Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 09/1801/1069. The contractual start date was in April 2011. The final report began editorial review in November 2013 and was accepted for publication in May 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Pinfold et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Study overview

This research study was carried out to understand how personal connections of social ties, activities and places of people with severe mental illness (SMI) were structured and had evolved in their local community. The purpose was to explore the impact of these connections on well-being, through people’s ability to utilise and exchange resources, and their influence on personal roles and identity. The study both mapped and documented what individuals described as important for well-being and explored the meaning of these connections; our epistemological approach worked between a realist stand point1 building on positivist traditions and a socially constructivist approach which emphasised changes over time and situated meanings. 2 Individual members of the research team understood the principles underpinning both of these approaches, and what they contributed to the research as a whole.

The study examined what happens in a personal network of people, place and activity connections using people’s own accounts; how community assets were used to support recovery from SMI; and the role of primary care and secondary mental health practitioners.

The research was interested in:

-

Inner resources: we approached this by describing the capacity within individuals to direct their own lives, make decisions and choices as well as reciprocally supporting others.

-

Personal relationships and social resources: we approached this by describing the personal relationships people had with others and the links and roles they had within social groups. These were positioned within specific sociocultural contexts and constitute a social framework that generates subjective meaning and value to life.

-

Meaningful activities and places as resources: we approached this by describing the everyday routines that people adopt and assessing those that were social or lone activities, those that were structured or unstructured, in meaningful place settings and their impact on well-being.

-

Organisational composition and collaboration: we approached this by describing formal organisations and groups existing within a local geographical area and the way in which these, through their practices, link together in terms of formally agreed or informally constituted working relationships.

The role of social networks for managing mental health and chronic illness has long been established. The Team for the Assessment of Psychiatric Services (TAPS) study in the 1990s3–5 documented the impact of deinstitutionalisation on the social networks of people with SMI. Studies of chronic illness have examined aspects of social support within social networks and particularly the role of the family with positive and negative impact on outcomes. 6,7 A recent conceptual framework for personal recovery in mental health8 identifies five processes including the importance of social networks as a dimension of connectedness, and having a purpose or meaning in life including roles and goals. It builds on previous conceptual work defining stages of recovery. 9,10 Having friends was important for recovery, and connecting with others through shared interests and activities can be therapeutic, although not all relationships and social interactions are experienced as positive or supportive. 11 Activities can provide structure and meaning, and the benefits of volunteering and work are well documented for people with SM1. 12 Conceptual definitions of recovery also emphasise the importance of personal responsibility in recovery – people as active agents in driving change in their lives. 9 The five ways to well-being approach13 highlights areas that are of interest for building social connections: connect, be active, take notice, keep learning and give.

People’s lives are affected by service structures, policy changes, the economy and other structural determinants. For people with SMI, primary care services and general practitioners (GPs)14 are increasingly important both as a monitor on physical health problems, incentivised through the Quality Outcomes Framework (QOF), and as a lead provider of care for people with mental health problems. Research has found a high proportion of cases of SMI are supported solely by a GP (31%) or with minimal secondary care input. 15 This was not a new finding. A review of the role of family practitioners reported about one-quarter of people with schizophrenia saw only their GP16 and only 64% of sampled service users were in contact with a psychiatrist. 17 However, there was a specific current discourse that many GPs were less keen on supporting people with SMI than other medical conditions,18 GPs lacked specialist knowledge and skills19 and they had clear ideas that the role should be limited to physical health checks and medication. 20,21 In the context of recovery-focused services, the dominance in primary care of a chronic illness management model was important to acknowledge. 22

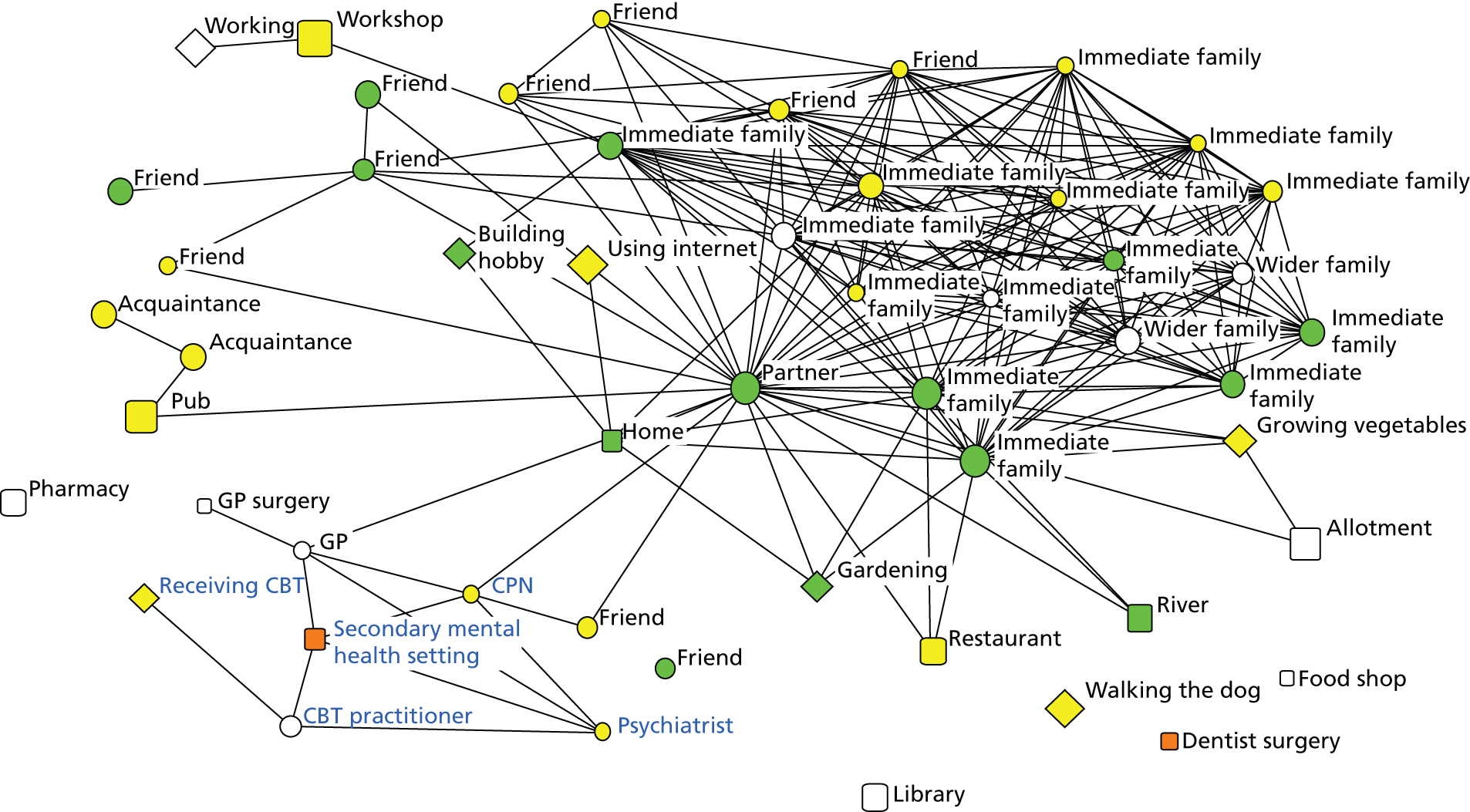

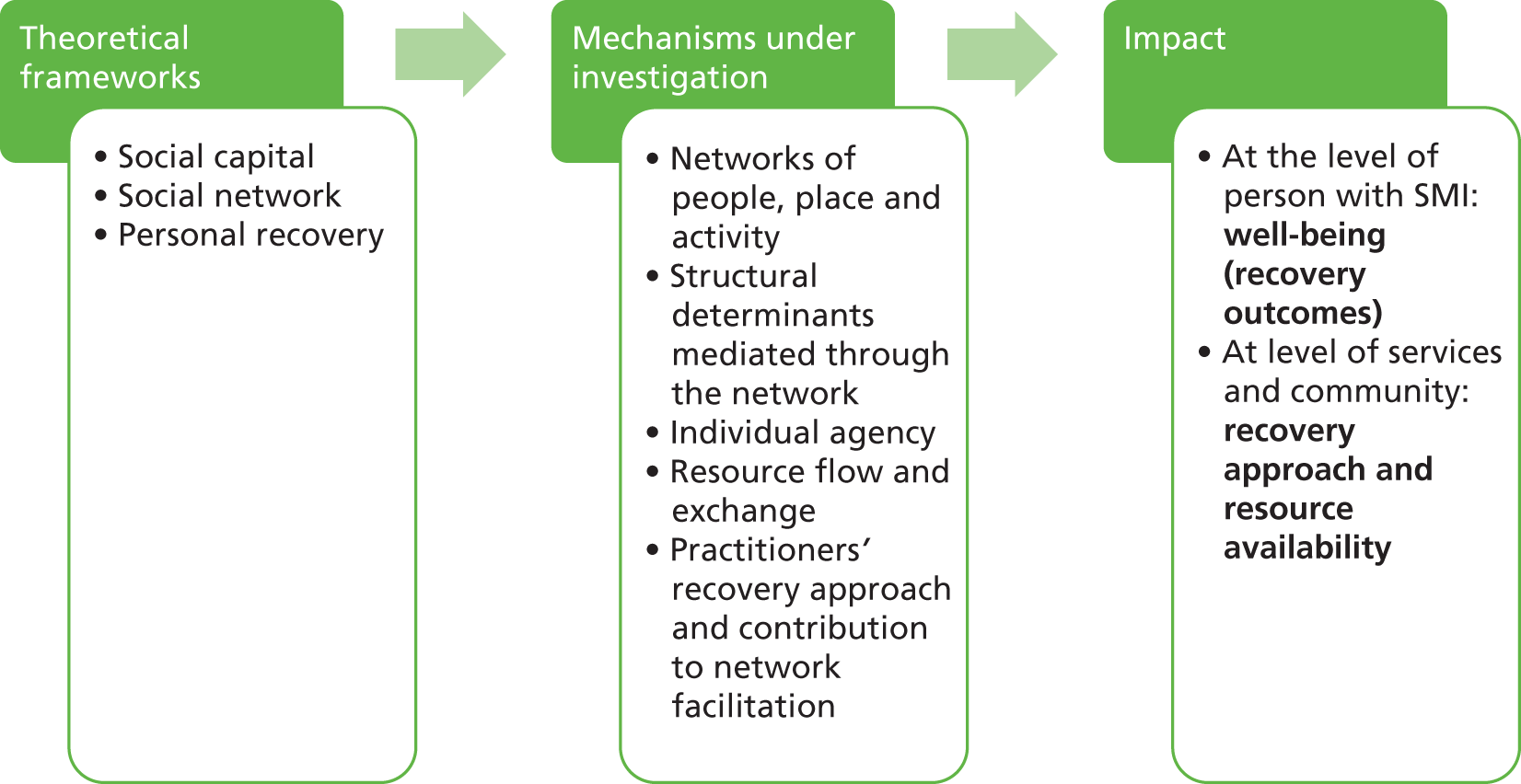

This research study considered both the individual with SMI and the systems in which they lived; it collected research data from people with SMI, community and health-care organisation leaders, and practitioners working with people with SMI to gather their own perspectives. Community health network (CHN) was conceived by the research team for the initial research proposal to help articulate the focus of the study. It was not a concept that was found in published literature. We instead started this study by exploring research that might explain connections to support health, well-being and recovery underpinned by several connected theoretical frameworks: social capital; social network analysis (SNA); and personal recovery (Figure 1). The focus of the investigation was the individual and their personal lives linking social contacts (relationships), activities (things people did) and place settings (where people went). Resource exchanges shape connections to people, places and activities and we emphasise agency and active strategy in our network approach. 23 We examined the lives of people with SMI using a network methodology and follow-up qualitative inquiry in order to understand possible health and well-being protective or facilitating factors and conditions. The study was exploratory and as such did not provide evidence to explain the variations we observe or infer causality; we can only describe the observed trends and provide possible explanations, leaving further research to test these suggestions. Our approach allowed an analytical perspective directing focus on individuals with SMI and how services and community resources may best support them, rather than taking services and systems as a departure point.

FIGURE 1.

Study approach to exploring networks of people with SMI.

Study aim

The main aim of the study has been to understand the personal network of people living with SMI from their own perspective and how their well-being, as well as mental and physical health, was supported by resource exchanges alongside roles of external structures and individual capacities using a CHN approach. Through this, we come to better understand how they could be supported by practitioners using network facilitation strategies, if these were prioritised by providers of mental health care, which could involve shrinkage or expansion of current people, place or activity connections.

Research questions

-

How do people with SMI use resources in their personal networks to support their health and well-being?

-

How do community-based practitioners and organisations support people with SMI to use their personal networks to support health and well-being?

-

How do primary care, community-based mental health providers and other organisations work together to develop effective personal networks for people with SMI to improve their overall health and well-being? What were the barriers and enablers to achieving this?

Research objectives

In order to answer the research questions, the following objectives were specified:

-

to map the personal networks utilised by people living with SMI to support their health and well-being using the CHN approach

-

to identify practitioners and organisations in primary care and community health services that contribute to developing effective personal networks for people living with SMI

-

to identify the enablers and barriers to organisations collaborating to provide effective support to people to develop their personal networks

-

to provide recommendations for practitioners, managers, service users, and health and well-being boards for organisational changes to establish and support, if appropriate, the CHN approach.

In our study the use of the term ‘network’ needs careful clarification. It has two meanings. Firstly it was used as a technical term used in SNA24,25 to describe the structure of ties between various nodes such as people and organisations. 26,27 Secondly it was used in a more general or lay sense to describe the connections to people, places and activities. Throughout the report care was taken to minimise the use of network as a general term, to avoid confusion with SNA, but at times it was included because this was an appropriate description of resource flows and connections within an individual’s life.

Policy context

The study’s policy departure point was longstanding preoccupations about the need for person-centred care provision in mental health and also three important mental health policy developments:28

-

Addressing the poor physical health outcomes of people with SMI. Research shows that this group are dying up to 25 years younger than the general population. 29–31

-

Addressing the stigma of SMI: combating stigma and discrimination through co-ordinated awareness-raising and behaviour change programmes targeting multiple audiences, including people with SMI, to address self-stigma. 32–34

-

Building recovery-focused mental health services acknowledging the importance of person-centred health and social care driven by the needs, goals and aspirations of an individual. The approach emphasises that personal recovery is different from the absence of clinical symptoms of mental illness. The individual with SMI leads the process of recovery towards ‘a life worth living’ with services supporting the development and achievement of personal goals, hopes and dreams. 35–37

These led us to the conclusion that, in order to develop appropriate person-centred services, a much greater understanding of what individuals’ personal networks of connections currently consist of and how individuals and practitioners contribute to these was needed. This would complement the primary focus of most service delivery: assessment, diagnosis and treatment with National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)-recommended interventions that emphasise medication management and psychological therapies for SMI. 38,39

Since the research project was commissioned, a new mental health strategy and implementation framework has been published30,40 and other significant mental health policy developments have been the introduction of the NHS outcomes framework31 alongside changes to commissioning arrangements within the NHS. The ambition of the strategy was that:

More people with mental health problems will recover: More people who develop mental health problems will have a good quality of life – greater ability to manage their own lives, stronger social relationships, a greater sense of purpose, the skills they need for living and working, improved chances in education, better employment rates and a suitable and stable place to live.

p. 631

Introduction of local Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs), health and well-being boards and directors of public health within local authorities from April 2013, informed by joint strategic needs assessments (JSNAs) of health and social care needs in the local population, provide another opportunity to reshape mental health service provision. In this structural change context there have been budget pressures, with public finance reviews driving cost reductions across all government departments in England.

Approach to literature reviewing

The academic literature context for this study was extensive. We undertook a focused and thematic background literature review of key themes that influenced how we studied the networks of people with SMI. We searched published literature and reports for factors that influence network composition, structure and outcomes, identifying in particular studies that had worked with people with mental health problems. The aim was to produce a list of potential factors for data collection to cover, or make explicit decisions to exclude. The key search terms included diagnoses and recovery as well as people-, place- and activity-related words.

