Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 16/53/03. The contractual start date was in February 2018. The final report began editorial review in August 2019 and was accepted for publication in January 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Keen et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Just 25 years ago, most commentators assumed that health services were generally safe. Then, in 2000, the Institute of Medicine in the USA published a report on patient safety: To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System. 1 The evidence presented in the report suggested that rates of adverse events – events that resulted in harm to patients – were far higher than anyone had realised. It proved to be a landmark report, not just in the USA but around the world. Ever since, policy-makers around the world have been acutely aware that treatment and care need to be safer.

The NHS in England has committed considerable resources to improving patient safety in the intervening 20 years. Overall, however, the rate of adverse events remains high and it is widely accepted that there is still considerable scope for improvement. 2 A range of interventions have been proposed by policy-makers, including quality improvement initiatives, the use of performance targets and comparative audits. A series of government policies and official reports published over the last 20 years have argued that health information technologies (HITs) can also improve patient safety. 3–5 This report investigates this argument. We have undertaken a realist synthesis of evidence about an important class of HITs, namely interoperable networks. These are networks that link the information technology (IT) systems of different organisations in a health economy, so that a professional based in one organisation can access data about a patient held in another organisation during the course of treatment and care. There is a continuum of technical solutions. At one end is a network that allows a user to access a remote patient database using a separate log-in, so that the user has to accept the layout and content of that database. At the other end is an integrated solution in which a user logs on once and sees a patient record that has a single consistent layout and for which data from all sources are easily accessed.

The effects of health information technologies on patient safety

When we bid for this evidence synthesis, we were aware of two systematic reviews that usefully summarised what we knew about HITs and patient safety, and helped us to pinpoint what we did not. Black and colleagues6 undertook a ‘review of reviews’ of a number of HITs that have been available for many years, including telehealth, electronic health records (EHRs) (used within organisations), decision support systems and hospital e-prescribing systems. Black and colleagues6 focused initially on experimental and quasi-experimental studies, but then broadened their searches to include a selection of observational studies of implementation. The majority of reported studies were conducted in hospital settings, with the main exception being studies of telehealth applications. Some of the studies reported positive results, notably for electronic medicines reconciliation, whereas others found mixed and negative results, including for telehealth. The authors commented on the poor overall quality of the literature and, in particular, on the small numbers of high-quality randomised controlled trials in the domain.

Second, Brenner and colleagues7 identified 31 systematic reviews that focused on HITs and patient safety. The authors7 reported on a range of systems, including computerised physician order entry (CPOE), order entry alerts (e.g. for contraindicated drugs), EHRs, clinical decision support systems, electronic medicines reconciliation and electronic clinical pathways software. They used a broad definition of patient safety, and the end-point measures included mortality, adverse drug events and infection rates. Twenty-five out of 69 included studies reported a statistically significant positive effect on the patient safety measure assessed. Overall, however, the authors concluded that, ‘many areas of health IT application remain understudied and the majority of studies have non-significant or mixed findings’. 7

These reviews led us to identify two significant gaps in the applied health research literature. First, we did not find any systematic reviews of the effects of interoperable networks on patient safety outside hospitals. There was evidence about telehealth, but a large England-based trial showed that telehealth was not cost-effective and systematic reviews of international evidence were, at best, inconclusive. There was no case for another systematic review. The one published review that shed light on interoperable networks focused on effects on resource use rather than on patient safety. 8

This state of affairs was a surprise, given that government policies in many countries had promoted investments in interoperable networks – or, to use the preferred US term, health information exchanges (HIEs) – for some years. In particular, the Barack Obama administration in the USA had allocated US$35B to HIT investments from 2009. A substantial proportion of the money was to be spent on information exchanges, linking hitherto separate IT systems in hospitals, family physicians’ offices, pharmacies and elsewhere. The benefits claimed initially included improvements in patient safety, cost savings and productivity improvements.

Information technology policies in England had also promoted investments in interoperable networks from 2015 onwards, although the central monies allocated were initially modest. 9 We were also aware of developments on the ground in a number of health economies. For example, health and social care organisations in the city of Leeds had been developing an IT platform, or information infrastructure, linking their various systems together for a number of years. Nurses, doctors and other professionals working in one organisation could already access patients’ records held in others’ systems. There was a gap, then, between investments in this sort of development and the evidence about their value, particularly in relation to patient safety.

The second gap concerned the ‘how and why’ of the deployment and use of HITs. We were struck by the effectiveness evidence: why was it so mixed and why were effect sizes so modest? Mobile phones and other consumer technologies have transformed the way we search for information, shop and communicate with one another. Why were no similar effects found in health and social care settings? We did not expect effectiveness studies to answer these questions, but we were aware of other literatures that might help us to do so. For example, a comprehensive review of evidence from the field of human–computer interactions revealed that, in contrast with applied health research, there was a long history of empirical studies stretching back to the 1980s. The review suggested that health professionals often found systems difficult to access and use. A range of problems was cited, including poor interface designs and the unreliability of hardware. 10 There was, again, more evidence about hospital than extra-hospital systems, but some evidence about the latter was presented. Similarly, sociological studies reported problems with integrating IT systems into routine clinical practice. 11–13

These literatures were consistent with reports that HITs could increase patients’ risks. A 2011 Institute of Medicine report neatly summarised the problem:

. . . some case reports suggest that poorly designed health IT can create new hazards in the already complex delivery of care. Although the magnitude of the risk associated with health IT is not known, some examples illustrate the concerns. Dosing errors, failure to detect life-threatening illnesses, and delaying treatment due to poor human–computer interactions or loss of data have led to serious injury and death.

A realist synthesis

Putting these lines of argument together, we decided to focus on interoperable networks that link organisations across health economies, and their effects on patient safety. Furthermore, we agreed with the Institute of Medicine that there were risks, as well as benefits, associated with HITs. It would therefore be important to go further than identifying the effects associated with interoperable networks, and explain how and why the networks produced these effects.

We needed, then, to identify an evidence synthesis method that would allow us to investigate the ‘how and why’ of interoperable networks, as well as their effects on patient safety. We would also need to be able to assimilate both narrative and quantitative evidence into the synthesis. Pope and colleagues15 have reviewed the methods that are available for the synthesis of ‘mixed’ health evidence, including narrative reviews and thematic analyses. Pope and colleagues15 emphasise that each method has strengths and weaknesses, and that each one is better suited to some topics and research questions than others. Following Pope and colleagues’ analysis,15 and drawing on our own experience, we judged that a realist synthesis would be appropriate. It would allow us to identify how and why interoperable networks led to particular outcomes, in our case how and why they led to changes in patient safety. As we show in Chapters 2 and 3, we took the caution about the weaknesses of the method seriously and actively sought to mitigate them in this review.

Aims and objectives

The aim of the study was to establish how and why networked, interorganisational HIT services improve patient safety, fail to do so or increase safety risks. We undertook a realist synthesis. The method involved identifying (1) programme theories that capture the chains of reasoning that lead from an intervention to its use and subsequent effects, and (2) reasons why the intended improvements are, or are not, achieved in practice, or indeed increase safety risks.

The objectives of the study were to:

-

identify initial programme theories and prioritise theories to review

-

search systematically for evidence to test the theories

-

undertake quality appraisal, and use included texts to support, refine or reject programme theories

-

synthesise the findings

-

disseminate the findings to a range of audiences.

Protocol change

One change was made to the protocol for this evidence synthesis. The intention was to run three nominal groups to consult with policy-makers, senior informatics managers and front-line clinicians in the theory development stage. We were able to organise the first two nominal groups but not the third, principally because front-line staff were not able to obtain permission for time off to attend the initial meeting. We used a different method, eliciting the views of seven health and social care professionals based in two localities in the north of England in semistructured telephone interviews. This method is described in Chapter 3.

Structure of this report

Chapter 2 provides an overview of the study design of the realist synthesis and shows how we made key decisions about the design. Chapter 3 describes our literature review, nominal group and interview methods. Chapter 4 sets out the findings of the theory development phase of the synthesis. The next four chapters present evidence search findings. Chapter 5 presents the findings for the co-ordination of services for older people. Chapter 6 presents the findings for searches on medication reconciliation undertaken in the course of care of older people. Chapter 7 presents the co-ordination of child protection services. Chapter 8 presents the evidence about economies of scope and scale resulting from the deployment and use of networked HITs. In Chapter 9 overall synthesis of the findings is presented and discussed, and the conclusions and recommendations are listed.

Chapter 2 Study design

Introduction

This chapter sets out the study design for the realist synthesis. The next section (see Theory development and programme theories) outlines the key features of a ‘standard’ realist syntheses, reported in many published accounts. Core elements of our study design are consistent with those accounts. We then note the diversity of study designs and methods reported in the literature. 16 Realist syntheses have common characteristics, notably in the development and testing of programme theories that investigate the relationships between interventions and outcomes. However, they also vary in the ways in which theories are developed and in which they are tested, and teams therefore need to make choices about their synthesis designs. The last section (see Mid-range theory) sets out the choices that we made and the ways in which they influenced our study design. The synthesis is registered with PROSPERO CRD42017073004.

Theory development and programme theories

The realist synthesis review method was first described in detail by Pawson in Evidence-Based Policy17 in 2006. The first stage, which we refer to as theory development in this report, involves the development of a programme theory. 18,19 A programme theory is a representation of the way in which an intervention is intended to work. It typically involves a sequence of decisions and actions that lead to a defined outcome, underpinned by reasoning about how those decisions and actions follow one another. A number of programme theories may initially be developed, reflecting different ways in which an intervention might lead to an outcome. Sources of programme theories can include government and other policy documents, and accounts by opinion leaders in journal editorials and elsewhere. It has become usual, in the last few years, for stakeholder consultation to be used as another source of information for developing programme theories.

Sometimes, established theories have already been published, and these can be used by the review team. On other occasions, no plausible, published sequences can be found. When this happens, review teams can instead identify potentially useful fragments, covering partial sequences of events, which are pieced together by the review team. Evidence is then identified and evaluated. This is to establish the actual sequence of events that links an intervention and an outcome, and whether or not the underlying reasoning is supported by empirical evidence. (Putting this a slightly different way, a rationalist approach to identifying an intended sequence of events is followed by empirical assessment of that sequence.)

