Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 09/2001/28. The contractual start date was in February 2011. The final report began editorial review in February 2016 and was accepted for publication in June 2016. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Charles Vincent reports personal fees from Cardiff University during the conduct of the study, personal fees from the Swiss Federal Office of Health, personal fees from haélò, personal fees from Wiley-Blackwell, personal fees from Healthcare at Home and grants from The Health Foundation outside the submitted work. Jonathon Gray reports other from Counties Manukau District Health Board and other from Victoria University of Wellington, Wellington, New Zealand, outside the submitted work.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by Mayor et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 The measurement of harm in inpatient settings: an overview

Background

Since the publication of the first Institute of Medicine reports on quality and safety in health care,1,2 there has been growing awareness of the number of patients unintentionally harmed in the course of health-care management. Global estimates of incidents using a common measurement strategy vary, but rates are normally reported to be around 10% of all inpatient admissions, with a range of 8–12%. 3 In the last decade considerable effort has been made to improve patient safety through programmes and campaigns,4 but questions persist as to whether or not these efforts are well directed. Are patients any safer as a result? For all the effort and resource devoted to patient safety, we still do not know how much progress has been made. The lack of the surveillance of harm in the health-care system,5,6 along with the difficulties encountered in using these kind of measures to demonstrate beneficial effects in the evaluation of patient safety and quality improvement programmes, continues to pose significant challenges to the quality improvement community internationally. 7–10

Welsh context for the study

Wales is in a unique position in relation to harm measurement and mortality assessment, being supported by strong health policy and strategic leads working collaboratively across government, NHS Wales and academia. In 2010, at the start of the study, all NHS providers voluntarily signed up to a national harm prevention campaign, undertaking Global Trigger Tool (GTT) reviews every month in order to monitor progress over time. Data collection preceded the launch of the 1000 Lives Campaign11 and a methodology was developed to quantify the number of episodes of harm averted on a quarterly basis. NHS Wales made an explicit commitment to the continuation of harm measurement across Wales for a 5-year period from April 2010. The study was therefore timely and designed to sit alongside the NHS work, providing evidence of impact and contributing to the ongoing development of a health-care quality measurement strategy for NHS Wales.

During the study period, Wales has developed an active Harm and Mortality Collaborative, in which senior members of health boards, the Welsh Government (WG) and Public Health Wales meet to review strategy and progress on organisational patient safety metrics every 6 months. Through this agenda, and development work undertaken by individual health boards, NHS organisations in Wales stopped undertaking GTT reviews in Wales in 2014, and a mortality review process was developed and, subsequently, mandated for every death occurring within acute care. A screening process was developed to identify those individuals for whom problems in care may have been in some way associated with the nature and cause of death for the purpose of organisational learning. These episodes of care were then intended to progress to a second-stage review, which was not prescribed and varied considerably in approach across organisations. This approach was endorsed by the Palmer review12 along with a suite of audit and critical incident investigations to generate holistic and triangulated assessment of quality of care through these methods.

The identified need for the study

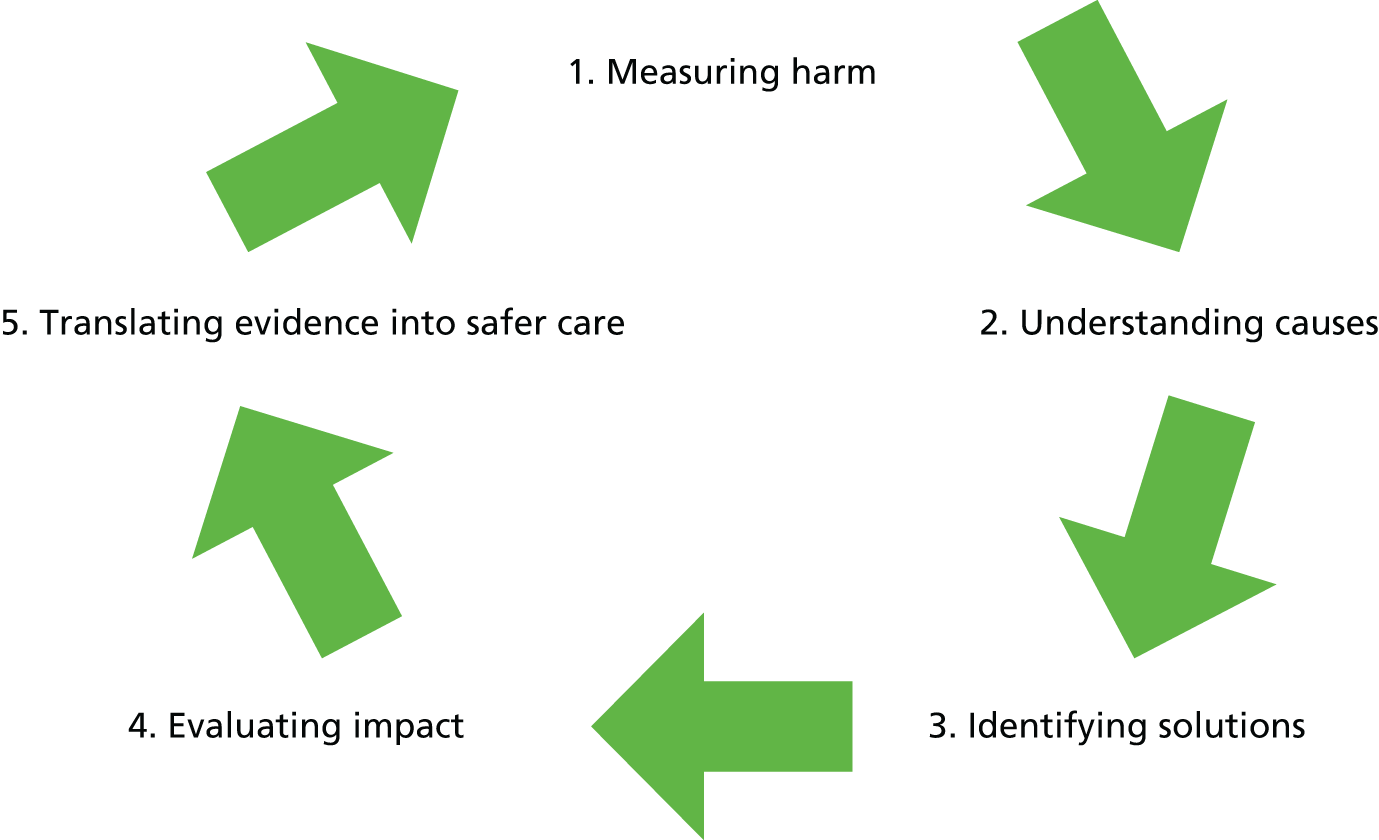

Wales did not have a benchmarkable national rate of harm in health care and, although GTT reviews were being undertaken and there was national guidance on the GTT process, there was variation in the composition of teams and the way in which the reviews were being undertaken. Some health boards opted for a multidisciplinary approach in which physicians were involved in determining adverse events (AEs), whereas others had an approach in which the reviews were undertaken by clinical governance staff. We wanted to determine how effective the GTT was in identifying health-care-related harm by comparing it with the two-stage retrospective case note review process and to use this learning to develop an approach for ongoing harm measurement. We know that system failures and causes of harm cannot be addressed efficiently until issues are identified. Furthermore, the quantification of the nature and extent of the problem provides the basis from which solutions and intervention programmes can be developed and subsequently monitored and evaluated. The starting point for this study was to quantify national rates of harm longitudinally across NHS Wales and to develop methodologies for the reporting of trends of common AEs, thereby providing organisations with the methodological know-how and data to complement current incident reporting practice and support the adoption and embedding of innovative ways of working and revised practices and processes.

The work fitted into a tripartite arrangement comprising the NHS, academic units and the WG (Figure 1). The aim was to develop a comprehensive programme of work describing the epidemiology of harm in NHS Wales hospitals, and to develop and evaluate methods for the systematic assessment of harm collected from a wide range of sources, with the end point being a move towards the active surveillance of salient events. 13 At the national level, the priority was the accurate and holistic measurement of harm14,15 as part of the development of national safety indicators. At the local level, the aim was to promote a culture of learning both from critical incident investigation and the identification of systemic issues in order to inform safety and quality improvement programmes.

FIGURE 1.

Tripartite arrangement addressing the epidemiology of harm in NHS Wales. HSMR, hospital standardised mortality ratio; RDG, research development group.

The measurement of harm

In the UK, a review of case notes from single study sites suggest that 8–10% of patients experience an AE during inpatient management. 14,16 One systematic review of international studies, published in 2008, attempted to gain an overview of data and quantification of what is widely recognised as a ‘serious problem in health care’. 3 The median overall prevalence of in-hospital events was 9.2%, with a median percentage of preventability of 43.5%. More than half of these patients experienced no or minor disability, and 7.4% were associated with, but not necessarily causally implicated in, the death of a patient. Although the reporting of snapshot prevalence data has its uses, we know that the examination of AEs in health care is complex. As seen in aggregate data from studies, summated AE rates are difficult to interpret and conceal a range in severity from minor injuries caused by hospital equipment to catastrophic wrong-site surgery. Work undertaken to date has provided little detail on how the measurement and characterisation of AEs informs learning and the development of interventions, which then have the potential to have a demonstrable impact on clinical processes and practices.

In recent years, as interest and awareness of patient safety issues in health care grows, different methodologies have been used in widely different settings and contexts and for various purposes. 17–21 Although progress on measurement and evaluation is being made within the emerging international agenda of improvement science, challenges remain. Despite comprehensive work undertaken to develop an international classification for patient safety,22 there is still evidence that key concepts and terms are not consistent across research studies and improvement efforts. Fundamental questions still exist around the prevalence and nature of AEs and, perhaps most importantly, opportunities for the effective targeting of interventions and prevention programmes. 23

Reporting systems, such as the National Reporting and Learning System in the UK, have been the principal mechanism through which AEs are reported into a centralised repository that is organised at both local and national levels. Vincent et al. 13 describe how these systems invite voluntary reporting of unspecific safety incidents with the aim of learning lessons and feeding the findings back into the system. Although providing useful examples of cause and effect for the purposes of both professional and organisational learning, the reporting systems are not representative of AEs in patient populations, and a number of studies give rise to concern of significant under-reporting. In one UK study, reporting systems detected only 6% of AEs found through the systematic review of inpatient records24 and similar findings have been reported within the US health-care system. 4 With heightened awareness of the number of patients being harmed as a result of health care, there is consensus across health, academic and policy settings that, although these systems are a valuable component of a safety system, they are primarily warning and communication mechanisms within organisations and will never act as a measurement system for safety. 13 In 2015, health-care organisations and strategists still continue to grapple with identifying reliable and valid, yet pragmatic, tools to measure the quality and safety of care routinely provided. 4

Methodology of adverse event measurement

Measurement describes events in terms that can be analysed statistically, and should be free from random and systematic error. 25 The measurement of errors and AEs in health care, however, is complex and AEs need to be assessed and understood in the context in which they occur. 26 James Reason’s27 ‘Swiss cheese model’ has increased our understanding that errors and AEs in health care are commonly the result of numerous latent errors in addition to an active error committed by a practitioner. 26 Despite this growing understanding and theoretical underpinning, the actual determination of an AE is still often a subjective and complex task for even the most experienced clinician.

The literature reports numerous methodologies used to quantify harm and error in health care, with each method being associated with strengths and limitations. 26 They include the review of post mortems and medico-legal claims, summative data outputs from reporting systems, clinical outcomes reported through administrative data set analysis, structured review of medical records, ethnographic observation of practice and the clinical surveillance of specific events. Methods differ in a number of ways. Although some methods are oriented towards detecting the number of AEs, others address their nature and contributory factors. The scale also varies significantly: some focus on single cases or a small numbers of cases with particular characteristics, such as claims, whereas others attempt to randomly sample a defined population. Thomas and Petersen26 suggest that the methods can be placed along a continuum, with active clinical surveillance of specific types of AE (e.g. surgical complications) being the ideal method for assessing incidence, and methods such as case analysis and morbidity and mortality meetings being more oriented towards causes. It is clear that there is no ideal way of estimating the incidence of AEs in health care and all methods give a partial picture of the true extent of the problem.

