Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 11/2003/56. The contractual start date was in October 2012. The final report began editorial review in February 2015 and was accepted for publication in July 2015. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Elaine McColl is an editor for the National Institute for Health Research Journals Library (Programme Grants for Applied Research) and her institution receives a fee for this work.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Wright et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

In July 2010, the White Paper Equity and Excellence: Liberating the NHS set out a vision for the NHS that was ‘genuinely centred on patients and carers’ (p. 8) and would ‘include much wider use of effective tools like . . . patient experience data and real-time feedback’ (p. 14). 1 In addition, the NHS Outcome Framework 2011/12 recognised ‘ensuring that people have a positive experience of care’ as one of the five key domains of quality, reflecting ‘the importance of providing a positive experience of care for patients, service users and carers’ (p. 24). 2 In drawing up this framework, the Department of Health noted that the National Quality Board identified urgent and emergency care as an important area for the development of quality standards related to experiences of care.

Historically, the patient had no real voice and professionals judged the quality of health-care services; now, the patient is central in the hope that this will contribute to quality improvement. Patients offer a complementary perspective to that of clinicians, providing unique information and insights into both the humanity and the effectiveness of health care. National surveys of patients’ experiences of health care have become a feature of NHS regulation. Patients’ views are no longer deemed optional in achieving high-quality care3 but their use is not without some challenges. 4

Gaining patients’ insights into adult intensive care, however, poses an additional challenge. Each year, over 100,000 adults are admitted to adult general intensive care units (ICUs) in the NHS and approximately one-quarter do not survive to leave hospital (yet the quality of the dying process is an important aspect of the humanity of intensive care). In addition, predominantly because of the acute severity of their illness, but also because of the treatments used to support them, patients who survive often are unable to participate in discussions regarding their care, as they have little recollection of the experience in the ICU. 5 Families, therefore, play a vital role. 6 Rather than restricting insights to a select subgroup of surviving patients who remember their intensive care experience and relying on family to act as proxy respondents for those who do not, an alternative approach has been pursued: to seek the views of family members directly, thus ensuring coverage for both surviving and non-surviving patients.

With greater recognition and acceptance of the contribution of patients, since the middle of the 1990s, there has been a large increase in the development of instruments (questionnaires) and a burgeoning research literature on their uses and benefits. Some have described family satisfaction with intensive care as an abstract concept, while others have gone on to describe it in some detail. The latter indicate that it reflects the extent to which perceived needs and expectations of the family members of critically ill patients are met by health-care professionals, and that it may be influenced by many factors including families’ expectations, information and communication, family-related factors (such as attitudes towards life and death, social, cultural and religious background, etc.), hospital infrastructure and process of care. 7 A number of tools have been developed but the most widely validated is the Family Satisfaction in the Intensive Care Unit questionnaire (FS-ICU)8 (see Appendix 1), which assesses family satisfaction and purports to measure two main conceptual domains: satisfaction with care and satisfaction with decision-making.

The original FS-ICU, developed in Canada, consisted of 34 items, which were generated from conceptual frameworks of patient satisfaction, quality end-of-life care, existing research on needs of critically ill families, existing literature on family satisfaction or dissatisfaction with medical decision-making, existing validated satisfaction surveys and a pilot study. 8 The questionnaire was designed with two conceptual sections. The first section broadly assessed overall quality of care (18 items) and the second section assessed satisfaction with decision-making (16 items). Following initial validation in a single hospital setting in Ontario, Canada, it was subsequently validated in a multicentre study in six sites across Canada. 9,10

Further studies have addressed the face/content, construct, sensitivity and responsiveness of the FS-ICU. 11 In 2007, it underwent further refinement, including reduction of the number of items from 34 to 24 by identifying items with poor response, poor discrimination (floor/ceiling effects) or redundancy (high Cronbach’s alpha) and those measuring another construct (identified by principal component analysis). The 24-item version (FS-ICU-24) increases its feasibility for future administration and performed well in head-to-head comparisons with other measures of ICU quality. 11

It is widely acknowledged that cultural and linguistic differences between, and even within, countries means that an instrument developed and validated in one place cannot simply be used in another without careful cross-cultural adaptation and checking of psychometric properties. The most common approach to developing cross-cultural instruments is the sequential approach,12 in which an instrument is initially developed and the psychometric properties are validated in one culture; it is subsequently translated (if necessary) and the properties re-established in other cultures. This approach is exemplified by the International Quality of Life Assessment project, which produced cross-cultural adaptations of the Short Form questionnaire-36 items (SF-36). 13 By showing that minimum standards (e.g. application of recognised criterion values, replication of original factor structures and tests of discriminant validity) are met across a range of cross-cultural adaptations, and that performance in a new adaptation is similar to that of the original version, one can have greater confidence that the instrument can be considered to have international applicability. 13 The SF-36 has been established as a valid measure for use in the UK following cross-cultural validation and extensive psychometric testing14,15 and population norms have been derived from large cohorts. 16

Cross-cultural validation of the FS-ICU has been conducted in North America11 and Switzerland17 but has not been undertaken in the UK. The measurement properties of the instrument need to be fully understood, including interpretation of the scores and what constitute clinically or socially meaningful differences in scores, as an important and necessary prerequisite before its introduction into quality improvement programmes in the NHS. In the UK, the feasibility and acceptability of using the FS-ICU has been assessed in a single-centre pilot study and, of 146 questionnaires distributed, 95 were returned (response rate 66%), with 71 (75%) rating the acceptability of the questionnaire as ‘very good’ to ‘excellent’. 18 In addition, if meaningful comparisons of providers are going to be made, then other issues need to be addressed: representativeness of the family members included; the sampling frame and sample size required; and the relationship between family experience and patient outcome.

The Department of Health has indicated that patients’ views are essential to achieving high-quality care. 1–3 The Family-Reported Experiences Evaluation (FREE) study directly addresses the challenges of incorporating patients’ views in intensive care by incorporating family members’ views (in recognition of the fact that a representative sample of patients’ views is unachievable) into improving the quality of adult intensive care services. There is no doubt that the benefits of gaining information and insights from family members could revolutionise quality improvement in adult intensive care and there is considerable evidence that the need to continue to involve patients/family members will be sustained within policy for the future. The FREE study is a necessary precursor to any direct incorporation of routine surveying of family members’ views into a quality improvement programme for adult intensive care services in the UK.

The overall aim of the FREE study was to inform valid, representative and cost-effective future use of the FS-ICU questionnaire into quality improvement programmes for adult intensive care services in the NHS in the UK. The objectives are:

-

to test the face and content validity and the comprehensibility of the FS-ICU

-

to establish the internal consistency, construct validity and reliability of the FS-ICU

-

to describe family satisfaction using the FS-ICU and explore how family satisfaction, measured with the FS-ICU, varies by

-

family member characteristics

-

patient characteristics

-

unit/hospital characteristics

-

other contextual factors

-

country

-

-

to model approaches to sampling to achieve representative sampling for feasible, cost-effective future use of the FS-ICU in quality improvement in the NHS.

The FREE study was a mixed-methods study divided into two phases directly related to the objectives as follows:

-

phase 1 – a preliminary, qualitative study to address the first objective above

-

phase 2 – a cohort study to address the remaining objectives.

Chapter 2 Phase 1 of the Family-Reported Experiences Evaluation study

Introduction

Phase 1 of the FREE study was a preliminary, qualitative study with the following objectives:

-

to test the face and content validity and the comprehensibility of the original FS-ICU-24 questionnaire11 (see Appendix 1)

-

to modify the FS-ICU-24, if required, for the UK setting/use in phase 2.

This chapter reports the methods and results of phase 1 of the FREE study.

Methods

The FS-ICU-24 is divided into sections as follows:

-

demographics – six questions asking for information about the respondent and their relationship to the patient

-

part 1: satisfaction with care – 14 items that contribute to the overall family satisfaction score and the satisfaction with care domain score

-

part 2: family satisfaction with decision-making around the care of critically ill patients – 10 items that contribute to the overall family satisfaction score and the satisfaction with decision-making domain score.

In addition to the above, the following questions are included at the end of part 2: family satisfaction with decision-making around the care of critically ill patients:

-

three questions for family members of patients who died in the ICU, asking for their views on the end-of-life care of the patient

-

three questions providing the respondent with an opportunity to provide comments to the ICU on how to make care provided in the ICU better and things that were done well; and suggestions that the respondent feels might be helpful to the ICU staff.

To test the face and content validity and the comprehensibility of the FS-ICU-24, this qualitative study comprised:

-

focus group discussions with health-care professionals and with representatives from the charity Intensive Care Unit Support Teams for Ex-Patients (ICUsteps)

-

cognitive interviews with family members of critically ill patients.

Research governance

The FREE study was sponsored by the Intensive Care National Audit & Research Centre (ICNARC) and phase 1 was co-ordinated by the Newcastle Clinical Trials Unit (CTU). An ethics application was made to the National Research Ethics Service Yorkshire and the Humber Research Ethics Committee on 14 August 2012 and received a favourable opinion on 17 October 2012.

The National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Clinical Research Network (CRN) Portfolio details high-quality clinical research studies that are eligible for support from the NIHR CRN in England. The FREE study was adopted onto the NIHR CRN Portfolio on 14 September 2012.

Global NHS permissions were obtained from the lead comprehensive local research network (CLRN) – Northumberland, Tyne and Wear – and local NHS permissions were obtained for the two NHS hospital trusts that participated in phase 1. A study site agreement, based on the model agreement for non-commercial research in the health service, was signed by each participating NHS hospital trust and the sponsor (ICNARC).

Study management

Phase 1 of the study was led by EM (coinvestigator) and SW (lead clinical investigator) with support from the Study Management Group (SMG), which comprised the chief investigator (KR) and other coinvestigators (DAH, SH, DKH, LH, AR, MR). An experienced research associate was employed to conduct, transcribe and analyse the focus group discussions and cognitive interviews.

Recruitment of NHS hospital trusts

Two NHS hospital trusts were recruited to take part in the study: one in Newcastle upon Tyne and one in London.

Focus groups

Four focus group discussions were conducted with:

-

health-care professionals involved in the delivery of intensive care (to inform whether or not the FS-ICU-24 covered all dimensions relevant to the quality of intensive care in the NHS and on which a family member might be expected to have a view and the relevance and redundancy of items)

-

representatives from ICUsteps (for a further perspective on the face and content validity of the FS-ICU).

Recruitment of health-care professionals

An invitation was sent by e-mail to health-care professionals working in ICUs within the North of England Critical Care Network and within the participating NHS hospital trust in London for expressions of interest to take part in a focus group discussion. Two focus group discussions were held; one was held in Newcastle upon Tyne and the other was held in London. The aim was to recruit between 8 and 12 participants for each focus group discussion, ensuring a representative sample of the multidisciplinary intensive care team including doctors, nurses, physiotherapists and other allied health-care professionals of varying grades of seniority.

Recruitment of representatives from Intensive Care Unit Support Teams for Ex-Patients

The charity ICUsteps circulated an invitation among its membership (which includes ex-patients, their family members and health-care professionals working in intensive care) for expressions of interest to take part in a focus group discussion. Two focus group discussions were held; one was held in Milton Keynes and the other was held in South Tyneside. The aim was to recruit between 8 and 12 participants representing patients, family members and health-care professionals working in intensive care.

Informed consent

Before focus group discussions commenced, participants were provided with written information about the study and informed that the focus group discussion would be recorded using a digital voice recorder and transcribed. Participants were informed that any information that could identify themselves, patients, hospitals or health-care professionals would be removed during the transcription process and that, following transcription of the discussion, the digital recording would be destroyed. Participants were invited to sign a consent form, which was countersigned in their presence by the research associate. One copy was given to the participant and one copy was filed in the investigator site file.

Conduct of the focus groups

The focus group discussions were facilitated by the research associate. At the beginning of each discussion, ground rules (e.g. that all views were welcome, that one participant should speak at a time and that confidentiality should be observed by all participants) were established and agreed by the group.

Health-care professionals

The focus group discussions started with a free-ranging discussion on the quality of intensive care. The participants were then presented with the FS-ICU-24 and asked to comment on the relevance and redundancy of each of the items. Participants were also asked to consider whether or not the FS-ICU-24 covered all dimensions they considered relevant to the quality of intensive care and on which a family member might be expected to have a view.

Representatives from Intensive Care Unit Support Teams for Ex-Patients

The focus group discussions started with a general discussion on participants’ experiences of intensive care. The participants were then presented with the FS-ICU-24 and asked to comment on whether or not the questions were relevant and important to their experience and whether or not all the main themes related to their views of family satisfaction with intensive care were covered, and, if not, what was omitted.

Transcription

The digital recordings of the focus group discussions were transcribed by the research associate. All identifiable information, such as names (e.g. of patients, family members or intensive care staff members), was removed. Once transcriptions were complete, the digital recordings were destroyed (confidentially).

Data analysis

Data from the focus group discussions were analysed by FS-ICU-24 item. The key themes and comments from each of the discussions were summarised for each of the FS-ICU-24 items by the research associate and reviewed by EM and SW in consultation with DKH. Any potential changes to the questionnaire that were indicated following the focus group discussions were discussed with the wider SMG before any changes were made.

Cognitive interviews

Up to three rounds of cognitive interviews were planned, each involving four to eight participants. 19 At the end of each round of interviews, the findings were reviewed by the research associate with EM and SW. The wording of items was modified, if necessary, and then tested in subsequent rounds of interviews. Interviews continued until no fresh insights emerged.

Participants: family members

Family members for the cognitive interviews were purposively selected to ensure a spread across sociodemographic factors likely to influence understanding of the FS-ICU-24, including age, sex, relationship to the patient, level of education, socioeconomic status and whether or not English was the first language (while translation was used in phase 2 of the FREE study, phase 1 was restricted to English speakers only).

Family members of patients admitted to three ICUs within the NHS hospital trust in Newcastle upon Tyne were invited to take part. As planned for phase 2 of the FREE study, a family member was defined as a person who had a close familial, social or emotional relationship to the patient and was not restricted solely to next of kin. Family members of patients who had spent 24 hours or more in a participating ICU were eligible to take part in the study if they were aged 16 years or more, unless they:

-

were unable to speak and read English

-

were considered by the research nurse to lack capacity to provide informed consent or the cognitive ability to complete and discuss the FS-ICU-24

-

were considered by the research nurse to be too distressed to be approached about a research study

-

had previously taken part in the study.

Screening and recruitment

Trained intensive care research staff identified and approached potentially eligible family members about participating. Verbal information about the study was provided to the family member, which included the purpose of the study, the consequences of participating, data security and funding. This information was also provided in a participant information sheet, along with the name and contact details of the lead investigators for phase 1 of the FREE study (EM and SW).

Family members were given at least 24 hours to consider whether or not they wished to participate. Once the research nurse was satisfied that the family member had read and understood the participant information sheet and that all of their questions about the study had been answered, the family member was invited to complete and sign the expression of interest form, which was passed on to the research associate. The expression of interest form requested the following demographic information to inform the purposive sampling: full name and contact details; age; sex; relationship to the patient; level of education; occupation; whether or not English was their first language; and ethnicity. The original completed expression of interest form was filed in the investigator site file, a copy was given to the participant and a copy was given to the research associate.

The research nurse notified the research associate of the patient’s discharge from, or death in, the ICU. If the family member met the purposive sampling criteria, the research associate telephoned them 3 weeks later to invite them to participate in a cognitive interview. If the family member agreed, then a meeting was arranged at a mutually convenient time and location: either the family member’s home or a quiet interview room at one of the hospitals within the NHS hospital trust or at Newcastle University.

Of the family members who expressed an interest in taking part in the study, there were some who were not needed for interview, either because the patient was still in the ICU when the study ended or because interviews had already been conducted with family members from their demographic group. In these cases, the research associate contacted the family member to explain and thank them for their interest in the study.

Conduct of the cognitive interviews

Before the interview started, the participant was asked by the research associate for permission to record the interview using a digital voice recorder and for the interview to be transcribed. Participants were informed that any information that could identify themselves, the patient, the hospital or health-care staff would be removed during the transcription process and that, following transcription of the interview, the digital recording would be destroyed. Participants were invited to sign a consent form, which was countersigned in their presence by the research associate. One copy was given to the participant and one copy was filed in the investigator site file.

The cognitive interviews were conducted by the research associate. Participants were asked to complete the FS-ICU-24 in ‘think aloud’ mode, indicating, as they completed it, how they were interpreting each item and formulating their response. If participants struggled with concurrent ‘think aloud’, then a cognitive debriefing approach was adopted instead. In these instances, the participants self-completed the FS-ICU-24 and were then probed by the research associate about their interpretation of each item and how and why they chose the response option they did. At the end of each interview, the participants were asked:

-

if they considered each of the questions in the FS-ICU-24 to be relevant and important to their experience

-

if, in their opinion, all the main themes related to family satisfaction with intensive care had been covered and, if not, then what had been omitted.

Transcription

The digital recordings of the cognitive interviews were transcribed by the research associate. All identifiable information, such as names (e.g. of patients, family members or intensive care staff members), were removed. Once the transcriptions were complete, the digital recordings were destroyed (confidentially).

Data analysis

Data from the cognitive interviews were analysed by FS-ICU-24 item. The key themes and comments from each of the cognitive interview participants were summarised for each question and reviewed by EM and SW in consultation with DKH. Any potential changes to the questionnaire that were indicated following each round of cognitive interviews were discussed with the wider SMG before any changes were made.

Results

Participating NHS hospital trusts

Local research and development (R&D) approval was obtained at the NHS hospital trust in London for the London-based focus group discussion (with health-care professionals) and at the NHS hospital trust in Newcastle for the Newcastle-based focus group discussion (with health-care professionals) and for recruitment of family members for the cognitive interviews.

Participants

Focus group discussions: health-care professionals

The first focus group discussion was held in Newcastle on 28 November 2012 with seven participants comprising two consultant doctors, two junior doctors, one sister/charge nurse, one staff nurse and one allied health-care professional.

The second focus group discussion was held in London on 16 January 2013 with seven participants comprising two consultant doctors, one junior doctor, two sister/charge nurses and two staff nurses.

Focus group discussions: representatives from Intensive Care Unit Support Teams for Ex-Patients

The first focus group discussion was held in Milton Keynes on 2 December 2012 with nine participants comprising five former intensive care patients, two family members of former intensive care patients and two health-care professionals involved in delivery of intensive care, of whom one was also a family member of a former intensive care patient.

The second focus group discussion was held in South Tyneside on 28 February 2013 with six participants comprising two former intensive care patients, three family members of former intensive care patients and one health-care professional involved in delivery of intensive care.

Cognitive interviews

Eighty-three family members of patients admitted to the three ICUs within the NHS hospital trust in Newcastle were approached about taking part in a cognitive interview. Of these, 41 (49.4%) expressed an interest in taking part and were given a participant information sheet and, of these, 30 (73.2%) completed and signed the expression of interest form.

Twelve family members of nine patients were successfully contacted and cognitive interviews were conducted with them. The 12 cognitive interviews were conducted in three rounds as follows: four interviews conducted between 11 and 15 January 2013; six interviews conducted between 26 and 30 January 2013; and two interviews conducted on 8 February 2013.

Characteristics of cognitive interview participants

Of the 12 participants, 11 were white British and one was Asian British. They ranged in age from 32 to 66 years, with a mean age of 48 years, and two-thirds (n = 8) were female. The average age at which participants left full-time education was 18 years, ranging from 15 to 21 years (Table 1).

| Round | Date of interview (2013) | Sex | Age (years) | Age on leaving full-time education (years) | Relationship to the patient |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 11 January | Male | 66 | 15 | Husband |

| 14 January | Female | 63 | 16 | Wife | |

| 15 January | Female | 32 | 18 | Daughter | |

| 15 January | Male | 32 | 21 | Stepson | |

| 2 | 26 January | Female | 36 | 18 | Daughter-in-law |

| 26 January | Male | 43 | 16 | Son | |

| 26 January | Female | 52 | 17 | Daughter | |

| 29 January | Female | 62 | 15 | Sister | |

| 29 January | Female | 52 | 21 | Mother | |

| 30 January | Male | 33 | 16 | Husband | |

| 3 | 8 February | Female | 38 | 21 | Daughter |

| 8 February | Female | 61 | 16 | Wife |

Thematic analysis

Themes that emerged from the focus group discussions and cognitive interviews have been combined and are presented for each of the FS-ICU-24 items below.

Demographics

The first section of the FS-ICU-24 comprises six questions asking for information about the respondent and their relationship to the patient.

Sex (response options: Male/Female)

There were no issues identified by participants and no changes were made.

Age (response required age to be indicated)

There were no issues identified by participants and no changes were made.

I am the patient’s (response options include: Wife/Husband/Son/Daughter/etc.)

Participants suggested adding relationship options, such as ‘friend’, ‘neighbour’ and ‘son/daughter-in-law’. It was acknowledged that it would be impossible to have a comprehensive list of options and that the response option of ‘other’ with a free-text space to enter the details would suffice. Additional relationship options were added.

Before this most recent event, have you been involved as a family member of a patient in ICU (Intensive Care Unit)? (response options: Yes/No)

There were no major issues identified and no changes were made. It is of note that a number of participants in the cognitive interviews took some time to recall the information required to respond to this question and one participant (during an interview with the 61-year-old wife and the 38-year-old daughter of an ICU patient) asked if this meant ‘any ICU ever?’

Do you live with the patient? If no, then on average how often do you see the patient? (response options: More than weekly/Weekly/Monthly/Yearly/Less than once a year)

Although this question was considered easy to answer, it generated debate during the focus group discussions about its purpose and what it implied about the strength of the relationship to the patient. There were discussions about how often a relative might visit the patient (if they did not share a home). Participants in the cognitive interviews who did not live with their relative (the patient) mentioned telephoning them to keep in touch. There was general agreement that perhaps the response categories were not sufficiently discriminating to capture the range of likely experiences; in particular, the gap between seeing someone ‘monthly’ and ‘yearly’. The SMG agreed to add additional response options: ‘every 2 to 3 months’ and ‘every 4 to 6 months’.

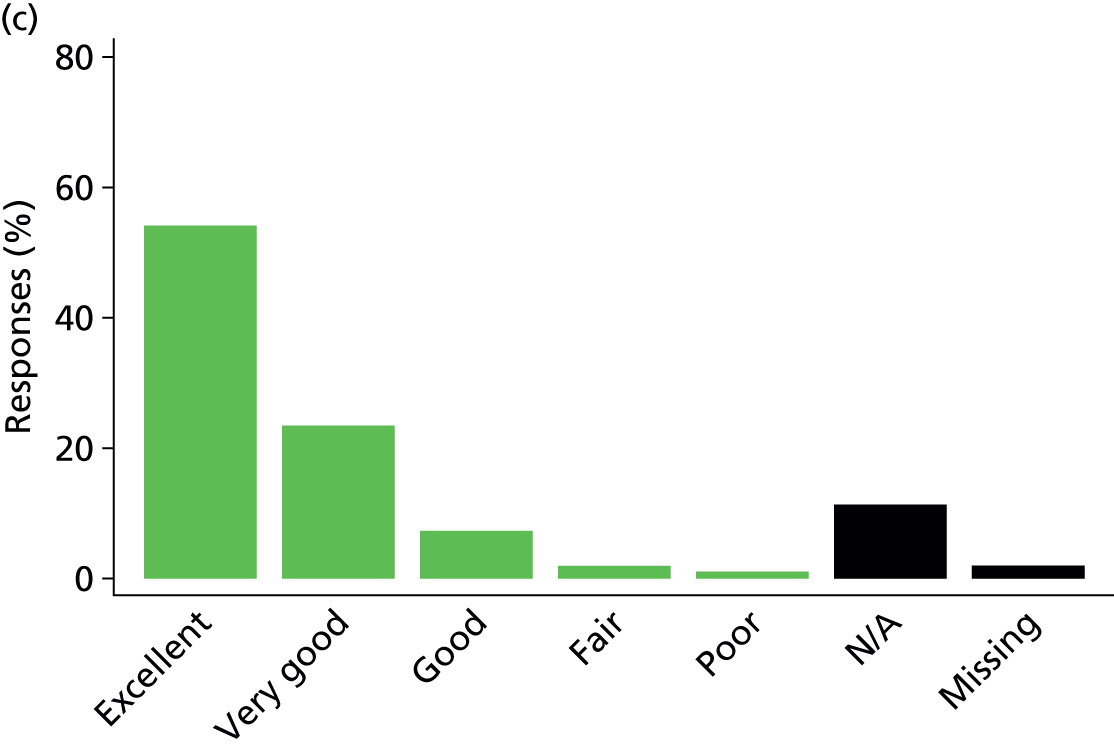

During the first round of cognitive interviews, participants also queried the purpose of this question. DKH confirmed that it was to gauge how well the family member knew the patient and their health and other issues. In response to participants’ comments, a new question was proposed to further tap into this construct as follows: ‘How would you rate your knowledge of the patient and their health issues? (response options: excellent/very good/good/fair/poor)’.

This question was tested in the second round of cognitive interviews. Further feedback indicated there was some confusion about the time frame of reference for this new item vis-à-vis the patient’s admission to ICU. The question was amended to ‘how would you rate your knowledge of the patient’s health issues prior to them coming to the ICU?’ This was then tested in the third round of cognitive interviews. No further issues with comprehensibility of the question were raised and the question was retained.

