Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number NIHR129663. The contractual start date was in January 2019. The final report began editorial review in February 2020 and was accepted for publication in April 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2023 Fulop et al. This work was produced by Fulop et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2023 Fulop et al.

Chapter 1 Context

Background

There is an internationally recognised need for transparent, integrated and timely processes for identifying quality and patient safety issues across health-care systems. 1 There may be indications of persistent performance issues in a health-care organisation long before a crisis comes to the attention of the public and regulators. Attention has been placed on failing health-care organisations, the characteristics of these organisations and the factors (internal and external) that might lead to low performance. These include low leadership capability, lack of open culture, antagonistic external relationships,2–4 inadequate infrastructure, lack of a cohesive mission and system shocks. 5 A hierarchical culture and leadership focused on avoiding penalties and achieving financial targets – rather than a patient-centred mission – are characteristics identified in many failing organisations. High-quality interventions that are capable of helping struggling health-care organisations to improve are essential. 5

The Special Measures for Quality (SMQ) regime is a targeted and time-limited regime in the NHS in England that has been agreed between the national regulators, the Care Quality Commission (CQC) and NHS Improvement. The regime emerged following the Keogh Review6 into avoidable mortality in 2013. Trusts are entered into SMQ only where serious care quality failings are identified and the leadership appears unable to resolve the problems without intensive support and external input. 7–9 The SMQ regime provides trusts with oversight and interventions from NHS Improvement to help them to address specific quality failings identified in CQC inspections. The CQC then re-inspects the SMQ trust within 12 months of starting SMQ. NHS Improvement perceives SMQ as a support regime to bring about improvement (email from interviewee, NHS Improvement, October 2018). In addition, challenged providers (CPs) that are at risk of entering SMQ are placed on a ‘watch list’ and also receive support. The list of CPs, unlike the list of trusts in SMQ, is not available in the public domain.

Interventions for trusts in SMQ/CPs typically vary between trusts and may include appointment of an improvement director (ID); review of leadership capability; access to financial resources for quality improvement (QI); an improvement plan, including options for diagnostic work on assessing medical engagement; buddying with other trusts; and commissioning external expertise. These interventions may be delivered in conjunction with other interventions and within a context of significant senior leadership changes.

Commentaries on the SMQ regime have highlighted potential unintended consequences for organisations, such as difficulties with recruitment and retention, lowering of staff and patient morale, increases in financial costs, and external pressures placed on already burdened management systems. 10 A recent evaluation of the CQC inspection regime categorises eight types of regulatory impact arising from the inspection regime (Table 1). 11 The impact of CQC inspections was found to vary considerably according to the type and size of provider; however, ‘directive’, ‘stakeholder’ and ‘organisational’ influences appear most applicable to providers that are asked by the regulator to take immediate action to improve quality and enter SMQ.

| Impact mechanism | Description |

|---|---|

| Anticipatory | Providers seek to comply in advance of regulatory interactions (e.g. inspection) |

| Directive | Providers take direct actions as requested by the regulator. Legal consequences possible in cases of non-compliance |

| Organisational | Providers instigate internal processes not explicitly related to directives on account of interaction with the regulator, such as addressing leadership or culture |

| Relational | Influence of (human, interpersonal) interactions between regulatory staff and regulated providers |

| Informational | Regulatory information on performance enters the public domain and informs decision-making |

| Stakeholder | Other stakeholders take action and interact with the regulated provider |

| Lateral | Regulatory interaction results in new interorganisational actions (across boundaries), such as peer learning |

| Systemic | Regulatory information on providers is used to identify wider issues in systems of care, beyond a single provider |

Our understanding of the impact of the SMQ/CP regimes and the interventions provided by NHS Improvement to support trusts is limited. To date, to the best of our knowledge, no academic studies have independently evaluated the interventions delivered when a trust enters SMQ/CP. Here we seek to understand how trusts respond to being placed in SMQ/CPs and whether or not and how the interventions provided impact the trusts’ capacity to achieve and sustain QIs over time.

The SMQ and CP regimes were ‘in transition’ during the evaluation and writing of the report, and there were several changes:

-

Matt Hancock was appointed Secretary of State for Health and Social Care on 9 July 2018, replacing Jeremy Hunt, who had been in the role since 2012.

-

Weekly ‘Care Meetings’ with the Secretary of State to review trusts in SMQ/CP regimes were replaced by monthly meetings with no ministers present.

-

We were informed that the CP regime ended in October 2019.

Study objectives

The objective of the study was to analyse the responses of trusts to the implementation of (1) interventions for trusts in SMQ and (2) interventions for trusts in the CP regime to determine their impact on these organisations’ capacity to sustain and achieve QIs.

The study focused on the main interventions that NHS Improvement has identified as forming part of the SMQ/CP regimes:

-

appointment and use of an ID

-

buddying with other trusts

-

the opportunity to bid for central funding to spend on QI.

We also remained open to any other interventions that participating trusts identified as being part of the SMQ/CP regimes and considered these interventions within a wider context of any leadership changes.

Research questions

-

What are the programme theories (central and local) guiding the interventions delivered to trusts in SMQ/CP regimes?

-

How and why do trusts respond to SMQ/CP regimes and the interventions within these regimes?

-

Which features of trusts in SMQ/CP regimes, and their wider context, contribute to their differing performance trajectories?

-

What are the relative costs of the interventions and how do these compare with their benefits?

-

How are data used by trusts in SMQ/CP regimes, and how do data contribute to their understanding of improvements in quality and service delivery, especially in areas where performance concerns have been raised by the CQC?

-

Do trusts in SMQ/CP regimes find it more difficult to recruit and retain staff?

Research overview

This study was conducted by the Rapid Service Evaluation Team (RSET). RSET, funded by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Health and Social Care Delivery Research (HSDR) programme, is a 5-year research programme that aims to rapidly evaluate health and care service innovations to produce timely findings of national relevance and immediate use to decision-makers. The topic of this report was identified through discussions between the NIHR HSDR programme and the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC). The provider policy and acute care team in the DHSC wanted to understand in greater depth how the SMQ and CP regimes were working and what lessons could be learned for the future.

There is limited knowledge about whether or not the interventions used to deliver support for trusts in SMQ/CP regimes drive improvements in quality, the costs of these interventions and whether or not the interventions strike the right balance between support and scrutiny. This study seeks to determine how provider organisations respond to these interventions, and whether or not and how these interventions impact organisations’ capacity to achieve and sustain QIs over time. Our study also provides a greater understanding of the programme theory, impact and staff views and experiences of the SMQ/CP regime.

We conducted a multisite, mixed-methods evaluation, involving eight case studies of purposively selected NHS trusts, that draws on multiple sources of national- and local-level data. The protocol was developed with input from relevant DHSC and NHS Improvement teams, by scoping relevant documents and with feedback from academic peers and patient representatives. The evaluation has been formative, with findings shared and discussed with key stakeholders during the study.

The study comprised five interrelated work streams:

-

literature review using systematic methods

-

interviews at a national level

-

multisite, mixed-method case studies

-

analysis of national indicators and workforce

-

economic analysis.

Structure of the report

Chapter 1 (background) presents the background and rationale for the evaluation. Chapter 2 (methods) presents the overarching design of the evaluation and provides an overview of the research methods employed (detailed information on methods is presented within each results chapter). Chapters 3–10 (results) present the findings of the study. With the exception of the literature review (see Chapter 3), the individual results chapters do not include discussion sections. The results are integrated and discussed in a final discussion chapter (see Chapter 11). Chapter 11 (discussion and conclusion) presents the implications and lessons learned from our findings for regulators and policy-makers, health-care providers, staff and health system leaders and for researchers conducting rapid evaluations. It discusses the strengths and limitations of the study. This chapter also proposes future areas for research and future evaluation methods.

Chapter 2 Methods

Overview

This chapter gives an overview of the methods used in the evaluation.

This chapter draws on the published study protocol by Fulop et al. 12 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Study design

We conducted a multisite, mixed-methods study that combined qualitative and quantitative approaches to analyse the implementation of interventions delivered to SMQ/CP trusts and the impact of these interventions on trust performance, quality of care, patient experience and costs. To allow the study to be undertaken within a 1-year time frame, data collection and analysis have followed a rapid research design13 involving teams of field researchers, participatory approaches and iterative data collection and analysis, with the research team meeting fortnightly to discuss progress and emergent findings.

Ethics and research governance approvals

The University College London Research and Development Office and Ethics Committee reviewed the study protocol and materials. The study was classified as a service evaluation, as defined by the NHS Health Research Authority, and did not require Research Ethics Committee approval. Guidelines for data security, confidentiality and information governance have been followed. An informed consent process, using participant information sheets and written consent, was used for recruitment to ensure informed and voluntary participation. We are aware of the sensitive nature of this research for organisations and individuals. The research team has experience in conducting research on similar sensitive topics. The independence of the research and the anonymity of participants and organisations has been upheld.

Approach to the evaluation

The study protocol12 was developed over a 6-month period (August to December 2018) through discussions with relevant teams at the DHSC and NHS Improvement, by scoping relevant documents and with feedback from academic peers and patient representatives.

This was a formative evaluation, and we took an active approach to sharing our interim findings with key stakeholders, including the DHSC, NHS Improvement central and regional teams, and CQC. For a full list of activities to date, see Report Supplementary Material 1. Key examples of ongoing engagement activity with stakeholders include:

-

presenting findings to the DHSC, NHS Improvement and CQC at their meetings and conferences

-

sharing findings with the case study trusts

-

publishing articles in peer-reviewed journals and presenting papers at academic and professional conferences

-

producing accessible summaries of our findings for wider distribution to a range of audiences, including trusts, regulators, policy-makers and patient groups.

Research methods

Our study consisted of five interrelated elements.

