Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 15/144/51. The contractual start date was in July 2017. The final report began editorial review in August 2020 and was accepted for publication in March 2021. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research, or similar, and contains language which may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2021 Towers et al. This work was produced by Towers et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2021 Towers et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background and rationale: the importance of measuring the contribution of care homes to the quality-of-life outcomes of older residents

Over 425,000 older people in England live in care homes because they have significant long-term health problems. 1 Many have reduced cognitive functioning, frailty and difficulties with communication (e.g. as a result of dementia) and live with multiple long-term health conditions. 2 Over one-third of those living in care homes will pay for their own care either completely or in part. 3 Otherwise, residents are supported by public funding: half of all care home residents are fully supported through their local authority, and the rest are supported either by NHS continuing care or through some combination of local authority, charity and NHS support. 3 In England, care homes operate in a quasi-market,4 with around 90% provided under contract from private and voluntary sector providers. Although care homes collect and use data about the health and care needs of their residents for their own records and regulatory processes, there is no single, agreed, minimum data set in the UK. 5 Furthermore, owing partly to the distinction between health and social care systems in the UK, data about care home residents held by primary and secondary care are not easily linked with data held by social care providers. Therefore, in such a large and fragmented system, measuring and improving care quality is a challenge.

How well residents’ personal and health-related needs are met is affected by the quality of care provided. A general definition of quality of social care services is that it consists of both quality of care and quality of life aspects. 6,7 Quality of care relates to the technical aspects of caring provided by the service itself, and is largely based on the staff working in the service, such as their level of training and skills, their responsiveness and the continuity of care provided. 7,8 Quality of life is subjective and is often related to residents’ satisfaction with life, including their level of control, privacy, interactions, safety and ability to go about their daily lives. 7

Service users will be involved in the co-production of many services (e.g. washing and dressing), and as a result the definition and measurement of social care quality have been the subject of academic debate for some time. 7 According to the Donabedian model of care,9 to assess quality, we require indicators that are sensitive to variations in quality relating to the structure, process and outcomes of care. Structural quality indicators are organisational characteristics of the care provider, for example the care home environment/building and the staff-to-resident ratios on site. Process quality indicators relate to the way the care is delivered by care workers, for example whether or not staff are caring, timely and skilled. Outcome indicators relate to the results of the care for the service user, for example whether or not the person is clean, dressed and fed, feels in control of their daily life and is able to spend their time doing things they value and enjoy.

The Care Act 201410 emphasises the importance of measuring and improving the well-being of users and their family carers, and previous research has shown that this is highly valued by older people and their families when considering a care home. 11 However, measuring person-centred outcomes is challenging, particularly when trying to assess the quality of life of people with cognitive impairment and communication difficulties. 2 The high prevalence of cognitive impairment in this population2 means that self-report is unlikely to capture the views of residents with both the greatest need and the highest capacity to benefit. Proxy report, for example by staff, rarely agrees strongly with residents’ own views12 and is best considered a different perspective rather than a replacement for a resident’s own voice. This places those with the greatest need at risk of living with under-reported and under-managed health and social care-related quality-of-life outcomes.

The Adult Social Care Outcomes Toolkit: a method for measuring the social care-related quality of life of service users

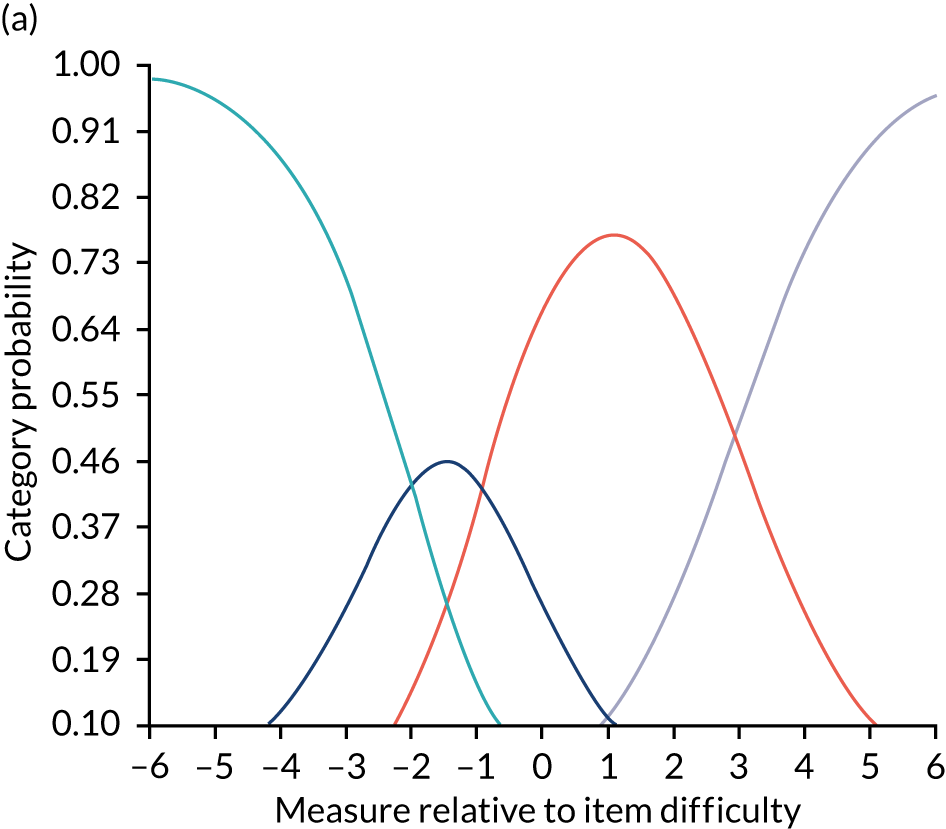

The Adult Social Care Outcomes Toolkit (ASCOT) was developed to measure the ‘social care-related quality of life’ (SCRQoL) of service users. 13 ASCOT is a preference-weighted utility measure with eight conceptually distinct domains of SCRQoL, which are described in Table 1. Each domain has four response options, reflecting four outcome states (ideal state, no unmet needs, some unmet needs and high unmet needs). Different tools are available, including self-completion questionnaires, interview schedules and a mixed-methods tool for use in care homes. The self-completion questionnaires and interviews are also available in an easy-read format for adults who have developmental and intellectual disabilities (www.pssru.ac.uk/ascot/).

| Domain | Definition |

|---|---|

| Basic domains | |

| Food and drink | The service user feels that he/she has a nutritious, varied and culturally appropriate diet with enough food and drink that he/she enjoys at regular and timely intervals |

| Accommodation cleanliness and comfort | The service user feels that their home environment, including all the rooms, is clean and comfortable |

| Personal cleanliness and comfort | The service user feels that he/she is personally clean and comfortable and looks presentable or, at best, is dressed and groomed in a way that reflects his/her personal preferences |

| Personal safety | The service user feels safe and secure. This means being free from fear of abuse, falling or other physical harm |

| Higher-order domains | |

| Control over daily life | The service user can choose what to do and when to do it, having control over his/her daily life and activities |

| Social participation and involvement | The service user is content with their social situation, where social situation is taken to mean the sustenance of meaningful relationships with friends, family and feeling involved or part of a community, should this be important to the service user |

| Occupation | The service user is sufficiently occupied in a range of meaningful activities, whether this be formal employment, unpaid work, caring for others or leisure activities |

| Dignity | The negative and positive psychological impact of support and care on the service user’s personal sense of significance |

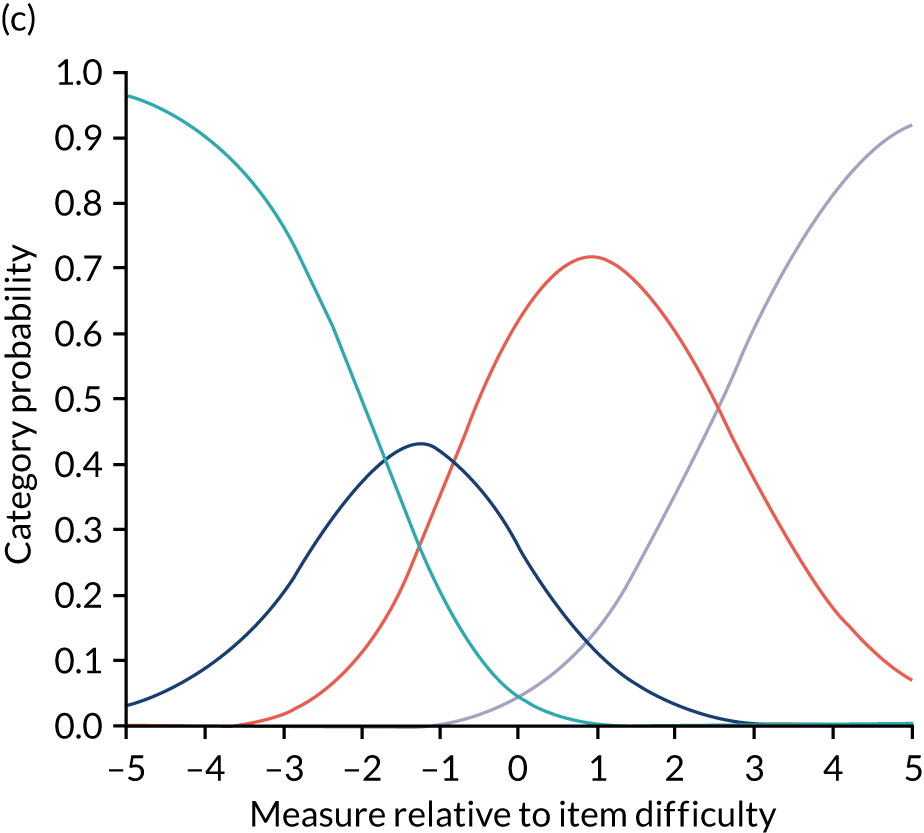

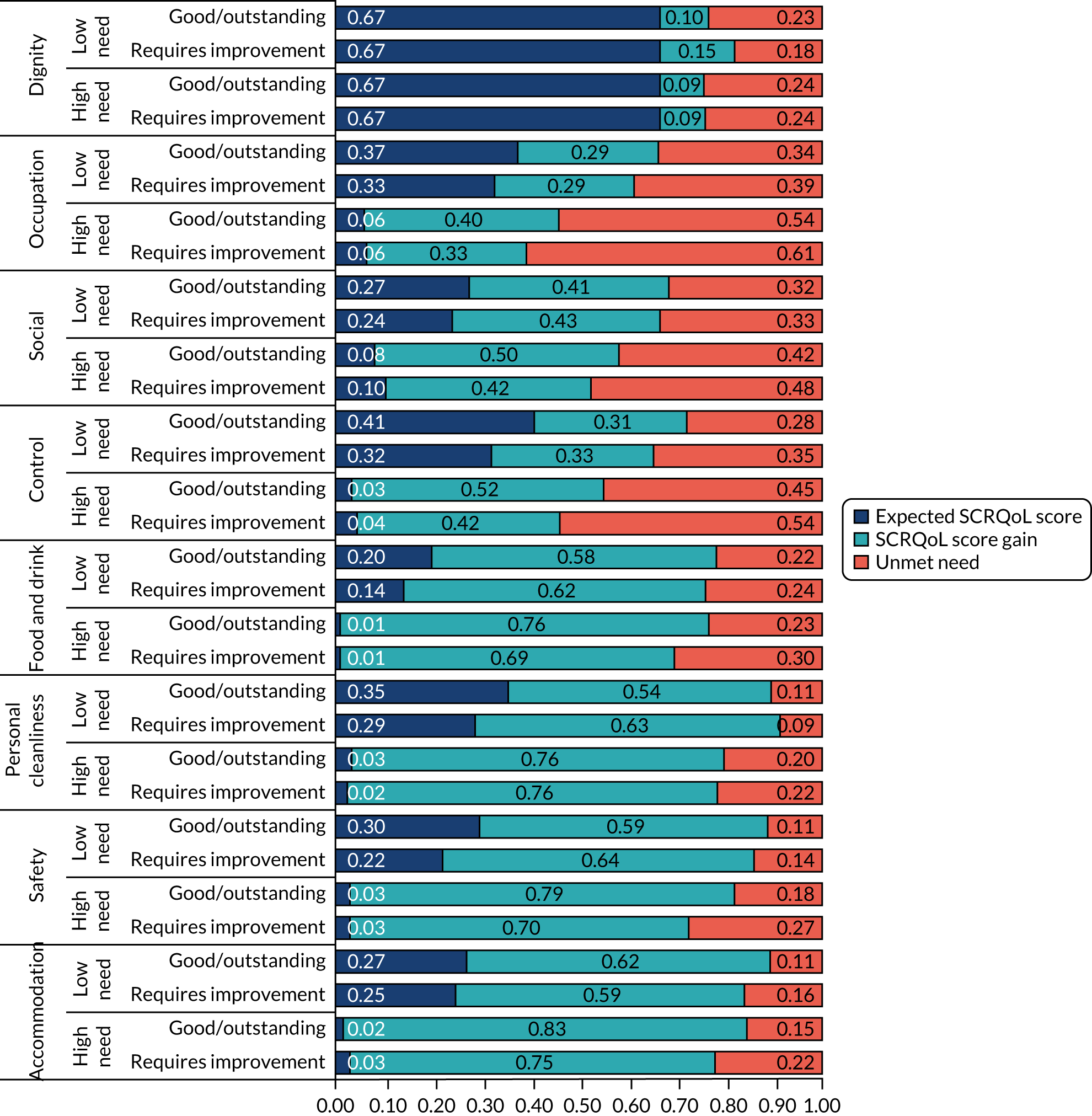

Adult Social Care Outcomes Toolkit scoring

Three scores can be derived from the ASCOT tools: current SCRQoL, expected SCRQoL and SCRQoL gain. All ASCOT tools measure current SCRQoL, which asks about the person’s situation now. The interview and mixed-methods tools also ask what the situation would be if services were not in place to support the person and nobody else stepped in. We call this expected SCRQoL. By taking the expected SCRQoL scores away from the current SCRQoL scores, we can estimate the impact that the service(s) are having on the person’s quality of life, which we call SCRQoL gain:

As ASCOT is a preference-weighted measure, responses to each domain for current and expected SCRQoL are weighted to reflect English population preferences and then entered into an algorithm (Equation 2) to calculate a score ranging from − 0.17 to 1:13

Scores of 1 represent optimum or ‘ideal’ SCRQoL and scores of 0 indicate a state that, according to the preferences exhibited by the general population, is equivalent to being dead. Negative scores indicate a state worse than being dead. 13

Psychometric properties of the Adult Social Care Outcomes Toolkit

Psychometric testing has consistently revealed that ASCOT has acceptable internal reliability. 13,15 Research with a wide range of social care user populations, including older adults, younger adults and adults with physical and sensory impairments, has established its validity, feasibility and reliability. 13,15,16

Expected SCRQoL, which is still relatively uncommon in quality-of-life research, has been shown to be a reliable indicator of social care need, as it is highly correlated with functional ability. 13,17 Recent work exploring the feasibility and validity of the expected SCRQoL questions found the approach both feasible and valid with a sample of social care users, with many people saying that they found the questions easy or very easy to answer. 17 Nonetheless, it is not without its limitations. In particular, the expected SCRQoL questions are not suitable for people with limited or low cognition. 17 Given that up to 80% of care home residents18 are believed to be living with dementia, these questions are entirely unsuitable for use in interviews with most care home residents.

