Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its proceeding programmes as project number 09/2001/25. The contractual start date was in May 2010. The final report began editorial review in August 2012 and was accepted for publication in January 2013. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors' report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

L Nasir received an honorarium and travel expenses for a presentation relating to this research at Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH, USA. Outside this submitted work L Nasir received payment for related lectures from the School of Nursing, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, NC, USA and from ZHAW, Department Gesundheit, Institut für Pflege, Winterthur, Switzerland. M Fischer declared a consultancy fee from the primary care trust in which the research took place for preparation, including stakeholder consultation, in 2009 of an (unsuccessful) National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) research proposal, which predated and informed the boundary-spanning intervention researched in the present work.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen's Printer and Controller of HMSO 2013. This work was produced by Nasir et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Aims

The primary objective of this study was to explore the impact of a ‘boundary-spanning’ intervention, the Westpark Initiative (WI), on knowledge exchange processes between different sectors, organisations and professions in support of horizontal and vertical health-care integration. We undertook an in-depth, longitudinal case study of the WI that took place in four specific topic areas in a deprived area of a primary care trust (PCT) during the period 2010–12 and assessed whether or not such processes lead to improvements in the quality of health care.

Our research hypothesis was that boundary-spanning processes will stimulate the exchange and creation of knowledge between sectors, organisations and professions and that this will lead, through better integration of services, to improvements as measured by both a range of quality indicators and patient and carer experience. We describe and assess the perceived value of boundary-spanning processes in each of the four topic areas by posing the following overall question: to what extent, and by what vertical and horizontal processes, has boundary spanning facilitated knowledge exchange and creation across sectoral, organisational and professional boundaries, and what impact has this had on the quality of patient care?

Chapter 2 Background

The background to our evaluation report begins with an overview of the contemporary NHS policy context and highlights how various policy streams and wider contextual factors are combining to make the horizontal and vertical integration of services a central goal (see The contemporary NHS policy context). The origins of the ‘boundary-spanning’ concept are then explored (see ‘Boundary spanning’: origins and applications) and we describe how it has been applied both outside and within the health-care sector to date and the types of boundaries that need to be crossed to ensure high-quality health care (see ‘Boundary spanning’ in the health-care sector). We then present the findings of a review of empirical studies carried out in the health-care sector (see A review of the empirical literature), which establishes that the existing evidence base mainly relates to the characteristics of individual boundary spanners and that there is a lack of studies of how boundary-spanning processes enable knowledge exchange and creation. We then identify and describe a framework for conceptualising knowledge creation and exchange processes across boundaries, which we will later use to analyse our primary research findings (see Conceptualising knowledge creation and exchange processes across boundaries: the socialisation, externalisation, combination, internalisation model). The chapter ends with an introduction to the particular boundary-spanning intervention under study and the setting for our evaluation (see The boundary-spanning intervention under study: the Westpark Initiative).

The contemporary NHS policy context

In the health-care sector it has been recognised since the 1970s that high-quality services, particularly for patients with complex needs, cannot be provided by one health-care discipline alone or by a single sector. Today, patients in most health-care settings typically interact with a variety of health-care professionals representing many different disciplines but do not necessarily experience patient-centred care or co-ordinated teamwork. Not all multidisciplinary teams function effectively as a unit; interprofessional work groups face additional barriers to reach the level of high-functioning teams, particularly those working in a complex health-care environment. Consequently, patients commonly receive services in several settings from professionals representing a variety of disciplines and amidst a fragmented set of professional silos, all of which create barriers to truly effective multidisciplinary care. At the same time, all health-care systems face the twin challenges of improving quality while increasing efficiency. In the contemporary challenging economic climate there is an even greater imperative for health-care systems to find ways to improve both the efficiency and the quality of service provision. A recent review has highlighted that quality improvement can in some cases lead to lower costs1 and, as Crump and Adli2 have pointed out, the work of key pioneers of quality, such as Deming, Juran and Kano, has shown the scope for improving quality and reducing cost in many sectors.

Consequently, there have been a variety of initiatives to promote intersectoral and interprofessional working; collaborative multiprofessional teamworking has become a major policy objective of successive governments and an international trend. These initiatives have included:

-

the organisation of professionals into multidisciplinary teams (e.g. community mental health teams)

-

geographical colocation of services

-

shared geographical boundaries and/or merger of health- and social-care agencies

-

initiatives to promote a better understanding of each other's roles (e.g. interprofessional education)

-

the blurring of professional role boundaries in the interests of generic flexible working.

In the health-care context, as well as boundaries between different professional groups (e.g. doctors and nurses, generalists and specialists), there are also typically boundaries between organisations (e.g. acute trusts and community health service providers) and between sectors (e.g. voluntary and social service sectors). More recently, many policy recommendations and deliberations in health-care policy-making have also been reliant, to a significant extent, on successful working across such boundaries. 3 As part of the ongoing debate about how best to enable cross-boundary working, there has been increasing interest in designing patient pathways coupled with routine monitoring of patient flow, satisfaction and clinical outcomes as a recipe for a high-quality and cost-effective health service.

One major policy response has been to advocate both the horizontal and the vertical integration of health-care services. The term ‘horizontal integration’ has been utilised in many industries, particularly in business and economics; in health care it refers to building connections between similar levels of care, such as using multiprofessional teams within the same sector, for example care provided by different services all within a primary or community-based care remit. Peer-based groups working across organisational boundaries or taking part in cross-sectoral work would also be examples of horizontal integration. 4 The term ‘vertical integration’ refers to links across different levels of care, such as between acute hospital care and secondary care services. 5 We are using vertical integration to describe care pathways between generalists and specialists for named conditions. 6 As Thomas and colleagues7–9 have argued, whole-system, or comprehensive, integration aimed at reducing health-care costs and bringing care closer to home requires that vertical and horizontal integration develop in tune with each other.

Unfortunately, there is a lack of clear empirical evidence demonstrating how integration can improve service delivery and, until recently, there has been no universal definition of integration as a concept, or as a model. Furthermore, a systematic review found that there is also a lack of standardised and validated tools for evaluating outcomes of integration. 10 A recent report provides the best overview to date,11 suggesting that ‘the working definition of integrated care may be around the smoothness with which a patient or their representatives or carers can navigate the NHS and social care systems in order to meets their needs’ (p. 15) and that it has three dimensions:

-

seeks to improve the quality and cost-effectiveness of care for people and populations by ensuring that services are well co-ordinated around their needs

-

necessary for anyone for whom a lack of care co-ordination leads to an adverse impact on their own care experiences and outcomes

-

the patient's or user's perspective is the organising principle of service delivery.

Commonly cited examples of successful integrated care services include the Torbay and Southern Devon Health and Care NHS Trust (which integrates health and social care) and the Kaiser Permanente model in the USA. The National Integrated Care Pilots evaluation12 looked at 16 specific projects in the NHS and drew the following conclusions:

-

most of the pilots focused on horizontal integration rather than vertical integration and the various models depended on local circumstances

-

staff generally believed that improvement in processes was leading to improvements in the quality of care

-

patients did not appear to share the sense of improvement (possibly because the changes were driven by professionals rather than users)

-

reductions in some forms of admissions were achieved, but not in emergency admissions.

Other large-scale pilots of integrated care services are currently under way in the NHS13 and the new regulatory framework under the Health and Social Care Act includes a duty on Monitor (the NHS regulator) to ‘exercise its functions with a view to enabling the provision of healthcare services provided for the purposes of the NHS to be provided in an integrated way’. 14 More broadly, the ‘architecture and landscape of the NHS has gone through fundamental change’ (p. 2)11 as a result of what is commonly acknowledged as the most significant reform since its foundation in 1948. Newly formed clinical commissioning groups (CCGs) are expected to play a crucial role in determining how health care will be delivered by overseeing the design of local health-care services.

For the ambitions of policy-makers to be realised, processes of knowledge exchange have to improve across sectoral, organisational and professional boundaries, which can present significant barriers15 and thereby undermine attempts to integrate health-care systems, and ultimately efforts to improve quality and efficiency. ‘Boundary-spanning’ roles have been proposed as one potential solution. However, a systematic review of the diffusion of innovations in health-care literature covering the period up to early 2005 found that empirical studies exploring the role of boundary spanners were sparse. 16 Most of these had explored knowledge exchange across single (e.g. profession to profession) rather than multiple (e.g. between professions in different organisation and sectors) boundaries. In the following two sections we explore the origins of the concept of ‘boundary spanning’ and how it has been applied in the health-care sector.

‘Boundary spanning’: origins and applications

In general terms, ‘boundary spanning’ describes the role of individuals who work in groups but who have ties across boundaries that divide their colleagues. 17 Such individuals have been described as organisational liaisons and ‘key nodes in information networks’ in theories introduced by Adams18,19 and Tushman. 20 The boundary-spanning role was traditionally described as dually serving to process information and provide external representation and, as such, is delineated from the role of the formal authority in an organisation. 21

Boundary-spanning components and boundary-spanning activities are concepts described in a seminal text from organisation theory, Organisations in Action. 22 Thompson explained that boundary-spanning units are established to adjust or adapt to increasingly complex structures as a response to necessary subdivisions that result from the sheer volume of interactions in a task environment. In this theory-building treatise, the author argued that, the more an organisation's environment grows, the more it becomes complex, diverse and/or unpredictable. Thompson noted that co-ordination among organisational units is a core issue and that units developed to span across unit boundaries would be troubled by ‘adjustment to constraints and contingencies not controlled by the organisation’ (p. 67). He further wrote that boundary-spanning units, although interdependent, would be judged by the ‘disappointments they cause for elements of the task environments’ (p. 96). Boundary spanning as an act was not conceived to be serving in an easy position, and the implication is that managers may not be able to fully direct workers in such bridging positions.

In an early literature review from the 1970s,23 boundary-spanning personnel were identified by terms such as ‘input transducers’, ‘linking pins’, ‘gatekeepers’, ‘unifiers’, ‘change agents’, ‘members of extra-organisational transaction structure’, ‘regulators’, ‘liaisons’, ‘planners’, ‘innovators’ or ‘marginal men’. Although they used the term ‘boundary-spanning activity’ in the title of their journal article, the authors Leifer and Delbecq23 noted that the specific term ‘boundary spanner’ was used only once, in an unpublished manuscript, among the 28 references cited at that time (1978) describing types of boundary-spanning personnel.

Difficulty working in the potentially undefined area between units was explored further in research by Michael Tushman in 1974,24 who first examined the notion of complexity and integration efforts in the industrial setting. Tushman and colleagues are widely credited with further describing how ‘boundary roles’ evolve to function as a link to the process of innovation in a system. In a growing and differentiating organisation, such as a research and development (R&D) laboratory, certain individual communicators serve as special types of liaison agents, connecting well in a two-step process by first communicating internally within an organisation and then communicating across multiple interfaces to areas of external information and back again. This study20 explored how high-performing projects might intentionally develop boundary roles to mediate external information, especially in response to high levels of work-related uncertainty. In describing ‘boundary-spanning activities’, Tushman and Scanlan25 referred to boundary spanners as ‘internal communication stars’ (p. 290). Attempts to understand information (or knowledge) transfer, particularly with an external orientation, was enhanced by application of the concept of boundary spanning, especially in describing organisations with laboratories and R&D departments working to create and disseminate new products. 25,26

Following these early discursive papers, the conceptual background of boundary spanning, and the empirical basis of its impact, has been further explored in the organisational studies and management literatures. Boundary spanners in teams have been said to serve in ‘ambassador activities’ (p. 640) and ‘task coordinator activity’ (p. 641) at the team level,27 or have been defined as ‘employees who operate on the periphery of an organisation’ (p. 296). 28 Leaders have been in part characterised by their role in boundary-spanning activities and their emotional intelligence. 29 The role of power and trust in relationships, and the brokering of system exchanges, have also been differentiated from boundary spanning. 30,31

Boundary work in teams has been described by examining the interactions among information technology (IT) knowledge teams and other technological industries, especially in studies seeking to understand how projects are accomplished both by teams32–34 and between organisations and partnerships. 35 Success on R&D teams has been tied to vertical leaders who are skilled at boundary management and managing external relations. 36 Authors have discussed the consensus that integration drives superior performance, and that boundary spanners serve as a source of innovation across functional areas. 37 The non-routine tasks of boundary spanners and the relationship to role stress and role overload have also been described in multiple studies,28,38–40 including across samples of engineers and nurses. 41

‘Boundary spanning’ in the health-care sector

In the health-care context, ‘boundary-spanning’ interventions have been proposed as having the potential to promote the closer integration of services in the interests of improving the quality of care and/or reducing costs. However, the processes through which they can produce improved co-ordination and knowledge sharing between different professions, organisations and sectors have not been determined. This section reviews the application of the boundary-spanning concept in the field of health-care organisations, exploring how it has been operationalised as part of increasing efforts to improve the vertical and horizontal integration of health-care services.

