Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 13/59/26. The contractual start date was in March 2015. The final report began editorial review in July 2017 and was accepted for publication in November 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by Shaw et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2018 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Research context and relevant literature

In this chapter, we provide an overview of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) brief and how our research contributes to it, describe the NHS landscape as our research context and summarise the evidence base, generally in relation to alternatives to face-to-face consultations (e.g. e-mail and telephone consultations) and, specifically, on the use of virtual consultations.

There is a significant push from national-level decision-makers for the NHS to make better use of digital technologies, including virtual consultations. However, the current evidence on the development and use of virtual consultations is sparse. The few studies conducted to date have shown great potential for the use of virtual media, such as Skype™ (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) and FaceTime (Apple Inc., Cupertino, CA, USA) for online communication between patients and clinicians. However, much of the literature uses experimental methods and classifies service models primarily by the nature of the technology and secondarily by the task supported by that technology. Although there are lessons to be learned about the potential of virtual consultations from this literature, we conclude that further work is needed to understand how and why individuals, teams and organisations do (and do not) adopt virtual consultations.

Introduction to the research

Health services face rising costs as a result of increasing disease prevalence, high ‘did not attend’ (DNA) rates and poor patient engagement, resulting in poor health outcomes and greater use of emergency care. 1,2 Most outpatient models fail to reliably provide responsive care when patients need intervention. Reducing hospital follow-up appointments is a priority in the NHS. Unless new ways of delivering care are found, chronic disease management will be unaffordable and undeliverable. Current policy places considerable faith in digital technologies and their potential to deliver more efficient, effective, patient-centric care in the community. 3–6 The UK’s National Information Board (see the glossary in Appendix 1 for a description of national organisations and initiatives) has argued that, in order to respond effectively to these demographic and epidemiological trends, we need a different kind of health service, in which the traditional outpatient consultation, for example, will become increasingly obsolete. 5 Technology-supported consulting is viewed as at least a partial solution to the current challenges of delivering health care.

Digital technology plays a significant (although varied) role in local plans across the NHS to reconfigure hospital services and transform the delivery of health services. 7 Attending regular clinics can be expensive, physically challenging and inconvenient for patients. Virtual consultations (using Skype or similar media) have the potential to fundamentally change the way in which patients interact with clinicians.

Following proof of concept work with NHS Choices, we were funded by the Health Foundation8,9 to explore the scope and feasibility of video outpatient consultations in the diabetes clinic in Newham. The Diabetes Appointments via Webcam in Newham (DAWN) project documented 62% acceptance rates across all ages, a reduction in DNA (from 40% to 23% at the end of year 1) and small efficiency savings of £63K. 8,9 Our subsequent project on Diabetes Review, Education And Management via Skype (DREAMS) was also funded by the Health Foundation (2012–14), and explored Skype-supported video consultations in ‘hard-to-reach’ patients with diabetes mellitus. 10 As well as improved clinical outcomes, DREAMS showed improved engagement and better self-management among regular users. 11

The online environment is known to produce subtle alterations in the dynamics of human interaction, with a potential risk that clinical clues will be missed or the clinician–patient dynamic will be altered adversely. 12 As a new service model, it also brings operational and cultural challenges, including training and supporting staff, as well as patients, in using digital technologies. For this reason, we sought to undertake further in-depth research.

Aims and objectives

As set out in our protocol published previously,13 the VOCAL (Virtual Online Consultations – Advantages and Limitations) study aimed to define good practice and inform its implementation in relation to clinician–patient consultations via Skype and similar media, addressing three key objectives:

-

at the macro level, to build relationships with key stakeholders nationally and identify from their perspective how to overcome policy and legal barriers to the introduction of remote consultations as a regular service option

-

at the meso level, to illuminate and explore the sociotechnical microsystem that supports the remote consultation, thereby identifying how organisations can best support the introduction and sustainability of this service model in areas where it proves to be acceptable and effective

-

at the micro level, to study the clinician–patient interaction in a maximum variety sample of 30–45 remote outpatient consultations in two clinical areas; in particular, to highlight examples of good communicative practice, to identify and characterise examples of suboptimal communicative practice and to propose approaches for minimising the latter.

The study addressed the following research questions:

-

At the macro level: what is the national-level context for the introduction of virtual consultations in NHS organisations and what measures might incentivise and make these easier?

-

At the meso level: how is a successful virtual consultation achieved in an organisation in which the processes and systems are mostly oriented to more traditional consultations?

-

At the micro level: what defines ‘quality’ in a virtual consultation and what are the barriers to achieving this?

In the following sections, we outline how our research contributes to the NIHR brief and describe the current evidence base relating to virtual consultations. The VOCAL study was designed as a multilevel study capturing macro-level barriers and incentives to, and facilitators of, supporting virtual consultations (objective 1), meso-level administrative and clinical processes that need to change to embed online consultations (objective 2) and micro-level details of the interactions in consultations (objective 3). As this included a significant research component focused on the national-level context, we set out the detail of the wider landscape in which virtual consultations are evolving in Chapter 3.

The National Institute for Health Research Health Services and Delivery Research commissioning brief

The VOCAL study was funded in response to a call from the NIHR Health Services and Delivery Research (HSDR) programme for ‘assessing alternatives to face-to-face contact with patients’ (HSDR call number 13/59). The call emphasised the rapid increase in new forms of interaction between patients and health professionals, including consultations by Skype, e-mail and webcam, and the potential that these new forms of contact hold for improving the quality and experience of patient care and securing cost-savings. The two themes were:

-

primary research evaluating the cost-effectiveness of non-face-to-face contact with health professionals

-

qualitative research on the impact of new forms on the clinician–patient dynamic, and appropriateness for hard-to-reach groups.

Our study responds directly to the second theme, which offered a unique opportunity to build on our previous work in setting up Skype consultations for the diabetes clinic at Newham. 8–11 Guided by the brief, we sought to examine in depth any changes in the dynamics of the clinician–patient interaction and communication in virtual consultations in three clinics spread across two clinical areas (the Adult/Young Adult Diabetes and antenatal Diabetes clinics in the Diabetes service, and the Hepatobiliary And Pancreatic Cancer Surgery clinic in Cancer Surgery, enabling comparison across different conditions, clinics and teams), the appropriateness and satisfaction of staff and different patient groups using virtual consultations (including young adults, older people and those from ethnic minority groups) and the ways in which wider organisational- and national-level environments shape virtual consultation services.

In the following sections, we review the current evidence generally on alternatives to face-to-face consultations, and specifically on virtual consultations, and provide an overview of the strengths and weaknesses of different methodological approaches.

The development of alternatives to face-to-face consultations

New technologies that support alternatives to face-to-face consulting are often seen by decision-makers as potentially providing more flexible and convenient ways for patients to interact with health professionals, while at the same time improving financial efficiency and the clinical effectiveness of services. 2,14,15 However, the use of alternatives to face-to-face contact with patients is a relatively new area of activity in health care, with limited evidence currently available to inform decisions about how best to develop and use a range of technologies. As well as video, these technologies include telephone, text messaging, e-mail consultations, online portals, telemedicine and telehealth. We summarise the evidence on each of these below.

Telephone

Telephone contact is used variably for assessment and triage of acute problems;16–33 general practice consultations;34–40 to offer health education;41,42 and to offer support for those with chronic illness43,44 or those in need of palliative care. 45 The literature on telephone consultations consists largely of small and heterogeneous primary studies, most of which had practical challenges or methodological flaws. Systematic reviews have tended to conclude that, although telephone contact may allow minor problems to be dealt with without a face-to-face visit (and sometimes with apparent cost-savings), it may miss rare but serious conditions and/or lead to higher rates of face-to-face visits in the days following. This is particularly the case when those responding to calls have limited training and are working largely to an algorithm, as, for instance, with NHS 111. 21 Telephone consulting, it seems, requires skill and judgement, perhaps because of the lack of visual cues. Detailed analyses of the clinician–patient interaction using conversation analysis have found that, compared with traditional face-to-face consulting, telephone consultations have a more linear format and tend to focus on a narrow range of preplanned themes, with fewer opportunities for the patient to raise ad hoc issues. 34,35 One study combined telephone consulting with video consultation to support patients receiving palliative care and reported that the combination offered both practical support and reassurance. 45

Text messaging and e-mail

There is a significant body of literature on text messaging as a means of, for instance, supporting people with chronic illness;46–48 facilitating adherence and/or attendance;49–52 conveying results of tests;53 or sending health promotion messages. 54–57 Systematic reviews have indicated that text messaging can be effective in facilitating short-term behaviour and medication adherence in particular. 51 However, the quality of studies is often poor, with research frequently conducted with population samples that may not be representative, and with limited understanding of long-term effectiveness and patient satisfaction. 52,58,59 Findings generally show that the text-messaging medium is popular with varied groups of patients, who use it both to send questions and to receive messages sent by health professionals and administrators. Similarly, systematic reviews of a large number of primary studies (mostly of weak methodological quality) have confirmed that it is technically possible to consult via e-mail, and that some patient groups value such contact. 60,61 Other studies have raised the possibility of increased inequality of access62–64 and professional uncertainty about safety, workload and remuneration, and about the ‘rules of engagement’ for online interaction. 64,65

Online portals

Studies of online portals (e.g. facilitating prescription ordering,66 appointment booking67,68 and patients’ access to their online record69) have demonstrated proof of concept. 70–72 However, such portals are often not widely used by patients beyond the research setting.

Telemedicine

Telemedicine involves the use of technology to deliver clinical care at a distance (including, potentially, video-based consultation), typically with one part of the health service, usually in primary care, linking remotely to another, usually in secondary care (e.g. teledermatology). There are many proof-of-concept studies73–77 and examples of up-and-running services, largely in remote regions (e.g. in rural Wales, UK78). However, the adoption, spread and sustainability of telemedicine tends to be disappointing, because of issues of cost, patient preferences and subtle but vital impacts on professional roles, interactions and work routines. 73,79,80

Telehealth

Telehealth (involving the exchange of data between a patient at home and their clinician, often via a remote monitoring centre, to inform diagnosis and monitoring) and telecare (involving the use of technologies, installed at home or attached to the person’s body, to allow remote monitoring of position or environment) are both the subject of considerable debate. Proof of concept (that the technology ‘works’) has been shown for many telehealth81–84 and telecare81,82,85–87 technologies, and some randomised trials have demonstrated improved outcomes, such as reduced hospital admission and mortality rates. 83 However, many trials have been criticised as being small, unrepresentative and methodologically flawed. To date, the largest trial achieved improvements in outcomes, but only at a significant cost that is out of reach within the NHS. 83

Combinations of different technologies

Combinations of different technologies (e.g. home-based and telemedicine services,84 or telephone and video consultation45) show that the efficacy, acceptability and costs of such services vary considerably.