Literature review using systematic methods

A rapid literature review of organisational failure in the public sector was conducted to guide our empirical research, particularly with respect to data analysis (see Chapter 3). Rapid-review methodology that uses a phased search approach was followed. 14 Rapid reviews follow a systematic review approach, but some steps are adapted to reduce the time required to complete the review (i.e. using large teams to review abstracts and full texts, and extract data; in lieu of dual screening and selection, a percentage of excluded articles are reviewed by a second reviewer and software can be used for data extraction and synthesis14).

Phase 1 of the review was based on a broad search of health services, business and management journals, and a review of the grey literature (e.g. think tank reports), to develop a theoretical understanding of the main characteristics of organisational failure and turnaround, and the types of interventions implemented to improve quality. This literature was used to develop a conceptual and theoretically informed framework that could be used to inform the phase 2 research questions (RQs), search strategy, inclusion criteria and interpretation of findings. We used the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) statement15 to guide the reporting of the methods and findings. The review protocol was registered with PROSPERO (CRD42019131024). The full details of the review methodology are described in Chapter 3.

The review sought to answer the following RQs:

-

Phase 1

-

How are ‘failing health-care organisations’ defined?

-

What are the theoretical approaches that have been used to explain organisational failure in and outside health care?

-

How is ‘organisational turnaround’ defined?

-

Which theoretical approaches have been used to study turnaround strategies (if any)?

-

-

Phase 2 (covering health care, education and local government)

-

What are the main interventions used to improve quality?

-

Do the studies highlight any specific issues with implementation?

-

What are the interventions classified as ‘successful’?

-

Have any of these interventions been evaluated? If so, what is the impact and sustainability of improvements produced by these interventions?

-

What are the costs of these interventions?

-

Analysis of policy documents and interviews at a national level

To understand the nature of the SMQ/CP regimes and the programme theories that underpin them (i.e. the underlying assumptions and expectations about the purpose of the intervention and the anticipated impact), we conducted qualitative interviews with staff at a national level at the beginning of the evaluation. We also collected and reviewed reports and documents (n = 20) that would help us to understand the origins of the approach of the SMQ and CP regimes, the regulatory and policy context, and how these dual approaches had evolved over time (see Chapter 4). A small number of internal documents were shared with the team by NHS Improvement and interviewees early into the evaluation, which were incorporated for review.

Semistructured qualitative interviews were conducted with six staff at the national level. To identify relevant staff to invite for interview, the research team contacted representatives of key stakeholder groups – NHS Improvement, CQC and DHSC – to ask for recommendations for individuals involved in the SMQ/CP regimes. These individuals were then independently invited by e-mail to take part in a research interview. The purpose of these interviews was to better understand the nature of interventions deployed to support trusts and how the interventions were perceived by different stakeholders in relation to their programme theory/theories, and which interventions are viewed as being particularly effective, and under what conditions. The interview guide (see Appendix 1) covered three broad topic areas: (1) aims of the SMQ/CP regimes; (2) policy and interventions and (3) impact. The national interviews were professionally transcribed and analysed by a researcher (JL), who produced a thematic summary document for review by the wider project team early in the evaluation.

Multisite, mixed-method trust case studies

We conducted eight case studies (four ‘high level’ and four ‘in-depth’) using qualitative and quantitative approaches. We used a case study approach to explore the implementation of interventions in SMQ/CP trusts and reflect on any observed changes in processes and outcomes reported across specified time points (e.g. point of entry into or exit from SMQ). Case study research is common in management, business and organisational research and policy evaluations. Yin16 defined the case study as an ‘in-depth inquiry into a specific and complex phenomenon’. 16 Case studies typically employ a range of data collection methods, quantitative, qualitative or a mixture of both, to ‘construct narratives of past events, or accounts of specific cases’. 17

Sampling of case study trusts

Inclusion criteria:

-

NHS trusts (ambulance, acute, mental health and/or community providers) placed in SMQ and/or CP regimes on or before 30 September 2018.

Exclusion criteria:

-

trusts placed in SMQ and/or CP regimes (for the first time) after 30 September 2018

-

trusts placed in Special Measures for Finance (SMF) only and never in SMQ/CP regimes.

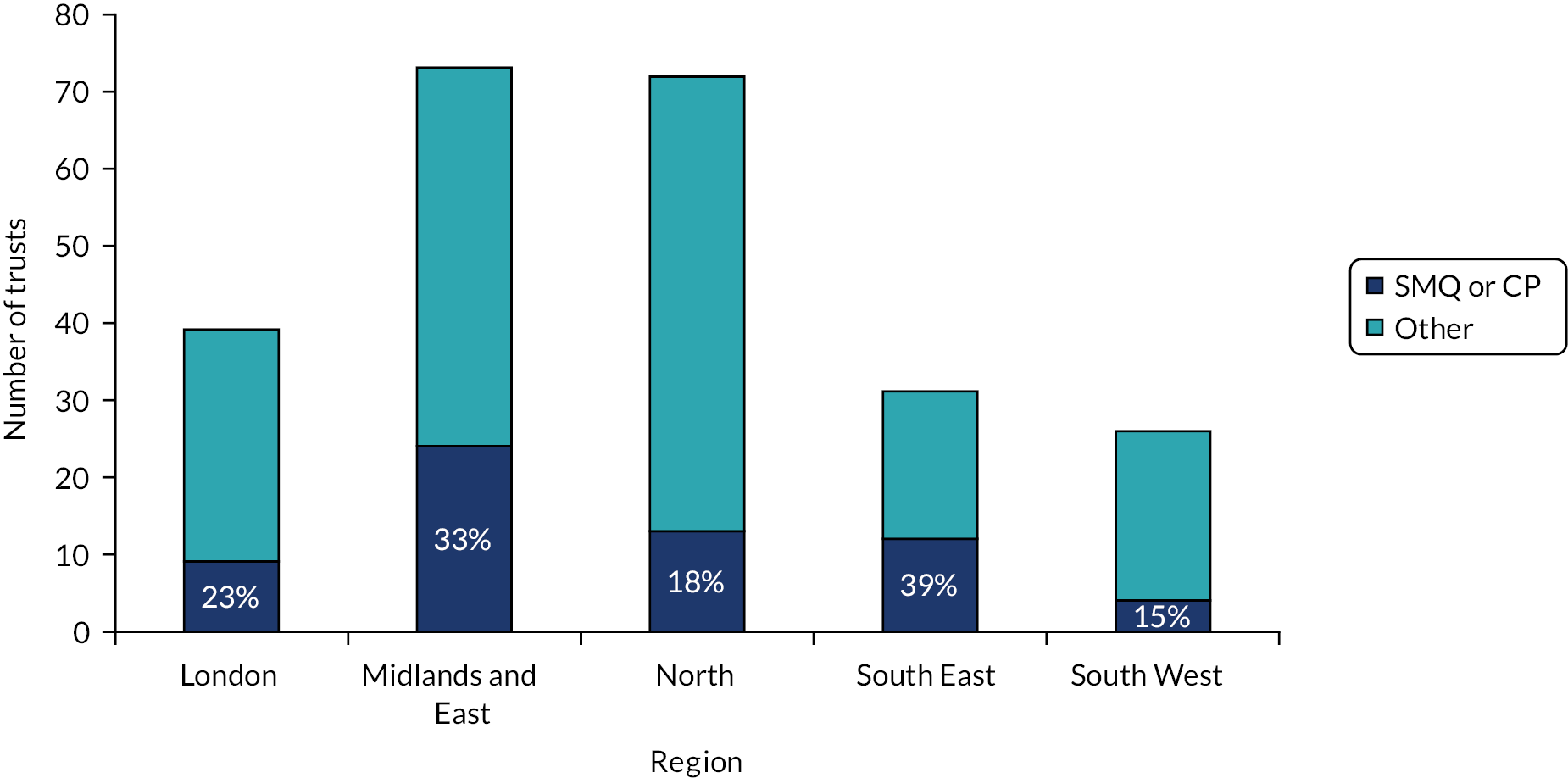

To identify potential case study trusts, we conducted a preliminary analysis of data supplied by NHS Improvement on trusts that had entered SMQ since the regime began in July 2013, up to 30 September 2018. A total of 35 trusts entered SMQ; four trusts returned to SMQ (giving 39 episodes), 25 had exited SMQ and, as of 30 September 2018, there were 14 trusts in SMQ. The ‘watch list’ of CPs was initiated in July 2015. These trusts received interventions to prevent them entering SMQ. On 30 September 2018, there were 17 trusts on this list. Since July 2015, 44 trusts have been placed on this list, with 17 trusts leaving the CP regime because they entered SMQ and one trust leaving the list and subsequently returning. A total of 59 trusts entered SMQ or became a CP between July 2013 and September 2018. As of January 2019, there were 234 trusts in England, meaning that roughly one-quarter of trusts had experience with the SMQ or CP regime (Table 2).

