Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 11/1023/10. The contractual start date was in February 2013. The final report began editorial review in May 2015 and was accepted for publication in November 2015. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2016. This work was produced by Sahota et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background: transition care theories

The transition of care from hospital back into the community is a vulnerable stage in patient care and recovery. As acute hospital care ends and follow-up care in the community commences, the continuity of patient care can often become disrupted and ‘de-coupled’. This can lead to difficulties in sharing relevant knowledge or information about a patient at a given time, thereby leading to poorly integrated care planning and limited rehabilitation. This highlights the importance of timely, accurate and relevant communication or, more precisely, the ‘transition of care’ among different care providers. Transition of care involves more than the communication of information; rather, it is the exchange and use of meanings, assumptions, practices and know-how to engender shared understandings and collaborative practices. There is growing evidence that persistent occupational and organisational boundaries, especially between acute hospital care and the community, can hinder integrated care at the time of hospital discharge. For example, acute and community services are often characterised by different ways of working, team and resource configurations, care philosophies and service cultures, and ways of organising care. More significantly, it is often the case that those working in the community setting are not always involved in discharge planning, which can mean that early rehabilitation becomes delayed or community teams experience an initial ‘reactive’ phase in which they rapidly adjust or reformulate care plans.

A related area of theory elaborates how professional boundaries can influence the integration of different care sectors and organisations. The sociology of professions literature shows how expert occupations, such as medicine and nursing, are defined by well-established social, cultural and legal boundaries that determine their areas of expertise, responsibilities and remit of practice. These boundaries are historical in character and are linked to wider (societal) factors, including policy-making and professional associations, as well as more localised and everyday practices, including the customs of interaction and supervision between occupational groups. In many respects, this division appears settled with relatively permanent boundaries and hierarchies; for example, it is typically argued that medicine remains dominant in the clinical division of labour and there is a division of responsibility between acute and community care.

The boundaries and jurisdictions between health-care professions and organisations can also inhibit new or more integrated ways of working when the division of responsibilities between groups needs to be redrawn to better address the needs of patients. Closer examination of these boundaries reveals many points of contact and conflict, especially when new or extended roles are introduced and when the division of responsibilities is redrawn to better address the needs of patients. For example, many service innovations and new technologies extend the jurisdiction of one profession into the realm of another or bring into tension-established boundaries1,2 suggests that major workforce changes witnessed over the last 20 years have significantly transformed the boundaries between health-care professions, including new forms of specialisation, diversification, and forms delegation and substitution. For example, doctors readily delegate more routine work to other professions if it enables more specialisation within their given field. These debates are significant in the context of more integrated working between acute and community care, because they highlight the potential for established professional and sectoral boundaries to be redrawn and negotiated.

A ‘transitional care strategy’ is an intervention or a group of interventions initiated prior to hospital discharge with the aim of ensuring the safe and effective transition of patients from one setting to another. Hospital-based transitional care interventions aim to smooth the transition from secondary (hospital) to primary (community) care, avoid adverse events and prevent unnecessary readmissions back to hospital. In a Cochrane review by Shepperd et al. ,3 a structured discharge plan tailored to the individual patient was shown to bring about small reductions in hospital length of stay (LOS) and readmission rates for older people admitted to hospital with a medical condition. Twenty-one randomised controlled trials (RCTs) (7234 patients) were included. Fourteen trials recruited patients with a medical condition (4509 patients), four recruited patients with a mix of medical and surgical conditions (2225 patients), one recruited patients from a psychiatric hospital (343 patients), one recruited patients from both a psychiatric hospital and a general hospital (97 patients) and one recruited patients admitted to hospital following a fall (60 patients). Hospital LOS and readmissions to hospital were significantly reduced for patients allocated to discharge planning [mean difference in LOS –0.91 days, 95% confidence interval (CI) –1.55 to –0.27; readmission rates relative risk (RR) 0.85, 95% CI 0.74 to 0.97; 11 trials]. For elderly patients with a medical condition (usually heart failure) there was insufficient evidence of a difference in mortality (RR 1.04, 95% CI 0.74 to 1.46; four trials) or hospital LOS (RR 1.03, 95% CI 0.93 to 1.14; two trials). This was also the case for trials recruiting patients recovering from surgery and a mix of medical and surgical conditions. In three trials patients allocated to discharge planning reported increased satisfaction.

In another systematic review and meta-analysis of RCTs of inpatient rehabilitation specifically designed for geriatric patients,4 17 trials (4780 patients) comparing the effects of general or orthopaedic geriatric rehabilitation programmes with usual care were included. Compared with those in the control groups, the weighted mean length of hospital stay after randomisation was longer in patients allocated to general geriatric rehabilitation (24.5 vs. 15.1 days). Meta-analyses of effects indicated an overall beneficial effect on all outcomes at discharge [odds ratio 1.75 (95% CI 1.31 to 2.35) for function, RR 0.64 (95% CI 0.51 to 0.81) for nursing home admissions, RR 0.72 (95% CI 0.55 to 0.95) for mortality] and at the end of follow-up [odds ratio 1.36 (95% CI 1.07 to 1.71) for function, RR 0.84 (95% CI 0.72 to 0.99) for nursing home admissions, RR 0.87 (95% CI 0.77 to 0.97) for mortality]. Limited data were available on impact on health care or costs.

With respect to readmission, highly targeted disease-specific hospital-based transitional care strategies have shown modest success in reducing readmissions for chronic heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma, but little is known about effective transitional care strategies for frail older people, many of whom have multiple comorbidities. Four different types of transitional care strategies have been shown to be effective in reducing readmissions: Project Better Outcomes for Older adults through Safe Transitions (BOOST), Project Re-Engineered Discharge (RED), Care Transitions Intervention (CTI) and the Transitional Care Model (TCM). These programmes have several similarities and include bridging interventions with a dedicated transition provider, either a nurse or case manager, as the clinical leader. There is an over-riding emphasis on having an advocate to facilitate the co-ordination of care and outreach to patients following discharge from hospital.

Project Better Outcomes for Older adults through Safe Transitions

Project BOOST is a transitional care programme supported by the Society of Hospital Medicine. 5,6 This quality improvement collaborative has been implemented across the USA in different hospital settings, focusing on general medicine populations, both medical and surgical. Experts in the field of quality improvement and transitions in care facilitate the development and implementation of a BOOST site-specific programme that addresses the needs of each hospital.

The BOOST toolkit includes several interventions including risk assessment, a medication review, a discharge checklist and a multidisciplinary team-based approach to the discharge process. A recent study of 30 hospitals showed modest reductions (2–6%) in 30-day readmission rates. 5

Project Re-Engineered Discharge

Project RED is focused on a multidisciplinary approach to patient care co-ordinated by a nurse discharge advocate. 7 The discharge advocate engages patients during their admission to hospital and provides clinical information and an individualised and illustrated plan post discharge. Following discharge, a pharmacist performs the telephone follow-up including a medication review with direct communication to the primary outpatient provider. In a RCT there was a non-significant 6% reduction in the 30-day readmission rate and a significant 8% reduction in the 30-day visit to the accident and emergency (A&E) department post discharge. 7

Care Transitions Intervention

The CTI is a multicomponent programme designed to facilitate patient engagement and promote direct patient and caregiver involvement in self-management following hospitalisation, including providing the necessary skills to be able to navigate the health-care system. 8–11 There are four components of the CTI: (1) medication management, (2) development of a personal health record that is carried from site to site, (3) close follow-up with a primary care provider and (4) the identification of ‘red flags’ and indications that would prompt patients to contact providers. An advanced practice nurse ‘transition coach’ performs post-discharge home visits and makes telephone calls, emphasising patient engagement and self-management in the care of chronic diseases. The programme has been studied in several different acute care settings and has shown statistically significant reductions in 30-day readmission rates (4–6%)8–9,11 and 90-day readmission rates (6–22%). 9–10

The Transitional Care Model

The TCM is another nationally recognised transitional care programme and includes a strategy focusing on hospital-based discharge planning and home follow-up. 12,13 A transitional care nurse follows patients from hospital to home, facilitates communication with outpatient providers and performs a series of home visits and telephone follow-up calls in the post-discharge period. The TCM emphasises a multidisciplinary approach to patient care, led by the transitional care nurse who remains in contact with other providers including physicians, nurses, social workers, discharge planners and pharmacists. A reduction in the 90-day readmission rate of between 13% and 48% has been reported. 12,13

Report structure

Chapter 2 provides an introduction to the study and its relationship to current NHS policy. Chapter 3 describes the design and methods of the study and Chapter 4 describes the main RCT findings. Chapter 5 describes the qualitative study design and methods, followed by a summary of the main findings. Chapter 6 details the methods and results of the health economics analysis. Chapter 7 discusses the main findings and learning points from the study.