An important context for the study was emerging work around recovery and mental illness that challenges services to undertake a values shift. 41 A central process within recovery theory is empowerment. 8 Personal recovery is a person-centred concept, led by the individual focusing on their strengths, not deficits;42 an active sense of self, including a determination to get better with a role for the person themselves in this process, was a feature. 43 Recovery pathways are often coproduced; people may require help to ‘own’ and lead their recovery journey but with the right kind of support can get to a place of greater self-determination. The study team were, however, aware that theory underpinning the recovery ‘movement’ was still developing, and wanted to contribute to this through empirical work rather than basing methods on it. We were also mindful of the wider pitfalls of normative assumption modelling and had been aware of assumptions such as ‘big was better’ in respect to social ties, meaningful activities and place-based connections, over-riding individual preferences linked to coping strategies, life context and health decisions. Much of the social network literature in mental health focused on social network size or number of relationships, reporting how people with psychosis tended to have smaller social networks than the general population. 44,45 Other research acknowledged that the nature of networks and their quality were as crucial as size. 46 While there may be potential benefits from larger social networks, we note the potential for negative effects of social relationships. We need to treat with caution the idea that larger social networks are a desirable and manageable outcome for all individuals. The team had therefore explicitly adopted a person-centred critical approach to the research, seeking to understand how people’s life-worlds can be examined through the lens of social, place and activity connections, and had not reviewed normalisation literature or any associated studies.

For some people and in some stages of illness, smaller networks of key contacts may be perceived as more comprehensible, manageable and meaningful, drawing on a sense of coherence theory, rather than a large network of ties that may lack emotional closeness and involve a complex set of roles or stressful relationships. Antonovsky’s sense of coherence theory regards coping and adapting in life as an active, dynamic and continuous process. A high level of sense of coherence was health promoting, predictive of how well people manage stressors and stay well. 47,48 Problems with social cognition associated with schizophrenia may also make relationships difficult to manage. 49 Moreover, the quality of relationships may be more important to well-being and recovery than the number of ties. 50 The approach was informed by critical realism and took a mixed-methods approach to enable the socially constructed and situated elements of meaning-making to be balanced against the quantitative network data. Social network studies had called for more qualitative work to understand the relative value of network characteristics and explanations for differences in network size, satisfaction, social support and well-being. 51 The mixed-methods approach adopted in this study assisted us with balancing network characteristics with meaning mapping.

Health and well-being

‘Health’ was defined in 1948 by the World Health Organization as ‘a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity’. 52 This has been contested but no new international definition agreed, though the British Medical Journal reported that global conversation has suggested health be defined as ‘the ability to adapt and self-manage in the face of social, physical, and emotional challenges’ (p. 343),53 recognising health was personally defined. Well-being has been less clearly defined. 54 A recent review of well-being55 proposed ‘a new definition of wellbeing as the balance point between an individual’s resource pool and the challenges faced’ (p. 230). Resources and challenges referred to the psychological, social and physical. These definitions bring concepts of health and well-being closely together but, as in the recovery literature, allowed for individuals with significant psychiatric ‘disorders’ to achieve a sense of well-being. 56,57

It is well established that attention is needed to improve the physical health of people with SMI58 because of consistent findings that their health was poorer than the general population. 31 Health issues include a higher prevalence of cardiovascular disease,59 diabetes,60 obesity61 and a shorter lifespan, estimated at 13–30 years less than the general population. 62 Our study deliberately sought to understand the connections people with SMI have, to address the neglected focus of physical health. The reasons behind these physical health issues appear to include both lifestyle factors as well as consequences of treatment. Antipsychotic medications are linked to weight gain and metabolic dysfunction, which in turn has a negative impact on quality of life. 63 A recent systematic review of evaluations of health behaviour interventions designed to improve physical health in people with SMI found that the majority produced positive effects. 64 One of the successful mechanisms in such interventions was increased regular physical activity within the local community, but sustaining engagement was challenging. 65,66 Within this study we were interested in the potential of network interventions for addressing health inequalities. Data were collected about strategies for maintaining physical and mental well-being.

The recovery approach

The recovery approach has been adopted by secondary mental health services. Its underlying theory is still in the early stages of development and includes several threads: (1) that the outcomes of interest include non-disease-specific constructs such as having a purpose or meaning in life; (2) that individuals should be central to setting goals and decision-making; (3) that engaging in a wide and inclusive range of activities and relationships will improve outcomes;32 and (4) that practitioners and services should work alongside and support individuals with mental illness rather than impose treatments based on disease labels. 14 There was strong policy leadership for recovery-orientated practices in the UK, and staff development and training programmes were beginning to show how to work in recovery-orientated ways. 67,68 In this study we were able to explore aspects of recovery, such as community engagement,69 housing,70 employment,18 stigma71 and social skills development,72 using a network perspective. The goal is for greater social inclusion and active citizenship for marginalised groups including people with SMI. Our network-mapping approach may help shed light on the extent to which individuals are integrated into the community or living in isolation.

A key resource within recovery-orientated mental health services was practitioners, who will need new education and training and new skills such as coaching techniques. 73 Services needed to adopt a different values base, requiring significant changes to practice, services and culture. 43 A review of recovery-orientated practice guidance found lack of clarity and suggested that four practice domains provided focus: promoting citizenship; organisational commitment; supporting personally defined recovery; and working relationships. 74 Our study explores the practitioner perspective of their role in network development, assessing the place of social interventions as a treatment priority in primary and secondary care.

Social networks, social support and friendship

Within the field of mental health, literature on social networks, social support and friendship overlapped. We provide only a brief summary of key points in this section. One qualitative study which influenced this project investigated friendship in the UK. 75 It explored individual micro-social worlds to understand the ‘role of friendship as a form of social glue’ (p. 156)75 shaping social life. Acknowledging the trap of deterministic labelling, the authors did look at how factors such as gender, education, ethnicity and age impact on friendship. In using a CHN approach to understand the range of friendship resources (confidant, emotional support, practical assistance and playmate), demographic information on social ties may be important alongside establishing how, when and why different relationships matter at points in time.

Social network analysis has been used to understand connections to people, places and meaningful activities. 76,77 A fundamental assumption of SNA was the importance of dynamic structures to understand observed behaviours and outcomes: the connections that individuals had; the impact of their actions and beliefs; access to resources; and outcomes through various socially constructed mechanisms. 24,25 Social network approaches allow examination of the social structure of connections that individuals have, and have therefore been used to understand how social capital78 and social support79 are accessed. However, the approach has been critiqued as paying insufficient theoretical attention to the role of human agency and culture alongside social structures in explaining network transformations. 80 In this study we seek to understand the dynamic interplay of socially structured and creative human actions on personal networks of people with SMI.

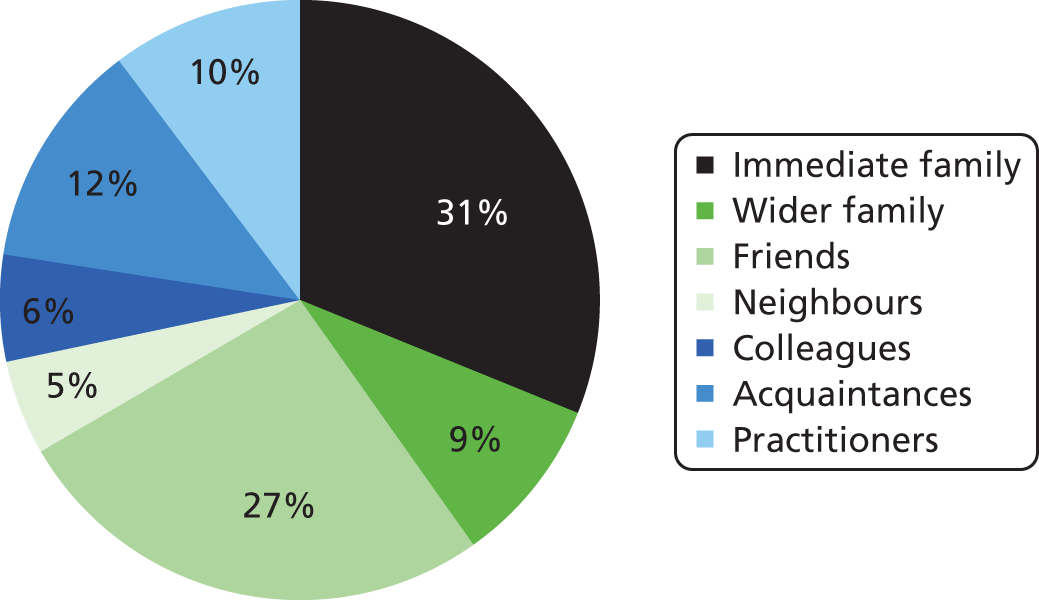

Social network studies of people with SMI have often used counts of relationships rather than formal social network structural measures as shown by Macdonald et al. 45 and studies comparing people with SMI with the general population. 46,81 Early work in the 1990s, such as the TAPS study, found people with SMI had small networks which did not increase in size after leaving hospital but the quality of relationships improved; while living in the community was much preferred, little social integration was achieved. 11 A study in Sweden reported similar results51 and emphasised the link between negative symptoms and social interaction. This finding has been replicated in studies which had also reported a lack of social support, and unmet needs around social interaction and community belonging. 82,83 Studies which examined composition of social networks of individuals with psychosis had found them to contain fewer friends46 and more service practitioners84 than the general population, and the onset of psychosis can involve changes in social networks and the loss of friends. 85 It is the multifaceted and dynamic nature of social networks that this study explores, looking beneath a map of connections to understand the negotiated meaning, sets of choices, capacity for growth and qualities such as reciprocity.

Social networks, and change in networks, may directly influence health and well-being. 86 Increased social interaction has been associated with improved quality of life and self-esteem for people with mental illness87 and, while some social ties can be negative, on the whole studies find a correlation between larger numbers of social ties and improved outcomes in this population. 88 One of the key mechanisms of this seemed to be social support, wherein social ties provided emotional, informational, instrumental and appraisal social support, which may help improve well-being79,89,90 and provide a stress-buffering role91 related to the perception that support was available to help an individual navigate and cope with stressful situations. 92

There was well-established evidence that the characteristics of an individual’s personal social network can impact on health behaviours and outcomes, through various mechanisms that may include social influence, sense of control and perceived support. 93 The influence of social network contacts such as family and friends can directly impact health-related behaviours such as use of health services,94 while network typologies had been developed to show that resourceful networks are linked to lower alcohol abuse and higher physical activity. 95 We also noted that the quality of social relationships rather than the number of ties may provide a better indicator of well-being; not all social ties are positive and supportive. 96 Having social support available, especially in the early years of mental illness, can reduce an individual’s perception of stigmatisation or rejection due to their mental illness97 and can improve access to services. 98 However, individuals with severe and enduring mental illness tended to have limited availability of this resource. 99 Within the field of chronic illness management, researchers had used social network methodologies to understand the types of social support or ‘illness work’ within personal networks of people with long term health-limiting conditions including mental illness. 100 A study comparing family support available to people with schizophrenia with those with physical conditions found the former had much lower levels of social support available in emergencies. 101 A literature review outlined how social networks influence a number of practices of self-care in long-term illness, including how the individual perceives their illness, norms and influences around physical activity and health service access. 102 This review team highlighted the importance of home life including social connections within the home in the day-to-day management of long-term conditions. This work emphasised the importance of incorporating resources and social context within individuals’ lives into self-care plans. 103

Networks are not simply sources of support but are integral to personal identity; individuals can have different identities in different settings, and access to a wider range of settings can facilitate the development of new identities central to the recovery process. 104,105 In contrast, having fewer identities, specifically the role of a sick person or being defined by one’s mental health only, can be damaging. 106 All relationships involve a role such as husband, sister, friend, teacher; it has been argued that these role identities and expectations provide behavioural guidance which in turn can foster healthy habits and well-being. 91 Engagement in wider social networks, meanwhile, can provide identity through shared roles and belonging.

Finally, there has been some evidence in the past that outreach programmes can improve the quality and quantity of the social networks of people with mental illnesses. 107 Interventions to help support people to build new social contacts may be particularly important, and effective, for those with especially limited social networks. 86 Interventions based on strengthening social networks and community engagement for people living with SMI may improve their subjective quality of life. 108–111

Social capital

‘Social capital’ refers to the set of resources embedded and accessed through social networks which can then be used for purposive action. 112 Social resources can include material resources provided by social ties such as goods or money, reputation and social credential benefits of having a particular social contact, access to other useful contacts through a social tie or symbolic and expressive resources such as advice and reassurance. 113 The concept can be divided into two main forms; structural social capital, referring to the composition of connections and roles, and cognitive social capital, referring to beliefs, values, norms and the qualities of relationships. 114 Social capital has received attention because there was evidence that measures of social capital are related to health outcomes. 115 It has also been critiqued in its application to mental health, with differences of opinion over the merits of applying it as a population- or individual-level concept. 116

In this study we apply social capital at the level of the individual. An important distinction has been drawn in the literature between three forms of social capital that can be accessed from different contacts: bonding, bridging and linking capital. ‘Bonding social capital’ refers to close intimate ties that offer support and which are characterised by common identities, and can be seen as capital that helps people ‘get by’. 117 ‘Bridging social capital’ refers to weaker ties through which one can access different groups of individuals demographically distinct from one another,118 through which resources and information flow, and through which one can ‘get ahead’. 119 ‘Linking social capital’ meanwhile, refers to vertical connections within power hierarchies, co-operative ties between individuals on unequal levels of power. 120 When personal networks for people with SMI were considered, linking capital was less prominent in practice and studies had not addressed it. 121

Importantly, the precise mechanisms through which social capital may affect health are still not fully understood. 122 However, social capital was relevant for understanding social inclusion, recovery and the social determinants of mental health. 114,119 At the individual level, cognitive social capital, such as trust, has been shown to be inversely associated with incidence of common mental disorders. Individuals who rated their own level of resources through networks and community participation as low had a higher incidence of mental illness. Current understanding of the link between mental health and social capital uses primarily cross-sectional data, for example Webber and Huxley,123 and therefore the nature of causation is not clear and may be bidirectional: lower social capital may increase vulnerability to mental disorder and as mental illness progresses it is possible that access to social resources decreases. 124 The evidence of collective social capital’s influence on health is still inconclusive and the strongest associations have been found at the individual level. 115 It has also been shown that, at the group level, social capital links to inequality and exclusivity. When accessed through groups, the resources that some individuals obtain will come at the expense of other people. 116

There are, however, a number of conceptual issues in the definition of social capital, particularly as the construct overlaps with other social concepts, such as social support and social participation. 117 It has been suggested that social capital should be seen only as a societal or whole network concept, in order to distinguish it from social support and personal social networks. 116,118 However, at the individual level, the concept of social capital can be useful in understanding the effects on health of resources an individual can access because of their position in different networks, and bonding and bridging forms of social capital offer a distinct conceptual approach to understand what types of network are beneficial or damaging to health, and for whom. 115 This potential also extended to social capital interventions which had challenged practitioners to actively nurture and develop approaches aimed at increasing the resources available to individuals through their social networks. 125

Meaningful activities

Having a purpose or meaning in life was one dimension of recovery,8 making meaningful activities important to understand. Meaningfulness for people with SMI (and most of us) refers to the sense of achievement, connection, routine, enjoyment, autonomy and purpose that people can attain from activities. 126 This engagement in meaningful activities was associated with life satisfaction for people with mental illness,127 and feeling competent and having pleasure in daily tasks and activities was linked to subjective quality of life. 128 We suggest that participation in activities results in different emotional and cognitive responses in different individuals at different times, and that this sense of connectedness, achievement and positive identity resulting from participation can be seen as dimensions of recovery outcomes such as well-being and quality of life. For example, a 3-year prospective study in the USA found that, while recovery outcomes were sustained in fewer than one in ten people with schizophrenia, the likelihood of such favourable outcomes was associated with factors such as being employed, undertaking independent leisure activities and more daily activities. 129

There was also some evidence that engaging in meaningful activities may have a beneficial role in supporting recovery from mental illness, independent of the social support that engaging in such activities often provides. 130 Hendryx et al. 130 suggest that specific activity type may not be vital but that having a choice over what activity people engaged in could contribute to building a sense of control and that having meaningful activity may be even more important where social support is lacking.