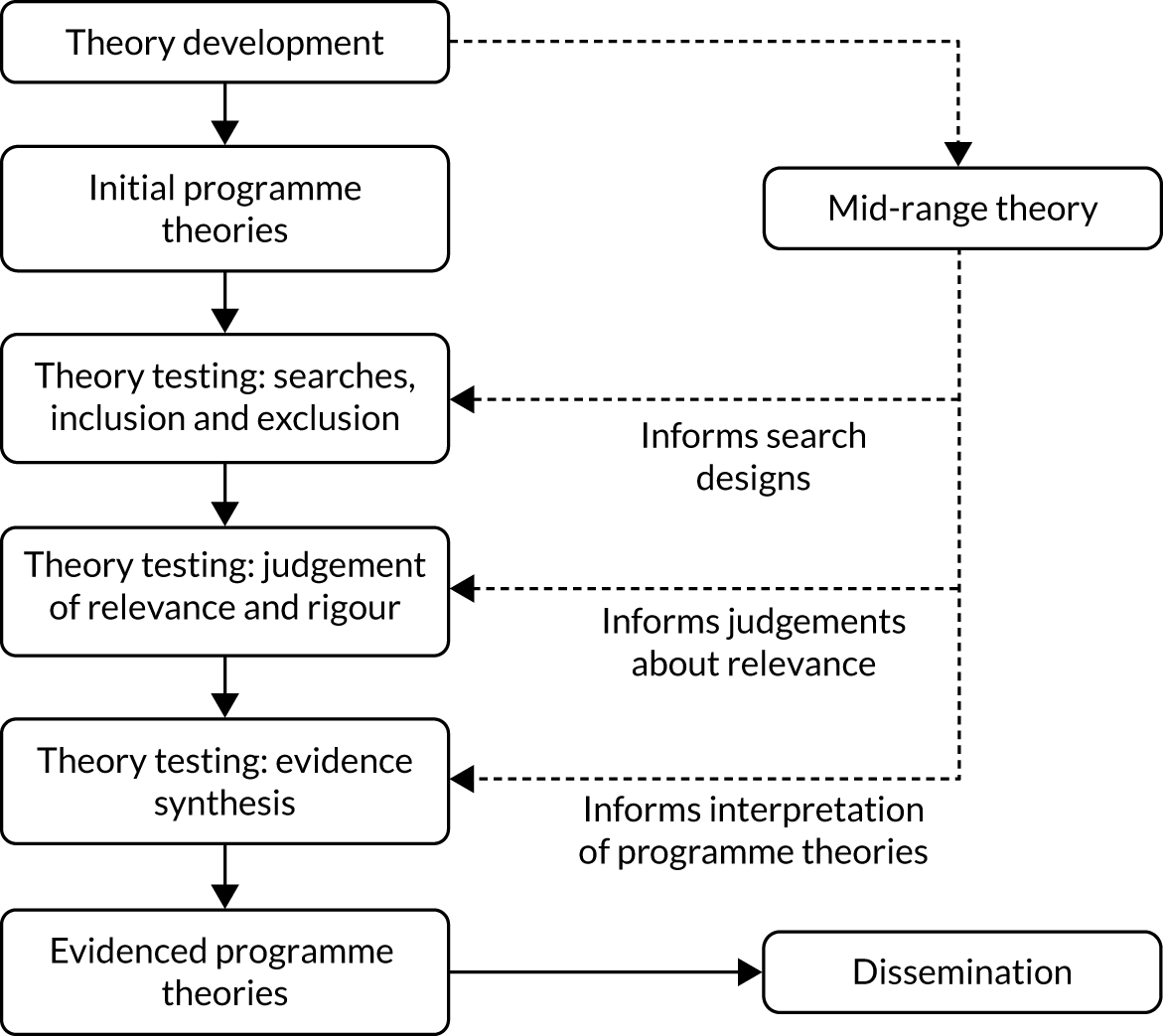

Most realist syntheses present evidence reviews in three distinct stages (Figure 1). First, key concepts are identified from the review question and used to design the literature searches. Inclusion and exclusion criteria are defined and used to identify articles for full-text review. The second stage involves close scrutiny of the full text of the included articles, which are assessed for rigour and relevance, with data and relevant theory extracted. Third, the data and theory in the included articles are synthesised and compared with the initial programme theories. Any one theory might be supported, refined or rejected. Pawson points out that the conduct of realist syntheses is typically iterative. Empirical evidence might, for example, suggest that there is evidence to support a proposed sequence of events, but there may be additional steps in the sequence that were not identified in initial programme theories. As a result, evidence has not been sought for these steps, and further searches need to be designed and conducted.

FIGURE 1.

Study design.

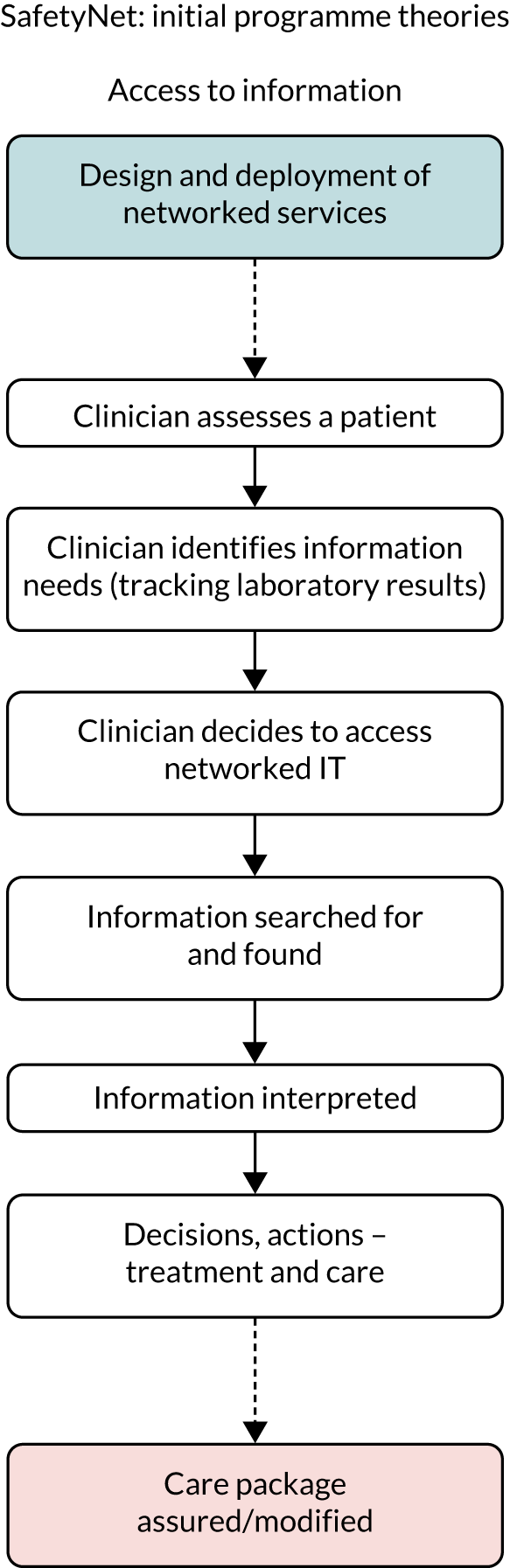

The design of our realist synthesis is consistent with the Realist And Meta-narrative Evidence Syntheses: Evolving Standards (RAMESES) guidance. The left-hand column in Figure 2 illustrates the flow of methods. The first stage involved developing initial programme and mid-range theories. These represented the intended changes and effects associated with the intervention (i.e. the use of interoperable networks). The methods used include literature searches and consultation with stakeholders, the latter using nominal groups and semistructured telephone interviews. The next three stages were designed to identify evidence about actual changes and effects. The evidence reviews comprised carrying out literature searches, screening reports against inclusion and exclusion criteria, assessing relevance and rigour, data extraction and synthesising evidence. The methods are described in Chapter 3.

FIGURE 2.

Study design, including mid-range theory.

Mid-range theory

As we have noted, there is also variation in published study designs, particularly in relation to the role of theory. The RAMESES guidelines on the conduct and reporting of syntheses provide general, rather than prescriptive, guidance, offering flexibility to each research team. 20 It can be argued that this state of affairs is reasonable: it gives teams the space to develop a still-new methodology and evaluate different ways of conducting one. It also means, however, that a team undertaking a realist synthesis today has to make some choices about its preferred study design and methods.

The right-hand column in Figure 2 represents a distinctive feature of our study design and reflects our thinking about the role of theory. Our starting point is the observation that programme theories are not neutral, for the straightforward reason that researchers from different backgrounds (psychology, sociology, geography and so on) might develop different programme theories about the same intervention. That is, they think about, or frame, their theories in different ways, reflecting the beliefs and assumptions of their host disciplines. It is therefore important, as a minimum, to know what beliefs and assumptions have framed any given programme theory.

In 2013, Pawson21 noted the diversity of ways in which theories are incorporated into study designs. Our reading of the realist synthesis literature in the course of this study supports this point; we found that published accounts offer three main options. One is to use concepts derived from classical systems theories, typically referred to as context–mechanism–outcome configurations. The key idea is that the course of a given sequence of events (i.e. the events represented in a programme theory) is directly influenced by the context in which those events occur. Evidence searches might show that an intervention that works in one context may not work in another; the differences between the two can shed light on how and why the sequences of events work, or fail to do so. We decided not to use this approach, because in this study interoperable networks seemed to be the context for behaviour change across a locality. That is, it seemed that interoperable networks were both contexts and mechanisms.

The second option, which appears to be the most popular in practice, is to rely solely on programme theories; a psychological, sociological or other theory is embedded in the programme theories (implying that the nature of the theory should be stated explicitly by the research team). We decided not to rely on programme theories alone for the reason given above: we felt that it was important to make any conceptual framing of theories explicit in the study design.

The third option is for a research team to identify a relevant theory, typically referred to as a mid-range theory. The theory used might be based on the team’s prior knowledge of a domain or on the initial reading in the course of the study, or a combination of the two. We decided to pursue this option. In doing so, we were able to draw on the work of authors who have identified and used mid-range theories to inform their deliberations. 22–24 We also drew on Pawson’s17 account of mid-range theories as ‘reusable conceptual platforms’ (they are reusable in the sense that the same underlying reasoning can underpin a number of programmes). 17

The mid-range theory needed to be integrated into the study design and we were not able to find published accounts that made it clear how this could be done. We took the view that mid-range theory performs different functions (represented by the dotted lines in Figure 2): informing the design of searches, serving as a source of criteria for judging the relevance of articles and facilitating the synthesis of evidence. Following the synthesis of findings, the theory was used to inform the generalisation outwards from programme theories across populations, interventions or settings. Overall, it acted as a sort of ‘glue’, helping to bind the stages of the synthesis together.

The decision to use a mid-range theory influenced other design decisions. One decision concerned the assessment of rigour and relevance, which we discuss in Chapters 2 and 3. Additionally, at the start of the study, we assumed that there would be both similarities and differences in the ways in which interoperable networks influenced processes and outcomes. We were already aware of relevant literatures, including the human–computer interaction literature and the sociological literature on the development of large-scale IT systems. Our initial reading and deliberation confirmed that a theoretical framework that might account for large-scale change, spanning organisational and professional boundaries, would be appropriate. As we will see in Chapter 4, our mid-range theory (our reusable conceptual platform) drew principally on the literature on information infrastructures. This is an example of an institutional theory: published realist syntheses have used institutional frameworks and we followed their example in this study. 25,26

Finally, the decision about mid-range theory influenced our thinking about programme theories. They are used in different ways, for example to characterise causal relationships between activities or to capture the underlying inferential logic of an intervention. 27 Our choice here was to develop programme theories that represented contingent sequences of concrete decisions and actions, ending in a defined outcome. In this synthesis the outcome was a change in patients’ or clients’ risks, consistent with arguments about outcomes made by Pawson and colleagues. 28,29 We sought to strengthen our confidence in findings about these contingent sequences by undertaking searches focusing on different functions of interoperable networks (e.g. supporting professionals co-ordinating care for older people and reconciling medication lists for older people) and different populations (older people, at-risk children). Comparing across functions and populations provided us with a means of identifying and interpreting any similarities and differences that we found between functions and populations.

Chapter 3 Methods

Introduction

In Chapter 2 we described the overall design of the realist synthesis and explained the rationale for key design decisions. In this chapter we describe our methods. The next section introduces the literature search methods, including the common features of methods used throughout the study. The following sections set out screening and selection, and data extraction and quality appraisal. The final section describes the stakeholder consultation that we undertook in the course of the review.

Literature search methods

We took the approach of conducting a number of literature searches throughout the review, rather than relying on a single ‘big bang’ search that could be used to address a number of questions. This allowed us to identify separate literatures that were pertinent to identifying theories and theory fragments in the theory development phase or to identifying empirical evidence in the theory testing reviews. 16 The following 19 information resources were searched:

-

Association for Computing Machinery (ACM)’s Digital Library (full text)

-

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s PSNeT Patient Safety Network

-

Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (via ProQuest)

-

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (via EBSCOhost)

-

The Cochrane Library (via Wiley Online Library), including Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects, Health Technology Assessment Database

-

Criminal Justice Abstracts (via EBSCOhost)

-

EMBASE Classic and EMBASE (via Ovid)

-

Epistemonikos (Epistemonikos Foundation, Santiago, Chile)

-

Google (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA)

-

Google Scholar (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA)

-

Health Management Information Consortium (via Ovid)

-

Health Systems Evidence (McMaster University, Hamilton, ON, Canada)

-

Inspec (via EI Village)

-

Ovid MEDLINE®, including Epub Ahead of Print and Ovid MEDLINE® In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations

-

PsycINFO (via Ovid)

-

Research Papers in Economics (EconPapers; Örebro University Business School, Örebro, Sweden)

-

Scopus® (Elsevier, Amsterdam, the Netherlands)

-

Sociological Abstracts (via ProQuest)

-

Web of Science™ Core Collection (Clarivate Analytics), including Arts and Humanities Citation Index, Book Citation Index – Social Sciences and Humanities, Conference Proceedings Citation Index – Science, Conference Proceedings Citation Index – Social Science & Humanities, Sciences Citation Index, Social Sciences Citation Index and Emerging Sources Citation Index.

