Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 15/70/26. The contractual start date was in September 2017. The final report began editorial review in December 2019 and was accepted for publication in June 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2021 Lister et al. This work was produced by Lister et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2021 Lister et al.

Chapter 1 Background

Severe mental illness

Definition of severe mental illness

Severe mental illness (SMI) describes a group of mental disorders that are persistent, cause serious functional impairment and substantially interfere with, or limit, major life activities. A key feature of SMI is the presence of psychosis, which is a loss of contact with external reality. Both the American Psychiatric Association1 and the World Health Organization2 (WHO) definitions of psychosis require the presence of hallucinations (i.e. perceptions occurring in the absence of corresponding external or somatic stimuli) and/or delusions (i.e. fixed false beliefs). These symptoms may be accompanied by cognitive impairment, disordered thinking and problems with motivation, energy and mood.

Although there is some debate about which conditions come under the SMI umbrella, there is consensus that the term includes schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and depression with psychotic symptoms. 3–5 Schizophrenia is characterised by diverse psychopathology including delusions, hallucinations and ‘negative symptoms’, such as impaired motivation, reduction in interest, limited spontaneous speech, social withdrawal and cognitive impairment. Psychotic symptoms tend to relapse and remit, although around 20% of people with schizophrenia may experience chronic unremitting residual symptoms. 6 Negative symptoms tend to be persistent and are associated with long-term effects on social functioning.

By contrast, bipolar disorder typically has an ‘episodic’ course, with recovery between relapses. It causes extreme mood swings ranging from mania or intense happiness, grandiosity, euphoria or irritability or decreased need for sleep, to low mood and depressive symptoms. Typically, a person with bipolar disorder cycles from one extreme to the other, while experiencing periods with few or no symptoms in between. Major depression is similarly a relapsing–remitting disorder, but it can have a chronic presentation. It is characterised by a persistent feeling of sadness or lack of interest in outside stimuli. When accompanied by psychotic symptoms, it is categorised as SMI.

Severe mental illness includes several other conditions, such as schizoaffective disorder and persistent delusional disorder, with symptoms that overlap with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder or severe depression. Apart from the presence of psychosis, these illnesses typically have a severe and enduring impact over the life course, affecting education, employment, relationships and wealth. 7–9

Global burden of disease due to severe mental illness

Although lifetime prevalence of SMI is < 5% (consistent across the world), these conditions contribute a large and increasing global burden of illness. The global age-standardised point prevalence of schizophrenia is estimated to be 0.28% [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.24% to 0.31%], but it contributes 13.4 (95% CI 9.9 to 16.7) million years lived with disability (YLD), equivalent to 1.7% of total YLD. 10 Similarly, the age-standardised prevalence rate of bipolar disorder is estimated to be 0.7% (95% CI 0.6% to 0.8%), contributing 1.3% of total YLD. 11

Treatment of severe mental illness

Treatment of SMI includes a combination of psychotropic medication, psychological therapies and psychosocial support.

In recognition of the high risk of comorbid physical conditions and the socioeconomic impacts of SMI, treatment guidelines also include provision of annual general practitioner (GP) health checks to monitor physical health; smoking cessation support; and supported employment, exercise and diet programmes. 12,13

The majority of people with SMI are likely to be prescribed antipsychotics, either typical (sometimes called ‘first generation’, developed in the 1950s) or atypical (sometimes called ‘second generation’, developed in the 1990s). 14 Although all antipsychotics have been associated with side effects such as drowsiness, tremors, muscle spasms and weight gain, atypical antipsychotics are thought to have fewer extrapyramidal (motor control) side effects, but some may be associated with greater metabolic side effects and weight gain. 14

Comorbid physical conditions and excess mortality and morbidity in severe mental illness

Burden-of-disease estimates do not account for the premature mortality and morbidity due to physical illnesses in SMI. People with SMI die, on average, 15–20 years earlier,15 with a death rate 3.7 times higher16 than the general population. Recent evidence indicates that this ‘mortality gap’ is widening for people with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. 17,18 Suicide accounts for around 15% of the increased mortality, but the majority of premature deaths are due to physical disorders, including non-communicable diseases, such as diabetes. Rates of such disorders are increased in people with SMI, typically being two to three times higher. 4,19,20 It is estimated that as many as two out of three premature deaths among people with SMI are due to preventable physical illnesses. 15

Most of the risk factors for developing conditions such as diabetes are likely to be the same in people with SMI and the general population, but there are multiple additional reasons that could explain the high prevalence seen in SMI populations and the excess mortality from physical disorders. Mental and physical disorders have a complex bidirectional relationship, sharing individual and socioenvironmental risk factors (e.g. childhood adversity and social and economic disadvantage). 21,22 Medications for mental illness are often associated with adverse metabolic side effects, increasing the risk of cardiometabolic disorders. Sedentary behaviour is common because of the motivational deficits associated with these disorders, or the side effects of treatment such as tiredness and sedation. Additional health risk behaviours such as smoking, alcohol use and unhealthy diets are also elevated. Problems with cognition, energy and motivation also pose challenges for accessing and adhering to medical treatment for physical conditions. Moreover, people with SMI may be less likely to receive adequate treatment because of ‘diagnostic overshadowing’, whereby health-care services attribute reported physical symptoms to mental illness, and, consequently, fail to fully investigate and treat these symptoms. 23

Comorbid physical disorders such as diabetes can therefore both drive, and be a consequence of, the significant health and socioeconomic inequalities faced by people with SMI. A better understanding of the determinants, and improved prevention and treatment of physical illness, could help to tackle the inequalities for this group.

Diabetes mellitus

Diabetes mellitus is a complex metabolic disorder characterised by chronic hyperglycaemia as a result of relative insulin deficiency, resistance or both. In 2019, the International Diabetes Federation estimated that 463 million people (1 in 11 of the global population) had diabetes and estimated an increase to 700 million by 2045. Approximately 4 million people in the UK are currently living with diabetes. 24

Diabetes is associated with several short- and long-term complications that cause considerable morbidity, reduced quality of life and shortened life expectancy. These include acute metabolic perturbations (hypoglycaemia, diabetic ketoacidosis and hyperosmolar hyperglycaemic state), macrovascular disease (coronary artery disease, peripheral vascular disease and stroke) and microvascular disease (retinopathy, nephropathy and neuropathy). Diabetes was responsible for approximately 4.2 million deaths worldwide, or 11.3% of all deaths, in 2017, outnumbering the combined number of global deaths from human immunodeficiency virus/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome, tuberculosis and malaria. 24

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), which results from a combination of insulin resistance and less severe insulin deficiency, is the commonest form of diabetes, accounting for 90–95% of all cases. The rapid rise in T2DM largely explains the global epidemic, which is driven by an ageing population, longer survival with T2DM, earlier age at onset and better diagnosis. The prevalence of T2DM has increased as rates of obesity have risen.

Several risk factors have been identified for T2DM. The major modifiable risk factors are poor-quality diet and reduced physical activity. Smoking, mental illness (and psychotropic medication) and decreased sleep have also been implicated. Environmental risk factors include urbanisation, poverty and toxins. Non-modifiable risks include family history, ethnicity, birthweight and fetal under- and over nutrition, and history of gestational diabetes. 25

It is estimated that, worldwide, approximately half of people with diabetes are unaware of their condition; however, this is lower in high-income countries, in part because of the introduction of screening programmes to systematically identify those with undiagnosed diabetes.

Once diabetes is considered, it is relatively easy to diagnose by the laboratory measurement of fasting plasma glucose (≥ 7.0 mmol/l), random glucose (> 11.0 mmol/l) or a 2-hour plasma glucose after a 75-g oral glucose tolerance test (> 11.0 mmol/l). The use of glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) (≥ 48 mmol/mol) was introduced by the WHO as an alternative method in 2011.

Prevention of diabetes

Clinical trials have shown that it is possible to prevent or delay the development of T2DM through lifestyle and/or pharmacological interventions. 26–30 Lifestyle interventions aim to reduce body weight and dietary fat intake, in particular saturated fat, while increasing dietary fibre and moderate physical activity, to ≈ 30 minutes a day. The UK has recently launched a National Diabetes Prevention Programme to support at-risk individuals to implement these lifestyle changes through referral to a behaviour change programme. 31

Management of diabetes

For most people, diabetes is a lifelong condition. People will manage diabetes themselves (self-management) for most of the time, with only a few hours per year spent in contact with health-care professionals. Consequently, people must develop the skills to manage their condition effectively. Structured self-management education programmes have been developed and are recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) as an integral component of diabetes management. 32,33

Diabetes is managed through a combination of lifestyle changes and, when needed, treatment with antidiabetes drugs or insulin. The latest guidance highlights the importance of certain foods and dietary patterns. 32 In common with the general population, people with diabetes should be encouraged to eat a healthy diet. For individuals who are overweight, losing weight is important; loss of 10–15 kg of body weight may trigger remission. 32,34 Increased physical activity has profound benefits, including improved fitness, reduced insulin requirement, better glycaemic control, lower cardiovascular risk and greater life expectancy.

Diabetes in people with severe mental illness

The prevalence of diabetes is two to three times higher in people with SMI, and around 10% of people taking antipsychotic medications live with diabetes. 35,36 A meta-analysis of 41 studies comprising 161,886 participants reported 9.0% (95% CI 7.3% to 11.1%) diabetes prevalence in SMI. 36 In people with multiple episodes of psychosis, the prevalence of diabetes was double that of the general population, with earlier age at onset. 37 The incidence rates of diabetes in SMI, however, are usually < 1%, meaning that the absolute risk for any one individual is small. 38,39 Although diabetes is rare in adolescents and young adults, the relative risk of diabetes in young people exposed to antipsychotic drugs appears to be increased, compared with healthy controls and people with psychiatric disorders but unexposed to antipsychotic drugs. 40 These increased risks are for T2DM; there is no evidence that the incidence of type 1 diabetes is increased in people with SMI. 41

There are multiple potential reasons for the higher incidence of T2DM in people with SMI, including living conditions, lifestyle and disease-specific factors, as well as the effect of antipsychotic medications on insulin secretion and action. 42–47 People with SMI tend to have a dietary pattern that includes increased intake of energy-dense foods that are rich in fat and refined sugars, with low levels of fruit and vegetable intake, and tend to have low levels of physical activity. 42,43 Smoking and social deprivation are also important risk factors for diabetes, and the risks of both are higher in people with SMI.

In the early 2000s, as the use of atypical antipsychotics rose, reports of substantial weight gain, diabetes and dyslipidaemia began to emerge. 48,49 It has now become apparent that rates of diabetes are higher among people taking typical or atypical antipsychotics than among the general population. Among people with SMI who have not yet started antipsychotic treatment, the prevalence of diabetes is low, but it rises rapidly after treatment initiation, suggesting that antipsychotics are involved in the aetiology of T2DM, with women and those with multiple episodes of psychosis being at higher risk. 44

Studies, including randomised controlled trials comparing different antipsychotics, indicate that the risk of developing diabetes differs between medications. 35,44,49–51 A consistently higher risk of diabetes is reported in people taking clozapine or olanzapine, with the lowest risks associated with aripiprazole, although all antipsychotics have been associated with increased risk of diabetes. 44 Clinical trial data are supported by real-world comparisons between atypical antipsychotics. 45,46 Diabetes risk also increases with the number and dose of antipsychotics prescribed. 47 Potential mechanisms mediating this increased risk include weight gain, which increases insulin resistance, and the direct effects of antipsychotics, which decrease insulin sensitivity of cells and also impair insulin secretory capacity. There is debate about the magnitude of increased diabetes risk, with estimates varying widely up to a 33-fold increase; typically, however, the relative risks are < 2. 52

Prevention of diabetes in people with severe mental illness

No diabetes prevention studies have been undertaken in people taking antipsychotics, but lifestyle interventions have been used to prevent weight gain or manage obesity. Short-term studies with follow-ups of < 6 months report weight loss of around 3.1 kg over a period of 8–24 weeks,53 but the results of longer-term studies are less consistent. 54 Similarly, there have been no studies of pharmacological interventions, but the use of metformin leads to a modest 3.3-kg reduction in body weight over 3–6 months, in association with improved insulin sensitivity. 53,55

Screening and diagnosis of diabetes in people with severe mental illness

Although regular screening for diabetes is recommended for people with SMI,56–58 many people taking antipsychotics are not screened regularly; further work is needed to understand why this simple measure has not been embedded into routine clinical practice. 59,60 In 2011, targets for monitoring blood glucose were included in the national Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF) to incentivise general practices to screen patients with SMI for diabetes. However, these targets were removed in 2014. 61

Management of diabetes in people with severe mental illness

Diabetes appears to have a greater impact on people with SMI than on the general population through an increased incidence of acute metabolic emergencies and diabetes complications. 62,63 Current NICE guidance12 suggests that diabetes in people with SMI should be managed in a similar way to diabetes in the general population. 64 However, the guidelines do not take into account the implications of antipsychotic use or the unique challenges people with SMI may face in managing their diabetes.

Additional challenges faced by people with severe mental illness

Although the principles of diabetes management are the same as for the rest of the population, people with SMI face additional challenges in achieving optimal diabetes outcomes. These include, but are not limited to:

-

health-care systems that separate diabetes and mental health

-

overshadowing when physical health problems are considered to be caused by the mental illness

-

excessive weight gain caused by antipsychotics and effects on insulin secretion

-

psychotic symptoms

-

poor cognition that interferes with decisions about self-management

-

lack of social support.

Given the burden of illness, and health and health-care inequalities for this population, improving diabetes care for people with SMI is a high priority for the NHS. 65 Little is known, however, about how SMI and other risk factors and challenges combine to generate high diabetes prevalence and poor diabetes outcomes, and how the quality and quantity of health-care services and interventions can influence these risk factors and outcomes in people with SMI.

Understanding this is a first step in developing health-care interventions to improve outcomes for people with diabetes and SMI. Better prevention and management of diabetes have the potential to significantly reduce the risk of diabetes complications, deliver large cost savings to the NHS and help reduce health inequalities (including life expectancy and morbidity) experienced by people with SMI.

In this report, we have focused on T2DM, as it is the most common type of diabetes in people with SMI. When the term ‘diabetes’ is used without specifying type, this refers to T2DM.

Social inequalities

Socioeconomic factors are powerful determinants of health outcomes, and a theoretical framework based on socioeconomic conditions is, therefore, appropriate for this study, in which social inequalities are likely to play a key role. 66,67 Under this framework, health gaps in morbidity and mortality arise for people living in disadvantaged circumstances, from reduced access to the material, financial, social or structural resources that the advantaged population leverage to maintain or improve health. People with SMI are more likely to be socially disadvantaged than people without SMI. 20,68–73 For example, only 6% of people with SMI in England and Wales are employed, whereas 58% are on long-term sick leave or are disabled and receiving benefits. 73

There are three related explanations for this. First, there is evidence that social disparities, including racism and the multifactorial stresses of urban living, are among the causative factors for incident SMI. 74–77 Second, the presence of severe and enduring illness patterns, and the physical and social consequences of these, thwarts efforts to maximise and improve social conditions. For example, SMI is diagnosed most often in early adulthood, and prodromal symptoms that interfere with functioning can be present months or years prior to onset. 78 This may disrupt secondary education and limit educational progression, thus constraining the greater economic opportunities afforded by further and higher education. Third, if poor social conditions are experienced, these are likely to compound over time, for example due to individuals not having the resources to invest in social contact, high rates of housing precarity that places individuals into increasingly deprived neighbourhoods, and further restriction in income due to potential discrimination against mental illness in the benefits system. 79–81 Deprived neighbourhoods are more likely to have environments that are obesogenic, where access to safe physical activity is limited and accessibility of poor-quality, calorie-dense foods is greater, increasing the risk of poor health. 82,83 Stigma and discrimination, represented through labelling, stereotyping, separating, emotional reactions and status loss, and enacted through behaviours, in public attitudes towards people with SMI, internally held beliefs about how one is viewed by others, and structural barriers can thwart efforts to obtain health care and prevent illness, and can perpetuate social disadvantage. 84–87

Given these details, it is not surprising that there is evidence that social inequalities play a role in driving poor mental and physical health outcomes for people with SMI. 88–92 A complicating, and further disadvantaging, factor is an increased risk of developing diabetes, which is itself socially patterned. 93 These greater health-care needs, combined with socioeconomic disadvantage, create a vulnerability that demands increased levels of care while simultaneously decreasing the likelihood of successful navigation of the health-care system. 94 Social disadvantage also reduces one’s capacity to take advantage of health promotion opportunities, and creates more barriers to taking up interventions designed to prevent or treat illness. Further details about how we applied this framework are presented in Chapter 3, Theoretical framework.

