Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 09/1004/04. The contractual start date was in January 2012. The final report began editorial review in June 2015 and was accepted for publication in October 2015. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

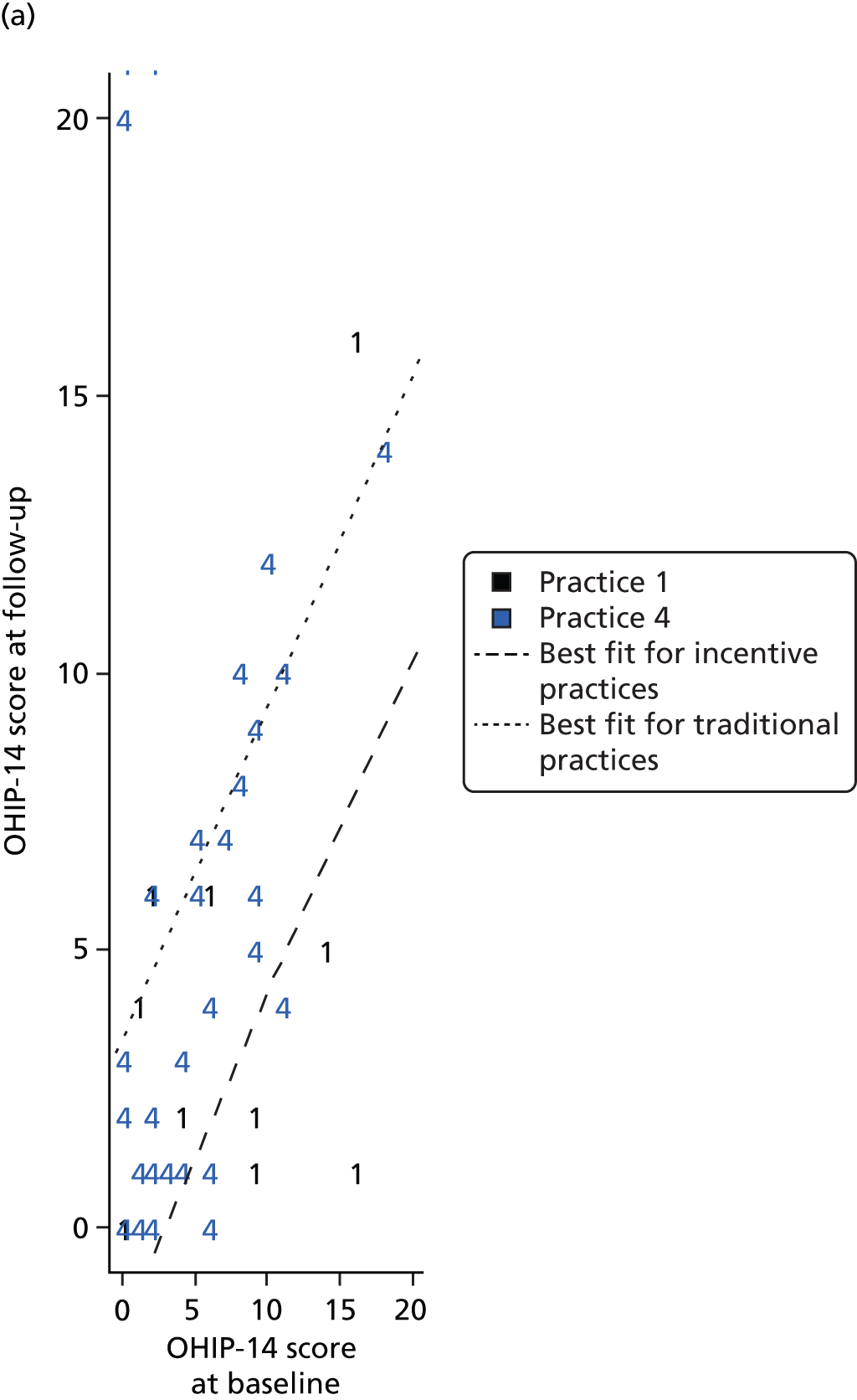

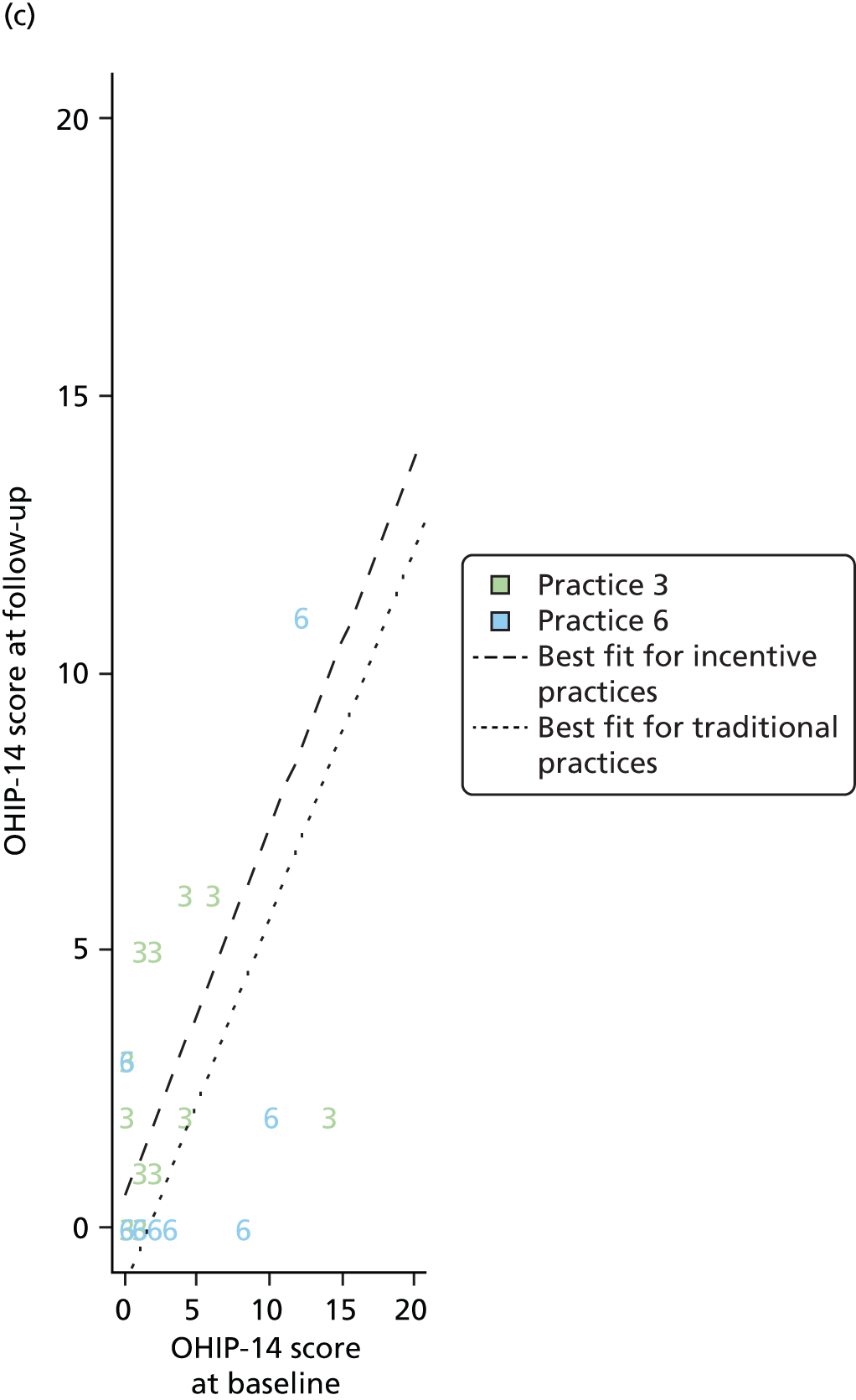

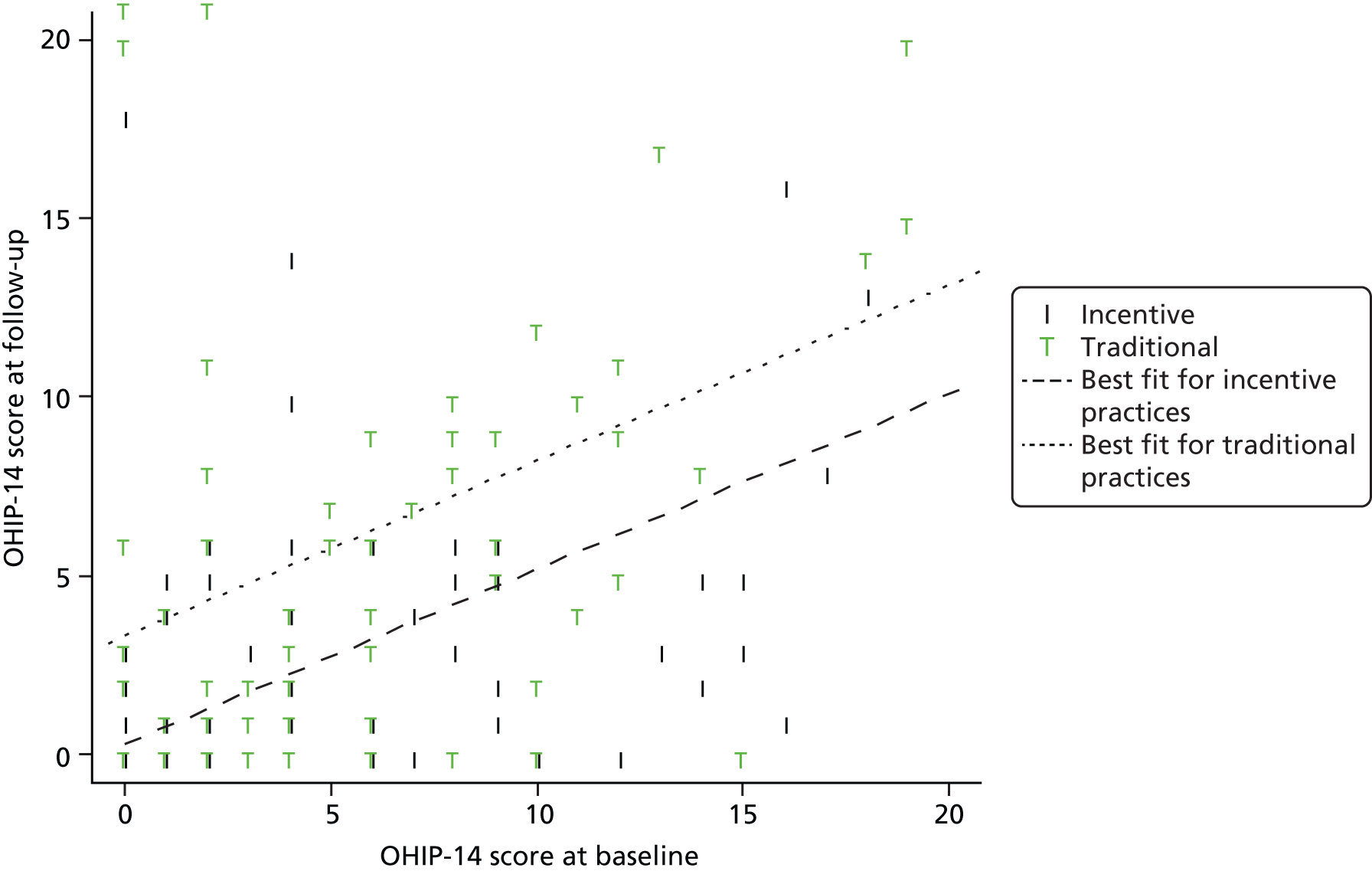

During the study Jenny Godson was employed within the primary care trust commissioning the dental services and involved in the procurement of the services.

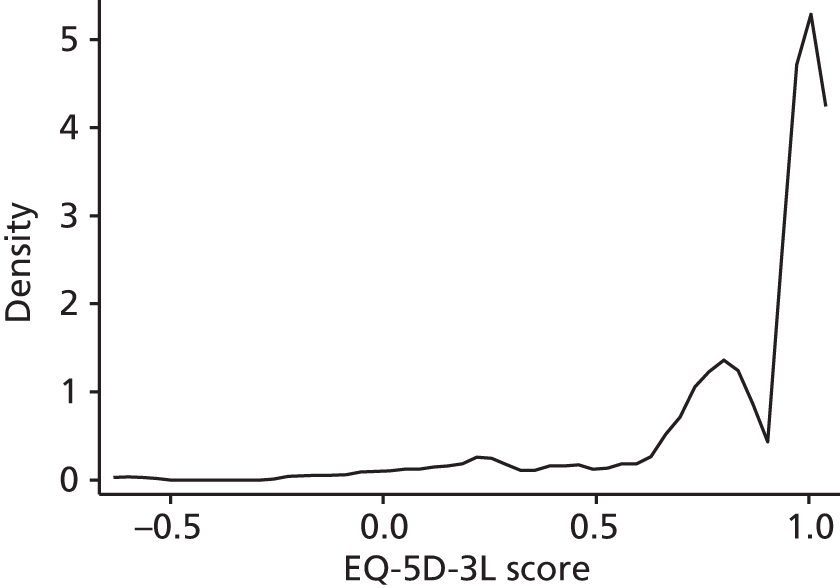

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2016. This work was produced by Hulme et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background

Use of incentives in dental care

There is an increasing trend towards the use of incentives in NHS primary care including dentistry. 1 Although dentistry has long been incentivised, over the past decade commissioning of primary care dentistry has seen the introduction of refinements, with contract currency evolving from payment for units of dental activity (UDAs) towards incentive-driven or blended contracts that include incentives linked with key performance indicators such as access, quality and improved health outcome. 2 This includes (as part of the Department of Health dental contract reform programme) a series of NHS dental contract pilots which opened in 2011 with the aim of exploring how the focus could shift from treatment and repair to prevention and oral health through the introduction of a new clinical pathway and new remuneration models. 2 Although there is a burgeoning field looking at the impact of these blended contracts on the process of care, there remains limited evidence on the impact of changes in dental oral health outcomes and patient, commissioner and workforce acceptability.

The policy context

In 2003, the Department of Health set out changes in governance as part of the Modernisation Agenda in order to create the right context, incentives and operational environment for their staff and frontline teams to transform patient services. 3 The changes transformed the NHS from a centrally directed service to a more complex system with devolved local commissioners [notably, primary care trusts (PCTs)] and a delivery structure composed of diverse providers. 4 In 2002, Shifting the Balance of Power: The Next Steps5 and its subsequent delivery document gave greater authority and decision-making power to patients and front-line staff, and changed organisational roles and relationships, giving PCTs new commissioning powers. This was then followed in 2005 by Commissioning a Patient Led NHS,6 which further strengthened the lead role of PCTs as commissioners of services to meet the needs of their local communities.

NHS Dentistry: Options for Change7 set out a vision for dentistry with prevention at its heart, which was widely supported by the dental community. Personal Dental Services (PDS) pilots tested these new ways of working between 1998 and 2006. In 2006, a new dental contract emerged, essentially devolving the commissioning of dental services locally to PCTs to meet the needs of their local population. The currency of the new General Dental Services (nGDS) contracts was UDAs divided into three levels of treatment bands, with the total number of UDAs in each contract based on historical activity and agreed between PCTs and dental practices. The nGDS contracts meant that the payment mechanism changed from a one-off fee per item of service to a system whereby providers were paid an annual sum in return for delivering an agreed number of ‘courses of treatment’, weighted for complexity (UDAs). PCTs became the local commissioners of dental services and were charged with demonstrating their competencies as ‘world-class commissioners’.

The PDS pilots (1998–2006) encompassed a wide variety of configurations and were widely evaluated. 8–12 Although the evaluations were largely positive there were concerns about whether or not the PDS agreements met local needs, the absence of measures of success or appropriate goals for commissioning and missed opportunities to harness skill mix. 9,12 More recently, the health committee implicitly rejected the PDS agreements as a precursor of the nGDS contracts when it criticised the lack of piloting of the latter contracts. 13 There has been little research to date on the implementation of nGDS contracts. There were some concerns among dental practitioners,14,15 particularly on whether the nGDS contracts would allow more time for prevention16 or restrict access to new patients and those requiring complex treatment. 17

The Steele report2 examined how dental services in England could be developed over the next 5 years. The review advocated a commissioning approach to align dentistry with the rest of the NHS services, to commission for health outcomes and to develop blended contracts rewarding not only activity but quality and oral health improvement (OHImp). It recommended that payments explicitly recognise prevention and reward the contribution of the dental team to improvements to oral health, reflected in patient progression along the pathway, adherence to nationally agreed clinical guidelines and the achievement of expected outcomes. 2 Commissioners were asked to support dentists to make the best and most cost-effective use of the available dental workforce. 2

Following the Steele report2 proposals were set out to pilot different types of dental contract. 18 Alongside these proposals was the Dental Quality and Outcomes Framework (DQOF), which advocated quality as a necessary part of future dental contracts. 19 Within the framework, quality consisted of three domains: clinical effectiveness, patient experience and safety. 19

A series of NHS dental contract pilots began in 2011. The aim was to shift focus from treatment and repair to prevention and oral health through the introduction of a new clinical pathway, supported by new remuneration models. 20 The new pathway begins with an oral health assessment (OHA), following which the patient is advised of their oral risk status using a red–amber–green (RAG) traffic light rating system and given advice on maintaining or improving their oral health. A follow-up appointment or review is then set based on their risk status.

