Notes

Article history

The research reported here is the product of an HS&DR Evidence Synthesis Centre, contracted to provide rapid evidence syntheses on issues of relevance to the health service, and to inform future HS&DR calls for new research around identified gaps in evidence. Other reviews by the Evidence Synthesis Centre are also available in the HS&DR journal.

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 13/05/11. The contractual start date was in May 2015. The final report began editorial review in September 2015 and was accepted for publication in January 2016. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2016. This work was produced by Rodgers et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

People with severe mental illness (SMI) [schizophrenia, schizotypal and delusional disorders; bipolar affective disorder; severe depressive episode(s) with or without psychotic episodes]1 have a lower life expectancy and poorer physical health outcomes than the general population. 2 Evidence suggests that this discrepancy is driven by a combination of clinical risk factors (e.g. comorbid diabetes mellitus or cardiovascular disease), socioeconomic factors and health-system factors. 3 A wide range of solutions have been proposed to address this issue through changes and improvements to existing health service arrangements.

The aim of this project is to explore what current provision exists in practice together with mapping recent evidence on models of care for dealing with the physical health needs of people with mental health problems at point of access in the mental health service setting.

Chapter 2 Background

Physical health of people with severe mental illness

People with mental health conditions have a lower life expectancy and poorer physical health outcomes than the general population. 2 Physical health and mental health are closely linked, and demands have been repeatedly placed on the NHS to deliver an equal response to the treatment of each. 4,5 Many patients with SMI remain underserved. In 2014, the National Audit of Schizophrenia revealed that only 33% of people with schizophrenia were adequately monitored for diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease, just 52% had their body mass index recorded and 36% of service users received an intervention to address impaired control of blood glucose on an annual basis. 6 Another review found that one-third of patients with SMI are seen only in primary care. 7 These recent reports indicate serious shortcomings in the physical-health monitoring and integration of services for this population group.

Services for mental health conditions have traditionally been separate from general health care for physical conditions but there is increasing emphasis on developing a whole-system approach to improve integration between the two, with particular focus on patient-centred development and delivery. 4 This is not new, a focus on patient-centred delivery of health services for people with mental illness has been advocated for many years. In 1991, the Department of Health introduced the ‘Care Programme Approach’ (CPA), which was subsequently updated in 2013. 8 The CPA is a national system setting out how secondary mental health services should help people with mental illness and related complex needs. Those eligible for CPA are entitled to a full assessment of health and social care needs, a care plan (overseen by a care co-ordinator) and regular reviews of health and progress, although Mental Health Trusts do not have to follow this guidance and may adopt their own policy. The personalisation agenda for people with serious mental illness also featured in the National Service Framework for Mental Health in 1999. 9

In 2006, the Department of Health produced a commissioning framework entitled Choosing Health: Supporting the Physical Needs of People with Severe Mental Illness. 2 This described the nature of pilot health improvement programmes in which a lead mental health nurse practitioner attached to an existing team [e.g. primary care team or community mental health team (CMHT)] would be responsible for conducting physical health checks, in-depth consultations (including providing relevant information, signposting, exploring broader health-related issues such as employment or education), referral to screening and health promotion services, and establishing specific one-to-one or group health improvement interventions. The prerequisites for this type of programme were defined2 and evaluations have emerged since. 10,11 However, there seems to be little available evidence of their wider implementation.

In terms of existing guidance and incentives to address the treatment and management of people with SMI, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines for various mental health disorders include those for psychosis and schizophrenia,12–15 and a Commissioning for Quality and Innovation (CQUIN) incentive is currently in place for secondary health-care providers to improve the physical health care of people with SMI. 16 This CQUIN helps ensure service users have their physical and mental health diagnoses recorded, and aims to promote effective communication between primary care, specialist mental health services and service users. In addition, in the latest proposal announced by NICE to improve the quality of care by family doctors, consideration is given to the introduction of new quality indicators to identify and support people with SMI who are at risk of cardiovascular disease. 17 These indicators will inform negotiations for the 2016/17 Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF).

Integrated care

Service integration (i.e. breaking down the barriers in how care is provided between family doctors and hospitals, between physical and mental health care, and between health and social care) is a key step in the proposed system change for the NHS. 5 Service integration encompasses the concept of integrated care; a potentially complex intervention with many different components. As yet, integrated care is not well defined and the terminology to describe the concept is diverse (e.g. collaborative care, holistic care, patient-centred care).

The present focus on improving integrated care for people with mental health needs appears to be from the perspective of access to health services for an acute or chronic physical health condition. 18 Information about the converse of this (i.e. addressing the physical health-care needs of patients with SMI at point of access in the mental health service setting) seems lacking. The latter represents the primary focus for this rapid review.

Chapter 3 Methods

General approach

This project was resourced as a rapid review of current practice and recently published evidence. There is no generally accepted definition of the term ‘rapid review’ and a number of other terms have been used to describe it as one that incorporates systematic review methodology modified to various degrees. Our intention was to carry out a review using systematic and transparent methods to identify, appraise and produce a synthesis of relevant evidence from 2013 to 2015. Our approach was necessarily pragmatic and iterative in nature. Inevitably the process would be less exhaustive and the outputs somewhat less detailed than what might be expected from a full systematic review.

The results of this rapid review should also be viewed in the context of evolving UK policy and the likelihood of ongoing change in relation to developing models of integrated care. Recent initiatives are summarised in Box 1.

Present policy in England is aiming to develop new models of care as part of the strategic plan for wider system change in the NHS. 5 A number of initiatives are under way, including several relating to the development of integrated care services. These include the following.

Vanguard sites19In January 2015, the NHS called for expressions of interest for individual organisations and health and social care partnerships to become Vanguard sites for the New Care Models Programme (outlined in the Five Year Forward View). 5 Twenty-nine organisations across the UK were selected to lead in supporting improvement and integration of services across three key areas: (1) integrated primary and acute care systems (i.e. GP, hospital, community and mental health services); (2) multispecialty community providers (transferring specialist care from the acute sector into the community); and (3) enhanced health in care homes (joining up health, care and rehabilitation services for older people).

Of the 29 Vanguard sites selected, nine subsequently focused on the first of these key areas (i.e. integrated primary and acute care systems). Of the nine sites, North East Hampshire and Farnham20 was the only one where integration across mental and physical health care was specifically mentioned by NHS England (although similar activity may be implicit in others). North East Hampshire and Farnham Clinical Commissioning Group report that five multidisciplinary integrated care teams are now operational. These comprise community nurses, occupational therapists, physiotherapists, social workers, a psychiatric nurse, a lead psychiatrist, a pharmacist, a geriatrician, GPs, the voluntary sector, and specialists in palliative and domiciliary care. 21

Integrated Personal Commissioning22In July 2014, NHS England and local government bodies invited health and social care leaders to become demonstrator sites to help develop a new IPC approach to providing care for people with complex needs. Eight sites were chosen in the first instance. IPC aims to move the balance of spending power to the individual, in terms of people being able to shape their own health and social care delivered (as appropriate) by various combinations of local authority, NHS and voluntary sector providers. The latest update indicates that local strategies are now being developed and discussed with senior figures at NHS England. 23

NHS England Mental Health Taskforce24In March 2015, a new taskforce was set up to develop a 5-year strategy for mental health across England. The taskforce was set up to explore variation in service provision, examine outcomes for service users and identify priorities for improvement. A particular focus of this strategy was to improve the physical health of people with mental health problems. The Mental Health Taskforce Public Engagement Survey findings were published in September 2015. 25 Although very little was reported on models of care to address physical health needs of people with SMI, findings identified priorities for mental health service users in general, relating to improved access, reduction of stigma, parity of esteem, early support/prevention, the need for a more joined-up system, and workforce-related issues such as attitudes and need for appropriate training. These findings informed a new Mental Health Strategy for England. 26

GP, general practitioner; IPC, Integrated Personal Commissioning.