Chapter 2 Introduction

The number of people aged ≥ 75 years in the UK is expected to double by 2025, compared with a 12% growth in the overall population [see www.ons.gov.uk/ons/index.html (accessed 4 January 2016)]. The proportion of acute emergency medical admissions contributed to by this age group has seen a significant rise in the last 5 years from 9.5% to 14%14 and, with ageing trends, this is expected to increase significantly over the next 10 years. Compared with younger patients admitted to hospital, for older people the hospital LOS is much longer, the risk of hospital-acquired complications is much higher, discharge planning is more complex and 28-day readmission rates are much greater. 15

In some hospitals in the UK there have been significant reductions in hospital LOS but an increase in the 28-day readmission rate. Nationally, over the last 6 years the 28-day readmission rate has increased from 11% to 14%. 16 (DH, Emergency Admission Rates, 2008). More locally, in Nottingham the mean LOS across the medical elderly care wards over the period 2007–10 (five wards, 6924 patients) has decreased from 14 to 9 days through the use of ward discharge co-ordinators, but the 28-day readmission rate has increased from 14% to 19% (local audit 2011, unpublished data). The reasons for these readmissions are multifactorial, but an important component is the availability of appropriate resources in the community that are able to respond to the needs of these patients in a responsive manner. Patient safety is often compromised during this vulnerable period, with high rates of medication errors,17–20 incomplete or inaccurate information on transfer21 and lack of appropriate follow-up of care22 collectively leading to fragmented discharge planning and increased rates of recidivism to high-intensity care settings. 21

In England and Wales, to address the problem of rising readmission rates, the Department of Health has allocated £300M as part of the funding for reablement linked to hospital discharge funding stream [see www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/215824/dh_123473.pdf (accessed 4 January 2016)]. This money was to be spent on developing local plans in conjunction with local authorities, foundation trusts/NHS trusts and community health services, to facilitate seamless care for patients on discharge from hospital and prevent avoidable hospital readmissions. Some Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) have invested in early supported discharge at home schemes, some have invested in community-based rehabilitation schemes and some have invested very little at all. Reviews of the literature suggest that it is currently unclear which are the most effective and efficient structures and organisation of community/intermediate care services in relation to their purpose. 2,14 However, a recent retrospective review of discharges for stroke and other cerebrovascular diseases from a single academic medical centre found that 53% of the readmissions were potentially avoidable and reported that gaps in care co-ordination, lack of timely follow-up of care and inadequate instructions at discharge were the main problem areas. 23

To address this problem we undertook a structured literature review and identified systematic and Cochrane reviews of early supported discharge, discharge planning from hospital to home and care transition interventions. 3–4,9,18,23–27 The key components of successful service models included (1) more intensive rehabilitation; (2) working more closely with the patient and his or her relatives; and (3) bridging interventions with a dedicated transition provider, either a nurse or a case manager, as the clinical leader, with an over-riding emphasis on having an advocate to facilitate co-ordination of care and outreach to patients following discharge from hospital.

Our review was followed by a series of multiperspective focus group meetings with service users, experienced health-care professionals and service managers and led to the development of the Community In-reach Rehabilitation And Care Transition (CIRACT) service [consisting of a senior occupational therapist (transition coach), senior physiotherapist and assistant practitioner], linked directly to a social services practitioner and working more closely across multiple boundaries with patients and their carers. The CIRACT service was set apart from other models of community care because, although the CIRACT team was employed by a community NHS provider (NHS Nottingham CityCare Partnership), it was based on the hospital ward. By working across these boundaries, it was able to provide earlier contact with patients while they were still in hospital, assess care needs, work with hospital specialists in a more integrated way and, by staying with patients following discharge, follow them up in the community and facilitate community rehabilitation and personal care as needed.

Elaborating the theory of this model further, there is an underlying assumption that acute and community services are de-coupled or separated by occupational and organisational boundaries. By colocating community teams within the acute setting these boundaries can be mediated based on routine work interaction or functional proximity. This can in turn lead to enhanced knowledge sharing and mutual understanding of where community therapists bring, into the hospital setting, specialist information and understanding about community rehabilitation, the availability of community-based services and a profile of service demands and expectations within the community. At the same time, acute care teams are able to share knowledge about the organisation and configuration of hospital services, the profile of demands and expectations and the broader organisation of care. The two-way flow of knowledge is thus over time able to support mutual understanding of the respective work processes and contributions of each service to patient care, which in turn can foster enhanced integration or co-ordination of work. This has the potential to enable community therapists to work earlier with hospital-based care teams in discharge and care planning, especially through developing more holistic, patient-centred, ‘community-ready’ care plans. It also enables community therapists to participate earlier in direct patient care, including interaction with hospital-based specialists and patients, to determine the appropriate package of care, commence rehabilitation earlier, ensure that longer-term rehabilitation aligns seamlessly with acute care and provide earlier education and support to patients and families.

A pilot (before and after) 4-month study comparing the CIRACT service with the standard hospital rehabilitation service across two CCGs (Rushcliffe CCG and CityCare CCG) demonstrated a trend towards a reduction in LOS and reduced readmission rates. 28 The aims of this research were therefore to evaluate the clinical effectiveness, microcosts and cost-effectiveness of the CIRACT service compared with the traditional hospital-based rehabilitation (THB-Rehab) service through a high-quality RCT.

The primary objective of the CIRACT trial was to assess whether or not length of hospital stay among people aged ≥ 70 years admitted to hospital as an acute medical admission was different for the CIRACT service compared with the THB-Rehab service.

The secondary objectives were to assess the effects of the CIRACT service compared with the THB-Rehab service on:

-

the readmission rate within 28 and 91 days post discharge

-

super spell bed-days (total time in NHS care) at day 91

-

functional ability at day 91

-

comorbidity at day 91

-

health-related quality of life at day 91

-

microcosts and cost-effectiveness.

A parallel qualitative appraisal was undertaken to provide an explanatory understanding of the organisation, delivery and experience of the CIRACT service from the perspective of key stakeholders and patients.

Chapter 3 Study design and methods

Trial design

This trial was a single-centre pragmatic RCT (1 : 1 allocation ratio) with an integral health economic study and parallel qualitative appraisal.

Participants

The participants in the trail were older people admitted to the general medical wards as an acute medical emergency.

Eligibility criteria

Patients were eligible for the study if all of the inclusion and none of the exclusion criteria were met:

-

inclusion criteria:

-

age ≥ 70 years

-

general practitioner (GP) registered within the Nottingham City CCG catchment area only (catchment population 300,000)

-

-

exclusion criteria:

-

bed bound prior to admission or moribund on admission

-

receiving palliative care

-

previously included in the trial on an earlier admission

-

unable to be screened and recruited by the research team within 36 hours of admission to the study ward (a 36-hour deadline ensured that there was not a delay in the participant receiving therapy and enabled the recruitment of a large proportion of patients admitted over a weekend when the research team was not available)

-

nursing home residents.

-

Study setting

General medical elderly care wards at the Queen’s Medical Centre, Nottingham (1800-bed hospital, serving a population of 680,000), with community follow-up.

Study intervention

The trial had two arms: (1) the CIRACT service (intervention arm) and (2) THB-Rehab (standard care arm).

-

The CIRACT service provided a comprehensive assessment of each participant’s ability to perform certain tasks, which was completed within 24 hours of randomisation, enabling the formulation of a rehabilitation plan. While in hospital the participants were treated daily (7 days a week if appropriate). During the hospital stay, the team liaised with each participant and his or her carer(s) to enable a visit to the participant’s home to assess and provide recommendations for equipment and make adaptations and/or modifications as required. The CIRACT service utilised the team’s expertise in community working to form links with the appropriate services to ensure a smooth and effective discharge. In more complex cases the CIRACT team took the participant out of the hospital for a home visit prior to discharge. Following discharge, the CIRACT team visited the participant at home within 48 hours to assess the level of rehabilitation required and further follow-up visits were provided as deemed necessary.

-

The THB-Rehab service was provided by the ward therapy teams (usually a band 6 occupational therapist and a band 6 physiotherapist) on weekdays only. The team jointly conducted an assessment of each participant’s ability to perform certain tasks and provided recommendation for rehabilitation. The service referred the participants to the appropriate community-based services for provision of equipment at home, personal care and ongoing rehabilitation when appropriate at discharge. Once discharged from hospital, participants had no direct contact with the THB-Rehab service.

In either group, if a participant became medically unwell at any point to the extent that he or she was no longer able to undertake rehabilitation activities, the treating team withheld further rehabilitation until instructed by the ward doctor that it was safe to recommence rehabilitation activities. The nursing and medical care provided by the ward staff did not differ between the two groups.

Primary outcome measure

The primary outcome was hospital LOS from randomisation to discharge from the acute medical elderly care ward.

Secondary outcome measures

The secondary outcome measures were:

-

Unplanned readmission rates at day 28 and day 91.

-

Super spell bed-days (total time in NHS care including hospital care and intermediate care) from admission to 91 days’ follow-up.

-

Functional ability at 91 days as assessed by the Barthel Activities of Daily Living (ADL) index. 29 This 10-item index is scored out of 20, with a score of 20 indicating the ability to get up and down stairs unaided and in and out of the bath or shower independently.

-

Health-related quality of life as measured by the European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions three-level version (EQ-5D-3L)30 at 91 days post discharge. The EQ-5D-3L is a standardized measure of quality of life including five domains – mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression – each with three levels.

-

Comorbidity as measured by the Charlson index31 at 91 days post discharge. The Charlson index codes a total of 22 comorbid conditions into a single score.

-

Mean cost per patient of the CIRACT and THB-Rehab services estimated using microcosting methods and cost-effectiveness analysis from a NHS and Personal Social Services (PSS) perspective, using data collected from a modified Client Service Receipt Inventory (CSRI) questionnaire,32 with quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) at 91 days post discharge.