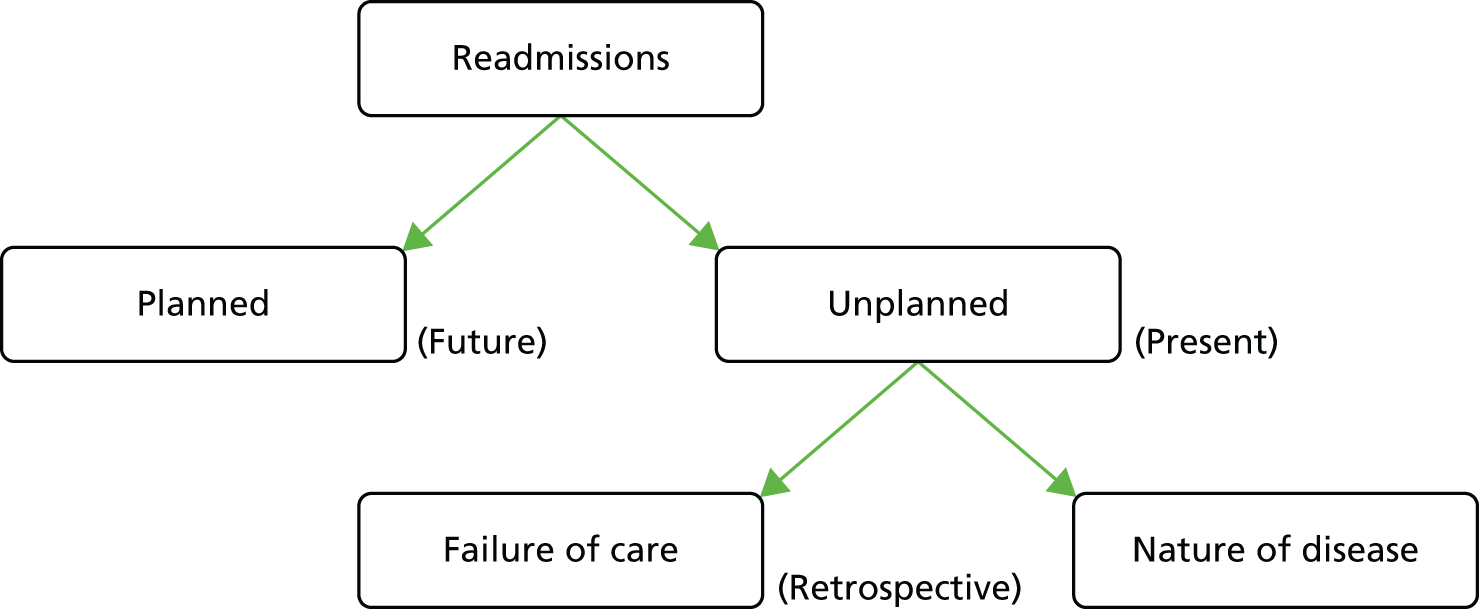

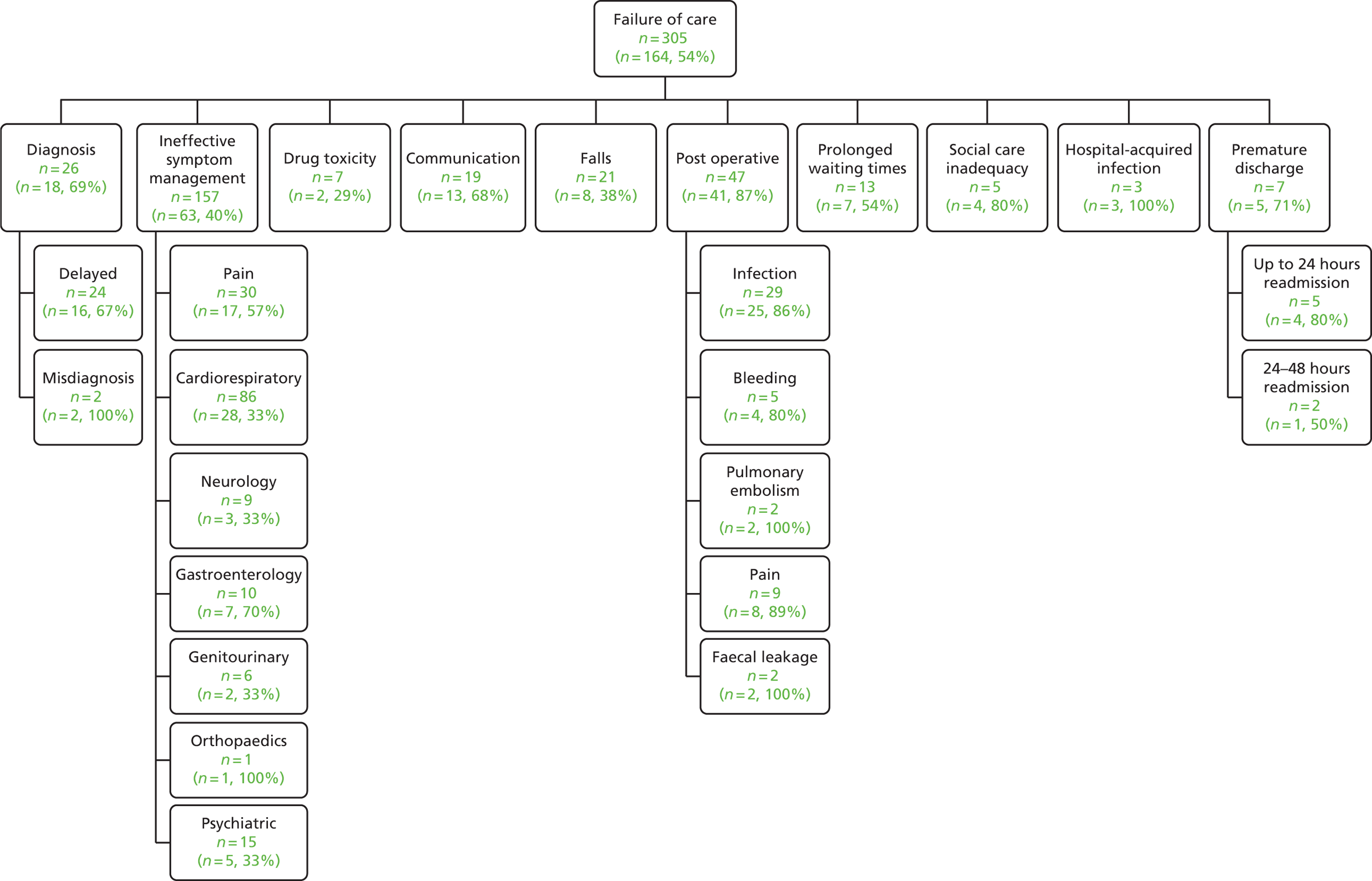

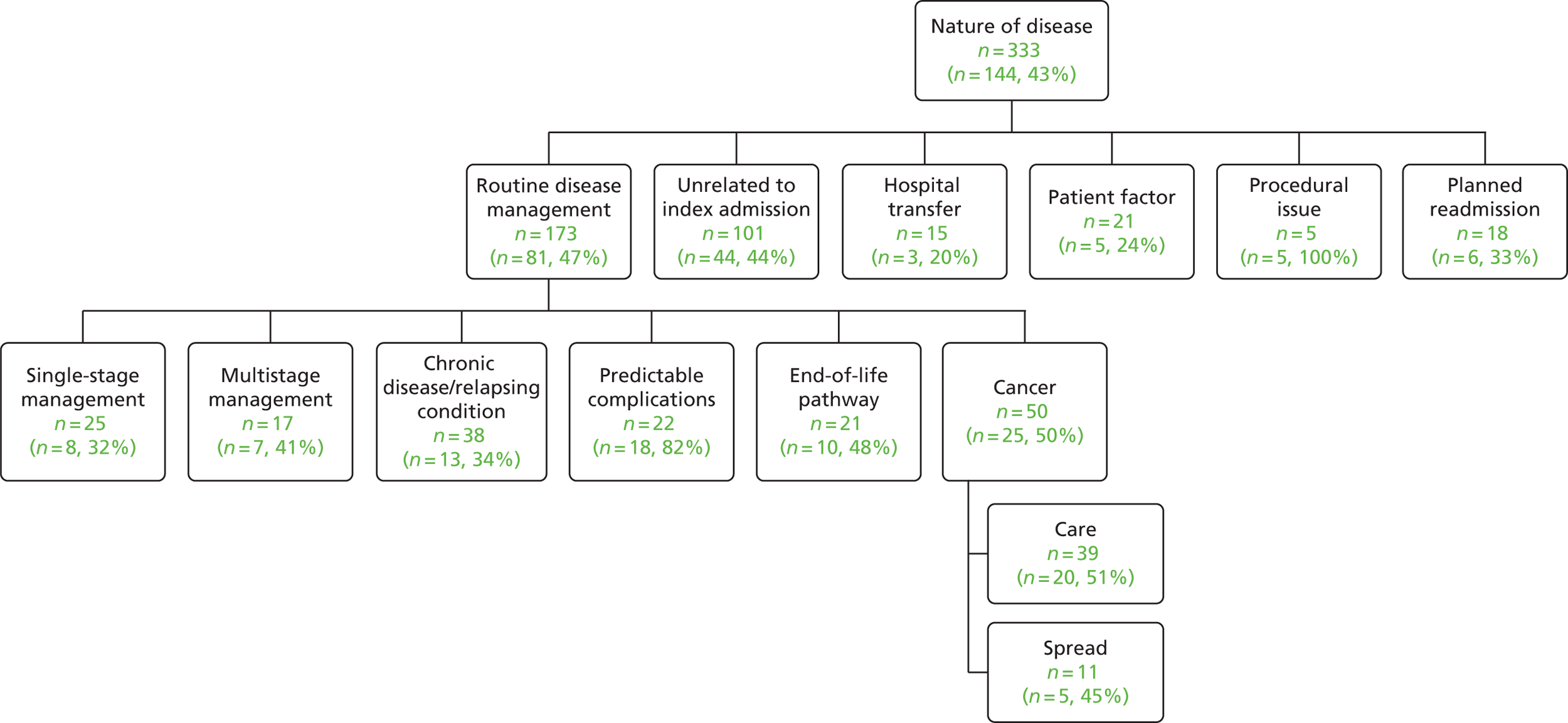

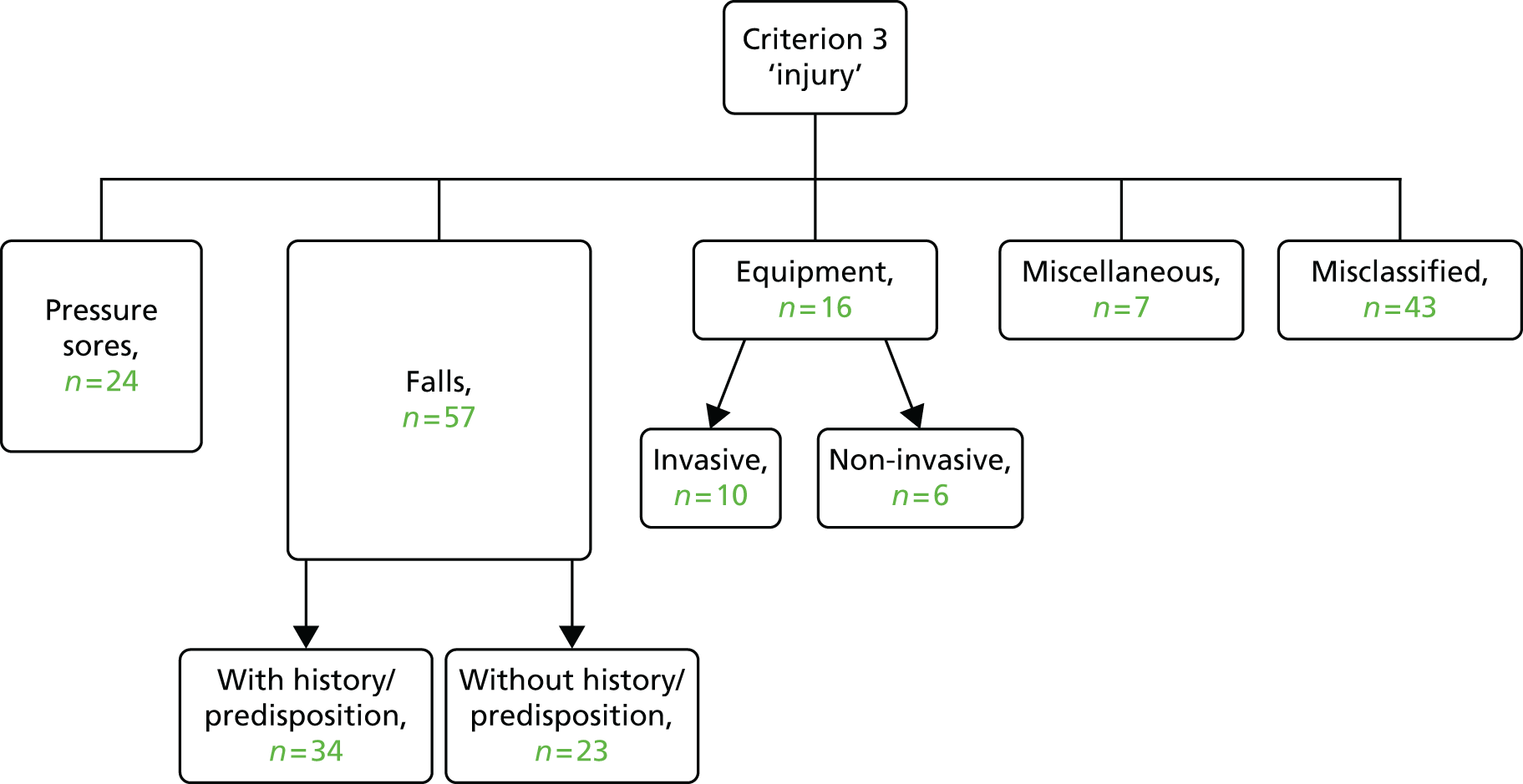

Retrospective case note review

Retrospective review of medical records has been for 25 years the methodology of choice in large-scale studies of harm in health-care systems. Originating from the Harvard Medical Practice Study,28,29 and adopted for UK use by Woloshynowych et al. ,30 the process aims to assess the nature, incidence and economic impact of AEs and to provide some information on their causes. An AE is defined as an unintended injury caused by medical management rather than the disease process that results in harm to the patient or, at the very least, additional days in hospital. The review is undertaken in two stages. In stage 1, and using the review form 1 (RF1), nurses or experienced clinical governance facilitators are trained to identify case records that satisfy one or more of the 18 well-defined screening criteria shown to be associated with an increased likelihood of an AE. These criteria include unexpected death, clinical complications such as myocardial infarction (MI) and deep-vein thrombosis (DVT), unplanned transfer to a higher level of care, and readmission to hospital within a specified time frame. 31 In stage 2, using the modular review form 2 (MRF2), doctors trained in the use of a standard set of questions analyse positively screened records in detail to determine whether or not they contain evidence of an AE. The basic method has been followed in all the major epidemiological studies,14,16,32–39 although there have been modifications to the review form and data capture methods. 30

Previous work in a UK setting,16,24 assessing the sensitivity of the two-stage review process, reported a sensitivity of 92% and a specificity of 62%. There was high inter-rater reliability between trained nurse reviewers in a subset of records (84%, κ = 0.68) and lower agreement by physicians on the presence (86%, κ = 0.64) and preventability of AEs (83%, κ = 0.44). In the largest study to date, undertaken in the Netherlands, the reliability of the assessment of screening criteria by nurses was reported to be good [82%, κ = 0.62, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.54 to 0.69], with lower reliability reported in (1) the determination of AEs by physicians (76%, κ = 0.25, 95% CI 0.05 to 0.45) and (2) the determination of the preventability of AEs (70%, κ = 0.40, 95% CI 0.07 to 0.73). 39 An in-depth analysis of the methods used to undertake case note review in a UK setting confirmed this trend; inter-rater reliability was higher when objective criterion-based tools, such as screening tools, were used than when more holistic assessment is required in order to make a clinical judgement on the quality of care provided (intraclass correlation coefficient 0.61–0.88 vs. 0.46–0.52).

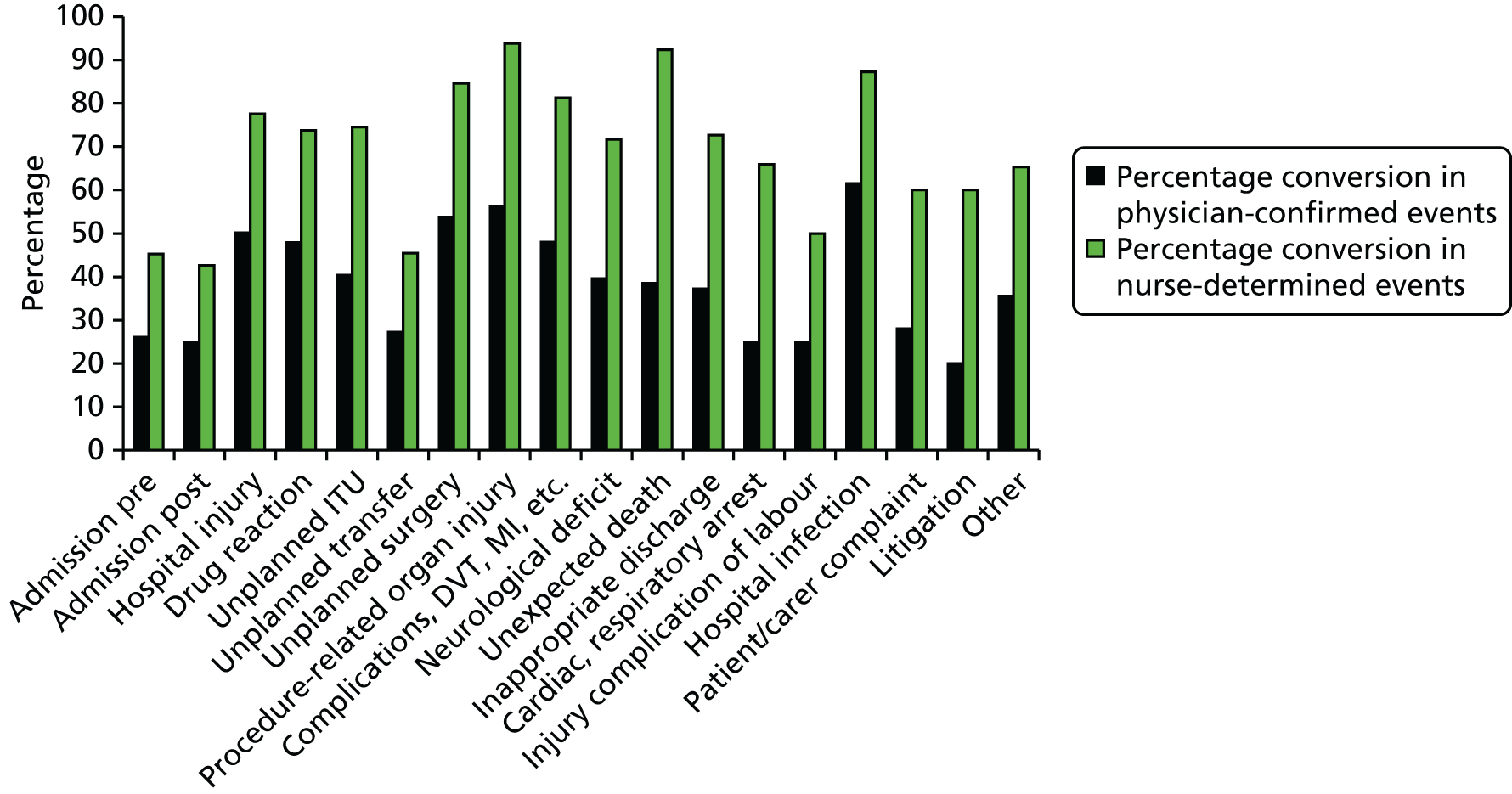

Professional determination of adverse events

The traditional methodology of AE determination involves nurse screeners examining records for criteria that are suggestive of an AE [known as explicit (criterion)-based assessment]; this is followed by an implicit (holistic) assessment, also referred to as a global assessment of care, which is undertaken by physicians. 18 Relying on physician review of whole episodes of inpatient care is time-intensive and expensive, a factor that is naturally prohibitive and has resulted in a trend in health-care organisations of using either nursing staff or trained clinical governance staff to complete retrospective case note reviews. Nursing review may well be the way that organisations can afford to invest in a longitudinal assessment of quality-of-care issues. However, it is important to ensure that organisations understand what different clinical groups are measuring and the attendant implications for the results reported through any such activity. Of interest, work undertaken in the UK indicates poor consensus between physicians and nurses when assessing the quality of overall care (intraclass correlation coefficient 0.24–0.43). 18 Detailed analysis of the clinical summaries of the episode provided by the reviewers has revealed that the professional groups provide detail on different aspects of care. Non-clinical staff reported facts from the notes, nurses provided commentary around the process of care, along with implicit judgement on the quality of care, and physicians focused on technical aspects of care, making explicit judgements on the quality of care. 18

Weingart et al. 40 also drew similar conclusions, reporting that nurse and physician reviewers often came to substantially different conclusions while examining the same episode of care. Professional groups agreed more often about complications of care than global quality-of-care assessment, but inter-rater agreement varies substantially by the nature of the complication being assessed. They concluded that ‘reviewers agreed more often about complications in surgical cases than medical cases (κ 0.59 vs. 0.36), but agreement about quality was little better than chance’. 40 Strategies have been proposed to improve the inter-rater consensus between reviewers by including multiple implicit reviewers and excluding reviewers with extreme ‘hawk and dove’ approaches to case note review, but these have little applicability to service-led quality improvement that is oriented around professional and clinical learning and, furthermore, have been found not to improve agreement in research studies. 39

The Global Trigger Tool: a pragmatic approach to case note review

The GTT is another retrospective method used to review medical records, which was developed by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) and is used throughout the world by countries adopting the IHI improvement methodology. It uses a time-limited pragmatic approach. The methodology centres on the random selection and limited case note review of 20 inpatient records per month per organisation. Qualified nurses and clinical governance facilitators commonly undertake reviews and the tool comprises similar criteria to those included in stage I of the two-stage review described previously in Retrospective case note review.

The largest reported study to date, which described temporal trends of AEs in 10 hospitals in North Carolina, USA, reported 25.1 AEs per 100 admissions. This rate of harm is significantly higher than rates reported using the two-stage retrospective review process, but statistically significant changes in rates over a 5-year period were not observed despite concurrent improvement efforts in the study sites. 19 Even higher rates of detection of AEs using the GTT methodology have been confirmed in other studies, for which AE rates in hospitalised patients are consistently reported to be > 30% of all inpatient admissions. 4,21,41–43

Naessens et al. 41 assessed the ability of nurse reviewers, using GTT methodology, to detect AEs in four US hospitals and reported favourable levels of detection of both triggers (κ = 0.63, 95% CI 0.58 to 0.68) and AEs (κ = 0.51, 95% CI 0.45 to 0.57). In a study evaluating the reliability of the GTT in tracking local and national AE rates, agreement by nurse reviewers was reported to be within a range of κ = 0.40–0.60. Significantly, internal teams were found to perform consistently better than external teams coming into organisations to undertake reviews of care.

A comparative analysis of the Global Trigger Tool and the Harvard method approaches

The GTT was conceived and developed to circumnavigate many of the challenges in implementing a resource-intensive multidisciplinary two-stage review process in routine clinical practice. The origins, key characteristics and measurement processes are described in Table 1, which is adapted from Unbeck et al. 42

| Characteristic of interest | Method | |

|---|---|---|

| Harvard | GTT | |

| Origin of tool | The Harvard Medical Practice Study | Quality improvement tool for clinical practice developed by the IHI |

| Medico-legal and focus on negligence in the first studies and, thereafter, quality improvement and preventability perspective | Track A&E rate over time in a hospital or a clinic | |

| Definition of harm | An unintended injury or complication that results in disability at discharge, death or prolonged hospital stay and is caused by health-care management rather than the patient’s underlying disease | Unintended injury resulting from or contributed to by medical care that requires additional monitoring, treatment or hospitalisation, or that results in death |

| Nature of harm | Includes both omission and commission | Includes commission, excludes omission |

| Sample | Random, big samples to measure the incidence and to generalise the result | Random, small samples sufficient for the design of safety work over time |

| Screening | Generally undertaken by one nurse who screens for 18 criteria in the medical record | First screening independent for one of 54 triggers by trained nurses (can be other professionals), focus on triggers, no comprehensive reading, reads just relevant parts related to found triggers; second reviewer provides consensus |

| Frame for inclusion | An AE had to have occurred before or during, and be detected during and/or after, index admission | 30-day inclusion period before and after index admission |

| Criterion/trigger | An indication that patient harm may have occurred. Directs the medical reviewer to relevant parts of the records by the notes | 54 triggers, mostly narrow |

| 18 criteria; some criteria/triggers are AEs by definition, for example health-care-associated infections and hospital-incurred injury | ||

| Review stage 1 | Comprehensive reading: non-time-limited identifies screening criteria indicating an AE may be present in the notes | Time limited |

| Finds triggers, describes the potential AE and categorises harm according to the NCC MERP’s Categorizing Medication Errors Index44,45 | ||

| Review stage 2 | Assess the AE by using different scales according to, for example, causation, severity, preventability, timing, causes and types | One physician, who does not generally review the record but does authenticate the consensus findings of the reviewers and the severity rating, and answers questions from reviewers in review stage 1 |

| No assessment of preventability | ||

| Number of harm events | Generally includes only one AE per patient, that is, the most severe | All identified AEs are included |

Although intending to measure the same construct, a few key differences emerge. First is the origin of development. The GTT aims to provide information to support patient safety efforts and monitor trends of harm events over time. In contrast, the Harvard tool, despite having origins in a medico-legal context, is now commonly used to provide point prevalence estimates of harm in health care on a national scale. The Harvard tool is labour-intensive; the GTT is time limited. Perhaps more significant differences emerge in the type of harm identified and the subsequent assessment of that harm. The Harvard tool directs the reviewer to potential harm events that include acts of both omission and commission, whereas the GTT detects only acts of commission. A physician confirms the presence of a harm event in the Harvard methodology and a physician who may have not read the record of the episode of care confirms the harm event in the GTT. Preventability is not assessed in the GTT, but, along with management causation, is central to the Harvard methodology. 46

The GTT and RF1 do, however, overlap in some of the methodological components and have criteria/triggers in common where it would be expected that there would be minimal variation in the identification of these in records. However, rates of AEs in the Harvard method are computed on the determination of harm and preventability and, in this respect, there are significant differences between the approaches. In the absence of a structured phase 2 process in the GTT, harm determination is viewed to be more prone to systematic bias. 5,41,43 Further questions arise as to what the GTT methodology is actually measuring, as, even when events caused by omission are not quantified, rates of reported harm are threefold higher than when the Harvard method is used. It might well be that triggers are being misclassified as AEs and/or multiple triggers relating to one AE are being classified as multiple AEs.

