Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 10/1009/24. The contractual start date was in October 2011. The final report began editorial review in August 2013 and was accepted for publication in June 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Spiby et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background, aims and objectives

Introduction

The concept of disadvantage is multifaceted. Within this report we will be taking a very broad definition which includes social deprivation, low income, social isolation, lone parenting, teenage parenting, drug or alcohol use, asylum seekers and refugees, mental illness, domestic abuse and safeguarding concerns. The different forms of disadvantage frequently coexist, frustrating attempts at narrower definitions. The maternal mortality rate for disadvantaged women is higher than for the general population. 1 Similarly, for babies born to disadvantaged women, the chances of dying around birth or within the first month of life are higher than for babies of women who are not in adverse circumstances. 2 Disadvantaged women have higher rates of smoking3 and formula feeding4 than other population subgroups and are less likely to access routine services such as antenatal classes. 5 Barriers include a lack of access to appropriate services (e.g. for asylum-seeking women6 and very young women7 and their partners), lack of staff training in culturally appropriate care and a lack of knowledge among health professionals about relevant interventions and services that they could refer to. 8 Recently published guidance for service provision for pregnant women with complex social factors recommends that such barriers be addressed; multiagency working should be supported and the care provided by different agencies integrated. 9

Support and care in pregnancy, labour and postpartum have positive impacts on women’s well-being and outcomes including reduced operative birth10 and increased breastfeeding rates. 10,11 In the UK, the provision of intrapartum support has traditionally been the role of the midwife. However, current midwifery staffing levels are low and it is challenging to provide women with the ongoing support they need in these vulnerable and formative months. There is evidence that a significant proportion of women are worried by feeling unsupported by health-care professionals during at least part of their labour. 12 This lack of support is often due to high workloads on busy labour wards and is unlikely to improve in the medium term, given the demographic profile of the midwifery workforce with a high number of retirements expected in the next 10 years. It is also recognised that services can offer care that is somewhat fragmented, with little co-ordination between midwives, health visitors, general practitioners (GPs) and social services, all of whom are likely to be involved in the care of families during pregnancy, birth and the early postpartum weeks. Such support and co-ordinated care is likely to be especially important in low-income communities and for young women, as women in these circumstances have lower rates of breastfeeding and increased rates of infant mortality, and are more vulnerable to problems with emotional and psychological well-being. 2

This research examines an award-winning innovative social enterprise service that has been established in one city and that is now rolling out to other sites. Based on principles derived from controlled studies conducted in other countries, the volunteer doula project offers lay support to women in vulnerable circumstances with the aim of enhancing support and improving the uptake of existing health and social services.

The lay support is offered by volunteer ‘doulas’, a term to denote women who support other women during pregnancy, birth and breastfeeding. The role is not one of a clinical professional but of a trained lay supporter and does not include the support provided by female members of the woman’s own family. Doulas offer emotional and physical support and companionship, and facilitate communications between the woman, her partner and health-care professionals and services. 13 In some situations, doula support may also include guidance with parenting. There is a substantial evidence base, derived from randomised controlled trials and other studies conducted in a diverse range of settings and systems, in countries including South America, the USA, Sweden, Finland and Belgium, that has demonstrated the benefits of doula support for childbearing women and their families. However, there is no contemporary evidence derived from UK settings.

Existing evidence

A rapid review of studies carried out prior to commencement of this research explored ‘doula support’ including systematic searches of the following databases: MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane and the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature. The search was not limited by country, date, methodology or language. Support during labour from trained doulas is associated with reduced length of labour,14 less pharmacological pain relief and oxytocin augmentation, and fewer instrumental or operative births. 15 In particular, instrumental and operative births are associated with increases in the risk of morbidity for women and their babies. This morbidity includes postpartum haemorrhage,16 genital tract trauma for the mother17 and increased risk of intracranial haemorrhage for babies. 18

In addition to positive impacts on labour outcomes, there is also evidence of positive impacts on breastfeeding,10 including increases in the proportion of women initiating breastfeeding and continuing with exclusive breastfeeding. 11 It is particularly noteworthy that these positive impacts have been achieved in groups where rates are frequently lower than national figures, including low-income, first-time mothers. These findings reflect the wider evidence base of breastfeeding support by peers19 and resonate with contemporary policies that encourage the implementation of peer support for breastfeeding. 20

Positive benefits for women’s psychosocial well-being include more positive feelings about labour and less anxiety,11 increased feelings of control and confidence as a mother,21 and fewer women experiencing postpartum depression and anxiety. 22 Evidence suggests that doula support during labour may also have potential positive effects on parenting behaviours and the relationship between a woman and her child,23 including increased acceptance of a baby immediately after birth and an increase in behaviours such as stroking, smiling and talking to their babies,24 and more positive parenting when babies are 2 months old. 25

All of these findings resonate with important aspects of the policy context and many also offer potential benefits to the NHS from reduced resource use, including shorter inpatient stay following normal birth than assisted birth and fewer referrals to specialist services, including mental health care. Evidence of benefit from doula care is particularly striking for women in situations of social or economic disadvantage, those with lower educational attainment and where supportive contact starts during pregnancy. There are also suggestions that the provision of doula support is associated with increased use of required health-care services. 26

The UK NHS spent £1.6B on maternity services during 2008. Part of this cost is attributable to the high rate of caesarean sections (C-sections), which increased from 12% in 1990 to 24% of all births in 2008, each costing between £1197 and £3194. 27 It was further estimated that the cost to the NHS for maternal care due to smoking in pregnancy is between £8M and £64M per year (depending on the costing approach);28 a further £12M to £23.5M per year is spent treating infant conditions attributable to smoking during pregnancy. Another study estimated that the cost of neonatal care for low birthweight babies was between £12,344 and £18,495 per child in English hospitals. 29 These items reflect those in the Quality Innovation, Productivity and Prevention (QIPP) Metrics included in the NHS Outcome Indicators for Maternity.

The impacts of doula care described above are derived from quantitative data generated by randomised controlled trials and included in systematic reviews. There is a relative dearth of qualitative evidence to enable understanding of the experience of receiving doula support. The evidence that is available from women who received doula support indicates a greater sense of participation during labour. 30 A study of the experience of receiving doula support in Sweden identified continuity, the ‘natural’ nature of the support provided and a human dimension to the birth experience as the key characteristics of doula support. Private doulas are available in the UK;31 these are usually accessed by women from higher-income groups who can afford to pay for their services, with the resulting potential to perpetuate inequalities in health and social support.

Although existing evidence from a range of countries identifies important benefits to the provision of lay support in labour, key questions remain. There is a paucity of UK evidence and doula support is rare in the UK, especially for disadvantaged women. Existing studies have as their major focus lay support in labour, yet there may be advantage in providing such support throughout the childbearing episode.

The original volunteer doula project

The first volunteer doula project was established as a social enterprise initiative and has provided support to women in situations of social disadvantage since 2005. The project developed in an area with high levels of social and economic deprivation, poor education, housing difficulties and health states lower than the general population. Women are referred to the service by health professionals, interpreters, social services workers and the Teenage Pregnancy Support Services. Support can be offered at any stage but commonly starts around the sixth month of pregnancy and continues until 6 weeks after birth. Following an initial facilitated meeting, subsequent contact occurs approximately fortnightly during pregnancy until the last month, when contact occurs weekly. This project therefore differs from many of the studies of doula support identified, several of which were limited to care in labour and the immediate postpartum period.

The original project also differs from others that have been reported elsewhere in what the doulas are trained to do. Women who volunteer to provide the doula service, who are themselves usually women from the local area with children, receive training for the role, accredited by the Open College Network (OCN). Topics included in the training are preparation for birth and the birthing process, breastfeeding, child protection, domestic abuse awareness training, cultural diversity and communication skills. The doulas are expected to work closely with existing services and to optimise women’s use of both health and social services, for example attending smoking cessation clinics, accessing Healthy Start and attending clinic appointments. Signposting women to other services is a key part of the doula’s role. Women referred to the service are matched with doulas according to personality, background, locations and availability. Volunteer doulas receive reimbursement of expenses, for example travel and childcare during training sessions. There are systems in place to provide ongoing support for the doulas through, for example, local project workers.

Descriptive data from the early years of the service indicated a range of benefit when compared with the whole population of the city; under normal circumstances, women with the deprivation profile of those cared for would expect substantially worse outcomes. There were also suggestions that experience as a volunteer doula had enabled subsequent access to employment and higher education, indicating a community development aspect to this work. 32 Descriptive data such as these informed the Department of Health’s (DH’s) decision, in March 2009, to provide 3 years’ funding (£267,000) to support roll-out and replication in up to eight additional sites. This funding supported the provision of a portfolio that informs establishing and running a volunteer doula service, including consultancy expertise for 1 year; support with issues related to human resources, volunteer recruitment and induction; ‘training the trainer’; promotional material and support; training for the first cohort in each roll-out site; and access to accredited training materials. Sites have to provide and fund their own staff. Identification of replication sites was slower than expected. By February 2011, four sites, which have substantially different service and demographic contexts from the original site, had confirmed service funding for replication.

Summary

The original doula service appeared a promising innovation, developed from an international and high-quality evidence base with demonstrable health benefits that aimed to maximise the use and efficiency of existing health and social care services. The technology, that of doula support, had been transferred from other countries, systems and settings and had been established in England for 4 years, where it had apparently been well received by women and well integrated with existing health and statutory services. It therefore met the criteria specified in the National Institute for Health Research Service Delivery and Organisation programme call for promising innovations in health care. DH funding had previously been awarded and four replication sites indicated a willingness to participate in this research. This research therefore offered the potential for an increased return on original DH investment while relating to several important policy areas.

An outline proposal was submitted to the National Institute for Health Research Service Delivery and Organisation programme on 30 March 2010 and a full proposal in October 2010. Funding was confirmed in January 2011. The research commenced in October 2011 and was carried out over a 21-month period in five settings in England.

Aims and objectives

The project aimed to answer four broad questions:

What are:

-

Objective 1: the implications for the NHS of a volunteer doula service for disadvantaged childbearing women?

-

Objective 2: the health and psychosocial impacts for women?

-

Objective 3: the impacts on doulas?

-

Objective 4: the processes of implementing and sustaining a volunteer doula service for disadvantaged childbearing women?

Specific objectives within these were:

Objective 1: implications for the NHS

-

To determine clinical and public health impacts for women and their babies, including type of delivery, low birthweight and admission to neonatal unit; to determine method of infant feeding planned during pregnancy, infant feeding initiated at birth and baby’s feeding method at 6 weeks of age; to determine impact on mothers’ smoking behaviour; and to compare these for women who have received the volunteer doula service with data for the general Hull Primary Care Trust (PCT) population, designated statistical neighbours and England averages.

-

To identify the impacts on and experiences of NHS maternity care services and providers (midwives and heads of midwifery).

-

To identify impacts on other NHS services including referral to and uptake of smoking cessation services.

-

To determine the actual and potential impacts on NHS maternity resource use of roll-out of doula support at scale.

-

To determine potential savings to the NHS through clinical events averted by the service.

Objective 2: health and psychosocial impacts on women

-

To identify underlying beliefs and theories about how the service works and the contexts in which it has more or less impact.

-

Based on this, to identify key outcomes which will allow the theories to be tested.

-

To identify the views, experiences and psychosocial impacts on women who have been recipients of the service.

-

To examine the characteristics and reasons of women who disengage from the service.

Objective 3: impact on volunteer doulas

-

To identify the views and experiences of the volunteer doulas and the impacts on their life course.

Objective 4: implementing and sustaining the service

-

To provide an independent assessment of the costs of providing a volunteer doula service, including training.

-

To identify the challenges, facilitators and barriers experienced by the manager and staff of the original initiative in establishing and maintaining the service.

-

To identify the process of agreeing funding for service costs and the main factors responsible for the positive decision.

-

To examine facilitators and barriers to implementation in the roll-out sites and the extent to which these differ between sites and from the original service.

-

To investigate the experiences of the replication package at the roll-out sites.

Chapter 2 Methods

Settings

Settings comprised five volunteer doula services, run by either the NHS or third-sector organisations: the original volunteer doula project and four roll-out sites. All are focused on providing a service for disadvantaged childbearing women. Two doula services are restricted to women from minority ethnic groups and a third serves an area with a very large minority ethnic population. All of the services work to support women in low-income communities. To protect the anonymity of individuals, the sites will be referred to throughout this report as site A (the original site) and sites W, X, Y and Z (the roll-out sites).

Sponsorship, ethics and governance

Sponsorship was provided by the University of Nottingham. Ethics approval was obtained from the University of York’s Department of Health Sciences Research Ethics Committee for preliminary data collection among key informants and from the National Research Ethics Service Committee West Midlands (see Appendix 1) for remaining components of the research. Permissions were obtained from the research and development (R&D) departments in five NHS trusts. We have endeavoured to achieve anonymity of individuals who contributed information to this evaluation and also of sites, wherever possible.

Advisory group and public involvement mechanisms

An advisory group was established and included a range of stakeholders for the doula service, public health and academic communities. Members were drawn from participating sites, across disciplines and the service user/advocacy community. We held two advisory group meetings during the course of the research and consulted individual members for advice on particular topics throughout, as needed. Advisory group members also contributed to commenting on draft data collection tools and piloting for relevance and clarity.

Two user panels were established: one of women who had received doula support and the second of doulas, both from the original site. Members of the research team met with both user panels twice, followed by e-mail consultations on draft questionnaires. Panel members contributed to identifying important issues in the experiences of women and doulas that required exploration and in pilot testing of questionnaires.

Design

Conceptual framework

This study takes a realistic evaluation perspective,33 in recognition of the complex intervention being investigated in a real-life setting. 34 The focus is therefore not so much on addressing the question ‘does it work?’ but rather on the subtler question of ‘what works for whom in what circumstances?’. The identification of Contexts, Mechanisms and Outcomes (CMOs) at an early stage of the project is key, as they were required to generate hypotheses about the circumstances under which the intervention works. These CMOs are generated both from the literature and from the beliefs of key informants, in this case doula managers and project workers in all sites and doulas and service user representatives in the original site. This approach meant that later data collection could not be fully specified until after the identification of CMOs.

Accordingly, following a description of the literature review, our methods for data collection will be described in two stages. We will first describe the methods used in the initial stage of the research and the outcomes of this stage, including the generation of CMO configurations (CMOcs). We will then present the methods for the second stage of the study, which arose from this first stage and involved some modification to our original plans.

Literature search

The original literature search was extended (see Appendix 2 for details of search strategy) to identify evidence that may suggest possible Mechanisms for how doula support might impact on women’s health and well-being. A total of 1561 abstracts were screened for relevance and full papers were obtained where appropriate, following discussion within the research team. Information extracted by team members was entered onto a Microsoft Word (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) proforma and included the following:

-

which research question it informed

-

setting, content of any intervention and problem addressed

-

how outcomes were measured

-

utility for any data collection tools for women, doulas and other groups of participants

-

possible CMO pathways defined

-

additional information that would inform a general background, discussion or the health economics component.

In excess of 100 papers were reviewed and data extracted, at which point no new themes emerged and it was considered that saturation was achieved. From this data extraction, potential CMOs were identified for subsequent refinement and testing, together with those emerging from the first stage of data collection described below.

Data collection from key informants

The purpose of the first stage of data collection was to understand key features of establishing a volunteer doula service and to explore with key informants their beliefs about how the intervention works, and for whom and in which circumstances. 33

Doula service staff

Information about the research was provided directly to current and previous managers and subsequently to other doula service staff at all sites. Following provision of informed consent, digitally recorded individual interviews were carried out with the current and former managers of the original doula project and a group interview with project workers at the original site whose role includes matching women and doulas. Interviews mapped how the service works in practice and explored underlying beliefs about how it works, the contexts in which it has more or less impact and the enablers and barriers to establishing a doula service.

Individual or group interviews were then carried out with the managers and project workers in each of the roll-out services, exploring the development of the service to date and aspirations for the coming year.

Across the five sites, 25 individuals were identified who contributed to the running of the service, either in the office or in a managerial role, hereafter referred to as ‘service staff’.

Volunteer doulas

A focus group was considered to be the best way of eliciting the views and experiences of volunteer doulas so that their different perceptions could be discussed between group members. Participants were identified with the assistance of project staff in the original doula service with the aim of representing a range of views and experiences including volunteers from different training cohorts and with different sociodemographic backgrounds. Participant information leaflets were forwarded to potential participants by staff of the doula service to maintain confidentiality, with the opportunity to raise questions either via the service staff or directly with the research team. Following permission to contact/expression of interest, the focus group was arranged by the research team and held independently of project staff. Written consent was obtained from participants and the digitally recorded discussion addressed a number of areas including what might constitute a ‘good match’, which women might particularly benefit from doula support and impacts on doulas themselves from volunteering. Eight volunteer doulas (current and past) from the original doula service attended and participated in the focus group. These doulas subsequently agreed to be a doula user panel that acted as a source of advice in subsequent stages of the research, joined in a second focus group by a further three.

Service users

As with volunteer doulas, a focus group was considered to be the best way of eliciting views and experiences. Identical processes were used as for the volunteer doulas, described above. Seven women attended and participated in a focus group. These women agreed to be a women’s user panel that acted as a source of advice in subsequent stages of the research. Three women who had taken part in the first women’s focus group participated in a second group discussion.

All recordings were fully transcribed and thematically analysed to support the development of CMOcs.

Development of Context, Mechanism and Outcome configurations

Realistic evaluation seeks to address the question ‘what works for whom, in what circumstances’ by theorising the Mechanisms that might result in particular Outcomes in particular Contexts. Understanding the ‘why’ is key. 35

Initial analysis produced a lengthy list of statements from our various data sources which linked some occurrence with some outcome. These were all far too specific (e.g. ‘because Sally knew Mary she was able to access some particular resource’) and needed to be refined to a higher level of generality (e.g. being well networked increases access to resources). In many cases only two of the three CMO elements were articulated and in these there was scope for considerable debate about whether some occurrence was a Context or a Mechanism, or alternatively a Mechanism or an Outcome. Given these ambiguities, and the need to reduce the CMOs to a workable number, we decided that we would initially focus on establishing possible Mechanisms, to be developed into more general CMO configurations at the next stage.