Data collection

The research team collected demographic data [including age, sex, Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) score33 and living circumstances] and outcome measures at baseline at face-to-face interviews and follow-up data through established hospital and community databases and participant telephone interviews [Nottingham Information System (NOTIS) hospital database: admission/discharge date data; Community System One: contacts with other services and equipment provision data; telephone interviews: outcome measure data].

Data were collected using trial data collection forms, which were monitored by the Nottingham Clinical Trials Unit (NCTU) for consistency, validity and quality. Missing data and data queries were referred promptly back to the recruiting site for clarification. For participants who withdrew from the study, data were collected up to that point (as specified in the consent form), with no further data collected. Participants were not replaced when they withdrew from the study. All reasonable attempts were made to contact any participants lost to follow-up during the course of the trial to complete the assessments.

Data management

All trial data were entered into a trial-specific database, with participants identified only by their unique trial number, date of birth and initials. The database was developed and maintained by the NCTU. Access to the database was restricted and secure. Data quality and compliance with the protocol were assessed throughout the trial by verification of trial data against clinical records and by data checking for accuracy and internal consistency.

Sample size calculation

The primary statistical analysis was to compare LOS for those allocated to receive the CIRACT service compared with LOS for those allocated to the THB-Rehab service (see Appendix 1 for the statistical analysis plan). Pilot data28 showed the log-transformed LOS to be normally distributed with a standard deviation (SD) of 0.9. Therefore, 111 patients per arm were required to detect a clinically important effect size of 3 days (equivalent to a geometric mean ratio of 0.7) with a 5% two-sided alpha and 80% power. Allowing for 5% non-collection of primary outcome data, 250 patients in total were recruited over a 13-month recruitment period.

Recruitment and consent

All eligible patients were made aware of the trial at the time of admission to hospital and invited to participate. Written informed consent was obtained by the research team in accordance with the International Conference on Harmonisation Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice [see www.ich.org/products/guidelines/quality/article/quality-guidelines.html (accessed 4 January 2016)]. For patients who were confused (who had dementia/delirium such that they were unable to understand the nature of consenting to a research study and the study process), consent was obtained from a carer following an established framework34 used in previous ethically approved studies in older persons with dementia.

Randomisation procedure

Once the research team had gained consent, patients were allocated to either the CIRACT service or the THB-Rehab service using the web-based randomisation service provided by the NCTU. Randomisation was determined by a computer-generated pseudorandom code using random permuted blocks of randomly varying size and held on a secure server. Participants were allocated with equal probability to either arm of the study. The randomisations were requested through a PC with Internet Explorer and internet access, located on a dedicated secure server within the University of Nottingham. All communications between the user’s PC and the server were fully encrypted (secure SSL 128 bit encrypted) and used a unique username and password.

Blinding

The research team collecting data and the research team analysing the data were blinded to treatment allocation. The participants and ward staff were not blinded to treatment allocation as the treating therapists liaised closely with ward staff to ensure optimal patient care. The 3-month follow-up data were collected by the research team blinded to the intervention.

Statistical analyses

Preliminary analyses

Preliminary analyses describing the proportions of participants who withdrew consent prior to discharge from hospital, died in hospital, were discharged from hospital and died post discharge from hospital were conducted.

Participants in the two trial arms were described separately with respect to age at inclusion, sex, Barthel ADL score, MMSE score, comorbidity scale and EQ-5D-3L health state score. Continuous data were summarised using mean, SD, median, lower and upper quartiles, minimum and maximum and number of observations. Categorical data were summarised using frequency counts and percentages.

Primary analysis

The primary analysis was hospital LOS for those who were discharged from hospital. Participants were analysed as randomised regardless of intervention received. The analysis was conducted using generalised linear regression modelling, with log-transformed LOS as a response. The primary effectiveness parameter was the LOS geometric mean ratio from admission to discharge between the two arms, along with the 95% CI and p-value.

Secondary analyses

We conducted the following additional analyses for the primary outcome:

-

including in the model participants in each arm who died prior to discharge, with a covariate specifying death or discharge

-

including in the model all randomised participants, with multiple imputation of missing LOS data

-

time to discharge analysed using Cox regression analysis including hospital death as a competing risk.

Secondary outcomes were analysed using appropriate generalised linear models, with choice of model and presentation of the estimated between-group effect dependent on outcome type (difference in means for normally distributed continuous outcomes, ratio of geometric means for log-normal continuous outcomes and risk differences for binary outcomes)

Qualitative appraisal

The parallel qualitative appraisal was concerned with understanding ‘how’ the CIRACT service:

-

was implemented, to develop evidence for future roll-out

-

was delivered and designed in terms of workforce configuration, to understand the barriers to and drivers of sustaining inter-occupational and inter-organisational working

-

interacted with other care processes and systems, to develop knowledge on their strategic alignment with existing care models

-

was experienced by clinicians, patients and families, to develop recommendations for improvement

-

impacted on established roles and relationships, to understand barriers to and drivers of change manifest in distinct professional knowledge, practice and cultural domains.

The appraisal was informed by a consolidated framework, drawing attention to a range of key factors that frame and are involved in the implementation of new practices. 35 The design of the qualitative appraisal involved a number of established methods of data collection and analysis, including non-participant observations, interviews and focus groups, which are further detailed in Chapter 5.

Health economic study

The integral health economic study was designed to evaluate the microcosts of service delivery and the cost-effectiveness of the CIRACT service compared with the THB-Rehab service. To determine the microcosts of service delivery, we proposed to use a time and motion study (TMS) microcosting methodology conducted through three phases (detailed in Chapter 6).

A TMS is used to understand existing work patterns with a view to informing a more efficient model and to aid microcost analysis. It directly observes and measures the time required to deliver a service. TMS methodology has its roots within business and was devised to improve work management. TMS was initially defined by Frederick Winslow Taylor36 in the 1900s and was designed to break down work into its component parts in order to streamline or redefine them to ensure maximum efficiency. TMS is increasingly being carried out within a health-care setting to ensure that systems are running as efficiently as possible, which in turn can lead to more cost-effective models for delivery. One part of this may be ascertaining resource use and valuing such resource use using microcosting, although other costing methods also exist. The microcosting method measures resource use and costs in detail at the individual patient level.

Differing methods of data collection for TMS have been used and include either self-report or observation. The choice of data collection method would depend on how intensive a job/role is and how many activities were being worked on over what period of time. Self-report TMS has been found to result in significantly less activities being described than with observer methods37 and therefore is regarded as being less accurate, although it is cheaper and more efficient as an observer is not required. For observation TMS there are two methods: work sampling or continuous observation. In work sampling the observer is external to the workforce and randomly records instantaneous observations. Because of this, observations can be made of multiple staff members, which may be required if the unit of work being observed is being carried out by a team rather than by an individual. Continuous observation is when either the person or the unit of work being observed is ‘shadowed’ by the observer and all predefined tasks of interest are noted using a data collection tool. Although the data collected with both observer methods are not significantly different,38 work sampling is a more economical and objective method (as the observer is more remote from the subject). However the choice of method used is dependent on the research question and resources available. To determine resource use in a TMS, a flow chart is usually drafted that includes all of the necessary steps to deliver the service. 39 This then allows the development of categories to be observed and systematic data collection. 40

Study harms/adverse events

Data were collected for each individual participant with regard to any falls that occurred while an inpatient on the ward until time of discharge. A fall was classed as an ‘adverse event’ and a fall resulting in a radiologically confirmed fracture was classed as a ‘serious adverse event’. The risks of taking part in the trial were regarded as minimal as the CIRACT service was not a different type of rehabilitation but a change in delivery of the THB-Rehab service that a participant would have received as part of his or her usual care.

Ethics

The study was approved by the National Research Ethics Service West Midlands – Staffordshire Research Ethics Committee (reference number 13/WM/0050) on 27 February 2013. The trial was conducted in accordance with ethical principles that have their origin in the principles of good clinical practice41 and the Department of Health Research Governance Framework for Health and Social Care. 42

