Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 11/2004/23. The contractual start date was in April 2013. The final report began editorial review in August 2016 and was accepted for publication in December 2016. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Simon Gilbody is a Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Evidence Synthesis Board member and a HTA Efficient Study Designs Board member. Catherine Hewitt is a HTA Commissioning Board member.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by Littlewood et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background

Perinatal depression: the health problem

Depression accounts for the greatest burden of disease among all mental health problems and is estimated to become the leading cause of disease burden in high-income countries by 2030. 1 Depressive symptoms are also a common occurrence in women during pregnancy and the postnatal period (collectively referred to as the perinatal period). 2 Perinatal depression is now well recognised and has become an important category of depression in its own right. 3 A number of high-income countries, including the UK, USA and Australia, have issued specific guidelines for the identification and management of the condition in clinical practice. 4–8

Perinatal depression is often identified in clinical practice and in research using reliable and valid measures of depression that include clinical assessments of depression [using diagnostic criteria such as the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)9 or the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Edition (ICD-10)10] and self-report symptom questionnaires. The core features of a depressive episode are a sustained low mood or loss of interest in pleasurable activities for most of the day or nearly every day, for at least 2 weeks, along with the presence of additional symptoms (such as fatigue or loss of energy, poor concentration, disturbed sleep/insomnia, feelings of worthlessness or guilt). The DSM Fifth Edition9 provides a ‘peripartum specifier’ for major depressive episodes with onset during pregnancy or within 4 weeks after delivery. In contrast, the ICD-10 criteria do not include a prenatal specifier for depression, although there is a separate code for disorders occurring within 6 weeks after delivery.

However, a common broader definition of perinatal depression is that it encompasses major and minor depressive episodes that occur during pregnancy (prenatal depression) or the first postnatal year (postnatal depression)11 and includes new and existing episodes of depression. 12

Prevalence and time course of perinatal depression

Prevalence rates of perinatal depression vary but well-cited estimates indicate that approximately 7.4–20.0% of women meet the criteria for a diagnosis of depression at some point during pregnancy,13,14 with up to 22% of women experiencing a depressive episode during the postnatal period. 11,15

The time course of perinatal depression remains under investigation. Historically, the majority of research has been conducted on postnatal depression, although research on prenatal depression (also often referred to as antenatal depression) is gaining momentum. 16 Some studies11,17,18 suggest that the prevalence of depression is comparable between pregnant and non-pregnant women, whereas others2,17,19,20 report that the prevalence of depression in women during the postnatal period is higher than at other times in a woman’s life.

Although perinatal depression may not be different from depression occurring in non-pregnant women,8,21 some women will experience depression for the first time during pregnancy or during the postnatal period; some women with diagnosed prenatal depression will continue to be symptomatic in the postnatal period; and some women will have pre-existing chronic or relapsing depression. Research investigating the trajectory of depression experienced by women during the perinatal period has reported mixed results. Evidence from a large longitudinal cohort study conducted in the UK22,23 suggests higher rates of depressive symptoms in women during pregnancy than during the postnatal period (up to 8 months postnatally), whereas a large US study2 found that episodes of depression began more frequently in the postnatal period (40.1%) than during pregnancy (33.4%) (with 26.5% of depressive episodes beginning before pregnancy). A systematic review15 of longitudinal studies similarly reported a higher prevalence of depression in the first year after birth, particularly the first 6 months after birth, than during pregnancy. Recent studies2,22 suggest that at least a third of cases of postnatal depression begin in pregnancy or before pregnancy.

Although around 50% of women will experience low mood in the first few weeks following birth (often referred to as the ‘baby blues’),24 this is often mild and transient. 25 The majority of cases of postnatal depression are believed to develop within the first 3 postnatal months. 26 Although some cases last around 3 months from onset and resolve spontaneously without treatment,26 > 50% of women remain depressed for > 6 months. 27 Moreover, up to 50% of women remain depressed for > 1 year following birth26,28 and around 14.5% of women continue to show depressive symptoms at 4 years post partum. 29 Less research has been conducted on the time course of depression during pregnancy. Systematic reviews11,13 report similar estimates of point prevalence of depression across the three trimesters of pregnancy, ranging from 7.4% to 12.8%.

Variations in reported estimates of the prevalence and time course of perinatal depression are typically dependent on various factors, such as the size, representativeness and country of the identified sample, the point at which depression was measured during pregnancy (e.g. first, second or third trimester) or the postnatal period (e.g. first 6 postnatal weeks, first 3 postnatal months), and the instruments or criteria adopted to determine the presence of depressive symptoms (e.g. self-report questionnaires using various cut-off scores) or a depressive episode (e.g. diagnosis via structured clinical assessment). 11

Risk factors for perinatal depression

A substantial literature exists on the evidence of risk factors for perinatal depression. 25,30 The strongest predictor of depression both during pregnancy and the postnatal period is a previous history of depression. 15,22,31–34 Significant risk factors for postnatal depression include anxiety during pregnancy (antenatal anxiety),22,35 poor marital or partner relationship,15,34 poor social support,15,31,32,35 stressful life events during pregnancy or the first postnatal months,15,31,32 low socioeconomic status,33 unintended pregnancy15,33 and domestic violence. 36,37 Many of these risk factors are also known to increase the likelihood of depressive symptoms during pregnancy. 33,35,37,38

Impact of perinatal depression

Perinatal depression is associated with a range of adverse outcomes for the mother, her baby and the family, in the short and longer term. 14,39,40 Perinatal depression can profoundly affect a woman’s well-being, quality of life and relationships16 and can lead to an increased risk of a range of psychological, behavioural and developmental problems in children.

Depression experienced during pregnancy has been shown to increase the presence of somatic symptoms (such as headaches and gastrointestinal problems)41 and has been linked to an increased risk of poor obstetric and neonatal outcomes including premature births, low birthweight and a decrease in breastfeeding initiation. 42–44 Such adverse consequences of prenatal depression have been shown to be associated with poor self-reported health and functioning,45 decreased perinatal care and poor use of antenatal/prenatal care services, and an increased risk of smoking, substance use and alcohol abuse. 14,46

Perinatal depression can lead to difficulties with parenting, particularly early mother–infant interactions47,48 and reduced maternal sensitivity and attachment with the infant,49 which can lead to an increased risk of poor child emotional, behavioural and cognitive outcomes. 39,50,51 The offspring of mothers with perinatal depression are more likely to experience emotional problems,52,53 such as difficulties with early emotional regulation and poor social skills in school years,54,55 and are at an increased risk of developing clinical depression during adolescence and at age 18 years. 51,56 Studies have also shown a link between perinatal depression and behaviour problems in children, particularly attention deficit hyperactivity disorder57 and conduct disorder. 30 Postnatal depression has shown consistent associations with poor cognitive functioning in children, including infant ability to learn and achieve developmental milestones, language and general cognitive development58–60 (see Stein et al. 39); this is particularly important when postnatal depression persists through the first year of life. 58,60,61 Women with perinatal depression are at an increased risk of suicide62 and postnatal depression has been linked with infanticide. 62,63

Maternal perinatal depression has been shown to be moderately correlated with depression in fathers, with an estimated 10% of men experiencing depression in the perinatal period. 64 Emerging evidence suggests an association between paternal perinatal depression and negative child emotional, behavioural and developmental outcomes. 65,66 Paternal postnatal depression also increases the risk of depression in offspring at 18 years. 56 Depression in mothers or fathers negatively impacts on the relationship, leading to decreased marital satisfaction and increased marital discord. 67

Perinatal depression and comorbidity

Depression is not always experienced in isolation, and epidemiological research shows that depression commonly coexists with other common mental health disorders, such as general anxiety and somatoform complaints. 68 Guidance issued by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)68 has highlighted the importance of recognising and assessing for coexisting psychological comorbidities to avoid the risk of delivering suboptimal treatment strategies. Limited research has been undertaken on the comorbidity of psychological problems with respect to perinatal depression.

A large study conducted in the USA17 reported a 13% prevalence of any anxiety disorder during the perinatal period, comparable to the prevalence found among non-pregnant women. Studies suggest that perinatal anxiety (including panic disorder and phobias) is commonly comorbid with perinatal depression,22,69 with around two-thirds of women with perinatal depression also having a comorbid anxiety disorder. 2,70

Identification of perinatal depression

Although perinatal depression is well recognised as a mental health condition, it often goes undetected by health professionals (HPs) in routine clinical practice, with recognition rates of < 50% for both prenatal and postnatal depression. 71,72 Despite the finding that clinicians are generally supportive of the need for routine strategies to identify perinatal depression, there is a lack of consistency in the translation of such strategies into routine practice. 73

Strategies for identifying perinatal depression

Screening or case-finding strategies have been advocated as a method of improving the identification, management and treatment of perinatal depression. 74 A distinction can be drawn between ‘screening’ (offering a test to a defined population) and ‘case-finding’ (offering a test to those at the highest risk of having the condition within a defined population), although the two terms are often used interchangeably in the wider literature. Screening is considered appropriate when the condition in question is an important and prevalent health problem, can be effectively treated and cannot be readily detected without screening. 75 The UK National Screening Committee (NSC) are responsible for making recommendations to ministers and the UK NHS regarding the adoption of a screening strategy and as such have a number of clear criteria by which a screening programme is assessed. 76 Based on these criteria, screening programmes should involve a screening test that is simple, safe and accurate and is acceptable to the target population, results in more effective treatment leading to better outcomes and has an acceptable ratio of costs to benefits. 77

In the UK, national guidance on screening/case-finding for perinatal depression has been inconsistent. 3 In 1999, the National Service Framework for mental health made an explicit requirement for all local areas to have protocols in place for the management of postnatal depression. 78 This resulted in the use of screening and case-finding strategies that focused on the routine or ad hoc administration of screening/case-finding instruments, most notably the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS; a 10-item self-report questionnaire asking about symptoms of depression over the past week79), in the postnatal period, to the extent that the EPDS became the most widely used screening/case-finding instrument to detect symptoms of postnatal depression. 3,76 In 2001, the NSC concluded that there was insufficient clinical and economic evidence to support the implementation of screening strategies for postnatal depression, highlighting the lack of evidence for the validity of the EPDS as a screening tool. 3,80,81 As a result, resources for the treatment of postnatal depression by health visitors (HVs) was withdrawn, prompting the NSC to modify its guidance. 82 Although the NSC continued to recommend that the EPDS should not be used as a screening tool for postnatal depression until further research had been conducted, it acknowledged that it could be used as part of the mood assessment in conjunction with professional clinical judgement and clinical interview. The initial NSC recommendation was reaffirmed in its 2010 review,3 reiterating that there was no evidence that postnatal screening would improve maternal and infant health outcomes for women.

The use of a national screening/case-finding strategy based on ad hoc screening/case-finding using the EPDS has attracted much criticism. 3,74 Such criticisms are based on the ethics of mass screening, concerns regarding the psychometric properties of available screening/case-finding instruments, the acceptability of such screening/case-finding strategies to women or HPs, the paucity of evidence for the cost-effectiveness of screening/case-finding strategies (particularly the costs associated with the management of incorrectly identified cases of perinatal depression) and the absence of evidence that screening/case-finding leads to effective management of perinatal depression and improved mother and infant outcomes. 3,74,76,81

Clinical guidelines for the identification of perinatal depression

Whether or not screening/case-finding for perinatal depression is recommended differs across various countries. Although clinical guidelines have been issued in several countries recommending the mental health assessment of women during pregnancy and after childbirth,4,7,8,83–85 these do not necessarily advocate a screening/case-finding strategy per se. For example, the US Preventive Services Task Force5,6 recommends screening for depression (including in pregnant and postpartum women), but only when this is done within the context of a package of integrated care to include accurate diagnosis, effective treatment and appropriate follow-up. Clinical recommendations issued in Australia4 recommend screening/case-finding for perinatal depression, using the EPDS, as part of an integrated and holistic package of perinatal care. In contrast, universal screening for depression has not been recommended in the UK as part of NICE guidelines,86,87 with these guidelines instead recommending that clinicians be alert to possible depression, particularly when there is a previous history of depression, and that they ask about symptoms of depression when there is a concern. Despite such differences, however, all guidelines agree that screening/case-finding instruments alone should not be used to diagnose women with perinatal depression, but should be used to identify those women at risk of perinatal depression who require a fuller assessment of their mental health.

Case-finding instruments for perinatal depression

In 2007, NICE issued guidelines on antenatal and postnatal mental health7,88 that set out recommendations for the detection and treatment of mental health problems during the perinatal period. These guidelines strongly advocated a ‘case-finding’ approach (rather than a screening approach per se) and recommended the use of two brief ‘case-finding’ questions (often referred to as the ‘Whooley questions’89) as a new strategy for HPs to identify perinatal depression. The NICE guidance7 states:

At a woman’s first contact with primary care, at her booking visit and postnatally (usually at 4 to 6 weeks and 3 to 4 months), healthcare professionals (including midwives, obstetricians, health visitors and GPs) should ask two questions to identify possible depression:

During the past month have you often been bothered by feeling down, depressed or hopeless?

During the past month have you often been bothered by having little interest or pleasure in doing things?

A third question should be considered if the woman answers ‘yes’ to either of the initial questions:

Is this something you feel you need or want help with?

