Complications, readmissions, QoL |

| Cardiac surgery (n = 6) | |||||||||||

| Arthur 2000,52 Canada | Preoperative intervention (Prehab) | Improve patients’ physical and psychological readiness for surgery, reducing LOS | Usual Care (TAU) | AEI; EX; REF; TEL |

Hospital, phone, patient home | Kinesiologists/exercise specialists nurses, psychologist, family | Complications, mental health, QoL | ||||

| Bennett 2020,37 UK | Cerebral oximetry (ERP) | Improve neurological and LOS outcomes | TAU (TAU) | COX | Tertiary referral cardiac centre | Anaesthetist and intra-operative team | Mental health, satisfaction | ||||

| King 2008,76 USA | Nurse-driven discharge-planning protocol (discharge planning) | Improve organisational efficiency, patient safety and patient satisfaction | TAU (TAU) | DP | DP | Post-procedure unit, hospital | Intervention registered nurses, electrophysiology physicians, mid-level providers, office staff, bedside caregivers and ancillary staff | Readmissions, patient satisfaction | |||

| Rief 2017 / Auer 2017,71,72 Germany | EXPECT (Prehab) | Optimise pre-operative expectations and improve coping with CABG | Standard medical care (TAU) | AEI; PSY |

Home or university department | Psychologists | Readmissions, complications, disability, mental health, physical function, QoL | ||||

| Sadlonova 2022,73 Germany | Multimodal perioperative intervention (ERP) | Improvements in HRQOL, self-efficacy, reductions in IL-6 and IL-8 levels and shorter lengths of ICU and hospital stay | Standard medical care (TAU) | TEL; AEI |

PSY | PSY; MM | PSY; MM | TEL | Hospital, home | Medical doctor, psychologist, other NR | QoL |

| Van der Peijl 2004,64 Netherlands | Exercise therapy (Rehab) | Facilitate recovery after surgery | Low-frequency exercise programme once a day, excluding weekends (TAU) | PT; EX |

Hospital | PT | Physical function | ||||

| Colorectal surgery ( n = 12) | |||||||||||

| Carli 2010,56 Canada | Bike/strengthening prehabilitation (Prehab) | Optimise recovery of functional walking capacity post surgery | Walking/breathing group (TAU) | EX | Patient home | NR | Mental health, physical activity, physical function, complications | ||||

| Carli 2020,55 Canada | Prehabilitation programme (Prehab) | Reduce 30-day postoperative complications in frail patients | Rehabilitation programme (Rehab) | EX | Hospital prehabilitation unit, home | Kinesiologist, nutritionist, psychology-trained nurse | Complications, mental health, physical activity, readmissions | ||||

| Bousquet-Dion 2018,54 Canada | Prehab+ (Prehab) | Improve walking capacity prior to surgery and reduce decline of physical function post-operatively | Rehabilitation (Rehab) | EX | Home and hospital | Kinesiologist, nutritionist psychologist, nursing staff | Complications, readmissions, physical activity | ||||

| Dronkers 2010,67 Netherlands | Preoperative therapeutic programme (Prehab) | Improve physical condition before surgery and improve recovery | Home-based exercise advice (TAU) | AEI; EX | Outpatient department, patient home | NR | Complications, QoL, physical activity, patient satisfaction | ||||

| Forsmo 2016,88 Norway | ERAS (ERP) | Reduce LOS | Standard Care (TAU) | AEI | CHL; PreM | ANE; FM | LAX; ANA; CATH; EON |

Hospital | MDT | Complications, mortality, readmissions, QoL | |

| Frontera 2014,82 Italy | Fast track (ERP) | Reduce LOS | Control (TAU) | nMBP | NGT; SURG; |

PONV; EON; FM; CATH |

Hospital | Clinical team | Pain, satisfaction, complications | ||

| Gillis 2014,59 Canada | Prehab (Prehab) | Reduce LOS | Rehab (Rehab) | AEI; EX; NUT; PT |

Patient home | MDT | QoL, mental health, physical function, pain, physical activity, complications, readmissions | ||||

| Khoo 2007,45 UK | Multimodal perioperative management protocol (ERP) | Reduce LOS, improve independence | Control (TAU) | NUT | ANE; FM; nNGT |

EON; EMOB; ANA; CATH |

Hospital | MDT | Complications, readmissions, satisfaction, service utilisation | ||

| Lee 2011,85 South Korea | Rehab programme (ERP) | Reduce LOS | Conventional care (TAU) | FM | EON; EMOB; LAX; CATH |