| Trust type | Trusts ever in the SMQ or CP regimes (n) | Trusts in SMQ (at September 2018) (n) | Trusts in the CP regime (at September 2018) (n) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Acute services only | 33 | 7 | 9 |

| Acute and community | 18 | 4 | 7 |

| Acute and mental health | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Ambulance | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Community and mental health | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Mental health | 4 | 1 | 0 |

| Total | 59 | 14 | 17 |

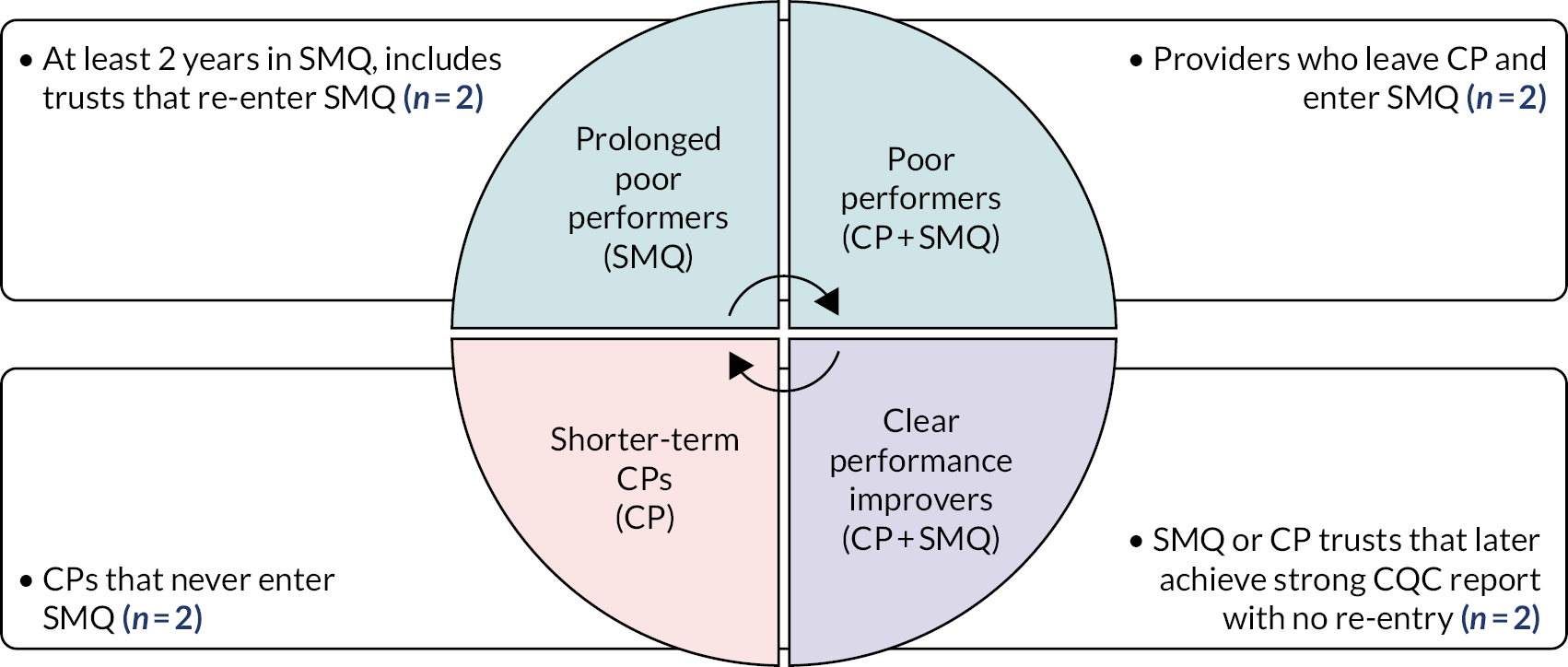

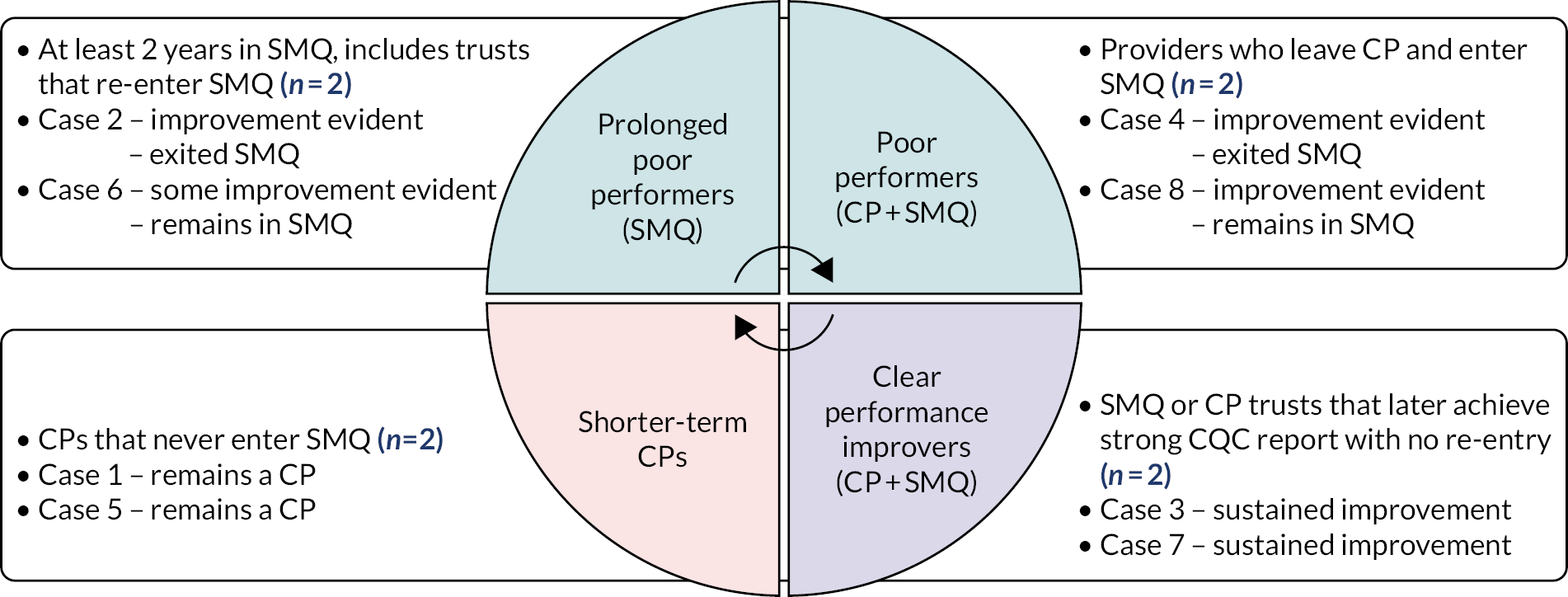

A total of 59 trusts met our inclusion criteria (see Table 2). We looked at the performance trajectories for these trusts and categorised them into four groups: prolonged poor performers, poor performers, shorter-term CPs and clear performance improvers (Table 3). Trusts were categorised based on the length of time spent in the SMQ/CP regimes and their progress over time, noting that some organisations were in the CP regime for only a short length of time and moved between categories. Therefore, although the categories are not fixed or absolute, our selected sites were in one of the categories at the time of sampling and met the criteria (e.g. re-entry into SMQ for a prolonged poor performer).

| Performance categorya | Performance category description | Trusts matching descriptionb |

|---|---|---|

| Prolonged poor performers | Trusts that have been in SMQ for ≥ 2 years since the introduction of the regime, including those trusts that re-enter SMQ after a period of exit | 19 |

| Poor performers | CP trusts that end up in SMQ | 12 |

| Shorter-term CPs | CPs that avoid entry into SMQ and have not previously been placed in SMQ. This may include trusts that merged with higher-performing providers. They are or were ‘challenged’ for < 2 years | 20 |

| Clear performance improvers | Trusts that have previously entered SMQ or CP but later achieved a good or outstanding overall CQC rating, without re-entry into either regime | 9 |

| Other trusts | Trusts that do not meet any of the other criteria (four trusts that were ‘challenged’ for a longer time, and one trust that left SMQ after a short period but has never been rated good or outstanding by CQC). These trusts were not sampled | 5 |

Given that the overall objective of the case studies was to understand dynamics within trusts and their local contexts at different ends of the performance spectrum, we purposively sampled eight case study sites, with two sites from each performance category (Figure 1). We also aimed to recruit case study sites from a range of geographical locations and types of trusts. Of the two case studies within each performance trajectory, one was conducted ‘in depth’ and one at a ‘high level’.

FIGURE 1.

Purposive sampling model for case studies. Reproduced with permission from Fulop et al. 12 This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY 4.0), which permits others to share and adapt this work for any purpose, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original figure.

Case study recruitment

Trusts were invited to participate via an e-mail to the chief executive officer (CEO); the e-mail explained whether the trust would be an ‘in-depth’ or a ‘high-level’ case study and what this would entail (see Report Supplementary Material 2). To recruit eight case study trusts, a total of 12 trusts were invited to participate (Table 4). Perhaps unsurprisingly, it was more difficult to recruit to the ‘prolonged poor performer’ and ‘poor performers’ groups.

| Group | Type of sampling | Invitations to trusts |

|---|---|---|

| Prolonged poor performers | In depth | 3 (2 declined) |

| High level | 1 | |

| Poor performers | In depth | 3 (2 declined) |

| High level | 1 | |

| Short-term challenged | In depth | 1 |

| High level | 1 | |

| Clear improvers | In depth | 1 |

| High level | 1 |

Qualitative fieldwork: data collection

Qualitative fieldwork combined semistructured interviews, meeting observations and documentary analysis (Table 5). Interviews and observations were used to understand the processes used to implement the interventions based on available data to plot a chronology of the changes in quality at each site. Internal (inner) and external (outer) contextual factors potentially influencing participation in the interventions, including senior-level leadership changes and perceptions from the wider community and stakeholders in the local heath economy, were considered. In addition, we remained open to understanding the interventions that trusts perceived to be part of SMQ/CP regimes, as well as those identified by NHS Improvement as being effective for driving change. To aid the quantitative analysis, qualitative data were collected on how people within trusts use data, with an emphasis on whether or not and how data are used to track improvements in quality of care. Similarly, to facilitate the economic analysis, qualitative data were collected about resource use and costs incurred by the different interventions, and the perceived impacts on quality and additional unintended consequences of the interventions (positive or negative).

| In-depth case studies | High-level case studies | |

|---|---|---|

| Qualitative components | ||

| Non-participant observation (e.g. board meetings and operational meetings) |

|

|

| Interviews |

|

|

| Documentary analysis |

|

|

| Quantitative components | ||

| Trust use of quantitative information relating to quality of care |

|

|

| Tracking of outcome measures against improvement actions |

|

|

| Trust use of metrics to monitor impact of SMQ/CP interventions |

|

|

Sampling and recruitment within case studies

Participants

‘Vertical slicing’ was used to guide sampling in the four ‘in-depth’ case studies, with the goal of conducting interviews across different organisational tiers and with external stakeholders, including local branches of Healthwatch (London, UK). The types of interviewees who were purposively sampled were dependent on the context of each case study trust; for example, in addition to divisional/clinical directors, it was relevant to include staff from a clinical unit that the CQC had flagged as ‘inadequate’ (e.g. maternity). In the four ‘high-level’ cases, we aimed to conduct interviews at the ‘top’ of the organisation and with key external stakeholders. Senior leaders and those involved in QI at each case study trust were asked to make recommendations for interview participants. At the in-depth case study sites, it was requested that an invitation e-mail was circulated to staff to invite them to take part in the study; staff were asked to respond directly to the lead researcher to discuss further if they would like to be interviewed confidentially. Other potential participants were identified by contacting local peer organisations and through snowballing from respondents.