Employment was a particularly important ‘meaningful activity’131 because it facilitates access to social interaction, a sense of identity, self-esteem and improved finances. 132 At a population level, unemployment was linked to poor mental health, while gaining employment can improve mental well-being and social inclusion. 133 While some aspects of employment can be stressful for some individuals, a 10-year study found that being in steady employment was significantly associated with a reduction in mental health service use over this time period. 134 However, individuals with SMI are much less likely to be employed than the general population,135 and face a variety of barriers to gaining employment such as poor functioning due to illness136 as well as stigma in the form of negative employer attitudes. 137 Furthermore, while we undoubtedly need to increase the level of employment for those with SMI, for some individuals certain forms of employment may be unobtainable.

Place

The final dimension explored in the literature to inform data collection was the importance of place as a therapeutic support for recovery. 138 The evidence base exploring place and mental health was weak; however, some research has linked factors such as poor housing and environmental noise to psychological distress. 139 Supportive and empowering environments in the community had been identified as enabling factors in recovery, while stigma and disempowering environments had been identified as inhibiting improvements in mental health. 140 An individual’s perception of their neighbourhood, in particular sense of cohesion, can affect mental well-being. 141

The existence of nearby green spaces such as parks and nature has been positively correlated with perceived health142 and mental health,143 particularly in urban environments linked to stress reduction and social cohesion. 144 People rate fresh air as particularly effective for improving mental health. 145 Green space can provide a buffer which reduces the impact of stress on an individual’s health and well-being146 through a number of mechanisms such as social interaction generated by recreational walking with friends. 143 In the field of sustainable development, natural capital in the form of access to resources such as green spaces was seen as one of the five forms of capital (alongside human, social, built and economic capital) that are needed for a community to flourish. 147

An important aspect of this study was rural and urban geography. Would living in the city shape networks of people with SMI in different ways from those living in rural communities? It was important not to import stereotypical views of rural148,149 or urban mental health landscapes. However, research does show higher levels of psychosis within inner cities and deprived communities,150 which could impact on our data. Neuroscientists are also interested in the impact of place. Research has shown greater rates of SMI in cities, leading to work looking at environment–gene theories and city neighbourhood studies to explore the impact of urban dwelling on mental health. 151 A promising area called social neuroscience was emerging from work linking urban upbringing and city living with stress processing. 152 By working in two distinct geographical areas, we were able to use the CHN approach to explore the impact of locality on network characteristics and report these as case studies in Chapter 7.

Stigma and discrimination

Most people living with SMI experience public stigma and discrimination153,154 and many people are also affected by self-stigma. 155 There was a large research literature documenting the conceptualisation of stigma and discrimination,34,156 as well as actions that can be taken to address public attitudes,157 self-stigma158 and discriminatory behaviours. 36 The present research did not measure stigma but the impact of stigma would probably be a feature of the world in which participants lived.

Summary

This brief review of literature relevant to personal networks of people, place and activity for people with SMI, and contextualised by the recent interest in the ‘recovery approach’, has emphasised the potential for connections in the network to generate well-being, or a range of recovery outcomes, as well as negative outcomes. We have emphasised that individuals’ networks can be seen as a means of resource exchange but we also recognise the roles of outside structures and individual capacities. The former might include the effects of structural social and financial inequalities, of policies and of geography, which may be manifested in the places and people individuals are connected to. The capacity individuals have to make decisions and engage in activities in different places includes their state of health, their cognitive abilities and their agency. Agency, a construct used to represent the ability of subjects to influence their own future and the world around them, can be seen as having three inter-related types:29

-

‘iterational’ agency or ‘habitual’ agency: ‘the selective reactivation of actors of past patterns of thought and action’ (p. 971)

-

‘projective’ agency: ‘the imaginative generation by actors of possible trajectories of action’ (p. 971)

-

‘practical-evaluative’ agency: ‘the capacity of actors to make normative judgments among alternative possible trajectories of action [in the present]’ (p. 971).

Similarly theory related to individuals’ roles and identity were potentially important when examining the network of connections of individuals with SMI. These diverse influences have not been covered in this focused review, but are considered during the analyses and interpretation of the results as we draw further on wider published literature. Finally it is worth emphasising that we have chosen to examine the worlds of those with diagnoses of SMI not because we consider the disorders to be precise entities but because as a group of individuals they face some similar challenges, including cognitive and social functioning,159 and because services are currently aligned with them as a group.

Chapter 2 Method

Ethical review and protocol changes

The study was reviewed by Central London Research Ethics Committee 4, on 2 December 2010. Favourable ethical opinion was received on 31 January 2011. We submitted four minor and three major amendments to the protocol and study materials. The study, with approval of the funder, changed in the following substantive ways:

-

The short-form health survey with 36 questions (SF-36) was replaced with the Short Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (SWEMWBS)160 and Dartmouth CO-OP charts161 (from the Dartmouth–Northern New England Primary Care Cooperative Information Project), as these were preferred by participants in piloting.

-

A survey of organisations was replaced by a practitioner interview study in response to study team concerns over survey response rates.

-

The application of study findings to a third site was replaced by dissemination events which will take place after the report is submitted, in response to feasibility concerns within the study timetable.

-

The recruitment of participants in primary care was extended to recruit through secondary mental health teams in both study sites because of slow recruitment rates.

Methodological overview

Mixed methods

In order to answer the research questions, the study used mixed methods162,163 and a three-stage synthesis process, including two context-specific case studies,164 to explore the lives of people with SMI. The study data collected from individuals with SMI aimed to be both descriptive of what was happening within personal networks using applied SNA,24,25 and be used to derive critical insights into network meaning for individuals with SMI. There were tensions in the approach adopted: we had a framework measuring incidences of connections – people, places and activities – sitting alongside reflexive analysis by lived experience researchers and the core study team. We have taken a priori research questions into the study, informed by published literature, and have carried out further consultations to understand concepts such as health and well-being or explored other published literature to make sense of emerging findings. Alongside these data sources we have integrated insights from other informants providing a practitioner perspective and organisation viewpoints. Thus the mixed-methods study has produced findings both grounded within the data and informed by deductive processing of research questions. The mixed methods were balanced, with no one approach overshadowing others either in the planning, collection of data or analysis stages. 165 Dual competency in methodological techniques166 was achieved by a team approach with all members trained in one method and some conversant in both.

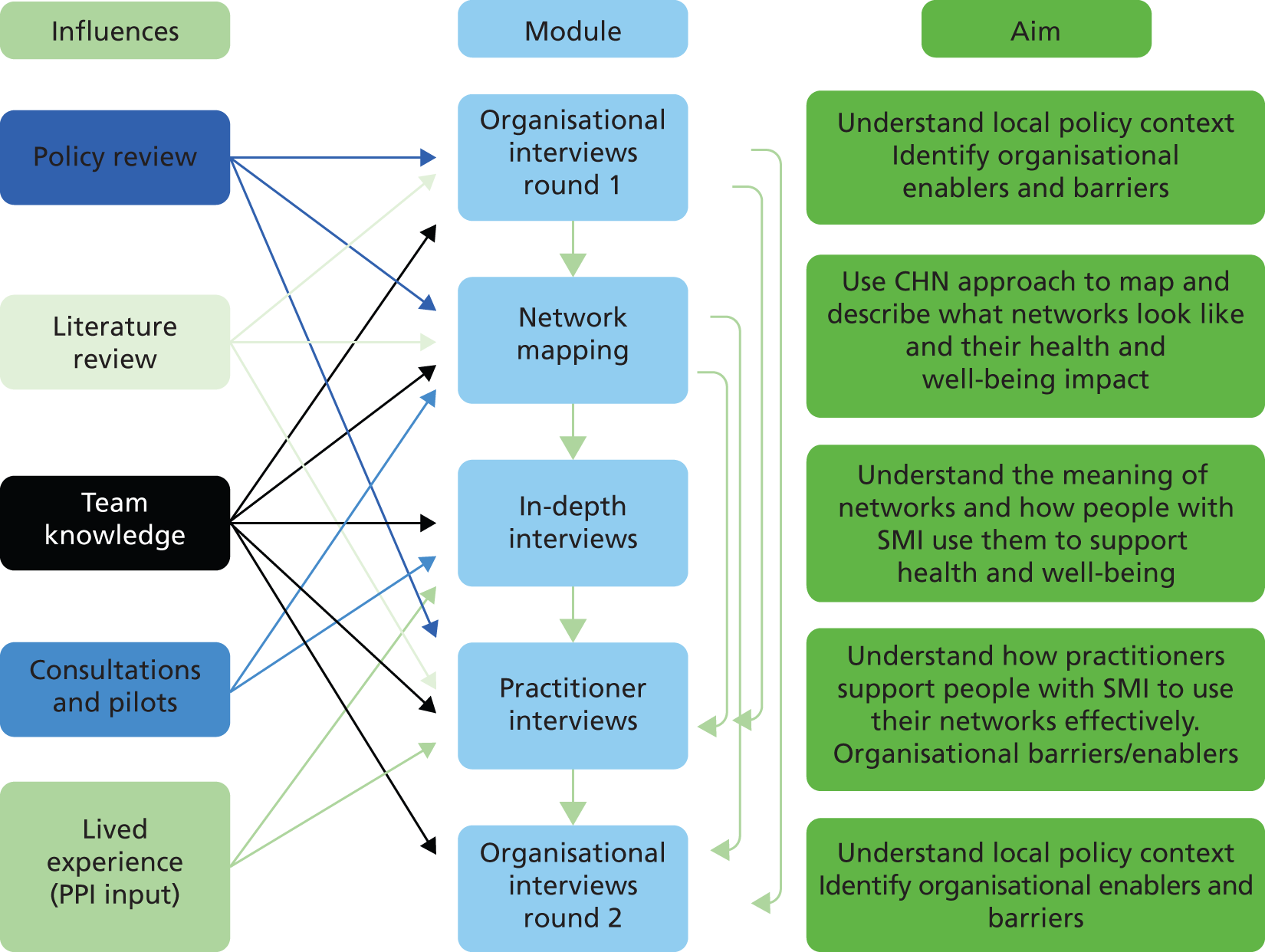

Figure 2 provides an overview of the individual data collection modules and how they inter-relate.

FIGURE 2.

Interaction between study modules: planning and data collection. PPI, patient and public involvement.

A specific focus of the study was using the CHN approach to map connections of people with SMI and follow up with interviews to explore meaning within these personal networks. In network studies, the population under investigation was often highly defined, for example examining the impact of drug use in the social networks of people with bipolar disorder. 167 However, we adopted an inclusionary and broad approach, as the study was exploratory. This broad approach does present methodological and analytical challenges because we were exploring many varying factors in people’s lives, situated in people’s own explanations, which describe heterogeneity, not network categories or types. We were mindful of these challenges and throughout the report emphasise that the work was largely descriptive and exploratory. Thus, we were cautious in our conclusions but forthcoming with potential explanations and definite recommendations based on data synthesis.

Approach to data collection and synthesis

It was important to emphasise that throughout the study, we have been grounded in emerging data and reflexive in making sense of these data. 168 We have worked iteratively and sought to explore the data by returning to literature or to further data collection and engaging our patient and public involvement (PPI) group to draw tentative conclusions. Thus, data sets were collected in sequence. First, network mapping (see Chapter 3) and in-depth interviews (see Chapter 4) were collected, as details from the former were used to recruit purposively for the latter and because the interviews involved reflecting on the mapping content and process. Second, the initial organisational interviews (see Chapter 5) and the last organisational interviews (see Chapter 7) were collected in sequence because the findings of the former, and other data sets within the study, were used both to select interviewees purposively and to refine the topics for discussion. Overall within the study the data were collected and analysed largely in parallel, as recommended, to allow for learning from one data module to inform the others throughout the data collection process. 164 The combining and synthesising of data allows the exact same phenomena to be examined from different perspectives, which should result in a more comprehensive multiperspectival understanding. Mixed methods are best suited to explore complex issues that can benefit from the integration of different types of data; it was at the synthesis stage that this approach yielded benefits. 169

Informal synthesis between the data sets took place throughout the study, as data were shared by the research team and used to both inform other modules as well as identify potential areas justifying deeper exploration; this was achieved by regular team data-sharing and discussion sessions including the PPI group members.

The formal synthesis took place in three stages. The first stage of synthesis (see Chapter 7) was the two case studies which combined data from the network mapping, in-depth interviews and organisational interviews. The goal was to understand ‘meaningfulness’ in our data: we understand this in the sense articulated by others who champion interpretive case studies as seeking not generalisable causal explanations but contextual understanding of the meaningfulness in human experience. 170 The two case studies were not designed to compare and contrast; rather they sought to explore the phenomena under study in a context-specific way. This included examining both how personal networks were influenced and moderated by the local context and also identifying and examining any salient features, within the context of each case study site, and the locally defined opportunities and resources that they might provide. The second stage involved working with our PPI group (see next section) to review the findings from Chapters 3–6 and interpret them using a reflexive methodology based on personal experiences of living with SMI. The final synthesis stage involved modelling the CHN approach to understand if it can usefully contribute to recovery theory and practice. 171 A matrix was used to test our model against data summaries from Chapters 3–7. Our model contained three dimensions: external structures and systems (shaping choice and change); individual agency (how individuals were impacted by their own agency or lack thereof); and available resources (access to people, places or activities).