Overview of routine health-care databases

This section describes the routine health-care databases used in this study; specific information about how they were used is provided in Chapter 5.

Clinical Practice Research Datalink

The Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD) GOLD is the world’s largest computerised database of anonymised longitudinal medical records from primary care. The CPRD data set (originally the General Practice Research Database) was established in 1987. CPRD data include records of clinical events (medical diagnoses), referrals to specialists and secondary care settings, prescriptions issued in primary care, records of immunisations/vaccinations, diagnostic testing, lifestyle information (such as smoking and alcohol status), and all other types of care provided as part of routine general practice. Data have been collected on > 17 million patients from a network of 718 general practices throughout the UK, representing around 8% of the UK population registered with a GP. 95 A cross-sectional study of the regional distribution of clinical computer systems in primary care found that 9% (636/7526) of general practices in England used Vision® (In Practice Systems Ltd, London, UK) software, from which the CPRD primarily draws its data. 95

Clinical information is captured in the CPRD database using ‘Read codes’, which are recorded by primary care practice staff as part of routine data entry. Read codes96 are a comprehensive hierarchical coding system of clinical terms used in primary care to classify diseases, history and symptoms, patient characteristics, procedures and tests. 97 The purpose of this coding system is to provide a standard language to enable accurate recording of patient information and more efficient retrieval of information for clinical or research purposes. 97

The CPRD data set benefits from being a large, retrospective and prospective longitudinal primary care record. Patient characteristics in the database are broadly representative of the general UK population in terms of age, sex and ethnicity. 98 Although other clinical computer reporting systems are used more commonly across the UK than the Vision system, patterns of area deprivation (based on the locations of general practices) have not been found to differ between these different systems. 95 Practices using the Vision software system are, however, geographically concentrated in the south and north-west of England – particularly around London and Manchester – with relatively few practices based in Yorkshire and the Humber, and the north-east. 95,98

Individual patient data in the CPRD can be linked electronically to external data sources, including Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) data for hospital admissions, Office for National Statistics (ONS) data for dates and causes of death, and the Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) to assess area deprivation in the locality. The CPRD provides a single extract of linked HES/ONS/IMD anonymised data.

Hospital Episode Statistics

The HES database contains patient records for inpatient admissions, outpatient appointments and accident and emergency (A&E) attendances at NHS hospitals in England. 99 Admissions recorded in HES include those for physical and mental health problems where the patient was admitted to an acute hospital (but admissions recorded do not include specialist mental health facility admissions). HES Admitted Patient Care data contain information on patients’ demographics, admission sources and methods, discharge methods and destination, and primary and secondary diagnoses, as well as procedures conducted during the stay.

Diagnoses from hospital admissions are classified using the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10), codes. Procedures are classified using the Office of Population Censuses and Surveys Classification of Interventions and Procedures version 4 (OPCS-4) codes.

Office for National Statistics mortality data

The ONS mortality data include information from a person’s death certificate, such as cause of death, and date and place of death, for all registered deaths in England and Wales. 100 These data are the most complete source of information on deaths based on information from medical practitioners and/or coroners.

Index of Multiple Deprivation data

The English IMDs provide a relative measure of deprivation at the lower-layer super output area (LSOA) level. There are around 35,000 LSOAs in England, each containing an average of 672 households. 101 The IMD rank used for the linkage is from 2010, and is a combined index of seven domains: income, employment, health and disability, education, crime, barriers to housing and services, and living environment deprivation. 102

Chapter 2 Study aims and objectives

The overall aim of this study was to understand the determinants of diabetes and the variations in diabetes outcomes and care for people with SMI. We also aim to identify health-care interventions that are associated with better outcomes, which can be tested further. The study feeds into a wider research programme to improve diabetes outcomes for people with SMI.

Research questions

Our key research questions were as follows:

-

What are the sociodemographic and illness-related risk factors associated with –

-

diabetes developing in people with SMI?

-

variations in diabetes and mental health outcomes in people with SMI and diabetes?

-

-

How do physical and mental health outcomes differ between people with SMI and diabetes and people with –

-

SMI without diabetes?

-

diabetes but no SMI?

-

-

What factors are associated with access to and receipt of diabetes health care for people with SMI, and how are diabetes health-care interventions experienced by people with SMI?

-

How, and at what cost, is diabetes monitored and managed in people with SMI, compared with people without SMI?

-

What health-care interventions (e.g. medication, referrals and care pathways) are associated with better diabetes outcomes for people with SMI and diabetes?

These questions are addressed in two studies, with seven objectives (see Study objectives). The quantitative study (see Chapter 5) addresses objectives 1–4, 6 and 7; the qualitative study addresses objective 5 and also contributes to objectives 2 and 7 (see Chapter 6).

Study objectives

-

In people with SMI: to identify which sociodemographic, illness, family history and lifestyle factors are associated with the development of diabetes (see Chapter 5, Objective 1: factors associated with the development of diabetes in people with severe mental illness).

-

In people with SMI and diabetes: to identify which sociodemographic, illness, family history and lifestyle factors are associated with variations in diabetes and mental health outcomes (see Chapter 5, Objective 2: factors associated with variation in diabetes and mental health outcomes in people with severe mental illness and diabetes).

-

In people with SMI: to compare the health-care interventions and physical and mental health outcomes of people with diabetes with those of people without diabetes (see Chapter 5, Objective 3: comparing health-care interventions and health outcomes in people with severe mental illness with diabetes with those in people with severe mental illness without diabetes).

-

In people with diabetes: to compare the health-care interventions and physical and mental health outcomes of people with SMI with those of people without SMI (see Chapter 5, Objective 4: comparing the health outcomes of people with diabetes and severe mental illness with the health outcomes of people with diabetes without severe mental illness).

-

To understand the factors that are associated with access to, and receipt of, diabetes care for people with SMI, and to explore the experience of diabetes health care by people with SMI (see Chapter 6).

-

To compare diabetes care provision for people with and people without SMI, and to estimate costs for these (see Chapter 5, Objective 6: comparing diabetes care provision and estimating health-care costs for people with and people without severe mental illness).

-

To identify which health-care interventions (e.g. medication, referrals and care pathways) may be associated with better diabetes outcomes for people with SMI and diabetes (see Chapter 5, Objective 7: identifying health-care interventions associated with better outcomes for people with diabetes and severe mental illness).

Deviations from the study protocol

The protocols for the overall study and for the quantitative study (study reference: 17_161R) have been published and are publicly available. 103,104

There were some changes to the study protocol for the quantitative analyses.

First, we planned to stratify all analyses by ethnicity. However, the small numbers in minority ethnic categories precluded doing this for some analyses.

Second, for objective 2 (see Chapter 5, Objective 2: factors associated with variation in diabetes and mental health outcomes in people with severe mental illness and diabetes), the methods were changed from repeated measures to patient-level analysis, as the former did not add value.