Reproduced with permission, pp. 117–187

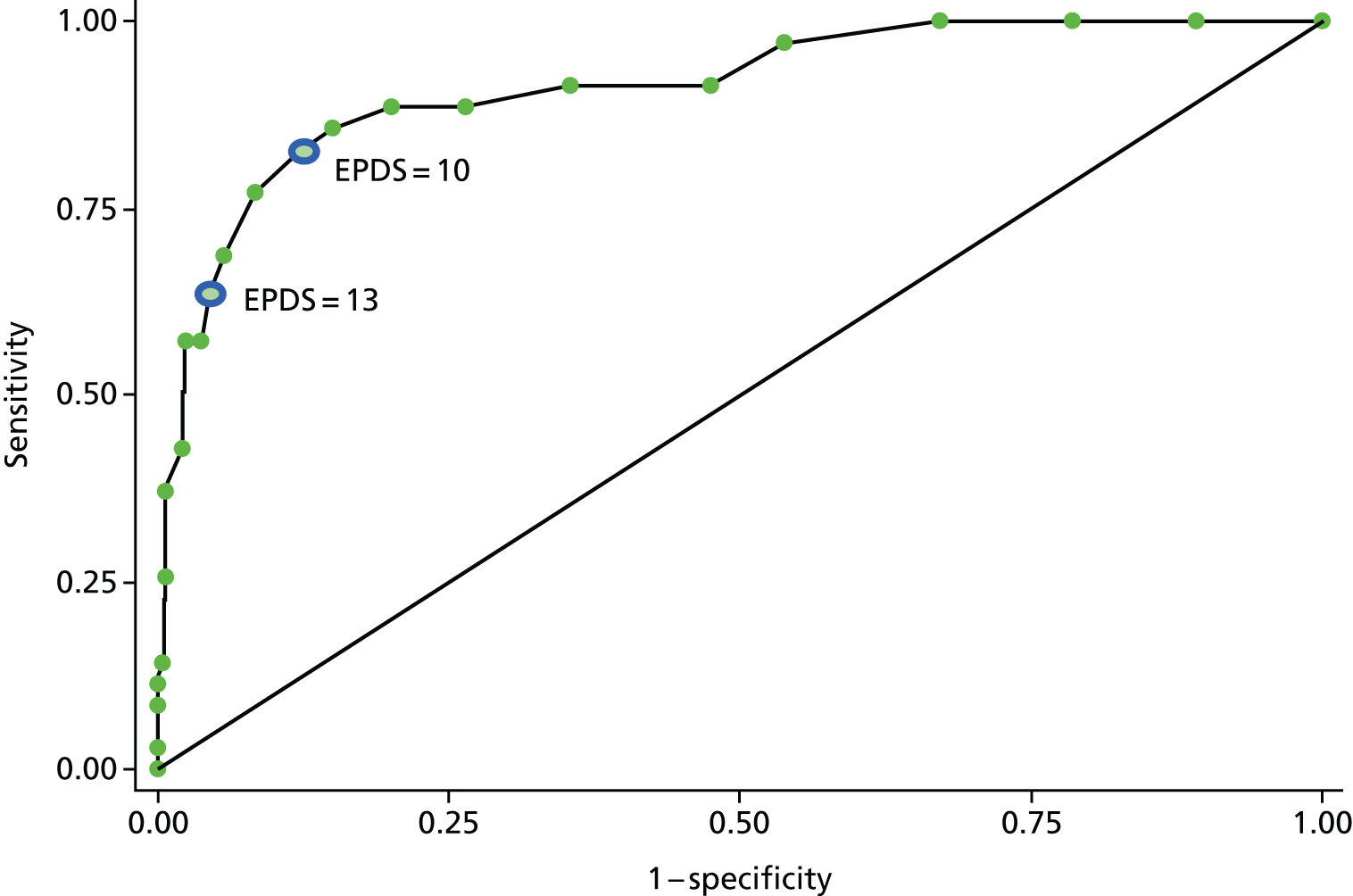

The guidance7 also recommended that ‘healthcare professionals may consider the use of self-report measures such as the EPDS, the HADS [Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale90] or PHQ-9 [Patient Health Questionnaire-991] as part of subsequent assessment or for the routine monitoring of outcomes’ (reproduced with permission pp. 117–18).

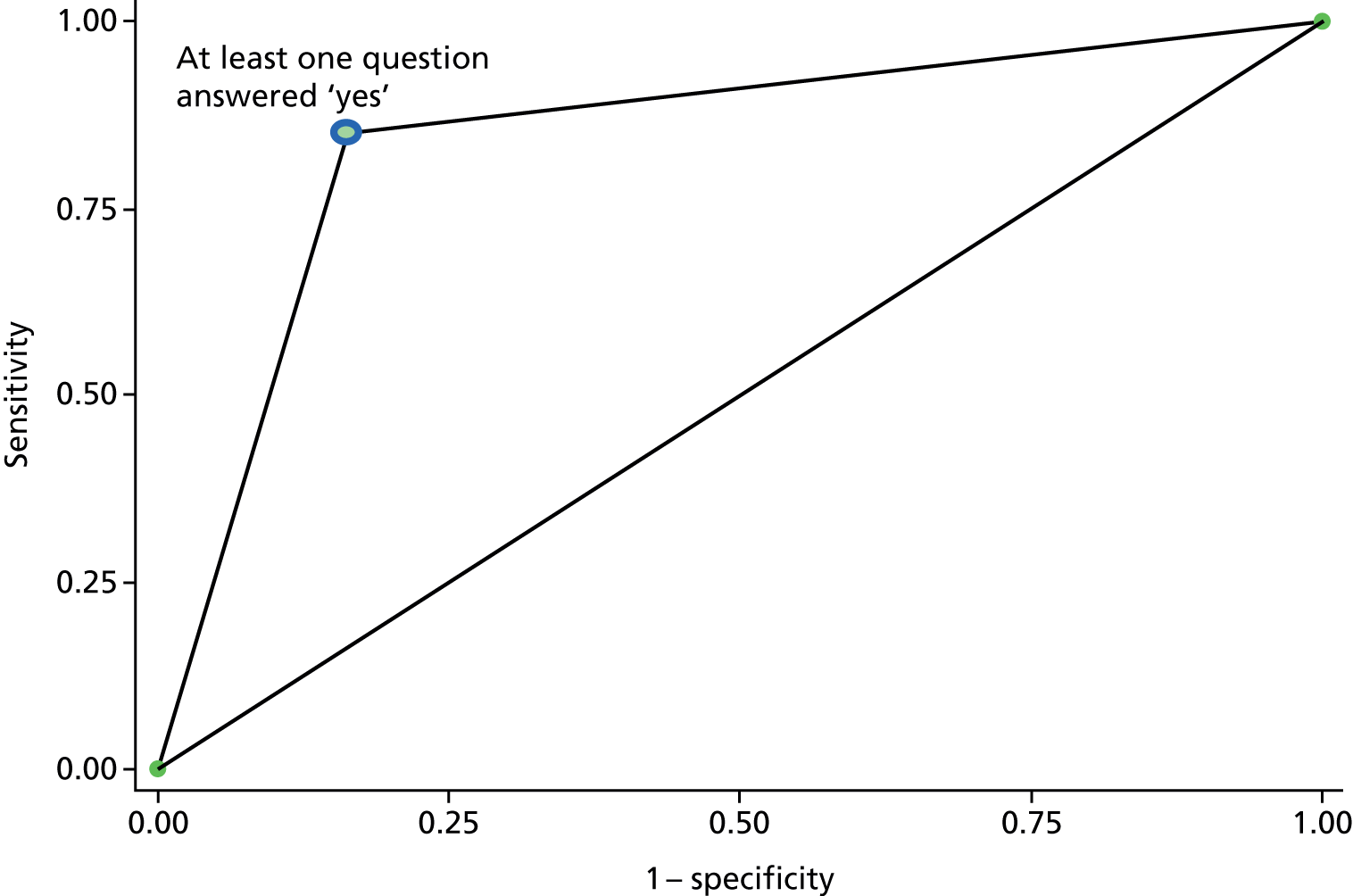

The NICE recommendation to use the Whooley case-finding questions to detect depression in women during the perinatal period was based on the current NICE guidelines for depression at that time,92 along with evidence from two studies89,93 of the diagnostic accuracy of the Whooley questions. Neither of these validation studies were conducted in a perinatal population. Although NICE identified eight studies that assessed the validity of the EPDS, the diagnostic performance of the instrument varied considerably between studies, as did the reported prevalence of perinatal depression. 7 As a result, NICE concluded that although the sensitivity of the EPDS was reasonably good, the lower specificity would mean that almost half of all women referred for further assessment (based on a positive screen) would be referred unnecessarily. 7 NICE argued that the value of the Whooley questions was in their brevity, making them appropriate for use across busy clinical practice settings, and that they lend themselves to use across the perinatal period. 7

The Whooley questions, derived from the Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders,94 were originally validated in a primary care population. In a US cross-sectional study,89 the two questions, along with a diagnostic interview (the Quick Diagnostic Interview Schedule-III-R95), were administered to 536 male veterans attending a medical centre. A positive response to either of the two questions had a sensitivity of 96% and a specificity of 57%, indicating acceptable evidence for the questions’ ability to rule out depression, but with a high number of false positives (FPs) (i.e. a high number of men were incorrectly identified as being depressed). An additional study93 examined the Whooley questions plus the third ‘help’ question in 936 patients attending primary care; the addition of the ‘help’ question increased specificity to 89%, without reducing sensitivity (96%) (as validated against the Composite International Diagnostic Interview96).

Given the lack of any validation studies of the Whooley questions in a perinatal population, NICE made a research recommendation for a validation study of the effectiveness of the Whooley questions (compared with a psychiatric interview) in women during the perinatal period. 7 A subsequent Health Technology Assessment,76 which involved a comprehensive systematic review of methods to identify postnatal depression in primary care, failed to identify any diagnostic accuracy studies that validated the use of the Whooley questions (against various gold standard diagnostic interviews conducted according to internationally recognised criteria such as ICD or DSM) for the detection of depression during pregnancy or the postnatal period. 76 Rather, this report found that the EPDS was the most commonly used instrument to detect postnatal depression, and was considered to perform reasonably well; sensitivity ranged from 60% (specificity 97%) to 96% (specificity 45%) for detecting major depression, and from 31% (specificity 99%) to 91% (specificity 67%) for detecting major or minor depression in the postnatal period. The authors concluded that research comparing the performance of the Whooley questions (and the ‘help’ question), the EPDS and a generic depression measure was needed. 76

A later systematic review97 identified one diagnostic accuracy study of the two Whooley questions against diagnostic gold standard criteria. The US study98 administered the two Whooley questions, along with depression component of the Structured Clinical Interview for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (SCID)99 as the gold standard, to 506 women attending well-child visits during the first 9 postnatal months; sensitivity and specificity across the duration of the study was 100% and 44% respectively. The review97 failed to identify any studies that validated the two Whooley questions and the additional help question against a gold standard diagnostic measure.

The Born and Bred in Yorkshire PeriNatal Depression Diagnostic Accuracy (BaBY PaNDA) study was therefore born out of the need to provide rigorous evidence of the diagnostic properties of the Whooley questions (including the additional help question) compared with the EPDS to identify depression in women during pregnancy and the postnatal period. Such evidence will inform future NICE guidelines and NSC policy recommendations in this area.

Given that the BaBY PaNDA study was conducted in response to the NICE research recommendation for a validation study of the effectiveness of the Whooley questions to identify perinatal depression, and that NICE has advocated the use of the Whooley questions as ‘case-finding’ questions in two iterations of NICE guidance,7,8 we will refer to the Whooley questions and the EPDS as ‘case-finding’ instruments throughout this report. However, we acknowledge that the BaBY PaNDA study could be viewed by some as evaluating the Whooley questions and the EPDS as ‘screening’ instruments. We therefore refer to both ‘screening’ and ‘case-finding’ as potential strategies to identify perinatal depression.

Research conducted since the design of the BaBY PaNDA study

The BaBY PaNDA study was in part informed by the results of a pilot diagnostic accuracy study,100 conducted by authors of this report, in which the NICE case-finding approached was evaluated. The diagnostic accuracy of the Whooley questions – and the additional help question – was assessed against gold standard psychiatric diagnostic criteria (SCID99) in a small but diverse sample of women during pregnancy and the postnatal period. A total of 126 women completed the Whooley questions and a diagnostic gold standard interview during pregnancy, of which 94 went on to complete these during the first 3 postnatal months. A positive response to either of the two Whooley questions had a sensitivity of 100% [95% confidence interval (CI) 77% to 100%] and specificity of 68% (95% CI 58% to 76%) during pregnancy, and a sensitivity of 100% (95% CI 78% to 100%) and specificity of 65% (95% CI 53% to 75%) during the postnatal phase.

These results, along with the previous validation study,98 provide initial support for a case-finding approach to rule out perinatal depression; however, rates of FPs were high in both studies. For those women with a positive screen, the additional question about the need for help improved specificity but, in contrast to the original validation study,93 resulted in lower sensitivity. Although the additional help question improved specificity and the ability to rule in perinatal depression, the reduced sensitivity increased the risk of perinatal depression being missed.