Despite the emergence of the concept of ‘boundary spanners’ in the fields of behavioural psychology18 and organisation theory24,42 as long ago as the mid-1970s, there is a relative paucity of empirical studies exploring the role of such individuals in health-care systems and only very limited evidence exists about how such explicit attempts to improve cross-boundary knowledge exchange have an effect on the quality of health care. Although a small number of studies of boundary spanning in the health-care setting have been carried out, few have utilised rigorous empirical methods or have focused on the detailed processes by which such interventions have helped improve the vertical and horizontal integration of health-care services, and the quality of patient care. Only a study by Byng and colleagues43 utilised an evaluation framework to identify the role of link workers in efforts to improve care. Furthermore, most studies have rarely taken the time to construct theories or explanations for what they observe or find in their analyses (see Grol and colleagues44 for a critique of the atheoretical nature of the vast majority of quality research in health care and a call to researchers to make more systematic use of theories in evaluating interventions). Clearly more studies are needed that can connect boundary-spanning activity to quality improvement efforts that have a real impact on patient care outcomes.

Although contemporary policy initiatives aim for combined vertical and horizontal integration, dominant ways of thinking about how to achieve this, coupled with inadequate training of clinicians and health-care managers and the existence of sectoral, organisational and professional boundaries, are nonetheless likely to emphasise the vertical dimension. More generally, the ability of collaboration and other network forms to achieve higher quality at lower cost is seriously questioned by the substantive literature (not least because there has not been an easy transition to collaborating across traditional sectoral, organisational and professional boundaries). Collaboration places considerable demands on professionals as they learn to work for purposes other than their personal or their organisation's interests. 45,46 Disparities of objectives and positions of power, as well as diverse organisational cultures and ontological frameworks, distort collaboration47,48 and inhibit learning and change. 49 Strategically orientated networks may increase organisational advantage among partner organisations, but often do so at the cost of excluding other communities of interest. 50,51 So it is that studies of public service networks find that, even after successfully achieving new modes of working, governing organisations may simply ‘revert to type’, re-establishing traditional hierarchical control. 52 Indeed, after many years of long-term research in the field, some scholars conclude that the challenges of interorganisational collaboration are so formidable, and tendency towards collective inertia so strong, that it should be avoided as far as possible. 53

Given this overall picture, the prospects for purposeful collaboration (or integration) appear discouraging to say the least. However, there is recent evidence that more effective, nuanced forms of collaboration may be emerging, not through explicit partnerships, but from interacting networks of committed and deeply engaged participants,54 and health-care reforms in Europe now commonly emphasise community participation, interprofessional learning and collaboration across the public and independent sectors.

A review of the empirical literature

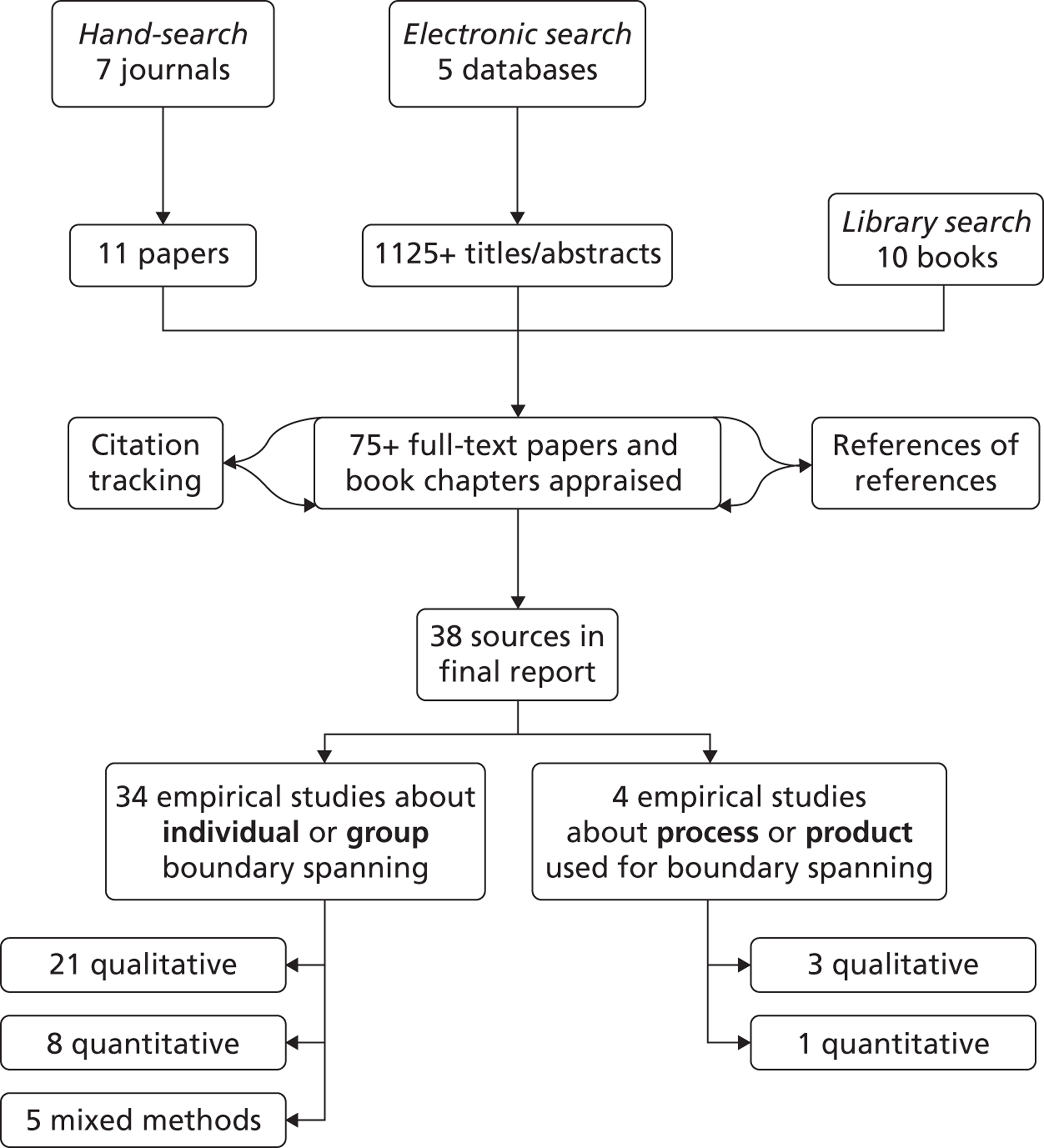

Before undertaking our fieldwork and designing our research tools we undertook a focused literature review to develop a clearer understanding of the findings from relevant empirical research studies. Our objectives were to identify empirical research that has examined boundary-spanning in health care, synthesise that literature by conducting a meta-ethnography, suggest key themes relating to boundary-spanning processes in health-care systems and establish whether current evidence suggests that these processes can contribute to improved quality and/or reduced costs. The methods we used to undertake the review are detailed in Appendix 1.

In total, 38 empirical articles15,55–91 published in a wide variety of journals were included in the review (see Appendix 1, Table 28, for summary details of each of these studies). Of the included studies, 17 were from the UK,15,56,61–64,68,70,75–77,79,80,82,83,90,91 13 were from the USA,55,58–60,65,66,71,73,84–86,88,89 four were from Canada,69,72,78,81 one was from Australia,74 one was from Ireland67 and one was from Israel. 57 Also included were two comparative case studies (one from the UK and the USA and one from the UK and South Africa). 82 Twenty-four studies (63.2%) used qualitative methods,15,55,56,58,59,61–64,66–70,75–82,87,91 of which 13 had a case study design56,58,61,62,66,69,70,75–78,79,82 and five were specifically ethnographic in their approach. 78–82 Nine studies used only quantitative research methods60,65,71–73,83–85,89 and eight utilised surveys or questionnaires;57,60,65,71,73,83,88,90 the majority (seven60,65,71,73,84,85,89) of the quantitative studies were from the USA. Five studies used a combination of qualitative and quantitative research methods. 57,74,86,88,90 Half of the studies were published since 2007,55–59,61–63,67,68,70–72,74–76,81,87,88 and the majority (n = 33, 86.8%) of research was published since 2000,15,55–59,61–72,74–78,79–83,86–88,90,91 reflecting increasing and continued interest in the subject of boundary spanning in the health services literature. Details of the direction of integration and the boundaries spanned in the included studies are shown in Table 1.

| Boundaries studied | Horizontal integration (n = 24) | Vertical integration (n = 14) |

|---|---|---|

| Sectoral | 14 | 3 |

| Organisational | 8 | 7 |

| Professional | 13 | 14 |

Overall, we found that the 14 studies of vertical boundary-spanning provide clear descriptions of how people at different levels of a health-care system relate to each other but are weak on process and evidence-based patient outcomes. 15,55,56,61–65,75–77,86,89,91 All of these studies addressed spanning professional boundaries to some degree, which may reflect contemporary research interest in examining power relations between disciplines. Top-down policy initiatives for collaboration were not found to have led to better co-ordinated services. Predefined roles for clinical boundary spanners appeared to be challenging to accomplish in reality and social (personal and political) factors played a greater than anticipated role in this. Political awareness and facilitation skills seemed important for inter- and intraprofessional working, particularly in this vertical dimension. For individuals in high-status positions, successful boundary spanning requires a willingness to work outside professional identity groups; for those in lower-status positions, gaining and communicating professional competency may be more important. In summary, although interdisciplinary and interorganisational boundary spanning is a well-described challenge, there is little research to demonstrate how effective vertical integration is accomplished by implementing boundary-spanning interventions.

Studies of horizontal integration appear to provide rather more positive support for boundary-spanning interventions than studies of vertical integration. More of the studies of horizontal integration examined the crossing of sectoral boundaries – 1357,59,60,66,67,69,71,73,82,85,87,88,90 compared with only three62,65,76 in the vertical integration articles – reflecting how non-health-care sectors experience horizontal relationships with clinical services. Efforts in the horizontal integration of primary care services are commonly implemented to improve access for patients seeking particular medical services. Boundary-spanning interventions in the form of online discussion forums, published resource guidelines and complex pathway guidelines have the potential to improve joined-up working, particularly in community settings. However, sustaining integrated solutions relies on the flexibility, adaptability and continued reflection and insight of those who are facilitating the intended change, and the receptiveness to this change in the wider environment. For individual staff, achieving boundary status is associated with accomplishment, but also ambiguity. Professionals with enhanced expertise but in new boundary-spanning posts, such as clinical nurse specialists, general practitioners (GPs) with special interests or dual specialists, may not be readily accepted either socially or politically, making system-wide integration sluggish.

The 38 empirical studies that met our inclusion criteria were then analysed using the seven iterative steps of meta-ethnography for evidence synthesis (see Appendix 1). The resulting important themes were:

-

the need for individual boundary-spanners to possess a wide range of communication skills

-

negotiating formal and informal boundary-spanning roles

-

recognising and responding to social and political influences on knowledge exchange processes

-

demonstrating evidence of the impact of boundary-spanning on the quality of patient care.