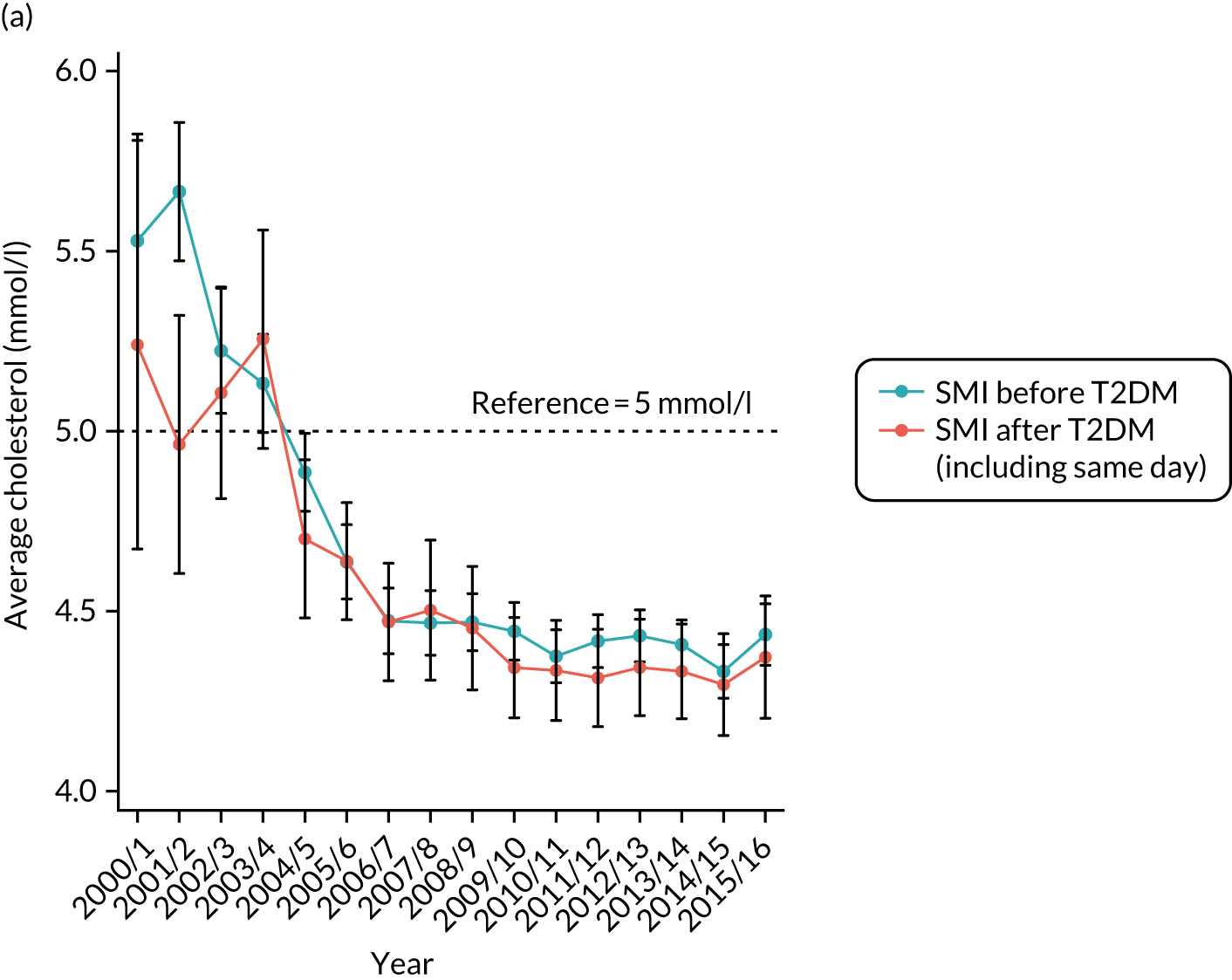

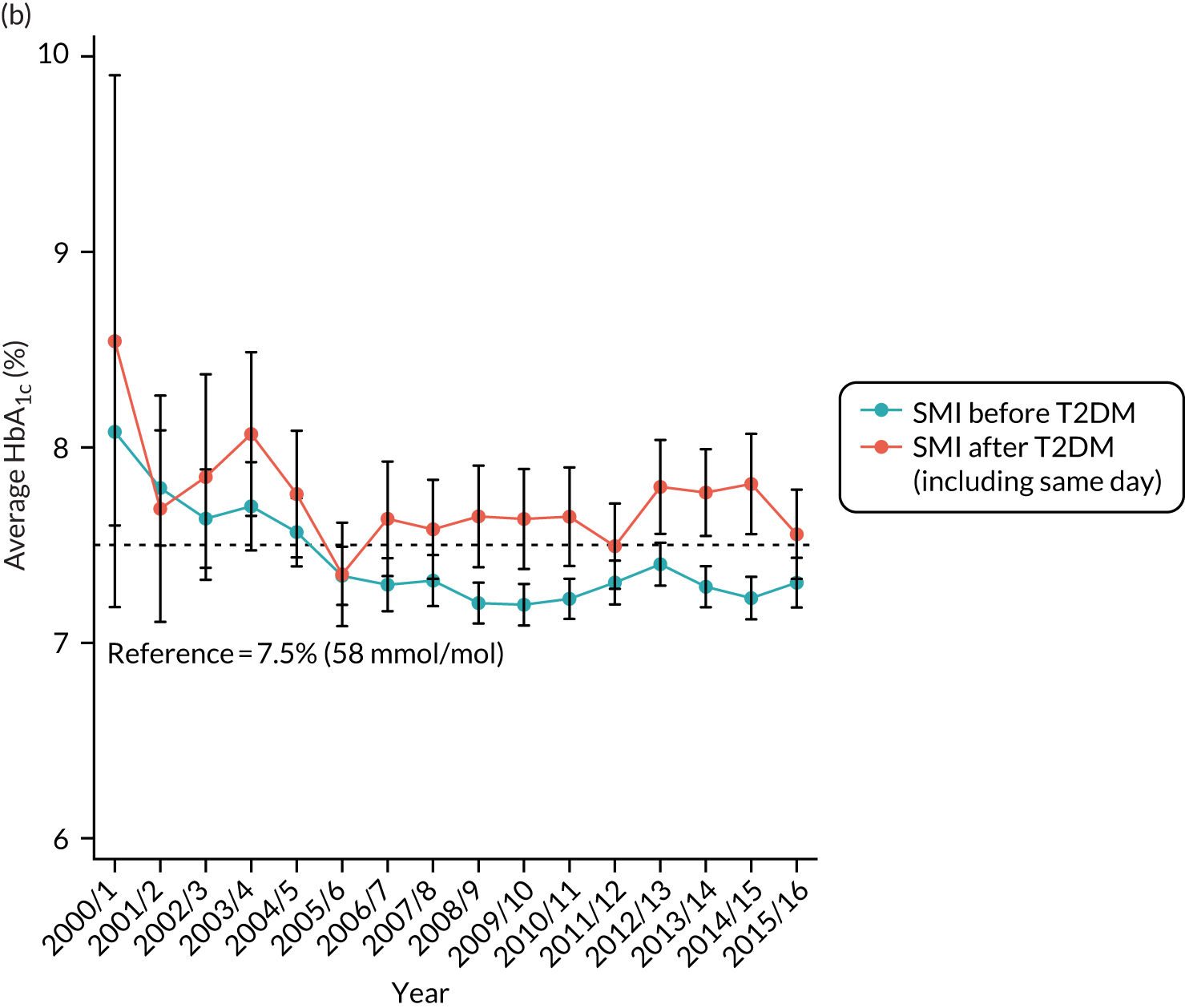

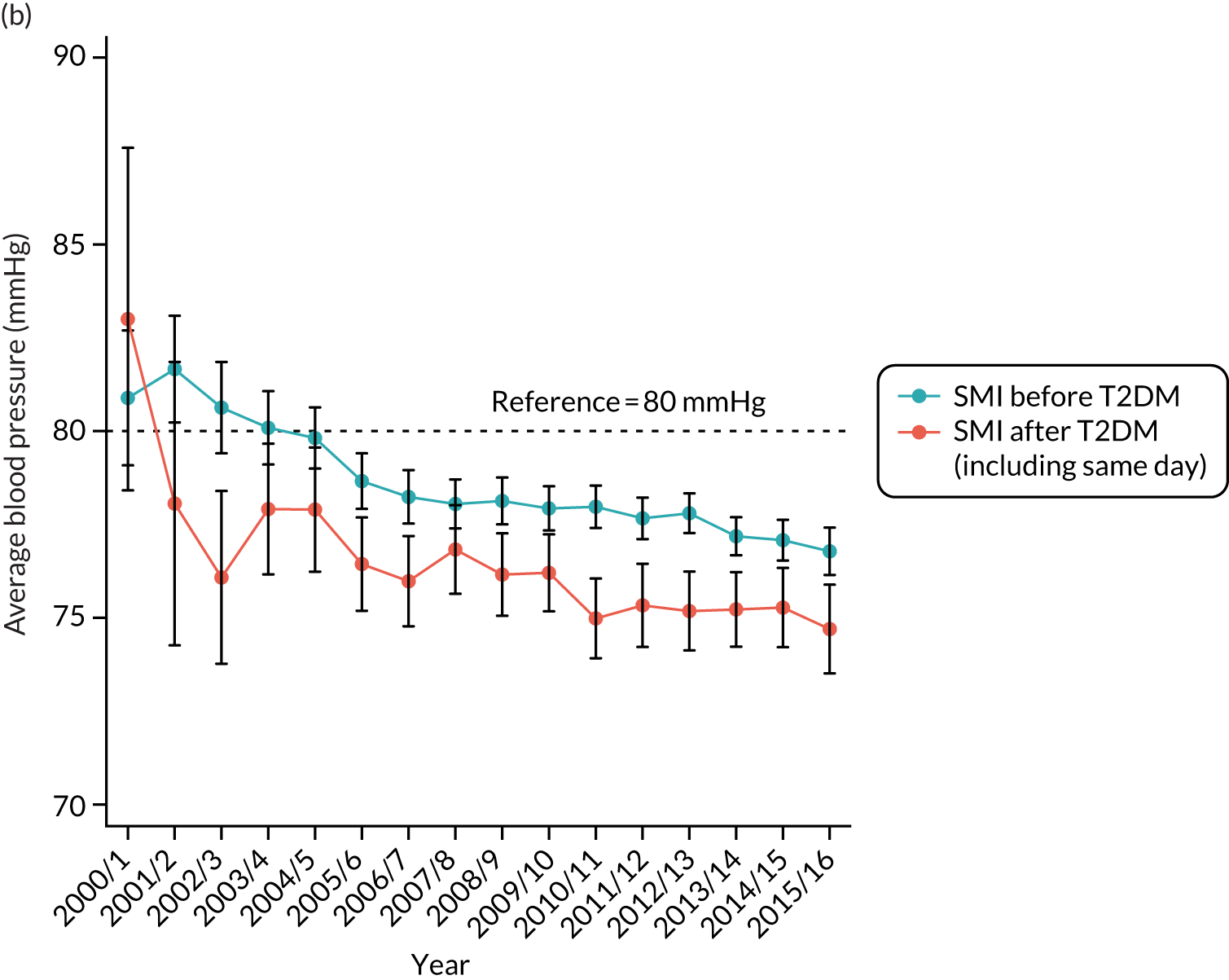

Third, for objective 7 (see Chapter 5, Objective 7: identifying health-care interventions associated with better outcomes for people with diabetes and severe mental illness), following discussions with clinical experts at a research team workshop, we had planned to look at several physical health checks including blood pressure, cholesterol, HbA1c, body mass index (BMI), retinopathy screening, diabetes education and influenza vaccination. However, we were unable to explore in detail all health-care interventions that we originally planned as a result of inconsistencies in the recording of relevant activities in patient records. We therefore prioritised investigating the most common physical health checks, including blood pressure, cholesterol, HbA1c level and BMI, for which recording was more complete.

Fourth, we identified that a significant proportion of the study population had diabetes diagnosed before the onset of SMI. Therefore, we needed to explore any potential order of diagnosis effects; these investigations were added to the planned analyses.

Fifth, for the final integration of study findings, we did not develop a logic model as proposed in the protocol, because of the tentative findings about how diabetes care provision may be associated with outcomes in people with SMI and diabetes.

There were no deviations from the study protocol for the scoping of the literature or the qualitative study.

Chapter 3 Study framework

Theoretical framework

This study sought to address important gaps in evidence about which people with SMI experience poor diabetes outcomes and why, and how health-care services could be changed to improve physical and mental health outcomes.

For our theoretical framework, we conceptualised socioeconomic conditions as a fundamental contributor to health outcomes. 66 As described in Chapter 1, Social inequalities, people with SMI are more likely to be socially disadvantaged,68,69,74,79 leading to a reduced ability to take advantage of resources that improve health, or prevent or treat illness, which ultimately contributes to the significant inequalities in health outcomes seen in this population. We acknowledge that, as a ‘downstream’ determinant of health,67 the health-care system cannot completely remediate the social causes of poor health. However, using a social inequalities lens, we aimed to understand how health-care delivery could better respond to the physical health needs of people with SMI and diabetes, and identify areas for action in which health care and its organisation appear to generate further inequalities in this vulnerable population.

Study design

We used a concurrent triangulation mixed-methods design,105 comprising:

-

A quantitative longitudinal observational study.

The quantitative study interrogated CPRD-linked primary care and hospital records, along with linked HES, ONS and IMD data of a large sample of adults with SMI, adults with SMI and diabetes and a sample of matched controls with diabetes but no SMI.

-

A qualitative interview study.

The qualitative study sought to identify the health-care needs and health-care delivery concerns of this population through thematic analysis of semistructured interviews exploring how diabetes is managed alongside SMI, and how diabetes care is experienced by people with diabetes and SMI, their family members and informal supporters, and health-care professionals. The study drew on critical realism as a guiding methodological framework,106,107 which acknowledges that there is an external reality to be observed (e.g. through interrogation of data such as CPRD), but that there is also a lived reality that can be accessed only through the perspectives of individual actors who make sense of, and interact with, the world in which they live.

The mixed-methods design was underpinned by a pragmatic paradigm, which acknowledges that each data type provides a different, but equally important, worldview, and that, merged together, they will enable us to develop a more complete understanding of health inequalities in this population than would be possible from using either method alone. 105 In particular, this approach allowed for an exploration of how people with SMI and diabetes navigate the health-care system and the range of factors that might influence their health and access to health care.

The definitive design for the study was informed by the results of an initial expert consultation and scoping of the literature, which aimed to develop a better understanding of the potential factors that could influence diabetes outcomes for people with SMI (see Chapter 4). This was used to determine which variables were important to explore in both the quantitative and qualitative studies and consider how to include them.

In line with the concurrent triangulation model, the quantitative and qualitative studies were conducted in parallel, and findings were merged at the interpretation stages to develop a fuller understanding of the factors contributing to poor outcomes and the drivers of improved health outcomes in SMI and diabetes. As part of the integration process, we conducted two co-design workshops involving members of the patient and public involvement (PPI) panel and participants from the qualitative interview study, and a final research team workshop, to iteratively make sense of and interpret the study findings and translate findings into key messages and implications for research and practice (see Chapter 7). Following Medical Research Council guidance for the development of complex interventions,108 we also used the co-design workshops to assess the potential acceptability and feasibility of potential interventions and service improvements into routine health care.

Figure 1 illustrates the four distinct components of the study and how they inter-relate. Each component will be discussed in detail in the upcoming chapters of this report:

-

scoping of the literature and expert consultation (see Chapter 4)

-

CPRD patient record analysis (quantitative longitudinal observational study) (see Chapter 5)

-

qualitative interview study with people with diabetes and SMI, their family members and health-care staff (see Chapter 6)

-

study integration, including co-design workshops (see Chapter 7).

FIGURE 1.

The four components of this study and the relationships between them.

Study organisation and governance

The study research team, comprising all co-applicants, was responsible for day-to-day management of the project, and held bimonthly project management meetings. A Study Steering Committee (SSC) with an independent chairperson and service user, and clinical, academic and commissioning representation was established, meeting every 6 months. The study was sponsored by Bradford District Care NHS Foundation Trust, which was also represented on the SSC.

Patient and public involvement

Overview of patient and public involvement

This study has been supported by DIAbetes and Mental illness: improving Outcomes aND Services (DIAMONDS) VOICE, a PPI group that has provided ‘expert by experience’ input to the study, with the aim of ensuring that the research remains relevant to people with SMI and that the outcomes of the research have the potential to have a meaningful impact on care and services.

Established in 2015, DIAMONDS VOICE comprises service users living with SMI and diabetes, and family members who provide support. The group is facilitated by a PPI co-ordinator and has 12 members who have been involved throughout the study, and a further two who have joined more recently. Three of these are family members or carers of people with diabetes and SMI. The group has met quarterly to discuss study progress, to offer advice on challenges faced by the research team and to undertake activities to support and inform the study. In addition, individual members of the group have contributed beyond the regular meetings, attending the co-design workshops and helping to raise the profile of the study through their networks and at local and regional dissemination events.

John Radford is a member of DIAMONDS VOICE and also a co-investigator on this study. He has participated in study research team meetings and SSC meetings, as well as co-design workshops (see Chapter 7, Co-design workshops).

Patient and public involvement activities

DIAMONDS VOICE has been engaged in project-related activities, starting from the grant application stages and continuing throughout the study duration (described below). The group has led the write-up of this section of the report.

Pre project

During the planning stages, the group assisted with the prioritisation of research questions, expressing a need for a better understanding of how diabetes is prevented and managed in people with SMI. The group suggested that it was important to understand the lived experience of comorbid SMI and diabetes, which influenced the research team to integrate qualitative inquiry into the study.

DIAMONDS VOICE representatives were invited to join the study research team and the SSC (see Study organisation and governance for study governance details) to ensure that the service user perspective was incorporated into the management and governance of the study.

Year 1

Activities included reviewing patient- and public-facing documentation, providing advice on interview topic guides and publicity materials, and suggesting ways to ask sensitive questions relating to finances and health. One member acted as a practice interviewee, which enabled researchers to refine the topic guide and to assess participant burden. In addition, members publicised the project across their own networks and at NHS events, for example running a stall at the sponsoring trust’s research and development conference in May 2018. Membership of DIAMONDS VOICE also expanded as a result of these engagement activities.

Year 2

DIAMONDS VOICE was involved in advising on participant recruitment, interpreting findings and in engagement activities. The research team had experienced difficulties engaging family members in the study, and advice was sought from the group on how to overcome this challenge. Members increased promotion of the study and expanded the stakeholder network, using their personal networks to engage family members supporting people with SMI and diabetes. This resulted in the creation of an ongoing connection with organisations such as Roshni Ghar, a local charity group that was able to provide input into the research and raise the study’s profile in the Asian community.

DIAMONDS VOICE also participated in the study co-design workshops, which took place in May and July 2019 (see Chapter 7, Co-design workshops). In advance of the workshops, members were asked to review invitation documents sent to potential service user and family member participants to ensure that they were clear and engaging. Group members also offered to support service user attendees with no previous experience of contributing to research workshops. During the sessions, members offered valuable insights into the authenticity of the interpretation of the study findings.

Group members played an important role in dissemination and engagement activities. For example, John Radford was a co-author on the protocol paper published in the Journal of Medical Internet Research. 103 In addition, members continued to play an active role in engaging varied audiences, for example at a regional National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) event on multimorbidity research.

Ongoing patient and public involvement

DIAMONDS VOICE will continue to be involved after this study ends, for example through advising on key events for dissemination, giving feedback on materials used in dissemination of research to the public to ensure that they are effective and appropriate, and advising about future research priorities.

Impact of patient and public involvement on the research

Patient and public involvement has had a clear impact on the design, management and dissemination of this study. Importantly, the DIAMONDS VOICE group influenced the choice of mixed methods through their recommendation to explore the lived experience of SMI and diabetes in addition to conducting analyses of longitudinal patient records.

The study has benefited from PPI representation at study research team and SSC levels of governance, which has ensured that the research has continued to address questions that are meaningful to people living with SMI and diabetes. For example, although sleep difficulties were not identified as an important variable in the scoping of the literature, DIAMONDS VOICE representatives highlighted the significance of the relationship between sleep and the day-to-day management of SMI and diabetes. As a result, and in recognition that CPRD recording of sleep difficulties would be incomplete, a decision was taken to explore this issue through the qualitative interviews.

Input from DIAMONDS VOICE has also had an impact at the operational level of the study. Group members reviewed all patient- and public-facing project documentation, indicating ways to improve clarity and readability. They also advised on ways to make promotional materials engaging and appealing and have been instrumental in promoting the study across their mental health networks and expanding the stakeholder network. Topic guides and recruitment strategies were refined in accordance with advice from the group.

Reflections on the experience of participating in patient and public involvement

Researcher and member feedback on PPI involvement in this and other studies is collected annually by the PPI co-ordinator (see Appendix 1, Reflections on the experience of participating in patient and public involvement).

Chapter 4 Identifying potential variables: determinants, outcomes and health-care interventions for diabetes in severe mental illness

Introduction

In preparation for the quantitative and qualitative studies, we undertook an iterative expert consultation and rapid scoping of the literature to identify the following: factors that might be associated with the development of diabetes, diabetes outcomes and diabetes health-care interventions for people with SMI.

The aim was to create a ‘longlist’ of the range of factors potentially relevant to our study and map which explanatory factors had been theorised or empirically demonstrated to have a relationship with the outcomes. From this longlist, we considered which factors were feasible to explore, for example which variables were available in the CPRD or could be explored in an interview. We planned that this approach would assist in the construction of key explanatory, outcome and health-care intervention variables for the quantitative study, and shape the topic guides for qualitative interviews.

Methods

We iteratively searched and aggregated evidence from a range of sources between January and March 2018 using an inclusive approach to capture a broad range of potential factors. Systematic reviews and meta-analyses known to the research team provided a starting point. We also drew on primary quantitative studies, literature reviews, expert consultation and clinical guidelines, as well as results from a pilot interrogation of CPRD data of around 1000 people with SMI and diabetes. The list of sources was reviewed and added to by the study research team and the SSC. Additional sources were identified through iterative targeted searches of specific variables in key databases [e.g. MEDLINE, EMBASE™ (Elsevier, Amsterdam, the Netherlands), Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews] for systematic reviews in the first instance, and, when these were not available, other study types. Only publications in the English language were considered.

Details of determinants (including social determinants), outcomes and interventions were extracted from each source to generate a longlist of potential variables. This was reviewed by the research team to ensure that relevant variables were included and appropriately labelled, and that duplicates removed or merged. Quality appraisal of sources was not undertaken. All evidence sources were imported into NVivo 12 (QSR International, Warrington, UK).

Tables containing each variable, type, titles and number of sources cited, and summary of justification (theory, research findings) were produced to inform plans for the quantitative and qualitative studies (see Appendix 2, Tables 28–31).