In 2014, after commencement of the BaBY PaNDA study, NICE updated its clinical guidelines on antenatal and postnatal mental health. 8,101 As part of this update it conducted a comprehensive systematic review aimed at evaluating appropriate methods and instruments for identifying depression (and anxiety) in women during the perinatal period. Case identification instruments reviewed included the EPDS, the PHQ-9, the Whooley questions and the Kessler-10 (K10). 102 The review identified 57 studies that evaluated the EPDS and two studies that evaluated the Whooley questions (both described above)98,100 against diagnostic gold standard criteria during pregnancy and/or the postnatal period. Based on the results of this review, along with preliminary evidence regarding the cost-effectiveness of a case-finding strategy (see Cost-effectiveness of case-finding instruments for perinatal depression), NICE continued to recommend the use of the two Whooley questions for the identification of depression during pregnancy and the early postnatal period, although the recommendation no longer included the additional question about the need for help. 8 In addition, the use of the EPDS or the PHQ-9, or referral to a general practitioner (GP) or mental health practitioner, was recommended as part of a full assessment if a woman screens positive on the Whooley questions, is at risk of developing a mental health problem or there is a clinical concern.

We are unaware of the publication of any subsequent validation studies that have evaluated the Whooley questions against gold standard diagnostic criteria since NICE issued its updated guidelines (although studies have since been published assessing the Whooley questions against other self-report measures of perinatal depression, e.g. Darwin et al. 103).

Acceptability of case-finding instruments for perinatal depression

The acceptability of the EPDS among most women is widely documented. 76,104 Hewitt et al. 76 conducted a systematic review evaluating the acceptability of the EPDS in the perinatal period. In the majority of the studies reviewed, the EPDS was found to be acceptable to women and HPs when a number of factors were considered, such as the need to forewarn women that they will be asked questions about their mental health; women’s preference for the EPDS to be administered in their home; and the importance of the interpersonal relationship between the woman and the HP.

Since the introduction of the routine use of the Whooley questions for case-finding for perinatal depression in the UK,88 there have been two evaluations103,105 of the acceptability of the Whooley questions among pregnant women and mothers in the postnatal period. Mann et al. 105 conducted an intramixed-methods cohort study, set in an antenatal clinic in an inner-city hospital in the north of England. They asked pregnant women attending a routine appointment at approximately 26 weeks’ gestation to self-complete the Whooley questions, along with a quantitative acceptability survey that included free-text commentaries on their views of the Whooley questions. Women were recontacted at 5–6 weeks postnatally and invited to complete these questionnaires again. A total of 152 and 97 self-report surveys were available for analysis in the prenatal and postnatal phases, respectively. The majority of pregnant (94.7%, n = 144) and postnatal (92.8%, n = 90) women answered ‘yes’ to the question about desirability of asking women about their mental well-being; eight (5.3%) pregnant women and seven (7.2%) postnatal women answered ‘not sure’. The majority of pregnant (99.3%, n = 151) and postnatal (96.9%, n = 94) women indicated that they felt ‘fairly’ to ‘very’ comfortable answering the case-finding questions. Free-text comments revealed that depressed and non-depressed women found the questions ‘easy, simple and straightforward to answer’. 105

The study by Darwin et al. 103 was conducted in an inner-city hospital in Scotland, also in the prenatal period, at the earlier time of around the woman’s booking appointment, typically around 8–10 weeks’ gestation. A purposive subsample of 22 women who had previously completed the Whooley questions (including the help question) as part of their routine clinical care followed by a research questionnaire containing the EPDS (n = 191) were subsequently interviewed. Women’s accounts identified that the context of assessment for depression and the perceived relevance of depression to maternity services influenced a woman’s approach to answering the Whooley questions. The importance of enabling environments has previously been identified when routine assessment for domestic abuse was introduced106 and in previous literature in relation to the acceptability of the EPDS. Practical considerations include the distractions and discomfort associated with completing the questions in a routine health-care clinic rather than at home, where there would be more privacy and time. 104 Furthermore, time constraints and work pressures have been identified as having a negative impact on patient-centredness, whereby a woman’s relationship with her HP is central to her feelings of comfort or discomfort in answering the questions. 107

In light of this limited but insightful evidence, the evaluation of acceptability (EoA) for the BaBY PaNDA study planned to utilise a cognitive framework to further investigate the acceptability of the Whooley questions and the EPDS as case-finding instruments and as individual questions. Cognitive interviewing is a research technique that identifies ‘interpretative measurement error’ as opposed to traditional components of measurement error, such as not reading the question as worded, or recording answers inaccurately. The cognitive interviewing technique provides a framework to measure performance in terms of a woman’s comfort in answering the question, her ease of understanding of the question and her ability to remember, and have confidence in, her answer. One recent study108 used cognitive interviewing techniques to explore patterns in answer mapping and comprehension of the PHQ-9 to ascertain whether or not the measure captures meaningful symptoms of low mood within a general health questionnaire. This study recruited 18 participants at the point of entry to a longitudinal primary care depression cohort study. Cognitive interviewing revealed that items on the PHQ-9 are interpreted in a range of ways, that patients often cannot ‘fit’ their experience into the response options, and therefore often feel that the questionnaire is misrepresenting their experience of meaningful symptoms of low mood.

The EoA for the BaBY PaNDA study utilised a mixed-methods approach with concurrent qualitative and quantitative phases and integrated data analysis. 109 Concurrent in-depth interviews with expectant and new mothers and HPs aim to achieve an in-depth understanding of cognitive acceptability of the Whooley questions and EPDS as case-finding instruments and their delivery in routine care, together with a large-scale acceptability survey to test generalisability of the cognitive performance of the Whooley questions and the EPDS. The opportunity to nest the cognitive evaluation within the cohort of women whose views and experiences of completing the case-finding instruments are grounded within the research study and their routine health-care assessments in the prenatal and postnatal periods will further enhance the strength of the in-depth interview technique. 110–112

Cost-effectiveness of case-finding instruments for perinatal depression

Perinatal depression is a growing public health concern; a substantial body of evidence suggests that it is associated with significant personal burden for the woman, her partner and child, both in the short and longer term (see above). Less is known about the economic costs of perinatal depression. A small UK-based study113 estimated the economic burden of postnatal depression to UK health and social services to be around £54M annually (range from £52M to £65M), although it has been suggested this figure may represent an underestimation of the true economic cost of the condition. 8 Mean mother–infant costs over 18 months after birth have been found to cost an additional £591 (uplifted to 2013 prices8) for women experiencing postnatal depression. 113 The health and social care costs associated with fathers with depression or fathers at risk of depression during the postnatal period is an additional £159 and £130, respectively, compared with fathers with no depression (£945) (at 2008 prices). More recent UK estimates calculate the cost consequences of adverse child outcomes for perinatal depression at around £8190 per child [including public sector costs, costs of reduced earning and costs associated with reduced health-related quality of life (HRQoL)]. 114 This evidence makes the case for identifying cost-effective approaches for screening/case-finding and treating perinatal depression.

Cost-effectiveness analysis is fundamental to decision-making. It brings together data on diagnostic performance of screening/case-finding strategies, prevalence of depression, relative treatment effects of therapies offered to positive cases, opportunity cost of incorrect diagnoses, and the costs and health benefits associated with diagnostic outcomes. The analysis is commonly conducted within the framework of a decision model that explicitly evaluates the clinical pathways and associated costs and outcomes;115 it then considers the value for money of screening/case-finding strategies in relation to willingness to pay (WTP) for health benefits as determined by the decision-maker. 116

In the UK context, we identified two recent cost-effectiveness models that evaluated case-finding strategies in the postnatal period: the decision model developed by Paulden et al. 81 and a second model reported in the NICE guidance on antenatal and perinatal mental health, issued in 2014. 8,81 Here we discuss both models in detail. We did not find any cost-effectiveness models for the prenatal period.