Summary

In summary, studies examining the potential of new technologies to support alternatives to face-to-face consultations suggest that many of the mediums set out above (text messaging, e-mail consultations and so on) offer potential for patients, clinicians and the wider health system. However, many studies are of poor methodological quality and questions remain unanswered about the relative cost and effectiveness of individual technologies and their combinations. Overall, the literature suggests that different technologies (particularly telephone and text messaging) offer potential as alternatives to face-to-face consultations for different patients in different clinical settings. For the VOCAL study, this raised questions about the potential and appropriateness of video-based consultations, as well as the adoption and spread of technology-mediated services in health care. For instance, qualitative findings on telephone consultations raised questions about whether and how the addition of a visual medium would mirror the ethos and interaction of the face-to-face environment. Findings from studies of other technologies raised the possibility of increased inequality of access, a need to review the ‘rules of engagement’ for online interactions between clinicians and patients, and changes to work routines required to embed technologies in the everyday work of health care.

Evidence relating to the use of virtual consultations

The evidence base on virtual consultations (using Skype or similar technology) has been steadily accumulating. 88–98 A number of published studies focus broadly on video or remote consulting (e.g. exploring issues of usability and acceptability). 45,99–113 Many focus specifically on the clinical use of Skype,91,114–123 either on its own or in combination with other technologies [e.g. WhatsApp (WhatsApp Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA) messaging124 or FaceTime125,126]. A handful of papers examine the perceived ethical, legal or technical issues relating to virtual consultations. 127,128 Studies generally report positive benefits, particularly in terms of patient satisfaction and increased accessibility. However, most are brief descriptions of small, pilot-stage projects (some with as few as five patients), or randomised controlled trials (RCTs) offering one or more virtual consultations compared with traditional face-to-face contact, often with limited follow-up.

Below, we extend the literature review that we conducted at the start of the VOCAL study,13 by reviewing the higher-quality primary studies from a 2015 review88 of 27 published studies of the use of Skype, which reported largely positive benefits. We focus on studies from the review that are most relevant to the VOCAL study, along with some additional studies published since 2015. In doing so, we have adapted and extended the literature review that was previously published in our study protocol in BMJ Open. 13

A number of studies have focused on the use of virtual consultations for the treatment of chronic diseases. A study of family based behavioural support for adolescents with poorly controlled type 1 diabetes focused on the ‘working alliance’ (the strength of the relationships between patients, caregivers and health-care professionals). 129 Findings showed that 10 sessions via Skype were as effective at preserving the working alliance as 10 face-to-face sessions. 114 Adherence to treatment and glycaemic control were also similar. 91 However, losses to follow-up were high: of the 47 (out of 92) participants randomised to Skype sessions, follow-up data were available for only 32.

In our work in Newham, we introduced virtual consultations for Diabetes in 2011, with 480 remote consultations documented in 104 patients between 2011 and 2014. 10,11 Findings showed that virtual consultations were popular with both patients (especially young adults) and staff. In patients who chose to use the remote service, it appeared to be associated with increased engagement (overall DNA rates were 13% in patients accepting the Skype option and 28% in those who chose not to use this option, although denominator populations for these figures were self-selecting and hence not strictly comparable), improved glycaemic control (the average glycated haemoglobin level pre and post introduction of remote consulting was 70 mmol/l and 65 mmol/l, respectively, for those who used the service) and fewer accident and emergency (A&E) attendances than those not using the remote service (raw data on this were statistically significant, although numbers were small). These figures were encouraging; however, patients were not randomised and there were multiple potential confounders, and 45 patients who initially signed up to the remote service subsequently withdrew from it.

A recently published RCT130 showed similarly positive results for patients with type 2 diabetes who were not responding to usual care. A total of 102 participants (n = 165) were randomised to either monthly video conferences with a nurse via tablet computer over 32 weeks or usual clinic-based care. Allocation to the trial group required participants to regularly self-monitor blood glucose, blood pressure and weight, and to upload results so that these were available to both the nurse and patient during video consultations. Authors reported a significant improvement in glycaemic control in the virtual consultation arm compared with those receiving clinic-based care. However, these differences were no longer significant at 6 months, and authors were unable to tease out whether it was the video conference per se, the effect of immediate response to increased measurements, increased personal contact or a combination that led to the initial improvement.

In a study of the management of depression in older housebound adults, participants were randomised to receive in-person problem-solving therapy, Skype-delivered problem-solving therapy or a weekly telephone call with no therapeutic content. 92 Both the in-person and Skype-delivered therapy were effective at reducing depression scores and disability outcomes. However, at the 36-week follow-up, the participants in the Skype arm experienced significantly better outcomes than those receiving in-person therapy. The authors ventured that the more focused nature of the Skype sessions may be responsible for sustained benefits.

A number of studies have examined the use of virtual consultations for clinical follow-up, either as an alternative to or an addition to face-to-face consultations. A 2014 study reported on the use of Skype for orthopaedic follow-up. 94 The Skype service was offered to 78 patients, following total joint arthroplasty. Participants were invited to consult with their surgeon via Skype in addition to scheduled follow-up appointments at 1, 3, 4, 6 and 9 weeks. Just under half of the participants (n = 34) underwent at least one Skype consultation. The remainder (n = 44) did not have appropriate electronic devices or internet connection to use the Skype service. There was no significant difference in clinical outcomes for the users and non-users of this service (however, the study was probably underpowered). However, those participants followed up using the Skype service had fewer unscheduled in-clinic visits. Those using the Skype service rated their postoperative satisfaction as higher than those who were not using it. A key finding in a follow-on paper with 228 participants was that time spent on the consultation, and patient-borne costs, were lower in the Skype group. 96 A linked economic evaluation showed that service costs were also significantly lower in the Skype group. 95 Although no issues were missed in patients in the trial, a subsequent commentary queried whether or not remote assessment might be less safe. 97

Skype was used to deliver follow-up training for ‘pursed lips breathing’ (a technique used to manage breathlessness in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease). An initial study with 16 participants reported that those who received the follow-up sessions had better breathlessness management than those with basic training alone. 115 A subsequent small-scale trial confirmed these findings. 116

A small trial (n = 55) comparing remote ‘video visits’ during follow-up after prostate cancer surgery with usual care found video visits to be ‘equivalent in efficiency’ to conventional outpatient visits, as measured by the amount of time spent face to face, patient wait time and total time devoted to care. 99 There were no significant differences in patient perception of visit confidentiality, efficiency, education quality or overall satisfaction. Video visits incurred lower patient-borne costs and were associated with similar levels of urologist satisfaction to conventional outpatient visits. Other studies have shown similar levels of patient satisfaction, particularly in terms of time saved (as a result of not needing to travel to clinics) and costs saved. 101,104,107

In a randomised trial of Skype sessions versus standard home care in supporting families with premature infants, the nine families randomised to Skype sessions reported very positive experiences. All found the technology easy to use, noting that virtual consultations were better than telephone calls. 131 Tellingly, the authors commented that ‘The families readily embraced the use of ICT [information, communication and technology], whereas motivating some of the nurses to accept and use ICT was a major challenge’,131 raising questions about the ways in which virtual media might be embedded in clinical work.

Virtual clinics via Skype have also been used for counselling and mental health consultations. Skype proved to be an effective medium for supporting independence and self-confidence among those aged 12–18 years with spina bifida. 98 In a 15-minute consultation once per week, the nurse supported patients with continence care and self-care. Participants reported that they felt more confident talking about personal issues via Skype than face to face. They also valued the privacy that consultations via Skype allowed (e.g. enabling young people to speak about their care from a private space at home rather than in a face-to-face consultation with a parent or carer), and increased the accessibility of the service (particularly for those patients with complex physical needs).

Issues surrounding privacy, security and reimbursement for virtual consultation services are the topic of significant public and professional debate. Despite this, and often being mentioned in passing in discussion sections of studies,108 such issues have rarely been systematically explored. 127 Technical difficulties are also typically mentioned in passing, but are rarely explored in any depth. Studies beyond the medical literature have shown that Skype is often ‘laggy’ (e.g. audio and video data can become unsynchronised). However, in one study that looked at the effect of collaborative song-writing as therapy, some participants reported that this lag could be helpful, making them select words with care and focusing them more on the interaction. 117 There are times when Skype compresses the video, so that facial expressions are hard to interpret. 117 It may be that the quality of hardware or bandwidth is critical to some (although perhaps not all) kinds of clinical consultation. 103,128

In summary, the research literature on virtual consultations remains sparse. The contribution of virtual media to consultations in health care has been studied mainly by using experimental methods (especially RCTs), but with no adequately powered randomised trials and only a handful of controlled before-and-after studies conducted to date. These studies have generally focused on evaluating the outcomes of the technology. To date, there have been no rigorous and theoretically grounded qualitative or mixed-methods studies of the kind undertaken in the VOCAL study.

Overall, the literature suggests that there is great potential for the use of virtual media tools, such as Skype, for virtual communication between patients and clinicians. Although the studies reviewed are broadly positive, the small sample sizes, select nature of samples and high losses to follow-up call into question any unqualified conclusion that the technology is ‘effective’, and the lack of negative studies raises questions about potential publication bias. For the VOCAL study, current evidence raises questions about the relevance of video-based consultations for different clinical conditions and patients, the accessibility and acceptability of Skype and other virtual media to both patients and (clinical and non-clinical) staff, the ways in which practical and technical issues (e.g. the availability of smart technology, delays in data transfer) shape virtual consultations and how ethical, legal, regulatory and payment issues shape the adoption of virtual media. In addition, none of the studies reviewed examined the detail of interaction and what gets either added in or left out of consultations when they take place virtually, raising the question for the VOCAL study about what a good-quality interaction means in the context of a virtual consultation.

Although the RCT is widely viewed as a gold-standard design for testing the efficacy of an intervention experimentally, the trials that have been undertaken on remote consultations have provided few or no data on the organisational complexities of implementing a radically new technology-based service, and they cannot address the question of how video consultation services emerge and become embedded in a real-world setting (i.e. outside the specific confines of a randomised trial and with a view to long-term sustainability). To fill this gap in the literature, studies are needed to explore the emergence of video consultation services naturalistically (i.e. by capturing real-world quantitative and qualitative data on the emerging services and documenting the challenges faced).