Chapter 4 Main randomised controlled trial results

Flow of participants into the trial

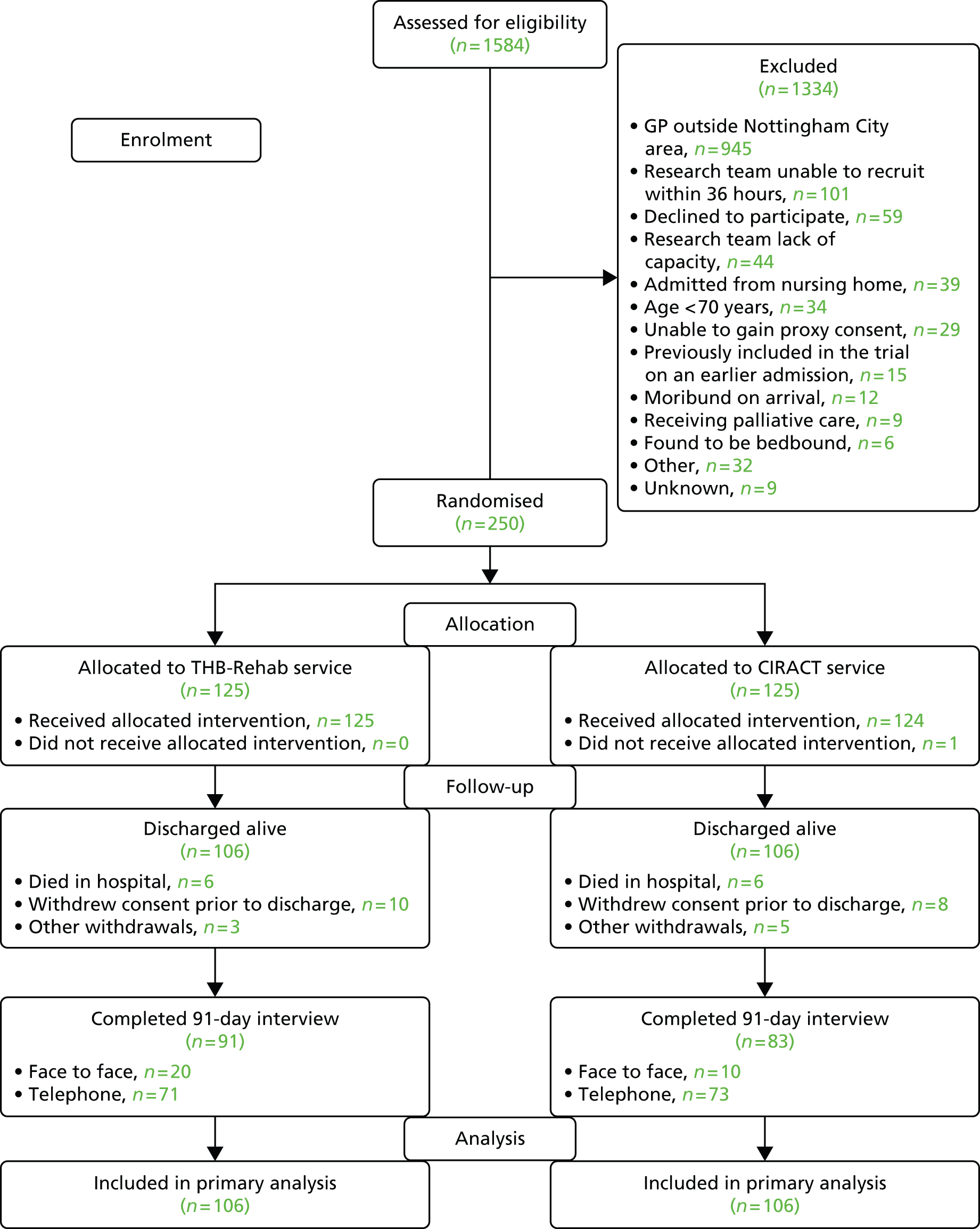

Study recruitment commenced on 23 June 2013 and ended on 31 July 2014, during which 1584 patients from three elderly care medical wards were screened for eligibility, of whom 250 were randomised into the trial. The dominant reasons for exclusion were GP registered outside the Nottingham City CCG catchment area, lack of research staff capacity and unable to gain consent from the participant (Figure 1). In total, 212 participants were followed up and included in the primary analysis.

FIGURE 1.

Participant flow.

Baseline characteristics of randomised participants

The baseline characteristics of the randomised participants are shown in Table 1. The mean age at randomisation was 84.1 years (range 67–99 years) and there was a slight predominance of women (64% of the total). The mean MMSE score was 21.7 out of 30 and the mean Barthel ADL score was 10.7 out of 20. There was a high prevalence of comorbidities among the participants, with a mean Charlson index score of 7.4. The groups appeared well balanced at baseline. This also held true between participants who had primary outcome data and those who did not within each arm, except for the Barthel ADL score, which was higher among those who had primary outcome data than among those who did not.

| Variable | Intervention arm | THB-Rehab | CIRACT | Total (n = 250) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary outcome collected | Primary outcome collected | ||||||

| THB-Rehab (n = 125) | CIRACT (n = 125) | Yes (n = 106) | No (n = 19) | Yes (n = 106) | No (n = 19) | ||

| Age at randomisation (years) | |||||||

| Mean (SD) | 84.5 (5.9) | 83.6 (6.6) | 84.3 (5.9) | 85.8 (5.7) | 83.8 (6.5) | 82.8 (7.4) | 84.1 (6.3) |

| Median (25th percentile, 75th percentile) | 85 (81, 89) | 84 (79, 89) | 84 (81, 88) | 86 (81, 90) | 84 (79, 89) | 85 (76, 88) | 84.5 (80, 89) |

| Min., max. | 70, 98 | 67, 99 | 70, 98 | 73, 94 | 70, 99 | 67, 93 | 67, 99 |

| n | 125 | 125 | 106 | 19 | 106 | 19 | 250 |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 46 (37) | 43 (34) | 38 (36) | 8 (42) | 33 (31) | 10 (53) | 89 (36) |

| Female | 79 (63) | 82 (66) | 68 (64) | 11 (58) | 73 (69) | 9 (47) | 161 (64) |

| Barthel ADL score | |||||||

| Mean (SD) | 10.5 (5.4) | 11.0 (6.1) | 11.4 (4.7) | 5.6 (6.5) | 12.1 (5.4) | 4.8 (6.1) | 10.7 (5.8) |

| Median (25th percentile, 75th percentile) | 10 (7, 15) | 12 (6, 16) | 11 (8, 15) | 4 (0, 13) | 13 (8, 16) | 1 (0, 12) | 11 (7, 16) |

| Min., max. | 0, 20 | 0, 20 | 1, 20 | 0, 17 | 0, 20 | 0, 16 | 0, 20 |

| n | 125 | 125 | 106 | 19 | 106 | 19 | 250 |

| Charlson comorbidity scale score | |||||||

| Mean (SD) | 7.3 (1.9) | 7.4 (2.2) | 7.2 (1.9) | 8.5 (1.8) | 7.4 (2.2) | 7.3 (2.1) | 7.4 (2.1) |

| Median (25th percentile, 75th percentile) | 7 (6, 9) | 7 (6, 9) | 7 (6, 9) | 8.5 (8, 9) | 7 (6, 9) | 7 (6, 9) | 7 (6, 9) |

| Min., max. | 4, 12 | 4, 13 | 4, 12 | 5, 12 | 4, 13 | 4, 11 | 4, 13 |

| n | 120 | 116 | 106 | 14 | 106 | 10 | 236 |

| MMSE score | |||||||

| Mean (SD) | 22.0 (6.2) | 21.4 (6.3) | 22.9 (5.3) | 16.2 (8.8) | 21.5 (6.4) | 20.2 (4.8) | 21.7 (6.2) |

| Median (25th percentile, 75th percentile) | 23 (19.5, 27) | 22 (19, 26) | 24 (20, 27) | 18 (8, 21) | 22.5 (19, 26) | 21 (17, 23) | 23 (19, 26) |

| Min., max. | 0, 30 | 1, 30 | 6, 30 | 0, 28 | 1, 30 | 14, 26 | 0, 30 |

| n | 80 | 87 | 70 | 10 | 82 | 5 | 167 |

| EQ-5D health state score | |||||||

| Mean (SD) | 54.5 (19.6) | 53.1 (22.7) | 54.7 (20.2) | 51.9 (6.5) | 52.9 (23.1) | 55.0 (15.5) | 53.8 (21.1) |

| Median (25th percentile, 75th percentile) | 50 (45, 0) | 50 (40, 0) | 50 (40, 0) | 50 (50, 7.5) | 50 (40, 0) | 50 (50, 5) | 50 (40, 0) |

| Min., max. | 10,00 | 0,00 | 10,00 | 40,0 | 0,00 | 30,0 | 0,00 |

| n | 114 | 111 | 106 | 8 | 104 | 7 | 225 |

Follow-up

In total, 212 participants were discharged from the hospital alive (106 in each arm), of whom 174 were followed up at 91 days post discharge (n = 91 from the THB-Rehab service and n = 83 from the CIRACT service) (Table 2). The main reason for not being followed up at 91 days post discharge was death post discharge.

| Outcome | Intervention arm | |

|---|---|---|

| THB Rehab (n = 125) | CIRACT (n = 125) | |

| Discharged alive | 106 (85) | 106 (85) |

| Followed up at 91 days | 91 (73) | 83 (66) |

| Not followed up at 91 days | ||

| Death post discharge | 11 (9) | 17 (14) |

| Withdrew consent post discharge | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Loss to follow-up post discharge | 3 (2) | 1 (1) |

| Discontinued for other reasons post discharge | 0 | 4 (3) |

| Death in hospital | 6 (5) | 6 (5) |

| Withdrew consent prior to discharge | 10 (8) | 8 (6) |

| Discontinued for other reasons prior to discharge | ||

| Found to be bed bound | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| GP not Nottingham City CCG registered | 0 | 2 (2) |

| Age < 70 years | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Receiving palliative care | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Unable to gain consent | 1 (1) | 0 |

| Moved to end-of-life care | 1 (1) | 0 |

In total, 12 participants died in hospital prior to discharge and another 18 withdrew consent prior to discharge. Eight participants were discontinued from the study prior to discharge for various post-randomisation eligibility breaches (see Table 2). These are categorised as ‘other withdrawals’ (see Figure 1).