All interview transcripts were reviewed for any evidence of a theme that we felt pointed to a Mechanism. We identified three levels of Mechanism – service level, doula level and woman level – with some Mechanisms working on more than one level.

All theorised Mechanisms identified by level are listed below:

-

service-level Mechanisms:

-

networking

-

transferable skills of staff/experienced staff

-

flexible staff

-

goodwill work and costs absorbed by host agency/organisation/other

-

service shaped to fit with local service drivers

-

responding to funding availability

-

fitting supply and demand

-

support for volunteers

-

joint/partnership/multiagency working

-

service differentiate from statutory and professional services

-

marketing

-

-

doula-level Mechanisms:

-

supported training

-

work experience

-

experience with/exposure to different backgrounds

-

choice of cases and workloads

-

supervision and support from services

-

being respected and valued and treated as an individual

-

reflection on personal experiences

-

-

woman-level Mechanisms:

-

being prepared for birth

-

doula support in labour

-

doula non-professional, non-medical support

-

doula not friend or family

-

doula someone can relate to/someone who can model behaviour

-

doula working with others as a team

-

doula exhibiting confidence in the birth process

-

doula imparting knowledge

-

doula explaining medical/technical language

-

doula as advocate

-

doula providing holistic/woman-centred support

-

doula non-judgemental, culturally aware, diplomatic and sensitive.

-

In addition to analysing the initial key informant data to identify Mechanisms, we retained a focus on the four key research questions. We organised the ensuing information into a table which captured theme (possible Mechanism), relevant research question(s), evidence (data), Mechanism level, site and data source.

One example of a dominant theme across all five sites was networking. This suggested a service-level Mechanism, possibly influenced by the Context of the service managers’ existing contacts, with a possible Outcome being referrals, volunteers or funding, thus establishing and/or sustaining a service. This potential CMOc pertains to key research objective 4:12 – to identify the challenges, facilitators and barriers experienced by the manager and staff (locality development workers) of the Goodwin volunteer doula initiative in establishing and maintaining the service – and objective 4:14 – to examine facilitators and barriers to implementation in the roll-out sites and the extent to which these differ between sites and from the original service. Table 1 is an example, an extract from the table of possible Mechanisms theorised from the key informant data, linked to research questions. Three Mechanisms are identified at the levels of service, doula and woman.

| Theme (possible Mechanism) | Research question(s) | Level(s) | Evidence (data) | Data sourcea | Site |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Networking | Objective 4:12 establishing and maintaining initial service Objective 4:14 establishing and maintaining roll-outs |

Service | Networking with other organisations to recruit volunteers | 8 | W |

| Liaising with local maternity services | 11 | Z | |||

| Liaising with midwives and linking with partners/organisations | 13 | X | |||

| Service known because of pilot; also a lot of networking done | 4 | A | |||

| Partnership working; links with other organisations; attending health and social care services meetings | 15 | Y | |||

| Support for volunteers | Objective 4:12 Objective 4:14 Objective 3: impact on volunteers |

Service Doula |

Identification of need for bereavement support for volunteers | 8 | W |

| Access to six sessions of counselling via occupational health | 2 | A | |||

| Monthly volunteer meetings | 11 | Z | |||

| Flexible staff | Objective 4:12 Objective 4:14 Objective 2: health and psychosocial impacts on women |

Service Women |

Volunteers assist women with benefits queries | 13 | X |

| Postnatal support period extended beyond 6 weeks when a baby is removed from its mother | 2 | A | |||

| Text rather than phone support offered when preferred by non-English-speaking women | 4 | A |

We next focused on the Outcomes that had been identified in the literature and by key informants, with a view to selecting a subset that doulas and users considered meaningful and which could be assessed in the main data collection and used to test CMO hypotheses. This element was informed by additional insights gained during further group discussions with our two reference panels (doulas and women who had used the service). Examples of Outcomes discussed with doulas included employability and personal growth and development, and with women being linked in to services, labour and birth, and infant feeding.

The outcomes identified from stage 1 for further investigation in stage 2 are listed by level below:

-

service-level Outcomes:

-

funding

-

volunteers recruited

-

volunteers retained

-

referrals/uptake

-

balance of supply and demand (volunteers and referrals/uptake)

-

-

doula-level Outcomes:

-

role satisfaction

-

knowledge of other cultures/confidence to talk to women of other cultures

-

economic impact (e.g. impact on paid work, childcare costs)

-

increased life choices

-

knowledge of field of work

-

personal growth including self-esteem, identity, self-efficacy and confidence

-

social capital

-

-

woman-level Outcomes:

-

birth experience

-

health of mother, baby and family

-

experience of health services

-

use of appropriate services

-

self-confidence, self-esteem, self-efficacy, empowerment, confidence as a parent

-

social isolation versus social integration

-

relationship with partner.

-

Outcomes were now reunited with Mechanisms and Contexts to reformulate CMO configurations by cross-referencing the Mechanisms identified with possible relevant Contexts based on the first stage of data collection. A table was constructed for each Outcome to identify possible intersections and CMOs.

Table 2 shows an example of cross-tabulation of Mechanisms and Contexts for a specific Outcome, in this case ‘Health of mother, baby and family’. Each number in the grid represents a different CMOc. For example, CMOc2 would be ‘If a doula is experienced then not being a friend or family member will have a greater impact on women’s health outcomes (than if she is inexperienced)’. In general we found that the CMOcs were not specifying that a given Context was necessarily a prerequisite for a particular Mechanism or Outcome but rather, as in the example given for CMOc2, they were hypothesising that the impact would be greater than it would be without this Context.

| Contexts | Mechanisms | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Doula non-professional/non-medical | Doula not friend/not family | Can relate to doula/doula can model behaviour | Doula imparts knowledge | |

| Woman level | ||||

| Age | 3 | |||

| Ethnicity related to language needs; communication needs | 8 | |||

| Parity and previous birth experience | ||||

| Education | 9 | |||

| Referred/self-referred (proxy for motivation) | 4 | |||

| Type of need (e.g. single, complex) | 1a | 5 | ||

| Relationship status (links to alternative of birthing alone) | ||||

| High-risk/low-risk pregnancy | ||||

| Doula level | ||||

| Ethnicity and language | 6 | |||

| Level of experience | 2 | 10 | ||

| Motivation for volunteering including past work experience | ||||

| Quality of match | 7 | |||

| Site level | ||||

| NHS vs. third sector based | ||||

| Length of time service established | ||||

| Experience/focus of staff | ||||

| Birth/maternity unit medicalised vs. natural birth | ||||

| Level of staffing | ||||

The final step involved incorporating the CMOs in the outcomes tables into CMOcs. The process of creating CMOcs was assisted by adopting the technique proposed by Jackson and Kolla36 whereby quotations are coded for each element of the CMOc. The CMOc hypothesises that there is a relationship between M and O and that this is different in different Cs. Thus questions follow the format of ‘if the right processes operate in the right conditions, then the programme will prevail’ (p. 184). 35 Contexts were defined as being at the levels of the woman, the doula and the doula service. This generated 18 service-level, 82 doula-level and 107 woman-level CMOcs. We were able to reduce this rather overwhelmingly large number by omitting all those which were not in fact testable within the research design that we were using. For example, some referred to the birth environment, about which we would have little information, and some referred to specific aspects of the doula–woman match, about which we would similarly be lacking information. A number referred to relatively rare occurrences for which we knew that our numbers would be inadequate. Those remaining were used to guide, but not to constrain, the second stage of data collection, as we were aware that considerable descriptive information would also be needed which had not necessarily yet appeared as part of a CMOc.

The initial approach was to seek to identify CMOcs that were potentially testable within our study design and within the data collection constraints. This approach was modified in the context of a limited sample size and instead we sought to explore statistically two of the three components of the CMOc and complemented this by using a qualitative and discursive approach. Testing a Mechanism–Outcome relationship may not find the expected relationship because the Mechanism ‘works’ only in certain Contexts; however, some Mechanisms (e.g. continuous labour support) may be viewed as ‘universally good/beneficial’ and therefore less dependent on Context. Linked to this is the idea that the research question is perhaps ‘what works best’. In other words, rather than the assumption that, all else being equal (i.e. programme fidelity), the doula programme does not work for some women, the assumption is that the programme has some universal benefit but works particularly well for some women.

The order below follows that of the research questions included in the original proposal.

To determine the impacts of volunteer doula support on key clinical and public health outcomes for women and their babies

Data sources

Women offered doula support

The original doula service has been collecting information and entering it into a bespoke database since 2007. Available data items include women’s age, smoking status, source of referral to the doula service, method of birth and whether or not their baby was of low birthweight. These data provided a basis for comparing women who were offered doula support with women in the same geographical area, and with other reference groups, for certain clinical and public health outcomes including health behaviours such as smoking and breastfeeding. In each case the most appropriate available comparison data sets were used.

Reference groups

Hospital Episode Statistics

Detailed analysis of Hospital Episode Statistics (HES)37 was undertaken by analysts at the Child and Maternal Health Intelligence Network (ChiMat, www.chimat.org.uk). Data items included for comparison with those from the doula service database were mode of birth, birthweight and the mother’s age, ethnicity and postcode district. Analysis was restricted to mothers whose PCT of residence was Hull (PCT code 5NX). While HES is known to have data quality issues, areas of known concern were avoided. Data were produced in line with the approach used by the Health and Social Care Information Centre when publishing data.

Maternity system at Hull and East Yorkshire Hospitals NHS Trust

Hospital Episode Statistics data indicate that 99% of women resident in Hull PCT give birth under the auspices of the Hull and East Yorkshire Hospitals NHS Trust (HEY). Data obtained from the maternity system at HEY were analysed and showed a large number of births to mothers living outside Hull. Only those mothers living in Kingston upon Hull (postcode districts HU1, HU2, HU3, HU4, HU5, HU6, HU7, HU8 and HU9) were included in our analysis. The fields available were postal area (postcode district), mode of delivery, financial year, feeding intention at delivery, smoking at delivery, ethnic category, mother’s age at delivery and admitted directly to neonatal unit. Unfortunately, because of system limitations, mother’s parity could not be reported with any accuracy. Consequently the intended analysis of parity could not, unfortunately, be carried out.

Published data

Published data were used as a comparison where local data sources were not readily available. The data sets do have some limitations, offering limited, if any, controllable variables. Published data were available at local authority or PCT, depending on subject and source.

Hull PCT and Kingston upon Hull local authority had coterminous geographical boundaries and are commonly used alongside each other in publications and analysis.

Primary Care Trust data

Published data sources38 were used including breastfeeding initiation, breastfeeding status at 6–8 weeks and smoking at delivery. 39 Comparisons were made with outcomes for demographically comparable subsamples within (1) the general Hull PCT population, (2) the designated statistical neighbours for Hull and (3) England averages. ‘Designated statistical neighbours’ are areas that have been identified as having similar key characteristics based on census data and a list of them is available from the Department for Education. Statistical neighbours were used only for published data. While there are known data quality issues with some areas, these were not considered an issue for the geographies selected.

Local authority data

Published data sources were used to compare demographic data about the mothers. The 2011 census40 provided data about age, ethnicity and population sizes. Kingston upon Hull was the reference group used.

Process

As no data dictionary was available, we met the administrative team in the Goodwin Volunteer Doula project in Hull to understand the database. This allowed confirmation of fields to be used and the interpretation of them. After a preliminary analysis and presentation of results, data quality issues were identified that required resolution prior to further analysis. Data quality checks were carried out to highlight missing data, obvious errors and conflicting observations such as the method of birth or feeding. Because of the amount of work required and resources available, data items were prioritised for checking and correction. A number of additional fields were added to the doula service’s standard report, including a flag when the mother had disengaged from the doula service, a common reason for missing data; person identification (ID); and previous number of children.

The data set on which the final analysis was based was extracted on 27 December 2012.

The data are reported from the doula database as three data sheets: ‘referral’, ‘mother’ and ‘outcome’. Data linkage across tables was possible through the creation of a unique identifier consisting of the person ID and another number based on the number of times the mother had used the service. On extraction, the fields in the doula database are represented as a ‘0’ (no), ‘1’ (yes), ‘–1‘ (not known) or blank (not known). Items were collated on the outcomes sheet, including the mother’s age, postcode district, ethnicity and previous number of children.

Additional data items were created. These included:

-

summary fields indicating feeding method at birth, feeding method at 6 weeks and mode of birth.

-

a field indicating financial year based on the baby’s date of birth; where the date of birth was missing, an assumed date of birth was created based on the date of matching. Previous analysis had indicated that, on average, the mother was matched with a doula approximately 3 months before giving birth

-

a grouping based on ethnicity where those defined as ‘white British’ were called ‘white British’ and all others were grouped into ‘non-white British’

-

mother’s age category, summarised as ‘under 20 years’, ‘20 to 24 years’, ‘25 to 29 years’, 30 to 34 years’, ‘35 to 39 years’ and ‘40 years and over’.

As the database included records for mothers who had not yet given birth, a cut-off point was established of 31 August 2012. This was the last month with almost complete data and was included in the data cleanse. Births after that date were ignored to ensure the data quality was as high as possible. Analysis of the number of live births showed they were consistent over the period reported and it was felt unnecessary to make any adjustments for this.

To determine the impacts on NHS midwives

Process

Heads of midwifery

After the research team had provided information and obtained informed consent, individual, digitally recorded telephone interviews were carried out with all heads of midwifery in the five NHS trusts providing maternity care closest to the doula service. These explored perceptions of the volunteer doula role, their voluntary status, communications and working between the doula and maternity services, and the future of doula support. Interviews were transcribed in full.

Midwives

The head of midwifery in each trust was asked to forward an e-mail from the research team to midwives asking those with experience of caring for a woman who had received doula support to attend a focus group, during working hours, at their place of work, to discuss their views and experiences. The sampling strategy was therefore purposive and midwives attended on a self-selection basis. The focus group discussion was digitally recorded and explored midwives’ views of the profile of the doula service; their experiences of providing clinical care to women supported by volunteer doulas; whether support during pregnancy, labour or following birth was most important; views of the boundaries of the doula role; and impacts on women’s use of maternity and other services. Focus group discussions were transcribed in full.

Analytical methods utilised are described later in this chapter, Qualitative data, and findings are presented in Chapter 3, The impacts on and experiences of NHS maternity care services and providers.

What are the health and psychosocial impacts for disadvantaged childbearing women?

A range of approaches was used to address this objective, with some changes to the methodology set out in the proposal, which had relied primarily on postal questionnaires. After discussion with the advisory group and our user panels, and in recognition of the high proportion of women who did not have English as a first language, or who might not be literate, we chose instead to offer a wider range of ways in which women could tell us their views. We were advised that women who were unable to speak and complete questionnaires in English might also not be able to read materials in their mother tongue. Rather than obtaining translations of consent forms and questionnaires, we decided instead to involve professional interpreting services, independent of the doula services, for the collection of data. We also hoped that this more personal approach might facilitate women’s involvement. We also decided not to offer online questionnaire completion as an option, as it was not considered likely to have a high uptake.

Our aim was to invite all women (n = 627) who had been offered doula support across all sites to contribute their views through at least one of the data collection methods: postal questionnaire, focus group discussion and assisted questionnaire completion by telephone with an interpreter if required. All information collected from women was retrospective because of resource constraints that precluded the follow-up of a prospective sample.

Data collected directly from women

Identifying and contacting women

To maintain confidentiality of information held by the doula service, women were identified from service records by local service staff, who were asked to forward invitations to participate on behalf of the research team. No service staff were directly involved in data collection.

Members of the research team consulted doula service staff in the development of guidance notes and monitoring logs for sites to complete, detailing the number of women approached, number of times approached, dates of contact, reasons for non-approach and reasons for not sending out research packs (e.g. where the woman declines).

Service staff were asked to attempt to contact all women who had ever been referred to the service (including women who subsequently failed to engage with the service but not those still in receipt of the service) in each of the five sites. Other exclusions related to women’s personal experiences where contact had the potential to increase a woman’s stress or vulnerability. The records of the doula service indicated a particular woman’s needs and circumstances. The services were asked to make the first approach using their standard practice (e.g. for a woman needing to be approached in a non-English language, approach by bilingual staff, or use of an interpreter).

The research team requested that, at the first approach, women be told about the independent evaluation and asked if they would be happy to be sent a pack containing further information about the research, including contact details for the research team, together with the questionnaire and information about the focus groups. Where a current telephone number was not available or contact could not be made after three attempts, the service was asked to send the information and questionnaire using the last known address. The research team provided doula service staff with prepared packs for forwarding to women following addition of an address label by doula service staff. The research team requested that anonymised information from the completed proforma be forwarded to the research team twice weekly. The information recorded in the proforma also provided a denominator for questionnaires sent and for calculation of response rates.

Questionnaires

It had originally been intended that questionnaires would be sent out in two waves. However, the advantages of this were subsequently judged not to outweigh the considerable extra work for the sites and so all contacts with women were made at what would have been the time for the second wave.

The packs included a covering letter from the research team, questionnaire and reply-paid envelope for direct return of the questionnaire to the research team, thus maintaining confidentiality of response. Terminology, for example the name used for the volunteer doula, varied across sites, and questionnaires and covering letters were individualised to sites accordingly. Centre codes (denoting the five sites) were printed on questionnaires. The covering letter contained all aspects pertaining to participation in the study, including the voluntary nature of participation, and contact details for the research team to enable the potential participant to ask any questions. It also informed women that they would be sent a £5 high street voucher on receipt of the completed questionnaire if they chose to provide their contact details. Contact details were not otherwise requested and were used only for the stated purpose.

