Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 14/156/16. The contractual start date was in April 2016. The final report began editorial review in April 2018 and was accepted for publication in June 2019. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Caroline Sanders was previously a Director (unpaid) for Affigo CIC (Altrincham, UK) (2016–17), a social enterprise providing digital health products for severe mental illness. Peter Bower reports grants from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) during the conduct of the study. Richard Hopkins reports that he is a current director of Affigo CIC, which promotes electronic monitoring of patient symptoms through the use of mobile application, outside the submitted work. Ruth Boaden reports that she was the Director of the NIHR Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (CLAHRC) Greater Manchester (2013–19), which was hosted by Salford Royal NHS Foundation Trust where she held an honorary (unpaid) as an Associate Director to fulfil her role as Director of the CLAHRC. She was also a member of the NIHR Dissemination Centre Advisory Group (2015–19) and the Health Services and Delivery Research Funding Committee (2015–19). She was a member of the NIHR Knowledge Mobilisation Research Fellowships Panel (2013–15) and chaired the panel (2016–18). She is a member of the NIHR Advanced Fellowships Panel (2019–present). Azad Dehghan is the Managing Director of DeepCognito Ltd (Manchester, UK) and a Data Analytics Advisor for KMS Solutions Ltd (Manchester, UK). William Dixon receives consultancy fees from Bayer AG (Leverkusen, Germany) and Google Inc. (Mountain View, CA, USA). John Ainsworth reports that he is a Director of Affigo CIC. Shôn Lewis reports that he is a Director for Affigo CIC. Humayun Kayesh reports he is a contract engineer for DeepCognito Ltd. Goran Nenadic reports that he was previously a Scientific Advisor (Non-executive) of DeepCognito Ltd.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Sanders et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background

Policy context

Collecting patient experience data is considered essential for enabling the delivery of high-quality patient-centred care. 1 Better patient care experiences are associated with higher levels of adherence to care, improved clinical outcomes, better patient safety and lower levels of health-care utilisation. 2 Evidence on what patients value most has been incorporated in the NHS Patient Experience Framework,3 including aspects such as respect and dignity, co-ordination/integration of care, information and communication, physical and emotional care, support for caregivers; and access and continuity. Patient satisfaction surveys are considered integral in the transition to value-based care. 4

In the UK, patient experience data have routinely been collected for the Care Quality Commission by the Picker Institute through the NHS patient survey programme. 5 Annual surveys of patient experience, such as the national GP survey and the national inpatient survey, have been conducted retrospectively by mail, with response rates. Recently, the Francis report6 and the Berwick review7 highlighted the need to collect data that are ‘real time’, or as near as possible to real time, as a means of enabling safe care.

The Friends and Family Test (FFT) asks whether or not patients would recommend a service to friends and family. The FFT has been used since 2012 as a means of gathering simple and timely patient experience feedback. A new indicator based on this test has also been included within the NHS Outcomes Framework3 to ‘enable more “real-time” feedback to be reflected in the framework’.

It is evident that, although policy-makers have highlighted the value of the FFT, there have been critical discussions of its inappropriateness (especially in sensitive circumstances), the limitations of the data generated and the lack of evidence of benefits for service improvement. 8 It has also been found that services are not very engaged with the FFT, with the purposes of collecting FFT data often unclear to staff. Many believed that the FFT was intended for performance management, resulting in low levels of local ‘ownership’ of data collection. 9 Recently, questions have been raised about whether or not use of the FFT should be mandatory if it generates limited insights. 10

Coulter et al. 11 identified the lack of impact that patient feedback appears to have on change in the NHS. Gleeson et al. 12 identified multiple barriers to collecting patient feedback, including the fact that surveys are perceived to lack specificity, that managers and clinicians often lack the skills needed to interpret findings and that reports are not seen to be timely. There are also questions about the impact of feedback (such as complaints) on clinicians and managers. 13,14

Facilitators of impact from patient feedback include a supportive culture for change, dedicated time to discuss results and improvements, and more context-specific data. There is also evidence of significant variation between, and within, organisations with regard to the use of, and approach to, patient experience data. For example, the size of a trust, dispersal of sites, history, demographics and corporate culture play a huge part in how well the collection and use of feedback for service improvement is undertaken. 15 In addition, improvement has been evident when there has been specific policy focus and investment, as well as incentives and penalties. 16 Sheard et al. 17 propose two conditions that need to be in place for effective use of feedback: first, normative legitimacy, whereby staff believe that listening to patients is worthwhile, and, second, structural legitimacy, which provides teams with adequate autonomy, ownership and resources to enact change.

The concept of patient experience

The policy emphasis on patient experience appears to underline its importance as a vital component of care. 18 The National Quality Board19 states that ‘experience’ can be understood in the following way: what the person experiences when he or she receives care or treatment. These experiences can be summarised in two ways: (1) the interactions between the person receiving care and the person providing care (i.e. ‘relational’ aspects of experience, including communication) and (2) the processes that the person is involved in or that affect his or her experience, such as booking an appointment (this is known as the ‘functional’ aspects of experience), and how that made him or her feel, for example whether or not he or she felt that he or she was treated with dignity and respect. 19

A literature review20 noted the absence of a common definition of patient experience but described a number of key themes, such as active patient engagement and person-centeredness and its integrative nature. However, questions remain regarding what constitutes patient experience, how it is best captured and how it is used to influence change in specific contexts and for specific groups of patients and carers.

Sociological perspectives on patient experience depict this as a dynamic concept: an exercise in testing versions of reality through ongoing respecification of objects, audiences and identities. 21 From the patient’s perspective, their experience is shaped by factors such as their social context, past and present health-care encounters, the dynamic between wellness and illness22 and interactions between conditions when living with multiple morbidities. 23 Given the potential variety of patient experiences, an understanding of the mechanisms whereby they are turned into knowledge is important. Mazanderani et al. 24 analysed the use of the internet to share experiences and highlighted the tension between similarity (such as sharing the same diagnosis or treatment) and difference [such as living with condition(s) in specific contexts]. This tension needs to be negotiated and can lead to a recognition of ‘being differently the same’, which allows for multiple experiences to become a source of knowledge and support. 24 Lupton25 offered critical reflections on the ways in which patient experience is shared in digital formats, and commodified forms of usable data, which placed consumerism as a factor in the centre of doctor–patient relationships.

The argument that patient experiences need to be captured in real time is important, yet implicitly accepts that it is possible to describe a dynamic and long-term experience with a single assessment at each point of service use. Vogus and McCelland26 argue that the factors that influence patient experience change over time: interaction and communication are more prominent when patients are asked their opinion immediately after their consultation, whereas health status and symptom resolution increase in importance over time.

Methods of collecting patient experience data

A 2012 survey27 found that most trusts report that self-completed paper surveys are the most frequently used data collection method, but that a large proportion also collect digital data (55% with the help of an administrator or volunteer; 42% by patients themselves during an inpatient stay). In addition, 27% of trusts were planning greater use of digital data capture and 23% of trusts stated that the Department of Health and Social Care could best help with data collection by providing better technology to help capture and analyse ‘real-time’ data. 27

In recent reports, the use of scores generated from the FFT for measuring and comparing the performance of providers has been viewed as problematic, but it has also been argued that the FFT can be useful for improving services and at least generating discussion about patient experience. 28,29 With regard to the FFT, patient comments have been perceived to provide the greatest value, but this does then raise questions regarding how to effectively analyse and utilise such comments.

Recent guidance states that qualitative sources of patient experience data are equally as valuable as quantitative surveys and local organisations are currently advised to supplement mandatory survey data with a range of data sources, including patient stories, complaints, Patient Advice and Liaison Service (PALS) data, incident reports and general feedback. 30 One study revealed that patients would like to see feedback as a mechanism to express their individual experience in detail and in context. 20 There is a perceived failure to ‘close the loop’ in the sense that people do not see the impact of their feedback in service change, either for individuals or at the organisational level. 18

Recent studies have been performed on how best to measure distinct components of feedback31 and the value of the collective judgement of feedback. 32 This debate about how to adequately capture the complexity of the patient experience can benefit from recent literature on the use of ‘big data’. Authors argue that the perspectives of both patients and staff highlight the limitations of formal forms of quantifiable data and point to the need for more small, informal data sets based on interactive and highly contextual mechanisms in order to facilitate a more detailed understanding of the process and experience of care. 12 Additionally, Ziewitz21 argues that mobilising patient experience to influence organisational change needs ethnographic approaches alongside quantitative methods in order to challenge and complement findings from ‘big data’ analysis.

There has been a growing focus on the value of patient narratives in audiovisual and textual forms and such stories have been drawn on for staff training and service improvement. 33,34 However, these stories represent limited numbers of individual patients and are time-consuming to produce. One of the tensions around different methods of collecting patient experience data is that between the depth of data and the burden associated with its analysis. Qualitative forms of data (such as narrative descriptions) hold out the promise of rich feedback specific to the particular clinical context, which may be more impactful and provide a better basis for action. However, such data are much more complex and time-consuming to analyse, unless effective ways can be found to automate the process.

Innovations in the analysis of patient experience data

There have been only a limited number of attempts to extract information such as patient feedback automatically, and this was typically for quite focused tasks. For example, Greaves et al. 35 analysed online patient feedback comments to understand the sentiment about overall care quality, including cleanliness and dignity. The authors applied a machine-learning classification approach that mapped each comment into relevant topics and associated sentiments. Similarly, Cole-Lewis et al. 36 extracted five predefined topics related to e-cigarettes, experimenting with different classification algorithms. Recently, a similar approach was followed by Gibbons et al. 37 to extract different aspects from free-text patient comments on doctors’ performance.

In contrast to supervised methods, Padmavathy and Leema38 experimented with a patient-opinion-mining system in which unsupervised methods were used to identify key topics. The topics were then clustered for sentiment extraction. Tapi Nzali et al. 39 applied a similar unsupervised approach to extract topics from social media text and to compare results against questionnaire responses. Wagland et al. 40 similarly compared the outcomes of a machine-learning approach with the outcomes from a manually conducted survey to extract patient perceptions of care.

Brookes and Baker31 used mixed methods to qualitatively analyse patient feedback (NHS Choices) after automatically extracting and then manually inspecting a small subset of the most frequently used words. They found that most comments are associated with treatment, communication, interpersonal skills and organisation. However, although they used a large data set, this was mostly manual analysis based on specific words appearing in patient comments.

Given the lexical variability and ungrammaticality of patient-generated comments, it is not surprising that the majority of work in this domain relies on using machine-learning approaches, aiming to learn from data. However, manually providing training data for supervised methods is a challenging issue and, therefore, unsupervised methods have been also explored. In relation to patient feedback, text mining is the processing of comments; a similar process occurs in other settings when customers provide product reviews by commenting on different features of products. Frequently mentioned topics in review comments are often referred to as ‘aspects’. Aspect-based sentiment extraction from product reviews has been an active research area for a long time; for example, in addition to unsupervised machine-learning techniques to identify aspects and detect associated sentiment (e.g. Brody and Elhadad41), there are additional examples of supervised approaches. 42–44 Recently, Hai et al. 45 proposed a method that combines both supervised and unsupervised machine-learning techniques.

The impact of patient experience data on service improvement

Most staff report that their directorate or department collects patient feedback (89.7% in 2017). 46 The proportion of staff reporting that this feedback is used to inform decision-making is significantly lower, although this has improved over time. In 2015, 55.6% of staff said that feedback was used to inform decision-making in their service area, with this proportion increasing slightly to 56.7% in 2016 (remaining the same for 2017). 46

Real-time experience

Some trusts have been pioneering the collection and use of real-time feedback using tablet devices for a number of years. For example, in 2011, St George’s University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust initiated such a system and has since introduced tablet computers to almost all patient areas.

Such systems emphasise the importance of making reports instantly available to highlight areas of especially good or especially poor performance, allowing staff to make improvements or share positive feedback as examples of good practice.

Why this research is needed now

Our overall research question was ‘Can the credibility, usefulness and relevance of patient experience data in services for people with long-term conditions be enhanced by using digital data capture and improved analysis of narrative data?’.

This research is important because NHS organisations are already investing substantial resources in collecting large quantities of data on patient experience. However, as highlighted above, there are major inefficiencies in current methods of collecting, analysing and using such data. To address our overall research question, this study had four aims:

-

Improve the collection and usefulness of patient experience data by helping people to provide timely, personalised feedback on their experience of services that reflects their priorities and by understanding the needs of staff for effective presentation and use of data.

Recent research has shown that professionals are often sceptical of the relevance of patient experience data to local services because they are based on generic questions rather than being tailored for specific service contexts and because it is perceived that vulnerable patients and carers are excluded. 47,48 It is crucial to understand the needs of staff regarding the feedback of patient experience data if they are to be used to stimulate service improvements. As previously mentioned, NHS organisations already collect a wide range of quantitative and qualitative patient experience data, but there is a lack of understanding regarding how best these different types of data can be presented and used by staff. Although qualitative data in the form of free-text comments is a large and potentially useful resource, questions remain regarding its representativeness and credibility from the point of view of staff. In addition, individual patient narratives may well be powerful but may not be considered representative of patient experiences more widely. In trusts collaborating with this study, patient stories have been used in the context of board meetings, as in many trusts across the UK; however, such stories are not routinely viewed by teams of front-line staff and the views of staff regarding the relevance and use of such data are unknown. This study sought to use qualitative methods to understand staff perspectives on data requirements.

-

Improve the processing and analysis of narrative data alongside multiple sources of quantitative data.

