Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 16/52/21. The contractual start date was in January 2018. The final report began editorial review in July 2020 and was accepted for publication in January 2021. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2022. This work was produced by Marshall et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2022 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Context: rethinking how research influences practice

Managers and clinicians in the NHS, as in all health-care systems, are under growing pressure to improve and redesign services in a way that both optimises health outcomes and controls costs. The research community has great potential to contribute to this process, by producing and disseminating evidence on a variety of aspects of service organisation and care delivery. And yet, the disconnect between, on the one side, the theory and empirical evidence underpinning how best to design and deliver high-quality health services and, on the other side, what actually happens in practice has challenged policy-makers, academics and practitioners for several decades.

How people respond to this challenge depends on whether they perceive the problem to be how academic knowledge is conveyed from researchers to practitioners (‘knowledge transfer’), or the fundamental nature of knowledge and how it is produced (‘knowledge co-production’). 1–4

Knowledge transfer

When framed as a knowledge transfer problem, researchers are seen as having expert knowledge that needs to be transmitted to decision-makers in the health service in an accessible and timely fashion. 5 Knowledge is perceived as a relatively tangible, bounded and moveable ‘product’, whereas the decision-making process is likely to be seen as time-limited, linear and rational. Research evidence, regarded as the most valid and reproducible form of knowledge, is ‘pushed’ from the research community, through guidelines or evidence summaries, or ‘pulled’ by practitioners who are (or should be) well informed about the benefits of using research evidence.

The emergence of sophisticated informatics and communication technologies in recent years, and their use by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and others, has helped to reinforce a view that the knowledge transfer model is the most appropriate way of closing the so-called ‘know–do gap’. 6 This may be a reasonable assumption in situations in which scientific knowledge is fairly unambiguous, easy to interpret and largely uncontested, such as is often the case (relatively speaking) for much of the clinical evidence underpinning the practice of evidence-based medicine. The transfer approach is more troublesome in the field of health services improvement or service redesign, where the issues that research attempts to address are more complex and the nature of the social science evidence is more contested. 7

Knowledge co-production

This recognition of the limitations of the knowledge transfer model has resulted in a reframing of the integration of research and practice, as requiring different approaches to the nature of evidence, its production and use, and the complexities of the challenges faced by care systems. 3,8

Rather than being separate processes, the production and utilisation of research evidence are seen to merge as complex, iterative and situated social processes. 9–12 That is, knowledge is created, understood, adapted, used and reiterated in the context in which it is needed, and through partnership between different actors.

Furthermore, decision-making by practitioners is regarded more as a situated, social and evolving process than as a one-off, rationally determined event. 6,11 Rather than research evidence needing to be fed into this in a linear and methodical way from outside, the emphasis becomes one of the integration of empirical evidence with other forms of knowledge in situ, including practical knowledge about how to improve and redesign services, and user knowledge about the experience of care services.

This integration is seen as a situated social process based on productive ongoing relationships, effective systems and conducive organisational cultures and contexts. 13–16 Increasingly, the literature in this area embraces a ‘complex adaptive systems’ way of understanding the world, as a means of understanding how actors have to overcome social and epistemic boundaries to helpfully facilitate knowledge processes. 17–19

Such a reframing suggests that the relationship between research producers and research users should focus on the ‘co-production’ of knowledge, rather than merely its transfer. 2,3,20–23 Co-production models of knowledge mobilisation are based on the assumption that knowledge created by researchers often needs to be adapted in some way if it is to be useful. Indeed, for knowledge to have influence, all participants need to be involved in its creation and use. 24 Researchers, using the scientific method as their predominant way of knowing, are not seen to have a monopoly on expert knowledge. Instead, they need to be willing to negotiate actively their forms of knowledge with others (‘a meeting of experts’, e.g. experts in research evidence and experts in improving health services), to recognise and act on power differentials in who dictates how knowledge is defined, and to adopt a more pluralistic orientation to knowledge to achieve change. 25,26

Broadly defined as joint working between people who or groups that have traditionally been separated into categories of user and producer, the term ‘co-production’ came to prominence in the 1970s27 and has gained much currency in public service discourse since. 28,29 When applied in health services research, it is increasingly used as a term to describe the co-production of research-informed knowledge through the engagement of policy-makers and practitioners with researchers. 30–33

However, the increasing popularity of the principle of co-production in public services comes on the basis of promising, but far from complete, evidence. 29,34–36 The literature highlights a range of dilemmas and challenges that need to be explored more fully; for example, is it desirable or feasible to bring researchers and practitioners more closely together, or might the logistical challenges and potentially greater costs than traditional approaches outweigh the benefits?32,37,38 What are the challenges of reconciling divergent or even incommensurate epistemologies?39 Should greater attention be paid to the political and social dimensions of co-production (e.g. the different interests, power and expectations of the parties)?30,31,39,40 Might co-production lead to a narrowing of focus towards problem-solving dimensions of research use,41 instead of encouraging important broader perspectives?23 Should the boundaries between researchers and practitioners be firmly drawn, or are there advantages in flexibility and in the blurring of boundaries?9,21 In what ways can researchers and service users get involved in the co-production of service redesign or improvement?42–44 And can health-care research that is co-produced in one location be translated effectively to other settings?32

The challenges posed by these questions have been exposed by the growing range of new initiatives that seek greater interactivity over research (and, by extension, knowledge co-production in some form) that have emerged in the NHS over the past two decades,17,45–47 as well as in the in the health systems of Canada,48,49 Australia50 and the USA. 51,52

Embedding researchers to encourage co-production

Many different terms and models have been used to describe approaches to research use that seek greater engagement and sustained interactivity, including knowledge brokers,53–60 NHS management fellows,12 Health Foundation improvement science fellows, National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) knowledge mobilisation research fellows, and researchers-in-residence. 61–65 What many of these models have in common is a desire to ‘embed’ researchers in service settings, for significant periods of time, to secure the sorts of sustained interaction thought necessary to promote knowledge co-production. Yet much of the literature is unclear about the relationship between knowledge co-production as a generic concept, ‘brokerage’ (the process by which knowledge is shared across boundaries) and ‘embeddedness’ (whereby researchers are, to a variable extent, located within practitioner teams).

Moreover, other aspects of the schemes that have emerged are highly variable and usually not well described. For example, schemes may vary markedly on the individuals involved (e.g. researchers, health professionals, managers, service users), the degree of close interaction or embeddedness of individuals (e.g. physical locations, contractual arrangements), the nature and degree of co-production sought (calling into question complex issues of epistemology and power) and the types of activities that take place (e.g. the balance between the brokering in of external knowledge and the co-creation of new knowledge in situ). These different models are emerging largely independent of each other, with little evidence of shared learning and only a very few examples of formal evaluation. What has been published mostly comprises descriptions of isolated initiatives, but little in the way of deep analysis and interpretation, and even less in terms of practical guidance.

Both the literature and current practice, therefore, highlight a rich research agenda around embedding researchers as a means to knowledge co-production and, hence, better research use. This includes a clear need to develop a better theoretical and empirical basis for such schemes in the NHS, and the need for evidence-informed practical guidance to support implementation of embedded co-production in practice. 32,38 This project addresses these gaps.

Research aims and objectives

The Embedded project aimed to increase the influence of health services research on decisions about the improvement and redesign of NHS services by:

-

developing insights and understanding about the nature, challenges and effectiveness of co-production initiatives in which researchers are embedded in service settings

-

producing practical guidance on the design and implementation of embedded models of co-production for managers and clinicians in the NHS, their academic partners and people who use services.

In addressing these aims, the project focused on the following specific objectives:

-

to review the theoretical and empirical health services, management and organisational literature relevant to embedded research initiatives and knowledge co-production, and identify the relationship(s) between the two (workstream 1)

-

to gather examples of embedded models in operation around the UK’s health services and public health sectors, focusing on examples where embeddedness and co-production co-exist, and to describe the features of these models, including their history, context, participants, scale, scope and content (workstream 2)

-

to undertake in-depth case studies in four of the examples identified, to understand their mechanisms, effectiveness and challenges (workstream 3)

-

to provide resources aimed at assisting in the recruitment of embedded researchers, alongside recommendations and guidance for their training and development, customisable for the different ways in which embedded co-production may be framed and specified, to allow those interested in developing and using such approaches to understand the design choices they face (workstream 4).

Overall study design

In this section, we set out the overall research strategy governing the four workstreams. Detailed descriptions of the research methods used for the three research-based workstreams (workstreams 1–3) are provided in Chapters 2–5. The activities underpinning workstream 4 (engagement, dissemination and influencing) were ongoing throughout the project, and are described here briefly, with specific outputs emerging from this work covered in Chapters 6 and 7. All appropriate research ethics and research governance permissions were obtained, with approval letters reproduced on the project web page [www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hsdr/165221/#/ (accessed 18 February 2021)].

Workstream 1 used two separate narrative literature reviews to identify and describe the principles and practices of knowledge co-production and of embedded research initiatives. The results were used to develop practical frameworks for understanding knowledge co-production and embedded research; these are described in Chapters 2 and 3, respectively.

Workstream 2 identified and described the breadth and scope of embedded researcher initiatives operating in health settings across the UK and how these were designed to enable knowledge co-production. The results were used to further develop the frameworks of knowledge co-production and embedded research from workstream 1 and to identify candidate case studies for further in-depth examination in workstream 3 (see Chapters 4 and 5). Taken together, the results of workstreams 1 and 2 were used to inform development of an initial framework for planning embedded researcher initiatives that enable knowledge co-production (elaborated on in Chapter 6).