Two versions of the questionnaire were developed, according to whether or not the woman accessed the support service (see Appendices 3 and 4). Completion and subsequent return of questionnaires was deemed to imply consent. Questionnaires were returned directly to the research team and the researchers’ independence from the service was stressed, as was the fact that any information provided by women would not be shared with anyone outside the research team in a way that allowed them to be identified.

Reminder postcards were sent to women by doula service staff after 3 weeks, thanking those who had already returned questionnaires and indicating that there was still time to return questionnaires, for those who had not yet done so. A phone number was given to allow women to request another copy of the questionnaire if needed; 578 women were identified for approach for completion of questionnaires.

Telephone-assisted questionnaire completion

In recognition of potential literacy issues, irrespective of preferred language, women were also offered the option of having a researcher (or interpreter appointed by the research team) telephone them to talk them through the questionnaire. If women indicated a wish for telephone-assisted completion, this information was passed from the doula service to the research team and a member of the research team or interpreter appointed by the team conducted a digitally recorded telephone completion after obtaining informed consent. The questionnaire was translated by the interpreter at the time of use. The data collection was fully structured and followed the questionnaire, which was adapted for telephone use. To make the questionnaire an acceptable length, a subset of the original questions was included. Women were interviewed in a language of their choice and translators, independent of the service, were identified for all required languages.

Questionnaire content

The questionnaire was piloted to ensure relevance and clarity with the support of members of our advisory group and women’s user panel. In addition to demographic information, for example education, employment status and whether or not the woman had a partner, questionnaires collected data in the following areas: relationship with doula and experiences of receiving doula support; health behaviours including smoking; emotional well-being, including the extent to which the woman feels in control of her life; and an assessment of the benefits and disbenefits of the service. These topic areas included those identified in work that developed CMOs in the first stage of the research.

It had always been intended that the questionnaires would include some items that would allow comparison of women’s experiences with a reference group. The Millennium Cohort Study and Family Nurse Partnership evaluation had provisionally been identified as comparators in the original proposal, but, after discussion at the first advisory group, it was apparent that these were not ideal. An alternative was identified in the surveys of women’s experiences of maternity care in England carried out by the Picker Institute, with findings available for individual NHS trusts. 41 Prior to our data collection period, the Picker Institute last conducted a survey of women’s experiences of their maternity care in 2010, and inclusion, with permission, of some of those questions thus provided a reference set of findings for those in our research.

Focus group discussions

We consulted doula service staff to identify the languages spoken by women in their sites to determine the predominant language, besides English in each site. In the roll-out sites, we planned to conduct at least one focus group in English in each site and one group in another language where the number of potential participants speaking a common language would support a focus group. In the original site, as the pool of women was potentially greater, we planned a maximum of three focus groups in English and one in another language. Participation in a focus group was offered as an alternative to questionnaire completion at site A. At the roll-out sites, because the number of women was so much smaller, it was offered as an option to all women, irrespective of questionnaire completion.

Following written consent, focus groups enabled the exploration in more depth of key topics identified through the initial data collection with the key informants and discussions with the user panels. Importantly, the group discussions allowed the exploration of those CMOs that could not be tested in questionnaires. A topic guide included the following: how doula support differed from other support; relationship with doula; doula support with feeding and use of other services; and why doula support is important. The discussion was digitally recorded.

Participant acknowledgements and reimbursement of expenses

Participants’ contributions were acknowledged with the provision of a £5 high street voucher for return of a questionnaire, a £10 voucher for participation in a focus group discussion and a £5 voucher for telephone completions. Women attending groups were informed that full reimbursement of transport costs was available. Refreshments (including lunch) were provided at the group discussions, together with a crèche facility.

Use of data collected by services

The information collected by doula services on their databases and paper-based service documents (including initial referral forms and service evaluation documents) provided an additional source of data that we had not been aware of at the time of writing our proposal.

In practice we did not find that these sources added materially to our data and they will not be reported in the body of this report, but further information about our use of these data and an overview of the findings are available in Appendix 5.

What are the impacts on volunteer doulas?

A postal questionnaire was sent to all volunteers (n = 258) trained by the five volunteer doula services, with a small number of follow-up telephone interviews to explore particular aspects of experience in questionnaire responses. In the questionnaire (see Appendix 6) we obtained some demographic information and explored the following areas: training to be a doula; becoming involved with the doula service; the doula role; workload; matching women and doulas; barriers to and challenges in supporting women; support for doulas; how the doula service fits and works with other services; impact of the doula role on women and doulas; ending the relationship with the woman; stopping volunteering; and a summary of the experience of being a doula. A second, shorter, version of the questionnaire was developed for those volunteers who had completed training but had not (yet) supported any women. This omitted sections that were not applicable and included questions about why no women had been supported and, if volunteering had ceased, the reasons for this (see Appendix 7).

The acceptability and ease of completion of the questionnaires were determined with the aid of members of the volunteer doula user panel and advisory group.

Process

To maintain confidentiality within doula services, we could not approach volunteer doulas directly. The process reported for contacting women (see To determine the impacts of volunteer doula support on key clinical and public health outcomes for women and their babies, Process) was also used to develop the sampling frame and for sending questionnaires to doulas.

The research team provided doula service staff with prepared packs for forwarding to doulas following the addition of an address label by service staff. The packs included a covering letter from the research team, questionnaire and reply-paid envelope for direct return of the questionnaire to the research team, thus maintaining confidentiality of response. The covering letter contained all aspects pertaining to participation in the study, including the voluntary nature of participation, and contact details for the research team to enable the potential participant to ask any questions. Centre codes (denoting the five sites) were printed on questionnaires.

We had originally planned for an initial and second wave of data collection to include doulas who completed training during the life of the research but for a number of reasons, including minimising demands on doula services and the protracted nature of governance processes, it became clear that a one-stage approach to this element of data collection, later than originally scheduled, was optimal.

The questionnaire asked volunteer doulas if they would be willing to take part in a telephone interview to explore any topics in more detail. Those who were willing completed a reply slip when returning the questionnaire providing their contact details and indicating their informed consent to contributing further. Respondents were not asked to provide contact details unless they wished to be contacted for participation in an interview. The sampling strategy for interviews was, therefore, a purposive one that enabled more detailed exploration of new issues identified in a questionnaire response.

Reminder postcards were sent to all volunteer doulas by doula service staff, 3 weeks after the mailing out of the questionnaires. This thanked those who had already completed questionnaires and invited completion from those who had not yet done so. If selected for participation in a telephone interview, doulas were contacted directly by a member of the research team using the details they had provided. The telephone interviews were digitally recorded (with one exception) and fully transcribed.

What are the processes of implementing and sustaining a volunteer doula service for disadvantaged childbearing women?

This component involved managers, doula service staff, local champions and commissioners at the five doula sites. Its purpose was to identify how each service works in practice and what the enablers, barriers and impacts had been. As the roll-out sites were at a relatively early stage of their development, our study had the opportunity to explore this development over time, by carrying out data collection at two time points, early in the study and later, to determine both experiences of the early stages and aspirations for the coming year and, subsequently, the extent to which these were achieved.

Doula service managers and staff

All staff employed by the doula services were identified by virtue of their professional role and invited to participate by a member of the research team. Doula service managers and staff were interviewed early in the evaluation, as already described, and a subset were reinterviewed a year later to identify changes and factors related to sustaining those services. In the proposal we had intended to limit second interviews to the roll-out sites, but it was recognised that issues of sustainability were equally important in the original site, so they were included in this aspect of data collection. A total of 11 staff contributed data.

Local champions and commissioners

Each roll-out site had at least one ‘local champion’: an individual who championed the adoption of the project and saw it through to successful commissioning. Their perspectives were considered essential to developing an understanding of this vital part of the process. At the stage of developing this research proposal, only four sites had secured local funding to become a replica service. Other sites had expressed interest but, at that stage, were unable to achieve funding. The question of what led four sites to achieve implementation of the roll-out required exploration.

Local champions and commissioners (with the exception of one site, which was not commissioned) were identified by service staff and approached by a member of the research team to take part in individual interviews. All potential participants received an information leaflet and written informed consent was obtained. Local champions were asked about the nature of their relationship with the doula service and ongoing role in it, their perceptions of the impact of the service and its future, and barriers to establishing and continuing it. Commissioners were asked to describe local commissioning arrangements and service level agreements, their relationship with the doula service, any challenges encountered in commissioning the doula services and their perceptions of the service’s future. Four champions and four commissioners contributed data.

Overview of maximum possible primary data collection

Table 3 presents the maximum primary data collection possible by method and participant group. Numbers in cells for women and doulas reflect the maximum numbers of participants and were included to inform resource requirements; numbers were informed by doula services where appropriate.

| Data source | Face-to-face/telephone interviews (n) | Questionnaires (n) | Focus groups (n) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heads of midwifery | 5 (1 per NHS trust) | ||

| Midwives | 5 (1 per NHS trust) | ||

| Women | 600 maximum available | 12 maximuma | |

| Volunteer doulas | Maximum 10 to follow up questionnaire responses | 160 maximum available | 2b |

| Doula service managers | 11 initial and follow-up interviewsc | ||

| Project workersd | 11 | ||

| Local champions | 5 | ||

| Commissionerse | 4 |

Data analysis

Clinical and public health outcomes for women and their babies

Microsoft Excel (version 2010, Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) was used to summarise the data in pivot tables. Generally filters were used to remove mothers who were not supported, those who had disengaged from the service and those who gave birth (or had been expected to give birth) after 31 August 2012. Analysis of some data also required the use of ‘postnatal support only’ as a filter.

Confidence intervals were calculated using approved methodologies for public health observatories. 42 The doula service data were plotted onto bar charts alongside available comparisons, including those of designated statistical neighbours. Ninety-five per cent confidence intervals were included to indicate whether or not there were any significant differences between the doula data and comparators. Chi-squared tests were used to compare percentages of births by caesarean sections, breastfeeding at delivery and smoking in the doula population with data available from the maternity system at Hull and East Yorkshire Hospitals NHS Trust. Comparisons were made between outcomes derived from the doula database and those obtained from the maternity system at Hull and East Yorkshire Hospitals NHS Trust. Unfortunately it proved impossible to obtain all of the requisite data from the Trust data set, so we were unable to control for certain variables, such as parity.

The findings of these analyses are presented in Chapter 3, Clinical and public health impacts for women and their babies and Outcomes for women and babies, and further utilised in Chapter 7, where they have informed the economic analyses. Full details of all data sources and analytic methods for calculation of doula service and NHS costs are included in Chapter 7.

Quantitative analyses: questionnaires completed by women and doulas

On receipt of a questionnaire, each participant was assigned a unique study identity code number, for use on study documents and the Statistical Product and Service Solutions (SPSS, version 20, IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) database. Separate databases were created for women and for doulas. The women’s database included both supported and unsupported women, whether they had completed the questionnaire themselves or with assistance, with or without an interpreter. The doula database similarly included all doulas whether or not they had yet supported a woman one-to-one.

Data were analysed using SPSS. Descriptive statistics (means, frequencies, etc.) are presented where appropriate. Within-sample comparisons (e.g. of sites) were carried out as sample size allowed, using chi-squared tests for proportions and t-tests or analysis of variance to tests differences in means. When expected cell sizes were small, exact tests were used instead of chi-squared.

Comparisons with the Picker Institute maternity survey

Selected items from the Picker Institute maternity survey were included in the women’s questionnaire. A chi-squared test was used to compare the proportion of cases from the doula sample with the proportion obtained in the local maternity survey. Analyses were restricted to the original doula site because of the small numbers available at the roll-out sites. Consistent with the HES analyses, comparison data were used for the Hull PCT, a subsample of the HEY data.

Hull and East Yorkshire Hospitals NHS Trust data are based on a survey of 201 women, representing a 50% response rate for the survey. Trusts drew their sample from mothers who had had a live birth in February 2010 and were aged 16 or older. Women who gave birth in a hospital, birth centre or maternity unit, or who had a home birth, were eligible. The survey was mailed between May and June 2010, with non-responders sent up to two reminder mailings.

Qualitative data

Data collected using interviews, focus groups and free text data in questionnaires were analysed using content analysis43 to identify themes within the data, underpinned by the framework of realistic evaluation.

Each data source was treated independently. The transcripts from the interviews and focus groups were read and reread to gain a detailed familiarity with the overall accounts, and then systematically coded line by line to identify emerging themes. These themes were grouped and collapsed into higher-order conceptual themes with subthemes. For data related to women and doulas, emerging themes were considered in the light of CMO configurations. The open text questionnaire responses were tabulated using an Excel spreadsheet to show horizontally all of an individual’s responses to the questions and vertically all of the responses received to any question. This facilitated coding of themes identified in the responses on a question-by-question basis, identification of disconfirming responses and the exploration of linked patterns between questions.

For data collected from women and doulas, the final stage of the analysis was to integrate the findings of the qualitative and quantitative analyses to provide a comprehensive and integrated narrative of their experiences.

The findings related to the experiences of women and doulas are presented in Chapters 4 and 5 respectively, and those relating to implementing and sustaining the doula services in Chapter 6.

Quantitative data: costs of doula services and NHS costs

Full details of data collected and analytic method for doula service and NHS costs are included in Chapter 7.

Chapter 3 Findings: implications for the NHS

Clinical and public health impacts for women and their babies

Women supported by the original doula service

The aim of the following analysis was to identify the characteristics of the mothers who had been referred to the original volunteer doula service. Data have been pooled to produce an overall profile. At the point of extracting the data, a total of 603 mothers had been referred to the original service, of whom 599 were matched to a volunteer doula and 507 subsequently supported.

Method of referral

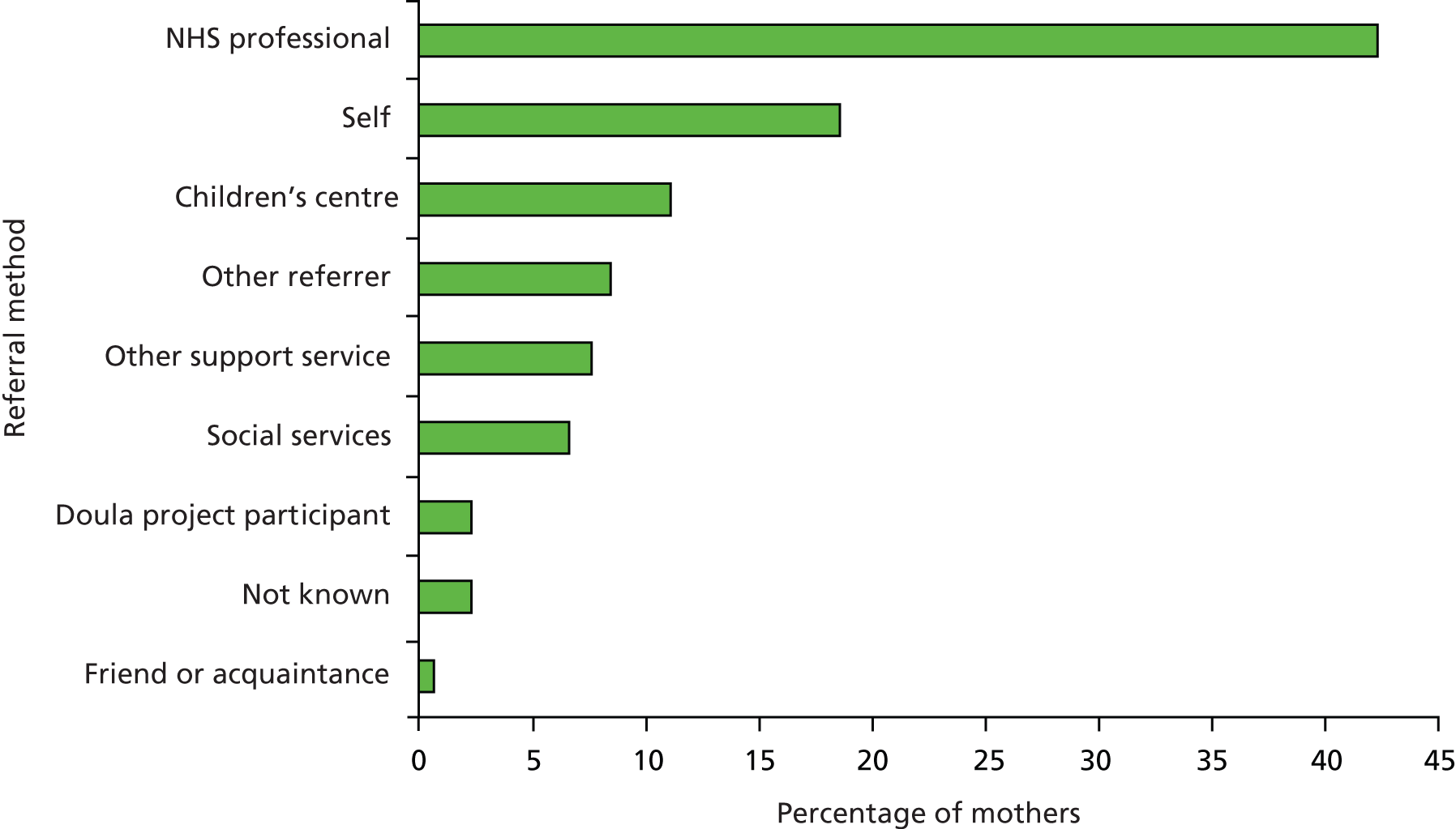

There were several routes of referral into the doula service. Referral sources were grouped together, as shown in Figure 1. Just over 43% of the 603 referrals were from a NHS professional and 23% by community midwives. The next largest category was ‘self-referral’.

FIGURE 1.

Method of referral summary, Hull doula mothers, all years, percentage. Source: developed from Goodwin volunteer doula database.