As highlighted above, patient experience data are often provided in narrative form, yet organisations lack the capacity to utilise these data effectively. Text-analytic techniques enable the automated and systematic analysis of large sets of qualitative data gathered from multiple sources of patient experience feedback. We aimed to explore how automated text-analytic techniques could be utilised49 to provide a means for the automated and continuous analysis of relevant textual data that are routinely collected.

-

Co-design a toolkit with patients, carers and staff to improve resources for enhancing the collection, analysis and presentation of patient experience data to maximise the potential for stimulating service improvements.

-

Implement the toolkit and conduct a process evaluation to explore implementation, potential mechanisms of effect, and the impact of context.

The original commissioning brief highlighted the importance of understanding the kind of organisational capacity needed in different settings to interpret and act on patient experience data. We proposed to develop a toolkit for enhancing the collection, analysis and presentation of patient experience data, based on an understanding of the views of patients and staff. We built into the toolkit appropriate text-mining techniques to provide efficient analysis of narrative data.

To explore the implementation and impact of the toolkit in routine NHS settings, we conducted a process evaluation. 50 The evaluation used qualitative methods to enable a detailed understanding of the needs of distinct organisational teams and how organisational capacity varies according to contextual factors, such as the distinct patient groups served, the size of the teams, management structure and the nature and flow of work. We drew on normalisation process theory (NPT), which has been developed and used to understand the actions and interactions influencing implementation and how new interventions and practices come to be normalised in health-care contexts. 51 There is a dearth of evidence on the relative costs of different methods to collect and use data, and how staff use varied data to inform service changes,11 and we provide costings associated with the toolkit to better understand the costs involved.

Choice of long-term conditions and health-care settings

A 2011 project from The King’s Fund48 focused on five key pathways (stroke, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes mellitus, depression and elective hip replacement) to explore patient experience. This report suggested that, ideally, patient experience should be measured in terms of the journey as experienced by the patient in order to capture transitions in care and continuity issues. It also suggested that generic surveys may need to be supplemented with condition-specific indicators.

In this study we focused on appropriate ways to collect, analyse and use patient experience data in the pathways for severe mental illness (SMI) and musculoskeletal (MSK) conditions.

A SMI, such as psychosis, affects 2% of the UK adult population. Patients with a SMI have a lower life expectancy (25 years less than the general population, mainly because of physical health problems) and are at greater risk of suicide and self-harm. 52 These are two examples of key issues for which feedback on patient experience might be used to ensure that services are meeting physical needs, as well as maintaining safety.

In the UK, 14.3% of adults report having a chronic MSK condition. 53 This has a major impact on health-care resources: it is one of the most common reasons for a primary care consultation, with one in four adults in Europe being on long-term treatment for a long-standing MSK problem. Common problems occur in managing long-term medications across primary and secondary care and in meeting needs for secondary care that could be reflected in patient experience feedback and could be used to stimulate service improvement.

These were important groups for research on the use of patient experience data because:

-

People with both types of condition show high levels of service use in primary and secondary care settings, allowing us to consider the need for patient experience data of multiple clinical teams.

-

These long-term conditions invoke common concerns regarding continuity of care and patient safety, often reflected in patient experience narratives. 54

-

Research suggests that there are particular safety concerns in relation to SMI, with aspects of the provision of mental health services able to affect suicide rates. 55

-

There is uncertainty around the applicability of Picker survey frameworks to severe mental health problems, especially because service users may be forced to receive care.

-

Both populations commonly have overlapping comorbidities and include those who are under-represented in current methods for capturing data on patient experience: older people with prevalent MSK conditions, vulnerable younger adults with SMI and carers in both cases.

The research focused on the use of patient experience data by staff teams in four sites:

-

site A – an acute trust (focusing on rheumatology outpatients)

-

site B – a mental health trust (focusing on a community mental health team and an outpatient clinic)

-

site C1 – a general practice

-

site C2 – a general practice.

The above focus aligns with the NHS Outcomes Framework,3 which highlights key improvement areas to ensure that patients have positive experiences of care, including patient experiences of community mental health services, patient experiences of outpatient services and access to general practice services.

Chapter 2 Methodology

Our main research question was ‘Can the credibility, usefulness and relevance of patient experience data in services for people with long-term conditions be enhanced by using digital data capture and improved analysis of narrative data?’.

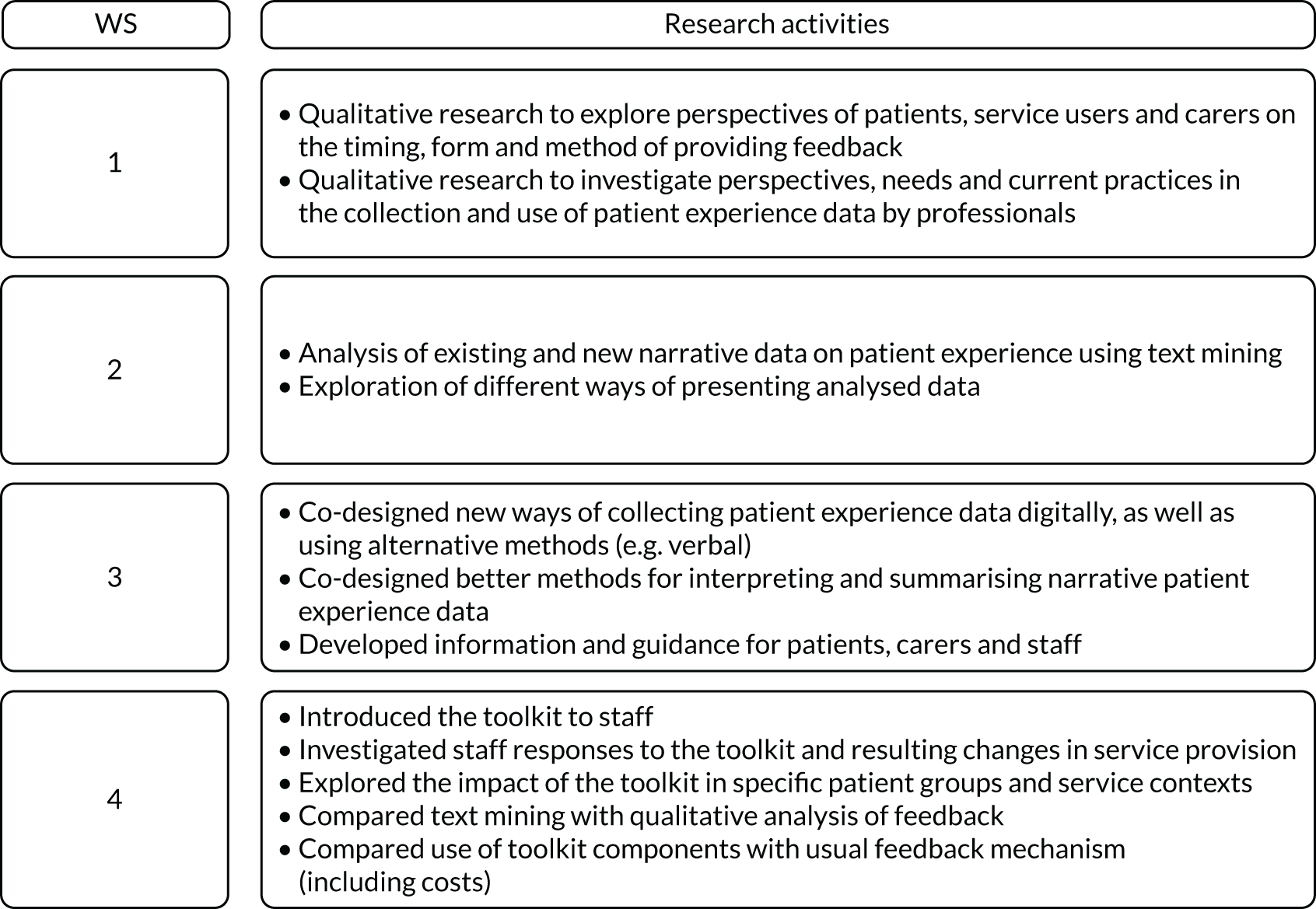

To address this, four aims mapped onto four workstreams (WSs) (Figure 1). The methods for each WS are summarised in the following sections, followed by some context for the setting and further methodological details for each WS.

FIGURE 1.

Summary of the WSs.

Summary of the aims and methods for each workstream

Workstream 1

Aim

To improve data collection and usefulness by helping people to provide timely, personalised feedback on their experience of services that reflects their priorities and by understanding the needs of staff for effective presentation and use of data.

Methods

We used qualitative methods to explore the perspectives of patients and carers on providing patient experience data. We used the same methods to investigate perspectives and current practices in the use of patient experience data by clinical teams, managers and information technology (IT) staff (when applicable).

Workstream 2

Aim

To improve the processing, analysis and presentation of narrative data.

Methods

We used computer science text-analytics methods49 to develop programs for routine, automated and systematic analysis of narrative data. We also explored different ways of presenting analysed patient experience data.

Workstream 3

Aim

To co-design a toolkit to improve resources for enhancing the collection and analysis of patient experience data and presentation to staff teams to maximise the potential for stimulating service improvements.

Methods

We used an experience-based design approach,56 drawing on the initial qualitative research, the computer science work in WS2 and insights from our patient and public involvement (PPI) group, to co-design ways to enable and support digital data capture, analysis and use of both quantitative and narrative data.

Workstream 4

Aim

To implement the co-designed toolkit and evaluate its impact for improving the collection, analysis and presentation of patient experience data.

Methods

We introduced the toolkit and trained staff in multiple service teams that participated in the initial qualitative research to use the tools. We then conducted a process evaluation50 by analysing participation rates to assess whether or not a greater degree of feedback was obtained in the multiple sites using the tools. We also used qualitative methods and drew on NPT51 to assess the impact of the toolkit for improving the usefulness of data and any influences on service changes. We also compared the text-mining approach to analysing free-text comments with a standard approach and investigated the time spent collecting and analysing data using the new tools to estimate costs.

Figure 2 provides a summary of the project aims and WSs.

FIGURE 2.

Summary of project aims and WSs.

Exemplar chronic conditions

The study focused on services for two exemplar long-term conditions, SMI and MSK conditions, with high levels of service use, comorbidity and concerns regarding the continuity and safety of care.

Setting

The study was conducted in four sites:

-

site A – a large acute trust focusing on one outpatient rheumatology department for the qualitative research

-

site B – a mental health and social care trust focusing on one community mental health team and an outpatient clinic for the qualitative research

-

site C1 – a general practice surgery based in an area of high deprivation within the same locality as site A

-

site C2 – a general practice surgery based in an area of high deprivation within the same locality as site B.

The sites were selected to ensure that diverse organisational contexts and variations in terms of the methods of collecting patient experience feedback were considered. For example, we included a well-resourced tertiary hospital, as well as a main trust providing mental health services, and community health services and small-scale practices.

Site A is an integrated provider of hospital, community and primary care services, including a university teaching trust. The trust provides local services to the city where it is located.

Site B offers a wide spectrum of mental health, social care and well-being services to meet the needs of adults of working age and older adults across a large city. Six community mental health teams based throughout the city provide assessment, care and support for adults of working age and older adults with mental health problems.

The two general practices, site C1 and site C2, serve a range of patients, including those with severe mental health problems and rheumatology patients.

Each setting had different practices for collecting and using narrative data, in addition to standard survey data, including the FFT. Most relied on pen- and paper-based surveys, with low levels of participation and challenges in terms of collecting and processing responses, with sites A and C2 also collecting digital responses by short message service (SMS) text (i.e. message). None of the sites routinely collected digital data on site, for instance in waiting rooms or reception areas in the outpatient departments or at the point of home visits for the community mental health teams. The acute trust collected digital patient experience data only occasionally from selected patients using a handheld digital device. The format of the narrative data varied across the settings, but included free-text comments made in response to an open survey question (e.g. following the FFT). These data also included individual audiovisual stories that were used for organisational activities, such as board meetings or training events, in each large trust (audio-visual stories were carefully produced, with very few patients selected because of some particular issues that may reflect wider problems that trusts were seeking to improve). Additional forms of feedback were collected to varying degrees through the study sites’ websites, other websites [e.g. Facebook (Facebook Inc., Menlo Park, USA)], letters to PALS and patient discussion groups. Table 1 shows examples of the different feedback data collection methods used in the different sites.

| Site | Data collection methods | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Website | Twittera | SMS | Facebookb | Letters to PALs | Audiovisual stories | Patient Voices programme | Dignity walks, community discussion | Pen and paper | |

| A | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ |

| B | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| C1 | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ |

| C2 | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ |

Details of methods for each workstream

Workstream 1: perspectives of patients and carers on providing patient experience data and perspectives of staff on the use and usefulness of data

Participants

Staff members were recruited from all four sites and patients and carers were recruited from sites A and B. Although we have used the term ‘service users’ to refer to those with mental health problems, for simplicity we have sometimes referred to those with mental health problems as ‘patients’ when referring to both participants with MSK conditions and participants with mental health problems.

Data collection

Focus groups, individual interviews and observation methods were used for data collection. The use of mixed qualitative methods and mixed participants allowed in-depth exploration of stakeholder views and experiences and also enabled triangulation of the data regarding emerging key themes.

The study was conducted within four WSs to achieve the overarching aim of collecting patients’ experience feedback to ensure the delivery of high-quality, effective and safe services that are sensitive to population needs.

The WS1 data collection took place between July 2016 and April 2017. Patients were recruited through staff in the clinical sites.