Workstream 3 built on the work undertaken in the first two workstreams by conducting four in-depth case studies to develop a deep understanding of how embedded models of knowledge co-production actually work in practice. The cases and methods of data gathering are detailed in Chapter 4, and the cross-case analysis is displayed in Chapter 5. Drawing on these insights, the implications for scheme design and an enhanced practical framework are set out in Chapter 6.

Workstream 4 used a range of approaches to engage stakeholders with the findings of the project, including developing, testing and disseminating practical guidance for managers, clinicians and academics. This work drew on all the emerging insights and outputs from workstreams 1–3. The processes deployed are described in the next section, and the practical outputs, tools and resources that emerged from that process are set out in Chapters 6 and 7.

Engaging and influencing (workstream 4 activities)

Throughout the project, considerable attention was given towards engaging with and influencing those already embarked on developing embedded research initiatives and those who might be interested in doing so. We aimed to engage with stakeholders to help shape our programme of work and to guide us in the production of useful materials, tools and resources for that community. This work addressed the objectives of workstream 4, namely that, as a consequence of undertaking the project, we wanted to see the following:

-

organisations already engaged in embedding researchers making fuller use of the evidence-based guidance, person specifications, training templates and training resources that we produced to optimise the effectiveness of their work

-

organisations that have not yet considered embedding and/or co-production models stimulated to explore their potential use in improving decisions that affect service delivery

-

future work commissioned to explore the effectiveness, cost and value of embedded research initiatives, focusing on those having the greatest potential to improve services.

Approach to engaging and influencing

The fundamental premise of this research is that knowledge needs to be produced in and through relationships with those who are going to use it (the rationale that underpins both embedded research and knowledge co-production). This, therefore, was also the approach that we took to knowledge creation in this research project. Hence, engaging and influencing key stakeholders were core elements of the proposal.

The principles underpinning our approach were aligned to the theory and practice of co-production models of knowledge mobilisation and to the principles of participatory research. 17,46,66 To that end, the influencing plan was co-produced by practitioners, service users and academics, and used approaches that focus on social interaction, as well as more traditional academic approaches to dissemination.

Audiences and actions

We identified three target audiences that we considered most likely to benefit from the new insights and the associated tools and resources. The primary audience was NHS and local government leaders, both managers and clinicians, whose provider and commissioning decisions could potentially be improved by making better use of health services research evidence.

The secondary target audience comprised the applied research and associated implementation communities, such as members of NIHR Applied Research Collaborations (ARCs) [formerly known as Collaborations for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (CLAHRCs)] and Academic Health Science Networks (AHSNs). The twofold aim here was both to encourage actors in these initiatives to explore the benefits and risks of engaging in embedded models of knowledge co-production and embedded research, and to contribute theoretical and empirical knowledge to the field.

The third target audience comprised front-line staff and service users; their interaction with embedded researchers are at the heart of the model. Helping those who want to access and use applied health research to see more clearly how the structural arrangements for the creation of that research affect its use is key.

The Embedded project team had extensive personal and professional networks in the field of NHS service management and knowledge mobilisation, in the UK and internationally. We used the team’s wider local and national networks in local health economies, ARCs/CLAHRCs, AHSNs and higher-education institutions to ensure that the outputs of the project had maximum impact.

A range of actions were devised to engage and influence these audiences.

Workshops

We hosted two participatory workshops during the study, each of which enabled us to co-produce practical outputs (see Chapters 6 and 7) and raise the profile of the project with target audiences.

Workshop 1 co-produced a framework of design options for embedded researcher initiatives and visual representations of the findings from the literature reviews (workstream 1) and the scoping exercise (workstream 2). Details of the design, attendees, process and outcomes are laid out in Chapter 6.

Workshop 2 co-produced a shared understanding and a clear narrative of the case study findings. Details of the design, attendees, process and outcomes are covered in Chapter 4.

A third planned workshop was precluded from taking place because of the COVID-19 crisis. This would have co-produced practical guidance and tools and resources for the design and implementation of embedded models. These goals were met instead by tapping into professional networks and through social media interactions, and by using data gathered from workshop 2.

Tools and resources

Working in partnership with the relevant stakeholders, we co-produced the following resources for use by health service and academic organisations to encourage and support the practical implementation of the learning from workstreams 1–3:

-

an animation to describe the role of embedded researchers in an engaging and accessible way

-

detailed guidance on the design and implementation of coherent embedded co-production models of knowledge mobilisation, presented in the form of webinars and interactive virtual workshops

-

job descriptions and person specifications to support recruitment to new embedded research posts

-

a description of the knowledge, skills and attitudes required of embedded researchers, and the different career pathways that could be pursued

-

guidance for the training and support of embedded researchers, together with resources that could be used by co-production knowledge mobilisers

-

an outline of how embedded researchers might prepare for their role and how organisations could create a conducive environment for them to thrive.

Additional information on each of these outputs is presented in Chapters 6 and 7, where we integrate the research findings from workstreams 1–3 with the engagement activities of workstream 4. The recruitment resource pack detailed in Chapter 7 can be found on the project web page [www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hsdr/165221/#/ (accessed 18 February 2021)]. Practical outputs are also documented on the project’s Embedded Research website. 67

Network

In the original application, we proposed identifying and supporting embedded researcher learning sets that we were aware had been established in a number of locations across the country. As part of our scoping work, we discovered that these networks were often short lived or only partially active. When we discussed the desirability of greater peer support at our first workshop, the participants expressed considerable enthusiasm to establish a self-managed and lightly facilitated network to allow researchers to support and learn from each other.

At the request of the participants, and with their express permission, a network was established, first using a Google Group (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA) and then a WhatsApp (Facebook, Inc., Menlo Park, CA, USA) group. We hoped that the group would provide a peer support resource for those involved in embedded research and a rich opportunity for the research team to get members’ input into our practical frameworks, emerging learning and influencing activities. Observations made through this network influenced the materials and tools created (presented in Chapters 6 and 7, and showcased on the project website). 67

Publications and presentations

To engage public sector leaders, senior clinicians and service managers, accessible audience-appropriate articles were prepared for the Health Service Journal and Local Government Chronicle. The emerging findings were also presented at national and international conferences and seminars, with more detailed reporting in academic journals (see Acknowledgements for a full list of publications and presentations). Through these means, we accumulated resources for the project website67 and prompted interest in and conversations about the emerging programme of work.

Social media

Working with our communications and influencing partner, Kaleidoscope Health and Care (London, UK), we established a website, Embedded Research,67 published regular blogs and set up an Embedded project Twitter account (@_embedded) (Twitter, Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA). In addition, we produced a series of webinars exploring key issues relating to embedded research (www.embeddedresearch.org.uk/resources/webinars/) and we designed an animation to popularise the key messages for audiences not yet familiar with embedded research. 67 The website and associated resources are described more fully in Chapters 6 and 7.

Patient and public involvement

Although progress is being made in involving patients and the public in the provision of their clinical care, in the broader issues of health service improvement and service redesign, patient and public involvement (PPI) has proved considerably more challenging. Experience-based co-design is a rare example of a specific methodology that brings service users and staff together to develop simple solutions to improve patients’ experiences of care. 68 However, moving the agenda from highly tangible but tightly bounded initiatives, such as experience-based co-design, to broader issues, such as how patients and the public can assist in ensuring research-based knowledge is used more effectively, has proved to be somewhat problematic. 69 The following approach has been gaining traction more recently in some jurisdictions (e.g. the USA and Canada): putting patients and service users at the heart of research teams, using patients as active partners and participants to ensure the relevance and applicability of applied research findings. 70 Nonetheless, despite these pockets of innovation, the field of knowledge mobilisation, in general, appears to have not yet been successful in finding a place for the patient voice. 3,4,71

We used the literature review and empirical work in this study to examine this challenge, with the aim of exploring and describing in detail examples of good practice in involving patients and the public in embedded knowledge co-production initiatives. As the subsequent chapters will show, embedded research initiatives involve patients to a varied extent and use diverse models. It was notable, however, that embedded scheme specifications rarely considered PPI in any depth, and the PPI that did occur was seen largely at the level of embedded research projects, but not usually at the level of the overarching embedded research initiative.

In addition to examining and conceptualising the role of patients and the public in embedded research, we specifically also wanted to make a practical difference. To achieve this, we wanted to seize the opportunity to involve patients and the public more substantively in knowledge co-production and to understand how to make an effective case for greater user involvement in this field. In our design of the project, we conceptualised patients as the main beneficiaries of a more evidence-informed health system. Indeed, we thought that patients, both existing and potential, should be central because it is primarily they who are disadvantaged when research-based knowledge is not used by health professionals and managers.

To that end, we framed the effective co-production of knowledge as being dependent on a number of different relationships. The primary focus for this research was on how researchers can build effective relationships with practitioners to co-produce knowledge and improve services, but we saw service users as a key element of the context in which these relationships are enacted, as stakeholders and as important motivators for change. The patient and public voice was therefore included from the early design stage of the proposal.

Our patient and public collaborators included a funded consultant (RP) with great experience as a PPI advisor to NIHR and as a member of the NIHR knowledge mobilisation research fellowship selection panel, who took on the explicit responsibility of challenging any tendency for service-centricity in the design and delivery of the proposal. In addition, the service co-applicants and collaborators were chosen for their commitment to PPI and their extensive contacts with patient groups, including user advisory groups that had been established specifically for knowledge mobilisation initiatives run by ARCs/CLAHRCs and AHSNs and within specific knowledge mobilisation roles. We also established a project PPI group comprising three additional lay members, two of whom already worked closely with the lead for workstream 2 and the other with the lead of workstream 4. We return to these issues in Chapter 8 to distil the learning from across workstreams on the role and potential of greater PPI.