ASCOT-CH4 and the social care-related quality of life of care home residents

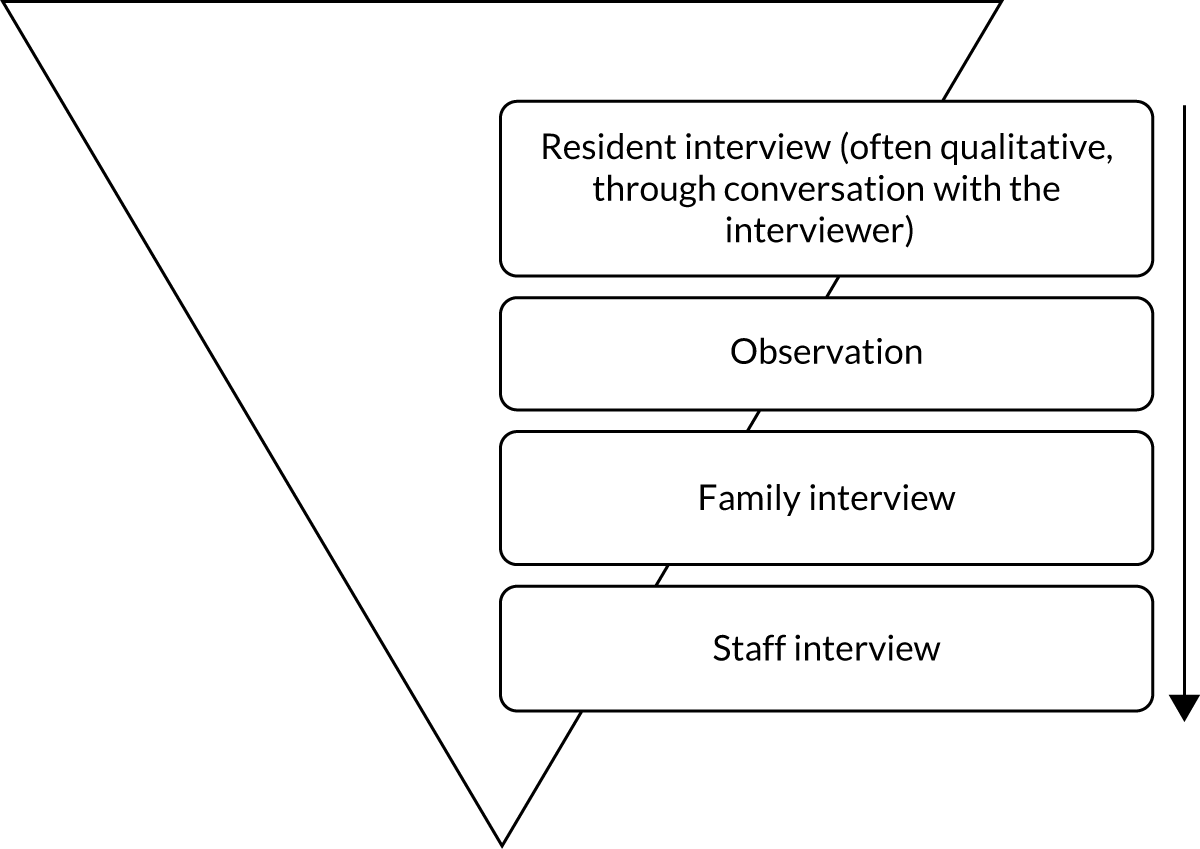

To measure the impact of services in this population, we needed to employ a mixed-methods approach. The mixed-methods version for use in care homes is called ASCOT-CH4 (Adult Social Care Outcomes Toolkit Care Homes-four levels; herein referred to as CH4) and was designed for residents who cannot self-report. Methodologically, CH4 involves structured observations of residents, alongside a staff proxy interview (for each resident; see Report Supplementary Material 12), a resident interview (to the extent that they are able; see Report Supplementary Material 11, 13 and 14) and a family proxy interview (where possible; see Report Supplementary Material 12). (See Appendix 1 for a detailed account of this method.) The mixed-methods approach has been found to have excellent face validity and inter-rater reliability. 19

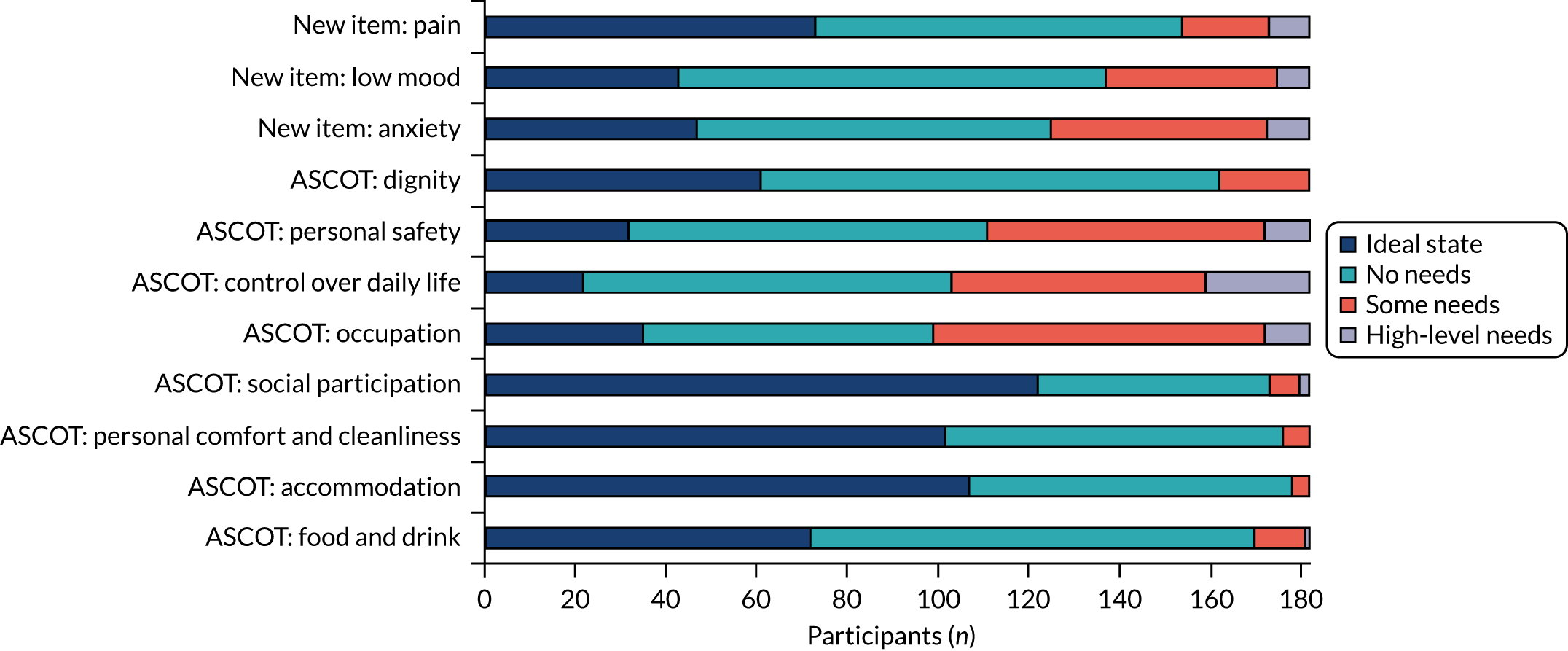

Previous studies taking this approach19–22 have found that residents’ needs are mostly met in the ‘basic’ domains (safety, accommodation, food and drink and personal cleanliness). However, there is evidence of unmet needs in the higher-order domains (Control over daily life, Social participation and engagement in meaningful Occupation), with some residents spending long periods of time disengaged. Staff recognise the importance of being occupied and staying socially active, but note that many residents decline to take part in organised activities or appear too tired and withdrawn. 21 The impact of skilled care and support to help and encourage people to remain active and engaged should not be underestimated. 23,24 However, at the same time, we should not ignore the possible contribution of unmet needs to other areas, including aspects of residents’ health-related quality of life (HRQoL). For example, unrecognised depression, anxiety or pain may lead to unmet needs in these domains.

Health-related quality of life: pain, anxiety and depression in care homes

Pain

Studies estimating the prevalence of pain among the care home population suggest that it is common. Indeed, this is the case for all groups of older people because they experience higher levels of chronic disease than younger age groups. 25 The actual pain prevalence estimates for resident populations vary considerably, although the usual estimate is between 30% and 60%. 26–39 A recent large-scale study using validated pain scales in England suggested that the prevalence of pain in this population is around 35%. 33

Although at least one-third of residents live with and experience pain, the consensus is that pain is often under-recognised and undertreated in care homes. 40–43 This is likely to be attributable to a variety of causal factors, including resource considerations and the attitudes of health-care professionals. 44 However, difficulty in detecting and assessing pain is one of the most widely cited reasons for this under-treatment. 44–46 Pain is a subjective experience47,48 and cannot be measured adequately using an objective diagnostic test, which is why mainstream approaches rely on self-reporting. As McCaffery48 notes:

Pain is whatever the experiencing person says it is, existing whenever he says it does.

McCaffery48

There are, however, a number of challenges to enabling care home residents to self-report and share their subjective experiences of pain. Although impairments more common in later life, such as hearing and sight loss, do present challenges,49 the key challenge to measuring these experiences is that a high proportion of residents live with dementia. 18 The characteristics of the group of conditions classified as dementia mean that the ability to communicate experience may be limited, particularly for those living with more severe dementia, and, thus, either research or diagnostic methods that rely on this may not be particularly appropriate for this group. 46,50–54 It is not, however, just the ability to communicate clearly that is required for accurate self-report. The resident must understand the request, be able to recall pain events – often in a given time frame – and interpret that internal experience with reference to an external framework. 55 All of these can be challenging for people living with dementia.

There is evidence that pain is under-recognised among residents living with dementia in studies comparing the numbers of older adults in care home settings who receive pain medication. Morrison and Sui56 found that, following hip fractures, cognitively intact older people received three times the level of medication received by older people living with dementia. This finding was echoed in studies conducted in Canada57 and the USA,58 both of which concluded that residents living with dementia in nursing homes were less likely to receive pain medication than residents who did not have dementia. This has also been found in other contexts, such as in the treatment of scabies. 59

Pain is associated with decreased functional ability, lower levels of activity and socialising, higher levels of falls, reduced appetite, poorer sleep, greater levels of irritability, aggression, anxiety and depression, and resistance to care. 25,60–66 Unsurprisingly, untreated pain has been found to be associated with poorer overall quality of life. 30,33,64,67,68 Specifically, for older adults living with dementia, untreated pain has been shown to exacerbate the symptoms of dementia, such as impaired cognition. 30,64,69,70

Depression and anxiety

Estimates in studies looking at the prevalence of mental health conditions suggest that large numbers of residents live with a mental health condition. The most common of these conditions is depression. 71–73 However, as with pain, estimates vary, complicated by differences in how studies define and measure depression. At the lower end is an international prevalence estimate of just under 10%; at the upper end this is just over 50%. 74–81 Considering specifically residents with a diagnosis of dementia, recent work in the UK has estimated that the prevalence of depression among this group is at the middle and lower end of this range. One study has estimated that 26.5% of older people living in residential care and 29.6% of older people residing in nursing homes experience depression,82 and another study places this figure at around 10% of the care home population. 77

Anxiety in later life has historically received less attention than depression, despite being quite common. 83–85 A systematic review in 201075 found only three studies that estimated anxiety among older adult care home residents. A review in 2016 found 18 studies,86 a number that, although still very small, suggests that studies focusing on anxiety in care homes are becoming more commonplace. The reviews reported the prevalence of anxiety disorders among residents as somewhere between 3.2% and 20%. However, clinically significant anxiety symptoms were found to be more widespread, with prevalence across studies ranging from 6.5% to 58.4%.

Living with anxiety and/or depression can have a range of negative impacts on an older person’s life, including lower quality of life,68,87–89 lower sociability and greater loneliness,90 and poorer health, including increased pain. 91–95 Anxiety and depression have also been linked to sleep problems and smoking,84,96,97 loss of independence and functional ability,87,98–103 cognitive decline,104–107 behavioural problems,94,108 suicide109 and higher mortality levels. 110–112

Even though the impacts of living with depression and anxiety in later life are, as outlined above, well documented, and the conditions themselves are often treatable,113,114 there is a large body of evidence suggesting that depression, in particular, is both under-recognised and undertreated or poorly managed, particularly in residents who live with dementia. 107,115–122 Less evidence exists around the under-recognition and undertreatment of anxiety in care home residents, but, given the lack of attention that anxiety has received in this setting,86 it is likely that both of these are very common.

