Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its proceeding programmes as project number 09/1002/02. The contractual start date was in July 2010. The final report began editorial review in January 2013 and was accepted for publication in July 2013. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors:

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2014. This work was produced by Ward et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

Health and well-being services, in common with many public services, cannot be delivered by a single organisation. Weight loss, exercise, smoking cessation and other programmes require the co-ordination of services delivered by several organisations in a locality. There is some evidence, mostly from other sectors, that middle managers play pivotal roles in this co-ordination. They have to find ways of co-ordinating services, such that organisations are able to meet their own objectives while working together, and issues raised by cultural and other differences can be overcome. In doing so, they have to find ways of explaining what they do, and what they need to get done, to one another. This study focuses on the knowledge creation processes that underpin these activities, in the context of health and well-being services.

Aims and objectives

Our objectives in this study were to develop a better understanding of the way that knowledge is created within and between health-care organisations, across different managerial levels, and of the role played by informal networks in those processes. We aimed to understand:

-

how health-care managers exchange knowledge to bring about changes in health-care delivery and organisation

-

the role played by the connections between the managers who are responsible for bringing about those changes.

In relation to (a), our specific questions were:

-

To what extent is the exchange of knowledge based on the identification of a specific organisational need?

-

What are the different types and sources of information which influence the exchange of knowledge?

-

How do the organisational circumstances surrounding the manager influence the exchange of knowledge?

-

What activities are undertaken by managers to share and exchange knowledge?

-

To what extent is the exchange of knowledge based on an assessment of the potential influence of that knowledge?

In relation to (b), our specific questions were:

-

What is the role of informal networks in exchanging knowledge across different organisational settings and boundaries?

-

How does the density of networks influence the process of exchanging knowledge?

-

Does the centrality of individual managers within an informal network influence the knowledge exchange process?

-

How do directional relationships within informal networks facilitate or constrain the exchange of knowledge within and between settings?

Study rationale and decisions

We set out our study design and methods in full in Chapter 2. Before we get to them, however, it is useful to be clear about the rationale for our approach. As in any field study, we had to identify methods for addressing the research questions, taking into account the characteristics of the sites, a number of conceptual issues and the ways in which the findings would be used. These three considerations – sites, concepts and uses – substantially influenced the study design and selection of methods. Specifically, they influenced decisions about the focus of the research, the way we thought about knowledge creation, and the nature of networks that link individuals and organisations to one another.

The focus of the research

Our research questions prompted us to look for settings where we would be able to separate out formal and informal relationships in order to expose, or reveal, the latter as far as possible. By formal relationships we mean those found in any large bureaucracy – line management, financial accountability and so on. Informal relationships, in contrast, are typically based on trust and often established over months and years. These are the relationships that people rely on, on a day-to-day basis, to get work done, and are not reflected in any organisation chart.

We took the view that we should look outside the main bureaucratic structures of the NHS and of local authorities, where formal relationships would be well developed. Health and well-being services seemed, to us, to fulfil our requirement. No single organisation can realistically hope to provide a full range of weight loss, exercise, smoking cessation and other programmes, and in any given locality health and well-being services have, for some time, been provided by several agencies working together. Indeed, some services are provided by combinations of public, private and voluntary organisations. While the organisations involved were likely to have formal meetings, successful co-ordination was likely to depend on managers liaising informally with one another, and it would be easier to observe informal relationships in these settings. Moreover, health and well-being matters. As we will see in Chapter 3, successive governments have placed great emphasis on the need to improve the health and well-being of populations. In recent years there has been a particular focus on populations in less advantaged areas, where people are more likely to have, or to develop, long-term health conditions.

Each service would have middle managers, working in offices in different locations, sometimes several miles apart. For much of the time, managers would be based in their home organisations, enmeshed in work with immediate colleagues. They would attend formal meetings, but were also likely to liaise in ways that could not readily be observed (e.g. by telephone). Moreover, some were likely to have established relationships with one another long before the fieldwork started, and it would be difficult to tell from meetings alone how these relationships shaped discussions. The challenge was to identify methods that allowed us to observe how managers were collectively creating knowledge (or, if they were doing so), even though relationships between them were likely to span organisational boundaries and geographies.

In the early part of the study we observed managers at formal meetings with one another. It became apparent that no single meeting would be attended by all, or even most, of the health and well-being managers of interest in any of our study sites. There was no straightforward way of knowing who was involved in health and well-being services in any one site, how their relationships with one another were created and sustained, and what kinds of knowledge they were able to create collaboratively. We would, therefore, have to establish ‘who’ and ‘how’ – who was involved and how they were interacting – as well as characterising knowledge creation processes.

The nature of knowledge

There are many different conceptions of knowledge creation and mobilisation. A review by Ferlie and colleagues1 emphasises the diversity of conceptualisations and methods used in both the health services research and broader management literatures. We had to decide, therefore, which conceptualisation to use in our study design. Flyvbjerg2 argues that most social researchers observe the production of one or three kinds of knowledge, namely universal scientific knowledge, technical knowledge and prudence.

Scientific knowledge is generally taken to be value-free universal knowledge, which exists independently of any observer. Today it is the dominant form of knowledge sought in health service research, and the primary type of knowledge that researchers seek to produce and disseminate in implementation science. Technical knowledge concerns ‘know-how’, the skills needed to undertake a task, whether it is mending a tap or liaising effectively with local communities. It does not claim universality: knowledge is embedded in people’s skills, and is used to understand and solve problems in particular contexts. Technical knowledge is often tacit: it is integral to the way that people do their work, and when asked how they solve problems they can find it difficult to explain how they do so. Prudence, or practical wisdom, refers to value-based – rather than analytical or instrumental – rationality. Experienced managers and clinicians are able to draw on their experience in arriving at judgements about the course of action to be taken.

Given our research questions, and our focus on health and well-being services, we sensed that managers might draw on all three types of knowledge. That is, they might draw on all three in the process of collectively creating the knowledge needed to solve problems.

The nature of networks

The third decision concerned the way we thought about networks. In one way, networks are very simple – they are arrangements of things linked together with one another. The challenge is that, as with knowledge, there is an array of different ways of conceptualising networks, and many methods for studying them. To give just three examples here, networks can be physical, with wires and wi-fi connections linking servers, tablets and smartphones; they can be composed of individuals, working in different organisations on shared programmes; or they can link people, objects and ideas.

In this study, we found that it was useful to make a broad distinction between analytically rational and narrative accounts of networks. The analytically rational view is that social and organisational networks are essentially like networks in nature. As Crossley3 puts it, analytical rationalists believe that networks are structures of something – neural connections in the brain, communication networks, or the interactions of genes and proteins. A key assumption is that the configuration of a network, and the interactions between its components, can help to explain its behaviour. Thus, individuals linked in a network interact with one another, and the interactions produce some behaviour of interest, such as the spread of a communicable disease.

The alternative, narrative, view is that networks reveal something useful about the underlying properties of social relationships. In narrative accounts social and organisational phenomena are irreducibly complex, and hence impossible ever to describe completely. Knowledge creation processes are therefore social processes, involving dynamic interactions between a number of people, and with those processes being open to influences from the environments that people work in.

Taking these three arguments together, about focus, knowledge and networks, we concluded that we should study knowledge creation principally as a social, or narrative, phenomenon. For the reasons given above, however, it was also important to be confident that we could characterise the networks that linked the individuals and organisations in our field sites. Accordingly, we also undertook a quantitative network analysis, nestled within the broad context of a narrative case study design.

Changes to our protocol

In our original research proposal, we planned an initial phase of work which would involve developing and sharing ‘tailored messages’ about vascular disease prevention with health and well-being managers at our study sites. These messages were to be drawn from a research project on improving the prevention of vascular disease (IMPROVE-PC) being undertaken within the National Institute of Health Research Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care for Leeds, York and Bradford. 4 The messages would be developed in collaboration with senior health and well-being managers at our study sites who, we believed, would be able to advise us about what they needed to know in order to help them to address local vascular disease prevention issues. This would provide us with valuable insights into the challenges sites had identified, and the scientific knowledge that might help them to address them.

As we began to undertake this phase of the project, we discovered that our plan to engage with the sites in this way was not practicable. They had considerable difficulty specifying their challenges in preventing vascular disease, and they were unable to suggest ways in which the scientific knowledge identified by the IMPROVE-PC project could be useful to them. As a result it proved impossible to identify information which our study sites might find useful. In taking stock and deciding how to proceed, we also realised that we would be in danger of influencing the naturally occurring problem-solving processes and networks that we were hoping to observe.

These insights led us to rethink our approach, and to make two substantive changes. First, we developed a ‘landscape mapping’ phase of work to help us situate our fieldwork in the context of specific vascular disease prevention issues at each study site and provide a focus for our observations. This work replaced the development element of the tailored messages. It was set out in an interim report submitted to the National Institute for Health Research’s (NIHR) Health Services and Delivery Research (HSDR) programme in August 2011. Further details of the landscape mapping method are presented in Chapter 2. Second, we moved the production of tailored messages to the end of our fieldwork, proposing to organise interactive engagement events, where we would provide structured feedback from our research to local health and well-being managers. This phase of the work is reported in Chapter 8. These changes preserved the integrity of the project, enabling us to remain focused on observing the ways in which middle managers create knowledge, while still providing our study sites with an opportunity to benefit directly from our research.

Organisation of the report

Chapter 2 will set out our study design and methods: a case study design employing both quantitative and qualitative methods, with data collected at three sites. Chapter 3 will provide the national policy context for the study. In Chapter 4 we will present a focused review of the knowledge creation literature. The empirical results in this literature have, in large part, been obtained in other settings – in industrial firms in Japan and the USA, for example. One of the issues in this study was, therefore, to establish whether or not the theoretical insights in that literature are useful in the context of health and well-being services in England.

Chapters 5 and 6 will set out our empirical results. Chapter 5 will present the qualitative findings from each of the three study sites. They illustrate the ways in which middle managers were able to use their relationships with one another to get useful work done. Chapter 6 presents the findings from our network analyses. Chapter 7 is the main discussion chapter and will draw together material from the preceding chapters. Chapter 8 will describe the interactive feedback events that were run at the three sites in the late autumn of 2012, where we used videos and graphs to convey our provisional interpretations of our findings. Chapter 9 will set out our conclusions.

Chapter 2 Study design and methodology

Introduction

This chapter sets out the study design and methods. The next section briefly outlines the overall design, a case study design, and the section after that describes the process of selecting the three study sites. The following sections describe the strategy used to undertake a focused literature review on knowledge creation, and the field methods that were used – landscape mapping, structured data collection for network analysis and latent cluster analysis, and semi-structured interviews for qualitative analysis. The analytical strategies used in the empirical components of the study are then outlined before we finally describe the three feedback events that were held at the end of the study, where we presented our provisional findings to each of the study sites.

Case study design

We used a case study design, focused on our case, or main phenomenon of interest, namely collective knowledge creation. 5,6 There are a number of different case study strategies, each of which is motivated by the need to study a case in detail, and in its broad social context. We might, in principle, have chosen to identify a number of hypotheses, or theories, about knowledge creation by middle managers, and gathered evidence in order to support or undermine each hypothesis. 7 As we note below, however, a review by Ferlie and colleagues1 highlighted significant gaps in our understanding, and the published literature was not robust enough to allow us to identify appropriate theories with any confidence.

An alternative strategy would have been to pursue a more naturalistic strategy, with features in common with ethnography, which has been used to investigate the long-term effects of health policies. 8 This strategy is feasible when all of the data sources are qualitative, but not – as here – when there is a quantitative component, and the case study requires the use of both qualitative and quantitative data.

We developed a case study design that allowed us to draw on both qualitative and quantitative data. It was based on a broad theoretical base, derived from a review of the knowledge creation literature (see Literature review section below), which allowed us make theoretical generalisations at the end of the study. The study design had two distinctive features. On the basis of our literature review, and of our own experiences early in the study, it became apparent to us that knowledge creation processes unfold over substantial periods of time, measured in months and – as we will see – years. If we relied solely on prospective data collection, we would run the risk of having to stop observing processes before they had run their course. We therefore opted for a retrospective approach to our analyses, and used process tracing to construct accounts of projects and programmes which had been running for some time. 9

The second feature follows from a point made in Chapter 1, about the importance of collecting both narrative and network analytical data. Having collected two very different types of data, we had to address methodological questions about ways in which they could be used together, in our quest to describe and explain knowledge creation activities at our study sites. The following sections set out our strategy, respecting the distinctive contributions of narrative and analytical data on the one hand, and using them both to shed light on knowledge creation processes on the other.

Site selection and recruitment

Health and well-being services pose major, novel co-ordination challenges to the NHS, social care and other services. It was clear from the start of the project that we would need to study the work of people in a number of different organisations in any locality we studied. On the basis of the time and resources available to us, we judged that we would be able to study three sites in depth over an 18-month period.

We discussed our research plans with senior regional public health managers. They helped us to identify localities in northern England where the development of health and well-being services was high on local agendas, and provided us with introductions to directors of public health in three localities, each of whom had a joint primary care trust (PCT)/local authority appointment. It became clear in the course of discussions that organisations had different boundaries, and it would therefore be important to identify the geographical boundaries for each study site. We decided, pragmatically, that the sites would be defined by PCT boundaries.

The three study sites had a number of general features in common. Their local authorities were all metropolitan boroughs, each including a number of towns and more rural districts. None of them was in the list of 20 most deprived local authority areas, as measured using the Index of Multiple Deprivation. 10 However, each had more than one Lower Layer Super Output Area that was in the bottom 10% of areas nationally; as we will see in Chapter 5, a number of projects and programmes were focused on these areas.

All three directors of public health who were approached approved the involvement of their own services, and also agreed to act as local sponsors for the research. As we explain in the sections below, the process of selection of participants was a key feature of the study design. The focus throughout the study was on middle managers, and our interviewees were selected on the basis that they fulfilled a basic definition of middle manager, that is they were not frontline service providers or board-level managers but sat between the two in their host organisations. As we will discuss in Chapter 7, the term middle manager proved, in practice, to cover a wide range of roles, some very close to frontline practitioners, and others working directly to senior managers (e.g. directors of public health) and not having daily contact with frontline workers.

We applied for NHS ethics approval to cover the whole study, and research and development (R&D) approval for the PCTs covering the three geographical areas. Research ethics approval was granted in December 2010, and NHS R&D approvals were granted in early 2011. Ethics and R&D documents are included in Appendices 1–4. We also complied with R&D processes in non-NHS organisations where we expected health and well-being managers to be working.

The approvals process was complicated by changes in NHS services, which saw NHS community service providers moving out of PCTs around the time that the study was beginning, and the move of public health to local authorities being planned for and then executed during the fieldwork. We dealt with the issues pragmatically, and applied for R&D permissions in some organisations only at the points where it became clear where health and well-being managers were based at the time that we needed to interview them.

Literature review

Ferlie and colleagues1 published a valuable, broad-based review of the literatures on knowledge mobilisation for the NIHR Service Delivery and Organisation programme, before the start of this study. They found that the literatures are fragmented, and contain important gaps, for example an absence of evidence about the effects of organisation design on knowledge mobilisation. The review saved us a great deal of effort at the start of the study and, in particular, confirmed that there was no single literature on which we should base our thinking. We would need to select a theoretical framework, and a supporting literature, from among the many options available. Given our research questions, we looked for a relevant literature which would help us to link together key elements of our study – knowledge mobilisation, network relationships and the roles of middle managers. We identified the knowledge creation literature, stemming from Nonaka and Takeuchi’s The Knowledge Creating Company,11 as the most comprehensive literature that did so.

The volume of publications in the knowledge creation literature in the last 20 years is substantial. 12 Initial searches, using the cited reference search facility on the Web of Science database, revealed almost 4000 articles or reviews which cited our chosen text. The annual rate of citation increased constantly until a peak of nearly 600 was reached in 2008–9, implying that the relevance or intellectual currency of the theory has not declined over time. Owing to our dual focus on knowledge creation and networks, we filtered the results using the search terms ‘network’ and ‘knowledge’ (recognising that the term ‘network’ is itself broad), for the period covered by the calendar years 1995 to 2011. This resulted in the identification of 554 potentially relevant papers. Abstracts from each paper were read and 135 relevant papers were selected. These papers covered a range of disciplines and topics, including organisational studies, communication studies, knowledge management, knowledge transfer, implementation science, communities of practice, professions, regional studies, leadership, innovation and entrepreneurship, and social psychology.

We then performed a further selection based on three considerations, namely:

-

Some papers were excluded on the basis of quality criteria.

-

Some papers were excluded owing to minimal engagement with the concept of knowledge creation or adoption of a non-relational understanding of knowledge creation.

-

Organisational studies were prioritised as the most relevant discipline, leading us to select a higher proportion of papers from organisational studies than from the other disciplines.

Our final selection comprised 34 key papers and 35 more papers which we felt had some conceptual relevance to the study, but which did not deal centrally with organisational knowledge creation. The results of the literature review are set out in Chapter 3.