Hospital | MDT, family | Complications, pain | |||

| Lee 2013,84 South Korea | Rehab programme (ERP) | Improve recovery in hospital | Conventional care (TAU) | EMOB; EON; LAX; CATH |

Hospital | Ward nurse | Complications, readmissions, QoL, pain, mental health | ||||

| Pappalardo 2016,83 Italy | Fast-track protocol (ERP) | Reduce LOS, morbidity, mortality and improve QoL | Traditional care (TAU) | ANE; AP; TP |

nNGT; ANA | EON; EMOB; | Hospital | MDT | Complications, mortality, QoL | ||

| Vlug 2011,65 Netherlands | Fast-track programme (ERP) | Reduce LOS | SC with laparoscopy or open surgery (TAU) | AIE; EX | CHL; nFAST;PreM | ANA; FM; PONV |

EON; EMOB; FM; NUT; LAX; CATH |

Hospital: multi-site | MDT | Complications, mortality, satisfaction, QoL, readmissions | |

| Lower-limb arthroplasty ( n = 22) | |||||||||||

| Beaupre 2004,53 Canada | Preoperative exercise and education programme (Prehab) | Improve functional recovery, health related quality of life and health service utilisation | Control group (TAU) | AIE; EX; LOG |

EX; LOG |

Hospital, home | PT | Pain, physical function, QoL, mental health, social function | |||

| Borgwardt 2009,66 Denmark | Accelerated recovery programme (ERP) | Reduce LOS with good clinical outcomes | Conventional Care (TAU) | AIE; OT |

ANE | ANA | TEL | Hospital | MDT | Physical function, pain, readmissions, service utilisation, satisfaction, QoL | |

| Cavill 2016,79 Australia | Prehab programme (Prehab) | Investigate the effect of prehabilitation on functional outcomes across the continuum of care | Standard care (TAU) | AIE; EX |

EX | Local community rehab centre, home | PT | Physical function, QoL | |||

| Fransen 2018,60 Netherlands | 2-day knee (2DK) protocol (ERP) | Achieve better daily clinical and functional outcomes in the first week after surgery, and compare outcomes up to 5 years after surgery | Routine protocol (TAU) | ANE; SURG;DRA; CATH; |

EMOB; ANA |

Hospital | NR (ward staff) | Physical function, pain, mental health, physical activity, QoL | |||

| Garriga 2019,39 UK | ERAS (ERP) | Improved patient outcomes: less knee pain and better knee function, fewer surgical complications, fewer revision operations and reduced LOS | Pre-ERAS period (TAU) | x | x | x | Hospitals | NR | Complications, readmissions, physical function | ||

| Garriga 2019,40 UK | ERAS (ERP) | Improved patient outcomes: less knee pain and better knee function, fewer surgical complications, fewer revision operations and reduced LOS | Pre-ERAS period (TAU) | x | x | x | Hospitals | NR | Complications, readmissions, physical function | ||

| den Hertog 2012,75 Germany | Pathway-controlled fast track Rehab (Rehab) | Improve recovery | Standard PO rehabilitation (TAU) | EMOB; MT; PT; SW |

Hospital, rehabilitation centre | NR | QoL, complications | ||||

| Higgins 2020,41 UK | Pathway management system (ERP) | Assess impact on LOS and compare effects on PROMS | Pre-ERP (TAU) | AIE; MM |

AIE; MM |

AIE; MM; TEL |

Hospital | Clinical staff, physiotherapist | Readmissions, complications, physical function, QoL | ||

| Hoogeboom 2010,63 Netherlands | Preoperative therapeutic exercise (Prehab) | Prevent decline of functional health status when waiting for surgery | Usual PrO/PO care (TAU) | EX | Patient home | NR | QoL, pain, physical activity, complications | ||||

| Hunt 2009,42 Salmon 2013,43 UK | Rapid discharge policy (ERP) | Reduce LOS, maintain functional recovery and QoL | Comparator 1: usual care in large regional centre surgical unit. Comparator 2: usual care in treatment centre (TAU) | OT; PT |

ANA; ANE; SURG |

ANA; EMOB; PT; SW |

TEL | Hospital, outpatient clinic | MDT | QoL, physical function, mental health, pain, service utilisation, satisfaction | |

| Larsen 2008,68,69 Denmark | Accelerated perioperative care and Rehab (ERP) | Reduce LOS | Usual care | AEI; EX; GOAL; NUT; OT; SW |