Structure of the report

The remainder of this report is structured as follows.

Chapter 2 presents the methods and findings of a focused literature review of knowledge co-production, drawing from writings on health care as well as in more diverse fields. What emerges is a practical framework of different types of knowledge co-production, from relatively orthodox views of collaborative knowledge creation and use, to more radical conceptions of the capacity of co-production to upend existing assumptions and to challenge established patterns of power. This provides an account of the first part of workstream 1.

Chapter 3 presents the methods and findings of a focused literature review of embedded research schemes (the second part of workstream 1) and the scoping review of extant schemes in UK health-care settings (workstream 2). The findings are brought together to provide a framework for understanding the key features of embedded research initiatives.

Chapters 4 and 5 present the findings from our intensive case studies of different types of embedded research initiatives in which knowledge co-production was a feature (workstream 3). Chapter 4 describes the methods of data gathering and provides accessible accounts of each of the initiatives studied (with additional detail on both methods and cases contained in associated supplementary materials). Chapter 5 details the analytic approach to cross-case analysis and thematic analysis, building on the domains identified and elaborated in workstreams 1 and 2.

Chapters 6 and 7 integrate the understanding that emerges from Chapters 2–5 into a series of practical tools and resources aimed at helping the design, analysis and management of embedded knowledge co-production initiatives. Chapter 6 also notes the contributions and outputs derived from the engagement strategy run through workstream 4. Chapter 7 presents the recruitment resource pack in detail.

Finally, Chapter 8 situates and reflects on this work in the wider research literature and contemporary policy and practice concerns. It also considers the role, implications and potential for PPI in such schemes, and offers directions for further research.

Chapter 2 Exploring ideas of knowledge co-production

Introduction

As outlined in Chapter 1, the organisation and delivery of health and social care services require multiple forms of knowledge and expertise drawn from a wide range of sources. 33,72 Service managers and health service researchers increasingly recognise the limitations of producing research separately from the sites where this knowledge will be applied. 66,73,74 What was previously interpreted as a knowledge ‘pipeline’ problem,75 a knowledge ‘gap’76 or a knowledge ‘transfer’ issue77 is now increasingly reconceptualised as a need for collaborative knowledge creation in context,65,78,79 or ‘knowledge co-production’, in short.

Knowledge co-production comes laden with a variety of positive expectations. 80,81 In the context of embedded research, there can be an easy assumption that co-production is integral or even ‘naturally’ occurring. Against this, we begin to see concerns voiced about a potential ‘dark side’. 82 Some suggest that knowledge co-production, undertaken without caution, can smuggle in hidden interests and disguised power relations, potentially outweighing any proposed benefits with unacknowledged risks. 38 Critiques also focus on the overly instrumental and normative nature of much co-production literature (and practice), both within and outside health care. 83

Ideas of knowledge co-production are germane to any understanding of embedded research, but there remains a lack of clear conceptual underpinning or any precise formulation as to how these ideas may play out in practice. One persistent challenge is the differing assumptions, expectations and frames of reference that collaborators bring with them, and the ways in which these influence methods of working together. 84 There is a need to unpack what is meant by knowledge co-production, to develop greater conceptual clarity and an appropriate language for discussing its components and varied manifestations. This narrative literature review, the first of two in workstream 1, set out to address this issue.

Methods

We conducted a narrative literature review, to ‘synthesise representative literature on a topic in an integrated way such that new frameworks and perspectives on the topic are generated’,85 carrying out a framework analysis of the academic literature on knowledge co-production. The scope of the review was literature exploring a direct collaboration of academic researchers and non-academic stakeholders aimed at generating new knowledge.

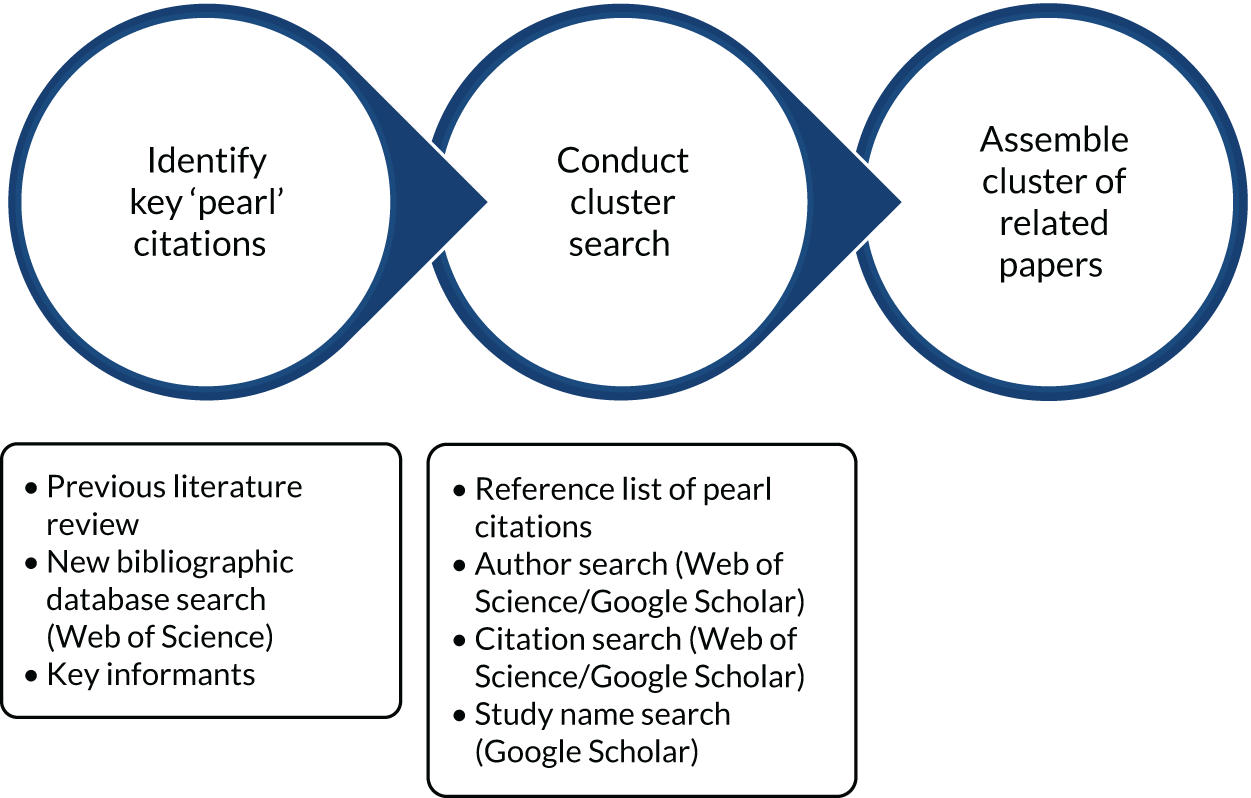

Assembling the published literature

To gather a wide array of perspectives, we collected literature that featured theoretical or conceptual discussion of knowledge co-production, including reports of co-productive research activities incorporating reflective and theoretical insights into knowledge co-production, and editorial/review articles in which the main focus was knowledge co-production.

We conducted systematic searches of the Web of Science™ Core Collection™ (Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, PA, USA) in March 2018. The search terms and strategy are set out in Table 1. Because we wanted to bring together insights from a wide range of health, science and social science fields, we did not limit this search by discipline or by year, although the earliest article that satisfied our inclusion criteria was from 2003.

| Domain | Details |

|---|---|

| Search terms |

[Co-produc* or coproduc*] AND [knowledge* or research*] AND [(concept* near/3 (model* or framework*)) or theor*] [Co-produc* or coproduc*] AND [knowledge* or research*] refined by review/editorial |

| Article type | Reports of knowledge co-production projects and activities, including theoretical content, reviews and editorials of knowledge co-production |

| People/actors | Academic researchers and non-academics in direct collaboration |

| Content | Theoretical or conceptual discussion of knowledge co-production |

Screening the search results, we removed sources in which knowledge co-production between academic researchers and non-academics was not the principal or main topic. We therefore excluded writings on value and service delivery co-production, public service co-production and other kinds of collaborative co-production not involving researchers working with non-academics, or an explicit concern to make knowledge.

Other relevant articles identified through the reading and networks of the project team were subject to the same process of formal inclusion/exclusion. The numbers of articles screened, removed and included are shown in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Flow chart of literature-gathering and screening.

The articles included for analysis are listed in full in Report Supplementary Material 1. As well as articles from health and directly health-related disciplines (n = 24), we reviewed articles from management studies (n = 15), environmental science (n = 15), sociology and social policy (n = 9), sustainability studies (n = 8), ecology (n = 5), human geography (n = 3), communication studies (n = 2), and one each from humanitarian and disaster studies, engineering, psychology and genomics. Source articles dated from 2003 to 2018.

Analysing the data

The framework analysis technique is well established for analysing large bodies of literature subsequent to searching, screening and preliminary reading. 86–88 This approach was appropriate because of its flexibility (allowing us to interrogate sources from diverse disciplines); its capacity for ongoing modification and revision in response to data reading, re-reading and re-interpretation; and its orientation towards descriptive understanding rather than prediction or normative goals. 89 Framework analysis facilitates an iterative, team-based approach to analysis, giving increased confidence that the categories and themes discerned have stability and interpretive utility.

An initial interpretive reading conducted by one member of the team (BR) aimed to discern and label groups of concepts occurring within and across the source articles. For instance, writers might report concerns around institutional politics, or the difficult emotions of perturbed professional identities, without necessarily using the words politics, identity or emotions.

