Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 11/1022/15. The contractual start date was in December 2012. The final report began editorial review in March 2017 and was accepted for publication in July 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Iain Pretty is involved with the delivery of referral management services to NHS England, for which he receives financial reward. He was involved with the development of early pilot models in referral management at NHS Trafford. He was involved in the evaluation of the Index of Sedation Need (IOSN) tool. Paul Coulthard chaired the Oral Surgery and Oral Medicine Working group that developed the Guide for Commissioning Oral Surgery and Oral Medicine. This guide advocated the use of referral management systems in pathway management. He was involved in the development of the IOSN tool.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by Goldthorpe et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2018 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Structure of the research and this report

This research project comprised two distinct projects. The first was a diagnostic test accuracy study and the second was an interrupted time study (ITS) that sought to examine the impact of the implementation of a referral management system with combined primary care oral surgery diversion.

The current chapter sets the context for the work from clinical, commissioner and patient perspectives, and provides the research questions to be addressed. Chapter 2 provides a brief literature review, highlighting the main evidence base for demand management and the issues identified in its implementation.

See Table 1 for a simple schematic of the study elements, with the relevant chapters highlighted.

| Components | Year | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| Diagnostic test accuracy | ITS | |||

| Elements | Efficiency of remote clinical triage | Health needs assessment | Consultant triage with primary care | GDP triage and primary care |

| Baseline data collection | Implementation | Referral diversions and impact | ||

| Chapter(s) | Mixed methods – Chapter 2 | Mixed methods – Chapter 3 | Referral metrics and health economics – Chapter 4 | |

| Qualitative assessments – Chapter 5 | ||||

Chapter 3 describes the diagnostic test accuracy study. This was conducted under ethics approval gained from the NHS National Research Ethics Service, London Fulham Committee, approval number 12/LO/1912.

The ITS element of the work is described in Chapter 4 for the initial non-intervention year, and in Chapter 5 (post intervention). The study gained favourable ethics approval (NHS Research Ethics Committee Grampian number 13/NS/0141).

Chapter 6 presents a summary and implications arising from the work.

Oral surgery

The specialty of oral surgery deals with the diagnosis and management of pathology of the mouth and jaws that requires surgical intervention. Oral surgery involves the treatment of children, adolescents and adults, and the management of dentally anxious and medically complex patients. Oral surgery care is provided by oral surgeons and by oral and maxillofacial surgeons, as the clinical competencies of these two specialties overlap. Oral surgery is a recognised specialty of dentistry, whereas the UK General Medical Council recognises ‘Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery’ as a medical specialty. 1

NHS England’s Commissioning Guide for Oral Surgery and Oral Medicine1 describes the provision of oral surgery within the English NHS. The guidance describes three levels of case complexity, known as Levels 1, 2 and 3. 1 Oral surgery complexity is generally assessed based on both the type of procedure and patient factors. For example, a very simple surgical procedure can be complicated by a patient’s medical history or degree of anxiety. A full list of procedures and conditions that would be treated in each complexity Level can be found in Appendix 1.

In England, oral surgery is typically delivered in one of three settings and by three distinct groups of clinicians:

-

Primary care general dental practice – most surgical procedures are conducted in general practice by general dental practitioners (GDPs). The removal of simple teeth and roots is covered under the mandatory services section of the General Dental Service (GDS) contract. 2 The extraction of one or more teeth or roots in a single course of treatment attracts a band 2 charge for the patient and results in a ‘payment’ of 3 Units of Dental Activity (UDAs) for the dental practitioner (UDA prices vary between practices, but an average value of £25 is usually used). Patients will typically be free of systemic disease and will not require adjunct sedation, and the procedure will not be technically demanding. Such procedures are known as Level 1 procedures. There is an expectation that all Level 1 procedures will be undertaken in practice unless there are patient factors that complicate management. If a GDP does not feel able to undertake the procedure, they should look within the practice to see if another clinician can assist. Ultimately, it is the provider’s (GDS contract holder’s) responsibility to ensure that Level 1 procedures are undertaken in practice.

-

Intermediate services, dentists with a special interest (DwSpIs) – these services provide Level 2 care, and are typically delivered by a clinician with enhanced skills and experience who may or may not be on a specialist register. Indeed, such services could be provided by a consultant-grade clinician operating and remunerated as a Level 2 provider. It is expected that most Level 2 services will be provided in a primary care setting (where additional equipment may be required) under Any Qualified Provider (AQP), GDS or Personal Dental Service (PDS) contracts, in which case patient’s charges will be levied. Level 2 procedures may be delivered as part of continuing care or, as is most usual, by referral. The basis for the development of the DwSpI services was the 2004 framework document produced by the Department of Health (DH) and the Faculty of General Dental Practice, which was followed in 2006 by guidelines for commissioning such services. 3,4

-

Consultant or specialist care – the commissioning guidance describes Levels 3a and 3b but, for the purposes of this report, Level 3 providers are typically consultant-led services delivered in, and by, NHS hospital trusts under NHS standard contracts. Although Level 3 services are led by consultants, they will typically engage a wider workforce, including specialty and associate specialist-grade clinicians and those in formal training positions. Hospitals delivering oral surgery services at Level 3 include district general hospitals, larger training hospitals (foundation trusts) and dental hospitals that have the additional requirement to train dental undergraduates. 5

Health needs assessments

Commissioning of primary care services often takes place with little needs assessment or knowledge of where referrals come from and where populations receiving care are based. Detailed knowledge of the population, their needs and treatment preferences are essential to ensure that primary care services can be delivered effectively. 6

There is no defined methodology for determining the needs of a population for oral surgery services, in contrast to, for example, orthodontic services, where there is a clear and well-defined approach. 7 The Adult Dental Health Survey, of 2009,8 reported that 8% of dentate adults had one or more untreatable teeth (on average 2.2 teeth), but it is difficult to know when or if this need for an extraction is or will be expressed as demand. For example, many decayed roots will be asymptomatic. Data from the NHS Business Services Authority (BSA) may provide indications of activity in relation to band 2 course of treatment provision (which includes tooth extraction, but also includes fillings and root fillings) and the number of extractions provided in primary care, while Hospital Episodes Statistics (HES) can provide similar information for secondary care. None of these methodologies provides information on case complexity; coding and tariff charges in secondary care are not consistently applied and the use of general anaesthesia (GA) or sedation in both settings is poorly understood. 9,10

Referrals from primary care

In 2006, a new dental contract was introduced in England that replaced a fee-for-item service with a banded course of treatment approach. UDAs are awarded based on the type of care delivered, for example 1 UDA for a check-up with preventative care, 3 UDAs for any number of extractions (although most frequently one), any number of fillings or root filings plus any treatment included in band 1, and 12 UDAs for work requiring laboratory input, such as crowns and dentures, plus any treatment included in a band 1 or 2 course of treatment. Co-payments or patient charges are levied according to the three bandings: band 1, £19.70; band 2, £53.90; and band 3, £233.70. These charges apply to services provided under GDS and PDS contracts, but do not apply to services provided under hospital contracts. An anomaly in the contract required dentists to claim the UDA tariff for the procedures that they were referring for and collect the appropriate patient charge revenue. This created a perverse incentive to refer: dentists would be paid the same fee to refer a patient as to undertake the procedure. This resulted in the NHS paying twice for activity: once in primary care, and then again in secondary care. The contract incentive was, in part, responsible for the increase in referrals seen since 2006. Other factors contributing to the seeming relentless increase in referrals,11 which has been mirrored in medicine,12 include a lack of oral surgery experience at the undergraduate level among junior GDPs,13 and the increasing proportion of older patients retaining their teeth but presenting with complex medical histories and polypharmacy. Despite the 2006 contract being causally linked to the increase in referrals, it had been recognised for some time that the capacity in oral surgery services was under pressure. 3 Kendall, in an assessment of English oral surgery services, demonstrated that in a 3-year period from 2004, referrals doubled from a monthly average of 182 to 364. 14