Research questions

We sought to address the following four questions:

-

What type of models currently exists for the provision of integrated care specifically to address the physical health needs of people with SMI when accessing mental health-care services?

-

What are the perceived facilitators and barriers to implementation of these models?

-

How do models implemented in practice compare and contrast with those described in the literature?

-

Can we identify high-priority areas for either further primary research or a full evidence synthesis?

Scope and definitions

The focus of the review was NHS health-care services that included steps to address the physical health needs of people diagnosed with SMI. We focused on where these services were provided in the mental health-care setting. We used the NICE definition of SMI to cover schizophrenia, schizotypal and delusional disorders, bipolar affective disorder and severe depressive episode(s) with or without psychotic episodes. 1 We adopted a broad definition for physical health outcomes, including the assessment and modification of cardiometabolic risk factors, anthropometric measures and physical functioning.

We did not consider the various interventions or services aimed at the broader needs (i.e. beyond health) of this group of people, or the integration of services spanning non-NHS settings (e.g. social care, education, employment, housing and voluntary sector provision).

Data sources

We considered two main data sources: conversations with our advisory group (comprising field experts and service users in the area of mental health) and the published literature.

Advisory group

We convened an advisory group primarily to extend our working knowledge of the topic area and understand more clearly some of the issues arising from the published literature. We contacted a number of known field experts who had an interest in our topic. Service users were identified through local contacts. Contacts were made on the basis that their advisory input would help us to (a) develop our research and (b) ultimately think about what might be useful to those commissioning and delivering future services. Early reading of the background and policy literature helped us to develop pro forma contact forms with a list of questions (see Appendices 1 and 2). Contacts were made by telephone or face-to-face meeting. Brief notes were recorded.

Literature

The aim of the literature search was to identify relevant reviews, studies, guidelines and policy documents relating to integrated care for the physical health of people with SMI. Early scoping searches to inform the protocol identified the previous systematic review by Bradford et al. 27 about the effectiveness of models of care that integrated medical and mental health care to improve medical outcomes of people with SMI. This systematic review was carried out in 2011 and updated in 2013. The review included four randomised controlled trials of US-based interventions, of which three were conducted in Veterans Administration (VA) outpatient mental health clinics, and the fourth was an evaluation funded by the National Institute of Mental Health. All four interventions included some form of nurse-led care co-ordination, with or without components such as a specific ‘liaison’ role, direct psychiatrist/family practitioner involvement, patient self-management support and guideline-based decision-support tools. The included interventions were associated with increased rates of immunisation and screening but had mixed results in terms of changes in physical functioning, and none reported clinical outcomes.

Building on the Bradford et al. 27 review we carried out searches to find and prioritise any new evaluative studies since the 2013 update, using an adapted version of the search strategy from the review.

The following databases were searched: Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects, Health Technology Assessment database, NHS Economic Evaluations Database, MEDLINE, MEDLINE In Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, EMBASE and PsycINFO. Searches for ongoing and completed trials were carried out on ClinicalTrials.gov. All searches were limited, where possible, to references added to the databases from 1 January 2013 onwards. As searches for the Bradford et al. 27 review ran from inception to 18 January 2013, our selected start date ensured that there were no gaps in the search. Retrieval was limited to randomised controlled trials or evaluation studies.

Searches of the National Guideline Clearinghouse and the Trip database were undertaken to identify UK and international guidelines relating to integrated care for SMI. In addition, the following websites were searched to identify any relevant English-language government policy documents from the UK, Australia, New Zealand, Canada and the USA:

-

UK Department of Health: www.gov.uk/government/organisations/department-of-health

-

Australian Department of Health: www.health.gov.au/

-

New Zealand Ministry of Health: www.health.govt.nz/

-

Health Canada: www.hc-sc.gc.ca/index-eng.php

-

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA): www.samhsa.gov/.

A further search of Google (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA) was carried out to locate UK reports relating to integrated care for SMI. Using the Google advanced search interface, the search was limited to UK portable document formats (PDFs) published in English. The first 100 results were scanned for relevance.

Alongside the more formal searches undertaken as described above, the project team collected relevant literature from experts and contacts working in the field of mental health and followed up any documents found to obtain further relevant literature. This ‘snowballing’ technique has been used in previous reviews.

All searches were carried out in May and June 2015. Full search strategies and results can be found in Appendix 3.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Study design

Empirical and descriptive study designs, including evaluative literature arising from the update of Bradford et al. 27 and policy/guideline documents.

Setting

Integration of services primarily within the health-care sector (e.g. NHS if UK-based). Models focused on the wider integration of services spanning non-NHS settings (e.g. social care, education, employment, housing and voluntary sector provision) were not eligible.

Population

People diagnosed with SMI (schizophrenia, schizotypal and delusional disorders, bipolar affective disorder or severe depressive episode(s) with or without psychotic episodes).

Intervention

Any health-care services that include bringing together care arrangements to address the physical health needs of people with SMI. Programmes primarily concerned with organisation and delivery of services rather than the implementation of discrete health technologies.

Outcome

Any outcome related to the provision and implementation of integrated care. For the evaluative literature, outcomes were restricted to those related to physical health (including sexual health).

Study selection and data extraction

Electronic search results were loaded into EndNote X7 (Thomson Reuters, CA, USA). At the initial screening stage, the results were divided between three reviewers to eliminate obviously irrelevant items. Decisions were recorded as ‘include’, ‘reject’ or ‘maybe’. A second screen was carried out by three reviewers independently, to arrive at a definitive list of ‘includes’ and ‘rejects’. Full-text copies were ordered for the included records. Papers identified from other sources (e.g. field experts) were added to the EndNote library and assessed in the same way.

A data extraction template was developed and piloted on 12 papers by three reviewers (see Appendix 4). Details included population and setting, approach to integrated care; Mental Health Foundation factors covered (1–9), barriers and facilitators to implementation, and details of evaluations. Revisions to the template were made where necessary. Subsequent data extraction was carried out by one reviewer and checked by a second reviewer. Disagreements were resolved by discussion or with the involvement of a third reviewer.

Quality assessment

Given the lack of detail reported in the studies and the lack of comprehensive evaluations, we did not assess the included papers for methodological quality; our aim was to describe interventions and their implementation rather than establishing risk of bias in their evaluation.

Synthesis

We carried out a narrative synthesis, building on the 2013 Mental Health Foundation inquiry. 28 This was a substantial piece of work based on a literature review on integrated health care and mental health care, three expert seminars attended by 31 people and a call for evidence on the best ways to integrate care that led to over 1200 responses. The scope of the enquiry incorporated both health and social care, and identified nine structural and organisational arrangements at the heart of good integrated care for people with mental health problems (Box 2).

-

Information-sharing systems.

-

Shared protocols.

-

Joint funding and commissioning.

-

Colocation of services (e.g. services brought together for physical and practical ease of access).

-

Multidisciplinary teams.

-

Liaison services (e.g. provision of shared expertise across service settings).

-

Navigators (e.g. named care co-ordinators).

-

Research (e.g. to ascertain the best way of delivering and evaluating integrated care).

-

Reduction of stigma.