The review team (BR, VW, HD and TT), which had access to the full set of sources as well as the evolving analytic categories, then discussed this working set of conceptual labels, or domains, for their face validity, coherence, completeness and overlaps, and made modifications as agreed. A closer re-reading of source articles was then conducted to see if the conceptual categories emerging provided a sufficient framework for interpreting the data. This second reading allowed us to identify additional content that would not fit easily into the domains, and to refine or develop further domains and, more significantly, subthemes within domains.

In discussions across the whole project team, it became evident that differing perspectives on knowledge co-production created tensions within each domain. We recorded and labelled these tensions and grouped them together into connected accounts of meaning.

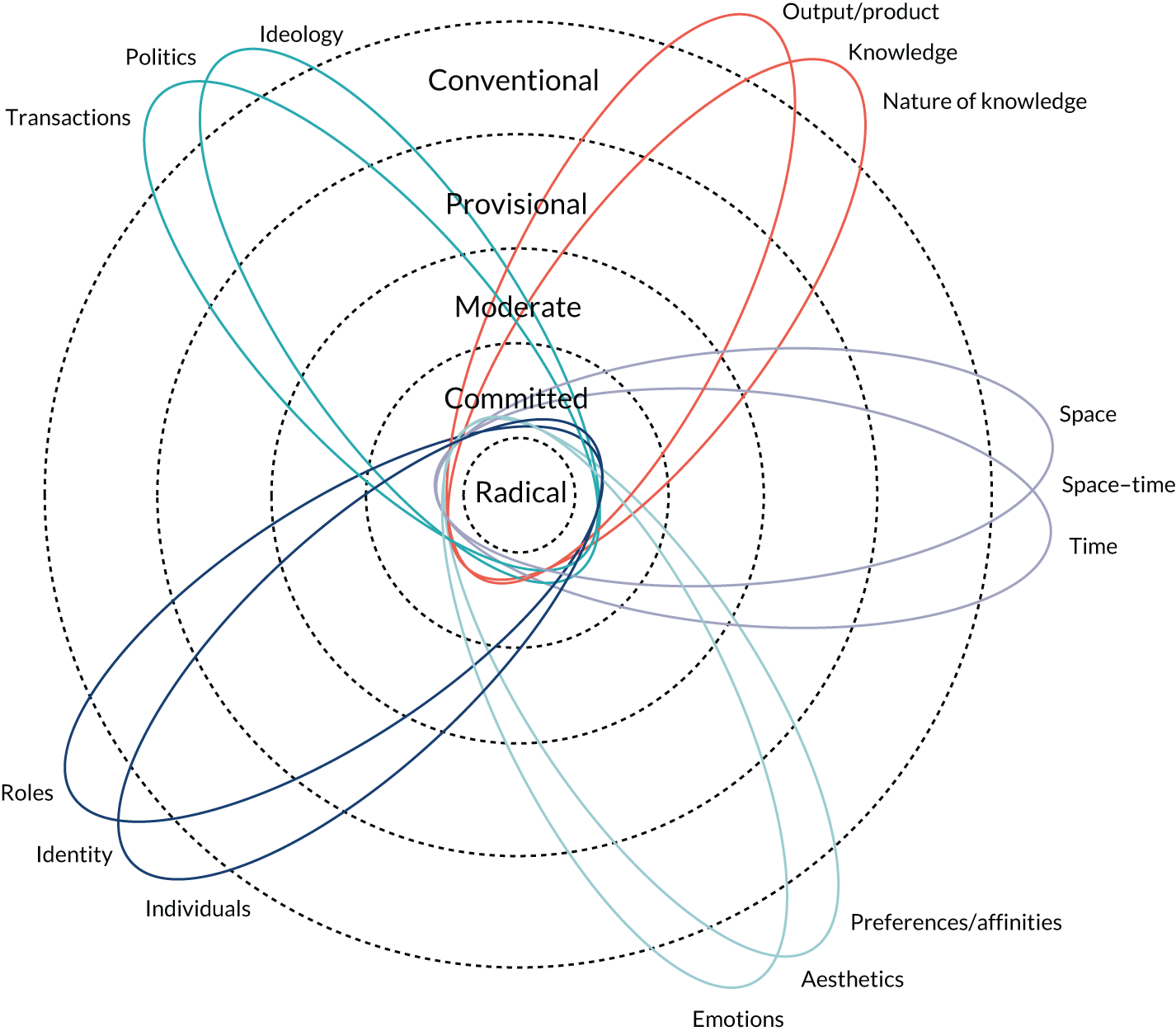

What emerged was a set of five conceptual domains overlaid with a continuum of perspectives from the conventional to the radical. A conventional view of knowledge-making would see the boundaries between different knowledges and different roles largely maintained, with the goal of worthwhile but incremental change. A more radical approach would see boundaries more thoroughly dissolved, in pursuit of a more substantial overhaul of priorities and possibilities.

Given our goal of creating a language of shared meaning that would make knowledge co-production easier to discuss, we sought categories that were defined and coherent enough to allow for shared understanding, broad enough to encompass the messiness of divergent practices, and flexible enough to allow ongoing debate and refinement. The structured reading we lay out is not the only one available, but it has survived repeated interrogation across the wider project team of knowledgeable, diversely experienced collaborators, and through presentations at various professional events.

Findings in outline

The key findings were that there are five key conceptual domains in knowledge co-production; that, in each domain, there is a continuous spectrum of differing perspectives; and that each domain comprises two subthemes, also characterised by a spectrum of perspectives.

Five domains of meaning

Meanings and perspectives in knowledge co-production can be located, understood and compared within five related domains of meaning: politics, knowledge, identity, space–time and aesthetics:

-

The politics domain brings to the surface those negotiated and meaning-laden processes (among large and small groups, and individuals) that in conventional knowledge production are obscured or unspoken.

-

The knowledge domain concerns implications around the tangible product that co-producing parties reach for – what is this knowledge, and what is it for?

-

The identity domain allows a close examination of people who co-produce knowledge – what makes them who they are, individually and collectively?

-

The space–time domain concerns the physical processes and happenings of knowledge co-production. More than just a practical question of ‘where and when’, it involves different configurations and enactments of collaboration.

-

The aesthetic domain makes visible aspects of knowledge co-production experience and expression that may seem intangible and subjective, but that are highly significant – human likes and dislikes, and emotions that escape easy expression but are fundamental to collaboration.

These five domains mark out a conceptual space in which to consider the complex interplay of diverse ideas and understandings involved in knowledge co-production.

Spectrums within domains

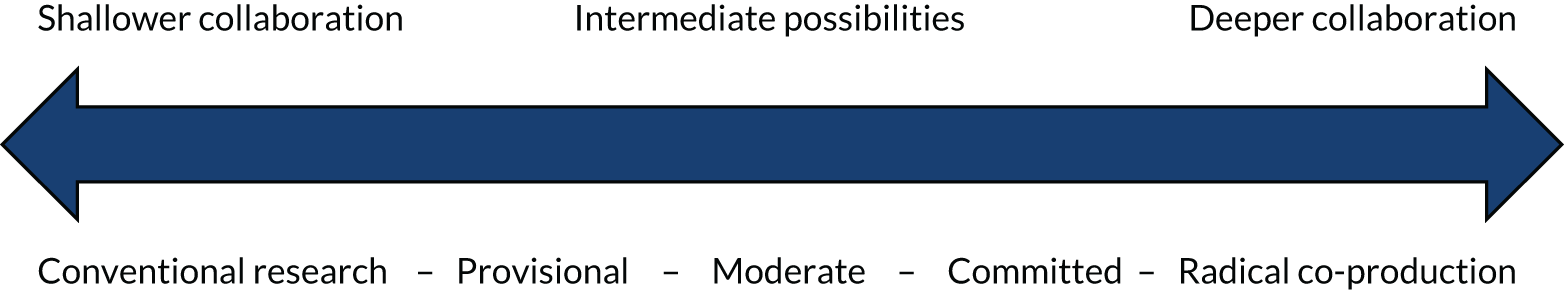

In each domain we found that, underlying any superficially isolated points of opposition and difference, there were subtle variations of thinking that merge and separate, creating a spectrum of interpretations and actions. These range from non-collaborative or reservedly collaborative approaches that leave existing boundaries relatively unchallenged (we term these ‘conventional’ research or ‘provisional’ co-production), to approaches that challenge or unravel such boundaries in pursuit of more disruptive and substantial change (what we term ‘committed’ or ‘radical’ knowledge co-production). This spectrum is set out in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2.

Styles of knowledge co-production.

The extremes of this spectrum (conventional and radical) serve as idealised anchor points for clear thinking, but also reflect knowledge-making processes actually (in some cases) performed. Rather than a barrier or problematic void between them, there is a rich space of variation among subtly different approaches. Real-life knowledge co-production mostly happens in this intermediate space. To guard against binary thinking, we included a middle category of moderate co-production, which models a roughly equal balance and interplay between ideals.

These labels proved useful to unpack, interrogate and lay out subtle contrasts within domains, but should not be thought of as overly rigid or proscriptive. Labelled marker points do not indicate static types of knowledge co-production, but dynamic approximations, signposts that we have settled on after repeated interrogations of the literature and discussions among the team.

Subthemes within domains

In further exploring and categorising the themes in the literature, we identified two subthemes within each domain:

-

politics includes ideological and transactional politics

-

knowledge includes the substantive product and output of collaboration, and is also something that exists and has nature in itself

-

identities includes both the roles fulfilled by individuals and the way in which those individuals are less or more socially intertwined

-

space–time incorporates time and space as distinct physical dimensions that can be configured in a variety of ways, according to how they are realised and occupied in collaborations

-

aesthetics includes the preferences and affinities of people and groups involved in knowledge co-production, and the valuation and influence of emotions in collaborative proceedings.