The needs assessment tool (RAG) was underpinned by the Salford and Oldham primary dental care service redesign project2 which found that the RAG scores:

-

‘Enabled the capture of oral health improvements as patients move RAG status. The project has learnt that, as some risk/modifying factors do not change, only the clinical components should be used as outcome measure

-

Motivated dentists to deliver clinical care appropriate to need through robust, consistent clinical and risk assessment

-

Incentivised dentists to perform detailed assessments and to value all patients the same through completing the same consistent, comprehensive assessment

-

Aided communication with patients through the use of the RAG status.’18

Three remuneration models were proposed in the pilot sites to identify the optimal single remuneration model. Dentists were not required to carry out a given number of UDAs but were required to adhere to the DQOF. 18 The three pilot contract types were based on (1) time spent on providing care for NHS patients as measured by the appointment time; (2) capitation payments weighted for individual patients (age, sex, deprivation) based on all care (preventative, routine and complex); and (3) capitation payments weighted for individual patients based on preventative and routine care only. 18 However, while a small element of remuneration within the models was weighted based on the DQOF, remuneration adjustments were not applied as the indicators required testing and refinements before they could be used. 18

Evidence of the effectiveness of incentive-driven contracting

Overall, the evidence of the effectiveness of use of contracting and incentives by health providers is still emerging. The Christianson and colleagues21 review found mixed results of the effect of payer initiatives that reward health-care providers for quality improvements. O’Donnell and colleagues22 found that the Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF) within the new General Medical Services contracts in primary care incentivised performance, motivating staff towards QOF targets. Similarly, McDonald and colleagues1 found incentives to be powerful motivators in the primary care workforce. A more granular view suggests that the process-based nature of incentives may limit their long-term effects on health outcomes. 23 There is also a risk that important activities lacking a target may be underemphasised. 23,24

Within dentistry, the Tickle and colleagues’25 analysis of longitudinal data of English adults explored the impact of the nGDS contracts and found that changes to incentive structures had a substantial impact on dentists’ behaviour with respect to their treatment prescribing patterns. Significant numbers of dentists were attempting to hit their UDA contract targets in the most efficient way possible (from their perspective), by shifting towards treatments with high rewards relative to costs, as opposed to selecting on the basis of clinical factors alone. This echoed the results of Chalkley,26 who found that the introduction of the nGDS contracts in England generated a large and significant increase in activity. However, these results are tempered by a recent Cochrane review27 that found generally low-level evidence from the two randomised controlled studies included28,29 (both were UK-based studies). Brocklehurst and colleagues27 concluded that changes to remuneration may change clinical activity in primary care dentistry, but further experimental research is needed – specifically into the impact on patient outcomes.

Early findings from the most recent dental contract pilots introduced following the Steele report2 have focused on patient and practitioner views of the new clinical pathway, reporting them to be strongly supportive. 30 More recent findings20 focus on adaptation to the new system but also report positive indications about clinical benefits in terms of a reduction of risk and health improvement (measured through the RAG status and a basic periodontal examination). However, the authors have quite rightly added the caveat that there are few comparable data from outside the pilot sites. 20

Structure of the report

The project aims to evaluate a blended/incentive-driven contract model compared with traditional contracts on dental service delivery in practices in West Yorkshire, England, UK. Although the blended/incentive-driven dentist contract model pre-dates the most recent national dental contract pilots and the Steele report,2 its specification was innovative and contributed to the ethos and recommendations of the report. The model was cited within the report as an example of good practice with regard to an emphasis on quality of care, achieving health outcomes and patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs)31 while improving access to NHS dentistry. Its introduction thus widens the evidence base underpinning the proposed introduction of blended contracts in NHS primary care dentistry.

In the INnovation in Commissioning primary dENTal care delIVEry (INCENTIVE) study we used a mixed-methods approach with three interlinked projects to evaluate a blended/incentive-driven model of NHS dental service delivery compared with contemporaneous traditional contracting. These three projects addressed questions of acceptability, dental efficacy and cost-effectiveness. Included in the study were three new dental practices with a blended/incentive-driven contract and three practices under the traditional contracts (see Chapter 2).

Our qualitative work (see Chapter 3) addresses questions of acceptability using focus groups, semistructured interviews and observations with stakeholders. Qualitative exploration is useful when there is little pre-existing knowledge, in this case when it was important to find out what changes to services meant to participants. The number of stakeholder groups and budget constraints necessitated a broad, policy-focused ‘framework’ approach, useful for a structured exploration of participants’ perspectives, and provided an advantage because findings were induced from their original accounts. 32,33 This approach enabled us to cover the broad tapestry of experiences emerging from this intervention.