AEI | PONV | EMOB; GOAL; LAX; OT; ANA; EON |

PT | Hospital | MDT, family | QoL, readmissions |

| Maempel 2015,47 UK | ERP (ERP) | Reduce LOS without adversely affecting functional recovery and ROM at 1 year post-op | Pre-ERP (TAU) | AEI; OT | AP | ANA | Hospital | MDT | Complications, readmissions, physical function | ||

| Maempel 2016,46 UK | ERP (ERP) | Improve joint function | Pre-ERP (TAU) | AEI; DP; OT |

AP | ANA; EMOB | Outpatient clinic, hospital | MDT | Readmissions, physical function, mortality | ||

| McDonald 2012,48 UK | ERP (ERP) | Reduce LOS, allow early mobilisation with satisfactory analgesia without increasing post-operative complications or affecting continuing rehabilitation | Pre-ERP period (TAU) | AEI; DP |

PreM | ANE; FM |

ANA; EMOB |

Hospital ward, clinic | Surgeon, PT, ward staff | Complications, mortality, pain, physical function | |

| McDonall, 2019,89 Australia | MyStay (ERP) | Support patient participation in their recovery after total knee-replacement surgery | Usual care (TAU) | MM | MM | Hospital | Nurses, PT | Complications, readmissions, pain, physical function, satisfaction | |||

| McGregor 2004,49 UK | Preoperative hip rehab advice (Prehab) | Aid patient recovery | Standard care (TAU) | AEI | NR | NR | QoL, pain, physical function | ||||

| Pour 2007,78 USA | Enhanced protocol (ERP) | Aid recovery | Group 3: standard incision, standard protocol. Group 4: small incision, standard protocol (TAU) | AEI; PT; OT |

ANA | ANE | ANA; DRA; EMOB; PT | Outpatient clinic, hospital | MDT, family | Complications, mental health, physical function, QoL | |

| Reilly 2005,50 UK | Accelerated recovery protocol (ERP) | Reduce pain to allow for early mobilisation | Standard care (TAU) | ANA; EMOB; EON |

AIE; TEL |

Hospital, patient home | MDT | Complications, pain, physical function | |||

| Siggeirsdottir 2005,86 Iceland | Preoperative education and training programme / rehab and nursing (ERP) | Reduce LOS | Conventional care (TAU) | AEI; EX | TP | EX; PT; OT |

Outpatient clinic, patient home | PT, OT | Complications, physical function, QoL, readmissions | ||

| Soeters 2018,77 USA | Preoperative physical therapy education (Prehab) | Achieve earlier readiness for discharge, shorter LOS, improve physical recovery | Usual care (TAU) | AEI; EX; DP; GOAL |

NR | PT | Pain, physical function | ||||

| Vesterby 2017,70 Denmark | Telemedicine support (Rehab) | Reduce LOS | Fast track (TAU) | PT; TEL | TEL; PT | Outpatient clinic, patient home | PT, support persona | Readmissions, complications, QoL, mental health, physical function | |||

| Williamson 2007,51 UK | Physiotherapy (Prehab) | Improve condition before surgery, improve recovery | Home exercise (TAU) | EX; PT |

NR | PT | Physical function, mental health, pain | ||||

| Pelvic surgery ( n = 1) | |||||||||||

| Frees 2018,58 Canada | ERAS protocol (ERP) | Reduce LOS | Standard care (TAU) | AEI | CHL; | FM; GUM; PONV |

EON | Hospital | Ward staff | Complications, readmissions, pain, QoL, satisfaction, | |

| Thoracic surgery ( n = 1) | |||||||||||

| Ferreira 2021,57 Canada | Prehabilitation programme (Prehab) | Improve post-op recovery | Rehabilitation (Rehab) | AEI; EX; NUT PSY |

Home | Kinesthesiologist, dietician, psychology-trained personnel | Readmissions, physical activity, QoL, mental health | ||||

| Surgery to remove tumours (various locations) ( n = 2) | |||||||||||

| Hempenius 2013,61 2016,62 Netherlands | Liaison Intervention in Frail Elderly (LIFE) study (PACP) | Prevent post-op delirium | Standard care (TAU) | AEI | University medical centre, teaching hospital, community hospital | Geriatric team | Complications, QoL, mortality, readmissions, mental health | ||||

| Schmidt 2015,74 Germany | Information booklet and diary (Prehab) | Develop patient empowerment to improve short- and long-term outcomes after surgery | Control group (TAU) | AEI; LOG |

