Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 12/136/79. The contractual start date was in April 2014. The final report began editorial review in October 2016 and was accepted for publication in March 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Alys Young sits on an expert reference group convened by the Royal College of Psychiatry and the charitable organisation SignHealth, in order to draw up guidelines for commissioners of primary mental health services for Deaf people. Katherine Rogers is chairperson of the British Society for Mental Health and Deafness. Steve Pilling is in receipt of funding from the National Horizon Scanning Centre to develop care pathways for the Improving Access to Psychological Therapies programme. Rachel Belk works part-time in a NHS clinical role as a genetics counsellor, where she occasionally works with Deaf patients. Claire Dodds works as a freelance British Sign Language/English interpreter, occasionally within health-care settings.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2017. This work was produced by Young et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background

Introduction

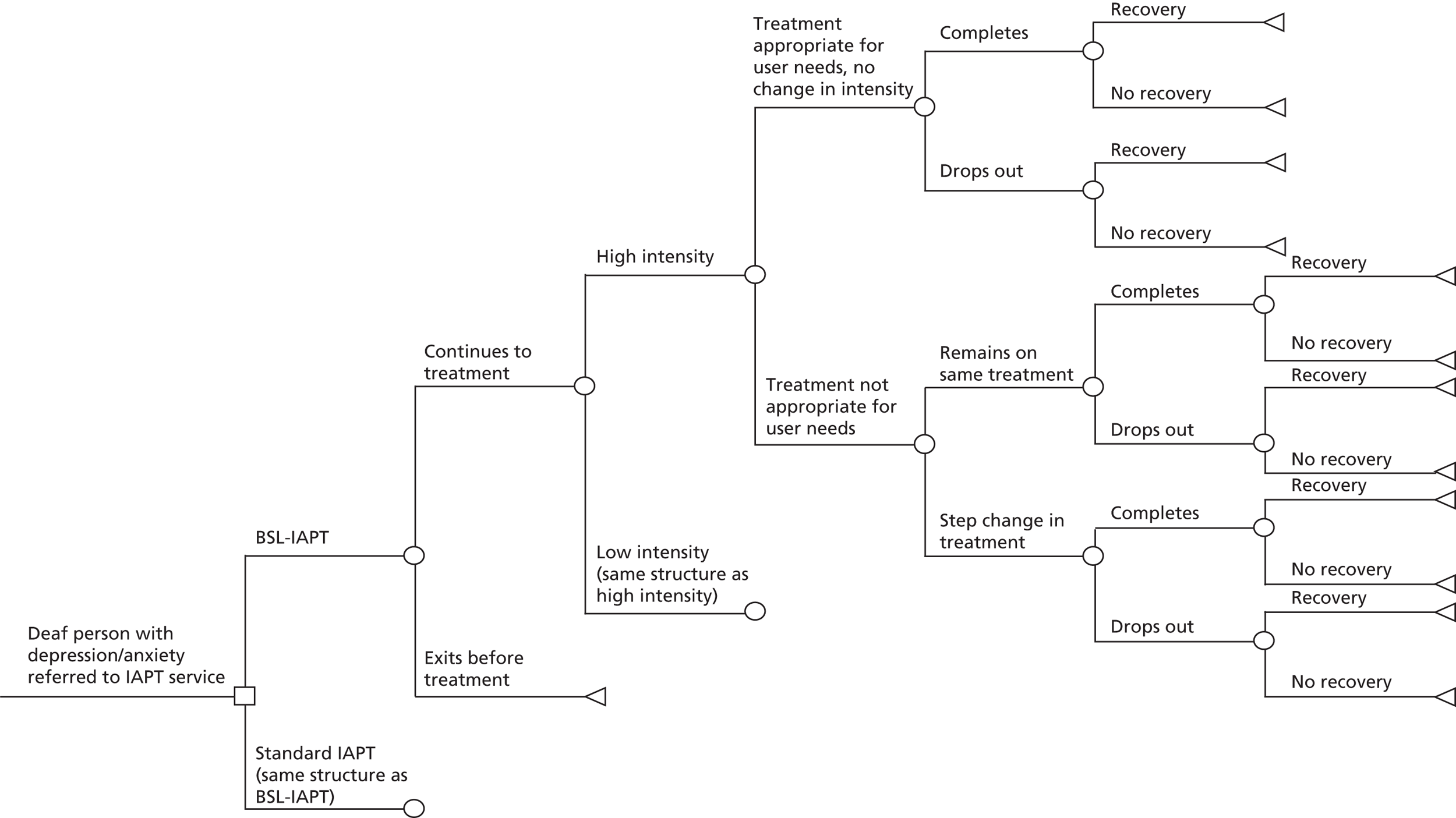

This exploratory, mixed-methods study is focused on adults who are Deaf, who use British Sign Language (BSL) as their first, preferred or strongest language, and who experience anxiety and/or depression. Specifically it addresses the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) programme in the delivery of psychological therapies for Deaf BSL users. IAPT services deliver approved psychological interventions to address anxiety and depressive disorders. Services are delivered in primary care settings1 and follow the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)-approved stepped care model, which includes low-intensity treatment at step 2 [e.g. cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) and guided self-help] and high-intensity treatment at step 3 (including CBT for individuals with an inadequate response to therapy at step 2, as well as those with more serious disorders). 1 This study is confined to step 2 and step 3 aspects of the IAPT service model. First, it compares the service delivery and clinical outcomes of two kinds of IAPT service accessed by Deaf BSL users: (1) the usual service that might be accessed via sign language interpreters and/or other reasonable adjustments, which is referred to in this study as ‘standard IAPT’; and (2) a bespoke adaptation of the IAPT service delivered in BSL by Deaf therapists to Deaf people that incorporates additional culturally orientated adaptations, referred to in this study as ‘BSL-IAPT’. Second, this study sets out to lay the groundwork required prior to considering any large-scale study, whether a randomised clinical trial or other controlled, prospective study design. This includes instrument design and adaptation, testing the feasibility of recruitment in sufficient numbers and engagement with the Deaf community.

British Sign Language and Deaf people

British Sign Language is a fully grammatical, living language, distinct from English,2 and its status as an indigenous minority language of the UK was recognised by the UK government in 2003. 3 In Scotland, in 2015, its legal position was further strengthened by the BSL (Scotland) Act. 4 Deaf people are, therefore, afforded the status of other minority groups whose access to services should not simply be protected, but actively promoted, under the provisions of the Public Sector Equality Duty 2011,5 following the Equality Act 2010. 6

In common with other language-using groups, distinct cultural norms, practices and traditions are associated with BSL users, who are thus regarded as constituting a minority cultural–linguistic community in the UK. 7 Deaf people who sign regard their language as a marker of positive cultural identity, not as a feature of failing to speak or having a hearing loss. 7 To be Deaf is not an audiologically determined definition but, rather, a culturally determined one. 8,9 This cultural–linguistic identity is conventionally marked by the use of upper-case ‘D’, as in Deaf, in the same way in which one might refer to French or Polish people. Lower-case ‘d’ (deaf) is usually reserved for those people with an acquired hearing loss or who prefer to communicate using spoken language. 10 We follow this convention throughout the report. Although some Deaf people may also use, to differing extents, the spoken language of the country in which they live, their signed language, such as BSL, is their first, preferred, strongest or, in some cases, only language. Literacy in the written word remains a challenge for many Deaf people, in part because of the phonological basis of learning to read. 11 It is erroneous to assume that information written down is accessible because it is not dependent on hearing. 10

Estimates of the Deaf population vary considerably as a result of how data are collected; in some cases there is a failure to distinguish between the ‘disability’ of deafness and cultural–linguistic identity, in others the question asked is too restrictive to permit viable extrapolations to be made. For example, the Ipsos MORI General Practitioner (GP) Patient Survey (2009/10) quotes a figure of 101,107 ‘Deaf Sign Language Users’ in England alone. 12,13 The Office for National Statistics (ONS) data release14 on languages records 22,000 sign language users in England and Wales, of whom 15,000 said specifically that their language was BSL. The Welsh Assembly Government estimates that BSL is the first or preferred language of 3000 people in Wales. 15 The Scottish Council on Deafness estimates that it is the first or preferred language of 6000 people in Scotland. 16 The Department for Communities in Northern Ireland suggests that there are 5000 sign language users, of whom 3500 use BSL and 1500 use Irish Sign Language. 17 Overall, conservative estimates indicate a UK population of Deaf BSL users of between 60,000 and 70,000.

Improving Access to Psychological Therapies

Improving Access to Psychological Therapies is a large-scale initiative within the NHS aimed at redressing long-standing imbalances between psychological therapy demand and supply. 1,18–20 The national IAPT census 201421 records 255 IAPT services, based on a 95% response rate. IAPT services deliver approved psychological interventions to address anxiety and depressive disorders in primary care settings. 1 IAPT services follow the NICE-approved stepped care model, which includes low-intensity treatment at step 2 (e.g. CBT and guided self-help) and high-intensity treatment at step 3 (including CBT for individuals with an inadequate response to therapy at step 2, as well as those with more serious disorders). 1 This study is confined to step 2 and step 3 aspects of the IAPT service model. IAPT practitioners are drawn from existing professionals, for example clinical psychologists, and, additionally, the IAPT initiative has included the training of a new workforce of psychological well-being practitioners (PWPs). 1

The adaptation of the IAPT service for Deaf people was provided by the health charity SignHealth under the title ‘BSL Healthy Minds’ and was supported by the British Society for Mental Health and Deafness. 22 It involved training Deaf people as PWPs in order to deliver therapy directly to Deaf clients who experienced anxiety and depression at step 2 and step 3 levels. 22 In other words, it was a linguistically and culturally matched service delivery model. We refer to this intervention model as BSL-IAPT throughout the report. However, during the course of the study, services other than BSL Healthy Minds started to offer specialist IAPT provision for Deaf people, a trend we explore in the course of this work in seeking to model ‘BSL-IAPT’ separately from its identity with an original sole provider (see Chapter 5). Elsewhere in England, Deaf people would routinely access IAPT through their usual local provider(s), although the kinds of adaptations that might be provided for such access and treatment were not known. We refer to this as standard IAPT throughout the report and explore the variations within its provision (see Chapter 5).

This naturally occurring experimental condition created a rare opportunity to compare the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of two models of IAPT delivery for Deaf people with depression and/or anxiety without the requirement to withhold, replace or enhance an intervention, as both were a usual standard of care depending on where a Deaf person resided. However, the achievement of this overarching objective, to compare the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the two models of delivery, required considerable groundwork. We report here the development of a number of components that were prerequisites to any future trial or large-scale observational study, but which also have independent value and implications for future research, clinical services and available information for commissioners of IAPT services.

Deaf people and mental health

Deaf people experience significantly poorer mental health than the hearing population, with the prevalence of some common mental health problems, such as depression and anxiety, being up to twice as high. 23,24 In only a minority of cases are mental ill-health and deafness causally connected (i.e. where the aetiology of deafness is coincidental with organic origins of mental illness/neurological impairment). Of greater significance is how early childhood deafness interferes with the usual processes of language acquisition and psychosocial development. The incidence of mental health problems in deaf children/young people is around 1.5 times greater than among their hearing counterparts. 25 In adulthood, although the incidence of major psychoses is broadly consistent with that among hearing people, the prevalence of depressive disorders and anxiety is significantly higher (33% of the Deaf population vs. around 20% of the hearing population). 26

Studies have demonstrated the inaccessibility of health services to Deaf BSL users,27–30 including mental health services, resulting in late diagnoses and loss of benefit from early preventative interventions. 31 Poor access to information about health-related matters in BSL results in poor awareness among Deaf community members of mental health issues, including personal support strategies, help-seeking behaviours, routes of referral and treatment options. Often Deaf people use mental health services only when a difficulty has escalated to the point at which secondary/tertiary care intervention is required. 23,27,28 Poor treatment outcomes are related, in part, to late access to preventative and primary mental health services. 23

The Department of Health (DH) review of mental health services for Deaf people27 resulted in significant strategic investment in NHS specialist services to address this health inequality. The latest investment is in primary care: IAPT.

Improving Access to Psychological Therapies and Deaf people

BSL-IAPT was originally offered in two health authorities before being offered in five areas from April 2013. However, service accessibility has been declining since April 2014 as a result of new commissioning arrangements subsequent to the transformation from a primary care trust (PCT) structure in England to Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) instead. 32

Moreover, in the course of this study it became apparent that a few service providers, other than BSL Healthy Minds, were starting to develop specialist provision for Deaf people, including using qualified Deaf PWPs. Provider and model of provision were no longer synonymous. We return to this issue in Chapter 5 where we explore key components of service models and provision and define the components of a BSL-IAPT intervention, independent of the original provider. However, at the start of the research project BSL-IAPT was distinguished by the following core components in its original form as delivered by BSL Healthy Minds:

-

standard assessment instruments [Patient Health Questionnaire-9 item (PHQ-9), Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) and the Work and Social Adjustment Scale (WSAS)] that are translated into BSL, and their internal reliability for use with Deaf people established by the applicants33

-

Deaf people trained as PWPs to deliver the IAPT programme in BSL

-

self-help guidance that is culturally adapted. 22

Where a BSL-IAPT service does not exist or is not commissioned, Deaf people access the usual IAPT provision in their locality, which we refer to in this report as standard IAPT. The range of adaptations, if any, made by standard IAPT services to meet the requirements of Deaf BSL users were not known at the start of the project, nor had their utility and effectiveness been previously explored. It is estimated that there are around 255 standard IAPT services in England,21 although at the start of the project it was not known how many Deaf people have used these services.

What is the problem and what is the opportunity?

It is not possible to determine whether or not the current investment in a core specialist service (BSL-IAPT as provided by BSL Healthy Minds) is justified and should be extended nationally. This is because it is not known if it confers any benefit for Deaf people over and above accessing standard IAPT services, particularly given the range of potential adaptations for Deaf people to the standard IAPT service, the effectiveness of which is also unknown. The cost-effectiveness of BSL-IAPT has not been investigated. A rigorous examination of effectiveness and cost-effectiveness is needed to guide decision-making about longer-term sustainability and appropriate targeted primary care intervention for this particularly hard-to-reach group.

Data from all IAPT patients, collected through universal key performance indicators (KPIs) and the IAPT minimum data set, are uploaded centrally, allowing for comparisons to be made by service provider and individual patient characteristics. This presents a major research opportunity because (1) internationally, most evidence concerning Deaf people’s mental health is drawn from hospital inpatient/outpatient population studies with very limited evidence from primary care; (2) although the internal reliability of the BSL-IAPT tools has been determined, validation of clinical cut-off points requires analysis based on a clinical sample; and (3) the effectiveness of BSL-IAPT depends on its culturally perceived acceptability, not just its linguistic accessibility, requiring investigation of the service delivery process.

This study will be the first step in determining whether or not BSL-IAPT is justified for Deaf people. Importantly, the study will provide valuable information to inform the need for and design of follow-on research to assess the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness questions. Although the proposed project concerns Deaf people specifically, it is an example of an important comparison relevant to many service sectors within the NHS. It asks what difference exists in terms of benefit, if any, between standard services made linguistically accessible to particular cultural–linguistic groups of patients, and adaptations of standard services designed specifically around the cultural identity and language preferences of specific groups.

Chapter 2 Overview of design and methods

Introduction

This exploratory, mixed-methods study has three objectives that deliver new evidence and outputs in their own right while laying the groundwork for any future larger-scale study, whether a randomised clinical trial or other controlled, prospective study design.

Objectives

-

To explore the following questions:

-

Is BSL-IAPT more effective than standard IAPT for Deaf people with anxiety and/or depression?

-

Is any additional benefit from BSL-IAPT worth any additional cost to provide it?

-

-

To establish relevant BSL versions of assessment tools and methods to answer research questions (a) and (b).

-

To gauge the feasibility of a larger-scale definitive study and inform its future design.

Methods

The component studies, the preparatory issue, they addressed and their individual objectives and methods are as follows.

Study 1: qualitative exploration of the acceptability of individual randomisation and development of trial-related terminology in British Sign Language (see Chapter 3)

Preparatory issues to be addressed

-

Deaf people are rarely provided with a service matched to their linguistic/cultural needs. The possibility of being randomised in to or out of a service perceived as specialist for Deaf people may be an impediment to adequate recruitment.

-

Deaf people have been routinely excluded from randomised controlled trials (RCTs). Terminology does not exist in common use for key concepts associated with trial participation that would support informed choice and recruitment to any future study.

Objectives

-

To investigate the acceptability of randomisation among Deaf service users.

-

To develop trial-related terminology in BSL to support informed choice and recruitment.

Method

-

Deaf-led focus groups in BSL with service users and members of the Deaf community.

Study 2: secondary data analysis of patient numbers and outcomes data (see Chapter 4)

Preparatory issues to be addressed

-

There are no valid outcome data on Deaf people who have used BSL-IAPT because the correct clinical cut-off points for the BSL assessment instruments used have not been established. Outcome data on Deaf users of standard IAPT have never been collected and analysed.

-

The comparability of the two populations of service users is unknown.

