Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 11/2000/11. The contractual start date was in July 2012. The final report began editorial review in April 2015 and was accepted for publication in October 2015. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2016. This work was produced by Gridley et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Dementia is a major and growing health concern across the world. With an imminent cure unlikely, providing good-quality and cost-effective care, over what is often a long period of need, is, and will remain, a major challenge for health and other care providers. The Department of Health (DH) has outlined improved quality of care in general hospitals, living well with dementia in care homes, and reduced use of antipsychotic medication as priority objectives for dementia. 1 Quality outcomes for people with dementia in the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Quality Standards2 similarly focus on improving health outcomes through improving care processes, and two quality statements emphasise the importance of understanding people with dementia via their life stories and biographies.

Listening to people with dementia and understanding that they have rich and varied histories is essential to good care. 3 ‘Life story work’ (LSW) is used increasingly for this and involves gathering information and artefacts about the person, their history and interests, and producing a picture book or other tangible output – the ‘life story’ – including storyboards and multimedia resources. 4 LSW has been used in health and social care settings for nearly three decades, with children,5 people with learning disabilities6 and older people. 7 Since the 1990s, there has been growing interest in its potential to deliver person-centred care for people with dementia. 8,9

The approach is distinct from reminiscence and ‘biographical work’ in dementia care, because it emphasises using the life story in day-to-day care to improve communication, relationships and understanding of the individual’s past life, and in its orientation to the future. Life stories, as tangible products, are owned and held by people with dementia and can travel with them to smooth the transition to other settings, for example into acute medical care or from home to long-term care. This makes life stories distinct from biographical ‘work’ in care settings10 or the simple logging of life history details in care records.

Two systematic reviews have explored LSW in dementia care and both suggest that the approach has considerable potential. The first11 reviewed LSW with a range of user groups and reviewed four qualitative studies focused specifically on dementia. These studies suggested that life stories can help staff to understand the person they are caring for in the context of their past, which in turn can help to explain their present behaviours. Staff valued life story books as care planning and assessment resources, but there was little reporting of patients’ and carers’ views. The review’s authors noted an absence of attempts to present conflicting evidence about the value of life stories in practice. The second review identified 28 studies of LSW with people with dementia in institutional settings. 12 All interventions contained some features important for achieving an enhanced sense of identity among residents. However, the focus of the studies tended to be the impact of the life story reminiscence process, generally conducted by researchers or therapists for limited periods, rather than the routine daily use of life stories. The authors concluded that there is still much to learn about how best to deliver LSW to people with dementia and that more attention should be paid to developing a sound theoretical framework.

Subsequent studies have suggested that life stories help staff to see clients with dementia as individuals, help family carers to uphold relatives’ personhood and enable those with dementia to be heard and recognised as people with unique stories. However, these studies have been very small in scale13,14 or remain unpublished (Cohen K, Johnson D, Kaiser P, Dolan A, Lancaster University, 2008, unpublished report).

The use of life histories (sic) has been advocated in the DH Dementia Commissioning Pack15 and this, in turn, refers to a Commission for Social Care Inspection report that commended the use of life histories in care planning. 16 However, LSW for people with dementia is under-researched, with little evidence about the most cost-effective ways to implement it in different settings or with different user groups. To date, there have been no large-scale, methodologically rigorous studies of the impact of LSW on outcomes for people with dementia, carers and staff, or any attempt to establish its costs. More basically, unlike reminiscence therapy,17 the mechanisms that might make LSW effective, or the contexts in which these might apply, have not been articulated; there is, thus, no developed theory of change that underpins its use. Finally, although descriptive accounts and practice-based knowledge show LSW being used in different ways in different dementia care settings, we have no systematic knowledge about who is using it, where, how, with what effect and at what financial cost.

Despite LSW’s use in dementia care settings in the NHS and elsewhere, its outcomes for people with dementia, their carers and staff, its costs and its impact on care quality remain unevaluated. With current moves towards embedding LSW in dementia care, robust evaluation of the technique, its outcomes and costs, and how it can best be applied is urgently needed. We need to understand how LSW might improve interactions and relationships between staff, carers and people with dementia in a range of health and long-term care settings; affect service users’ and carers’ quality of life (QoL) and other individual outcomes; and reduce the use of antipsychotic drugs for behavioural ‘problems’. There is also a need to establish the likely costs and benefits of implementing LSW more widely in health and long-term care settings.

As LSW is a complex intervention, formal evaluation must be preceded by development and feasibility/pilot stage research, as recommended in the most recent Medical Research Council (MRC) guidance. 18 Our project was, therefore, planned to provide theoretical underpinnings for LSW, explore good practice in its use, establish where and how it is used in health and social care settings in England, outline its possible costs and benefits in such settings and establish the feasibility of formal evaluation.

The work was designed to generate a robust theory of change and a good practice framework to underpin growing use of LSW in dementia care for the NHS management community to use. We hoped that elucidating LSW’s potential outcomes, impact on care quality and costs might inform commissioning decisions about where and how best to use it. Future formal evaluation of LSW, building on our work, would, further, provide robust, generalisable evidence of effectiveness and costs.

The formally stated aim of the project was to carry out the development and initial feasibility stages of evaluation of a complex intervention – LSW – for people with dementia.

The objectives were to:

-

develop a theoretical model of LSW (including its potential outcomes) and establish core elements of good practice in using and applying the approach

-

benchmark the current use of LSW in dementia services in England against good practice

-

scope the potential effects and costs of using LSW in specialist inpatient and long-term care settings

-

explore the feasibility of formal evaluation of LSW in health and long-term care settings

-

disseminate findings to providers, planners, commissioners and users of dementia services.

The research questions were:

-

How might LSW improve outcomes for people with dementia, carers, staff and wider health and social care systems?

-

How cost-effective could this be?

-

Is formal evaluation of LSW feasible?

Overview of design and methods

Each main chapter describes in detail the design and methods used to address the research questions. Here, we provide a brief overview of the rationale for our choices.

Medical Research Council guidance points to the special challenges that evaluation of complex interventions poses for evaluators. 18 The guidance suggests that before formal evaluation of effectiveness and costs, understanding of the existing evidence base, a developed theory of change, process and outcome modelling, and a clear understanding of the feasibility of formal evaluation must be in place. These elements were not in place for LSW when we wrote our proposal. We thus focused on the development and initial feasibility work required before full evaluation in two main stages: (1) reviewing the evidence base and identifying and developing theory and components of good practice; and (2) data collection to support modelling of processes and outcomes and judgement about the feasibility of full evaluation. A mixed-methods approach was used throughout. Table 1 sets out how each objective was addressed by the project methods.

| Objective | Methods |

|---|---|

| 1: Develop a theoretical model of LSW, including its potential outcomes, and establish core elements of good practice in using and applying the approach | A systematic review of literature (stage 1a) published in or after 1984 on LSW with people with dementia to identify reported outcomes and their sizes, underlying theories of change and any reported elements of good practice in creating and using life stories |

| A qualitative study (stage 1b) using focus groups with people with early-stage dementia, carers and professionals, who have experience of LSW to ascertain what outcomes are experienced or expected, for whom, under what circumstances and by which causal routes; as well as participants’ views about core elements of good practice in LSW | |

| 2: Benchmark the current use of LSW in dementia services in England against good practice | A survey of health and social care providers of dementia services (stage 2a) and of informal carers (stage 2b) to establish how LSW is used in different care settings. Good practice elements identified in stage 1 will influence the survey content, enabling us to benchmark use against good practice |

| 3: Scope the potential effects and costs of using LSW in specialist inpatient and long-term care settings | Two small-scale feasibility studies (stage 2c) – one with a stepped-wedge design in care homes, the other with a pre-test post-test design in a NHS assessment unit – to examine the potential size of outcomes from and costs of using LSW in these settings. Relevant resource inputs will be identified, measured and then valued using local or national unit costs to establish the costs of LSW relative to other approaches Using these preliminary data, and assuming that we have observed any effects, we will create a probability tree for effectiveness of LSW in relation to outcomes and then a Markov model of effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of LSW (stage 2d). This will help to assess whether or not future, formal evaluation of LSW would be worthwhile |

| 4: Explore the feasibility of formal evaluation of LSW in health and long-term care settings | In addition to producing data on potential costs and outcomes of LSW, these small-scale studies (stage 2c) will provide valuable learning on the practical feasibility of formal evaluation of LSW in different settings and for two different designs |

We also planned a dissemination phase, including with a short film, produced with the advice of people with dementia, and a four-page plain English summary.

Outline of the report

Chapter 2 reports the literature review that we used to explore good practice in LSW and to develop a theory of change, while Chapter 3 reports the qualitative work with people with dementia, family carers and professionals that addressed the same issues through empirical exploration. In Chapter 4 we explain how we used the findings in Chapters 2 and 3 to identify outcomes for the feasibility study and how we chose instruments to measure them. The two national surveys of the use of LSW in health and social care settings and the experiences of carers of LSW are reported in Chapter 5. Chapter 6 reports our in-depth exploration of the feasibility of formal evaluation, while Chapters 7 and 8 report the outcomes and costs measured in the feasibility study. Chapter 9 reports the qualitative work carried out at the end of the study to explore the experiences of those who had been involved in it. The final chapter contains discussion of our results and conclusions.

Chapter 2 Review of the literature

An important element of the initial development stage of our research was a review of the existing literature to inform the development of a theoretical model of LSW, including its potential outcomes, and to establish core elements of good practice in using and applying the approach (project stage 1a, objective 1). The main research questions here were:

-

What outcomes and of what size have been reported for LSW?

-

What underlying theories of change for LSW are articulated in the literature?

-

What elements of good practice in creating and using life stories are reported in the literature?