Chapter 2 Methods

Study design

In contrast to much of the published research literature described in the previous chapter, which has tended to compare ‘technology on’ with ‘technology off’ in an experimental or quasi-experimental design, the design of our study was oriented to teasing out the (often subtle) social and material interactions occurring between patient, staff member and technology(ies). Although experimental studies have their place, technology-focused approaches are crude and deterministic. 81,132–136 In-depth qualitative studies can reveal how individual identity, experience, expectations and material skill might shape and alter these technology-mediated interactions and make them more (or less) efficient and effective. 137

We conducted a multilevel mixed-methods study of virtual consultations with macro-, meso- and micro-level components. At the macro level, we combined interviews with 12 national policy-makers and other key stakeholders with analysis of national-level policy documents in order to explore barriers and incentives to, and facilitators of, supporting virtual consultations. At the meso level, we mapped the administrative and clinical processes that needed to change to embed online consultations [e.g. changes to clinical pathways, changes to staff roles, rethinking the use of traditional outpatient space, updating information governance (IG)]. At the micro level, we studied interactional dynamics by generating a multimodal data set (audio transcript, video and computer screen capture) of 30 virtual consultations in Diabetes and Cancer Surgery, alongside a matched data set of 17 (audio-recorded) face-to-face consultations.

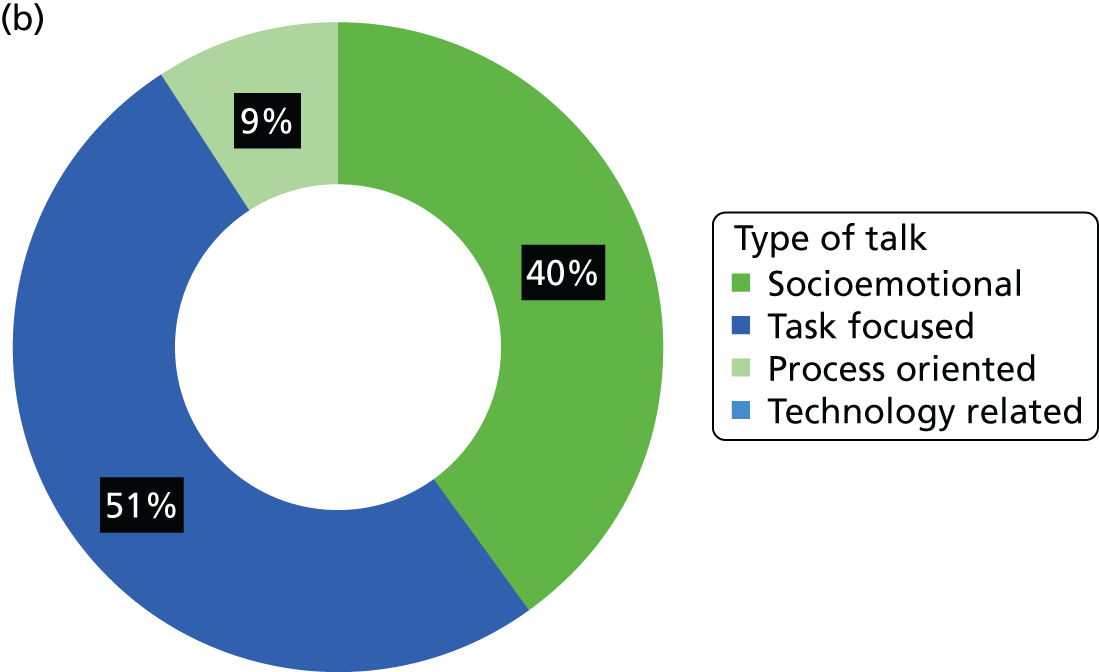

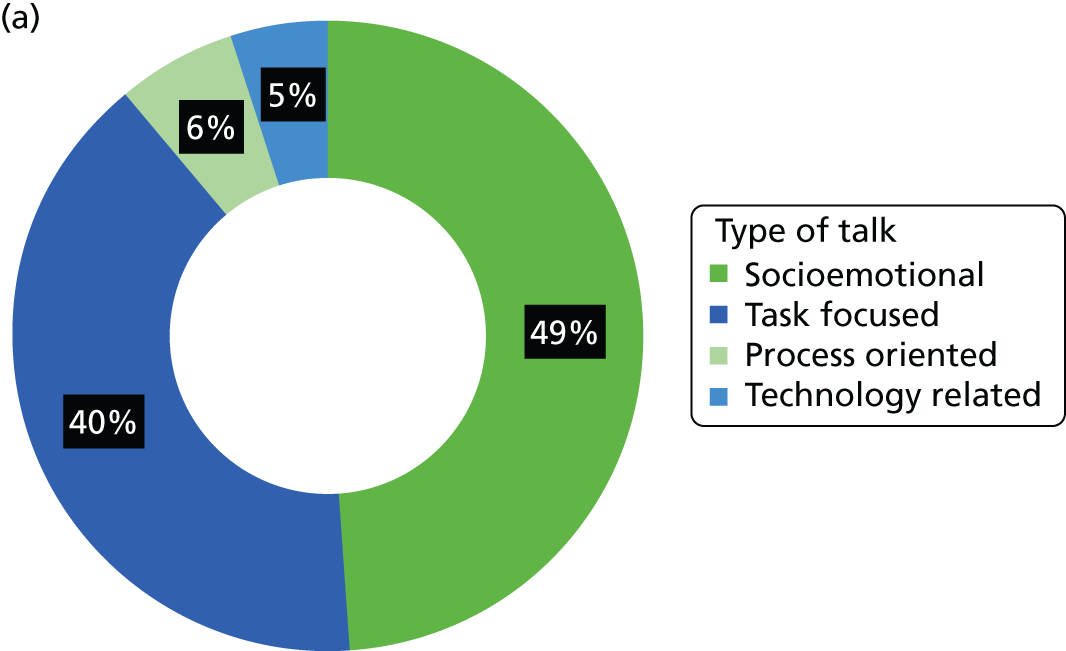

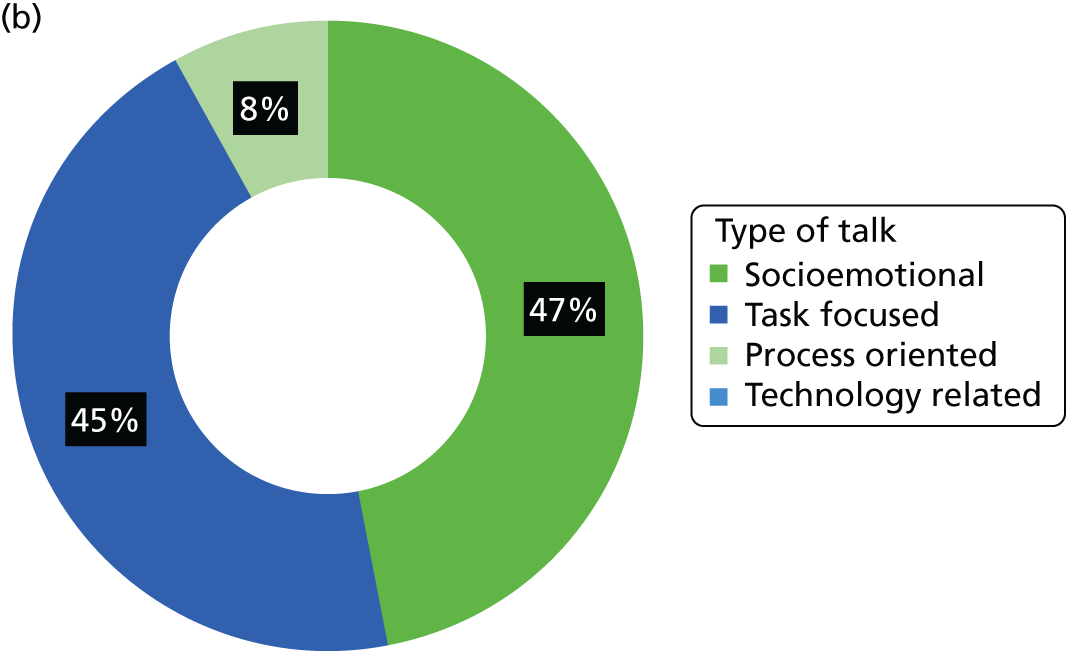

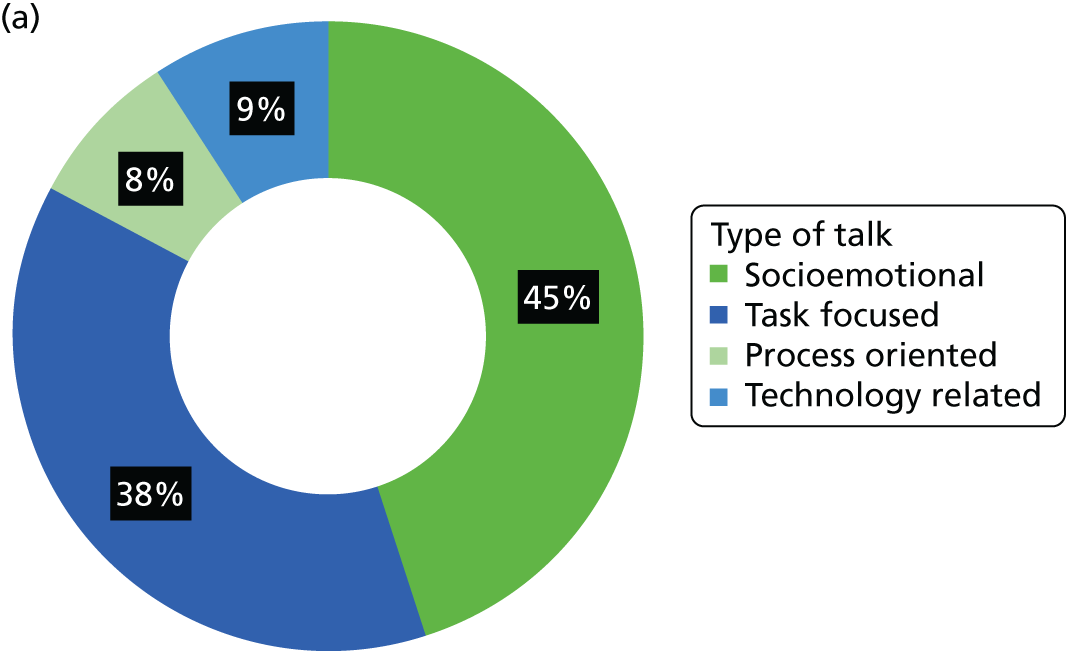

Changes to the study protocol

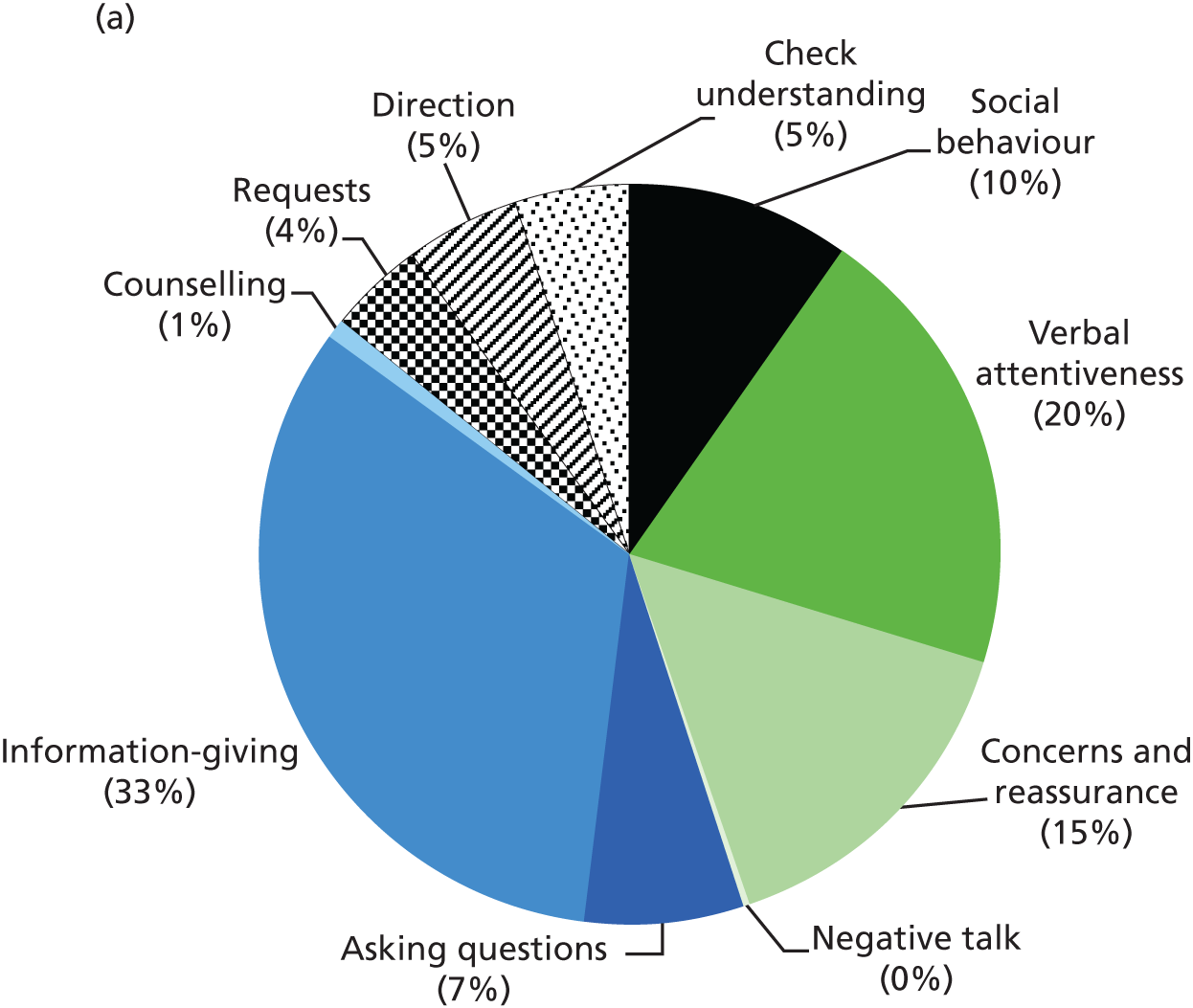

In our original study protocol, we proposed collecting 30–45 virtual consultations between patients and clinicians in Diabetes and Cancer Surgery (10–15 in Cancer Surgery and 20–30 in Diabetes) and then, using fine-tuned linguistic techniques, examining the detail of the interaction. As we began to analyse these micro-level data and examine the interactional dynamics, we quickly realised that it would be helpful to compare these with usual care (i.e. traditional face-to-face consultations) and examine if/where any interactional differences occur. We therefore adapted our study design and protocol to incorporate a comparable sample of face-to-face consultations in Diabetes and Cancer Surgery, audio-recorded to enable analysis of the type of talk that takes place. We used the Roter interaction analysis system (RIAS) to compare different categories of talk in face-to-face and virtual consultations. As we found few significant differences in communication practices (see Chapters 5 and 6), we limited our proposals to minimise suboptimal communicative practices (objective 3) in the guidance for patients and providers on using Skype and similar virtual media for remote consultations (see Practitioner Resources on the NIHR Journals Library website: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hsdr/135926/#/).

Theoretical approach

Our study drew on strong structuration theory (SST),138,139 which sees society (through rules, values and norms) as profoundly shaping human behaviour, and human behaviour (through peoples’ interpretations and choices, as well as technology-mediated actions), in turn, changing society.