-

The feasibility of recruiting sufficient numbers to a large-scale study is yet to be established.

Objectives

-

To establish the clinical cut-off points for the BSL-IAPT assessment tools (PHQ-9 and GAD-7) for patients with anxiety and/or depression.

-

To explore the population characteristics of BSL-IAPT and Deaf users of standard IAPT services, including demographic characteristics, referral routes and adherence, and to compare clinical outcomes.

-

To map probable numbers of users of BSL-IAPT and Deaf users of standard IAPT who would be eligible for recruitment to a large-scale study.

-

To establish effect size and estimate recruitment targets should a full trial be indicated.

Method

-

Secondary data analysis of pre-existing clinical data.

Study 3: mixed-methods modelling of BSL-IAPT and standard Improving Access to Psychological Therapies as accessed by Deaf people (see Chapter 5)

Preparatory issues to be addressed

-

Although BSL-IAPT was initially synonymous with a single provider in specified regions, it became available in some other parts of England as a component of standard provision. Therefore, what constitutes BSL-IAPT required definition if it were to be operationalised in any future comparative study.

-

The range and nature of adaptations for Deaf people who accessed standard IAPT were unknown and, therefore, it could not yet adequately be modelled as an intervention if it were to be operationalised in any future comparative study.

Objectives

-

To produce a replicable description of ‘standard IAPT’ when implemented with BSL users.

-

To produce a replicable description of the core components of BSL-IAPT differentiated from its delivery by a single-service provider.

Methods

-

Online survey and individual interviews with a subsample of BSL-IAPT and standard IAPT providers.

Study 4: translation and validation of the EQ-5D-5L version in British Sign Language and exploratory analysis of appropriate utility weights (see Chapter 6)

Preparatory issues to be addressed

-

There is no BSL version of this common health outcome instrument routinely used in research and evaluation studies that has been validated. (There is no validated version in any signed language in the world.)

-

Pre-existing utility weights may not be suitable for this population.

Objectives

-

To translate and test the reliability of a BSL version of the EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L).

-

To conduct further analyses of the BSL EQ-5D-5L data collected as part of this study (study 5), to inform future research with this population.

Methods

-

Translation via accepted protocols with adaptations for visual languages. Online data collection from users of the BSL version and analysis of psychometric properties.

-

Systematic literature review and secondary analysis of data collected in this project to establish appropriate utility weights.

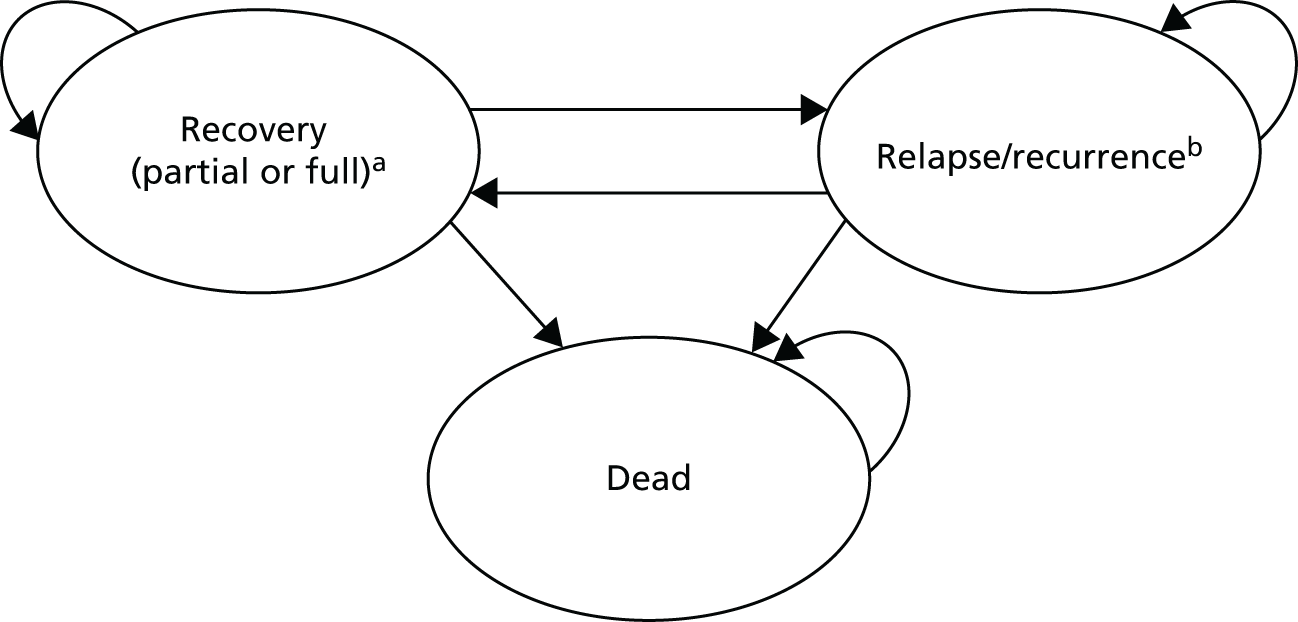

Study 5: exploratory economic evaluation (see Chapter 7)

Preparatory issue to be addressed

-

An exploratory economic evaluation would be required prior to any future feasibility study or full trial.

Objectives

-

To explore the potential costs of health and social care, and the health benefit in terms of quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) for Deaf users of BSL-IAPT and Deaf users accessing standard IAPT.

-

To estimate the net cost per QALY gained by BSL-IAPT.

The key research questions were:

-

Is BSL-IAPT potentially cost-effective compared with standard IAPT, when service-specific PHQ-9 and GAD-7 tools and cut-off points were used to identify people with depression/anxiety and to measure recovery?

-

Does the potential cost-effectiveness of BSL-IAPT vary if different assumptions are made about the probability, costs or QALYs of treatment events?

Methods

-

Systematic, focused economic literature review and secondary analysis of data collected in other studies within the project.

Patient and public involvement

Deaf service users and members of the general Deaf population were engaged throughout the study in a variety of different ways. Both the Project Advisory Group (PAG) and the Study Steering Committee (SSC) benefited from the input of several lay community members, some of whom had experience of mental health services. Minutes and meeting notes were made available in BSL before and after meetings, and alternative ways of contributing were explored with those who could, on occasion, not attend in person [e.g. video-conferencing, individual discussion and contribution via skype™ (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA), etc.].

Deaf BSL users were also the lead participants in the exploration of trial-related terminology in study 1 (see Chapter 3). Building on that work, a separate patient and public involvement (PPI) group was established, consisting entirely of Deaf community members, to further comment on the findings of study 1, and to co-develop the additional project output of the BSL glossary of terms commonly used in recruitment materials and trial-related information (see Appendices 1 and 2). Further to this, the PPI group developed an additional resource aimed at supporting active public involvement in NHS, public health and social care research. Aimed at professionals and Deaf people alike, the video allowed Deaf BSL users to share their experiences of PPI within this project and in other areas, including examples of good practice with relevance for future studies (see Appendix 3).

Ethics approval

Studies 1, 3 and 4 received ethics approval from the University of Manchester Research Ethics Committee (REC) (reference numbers: 14183, 150715 and 14183, respectively). Study 2 received ethics approval from the NHS REC – Proportionate Review Subcommittee of the National Research Ethics Service (NRES) Committee London – Camberwell St Giles (reference 14/LO/2234).

The University of Manchester and NHS protocols for data protection were adhered to.

Chapter 3 Qualitative exploration of the acceptability of individual randomisation and development of trial-related terminology in British Sign Language (study 1)

Some parts of this chapter have previously appeared in Young et al. 34 This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly credited. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated. When paragraphs are repeated here verbatim, they have been displayed as quotations with reference to the original paper.

Background

Failure to recruit adequate numbers is a common reason for trials not succeeding. 35–37 Among a range of factors that have been identified as underlying poor recruitment is whether or not randomisation is perceived as acceptable among the population(s) to be recruited. 38,39 Previous research identifies two main aspects of acceptability of randomisation to be considered: understanding for informed consent and treatment-specific preferences.

With regard to understanding, studies have demonstrated that some terms commonly used in trial recruitment (such as ‘randomisation’, ‘trial’, ‘placebo’, ‘arm’) may be unfamiliar to participants, but also that participants apply their understanding of terms gained from a familiar context to the unfamiliar one of trial participation, resulting in potential misunderstandings. 40–42 In addition, studies of language in trials have demonstrated ‘that there is a difference between understanding the mechanics of a process, such as randomisation (how it occurs), and participants’ comprehension of the purpose of that process (why it is necessary and its implications). 41,43 It is argued that both are required for informed consent and recall of one might hide misapprehension of the other’. 34

In the case of Deaf people’s understanding of key trial-related terminology, the situation is more complex. There are very low levels of awareness, even in lay terms, of such concepts as randomisation, trial and informed choice. In part this is because of a lack of history of Deaf people’s involvement in clinical research. RCTs routinely exclude them because of the confounding factors that their participation might bring, whether these are perceived in terms of disability (hearing loss) or in terms of language use. 34,44 Deafness also impacts on general knowledge. Deaf people commonly experience highly limited access to information on a wide range of everyday subjects because it is not available in a signed language. 8,45 Means of incidental learning, such as overhearing, accessing popular media or interactions with multiple peer groups, are also affected. Consequently, it is recognised that many Deaf people experience what has been termed a ‘low fund of information’. 46 Therefore, many Deaf people who are potential trial participants might not be even casually familiar with the terms and concepts used in participant information sheets or informed consent forms, even if these are presented in BSL. Furthermore, because of Deaf people’s lack of involvement in or incidental awareness of clinical trials, there is no pre-existing agreed or familiar lexicon for most of the terms that would be used in recruitment and information materials for potential participants to any future trial. This dearth of vocabulary, or usual means of expression, is not a result of any failure in the capacity of BSL. It is simply a result of a lack of contact with the context, which has meant that vocabulary has not been necessary and is yet to evolve. It is a situation similar to that in spoken languages prior to the digital age, where words did not exist for concepts such as ‘online’, ‘log on’ or ‘texting’ because they had not previously been required. Objective ii in the study reported here addresses the exploration and development of trial-related terminology in BSL. 34

The second aspect of the acceptability of randomisation concerns perceived preferences for a particular intervention. For example, as a systematic review of barriers to cancer trial participation has demonstrated, if there is a strong lay perception of one treatment being better than the other, or one not being regarded as appropriate or desirable, then this can act as a barrier to consent to randomisation and trial entry. 47 However, other studies have shown that, even if participants have a preference for one arm of a trial over another, or a belief that one is likely to be more effective than another, they may still consent to randomisation. In part this response may be attributed to participants perceiving that random allocation gives them a chance of treatment that they believe is superior to the alternative, and that they would not otherwise have been able to access. 48

With respect to Deaf people, perceived treatment preferences that may influence the acceptability of randomisation are likely to be fundamentally connected with language and culture. It is well evidenced that Deaf people experience significant health inequalities in terms of access to services and health outcomes in a range of domains. 23,31,49,50 In part this results from a failure to adequately provide sign-interpreted access to health care despite the requirements of the Public Sector Equality Duty5 and the NHS Accessible Information Standard. 51 Lack of cultural competence of health practitioners also plays a part in Deaf people’s less than optimum engagement with treatment. 45,52–54

In this context it is, therefore, very rare for any health service to be offered to Deaf people where the practitioner is Deaf themselves and shares a common culture, and where the treatment/intervention might be delivered directly without the requirement of an interpreter being present. The BSL-IAPT service that potentially formed one arm of a future trial was a rare exception to this situation in being directly delivered by Deaf people in BSL to other Deaf people. However, in its original form as BSL Healthy Minds, it was available in only a few regions of England. Consequently, there were four potential randomisation scenarios:

-

randomisation to BSL-IAPT and living in an area where BSL-IAPT is provided (= usual care)

-

randomisation to BSL-IAPT but living in an area where it is not provided (= access to a previously unavailable service)

-

randomisation to standard IAPT and living in an area where standard IAPT is usually provided (= usual care)

-

randomisation to standard IAPT and living in an area where usually BSL-IAPT is provided (= access to a service usually not available).

It was not known how these potential randomisation scenarios would be regarded in the context of the same service potentially delivered directly by a linguistically and culturally matched practitioner or via an interpreter from a hearing person. Objective i therefore sought to explore factors influencing the acceptability of randomisation from Deaf people’s cultural–linguistic perspective and is reported below.

Objectives

-

To investigate the acceptability of randomisation among Deaf service users.

-

To develop trial-related terminology in BSL to support informed choice and recruitment.

Methods

Design

The qualitative study was underpinned by a phenomenological approach, with data being collected by means of focus groups. Phenomenology55 suited the focus of this study, which was on both how key concepts are understood and the assumptions that might underpin the meaning participants bring and attribute to such issues as randomisation. 56 Focus groups were used because of their appropriateness in cultural terms as well as the exploratory nature of the research objectives. It has been remarked that Deaf culture is a particularly collective, rather than individualistic, culture,7,57 and Deaf people often prefer group discussion over individual interviews to explore new ideas or information because this is more culturally coherent,45 a trait observed in other cultural communities internationally such as Maori and First Nation peoples. 58

Inclusion criteria

A purposive sample was sought of Deaf people aged 18 years or over, who used BSL as their first or preferred language. Anyone currently receiving support through the IAPT programme was excluded because additional ethical permissions would be required for participants who were current patients of the National Health Service in England.

Young et al. 34

Recruitment

An explanation of the study in BSL was posted on the research group website and advertisements to participate in the focus groups were placed on a signed Facebook [Facebook, Inc., Menlo Park, CA, USA] site accessed by the Deaf community and through email, shared networks and word of mouth/word of hand.

Young et al. 34

Ethics

The study was approved by the University of Manchester Research Ethics Committee (Ref: 14183). Informed consent was obtained from all participants. Participant information sheets were made available in advance of the focus groups in BSL on a website as well as in plain English. Prior to the focus groups, the researchers clarified the information in BSL again, face to face, and participants had the opportunity to ask questions. All participants were provided with a pre-written, postage paid withdrawal form to facilitate easily withdrawal of consent for their data to be used subsequent to the focus groups.

Young et al. 34

Data collection

The focus groups were facilitated by two Deaf native BSL users who were part of the research team: one had a higher degree in research and was very experienced in focus group facilitation; the other was new to research but had worked for many years in the Deaf community in various social and support roles. Both facilitators were known to Deaf participants insofar as the Deaf community is small and it is not unusual to know or know of other Deaf people; however, neither had a personal or close professional relationship with any of the participants. Deaf facilitators ensured that data could be collected directly, without the more usual circumstance of an interpreter being required to facilitate discussion and, because Deaf participants and facilitators shared a common cultural background and identity, it was assumed that this would aid open and relaxed discussion. However, some participants remarked in the course of the focus groups that they perceived the facilitators to be ‘clever Deaf people’ and therefore different from themselves because the facilitators were more familiar with the kinds of issues that were being addressed in the groups.

At times, this meant that facilitators had to resist requests from participants to explain clearly what randomisation meant and why there might be an issue about acceptability. The notion of another Deaf person standing back and facilitating discussion that explored ideas rather than conveying face-to-face reliable information was difficult for some of the participants as it transgressed their expectations of Deaf people’s obligations to each other to support information access and understanding. As previous studies have documented,59 Deaf people experience a strong sense of collective obligation to each other to convey new information and knowledge when acquired in BSL because of the usual barriers that Deaf people experience to the acquisition of information that is mostly disseminated in English/spoken language.

The group sessions were in two parts, each lasting between 1.5 and 2 hours, with refreshments provided. In part 1, participants were introduced to the purpose of the study and clinical trials in general. They were introduced to the concept of randomisation and why researchers might want to do that. They were then invited to explore together what the implications of randomisation might be for someone who participated in a study about BSL-IAPT compared with standard IAPT, with adjustments for Deaf people’s access. In part 2, discussion focused more specifically on how to provide good information in BSL to support recruitment and informed consent. The specific terms that the group were asked to discuss were ‘randomisation’, ‘feasibility’, ‘informed choice’, ‘trial’, ‘consent’ and ‘experimental study’.

Three cameras were used to capture the discussions. These were time-coded enabling the later simultaneous display of all interactions and communication for purposes of analysis. PowerPoint [Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, W A, USA] was initially used as a prompt to different sections of the discussion. In some instances the prompts were visual diagrams, e.g. showing two arms of a trial and how it relates to initial recruitment of a sample; in others the prompts were specific words written in English that could be referred back to as prompts during the discussion.

Young et al. 34

Data analysis

All data were kept in their source language for purposes of analysis. The video files were uploaded to NVivo 10 [QSR International, Warrington, UK] which has the facility to tag and segment video data, in this case visual language data, for purposes of thematic coding without the need to transcribe data. This was important because if the data were transcribed this would equal translation in the case of BSL data, as BSL has no written form. This contrasts with many spoken languages where to transcribe data is only to change its modality (from spoken to written) and not to translate. 60–63

Young et al. 34

‘All data were watched and re-watched independently by two researchers (CD and CNG) with the aim of creating an initial coding framework’ (p. 5). 34 Two separate coding frameworks were developed from the same data. The first addressed the specific question of the acceptability of randomisation (objective i) and the second addressed terminology and ways of conveying key concepts associated with recruitment to RCTs (objective ii). The coding frameworks for each, including the themes and subthemes, are shown in Tables 1 and 2. Although the intention had been to code for each objective separately, inevitably when watching the same material, there was some overlap in tagging data segments for different purposes.