Perspectives of service providers

Staff participants were invited to take part in either a focus group or a face-to-face individual interview, or both, as determined by participant preference. In total, 66 staff participants took part in the qualitative components of WS1 to understand their perspectives on what data need to be collected to be useful for staff and the current practices in each setting. In relation to staff participants, 21 individual interviews were undertaken (four of these participants chose to take part in both an individual interview and a focus group) and 49 participants took part in one of the staff focus groups in each site.

We sought participants’ views on the credibility and usefulness of different types of data, including narrative and textual sources. Views and experiences of clinical teams and managerial and IT staff were sought regarding current practices, organisational capacity for using various data sources and current barriers. We achieved a diverse sample of staff participants with roles in management and patient experience, clinical practice and IT, reflecting the various categories of interest in each organisation.

In site A, there were 20 staff participants (lead IT/governance/patient experience managers, n = 7; nurse managers, n = 4; consultant specialists, n = 8; occupational therapist advanced practitioners, n = 1). In site B, there were 22 staff participants (lead governance managers, n = 1; team managers, n = 3; consultant specialists, n = 3; care co-ordinators, n = 13; carer support workers, n = 1; administrators, n = 1). In site C1, there were 13 staff participants [general practitioners (GPs), n = 3; nurses, n = 2; health-care assistants, n = 2; practice managers, n = 2; administrators/reception staff, n = 4]. In site C2, there were 11 staff participants (GPs, n = 5; nurses, n = 3; health-care assistants, n = 1; practice managers, n = 1; finance managers, n = 1).

Perspectives of service users, patients and carers

In total, 41 patients and 13 carers in sites A and B took part in the qualitative components of WS1 to provide patient experience data and to define what forms of data they were willing to provide using different methods (Table 2). In total, 20 individual interviews were undertaken with patients with MSK conditions (site A), 10 individual interviews were conducted with service users (site B) and another 11 service users took part in a large focus group (site B). We also conducted five individual interviews with carers of patients with MSK conditions (site A) and eight individual interviews with carers of service users (site B).

| Participants | Site | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C1 | C2 | Total | |

| Staff focus groups | 10 | 15 | 13 | 11 | 49 |

| Staff interviews | 12 (2) | 9 (2) | 0 | 0 | 21 (4) |

| Total staff | 20 | 22 | 13 | 11 | 66 (4) |

| Patient focus groups | 0 | 11 | 11 | ||

| Patient interviews | 20 | 10 | 30 | ||

| Total patients | 20 | 21 | 41 | ||

| Carer focus groups | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Carer interviews | 5 | 8 | 13 | ||

| Total carers | 5 | 8 | 13 | ||

| Total | 45 | 51 | 13 | 11 | 120 (4) |

Our patient and carer WS1 sample was less diverse than our staff sample. In site A, there were more female than male patient participants (14 women, 6 men); the median age of participants was 60.5 years and 18 participants were of white British ethnicity, one was of mixed ethnicity and one was of Asian/black British ethnicity. All five carer participants from site A were male; the median age of participants was 65.5 years and participants were predominantly of white British ethnicity, with one participant of Asian British ethnicity. Conversely, in site B there were more male than female patient participants (11 men, 10 women); the median age of participants was 19 years and participants were predominantly of white British ethnicity, with one participant of black African/Caribbean/British ethnicity. Five of the eight carer participants in site B were female; the median age of participants was 49 years and all were of white British ethnicity.

Ethics issues and real or potential barriers to participation were also considered.

We investigated perspectives on providing textual data and the structured questions considered most suitable for capturing experiences of the specific service user groups. We also explored views about how to provide feedback to best reflect patients’ concerns and needs, for example whether or not people want to provide data digitally and what is the best way to do this – using a handheld or fixed device in service settings, by mobile phone or by computer. We considered specific needs in each group, for example concerns that mental health service users have that are specific to their care pathway, such as involvement in care planning, concerns about enforced inpatient care and how positive and negative experiences of these aspects of care can be conveyed. We also asked for participants’ views about providing both experience and outcome data simultaneously and the best ways of capturing these multiple forms of data.

All interviews and focus groups were transcribed, collated and analysed thematically, drawing on techniques of a grounded theory approach57 and using NVivo 11 qualitative analysis software (QSR International, Warrington, UK). A process of open coding by the research lead for each site provided an initial framework, which was discussed collectively and refined for consistency and focus by the research team. Through the coding and discussions regarding links and distinctions across cases, we were able to generate a smaller number of selective codes.

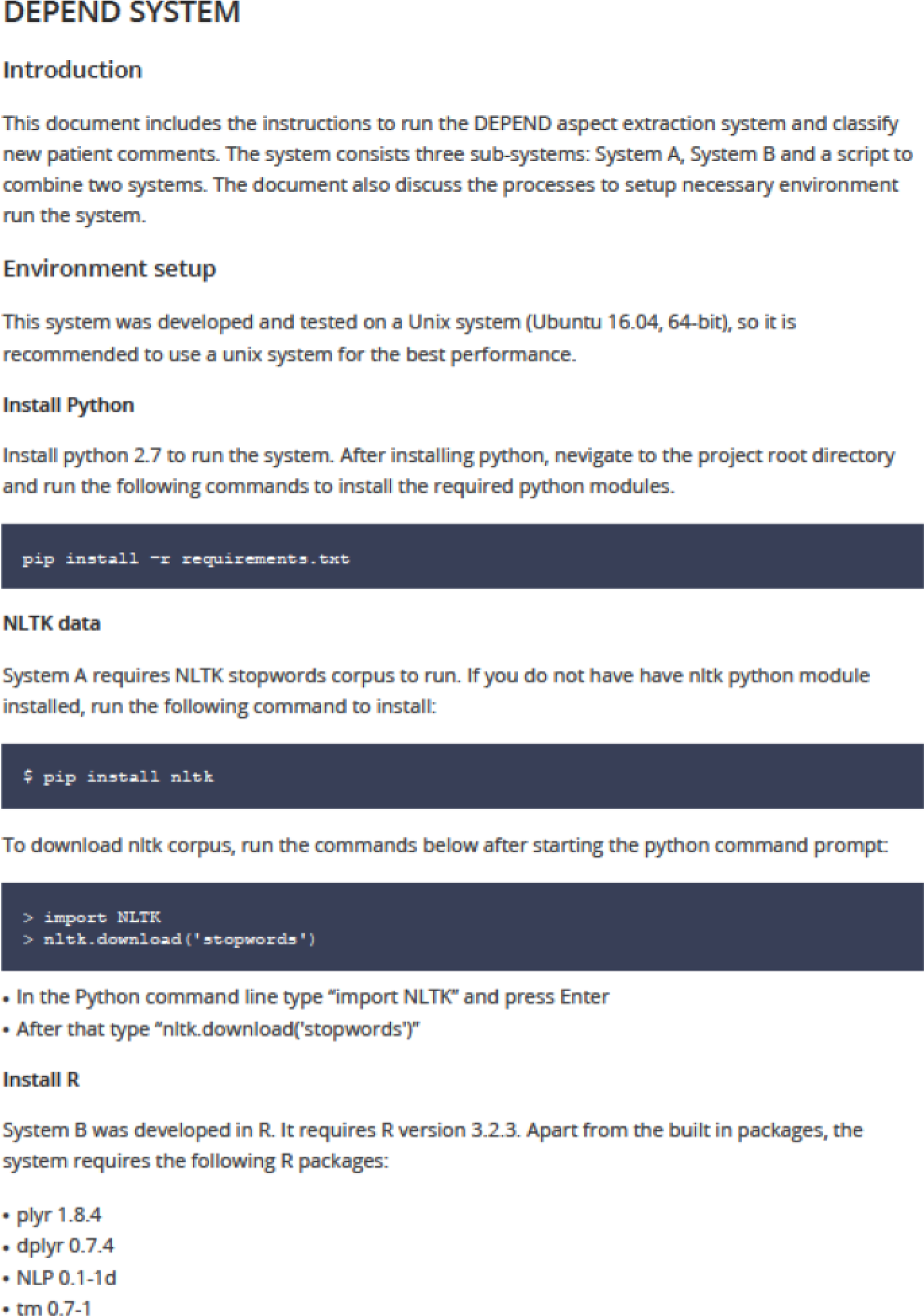

Workstream 2: text mining, analysis and presentation of data

The main task in WS2 was to explore the feasibility of automatic analysis of free-text comments to identify themes (also known as topics, aspects or categories) and associated sentiments (positive, negative or neutral). This WS was divided into four steps:

-

manual coding of data with labels to support the design of text-mining methods that are based on searching for specific labels

-

development of text-mining programs to identify themes and sentiments (whether themes are positive or negative)

-

identification of comments that are representative of the labels assigned to them

-

creating report templates to present the analysed data.

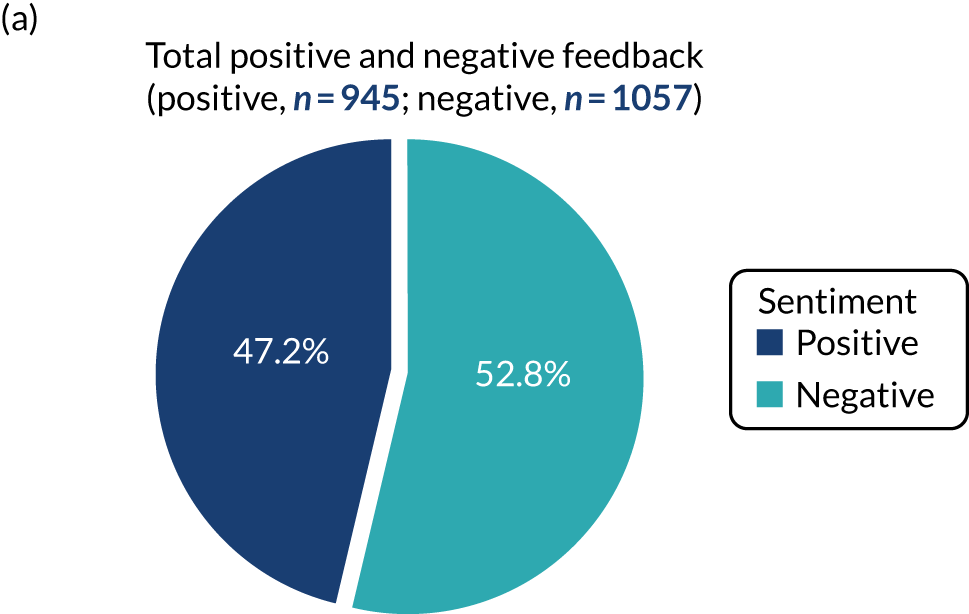

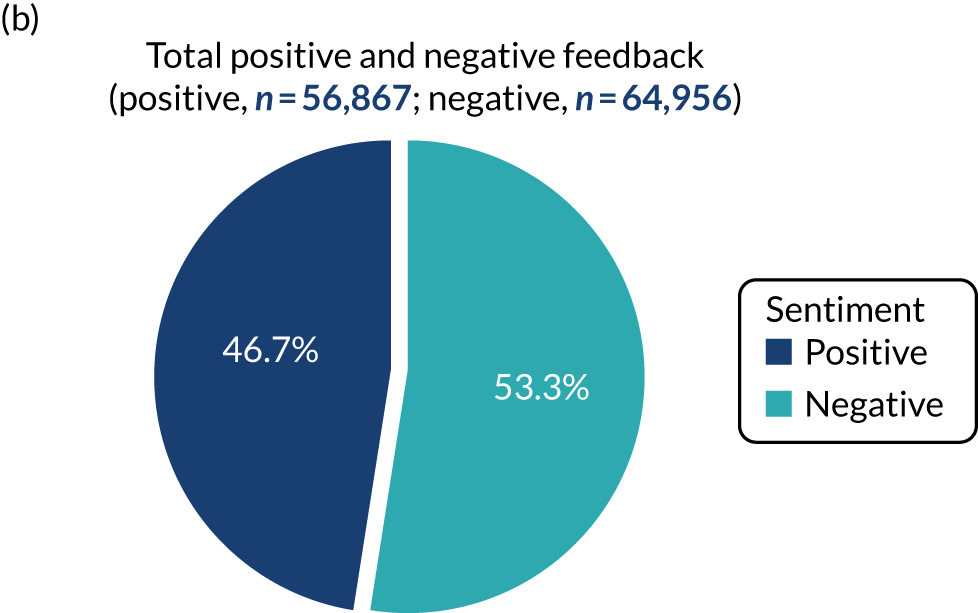

To support this WS, we obtained two data sets containing free-text comments extracted from various patient experience surveys (e.g. FFT, Picker survey). The raw data set from site A contained 110,854 comments (2,114,726 words) and the site B data set contained 1653 comments (50,177 words).

Manual annotation of data

The aim of this step was to produce a high-quality, manually analysed data set that provides examples of free-text comments and associated themes and sentiments. After an initial manual inspection of a sample of the available data sets, we focused on nine themes (waiting time, staff attitude and professionalism, care quality, food, process, environment, parking, communication, resource) and two additional classes (‘not feedback’ and ‘other’) (see Appendix 1, Table 19, for a description of each theme).