Under objective 7, we planned to explore which health-care interventions were associated with better diabetes outcomes for people with SMI and diabetes, subject to data availability in the CPRD and completeness of recording by practices. As these interventions needed to be from the UK, we identified candidate interventions from the following sources:

-

Diabetes and SMI QOF indicators that could be identified in CPRD data. The QOF is a national programme that offers financial incentives to general practices for meeting quality-of-care targets across a range of conditions, including SMI and diabetes. 109,110 These indicators include, for example, annual monitoring for key biological measurements such as blood glucose and blood pressure, dietary review, foot examination, retinal screening, and structured education and comprehensive care planning. 111

-

Diabetes interventions recommended by NICE. 32

-

Interventions identified from the systematic review and service user engagement completed in NIHR study 13/54/40,112,113 which identified a number of diabetes-related indicators of primary care quality (e.g. diabetes screening, monitoring concomitant antipsychotic medications, BMI and weight loss, retinal and foot examination, and education about nutrition and physical activity).

-

Interventions identified from the DIAMONDS systematic review114 and PPI consultation, and through ongoing consultation with the study research team, collaborators and steering committee, and the wider DIAMONDS research group, DIAMONDS VOICE panel, and virtual stakeholder network.

-

Results of our pilot interrogation of CPRD data carried out by the DIAMONDS research group to characterise the population and to develop and test clinical (Read code) lists in preparation for the study. 115

-

Interventions identified from systematic reviews as being potentially effective in the UK for reducing inequalities in diabetes or SMI care and outcomes. 116–121

Results

Fifty-six sources were used to identify variables, as shown in Table 1. The full list can be found in Appendix 2, Tables 28–31.

| Study type | Number |

|---|---|

| Systematic review and meta-analysis | 12 |

| Meta-analysis | 1 |

| Systematic review | 11 |

| Primary quantitative study | 30 |

| Literature review | 2 |

| Total | 56 |

The list of variables (Table 2) was reviewed by the study research team to check for clinical significance, duplication or missing variables, and to determine which variables could be investigated in CPRD data. Any that could not be identified or that would potentially be biased were considered for inclusion in the qualitative interview topic guides.

| Variable | Number of associated sources | Explored in quantitative study? |

|---|---|---|

| Factors associated with the development of diabetes in people with SMI | ||

| Sociodemographic variables | ||

| Age | ≥ 20 | Objectives 1–4, 6 and 7 |

| Ethnicity | 10–19 | Objectives 1–4, 6 and 7 |

| Sex | ≥ 20 | Objectives 1–3 |

| Poverty and disadvantage | 10–19 | Objectives 1–4, 6 and 7 |

| Regional variation/rurality and urbanicity | < 10 | Not explored (no linkage to these data) |

| Medication use | ||

| Antidepressant use | < 10 | Objectives 1–4, 6 and 7 |

| Antihypertensive use | < 10 | Objectives 1–4, 6 and 7 |

| Antipsychotic use | ≥ 20 | Objectives 1–4, 6 and 7 |

| Lipid-lowering medication | < 10 | Objectives 1–4, 6 and 7 |

| Illness features/physiological characteristics | ||

| Comorbidity or multimorbidity (e.g. comorbid depression, hypertension) | < 10 | Objectives 1–4, 6 and 7 |

| Cognitive functioning | < 10 | Objectives 1–4, 6 and 7 |

| First-episode vs. multi-episode psychosis | < 10 | Not explored |

| Genetic link/family history | 10–19 | Objectives 1–4, 6 and 7 |

| Gene–environment interaction | < 10 | Not explored |

| Hormonal imbalance, including HPA axis dysfunction and stress | 10–19 | Not explored |

| Immune dysfunction and chronic inflammatory state | < 10 | Not explored |

| Lipid dysregulation | < 10 | Objectives 1–4, 6 and 7 |

| Obesity | 10–19 | As above |

| Sleep | 10–19 | Not explored |

| Lifestyle factors | ||

| Lifestyle factors (general) | < 10 | Not explored |

| Alcohol use | < 10 | Objectives 1–4, 6 and 7 |

| Poor diet | < 10 | Not explored |

| Relational context | < 10 | Not explored |

| Sedentary lifestyle | < 10 | Not explored |

| Smoking | < 10 | Objectives 1–4, 6 and 7 |

| Substance use | < 10 | As above |

| Additional factors that may influence diabetes outcomes in people with SMI | ||

| Service providers’ adherence to care guidelines and quality of care | < 10 | Not explored |

| Care ambiguity | < 10 | Not explored |

| Non-adherence to diabetes medication | < 10 | Not explored |

| Non-treatment | < 10 | Not explored |

| Polypharmacy (antipsychotic or antidiabetes) | < 10 | Not explored |

| Underdiagnosis of metabolic dysfunction | < 10 | Not explored |

| Stigmatisation | < 10 | Not explored |

| Interventions that may influence diabetes outcomes in people with SMI | ||

| Medication | ||

| Antihypertensive medication | < 10 | Objectives 1–4, 6 and 7 |

| Antipsychotic switching | < 10 | Not explored |

| Antidiabetes medication | 10–19 | Objectives 1–4, 6 and 7 |

| Lipid-lowering treatment | < 10 | Objectives 1–4, 6 and 7 |

| Mood stabilisers | < 10 | Not explored |

| Monitoring and examinations | ||

| Monitoring: blood pressure, HbA1c, lipid profile, BMI | 10–19 | Objectives 1–4, 6 and 7 |

| Examinations: retinopathy screening, foot surveillance, nephropathy testing | 10–19 | Not explored |

| Self-management | ||

| Self-management and education (general) | 10–19 | Not explored |

| Outcome measures | < 10 | Not explored |

| Predictors of self-care behaviours | < 10 | Not explored |

| Social or family support | < 10 | Not explored |

| Theoretical frameworks of interventions | < 10 | Not explored |

We used the variables list to construct explanatory (e.g. age, obesity, type and severity of SMI) and outcome variables (e.g. complications, cardiovascular control, mental illness relapses) and to shape the topic guides for qualitative interviews (see Report Supplementary Material 1). Although it was important not to be constrained by preconceived notions about participants’ experiences, being aware of the potential influence of, for example, social determinants of diabetes in people with SMI steered researchers towards initiating discussion around topics such as financial constraints and barriers to service access.

Chapter 5 Interrogation of patient health records

Introduction

The interrogation of patient health records study addressed the following research questions:

-

What are the sociodemographic and illness-related risk factors associated with –

-

diabetes developing in people with SMI?

-

variation in diabetes and mental health outcomes in people with SMI and diabetes?

-

-

How do physical and mental health outcomes differ between people with SMI and diabetes and people with –

-

SMI without diabetes?

-

diabetes but no SMI?

-

-

What factors are associated with access to, and receipt of, diabetes care for people with SMI?

-

How and at what cost is diabetes monitored and managed in people with SMI, compared with those without SMI?

-

What health-care interventions (e.g. medication, referrals and care pathways) are associated with better diabetes outcomes for people with SMI and diabetes?

These correspond to study objectives 1–4, 6 and 7 (see Chapter 2, and the objective sections later in this chapter). For all objectives, we conducted analyses in line with the inequalities framework to quantify the relative effect of social inequalities on quality of care and outcomes. Specifically, we used deprivation and disadvantage markers, such as the IMD, as independent variables to estimate gap or gradient effects. We planned to stratify analyses by ethnicity, but were limited by the small numbers of people in minority ethnic categories for most analyses.

Data and methods

Ethics approval

A data-use agreement for CPRD records and linked HES and ONS mortality data was granted by the International Scientific Advisory Committee (reference: 17_161R).

Data sets

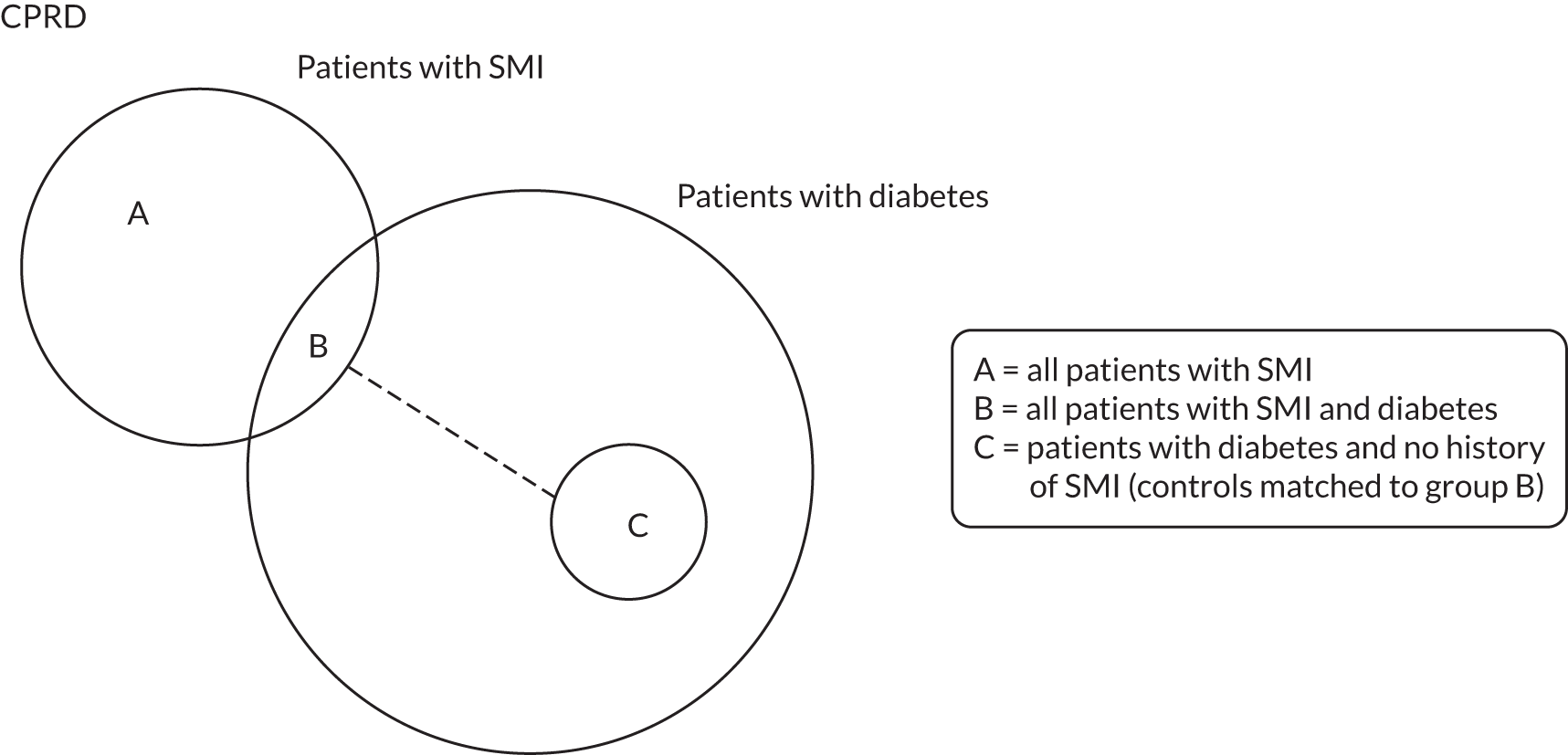

Three data sets were extracted from the CPRD for the quantitative analyses; the relationships between these data sets are shown in Figure 2. Data set A contains anonymised longitudinal health records of a cohort of 32,759 people with SMI. Records were extracted from the CPRD GOLD population cohort if they:

-

had at least one clinical or referral event with a SMI diagnostic code in their medical history (see Report Supplementary Material 2, Table S1, for the code list)

-

were actively registered with one of the contributing general practices in England in the study period from 1 April 2000 to 31 March 2016

-

were eligible for the linkages required (HES, IMD and ONS death)

-

were aged ≥ 18 years when SMI was diagnosed

-

had continuous health data up to research standard [up to standard (UTS)] in the study period. 98

FIGURE 2.

Venn diagram illustrating the relationship between CPRD data sets.

Data set B is a subset of data set A and contains records of 2761 people with SMI who also had T2DM. T2DM was defined as the presence of at least one clinical diagnostic code in a patient’s clinical or referral records (see Report Supplementary Material 2, Tables S2 and S3). We excluded people who had a record of type 1 diabetes mellitus after their diagnosis of T2DM.

Data set C comprises a cohort of 9573 control patients with a diagnosis of T2DM and no record of SMI who were matched to people in data set B (cases). These controls, with a diagnosis of T2DM and no record of SMI, were matched to cases based on age, sex and practice in a ratio of 4 : 1.

Variables

Using the longlist identified, as described in Chapter 4, Results, we constructed a range of candidate variables associated with the development of T2DM and with physical and mental health outcomes based on whether or not (1) the risk factor could be measured using the information in the CPRD and its linked data sets, (2) the data had been collected in the CPRD and its linked data sets and the quality of data recording was systematic enough for analysis and (3) it was likely to have an impact on the outcomes of interest.

Table 3 summarises the data sources and construction methods for the candidate risk factors that were used to measure patients’ baseline characteristics.

| Candidate explanatory variable | Type | Data sources and description |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic | ||

| Age | Continuous |

|

| Sex |

|

CPRD sex |

| Ethnicity |

|

CPRD and HES ethnicity |

| Socioeconomic status | ||

| Deprivation (patient level) | Categorical (by quintiles) | 2010 English IMDs102 at LSOA level, matched using patients’ residential postcodes |

| Status of SMI | ||

| Type of SMI |

|

|

| Duration of SMI | Continuous (years) |

|

| Status of diabetes | ||

| Duration of T2DM | Continuous (years) |

|

| Family history of diabetes | Binary |

|

| Comorbidities | ||

| Cardiovascular disease | Binary |

|

| Hypertension | Binary | As above |

| Dementia | Binary | As above |

| Learning disability | Binary | As above |

| Number of Charlson Index comorbidities | Count |

|

| Medication | ||

| Antidepressants | Binary |

|

| Antipsychotics | Binary (by typical and atypical) | As above |

| Antidiabetes | Binary | As above |

| Antihypertensive | Binary | As above |

| Lipid-lowering drugs | Binary | As above |

| Lifestyle factor | ||

| Smoking status |

|

|

| Alcohol intake status |

|

As above |

| Substance use | Binary |

|

| Biometric measure | ||

| BMI (kg/m2) |

|

|

| HbA1c (%) |

|

|

| Serum cholesterol (mmol/l) |

|

As above |

| Blood pressure (mmHg) |

|

As above |

It should be noted that patients’ follow-up periods varied for each objective, depending on the patient samples and research questions. We provide a detailed definition of follow-up period for each objective in the sections that follow.