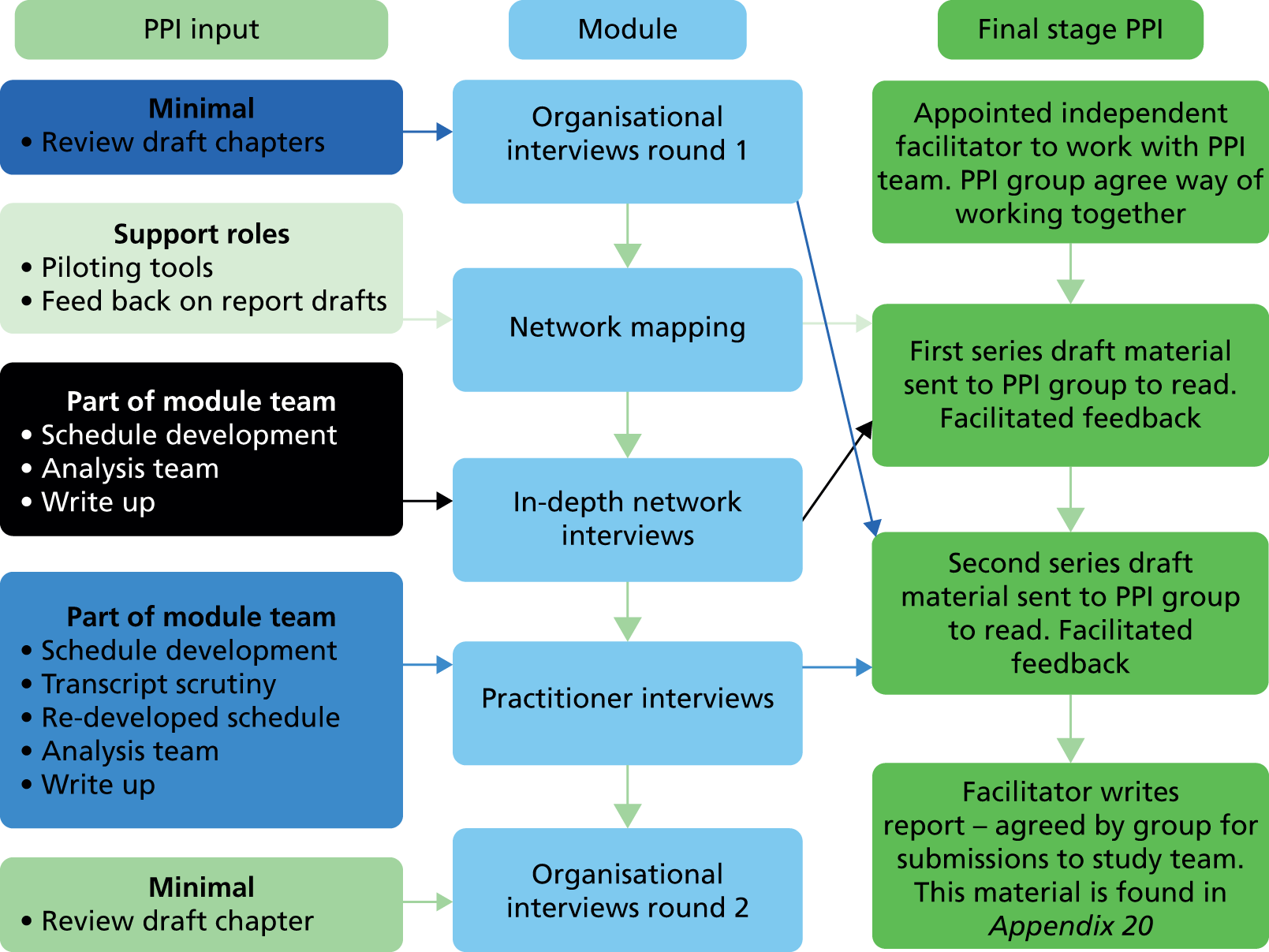

Patient and public involvement

A key part of the study methodology was the integration of lived experience expertise to understand local community resources in the two sites, the design and redesign of study materials and the interpretation of study findings. A team of six lived experience researchers worked on the study as a PPI group, with five completing the reflections analysis process at the end facilitated by an independent lived experience research consultant (full report in Appendix 1). A summary of PPI input for each module is provided in Figure 3. The two modules with the highest level of involvement in both planning and analysis were SMI in-depth (see Chapter 4) and practitioner interviews (see Chapter 6). The team were recruited to provide a diversity of perspective in terms of lived experience of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder or other psychosis as well as age and gender. We attempted but did not successfully recruit a black and minority ethnic (BME) perspective into the PPI group, which was a limitation of the study.

FIGURE 3.

Patient and public involvement in the CHN study.

Data collection and initial analysis

Organisation interviews: series 1

Over the initial months of the project, face-to-face semistructured interviews were conducted with the aim of gathering contextual information on the organisation of services, and provision of support for people with SMI in both study sites.

Data collection

Data sample

Thirty face-to-face semistructured interviews were conducted (Table 1).

| Participant type | South West | London | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trust/social care leadership | 5 | 5 | 10 |

| Mental health third sector | 3 | 2 | 5 |

| Primary care | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Community organisations | 5 | 7 | 12 |

| Commissioner | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Total | 13 | 17 | 30 |

Recruitment

Key organisations were identified by the study team, chosen to reflect the composition of local services at both sites: health, education, sports, employment and job creation, arts and culture. Invitation to participate was via e-mail and follow-up phone calls. We used snowball sampling; where people were unavailable we asked for suggestions of alternative contacts to approach.

Development of interview guide

The study team developed a semistructured interview schedule (see Appendix 2) to explore how local organisations worked with individuals, and with each other, and make active use of individual’s networks to support well-being of people with SMI. The research themes were addressed in a focused way, and flexible space was also allowed for fresh ‘off script’ concepts to emerge. Interviews were digitally audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Data analysis

A framework approach was applied with the support of the NVivo 9 (QSR International, Warrington, UK) data management tool. The framework analysis method entails organising and summarising research data resulting in a robust matrix which allows researchers to conduct analysis by case and by theme. It was a focused, well-defined approach that allows for the inclusion of a priori as well as emergent concepts, and was suited to addressing specific research questions. 172 We followed the five-step analysis process for framework analysis, with a modification to the mapping and interpretation stage, detailed below. 173

-

Familiarisation: this was carried out by two of the research team (one from each site), who had contributed to developing the interview schedule and carried out the interviews. The checking and anonymising of the transcripts contributed to the familiarisation process.

-

Identifying a thematic framework: the thematic framework combined both a priori concepts previously identified as being important for these data and inductively generated themes. The inductive generation included the two researchers who had undertaken the ‘deep familiarisation’ and two other members of the research team who had either conducted some of the interviews or listened to some of the audio recordings. Seven main ‘themes’ were generated from both the study research questions and deductive insights matching research literature and study data (care provided, change, encouraging reciprocity, organisational partnerships, organisation’s relationships with service users, personal networks, other challenges).

-

Indexing: one of the researchers who had undertaken the familiarisation process then applied the themes to the transcripts within the framework format using the NVivo 9 data management tool. The application of the coding was validated by the other researcher who had participated in the familiarisation process; they paid particular attention to contextual details that could have influenced the interpretation of the data coming from the site at which they were based. Another qualitative researcher from within the research team checked that the data were being allocated within the framework consistently.

-

Charting: this was initially conducted by the researcher undertaking the indexing, discussed with them and the researcher responsible for consistency and then validated with the wider research team.

-

Mapping and interpretation: the findings for each theme were summarised by the researcher who had applied the indexing and charting. Any divergent findings and any differences in data between the two sites were noted. Extensive discussions within the wider research team agreed that surfacing cross-cutting themes would not add any value to the products of the analytical process. The team agreed that what was most relevant in the products of the analysis was what was not there. This stage was modified to allow the researcher to re-examine the data to see whether this was an unintended consequence of the analysis process followed or these were true ‘gaps’ which may need to be addressed in other areas of data collection.

The summaries of the themes and the ‘gaps’ identified in the data were then used to answer research questions 2 and 3, the results of which are reported in Chapter 5.

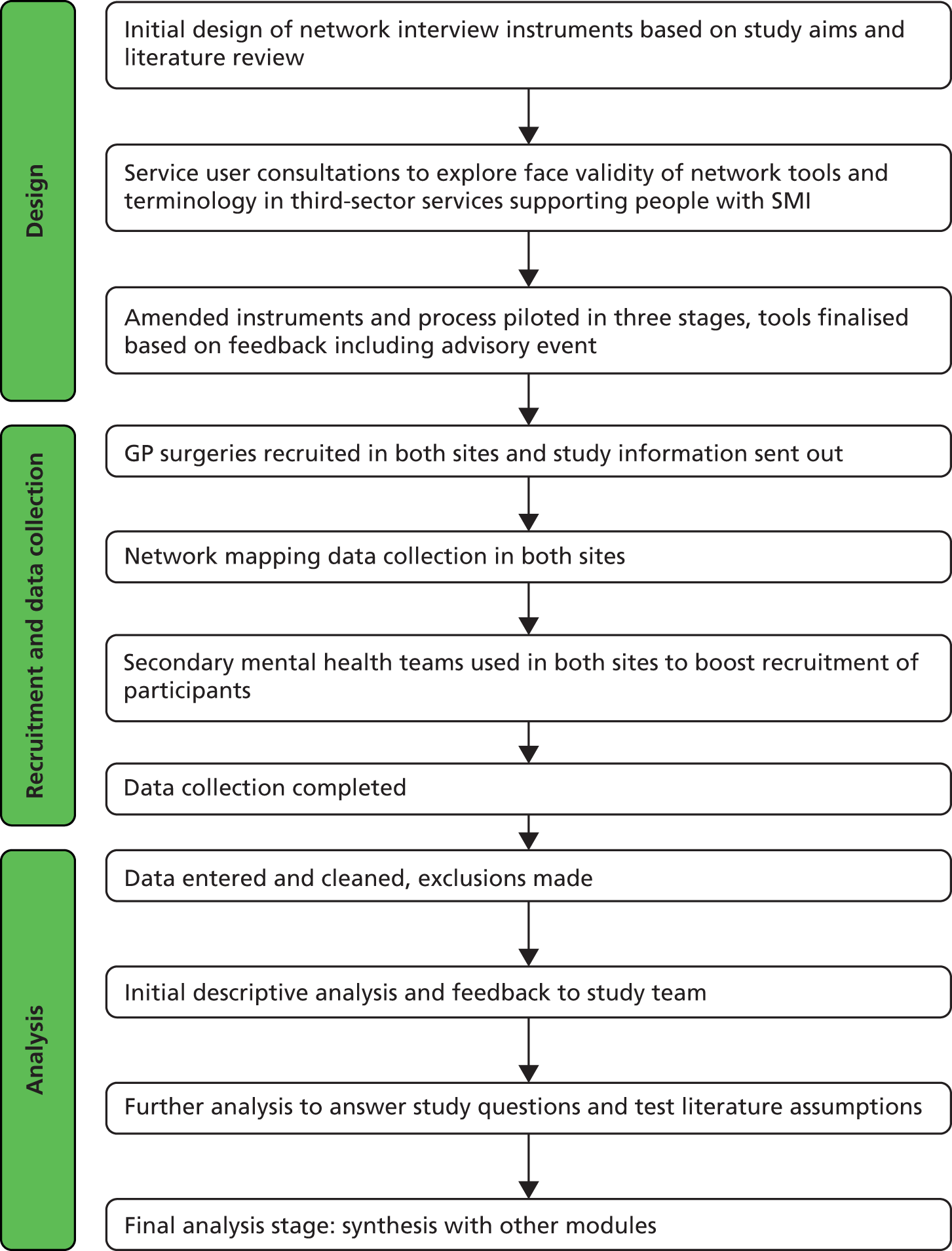

Network mapping

The primary aim of mapping interviews was to collect data from individuals with SMI on their current personal networks. This module involved a number of stages (see Figure 4), which are outlined in more detail below.

FIGURE 4.

Flow chart of network-mapping methodology.

Data collection instruments

The mapping interviews used the following instruments (a copy of these and more detailed methodological information can be found at www.mcpin.org):

-

Demographics: a questionnaire collected key sociodemographic data including age, gender, employment, relationship, education and housing status alongside background data on mental health, such as current diagnosis, medication, length of contact with services and inpatient history (see Appendix 3).

-

SWEMWBS: the short seven-item version chosen to measure current well-being asking participants about their experience of seven different thoughts and feelings over the previous 2 weeks; shows strong validity and high correlation with the longer version. 174

-

Dartmouth CO-OP charts: chosen to measure physical, social and emotional functioning for ease of completion and comprehensive dimensions. They consist of nine measures which ask about physical fitness, social activity, daily activity, pain, social support, emotional distress, quality of life, change in health and overall health. 175

-

Resource Generator UK (RGUK): this measures access to social capital within personal social networks and has four internal scales: access to domestic resources, expert advice, personal skills and problem-solving resources. It has been validated122 (see Appendix 4).

-

Health Resource Generator (HRG): consultations and pilots indicated the RGUK did not fully measure the types of resources that were relevant to the study with its particular interest in health capital. The study team therefore devised a pilot scale in the format of the RGUK and based on resources that were identified in focus group consultations to capture access to health- and well-being-related resources (see Appendix 5).

-

Community health network-generating schedule: the team developed a version of the name-generating and name-interpreting procedure used in SNA76 to map social ties, meaningful activities and meaningful places (see Appendices 6 and 7). This tool emphasised the connections within personal networks that support health and well-being.

The aim of the network-generating schedule was firstly to accurately map networks of people, place and activity, to understand how they were composed and then to understand their impact in terms of well-being. From the beginning, the team were aware of the challenges posed by this methodology when applied to participants with mental illness. Network generation was time-consuming and cognitively demanding, with concerns over accuracy of network recall having been raised by various previous studies,76 including recalling colleagues and members of groups and friends. 176 Extending the method to collect data on connection to people, places and activities and collecting the data on this population could potentially heighten these issues. The team were also aware that talking about potentially difficult relationships could cause participant distress. To tackle this, the network interview process was streamlined to have strong face validity and was designed to be as engaging as possible, with clear protocols for minimising and responding to participant distress. Studies have shown that the choice of name generator questions have a strong impact on the network mapped, impacting heavily on size, density and diversity. 177 Consultations and piloting assessed which network questions were most appropriate for mapping networks. We picked standard name generators and added extra items on the basis of consultations. These were refined based on whether or not they generated new names in piloting (if they did not, they were removed). Activity and place were ‘domain-specific’ or contextual name generators, providing extra prompts that improve recall and accuracy.

