Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as award number NIHR128799. The contractual start date was in October 2020. The draft manuscript began editorial review in February 2023 and was accepted for publication in September 2023. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Forbat et al. This work was produced by Forbat et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Forbat et al.

Chapter 1 Background

Context

Size and impact of the problem

Care homes (CHs) now operate as subacute units with high levels of morbidity and mortality. 1 Care homes will be the leading place of death by 2040, and mortality can be as high as 56% within a year of admission. 2 Consequently, there is an urgent need to find methods and approaches to optimise end-of-life care for this population.

Although some specialist palliative care (SPC) teams offer services to CH residents, recent surveys in England, Wales and Scotland3–5 demonstrate that referrals are usually reactive rather than anticipatory, but there is considerable goodwill from SPC to support residents in CH. 6 The National Audit of Care at the End of Life has prioritised systems and processes that support CH residents to receive personalised end-of-life care. 7

Some CH residents (hereafter ‘residents’) experience multiple admissions to hospital prior to their death,6 despite some admissions being preventable. 8 Hospital admissions are costly and may prompt futile or burdensome interventions that can cause distress to residents and family members. 9 Many residents will require SPC to enable CH staff to manage complex symptoms1 to avoid hospitalisation at end of life. Well-managed death and dying is contingent on high-quality interdisciplinary care,10 anticipatory care11,12 and resident-centred planning. 13

Care homes can be homely, warm and supportive environments. Supporting these establishments to improve the care they give at end of life can make them even better places for people to spend their final months and weeks of life, especially when compared with clinical settings like hospitals. CHs are an important location in the nexus of service provision for older people and are the de facto hospice. 14

Supporting residents to die in the care home

Care home staff wish to reduce preventable hospitalisations, yet often lack clear methods of doing so. 15 Palliative care interventions for residents in CHs report positive outcomes including reducing hospitalisations16 and improving advance/anticipatory care planning (ACP),17 while advocating for the role of specialist senior nursing practitioners. 18 Increasing anticipatory planning (including Advance Care Plans and anticipatory prescribing) improves the confidence of care staff to discuss goals of care with residents, their families and friends and supporting healthcare professionals and can lead to a reduction in hospitalisations. 19 Some studies issue caution on the impact on hospitalisations, but report improvements in preferred place of death. 20

Nurses in CHs who are supported to administer anticipatory medications can reduce hospital admissions and facilitate faster symptom management. 21 Provision of support to CH staff has been shown to improve end-of-life care for residents. 22 Needs Rounds have clear benefits for residents’ health outcomes: reducing admissions to acute care and improving quality of dying, and increasing workforce knowledge and confidence. 23–25

Telehealth is increasingly used to support CHs engage in early palliative care discussions and is acceptable to CH staff and relatives. 26 Such evidence supports changes to practice due to COVID-19,27 and telehealth has been used in Australian Needs Rounds adaptations, with positive outcomes reported. 28

Supporting the palliative care education of CH staff (despite it not being part of statutory training) needs to be seen as a priority to improve outcomes both for staff and for residents requiring a palliative approach. 29,30 Education in ACP, as part of palliative care provision, has led to increasing rates of completed plans and advance directives, improving consistency of clinical decision with resident preferences. 11,31 Advance care planning interventions mitigate distress and improve communication with relatives. 32 Yet, in a recent systematic review of 16 trials with a staff education component,33 many interventions did not result in improved quality of life, quality of death or reduced hospitalisations. Educational interventions can lack sufficient power to result in different clinical behaviour, programmes can be inconsistent and the necessary steps for sustainable change are often lacking. 29,34 Calls for standardisations in palliative care education in CHs may be helpful,35 yet this risks education not being tailored to specific contexts and circumstances. 36 Furthermore, the wider workforce context means there are inherent difficulties in providing coherent training and education where there is high turnover of staff. 35

Workforce issues continue to hamper many initiatives in improving palliative care in CHs,37 though some studies report that retention and burnout were not related, and indeed that burnout rates were unexpectedly low. 38 Maintaining few staffing vacancies is associated with greater likelihood of CHs being rated good or outstanding by the regulatory body. 39

Providing end-of-life support to CHs is an increasingly important area of service development. UK service delivery innovations such as ECHO,40 Gold Standards Framework (GSF),41 Macmillan’s education for carers ‘Foundations in Palliative Care’, Six Steps to Success,42 the EU funded PACE work43 and person-centred dementia care with the Namaste programme44 offer staff training and development, but rarely provide facilitation of evidence-based clinical input for people who are dying. Currently, only the PACE study has been fully tested in a randomised controlled trial across six European countries. The English Enhanced Health in Care Homes (EHCH) approach aims to improve links between CHs and primary care, yet it had patchy implementation due to multiple barriers such as communication, appropriate outcomes, trust and complexity. 44

Hospital prevention studies form an important backdrop to CH research. 45,46 Care Home Innovation Partnerships (CHIP) in Liverpool, for example, paired community matrons with CHs to review residents, develop ACP and treat minor ailments. The study reported a 15% reduction in emergency calls and a 19% reduction of hospital transfers. 47 Integrated care approaches, with health and social care working together, show promising impact on hospitalisations,48,49 alongside active management of long-term conditions. 50 Determining what constitutes an inappropriate admission, however, is not straightforward. 51

Advance care planning is an important tool in ensuring tailored and appropriate care. Studies suggest that while staff knowledge is important,52 their self-efficacy also plays an important role in engaging in ACP conversations. 53 However, training CH staff in conducting ACP conversations is a recognised deficit. 54 Involvement of family members can be important in ACP. 55 It is likely that ACP is one of several tools which need to be used to avoid unnecessary hospitalisations. 56

COVID-19 in care homes

Since commencing this study, publications on CH research have focused on responses to, and experiences of, the COVID-19 pandemic. In England, there were already 29,542 excess deaths in CHs by 7 August 2020. 57 In Scotland, estimates of years of life lost by CH residents were calculated at 5600 years. 58 Data from before COVID-19 suggest that relative risk of dying in CHs had already increased, with shorter intervals from admission to death. 59 Recommendations from a mixed-methods study on COVID-19 on CHs in England suggested a need for greater training and support for CH staff providing palliative care. 30 Evidence suggests an increase in ACP in CHs during the pandemic, which was helped by education/training for staff to promote their confidence and competence in having these conversations. 60,61 The increase in resident mortality alongside increased responsibility for end-of-life care took a considerable toll on staff mental health. 62 COVID-19 also brought about new practice developments63 and research examining ACP in the broader health and social care community, including the role of GPs64 and SPC teams. 65

Despite these studies, there is a need for greater understanding of the delivery of palliative care during the pandemic to CH residents. 66

National Health Service policy and practice

There is currently no statutory training requirement and no robust approach to delivering optimal palliative care to CH residents. NHS England wants to improve care in all settings and has committed to ‘explore improvements’ (p. 13)67 for residents in CHs but recognises that there are substantial difficulties in providing adequate care in these settings. The Care Quality Commission (CQC) articulates a requirement for ‘a clear focus on end of life care and applies in all services where end of life is delivered. The approach includes […] care homes’ (p. 21). 67 The CQC further states that there is more outstanding care by hospices than any other service, yet their data separate hospice care from nursing/CH care. This underlines a fundamental problem that CHs are not yet considered to be providing effective palliative care, despite the evident morbidity and mortality of residents.

Facilitating improved end-of-life care in CHs is an explicit driver for NHS England. 68 The ‘Ambitions Framework’ for palliative and end-of-life care has yet to be fully realised, but includes important elements such as fair access to care and staff/communities able to provide care and talk about death/dying. Clinical commissioning of palliative care clinical and education services across England is variable. 69

In the UK, while some SPC teams are based in hospitals and generalist palliative care is provided by primary care, it is the hospice teams who provide at-home support and care to people living in the community with advanced disease.

The Scottish Government’s 2015 Strategic Framework for Action on Palliative and End of Life Care sets out a vision of universal access to palliative care by 2021. This includes individuals, families and carers having timely, focused, conversations with appropriately skilled professionals to plan end-of-life care, in accordance with their needs and preferences. The vision sought to widen the range of health and social care staff providing palliative care, delivering appropriate training and supporting clinical and health economic evaluations of palliative and end-of-life care models. Furthermore, Healthcare Improvement Scotland commits to testing and implementing improvements to identify those who can benefit from palliative and end-of-life care,70 yet at present, there is no delivery model for this in CHs.

Wales set out a priority action in Health Boards providing access, support and education from SPC to CHs,71 but with no dominant model being offered beyond each community clinical nurse specialist linking with one or more CH. Northern Ireland guidelines recommend a designated nurse within the SPC team for CHs. 72

CH culture inevitably impacts working practices and resident care/experiences. 73 There is a need for high-quality leadership and facilitation alongside innovation41 and consideration of the nursing workforce and culture of education. 74 CH context, including the level of anticipatory and scheduled contact with primary care, is an important facet in effective healthcare in residential care, alongside joint working where residents’ needs are discussed, prioritised and responded to with a common purpose and shared values. 75

Understanding context and adjusting implementation in response to CH culture, including local priorities, readiness for change and facilitation champions are all important. 76 CH culture, and the culture change movement, has become a research focus seeking to identify characteristics which lead to care improvements. 77–80 Indeed, CHs which embrace culture change are more likely to provide better resident care. 81

The context in which CHs operate is complex, with stretched social care funding budgets from years of austerity, residents with complex needs and high levels of multiple morbidity, alongside suboptimal continuity of care within primary care services. 82 While approaches such as EHCH and My Health My Care My Home83 seek to address some of the multisector issues, this continues to be a complex space for providers, commissioners, service users and families. 84

Why is this research needed now?