Non-participant observations

We observed public trust board meetings and quality-focused or performance-focused meetings at the divisional level at the four ‘in-depth’ cases after securing prior permission and gaining verbal consent from participants at the time of the meeting. We used the board QI maturity framework18 in our observations of boards and other relevant meetings to support the analysis of observational data. Our aim was to focus on critical quality incidents or service issues where progress in QI appeared to be ‘transparently observable’ or where improvements were proving especially challenging for the organisations. 19 Thus, we were open to studying a particular clinical unit that had been flagged as in need of improvement in earlier CQC inspections or a new intervention that the trust had introduced to support staff engagement in QI, such as ‘quality huddles’.

Documents

We collected and analysed documents developed by trusts to operationalise improvement efforts and recommendations from the regulator to help triangulate findings from interviews and observations. Documents included relevant meeting minutes (e.g. board meetings and operational units), quality committee meeting minutes, strategic performance documents (e.g. QI plans, where available or shared with the researchers) and business plans.

A summary of the interviews, observations and documents obtained for each case study is presented in Table 6.

| Case study site | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data source | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | Total |

| Senior team interviews | 6 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 6 | 6 | 44 |

| Divisional-level interviews | 5 | 2 | 3 | 2 | – | 1 | – | – | 13 |

| External interviews | 2 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 2 | – | 3 | 4 | 21 |

| Total interviews | 13 | 8 | 13 | 12 | 8 | 5 | 9 | 10 | 78 |

| Total meeting observations | 2 | – | 5 | 2 | – | 2 | – | – | 11 |

| Documents | 27 | 29 | 71 | 33 | 52 | 55 | 14 | 10 | 291a |

The use of data by trusts

To complement the qualitative analysis, we looked deeper into the way that data were being used by case study trusts, focusing specifically on how trusts monitor the impact of quality interventions and track improvements, and whether or not they perceive that they have the capabilities and resources to do so effectively. We assessed any changes in the way that trusts use data once being placed into SMQ or CP, including investing resources to support more accurate data collection and monitoring. We also analysed whether or not and how trusts track progress against required improvements, as these examples could offer helpful insights into whether or not trusts will be resilient to future challenges.

This work links with the qualitative analysis described above, wherein trust interviews provide on-the-ground insight into how being in SMQ/CP regimes influence their approach to the collection of data and how they monitor quality. The qualitative interview topic guides included questions focused on the trust’s use of information.

Other sources of information included CQC inspection reports; documents produced by, or on behalf of, trusts (e.g. board reports, quality accounts); NHS Improvement monthly monitoring of trusts and changes in their performance [e.g. NHS Improvement Single Oversight Framework (SOF) segmentation]; and, for wider context, the findings of the rapid literature review.

The analysis included monitoring relevant improvement actions highlighted by these documents where they can be appropriately linked to outcomes observed in data. For example, if CQC raised concerns about a stroke service, we would be interested in how the trust used data to track outcomes and to provide assurance that the quality of the stroke service was improving. There may also be evidence to suggest that pressures on some outcomes are related to performance of other providers in the local health system, which will be investigated, where feasible. For some measures, data would be available to put the trust’s changes in outcomes within a national context; possible sources include material published by the trusts (e.g. board papers), published statistics and patient-level records from Hospital Episode Statistics (HES), and national monitoring reports produced by NHS Improvement (e.g. monthly SOF segmentation spreadsheets). (Note that we have approval from NHS Digital covering all projects conducted by the RSET.)

Case study data analysis

Interviews were professionally transcribed and made centrally available, along with documents and observational data (field notes), for analysis by multiple members of the research team.

Triangulation of interview, observational, cost information, documentary and quantitative data was performed to produce eight local case studies that were analysed thematically and comparatively, consistent with suggestions in academic literature on analysing processes of change in organisations19–21 and on receptive contexts for sustaining QI in health care. 22,23

Documentary analysis was used to identify organisational strategies and variables that appear to indicate change over time (i.e. since point of entry into SMQ), such as shifts in organisational composition (e.g. workforce numbers and vacancy levels) and changes in organisational structure (e.g. new governance systems or mergers). Documentary analysis was also used to allow comparisons between central and local theories guiding QI efforts.

Throughout the data collection process, the data were summarised in the form of rapid assessment procedure (RAP) sheets (see Report Supplementary Material 3). 13 The RAP sheets were used to facilitate consistency in data collection across researchers and allowed the team to identify gaps in data collection that needed to be addressed before the end of fieldwork. The RAP sheets also facilitated analysis, allowing the researchers to readily compare specific data categories between trusts and to conduct within-case and cross-case analyses. 24

A number of conceptual frameworks guided the case study analysis. We used a board maturity framework developed in previous research, which found that boards with higher levels of maturity in relation to governing for QI were able to effectively balance short-term (external) priorities against long-term (internal) investment in QI, and engage staff and patients in the process of change. 18 We created a template for mapping meetings and papers to the ‘Organisational Maturity Framework’ developed by Jones et al. 18 (see Appendix 2), which was applied to the four in-depth case study trusts as a means of gauging their board maturity (see Chapter 7). To understand processes of QI beyond board level, especially among ‘clear improvers’ that exit SMQ and sustain change, we used the concepts of ‘absorptive capacity’ and ‘dynamic capabilities’ from the strategic management literature to identify any routines or processes that have helped staff, from senior leaders to front-line clinicians, to learn from external information about performance and quality to sustain performance objectives (see Chapter 7). 25 Absorptive capacity refers to the ability of organisations to acquire and exploit new information and knowledge, and successfully transfer it internally, across organisational subunits, to support learning and performance. 26 Dynamic capabilities refers to patterned activities and routines that require dedicated resources and long-term commitment to effect impactful change. 27 Applying such concepts has helped us to distinguish between evidence of incremental or evidence of ad hoc changes in trusts arising from externally driven SMQ interventions, and more radical or novel service innovations that improve quality and trust performance and have become embedded in new ways of working over time at trusts (see Chapter 7).

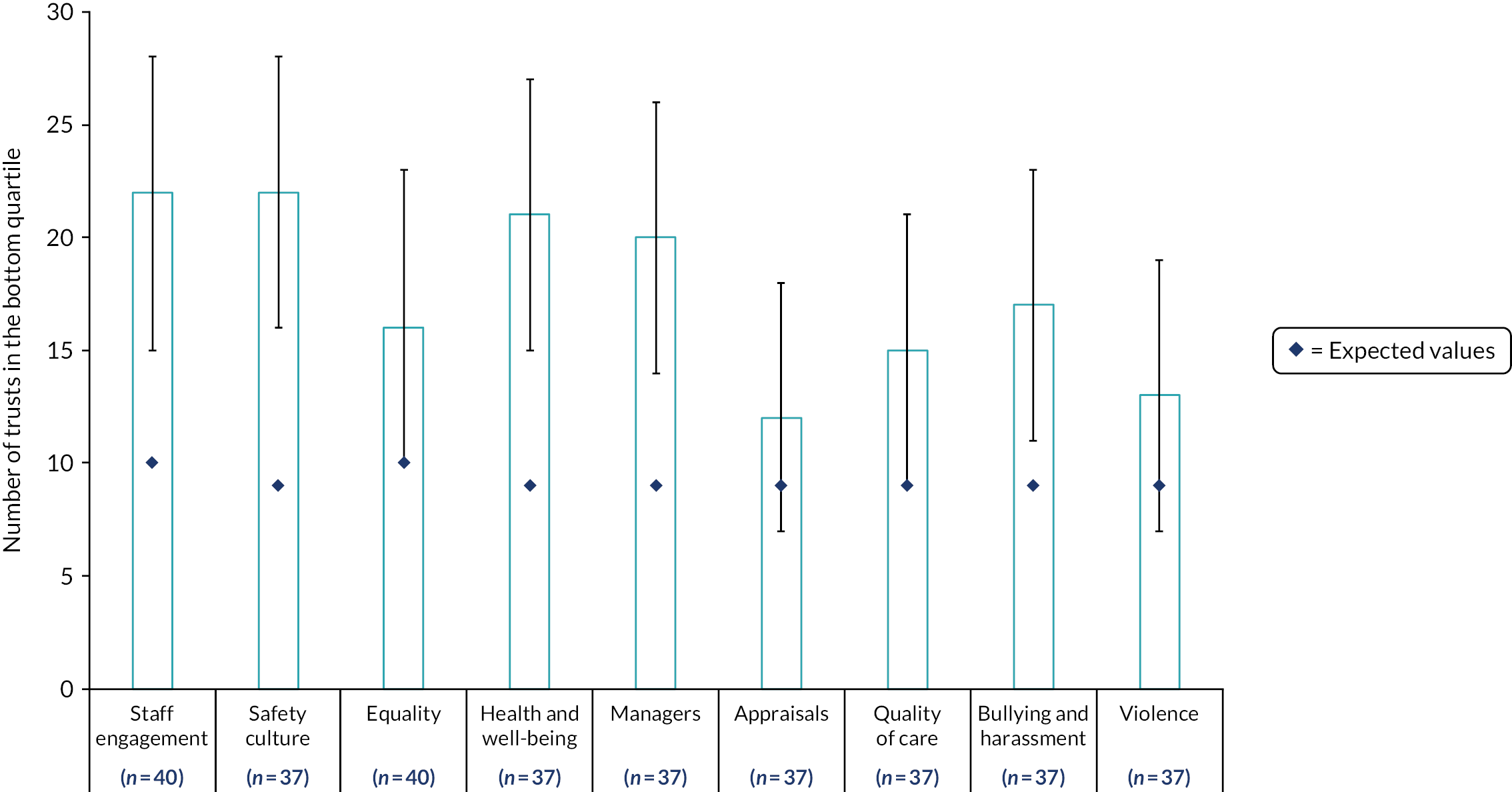

Analysis of national indicators and workforce

This quantitative component of the evaluation explored relationships between being in a SMQ/CP regime and a set of performance and workforce indicators. For workforce, we were particularly interested in whether or not trusts found it more difficult to recruit and retain staff at different levels and evidence of the impact of interventions on the staff themselves. For the case study sites, these data were combined with trust inspection information from CQC. The workforce analysis was exploratory and was subject to the construction of a consistent and comparable workforce data set and sufficient sample sizes to establish any statistical links. One of our aims was to raise hypotheses that could be tested more robustly in future studies and reflected back to the case study sites for their qualitative insights.