Table 4 summarises the outcome variables under examination, along with their associated data sources, analysis methods and related objective(s).

| Outcome variables | Data sources and description | Type and analysis methods | Objectives |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical health outcomes | |||

| Diabetes status |

|

Multilevel mixed-effects logistic regressions with practice-level random intercepts | 1 |

| Time to onset of diabetes |

|

Cox proportional hazards regressions | 1 |

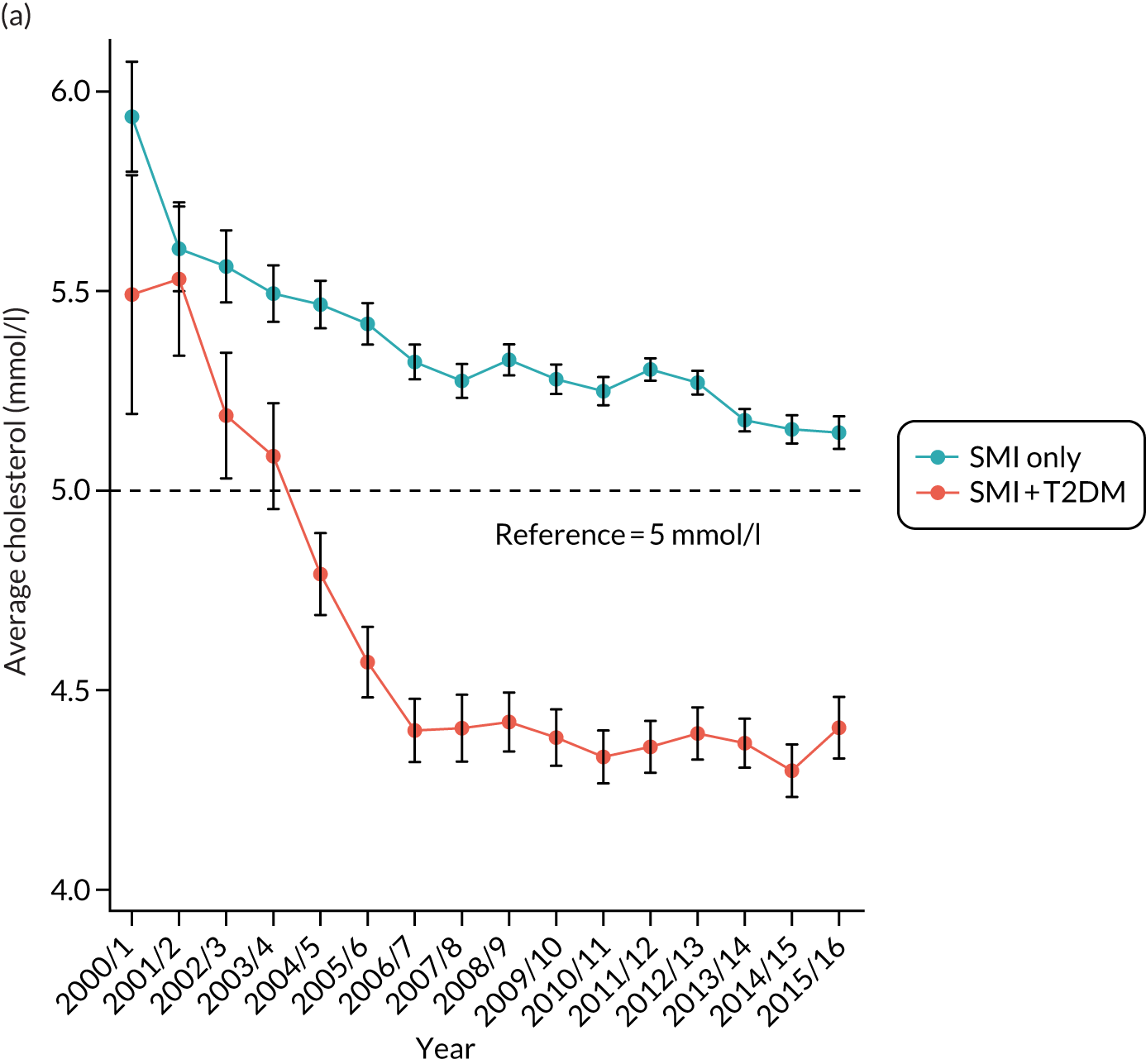

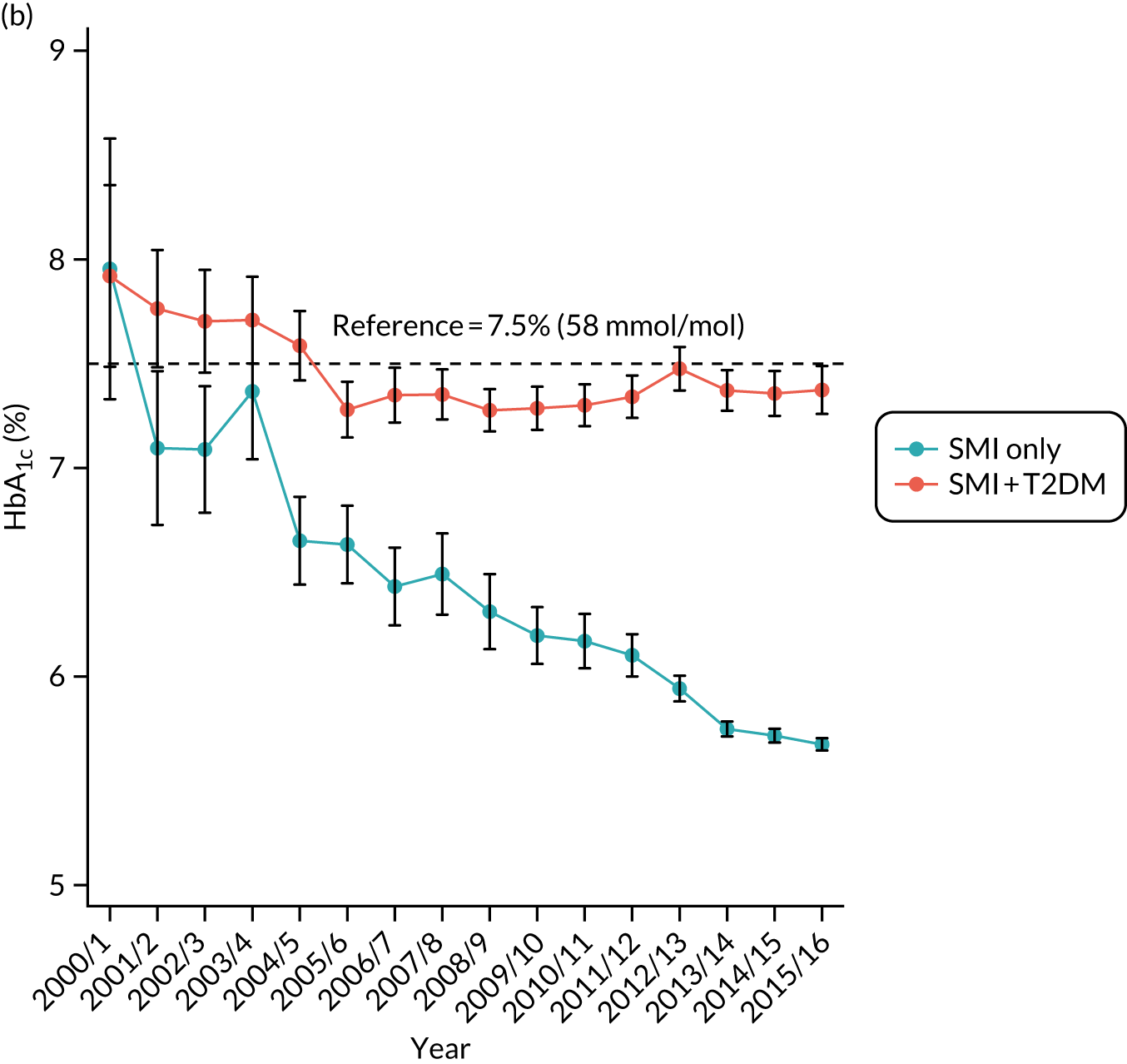

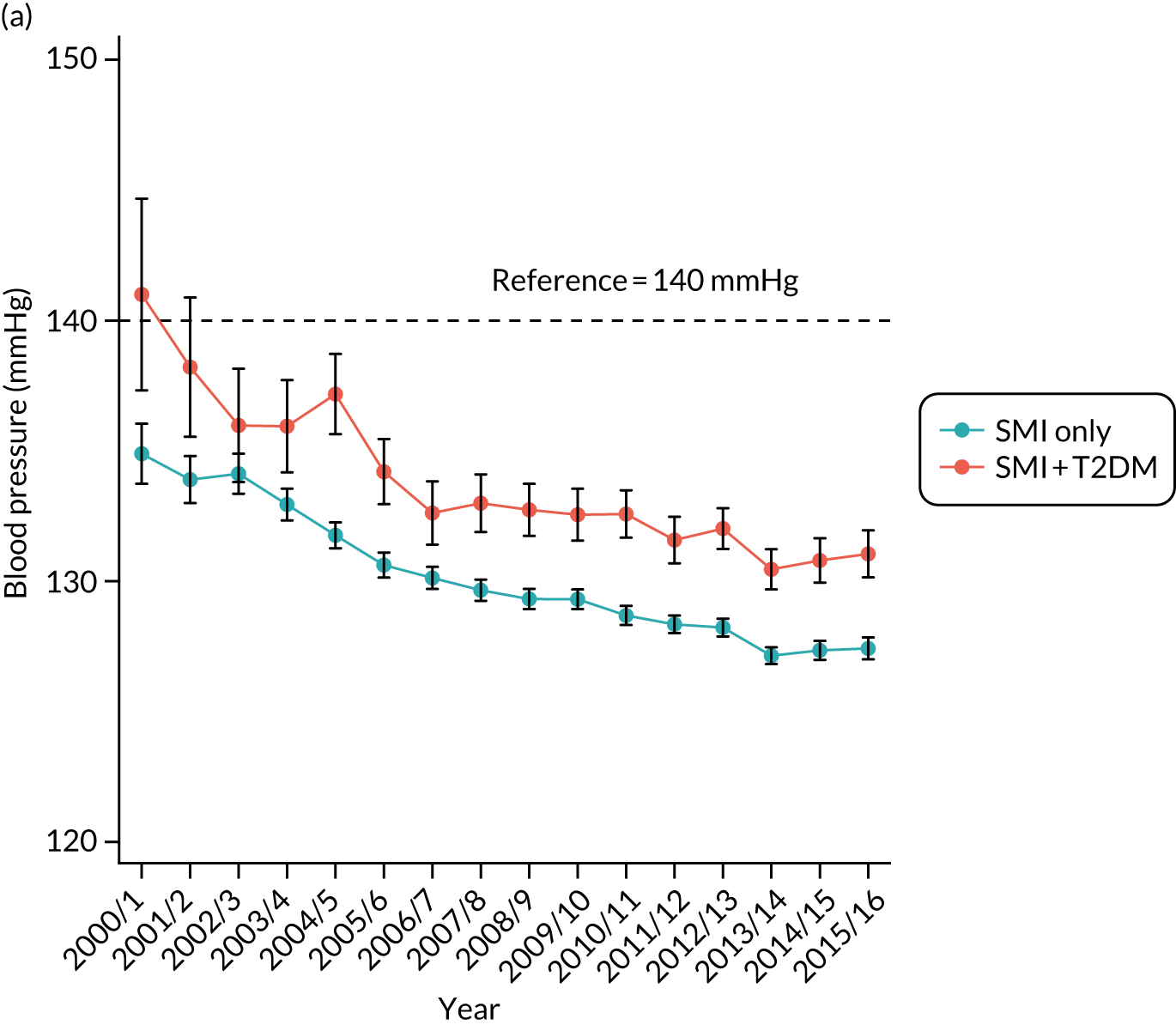

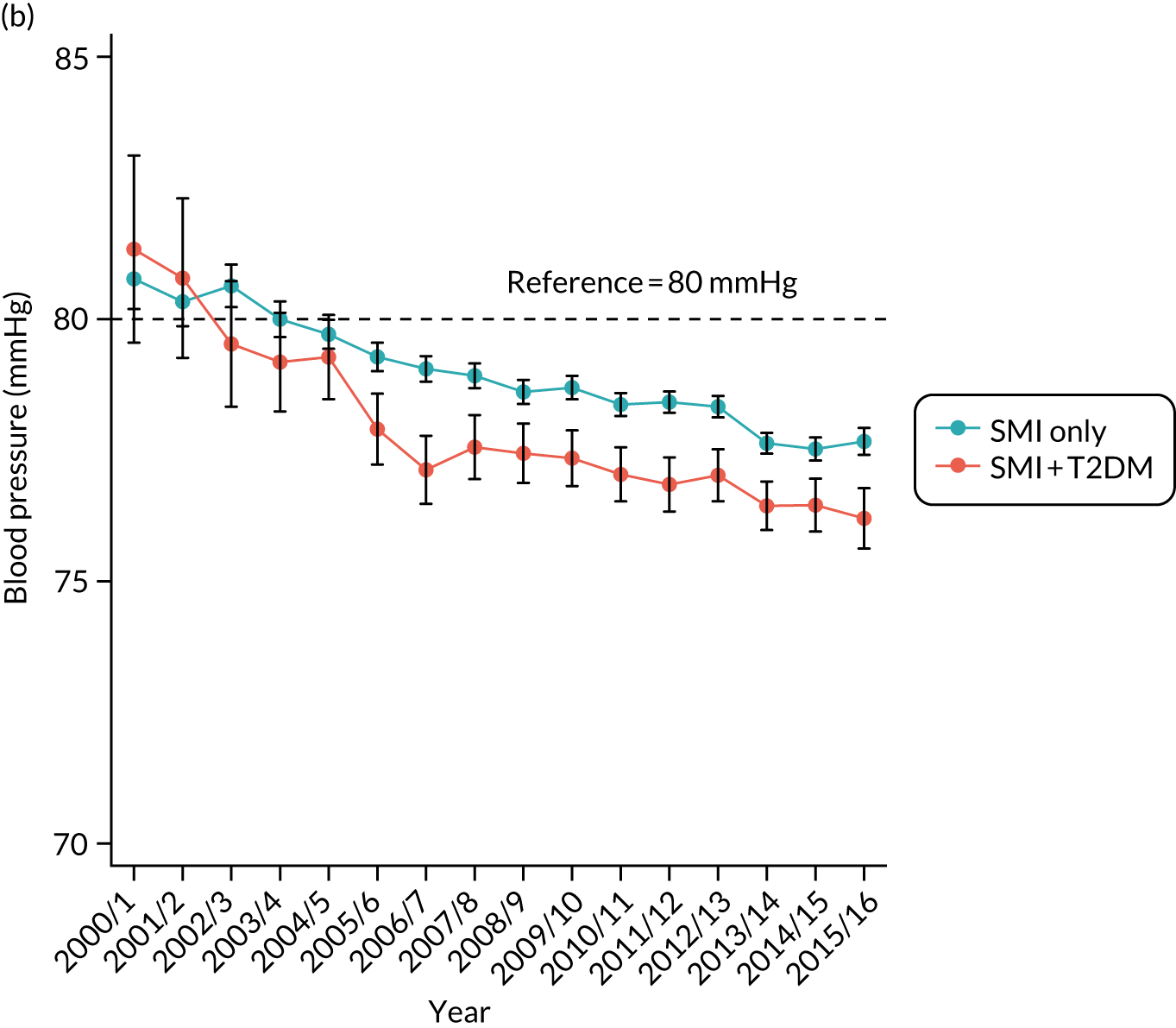

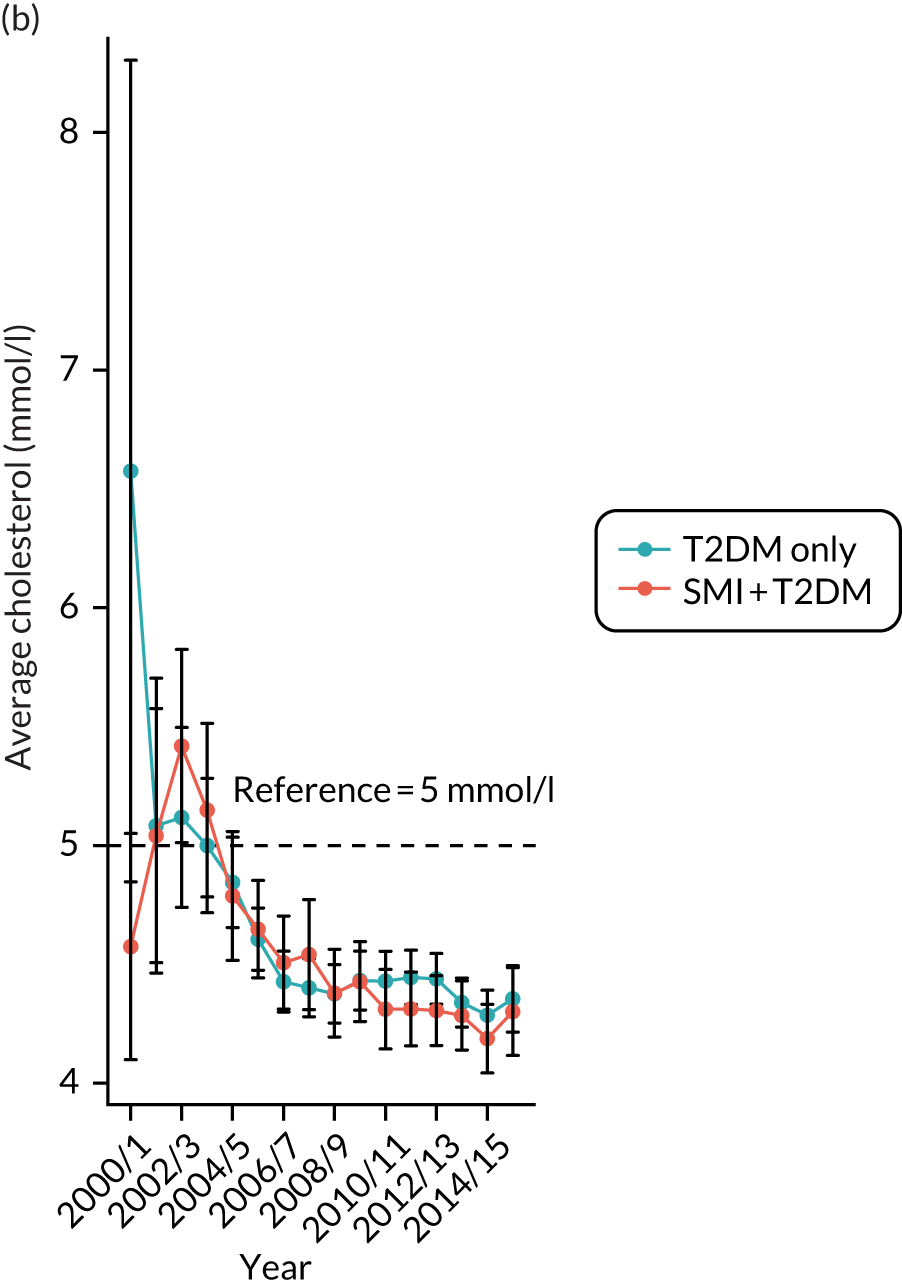

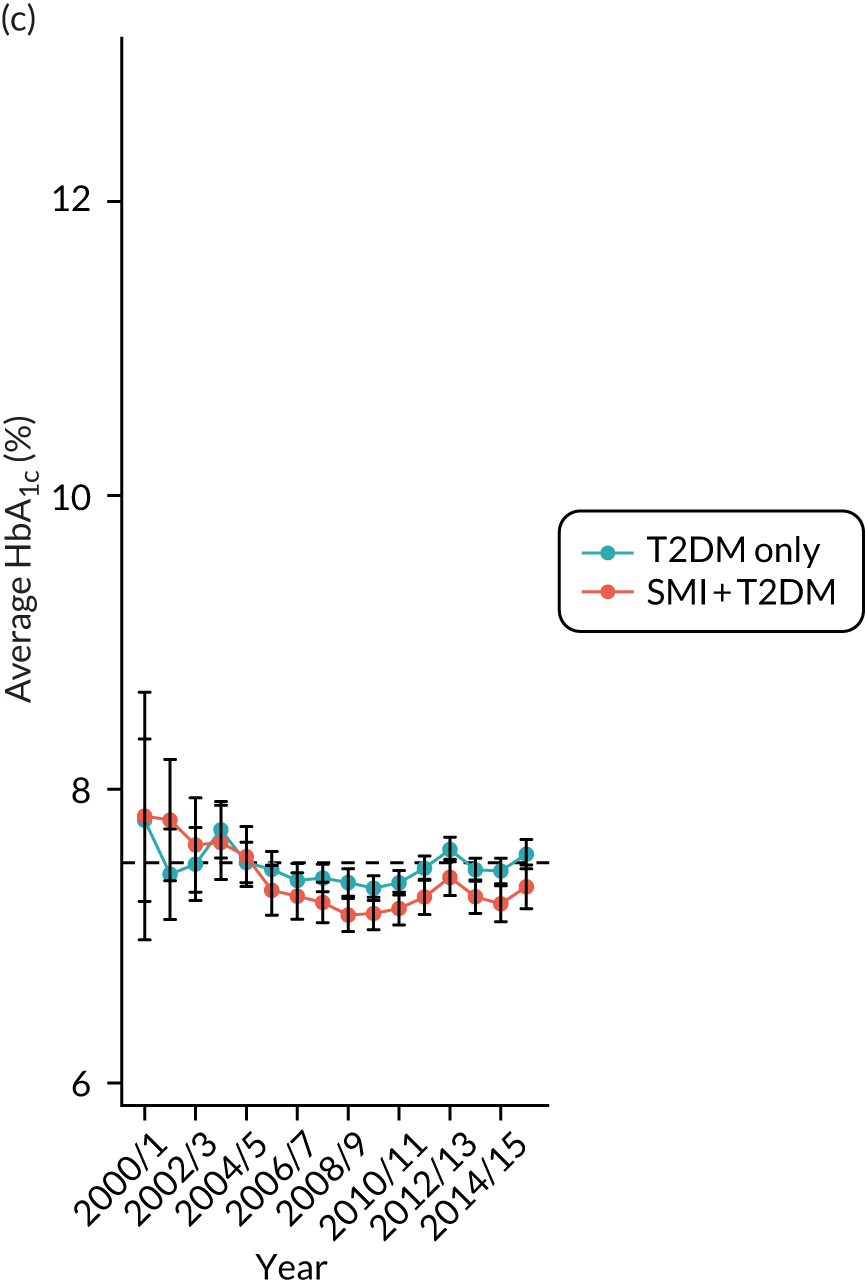

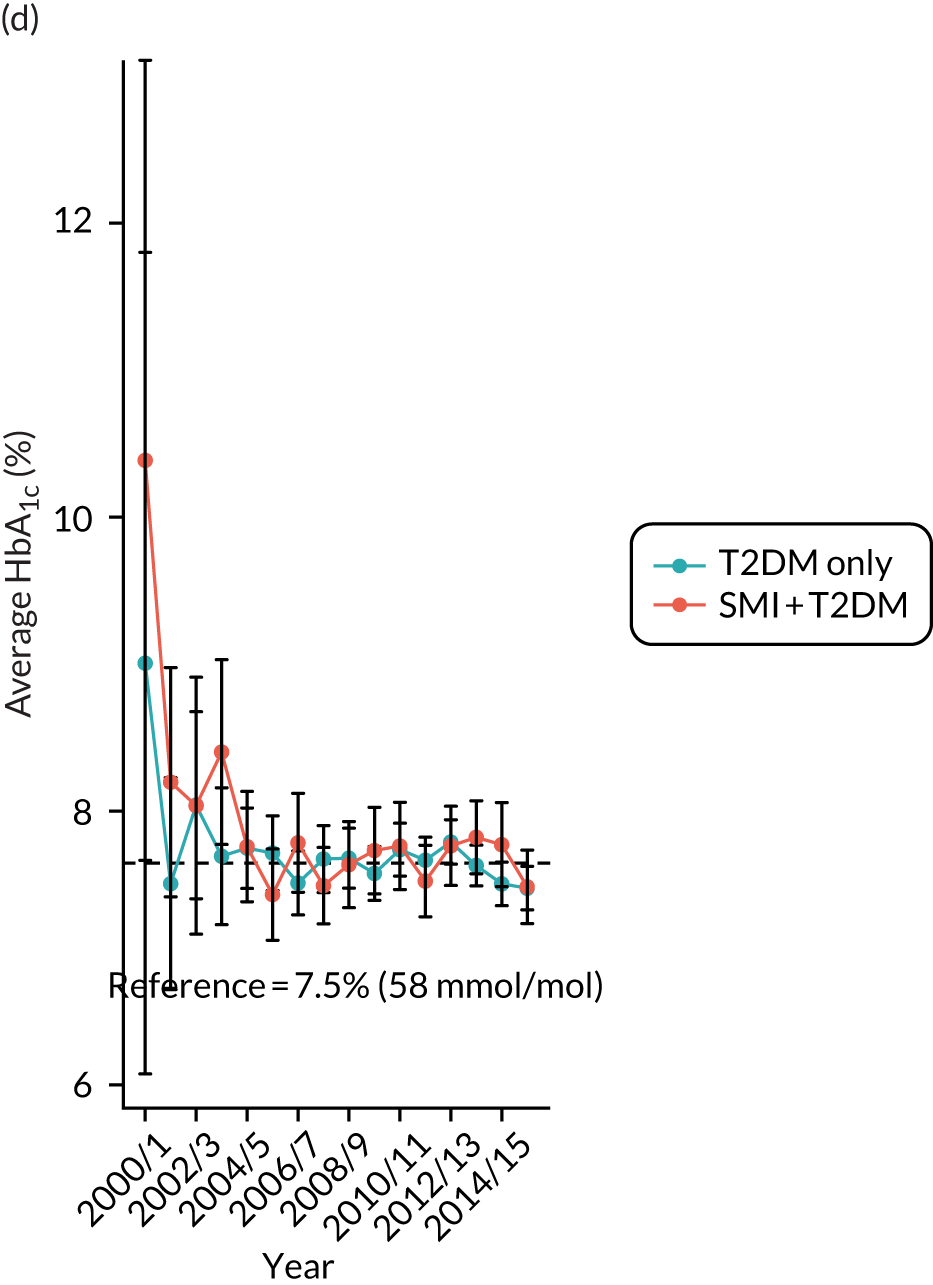

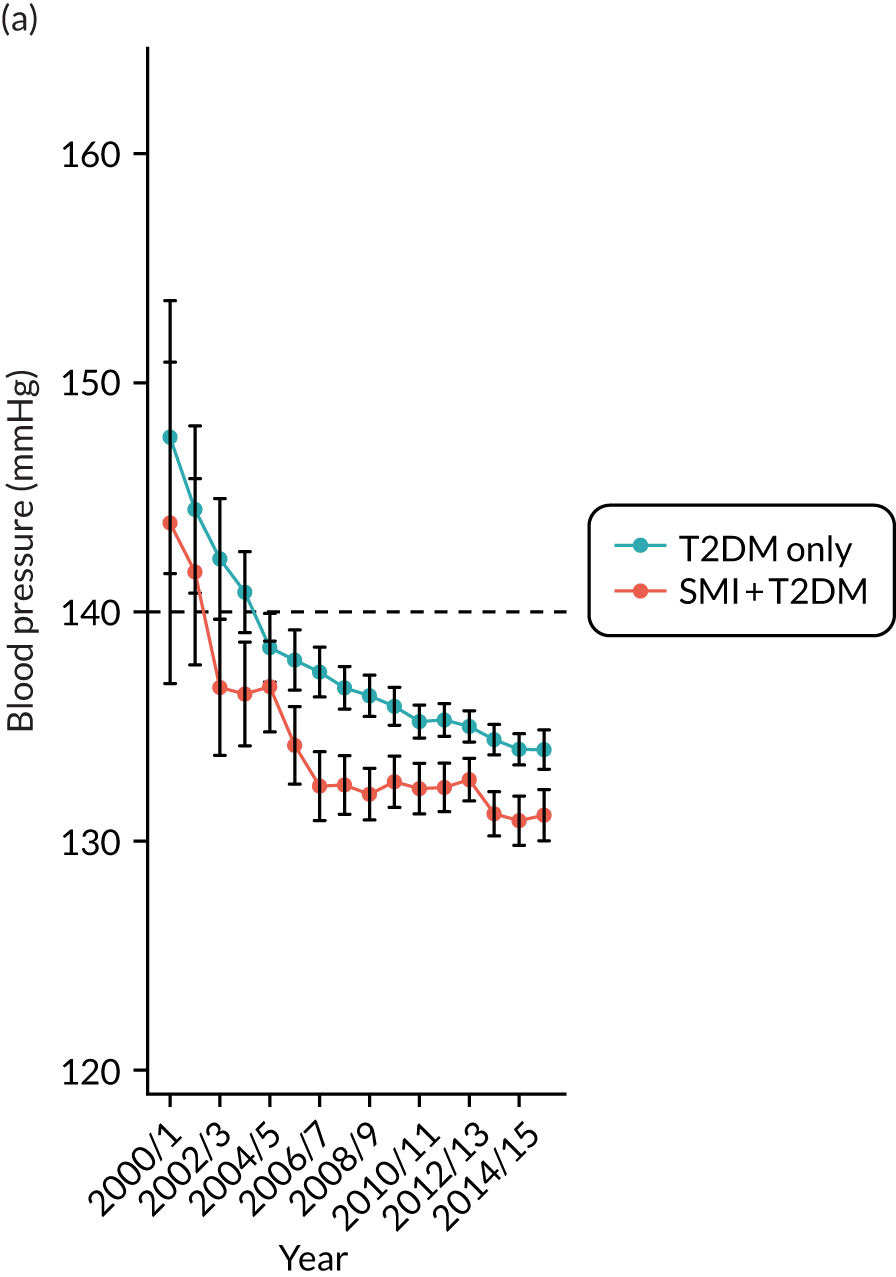

| Glycaemic and cardiovascular control (HbA1c, serum cholesterol and blood pressure) |

|

Time trends plotted in graphs | 2–4 |

| Diabetes complications (hyperglycaemia and hypoglycaemia) |

|

Summarised using descriptive statistics | 2–4 |

| Microvascular complications (retinopathy, neuropathy and nephropathy) |

|

Cox proportional hazards regressions | 2 and 3 |

| Summarised using descriptive statistics | 4 | ||

| Macrovascular complications (myocardial infarction, peripheral vascular disease and stroke) |

|

Multilevel mixed-effects logistic regressions with practice-level random intercepts were applied on unmatched patient-level data | 2 and 3 |

| Conditional logistic regressions were applied on matched control data to generate ‘within’ estimators | 4 and 7 | ||

| Hospital admissions for macrovascular complications (ischaemic heart disease, peripheral vascular disease and cerebrovascular disease) |

|

Multilevel mixed-effects negative binomial regressions with practice-level random intercepts were applied on unmatched patient-level data | 2 and 3 |

| Negative binomial regressions with fixed effects by case–control clusters were applied on matched control data to generate ‘within’ estimators | 4 | ||

| All-cause mortality |

|

Cox proportional hazards regressions were applied on unmatched patient-level data | 2 and 3 |

| Cox proportional hazards regressions stratified by case–control clusters were applied on matched control data to generate ‘within’ estimators | 4 | ||

| Mental health outcome | |||