Most of the referrals by ‘other support services’ were from ‘asylum seekers/refugees support’ (3.3%) and ‘teenage pregnancy support’ (1.8%).

Mother’s postcode

Figure 2 shows the postcode districts of the 507 mothers supported by the original volunteer doula service in Hull. Most mothers lived within postcode districts HU1 to HU9, which match the boundaries of Kingston upon Hull local authority. Comparison data from HEY and the Office for National Statistics have been restricted to these postcodes.

FIGURE 2.

Mother’s postcode district, Hull doula users compared with female population, deliveries in Hull PCT and births in Hull and East Yorkshire Hospitals NHS Trust, all years, percentage. Sources: Goodwin volunteer doula database (all years); Hull and East Yorkshire Hospitals NHS Trust; Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) Copyright © 2013, reused with the permission of The Health and Social Care Information Centre. All rights reserved; Office for National Statistics (Census 2011). ONS, Office for National Statistics.

The Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) 2010 is a commonly accepted measure of deprivation. Kingston upon Hull is one of the 20% most deprived local authorities in England. Within Kingston upon Hull, as with most local authorities, there are differences in levels of deprivation across the area. Table 4 shows the percentage of women aged 16–44 years by postcode district in each national deprivation quintile.

| Postcode district | Deprivation quintile | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (most deprived) | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 (least deprived) | |

| HU1 | 99.8 | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| HU2 | 100.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| HU3 | 85.5 | 14.0 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

| HU4 | 43.6 | 14.5 | 24.1 | 6.7 | 11.2 |

| HU5 | 16.6 | 44.9 | 26.5 | 8.9 | 3.1 |

| HU6 | 53.4 | 5.9 | 24.8 | 15.9 | 0.0 |

| HU7 | 49.7 | 13.3 | 18.7 | 18.2 | 0.1 |

| HU8 | 37.7 | 22.3 | 19.1 | 13.3 | 7.6 |

| HU9 | 71.6 | 13.5 | 14.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 |

The majority of the population of HU1, HU2 and HU3 are in the 20% most deprived areas. It would suggest that the Goodwin volunteer doula service is used by mothers from areas of deprivation. The exception to this is the HU9 postcode district. Only 14.4% of Hull doula mothers come from this area compared with approximately 18.1% of both the deliveries in Hull PCT and babies being born in HEY to mothers from Kingston upon Hull. The children’s centre from which the Goodwin volunteer doula service operates is based in HU3 and close to HU1 and HU2.

Mother’s age

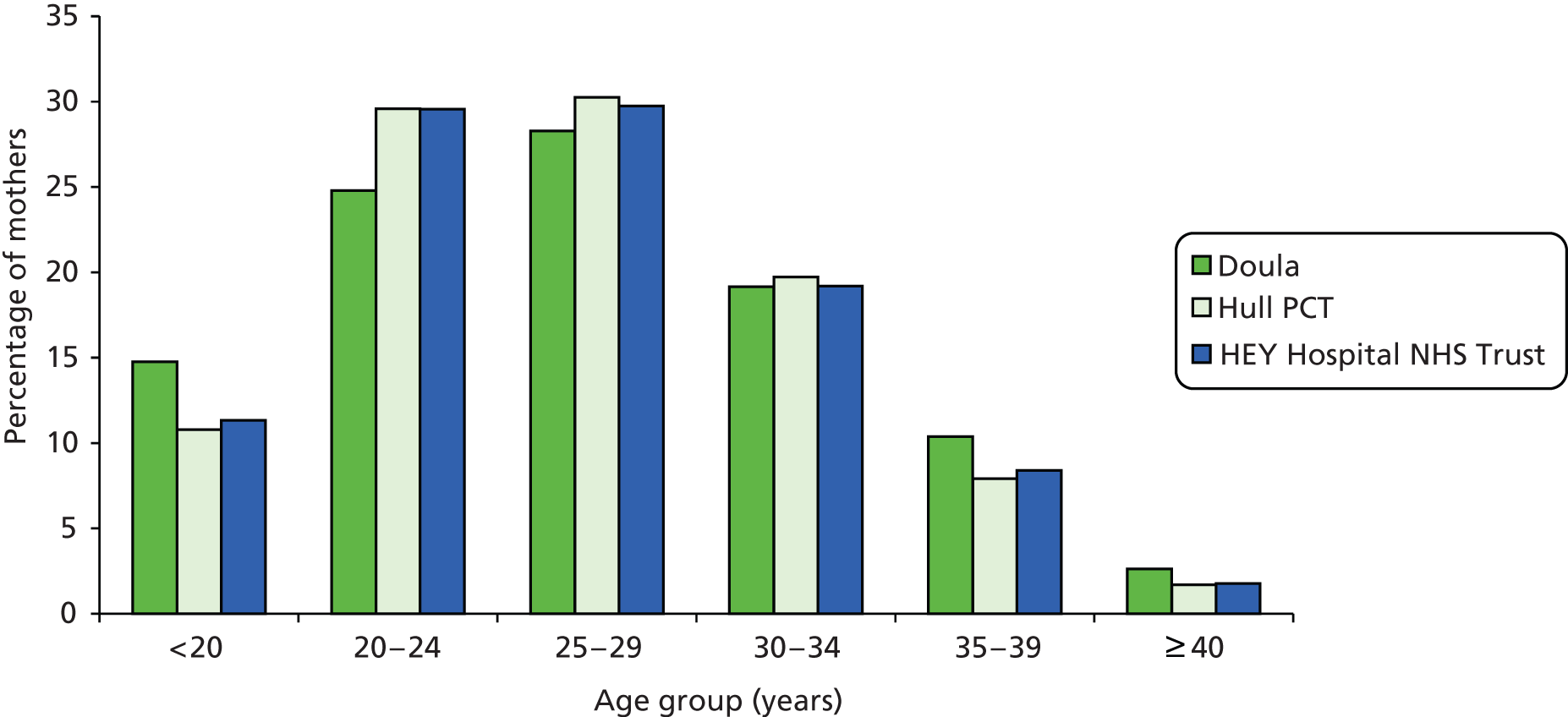

The ages of women referred to the doula service ranged from 15 to 43 years (n = 599, mean 26.7 years, mode 26 years). Figure 3 compares the age of mothers using the Hull doula service with mothers who had a child in Hull PCT and with those who lived in Kingston upon Hull and had a baby in HEY. The age profile of women offered doula support reflects the overall profile of that for Hull PCT and HEY. Mothers under 20 years of age accounted for 14.8% of all doula service users compared with 10.8% of deliveries in Hull PCT and 11.3% of deliveries to Hull mothers in HEY. Mothers aged 35 years and over were slightly over-represented among doula referrals, while those aged 20–35 years were somewhat under-represented.

FIGURE 3.

Mother’s age, Hull doula mothers compared with Hull PCT and HEY, percentage. Sources: Goodwin volunteer doula database (all years); Hull and East Yorkshire Hospitals NHS Trust, Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) Copyright © 2013, reused with the permission of The Health and Social Care Information Centre. All rights reserved.

Ethnicity

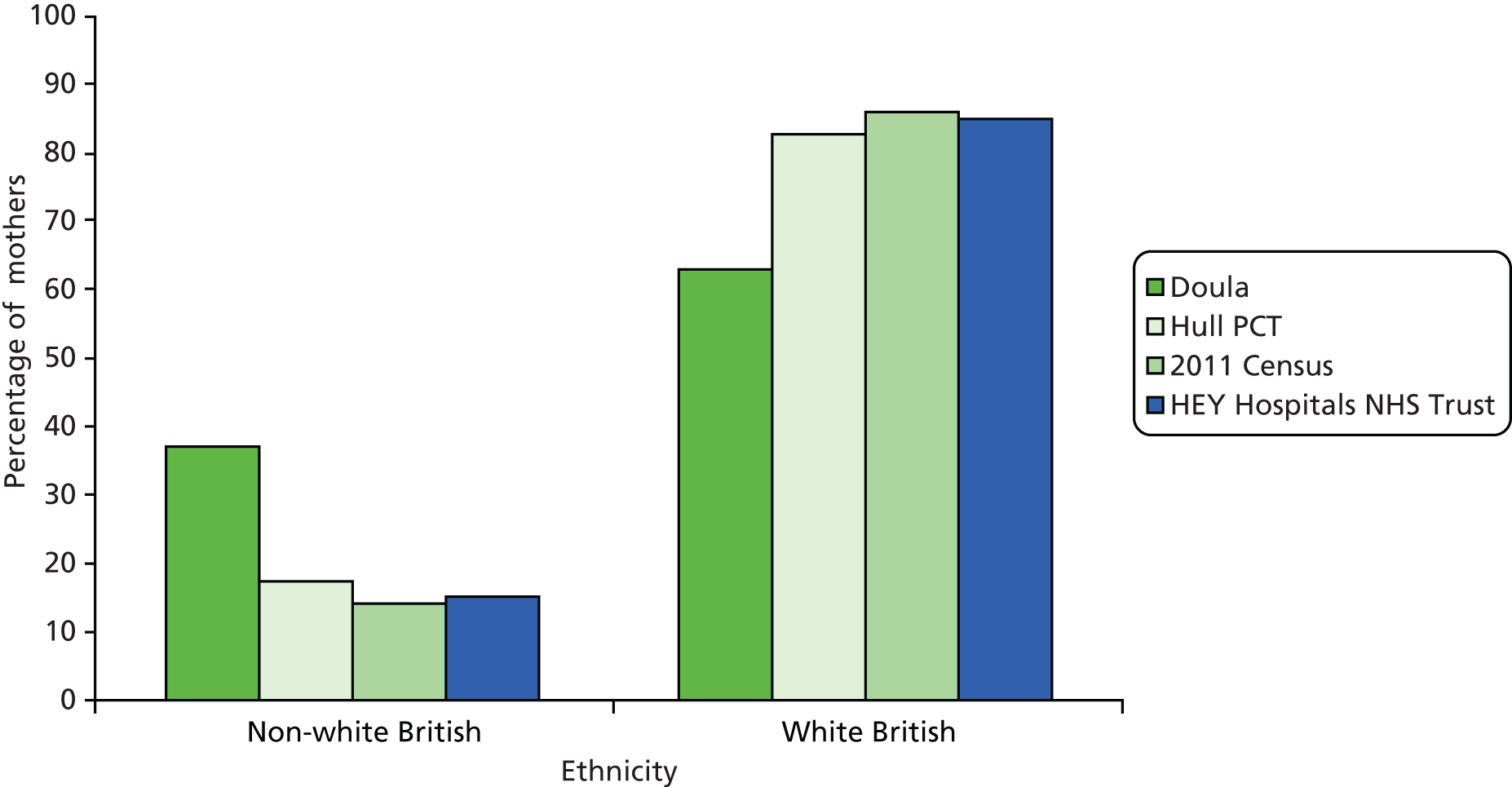

Figure 4 shows the ethnicity of mothers referred to the service. Although greater detail is available, for comparison the mothers were grouped into ‘white British’ and ‘non-white British’. ‘Non-white British’ mothers are all those mothers who are not ‘white British’. Thirty-seven per cent of women referred to the doula service were from a non-white British background. This is over twice as many as the local population rates.

FIGURE 4.

Ethnicity, Hull doula mothers compared with Hull PCT, HEY and 2011 Census, all years. Sources: Goodwin volunteer doula database (all years); Hull and East Yorkshire Hospitals NHS Trust, Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) Copyright © 2013, reused with the permission of The Health and Social Care Information Centre. All rights reserved; Office for National Statistics (Census 2011).

Further analysis of the doula service database showed the most frequent non-white British groups were ‘white – other’ and ‘black – African’, which each accounted for approximately 10% of the doula mothers. While definitions may vary slightly, as a comparison the 2011 Census indicated 4.0% of females (all ages) in Kingston upon Hull considered themselves as ‘white other’ and only 1.2% of females (all ages) considered themselves as either ‘black/African/Caribbean/black British: African’ or ‘mixed/multiple ethnic group: white and black African’. 46

Parity

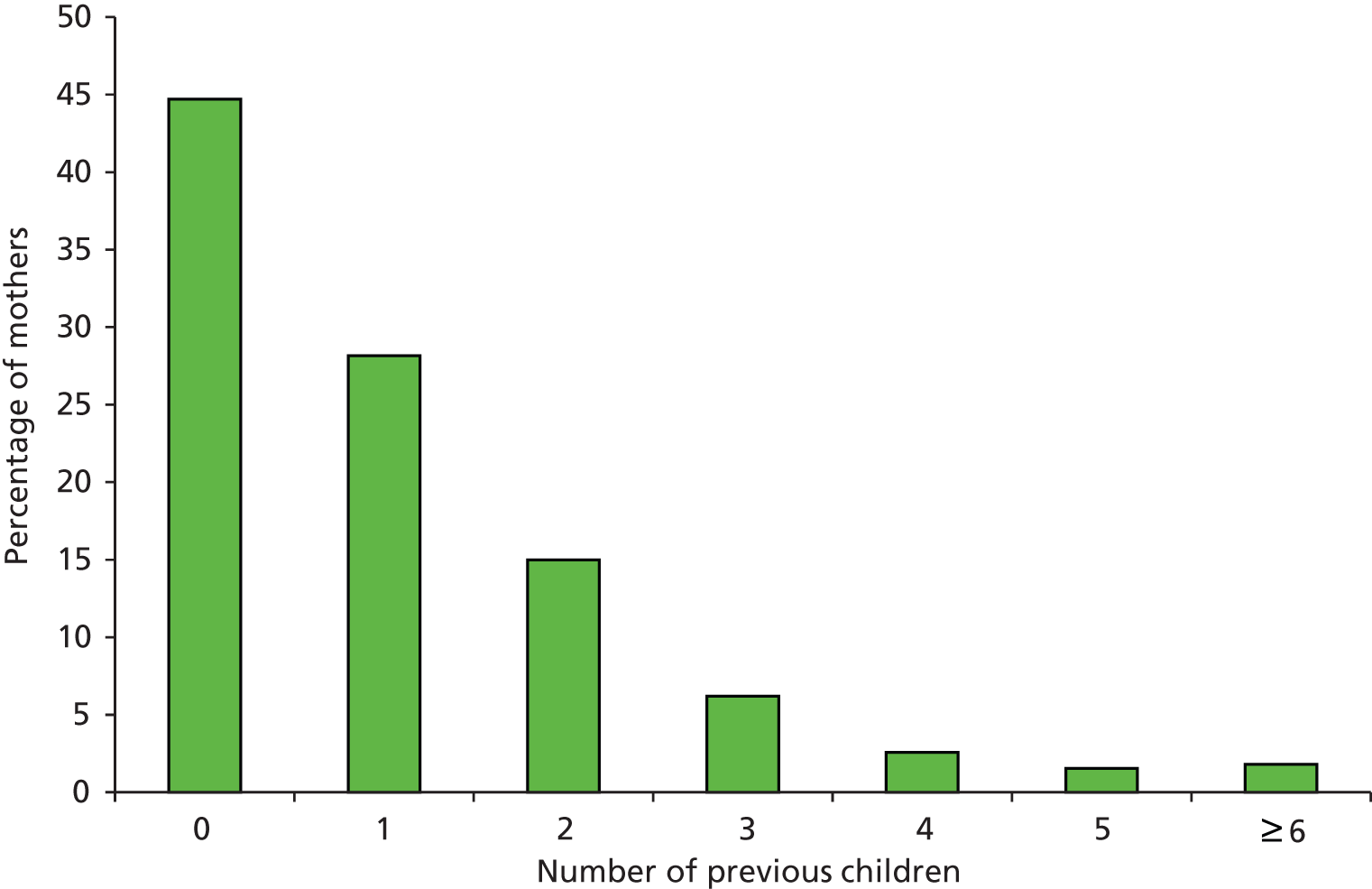

Figure 5 shows the number of previous children born to the 387 mothers who were supported and were engaging with the doula service in Hull. The number of previous babies ranged from none to eight. Almost 45% (173) of supported and engaging users were first-time mothers. A further 28.1% of mothers had one other child.

FIGURE 5.

Previous number of children, Hull doula mothers, all years. Source: developed from Goodwin volunteer doula database.

Among non-white British mothers, 46% were expecting their first baby, compared with 44% of white British mothers.

Disengagement

Almost 20% of mothers who were referred to the doula service were recorded as having disengaged from the service. As a result, there were fewer records available for analysis of outcomes than expected. The majority of these analyses are based on a sample size of around 330 mothers.