Hospital | NR | Complications, pain, mental health, QoL, readmissions | ||||

| Upper abdominal surgery ( n = 3) | |||||||||||

| Dunne 2016,38 UK | Prehabilitation exercise programme (Prehab) | Improve fitness to improve recovery | Standard Care (TAU) | AEI | NR | NR | Readmissions, QoL mental health, physical function | ||||

| Jones 2013,44 UK | ERP (ERP) | Reduce morbidity and LOS | Standard care (TAU) | AEI; NUT |

DRA; FM | DRA; CATH; EON; FM; NUT; ANA |

Hospital | MDT | QoL, pain satisfaction, complications, readmissions | ||

| Kapritsou 2017,80 Greece | Fast-track recovery programme (ERP) | Improve care, improved management of stress and pain | Conventional care (TAU) | nNGT | EMOB | Oncology hospital | MDT | Mental health, pain, complications | |||

All 16 Prehab interventions included components delivered prior to admission, as did 15 of 28 ERP interventions. 41,42,44,46–48,58,65,66,68,69,73,78,86–88 The pre-admission period was used as an opportunity to help prepare patients for surgery, and this usually involved assessment, information or education, and an exercise programme. The most comprehensive pre-admission intervention content was delivered by Larsen and colleagues, and involved information, exercise, goal-setting, nutritional intervention and time with an OT and a social worker. 68,69

The pre-operative period following admission to hospital often contained intervention components in ERP approaches. The period used to directly prepare for surgery, elements such as thromboprophylaxis, absence of mechanical bowel preparation, carbohydrate loading and reduced fasting were implemented. The perioperative period was targeted exclusively by ERP interventions, with adaptations to surgical approach, anaesthesia, prevention of nausea and vomiting, catheter and drain protocols and absence of a nasogastric tube being typical intervention components.

The post-operative period, prior to discharge, featured early mobilisation in 17 studies42,43,45–48,50,60,65,68,69,75,78,80,81,83–85,87 and early oral nutrition in 13. 44,45,50,58,65,68,69,81–85,87,88

Post-discharge components were only present in 11 studies. 42,50,66,68–73,76,79,86,87 Telephone contact was employed by six of these,42,43,50,66,70,73,87 and exercise by two. 79,86

Comparators were usually described as ‘usual care’ or a similar term; however, in 12 studies an active comparator was specified: rehabilitation (n = 4 studies),54,55,57,59 home exercise (n = 2),51,67 low-frequency exercise (n = 1)64 and a walking and breathing protocol (n = 1). 56 In the case of six UBA studies, the pre-intervention period was the comparator. 39–41,46–48

Outcomes of interest included those in the domains of quality of life, mental health, physical activity, physical function, physical activity, pain, patient satisfaction, complications, readmissions, mortality and service utilisation.

Quality appraisal

Quality ratings are displayed in Table 3, with the full breakdown of scores for each item provided in Report Supplementary Material 3. There were only six studies,39,52–54,57,77,81 five of which were RCTs, that received an overall global study quality rating of ‘strong’ using the EPHPP tool. 32 Nineteen studies,37,38,40,50,51,58,60–62,66,68–75,80,82,84,85 of which 18 were RCTs, received a ‘moderate’ quality rating, and the remaining 2241–49,56,59,63–65,67,76,78,79,83,87–89 (17 RCTs) were given a weak rating.

| Study (first author, date) | Component rating (1 = strong, 2 = moderate, 3 = weak) | Global rating of paper | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Selection bias | Study design | Confounders | Blinding of assessors and participants | Data collection methods | Withdrawals and dropouts | Is it clear how LOS and PROMs are defined? (Y/N)a | Strong = no weak ratings, Moderate = 1 weak rating, Weak = 2 + weak ratings | |

| Abdominal surgery | ||||||||

| Kapritsou 202081 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | Y | Strong |

| Takagi 201987 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 1 | Y | Weak |

| Cardiac surgery | ||||||||

| Arthur 200052,a | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | Y | Strong |

| Bennett 202037 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | Y | Moderate |

| King 200876 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | Y | Weak |

| Rief; Auer 201771,72 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | Y | Moderate |

| Sadlonova 202273 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2 | Y | Moderate |

| van der Peijl 200464 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | N | Weak |

| Colorectal surgery | ||||||||

| Bousquet-Dion 201854 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | Y | Strong |