As we have set out in previous work,67,139,140 structuration theory links the macro of the social environment (social structures) with the micro of human action (agency) and considers how the relationship between structure and agency changes over time. 141 The structure–agency link is mediated through ‘scripts’ (patterns of behaviour and interaction in social settings, including the adoption and adaptation of particular technologies), which gradually change over time. 137 Scripts link to organisational routines and, hence, to the potential for innovations to become embedded and routinised in everyday practice. 142

Strong structuration theory proposes that external social structures (social norms, rules and so on) are mediated largely through position-practices (defined as a social position and associated identity and practices), together with the network of social relations that recognise and support it (‘position-practice relations’, of which the clinician–patient relationship is a good example). It also sees human agency as crucial to engaging with technologies. 143 Within the VOCAL study, SST therefore offered the potential to theorise human characteristics, such as identity and social role (e.g. what it means to be a ‘clinician’, ‘carer’ or ‘patient’), interpersonal relationships (e.g. the clinician–patient relationship), situational knowledge (e.g. patient expectations of a consultation) and the capabilities needed to operate technology.

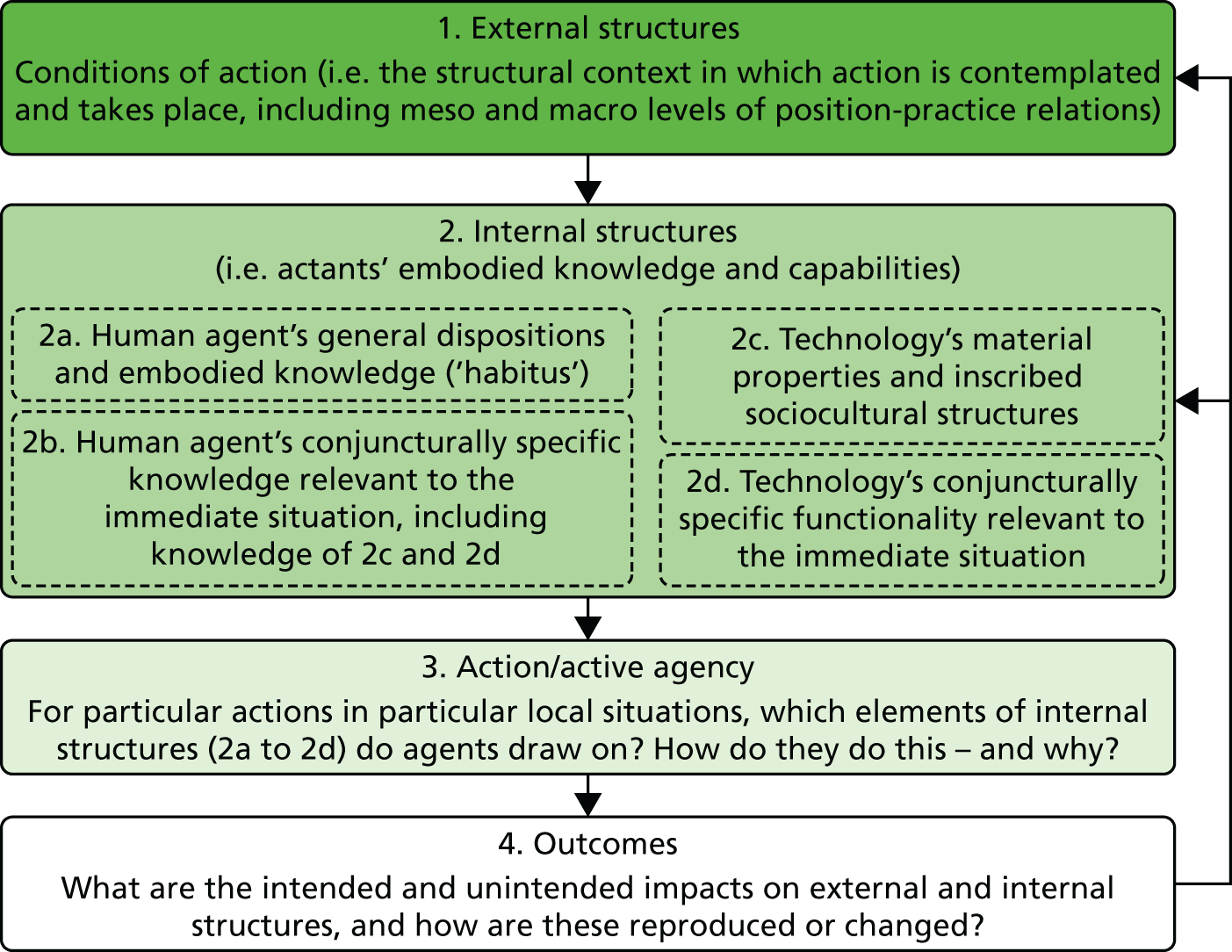

Four components of SST guided our thinking and analysis of virtual consultations in the VOCAL study: external structures, internal structures, actions and outcomes (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Strong structuration theory, adapted to encompass a technology dimension. Reprinted from Social Science & Medicine, Volume 70, Issue 9, Greenhalgh T and Stones R, Theorising big IT programmes in healthcare: Strong structuration theory meets actor-network theory, 1285–1294, Copyright 2010, with permission from Elsevier. 139

The first component of SST, ‘external structures’, refers to the position-practice relations that characterise the meso (organisational) and macro (national-level policy and decision-making) levels, and that change over time (e.g. the ways in which the medical profession is, arguably, less trusted in the face of media reporting about errors).

The second component of SST, ‘internal structures’, refers to the representations of society that we all have in our heads. They include general dispositions (e.g. discourses and world views, moral principles, attitudes, technical and other embodied skills and personal values – what Bourdieu called ‘habitus’144), as well as specific knowledge of an aspect of the world and how one is expected to act within it (e.g. a nurse’s understanding of what is involved in supporting patients with their self-management of diabetes).

The third component of SST is ‘activation/active agency’. We used ethnography to study specific examples of interactions – what SST calls ‘conjunctures’ (the medical consultation is a good example) – to capture how people play out their position-practice relations, behaving in a way that they believe is appropriate and responding in a moment-by-moment way to the other party(ies). To study the agency (i.e. human intention) behind these actions, SST incorporates theories from phenomenology (the study of people’s shifting fields and horizons of action arising from the focused activity at hand145), ethnomethodology (the study of how one person responds, moment by moment, to the talk and action of another146) and symbolic interactionism (the study of the subjective meaning and interpretation of human behaviour147).