A wide range of communication skills

Martin and Tipton55 compiled a typology of communication roles from a purposive sample of non-clinical, salaried patient advocates who, as boundary spanners, might review medical charts, facilitate selection of doctors for second opinions or socialise with waiting family members. The roles were liaison, feedback/remediation, counselling and support, system monitor, troubleshooter, investigator and group facilitator. Although this research suggested, theoretically, that as boundary spanners these advocates may serve as system change agents – particularly when responding to patient complaints – the descriptive nature of the research did not build empirical evidence for vertical integration. Similarly, Abbott56 found that to be effective, nurse consultants needed to be credible leaders, be familiar with relevant policies and organisational structures, build and maintain effective relationships and apply communication skills (including facilitation of conflict).

In another mixed-methods study,57 three structural variables (team informational diversity, team boundedness and extra team links) were used to understand how to increase interorganisational boundary spanning in health promotion teams. Three types of boundary spanning were reported as being associated with team effectiveness: scouting, ambassadorial and co-ordinating. The author suggests that the most effective teams should maintain an open team configuration, invite experts and change team composition over time (including part- and full-time members). In this way, increased scouting implied greater informational diversity, and greater interorganisational team effectiveness, even in less bounded teams with more part-time members.

Tools, and processes, can serve as boundary-spanning entities as well. Three studies58–60 examined how knowledge sharing was accomplished through boundary-spanning methods. Hara and Hew58 observed an online community of practice for advanced practice nurses, finding that the non-competitive and asynchronous nature of online communication facilitated the improvement of current knowledge and validated best practice. A study of health behaviour change explored the use of referral guides along with support people external to the organisation to implement linkages in the community. 59 Connecting strategies, such as paper or electronic databases were developed to bridge primary care and community resources, especially for patient referrals. However, hurdles were discovered in both resource availability and accessibility to patients, and affordable infrastructure to support boundary-spanning activities was needed. Often boundary-spanning individuals were needed to fill in the gaps, and marshal the use of technology, when paradigm shifts in practices had not yet occurred.

As translators and diplomats, boundary spanners may serve to communicate new ideas across a divide. How that knowledge is shared, and whether or not it is adopted, is a sign of its impact. In a study of health planning staff and board members it was found that effective performance as boundary spanners improved collaboration. 60 As a study of communication strategies, staff members and board members influenced each other by the extent to which they answered each other's questions; seeking information became a mark of a good board member. Open communication appeared to enable the ability to act on shared objectives. Knowing the staff views and agency routines increased the perception of board effectiveness.

Formal and informal role negotiation

The development of new professional roles to bridge treatment areas is a relatively recent innovation in the UK. With the development of these roles comes ambiguity in task definition and efforts to build professional credibility. Examining pilots that sought to train GPs in specialist genetics and cancer roles, it was found that recruiting for such hybrid roles was difficult because of the day-to-day work of GPs; sustainability of the project was a major concern. 61 GPs with special interests were described as defining their legitimacy through relations with experts and through the motivation to extend clinical competency. However, between geneticists and GPs, the power of knowledge and jurisdiction (‘turf’) remained disputed in the professional hierarchy. Consensual divisions of labour may be backed by institutional goals, but, at the micro level, how roles were negotiated was not entirely clear. For example, a mutually agreeable role for the boundary-spanner clinician was delimited (by the specialist) to be less clinical and oriented towards a more educational role (similarly, nurse consultants are described as struggling to negotiate their role as either autonomous expert or process supporter, with a common experience of having difficulty identifying priorities56). An awareness of stakeholders' different priorities, social capital and established relationships was key for developing collaborations across organisational and sectoral boundaries. Short-term economic incentives were difficult to address with long-term preventative cost-saving calculations. In this way, politics was identified as an important aspect of role definition for boundary spanners. In these examples, beneficial evidence from putting a clinician in a boundary-spanner role was difficult to collect, and the role was constantly renegotiated within the context. When considering intentional efforts to vertically integrate services, the authors noted that colocated specialists and practitioners in hospitals had not only a supervisory relationship but also a more dialogical and informal relationship. Practitioners not located in the tertiary setting but working in primary care appeared to have more clinical–governance relationships with the hospital-based specialists. This latter relationship was considered time-consuming for the geneticist who had to check the risk assessments carried out by practitioners who might have had ‘inadequate’ training. 62 Defining a boundary-spanning role by task orientation and job description does not fully reveal the negotiations that happen on a daily basis.

Negotiating disciplinary boundaries between specialists and generalists may be mediated by disciplinary values (which may be semantic, historical, practical and unrelated to patient need or disease trajectory). In a role study in palliative care – and despite policy guidelines to share care – covert and overt tensions between services were noted, particularly in the practice of referrals. 63 Personal commitment and local organisational goals appeared to highlight dilemmas posed by uncertainty of prognosis, particularly in patients with heart failure. In these ways, boundary-spanning managers and newly appointed link workers who were perceived to have less clinical knowledge had less ability to influence others in the vertical dimension, even if supported by policy initiatives, newly funded posts or intentional clinical or managerial placement. Vertical integration may be suggested by policy, but professionals make individual decisions to collaborate, or move patients across boundaries, based on many other factors.

French64 describes four contextual factors (physical, social, political and economic) that influence how work group participants use evidence to make policy decisions. Doctors, managers and nurses working in different settings may have varying perspectives of what is needed for patient care. For example, in the social context of care, respondents reported using independent action, involvement in teaching and direct challenge to influence the care decisions by medical staff. Subterfuge and adaptation were also described as covert strategies used to influence care patterns. In the wider context of care, researchers observed that influencing commissioners, adapting decisions and informally ‘trading’ equipment were other strategies used to manage economic constraints. 64 In these ways nurses used different strategies to close gaps in services.

Finding time to engage in vertical integration activities was also a challenge for clinicians. Nurse consultants working in boundary-spanning positions were described as needing additional time to negotiate priorities and relationships, which limited the time that they were available for patient care,56 whereas cardiac surgeons reported that time constraints may contribute to inaccurate medical stories that are reported to newspapers. 65

Boundary spanners have been placed as intentional links between programmes in an effort to create a more seamless service for clients. For example, expanding the roles of mental health workers to bridge the hand-offs between the courts and components of the mental health system was a solution explored in one case. 66 Attempts to build this innovative programme as a model were complicated by the varying engagement of different stakeholders and by a lack of client health insurance (in the USA). An assessment to gauge interagency co-ordination was mentioned but not reported in detail.

For mental health link workers it was found that, although there was potential for these liaisons to improve communications between secondary education services and child and adolescent mental health services, staff were concerned that some increase in workload might result in the short term. 67

Another study examined the changing roles of practice nurses in the primary health-care setting in terms of them taking greater responsibility for the management of chronic disease. 68 The realignment of boundaries demarcating work previously carried out by GPs motivated nurses to increase their technical knowledge base to a less routine level of practice and to an increased level of professionalism, but raised some tensions in role definition.

Trust and communication, and power and conflict, were explored in a case study of multisectoral collaboration in the domain of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) community. 69 Boundary spanners were recognised as being in ‘dual roles’ – both collaborative partner and organisational representative – causing tensions to arise. Juggling the conversations between constituencies required a chain of conversations, which was framed as a creative process central to organising; the tension was positive and necessary for seeking change. In this case study the tenuous space between collaborators is described as a source of potential energy.

Attempts to map out a mental health safety care pathway also met challenges, because of complex assumptions about work arrangements, and attempts to connect the expectations of clinicians, managers and service users. 70 Negotiating the use of a guideline as a tool was unworkable when it was conceived of as an ideal document of standardisation. To co-ordinate services, and accommodate to variation, the pathway needed to become more abstract in its scope. As a boundary object the author describes the imprecision and looseness of the resulting pathway as an effective alignment and compromise between stakeholders. Creative solutions can resolve such tensions, while balancing the needs of standardisation with diversity of purpose. 70

Two quantitative studies71,72 in the vertical dimension measured time spent (number of hours engaging) in boundary-spanning functions as a positive characteristic of a supervisory position. Substance abuse programme directors, who were also treatment counsellors, were found to spend more time making community presentations and liaising with monitoring organisations, which the authors assume (but did not measure) may have improved treatment practices and political leverage. 71 Front-line nurse managers with a larger number of direct report staff reported lower supervision satisfaction with highly transformational leadership, except when operational hours were extended. 72 These boundary-spanning managers found more satisfaction in the transformative behaviour of performing ‘citizenship’ activities within the organisation, than simply having more time with staff, although having more time was a factor. The leadership activities that characterise boundary spanning appear to mediate contextual pressures, but further studies would need to explore this issue more fully.

Two studies73,74 used quantitative methods to evaluate the impact of perceived uncertainty on boundary-spanning behaviours. In an early field study of work units in health and welfare organisations,73 positive relationships were found between three variables: an organic management structure, frequency of boundary-spanning activity (verbal and written interactions) and perceived environmental uncertainty. The study used a composite variable of ‘organicness’ in management structure by using six scored measures, including extent of participation in strategic decisions, participation in work decisions, division of labour (specialisation), impersonality, formalisation and hierarchy of authority. Perceived environmental uncertainty was measured by questionnaire items rating whether or not subjects knew what to expect of people in the organisation. Frequency of boundary-spanning activity appeared to mediate environmental uncertainty and organisational structure. Organicness was strongly associated with frequent boundary-spanning behaviour; environmental uncertainty was not. By examining the individual as the unit of analysis, this attempt to understand the different effects of organisational structure and uncertainty made strides in adding contextual factors to the analysis of boundary-spanning activities, but limitations remain in measuring such linkages in context. Similarly, in their study of service providers working as boundary spanners in primary care partnerships in Australia, Walker and colleagues74 suggest that such individuals function to interpret environmental context for decision-makers, mediating risk and uncertainty. Service providers perceived less risk and uncertainty in the collaborative work and, so, experienced unproblematic relationships based on trust. In contrast, organisational managers perceived more risks from breaches of trust, particularly as a result of political partnerships, which also might result in more consequences and harmful uncertainties. Competitive allocation of funds and established system practices impacted these experiences, placing an importance on an institutional environment that supports trust across professions.

Social and political contextual influences on sharing knowledge

Twelve15,55,61–64,75–77,86,89,91 of the 14 studies of vertical exchanges specifically addressed the social and political contexts in which different disciplines function, particularly the two studies by Currie and colleagues. 75,76 These studies found that role and status seem to determine research uptake in professional groups, as opposed to managerial behaviour. Social and political relations between team members were identified as the medium for sharing knowledge in organisational change efforts. 76 A case study of how knowledge was shared between two NHS teaching hospitals, district general hospitals, PCTs, a strategic health authority and a university medical school took a neo-institutional perspective. 15 This study suggested that knowledge sharing could be enabled within similar organisations but that this was much more problematic across different organisations and professional groups. In this study hospital doctors were found to focus their knowledge-sharing activity on relationships with their peers within the hospital boundary and they downplayed any contribution that GPs or commissioning managers might make to service development.

The hierarchy of professional exchanges across disciplinary boundaries, and the tendency of higher-status clinicians to withhold rather than share knowledge, was described in a study of the barriers to the spread of innovation in multiprofessional health-care organisations in the UK. 77 Specialists hold overt power in the hierarchy of organisations and strong professional identity is associated with more reluctance to share knowledge. These researchers found that strong uniprofessional communities of practice can block external input from other groups and retard innovation. A key theme in both the horizontal and the vertical integration of services is therefore how credibility is inextricably linked to professional competency and expert knowledge. 77,78,92

Five ethnographic case studies78–82 examined the role of boundary spanners in horizontal integration. The advantages of observing the sociocultural and knowledge context of group work allowed these researchers to explore the factors that impede or enhance collaboration, whether in the tertiary care hospital or in the community clinic. Recognising the need for someone who sits outside of the usual routines – albeit temporarily – was noted in these studies. MacIntosh-Murray and Choo78 suggest that nursing staff – busy with prosaic tasks – may find that meetings and other forms of communication appear to be time-consuming with little time for critical thinking to solve knowledge gaps. The rhetoric of accountability (and risk of consequences) can focus busy staff on tasks rather than quality improvement and, with managerialist discourses, doers may feel burdened or disempowered by a perceived need to put in extra effort to fix problems. A boundary-spanning ‘surrogate’ was able to identify the information needs of others and act as a knowledge translator, but could not fix routines or inherent competence problems in individuals. 78 In another study,79 high workload demands in a complex environment were addressed by staffing flexible and transient teams in operating theatres; however, shared knowledge was at risk as was having a predictable knowledge composition of the teams. In this way, flexibility in coping with care delivery demands was found to undermine the acquisition of knowledge; risks to safety were implied, but evidence was not gathered to support this. Ambiguity can affect people working in boundary areas (such as volunteers working in formal organisations), which may cause confusion for the paid staff working with them. ‘Lay’ workers may be asked to share knowledge and experience but not to give advice, which poses particular tensions and the potential for conflict. 80 Salhani and Coulter81 describe how nurses in a psychiatric hospital ‘went underground’ with ‘guerrilla action’ to use a primary therapeutic nursing model to address biopsychosocial factors with patients, despite rejection from ward psychiatrists. Micropolitics and strategies to organise among the nurses were key factors in the description of interprofessional relationships in this study, as the ‘elite nurses’ intentionally expanded their jurisdictional boundaries through loyalties, logos and celebrations to oppose the dominant medical culture. In another study,82 working as ‘boundary people’ at the interface between community and statutory organisations in itself was a prized end, suggesting that empowerment may have its place in system change. In this case study, building change through ‘small steps’ and ‘good enough’ solutions were strategies used to build partnerships.