The assessment of internal validity of the GTT is challenging. In a European context, von Plessen et al. 47 examined rates of harm using the GTT in five Danish hospitals and reported significant variation between hospitals ranging between 18% and 33%. However, in another, more regulated, smaller study comparing the identification of AEs in 350 orthopaedic admissions in Sweden, the Harvard method detected 155 AEs, compared with 137 events detected by the GTT. AEs causing harm without disability accounted for most of the observed difference, with the positive predictive value being 40.3% and 30.4%, respectively. 42 Importantly, this suggests that, within a controlled study environment, the performance of the methodologies can be reasonably similar.

Retrospective case note review in inpatient deaths

Using case note review as a way of examining the quality of care in patients who die has always been a traditional part of modern surgical practice. Following the introduction of the hospital-wide mortality ratio in the early 2000s, the scope of hospital death reviews widened as they became a mechanism for understanding the underlying causes of variations in these measures and determining if ‘excess deaths’ identified represented deaths that were attributable to avoidable health-care-related harm. In 2010, the Mid-Staffordshire Foundation Trust scandal focused attention on the issue of avoidable deaths in the NHS and prompted the WG to mandate case note review of all deaths in health boards to provide reassurance for patients and quality assurance within the Welsh NHS. 48,49 The approach built on local mortality review processes, which were variable in terms of the number and clinical background of reviewers, sampling, review tools and organisation. In 2012, an element of standardisation was introduced with the adoption of a single screening tool. The majority of hospitals in England have also been developing systems for mortality review and, as in Wales, the approaches adopted have varied between sites.

Mortality review can provide a window on a hospital’s safety and quality. Patients who die as inpatients tend to be older, have more comorbidity and require more complex interventions. Such patients test the system and reveal weaknesses that, in turn, may generate harm. Evidence from retrospective case note record review studies does indicate that the types of problems in care experienced by patients who die are different from those who survive, with more diagnostic errors and problems related to clinical monitoring and relatively fewer problems related to surgical or technical procedures. 29,32,39 Mortality review is not just an efficient approach to identifying avoidable health-care-related harm, but also provides a window on the quality of the clinical care received by the patient, particularly during the dying process. With a growing elderly population, and the recent withdrawal of the Liverpool Care Pathway following some high-profile abuses,50 this area of care has been attracting increasing scrutiny in the UK. Moreover, clinicians are concerned about deaths and these concerns act as a rallying cry to engagement in quality improvement initiatives.

There are obvious limits to the scope of feedback on quality and safety that can be provided by reviewing deaths. Fewer than 1.5% of the 15 million admissions to the NHS in England and Wales each year end in death, and some specialties, such as ophthalmology or dermatology, will experience such an event only very rarely. 51 Examining deaths at the hospital level may result in uncovering relatively few heterogeneous quality and safety problems, making it challenging for staff to know where best to direct their improvement efforts. Over half the population end their natural lives in hospital,52 and judgements on whether or not a death was caused by health care and, therefore, avoidable are notoriously difficult in patients with only hours or a few days of natural life remaining. For these reasons, any comprehensive hospital-based surveillance programme requires identification of health-care-related harm across the full spectrum of patient admissions, both those who die and those who are discharged alive. The approach taken to date in Wales includes assessment of harm events across the whole inpatient population and an overview assessment of every patient death, ensuring that there are no concerns identified in the care provided in the final inpatient episode.

Summary

Over the last 25 years there has been concerted effort internationally to quantify the safety of health-care delivery. The original Harvard method, which was developed primarily as a research tool, informed the development of a more pragmatic method for routine surveillance and patient safety work. As the Harvard tool is predominantly used in academic settings, Wales adopted the GTT as a routine surveillance and patient safety tool across Welsh health boards and was gaining experience in its use. The GTT was used as part of a measurement strategy in both the Health Foundation’s Safer Patients Initiative and the 1000 Lives Campaign,11 and with some success. However, the experience of NHS Wales Hospitals using the IHI GTT was similar to that reported in Danish hospitals,47 and there was significant variation in rates and experience in its use across hospital sites. As Wales was committed to ongoing harm measurement and monitoring, we set out to compare the methodological approaches in order to identify the optimal approach to quantify the nature and extent of AEs occurring across NHS Wales’s acute hospitals over time and ensure the robustness of our current approach. Furthermore, we aimed to explore the contribution of harm measurement within a broader health-care quality metric framework and, most importantly, to understand how harm data can be used to inform and evaluate improvement efforts.

Study aims and objectives

Research question

What is the nature and extent of AEs occurring in the Welsh population admitted to hospital over a 4-year period?

Study aims

This study aimed to obtain definitive data on harm in NHS Wales hospitals and to compare the performance of the GTT with the two-stage retrospective review process, using findings to develop an approach to ongoing surveillance of harm in the Welsh NHS.

The specific aims over the course of the project are as follows:

-

to gain an in-depth understanding of the nature and extent of AEs occurring in the Welsh population admitted to hospital over a 4-year period comparing the use of both the retrospective two-stage process and GTT process

-

to compare the scale and scope of health-care-related harm identified by the retrospective two-stage process and GTT process

-

to develop a robust measurement system for harm

-

to embed this harm surveillance in organisations and determine the organisational response.

Study outcome definitions

Adverse event

We defined an ‘AE’ as an ‘unintended injury or complication causing temporary or permanent disability and/or increased length of stay (LOS) and resulting from health-care management’.

Preventable adverse event

A six-point scale was used to assess the likelihood of a causal link between the care given and the injury and the likelihood that the event was preventable. The assessment of preventability was restricted to the research team and MRF2 reviewers, as the assessment of preventability is not a component of the GTT methodology. 46 A judgement was therefore made by research physicians on the likelihood that the harm event may have been prevented (if care was delivered to the standard you could expect in that particular situation). Preventability was reported in three major categories as outlined in Box 1.

1. Virtually no evidence for preventability.

Low preventability2. Slight to modest evidence of preventability.

3. Possibly preventable, but not very likely (less than 50–50, but close call).

High preventability4. Probably preventable (more than 50–50, but close call).

5. Strong evidence for preventability.

6. Virtually certain evidence of preventability.

Adapted with permission from BMJ Publishing Group Limited (Case record review of adverse events: a new approach, Woloshynowych M, Neale G, Vincent C, vol. 12, pp. 411–15, 2003). 30

Severity of adverse events

The assessment of the severity of harm in the MRF2 second stage of the two-stage process is rated in both physical impairment and emotional trauma terms, and ranges from no impairment or trauma to death and severe trauma lasting more than 1 year. The scale is outlined in Table 2.

| Level of physical and emotional impairment | Description of level of impairment |

|---|---|

| Physical impairment | |

| 0 | No physical impairment or disability |

| 1 | Minimal impairment and/or recovery in 1 month |

| 2 | Moderate impairment, recovery in 1–6 months |

| 3 | Moderate impairment, recovery in 6 months to 1 year |

| 4 | Permanent impairment, disability 1–50% |

| 5 | Permanent impairment, disability > 50% |

| 6 | Permanent nursing |

| 7 | Institutional care |

| 8 | Death |

| 8.1 | Death unrelated to A&E |

| 8.2 | Minimal contribution from A&E |

| 8.3 | Moderate contribution from A&E |

| 8.4 | Death entirely due to A&E |

| 9 | Cannot reasonably judge |

| Emotional trauma | |

| 0 | No emotional trauma |

| 1 | Minimal emotional trauma and/or recovery in 1 month |

| 2 | Moderate trauma, recovery in 1–6 months |

| 3 | Moderate trauma, recovery in 6 months to 1 year |

| 4 | Severe trauma, recovery lasting longer than 1 year |

| 5 | Cannot reasonably judge |

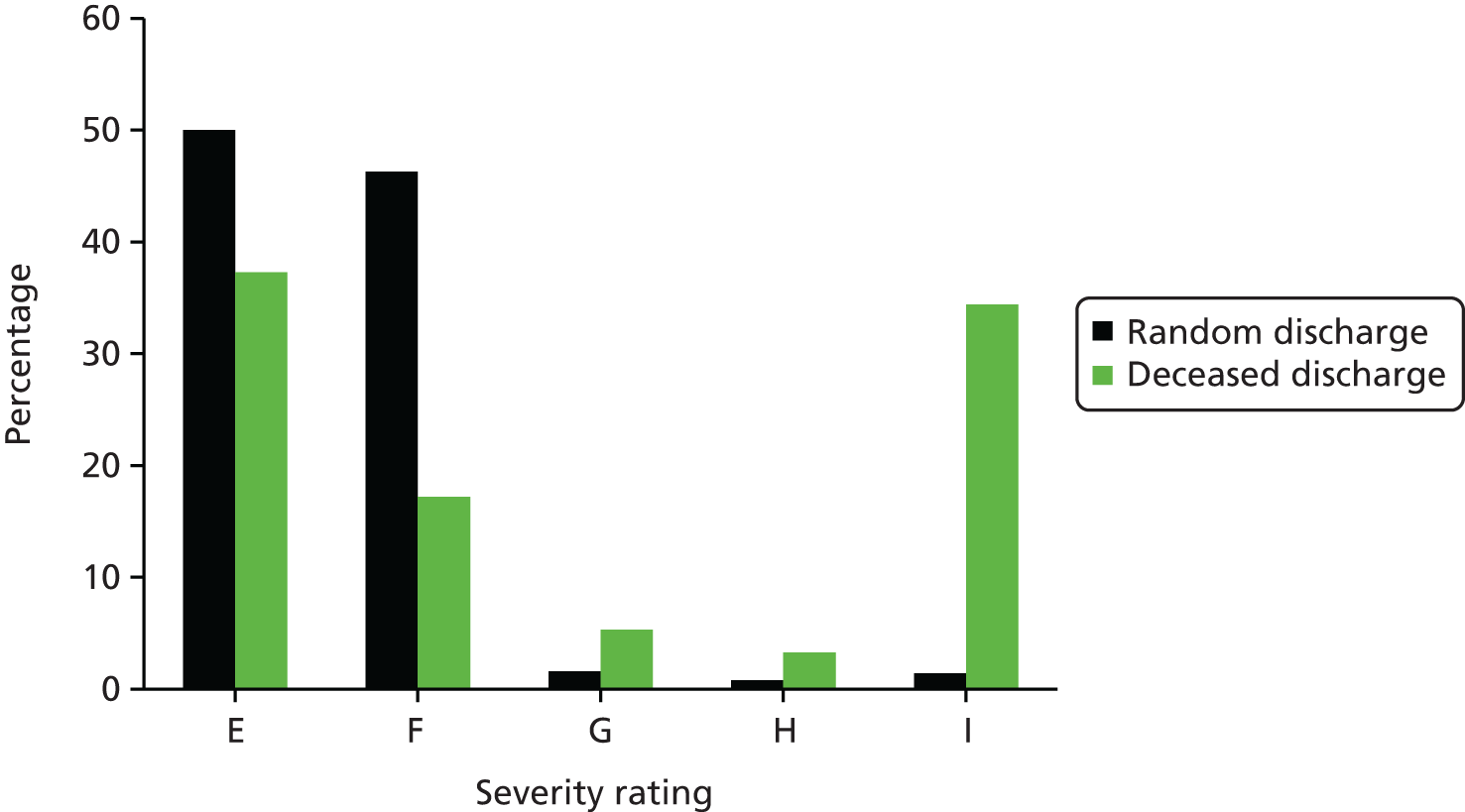

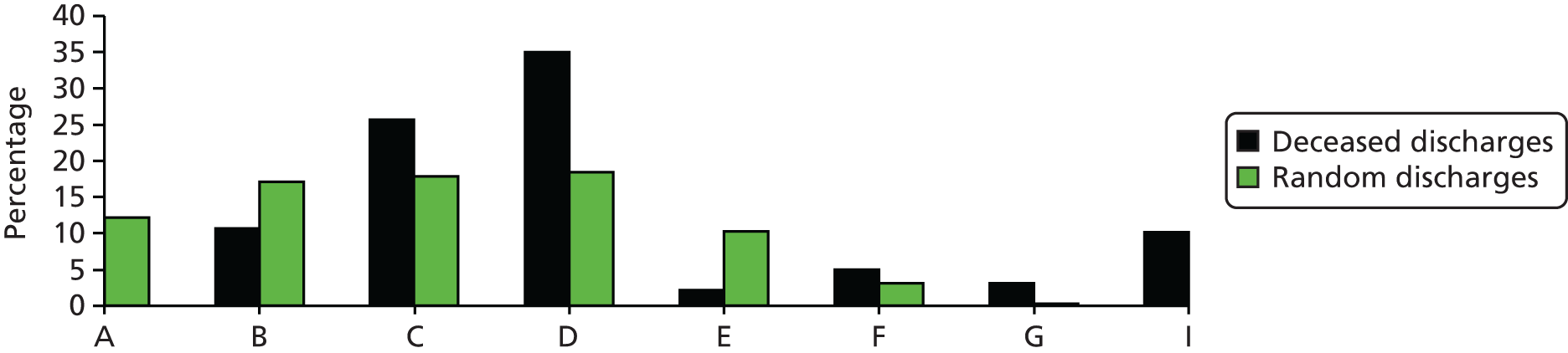

In the GTT, severity is rated using categories E to I of the National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention (NCC MERP)’s Categorizing Medication Errors Index53 (Table 3).

| Level of severity of harm event (category) | Description of severity of harm event |

|---|---|

| E | AE causing temporary harm and requiring intervention |

| F | AE causing temporary harm and hospitalisation and/or extended stay |

| G | AE causing permanent harm |

| H | AE requiring life-saving intervention |

| I | AE contributing to or causing patient death |

Overview of study design

The overall aim of phase 1 was to compare outcomes and rates of harm from both the retrospective Harvard and GTT methods. Using a common sample, NHS teams undertook harm assessment using the GTT and the research team used the Harvard method. Aggregate levels of harm were compared in the two methodologies using the same methodology. Secondary analysis involved linking generated data sets by unique study number and examining the consensus between methods and professional groups on the identification of AEs. Findings and experience from phase 1 were used to inform the national case note review process in phase 2.

The study transition from phase 1 to phase 2

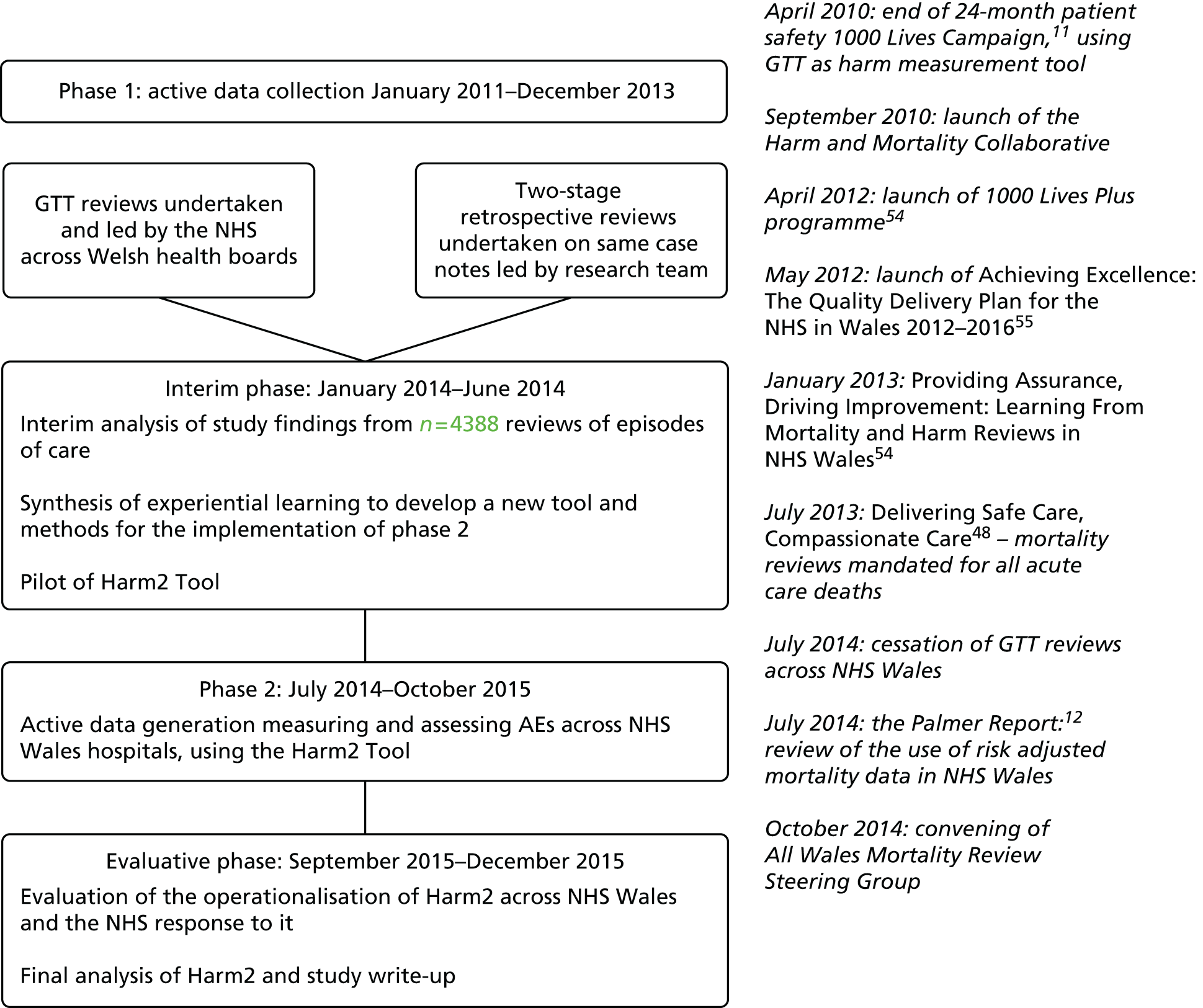

A transition phase from phase 1 to 2 was not originally built into the project plan. A no-cost extension was sought, as we undertook analysis of the data and synthesis of the learning from the comparative data generated from phase 1. This development period ensured that evidence, experiential learning and the current NHS and policy environment informed the method and implementation of phase 2. Phase 2 aims and methods were subsequently agreed with the National Institute for Health Research Health Services and Delivery Research programme and operationalised 6 months after completion of phase 1 (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Schematic diagram of the study process and corresponding national harm and mortality publications or activity.

Considerations for the development of harm phase 2

There are a number of factors that influenced the way we planned and executed the second phase of the study, and these are detailed as follows.

NHS Wales’ decision to stop using the Global Trigger Tool methodology

Prior to any recommendations from the study team, NHS organisations in Wales had already made the decision to stop using the GTT, as it did not meet organisational requirements to understand harm occurring within the system and provide accessible data to inform and evaluate remedial or improvement activity. Most organisations, however, continued with the process, facilitating the completion of phase 1 aims. This NHS stance was confirmed in the interim descriptive analysis of our data, which demonstrated the variability in the identification of AEs using this tool across study sites and the paucity of information on whether or not the harm event was caused by health-care management or was preventable, thereby limiting clinical learning and prioritisation. The last Welsh health board to stop using the GTT did so in July 2014. At this point, the GTT ceased to be a viable option for NHS Wales and hence for the study going forward into phase 2.