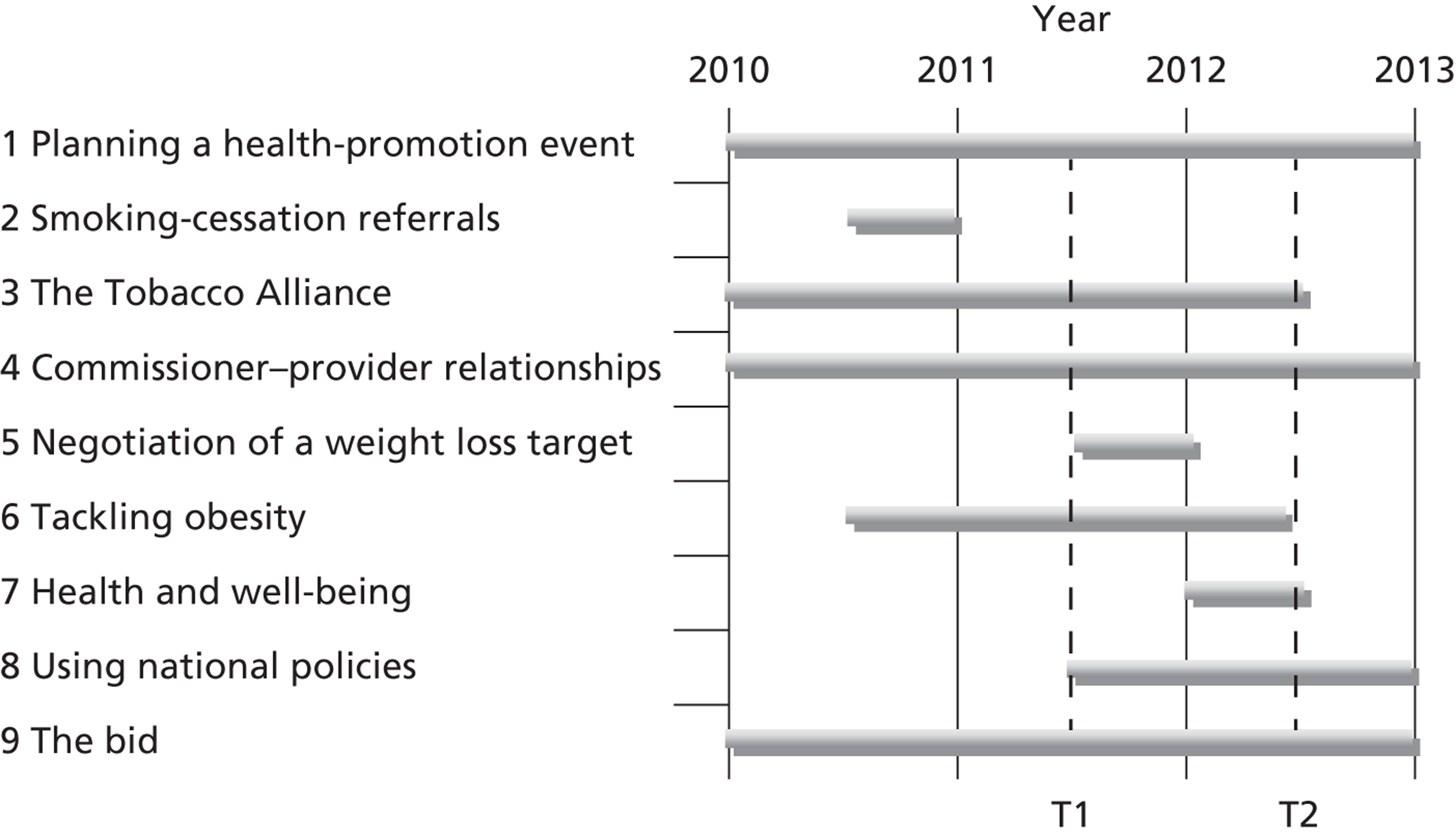

Landscape mapping

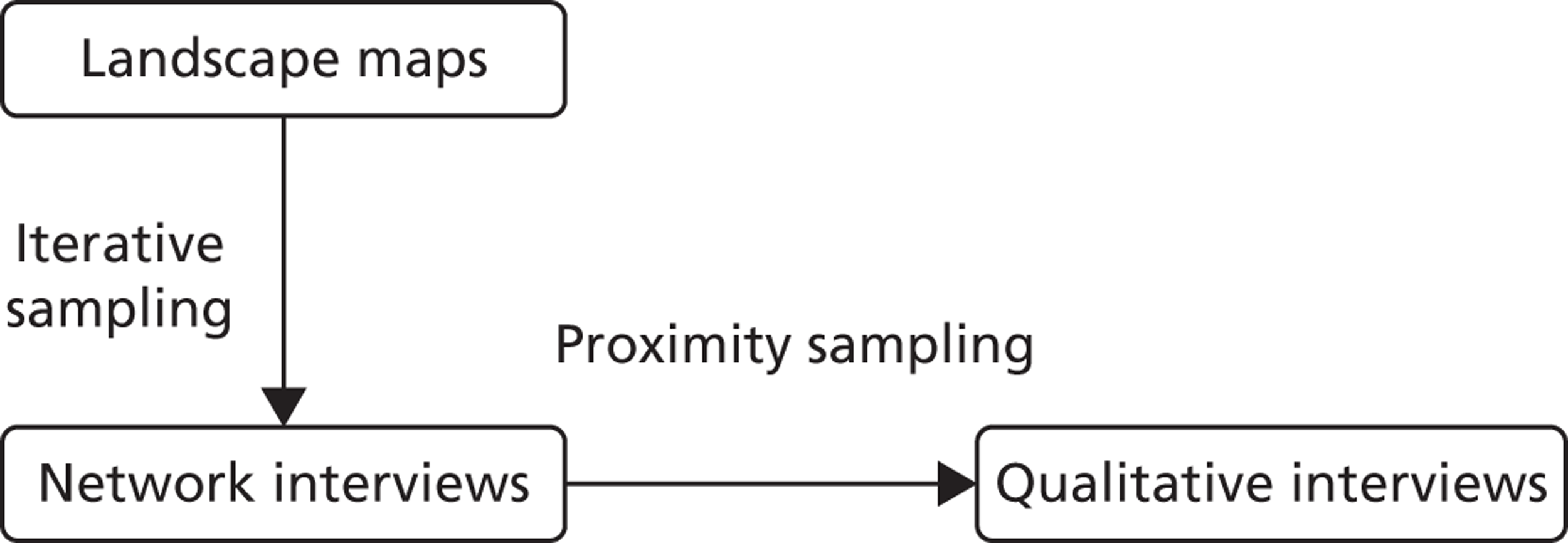

Health and well-being is a broad topic, increasingly seen as ‘everyone’s business’, involving many agencies in any given locality. Our initial challenge, therefore, was to identify the organisations and the people that we should focus on in our fieldwork, in each of our study sites. That is, we needed to identify a sampling strategy (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Study design: sampling strategy.

One option was to follow the lead of several other network studies and identify the core and periphery of our network, by taking a relatively restrictive definition of our target population, for example everyone who was invited to key meetings. 13–15 A second option was to compile a complete list of actors which represented the entire study population. 16 These options were unsuitable for two reasons: one practical and one methodological. The practical reason was that there was no authoritative list, at any of the sites, which we could use to identify meetings that we could observe, or middle managers that we should interview. The methodological problem was that the approaches inevitably introduce artificial boundaries, which either follow pre-existing organisational contours or flow from assumptions made by the research team, which cannot subsequently be tested. 17

A third option for identifying the population was to use snowballing, where researchers begin with a small number of actors and ask them to nominate others who are involved in the network. Each of their nominees is then asked for further nominees. The process generally ends when there are very few, or no, new nominees. 16 Snowball sampling approaches have been widely criticised because they potentially lead to bias in the analysis, where the resulting network is substantially determined by the connections of the first few actors. 17

We were concerned to avoid some of the pitfalls of these sampling strategies. Our solution was to develop a method which we called landscape mapping. The essence of the method is to interview people who are not in our target group (i.e. middle managers of health and well-being services), but who nevertheless know who they are and where they work. Landscape mapping interviews were undertaken with senior managers at each of the three sites, who we judged would have a good overview of the people and organisations involved in managing health and well-being services across each PCT area18 and could help us to identify a pressing local health and well-being issue, which would frame our subsequent data collection. At least one of the interviewees at each site was a director or deputy director of public health.

Each mapping interview lasted 60–90 minutes (two were undertaken at two sites, and three at the third), and involved populating an A3 sheet of paper with the names of all of the organisations and people that interviewees told us were involved in managing health and well-being services relevant to a pressing local issue. 19,20 This allowed us to mitigate the biases associated with snowball sampling because – for sampling purposes – the senior managers were independent of the people they named.

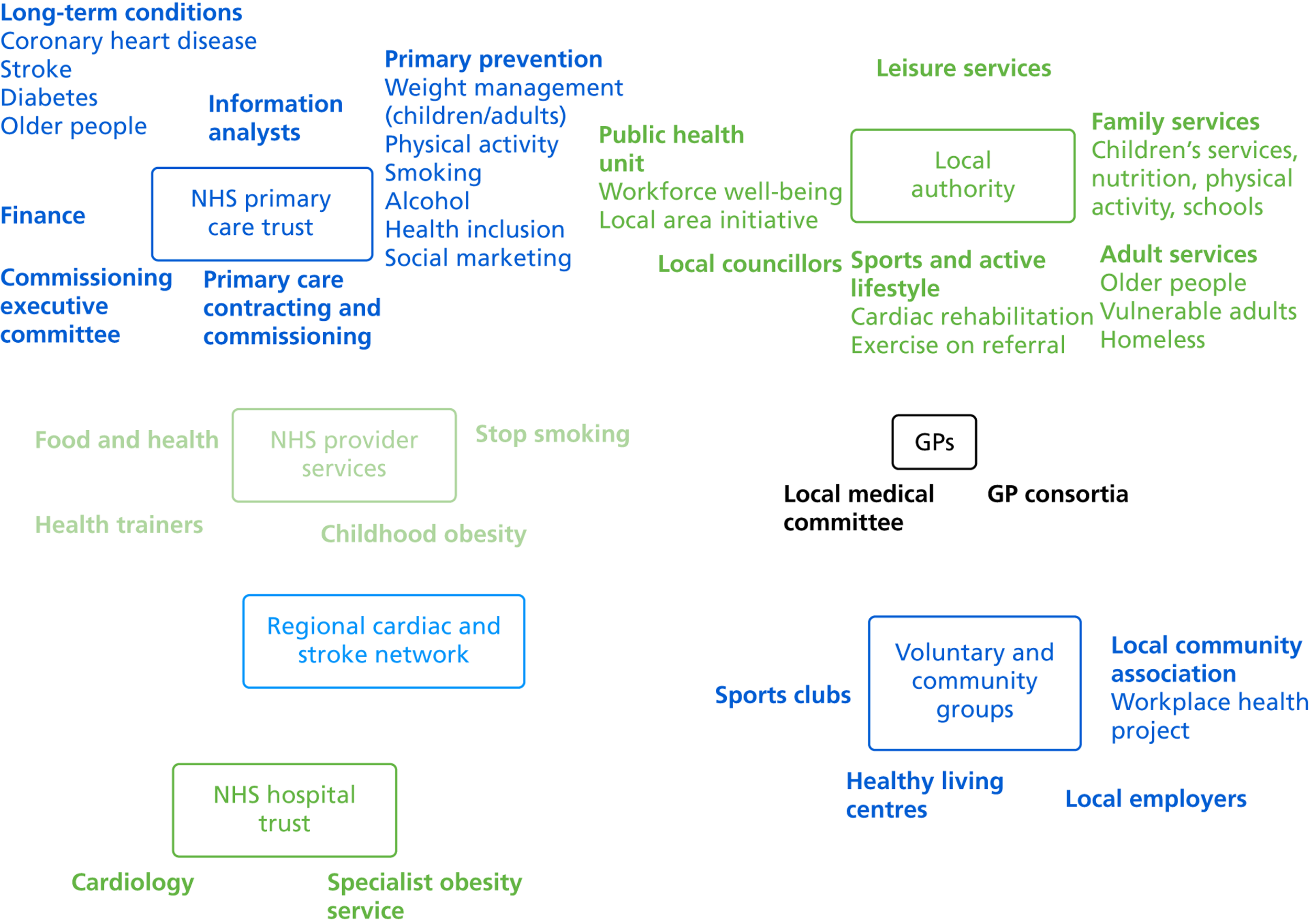

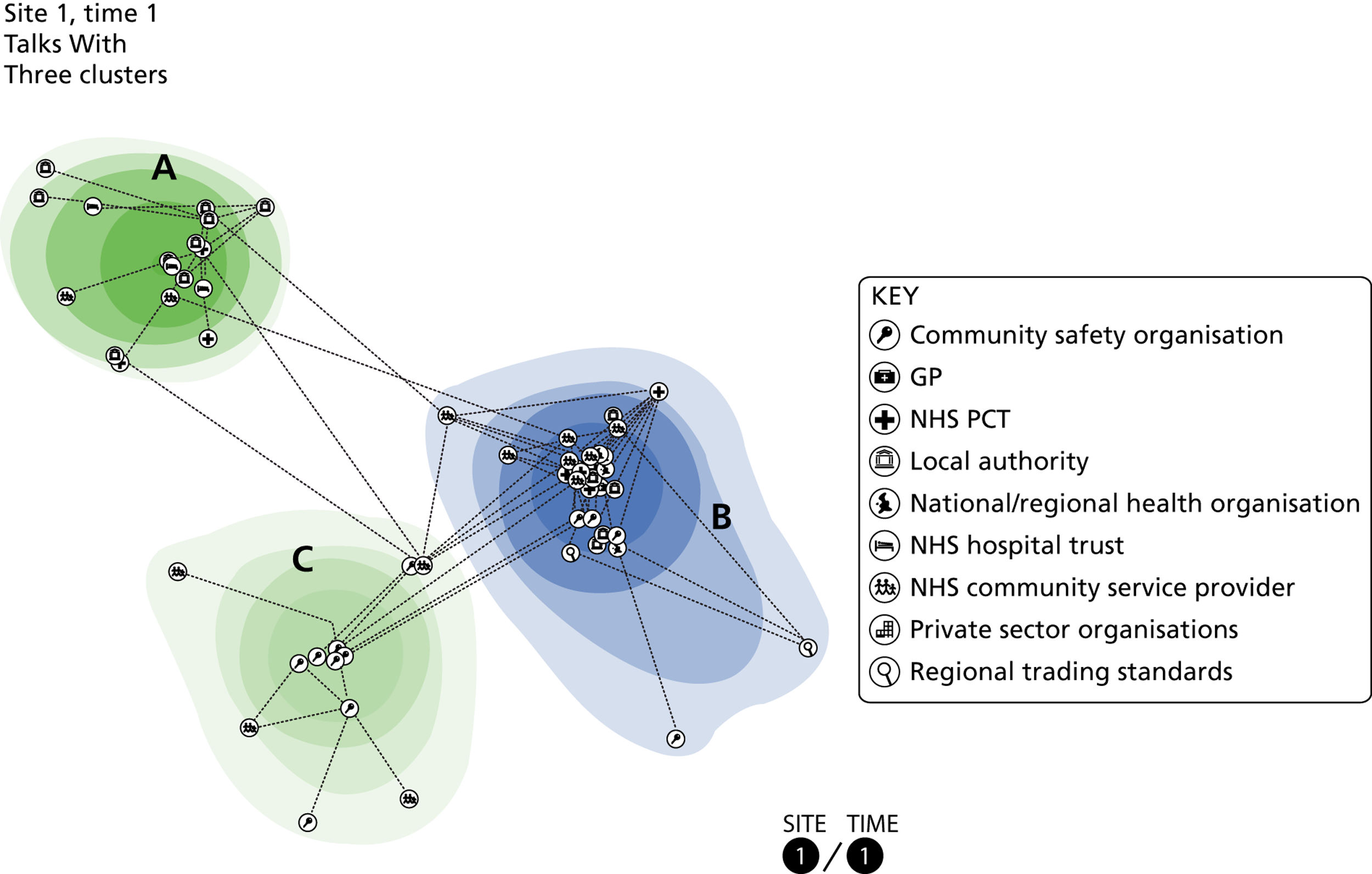

Interviewees provided information about managers involved in health and well-being services within their local PCT boundaries. We recorded job titles and responsibilities (e.g. smoking or weight loss). We did not explicitly ask interviewees to draw any links between individuals or organisations, but interviewees sometimes added connections to the map to emphasise particular relationships. Figure 2 is an example of a composite map from two interviews at one of the study sites.

FIGURE 2.

Landscape map. GP, general practitioner.

Network study: iterative sampling

The results of the landscape mapping interviews were used to identify an initial sample of four middle managers at each study site. We selected them on the basis that they covered key areas of the local landscape between them; for example, we ensured that PCTs and local authorities were included, and that they were reported as working across organisations and/or professional groups.

We used structured network interviews: the data collection form is in Appendix 6. Other commonly used data collection techniques such as postal questionnaires were considered but we judged that structured, face-to-face interviews were most likely to ensure data quality and participation. Face-to-face interviews have also been used successfully in study designs similar to ours. 21,22 Interviews combined free recall and fixed-choice strategies;16,23 that is, we asked interviewees to name people in response to our two questions, but allowed them to list only up to five people. Our reasoning was that although we had defined a loose boundary for our network, we were most interested in identifying the core of the network, which would best be revealed by asking people to nominate their most important relationships rather than all relationships.