Reasons for referral from primary to secondary care vary, but a questionnaire completed by dentists in Greater Manchester15 found the following:

-

anticipated surgical difficulty (69% of cases)

-

medical history issues (49% of cases)

-

require a second opinion (32% of cases)

-

practitioners do not undertake surgical procedures (29% of cases)

-

practitioners lack appropriate facilities or staff (28% of cases)

-

patients require emergency management of pain, swelling or haemorrhage (11% of cases).

Reasons for referral were not mutually exclusive.

The costs of providing oral surgery in secondary care are substantial. In 2009/10, in the north-west region alone, the total cost amounted to £53,864,857. In addition to the cost element, the increase in referrals has caused issues around workforce insufficiency and capacity, and has negatively impacted on 18-week referral to treatment targets. Although some trusts have welcomed the increased activity, others, especially those departments in district general hospitals (DGHs) staffed by oral maxillofacial surgery (OMFS) services, have found that the oral surgery referrals deflect activity from their core offering and that many are inappropriate.

Primary care (Level 2) services

As with many service developments in the NHS, formal evaluation and published reports on primary care oral surgery services are sparse. Kendall provided one of two such descriptions of how a Level 2 provider might work14 and this is described below, while Bell describes a retrospective audit of a primary care scheme designed to address issues in provision of services to remote areas. 16

Utilising two GDP practices in the Croydon area, combined with a simple referral management system, all non-urgent referrals for oral surgery procedures were captured and then subjected to a two-stage triage process. The first was an administrative check of the paper referral form and the second was a clinical assessment of a patient’s suitability for primary care treatment. The scheme reported no reduction in the total number of referrals received, but the offer of a primary care service did not appear to stimulate demand or increase Level 1 (work that should be performed by a GDP) referrals from GDPs. Of the 3117 non-urgent referrals, 36% were sent to secondary care and 59% to primary care (data were missing in 5% of cases). No referrals were returned to the GDP as being unsuitable – that is, at Level 1.

The removal of a substantial amount of activity from a single trust (nearly 60% of referrals) could cause concern over the stability of the service. Kendall states, however, that, rather than destabilising the unit, the reduction enabled a balance to be obtained, a reduction in waiting times and a re-focus on the core provision of oral maxillofacial procedures rather than oral surgery. 14

The service was revisited in both 201117 and 2012. 18 Kendall reported that, after 2.5 years of service, the background referral numbers continued to rise but the proportion of referrals directed to the primary care (Level 2) service had also increased, from 60% in 2004 to nearly 80% in 2010. With so many referrals being appropriate for Level 2 services, this suggests that much of this work was being undertaken in GDS and, with the provision of a service to deliver this, it is now being referred outwards. The number of Level 1 referrals remained low, at 1.1%. 17 Kendall reports a basic economic analysis with referral management costing around £7 per referral and a £600 saving per case seen in primary care. However, a system-wide economic appraisal was not undertaken and a formal health economic evaluation of costs and effects was not possible from the data available.

Referral management

The recognised increase in referrals from both GDPs and general medical practitioners (GPs) into hospital services has initiated several approaches to management of the problem. A Cochrane systematic review divided these approaches broadly into three main groups: (1) financial, (2) managerial or (3) professional education. 19 Each of the main groups involves varying degrees of active interruption to the referral process:

-

Professional education involves the production, dissemination and support of clear referral guidance, often using harmonised referrals forms to encourage collection of appropriate data, and often supported by targeted continuing professional development initiatives.

-

Managerial systems include the use of referral management services, clinical assessment services, clinical assessment and treatment services and as ‘in-house’ second opinions or peer review.

-

Financial approaches (at least those of relevance to the NHS) are based on fundholding by referrers and, hence, they incentivise care provided within the practice or referred to lower-priced primary care facilities.

The Cochrane review concluded that research into the management of referrals was limited. 19 Preliminary findings suggested that passive systems, such as the introduction of referral guidelines, were unlikely to change referral behaviours. The use of structured referral forms has some potential, but informatics support would be needed to make such forms useable in a practice environment (i.e. to force adherence to completion of mandatory fields). Financial methods risked the application of unselective reductions in referrals and negative impacts on patient care. 19 None of the studies examined a formal referral triage and capture service, such as that employed by Kendall. 14,17

The King’s Fund reviewed referral management systems,20 recognising that such systems can be as simple as a referral guideline through to active interventions in the referral pathway. It summarised that not all referrals were needed, but some patients who needed a referral did not receive one. The review found that the quality of referral letters was often poor, and appropriate primary care treatment or investigations had often not been undertaken prior to referral.

Focusing on capture and assessment referral solutions, the report found a range of strengths and weaknesses (including the filtering of inappropriate referrals, improving quality of referrals and providing commissioning intelligence), but also potentially increasing costs, delay to a patient’s journey and the creation of barriers between primary care and secondary care colleagues. 20 Of interest was the reported belief by primary care trusts (PCTs) that their referral management systems were reducing activity despite the fact that the data from acute trusts did not support this supposition.

A study by Cox et al. 21 highlights this anomaly. Using data from NHS Norfolk and using an active referral management centre (RMC) approach, Cox et al. 21 found that, in all cases, the use of the RMC approach increased referrals rather than decreased them. The authors concluded that the RMC approach, as the most expensive management option, was the least effective. 21 The authors’ retrospective time series design looked only at decreasing attendance, that is, reducing overall referrals, and there were no primary care redirection services. Their approach, therefore, would reduce only those referrals that evidence clearly showed were inappropriate. Referrals that were incomplete or poor quality, although initially returned, would be corrected and resent, thus increasing the number of referrals. These findings are consistent with those of Kendall’s work in dentistry, which revealed very low rates of Level 1 referrals – that is, those that might be considered inappropriate. 14

Two recent comprehensive reviews have examined demand management. 22,23 The key findings of these reviews provide the current context for our study, and, rather than duplicate the reviews in a formal literature review chapter, the key findings of these two large reviews are summarised here. The first, by Blank et al. ,22 sought to examine interventions related to referrals from primary care to specialist services. The work focused exclusively on referrals from GPs and excluded dentistry. The systems of referral were described as complex because of the interplay of local factors, such as waiting times, the directory of services and access to specialists. The review found stronger evidence to support interventions that involved peer review, improved the quality of referral information, offered specialist contact prior to referral, electronic referrals and the provision of community specialist services. 22 It found weaker and conflicting evidence over the use of gatekeeping systems and alterations in remuneration. The current work reported here addresses the issues raised in the review, apart from specialist contact prior to referral. By incorporating a standard referral form with mandatory fields, referral quality is improved, an electronic-only submission route can be implemented and a primary care service for the delivery of appropriate oral surgery procedures is introduced. The referral management and triage process can be considered a ‘gatekeeper’ with the potential to divert referrals and reject those considered ‘inappropriate’.