As with pain, the assessment of depression and anxiety in care homes is made more challenging by the characteristics and symptoms of dementia. 114,123 However, there are other challenges, including a lack of suitable tools124 (as many of the tools available have been developed for younger populations), lack of training and knowledge on depression and anxiety among care home staff115,125 and the difficulty in isolating symptoms of depression and anxiety from other conditions and somatic complaints. 126

A new approach to measuring pain, anxiety and depression in care homes

Although measures of pain, anxiety or depression have been used with older people and those living in care homes, unlike the ASCOT for SCRQoL, none of them aims to measure the impact of social care services. Existing measures focus on the person’s current situation or diagnosing a condition without any reference to input from services or support and without a mechanism for attributing improvements or change in outcomes to those services. There is also no evidence to suggest that tools have attempted to use innovative methods or adapted forms of communication to support the inclusion of people with cognitive or communication difficulties. This is important in care homes, where many residents live with dementia and have physical and sensory impairments that make self-completion or self-report challenging or impossible19,127 and places care home residents at risk of living with unmet needs in both their health and social care-related quality of life. 87,128–130

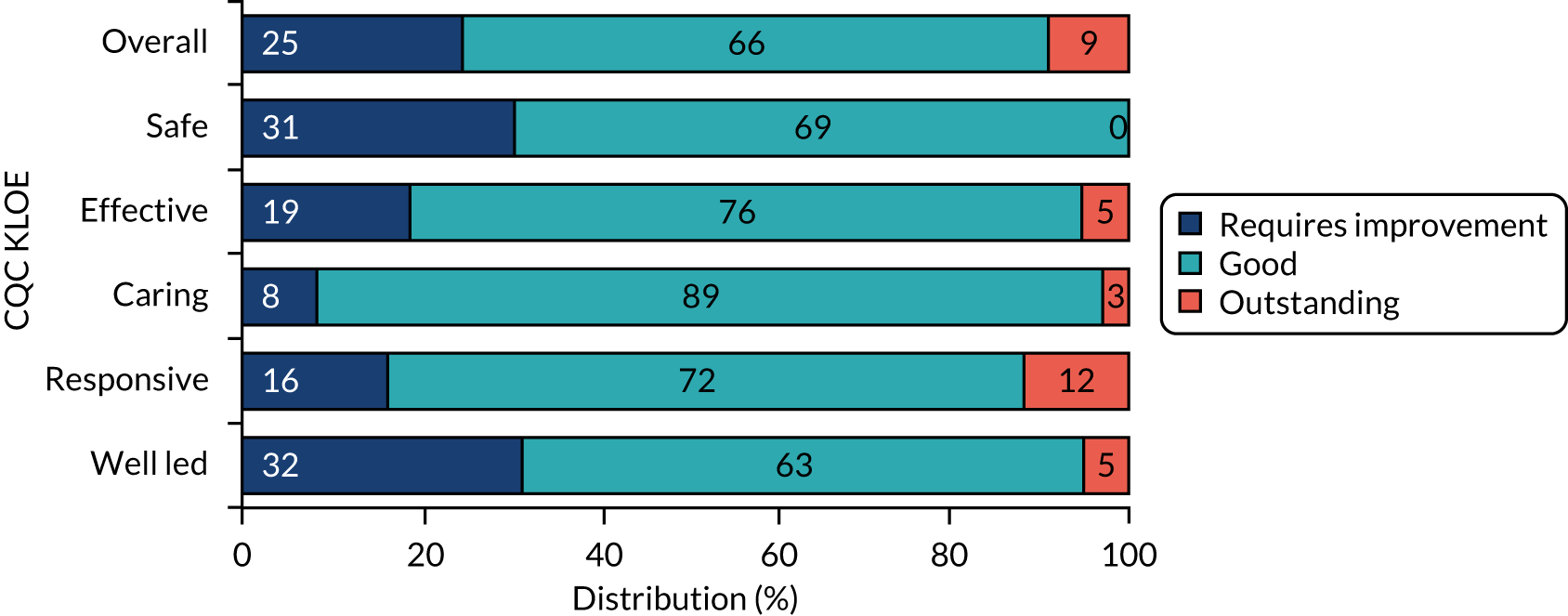

Measuring the quality of care homes

In England, the quality of adult social care provision is regulated by the Care Quality Commission (CQC), which conducts inspections and awards publicly available ratings to drive up quality and inform service user choice. Quality ratings are based on an assessment of evidence gathered using five key lines of enquiry (KLOEs): ‘safe’, ‘effective’, ‘caring’, ‘responsive’ and ‘well led’ (Table 2). CQC inspectors draw evidence from four sources of information: CQC’s ongoing relationship with the provider, ongoing local feedback and concerns, pre-inspection planning and evidence-gathering, and the inspection visit. During site visits, the inspector:

. . . speaks with people using the service and their visitors, staff, volunteers and visiting professionals to assess all of the key questions. They also review relevant records and inspect the layout, safety, cleanliness and suitability of the premises, facilities and equipment . . .

Care Quality Commission. 132

An overall rating is aggregated from ratings for each of the five KLOEs, with ratings awarded on a four-point scale: ‘outstanding’, ‘good’, ‘requires improvement’ or ‘inadequate’. 132

| KLOE | Definition |

|---|---|

| Safe | People are protected from abuse and avoidable harm |

| Effective | People’s care, treatment and support achieves good outcomes, promotes a good quality of life and is based on the best-available evidence |

| Caring | The service involves and treats people with compassion, kindness, dignity and respect |

| Responsive | Services meet people’s needs |

| Well led | The leadership, management and governance of the organisation assures the delivery of high-quality and person-centred care, supports learning and innovation, and promotes an open and fair culture |

Social care establishments are inspected by the CQC between 6 and 12 months after they start (or resume service) and regularly thereafter. The frequency of inspection depends on the establishment’s rating. Establishments rated ‘good’ and ‘outstanding’ are inspected within 30 months of the last comprehensive inspection report and those rated ‘requires improvement’ are inspected within 12 months of the last inspection report, with establishments rated ‘inadequate’ (or rated overall as ‘requires improvement’, but with at least one KLOE rated ‘inadequate’) inspected within 6 months of the last inspection report. These timescales are maximum time periods during which the CQC will return to inspect, but establishments may be inspected at any time. 132

Staff and quality of care

Quality of social care services varies for many reasons, but the nature and characteristics of the workforce, and their approaches to care, are likely to be major determinants. As noted above, quality of social care services is formed of quality of care, that is, technical aspects of care delivery, and quality of life, that is, individual resident aspects relating to their satisfaction with life and health and social care outcomes. The competency and quality of care home staff will directly influence the quality of care, given their duties and role. Care home staff are also likely to, at least indirectly, influence quality of life. For example, staff and staffing characteristics have been found to have an impact on satisfaction133,134 and the perceived quality of service in social care. 135

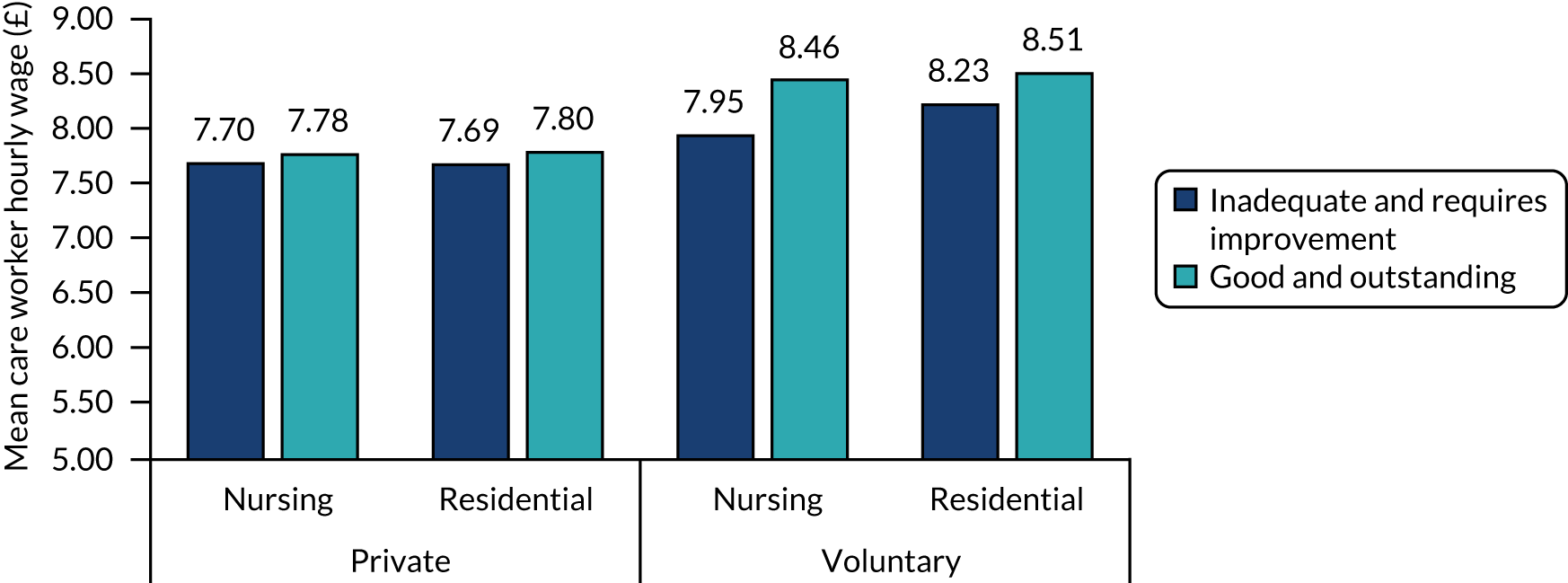

Staff in social care tend to be low paid, often at minimum wage, and there is a high staff turnover in social care in England. 136 Despite their low pay, staffing will account for a large proportion of costs in a care home, and in England this is typically 50–60% of revenue. 1 Working in care homes, particularly as a care worker, has often had a negative perception, as the role is seen as low paid and low skilled (i.e. little or no education required) and with little in the way of career progression. 137 However, there is growing recognition of the need to reframe the skills and identity of the social care workforce. 138 Staff working in social care tend to do so for intrinsic reasons and tend to have high levels of informal skills,139 and may accept a low wage because of their caring motive. 140

These workforce employment conditions could have a negative impact on care outcomes, given that issues of pay, training, status, terms and conditions are likely to influence quality. 141–143 More generally, economic theory provides a direct link between training, wages and the productivity of workers. 144,145

A small body of literature exists on the impact of workforce characteristics (e.g. staff turnover) on care home quality. 141,146,147 Much of this literature is US based and focuses on clinical markers of quality or other process measures, not on final outcomes or quality of life. Previous analyses of care homes in England found that quality had a significant positive relationship with staff retention and a significant negative relationship with job vacancies148 and that a lack of staff could lead to closure. 149 However, there is very little statistical evidence in England linking wages and training levels to care quality outcomes. Furthermore, only a very few analyses use appropriate statistical methods to address the potentially complex inter-relationship between quality and staffing. 150,151

Aims and objectives of the study

The overarching aim of the Measuring and Improving Care Home Quality (MiCareHQ) study was to assess how care home quality is affected by the way the care home workforce is organised, supported and managed. We sought to understand the relationship between workforce employment conditions and training, CQC quality ratings and the health- and care-related quality of life of care home residents.

The objectives were to:

-

develop and test measures of pain, anxiety and depression for residents unable to self-report [work packages (WPs) 1 and 2]

-

assess the extent to which CQC quality ratings of a home are consistent with indicators of residents’ quality of life (WPs 2 and 3)

-

assess the relationship between aspects of the staffing of care homes and the quality of care homes (WP3).

Overview of methods

MiCareHQ was a mixed-methods study, involving qualitative fieldwork and quantitative analysis in three interlinked WPs.

Work package 1: measuring health and social care-related quality of life

Aims

This WP aimed to develop and cognitively test new measures of pain, anxiety and depression, which could be used alongside CH4 in care homes with residents who cannot self-report.

Methods

A scoping review of existing measures, with a particular focus on tools that already incorporate observational methods was undertaken to inform the development of draft tools (see Chapter 2). The draft tools were shared with stakeholders (including care home staff) in focus groups in order to explore the face and construct validity of the items. Following revision, the new measures were cognitively tested with a sample of staff and family members of care home residents using a combination of verbal probing techniques and thinking aloud (see Chapter 3). 152 Lay co-researchers were involved in the focus groups and subsequent revisions of the new measures (see Chapter 7).

Work package 2: psychometric testing using the mixed-methods ASCOT with new health-related measures

Aims

This WP aimed to pilot and psychometrically test the new measures of pain, anxiety and low mood. It also collected information about care home residents’ care and HRQoL outcomes that fed into analysis in WP3.

Methods

Primary data collection was undertaken using a cross-sectional design, in which researchers spent time in each care home carrying out observations and interviews with staff, and (where possible) residents and family members using CH4. Additional data about the residents were collected from staff using questionnaires, including demographic information, health status and ability to complete activities of daily living (ADLs).

In total, 182 residents from 20 care homes for older adults (10 nursing and 10 residential) were recruited to the study from four local authorities in South East England. To explore the construct validity of the new health items developed in WP1, questionnaires also contained staff-rated, validated scales relating to these concepts so that we could explore hypothesised relationships with the new attributes in the analysis.

The results of the psychometric testing of the new CH4 items developed in WP1 are in Chapter 4.

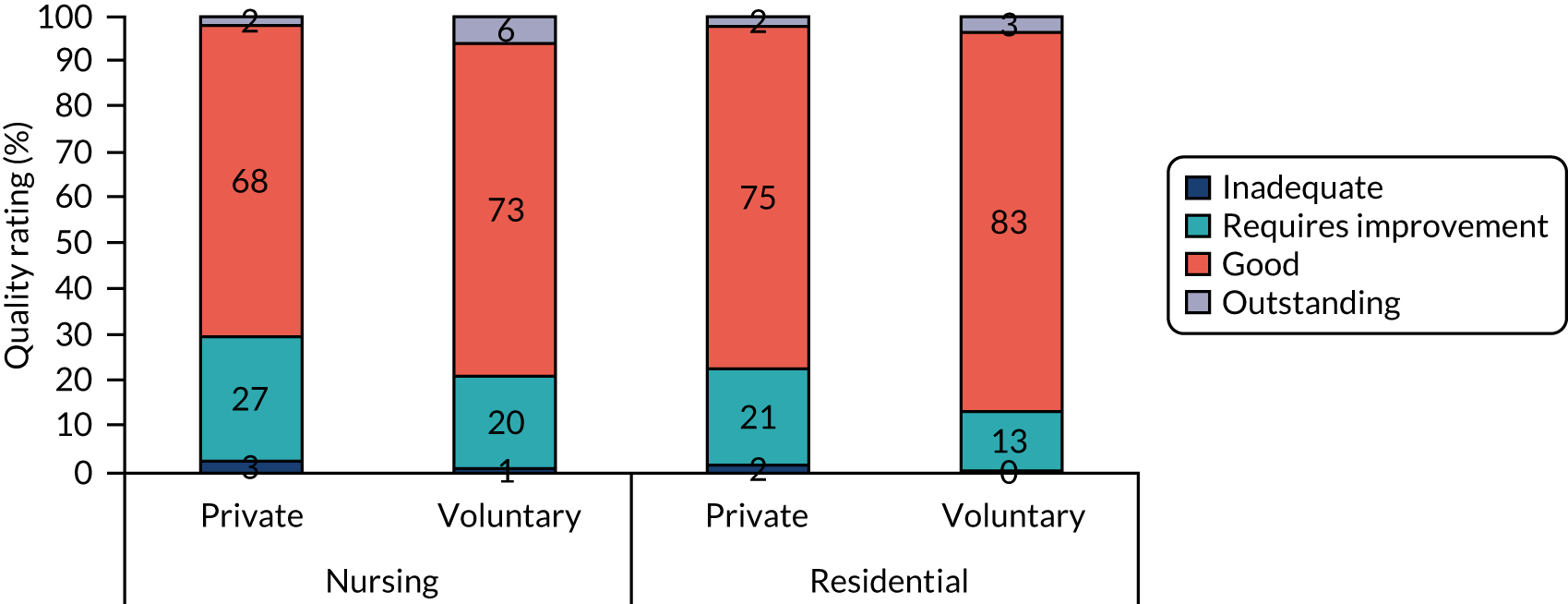

Work package 3: care home quality, resident outcomes and care workforce

Aims

This WP aimed to assess the relationship between care home quality and residents’ quality of life, and between care home quality and workforce characteristics and deployment.