In the subsequent section, we summarise each domain and subtheme, giving examples from the literature. These discussions are encapsulated graphically in Figure 3, and also in Table 2).

Findings in detail

Domain 1: politics

The politics domain incorporates ideologies of research, ranging from the apolitical (conventional co-production: politics seen as separate from knowledge-making) to the emancipatory (radical co-production: knowledge-making as a tool for social justice and structural change). Intermediate points are the utilitarian (provisional co-production: knowledge for instrumental application), the engaged (moderate co-production: research and practice/policy substantially shape each other) and the transformative (committed co-production: sustained micro- and meso-level change is part of the programme).

This domain also incorporates the instrumental politics of transactions, the often mundane institutional politics of co-producing knowledge. Attitudes across that subthematic spectrum range from politics as pollution (conventional), through politics as necessary (provisional) or valuable (moderate), to politics as essence (committed), and politics as all-encompassing (radical).

Politics as ideology

Diverse authors have observed the contrast between politically provocative styles and more functional styles of knowledge co-production. Orr and Bennett31 (social policy context) distinguish between co-production ‘based on a critique of the status quo’ and the de-politicised ‘anodyne’ use of co-production terminology in service of established interests, ‘not necessarily advancing the broader interest or public welfare’. Similarly, Lövbrand (climate science context)90 identifies:

. . . tension between the critical/reflexive ambition built into the co-production idiom, and the more utilitarian interpretation of the term. Whereas the former sets out to expose and interrogate the ontological assumptions underpinning public policy, the latter seeks to be useful by responding to the knowledge needs of societal decision-makers.

Analytically, one could accentuate the mutual distinctiveness of these positions. 91 In the narratives we reviewed, however, we found instability and equivocation between utilitarian and critical co-production styles. ‘Useful’ forms of knowledge co-production do not necessarily preclude more thoroughgoing change. Co-production with a stated transformative intent, meanwhile, often also carries slower-moving and locally specific change processes. Both understandings frequently pertain within projects, and between collaborators in how they see the value of a project developing; hence the value of exploring intermediate points along a spectrum. Dynamic exchange between intermediate points softens the edges of opposition between extremes.

Transactional politics

Alongside ideological politics, we have the prosaic politics of social interactions between institutions, organisations, policy bodies, academic disciplines, professions and service user groups. Negotiating the intricate mechanics of such transactions is necessary to secure and maintain a productive connection between stakeholders. 92,93 Hewison et al. 37 report an initiative that aspired to full engagement with non-academic collaborators,94 but whereby mutually incompatible policies and pressures on employees in the collaborating institutions made this impossible in practice. Subsequently, McCabe et al. 23 developed a typology among ‘contextual factors of partnerships’ in which collaborative structures determine what kinds of knowledge gains can practically be made.

Although the transactional politics of collaboration are usually difficult and demanding, this is sometimes seen as productive and valuable in itself. 95 Klenk and Meehan’s96 critique (environmental science context) of imperatives towards ‘integration’ of stakeholder contributions, which they argue neutralises the critical value of non-academic perspectives, advocates that disparate, incompatible voices should be protected. Such contributions imply a committed disposition in which transactional politics hold the value of co-production, contrasted with a more provisional disposition in which they are a barrier to be negotiated to arrive at expected knowledge products, amalgamation of perspectives, and effective knowledge use.

To be clear, the value of a politics lens on knowledge co-production is not in theoretically settling the political-or-otherwise status of research knowledge. 97 What differentiates styles of knowledge co-production is where the different stakeholders draw the boundaries between knowledge production and politics. Do they encourage a restricted, instrumental political engagement towards a foreseeable output? Do they confidently pursue a political re-ordering of knowledge processes and hierarchies? Or is there some hybrid of these? Whichever they choose, the collaborative political process is made visible, conscious and deliberate, instead of being kept below the threshold of awareness. 21,98 Politics becomes intentionally woven together, in contestable ways, with knowledge.

Domain 2: knowledge

The knowledge domain incorporates perspectives on the outputs of knowledge co-production, and implied positions on the nature of knowledge. Beyond being a pure commodity made for truth’s sake (conventional co-production), knowledge can have utility, transfer and ‘impact’ potential (provisional co-production). Or knowledge can be something through which people become inclusively engaged in social life (moderate co-production), or through which they gain new productive capacities (committed co-production). Knowledge may even enable actors to become empowered (radical co-production). Accordingly, knowledge has different kinds of existence: as an object in itself; as something exchanged or negotiated among those who hold it; as something held communally by ever-changing collections of people; or finally, as a constitutive property of a wider collective group, in a deeper, ongoing and embodied sense.

Output/product

A common framing in knowledge co-production literature is the agenda for research impact,92,95,99,100 reflecting a utilitarian impulse to show use-value and policy relevance. 101 Antonacopoulou102 upheld this view of co-produced knowledge, inviting researchers to pursue delivery that had an impact, explicitly turning away from political preoccupations (a provisional approach). In contrast, Pain et al. 103 (human geography context) critically explored the tensions between impact as an issue of economic accountability and as a matter of social responsibility – both inescapably political concerns. They advocated co-production as a way to ensure socially equitable and ‘radically transformative’ knowledge outputs. 103

Capacity-building (committed) and empowerment (radical style) are also common framings in the literature,40,104–106 whereas others speak of engagement, engaged scholarship and inclusion (a moderate style). 24,107,108 Each of these indicates a subtly different narrative of who and what knowledge is for.

Nature of knowledge

Associated with this array of output purposes are implicit understandings on the nature of knowledge itself, frequently presented through metaphor.

For Rycroft-Malone et al. ,33 the first move of health-care knowledge co-production is to challenge ‘pipeline’ conceptualisations of knowledge, knowledge transfer, implementation, the gap, and the ‘two communities’ model of knowledge production and use. 21 A pipeline conceptualisation imagines knowledge as a thing that must originate on the outside and be transported to the context where it is applied, or as Kitson and Harvey109 see it:

. . . the process by which knowledge moves from where it was first created and refined to where it has to get to in order to make an impact.

To sustain a ‘gap’ conceptualisation, these two places must be different, with knowledge travelling as an object package from one to the other. To discuss knowledge implementation techniques in terms of the success or failure of their transfer to the point of use109,110 is to retain a conventional sense of knowledge as a commodity that exists autonomously and is delivered post production to people and places without altering its nature.

Radical knowledge co-production, rejecting the object-and-transfer conceptualisation, imagines knowledge instead as a valued attribute of people located in time and place, a process performed and embodied, a presence that empowers and includes, a pervasive energy in movement and change, and a collective and communal good. In short, knowledge as a positive mode of human being. 111 For Kothari and Wathen,112 this understanding:

. . . is not just about knowing but encompasses ways of being and relating . . . making space for an additional ‘value-added’ communal perspective.

Between these idealisations is a middle ground of ambivalent metaphors. The idea of knowledge exchange, for example, imagines collaborators each contributing a genre of object-like knowledge to a sharing process that simultaneously creates knowledge anew, collectively. 18 Some emphasise tension in this dialogue, a ‘balancing act between imposing control’ (provisional) and ‘opening up a plurality of voices’ (committed). 113

When knowledge is said to be negotiated in co-production,114 a knowledge object again precedes the interaction, which results in a more diffusely social knowledge (moderate style). However, when there is any seeking of shared wisdom and ‘integrated or transformational understanding’ (committed style – Schuttenberg and Guth115), there is also the possibility of troublesome conflict and re-assertion of power status (provisional),98,114 felt as a ‘need to exercise a stronger voice’. 115

These tensions are political, not merely between related actors, but between perceiving knowledge as an object property held individually, unequal but shared and received, or an elusive and transient presence realised through communion. Terms such as impact, negotiation, exchange and transformation carry variable meanings in the literature, suggesting a range of tangled understandings that might be disaggregated, given the right tools for dialogue.

Domain 3: identity

Politics experienced at the individual level can be conceptualised through identity, both in terms of the roles that participants occupy, and by acknowledging individual feelings, affinities and sensibilities.

We found that roles in co-production might be separate and securely fixed (conventional style), or they might fit together as complementary and negotiable where they meet (provisional style, in which case conflict is more likely found to be counterproductive). Sometimes there is an expectation that roles naturally overlap (moderate style), interfere and contradict (committed style), or disintegrate and multiply (radical style), in which cases conflict may be naturalised and valued as significant.

The individuals involved might be thought by nature to be autonomous, or connected to each other in singular, transactional ways; they might be more interwoven and interdependent; or, in the extreme cases, less clearly separable from each other in terms of the multiple knowledge roles they embody.

In this domain, it is useful to hold in mind some typical characters in narratives of knowledge co-production. The basic players are academic researchers (whose accounts are usually of central interest for academic writers and audiences, even under committed and radical modes of co-production) and non-academic stakeholders, such as (health) professionals, policy-makers and service users (whose accounts rarely surface in enduring forms). Recurring figures include non-academics who gain skills and empowerment from involvement in research,116 researchers who skilfully ‘surf the boundary between ways of knowing’96 and ‘critical friends’. 117,118 ‘Critical friends’ implies researchers who are aligned with non-academic institutions, but remain able to be critical, or non-academics who develop an expert voice and agency in knowledge production by virtue of their insider status. 119

Role

This spectrum spans the ways in which people are understood to occupy their socially designated roles.