The second review, by Winpenny et al. ,23 focused on the effectiveness and efficiency of moving hospital services (outpatients) into primary care, and examined 184 studies, some of which included dental settings. They found that minor surgical procedures could be carried out in primary care safely and effectively, but that provision of such services could stimulate demand by addressing previously unmet need. The cost-effectiveness of these services was likely to depend on local contracting, and this also applied to general practitioner with a special interest (GPwSI) services, which also demonstrated evidence of supply-induced demand. 23 The review found that direct access to specialist services in some cases (such as audiology for hearing tests) offered obvious benefits, but that in other cases (such as musculoskeletal services) it risked generating a substantial increase in demand. The review considered referral management services as a substudy group and included a qualitative study element with individuals working, commissioning or implementing such services. The group identified four emerging themes from their interviews:

-

the lack of clarity relating the aims of functions of referral management services

-

the challenge of stakeholder adoption and buy-in

-

practical and administrative difficulties

-

the impact of perceived effectiveness of the aims and priorities of such services.

The group recommended that future schemes should have clarity of aims and defined indicators of success. In addition, the group identified a research need in the evaluation of clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of RMCs.

Electronic referral management systems

The NHS ‘Choose and Book’ system, now known as the NHS e-Referral Service (eRS),24 is an example of a large, national electronic referral system. Choose and Book has reduced the administrative burden associated with appointment booking and may have reduced the non-attendance rate at secondary care clinics. 24,25 However, this system may not be appropriate for all specialties and in all contexts. Prior to and following the introduction of Choose and Book, independent electronic referral management systems were developed. For example, Maddison et al. 26 evaluated electronic referral management with central triage and an adjunct specialist primary care service for uncomplicated musculoskeletal conditions. They found that, although the number of referrals greatly increased following the introduction of referral management, waiting times fell. In addition, duplicate referrals disappeared and a high degree of patient satisfaction was reported. However, Kim et al. 27 found that, although electronic referral management improved access to care, there were some barriers to implementation. Some referring clinics reported that multistep login procedures and a lack of computer access and reliable internet connection contributed to electronic referrals taking longer to complete, which was associated with lower satisfaction with overall clinical care. Again, this finding highlights the importance of considering the context in which the referral management interventions are implemented.

Consultant triage

When GDPs are aware that their referrals are being scrutinised by a peer with a specialist training, their referral behaviours may alter around who and how they choose to refer to secondary care. Studies of peer-reviewed interventions, in which referral quality has been judged by consultants and fed back to GPs, have resulted in some improvement in the quality of referral information and a reduction in the number of overall referrals into secondary care,28–30 although it may not lead to permanent changes in practice. 31 In addition, electronic referrals directly from GPs to consultant triagers prior to making Choose and Book appointments were found to be associated with shorter waiting times for appointments than paper referrals. 25 There is some evidence to suggest that the consultant triage element may improve the quality and appropriateness of dental referrals; however, GDPs may feel that their clinical autonomy is compromised by examination of their referrals during the triage process.

Despite the apparent lack, or contradictory nature, of evidence to support active referral management systems, by 2009, 91% of PCTs had some form of referral management system in place for GPs. 21 These systems seek to influence either the decision to refer, the destination of the referral or the quality of the information provided in the referral. At the time of writing there are several referral management systems in place across NHS England Area Teams (ATs) for dentistry – largely resulting from the guidance issued in the Dental Commissioning Guides in which RMCs are central to the process of directing referrals into Level 2 services. 1

Quality of referrals from general dental practitioners

In addition to managing waiting lists, reducing costs and improving overall patient satisfaction, referral management has the potential to improve the quality of referrals from primary care, which may improve triage efficiency and the overall diagnostic accuracy of the content of referrals. 20 Qualitative work around quality and appropriateness of referrals from GPs assessed by senior NHS clinical and managerial staff in five PCT areas in England32 found that important attributes of appropriate referrals were:

-

Necessity – should the patient be referred based on clinical examination, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines or their own medical history?

-

Destination – could and should the patient be treated in an intermediate setting rather than in secondary care?

-

Quality – is the information contained in the referral relevant and thorough, and have the necessary investigations taken place?

This is congruent with the NHS Quality, Innovation, Productivity and Prevention (QIPP) agenda around promoting quality while making efficiency savings, and offers evidence to suggest that referral management interventions do have the potential to be cost-effective while supporting improvements in quality. In 2011, a commentary on the implications of QIPP for dentistry identified the development of centralised assessment and triage services and establishment of primary care-based specialised services as innovations that could contribute to the QIPP agenda. 33

Many audits have assessed the quality of referrals from GDPs into all specialties. The results are usually poor, with ‘Dear Sir’ letters still being commonly employed, which contain little in the way of clinical detail, rationale for treatment, results of special investigations or the provision of radiographs. 34,35 Increasing the quality of referrals facilitates the provision of triage, informs commissioning (if data are appropriately captured) and increases the efficiencies of primary and secondary care services by enabling appointment scheduling and clinical staff allocation to be appropriate to complexity.

The King’s Fund describes the financial challenges facing the NHS, stating that difficult ‘trade-offs’ will be required. 36 Cost-saving measures in the NHS are rarely welcomed and often viewed as reducing quality and impacting on patient choice. However, beyond the clear need for dentistry to contribute to savings the NHS must make, there is the possibility that referral management allied to primary care diversion has much to offer in terms of quality enhancement, for example:

-

care closer to home

-

more convenient appointment times and extended opening hours

-

reduced waiting times (Kendall reports 6 weeks in primary care vs. 18 weeks in secondary care14)

-

single ‘see and treat’ appointments reducing opportunity costs for patients

-

greater productivity leading to increased capacity.

Concerns and consequences

Despite the apparent ‘easy win’ that centralised triage and primary care-based oral surgery services offer for patients and the NHS, concerns have been voiced. The removal of ‘simpler’ cases from secondary care is a potentially destabilising move, and the resultant shift of case mix to more complex patients is a perceived risk to the training of both undergraduates and specialist trainees. 13 Indeed, the use of a referral management system could, by reducing undergraduate training experiences, result in an increase in referrals from a population of graduates with no oral surgery skills. Hospital trusts may argue that the current tariff arrangements are based on the assumption that hospitals treat a wide range of cases, with payment for simpler procedures helping to generating revenue to offset the higher costs incurred in treating more complex cases that cannot be fully recovered from the tariffs. 22

Clinicians in secondary care have argued that, although care can be delivered in primary care, there is not always a compelling reason why it should. The reduced governance in primary care (for example, wrong site surgery reporting) combined with the single-handed nature of oral surgery provision in primary care, compared with a team approach in hospital, threatens, it is argued, the quality of the care provided. If patients experience complications, these will largely need to be managed by secondary care and, hence, savings are lost, patients experience poor outcomes and the system fails. 23

A further concern is that implementing primary care specialist services adds another service to the system without adequately managing the supply side, that is, without ensuring that there is corresponding downsizing of secondary care services. So instead of substitution, supplementation occurs, producing an overall increase in costs, which is a significant risk for a financially strapped NHS. A good example of possible pitfalls is described by Richardson et al. 37 in the context of developing skill mix by introducing nurse practitioners.