The majority of the recent evidence identified in this rapid review relates to complex and/or multicomponent programmes that incorporated several of the nine factors key to good integrated care (see Box 2). 28 We used these nine factors as a guiding framework to help answer our four research questions and to explore the elements of interventions or care models. We also discuss further issues to emerge from the evidence; for example, we incorporated in our synthesis any other relevant factors identified during data extraction and from discussions with advisory group field experts and service users, particularly wider-system factors that might underpin the successful implementation of integrated care interventions.

Chapter 4 Nature of the evidence

Advisory group

We spoke to 13 field experts (five provided detailed information) and two service users involved in the area of mental health services. We used their insights primarily to extend our working knowledge of the topic area and understand more clearly some of the issues arising from the published literature.

Literature

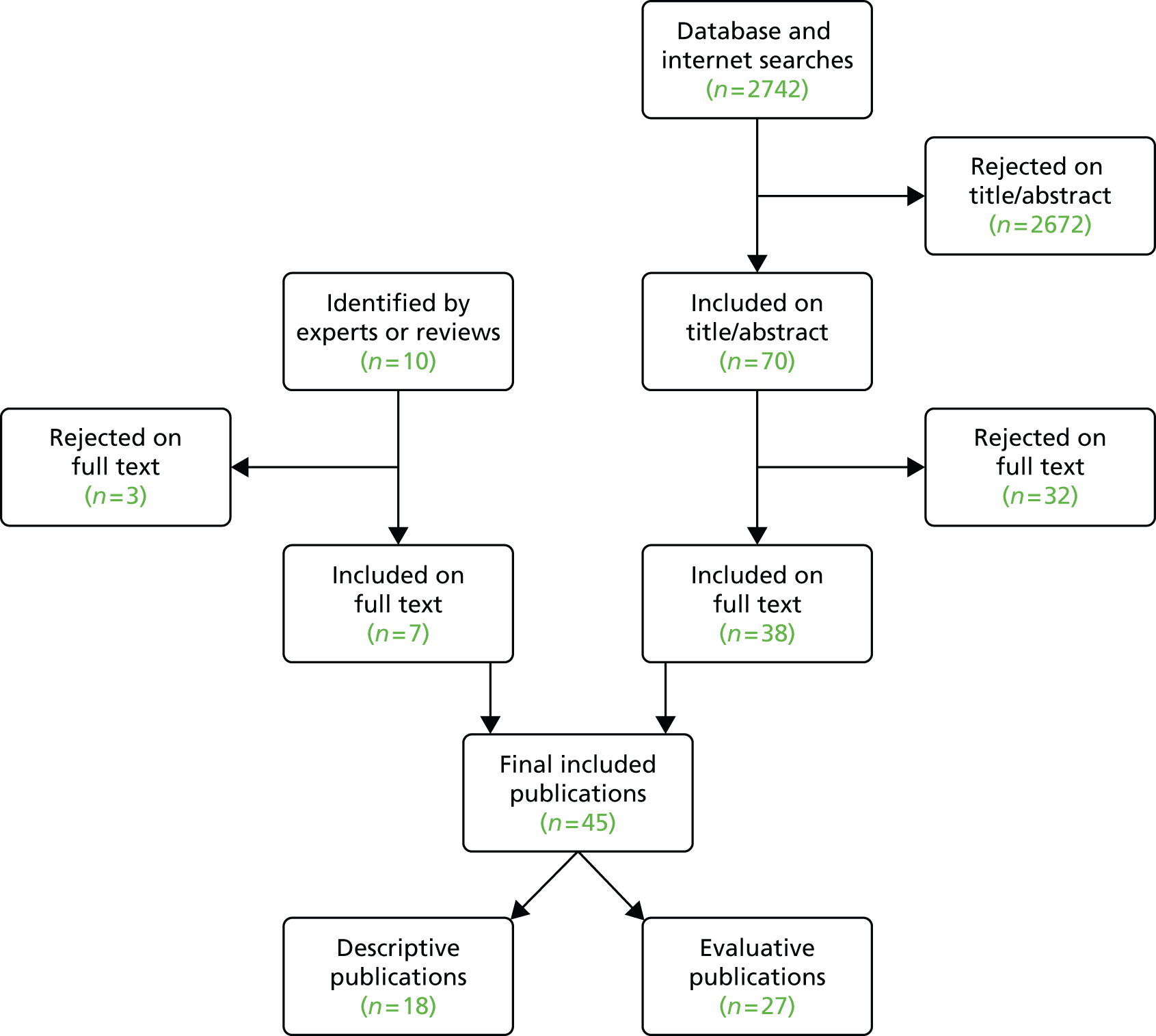

The search strategy retrieved 2742 records. Seventy records were included on the basis of screening titles and abstracts. Thirty-eight were retained and data were extracted after reading the full paper; 32 were rejected. A further 10 papers were identified, four following discussions with field experts and six from the retrieval of relevant primary studies from rejected reviews. Seven of these 10 papers met our inclusion criteria and were included and data were extracted; three were rejected. In total, 45 papers describing 36 approaches to integrating physical health needs into the care of people with SMI were included in this rapid review (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Flow of identified literature.

Some papers were retrieved outside the database search strategy (i.e. from website searching and via field experts) and had publication dates prior to 2013 (i.e. prior to our electronic search start date). Brief data extraction tables for all included studies are available in Appendix 5. For detailed information, readers are advised to consult the full reports.

The included papers comprised a range of study designs including systematic reviews and other literature reviews, various primary studies, book chapters, conference abstracts and dissertations, policy and guidance documents, feasibility studies, descriptive reports and programme specifications. We identified 27 papers reporting on 25 distinct evaluations of programmes or interventions,2,27,29–53 few were described in detail and fewer still were comprehensively evaluated. Details of study characteristics are presented in Appendix 5.

Table 1 presents a classification of the included publications showing our interpretation of how the programmes or interventions correspond with the nine factors of good integrated care. 28

| Publication | Study design | 1. Information sharing systems | 2. Shared protocols | 3. Joint funding and commissioning | 4. Colocation of services | 5. Multidisciplinary teams | 6. Liaison services | 7. Navigators | 8. Research | 9. Reduction of stigma |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bartels et al.32 | E | • | • | |||||||

| Bellamy53 | E | • | • | • | • | • | ||||

| Bradford et al.27 | E | • | • | • | • | • | • | |||

| Chwastiak et al.37,45 | E, E | • | • | • | ||||||

| Curtis et al.49 | E | • | • | |||||||

| De Hert et al.54 | P | • | ||||||||

| Department of Health2 | P, E | • | • | • | • | |||||

| Department of Health4 | P | • | • | |||||||

| Druss et al.52 | E | • | • | • | ||||||

| Greater Manchester CLAHRC46,47 | E | • | • | • | • | • | ||||

| Happell et al.29,55–57 | D, E | • | • | • | • | |||||

| Hardy et al.30 | E | |||||||||

| Jones et al.39 | E | • | ||||||||

| Kelly et al.31 and Brekke et al.43 | E | • | • | |||||||

| Kern58 | D | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • |

| Kilany42 | E | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • |

| Kilbourne et al.33,35,36,59 | E, D | • | • | |||||||

| Lee40 | E | • | • | |||||||

| Maki and Bjorklund44 | E | • | • | |||||||

| Mental Health Foundation28 | D | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • |

| NHS IQ50 | E | • | • | • | • | |||||

| NHS London60 | D | • | ||||||||

| Nover61 | D | • | • | • | ||||||

| Parks62 | D | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • |

| Pirraglia et al.41 | E | • | ||||||||

| Rubin et al.51 | E | • | • | • | • | |||||

| Shackleford et al.63 | D | • | • | |||||||

| Solomon et al.64 | D | • | ||||||||

| Stark and Walker65 | D | • | • | • | ||||||

| Tallian et al.66 | D | • | ||||||||

| Ungar et al.67 | D | • | • | • | ||||||

| Vanderlip et al.68 | D | • | • | |||||||

| Vinas Cabrera et al.34 | E | • | • | |||||||

| von Esenwein and Druss38 | E | • | ||||||||

| Welthagen et al.69 | D | • | • | |||||||

| Yeomans et al.48 | E | • |

Chapter 5 Findings and discussion

Information sharing systems (13 studies)