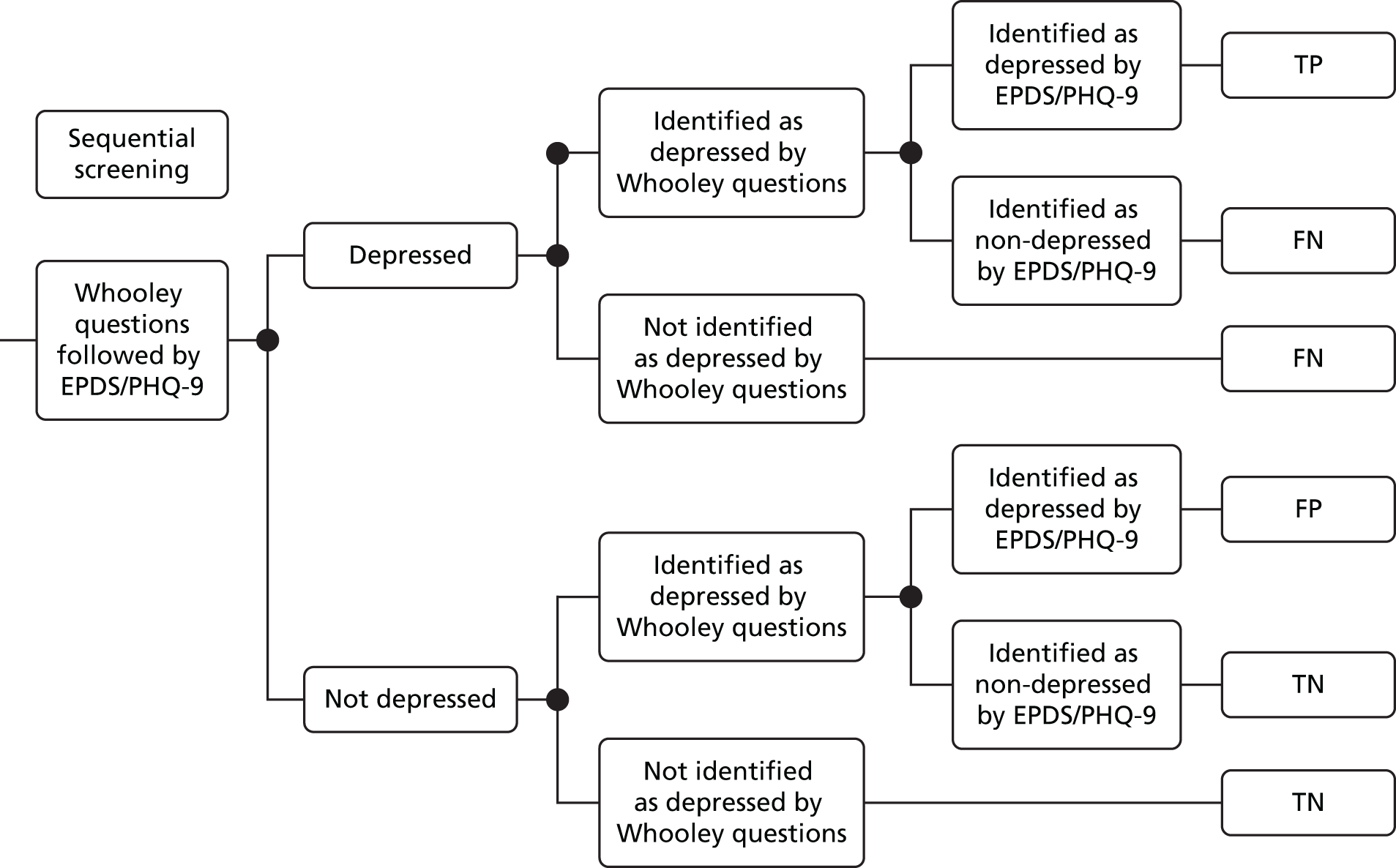

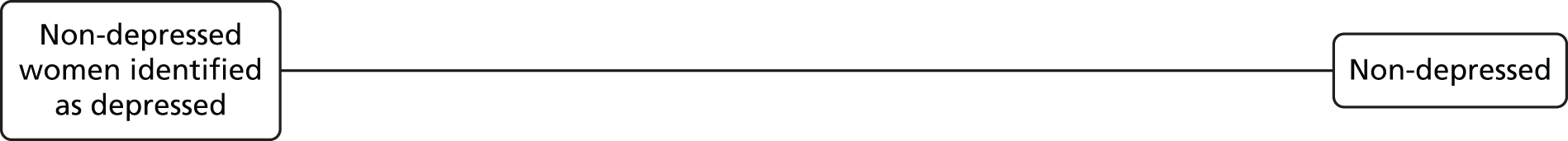

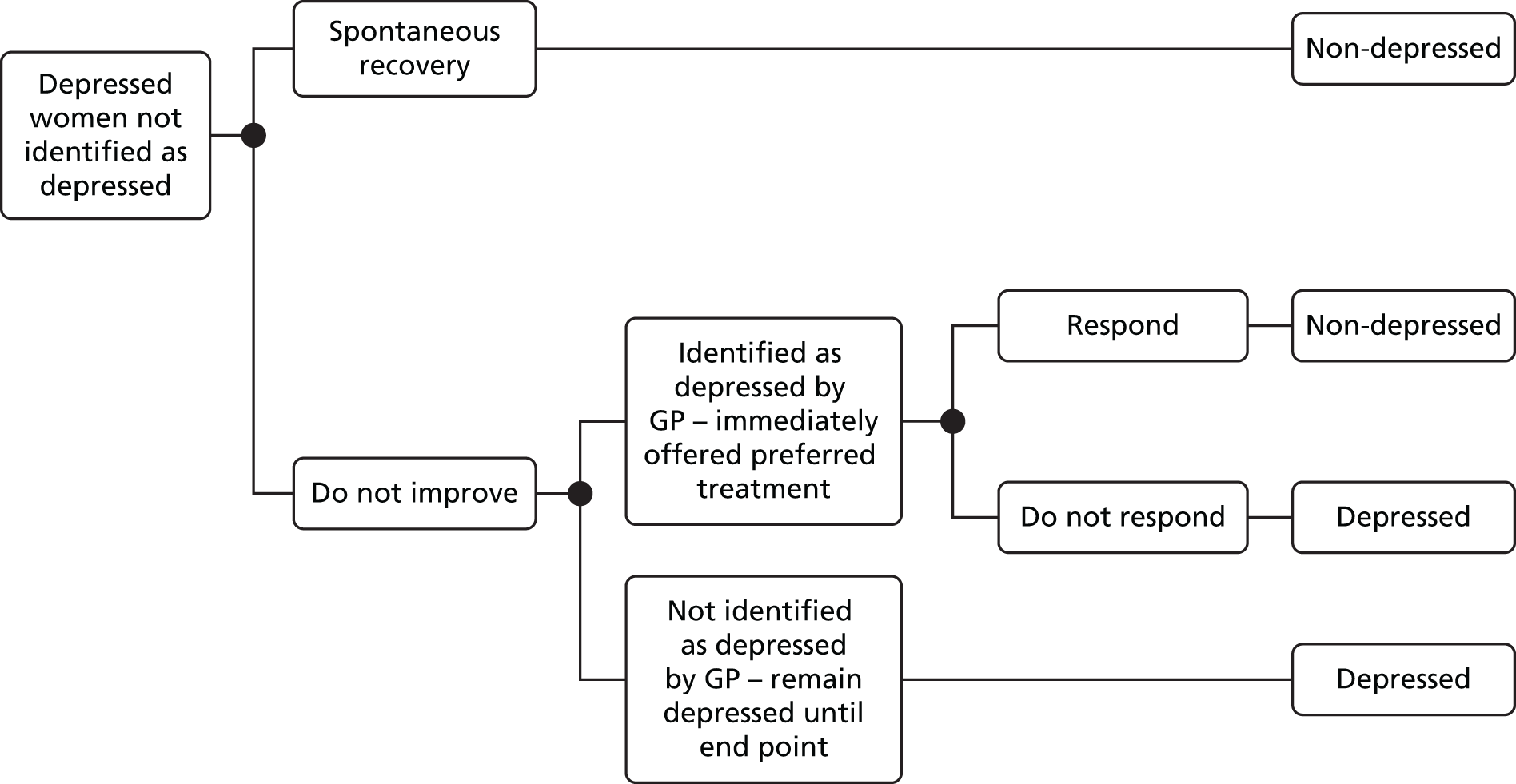

Paulden et al. 81 evaluated cost-effectiveness of using case-finding instruments to complement routine care case identification by a GP or HV. The case-finding instruments were given only to women who were identified as depressed in routine care (hence, they were not used as primary case-finding strategies). Paulden et al. 81 compared the EPDS, Beck Depression Inventory117 and Whooley questions with no complementary screening/case-finding. The model had two linked components: a diagnostic model and a treatment model. In the diagnostic model, women who were identified by their GP/HV as possibly depressed were given one of the above-mentioned instruments, and were then classified as true positive (TP), FP, true negative (TN) or false negative (FN) by case-finding strategies. A treatment model followed the diagnostic model for those who were identified as TP or FP. In line with the NICE guidance available at the time, positive cases were offered structured psychological therapy with additional care. 7 Women who were FN were assumed either to improve spontaneously or to be identified by their GP through routine care and offered the same treatment as above. TN cases did not receive any further treatment. The model derived diagnostic accuracy data by conducting a diagnostic meta-analysis. Resource use data were based on published data sources, whereas unit costs were derived from national cost databases. The model used the NHS and social services perspective and a time horizon of 1 year after screening/case-finding.

Paulden et al. 81 found that complementing routine case-finding with a formal screening strategy (i.e. EPDS, Beck Depression Inventory or Whooley questions) was not cost-effective at conventional WTP thresholds used in the UK (£20,000–30,000) for a gain of 1 quality-adjusted life-year (QALY). All of the above case-finding strategies were associated with an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) of > £40,000 per QALY. In a sensitivity analysis that assumed that FP cases would incur lower costs of treatment, the EPDS (cut-off point of ≥ 10) was found to have an ICER of £29,186 per QALY (i.e. just below the highest conventionally used threshold). Another conclusion of the study was that using Whooley questions was never a cost-effective option as a complementary case-finding instrument.

The Paulden et al. 81 model has a number of limitations. First, it evaluates case-finding instruments as complementary to routine case-finding, rather than as primary case-finding strategies. This is an important limitation for the UK decision-making context because the above instruments are commonly used as primary case-finding strategies by HVs. Moreover, it is not clear whether or not one or more of these instruments are already part of the initial case identification by the GP. Second, the study assumes that women who are identified as depressed by the HV/GP but incorrectly diagnosed as non-depressed by the case-finding instrument will still be considered positive and offered treatment. The NICE report also highlights that the Paulden et al. 81 model assumed a zero false-positive rate (FPR) for standard care, which is unrealistic. 8 Third, the Paulden et al. 81 model did not consider two-stage sequential screening/case-finding after implementing Whooley questions to improve specificity of case-finding – this is highly relevant to the context of perinatal depression owing to the high FPR of Whooley questions. Finally, some of the key parameters in the model (including, diagnostic performance of Whooley questions, and quality-of-life data) were based on the general population of depressed patients in primary care, rather than the postnatal population.