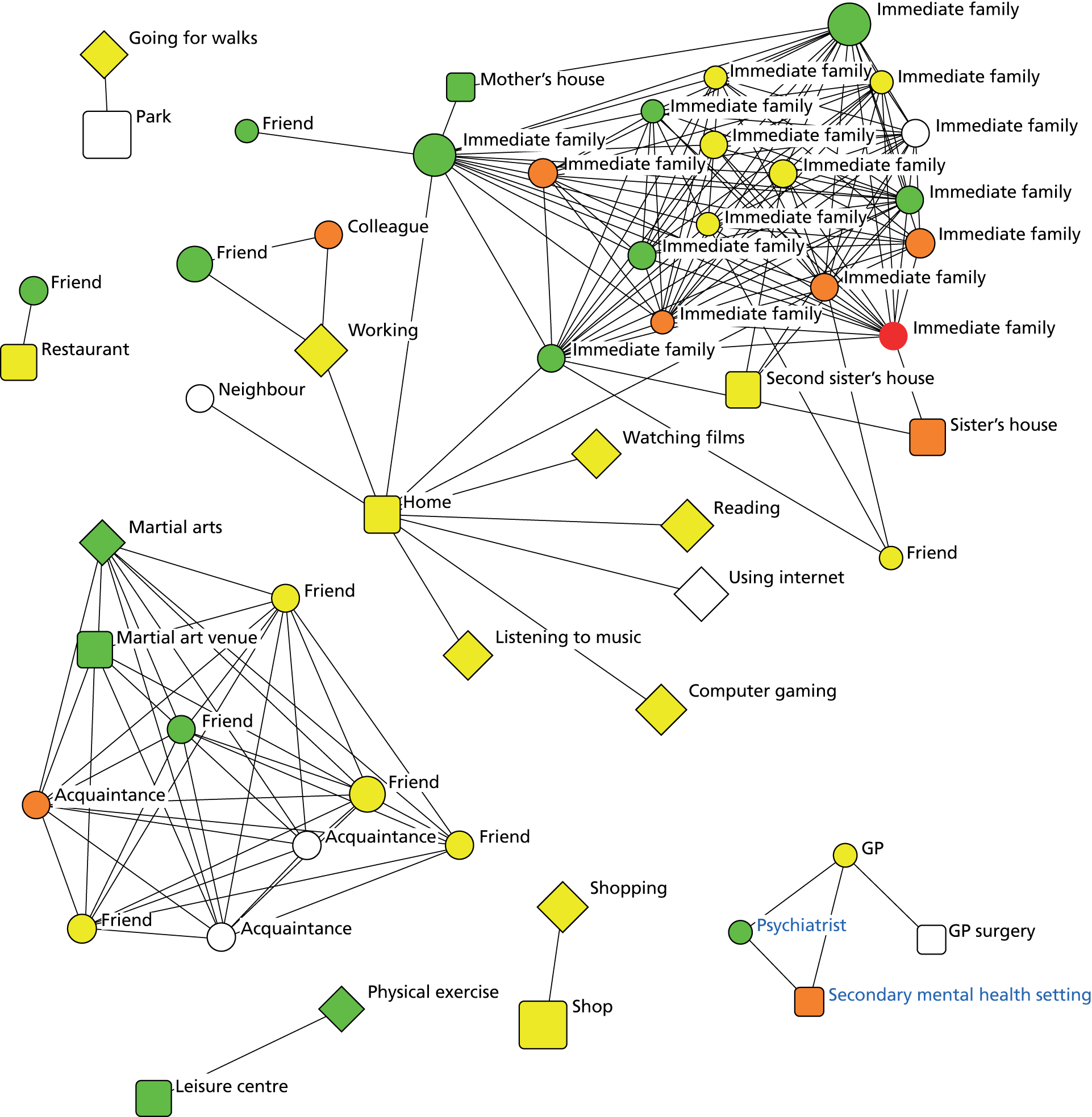

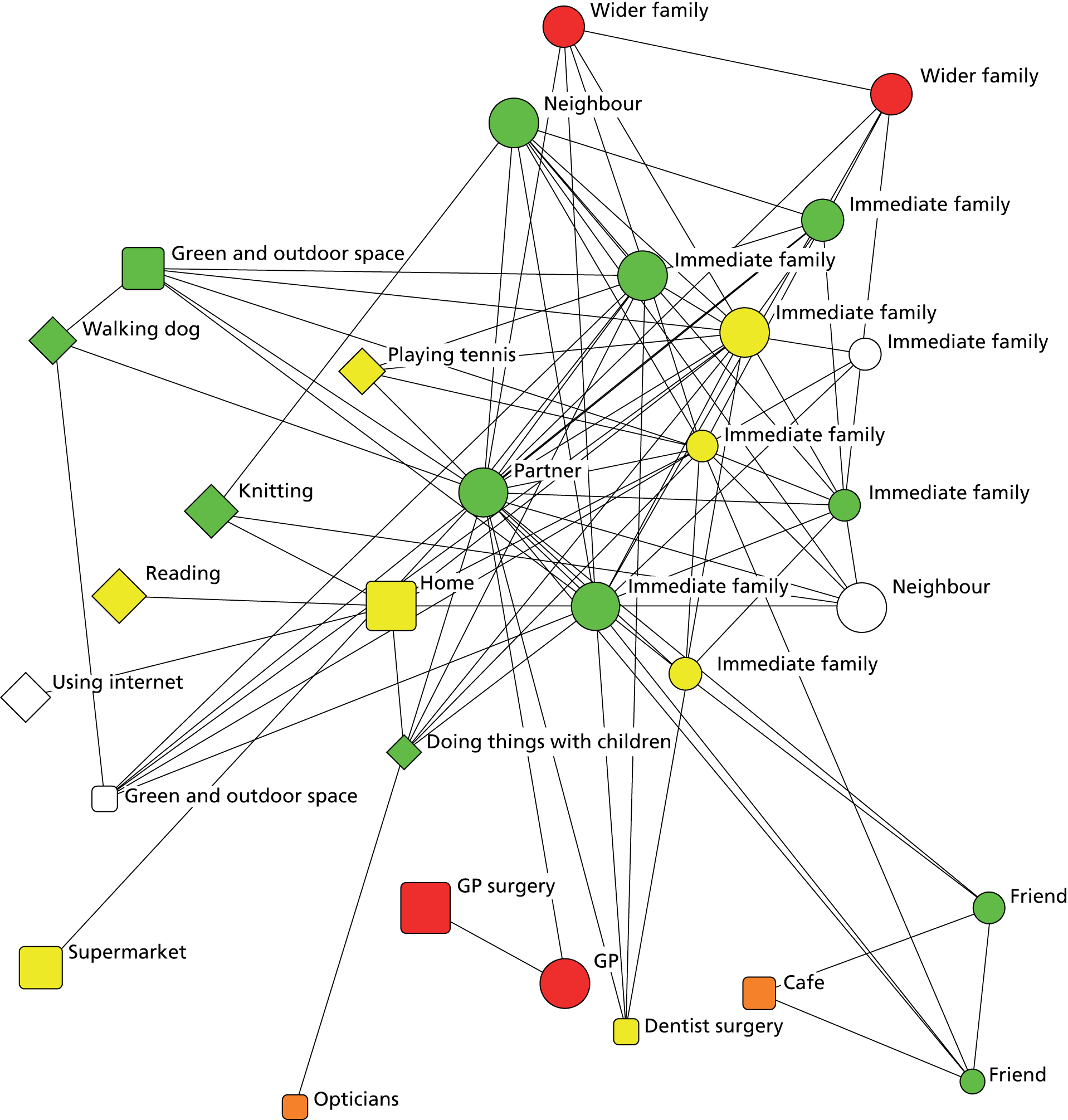

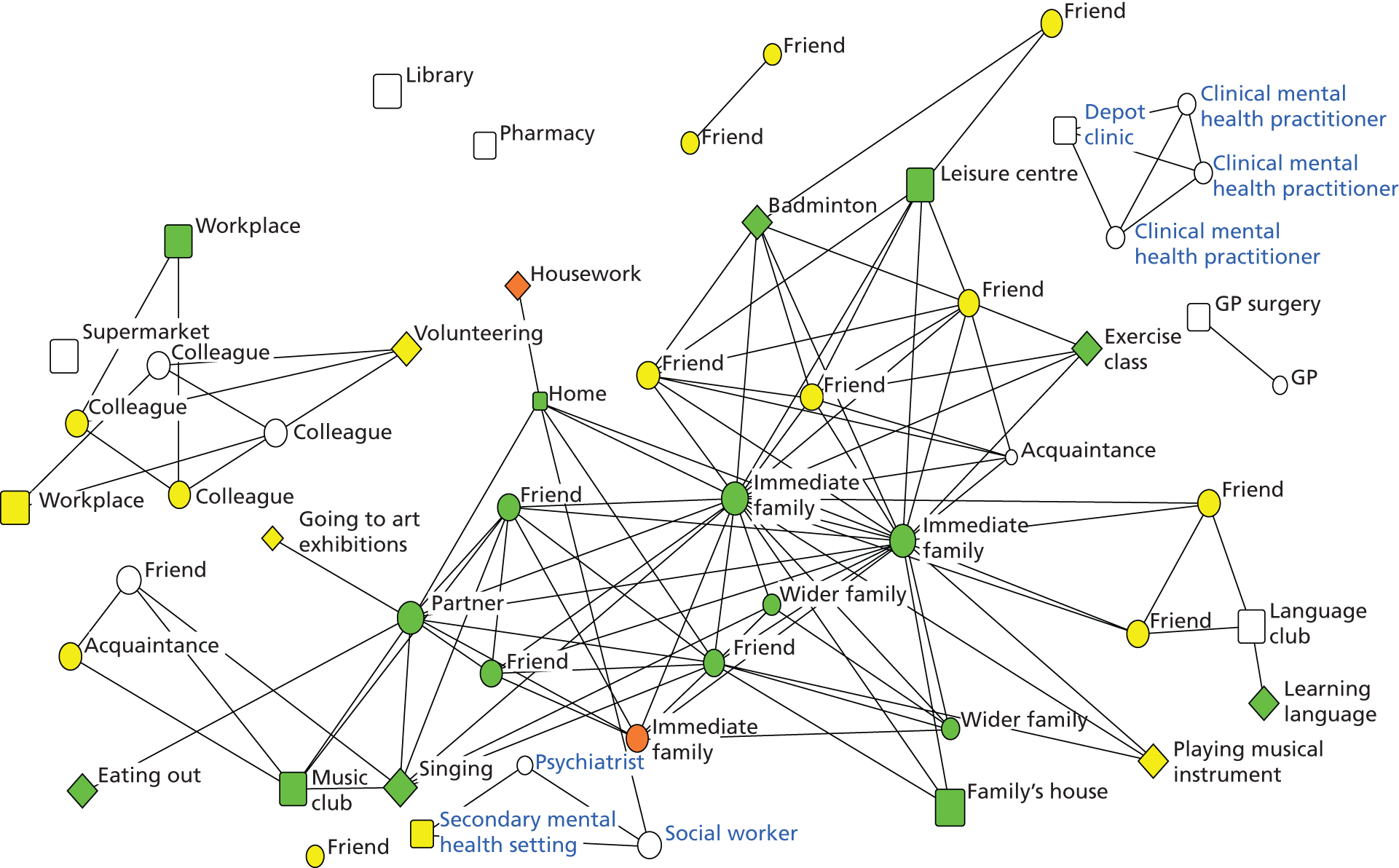

The final process is shown in Figure 5. For all three levels of network, boundaries were drawn by limiting connections to those which were current and regular interactions, or which were meaningful to the individual. The mapped networks were at a single point in time – the time of the interview. Questions used to elicit these networks can be found in Appendices 6 and 7.

The sample of 150 was based on a sample size calculation to detect differences in mental and physical health between a higher-need group, such as those in secondary mental health services, and a lower-need group, such as those supported in primary care alone, using a social networks study of day hospital and day centre service users. 46

FIGURE 5.

Final interview process chart.

Recruitment

Recruitment process

The first wave of recruitment was exclusively through primary care. Invitations to take part in the study were sent to all GP surgeries in study sites and the Primary Care Research Network (PCRN) assisted with this process. Study researchers also presented to individual practice managers directly. When surgeries responded with interest, members of the study team met relevant contacts to explain the recruitment process, including the inclusion and exclusion criteria and a recruitment log was used in primary care to document each step of the recruitment process.

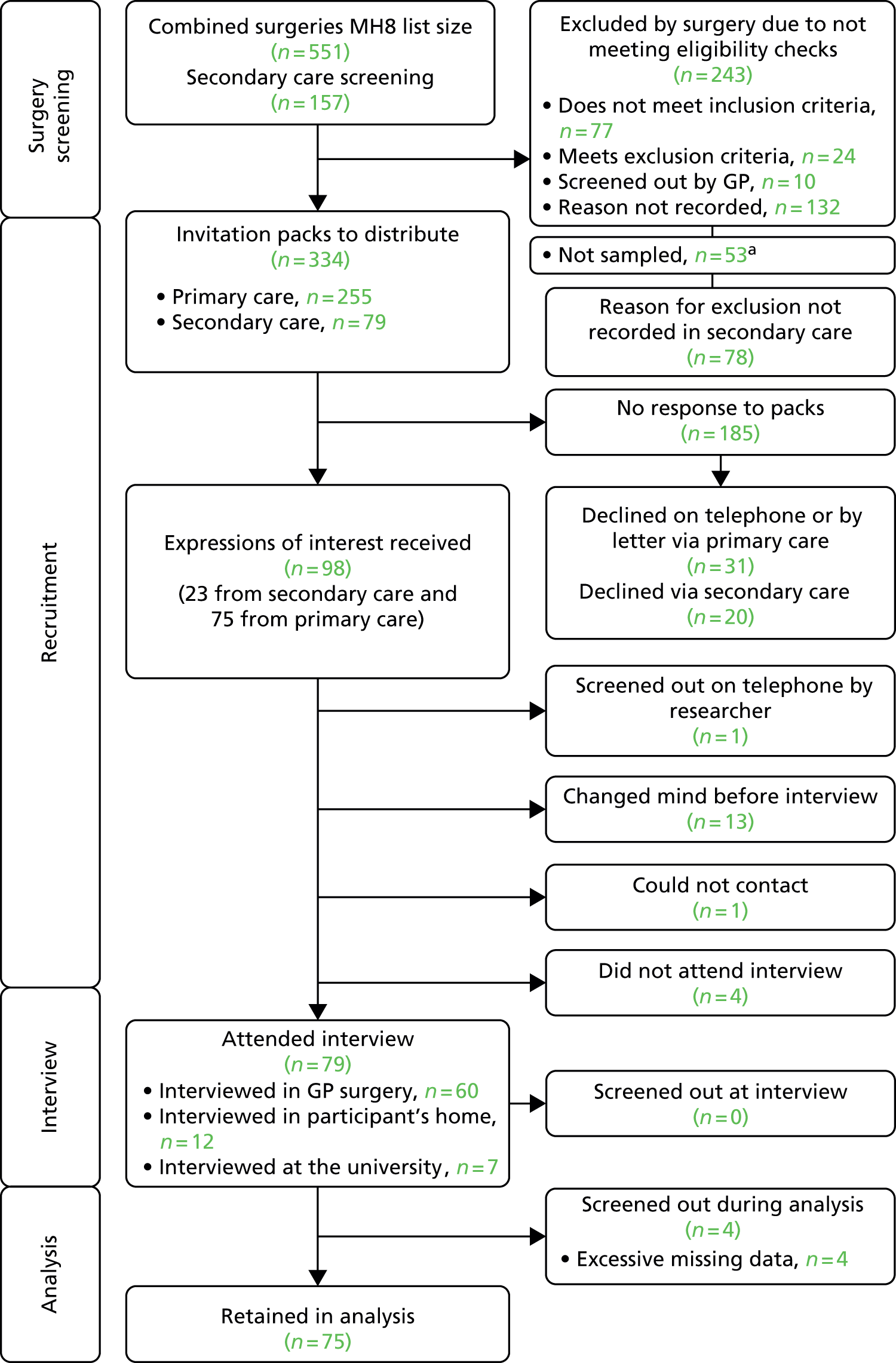

A second wave of recruitment was extended to secondary care, through early intervention services and community mental health and recovery teams, as a result of slow response rates in primary care. We targeted teams that covered the same geographical region of the South West (SW) as our GP surgeries, and those serving our London borough. The recruitment process through secondary care was that Mental Health Research Network (MHRN) staff presented the study to the team, who identified people who met our exclusion/inclusion criteria and approached them with an invitation pack. We were not able to track how many people were excluded by secondary care; we know only how many packs the teams were sent but not how many they handed out. This has impacted on our response rates, as we were unable to accurately assess how many service users were invited to take part. Our data, as presented in Figures 6 and 7, show 154 packs were given to secondary care practitioners to distribute. See Table 2 for summary of final study population by recruitment route.

| Recruitment route | SW (n = 75) | London (n = 75) | Combined (n = 150) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary care | 80 | 82.7 | 81.3 |

| Secondary care | 20 | 17.3 | 18.7 |

Data collection

The majority of interviews were conducted by the two study researchers; however, in London MHRN staff were trained and supervised to carry out 14 interviews and a second SW researcher did 24 interviews. All participants received a £20 high street shopping voucher as a gratuity for their time and contribution.

FIGURE 6.

Consort diagram for London recruitment. MH8, a register of patients with schizophrenia, bipolar affective disorder and other psychoses. a, In larger GP practices not all patients were sampled, we randomly selected 60 people to approach.

FIGURE 7.

Consort diagram for SW recruitment. MH8, a register of patients with schizophrenia, bipolar affective disorder and other psychoses. a, In larger GP practices not all patients were sampled, we randomly selected 60 people to approach.

Data analysis

Analysis involved detailed stages:

-

Data entry, checking and cleaning: Microsoft Excel and Access (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) databases were used to store data, which were converted to SPSS (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 21.0, IBM Corp, Armonk, NY) and UCINET (UCINET for Windows, Version 6, Analytic Technologies, Harvard, MA) for further analysis. Random accuracy checks were conducted in each site based on paper copies of data. Data were cleaned to deal with missing cases and to categorise place, activities and people (see Appendices 8 and 9).

-

Initial SPSS and UCINET analysis: this created network variables for each participant that were imported into a master SPSS file. This included use of Burt’s network efficiency to describe network density because this measure was least sensitive to network size in our data set. 26,27

-

Detailed data exploration examining descriptive and univariate statistics to draw out significant variables: this process was exploratory and reflexive, with initial results presented to team members to guide further analysis.

-

Clustering and regression models: these characterised network types and examined outcomes. Regression models were also used to study the relationship between independent variables and key outcome measures. Multicollinearity was tested using a variance inflation factor (VIF).

-

RGUK data: 149 out of 150 participants completed the resource generator. Missing data were few: out of a total of 4023 responses the total number missing from those who completed was 49, or 1.22% of total possible responses. Missing data were treated as not having access to a specific resource in line with other studies that have used the RGUK (e.g. Webber and Huxley123).

-

HRG validation process, which removed one item from the pilot scale: the distribution of scores on the scale was not normal. The majority of participants had higher scores and, therefore, the scale was split into two groups, low HRG scores from 0 to 12 (51% of respondents) and high HRG scores from 13 to 15 (49%). We had no comparative data, as the study team created and validated this scale. Missing data were treated as not having access to the resource, as with the RGUK.