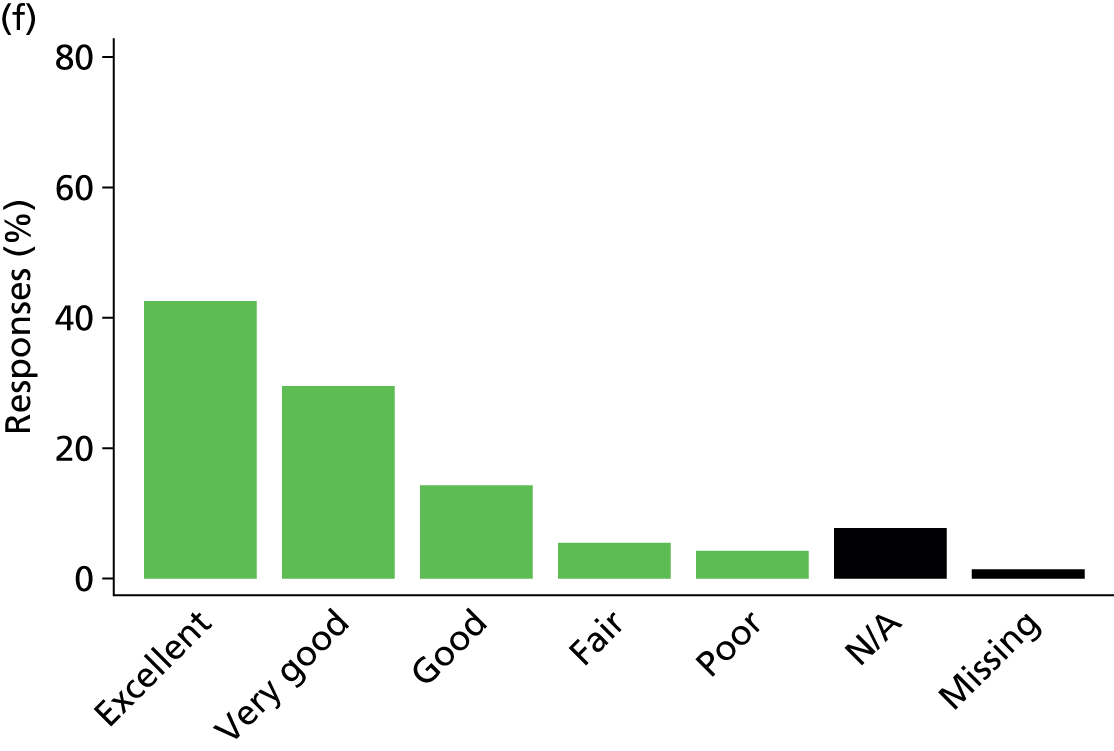

Where do you live? (response options: In the city where the hospital is located/Out of town)

A number of participants found the response option ‘out of town’ to be an imprecise term and hard to interpret. The majority of cognitive interview participants considered that they were from ‘out of town’, a pattern of response which could be related to the recruiting NHS hospital trust being a tertiary referral centre within the north-east of England.

At the focus group held with health-care professionals in London, there was discussion about the possibility that the difficulty in travelling across a large city was comparable with coming from ‘out of town’. Participants suggested that this question should ask more directly about the ease of travel to the ICU for family members, which DKH confirmed was the intention of the question. A replacement question was proposed as follows: ‘How would you rate the ease of travelling from your home to the hospital? (response options: excellent/very good/good/fair/poor)’. This was tested in subsequent cognitive interviews and discussed at the final focus group (held in South Tyneside with representatives from ICUsteps) and found to work well. The reworded question was retained.

Part 1: satisfaction with care

The second section of the FS-ICU-24 comprises 14 items that contribute to the overall family satisfaction score and to the satisfaction with care domain score. The 14 items were divided up under six subheadings: ‘how did we treat your family member (the patient)?’ (four items); ‘how did we treat you?’ (four items); ‘nurses’ (two items); ‘physicians (all doctors, including residents)’ (one item); ‘the ICU’ (one item); and ‘the waiting room’ (two items).

Response options to the first 13 of the 14 items were ‘excellent/very good/good/fair/poor’, with a further option of ‘not applicable’. The response options to the last item were ‘very dissatisfied/slightly dissatisfied/mostly satisfied/very satisfied/completely satisfied’.

How did we treat your family member (the patient)?

Q1: Concern and caring by ICU staff [the courtesy, respect and compassion your family member (the patient) was given]

During one of the focus group discussions and during the first round of cognitive interviews the concept of ‘dignity’ was mentioned and participants commented that a lot of NHS literature and posters refer to ‘dignity’. In the later rounds of cognitive interviews, participants were specifically asked about the construct of dignity. Participants thought that courtesy, respect and compassion were all important characteristics. One participant commented that courtesy, respect and compassion are separate characteristics and that it would be possible for a member of ICU staff to exhibit courtesy and respect but without showing compassion. It was suggested that this question could potentially be split into two, with one question asking about courtesy and respect and a separate question asking about compassion.

The SMG considered whether to substitute (with ‘dignity’) or drop the word ‘courtesy’ but it was concluded that this might alter the sense of the item and have an adverse impact on the validity of the FS-ICU-24. These decisions took into account advice from DKH and the intent of the item, which was to obtain the family member’s overall assessment of the constructs of concern and caring, and the words ‘courtesy’, ‘respect’ and ‘compassion’ were simply to orient family members to this construct. No changes were made.

Symptom management (how well the ICU staff assessed and treated your family member’s symptoms)

Q2: Pain

There were no issues identified by participants and no changes were made.

Q3: Breathlessness

There were no issues identified by participants and no changes were made.

It is of note that some participants suggested that a family member’s assessment of breathlessness could be subjective, which was deemed reasonable.

Q4: Agitation

There were no major issues identified by participants and no changes were made.

It is of note that participants commented on the different types of agitation they had witnessed in their family members (the patients). For example, one participant noted that the patient had been agitated because the bed was uncomfortable, while two others (a 52-year-old mother of an ICU patient and a 32-year-old male relative of an ICU patient) noted it was because the patient was unable to speak because of the ‘breathing tube’. Participants also commented that it is common for patients to panic on waking up but acknowledged that the word ‘panic’ would not work as an alternative to the word ‘agitation’.

How did we treat you?

Q5: Consideration of your needs (how well the ICU staff showed an interest in your needs)

There were no major issues identified by participants and no changes were made.

None of the participants in either the focus group discussions or the cognitive interviews suggested there was any need for changes to this item. It is of note that the health-care professionals (who participated in the focus group discussions) interpreted the needs of family members as being around facilities at the hospital/ICU such as car parking or availability of refreshments. In contrast, family members (who were interviewed) considered that their own material needs were secondary and indicated that they were more concerned with communication and being kept informed of the patient’s progress. Although these differing perspectives provided interesting insights, it was not felt that any changes to this item were indicated.

Q6: Emotional support (how well the ICU staff provided emotional support)

There were no major issues identified by participants and no changes were made.

It is of note that participants in the focus groups discussed how ‘needs’ of family members (referred to in Q5 above) and ‘emotional support’ could be regarded as being similar or the same, as the principal need of some family members is emotional support. Participants in the cognitive interviews who identified themselves as the next of kin felt that this concept of emotional support was important; however, they felt it was likely to be less important or relevant to more distant relatives, such as a son-in-law/daughter-in-law.

Q7: Co-ordination of care (the teamwork of all the ICU staff who took care of your family member)

Some participants in the cognitive interviews talked about poor handovers between staff, and good and poor teamwork, and made comparisons with their previous experiences at other ICUs and hospitals. This was considered likely to amplify responses from family members rather than indicative of a need to change the wording of this item.

Some participants in the focus group discussions asked why this item was included under the heading of ‘how did we treat you?’ They suggested that this item should be moved or placed under a separate subheading. The item was moved to come under a new subheading, ‘teamwork’, which was added.

Q8: Concern and caring by ICU staff (the courtesy, respect and compassion you were given)

Participants in one focus group commented that this question seemed to be returning to the issue of emotional support, which had already been addressed in Q6. It also prompted further discussion about how ‘courtesy’, ‘respect’ and ‘compassion’ differ. Participants in the cognitive interview reiterated that a nurse can be polite without being compassionate. As for Q6, participants also mentioned the concept of dignity being an important consideration.

In response to the feedback from participants, a change to the wording of this item was considered. It was decided, however, that the original wording should be retained to facilitate comparison with other studies that have used the FS-ICU-24. Furthermore, there was no other wording of the item that was universally preferred.

Nurses

Q9: Skill and competence of ICU nurses (how well the nurses cared for your family member)

There were no major issues identified by participants and no changes were made.

It is of note that, during the focus group discussions, some of the health-care professionals questioned whether or not family members can judge the skill and competence of the nurses. In addition, one of the participants in the cognitive interviews commented that they did not feel that they could make this judgement.

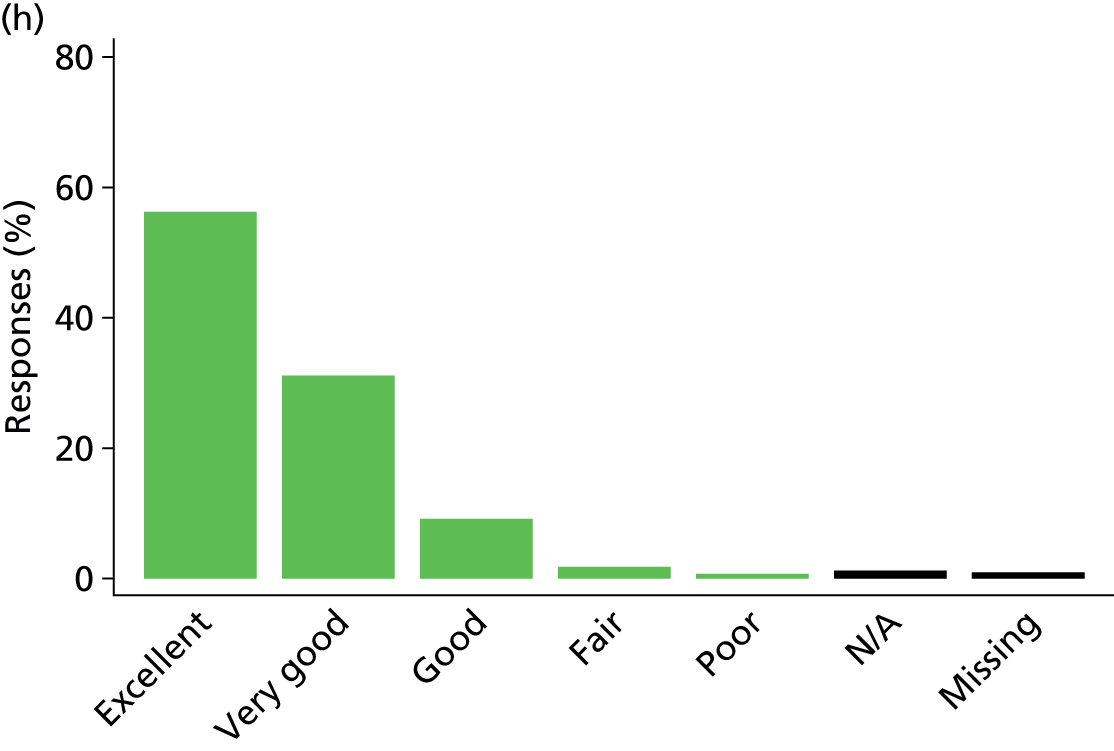

Q10: Frequency of communication with ICU nurses (how often nurses communicated to you about your family member’s condition)

The item was regarded as a potential problem by some of the cognitive interview participants. Participants recruited from the same ICU provided responses to this question that ranged from ‘excellent’ to ‘poor’. Some participants commented that they felt that the nurse should approach them and provide information about the patient. If this had not happened, then they tended to provide a negative response such as ‘poor’. Family members who were not the patient’s immediate next of kin tended to respond more negatively to this item, possibly reflecting the fact that they were less likely to have received the same amount of information as, for example, the patient’s immediate next of kin.

Health-care professionals participating in the focus group discussions commented that doctors tend not to volunteer information immediately upon meeting a family member. One participant (an ICU nurse who worked in a follow-up clinic) noted ‘You would introduce yourself and establish who they are and use discretion if they want information.’

The SMG agreed that the comments from participants provided useful insight into why responses might vary within and across ICUs and between different family members for the same patient, but no changes were made to this item. It was noted that one of the objectives of phase 2 of the FREE study was to explore how family satisfaction varied by family member and ICU/hospital characteristics (see Chapter 7).

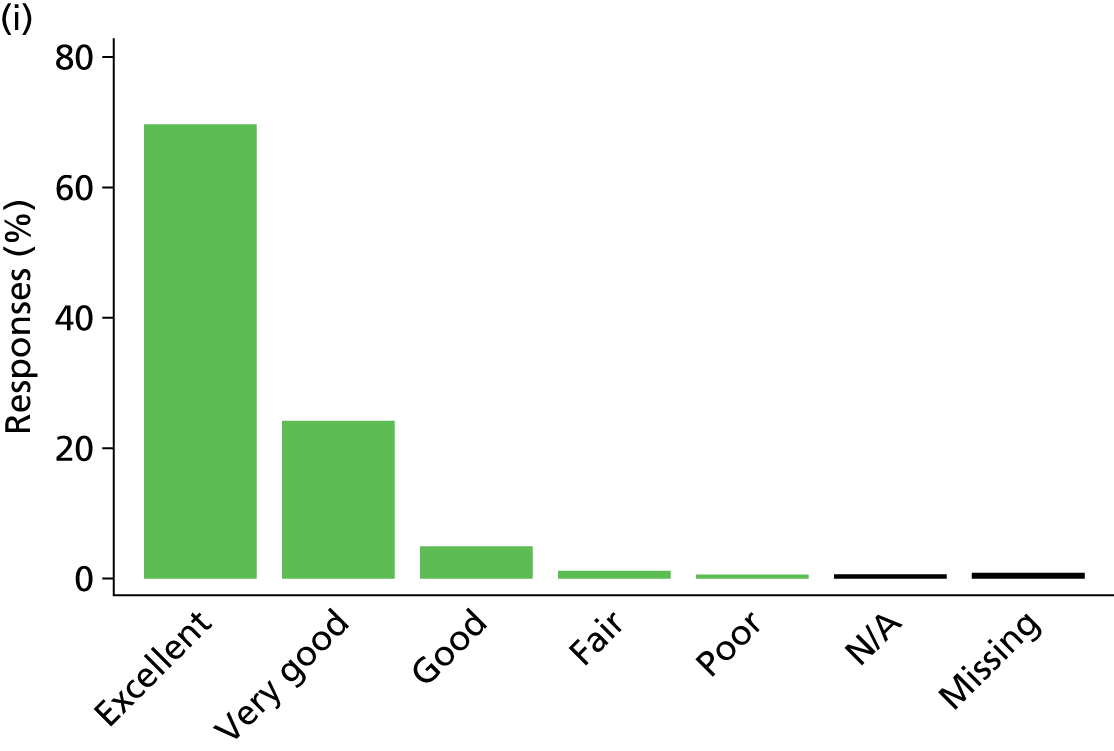

Doctors

Q11: Skill and competence of ICU doctors (how well doctors cared for your family member)

There were no issues identified by participants and no changes were made.

The ICU

Q12: The atmosphere of the ICU was?

During the first round of cognitive interviews, participants commented that they found the word ‘atmosphere’ to be ambiguous. Their responses to this question indicated that they were variously thinking about concepts ranging from the temperature of the ICU to the friendliness of the ICU. Participants suggested that the word ‘mood’ or ‘environment’ might be better alternatives. DKH confirmed that the intent of the question was to capture family members’ impression of the general ‘feel’ of the ICU. For subsequent rounds of cognitive interviews, ‘atmosphere’ was replaced with ‘mood’. However, participants found ‘mood’ ambiguous and suggested that the (original) word ‘atmosphere’ would be better. The SMG concluded, therefore, that the word ‘atmosphere’ should be retained but with the word ‘mood’ in parentheses to convey the sense of what was meant by ‘atmosphere’ as follows: ‘The atmosphere (mood) of the ICU was?’

The waiting room

Q13: The atmosphere in the Waiting Room was?

During the cognitive interviews, there were similar comments as for Q12 relating to the word ‘atmosphere’. DKH confirmed that the intent of the question was to capture family members’ impression of the general ‘feel’ of the waiting room. This question was therefore worded along similar lines to Q12, as follows: ‘The atmosphere (mood) in the ICU waiting room was?’

Q14: Some people want everything done for their health problems while others do not want a lot done (how satisfied were you with the LEVEL or amount of health care your family member received in the ICU?)

Participants felt that this was an important item; however, many of the participants in the cognitive interviews commented on the phrasing of the question and found it difficult to interpret the meaning of the question. Participants said that they felt that family members would want as much as possible done for their relative in the ICU. One participant asked if the question was about end-of-life care. Some of the health-care professionals, who took part in the focus group discussions, considered the first sentence of this question to be patronising. Other focus group participants disagreed with the reversal of the response options for this item, ranging from ‘very dissatisfied’ to ‘completely satisfied’ as opposed to the response options ranging from ‘excellent’ to ‘poor’ for the previous items.

Based on comments from participants during the first two focus group discussions and the initial round of cognitive interviews, the wording of the question was modified for the subsequent round of cognitive interviews to ‘how satisfied were you with the LEVEL or amount of health care your family member received in the ICU bearing in mind their likely wishes?’ The intention was to focus the question on the patient and what they might want rather than what the family member might want for the patient.

Participants who took part in subsequent rounds of cognitive interviews did not find the revised wording of the question to be any clearer than the original. This view was echoed during the final focus group discussion. In particular the rider ‘bearing in mind their likely wishes’ was not considered to be helpful.

The SMG was concerned that removing the introductory sentence might change the meaning of this item. Furthermore, DKH noted that studies in Canada11 had found this item correlated well with overall family satisfaction. Given this, combined with the feedback from participants, the SMG agreed the question should not be modified. The order of the response options (i.e. reversed) was also retained because of concerns that any change would affect the factorial validity of the FS-ICU-24; however, a rider was added to alert the respondent to the order of the responses.

Part 2: family satisfaction with decision-making around the care of critically ill patients

The third section of the FS-ICU-24 comprises 10 items that contribute to the overall family satisfaction score and to the satisfaction with decision-making domain score. The 10 items were divided up under two subheadings: ‘information needs’ (six items) and ‘process of making decisions’ (four items).

Response options to the first six items were ‘excellent/very good/good/fair/poor’ with a further option of ‘not applicable’. The response options to the remaining items are provided below with the item.

Comments from participants in the cognitive interviews indicated that the instructions for this part of the FS-ICU-24 were clear; however, several participants stated that they had had no involvement in decision-making relating to the patient’s (their family member’s) health care. Clinical members of the SMG (DKH, AR, SW) noted that, although in both Canada and the UK the aim is to involve family members as much as possible in the decision-making process in an intensive care setting, there are contextual differences with respect to legal frameworks. In Canada, if an adult loses the mental capacity to make decisions about their health care, a substitute decision-maker is appointed, who is usually the next of kin. This is in contrast to the situation in England, where doctors, working under the Mental Capacity Act 2005,20 make decisions in the patient’s best interests, taking into account the views of family members.

Information needs

Q1: Frequency of communication with ICU doctors (how often doctors communicated to you about your family member’s condition)

There were no major issues identified by participants and no changes were made.

Notably, many of the participants in the cognitive interview commented that they had little contact with the doctors. It was noted that more distant relatives (i.e. not the immediate next of kin) would be likely to have less contact with doctors and might, therefore, give a more negative response to this question. Participants suggested that this item should be moved to follow the item asking about communication with the nurses (Q10 in part 1: satisfaction with care). This was considered by the SMG and rejected because of the impact that reordering items might have on the construct validity of the FS-ICU-24; DKH indicated that the item asking about communication with the nurses was designed to address the construct ‘process of care’ whereas this item asking about communication with doctors was designed to address the construct ‘process of decision-making’.

Q2: Ease of getting information (willingness of ICU staff to answer your questions)

There were no issues identified by participants and no changes were made.

It is of note that some of the participants in the cognitive interviews commented that the ease of getting information depended on whether communication was face to face or by telephone. That is to be expected; it is generally easier to get information face to face than by telephone.

Q3: Understanding of information (how well ICU staff provided you with explanations that you understood)

There were no issues identified by participants and no changes were made.

Q4: Honesty of information (the honesty of information provided to you about your family member’s condition)

There were no issues identified by participants and no changes were made.

It is of note that the health-care professionals who took part in the focus group discussions did not like the word ‘honesty’ used in this context because the antonym is ‘dishonesty’ and they felt that the wording of the question ‘implies we would lie’ (ICU nurse). Participants suggested the words ‘openness’ or ‘transparency’ as alternatives to ‘honesty’. However, participants in the cognitive interviews and in the focus groups with representatives from ICUsteps had no concerns with the word ‘honesty’. In the light of this, the SMG agreed no changes should be made.

Q5: Completeness of information (how well the ICU staff informed you what was happening to your family member and why things were being done)

There were no issues identified by participants and no changes were made.

Q6: Consistency of information (the consistency of information provided to you about your family member’s condition – did you get a similar story from the doctor, nurse, etc.)

There were no issues identified by participants and no changes were made.

It is of note that the health-care professionals disliked the rider ‘did you get a similar story from the doctor, nurse, etc.’ They specifically disliked the word ‘story’, which implies that information given to family members is not honest. Participants in the cognitive interviews raised no issues with this item. The SMG agreed that this item should remain unchanged.

Process of making decisions

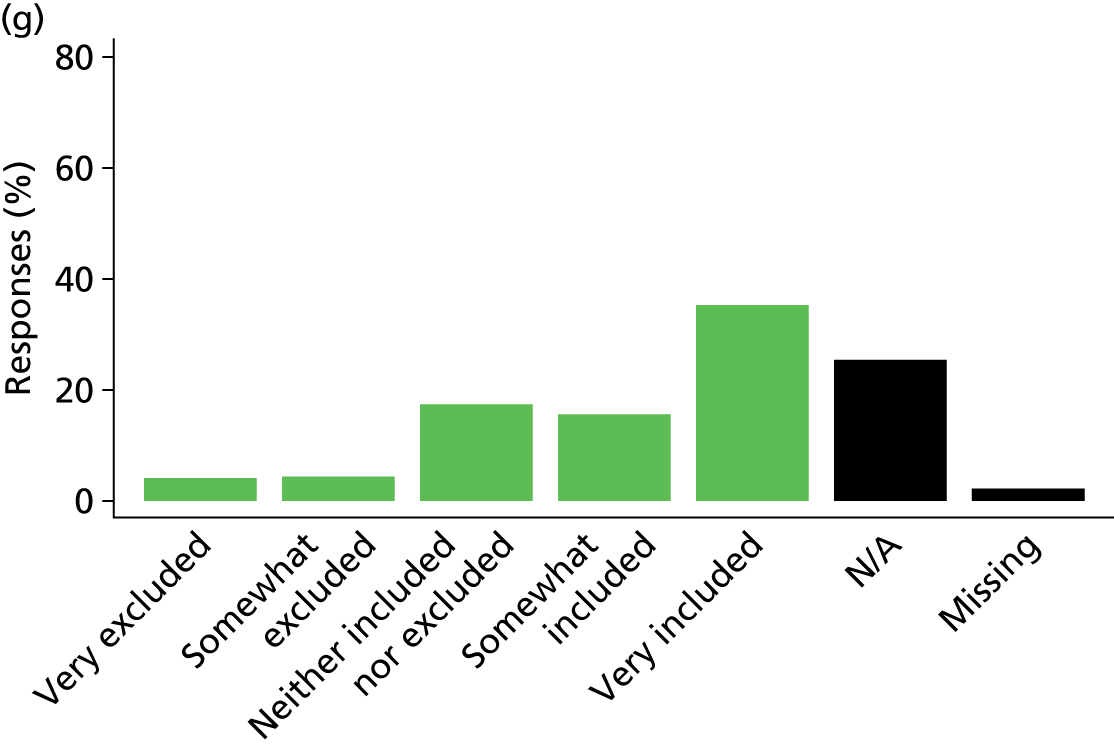

Q7: Did you feel included in the decision-making process? (response options: I felt very excluded/I felt somewhat excluded/I felt neither included nor excluded/I felt somewhat included/I felt very included)

Some participants in the cognitive interviews felt that this question was not applicable to them because, for example, the patient’s admission to the ICU had been planned following elective surgery. In these instances, participants had commented that the patient had usually been conscious and had retained the mental capacity to make their own decisions throughout their stay in the ICU.

Other cognitive interview participants commented that, although they were kept informed about the decisions being taken by the intensive care staff, they were not actively involved in the decision-making process. More distant family members (i.e. not the immediate next of kin) reported having had less communication with the intensive care staff and not being involved in the decision-making process. In the light of these comments, the SMG agreed a ‘not applicable’ response option should be added.