To properly integrate care, the Mental Health Foundation inquiry identified the need for a compatible information system within and across different care organisations that could establish individual electronic records of service users’ integrated health and social care needs and interventions. The proposed system would also have the ability to anonymise and aggregate health and social care records to inform a needs assessment of the local population. 28

One of the quality indicators in the General Medical Services contract is the establishment and maintenance of a register of people with SMI. It also requires the establishment of a comprehensive care plan and recording of physical health-related measures (e.g. blood pressure, alcohol consumption, cervical screening, lithium monitoring) for a defined proportion of SMI service users. 70 The collection and maintenance of such information necessarily requires an adequate information technology (IT) infrastructure.

Like the General Medical Services contract, the US SAMHSA’s Primary and Behavioural Health Care Integration (PBHCI) funding programme recommends a registry/tracking system for all primary care needs of, and outcomes for, clients with serious mental illness. 58,71 However, PBHCI grantees have noted both technical and legal barriers to implementing the required shared information systems. For example, web-based registry software has thus far proved to be inadequate, resulting in organisations relying on less-useful paper or Excel-based versions (Microsoft Excel®, Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). 58

Regulatory and medicolegal issues

Being able to access information from single or multiple electronic medical records (EMRs) is an important facilitator, as it allows providers to identify and track SMI populations and individuals needing physical health services. 62 However, behavioural health-care providers in some US states have been prevented from being able to share EMRs as a consequence of federal privacy laws regarding drug and alcohol information. Regulatory barriers that limit information exchange between primary and mental health care have been identified as particularly problematic. 37 It is not clear from the published evidence to what extent such barriers have been overcome by self-contained US funding systems, such as the VA, where integrated registry and EMR data have been used to target the physical health-care needs of people with SMI. 27,33,35,36,52,59 However, a recent plan to merge VA EMRs with US Department of Defence records proved costly and was abandoned in favour of an ‘interoperable system’. 38

Some authors have proposed allowing service users to opt-in to release health information into the shared system to overcome medicolegal barriers,38 although this may raise questions about informed consent, particularly among SMI populations.

In the UK, the Data Protection Act (1998)72 and the Human Rights Act (1998)73 govern the sharing and confidentiality of health records, and the Health and Social Care Information Centre has produced guidance on handling confidential information. 74

Data collection

Some of the published evidence discussed facilitators and barriers to the initial identification and collection of service user data. For example, in the absence of a central register, a Californian programme that aimed to integrate primary care and mental health services for people with SMI reported spending several months of the 16-month project trying to identify eligible service users through chart review. 61

Much of the literature is concerned with conducting physical health checks in people with SMI, but even where such checks have been undertaken, there is evidence that the subsequent results are either incompletely recorded or inaccessible to other care professionals. The problem of missing laboratory data (such as glucose and lipids) has been noted in the literature35,44,61 and was raised as an issue by several of our field contacts. However, recent evidence from the Bradford and Airedale region suggests that incorporating a computerised template into the primary care information system improved the rates of both adherence to NICE standards for annual physical health checks and detection of significant cardiovascular risk. 48 Although a number of physical screening templates have been proposed and implemented, some form of computer assistance may be necessary to ensure sufficiently high-quality data collection.

One of our field experts described attempts to implement such a screening template for collecting more comprehensive physical health data than the existing admission checklist used in his local psychiatric hospital. However, he noted a number or barriers to implementation, the most significant being the technical and bureaucratic difficulty of being able to introduce any new template into the existing IT system.

Elsewhere, programmes have reported attempts to streamline the process of electronic data gathering by providing handheld units or desktop computer kiosks to allow service user self-entry of data such as depression rating scales,58 although such technologies may not be accessible for people with low digital literacy and their overall impact is not clear. 38

Data sharing

The most commonly reported technological barrier to the integration of physical and mental health care is the failure to accurately and effectively share service user data between providers.

One NHS field expert noted that access to and sharing of information with primary care is very difficult for physical health clinics provided in secondary care, as secondary and primary care use different electronic systems [PARIS (Civica, London, UK) and SystmOne (TPP UK, Leeds, UK), respectively]. This impedes efforts to intervene on the basis of the results of screening or monitoring. Another field expert noted that the difficulties with the co-ordination of information systems extended beyond primary and secondary care to community mental health and social care settings.

The absence of ‘joined-up’ information systems is also apparent to service users. One respondent mentioned routinely being asked to physically hand over printouts of clinical information from one service provider to another, and gave an example where this resulted in a psychiatrist fortuitously identifying an otherwise unidentified risk of an adverse drug interaction. Such ad hoc approaches to data sharing are clearly inadequate for properly integrated care.

Various forms of shared electronic record have been proposed and implemented, including electronic personal health records that shift the locus and ownership of records to the service user,38 and records that attempt to fully integrate health and social care data. However, these also raise questions about how to negotiate issues of permissions and privacy.

Currently, NHS service users are automatically opted into having a summary care record containing limited information primarily related to medications and allergies that can be shared between providers. Service users can request further information to be included in the summary care record, although it is not clear to what extent most service users are aware of this option. Some Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) have started to integrate service users’ health and social care records more broadly, with Camden CCG being one of the local commissioners to pioneer this ‘integrated digital record’ approach. 74 This allows authorised health and social care workers to access information relevant to their role.

Shared resources

Beyond individual service user data, some respondents mentioned shared resources such as Directory of Healthy Living Services being made available and distributed to all staff in a CMHT. 46,47 However, this required continual monitoring and updating by a dedicated person, so, although initially successful, it was not considered sustainable.

Shared protocols (10 studies)

Despite noting difficulties around dissemination, communication and ‘territorialism’ relating to the use of shared protocols, the Mental Health Foundation inquiry was broadly supportive of such protocols within and between the organisations that support people with mental health problems. 28

Responsibility and accountability

Prior to February 2014 QOF payments were used to incentivise primary care providers to undertake annual health checks in people with SMI. However, since then a new CQUIN incentive has placed greater emphasis on mental health trusts to monitor and improve the physical health of SMI service users while supporting and facilitating closer working relationships between specialist mental health providers and primary care. 16 The first indicator of the CQUIN requires cardiometabolic parameters (such as smoking status, lifestyle, body mass index, blood pressure, glucose regulation and blood lipids) be collected, reported and treated according to NICE guidelines, through appropriate referral where necessary. The second indicator requires that an up-to-date care plan (incorporating diagnoses, medications, physical health conditions and recovery interventions) be shared with the service user’s general practitioner (GP).