The decision to use k-means clustering was based on the complexity of data and the number of available network variables that made interpretation and write-up difficult. Clusters were based on network variables only, rather than social capital or well-being data, as we were interested in describing types of network based on characteristics of people, place and activity, and relating these to health factors. Sorting individuals into small numbers of relatively homogeneous clusters provides a convenient summary of the network data, aids in interpretation and may have important theoretical and practical implications. 178

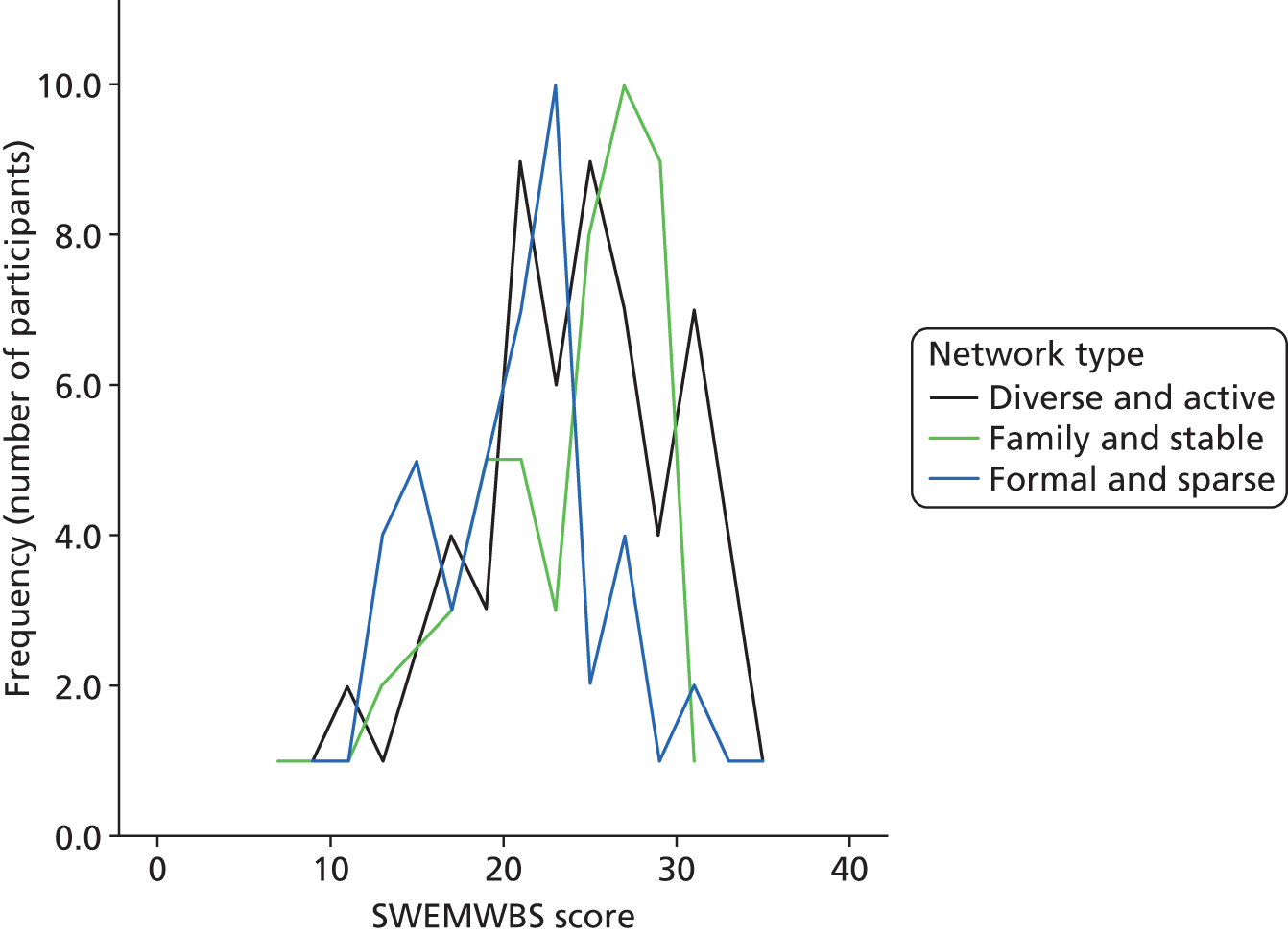

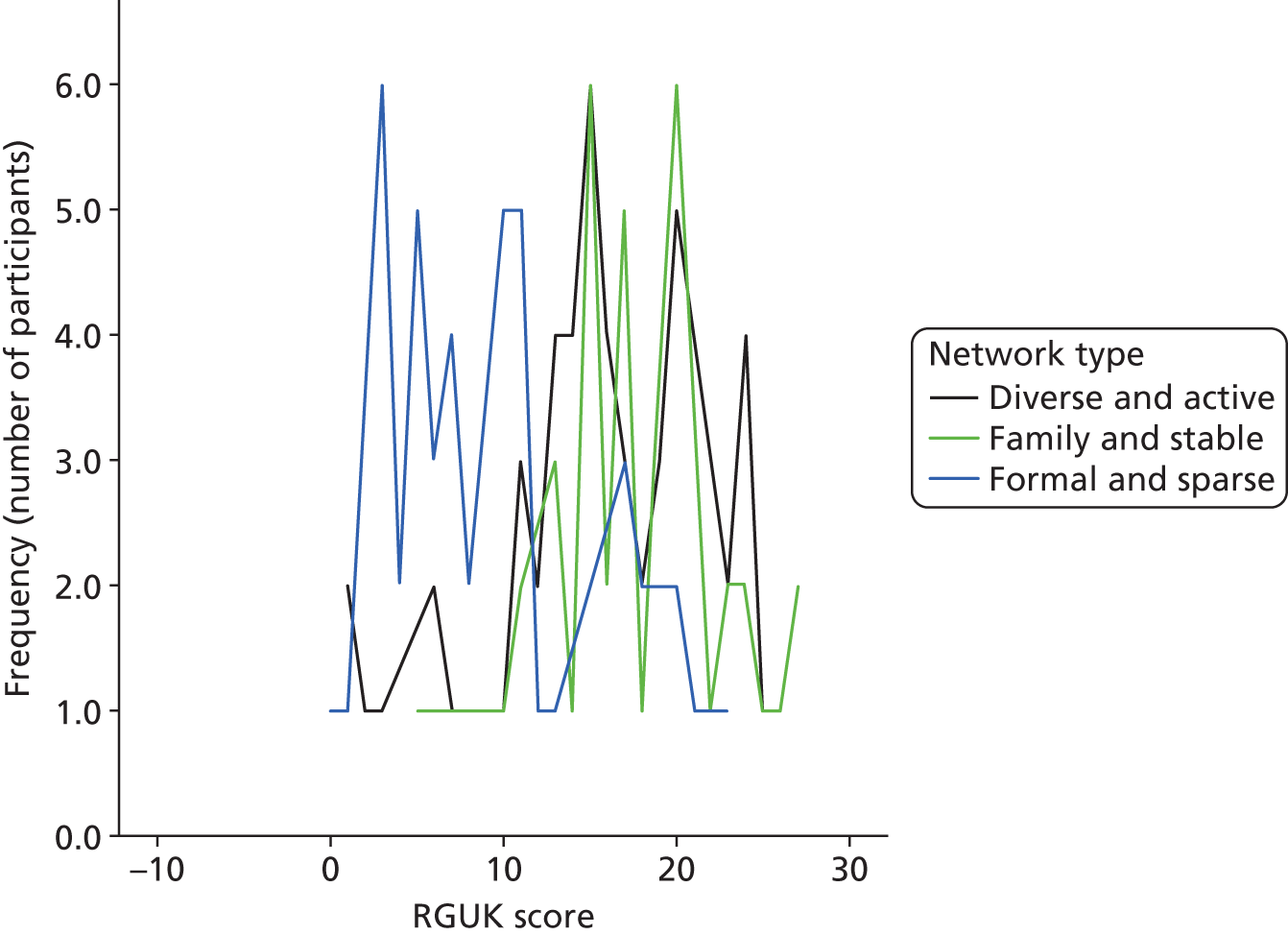

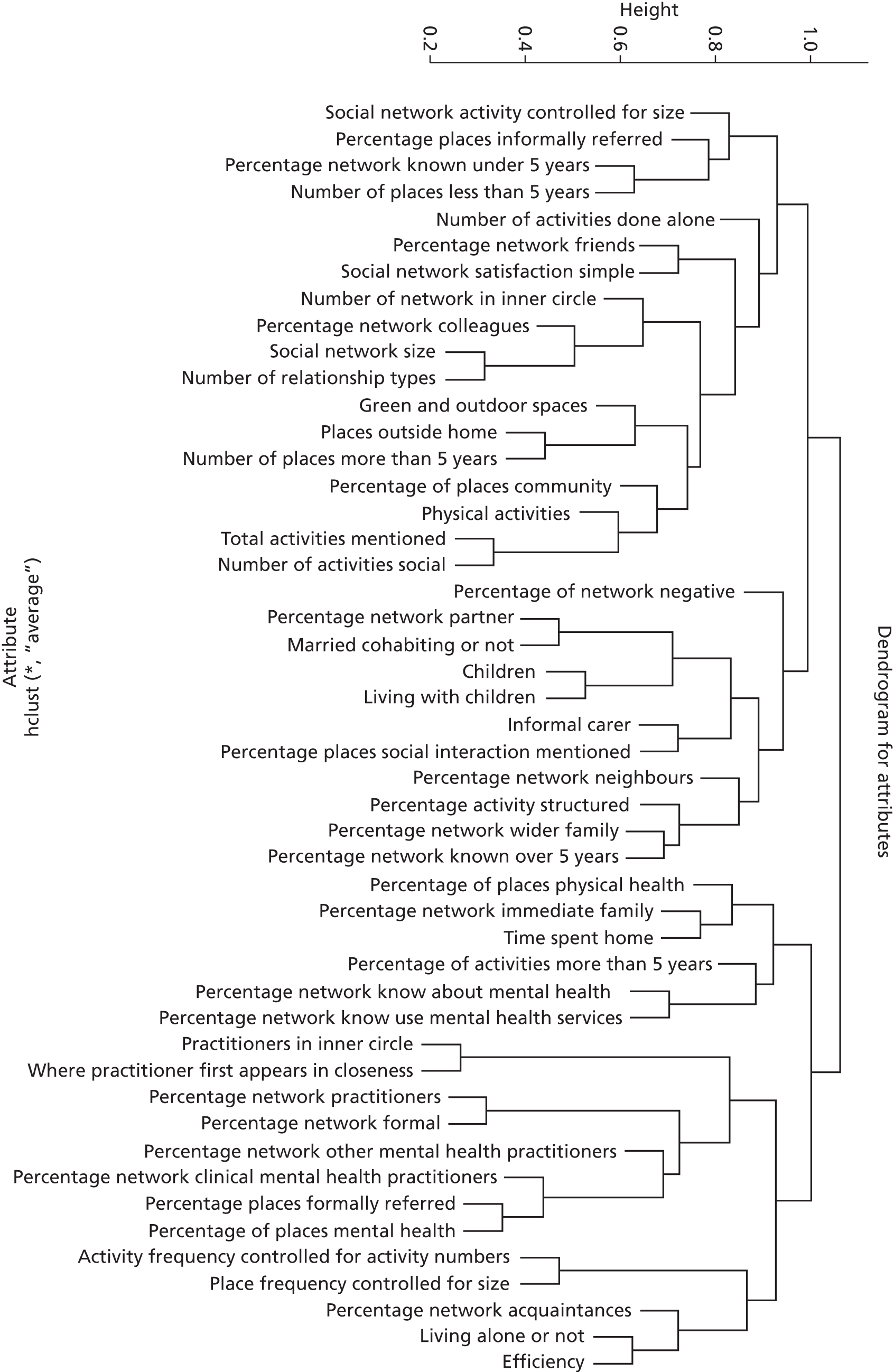

Network types were identified based on 48 selected variables covering social network, place and activity data. This number was reduced from 61 by removing highly correlated variables. The clustering procedure involves both variables and cases; with reference to previous work on creating network types. 179 We used an agglomerative clustering approach to approximate the number of clusters for the 48 variables, producing a dendrogram (see Appendix 10). The number of clusters was identified from the dendrogram based on a ‘large’ change in level, aided by the fact that three clusters made more conceptual sense to the research team when detailed analysis was carried out on each cluster. Four clusters were also tested but analysis on the three-cluster model produced stronger differences and made more conceptual sense. A k-means clustering approach was used to assign each participant to an identified cluster. Following this process, we used a frequency table (see Appendix 11) to explore the direction of variables assigned to each cluster in order to interpret and name them. In the report we refer to the clusters as network ‘types’.

Regression models180 were used to model predictors of key outcome measures (social network size, network type, RGUK score, HRG group, mental health contact type, SWEMWBS score), and the process is explained in Appendix 12. This modelling was exploratory because of the large number of sociodemographic, health status and network variables available.

Response rate

The response rate for the network interview data collection phase was disappointing. The overall response rate in London was 15.01% (80 out of 533 potential eligible participants) and in the SW 22.45% (79 out of 334). These are inaccurate, as, although we provided detailed log records to track recruitment in each GP surgery, completion of the logs by some surgeries was poor. We suggest that actual response rates based on participants successfully contacted were likely much higher but cannot accurately be estimated because of the following challenges:

-

In secondary care recruitments, teams were handed printed packs. This number was an estimate of those they told us would be eligible for the study: 75 in London and 79 in the SW. However, no records were kept on how many people were actually approached to take part. These data were requested but not recorded by the participating teams.

-

In London there were 340 packs sent by GP surgeries for which no response was received. No contact was achieved by follow-up telephone call. It was highly likely that a portion of these did not reach the participant because the surgery had the wrong address details, people on GP databases had moved away from the area, people were living in accommodation where post was less likely to reach its intended recipient and there were errors by postal services. These factors were likely to be more prevalent in London than in the SW according to feedback gathered by the study researchers. This figure was lower in the SW, with 185 packs distributed with no response received. For 61% of the potential recruitment population we have no way of knowing if they ever received our invitation to participate in the study.

We did not have data on those who did not respond or declined to participate, except that they were on the QOF GP database under the mental health indicator ‘MH8’ (MH8 is a register of patients with schizophrenia, bipolar affective disorder and other psychoses) or on team case loads in secondary care, so we cannot compare non-responders with the 150 participants on key variables to assess the likely impact of sample bias with such low response rates. We did try to obtain locality population-level data on people with psychosis but this information was not kept at borough or locality level.

In-depth interviews

Data collection

At mapping interviews, participants were asked if they would take part in the follow-up; most (127 people) consented. We selected 41 respondents to participate. People were purposively sampled to represent variation in gender, ethnicity, site, age, network size, diagnosis, length of contact with services and inpatient history (Table 3).

| Characteristic | SW (n = 20) | London (n = 21) | Total in-depth interview population (n = 41) | Network-mapping component (total study population) (n = 150) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 12 | 11 | 23 | 85 |

| Female | 8 | 10 | 18 | 65 |

| Age range (years) | 26–64 | 21–59 | 21–64 | 19–65 |

| Diagnosis | ||||

| Schizophrenia | 7 | 10 | 17 | 59 |

| Bipolar disorder | 8 | 7 | 15 | 65 |

| Other psychosis | 6 | 4 | 10 | 26 |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| White British | 20 | 7 | 27 | 103 |

| White other (Greek, French, Irish) | 0 | 4 | 4 | 12 |

| Asian | 0 | 3 | 3 | 7 |

| Black African/black Caribbean | 0 | 4 | 4 | 15 |

| Mixed | 0 | 3 | 3 | 13 |

| Network size range | 6–43 | 8–38 | 6–40 | 5–64 |

| Years since first mental health contact (range) | 1–45 | 3–37 | 1–45 | 1–45 |

| Has ever been an inpatient? | 15 | 15 | 30 | 122 |

Some participants were excluded because they had difficulties fully participating in the original interview process. In the later stages of sampling, a decision was made to oversample purposively from those with high levels of need, those living in supported housing, people from ethnic minorities and younger people with a diagnosis of schizophrenia in the SW, to ensure that these needs and vulnerabilities were represented, which might not have been the case if representative sampling had been used. 181

The interviews were carried out by the study’s two researchers, who undertook two pilot interviews to redefine the data collection schedule. Written informed consent was taken and participants received a £20 high street shopping voucher.