| SMI relapses |

|

Multilevel mixed-effects logistic regressions with practice-level random intercepts | 2 and 3 |

| Depression and anxiety |

|

Multilevel mixed-effects logistic regressions with practice-level random intercepts were applied on unmatched patient-level data | 2 |

| Conditional logistic regressions were applied on matched control data to generate ‘within’ estimators | 4 | ||

| Physical health checks | |||

| Glucose, HbA1c, serum cholesterol, blood pressure and BMI |

|

Multilevel mixed-effects negative binomial regressions with practice-level random intercepts were applied on unmatched patient-level data | 3 |

| Negative binomial regressions with fixed effects by case–control clusters were applied on matched control data to generate ‘within’ estimators | 4 and 7 | ||

| Resource use and costs | |||

| Resource use (consultations, drug prescriptions and diagnostic tests in primary care settings and inpatient stays at general hospitals) |

|

Generalised linear regressions with gamma distributions and log link functions | 6 |

| Medical costs (costs of consultations, drug prescriptions and diagnostic tests in primary care settings and inpatient stays at general hospitals) |

|

Generalised linear regressions with gamma distributions and log link functions | 6 |

Methods

To improve data quality, we developed and applied four common inclusion criteria to the extracted data set before carrying out analyses. These criteria were designed to account for the nature of SMI and diabetes, as well as for the features and limitations of this longitudinal data set:

-

First, we identified the diagnosis dates of SMI and diabetes. Diagnosis date is commonly identified as the date when the earliest diagnostic code was recorded in primary care. Because the first contact for (and diagnosis of) SMI can be in secondary care, we identified the diagnosis date for SMI as the earliest of the date of first GP diagnosis or the date of the first hospital admission for the condition. We also applied this method to the identification of diabetes diagnosis, although this condition is more commonly diagnosed in a primary care setting. This increased the number of people with SMI (data set A) to 32,781 and people with both SMI and T2DM (data set B) to 3448. Our matched controls (data set C), therefore, decreased in number to 9551 people.