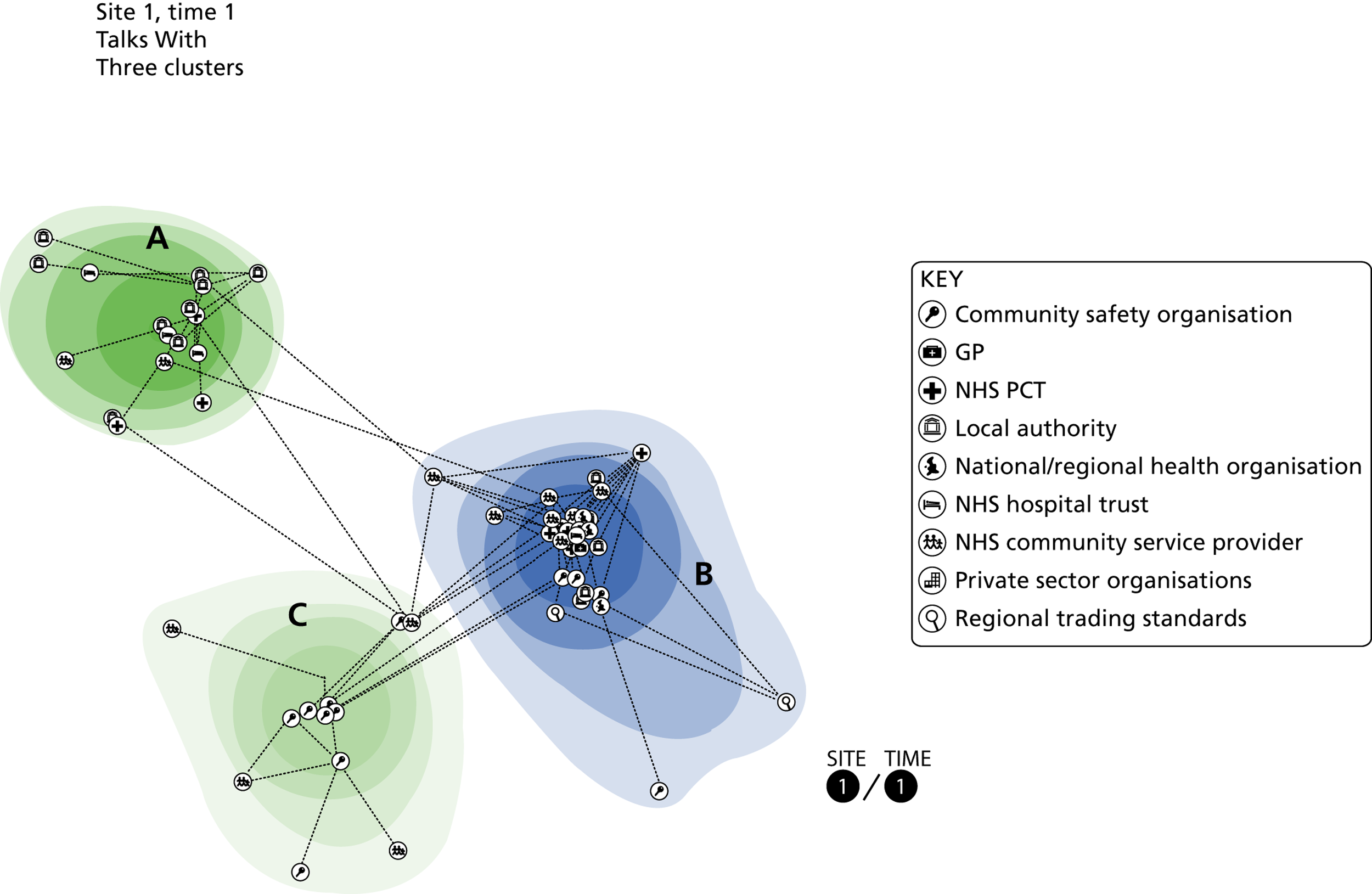

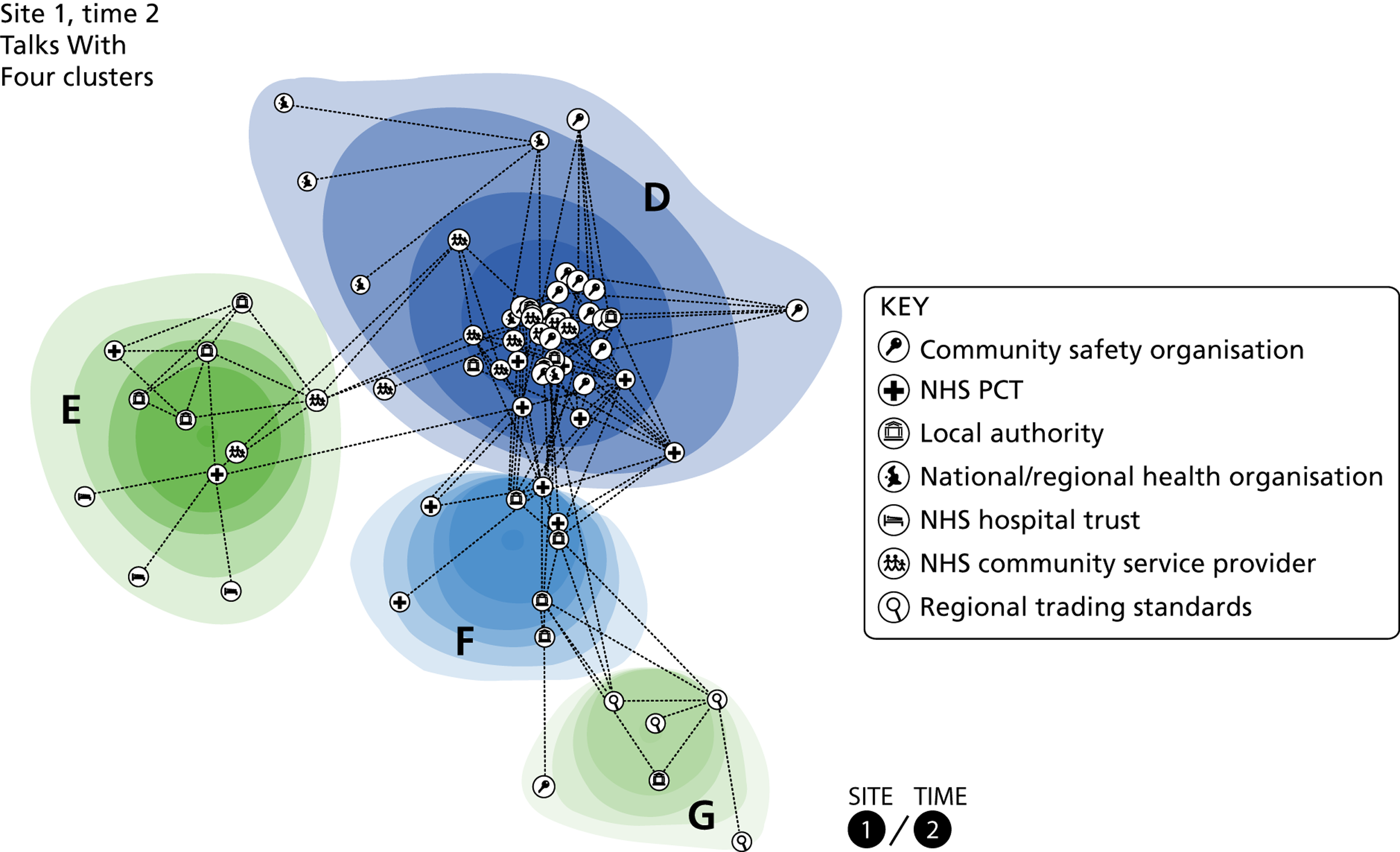

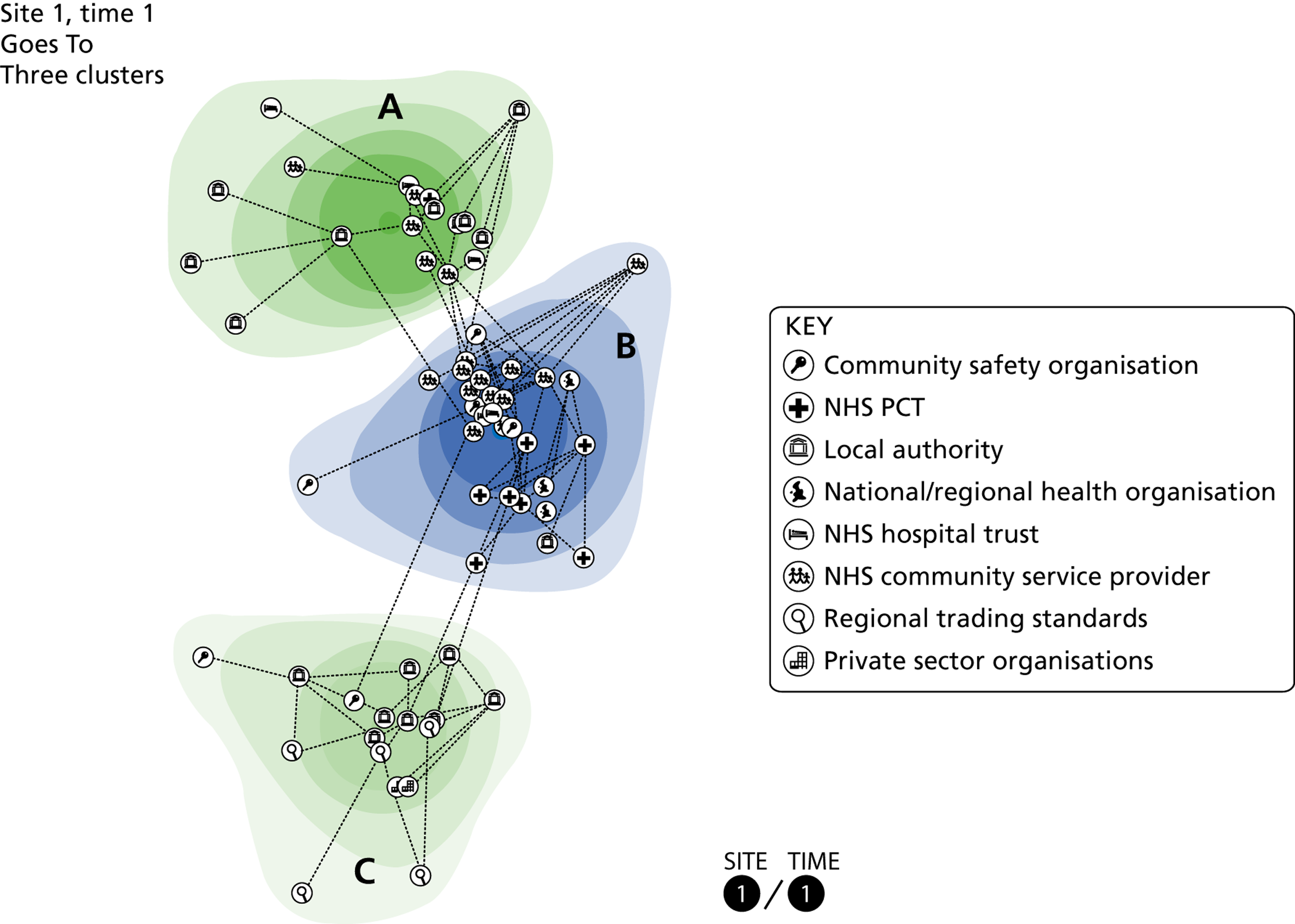

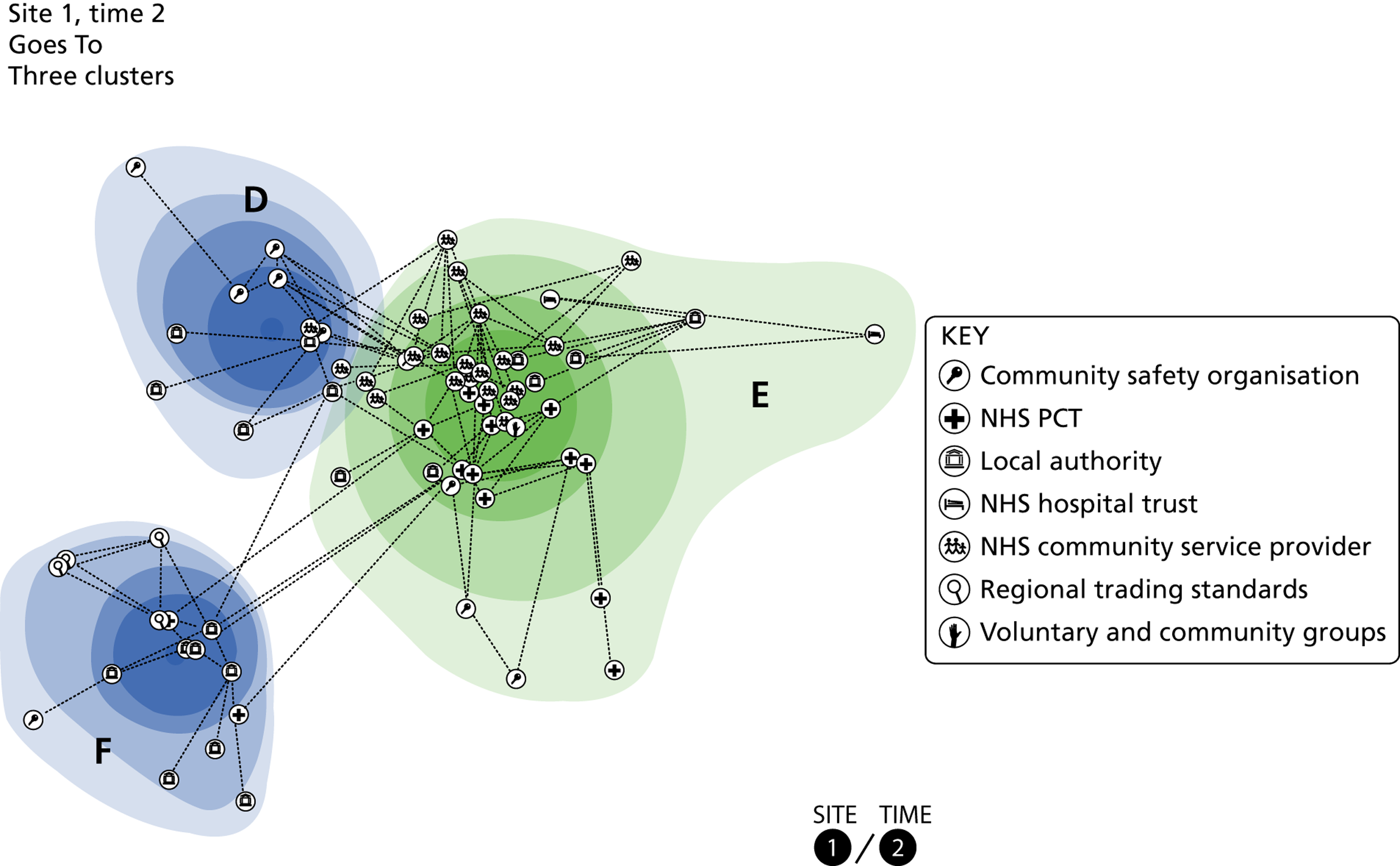

Although we focused on the ‘core’ of each network, we were also aware of the need to gain sufficient coverage of the landscape. This posed a practical challenge as the potential size of our networks (as revealed through the landscape mapping exercise) was large. Owing to resource constraints, we would not be able to interview all of the managers identified on the landscape maps. We had to find an economic approach to collecting data about relationships across the landscapes at our three sites. Our solution was to gather ‘secondary data’ by asking interviewees to name people who their nominees talked with or went to. This method has been validated in the context of criminal networks, where research showed that the relational knowledge of a few informants compensated for the lack of objective knowledge arising from low response rates. 24 If we subsequently interviewed someone for whom we had secondary data from other respondents, we used their actual responses when constructing our data set.