Appendix 1 provides a detailed listing of databases, sources and search strategies used for each individual search.

The databases and sources used for each search were selected based on the type of study or publication being sought (e.g. policy document, systematic review) and the question posed for each search (e.g. the nature of co-ordination problems, users’ experiences of interoperable networks). Populations, interventions, comparators, outcomes and settings (PICOS) were identified before some of the theory development and all of the evidence searches to aid search strategy development. All of the searches were performed and peer-reviewed by information specialists (NK and JW). Search terms and synonyms were identified by the project team and from known relevant papers. Structured search strategies were developed using free-text words, synonyms and subject index terms, organised into search concepts. Further complementary searches, including forwards and backwards citation searches, were undertaken by both the information specialists and the reviewers; the team members who undertook the searches are stated in each instance.

Searches that were designed to retrieve particular study types, such as systematic reviews or narrative research articles, used one of three strategies, namely (1) database ‘limit’ features (e.g. systematic reviews publication type limit in Ovid MEDLINE), (2) a ‘study type’ search strategy developed by the University of Leeds information specialists, or (3) a published search strategy. Each of the three options was tried and tested before it was decided which was the most appropriate for each search.

Theory development

In February and March 2018 we undertook five types of search to identify programme and mid-range theories. We aimed to find literature that, taken together, captured the sequences of events that policy-makers and other stakeholders believe link the deployment of interoperable networks to effects on patient safety. An update search for systematic reviews was conducted in July 2019 to identify any new theoretical explanations for the effectiveness or lack of effectiveness of interoperable networks on patient safety. Appendix 1 provides a detailed listing of databases, sources and search strategies used for each search.

Government policies and official reports

We were aware at the start of the study of policies and reports that might contain programme theories or theory fragments. We collected all of the policies and reports for England and the USA that had been cited in our research proposal, plus additional reports that we were aware of, and traced further reports via references and through pragmatic Google searches.

Structured subject searches

Two searches were conducted in three health databases for studies that presented theories or theory fragments associated with terms that identified relevant HIE-type technologies and either ‘patient safety’ terms or ‘interoperability’ terms (see Chapter 1 for definitions of HIE and interoperability).

Named author searches

Searches were undertaken to identify articles by or citing two opinion leaders, Robert Wachter (author of an influential 2016 report30 on IT in the NHS in England) and David Bates (the most highly cited author in the academic health informatics literature). Slightly different search methods were used owing to the large volume of literature authored by Bates compared with that by Wachter. We searched three health databases and one multidisciplinary database (Web of Science Core Collection) for both. In addition, we identified studies by Wachter on the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Patient Safety Network Portal. The Bates search in Web of Science involved a further search using the ‘usage count’ search feature, which identifies the most prominent or popular articles by ranking those that are accessed the most. This was to ensure that we had captured and reviewed key papers by Bates that may have had valuable insights but had not been found by the standard ‘Bates AND HIT terms’ search. We looked at (1) articles authored by Bates mentioning HIT terms and (2) any article he authored or any article in which he was mentioned with a usage count ≥ 20 (at least 20 records or full-text downloads).

Systematic review searches

We searched seven health databases for systematic reviews that included theories or theory fragments linking HITs, including, but not limited to, interoperable networks and patient safety. We were not at this stage, concerned with the evidence in the reviews, but rather the discussion sections that offered explanations that could help with theory development.

‘Usage count’ search

In the Web of Science Core Collection, usage counts measure the level of interest in a specific record since a given date (e.g. 1 February 2013). This is calculated by users either downloading it into reference management tools or linking to the article’s full text. The usage count demonstrates current activity and interest in a record and can help identify recently published articles that may not register using traditional citation counts, which tend to favour older publications. We searched for interoperable systems or HIEs, selecting results with a usage count of ≥ 50 since 2013. We also used this technique to identify key articles by Bates, which were detailed and recorded in the author searches above.

Evidence review

The co-ordination of services for older people living at home

We identified three linked search questions that between them, were designed to provide evidence about the main programme theory (presented in Figure 9). The intuition here was that we needed to identify empirical evidence about the nature and extent of co-ordination problems. Were problems amenable to IT-based solutions or were they problems of a different kind (e.g. attributable to differences in objectives and values between the different professionals who care for older people)? If some problems were amenable, then this might help us to focus later searches. If, on the other hand, there was a mismatch between the proposed solution (interoperable networks) and the nature of co-ordination problems, we would want to investigate the reasons for the mismatch. For each search we tested subject headings and search terms iteratively until we agreed on a search strategy that identified a representative evidence base and that we were also able to screen in the time available to us. We used a modified version of the DeJean and colleagues31 qualitative search filter to identify qualitative studies and our internally validated reviews of search strategies to identify systematic reviews. 31

What is the nature and extent of care co-ordination problems for frail older people living at home?

Five health and social science databases were searched in August 2018 for either reviews or qualitative studies describing the care co-ordination for frail older people. Engineering databases were not searched as we were not concerned with technical aspects of care co-ordination systems. We also hand-searched the Integrated Care topic page and the Integrated Care and Partnership Working reading list from The King’s Fund. 32

What are the experiences of professionals using interoperable networks in the course of care co-ordination?

We searched initially for studies of experiences gained in the course of treating and caring for frail older people living at home. This produced a small number of papers that, on screening, seemed unlikely to shed any useful light on the question. In September 2018, we revised the search to cover services for older people, rather than focus on frail older people. At the same time, we restricted the search to review articles. Seven health, social science, engineering and multidisciplinary databases were searched.

We also undertook a forwards citation search of the four databases and search engines of Fitzpatrick and Ellingsen’s10 2013 review of 25 years of computer-supported co-operative work in health care. This was in our personal library at the start of the study, and at the end of the theory development phase it was still the most relevant review that we were aware of on the topic of users’ experiences.

Do interoperable networks improve patient safety outcomes for frail older people living at home?

In March 2019 we conducted structured database searches in six health, social science, engineering and multidisciplinary databases to identify evaluation studies of interoperable networks or HIE and care co-ordination.

We undertook additional forwards and backwards citation searches using Google Scholar for three included studies. 33–35

Medicine reconciliation for older people living at home

We identified three search questions.

What is the nature and extent of the medicine reconciliation problem among older people?

In December 2018, we conducted structured database searches of three health databases and one multidisciplinary database to identify reviews or qualitative studies investigating medicine reconciliation for older people living at home. Two further searches were conducted in Google Scholar.

What are professionals’ experiences of using interoperable networks in medicine reconciliation for frail older people?

In November and December 2018, we searched for users’ experiences of interoperable networks in medicine reconciliation processes. Our initial search and screening was not fruitful. We consulted with colleagues in the study team and, through them, with colleagues with specialist knowledge of the literatures on medicine reconciliation. This led to the pragmatic identification of a book chapter, which we used as the basis for a cluster search that identified a further two relevant articles. 119,120,124 Structured database searches were then designed using terms found in the two articles to identify studies of medicine reconciliation and cognitive reasoning. We ran the search in two health databases and one multidisciplinary database.

What are the patient outcomes of using interoperable networks in medicine reconciliation?

In December 2018, we conducted structured database searches in four health databases and one multidisciplinary database to identify any reports of medicines reconciliation, prescription errors and HIE (or interoperable health records). The searches were not limited by study type.

The co-ordination of services for at-risk children

The searches were designed to address three questions.

What is the nature and extent of the co-ordination problem in services for at-risk children?

In May 2019, we conducted structured searches of four health databases for literature reviews of care co-ordination in child protection services.

What are clinicians’ and other professionals’ experiences of using interoperable health information technology to co-ordinate the care of children at risk and what are the effects of interoperable networks on outcomes for at-risk children?

In March 2019, we conducted searches to cover the second and third questions (i.e. to retrieve any type of study on HIE or interoperable records and child protection services). We searched four health databases, one social science database, one engineering database, one criminal justice database and one multidisciplinary database.

Economies of scope and scale in health economies

In June 2019, structured searches were conducted of three health databases, one economics database and two multidisciplinary databases to identify studies of HIE (or networked IT) and economies (or efficiencies) of scope or scale.

Records management and tracking

All database search records were downloaded and stored in an EndNote library (version 9.2; Clarivate Analytics), the same library used in the theory development searches. Duplicates were removed from the EndNote library every time a new set of searches (for a new review subquestion) was added. Records were clearly labelled with the review subquestion for which they had been identified. Some records were found and screened several times for different review subquestions.

We were unable to download the results of some website and complementary searches into EndNote. In these cases, we screened the search results for potentially relevant report records during the search and manually created EndNote records from the selected results.

The details of all search activities were recorded in a summary spreadsheet, so that we had an evolving overview of the number and nature of searches that we conducted. The spreadsheet included the date of the search, the information resource, the purpose of the search and the numbers of records found.

Screening and study selection methods

Inclusion and exclusion criteria were identified for screening for programme theory development and evidence reviews. The following inclusion criteria were common to all searches:

-

written in the English language

-

published in 2000 or later (following the publication of the Institute of Medicine’s To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System;1 see Chapter 1).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for the specific searches are described in the following section (see Evidence review: the co-ordination of services for older people living at home). Throughout the study we adopted a cautious approach to inclusion and exclusion, preferring to include or ‘provisionally include’ articles until we were confident about our judgements.

Theory development

Screening was performed by three members of the review team (MA, JK and JG). Initially, 20% of the records from all the searches were double screened by two reviewers. Following this, all of the titles and abstracts were screened by one reviewer. The remaining records were categorised as clearly included or potentially included, and these were then independently assessed by a second reviewer. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion.

Evidence review: the co-ordination of services for older people living at home

As noted above, the searches were designed to address three questions about the co-ordination of services for older people and the effects of interoperable networks. Screening in this and the next two sets of searches (medicine reconciliation and at-risk children) was undertaken by three members of the review team (MA, JK and JG).

The nature of co-ordination problems

We identified separate inclusion and exclusion criteria for systematic reviews and individual narrative studies. We included systematic reviews if they were:

-

articles that described and explained the nature of care co-ordination problems across health and social care organisations in frail older people (later expanded to all older people)

-

literature reviews of any type that searched at least two academic databases.

We excluded:

-

non-peer-reviewed reviews

-

studies that were condition or disease specific (as opposed to studies focusing on services for frail older people in the round).

For individual studies we included:

-

narrative or mixed-method studies that described care co-ordination problems for frail older people

-

studies published from at least 1 year earlier from the date of the most recent review of evidence of care co-ordination problems in elderly patients (this was identified later as 2016–present).

We excluded:

-

studies that focused on single conditions or diseases

-

surveys and intervention studies.

Users’ experiences of interoperable networks

We included articles if they were:

-

reviews or studies that included evidence about users’ experiences of interoperable networks

-

focused on older people or on the general adult population (i.e. did not specify an age limit)

-

literature reviews of any kind, or individual observational studies.

We excluded:

-

studies that described professionals’ experiences of using single databases

-

surveys.

Patient safety outcomes

Studied were included if they met the following criteria:

-

study design – literature reviews, observational and interventional studies

-

population – older people living at home

-

outcomes – any measurable change in patient risk, defined in the article.

We excluded studies if they were:

-

reports of tools and technologies based on single patient databases or in other settings (e.g. within-hospital networks)

-

studies that did not include evidence about the effects of interoperable networks

-

studies of condition- or disease-specific outcomes

-

implementation studies or surveys.

Evidence review: medication reconciliation for older people living at home

We defined medicine reconciliation as the process by which any two or more lists of medications are reconciled with one another, or two or more lists that are reconciled with an assessment of a patient, to identify the appropriate medication list. Some definitions allow for reconciliation of a single medication lists against a patient’s assessed need, but in this study our interest was in the reconciliation of two or more lists, on the basis that interoperable networks might have roles in their reconciliation, not least because two or more patient records linked in the network would be available to professionals.

The nature and extent of medicine reconciliation problems

We included studies that were:

-

observational studies that explored the nature of the medicine reconciliation problem (independent of any given technology)

-

focused on services for frail older people (later expanded to adult populations) living at home

-

literature reviews or single observational studies.