A stratified random sample of comments (a roughly equal number of comments across their associated original Likert scales) was extracted and subsequently manually labelled as a ‘gold standard’ data set with associated themes and sentiment by up to five researchers. Table 3 provides the basic statistics about the coded data sets.

| Characteristic | Site | |

|---|---|---|

| A | B | |

| Total number of comments | 408 | 727 |

| Total number of words | 12,581 | 26,145 |

| Total number of unique words | 1924 | 2716 |

| Total number of sentences | 732 | 1648 |

| Minimum number of sentences per comment | 1 | 1 |

| Maximum number of sentences per comment | 11 | 18 |

| Shortest sentence length | 1 | 1 |

| Longest sentence length | 136 | 113 |

| Average sentences per comment | 1.79 | 2.27 |

| Average words per comment | 30.84 | 35.96 |

Three of the researchers carrying out the coding tasks came from a social science background and had extensive qualitative research experience; the other two researchers were computer scientists. All annotators contributed to defining the annotation guidelines based on discussions about the content of the data and discussions with staff during initial meetings in the study sites providing the data (see Appendix 1, Table 19).

Initially, the researchers independently coded a small common set of comments, which were subsequently reviewed and the inter-rater agreement assessed (see Chapter 4). As a single comment could contain multiple themes, each with potentially different sentiments, the researchers were asked to identify text fragments that expressed a single theme (referred to as ‘segments’) and assign a theme and sentiment to them (see example in Box 1). The process was repeated on new samples until it was noted that there were no significant changes in the level of agreement.

[The service I got was really good.] [The staff was helpful and understanding.]

(Care quality, Positive) (Staff attitude and professionalism, Positive)

Text in ‘[]’ indicates the segments. The associated theme and sentiment are provided below within ‘()’.

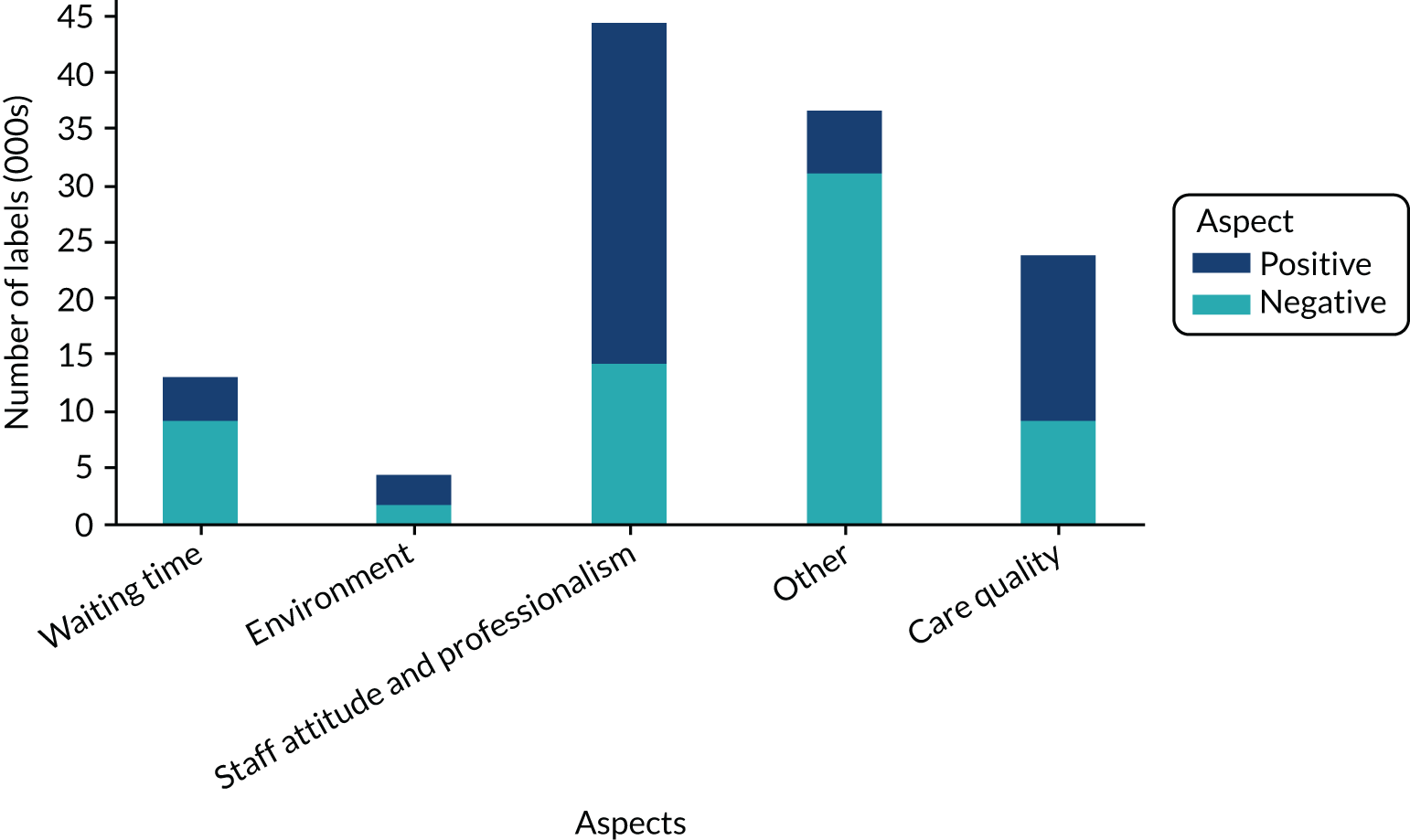

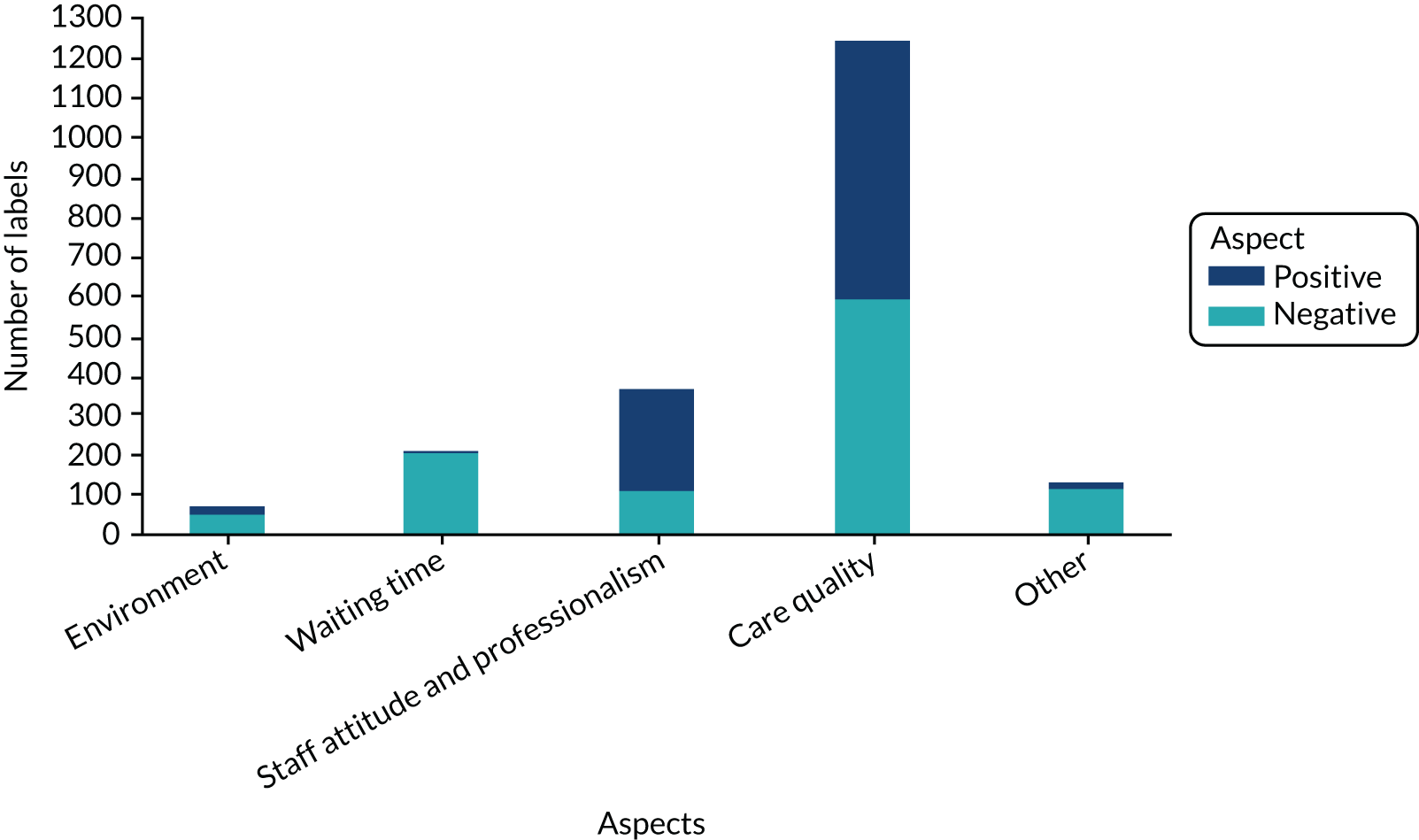

Subsequently, the main coding task of labelling the data commenced. Owing to low numbers of comments attributed to some themes, relatedness across themes (e.g. similarities between parking, food and environment) and lower inter-rater agreement (see Chapter 4), we merged a number of themes to provide a final set of five themes (staff attitude, care quality, waiting time, environment, other) (see Appendix 1, Table 20). In addition, we merged negative and neutral sentiments following feedback from the clinical staff. The final data set used to develop and validate our text-mining programs included the merged themes (see Appendix 1, Table 21, for the final theme distribution in this data set).

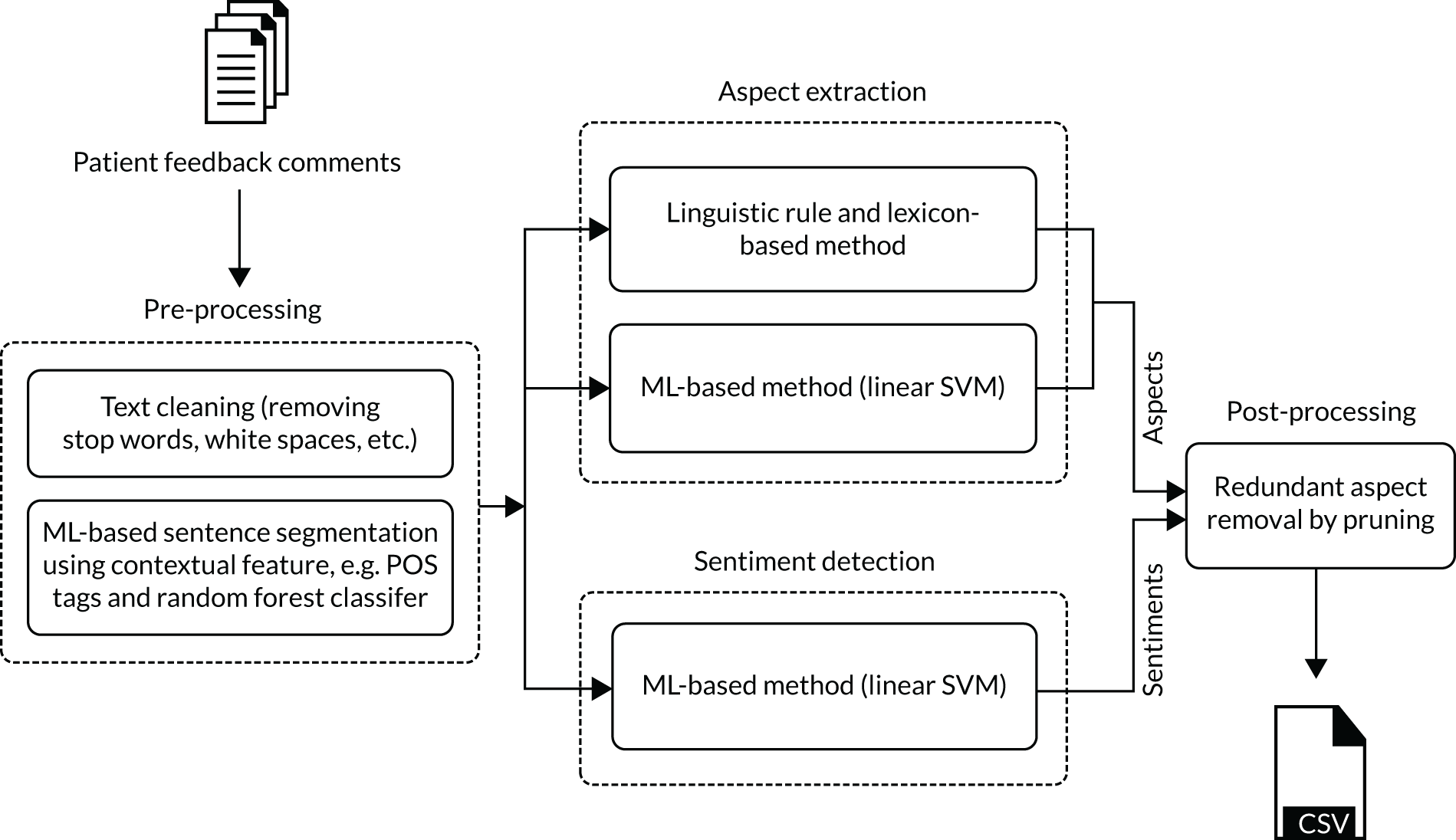

Text-mining methods for theme and sentiment identification

We designed, developed and validated two text-mining programs based on the coding labels developed during the initial coding phase (known as supervised machine-learning methods). A third system combined outputs of the programs using confidence thresholds based on which performed the best analysis.