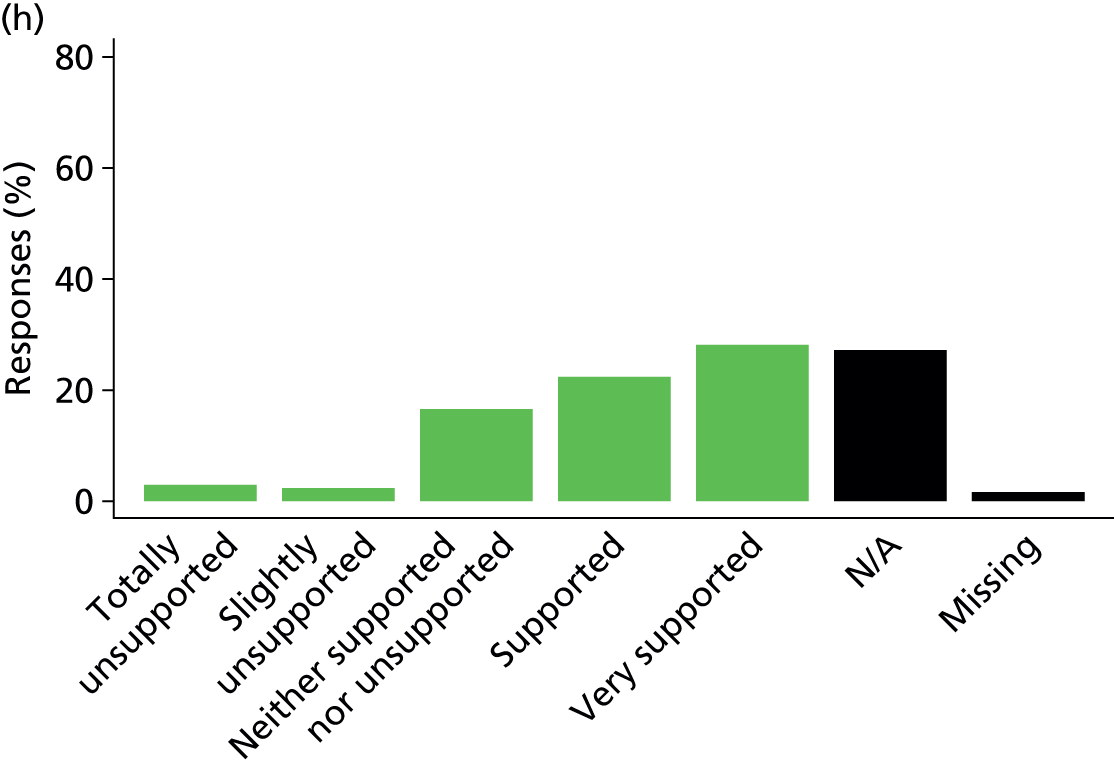

Q8: Did you feel supported during the decision-making process? (response options: I felt totally overwhelmed/I felt slightly overwhelmed/I felt neither overwhelmed nor supported/I felt supported/I felt very supported)

In considering the response options to this item (listed above), participants who took part in the early round of cognitive interviews commented that one could be ‘totally overwhelmed’ but still be ‘well supported’. Participants suggested that the word ‘overwhelmed’ should be replaced by the word ‘unsupported’ in the response options to this item. The revised response options were tested and performed well in the subsequent round of cognitive interviews and at the final focus group discussion. This change to the response options was therefore retained. The SMG agreed that a ‘not applicable’ response option should be added.

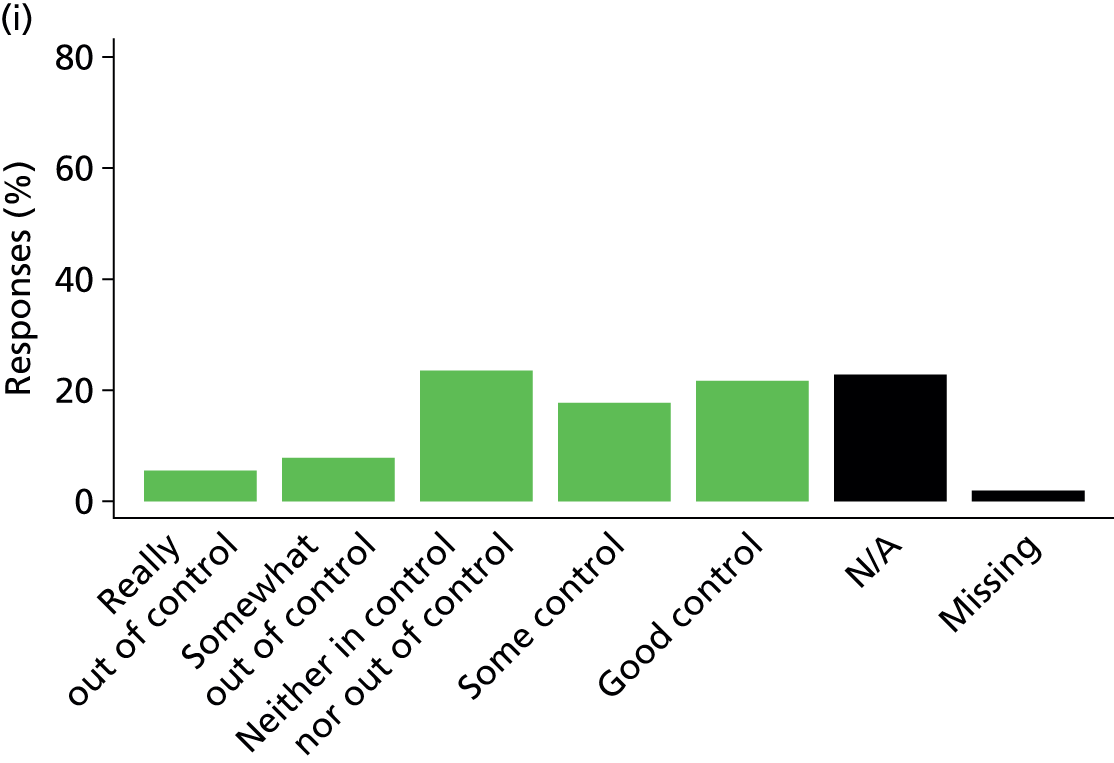

Q9: Did you feel you had control over the care of your family member? (response options: I felt really out of control and that the health care system took over and dictated the care my family member received/I felt somewhat out of control and that the health care system took over and dictated the care my family member received/I felt neither in control nor out of control/I felt I had some control over the care my family member received/I felt that I had good control over the care my family member received)

Most of the participants in the cognitive interviews felt that this item did not apply to them, while others expressed uncertainty whether or not they would have expected to have good control over the care their family member received. Similar views were expressed by participants who took part in the focus group discussions.

The SMG discussed the background to this question and the differences in the legal frameworks between Canada and the UK as regards adults who lose the mental capacity to make decisions about their health care (see above). The SMG acknowledged that contextual and cultural differences might result in lower scores for this item in a UK setting but there were no compelling reasons to drop it. A ‘not applicable’ response option was added.

It was agreed, however, that a new question should be added to assess satisfaction with the amount of control the respondent (family member) felt they had over the care of their family member (patient) as follows: ‘How satisfied were you with the amount of control you had over the care of your family member? (response options: excellent/very good/good/fair/poor)’.

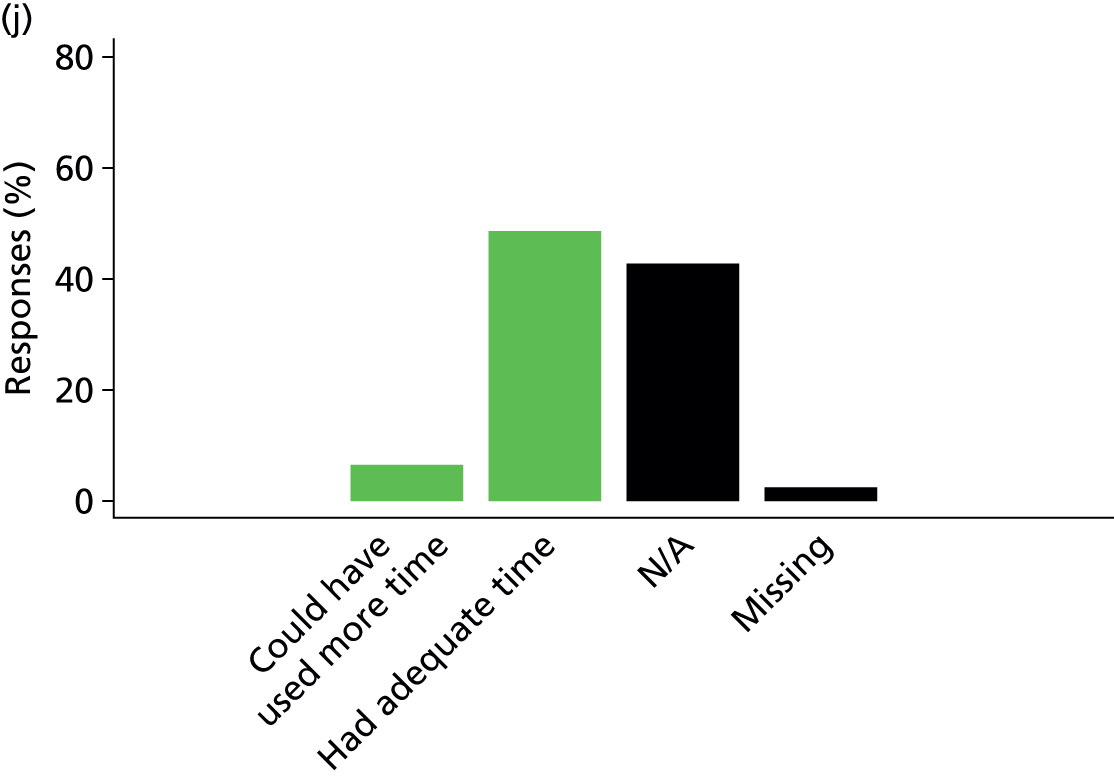

Q10: When making decisions, did you have adequate time to have your concerns addressed and questions answered? (response options: I could have used more time/I had adequate time)

Many of the cognitive interview participants commented that in an intensive care setting decisions often need to be made very quickly and therefore felt that a ‘not applicable’ option was needed for this question. The SMG agreed this option should be added.

For family members of patients who died in the intensive care unit

Three questions are included in the third section of the FS-ICU-24 for family members of patients who died in the ICU. These questions do not contribute to the overall family satisfaction score or to the satisfaction with care and satisfaction with decision-making domain scores.

If your family member died during the ICU stay, please answer the following questions (11–13). If your family member did not die, please skip to question 14.

The health-care professionals expressed concern about the appropriateness of these questions and potential distress to bereaved family members, particularly as, during phase 2 of the FREE study, family members would receive the questionnaire 3 weeks after the patient had died in the ICU. However, participants in the cognitive interviews, who were all family members, were less concerned about the 3-week time frame. The questions were considered to be important and some participants suggested that they might be better in a separate questionnaire. Given concerns about potential distress to bereaved family members, participants commented that consideration needed to be given to how these questions were introduced to make them more acceptable. To this end, the SMG agreed that a rider should be added to orient respondents to the theme of the three questions and to explain the reason for asking the questions as follows:

If your family member died in the ICU, we would like to ask your opinion on how things went in those final days. We know it may be difficult to answer these questions but we would greatly value your input so we can improve the care we provide dying patients.

Q11: Which of the following best describes your views? (response options: I felt my family member’s life was prolonged unnecessarily/was slightly prolonged unnecessarily/was neither prolonged nor shortened unnecessarily/was slightly shortened unnecessarily/was shortened unnecessarily)

Many of the health-care professionals felt uncomfortable with this question and the response options. They talked about the Liverpool Care Pathway and the negative publicity around its application in the NHS. Many were concerned that some of the response options might precipitate the start of a complaints procedure. Similarly, some cognitive interview participants commented that if a family member selected the response option ‘I felt my family member’s life was slightly shortened unnecessarily’ or ‘I felt my family member’s life was shortened unnecessarily’ it might trigger the start of legal action against the NHS hospital trust. DKH noted that the experience in Canada has been that most respondents have tended to choose the response option ‘I felt my family member’s life was neither prolonged nor shortened unnecessarily’.

Q12: During the final hours of your family member’s life, which of the following best describes your views? (response options: I felt that he/she was very uncomfortable/was slightly uncomfortable/was mostly comfortable/was very comfortable/was totally comfortable)

There were no major issues identified by participants and no changes were made.

It is of note that the health-care professionals were generally comfortable with this question and the response options. Participants in the cognitive interviews commented that this would be an important question for some family members.

Q13: During the last few hours before your family member’s death, which of the following best describes your views? (response options: I felt very abandoned by the health care team/I felt abandoned by the health care team/I felt neither abandoned nor supported by the health care team/I felt supported by the health care team/I felt very supported by the health care team)

There were no major issues identified by participants and no changes were made.

It is of note that the word ‘abandoned’ was considered to be emotive by many participants (both family members and health-care professionals) but there were no suggestions for an alternative word apart from ‘unsupported’. However, participants acknowledged the concept of abandonment and felt that it was important.

Summary of changes to the 24-item Family Satisfaction in the Intensive Care Unit questionnaire

The changes, agreed by the SMG, to the original FS-ICU-24 are summarised below. KR and EW led on implementing the agreed changes and on the reformatting/redesign of the questionnaire to enhance response.

About you

The section heading ‘demographics’ in the original FS-ICU-24 was changed to ‘about you’ to simplify the language. Changes made to this section were as follows:

-

Additional response options were provided for the question asking about the respondent’s relationship to the patient.

-

A question asking ‘are you the patient’s next of kin?’ was added to ascertain if the respondent considered themselves the patient’s next of kin.

-

Additional response options were provided for the question asking about how frequently the respondent saw the patient if they did not live with them.

-

A question ‘how would you rate your knowledge of the patient’s health issues prior to them coming to the ICU?’ was added, with five response options ranging from ‘excellent’ to ‘poor’.

-

The question ‘where do you live?’ on the original questionnaire was replaced with the question ‘how would you rate the ease of travelling from your home to the hospital?’ with five response options ranging from ‘excellent’ to ‘poor’.

Satisfaction with care

The section heading in the original FS-ICU-24 was kept. Changes made to this section were as follows:

-

The item asking about co-ordination of care (originally one of four items under the subheading ‘how did we treat you?’) was moved to come under a new subheading, ‘teamwork’, and follows ‘how did we treat you?’

-

The subheading ‘physicians’ was replaced with ‘doctors’, as this term was more familiar to a UK population.

-

The item ‘the atmosphere of the ICU was?’ was modified to read ‘the atmosphere (mood) of the ICU was?’

-

The item ‘the atmosphere in the ICU waiting room was?’ was modified to read ‘the atmosphere (mood) in the ICU waiting room was?’

-

A rider ‘please pay attention to the order of responses’ was added to the item asking about satisfaction with the level or amount of health care the patient received, to alert respondents to the order of the response options (in reverse order), and a new subheading, ‘level/amount of health care’, was added.

Satisfaction with decision-making

The section heading in the original FS-ICU-24 was kept. Changes made to this section were as follows:

-

For items 7–10 under the subheading ‘the process of decision-making’, the following sentence was added to the guidance notes: ‘If your family member was able to make decisions for themselves while in the ICU, then some questions may not be applicable to you; in that case, please tick not applicable’.

-

A response option of ‘not applicable’ was added to the items related to the process of making decisions.

-

The response options for the item about how supported the respondent felt during the decision-making process were modified slightly – the word ‘overwhelmed’ was replaced with ‘unsupported’.

Additional questions

In addition to the 24 items that contribute to the satisfaction with care and satisfaction with decision-making domain scores, there are three questions for family members of patients who died in the ICU, which ask for their views on the end-of-life care of their family member (the patient).

The following change was made to the guidance notes: ‘If your family member died during the ICU stay, please answer the following questions (11–13)’ was replaced with ‘if your family member died in the ICU, we would like to ask you your opinion on how things went in those final days. We know it may be difficult to answer these questions but we would greatly value your input so we can improve the care we provide to dying patients.’

Following the three questions above, a question was added for all family members, as follows: ‘How satisfied were you with the amount of control you had over the care of your family member?’, with five response options ranging from ‘very dissatisfied’ to ‘completely satisfied’.

Finally, for consistency, the word ‘hospital’ was replaced by the word ‘ICU’ for the last question, asking for comments and suggestions that the family member felt might be helpful to staff.

In addition, a cover page was created with three additional questions (not included in the original FS-ICU-24) as follows:

-

‘today’s date’, to establish when the questionnaire was completed in relation to the patient’s discharge from, or death in, the ICU

-

‘did you complete the questionnaire alone/with help?’, to establish whether the questionnaire had potentially been completed by one or more family members

-

‘approximately how many times did you visit your family member in the ICU?’, to establish the frequency with which the family member visited the patient in the ICU.

In addition, a reminder of the definition of a family member was provided.

General formatting

The UK FS-ICU-24 was designed in the form of a booklet and titled ‘The FREE Study Questionnaire’ to ensure that family member participants in the cohort study (described in Chapter 3) identified the questionnaire as related to the FREE study. The FREE study logo was incorporated and the colours of headings, page borders and questionnaire item numbers were selected to reflect the logo colour scheme and to enhance the aesthetics of the questionnaire. Headings and subheadings were enlarged to varying degrees to help respondents navigate the questionnaire. The guidance notes were presented in the form of bullet points (rather than paragraphs of text) to make the information easier to read and understand. Phrases such as ‘check the box’ were translated to the UK English equivalent, for instance ‘tick the box’. For each item, a tick box was provided for each of the response options to clearly signpost how the response should be provided, as well as being aesthetically pleasing.

The UK 24-item Family Satisfaction in the Intensive Care Unit questionnaire

The final version of the UK FS-ICU-24 questionnaire (see Appendix 2), adapted from the original Canadian FS-ICU-24 questionnaire, is outlined below. The questionnaire comprised three parts: demographic information about the family member completing the questionnaire (under the heading About you), satisfaction with care and satisfaction with decision-making.

The first part of the questionnaire asked for information about the family member completing the questionnaire as follows:

Part 1: about you

Q1: I am . . . (Response options: male/female.)

Q2: I am . . . (Response: age in years.)

Q3: I am the patient’s . . . (Response options include wife/husband/mother/father/etc.)

Q4: Are you the patient’s next of kin? (Response options: yes/no.)

Q5: Before this most recent event, have you been involved as a family member of a patient in an ICU (intensive care unit)? (Response options: yes/no.)

Q6: Do you live with the patient? (If the patient has died, did you live with the patient?) (Response options: yes/no.)

If NO, then on average how often do you see the patient? (If the patient has died, how often did you see the patient?) (Response options: ranging from more than once a week to less than once a year.)

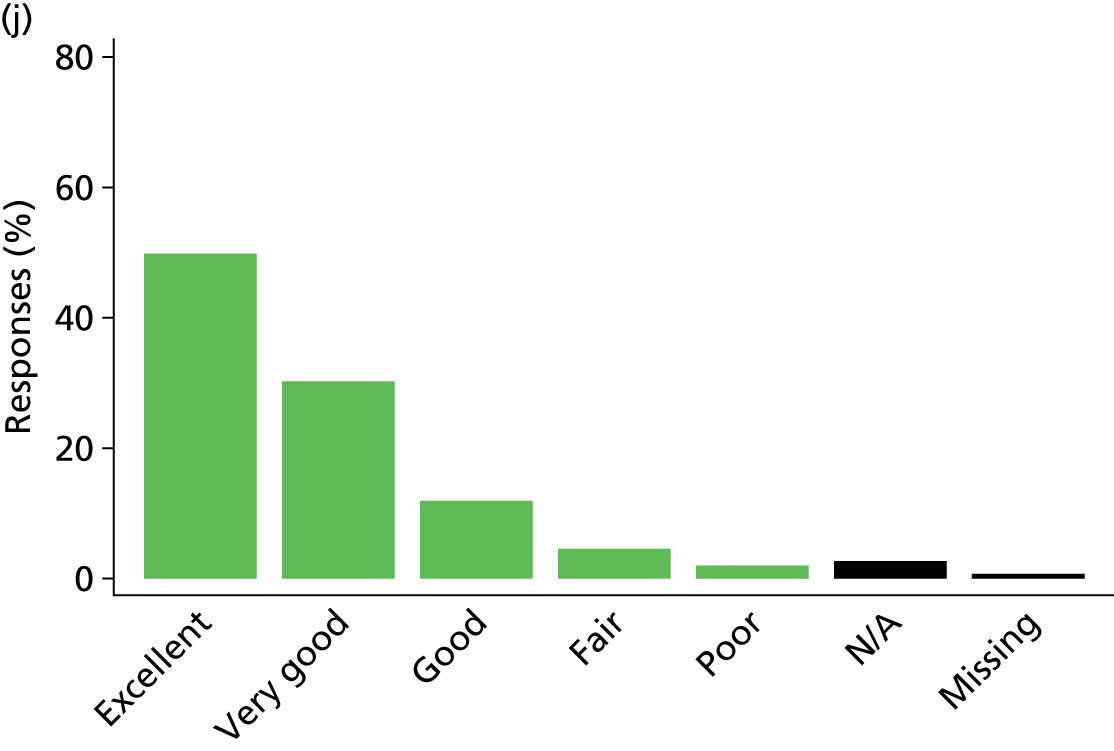

Q7: How would you rate your knowledge of the patient’s health issues prior to them coming to the ICU? (Response options: excellent/very good/good/fair/poor.)

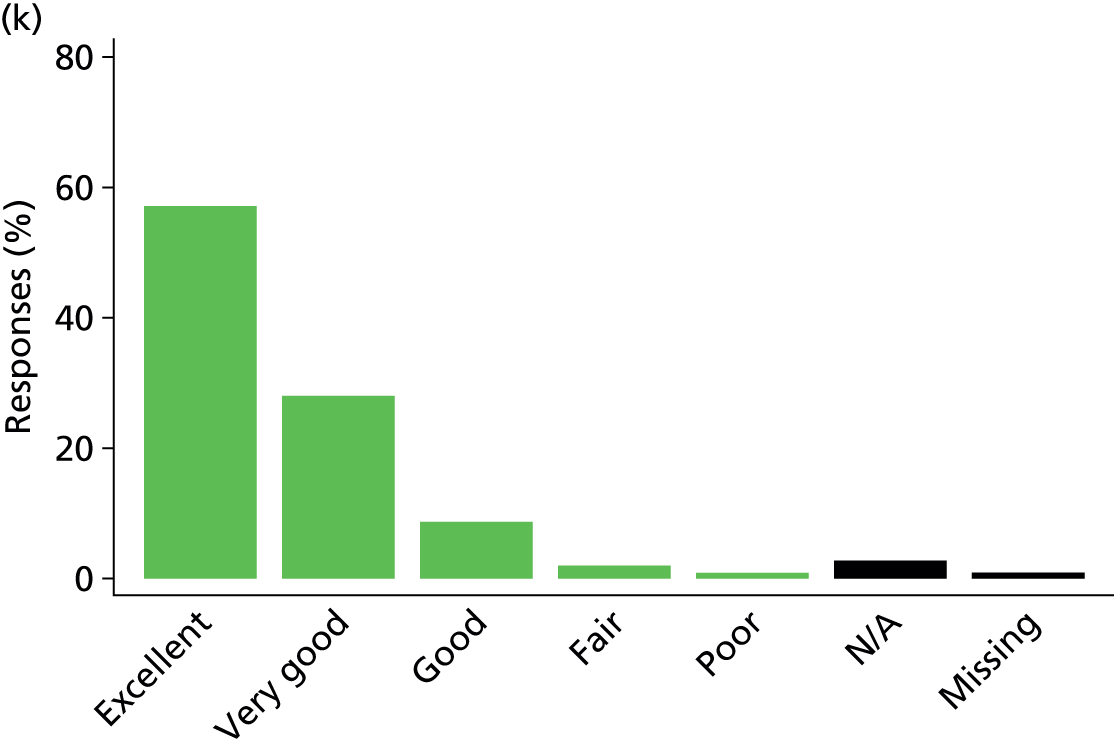

Q8: How would you rate the ease of travelling from your home to the hospital? (Response options: excellent/very good/good/fair/poor.)