The two researchers carrying out the analysis brought different personal and professional biographies to the task: one is a native Deaf sign language user from a Deaf family who has worked for over 10 years in research roles; the other is a hearing researcher who learned BSL as an adult and who has been a qualified and registered sign language interpreter for 11 years, in addition to her research role. Their initial coding frameworks were compared and discussed with a third researcher (AY) who was overseeing the analysis (a hearing, late learner signer who has worked in the Deaf studies field for 25 years). Many of the same themes had been identified arising from specific examples in the data but were not clustered in exactly the same way in how they had been organised by the two researchers. Further discussion led to a framework consisting of the following four areas under which there were additional layers/sub-themes.

Young et al. 34

| Theme | Subtheme |

|---|---|

| Participation in research | Value for Deaf people |

| Obligation to the community now and in the future | |

| Choice | Who chooses? |

| Control of access and outcome | |

| Preferences | Language and communication |

| Cultural considerations | |

| Evidence | Shared cultural understanding |

| Deaf epistemology |

| Theme | Subtheme |

|---|---|

| Strengths and challenges arising from properties of a visual language | Acceptance of generality/specificity |

| Verb directionality | |

| Conceptual understandings/misunderstandings of common terms | Orientation towards avoidance of misunderstanding |

| Substitution of alternative words/expression | |

| Bilingualness and English influences on understanding and expression | Visual decoding of English words |

| Tests not discussion | |

| Power differentials in acquiring and generating new knowledge | Perceptions of class |

| Language-in-use |

Results: participants

Four focus groups were convened in various locations across England. All participants were aged ≥ 30 years, with three aged ≥ 61 years. Of the 19 participants, two were unemployed and four were retired. The rest were in employment, although the majority of these were in part-time employment. The entire sample had a self-declared strong Deaf identity. Table 3 shows distribution of numbers per group and characteristics.

| Group | Participants | Characteristic | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Ethnicity | Deaf parents? | Age BSL acquired | Involvement in Deaf community | I feel I am culturally Deaf | Highest qualification | ||

| 1 | 1a | Male | White British | Yes | From birth | Often involved | Very much so | Postgraduate diploma |

| 1b | Male | White British | No | 4–7 years | Often involved | Very much so | Vocational qualification | |

| 1c | Female | White British | No | 12–16 years | Often involved | Quite so | School leaving certificate | |

| 1d | Female | Asian Indian British | No | ≥ 25 years | Very involved | Very much so | Vocational qualification | |

| 1e | Female | White British | No | Missing | Often involved | Quite so | Professional diploma | |

| 2 | 2a | Female | White British | No | 1–3 years | Missing | Very much so | On the job training |

| 2b | Female | White British | No | 4–7 years | Very involved | Very much so | Vocational qualification | |

| 2c | Female | White British | No | 4–7 years | Very involved | Quite so | Missing | |

| 2d | Female | White British | No | 4–7 years | Started age 40 years | Very much so | Vocational qualification | |

| 2e | Female | White British | Yes | From birth | Often involved | Very much so | Missing | |

| 3 | 3a | Male | Asian Indian British | Yes | ≥ 25 years | Often involved | Quite so | Missing |

| 3b | Female | White British | No | 1–3 years | Often involved | Very much so | Professional diploma | |

| 3c | Male | White British | No | From birth | Often involved | Quite so | Professional diploma | |

| 3d | Female | White British | No | 8–11 years | Often involved | Very much so | Postgraduate certificate | |

| 3e | Female | White Jewish | No | ≥ 25 years | Often involved | Somewhat | Professional diploma | |

| 4 | 4a | Female | White British | No | 4–7 years | Very involved | Very much so | University degree |

| 4b | Female | Jewish | No | 17–24 years | Often involved | Somewhat | Missing | |

| 4c | Female | White British | No | 17–24 years | Very involved | Very much so | Postgraduate certificate | |

| 4d | Female | White British | No | ≥ 25 years | Often involved | Quite so | Professional diploma | |

Results: the acceptability of randomisation

Introduction

Through the two-part focus group structure, participants had the opportunity first to gain an understanding of what a RCT would mean in practice; the underlying rationale for it, including the key concept of equipoise; whether or not participants were permitted to change their mind or drop out of a trial; and the crucial importance of informed consent. Therefore, the subsequent guided discussions about the acceptability of randomisation and participants’ views of participation in a RCT were based on this new knowledge and group reflections on it. The purpose of the study was not to reveal ignorance but, rather, having supplied information directly in participants’ preferred language and given them the opportunity to assimilate this through Deaf-led facilitated discussion, to see what views were revealed and what might underpin those. The main themes to emerge are discussed in turn.

Participation in research

Rather than addressing participation within a RCT directly, many group members addressed participation in research in general, seeing randomisation within one particular kind of research as a subset of the general issue about Deaf participation in research studies. Participation in research that was about Deaf people was seen overall as something that was very positive, primarily because it had the potential to improve services for Deaf people or make Deaf lives ‘easier’. In this respect, several participants discussed what they perceived as the general ignorance of service providers about their needs and the perceived lack of priority given to quality health and social care services for Deaf people. Therefore, if participation in any form of research might assist with improving services or lobbying for new support to address Deaf people’s needs, group members argued that it was to be welcomed.

Research and the evidence it might produce, therefore, was seen as form of leverage. To some extent, participation by Deaf people was perceived and talked about as a political act. However, it was also perceived as an altruistic act in that participation was about benefiting the needs of all Deaf people without necessarily accruing benefit for the individual who participates. This motivation was linked, by those group members who discussed it, with a sense of collective responsibility to assist in improving the lives of all Deaf people today, and for future generations.

From a cultural perspective, this response should be understood in terms of many Deaf people holding a strong sense of the value of what other Deaf people in prior generations did to enable a better future for the Deaf community. Examples often cited include the respect for elders who are seen as having kept BSL alive when it was disallowed or unrecognised within public, educational and political structures. 64 In addition, the cultural value given to heritage and the continuation of Deaf culture through social bonds and structures over hundreds of years65–67 is seen as part of the multigenerational legacy to which Deaf people today also contribute. This orientation towards the collective good is of particular importance where culture is not predominantly transmitted through family structures, as most Deaf people have hearing, non-signing families.

In terms of the acceptability of randomisation, this view of the value of research participation in terms of the whole community, not just the individual, prompted the response among some participants of ‘why not give it a go?’, ‘let’s just do it’ and ‘what is there to lose?’. This was particularly the case in two of the focus groups where there was a greater tendency to whole group agreement and the adoption of group views, rather than differences between individuals within the groups. A small minority of group members had a more specific response, which was, if such a research design had the potential to be definitive about what was the most effective means of delivering therapy for Deaf people then, on that basis, they would want to participate in the research. However, participation was still framed in terms of the collective good even though it was an individual decision.

In summary: The question of the acceptability of randomisation is subsumed under a perception of the value of research in general for future generations of Deaf people. The details of what randomisation might imply are of less importance than a perceived cultural obligation to participate if to do so will benefit Deaf people.

Choice

There was a great deal of discussion in all of the focus groups about choice. With respect to randomisation, the abstract idea that participants would be allocated to a group through a process of randomisation was more informally understood to imply that someone would choose into which group an individual might be put. Even though the facilitators explained what randomisation meant, using a range of metaphors and examples, it still prompted many questions about ‘who’ does the choosing rather than the method by which allocation might be done. For example, the commonly used explanation about randomisation being like tossing a coin with a chance of heads or tails still prompted the question ‘but who tosses the coin?’. The explanation of a computer being used for allocation still promoted enquiries about who controlled that computerised process. Some group members found it hard to get past the notion that even if random meant by chance, someone must still, somewhere along the process, exercise some choice about what the possibilities are for any given individual.

One potential explanation for this response is related to the cultural resonance for Deaf people that choices are usually made ‘for’ them, or denied to them, by hearing people who are not cultural kin. Therefore, what is perceived as an outcome over which they have no control (to which group they are allocated in a RCT), is easily equated with many examples in Deaf life of disempowerment where the choices available are restricted or controlled by others. 68 To some extent this attitude is historical in that the history of social welfare, particularly with respect to Deaf people, is one of dependency creation by hearing people who largely controlled the flow of information and the structures of Deaf people’s lives, including who Deaf people might marry, which jobs they might have and how and where they might meet. 69,70 Even as late as the 1980s, and before the establishment of sign language interpreting as a regulated and qualified profession, Deaf people had to be clients of social services to access any form of interpreting. 71 Today, some rules within public offices and structures still disallow fundamental expectations and rights of citizenship such as jury service. 72,73

The question of the acceptability of randomisation is influenced by experiences of restriction of choice and disempowerment that have a strong historical resonance for Deaf people today.

Perceptions of service delivery models

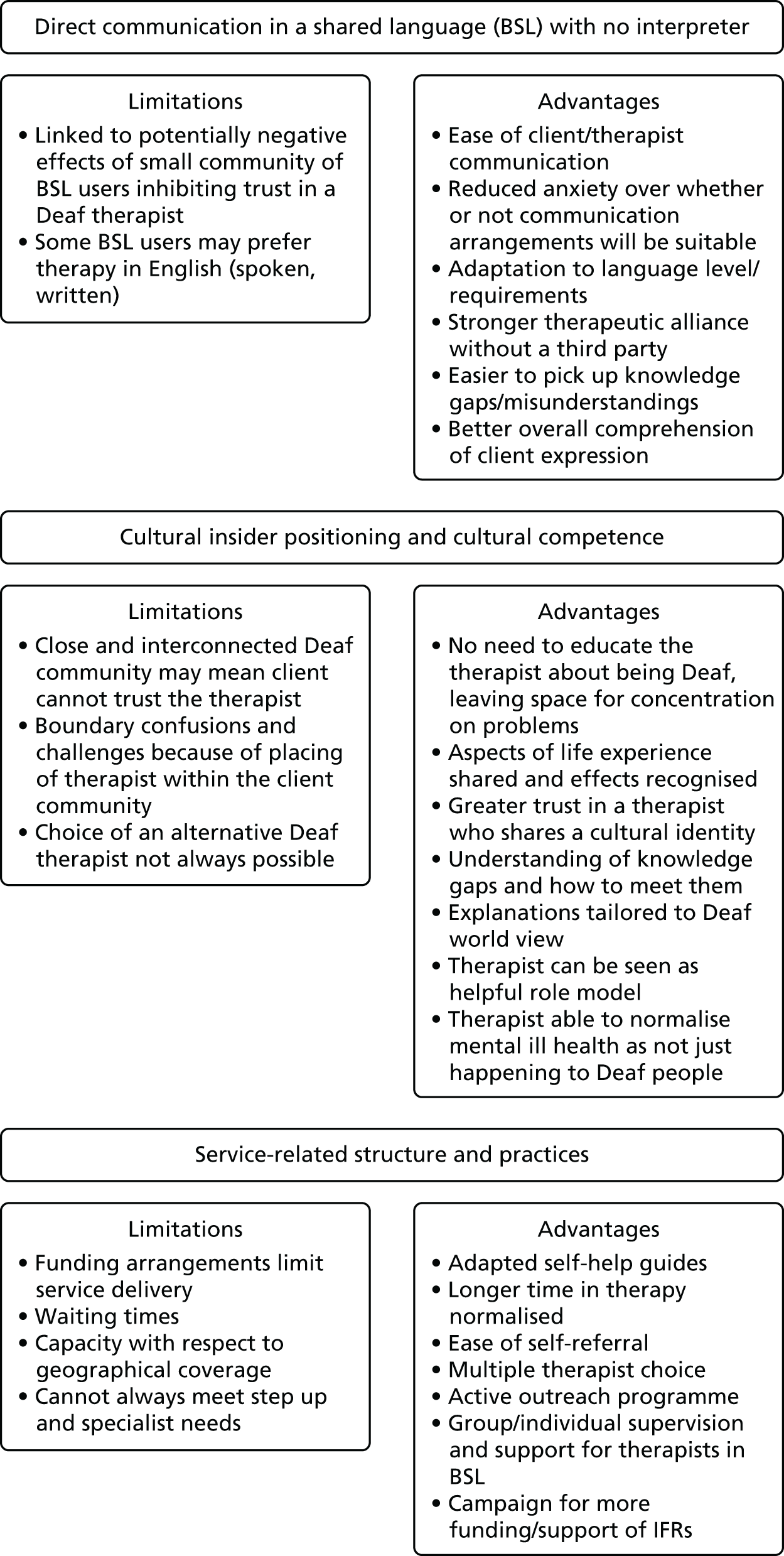

Of the total number of 19 people who participated in the focus groups, two had personal experience of having used standard IAPT, BSL-IAPT or both, and a further two had experience of both Deaf counsellors and hearing counsellors with an interpreter. The others had no similar experiences, but were well aware that there was a BSL-IAPT service that was delivered by Deaf, trained PWPs directly in BSL without an interpreter. It was clearly explained that ethically a RCT could not be undertaken unless there was no clear evidence that one treatment is more effective than another. Groups were invited to discuss their views on that position and whether or not they agreed that that a trial could be undertaken on that basis. As this was a new concept, there was a great deal of clarification required and checking of understanding prior to moving on to discussion of opinions about it. Nonetheless, all of the groups became far more engaged in discussing issues of preference for one approach to therapy or another and the relative merits of each rather than whether or not it was reasonable to proceed on the basis of no strong evidence of one being more effective than the other. The perceptions of service delivery models shared are enlightening for a range of issues that might influence a person’s willingness to be randomised in a trial comparing standard IAPT with adjustment for Deaf people with BSL-IAPT.

Preference-related issues included communication and language concerns. On the one hand, some group members expressed dissatisfaction with the prospect of engaging with an IAPT therapist through an interpreter. This was because the experience of indirect communication would, in their view, result in a less satisfactory relationship because it would be harder to express sensitive issues, make emotional responses clear, and participate in therapeutic discussion if the therapist were not directly engaged with them. In addition, a few participants expressed concerns about the interpreters, namely whether or not they would be familiar with the range of therapeutic concepts and vocabulary or whether or not, as a Deaf client, they would in fact also become a language resource for the interpreter, teaching the interpreter the appropriate terminology? The problem with this was the time it would take away from addressing their own problems and needs within the therapeutic session.

That said, not everyone who expressed concerns about an interpreted IAPT experience saw it as an absolute reason not to engage in a process of randomisation that might mean that they were randomised into standard IAPT. One group in particular spent time thinking about potential solutions. These included the possibility of any future trial ensuring that the interpreters likely to be used within the standard IAPT arm are given additional training prior to the trial starting, so that participants could be assured of a good experience if randomised into that arm. Part of that good experience was linked with taking away any potential stress or anxiety that might be caused by concerns about who the interpreter might be and if they were going to be experienced enough in this particular domain of work. Thus, from group members’ perspectives, trusting the skills and experience of the interpreter had the potential to render randomisation into a standard IAPT service acceptable. However, there was no perception that by implementing such measures one would actually be changing the ‘usual service’, which might be the comparator arm in any future trial design.

From a different perspective, a minority of group members were anxious about language and communication for an alternative reason. For them, the main concern would be that any future research would too easily assume that if an individual used BSL then she/he would automatically prefer BSL-IAPT because it would be a directly delivered therapeutic service from a Deaf professional. One group member in particular felt strongly that such an assumption was itself discriminatory and, in their experience, using spoken language directly with a therapist and lip-reading that therapist, or using an interpreter for receptive communication from a therapist but speaking for themselves within the session, was more satisfactory. For this person, as well as for many others in the groups, the issue of individual preference and individual comfort, whatever that might be, would trump all other considerations.