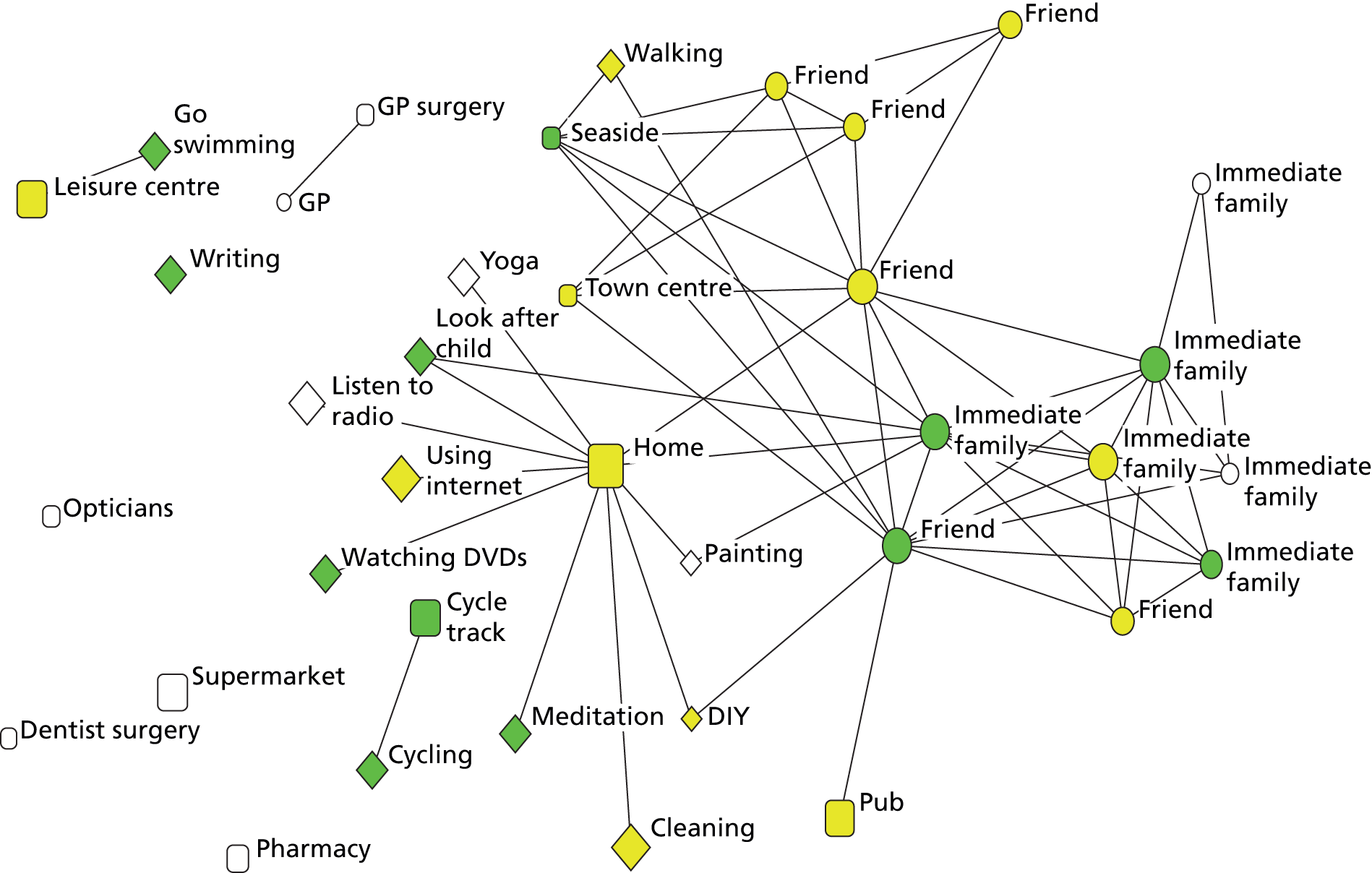

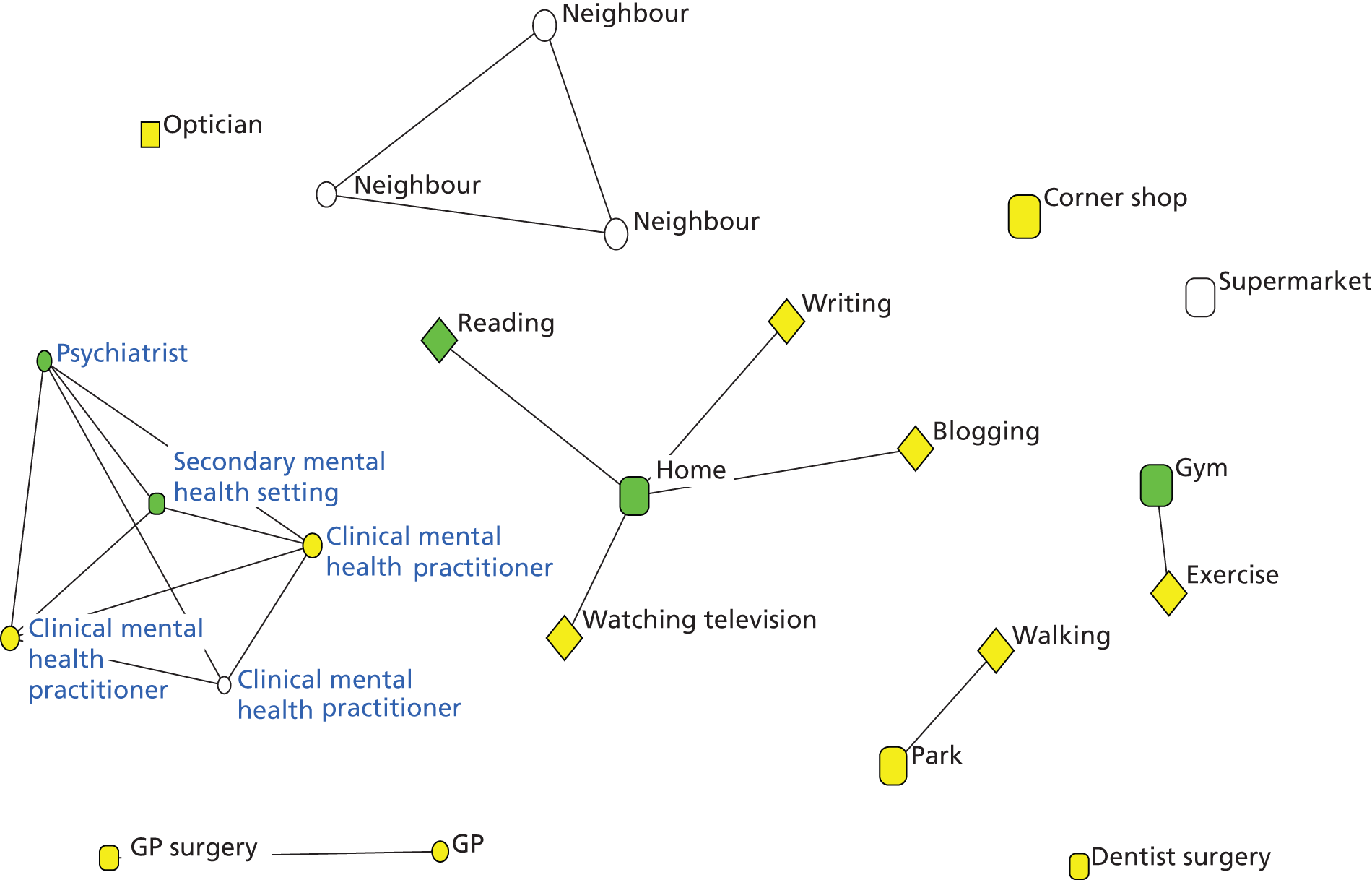

The topic guides (see Appendix 13) began by reflecting on and deepening understanding of an individual’s personal network. Each participant was presented with their visual network emotional closeness map, from the first interview, and their three network descriptor words to anchor the interview initially in the data previously provided. The topic guides then progressed to questions about changes over time and what participants did to help themselves stay well. Review of some of the early interviews by two members of the PPI group resulted in changes to the topic guide which reduced the overall number of questions and encouraged the researchers carrying out the interviews to have the confidence to allow people to talk, without worrying too much about ‘going off topic’. Interviews were digitally audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim and anonymised before analysis. The schedule was not used to elicit the social network or discuss network concepts as with some other studies167 but instead used the quantitatively mapped network as a springboard to explore how and why connections developed, the impact of illness over time, the role of practitioners and of self in shaping choices and access to resources.

Data analysis

The data analysis process took place in three stages; preliminary thematic analysis; within case, interactions between themes; and full thematic analysis and reflection. Data presented in Chapter 4 were based on the full thematic analysis but answer specific questions from emergent network dimensions prioritised as important from Chapter 3, making use of the within-case maps to support the process.

Stage 1: data immersion and theme production

Broad themes were inductively developed following the principles of working with ‘reflecting teams’, who discuss transcripts line by line, in a group, to consider all the possible layers of meaning. 182 Using this technique for data immersion allowed the academic researchers to work in partnership with the lived experience researchers. Jones states that it was more important that the members of the team work creatively and imaginatively in partnership than that they have any specific knowledge of research methods. 183

The academic researchers (two) and lived experience researchers (two) read through individually, and then as a group, three transcripts and discussed what they thought were the most important things within these transcripts. All members of the reflecting team made detailed notes on the transcripts, creating memos of their thoughts both while reading and as a result of the group discussions. The group discussion included considering whether or not differences in opinion were influenced by differences in experience and/or training. The aim of this part of the discussion was not to resolve who was ‘correct’ in a positivist sense, but to gain an understanding of the others’ perspectives. At the end of this session a list was produced of the emergent areas of what seemed to be of interest in the transcripts from the perspectives of research question 1 and what the research participants chose to talk about to the researchers.

The ‘reflecting team process’, as detailed above, was carried out twice more with one of the academics and one of the lived experience researchers on a further four transcripts. At the end of this process eight broad themes had been agreed on. Three of these were agreed to have emerged as important because interview participants had been prompted to discuss them in the initial network interviews (activities you participate in; strategies for keeping well; people). These broad themes could be considered to be deductively generated. Three broad themes were agreed to have emerged as important because of the temporal dimension that this more reflective interviewing style facilitated (past, future, changes in networks over time). One broad theme was agreed to have been inductively generated by the involvement of the lived experience researchers who identified hope and possibilities in what people had and could achieve, when the academic researchers were hearing predominantly negative narratives (building blocks to doing things for you). An eighth broad theme was introduced to cover information that was felt to be important, but which otherwise might be lost (other). Information about physical health and reflections on taking part in the network-mapping exercise were both covered by this theme.

These themes were applied, using the NVivo 10 data management tool, to all of the transcripts by two researchers who checked each other’s coding and discussed refinements to the theme definitions. The convergences, divergences and newly emergent stories within each theme were examined and discussed first within the analysis team and later with the wider research team.

For each participant a summary paragraph was also constructed blending key features of the network data from Chapter 3 with the in-depth interview material; this included three network words or phrases chosen by participants, demographical information, and diagnosis and key life events information.