Methods

Work package 3 used two approaches. First, resident outcome data were collected from two studies and used to model the relationship between CQC quality ratings and residents’ quality of life (see Chapter 5). Study 1 is the Measuring Outcomes Of Care Homes (MOOCH) project, funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) School for Social Care (2015–18). 20,153,154 This study recruited 294 older care home residents from 34 care homes (20 nursing and 14 residential) in two local authorities in England. Study 2 collected primary data as part of this research (see Chapter 4). Both studies used a cross-sectional design, in which researchers spent time in each care home carrying out observations and interviews with staff, and (where possible) residents and family members using CH4. Additional data about residents were collected from staff using questionnaires, including demographic information, health status and ability to complete ADLs.

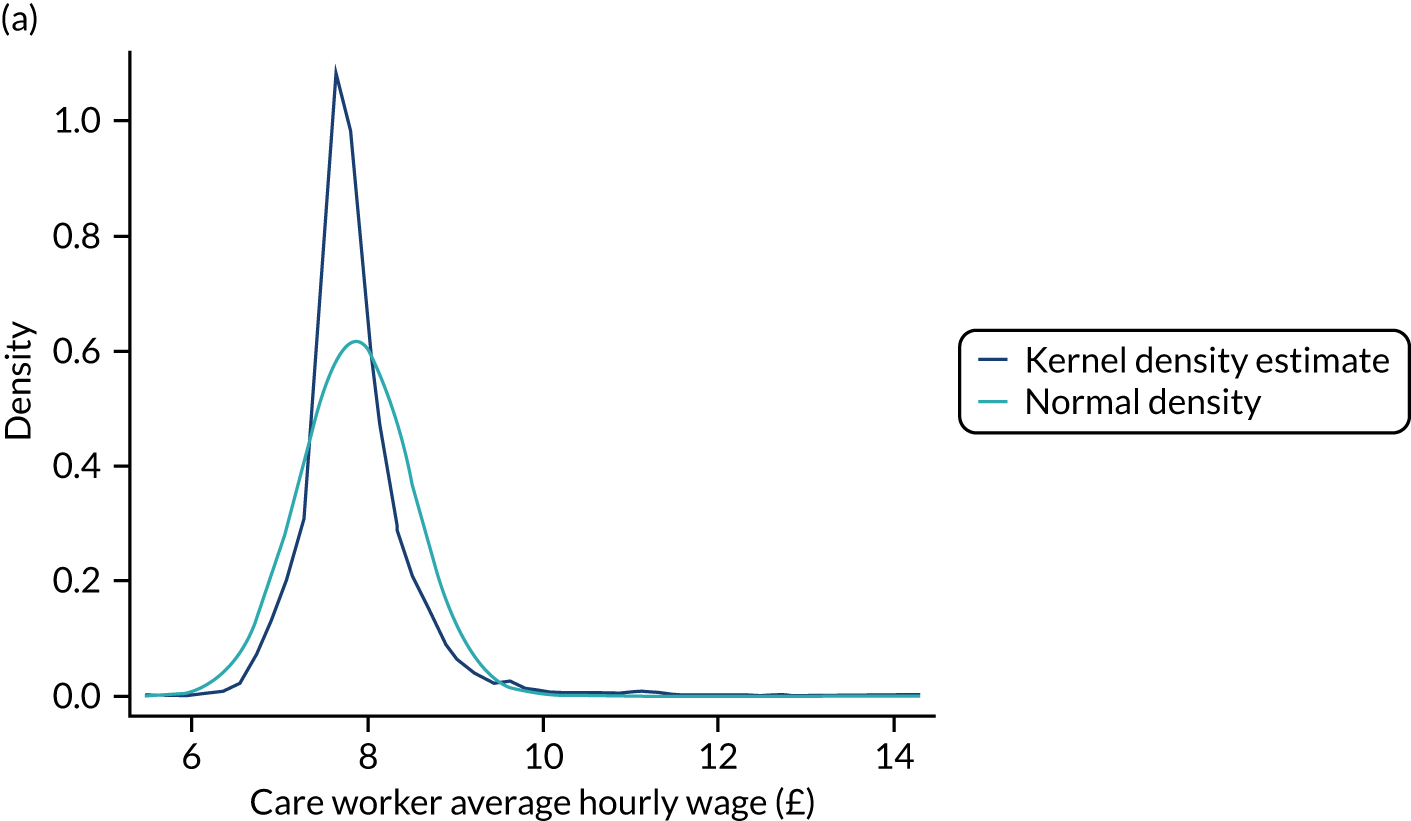

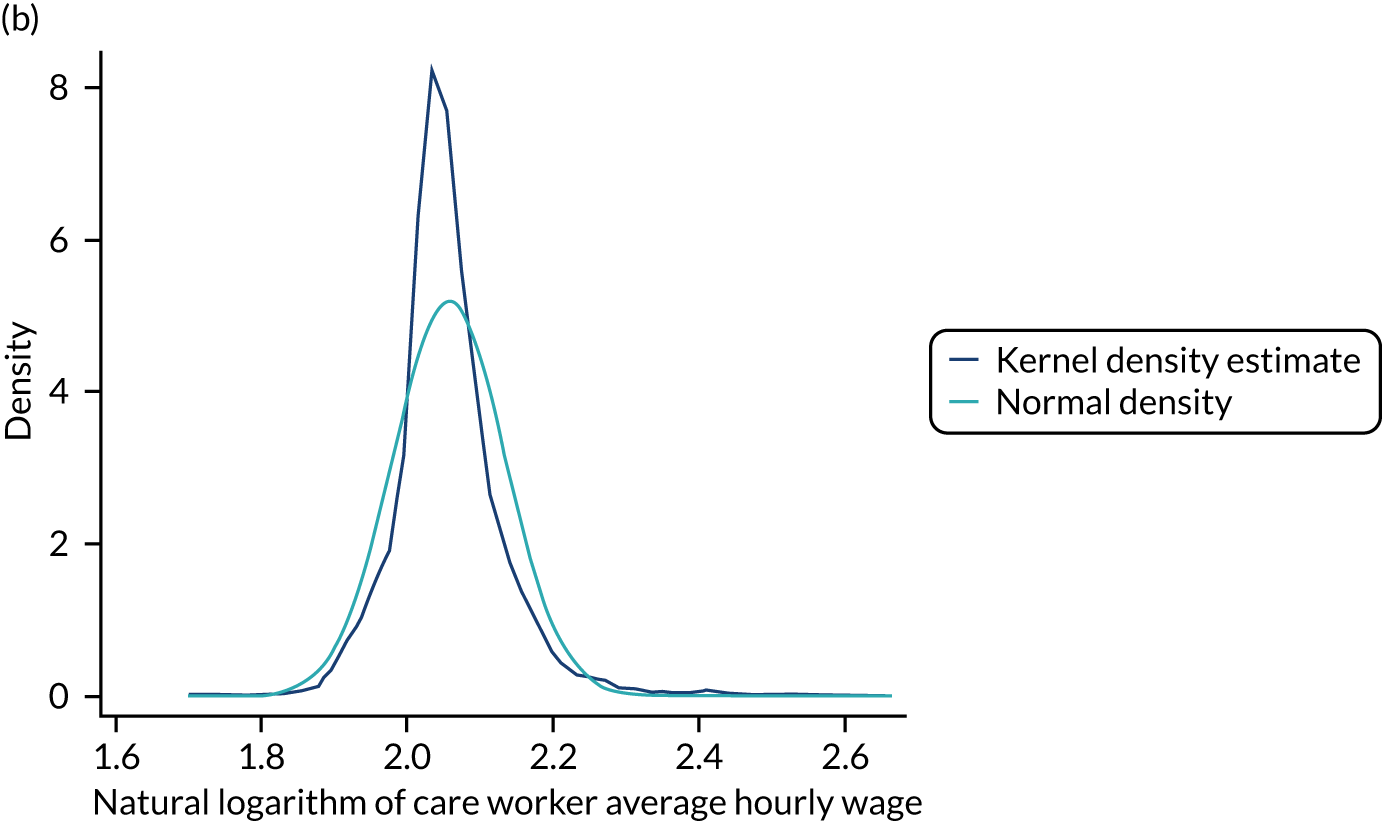

Second, we conducted an analysis of existing data to model the relationship between CQC quality ratings and workforce characteristics, controlling for confounding factors (see Chapter 6). We focused on the association between training provided to staff and staff terms and conditions (e.g. wages and turnover/vacancy rates) and the quality of care homes. All of these variables, which can be affected by policy, were expected to be important determinants of quality. Using data on around 5500 care homes, we used the following econometric methods to assess the relationship between quality and workforce characteristics: longitudinal models using data from 2016 to 2018, multiple imputation to address missing data, and an instrumental variable approach to control for potential endogeneity between quality and workforce characteristics, in particular staff wages.

Public involvement and engagement strategy

Public involvement and engagement was an integral part of the study from the design stage, when the application was reviewed by five members of the public from the Personal Social Services Research Unit’s (PSSRU) Research Advisors Panel. During the study, patient and public involvement (PPI) was delivered in the following ways:

-

Study Steering Committee – two members of the public with experience of social care were recruited as lay representatives to the Study Steering Committee. One was a partly retired care home manager and the other was an informal carer whose relative had lived in a care home. Their role on the Study Steering Committee was to attend meetings, give a public/patient perspective on issues that arose and comment on emerging findings.

-

Co-researchers in WP1 – we recruited three lay co-researchers from the PSSRU’s Research Advisors Panel to assist with the focus groups with staff and contribute to the development of the new measures of pain, anxiety and depression. This is described in detail in Chapter 3.

-

Contributions to study outputs – lay advisors from the Study Steering Group contributed to the drafting of the Plain English summary of this report and reviewed it for written quality and clarity. The co-researchers from WP1 co-authored Chapter 7.

Ethics approvals

Ethics approval was required for the primary data collection undertaken in WP1 and WP2. WP3 drew on both the primary data collection undertaken in WP2 and publicly available data sets. The analysis of publicly available data received a favourable ethics approval by the University of Kent (SRCEA 201).

The primary data collection received a favourable opinion for ethics approval from the Health Research Authority, which governs research ethics in the UK (reference 18/LO/0657). As this was a social care study, approval was sought and received from the Association of Directors of Social Services (ADASS) and by each local authority involved in the study.

The main ethical issues were around participant consent and the participant observations being conducted in communal areas of the care home.

Participant consent

The study consent procedures complied with the Mental Capacity Act155 and Code of Practice. 156 Where residents lacked the capacity to consent, personal consultees were asked for their advice about including the person in the research. Thereafter, consent was treated as a continuous process, with researchers being sensitive to both verbal and non-verbal indications of residents’ unwillingness to participate in the research.

Participant observations

Observations were carried out as unobtrusively as possible in communal areas of the homes (e.g. lounge, dining area, activity areas, gardens and corridors). Informed written consent was sought only from study participants who were the subject of the observations and interviews. As care homes are communal environments, non-participatory residents, staff and visitors were present during the observations. To ensure that observations were conducted with the full knowledge of those living and working in the home, and to confirm that people were happy with our presence, we asked homes to display posters raising awareness of the research, with the names and photographs of the research team, 2–3 weeks before data collection. On the day of fieldwork we were also given a tour of the home and introduced to those present. At the end of the observational period, we said goodbye to those present and notified the staff and manager that we had stopped observing.

Summary

Care homes provide fundamental long-term care and support to around 425,000 older people in England, many of whom have multiple complex conditions, including dementia. They aim to provide high-quality care that improves the health and care-related quality of life of residents. However, in the absence of a minimum data set for care homes, measuring the impact of care is challenging. Regulator quality ratings have an important role to play, but the extent to which these reflect residents’ health and social care-related quality of life is unclear. Furthermore, reliable, robust methods of measuring patient-reported outcomes traditionally rely on self-report, which is unsuitable for many care homes residents.

This study aimed to explore the health and care-related quality of life of care home residents and regulator quality ratings, and their relationship to workforce and job characteristics. To this end, we undertook three interlinked packages of work to (1) develop new measures of pain, anxiety and depression suitable for residents who cannot self-report, (2) validate these measures’ use and psychometric properties alongside the ASCOT and (3) understand how care home quality relates to workforce employment conditions and training and to residents’ care-related quality of life.

Chapter 2 Rapid reviews of tools measuring pain, anxiety and depression

Chapter 1 described how, despite being different conditions, a common picture emerges when exploring pain, anxiety and depression in care home residents. First, they are experienced by a significant number of care home residents. Second, each of them is associated with negative health and quality of life, and finally, it is generally agreed that they are under-recognised and undertreated. One of the barriers is that it is difficult to collect this health-related information from residents using traditional methods of self-report. This is particularly salient when thinking about residents living with dementia or other cognitive impairments that impact on the ability to communicate one’s views and experiences.

Aims and objectives

The overarching aim of WP1 was to develop new items for measuring pain, anxiety and depression, which could be used alongside the ASCOT-CH4 with care home residents who cannot self-report.

This chapter addresses objective one of WP1, to undertake a review of tools measuring pain, anxiety or depression, which were developed, tested or validated for use with older people, people living with dementia or older people living in care homes.

For ease, throughout this chapter we use the term ‘care home’ and ‘residents’ to specifically refer to care homes for older adults (residential and nursing) and the people who live in them.

Methods

Two rapid reviews were conducted. The first focused on pain tools, aiming to:

-

identify pain measures designed for or tested with older adults including those who may have difficulty with self-report, such as people living with dementia and/or

-

identify pain measures designed for or tested with older adults that contain an observational/behavioural element.

The second focused on tools that measure anxiety and depression, again aiming to:

-

identify anxiety and depression measures designed for or tested with older adults including those who may have difficulty with self-report, such as people living with dementia and/or

-

identify anxiety and depression measures designed for or tested with older adults that contain an observational/behavioural element.

The rapid review method is a form of knowledge synthesis. It is a streamlined version of the full systematic review,157 and usually omits and simplifies elements of the systematic review. In this study, the rapid review was adopted as it enables reviews to be completed in a shorter time period than full systematic reviews which often take at least 12 months. 158,159

Search strategy

We searched five databases {MEDLINE, CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature), the Cochrane Library, PsycInfo® [American Psychological Association, Washington, DC, USA; via EBSCOhost (EBSCO Information Services, Ipswich, MA, USA)] and Abstracts in Social Gerontology}. The searches for the review focusing on pain tools were conducted between mid-November 2017 and mid-December 2017. The searches for the review looking at anxiety and depression tools were carried out in January 2018. We used a combination of search terms related to our population and constructs of interest (see Appendix 2 for the full search strategy). Owing to the large number of papers on pain, anxiety and depression, we focused on original and review articles published in the previous 10 years (from 2007), which tested or reviewed more than one tool with older adults. Only studies published in English were included.

In both reviews, following the literature search and tool identification outlined below, data were extracted on each tool and used to populate a spreadsheet. The data extracted were organised around the following headings, which related to characteristics of the tool:

-

review article identifying the tool

-

name of tool

-

original article outlining tool

-

availability of the tool

-

main population designed/tested with

-

other populations used with

-

aspect(s)/dimensions of pain measured

-

method(s) of data collection

-

details of measurement scale/rating/scoring

-

details of development and testing

-

other (methodological issues, reflections on the tool).