| Carli 201056 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 1 | N | Weak |

| Carli 202055 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | Y | Moderate |

| Dronkers 201067 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 1 | N | Weak |

| Forsmo 201688 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 3 | Y | Weak |

| Frontera 201482 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | N | Moderate |

| Gillis 201459 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 1 | N | Weak |

| Khoo 200745 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 1 | N | Weak |

| Lee 201185 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | N | Moderate |

| Lee 201384 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | Y | Moderate |

| Pappalardo 201683 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | Y | Weak |

| Vlug 201165 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | Y | Weak |

| Lower-limb arthroplasty | ||||||||

| Beaupre 200453 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | Y | Strong |

| Borgwardt 200966 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | N | Moderate |

| Cavill 201679 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 1 | Y | Weak |

| den Hertog 201275 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | Y | Moderate |

| Fransen 201860 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2 | Y | Moderate |

| Garriga 2019 (Hip)39 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | Y | Strong |

| Garriga 2019 (Knee)40 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | Y | Moderate |

| Higgins 202041 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2 | N | Weak |

| Hoogeboom 201063 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | N | Weak |

| Hunt 2009;42 Salmon 2013,43 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | Y | Weak |

| Larsen 200868,69 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | Y | Moderate |

| Maempel 201547 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | N | Weak |

| Maempel 201646 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 1 | Y | Weak |

| McDonald 201248 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 3 | Y | Weak |

| McDonall 201989 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 1 | N | Weak |

| McGregor 200449 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 1 | N | Weak |

| Pour 200778 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 1 | N | Weak |

| Reilly 200550 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 1 | N | Moderate |

| Siggeirsdottir 200586 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 1 | N | Weak |

| Soeters 201877 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | Y | Strong |

| Vesterby 201770 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | N | Moderate |

| Williamson 200751 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 3 | N | Moderate |

| Pelvic surgery | ||||||||

| Frees 201858 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 2 | Y | Moderate |

| Thoracic surgery | ||||||||

| Ferriera 202157 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | Y | Strong |