An NHS primary care-based study used a survey to examine how boundary spanners' characteristics and behaviours related to the effectiveness with which different groups jointly work together. 83 The study found that the productivity of group collaboration was predicted by boundary spanners who had frequent intergroup contact and high organisational identification. The authors suggest managerial implications (e.g. promoting individual boundary spanners to boundary positions when strong ties to their organisation can be used to overcome ineffective intergroup relations) but no interventions were tested.

Boundary-spanning strategies are used by organisations as well as individuals and groups. For hospitals in the USA, membership in a larger organisational (multihospital) system increased the likelihood that bridging strategies would be used for outreach, likely because of corporate policies to reduce costs. 84 Freestanding hospitals were less likely to seek external service linkages through planning groups or consortia. Confirming the idea that the hospital system is fragmented, this research suggested that hospitals do not have a uniform response to environmental pressures and noted that regulatory pressure did not increase boundary-spanning activity as expected. Retrenchment at the administrative level might be more likely as a response to vertical integration pressures, by increasing the size of boundary-spanning governing boards rather than increasing technical capacity. In another study of hospitals in the US health-care system85 it was found that inpatient psychiatric departments increased the number of boundary-spanning and buffering structures as they increased in size. Organisational performance was inversely related to department size as assessed by discharge rate, cost of discharge and cost per patient-day. Public hospitals had more secure government funding and were more likely to increase the number of professional staff, whereas private hospitals were more likely to use non- or paraprofessional staff to reduce costs.

Callister and Wall,86 in a mixed-methods study from the USA, specifically used conflict incidents to explore the interactions between managed-care representatives and service providers. Organisational power and status differences were the independent variables, and behavioural responses of the managed-care representatives and expressed negative emotions of providers were the dependent variables. The researchers noted that the individual boundary spanners with the most power (e.g. representatives of the larger managed-care organisation) were less compromising and collaborative when negotiating with smaller organisations, and anger resulted when decisions were blocked by a lower-status representative. Describing a ‘double power asymmetry’ the researchers also noted that the organisation that is larger and controls revenue streams can exert power over the medical doctor as provider; however, this is reversed if the boundary spanner from the managed-care organisation has a lower status (a clerk or a nurse) than the medical expertise of the provider. It is interesting to note that the boundary-spanning post can be both problematic and a proposed solution; the boundary-spanning representative in the middle of a conflict can experience stress and potential job turnover, which might be addressed by putting more doctors in boundary-spanning positions.

In a case study of successful local health partnerships,87 boundary spanning was accomplished both ‘downwards’ and ‘across and upwards’, meaning that community advisors had the responsibility for engaging multiple stakeholders, including programme recipients. Momentum was maintained for ongoing dialogue because of the trust engendered through the enthusiasm and optimistic personality of the boundary spanner. Positive results were reported as ‘100% uptake of energy efficiency measures’ and ‘high levels of satisfaction’, which were attributed to the increase in detailed local knowledge. Being a ‘community-led’ project was also held to be a positive aspect of the success of the strategic planning partnerships. The movement of knowledge across boundaries appears to be inextricable from the communicators of the process.

In another example of community partnerships, public health and faith collaborations were designed in an effort to address health disparities. 88 Boundary leaders were trained in methods of community system change at an educational institute and pre/post assessments of knowledge and skills were gathered from each participant. Despite reporting success on leadership measures of renewed sense of faith and team accomplishments in planning programmes, no impact on health disparities could be reported. Inducing plans for change can be an indicator of the effect of boundary-spanning interventions but does not provide clear and direct evidence of an impact on health outcomes, as is often demanded by stakeholders and funders.

Evidence of impact on the quality of patient care

Of the 14 studies15,55,56,61–65,75–77,86,89,91 that examined the impact on health-care quality of some form of vertical boundary-spanning intervention, only one examined patient outcomes as a result of a boundary-spanning initiative. Thompson and colleagues89 used key indicators (through retrospective chart audit) to determine the quality of peritoneal dialysis before and after a collaborative mapping project. Inpatient and ambulatory nursing representatives met to identify and change process flow charting for equipment utilisation (by patients and clinicians) across a service boundary. As an intentional quality improvement effort, patients who received care after the new jointly developed guidelines were implemented showed a decrease in transfer time between units, faster diagnosis and faster treatment of complications; plans for interdisciplinary collaboration for changing practice responses for hypovolaemia were also being monitored. In this study, how different professionals were brought together for discussions was not qualitatively examined, but the impact of the effort was well illustrated.

A postal survey and interviews90 identified five perspectives relating to the role of boundary spanners – networker, innovator, ‘cultural broker’, collaborator and leader – and explored how the factors of otherness and trust contributed to whether or not such individuals are ‘born and not bred’. The author concluded that research evidence was ‘weak on processes and effectiveness’ and failed to explain the link between individual and team behaviour and outcomes. The study confirmed the image of individual boundary spanners as being able to work in non-hierarchical decision environments by brokering resources and connecting problems to solutions; however, the link between competency and performance effectiveness was not explored.

Summary

Boundary spanning as a concept is well described in the organisational studies literature and many insights from our literature review confirm previous findings in other industries (i.e. broader insights do seem relevant to contemporary challenges relating to the vertical and horizontal integration of health-care services). However, although it is accepted that boundary spanning contributes to knowledge transfer in the technology industry, sectoral, organisational and professional boundaries in health-care systems can present significant barriers to the exchange of knowledge. 15 These can undermine attempts to integrate health-care systems and ultimately efforts to improve quality and efficiency.

Our review of the literature shows that boundary spanning is often regarded as a potential solution to the challenge of service integration. Although the 38 studies that we reviewed differed in terms of whether they took a quantitative or a qualitative stance, whether they studied boundary spanning as an informal or a formal activity and whether they focused on the co-ordination of teams within or between organisations, overall we found a quite strong normative emphasis in the literature. ‘Boundary spanning’ appeals as an ‘obvious’ solution and also tends to be quite reified through individuals being identified as ‘boundary spanners’ who extend collaboration and integration in health-care services. What is less clear, however, is how boundary spanners perform their role – or should perform their role – to improve the quality of care. But we would also note that some commentators45,46,50,51 perceive boundary-spanning processes as problematic, not just failing in implementation but also hindering and even jeopardising intended facilitation and change.

A recent review of current policy frameworks for supporting evidence-based health care93 specifically argues for greater attention to be paid to fostering ‘new boundary-spanning mechanisms to encourage knowledge flow across professional boundaries’ (p. 847) and to the means by which different professions can share and debate their ‘knowledge’ and then embed it into local practice. Our review found that, although the characteristics and experiences of individuals in formal or informal boundary-spanning roles have been studied in the health-care context, relatively little attention has been paid to date to the core focus of our study: the processes by which ‘boundary spanning’ can support horizontal and vertical health-care integration. Importantly, our review also demonstrated a lack of evidence of change in practice.

Conceptualising knowledge creation and exchange processes across boundaries: the socialisation, externalisation, combination and internalisation model

As the findings of our literature review illustrate, although the characteristics and experiences of individuals in formal or informal boundary-spanning roles have been studied in the health-care context, relatively little attention has been paid to the core focus of our study: the processes by which ‘boundary spanning’ can support horizontal and vertical health-care integration through enabling knowledge exchange (as well as knowledge creation). In the light of the limitations of the existing literature, in this section we briefly describe a conceptual framework that we shall use as a working heuristic to help analyse our findings in terms of the impact of a boundary-spanning intervention on knowledge exchange processes between different sectors, organisations and professions. Our initial data were analysed to generate candidate theories and we selected the socialisation → externalisation → combination → internalisation (SECI) model (see below) because of its distinctive combination of structure and process, and particularly the emphasis in the model on the importance of micro interactions and the impact of these at the meso and macro levels, an important theme in our emerging findings.

Outside of the health-care literature, Ikujiro Nonaka94 has proposed that organisational knowledge creation progresses in a spiral model of continual dialogue between tacit and explicit knowledge. Nonaka draws on the distinction between different types of knowledge: explicit knowledge consists of facts, rules, relationships and policies that can be faithfully codified in paper or electronic form and shared without the need for discussion, whereas tacit knowledge is engrained in the analytical and conceptual understandings of individuals (‘know what’) and also embodied in their practical skills and expertise (‘know how’). Tacit knowledge is seen as being uniquely personal and embodied, whereas shared experience and deep mutual trust facilitate the conversion and change towards the experience of a simultaneous rhythm and synchrony of action.