The health-care setting is heavily institutionalised, and behaviour is often ritualised (i.e. we know, and play out, the roles expected of us as doctors, patients and so on). Behaviour in the consultation is strongly influenced by such things as regulations and other governance measures, norms, beliefs, professional and lay codes of practice and deeply held traditions (all of which are embodied and reproduced by human agents, including clinicians, administrators and patients), rather than exclusively by business concerns, such as efficiency and profit. A person’s knowledge of these institutional structures (in SST terms, the ‘strategic terrain’) may be more or less accurate and more or less adequate. A good example of this might be the older patient who retains the perception that it would be rude to offer suggestions to the doctor, whereas, in reality, the doctor is keen to promote shared decision-making.

The fourth component of SST is outcomes (see Figure 1). The outcome of human action in the consultation may be intended or unintended, and will feed back on external and internal structures – either preserving them or changing them as they are enacted. A good example of this in our study is whether or not a virtual consultation that is experienced positively will increase the likelihood that the patient will adhere to treatment and attend the next consultation (in person or virtually).

The clinical consultation is a social encounter shaped by social and institutional forces. For instance, clinicians resist technologies that (in their opinion) interfere with good clinical practice and the exercise of professional judgement,67 consulting patients will be more or less sick and have socioculturally shaped expectations of being cared for and comforted and their circumstances and/or illness may affect their ability to use the technology (e.g. those consulting virtually may be reliant on a relative or carer at home to access and use the technology). SST enabled us to focus on how bodily, emotional and cognitive functions interact with an individual’s disposition, symbolic interpretation and (imperfect) knowledge to affect how the consultation unfolds, and to consider the ways in which wider organisational, institutional and regulatory environments shape interactions in and around virtual consultations.

Action research

Our interests lay in studying the ways in which virtual consultations did (and did not) become embedded in the work of Diabetes and Cancer Surgery clinics. We were therefore keen to work with local managers and commissioners to understand the organisational change required to embed (and potentially spread) the virtual consultation option. Our study was therefore informed by the principles of action research. 148,149

Action research has been described as ‘a mutual learning process within which people work together to discover what the issues are, why they exist, and how they might be addressed’. 150 The idea is that practitioners and researchers work together to identify and seek to address issues as they arise in the context of research, and, in this case, in the development of a virtual consultation service. This meant that we keenly responded to requests for input (e.g. regarding issues with loading and updating Skype on clinic computers or plans to spread virtual consultations beyond Diabetes and Cancer Surgery clinics), and judiciously fed back emerging findings to local- and national-level decision-makers whose work was concerned with developing or spreading virtual consultations (e.g. relating to national payment systems).

Below, we summarise the main focus of our action research-related activities across the different levels of the study. Given that a virtual consultation service had already evolved in the Adult/Young Adult Diabetes clinic prior to the start of the study and the focus of Barts Health NHS Trust was on considering the potential for roll-out elsewhere within the organisation, much of our focus was at the organisational level, which appeared to be integral to the ongoing and measured development of virtual consultation services. Although all of our activities were broadly guided by the action research cycle (plan, act, observe, reflect148) and aimed to feed into service development, our contact with local and national stakeholders provided opportunities for increased insight and our extended fieldwork enabled insights into the complexities of relevant policies, organisational and decision-making processes that would not have been available to us through standard interviews or observations alone.

Macro level: national and wider social context

Our approach to interviewing national-level stakeholders (see Sampling: macro level) involved a two-stage process of an initial informal interview with all those identified, followed by in-depth interviews with a subsample of individuals. This provided an important opportunity, not only to collect data for the macro level of the study, but also to engage stakeholders and discuss emerging findings. Discussions typically related to the set-up of virtual consultation services (something that had taken place in the Adult/Young Adult Diabetes clinic prior to the VOCAL study), an overview of organisational activity and a discussion of overall approach and methodology. In several cases (with representatives from industry and NHS England), this led to repeated contact and ongoing discussion about the evolution of virtual consultation services.

The main focus of our work in this area related to national payment systems. In the first year of the study it became clear that there was interest, from within Barts Health NHS Trust and more widely, in extending the (local) spread and (national) scale-up of virtual consultation services. This was coupled with concerns over the lack of a nationally agreed tariff for virtual consultations (i.e. each service being required to negotiate locally with commissioners as to the cost of a virtual consultation). Although a small tariff existed for a telephone consultation, this was substantially different from that for a face-to-face follow-up, resulting in a significant disincentive for NHS trusts to explore this option. In other words, it made more financial sense to bring someone physically to the clinic for follow-up than to carry this out online and risk, for instance, being paid the equivalent of a telephone consultation.

To explore this further, we met with a representative from pricing development at NHS Improvement (then Monitor, see Appendix 1), and with colleagues from NHS England, to discuss potential ways forward. It quickly became clear that this was not an issue that we could resolve in the short term. However, we gained an appreciation of the ways in which a new tariff might be established, fed this back to colleagues at Barts Health NHS Trust and, given the limited in-house capacity, we jointly agreed to focus efforts elsewhere in the short term. We subsequently continued to raise the issue of the tariff in discussions with relevant decision-makers and, in partnership with a colleague from NHS England, have since incorporated the issue of national payment into further work (funded by the Health Foundation; see Chapter 6) that seeks to extend the spread and scale-up of virtual consultations.

Other activities involved meeting with a member of the NHS Chief Executive’s team to explore the role of virtual consultations in relation to the development of a new innovation and technology tariff, reviewing the Care Quality Commission’s inspection framework for digital health, and feeding into national guidance on IG requirements (see Meso level: organisational context).

Meso level: organisational context

With virtual consultations already set up in the Adult/Young Adult Diabetes clinic prior to the start of the VOCAL study, a significant amount of work needed to be done at the organisational level to begin working towards virtual consultations becoming ‘business as usual’ in the trust. In this respect, a significant amount of our action research-related activity focused on the following four areas.

First, following requests from all three clinic teams, we sought workarounds to organisational barriers to developing virtual consultations. For instance, early on in the study, it became apparent that those seeking to use Skype for virtual consultations were experiencing problems in both downloading and upgrading the software. In the Adult/Young Adult Diabetes clinic, team members were unable to perform regular upgrades (required by Skype) and required support from the ICT department, and in the Antenatal Diabetes clinic, the team was unable to gain agreement from the ICT department that they could have Skype on their computers. Formal requests from both teams via the generic ICT support e-mail hit a brick wall. Facilitated by the trust’s chief clinical information officer (CCIO), we engaged with the ICT department members directly to explore how their priorities might align with what the clinics were trying to do in providing virtual consultations. A number of issues came to light, including that there was no formal agreement within Barts Health NHS Trust for the use of Skype and, hence, no agreement with the ICT department to support Skype or to respond to related requests, as well as concerns over IG, network capacity to cope with demand for Skype and the potential impact of Skype-related requests on (already stretched) staff time and resources. Taking these concerns into account, we worked with the ICT department to find a workaround that would enable virtual consultations to run in a handful of clinics. This involved requests for Skype support going directly to a nominated ICT manager, who then passed them on to the relevant person within their team to resolve, and so enabling the development of virtual consultation services in the three clinics participating in the study.

Second, we supported the development of IG guidance. In an effort to address the ICT department members’ concerns about IG (see above), we worked with the trust’s IG department, which was aware that Skype was beginning to be used, but (at that stage) was unsure of how best to support it. Along with a colleague in one of the local Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs; with expertise in IG), we drafted IG guidance, with regular input and clarifications from the Barts Health NHS Trust IG department. The guidance was subsequently approved by Barts Health NHS Trust. In parallel, a member of the VOCAL study steering group connected us with the Information Governance Alliance (IGA; at NHS Digital, formerly the Health and Social Care Information Centre – see Appendix 1), which we worked with to pool materials, informing the IGA’s own guidance and gaining IGA approval for the Barts Health NHS Trust’s own guidance.

Third, we sought to develop a community of practice of those interested in, or actively developing, virtual consultations. This largely involved us in linking key individuals, clinical teams and departments within Barts Health NHS Trust, but, as the study progressed, increasingly involved us in linking with external partners (e.g. industry partners, other NHS providers) interested in either supporting or learning more about the work being undertaken at Barts Health NHS Trust. Within the trust, we also proactively set up two consolidating learning workshops involving staff from the Diabetes teams (i.e. Adult/Young Adult and Antenatal clinics) to gather feedback from all those involved in, or impacted by, the virtual consultation model. We chose not to undertake further workshops, as we were welcomed into mainstream governance structures and working groups (see below) and found it helpful to concentrate our efforts there.

Finally, and fourth, a significant proportion of our time was focused on facilitating or unblocking barriers to video conferencing within the three study clinics; however, as the study progressed and the trust became increasingly interested in virtual consultations, so our attention turned to rolling out the service to other departments. Initially, this led us to liaise with members of the trust’s senior management team to feed in emerging evidence from the study. We then sought to monitor and support plans to roll out virtual consultation services via two main activities:

-

Establishing an outpatient project strategy group to facilitate dialogue and co-ordinate efforts across different clinics (including endocrinology, haematology and neurology) and other departments involved in setting up and running virtual consultations. This included clinic representatives, ICT and IG and operations and business strategy. The group met monthly to discuss developments and was led by a senior member of the Barts Health NHS Trust operations and strategy department. Members of the VOCAL study team (SV, JM and JW) formed part of the advisory group and provided direct input on developments.

-

Developing guidance and protocol documents (drawing on findings from the VOCAL study) to guide roll-out, including standard operating procedures (SOPs), service set-up protocols and guidance templates (see Practitioner Resources on the NIHR Journals Library website). These materials were internally approved within the trust, and are routinely used as part of service development.

Micro level: virtual consultations

At the micro level, we were oriented to practical support for virtual consultations facilitated by the presence of a researcher (typically at the patient end) who was able to, for instance, help resolve technical issues with the equipment. Our contact with patients also provided helpful insights into perceptions (and the potential use) of virtual consultation services. We fed such insights back to clinic staff members, who, in turn, shaped and modified their own virtual consultation service accordingly. For instance, in Cancer Surgery, staff had initially assumed that patients needed to come into the clinic for a post-operative follow-up appointment that involved breaking ‘bad news’, and so had selectively invited patients for virtual consultation on the basis that they would receive only ‘good news’ virtually. Patients’ feedback indicated that people would prefer to receive bad news in their own home with their family/carer nearby and without the need for (sometimes extensive) travel before and after their appointment. This led to staff rethinking the basis on which they offered virtual consultations to patients.