A UK-wide focus on inpatient deaths as a system-level measure of quality

Learning from the Mid-Staffordshire Inquiry, in 2013 Wales mandated that every death occurring within the secondary care setting be assessed by a review of the inpatient episode of care. 48,49 A screening process was developed by the Harm and Mortality Collaborative (NHS led) to identify those individuals for whom there were concerns about the nature and cause of death for the purpose of organisational learning. These episodes of care were then to proceed to a second-stage review identifying contributory factors and clinical and organisational learning. This development was aligned with the future expectations of the medical examiner role, and a national steering group was set up to co-ordinate strategy, activity and monitoring of implementation.

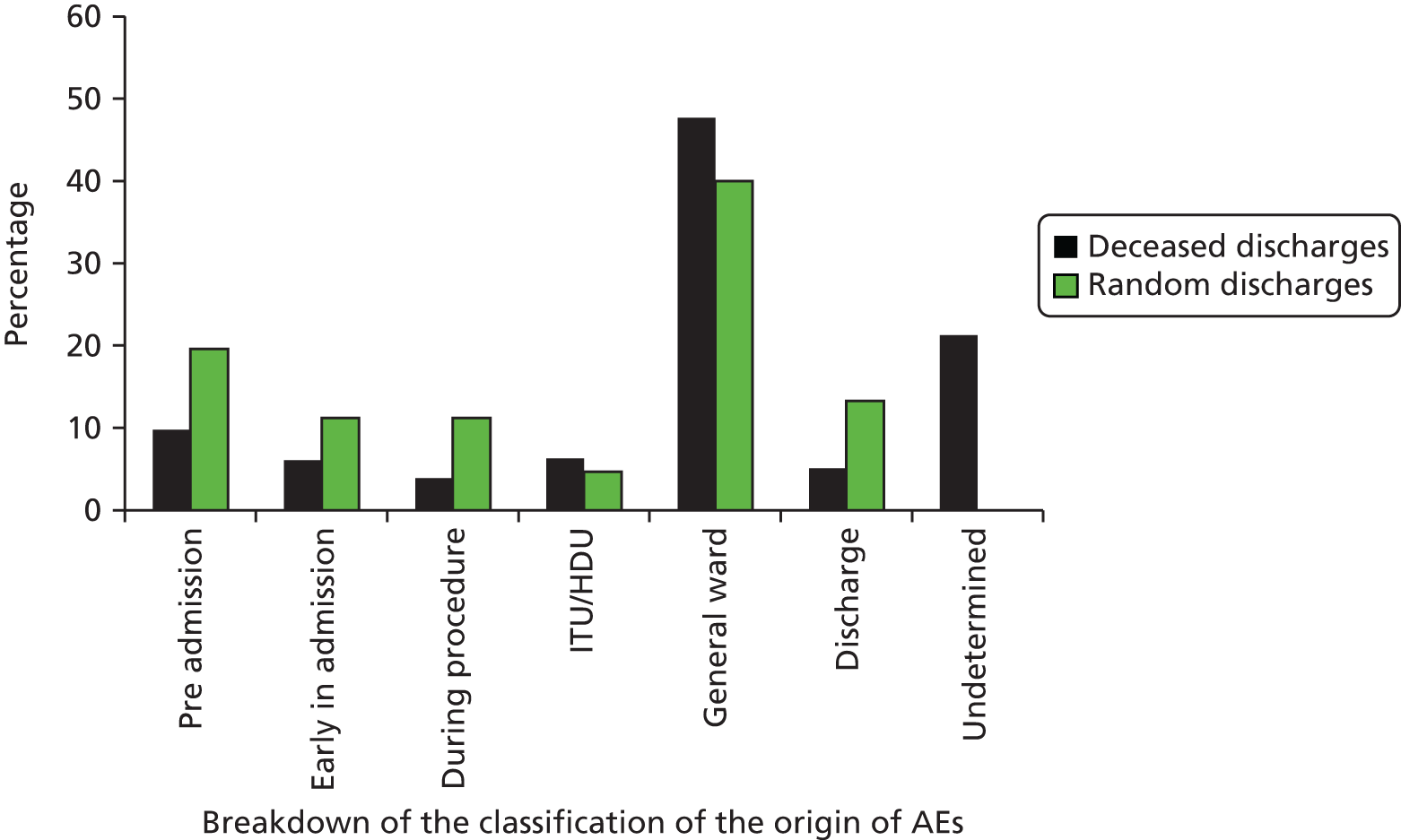

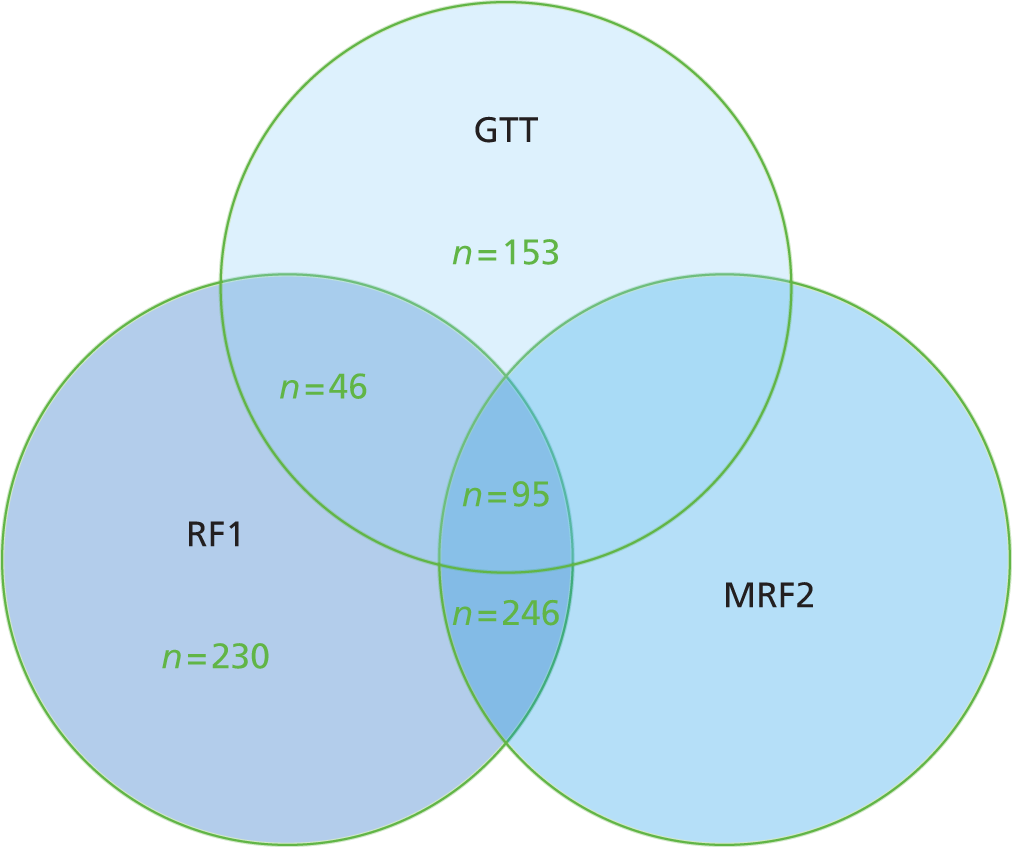

Although the Welsh mortality review process did not set out specifically to measure AEs and was focused more on overall quality-of-care issues, a number of health boards were using GTT or RF1 screening criteria to identify AEs during the mortality review. At the time of phase 2 development, there was no peer-reviewed international literature examining AEs occurring in patients who die in the hospital setting. No study had reported on whether or not AEs in inpatient deaths have the same profile and composition of AEs as those occurring in the remaining 98% of the inpatient population. It is thus unclear if targeting deaths is an effective mechanism for identifying problems in care and prioritising quality improvement at the organisational level. Conversely, NHS leads for patient safety made the point that in respect of assessing quality across inpatient populations, the measurement and monitoring of harm across the inpatient population may provide more opportunities for learning. The identification of inpatient AEs gives a greater level of assurance of system-level organisational safety and quality issues. A decision was made to include in our sample patients whose inpatient episodes resulted in death in order to make a direct comparison in these groups and thereby rationalise and provide an evidenced-based perspective on national-level priorities for patient safety monitoring.

NHS Wales’ reluctance to implement a two-stage review process for routine harm monitoring

Every health board in Wales had committed resources to innovatively evaluate the quality of health care through the review of every death occurring across the system. The resource issues associated with adopting an additional two-stage review as part of routine harm assessment was something that would not be sustainable at the end of the study period and the study team agreed with the NHS and policy leads that this would not be an approach that we would pursue. This meant that neither the GTT nor the Harvard method was a candidate tool for sustainable implementation in Wales, and further work was needed to identify a method that had robust characteristics and was fit for purpose for ongoing routine harm monitoring across NHS Wales.

Recognition that current tools may be effective in identifying adverse events caused by commission but under-report and characterise events caused by omission

The GTT does not include AEs caused by acts of omission and nor are these acts explicit in the RF1 criteria. As part of our interim and exploratory analysis, we undertook thematic analysis of selected clinical summaries generated in phase 1 of the study. This analysis enabled a characterisation of AEs arising from specific areas of clinical or managerial risk, such as readmission and unclassified risk, which did not fit into any screening criteria. What emerged from this analysis were AEs that were caused by acts of omission, which included delayed and missed diagnosis. Including these acts of omission in the screening criteria offered the opportunity to expand the characterisation of the risk of AEs in secondary care settings and became a key focus for phase 2 of the study.

As a result of the interim thematic analysis, the comparative data on the two most commonly used methods to measure harm in a health-care system and our experience of using both methodologies over a period of time, we were well placed to undertake an evidenced-based assessment of how NHS Wales could continue to measure the safety of care delivered across health boards.

The review of phase 2 aims

In our original proposal, the focus of phase 2 was to robustly monitor AEs over time. As described, the amount of learning from phase 1 superseded what became a blunt aim and we identified a number of additional aims that were included in the revised protocol. These are detailed as follows.

To develop a robust measurement system for harm

One of the key points of learning emerging from phase 1 of the study was the need to rationalise the data collected during the case note review process. The GTT provided a paucity of data and the Harvard methodology gave data sets that were unwieldy and labour-intensive both to collect and input. At this point, these tools had been used repeatedly over studies and improvement initiatives with few structural changes made to the original versions. Some countries, for example Sweden, were beginning to supplement the GTT with components of the Harvard methodology, such as the assessment of preventability. We had as our focus efficient data generation that could be used directly by NHS organisations but was still aligned in measurement and definitional structure to robust AE determination.

Having data generated from > 4000 reviews using both methods, we set out to examine the components of both tools, the data generated from each tool and how the tools fitted in with both national and organisational priorities for safety and quality metrics. We also attempted to identify any changes that had been made to the tools, as reported in quality improvement or research reports. In addition, as the review of deaths was a key focus across UK countries, we also included a review of the PReventable Incidents Survival and Mortality (PRISM) study tool for the assessment of avoidable mortality. This assessment led to the subsequent development of the Harm2 tool, of which the main characteristics are pragmatic GTT structure and a Harvard method AE measurement structure, with an assessment of preventability and contributory factors.

In addition to implementing this tool and assessing its performance against the Harvard method, phase 2 offered the opportunity to provide an evidenced-based perspective on AEs occurring in patients who die during their period of hospitalisation. Not only was this intended to provide a comprehensive view of AEs across the inpatient spectrum, but we believed that this could inform and clarify future priorities for national system-level metrics for quality and safety based on empirical evidence and distanced from the controversy surrounding the use of metrics, such as the hospital standardised mortality ratio. Although aligned in terms of building the evidence base around safety in inpatient settings using structured case note review, it differed from the work led by Hogan et al. 20,56 (PRISM study), asking different questions (what is the proportion of patients experiencing AEs? as opposed to what is the proportion of avoidable deaths?), and being heterogeneous in terms of measurement end points (AEs vs. problems in care) and sampling procedures (longitudinal monitoring vs. random snapshot).

A number of additional components were added to the tool, such as the assessment of comorbidity at the time of inpatient management and the specific identification of issues (such as learning disability and dementia) to increase our understanding across a national health-care system on the epidemiological characteristics of AEs.

To embed this harm surveillance in organisations and determine the organisational response

The Harm2 tool was operationalised in a similar way to phase 1. After training, research nurses screened a random sample of inpatient records before making judgements on the presence of AEs and their severity and preventability. A 10% sample of records was double reviewed using the Harvard method and research physicians were used to confirm or refute the presence of AEs.

The tool was shorter and data fields designed to be entered easily into a spreadsheet. Improved timeliness in terms of data entry enabled us to feedback periodically into organisations the summary findings and the details of episodes of care for which AEs were identified. As this was a new tool with novel data and information feedback, we undertook a service evaluation involving both the research team and NHS sites to explore issues of logistics, feasibility, face validity and implications for quality improvement and assurance at both the organisational and national level.

Chapter 2 Measuring harm in Wales

Aim 1

To compare outcomes and the extent of harm in a random sample of NHS Wales admissions from both the retrospective two-stage process and the GTT process.

Objectives

-

To provide a baseline estimate of the number and percentage of Welsh service users who are harmed during the course of their inpatient admission.

-

To examine harm events and make a judgement on their preventability.

-

To examine harm events and categorise them in terms of severity and the specialty and health-care intervention resulting in the harm event.

-

To examine episodes of harm in detail and characterise the service users most likely to experience a harm event during their period of hospitalisation.

Methods

The retrospective two-stage process was undertaken alongside the current infrastructure of NHS-led GTT reviews, in order to compare the rates and quality of information generated on inpatient harm at the health board and national level.

The review tools

The two-stage retrospective review process methodology originally devised in the early 1970s for the Californian Insurance Feasibility Study was refined for use in the Harvard study and subsequently used internationally. 14,16,32–39 The study groups all made sequential changes to the original form by adding or subtracting questions, but maintaining the basic format. Charles Vincent and his group made revisions to the review forms, providing a stronger focus on causation and a more tightly structured format after using the tool in a UK setting; this iteration, known as the MRF2,30,31 is the one used in the study and found in Appendix 1.

Structurally, in terms of the screening criteria, the RF1 remained the same as used in previous studies. We did, however, introduce to the RF1 a narrative of the inpatient episode to provide context to any positive criteria or conversely any episode of care determined to be a negative screen. Furthermore, because we were interested in examining the nursing cohort’s determination of AEs, we asked nurses to make their own determination of AE occurrence at the end of the screening process and rated their confidence in their decision on a 1–5 scale (1 being not at all confident and 5 being very confident). This nurse-led process was structurally similar to the GTT process, in that a timely screening review was followed by AE determination. A copy of the amended RF1 is found in Appendix 2.