We proposed to undertake the review following Centre for Reviews and Dissemination guidance,19 using a narrative synthesis20 of the extracted material, and a ‘realist’ approach21 – establishing what types and size of outcomes were reported, for whom, under what circumstances (including good practice components), and by which (implicit or explicit) causal routes. We further proposed synthesising evidence by the type of LSW used and the characteristics of participants and care settings.

Search strategy

The literature searches involved electronic searching of a range of databases covering the fields of health, mental health, nursing and social care (see Appendix 1, Table 8; all tables for this chapter can be found in Appendix 1). The search strategies were devised using a combination of subject indexing terms (when available), such as medical subject headings (MeSHs) in MEDLINE, and free-text search terms in the title and abstract. The search terms were identified through discussion within the research team and by scanning background literature.

The search strategies focused on the retrieval of published studies and ‘grey literature’ (dissertations, reports, etc.) in which interventions were described explicitly as life story/life history/life review or life narrative within the title/abstract. Related terms such as oral history/biography/reminiscence were not searched, in order to reduce the retrieval of irrelevant studies. The decisions to restrict the searches in this way were made after the inclusion of these wider terms was piloted. The results of the broader search were compared with those from the more focused search and a decision was taken to use the more specific terms only.

The search strategies used to identify studies are included in Appendix 2. The searches were not limited by date, but were limited to English-language results only.

The results were loaded into EndNote bibliographic software (Thomson Reuters, CA, USA) and deduplicated using several algorithms.

The reference lists of all included review articles were searched for apparently relevant additional studies.

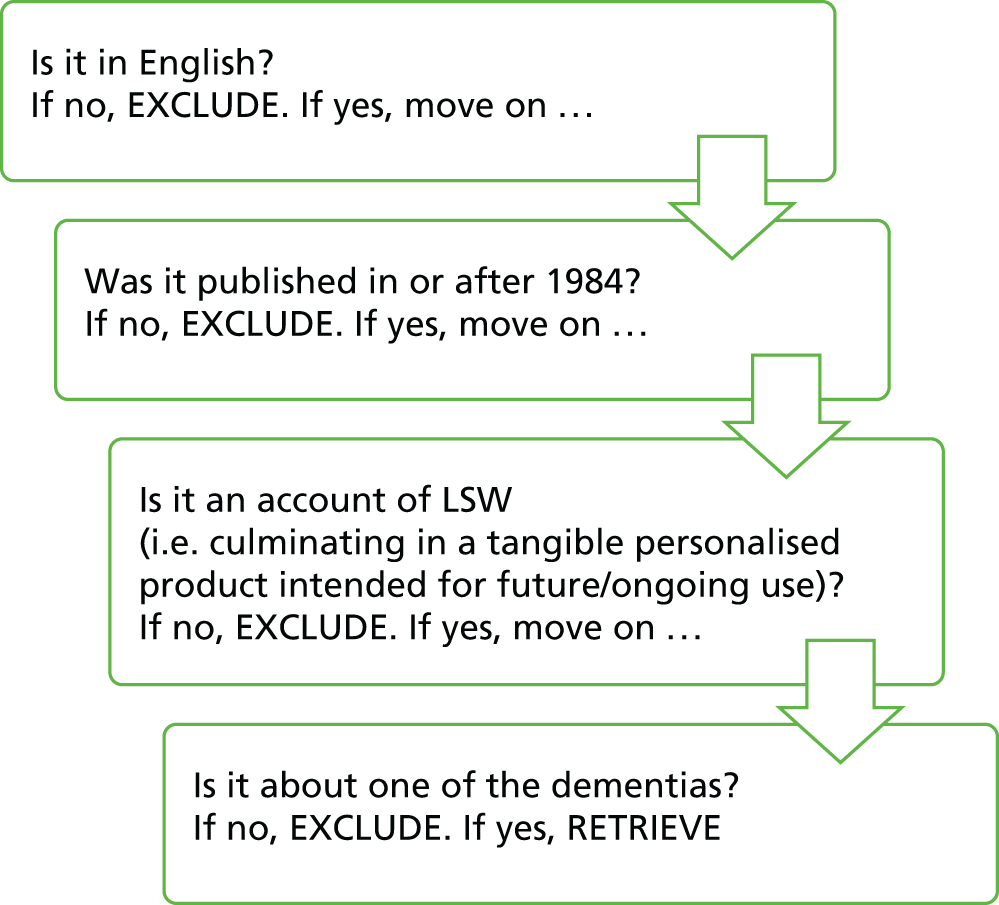

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

As with most reviews of complex interventions, it is good practice to finesse the inclusion and exclusion criteria for selection for relevance after the first phase of searching. 22 However, we had developed some initial inclusion and exclusion criteria based on our existing knowledge of this literature, which we outlined in our proposal. These were:

-

inclusion: any published account of LSW or life stories that is also about one of the dementias and refers to outcomes; any care setting, including own home; any country (UK and non-UK); any empirical study type; any theoretical account, including guidance and training documents.

-

exclusion: opinion pieces, letters; published before 1984; not English language.

Once the project started, we further developed the inclusion and exclusion criteria in consultation with the project steering group and our project advisers. They were finalised through an iterative process during the early stages of searching and were as follows.

Inclusion criteria

Types of participants

Studies that included, and papers that were about, people with dementia or Alzheimer’s disease (including ‘confusion’ or ‘memory problems’).

Phenomena of interest

Studies that evaluated or that elucidated the theoretical underpinnings of LSW with people with dementia.

Types of outcomes

Any outcomes reported.

Study designs

Any study design, qualitative or quantitative.

Date

Studies published in or after 1984.

Exclusion criteria

-

Literature on LSW outside the dementia/Alzheimer’s context.

-

Opinion pieces and letters.

-

Studies not in English.

Selection of studies for relevance

We first went through the identified studies to assess their relevance to the aims and objectives of the review, using titles and, when available, abstracts. We developed a simple algorithm to help us in this (see Appendix 3). Two researchers (KG and GMP) worked individually and then as a pair to agreement about relevant studies.

We obtained full copies of the studies selected for relevance and read them before making a final decision about inclusion for review. Again, we developed guidelines for this process to ensure consistency across the team (see Appendix 4). Three members of the team (KG, GMP and YB) worked individually and then in pairs to agreement about relevant studies. When we could not reach agreement in pairs, the third member of the review team arbitrated.

Assessment of methodological quality

Given the limited literature on LSW and the largely scoping and qualitative nature of our research questions, we did not include or exclude papers based on their methodological quality.

Data extraction

The focus of data extraction was on outcomes that authors reported as arising, actually or potentially, from LSW, for whom these outcomes arose, explicit or implicit theoretical assumptions about causation, and any information on changes in outcomes.

We also extracted details of the type of LSW described, participants, the care setting, study design and any data or discussion related to good practice in creating and using life stories.

Data extraction headings

Data extraction headings were developed after the first reading of the included studies and were discussed both in the research team and with the project steering group. The headings were then used to create data extraction forms in Microsoft Excel® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA).

For the best practice part of the review, the final data extraction headings in relation to ‘doing’ LSW were format of the LSW, contents to include, contents to exclude or avoid, style of the LSW product, which people with dementia should do LSW, who should be involved in doing LSW, when LSW should be done, and ethical issues. Headings for organisational ‘best practice’ issues were the culture of care, leadership and management support for LSW, resources and time, support for staff doing LSW, training and preparation for staff/volunteers doing LSW, and incentives.

For the theory of change review, we were interested in any causal links that authors argued – either explicitly or implicitly – existed between doing LSW and outcomes (whether for people with dementia, family members or care staff).

For this part of the review, then, the data extraction headings were type of LSW (as defined by analysis of the first stage of the review – see Results, Good practice in life story work), argued causal links between LSW and outcomes, types of primary outcomes, types of intermediate or process outcomes, and contextual influences and factors that might affect outcomes.

All data extraction for both parts of the review was carried out by one researcher (GMP). The progress and initial findings of the extraction process were shared with other members of the team and with the project steering group.

Data synthesis

All findings were analysed qualitatively and, when possible, metasynthesised. This involved aggregating or synthesising conclusions from the reviewed publications to generate a set of statements that represented that aggregation. The aim of meta-synthesis was to produce a single comprehensive set of synthesised findings. For the theory of change analysis we also used mind-mapping software in the first stages of analysis.

Results

Numbers of papers identified

The electronic searches identified 1199 records (see Appendix 1, Table 9). Following deduplication, 638 records were available to be assessed for relevance. A further 19 studies were identified at a later stage from the reference lists of papers included for review.