-

Second, we excluded patients whose diagnosis of SMI and diabetes was recorded in the 90 days following registration with their current practice. As patients’ primary care records could be transferred between practices, we used this step to exclude those patients whose earliest primary care records of SMI and diabetes were likely to be updated from medical history because of changes of practices, rather than a new diagnosis.

-

Third, we excluded patients who were diagnosed with SMI and diabetes before the age of 18 years, using our modified diagnosis dates.

-

Fourth, we identified the patients with diagnosis codes of both type 1 diabetes and T2DM and removed people with potential type 1. For the patients with codes of both types, we followed an existing identification algorithm (from study NIHR 14_168R113), which categorised patients as potentially having type 1 diabetes if (1) their first diagnostic code of diabetes was recorded before 18 years of age or (2) there was a diagnostic code of type 1 recorded before 18 years of age or (3) they had been treated with insulin only.

Most analyses were conducted on patient-level data sets that typically had two levels of hierarchy: (1) patient-level observations nested within (2) practices. We accounted for the data structure by applying multilevel mixed-effects models with practice-level random intercepts.

Although a rich medical information source, these routine primary care data have been collected for administrative purposes, and the data quality depends on various factors such as the accurate and complete utilisation of the computerised recording system, standardised coding and the introduction of financial incentive schemes (such as the QOF) that reward general practices for performing incentivised Read-coded activities. We therefore identified an UTS follow-up period for each patient, which included comprehensive medical records for research. The start of the UTS period was defined as the later date between patient current registration and practice UTS dates; the end of this period was identified as the earliest among patient death, transfer-out and practice last collection dates.

We took a step-by-step forward approach to build the models from the most basic form (including only exposure variables) to expanded models with a wide range of adjustments. This approach was adopted to detect the potential confounding effect one variable might have on another, such as the association between SMI status and health outcomes attributed to older age. We adjusted for patient characteristics and time in all the final models as reported in this report (see Variables and statistical methods and Report Supplementary Material 3). Other candidate explanatory variables were included in the final models if they had significant association (p < 0.1) with the outcome of interest or their inclusion had improved the goodness of fit of models. We used c-statistics to compare logistic models and the Akaike information criterion and Bayesian information criterion (BIC) for negative binomial and Cox proportional hazards models. In the results tables (see Tables 6, 9, 13, 16, 22 and 23, and Report Supplementary Materials 4–12), we report a core model including only risk factors with good data quality and an extended model that also included covariates with less complete data, such as lifestyle and biometric measures.

Objective 1: factors associated with the development of diabetes in people with severe mental illness

Objective

The objective was to identify which sociodemographic, illness, family history and lifestyle factors are associated with the development of diabetes in people with SMI.

Study population

We used data set A (see Figure 2) containing records of 32,781 adults with SMI and applied the four common inclusion criteria, as outlined in Methods. From the remaining sample, people were included in the analysis if they (1) were diagnosed with SMI in their UTS continuous data period, (2) either had no record of T2DM in their medical history or had T2DM diagnosed only after SMI and (3) had a follow-up period of at least 1 day.

The follow-up period of eligible patients started from the later date between SMI diagnosis and UTS period start plus 15 months, to ensure that at least 15 months’ UTS continuous data were available for extracting baseline patient characteristics. The end of the follow-up period was identified as the end of the UTS continuous data period or the end of the study period, whichever was earlier. The final sample eligible for analysis included 14,838 people with SMI and without T2DM at baseline.

Variables and statistical methods

Descriptions of the outcome and candidate explanatory variables used in analyses for this objective, and their associated data sources and analysis methods, can be found in Tables 3 and 4. Further details on the statistical model specification have been provided in Report Supplementary Material 3.

For the status of diabetes, we adjusted for the length of follow-up (in years) and financial years to account for the effect of time in the multilevel logistic regressions. Robust standard errors for correlations by practices were specified in these regressions.

Results

Descriptive statistics

The distribution of patient characteristics at baseline was summarised according to diabetes diagnosis (Table 5).

| Patient characteristic | People with SMI (N = 14,838) | |

|---|---|---|

| Without T2DM | With T2DM | |

| Patients, n (%) | 14,131 (95.2) | 707 (4.8) |

| Diagnosis age (years), mean (SD) | ||

| SMI | 45.29 (19.38) | 50.70 (15.06) |

| T2DM | 55.56 (14.46) | |

| SMI type, n (%) | ||

| Schizophrenia | 7001 (49.5) | 340 (48.1) |

| Schizoaffective disorder | 429 (3.0) | 34 (4.8) |

| Bipolar disorder | 4893 (34.6) | 233 (33.0) |

| Depression and psychosis | 1433 (10.1) | 89 (12.6) |

| Other affective disorder | 337 (2.4) | 9 (1.3) |

| Mixed | 38 (0.3) | 2 (0.3) |

| Missing | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Age at follow-up start (years), mean (SD) | 45.39 (19.36) | 50.82 (15.04) |

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| Male | 6794 (48.1) | 342 (48.4) |

| Female | 7337 (51.9) | 365 (51.6) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||

| White | 11,907 (84.3) | 596 (84.3) |

| Asian | 469 (3.3) | 44 (6.2) |

| Black | 442 (3.1) | 30 (4.2) |

| Mixed | 168 (1.2) | 5 (0.7) |

| Other | 203 (1.4) | 11 (1.6) |

| Unknown | 942 (6.7) | 21 (3.0) |

| Deprivation (IMD), n (%) | ||

| 1st quintile (least deprived) | 2253 (15.9) | 79 (11.2) |

| 2nd quintile | 2595 (18.4) | 122 (17.3) |

| 3rd quintile | 2745 (19.4) | 124 (17.5) |

| 4th quintile | 3194 (22.6) | 176 (24.5) |

| 5th quintile (most deprived) | 3319 (23.5) | 206 (29.1) |

| Missing | 25 (0.2) | 0 (0) |

| Follow-up length (years) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 5.03 (4.57) | 9.17 (4.87) |

| Median (minimum–maximum) | 3.63 (0.003–25.46) | 8.85 (0.16–25.66) |

| Family history of diabetes, n (%) | 1105 (7.8) | 100 (14.1) |

| Comorbidities | ||

| Cardiovascular disease, n (%) | 823 (5.8) | 61 (8.6) |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 1617 (11.4) | 146 (20.7) |

| Learning disability, n (%) | 141 (1.0) | 3 (0.4) |

| Dementia, n (%) | 257 (1.8) | 6 (0.9) |

| Charlson Index score, mean (SD) | 0.36 (0.66) | 0.38 (0.65) |

| Medications, n (%) | ||

| Antidepressants | 7869 (55.7) | 419 (59.3) |

| Antipsychotics | ||

| Typical | 1530 (10.4) | 135 (19.1) |

| Atypical | 3976 (28.1) | 224 (31.7) |

| Antihypertensive | 2402 (17.0) | 212 (30.0) |

| Lipid-lowering drugs | 976 (6.9) | 86 (12.2) |

| Statins | 940 (6.7) | 84 (11.9) |

| Lifestyle factors, n (%) | ||

| Smoking | ||

| Non-smoker | 2355 (16.7) | 119 (16.8) |

| Ex-smoker | 1299 (9.2) | 63 (8.9) |

| Current smoker | 3423 (24.2) | 145 (20.5) |

| Missing | 7054 (49.9) | 380 (53.8) |

| Drinking | ||

| Non-drinker | 931 (6.6) | 47 (6.7) |

| Ex-drinker | 342 (2.4) | 19 (2.7) |

| Current drinker | 2717 (19.2) | 108 (15.3) |

| Missing | 10,141 (71.8) | 533 (75.4) |

| Substance use | 424 (3.0) | 13 (1.8) |

| Biometric measures | ||

| BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 26.42 (6.24) | 31.57 (7.30) |

| < 20, n (%) | 594 (4.2) | 8 (1.1) |

| 20–24, n (%) | 1727 (12.2) | 42 (5.9) |

| 25–29, n (%) | 1426 (10.1) | 88 (12.5) |

| 30–40, n (%) | 989 (7.0) | 115 (16.3) |

| > 40, n (%) | 180 (1.3) | 39 (5.5) |

| Missing, n (%) | 9215 (65.2) | 415 (58.7) |

| HbA1c (%),a mean (SD) | 5.77 (1.19) | 7.18 (1.86) |

| ≤ 7.5, n (%) | 520 (3.7) | 41 (5.8) |

| > 7.5, n (%) | 19 (0.1) | 12 (1.7) |

| Missing | 13,592 (96.2) | 654 (92.5) |

| Cholesterol (mmol/l), mean (SD) | 5.19 (1.16) | 5.39 (1.36) |

| ≤ 5, n (%) | 1371 (9.7) | 84 (11.9) |

| > 5, n (%) | 1463 (10.4) | 115 (16.3) |

| Missing | 11,297 (79.9) | 508 (71.9) |

| Diastolic blood pressure (mmHg), mean (SD) | 77.39 (10.42) | 81.24 (10.56) |

| ≤ 80, n (%) | 5117 (36.2) | 239 (33.8) |

| > 80, n (%) | 2394 (16.9) | 188 (26.6) |

| Missing, n (%) | 6620 (46.9) | 280 (39.6) |

| Systolic blood pressure (mmHg), mean (SD) | 128.05 (18.50) | 134.59 (19.27) |

| ≤ 140, n (%) | 6054 (42.8) | 298 (42.2) |

| > 140, n (%) | 1457 (10.3) | 129 (18.3) |

| Missing, n (%) | 6620 (46.9) | 280 (39.6) |

Of the 14,838 people with SMI at baseline, 707 (4.8%) were diagnosed with T2DM in the follow-up period. This rate is lower than estimates from previous studies,44,122 and led us to further explore the sample characteristics.

The estimate above excludes those who developed diabetes before the onset of SMI. We found that, if we removed the criterion to have the recorded T2DM diagnosis after the diagnosis of SMI, in the 15,984 eligible patients whose SMI diagnosis was within the UTS data period, 1452 (9.1%) had a diagnosis of T2DM; of these, 782 (53.9%) had SMI diagnosed before T2DM and 670 (46.1%) had SMI diagnosed after or on the same day as T2DM. These figures are comparable to findings from the 2016–17 National Diabetes Audit (NDA),123 which reported that 34.9% of people with SMI and T2DM were diagnosed with SMI first, but are unexpected, as it is generally thought, from clinical experience, that most people with comorbid SMI and diabetes develop SMI first.

In the total sample of 29,281 people with SMI (not restricted to the UTS period), we found that 2984 (10.2%) patients had T2DM, and that 2209 (74.0%) of these had SMI before T2DM, which is more consistent with reported prevalence in the literature and with experience of diagnosis order from clinical practice. This demonstrated that, by restricting SMI diagnosis within the UTS data period in our initial analysis, we selectively excluded patients diagnosed with SMI at an earlier age; therefore, the patients remaining in the sample were more likely to have late-onset SMI.

Using the restricted UTS sample of 14,838, people who developed T2DM were diagnosed with SMI at an older age were more likely to be of Asian or black ethnicity and were more likely to live in the most deprived neighbourhoods than patients with no record of T2DM. Furthermore, people with T2DM had a higher baseline prevalence of cardiovascular disease and hypertension and were more likely to have been prescribed the medications under investigation.

Table 5 also shows that a large proportion of the sample had no baseline records for lifestyle factors and biometric measures. Based only on available data, the descriptive statistics showed that people with T2DM were more likely to be overweight; to have higher baseline levels of blood pressure, cholesterol and HbA1c; and to have a family history of diabetes.