The Global Trigger Tool process

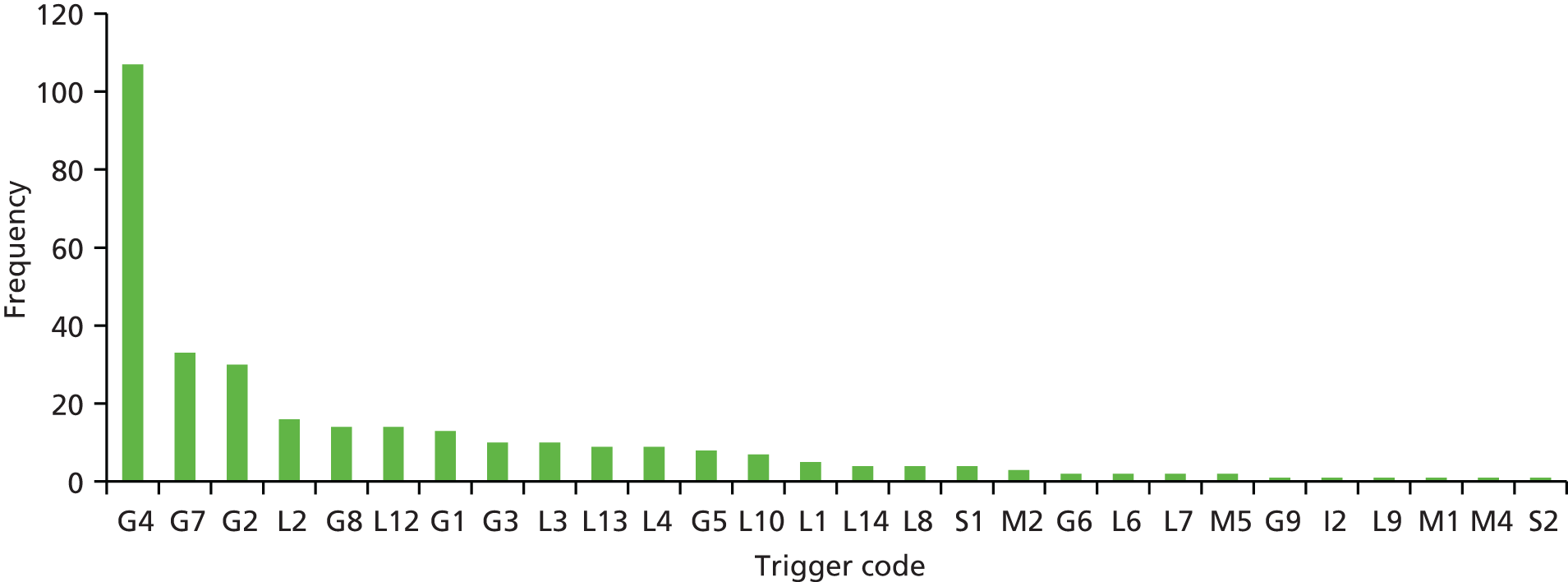

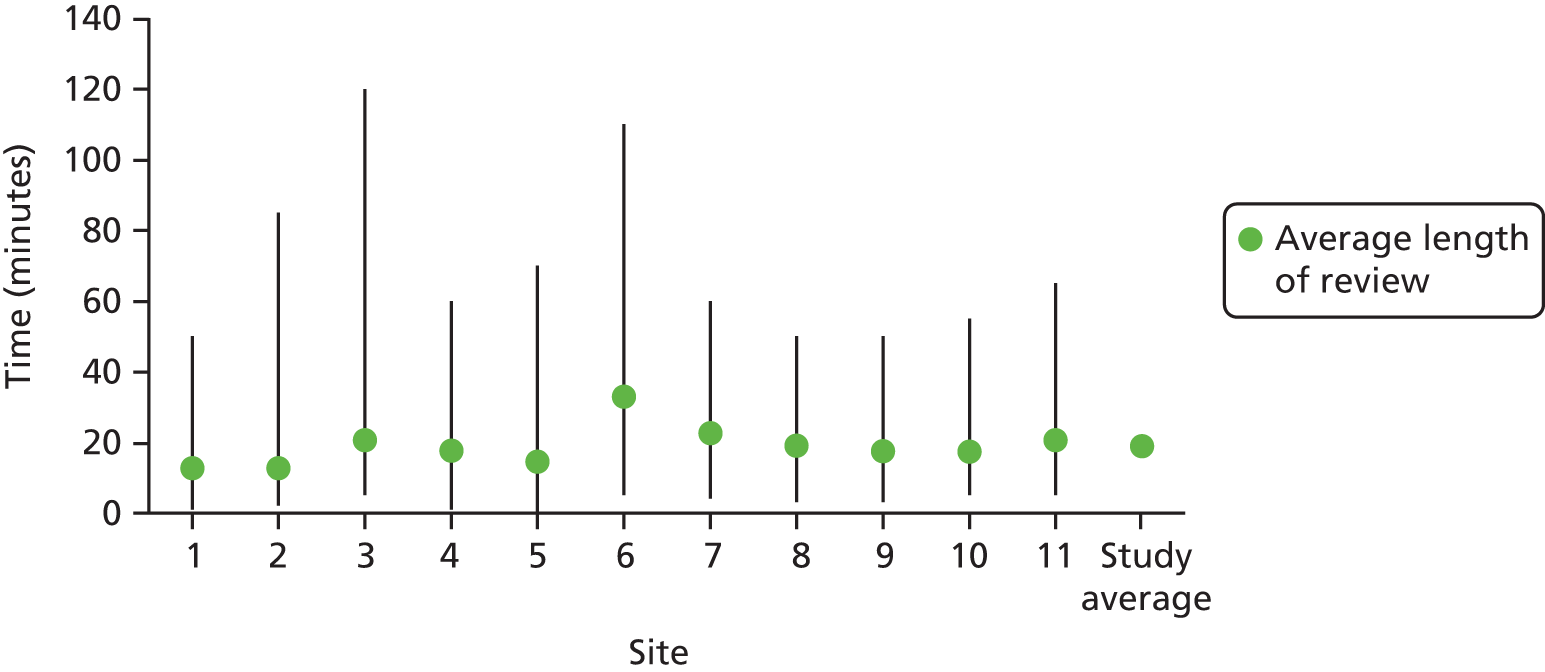

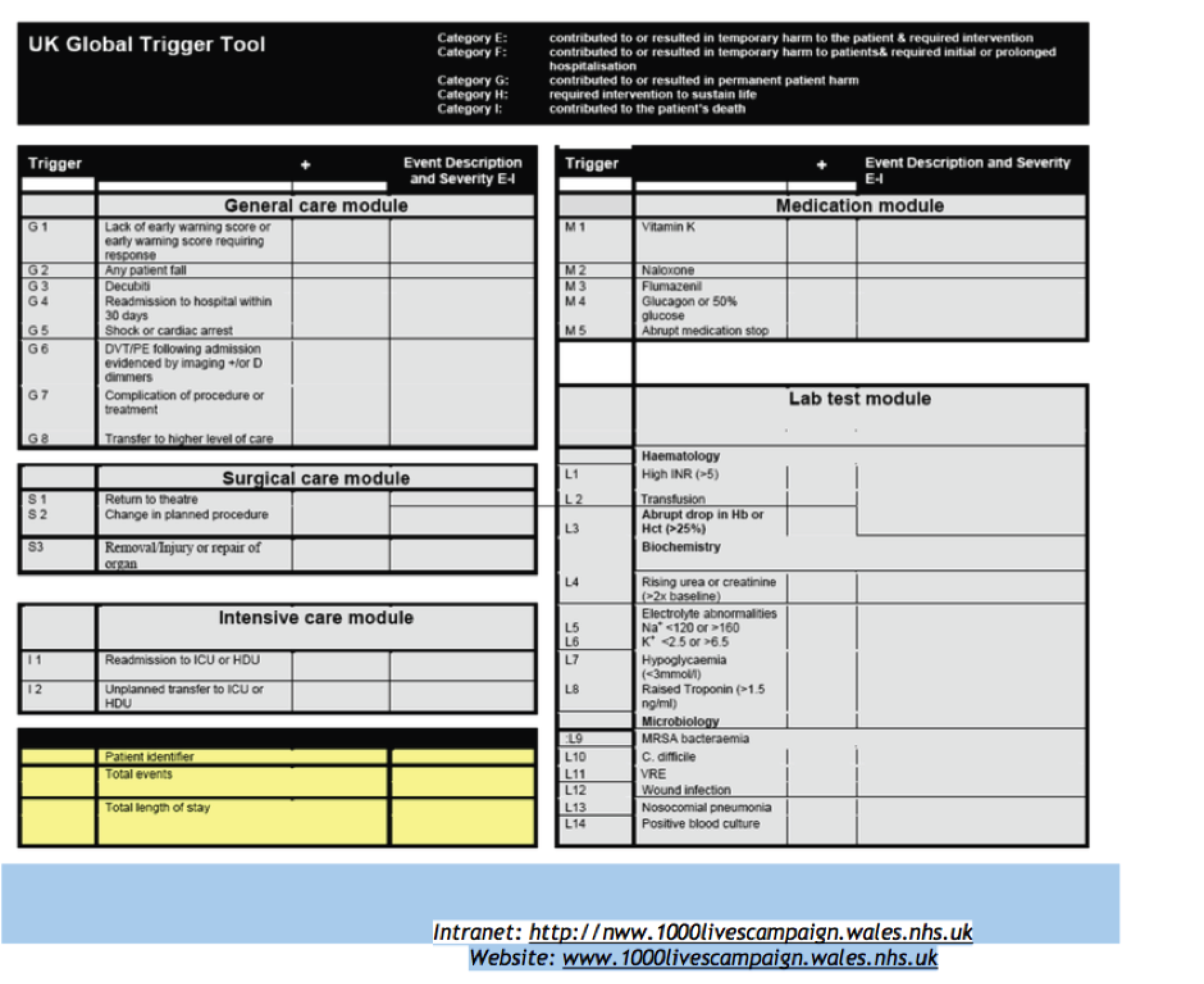

No changes were made to the current practice and protocols for undertaking GTT reviews across NHS Wales during the study period. The GTT reviews were undertaken using a structured Welsh GTT pro forma derived from the IHI process,46 with teams being advised to spend no longer than 20 minutes reviewing the discharge summary, medication charts, laboratory results for that admission, operative/theatre documentation, and nursing and medical documentation. If a trigger was identified in the notes, the reviewers made a decision on whether or not harm had occurred and rated its severity using the NCC MERP’s Categorizing Medication Errors Index. 44

Study sample

The study sample comprised all the six health boards providing acute/general inpatient care within NHS Wales. Two hospital sites were chosen from each health board to represent a 50–50 split of acute/emergency care and less acute district general hospital-level care. Eligibility for study inclusion was being over the age of 18 years at admission, having a LOS of > 24 hours and not being treated in a designated mental health or obstetric facility. Two-stage retrospective case note review was conducted on the case records that were sampled for the GTT process. Welsh NHS organisations randomly selected and retrospectively reviewed 20 sets of case notes each month, post discharge and after discharge summaries and coding had been completed. Case notes for review were identified by NHS organisations by generating lists of all hospital discharges fulfilling the inclusion criteria for the month in question and using a random number generator to select 30 inpatient episodes for the period covered. Oversampling in this way was required to ensure that at least 20 sets of notes had been through coding and had been returned to the filing library.

Sample size

The sample size for phase 1 was estimated on previous work undertaken in the USA, Australia and the UK. A systematic review on AEs in health care reports a median percentage of AEs at 9.2%, with a range of 8–12%. 3 The largest single UK-based retrospective review study, to date, on 1008 inpatient records reports a percentage of records with at least one AE of 8.7%. 16 If the percentage of AEs in Wales is around 10%, we required a sample of 3457 records to detect a one-sided difference of 1%, with the reference value with a power of 0.97 and an alpha from 0.05. If the incidence of AEs during hospital admission is lower at 8%, a sample of 4200 admissions is necessary to detect a one-sided difference, with the reference value with a power of 0.80 and an alpha from 0.05.

The review process

In the first stage of the Harvard method, the case notes were screened for potential harm by a team of clinical research nurses (n = 24) and research assistants (n = 2) from the National Institute for Social Care and Health Research (NISCHR) Clinical Research Collaboration (CRC) infrastructure. The team was trained in the use of the RF1 tool through face-to-face meetings with members of the research team, who then supervised the first two case note review sessions in each site to troubleshoot any issues arising and to ensure that the reviewers were confident in the use of the tool. The two non-clinically trained assistants were partnered with experienced research nurses for review sessions. Three research nurse teams covered the three geographic areas of Wales: north, south-east and south-west. If an episode of care screened positive for any of the 18 criteria for an AE, the reviewers described how the criterion was met in a free-text box. At the end of the review, a summary of the episode of care was written irrespective of whether or not positive screens had been identified. There was no restriction set on the time the research nurse review teams spent examining each set of notes.

Admissions that screened positive on at least one screening criterion were examined within the research office before a decision was made on whether or not a full examination of the record needed to be conducted by a senior research physician. This was undertaken to check for accuracy in the completion of the forms, to identify if there was any potential for missed AEs and to ensure that screening criteria were met in full, thereby rationalising the use of the intensive two-stage review when there was no indication that a harm event had occurred. We therefore referred a small number of reviews for which screening criteria did not identify any potential for harm but the clinical summary stated, for example, that a patient was readmitted after a knee replacement with serous fluid oozing from the wound, or stated that no obvious criteria were present but that this was a complex episode of care that would benefit from physician review. Conversely, we did not refer cases for in-depth review when the narrative describing the positive screen indicated that a fall had occurred but under the description of the criteria was documented, ‘no injury sustained’, when the descriptor for pressure ulcer read ‘buttocks red, cavalon applied’ or ‘moisture lesion present’ but tissue damage did not develop, when adverse drug reaction mentioned rash or an isolated episode of diarrhoea but drugs were continued with no systemic ill effect, and when readmission occurred in different clinical specialties with no connection. This was undertaken in the research office and was independent of the nurse process and was part of a quality assurance process.

Referred notes from phase 1 went on to a second-stage review, in which 12 research physicians, who were experienced in record review through involvement with similar studies, used the MRF2 tool to judge the occurrence, nature, preventability and consequences of the referred event on a per diem basis. The research physician reviewed the admission in question and episodes of care either side of the admission before making a determination on whether or not the patient experienced an AE before its subsequent categorisation. The inter-rater reliability was assessed in a 10% sample of admissions, which were double reviewed at both the nursing screening and physician confirmation stages and proportional to the contribution made by each participating organisation.

Statistical analysis

The GTT is conventionally analysed using a three-step method. The aggregated data are converted from episodes of harm into a harm rate and then compared with a baseline. We used the same methodology to compare aggregate rates in the two methodologies. Secondary analysis involved linking GTT and RF1 (nurse-generated) and MRF2 (physician-generated) data by unique study number and examining the consensus between methods and professional groups on the identification of AEs.

The two-stage review data were analysed to determine the percentage and corresponding CI of patients who experienced an AE during the period of hospitalisation and the severity and level of preventability of the incident both in individual hospital sites and nationally. Univariate logistic regression assessed the relationship between patient variables and the presence of an AE in physician-determined AEs. An unweighted kappa coefficient was used to assess inter-rater reliability with corresponding 95% CIs and the percentage of records that were concordant and discordant, respectively. Missing data were assessed and, because of their infrequency, (1) were presumed to be missing at random and (2) were analysed on the available data set. Weighted means were calculated using simple techniques to calculate a weighted average of the percentage of AEs in each study site, adding weights together and dividing by determined events.

Time series analysis was undertaken by plotting percentages of AEs by quarter and calculating the beta of the coefficient with corresponding CIs. Statistical analysis was undertaken using Stata version 14 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Data from different tools (RF1, MRF2 and GTT) were linked via the VLOOKUP function in Microsoft Excel® (2016; Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). GTT cases were identified by their hospital number, and the study data, including the MRF2 reviews, were identified through a unique study number. An independent database, held separately from the study data, provided patient identification fields for the match between hospital and study numbers. Cases of harm from the GTT and MRF2 review were identified and matched together using this reference data and the VLOOKUP function in Microsoft Excel.

Ethics approval was granted from the Wales Ethics Committee 1 (integrated research application system project identification 54861). Section 251 support was granted from the National Information Governance Board [ECC-5-02(FT2)12011]. Research and development approval was granted from every participating health board.

Findings: measuring harm in Wales

Aim 1

To compare outcomes and rates of harm from both the Harvard and GTT methods.

Findings

The findings are presented here in four parts. Part 1 describes the sample and extent of AEs determined from the Harvard method. Part 2 outlines the nature and characteristics of the AEs and part 3 the efficiency of the RF1 screening criteria in converting to harm events and their use in characterising AEs in secondary care settings. Finally, part 4 compares the percentage of patients experiencing AEs generated from both the two methods.

Part 1: percentage of patients with determined adverse events identified from the Harvard methodology

Sample size and quality of records

Twelve NHS hospitals across NHS Wales were invited to participate in the study, with 11 actively taking part from the study commencement. Individual samples from study sites ranged from 174 to 560, but the sample over time was significant, with one health board (sites 1 and 2) providing a larger sample than provided in any other previous similar study in a UK setting (Table 4).

| Site | Number of reviews undertaken | Number of reviews included in analysis | Second-stage review MRF2 undertaken (percentage of total records reviewed) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 560 | 553 | 98 (17.5) |

| 2 | 537 | 530 | 65 (12.1) |

| 3 | 441 | 432 | 99 (22.4) |

| 4 | 394 | 375 | 53 (14.5) |

| 5 | 338 | 309 | 73 (21.6) |

| 6 | 174 | 172 | 49 (28.2) |

| 7 | 317 | 290 | 57 (18.0) |

| 8 | 341 | 330 | 55 (16.1) |

| 9 | 413 | 393 | 64 (15.5) |

| 10 | 494 | 484 | 111 (22.5) |

| 11 | 527 | 520 | 97 (18.4) |

| Total | 4536 | 4388 | 821 |

Record exclusions

Episodes of care were excluded from the final analysis on the basis of (1) errors in the patient record retrieved for review, (2) incomplete documentation in the patient record preventing the completion of the review and (3) not meeting age and inpatient LOS inclusion criteria. The percentage of reviews excluded from analysis at the individual organisational level ranged from < 1% to 9.17%.

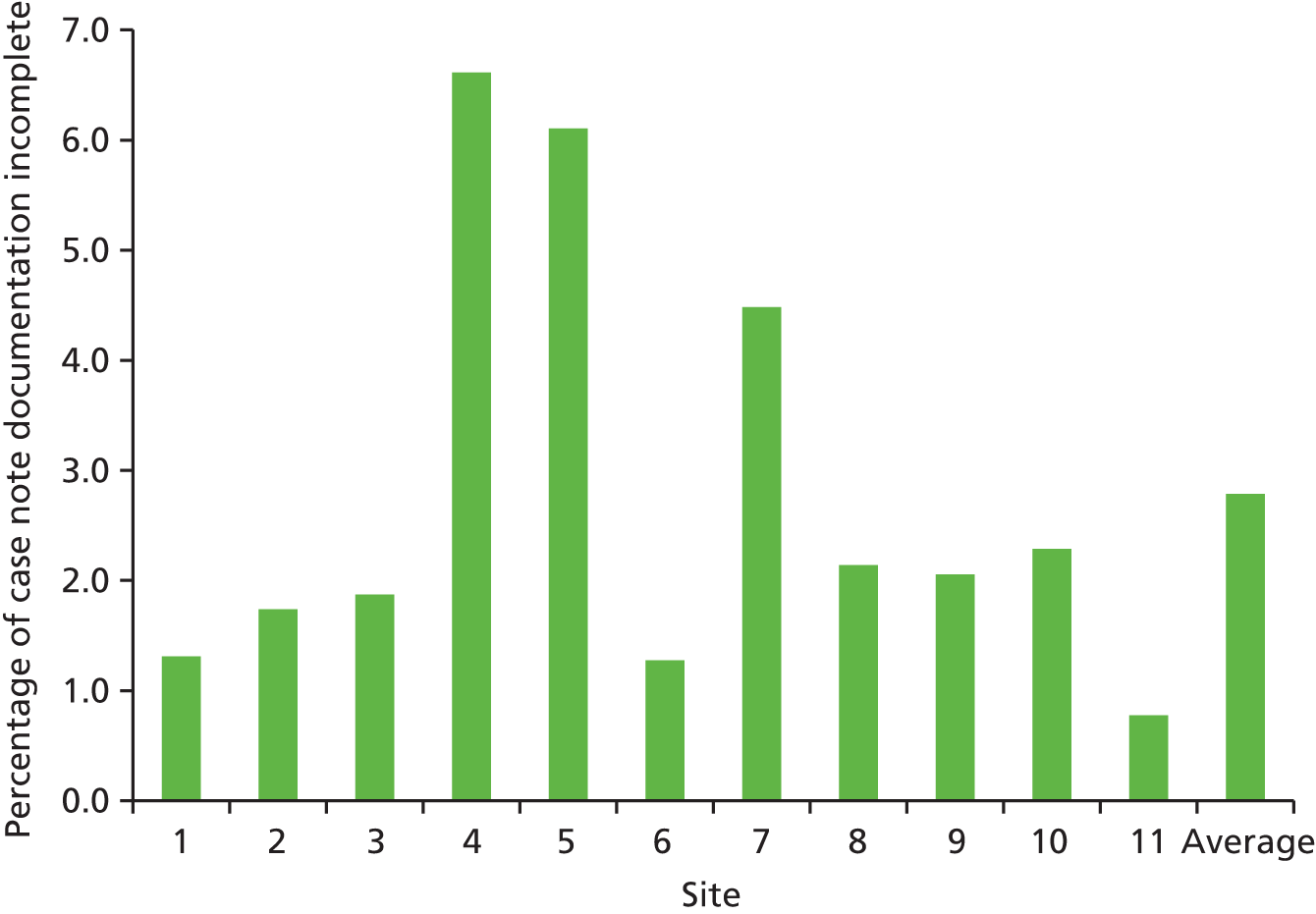

As part of the review process, an assessment was undertaken of the completeness of the inpatient record. The percentage of records with insufficient information to undertake a robust appraisal of the episode of care, that is, inadequate documentation, ranged from < 1% to > 6% (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Percentage of records with incomplete documentation across participating study sites.