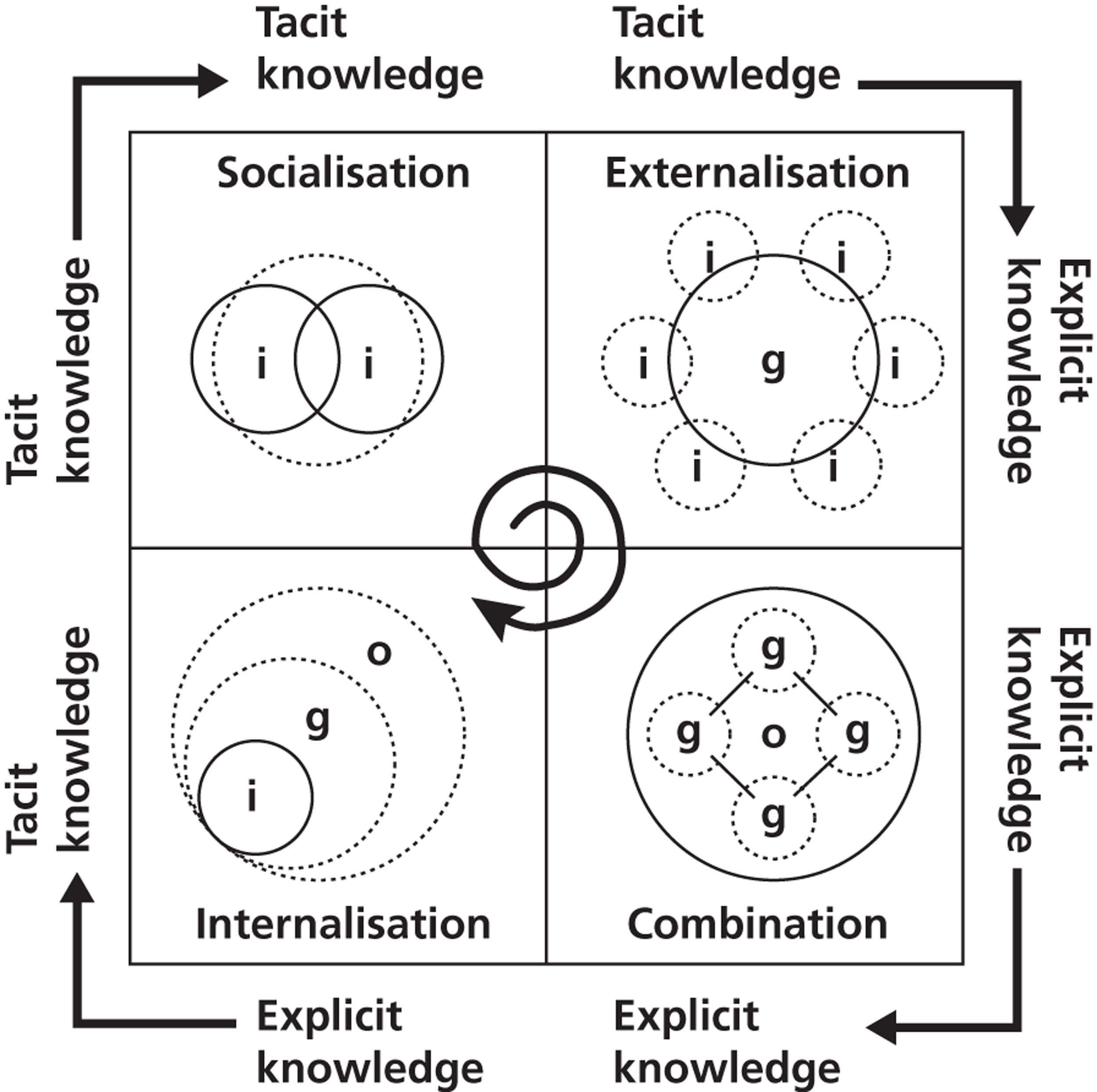

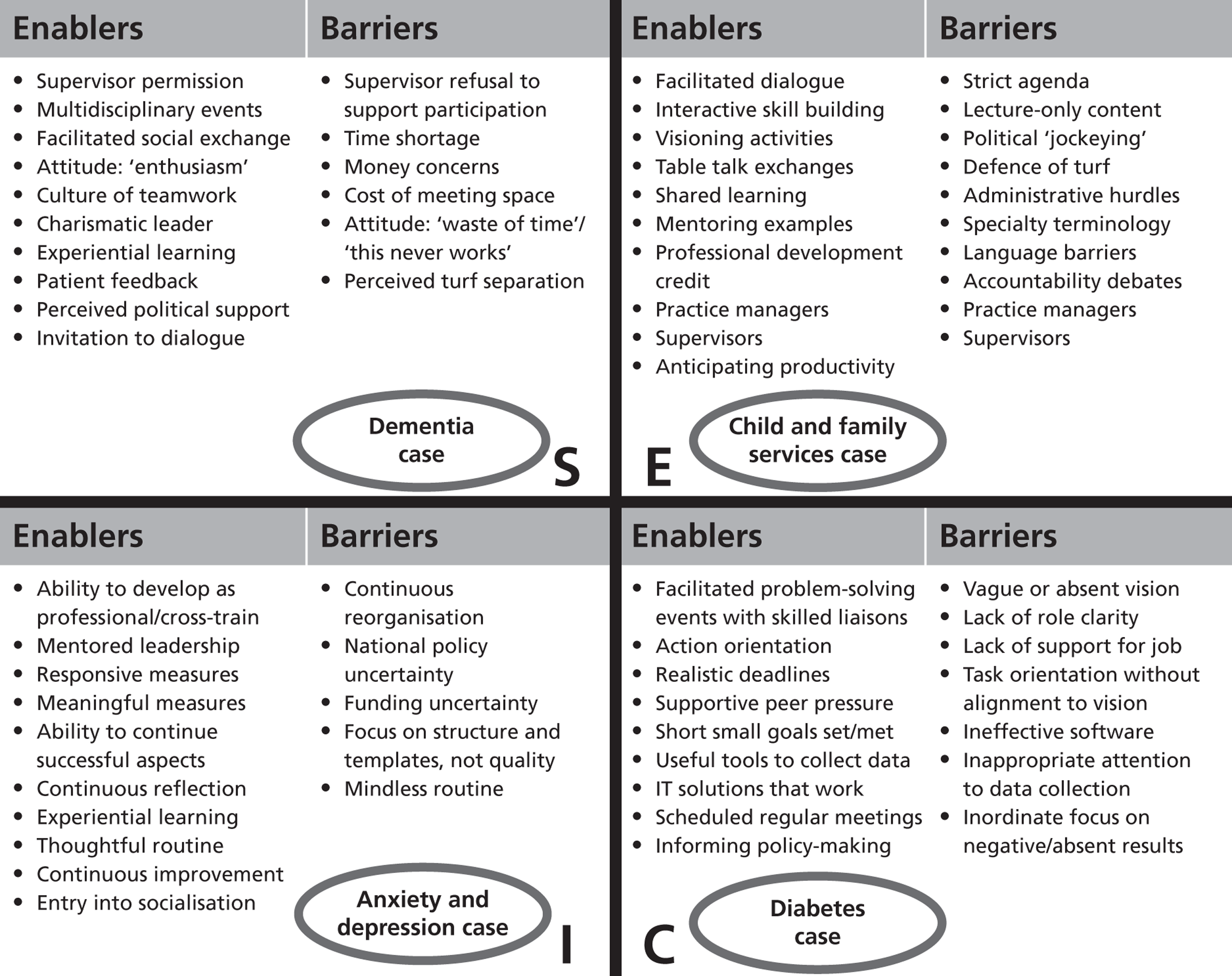

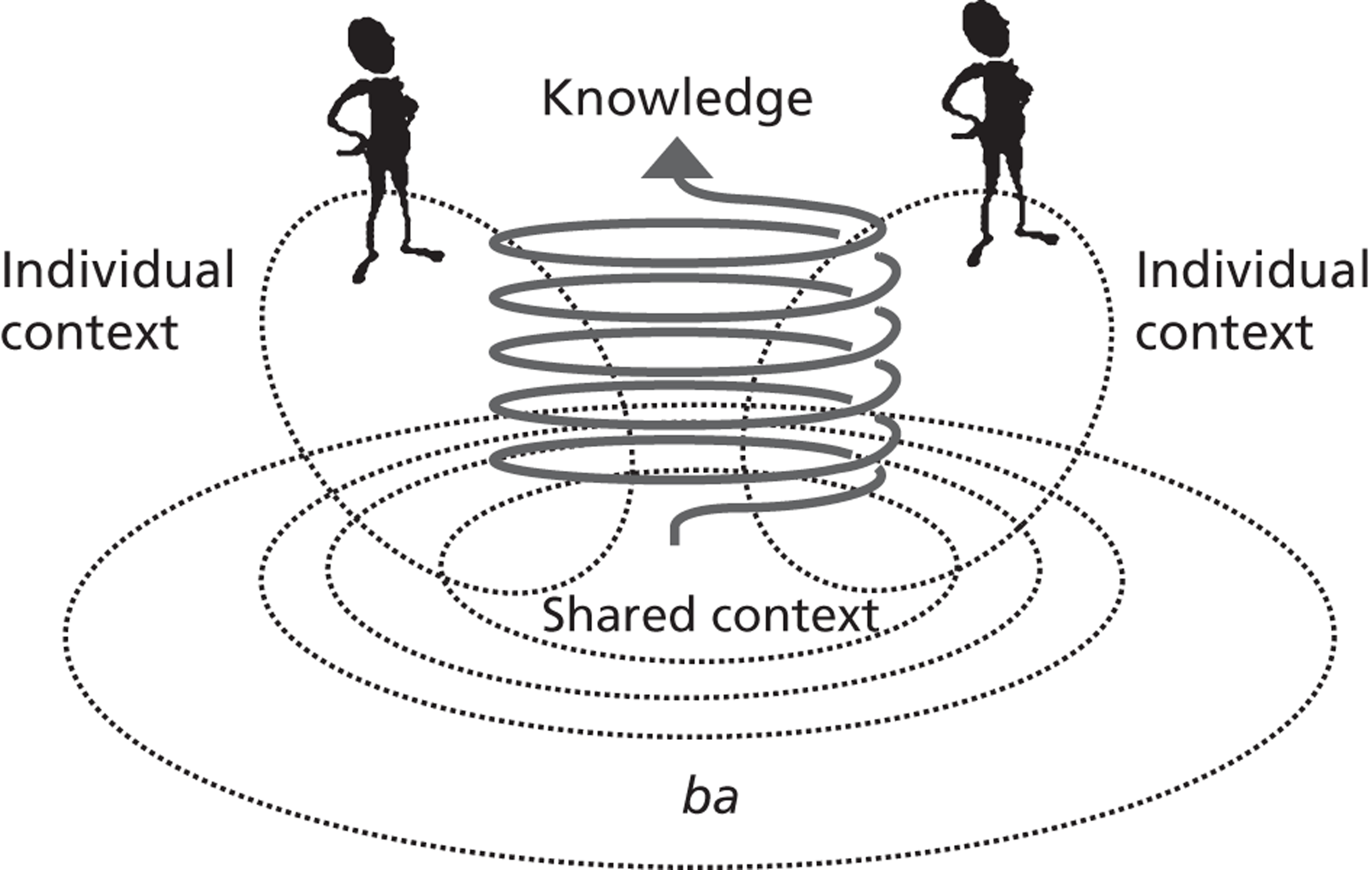

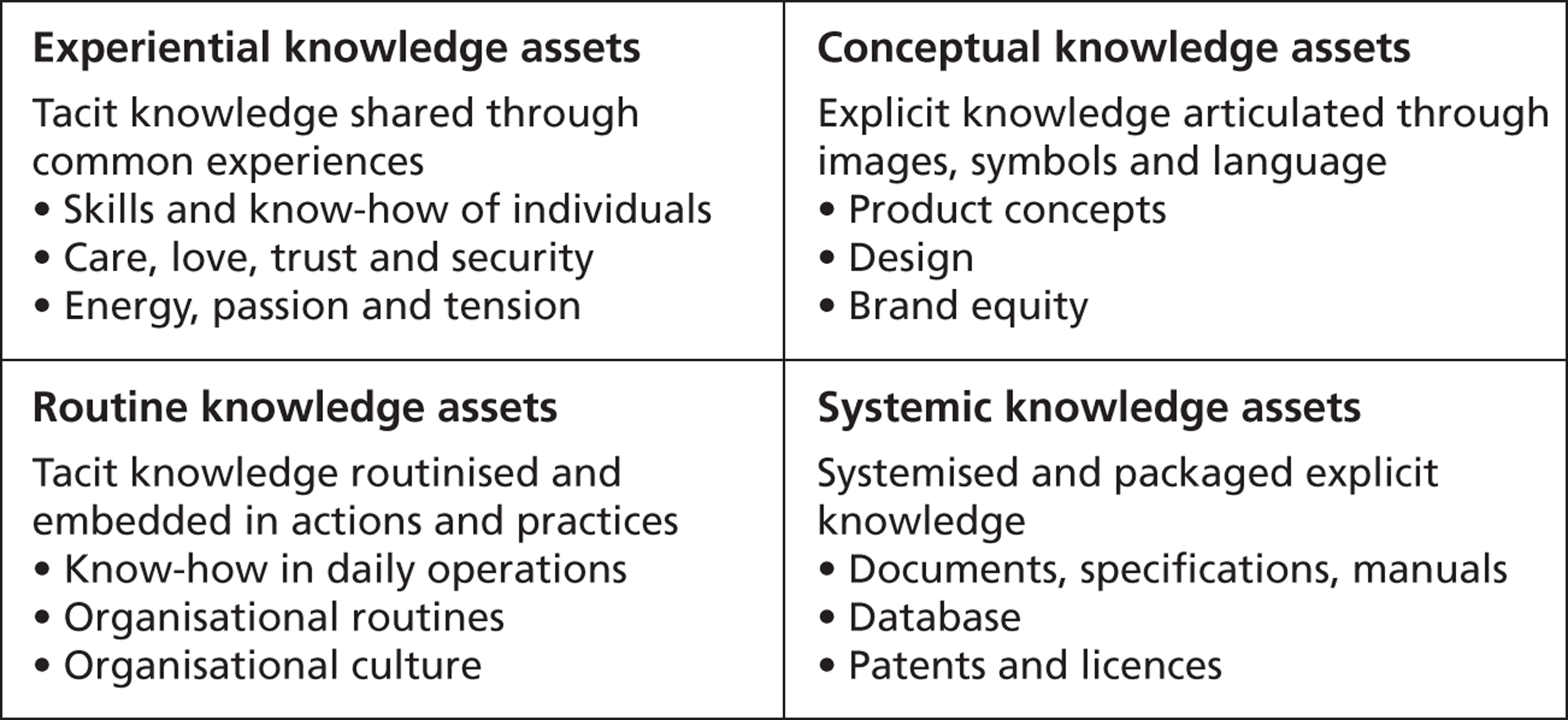

Although much has been written about the sharing of knowledge through artificial intelligence and computer systems, Nonaka's model emphasises the social aspects of how individuals and groups function in an organisation, and how these different types of knowledge (tacit and explicit) move across, or span, boundaries. Nonaka describes four modes of knowledge conversation – socialisation, externalisation, combination and internalisation (SECI). As demonstrated in Figure 1, the two different types of knowledge are converted from one mode to another through these four different processes. Knowledge is created and expands between individuals (i), groups (g) (or, in our terms, teams) and organisations (o) in a continuous manner of knowledge conversion through the four-stage process represented by SECI, which has been tested empirically.