The data were then summarised in chart form (see Appendix 2, Tables 21 and 23).

Findings

Pain tools rapid review

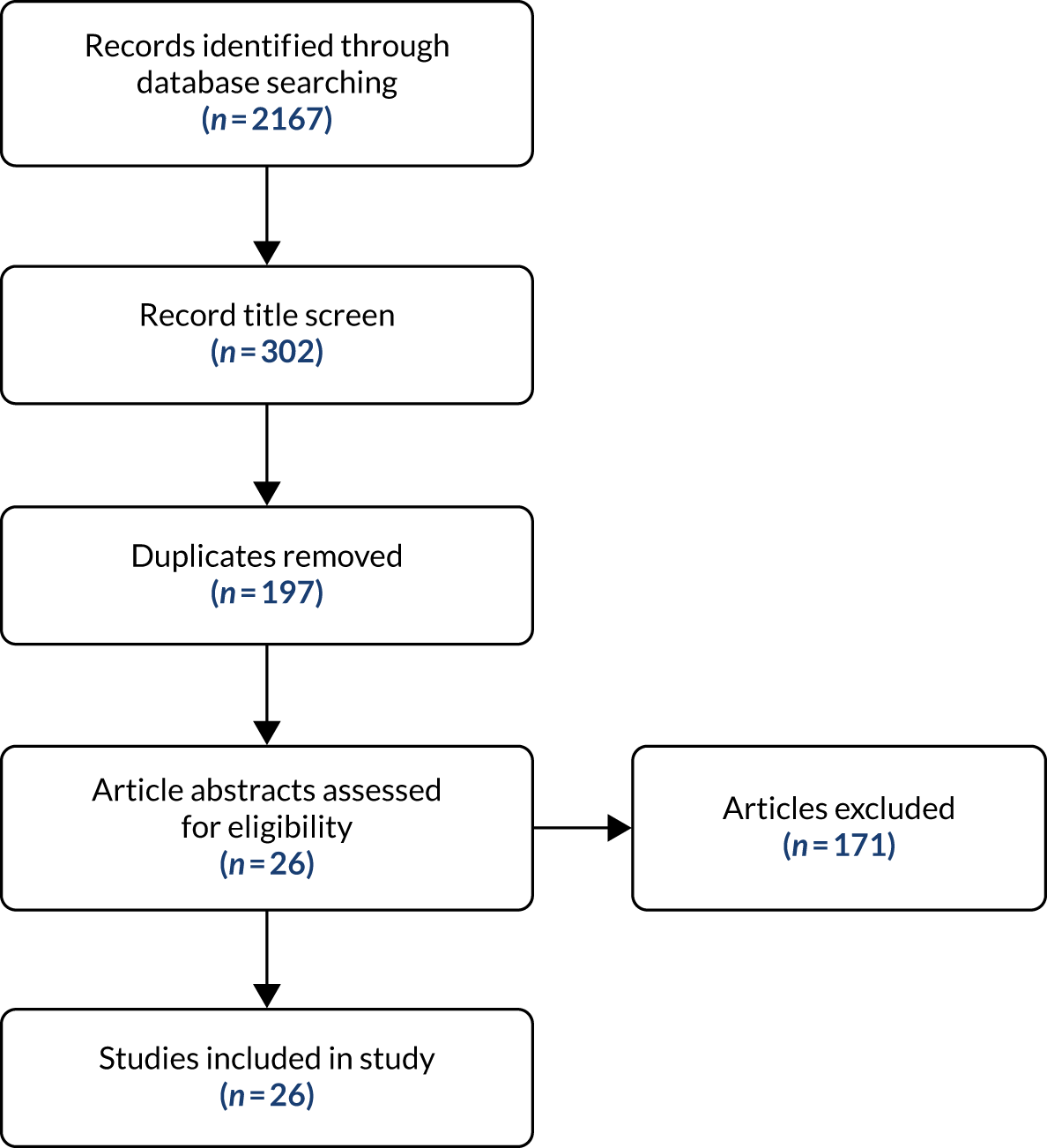

The search strategy (see Appendix 2) yielded a total of 2167 papers. Following a review of the titles, 1865 of these papers were rejected. When duplicates were removed, there were 196 unique papers.

The title and abstract of each of the 196 papers were reviewed for relevance and adherence to the inclusion criteria (see Appendix 2). Twenty-six papers were included in the final rapid review, the majority of papers being rejected as they focused on a single tool (Figure 1). A total of 22 tools for measuring pain in older people, people living in care homes and people living with dementia were identified from these final 26 papers. The identified pain tools are presented in Table 3. Further details of the key characteristics of these tools can be found in Appendix 2, Table 21.

FIGURE 1.

The PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses)160 flow diagram of pain tools search.

| Self-report | Proxy | Observation |

|---|---|---|

|

21-Point Box Scale Color Analog Scale Faces Pain Scale (FPS) Functional Pain Scale Iowa Pain Thermometer McGill Pain Questionnaire Numeric Pain Rating Scale Verbal Descriptor Scale Visual Analogue Scale interRAI Long-Term Care Facilities |

Pain Assessment for the Dementing Elderly Pain Assessment Instrument in Non-Communicative Elderly interRAI Long-Term Care Facilities |

APS CNPI Doloplus-2 DS-DAT MOBID-2 NOPPAIN NPAT Observational Pain Behaviour Assessment Instrument PACSLAC PAINAD interRAI Long-Term Care Facilities |

The tools identified in the review can be categorised by mode of data collection. Three different modes were identified among the tools: self-report, proxy report and observation. Most tools tend to use just one mode of data collection, although the interRAI Long-Term Care Facilities tool161 uses all three. However, it should be noted that many of the observational tools include verbal manifestations of pain, such as saying ‘it hurts’, in their evidence for rating the presence or intensity of pain, for example negative vocalisations in the Pain Assessment in Advanced Dementia (PAINAD)162 or ‘vocal complaints: verbal’ in the Checklist of Nonverbal Pain Indicators (CNPI). 163

Ten tools identified in the review use self-report methods and have been tested or validated for use with older people, people living in care homes or people living with dementia. These tools were usually not developed specifically for older people or people living with dementia and other cognitive impairments. Instead they tend to be tools developed for use either with the general population or with children, such as the Faces Pain Scale (FPS). 164 The self-report tools usually, although not exclusively, focus on the measurement of pain intensity and use a range of approaches to facilitate self-report, including words, numbers and visual representations of pain. Often these different methods are combined in a single tool. For example, the 21-Point Box Scale uses a number scale anchored by words at either end165 and the Iowa Pain Thermometer166 uses a visual representation for pain alongside words to add further clarity to its representation of pain intensity.

The pain tools use a variety of words to describe different pain states. For example, the McGill Pain Questionnaire167 begins with ‘no pain’ and follows with words that represent increased intensity of pain (mild, discomforting, distressing, horrible . . . excruciating). Similar approaches are used in other scales, such as the various versions of the Verbal Descriptive Scale, including the Verbal Descriptive Scale (pain thermometer),166 on which the six-point scale ranges from ‘no pain’ through increasing severity (mild, moderate, severe) up to ‘as bad as it could be’. Words are also used in tools and sections of tools that focus on aspects of pain beyond intensity, such as the experience of pain (e.g. McGill Pain Questionnaire167). Numbers are used by some tools to represent pain intensity, with different scales using sets of numbers. Different versions of the Numeric Pain Rating Scale168 use different scales. The most common was 0–10 or 0–100 points, but other numerical scales are also used (e.g. the 21-Point Box Scale165). On all of the scales, greater intensity of pain is represented by a higher number.

As noted above, visual methods are also employed to represent and capture the intensity of a person’s pain. For example, many of the numerical scales are presented visually on a scale resembling a ruler. Other visual methods include the Visual Analogue Scale and the aforementioned pain thermometer or the Colour Analog Scale,169 on which visually greater levels of pain are represented by the top of the thermometer, where the colouring is more intense. Another form of visual representation used in pain tools is faces. The various versions of the FPS164,170,171 use faces with different expressions to represent different pain states.

Because of the subjective nature of pain, self-report is, quite understandably, viewed as the ‘gold standard’ of pain measurement and diagnosis. 65,172 However, high levels of cognitive impairment in residents of older adult care homes,18 and the associated challenges of recognising and reporting pain, have often demonstrated that self-report pain scales, and, indeed, self-report scales more generally, are inappropriate for use in long-term care settings. 55,173–178 Thus, the focus of pain measurement tools specifically for older people and especially for older people living with dementia has moved to observational methods.

Most reviews of observational-based pain tools agree that, although self-report is preferable, where people are not able to reliably self-report, observational methods are the most appropriate55 approach to the measurement or diagnosis of pain. 46,55,70,179 Moreover, specific observational pain tools are recommended by professional bodies. For example, the Abbey Pain Scale (APS)180 is recommended in the UK by the Royal College of Physicians, the British Pain Society and the British Geriatrics Society. 45 We found 11 pain tools that use observation to investigate, measure or diagnose pain among older adults, people living in older adult care homes and people living with dementia.

Unlike the majority of the self-report tools, these tools were almost exclusively developed for people living with dementia. The most common approach employed by the observational pain tools in this review is the identification of pain behaviours, which in turn populate a pain intensity score, such as in the PAINAD,162 where pain is scored on a range of 0–10. In this tool, 1–3 is a reflection of mild pain, 4–6 is a reflection of moderate pain and 7–10 is a reflection of severe pain. Some tools measure other aspects of pain. For example, the CNPI163 focuses on the presence of pain, and one of the earliest observational tools, the Discomfort Scale in Dementia of the Alzheimer’s Type (DS-DAT),181 measures the frequency and duration of pain. The Mobilisation–Observation–Behaviour–Intensity–Dementia-2 Pain Scale (MOBID-2)182 looks at the location of pain in addition to its intensity. In some tools, such as the APS180 and Doloplus-2,183 the severity behaviours themselves are also rated. The pain behaviour items in the observational tools found in this review are presented in Appendix 2, Table 22.

Many of the observational-based tools in the review were designed to be administered by care workers, nursing assistants, nurses and health professionals rather than by researchers. This is often reflected in the way the tools were designed to be used. Nearly all are short tools – with the exception of the 60-item Pain Assessment Checklist for Seniors with Limited Ability to Communicate (PACSLAC)184 – and developers claim that they can be administered in under 5 minutes, and, in the case of the APS, about 1 minute. 180 However, many of these tools were not designed to provide a one-off snapshot of the pain experienced by a resident. For example, the APS and the Doloplus-2 were designed to be used on multiple occasions to understand a person’s pain. Other tools were also clearly designed for use in practice, as they stipulate that the gathering and rating of pain behaviours should occur during activities. The MOBID-2, for example, sets out five different movements that should be carried out by the person being assessed. These include turning to both sides in bed and opening both hands, one at a time. A different pain assessment is made for each movement. Similarly, the Non-Communicative Patient’s Pain Assessment Instrument (NOPPAIN)185 was designed to be used to assess pain during a range of activities, including dressing and bathing.

A number of the tools listed above have been widely used and are well tested and validated. In particular, the APS, the Doloplus-2, the PACSLAC and the PAINAD tend to perform best in validity, reliability and psychometric testing. 70,172,178

There are, however, a number of caveats and concerns around the use of observational pain measures. One of the most salient concerns about using observational means to assess pain is that they focus inherently on behaviours. Although the behaviours used as indicators of pain are clearly actions and behaviours that people might engage in when in pain, it has been pointed out that many can also be indicative of other states, such as hunger, thirst, delirium, depression or anxiety. 46,55,186 There are also concerns that an observational-based pain tool cannot assess the intensity of a person’s pain, only its presence. 185,187 A number of studies have suggested, however, that this concern has been overstated and note the high level of agreement on pain intensity between self-report and observer-rated pain scores. 70,179,188 In the light of these concerns, many reviews of observational-based pain tools have concluded that best practice should involve attempts to elicit self-report, supplemented, where needed, by observation and other methods to assess pain in older people with cognitive impairments, such as physical examination, medical history and reports from family members. 46,65

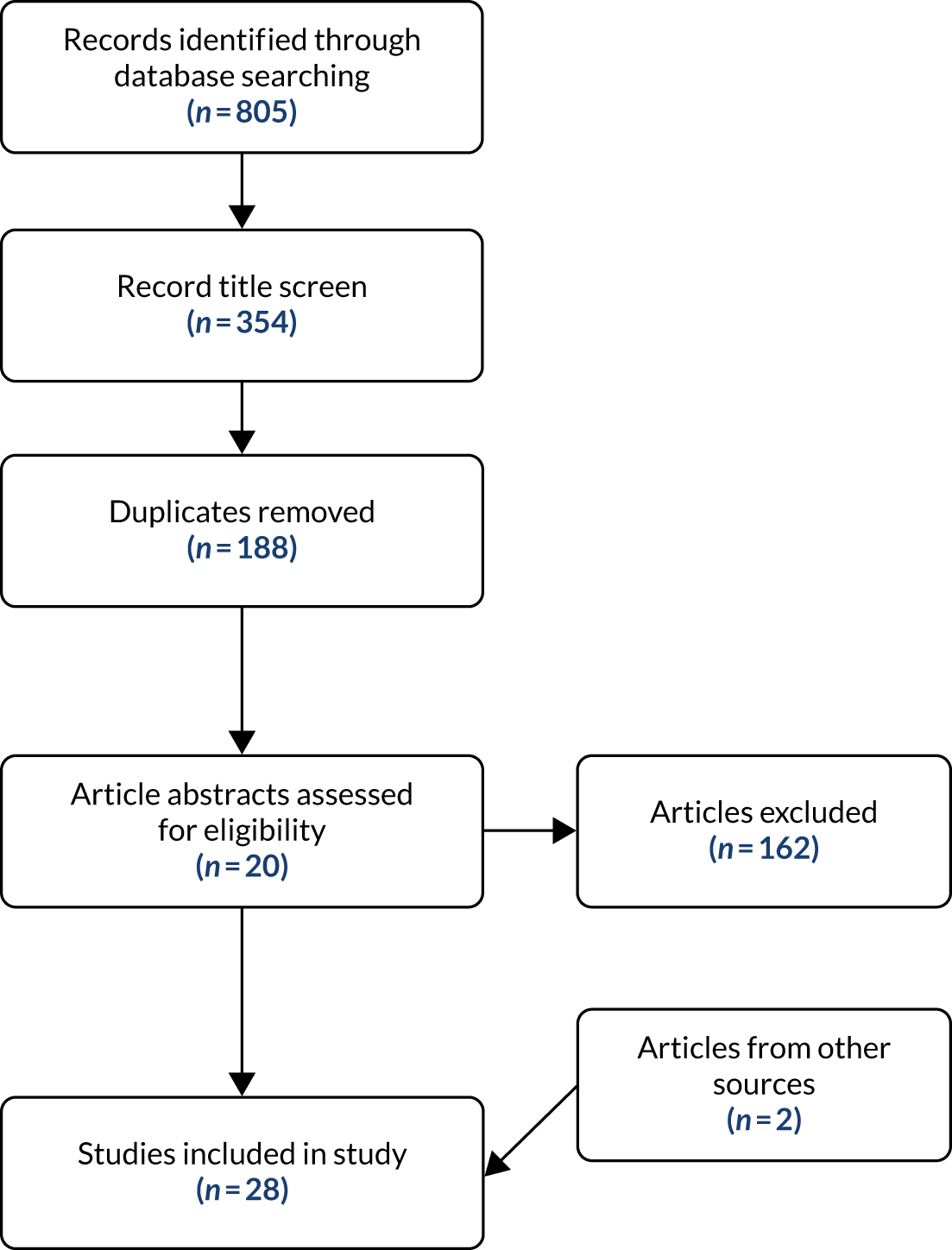

Anxiety and depression tools rapid review

The search strategy (see Appendix 2) yielded a total of 805 papers. A screening of the article titles removed 451 papers. When duplicates were removed from the remaining 354, there were 166 unique papers. The title and abstract of each were reviewed for relevance and adherence to the inclusion criteria. This resulted in 20 papers being assessed as eligible for the review. The majority of the excluded items looked at only one tool. During the review itself, two other papers were identified from citations in the review papers. Twenty-two papers were included in the final rapid review (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

The PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) flow diagram of anxiety and depression tools search.