Aims and objectives

Considering the identified evidence gaps and the pressing need for the NHS to understand the quality and financial impact of referral management services, there is a need for a high-quality, contemporary evaluation of this change in service organisation and delivery. 22,23,38

This project aimed to evaluate the introduction of an electronic referral management system with consultant-level triage and the introduction of a new primary care service for oral surgery within a defined health-care system containing a diverse set of hospital providers. The study design used a mixed-methods approach with ITS design.

In addition, a diagnostic accuracy study of remote clinical triage was undertaken to assess the efficiency of this important stage in the referral management process. The research programme contains the necessary elements to address the research gaps identified by the previous systematic reviews,20,22,23 primarily the impact on quality of referrals, use of electronic referrals, the provision of community specialist services and the effect of gatekeeping systems.

The main research question to be addressed by this work was the following:

-

How does a robust online referral management and triage system, allied to provision of a specialist primary care service, impact on the costs and quality of oral surgery services provided by different providers in different settings in a defined health-care system?

At the highest level, we wanted to know if we can change the behaviour of referring GDPs without destabilising a complex, interdependent acute sector, to ensure that only those who need hospital care are managed in this setting. In order to fully answer this main research question, the following secondary research questions were formulated:

-

Chapter 2 , Efficiency of remote clinical triage

-

How do remote clinical triage outcomes conducted by an experienced consultant compare with outcomes of face-to-face examination (reference test) performed by the same consultant?

-

How do remote clinical triage outcomes performed by GDPs and different consultants compare with outcomes of face-to-face examination performed by an experienced consultant (reference test)?

-

What are the views of triagers on the benefits and problems of a remote clinical triage system and how can the system be improved based on their experiences?

-

-

Chapter 3 , Implementation and health needs assessment (phase 1)

-

What are the practical issues for the NHS in introducing an all-electronic referral system from scratch?

-

What is the effect of all-electronic referral system on

-

the total number of referrals

-

the quality of referrals including an assessment of compliance with national referral guidelines

-

the time taken to complete referrals?

-

-

What are the views of key stakeholders on the benefits and problems of the electronic referral system and how can the system be improved based on their experiences?

-

-

Chapter 4 , Active referral management with consultant and general dental practitioner triage: quantitative findings including economic evaluation (phases 2 and 3)

-

What are the differences in referral numbers, referral quality and the mean cost per referral between virtual management (phase 1) and consultant-led active management (phase 2)?

-

What are the differences in referral numbers, referral quality and mean cost per referral between the year of virtual management (phase 1) and GDP-led active management (phase 3)?

-

How do these findings (differences in referral numbers, referral quality and the mean cost per referral between study phases) differ by the provider of secondary care?

-

Does consultant-led triage offer improved costs over GDP self-determined provider choice (phase 2 vs. phase 3)?

-

How do the views and experiences of patients differ between those using primary and secondary care services?

-

-

Chapter 5 , Active referral management with consultant and general dental practitioner triage: qualitative findings (phases 2 and 3)

-

The use of the ITS methodology with robust adjunct and parallel qualitative components enables these issues to be addressed from both a metric and a narrative perspective.

-

What are the issues encountered when establishing a new primary care oral surgery service?

-

What are the views of stakeholders on the development and implementation of the primary care service?

-

What are the views of service users on the quality of service they received from the referral management and triage system?

-

Public and patient involvement

Public and patient involvement has been a key element of this work, from the design stage, in which consent and patient information sheets were reviewed and revised, through to the extensive involvement of patients (see Appendix 2) in the qualitative component of the research. Patients’ voices are heard and reflected strongly in the current work, as their views and experiences are key to meeting the aims of the research. Service redesign impacts multiple stakeholders and, although professional views are often heard, we have sought to ensure that those of service users in Sefton are recognised and reflected.

Chapter 2 Efficiency of remote clinical triage

Introduction

To manage demand, focus services on need and ensure that patients are seen in the correct setting, a gatekeeper function has been introduced by services within both oral surgery pathways and the wider NHS, for example in dermatology services. 17,39 Such gatekeeper services vary in their design and implementation in terms of what is assessed, and by whom, and how it is delivered, but all can be considered a form of clinical triage. The concept of primary care services underpinned by effective clinical triage has been advocated by NHS England in its commissioning advice to ATs, although there is little detail on how this might be achieved. 1,6

The provision of Level 2 services within primary care is predicated on the safe and efficient diversion of suitable patients to such services. This can be achieved in several ways, such as by:

-

undertaking a face-to-face clinical assessment of the patient

-

enabling referrers to select determine the case complexity

-

using machine learning or algorithms to classify the case complexity

-

clinical assessment of the referral – remote clinical triage by consultant staff.

There are advantages and disadvantages to each of these approaches. The use of face-to-face clinical assessments would be expensive, would require significant expansion of the clinical workforce, estate and support staff and would delay the patient journey by introducing an additional step. These factors seem at odds with the primary drivers for introducing Level 2 services and, hence, such an approach could not be recommended. 40

Referrer-based triage makes broad assumptions that the population of referring dentists can adequately assess case complexity, has a good knowledge of the various complicating factors that can affect patient care and understands the local directory of services available for individual procedures. However, such an approach is relatively inexpensive and ensures rapid referral to a provider without a delay to the patient journey. It preserves and enhances clinical autonomy, and it can be argued that dentists know their patients best, as they have had the benefit of making a full clinical examination. However, GDP decision-making may be biased and influenced by patient demands (e.g. for GA or sedation) or by a wish to continue to send patients to ‘known’ consultants or to support colleagues in primary care. Of course, the patient could be allocated to an inappropriate service, leading to either a failure to reduce the burden in secondary care or the need for an onward referral if inappropriately assigned to a primary care service. However, this approach (peer assessment) is endorsed by The King’s Fund20 and is explored in phase 3 of this study (see Chapters 4 and 5).

The use of artificial intelligence, or algorithmic triage, is in its infancy. A number of systems have been assessed in emergency medicine departments and for trauma management. 41 Such systems generally support clinical decision-making rather than taking full control over the process of triage. In dentistry there have been some studies that have examined machine learning for treatment planning. 42 The development of an algorithm that captured, via the referral process, key elements of the pathway would be a simple matter – that is, identify those ‘red flags’ that would indicate a Level 3 patient. However, GDPs may be become familiar with the process and seek to circumvent it to get their patient to their preferred provider. Automated triage does have several benefits, as it:

-

could almost instantly send a referral to the provider, ensuring no delay to a patient’s journey

-

would be workforce neutral and, hence, capacity to deliver triage is limitless

-

would be more economical as there are no costs associated with the number of referrals

-

can be audited and assessed by appropriate clinicians to determine accuracy and appropriateness.

In the current work, it was decided not to deploy an algorithmic solution. The use of primary care Level 2 providers was in its infancy at the start of the study, and it was felt that the evaluation of algorithms would be more appropriate with mature services for which data were available to help support the development and assessment of automated decision-making.