There were a range of other factors associated with preference that were not directly related to language/communication but more related to cultural perspectives and the nature of the Deaf community. For example, the Deaf PWPs who may be encountered in BSL-IAPT were by definition members of the Deaf community like the clients they served. They were therefore likely to be well known and also to have been encountered by clients in other social or professional settings. This phenomenon is not unusual for Deaf people, and the situational and individual ethical issues it may provoke have been written about previously in terms of small communities of practice. 58 Consequently, some participants expressed concerns about whether or not their confidentiality would be kept if they had a Deaf PWP. The point here was not so much that they did not trust the Deaf PWP, but rather that it would be a nagging consideration in the back of their mind, and for someone struggling with anxiety this could be an added burden. On the other hand, the idea of a hearing person with little or no understanding of Deaf culture or Deaf people being the therapist was also a concern. The main problems were perceived to be the need to explain about Deaf people and the Deaf way of life as they went along rather than trusting the therapist would just ‘get it’. In effect, clients would have to become their own cultural broker too, and group members were concerned that this could be potentially detrimental to the well-being of someone experiencing depression and/or anxiety, despite being part of an intervention designed to help them. A similar concern has been recorded in a small interview study of Deaf people with experience of BSL-IAPT. 74

Some group members also worried about the qualifications and skills of a Deaf person working as a PWP. Although, from a communication perspective, a hearing therapist with an interpreter was not ideal, the hearing professional in their view was likely to be more experienced and to understand more about the work they did than the Deaf professional. There were two roots to this point of view. The first was that Deaf PWPs were very new and there is not a long history of Deaf professionals’ involvement in mental health as therapists in the community; therefore, the range of experience they were likely to have built up was seen as less than the wider pool of hearing therapists. The other was an expression of a common perception, particularly among older Deaf people, that hearing people are likely to know best and be better qualified because they have more access to information, have a greater possibility of gaining professional experiences, and work in the mainstream of general society. This point of view has previously been analysed as one of internalised oppression akin to that recorded among cultural groups which have experienced colonisation. 7,75

The possibility of randomisation represented a threat to the expression of an individual’s linguistic and cultural preferences which were considered a key priority in engagement with therapeutic services. These preferences varied and it was not a foregone conclusion that everyone would prefer a Deaf, BSL-using PWP. The possibility of not having linguistic preferences and cultural needs met was seen as detrimental to mental well-being and therefore randomisation could be seen as detrimental to well-being for some people.

Evidence

In the course of facilitating the focus groups, the two Deaf researchers ensured that they too modelled equipoise. Throughout, they repeated and maintained a stance that there was currently no evidence that one service delivery model (BSL-IAPT or standard IAPT with reasonable adjustments such as an interpreter) was more or less effective than the other. However, in all of the groups, there were challenges to this position from group members, cast in terms of cultural collusion. For example, some group members suggested that the researchers ‘had to say’ that they believed that, but as Deaf people of course they could not. In another group, members said they would ‘go along’ with the assumption for sake of the discussion but everyone of course knew that the two service delivery models could not be ‘equivalent’. What was interesting about dialogue such as this was the lack of attention to the notion of objective research evidence, in terms of outcomes and recovery, and the greater priority given to shared cultural knowledge, experience and understanding. Group members were appealing to facilitators, who were Deaf like them, to acknowledge that Deaf people’s understanding about the superiority of an intervention delivered in one’s own language was self-evident, a view that they thought was bound to be shared.

Although other literature concerning lay understanding of randomisation has recorded the appeal to common-sense notions of what must be better or preferable,41,76 the discussions in this study were a little different. They were stressing the importance of cultural, collective understanding. This has more recently been debated in the literature in terms of Deaf epistemologies in acknowledgement of diversity within a cultural group. 77–80 It is argued that knowledge generated, owned and expressed by Deaf people, which is formed from within a Deaf world view and Deaf ontological experience of life, should not only be regarded as legitimate, but as having priority setting or directive worth. 81,82

This approach highlights a different form of evidence. It is one that is increasingly important in trial design, particularly in the feasibility and modelling phases of the Medical Research Council’s Framework for Complex Interventions,83,84 but one that generates a different standard of evidence than that for which RCTs are intended. Group members, however, appealed to it, in suggesting that perhaps any future research might be designed to give patients experience of both approaches to IAPT delivery and ask them which they preferred and why. Although it was acknowledged as helpful for researchers to be Deaf people, as in this project, the importance of lay Deaf people was also emphasised, as not all Deaf knowledge is the same because of the roles and positions Deaf people find themselves in. The researchers were identified as ‘clever Deaf’ people, for example, and were contrasted by group members with the alternative lives of many ordinary Deaf people who struggle with education, employment and literacy.

There is a strong appeal to cultural common sense that access to a service in one’s own language and that is culturally matched is preferable. Randomisation may be resisted for its failure to acknowledge Deaf epistemological positioning.

Conclusion

Evidence from this study highlights a confluence of factors affecting the acceptability of randomisation that are deeply embedded in Deaf people’s historical and contemporary experiences of society, as well as shared cultural characteristics. Although individual preferences, along with perceptions and misperceptions of what randomisation implies, have some influence, the culturally contextual nature of Deaf people’s thinking predominates. This does not mean, however, that a service delivered by a Deaf person in BSL is automatically to be preferred or perceived as more appropriate. The four main influences on Deaf people’s attitudes and conclusions about the acceptability of randomisation were:

-

Research involving randomisation is a subset of research in general, which, if it benefits Deaf people today and in the future, is perceived as acceptable.

-

Randomisation can be perceived as an example of forced choice without personal power, which is a common experience for Deaf people, and on that basis may be unacceptable.

-

If randomisation implies not having personal linguistic preferences and cultural needs met, then it is of itself a threat to personal well-being.

-

Randomisation may be resisted on grounds of its perceived denial of the value of Deaf people’s common sense, knowledge and belief in what is best for them, which happens often in Deaf people’s lives.

There was, therefore, no clear picture about the acceptability of randomisation and, in fact, some helpful suggestions arose in the course of discussion about how to allay fears and concerns that may be a barrier to participation in RCTs. There was not an absolute rejection of the possibility of participation in research involving randomisation. Instead there was a strong appeal to see its implications from a cultural not just a linguistic access or service model perspective.

The nature of the sample and small scale of the exploratory work is a limitation to these findings because the generalisability of these views across the diversity of the Deaf community is untested. Results tentatively suggest that there are grounds for moving towards a feasibility study as randomisation has not been rejected outright, provided that the implications of the culturally embedded perspectives expressed here are incorporated into how recruitment might be undertaken in the future. The second element of effective recruitment would involve language, terminology and the provision of information, which we address in the trial-related terminology in BSL study reported below.

Results: trial-related terminology in British Sign Language

This study has been published in Trials34 as an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Results and implications

The principal results and conclusions (reproduced from the abstract of the original article) were:

Six necessary conditions for developing trial information to support comprehension were identified. These included:

developing appropriate expressions and terminology from a community basis, rather than testing out previously derived translations from a different language;

paying attention to language-specific features which support best means of expression (in the case of BSL expectations of specificity, verb directionality, handshape);

bilingual influences on comprehension;

deliberate orientation of information to avoid misunderstanding not just to promote accessibility;

sensitivity to barriers to discussion about intelligibility of information that are cultural and social in origin, rather than linguistic;

the importance of using contemporary language-in-use, rather than jargon free or plain language, to support meaningful understanding.

Young et al. 34

Additionally, the study identified six necessary conditions that need to be met when developing signed participant information for Deaf people so that it is acceptable, accessible, transmitted accurately and understood as intended. The authors conclude that these are relevant to all signed languages, not just BSL, and potentially apply to further development of written and spoken information for hearing participants for whom the majority language (English) is not their first or preferred language. The conditions identified were:

1. A community-participatory, exploratory approach to arriving at appropriate clinical trial terminology is highly effective in instances where languages, in this case BSL, have not yet had the contact with a topic that would mean a common vocabulary/preferred means of expression has developed.

2. Languages have properties associated with their form and grammar that naturally enable some approaches to explanation to support comprehension that others may not. In this case, verb directionality, expectations of specificity and simultaneous contextual, semantic layering within expressions enabled features of the underpinning trial design to be clarified and remain consistent.

3. It is important to take into consideration bilingual influences on comprehension even when information is presented monolingually; this is a decoding strategy for unfamiliar terms and concepts that is available to those who are bilingual and multi-lingual and can be a source of both strength and misunderstanding.

4. Orientation of information to avoid misunderstanding is an important axis to consider when creating new information for a cultural-linguistic group unfamiliar with the topic. It is subtly different from an orientation designed to support comprehension and may, as in the case of the sample in this study, be a preferred orientation.

5. The researcher should understand cultural, contextual or social barriers that participants might face in engaging in open, constructive discussions of the information materials and consent procedures, over and above those that might be created by language per se. In the case of Deaf people, these barriers might derive from negative historical experiences of the education system, and class differentials.

6. Clarity of expression, in the sense of plain language or avoidance of jargon, is not sufficient to promote comprehension. Attention to language-in-use in contemporary discussion is an important means of expression to effectively communicate complex concepts because it reflects common cultural usage.

Young et al. 34

The study reinforces the ethical imperative to ensure that trial participants who are Deaf are provided with optimum resources to understand the implications of participation and to make an informed choice. We include, as one of the products of this study, a glossary of terms and their alternatives in BSL for key concepts associated with trial participation and the production of recruitment and information materials in BSL (see Appendices 1 and 2).

Chapter 4 Secondary data analysis of patient numbers and outcomes data (study 2)

Some of this study has previously appeared in Belk et al. 85 This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated. When paragraphs are repeated here verbatim, they have been displayed as quotations with reference to the original paper.

Background

Previous studies of primary mental health care with respect to Deaf populations have been hampered by small sample sizes because of the dispersed nature and minority status of Deaf people in the general population. Diagnostic uncertainty has also been a problem in drawing conclusions from studies that have relied either on patient self-report or on assessment by clinical personnel unused to working with Deaf sign language users. 33,86,87 Consequently, knowledge about the prevalence of anxiety and/or depression in Deaf populations has been limited both in the UK and internationally. 33,85 A well-cited study suggests a prevalence of 33% in the adult Deaf population. 26 Studies of anxiety and/or depression among Deaf people have been further hampered by the lack of clinical assessment tools in BSL (and in other signed languages) whose validity and reliability have been tested and established. 86,88

However, since 2011, the screening and assessment instruments used within the NHS IAPT programme have been available in BSL versions, whose psychometric properties have been investigated and found to be good. 33 These are the PHQ-9 BSL and GAD-7 BSL, both of which were translated in collaboration with the originators and validated on a population of Deaf people in the UK. 33 Furthermore, they have been used since 2011 by Deaf PWPs in the adaptation of the IAPT programme that was established for Deaf people that we refer to as BSL-IAPT. 22 Therefore, the possibility existed of analysing a data set of Deaf people with a certain diagnosis of anxiety and/or depression, who were screened at point of access to a service and whose progress was regularly monitored using tools known to be linguistically and clinically valid. In its own right, this would represent, as far as we are aware, the largest data set of its kind in primary mental health care with Deaf people anywhere in the world, from which a great deal of knowledge could be gained. More specifically, the analysis would permit several outcomes to be established that would be crucial to any further study, as well as being significant in their own right.

First among these was to establish the appropriate clinical cut-off points to be used for the BSL-IAPT assessment tools (PHQ-9 BSL and GAD-7 BSL). As is the case with any translated version of a standard instrument, the clinical cut-off point that is in use for one cultural–linguistic population may not be appropriate for another; it cannot be assumed to have the same sensitivity and specificity as for the population in which it was originally validated. 89 Field testing in the linguistic and cultural population in which the translated version is applied is required not only to measure operating characteristics of reliability and validity,90–92 but also to establish whether the clinical cut-off point is the same or different. Such testing has been carried out for many translations of GAD-7 and PHQ-9 into languages other than English,93 and also with respect to English versions used with populations with cultural differences or particular distinguishing characteristics (e.g. a group in another English-speaking country, one with a specific illness or one based in primary care). 85,94–97 No such field testing had yet been carried out with the BSL population. Furthermore, the analysis of a large data set of patients who had used BSL-IAPT in terms of referral rates, adherence and clinical outcomes would enable calculation of recruitment targets should a full trial be indicated.

BSL-IAPT, however, was available in only a limited number of areas in England;32 this ranged from two to five PCTs over the life of the research project. Therefore, although it was assumed that Deaf people were accessing IAPT through standard services elsewhere in England, the number of patients was unknown. The minimum data set required of IAPT providers for monthly upload to the Health and Social Care Information Centre (HSCIC) does not include a requirement to identify the language of the patient, therefore it was not possible to readily identify BSL users. 98 Additionally, the disability field in the minimum data set that included ‘hearing’ did not differentiate spoken or signed language. 98 It was not clear if the barriers to health-care access and uptake experienced by Deaf people in other parts of the health service24 would also apply with respect to primary mental health care. In addition, the patient characteristics of those Deaf people accessing standard IAPT could be different from those accessing BSL-IAPT. For example, in an area where no service was available in BSL it might be the better-educated Deaf people who were assertive and confident enough to seek out a service where one was not readily available in their preferred language. In an area where a BSL service was available there might be a greater diversity of Deaf patients. However, all such potential variables were unknown at the start of the project and hypotheses untested. Should any future feasibility study or clinical trial be justified, then the comparability of the Deaf populations accessing standard IAPT and BSL-IAPT would require investigation. Finally, without analysis of the outcomes for patients who had used standard IAPT in comparison with those who had used BSL-IAPT, it would not be possible to estimate an effect size or whether or not any scaled-up study might be justified.

Objectives

-

To establish the clinical cut-off points for the BSL-IAPT assessment tools (PHQ-9 and GAD-7) for patients with anxiety and/or depression.

-

To explore the population characteristics of Deaf users of BSL-IAPT and standard IAPT services, including demographic characteristics, referral routes and adherence, and to compare clinical outcomes.

-

To map probable numbers of users of BSL-IAPT and Deaf users of standard IAPT who would be eligible for recruitment to a large-scale study.

-

To establish effect size and estimate recruitment targets should a full trial be indicated.

Each of the objectives will be addressed in turn in this chapter.

Objective i: to establish the clinical cut-off points for the BSL-IAPT assessment tools (PHQ-9 item and GAD-7) for patients with anxiety and/or depression

Methods

Study design

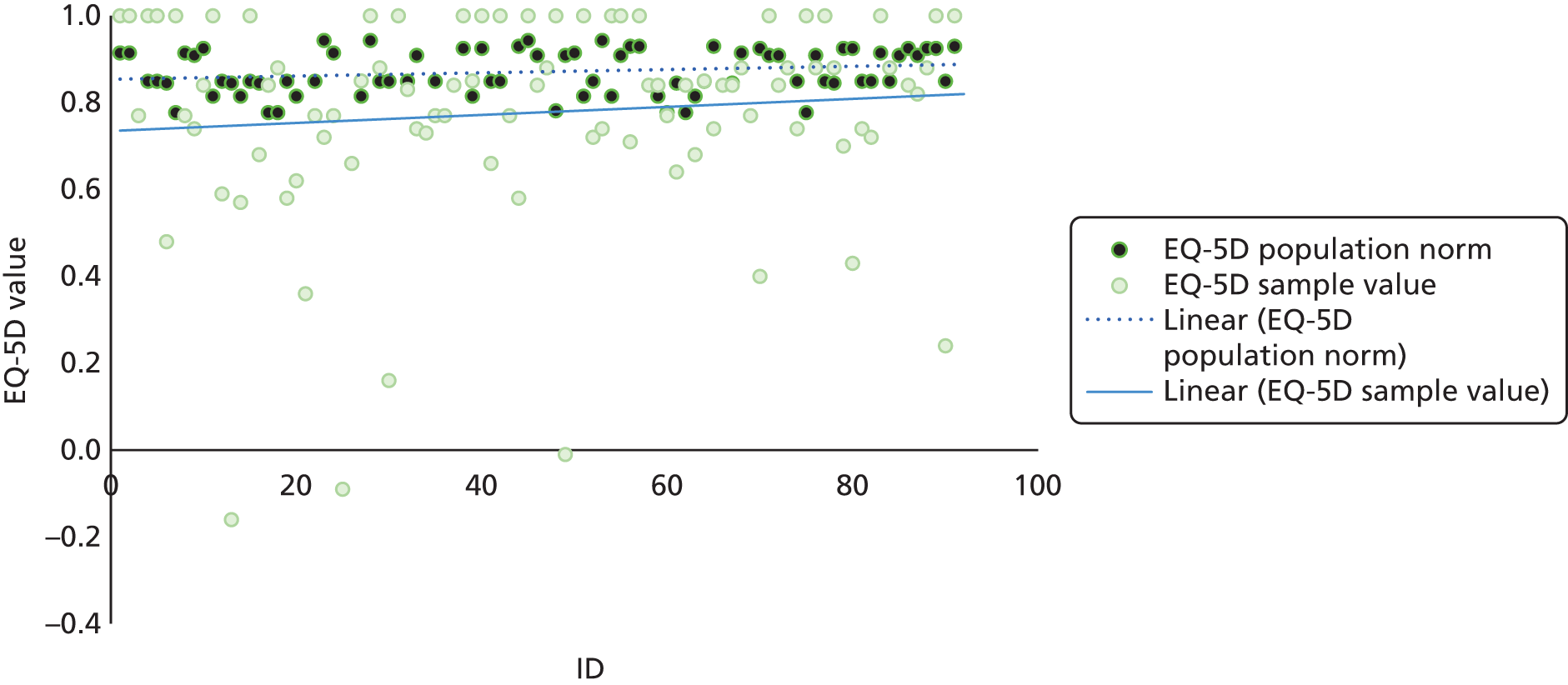

A secondary data analysis was used to establish the clinical cut-off points of PHQ-9 BSL and GAD-7 BSL, which involved two data sets: (1) data set 1 (n = 502) contains Deaf BSL users who had used the BSL-IAPT service defined by the single-service provider BSL Healthy Minds; and (2) data set 2 (n = 85) contains Deaf participants from the study by Rogers et al. 33 who reported that they had no mental health difficulties and had not used a mental health service in the past 12 months, at the time when that study was carried out. Both of the data sets contain the data of Deaf people who had completed the PHQ-9 BSL and GAD-7 BSL.