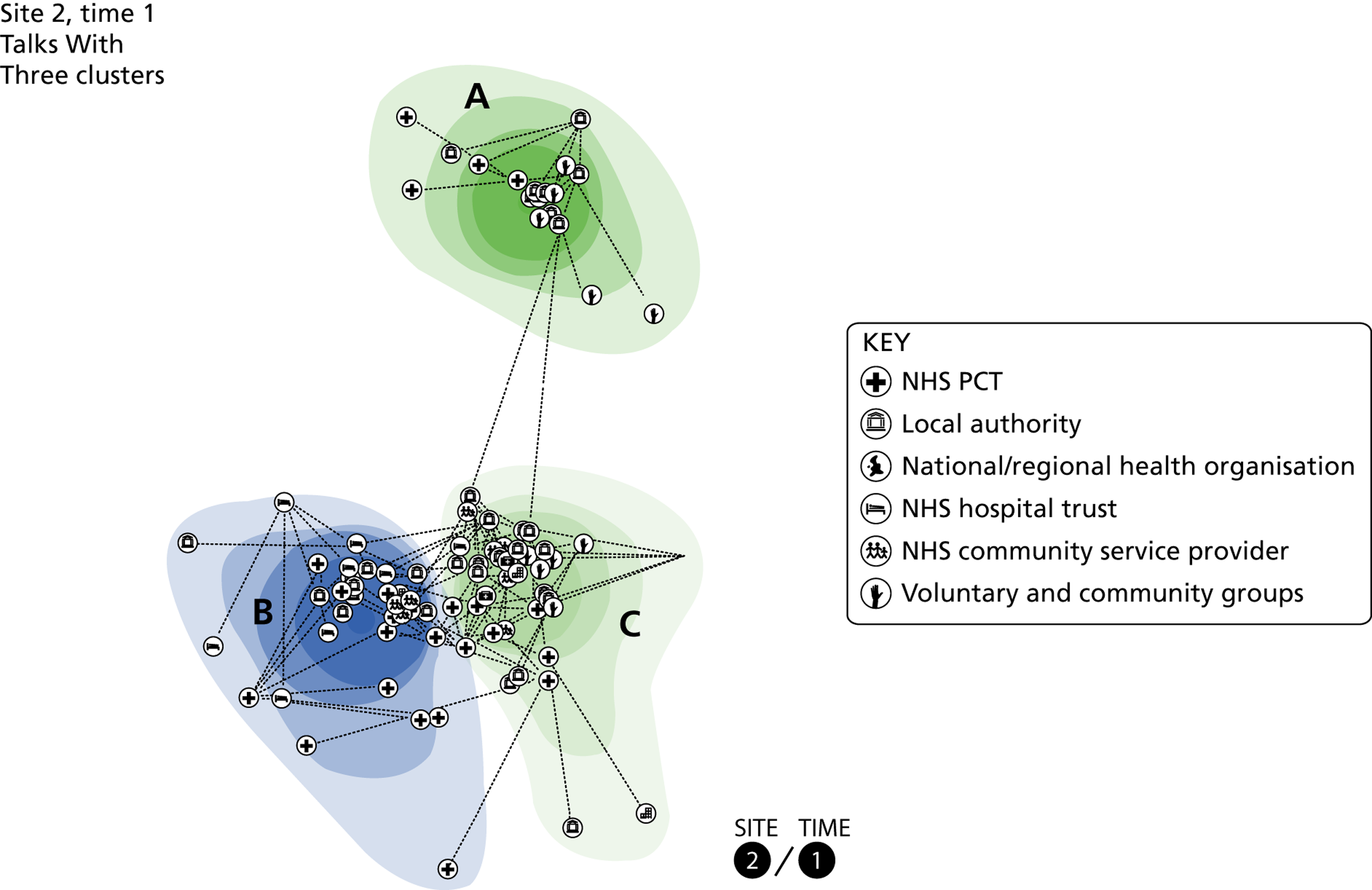

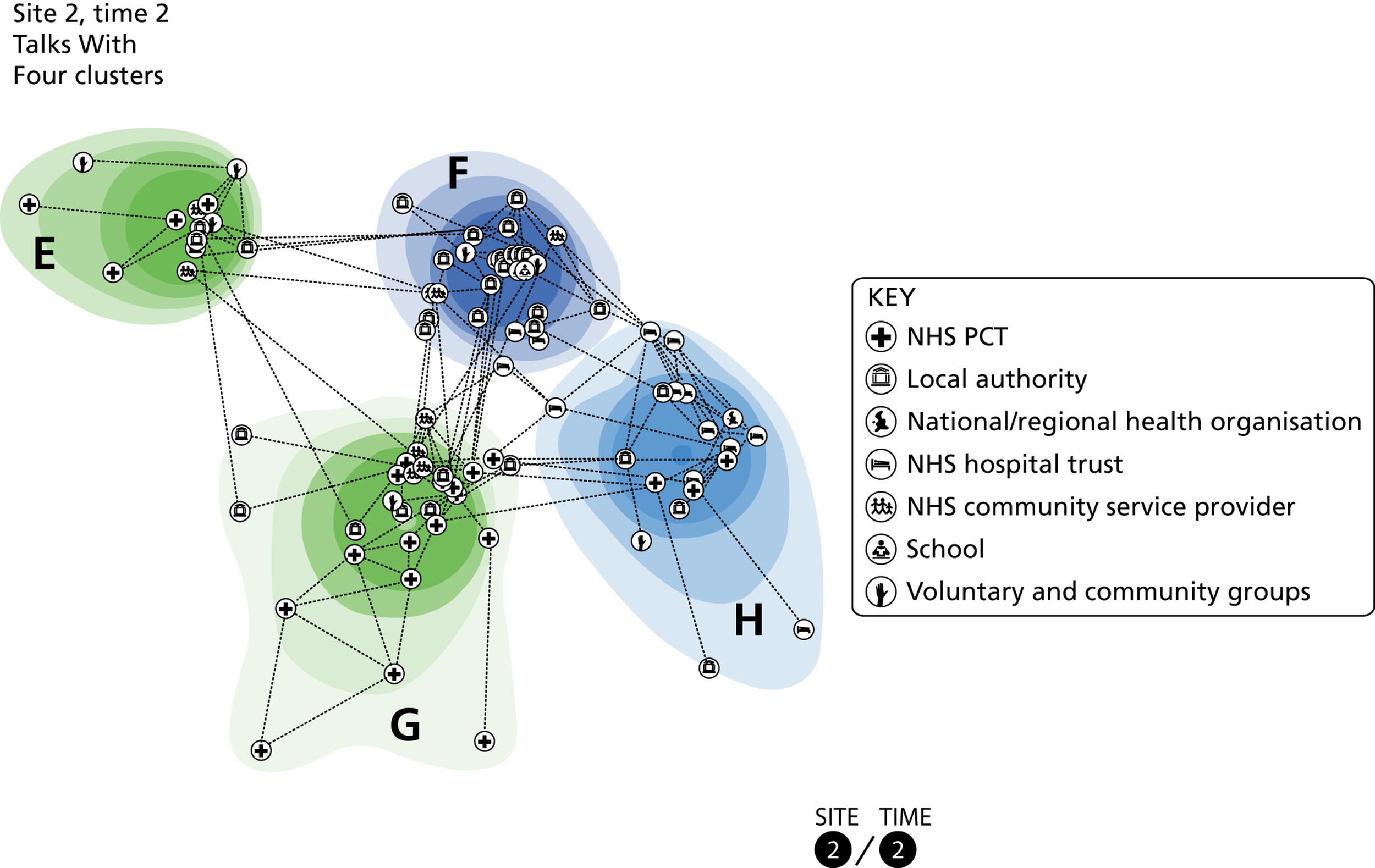

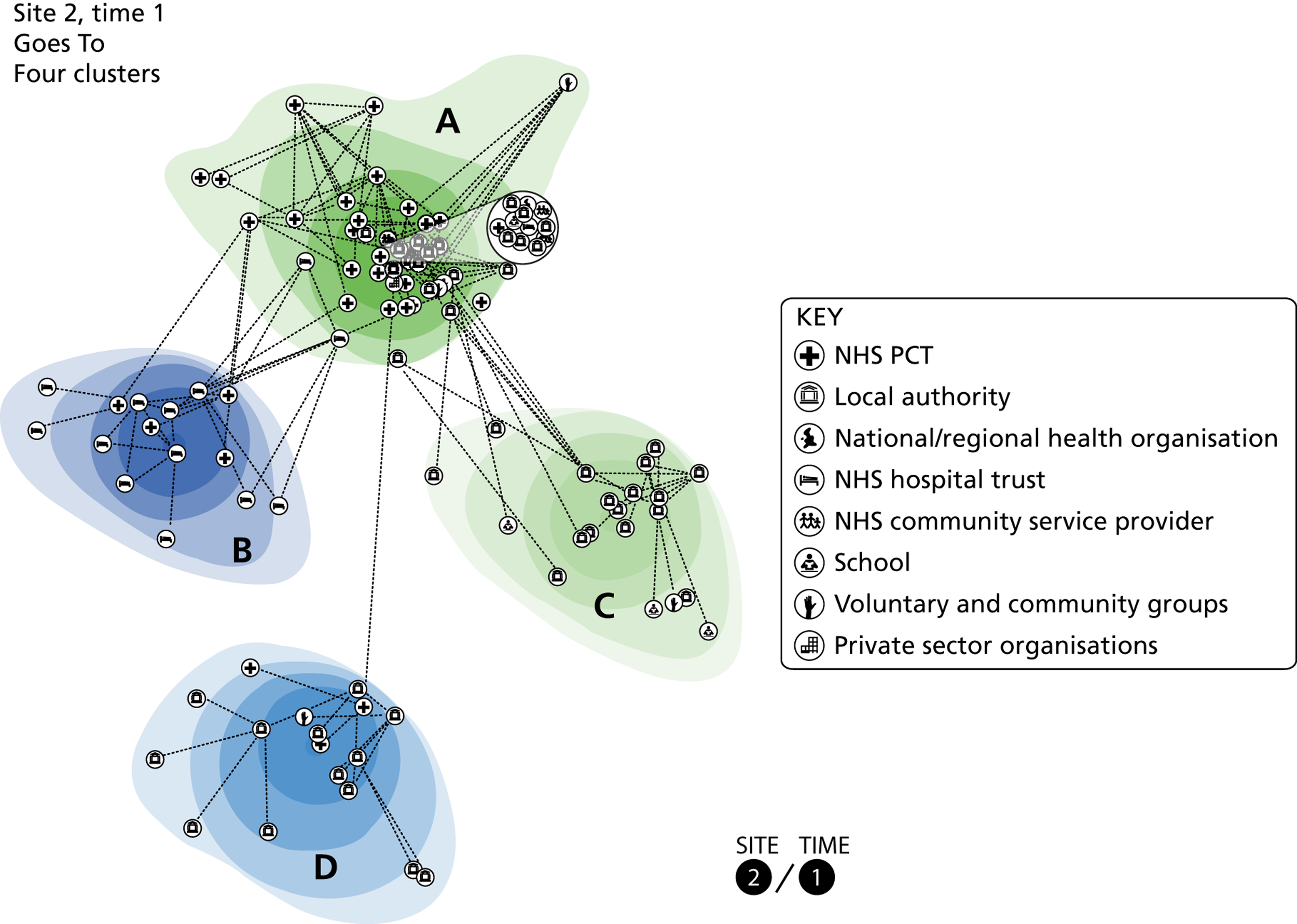

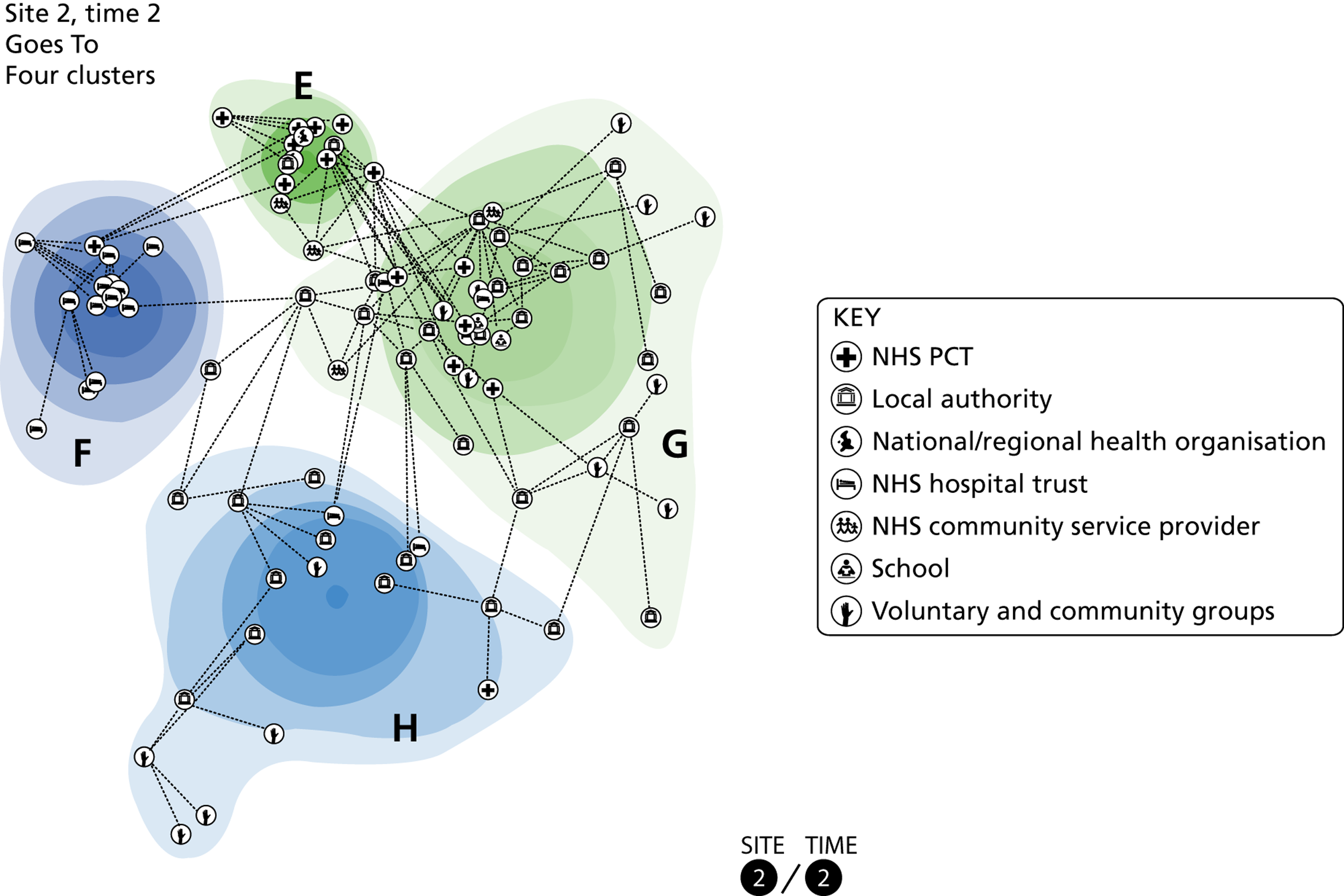

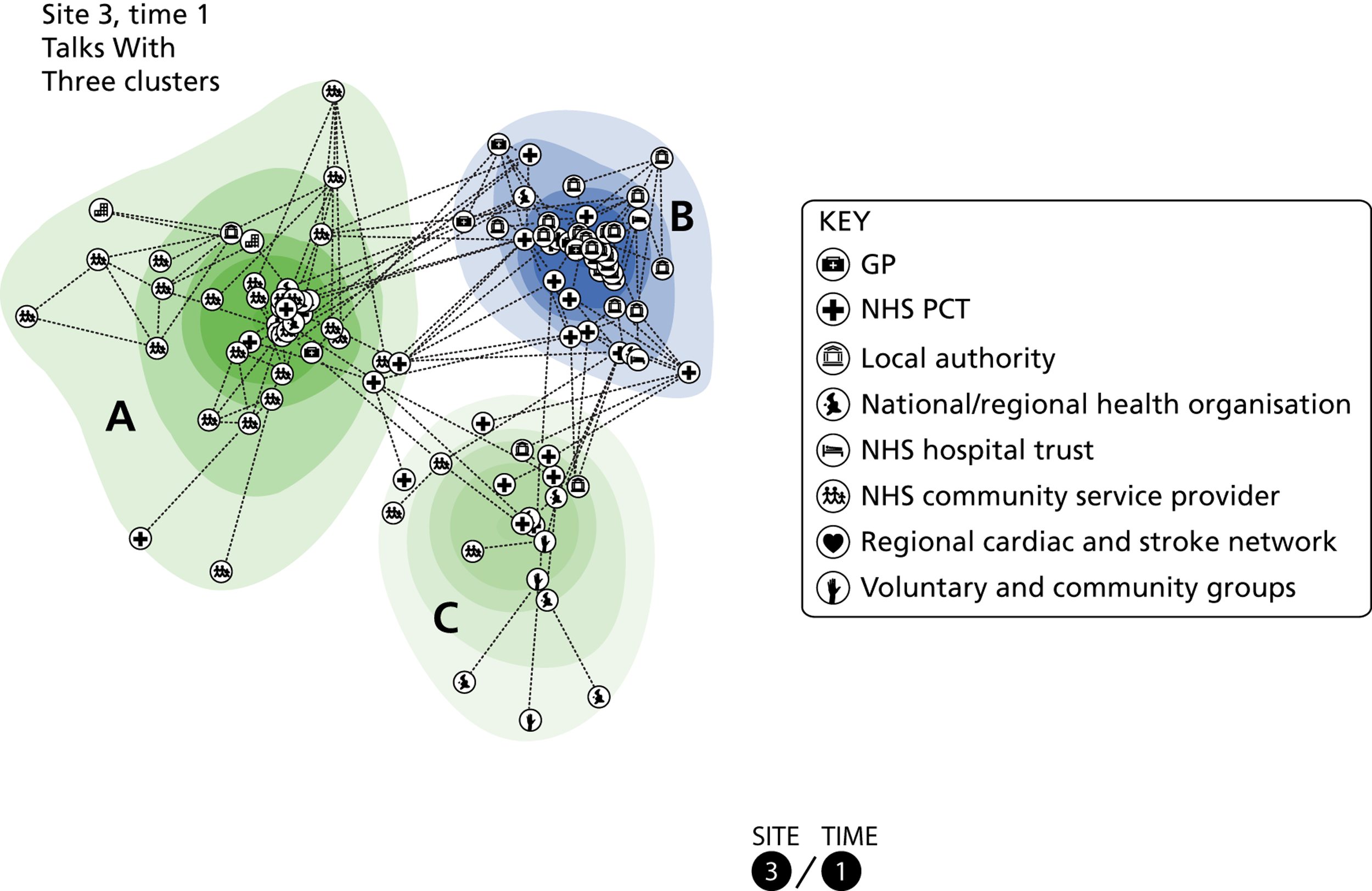

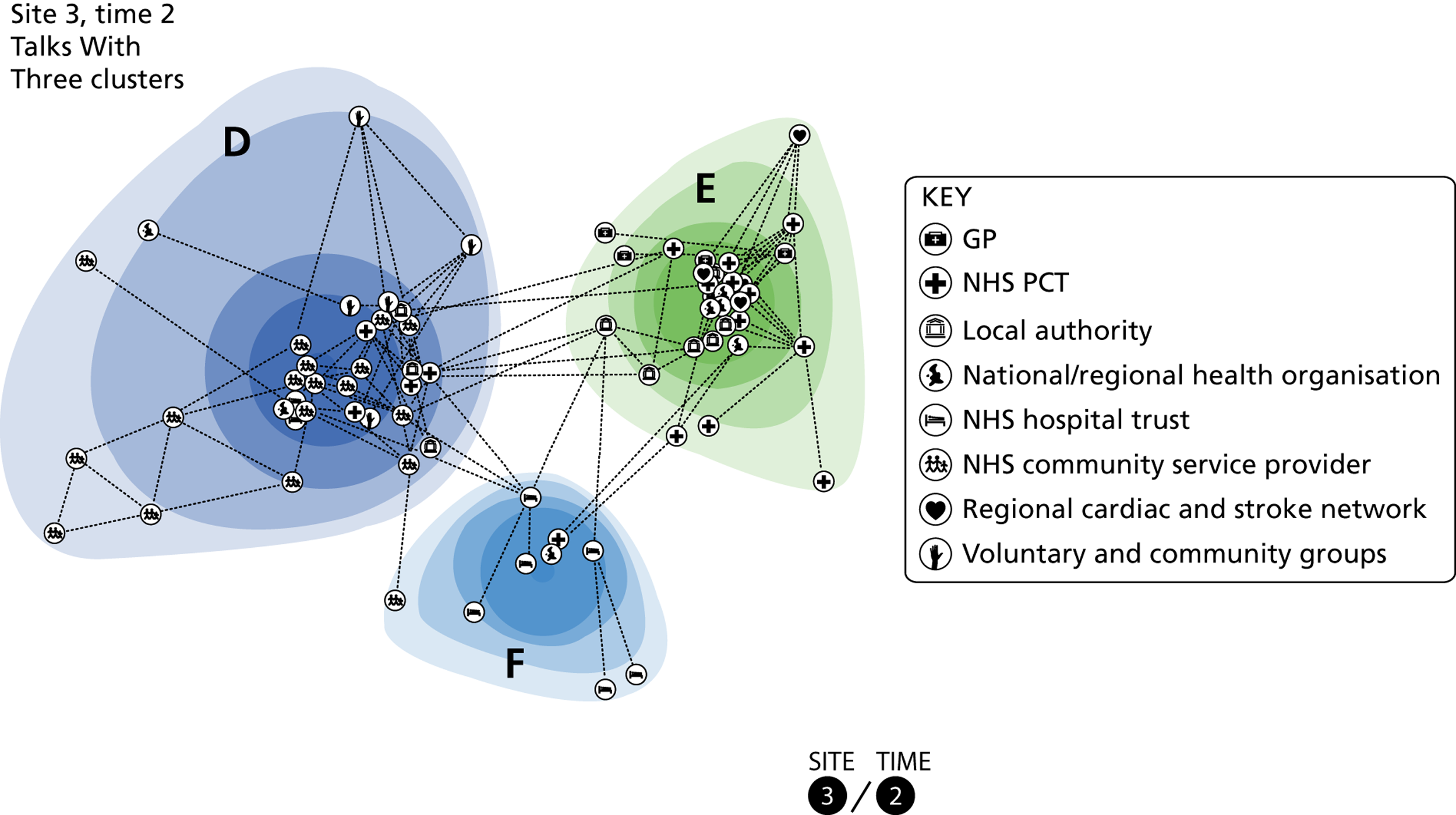

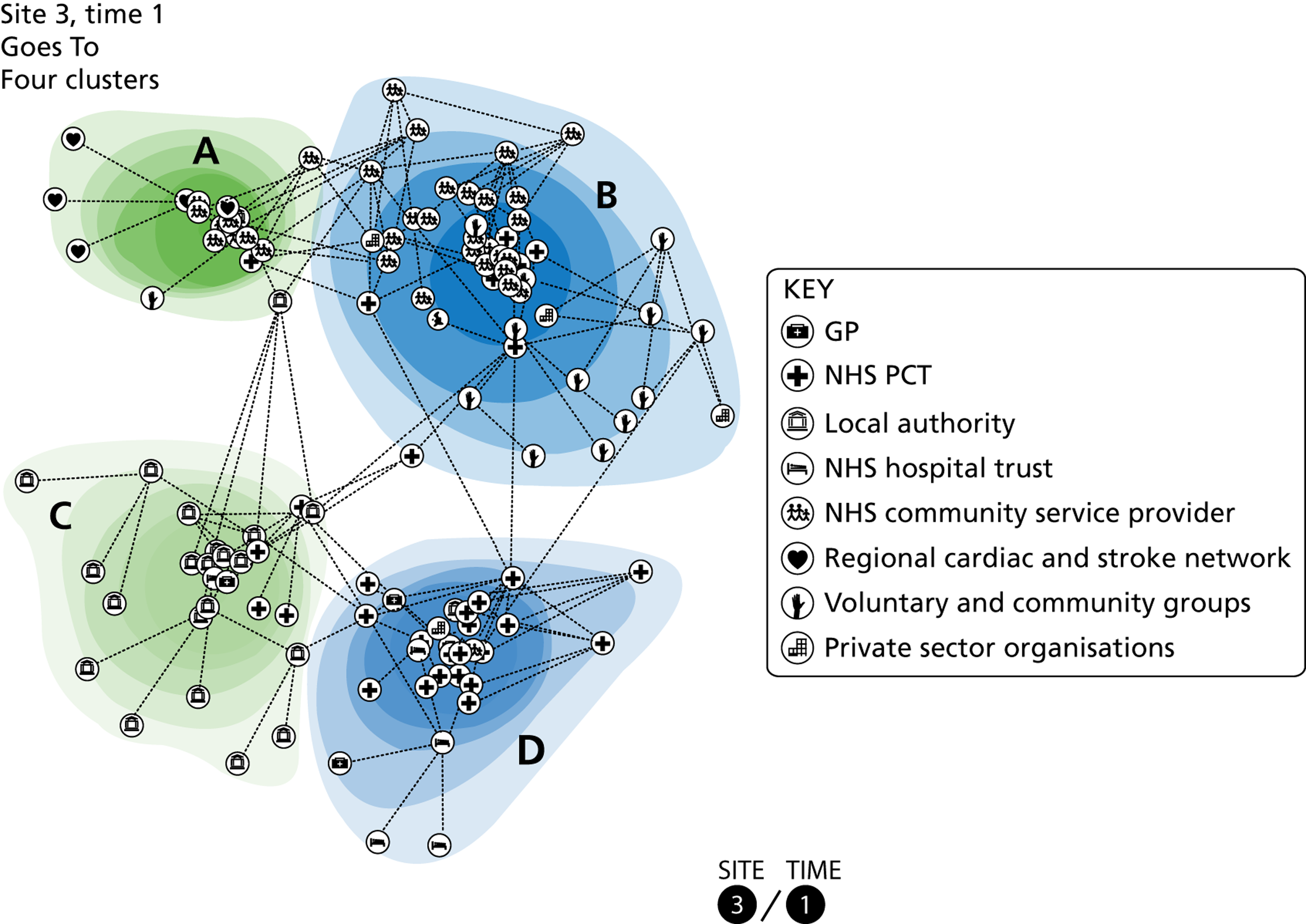

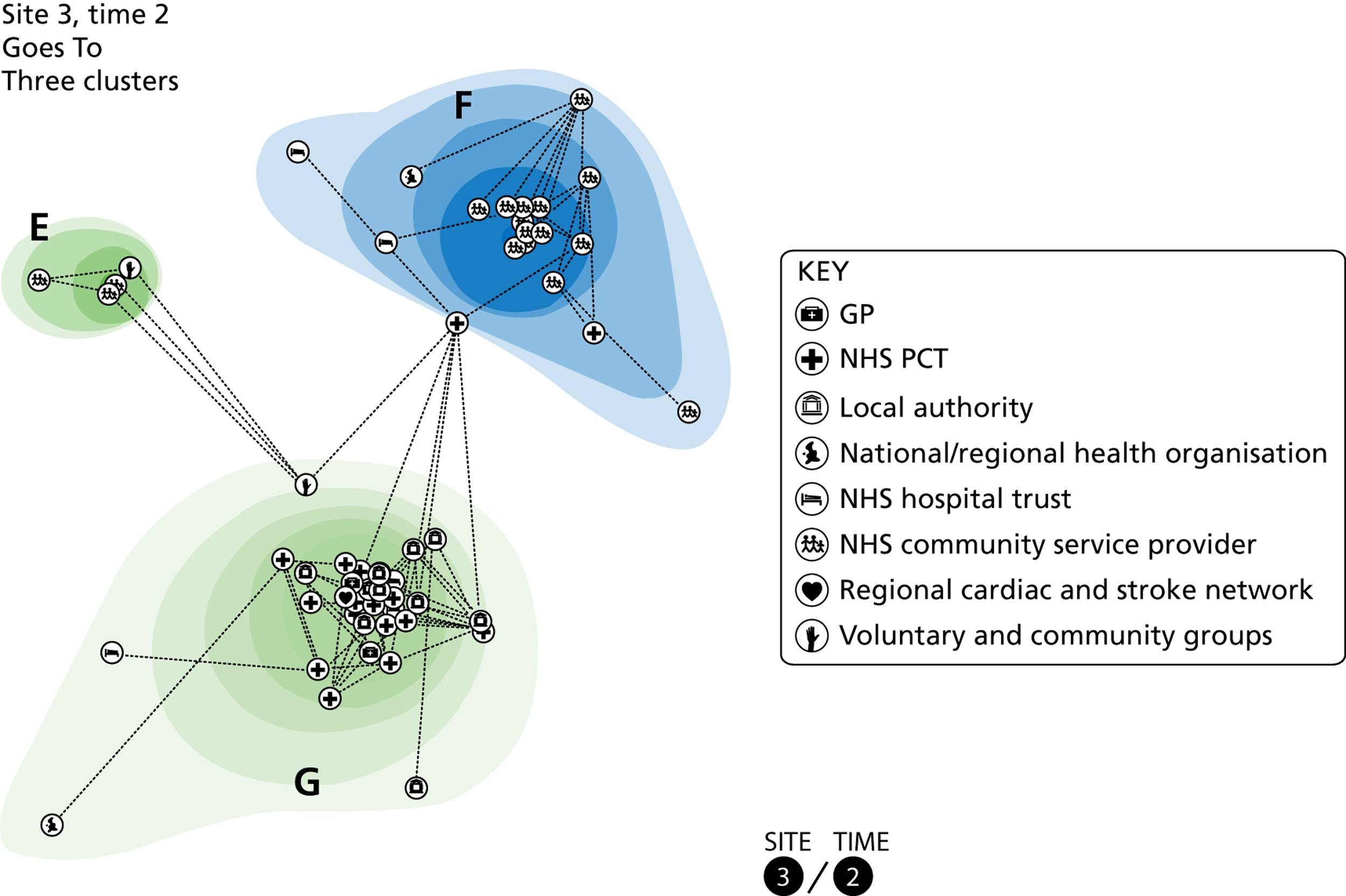

We took the view that two types of relationships would be of particular interest in relation to knowledge mobilisation. The first was ‘talks with’, which involved asking participants, ‘Who do you talk with about [the pressing local topic/problem]?’ The second was ‘goes to’, which involved asking participants, ‘Who do you go to get things done about [the pressing local topic/problem]?’ These questions broadly correspond to the sociological concepts of speech and action. We also asked interviewees to provide further details (organisation or role/job title) about each of the people they named.