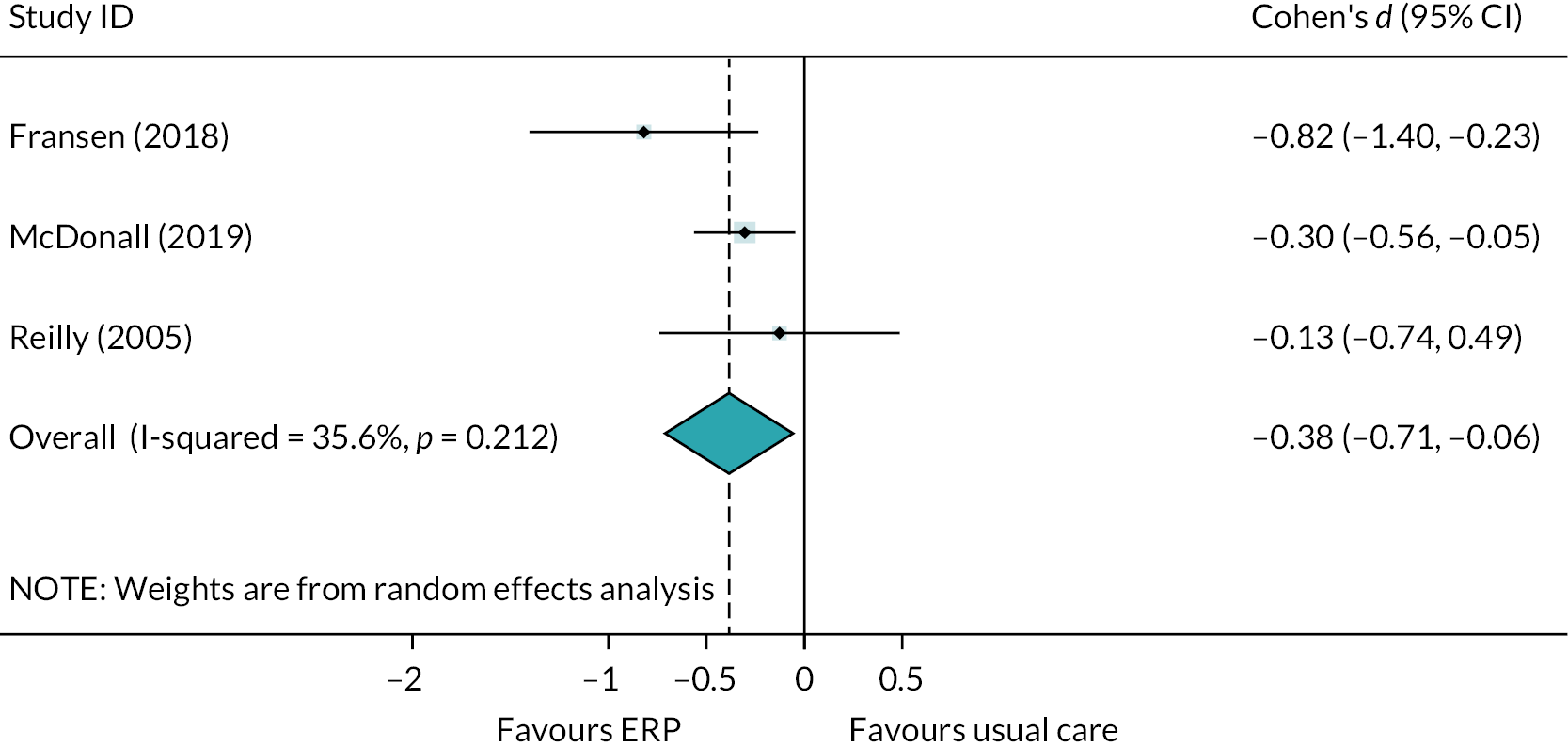

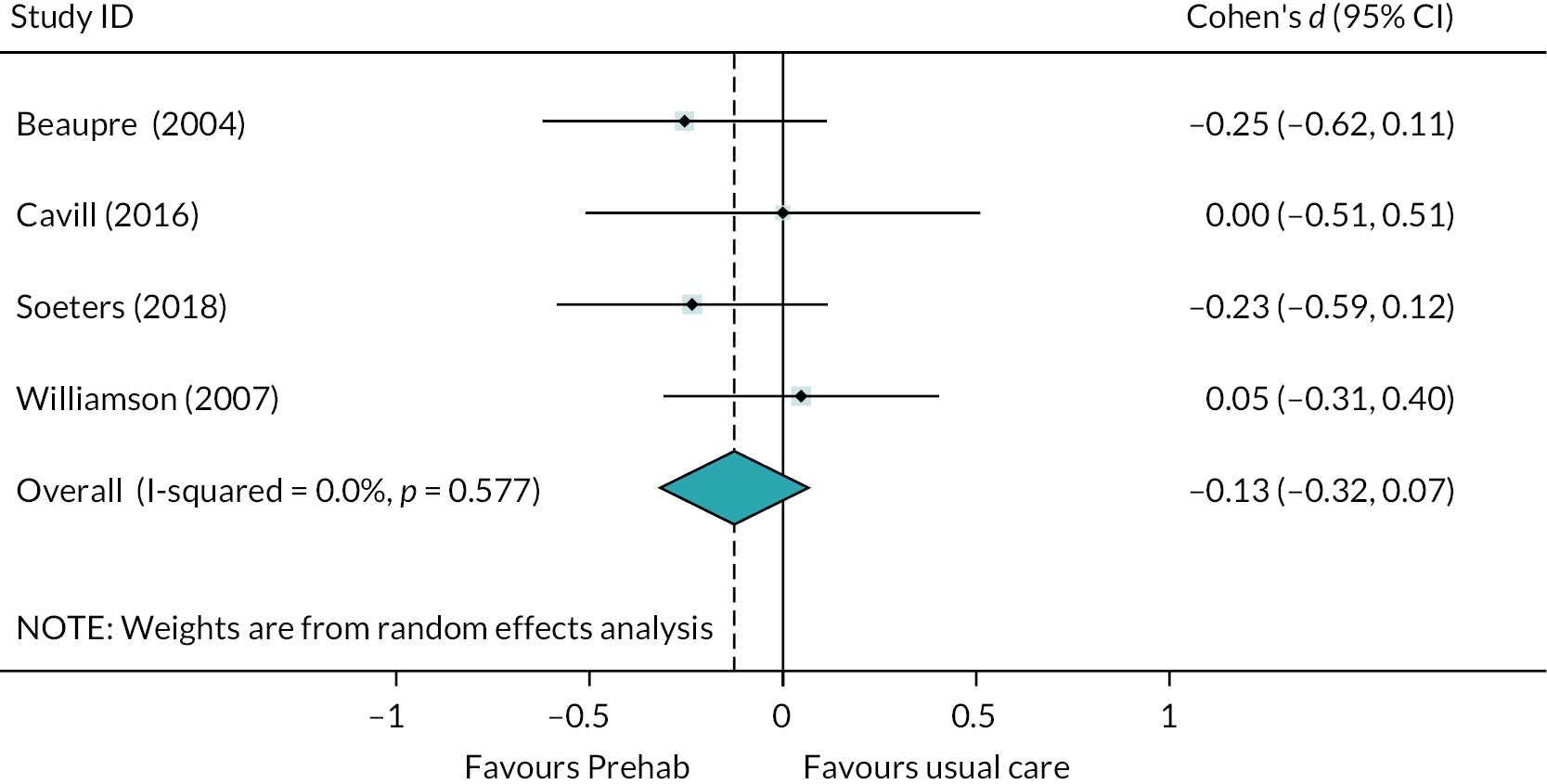