Parameter estimates, including the area under the curve (AUC) value, sensitivity, positive predicted value and negative predicted value, were used in the calculation of the clinical cut-off points of PHQ-9 BSL and GAD-7 BSL, which were reported in greater detail in Belk et al. 85

Setting

The BSL-IAPT clinical data set (data set 1) contains the data for those Deaf people who had used the BSL-IAPT service in a small number of areas in the UK between December 2011 and February 2015. Data set 2 from the Rogers et al. study33 was collected in 2011/12.

Participants

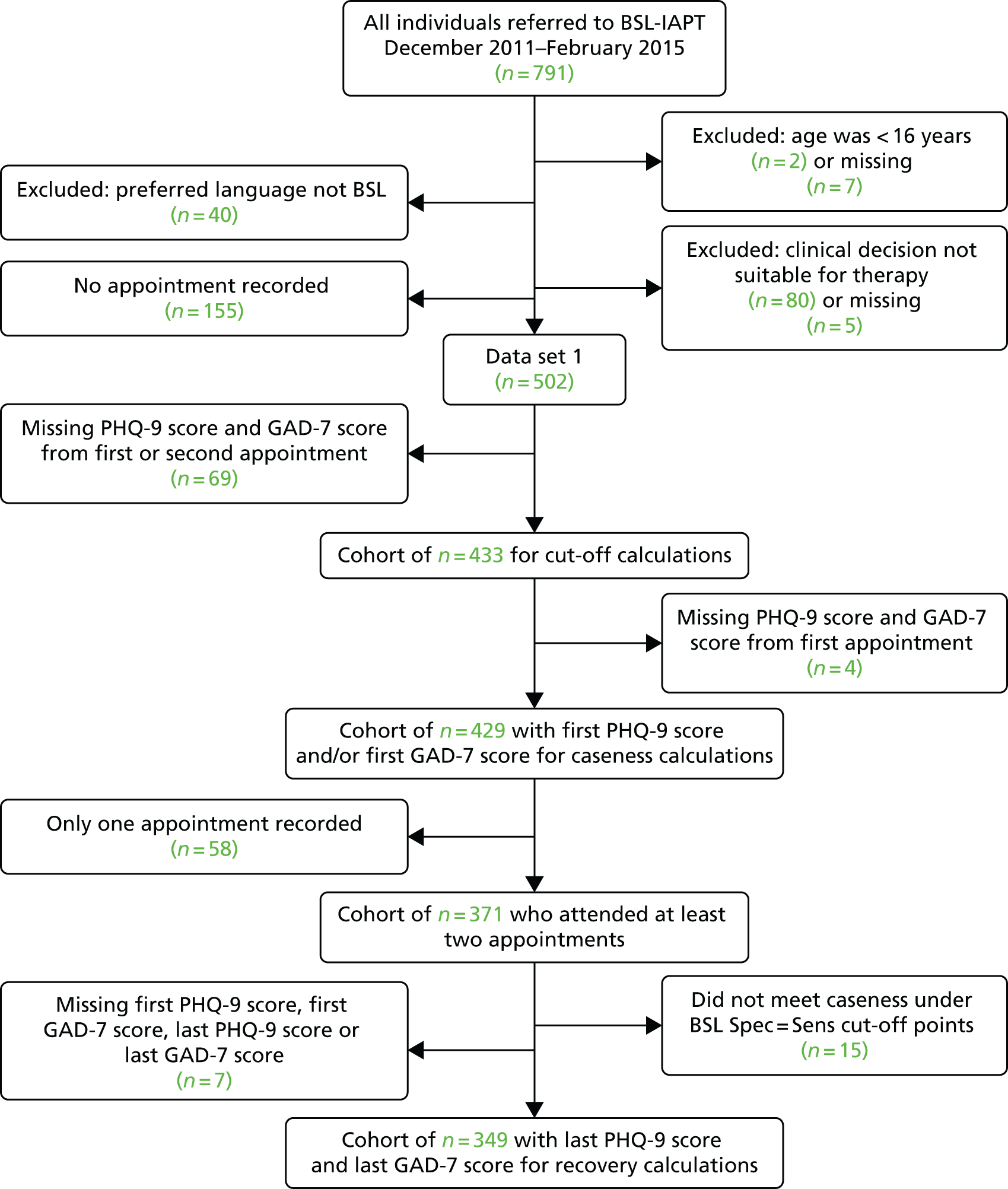

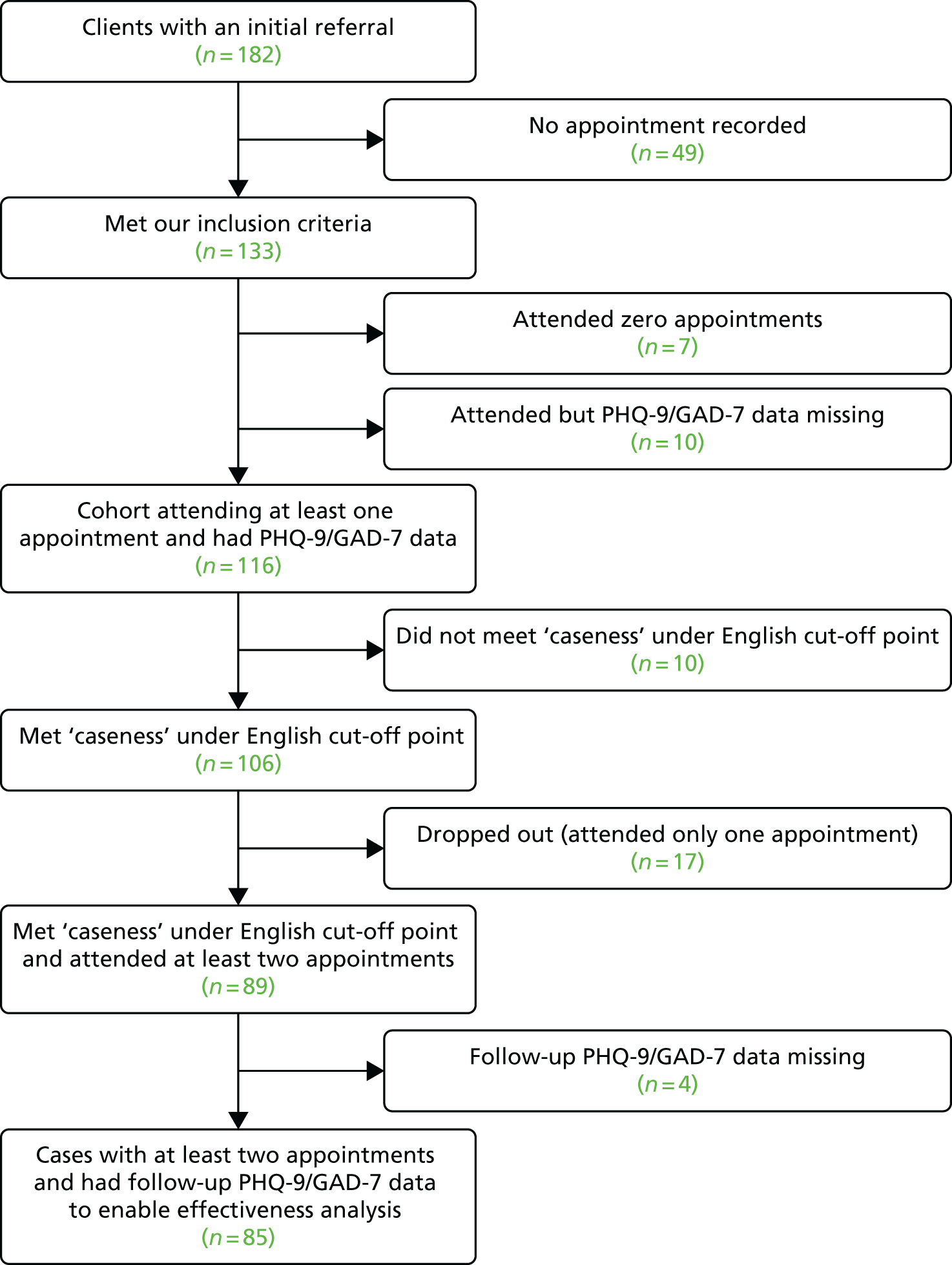

To meet the inclusion criteria for this study, a person in data set 1 needed to be ‘a Deaf sign language user, aged 16 years or over, had accessed BSL-IAPT services since December 2011, had received a step 2 or step 3 service and had attended a minimum of one therapist contact session’. 85 These inclusion criteria for data set 1 resulted in a total number of 502 (see figure 1 in Belk et al. 85).