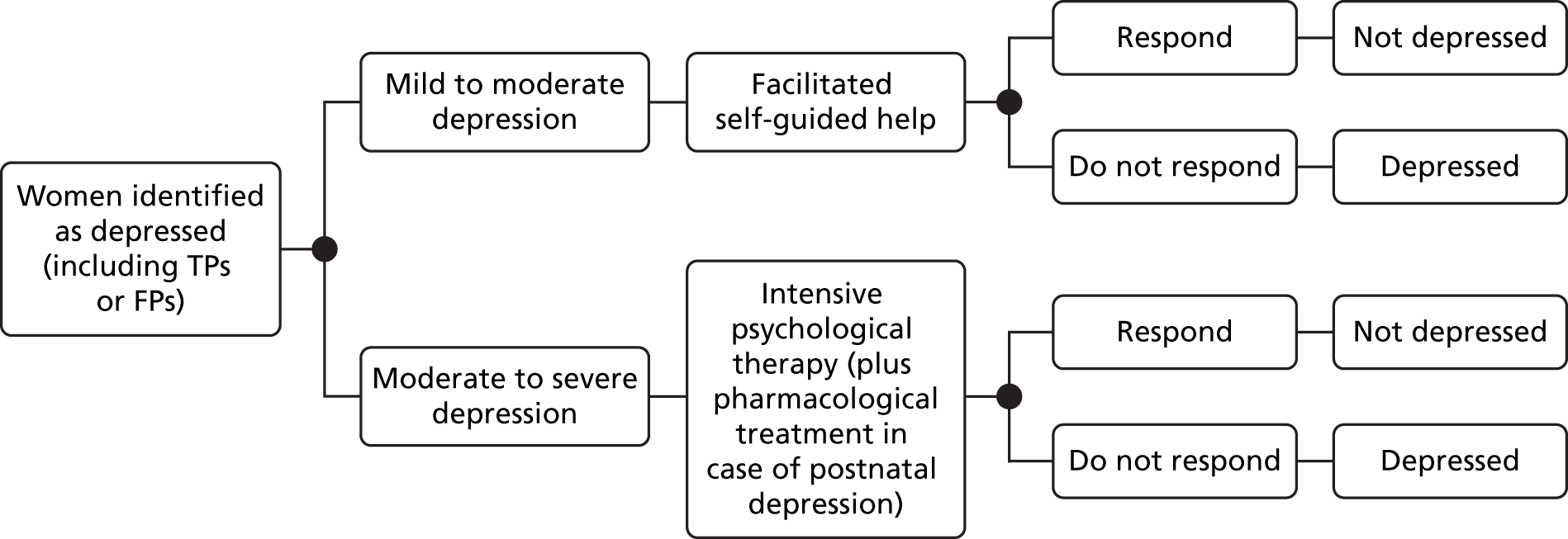

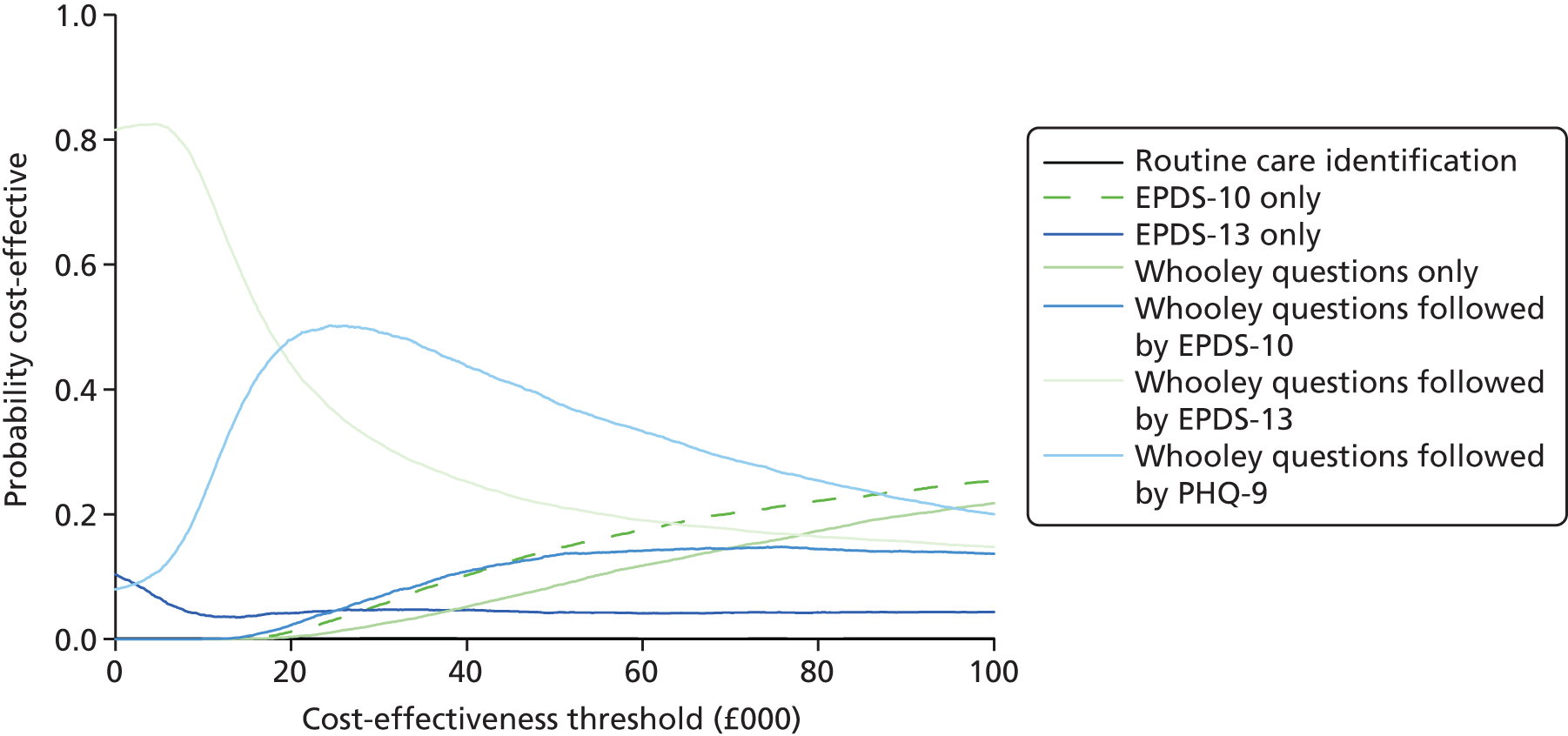

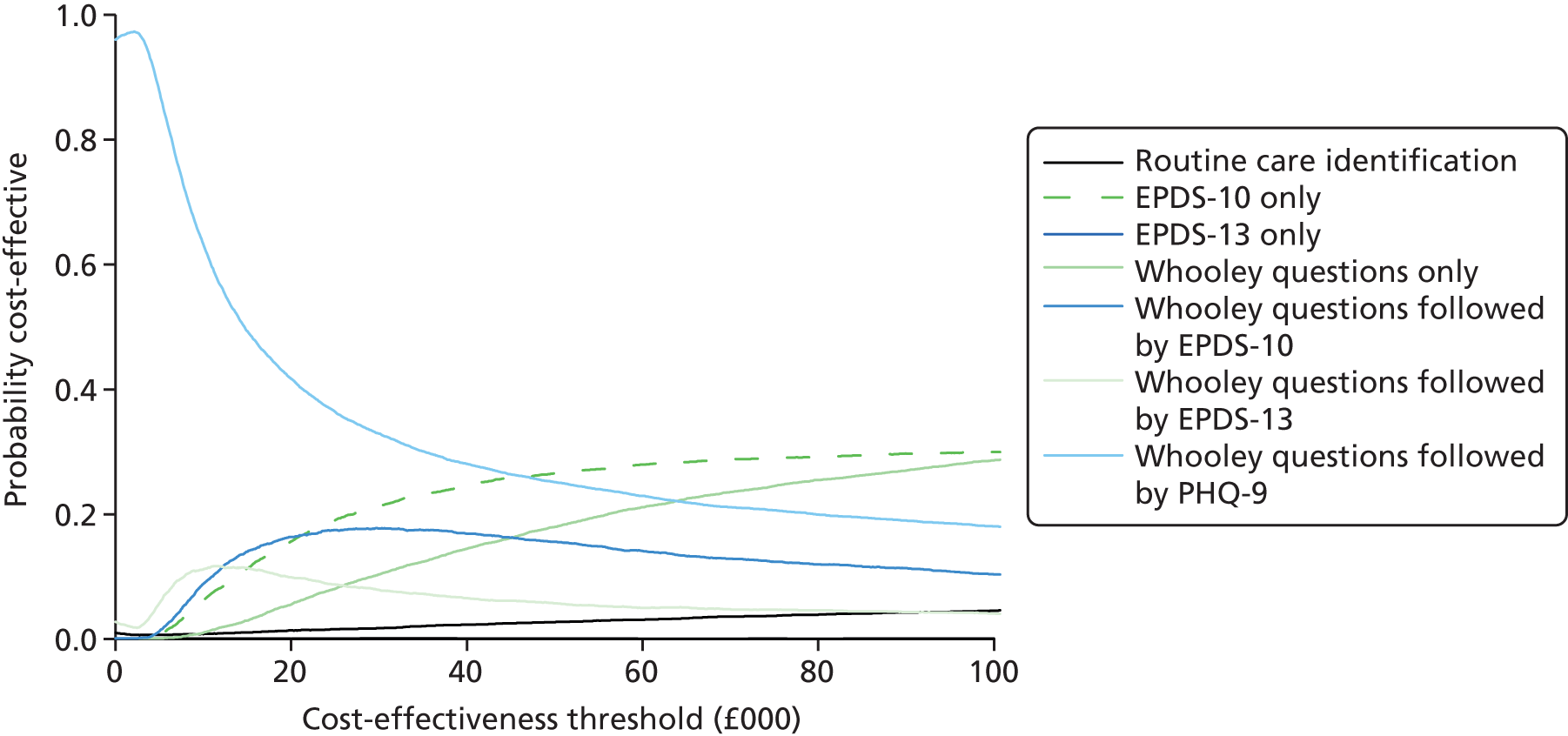

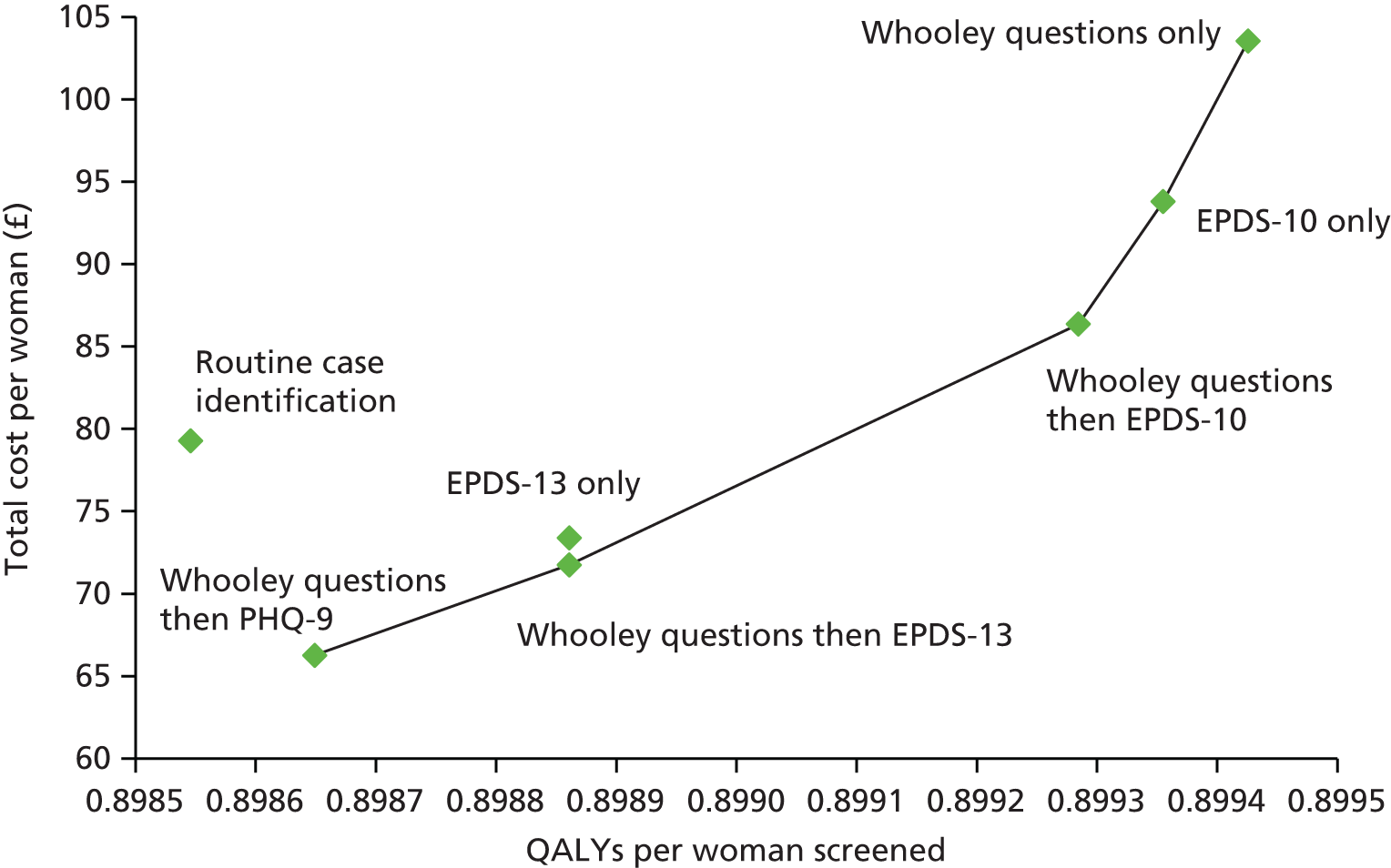

Based on the above limitations, the most recent NICE guidance,8 issued in 2014, developed a new model to compare cost-effectiveness of case-finding instruments as primary case-finding strategies. Our cost-effectiveness analysis is based on this NICE model; hence, a detailed description of this model is presented in Chapter 7 of this report and a brief summary of the model is presented here. The NICE cost-effectiveness model also had diagnostic and treatment components. However, unlike the Paulden et al. 81 model, it evaluated both one- and two-stage case-finding strategies using Whooley questions only, EPDS only (cut-off point of ≥ 10), Whooley questions followed by EPDS (cut-off point of ≥ 10), Whooley questions followed by PHQ-9 (cut-off point of ≥ 10) and routine care case-finding. TP and FP cases received either facilitated self-help (FSH) (72% of cases with mild to moderate depression), intensive psychological therapy (20% of cases with moderate to severe depression) or pharmacotherapy with sertraline (Zoloft®, Pfizer) (8% of cases with moderate to severe depression). FP cases were assumed to receive 20% of the TP treatment (based on the clinical advice from the Guidance Development Group), and were also assumed to have utility reduction by 2% as a result of false diagnosis. As in the case of the Paulden et al. 81 model, the NICE model8 assumed that FN cases would spontaneously recover (33%), be diagnosed through routine care (8%) or remain depressed. The model used the NHS and social services perspective and a time horizon of 1 year from birth.