A major theme to emerge from the literature and advisory group was the importance of responsibility and accountability. Two field experts felt that there is currently insufficient clarity about who is responsible for the physical health needs of people with SMI. Both mentioned the physical health care of SMI service users falling to secondary care for the first 12 months post-diagnosis, followed by (where clinically appropriate) transfer of responsibility to primary care, in line with the shared care arrangements outlined in NICE Quality Standard 80. 75 However, several respondents also mentioned an ongoing lack of clarity and/or disagreement about roles and responsibilities (‘Everyone thinks it is someone else’s business’). Although some of this confusion may be attributable to changes in the incentive structures, the wider literature suggests that maintaining absolute clarity about who is responsible for each aspect of physical health care is difficult but crucial to the success of integrating physical and mental health care.

Existing protocols

The CQUIN for physical health in mental health mentions the ‘Lester’ resource for physical health assessment in secondary care. 76 This tool provides a framework for the assessment and management of the cardiometabolic health in people experiencing psychosis and schizophrenia. It provides clear guidance on necessary measures and their timing, thresholds indicating the need for intervention, specific interventions or guidance to be implemented and target outcomes. However, it is not prescriptive about who is responsible for monitoring service-user health and effects of antipsychotic medication beyond the requirements of the NICE Quality Standard (i.e. psychiatrist for 12 months or until condition has stabilised, primary care thereafter under shared care arrangements). 75 The European Psychiatric Association, European Association for the Study of Diabetes and European Society of Cardiology have previously published a joint position statement outlining a similar cardiovascular risk management protocol, although with greater emphasis on psychiatric co-ordination of care. 54

NHS Improving Quality is currently piloting a national roll-out of an updated ‘Lester 2014’ resource. 65 The pilot evaluation sites intend to use the Lester tool as the basis for integrating care through improved record keeping, data quality and communication both within trusts and with primary care and the community. 65 A final report of the results of this pilot has recently been published. 77

The charity Rethink Mental Illness in collaboration with the Royal Colleges of GPs, Nurses and Psychiatrists has responded to the CQUIN with an Integrated Physical Health Pathway, which broadly outlines the responsibilities of primary and secondary care in relation to initiation of treatment or admission to inpatient setting, CPA review and annual health checks. 78

A number of initiatives have aimed to set out the responsibility of each organisation (or part of organisation) in meeting the physical health needs of people with SMI. For example, Manchester Mental Health and Social Care Trust has piloted a multicomponent intervention that included joint action plans for the physical health management of service users. 46,47 The main components of the programme included: (1) a time-protected community physical health co-ordinator (CPHC) role; (2) regular multidisciplinary team meetings between the CPHC and GP practices to establish shared care with the local CMHT; (3) identification of training needs among the CMHT staff and delivery of appropriate training to improve capacity to address physical health needs and support lifestyle changes; (4) regular physical health assessments delivered in a community setting by the CMHT; and (5) increased utilisation of existing physical health resources through a collaborative training day for CMHT and community lifestyle service staff. One of the key enablers for change identified by the authors was standardisation, which included implementation ‘ingredients’ such as a clearly defined CPHC job description and a flowchart of responsibilities; a defined process for identifying service users to raise for discussion at the multidisciplinary meetings; joint action plans documenting who is responsible for each action agreed at multidisciplinary team meetings; a clinical guidance document to assist care co-ordinators carrying out physical health assessments; and the previously mentioned lifestyle services directory being made available and distributed to all CMHT staff via the intranet.

A recently published survey of Australian mental health nurses’ attitudes towards the introduction of a specialist ‘Cardiometabolic Health Nurse’ role identified concerns about ‘muddying the waters’ around roles and responsibilities, possibly increasing the risk of mental health nurses believing that physical health must be ‘someone else’s business’. 56 This suggests that structured supportive measures such as those employed in the Manchester CPHC pilot should be considered by any model seeking to reorganise the integration of physical and mental health services.

Joint funding and commissioning (eight studies)

The Mental Health Foundation report concluded that separate funding streams hinder integrated care, while pooled funding and services commissioned across boundaries increase the likelihood of service users receiving better care. 28 A recent review of 38 schemes that integrated health and social care funds challenged the assumption that integrated funding leads to better health outcomes and lower costs. Rather, improved integrated care tends to uncover unmet needs, with total care costs likely to rise. Nevertheless, better integration may still offer value for money if additional costs are offset by improvements in quality of life. 79

Much of the US literature has focused on overcoming funding barriers in the provision of collaborative stepped care. This has recently included the provision of integrated primary care services for people with SMI within community mental health centre settings, funded through the SAMHSA PBHCI programme. However, alternative administrative arrangements can include global payment systems for physical, mental and dental care for Medicaid beneficiaries (via co-ordinated care organisations) and self-contained systems (VA, Department of Defence, private insurers). 27,52,58 Although the organisation of services may vary across PBHCI grantees, receipt of funding is contingent on community mental health centres establishing a formal link with a primary care partner.

Some of the problems noted in the US literature – such as insurance companies refusing to pay for lipid panel orders for service users not taking second-generation antipsychotics44 – may not be directly relevant to the UK, but such observations highlight how fragmented funding can undermine the implementation of integrated care programmes.

Several advisory group field experts discussed funding issues related to the integration of Healthy Living Services for people with SMI. One such existing service comprises dietitians, physiotherapists and healthy living advisors who provide advice and support (on healthy eating, physical activity, smoking cessation, sensible alcohol use) for service users in inpatient units. In addition, a health improvement specialist oversees public health work within the trust and supervises the healthy living advisors. The latter role is partly supported by local authority public health funds. The field expert considered commitment from both health and public health arms necessary to support and fund such a model, given the health inequalities in this population and the need for prevention as well as intervention. This was echoed by another respondent who noted that Public Health England might also have a significant role to play in terms of health-needs assessment for this population. In the current NHS commissioning structure, local secondary care, community and mental health services are typically funded through local CCGs, whereas local public health services are supported by local authority funding. Close co-operation of local (and possibly national) commissioners will be necessary to facilitate the kind of Healthy Living Services described here.

In July 2014, NHS England announced a new Integrated Personal Commissioning (IPC) approach to providing care for people with complex needs, including those with significant mental health needs. IPC aims to move the balance of spending power to the individual, in terms of people being able to shape their own health and social care delivered (as appropriate) by various combinations of local authority, NHS and voluntary sector providers. The success of this approach will depend to some extent on the ability of individuals with SMI to negotiate their own integrated care. As noted by the Mental Health Foundation, arrangements will be needed to ensure that disadvantaged individuals are able to benefit from IPC, to avoid the risk of further exacerbating their experience of inequality.

Colocation of services (19 studies)

The Mental Health Foundation inquiry looked at evidence on community-located psychiatric services, mental health professionals in primary care and merging of entire trusts or funding bodies. It concluded that the colocation of primary care and specialist mental health staff could provide significantly improved integration of care for people with mental health problems, but only if the staff understand their roles and responsibilities and work willingly and collaboratively together,28 emphasising that people rather than organisational systems or structures are primarily responsible for the successful integration of care.

Much of the published evidence on colocated care identified through this rapid review was concerned with primary care professionals providing clinics in community or inpatient mental health settings. 32,37,41,52,58,63,67,69 However, these might also be considered ‘liaison’ services that happen to be colocated; other publications have described similar clinics within virtual ‘Health Home’ organisations where colocation is not strictly necessary. 62 Therefore, issues relating primarily to liaison are discussed in Liaison services (17 studies).

Where factors relating to colocation were discussed, these broadly supported the Mental Health Foundation conclusions around staffing, highlighting the need for willing, interested, committed and passionate staff67 plus commitment from leaders and administrators. 37 These themes recurred repeatedly in both the literature and our discussions with field contacts and are further discussed in Chapter 6.