Recognising the scale of people dying in CHs, the clinical risks associated with hospitalisation, and hence the drive to enable people to remain in their CHs with appropriate advance planning and support for staff, creates a context of urgent clinical innovation. Without a clear national model with robust evidence base, suboptimal care is a risk. However, there is a model of providing SPC in CHs in Australia which provided compelling data to improve care, called Palliative Care Needs Rounds (hereafter referred to as Needs Rounds). The definitive stepped-wedge trial of Needs Rounds85 provided robust evidence from 1700 residents that the new approach to care can substantially improve outcomes for residents, staff and the acute sector.

In order to deliver the Needs Rounds model in the UK, adaptation is required due to the different service organisation and delivery models and the need to engage with key stakeholders such as residents, carers, palliative care services, CHs and the acute care sector. 86

Needs Rounds: intervention description

Needs Rounds were developed and tested in Canberra. The Australian approach includes three components:

-

Monthly hour-long triage meetings focused on 8–10 residents in each CH who are at risk of dying without a plan in place. A checklist24 (see Report Supplementary Material 1) is used to identify the most appropriate residents to review. Needs Rounds are facilitated by a palliative care specialist where they discuss with CH staff, residents’ physiological, psychosocial and spiritual needs. The palliative care specialist provides education at each Needs Rounds based on the residents discussed, for example, on recognising deterioration/dying, medicine side effects or anatomy/physiology. Discussions instigate actions, which are always personalised for the individual, including medication reviews, and ACP.

-

Case conferences/family meetings to discuss resident goals of care and communication with family and wider multidisciplinary team (MDT).

-

Direct clinical work from the SPC clinician with the CH resident, focused on requirements identified in the Needs Round triage meeting.

Each component of Needs Rounds is usually delivered in the CH. However, some elements (e.g. 1 and 2) can be delivered using videoconferencing,28 either in situations of excessive distance or when required due to infection control measures.

Needs Rounds outcomes

The pilot Needs Rounds intervention outcomes in Australia support UK strategic priorities, such as decreasing length of hospitalisations [p < 0.01; confidence interval (CI) −5.05 to −1.41 days], improving rates of residents dying in their preferred place23 and enabling staff to normalise death and dying25 by adopting an outreach model of SPC. A further Australian stepped-wedge trial of Needs Rounds with 1700 CH residents achieved reduced acute length of stay (p = 0.048) and evidenced improvements in residents dying with dignity, compassion and comfort (p = 0.019) and improved workforce confidence (p = 0.09). 85

Goals of the elements essential to the intervention

Needs Rounds draw together requirements for looking after older people in care, including case management and specialist outreach services,87 increasing ACP88 and staff education. 49,89 Needs Rounds strengthen current models by widening the beneficiary beyond those with advanced dementia90 and meeting core strategic targets such as improving symptom management,91 increasing preferred place of death92 and providing a framework for person-centred care to residents. 93

Creating a basic organisational structure that promotes palliative care collaboration through monthly multidisciplinary meetings (both internal and external health and social care professionals) is an important first step to build a solid foundation to provide palliative care. Such a foundation helps to break the isolation of CHs and can promote greater sustainability of further initiatives.

The context of Australian and United Kingdom care homes using Needs Rounds

While Australian CHs and UK CHs vary, many of the practicalities are similar. Both countries face similar tensions in service delivery for example high turnover of staff and residents with complex multiple morbidities. Usual care in the area of Australia where the stepped-wedge trial was conducted had reactive provision of direct clinical care from the local SPC team. This is very similar to most UK provision. 3,4

The four core elements by which the two countries’ CH contexts differ are as follows:

-

The sites involved in the Australian study all employed a registered nurse, which is an important difference in adapting and implementing Needs Rounds for the UK. This may mean that UK Needs Rounds require greater links with primary care (not just SPC). In the UK, SPC will require primary care to facilitate prescribing and, in CHs with no on-site nurses, administering of medication. It may also mean that the Needs Round ‘case-based education’ component of the model will include greater emphasis on core information and skills.

-

Australian CHs tend to be larger than the average size in the UK (average Australian size in the stepped-wedge study was 90, whereas the average in England is 29.5 and 38 in Scotland). 94 This means that the delivery of Needs Rounds will be to fewer residents and smaller staff groups in the UK.

-

Australia has a larger proportion of adults over the age of 65 residing in CHs (5.2%)95 compared with England/Wales (3.2%). 96 It is not clear, however, whether the acuity of residents’ symptoms is comparable across countries.

-

Both countries operate CHs without mandatory training for their staff on palliative or end-of-life care. In Australia, however, CH staff are able to access a national education programme (PEPA – Programme of Experience in the Palliative Approach https://pepaeducation.com/) which enables CH staff to attend a workshop on palliative care, and some days shadowing staff from SPC (e.g. in an inpatient unit). By contrast, in the UK, education is provided via initiatives such as ECHO, Six Steps or the GSF.

Aims and objectives

The implementation objectives were to:

-

co-design a UK version of Needs Rounds, which is responsive to the different (macro, meso and micro) contextual characteristics of the UK CH sector (Phase 1)

-

implement the adapted model of care, assess feasibility, acceptability and effectiveness, and ultimately propose how the model of care can be further refined and adopted in the UK context to reap the benefits demonstrated in the Australian work (Phase 2).

The intervention objectives were to:

-

determine the transferability of the core elements of the Needs Rounds intervention in the UK context (Phase 1 and 2)

-

delineate the mechanisms of action (individual and group) that enable more effective palliative and end-of-life care practices to be realised in UK CHs (Phase 2)

-

identify the relationships between (1) the mechanisms of action embedded in Needs Rounds, (2) how these mechanisms function in different CH contexts and (3) the outcomes arising for different stakeholders and parts of the care system (Phase 2).

The process evaluation objectives were to:

-

document the outcomes of UK Needs Rounds on hospitalisations (including costs), quality of death/dying and staff capability (Phase 2)

-

assess and report the perspectives of CH residents, relatives, CH staff and palliative care staff on using UK Needs Rounds (Phase 2).

The primary aim was to improve palliative care, through developing the Needs Rounds approach for CH residents/staff to access SPC. The primary outcome was to understand what works for whom under which circumstance and why, when using the UK model of Needs Rounds.

Structure of the report

This report is formed of eight chapters.

Chapter 1, this background chapter, introduces the research. Chapter 2 outlines the study’s methodology. Chapter 3 reports the sample and ‘what works for whom under what circumstances’. Chapter 4 reports data on core quantitative outcome measures, specifically staff ability to adopt a palliative approach, the quality of death and dying of residents, and family perceptions of care. Chapter 5 reports the treatment effect and cost–benefit analysis. Chapter 6 outlines the patient and public involvement and engagement (PPIE) evaluation, and Chapter 7 reports research engagement by CH. Chapter 8 presents the discussion and conclusions.

Chapter 2 Methodology and methods

Research design

This pragmatic critical-realist implementation study used the integrated Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services (i-PARIHS) framework in six case studies. Each case comprised a SPC team working with three to six CHs each.