Primary outcome

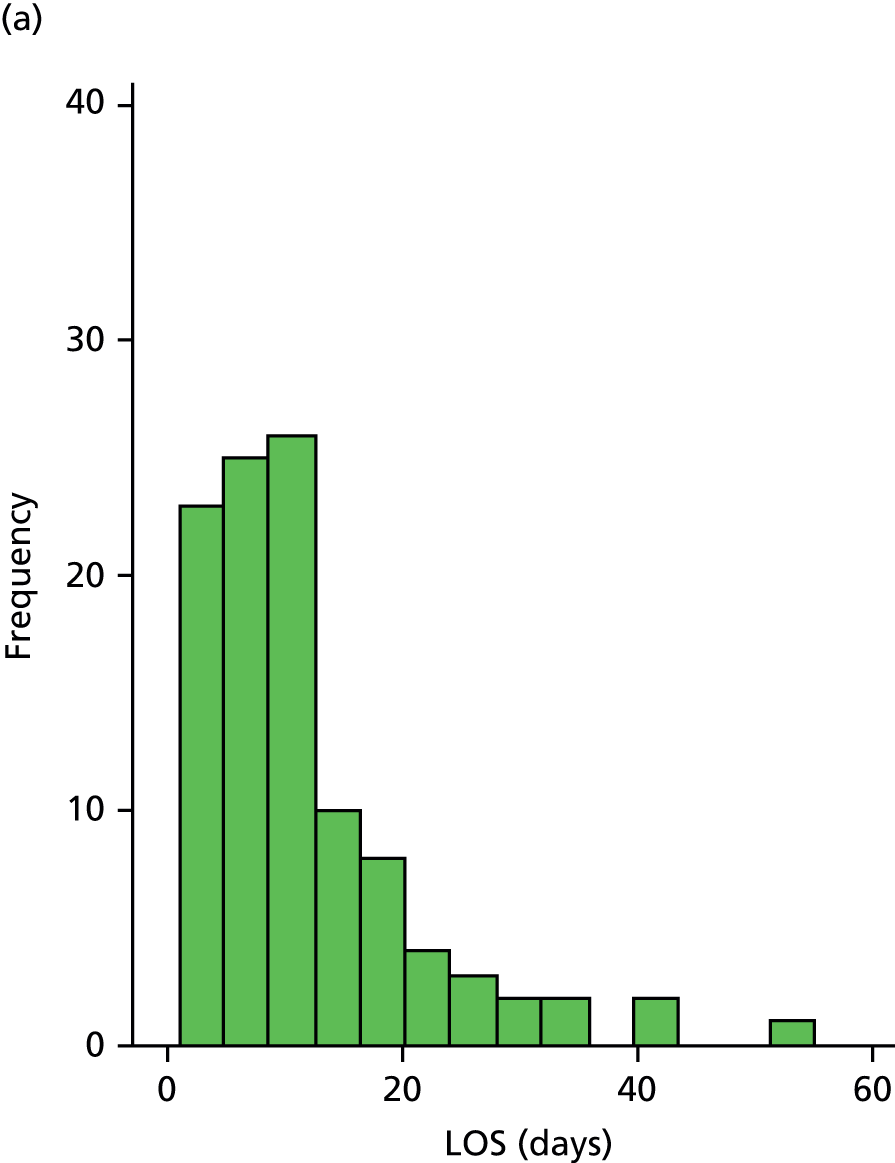

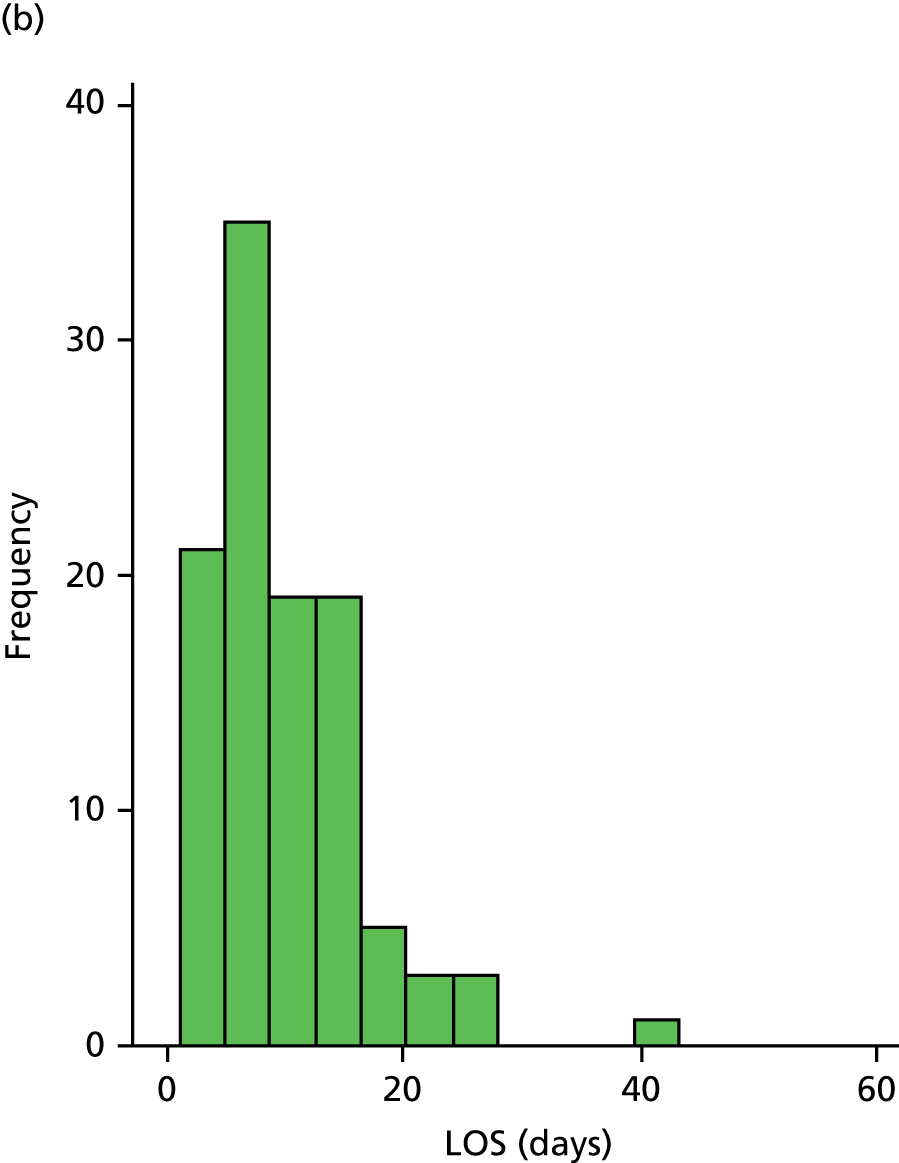

The distribution of LOS for participants discharged is shown in Figure 2. This was skewed, with a peak proportion discharged at day 8 in the CIRACT group and at day 12 in the THB-Rehab group.

FIGURE 2.

Distribution of LOS for participants discharged alive. (a) THB-Rehab; and (b) CIRACT.

There was no significant difference in LOS between the CIRACT service and the THB-Rehab service (median 8 vs. 9 days; geometric mean 7.8 vs. 8.7 days, mean ratio 0.90, 95% CI 0.74 to 1.10), which was supported by the sensitivity analyses (Table 3).

| Outcome | Intervention arm | Analysis type | Ratio | 95% CI | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| THB-Rehab | CIRACT | |||||

| LOS | ||||||

| Geometric mean (95% CI) | 8.7 (7.5 to 10.1) | 7.8 (6.9 to 8.9) | (1) Primary analysis | 0.90 | 0.74 to 1.10 | 0.303 |

| Median (25th Q, 75th Q) | 9 (5, 15) | 8 (5, 13) | ||||

| Min., max. | 2, 55 | 1, 41 | ||||

| n | 106 | 106 | ||||

| LOS | ||||||

| Geometric mean (95% CI) | 8.9 (7.7 to 10.2) | 8.0 (7.0 to 9.2) | (2) As in (1) with deaths in hospital | 0.90 | 0.75 to 1.10 | 0.316 |

| Median (25th Q, 75th Q) | 9 (5, 15.5) | 8 (5, 14) | ||||

| Min., max. | 2, 55 | 1, 62 | ||||

| n | 112 | 112 | ||||

| LOS | ||||||

| Geometric mean (95% CI) | 9.1 (7.9 to 10.5) | 8.3 (7.2 to 9.5) | (3) As in (1) with missing data by imputation | 0.91 | 0.75 to 1.09 | 0.307 |