Economic analysis

The economic analysis aimed to quantify the costs and benefits of different combinations of interventions used in SMQ/CP regimes from an NHS perspective using a cost–consequences analysis (CCA) approach (see Chapter 9). A CCA compares interventions in which the components of incremental costs (direct or indirect) and consequences (e.g. knowledge, behaviours and processes) are computed and listed, without aggregating these results into a cost-effectiveness ratio. 28 This approach enables one to look into process measures and qualitative findings in a quantitative manner, allowing for some insight as to how potential benefits compare with the cost of interventions.

A feasibility study for the economic analysis found that:

-

A CCA was feasible, but it would be possible to evaluate different combinations of interventions only (i.e. it would not be possible to evaluate the benefits of each intervention individually). It would need to account for likely variation in the type and intensity of these interventions, for example the percentage of full-time equivalent time that the ID spends at the trust, different buddying models and varying receipt of funds spent in different ways. We will explore the impact of this variation on both costs and consequences.

-

Costs could be measured using resource use and unit cost data collected during the multisite mixed-methods study.

-

Consequences could be measured using qualitative data collected during the multisite mixed-methods study and/or combining it with quantitative data.

Cost analysis

We looked at the direct costs of the interventions at both the national level and the level of our eight case study sites. For the case studies, we examined data on funds received to support improvement (CP trusts may access up to £200,000, while SMQ trusts may access up to £500,000) and how these funds, when received, were spent. We have also considered opportunity costs that were incurred as a result of the trust being under the SMQ or CP regime.

Cost–consequences analysis

Two types of consequences were considered: primary consequences (relating to the entry and exit of the trusts in SMQ/CP regimes) and secondary consequences (relating to staff experiences and cultural changes within the trusts that were derived from the findings of the NHS staff survey 2014–18, and the financial stability of the trusts).

Presentation of findings from the case studies

To ensure the anonymity of the participating organisations and individuals in this potentially sensitive study, we present the findings in the following ways: indicating the numbers of cases in relation to particular points, rather than which cases, and for quotes we have used generalised job titles (e.g. ‘senior director’ for all executive directors) without reference to the specific case study.

Patient and public involvement

We undertook two main steps to ensure patient and public involvement (PPI) in the evaluation design. First, we presented the topic to a local research advisory panel on 16 January 2019, a group comprising 10 patient representatives and members of the public. This group was sent a three-page summary document in advance of this meeting outlining the remit of the RSET, the pipeline of current studies and an outline of the ‘Special Measures for Quality’ study. The panel were asked to reflect on the following three questions that would be explored in the meeting, as well as general points about ‘rapid evaluation’:

-

What questions would you have for staff at a hospital that was placed in SMQ by the health regulator (the CQC)?

-

What questions would you have for the senior leadership team and hospital board?

-

What questions or concerns might you have about SMQ if this was your local NHS hospital?

Two researchers (JL and JS) presented further information about the evaluation and explored these questions with the panel, which resulted in a lively discussion that was supported by a PPI and communications officer. Minutes were taken from the meeting. Questions that the panel asked of the researchers included wanting to understand why regulators were brought into health-care organisations and whether or not this occurred on an annual basis across all organisations (at trust and hospital levels), and if patients could find out about CQC reports. The panel wanted reassurance that the researchers would have access to an organisation’s leadership team, as well as historic information to find out what had arisen within the organisation over time, especially where other senior staff had left. It was noted that the model was similar to regulation in schools undertaken by Ofsted. Several key points and recommendations were summarised and reported back to the wider team to inform the study protocol:

-

Clarity about where SMQ sits (i.e. directorate, trust or hospital level).

-

Visibility and publicity about SMQ (e.g. how is it communicated to the staff and public?).

-

Access to leadership (ensure during the study).

-

Can anything be found out about preventing entry to SMQ?

-

Engage with local patient groups, such as Patient Advice and Liaison Service (PALS) (although check they are independent and separate from the complaints department) and the local Healthwatch.

The second stage involved two patient representatives (also PPI panel members) providing more detailed feedback on the revised study protocol through a process of ‘light touch’ peer review. A summary of the feedback obtained through this process and how it informed the updating of the final protocol submitted to the NIHR is presented in Appendix 3. The two patient representatives also gave feedback on the Plain English summary included in this report. Our protocol included a local involvement and engagement strategy linked to case studies. However, our rapid approach meant that we did not have time to do this.

Chapter 3 The implementation of improvement interventions for ‘low-performing’ and ‘high-performing’ organisations in health, education and local government: a phased literature review

Overview

This chapter draws on Vindrola-Padros et al. 29 ‘The implementation of improvement interventions for ‘low performing’ and ‘high performing’ organisations in health, education and local government: a phased literature review’ (submitted to the International Journal of Health Policy and Management, April 2020). The review examines underlying concepts guiding the design of interventions, processes of implementing these interventions, their unintended consequences and the impact on costs and quality of care. The purpose of the review was to inform our empirical study.

What was known?

-

There is a limited understanding of whether or not and how improvement interventions aimed at improving the performance of health-care organisations are effective.

What this chapter adds

-

Successful interventions included restructuring senior leadership teams, inspections (in schools) and internal reorganisation by external organisations.

-

Most interventions were designed and implemented at an organisational level, without considering system context.

-

Limited attention was paid to the potential negative consequences of the interventions and their costs.

Background

There may be indications of persistent performance or quality issues in a health-care organisation long before a crisis comes to the attention of the wider public and regulators. This highlights the need for transparent, integrated and timely processes for identifying quality and safety issues within organisations and across health-care systems. 1 Attention has been placed on failing health-care organisations, the characteristics of these organisations and the factors (both internal and external) that might lead to low performance. These include, for example, low leadership capability (as indicated by, for example, lack of ability to engage with staff or to be transparent), ‘closed’ culture and antagonistic external relationships. 2 There are also a number of analyses of organisational failure, and sometimes turnaround, in various sectors, for example in the corporate sector, such as Enron (Houston, TX, USA)30 and Marks & Spencer (London, UK),31 the financial crash of 2008,32 and the health sector (including failures in hospital organisation and management),33 which identify reasons for failure and how they might be addressed.

A recent systematic review5 of research on the characteristics of failing health-care organisations in multiple countries and settings identified five characteristics shared across failing organisations: (1) poor organisational culture; (2) inadequate infrastructure; (3) lack of a cohesive mission; (4) system shocks; and (5) dysfunctional external relations with other hospitals, stakeholders or governing bodies. 5 More specifically, a hierarchical culture and leadership focused on avoiding penalties and achieving financial targets, rather than a patient-centred mission, are characteristics identified in many failing health-care organisations. 34–36

Available reviews, such as that by Vaughn et al. ,5 suggest that an important next step after diagnosis of problems is the development of high-quality interventions capable of helping struggling health-care organisations to improve. However, there is limited understanding about whether or not and how improvement interventions are effective in supporting failing organisations and improving the quality of care in high-performing organisations in the public sector. The aim of this review is to examine the underlying concepts guiding the design of these interventions, processes of implementation and unintended consequences of implementing the interventions, and their impact on costs and quality of care. The review includes articles in the health-care sector, as well as other public sectors such as education and local government, to learn from the extensive research carried out in these non-health-care sectors.

Methods

Design

The review was based on the phased rapid review method proposed by Tricco et al. 14 and expanded the review of organisational failure published by Vaughn et al. 5 The rapid review method followed a systematic review approach, proposing adaptations to some of the steps to reduce the amount of time required to carry out the review (i.e. the use of large teams to review abstracts and full texts, and extract data; in lieu of dual screening and selection, a percentage of excluded articles is reviewed by a second reviewer, and software is used for data extraction and synthesis, as appropriate14).