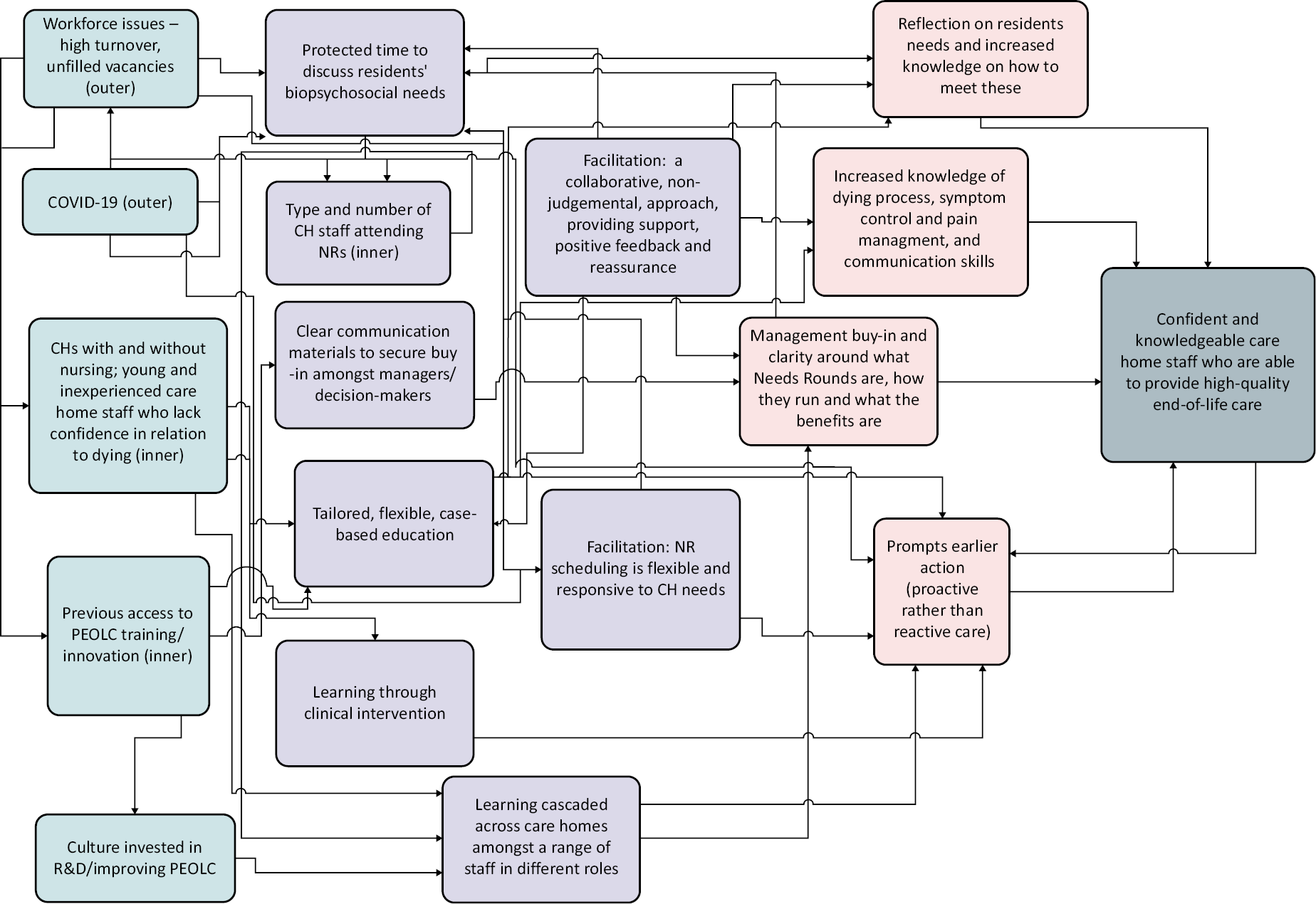

Integrated Promoting Action on Research Implementation in Health Services represents an integrated approach, recognising that most implementation is complex, requiring attention to multiple factors simultaneously for an innovation to be successful. The development of theory is central to i-PARIHS to enable effective implementation of research evidence into everyday practice. Programme theories explaining micro changes and transactions, such as working hypotheses or local theories of change, are explored to elucidate core concepts. For this study, theory was generated regarding (1) influential components of the UK context and (2) the mechanisms of how to implement Needs Rounds in UK CHs to (3) deliver desired outcomes.

The study was designed prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. Changes required to the protocol and impacts on data collection are detailed in subsequent sections and summarised in Summary of changes to protocol.

The following guidelines have been drawn on in reporting the study: CHEERS (health economics),97 GRIP Longform (PPIE),98 RAMESES II (realist evaluations),99 TIDieR (intervention description and replication)100 and StaRI (implementation science) (see Report Supplementary Material 2–6). 101

The implementation strategy was to adjust the Australian model, based on feedback in Phase 1 and 2 (qualitative interviews and workshops) to create a UK adaptation.

Study phases

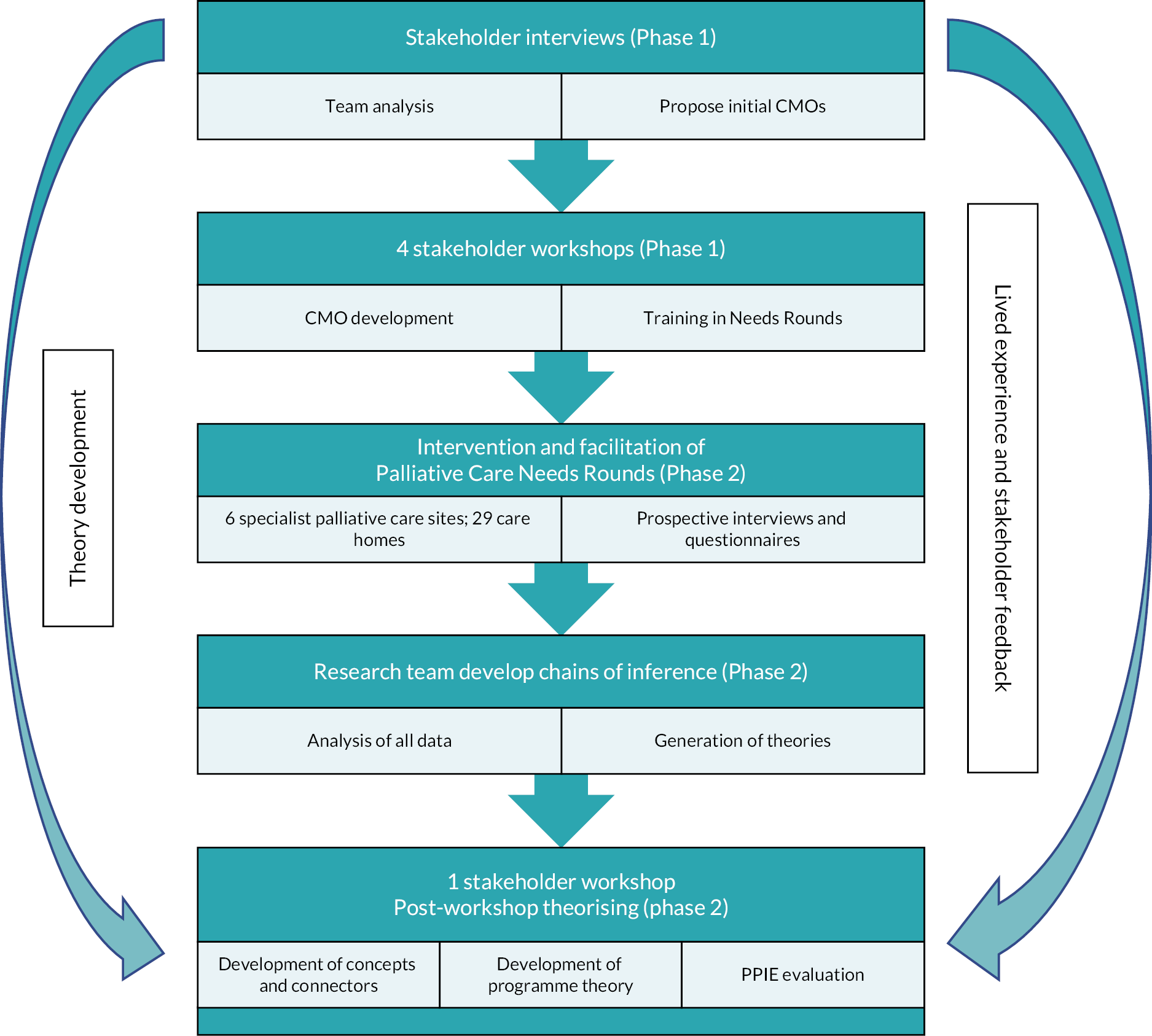

The study had two core phases. The phases and core activities are depicted in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Co-design process in developing a candidate programme theory.

Overview of Phase 1

Purpose: Phase 1 sought to generate an initial programme theory of ‘what elements of Needs Rounds would work for whom in what circumstances and why, in the UK context’.

-

Qualitative interviews were conducted with key stakeholders to understand how Needs Rounds could be used.

-

The findings from the interviews were presented to participants during two online workshops. Workshop discussion focused on whether the data reflected participants’ experiences, any identified gaps and the anticipated mechanisms of change required for Needs Rounds to be successfully implemented.

-

Team analysis of interview and workshop data led to the development of five theories and an initial programme theory.

-

A third workshop was held to generate feedback on the initial programme theory and the context, mechanism outcome (CMO) configurations. The five theories’ CMOs were communicated within the workshop using fictionalised vignettes – to help illustrate the interconnections by describing example residents (see Report Supplementary Material 7–11 for vignettes). Discussions arising from the presentation of CMOs focused on overarching themes and connectors between the theories. Discussions were captured by the investigator team (including academics and PPIE).

-

A fourth Phase 1 workshop was run, focused on presenting the initial programme theory and providing training on the UK Needs Round approach.

Workshop participants included Phase 1 interviewees and a wider pool of stakeholders. The workshops created the collaborative space to co-design the UK approach to Needs Rounds. All workshop discussions were audio-recorded. Phase 1 ran for 6 months, from January 2021 to June 2021.

Overview of Phase 2

Purpose: to implement UK Needs Rounds and finalise the programme theory of ‘what works for whom under what circumstances and why’. Secondary aims were to generate data relating to cost–benefit of the intervention, determine the impact on resident quality of dying, family perceptions of care and evaluate the PPIE across the study.

-

Implementation of the UK Needs Rounds model was conducted with six SPC teams, each of whom were working with three to six CHs in their locality. Implementation ran for 12 months, from July 2021 to June 2022.

-

Implementation involved the three-part model described in Needs Rounds: intervention description, with a minor modification that sites could choose to integrate with local primary care services in ways that suited usual provision, including where there were GP retainers, EHCH or regular primary care rounds.

-

Throughout Phase 2, prospective interviews were conducted with SPC and CH staff using Needs Rounds to understand their reflections on the intervention.