Segmentation-based model

The segmentation-based model (SBM) focused on the main observation that each comment may have several segments that refer to different themes. A model is therefore trained at the segment level and provides predictions at the segment level. This means that the program splits each comment into segments prior to being labelled according to themes and sentiment. Comments were also split into individual sentences before segmentation. Appendix 1 shows the overall workflow (see Figure 11) and defines the technical components and stages (see Box 2) for this model.

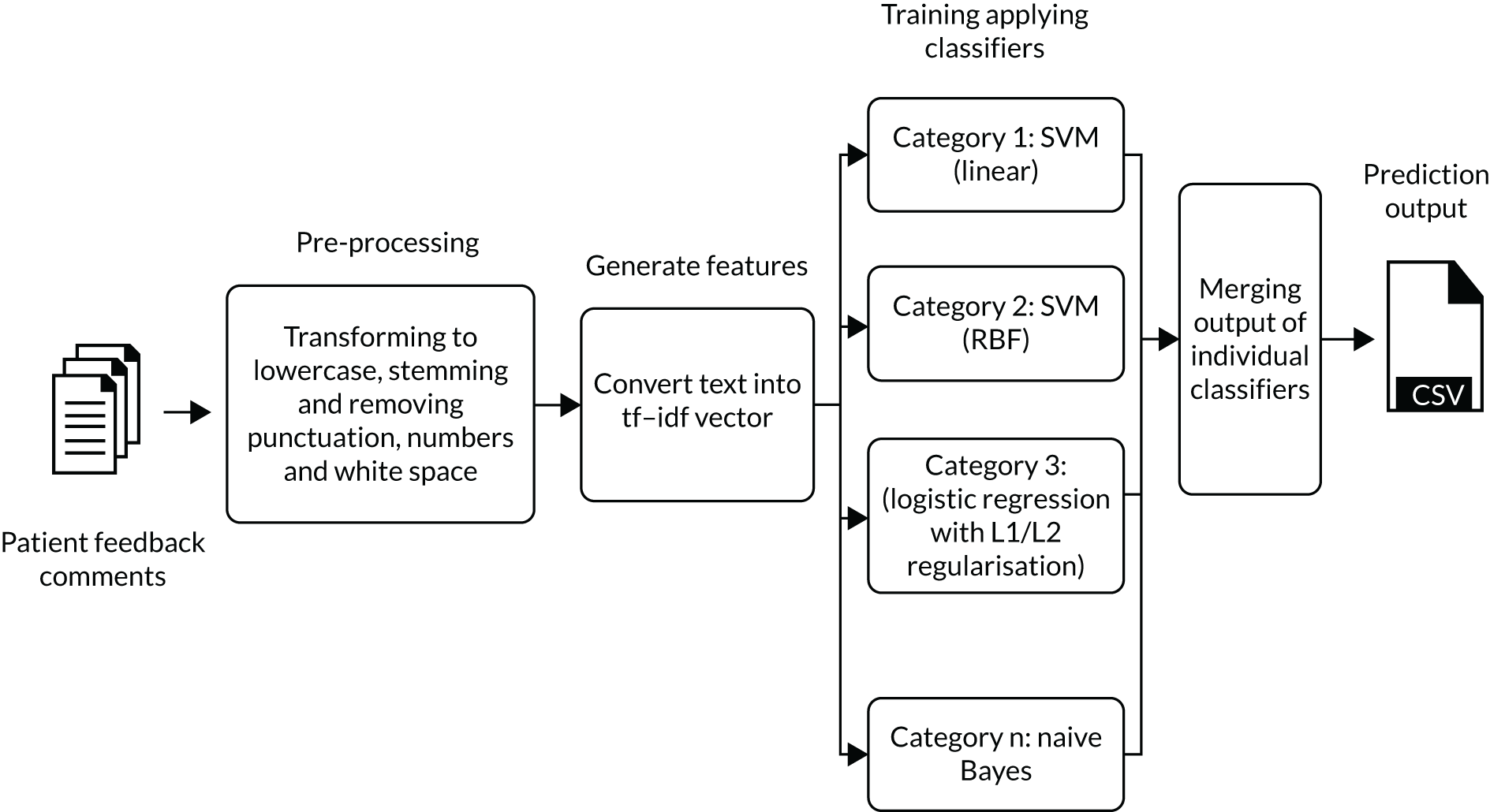

Comment-level model

The comment-level model (CLM) takes segments as input but the predictions (themes) are made for the whole comment. The system was trained using the one-against-all approach (i.e. one classifier per topic). Appendix 1 shows the overall CLM workflow (see Figure 12). We experimented with several different ways of classifying the comments (see Appendix 1, Box 3, for technical details).

Integrated system

The outputs of the SBM and CLM systems were combined using confidence thresholds. Each system has a separate set of confidence thresholds determined by cross-validation (see Chapter 4), which corresponds to a given theme (i.e. five thresholds for each system). The assigned themes are combined using a union operation applied to the outputs with confidence values higher than the predefined threshold.

Identification of representative comments

One suggestion from the staff teams was the inclusion of representative comments to provide examples of both negative and positive sentiments to help identify areas of improvement for the former and to highlight what works well in practice for the latter. The confidence values assigned by the classifiers were used to determine a representative set of comments for each theme, consisting of comments with the highest confidence values. This was combined with additional criteria (explained in the following section) to present representative feedback.

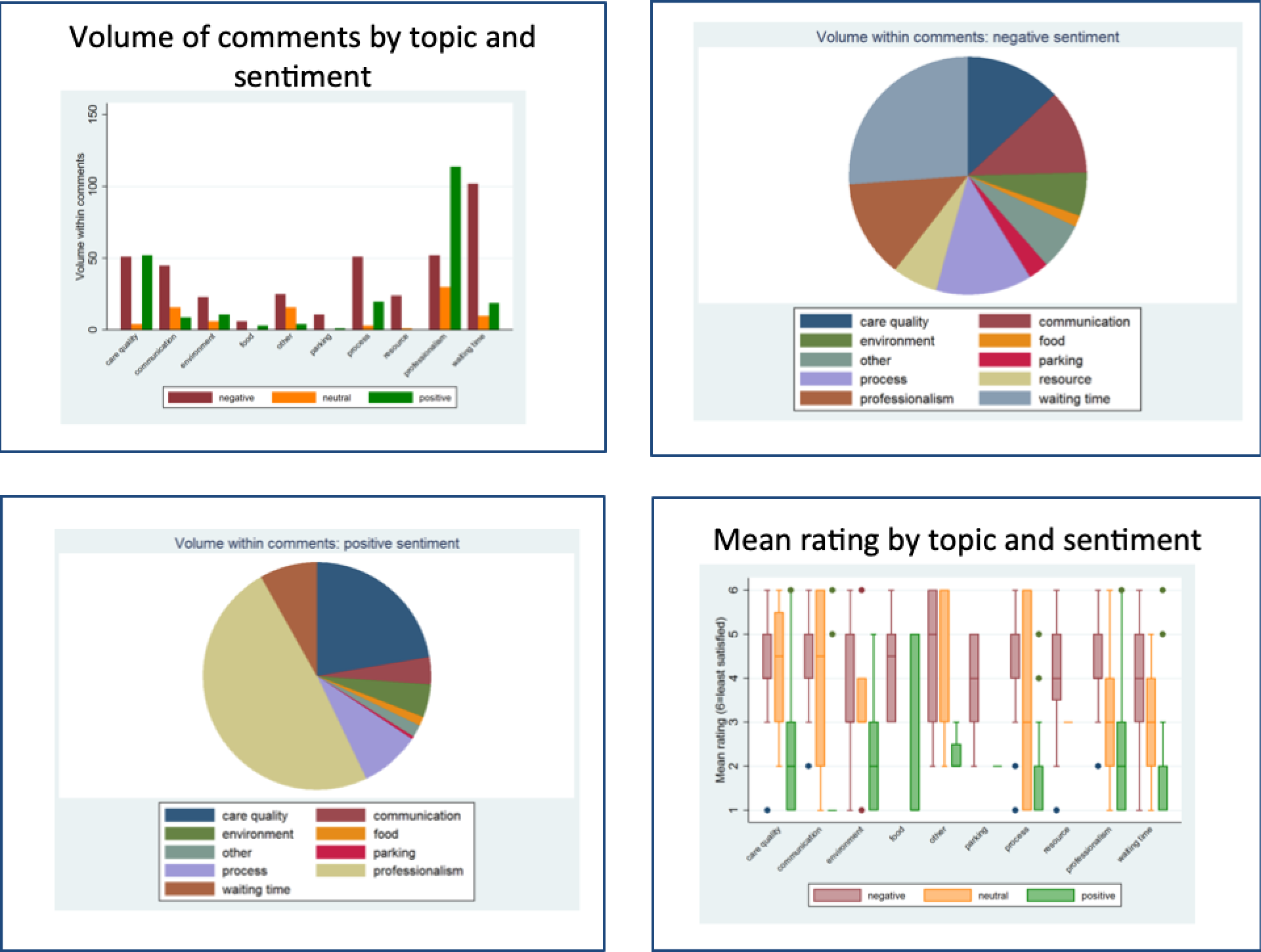

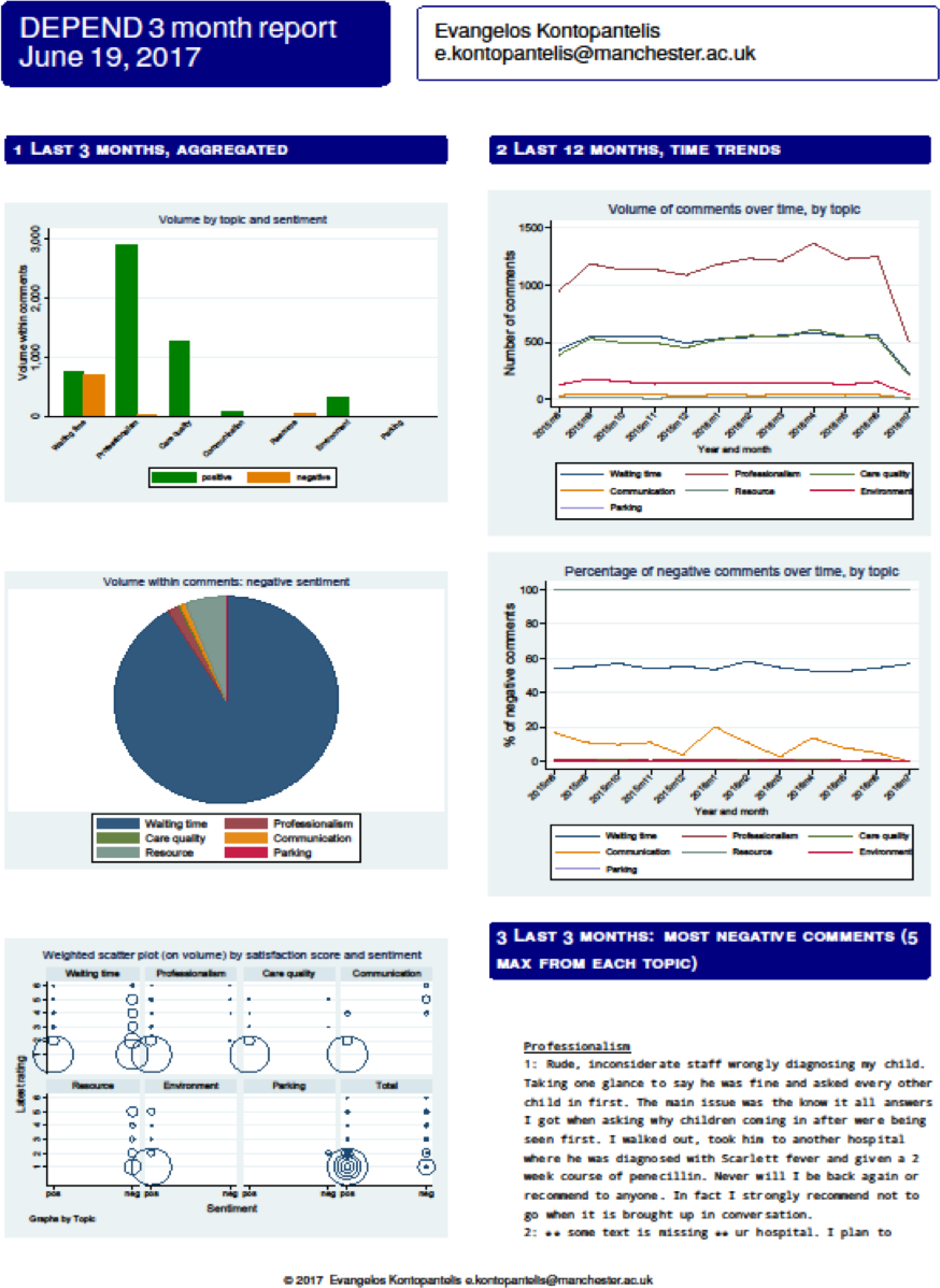

Creating report templates to present analysed data

Following classification with the machine-learning techniques and the association of each comment with a number of themes and associated sentiments (step 2), the data sets were organised for analysis and visualisation in Stata® version 14.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). We first conducted within-team discussions and meetings with data scientists from site A to inform on the aspects of the data that would be useful and informative but not burdensome for patients, health workers and managers. The biggest challenge appeared to be meeting the disparate needs of these different user groups in a single report, especially considering their various levels of statistical literacy. The consensus was to not compromise on the quality of the information, even if some aspects could be challenging to comprehend. The outputs were primarily directed at managers, although other user groups could find most aspects of the outputs informative, especially if the more advanced aspects were accompanied by explanations. It was also agreed that certain themes, such as ‘other’, were not informative and should not be reported.