It has been proposed that a hybrid of these two systems can be adopted: a system that provides the governance, clinical leadership and independence of the face-to-face approach while mitigating the costs, time and estate requirements of it. Remote clinical triage involves the assessment of standardised referral forms and appropriate attachments (most frequently dental radiographs) to undertake a case complexity assessment. Triagers are asked not to recommend a treatment plan, direct to a specific service or otherwise assess the referral, but to assign a Level 1, 2 or 3 complexity score to each referral. Once scored, an algorithm is applied to the referral to send it to an appropriate provider, and in most systems this is determined by patient choice for secondary care and geographical proximity for primary care Level 2 services (usually based on home postcode).

Remote clinical triage has been utilised in several settings43 and for various clinical disciplines, but the efficiency of this approach for oral surgery referrals based on the described case complexity assignments has not been assessed. 44,45

The use of consultant-level triage was considered as a ‘reference standard’, and designating an experienced clinician to lead the service was thought, by many, to ensure safe and appropriate triage in the absence of established pathways. The use of consultant-led (if not actually delivered) triage is also recommended in the current NHS oral surgery commissioning guides. 1

Consultants involved in the triage process will be aware of appropriate clinical guidelines (e.g. NICE guidance on the removal of third molars35) and the type of procedure and anaesthetic requested. This guidance, along with further obligatory information, such as medical history, social demographic information and levels of anxiety, will be common factors driving decision-making. The referral trajectory, however, involves GDPs initially carrying out a consultation and examination with the patient face to face, deciding there is a need to refer the patient for specialist treatment, then entering the appropriate referral data. Consultants then interpret the referral data and decide on the appropriate level of specialist care.

There are a number interactions taking place among individuals and organisations that may be subject to other influences and drivers, additional to official guidance and system parameters. For example, ‘intuition’ of clinicians is frequently cited as a factor involved in triage decision-making;46 however, this is a phenomenon that is difficult to define. 47 Considine et al. 48 state that knowledge and experience influence triage nurses’ decision-making; the integration of factual knowledge (a series of facts relating to a patient), procedural knowledge (decision rules, clinical guidance) and conceptual knowledge (assimilation of prior knowledge and new information) result in a unified comprehension that is applicable to a range of situations. Clinician experience is defined as a combination of the passing of time and gaining skills and exposure to an event. Together, the combination of knowledge and experience may form the elusive ‘intuition’ that is observed in experienced consultants, particularly as focusing on a specialty affords more opportunity to develop conceptual knowledge through exposure to events in a specific area.

Clinicians undertaking triage may consider several factors, in addition to clinical information and guidelines, in assessing a referral. Most literature around triage decision-making is based in acute emergency settings when the patient is present and available for examination. 41,46,49 Edwards44 investigated decision-making using telephone triage in accident and emergency departments and concluded that experienced nurses considered several additional factors, such as contextual information and risk minimisation, in addition to purely medical information, when making decisions around treatment. In addition, lifestyle factors were found to be important in orthopaedics when deciding whether or not patients should be recommended for planned total joint replacement. 47,50 There is, however, a dearth of research examining the complexities of remote clinical decision-making in the absence of the patient for elective treatment.

Although many consultants in oral surgery would have ‘triaged’ their own referrals – for example, a desk-based exercise to prioritise referrals or determine staff allocation – there were no data on the efficiency of a formal triage process where decision-making was based on case complexity and the diversion of patients to primary care. This study was therefore undertaken to determine the use of such triage in a diagnostic test accuracy study.

Aims

The aim of this research was to undertake a diagnostic test accuracy study of the accuracy of remote clinical triage performed by both GDPs and consultants, compared with a reference standard of face-to-face clinical consultation performed by an experienced consultant.

Recognising that clinical decision-making is a complex area, and that agreement levels between and within clinicians will vary, a qualitative element of the study sought to understand the reasons for this by examining the impact of variation on the feasibility of such services, and suggesting how remote clinical triage may be improved or enhanced.

More specifically, we sought to answer the following research questions:

-

How do remote clinical triage outcomes conducted by an experienced consultant compare with outcomes of face-to-face examination (reference test) performed by the same consultant?

-

How do remote clinical triage outcomes performed by GDPs and different consultants compare with outcomes of face-to-face examination performed by an experienced consultant (reference test)?

-

What are the views of triagers on the benefits and problems of a remote clinical triage system and how can the system be improved based on their experiences?

Methods

Ethics approval was sought and gained from NHS National Research Ethics Service, London Fulham Committee, approval number 12/LO/1912. The research was divided into two main stages:

-

The first stage was an assessment of remote triage versus face-to-face clinical assessment.

-

The second stage examined the use of different examiners in the assessment and triage of referrals.

A qualitative component featured in both stages. Patients recruited to the study were > 18 years of age, able to consent and had been referred to a secondary care facility by their GDP for an oral surgery procedure. The setting where the study took place was Greater Manchester, as NHS Manchester had recently implemented remote clinical triage as part of a centralised referral management system.

Stage 1: assessment of remote triage versus face-to-face clinical assessment by a single consultant

A total of 282 referrals to the NHS Manchester referral system were assessed (based on the level of acceptable precision at a 95% confidence level, a minimum sample size of 279 participants was calculated) to investigate sensitivity and specificity of referrals triaged to secondary or primary care. It is important that there is high precision when comparing triage methods and that erroneous referrals should ideally to be sent to secondary care rather than to primary care, to ensure patient safety and service quality. Therefore, our sample size was calculated based on a sensitivity of 0.98 and a specificity of 0.88. 51

Sample size calculation

A total of 279 referrals were required, if taking the most conservative estimate, given a primary care prevalence of 30% and a sensitivity of 0.98 based on people referred to secondary care via assessment of standardised referral form only out of people referred to secondary care from face-to-face triage:

Process

A single consultant in oral surgery (PC) first examined all the referral forms. These were supplied on the agreed oral surgery pro forma that requires a minimum data set to be provided and adequate radiographs supplied. To reduce incorporation bias, all non-relevant patient-identifiable information, such as patient name and address, was removed from the e-referral form that incorporated the pro forma. A decision was rendered in each case from the following options:

-

suitable for secondary care consultant-led services (Level 3)

-

suitable for primary care advanced services, such as those offered by DwSpIs or those on the oral surgery specialist list (Level 2)

-

suitable for primary care – any competent GDP should be able to provide this treatment safely and effectively within general dental practice (Level 1)

-

rejected – sent back to original GDP as a result of incomplete form or missing radiographs.

Following a washout period of at least 3 weeks, the same consultant (PC) clinically examined the same patients ‘face to face’ (blinded to his previous remote triage decision) to determine a reference standard clinical triage. At the face-to-face assessment, decisions were made and noted regarding the most suitable hypothetical setting for treatment (although all patients in the study were ultimately treated in hospital). Study triage examinations took place as part of standard initial consultation prior to oral surgery procedures.

For the qualitative element of stage 1, an experienced qualitative researcher carried out detailed observations of a purposive sample (n = 30) of the consultant’s clinical (face-to-face) sessions. Cases were selected to be representative of types of clinical diagnoses, medical complexity and patient demographics, such as gender and age. During paper-based decision-making, the consultant was asked to articulate decision-making processes in real time (thinking aloud). Both procedures were audio recorded and transcribed prior to analysis and data were scrutinised to consider key factors that simplify or complicate decision-making. This approach was utilised to illuminate the processes of clinical decision-making.