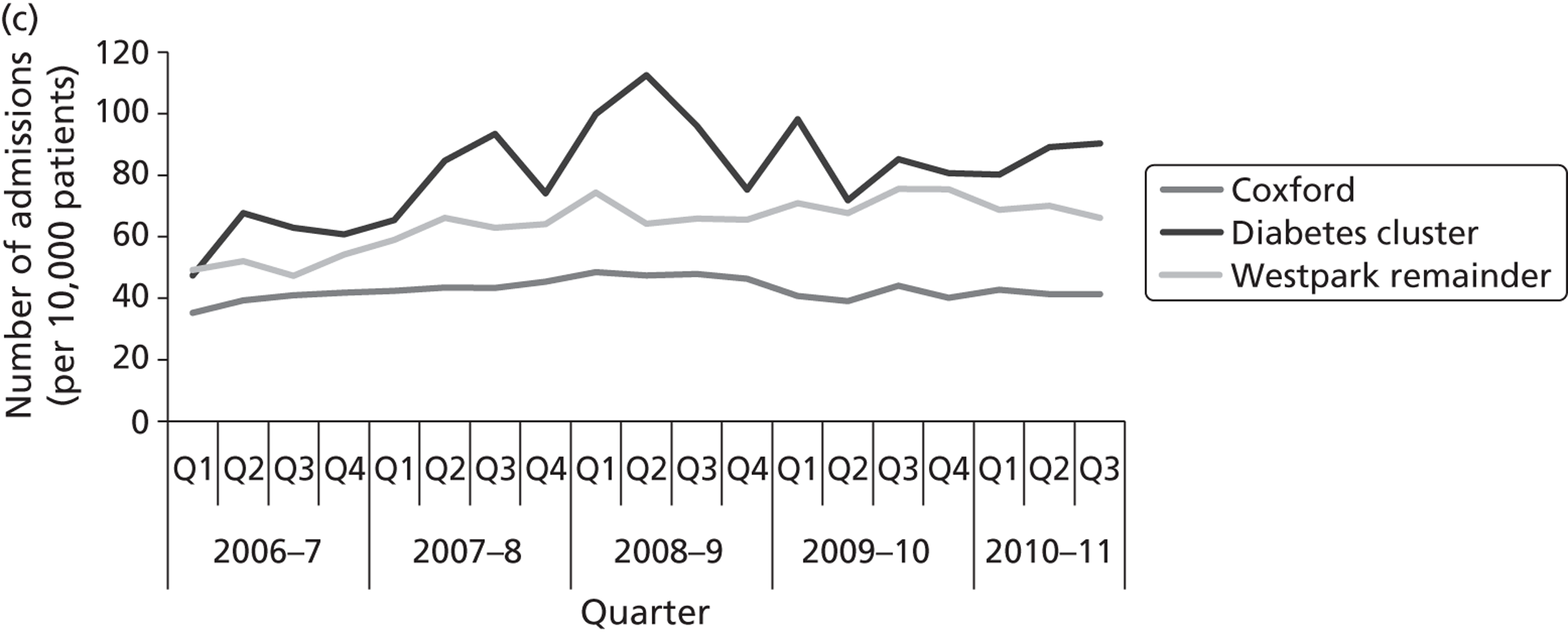

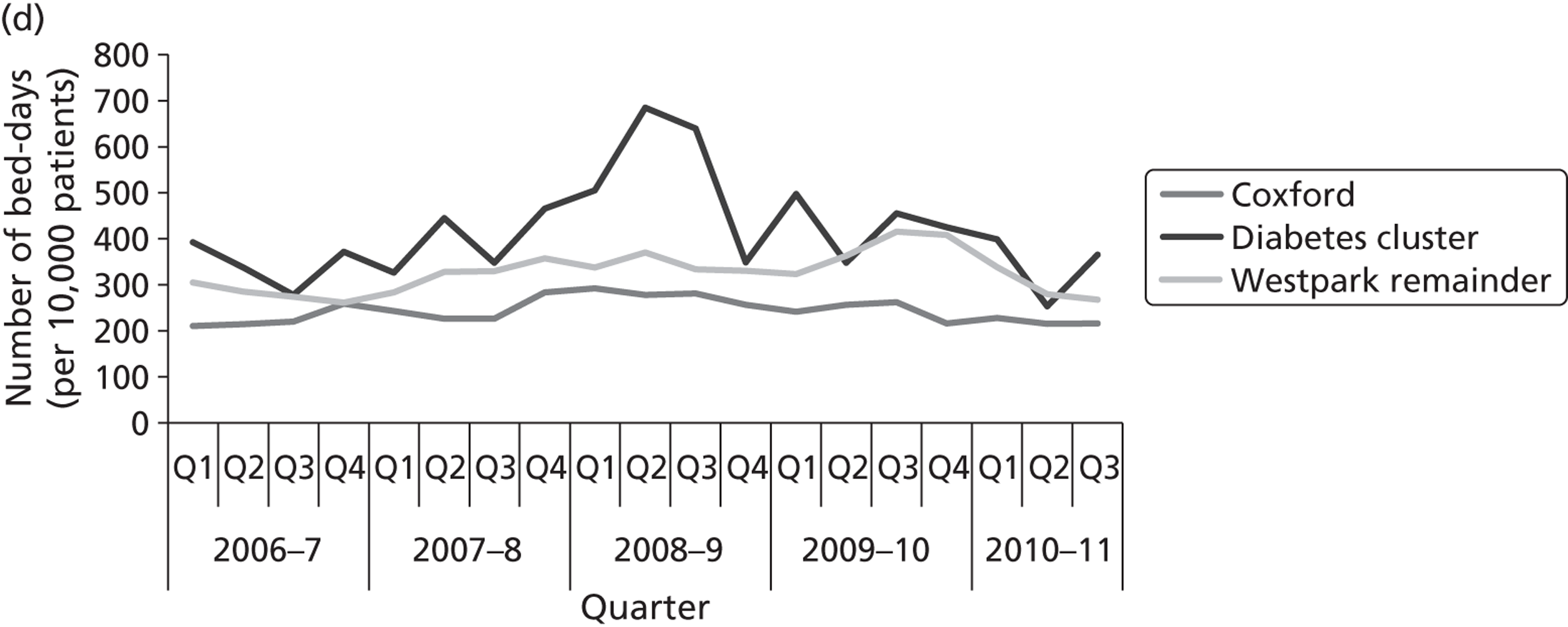

FIGURE 1.

The SECI model. g, Group; i, individual; o, organisation. Source: Figure 1 entitled ‘Spiral evolution of knowledge conversion and self-transcending process’. Reproduced with permission from Nonaka I and Konno N, ‘The concept of “ba”: building a foundation for knowledge creation’ in California Management Review, vol. 40, no. 3, Spring 1998. © 1998 by the Regents of the University of California. Published by the University of California Press.

At the initial socialisation stage of the SECI model, creativity for system-wide problem-solving is potentially spurred by the sharing of tacit knowledge between individuals and builds on their own personal skills and enthusiasm. In the second stage of the process, exchanges move beyond the sharing of tacit knowledge among individuals and towards the design of explicit knowledge assets – externalisation – that can then be shared among ‘groups’ (whether teams or professions). In the third stage, explicit knowledge is clarified and put into place with more systemised approaches, including publishing documents, building databases and authoring policies: combination. Finally, systems and individuals at the internalisation stage are recognisable by their embedded routines within organisational culture and explicit skills in daily operations. Internalisation is not the final stage as the process is a continuous dynamic.

Exploring and experimenting with how to define problems, and discovering new solutions, removes individual limitations and intensifies interactions to expand the boundaries of knowledge. A knowledge outcome can include a justified belief in what is true as the team comes to a collective understanding of the new problems, different solutions and diverse tasks with which they are faced. This provides the team with an enhanced capacity to take action to improve problem-solving performance. Social practices then offer stability and routine to processes within the organisation. However, how knowledge conversation impacts on emerging social practices is not well understood. 96

Nonaka has applied this model to cross-functional teams and their business activities, particularly explaining how boundaries are spanned both inside and outside the organisation. The shared context for dynamic knowledge creation is ‘ba’ (building or place), which is an experience of interaction, not merely a physical space. Significantly for our study, Nonaka and colleagues97–99 argue that leaders can aid or impede the knowledge conversion process across organisational layers and boundaries. The ‘knowledge management system’ within an organisation is part of the context of this process.

Von Krogh and colleagues99 argue that the role of empowerment and combinations of distributed or shared leadership is not well explored in the current literature, but needs to be. Distributive leadership can initiate and shape activities and conditions by allocating resources, defining vision and describing organisational forms to link contexts, assets and processes within and across the organisation. An individual's knowledge must enlarge, and a leadership that promotes all four modes of knowledge conversion implies room for effective communicators to develop new concepts and new kinds of verbal and non-verbal language. An enabling characteristic of the organisational knowledge creation process includes chaos or fluctuation, in which crises are presented as problems needing new solutions. The challenge requires reflection and deep mutual trust, or else there will be destructive not creative chaos. 94 Von Krogh and colleagues99 therefore propose a leadership framework that combines centralised (planned, autocratic, directed) and distributed (participative, spontaneous and fluid) leadership for spanning organisational boundaries, as negotiating boundary crossings is often problematic. But little research has described how leaders can integrate SECI, knowledge assets and ba. The authors call for more attention to be paid to discovering the form and function of boundary negotiations. They also highlight the lack of research that combines the micro and macro levels in organisational processes, arguing that knowledge is not strictly individual or collective, and knowledge creation interactions should be examined at all levels. 99

To explore the complexities of how such boundaries are spanned in health care, we have chosen an ethnographic study with mixed methods. In Chapter 4 (see Multilevel, cross-case comparison: socialisation, externalisation, combination and internalisation and the four teams) we use the SECI model of knowledge creation as a holistic framework to evaluate the quality improvement activities of the four teams participating in the boundary-spanning intervention under study. We believe that the SECI model is particularly useful for analysing the barriers that boundary spanners reach across, allowing us to identify, and potentially anticipate, barriers and enablers. In the WI the four teams and team leaders and their impact will be examined by applying this SECI model and Nonaka's further theoretical developments. Primarily applied to information and technology organisations, most research and theorising related to SECI is in the management literature. We are not aware that the model has been previously applied to any health-care organisations.