Measurement

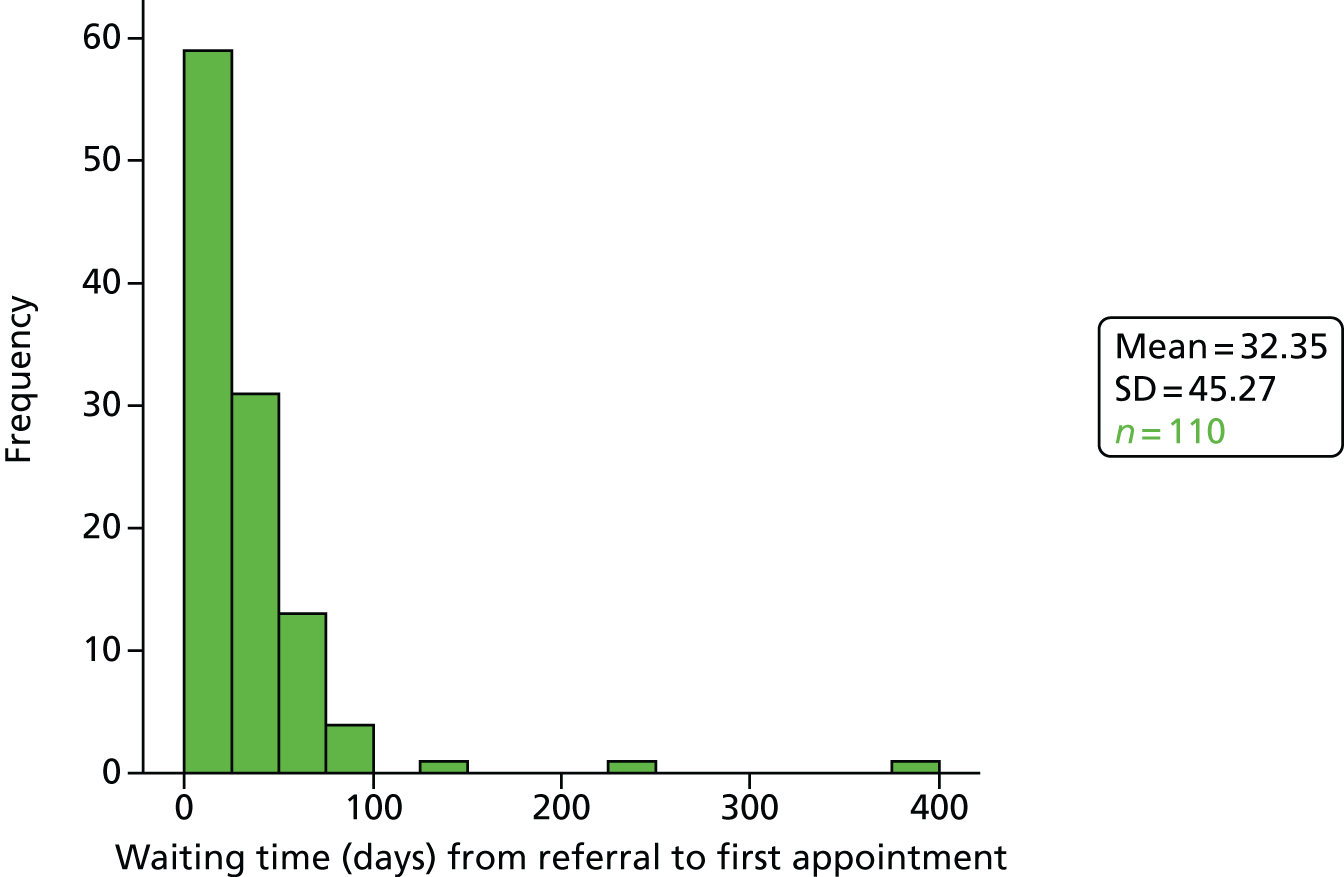

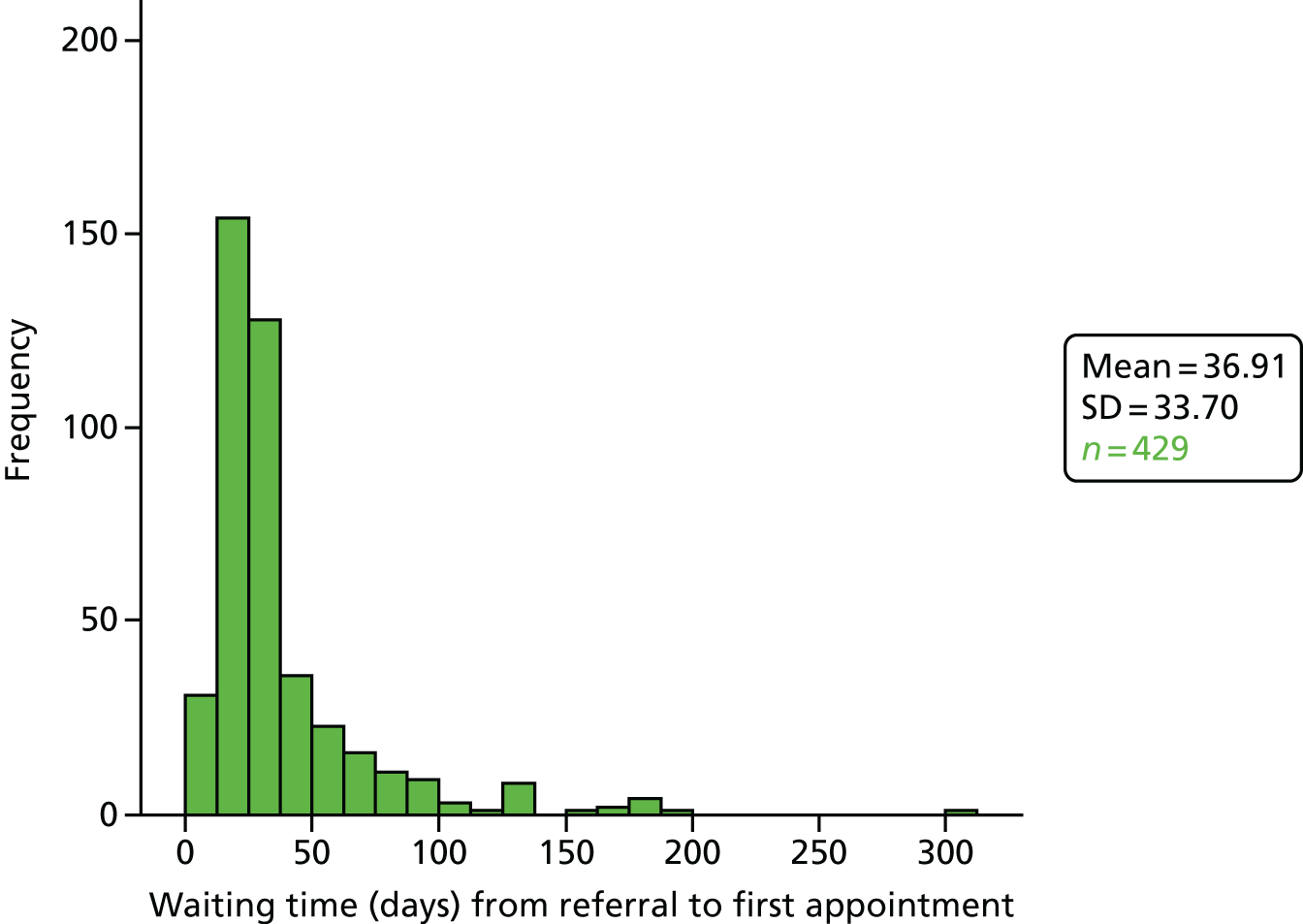

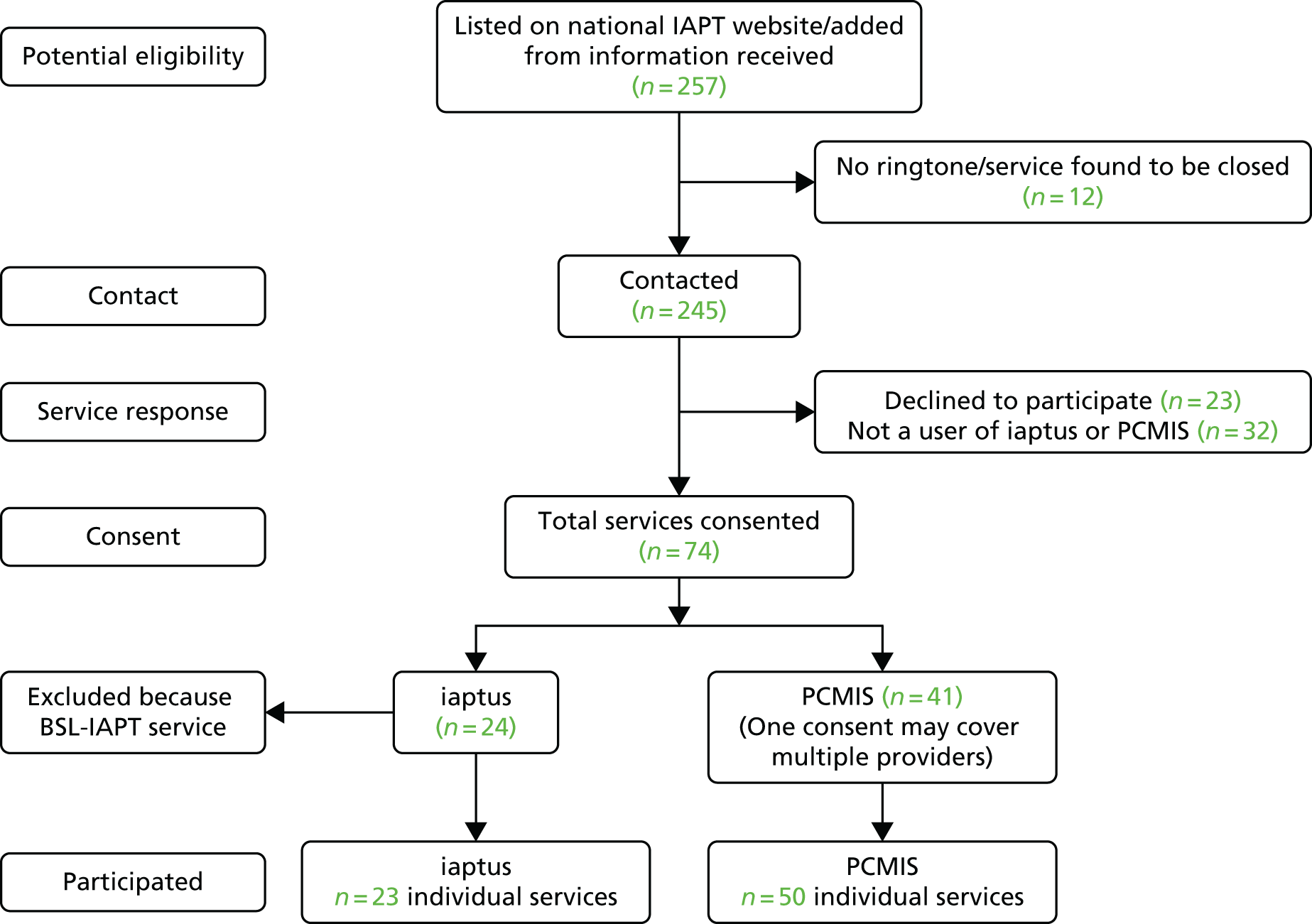

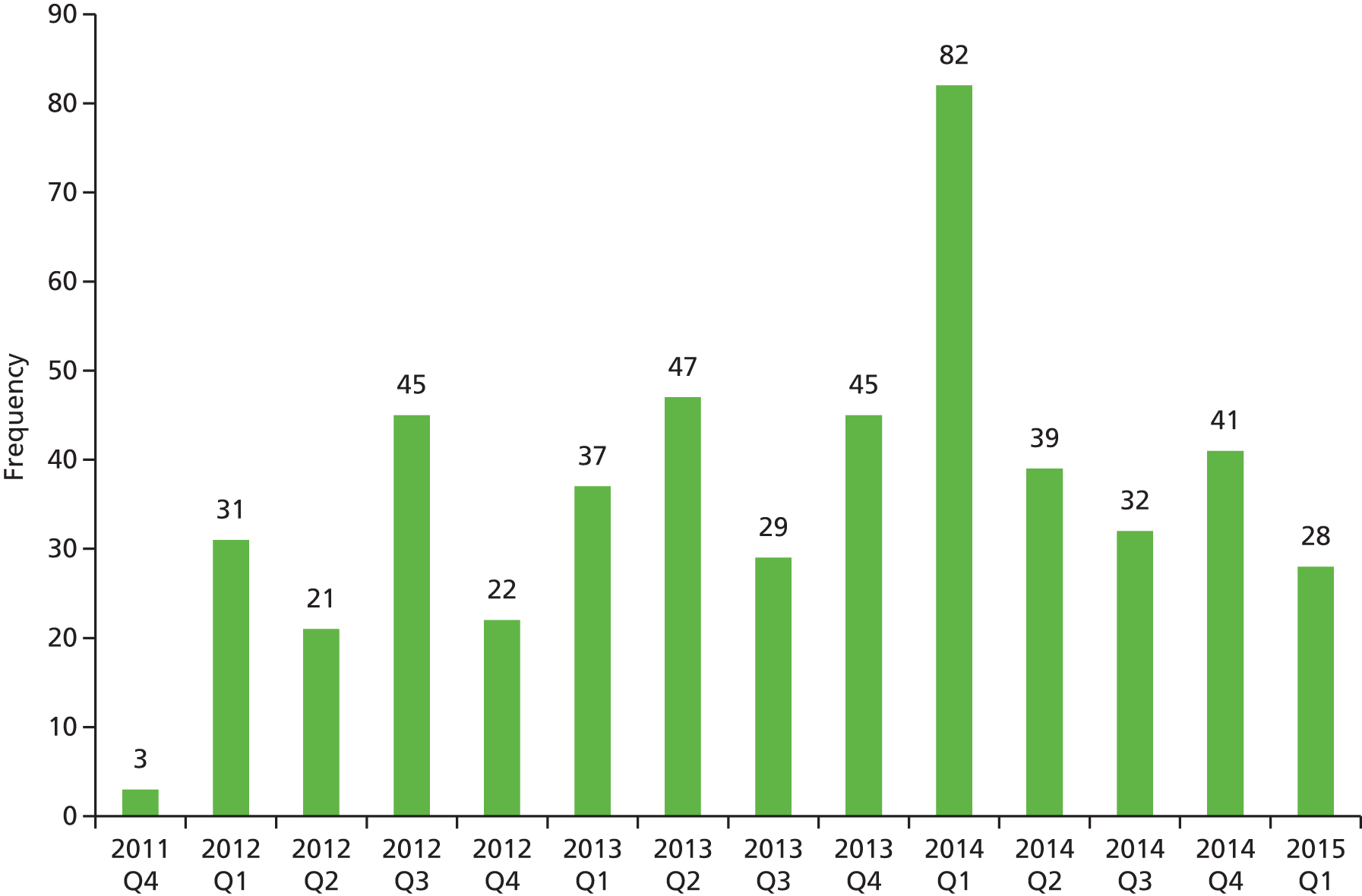

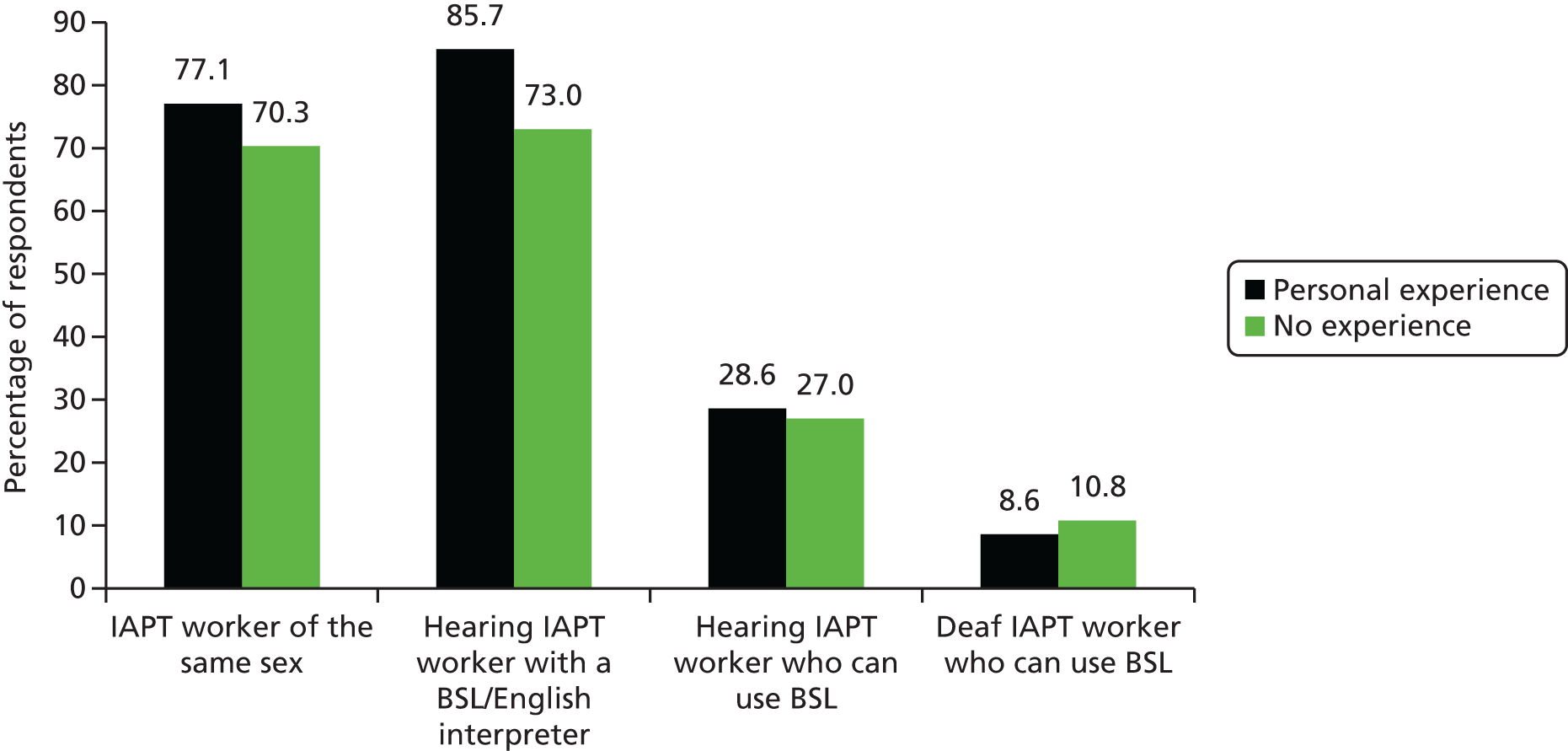

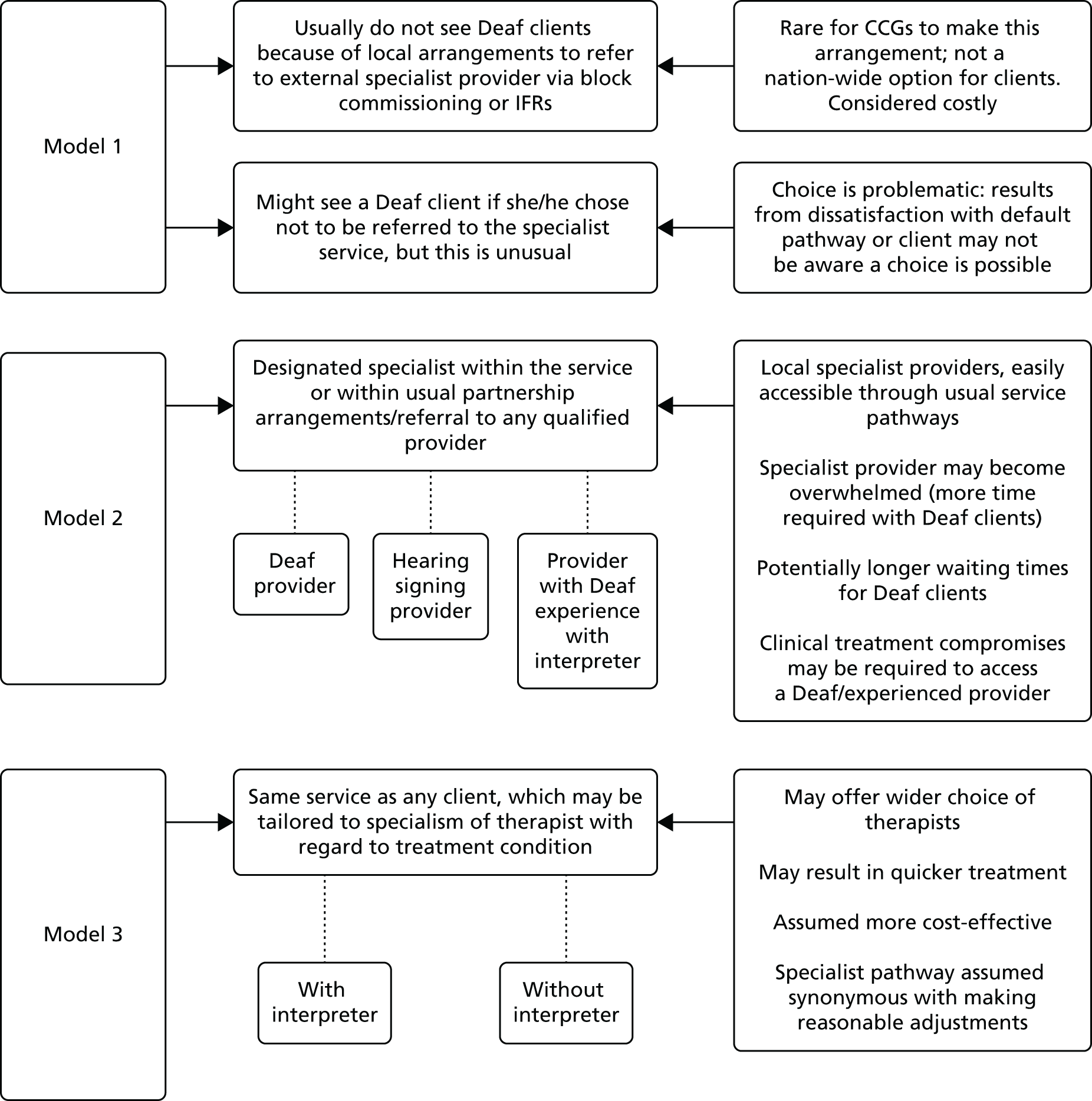