We excluded:

-

studies that focused solely on IT-related problems, or were studies of technologies, including applications, for single users

-

studies evaluating the impact of medicine reconciliation on patient outcomes

-

quantitative studies of patient-related risk factors for medication discrepancies

-

studies based in other settings (e.g. hospitals or care homes)

-

surveys.

Users’ experiences of interoperable networks

We included studies that:

-

explored networked IT-supported medicine reconciliation across health and social care organisations

-

described the cognitive process of professionals (pharmacists, doctors, nurses) in medicine reconciliation

-

explored these processes in the context of services for older people living at home (later expanded to the adult population).

We excluded:

-

studies of medicine reconciliation in single organisations

-

studies of medicine reconciliation for patients who were not living at home (e.g. in a care home)

-

surveys.

Patient safety outcomes

Our inclusion criteria were:

-

study design – literature reviews, observational and interventional studies

-

population/setting – older people living at home who may have experienced a care transition (e.g. from hospital back home)

-

intervention – interoperable networks

-

outcomes – any measurable change in patient risk, defined in the article.

We excluded:

-

studies that reported on tools and technologies based on single patient databases or in other settings (e.g. within-hospital networks)

-

studies that did not include evidence about the effects of interoperable networks

-

studies of condition- or disease-specific outcomes

-

surveys.

Evidence review: the co-ordination of services for at-risk children

As with earlier searches, we undertook searches to establish the nature and extent of co-ordination problems, users’ experiences and outcomes.

The nature and extent of co-ordination problems

We included studies that met the following criteria:

-

literature reviews (of any kind)

-

studies that described care co-ordination problems for at-risk children living at home.

We excluded studies if they:

-

discussed children receiving routine services, including children in accident and emergency departments who were not deemed to be at risk

-

described only IT-related problems

-

were experimental studies of individual patient records systems or IT applications

-

were quantitative studies of patient-related risk factors.

Users’ experiences of interoperable networks and patient safety outcomes

Inclusion and exclusion criteria were developed for both questions. We included studies if they satisfied the following criteria:

-

described users’ experience of interoperable networks or patient safety outcomes (with outcomes defined in the articles)

-

included at-risk children (aged < 18 years) living in their own home.

Excluded were studies that:

-

focused on children living in settings other than their own home (e.g. in institutional care)

-

described professionals’ experiences of using single patient databases.

Economies of scope and scale in health economies

One member of the team (SN) screened all of the abstracts, and two members of the team (SN and JK) read seven of the full-text articles and together made the final selection. Data extraction and quality appraisal methods were not required, as there were no relevant full-text papers to synthesise.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We included studies that satisfied the following criteria:

-

Interoperable networks that linked two or more organisations outside (but possibly including) hospitals in a health economy.

-

Interoperable networks supported direct treatment and care.

-

Studies that included empirical evidence about the added value of interoperable networks, as measured by economies of scope and scale.

We excluded studies if they:

-

described hospital-only IT systems

-

described systems that did not link two or more distinct organisations in a health economy

-

focused on IT systems that supported secondary uses of data (e.g. for service planning, research).

Data extraction and quality assessment

Theory development

For each included article, we recorded the details of studies (authors, publication year) and text that described potential programme theories or theory fragments. As can be seen in Chapter 4, we did not find any complete programme theories, but we identified a substantial number of theory fragments. As noted in Chapter 2, we were looking for theory fragments, and so either copied all of the relevant text, which might be a few sentences, or recorded the location of larger sections of text for later analysis. Similar fragments that dealt with a particular topic, such as users’ experiences of interoperable networks, were grouped together. The groups of fragments were then pieced together so that initial programme theories could be developed both in text form and as visual representations. When possible the representations were annotated with claims about the reasons why programmes succeeded or failed in practice. The programme theories were used as the basis for consultation with three groups of stakeholders: (1) policy-makers, (2) senior IT managers and (3) front-line clinicians.

We undertook two broad types of evidence search. One focused on components of programme theories (e.g. users’ experiences of using interoperable networks) and the other focused on evidence of the outcome (which in this review was a change in patients’ risks of harm). For the former, data extracted included the study identifiers (author, publication year and country), information about study methods (the methods used and the numbers and types of participants), the evidence itself and information about the theoretical approach used. In this study, most of the evidence identified was narrative and extracted wholesale from papers (i.e. it was not summarised before synthesis), in part to retain the relationship between data and theoretical frameworks. Data extraction was undertaken by one researcher and checked by a second researcher (one MA, JG or JK).

For evidence about outcomes, a customised data extraction spreadsheet was designed for the recording of study identifiers, objectives, settings and a description of the intervention. Information that allowed us to judge the rigour of the study, including study design, participants, duration and theoretical framework, was also extracted. Finally, we extracted the findings of the study in terms of safety-related outcomes in quantitative studies, and quotations and comments in narrative studies. Critical Appraisal Skills Programme quality assessment checklists were used to appraise the rigour of systematic reviews and narrative and cohort studies.

Rigour and relevance

Most published accounts of realist syntheses include the assessment of the rigour and relevance of included articles. Rigour is concerned with the technical quality of the methods used in an article. In realist syntheses and any other review method that incorporates a range of experimental and observational methods, the approach is to judge technical quality against accepted standards appropriate for the methods used. In this review, we drew on the approaches used by other teams. 36,37

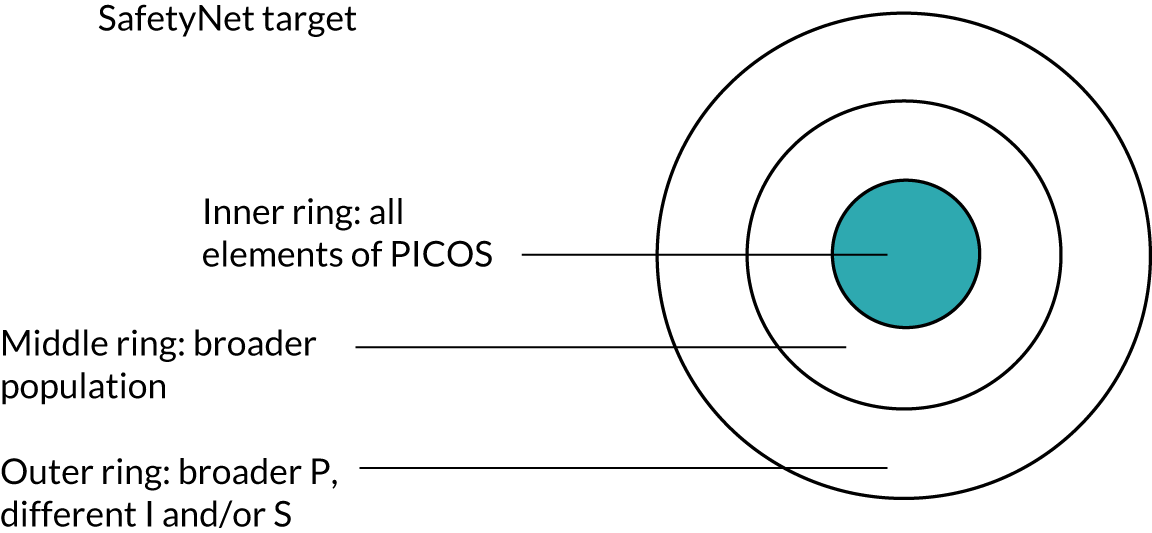

One consequence of the decision to use a mid-range theory (see Chapter 2) was in the ways in which judgements were made about the relevance of articles. Clear accounts of judgements about relevance are less common than those of judgements about rigour, but our approach was similar to that taken by Greenhalgh and colleagues38 in their review of patient-reported outcome measures. We took the view that the judgement criteria should be independent of, not derived from, the articles being assessed, and of the methods used to identify and assess them. We extended the method by developing a pragmatic ‘target’ akin to an archery target (Figure 3). Articles that clearly met the inclusion criteria were placed in the bullseye. Those that met most of the criteria, but not the population (e.g. all adults, rather than older people) criteria, were placed in the next ring. Articles that did not strictly meet the population, intervention or setting criteria, but were nevertheless deemed potentially relevant, were placed in the third ring. The use of the two outer rings is consistent with the view in realist syntheses that evidence can be included as long as it sheds useful light on a programme theory (i.e. articles were included if they shed light on the processes that linked an intervention and an outcome).

FIGURE 3.

Relevance ‘target’ diagram. I, interventions; P, populations; PICOS, populations, interventions, comparators, outcomes and settings; S, settings.

The ‘target’ was not used in the theory development searches. These were satisficing searches, which means that we did not conduct exhaustive searches, but rather we made practical judgements about the points for which we had identified sufficient evidence to answer the search question.

Stakeholder consultation

Alongside gathering literature to inform theory development, we consulted with stakeholders.

Nominal groups

We originally intended to use nominal groups with representatives of three groups of people: (1) policy-makers, (2) senior IT managers and (3) front-line clinicians. In the event, we ran nominal groups with the first two and conducted semistructured telephone interviews with front-line clinicians. The telephone interviews are described below (see Telephone interviews).

The nominal group technique involves an initial meeting with stakeholders at which a topic of interest is discussed and initial agreement or consensus is reached. The extent of agreement is then tested in one or two rounds of electronic consultation, typically e-mail or web based. Nominal groups were appropriate in this study because the underlying mechanisms linking interoperable networks and patient safety are poorly understood. We developed initial visual representations of programme theories, supported by text. Participants were sent the visual representations and text in advance of the meeting (see Appendix 2). The first meeting was with three senior NHS IT managers, all of whom were responsible for interoperable networks. It was held in May 2018 and was audio-recorded. At the meeting participants were asked to:

-

comment critically, on the basis of their knowledge and experience, on the initial programme theories

-

develop and then prioritise theories, or particular sequences of decisions and action within theories, for detailed study.

The prioritisation took account of the types of networked health and care systems that the participants were responsible for. That is, they were encouraged to identify questions that they were asking about their own networks (e.g. concerning the functions that appeared to be most closely associated with safety risks or improvements).

The second meeting was held with five managers from NHS Digital and NHS England in June 2018, and was also audio-recorded. As with the first group the participants were sent the initial programme theories in advance and were asked to comment critically on them, and to prioritise theories, or elements of theories, for detailed study.

In July 2019, both groups were sent a paper that summarised the findings of the evidence searches and the implications for our programme and mid-range theories (see Appendix 3).

Telephone interviews

It was not possible, in practice, to convene a nominal group of front-line clinicians. We spoke to a number of clinicians who explained that it was very difficult to obtain permission for time away from clinical duties. We consulted with our Steering Group, who advised us to conduct interviews instead. We obtained ethics approval to include a short topic guide for the telephone interviews (see Appendix 4). In common with the nominal group meetings, we sent the initial programme theories and supporting text in advance, and asked the clinicians to comment critically on the proposed programme theories and to prioritise the theories that they would like us to test. Potential interviewees were approached in two ways: via a short article in the Clinical Human Factors Group’s newsletter (circulated in October 2018) and through personal contacts in two cities that had interoperable networks routinely used by clinical staff. Seven interviews were conducted in November 2018.

Analysis

The nominal group meetings and interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed. Open coding was used to identify broad themes, on the basis that we were interested in insights into our programme theories, rather than the meaning inherent in anyone’s comments. Implications for our programme theories were identified pragmatically by members of the study team (MA and JK). The outputs of the nominal groups were summarised, and possible implications were noted and shared with the patient and public involvement (PPI) panel and the Steering Group. The comments of the nominal groups, PPI panel and Steering Group were all taken into account when refining the initial programme theories. The interview programme was undertaken later; the study team used the interviews to feed into thinking about the framing of the programme and mid-range theories.