| Median (25th Q, 75th Q) | 9 (5, 16) | 8 (5, 14) | ||||

| n | 125 | 125 | ||||

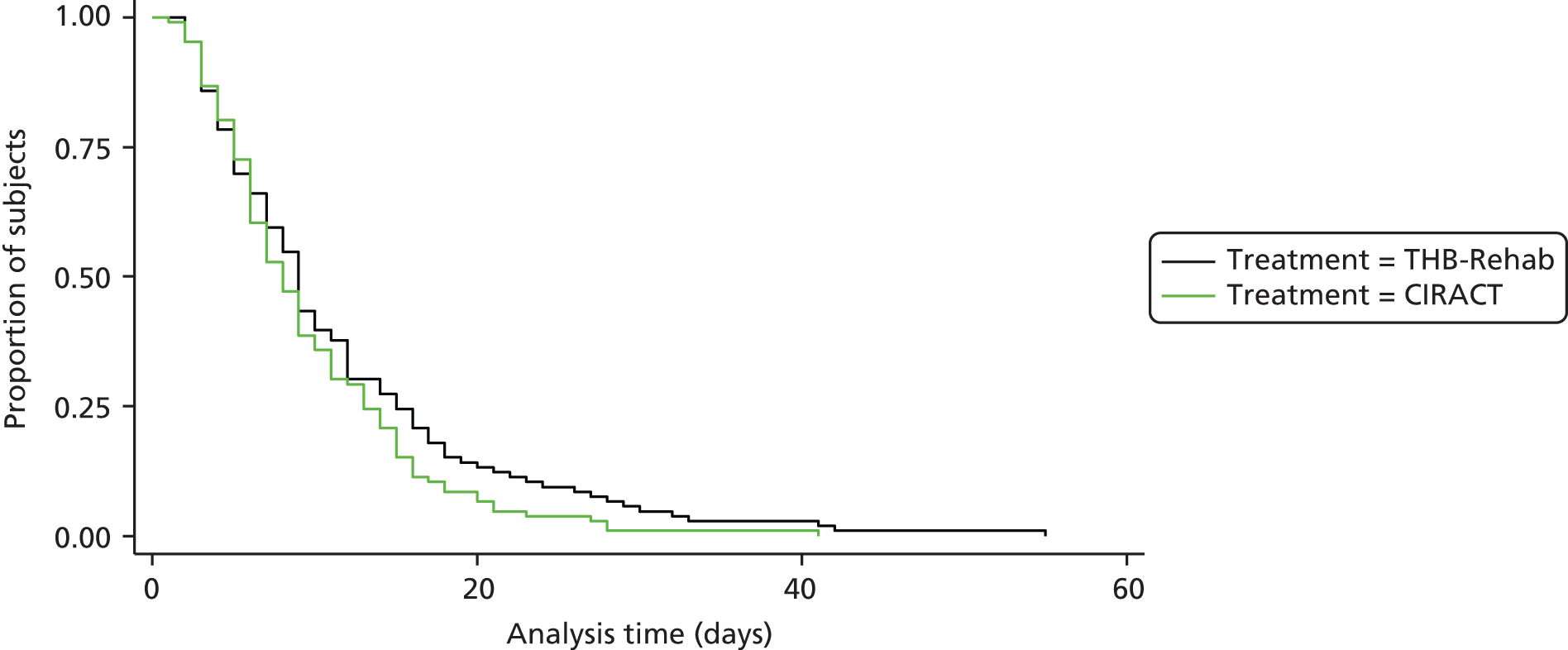

The Kaplan–Meier estimates (Figure 3) similarly showed no significant difference in LOS between the groups and there was also no significant difference in LOS between the groups with in-hospital death as a competing risk (Table 4).

FIGURE 3.

Kaplan–Meier plot of time to discharge excluding in-hospital deaths.

| Type of service | Sub-distribution hazard ratio | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| CIRACT vs. THB-Rehab | 1.14 | 0.88 to 1.48 | 0.327 |

Secondary outcomes

There were no significant differences in any of the secondary outcomes between the two arms (Table 5). There were a median of 15 and 17 super spell bed-days for the CIRACT and THB-Rehab groups respectively (geometric mean ratio 0.96, 95% CI 0.76 to 1.21). Of participants discharged from hospital, 17% and 13% were readmitted within 28 days post discharge from the CIRACT service and the THB-Rehab service respectively (risk difference 3.8%, 95% CI –5.8% to 13.4%) and 42% and 37%, respectively, were readmitted by 91 days post discharge (risk difference 5.7%, 95% CI –7.5% to 18.8%).

| Outcome | Intervention arm | Effectiveness parameter | 95% CI | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| THB-Rehab | CIRACT | ||||

| Super spell bed-days | |||||

| Geometric mean (95% CI) | 15.6 (13.2 to 18.6) | 14.9 (12.4 to 17.9) | 0.961a | 0.76 to 1.21 | 0.713 |

| Median (25th Q, 75th Q) | 17 (9, 31) | 15 (7, 32) | |||

| Min., max. | 2, 112 | 2, 120 | |||

| n | 112 | 112 | |||

| Readmitted to hospital at 28 days post discharge | |||||

| n (%) | 14 (13) | 18 (17) | 3.8%b | –5.8% to 13.4% | 0.442 |

| N | 106 | 106 | |||

| Readmitted to hospital at 91 days post discharge | |||||

| n (%) | 39 (37) | 45 (42) | 5.7%b | –7.5% to 18.8% | 0.399 |

| N | 106 | 106 | |||

| Barthel ADL score | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 12.6 (5.7) | 14.3 (5.5) | 1.02c | –0.41 to 2.44 | 0.161 |

| Median (25th Q, 75th Q) | 14 (8, 17) | 16 (10, 18) | |||

| Min., max. | 0, 20 | 0, 20 | |||

| n | 90 | 83 | |||

| Charlson comorbidity score | |||||

| Mean (SD) | 7.5 (2.1) | 7.6 (2.1) | –0.06c | –0.31 to 0.20 | 0.663 |

| Median (25th Q, 75th Q) | 7 (6, 9) | 7 (6, 9) | |||

| Min., max. | 4, 13 | 4, 13 | |||

| n | 92 | 85 | |||

There were 15 protocol deviations in the CIRACT group and eight in the THB-Rehab group (Table 6). The deviations in the CIRACT group are shown in Appendix 2.

| Category | Intervention arm | |

|---|---|---|

| THB-Rehab (n = 125) | CIRACT (n = 125) | |

| Inclusion/exclusion criteria | 3 (2) | 5 (4) |

| Informed consent | 0 | 4 (3) |

| Other | 5 (4) | 6 (5) |

Adverse events

There were seven non-severe falls recorded from seven participants (n = 4 CIRACT service, n = 3 THB-Rehab service) (Table 7). No safety concerns were raised by the Trial Steering Committee (TSC).

| Patient number | Intervention arm | Adverse event | Severity | Relatedness to intervention | Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1096 | CIRACT | Fall | Mild | Not related | Recovered/resolved |

| 1097 | THB-Rehab | Fall | Mild | Not related | Recovered/resolved |

| 1132 | THB-Rehab | Fall | Mild | Not related | Recovered/resolved |

| 1138 | CIRACT | Fall | Mild | Not related | Recovered/resolved |

| 1164 | THB-Rehab | Fall | Mild | Not related | Recovered/resolved |

| 1190 | CIRACT | Fall | Mild | Not related | Recovered/resolved |

| 1193 | CIRACT | Fall | Mild | Not related | Recovered/resolved |

Chapter 5 Qualitative appraisal methods and results

In parallel with the main RCT we undertook a detailed qualitative appraisal, encompassing three main activities:

-

activity 1 – organisational profiling

-

activity 2 – study of the CIRACT and THB-Rehab services in action

-

activity 3 – patient tracking.

Activity 1: organisational profiling

Organisational profiling aims to understand the outer and inner context within which new interventions, such as CIRACT, are translated and implemented into practice. This can be seen as ‘setting the scene’ of enquiry or orientating the subsequent study of CIRACT ‘in action’. Accordingly, the objective of organisational profiling is to gather contextual data about local services in which new interventions or controls are in operation. This includes information on:

-

the spatial configuration of service areas

-

service goals, strategy and policy

-

staff and resource profiles

-

patient numbers, throughput and LOS

-

management and governance structures and processes

-

leadership roles and approaches

-

team structures and processes

-

financial and commissioning arrangements

-

performance management, including relevant data on performance levels.

Organisational profiling was carried out across two of the three wards during the initial months of the trial. In line with the consolidated framework and building on similar research carried out by the qualitative team,43 a profiling template was developed to guide these initial enquiries reflecting the themes listed above. This was completed through a series of linked research steps.

First, research gatekeepers (local sponsors) and key informants (service leaders) were engaged in ‘fact finding’ during which they were asked about the history of the service, the general configuration and current work pressures. Second, further semistructured qualitative interviews, lasting between 30 and 90 minutes, were carried out with six service leaders and key staff: service managers, clinical leaders, sisters and research co-ordinators. Third, service leaders provided ‘guided tours’ of each service area, including walking tours and introductory meetings with staff groups and attendance at scheduling staff meetings. Fourth, the qualitative study was introduced to clinical teams and groups working in the ward areas, usually during team briefings or rest breaks, at which more informal information and insight was provided about the service through a process of questions and answers. Finally, service leaders provided access to relevant documentary sources, including local policies and procedures, and performance-related data. Through these initial activities a broad contextual picture was developed of each service from which to direct subsequent and more fine-grained analysis.

Activity 2: study of the Community In-reach Rehabilitation And Care Transition and traditional hospital-based rehabilitation services in action

The second and largest period of data collection involved an in-depth ethnographic study of how the CIRACT and THB-Rehab services were organised, delivered and experienced as a situated, social process within a given context. This focused first on mapping and then understanding the organisation and delivery of each service in terms of (i) the structure and flow of the care pathway; (ii) the allocation of roles and responsibilities across the pathway; (iii) key decision-making and communication points across the pathway; (iv) variations in periods of care, support and education; and (v) handovers between care teams and interactions with external agencies. As such, data collection ‘zoomed in’ from the broader organisation of care and division of labour to a more focused analysis of clinical practices, interactions and care-giving processes.