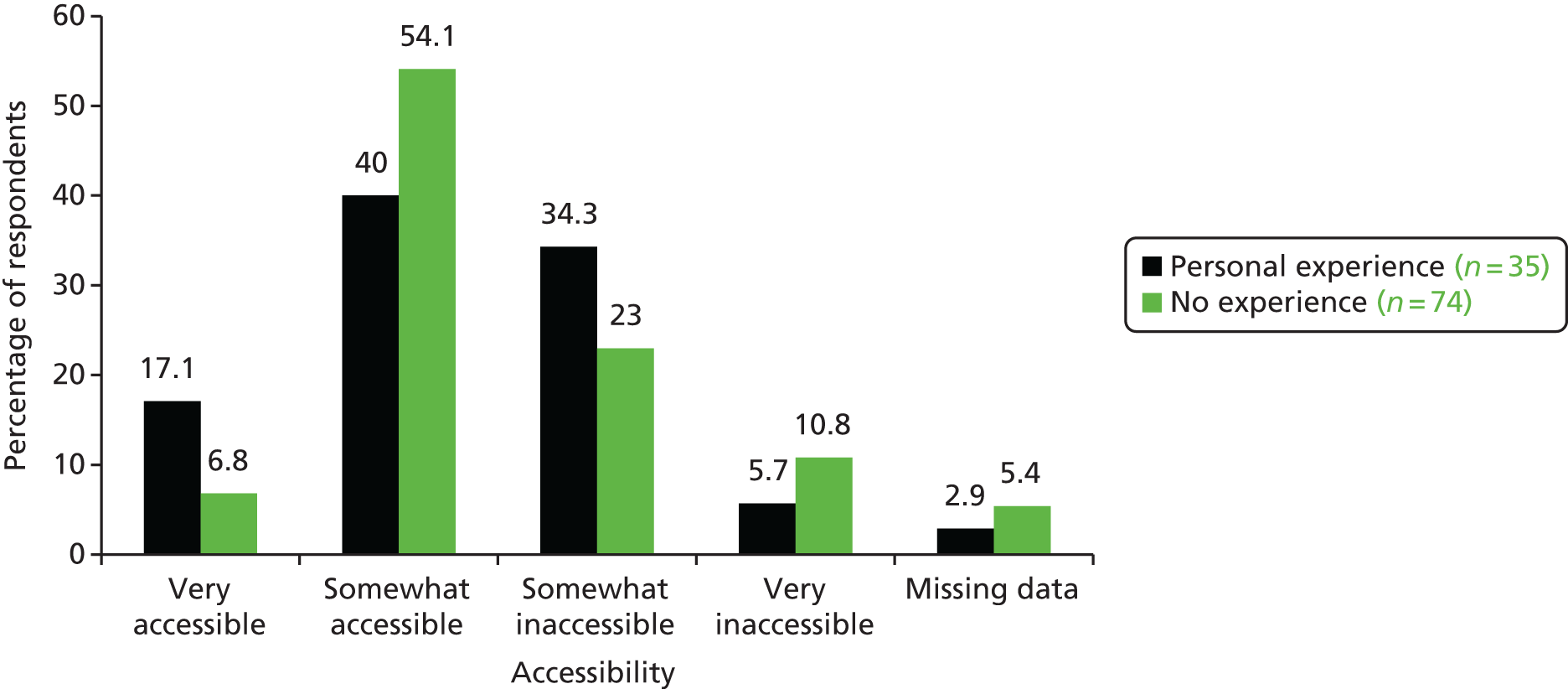

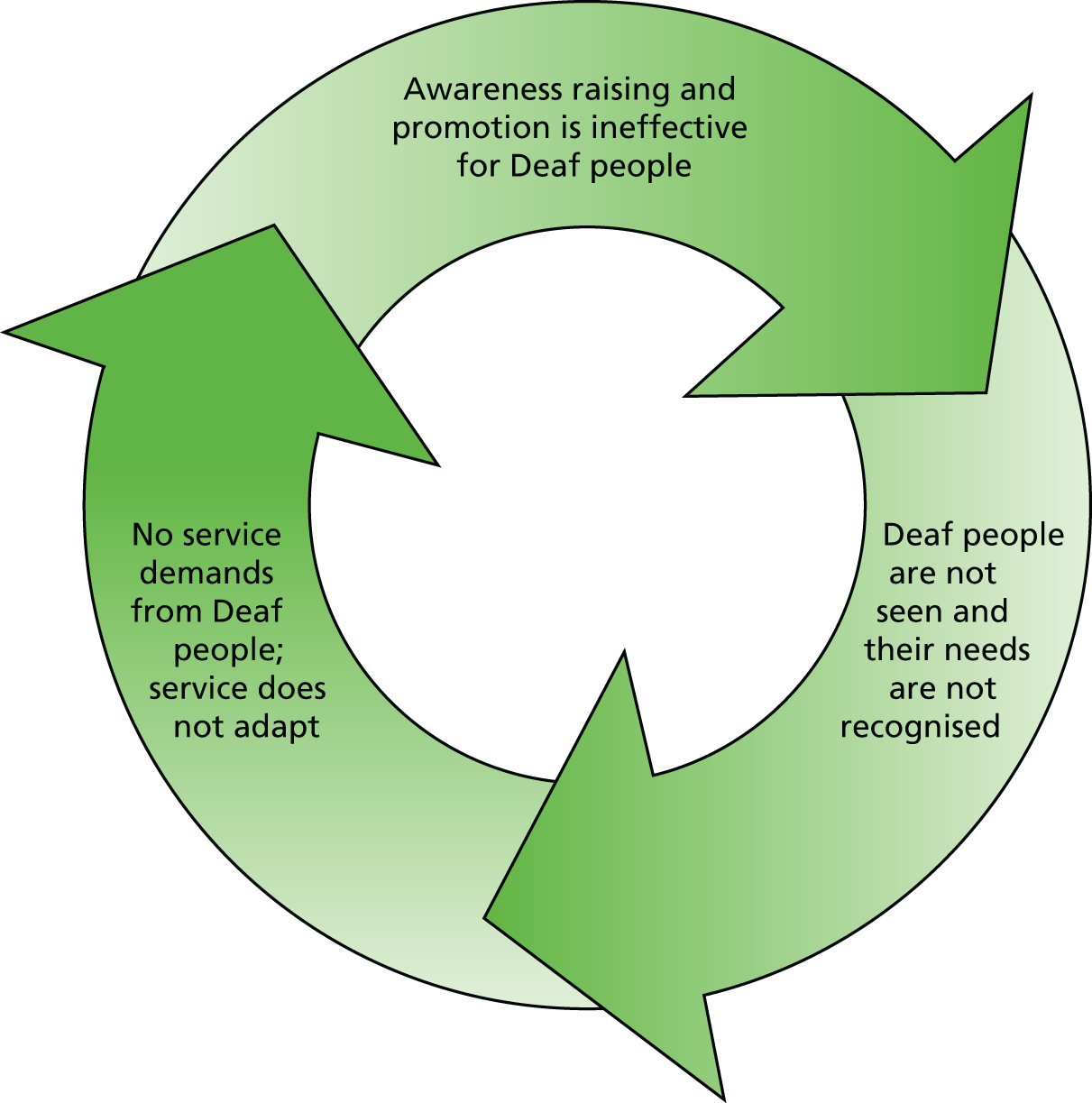

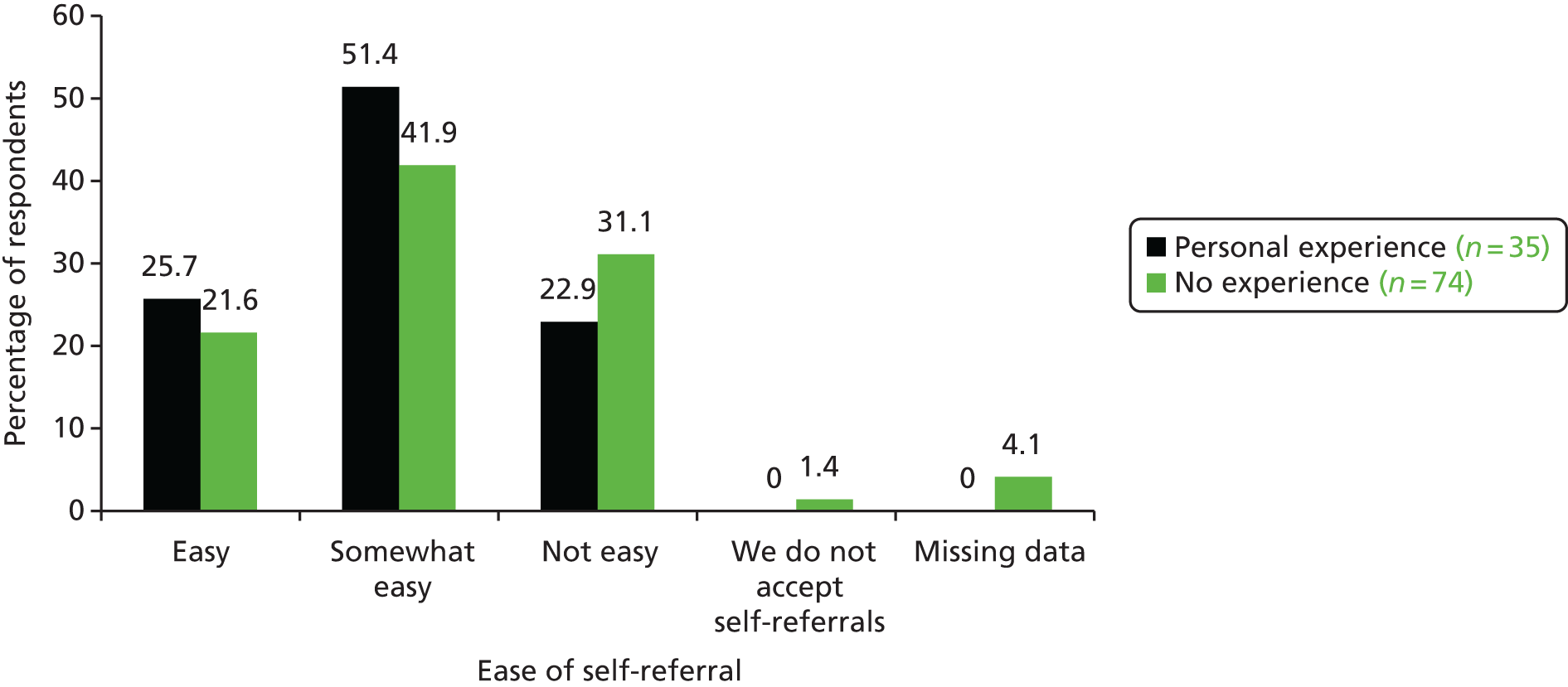

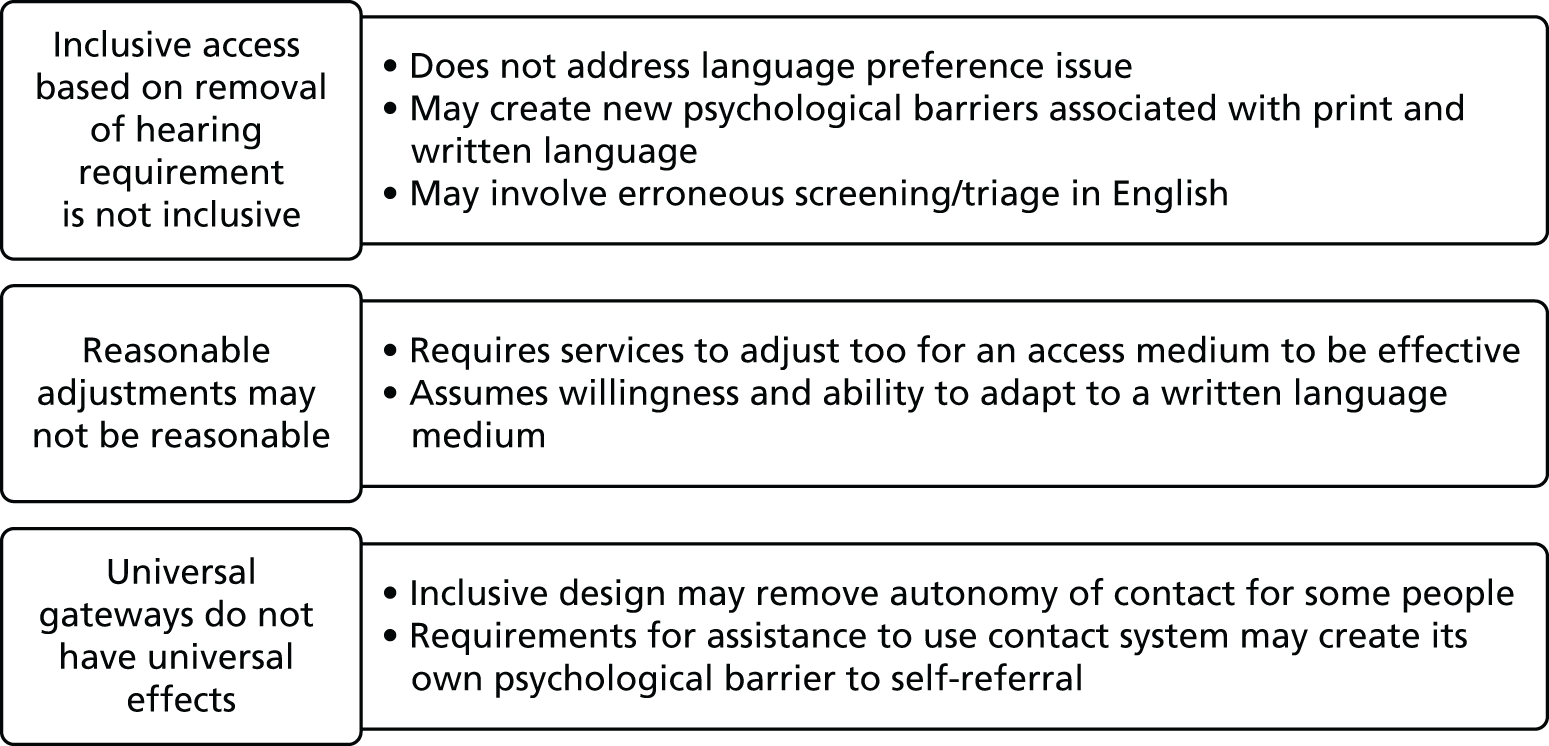

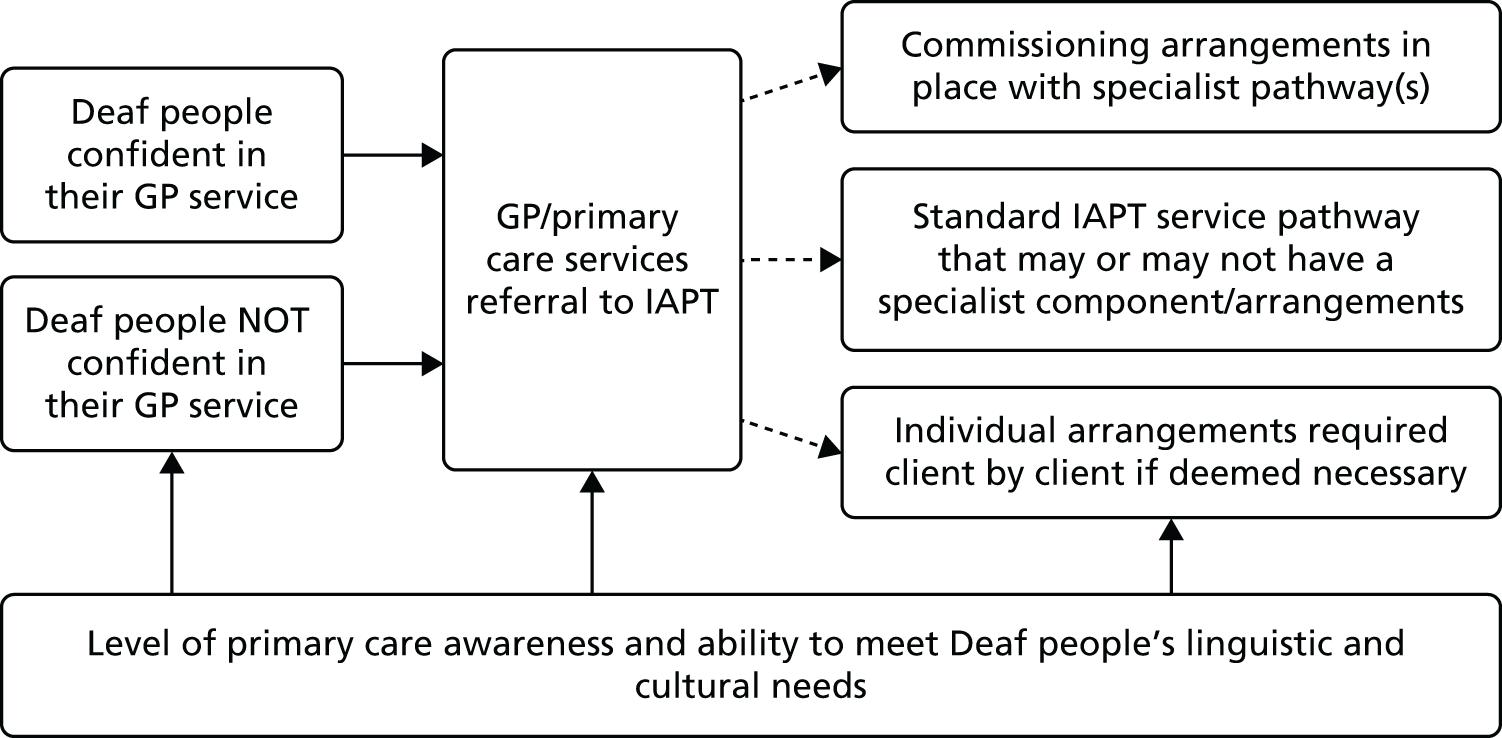

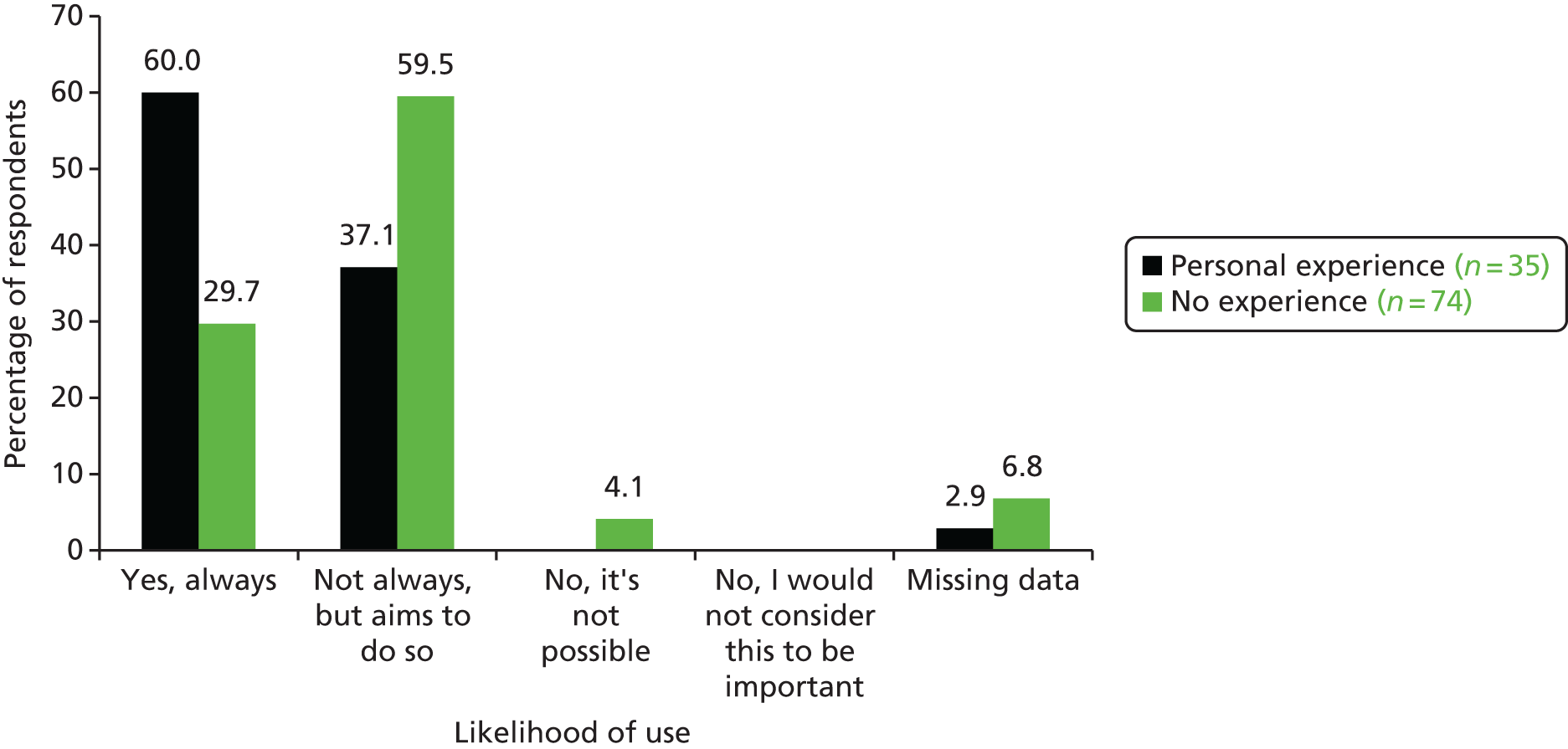

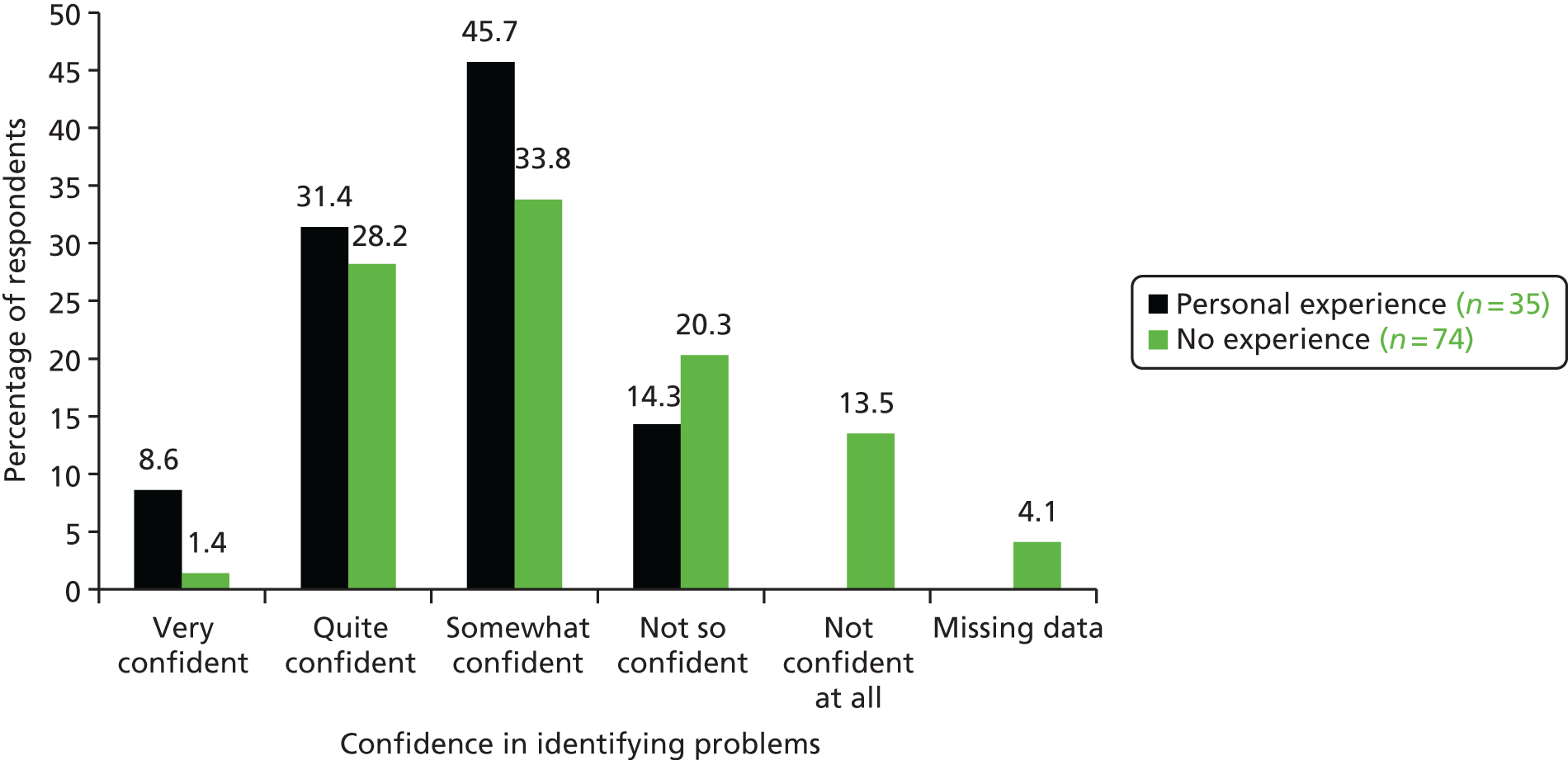