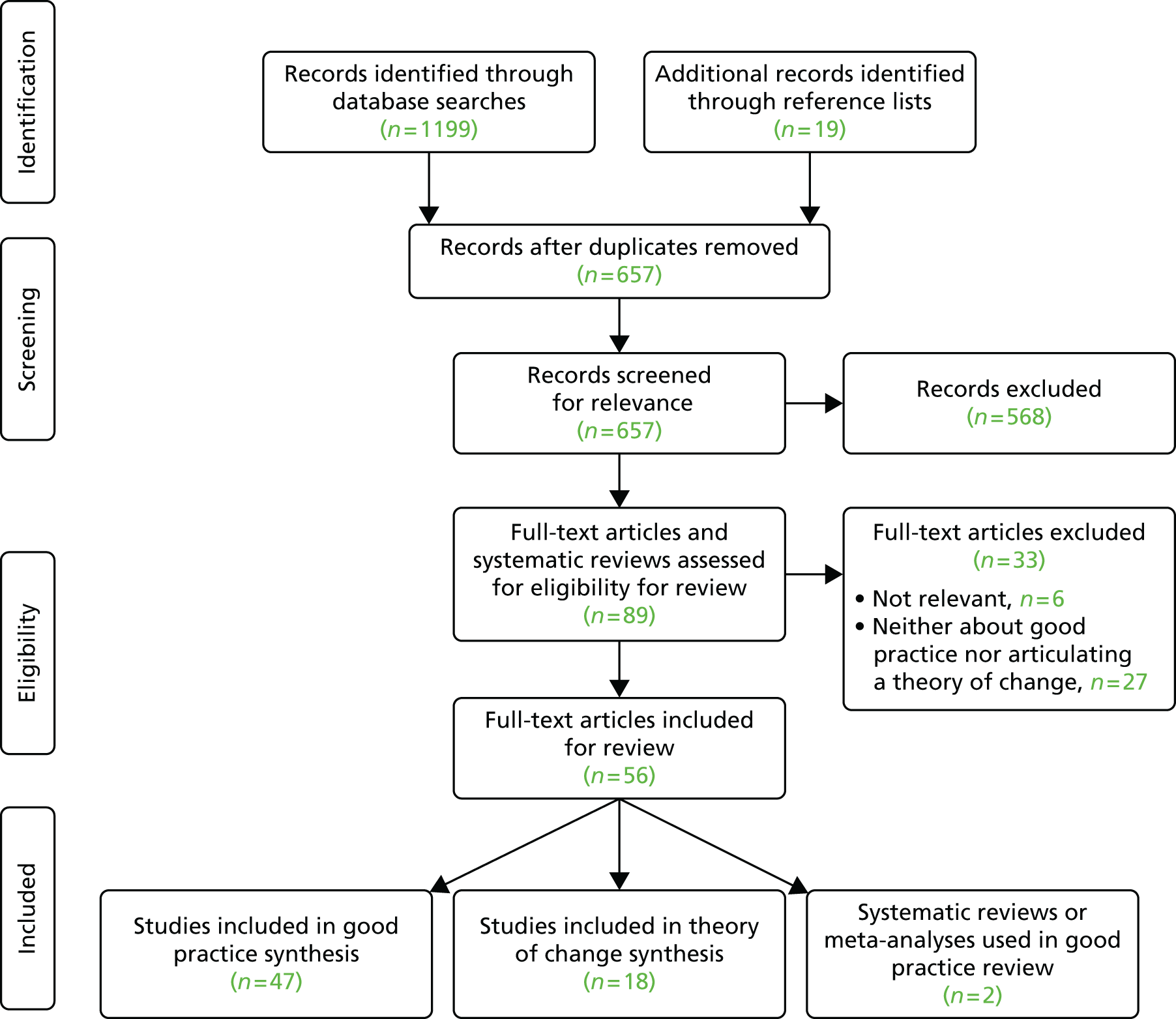

The PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) diagram (Figure 1) shows the process through which the identified studies7,9–11,14,17,24–104 were reduced to a final selection of 56 papers; of these, 47 were used in the good practice review and 18 were used in the theory of change review (see Appendix 1, Table 10).

Two of the six existing systematic reviews or meta-analyses11,105 also provided material for the good practice review (see Appendix 1, Table 11).

Details of the types of primary studies included in the two reviews are in Table 12 (see Appendix 1).

As Figure 1 and the tables show, the majority of selected papers contributed to the good practice review, but few articulated any explicit or implicit explanation of why LSW might lead to better outcomes for people with dementia, their family members or care staff.

Good practice in life story work

In this part of the review we first identified which selected publications contained any ‘how to do it’ material about LSW, so that we could focus on what authors believed was good practice in relation to LSW. We looked for publications that said anything about one or more of the following issues: format of a life story, contents to include in a life story, contents to be excluded or avoided, style to be used, who should be involved in LSW, when LSW should be done, and ethical issues. We also looked for publications that said anything about the organisational context to support LSW. The issues here were culture of the care setting, leadership and management support, resources and time commitment, support for staff in settings where LSW was being done, training or preparation for staff or volunteers doing LSW, and ‘incentives’ that might encourage LSW to be undertaken.

The literature we included in this part of the review revealed a number of distinct models of LSW and ideas about best practice within them. We have tentatively labelled these as follows: narrative approaches; biographical or chronological approaches; care-focused approaches; and care-focused approaches with a narrative orientation. We deal with these approaches in separate sections below, exploring first what characterises each approach and then what the publications say about what should be done (the LSW product), when, by whom, how and with what type of involvement of which people. We then move on to discuss how each approach deals with issues around what should not be included in a life story, dealing with distress and consent to use.

We deal with the organisational context for LSW in a final subsection of this part of the chapter.

Narrative approaches to life story work

What is a narrative approach to life story work?

Publications in this category were those that most frequently talked about LSW as a process tantamount to writing a novel. Thus, LSW was not about documenting ‘objective facts’ but rather about the personal interpretation of facts24 and identifying the strength of the person living with dementia and the wisdom that they had accumulated during life. 25 As a result, the main issue in doing a life story was not accuracy, but capturing the emotions that accompanied that story, engaging with the person and hearing what they had to say about their identity and feelings. 25,26 Similarly, it was felt that there was no one way to ‘do’ LSW or to decide what content it should have; rather, it should be regarded as a process whereby doing one element of LSW might lead to another. 27,28

Given this narrative approach, it was not surprising that the person living with dementia was seen as being firmly at the centre of the work29 or as the virtual director (of a filmed life story). 30 LSW was a process, not just a form to be filled in,29 and the story produced, via a dignified and respectful process, enhanced a person-centred approach. 28 Some also felt that a narrative approach produced a life story that was easier to read and engage with, both for the person living with dementia and for those who lived and worked with them. 28,31 Further, a narrative could be a living thing that recorded not just the past but also the present. 29,30

Even in the description of an entirely carer-led life story process, a distinction was made between ‘social histories’, typically gathered in nursing homes, and the attempt in LSW to illuminate as well as report on a life. 32–34 These papers did talk about capturing facts, but also about communicating the essence of the person living with dementia and what made them unique.

Good practice in narrative approaches to life story work

Fourteen of the papers that represented a narrative approach also included details about how best to do LSW, although three of these were about the same intervention. There was a high degree of consistency about what this approach should contain and the process it should follow.

The strongest common message was that the LSW process should focus on feelings, opinions, meaning and emotions25,28,31 and reflect the themes, topics or objects that are most important to the person living with dementia. 31,35,36 This means that the person living with dementia should choose the topics and material to be included and the way in which these are presented. 35,36 This orientation was reflected in some commentators’ views that carers could be involved with creating a life story, but only with the permission of the person living with dementia. 29,36

As outlined above, we did find accounts of a strongly narrative approach to LSW that was entirely carer led, but, even here, it was argued that the emphasis should be on key themes that illustrated the person’s life rather than a list of facts about them. 32–34

Several writers also talked about the importance of the life story not just being about the past but also being a ‘living’ or continually evolving account. It should thus be able to include current hopes and future wishes,26,29 record aspects of current life,30 add new stories and ideas and allow ‘editing of the past’ to match the current viewpoint of the person living with dementia. 24,31

The emphasis on meanings and emotions underlines a need for a high degree of emotional intelligence in the person facilitating the life story production. One paper emphasised that the person who helps the person with dementia to create the life story needs to be ‘emotionally present’, prepared to be the ‘validating witness’ for the story, and receptive, open and non-judgemental about the story being told. 27 This recognised that whatever story is being told, it is of consequence to the teller and has been shared at an emotional cost. Others talked more generally about the importance of building strong rapport and a trusting relationship, without which nothing can happen. 30,35

However, this emphasis on feelings and meaning may bring up issues that the life story process cannot resolve, in and of itself. One writer clearly states that LSW should not try to resolve either past or present problems; it is not therapy, even if it might be therapeutic. The issues of material that should not be included in a life story, and with whom the life story might be shared, are thus important too. Some researchers acknowledge that, although people with dementia are likely to express a wide range of preferences in relation to sharing and privacy,25 the process might reveal issues that should never be revealed to anyone else without ‘express permission’. 27 This means that the person to whom the life story belongs must be able to choose how much of it they want to share with others. 24

When the process is carer led, carers themselves should choose to tell only the stories that they believe the person with dementia would tell, and keep private those they would keep private,32–34 thereby viewing the process in the same way that they would view surrogate decision-making. 34 By contrast, two descriptions of a narrative approach argued that, although carers could be involved in LSW, this should be only with the permission of the person living with dementia. 29,36 Although some papers included clear statements about ownership of the LSW, one gave a somewhat confused account, reflecting the experience that if ownership is not properly negotiated at the start of the process, then problems and conflict may emerge later. 30

The issue of what material should and should not be included and/or shared in a life story was also related in some writers’ accounts of which people living with dementia should or should not be offered the opportunity to do LSW. Some publications advocating a narrative approach stated that LSW could be done regardless of the stage or type of dementia26,37 – which may be true – or that it should be started as early as possible. 31 However, it is necessary to select carefully those to whom LSW is offered,38 taking into account both personal preference and the likelihood of causing distress. 26,36

Biographical or chronological approaches to life story work

What is a biographical or chronological approach to life story work?

The approach evident here is distinct from a narrative approach in its emphasis on a relatively ordered, chronological recording of the life of the person living with dementia. Writers thus talked about a final product that follows the life course, from birth to the current day, with material that is displayed or recorded chronologically, even if it is not necessarily gathered systematically. 39–42 There is thus an emphasis on remembering and memories,43 on lists of topics to be addressed39 and on timelines,41 rather than on feelings and meaning. Perhaps as a corollary to this more structured approach, there is less reference here to validation of the life portrayed (Gibson and Carson39 being a notable exception).