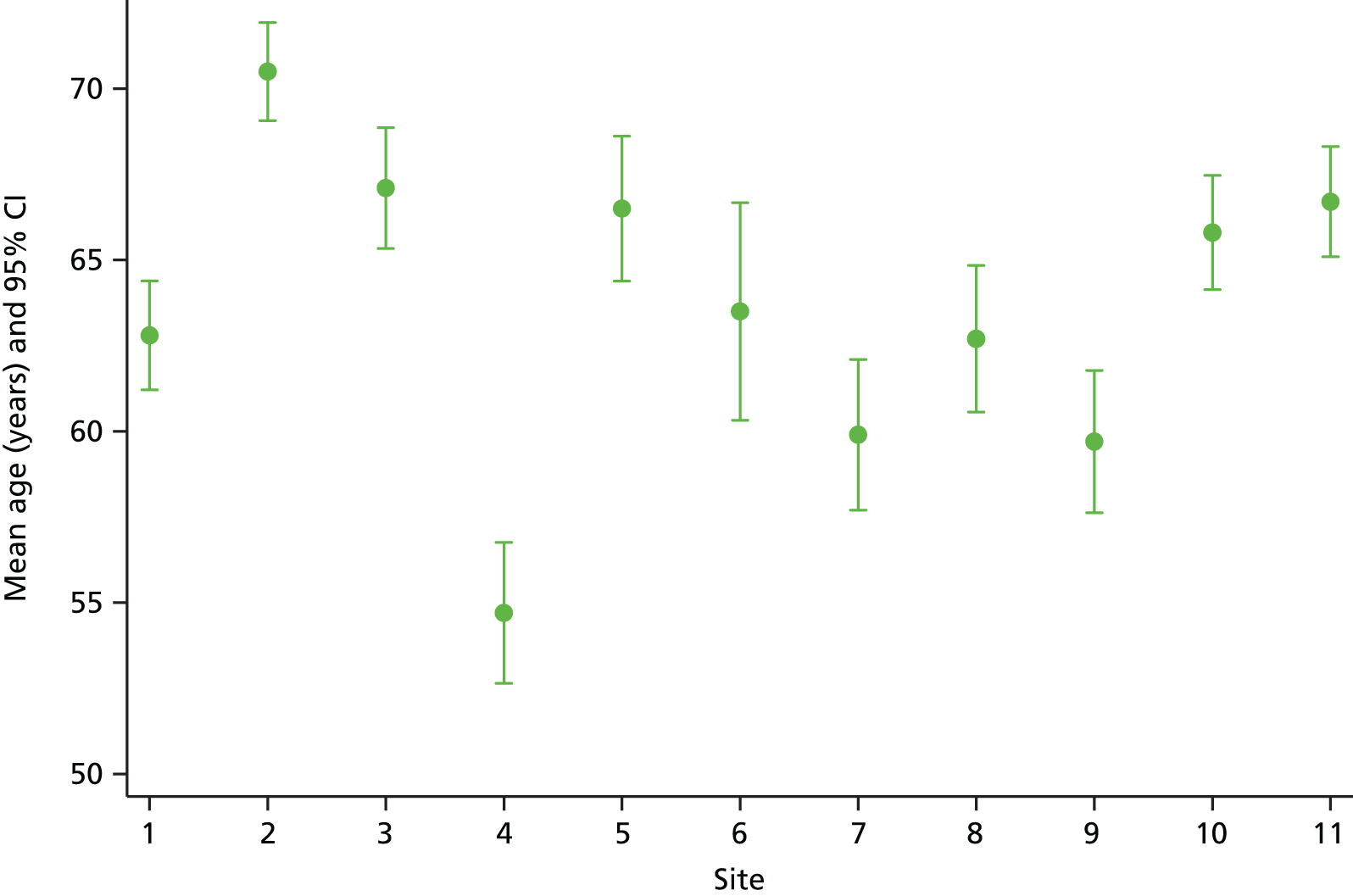

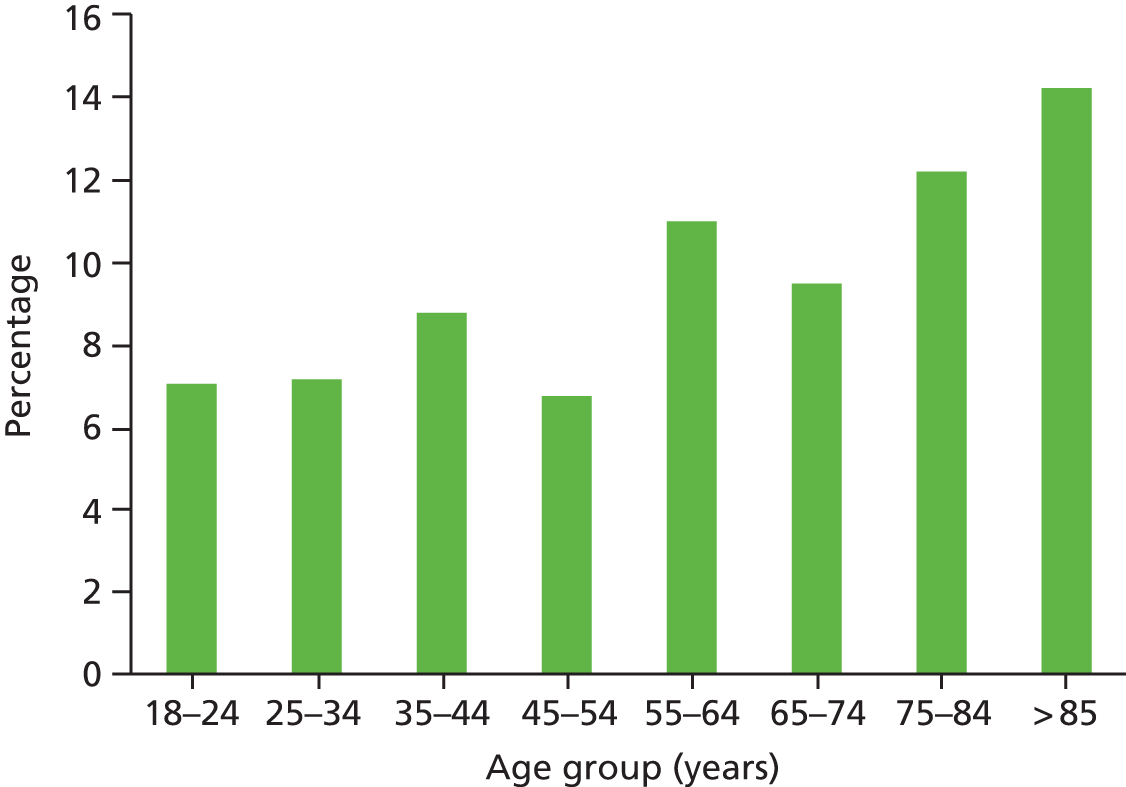

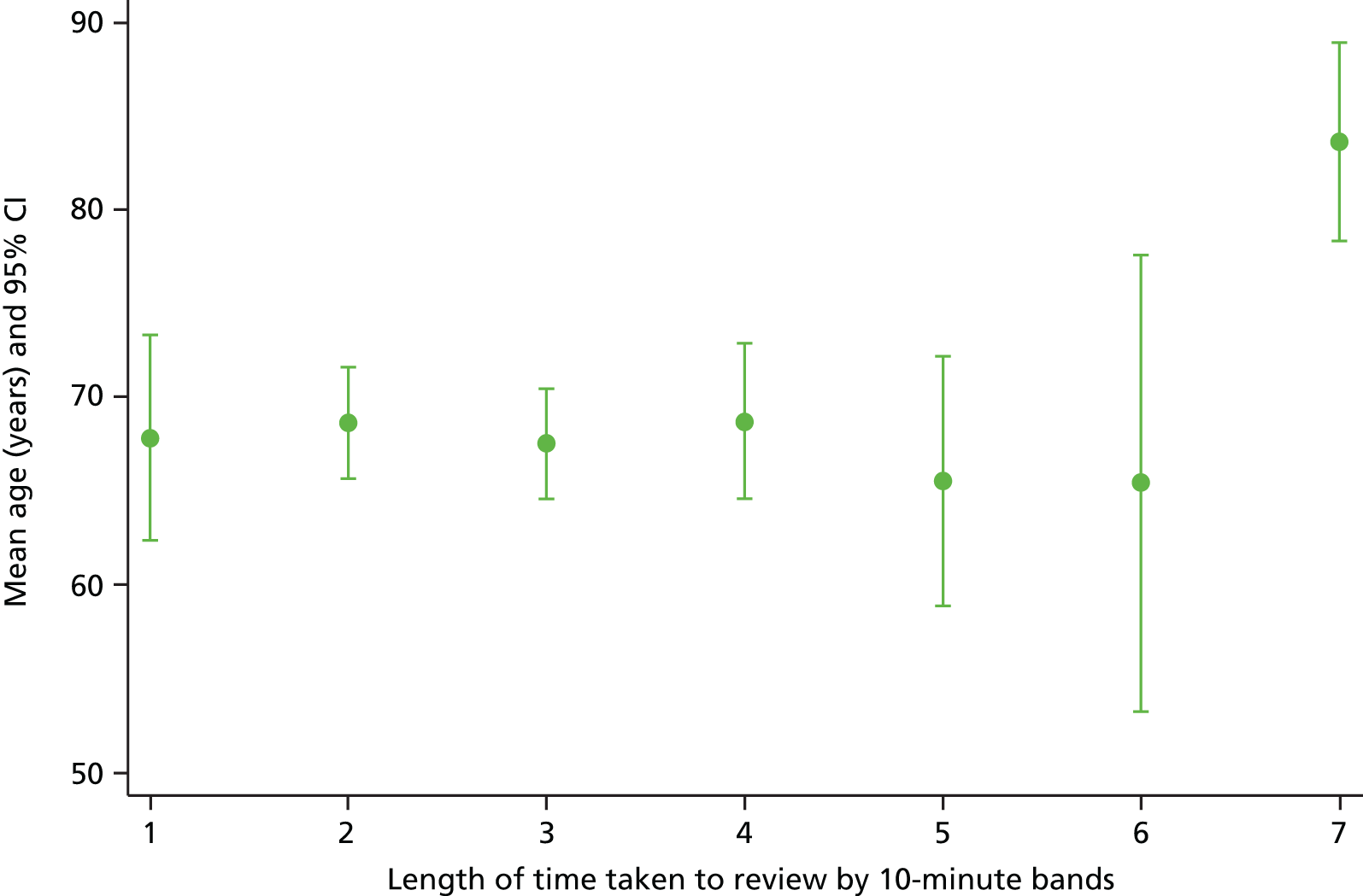

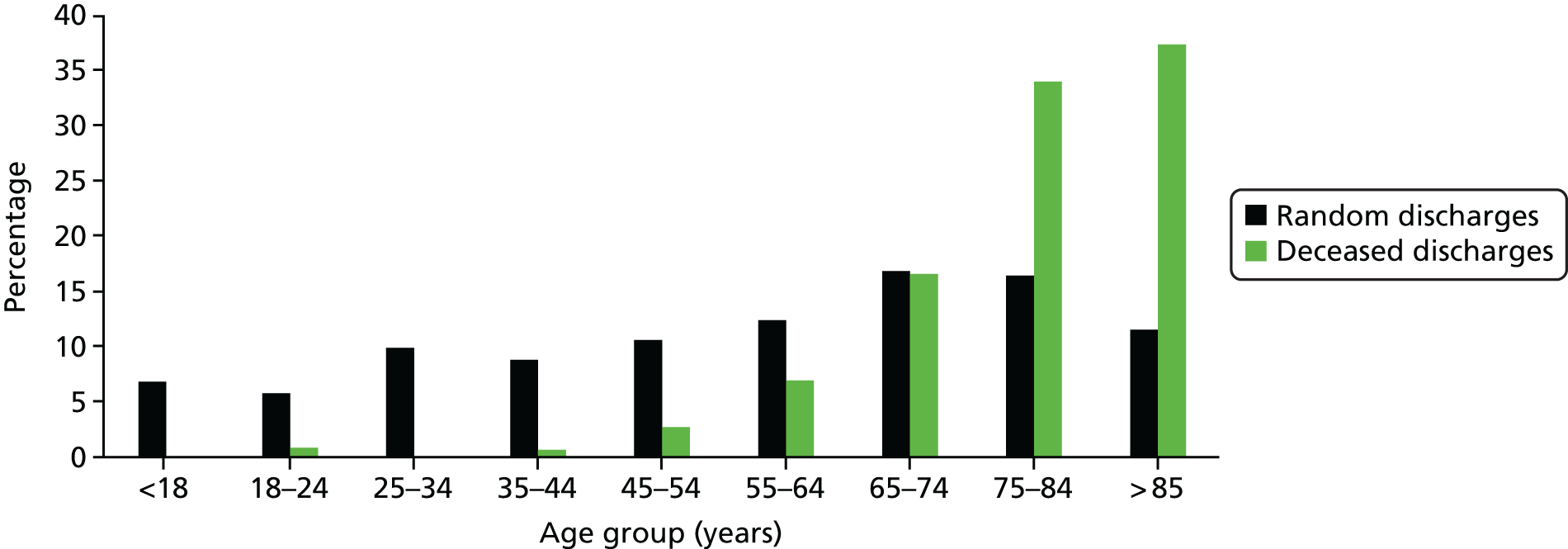

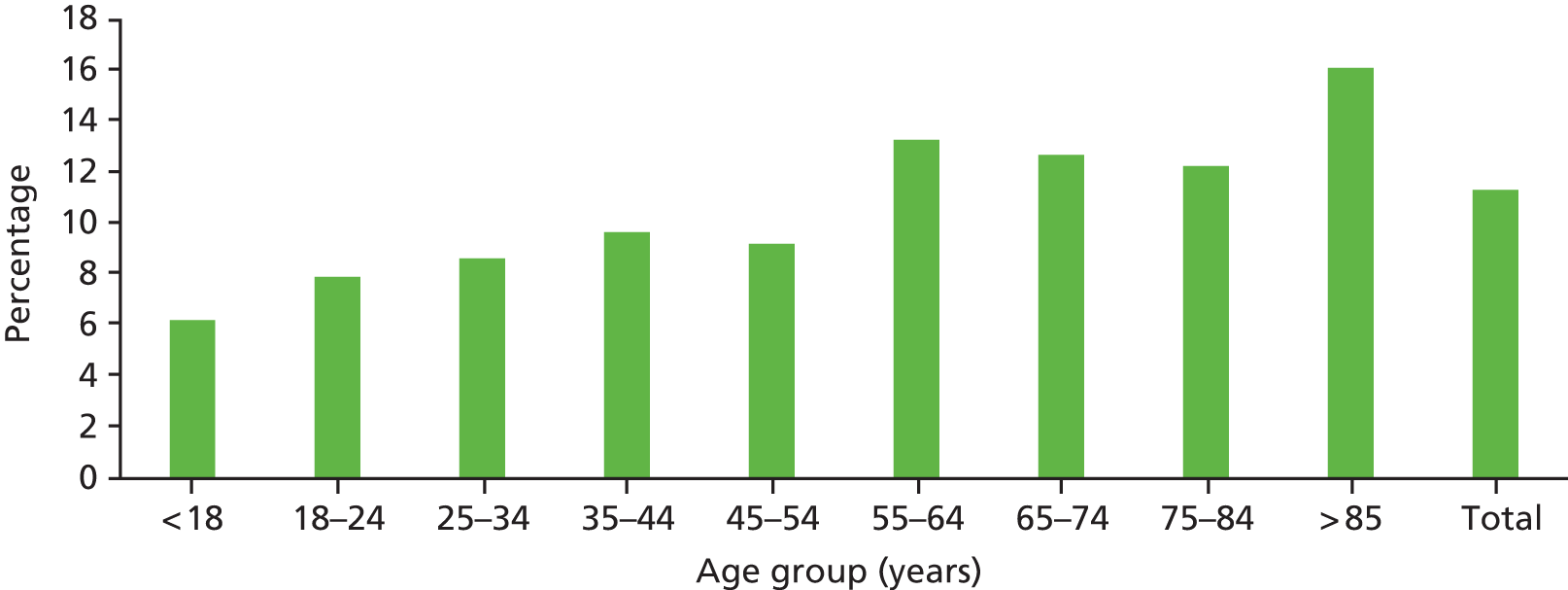

Valid observations on key demographic characteristics were available for 4361 episodes of care (99.4%) and the mean age of the patient during the index admission under review was 64.1 years (95% CI 64.48 to 64.66 years). The mean age of our study sample is older than the reported breakdown of hospital admissions nationally, in which 43% of patients discharged from hospital nationally are over the age of 65 years, compared with 56% in our study sample. It is likely that the non-inclusion of day cases and paediatric admissions in our study sample accounts for most of this difference. All inpatient episodes were stratified by age band and, as seen in Figure 4, the full age spectrum was represented in the study sample. Representation increased sequentially until the over-85s age group, when there was a significant drop in the number of reviews undertaken. Age-related data were unavailable in 27 episodes of care.

FIGURE 4.

Age distribution of the study sample across all participating sites.

The sample varied across participating organisations and one site (site 4) had a younger demographic profile, which was explored by the research team at the interim analysis stage (Figure 5). We identified potential problems with their sampling strategy, which was subsequently amended on request.

FIGURE 5.

Mean age (years) with corresponding CIs of study participants across 11 NHS study sites.

There was a 47% to 53% male to female gender split in the 4371 inpatient records examined, and in 17 cases (0.39%) age was not recorded.

On completion of the RF1 screening process, 1430 (32.6%) inpatient episodes of care were identified that had at least one identified positive screening criterion for potential AEs and, of these, 821 inpatient episodes (18.1%) were referred after review by the research team for in-depth implicit physician review. At the time of the second-stage reviews, a further 31 records were irretrievable for secondary review within hospital sites and a total of 790 MRF2 reviews were completed (96.2%). The percentage of cases with one or more positive criterion for harm ranged between 23% and 43.8% (Table 5).

| Site | Number of reviews | Number of valid reviews | Criteria present in data set (% of total number of valid reviews) (n = 4388) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 560 | 553 | 153 (27.7) |