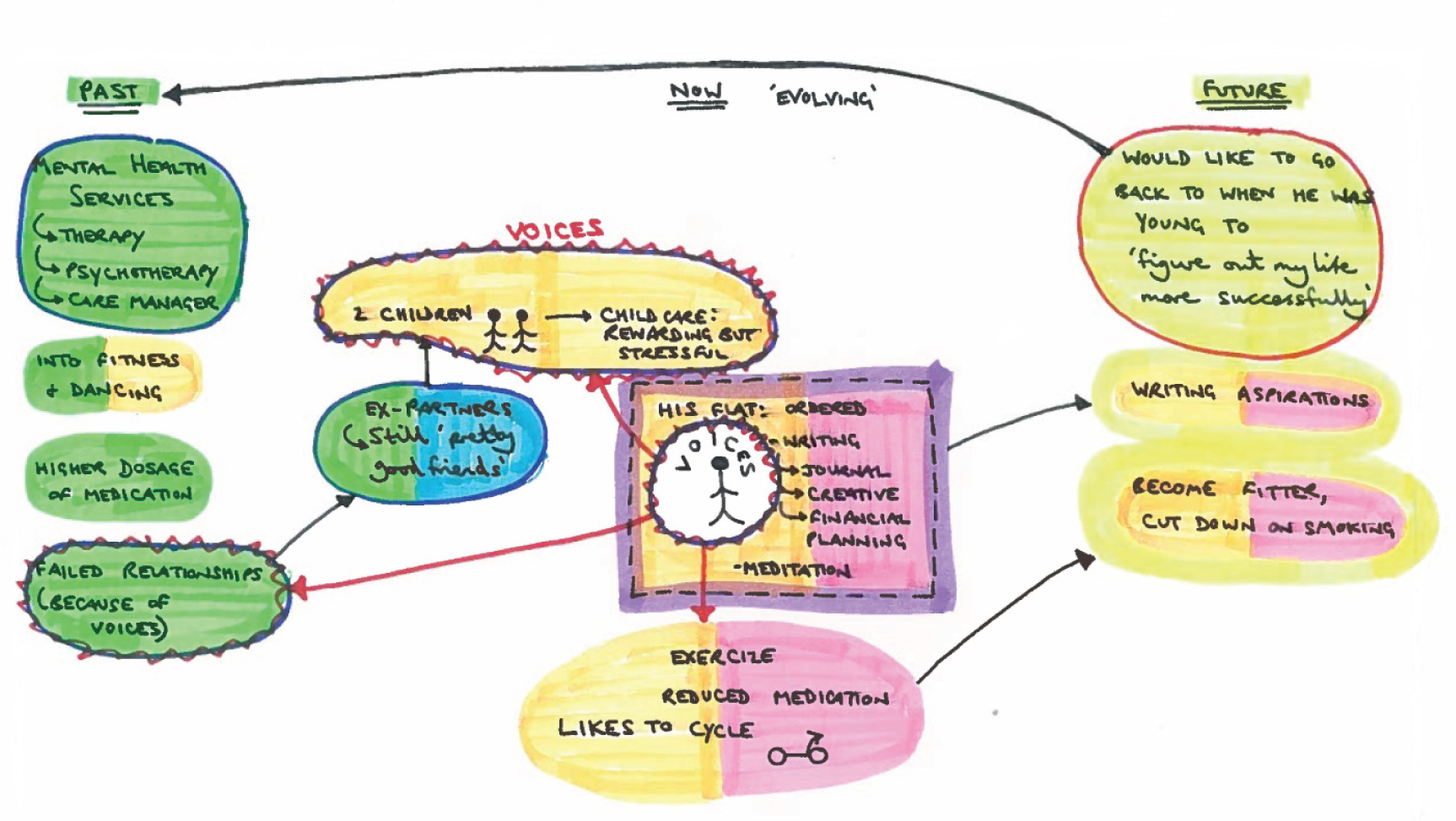

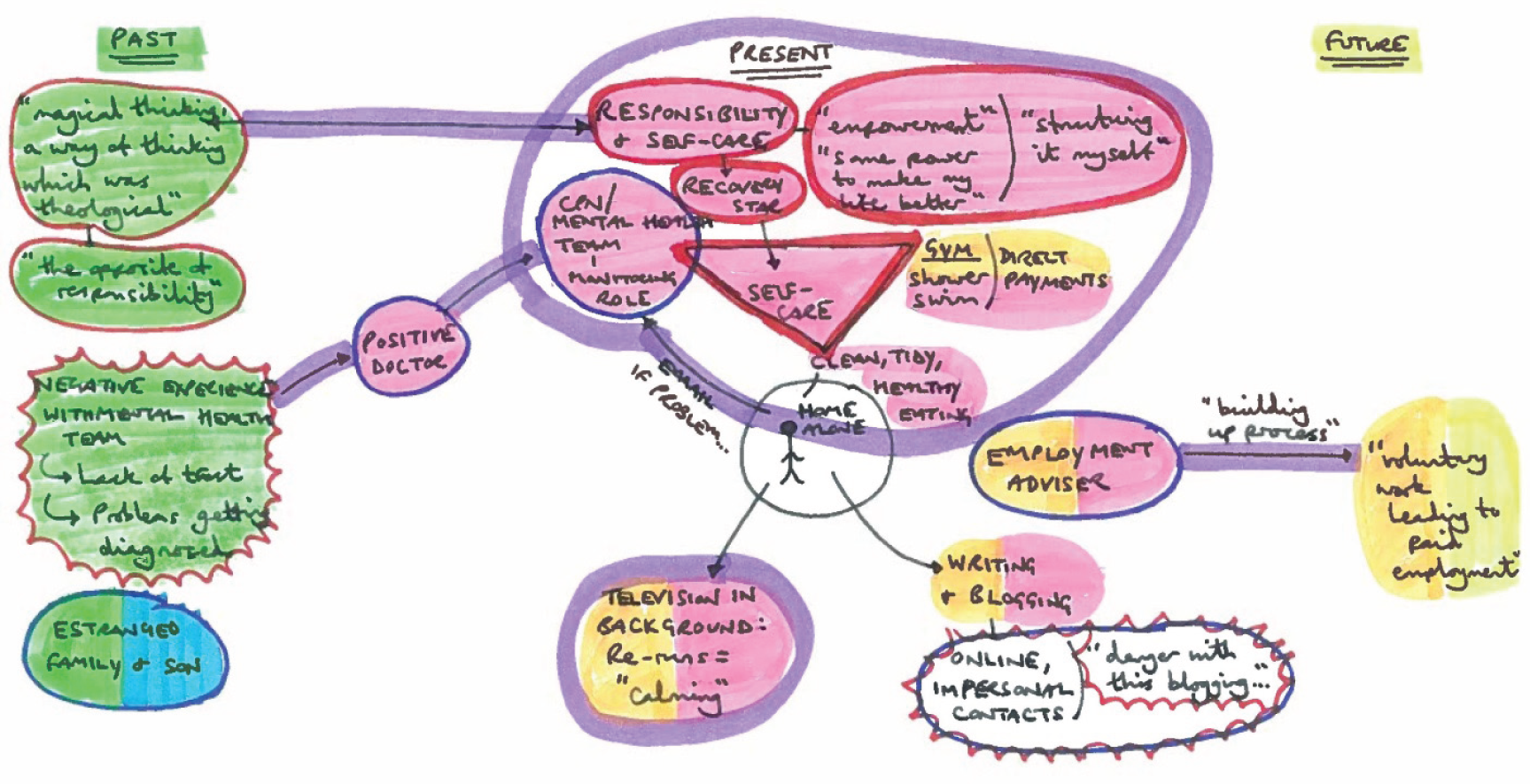

Stage 2: within case, interactions between themes, analysis

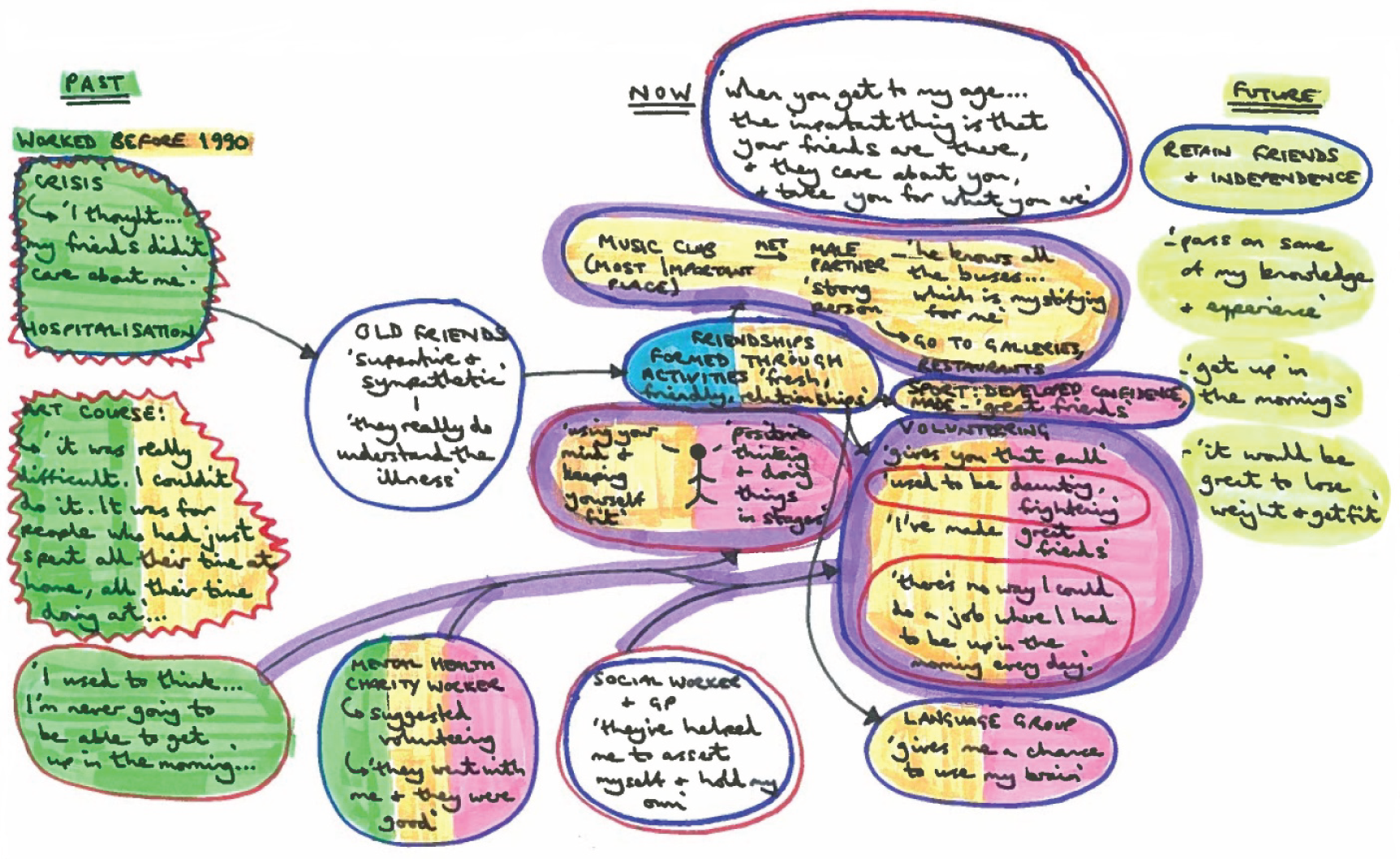

We were interested in what was important to individuals and their experiences, rather than producing generalisable themes across interviews. Instead of undertaking a cross-case thematic analysis we were interested in what was important about these themes for the participants. Each broad theme, from stage 1, was allocated a colour, and visual within-case analysis was carried out for each of the participants to examine the interactions between themes within their accounts. 184 A landscape-oriented piece of white A4 paper was used for each participant185 (see Figure 8 for an example). On the left-hand side of the page factors that had been coded as being significant in participants’ ‘past’ were drawn, or written. On the right-hand side of the page the ‘future’ was represented. In the middle of the page a figure of a person was drawn and under this was listed information from ‘other’. ‘Activities’, ‘Strategies’, ‘People’, ‘Changing Networks’ and ‘Resilience’ were then all drawn or written around the remaining white space, with interactions between any of the parts of the themes being indicated with arrows.

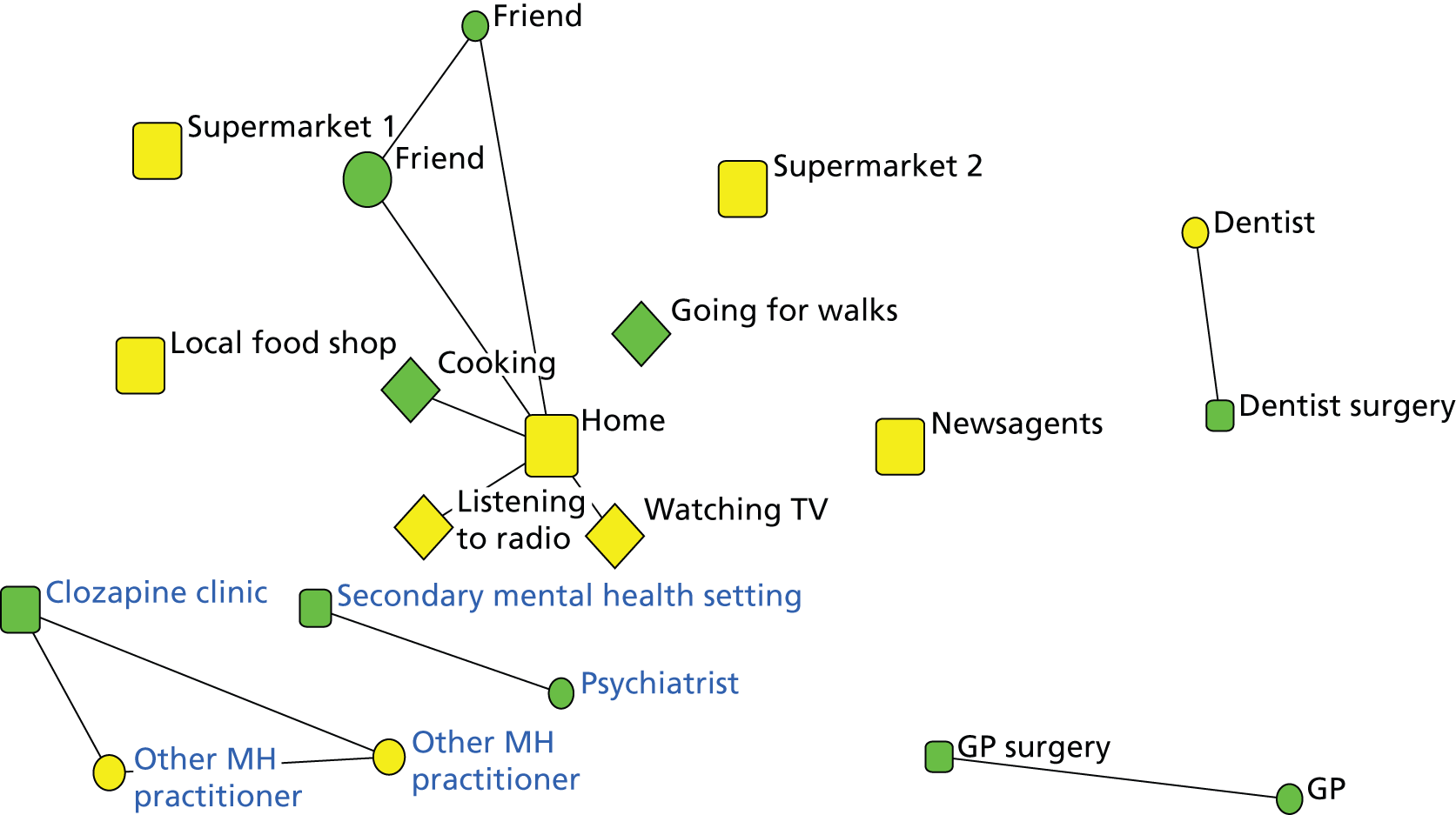

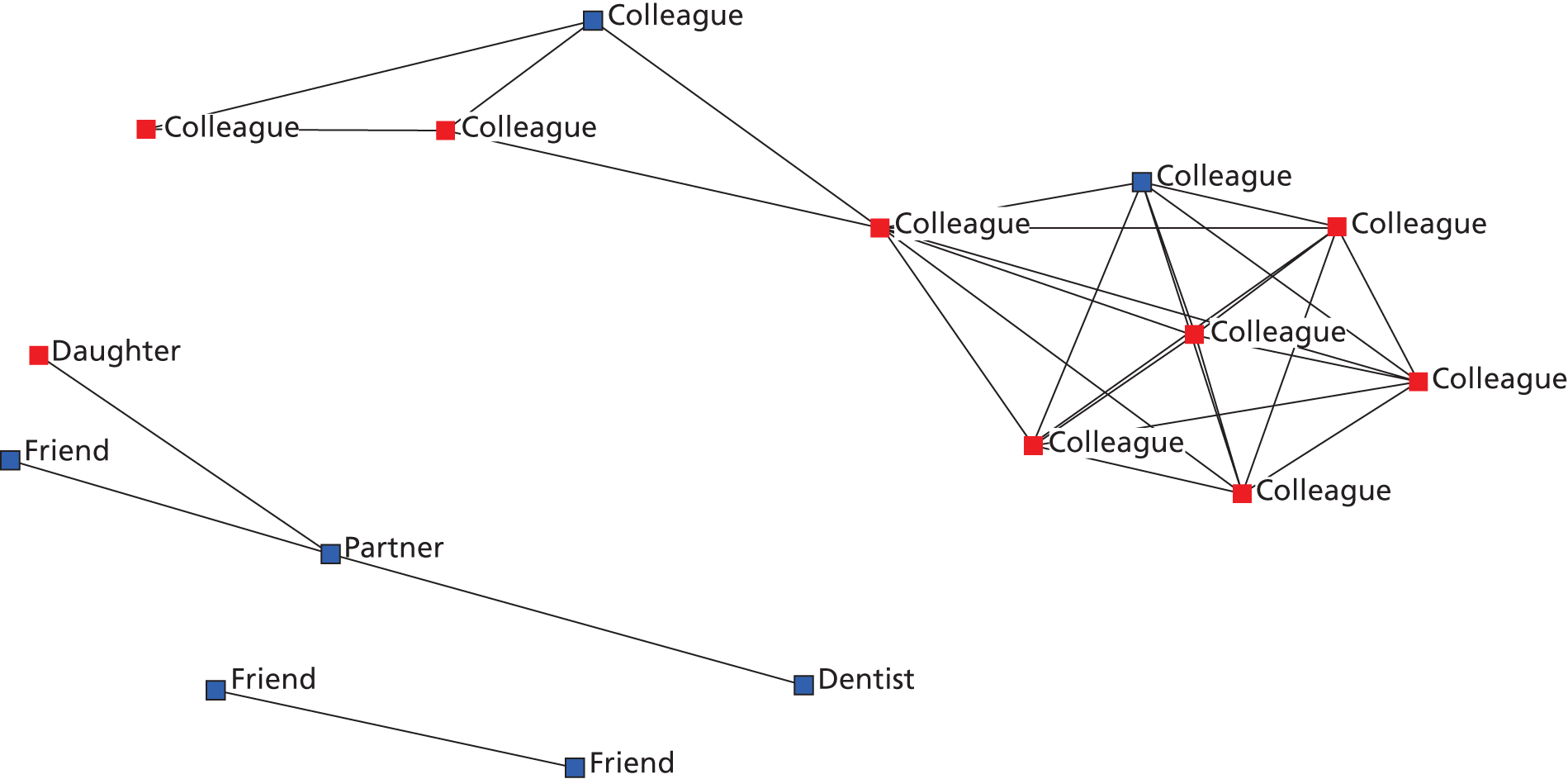

FIGURE 8.

Example of a within-case analysis picture. Key: green, past; pink, strategies; yellow, future; orange, activities; purple, building blocks; light blue, change in networks; blue circles, people; red circles, other information, usually statements about health or beliefs; red jagged edges, particularly stressful things in life, including voices.

We asked the lived experience researcher who worked closely with the study team on this module to provide feedback on their role. The researcher summed up the involvement experience in three words:

-

energising

-

confirming (that I do have a valuable contribution to make)

-

committing (I was committed to the team and the project in the same way they were committed to supporting me in my work).