Part 2: satisfaction with care

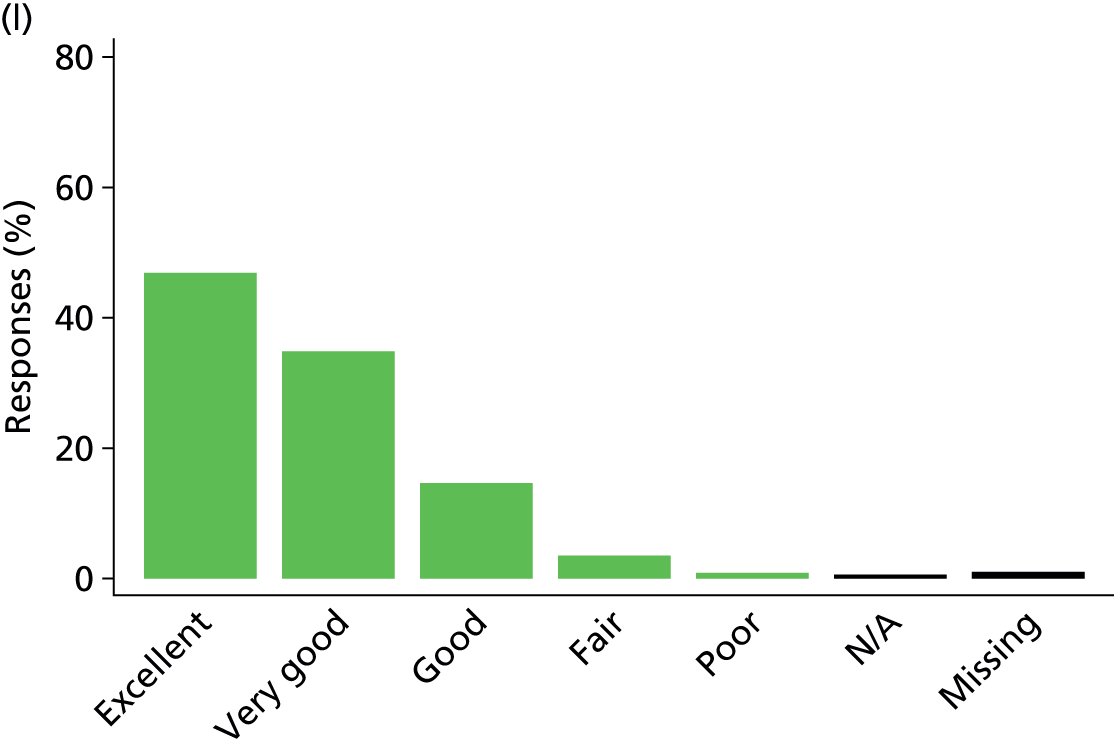

Fourteen items covered satisfaction with care; note that item 2 (Q2) was split into three parts, all asking about symptom management. For 13 of the 14 items, the response options were ‘excellent/very good/good/fair/poor’ with an additional option of ‘N/A’ (not applicable). For item 12, about satisfaction with the level or amount of health care, the response options were ‘very dissatisfied/slightly dissatisfied/mostly satisfied/very satisfied/completely satisfied’.

How did we treat your family member (the patient)?

Q1: concern and caring by ICU staff [the courtesy, respect and compassion your family member (the patient) was given].

Q2: Symptom management (how well the ICU staff assessed and treated your family member’s symptoms):

-

pain

-

breathlessness

-

agitation.

How did we treat you?

Q3: consideration of your needs (how well the ICU staff showed an interest in your needs).

Q4: emotional support (how well the ICU staff provided emotional support).

Q5: concern and caring by ICU staff (the courtesy, respect and compassion you were given).

Teamwork

Q6: co-ordination of care (the teamwork of all the ICU staff who took care of your family member).

Nurses

Q7: skill and competence of ICU nurses (how well the nurses cared for your family member).

Q8: frequency of communication with ICU nurses (how often nurses communicated to you about your family member’s condition).

Q9: skill and competence of ICU doctors (how well doctors cared for your family member).

The intensive care unit

Q10: the atmosphere (mood) of the ICU was . . .?

The waiting room

Q11: the atmosphere (mood) in the ICU waiting room was . . .?

Level/amount of health care

Q12: some people want everything done for their health problems while others do not want a lot done. How satisfied were you with the LEVEL or amount of health care your family member received in the ICU?

Part 3: satisfaction with decision-making

This part of the questionnaire included 17 questions. All family members were asked to complete the first 10 items, which cover satisfaction with decision-making around the care of the critically ill patient. For 6 of the 10 items the response options were ‘excellent/very good/good/fair/poor’ with an additional option of ‘N/A’. For the remaining four items, the response options are provided with the item.

Family satisfaction with decision-making around care of critically ill patients

Information needs

Q1: frequency of communication with ICU doctors (how often doctors communicated to you about your family member’s condition).

Q2: ease of getting information (willingness of ICU staff to answer your questions).

Q3: understanding of information (how well ICU staff provided you with explanations that you understood).

Q4: honesty of information (the honesty of information provided to you about your family member’s condition).

Q5: completeness of information (how well ICU staff informed you what was happening to your family member and why things were being done).

Q6: consistency of information [the consistency of information provided to you about your family member’s condition (did you get a similar story from the doctor, nurse, etc.)].

The process of making decisions

Q7: did you feel included in the decision-making process?

-

I felt very excluded.

-

I felt somewhat excluded.

-

I felt neither included nor excluded.

-

I felt somewhat included.

-

I felt very included.

-

Not applicable.

Q8: did you feel supported during the decision-making process?

-

I felt totally unsupported.

-

I felt slightly unsupported.

-

I felt neither supported nor unsupported.

-

I felt supported.

-

I felt very supported.

-

Not applicable.

Q9: did you feel you had control over the care of your family member?

-

I felt really out of control and that the health-care system took over and dictated the care my family member received.

-

I felt somewhat out of control and that the health-care system took over and dictated the care my family member received.

-

I felt neither in control nor out of control.

-

I felt I had some control over the care my family member received.

-

I felt that I had good control over the care my family member received.

-

Not applicable.

Q10: when making decisions, did you have adequate time to have your concerns addressed and questions answered?

-

I could have used more time.

-

I had adequate time.

-

Not applicable.

Family members of patients who died were asked to complete the questions listed below. Family members of survivors were asked to go to question 14.

Q11: which of the following best describes your views?

-

I felt my family member’s life was prolonged unnecessarily.

-

I felt my family member’s life was slightly prolonged unnecessarily.

-

I felt my family member’s life was neither prolonged nor shortened unnecessarily.

-

I felt my family member’s life was slightly shortened unnecessarily.

-

I felt my family member’s life was shortened unnecessarily.

Q12: during the final hours of your family member’s life, which of the following best describes your views?

-

I felt that he/she was very uncomfortable.

-

I felt that he/she was slightly uncomfortable.

-

I felt that he/she was mostly comfortable.

-

I felt that he/she was very comfortable.

-

I felt that he/she was totally comfortable.

Q13: during the last few hours before your family member’s death, which of the following best describes your view?

-

I felt very abandoned by the health-care team.

-

I felt abandoned by the health-care team.

-

I felt neither abandoned nor supported by the health-care team.

-

I felt supported by the health-care team.

-

I felt very supported by the health-care team.

All family members are asked to complete question 14 as follows:

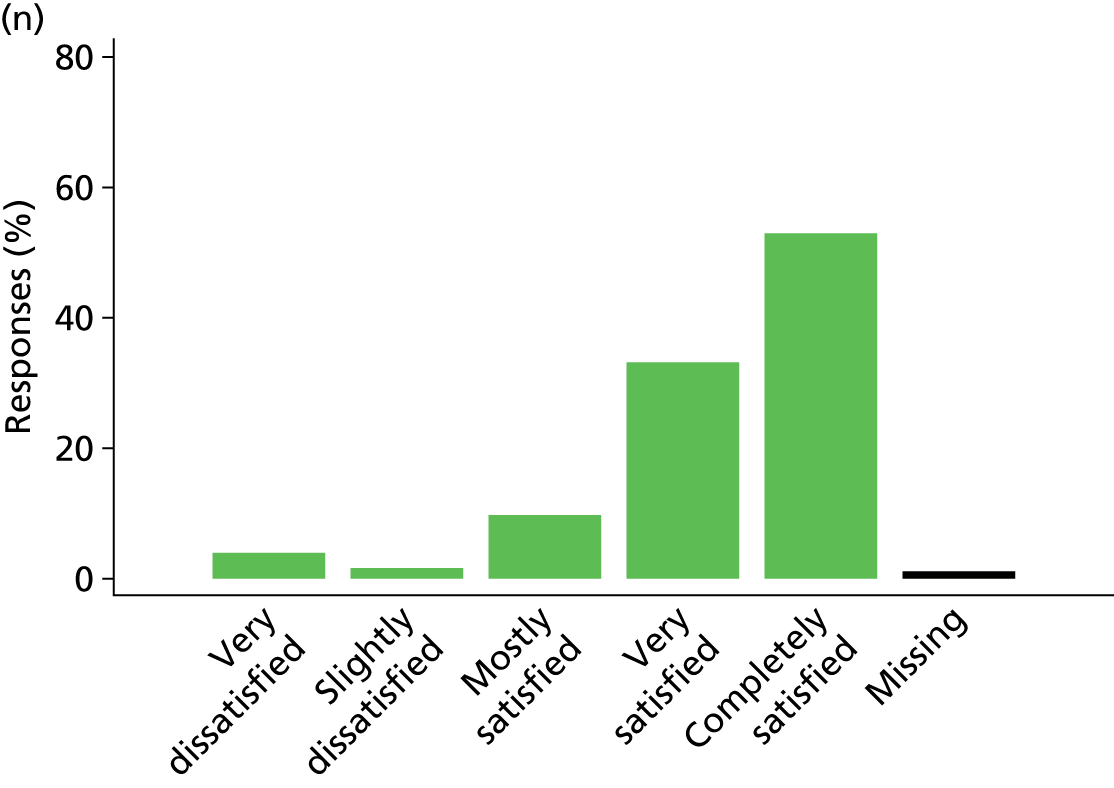

Q14: how satisfied were you with the amount of control you had over the care of your family member (response options: very dissatisfied/slightly dissatisfied/mostly satisfied/very satisfied/completely satisfied)?

The last three questions have free-text responses, providing an opportunity for family members to make comments and suggestions on the care provided in the ICU.

Q15: do you have any suggestions on how to make care provided in the ICU better?

Q16: do you have comments on things we did well?

Q17: please add any comments or suggestions that you feel may be helpful to the staff of this ICU.

Scores

The domain scores and the overall family satisfaction score are derived from the 14 items that comprise the domain satisfaction with care and the 10 items that comprise the domain satisfaction with decision-making. Each item response is scored on a scale from 0 (least satisfied) to 100 (most satisfied) as follows: poor/very dissatisfied, 0; fair/slightly dissatisfied, 25; good/mostly satisfied, 50; very good/very satisfied, 75; and excellent/completely satisfied, 100. Responses to items 7, 8, 9 and 10 in the domain satisfaction with decision-making are scored as follows:

Q7: did you feel included in the decision-making process?

-

I felt very excluded, 0.

-

I felt somewhat excluded, 25.

-

I felt neither included nor excluded, 50.

-

I felt somewhat included, 75.

-

I felt very included, 100.

Q8: did you feel supported during the decision-making process?

-

I felt totally unsupported, 0.

-

I felt slightly unsupported, 25.

-

I felt neither supported nor unsupported, 50.

-

I felt supported, 75.

-

I felt very supported, 100.

Q9: did you feel you had control over the care of your family member?

-

I felt really out of control and that the health care system took over and dictated the care my family member received, 0.

-

I felt somewhat out of control and that the health care system took over and dictated the care my family member received, 25.

-

I felt neither in control nor out of control, 50.

-

I felt I had some control over the care my family member received, 75.

-

I felt that I had good control over the care my family member received, 100.

Q10. when making decisions, did you have adequate time to have your concerns addressed and questions answered?

-

I could have used more time, 0.

-

I had adequate time, 100.

Summary overall family satisfaction scores and domain scores (satisfaction with care and satisfaction with decision-making) are calculated by averaging the item responses for the items included overall and within each domain, provided at least 70% of items are complete (i.e. 17 out of 24 for the overall family satisfaction score, 10 out of 14 for satisfaction with care, 7 out of 10 for satisfaction with decision-making). 21

Discussion

In summary, the face and content validity and comprehensibility of the FS-ICU-24 was good and adaptation to the UK setting required relatively minor edits. These included changes to section heading titles, clarification of wording of questions, addition to existing guidance, clarification of North American English to UK English, general formatting and enhanced design of the layout.

Chapter 3 Set-up and delivery of the cohort study

Introduction

Phase 2 of the FREE study comprised a cohort study, which collected data on family satisfaction with intensive care using the UK FS-ICU-24. This chapter reports the methods and results of the set-up of the study, recruitment of adult general ICUs, recruitment of family members and administration of, and response to, the FS-ICU-24.

Methods

The cohort study was a multicentre study nested in the Case Mix Programme (CMP), the national clinical audit of adult general ICUs in England, Wales and Northern Ireland, established in 1995 and co-ordinated by ICNARC (Scotland has its own separate national clinical audit). Since 2010/11, the National Advisory Group on Clinical Audit and Enquiries has listed the CMP in the Department of Health’s ‘Quality Accounts’ as a recognised national audit. 22