Stage 2: examining the use of different examiners in the assessment and triage of referrals

In the second stage of the diagnostic accuracy and ‘workability’ test, the paper referrals of the cases that had been assessed face to face were provided to four other clinicians (one further consultant in oral surgery, one consultant in OMFS and two GDPs with experience in oral surgery). Each was asked to undertake a triage with the same options as described above. The decisions from these groups were compared with the reference decision (face to face) performed by a single consultant in oral surgery (PC). Although it was intended that this study would utilise consultant-led triage, we felt that it was important to explore if there are any major discrepancies between consultants and other dental professionals in where they believe certain cases should be referred to.

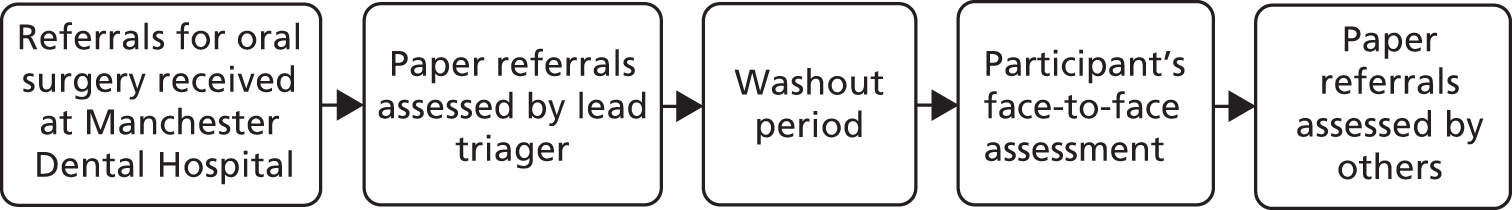

The sensitivity and specificity of the clinicians’ decisions were tested against the original consultant’s face-to-face examination decision. Additionally, tests for paired sensitivities were undertaken to determine the equality between the additional examiners using the median sensitivity score. The participant flow diagram is shown in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Participant flow in the diagnostic test accuracy study.

For the qualitative element, where discrepancies in the decision-making between examiners were identified, referrals were selected for case presentations to be discussed in two focus groups. For the composition of the focus groups, see Table 2.

| Focus group | Anonymised code for transcript | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | |

| Facilitator 1 | Facilitator 2 | F1/F2 |

| Consultant oral surgeon (reference standard clinician) | Consultant oral surgeon (reference standard clinician) | C1 |

| Consultant oral surgeon | Consultant oral surgeon | C2 |

| GDP (> 25 years’ experience) | GDP (> 25 years’ experience) | GDP |

| Dentist with specialist oral surgery contract | Dentist with specialist oral surgery contract | SPD |

| Research team project manager | Newly qualified dentist (3 years) | NQD1 |

| Newly qualified dentist (2 years) | NQD2 | |

-

Cases were selected if there was a discrepancies existed between decision-making following the reference standard face-to-face examinations and the reference consultant’s (PC) decision-making following examination of the corresponding paper referral.

-

Cases were selected based on referrals resulting in differences in decision-making between different clinicians (GDPs/consultants).

Qualitative data analysis

Observations and the consultant’s narration for the triage process in stage 1 and the discussion of the focus groups in stage 2 were digitally recorded and transcribed. All transcripts were anonymised and checked for accuracy. Analysis drew upon some common techniques of grounded theory approaches (after Glaser and Strauss52), including the technique of constant comparison, whereby analysis was carried out concurrently with data collection so that emerging issues could be explored iteratively. Stages of coding consistent with a grounded theory approach, comprising initial coding of text segments, followed by recoding and memo writing to generate conceptual themes, were carried out. Themes were constantly compared within and across cases, paying attention to negative cases and possible reasons for differences. The data were organised with the aid of qualitative data software package NVivo 11 (QSR International, Melbourne, VIC, Australia). Two researchers discussed emerging themes regularly to enable refinement of conceptual categories and to identify common threads or differences across the different respondent groups. The team ensured that an audit trail of all stages of the analysis, to maximise credibility, dependability, confirmability and transferability,53,54 was made available.

Results

A total of 551 eligible referrals were considered, of which 460 were booked into study clinics and, following consent, accounting for non-attendance and clinic cancellations, a total of 282 participants were recruited to the study. All participants required an oral surgery procedure. The mean age of participants was 42 years (± 10.2 years) and 53% were female. No adverse events arising from the face-to-face assessments were reported.

Stage 1: assessment of remote triage versus face-to-face clinical assessment by a single consultant

Quantitative results

The decisions made by the reference triager (experienced oral surgery consultant – PC) are shown in Table 3. Table 4 demonstrates these decisions based on their efficiency. For example, if a Level 2 case is directed to Level 3, it is considered efficient as care can be provided (although there is potential loss to primary care and any associated savings). A Level 3 case sent to Level 2 is considered as inefficient, as this will require an onwards referral to secondary care and this impacts on the patient’s journey and may incur charges in both settings.

| Face-to-face decision | Remote triage decision | Total (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level 1 | Level 2 | Level 3 | ||

| Level 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1) |

| Level 2 | 3 | 173 | 26 | 202 (71) |

| Level 3 | 0 | 40 | 39 | 79 (28) |

| Total (%) | 4 (1) | 213 (76) | 65 (23) | 282 (100) |

| Decision type | Frequency | Per cent | Total per cent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Equal | 213 | 75.5 | 75.5 |

| Efficient triage error | 33 | 11.7 | 87.2 |

| Inefficient triage error | 36 | 12.8 | 100.0 |

| Total | 282 | 100.0 |

Data collected on the benefit of face-to-face assessment showed that there was a consistent collection of metrics that contributed to the change in decision. For those Level 3 cases sent to Level 2, this was a result of the treatment plan being different from that originally indicated on the referral (13 cases), additional radiography demonstrating increased case complexity (13 cases), discrepancies in the medical history (six cases) and the patient’s anxiety being higher than expected (four cases).

For sensitivity and specificity assessment, the decisions were dichotomised. Given the very small numbers of Level 1 referrals, these were combined with Level 2 referrals to provide an indication of primary care, and Level 3 referrals became the positive diagnosis. Therefore, a test with high specificity (88%) in this example will correctly identify those cases suitable for Level 2 care, but will send some Level 2 cases into Level 3, hence efficient triage error. High specificity was seen throughout the experiment.