A total of 20 tools for measuring anxiety and depression in older people, people living in care homes and people living with dementia were identified from the 26 papers. A number of the tools had multiple versions. Some were revisions of a tool over time (e.g. the Beck Depression Inventory), whereas others were different versions of tools that used different methods (e.g. the Patient Health Questionnaire, which is available in self-report and observational versions). Two more tools were included in the review of tools. The Minimum Data Set Depression Rating Scale (MDS-DRS)189 was identified in the pain review, and the Dementia Mood Assessment Scale (DMAS)190,191 was identified while exploring the properties of the Hamilton Depression Scale (HDRS),192,193 the tool on which the DMAS is based.

The identified anxiety and depression tools are presented in Table 4. Further details of their key characteristics can be found in Appendix 2, Table 23.

| Name of tool | Symptom measured | Mode |

|---|---|---|

| Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV (ADIS-IV) | Anxiety | Clinical interview |

| Beck Anxiety Inventory | Anxiety | Self-report |

| Beck Depression Inventory/Beck Depression Inventory II | Depression | Self-report |

| Brief Measure of Worry Severity | Anxiety | Self-report |

| Centre for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) | Depression | Self-report |

| Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia (CSDD) | Depression | Clinician interviews (proxy and patient) |

| DMAS | Depression | Clinician interview (input from proxies) |

| Evans Liverpool Depression Rating Scale | Depression | Self- and proxy report |

| Generalised Anxiety Disorder Questionnaire for DSM-IV | Anxiety | Self-report |

| Generalised Anxiety Disorder Severity Scale | Anxiety | Clinician interview |

| Geriatric Anxiety Inventory (GAI) | Anxiety | Self-report |

| Geriatric Anxiety Scale (GAS) | Anxiety | Self-report |

| Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) | Depression | Self-report (plus proxy) |

| Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A) | Anxiety | Clinician interview |

| HDRS | Depression | Clinician interview |

| Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) | Depression and anxiety | Self-report |

| MDS-DRS | Depression | Observation (staff) |

| Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) | Depression | Observation and interview by clinical staff |

| Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9)/Patient Health Questionnaire-9 Observation Version (PHQ-9 OV) | Depression | Self-report/observation (staff) |

| Penn State Worry Questionnaire (PSWQ) | Anxiety | Self-report |

| Rating Anxiety and Dementia Scale (RAID) | Anxiety | Clinician interview (patient and proxy) |

| State–Trait Anxiety Inventory | Anxiety | Self-report |

Of the tools identified, 11 focus solely on anxiety, 10 focus on depression, and one, the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS),194,195 measures both. Among the tools, four modes of data collection were identified: self-report, proxy report, clinician interview/rating and observation. Although most tools adopt a single approach to gathering information, some do combine methods. For example, the Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS)196,197 combines observation with clinical interview, and the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9)198–200 has both a self-completion version and a version based on observations.

By far the most common mode of information collection was self-report. Indeed, even when the tools utilise clinician-based ratings, this is often based on clinical interview with the person reporting their experiences. In total, 13 tools, six solely looking at anxiety, six looking just at depression and one rating both conditions, use self-report. Of these, two, the Evans Liverpool Depression Rating Scale201 and the Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS),202–204 supplement self-reports with proxy reports. Most of the tools were designed to be administered using pencil and paper but a number have been validated for administration in an interview.

Four anxiety and four depression tools use the clinical interview as their source of data. In a number of these tools, the views of a proxy are also sought either as a supplement or, in cases where the patient could not self-report, as a replacement. Depending on the tool, the proxy may be a family member or a caregiver who knows the patient well. Some of the clinical interview tools are, however, closer to self-report tools, in that, although the interview is administered by a clinician, its format is highly structured and the data recorded are essentially self-reported. Tools in this mode include the Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia (CSDD). 205 In other cases, the clinical interview diverges from direct self-report as the rating of items is completed by clinicians themselves, albeit based on evidence collected in interviews. Examples of this type of tool include the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV (ADIS-IV),206 a semistructured interview tool with prompts to inform the interview, following which the clinician rates the patient’s anxiety disorder, or the HDRS192 and the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A),207 which have traditionally used unstructured clinician interviews to provide the evidence for their ratings.

Only three tools explicitly use observation as a method of data collection. All of these tools focus on measuring or diagnosing depression. The review found no tools that took an observational approach to measuring or screening for anxiety. Each was designed for either clinical or care staff to use rather than researchers. For example, the MADRS is a tool designed for use only by clinicians, whereas the MDS-DRS189 rates depression by drawing on the routine, daily observations of care staff. Not surprisingly, the tools based on observational methods were often developed for populations who may struggle with self-completion. The MDS-DRS was developed specifically for use in long-term care settings, as was the observational version of the PHQ-9 (PHQ-9 OV). Although the MADRS was developed for and widely used with the general population, it has been well used and tested in older adult residential and nursing care settings. 115,125 The key observational markers of depression found in these tools can be seen in Appendix 2, Table 24.

Across both the self-report and clinician interview tools, there are those that have been developed for the general population and those developed for older people more specifically, such as the Geriatric Anxiety Scale (GAS)208,209 and the Geriatric Anxiety Inventory (GAI). 210 However, tools using either proxy report or observation are much more likely to have been developed for use with older people living with dementia or other impairments that may make self-report more challenging. The DMAS,190,191 the Rating Anxiety and Dementia Scale (RAID), the CSDD and the Evans Liverpool Depression Rating Scale all combine data collection from the person themselves and a proxy to understand, whether by screening or by measurement, the mental health of a person living with dementia. Three depression tools, the MADRS, the MDS-DRS and the PHQ-9 OV, use observation, at least in part, to inform their ratings of depression. Of these, only the MDS-DRS was designed to be used primarily with older adults in long-term care settings. The other two were designed for use in the general population, but their ability to utilise observational methods, either alongside MADRS or in place of the PHQ-9 OV self-report or clinical interview, means that they have been widely used in older adult care homes. 107,115,120,125,211

The focus of both the anxiety and the depression tools is primarily the symptoms of these conditions. Unlike pain, for which self-report tools reflect the subjectivity of the experience by asking the person to rate their pain on a given scale (e.g. 1–100 or ‘none, mild, moderate, severe’), tools looking at depression and anxiety on the whole do not treat these conditions as something that the person experiencing them can rate directly. Instead, the conditions are broken down into common symptoms that are self-rated, rated by proxy or rated by the investigator (usually a clinician) based on interview or observation. Some tools, especially those used for screening, such as the GAI or the GDS, ask about the presence, usually dichotomously, of each symptom to screen or diagnose. However, many of the tools look to establish a level of severity of either depression or anxiety based on the data collected. Most commonly, this is achieved by one of two – usually, but not always, mutually exclusive – approaches: (1) items that investigate the severity of a symptom or impact of the given condition or (2) items that investigate the frequency of a symptom or impact of the given condition.

The first approach is operationalised by statements, for example in the Beck Depression Scale I/II,212,213 that reflect different states within a symptom, such as appetite, or by a scale, for example in the HAM-A or the HDRS. Each of the included symptoms of anxiety or depression is rated on a five-point scale ranging from ‘not present’ to ‘very severe’. Similarly, the second approach, focusing on frequency, also uses both statements, such as in the HADS, to reflect different frequencies within an item representing a symptom of anxiety or depression, and scales, such as the four-point scale used in the State–Trait Anxiety Inventory,214 which runs from ‘almost never’ to ‘almost always’.

In terms of overall scoring, screening tools (e.g. the GDS and the GAI) are often based on clinically significant scores at which a person might be considered to have anxiety or depression. Tools measuring severity of depression or anxiety usually have several cut-off points on a total score range to indicate various severities of the condition. Some simply suggest that the higher the overall score, the greater the severity of the condition, for example the Centre for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D). 215,216

Most tools use variations or extensions of mild, moderate and severe to label the severity of the condition. For example, the GAI is scored using the categories low anxiety (0–21), moderate anxiety (22–35) and potentially concerning levels of anxiety (> 36), and the MADRS uses the categories normal (0–6), mild depression (7–19), moderate depression (20–34) and severe depression (> 34). As demonstrated in these two examples, some tools assume the presence of either condition, whereas others, including all those designed to screen, allow for a score that reflects ‘no’ or ‘normal’ levels of anxiety or depression.

Conclusion

This chapter outlines two rapid reviews of tools used to measure pain, anxiety and depression in older people, people living with dementia and people living in older adult care homes. Using our search criteria, we found 22 pain tools and 22 tools that measure either anxiety or depression. These tools utilise a range of methods, including self-report, proxy report, clinician rating and observation. Because of the cognitive and communication difficulties that often characterise dementia, tools developed specifically for people living with dementia tend to avoid relying solely on self-report. In the field of pain, this challenge has been more thoroughly addressed, as evidenced by the range of dementia-specific tools using observational methods. By contrast, in anxiety and depression, tools often rely on the clinical interview to rate, or in many cases diagnose, anxiety or depression.

The fact that the reviews identified a large number of existing tools invites the question of whether or not there was a need for this project to develop new tools. Indeed, some researchers who work on the measurement of pain experienced by older people have called on research to focus its attention on testing and validating existing tools rather than developing new ones. 30 However, this view was not expressed without caveats. The development of new tools is justifiable if, according to Lichtner et al. ,30 the conceptual framework underpinning them is different from those underpinning existing tools.

The new items for measuring pain, anxiety and depression in this study differ from the tools reviewed in a number of important ways, including the conceptual underpinning. Foremost, the differences relate to purpose. The tools reviewed here broadly focus on measuring the severity of, or screening for, the condition (in the case of depression and anxiety) and measuring the intensity of the state (in the case of pain). They were also often designed to be used in diagnostic/clinical practice; indeed, many stipulate that they should be administered only by a clinician. Often they are used to inform treatment. Pain is assessed so that it can be managed, and anxiety or depression are diagnosed in order to facilitate treatment. Treatments often include a pharmacological element,65 the strength of which is often determined by the intensity or severity of a condition. Although these tools could be used, for example over time, to infer the impact of a service or intervention on quality of life, that is not their core focus.

The purpose of ASCOT is very different. Although it can inform practice,217 it is not a diagnostic or clinical tool. Instead, it aims to measure the impact of social care services and interventions on aspects of quality of life. The items for the three new domains should also reflect this focus on quality of life and not replicate screening and clinical tools, of which there are many.