Having completed these initial interviews, we needed a strategy for sampling further interviewees without resorting to snowball sampling (for the reasons discussed above). Our solution was to select further interviewees by modelling the data from the first sample (hence the term ‘iterative sampling’ for this section). Because we were particularly interested in the collective thoughts and actions of middle managers, we modelled these partial networks using a method specifically designed to reveal clusters – latent cluster analysis. We judged that identifying clusters would help to identify any ‘holes’ in the networks – gaps between groups within a network. In order to identify clusters, we used an approach which uses the concepts of latent position network models25 and cluster latent position models. 26 Further details about our modelling methods can be found in Network analysis: latent clusters, below.

We also referred back to our landscape maps, in order to ensure that our sampling achieved the most extensive coverage of the landscapes possible with the resources available to us. Our selection was made using the following criteria:

-

Actors near the centres of the clusters are sufficiently well specified in terms of their network links and need not be selected for interview (i.e. we knew enough about them already).

-

Those near the edges of clusters had network links which might be less well specified, and could, therefore, reveal links with parts of the landscape that were not yet covered. These actors should be selected for interview.

-

Individuals ‘outside’ clusters may be isolates, on the periphery of the network, or beyond our loosely defined boundary, but they could still be a key link to other parts of the landscape. They should be selected for interview if other sources (e.g. documents, observations or local knowledge) suggested that this might be the case.

Having identified, and collected network data from, the second phase sample, we modelled the network again. At this stage, we found that saturation of some parts of the landscape was already apparent. Equally, it was sometimes difficult to identify middle managers who would link to areas of the local landscape not yet covered. For our third and final phase of sampling, therefore, we focused on sampling individuals who had already been identified as particularly well connected in order to collect primary data in place of secondary, and to establish whether or not the managers identified in the landscape maps were linked to one another in practice.

We were aware, throughout, that there are always questions about the location of the boundaries of a network. Network and system theorists both emphasise that social systems are open, in the sense that they do not have well-defined boundaries with their ‘environments’, and are continuously subject to external influences. 3,27,28 As some of the preceding points suggest, we addressed the problem in two ways. First, we felt that it was reasonable to assume that interviewees would name people who were the most important members of a network and, by implication, not located close to any boundaries. Second, some of our interviewees were selected on the basis that they spanned the landscape (in our landscape maps), and this selection strategy gave us some confidence that we were able to achieve reasonable coverage within boundaries that were defined by our interviewees.

The network interview process was repeated approximately 8 months after the initial round of network interviews. For the second round of interviews, we did not develop the sample iteratively, but rather reinterviewed all round 1 participants. Where this was not feasible (e.g. owing to interviewees having left their posts), interviewees were replaced with individuals who were currently performing the same or a similar role within the organisation.

Qualitative study: proximity-based sampling

We also needed to identify a sampling strategy for the qualitative interview programme at each site. The networks we identified were large, with at least 70 members at each site. We did not have the resources to interview this number of people, and we therefore needed to identify a manageable number, such that an interview programme would still allow us to address our study questions. For the first round, in the summer of 2011, we identified middle managers who were positioned close to the centre of each of the clusters in the ‘Goes To’ and ‘Talks With’ networks (n = 6 at each of our three sites). We undertook semi-structured interviews, lasting 60–90 minutes. We decided that we could not ask interviewees how they created or mobilised knowledge – the question would not have made any sense, however we phrased it. (If our chosen literature was correct, interviewees would have a tacit understanding of many of their own work practices and would not be able to articulate the knowledge underpinning them.) Our strategy was, instead, to ask interviewees about their work with other middle managers. Their accounts of particular projects, or problems that they had to solve, would, we judged, allow us to infer any knowledge creation that had occurred.

The initial sampling strategy was only partially successful and, for the second round of interviews, conducted in the early summer of 2012, we focused on interviewees who were close to the centre of a single cluster, had a high degree of connection within a cluster, and who connected the cluster of interest to other clusters. The topics covered in the interviews were the same as in the first round; a topic guide is in Appendix 7.

Because these interviews marked the end of the fieldwork phase of the study, we were able to share some of our initial findings with interviewees without jeopardising the quality of data collected earlier. Drawing on the experiences of other network researchers,24,29,30 we showed interviewees the ‘goes to’ latent cluster diagrams from the second round of network interviews, for their own site. Data protection considerations meant that we could not reveal the names of individuals in each diagram, but we were able to show each interviewee where he or she was located. This process provided us with the opportunity to assess the face validity of the results of the network analysis, and fed into our interpretation of the network data, presented in Chapter 6.

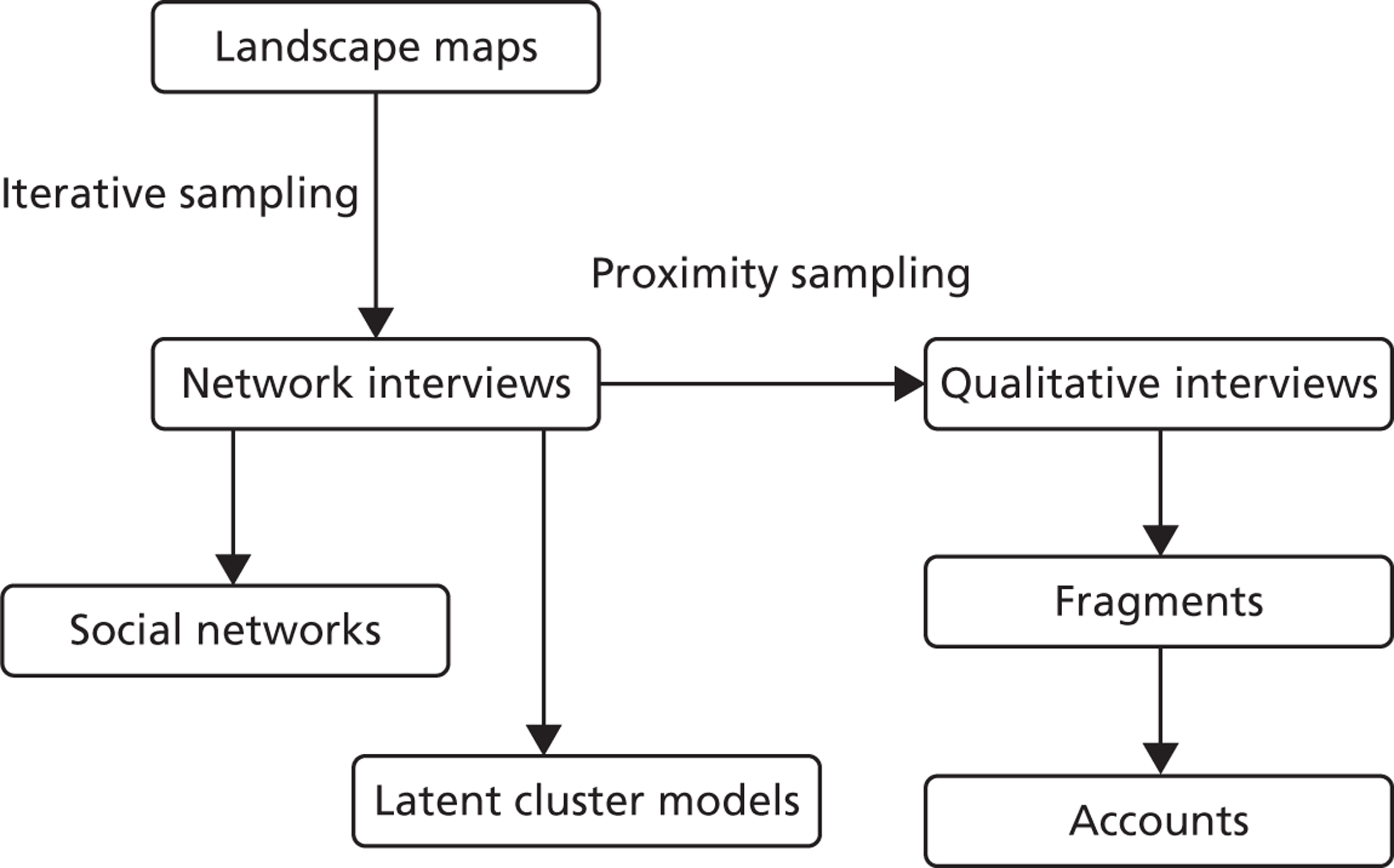

Analysis: qualitative to quantitative relationship

As noted earlier, we used a process tracing method9 to analyse the qualitative data. The framework for the analyses of our qualitative and network data is shown in Figure 3. This is the point where the arguments set out in the section Analysis: Qualitative to Quantitative Relationship in Chapter 1 have had the greatest influence on our study design. If we were working in an analytical rational tradition, we would place the greatest weight on our network analyses, taking the view that the network structures corresponded to relationships ‘in the real world’ – if we can understand the networks, we will understand something of this interesting part of the world. The qualitative data might embellish any structural explanations we produced but would play second fiddle to the network data. The reader would expect to see the network analysis first, followed by the qualitative analysis.

FIGURE 3.

Study design: analysis.

We took the alternative, narrative, view in this study. The key point is that network data, of the kind we collected, indicate underlying patterns of relationships at our study sites. They are useful abstractions and representations, but are embedded in complex webs of relationships, where trust, legitimacy and other social and organisational phenomena matter – and which are not captured by ‘talks with’ and ‘goes to’ questions. The practical effect of this approach was that, when we came to the analysis, we considered the qualitative data first. Thus, the sampling strategy took us from networks to qualitative results but the logic of the analysis is the other way around, starting with qualitative findings and then considering ways in which the network data help us to interpret, and refine our understanding of, the qualitative interviews.

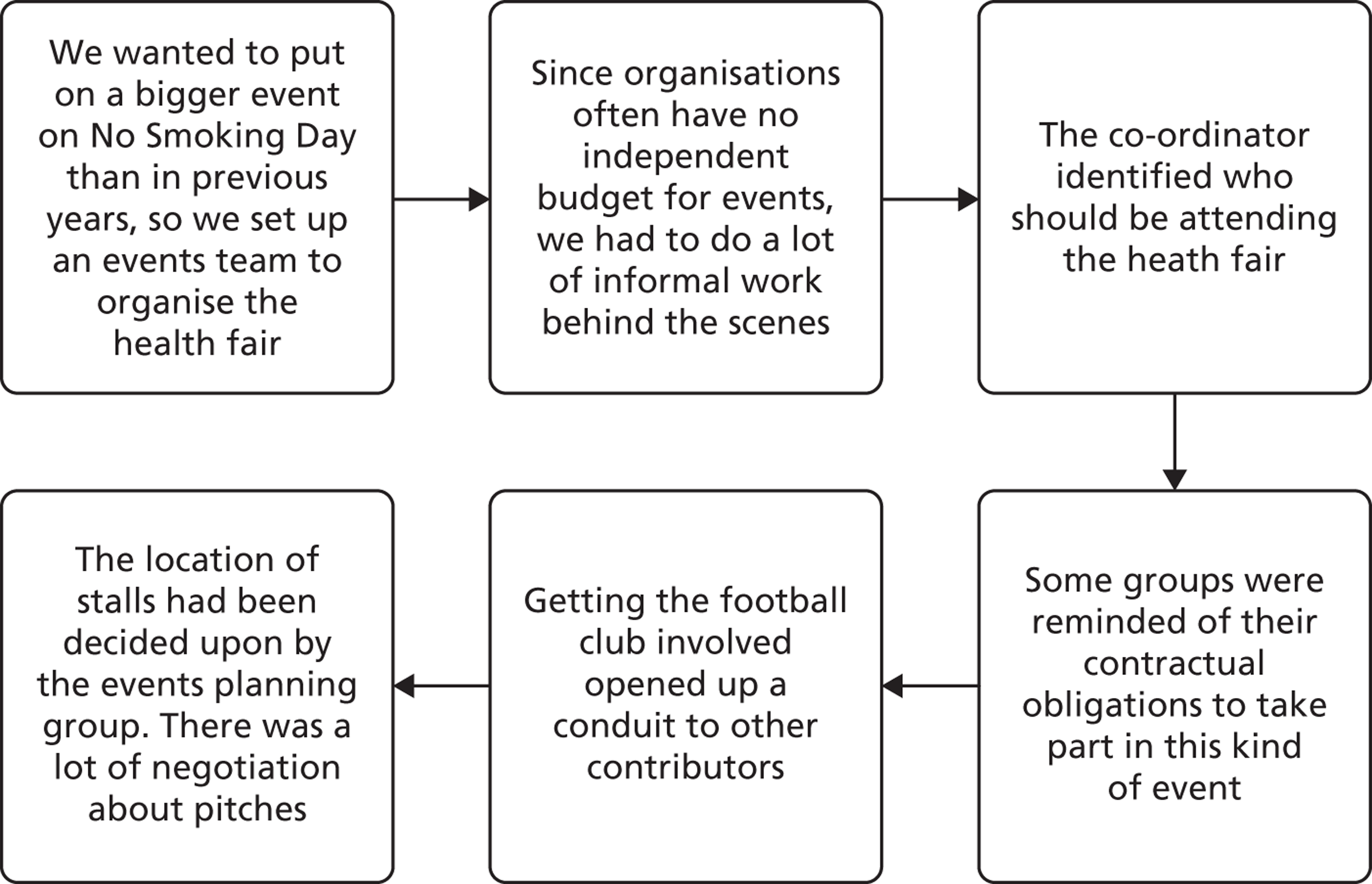

Qualitative analysis

In the round 1 qualitative interviews, in 2011, we had two objectives – to begin to shed light on middle managers’ knowledge creation at the study sites and to inform the design of the second phase of the study in 2012. Two members of the research team read the interview transcriptions and post-interview notes, and produced detailed thematic summaries using a flexible template that covered service priorities, the purpose and structure of networks, knowledge exchange and networking activities, networking problems and network effectiveness, while allowing for the emergence of further themes that were often specific to particular interviewees. The summaries were then shared and discussed among the research team, focusing particularly on comments shedding light on knowledge creation. We concluded that the interviews, taken together, did not allow us to shed light on knowledge creation processes. We changed our data collection strategy for Phase 2 of the study.

In Phase 2 we interviewed middle managers who, on the evidence of our ‘goes to’ network data, occupied similar positions in our graphs (i.e. were located in a single cluster). We produced accounts of knowledge creation relating to particular activities, such as organising a health promotion event, drawing on Greimas’s conceptualisation of speech act theory. 31 The approach is based on the premise that the language we use provides important clues about the way we think about problems – the way we make sense of them and work out how to tackle them. The approach has previously been used in studies of technology implementation32 and of public discussion,33 as well as of organisational routines, important in this study. 34

Three members of the research team undertook the analysis, which proceeded as follows:

-

Using Qualitative Data Analysis (QDA) Miner (v.2.0, Provalis Research, Montreal, QC, Canada), a qualitative data mining and visualisation tool,35 we searched all of the interviews at one site, and identified passages of text which referred to specific activities at that site,34,36 for example using central government funding to launch a new local service.

-

Using the framework function in NVivo version 9.2 (QSR International, Victoria, Australia), we grouped the passages referring to each activity into framework tables, and then analysed them. For each one, we looked for evidence about participants’ intentions and actions, on the basis that these would help us to identify the knowledge creation processes underpinning them. We coded text which indicated managers’ obligation and desire (‘have to’, ‘want to’), and their competence and know-how (‘able to’, ‘know how to’). 31 This process was repeated for activities at each of the three study sites.

-

We summarised the material in the framework tables in accounts of projects and programmes. 37 At this stage of the analysis, we also selected accounts to focus on in the subsequent phases of our analytical work using the following criteria: participants attributed significance to the activities, the accounts were told from at least two perspectives, they contained evidence about peoples’ intentions and actions, and we could describe the nature of the knowledge being created. This resulted in three accounts at each of the three sites, presented in Chapter 5.