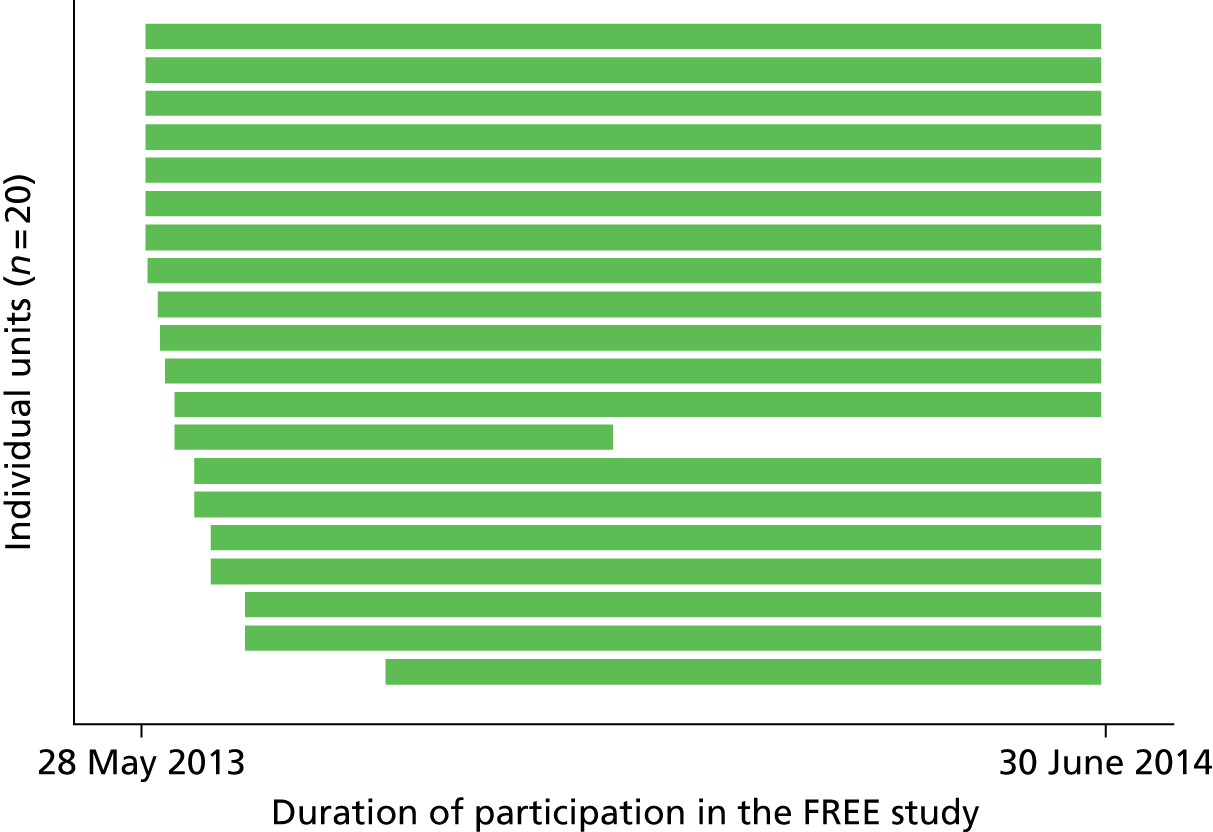

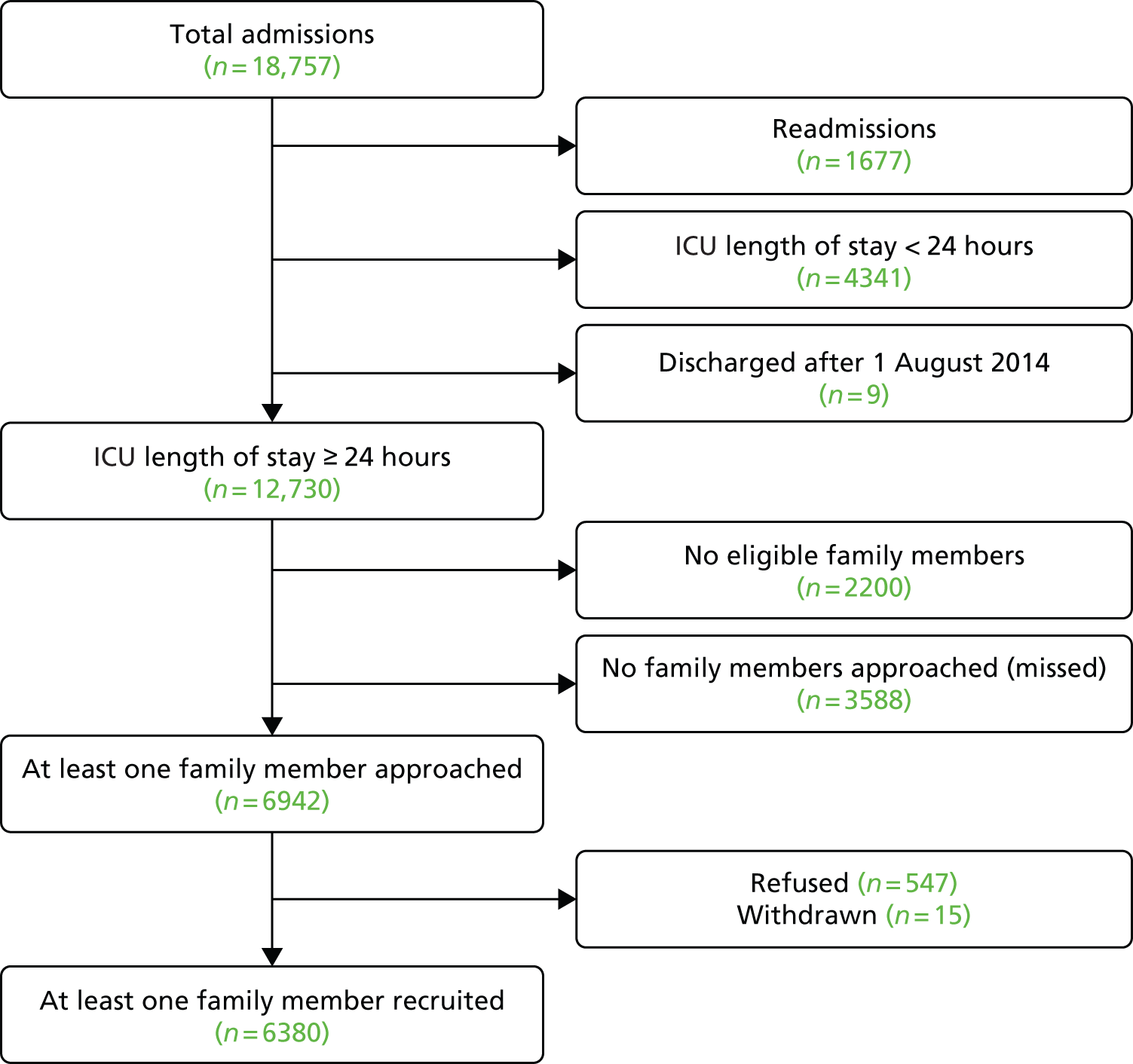

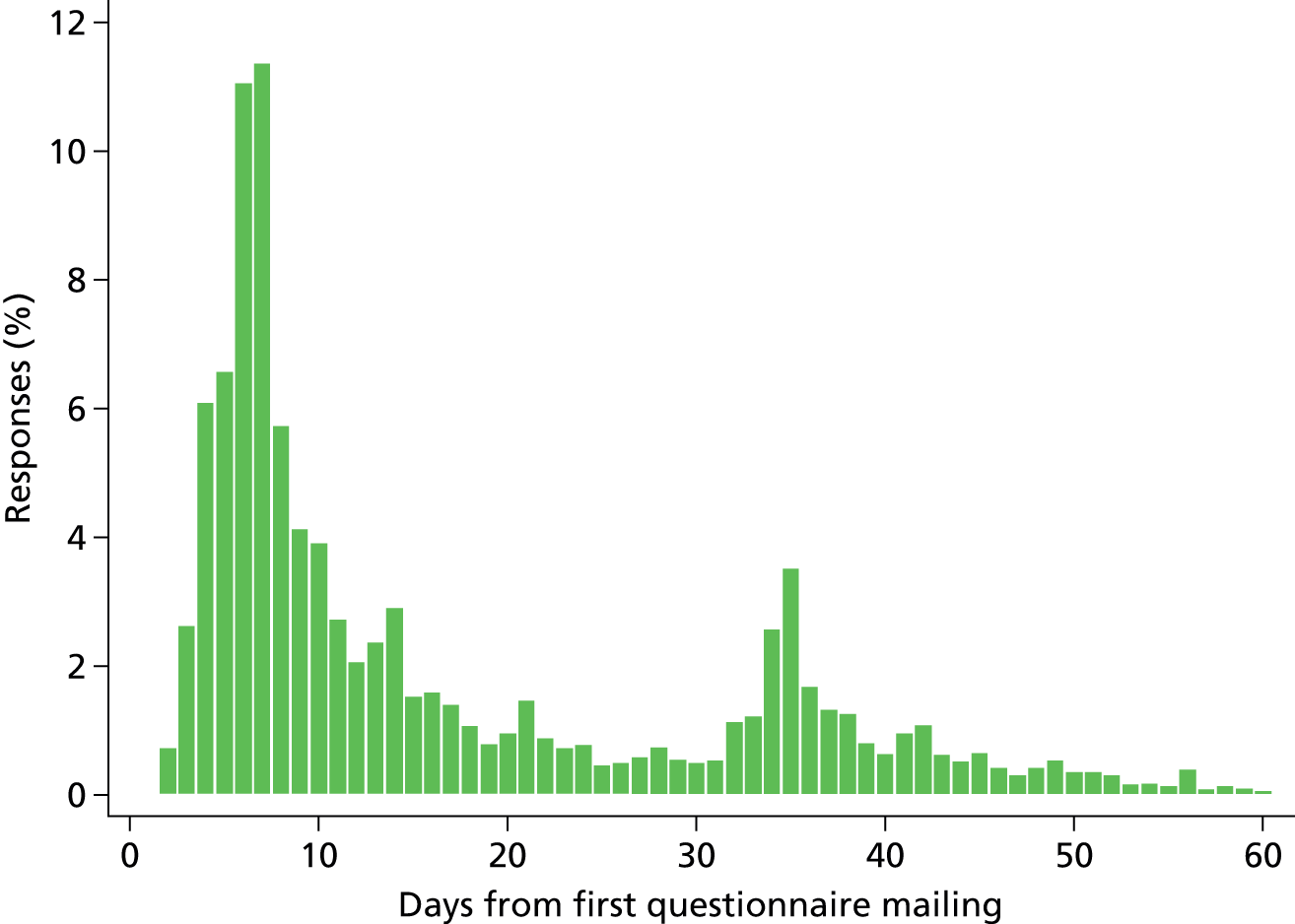

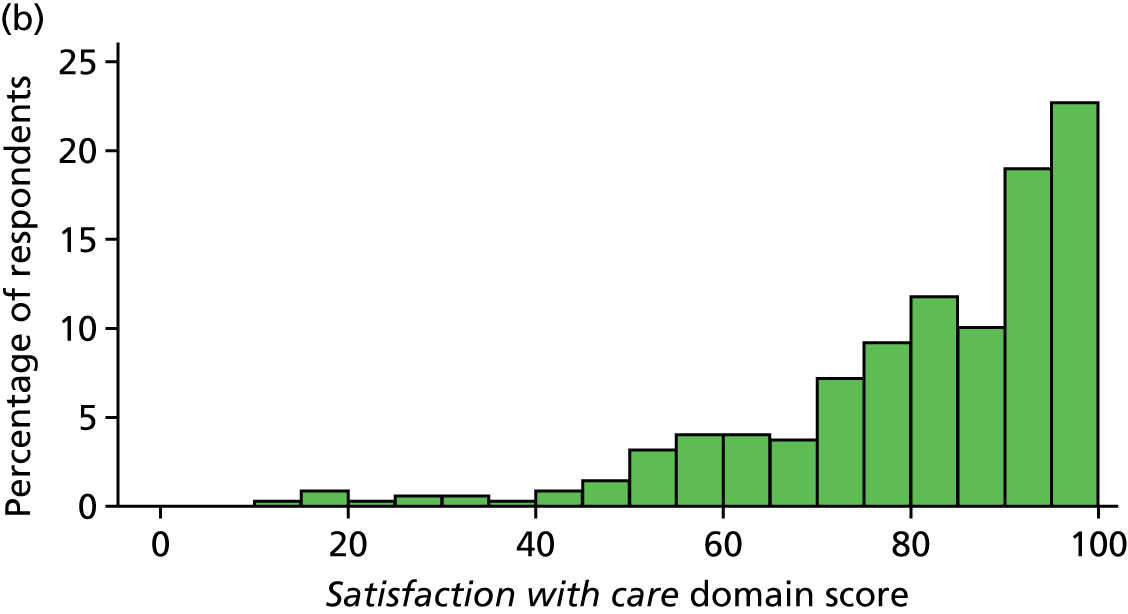

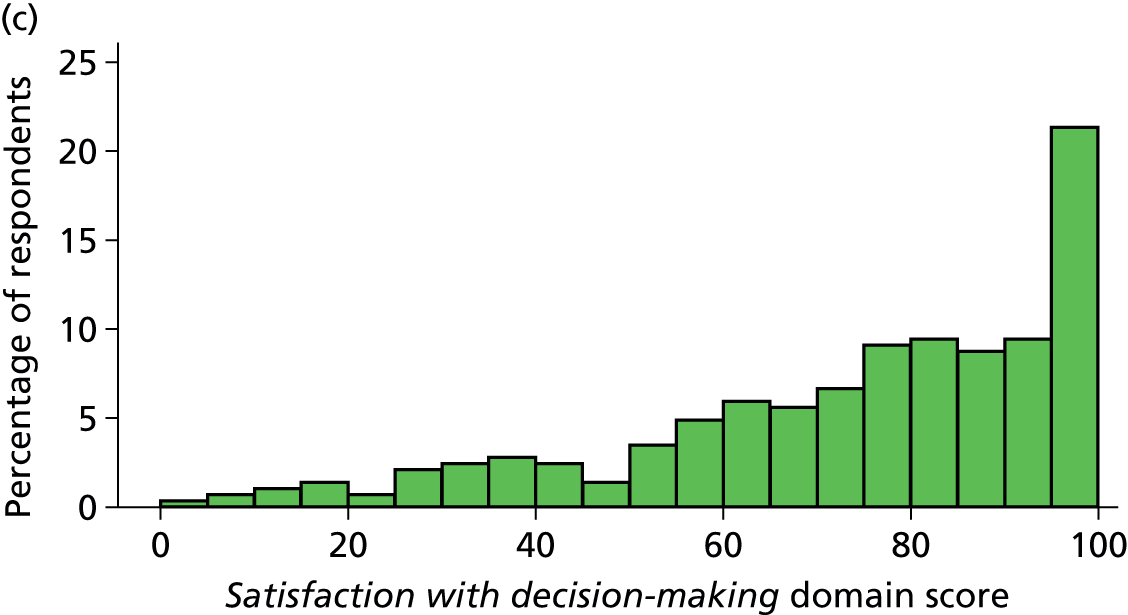

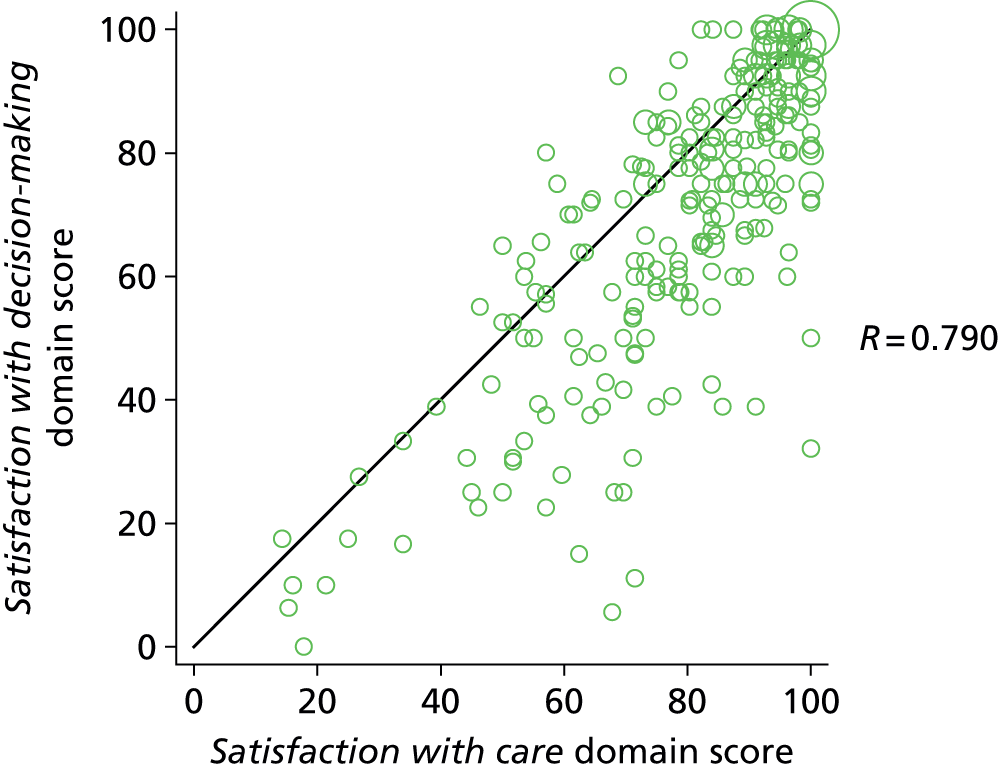

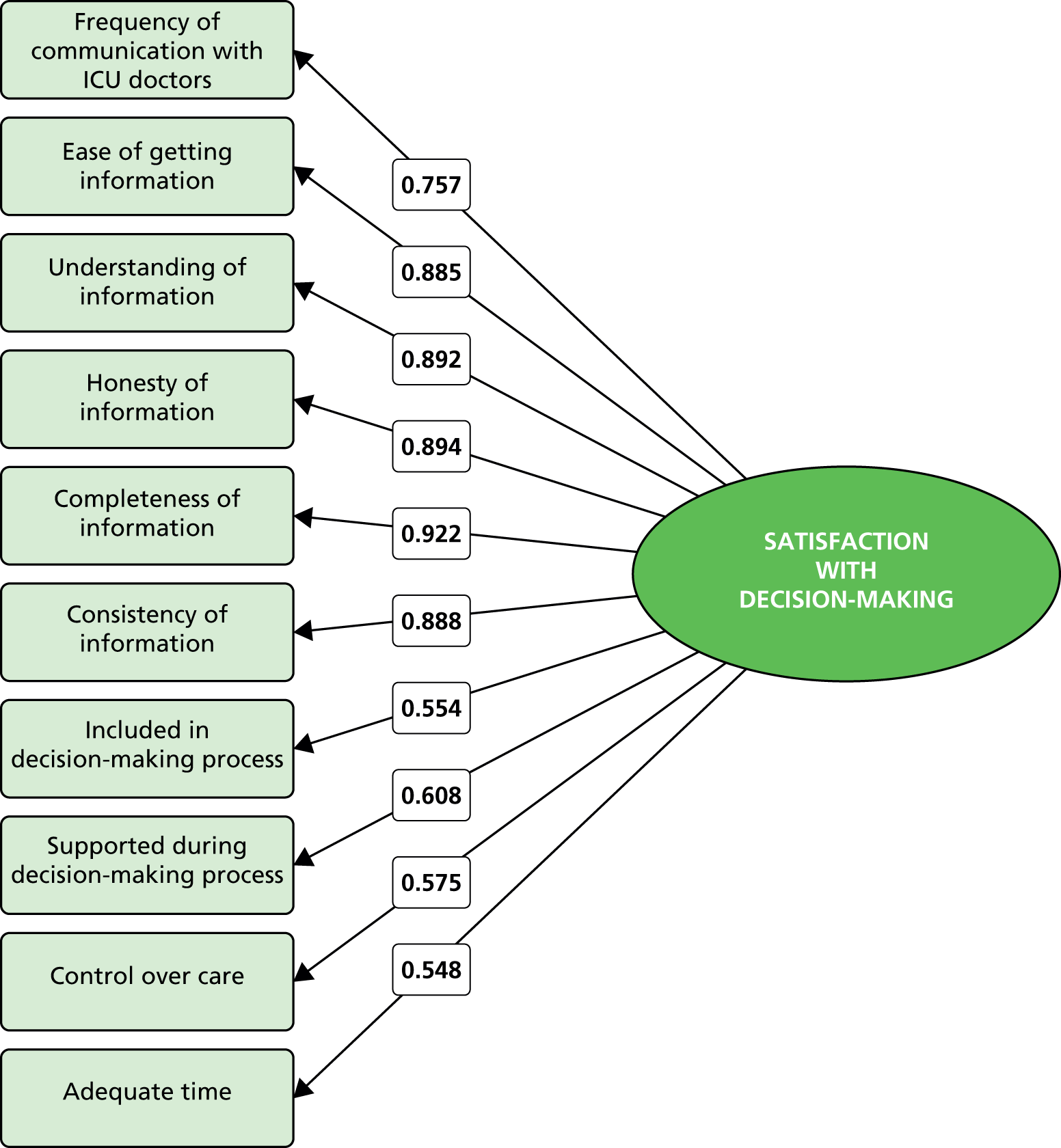

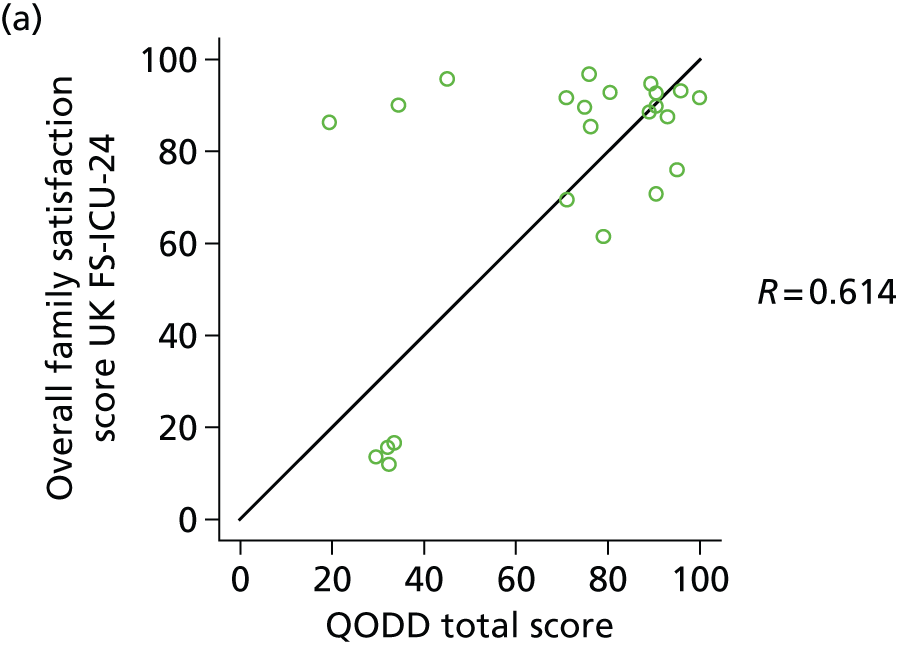

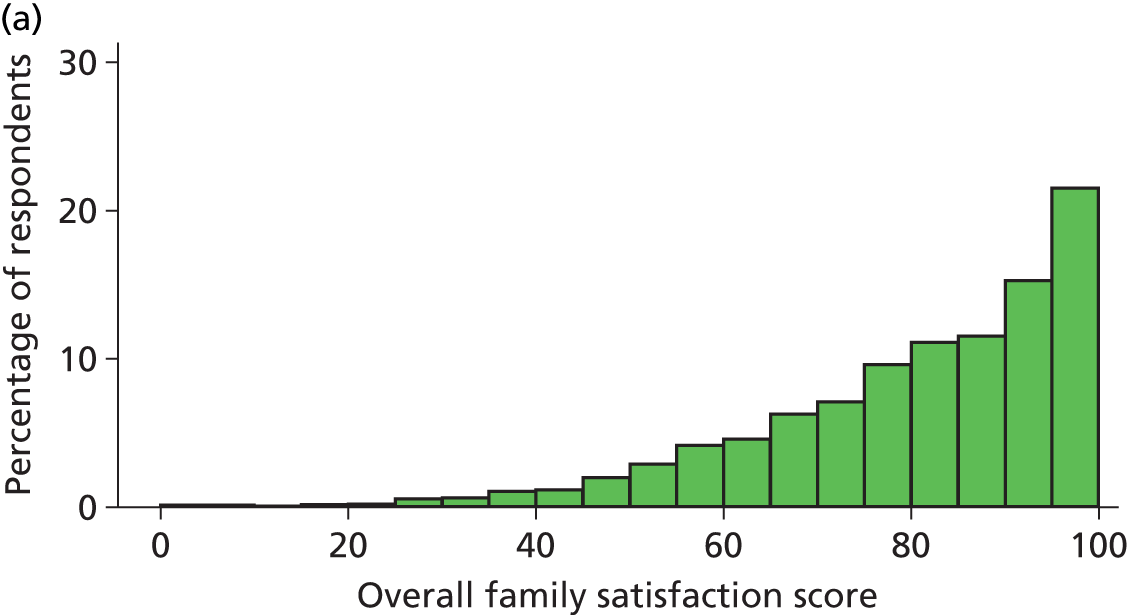

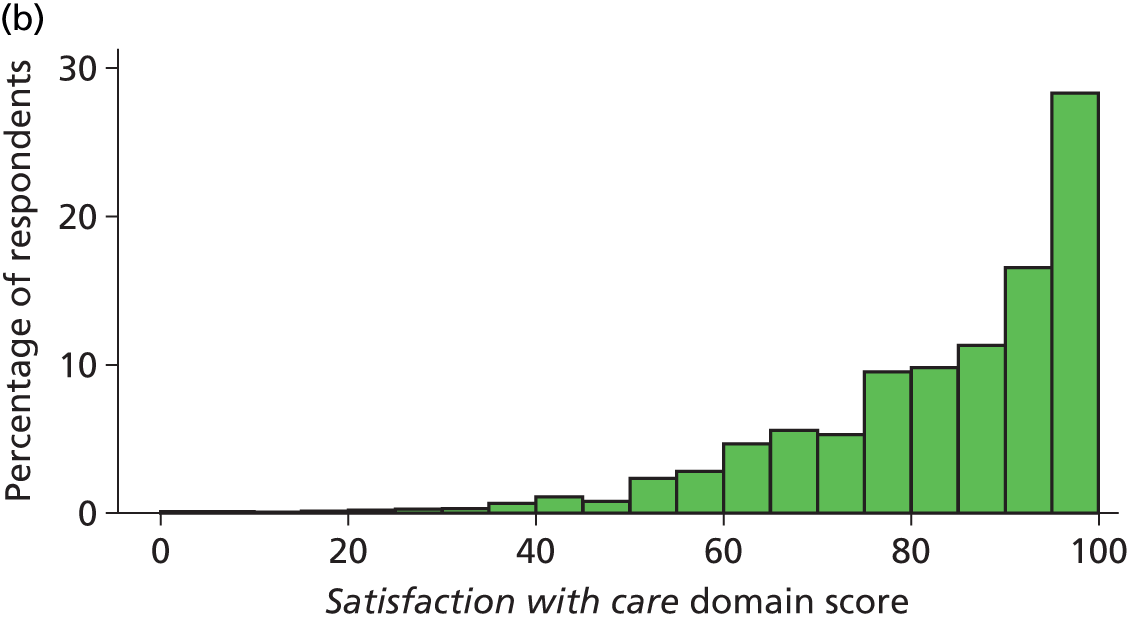

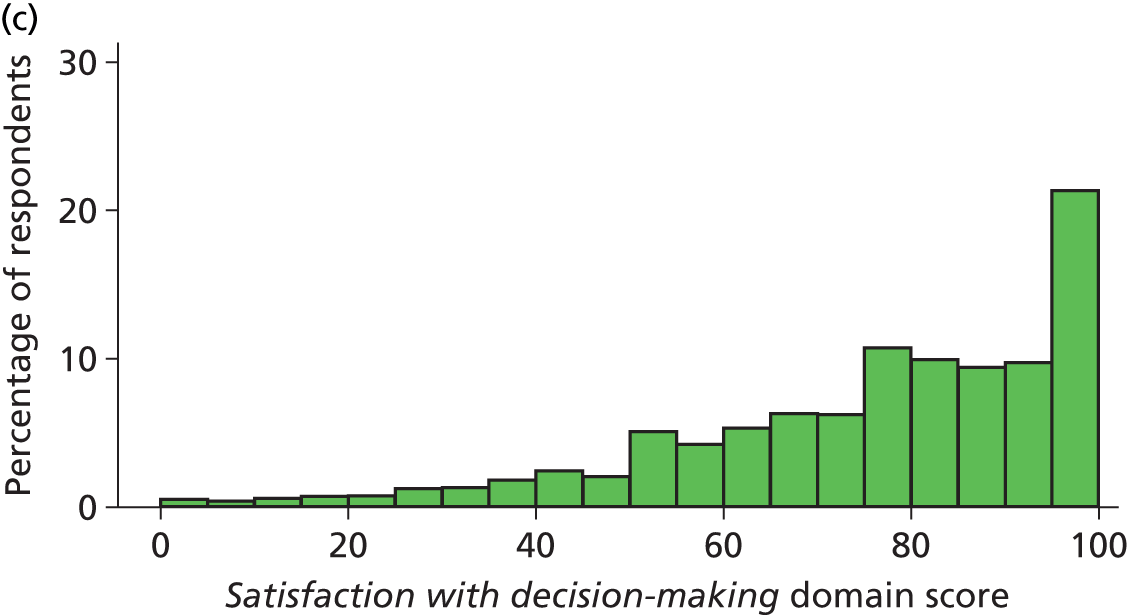

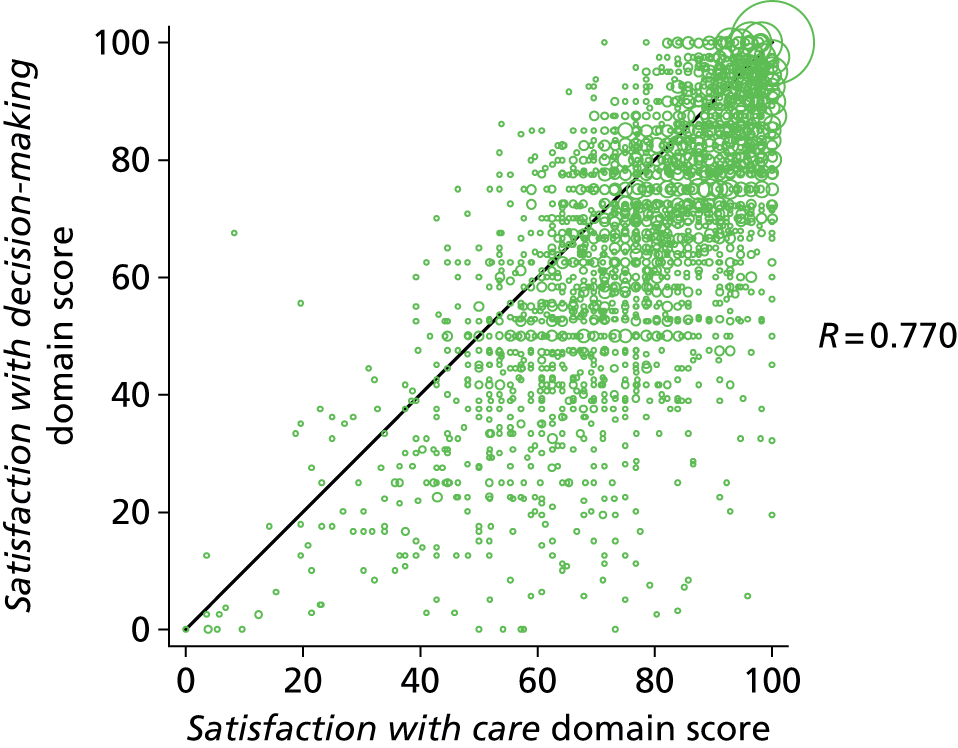