Descriptive statistics were used to evaluate the distribution of the number of topics within comments and sentiments within topics. The focus of the analysis was visualisation, and numerous graphs were generated for inclusion in reports. Each comment was also linked to a self-reported overall satisfaction score. After reviewing these in team discussions, three cross-sectional (i.e. last time point) and two longitudinal graphs were selected for inclusion:

-

a bar chart of volume by topic and sentiment (cross-sectional)

-

a pie chart of volume by topic for negative sentiment only (cross-sectional)

-

a weighted scatterplot (on volume) by satisfaction score and sentiment (cross-sectional)

-

the volume of comments over time by topic (longitudinal)

-

the percentage of negative comments over time by topic (longitudinal).

In addition to the graphs, the team considered the inclusion of representative positive and negative comments. Because of size constraints, priority was given to negative comments. To deliver this, an algorithm was developed that selected comments on certain (editable) criteria and exported them in LaTeX format (*.tex) so that they could be incorporated into reports automatically. The criteria were (1) inclusion of comments in the last 3 months only, (2) ranked on the lowest satisfaction rating so comments with the worst satisfaction scores would be selected, (3) organised by topic but limited to professionalism, care quality and communication because it was felt that other aspects were less likely to be directly relevant to health professionals (e.g. waiting time) and (4) a maximum of five comments per topic, to limit the size of reports to two pages. All of these criteria are easily editable to provide tailored reports.

The final step involved creating a report template in LaTeX that used the exported five graphs and the *.tex comments file, to generate a report automatically. Each step of this process is automated in code (see Appendix 6) and requires almost no knowledge of the packages used, that is, Stata and LaTeX (e.g. MiKTeX and TeXnicCenter).

Workstream 3: co-design of a toolkit

For this WS, an experience-based design approach was adopted, drawing on the initial qualitative research (WS1), the computer science work (WS2) and insights from our PPI group, to co-design ways to enable and support digital data capture, analysis and use of both quantitative and narrative data.

These methods have been used to formulate a toolkit comprising:

-

a survey utilising the FFT with space for free-text comments to be completed using digital kiosks in study sites, a website or a pen and paper version (see Report Supplementary Material 1)

-

guidance and information for staff, patients and carers to support use of the new tools

-

new text-mining programs for analysing patient feedback data

-

new templates for reporting feedback from multiple sources

-

a new process for eliciting and recording verbal feedback in community mental health services.

Qualitative data collected from staff, patients with MSK and service users with SMI in WS1 were summarised and discussed in follow-up focus groups in WS3, with 57% of staff and patient/service user participants having previously taken part in the qualitative components in WS1 (Table 4). Of note, no carer participants were recruited in either site A or site B for WS3.

| Participants | Site | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C1 | C2 | ||

| Staff focus groups | 10 (5) | 12 (5) | 9 (6) | 14 (7) | 45 (23) |

| Staff interviews | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total staff | 10 (5) | 12 (5) | 9 (6) | 14 (7) | 45 (23) |

| Patient focus groups | 0 | 12 (7) | 12 (7) | ||

| Patient interviews | 8 (7) | 0 | 8 (7) | ||

| Total patients | 8 (7) | 12 (7) | 20 (14) | ||

| Carer focus groups | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Carer interviews | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Total carers | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Total | 18 | 24 | 9 | 14 | 65 (37) |

Collectively, 65 participants contributed to WS3, with 37 participants having previously taken part in WS1. We conducted one follow-up focus group with staff participants in each site (site A, n = 10; site B, n = 12; site C1, n = 9; site C2, n = 14), individual interviews with patients with MSK (n = 8) and one focus group with service user participants (n = 12). These discussions enabled us to define priorities for capturing and using patient experience data. Using the new reporting templates, the extracted data were presented to participants to facilitate integration and the contrasting of data with data from other sources.

We achieved a diverse sample of staff participants with roles in management and patient experience, clinical practice and IT, reflecting the various categories of interest in each organisation. In site A, there were 10 staff participants (lead IT/governance/patient experience managers, n = 2; specialist nurses, n = 2; consultant specialists, n = 6). In site B, there were 12 staff participants (team managers, n = 2; care co-ordinators, n = 3; social workers, n = 3; community psychiatric nurses, n = 3; support workers, n = 1). In site C1, there were nine staff participants (GPs, n = 2; health-care assistants, n = 1; practice managers, n = 1; administrators/reception staff, n = 5). In site C2, there were 14 staff participants (GPs, n = 6; receptionists, n = 2; practice nurses, n = 3; pharmacists, n = 1; practice managers, n = 1; finance managers, n = 1).

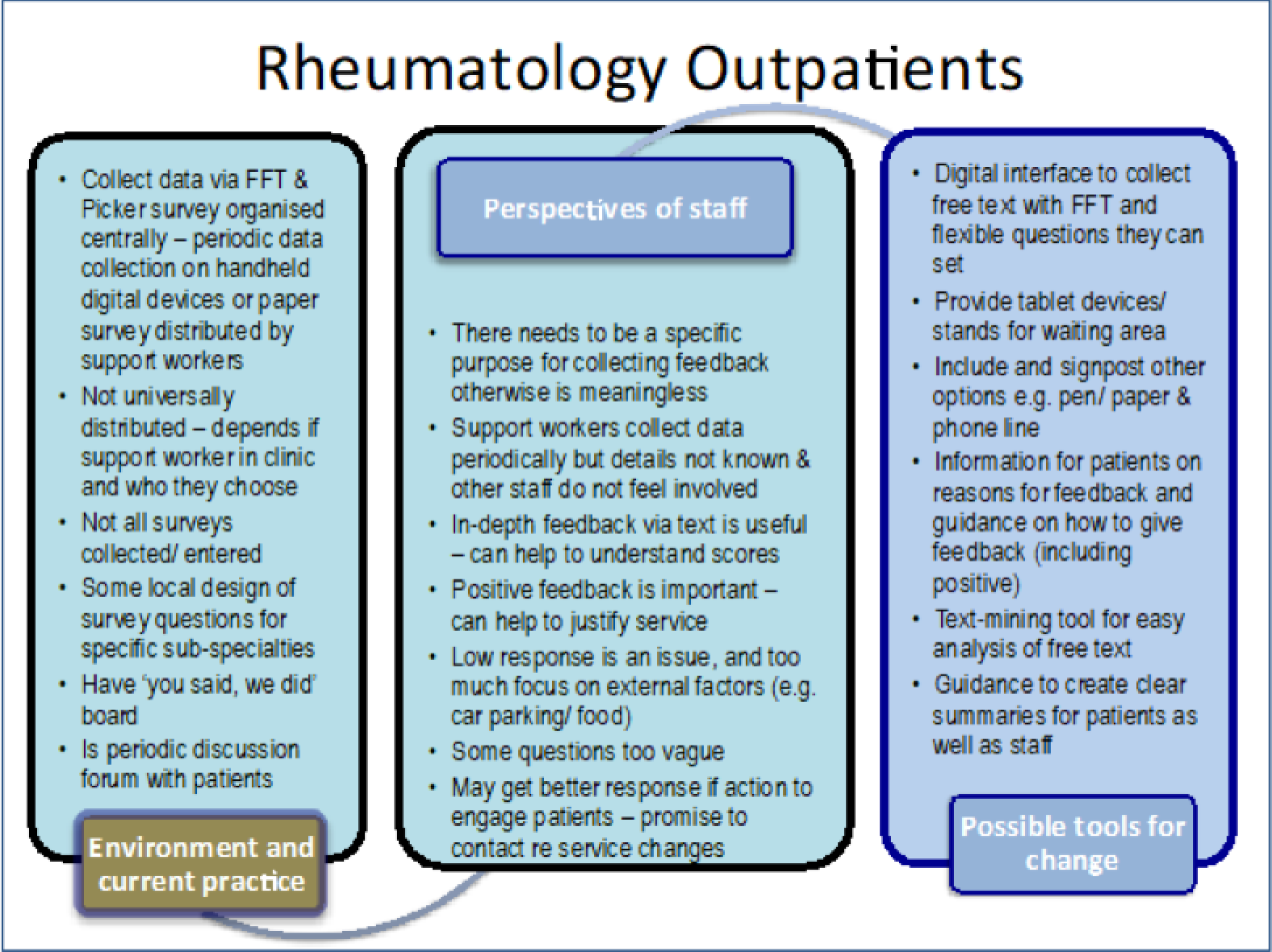

We developed summaries of findings from WS1 and used Microsoft PowerPoint® 2011 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) slides to present these findings and trigger discussions on what tools might be best suited to improving the collection and usefulness of patient experience data for service improvement (see Report Supplementary Material 2). Figure 3 provides examples of summaries discussed in staff focus groups.

FIGURE 3.

Slide from presentation summarising the links between current context, views of staff and possible tools for change in site A.

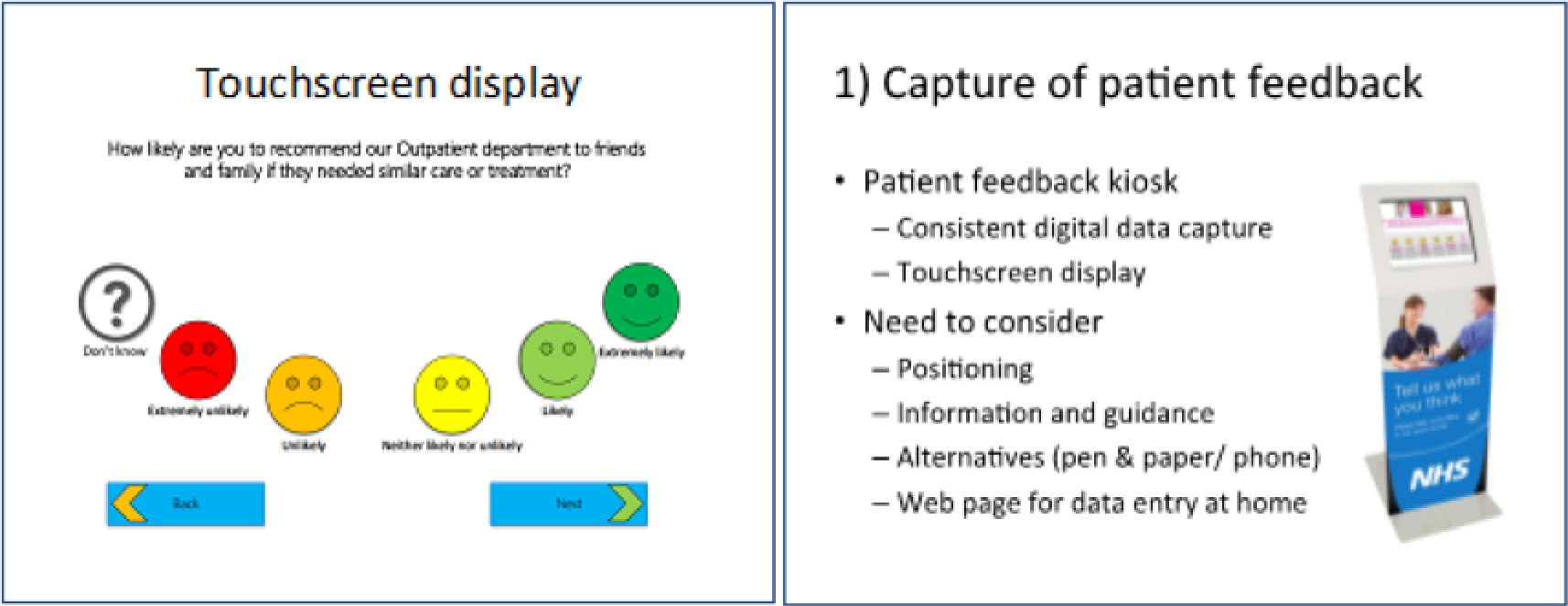

In addition to summarising the existing processes and the perspectives of staff, we also summarised the perspectives of patients in each of the sites for discussion with staff, alongside various ways of capturing and presenting the data based on analysis undertaken in WS2 (Figures 4 and 5).

FIGURE 4.

Examples of slides used to show participants various ways of capturing the data.

FIGURE 5.

Examples of slides used to show participants potential graphs for displaying analysed data using text mining.

Workstream 4: implementation and evaluation

Implementation

To implement the new tools into the four sites, a question-and-answer document was devised for each site and circulated to all staff members. Additionally, members of the research team visited each site and conducted an introductory session to describe the finalised toolkit and describe how the different components would be tested during the evaluation period.

Qualitative evaluation

A process evaluation50 was conducted using qualitative methods to assess how the tools were used in practice. This included using interviews and focus groups to understand the perspectives of patients and staff on the new tools. Observation sessions were also conducted in each site to determine the degree to which patients, service users and carers automatically approached the self-standing kiosk (or when the kiosk was manned by a volunteer) and typed their feedback using the touchscreen or wrote feedback on a paper survey.