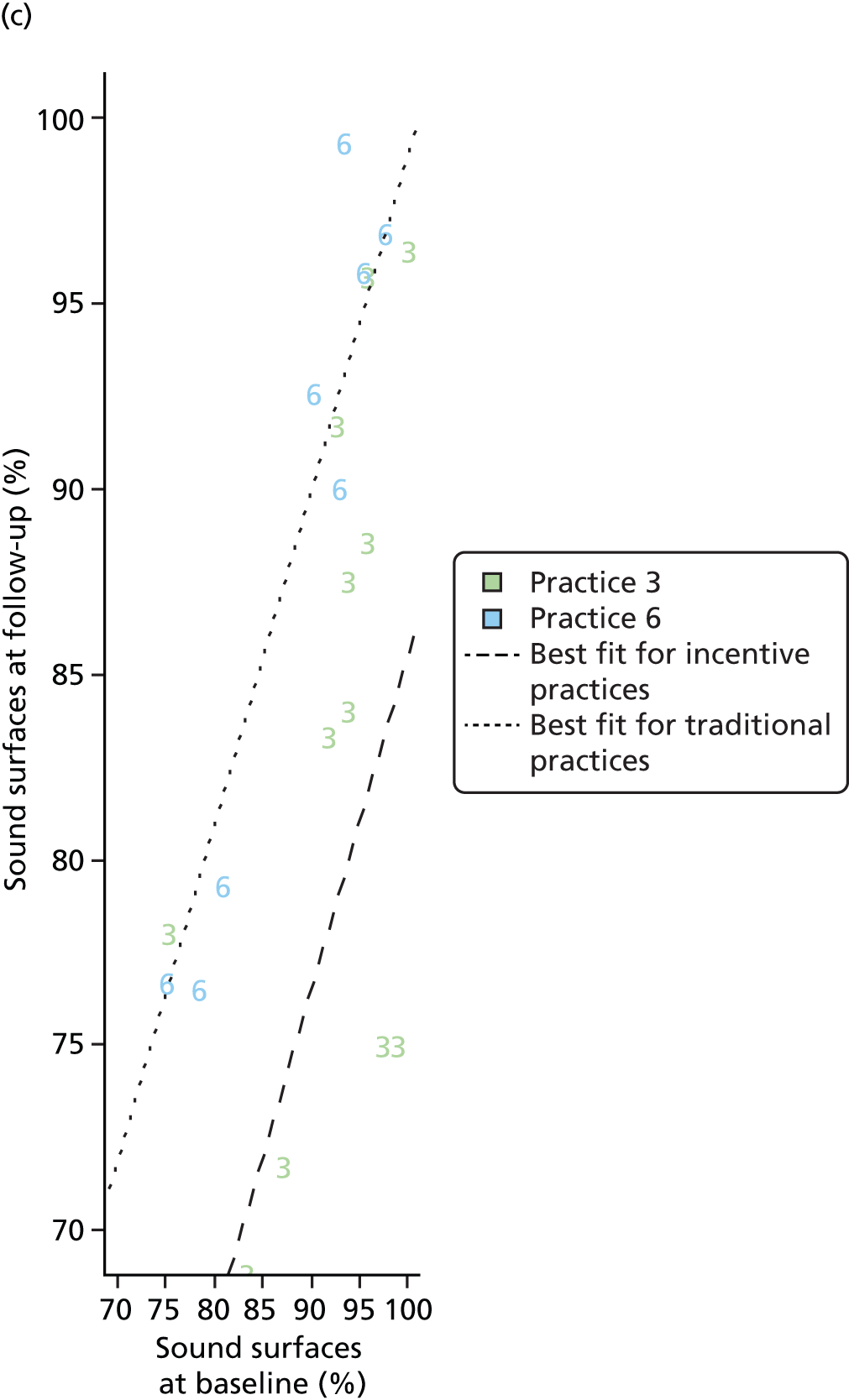

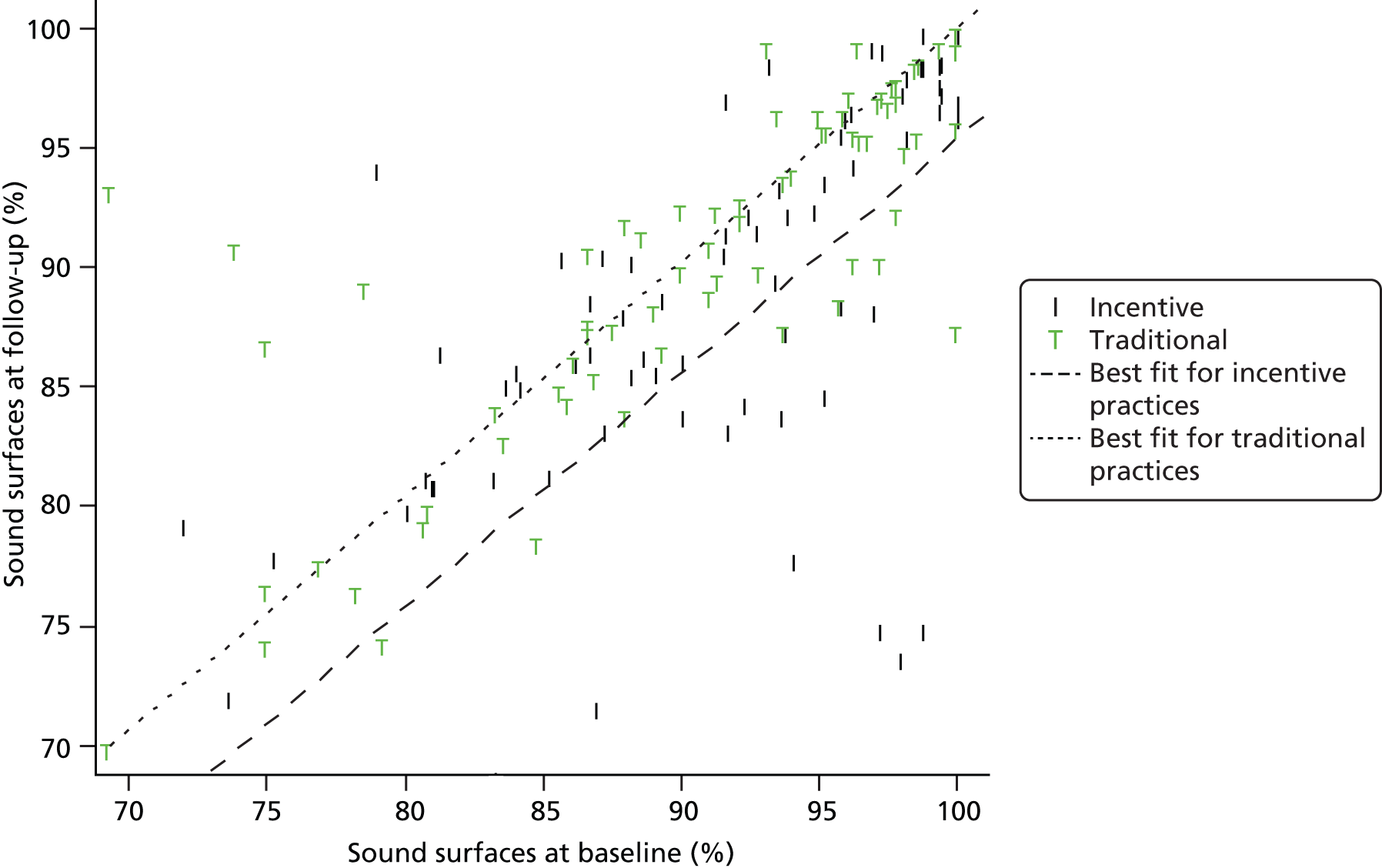

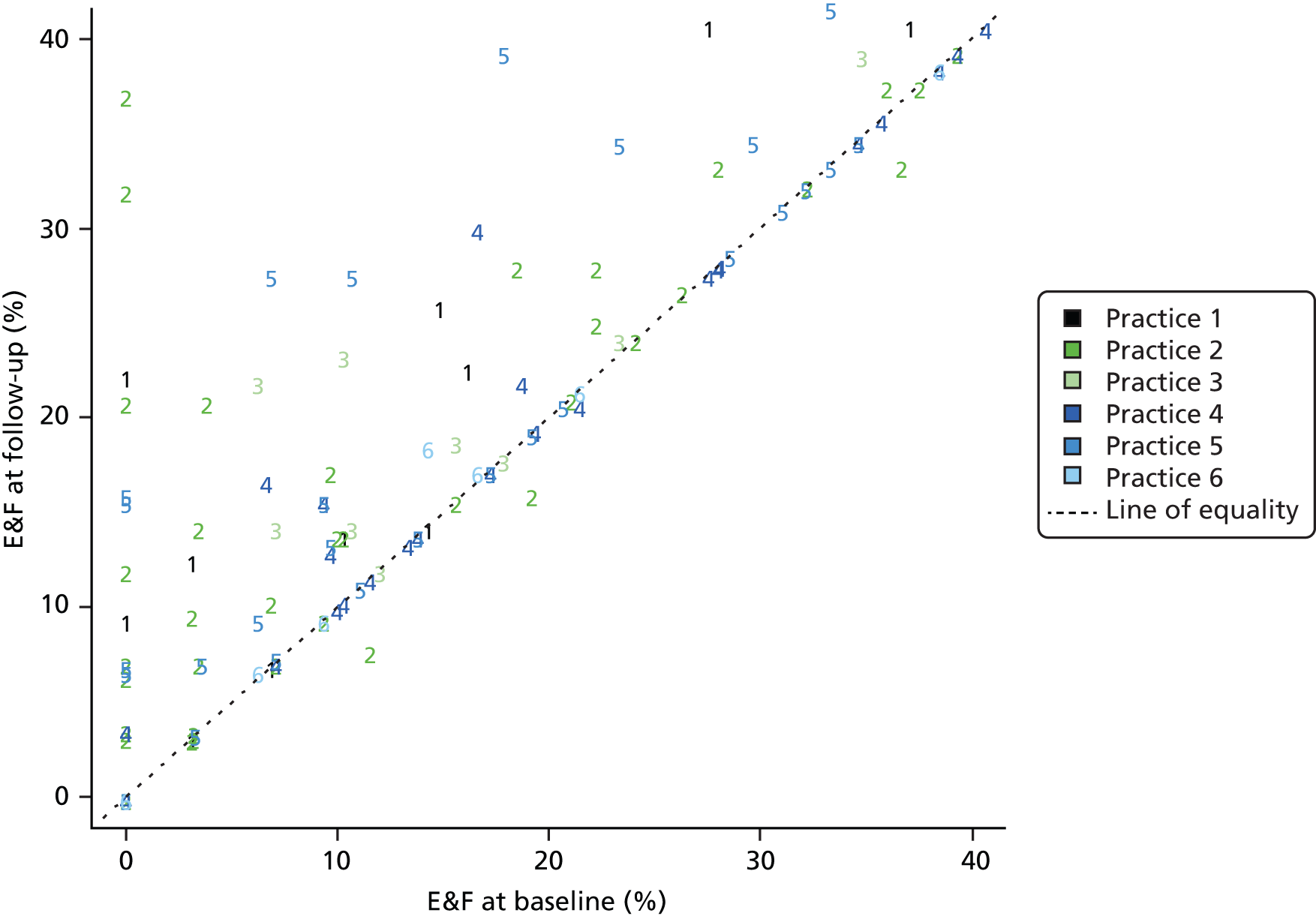

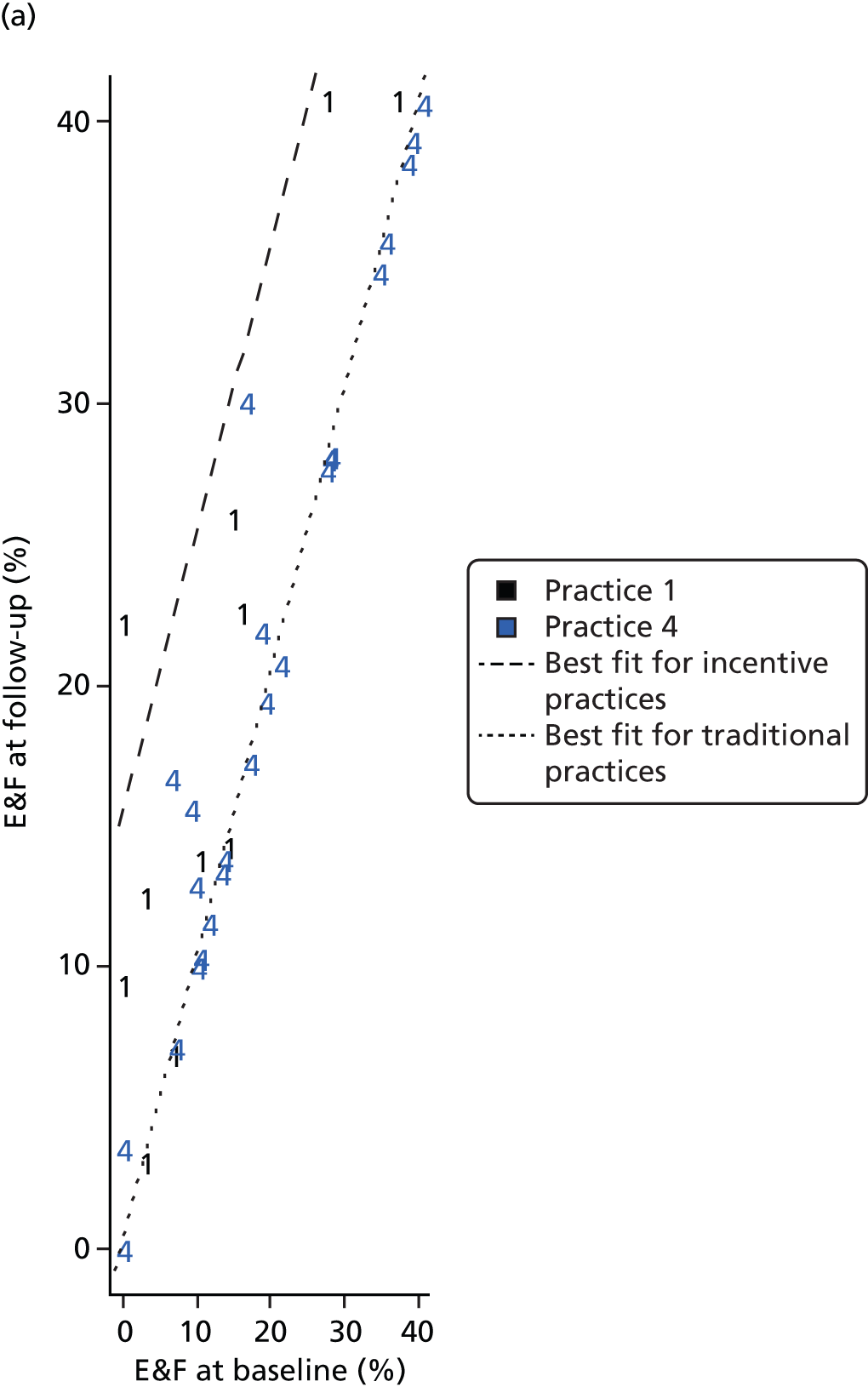

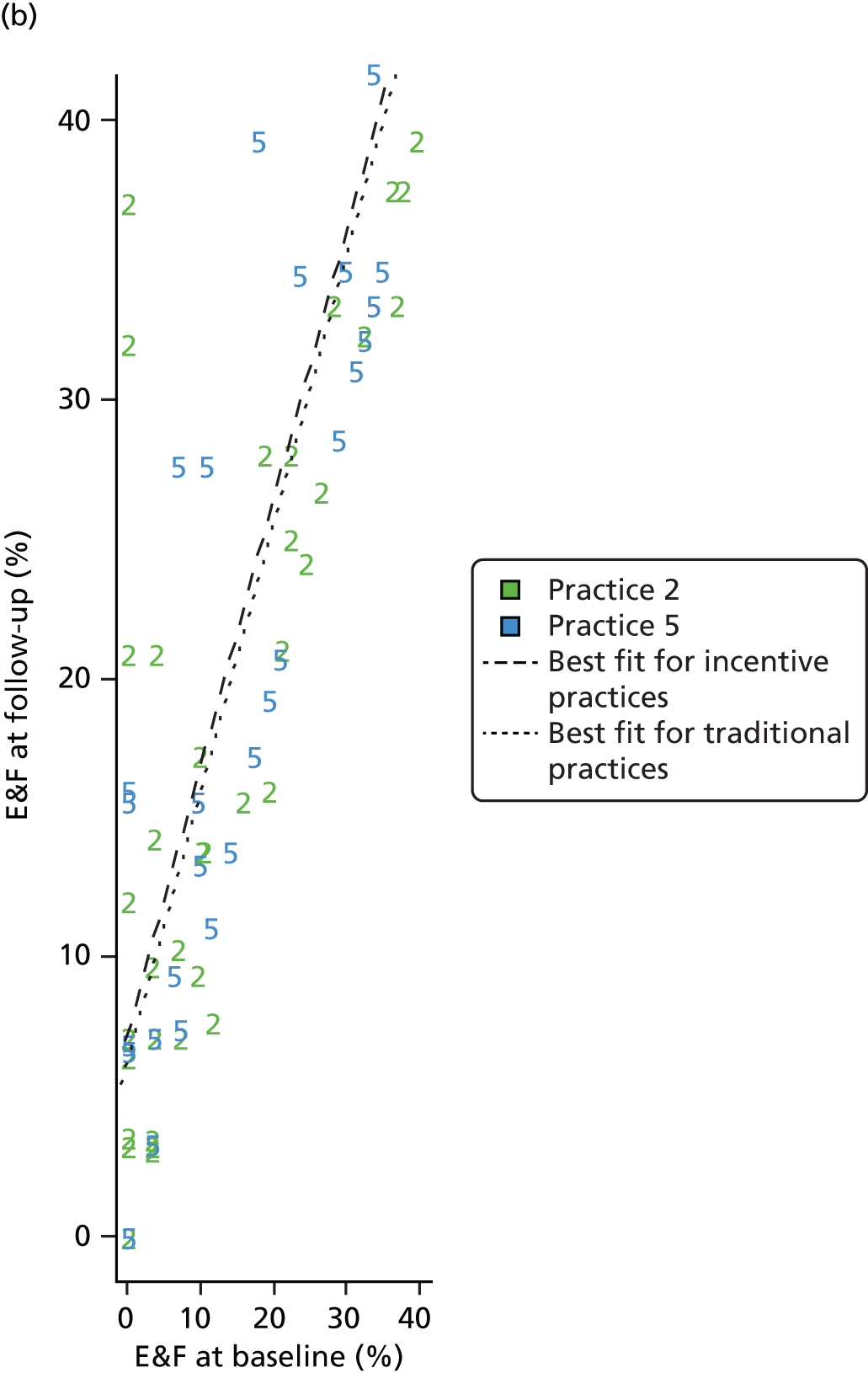

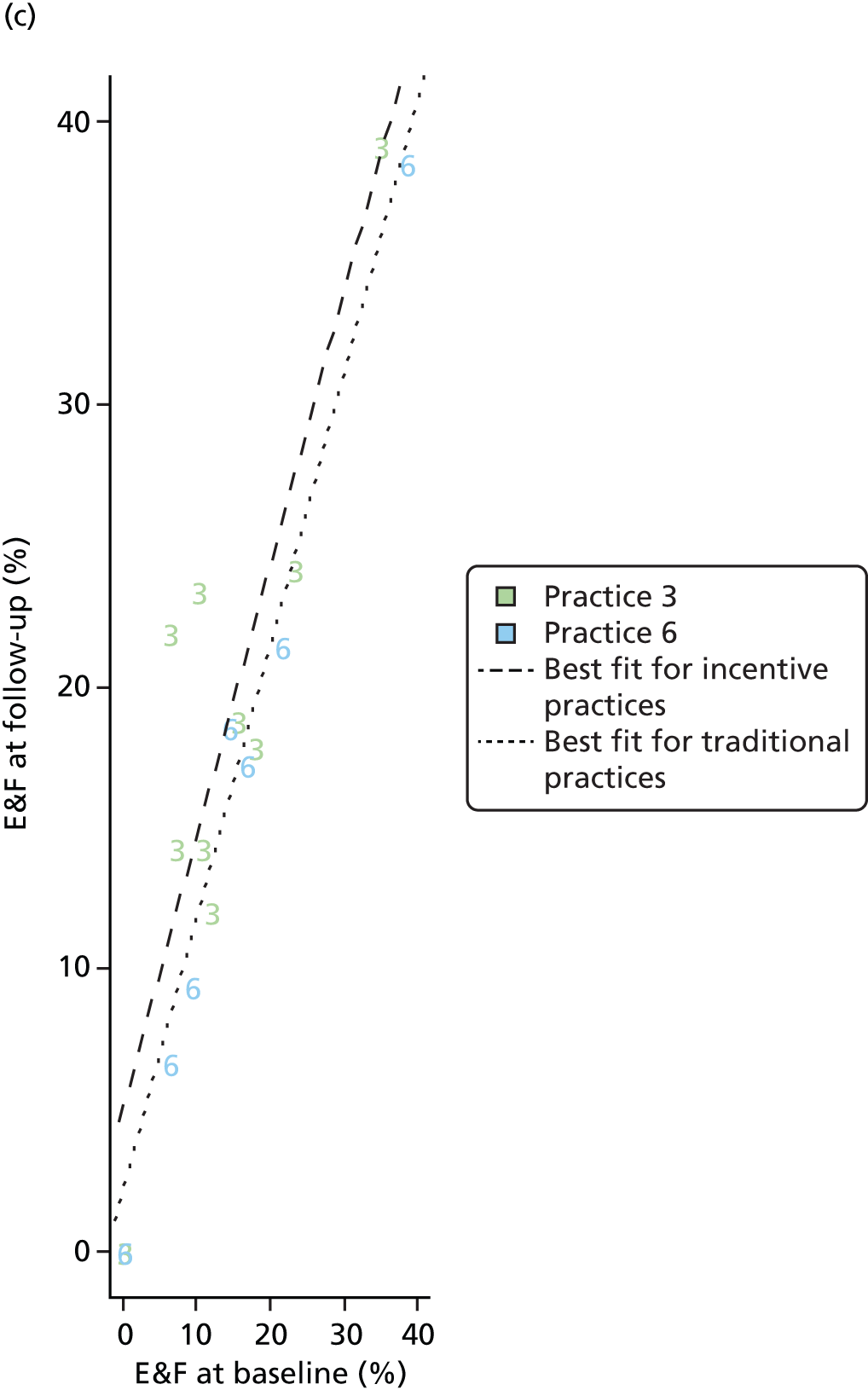

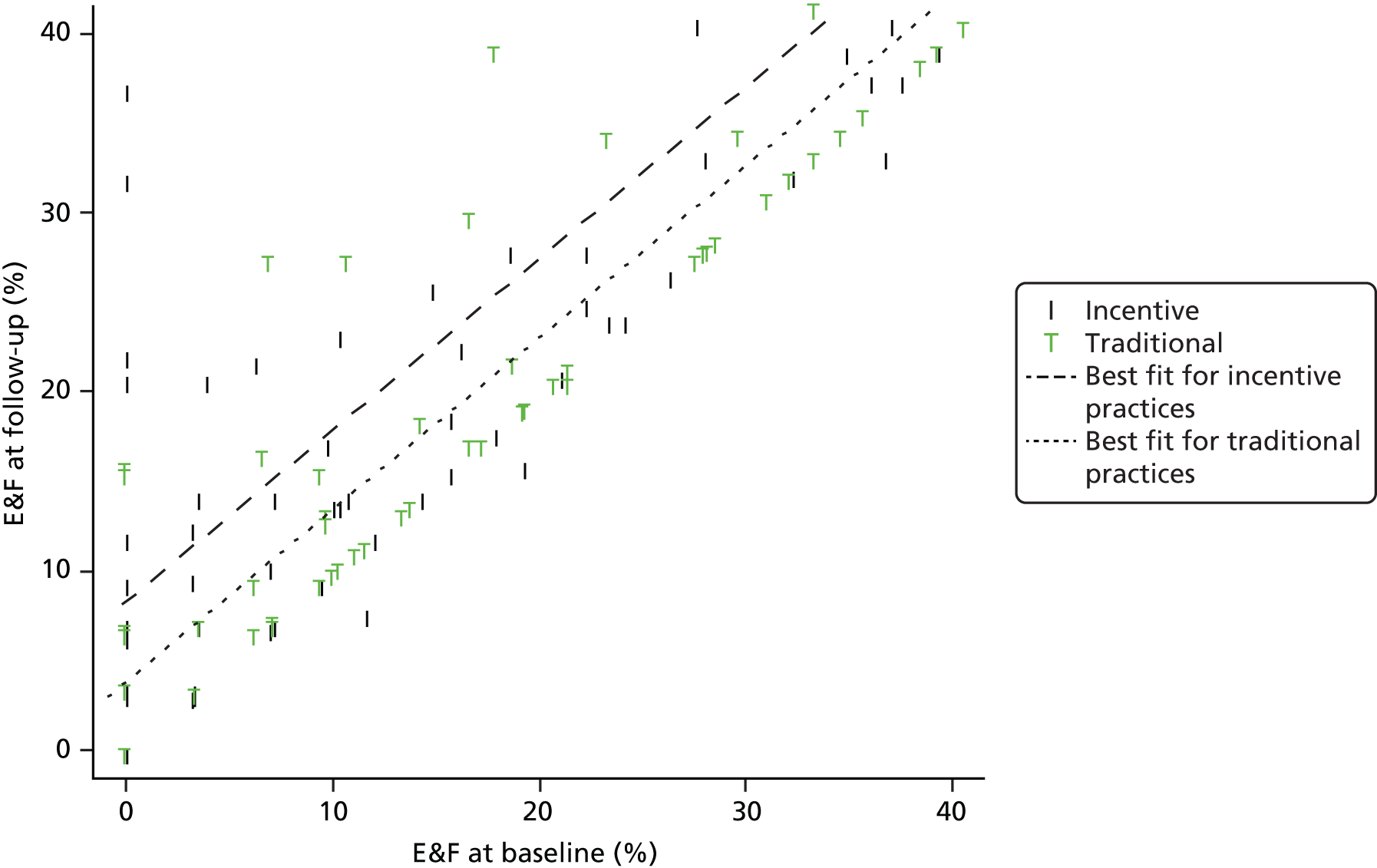

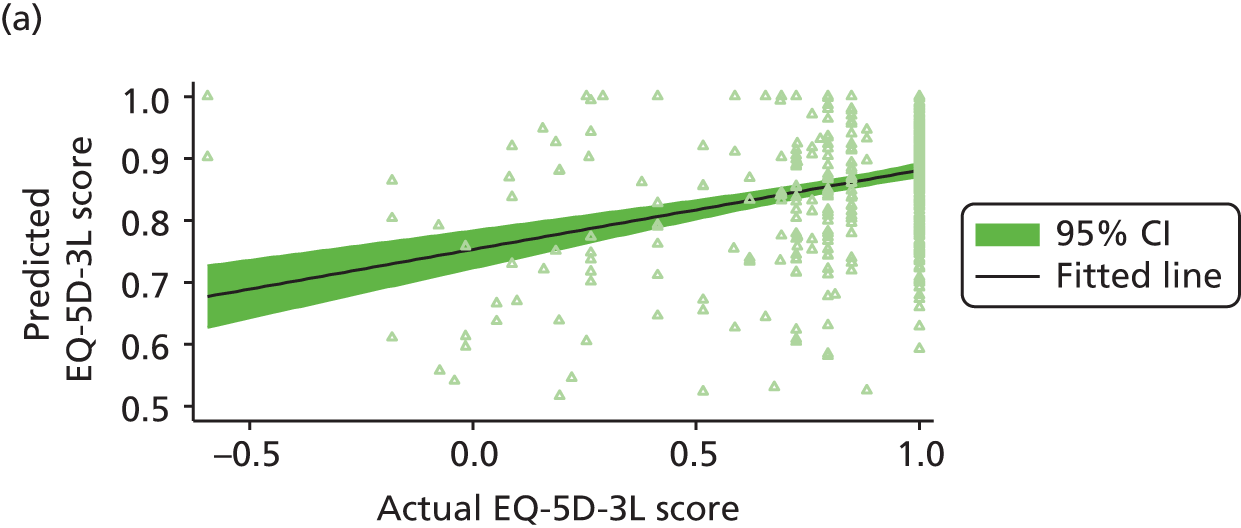

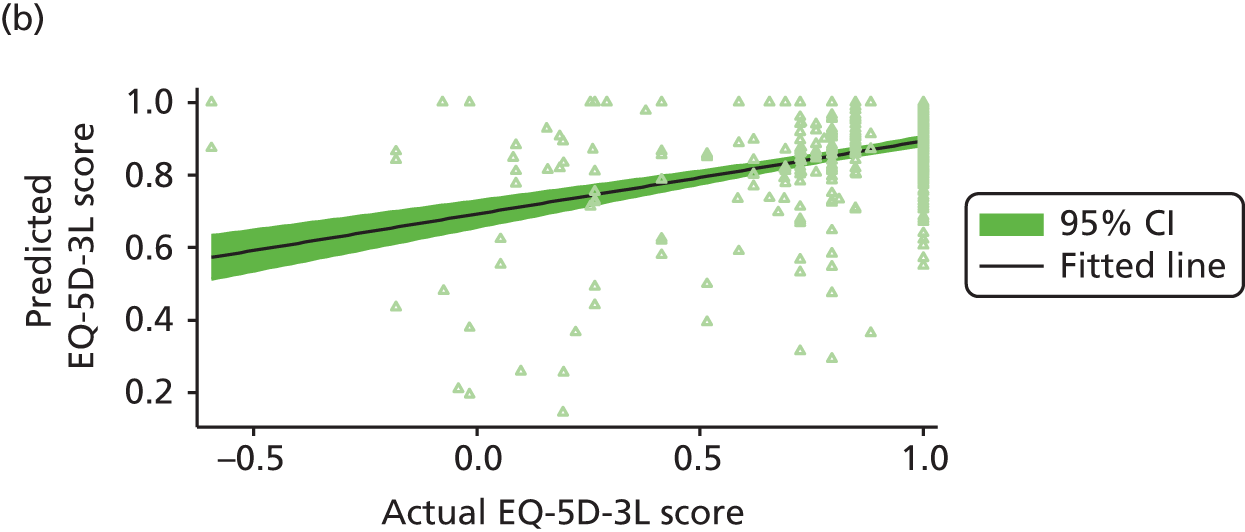

Our quantitative work (see Chapter 4) includes an assessment of the clinical effectiveness of the blended/incentive-driven contract comparing three newly commissioned dental practices with three existing traditional practices. In addition, we used an exploratory study to assess whether or not the traffic light (RAG) risk assessment within the model was fit for purpose.

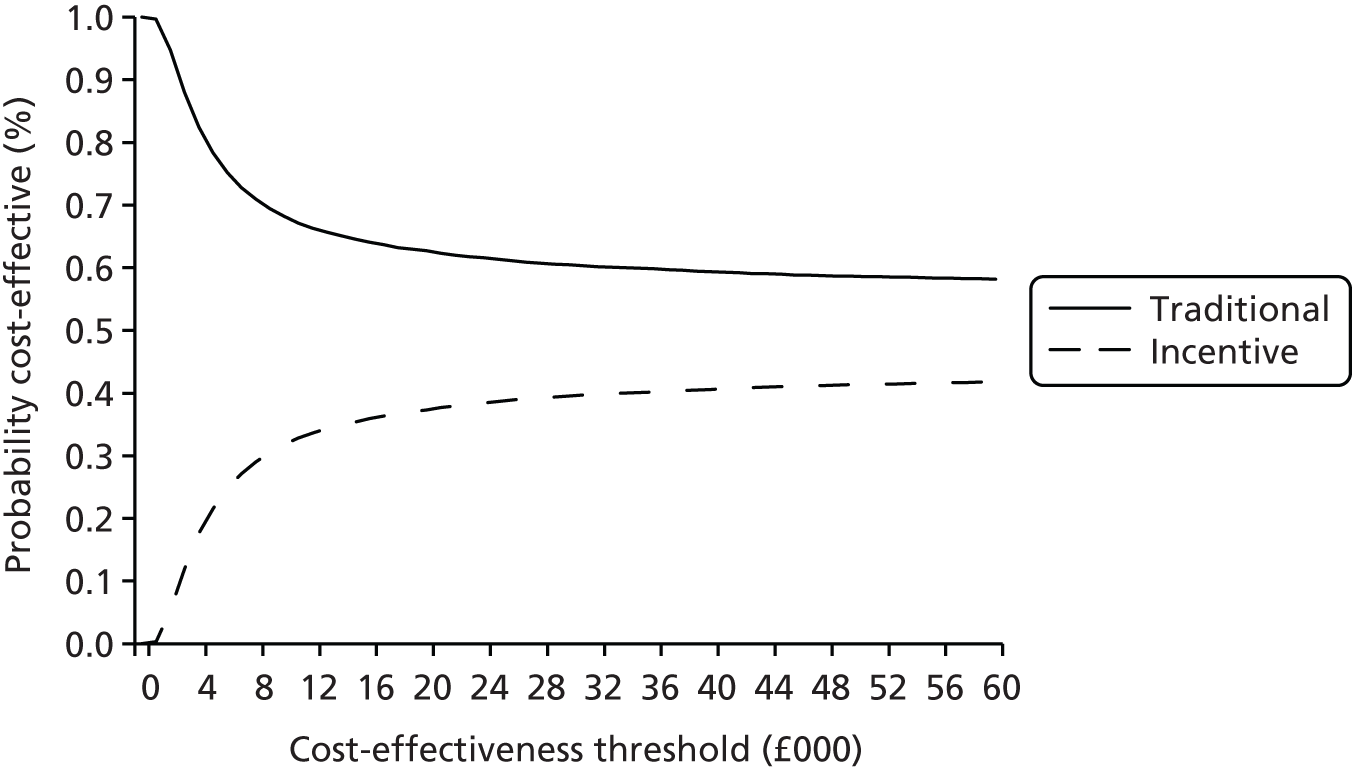

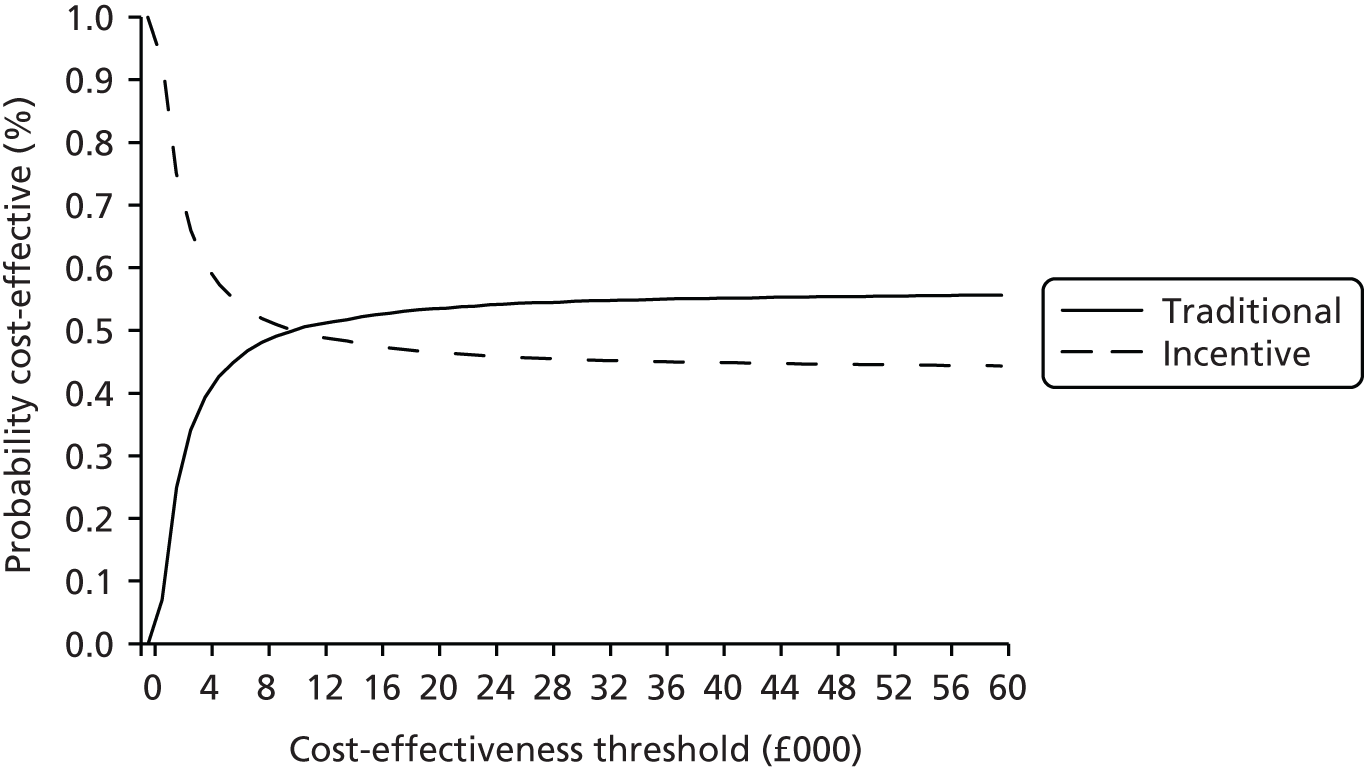

A key question within the study is whether or not the blended/incentive-driven model of service delivery provides value for money, and our third project (see Chapter 5) assesses the cost-effectiveness of the new model compared with the traditional contract. The report concludes with a synthesis of our main findings (see Chapter 6) and a timely discussion of the implications for designing and commissioning future NHS dental services in light of the planned dental contract reform and further national testing of prototype models.

Chapter 2 Research objectives and intervention

Aim and research objectives

The overall aim of the INCENTIVE research study is to evaluate a blended/incentive-driven model of dental service provision implemented in West Yorkshire in the north of England. An ideal commissioning model will complement population-based health improvement measures with sufficient capacity to meet population needs using effective and efficient prevention and treatment to enhance the clinical status and patient-reported outcomes in the patient base. The model evaluated here uses a blended/incentive-driven approach to commission improved health outcomes through the incentivised delivery of evidence-based prevention, care pathways, skill mix and increasing access to dentistry in response to identified needs. The implementation of this novel contract provided an opportunity to evaluate an innovation in health-care delivery that was already being piloted and applied ideas from other settings offering substantial potential benefit for patients and the future commissioning and delivery of dental services throughout England.

Our primary objectives in the INCENTIVE study were to:

-

explore stakeholder perspectives of the new service delivery model

-

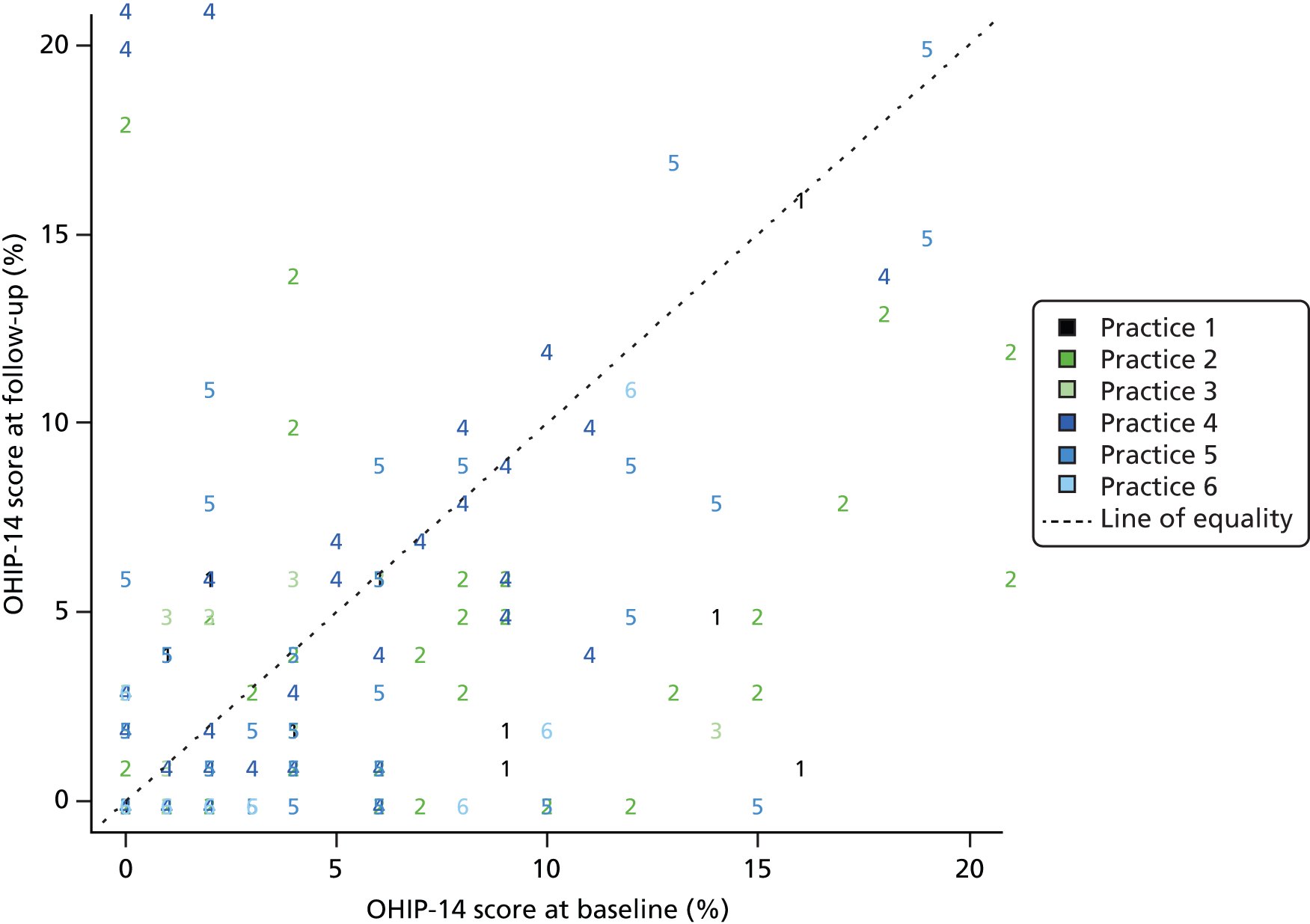

assess the clinical effectiveness of the new service delivery model in reducing the risk of and amount of dental disease and enhancing oral health-related quality of life (OHQoL) in patients

-