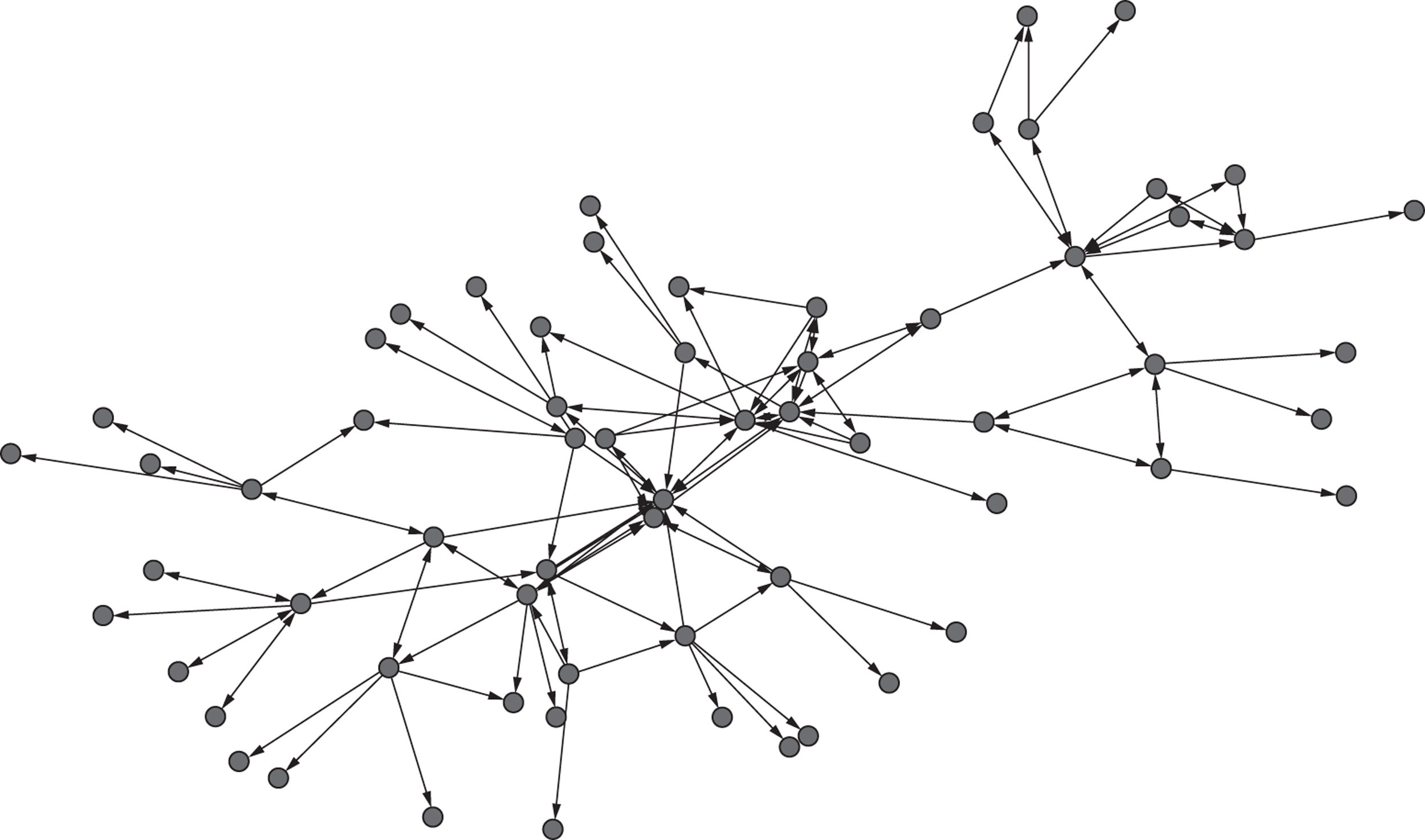

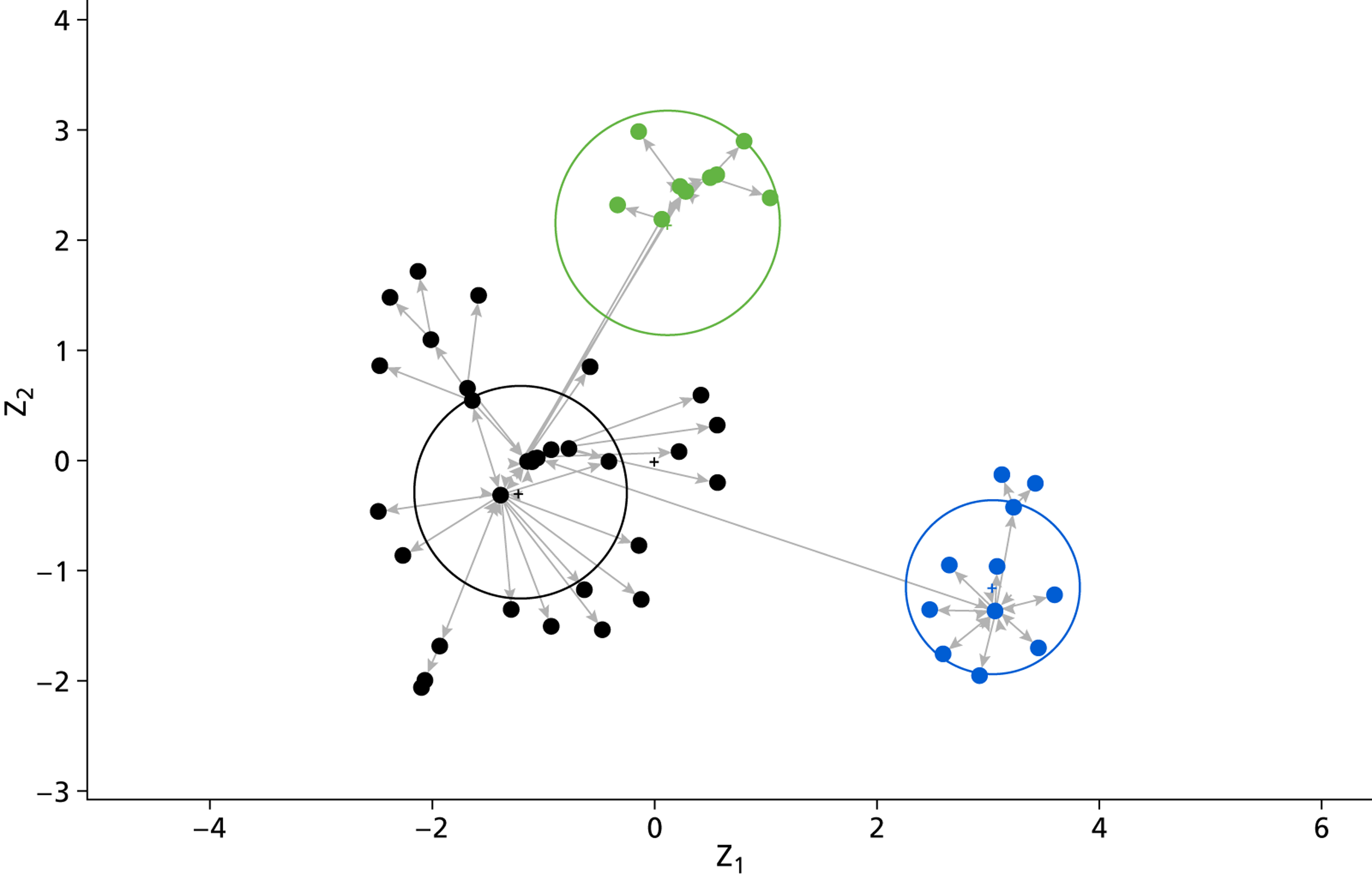

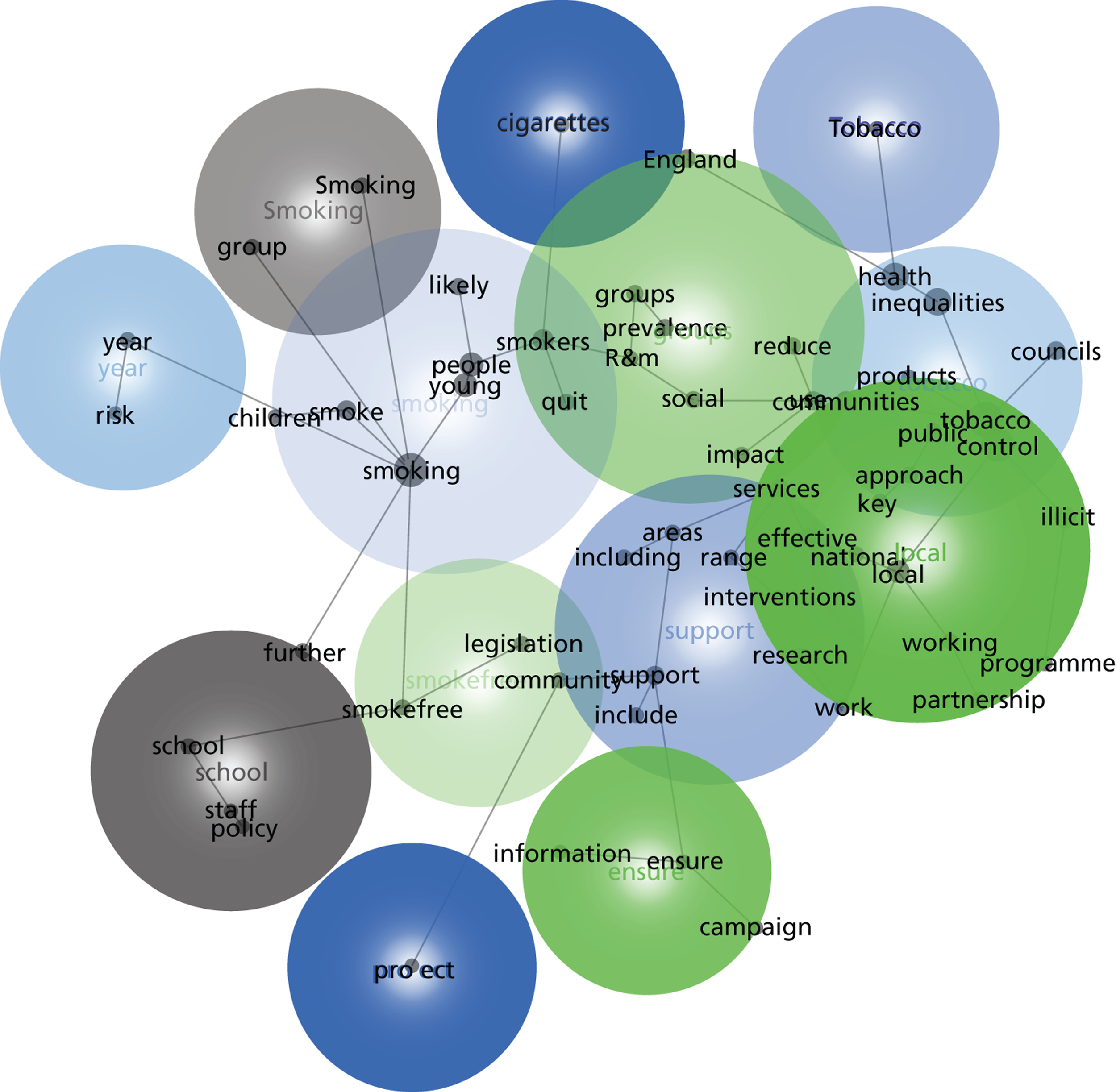

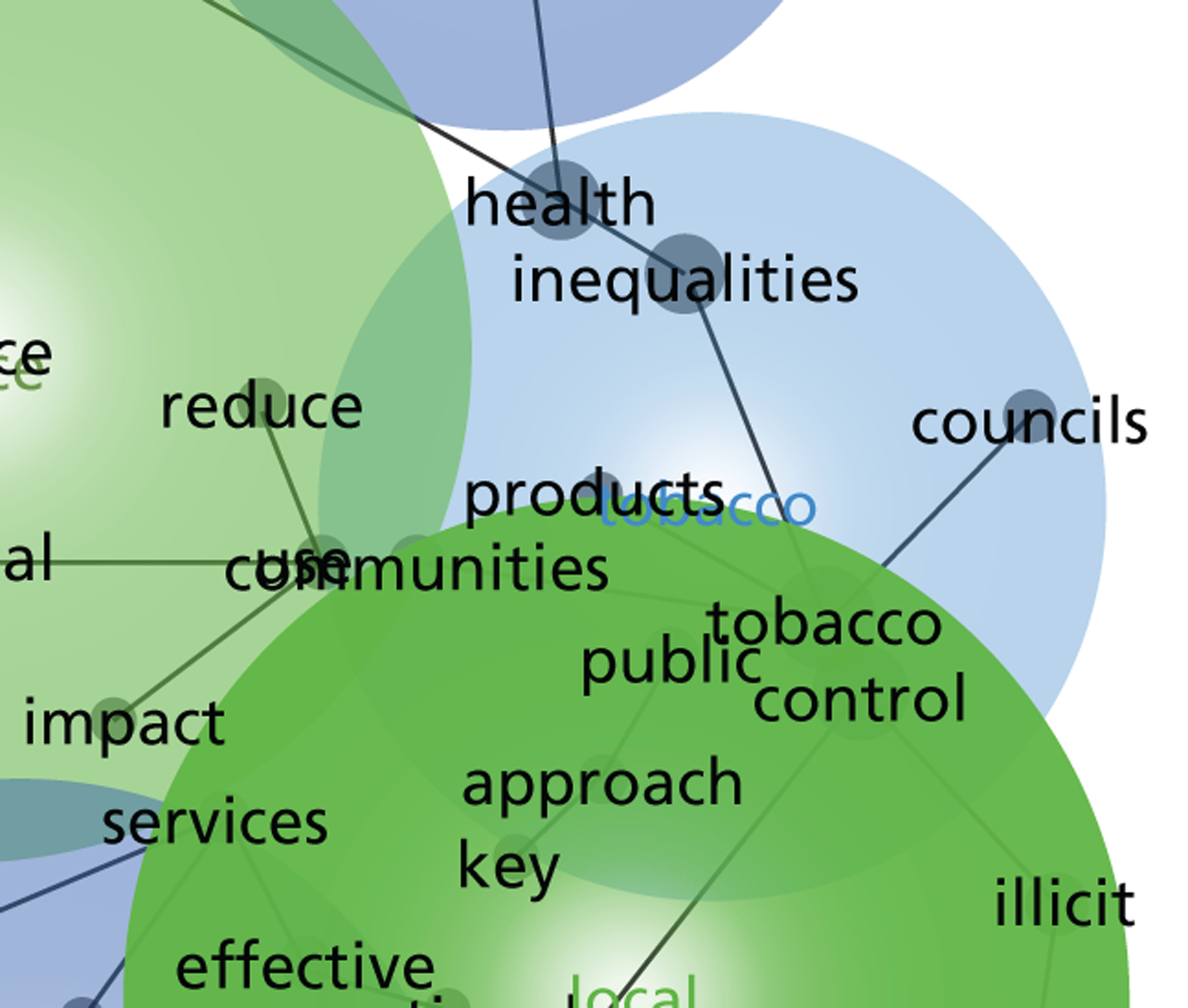

Network analysis: latent clusters

The most common approach to network analysis makes use of graph theory to express the pattern of connections between actors. Diagrams, or sociograms, such as that shown in Figure 4, are usually used to visualise relations in networks. The positioning of the actors on the page and the relative length of their connections is not important, meaning that sociograms are drawn with lines of equal length wherever possible. 17

FIGURE 4.

Sociogram of a network with 64 nodes and 134 links.

It is also usual to generate measures of a network to show the importance of actors within it, for example by establishing the degree or number of connections with others, for members of the network. For our study, identifying degrees was of limited value, because we had limited the number of connections named by participants to five: the method must have influenced the degree statistics. We therefore used other summary network statistics defined as below.

Eigenvalue centrality: This aims to measure the influence of an individual actor within a network. An actor’s centrality, or influence, becomes greater if he or she has more influential alters, that is if he or she is connected to more influential people. As the influence of the alters is defined by the influence of their alters, the calculation of the measure is not straightforward and involves an eigenvalue decomposition. Numerically, this involves recursive calculation and is not difficult for the size of networks encountered in this project. A value is assigned to each actor in the network describing their influence based on all of the connections within the network.

Betweenness: This aims to measure the dependence of the connectedness of a network on the links identified by each actor. An actor will have high betweenness if many paths (through multiple actors) pass through him or her. Then removal of that actor from the network will impact on the overall connectedness. As with eigenvalue centrality, betweenness is defined recursively and is expressed as a numerical calculation based on the connection matrix (i.e. adjacency matrix). An actor who helps to link groups of people to one another will have high betweenness. 16

These network measures focus on the roles of individual actors within a network. However, our research questions in Chapter 1, and the literature on knowledge creation in Chapter 3, suggest that groups or teams are important. We therefore agreed with Crossley,3 who argues that a number of important network phenomena sit between the two poles of structure and agency – in clusters. In addition, we felt that clusters would be easier for managers at the study sites to interpret: they might make more intuitive sense than conventional network diagrams (see Interactive feedback workshops, below).

Our network modelling approach used the concepts of latent position network models25 and cluster latent position models. 26 We used these models to identify clusters of people within networks, and people who acted as bridgers between clusters. It also helped us to identify any ‘holes’ in the networks; that is, social gaps between groups within a network. Krivitsky and Handcock38 have provided software tools for the necessary analyses. During the course of the project, new software was released with much improved convergence properties. This is the variational Bayes latent position cluster model (VBLPCM) R package. 39

The key aspects of the method are:

-

Data from the network interviews were used to model the relationship (tie) between two individual actors. Ties are represented by lines in the diagrams and actors are represented by small filled circles (Figure 5).

-

A two-dimensional latent social space was used such that individuals were more likely to be connected when placed close together.

-

An additional condition was imposed such that individuals were associated with clusters. In the diagrams, individuals were coloured according to the cluster with which they were most strongly associated. Within the latent social space, a cluster has a centre indicated by a small coloured cross and surrounded by a large open circle representative of the spread of the cluster in the social space.

-

The model with clusters in social space was fitted using a Markov chain Monte Carlo method. Details of the method can be found in the references above and software is available for the R statistical software package (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

-

The number of clusters was initially determined by calculating a Bayesian information criterion for an increasing number of clusters, starting with one large cluster. The idea here was that we wanted to minimise the information lost by the model representation of the network. This was achieved by increasing the value of the likelihood function, indicating a better fit, as more clusters were permitted but penalised by the greater number of parameters needed for a more complex model. The Bayesian information criterion provided a mathematical strategy for achieving a practical balance between fit and complexity. The smallest value of the Bayesian information criterion suggests the optimum fit, least information lost relative to the complexity, and indicates the strongest candidate for the number of clusters. In all cases, further support for the initial candidate was found in the form of practical explanation, and that number of clusters adopted as best representing the structure within the network.

-

When the representative circles for the most likely number of clusters did not overlap in the social space plot, as in Figure 5, there was support for the possibility that individuals belonged to distinct clusters. The circle radii were equal to one standard deviation, so that when circles did not overlap, the clusters were well separated (by ‘two = one plus one’ standard deviations). Although not constituting a formal hypothesis test (achieved otherwise through the information criterion), this was, at the least, a useful visual guide.

-

The clustering clearly identified limitations of influence. Most influence from an actor was within the cluster to which he or she was assigned. Owing to these limitations, concerns regarding boundary influences (actors not identified and included in the network but influencing from just beyond the observed network) were much reduced, as clusters could be seen to be mostly complete.

-

The diagrams output from the VBLPCM software package were further enhanced. The small circles representing actors were replaced by circular symbols indicating the organisation to which the actor belonged. For each actor, the probability of being assigned to each cluster was calculated. For the purposes of the enhanced diagrams, actors were assigned to the most probable cluster: that is, they were modally assigned. To make the representation comprehensible, coloured regions were extended around the actors belonging to the same cluster (all diagrams in Chapter 6 are coloured in this way).

-

Once we had produced cluster diagrams, we sought a finer-grained understanding of the network models by focusing on the attributes of individual actors. To do this we used the details collected during network interviews and membership lists from key meetings (which we also collected in the course of the fieldwork), focusing on seniority (senior manager, middle manager or frontline worker), organisation, role/area of work and meetings attended. This allowed us to focus in more depth on the organisational membership of each cluster and the official roles and responsibilities of actors in relation to health and well-being services.

FIGURE 5.

Latent position cluster model showing three distinct clusters.

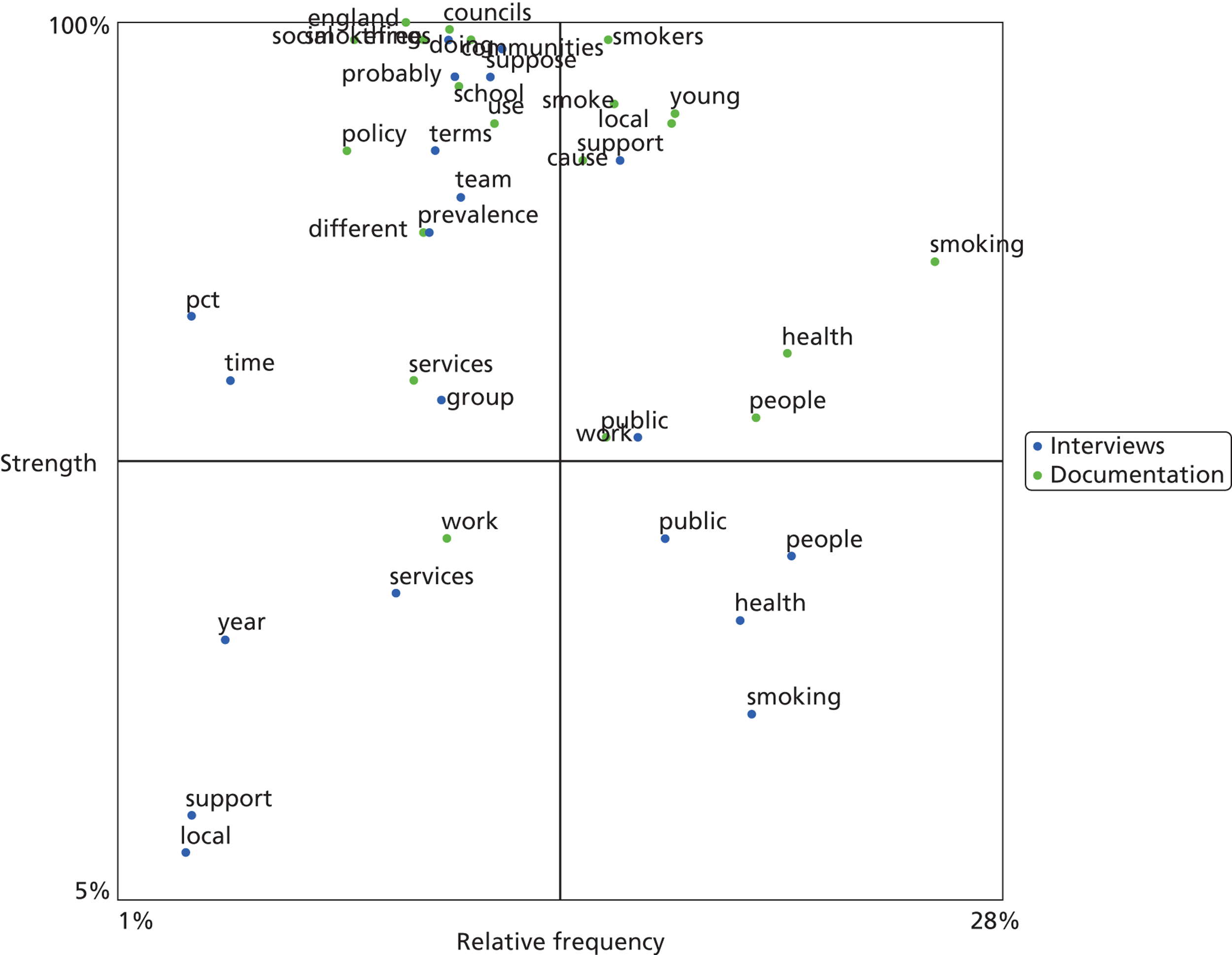

Leximancer: a bridge between paradigms?