Finally, prompted by discussions with the IG department (see Meso level: organisational context above) about security and privacy, we developed a leaflet summarising what patients can expect from a Skype consultations (see Practitioner Resources on the NIHR Journals Library website).

Project management and governance

The study was delivered by a core working group (TG, SV, JW, JM and SS), supported by a 6-monthly independent steering group and a patient advisory group (PAG; see Patient and public involvement). The steering group had a lay chairperson and cross-sector stakeholder representation, including patients, NHS stakeholders and national-level decision-makers (see Appendix 2).

The study received ethics approval from City Road and Hampstead NHS Research Ethics Committee on 9 December 2014 (reference number 14/LO/1883).

In line with changes to the VOCAL study protocol (see Changes to the study protocol), the following substantial amendments were sought and approved:

-

substantial amendment 1: audio-recording face-to-face consultations for comparison with Skype consultations; approved on 23 February 2016

-

substantial amendment 2: sharing selected video recordings (with patient consent) with technology developers to inform and improve the design of remote consulting technology; approved on 1 December 2016.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and their carers have been key to the VOCAL project and, in fact, the original impetus (in 2011) to use virtual consultations was initiated by service users (many from deprived backgrounds and/or minority ethnic groups) within the Diabetes clinic in Newham. At that time, we sought patient feedback as an integral part of both service development and ongoing evaluation (e.g. from focus groups, in-depth telephone surveys and online questionnaires, to refine the intervention in the Diabetes clinic10).

We set up a dedicated PAG in 2015. The main purpose of the PAG was to continue to incorporate patient feedback within our work and help to capture patients’ experiences of both the research process and the proposed virtual consultation services. The group was facilitated by Anna Collard, who has a background in community anthropology. The intention, set out in its terms of reference, was that the PAG would provide advice and feedback to the VOCAL research team and steering group. The intention was that the VOCAL research team and steering group would inform the PAG about research findings as they went along. The focus of the group was on the interactions between the clinician and the patient in Skype consultations, and not on any one particular condition (i.e. either diabetes or cancer). Patients from the PAG were also asked to review key documents, such as patient information leaflets.

Summary of patient advisory group meetings

The PAG was set to meet every 6 months (or four times over 2 years, 2015–17). In the event, the group met three times during the lifetime of the project (one meeting was cancelled, as a mutually convenient date and time could not be found). In place of the formal meeting, a number of members were contacted by the research nurse (DC-R) and asked to provide comments either by telephone or e-mail on a summary update of the VOCAL research that was circulated to them. Following completion of the project in July 2017, we also followed up with one volunteer member of the PAG to discuss key findings and provide tailored input to a lay summary of the study.

At first, patients were recruited directly by clinicians in the Adult/Young Adult Diabetes, Antenatal Diabetes and Hepatobiliary and Pancreatic Cancer Surgery clinics. After that, other approaches were also used to involve patients in the PAG (see Widening patient involvement).

A total of 12 patients and one spouse attended across the three PAG meetings, with attendance at each meeting ranging from three to nine members, plus facilitators. In one case, a patient with cancer was recruited by snowballing from his son, who had diabetes and had been recruited via the Diabetes clinic. Formal demographic data were not collected on the 12 PAG members, as this was considered intrusive. Participants represented a range of ethnic backgrounds, including South Asian, African Caribbean, sub-Saharan African, white Irish and white British, as well as a wide age range (from recent college leavers to one participant who described himself as being ‘in my 80s’). Their experiences as patients included having insulin-treated and tablet-treated diabetes, gestational diabetes and cancer.

One of the PAG meetings was attended by Professor Trisha Greenhalgh, the VOCAL study academic lead, and the final meeting by Joseph Wherton, the VOCAL Research Fellow. Both updated patients on the VOCAL study and findings to date, answered questions and reported back patient comments and/or queries to the steering group.

Focus of the patient advisory group meetings

In general, each PAG meeting focused on three key issues: (1) the VOCAL study itself, progress and feedback; (2) discussions on the general use of Skype, experiences, advantages and limitations; and (3) developing a wider virtual consultation service and evaluating its strengths and limitations.

In one of the PAG meetings, the group was shown (with the written consent of the patients involved) two video clip recordings of virtual consultations, one as part of a filmed VOCAL consultation and one from a different research study (also led by TG) as the basis for discussion. These two consultations were very different (e.g. one was for antenatal diabetes and one for heart failure; in one, the patient used a personal computer, and in the other, a mobile phone; one was with a doctor and one was with a nurse; and the clinician in each case had a different style).

Two representatives from a Newham-based international charity to address female genital mutilation (FGM) were invited by our patient participants to attend their group on one occasion. They shared their experiences of setting up and using a Skype service to provide remote counselling to women and girls who had experienced (or were at risk of) FGM. Common issues included the use of the Skype medium for discussion of sensitive issues, privacy and security concerns, and the technical and practical challenges of establishing and maintaining contact when the end-user may be unfamiliar with the technology. Overall, these experienced users of Skype for FGM support were positive about its benefits, reassuring about the discussion of sensitive topics and able to describe to our patient group how potential practical and technical challenges could be creatively overcome.

In the final PAG meeting, patients were asked to comment on a patient leaflet designed to introduce patients to Skype use for appointments.

Widening patient involvement

As reported, it proved to be difficult to sustain patient engagement in the PAG, in part, because of the reliance early on in the study on referrals to the PAG from clinicians. As a result of the difficulties, different approaches to engaging patients in discussions about the VOCAL study were explored in an effort to incorporate a wider set of views that went beyond ‘self-selecting’ patients. Approaches used included a visit to a prenatal diabetes education session, which nine mothers and one spouse attended. As part of the wider appeal, the PAG facilitators were also in touch with a number of other patient groups for feedback on the VOCAL study. These included one group promoting peer support for younger people with diabetes, and another working to prevent mothers with gestational diabetes developing type 2 diabetes. In addition, a voluntary sector group providing support to patients with cancer was contacted. The October 2016 PAG meeting was also publicised through the local Healthwatch newsletter.

In addition to the PAG, the VOCAL steering group had an independent lay chairperson and included one patient representative (see Appendix 2). The patient representative was not a member of the PAG.

Summary of comments from the patient advisory group

The PAG members had diverse views on many aspects of the study. Three areas of strong agreement among the PAG members were striking, however. The first was that Skype consultations were not, and should never be, a replacement for traditional face-to-face consultations. The second was that if Skype consultations were offered, they should be offered to all patients attending the clinic and not just to ‘selected’ ones. The PAG influenced our thinking in this regard: although clinicians felt that it was their duty and prerogative to ‘select’ patients to be offered the Skype option, the PAG was of the view that it was the patient’s ‘right’ to have the option of a Skype consultation. Patients did, however, consider that the potential benefits of virtual consultations were dependent on the type of consultation (i.e. what it is for), the level of familiarity between patient and clinician, and the link with test results (with receiving routine blood test results in particular being perceived to lend itself to online contact). The third was that there were few (if any) concerns about security and confidentiality, with virtual consultations assumed to be as confidential and secure as face-to-face and telephone consultations. Some patients also felt that they were a potential resource to support the evolution of virtual consultation services, by providing ‘Skype training’ to other patients who are not familiar with its use.

Setting and context

We have been working for several years with the front-line clinical team in the Diabetes clinic to develop virtual consulting as part of business as usual in Barts Health NHS Trust, the UK’s largest acute trust (formed in 2012 when three trusts in different boroughs merged).

We studied three clinics on different sites: Diabetes (Adult/Young Adult), based at Newham hospital and with a community outreach clinic in a local general practitioner (GP) surgery (Shrewsbury Road), the Antenatal Diabetes service based at Mile End Hospital and the Hepatobiliary and Pancreatic Cancer Surgery service at the Royal London Hospital. These sites are located across adjacent London boroughs (Newham and Tower Hamlets), both of which are characterised by a high level of socioeconomic deprivation, ethnic and linguistic diversity, and a high burden of disease. 151,152 Like many acute trusts, Barts Health NHS Trust is under pressure to deliver services more cost-effectively, while responding to rising need and demand. 153,154