If those roles are thought of as naturally ordered, given and fixed to individuals, it indicates a conventional or provisional style in which one simply ‘is’ an academic or non-academic, and remains unproblematically so. If roles become partly negotiable, this typifies moderate co-production. In committed or radical styles, roles become performances, contingently (re)made by people and subject to ongoing change; possibilities arise of people disconnecting from rigidly defined roles, crossing role boundaries and enacting multiple performances, actively and creatively. In recognising an underlying common humanness at this end of the spectrum, researchers can, as Greenhalgh et al. 95 note:

. . . view research as a creative endeavour, with strong links to design and the human imagination . . . [placing] individual experience at the heart of this creative design effort.

Klenk and Wyatt120 (environmental-economics context) similarly advocate ‘engagement with partners that is creative and transformative rather than mainly informative’, suggesting experimentation with role boundaries, and scepticism of pre-conceived roles and duties.

Fenge et al. 121 (health and social care context) describe knowledge co-production ‘involving lay people, volunteers, service users and carers in scholarly writing and dissemination’, exploring how academia can embrace the expertise of these non-academics. Usually this suggests a single identity, such as a patient, professional or health-care policy-maker, that serves as a warrant for involvement, but becomes plural as collaborators contribute, not just information, but part of their personhood to knowledge-making. 122

Almost always, original role markers remain meaningful. The truly radical possibility is to abandon them entirely and see all collaborators as people originally equal, communally connected through their shared interest.

Individuals

Collaborative work can place demands on individuals. We see this reflected in O’Hare et al. ’s118 interest in ‘coping strategies’ for critical tensions, Orr and Bennett’s123 reflections on their ‘at times disturbing and debilitating’ experiences of co-production, and Vindrola-Padros et al. ’s65 account of researcher-in-residence strategies for facing challenges to their professional identity. This implies an individual consciousness that is separable from the role a participant occupies and is able to reflect on competing demands.

For researchers, knowledge co-production brings perceived risks, such as dominance by particular stakeholders, eroded independence and credibility, interpersonal conflict, burnout and stress, and damaged careers. 82 These threats relate to the individual status of the researcher, which, under the individualistic model of personal worth dominant in academic research, is vulnerable.

For non-academics, collaboration is largely expected to be an edifying and empowering process. By challenging the individualistic academic culture and directly confronting knowledge inequalities and cultural boundaries, it could be seen to ‘democratise knowledge’. 124 But such a framing, although notionally moving non-academic individuals into positions of power, may also place considerable responsibilities and expectations on them.

Underlying such anxieties are equivocations over the nature of people as reflexive individuals. If people are thought to be comfortable as autonomous beings (conventional style) then provisional or moderate ways can be found to account for their connections, but more committed or radical approaches are problematic. If the natural state of people is thought to be as communal, interconnected and multiply oriented beings, then the challenges of more radical co-production may be considered worthwhile and intrinsically valuable for the way they decentre individualistic orthodoxies.

This ontology of individuals meshes with an ontology of roles as fixed and stable (if restrictive) at one extreme, or mutable and multiple (allowing for creativity, if sometimes disorienting) at the other. The space between has possibilities for dialogue and the ongoing reconstruction of roles, and of the reshaping of the identities of the individuals occupying those roles.

Domain 4: space–time

Time and space are highly visible points of interest in knowledge co-production literature. Conventionally, time is imagined in a linear way, with knowledge first produced, then moved into policy or practice settings; provisional arrangements may be made around a variable but linear process of production and dissemination. Moving along this spectrum, time can enfold different collaborative stages that repeat and overlap or become more consciously iterative. In the radical ideal, ongoing production and ongoing application are in a mutually constitutive continuous cycle of renewal.

Space may be strictly divided between separate research and practice locations, or attention may be given to in-between, liminal meeting points where institutions begin to overlap. A blurring of boundaries and conscious challenging of spatial designations characterise more committed and radical forms of co-production.

Time

Time is crucially important in knowledge co-production. With non-academic contributors, time is usually prioritised by their primary identities (as managers, practitioners, etc.); negotiation is often necessary to divert that time towards knowledge collaboration. Co-ordinating the schedules of diverse stakeholders for meetings is a basic difficulty. 37 Supposing collaborators are brought together in a timely way, writers often emphasise the long time required to nurture collaboration: time invested in building trusting relationships and accumulating confidence among collaborators, and time taken to agree and implement knowledge-making plans, with the implication that the added value of outputs should correspond to added time inputs. Lehmann and Gilson125 speak on behalf of many co-producing researchers:

We spent an awful lot of time in meetings, formal and informal, big and small, in cycles of conversations to plan and implement strands of work, reflect on their outcomes and replan.

These cycles of conversations allude to a characteristic aspect of committed and radical styles: the iterative nature of knowledge co-production, in which different stages of the research process overlap more than in orthodox research – ‘planning, execution, dissemination and implementation are not separate and linear phases but interwoven’. 95

This contrasts also with provisional co-production in which consultations at specific points punctuate the path of knowledge into practice. A moderate style of co-production signifies ambiguity and overlap between pre-made knowledge being moved into application, and an ongoing process of making and modifying knowledge at the same time as ‘using’ it. 107

Space

In the conventional ideal, a ‘gap’8,78 envisages a one-way flow of knowledge in space from sites of production to adoption and routine use. In the radical ideal, knowledge attaches to communities in places, so is made just as it is inhabited and enacted, in a closed, reflexively aware loop. In between these extremes are a range of possibilities for co-production embedded in space and place.

Ideas about the in-between spaces that separate and connect institutions are ever present in knowledge co-production. These liminal interstices are valuable, for example, in creating ‘a shared space where multiple communities can come together’,23 and where collaborators are ‘able to challenge ideas and existing policies or entrenched beliefs’126 in ways otherwise not possible.

Rather than refer directly to specific physical sites important for knowledge co-production, writers sometimes evoked space through social-psychological metaphors. They wrote of space beyond hierarchies and boundaries; indeterminate social space; permeable space;114 exploratory space;79 nurturing, safe and inclusive space;127 space ‘both embedded in and insulated from research and practice’ and spaces ‘open, autonomous, unpredictable, dynamic, reflexive, and shared’;128 and spaces of ‘dialogic co-inquiry’ and the ‘cramped’ space of co-production. 40

Across the intermediate spectrum of spatial designations, these metaphors range from those that look for liminal gaps between original single-purpose spaces (provisional), those that bring different purposes to coincide and overlap in one space (moderate), and those that challenge and blur the boundaries between spaces (committed).

All of these pragmatically repurpose and reinterpret the physicality of extant institutions, whereas, in radical knowledge co-production, there is an acknowledged political awareness in the redefining of spaces. Bremer and Funtowicz129 draw on the political geography of Doreen Massey to highlight this awareness of distinct narratives of space that ‘coexist, meet up, affect each other, come into conflict or cooperation’. For many collaborative purposes, however, a language of spanning and blurring boundaries, temporarily displacing orthodox routines and interactions, and flexibly redrawing the borders between institutions – a metaphorical language of space – is found sufficient.

Domain 5: aesthetics

Knowledge co-production involves an aesthetics of attitudes, dispositions and emotional attunement that resonates across domains. Preferences for simplicity, rigidity and predictability in more conventional forms merge into a tolerance and interest in social complexity in intermediate forms of knowledge co-production. Beyond this, there is a positive solicitation of emergent outcomes, and an attraction to collective knowledge states that cannot be foreseen (implied in more radical approaches).

Alongside this, we find different valuations and language around emotions. Emotions can be marginalised, or a manageable complication to knowledge mobilisation and application; can be a complementary and useful form of rationality; or can be of foundational value in themselves as part of knowledge-making processes. At the radical extreme, the emotion/rationality distinction disappears, as communal production becomes shared, embodied and affect infused.

Preferences

Preferences, affinities and aversions in co-production writing are easily detected in the literature we reviewed, although not always so openly acknowledged. Our interpretation brings these recurring themes into open conversation. For instance, appreciative considerations of multifaceted, evolving connections between co-producing individuals and institutions suggest an ethic of connectedness and mutual responsibility between academia and other social sectors. 130 This leads away from a simple schema of entities with isolated purposes towards complexity of social patterns and trajectories. 131 A complex system is more likely to appear untidy, or messy, and lead to outcomes that are unforeseeable or not predictable, and is often thought to be more valuable for that.

Borg et al. ,132 writing on ‘valuing uncertainty’, tell of attempts to explore multifaceted realities through complex processes that ‘can be intense, unpredictable and at times rather chaotic’. Interest in complexity,21,133,134 in messiness105,135 and tolerance of messiness,33 in plurality and mutability136 and unpredictability95,128 is woven through narratives of knowledge co-production. These tropes create a graded succession, from knowledge transfer that is accountable and predictable (provisional), knowledge exchange that is attentive to complexity (moderate), and co-productions seeking creativity and social innovation (committed). Radical intentions are signalled by a challenge and subversion of orthodox constructions and a scepticism of norms conventionally made to appear simple, in which messy boundary work is moved backstage, out of view. 137,138

Emotions

Human actors embedded in messy realities may not be well placed to grasp and govern their situations in the manner of singular purposive and rational minds holding unitary object knowledge. They must find ways to create collective wisdom, drawing on diverse sources and expressions of connectedness to the world,139 indicating the importance of the ‘more-than-rational’. 139 Orientation to emotional knowledge and things known instinctively through experience,140 as well as attention to shared feelings and affect,141 are often active in knowledge co-production.