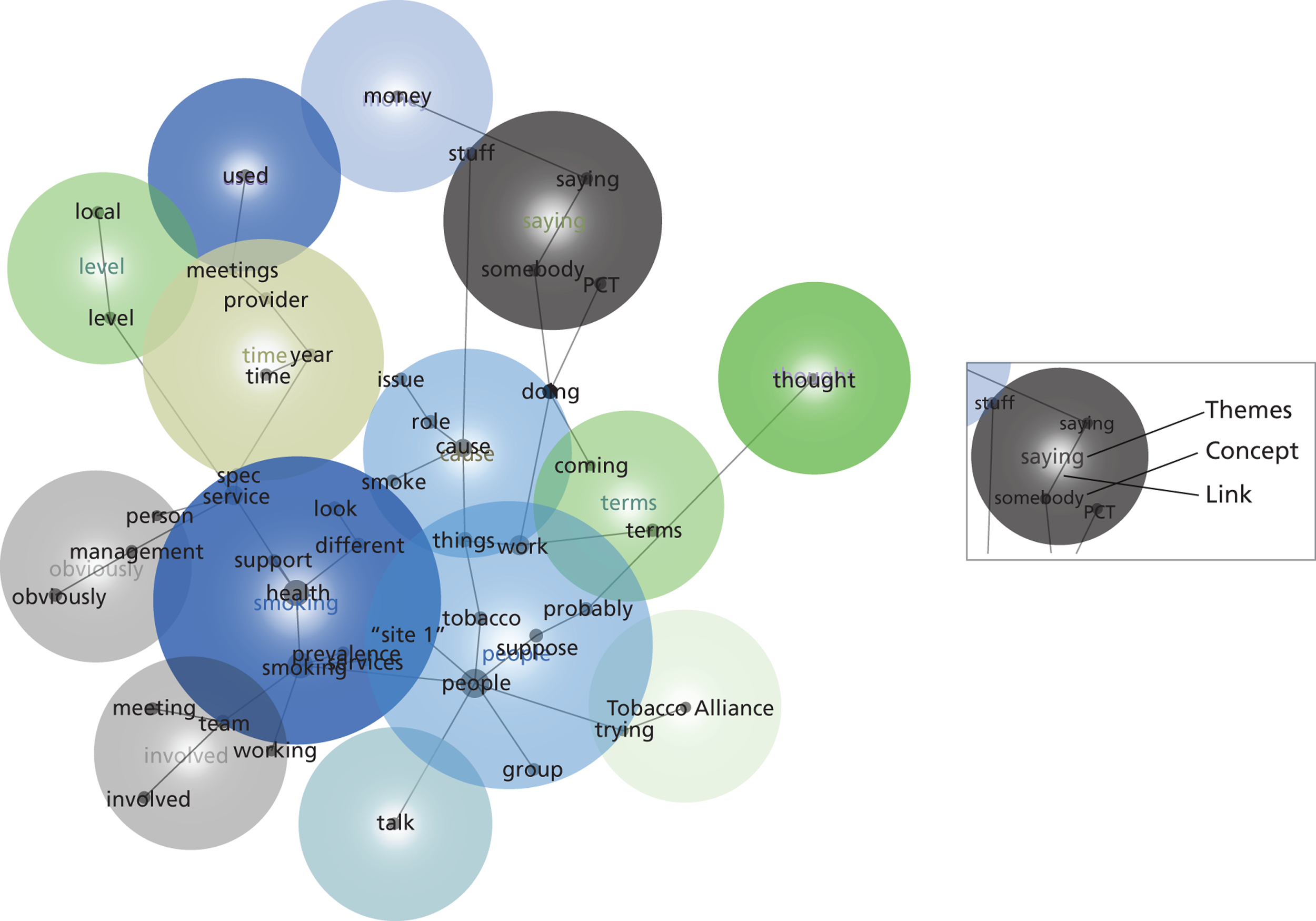

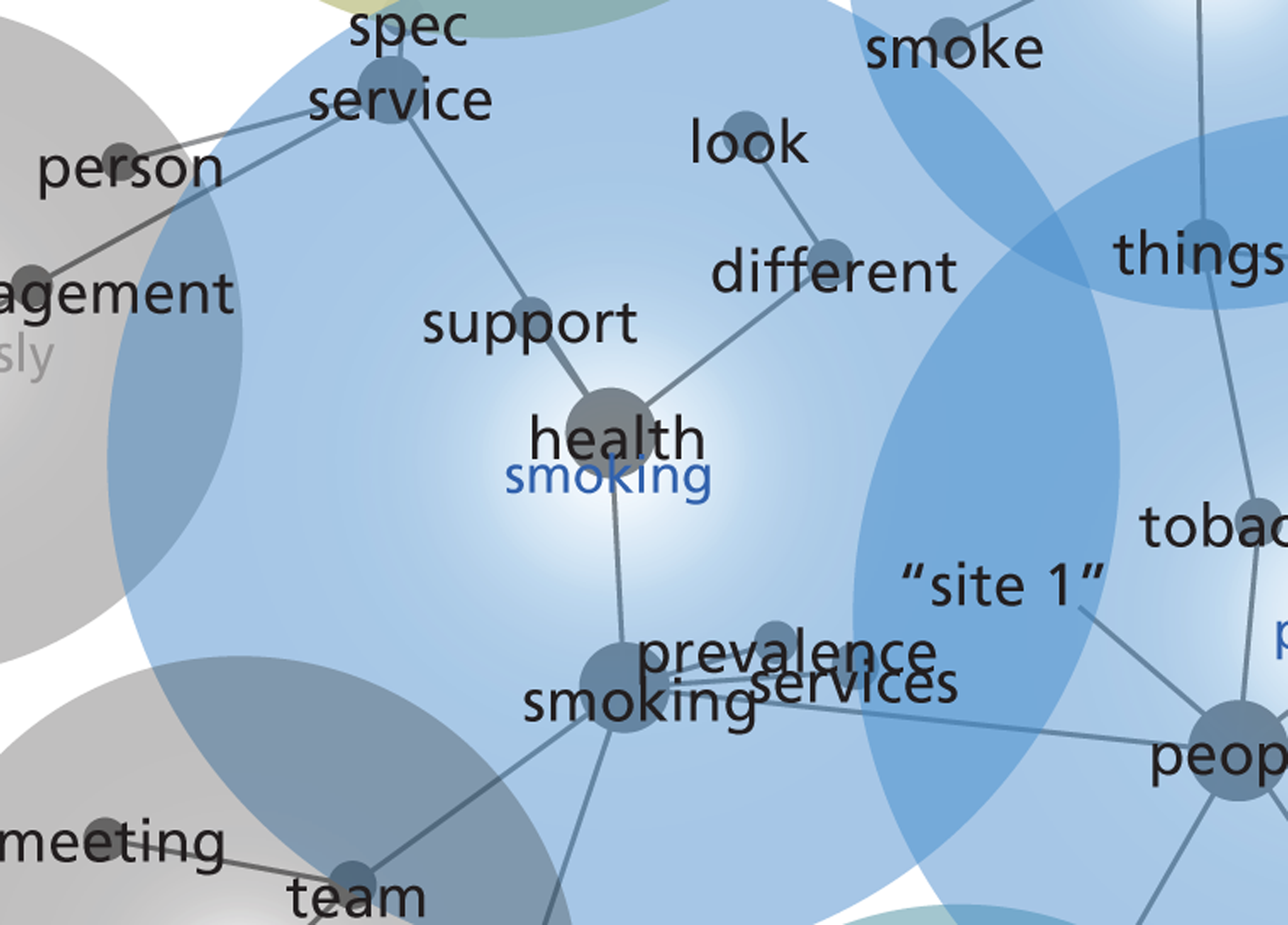

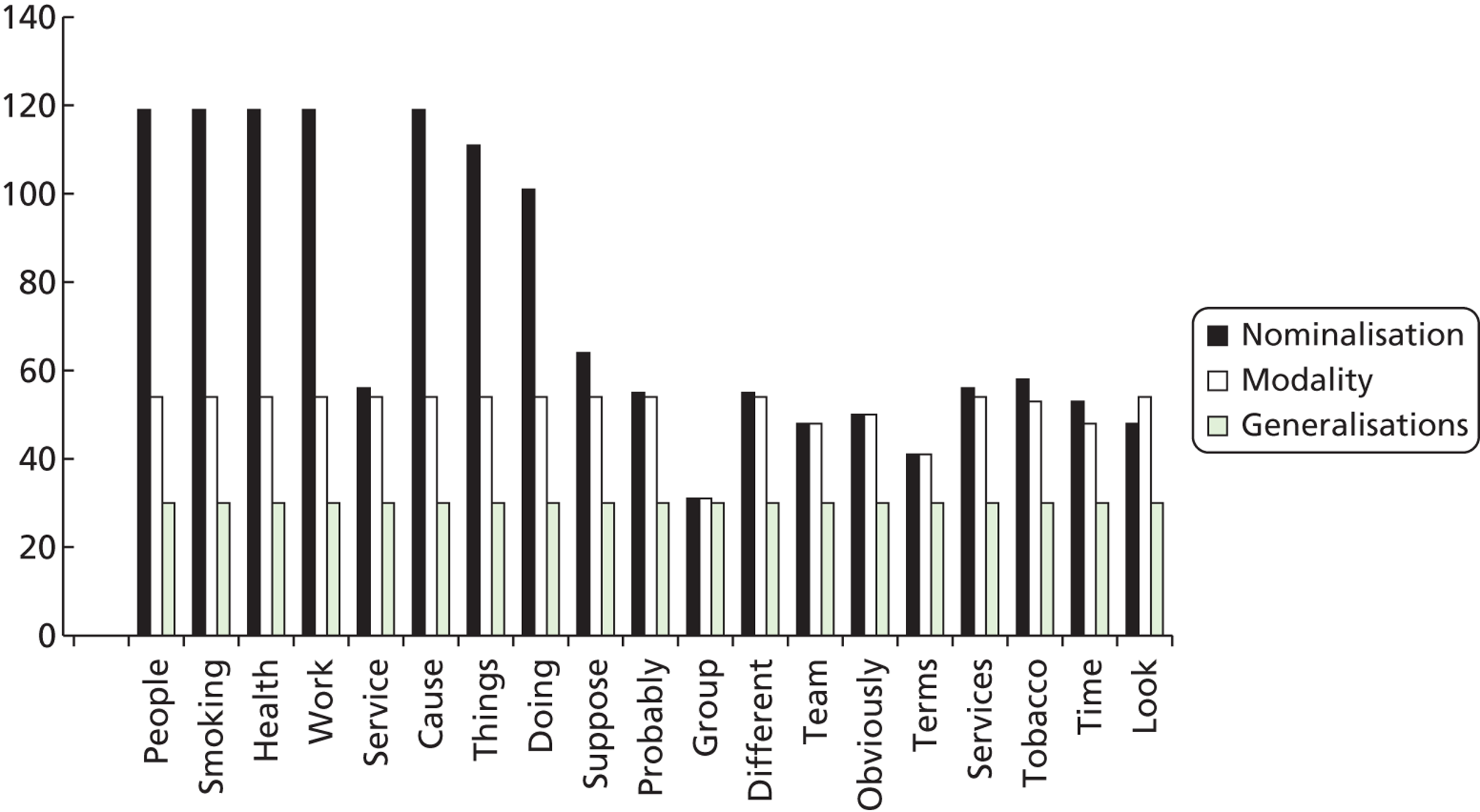

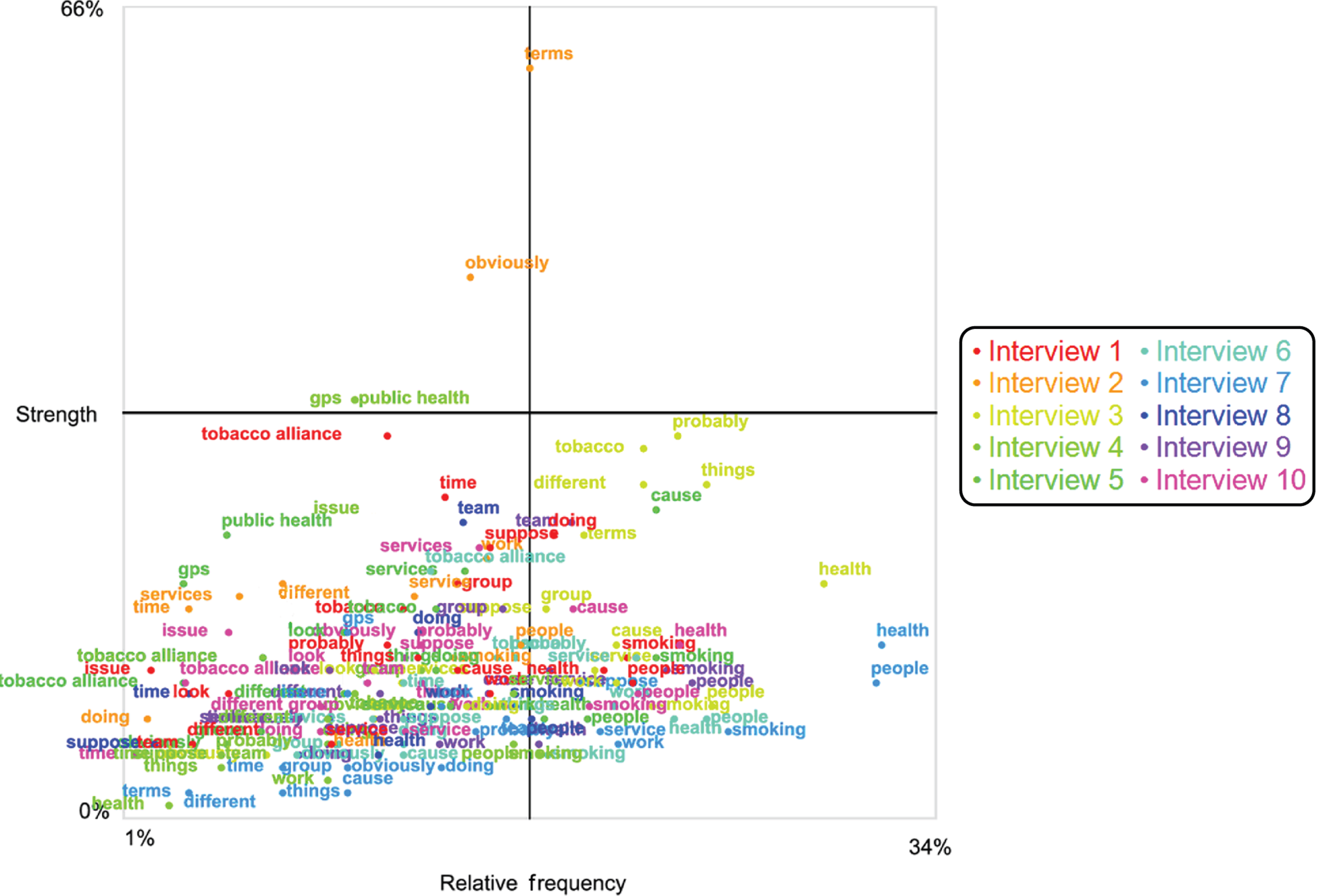

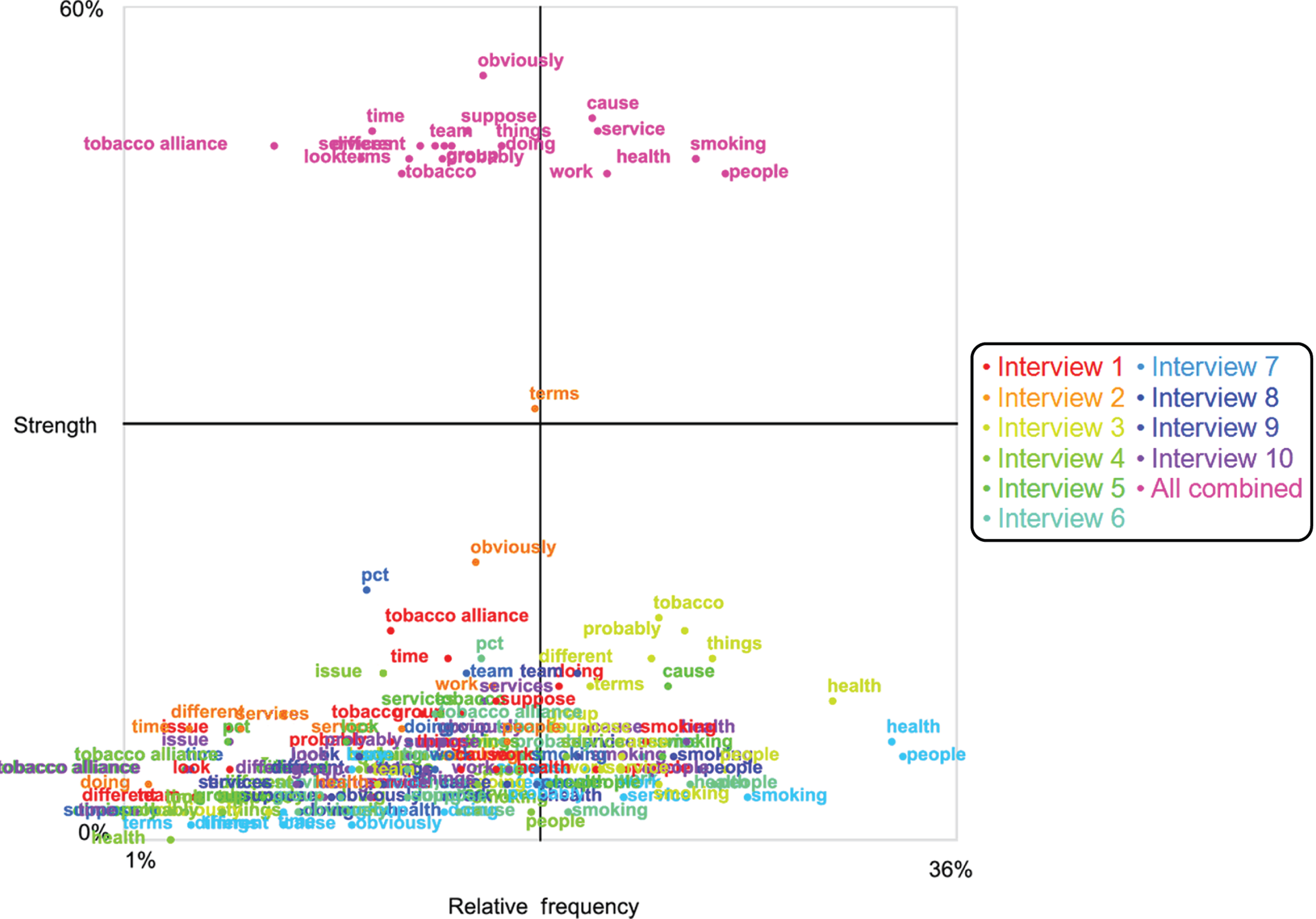

One of the obvious features of our study design is that it is based on two distinct pillars, with their foundations in different research paradigms. We looked for ways of creating an ‘empirical bridge’ between the two, so that it would be possible to link the qualitative and network analyses at each site in some way. The most promising approach, we felt, was likely to be based on an analysis of the network-like patterns contained in the qualitative interviews: it might be possible to compare these patterns with the patterns generated by the cluster analyses.

We used Leximancer (Leximancer, Brisbane, QLD, Australia), a computer software package that conducts quantitative content analysis on text files, using a machine learning technique, to analyse the set of qualitative interviews at each site. We concluded that, while Leximancer produced some interesting results, it did not fulfil our objective for it: that is, enabling us to link the qualitative and network findings empirically. The details of the method, and the outputs, are presented in Appendix 8. While Leximancer did not produce the results we hoped for, it was nevertheless important in shaping our thinking about what we could do to maximise the value of our two sets of findings. Our approach is set out in the next section.