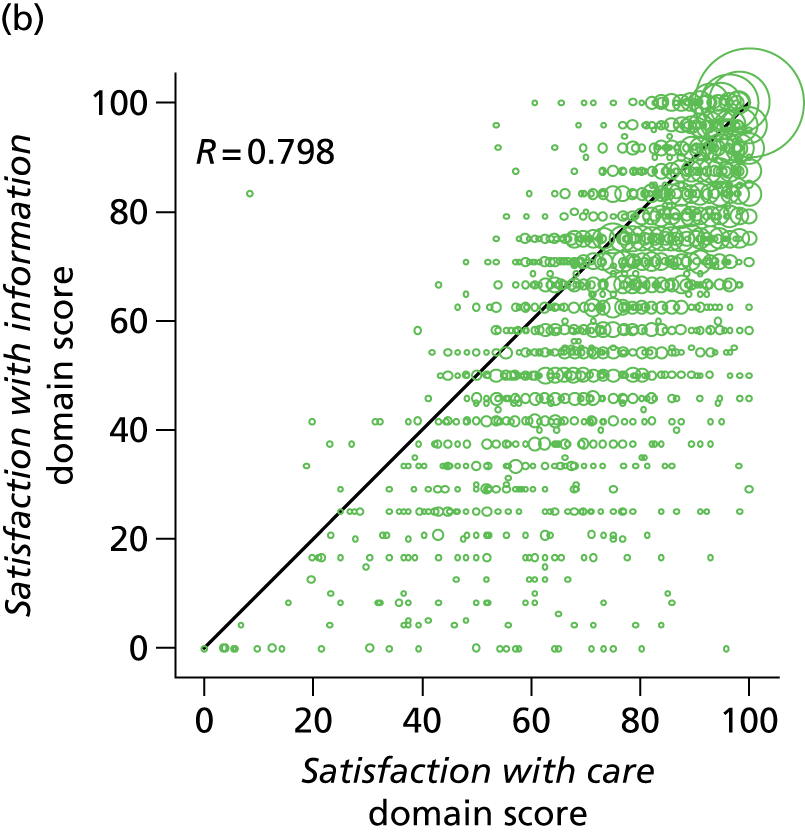

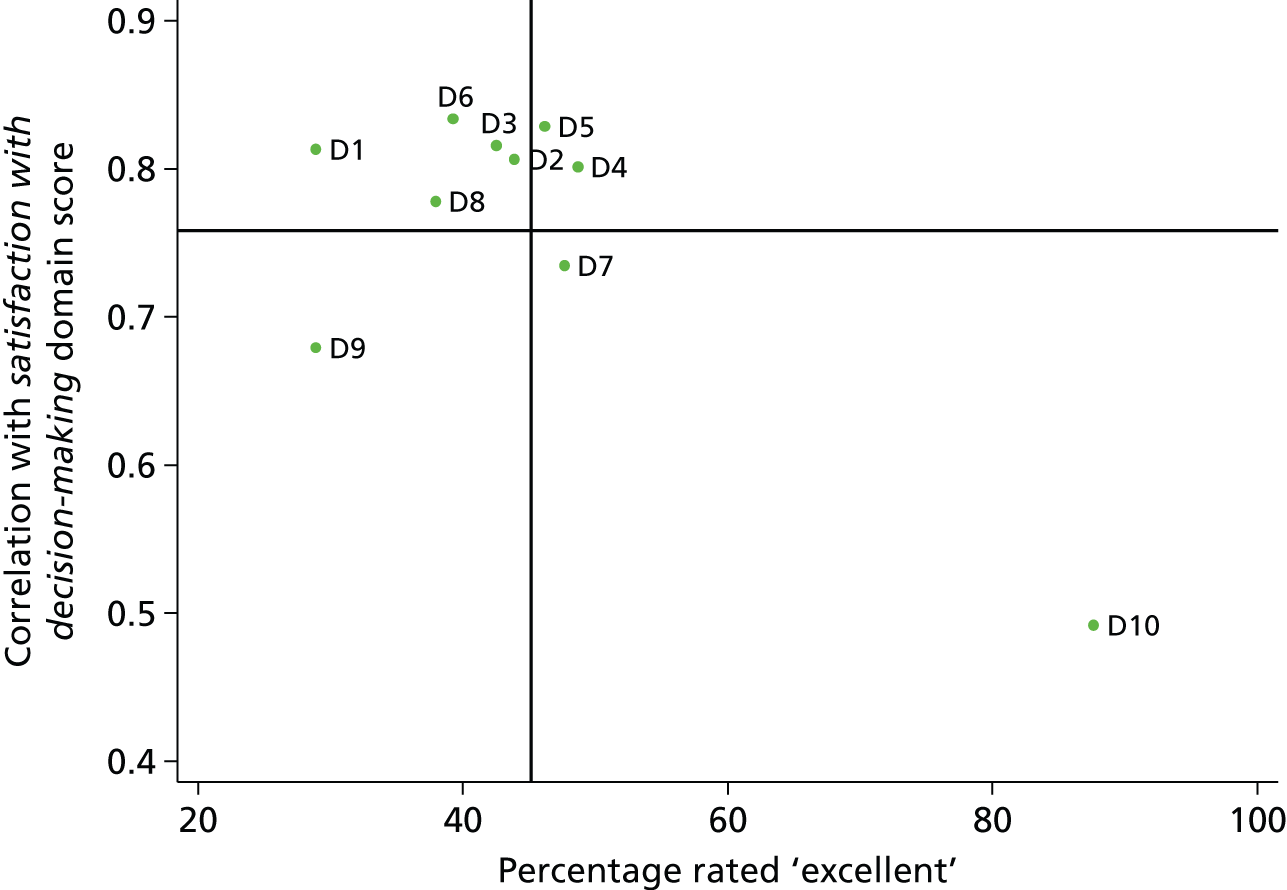

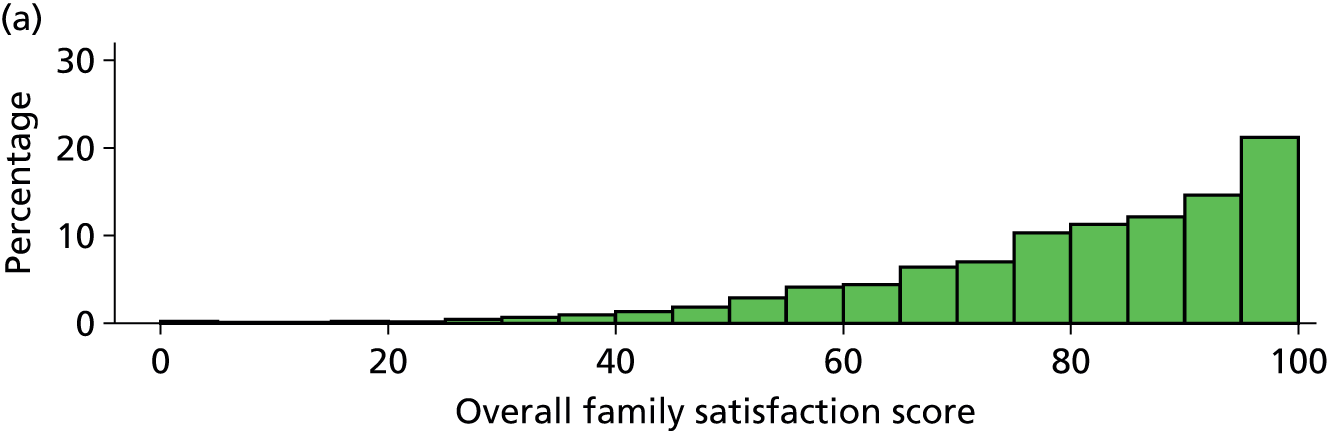

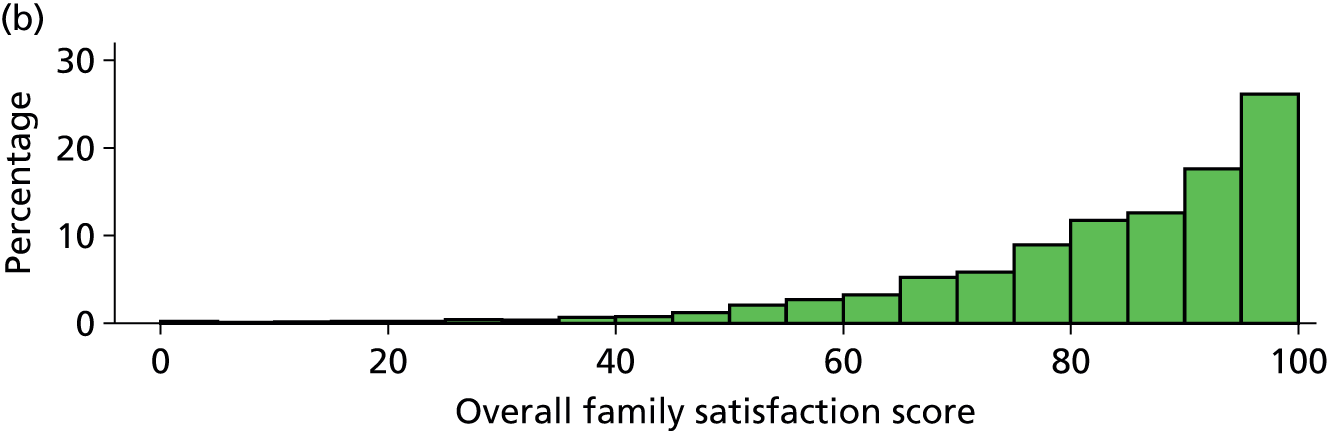

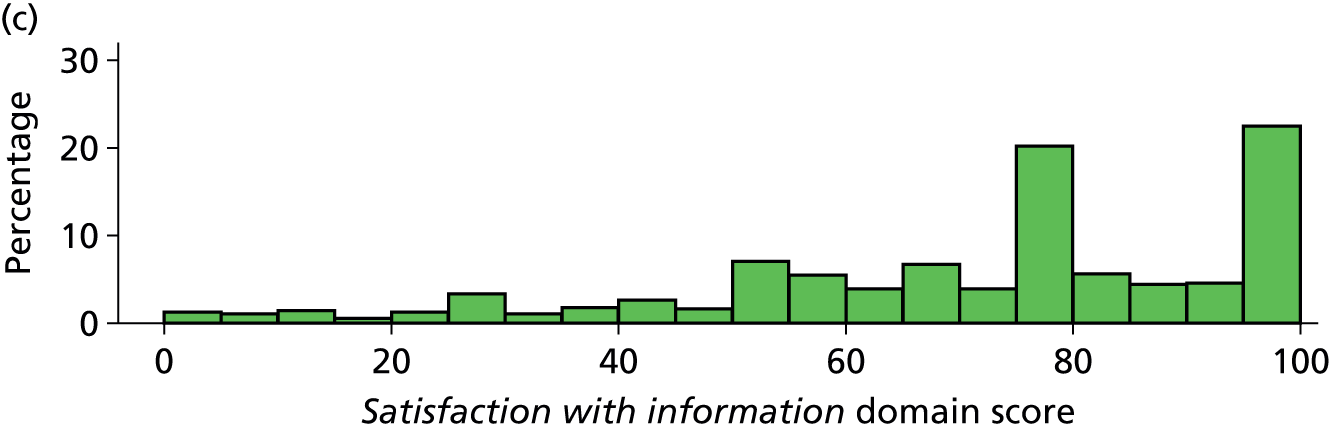

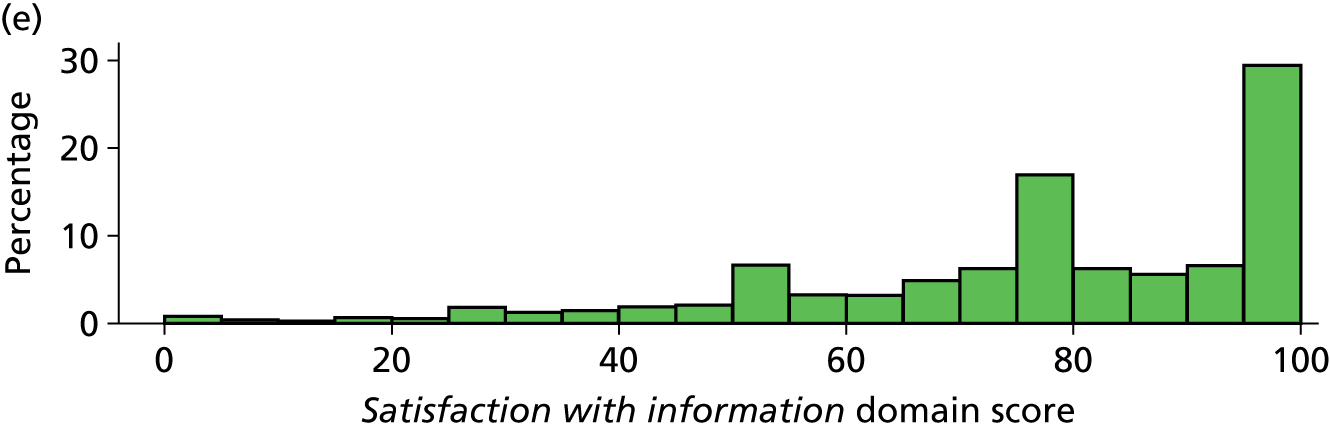

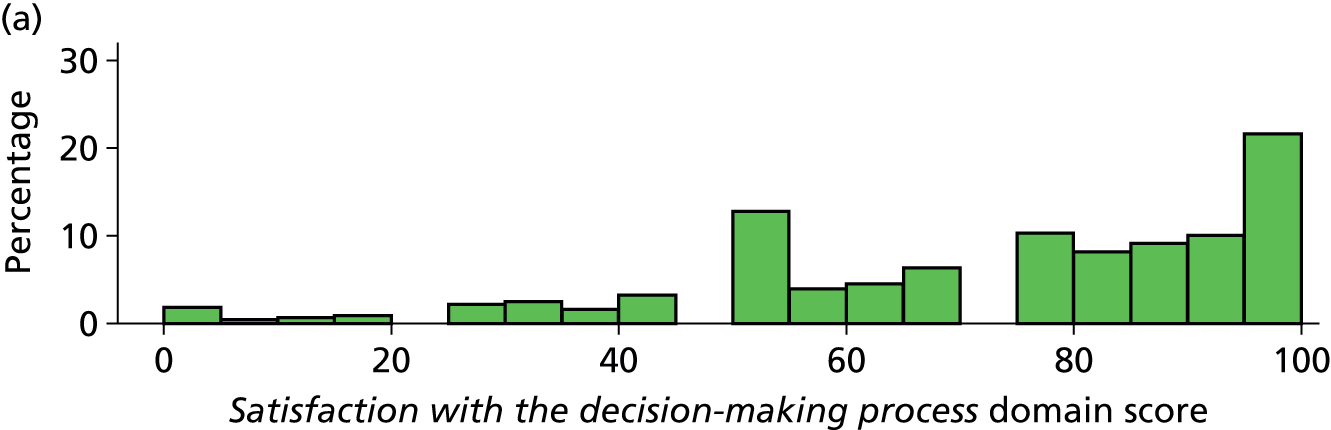

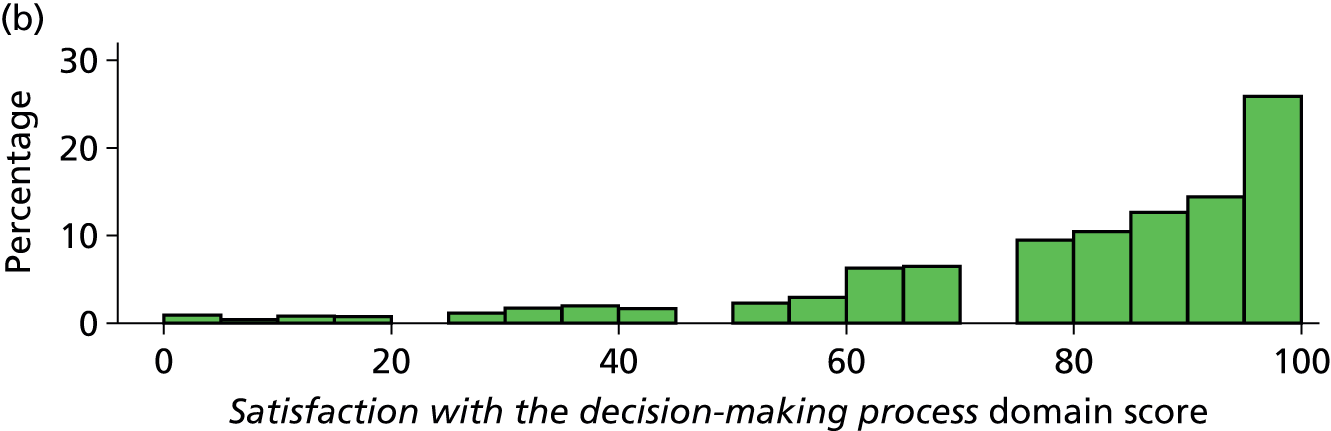

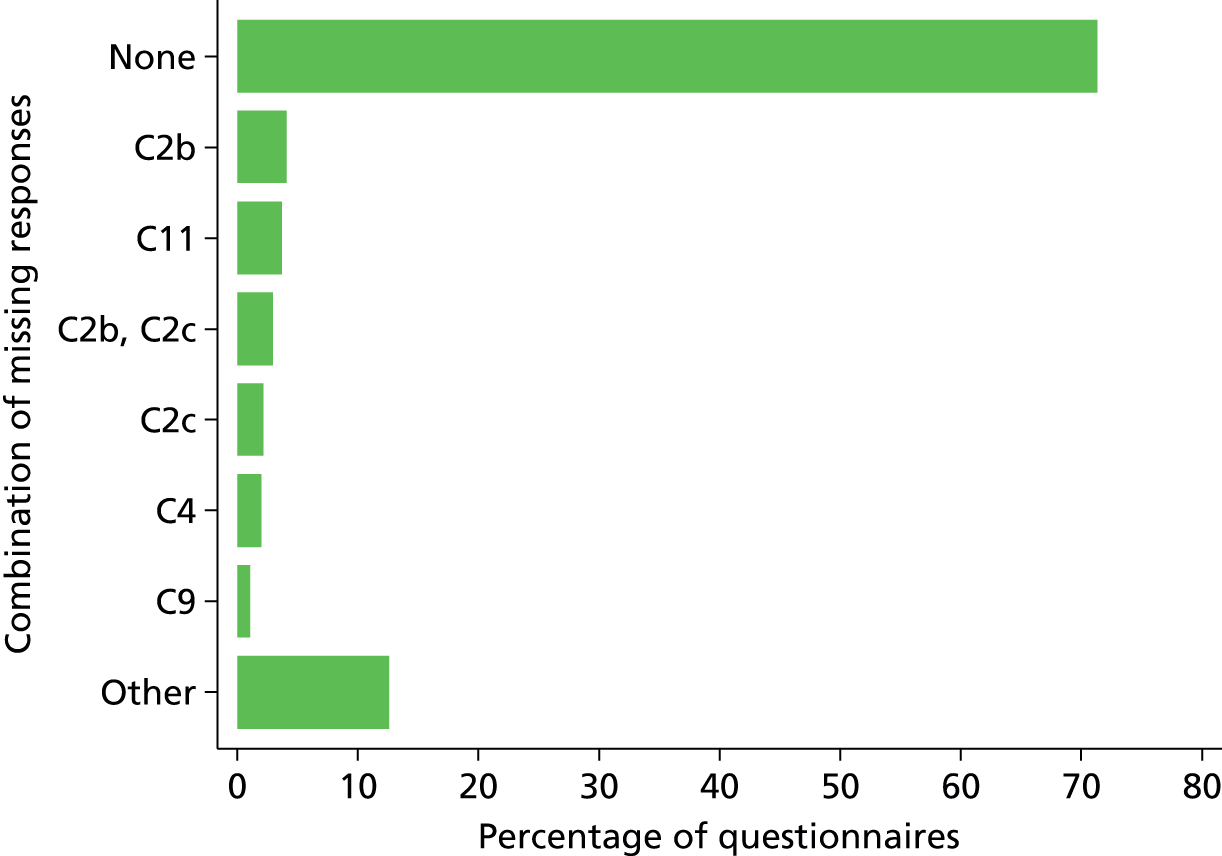

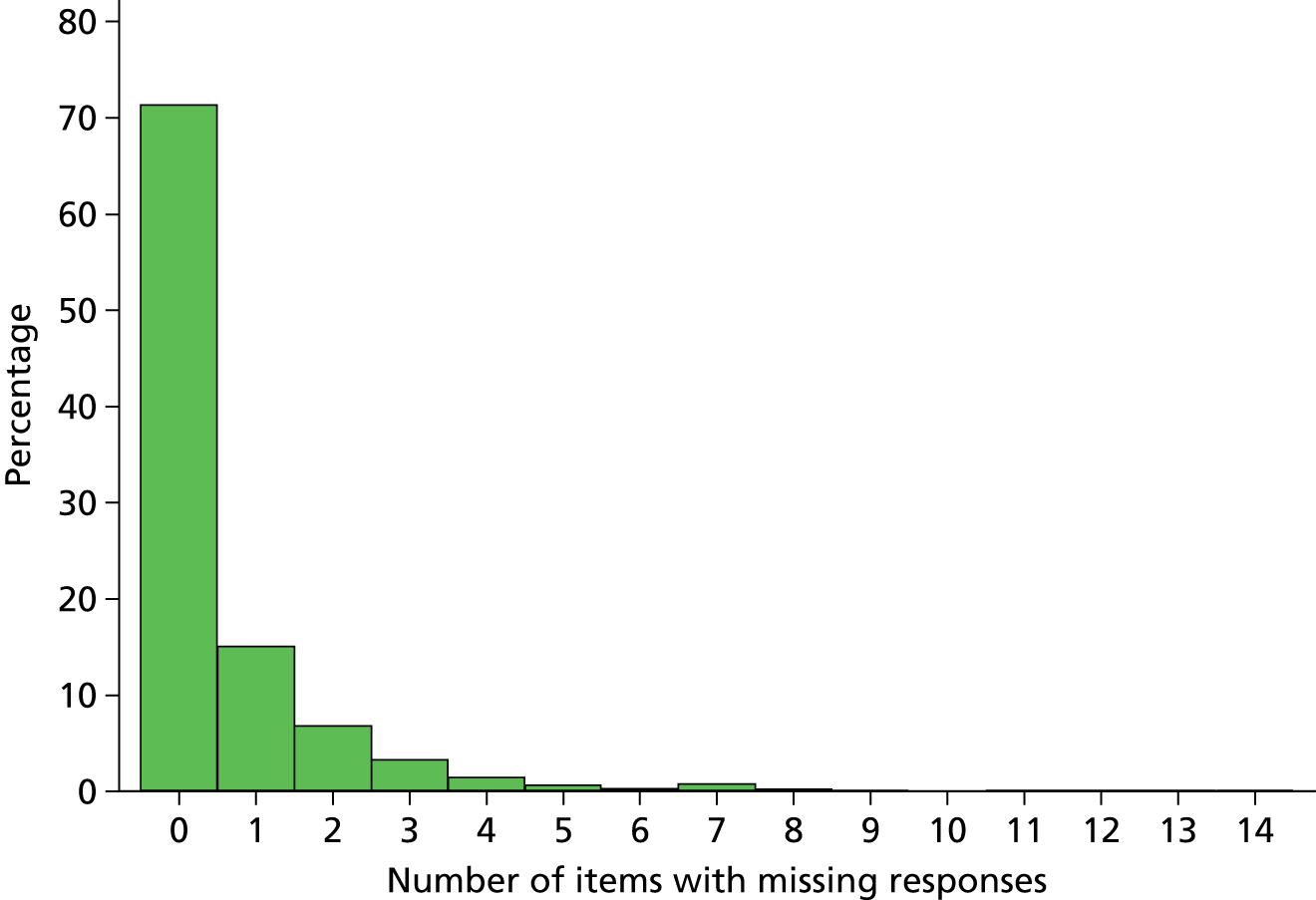

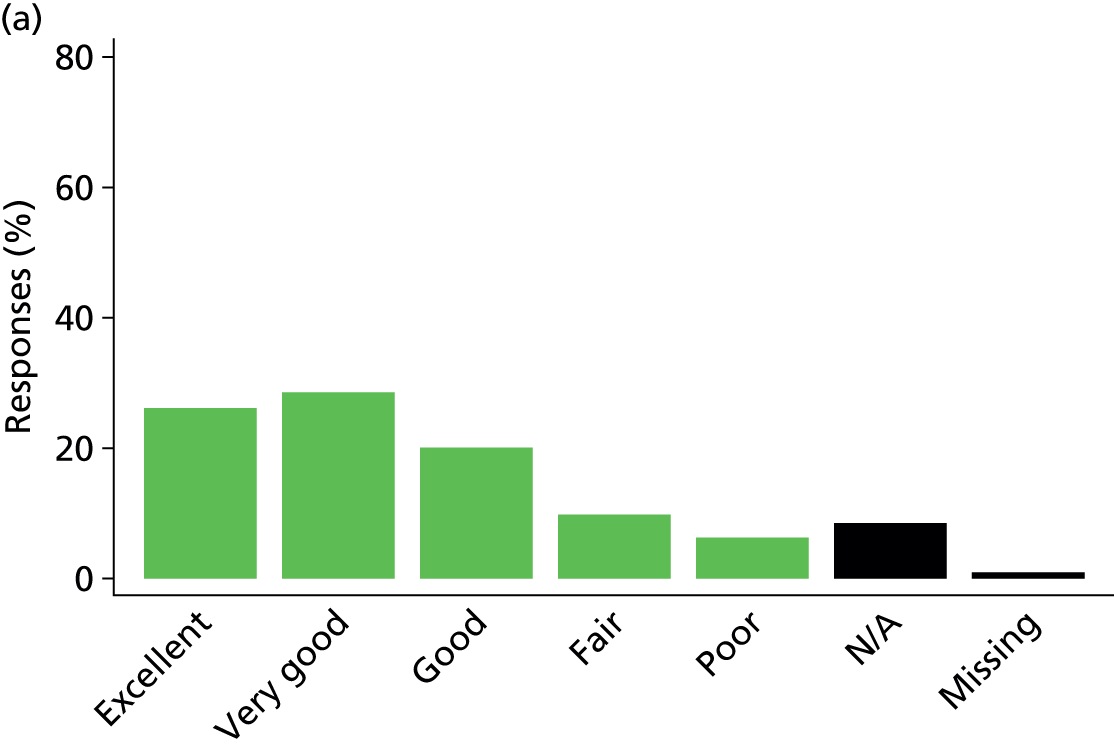