-

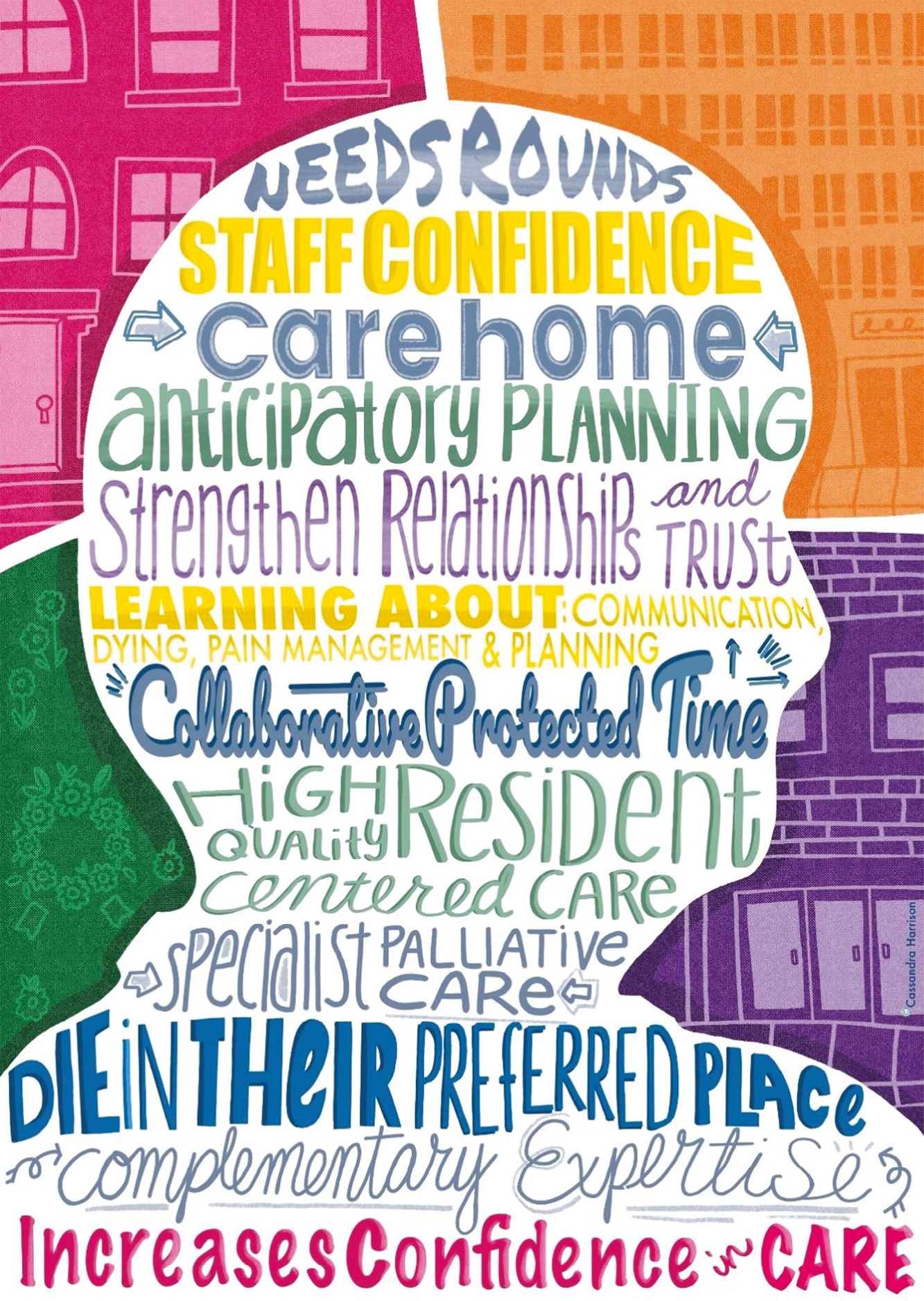

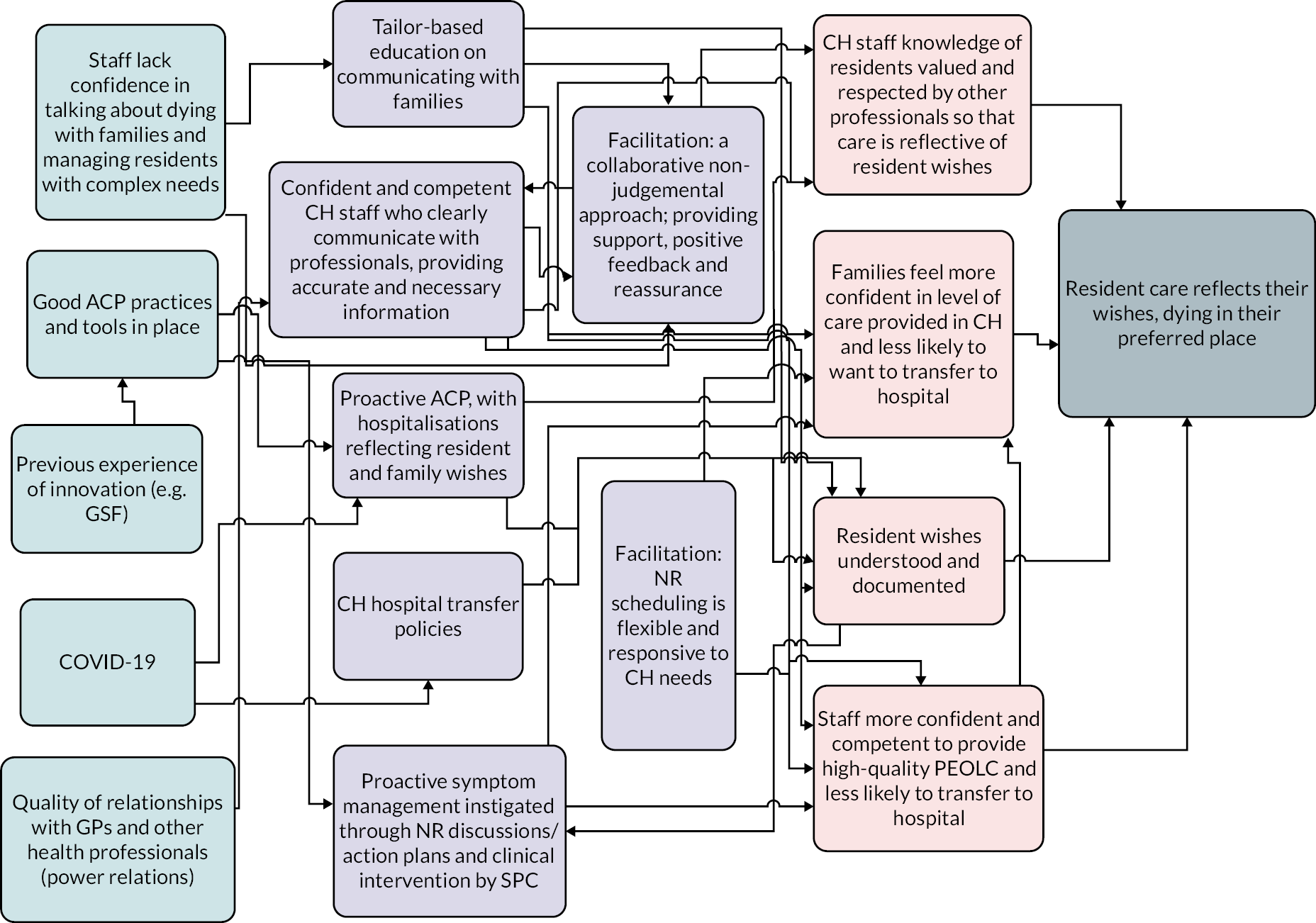

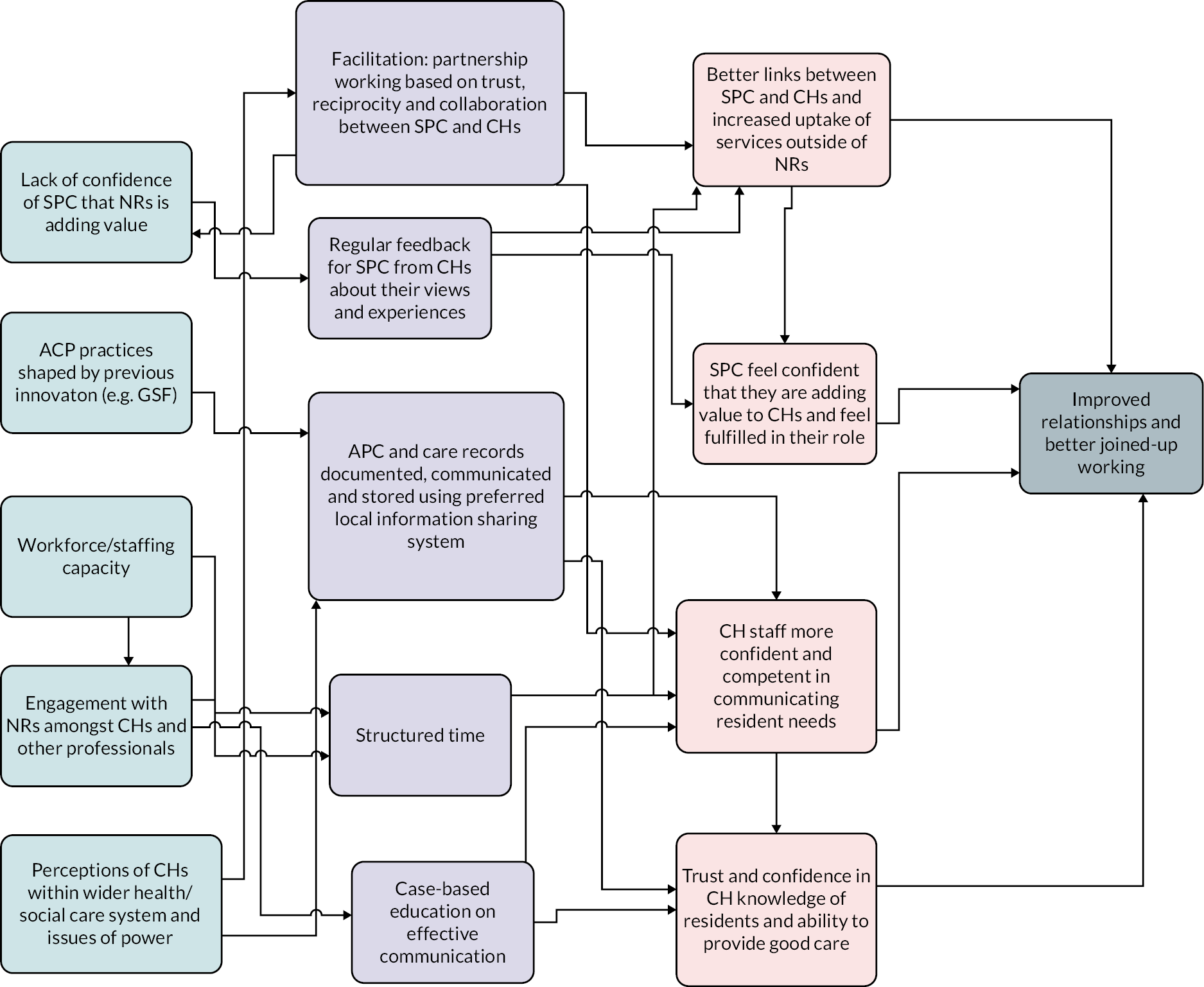

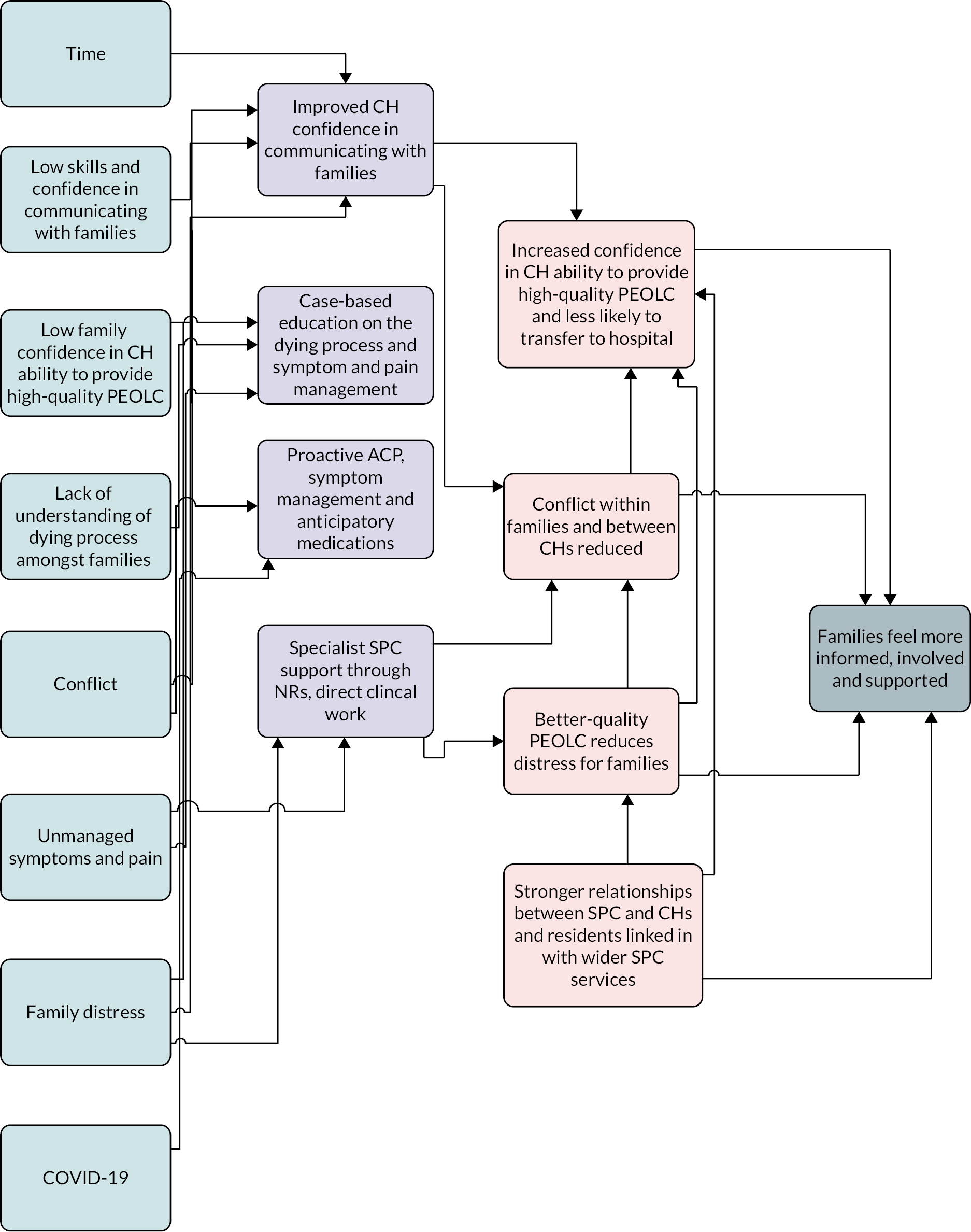

In May 2022, towards the end of the implementation period, a workshop was held to refine the overarching programme theory based on the prospective interviews and views articulated during the workshop. The workshop sought to elicit further feedback on implementation and post-study implementation, confirm and agree preferred dissemination methods for stakeholders and discuss study dissemination. Discussion of the theories was aided by an artist providing an illustration of each of the theories, coupled with live illustrations of the unfolding workshop conversation. The illustration produced of the five theories is available in Report Supplementary Material 12; Chapter 3 contains the illustration of the final programme theory (see Figure 3).

Workshop participants in Phase 2 involved people involved in delivering the intervention, from the CHs and SPC services.

-

Phase 2 also included a qualitative evaluation of the PPIE process and outcomes for the study; data collection to determine cost–benefit analysis; impact on other outcomes of interest such as staff capability of adopting a palliative approach (CAPA), quality of resident dying and family perceptions of care.

Woven throughout, Phase 1 and Phase 2 were reflexive analytic research team meetings to discuss the chains of inference connecting the theories and the overarching programme theory. These team meetings provided space to reflect on how academic, clinical and lived experience impacted our interpretations.

Data sources

Recruitment to the study

Specialist palliative care sites were recruited to the study first. Existing networks of the principal investigator (PI) were approached with study materials outlining the aims, objectives and methods of the study. These sites were named in the protocol and hence agreed prior to funding. One hospice withdrew after the study was funded, and consequently, further recruitment activity took place to identify an additional site. This site was confirmed and in place prior to commencement of the study.

Subsequently, hospices that agreed to participate in the study identified local CHs to invite to participate.