The boundary-spanning intervention under study: the Westpark Initiative

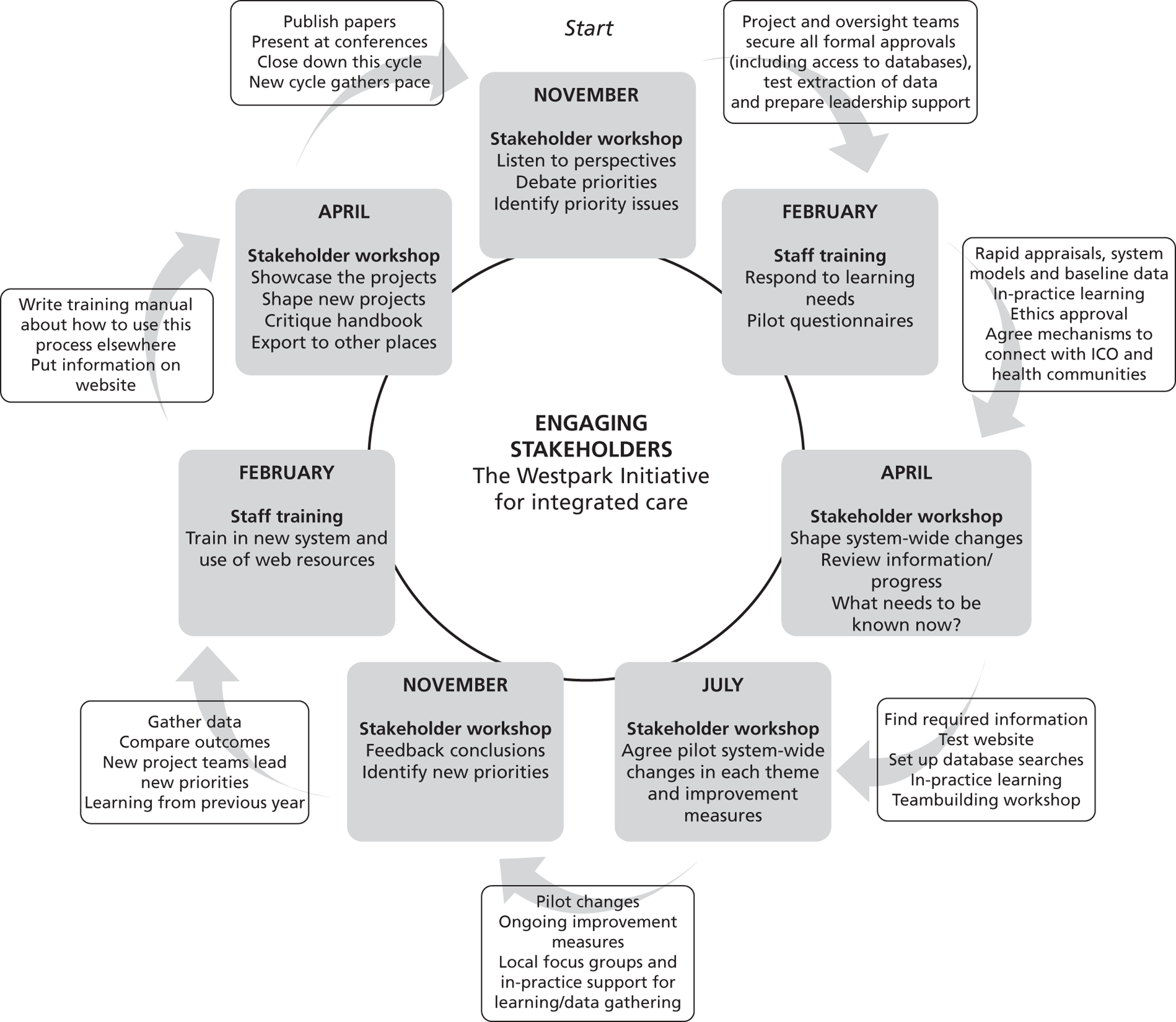

As described in the WI materials, the boundary-spanning intervention was a project designed to improve services through collaboration between GPs, community services, voluntary groups and acute specialists in ‘Coxford’ during the period 2009–11. The project included the development of a network of leaders across organisational and community boundaries to facilitate knowledge exchange and was directly linked with a programme of ‘whole-system’ stakeholder conferences (in November 2009, April, July and November 2010 and April 2011, as indicated in Figure 2) to create organisational learning and change, together with community development. The project took place in Coxford PCT where there was – it is claimed – ‘sustained political support and understanding for this way of working from local statutory organisations, in partnership with voluntary sector agencies’, as explained in a letter provided by the initiative leader Chris. The WI used an annual cycle of service improvement for whole-system change, as initiated by a community leader and GP (Chris) (see Figure 2 for an overview of the annual learning cycle as we observed it).

FIGURE 2.

Westpark Initiative: cycle of service improvement, 2009–11. ICO, integrated care organisation.

Stakeholder workshops were expected to be held quarterly, during the evening, with attendance from a wide variety of representatives from social care and the third sector as well as clinical staff from primary care and mental health.

Staff training events were held at different times for staff across the borough, with a variety of topics and sponsors. The intent was that two training events for GP surgery staff would be hosted by each of the WI teams based on their annual work.

In Coxford a set of masterclasses (local off-site educational sessions) were funded through a grant to the Development & Research (D&R) network, led by Chris, and overlapped with the WI structure, although not as a formal part of the initiative. These were designed to be monthly, during the afternoon, on a variety of topics, and all local clinical and non-clinical staff from the PCT and GP surgeries were invited. An applied research unit had been founded by the PCT in 2008 as part of a D&R network to improve practitioners' and managers' critical skills, in a cluster of GP surgeries, and to improve relationships with academics. D&R networks were introduced in the UK in 2003 by the National Educational Research Forum to serve as iterative programmes to enhance communications and increase opportunities for exchange between researchers and developers and particularly to increase capacity in local research efforts. 100 With a background as a teacher for local colleges as well as a GP trainer, Chris intended that staff could, and would, attend these training sessions to build competence in their skill set for participating in local quality improvement and research efforts. To this end, continuing professional development (CPD) credits towards a university certificate were offered as an incentive. Dates and rooms were scheduled on a monthly basis, through 2010 and 2011, with topics to be announced, although some were to be run by the local Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (CLAHRC) and overlapped with WI stakeholder events.

Annual ‘residential’ retreats had been scheduled for use by the Coxford D&R network since 2008 and were usually held by invitation for GPs and PCT and primary care staff. Although not a formal part of the WI annual cycle, the booked off-site setting served as a supportive learning environment in 2009 and 2010 where Chris facilitated workshops for invited WI participants to share interdisciplinary experiences and plan for service improvement efforts. Funding for the overnight stays at the site was a factor in who was invited and how the agenda was determined from one year to the next.

From October 2009 to early 2012, three (later four) boundary-spanning multidisciplinary teams were to work to develop their own solutions to local problems through the annual cycles of shared learning represented in Figure 2. Team membership was voluntary, multidisciplinary and shifted frequently and was not assigned by work duties. Team members were invited to ‘dip in’ to masterclasses, training events, stakeholder events and residential retreats as they were able. Some time after the topics areas were agreed and the teams began work, the leader of the WI began to frame each of the teams as working to span different types of boundaries, namely between primary care and:

-

mental health care [anxiety and depression in black and minority ethnic (BME) populations]

-

social care (dementia)

-

community care (child and family health services)

-

acute care (diabetes).

The study setting

Our study took place in an area within an inner-city borough that is dominated by the Asian, particularly Punjabi, community. Although there are many Muslim and Hindu residents, the largest portion of the borough's population is Sikh (23.2%). The borough has a population of approximately 300,000 residents, > 40% of residents were born outside the UK and about 25% of adults have no academic qualifications. In the borough as a whole, many children do not speak English as a first language.

Overall, the area in which our study was conducted ranks high on all deprivation scores and is impacted by many chronic diseases, reflected in higher than expected mortality rates. The Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) for the study area – a summary score measuring deprivation in relation to employment, income, education, skills and training, health and disability, barriers to housing and services, and living environment and crime – was the highest in the borough. A high proportion of housing in the area is overcrowded and the area has the highest scores in the borough for child poverty and deprivation affecting older people. One particular ward within our study area had the highest percentage of low-birthweight babies (10%) born between 2002 and 2004. The area also has four wards with the highest admission rates for depression in the borough and there are also high rates of admission for psychosis. The area as a whole has the highest prevalence rate for diabetes in the borough (12.6% in males), which is also more common in people of South Asian origin.

The boundary-spanning intervention that we studied was one local project designed to build connections between community services to improve local health and well-being. Clearly the wider local context was, on one hand, a challenging one in which to implement this intervention. On the other hand there was an extensive and vibrant network of community groups active in the locality and keen to engage in projects such as the WI.

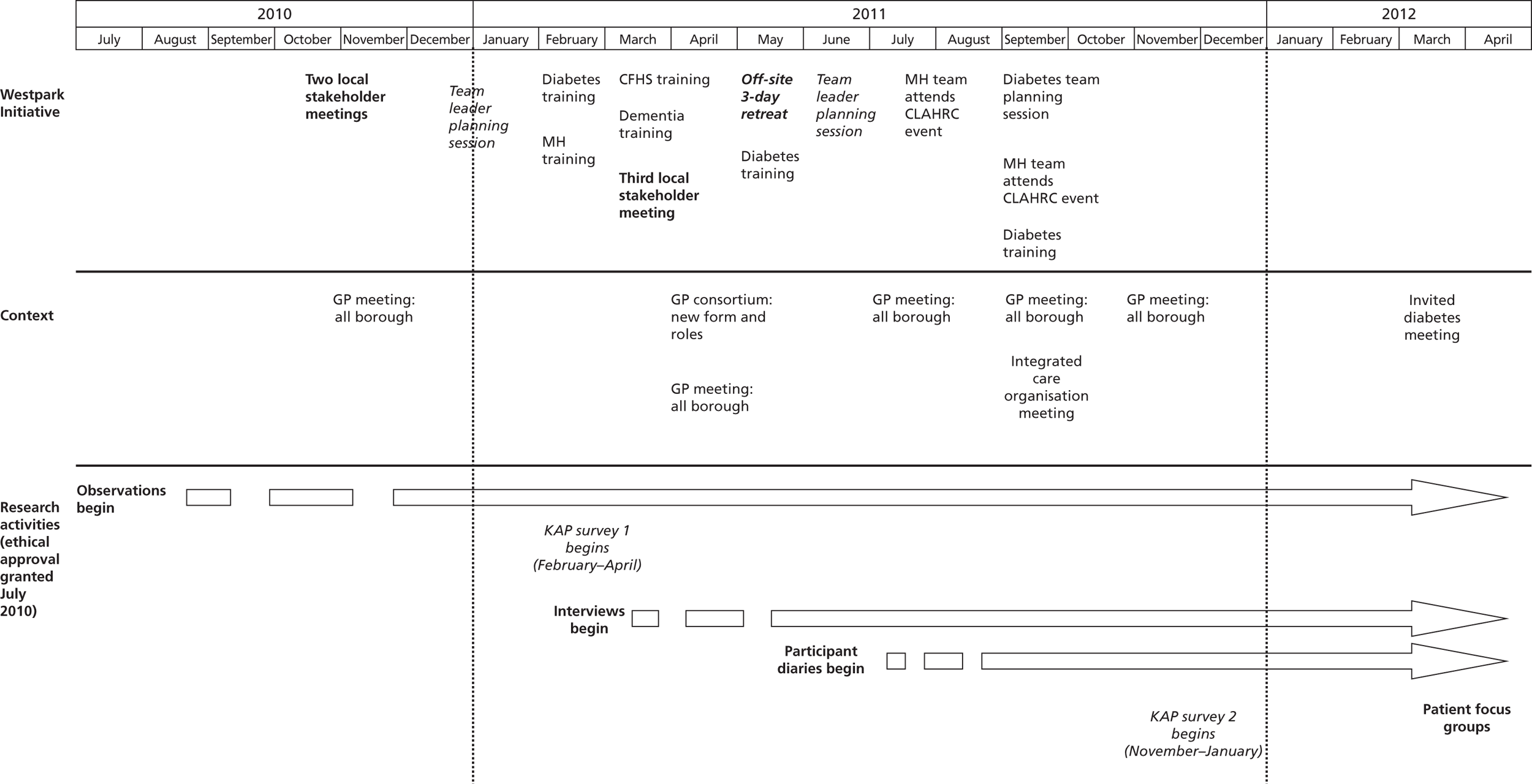

Chapter 3 Study design and methods

Our evaluation of a boundary-spanning intervention – the WI as enacted by four multidisciplinary teams – is based on a longitudinal nested case study design using mixed methods. The study protocol is provided in Appendix 2. Ethical approval for our fieldwork was granted in July 2010.