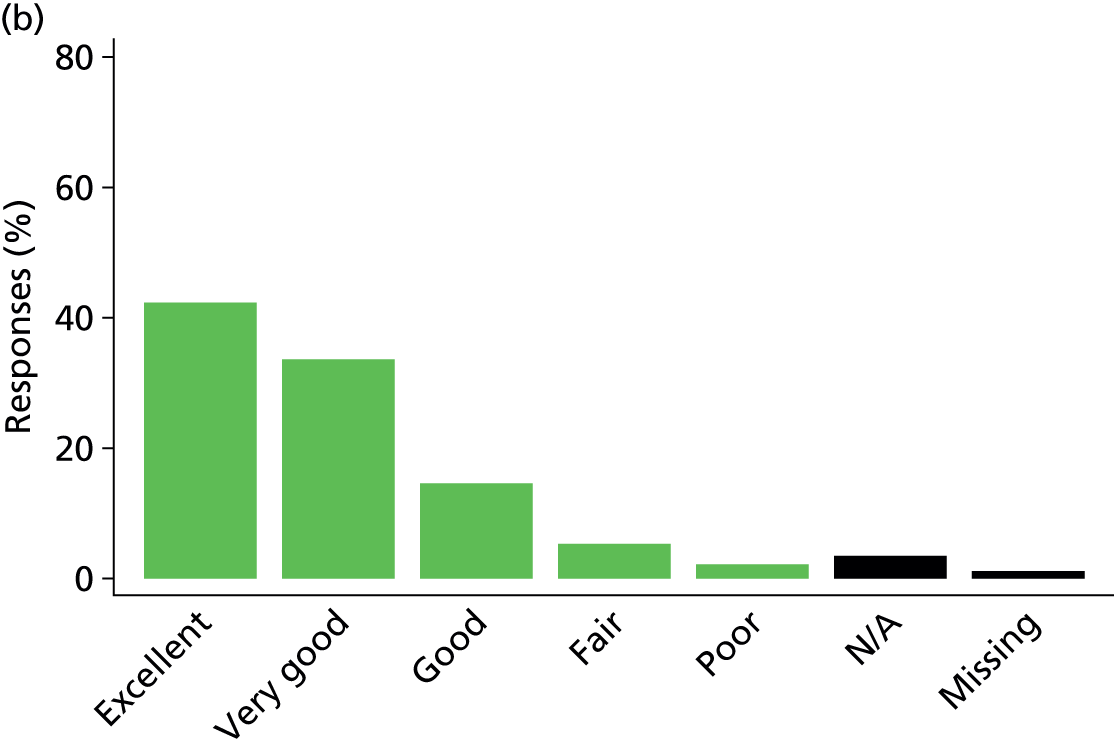

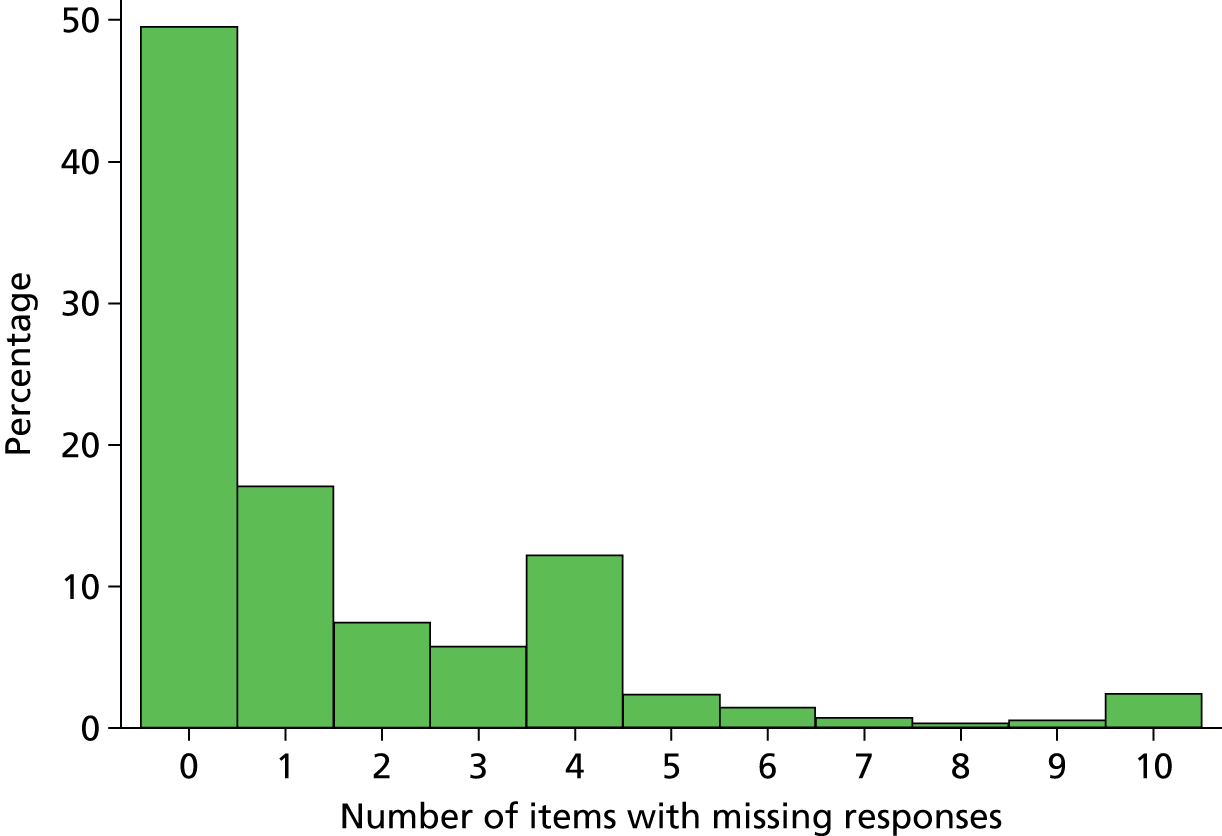

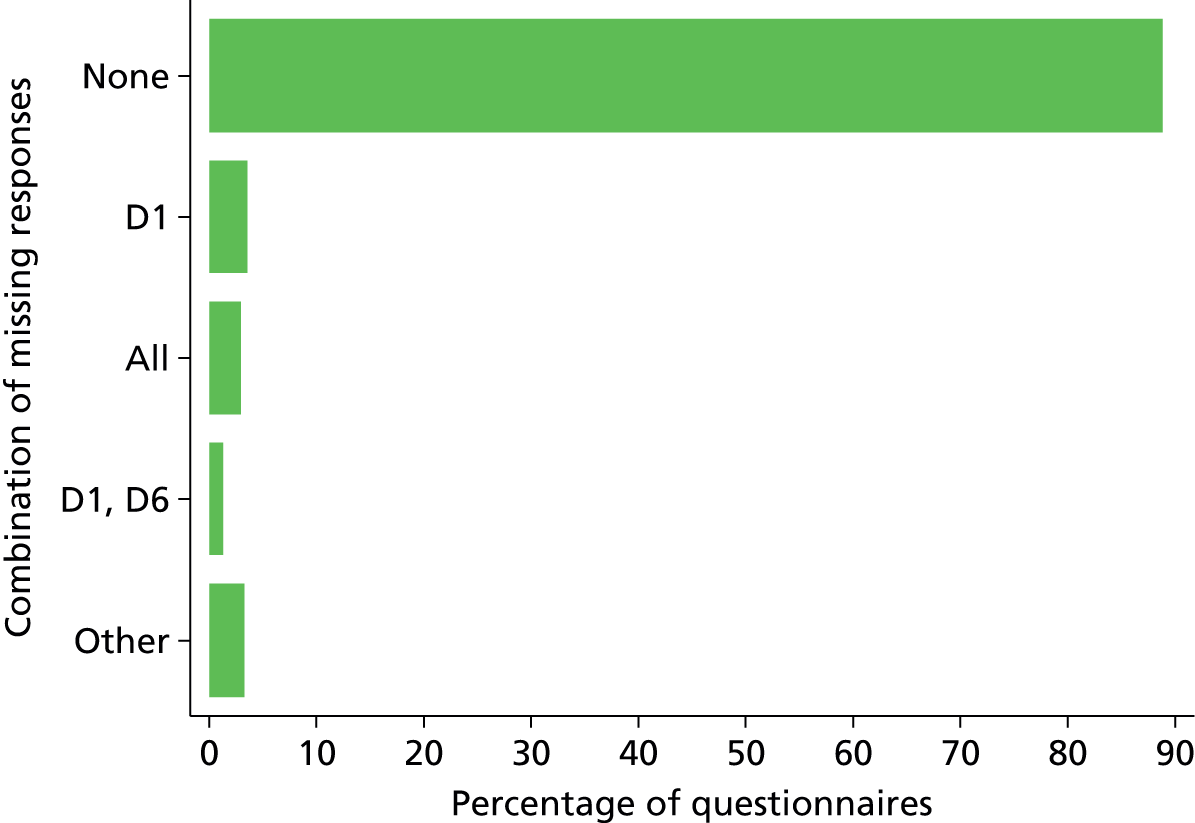

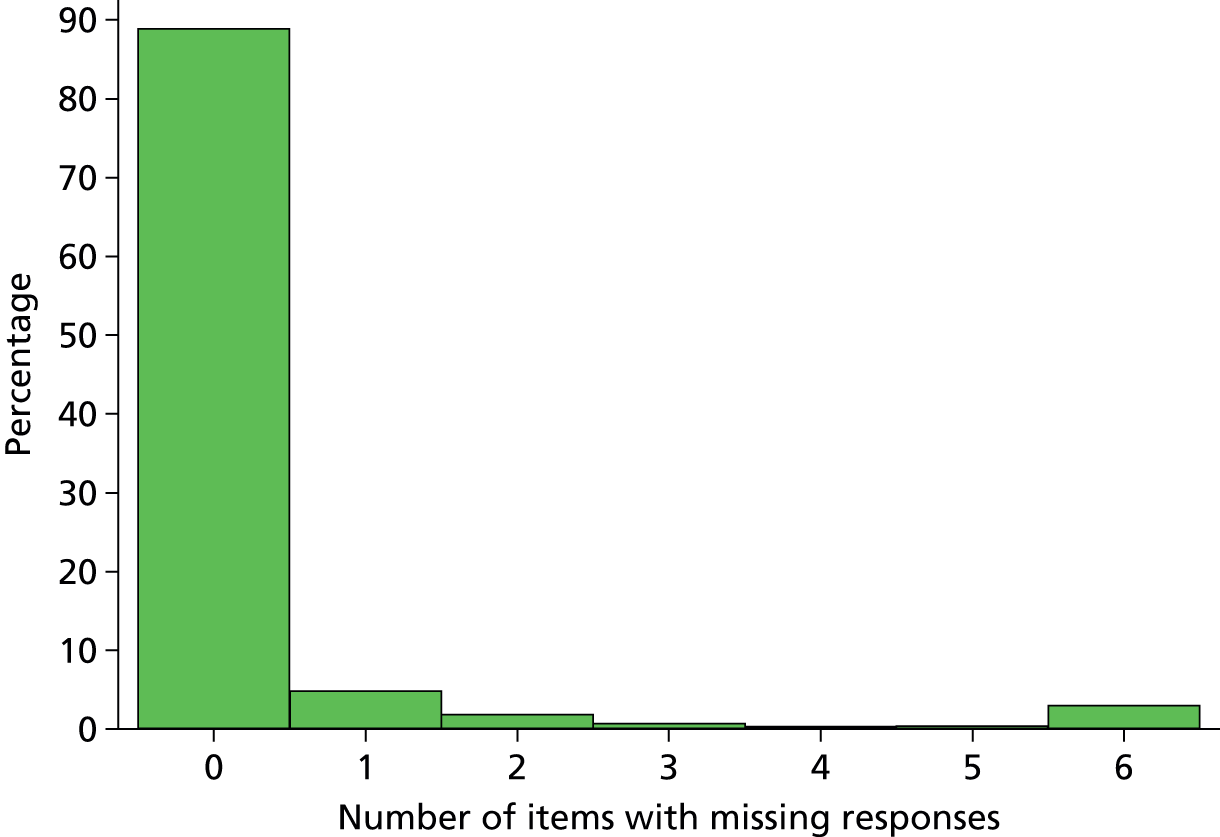

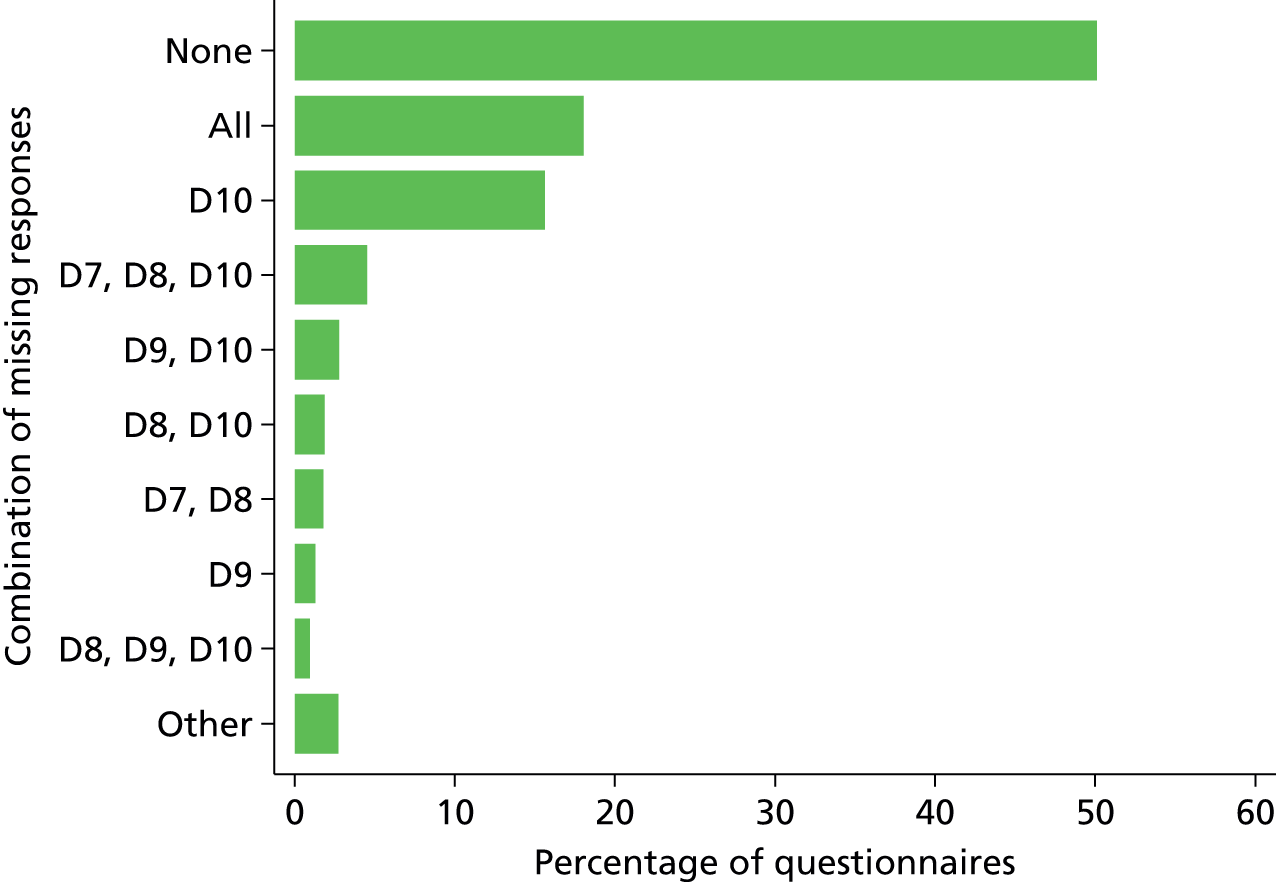

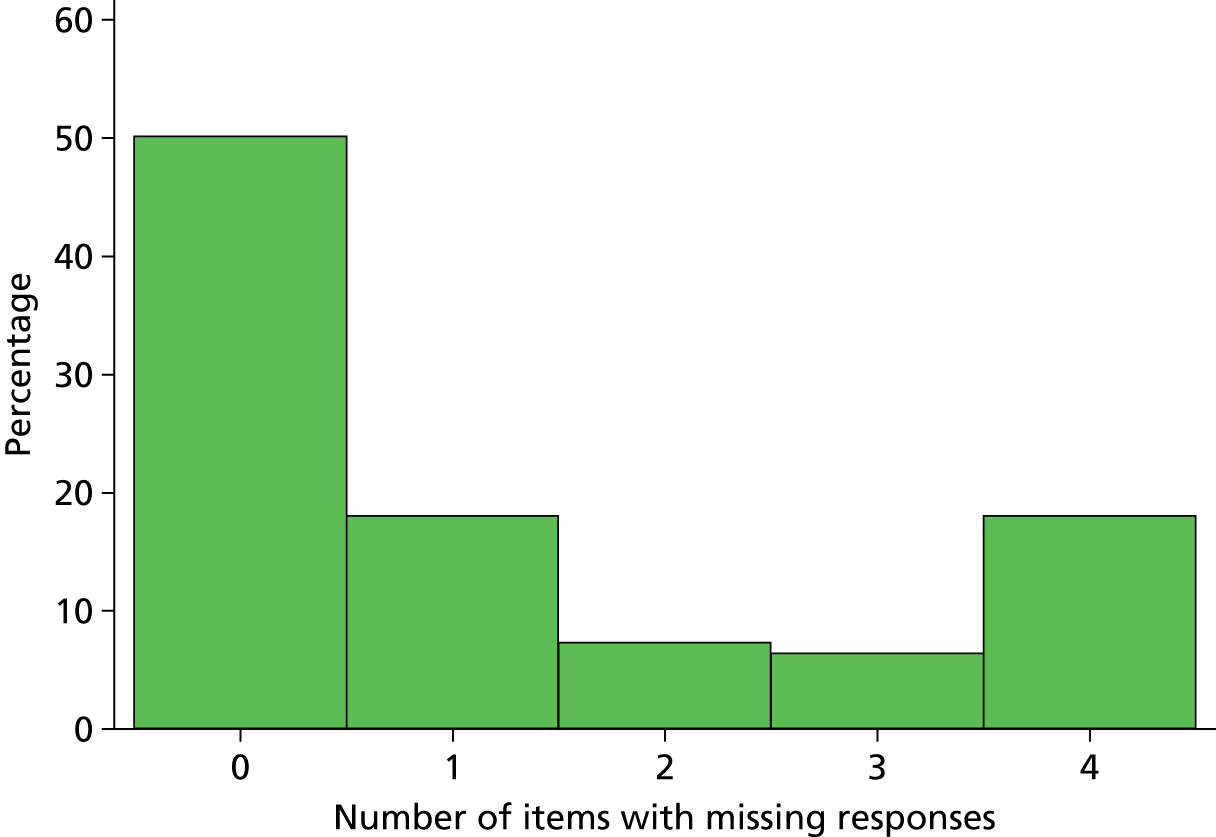

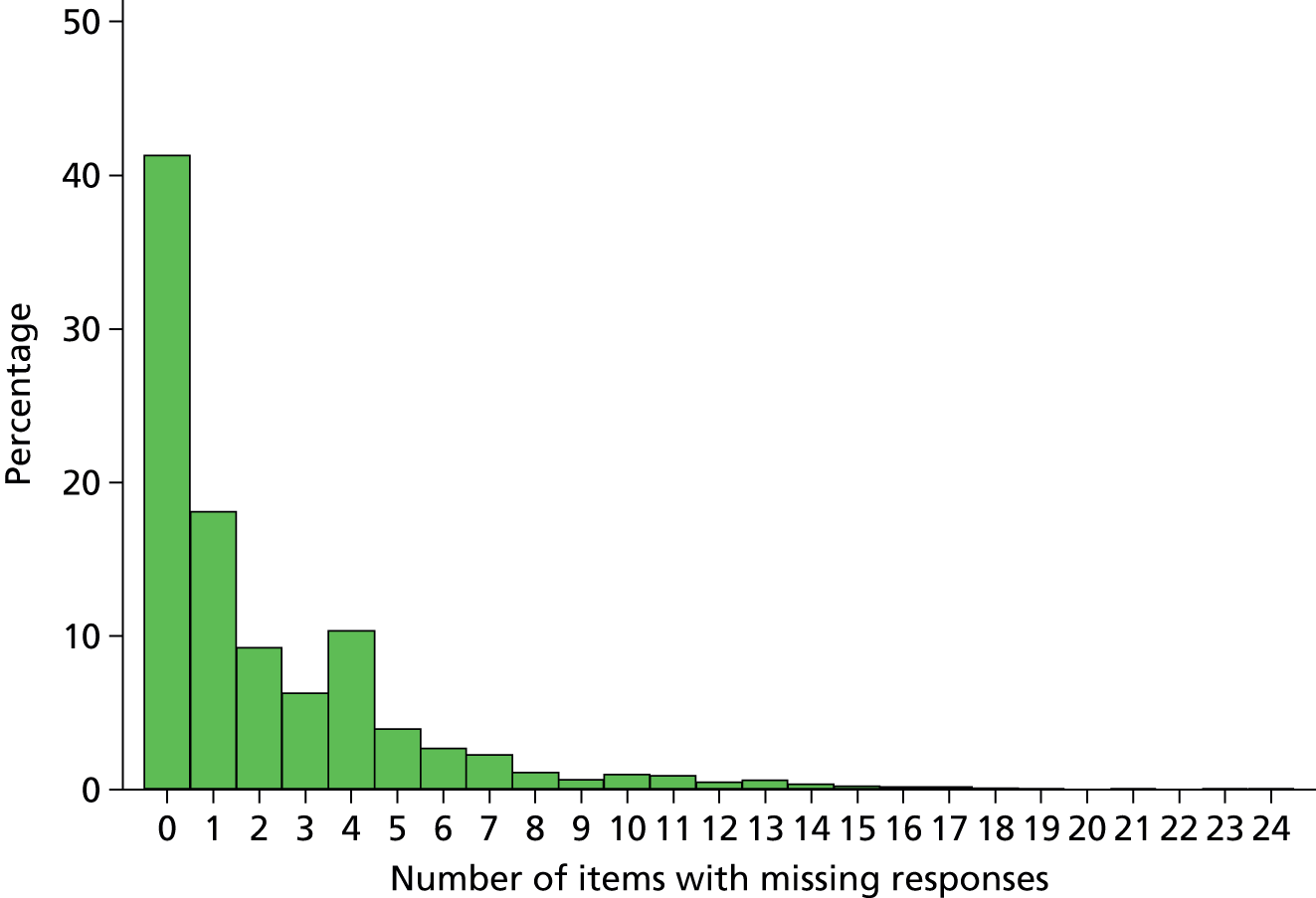

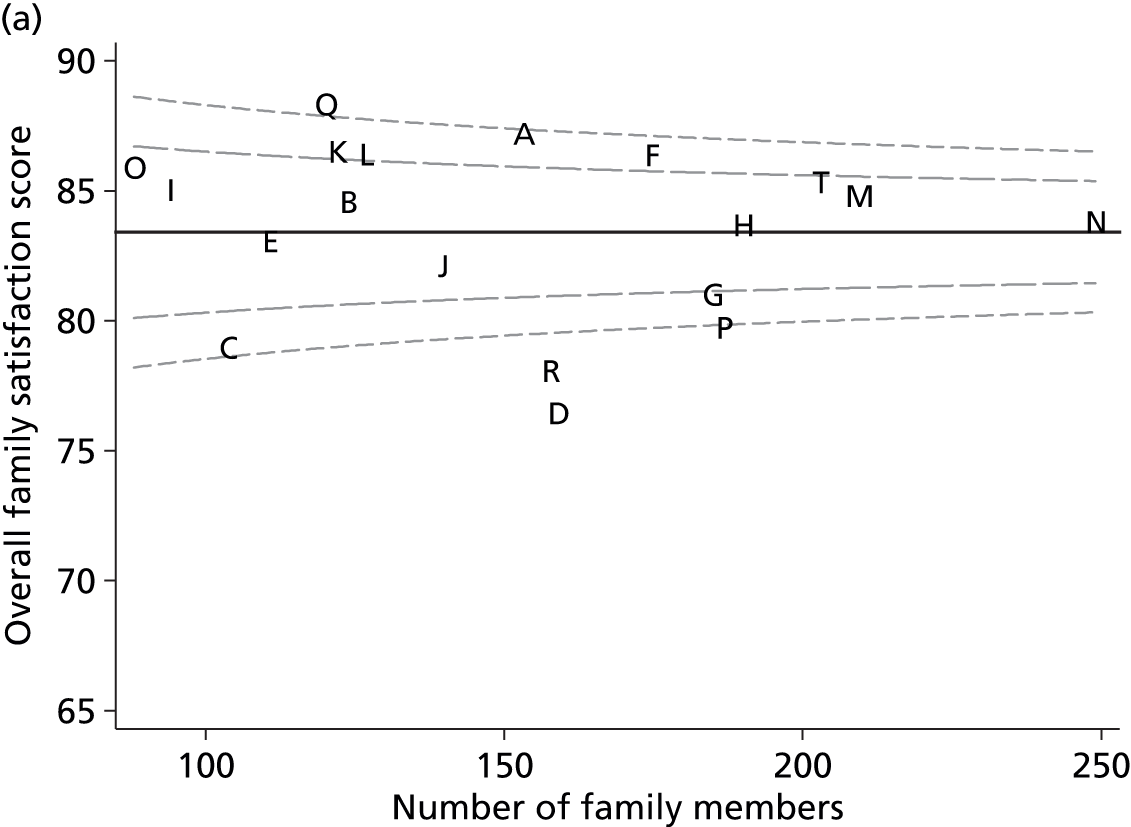

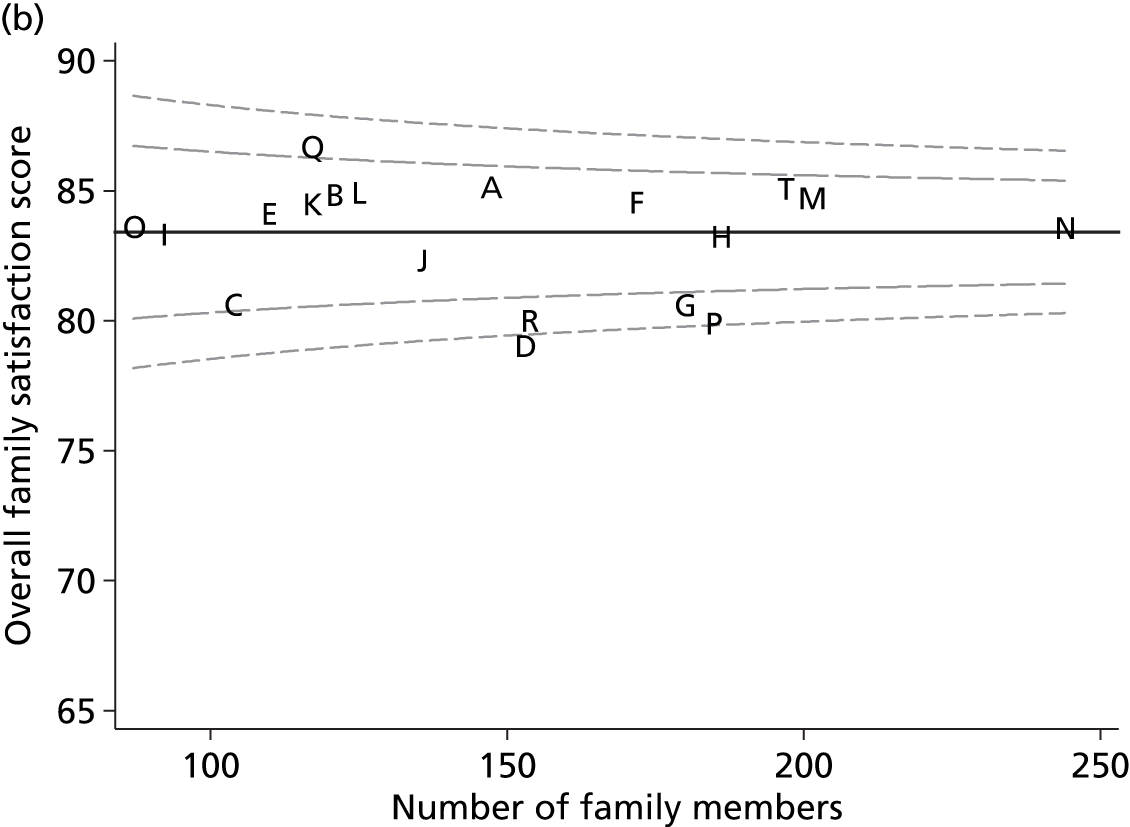

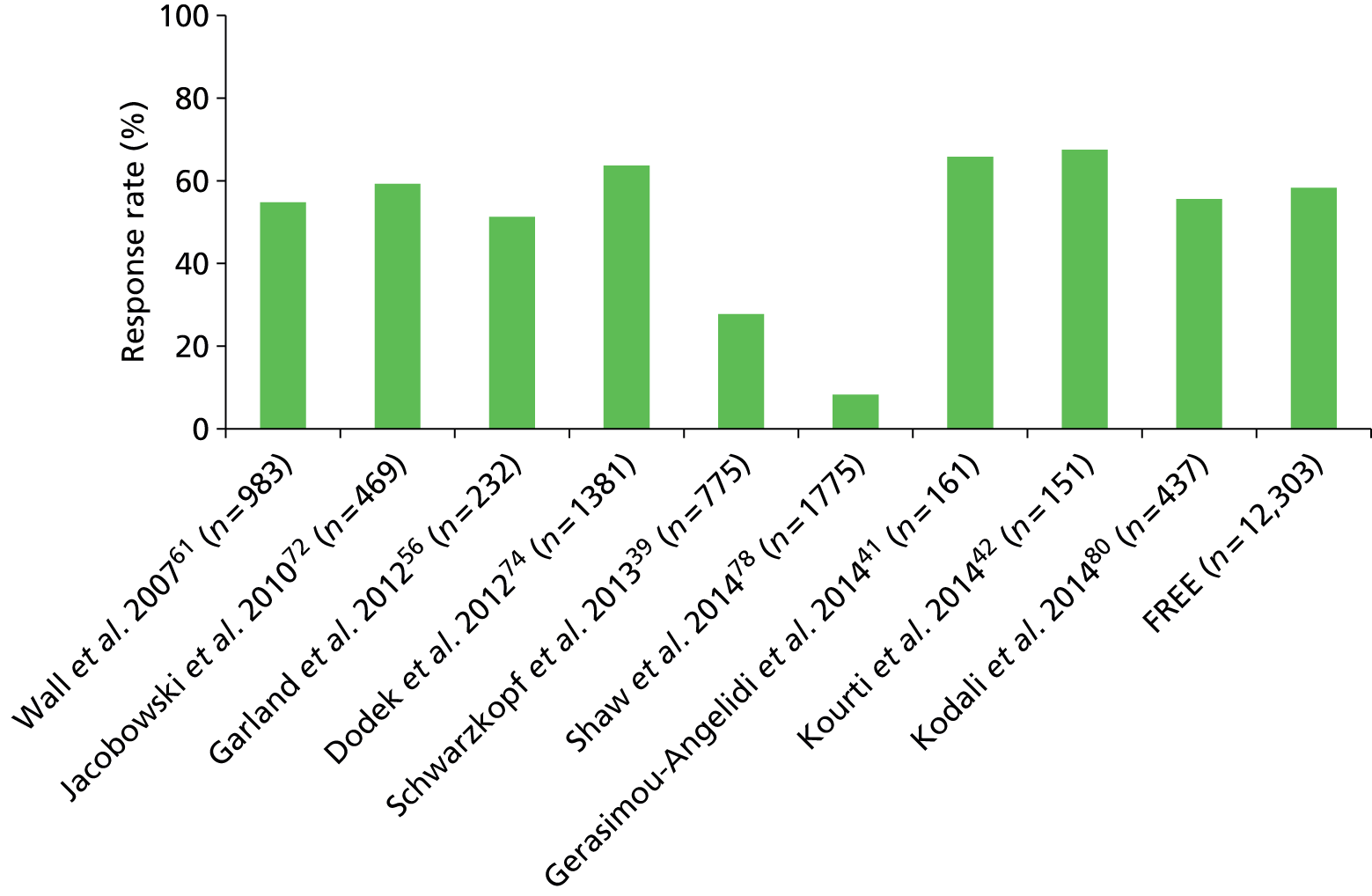

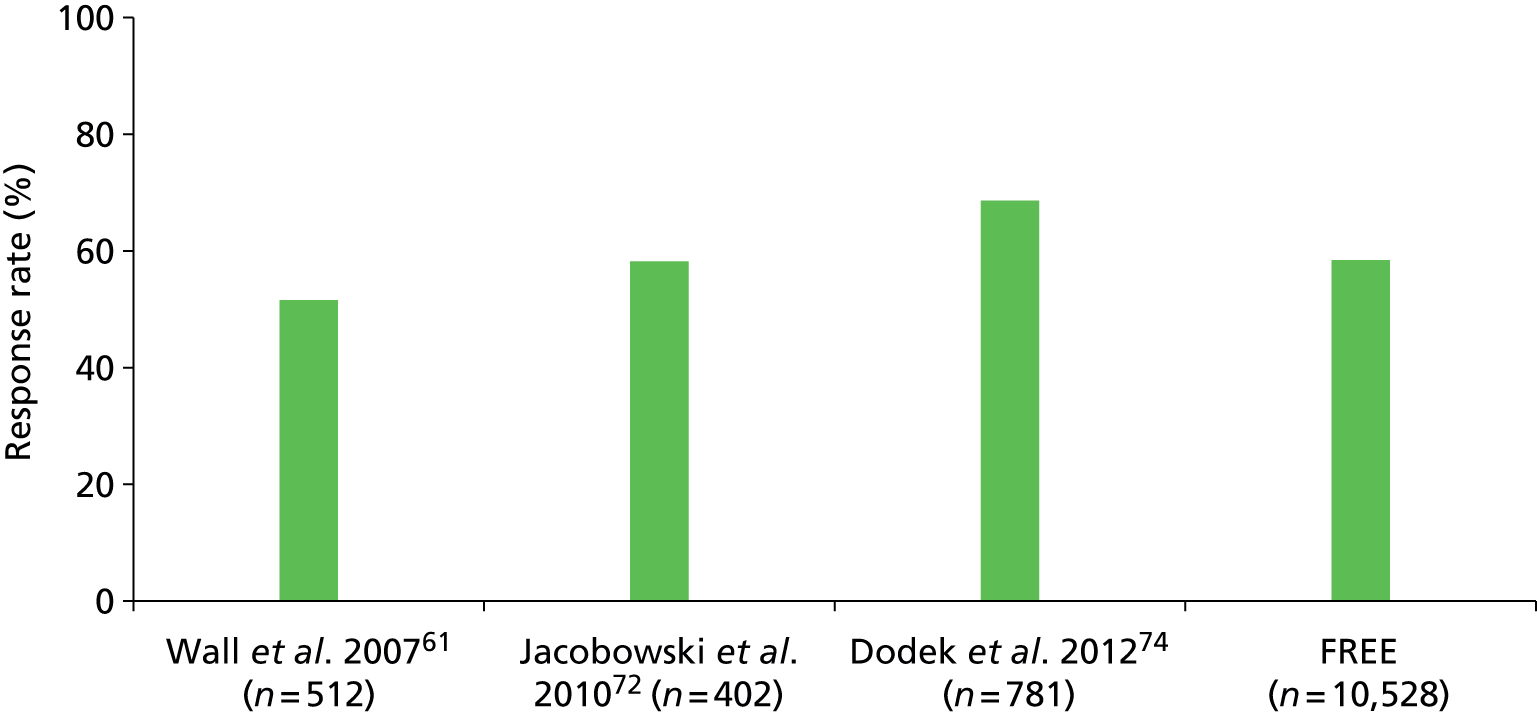

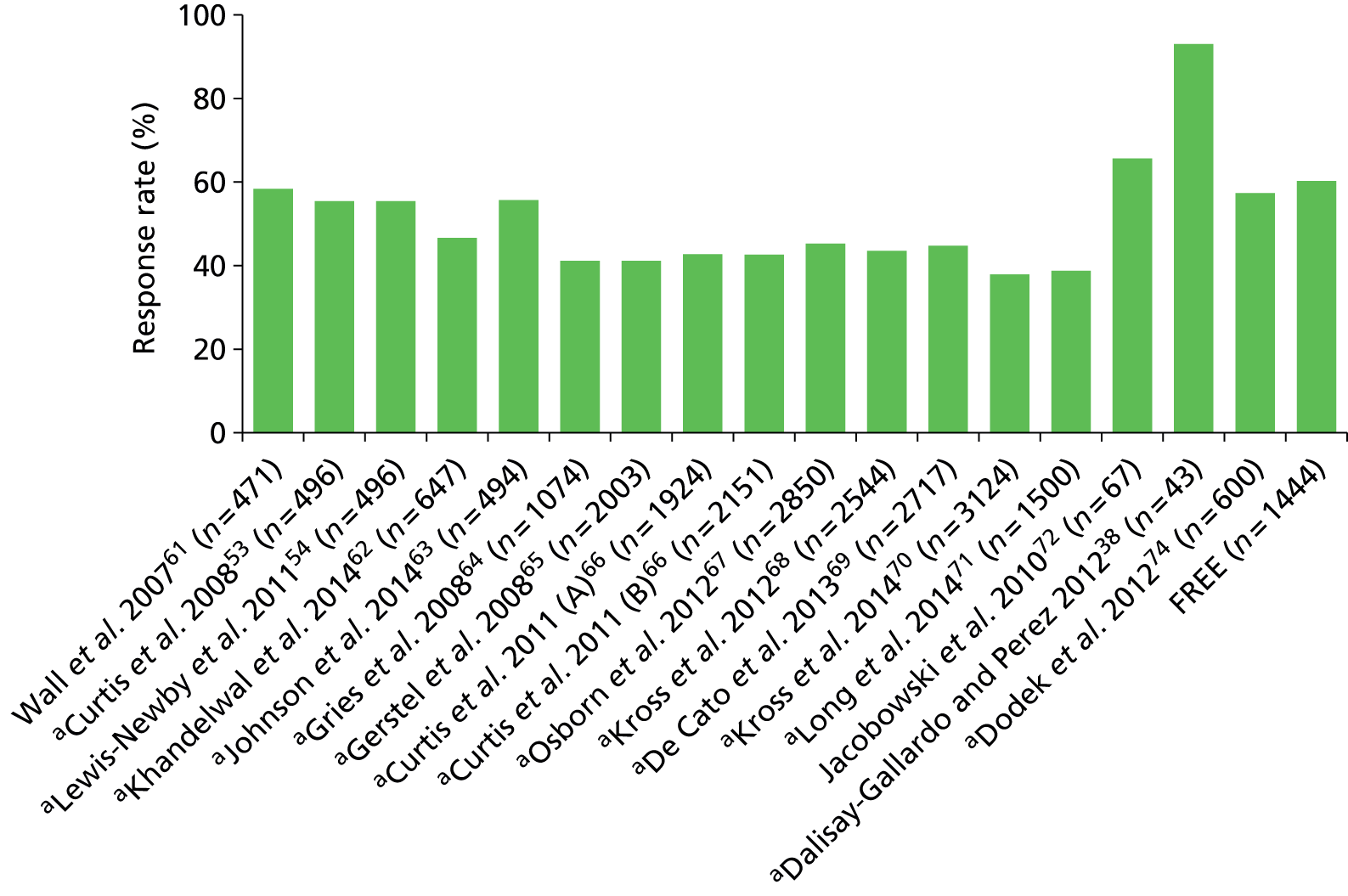