Recruitment was augmented by ENRICH, a UK network focused on enabling research in CHs. ENRICH holds databases of CHs who have demonstrated an interest in participating in studies, and they contacted CHs in some of the case study areas to invite eligible homes to participate.

Interviewees were recruited through the collaborating CHs and SPC sites, using snowballing and personal networks to identify relevant stakeholders in the local communities.

Recruitment was sought across England and Scotland, with four sites in England (west Midlands, Midlands, East Anglia and South) and two in Scotland (central and northern). Purposive maximum variability sampling of SPC services focused on recruiting a heterogeneous and information-rich sample, including urban/rural, service size, deprivation, cultural demographics, use of ECHO or other SPC input models and funding models. CH recruitment sought diversity by being part of a national chain or independently run and size. These variables reflect the dominant contextual influences which were likely to impact how Needs Rounds are used in the UK.

Due to COVID-19 restrictions, recruitment was all conducted remotely, using e-mail, phone calls and video calls, rather than a combination of these approaches alongside in-person meetings.

Inclusion criteria

Stakeholders (for interviews in Phase 1 and workshop participants)

-

Work for SPC or a CH in one of the six cases, are a resident in one of the CHs, are a relative of a CH resident in one of the six cases or work in acute care impacted by hospitalised CH residents.

-

Willing to provide informed consent.

-

Have capacity to provide their own consent to participate.

-

Not engaged in any current safeguarding investigations.

Care homes (to use UK Needs Rounds)

-

Located within the service area of the SPC service.

-

Provide care to residents who have high clinical nursing/medical needs.

-

Willing to sign a memorandum of understanding with the research team, outlining provision of hospitalisation data, facilitate access to staff for interviews and engagement in delivering Needs Rounds.

-

A range of medium and large sizes (focusing primarily on larger CHs), sole traders and large corporate provider and with a range of funding models (social care and self-funded residents).