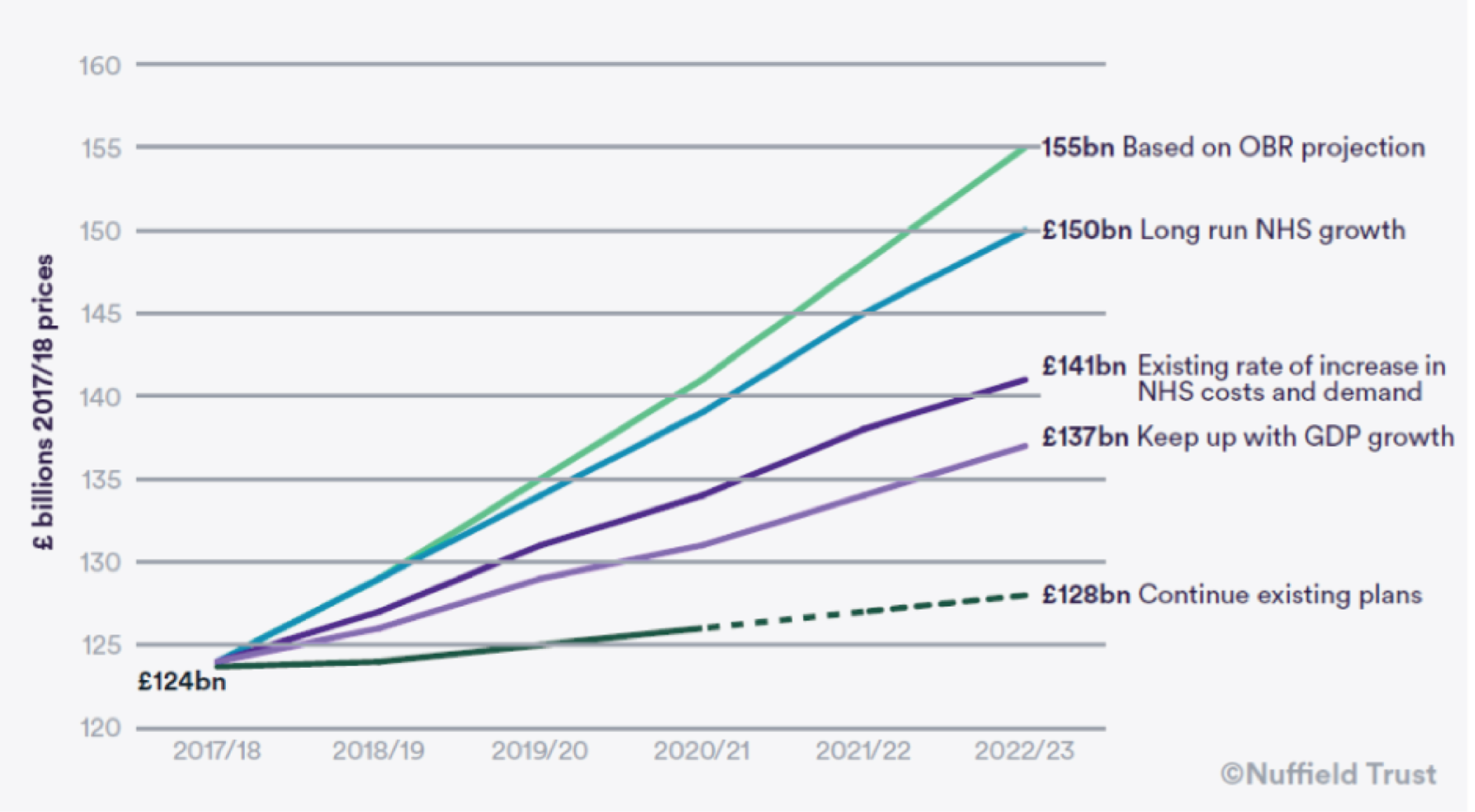

At the time of our study, the national health-care landscape was characterised by significant financial pressure, with NHS organisations struggling in the face of constrained budgets and growing demand, and technology being seen as a logical route towards achieving cost-savings and increasing quality. This national picture was mirrored in Barts Health NHS Trust, where remote consultation services in the Diabetes clinic and Cancer Surgery evolved in the context of considerable financial, organisational and staff pressures. 153,155 Barts Health NHS Trust serves a population of around 2.5 million in east London, with around 2000 clinics across eight different locations, over 15,000 staff and an annual turnover of £1.4B. In 2015, Barts Health NHS Trust was rated as ‘inadequate’ by the Care Quality Commission (the independent regulator of health and social care in England; see Appendix 1), with significant concerns reported in safety, effectiveness and responsiveness, and with the leadership of the trust. 156 The trust was also put into ‘special measures’ (a set of measures applied to NHS bodies with a view to resetting expectations of financial discipline and performance) in September 2016, following substantial and mounting financial deficits. 157 It is against this background that Barts Health NHS Trust set out a significant programme of improvement, both within the trust and with the relevant health and social care agencies (commissioners and providers), called Transforming Services Together: Strategy and Investment Case (TST). 158 The focus of TST is on radically changing the way in which services are designed and delivered, and this has fed into subsequent sustainability and transformation plans (see Appendix 1 for an overview). This includes the redesign of outpatient pathways, enabling quicker access to specialist advice, both virtually and face to face. As part of this work, and in line with the national-level impetus for technology-enabled care, Barts Health NHS Trust established an outpatient project strategy group (see Action research) focused on the potential roll-out of virtual consultations beyond those Diabetes and Cancer Surgery clinics included within the VOCAL study.

Adult/Young Adult Diabetes Services

The Adult/Young Adult Diabetes service has a long tradition of applied research and quality improvement activity aimed at ensuring that services are accessible, culturally congruent and oriented to meeting the needs of the most vulnerable patients (e.g. limited English speakers with low health literacy). A key component of this work has been developing links with local GPs and deploying specialist nurses and bilingual health advocates in community outreach roles. Unusually, a high proportion of patients with diabetes in this catchment area are young. Newham has one of the youngest populations in the UK, and the UK’s highest prevalence of type 2 diabetes in the 16- to 25-year age group (0.57/1000), attributable to a combination of risk factors (e.g. poverty, ethnicity, diet).

Engagement with traditional health service models is typically low, with poor health outcomes (e.g. young adults with poorly controlled diabetes have an increased risk of sight-threatening retinopathy and adverse pregnancy outcomes) and increased use of unplanned care through the A&E department. At the time of our study, outpatient consultations via Skype for patients who choose this option were already an integral part of the service.