Chapter 4 Theory development

Introduction

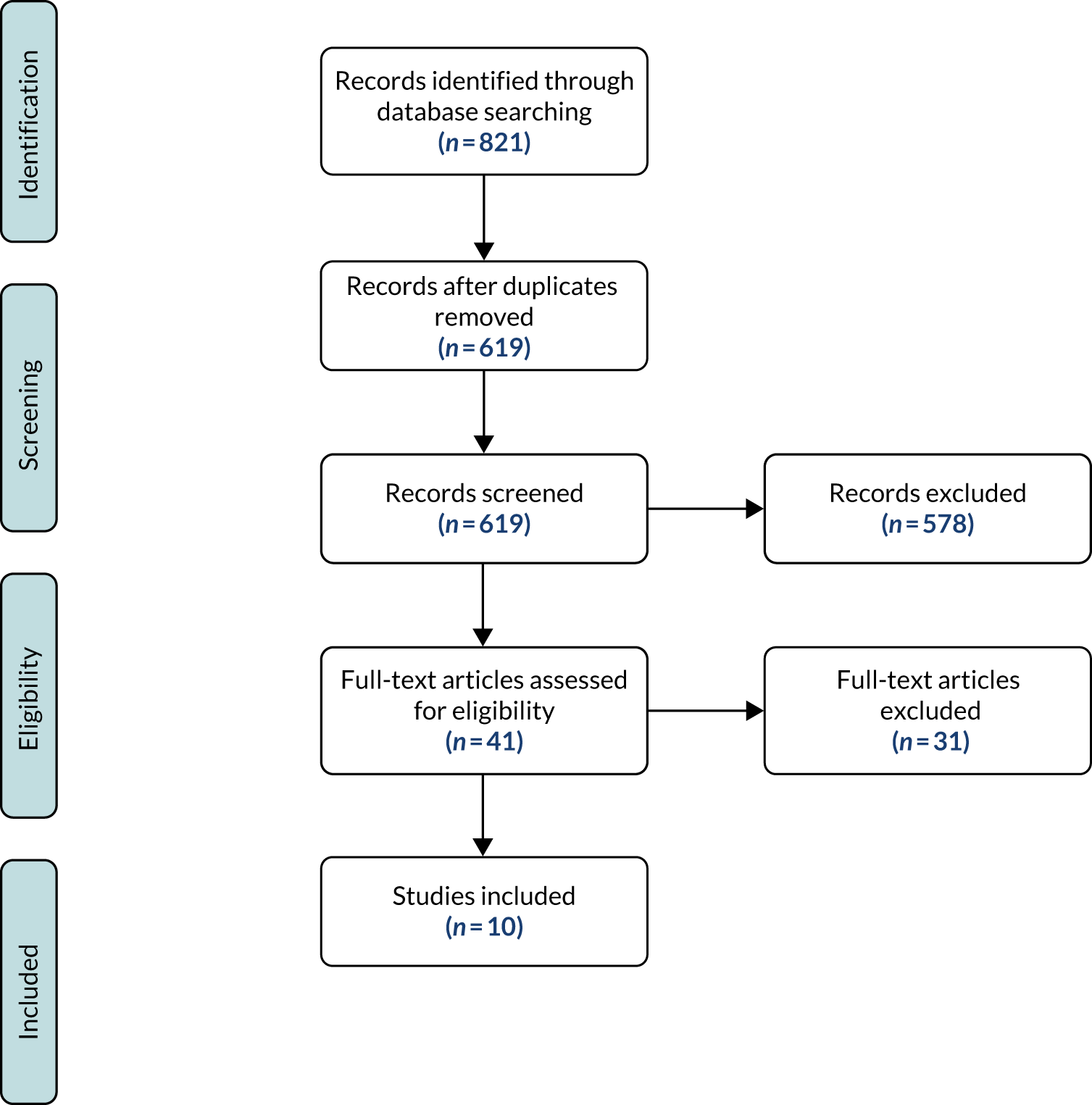

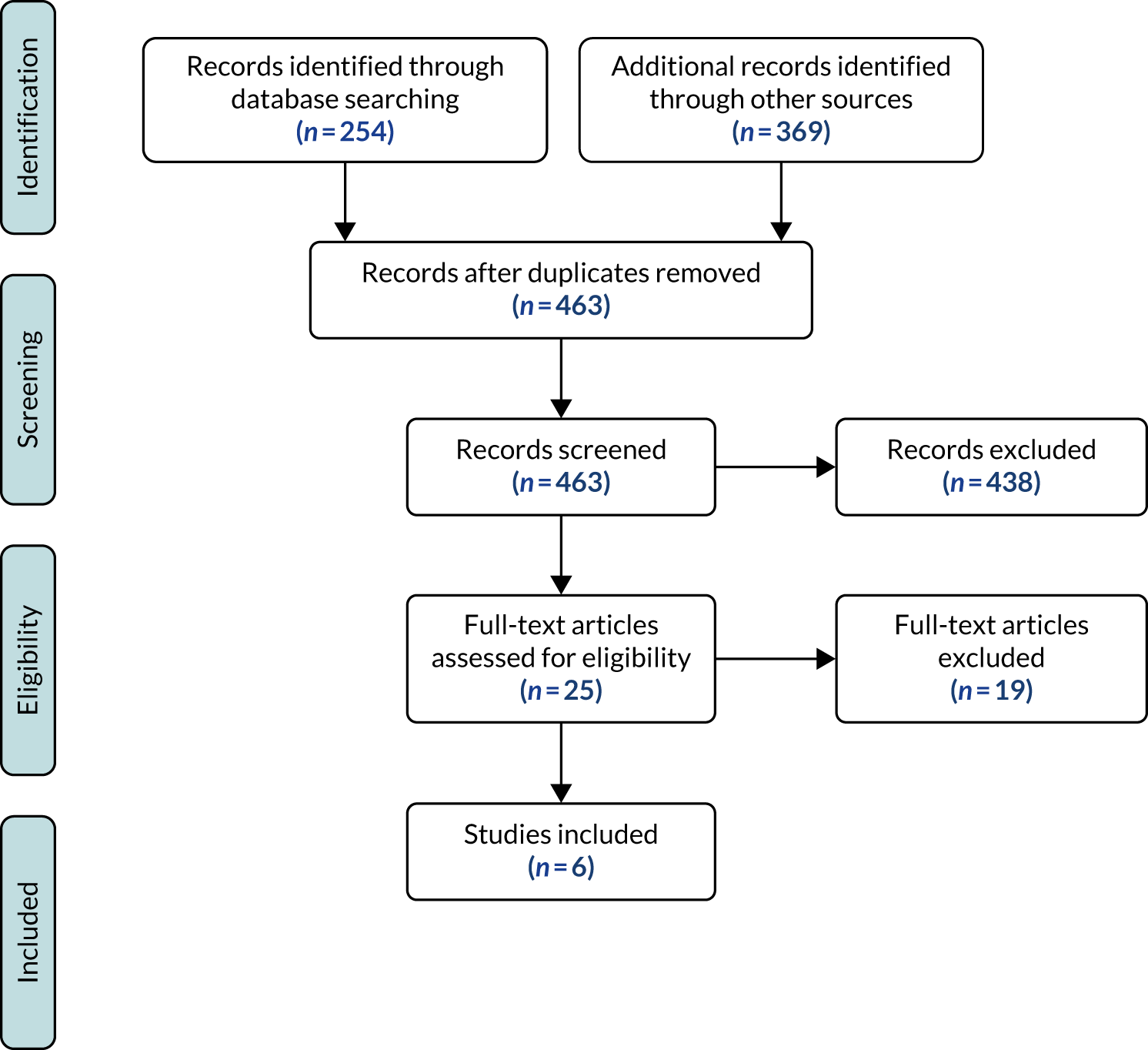

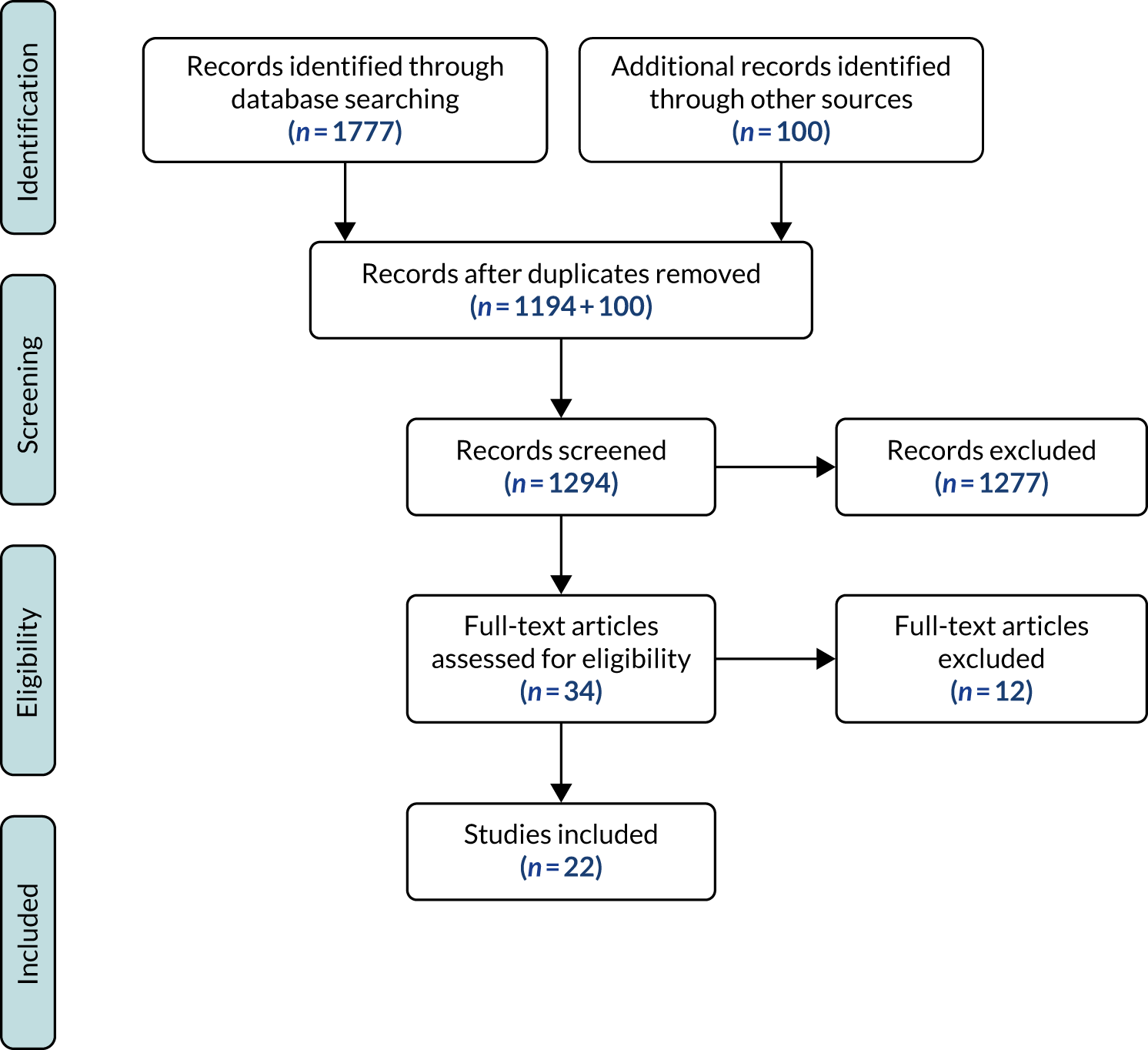

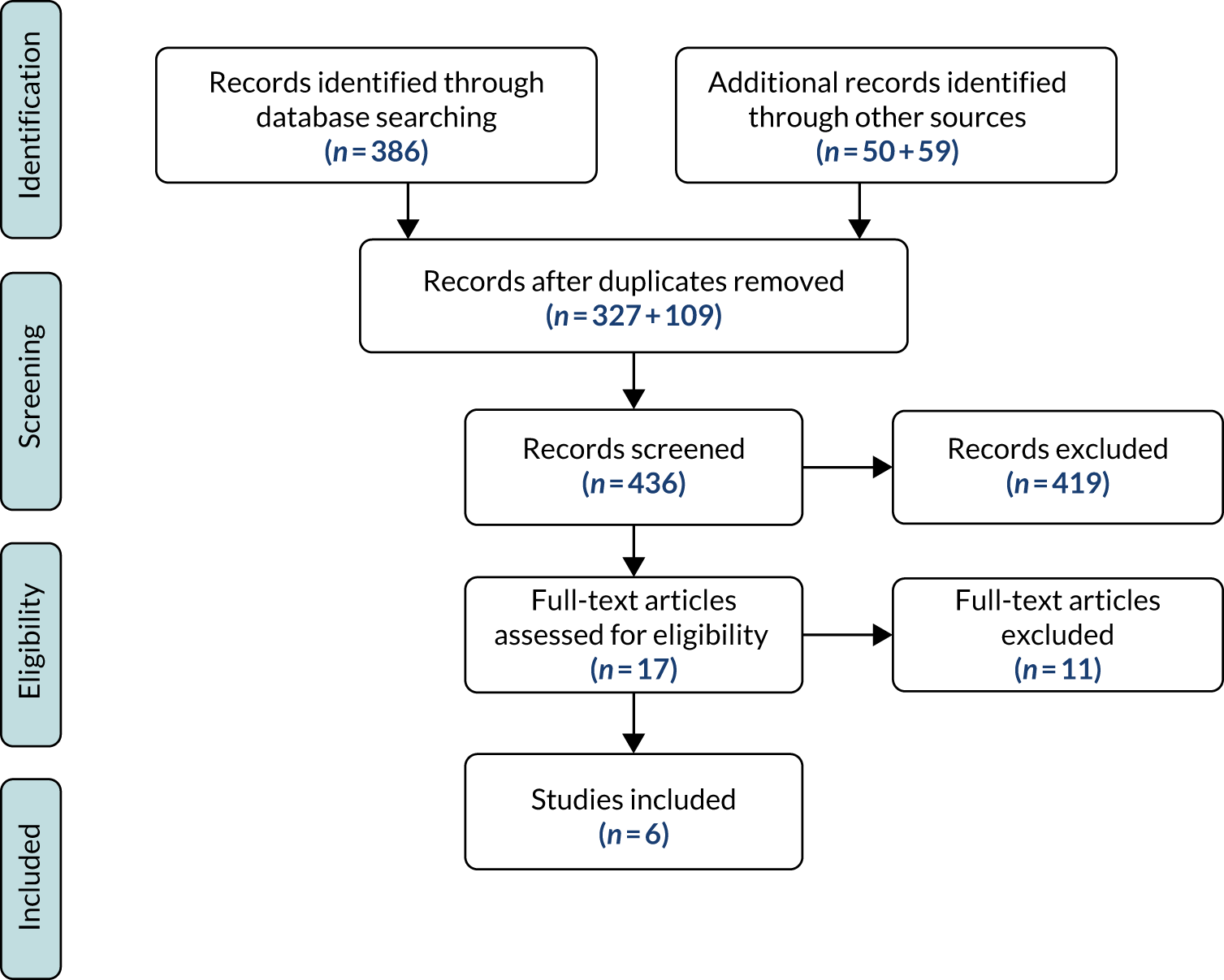

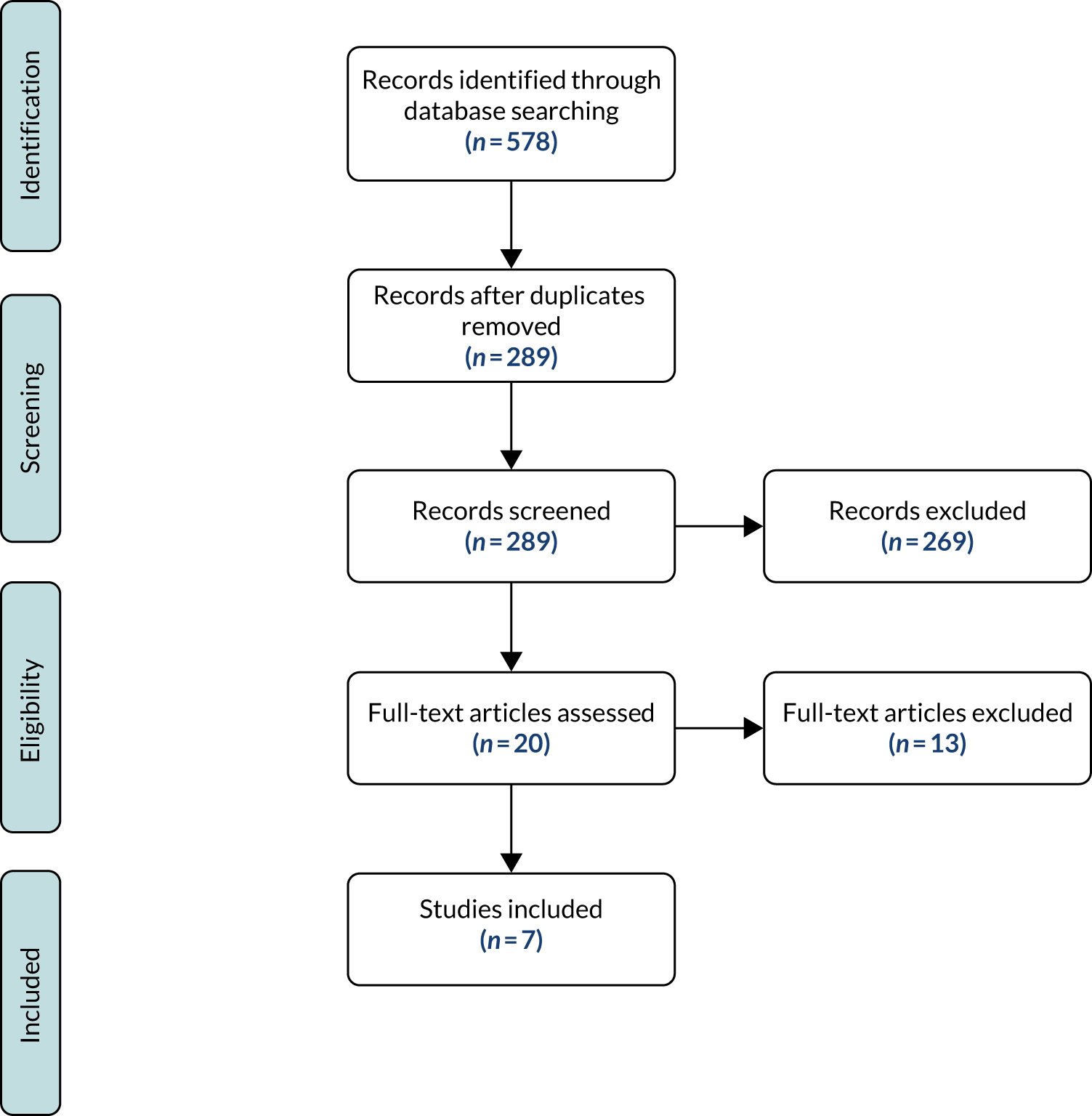

This chapter presents the findings of the systematic and grey literature searches undertaken to support the development of programme and mid-range theories. The searches identified 1302 records to be screened, of which 46 were included in the synthesis [see the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram39 in Figure 4].

FIGURE 4.

Theory development PRISMA flow diagram.

Government policies and official reports

We were aware of a number of relevant government policies and official reports at the start of the study (these are recorded as being in our personal library in Chapter 3). These were reviewed first for statements about the nature and role of interoperable networks, or patient safety or, ideally, both together. We identified additional documents via two routes: (1) references made to them in our initial reading and (2) informal means (e.g. in conversations with colleagues and in incidental ‘finds’ in the course of other searches). These additional documents were not identified in formally structured searches and were therefore added to our personal library as we came across them.

At this early stage, we included any relevant statements irrespective of the settings described, and so included statements about hospital IT systems as well as interorganisational networks. For reasons of time, we did, however, focus on documents about the NHS in England and national health-care policies in the USA. Interoperable networks have been an important element of current IT policies in England in the last 5 years and attracted considerable federal investment in the USA after 2009.