Residents who are discussed at Needs Rounds

-

Resident in a collaborating CH in one of the six case study locations.

-

An anticipated life expectancy of < 6 months or a deteriorating condition where they are at risk from dying without an adequate care plan in place.

-

Experiencing suboptimal biopsychosocial symptoms.

Relatives completing the CANHELP Lite (family’s perceptions of care) questionnaire

-

Relative of a resident who was discussed in Needs Rounds.

-

Able to provide their own informed consent.

Interviewees for the patient and public involvement and engagement evaluation

-

Coinvestigator or staff at one of the case study sites.

-

Able to provide their own informed consent.

Phase 1

Data were generated from two sources: (1) interviews and (2) a sequence of four workshop discussions.

Twenty-eight interviews (individual or paired) were conducted with participants from six case study sites. Interviews involved relatives (n = 2), clinicians/managers in CHs (n = 12), clinicians in SPC (n = 7) and their related acute/primary care staff (n = 5), allied health practitioners (n = 1) and one CH staff member who did not specify their role. Formal respondent checking of transcripts was not used, since the workshops provided opportunity to clarify, check accuracy and validate ideas/opinions with participants.

Staff participants were asked about their local context, such as services’ geography, policy, structure, funding and practice elements. Relatives were asked about their experiences of their family member’s care including symptom management, goals of care and ACP and communication and responsiveness.

These data were analysed to develop realist theories regarding how implementation would work in practice, what might influence implementation in each case study site, to identify CMOs. Interview data were collected between February 2021 and April 2021. Interviews ranged from 37 to 119 minutes, with an average of 56 minutes.

The analysis from these interviews was then presented to participants during two online workshops. Workshop discussion focused on whether the data reflected participants’ experiences, any identified gaps and the anticipated mechanisms of change required for Needs Rounds to be successfully implemented.

Team analysis of both the interview data and the two workshop discussions led to the development of five theories and an initial programme theory. These five theories and programme theory were then presented for discussion and examination at a third workshop, to generate feedback on (1) the initial programme theory, (2) the CMO configurations and (3) overarching themes and connectors between the theories.

A fourth workshop was then held to present the initial programme theory and use feedback from participants to make revisions to it. This fourth workshop also included training on the UK Needs Round approach for the CH staff and SPC staff who would be delivering the intervention.

Forty-three unique participants attended the workshops in Phase 1. These participants were from 23 organisations including CHs, SPC organisations, and people with PPIE experience. The workshops were conducted in April and June 2021 and lasted for approximately 3.5 hours each.

Throughout the four workshops, the research team, including PPIE members, made notes capturing key parts of the discussion. Transcripts of the workshop discussion were also used as data sources and hence were subject to analysis.

It was intended to conduct interviews and workshops face to face. However, due to ongoing COVID-19 restrictions, reduced willingness/ability to travel and greater familiarity with online platforms, all data collection was conducted online.

Phase 2

Staff accounts of the intervention

During the intervention phase, qualitative interviews with key stakeholders, in each case study site, were conducted to determine the mechanisms of change and examine the CMOs/theories that were generated in Phase 1. Interviews collected prospective data on acceptability, appropriateness, feasibility, implementation cost, coverage and sustainability. Further data on providers’ context were also examined alongside how the intervention was delivered in each site (mechanisms including resources and reasoning, such as preparedness of sites and agency to affect practice). In the final interviews, stakeholders were asked to reflect on mechanism to disseminate the findings.

Interview questions pertaining to the CH context were drawn from conceptual work by Estabrook et al. 102 to dynamically explore each CH’s culture. Interview topics covered, for example, leadership, culture, time/space, staff/resident turnover or introduction of new policies/procedures and prioritisation of the intervention in workload.

Audio-recorded interviews were conducted at:

-

four months (capturing early adoption, n = 19 interviews/21 participants; 4 nurses, 9 management, 1 carer, 6 SPC clinicians and 1 nurse and deputy manager)

-

eight months (mid-range, n = 21 interviews/22 participants; 12 management, 3 nursing, 6 SPC clinicians and 1 nurse and deputy manager)

-

eleven months (longer-term implementation, n = 14 interviews/15 participants; 6 management, 2 nursing, 6 SPC clinicians and 1 nurse/deputy manager).

The Australian Palliative Care Needs Rounds stepped-wedge trial showed that 6 months allows time for clinicians and services to become sufficiently familiar with the Needs Rounds model. The Australian study indicated month-on-month improvements in staff capability over time, and hence this 12-month time frame allowed analysis over the course of implementation.

Interview duration in Phase 2 reflected the clinical/care pressures within the CHs. Interviews ranged from 16 to 117 minutes, with an average of 35 minutes. Interviewees in Phase 2 had not been interviewed in Phase 1 since many were not in role until implementation commenced.

Data from these interviews were presented for discussion in a final workshop, held online in May 2022, in the penultimate month of the implementation period. The purpose of this final workshop was to refine the overarching programme theory (and by default also the five theories). The workshop sought to elicit further feedback on implementation, post-study implementation and develop a dissemination plan. Workshop discussion was aided by an artist who prepared an illustration of each of the five theories (available in the Report Supplementary Material 12). The artist also attended the workshop and produced further live illustrations of the unfolding conversation (which is presented in Chapter 3, showing the final programme theory).

Workshop participants in Phase 2 involved people who were delivering the intervention, from the CHs and SPC services.

Data were intended to be collected through a mixture of face-to-face and phone interviews, alongside in-person workshops. However, with ongoing COVID-19 restrictions in visiting CHs, all data collection was conducted online/via phone. Sample size was focused on theoretical sufficiency, which was achieved. Transcripts were not returned to interviewees, but participant checking was facilitated through the workshop discussions. These data are reported throughout Chapter 3 and in Qualitative appraisals of costs.

Resident data

A bespoke spreadsheet was developed to capture resident data. This included basic demographic information including age, ethnicity, first language, number of deaths and Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance scale. The ECOG describes an individual’s level of functioning in terms of their ability to care for themself, daily activity and physical ability. Scores ranged from 0 to 4, whereby lower scores represent higher levels of functioning and independence.

Preferred place of death (and actual place of death if they died during the study) and health service use during the 3-month data collection periods (name of hospital, duration of admission, speciality/ward of admission, mode of transport to hospital, gender, age and contact with primary care) were also requested.

Data were collected by CH staff. COVID-19 lockdowns precluded external researchers attending. Further, ethical approval permitted access to residents’ personal data only by routine members of the care team.

Training and support were provided to CH staff to increase the robustness of data collection and reporting. Videos were made to demonstrate data capture, and individualised phone calls, video calls and e-mails were used with each CH to support data reporting. The spreadsheet was revised and simplified during baseline data collection to aid reporting. The data collection tool was revised again during the follow-up period and formatted as a Word document to increase response rates.

Specialist palliative care clinicians were asked to report information regarding the assessments and interventions triggered by Needs Rounds. This included, for example, physical assessments, blood/urine tests or other clinical investigations, referrals to other NHS services, changes in pharmacotherapy and commencement of syringe drivers.

Data on resident demographics are reported in Chapter 3, Sample.

Economic evaluation

Economic evaluation planned to involve a cost–benefit analysis103 drawing on the following data (Tables 1 and 2).

| Cost type | Cost detail | Measurement of costs |

|---|---|---|

| Direct costs | Intervention costs on-site:

|

Included within the project budget and therefore directly recorded. Where appropriate additional detail was collected directly from the CHs |

| Additional NHS staff time attending CH Additional prescriptions |

Estimated in the SoECAT, with additional costs recorded by intervention staff as required | |

| Indirect costs | Wider additional costs incurred by the CH, including

|

These changes, and their associated costs, were collected from CHs in a proforma through the interviews |

| Intangible costs | Inconvenience to staff, residents, family and carers as a result of the intervention | Explored in the qualitative interviews in Phase 2 |

| Cost type | Cost detail | Measurement of costs |

|---|---|---|

| Direct costs | Costs of ambulance journeys | Estimated from the 2019/20 National Tariff Payment System105 |

| Hospital stay cost | Hospital-specific PLICs data for England106 and Scotland107 on stay costs by age and gender to estimate a day rate to use in the hospital costing | |

| Primary care usage | Explored in the qualitative interviews in Phase 2 | |

| Indirect costs | Wider additional costs incurred by the CH, in connection with resident hospital admissions, including staffing, travel, equipment or facilities | Explored in the qualitative interviews in Phase 2 |

| Intangible costs | Inconvenience to residents and their family/carers arising from hospitalisation | These were not measured directly but were explored in the qualitative interviews in Phase 2 |

Linked hospital data were not sought, as this would have required considerable additional resource (time and personnel) and result in reduced data of less robust quality for drawing generalisable conclusions. The reduced volume and robustness of data would occur because individual-level consent would be required to access such information, effectively reducing the pool of data to those without cognitive impairment. Since the average prevalence of dementia in CH residents is 69%,108 this presented an unacceptable reduction in sample size.

In a change to the protocol, the cost–benefit analysis was unable to be completed. This was caused by two main issues, both COVID-19-related.

First, challenges in the recruitment of CHs and paucity of CH data received from those who did participate affected both the sample size and the level of data available to the project for economic analysis. Estimation of the benefit (in reduced hospitalisation) was compromised both by sample size and the confounding effect of COVID-19 on the pre/post research design.