Chi-squared tests were used to examine whether or not disengagement varied by ethnic group or parity (Tables 5 and 6). Mothers who disengaged were more likely to be ‘white British’ than ‘non-white British’ [χ2 = 20.3, 1 degree of freedom (df); p < 0.05] and to be first-time mothers than women with other children (χ2 = 10.6, 1 df; p < 0.05).

| Ethnicity | Disengaged n (%) | Engaged n (%) | Total n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-white British | 28 (23.3) | 180 (46.5) | 208 (41.0) |

| White British | 92 (76.7) | 207 (53.5) | 299 (59.0) |

| Total | 120 (100) | 387 (100) | 507 (100) |

| Parity | Disengaged n (%) | Engaged n (%) | Total n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| No previous children | 74 (61.7) | 173 (44.7) | 247 (48.7) |

| Previous children | 46 (38.3) | 214 (55.3) | 260 (51.3) |

| Total | 120 (100) | 387 (100) | 507 (100) |

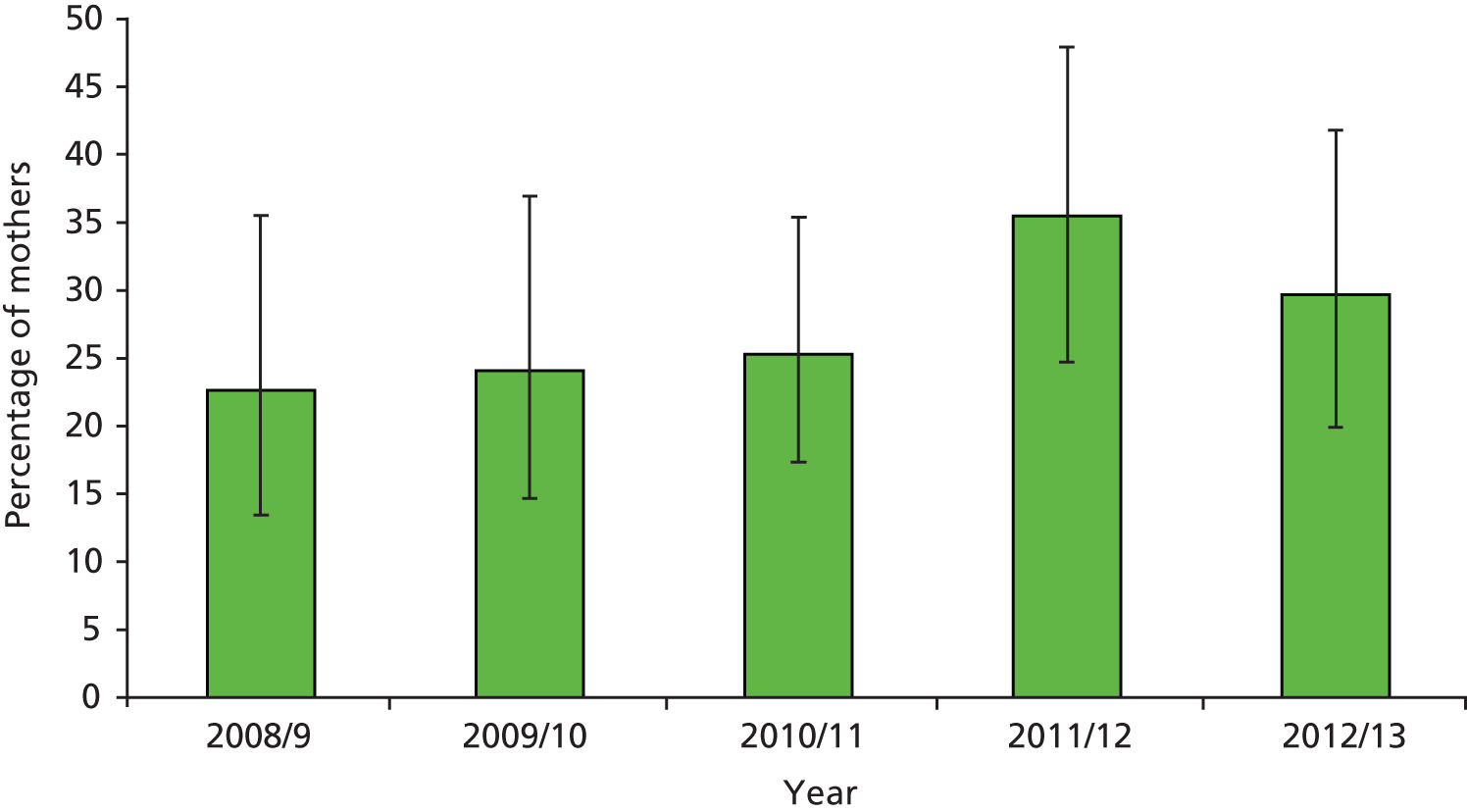

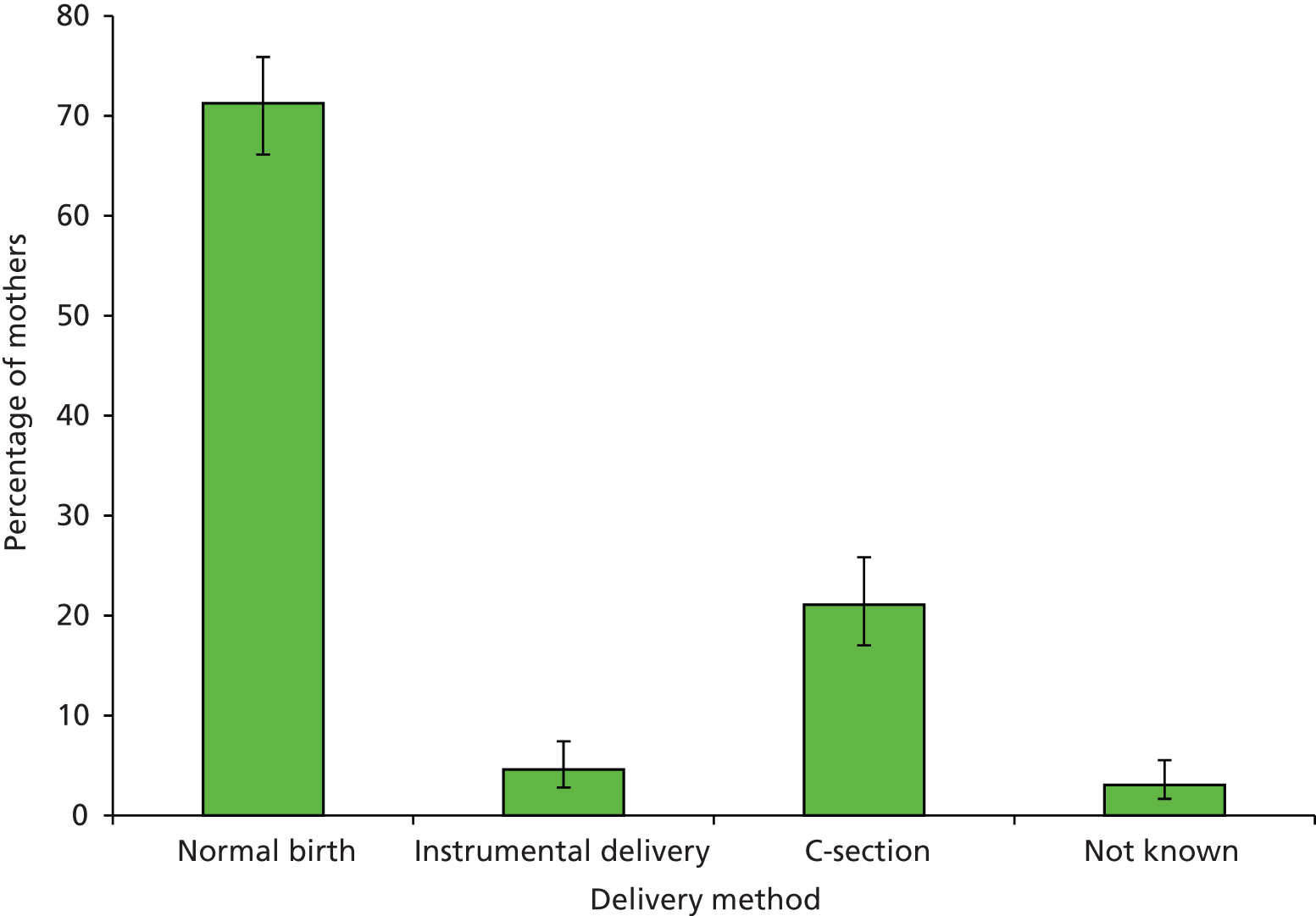

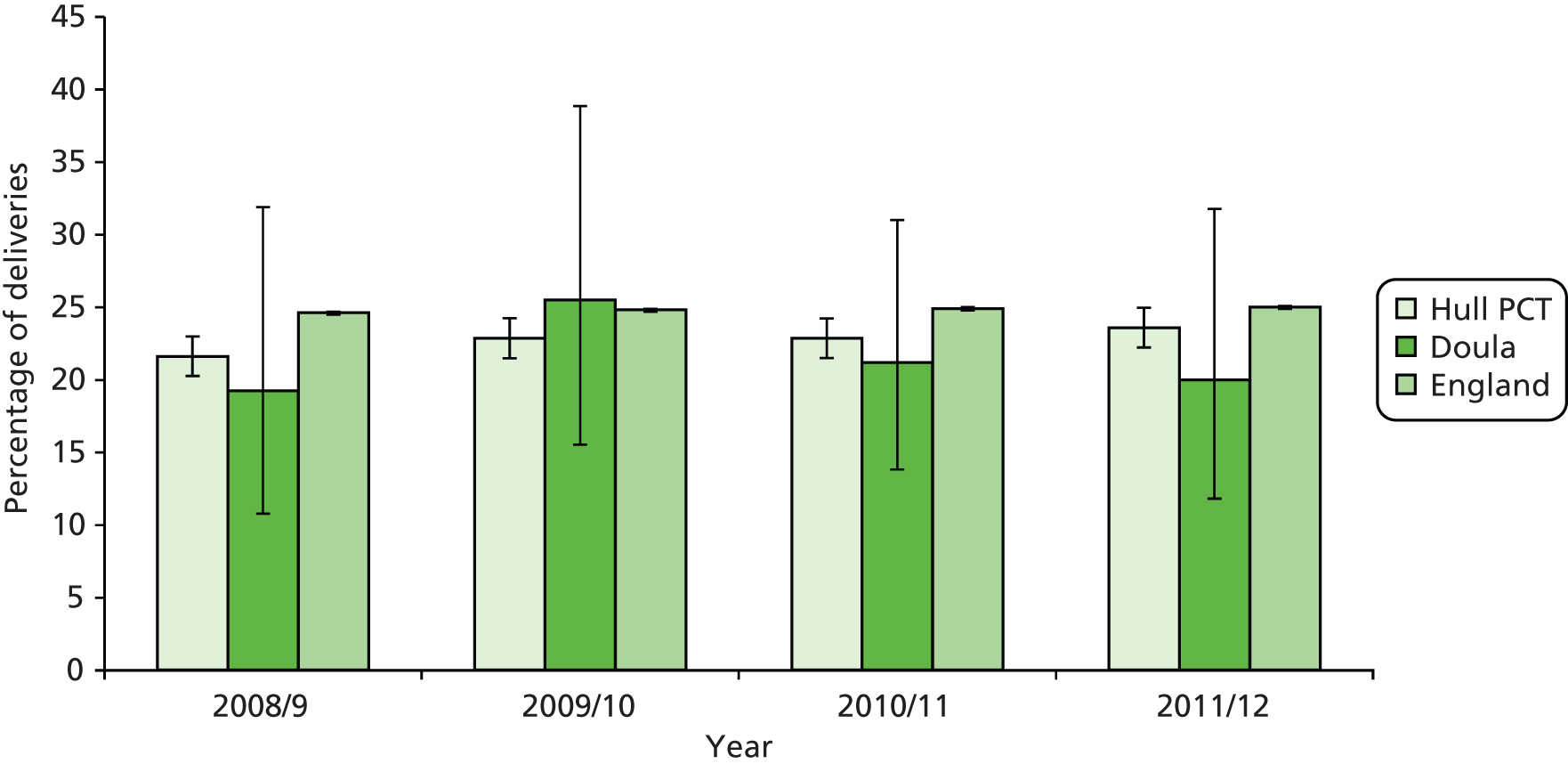

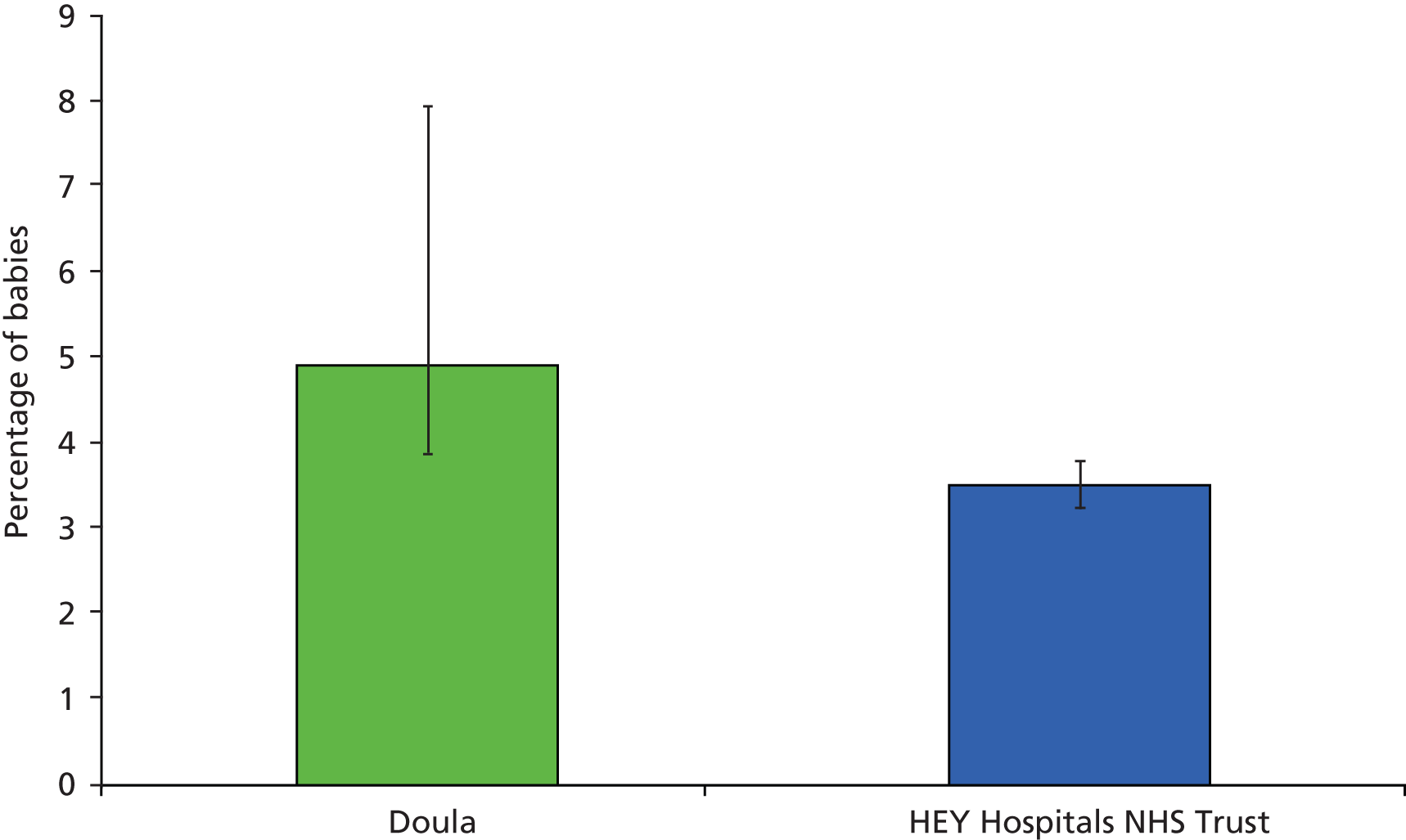

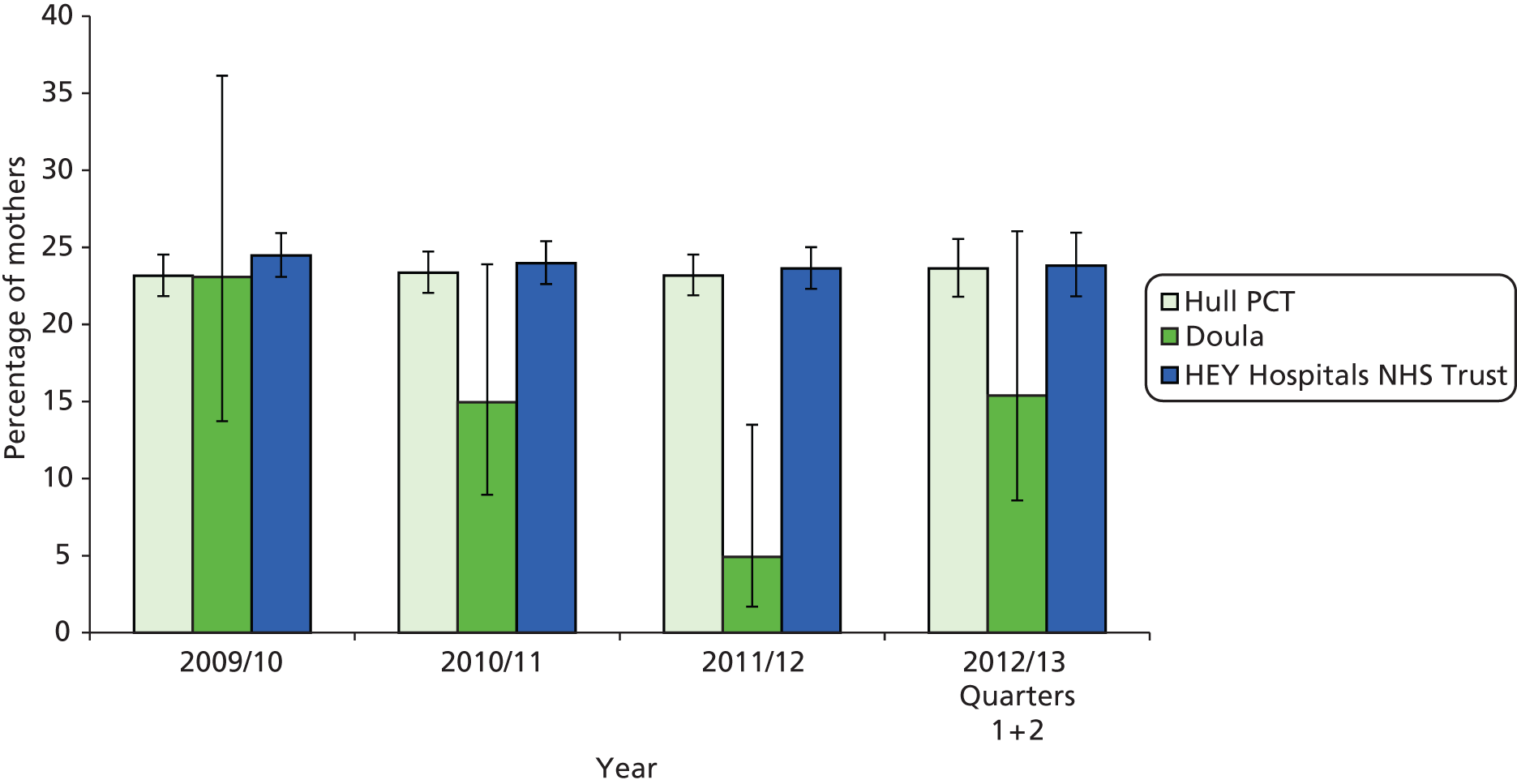

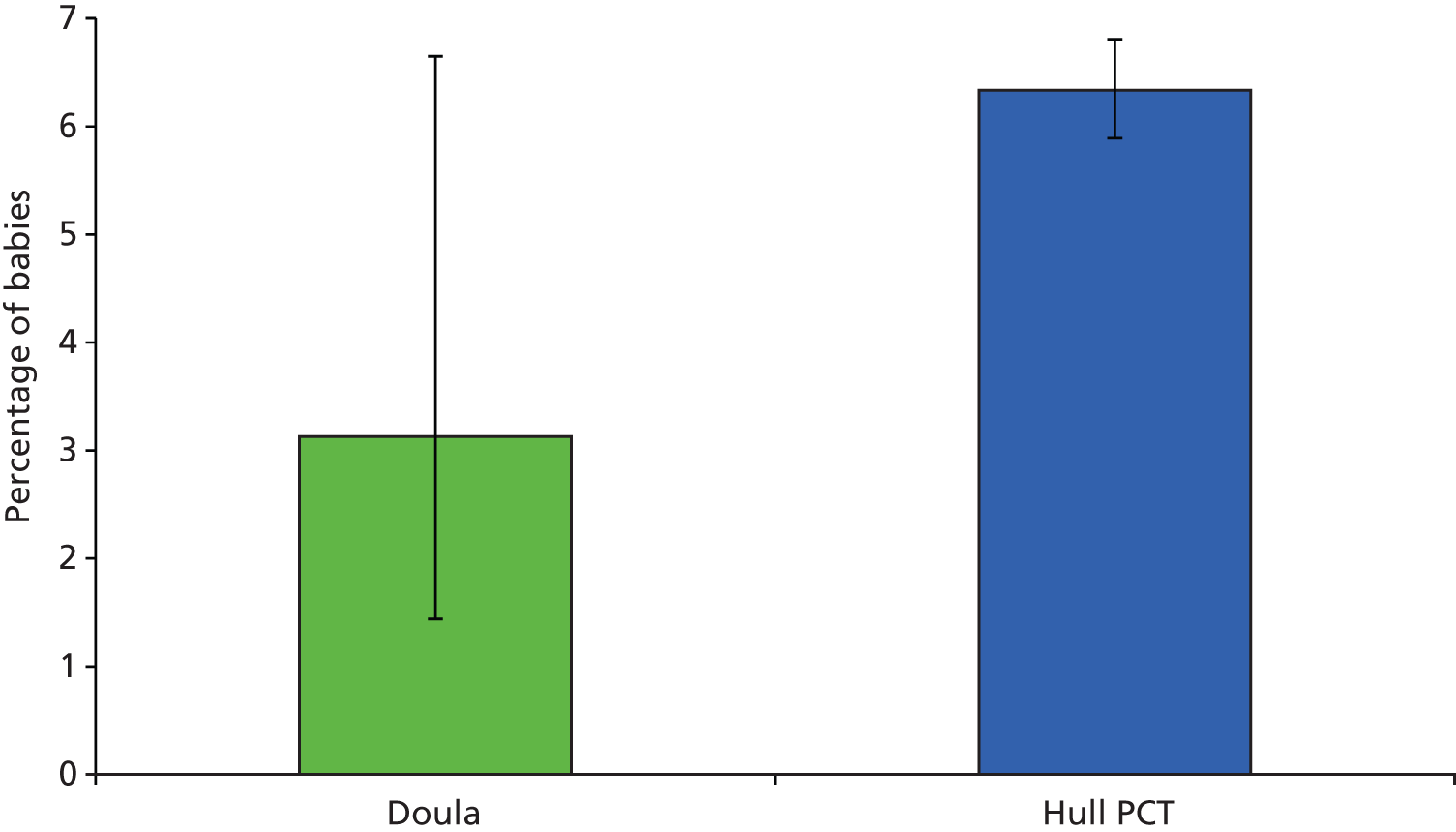

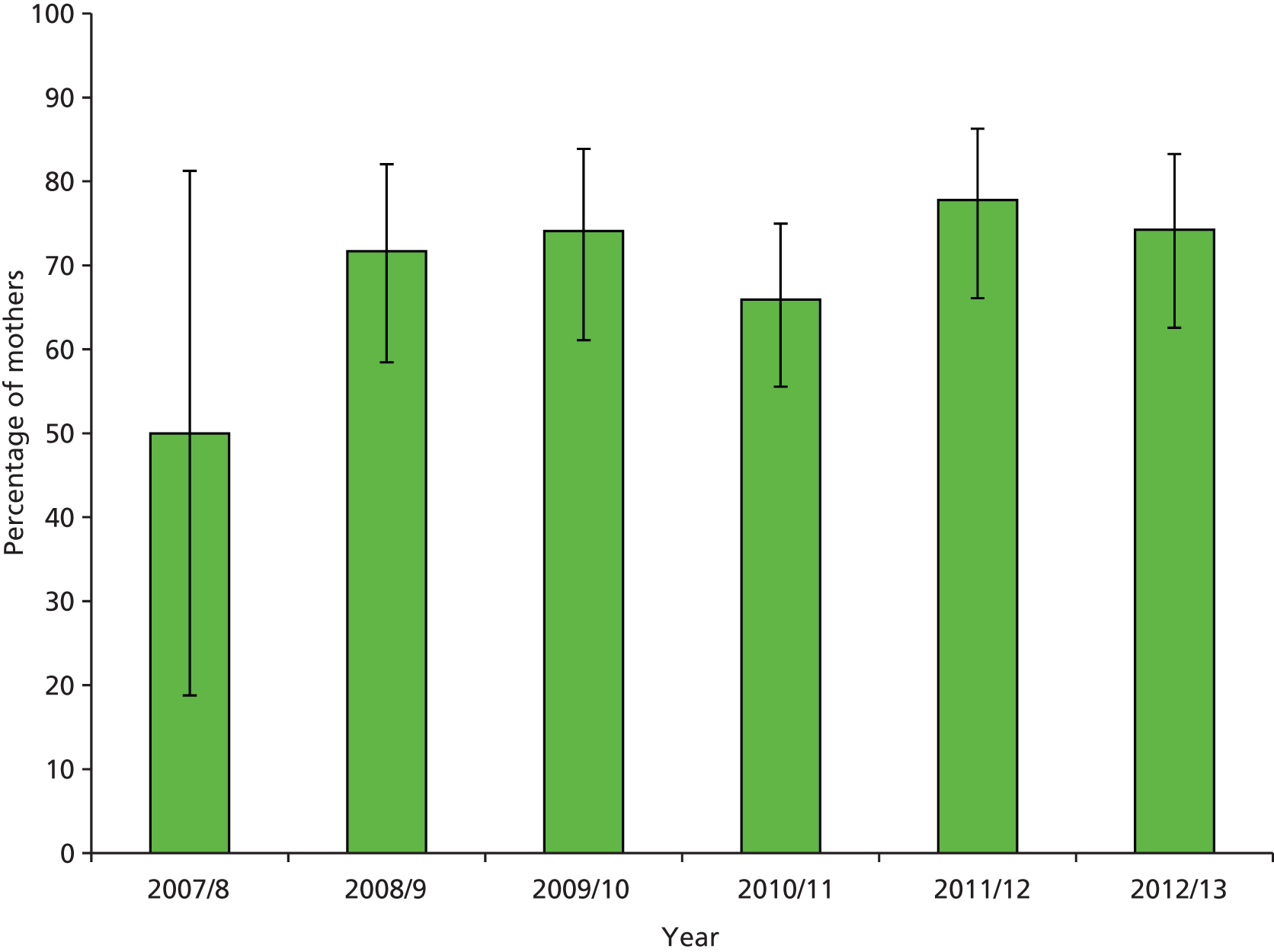

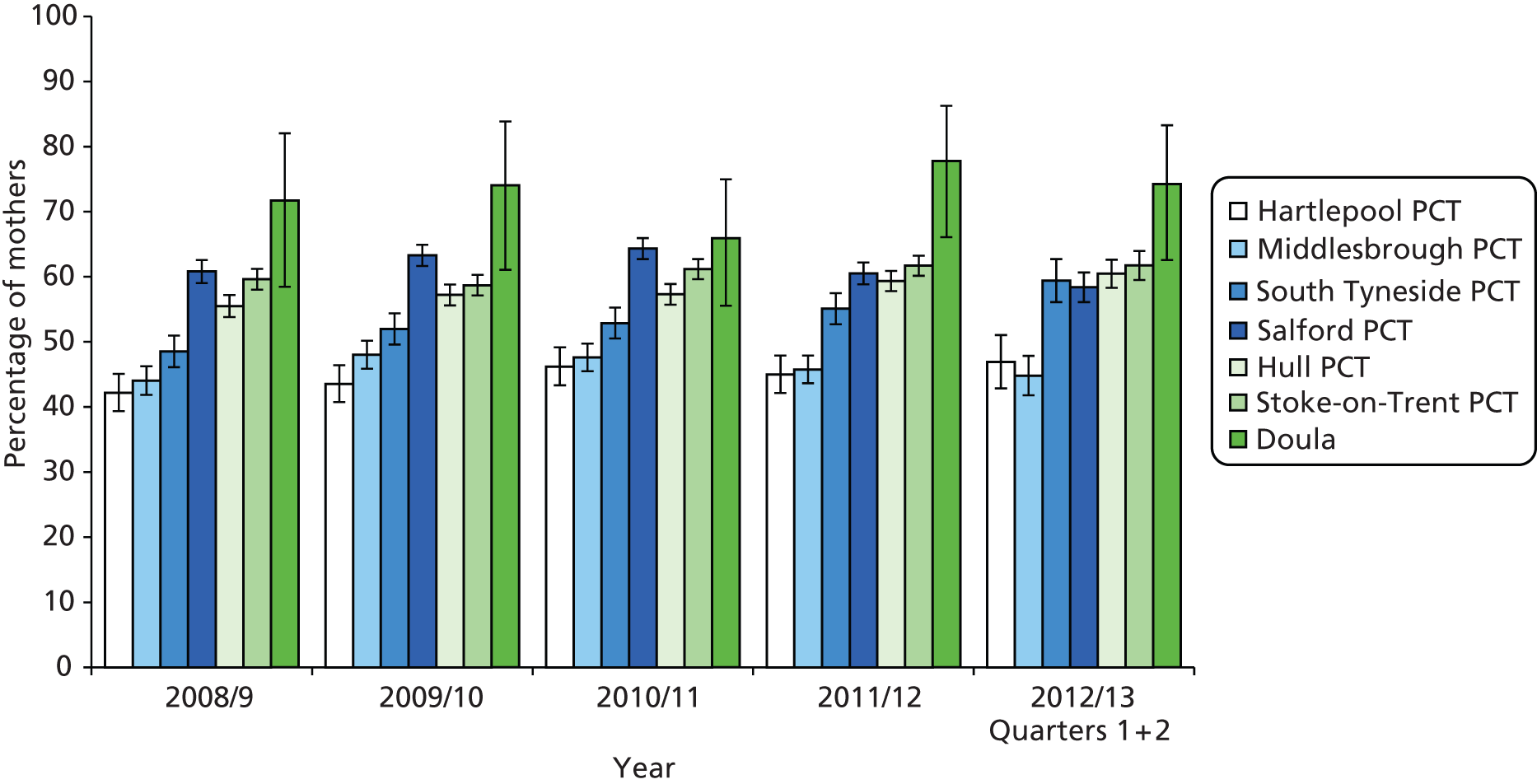

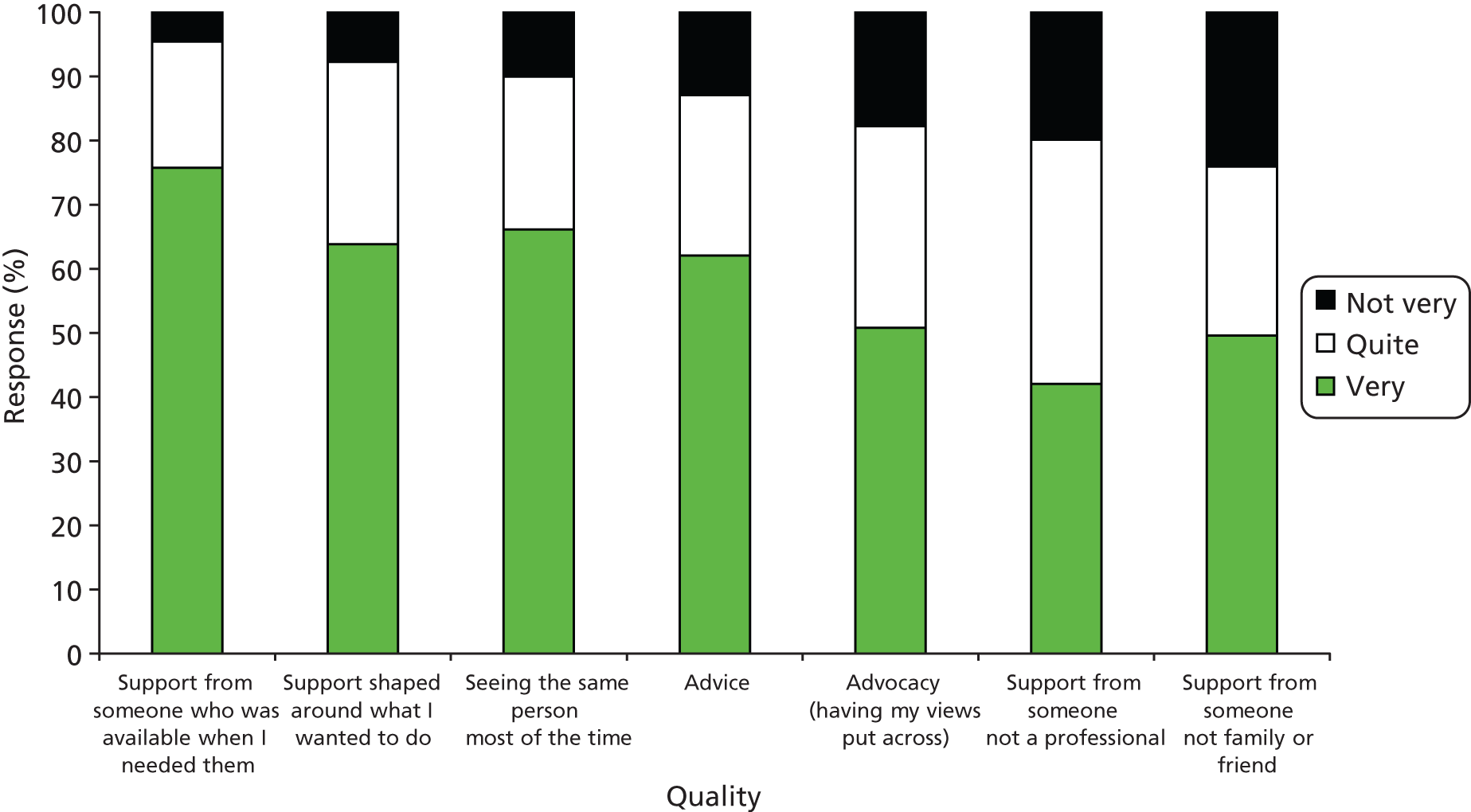

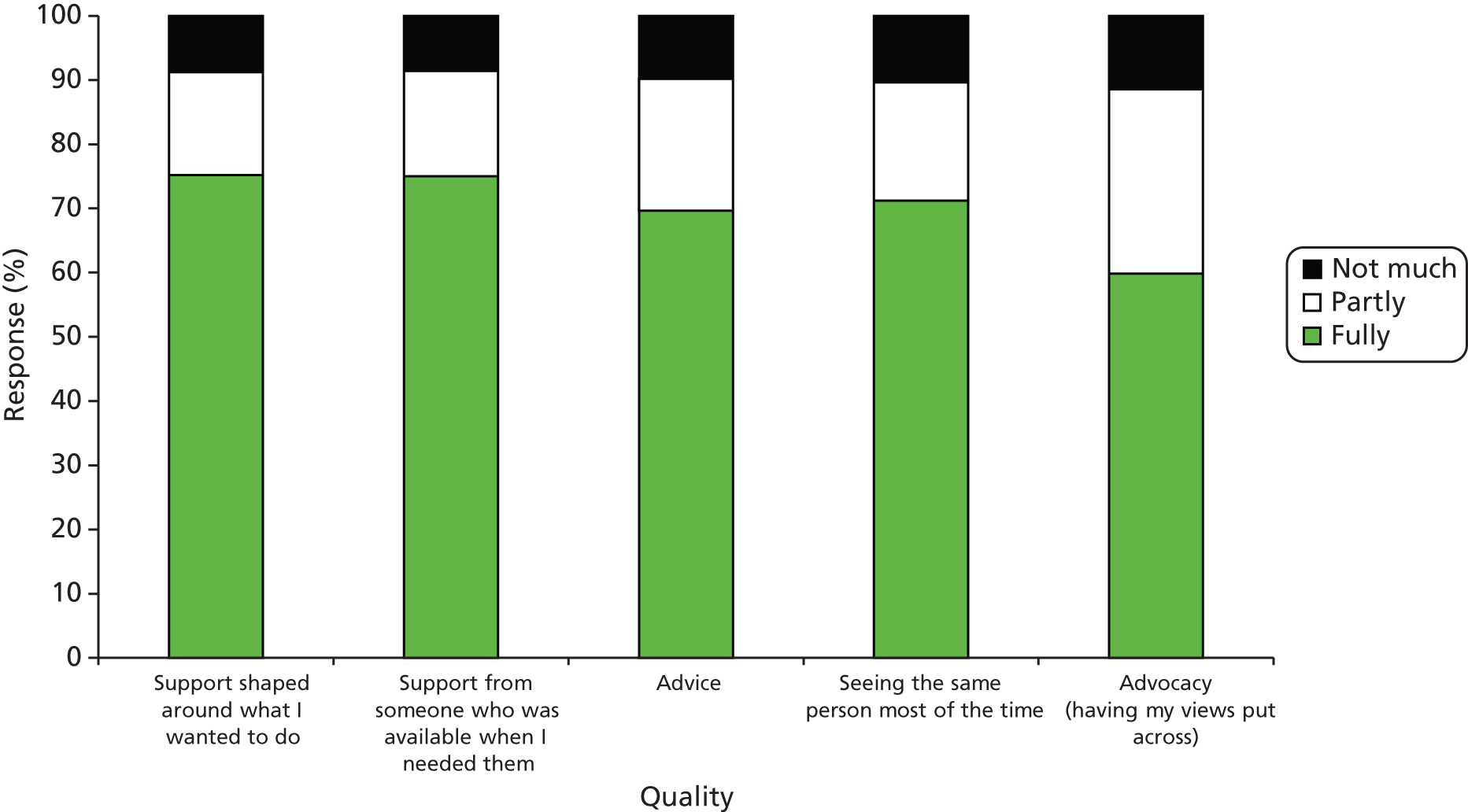