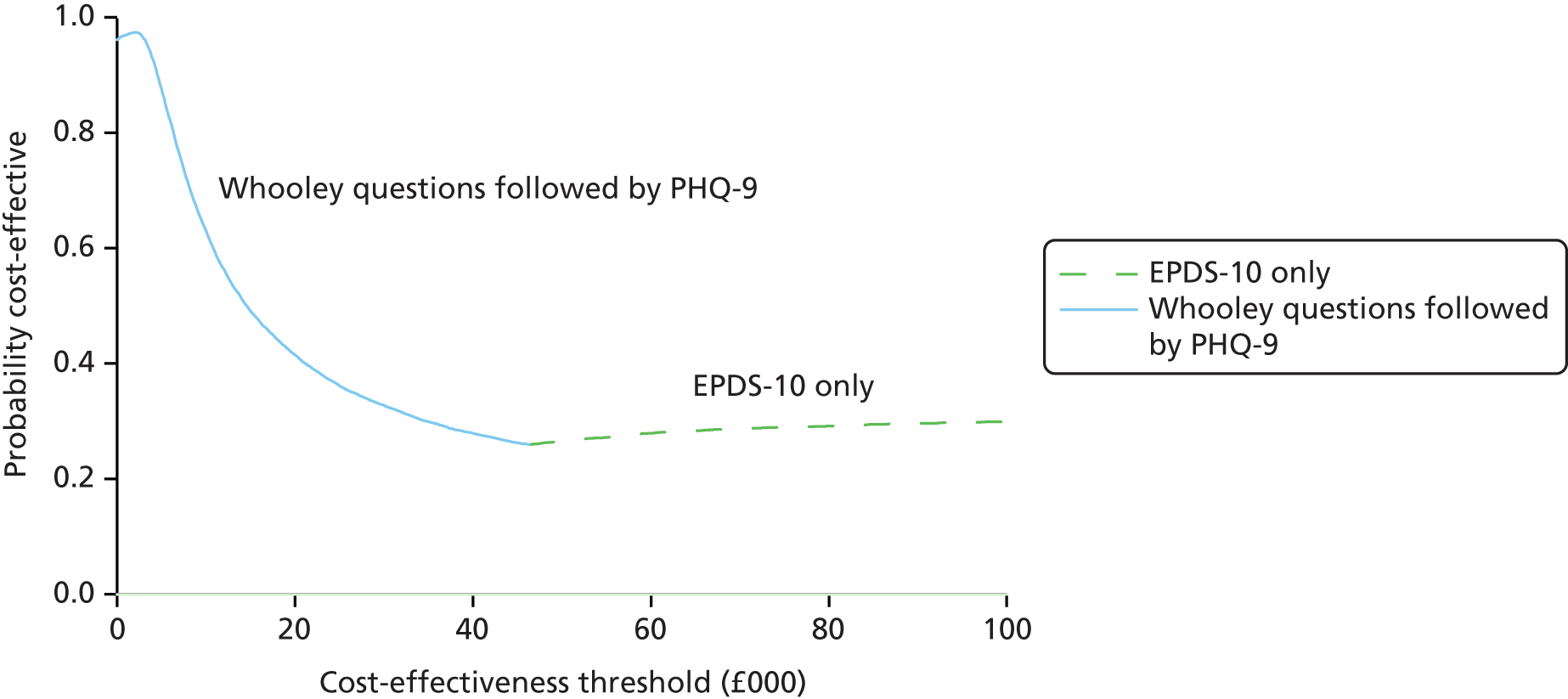

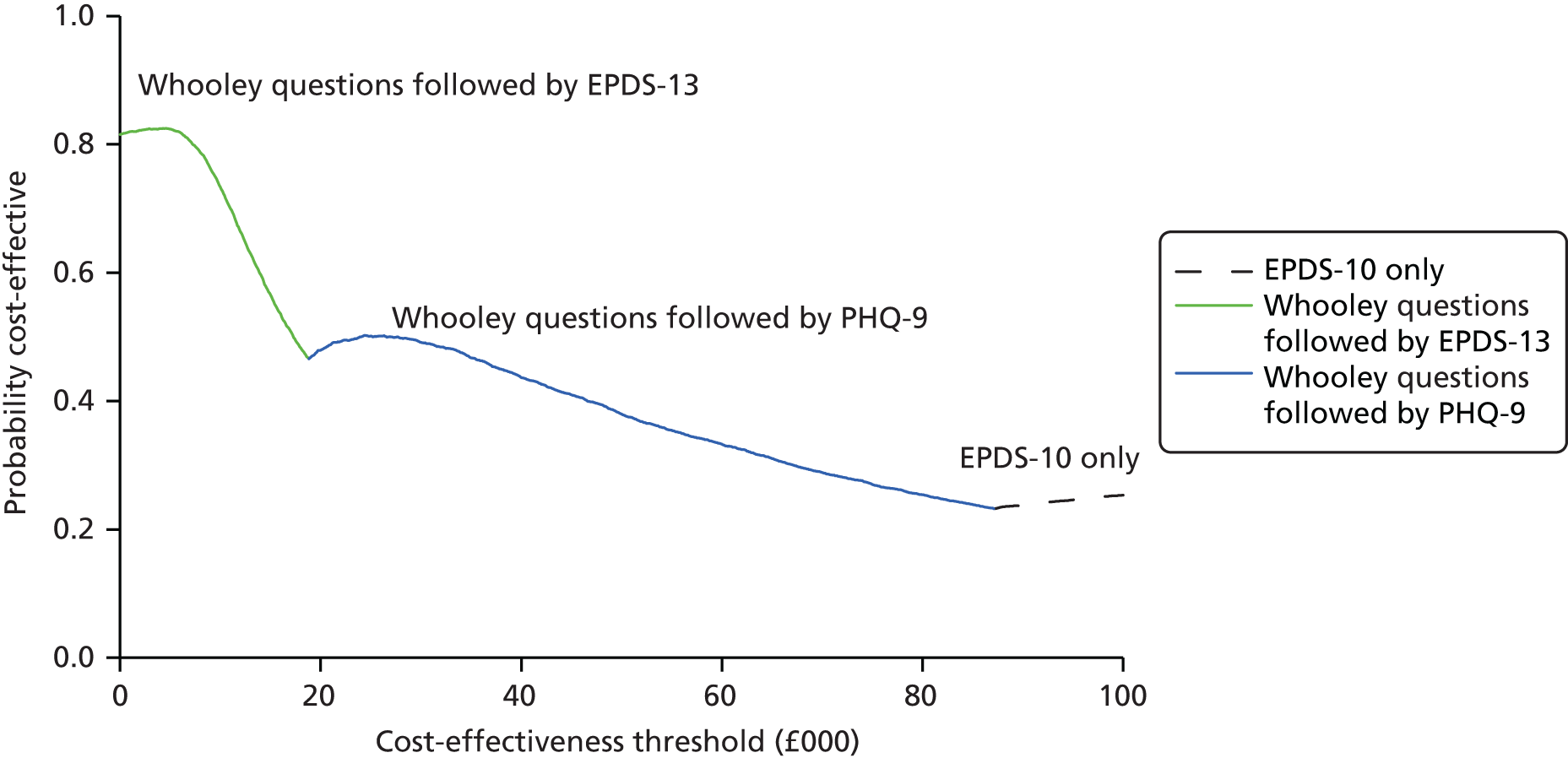

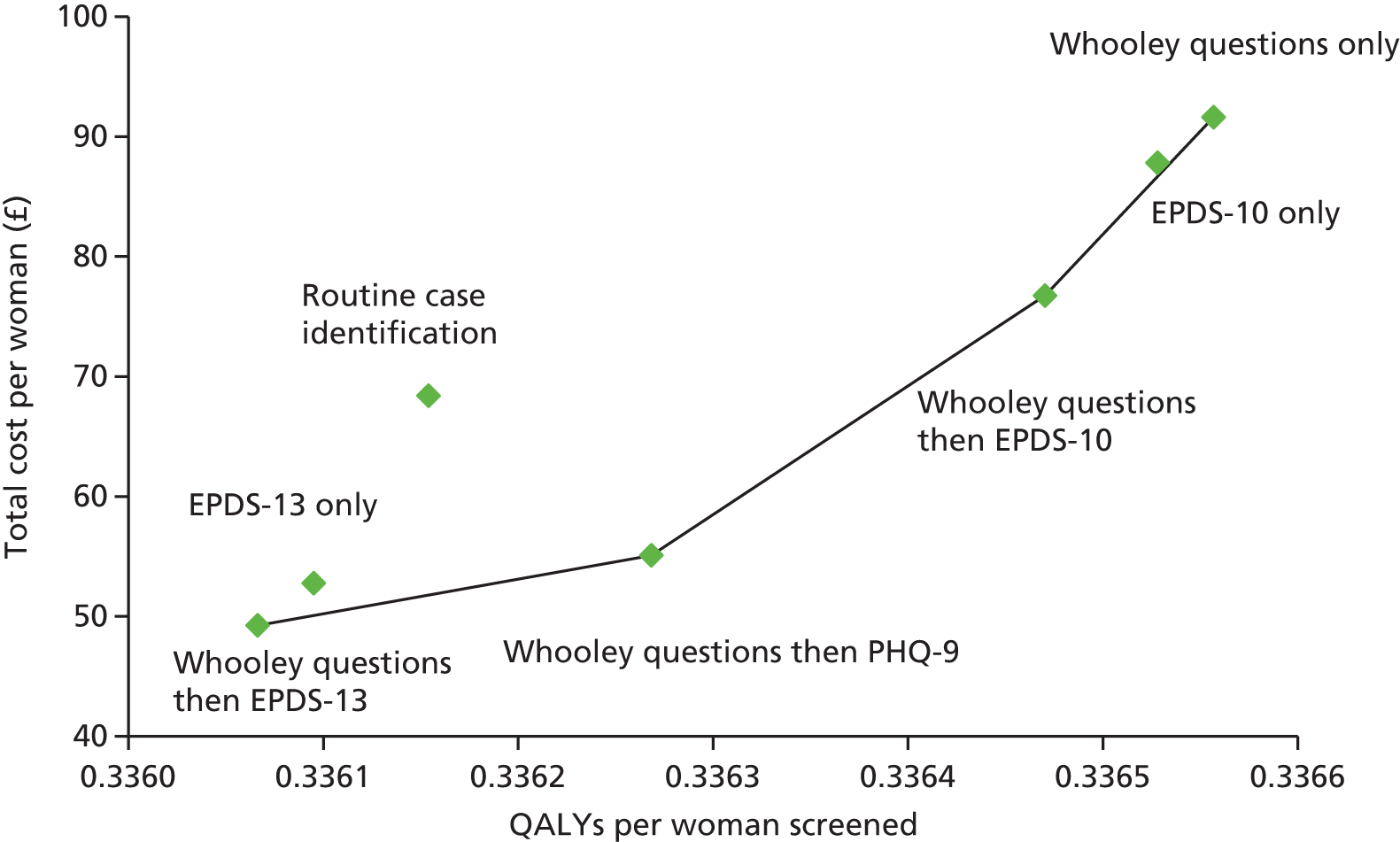

The NICE model8 found that ‘Whooley questions followed by PHQ-9’ was the most cost-effective case-finding strategy in the postnatal period. This was also the cheapest strategy, at £75,354 per 1000 women screened, with total QALYs of 751.98. The ICER compared with the next cheapest strategy, ‘Whooley questions followed by EPDS (cut-off point of ≥ 10)’, was £45,593 per QALY, which is above the conventionally used WTP threshold. Moreover, the model found that ‘EPDS only’ and routine care case identification were dominated by other strategies. One-way sensitivity analysis found that ‘Whooley questions followed by EPDS (cut-off point of ≥ 10)’ would be cost-effective only if the prevalence of postnatal depression was approximately 20%, which is higher than the prevalence reported in most published studies. The report also highlighted that the results were highly sensitive to the diagnostic performance of the instruments, although ‘Whooley questions alone’ was never a cost-effective strategy. Finally, the results were also sensitive to the consultation time required to conduct screening/case-finding such that, when consultation time of EPDS was reduced, ‘Whooley questions followed by EPDS’ became the most cost-effective strategy.

It should be noted that, although the differences presented per 1000 women appear to be large, these are small differences per individual woman. For instance, per woman screened, the difference in QALYs between ‘Whooley questions followed by EDPS’ and ‘Whooley questions followed by PHQ-9’ was only 0.0001 and the difference in cost was only £5.20. This gives a large ICER of £45,593 per QALY; however, the difference in terms of net monetary benefit [i.e. (QALYs × WTP threshold) – cost] per woman was only £2.96 at a WTP threshold of £20,000 per QALY. This shows that the difference between strategies in terms of net monetary benefit is very small.

The NICE model is highly relevant to the UK decision-making context and makes useful comparisons between one- and two-stage strategies that are relevant to clinical practice. However, the model has a few limitations. First, diagnostic performance data for PHQ-9 are not specific to the postnatal population. Second, owing to lack of data on second-stage diagnostic performance, the model assumes that sensitivity and specificity of Whooley questions and subsequent use of EPDS or PHQ-9 are independent of each other (i.e. sensitivity and specificity of first-stage screening/case-finding holds at the second stage). This is clearly an important limitation of the model. Third, the model is deterministic and does not take account of uncertainty in parameter estimates [i.e. it does not include a probabilistic sensitivity analysis (PSA) to account for distributions of input parameters]. This is important in estimating the probability of each strategy being cost-effective at different WTP threshold levels. Given small differences in the deterministic results, the probabilistic analysis may play an important role in understanding decision uncertainty.

We note that both models highlight the significance of diagnostic performance of screening/case-finding strategies in general, and specificity in particular. Both models found that the screening/case-finding strategies that had the highest specificity had the highest probability of being cost-effective. This is because, given the prevalence of postnatal depression, a small change in specificity results in a large number of FP cases that are unnecessarily treated and therefore incur high costs. Moreover, regarding the cases that are missed due to low sensitivity, a significant proportion of them either recover spontaneously during the follow-up period or are identified as depressed in routine care. Likewise, the relatively modest treatment effects of therapies imply that the health benefit of higher sensitivity only results in modest gains in health benefits that are partly offset by reduction in quality of life of FP cases. In conclusion, specificity has been found to be an important factor in the cost-effectiveness of screening/case-finding strategies in perinatal depression.

Chapter 2 Research objectives

The overall purpose of this research was to determine the diagnostic accuracy, acceptability and cost-effectiveness of case-finding questions to identify perinatal depression in women. The objectives of the study were as follows.

-

Instrument validation: to determine the diagnostic accuracy of the Whooley questions and the EPDS against a diagnostic reference standard for the identification of depression during pregnancy (around 20 weeks) and the early postnatal period (around 3–4 months after birth).

-

Longitudinal assessment: to assess the temporal stability of positive and negative depression screens between pregnancy and the early postnatal period, and to ascertain whether or not there is an optimal time to screen for perinatal depression.

-

Assessment of comorbidity: to investigate the coexistence of depressive symptoms alongside other common mental health problems during the perinatal period.

-

Evaluation of Acceptability: to determine the acceptability of the Whooley questions and the EPDS to expectant and new mothers and to HPs, and to determine the potential implications for the care pathway during the perinatal period.

-

Estimates of cost-effectiveness: to assess the cost-effectiveness of the Whooley questions and the EPDS as case-finding strategies for the identification of perinatal depression.

Chapter 3 Methods

Some of this information is reported in Littlewood et al. 118

Study design

The BaBY PaNDA study was a prospective diagnostic accuracy study of two depression case-finding instruments in a UK perinatal population. The NICE-endorsed (‘ultra-brief’) Whooley questions and the EPDS (the index tests) were validated against a diagnostic gold standard clinical assessment of depression [the Clinical Interview Schedule – Revised (CIS-R)119 as the diagnostic reference standard], during pregnancy (around 20 weeks) and the early postnatal period (around 3–4 months postnatally). Women were followed up 12 months postnatally to provide a longitudinal assessment of psychological comorbidity during pregnancy and the first postnatal year. The study included a concurrent qualitative evaluation of the acceptability of the Whooley questions and the EPDS to women and HPs, and a concurrent economic evaluation of the cost-effectiveness of routine screening/case-finding for perinatal depression. The study was embedded within the framework of the existing Born and Bred in Yorkshire (BaBY) cohort study (described in BaBY cohort).

Approvals

The BaBY PaNDA study was submitted as a substudy of the existing BaBY cohort study and received approval from North East – York Research Ethics Committee (REC) on 23 April 2013 (reference number: 11/NE/0022) and was subsequently approved by the relevant NHS trust’s research and development (R&D) committees.

BaBY cohort

Born and Bred in Yorkshire is a population-based cohort of babies and their parents. It was established in 2011 and recruited women during pregnancy, their partners and babies. Data were collected on a range of clinical outcomes during pregnancy, labour and the neonatal period, including obstetric and maternal morbidity, mental and physical health, and infant health. Data were also collected on the psychological well-being of women and their partners during pregnancy (around 26 weeks of gestation) and for 12 months after their baby’s birth (at around 8–12 weeks and 12 months postnatally). The cohort initially recruited for 1 year in York and later extended recruitment to Harrogate, Hull, and Scunthorpe and Goole – representing a target area with around 13,500 births each year. Recruitment to BaBY was estimated at around 60% of women booked for delivery within each of the four regions (further details about recruitment to BaBY are described in Recruitment).

The BaBY cohort was a collaboration between the Mental Health and Addiction Research Group and the Epidemiology and Cancer Statistics Group within the Department of Health Sciences at the University of York, Hull York Medical School and colleagues within local NHS trusts. The overarching aim of the BaBY study was to establish a local infrastructure, accessible to the NHS and other health researchers, that should provide a high-quality resource with which to explore questions of real clinical importance to the NHS and other health researchers. Data collected as part of the BaBY study gives potential for wide-ranging research in many areas of adult and child health, including investigation of short- and long-term outcomes.

Study sites

The BaBY PaNDA study was conducted across four regions within Yorkshire and the Humber, and North Lincolnshire: Harrogate, Hull, Scunthorpe and Goole, and York.

Participant eligibility

Eligible women were identified from the wider BaBY cohort. All women invited to take part in the BaBY PaNDA study had previously provided their consent to take part in the BaBY cohort study.

Inclusion criteria

Limited inclusion criteria were applied to ensure recruitment of a representative sample of pregnant women from the wider BaBY cohort sample. Pregnant women were eligible to take part in the BaBY PaNDA study if they met the following criteria.

-

They had consented to take part in the wider BaBY cohort and had agreed to be contacted again as part of that consent.

-

They were < 20 weeks pregnant.

-

They were aged ≥ 16 years.

-

They currently lived in an area covered by one of the four study sites.

Exclusion criteria

Women were excluded from taking part in the study if they met any of the following criteria:

-

They were non-English speaking.

-

They were > 24 weeks pregnant at the time of receipt of a completed consent form.

Women with literacy difficulties were not excluded from taking part; in these cases, all study information and questionnaires were read out to them by the study researcher.

Recruitment

Recruitment to the BaBY cohort

Recruitment to the BaBY cohort took place between August 2011 and March 2015. Women were invited to take part in the BaBY study at around 12–14 weeks of gestation by a member of the midwifery team responsible for their care, or by a trained member of the BaBY team, either at their first antenatal appointment (which may be with their community midwife or in a hospital antenatal clinic) or at the time of their first ultrasound scan. At this point, women were given a study information pack, containing a parent information leaflet, maternal and partner consent forms, a family details sheet and a pre-paid return envelope. Consent forms for both parents were given to the woman; it was for the woman to decide whether or not to give the consent form to her partner. Parents could either provide their written informed consent by completing a consent form at the time of discussing the study with a member of the midwifery or BaBY team or by posting a completed consent form to the BaBY research team. Parents could also choose to consent to the study online using a secure website.