In addition, some studies highlighted the need to plan for, and provide sufficient physical space for, any primary care services to be located in a mental health clinic. 58,61 Others highlighted the need for colocated care sites to be both highly visible and easily accessible, including open-access arrangements that allow walk-in care for people with SMI. 41,58

Multidisciplinary teams (19 studies)

As acknowledged by the Mental Health Foundation inquiry report, the principles of multidisciplinary care are already well established in mental health services through the use of CMHTs and the CPA. CMHTs can include professionals such as psychiatrists, psychologists, community psychiatric nurses (CPNs), social workers and occupational therapists. Assertive Outreach and Crisis Teams also typically involve multidisciplinary teamwork. In addition, healthy lifestyle services may include healthy living advisors, dietitians, physiotherapists and health improvement specialists, whose work may be further supported by pharmacists (e.g. through prescribing nicotine replacement therapies).

Communication and relationships

Although effective communication between multiagency health professionals has long been acknowledged as necessary to improve the physical health of people with SMI,2 both field experts and service users told us that communication often remains poor, particularly between primary and secondary care. Similarly, a survey of Australian nurses taking part in boundary-crossing roles emphasised the importance of a strong relationship between the co-ordinating mental health nurse and GPs. 55

One service user described regular physical health checks at a clozapine clinic, which she felt could be used to provide relevant advice on smoking cessation and/or weight loss, either on site or through referral to relevant Healthy Lifestyle Services. However, these regular physical checks were solely focused on drug monitoring and such opportunities were missed. She also noted an apparent absence of information sharing between psychiatrist, CPN and GP.

The previously mentioned Manchester Mental Health and Social Care Trust pilot programme noted how the role of an overall CPHC could be used to facilitate effective communication and collaboration between services. The CPHC would hold regular multidisciplinary team meetings with GP practices (involving at least a GP, practice manager/administrator, practice nurse/health-care assistant) to establish shared care with the local CMHT. The CPHC would co-ordinate each meeting with the lead GP, obtaining relevant client info from care co-ordinators in the CMHT, capturing actions and then feeding back to the care co-ordinators and consultants. In addition, the CPHC would hold a definitive list of lifestyle services and liaise with practice managers and GPs in between multidisciplinary team meetings. Among the various training needs identified for CPHCs, the authors suggested training in conflict management, facilitation, negotiation and physical health management would enable multidisciplinary team meeting success. 46,47

Resources

A multidisciplinary ‘lifestyle medicine programme’ designed for young people with psychosis and bipolar disorder under the care of Worcestershire Early Intervention Service and South Worcestershire Recovery Service is currently being evaluated as part of the NHS Improving Quality ‘Living Longer Lives’ programme. 50 This was based on an existing Australian model identified in our searches. 49 The 12-week ‘Supporting Health And Promoting Exercise’ (SHAPE) education and exercise programme includes a baseline physical health assessment, followed by group health education sessions on healthy eating, smoking cessation, substance abuse, dental care, sexual health and stress management. 50 Participants also receive weekly individual sessions with a dietitian and an exercise physiologist plus group cardiovascular exercise sessions and advice on how to access these locally. A 12-month gym membership to a local university gym is provided, along with access to peer support to help with goal setting, one-to-one encouragement and fitness training or taking part in team sports. Unlike other interventions aimed at improving the physical health of people with SMI identified by this rapid review, this programme involves the early intervention service working in partnership with organisations outside the health and social care services (principally with a local university gym and well-being centre). Should the pilot model prove effective, its wider implementation is likely to rely on the availability of local health and fitness organisations and their willingness to engage in partnership with mental health service providers.

A randomised trial of an integrated care clinic staffed by a nurse practitioner, part-time family practitioner and nurse case manager within a VA mental health clinic in the USA considered the provision of additional staff resources to improve access and adherence to care (case manager outreach, extra appointment time, scheduling flexibility) to be key to improved outcomes. 52

Liaison services (17 studies)

The Mental Health Foundation inquiry was strongly supportive of the concept of liaison services – both psychiatric liaison services in physical health-care settings and physical health care in mental health settings. 28 In addition, advisory group service users told us that they would like to know that there is someone with responsibility for the physical health needs of SMI service users, particularly in the inpatient setting.

One advisory group field expert described the emergence of physical health clinics in the NHS intended to meet NICE recommendations on physical health monitoring and screening for SMI users in secondary care. We also found several published descriptions of primary care clinics or placement of physical health practitioners in inpatient51,69 and outpatient29,52,56–58,63,67 mental health settings. While the US PBHCI model typically involves the placement of primary care specialists in behavioural health facilities, this can also take the more indirect form of consulting primary care practitioners supporting psychiatrists who provide medical care for common conditions (e.g. hypertension, diabetes mellitus, dyslipidaemias). 58 Field experts also described existing services such as dedicated GP sessions on forensic wards and in-reach specialist diabetes mellitus nurses.

One feasibility study noted that service user anxiety about seeing someone other than a psychiatrist could be a barrier to the implementation of a weekly primary care service on acute psychiatry wards and highlighted the importance of the primary care doctor being perceived as professional, kind and understanding. 69

One US study described a half-time primary care clinic within a community mental health clinic, staffed by two nurse practitioners and one family physician. Referral was informal, with a mental health provider directly placing their service user on the clinic schedule or discusses the referral with the primary care nurse liaison. Although referral criteria were not formalised, the aim was to capture people with a chronic medical illness who are unable to navigate a traditional primary care setting. 63

Navigators (15 studies)

One of our advisory group field experts noted that continuity of care is particularly important for the SMI population, but noted that such continuity is becoming increasingly rare within primary care. In response to observations of this nature, several models have proposed the role of a single named individual who can help people navigate their way through complex systems.

Among these is the existing CPA model, which aims to ensure people with mental illness receive a care co-ordinator who can arrange a full assessment of both their health and social care needs, and then help develop a plan to address those needs. Care co-ordinators may be a CPN, social worker or occupational therapist.

Although navigators or care co-ordinators are generally thought to negotiate the boundaries between health, social care, education and housing sectors, this role can be just as important for helping people with SMI negotiate boundaries within heath care, between physical and mental health services, or between primary and secondary care. At the core of the Manchester Mental Health and Social Care Trust pilot was the CPHC role. In the pilot, this CPHC role was undertaken part time (0.4 hours whole-time equivalent) by care co-ordinators already working within the CMHT. The authors stated that it was essential for the CPHCs to also continue in their care co-ordinator role in order to retain their skills, continue to have contact with service users and colleagues, and to allow access to relevant meetings and discussions with other CMHT staff. CPHCs also felt that respect was a key facilitator for gaining the trust and support of other care co-ordinators. 46,47

The Manchester model differs from some other ‘navigator’ programmes in the literature in that the CPHC role was deliberately focused on facilitating communication between services without the additional responsibility of undertaking physical health checks or other clinical tasks. By contrast, a US evaluation of a transitional care (‘TCare’) model for people with SMI being discharged from hospital to community care employed a psychiatric nurse practitioner (trained in medical and psychiatric assessment/treatment/prescribing) as the navigator. 64 The intervention consisted of 10 components: (1) co-ordination of care by a psychiatric nurse; (2) a plan developed prior to hospital discharge; (3) home visits from the nurse for approximately 90 days post-hospital discharge and available 7 days a week; (4) co-ordination with physicians in the community, including accompanying service users on visits; (5) inclusive focus on health needs of the service user; (6) involvement of both service user and family in care through education and support; (7) early detection and quick response to health-care risks and symptoms; (8) service user, family caregiver and providers functioning as a team; (9) collaboration of nurse and physician; and (10) information sharing among all team members. Interestingly, this evaluation noted difficulties in engaging mental health case managers with the TCare programme. The authors attributed this to case managers’ heavy caseloads forcing them to focus on dealing with crises at the expense of clients who are seen to be already receiving some form of service. This observation would appear to support the idea that physical health navigators should have a role that can be influential in the wider co-ordination of services for people with SMI.