Stage 2: examining the use of different examiners in the assessment and triage of referrals

Table 5 demonstrates the comparison of the primary examiner’s (PC) remote and face-to-face triage sensitivity and specificity results, and then demonstrates the results from additional examiners. The results of a comparative analysis show that there were no differences in the specificity scores of any examiner, although the primary examiner had consistently and significantly higher sensitivities than the other examiners.

| Examiner | Prevalence of Level 3 referrals | |

|---|---|---|

| Referrals, % (N = 238) | 95% CI | |

| Primary examiner | ||

| Sensitivity | 51.5 | 38.9 to 64.0 |

| Specificity | 88.4 | 82.6 to 92.8 |

| Oral surgery consultant II | ||

| Sensitivity | 18.2 | 9.7 to 29.6 |

| Specificity | 94.8 | 90.3 to 97.6 |

| OMFS consultant | ||

| Sensitivity | 12.1 | 5.3 to 22.5 |

| Specificity | 94.8 | 90.3 to 98.7 |

| GDP 1 | ||

| Sensitivity | 19.7 | 10.9 to 31.3 |

| Specificity | 95.9 | 91.8 to 98.3 |

| GDP 2 | ||

| Sensitivity | 10.6 | 4.3 to 20.6 |

| Specificity | 92.4 | 87.4 to 95.9 |

Qualitative results

The participant codes are shown in Table 2. The qualitative results of stage 1 [observation and think aloud by the reference triager (PC)] and stage 2 (focus groups) are presented together because of the complementary nature of the outputs. Focus groups revealed several processes involved in triage decision-making. Where the discrepancy between remote triage and face-to-face consultation decisions resulted in the face-to-face patient being ‘diverted’ to secondary care, there was often missing or inaccurate information on the referral form or the radiograph was inadequate. Patients also disclosed additional clinical details at their face-to-face consultation, often around sensitive but relevant subjects, such as alcohol intake and mental health. The main themes that arose from the data were as follows:

-

Quality of information: quality of referral information was discussed frequently in the focus groups, where issues were raised around the minimum data set needed to carry out remote triage accurately. Some pragmatic suggestions were made for minor alterations to the online pro forma.

-

Holistic view of patient: clinicians habitually attempted to construct a narrative and context for the patient in the referral in the absence of the individual, resulting in attempts to form a holistic view of the patient. At times, it was reminiscent of the treatment planning process rather than the simple assessment of case complexity.

-

Organisational context: treatment decision-making must be made pragmatically, in the context of available resources. This is especially relevant when considering the capacity for primary care to deliver certain information about patients, such as sedation assessments, and availability of panoramic radiographs.

-

Quality of information: accurate information surrounding diagnoses and medical history of the patient is vital for case complexity assessment, both for remote triage and during face-to-face consultations. When the patient is present, questions can be asked, an examination can be carried out and the patient can influence the consultation by expressing preferences and fears. However, to decide on case complexity based on referral information given by a GDP in the absence of the patient, it is essential that the clinical detail and information relating to medical history is thorough and accurate. In addition, good-quality radiographs are an important element in the assessment of case complexity, especially in relation to more complex tooth extractions.

A combination of an inadequately completed medical history and either no or a poor-quality radiograph can result in a referral that is difficult to triage. The following describes a case in which a consultant had triaged the patient to primary care based on the information on the referral form. However, following examination of a good-quality radiograph, he was sure the patient should be treated in hospital because of the position of the inferior alveolar nerve in relation to the tooth (with an attendant risk of postoperative paraesthesia):

. . . we’re saying that he needed the X-ray to make a decision and that showed [after] he did get an X-ray but I changed this because it’s close to the nerve . . .

C1 (focus group 2)

When information is missing or inaccurate, an inappropriate referral decision can be made. The example below describes a patient who was correctly reported as having epilepsy. However, during consultation it was found that the epilepsy was controlled to a much lower extent than reported in the referral information and it was decided the patient should be treated in a hospital. This resulted in an adjustment to the previous decision that the case was suitable to be seen in primary care:

But added to it but probably the main thing was the fact that his epilepsy was not controlled . . .

C1

Aha, because the difference [evidence in the transcript of the consultation] . . . consultant has changed his mind from primary to secondary because the epilepsy was not reported accurately.

C1 (focus group 1)

Supplementary information contained on the forms, such as the Index of Sedation Need (IOSN), also influenced decision-making for triage, as the patient needs to be diverted to the provider with the facilities to administer the appropriate adjunct sedation. 9,10,55 For example, simple surgery may be Level 1, but a request for sedation and supporting information to justify that sedation is required may move a referral to Level 2:

So I have assessed to the primary care specialist because it’s multiple surgicals, more than a GDP could handle. In terms of additional information, the patient is anxious and needs sedation, but again it could be primary care, but it would have to be primary care with sedation service – that wasn’t clear from the referral letter – the box hadn’t been ticked to indicate either way and again there is no IOSN or mention of anxiety.

C1 (C1 decision-making transcript)

Holistic view of the patient

Clinicians attempted to construct a narrative and context for the patient, looking for cues that might indicate an individual’s lifestyle and social circumstances, and using this to create a holistic view of the patient upon which they based their decision-making. Experienced clinicians described attempting to go beyond descriptive clinical information to form a holistic view of the patient behind the referral. One consultant describes this succinctly as:

The difference between treating the picture in the X-ray and the patient.

C2 (focus group 1)

The following triager described an attempt to form a holistic picture of the patient from the information provided on the referral form. It appears that he appraised the information available to attribute causes for the patient’s carious teeth. In the absence of this information, he exercised caution and selected secondary care treatment for this patient:

Incomplete information, because it doesn’t tell us whether they want that [IV sedation] or not. It just said, ‘difficult extraction’, great. There’s no selected choice for sedation and no indication of sedation needs or the patient’s anxiety . . . But how come they have got to that state, why have they got multiple teeth that are like, grossly carious and requiring surgical extraction? It could be, anxiety could be a reason, it could be economic reasons or education. You don’t know. But again, we haven’t got enough information to make a decision, so again I was moving up [to secondary care] rather than down [ to primary care] because I wasn’t sure.

C1 (focus group 1)

The process of decision-making when information regarding patients’ lifestyle, behaviours and anxiety levels was absent or ambiguous appears difficult for consultants who may be used to a shared approach. The process was articulated well in the discussion below around two key factors: the clinical information from the referral and the hypothetical patient. Again, when in doubt, the default approach was to refer to secondary care:

You have, it’s got here, GA justification for access medical.

But, they’re case complexities but what I think I’m hearing is . . .

It’s patient complexity.

. . . it’s very difficult to disassociated these two things and that you can’t just . . . because that case complexity is level one isn’t it?

. . . complexity of procedure is one, but the whole patient.

But, the information you do have, they’ve had a bad experience at the dentist before it may be better to have someone that’s a bit slicker when they go to hospital . . .

Organisational context

Organisational considerations, such as costs, resources and efficiencies for both patients and health services, influenced treatment decision-making. Clinicians making triage decisions had local knowledge regarding the services and estate available with different providers and wanted to minimise the need for multiple appointments. Cost and time implications for patients were considered, even if clinical indications suggested that a procedure could be carried out in primary care. For example, if it is likely that a detailed (panoramic) radiograph will be needed, and possibly a general anaesthetic because the patient is anxious, a clinician may be more likely to refer to secondary care, where these services are available, thus reducing the potential number of appointments needed. In addition, where medical history indicates potential complications, it may be not only safer, but also more efficient, for the patient to be referred to secondary care because of access to other services and specialties:

Patient is on warfarin has a history of alcoholism and problems with his liver. I think that’s high risk to do that. I wouldn’t even want to do restorative with IV block on somebody who has got…I wouldn’t want an IV block you could end up killing them . . .

So, again I’m basing it on the inconvenience to the patient.

And, how to get rid of that inconvenience, where they could just go to hospital have the test, the next day have the tooth out . . .

Yes, inconvenience, also cost effectiveness, you know, going to the doctor, getting the blood test. They have got to take the blood, send the blood to the hospital. Get the hospital or lab, get the blood results back . . .

So, what’s actually driving this here, is not necessarily the case complexity around surgery again, it’s the facilities that are available in the hospital.