In line with the ethnographic approach, this involved a combination of non-participant observations (122 hours) and semistructured and ethnographic (conversational) interviewing over a period of 6 months (see Appendices 3 and 4 for details of observations). Observations were made of different activities, building on the guided tours and on the rapport developed with service providers:

-

Work process observations. In-depth workplace observations were undertaken over a period of 2 months, which involved mapping the temporal and spatial organisation of daily work (schedule of ward rounds, meetings, handovers, discharge times), identifying key events and activities [multidisciplinary team (MDT) meetings, drug rounds], identifying key individuals or groups (discharge co-ordinators, clinical leads) and drawing together these data into a complex descriptive account of the social setting and care process. Observations were undertaken on a daily basis (3–4 days per week, including evenings and weekends) over 8 weeks, with additional observations undertaken in community settings with the CIRACT team.

-

In-depth observations of situational activities, tasks and settings. Prolonged follow-up observations were undertaken of key activities, tasks and settings to deepen knowledge of service delivery. Each setting or activity was observed at least three times and some, such as weekly MDT meetings, were observed up to 10 times. This included observations of:

-

morning handovers with the MDT on each ward

-

home visits prior to discharge

-

patient and family consultation meetings

-

social services assessments

-

use of information communication technology (ICT) and manual records about rehabilitation progress and discharge planning

-

referrals to multiple agencies by telephone and fax

-

ordering equipment and home adaptation, including telecare monitoring and adaptive devices

-

patient education and support

-

carer education and support

-

home visits after discharge

-

end-of-life care support across locations

-

referral to community agencies for longer-term support in person, by telephone or by fax.

-

-

Shadowing of individuals. To deepen the understanding of the roles and contributions of certain individuals or groups, shadowing observations were also undertaken with key individuals or representatives from professional groups. Observations ranged from several hours (ward clerks) to several days (discharge co-ordinators) as the individuals went about their day-to-day work. The individuals observed included:

-

CIRACT team leader (transition coach)

-

therapists

-

ward clerks and administrators

-

occupational therapists

-

physiotherapists.

-

All observations were recorded, first in hand-written field journals, including rich descriptions and separate interpretations, which were later typed up electronically as corresponding text and interpretations along with a summary overview of the key points. It is important to note that observations were not focused on intimate, personal or challenging patient care. All observations of patient–clinician interactions involved prior written and verbal consent and focused primarily on the activities and work of the clinical team member, not the patient.

As indicated earlier, alongside these observations members of staff were engaged in a large number of conversational-style ‘ethnographic interviews’. Ethnographic interviewing involved small conversations and interactions with clinicians and other study participants in the normal cause of their work or practice. They were usually short (i.e. 5–10 minutes) and were used to clarify observations, elaborate the reasons behind decisions or actions and gain reflective insight from participants about activities in ‘real time’. As these were informal, they were recorded only in field journals alongside observation records. It is estimated that 200 such short ethnographic interviews were carried out over the study.

More formal semistructured interviews were also carried out alongside observations. These aimed to develop more reflective accounts or narratives of the respective services (CIRACT and THB-Rehab) from the perspectives of different stakeholders. Interviews were carried out with 13 participants across the CIRACT and THB-Rehab services: two managers, six therapists, two discharge co-ordinators, one senior nurse, one social worker and one care home manager (Table 8). The interviews were arranged at the convenience of participants and, in most cases, were conducted in a private setting. They ranged from 40 to 90 minutes in length and most were digitally recorded. The interviews followed a broad guide that covered the following topics:

-

the implementation and development of the CIRACT service (or THB-Rehab service), including translation into practice, training and supporting and changes in design and delivery

-

the organisation and delivery of the CIRACT service (or THB-Rehab service), including service configuration, daily work planning, decision-making and communication, discharge planning and delivery of patient care

-

interprofessional and interorganisational working, including the barriers to and drivers of integrated working

-

the perceptions of therapy and the value of the CIRACT service from a professional viewpoint.

| Intervention arm | Interviewees |

|---|---|

| CIRACT | Service designer and academic adviser |

| Community care (NHS) manager | |

| Senior occupational therapist and team lead | |

| Senior physiotherapist (band 6) | |

| Social worker | |

| THB-Rehab | Senior occupational therapist |

| Senior physiotherapist | |

| Senior nurse (band 7) | |

| Physiotherapist | |

| Therapy assistant (band 3) | |

| Discharge co-ordinator ×2 | |

| Residential and nursing home manager |

Activity 3: patient tracking

Patient tracking aimed to develop a highly detailed and, importantly, patient-centred understanding of care processes and experiences. It focused on the interactions and care processes of a small sample of patients as their care progressed and as they moved between care teams and settings. As such, the method aimed to place the patient at the centre of analysis with the aim of understanding the web of interconnecting care processes that contribute to care planning, delivery and transition. This approach combined first-hand observations of care activities and processes, such as patient assessment, decision-making, communication and therapy, with a series of short structured interviews with patients as they moved along the care pathway and transitioned from hospital to a community setting. As such, it can lead to a highly developed, longitudinal (time–space) understanding of the patient experience.

In the first instance, the patient/family were approached in hospital, usually when the patient had been allocated to the CIRACT service or the THB-Rehab service. In collaboration with the patient’s designated care team, the research aims and methods and the patient tracking method were explained to the patient/family. Those who consented were then involved in a series of three to four observations of patient–clinician interactions on the ward and then at home, for example assessment, care planning, education and therapy. Each patient was also asked to participate in a series of short interviews to acquire further understanding of the patients’ experiences and views about their care. These started in hospital (usually two short conversations after observations of therapy on the ward) and then continued in the community at 1 week post discharge. Although every effort was made to schedule interviews at these times, in some instances they needed to be moved by ± 1 week because of other appointments. Furthermore, not all patients were able to participate in the full series of interviews because of withdrawal (their health had worsened), readmission to hospital, transfer to another care setting (i.e. left the CIRACT service) or death. The patient tracking data were initially recorded in reflective field journals and were then summarised within a common template to enable data management and comparison (see Appendix 5).

Data analysis

All data were managed in accordance with NHS and university research governance frameworks. All interview transcripts were anonymised with pseudonyms and all identifiable information, such as contact details, was securely filed. Hand-written ethnographic notes did not include identifiable names or locations and were archived within 48 hours into locked cabinets. Electronic data were stored within encrypted and secure external drives and back-up copies were kept within a locked location within the university.

Interpretative qualitative data analysis was undertaken to develop a descriptive and contextualised understanding of the respective care services, especially the implementation, organisation and delivery of the CIRACT service. This involved an iterative process of close reading of the data, coding, constant comparison, elaboration of emerging themes and re-engaging with the wider literature. In the first instance, one member of the research team independently reviewed a sample of transcripts and observation records to develop an initial case description and coding strategy. This was presented and discussed with the wider research team and qualitative methods advisors. Following feedback from these discussions, all data were systematically coded and categorised in line with the consolidated implementation framework and research questions. With regard to the reliability of the coding process, codes and categories were reviewed on a monthly basis by the wider team to ensure the accuracy of interpretation and the internal consistency of codes. Through this iterative process a number of common themes were developed in relation to four over-riding questions:

-

How was CIRACT designed, implemented and translated into practice?

-

How was CIRACT (and THB-Rehab) organised and delivered in context?

-

How was CIRACT (and THB-Rehab) experienced by participants and professionals?

-

How did CIRACT impact on clinical roles and how might services be developed?

Results

Service implementation

With regard to implementation, the study found that a combination of national priorities and pressures, together with innovations in local service delivery in the face of contextual pressures and drivers, contributed to development of the CIRACT service. National policies repeatedly call for more integrated, patient-centred and efficient care, especially when acute care is regarded as costly, and in recent months a number of initiatives were developed to better manage patient care in the community setting. Although many of these were targeted at reducing unplanned admissions, an important part of the problem remained delays in supporting discharge from hospital and, further still, inappropriate or poorly supported discharges that result in readmission. The CIRACT service directly addressed this challenge. Its design and development appeared to reflect the innovative practices of local service leaders, especially those in community health care, and also the willingness of both acute providers and care commissioners to support new ways of working:

So this service [CIRACT] I think is needed because there’s so many people that would fall through the gap otherwise. That don’t need four weeks of rehab, intense rehab, or they don’t need specific stroke goals, cognitive goals. They just need somebody to support them in that transfer home. Making sure the home is set up well, the hazards are removed. They’ve got everything they need.

CIRACT team lead and occupational therapist interview, 10/12/13 (lines 82–90)

When I was a hospital OT [occupational therapist] I was very frustrated a lot of the time that we’d try our best for a patient. We’d set them up as well as we thought, they could go home, and then you hand over maybe to the social worker in the hospital, you hand over to maybe a rehab team. That person is readmitted a few days later and you think, ‘We’ve done all these things. That was an unnecessary admission just because there isn’t that communication there.

CIRACT team lead and occupational therapist interview, 10/12/13 (lines 113–18)

Furthermore, the service was continually modified and adapted in the light of inner contextual factors, especially staffing and resource shortages and also ongoing feedback from service users. In addition, it is important to note that factors both in the acute hospital setting and in the community setting continue to exert an influence on the service, resulting in continuing elaborations and modifications, as seen during the winter pressures. Although it is useful to work towards a core service specification, it also remains useful to maintain a degree of flexibility in new services so that they can align where necessary with pre-existing ways of working.