Regression analyses results for the risk factors for development of type 2 diabetes

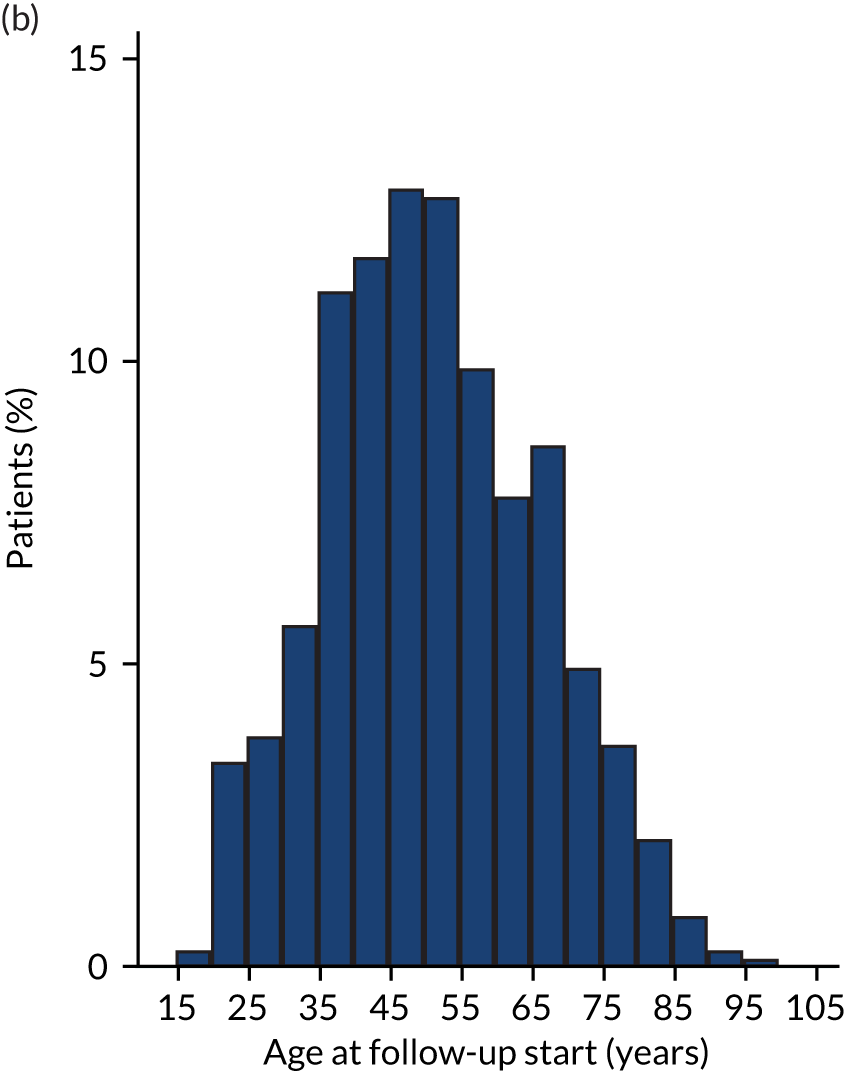

Regression results are summarised in Table 6, and Appendix 3, Figure 10, illustrates the non-linear impact of age on the risk of diabetes.

| Adjusted risk factor | Logistic regression | Cox proportional hazard regression | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Core model | Extended model | Core model | Extended model | |||||||||

| OR | 95% CI | p-value | OR | 95% CI | p-value | HR | 95% CI | p-value | HR | 95% CI | p-value | |

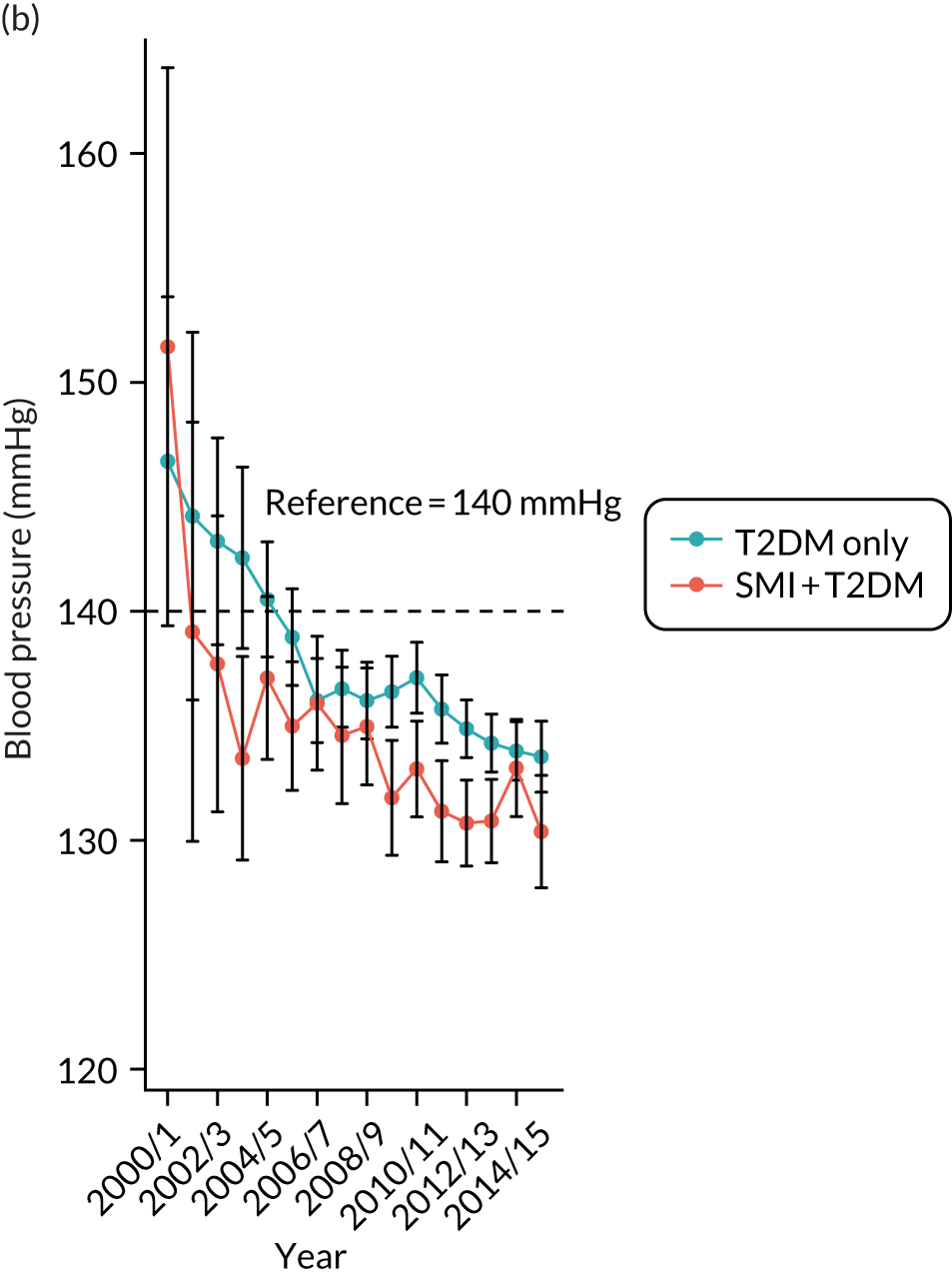

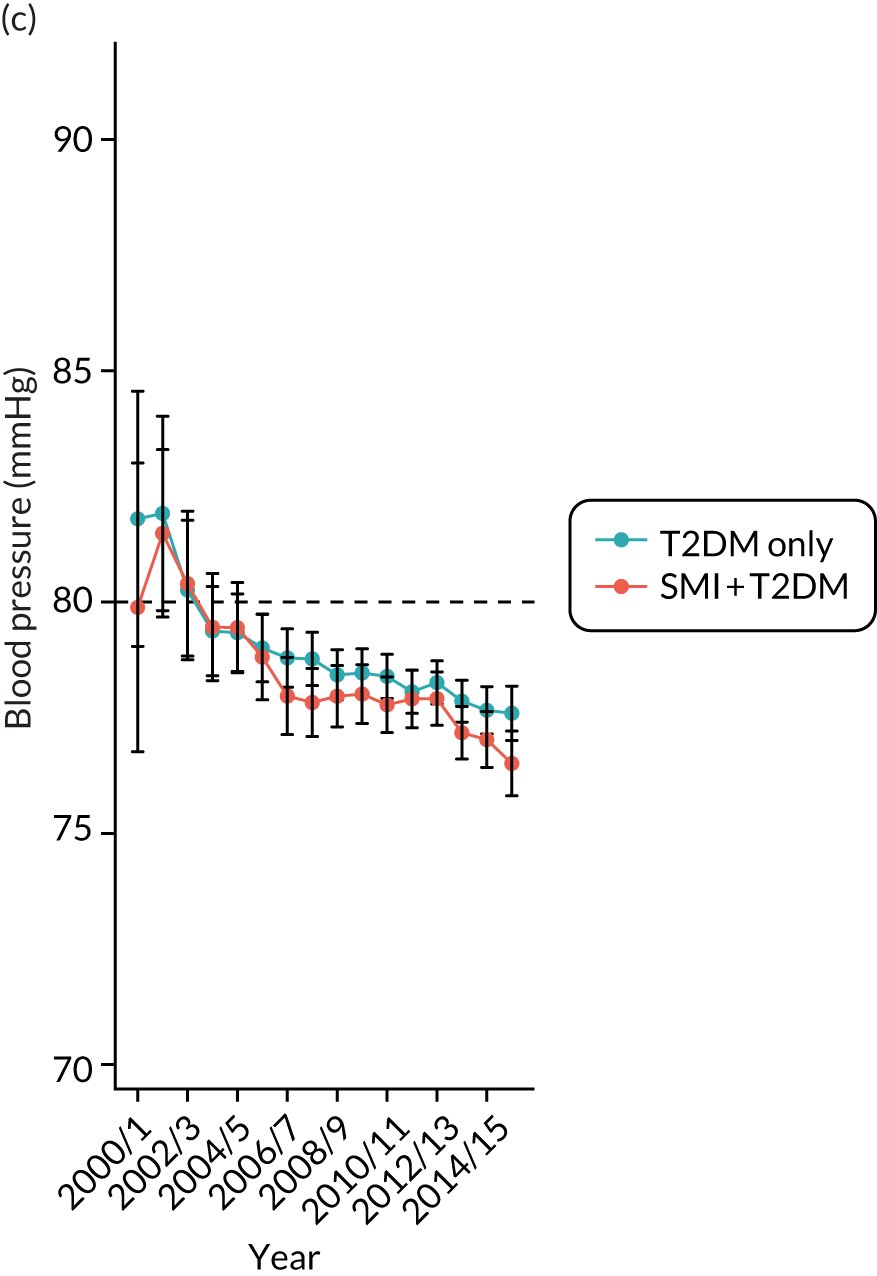

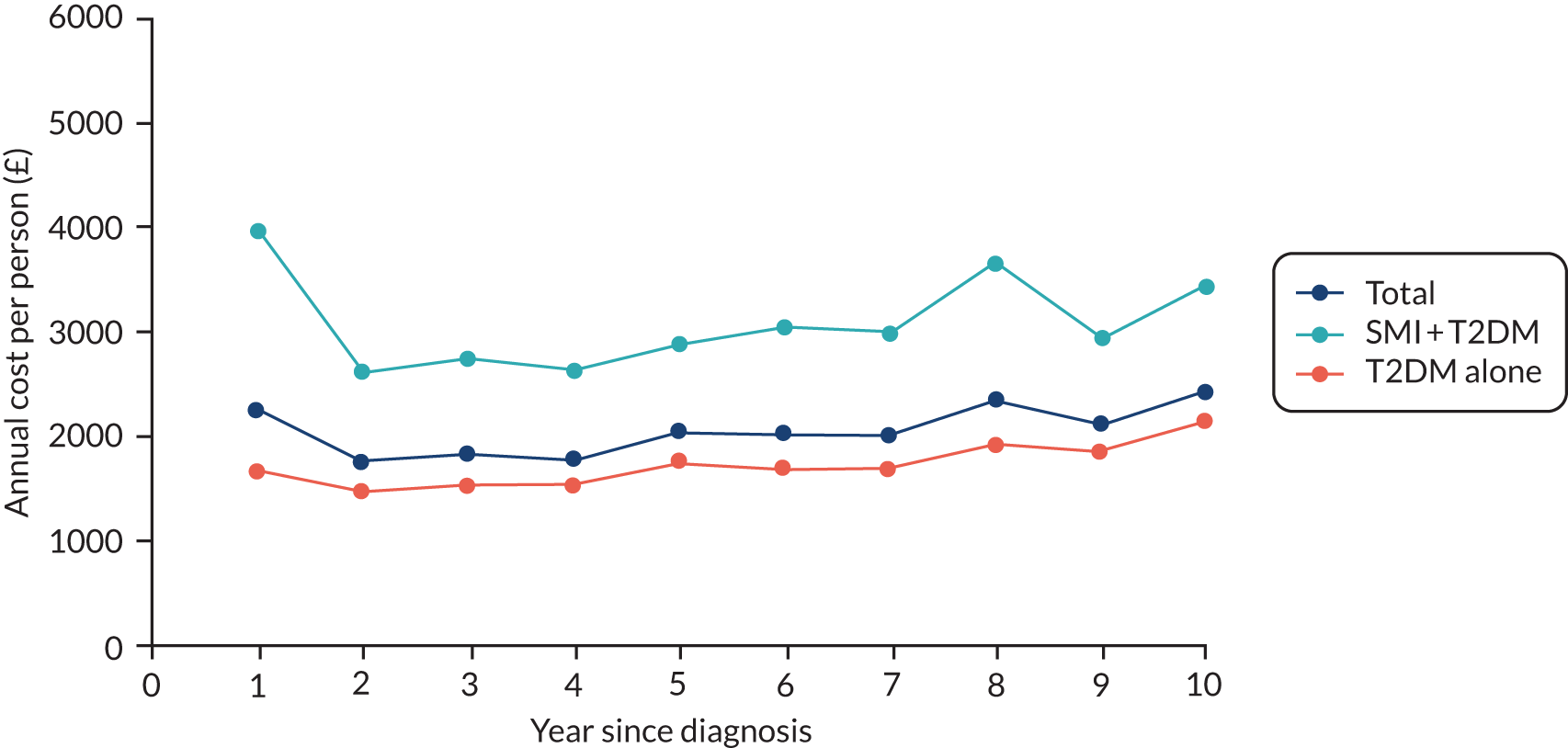

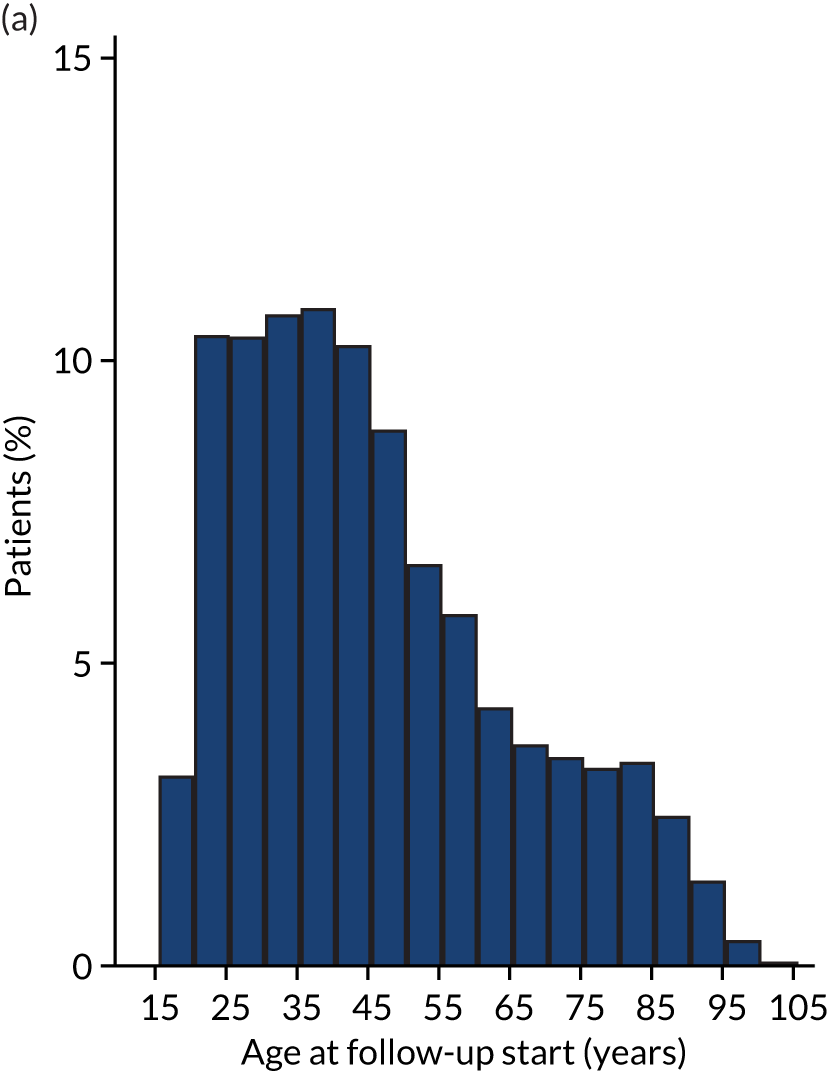

| Age (years) (at follow-up start) | 1.171 | 1.135 to 1.207 | < 0.001 | 1.150 | 1.114 to 1.187 | < 0.001 | 1.159 | 1.125 to 1.194 | < 0.001 | 1.141 | 1.107 to 1.177 | < 0.001 |