A US pilot programme, ‘The Bridge’, aimed to use a time-limited peer health navigator intervention to give clients the skills and experience to self-manage their health-care activities to the greatest degree possible. 31,43 The intervention comprised four components: (1) service user health assessment and health navigation planning; (2) co-ordinated linkages/activities to help service users navigate the health-care system and follow-up/adherence to treatment plans; (3) consumer education including partnering with medical care providers, treatment compliance, self-advocacy and interaction skills, health and wellness, and benefits and entitlements; and (4) cognitive–behavioural strategies to support health-care use behaviour change and behaviour maintenance. The 6-month intervention included a 4-month phase of intense contact between service user and navigator, followed by a less intensive ‘monitoring’ period. Although the intervention appeared to improve some aspects of physical health and health-care utilisation, the pilot included only a single peer navigator, who had been involved in the intervention development, and received both extensive training and close supervision. There are a number of questions about whether or not such a model could be generalisable or sustainable in addition to ethical concerns around duty of care and accountability. However, particularly in the USA, ‘peer navigation’ remains an area of interest. 53

An advisory group service user contributing to this rapid review described her CPN providing the co-ordinating role between mental and physical health care, particularly in terms of support and signposting to mainstream services. However, she also described being dropped from her dental practice because of missed appointments as a result of mental illness episodes. She had to be forceful in explaining the difficulties, but remains without dental care for the time being. Although she feels confident at speaking out when things are not right, not everyone is able to do this. This raises questions about the extent that navigators such as care co-ordinators in the CPA model should engage in advocacy for service users, particularly when dealing with services less accustomed to SMI. One study of the CPA found that failings were often because of the care co-ordinator having insufficient authority to exert control over other care professionals to ensure care is properly integrated. 80

Research (six studies)

A review of factors that influences integrated health and social care published by the Social Care Institute for Excellence81 concluded:

The evidence base underpinning joint and integrated working remains less than compelling. It largely consists of small-scale evaluations of local initiatives which are often of poor quality and poorly reported. No evaluation studied for the purpose of this briefing included an analysis of cost-effectiveness. There is an urgent need to develop high-quality, large-scale research studies that can test the underpinning assumptions of joint and integrated working in a more robust manner and assess the process from the perspective of service users and carers as well as from an economic perspective.

The Mental Health Foundation enquiry echoed these conclusions, recommending that more research into how best to support people with complex, comorbid needs is required that addresses both effectiveness and economic assessment of integrated care models. 28

Similarly, most of the programmes identified through our update searches and contact with field experts have been either not evaluated, or evaluated only on a small scale within a local context.

Future evaluations of programmes to improve the physical health of people with SMI will need to have sufficiently long follow-up to collect meaningful physical outcomes, and/or collect appropriate process and surrogate outcomes. One advisory group field expert described developing a bespoke outcome measure based on the Theory of Planned Behaviour to allow healthy living advisors to measure impact on service-users’ attitudes towards healthy living, perceptions of social pressure/support and perceived barriers to healthy living.

Reduction of stigma (eight studies)

Attitudes and beliefs of staff

Both service users and field experts from our advisory group reported that GPs and non-mental health specialists can appear reluctant to tackle mental illness. Some attributed this to the perception that the SMI population can be ‘troublesome’ or excessively difficult to deal with, generally because of non-attendance of appointments and non-compliance with treatment advice. The published literature has noted that primary care practitioners may be uncomfortable and find it difficult to deal with the complexity and/or the slow pace of working with people SMI relative to the wider primary care population. 58

Concerns about stigmatising attitudes and behaviours were also raised in relation to administrative staff and processes. A service user suggested that receptionists and booking systems in mainstream services need to be more sensitive to the needs of SMI service users when arranging appointments. Examples included difficulties with feeling tired because of medication, yet having to telephone first thing in the morning to get an appointment at the GP, and having to complete forms to declare a diagnosis of SMI and/or antipsychotic medication use. A clinical expert described instances where physical health services for people with SMI were not regarded as ‘core business’ by practice management.

Consequences of stigma

An issue of major concern raised both in the literature and among respondents is ‘diagnostic overshadowing’, whereby signs and symptoms of physical illness can be misattributed to mental illness, leading to underdiagnosis and mistreatment of the physical condition. 28

Even within mental health services, an overemphasis on managing psychosis may mean also that physical health concerns are addressed too late. An advisory group field expert noted that around half of service users have an increase in body weight of more than 7% in first year of treatment, with other adverse changes being possible within days of antipsychotic initiation. He suggested that a preventative approach should be taken to physical health in SMI, similar to the way in which early intervention is used to avoid crisis and hospitalisation.

When discussing the possible adverse effects of antipsychotic medication with service users, both service users and field experts commented on the need for prescribers to balance their concerns about the risk of non-compliance with the longer-term consequences of not discussing adverse events.

One area of physical health that a service user considered to be seriously neglected in people with SMI is sexual health. Here, she noted that the focus is on risk and safeguarding rather than tackling positively the effects of SMI and medications on relationships and sexual activity, starting a family or bringing up children. CPNs and other health professionals can feel uncomfortable in addressing sexual health issues (and some may even be resistant to the idea that this is important to people with SMI).

Reducing stigma

The Mental Health Foundation report recommends staff training and education to counter the potentially dangerous discrimination that can arise from diagnostic overshadowing, and calls for more research on the potential benefits of interpersonal contact with people with SMI as a way of reducing stigmatising attitudes and behaviour among non-mental health-care providers. 28

Of the recently published literature, only the SHAPE programme described its intervention in terms of stigma overtly, where access to a university gym was partly intended to allow young people with SMI to interact with other young people in a safe environment without feeling stigmatised. 50

Other factors emerging from the evidence

Staff, skills and training

The Mental Health Foundation report identified cross-boundary interprofessional training and education as essential for the better integration of physical and mental health care. 28

The need for training and education to foster appropriate skills and attitudes among health-care staff was a major theme to emerge from both the recent literature and our discussions with field experts and service users. A review by Health Education England sets out a number of recommendations relevant to this area of our review in relation to the future education and training of nurses and care assistants in health-care services. 82

Basic clinical training

Several respondents mentioned the need for improved general knowledge of mental health issues in general practice and nursing professions, with one service user emphasising the importance of including mental health in undergraduate nursing degrees, dental training and other clinical professions. This echoed the Mental Health Foundation’s recommendation for basic education on the indivisibility of mental and physical health. 28 Authors have noted the need for ongoing reinforcement of the need for integration with staff alongside continuing professional development. 28,58

Training and education for primary care practitioners

As mentioned previously, advisory group service users reported that not all GPs and nurses appear equipped to deal with the needs of SMI, with the impression that the system becomes less co-ordinated/integrated at the point of discharge from their CPN to GP care. A publication by the now-defunct NHS London Health Programmes suggested that competence and capacity in primary and shared care could be improved both through the commissioning of formal training, and ongoing supervision and coaching of primary care staff by mental health specialists. This proposed that frontline staff in access points such as accident and emergency departments and GP surgeries should undertake training so that they have a basic awareness of mental health problems and communication skills that avoid exacerbation of mental health crises. 60