assess the cost-effectiveness of the new service delivery model in relation to OHQoL.

Over the course of this study, although our objectives have remained true to our original aim, there was a substantial move towards the introduction of blended/incentive-driven contracts in NHS primary care dentistry subsequent to the Steele report,2 specifically the introduction of the national dental contract pilots and more recent prototypes. It is important to note that the blended/incentive-driven contracts evaluated here pre-date the national dental contract pilots and the Steele report. 2 However, the specification was innovative and reflected the ethos and recommendations of the Steele report2 with regard to an emphasis on quality of care, achieving health outcomes and PROMs. 31 This evaluation therefore complements the national pilots and recent prototypes by not only providing insight into the acceptability of blended/incentive-driven contracts for all stakeholders, but also adding the important perspective of clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness.

The intervention

In 2007, NHS Bradford and Airedale commenced a dental service delivery procurement for three new dental practices. Providers were sought through a national procurement exercise. There was considerable interest from a wide range of providers. Nineteen pre-qualification questionnaires were submitted and, of these, 12 were invited to tender, with seven subsequently interviewed. The PCT was actively seeking bidders who both understood the principles of the Bradford and Airedale service delivery model with its focus on the delivery of OHImp, quality and activity, and had a robust business case and operational plan for delivery. The successful bidders came from a variety of provider models, an independent contractor, a dental body corporate and a not-for-profit corporate.

In 2011, 522,500 people lived in Bradford and Airedale, and population projections expect this to increase at a much higher than average rate to approximately 600,000 by 2030. The three new dental practices were carefully sited to address both oral health needs and demands for NHS dental care. The largest practice was located in an area with a predominantly white population with high levels of material deprivation; the second was also located in an area of material deprivation but with an ethnically diverse population; and the last practice was located in an affluent area (the ward is among the 10% least deprived in the country) with a predominantly white population but lacking access to NHS dental care. These communities represented a rich diversity in terms of ethnicity, material deprivation and age profile, allowing the service delivery model to be tested with a variety of practice populations and a range of providers which in turn allowed the findings to have a wider generalisability and applicability.