The study found that there was a high degree of uncertainty about how the new service was communicated and introduced to pre-existing care providers. This resulted not only in role uncertainty and ambiguity but also in the potential for conflict over patients and tasks. As such, greater engagement and communication might be needed when implementing new services such as CIRACT. Additionally, local resource profiles, especially bed availability and staffing, influenced the implementation of the CIRACT service. Of note, increased winter bed capacity appeared to divert patients away from the CIRACT service, thereby rendering it marginal to service delivery, and, later, the lack of specialist staffing further reduced the capacity of the CIRACT service. Although the CIRACT service remained an important and innovative solution to the problems of hospital discharge, in this particular context it appeared to be an experimental solution to a specific set of service problems associated with undercapacity in both the acute and the rehabilitation sectors. Furthermore, it was not necessarily clear whether, as implemented, the CIRACT service was expressly concerned with fostering longer-term integration or closer working between acute and community settings.

Service organisation and delivery

In terms of how the CIRACT service was organised and delivered, the key differences between the CIRACT service and THB-Rehab are shown in Appendices 6 and 7. The study found that it represented a relatively discrete model and pathway of sustained and continuous patient care provided by a relatively small but specialist team, including skills in both acute rehabilitation and therapy but also service planning and co-ordination. The care pathway is distinctive because it demonstrates the spanning of the CIRACT service from the point of admission to as much as 12 weeks post discharge. Significantly, by working both within and across the hospital and community setting, the CIRACT team was better able to develop closer and more aligned working relationships with these distinct service providers, to close the gaps between these providers and to establish close working relations with the patient and family, leading to enhanced continuity of care.

Daily contact with patients supports progressive tailored planning for therapy and discharge; however, there can be a sense of isolation when the team ends its work with patients:

It’s somebody taking ownership of that patient and that patient’s journey through the acute service and once they’re at home, and I think that’s a really, really strong benefit of this service is that we get to know the patient really well. We get to draw them back home and support them there.

CIRACT occupational therapy lead interview, 10/12/13 (lines 103–6)

The integration of the CIRACT service within existing service configurations was found at times to be problematic, and competing demands and pressures within the wider health system could easily place unanticipated demands on the THB-Rehab service, which could impact on the CIRACT service. It might be important to establish clear lines of accountability for the CIRACT team, given that their work within and across the boundaries between acute and community care can make the service vulnerable to various local contextual pressures.

Furthermore, line management within the acute setting might be clearly demarcated from but, when relevant, integrated with other clinical accountability and reporting channels. For example, it often seemed unclear who the members of the CIRACT team were accountable to for their performance and they could easily be drawn into local ‘ward politics’. In addition, staff shortages and recruitment problems could easily disrupt the CIRACT service, especially as team members needed a particular set of competencies in different aspects of patient assessment, rehabilitation and care planning before, during and after discharge. In some respects, the unique skills and knowledge profile of the CIRACT team could make it vulnerable to future staffing problems and when reliance on locum staff was problematic.

Distinctions between the two service approaches are important because they offer different models of care and are characterised by different ways of organising work and care and subsequently meet patient needs in different ways. CIRACT can be interpreted as a boundary-spanning and responsive service. That is, it aimed to respond to longer-term patient needs beyond the single episode of acute hospital care and provide care across the boundaries between acute and community settings. For example, the service was premised on the assumption that the quality and effectiveness of post-hospital care could be increased if rehabilitation and support started earlier within the hospital, before discharge, and if the same care team provided ongoing support.

This resulted in two key service requirements that differentiated the CIRACT service from the THB-Rehab service. The first involved the provision of earlier intensive rehabilitation and therapy, with an explicit focus on the longer-term and holistic needs of the patient. The second was that this therapy should ideally be tailored to and, when possible, provided within the context of the patient’s home, where they could learn to manage their care in a relevant setting, rather than the more ‘artificial’ one of an acute hospital. To achieve these requirements the CIRACT service was designed to enable intensive therapy across and within acute hospital and community settings.

By contrast, the THB-Rehab service model was solely located in the acute hospital and demonstrated a model of care that sought to prepare the patient for the end point of discharge, rather than supporting longer-term care and therapy needs after discharge. The THB-Rehab service was predominantly task orientated, with an emphasis on getting jobs done, which limited the opportunities to deliver more holistic care. In particular, the THB-Rehab service gave limited scope for sustained knowledge sharing or a mutually beneficial learning relationship between the patient and therapists to develop, because of constraints on the frequency of contact alongside other ward-based duties. As THB-Rehab service therapy was confined to the acute hospital setting, home visits prior to discharge were exceptional (two a year per ward) compared with more frequent visits for the CIRACT patients. This meant that it was difficult to determine the extent of patient need following discharge, with decisions usually based on observed patient recovery and progress while on the ward:

Our stairs are completely different and just because they’re able to it here, doesn’t mean they’ll be able to do it at home, or if they can’t do it here, it doesn’t mean they won’t be able to do theirs at home. And we might change things or arrange things based on something that isn’t representative of what they’re able to do.

Senior physiotherapist interview, 31/01/14 (lines 51–5)

In terms of the organisation and planning of hospital care transition, it was also observed that hospital discharges in the THB-Rehab service were far from uniform across the week, with peaks of activity on Mondays and Fridays in response to the admission demands within the system. This uneven distribution of discharges had the knock-on effect of reducing standard service therapy sessions for inpatients and so many went without therapy from Thursday to Tuesday of each week, leading to a bottleneck of demand midweek. By contrast, the design of the CIRACT service across 7 days led to a more even distribution of therapy and discharge activities within the acute setting:

I think they [the trust] seem to forget the patients on the wards. It’s soon as they’re admitted, then they seem to be forgotten and it’s just all about the people who are coming in, not the people that are here already.

Discharge co-ordinator interview, 02/12/13 (lines 403–6)

Although the staffing capacity of the THB-Rehab service was greater than that of the relatively small CIRACT service, the THB-Rehab service teams of two therapists plus one assistant also managed the care needs of a greater number of patients (usually 28 per team). With this number of patients it was seen as being difficult to provide intensive therapy on a par with that provided by the CIRACT team. As such, it was acknowledged that the THB-Rehab service could not aspire to provide rehabilitative therapy beyond reaching the patient’s functional baseline. As such, the THB-Rehab service was predominantly resource led, with a focus on getting the older person ready to move on, whereas the CIRACT service was predominantly patient needs led, with a view to maximising resources for maximum patient outcomes.

Service experience

Patients

Patients’ early experiences of hospital admission, including the CIRACT service, were inevitably shaped by their expectations of care, including previous admissions, community care and being carers themselves. Patient expectations of hospital therapy and discharge planning were generally low, with patients expecting minimal contact with ward-based staff and little longer-term help or guidance for going home. Patients who had previously experienced a THB-Rehab service found it difficult to remember the standard service received, but social worker interventions, such as securing care packages, were more readily remembered. Carers recounted stories of minimal support or care packages that were so short that staff could not give the standard of expected care, such as bathing rather than strip washing.

Through observations of admission assessments, patients were receptive towards the CIRACT staff and most were able to express the reasons for their admission and their immediate and longer-term worries about the future. Some patients were very tired, and often in pain, and resented having to see another professional to explain their needs. Duplication of information giving was openly acknowledged by the team, who tended to focus on establishing core information related to abilities prior to admission rather than on a summary of medical information or home circumstances.

The continuous assessment element of the CIRACT service was also seen to be well received and experienced by patients as previous activities and plans were reviewed and progress towards recovery and discharged was monitored. Patients did not comment on this graduated information-seeking approach but did note that their interactions with the CIRACT team involved in-depth discussions about their goals and future plans, in addition to actual therapy. This was valued by the majority of patients, who felt able to disclose family issues that may not have been discussed during the initial assessment, such as ‘mentally ill carers and being left for days with no assistance’ (observation, 11/01/14). Patients also valued the continuous assessment approach to their care as it enabled them to express their anxieties and also raise issues as they happened. This was a benefit to carers who often felt able to ask if they were doing things right, including using equipment, meeting hygiene needs and maintaining safety. More broadly, the continuous assessment and interaction with the patient provided a more tangible sense of progress and recovery for the patient.

Patients were generally positive about the daily therapy approach operated by the CIRACT service and were happy to be regularly consulted about their therapy plans and progress. One patient suggested that confusing professional jargon was used by the therapists, such as ‘baseline’; this patient did not understand the term, thinking that it could relate to either anticipated deterioration or a return to minimum ability (observation, 02/03/14). Another patient could not fully hear the therapist when she had her head down, guiding her feet forward, and so was unsure of how to follow instructions. However, most patients liked the way in which the team found time to discuss progress and to decide on the next steps in therapy:

It’s nice to know there’s a service like that available. I didn’t know anything about that . . . it’s been more than adequate. They seemed to know what I needed more than I did myself. I’m a very independent sort of person and to be told that you needed this, that and the other. It was good advice.

Patient 6 interview, 02/03/2014 (lines 164–5)

Two male patients did not expect to receive daily therapy and thought this excessive as they regarded their prime task as a patient was to rest. One of the two did not want to leave hospital and thought the therapy to be an intrusion on his stay. In such cases the team balanced the intensity of therapy according to the ability of the patient on the day and were often seen to adapt and adjust to fluctuations in health, mood and motivation. Age was not considered a barrier to therapy by the team, who sought to maximise the identified potential of each patient. However, some family carers did consider that some of the therapy was too optimistic considering the extreme old age of their relative. Attitudinal barriers were usually addressed by banter and giving evidence of progress made. Fatigue was described as being an important factor in the daily therapy and could impact on information giving and the planning of care.