Second, the secondary outcome of cost–benefit was predicated on pre-COVID-19 clinical concerns about high rates of hospitalisation and transfer to/from hospital of CH residents. COVID-19 led to substantial changes to health service use and in particular reducing hospitalisations (including circumstances where hospitals have refused transfers from CH residents and vice versa). Consequently, the impact of our Needs Rounds intervention in reducing hospitalisations costs cannot be disaggregated from the impact of COVID-19 on health service use and its development during the study.

Data on economic analysis are reported in Chapter 5.

Staff capability

Care home staff CAPA was assessed on a nine-item validated self-report questionnaire (see Report Supplementary Material 13) (He, 2016, personal communication). Capability of adopting a palliative approach has a unidimensional scale; higher scores indicate greater capability. Internal consistency is very high with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.95 and a split-half reliability coefficient of 0.93 (He, personal communication). Data were collected from a range of staff members, predominantly nurses, care assistants and managers, between July 2021 and July 2022. Although the aim was to collect data each month from those attending Needs Rounds, the average response rate from CHs was 3 months of data, not necessarily from the same staff members each time. Questionnaires were completed by CH staff, either hard copy or online depending on site preferences.

Data on staff capability are reported in Staff capability of adopting a palliative approach.

Quality of death and dying

The Quality of Death and Dying Index109 (QODDI) was requested to be completed by CH staff for each decedent resident prospectively at the time of death throughout the study (see Report Supplementary Material 13). This 17-item questionnaire examines four correlated but distinct domains: symptom control, preparation, connectedness and transcendence. The decedent’s experience is rated on a 0–10 scale, where higher scores indicate a better death. The Cronbach’s alpha for the QODDI total score is 0.89. Following correspondence with the scale’s originator confirming psychometric robustness of excluding items, one item on access to euthanasia was removed, as this is not legal in England or Scotland.

The QODDI was designed for completion by relatives; however, staff are more consistently likely to have seen the resident in the weeks prior to death (primarily due to COVID-19 visiting restrictions). Hence, staff completion resulted in more reliable and valid data. No suitable staff measure exists, and the questionnaire worked well in the Australian stepped-wedge trial. 85 Questionnaires were completed in either hard copy or online, depending on site preferences. Data were collected between July 2021 and June 2022.

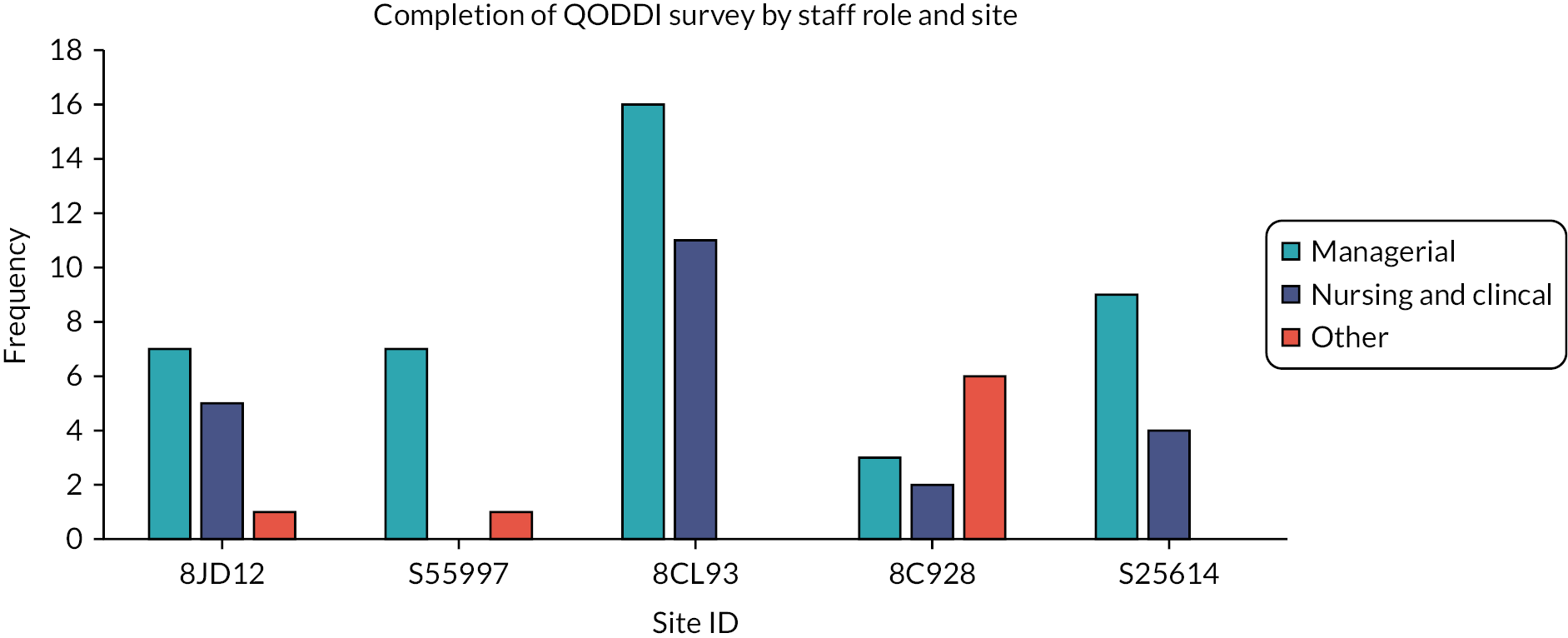

Data on the QODDI are reported in Quality of death and dying.