A primary care field expert also noted that GPs and practice nurses in primary care training needed to deal with basics and sensitivities in SMI. One proposed example of a relevant training package was the ‘Practice Nurse Masterclass’ programme for north-east and central London that is designed to improve case identification and signposting in primary care to support earlier intervention; enable safe discharge from secondary to primary care; improve communication between primary and secondary care; and decrease the stigma of mental illness. 83

Training and education for mental health practitioners

Insufficient training has also been identified as a barrier to mental health service providers being able to take on more responsibility for medical care. 68

One advisory group field expert described research undertaken within their trust that identified a number of staff-related barriers to improving physical health for people with SMI, including knowledge (e.g. a lack of knowledge of recommendations); skills (e.g. a lack of physical health-care skills, difficulty raising topics with service-users); and beliefs about capabilities (e.g. a lack of confidence in providing physical health care). In particular, the absence of confidence among many mental health practitioners about their own physical health-care skills – and the need for training to address this – was raised by several respondents. One field expert mentioned mental health staff feeling uncomfortable and worried about accountability, attributing this to the absence of relevant physical health education as part of specialist mental health nursing training.

Acting in concert, the barriers described above can result in serious failures of care. For example, one service user described the experience of a friend with SMI who had undergone surgery and was later sectioned. With the district nurse not attending to her on the mental health inpatient ward, and the mental health nurses not sufficiently experienced or confident to attend to this specialised type of physical health need, the service user had to refer to YouTube (YouTube, LLC, San Bruno, CA, USA) to find out how to change her own surgical dressing.

One proposed solution included implementing mandatory physical health education sessions provided by physical health nurses for all inpatient and community staff (including care co-ordinators), plus a collaborative training day for CMHT and lifestyle service staff. However, it has been observed that accommodating additional training can be difficult for CMHT staff with heavy caseloads. 46,47,58

Several of the programmes identified through our searches supplemented training with some form of clinical guidance or decision support resources related to the physical health of people with SMI. 29,30,33,35,36,39,40,44,46,47,56,57,59

Organisational culture and environment

The second underpinning essential of integrated care identified by the Mental Health Foundation was having the right people in the organisation,28 including leaders who will drive forward integration at a strategic level. This was supported by more recent published evidence that emphasised the importance of commitment from key leaders and administrators,37 and the development of a supportive organisational culture. 46,47

In part, this might be achieved by obtaining staff ‘buy-in’ and commitment through raising awareness and appropriate incentivisation. 28 One field expert noted that many of the issues in this area are similar to the introduction into primary care of incentivised diabetes mellitus care in the 1980s (i.e. strong emphasis on preventing cardiovascular disease, developing appropriate education and training for nurses) and that similar steps should be taken to adapt the existing culture.

Elsewhere, authors have highlighted the need for organisations to be flexible, acknowledging that practitioners need time to collaborate on service user care. 37,58 This is particularly the case in clinical settings with heavy caseloads. 44 For example, the CPHC pilot described care co-ordinators’ lack of time as a barrier to performing community physical health assessments. It identified management commitment to protect time and resources, both for physical health assessments and the wider CPHC role, as a key implementation ingredient. 46,47

The pilot of a one-morning-per-week physical care clinic for mental health service users in a Canadian secondary care setting described an initial lack of administrative and institutional support because of a perceived increase in financial cost, unnecessary colocation and absence of a specified/earmarked budget. 67 The authors noted that for integrated care to be successful senior decision-makers need to retain a system-wide and integrated vision of service delivery and resource allocation. Although the funding arrangements in the UK NHS differ from those in the Canadian setting, similar considerations apply.

One factor not explicitly addressed in the literature is the impact of the physical environment on the physical health of people with SMI. Reflecting on her experience as an inpatient, one service user described an environment that was ‘toxic to physical health’. This included very poor-quality and highly calorific food (e.g. cream cakes) that could exacerbate medication-induced weight gain, a lack of opportunities for exercise (e.g. broken exercise bike on the inpatient ward), and outdoor activity being restricted and geared towards those who smoke (through smoking breaks). This demonstrates how the culture and environment in one part of the service can unintentionally undermine efforts to improve physical health delivered elsewhere.

Chapter 6 Conclusions

This rapid review is intended to give a snapshot of the approaches most recently used to address the physical health needs of people with SMI since two wide-ranging reviews of integrated in care were published in 2013. We identified the approaches by searching the international published literature and speaking with UK service users and field experts.

What types of models currently exist for the provision of integrated care specifically to address the physical health needs of people with severe mental illness when accessing mental health-care services?

The majority of service models identified in this review were multicomponent programmes incorporating two or more of the factors that have previously been identified as facilitators of integrated care: information-sharing systems; shared protocols; joint funding/commissioning; colocated services; multidisciplinary teams; liaison services; navigators; research; and reduction of stigma.

The majority of programmes were in community and/or secondary care mental health settings in the UK, North America or Australia.

Programmes rarely focused on a single delivery component, rather most described the complex interaction of multiple components. However, few programmes were described in detail and fewer still were comprehensively evaluated. This raises questions about the replicability and generalisability of much of the existing evidence.

One of the few clearly described and evaluated programmes was that piloted by Greater Manchester Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care, which evaluated the impact of introducing a core time-protected CPHC role to improve communication between primary care and CMHTs. Other ingredients of the programme were multidisciplinary team meetings, targeted training, physical health assessments and shared information resources. The team behind this programme has produced guidance for future implementation that other sites could use to replicate or further refine this promising approach. 46,47

Many other variants of the ‘navigator’ model have been described in the literature, although where evaluations were available, these tended to be somewhat superficial with little clarity about implementation. However, the available evidence suggests that any individual tasked with co-ordinating care needs to be empowered with the authority to influence other care professionals. Although peer (as opposed to professional) navigator models have also been proposed, both the ethics and the sustainability of such approaches need to be considered carefully.

What are the perceived facilitators and barriers to implementation of these models?

As has been previously noted, a fundamental requirement for successful integration of physical and mental health care is having the right people with the right skills and attitudes in place. The Mental Health Foundation emphasised the need for strong leaders, along with committed and willing staff, supported by cross-boundary interprofessional training and ongoing professional development. 28

Our findings further underline the importance of considering the impact of any planned structural changes on the attitudes, skills and behaviours of the people interacting within and across health organisations, be they health professionals or service users. Many of the factors that authors, experts and service users identified as facilitators were those that either empowered individuals and/or minimised the effort needed for individuals to provide integrated services.

Wherever possible, training for mental health professionals who fail to address the physical health needs of their service users should aim to increase self-confidence in their own skills and give greater clarity about their responsibilities in relation to physical health. Care co-ordinators/navigators may have an empowerment role by providing advocacy for service users in certain settings, and might themselves benefit from greater formal authority over care integration. All health professionals will need time to undergo training and to collaborate on service user care, which can be difficult in clinical settings with heavy caseloads. Management commitment to protect time and (where necessary) resources for such activities has been raised as a potentially worthwhile investment.

Factors such as integrated information systems and individual electronic records have yet to be properly implemented because of various technical, legal and organisational barriers. However, these remain the most promising means of simplifying communication and collaboration among professionals in order to provide care for service users across multiple services. We encountered potentially useful local innovations that could not be implemented because of IT incompatibility or inaccessibility issues. Improved communication and understanding between clinical, administrative and technical staff can be crucial in overcoming such barriers to innovation.