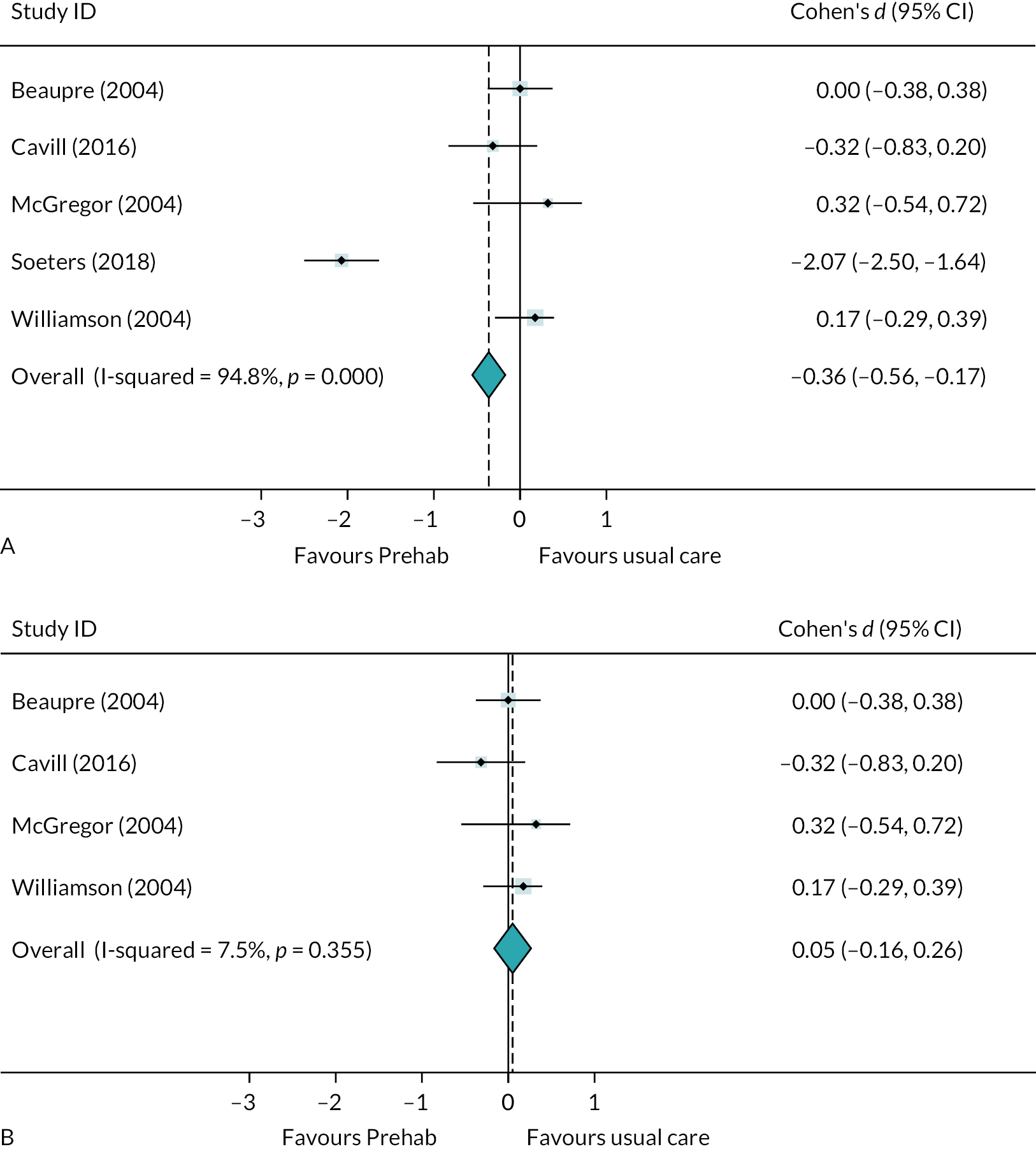