One example of emotionally rich language is the motif of ‘nurture’ common in this literature, whether used appreciatively102,112 or sceptically. 38 ‘Trust’ is also usually cited as a foundational condition of successful partnership. 142–144 The nature and conditions of this trust may suggest a strategic management and positive use of emotion, for example when Jagosh et al. 116 carefully engaged community members ‘who were already known to be knowledgeable, sincere, compassionate, and understanding’, so that others would ‘feel safe participating’. In other cases, emotional currents are detectable as forces motivating co-production. For instance, when Klenk et al. 145 envisage knowledge practices that ‘move and affect not only present concerns but also future solutions’, hope is a foundational emotion for energising the project.

Attunement to emotional knowledge does not imply positive emotional states. More often than being joyous, the emotional relations of knowledge co-production are fraught and difficult. What distinguishes styles of co-production is the extent to which emotions are given legitimacy in juxtaposition with rational object knowledge. In moderate styles of co-production, emotions and rationality are imagined to complement one another in working towards consensus or productive difference. In committed knowledge co-production, emotions may be foregrounded as sources of knowledge, emphasising the human and creative processes of project design. In radical knowledge production, mirroring the collapse of a knowledge–politics binary, the dichotomy of reason and emotion is more unstable. Rational and affective streams of consciousness are woven together into a thinking–feeling fabric of being.