Good practice in biographical or chronological approaches to life story work

The more structured underlying approach here gives rise to a more directive feel to recommendations about how life stories should be recorded. Books, albums, workbooks and topic-based templates are recommended or described,39–41,43 while timelines and visual and auditory ‘prompts’ and triggers to memory are suggested as useful adjuncts. 41,42,44 There are also recommendations about ensuring that books and albums are attractive40,41 and immediately recognisable as belonging to the person living with dementia. 40

The involvement of the person living with dementia does not seem as central in these approaches as in the narrative ones. In two of the models described, the person’s memories are recorded and transcribed by others, based on audio-taped ‘life review’ sessions43 or weekly, one-to-one reminiscence sessions in which a member of care staff acts as an ‘amanuensis’. 39 One account suggests that a life story can be constructed based on what the ‘helper’ already knows about the person living with dementia, but points out that both the process and the end product are more meaningful if the person is included in the process. 41 This seems a much weaker commitment to the centrality of the person living with dementia than was evident in the descriptions of narrative approaches.

The role of family members or carers in LSW is also more evident here, with suggestions that they can encourage or facilitate the involvement of the person living with dementia40,43 or indeed that they are ‘integral’ to the process. 44 One account reported that, although family members had been initially reluctant to discuss the past with their relative, fearing that they would cause distress, they had actually managed to have meaningful and pleasant discussions while doing LSW. 40

One publication in this group (in which the production of a life story was tied in to ‘life review’) was clear that LSW was best done with people who were in the early stages of dementia and with those who were interested and had the cognitive, emotional and physical capacity to participate in life review activities. 43 By contrast, the authors who described an evaluation of a video photo show approach to LSW felt that it worked best for people with moderate to severe dementia, because they were less likely than people with lower levels of impairment to lose interest while watching the video on multiple occasions. 42

The only other practical recommendation that emerged from this set of publications was the importance of using statements rather than questions in the final LSW product; this was in relation to a video-based life story, but might well also apply to text- or audio-based products.

The publications in this group were, overall, less reflective than those in the narrative group about how to deal with ‘difficult’ material. Some accounts simply suggested that the person might not want to discuss some things and that LSW should ‘avoid’ some types of memories or topics and concentrate on enjoyable memories;41,42 most did not refer to the possibility of difficult issues arising at all. There was, similarly, little routine acknowledgement of issues of privacy or confidentiality. The single publication in the whole review that was specifically about people living with dementia who were lesbian or gay45 talked about the person needing to feel comfortable with the level of detail included in their ‘autobiography’ and that LSW could raise issues of privacy and confidentiality. However, only one description of LSW in this subgroup talked specifically about issues of consent and future use, which, it was suggested, should be logged and recorded in the life story, and, in the case of consent (or assent), should be assured on a continuing basis. 39 Perhaps in implicit recognition of the possibility of having to deal with ‘difficult’ issues, two papers did suggest that untrained staff, or volunteers (even if trained), should not do LSW. 39,43

Care-focused approaches to life story work

What is a care-focused approach to life story work?

We defined a third group of publications about LSW based on their strong focus on practical advice about LSW done in care settings or by care staff. They are distinct from the other two groups described above by their emphasis on ‘how to do it’ and a generally lower level of reflection on ‘why’ and ‘what for’ questions about doing LSW. Indeed, only four of the publications in this section reflected on what LSW might be. One discussed the role of LSW as a device for ‘cognitive stimulation’, with the aim of maximising independence, engagement and well-being. 46 Another spoke of LSW as an opportunity to focus on ‘memory windows’ for people living with severe dementia and to identify specific and personally relevant triggers to memory. 47 A third publication spoke of the importance of seeing a life story as an ‘interactive tool-box’ for the person living with dementia, family and care staff, and not just as a source of information. 48 A single publication referred to the need for an holistic approach to underpin LSW. 49

Good practice in care-focused approaches to life story work

Many different life story formats were referred to in these publications: books, collages, photo albums, videos, digital versatile discs (DVDs), boxes of items, and albums with both text and relevant artefacts. As this might suggest, many writers argued that there should be no rigid approach to the LSW ‘product’: that the chosen format should be discussed and agreed with the person living with dementia;49 that life story ‘albums’ should be as individual as the person they were about;48 that it was important to avoid a ‘story book’ format and to include belongings and photographs;50 that any artefacts included should be personally meaningful and significant for the person living with dementia;46 and that the topics in life stories should also follow no rigid format. 51

Although these papers that were advocating a wide range of formats underlined the person-centred decision-making that should determine choice, others suggested that choice was more likely to be or should be determined by the stage of dementia51 or the care setting. 52 Thus, collages were suggested as more appropriate vehicles for life stories in continuing care settings. 52 Further, in contrast to the laissez-faire approach to format, two publications suggested the use of topic lists or templates for creating a life story. 53,54

There seems to be more emphasis in the publications in this group on other people being involved in collecting and recording information than just the person living with dementia and a life story worker. Thus, one publication states clearly that family members compiled the life story books;51 others state that staff recorded memories prompted in reminiscence sessions,54 typed up notes about memories and added photos to them54 or found or added photos and sensory objects related to the ‘main themes’ addressed during LSW. Two writers, however, do underline the importance of ensuring that information recorded by staff, and its use, should then be agreed with the person living with dementia. 49,55 One of these further states that it is the role of the care worker not to ‘steer’ the person living with dementia but to value their reflections and negotiate where in the life story content should be placed. 55

The role of family members is more prominent in this group of publications, although not all writers agree about their role. Views included that mentioned above – that family members should actually compile the life story – and an assertion that the life story should belong to the carer when the family member is living with dementia. 7 Some writers suggest that staff should gather family members’ and friends’ recollections7,47,54 and that they could provide photos or other supplementary material. 46,47,54 Only one paper suggested that the person living with dementia should be asked to give their permission before staff talked to family members and carers. 55 Overall, then, publications in this section see family member or carer involvement in LSW as unproblematic. Indeed, one suggests that staff should ensure that family members are happy with the life story’s contents, but does not make the same suggestion about the person living with dementia. 56

Perhaps because of the care-focused nature of these publications and, therefore, the possibility that they were targeted at care staff working with people living with later stages of dementia, some of them position LSW clearly within the routines and processes of the care setting. Thus, LSW is argued to start with assessment46,49 and to draw on information about the person living with dementia drawn from files, from other staff members and from interactions and observations in the care setting. 46,47,49

Only one publication in this group talked specifically about consent in relation to LSW and this emphasised that consent should be an ongoing and renegotiated process. 54 Another talked about the need to establish trust before any LSW was started. 7 Privacy and confidentiality were raised more often and particularly in relation to ‘personal’ information;7,55 one paper reported LSW where ‘sensitive’ information about the person with dementia was collected from family members but not ‘posted’ in the life story itself. 56

Responding to sensitive or difficult issues was also mentioned, with recommendations that staff helping people with dementia to do LSW should be aware of what type of material might provoke strong or upsetting emotions47,49,54 and perhaps avoid or move away from such material. 54,55 By contrast, it was also important to acknowledge or empathise with strong feelings during LSW,49,55 not least because not acknowledging ‘difficult’ things could be a barrier to understanding. 56 One publication went so far as to say that LSW could be a good vehicle for exploring feelings if staff had counselling skills. 51 Alone among all the publications included in the good practice part of our review, a publication in this subsection raised the ethical issue of the loss of close personal communication that might be experienced by the person with dementia when LSW was completed. 55

Hybrid approaches to life story work

What is a hybrid approach to life story work?

A small number of publications (five, reporting four different types of LSW9,57–60) were hybrids, in that they were mainly about LSW in care settings but included some narrative elements in the description of how LSW should be carried out. These publications were least likely of all those reviewed here so far to articulate a view about what LSW actually is. What characterised them as having elements of a narrative approach, however, was their emphasis on the centrality of the person living with dementia. They argued that a life story should reflect the issues and events of most importance to the person living with dementia,9,57 that it should use the words of the person living with dementia58 and that it should be written in the first person. 59

Good practice in hybrid approaches to life story work

Although publications in this group emphasised that there was no single format that LSW might use, in effect all were predominantly about life story books. 9,57–59 One publication emphasised the importance of making the life story product attractive to hold and look at, involving the person living with dementia in the choice of colours and design, and using high-quality materials to avoid any association with ‘childish’ activity. 58

The two publications related to life review suggested recording life review sessions to guide the process of creating the life story,57 using the Haight Life Review and Experiencing Form as a framework for the LSW process. 60 For others, objects and photographs could be ‘starting points’ for the reminiscing that informed LSW and served as illustrations for the book. 9,58 When such ‘starting points’ were absent, however, one publication suggested that finding alternatives or taking new photographs might stand in their stead. 60 Illustration might also be more useful than text in the later stages of dementia.

The authors in this section also pointed out that a life story did not have to be chronological, could include current information and details, should be kept up to date and could be edited to add new material. 9,58,59 However, one publication warned against the ‘diary/log of outings’ approach to keeping a life story up to date. 59 The life review-based publications did not talk about these sorts of issues, presumably because once a life review is finished it is considered complete.

Several authors acknowledged that LSW was not for everyone, whether because of personality or stage of dementia. Some people simply might not want to reminisce. 9 At later stages of dementia it might be difficult to do LSW,9,58,59 particularly if the work relied on life review;58 and in later stages people needed a product that they could look at rather than being involved in producing it themselves. 58 Overall, then, it was better to do LSW earlier rather than later. 9

Despite what appeared to be a commitment to the centrality of the person living with dementia, the publications in this group took different views about who should be involved in LSW and when. Those that saw the life story as a product of life review work were consistent in their view about family carer involvement. While acknowledging that family carers could contribute material to LSW, they argued that carers could not and should not direct the contents of a life story book, and that any involvement in the book should be after life review work was complete, and then only with the permission of the person living with dementia. 57 As a result, staff and participants carried out LSW. 60 There was also a suggestion that family carers should do their own life story at the same time as the person living with dementia. 57 By contrast, other publications suggested that carers could provide material for LSW, after it had been fully explained to them, and that when people living with dementia were too severely affected to do LSW themselves, then carers could contribute. 9 One also felt that templates were useful for LSW because they provided questions and prompts for staff and family members not experienced in LSW,58 suggesting that family members might themselves be doing the LSW with the person living with dementia.