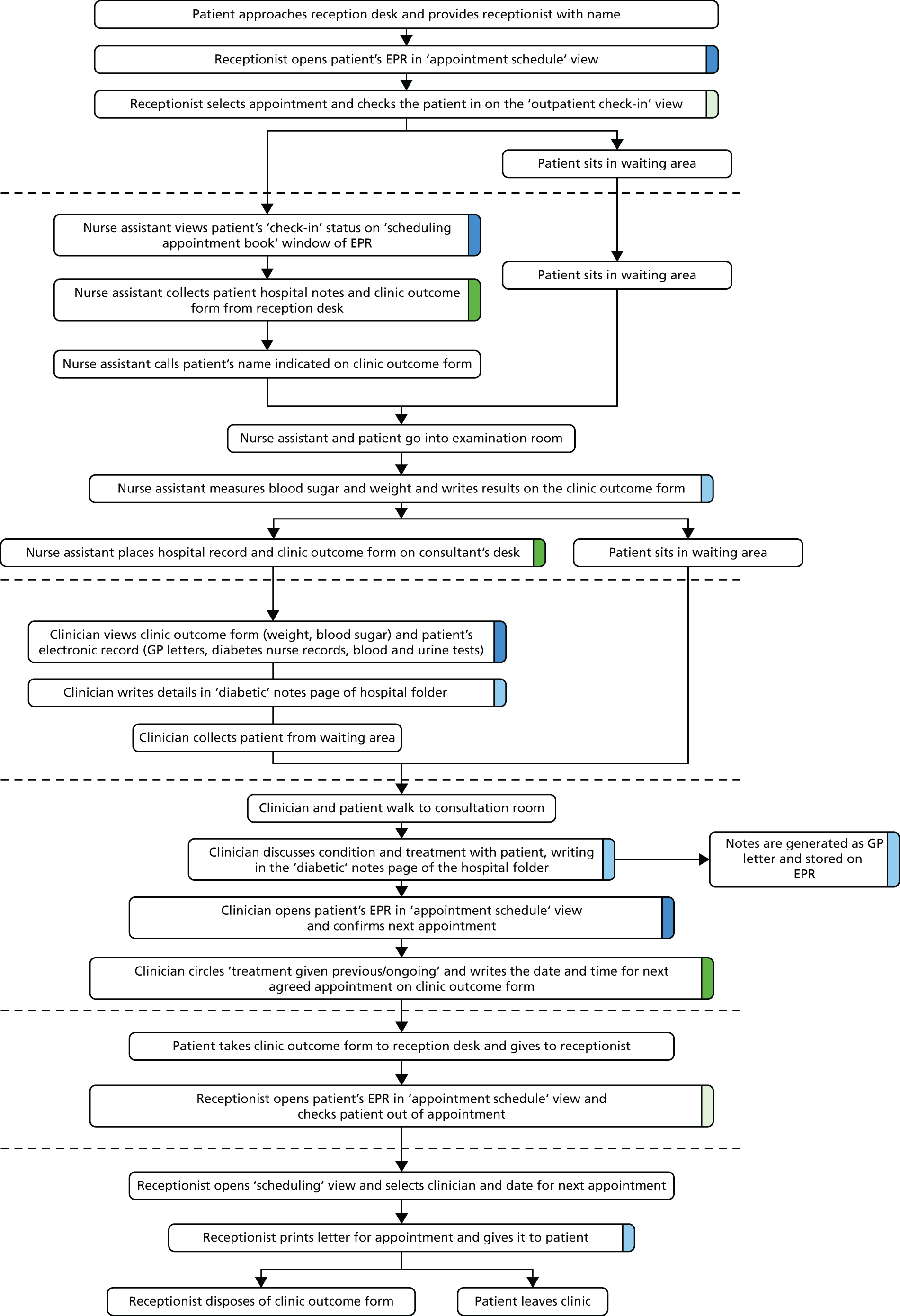

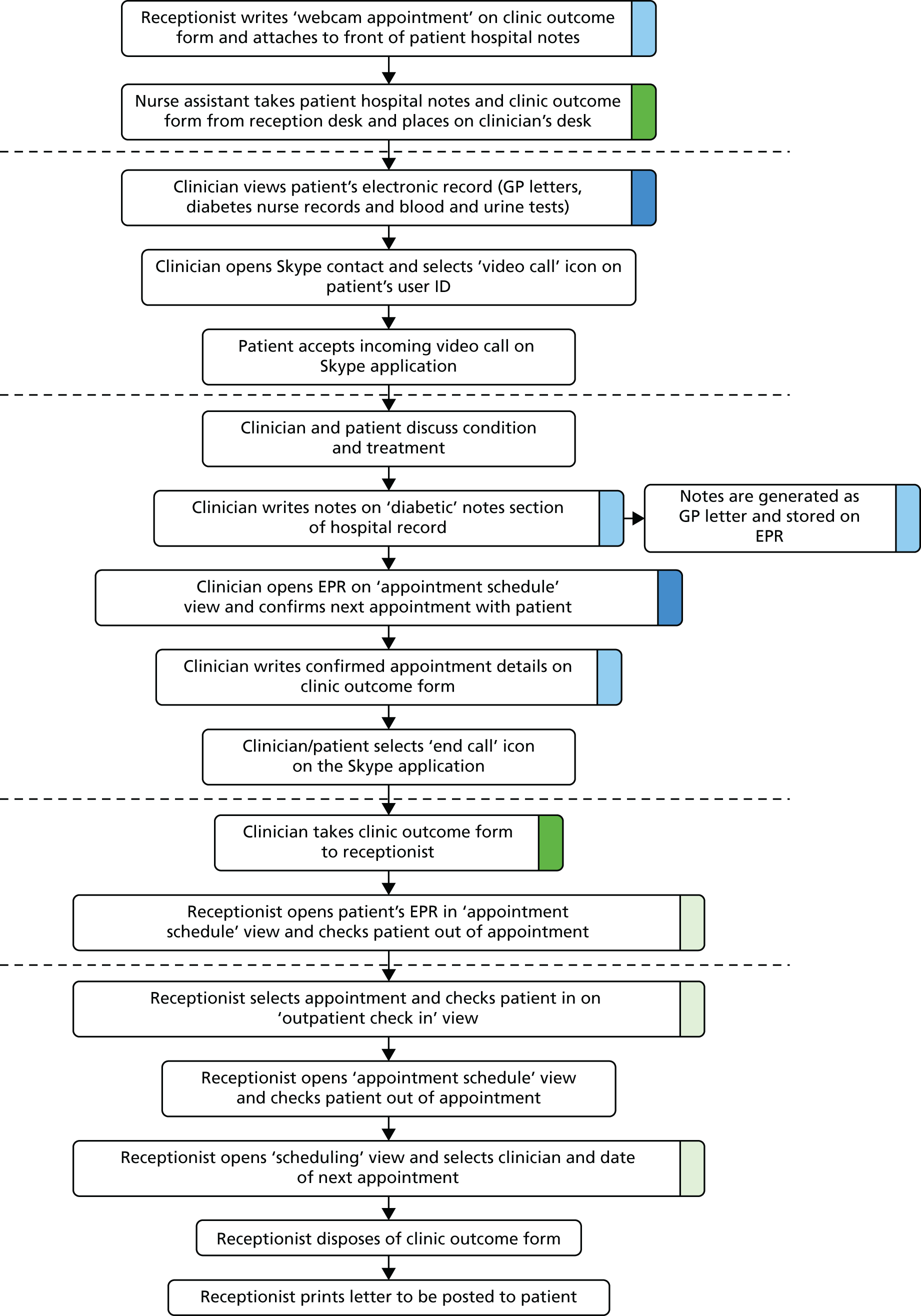

The Adult/Young Adult Diabetes service is an integrated community diabetes service, in which the consultants provide 6-monthly reviews of the patient’s condition, treatment and medication, with ongoing support from diabetes nurse specialists (from a partnering trust, the East London NHS Foundation Trust). The Adult/Young Adult Diabetes clinic is led by a diabetologist, who runs two weekly clinics on a Monday and Wednesday morning. The appointments are run for young adults (aged 16–26 years), adults and patients with insulin pumps. The diabetologist works closely with five other diabetes consultants running separate clinics, including Adult General Diabetes, a foot clinic and antenatal care. The lead diabetologist offers virtual consultations to all her adult and young adult patients as an alternative to follow-up appointments. She would typically conduct 40–50 follow-up appointments per month (i.e. virtual and face-to-face consultations), with each appointment lasting up to 30 minutes.

At each clinic, the consultants are supported by a nurse assistant who conducts the pre-appointment medical tests and checks (weight, blood pressure and recent eye test results), adds these to the patient’s clinic outcome form and provides this to the consultant (along with the patient’s hospital notes) to support the consultation. The nurse assistant also plays a key role in helping to co-ordinate the running of the clinic, by informing the consultant when the patient is ready to be called in for their consultation (by placing the patient’s medical notes and outcome form on the clinician’s desk after the pre-appointment checks) and bringing any remaining medical files for DNA appointments to the clinician at the end of the clinic.

There are six nurses in total: three running appointments with young adults and three with adults who also offer a diabetes pre-pregnancy service. The virtual consultation option is offered by the nurses supporting young adults. They work with the same patients, with one nurse specialising in supporting those with insulin pumps. The nurses provide diabetes management support, including adjustments to insulin doses, diet review/management and education on the ‘DAFNE’ (Dose Adjustment For Normal Eating) guidelines. The number of patients seen by the nursing team varies greatly depending on the availability of the nurses at the clinic and changes in the needs of their patients. Typically, there is at least one nurse at clinics running from Monday through to Thursday, with between 35 and 45 patients seen in total each month. The duration of nurse appointments (approximately 45 minutes) tends to be much longer than that of consultant appointments, as they involve more in-depth discussion about blood sugar readings, diet and diabetes management.

One receptionist manages the booking and checking in of patients for the 6-monthly scheduled appointments with the consultant. This includes scheduled face-to-face and Skype appointments. The receptionist checks the patient into their appointment using the Cerner (Cerner Corporation, North Kansas City, MO, USA) electronic patient record (EPR) on their arrival (indicating their arrival to the nurse assistant) and checks them out after the appointment. In most cases, the receptionist will book the patient in for their next follow-up appointment and print off the appointment letter at the reception desk. In addition to managing the appointment bookings and recording attendance, the receptionist is also responsible for ordering and preparing the patient medical folders. This involves reviewing the clinic schedule (approximately 2 weeks prior to clinic) and ordering (and often chasing up) hospital notes from central storage at the main hospital building. When the required hospital notes arrive, the receptionist is responsible for ensuring that they are organised and labelled for the appropriate clinic and clinician. Immediately prior to the clinic, the receptionist will also print a list of all patients to be seen (with basic personal information) for the nurse assistant and consultants. At the end of each clinic, the receptionist will record the DNA appointments in the EPR and box up the hospital notes for collection and central storage. Additional administrative support includes a service manager to manage the running of the clinic, including staff time and resources, working space and budget. The consultant also has a secretary, who is primarily responsible for dealing with the patient databases and the transcription, generation and postage of GP letters.

Antenatal Diabetes services

The Antenatal Diabetes team consists of three diabetes consultants, three obstetricians, two nurses (diabetes and endocrinology nurse specialists), one midwife, one service co-ordinator and an administrator. The service provides care to approximately 350 patients per year, nearly all with gestational diabetes. The weekly Antenatal Diabetes clinic runs on a Friday morning, with up to 50 patients per clinic. A Wednesday morning ‘spill over’ clinic is also conducted, which tends to be used for new patients.

Much of the medical information used to support the consultation is held within the patients’ maternity folder. Key medical information is replicated in the hospital records. However, day-to-day insulin doses and blood sugar readings, as well as appointment notes and recent medical tests (e.g. scans, blood tests), are stored in the patient-held maternity folder, and it is therefore a key artefact in the consultation. Although patients are assigned appointment slots, there is still much flexibility as to when patients are seen, and the diabetes consultants and midwife clinicians will often decide among themselves as to who will, and when to see, particular patients. In addition to the outpatient clinic consultations, the midwife conducts a weekly virtual (telephone) clinic to keep in touch with patients they wish to monitor more closely (e.g. patients struggling to manage their blood sugar levels). These patients are asked to call the midwife during a fixed time period, although it generally involves the midwife needing to initiate contact.

Like the Adult/Young Adult Diabetes clinic described above, the Antenatal Diabetes clinic requires pre-appointment tests and checks. This is supported by a team of 3 or 4 nurse assistants who call the patients’ names at the waiting room and take them into an examination room for pre-appointment check (weight, blood pressure, ketones), documenting these in the patient’s maternity folder. The outpatient clinic has one main reception desk (usually with two receptionists) to manage the flow of patients into the clinic. This involves booking patients in and out of the appointments on the Cerner EPR, but also tracking their order of arrival to ensure some consistency and fairness in waiting time. This allows greater flexibility for the clinicians to decide when to see patients and maintain a constant flow of appointments. This is an important task, given the large number of patients and multiple staff and appointment types involved. The receptionists also organise the hospital records prior to the clinic, so that these can be taken (along with the maternity folder) during the consultation.

Booking of subsequent appointments following the consultation is done by an antenatal diabetes administrator, who remains present at the outpatient clinic to obtain the clinic outcome forms and book the required appointment. The service co-ordinator remains in a separate office and leads on the overall management of the patient appointments, and is responsible for contacting patients to confirm or rearrange appointments when needed and for making sure that the hospital records are prepared and stored before/after the clinic.

Hepatobiliary and Pancreatic Cancer Surgery service

The Royal London Hepatobiliary and Pancreatic Cancer Surgery service is a tertiary service to which patients often have to travel long distances. It provides contrasting organisational, demographic and clinical challenges to the diabetes example, while also being nested, broadly speaking, in the same meso-level context. Patients with pancreatic and liver cancer have a very diverse demographic and may live up to 200 miles from the clinic. They have in common a life-threatening diagnosis, major surgery and a prolonged postoperative phase, in which they have to cope with multiple physical, emotional and practical challenges. Almost all patients have a direct and ongoing relationship with both the consultant surgeon (SB) and the specialist nurse (SR), sometimes going back several years. At the start of our study, the service had just begun to introduce virtual consultations in order to spare selected patients unnecessary travel.

The Hepatobiliary and Pancreatic Cancer Surgery clinic runs on Monday mornings, led by a consultant surgeon and supported by two specialist registrars and a hepatopancreatobiliary (HPB) clinical nurse specialist. Up to 25 patients can be seen during one clinic, with around 10–15% of these being related to postoperative cancer follow-up. The HPB nurse specialist leads on the planning and co-ordination of the clinic, preparing the lists and notes of patients to be seen, and allocating patients to the particular consultants, depending on their availability and the complexity of the patient’s condition or stage in their treatment. The HPB nurse specialist also takes a leading role in contacting, and being the contact point for, patients to address or follow-up on queries or issues related to their treatment. The HPB nurse also plays a key role in compiling relevant test results (e.g. from blood tests) needed for upcoming consultations.

The Hepatobiliary and Pancreatic Cancer Surgery clinic is run in a shared hospital space alongside other clinical services. The clinical team is supported by a team of nurse assistants based within this space, who support all of the clinic services running during the Monday morning clinic. The nurse assistants conduct required pre-appointment checks and inform the HPB nurse specialist when the patient is ready to be seen. The reception desk (with a team of up to four receptionists) check patients into their appointments on the Cerner EPR on arrival, and then books them out when leaving. As is the case in the Adult/Young Adult Diabetes clinic, the receptionist will book the patient into their next appointment (indicated on the clinic outcome form). However, the appointment letters are printed and posted to the patient via a centralised printing room. The GP letters are typed by the consultant or specialist registrars immediately after the appointment and sent on to the team secretary for printing and posting.

The team office space is spread across different parts of the main hospital building. However, much of the team members’ time outside the outpatient appointment is spent in theatre and on hospital walk-rounds.

Sampling

Sampling: macro level

To sample for the national-level interviews, we began with individuals charged with delivering IT strategy in NHS England. Alongside a review of policy documents (from 2000 onwards), we used a combination of purposive sampling (identifying a range of potential interviewees from policy documents and colleagues (e.g. steering group members) and snowball sampling (asking each interviewee to nominate a colleague) to ensure maximum variation in our sampling frame and enable us to build up a rich picture of the national context. We initially identified 45 potential stakeholders from across the government (e.g. NHS England, Care Quality Commission, NHS Improvement), professional organisations (e.g. the Royal College of Physicians, Medical Protection Society), patient groups (e.g. National Voices), industry (e.g. Microsoft) and charitable and third-sector organisations (e.g. the Health Foundation). We then invited a maximum variety sample of 39 of these stakeholders to talk informally with the study team. Of these, we spoke with 36, and three were uncontactable. We then undertook semistructured interviews with a purposive sample of 12 of these stakeholders, ensuring variation in the number of different institutions, groups and perspectives represented.

Sampling: meso level

The goal of sampling in the meso-level study was to map the people, interactions and organisational routines that support the virtual consultation, with a view to building a rich ‘ecological’ picture of the sociotechnical microsystem159 (and its wider embedding in the organisation) needed to make this model work as ‘business as usual’. We began from each of the three clinics where virtual consultations were held, mapped the individuals and technologies involved there and then moved outwards to include finance and clinical informatics departments (among others) in order to explore the organisational change required to embed online care within the NHS.

Sampling: micro level