| 2 | 537 | 530 | 122 (23.0) |

| 3 | 441 | 432 | 189 (43.8) |

| 4 | 394 | 375 | 105 (28.0) |

| 5 | 338 | 309 | 114 (36.9) |

| 6 | 174 | 172 | 66 (38.4) |

| 7 | 317 | 290 | 108 (37.2) |

| 8 | 341 | 330 | 139 (42.1) |

| 9 | 413 | 393 | 142 (36.1) |

| 10 | 494 | 484 | 151 (31.2) |

| 11 | 527 | 520 | 141 (27.1) |

| Total | 4536 | 4388 | 1430 (32.6) |

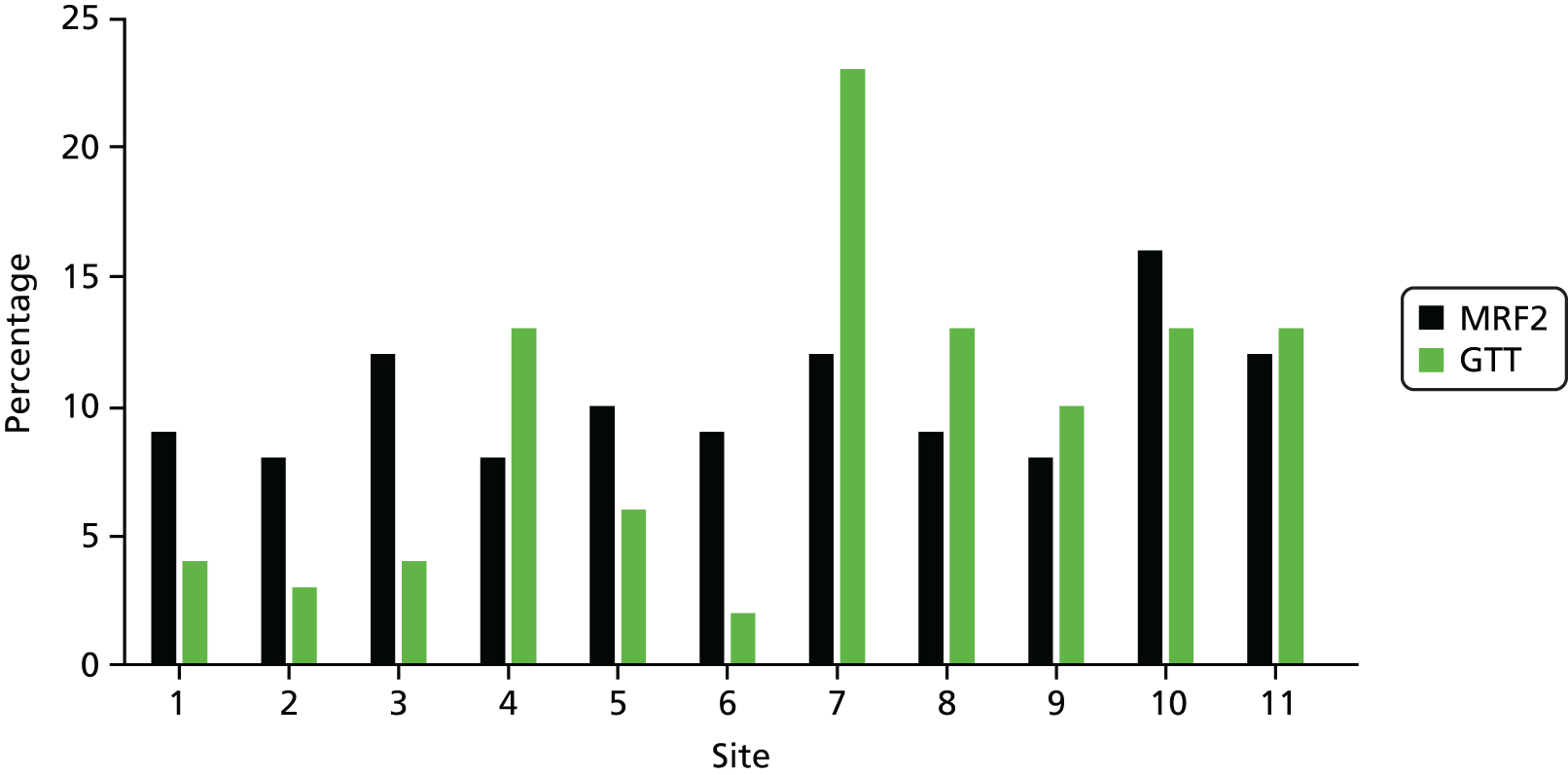

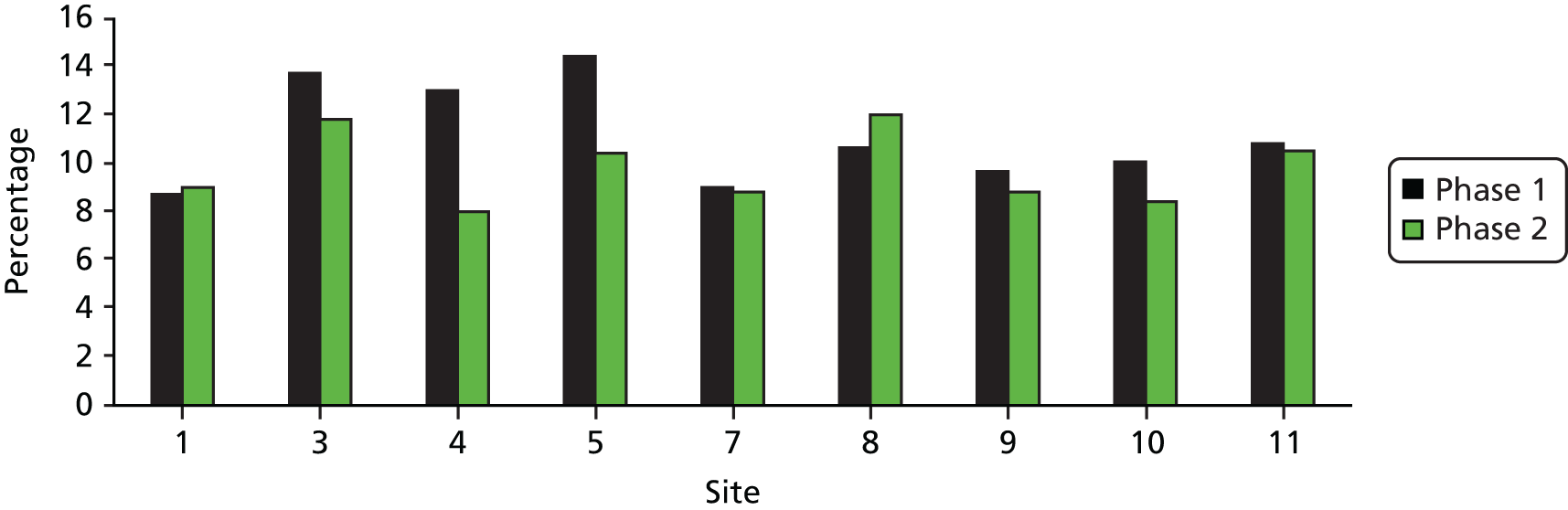

After MRF2 review, at least one AE was determined in 450 out of 4388 (10.3%) discrete episodes of care examined, with a corresponding 95% CI of 9.4% to 11.2% [median 9%, standard deviation (SD) 2.44%]. Nearly 10% of episodes had a further AE documented (n = 42). When the overall percentage of patients with AEs was weighted for the proportional contribution of individual study sites to the study, the weighted AE rate increased to 10.83% (95% CI 9.91% to 11.75%). Percentages of AEs by individual study sites ranged from 7.9% to 16.1%, with 10 of the 11 participating organisations falling within the range reported in previous two-stage retrospective review studies (Table 6).

| Site | Total number of RF1s | Number of included RF1s in analysis | Total number of MRF2s requested | Total number of MRF2s undertaken | Number of injuries or complications identified though review | Percentage of AEs identified |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 560 | 553 | 99 | 88 | 50 | 9.0 |

| 2 | 537 | 530 | 65 | 63 | 42 | 7.9 |

| 3 | 441 | 432 | 99 | 99 | 51 | 11.8 |

| 4 | 394 | 375 | 53 | 52 | 30 | 8.0 |

| 5 | 338 | 309 | 73 | 68 | 32 | 10.4 |

| 6 | 174 | 172 | 49 | 47 | 15 | 8.7 |

| 7 | 317 | 290 | 56 | 54 | 35 | 12.0 |

| 8 | 341 | 330 | 55 | 52 | 29 | 8.8 |

| 9 | 413 | 393 | 64 | 60 | 33 | 8.4 |

| 10 | 494 | 484 | 111 | 108 | 78 | 16.1 |

| 11 | 527 | 520 | 97 | 96 | 55 | 10.5 |

| Incomplete information contained in review | 3 | |||||

| Total | 4536 | 4388 | 821 | 790 (96.2%a) | 450 | 10.3 |

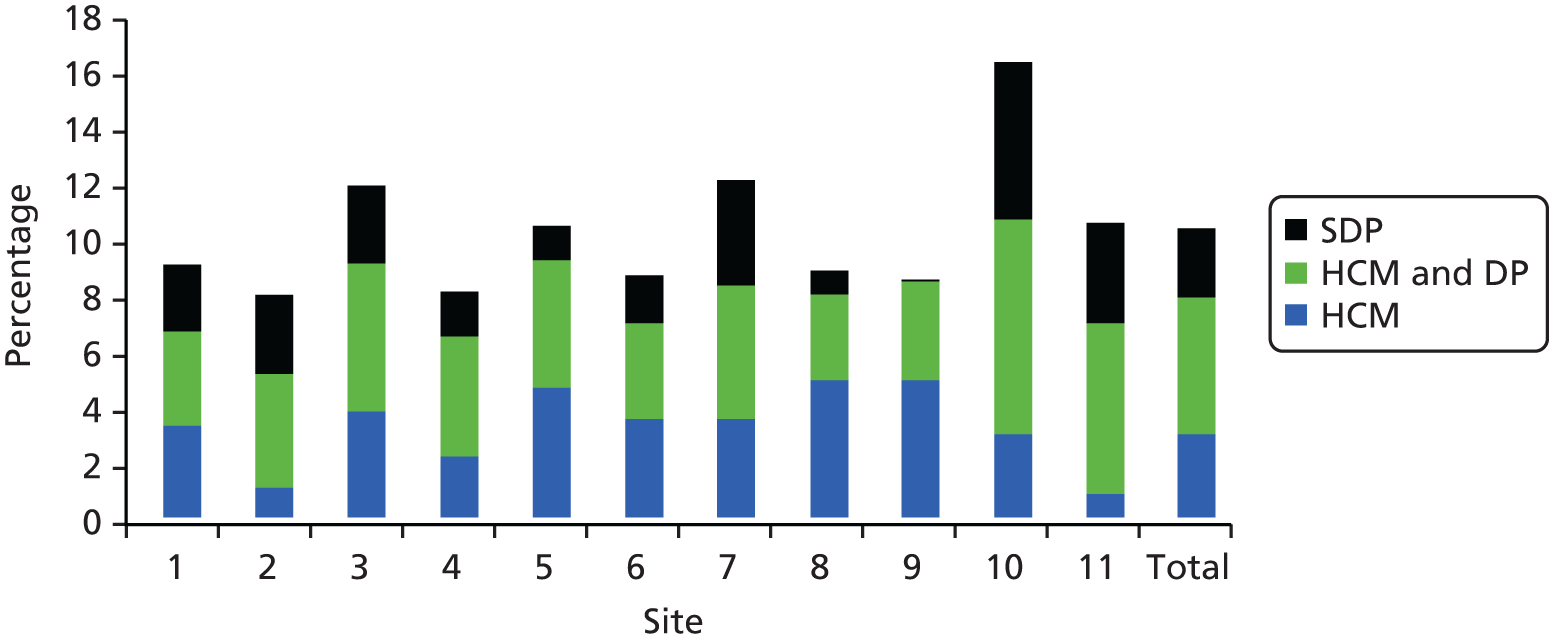

For all episodes of care, we were able to categorise the primary AE into whether it was caused (1) by health-care management, (2) by health-care management interacting with the disease process and (3) solely by the disease process. The breakdown is shown by individual study site in Table 7.

| Site | Causes of AEs | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Health-care management | Health-care management interacting with the disease process | Solely the disease process | |

| 1 | 17 | 20 | 14 |

| 2 | 6 | 26 | 10 |

| 3 | 16 | 23 | 12 |

| 4 | 8 | 16 | 6 |

| 5 | 13 | 13 | 6 |

| 6 | 6 | 6 | 3 |

| 7 | 10 | 14 | 11 |

| 8 | 16 | 10 | 3 |

| 9 | 18 | 15 | 0 |

| 10 | 17 | 39 | 21 |

| 11 | 5 | 32 | 18 |

| Total | 132 (29.3%a) | 214 (47.5%a) | 104 (23.1a) |

Just over three-quarters of all determined AEs resulted from health-care management or health-care management interacting with the disease process, with the remaining events being complications or unavoidable events arising from an individual’s underlying health status. Figure 6 demonstrates that when the cases that were deemed to arise solely from the disease process are removed from the AE rate, there is a reduction in the variability of rates across NHS Wales sites.

FIGURE 6.

Causes of AEs by study site across NHS Wales. SDP, solely the disease process; HCM, health-care management; HCM and DP, health-care management interacting with the disease process.

Adverse events were also categorised according to the level of management causation on a scale of 1–6, for which 1 is virtually no evidence for management causation/system failure and 6 is virtually certain evidence for management causation. Of the 448 events classified, 195 (43%) events were graded 1 or 2 (i.e. no or low evidence of management causation), 132 (29%) were graded as moderate in terms of evidence of management causation and 121 (27%) were graded as highly likely to be caused by health-care management (Table 8).

| Level of confidence by physicians irrespective of preventability of the management causation of the AE | Number of AEs classified as | Percentage of the total number of classified AEs |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Virtually no evidence for management causation/system failure | 107 | 23.7 |

| 2. Slight to modest evidence for management causation | 88 | 19.6 |

| 3. Management causation not likely: < 50–50, but close call | 42 | 9.3 |

| 4. Management causation more likely than not; > 50–50, but close call | 90 | 20.0 |

| 5. Moderate/strong evidence for management causation | 65 | 14.4 |

| 6. Virtually certain evidence for management causation | 56 | 12.4 |

| Not classified | 2 | 0.5 |

| Total | 448 |

This judgement was made after consideration of all the clinical details of the patient’s management, irrespective of preventability and is a measure of the level of confidence that the health-care management caused the injury. In just under half of all cases (46.8%) there was sufficient confidence from the record of care that there was a likelihood that health-care management was directly responsible for the AE. The cases for which there was no evidence for management causation (23.7%) corresponds crudely to the 104 cases (see Table 7) for which the physician judged that the AE was directly attributable solely to the patient’s underlying disease status.

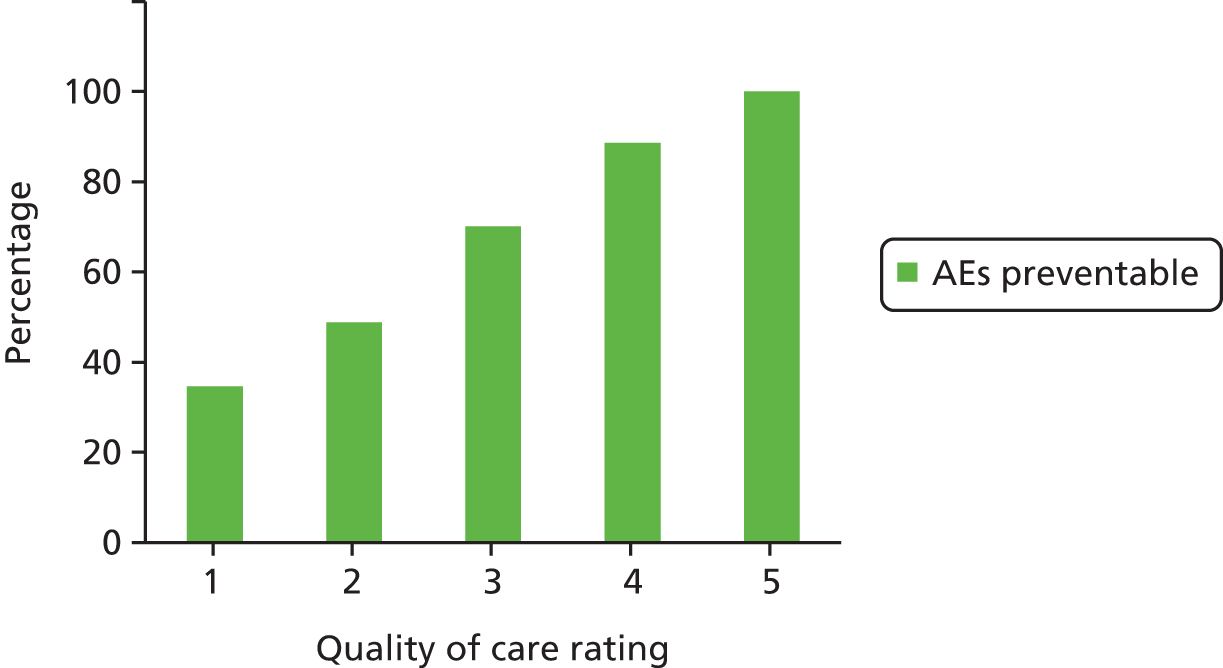

Across all study sites, 51.5% of AEs were identified as having at least some evidence of preventability when defined as events resulting from care not being delivered to a standard considered to be good clinical practice, in normal circumstances (median 55%, SD 13.30%, 95% CI 46.88% to 56.12%) (Table 9).

| Site | Valid RF1s | MRF2 undertaken | Number of injuries or complications | Number of preventable AEs | Percentage of preventable AEs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 553 | 88 | 50 | 27 | 54 |

| 2 | 530 | 63 | 42 | 17 | 40 |

| 3 | 432 | 99 | 51 | 28 | 55 |

| 4 | 375 | 52 | 30 | 16 | 53 |

| 5 | 309 | 68 | 32 | 18 | 56 |

| 6 | 172 | 47 | 15 | 13 | 87 |

| 7 | 290 | 54 | 35 | 20 | 57 |

| 8 | 330 | 52 | 29 | 16 | 55 |

| 9 | 393 | 60 | 33 | 22 | 67 |

| 10 | 484 | 108 | 78 | 32 | 41 |

| 11 | 520 | 96 | 55 | 23 | 42 |

| Total | 4388 | 790 (96.2%a)b | 450 | 232 | 51.5 |

When the percentage of preventable AEs was weighted by the individual organisation’s contribution to the study sample, the mean percentage of preventability increased slightly to 53.13% (95% CI 48.52% to 57.74%). Preventability was also examined on a six-point Likert scale and in three main categories (Table 10).

| Site | Level of preventability | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage of AEs that were preventable | Number of preventable AEs greater or equal to a score of 2 (slight to modest evidence) | Number of AEs greater than a score of 4 (probably preventable) | |

| 1 | 54 | 27 | 19 |

| 2 | 40 | 17 | 3 |

| 3 | 55 | 31 | 7 |

| 4 | 53 | 16 | 7 |

| 5 | 50 | 17 | 12 |

| 6 | 87 | 13 | 10 |

| 7 | 57 | 20 | 11 |

| 8 | 55 | 16 | 6 |

| 9 | 66 | 20 | 10 |

| 10 | 41 | 29 | 13 |

| 11 | 42 | 20 | 12 |

| Total | 51.5 | 226 (50.2%a) | 110 (24.4%a) |

The majority of all AEs (n = 226, 51%) was classified as having at least ‘slight to modest evidence for preventability’, corresponding to scores of between 2 and 6 on the Likert scale (95% CI 46.88% to 56.12%). In only 24% (n = 110) of cases, the level of preventability was determined to be ‘probably preventable; > 50–50 but close call’ corresponding to a score between 4 and 6 on the Likert scale (95% CI 20.43% to 28.37%).

Ten per cent of all records were double reviewed at both the RF1 and RF2 stages and the level of agreement between reviewers was assessed, which is reported in Table 11.

| Site | Total number of reviews | Number of pairs | Unweighted kappa | 95% CI | Altman scale 199157 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concordant | Discordant | |||||

| 1 | 58 | 45 | 13 | 0.29 | 0 to 0.63 | Fair |

| 2 | 56 | 45 | 11 | 0.43 | 0.13 to 0.73 | Moderate |

| 3 | 49 | 33 | 16 | 0.32 | 0.05 to 0.60 | Fair |

| 4 | 48 | 36 | 12 | 0.37 | 0.06 to 0.68 | Fair |

| 5 | 32 | 23 | 9 | 0.43 | 0.13 to 0.75 | Moderate |

| 6 | 20 | 13 | 7 | 0.27 | 0.0 to 0.70 | Fair |

| 7 | 29 | 24 | 5 | 0.63 | 0.33 to 0.92 | Good |

| 8 | 41 | 32 | 9 | 0.56 | 0.30 to 0.81 | Moderate |

| 9 | 54 | 41 | 13 | 0.51 | 0.28 to 0.74 | Moderate |

| 10 | 53 | 43 | 10 | 0.59 | 0.48 to 0.82 | Moderate |

| 11 | 49 | 33 | 16 | 0.34 | 0.07 to 0.60 | Fair |

| Total | 492 | 377 | 121 | 0.47 | 0.39 to 0.55 | Moderate |

The overall agreement on episodes of care having at least one positive criterion for harm after assessment was moderate (the kappa falling between 0.41 and 0.60 on the Landis Koch Benchmark scale) (κ = 0.47, 95% CI 0.39 to 0.55) or 76.6% concordant and there was significant variation in the reliability performance across the participating study sites.

Eighty-seven double reviews were undertaken for implicit MRF2 inter-rater reliability assessment. Agreement between reviewers was achieved in 83% of cases (n = 72), with a kappa of 0.63 and a corresponding 95% CI of 0.46 to 0.80.