Despite this divergence of views about who could be involved in doing LSW, most publications in this section were clear that the life story product was the property of the person living with dementia,9,57,58 although they were less likely to deal with access issues. One suggested that during the process of gaining consent for doing LSW, the person living with dementia should be shown an example of a life story book and be given clear examples of who might see and use the book once produced. 9 Another said that the person living with dementia should guide the current use, access to and future use of the book. 57

Only one publication in this hybrid group specifically mentioned issues of what and what not to include in the life story product, stating that the boundaries of what should be included or not should be provided by the person living with dementia and their carer and then respected during LSW. 9 Further, this publication warned that perceptions of an invasion of privacy might be more evident when a ‘task model’ of LSW was predominant.

Only two publications9,59 dealt with what to do if difficult issues came up during LSW. They counselled against ignoring expressions of emotion and underlined the importance of skilled listening, but also acknowledged that staff involved in LSW were not there to resolve problems and ‘make things better’. 9 One also talked about the importance of not letting the person with dementia get ‘trapped’ in negative memories. 59

Organisational issues around life story work

In this final section of the good practice review, we turn to what the documents said about how LSW should be organised or presented within the settings in which it was being carried out. We identified several themes here: the culture of care in the organisation; leadership and management support for LSW; the resources or time required for doing LSW; the support provided to staff involved in the setting where LSW was being carried out; and training or preparation for staff and/or volunteers doing LSW in partnership with people living with dementia. Thirty-five of the 47 publications reviewed here said something about one or more of these themes. 7,9–11,14,25,26,31–34,36–40,43–45,49,50,52,54–56,58–66,70

The culture of care

The publications that talked about the culture of care in the LSW setting were all agreed that, in order to be successfully adopted and carried out, LSW had to be embedded in and ‘match’ the culture or service philosophy of the care setting. 10,14,32,34,40,60 If LSW was being proposed from ‘outside’, then it was important to examine the culture of care implementation to ensure that this matched.

To assist the proper embedding of LSW, the care setting itself had to have an overall culture of person-centred care14,33,40 and also to believe in the importance of partnership between care staff and families. 14,33,34 One publication said that without these cultural underpinnings it was more difficult to secure staff commitment to doing LSW. 34

Furthermore, LSW had to be an integral part of everyday care and not an additional ‘task’,10,40 or one that was ‘assigned’ to some staff and not seen as a team responsibility. 32,40

Leadership and management support

Active support from the leaders, senior managers or owners of care settings was clearly seen as crucial to the successful implementation of LSW,7,11,32,34,36,39,40,44,50,52,61,62 and without this support it would probably be difficult to secure staff and/or team participation. 34,52,59,60

The appropriate commitment of leaders and managers was needed to ensure that LSW was implemented as part of a well-thought-out strategy,11 accompanied by facilitation and supervision for staff doing LSW14 as well as policies and guidelines about how LSW was to be carried out and how its products were to be used. 40,63

One particularly important study in this group specifically explored the factors that influenced implementation and argued that ‘Consistent, convinced leadership, careful prioritisation of resources and competent management (particularly over small details such as staff rosters) are all essential if lasting improvements are to be made’. 39

Resources and time needed for life story work

The major issue identified here was the time needed for doing LSW well.

Some publications talked about the actual amount of time or number of ‘sessions’ that needed to be dedicated to doing LSW: a minimum of 2 hours per week per person,39 50 hours over 6 months for each person,54 a minimum of six one-to-one sessions with the person living with dementia. 26 Others just acknowledged that LSW is time-consuming40,58 and that time has to be spent getting to know, or building trust with, the person living with dementia before starting LSW,7,11 a particular issue for those who might be working with lesbian or gay people living with dementia. 45

However, the length of each LSW session will be influenced by the attention span, motivation and emotional state of the person living with dementia at any given session. 55 It is thus presumably difficult to predict with any accuracy how long it will take to complete LSW for any given individual.

Much discussion revolved around a lack of dedicated resources or time as the biggest obstacle both to doing LSW and then to using its products in care. 7,10,11,34,39,44,49,52,56,59,60 As a corollary, adequate and dedicated resources and staff time were seen as the sine qua non for successful LSW to take place. 7,26,36,39,54,58,59

All of the comments above suggest that LSW is seen as something separate from the normal routines of care. However, one writer argued strongly that LSW should be a part of ongoing, interactive ‘joint production’, and not a ‘task’ to be completed in a given place at a given time. 9 The use of life story products should also be built into everyday routines. 59

Practical resources are also necessary to support LSW; laptops or PCs, scanners and digital cameras are essential,26 as are the skills in using them. 52 Somewhere quiet or private to do the work is also necessary, but often surprisingly hard to find in care settings. 26,39

Some publications talked about the need for trained facilitators, project workers or co-ordinators to support LSW,7,52,54,63,64 again suggesting that LSW is seen as something rather separate from everyday care.

Support for staff carrying out life story work

Related to the issue of resources and time was the theme of the nature of support offered to staff involved in doing LSW. Here, training for LSW was the main concern,7,40,58–60,65 to enable staff to both do LSW and use its products. Only two publications, however,54,65 suggested that staff might be encouraged to create their own life story.

Life story work training might not be enough in itself, however; staff might need help to develop their communication skills,40 or support and encouragement to enable them to explore the stories of people living with dementia without feeling ‘nosey’ or ‘intrusive’. 60 Appropriate supervision or mentorship should also be in place to support staff in setting appropriate professional boundaries and in case ‘difficult’ material is revealed while helping a person living with dementia to create their life story. 11,14,37,63

Finally, there was a subtheme about the importance of a team approach to LSW. LSW should be developed as a mutually supportive team effort, even if not everyone is involved in actually doing it; it should not be left to a limited number of staff whose work might be ‘sabotaged’ by others who do not understand or respect the approach. 39. 52,56,60 The role of a facilitator in developing LSW and supporting staff in this way was seen as crucial in one study that followed the implementation of LSW in a long-term care setting. 52

Training for life story work

Twenty-three of the included studies mentioned training as an issue in LSW. Most were clear that anyone doing LSW should be trained7,11,38–40,52,64,70 or that trained facilitators or ‘champions’ were essential to good practice. 32,33,39,52 Training for ‘other’ staff, or at least ensuring that all staff understood LSW and could support its use in the care setting, was also recommended. 7,31,39,52,59

Other publications placed less emphasis on the need for training, suggesting that LSW could be done with minimal training if it was accompanied by supportive supervision,66 or that volunteers could ‘graduate’ from family LSW workshop groups to run groups themselves. 33 However, one publication cautioned against the use of volunteers in LSW because of their potential vulnerability and the possibility that ‘difficult’ issues might emerge during LSW,43 while another – that had used an informal ‘monitor’ approach to rolling out LSW training to staff – had had to put in additional training to make this model work. 7

In terms of suggestions about the content of training, publications fell into two main groups.

First, there were those that were mostly practical in orientation. These recommended that training should include information about dementia itself25 and how to ‘select’ people with dementia to do LSW;38 about the different ways in which LSW might be presented;25,38,54 about technical support for LSW such as scanners and computers, library and internet resources;54,65 and about the principles of capacity and consent. 36

The second group of publications concentrated more on aspects of emotional intelligence in relation to LSW, where learning to deal with ‘difficult’ issues was predominant. This grouping included methods for recognising and dealing with difficult issues11,38,60 and emotions;9 developing communication skills and empathy;40 learning how to maintain boundaries37 or, by contrast, becoming willing to scrutinise interpersonal relationships with care home residents;60 and learning to be sensitive to family members. 56 Producing one’s own life story product54,65 or reflecting on one’s own life story more generally49 and reflective practice learning39 were possible routes to enhanced emotional intelligence in LSW practice with others, but could also be empowering for staff in their own right. 65

Underlying theories of change

One of the acknowledged weaknesses of much research that has tried to evaluate complex interventions in health and social care settings is that it has searched for improved outcomes without any pre-existing theory about why we might expect the particular intervention to affect the given outcome. 18 This is the case with LSW: there is enthusiasm for it as an approach and practitioners feel that they observe change when they use it, but it is difficult to pin down any underlying theory of change about why these changes might have occurred. There is, thus, the danger that evaluative research might choose the wrong outcomes to assess – both intermediate and final – and thus fail to demonstrate change.

This next part of our review work was, therefore, designed to develop a theory of change, based on the literature selected for review.