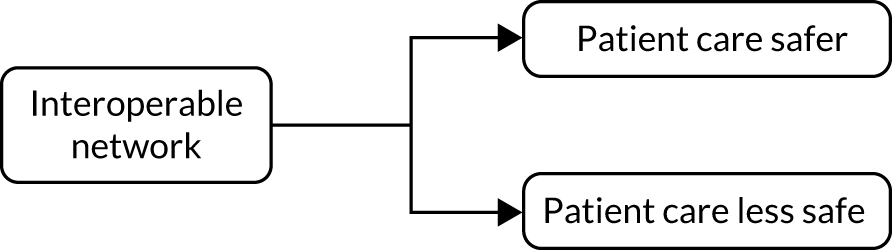

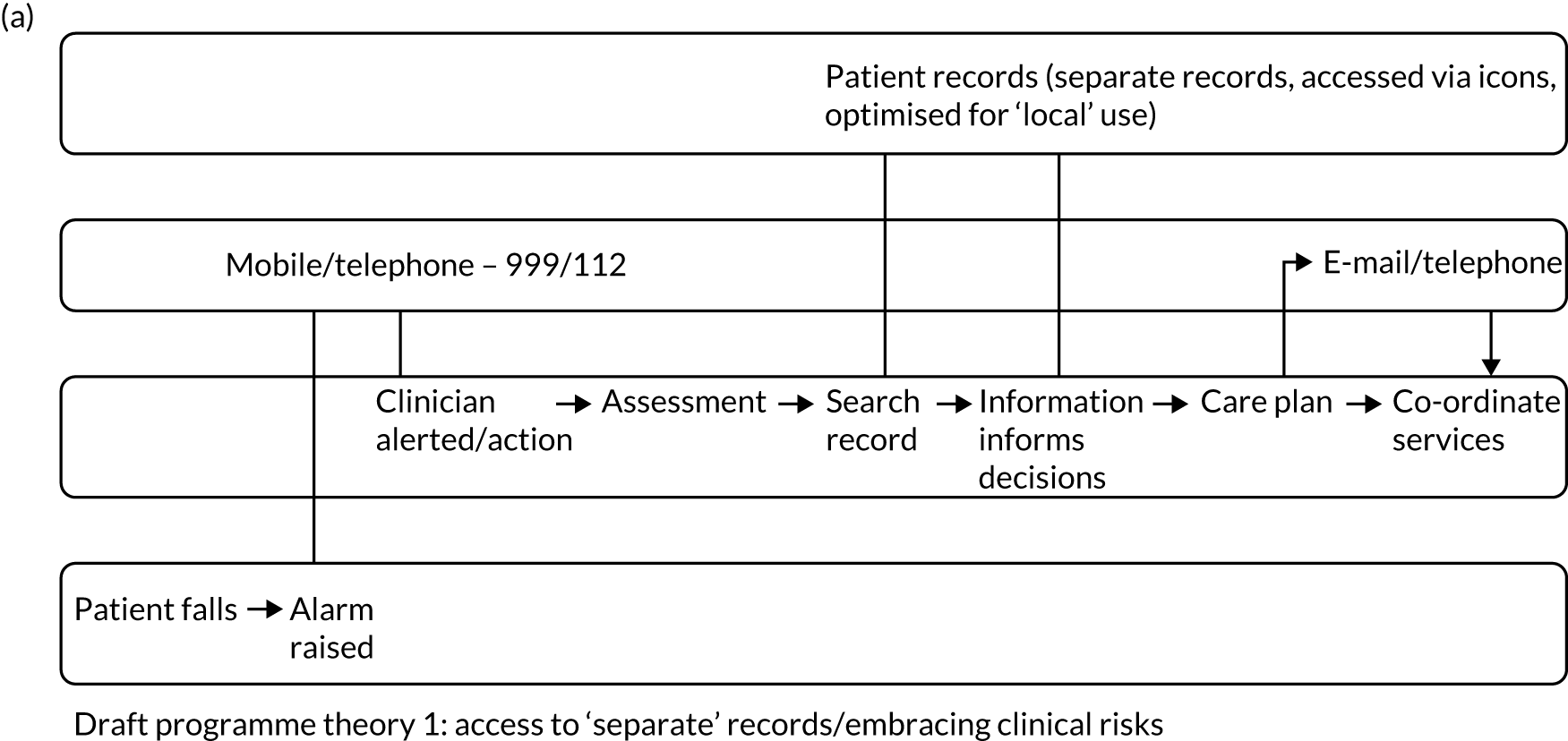

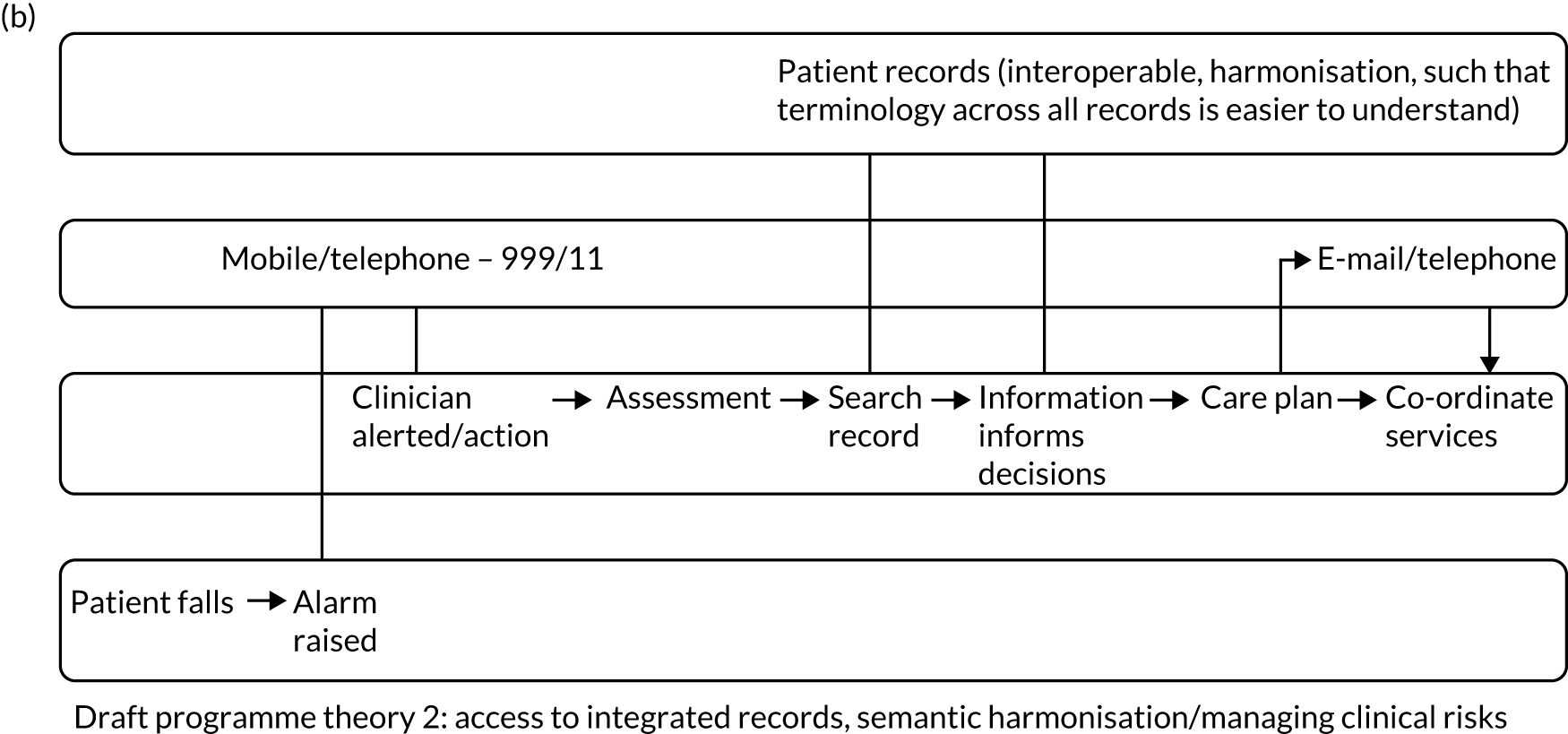

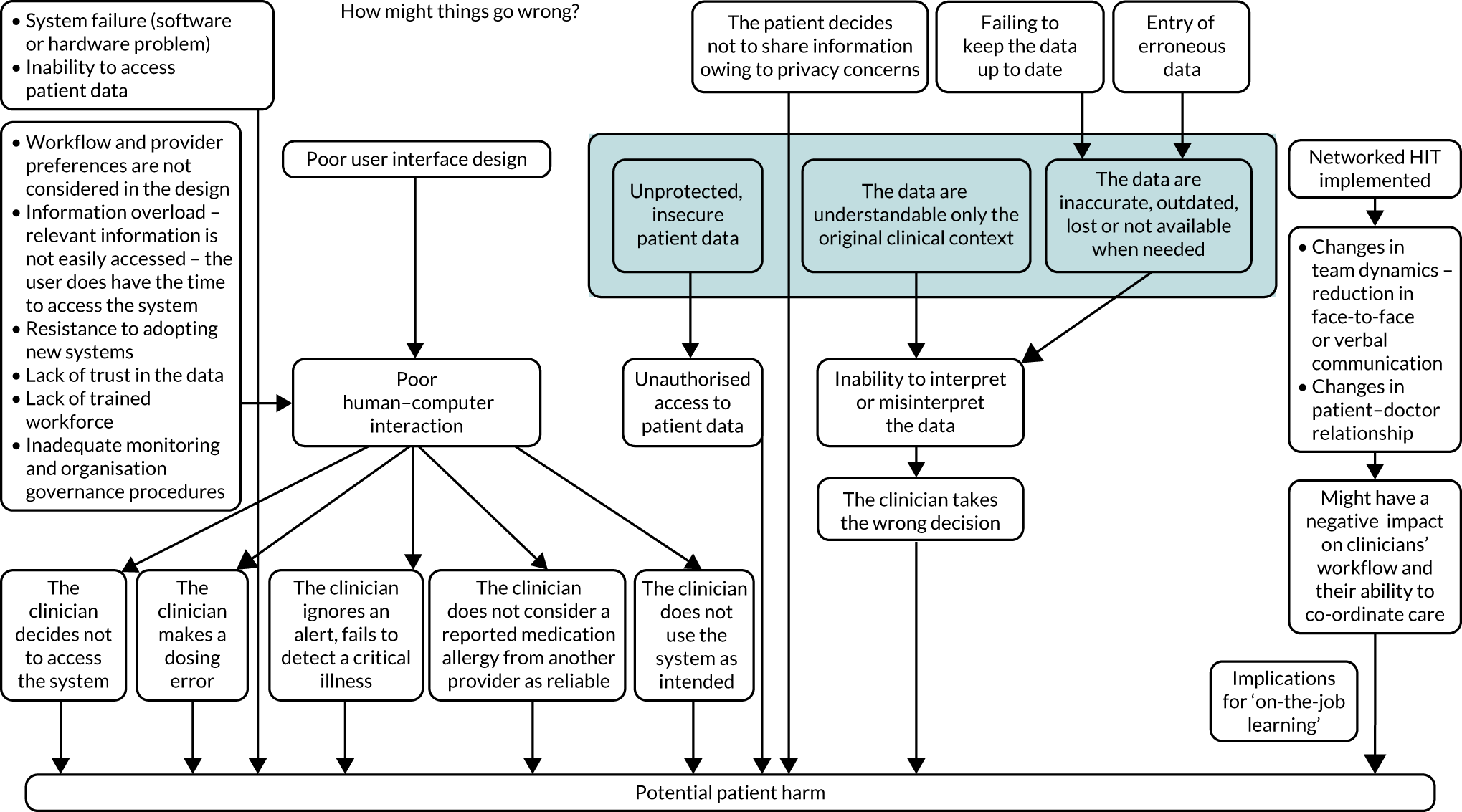

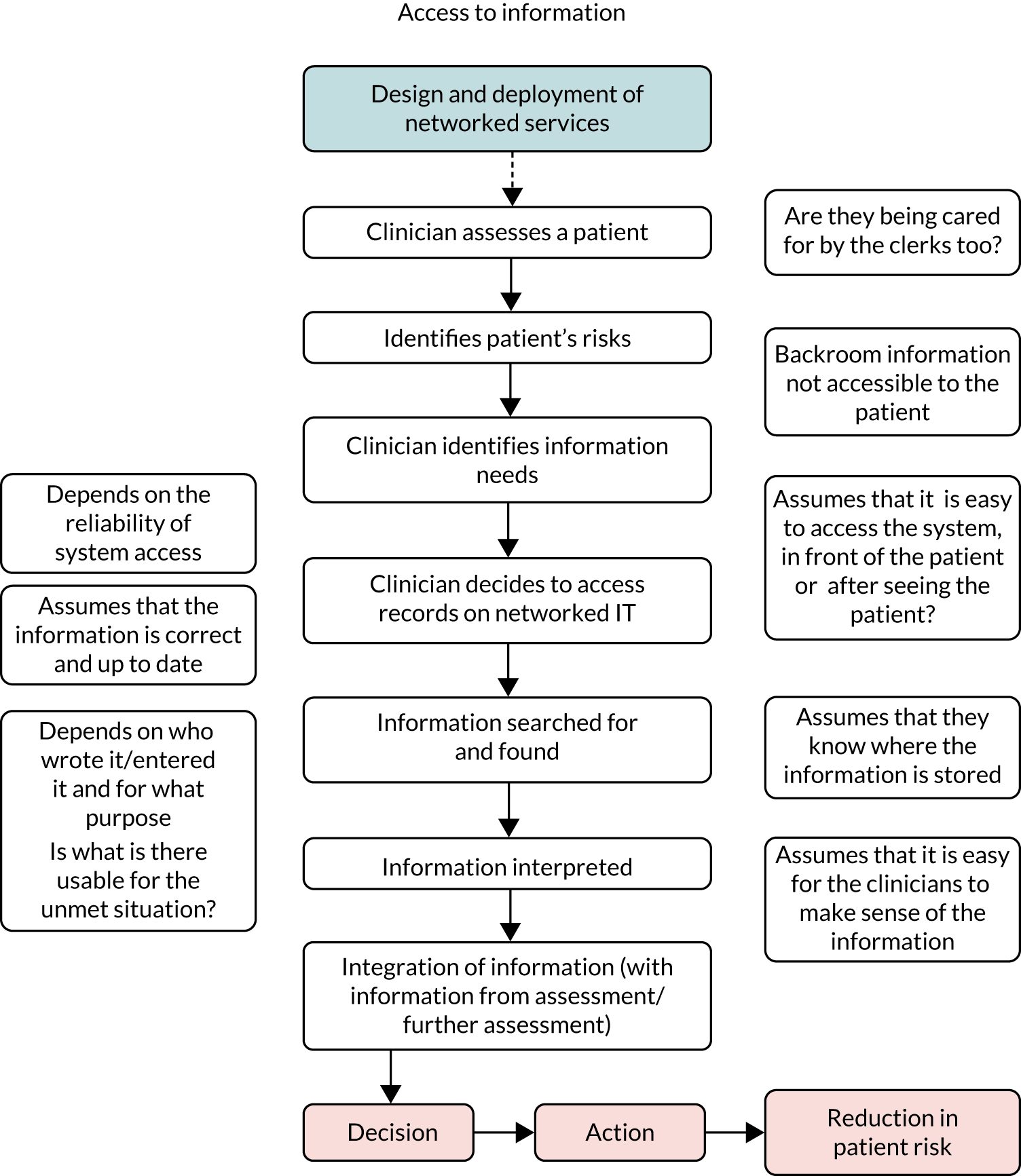

Taking US policies first, we noted in Chapter 1 that the Institute of Medicine published To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System in 2000. 1 The report focused principally on ways in which the overall design of a health-care system makes errors and adverse events more or less likely. The report took a measured view of the role of HITs in helping to improve system design and hence patient safety. On the one hand, it observed that all technologies introduce new risks and hence the possibility of harm to patients. On the other, it recognised that technologies have the potential to support better clinical processes and decision-making. It recommended that research was needed to establish where and how that potential could be realised. The report provided us with a very simple initial programme theory: the deployment of HITs might lead to safer care or might increase patients’ risks, or both (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5.

Official policy and report programme theory.

A great deal has been written about the HIT policies during the era of US President Barack Obama. We reviewed a substantial number of reports but did not find any detailed accounts of ‘how and why’ interoperable networks were expected to improve patient safety. Rather, the reports commented on ongoing problems with achieving interoperable networks. Typical of the documents we reviewed is an Institute of Medicine report14 that stated that:

Lack of interoperability is a barrier to improving clinical decisions and patient safety, as it can limit data available for clinical decision making.