We undertook at least one follow-up focus group with staff in each site (site A, n = 5; site B, n = 19; site C1, n = 8; site C2, n = 8) and individual interviews with staff in three sites (site B, n = 7; site C1, n = 2; site C2, n = 2) (total staff, n = 51) (Table 5). Of note, 35 WS4 staff participants had taken part in previous components of the study.

| Participants | Site | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C1 | C2 | ||

| Staff focus groups | 5 (5) | 19 (8) | 8 (5) | 8 (6) | 40 (24) |

| Staff interviews | 0 | 7 (7) | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | 11 (11) |

| Total staff | 5 (5) | 26 (15) | 10 (7) | 10 (8) | 51 (35) |

| Patient focus groups | 0 | 13 (6) | 0 | 4 | 17 (6) |

| Patient interviews | 6 (6) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 7 (6) |

| Total patients | 6 (6) | 13 (6) | 0 | 5 | 24 (12) |

| Carer focus groups | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| Carer interviews | 1 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| Total carers | 1 | 6 | 0 | 1 | 8 |

| Total | 12 | 45 | 10 | 16 | 83 (47) |

We also undertook focus groups with patients in two sites (site B, n = 13; site C2, n = 4) and individual interviews with patients in two sites (site A, n = 6; site C2, n = 1) (total, n = 24). Additionally, we facilitated focus groups with carers in two sites (site B, n = 2; site C2, n = 1 – this carer participant took part in a focus group with patient participants) and undertook individual interviews with carers in two sites (site A, n = 1; site B, n = 4) (total, n = 8).

Of note, of the participants included in this phase (n = 83), 47 had taken part in the initial focus groups and interviews in WS1 and/or WS3 (see Table 5 for the numbers of participants who had taken part in previous components of the study). Crucially, these discussions enabled us to understand perspectives on how the new tools worked in practice and further explore some of the issues raised in the earlier qualitative research.

Observations were conducted to evaluate the barriers to and opportunities for providing patient experience feedback using the newly implemented methods of the standing kiosks, the website and the pen and paper version. Each observation episode varied between a minimum of 1 hour and a maximum of 3 hours. Staff meetings to discuss feedback during the evaluation period were also observed in the study sites (Table 6).

| Observation session | Site | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | B | C1 | C2 | ||

| Patients | 11 | 8 | 11 | 8 | 38 |

| Staff meetings | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

Normalisation process theory, which has been applied to implementation in varied health-care contexts,51 was drawn on for analysis. NPT focuses on social practices and interaction and is operationalised via four key constructs: coherence (meaning and understanding of new technology/practices), cognitive participation (relational work to sustain a community of practice for a new intervention), collective action (operational work to enact new practices) and reflexive monitoring (work carried out to monitor and appraise new practices). First, we coded the data using a modified grounded theory approach58 and then mapped the emerging themes against NPT constructs.

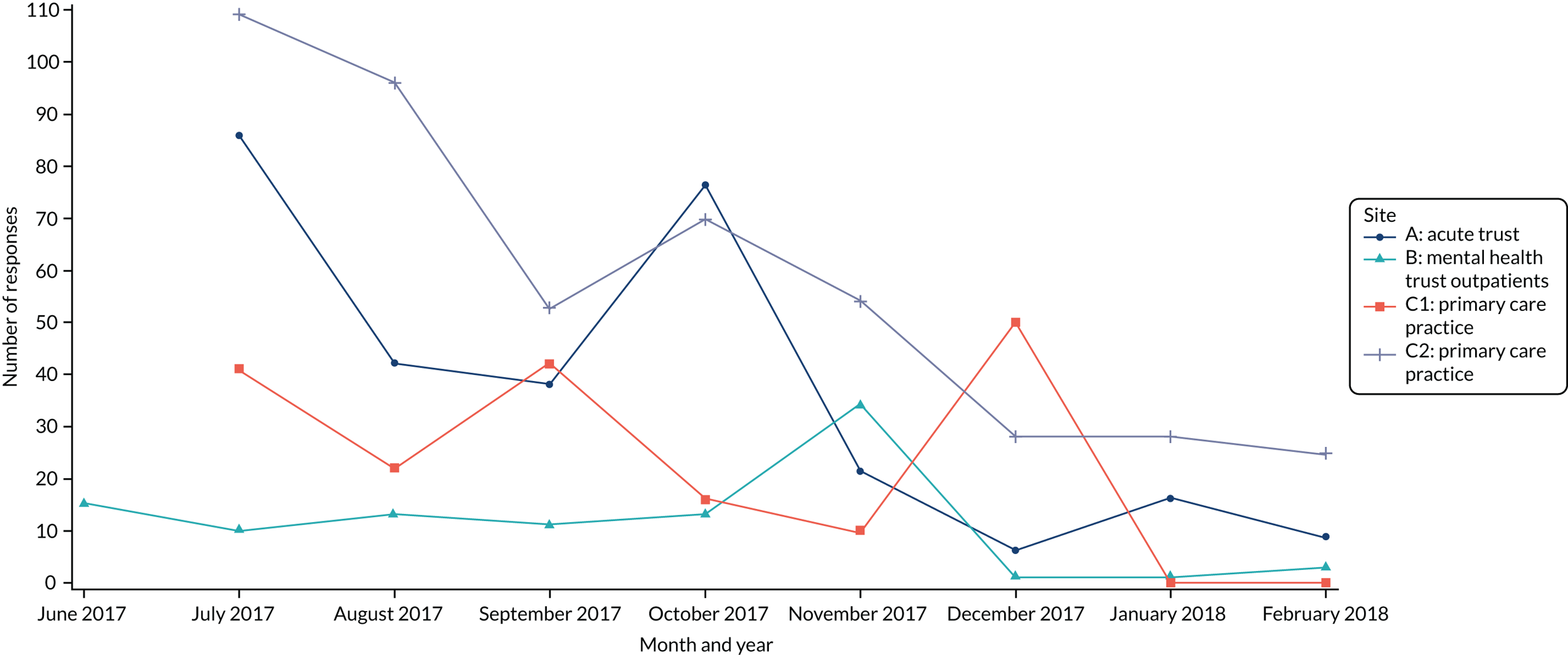

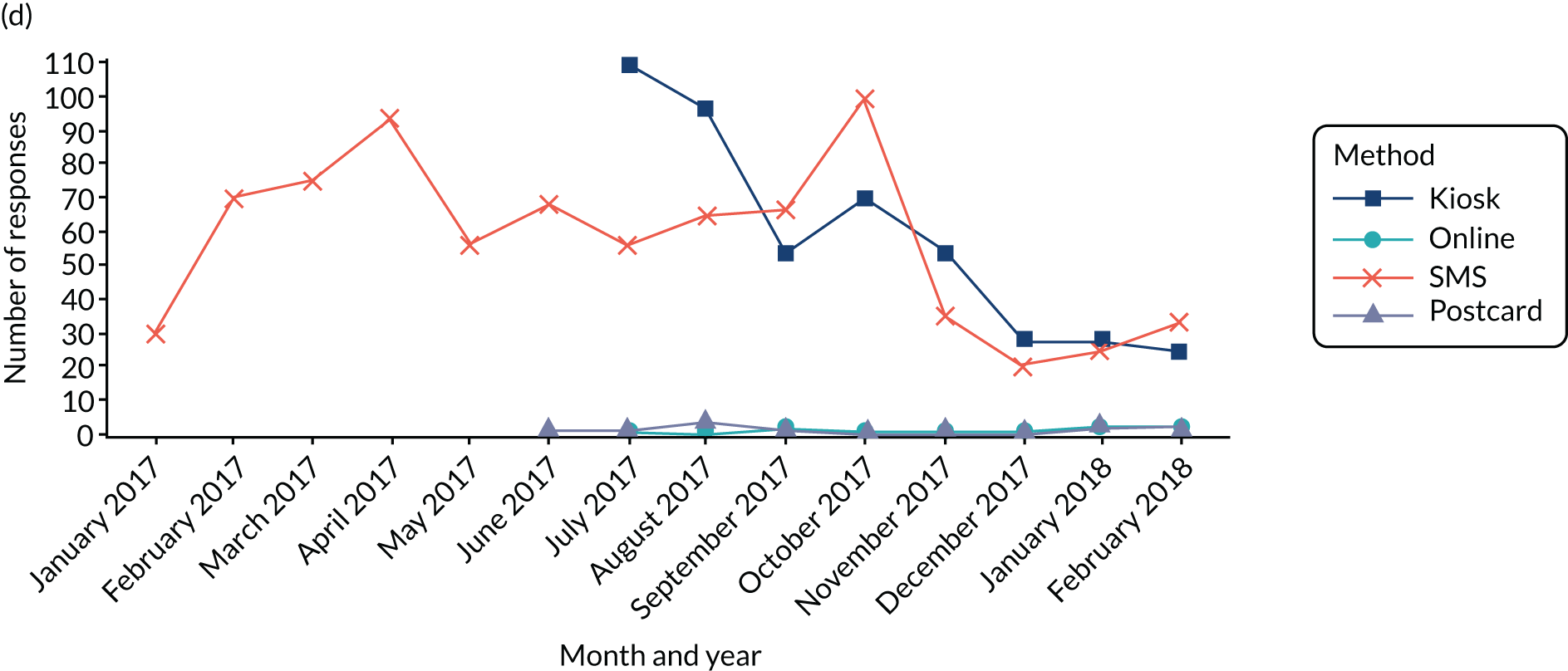

Quantitative evaluation of pre- and post-participation rates

Response rates for patient experience questionnaires and levels of participation pre and post implementation of the toolkit were compared to investigate the impact of the toolkit for widening participation levels in multiple settings.

Health economics

The planned health economics work, to develop a decision model to explore the potential costs and benefits of the toolkit/kiosk approach, was modified as the programme progressed. In particular, the uncertain evidence about the benefits of the FFT for generating quality improvements and changes in local trusts, combined with recent challenges about its worth and the results of the toolkit/kiosk evaluations, limited the feasibility and value of such an exploratory model. Accordingly, we focused instead on estimating the costs of developing and implementing the toolkit developed in this programme to inform future development and evaluation of this or similar tools. Our research questions for this part of the study were:

-

What are the costs of co-design activities to develop the toolkit components?

-

What are the costs of developing the text-mining and reporting elements of the toolkit?

-

What are the costs of initial implementation of the toolkit/kiosks in each of the sites?

-

What are the costs of analysing and reporting the data generated by the toolkit/kiosks?

The costs of developing and implementing the toolkit were estimated from data on the staff time and resources used in this programme to develop and implement the toolkit in the different sites. The staff time and resource use data were collected from diaries and other records of activities of those involved in developing and implementing the toolkit, as well as from the qualitative interviews and observational studies. The staff time data also included the time spent developing and implementing the analytic approaches used to analyse the data generated by the toolkit and the FFT data available to the team.

National salary scales were used to estimate the costs of university research and NHS staff whereas the payments made as part of the evaluation were used to cost the time of volunteers and non-staff participants in the co-design activities. The costs of equipment and consumables used as components of the toolkit and used to analyse the data were estimated from actual expenditure.

In addition, we reviewed published literature and Department of Health and Social Care policy and guidance to identify the costs of the FFT at the local level. Searches of electronic databases and the Department of Health and Social Care website were conducted for all years up to December 2017, using a simple electronic search strategy. These were updated to March 2018. The electronic databases searched included the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews; ACP Journal Club; Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects; Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials; Cochrane Methodology Register; Health Technology Assessment; NHS Economic Evaluation Database; Allied and Complementary Medicine Database; EMBASE, Health Management Information Consortium (HMIC); Maternity and Infant Care Database (MIDIRS); MEDLINE; and PsycINFO. The search terms included ‘friends and family test’, ‘patient experience’ and variants of each term. Initial searches excluding terms related to cost and economics indicated that a low number of studies were available (n = 36). Accordingly, the cost-related terms were not included in the electronic search, but were included in the inclusion criteria used to screen full studies. Only studies reported in English were included. The full papers for all of the included studies were obtained. These were reviewed and any resource use or cost data were extracted by one researcher (LD).

Text mining versus qualitative analysis of free-text feedback received in general hospital and mental health service settings: a descriptive comparison of findings

This study set out to compare the findings produced by text mining against those produced by qualitative researchers working on the same data sets. The same data sets were analysed in an independent and blinded fashion by machine-learning algorithms (as described above) and by ‘human analysis’ using grounded theory coding. A secondary aim was to compare feedback gathered in mental health settings with that gathered in general hospital settings, using both the same and different analytic methods.

The data sets

The data sets used were a subset of those employed in the text-mining work described in WS2. Analysis was conducted on general hospital trust (site A) data for 1 complete calendar month (June 2016, the most recent complete month for which data were available). Using only 1 month of mental health data would have yielded only around 40 comments, so 6 months of data were used for site B.

Data analysis

The qualitative analysts used ‘open coding’ principles of grounded theory analysis by Corbin and Strauss,59 enabled by the use of NVivo 11. The grounded theory approach [hereafter referred to as adapted grounded theory (AGT)] was ‘adapted’ or ‘expanded’ in that count data on categories (or ‘topics’, as in the text-mining analysis) were also collated and described and were subsequently organised by sentiment to facilitate comparison with the text-mining results. The qualitative researchers began by independently coding a sample of around 500 comments received by both health trusts. They then compared results and used this discussion as a basis for drawing up a draft list of around 75 codes in 10 preliminary categories.

The final coding framework consisted of 125 codes (or ‘child nodes’) in eight nodes (or ‘themes’): access process and discharge, communication from and with clinical staff, positive aspects of service, specific complaints, qualified comments, staff attitude, the service made me feel and this service is better than others.

Ethics and consent

Ethics approval was granted by the National Research Ethics Service West Midlands – Black Country Research Ethics Committee (REC) (reference number: 16/WM/0243).

All staff, patient and carer participants were given a participant information sheet explaining the study and provided written consent to take part in a focus group discussion, an individual interview or both, dependent on participant preference (see Appendix 2 for an example of an information sheet for staff). The researcher(s) stressed the voluntary nature of participation in the study (see Appendix 2 for an example of a consent form used in the study).