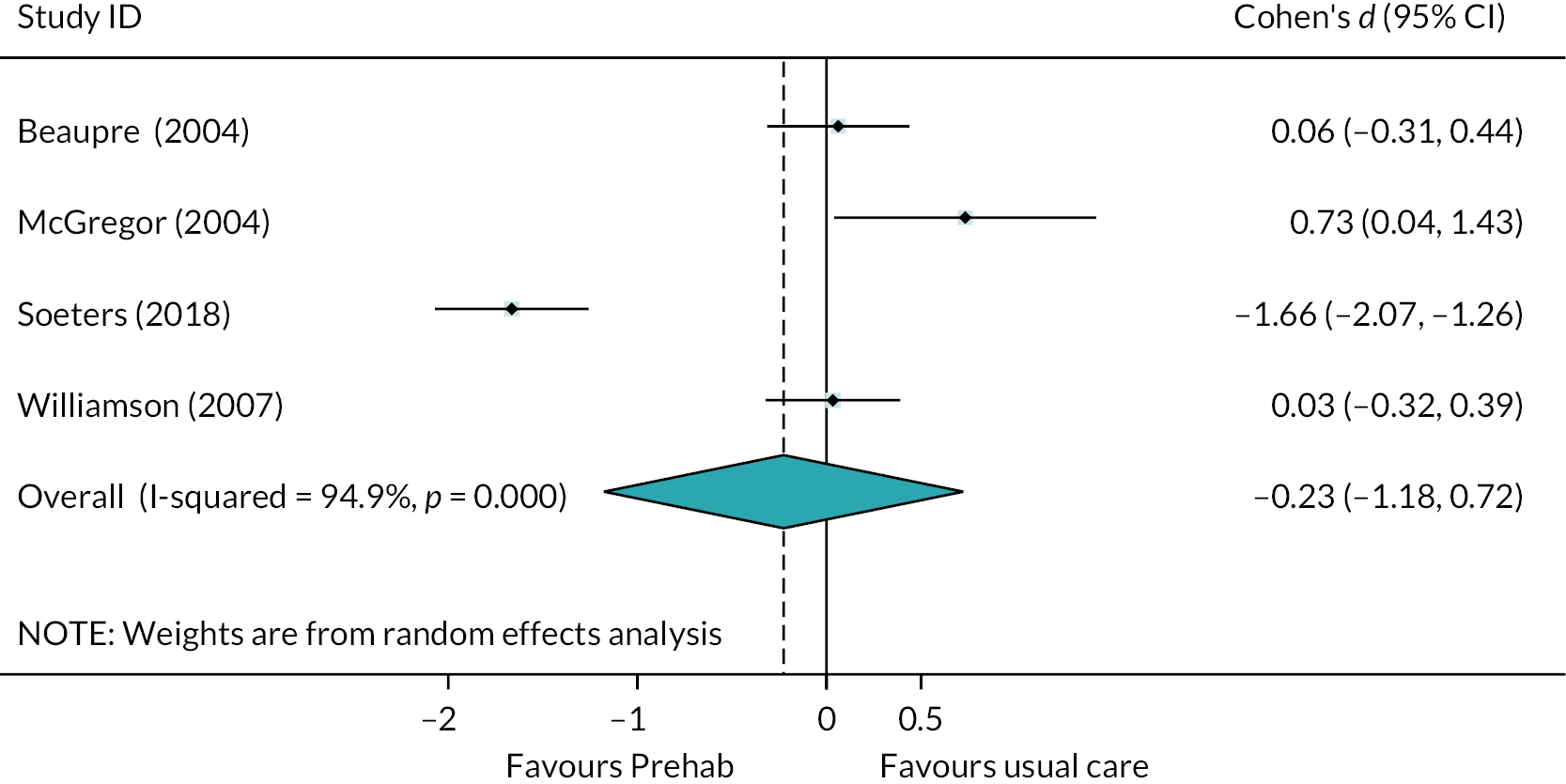

| Surgery to remove tumours | ||||||||