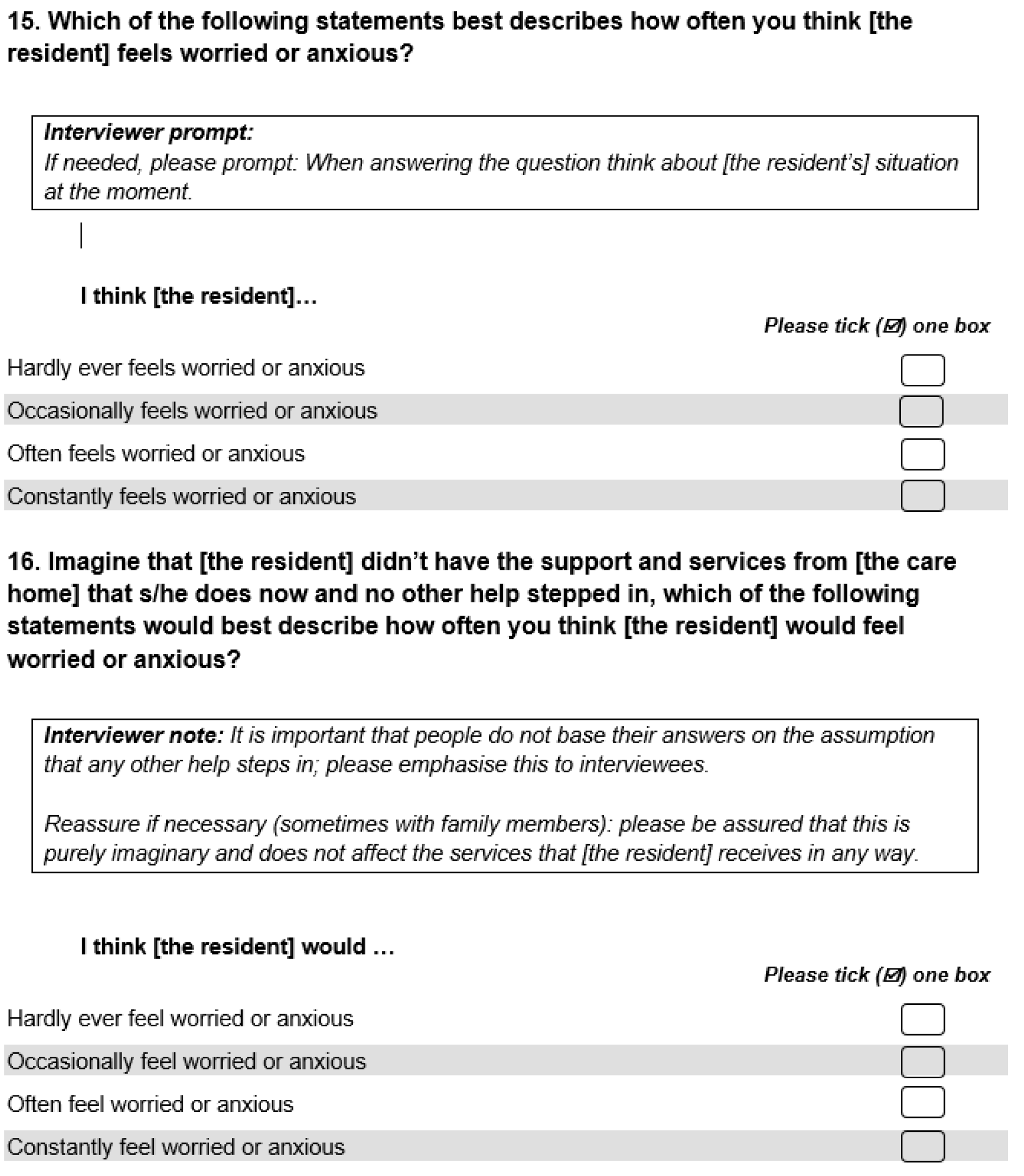

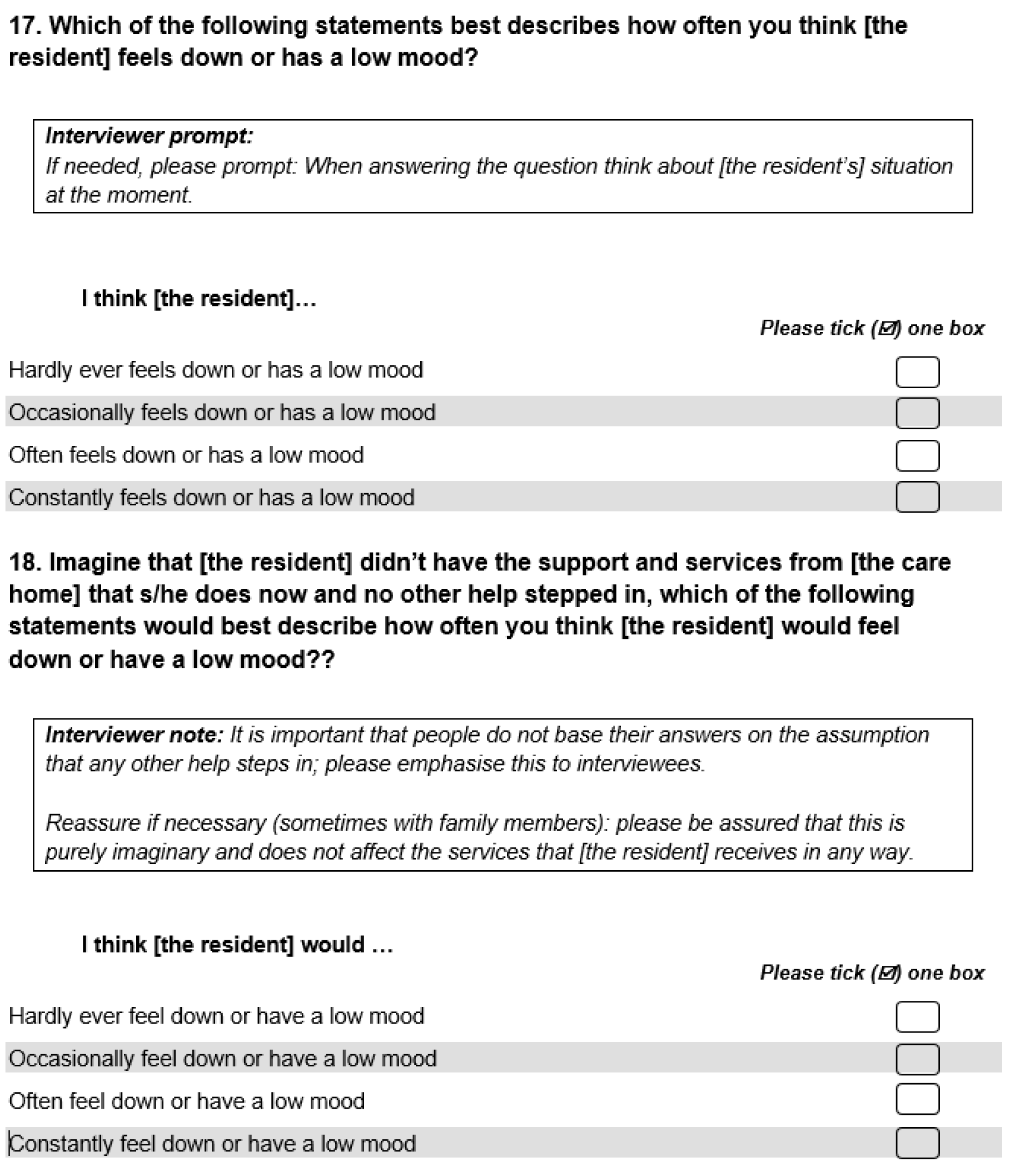

Often, social care services will be required to manage clinical states, sometimes to their elimination. However, it is likely that there will be situational anxiety, episodes of pain, and depressed mood following various kinds of loss, as in everyday life for most people, and, therefore, complete elimination may not always be an appropriate, or achievable, goal in social care. Therefore, the new measurement items should focus on the frequency of the condition, be it pain, anxiety or feelings of depression, rather than on the intensity of the condition.

The review also broadened the conceptualisation of the new measurement items. Our initial proposal suggested creating only two domains: one to focus on pain and the other to focus on anxiety and depression. However, most of the tools identified and reviewed in the second rapid review looking at anxiety and depression focused on either of these conditions rather than trying to measure, screen or diagnose both. The review clearly demonstrated that, although these are related states, they are conceptually different and, for measurement, are best kept separate, particularly when these domains are captured by a single question.

Limitations

This study employed a pragmatic, rapid review methodology so that the reviews could be completed in a timely manner to ensure that they could feed into the development of the three new items reported in Chapter 3. A limitation of this approach is that we focused only on tools designed to measure the constructs of interest and did not include quality-of-life measures containing items relating to the constructs. This meant that some well-known scales, such as the EuroQol-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D),218 which has a proxy version for care staff to use, were not included in the review itself. However, perhaps more appropriately, we did include the EQ-5D in the analysis reported in Chapter 4 to validate the construct validity of the new items.

Chapter 3 Developing new measures of pain, anxiety and depression for older adult care home residents

Introduction

Chapter 2 outlined two rapid reviews, one focused on pain tools, the other on tools measuring anxiety or depression. The reviews, which were the first stage in the process of developing new items to measure pain, anxiety and depression, clarified the focus and, also, the purpose of the proposed new ASCOT-CH4 items. Drawing on the reviews, the new items were to be:

-

divided into three separate constructs (pain, anxiety and depression)

-

focused on frequency rather than intensity of symptoms

-

conceptually distinct from existing measures in that they follow the ASCOT approach of measuring the impact of social care on each attribute

-

designed for a mixed-methods approach to data collection, using observation, interviews with residents (where possible) and interviews with staff and family proxies.

Aims and objectives

The work reported here builds on the reviews reported in Chapter 2. Using the findings as a starting point, this stage of the study aimed to develop beta versions of the new ASCOT-CH4 items of pain, anxiety and depression ready to be piloted with care home residents (see Chapter 4). There were three consecutive stages of activity, each with its own aims.

Stage 1: desk-based drafting of tools for each item

Specifically, the aim of this stage was to develop the following draft tools for each item:

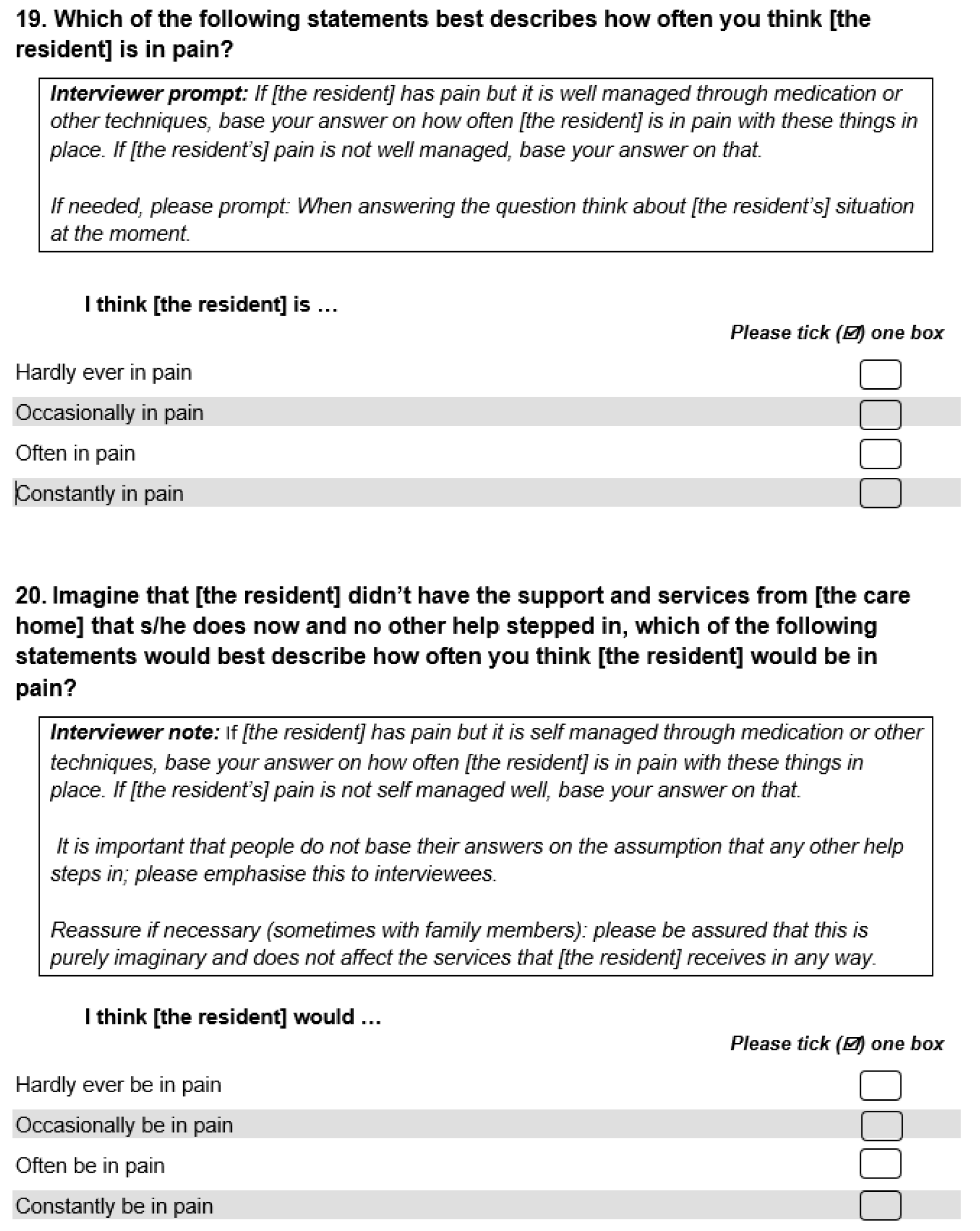

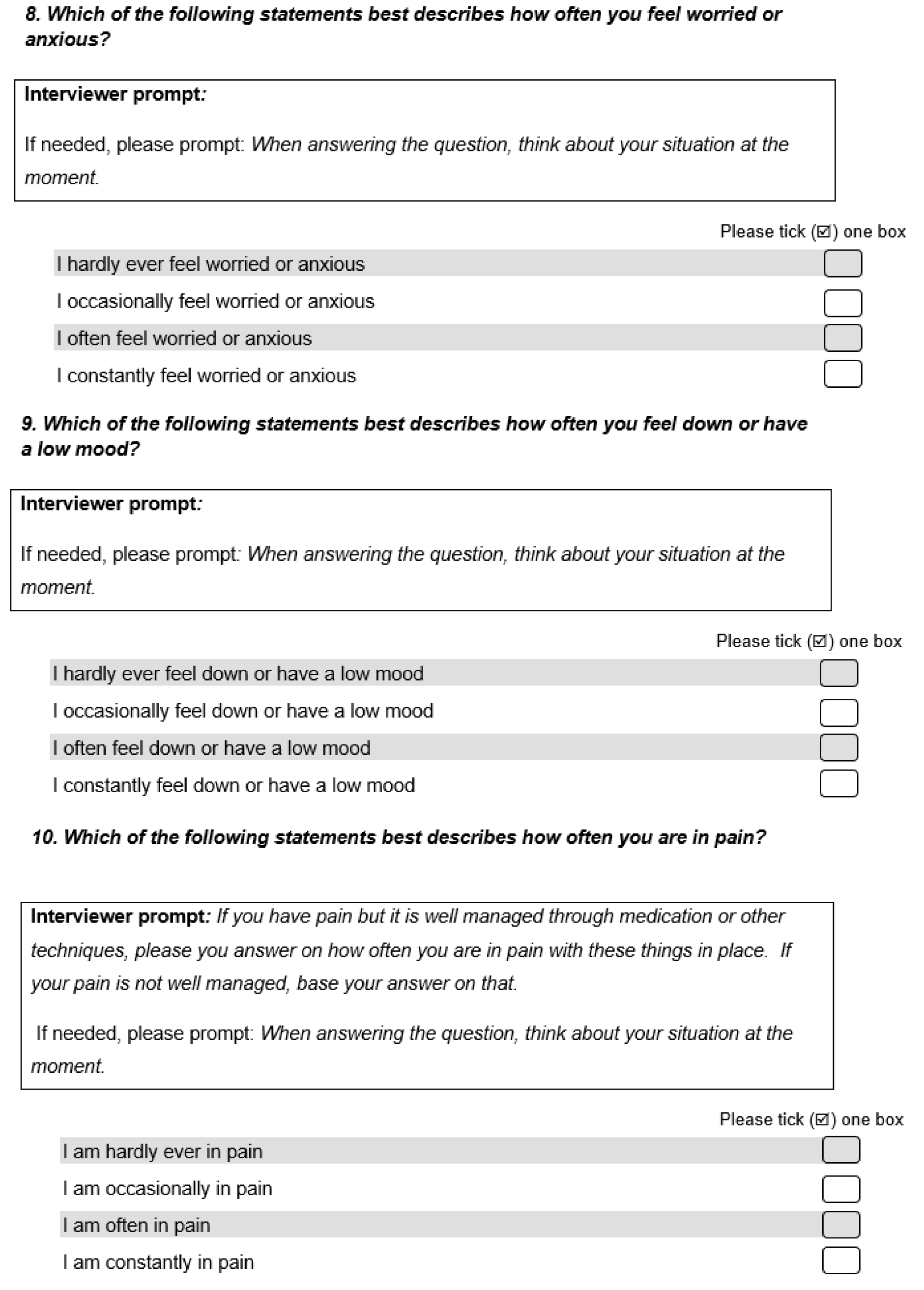

-

resident self-report questions and response options focused on the resident’s current frequency of pain, anxiety and depression

-

proxy questions and response options asking staff and family members about the resident’s ‘current’ and ‘expected’ (see Chapter 1) frequency of pain, anxiety and depression

-

initial observational guidance for each domain, drawing on the observational markers outlined in the tools.