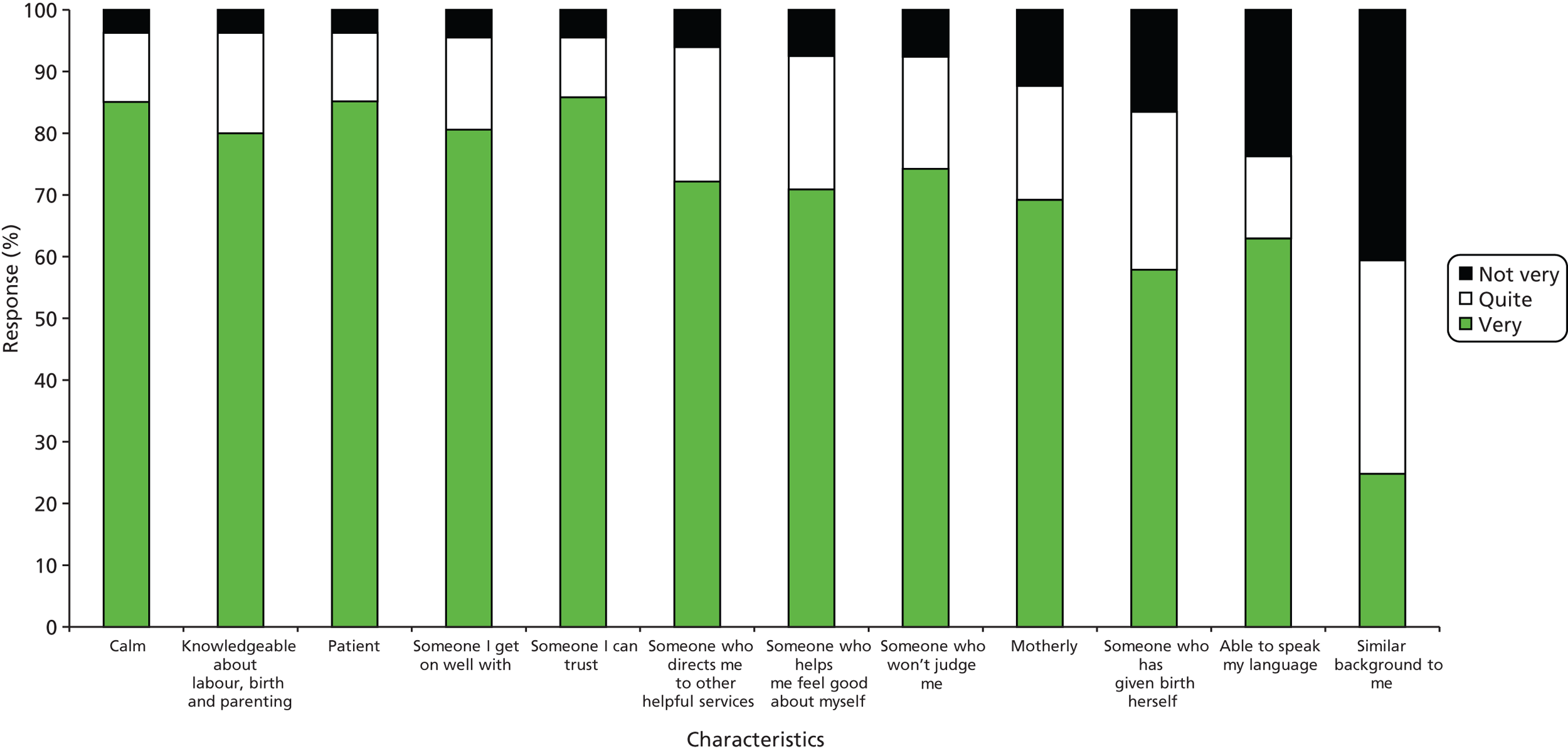

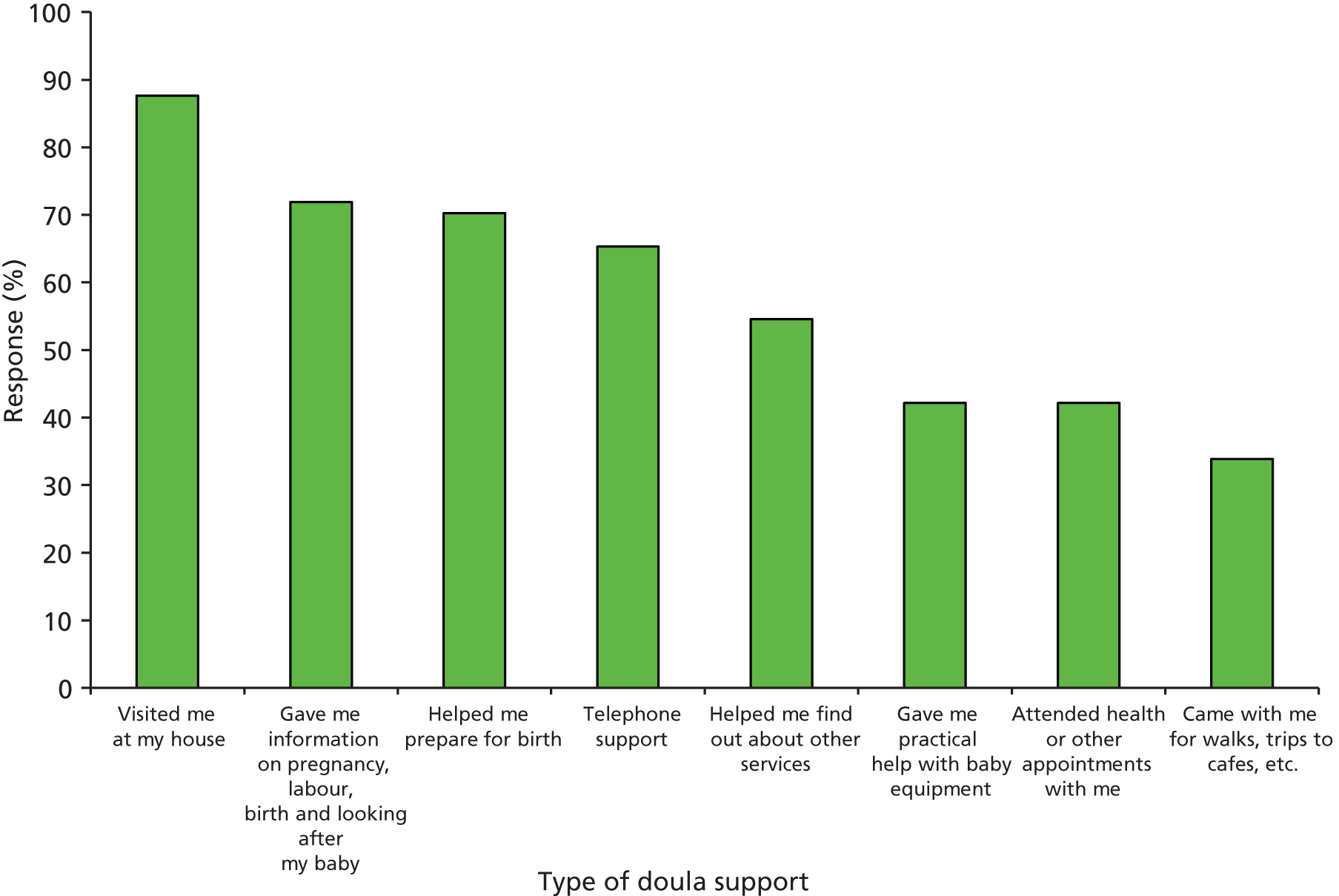

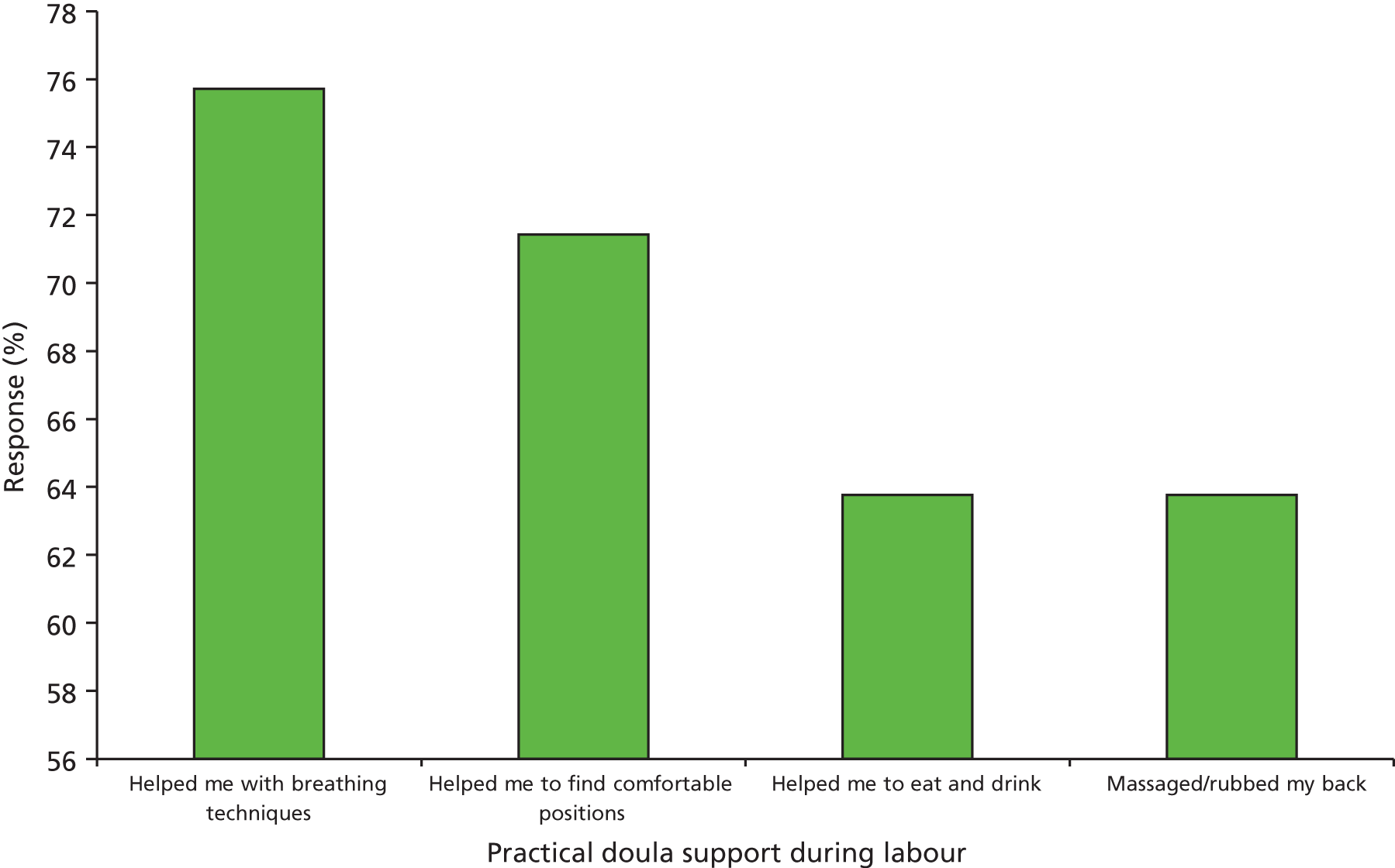

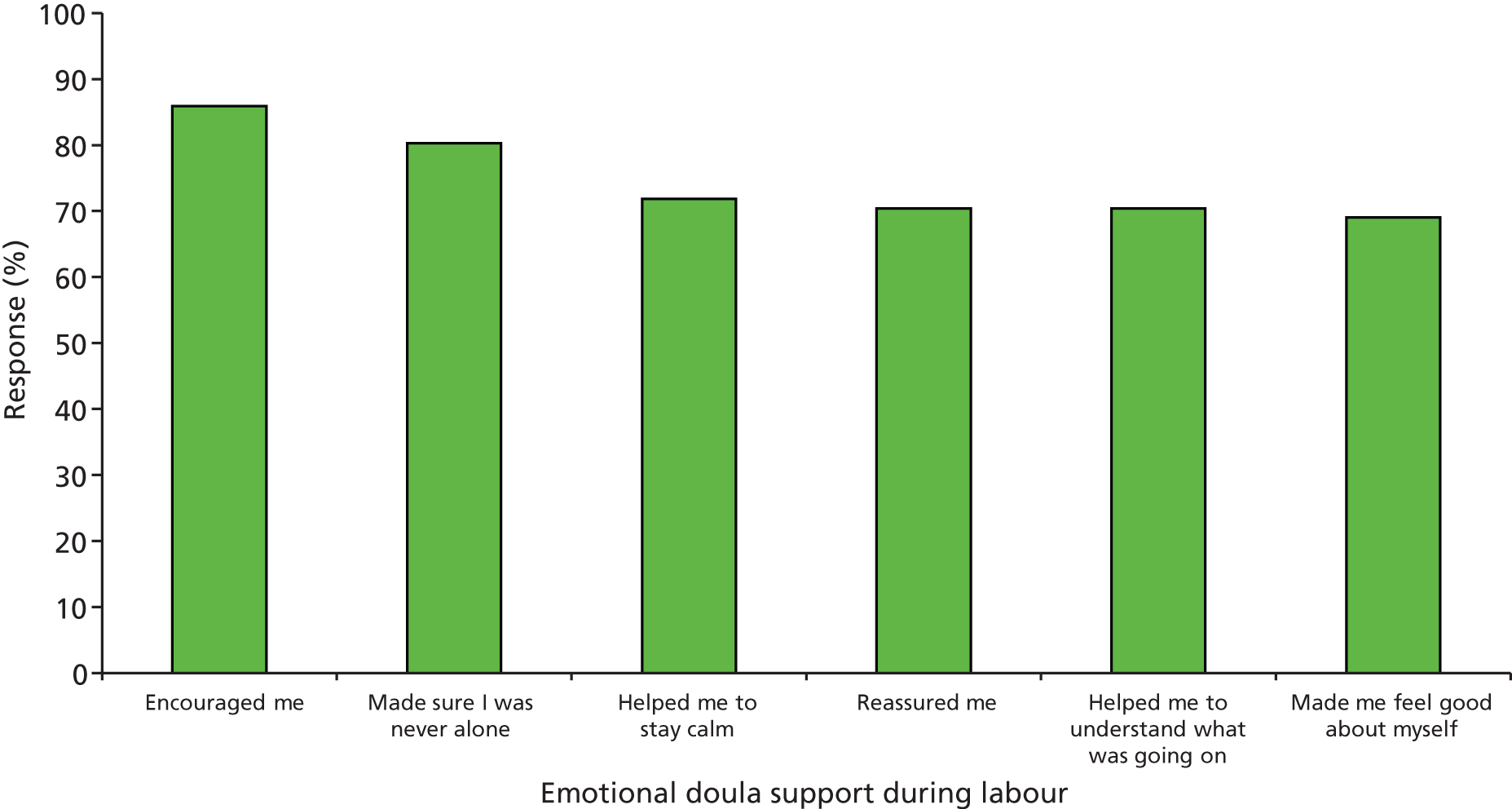

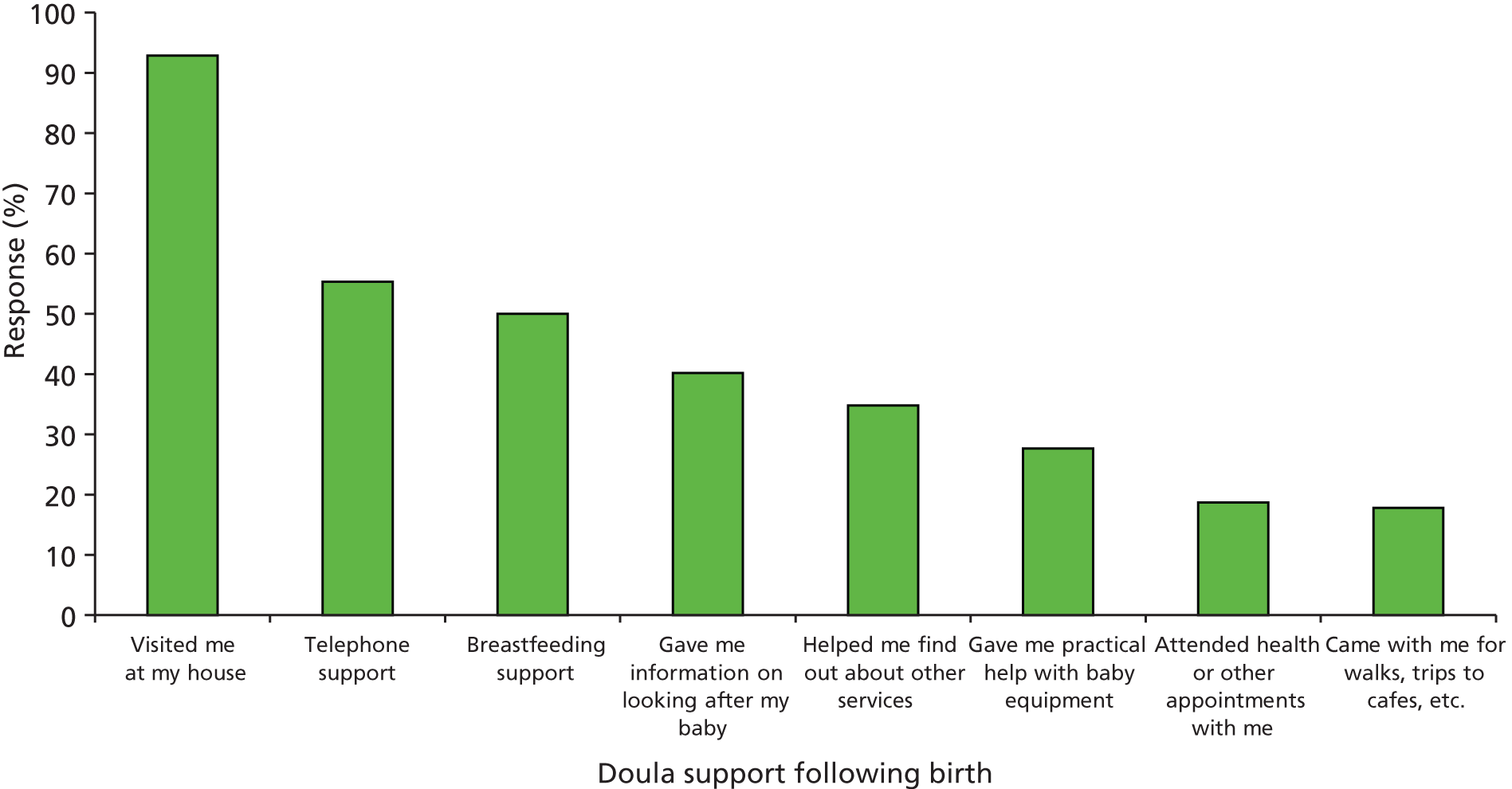

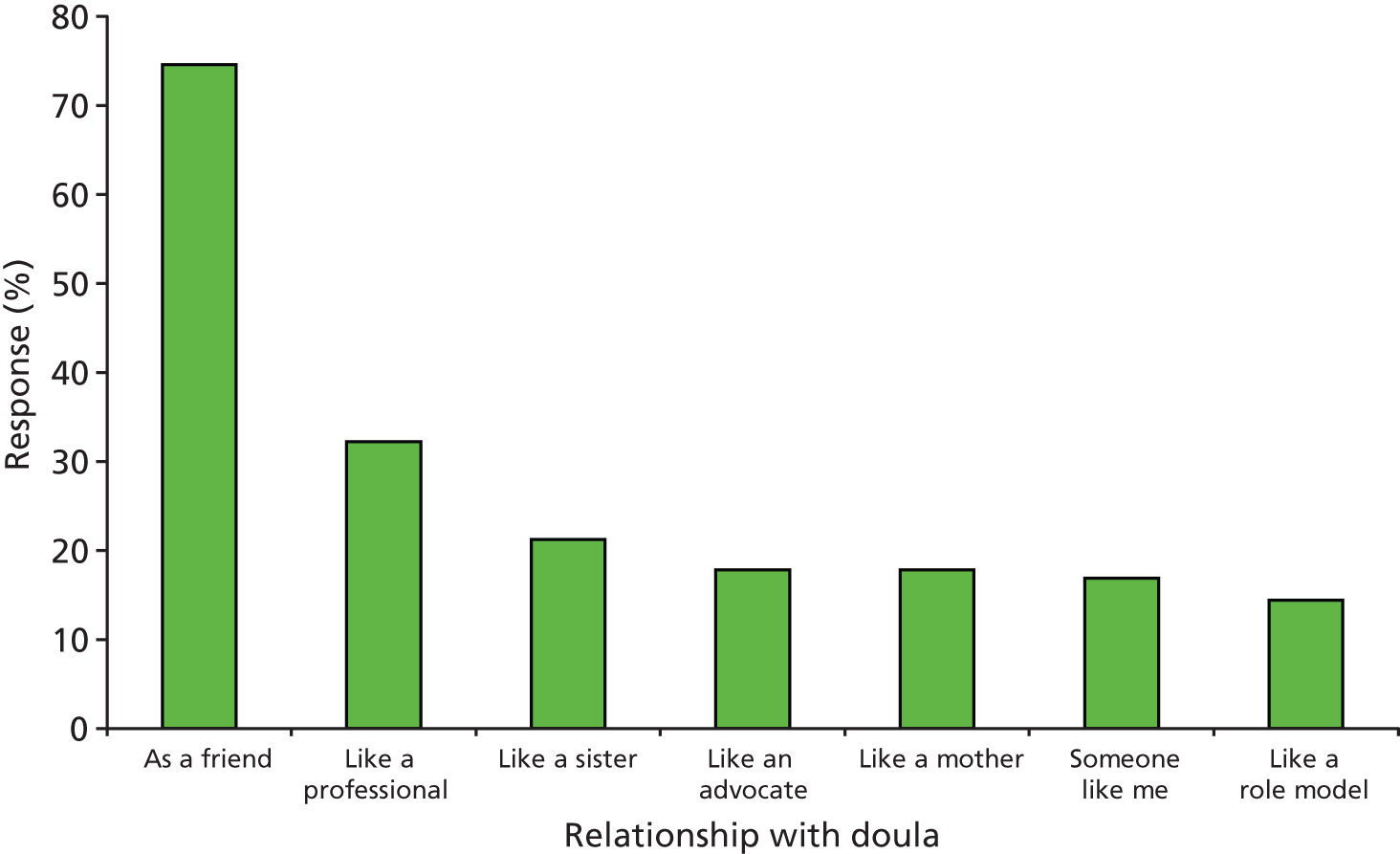

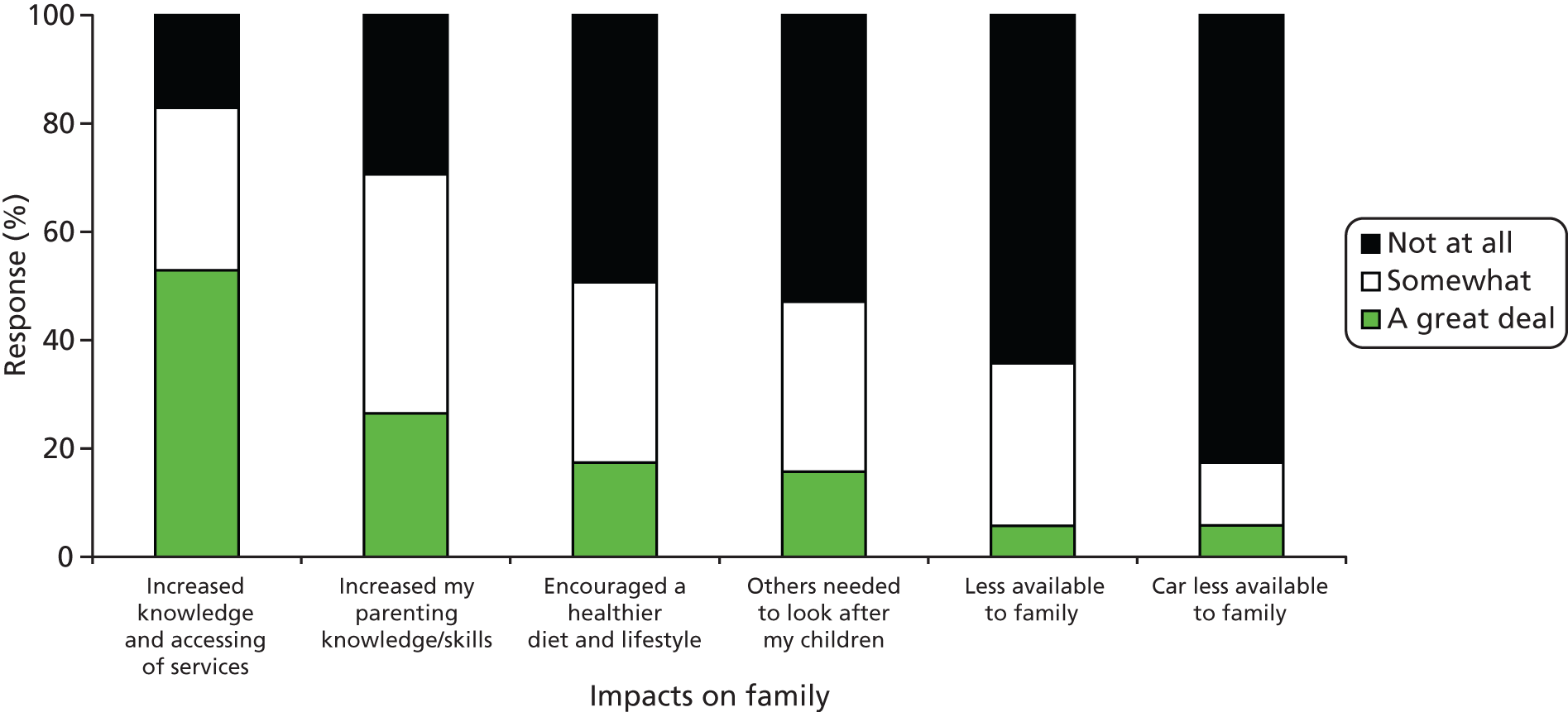

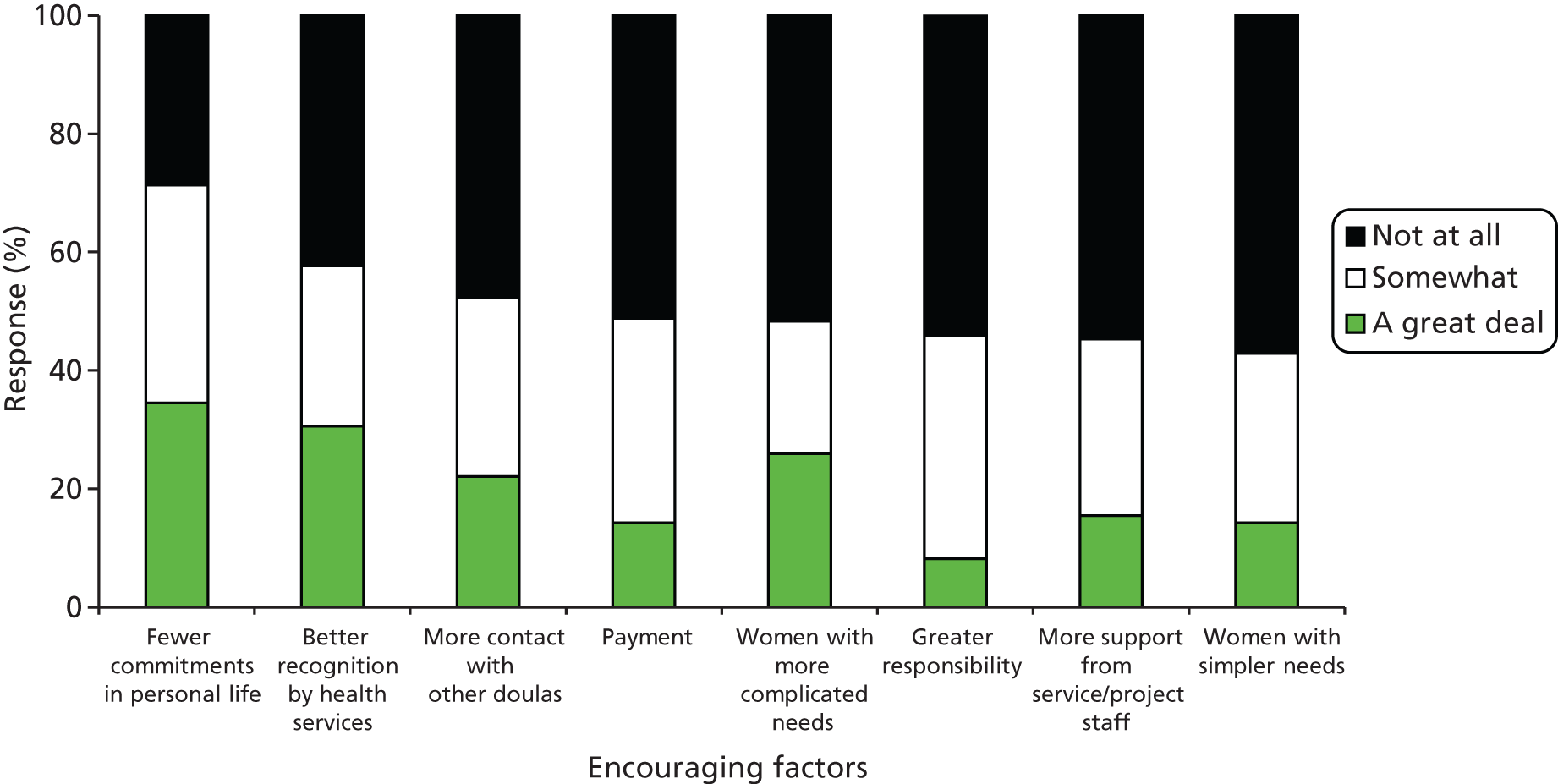

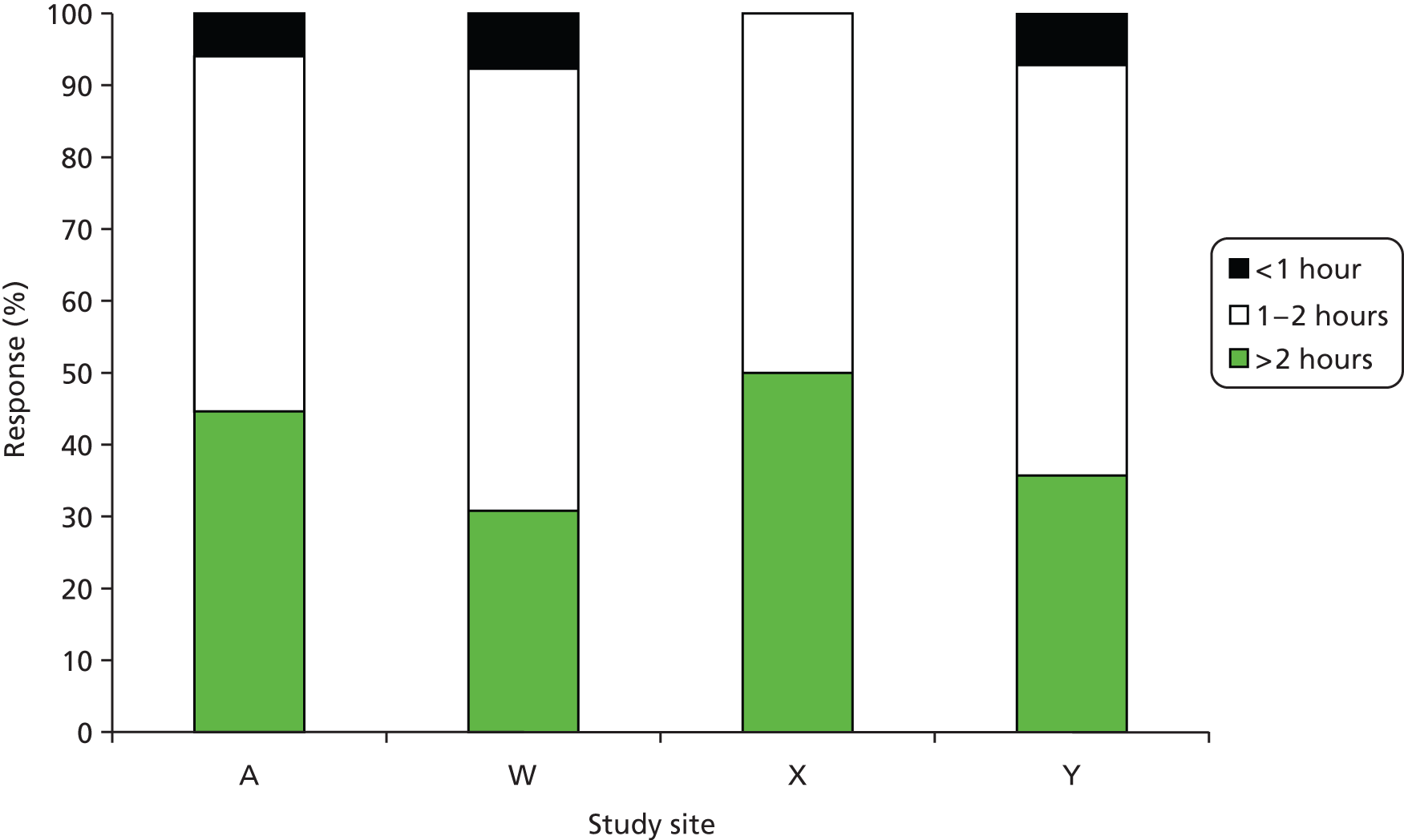

Similar comparisons found no relationship between disengagement and postcode district.