The review included two phases. Phase 1 was based on a broad search of health services, business and management journals, and a review of the grey literature (e.g. think tank reports) to develop a theoretical understanding of the main characteristics of organisational failure and turnaround, and the types of interventions implemented to improve quality (for an example of this approach, see Ferlie et al. 37). This literature was used to develop a conceptual and theoretically informed framework (see Table 7). The framework was used to inform the phase 2 RQs, search strategy, inclusion criteria and interpretation of findings. We used the PRISMA statement15 to guide the reporting of the methods and findings. The review protocol was registered with PROSPERO (CRD42019131024).

| Domain | Description | Disciplines (classified based on journal) | Examples in the literature |

|---|---|---|---|

| Organisational failure/success | |||

| A. Concepts used separately or in combination | |||

| 1. Failure as decline | ‘Existence-threatening decline’ in the performance of the organisation. Focus is on the organisation | Management, business | Pandit41 (2000), Mellahi and Wilkinson42 (2004) |

| 2. Failure as crisis | Focuses on the peak of failure, considering it as an acute process or sudden onset (considers the possibility of crisis denial and hidden crisis to account for more gradual representations of failure). Focus is on the organisation | Management, business | Slater43 (1984), Weitzel and Jonsson44 (1989) |

| 3. Failure as below acceptable performance levels | Organisational performance is persistently below some minimally acceptable level. Distinguishes between the minimum acceptable level of performance and performance that is ‘persistently’ below this acceptable level. Focus is on the organisation | Management, business | Hambrick and Schecter45 (1983) |

| 4. Success as a system property/structural processes involved in failure | High-performance results from properties of the system and not characteristics of the individuals. Focus is beyond the organisation and attention is paid to the structures of inspection and performance | Health services research, education | Baker et al.46 (2008), Bate et al.47 (2007), Taylor et al.48 (2015), Willmott49 (1999), Perryman50 (2005) |

| B. Theoretical frameworks | |||

| 1. Industrial organisation | Organisational failure is caused primarily by changes in the external environment, which are the result of a range of technological, economic, regulatory and demographic factors | Management, business | Mellahi and Wilkinson42 (2004) |

| 2. Organisational ecology theory | Applies a natural selection model to organisational dynamics. It is based on a biological analogy, in which organisations scan the environment and compete and recognise situations, mechanisms and processes underlying emergence, growth, regulation and demise | Management, business | Hannan and Freeman51 (1989) |

| 3. Industry life cycle theory | Organisational failure is considered a natural and objective event (i.e. likely to occur), the outcome of factors such as saturation of demand, running out of supplies, and introduction of new technology | Management, business | Klepper52 (1997) |

| 4. Organisational psychology | Views failure and success as a result of internal rather than external and environmental factors (i.e. leadership capacity, composition of top management teams, governance models, organisational arrogance and myopia) | Management, business, health services research | Mellahi et al.31 (2002), Curry et al.35 (2011) |

| 5. Failure and organisational learning/organisational culture, role of emotions | Failure is caused by lack of, limited or dysfunctional organisational learning. Preventing failure is dependent on changes in organisational culture | Health services research, education | McKiernan53 (2002), Fulop et al.54 (2005), Walshe and Shortell55 (2004), Harvey et al.25 (2015), Jones et al.18 (2017), Dixon-Woods et al.56 (2014), Willis57 (2010), Nicolaidou and Ainscow58 (2007), Leithwood et al.59 (2008) |

| 6. Failure and success within regimes of surveillance | Foucauldian outlook on surveillance, monitoring and performance, seeing external actors such as Ofsted as reproducing disciplinary power. Critique of dualisms. Focus on discourse and view of inspections (or the threat of inspections) as the mechanism through which discipline is reproduced | Education | Willmott49 (1999), Perryman60 (2005), Perryman50 (2006), Ferlie et al.37 (2012) |

| 7. Contextual factors leading to failure (internal and external) | Failure is usually caused by a combination of different factors (both internal and external). Management is unlikely to be the sole cause of decline and managers may be symptoms of failure as much as causes. Recognises the need to consider system-wide factors when addressing failure | Management, business, health services research, education | Fulop et al.54 (2005), Walshe and Shortell55 (2004), Ravaghi et al.4 (2015), Smithson et al.11 (2018), Taylor et al.48 (2015), Vaughn et al.5 (2019), Dixon-Woods et al.56 (2014), Chapman61 (2002), Chapman and Harris62 (2004) |

| Turnaround | |||

| C. Concepts | |||

| 1. Turnaround as recovery | The actions taken to bring about recovery in performance in a failing organisation | Management, business | Pandit41 (2000) |

| 2. Turnaround as a potential stage in wider analysis of organisational failure (i.e. McKieran’s six-stage model, Argyowasmy’s two-stage model) | Explains the process of decline and/or turnaround as occurring in sequential stages that may result in the survival and performance improvement or failure of an organisation | Management, business | Chowdhurry63 (2002), Fulop et al.54 (2005), Paton and Mordaunt64 (2004) |

| 3. Turnaround as a complex (non-linear) process | Considers turnaround as a complex process involving intraorganisational areas (including human relations, organisational behaviour and group-level behaviour). Considers turnaround in the context of any radical organisational change and not just recovery from a crisis | Management | Beeri65 (2009), Beeri66 (2012) |

| D. Theoretical exploration of turnaround strategies | |||

| 1. Turnaround based on replacement | Strategies put in place to reshape organisational structures | Management, business, health services research | Harvey et al.67 (2005), Fulop and Scheibl68 (2004), Paton and Mordaunt64 (2004), Walshe et al.1 (2004), Jas and Skelcher69 (2005), Ravaghi70 (2007) |

| 2. Turnaround based on retrenchment | Strategies are put in place to limit the use of resources and ‘save’ the organisation (i.e. cost cutting and asset reduction) | Management, business, health services research | McKiernan53 (2002), Greenhalgh71 (1983), Hardy72 (1987), Sutton et al.73 (1986), Ravaghi70 (2007) |

| 3. Turnaround based on renewal | Activities utilised to reorient the direction of an organisation and its vision, with the aim of ensuring long-term successful survival | Management, business, health services research | Protopsaltis et al.74 (2002), Fulop and Scheibl.68 (2004), Walshe et al.1 (2004), Boyne75 (2008), Ravaghi70 (2007) |

| 4. Turnaround based on external episodic intervention | Hands off and focused on performance outcomes and not process. Use of regular inspections | Management, business, health services research | Jas and Skelcher69 (2004), Harvey et al.76 (2006) |

| 5. Turnaround based on relational/mutual arrangements | There is agreement between all parties and it is based on monitoring | Management, business, health services research | Jas and Skelcher69 (2004), Harvey et al.76 (2006) |

| 6. Turnaround based on mandated approaches | External actors take over the organisation, allowing little room for negotiation | Management, business, health services research | Jas and Skelcher69 (2004), Harvey et al.76 (2006) |

Research questions

The review sought to answer the following RQs:

-

Phase 1 (covering health services research, management and business studies)

-

How are ‘failing organisations’ defined?

-

What are the theoretical approaches that have been used to explain organisational failure?

-

How is ‘organisational turnaround’ defined?

-

Which theoretical approaches have been used to study turnaround strategies (if any)?

-

-

Phase 2 (covering health care, education and local government)

-

What are the main interventions used to improve quality?

-

Do the studies highlight any specific issues with implementation?

-

What are the interventions classified as ‘successful’?

-

Have any of these interventions been evaluated? If so, what is the impact and sustainability of improvements produced by these interventions?

-

What are the costs of these interventions?

-

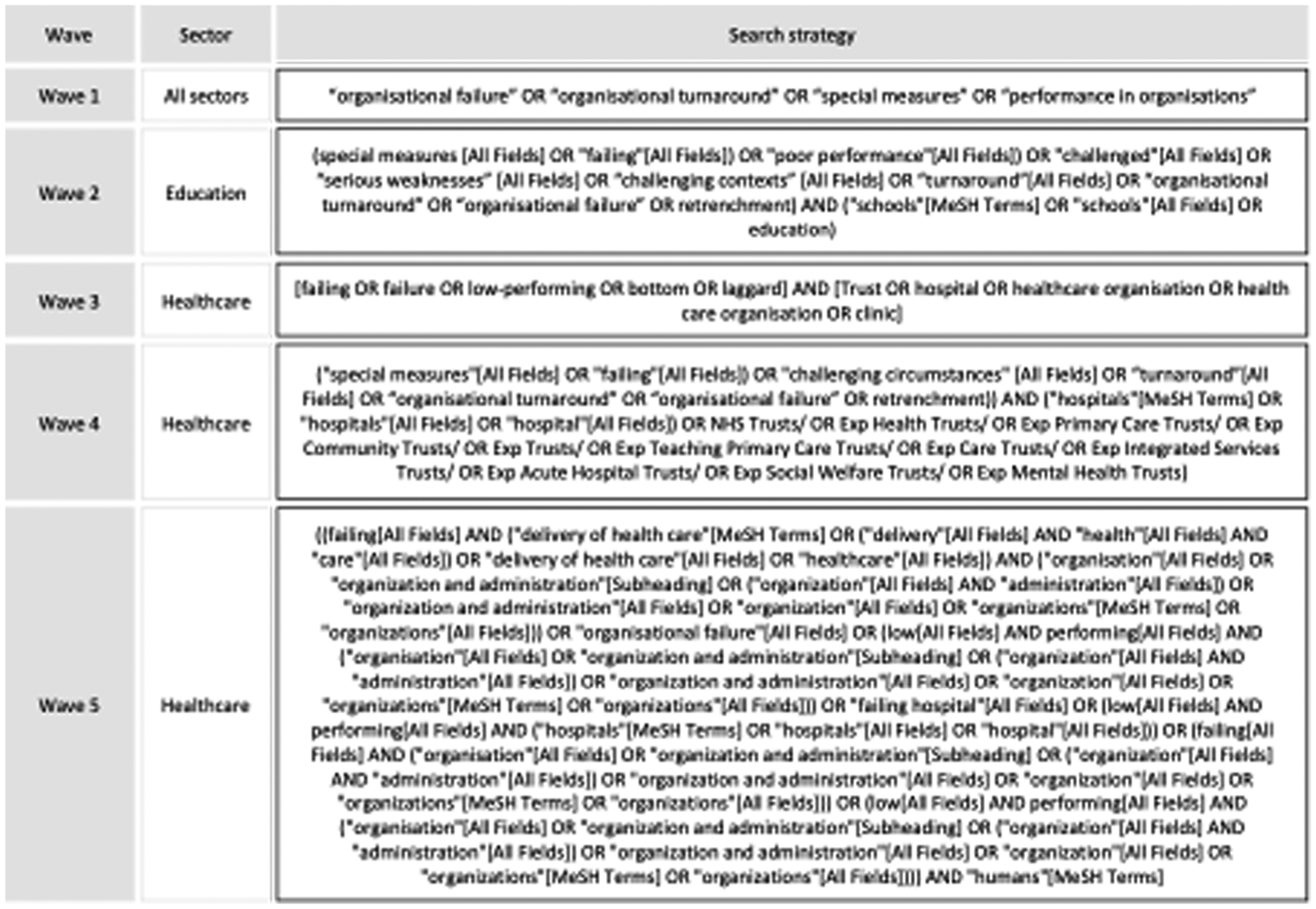

Phase 1

We used a phased search approach. 14 The first phase was broad, covering literature from the fields of health services research, management and business studies to identify overarching themes and definitions on regulation, performance and QI in health-care organisations and the public sector. Broad terms such as ‘organisational failure’, ‘organisational turnaround’, ‘special measures’ and ‘performance in organisations’ were used to identify initial relevant literature across the public sector. A second search targeted literature in the education sector. All other searches (3–5) focused on the health sector. Using a snowball technique, additional terms were found and inserted into a search strategy for five databases [MEDLINE, EMBASE™ (Elsevier, Amsterdam, the Netherlands), Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) Plus, Web of Science™ (Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, PA, USA) and OpenGrey], creating longer and more complex search strategies (see Appendix 4). These databases were selected in consultation with a librarian who sought to identify the most relevant databases for the review topic.