Case study research is an iterative process that includes both direct observation of processes and capturing the reflections of individuals involved in those processes (through a combination of interviews, diaries and surveys in this particular study). The method is appropriate for answering research questions inquiring why and how something happens. The nested case study design and the ethnographic stance of an embedded clinician-researcher allowed us to investigate the complexity of real phenomena – boundary-spanning processes – in the context in which they took place. Given the focus of the study an emphasis on qualitative methods was warranted as they best enable the capture of lived experiences and enabled the research team to explore meaning within interactions in a given social context. 101

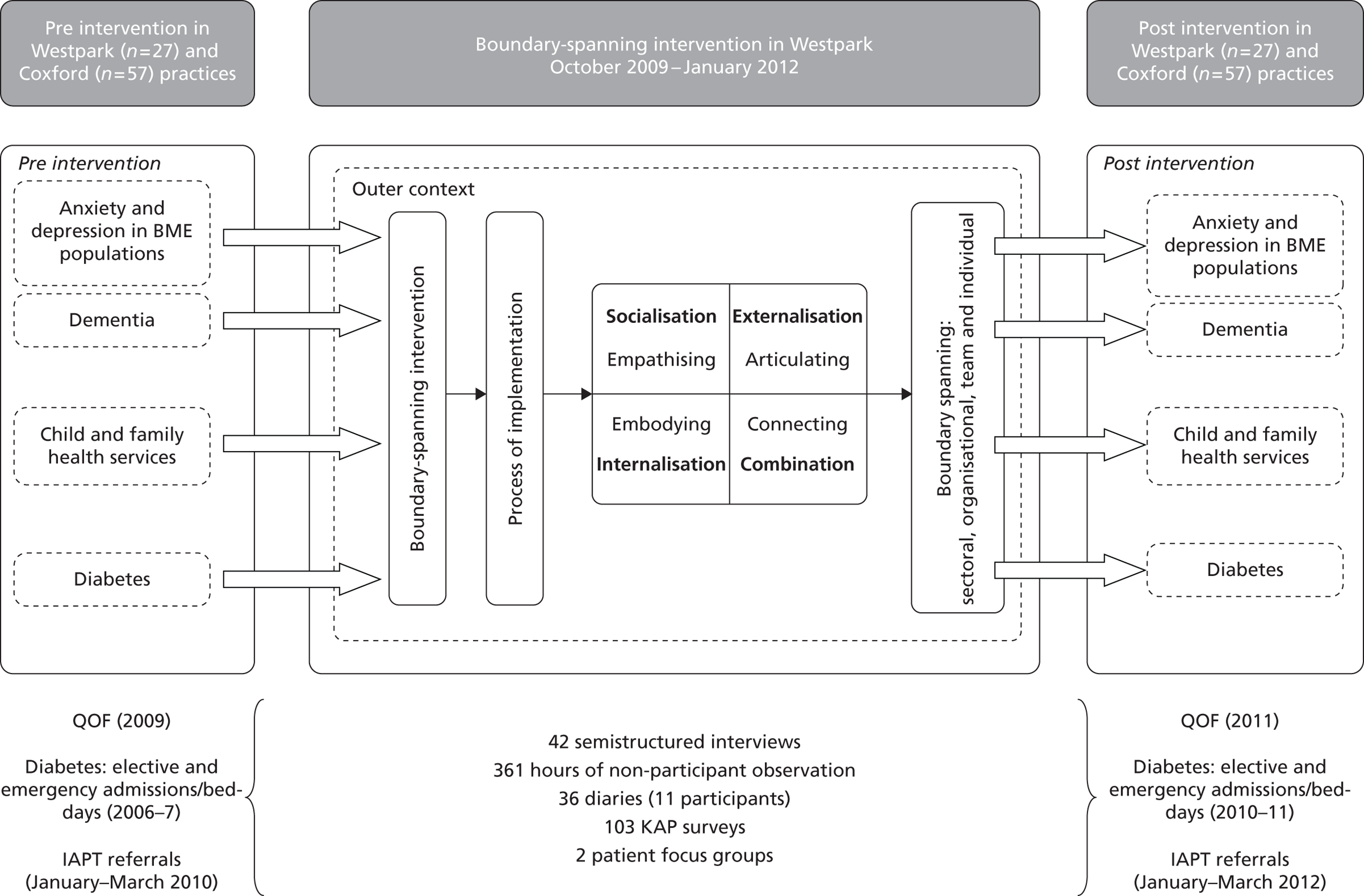

Overall framework for the evaluation

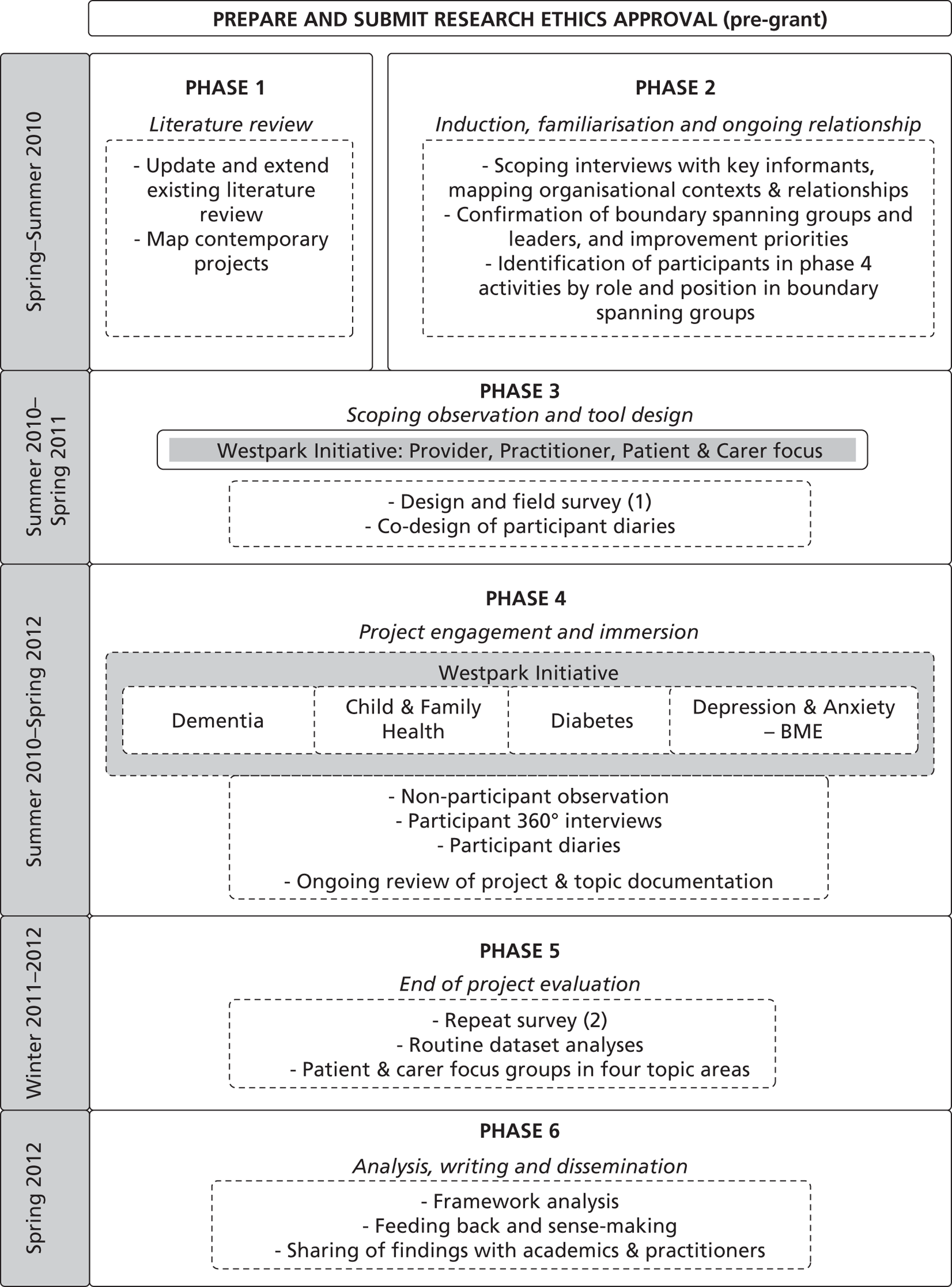

During our fieldwork we collected a range of qualitative and quantitative data (Figure 3) to study the process of implementing the boundary-spanning intervention in its local context and explore whether or not it enabled knowledge exchange across sectoral, organisational and professional boundaries in the four topic areas.

As outlined in our research protocol, our ethnographic research methods included ongoing review of project documentation, non-participant observation, semistructured interviews with the leaders of the WI and individuals in the four boundary-spanning teams, online serial diaries completed by team members, and patient focus groups. This qualitative fieldwork was supplemented with a pre- and post-survey questionnaire and secondary analyses of routine data sets. We describe each of these methods in the following sections.

FIGURE 3.

Evaluation framework. The items listed below the figure are all data sets. IAPT, Improving Access to Psychological Therapies; KAP, knowledge, attitudes and practices; QOF, Quality and Outcomes Framework.

Project documentation

Progress towards team goals in the four nested case studies was tracked through project documentation throughout the fieldwork period (July 2010 to early 2012). Researchers were included in several e-mail LISTSERVS, which included invitations to staff in Coxford to a variety of events led by the PCT. Relevant historical documents from 2009 onwards, such as presentations, reports and planning paperwork, were made available to the research team and included in our analysis.

Non-participant observation

Given the exploratory purpose of our study we observed teams in the WI in their ‘natural’ (as opposed to ‘created’) settings. As a group method of research, being able to observe individuals from the four teams interacting with each other also allowed the research team to evaluate the overall impact of the WI on boundary-spanning behaviours. Trained as a primary care clinician (nurse and family nurse practitioner), Nasir was the key observer at most events. The purpose of the observation was to identify examples of knowledge exchange and collaborative working between individuals from different parts of the health service or to note opportunities for these activities that were missed. Thus, the focus of observation was on interactions and activities. As a consistent observer, researcher interaction and feedback were invited by participants, lending an ‘embedded’ style to the field study.

Non-participant observation took place at planned stakeholder events (one every 3–4 months) once ethical approval had been granted for our study in July 2010. In total, seven stakeholder events were observed. Additional observations were carried out at four masterclasses and 10 PCT-wide meetings that overlapped the WI; 37 planning, administrative and other sessions related to the WI (attended by the WI facilitator, leaders and/or team members); and other events hosted by the WI including eight staff training events related to disease management topics and 6 days at two annual residential retreats in 2010 and 2011. A total of 361 hours were observed with written field notes (observations lasted for 128.5 hours, 203 hours and 29.5 hours in 2010, 2011 and 2012 respectively; see Appendix 3 for details).

Field notes were written in a reflective style as informed by ethnographic principles and captured four categories of material on each page:

-

Explicit activities were noted with stated agenda items matched with times, physical room layout, number of people, roles of attendees and topic being discussed.

-

Observations of mood, tone and points of perceived tension were noted in a column parallel to the agenda.

-

Boundary-spanning themes, emerging concepts and fieldworker insights were noted in coloured ink, making connections across the two main columns.

-

A ‘to do’ list was included at the bottom of each page to capture ideas of further people to interview or concepts to pursue at a later date.

This field note style allowed for multiple insights to develop and be gathered during lengthy and often complex meetings and interactions. As Tushman24 noted of the study of organisations, exploratory fieldwork requires the accumulation of a necessary background, and flexibility to make frequent adjustment to provisional hypotheses and consequent data collection. Notes were gathered during meetings and impressions noted afterward. Telephone calls and informal interactions were also written up contemporaneously in field notebooks. Analysis began during the fieldwork as qualitative data were regularly discussed to shape ongoing data collection and to allow for refined directions of inquiry. Field notes and impressions from the embedded researcher were reviewed in monthly oversight meetings with the project team and were iteratively reviewed during the analysis phase of the project.

Semistructured interviews