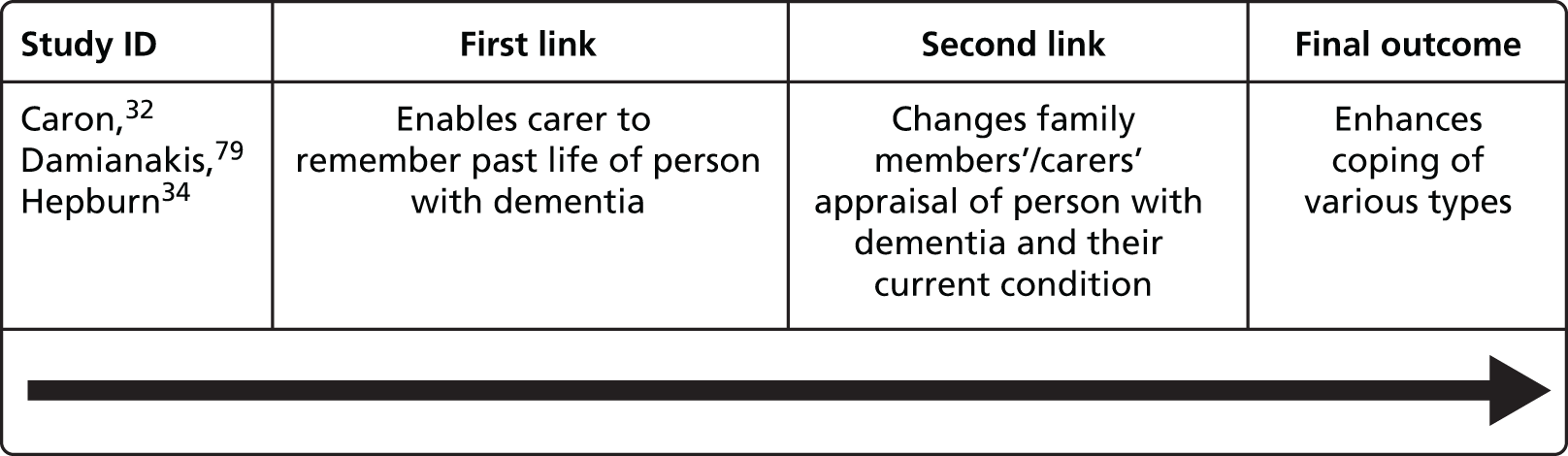

We gave an example of how we envisaged this work in our proposal:

The results of one life story project57 have been described thus: ‘The group that participated in a dyadic life review (caregiver and care receiver) seemed to gain most from the intervention, particularly in their assessment of the care receiver’s problem behaviours. Possibly . . . because they were enjoying the process simultaneously and were sharing an event again.’

p. 171106

Here, the underlying theory seemed to be that the carers’ assessment of the care receiver’s problem behaviours improved (final outcome for family carer) because the dyadic life story process (LSW) was shared (implicit causal link) and was enjoyed (implicit causal link).

This generates a theory of change that can be expressed in a linear fashion:

Type of LSW → that was a shared process → that was enjoyed → changed carer’s assessment of ‘problem behaviours’.

As this example suggests, such theoretical models are often embedded in descriptive or discursive text, rather than articulated explicitly as a hypothesis to be tested.

Analysis

In our analysis of the 16 papers that expressed an underlying theory,7,10,14,31,32,34,38,42,56,57,59,60,67–70 we identified the causal links between LSW and the outcome or outcomes that the authors were arguing for LSW, as given in the example above. In some papers there was a single such theory; in others there were several. We first summarised these theories into our Excel spreadsheet using the data headings outlined above, and then mapped them all in a mind map. This was done twice: once for the theories articulated in the introductory sections of each paper (initial theories of change) and again for the theories articulated in the discussion and concluding sections of each paper (concluding theories of change). In both cases, we concentrated on theories that the authors themselves were arguing, not on theories that they were repeating or reviewing from others’ publications.

After completing the initial mind-mapping, we synthesised the material using a set of overarching outcomes. Given that most of the papers had included some empirical work, we took the concluding theories of change as the basis for this final stage of analysis, assuming that these would be a more accurate reflection of the authors’ views about LSW, its outcomes and the routes by which it achieved these outcomes.

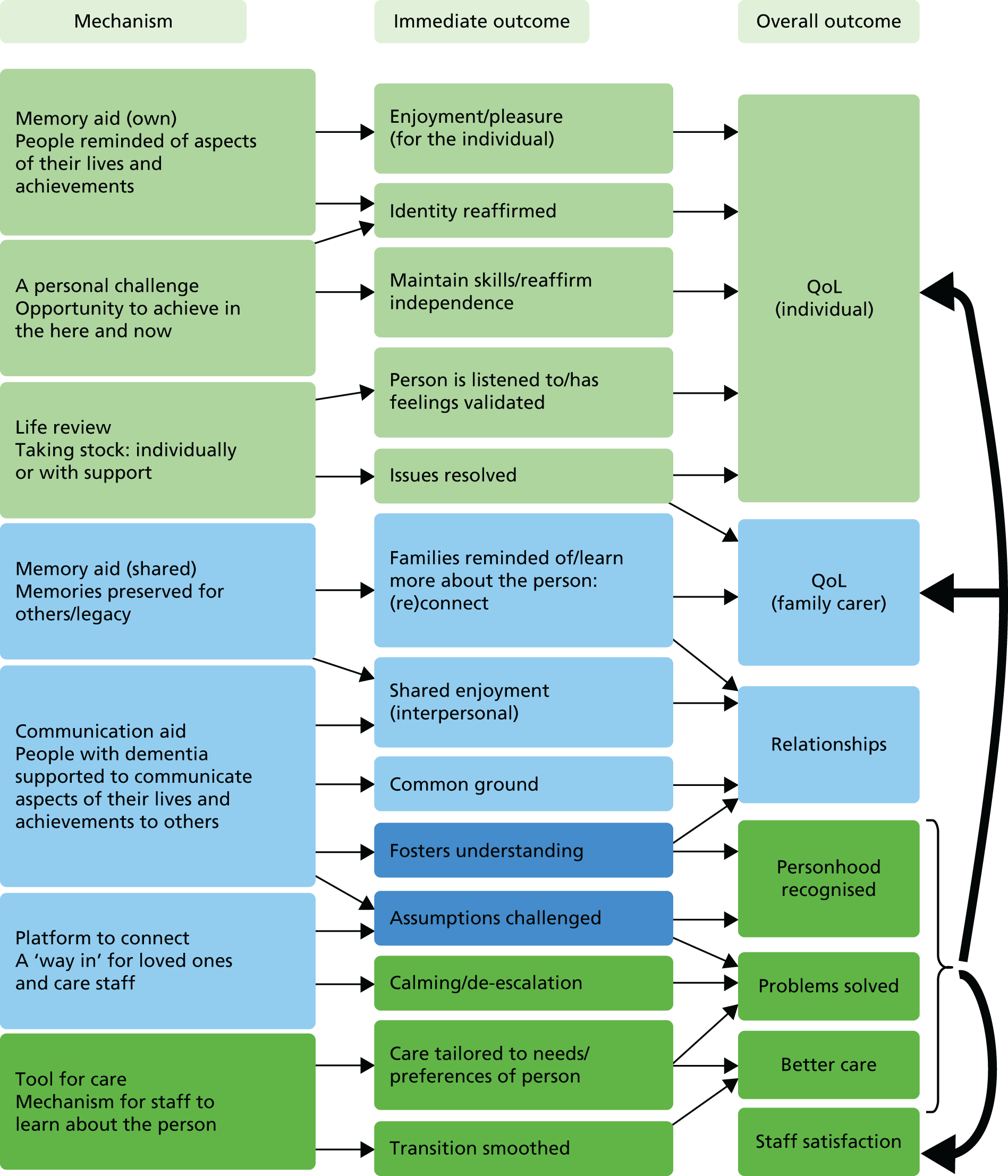

Theories of change

The initial mind-mapping generated complex and complicated pictures of both initial and concluding theories of change (see Appendix 1 and Boxes 1 and 2). The 18 papers outlined 26 theories of change initially, but 47 in their conclusions.

As Tables 7 and 8 show, some theories of change were relatively simple, with only one intermediate outcome between LSW and a final outcome. So, for example, concluding theory of change 3 was that LSW leads to interactions between care staff and family members, thus strengthening understanding of, and the relationship with, family members.

Others theories of change were much more complex, and sometimes argued two separate final outcomes from the same causal chain. For example, concluding theory of change 24 (final outcomes in bold) was:

24: [LSW] enables staff to gain fuller and more dynamic picture of person with dementia

24.1: which increases their knowledge of the person

24.1.1: which enables them to find out more about person’s needs and behaviour AND

24.1.2: which helps staff see person in context of whole life rather than in terms of their medical condition/physical needs AND

24.1.3: which provides a talking point between staff and person with dementia

24.1.3.1: which helps develop common bond between person with dementia and staff.

Here we see two intermediate outcomes (24, leading to 24.1) that led to two final outcomes (24.1.1 and 24.1.2) and one further intermediate outcome (24.1.3), which itself led to an additional final outcome (24.1.3.1).

As is also clear from the tables, there were overarching final outcomes in the theories of change. Our next stage of analysis was to identify these outcomes and synthesise the causal links that the literature suggested led to them. In doing this, we confined the analysis to outcomes that at least four papers identified as resulting from LSW. Then, within each outcome, we confined analysis to theories of change in which at least two studies had argued that the same or similar causal links led to these outcomes. In total, we identified seven outcomes and 12 theories of change.

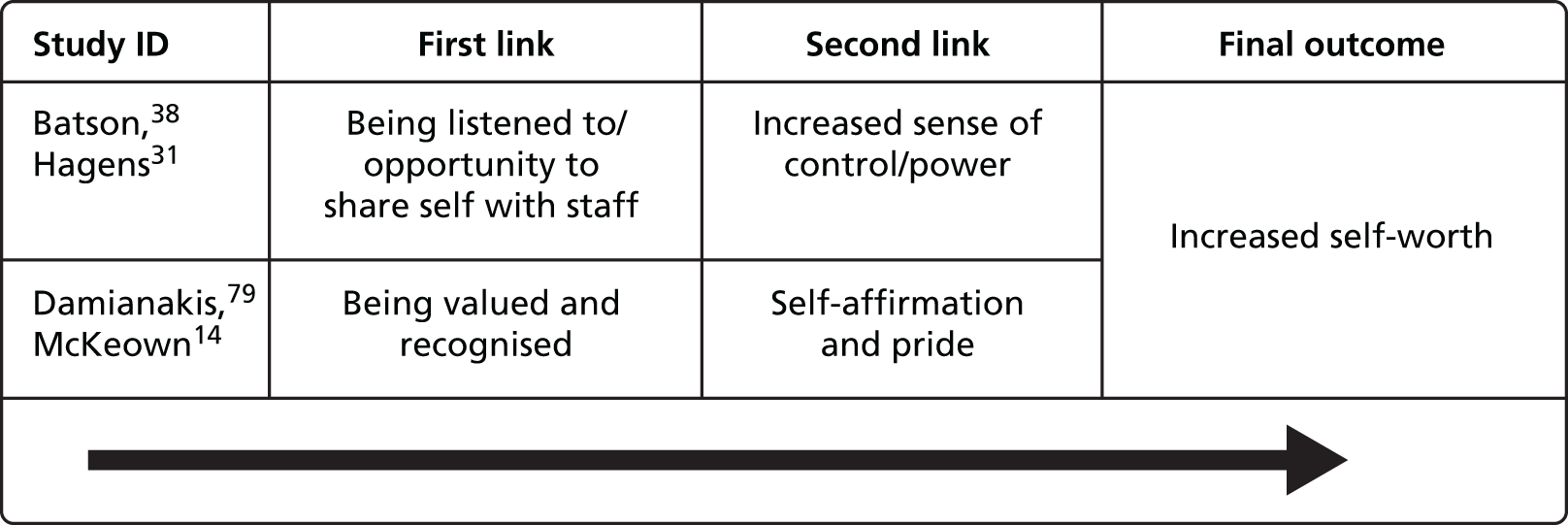

The overarching final outcomes for the person with dementia were:

-

LSW supports the self-worth and empowerment of people with dementia, for example increased sense of control, pride in their lives and opportunity for reciprocity. 14,31,38,67

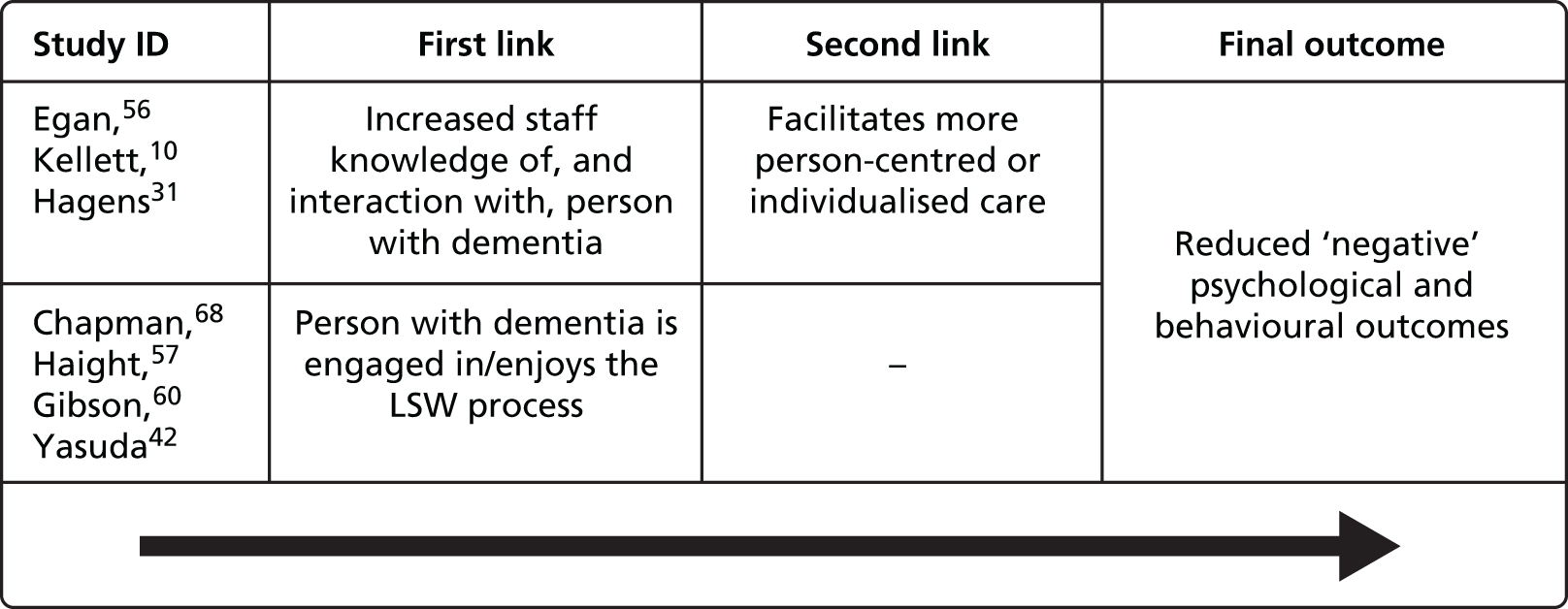

-

LSW affects a range of individual outcomes positively, for example anxiety, depression, agitation, mood and behaviour. 10,31,38,42,56,57,59,60,67,68

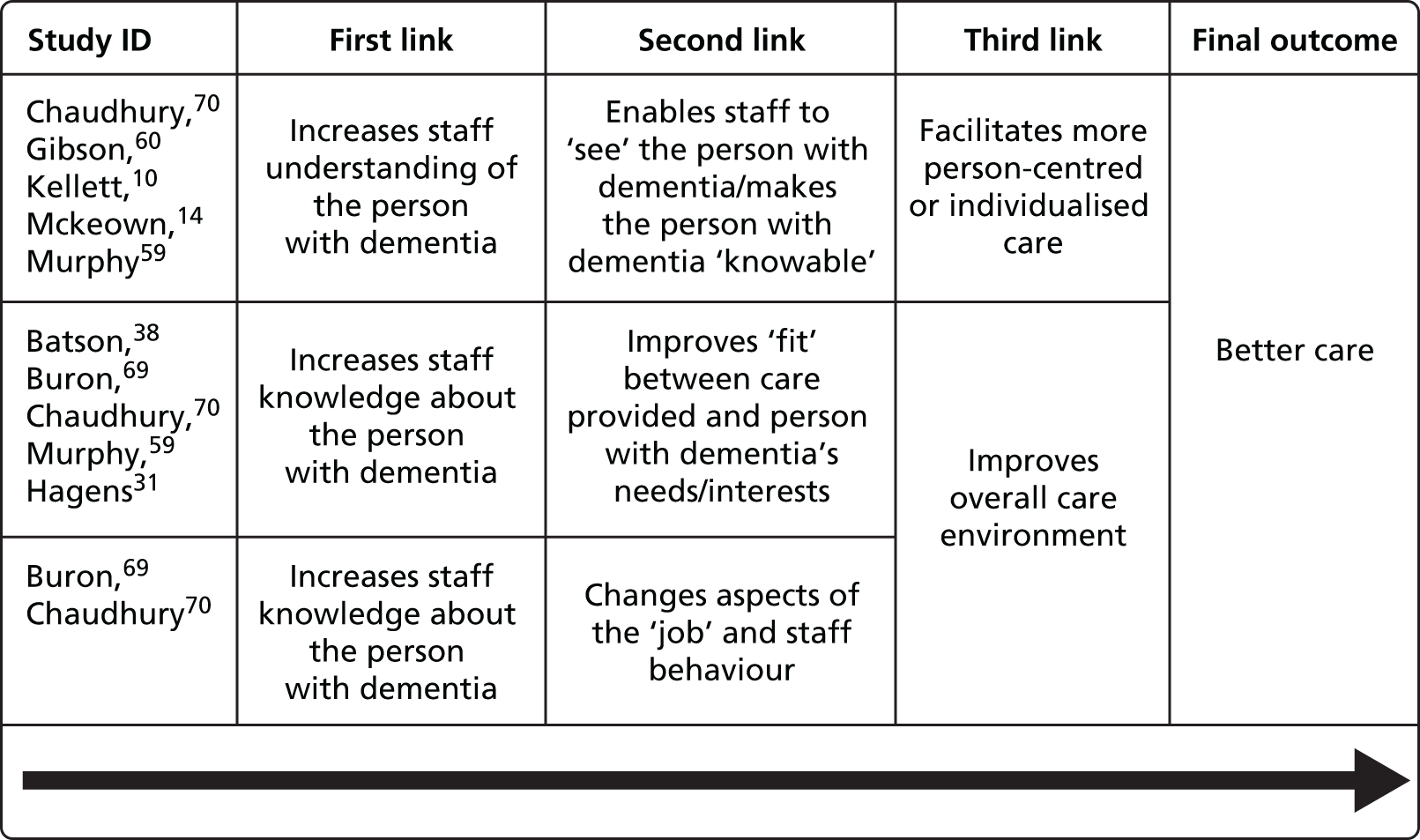

Final outcomes in relation to the care setting were:

-

LSW improves relationships between care staff and the individual person with dementia. 7,31,59,69

-

LSW leads to better care, for example more person-centred, individualised, less ‘pathological’ care on a one-to-one basis. 10,14,31,32,38,59,60,69,70

For family members and carers, the final outcomes were:

-

LSW allows more effective engagement of family members/carers within the care setting, for example enhanced communication with staff and more meaningful involvement in care planning and delivery. 7,10,32,67,69

The theories of change are summarised in Figures 2–7.

FIGURE 2.

Theories of change for increased self-worth of the person with dementia.

FIGURE 3.

Theories of change for improved individual outcomes for the person with dementia.

FIGURE 4.

Theories of change for improving relationships between staff and the person with dementia.

FIGURE 5.

Theories of change for improving care.

FIGURE 6.

Theories of change for more effective engagement of family/members in care setting.

FIGURE 7.

Theory of change for helping family members/carers to cope better.

The identified final outcomes from this part of the review were subsequently used to inform discussion and the final choice of outcome measures for the feasibility study (see Chapter 4).

Chapter 3 Life story work outcomes, challenges and good practice: findings from the focus groups

Introduction

The objective of this part of the study was to carry out a qualitative study of experiences of LSW, including people with dementia, family carers and professionals (objective 1). The overall aim was to develop a theoretical model of LSW, including its potential outcomes, and establish core elements of good practice in using and applying the approach.