During the study, the research team, staff and patients reflected on a number of ethics issues related to the collection of feedback. Staff in multiple sites reflected on concerns that patients might feel pressured to give positive feedback if they were encouraged to use the digital kiosks and that there may be concerns that the feedback would not be anonymous. In response to this, care was taken to ensure that information given to patients made it clear that giving feedback was their choice. They were also reminded of the multiple other ways by which they could give feedback.

Although the patient experience data obtained from sites A and B were classified as anonymised data, the free text sometimes contained identifiable details (e.g. names, telephone numbers). Care was taken to ensure that data were transferred and stored securely in line with our NHS and Health Research Authority ethics approval and that only anonymised data were used to illustrate themes from analysis.

Within the community mental health team the ethics issues regarding the recording of verbal feedback in the professional–client clinical visits were discussed actively during focus groups and interviews. Many drew links with the conversations about care that were a normal part of care-planning processes, but also identified that the main concern would be to remind service users of the different routes by which they could give formal feedback outside clinical relationships with staff.

Our researchers followed the University of Manchester lone worker policy when visiting both sites and participants’ homes.

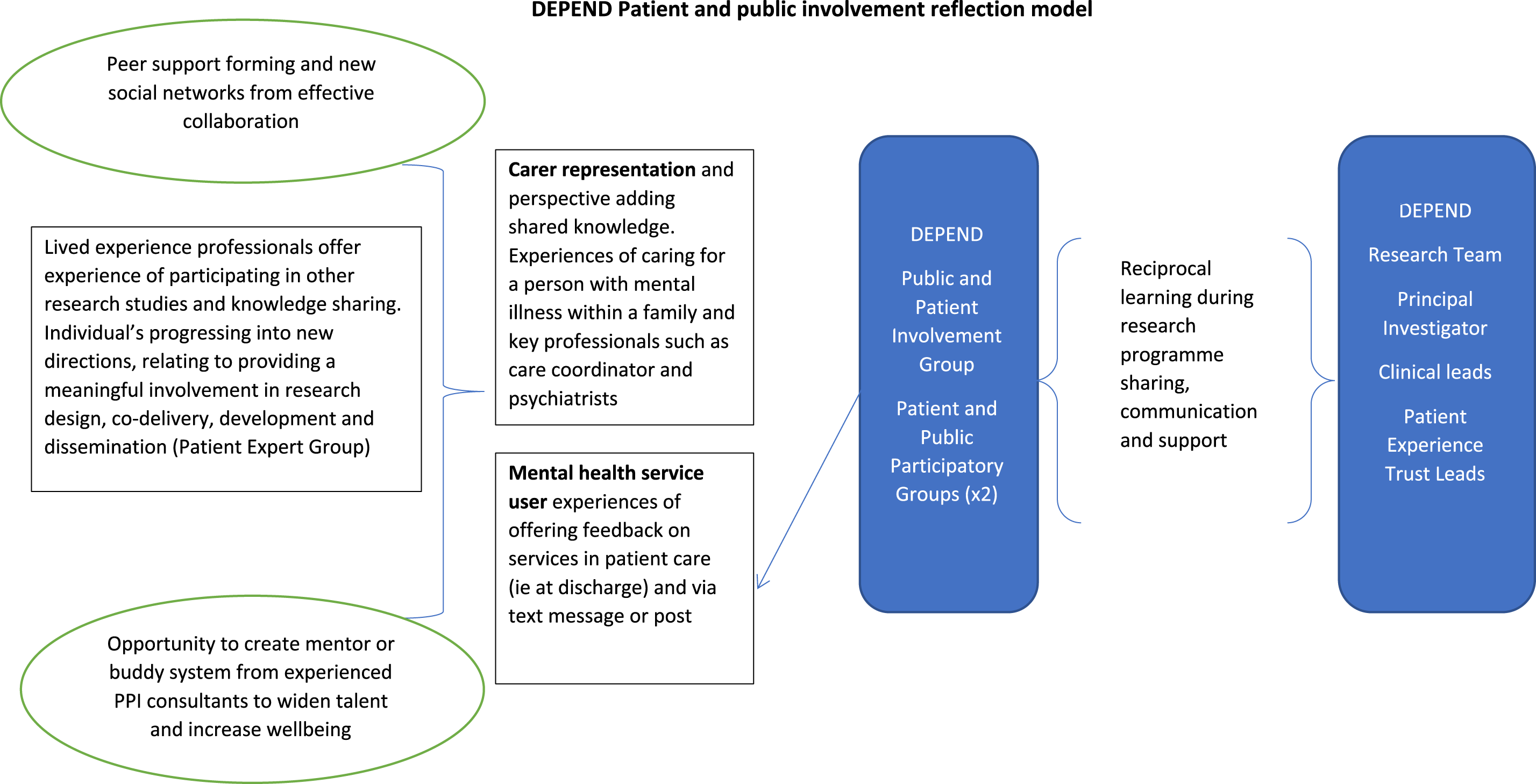

Chapter 3 Patient and public involvement

Introduction

National policy is increasingly encouraging PPI in research as a means to improve both the relevance and the meaningfulness of applied health research in England. In this chapter, we describe our PPI work for the study. From the outset, we asked our PPI contributors to be actively involved in the conception of the Developing and Enhancing the usefulness of Patient Experience and Narrative Data (DEPEND) study, the investigation and the evaluation and dissemination of the results, bringing insight into each WS because of their experiences of living with a long-term condition and using health services.

Patient and public involvement contributors

We created a core PPI advisory group to represent a range of experiences and preferences concerning feedback among our exemplar physical and mental health long-term conditions. In total, eight members of the public with one of our exemplar conditions joined the core PPI advisory group. Three members had experience of a MSK condition and five members had experience as users of mental health services. Two members represented a dual perspective, as a carer and a service user. All members were paid for their time at INVOLVE rates and claimed additional expenses where applicable.

There were two PPI leads for the core PPI advisory group (AL and NS), who were also co-investigators in the study and had worked with us from the initial planning phase on the design of research questions and plans for the pre-funded proposal. They also had input into the management of the research by attending project management group and study steering committee meetings.

Members had various experience of PPI research work to date. At the start of the study, all of our PPI advisors had experience of working with researchers as PPI advisors. Two members were previous consultants of a PPI advisory group and one member had undertaken PPI research training developed in-house in another department at our institution.

Patient participation groups

We also drew on the perspectives of volunteers of two patient participation groups (PPGs), which are groups set up to enable public participation in primary care organisations. PPGs hold regular meetings to discuss the services provided and how improvements can be made for the benefit of patients and the practice [National Association for Patient Participation; see www.napp.org.uk/ (accessed 14 December 2019)], and attempts should be made to ensure that such groups are representative of the practice population. We found each PPG to be quite different in terms of the group composition, management and levels of engagement with the DEPEND study. The PPG in site C1 is a relatively small group with nine PPG members; four core PPG members worked with us as PPI contributors to the DEPEND study. Virtual PPG participation is enabled at this site through the practice website, but we engaged only with those PPG members who attended face-to-face engagement PPG meetings on site. Of note, this site faced challenges in trying to get a core PPG together. It was eventually decided that a random cross-section of patients would be asked their opinions regarding the practice and to participate as a PPG member by completing an online patient group form. Currently, the assistant practice manager manages the PPG, circulating the minutes from each face-to-face meeting and uploading the minutes to the practice website. The practice manager liaises with members mainly by telephone; only a few members have an active e-mail address.

In comparison, the PPG in site C2 is considerably larger, with 40 members; we worked with seven active core PPG members. Virtual participation is also enabled at this site through the practice website but, again, we engaged only with those PPG members who attended face-to-face PPG meetings in the site C2 reception area. A trainee GP set up this PPG with the practice manager when she was a GP registrar at the practice in 2011.

Meetings

Feedback from the first PPI meeting focused on further clarity about the purpose of our core PPI group and highlighted the importance of establishing ground rules for each meeting. As a result, a ‘terms of reference’ document was circulated and discussed at the second PPI meeting.

To optimise PPI involvement, separate PPI groups were held, focusing on each long-term condition of interest, SMI or MSK conditions. During the 2-year study, the PPI group members met face-to-face four times within the Centre for Primary Care. We also facilitated a total of five face-to-face PPG meetings per site (C1 and C2) during each WS. The PPG at site C1 met upstairs in the practice manager’s room during the early evening after practice hours; the PPG at site C2 met in the seated reception area over a lunchtime when the practice was closed.

We accommodated PPI representatives in terms of access and health. For instance, we enabled virtual participation via Skype™ (Microsoft Corporation) to reach PPI contributors who could not travel. Nicola Small took overall responsibility for the co-ordination and management of the PPI group, with input from the chief investigator (CS). Each PPI face-to-face meeting was chaired by the principal investigator (CS) and co-facilitated by Nicola Small and Papreen Nahar, with refreshments provided at each meeting.

Our PPI group met face-to-face, as well as remotely, for specific input on the content of each WS, the co-design of the toolkit components and accompanying bespoke guidance and the evaluation and dissemination activities. Each PPI meeting was constructed around each WS of the project and comprised an overview of the minutes from the previous group, a PowerPoint presentation consisting of a recruitment and project update with key findings to date and a PPI-led discussion. We made sure that what our PPI contributors had advised in relation to progress to date was always summarised in our slide set. Project documents were provided ahead of each meeting and hard copies were available on the day. Following the meeting, minutes were circulated by the co-ordinator, alongside PowerPoint slides. In between the core PPI meetings, regular communication took place by e-mail to the PPI co-ordinator (NS) and core documents were read and commented on using Dropbox (Dropbox Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA), by e-mail or face-to-face.

Some challenges and lessons learnt

During the course of the project, we faced some major challenges and upsetting events associated with our PPI work. Sadly, two members of our team died unexpectedly: Neal Sinclair and Jane Reid Peters brought their energy, enthusiasm and valuable experiences and expertise to our work. It was a shock to both researchers and fellow PPI group members when they died within a relatively short period of time. This made us reflect on the relationships developed during the course of carrying out PPI work within research and on how to manage difficult situations. Working closely together as researchers and PPI contributors entails sharing a lot of personal experiences and building long-term relationships, which are quite different from those that develop when researchers are carrying out one-off interviews or focus groups. This can result in researchers, and also PPI members, having a sense of responsibility towards fellow team members. When a member of a group dies it may be difficult to know what to do to support other members of the group, who may already feel vulnerable. In our case, we found a way to manage and support each other during an upsetting time, but we found it difficult to find information about similar circumstances and what might help. We also found that there is little formal support available unless it is explicitly planned for. For example, we thought that it might help other members of the PPI group if they were able to access a counselling service easily should they need it. This is difficult because universities, for example, provide counselling for staff and students but not for PPI members. This has prompted us to work with our Centre for Social Responsibility to build better support for managing difficult situations associated with PPI. Caroline Sanders has been working with the NIHR-funded Primary Care in Manchester Engagement Resource (PRIMER) group and the NIHR-funded Greater Manchester Patient Safety Translational Research Centre (GM PSTRC) to develop this work further. We hosted a workshop on this topic in February 2018 [see https://gmpstrc.wordpress.com/2018/02/01/managing-difficult-situations-in-patient-and-public-involvement-workshop-event/ (accessed 9 October 2019)].

Our experience has taught us that fellow PPI group members may need additional support when someone in the group dies; researchers may also need support and it is also important to follow up with family members to ensure that they know how much the work carried out by the PPI member has been valued.

Participant experiences

As the PPI co-design meetings progressed, one of our PPI members (DA) became more involved in our recruitment activities. She was able to help recruit carer participants within site B using her existing carer networks. During year 2 of the study she was also able to spend dedicated time working in our centre and was provided with an IT account to enable her to contribute to core project documents. Our PPI co-investigator (AL) also spent dedicated time reviewing components for the toolkit during the co-design phase of the project and we were able to supply her with an iPad mini (Apple Inc., Cupertino, CA, USA) to enable her to complete some of this work remotely.

We had originally planned for both PPI co-investigators to work with us in conducting interviews and focus groups. However, this was not possible because of health problems and other constraints, limiting the time available for the training and governance requirements to enable this.

Results

In this section we present feedback from our PPI group for our four WSs: (1) topics to explore at interview to enhance current feedback collection methods, (2) text mining, analysis and presentation of narrative data, (3) co-design of a suite of tools and (4) development, evaluation, implementation and dissemination of the toolkit. In addition, the recommendations that were developed as a result and how they were acted on are also presented.

Topics to explore at interview to enhance current feedback collection methods

We sought general feedback from our PPI group on current feedback collection methods.

Our PPI SMI group felt that the importance of collecting positive feedback needs to be emphasised and that there should be a range of methods available for giving feedback, either through structured survey questions or narratively. Additionally, the mode of feedback should be considered to encourage wider participation. Privacy may be facilitated by the use of a booth and iPads, video and audio. Simple emoticons could be used for giving feedback, with an option for adding brief text, alongside survey questions. Further, a ‘feedback period’ might be used to encourage participation in each method and waiting time could be used more effectively for collecting feedback. When feedback is based on previous experience, or expectations, this might be documented in a ‘gratitude diary’, with examples of positive feedback collated. Finally, feedback co-ordination was emphasised by the group as being essential for ‘linking up the services’ and ensuring that all professionals are aware of the full patient experience. It was thought that a ‘feedback incentive process’, such as the Amazon (Amazon.com, Inc., Bellevue, WA, USA) virtual system of allocating stars to services, might increase interest in prioritising feedback.