Recruitment to the BaBY PaNDA study

Recruitment to the BaBY PaNDA study took place over a 14-month consecutive period from July 2013 to August 2014. All pregnant women who consented to participate in BaBY and who met all the BaBY PaNDA inclusion criteria (including having provided their consent to be contacted again) were invited to take part in the BaBY PaNDA study.

Eligible women were sent a study information pack at around 15–18 weeks of gestation containing an invitation letter, participant information sheet (providing full details of the study), a summary information sheet (describing the key aspects of the study), a consent form, a contact details sheet and a pre-paid return envelope (see Appendix 1). Both the participant and summary information sheets provided contact details for the project team should any women wish to discuss the study in further detail before making a decision on whether or not to participate. The summary information sheet was also made available to women who were interested in taking part in the BaBY cohort either during visits to hospital antenatal clinics and/or during contact with members of the BaBY study team. Women interested in taking part in the study were asked to complete and return the consent form and contact details sheet to the BaBY PaNDA research team. Women who did not return a completed consent form within 2 weeks of being sent the study information pack were contacted by a member of the BaBY team to provide an opportunity to discuss the BaBY PaNDA study and to provide them with an opportunity to ask any questions they may have about the study. Women were contacted by telephone, e-mail or text, depending on the method(s) of contact they had provided as part of their consent to the BaBY cohort study. Women who were interested in participating in the BaBY PaNDA study following this contact were still required to complete a consent form and return this to the BaBY PaNDA research team.

On receipt of a completed consent form, women were contacted by a member of the BaBY PaNDA research team to arrange their prenatal assessment (see Assessments). During this contact, the researcher provided an overview of the study, confirmed that the woman understood why the research was being conducted and what she would be asked to do during the study, and answered any questions that the woman may have about the study. One copy of the woman’s completed consent form was sent to her GP (with the woman’s consent) along with a letter informing them that their patient had been included in the study and a copy of the participant information sheet. Women who were > 24 weeks pregnant at the time of receiving their completed consent form were advised that they were no longer eligible to take part in the BaBY PaNDA study.

Information about the BaBY cohort and BaBY PaNDA study was sent to all GP practices in the recruiting regions and were displayed (when possible) in locations where pregnant women attend as part of their maternity care pathway [e.g. antenatal clinics, National Childbirth Trust (NCT) classes, GP surgeries, children’s centres] and was provided online via the BaBY cohort website. Information about the studies was also promoted via regional press releases and local press activities.

Assessments

Women undertook three assessments during the course of the study:

-

prenatal stage – prenatal assessment (at around 20 weeks of gestation)

-

postnatal stage – postnatal assessment (at around 3–4 months postnatally)

-

follow-up stage – follow-up assessment (at around 12 months postnatally).

The diagnostic accuracy of the two depression case-finding instruments (the Whooley questions and the EPDS) was determined against a diagnostic gold standard clinical assessment of depression (the CIS-R119) at two time points: the prenatal stage and the postnatal stage.

The Whooley questions, EPDS and CIS-R were also completed at the follow-up stage to determine the prevalence of depressive symptomatology 12 months postnatally. Additional measures were also completed at each of the three stages (prenatal, postnatal and follow-up) to provide a longitudinal assessment of psychological comorbidity, HRQoL, acceptability and resource use (see Additional outcome measures).

Diagnostic accuracy measures

The study involved validating two separate index tests, the Whooley questions and the EPDS, against the same diagnostic reference standard, the CIS-R, at two time points: the prenatal stage and the postnatal stage. The index tests were completed before the diagnostic reference standard. At each of the two stages, the index tests and diagnostic reference standard were completed within the same assessment session by one researcher. If it was not possible for women to complete the index tests and diagnostic reference standard within the same assessment session, the diagnostic reference standard was completed within 2 weeks of women completing the index tests; if this time elapsed, the diagnostic reference standard was not completed.

Index tests

Whooley questions

Women were asked the two Whooley89 questions verbatim by a study researcher at the prenatal, postnatal and follow-up stages:

-

During the past month, have you often been bothered by feeling down, depressed or hopeless?

-

During the past month, have you often been bothered by having little interest or pleasure in doing things?

A ‘yes’ or ‘no’ response was required for each question. A ‘yes’ response to either question 1 or 2 was considered a ‘positive screen’ for perinatal depression; in these cases, women were then asked the ‘help’ question (question 3), which required a ‘yes’, ‘yes, but not today’ or ‘no’ response:

-

Is this something you feel you need or want help with?

Women who responded ‘yes’ to this help question were advised to speak to their GP [and any other HP, such as a midwife (MW) or HV] about their feelings and symptoms and that information about perinatal depression could be found on the NHS website.

The Whooley questions have been previously validated in primary care populations89,93 and a number of clinical populations. 120–122 As detailed in Chapter 1, the Whooley questions have since been validated against diagnostic criteria in two perinatal populations;98,100 these reported sensitivities of 100% and specificity in the range 44–68%.

The Whooley questions were chosen as the primary index test of investigation, as these were the questions recommended by NICE for use by HPs to aid the identification of depression during the perinatal period7 and validation studies conducted in a perinatal population were limited (at the time of commencement of the study).

Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale

Women self-completed the EPDS79 at the prenatal, postnatal and follow-up stages. The EPDS is a 10-item self-report questionnaire measuring depression symptoms over the past 7 days (e.g. ‘I have been anxious or worried for no good reason’, ‘I have been so unhappy that I have had difficulty sleeping’, ‘I have felt sad or miserable’). Each item is scored on a 4-point Likert scale (0–3) with a total score ranging from 0 to 30, with higher scores indicating a greater degree of depression symptomatology. Hewitt et al. 76 report an optimal cut-off point of 13 to detect major depression and a cut-off point of 10 to detect major and minor depression combined. A recent comprehensive review by NICE8 reported pooled sensitivity in the range of 68–83% and specificity of 85–92% for detecting combined depression in the postnatal period when applying these cut-off points. For detecting combined depression in pregnancy, pooled sensitivity in the range of 61–74% and specificity in the range of 86–94% have been reported when applying these cut-off points.

The EPDS was chosen as one of the index tests of investigation as it has been shown to be the most commonly used measure to detect symptoms of postnatal depression in maternity and child services. 123,124 It has also been validated for use in pregnancy. 125 The EPDS is widely used in perinatal mental health research including both prenatal and postnatal populations. 126

Time taken to administer index tests

The time taken to administer each of the index tests (Whooley questions and EPDS), to include time taken to introduce the questionnaire, time taken to ask the questions (Whooley questions) or provide women with the questionnaire for self-completion (EPDS), time taken for women to provide their responses, and time taken for researchers to record women’s responses, were recorded at the prenatal and postnatal stages using a pre-specified template (see Appendix 2). These data were used to calculate administration costs as part of the economic evaluation (see Chapter 7).

Diagnostic reference standard

Women self-completed the computer-based version of the CIS-R. 119 The CIS-R is a fully structured assessment that assesses 14 symptom domains including depression/depressive ideas, anxiety, somatic symptoms, worry, sleep, fatigue, panic, phobias, compulsions, obsessions, irritability, concentration and worry over physical health. It generates diagnostic categories (including depression severity and diagnosis) according to the ICD-10 criteria10,127 and provides basic demographic information (e.g. age, sex, ethnic group, employment status and type, and housing type).

The CIS-R has been validated in primary care samples with good reliability and has been used in national psychiatric morbidity surveys. 119,128 It has also been validated for use over the telephone. 129 It has been included as a diagnostic gold standard in systematic reviews of case-finding instruments for common mental health problems, including perinatal depression. 8,76,130

In an attempt to minimise the potential for incompletion of the diagnostic reference standard, and thereby reducing the study’s statistical power to estimate the diagnostic performance characteristics of the index tests, the study design involved one researcher administering both the index tests and the diagnostic reference standard in a single session. The CIS-R was therefore chosen as the diagnostic reference standard due to its self-complete format; the researcher was required only to set up and initiate the CIS-R program. Instructions on how to complete the CIS-R were provided as part of the program (although the researcher was present to ask any questions if necessary; see Blinding of index test and diagnostic reference standard results).

Blinding of index test and diagnostic reference standard results

The index tests were completed before the diagnostic reference standard and both the index tests and the diagnostic reference standard were administered in the same session by one researcher. Therefore, the results of the index tests were known to the researcher before the woman completed the diagnostic reference standard. However, despite this design, the level of potential bias within an assessment session was considered minimal; the EPDS (index test) and CIS-R (diagnostic reference standard) are both self-reported measures that women self-completed on paper (EPDS) or on a computer (CIS-R) with only minimal interaction with the researcher (as described above).

However, although the researcher did not specifically ask, women could provide information about their circumstances (current or past) at any point during the assessment session. To capture any potential sources of bias during the assessment session, researchers completed a ‘participant assessment record sheet’ (PARS) following all assessment sessions with women (see Appendix 3). This included recording details of any questions raised by women during completion of the index tests and diagnostic reference standard; any other additional outcome measures completed as part of the assessment session (see Additional outcome measures); and any information provided by the woman about her circumstances (current or past), such as whether she currently has or has previously had depression, if she is receiving any treatment for depression, etc.

In order to maintain blinding of index tests and diagnostic reference standard results across the different assessment stages (prenatal stage to postnatal stage, and postnatal stage to follow-up stage), the assessments of each woman were conducted by different researchers (unless it was deemed more sensitive for the same researcher to conduct all assessment sessions).

The level of potential bias recorded within the study is reported in Appendix 4.

Additional outcome measures

Women completed a number of additional outcome measures at each of the three stages (prenatal, postnatal and follow-up) to provide a longitudinal assessment of psychological comorbidity, HRQoL, acceptability and resource use during pregnancy and the first postnatal year.

Psychological comorbidity

Outcome measures assessed a range of psychological comorbidities using a number of validated self-report questionnaires administered at the prenatal, postnatal and follow-up stages. Women completed the following questionnaires.

Patient Health Questionnaire-9

The PHQ-991 is a nine-item self-report questionnaire that assesses depression severity and symptomatology over the previous 2 weeks based on DSM diagnostic criteria for major depressive disorder. Each item is rated on a scale of 0–3 based on the frequency of depressive symptoms (0 = ‘not at all’ to 3 = ‘nearly every day’). A cut-off point of ≥ 10 is known to detect clinical depression in a UK primary care population. 131 It has been shown to have good sensitivity (74–85%) and specificity (73–84%) for detecting major depression in pregnancy, and excellent sensitivity (82–89%) and moderate specificity (65–84%) for detecting major depression in the postnatal period. 8 It is one of the instruments (along with the EPDS) recommended by NICE as part of further assessment if perinatal depression is suspected following initial case-finding with the Whooley questions. 7,8

Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7

The Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7)132 is a seven-item self-report questionnaire rating anxiety symptoms over the previous 2 weeks. Each item is scored on a four-point scale (0 = ‘not at all’ to 3 = ‘nearly every day’). It has been validated in primary care samples,132–134 although current diagnostic accuracy estimates are based on non-pregnant populations. 8,130 The GAD-7 is currently recommended by NICE as part of further assessment if anxiety symptoms are suspected in women during the perinatal period following initial case-finding with the shortened version of the GAD-7 – the Generalised Anxiety Disorder-2 (GAD-2). 101,133

Patient Health Questionnaire-15

The Patient Health Questionnaire-15 (PHQ-15)135 is a 15-item self-report questionnaire that assesses somatic symptom severity (the experience of physical symptoms in response to psychological problems/stressors) over the previous 4 weeks. Each item is scored on a 3-point scale (0 = ‘not bothered at all’, 1 = ‘bothered a little’, 2 = ‘bothered a lot’). It has been validated in primary care populations. 135,136

Clinical Interview Schedule – Revised

The CIS-R119 was also used to identify other common mental health problems, including mixed anxiety and depressive disorder, generalised anxiety disorder, panic disorder, obsessive–compulsive disorder and phobias.

Health-related quality of life

Women completed two generic measures about their HRQoL at the prenatal, postnatal and follow-up stages.

Short-Form Health Survey-12 items

The Short-Form Health Survey-12 items version 2 (SF-12v2®)137 is a 12-item self-report questionnaire that assesses individuals’ perception of their general health over the past 4 weeks (standard version). The SF-12v2® Health Survey is copyrighted by QualityMetric Incorporated [SF-12v2™ Health Survey © 1992–2002 by Health Assessment Lab, Medical Outcomes Trust and QualityMetric Incorporated. All rights reserved. SF-12® is a registered trademark of Medical Outcomes Trust. (IQOLA SF-12v2 Standard, English (United Kingdom) 8/02)]. It measures health on eight dimensions (physical functioning, role physical, bodily pain, general health, vitality, role emotional, social functioning and mental health) and yields two summary scores [physical component score (PCS) and mental component score (MCS)]. The SF-12v2 is a reliable and well-validated questionnaire138 and has been used as an outcome measure in a wide variety of patient groups, including patients with depression139 and women with postnatal depression. 140

European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions

The European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D)141 is a generic preference-based measure of health state covering five dimensions (mobility, self-care, usual activity, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression) according to three possible levels of severity (no problems, some problems and major problems). Individuals are asked to rate their personal health state on that day for each of the five dimensions and also on a visual analogue scale, for which 100 represents the best imaginable health state and 0 represents the worst imaginable health state. The EQ-5D has been validated in UK populations and has been used to measure HRQoL in patients with depression139,142 and women with postnatal depression. 143

Acceptability survey

Women completed a self-report acceptability survey at the prenatal and postnatal stages; this was completed immediately following completion of the Whooley questions and the EPDS (index tests). The acceptability survey was originally developed to assess acceptability of the EPDS in a postnatal sample of Australian women144 and later adapted to include an assessment of the acceptability of the Whooley questions in women during pregnancy and the early postnatal period. 105 The survey was further adapted for use within the BaBY PaNDA study (see Appendix 5) in order to assess a range of concepts regarding the acceptability of the Whooley questions and the EPDS as perinatal depression case-finding instruments, along with the processes for completing the questions (a more detailed description of the acceptability survey is provided in Chapter 6).