Phase 1 focused on identifying the theoretical content from the literature on organisational failure and turnaround to develop a thematic framework to guide the review. We followed the approach for building thematic frameworks for reviews used by Ferlie et al. 37 Definitions for key concepts, such as ‘organisational failure/success’ and ‘turnaround’, were identified. Furthermore, we searched for the main theoretical frameworks used to explain these processes and synthesised their main characteristics. We sought to create a high-level overview of the different perspectives that have been used to explore failure, success and turnaround in organisations. The findings from phase 1 informed the RQs developed to guide phase 2 of the review.

Phase 2

Search strategy

The second phase was more targeted and focused only on organisational failure and turnaround in health-care, education and local government settings. The search strategy was designed in relation to the PICOS (Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcome, Setting) framework, the findings from phase 1 and strategies used in other reviews on improvement and low- and high-performing organisations. 5,38,39 We conducted a review of published literature using multiple databases: MEDLINE, CINAHL Plus, EMBASE™ and Web of Science™. Results were combined into Mendeley (Elsevier) and duplicates were removed. The reference lists of included articles were screened to identify additional relevant publications. We also hand-searched other relevant databases, such as The King’s Fund library. We searched for relevant grey literature using OpenGrey and TRIP (a medical sciences database).

Study selection

Following rapid review methodology,37 one researcher screened the articles in the title phase and three researchers cross-checked 20% of exclusions in the abstract and full-text phases. Disagreements were discussed until consensus was reached. The inclusion criteria used for study selection were (1) focus on the delivery of interventions in failing organisations, defined as not meeting the required quality standards (self-defined); (2) focus on the delivery of interventions in high-performing organisations (self-defined); (3) describes empirical research; (4) describes a study in a health-care, education or local government setting; (5) published in last 20 years; and (6) published in English.

Data extraction and management

The included articles were analysed using a data extraction form developed in REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture). The form was developed after the initial screening of full-text articles and piloted independently by two researchers using a random sample of five articles. Disagreements were discussed until consensus was reached. The data extraction form was finalised based on the findings from the pilot.

Data synthesis

Data were exported from REDCap and the main article characteristics were synthesised. The information that was entered in free-text boxes was exported from REDCap and analysed using framework analysis. 40 We used the thematic framework developed in the first stage of the review to guide our exploration of themes.

Results

Phase 1 thematic framework

The main components of the thematic framework are summarised in Table 7. The five waves of searches for phase 1 provided a working list of 56 relevant publications. Key examples of this literature are included in Table 7.

We found that three definitions of failure are common in the literature (as decline, crisis and below previously established performance level), but only one of these considers failures at a system level (i.e. beyond individual organisations and including multiple organisations) (see Table 7). Some authors argued that failure and success should not be considered discrete, opposite concepts, but should be understood as in a dialectical relationship (highlighting the contradictions and inherent tensions between components). The seven theoretical frameworks used to explain organisational success or failure (see Table 7) reproduce this focus on the organisation as the unit of analysis and neglect of system-level pressures, with the exception of two of the more recent ones (see Table 7, Section B – 6 and 7). Concepts of turnaround tend to privilege a linear conceptualisation of organisational recovery processes, with only one approach considering turnaround as a non-linear complex process (see Table 7, Section C– 3). Turnaround has also been explored as either an internal or an external approach, with limited discussion of the interaction between internal and external strategies.

The findings from phase 1 informed the RQs developed to guide phase 2 of the review. We sought to explore the interventions delivered in low-performing and high-performing organisations, identifying the underlying ideas that guided them, such as their conceptualisation of failure/success as an organisational or system-wide feature, the perception of turnaround as a linear or non-linear process, and the extent to which they considered the interactions between internal and external strategies to guide turnaround processes. As a result of the findings from this phase, and the consideration of success and failure in a dialectical relationship, we decided to develop a phase 2 that explored the experiences of both low-performing and high-performing organisations.

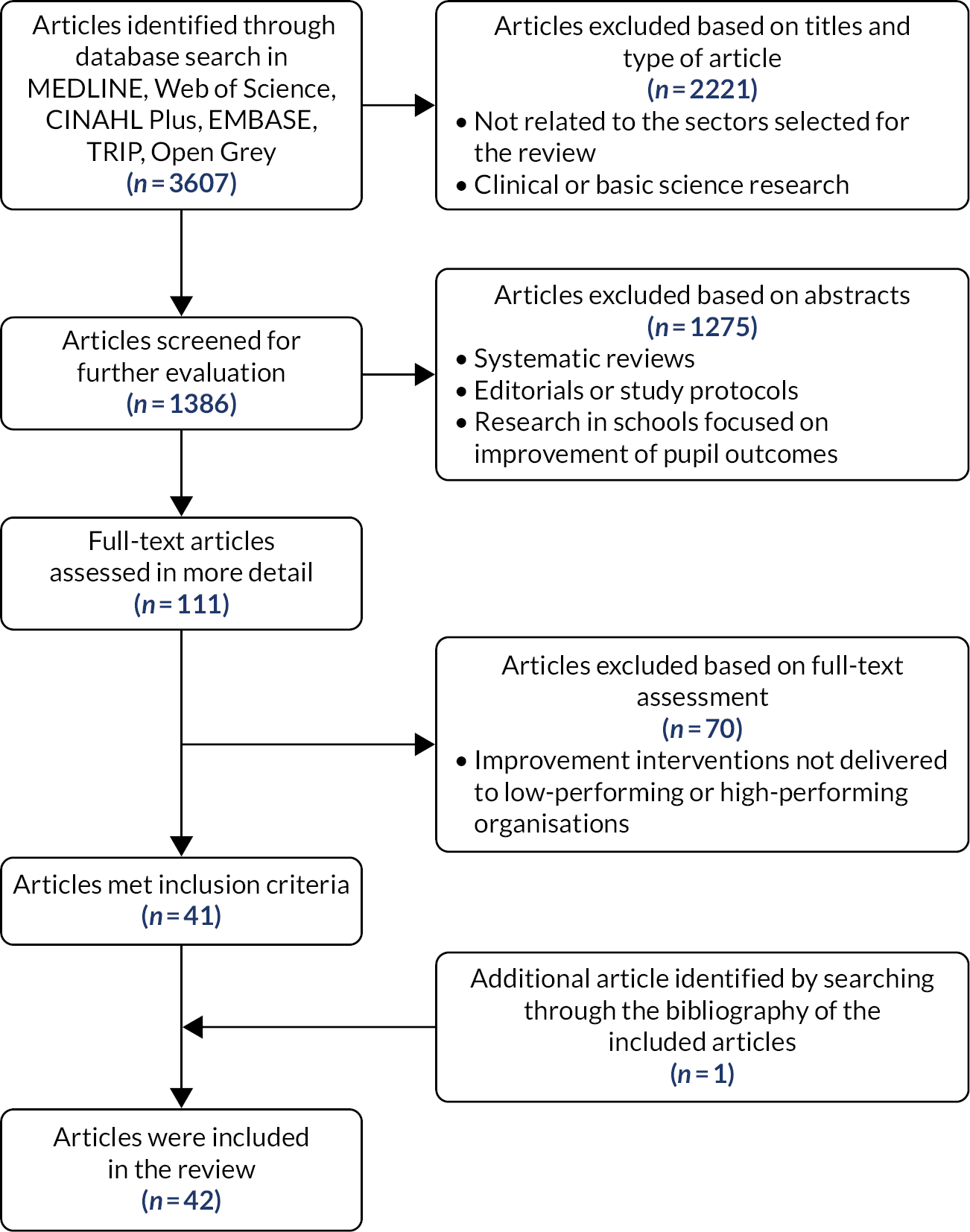

Phase 2 results

The initial search yielded 3607 published articles (Figure 2). These were screened based on their title and the type of the article, resulting in 1386 articles. These articles were further screened on the basis of their abstracts, which left 111 articles for full-text review. Full-text review of these articles led to 41 articles that met the inclusion criteria. One additional article was identified by reviewing the bibliography of the included articles, leading to 42 articles being included in the review. We excluded articles that focused on improvement in individual pupil outcomes (i.e. reading levels) and not general school performance, or articles that did not discuss specific interventions used for improvement.

FIGURE 2.

Study selection procedure.

Characteristics of the included studies

Seventeen of the studies took place in the USA, 20 were from the UK, one took place in the UK and the USA, one took place in Canada, two took place in Israel and one was a comparison across six European countries (Table 8). The publications were relatively recent, with most articles published post-2010. Study designs varied, but most studies were qualitative, followed by quantitative and mixed-methods designs.

| Characteristic | Education (n = 18) | Local government (n = 10) | Health care (n = 14) | Total (n = 42) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study location |

|

|

|

|

| Publication date range | 1999–2019 | 2004–14 | 2005–18 (most 2010 onward) | 1999–2019 (most post-2010) |

| Study design |

|

|

|

|

Definitions of failure and turnaround

We examined definitions of failure and success in the articles in relation to the thematic framework that we developed in phase 1 (see Table 7). Failure/success appeared to be defined in most studies as ‘organisational performance that is persistently below or above some minimally acceptable level’45 (see Table 7, Section A – 3). Low-performing and high-performing organisations were defined as such in relation to nationally established ratings or indices (i.e. Audit Commission Comprehensive Performance Assessment ratings or Academic Performance Index). This definition distinguished between the minimum acceptable level of performance and performance that is ‘persistently’ below and above this acceptable level. The focus of this definition of failure/success tended to be on the organisation and was not applied to the wider system.