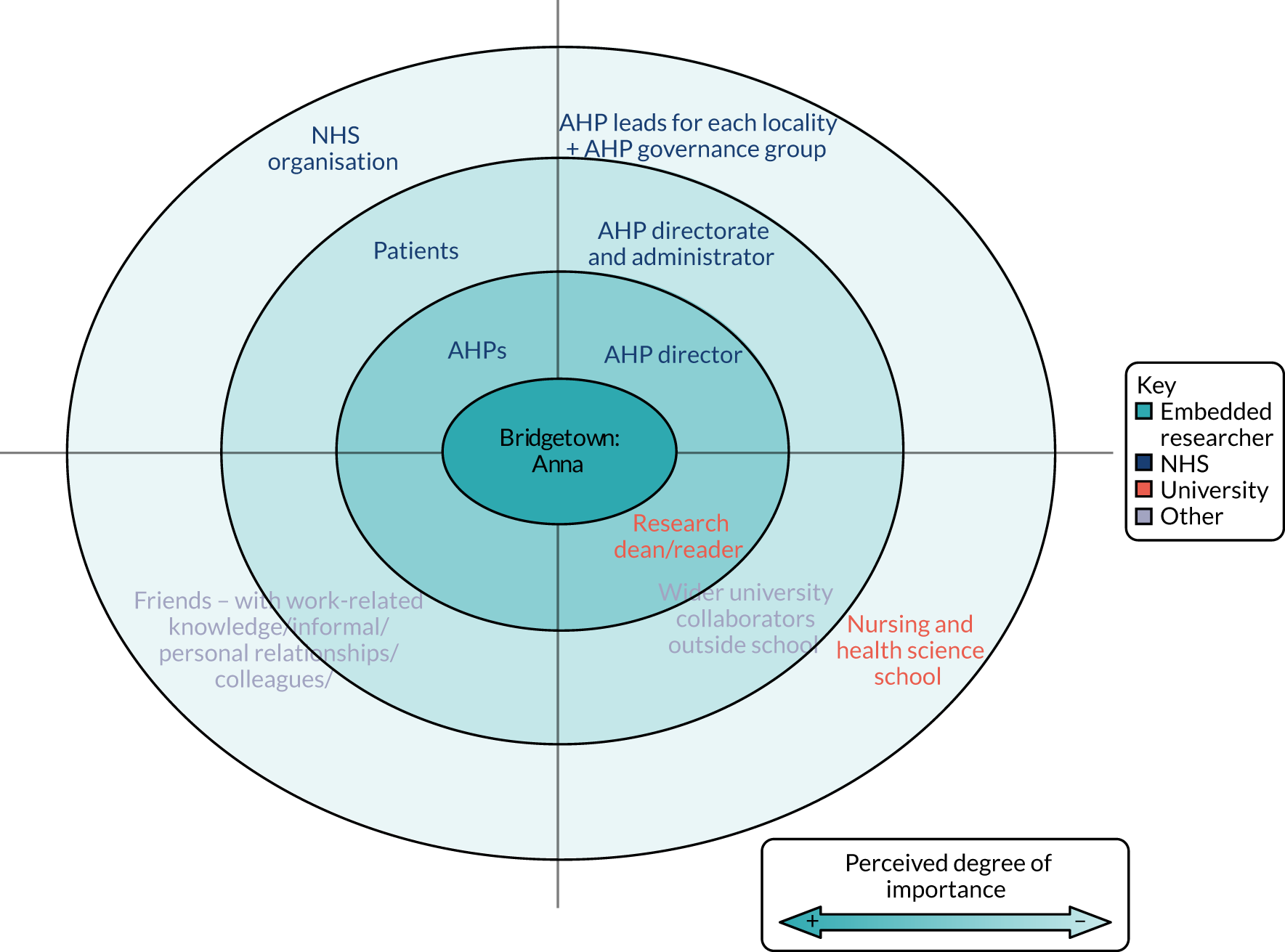

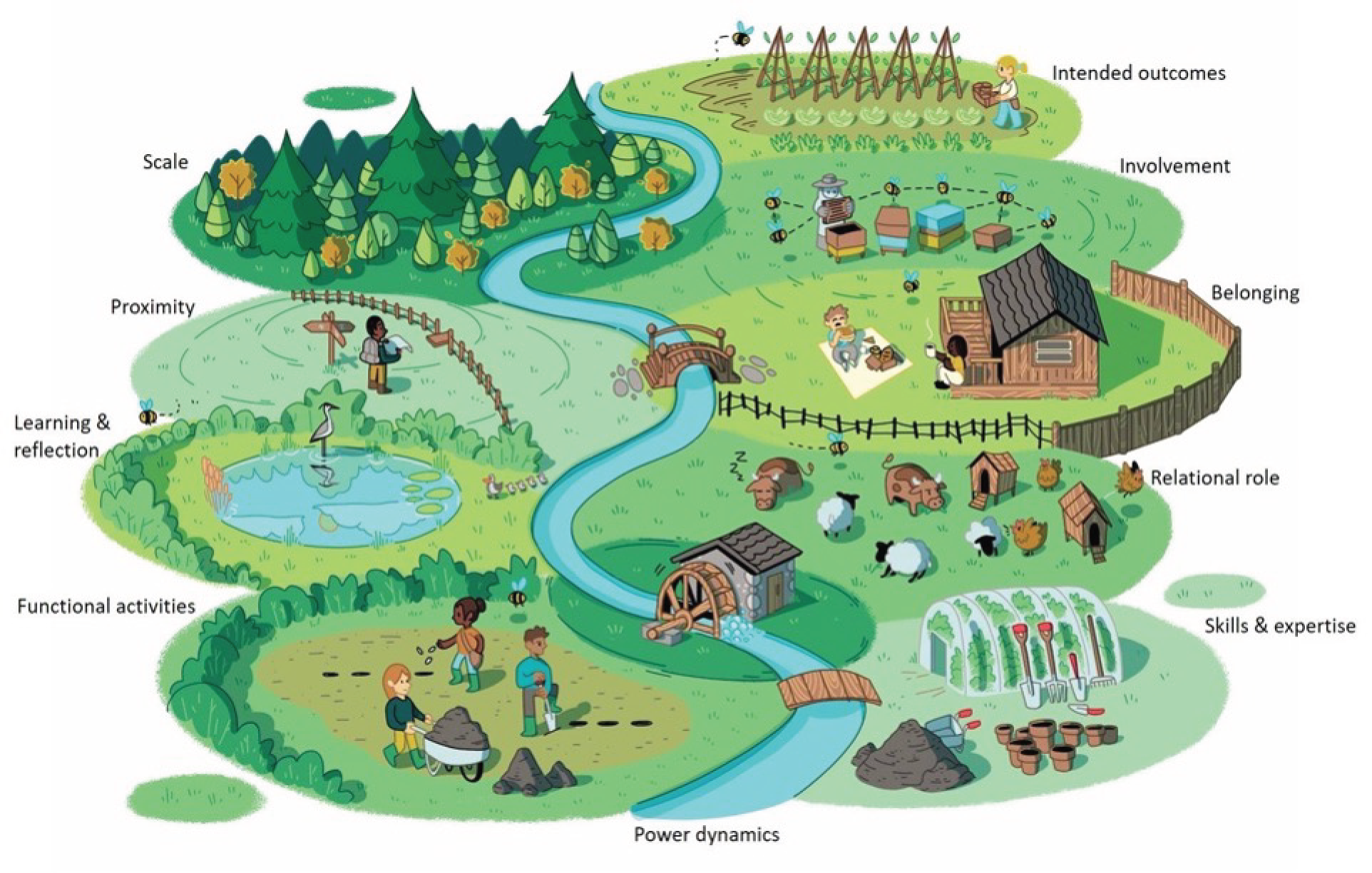

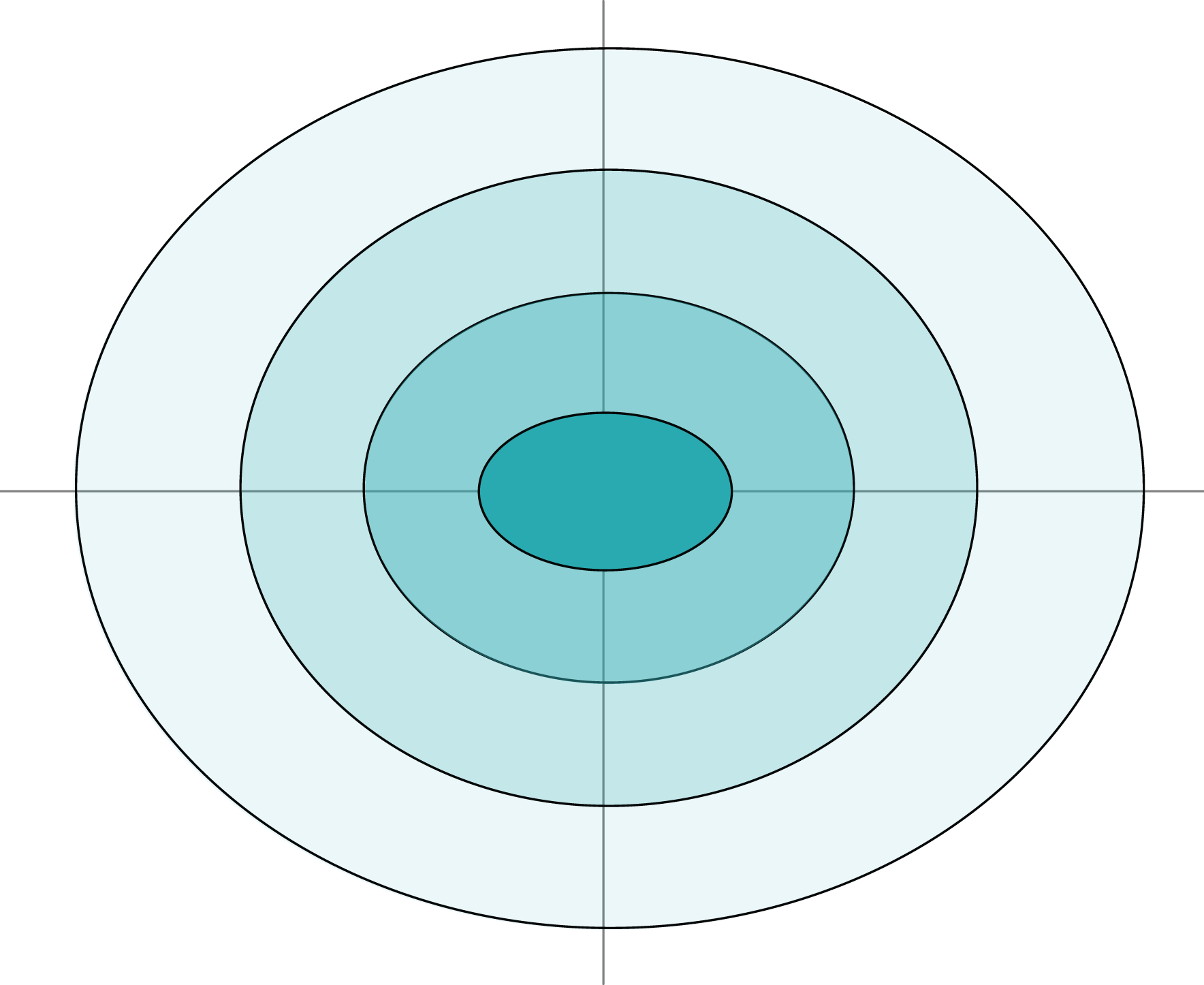

Representing the conceptual framework

To visualise the five-domain framework, we created a diagram (Figure 3) in which co-production styles appear as concentric circles, and domains and subthemes as pairs of ellipses arranged around a central locus. An arrangement with conventional research on the outside and radical co-production at the centre evokes the impression of distancing and separateness in the conventional style, and of closeness and intensity in radical co-production. The ellipses representing each subtheme convey a dynamic sense of motion, we hope, as projects and collaborators may fluctuate between possibilities.

FIGURE 3.

Domains and subthemes of knowledge co-production.

Table 2 characterises each marker point along the subthematic spectrums with a word or two, creating a grid of possibilities for co-production projects that can be read horizontally (to see progression across spectrums) or vertically (to see the properties of each style). Gradations in shading suggest the idea of blending between styles. A perspective that is in some ways committed, for example, could be, in other ways, radical or moderate, but is less likely provisional or conventional, if our domains are a sound analysis of thinking around co-production. However, all approaches are legitimate; dissonance between aspects of a project may indicate tension and dysfunctionality, but may also reflect different goals and intentions co-existing within a project, or changes in a project’s character over time. To emphasise, we propose these labels of recurring patterns to be descriptive, not normative.

| Spectrum | Style of knowledge co-production characterised as | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional | Provisional | Moderate | Committed | Radical | |

| Politics spectrums | |||||

| Ideology is | Apolitical | Utilitarian | Engaged | Transformative | Emancipatory |

| Transactional politics are | Pollution | Necessary | Valuable | Essential/essence | All-encompassing |

| Knowledge spectrums | |||||

| Output/product is | Pure knowledge | Application, impact | Engagement, inclusivity | Process, capacity | Empowerment |

| The nature of knowledge is | Object | Transactional | Negotiated, exchanged | Communal | Embodied being |

| Identity spectrums | |||||

| Roles are | Separate, fixed | Complementary | Consensual, negotiable | Conflictual, problematic | Unstable, multiple |

| Individuals are | Autonomous | Connected | Interwoven | Communitarian | Inseparable |

| Space–time spectrums | |||||

| Time is | Linear | Variable-linear | Overlapping | Iterative | Cyclical |

| Space is | Separate | Liminal | Overlapping | Blurred | Contestable, politicised |

| Aesthetic spectrums | |||||

| Preferences are | Simple | Predictable | Complex | Emergent | Unforeseeable, subverted |

| Emotions are | Marginal | Manageable | Informative | Foundational | Ubiquitous |

Concluding remarks

Through our narrative literature review and detailed framework analysis, we have offered some conceptual categories, language and metaphors for articulating and disaggregating knowledge co-production aims and processes. These were derived from academic literature on knowledge co-production from a wide range of fields and traditions. We have provided a theoretically rich, yet robust and pragmatic, way of understanding and talking about the different aspects of knowledge co-production.

Conceptually, the framework explores five domains of meaning seen repeatedly in the literature, each with two distinct subthemes. Representing these on a spectrum, from more conventional knowledge production (shared subsequent to being created) to more committed or radical co-production, has allowed us to see the variegated nature of co-production possibilities. Should this way of mapping the field take hold, there is the possibility of greater depth and nuance to conceptual conversations, and more precision in theoretically informed empirical explorations of co-production practices.

More practically, the framework provides a coherent and consistent language for surfacing assumptions, sharing perspectives and making sense of difference. Therefore, we hope that knowledge collaborators, such as those embarking on embedded research initiatives, will use the framework to articulate their views on shared projects, both at inception and as they evolve. Primarily, we hope they will use it to identify their own and each other’s positions, to better communicate around and organise projects, and hence to be more successful in delivering those projects to meet various goals and outputs.

Of course, such a process may be as revealing of dissonance and divergence as alignment. For example, any specific project may have aspects that suggest different points on different spectrums at the same time. Sometimes such differences could promote productive tensions; at other times they may be sources of conflict and misunderstanding. Moreover, dynamic change, not static positioning, is to be expected: projects may shift between points on the various spectrums over time. The language and labels we have presented may thus be useful for analysing coherence or incongruence, and for articulating and examining dynamic shifts.

Through this review work, we have revealed the considerable complexity, nuance and contestability of simple ideas of knowledge co-production. But we have done so in a way that provides a practical framework for interrogating the idea and translating its aims and methods into practice. The second part of workstream 1 (and the second literature review) moves, in turn, to unpack ideas of embedded research practice (see Chapter 3). In this way (through these two reviews combined), we can get a better conceptual grasp of the diverse models of embedded knowledge co-production that lie at the heart of this project. The nature and findings from that second literature review are presented next.

Chapter 3 Exploring ideas of embeddedness

Text throughout this chapter has been reproduced with permission from Ward et al. 146 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Introduction

As noted in Chapter 1, and in line with the growing interest in knowledge co-production explored in Chapter 2, there has been a recent surge of interest in embedded approaches to research, particularly within health care. These have tended to focus on developing more productive ongoing relationships and increased social interaction between researchers and those in organisations. Examples include the incorporation of evidence-generating organisations into the wider health service delivery system,147,148 research–practice partnerships149 and local participatory research initiatives. 150

An increasingly popular form of embedded research involves physically locating researchers in non-academic organisations. In this incarnation, embeddedness refers to researchers being ‘in residence’ in the organisation,47,151 and ‘research’ is used to denote at least three things: the knowledge and expertise that researchers bring with them, the research-based knowledge that they broker into the organisation, and the new insights that are developed from data gathered and interpreted in situ. The negotiation of expertise, the contextualising of external knowledge and the co-production of new understandings are often key tenets of this type of initiative, leading to its comparison with the notion of ‘engaged scholarship’. 65,152,153 This is perceived to lead to greater organisational ownership of the knowledge being produced, ultimately leading to its incorporation into the work of the organisation. 65,154

A growing literature has started to highlight the multiple challenges that face embedded researchers and those with whom they work. 155,156 These include the challenges of establishing and maintaining relationships in the face of busy work schedules and tightly controlled service delivery spaces, defining and adapting the scope of the knowledge production work being undertaken, and maintaining an academic identity. 65 The literature has also started to highlight the aspects of an embedded research initiative that facilitate change, including trusting relationships, shared-decision-making, clear communication about the focus and function of the embedded researcher’s role and negotiating the different understandings that those in the organisation may have of the researcher’s role. 152