Resource use questionnaire

Women completed a self-report questionnaire to assess resource use at the prenatal, postnatal and follow-up stages (see Appendix 5). The questionnaire asked women about their use of health and social care services (including hospital- and community-based services) and their use of medication for mental health problems (when applicable) in the previous 6 months (when completed at the prenatal stage) and in the time since their previous completion of the same questionnaire (when completed at the postnatal and follow-up stages). Women were also asked to rate how happy they were feeling at that moment on a visual analogue scale, in which 0 represented completely unhappy and 10 represented completely happy. Women were asked about their employment status (including type of occupation, gross pay, weekly hours worked, days absent from work, weeks unemployed) at the prenatal stage only.

Biographical information

Women were asked to complete a brief bespoke biographical questionnaire at the prenatal stage only (see Appendix 5). This asked about their highest educational qualification and whether or not they had children already (and if so, how many children). It also asked if they had ever suffered with anxiety or depression. If the woman reported that she was currently suffering with anxiety or depression or had previously suffered with anxiety or depression, she was asked to indicate if she had been prescribed antidepressants, and whether or not she had seen anyone other than her GP for help with her anxiety or depression, and if so, who she saw (e.g. psychiatrist, psychologist, counsellor, etc.).

Method of data collection

Assessment sessions were conducted face to face at the prenatal and postnatal stages. At the follow-up stage, and for those women unable to attend a face-to-face session at the postnatal stage, outcome measures were collected by telephone (initial option) or a combination of post (self-report questionnaires including the Whooley questions and EPDS) and telephone (CIS-R). Face-to-face sessions were arranged for those women who specifically requested this method of data collection at the follow-up stage. Face-to-face assessment sessions were conducted at a time and place of the woman’s choice (e.g. hospital antenatal clinic, the woman’s home). Women were advised via the participant information sheet and during discussion with the study researchers that each assessment session would last approximately 30–40 minutes.

All study researchers underwent training in all aspects of the study including study recruitment, study protocol, and administration and interpretation of all outcome measures, including the Whooley questions and EPDS (index tests) and the CIS-R (diagnostic reference standard). Robust protocols were in place to deal with any risk issues that may arise during the assessment sessions, including the identification of women at risk of depression (see Assessment of risk), and all study researchers underwent training on these risk protocols.

Assessment of risk

Robust protocols were in place to deal with instances when cases of depression or anxiety were identified. Women identified as currently experiencing depression or anxiety as the probable primary diagnosis on the CIS-R were advised that their responses suggested that they may be experiencing some symptoms of depression or anxiety and were advised to discuss their feelings and symptoms with their GP or any other HPs (i.e. MW, HV). In addition, for cases when the probable primary diagnosis was a depressive episode, consent was also sought to write to the woman’s GP to advise them of the outcome of the assessment (to include information regarding the probable primary diagnosis and the PHQ-9 score). Researchers were advised to discuss any participant concerns regarding risk issues with a clinical member of the team. Researchers were required to document all cases of risk of depression or anxiety identified during an assessment session on a depression/anxiety risk form that was countersigned by a clinical member of the team. Protocols were also in place to deal with any instances of risk of self-harm or suicide identified during the assessment session (via the CIS-R or question 9 of the PHQ-9).

In addition, any women who screened positive on the Whooley questions and subsequently responded ‘yes’ to the help question ‘Is this something you feel you need or want help with?’ (see Whooley questions) were advised to speak to their GP (and any other HP, such as a MW or HV) about their feelings and symptoms and that information about perinatal depression could be found on the NHS website.

Sample size

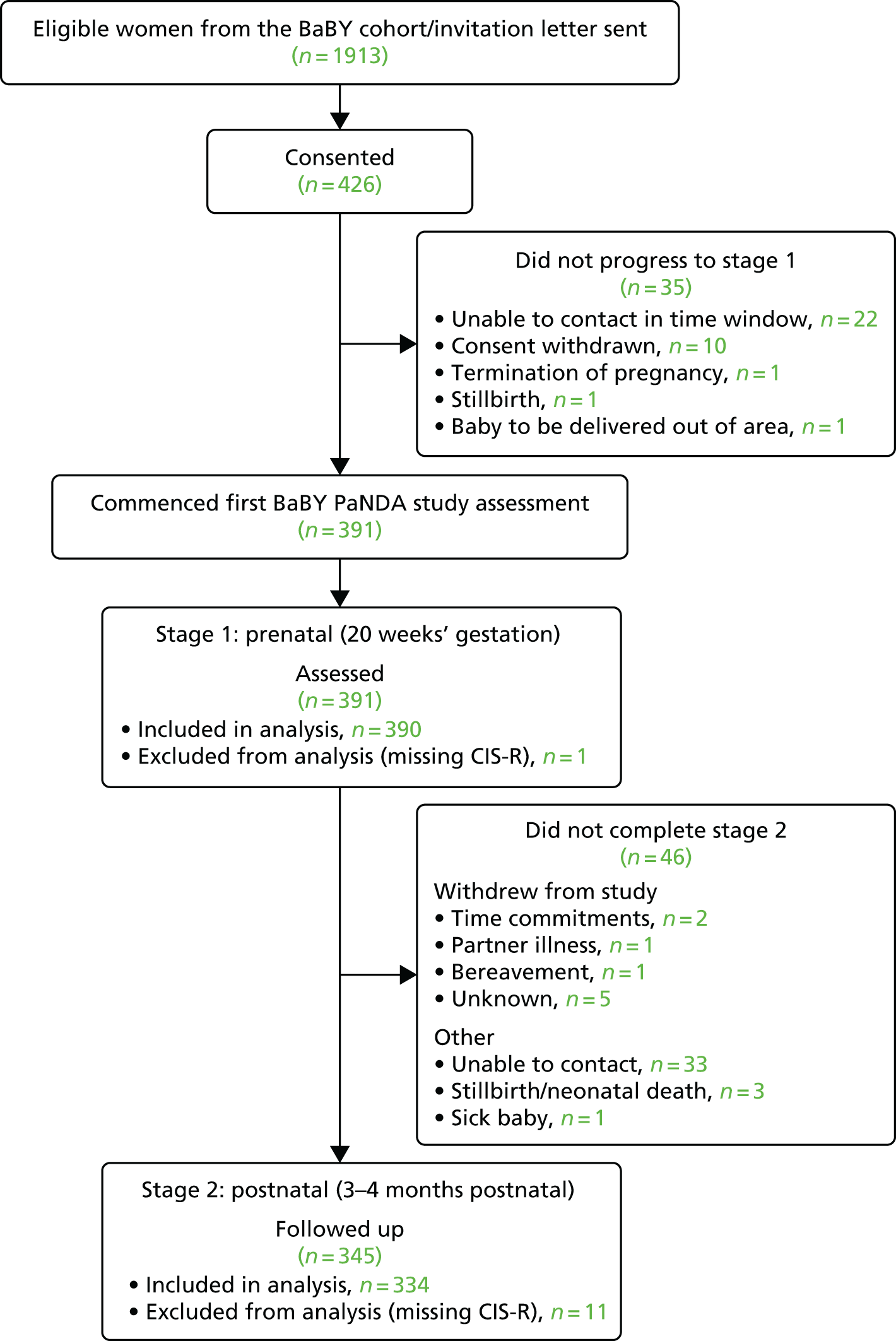

The sample size calculation was based on a previously developed method for design accuracy in diagnostic accuracy studies. 145 For an expected sensitivity of 95% and a minimal acceptable lower 95% CI of 80% to be detectable with 95% probability, a total of 50 women with depression (according to the diagnostic reference standard) in the perinatal period would be required. With an estimated prevalence of perinatal (prenatal and postnatal) depression of 20%11 and assuming 34% attrition between the prenatal (stage 1) and postnatal (stage 2) assessment stages (based on a previous validation study of the Whooley questions in a perinatal population100), the required recruitment target was 379 pregnant women.

Study completion

Women were deemed to have exited the study when they:

-

had completed their assessment session at the follow-up stage (around 12 months postnatally)

-

expressed a wish to withdraw from the study.

Data were retained for any women who wished to withdraw from the study up to the date of withdrawal, unless they specifically requested that this information be removed.

Following consent to the study and completion of the assessment session at the prenatal stage (around 20 weeks of gestation), any women who subsequently suffered a fetal loss (such as a miscarriage, termination of pregnancy, stillbirth or neonatal death) was not automatically withdrawn from the study. Women were contacted by letter to offer the study team’s condolences, thank them for their interest and/or involvement in the study and to provide them with the opportunity to remain in the study should they wish to do so. Women who did not respond to this letter were not contacted again by the BaBY PaNDA team (the letter advised of this). Data were retained for these women up to the date of the event, unless they specifically requested that their information be removed. Robust protocols were in place via the wider BaBY cohort study (and in liaison with clinical teams using routine NHS systems at each of the study sites), which acted to alert the BaBY PaNDA study team of such events.

Statistical analysis of clinical data

Methods for conducting the statistical analysis of collected data, including diagnostic accuracy at each time point, will be reported alongside the statistical results in Chapter 5.

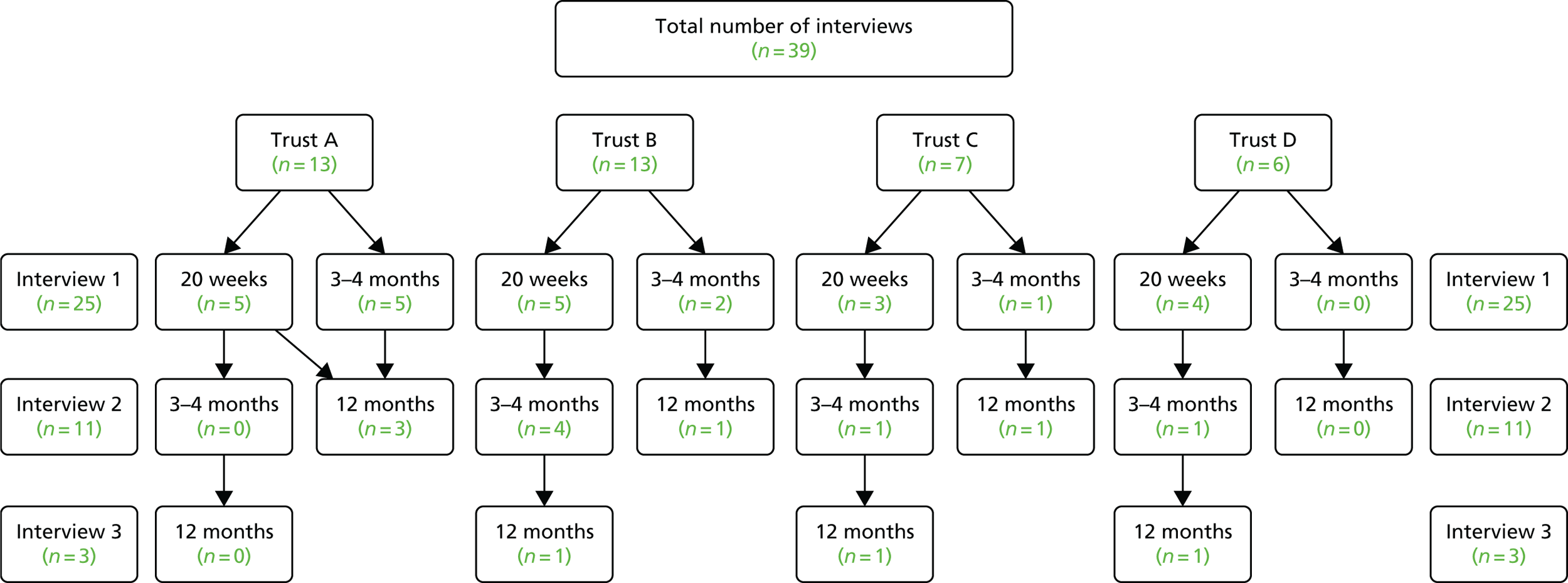

Evaluation of acceptability

A concurrent qualitative evaluation was conducted with women and HPs to examine the acceptability of the Whooley questions and the EPDS, the extent to which these instruments capture appropriate information for the effective case-finding of perinatal depression in routine perinatal care, and the implications for the care pathway of delivering such perinatal depression case-finding instruments in routine care.

Overview of acceptability study design

The qualitative evaluation utilised a mixed-methods approach that included the use of both a quantitative survey tool (the adapted acceptability survey) and in-depth interviews.

Interviews with women