The Bradford and Airedale service delivery model instigated in 2007 was based on blended/incentive-driven contracts to address local NHS dental access needs and deliver quality and OHImp in addition to UDAs. The procurement remained timely and in line with subsequent recommendations of the review of NHS dentistry in Equity and Excellence: Liberating the NHS,34 that commissioning should be focused on health outcomes. This delivery system enables quality to be rewarded with payment linked to evidence-based management and monitoring of oral health outcomes. It also allows for continuous improvement through thresholds for payments and emphasis on outcomes by weighting payments. The service was, additionally, implementing quality and outcome measures that allowed us to evaluate their implementation and use.

The three practices operating under blended/incentive-driven contracts were matched with three practices operating under the traditional UDA-based contracts, by demographics, list size and number of dentists. Table 1 details differences between contracts and reimbursement as a result of the new commissioning together with the incentives and levers and how these were expected to impact on process and service delivery.

| Characteristics | Traditional practices | Incentive practices |

|---|---|---|

| Contract type | nGDS contract | A blended/incentive-driven contract |

| Mode of reimbursement | Activity-based, weighted bands of dental activity | Activity: 60% of contract value – UDAs |

| Contract currency UDAs | Incentives: 40% of contract value. (1) 20%, quality (systems, processes and infrastructure); (2) 20%, OHImp | |

| Incentives and levers | Driven by delivery of UDAs, with no incentives for preventative approach | Allocation of payment allows commissioners to incentivise key structures, processes and outcomes for quality and OHImp |

| Health professional responsible for delivery of care | Dentist (with no incentives for therapist and hygienist support) | Blended contract incentivises use of skill mix to deliver preventative focused care |

| Care pathway and recall | Prescribed by individual performers | Risk-assessed (using the RAG system) evidence-based preventative care pathway |

| Risk-assessed recall interval variations recorded | ||

| Stakeholder feedback on delivery and impact of care | Standard complaints/comments | Patient forum |

In detail, within the new practices, 60% of the contract value is apportioned to delivery of a set number of UDAs. The remaining 40% is dependent on the delivery of quality: 20% systems, processes and infrastructure [e.g. cross-infection, policies, Standards for Better Health (latterly becoming Care Quality Commission domains)] and 20% OHImp. The blended/incentive-driven contracts were aimed at ensuring evidence-based preventative interventions (based on Delivering Better Oral Health: An Evidence Based Toolkit for Prevention35) were delivered in line with identified needs for a defined population, increased access to NHS dentistry, and that care was provided by the most appropriate team member to encourage skill mix. It was intended that all the incentive-driven practices would fully utilise skill mix including, for example, dental therapists and hygienists and extended duty dental nurses.

Skill mix

One area of potential advantage in the blended incentive-driven model of delivery is more effective use of the dental team. For example, dental hygienists/therapists can carry out courses of treatments recommended by the dentist who has examined the patient. Dental hygienists can carry out treatments such as scaling and polishing, oral health promotion and fissure sealants. A dental therapist can perform additional treatments such as fillings, pulp treatment/stainless steel crowns and extractions on children. Additional skills dental nurses may be trained and competent to give preventative advice and apply preventative fluoride varnishes to teeth. Intuitively, the delegation of treatment to staff who specialise in only a specific range of treatments could reduce costs and increase access to care but this hypothesis needs testing. 36

Skill mix is advocated in several current proposals that continue a trend seen in UK dentistry over the last 20 years. 2,7,37,38 For example, dental therapists may now work in general dental practice7 and their clinical remit has expanded. 39,40 The number of training places has increased and several educational establishments have instituted programmes. The potential contribution of dental therapy is considerable. Evans and colleagues41 found that, within their current remit, therapists could undertake the treatment provided in 35% of dental visits and in 43% of clinical time. Yet dentistry has not harnessed this potential. Dentists may need models to help them employ dental hygienists/therapists profitably and fully use their skills and there have been calls to develop a system that encourages dentists to use dental hygienists/therapists differently. 42,43 The PDS pilots failed to fully involve the wider skill mix available (i.e. dental care professionals or improve their conditions to recruit and retain them). 9

Although there are few hard data to support skill mix in dentistry36 some data are beginning to emerge. A recent practice-based study found the success of fissure sealants to be comparable whether placed by dentists, hygienists or therapists. 44

There is a trend towards greater professional acceptance of therapists,43,45–49 with approximately 60–70% of dentists prepared to consider employing a therapist in the more recent studies. 50,51 Despite this, some dentists remain uncertain of the role of dental therapists. 51,52

There is also some uncertainty about public acceptance of dental therapists. Two recent surveys and a qualitative study suggest that few lay people are aware of dental therapists as a professional group. 53,54 Furthermore, even after the training of dental therapists was explained to them, only 61% of adults were willing to receive simple restorative treatment from a therapist. 53,54 The provision of dental care is influenced by the NHS contract for dentists. The existing UDA contract does not make any allowance for treatment provided by dental therapists, although since 2013 dental hygienists and therapists can carry out their full scope of practice without a prescription or the need for the patient to first see a dentist; this is known as direct access and the impact of this on dental team delivery is yet to be realised. Research is therefore needed to assess if new models of delivery and service design will encourage their use and whether or not they are acceptable to dentists and patients.

Care pathways

The Bradford and Airedale new service delivery model (incentive) was designed to encourage a care pathway approach in which all patients have an OHA on joining the practice and at each subsequent recall. Four sets of information [age group, medical history, social history (self-care, habits/diet) and clinical assessment] are used to inform a traffic light (RAG) risk assessment for patients with high (red), medium (amber) or low (green) risk of oral disease (Table 2).

| Risk | Descriptor | Example indicators |

|---|---|---|

| Red: high | High risk of disease identified through clinical assessment and social history | Clinical: active decay in more than one tooth, BPE Social history: never brushes teeth |

| Amber: medium | Medium risk of disease identified through clinical assessment and social history | Clinical: active decay in one tooth, BPE score of > 2 in two sextants Social history: brushes once per day |

| Green: low | Low risk of disease identified through clinical assessment and social history | Clinical: no active decay, BPE score of 2 confined to one sextant Social history: brushes twice a day |

Within the model, each patient follows a care pathway according to the protocol. The care pathway includes evidence-based preventative treatment and advice, suitable recall interval and restorative care as appropriate (e.g. the red risk category limits patients to stabilisation and lowering their risk status). The care pathway’s evidence base was based on the Department of Health’s Delivering Better Oral Health: An Evidence Based Toolkit for Prevention. 35 Each patient’s status is reviewed on their next OHA. Patients may therefore move between risk categories. Monitoring in practices ensures that evidence-based preventative interventions are delivered in line with identified needs and monitored access to dentistry. OHImp is assessed through the delivery of a performance framework. This framework is based on the transfer of ideas from the general practitioner contract QOF. (It is of note that this contract pre-dated the DQOF. 19)

There is little literature regarding care pathways in primary dental care, though the concept has been around for a number of years. The concepts and benefits of the care pathway approach in dental primary care were described by Hally and Pitts. 55 As a result of recommendations within NHS Dentistry: Options for Change,7 the first widely disseminated care pathway in UK dental primary care was the OHA within the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance on dental recall intervals. 56 The OHA care pathway was designed to enable more prevention within personalised care plans taking into account patients’ social and dental histories as well as clinical findings.

The type of risk assessment (the RAG traffic light system) included in the blended/incentive-driven contract in our study has hitherto not been fully evaluated. Examination of different RAG models in other dental settings is ongoing in the north-west of England. 57 Early findings from the NHS dental contract pilots suggest small improvements in risk reduction over the short term. 20

In summary, the incentive dental contracts are aimed at ensuring that evidence-based preventative interventions are delivered in line with identified needs for a defined population; ensuring increased access to dentistry; and ensuring that care is provided by the most appropriate team member to encourage skill mix. Quality indicators linked to contracts and payments have been used widely in other branches of health care, and the results are complex. The indicators can drive organisational change towards best practice, but may also be a disincentive to important but non-rewarded activities. 24 Used alongside demographic data, the indicators can measure practice performance, identify areas for development and assist sharing of best practice. 58 The indicators often increase the quantity of service provision, but not always the quality. 59 Furthermore, the indicators can affect the dynamic of professional relations and the doctor–patient interaction. 60 Although offering great potential, the DQOF with embedded quality indicators has not been comprehensively evaluated in dentistry. A recent systematic review was only able to provide a framework for how such indicators might work. 61 The blended/incentive-driven contract in West Yorkshire provides an opportunity for a comprehensive evaluation to inform the next dental contract reform.

Chapter 3 Stakeholder perspectives of the blended/incentive-driven service delivery model

Introduction

As outlined in Chapter 2, in 2007 the PCT in Bradford and Airedale commenced procurement for three new dental practices to address access to NHS dentistry and to pilot a new service delivery model. The model was based on a blended/incentive-driven contract and, although it pre-dated the Steele report2 and the NHS dental contract pilots, its specification although innovative actually reflected the ethos and recommendations of the report placing an emphasis on quality of care and achieving OHImp in accordance with the Steele report2 and Equity and Excellence: Liberating the NHS34 that followed. The successful bidders represented three provider models: an independent contractor, a dental body corporate and a social enterprise organisation.

The contract blends novel incentives to demonstrate quality and OHImp as well as volume of service (measured in UDAs) and, therefore, shares features with the reformed dental contract piloted by the Department of Health. 18 Most of the contract’s value (60%) arises from the delivery of UDAs. The remainder is divided equally between delivery of quality including systems, processes and infrastructure (e.g. infection control) and on OHImp (implementation of Delivering Better Oral Health: An Evidence Based Toolkit for Prevention35). Thus, the contract is intended to promote evidence-based preventative interventions, widen access to dentistry and encourage the use of skill mix.

A central feature of the contract is a ‘care pathway’, whereby an initial OHA for each patient joining a practice determines the risk of poor oral health and guides treatment and the frequency of recall appointments. These decisions are informed by the patient’s age, medical history, social history (e.g. self-care, habits or diet) and the clinical assessment. Patients are categorised according to RAG status with high, medium or low risk of oral disease. The treatment protocols consist of evidence-based preventative care and advice, restorative care and designated recall intervals. Patients who are considered ‘red’ are limited to stabilisation and lowering risk status. Statuses are reviewed at future appointments with the potential for patients to move between groups, for example moving from ‘red’ to ‘amber’ (see Table 2).

The three newly commissioned dental practices were in areas of high oral health need and with high demand for NHS dental care. The largest practice (practice 2) was located in an area of Bradford with a predominantly white population with high levels of deprivation. Practice 1 was in a neighbouring town in an area of material deprivation but with an ethnically diverse population (over 50% of Pakistani/Bangladeshi origin). Practice 3 was the smallest practice with only two surgeries. It was located in a predominantly white affluent area (among the 10% least deprived wards in the country), yet lacked access to NHS dental care.

In this chapter we report on the qualitative research to explore stakeholder perspectives of the new service delivery model. We describe meanings of key aspects of the model across three stakeholder groups {lay people [i.e. patients and non-patients (non-patients are defined as individuals not having a dentist)], commissioners and the primary care dental teams}, with framework analysis of focus group and semistructured interview data.

Methods

Our focus lies on the three newly commissioned dental practices working under the blended/incentive-driven contracts (incentive practices) and three dental practices working under traditional nGDS contracts (traditional practices). The traditional practices were included in the study as comparators and were matched with the incentive practices by deprivation index, age profile, size of practice and ethnicity. Details of all six practices are given in Table 3.

| Demographics | Incentive practices | Traditional practices | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of contract | Blended contract: UDA and incentives for health promotion/prevention activity | Working under 2006 NHS dental contract (nGDS contract) | ||||

| Practice | Practice 1 | Practice 2 | Practice 3 | Practice 4 | Practice 5 | Practice 6 |

| Established | 2008 | 2009 | 2009 | > 10 years | > 10 years | > 10 years |

| Operated as | Part of a large corporate provider | Independent provider | Part of a social enterprise organisation | Part of a large corporate provider | Independent provider | Independent provider |

| Location | Centre of large town | South-east Bradford | In an affluent market town | Centre of large town | North-west Bradford | South-west Bradford |

| Percentage of households with at least one dimension of deprivation (employment, education, health and disability, housing)a | 74.6 | 71 | 42. | 74.6 | 51 | 53.9 |

| Number of GDPs | 4 | 5 | 2 | 6 | 7 | 2 |

| Multidisciplinary team (e.g. hygienists or therapistsb) | 1 therapist | 2 therapists | 1 therapist | 2 hygienists | 1 hygienist | None |

| Number of surgeries | 5 | 5 | 2 | 7 | 6 | 2 |

| Population ethnicitya | 51.3% Pakistani/Bangladeshi | 79.4% white British | 94% white British | 51.3% Pakistani/Bangladeshi | 92.8% white British | 89.2% white British |

The qualitative study uses focus groups and semistructured interviews, supplemented with observations made during dental appointments of the delivery of dental care in the incentive practices and the traditional practices.

Purposive sampling via a sampling matrix supported recruitment of participants with different experiences of the model. The three stakeholder groups were lay people (i.e. patients and non-patients), dental teams (i.e. dental practitioners, dental care professionals and practice managers) and service commissioners.

Encounters were observed in two incentive and two traditional practices. Staff were purposively sampled across the range of skill mix so that similar numbers (15 each) of dentists and dental hygienists/therapists were observed. All eligible adult patients (aged ≥ 18 years) with appointments with the participating staff on the scheduled day of observation were invited to participate. At 2 weeks before their appointments, patients were sent a letter informing them of the study, a study information leaflet and a consent form. Patients who expressed interest in the observations were given the opportunity to ask any questions and give consent on the day of their appointment. The ‘non-participant’ observer attended appointments passively at a distance close enough to hear the conversation to take comprehensive field notes. A brief analysis of observations was conducted as soon as possible after the observation (the same day or the following day).

Observations were followed by interviews with clinicians, resulting in the participation of four dentists and four dental hygienists/therapists that took place on the same day. Staff were asked to comment on the observed encounters and share their views on what had taken place. Questions asked at the post-observation interview were influenced by the nature of the activity in the encounters and the team member’s attitude, expectations and impressions and reflections on the experience. Interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Interviews were also conducted with patients, lay people recruited through community settings, commissioners and dental team members (see Tables 4 and 5).

Lay people were recruited for the interviews in two ways. The research team gave practices information packs to mail to patients. Potential participants indicated interest in the research by returning their contact details in a Freepost envelope and were then contacted to arrange an interview. Lay people who were not patients included representatives of community groups in the locality. The researcher contacted the gatekeeper of community organisations to explain the study and provide research information and enlisted their help in recruitment. Focus groups were held with groups attending a community centre, including one aimed at parents with young children and another attended by older residents. In addition, snowball sampling entailed existing participants passing the study information and the researcher’s contact details on to acquaintances to invite them to take part. 62 The inclusion criteria for lay people were that they should be aged ≥ 16 years and willing to be interviewed. People with no natural teeth were excluded.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was obtained from the National Research Ethics Service (NRES) Committee [London – Bromley, Research Ethics Committee (REC) reference 12/LO/0205] on 5 April 2012. Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to any qualitative enquiry. The study was sponsored by the University of Leeds, Leeds, UK.

Data were collected between August 2012 and February 2014 by two research associates, who were social scientists rather than dentists. Interviews and focus groups followed a topic guide, partly informed by the theoretical framework (see Appendices 1 and 2) but supplemented with themes that emerged from the observations and previous interviews. Interviews with dental team members took place at the dental surgery, while interviews with patients took place in patients’ homes. All were recorded and transcribed verbatim. Interviews lasted between 15 and 70 minutes.