Some studies have tried to incorporate a ‘success/failure as a system property’ approach by considering the relationships between the provider organisation and other external organisations; however, even in these studies, consideration of system-level properties was limited. In most studies, failure was considered to be produced by limited or dysfunctional organisational learning (see Table 7, Section B – 5).

Preventing failure and producing improvements were dependent on changes in organisational culture. Some studies indicated that individual interventions aimed at QI were not effective if they did not address problems in organisational culture. 82

In relation to turnaround strategies, none of the 11 studies in the health-care sector described turnaround strategies imposed by external parties, yet these strategies were frequent in studies from education and local authorities. For instance, Jas69,78 argued that for turnaround to be effective in local authorities, it needed to be externally driven. In health care, most of the turnaround strategies were based on relational/mutual arrangements. Some studies framed turnaround under RRR (replacement, retrenchment and renewal), which we previously identified in phase 1 (including these three aspects of the intervention or only some of them). Replacement can refer to the replacement of executive members of a board, retrenchment is based on using stricter financial controls and focusing on performance targets, and renewal strategies could involve changing organisational culture and improving stakeholder engagement. 4 Most of the interventions that we analysed followed a renewal approach, with few examples of replacement. In local authorities, retrenchment (i.e. reduction of spending in particular areas) was seen as producing negative consequences.

Type of intervention

One of the aims of the review was to explore the types of interventions used to improve quality in low-performing and high-performing organisations. The types of interventions varied by sector, but we found overlap in a few of these. We were able to group the interventions into 10 main categories (Table 9):

-

financial incentives (including pay for performance schemes and grants)

-

external partnerships and sharing of practice

-

QI training

-

reorganisation at multiple levels, including senior leadership level, and the use of external interim managers

-

development of existing leadership and/or middle management

-

identification of organisational goals or priorities

-

use of routine data and establishment of performance standards (including dashboards)

-

standardising care practices

-

RRR (replacement, retrenchment and renewal)

-

interventions involving external inspections.

| Sectora | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention type | Education | Local government | Health care |

| Financial incentives (including pay for performance schemes and grants) | Rice et al.79 (2012); Rosenberg et al.77 (2015) | Werner et al.80 (2008) | |

| External partnerships and sharing of practice | Marsh et al.81 (2017) | Mannion et al.82 (2005) | |

| QI training | Hochman et al.77 (2016) | ||

| Reorganisation at multiple levels, including senior leadership level, and the use of external interim managers | Heck and Chang83 (2017) | Beeri66 (2012), Beeri84 (2013), Beebe13 (2014), Yapp and Skelcher85 (2007) | Mannion et al.82 (2005), Hochman et al.86 (2016) |

| Development of existing leadership and/or middle management | Meyers and Hitt87 (2018), Nicolaidou and Ainscow58 (2007), Orr et al.88 (2008), Van Gronigen and Meyers89 (2019) | Beeri84 (2013), Jas and Skelcher69 (2005), Jas78 (2013) | Gagliardi and Nathens90 (2015) |

| Identification of organisational goals or priorities | Finnigan et al.91 (2012), Chapman and Harris62 (2004) | Tsai et al.92 (2015), Hochman et al.77 (2016) | |

| Use of routine data and establishment of performance standards (including dashboards) | Mintrop and Trujillo93 (2007) | Turner et al.94 (2004) | Chang et al. 201895; Tsai et al.92 (2015), Gagliardi and Nathens90 (2015), Aboumatar et al.96 (2015) |

| Standardising care practices | Curry et al.35 (2011) | ||

| RRR (replacement, retrenchment and renewal) | Beeri65 (2009), Beeri66 (2012) | ||

| Interventions involving external inspections | Willis57 (2010), Wilmott49 (1999), Parsons97 (2013), Perryman60 (2005), Perryman50 (2006), Gorton et al.98 (2014), Ehren et al.99 (2013) | Jas and Skelcher69 (2005) | Allen et al.100 (2019), Boyd et al.101 (2016), Castro-Avila et al.102 (2019) |

Features of ‘successful interventions’

Some of the articles described interventions that produced and maintained improvements in quality. The authors reflected on the features that made these interventions successful. These included the need to (1) consider the hospital-wide co-ordination of interventions, not limited to specific departments or services; (2) establish protected time for staff to implement the changes; (3) ensure staff engagement in the identification of problems and development of the interventions (to guarantee ownership); (4) develop strong relationships with other organisations (to share good practice); and (5) identify clear goals and targets to meet as a result of the intervention and use data to monitor progress.

Issues to consider in implementation

We identified a few trends across sectors in relation to lessons learned in the design and implementation of improvement interventions for low-performing and high-performing organisations. Our review confirmed the findings of previous reviews that have stated that improvement interventions are shaped by the organisational culture, with negative cultures framed by limited ownership, lack of collaboration, hierarchies and disconnected leadership. 5 Features of organisational cultures associated successful implementation of improvement interventions include a ‘can-do attitude’ and the desire to improve on the part of staff, as well as engaged leadership. Our review also revealed interesting reflections on the need to consider processes of implementation. For instance, in the case of school inspections, Ehren et al. 99 argued that, although these might be beneficial for schools, this was contingent on the content of the feedback and how the feedback was communicated to schools after inspections. The authors found that feedback was more effective if it included detailed information on performance expectations and a clear understanding of current teaching conditions. 99 Studies on the process of carrying out inspections in health care have indicated that inspections were more reliable if carried out by larger teams and if inspectors were allowed to have discussions and received appropriate training. 101

No effects, potential negative outcomes and unintended consequences

Some of the studies in schools highlighted the negative consequences of being labelled as a failing organisation; for instance, there were important implications for recruitment and retention of both staff and pupils, relationships with parents and the community, and links with the local authority. Chapman and Harris62 found that top-down reform that treats all schools as the same is unlikely to secure long-term improvement and change, as schools should be free to select the approaches to change that suit their particular needs. External pressures were also seen as negative, as in some cases they resulted in the ‘repackaging’ or ‘recycling’ of ideas and approaches (in the case of this study, restructuring plans) that did not support the meeting of organisational goals or contribute to learning. 91

The external versus internal debate was also present in studies focusing on school inspections and special measures, and some authors argue in favour of the use of school self-evaluations rather than external inspections. 98 Recent research on the use of inspections in health care has also shown that external inspections have no effects on performance. 100,102

Costs associated with the interventions

We found that limited attention was paid to the costs of the interventions or cost savings produced by the interventions. Furthermore, the studies did not explore opportunity costs involved in implementing the interventions, the use of the time and resources to make different changes, and the extent to which the changes could have been carried out without the intervention.

Implications for future research

The articles included in the review identified gaps in research. One proposal was to explore how turnaround strategies change through time, taking into consideration the historical context of organisations. Many studies captured only a snapshot of the intervention and organisational culture, missing the nuances of how change was negotiated. Another gap identified was the need to take into account whether improvement approaches were internally or externally driven interventions by regulatory bodies, for example. The role of external partnerships in creating and sustaining improvements is currently being explored in an ongoing review,103 yet additional work is required to identify the components of interventions that might respond better to internal drive compared with those that might benefit from external support (or a combination of both). In relation to this, some articles highlighted the need to make sure that studies of these types of intervention capture the experiences of staff members across all layers of the organisation, particularly front-line staff and lower management (as many studies have focused on changes taking place at senior leadership levels).

Discussion

In this review, we sought to explore the delivery of improvement interventions for low-performing and high-performing organisations while considering the underlying concepts used to define success/failure and turnaround. We found that most improvement strategies in health, education and local government settings continue to define failure in relation to the inability of organisations to meet pre-established performance standards. Turnaround is often considered as a linear process designed to fix problems and bring organisations up to the ‘appropriate’ level. In most cases, the causes of failure and success are considered in relation to organisational features or characteristics (i.e. organisational culture and leadership arrangements) without a wider consideration of the system in which these organisations operate or their history. Improvement interventions are designed accordingly, that is are focused on specific areas of the organisation or the organisation as a whole, with limited system-level thinking.

The literature that we reviewed has hinted at the problems associated with the definitions outlined above. Some authors have highlighted the limited scope of some interventions, which did not take into consideration issues at a system level, such as regional financial pressures, fragmented care and workforce challenges (e.g. recruitment and retention in particular geographical areas). Others have questioned the roll-out of ‘one size fits all’ interventions across multiple organisations, without recognising the need to adapt improvement interventions to the local context. 62,98 The recycling of ideas from other organisations that did not suit the local context was also found in some studies.

Related to the last point, a domain of literature that did not come up explicitly in this review (because of the key words and targeted focus), yet has relevance, is the process of recycling popular ideas to support QI and performance that originate from external organisations, sectors and global institutions. This is a theme long explored by institutional theorists,who trace the flow and adoption of different types of knowledge found internationally. 104,105 The movement of management and QI ideas and innovations to support health-care delivery has received particular attention from social practice theorists, who discuss the ‘Sociology of Translation’ in health care and ‘knowledge mobilisation’; these are concepts that help us to understand why certain ideas, such as Root Cause Analysis, gain traction in health-care settings and the effort required to embed them into local practices and behaviours (e.g. Nicolini et al. 106). This review did identify some studies that observed that the re-use of ideas did not necessarily suit the local context of their application,91 a finding also supported by the knowledge mobilisation literature, which suggests that, although ideas for improvement may easily spread across boundaries, they might not achieve local buy-in and a good ‘epistemic fit’ within local contexts, especially if there is a lack of knowledge brokering and senior support to encourage organisations to be receptive to the new ideas. 107