Stage 2: focus groups with care home staff

The aims of the focus groups were to:

-

understand how care home staff recognise when residents are in pain or are feeling anxious or depressed

-

find out which words care home staff use to describe residents’ anxiety, pain and depression.

In addition, the groups were used to provide an initial review of the proxy questions.

Stage 3: cognitive interviews with staff and family members

The aims of the cognitive interviews were to improve, revise and finalise the item questions and response options for the interviews to be used in the data collection outlined in Chapter 4.

This chapter presents each stage of work separately, with its own methods and results.

Stage 1: desk-based drafting of tools for each item

Methods

Informed by the reviews, the research team created draft items for each of the three domains. For the observational guidance, the observable indicators of pain, anxiety and depression identified in the two reviews were collated. The initial draft was just a list of these markers (see Appendix 2, Tables 22 and 24).

For the self-report and proxy questions, a number of different question options were developed. The process involved thinking about frequency statements that reflected the four outcome states of the ASCOT: ideal state, no (unmet) needs, some (unmet) needs and high (unmet) needs (see Chapter 1). A number of different options were created (see Appendix 3, Box 1, for examples). In this stage of the development, the focus was on formulating questions to understand what the resident’s experience was now, while they were living in the care home (with help and support in place). Using ASCOT terminology, these would be the questions relating to ‘current’ frequency of pain, anxiety or depression (see Chapter 1). These were reviewed at a research team meeting, and then revised and reviewed by the team again.

Results

The first team review considered a number of possible question options (see Appendix 3, Box 1, for examples). This led to further refinement of question options and revision of those that remained. Decisions following the team review are outlined below.

Question stems should focus explicitly on frequency

Although all the answer options related to frequency of the state, not all of the different question stems did. Some were more vague, for example ‘which statement best describes how much anxiety you usually feel’ and ‘which of the following statements best describes how you feel?’. The team review concluded that, for clarity, questions that aimed to measure frequency should explicitly state this in the question stem.

Questions should use the same answer option scale across the three domains

Across all the draft questions a number of different scales were used. All questions and response options needed to fit within the ASCOT outcome states framework (see Chapter 1), so the team decided that there should be a common frequency scale across the three items. It was also felt that this would support respondents during completion.

Answer options should not have any reference to daily basis

Although none of the draft scales developed were entirely prescriptive about frequency, some answer options used terms such as ‘on a daily basis’ or ‘daily’. Others were more subjective or open to interpretation, using terms like ‘generally free form’ and ‘sometimes’. The team felt that the four-point scales would have more coherence if they applied a consistent approach across all three items. Moreover, terms like ‘sometimes’ and ‘often’ allowed the respondent (the care home resident or their proxy) some ability to rate the domains subjectively, which is central to the aim of quality-of-life measurement and the ASCOT tools.

The pain question should ask about being ‘in pain’

The pain questions used a number of different descriptors of pain states, including ‘experiencing pain’, ‘feeling pain’, being ‘free of pain’ and ‘pain free’. The team felt that the term ‘in pain’ most closely aligned with how people generally spoke about this. One of the question stem options used the term ‘discomfort’ alongside pain. The team felt that this was a broader term that could be used to describe a number of different states not necessarily linked to pain, for example feeling too hot or too cold. Not only did this have the potential to make the question too vague, it also overlapped with existing ASCOT domains, such as personal cleanliness and comfort, and accommodation cleanliness and comfort.

The pain domain requires additional information to clarify pain management

During the initial review, the research team felt that the draft pain questions needed some additional clarification around pain management. In ASCOT, ‘current’ ratings are what the person’s situation is now, which in care homes means ‘with all the care and support of the home and its staff’ in place. Thus, if medication is given by staff to manage pain, anxiety or depression, then the ‘current’ ratings should be based on what the person’s experience is with that in place. The ‘expected’ rating, conversely, is where we measure what the person’s symptoms or experiences would be without that care and support (e.g. administration of pain medication by care staff).

The anxiety question should ask about feeling ‘worried or anxious’

The draft anxiety questions used a number of different terms to describe the focus of the question, including ‘feel anxious’, ‘worried and concerned’ and ‘free from worry and anxiety’. The term ‘anxious’ on its own was felt to be too close to the clinical category of anxiety. The team concluded that changes were needed to reinforce the question’s quality-of-life focus by placing ‘anxious’ alongside a clearly non-medical term. The aim was to prevent the question being interpreted as requiring a diagnosis or being perceived as a screening tool. After some discussion, the team settled on ‘worried’, as this reflected the way in which many people, including older care home residents, would talk about feeling anxious.

The appropriateness of the ‘never’ or ‘free from’ answer option in the anxiety question

The ideal outcome state in the draft anxiety questions was usually defined by the complete absence of anxiety. A range of different terms were used to note this, including ‘never’ and ‘completely free from’. In the team review, it was suggested that ‘never’ experiencing anxiety was a problematic answer option. Anxiety, it was argued, was a normal state to experience sometimes, and that, clinically, never feeling anxious was often a marker of other psychological issues. Conceptually, however, the team felt that ‘never’ was a closer reflection of the ASCOT ideal state. The team agreed that revisions to the draft questions would explore an alternative scale that was not anchored at ‘never’, or an equivalent term, to be tested in the next stage.

The depression question should ask about feeling ‘down or depressed’

Most of the draft depression questions used the term ‘depressed’. The review concluded that this should be revised to help emphasise that the aim of the question was not to diagnose or ask about clinical depression, but that it was part of a quality-of-life instrument. To achieve this, it was felt that the term ‘feels depressed’ should be replaced with the more colloquial ‘feels down’.

Drawing on the discussion and conclusions of the research team review, two sets of draft questions were developed for testing in the next stage of development. These can be found in Appendix 3, Box 2. In all cases, the question stems incorporated the conclusions from the first team review. Where the two sets of questions differed was in the response option scale. One was anchored to the term ‘never’ and the other was anchored to the term ‘hardly ever’. In both scales these terms reflected the ideal state in ASCOT terminology.

Stage 2: focus groups with care home staff

Methods

Focus groups were conducted with care home staff to elicit a range of views and uncover collective views and meanings. They have been used previously in the development of ASCOT and other research tools and questionnaires. 219–221 Four older adult care homes were recruited to the study, the aim being to hold one focus group in each home. Located in South East England, all of the homes were run by a large national chain and were registered for older adult residential and nursing care. Recruitment to the individual groups was administered by the care home managers, who received guidance from the research team. Managers were asked to recruit between five and eight people to each group222 and to choose a range of staff who had interacted directly with residents, such as care, nursing and activity staff. Some homes invited other employees, such as maintenance staff and receptionists, to the groups as they felt that all staff in the home helped, supported and knew the residents.

The focus groups themselves were dual-moderator groups,223 with the administration shared between an academic researcher and a PPI co-researcher. As well as co-moderating the focus groups, the three project PPI co-researchers were involved in planning the focus groups and analysing the data from the focus group sessions. More information about the PPI co-research can be found in Chapter 7.

The groups consisted of an introduction and three substantive sections reflecting the aims of the group (the focus group topic guide can be found in Appendix 3, Box 3):

-

how staff recognise when residents are in pain, or are feeling anxious or depressed

-

the words staff use to describe residents’ anxiety, pain and depression

-

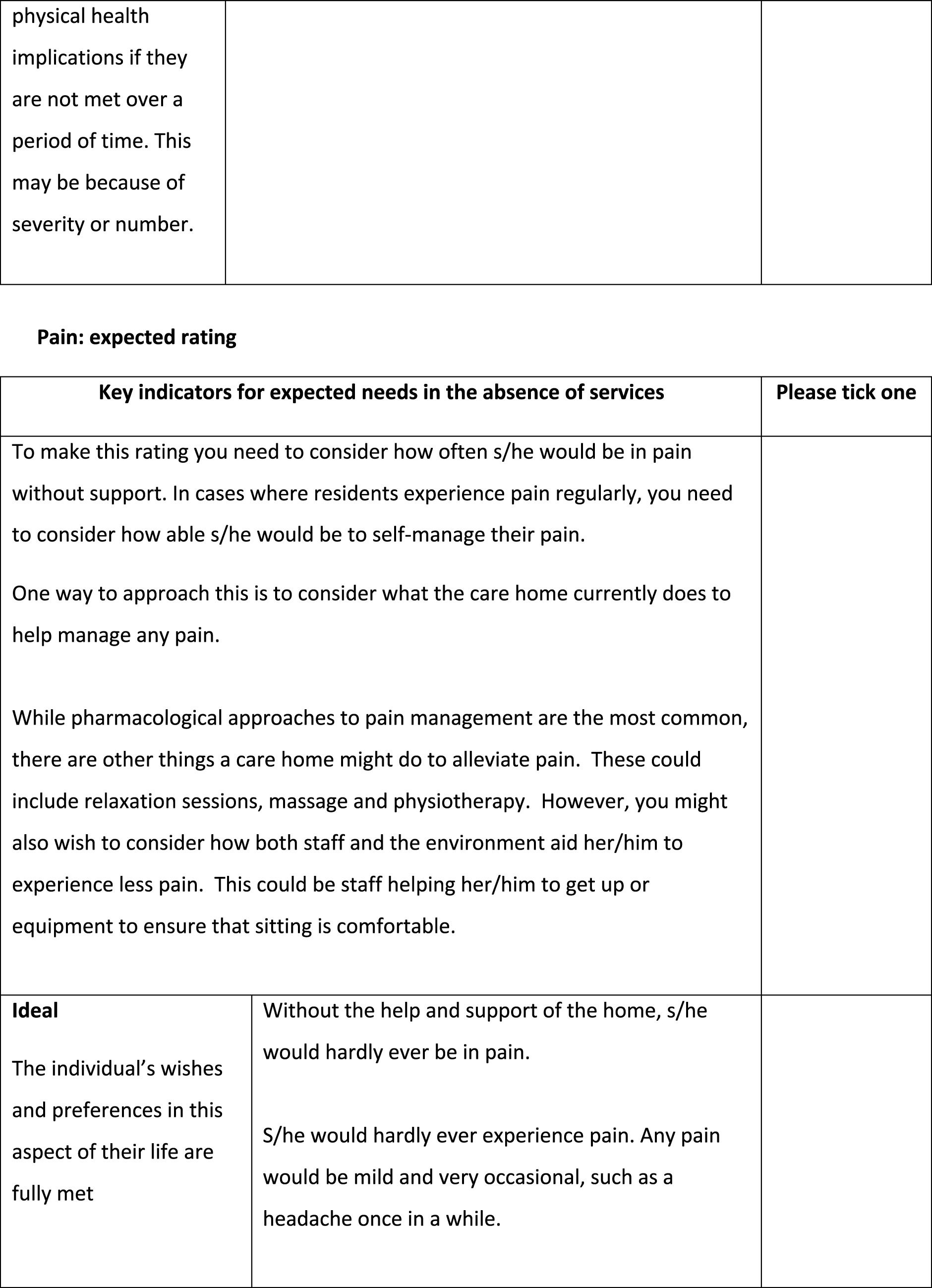

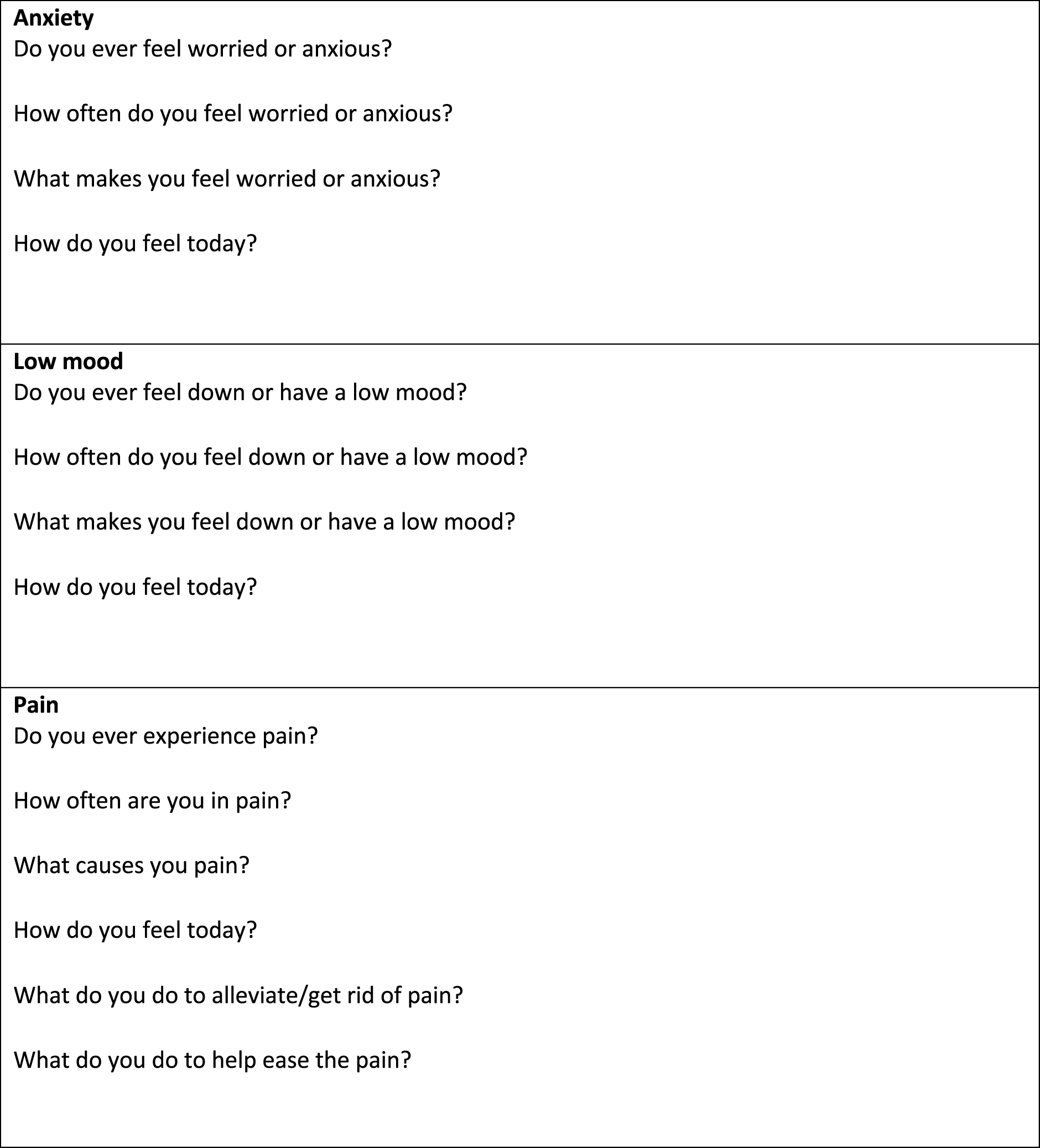

a review of two draft proxy questions on pain, anxiety and depression.