Theoretical framework

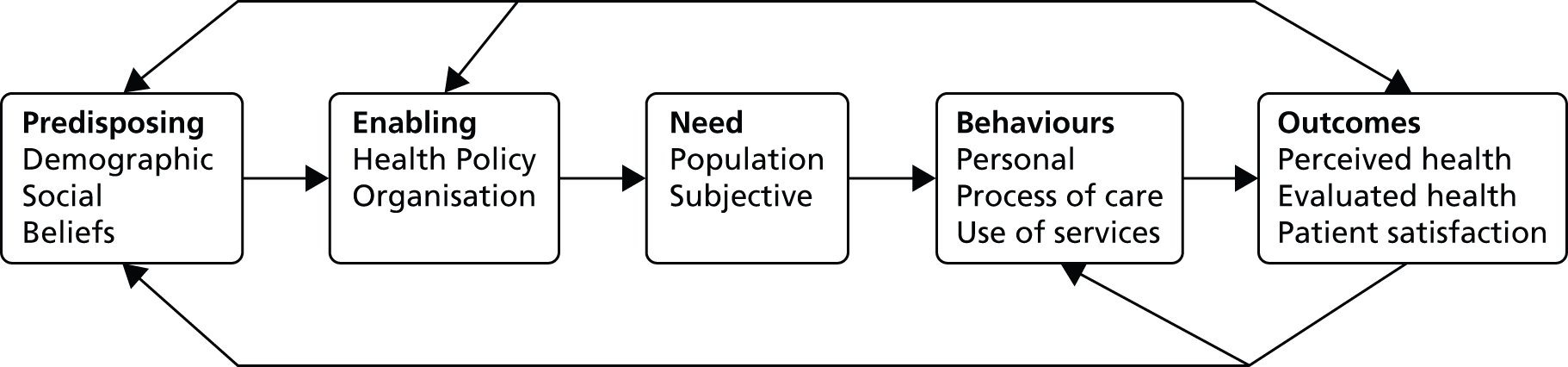

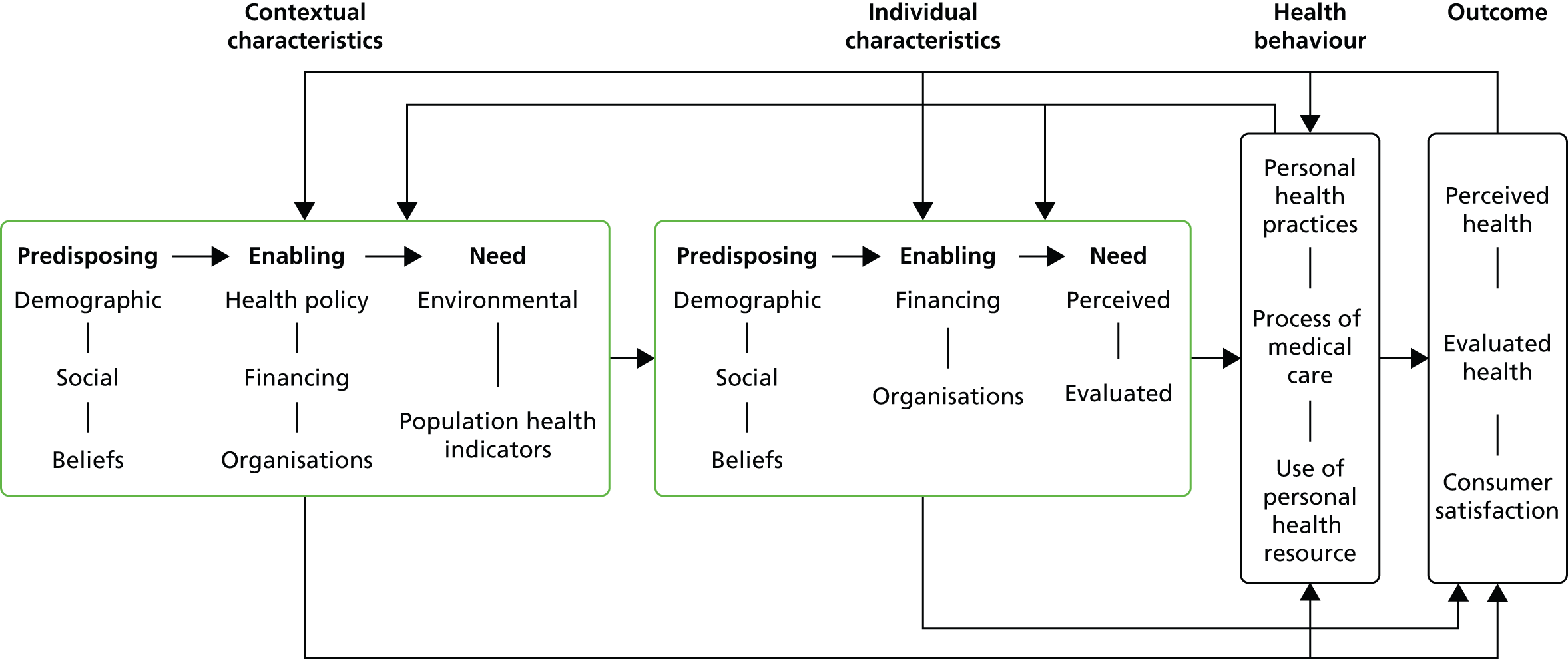

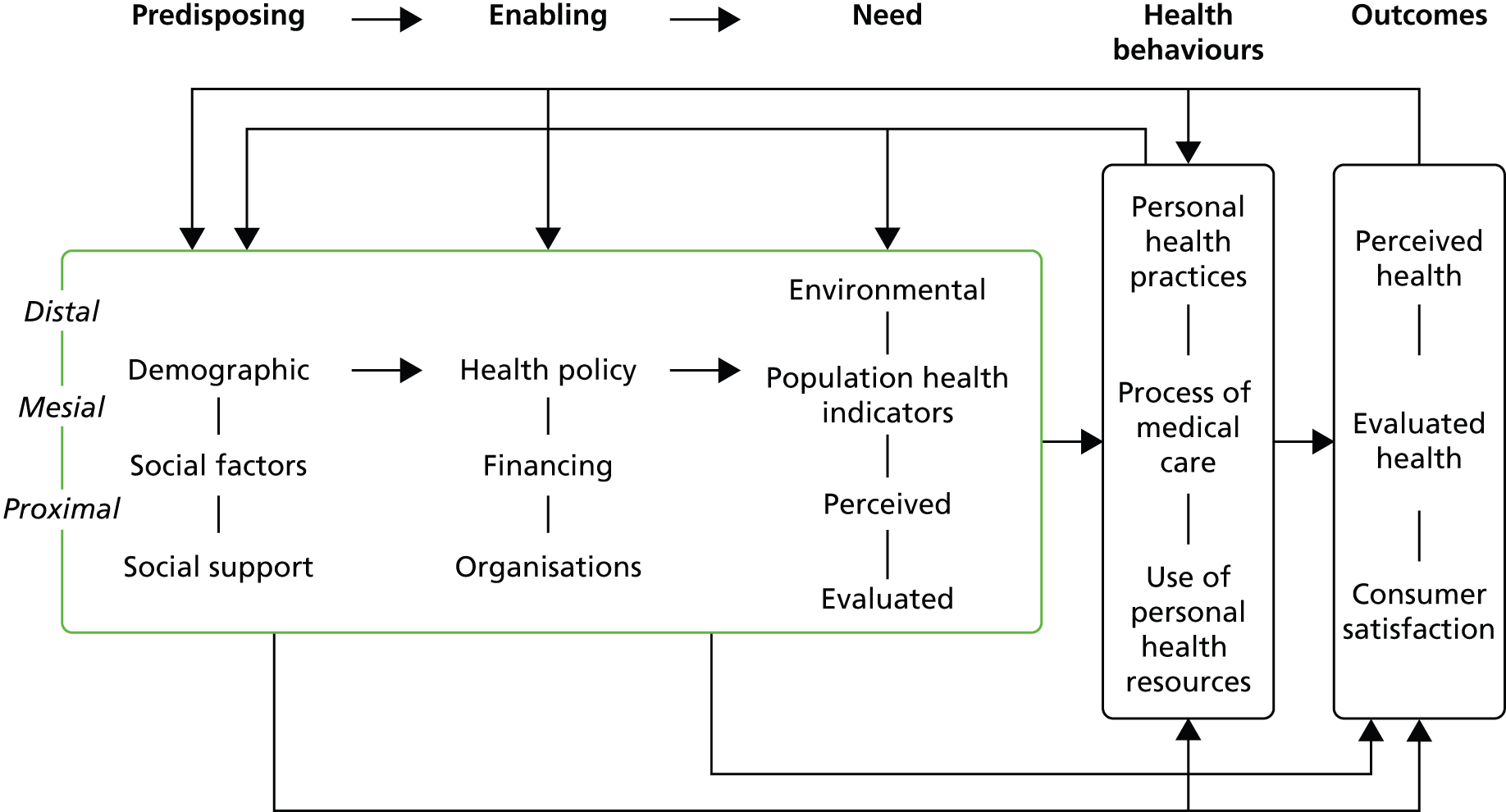

The Andersen behavioural model of access was employed as the theoretical framework for the qualitative analysis (Figure 1 shows a simplified depiction). The model sees access as ‘the use of personal health services and everything that facilitates or impedes their use’63 and distinguishes between ‘potential’ and ‘realised’ access. Potential access is measured according to enabling variables such as the availability of care or supply of health-care workers. ‘Realised access’ refers to services actually used or ‘utilisation’. 63

Originally developed 40 years ago as a model of health-care utilisation, the model has evolved in line with advances in understanding that have moved from an individual focus to incorporate the interaction between the individual, the health-care system and the external environment. 63–65 The revisions have not altered its basic foundations, but have added components to it. Later versions introduced health and patient satisfaction as desirable outcomes of health care, which were said to be determined by predisposing and enabling factors, behaviours and need. Findings from studies in many areas of health care, and dentistry in particular, support its use. 66,67

Enabling factors relate to the policies, facilities, staff and the organisation of services that might influence utilisation. 65 It is helpful to consider enabling factors as a spectrum, with different qualities of the same factors either facilitating or challenging service use. Policies, guidelines, rules, practices, contracts, resources and reform define the nature and delivery of care. Financial factors can include the funding and affordability of health care. Organisational factors refer to the structures and processes that influence the availability and distribution of health services, and the personnel and how accommodating they may be to patients’ needs.

From this perspective the blended/incentive-driven contract being evaluated in this study is an enabling factor with health policy, financial and organisational facets. The government has made policy commitments to oral health and dentistry with focus on improving the oral health of the population, particularly children, introducing a new NHS primary dental care contract and increasing access to NHS dentistry. 18,68 Other relevant drivers included the recommendations of the Steele report2 and the evidence-based prevention of Delivering Better Oral Health: An Evidence Based Toolkit for Prevention. 35

The contract replaces some of the financial emphasis on the volume of treatment with incentives for quality and changed outcomes. These incentives were based on the concept of providing care for a population rather than patients via organisational changes such as the use of care pathways, the provision of evidence-based care and the use of skill mix.

Health-care need may be seen as the potential to benefit from care and requires both a health problem and an effective intervention. 69 Health needs may include health education, disease prevention, diagnosis, treatment, rehabilitation and palliative care.

The Andersen behavioural model distinguishes between evaluated (professionally defined or normative) and perceived (personally defined or felt) need70 but recognises that there are social aspects of evaluated need, which can be influenced by technological developments and clinical guidelines.

In some versions of the model predisposing, enabling factors and need are distinguished at the contextual or individual levels. Contextual characteristics operate at a population or combined level, drawing attention to the environment or the circumstances in which health care is delivered. The most recent versions of the model have seen the context and individual levels arranged sequentially with contextual predisposing and enabling factors and need influencing similar factors for individuals.

In turn, these components could influence personal and professional health behaviours. Personal behaviours are activities that shape health status, such as oral hygiene, diet and tobacco use. Health service use is treated as behaviour in itself. Professional behaviours relate to the processes of medical care, such as health education, clinician–patient communication and prescribing behaviour. Both personal and professional behaviours may be amenable to changes via enabling factors and will influence the nature and volume of treatment provided.

The outcomes are (1) perceived and evaluated health status and (2) patient satisfaction. The maintenance and improvement of health should be the primary outcome of access and is a central target of the dental contract reform programme. 68 Perceived health status indicates how much an individual can live a ‘functional, comfortable and pain free existence’. 65 This definition is akin to OHQoL, which may be defined as ‘the impacts of oral disorders on everyday life that are important to people and of sufficient magnitude to affect perception of their life overall’. 71 However, other patient-reported outcomes could be used, such as general health perceptions. Evaluated health status requires a professional assessment of clinical status. Patient satisfaction has a bearing on patient health outcomes, with greater satisfaction being related to health improvement via adherence, involvement with treatment and continued use of services.

An important feature of the model is its recursive nature, with feedback loops so that the outcomes of access have the potential to influence future predisposing and enabling factors, population needs and use of services.

Analysis

Data were analysed in two phases. First, pen portraits of the practices are used to give the data context.

Within the second phase the principal approach used framework analysis to induce the results from the variety of original accounts across stakeholder groups within the structured policy focus of the research. 32,33 The focus of the analysis was to explore the effect of the contract as it interacted as an enabling factor with other stages of the model. Analysis adhered to the following process:

-

familiarisation with the data

-

identifying the thematic framework

-

indexing

-

charting

-

mapping and interpreting. 32

A member of the research team (MH) studied the field notes and transcripts of the post-observation interviews. This process of familiarisation (familiarisation with the data) enabled identification of emerging themes in the data set. 72 Although Andersen’s behavioural model guided the thematic framework in principle, data were not forced into an a priori model. Instead, the framework was refined as required (identifying the thematic framework). Data generated from the post-observation interviews were indexed according to the particular theme to which they corresponded (indexing) and lifted from their original text and placed under subheadings derived from the framework (charting). The themes were flexible and modified as necessary. Data were organised by theme to enable a process of constant comparison across themes and cases. The framework analysis served to either confirm or challenge the model. A form of deviant case analysis was intended to be used to add new categories or revise the model.

The validity of the findings was supported by discussion of interim and final results for triangulation and corrections with participants in focus groups. The results were also compared against existing knowledge, such as the evaluations of the NHS dental contract pilots. 30

Results

Pen portraits of the practices are presented in Table 3 to set the context of the study. The qualitative results of the principal analysis are presented in two stages. First, the major themes in the data are outlined. Second, the interactions between the themes, focusing particularly on the interactions between enabling (i.e. service organisation) and other factors, are described.

Three study practices (1, 2 and 3) were using the blended/incentive-driven contract approach, referred to as incentive. These were matched to three control practices (4, 5 and 6) operating nGDS contracts, referred to as traditional, according to the number of general dental practitioner (GDP) surgeries in the area, list size and the deprivation index and ethnicity of the local populace.

Practice 1

Practice 1 is situated in the centre of a large town several miles from Bradford. The practice is based within the one of the 10% most deprived wards in the country, with associated adverse income, living environment, education, health and employment indicators. The practice estimates that approximately 80% of its patients are eligible for benefits and a similar proportion are white British, despite the ethnicity of around 50% of the local population being of Pakistani/Bangladeshi origin. The practice was established in 2008 and is operated by a very large national corporate provider. Its team consists of four GDPs and one dental therapist.

Practice 2

Practice 2 is located at the south-east edge of Bradford, adjacent to a large council estate. Bradford ranks 16th in the most deprived local authority areas in England. The area served by the practice originally had a white British population, although it has become more ethnically diverse in recent years and has a traveller community. The people of this area had experienced difficulties with access to dental care for many years, with limited care available in the area and a local unwillingness to travel for care.

Established in 2009, the practice is owned by an independent contractor with two other practices (not part of the blended/incentive-driven contract). The practice has five surgeries, a separate decontamination room and staff training room. It employs five dentists and two dental therapists. Almost all of its treatment is provided under the NHS (99.5%).

This practice experienced a higher staff turnover than the other study practices, which was attributed anecdotally to the associates being early-career dentists eager to take up a post but not necessarily a commitment to practising in the locality in the long term. Lack of opportunities to carry out complex treatments was also thought to be a factor.

Practice 3

Practice 3 is located in an affluent market town several miles from Bradford, which has lacked NHS dental provision. It was established in 2009 and the provider is part of a social enterprise organisation. It has two surgeries, two dentists and one dental therapist. During the research, one GDP left this practice. The original practice manager was replaced, but later returned.

Three comparison practices (4, 5 and 6) continued to work under the terms of the 2006 NHS dental contract and were matched to the blended/incentive-driven practices according to the number of GDP surgeries, list size, and the deprivation index and ethnicity of the local populace.

Practice 4

Practice 4 is close to practice 1 and part of a group that operates more than 200 practices in the UK. With more than 10,000 NHS patients the practice is not currently taking on any new patients. Almost all (96%) of the work is provided under the NHS. There are seven surgeries, staffed by six GDPs. Two dental hygienists are employed.

Practice 5

Practice 5 is an independent practice on the outskirts of Bradford and is the longest serving practice in the study (over 30 years). It has six dental surgeries with seven GDPs and one dental hygienist, who is available on a private basis. One dentist’s services include non-surgical procedures such as fillers.

Practice 6

Practice 6 is an independent practice run by two dentists. There are no dental hygienists or therapists, but the practice provides a full range of NHS treatments (except orthodontics) to all members of the public. It also provides private treatment including sedation for anxious patients.