Successful evaluation requires an understanding of what an intervention is intended to achieve and how different approaches to this intervention may determine different outcomes for different groups. 107 MRC guidance recommends drawing on existing evidence to develop a theoretical understanding of the likely process of change, but also suggests supplementing this with new primary research if there are gaps in the literature. 18 Earlier reviews of the literature on LSW concluded that more work was needed to develop a sound theoretical framework12 and, in particular, emphasised that there had so far been only limited reporting of patients’ and carers’ views. 11 We know that people living with a condition can have very different views about outcomes from policy-makers and clinicians. 108–110 This stage of the study, therefore, aimed to collect primary qualitative data about outcomes and good practice from three different perspectives: people with dementia; family carers; and staff and professionals with experience of LSW.

Aims

-

To identify potential outcomes of LSW (to be measured in the feasibility study).

-

To identify potential challenges or problems with LSW and possible solutions.

-

To establish core elements of good practice.

-

To use these findings, together with those from the review, to develop a theoretical model of LSW.

Methods

Ten focus groups were held: four with people with dementia [organised and co-facilitated by Innovations in Dementia community interest company (CIC) and KG]; three with family carers (organised and co-facilitated by Uniting Carers and KG); and three with staff, professionals and volunteers with experience of LSW, recruited through the Life Story Network CIC and co-facilitated by KG and GMP. Research ethics approval for this stage of the project was obtained from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Social Care Research Ethics Committee (SCREC) for England in October 2012 (Research Ethics Committee reference number 12/IEC08/0046).

Focus groups with people with dementia

We originally planned to conduct three focus groups for each group, each with 5–10 participants. We added a fourth session with people with dementia to bring in a wider range of views and anticipating that groups of people with dementia may need to be smaller to accommodate communication and cognitive impairment. Focus groups with people with dementia were held in settings already known to and attended by participants, in order to maximise comfort and familiarity. This also meant that known and trusted group facilitators were on hand to help with the consent process and to support anyone who chose, on the day, not to take part.

Recruitment

Recruitment was purposive and designed to include people with dementia from a range of community settings and experience of LSW. Stages of recruitment were:

-

Innovations in Dementia CIC approached some groups they already worked with, as well as new contacts, via group facilitators.

-

Innovations in Dementia then visited interested groups (usually with KG) to inform potential participants about the project, answer their questions and invite them to take part (see the information sheet in Appendix 5).

-

If the group, or a number of the group’s members, were interested in taking part, a date was set for KG and Innovations in Dementia to return to conduct a focus group. Consent was taken at this stage (see below).

-

After the focus group, a further visit was planned to feedback to participants (and group facilitators).

Details of the people with dementia that took part are included in Table 13 (see Appendix 1, where other tables for this chapter can be found). In total, 25 participants with dementia (15 female and 10 male) took part across four groups.

Consent

Only people with the capacity to give informed consent were included in this stage of the project, as participation in a focus group requires an understanding of the concepts under discussion and the ability to express views. Group facilitators discussed capacity before the first visit from Innovations in Dementia to gauge whether or not at least some of the group members would have the capacity to consent. At the first visit, Innovations in Dementia and/or KG talked through the project information sheet with the group and answered any questions, and then revisited the information sheets with each individual on the day of the focus group before consent was given.

The use of written consent forms (see Appendix 5) was not straightforward, and in some cases presented an active barrier to participation. People with dementia who understood the premise of the research and expressed (verbally) that they were happy to take part sometimes struggled when presented with a lengthy consent form with a number of separate statements for them to agree to before signing. These statements are a SCREC requirement and must be included on all participant consent forms. However, asking people to agree or disagree to each of these and then sign, after they had already discussed each point (while talking through the information sheet) and indicated verbally an intention to proceed, was burdensome and fatigued some before the focus groups had even begun. Moreover, some people with dementia found it physically difficult to hold a pen and sign their names. Signing a document may also feel like a significant act for a person who is losing control over aspects of their life and we became concerned that this might be causing unnecessary worry for some of our participants. We decided therefore to build the facility for verbal consent with a witness into future consent processes with people with dementia, and received approval from SCREC to use these in the final stage of the project (see Chapter 6).

Format of the sessions and topics covered

We had planned only to include people with dementia with experience of LSW in the focus groups. However, after further consideration we agreed to include people with a range of experience of LSW. This recognised that some people with dementia may have actively chosen not to undertake LSW, while others might not have come across the idea but still have views on recording and sharing aspects of their life. To understand good practice we needed to hear from the full range of potential LSW participants, not just from those who had successfully engaged in it.

To ensure that all participants understood what we meant by LSW, we produced four specimen life stories and took these to each session to share with the group. These were:

-

a structured life story book, based on a template

-

an unstructured life story folder, with photographs and text

-

a life story box with objects, photographs and documents

-

a digital life story accessible via a touchscreen tablet.

On the advice of our advisory group, we also encouraged participants to bring in their own life story products or an object or photograph that they would be happy to share with the group. The focus groups then began with a discussion of these specific products and artefacts before moving on to more general topics such as the outcomes of recording and sharing life stories and the best ways to do this (see Appendix 6 for the topic guide). Sessions were co-facilitated by Innovations in Dementia and KG, with the existing group facilitators on hand in case participants required support from a familiar worker.

Focus groups with family carers

We held three focus groups with family carers of people with dementia with experience of LSW, all recruited through the Dementia UK network Uniting Carers. Dementia UK hosted two focus groups in London and we held a third in York. Uniting Carers and KG co-facilitated all three groups.

Recruitment

Carers were recruited through the Uniting Carers e-network as follows:

-

Invitations were circulated to the e-network of carers of people with dementia.

-

Interested carers contacted Uniting Carers who gave full information (see participant information sheet in Appendix 5) and answered carers’ questions.

-

Dates for focus groups were confirmed by telephone or e-mail and participants confirmed attendance.

-

KG and Uniting Carers co-facilitated three focus groups. Consent was taken at this stage.

-

Feedback on the overall findings from this phase of the research was circulated to participants by e-mail and comments were requested.

Table 14 (see Appendix 1) gives details of the focus groups held and the types of carers who took part. In total, 21 carers (16 female and 5 male) took part across three groups.

Consent

Written consent was given on the day of the focus groups (see Appendix 5). All participants received the information sheet in advance and again on the day of the focus group and had the opportunity to ask questions.

Format of the sessions and topics covered

Uniting Carers and KG jointly facilitated the focus groups with carers. Each began with an ‘icebreaker’ exercise and moved on to topics such as personal experiences of doing LSW, outcomes and challenges, and general views about good practice (see Appendix 6 for the topic guide).

Focus groups with professionals

Three focus groups were held with professionals from health and social care settings who had experience of doing LSW with people with dementia. The Life Story Network CIC helped to identify potential participants, as did other networks including DeNDRoN (Dementias and Neurodegeneration Network). Two focus groups were held in York and one was held in London. KG and GMP facilitated two groups together, and KG facilitated one alone.

Recruitment

Professionals were recruited as follows:

-

Invitations were circulated to a number of e-networks including the Life Story Network, local DeNDRoNs and a dementia-training network.

-

Interested professionals contacted KG, who gave full information (see participant information sheet in Appendix 5) and answered questions.

-

Dates for focus groups were confirmed and participants confirmed attendance.

-

Three focus groups were facilitated by the research team. Consent was taken at this stage.

-

Feedback on the overall findings from this phase of the research was circulated to participants by e-mail and comments were requested.

Table 15 (see Appendix 1) gives details of the focus groups held and the types of professionals who took part. In total, 27 participants (26 female and 1 male) took part across three groups.

Consent

Written consent was given on the day of the focus groups (see Appendix 5). All participants had been given the information sheet in advance but received it again on the day of the focus group and had the opportunity to ask questions.

Format of the sessions and topics covered

As well as the topics addressed with all groups, professionals were also asked about drivers of resource use in dementia care settings and what changes, if any, they would expect to see in these if LSW was carried out (see Appendix 6 for the topic guide). This material was used specifically to inform data collection in the feasibility study (see Chapter 6).

Analysis

All the focus groups were audio-recorded, with participants’ permission. They were transcribed and analysed thematically using the Framework approach. 111 The aim was to produce a realist account21 of what works, for whom and in what circumstances, from the perspectives of people with dementia, family carers and professionals.

Findings

By adopting a ‘realist’ approach, we were interested in the types of outcomes experienced or expected by different groups, as well as any situations in which such outcomes might not be achieved. By exploring the circumstance in which positive outcomes are experienced, and considering what went wrong when experiences were less positive, we also gained a better understanding of good practice. First, the findings of this stage of the research are presented in terms of outcomes – for individuals with dementia, for interpersonal relationships and for better care. Second, we examine the challenges involved in doing LSW, and what these might tell us about good practice.

The outcomes of life story work

Outcomes for people with dementia

It was clear that some people with dementia gained immense pleasure from talking about their memories. Reminiscence activities have been used in dementia care for some time8 and LSW can involve a specific form of reminiscence: that which focuses on the individual’s life history. In each focus group with people with dementia some participants told us they found it enjoyable to talk about memories. More specific to LSW, some felt that it was important to record memories, so that they had them to look back on and could share them with others:

What are you going to use them [the life story books] for?

[Pause] For memories.

For yourself?

For myself, and the family, they’ve all seen them. It’s – I think it’s nice just to have a look and think – I used to look like that once!

However, the benefits of this tool for looking back, highlighting and sharing important memories seemed to go further than simply the ‘comfort in recall’ (as one participant put it).

We asked participants in the dementia groups to bring in objects or photographs of something from their lives to act as a starting point for the discussions. Most brought things that reminded them of people or achievements that they were proud of, such as their children’s certificates or photographs from their wedding day. Highlighting and celebrating past achievements was clearly a priority and one that appeared to bring much pleasure. Moreover, each object or photograph came with a story.