The report referred to the role of human–computer interaction and its impact on clinical working practices:

The process of implementing software is critical to optimizing value and mitigating patient safety risks. A constant, ongoing commitment to safety – from acquisition to implementation and maintenance – is needed to achieve safer, more effective care.

Similarly, a 2016 report for the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology, Report of the Evidence on Health IT Safety and Interventions,40 argued that:

Interoperable health information exchange (HIE) . . . can improve . . . safety by improving the timelines and completeness of important patient health information.

Graber and colleagues, p. 11. 40

The report then went on to argue that interoperability was desirable, but that a number of hurdles still had to be overcome, including a lack of data standards and of interfaces that avoided overloading clinicians with patient data. In practice, limited progress with implementation meant that clinicians encountered problems with access to patient data held on IT systems in other organisations.

Turning to English reports and policies, the 2001 Bristol Inquiry report into the deaths of adults and children in cardiac surgical services argued that ‘The need to invest in world-class IT systems must be recognised . . .’ (recommendation 154, p. 456; © Crown copyright). 5 Similarly, the 2003 Bichard41 report into the murders of two girls in Soham recommended the implementation of a national IT system to monitor sex offenders. It was initially envisaged that the system would link police forces, but later iterations expanded the scope of the system to include a range of agencies. The NHS National Programme for IT was launched in parallel with these reports in 2002, with significant funding that eventually totalled > £10B. At the outset it was claimed that this would drive a transformation of NHS services, including improvements in patient safety. 42 None of the authors of these reports and policies elaborated on why they believed that HITs would improve safety.

The numbers of incidents and complaints remained large throughout the 2000s. The problems were highlighted most dramatically by the scandal at Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust. 43 Sir Robert Francis’ second report on the trust in 2013 made a number of recommendations about HITs, including that all provider organisations should:

. . . develop and maintain systems which give them:

effective real-time information on the performance of each of their services against patient safety and minimum quality standards

effective real-time information of the performance of each of their consultants and specialist teams in relation to mortality, morbidity, outcome and patient satisfaction.

Francis, Recommendation 262. 43

These recommendations were accepted by the government in its formal response to the report in November 2013. 44 The government also commissioned a report from the respected US clinician and analyst Donald Berwick. 45 The Berwick report also identified a potential role for HITs:

Most health care organisations at present have very little capacity to analyse, monitor, or learn from safety and quality information. This gap is costly, and should be closed.

Berwick, p. 27. 45

Again, the statements in the reports were general. They did not specify how HITs would improve patient safety, or the clinical settings in which the improvements were most likely to be achieved.

A number of HIT policies that included relevant statements were published from 2012 onwards. The Power of Information: Putting All of Us in Control of the Health and Care Information We Need was published in 2012. 3 It set out a 10-year framework for information and IT investments in the NHS in England. The report stated that current information systems were disjointed and that paper records could get lost. It gave examples of services that could be improved if professionals had access to information from other organisations:

The Accident and Emergency doctor does not always have the information needed, such as details of important allergies or information about vulnerable children at risk, to be able to treat the sick person in front of them safely. On discharge to a care home, the busy care worker has inconsistent paper medication records to interpret.

Department of Health and Social Care, p. 43 ©

The report3 also made the first explicit statement that we found about the value of interoperable networks in the NHS, particularly for people with complex care needs:

Connected information and new technology can help health care professionals to make informed decisions and provide safe patient care through faster access to test results in hospitals or by ensuring a care worker gives the right medicines to the right person in a care home.

Department of Health and Social Care. 3

The policy also argued that failing to share information had the potential to do more harm than sharing it.

NHS Digital is responsible for two clinical safety standards, which were first published in 2013. 46,47 They mark a departure from earlier English policies in echoing To Err Is Human1 and emphasising both the risks and the benefits associated with HITs:

[HITs] . . . can deliver substantial benefits to NHS patients through the timely provision of complete and correct information to those healthcare professionals that are responsible for administering care. However, it must be recognised that failure, design flaws or incorrect use of such systems has the potential to cause harm . . .

The next policy document was Personalised Health and Care 2020: Patient, Carers and Service User Vision, published in 2014. 4 It pledged an ‘information revolution’, with the aim of putting people first and providing what it called ‘transparent’ care. It observed that most hospital information systems could not be accessed by care professionals outside hospitals, including those in nursing homes and hospices. It identified the lack of interoperability as a major problem. 4 The policy also noted a number of barriers to the more effective use of HITs, including lack of consideration of the clinician’s working practices in their design.

Making IT Work: Harnessing the Power of Health Information Technology to Improve Care in England – Report of the National Advisory Group on Health Information Technology in England,30 often called the Wachter Report after the chairperson of the group, was published in 2016. 30 It made recommendations about many aspects of HITs, including education and training. One of them was that the NHS should:

. . . ensure interoperability as a core characteristic of NHS Digital ecosystem – to support clinical care and to promote innovation and research.

National Advisory Group on Health Information Technology in England. 30 ©

The report suggested that the end goal of interoperability is not solely exchanging digital data, but enabling integrated workflow, service redesign and clinical decision support. There were, further, general statements about how digital systems could improve patient care. Implicitly, at least, the statements assumed that patient information would be widely available, presumably via interoperable networks:

We cannot emphasise enough that the purpose here is not to computerise . . . The purpose is to radically improve the chances that important information will be available when and where it is needed, because no health system or clinician can perform at the top of their potential if it is not . . .

National Advisory Group on Health Information Technology in England. 30 ©

The most recent policy document is The Future of Healthcare: Our Vision For Digital, Data and Technology in Health and Care, published in 2018. 48 It picked up, and greatly expanded on, the interoperability theme in Personalised Health and Care4 and Making IT Work. 30 In a section headed ‘Infrastructure’, it states that:

The ability to share records between hospitals, GPs [general practitioners], community pharmacies and care providers is inconsistent and people are frequently discharged from hospital without sufficient or accurate information about their care needs.

Department of Health and Social Care, Section 1. 48

The policy emphasises the extent to which successful deployment of interoperable networks will require NHS organisations and suppliers to adhere to common data and technical standards, and meet users’ needs. Once again, however, there is no account of the ways in which networks will improve patient safety (or other desired outcome). As things stand, therefore, it seems reasonable to summarise the official reports and policies by saying that, (1) interoperability has become increasingly important in the last 5 years, but (2) they do not spell out in any detail how they, or HITs more generally, might improve patient safety. Figure 5 therefore represents current thinking, as represented in the documents discussed in this section.

Structured subject searches

We tested a number of search terms, and combinations of terms, and found that two terms that described our technology of interest produced distinct and useful results. These terms were HIE and ‘interoperability’, which we discuss in turn.

We came to understand, through these searches, that the term HIE is used in two ways in the literature. The first of these is general in nature, particularly in the USA, where it is used as a shorthand for the major Obama-era IT investment programme. One reason to use HIE as a search term was, indeed, to identify articles discussing that programme. The second is more technical, and refers to the ability to move data between any two or more IT systems. HIE’s are therefore necessary for interoperability, which we discussed in Chapter 1, which refers both to technology and to the use of data. Put another way, interoperability is a broader term than HIE.

Health information exchange structured subject search

We did not find any articles that set out a detailed programme theory. We therefore sought to identify theory fragments and identified three types of fragment in 13 articles49–61 (Table 1). The first type concerned the value of HIE, one centred on access to remotely held patient data. HIE could provide health-care professionals with a more comprehensive view of a patient’s information and thereby avoid or decrease medication-related errors. In the second type, HIEs could be used to facilitate communication between professionals. This might avoid delays in clinical decisions or facilitate improved co-ordination of care.

| Study | Topic | Theory fragment(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Alvarez49 | Canada Health Infoway, part of a pan-Canadian interoperable EHR solution | Discussion article. Argued that co-ordinated national EHR initiative would cost less, save lives and prevent reduce harm. It then described Infoway, a Canadian initiative intended to improve electronic access to accurate and timely health information, which would improve safety, quality, accessibility, cost-efficiency and the sustainability of the health-care system. Patient safety was described as a cornerstone of Infoway’s activities |

| Bowden and Coiera50 | Impact of accessing primary care records during unscheduled care | Review article. It concluded that:no study reported on clinical outcomes or patient safety, and no economic studies of shared electronic record access during unscheduled care were available. Design factors that may affect utilization included consent and access models, shared electronic record content, and system usability and reliability50 |

| Cotter51 | Benefits of HIT | Opinion article. Argued that the creation and implementation of a comprehensive clinical information system would entail many difficulties, particularly in regard to patients’ privacy and control of their information, standardisation of EHRs, cost of adopting IT, unbalanced financial incentives and the varying levels of preparation across providers of care. There will also be potential effects on the physician–patient relationship |

| Fontaine et al.52 | Survey of primary care practices regarding plans and motivation to invest in HIE | Primary research article. This was an original article describing the use of HIE in primary care practices in Minnesota, USA. Internal ‘motivators’ to use were anticipated cost savings, quality, patient safety and efficiency. The most frequently cited barriers were lack of interoperability, cost, lack of buy-in for a shared HIE vision, security and privacy, and limited technical infrastructure and support |

| Foley53 | Confidentiality and shared clinical records | Letter. Author expressed concerns about the risks to confidentiality associated with shared patient records |

| Goroll et al.54 | Experiences of Massachusetts eHealth Collaborative | Case report. The authors reported that, despite initial enthusiasm, progress with implementation was impeded by a range of challenges, including lack of technical standards, costs of converting paper to electronic records, and concerns about privacy and confidentiality |

| Gottlieb et al.55 | Policy and regulatory barriers to successful clinical data exchange project in Massachusetts, USA | In this article, the authors described a number of barriers and lessons learned from piloting the use of data exchange project in emergency departments in Massachusetts, USA. This included privacy concerns, accessibility, data quality and technical issues with the software, which led to challenges in use and uptake of the project by the clinicians |

| Hawking56 | Medicolegal issues with shared electronic records | Letter. GP voiced concerns about the use of shared EHRs in primary care, including problems with functionality and governance. He had particular concerns about data entry errors and responsibility for updating medication information in a shared record environment |

| Hillblom et al.57 | Impact of HIE on pharmacy practices | Opinion article. Argued that HIEs will knit together unrelated information sources to provide health-care professionals with a more comprehensive view of a patient’s medical information |

| Hopf et al.58 | Health-care professionals’ views on linking patient data | Systematic review. Facilitators of use of a network included having trust in the system, including in its reliability. Barriers included costs and information governance and technical issues. Possible effects on the physician–patient relationship and on workload were also identified as barriers. Health-care professionals supported the idea that an integrated system would improve patient safety |

| Ishikawa et al.59 | Proposals for an integrated, networked EHR | Primary research article: survey. The authors argued that a system should be designed to share information among all professionals, which would promote team practices and, in turn, improve patient safety. System security and reliability were acknowledged to be risks |

| Traynor60 | Commentary on Institute of Medicine report1 | Opinion article. The author noted a lack of robust evidence that HITs can improve patient safety. There is also limited evidence about the harms resulting from HITs |

| Zimlichman and Bates61 | National priorities in the patient safety agenda in the USA and Canada | Opinion article. Argued that harnessing HIT to promote patient safety was ‘pivotal’ because it extended to all providers |

For the third type, some articles commented on the potential risks arising from poor data quality and consequent risks to accurate diagnosis and treatment. Authors mentioned system reliability and poor user interface design, and the implications of these for patient safety. Privacy and confidentiality were also mentioned; Foley,53 for example, argued that:

Workers in hospitals or general practice surgeries might seek inappropriate access to medical records because of curiosity or malice, commercial gain, or simple errors.

Foley53

Interoperability structured subject search

We also used interoperability (replacing HIE) as a key search term. Seven articles were included, and these are described in this section.

Most of the theory fragments were general in nature. The most commonly cited theory fragment concerned access to additional patient data via an interoperable network. A report commissioned by the European Union argued that access to patient records would lead to more accurate diagnosis and better-quality treatment and care delivery, as well as potential for improved patient safety through:

-

improved knowledge of the patient’s health, social status, family and personal history

-

improved care co-ordination between health-care professionals

-

more and higher-quality communication between health-care professionals and patients

-