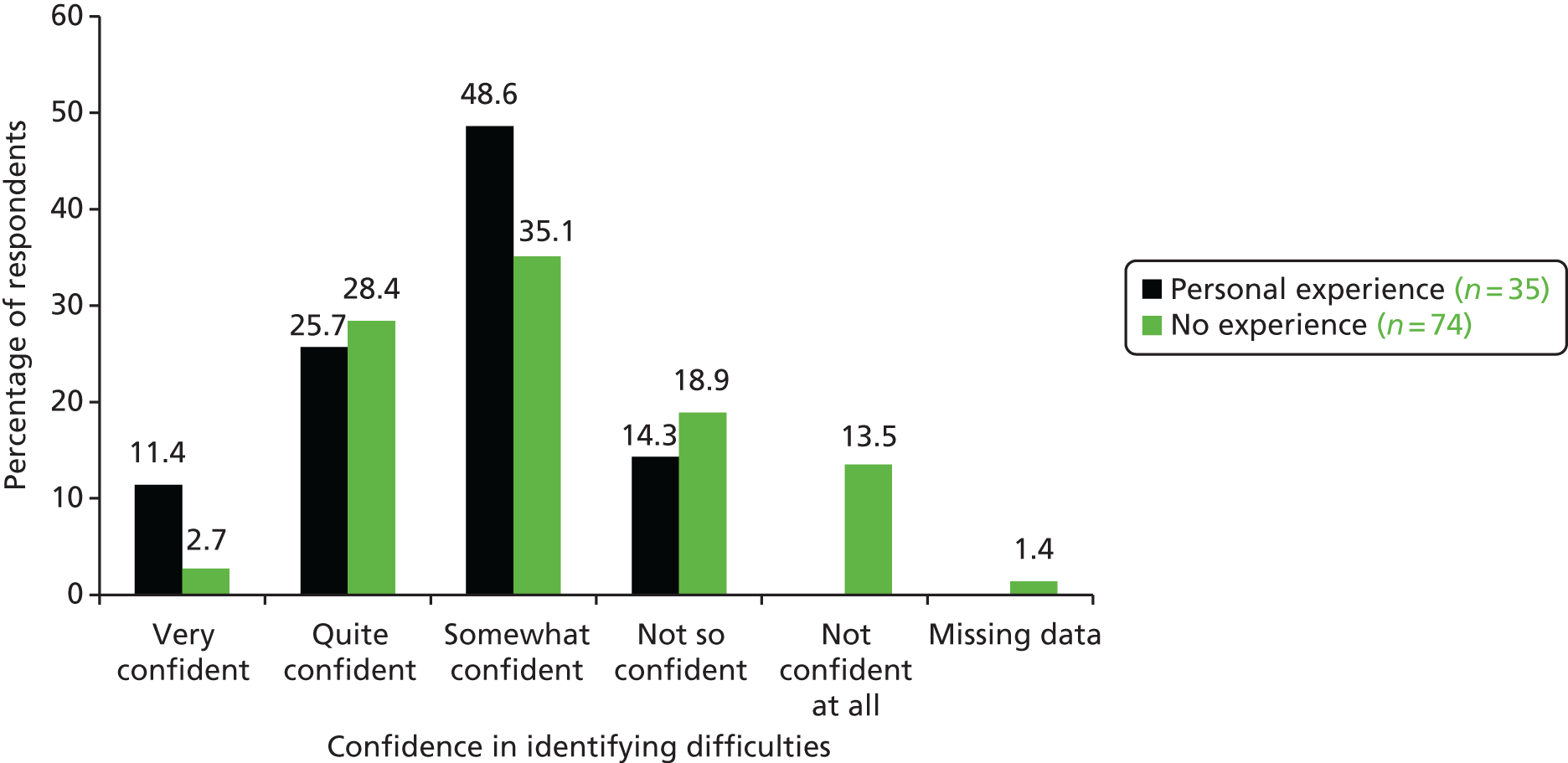

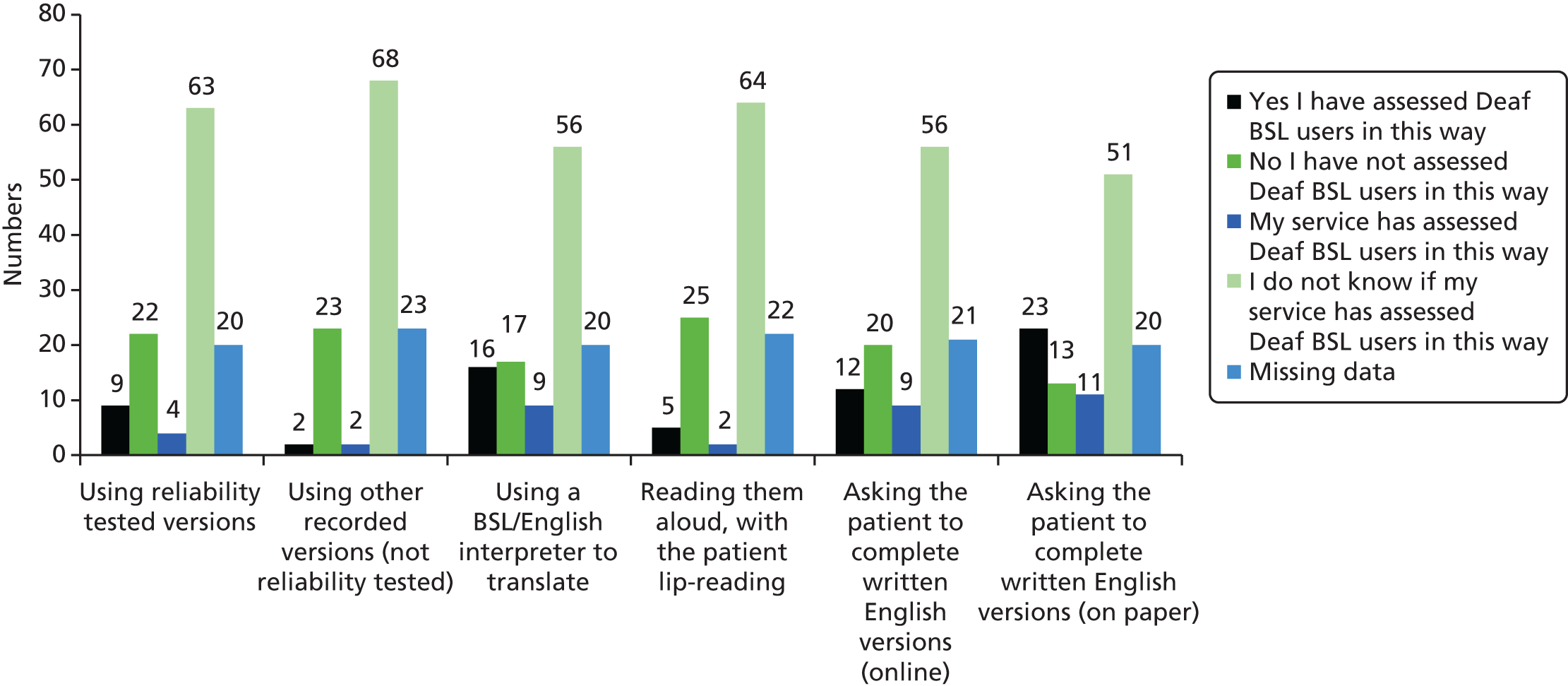

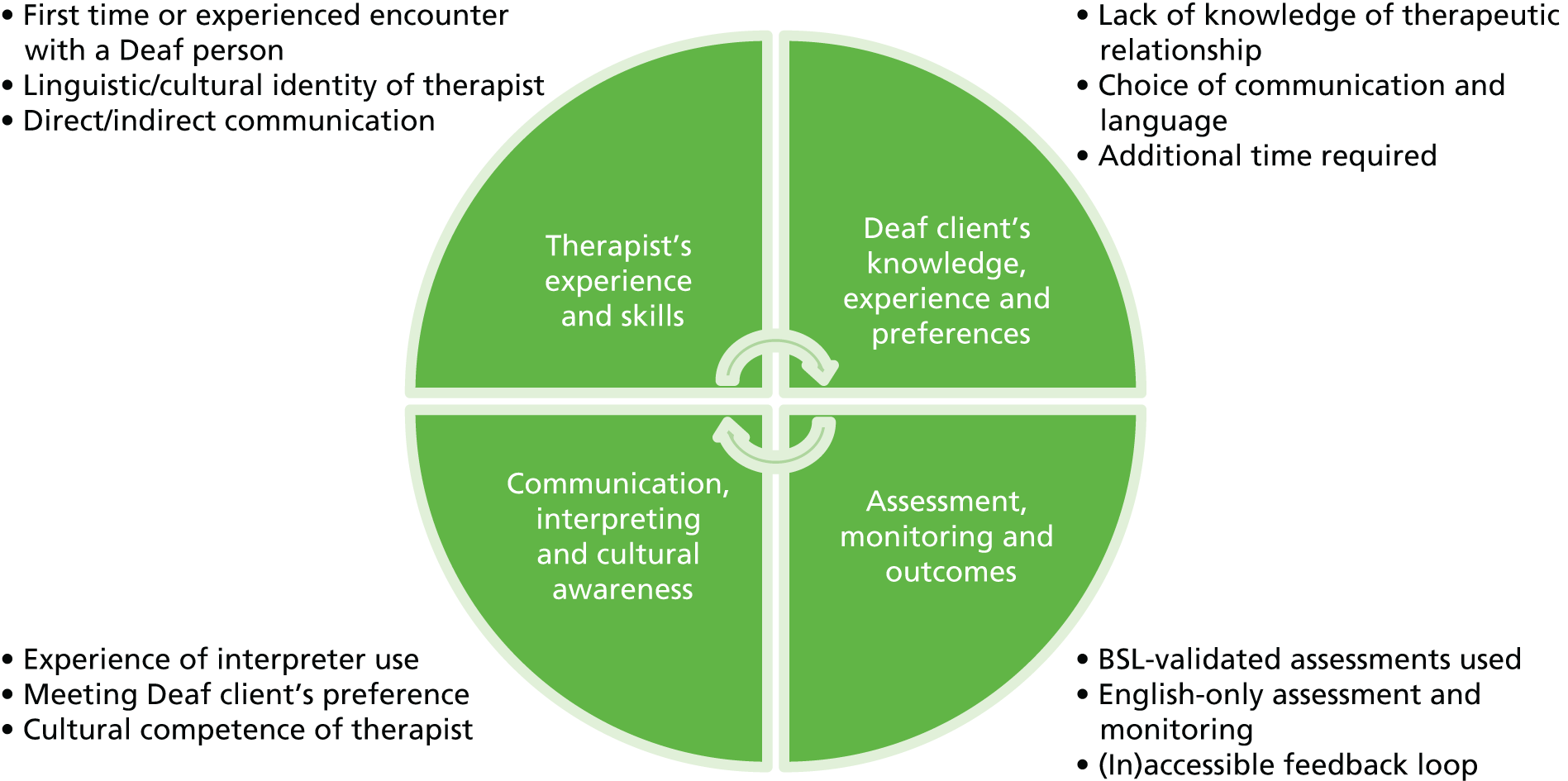

The data collected included the PHQ-9 BSL and GAD-7 BSL scores. The PHQ-9 BSL and GAD-7 BSL were translated from the original English versions:33