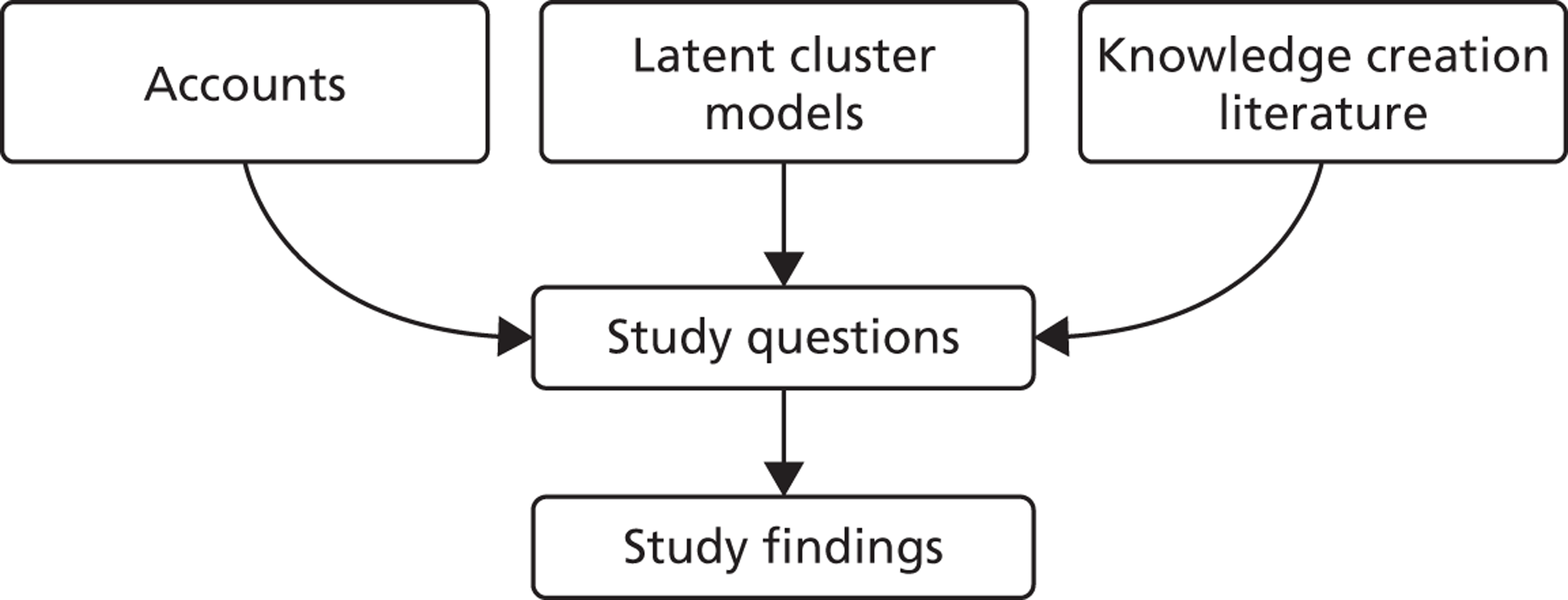

Addressing our study questions

The final stage in the study design is represented in Figure 6. Our experiences with Leximancer, while producing some interesting results, led us to conclude that we could not construct an empirical bridge between the two main components of our study. We could, however, identify recurring patterns in both sets of findings and use them to address our study questions. The first of our two questions concerns the nature of knowledge creation by middle managers, and the qualitative findings shed light on that question. The second question concerns the relationships between managers, and that question can be addressed – in different but complementary ways – by both the qualitative and network analytic findings.

FIGURE 6.

Study design: interpretation.

In addressing the study questions, we draw on the knowledge-creation literature, described in Chapter 3. We are able to use the literature to help to interpret our findings, and conversely use our findings to reflect on the extent to which the knowledge-creation literature is relevant to our chosen settings, in health and well-being services.

Interactive feedback workshops

Towards the end of the study, in the late autumn of 2012, we presented our provisional findings at each study site, at events that they organised for their own purposes (e.g. to review a local strategy or to discuss the setting up of a formal public health network). For us, the events had two purposes. The first was that we wanted to ‘road test’ a method for feeding back the findings of our study that went beyond the standard methods of written reports and presentations. Second, we were tasked with identifying ‘actionable findings’. We reasoned that, if managers at the study sites thought that the findings were valuable, this would provide suggestive evidence that they might be valuable to managers in other localities.

The local organisers identified and invited colleagues, including senior and middle managers. Between 15 and 25 people attended each event, in each case representing a wide range of local organisations.

At each event, we presented selected qualitative and network material. Qualitative material was presented in video monologues where individual actors, filmed in advance of the events, ‘told the story’ of selected projects at a site. That is, although a number of people were involved in each account, the videos presented each account as a monologue. The accounts were fictionalised and embellished, in small ways, by the actors in order to protect the identities of the managers who were involved. Three monologues were used at each event. The first was an account from one of the other sites, used to ‘set the scene’ and introduce attendees to the focus of our study. Then, two videos based on accounts at that site were shown. Our network material was presented in professionally produced diagrams.

Chapter 3 Literature review

Introduction

The review undertaken by Ferlie and colleagues1 provides a valuable overview of the literatures on knowledge mobilisation. It emphasises that the literatures are diverse and contested, and that there is no unified theory which covers the whole field. It also identifies important gaps in our understanding, notably in relation to the role of organisational form in shaping knowledge mobilisation, and knowledge mobilisation involving managers. This study was designed to contribute to the literature in both of those gaps.

It was clear at the start of the project, therefore, that there would be little merit in undertaking a further wide-ranging review of knowledge mobilisation. It was also clear that we would be working in a topic area with relatively limited published evidence and argument to guide us. More positively, however, we were able to identify a coherent subliterature that we could use in this study. This was the literature on organisational knowledge creation, whose foundational work is Nonaka and Takeuchi’s The Knowledge Creating Company. 11 The literature links three of the four key topics in our research questions: namely, knowledge creation, the work of groups or teams, and middle managers. It does not deal with networks in the way that we do in this study, but we are not aware of any literature that combines knowledge mobilisation/creation with quantitative network analysis. As in many studies, we might have alighted on a different subliterature, for example theories of practice, but our judgement was that the knowledge creation literature would provide a useful, if general, theoretical context for our study.

The work of Nonaka and Takeuchi, and those who have followed them, is based on the argument that knowledge creation involves tapping the tacit, and often highly subjective, insights of employees about their working environments. Tacit knowledge consists partly of technical skills – the informal skills often referred to as ‘know-how’. Experienced individuals, who have spent years developing their skills, typically find it difficult to explain to anyone else how they do what they do. The challenge is to make tacit knowledge explicit, in order that it can be discussed with colleagues and acted upon – used to work out a new way of delivering a service, for example.

In the knowledge creation literature this involves people with different backgrounds working together on shared problems. The process requires everyone to find ways of explaining what they know to colleagues, often by using metaphors on the basis that metaphors can be grasped by everyone, even though they do not have – and cannot ever have – a detailed understanding of their colleagues’ working practices. Nonaka and Takeuchi also argue that middle managers are singularly well placed to foster knowledge creation, because their roles naturally involved co-ordination across traditional organisational boundaries. Middle managers are the glue, often invisible to outsiders, that binds organisations together.

The main themes

The method for the literature review is described in Chapter 2. In the following section we briefly summarise the main themes that we identified in the literature. The papers are summarised in Table 1. The table has five columns, covering the main conceptual insight(s), the main empirical findings, and then the theoretical, methodological and managerial implications for our study. By managerial implications, we mean the ways in which authors think about the roles and actions of middle managers.

| Paper | Main insight on organisational knowledge creation | Main empirical findings | Conceptual implications | Methodological implications | Managerial implications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Locus of knowledge creation: group | |||||

| Brown and Duguid 200140 | Tradability of knowledge not a function of explication but of social–epistemic bonds created through common practice: challenge for organisations is to mobilise the dynamism of communities that make them up by facilitating intercommunal negotiation. Network of practice concept deals with knowledge flows beyond organisational boundaries | Focus on knowledge disembedding and re-embedding circumstances | |||

| Erden et al. 200841 | Typology of intra- or interorganisational groups based on quality of group tacit knowledge: higher levels provide ‘collective mind’ or ‘collective intuition’ but incur higher opportunity costs | Model claims practical relevance for selection, specification and management of project groups | |||

| Nonaka and von Krogh 200942 | Reaffirms individualism by appealing to a biographical perspective, which enables analysis to account for broader historical trajectories and fuzzy organisational boundaries. Concedes inadequate consideration of roots of knowledge creation in social practice, i.e. scope for combination with communities/networks of practice perspective | Cites numerous studies offering empirical corroboration of key contentions | Be explicit about normative assumptions, e.g. what kind of knowledge processes you are trying to explain: we require different kinds of theory to grasp conservation of tacit knowledge or innovation | Focus on network clusters with high internal diversity of experience and background, where (according to the theory) knowledge conversions are likely to be more frequent | |

| Nonaka et al. 200643 | Stock-take of progress in development of ‘organisational knowledge creation theory’ sees two waves of take-up: defining the facilitating conditions, and implications for the nature of the firm as a social institution. Defence of individualism as attempt to leverage insights from cognitive psychology overlooked by management theory, while insisting the individual–social axis remains an ‘open problem’ for the theory | Knowledge-creation theory understood in relation to context (facilitating context). More research needed on how organisations can manage context | Call for longitudinal studies exploring trajectories and processes and relations between knowledge assets (the past), knowledge creation (the present) and knowledge visions (the future) | ||

| von Krogh 200944 | Locus of organisational knowledge creation in the group; individual heterogeneity seen as vital to organisational creativity. Information systems research highlights declining costs of participation and new patterns of reuse of collective knowledge | Individual mobility and diversity of career paths revives traditional concerns of individualist perspectives on organising | |||

| Locus of knowledge creation: project ecologies | |||||

| Grabher 200245 | A project ecology distributes knowledge and design, responsibility and accountability ‘across professional domains and across organizational boundaries’, but lacks a strong organisational memory and the conventions that underlie trust in other kinds of knowledge network (e.g. professions) | Does organisational culture evaporate in a project environment? What project models are utilised in a particular setting (e.g. studio, agency, consultancy, partnership)? | |||

| van Wijngaaarden et al. 200646 | Learning can occur in interprofessional project teams via process and professional practice alignment even if structures are not conducive | Network learning transpired spontaneously when project teams had access to performance data for collective evaluation | Provide groups with performance data to stimulate network learning | ||

| Locus of knowledge creation: individual agents including managers | |||||

| Akiyama 201047 | Middle managers act as boundary spanners | Top managers lacked a strong enough interface with employees to act as ‘moral managers’ | |||

| Alin et al. 201148 | Knowledge exchange viewed as interpersonal, and organisational knowledge embedded in work practices | Outcome of dialogue across boundaries more likely to be altered knowledge when there is diversity with aligned interests, but new (synthesised) knowledge where interests also diverge | Diversity plus conflict necessary to stimulate new knowledge creation | It is at the level of sequences of speech acts that knowledge transformation was observable | Benchmarking-like settings for people of similar background from different organisations help alter individuals’ knowledge; tightly-scoped context-specific innovations call for cross- specialisation settings; uncertain goals call for settings where both boundaries are crossed |

| Collinson and Wilson 200649 | Knowledge management as the management of interactions between knowledgeable specialists within and beyond the firm | Stable networks disincentivised organisational knowledge search, and were affected by labour market trends | Do not make network stability a fetish | ||

| Currie et al. 200650 | Organisations risk exclusion from professional knowledge exchange, which is increasing in significance with the growth of boundary-less careers | Middle managers were pivotal in organisational knowledge processes | Consider how to retain knowledge in the face of occupational mobility | ||

| Kuk 200651 | Deals with participation equality in knowledge creation networks (online) | A certain degree of participation inequality facilitates knowledge reuse, recombination and self-expression | Pay attention to ephemeral microstructures of knowledge creation | Do not intervene correctively unless participation highly unequal | |

| Lindsay et al. 200352 | Individual agency is central to knowledge creation; middle managers as knowledge entrepreneurs | Middle managers in peripheral network positions (e.g. overseas subsidiaries) had to contend with indifference from the centre to local knowledge, using informal contacts, often pre-dating current employment, in knowledge strategies | |||

| Locus of knowledge creation: the organisation | |||||

| Nahapiet and Ghoshal 199853 | Seminal contribution to knowledge-based theory of the firm, arguing that organisations are institutions for developing social capital, which in turn facilitates knowledge creation, but there are costs as well as benefits to this process | ||||

| Spender 199654 | Attempt to bring collective knowledge centre-stage as a public good for holding together the firm as a semi-autonomous field | Proposes a four-way matrix for studying knowledge: tacit-explicit and individual-social, arguing different knowledge-based theory of the firm needed for each type | Calls for longitudinal, case study and novelistic analysis of organisational knowledge dynamics | ||

| Locus of knowledge creation: external context (public sector) | |||||

| Hartley and Benington 200655 | Relational approach to interorganisational knowledge creation | Macro-contextual constraints: UK government policy favourable to collaborative knowledge creation but also source of barriers, notably the audit culture | Organisational knowledge-creation theory may need adapting for public sector, e.g. more fluid organisational boundaries, internalisation of competing interests | ||

| Kim and Lee 200656 | Individualist assumption that employees are the drivers of knowledge creation, through partially self-organising structures within organisations | Public and private sector knowledge sharing compared: public sector managers face more organisational constraints; hierarchy did not prevent sharing but work experience encouraged it | |||

| Rashman et al. 200912 | Practice-based conception of knowledge creation. Qualifies the transferability of organisational learning and knowledge creation theories from private to public sector contexts, arguing that there are specific features of external and internal organisational context in public services | Public sector has complex interorganisational links and strong professional subcultures, multiplex group belongings, and is subject to conflicting demands regarding outcomes | Social practice perspective and network governance theory seen as especially relevant/applicable to public sector (knowledge networks that span organisational boundaries, learning through collaboration) | Crucial to describe context-specific factors and to clarify authority of group membership | |

| Locus of knowledge creation: space/geography | |||||

| Amin and Roberts 200857 | Different modes of ‘knowing in action’ have differing organisational forms and geographies of knowledge creation | Professional mode of knowing in action characterised by two-phase learning (co-location important for induction but updating skills often virtual) and significant intersections between professions | |||

| Araujo 199858 | Knowledge practices develop in locales that are ‘momentary interaction settings embedded in a wider network of relations’ | ‘Situated’ does not mean immobile; mediation and propagation connect locales: focus on how knowledge is repeatedly re-embedded | |||

| Cohendet et al. 199959 | Multiscaled model of knowledge creation involving nested network clusters. Specific sequences of knowledge conversions may be important for bridging cultural boundaries | Measure similarity and difference within and between network clusters, and look for a correlation between intranetwork breadth and diversity | |||

| Goodall and Roberts 200360 | If knowledge is socially embedded and presumes intersubjective communication, distance is a problem for knowledge-creation theory. Knowledge-ability (hyphenated to capture active dimension) needs to be continually repaired through reputational work, since participation conditional on being recognised as ‘someone who might create valid knowledge’ | Onus for maintenance of knowledge-ability fell disproportionately on those in peripheral network positions | Knowledge-ability deteriorates without co-presence | ||

| Rutten 200461 | Critical of overemphasis on stability to network learning (the social capital argument). More confident about agency and effectiveness of design choices | Long-term relations were not necessary for trust and openness to emerge in an interorganisational network | Emphasises content and process design over structure in knowledge creation networks | Difficult question in network studies is: What is actually embedded? Rutten’s answer: ‘understand the process of knowledge creation first and then look at how this process is embedded in various layers of social and organisational context’ | Deliberately layer networks so that knowledge can flow freely at operational level |

| Locus of knowledge creation: politics/conflict/networks of power | |||||

| Argote and Miron-Spektor 201162 | Knowledge creation is a subprocess of organisational learning. Members, tools and tasks combine to form knowledge-creation networks | Member turnover less detrimental to knowledge retention in hierarchical organisations or strong procedural rules | Call for more research on the characteristics of knowledge-creating teams | Procedural rules may mitigate negative effects of turnover | |

| Bogenrieder 200263 | Organisational learning produced from constructive sociocognitive conflict. Knowledge creation typology starts from different problem situations (degree of goal and technical uncertainty). Structural embeddedness of networks more important than tie strength alone except when both types of uncertainty high | Define problem situations, e.g. those with clear goals but high technical uncertainty make tacit knowledge central to participation legitimacy and network structure important to ‘force’ interaction | |||

| Rodan and Galunic 200464 | Knowledge diversity seen as critical to innovation, but enrolling political support and buy-in from advocates also important, especially in early stages | Relational content at least as important as network structure in explaining innovation but structural factors may protect nascent ideas from ‘sceptical scrutiny’ | Assess knowledge heterogeneity alongside network structure when studying knowledge creation | Do not pursue networking for its own sake: network maintenance is costly, and it is not the only way to access diverse knowledge | |

| Swan and Scarbrough 200565 | Posits generative relationship between power, knowledge integration and network formation, highlighting co-ordinating power of key actors to recruit network members with diverse knowledge assets and co-ordinate interaction | Innovation champions were able to overcome weak organisational positions through process power and meaning power | Structural features of networks can matter less than other types of power | ||

| Locus of knowledge creation: tacit knowledge processes | |||||

| Breschi and Lissoni 200166 | Tacitness relates to knowledge flows not stocks | Knowledge externalities often mediated by local labour markets | Need to study career mobility to understand regional knowledge spillovers | ||

| Doak and Assimakopoulos 200767 | Tacit knowledge embedded in collective social arrangements | Hierarchies determined by belonging to communities of practice outlasted organisational changes/transfers | Look at knowledge creation network dynamics over different time scales | ||

| Siemsen et al. 200968 | Examines psychological factors in knowledge sharing, highlighting two: willingness to take reputational risks and confidence that own tacit knowledge justified and accurate | Communication frequency was important to tacit knowledge sharing | Study of knowledge sharing incidents within dyads can reveal important features of knowledge networks | Encourage frequent communication if tacit knowledge exchange important | |

| Locus of knowledge creation: content of relational ties | |||||

| Cross et al. 200169 | Organisations are transactive knowledge systems, producing meaning interactively | Diversity in sourcing of information support, emphasising friendship and trust over organisational status. Organisational affiliation explained networking for legitimacy support, but not for more practical exchanges of advice | If knowledge production is highly distributed (specialised) indexing is important so that individuals can find one another | Go beyond the usual questions asked in analyses of work-based advice networks (e.g. ‘who do you usually go to for advice on work-related matters?’) and inquire after the content of each relation | |

| Obstfelt 200570 | Deals with the relationship between types of knowledge creation and two different social networking mechanisms/logics | Co-ordinating and introducing behaviour produced dense knowledge exchange networks | Collaboration associated with incremental innovation, competition with radical innovation | ||

| Locus of knowledge creation: activity systems | |||||

| Blackler et al. 200071 | The organisation is a network of overlapping activity systems (Vygotski, Engestrom): what people do, how and with whom, and how they shape the context of knowledge practices are central concerns | Study practices as transformative activity, located in history, looking for disturbances that stimulate learning | Analysis needs to be multilayered: explore relations between communities of activity | ||

| Macpherson 200572 | Knowledge is an activity structured by systems of knowing such as organisational routines, which are in turn shaped by the agency of managers though negotiation, persuasion and rhetoric to build collective understandings of legitimate action | If knowledge is a social process, research on knowledge creation should incorporate member checking | |||

Most of the papers focus on knowledge creation as a collective process, taking place in groups or teams. This includes work by Nonaka and his collaborators41–44 as well as authors adopting a social practice perspective. 40 Authors concerned with knowledge creation in ‘project ecologies’,45,46 with project teams working in parallel, also treat the locus of knowledge creation as a team or group. Most papers report groups as being relatively fluid entities that co-ordinate the knowledge flows between individuals and higher levels of organisations. As we will see in Chapters 6 and 7, this fluidity turned out to be a feature of our study sites.

In contrast, some authors emphasise the roles of agency and individual ‘knowledge assets’, either in general48–51 or by attributing a special role to (middle) managers. 47,52 This appears to reflect the diversity in the wider field of organisation studies, where some authors emphasise the roles of individuals (or agency) while others emphasise the importance of institutions and the ways in which they shape (and are shaped by) the behaviour of individuals.

There is also a literature on the institutional contexts within which knowledge-creating organisations operate. Two papers on knowledge-based theories of firms53,54 emphasise the importance of collective knowledge creation, contrasting this stance with more market-based or contractual theories of the firm. Three papers12,55,56 focus on the influence of the wider context for organisational knowledge creation, arguing that there are substantive differences in the contexts within which teams in private and public sector organisations work. A distinct spatial perspective is offered by a number of authors, whose interest is in regional science initiatives, demonstrating how knowledge practices develop in distinct locales or exhibit particular geographies. 57,58,60,61

Several authors discuss the nature of knowledge created, focusing either on the particular role of tacit knowledge66–68 or on the nature of relational ties in knowledge networks. 69,70 These papers point to the range of information and ideas that can be integrated into collective problem-solving processes, echoing the points made in Chapter 1.

The remaining papers include some which focus on the politics of knowledge creation, suggesting that knowledge networks can reflect power relationships62,64,65 or can involve constructive sociocognitive conflict as problems are debated by people with different skills and viewpoints. 63 Conflicts of interest across professional and organisational boundaries are accentuated by Alin et al. 48 Finally, a distinctive approach is taken by two papers which apply Vygotskian activity theory to the study of organisational knowledge creation. 71,72

Relevance to the study