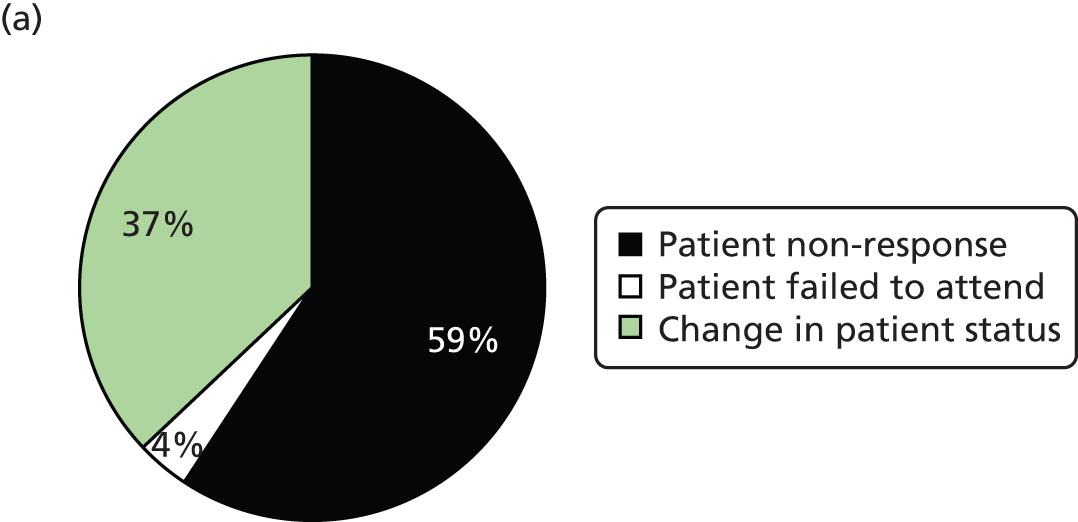

Qualitative results

Observations were made during 30 dental appointments. Eighteen lay people, 15 dental team staff and a member of the commissioning team took part in the interviews and focus groups (Tables 4 and 5).

| Pseudonym | Practice | Details |

|---|---|---|

| Michael | 2 | In his early forties, recently made redundant, former army, cohabiting with partner |

| Shazia | 2 | Community worker, in her thirties, married with children |

| Katie | 2 | Mother of two, in her twenties, lives with partner, receiving benefits |

| Tony | 2 | Tony and Jeanette are a married couple. Tony is aged 66 years and is visually impaired. Jeanette (aged 65 years) is in a wheelchair following a stroke. Moved to practice 2 because their previous dentist lacked wheelchair access |

| Jeanette | 2 | |

| Ian | 3 | Married couple in their mid-forties |

| Grace | 3 | |

| Martin | 3 | Married police officer, in his forties, with two children |

| Lara | 1 | Housewife, in her thirties, married with children |

| Nanush | 1 | Married housewife with three children, in her thirties |

| Alison | Patient at a traditional practice | Working mother of one, in her thirties |

| Carol | Patient at a traditional practice | Stay-at-home mother of two, in her forties |

| Kat | Patient at a traditional practice | Stay-at-home mother of two, in her twenties. Her children attend an incentive practice |

| Natalie | No dentist | Mother of two, in her twenties, lone parent, receiving benefits |

| Johanna | No dentist | Focus group with three women in their seventies and eighties. Each had dentures to varying degrees |

| May | No dentist | |

| Mary | No dentist | |

| Ann | Discontinued incentive patient | Housewife in her fifties |

| Participants | n |

|---|---|

| Traditional practice dentists | 4 |

| Incentive practice dentists | 8 |

| Dental practice managers | 2 |

| Dental therapists | 1 |

| Commissioners | 1 |

The Andersen behavioural model framework was sustained in the data, with the only revision being the addition of trust as an outcome of access. During the analysis, the implications of the epistemological position of the model became apparent. A wider debate may be required about enabling the use of social resources for health and the position of health services within that. This debate is introduced in the discussion. The results described are supported by anonymised quotes from the data.

The qualitative results are presented in two sections. The first demonstrates the fit between the data and the Andersen model and the second examines the effect of the new contract as interactions between enabling and other factors in the model.

Predisposing factors

Predisposing factors could be characterised as demographic and social characteristics and beliefs. For example, family commitment could facilitate or hamper service utilisation and one participant (Grace) noted the effect of changing attitudes over time.

I can’t remember where I go, I wish I could. My daughter takes me to all my appointments.

Mary, no dentist

I think the danger is when you’re a professional this is what you do for a living, it’s a danger as its making an assumption that everybody else thinks it’s as important as you, and it is down to education and you know we see ourselves very much as a practice set up to educate and to inform. When you’re dealing with the demographic and you know the type of community we are working with, you’ve got to be very careful not to be patronising, you have to be very careful because you know everybody’s need is different and everybody’s circumstances, you know we shouldn’t just assume that because we think it’s important that they will.

Sarah, incentive dentist

I think and it’s something that kind of you’re very aware for your children as well aren’t you? I think when I was younger there was a different kind of attitude towards it and I only went to the dentist if there was a problem and I think attitudes have changed now and I think that its, you know you’re much more proactive in making sure that your children go and they get seen and that type of thing.

Grace, incentive patient

These data suggest that from the patients’ perspectives predisposing factors are things that either hamper or enhance their ability to access care. For the providers it involves fitting the service to what the dentist thinks the patient needs. The last quotation indicates a generational change and changing attitudes to the dentist.

Enabling factors

Compatible with the underlying framework, enabling factors fell into three subthemes of health policy, finance and organisations. The influence of health policy appeared in the data between the extremes of the changes associated with implementation of the blended/incentive-driven contract right through to an apparent lack of policy in some practices.

There’s going to be challenges in terms of its new, so you’ve constantly got perhaps a more demanding type of commissioning process. From a commissioner’s perspective as I mentioned earlier it takes more time.

Service commissioner

We don’t have any guidelines or anything.

Dentist at feedback event, traditional practice

A key part of the contract was the remuneration of dentists and thus finance was a rich theme. On the one hand traditional models of service use were problematic for the treatment of complex cases, whereas the problem for incentive practices became much more focused on the costs of OHAs and building relationships with patients that would enable more prevention.

The current [2006] contract works to an extent but means treating complex cases is difficult. I’m here to make a profit and a living. There’s no point me being here if that’s not going to happen. I’ve trained for a long time, I have laboratory costs to cover, I need to make money. Complex cases are difficult in this contract.

Adam, traditional practice dentist

The cost of doing that [OHAs] is far higher than was first anticipated, so if we were to put that as a separate issue we would say that it’s the costs prediction. The estimation of what it would cost to run this has been very underestimated, because it does take more time. It takes us away from doing, because we’re trying to get patients, encourage them, chase them so much it actually takes an hour for a clinician to build that relationship in the first place and then it’s about compliance and so that was collaboration, its maintaining that, it’s very hard to do.

Business manager, incentive practice

Computing problems featured as organisational factors.

Some of the challenges around things like the software I think have been hard and that’s been symptomatic because we’re using a software system that has to generate, its geared up for payment system as well as a clinical and reception management, patient management system and we’re trying to alter it to continue to provide some of the data that the contract demands around UDA generation but also around capturing some of the data that we want and because we’re such a small customer, it’s hard to influence that.

Service commissioner

The only disadvantage is I think in my opinion is the software, there are so many different varieties of software around and they have not prepared themselves to be really in tune or to deliver the type of things which are needed for this pilot, for this kind of service so that is very generic dental software, dental services software. Well in my opinion, the software should have been tweaked much before implementing this contract.

Amiya, incentive dentist

Need

Evaluated and environmental need and population health indicators were manifest in the data. Two localities in the study are characterised by material deprivation, poor oral health and long-standing undersupply of care. Unsurprisingly, this influenced dental treatment needs in these areas.

It would add up to perhaps eight dental visits just for one course of treatment and that will be just to stabilise the patients. There were an awful lot of extractions that were needed. Some patients do struggle obviously with substance misuse, and smoking is quite a major factor as well . . . We still do get those new patients who come in more or less the same state who require an awful lot of dental treatment.

Jennifer, incentive dentist

Treatment needs are so high and there’s a lot of neglected mouths. Some haven’t seen a dentist in years. Some have lost the motivation to maintain their oral health because of this. So there’s a lot of preparatory work.

Donna, incentive therapist

Health behaviours

Health behaviours involve personal health practices (such as teeth brushing or sugar consumption), the process of care (e.g. the delegation of care or other dental team behaviours) or the use of health resources (such as attending or not attending appointments). Personal practices can influence oral health positively or negatively:

There’s relationship between what you eat and your teeth and your health . . . They told us about what toothpaste to use and gave us some. They told us about drinking fizzy, time of day to brush teeth. I’ve changed it a bit and drink water now.

Jennifer, incentive patient

A novel aspect of the process of care involved the assessing patient’s risk of disease. Dental team members commented on the relative imprecision of the traffic light system and its three categories. However, concerns about imprecise systems were not restricted to the risk assessments.

Patients who are amber may be very red because of their diet and because of other things so a couple of amber should make it red, not amber. The software doesn’t pick out some of the differences.

Suneeta, incentive dentist

Focusing on UDAs, the three bands I think can be an issue, some of the dentists have said they think there should be more bands obviously just lumping all restorative work, apart from that needing lab work, into band 2, it could be anything from a simple filing to a very complex molar re-root canal treatment, it does seem a bit wacky.

Business manager, incentive practice

Attitudes and practices towards prevention varied appreciably among the dental teams:

All the dentists do give advice, you know the preventative advice, to all the patients whether under the contract or not.

Suneeta, incentive dentist

I have been here 12 years and have well-established relationships with my patients. I do find it hard to talk about their health – I’m trained to drill and fill.

Ian, traditional practice dentist

The use of health resources might involve attending or not attending appointments and accessing the wider dental team such as a dental hygienist.

I went through like a stage where I didn’t go for about 3 years but that was, I went back about 5 years ago, I don’t know why I didn’t go, I just stopped going and I think then you get thrown off the register.

Alison, traditional patient

They gave me an appointment because I need a filling and when it came day before I were panicking and worrying, I just cancelled it because at end of day I’m not going through that you know tight chest and I’m not going through all that because at end of day it’s not my fault is it? Sweets I’ve had.

Ann, incentive patient

I’ve started going to this one I’ve actually seen an oral hygienist, whilst I was private dental care I was never even offered to see somebody so this is the first time I’ve actually seen one.

Holly, incentive patient

Outcomes

Evaluated or perceived health and satisfaction with care were present in the data, as was the concept of trust. A dentist noticed his patients’ improved health and patients trusted and were satisfied with their dentist, although one disliked an interval of 2 years before they could have another assessment:

I think according to recalls they have improved their brushing, they are using fluoride toothpaste more, they have started smoking less so there is general improvement in their oral health as well and their attitudes towards oral health.

Manish, incentive dentist

They’re really good. I think they’ve got more of a modern approach there whereas the other ones still a bit, I don’t know seems a bit dated.

Kat, parent of an incentive patient, patient at a traditional practice

I do trust them here – they treated me, gave me root canal treatment and saved my tooth, without them, I’d have been minus a few teeth and my appearance would not have been good.

Nanush, incentive patient

The effects of the blended/incentive-driven contract: interactions in the data

The blended/incentive-driven contract changes the finance and organisation of dental practices to implement health policy. Its effects can therefore be seen as interactions between these enabling factors and other stages in the model.

Enabling and predisposing factors and need

The incentive practices were located in areas of high need, either associated with deprivation and disease or with the poor availability of NHS care.

We’d carried out quite a robust oral health needs assessment prior to commissioning these practices and we’d looked very closely at equity in terms of access to dental care, so we’d looked for places where there was very poor oral health and also looked at areas where there was limited access to services and we wanted a combination of those. The sites of the practices therefore were chosen on oral health needs, current access to NHS care, transport systems and so on.

Service commissioner

For some participants, the incentive practices marked a shift from no dental care, whereas others moved from private to NHS provision. Participants reported the impact of the new services that suited their needs in terms of location, personnel and ease of getting an appointment. Participants referred to the difficulties they had encountered accessing a NHS dentist:

Finding an NHS dentist has been really, really difficult and that’s why I have quite strong views on that to be honest with you. We lived somewhere else and we had an NHS dentist and then when we moved, you know what it’s like and then you lose your place and then you end up on a waiting list waiting for absolutely ages. Then we heard about this one.

Jane, incentive patient

Enabling and behaviour

The effects of the new contract could be detected on the processes of care, on personal health practices and the use of personal health resources. In turn, the process of care appeared to be affected in three ways: by the use of the care pathway, by increasing the amount of prevention and the use of skill mix.

The care pathways form an important feature of the Steele report,2 the reformed NHS contract pilots18 and the blended/incentive-driven model reported here. Initial OHAs for each patient guide treatment and the frequency of recall appointments. Participants reflected on their experiences with the pathways. Benefits included the clear link between the risk assessment and care pathways.

I think some of the people were saying you know if you have a red patient there’s only limited treatment options available for that patient until they start moving from red to amber or green, whichever. And I think that was quite a contentious issue, just to leave them in the state and then wait until they got more progressed through from each stage before you can start doing treatments. But I mean the actual process makes sense in the sense that you know there’s no point carrying out such complex treatment on someone who can’t, who is failing to kind of maintain that level of oral hygiene because it can just make it worse.

Amiya, incentive dentist

The blended/incentive-driven contract formalised Department of Health guidance35 from the perspective of clinicians. As treatment plans incorporated preventative treatment, these approaches became standard procedure.

Red, amber or green and then they do get the fluoride varnish, the smoking cessation and alcohol use is being taken automatically. And then obviously depending on the age groups with the fluoride varnish, depending on the categories, while the schedule of the appointments are set then and the recalls so it’s kind of, it’s part of our contract. We don’t do anything else.

David, incentive dentist

The blended/incentive-driven contract can be contrasted directly with the traditional practices (i.e. those operating under the 2006 contract). In this case the focus of care in the incentive contract had penetrated a traditional practice, causing them to reflect on their processes of care:

We are pushed towards UDAs rather than improving oral health . . . The prevention emphasis is an issue – we are expected to talk about perio disease and smoking and diet and have to squeeze that in. We did that before under the old system and it worked to an extent, but we have to do more and more without getting paid anymore. We have to do more in less time.

Sidney, traditional practice dentist

The feeling about the incentive/blended-driven contract as an enabler of preventative approaches was echoed by clinicians in all three incentive practices. Although such systems are not specific to the incentive model and reflect long-standing guidance,35 the formalisation of such procedures under this model was valued by service providers. Practitioners felt that it gave them time and space to care for patients.

By contrast, communication of the ratings was not always apparent in the observations. Moreover, patients might not be aware of it:

Thinking back to your initial assessment as well, I don’t know if your dentist, do they use the traffic light system?

No, what’s that?

There’s nothing where they kind of rate your oral health or anything like that?

No.

Katie, incentive patient

The incentive practices were not required to use multidisciplinary teams, but the successful bidders employed business models that utilised dental hygienists and dental therapists to deliver prevention-focused care. This wider use of skill mix has been advocated by repeated policy documents but not widely implemented. 7,37,73,74 One novel approach was for dentists to examine the patients and formulate treatment plans, but the practices did not deduct the value of the delegated treatment from dentists’ incomes.

The biggest advantage as well is, is that, it’s about mind set as well, if you are working in a normal practice your dentists, your associate will be charged with using the therapist, the hygienist and so therefore your dentist is, your associate is less likely to use your therapist and hygienist because they don’t want to pay for them. Here they get it for absolutely free.

Anna, incentive practice manager

They readily work with each other. I mean our therapist and the hygienist are generally busy the whole day, which they say they don’t normally get in other practices so, and we pay them on a fixed rate and the therapists are very happy with that because they’ve got full time work, they’re busy, the associates are happy because they’re not having to pay for them . . ., the patients get benefit because they get access to a therapist, . . . it may cost more for us to do it but it’s a more sensible way of running a business because everybody is working together for the same aim.

Claire, incentive practice manager

That’s definitely an advantage obviously because there’s more appointments available now so you can see more patients.

Fiona, Dentist, incentive practice

The new contractual arrangements were seen to influence personal health practices and the use of personal health resources. Lara changed her personal routines and attended the dental hygienist.

I’ve been prescribed Duraphat® [(Thepenier Pharma Industrie, SAS, Mortange, France)] fluoride toothpaste, I use interdental brushes and see the hygienist. I take advice on board and I don’t want to get told off. So I’ve changed my routine. I didn’t know you could go to a hygienist until I came here.

Lara, incentive patient

Enabling and outcomes

The blended/incentive-driven contract also influenced outcomes of perceived and evaluated health and patient satisfaction.

They managed to sort my mouth so that I can actually smile now and feel confident about my smile, I don’t feel like it’s, or people are looking at my teeth anymore which, I mean it’s a massive improvement, it makes you confidence so much more, it makes you feel better about yourself when you know that someone is helping you sort something that you know is a big problem. You feel self-confident about it.

Shazia, incentive patient

I have been working here for 2 years plus so I can see that the patients from the deprived area, yes, I think according to recalls they have improved their brushing, they are using fluoride toothpaste more, they have started smoking less so there is general improvement in their oral health as well and their attitudes towards oral health.

Jane, incentive dentist

Generally making you feel better at going, I feel much happier going to the dentist now than I did a year ago.

Carol, incentive patient

That’s really good because I don’t know maybe the hygienists have got a bit more time and if it’s something they’re trained to do that’s fine rather than taking up the dentist time which is more specialist work. I mean I know my daughters been to see the hygienist, you know about brushing her teeth and they gave her some Duraphat cream.