Clinicians argued that good-quality radiographs are vital for accurate triage, and this was an issue highlighted consistently in the discourse. However, since the introduction of the 2006 dental contract removed the financial incentive for investing in panoramic imaging machines (there is no longer a specific fee for item for these larger, more expensive radiographs) there has been a reduction in the number of primary care practices offering this radiographic service. This type of radiograph is particularly helpful for diagnosing third molar (wisdom teeth) problems, particularly the shape of the root and the proximity to the inferior alveolar nerve (damage to which is a common risk factor for such surgery). Radiographs that are of poor quality or otherwise inadequate could affect decision-making, as triagers were instructed to take a default position of referring to the higher level of care when in doubt:

. . . Just as R’s saying, because there’s no decent X-ray you can’t actually make the decision. So whatever you write is right and wrong, isn’t it? So we just don’t know. We’re just guessing.

So it needs a referral just from an imaging point of view.

There were more DPT [dental panoramic tomography] machines around and now there are fewer than ever.

Often, GDP practices have access only to bitewing and periapical radiographs, which show only the first six teeth of each quadrant. This is insufficient to make some diagnoses, as demonstrated by the following observations from a hospital consultation:

We’ll need to get another X-ray today as well – they knew that when they sent you, just with those ones in your mouth there is a limit to how far back you can hold that, but we need to see the whole tooth to see the shape of the root – we’ve just got the very front of it on the X-ray. So we do a different sort that’s from outside your mouth so you haven’t got that problem of holding it steady

C1 (C1 P1 98–115)

The following extract from focus group 2 highlights how the issue of access to high-quality radiographs has been a long-standing problem. Clinicians have considered the situation to be problematic to the extent that possible solutions were debated:

There is a common theme here that, especially for the last ones. For the vast majority of wisdom teeth actually the imaging is inadequate and actually . . . so you wonder whether a default would be, you know, if you haven’t got a DTP [dental panoramic tomography] in your . . . you know, that should be a reason for referral because the general consensus that the vast majority of imaging is pretty rubbish and then you . . .

I think . . . and we also . . . I mean we, at the [name of] practice, take local practices’ referrals for DTPs [dental panoramic tomographs] . . .

It’s tricky, isn’t it, because what the ideal is the NHS to be supporting general practice and us to all have DPT machine so they can send that image digitally so you can make the right decision, but that would be very expensive. Your way would be cheaper but would a dentist want to do that? So the patient might come to your place and say, oh this is impressive, because you’ve got this machine, why has my dentist not got this machine, and they start coming here.

Local practices may be unable to provide radiographs of adequate quality to support triage if they do not have the appropriate equipment, and this can affect triage decisions. Sometimes a pragmatic decision needed to be made around convenience and cost for the patient:

See the trouble I have at the moment is I don’t have a practice. I don’t have an OPG machine in the practice. Now I can do . . . being a DwSpI I can do the surgery but because I don’t have an OPG machine means I’m having to refer them to [a district general hospital]. Do I then muck around and get the patient to go into [a district general hospital], do an OPG and then come back to me for the treatment or do I . . . ? I might as well just make the referral, get their OPG done and have it done there.

I know. It’s not as slick as it should be.

No.

It’s messing the patients around at the moment, isn’t it, because it’s not easy to image.

Currently, records held by GDPs are not linked to other NHS records, such as those held by GP practices. Therefore, obtaining accurate information for the referral form is reliant on patients disclosing accurate information, particularly about their medical history. The following discussion related to a consultant describing a discrepancy between a decision made during paper triage (decision to refer to specialist primary care) and following a face-to-face consultation, during which the patient disclosed a higher quantity of alcohol consumption:

. . . So, again, that’s . . . it’s often the case there, I guess sometimes that happens between a consultation thing I’ll have something like [alcohol consumption] and the patient might deny something. Then they go through to see the nurse for a pre-op assessment for a GA or something and they confess to lots more because they’ve had a few minutes to think about it. So it could be that they do deny it to the general dentist and then somebody asks the same questions and they start thinking, oh well maybe there is something I need to tell them.

C1 (focus group 2)

A possible driver for an initial referral to specialist or secondary care from general dental practice may be the time and effort taken to carry out a procedure versus remuneration available in primary care. The following quotation is from a GDP who described possible reasons for a referral for a procedure that he felt was uncomplicated:

One of the drivers for multiple quadrants being referred out and the situation for even cons [fillings] for sedation is the fact that GDPs can only claim three UDAs for it. So, that’s the driver from the primary care side. But, if you look at each, what you can see on the radiograph, if it was just that tooth in isolation, it’s not technically difficult to take that out.

GDP (focus group 1)

Clinician specialty and experience

Clinician experience is defined as a combination of the passing of time and gaining skills and exposure to an event. Focusing on a medical specialty, such as oral surgery, affords more opportunity to develop conceptual knowledge and increases exposure to events specific to this area of expertise. 48 Where differences were found in the decision-making of GDPs and consultants, GDPs tended to focus on the clinical information, whereas consultants tended to try to form a holistic view of the patient. It seems that their experience had taught them to focus on the severity and management of existing illnesses and to not assume that existing conditions are necessarily well controlled.

Although experienced GDPs undertaking triage of referrals might consider themselves to be more than capable of carrying out certain procedures, newly qualified GDPs and consultants were more likely to triage referrals to a specialty or secondary care service:

I think that if I was a patient that sore and someone brushed me off and sent me for a referral waiting 8/12 weeks . . . I’d be annoyed. But what if you fractured it and it was very sub gingival and you haven’t got the surgical [skill]? You’re then having to refer to have the rest of it retrieved out.

I think you’ve got to start off knowing that it is going to be surgical.

. . . Clinical experience is something that is accumulative isn’t it? As your decision-making evolves, your ability to carry out procedures evolves?

Consultants were more likely to consider the patient’s medical history and draw on their experience of complications that can result during surgery:

And, if you look at them, I mean you can’t really see what’s on the right, but if you look at the molar, what does that look like? It doesn’t look like it’s going to be a particularly traumatic extraction . . .

But, I would argue even if it is someone with more experience it’s risky to do that in practice. Just like people don’t get caught out very often, but sometimes they do, they end up sending them to A&E [accident and emergency] because the patient . . . or they don’t even know, because three days later the patient is still bleeding, goes to A&E and get transfused, and it happens. They get transfused and all sorts of problems.

I think where maybe in . . . sometimes the practice you get a biased view and that’s because of nine times out ten you don’t have a problem. But, we’ve also had a biased view, because we see the ones that don’t get away with it in our chequered history.

Discussion

Triage is described as:

The medical screening of patients to determine their priority for treatment; the separation of a large number of casualties, in military or civilian disaster medical care, into three groups: those who cannot be expected to survive even with treatment, those who will recover without treatment, and the priority group of those who need treatment in order to survive.

Stedman’s Medical Dictionary 56

This definition of triage still permeates the medical literature today (with findings of variation not dissimilar to those reported here), with examples from emergency medicine and military field operations. 57 However, the picture is changing, with the implementation of telephone triage on helplines such as 11144 and remote dermatology services. 39,58 Triage is not merely the selection of those who need care to survive but is becoming a tool by which the complex map of medical services can be navigated to ensure that patients receive the right type of care, in the right setting, delivered by the most appropriate clinical team with the most efficient use of resources.