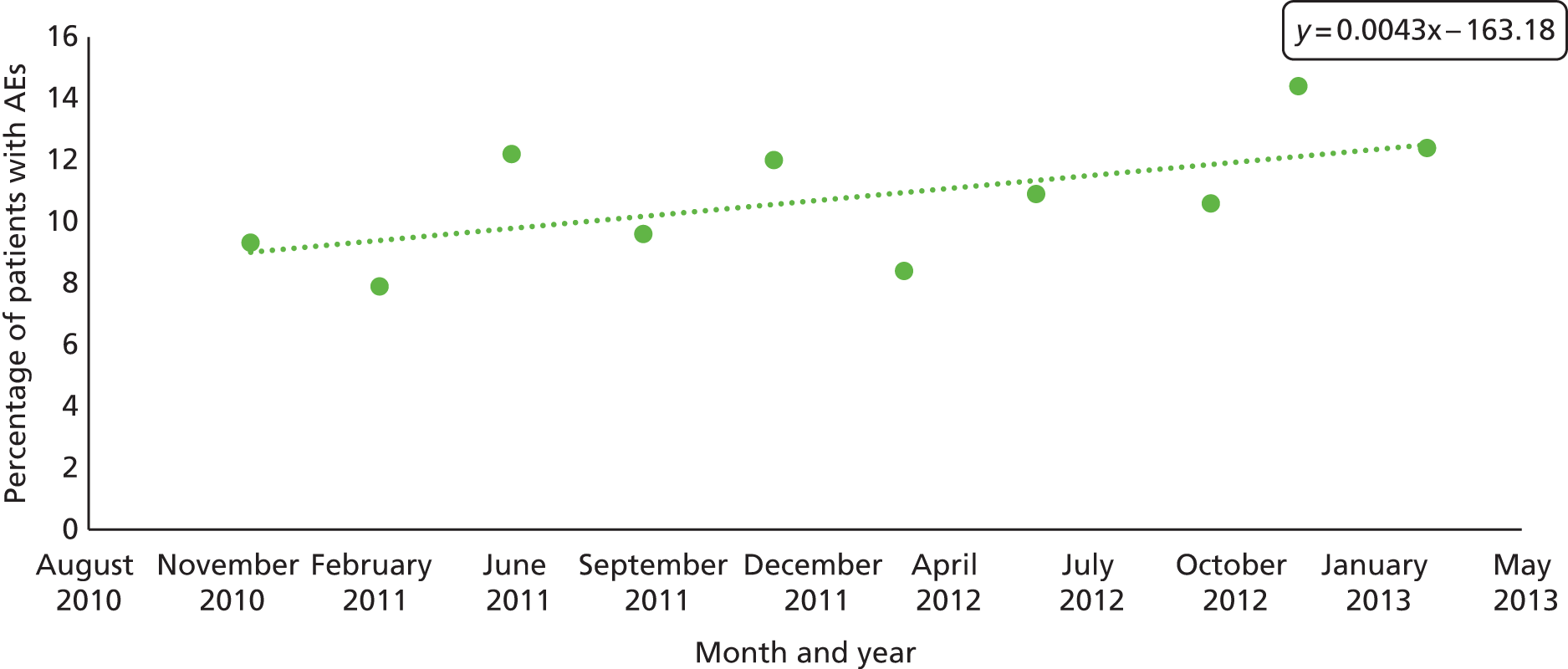

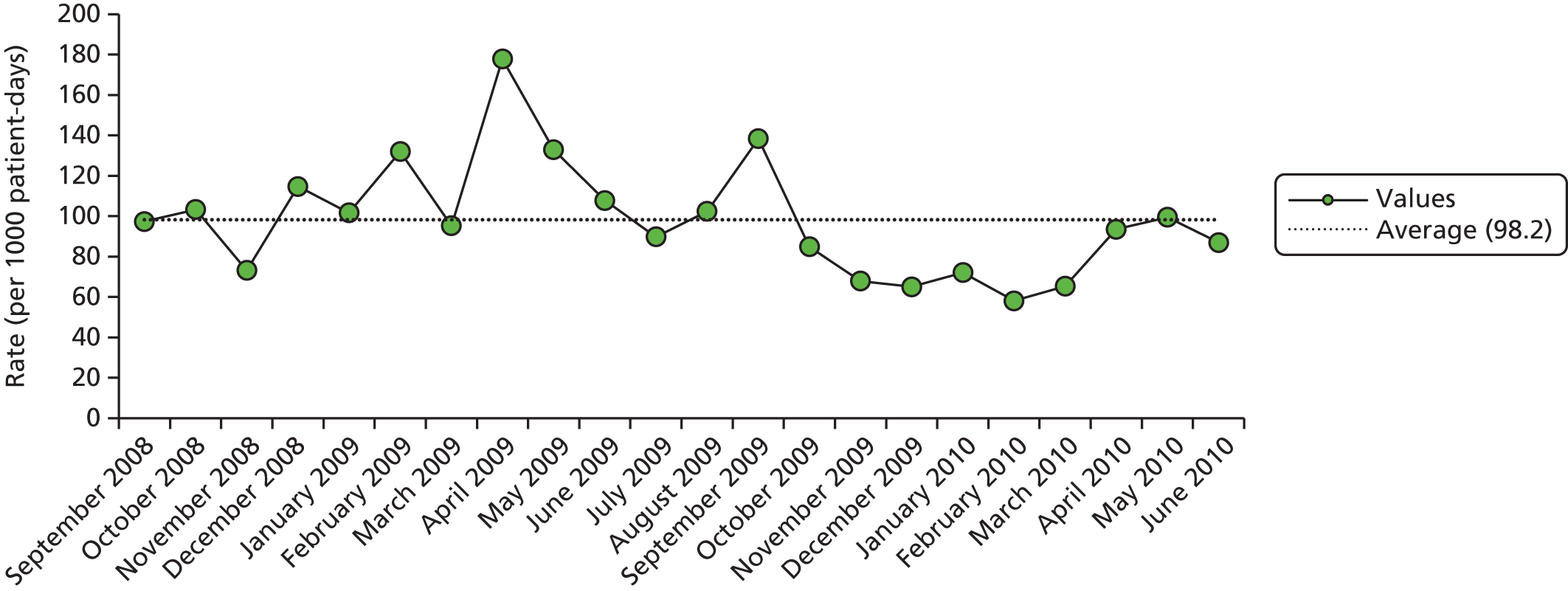

Our study sample was longitudinal in nature and rates of AEs were plotted over the phase 1 period. Figure 7 reports crude rates of AEs determined by research physicians after MRF2 review per quarter. Although a trend is suggested, this was not statistically significant in linear regression. The beta of the coefficient was 1.58 (95% CI –0.16 to 3.34; p = 0.070).

FIGURE 7.

Trend of physician-confirmed AE determination, by quarter, across NHS Wales: October 2010–March 2013.

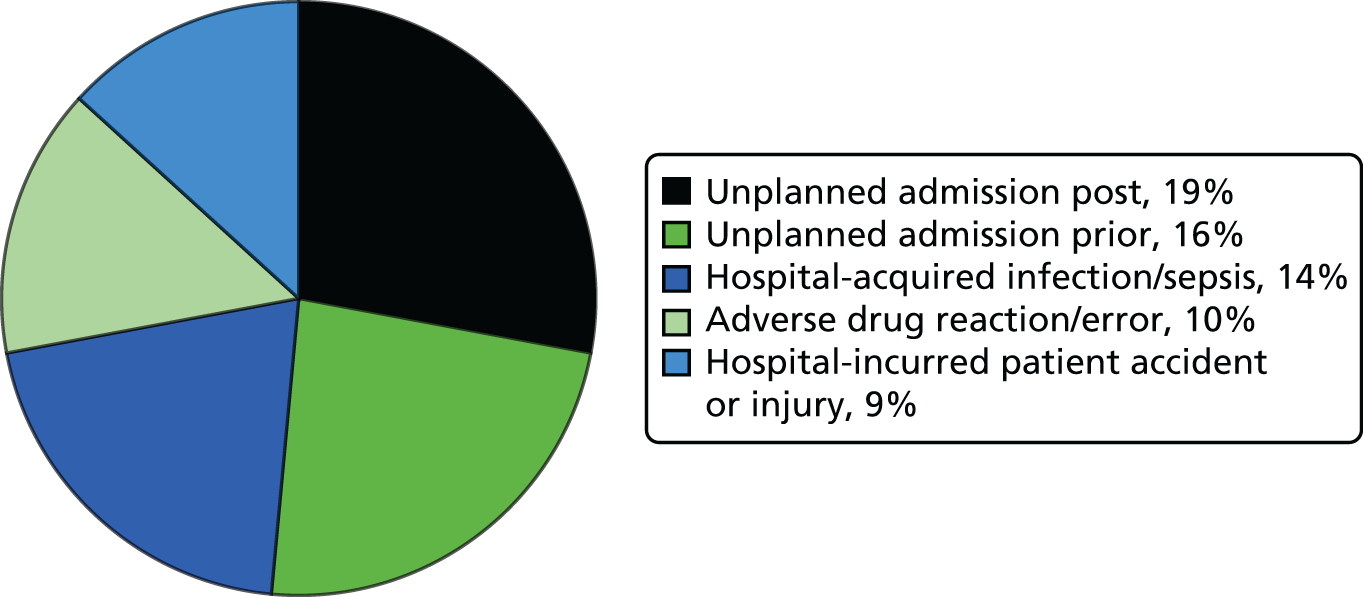

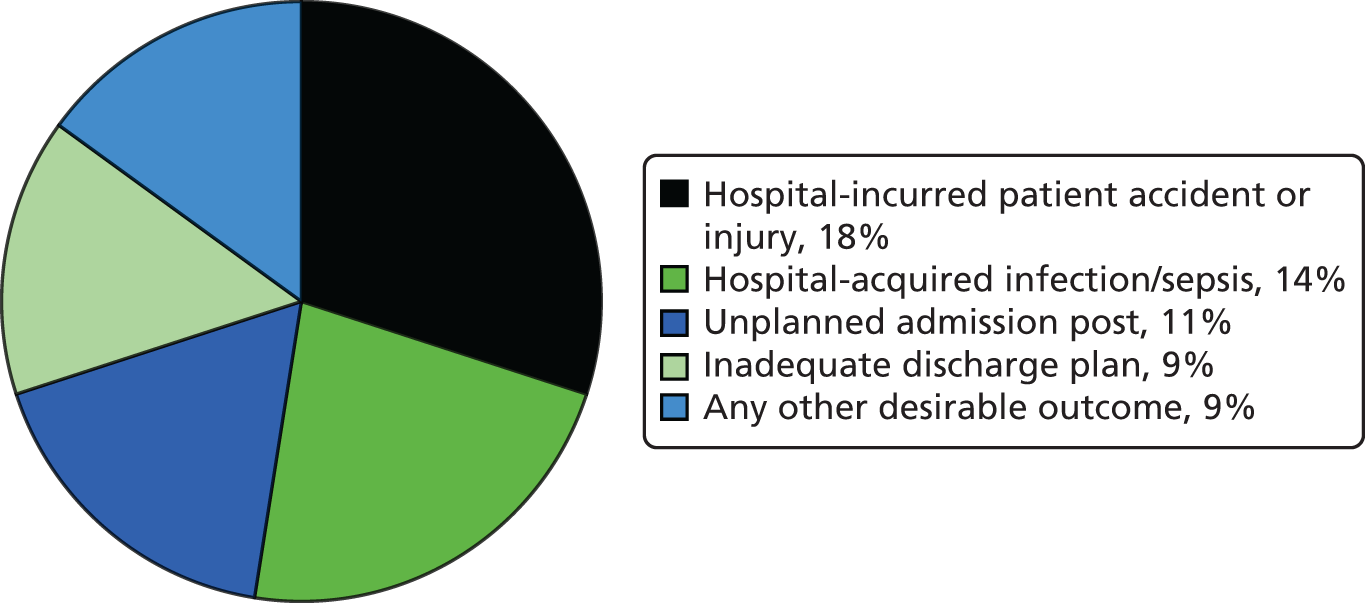

Part 2: the nature and severity of adverse events across NHS Wales

Physicians identified the principal problems in care that resulted in the occurrence of an AE. Table 12 shows the distribution of problems in care across the inpatient episodes examined and categorised when management causation was established (n = 343). Failure in clinical monitoring and management was an issue identified in one-third of all events (n = 115, 33.5%). Other significant problems arose from failure to manage and prevent infection (n = 101, 29.4%), issues directly related to a problem with an operation or procedure (n = 73; 21.2%) and problems in the prescribing, administration or monitoring of drugs and fluids (n = 64; 18.7%). When assessed at the individual hospital site, variations in the relative importance of problems in care are observed, but it is evident that patients are at risk as a result of failures in clinical monitoring, infection control-related procedures and drug and fluid administration across all sites.

| Problem in care category | Frequency | Percentage of total AEs |

|---|---|---|

| 1. AE relating to diagnostic or assessment error | 47 | 13.7 |

| 2. AE from failure to appreciate patient’s overall condition | 18 | 5.2 |

| 3. AE arising from a failure in clinical monitoring management | 115 | 33.5 |

| 4. AE in relation to failure to prevent/control/manage infection | 101 | 29.4 |

| 5. AE directly related to a problem with an operation or procedure | 73 | 21.2 |

| 6. AE relating to prescribing, administration or monitoring of drugs or fluids including blood | 64 | 18.7 |

| 7. AE relating to resuscitation | 1 | 0.3 |

If the occurrence of these common events identified through case note review is crudely extrapolated across the total number of hospital discharges in Wales, per annum (760,418 events), they would equate to around 19,900 events relating to failures in clinical monitoring, 17,500 AEs resulting from failures in infection control, 12,650 events relating to problems with operations and procedures and 11,000 AEs relating to the administration of drugs, fluids or blood. This reflects significant excess resource utilisation and expenditure.

Adverse events have significant clinical impact but are also costly in terms of excess days in inpatient settings with attendant excess treatment costs. Table 13 outlines the percentage of (1) patients with physician-confirmed AEs across NHS Wales who were discharged with a level of disability not present at admission; (2) patients who required an extended LOS and additional treatments and/or no extended stay but additional treatment; and (3) patients whose AEs were associated with but not necessarily causally related to, inpatient death. Nearly three-quarters (n = 329) of our cohort of patients with AEs needed additional treatment and/or days in hospital, 71 (16%) were discharged with a significant impairment in their functional status and in 40 patients (9%) the AE may have been associated with but not necessarily causally related to, the patient dying during the inpatient episode.

| End point of AE | Frequency | Percentage of patients with AEs with a defined outcome | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Disability | 72 | 16.0 | 12.6 to 19.4 |

| Prolonged stay/subsequent treatment | 328 | 72.9 | 68.8 to 77.0 |

| Death | 41 | 9.1 | 6.45 to 11.8 |

The severity of the injury across NHS Wales

Physicians were asked to make an additional assessment of the severity of the event, in terms of both the physical and emotional impact on the patient. This is reported in Table 14. An assessment of physical disability was made in the 323 events reported (72%). Reviewers did not make an assessment of disability in cases in which the AE was determined to have been caused solely as a result of the disease process. Nearly 74% of the events assessed resulted in no or minimal physical impairment, with an expected recovery within 1 month. At the other end of the spectrum, the physician determined in only 26 cases that the event was associated with the patient’s death and in six cases that it was responsible for the death of the patient.

| Level of disability | Number of AEs |

|---|---|

| Physical disability | |

| Minimal impairment and recovery expected in 1 month | 115 |

| Moderate impairment, recovery in 1–6 months | 41 |

| Moderate impairment, recovery in 6 months to 1 year | 6 |

| Permanent impairment, disability | 11 |

| Death | |

| Death with minimal contribution from the AE | 5 |

| Death with moderate contribution from the AE | 13 |

| Death entirely attributable to the AE | 6 |

| Death, but cannot judge association with the AE | 2 |

| Emotional trauma | |

| Minimal emotional trauma and/or recovery in 1 month | 78 |

| Moderate trauma, recovery in 1–6 months | 29 |

| Moderate trauma, recovery in 6 months to 1 year | 7 |

| Severe trauma, recovery lasting longer than 1 year | 3 |

The impact of the injury in terms of the likely emotional trauma experienced by the patient was less comprehensively assessed, with categorisation available for 309 out of 450 AEs. The severity reported follows a similar trend, with 61% of events categorised as no or minimal trauma and < 3% of events classified as causing moderate to severe trauma, with recovery predicted to last over 6 months.

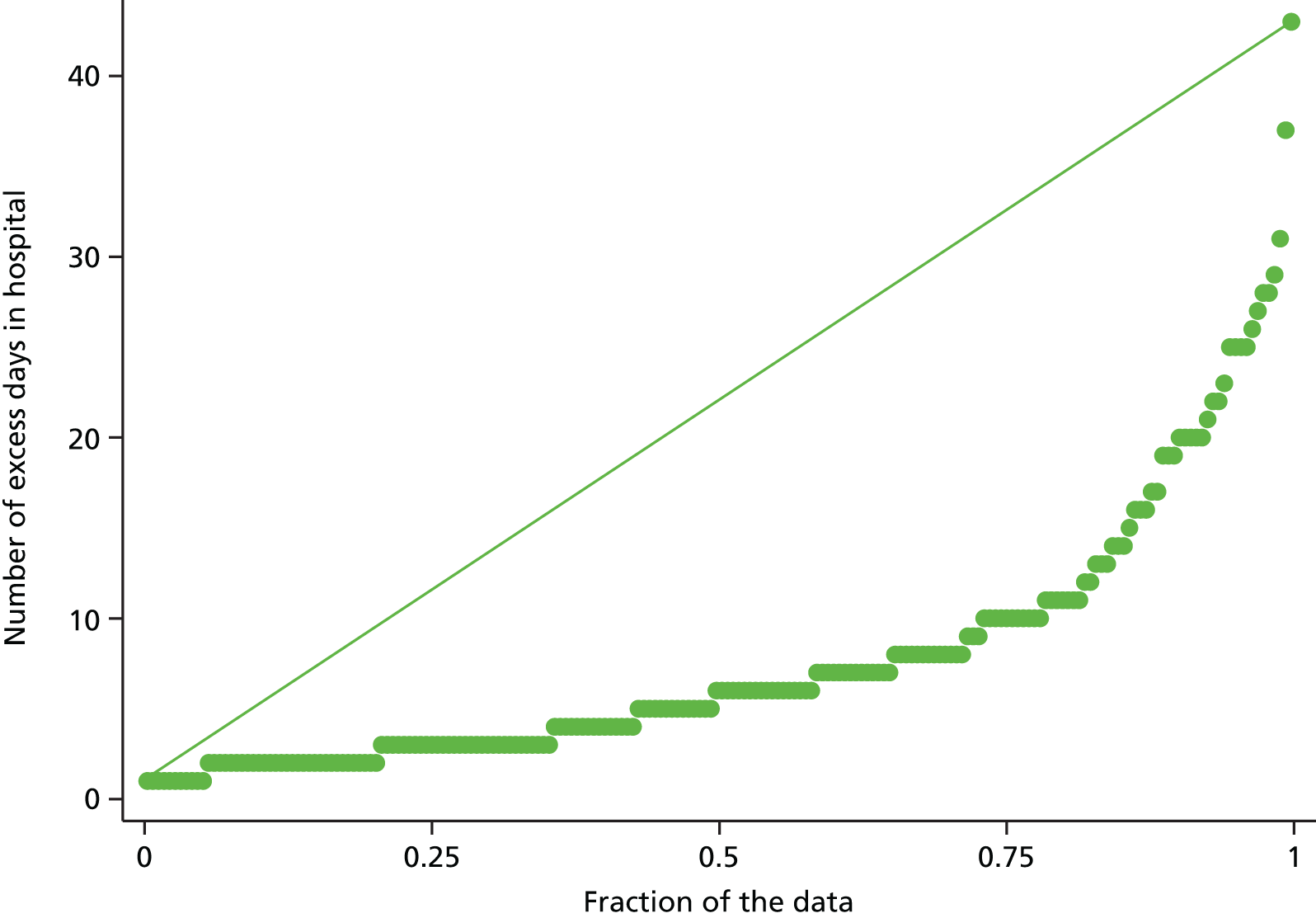

Adverse events and excess length of stays