Grace, incentive patient

Far-reaching effects

The interactions could ripple throughout the model to have far-reaching effects. For example, the RAG ratings could influence patients’ perceptions of their own needs, leading to personal behaviour changes and satisfaction (an outcome).

I think it’s good because if you know, if someone says to you, you know on this rating you are more at risk, you’re more likely to do something about it aren’t you, as opposed to someone not saying anything to you, you know, I think you are likely to be more active. I would be more active but I think it gives people that, again it’s about having that bit more choice and a bit more involvement in your own kind of care which I think is a good thing.

Grace, incentive patient

Using the ratings to determine recall intervals liberated more time for the process of care and allowed observation of increased health but influenced patient satisfaction both positively and negatively:

The recall intervals will be according to the risk assessments that we are doing and the risk assessment is based on their medical, their social and their clinical domains and patient to understand it and they are really happy, the majority of them 99% are very happy to have the recall intervals as dictated by their risk assessment . . . The recall intervals of 2 years and a year for the green and the amber patients so we are definitely seeing more patients and as the amber ones move towards green or the reds move towards green so we would be having more appointments for the patients to be seen.

Manish, incentive dentist

2 years seemed a long time to wait . . . I sort of think umm would I be prepared to pay a premium price and go back to private care as a result of that and that’s something that I’ll have to consider really.

Martin, incentive patient

These data suggest a need to reconcile contrasting views. From the dentist’s perspective there is the ability to see more patients and hence increase access. At its best, the incentive model seems to enable greater access because it prioritises those who need treatment and rebalances appointments around need. However, the patient was not happy with waiting 2 years for another assessment and may consider seeking alternative or additional care.

In a wholly positive example, a patient satisfied with her own care encouraged her partner to attend so that professional behaviour enhanced satisfaction to change predisposing factors to increase access to care.

. . . fantastic and the dentist themselves are really friendly. They’re really understanding, I mean for me I’m not somewhat scared of the dentist as my partner and it’s made a real improvement for my partner because he’s terrified of them so, and we’ve actually managed to get him there and he’s having work done there which is an improvement, usually trying to get him through the door of the dentist was a real effort, it took a day to get him there, get him sorted and get him home again. So I mean from that point of view they’ve just been absolutely fantastic with both him and me.

Holly, incentive patient

In summary, participants’ observations are compatible with existing knowledge of access to care, but highlight possible effects of the incentive contract (Figure 2). In particular, patients’ needs were seen to influence the siting of practices. The contract had a number of direct effects on practice orientation and costs. However, participants related these effects to better health-related behaviours on the part of patients and changes in dental practice behaviours regarding assessments, prevention, patient communication, the use of skill mix, the number of patients seen and recall intervals. In turn, these changes were related to improvements in perceived and evaluated health, patient satisfaction and trust.

FIGURE 2.

Summary of stakeholders’ perspectives on the incentive contract.

Discussion

This chapter has reported the exploration of stakeholders’ views of the new contracting arrangements. There were perceptions that the blended/incentive-driven contract increased access to dental care, with the contract determining dentists’ and patients’ perceptions of need, their behaviours, evaluated and subjective health outcomes and patient satisfaction. These outcomes were then seen to feed back to shape people’s predispositions to visit the dentist. The data hint at appreciable challenges related to a general refocusing of care and especially to perceptions about preventative dentistry and use of the risk assessments and care pathways. There are also obstacles to overcome to realise any benefits of the greater deployment of skill mix. Dentists may need support in these areas and to recognise the differences between caring for individual patients and caring for segments of the population, such as that formed by the patient base of a practice.

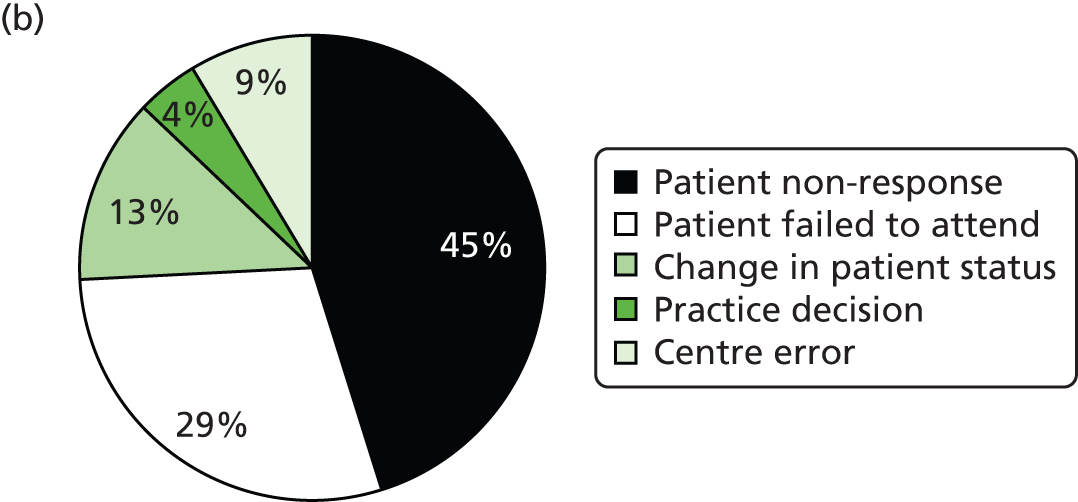

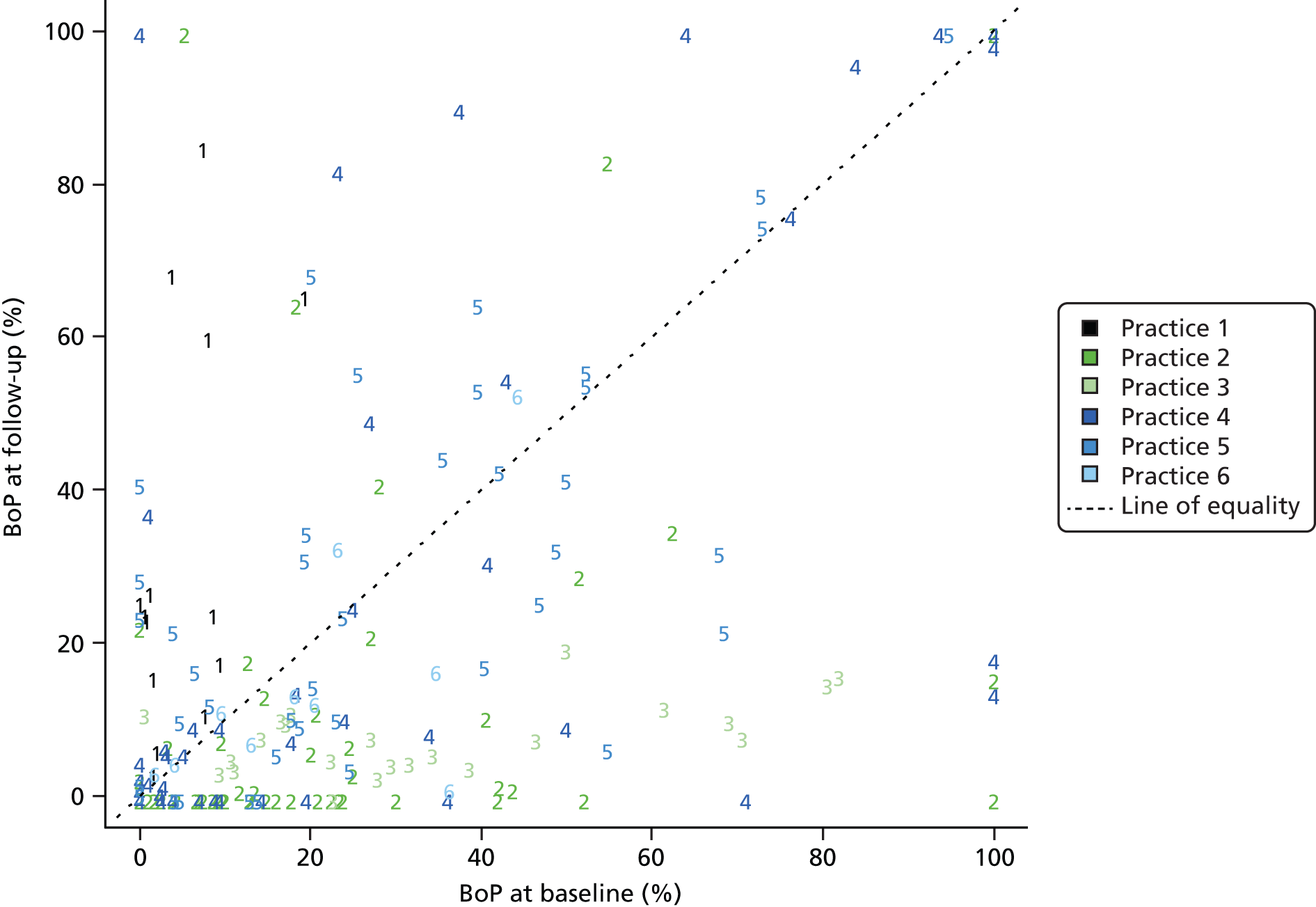

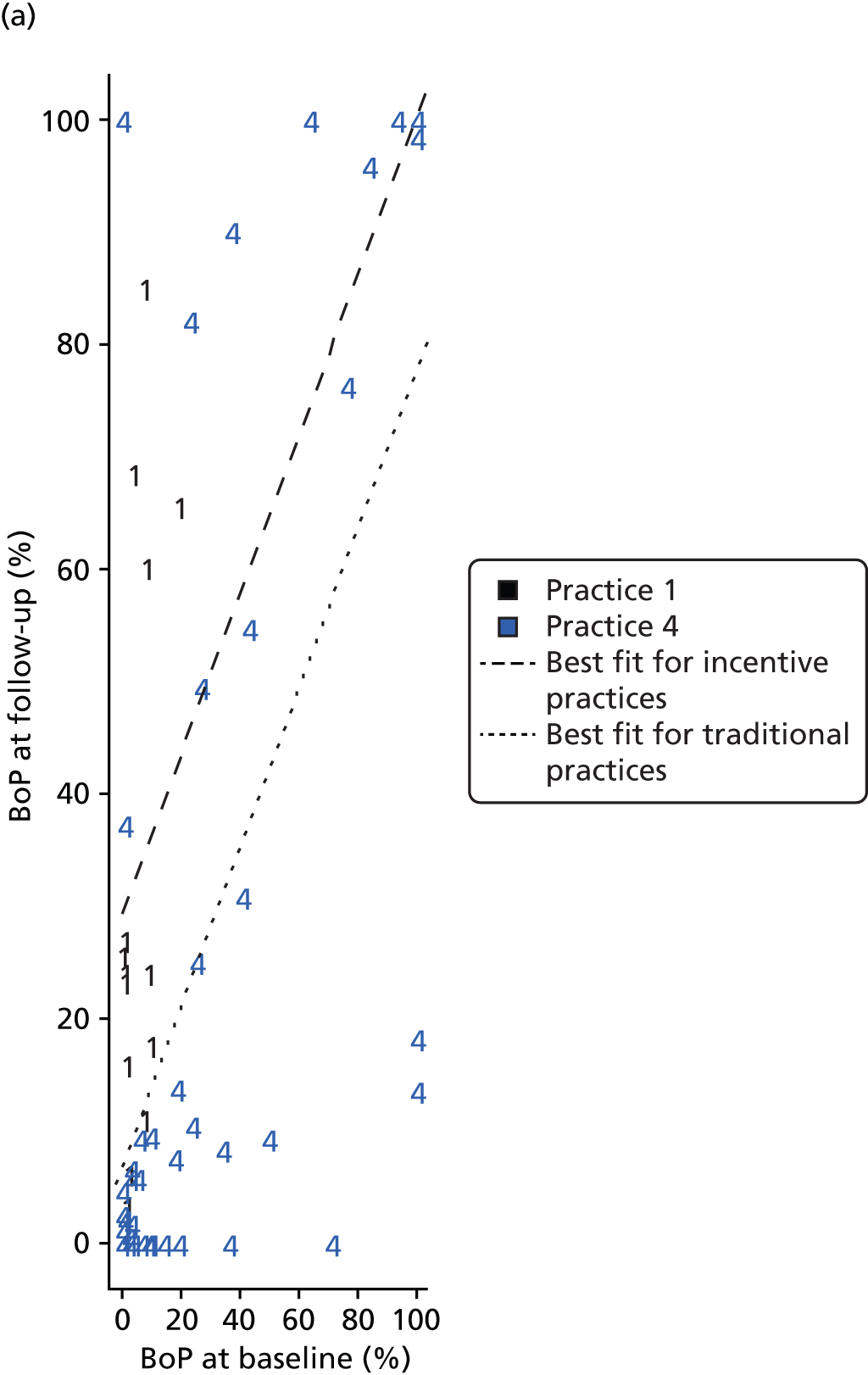

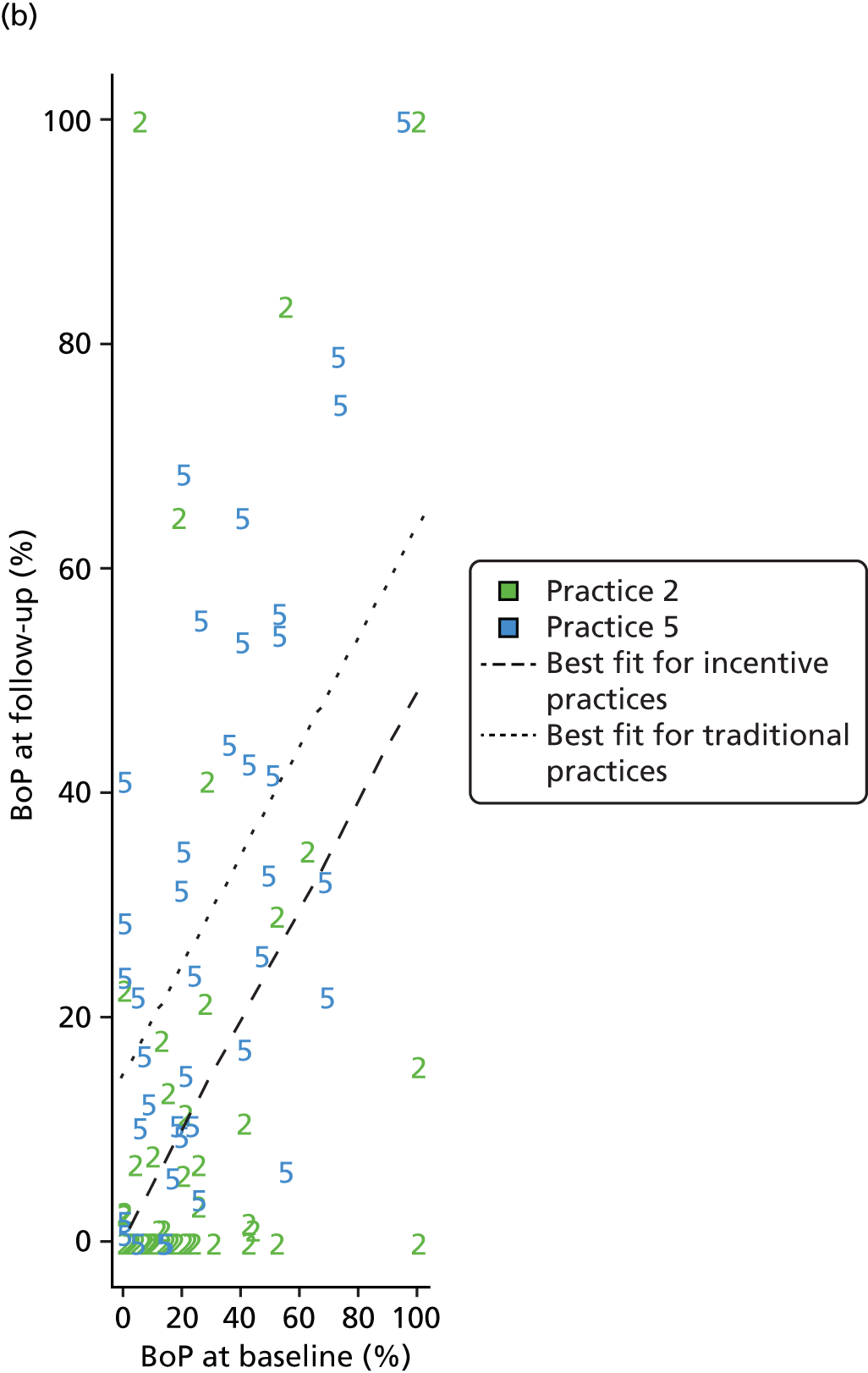

The impact of the contract is evident as interactions with other stages in the model. There was ample evidence of such interactions.