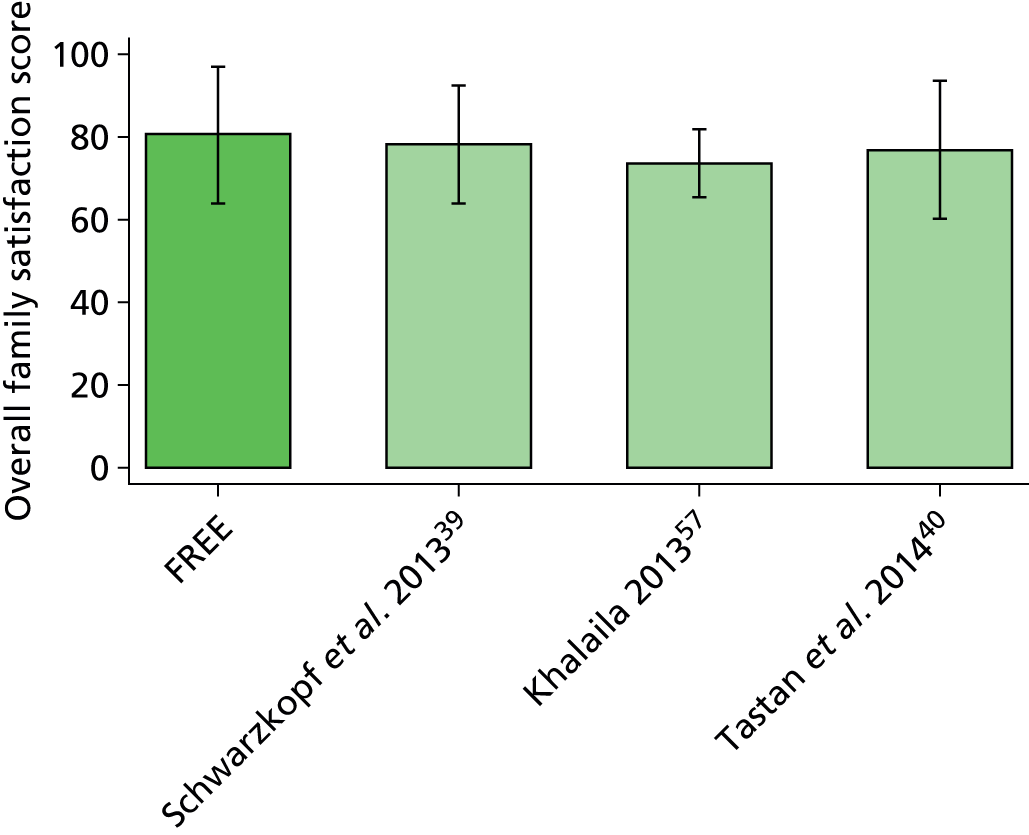

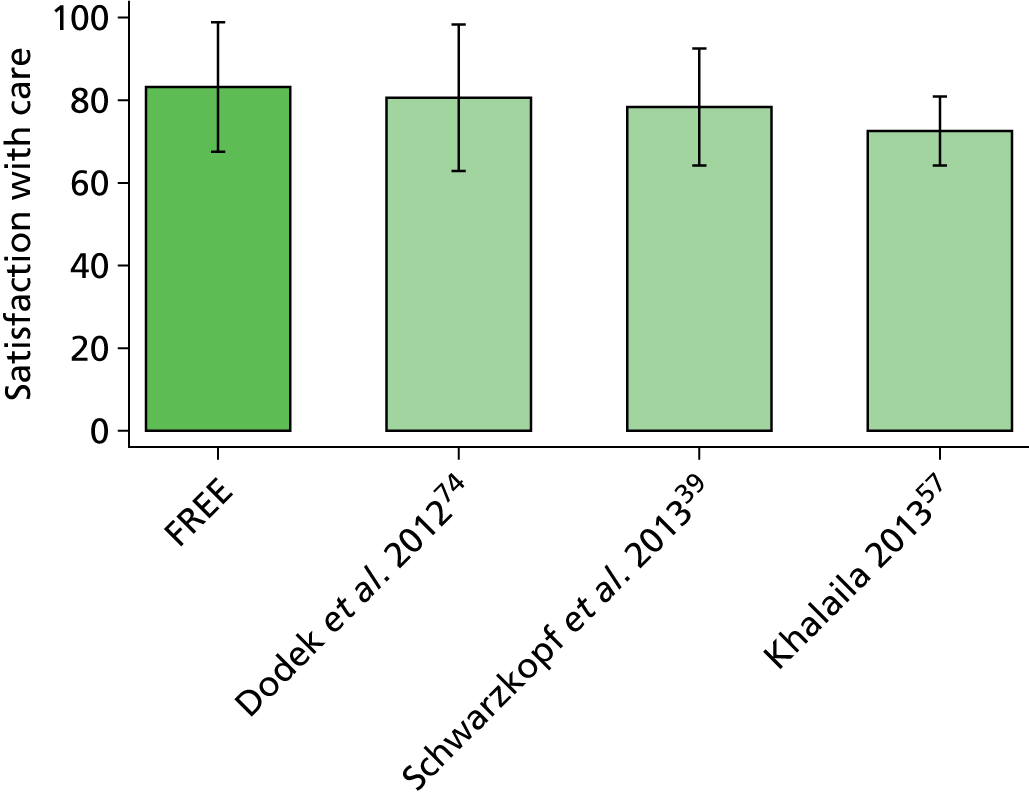

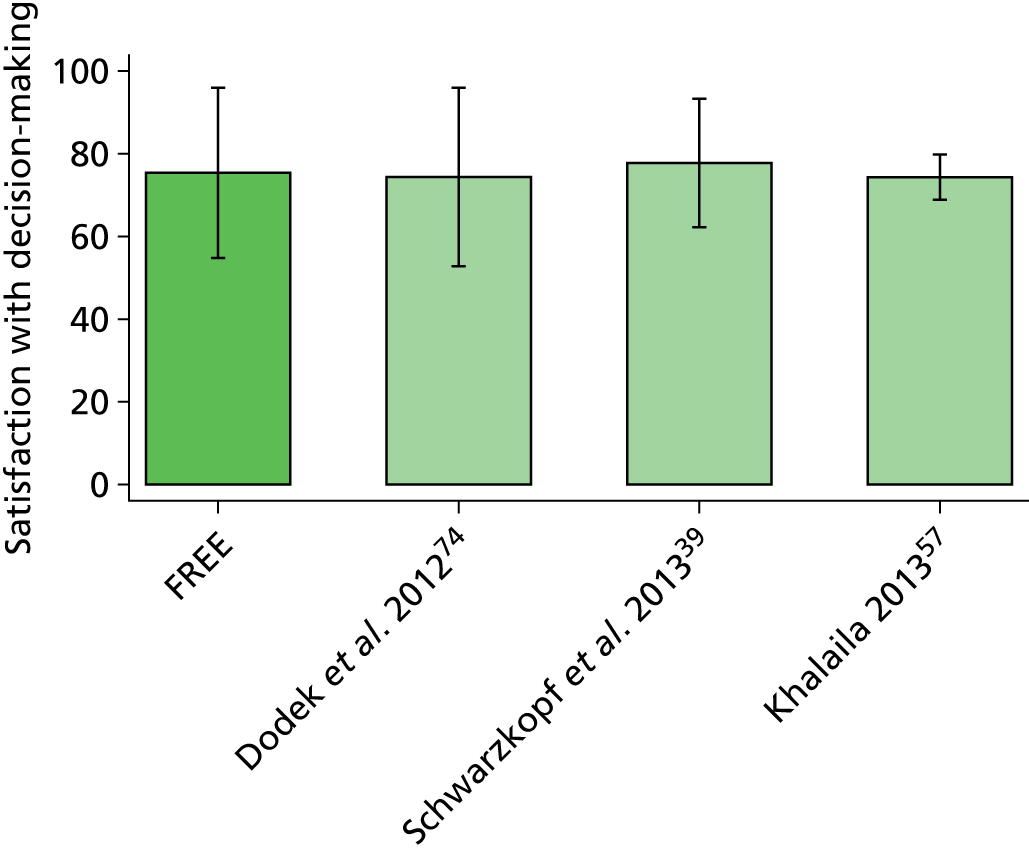

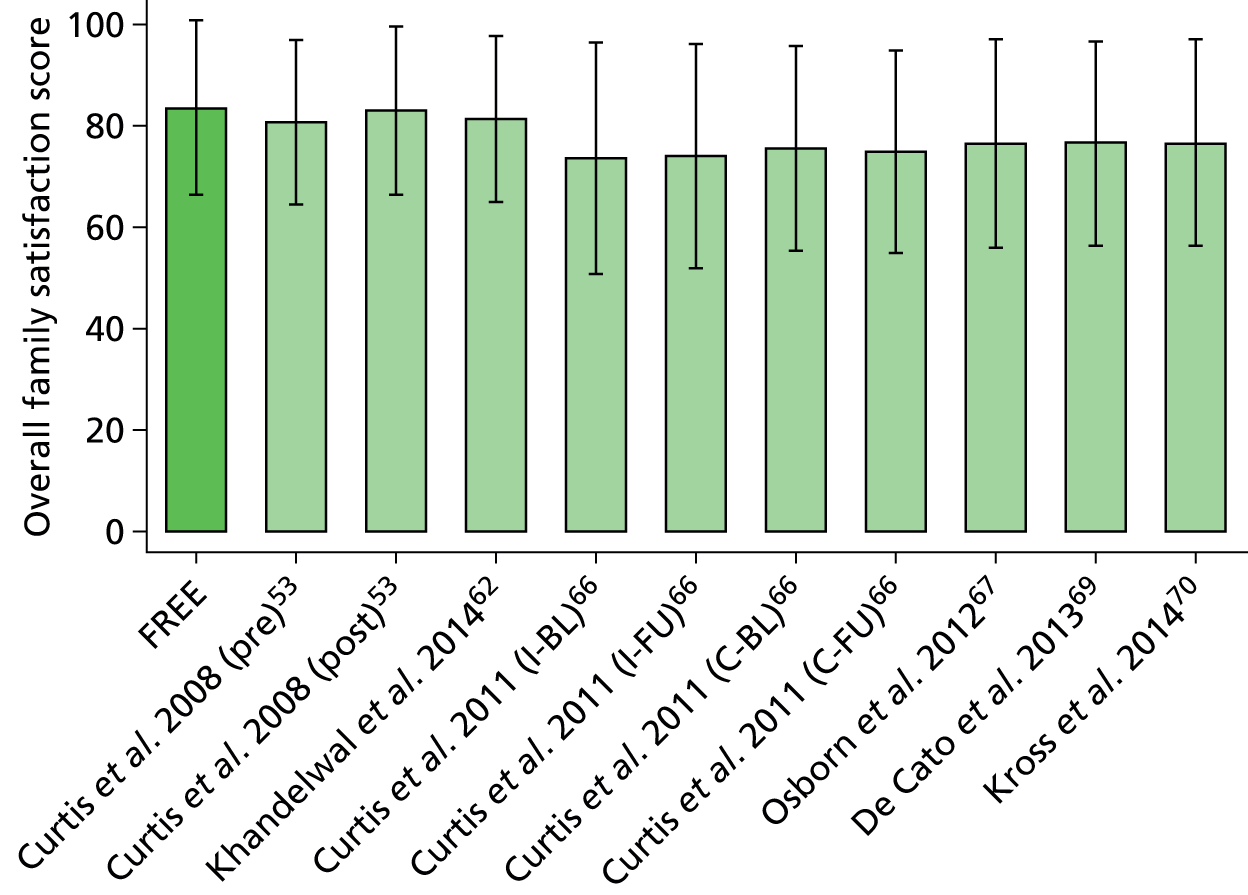

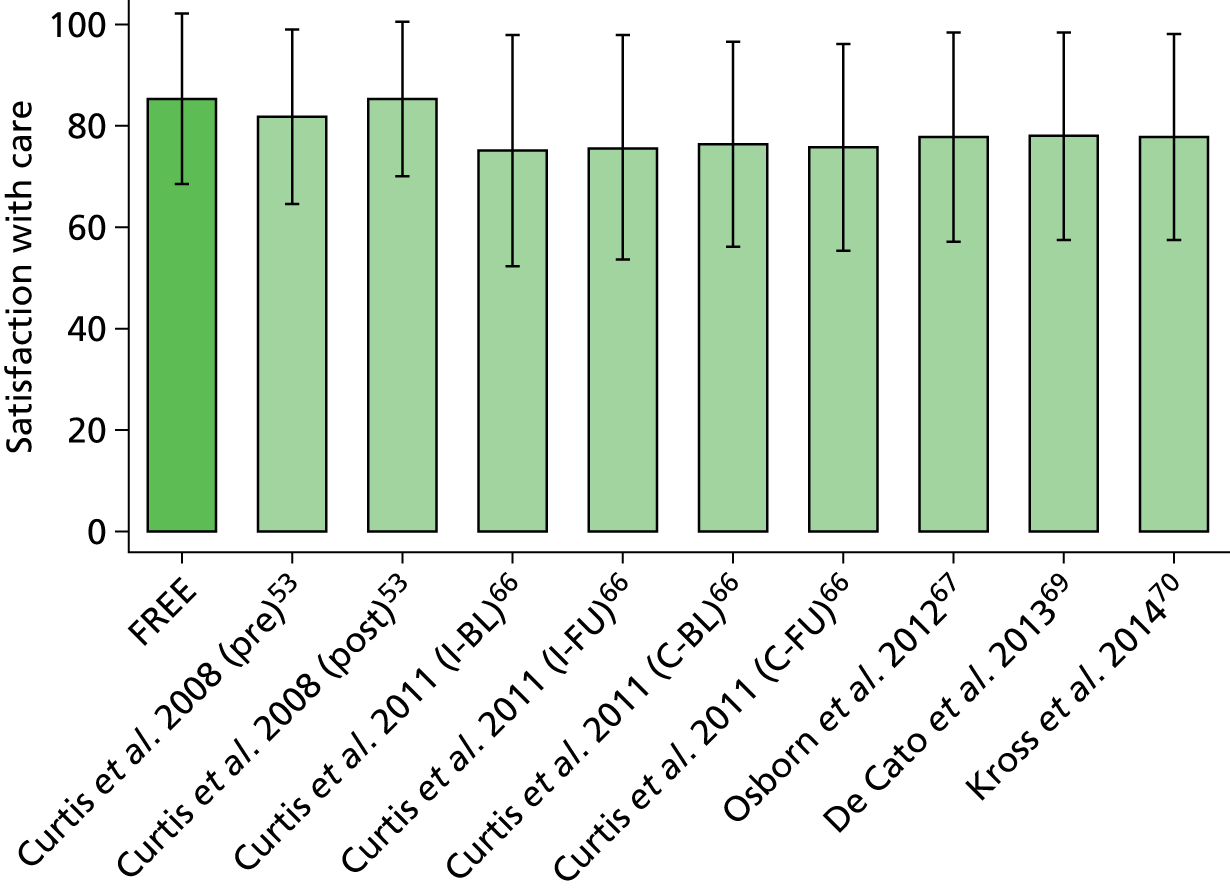

Nesting the FREE study in the CMP ensured an efficient design (with respect to participating units and data collection) and facilitated efficient management of the study, including monitoring recruitment and adherence to the protocol at participating units.