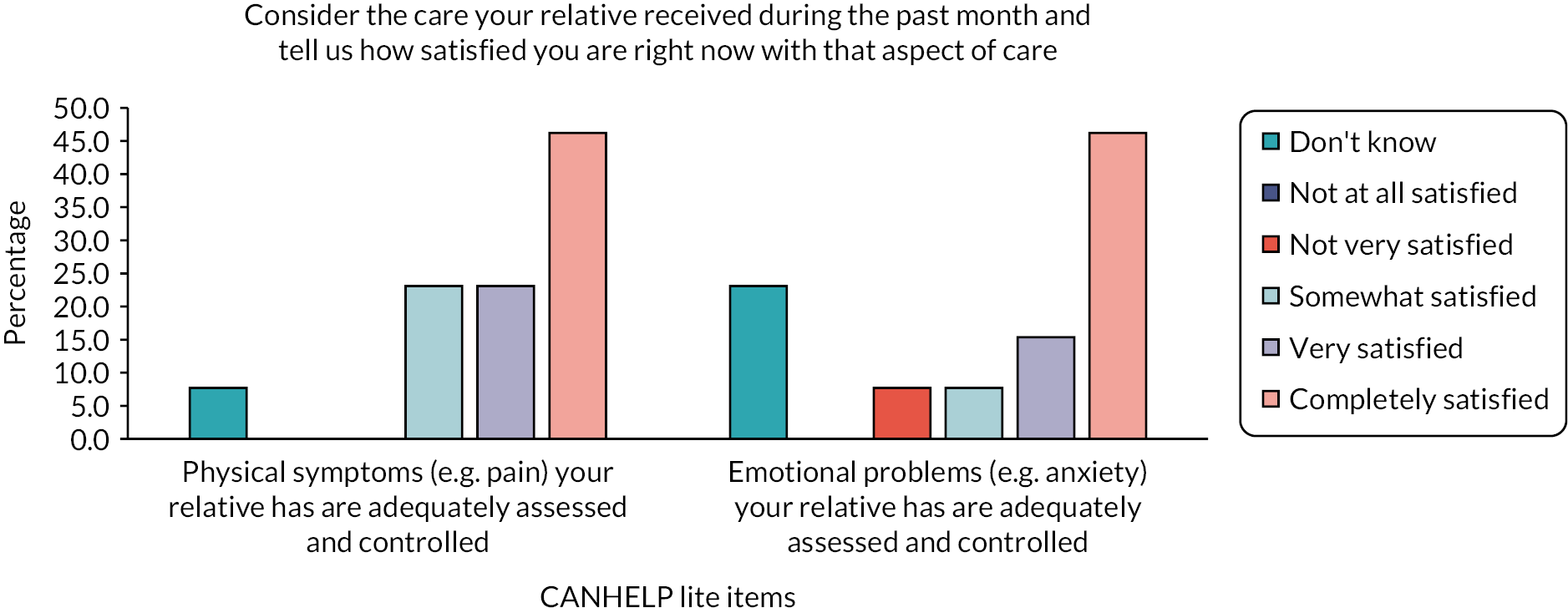

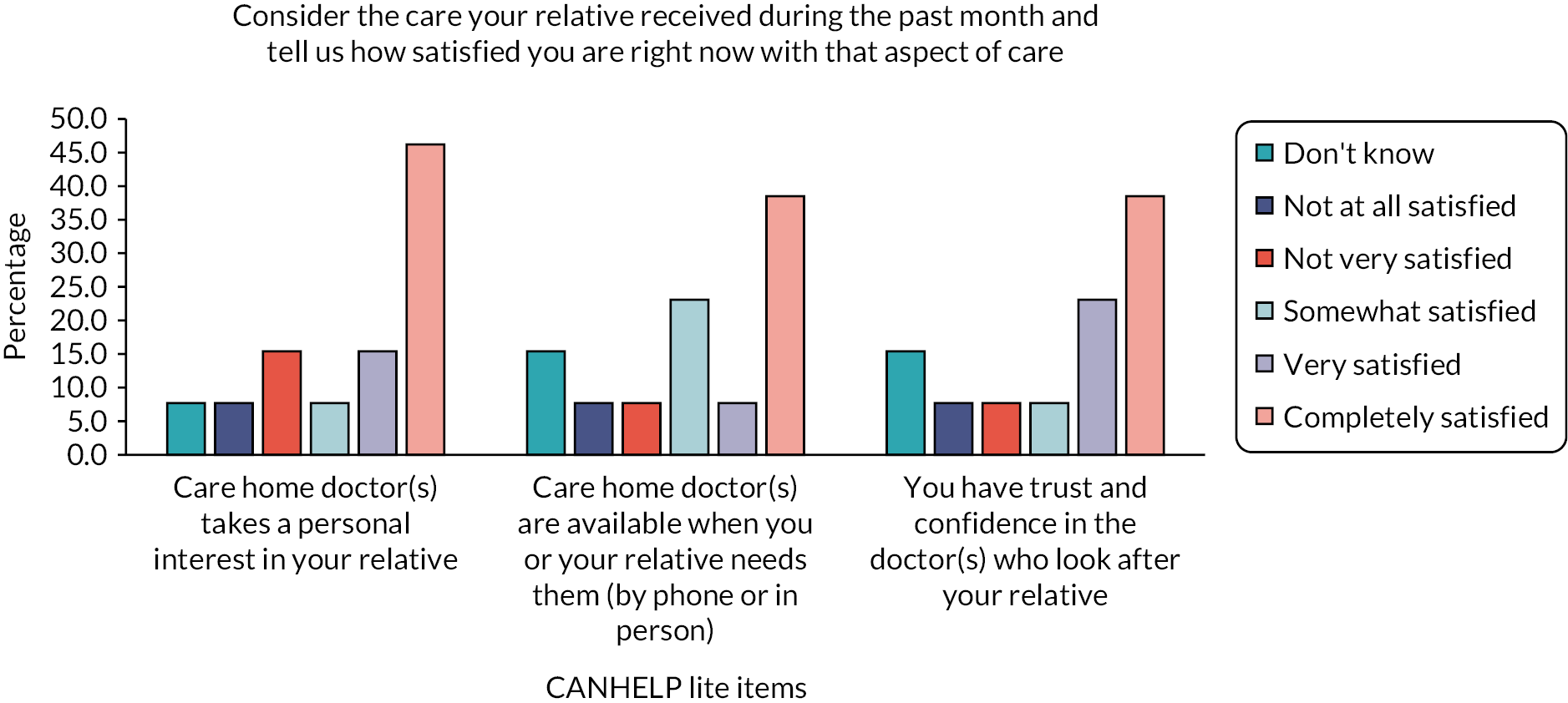

CANHELP Lite: Families’ perceptions of care

Relative reports of care quality were focused on those where residents were discussed at Needs Rounds, using the CANHELP Lite (see Report Supplementary Material 13). 110 The second part of the questionnaire was used, which focuses on satisfaction with care. This involved 22 items collecting self-report data on family views of CH staff, illness management, communication, relationships with clinicians and relative involvement. The Cronbach’s alpha for the total score is 0.88–0.94. Questionnaires were completed either in hard copy or online, depending on family/site preferences. Relatives were only asked once to complete this measure, even if the resident was discussed at Needs Rounds more than once. Data were returned between August 2021 and May 2022.

Data on the CANHELP Lite are reported in Families’ perceptions: CANHELP Lite.

Audio recordings of monthly Needs Rounds

Sites were requested to record Needs Rounds discussions, to allow analysis of how monthly meetings proceeded, including the case-based learning and assessment of adaptations made by clinical teams for their local areas. Recordings were made from July 2021 to June 2022.

Data from the audio recordings were used to inform assessment of fidelity, which is reported in Fidelity.

Patient public involvement and engagement interviews

All research team members (including academics, clinicians and PPIE members) were invited to participate in a one-off interview focused on their experiences and process of PPIE throughout the study. One-to-one phone/video-conference interviews were conducted to examine the successes and opportunities of patient/public involvement in this study to enhance future PPIE work.

Data were collected and analysed by an independent researcher in October and November 2022. This component of the study was conducted by one female qualitative researcher completing her doctorate in the social sciences. Prior to the study, the independent researcher had no relationship to any of the PPIE members and only a limited relationship with three of the academics, who she knew on an informal basis through university networks. Interviews ranged from 23 to 72 minutes, with an average of 49 minutes. Interviews were recorded and transcribed. Transcripts were then anonymised; interviewees are referred to in this report via their role in the study (e.g. academic 1 or PPIE 1).

Data on the PPIE evaluation are reported in Chapter 6.

Care home survey

A third phase was suggested by the project Steering Group, to conduct a survey of CHs across the UK. The survey would gather feedback on the fit of the UK Needs Rounds approach for services not involved in the intervention study. This component was not integrated into the original funded protocol, but was part of the published intervention protocol. 104 Further discussions with study team and steering group identified that a national survey would not be possible within the time span of the study, and that ongoing workforce issues exacerbated by COVID-19 would likely result in a low response rate, precluding generalisability.

Modes of analysis/interpretation

Qualitative data

Transcripts of audio data and documentary evidence were stored and organised using Nvivo 11, 12 and 20.

Critical realism informed the thematic analysis used with all qualitative data, following the five-step process outlined by Braun and Clarke. 111 Stage 1 involved familiarisation with the data set through repeated rereadings. Stage 2 involved identifying an initial thematic framework, which was used in Stage 3 where data were indexed with reference to the thematic framework. In Stage 4, data were synthesised from across respondents into consolidated themes. Stage 5 focused on interpretation and finalisation of key themes generated from the data.

Within- and between-case analysis was conducted inductively (inferring from specific data to draw conclusions and develop theory), drawing on process tracing and constant comparative methods, respectively. Deductive analysis (testing the theories with reference to data) was also used to refine the CMO theories. Following realist approaches, data analysis also drew on a ‘retroductive’ approach, to move beyond induction and deduction to allow for ‘the identification of hidden causal forces that lie behind identified patterns or changes in those patterns’ (p. 1). 112 Retroduction describes the team’s interpretation of generative causation in identifying and naming contexts and mechanisms which lead to the intervention outcomes.

Phase 1 (pre-implementation) data were analysed to create an initial programme theory to be tested during implementation. Analysis focused on identifying the contexts (in which Needs Rounds would run), mechanisms of change and outcomes. Contexts were analysed as either inner/micro/meso context (individual or organisational level) or outer/macro (such as the wider policy/cultural context). Mechanisms of change were organised into categories to include facilitators (people), facilitation (process), resources and reasoning. Innovation focused on understandings of Needs Rounds, perceptions of value and degree of fit. CMO configurations and their chains of inference were generated for five theories from these data.

Qualitative data collected in Phase 2 (at months 4, 8 and 11 of implementation) were used to refine the programme theory. The coding was organised in relation to the five theories (see Theory 1: confidence and competence and Theory 5: supporting families), identifying CMOs. CMO configurations were updated based on what worked or did not work during implementation. Analysis was an iterative process, examining differences between the initial programme theories and Phase 2 implementation data.

Further coding was developed to allow analysis of engagement of sites in the data collection by CH staff. Tables were created identifying the main CMOs under each theory with illustrative data.

The PPIE evaluation analysis was conducted by the independent researcher to maintain the confidentiality of respondents. All other qualitative data were analysed by three experienced female qualitative researchers (all of whom hold PhDs) who had ongoing contact with staff at all study sites. Codes and themes were discussed between those three team members to develop consensus on data interpretation.

The guiding principle for analysis and sampling was theoretical sufficiency113 with triangulation used for all data sources to aid development of the theory.

Survey data

The quantitative analysis was conducted by social scientists with expertise in statistics, who were not involved in data collection. Therefore, the researchers responsible for analysing the survey data had no interaction with either CH staff or hospice staff. During the analysis, ID numbers were used (e.g. ST00335) in place of organisations’ names, creating a quasi-blinded state whereby the researchers analysing the survey data were not connecting results to specific CHs or case study identity during analysis.

Staff capability: CAPA

Scores for each of the nine CAPA items were coded one to five and summed to give an overall CAPA score (ranging from 9 to 45) whereby higher scores indicate greater capability.

Data were analysed using generalised least squares random-effects models with robust standard errors. This allowed adjustment for repeated observations from the minority of CH staff members that completed the survey more than once (16.4%). Regressions were conducted for overall CAPA scores and for each of the nine CAPA items individually. In each of the analyses, the main predictor variable was staff role, with variables to control for date of survey completion, size of CH, ownership of CH (private or voluntary, not for profit) and hospice. To determine size of the CH, the number of beds reported at each site was categorised as medium (11–49 beds) or large (50 + beds) based on categories defined by the CQC. 114 There were no CHs in the study categorised as small (1–10 beds).

Additionally, a paired t-test was carried out using the subset of CH staff members with multiple responses (n = 28). Most (60.7%) completed the CAPA survey only twice; however, for those with three or more responses, their first and last submitted CAPA scores were compared.

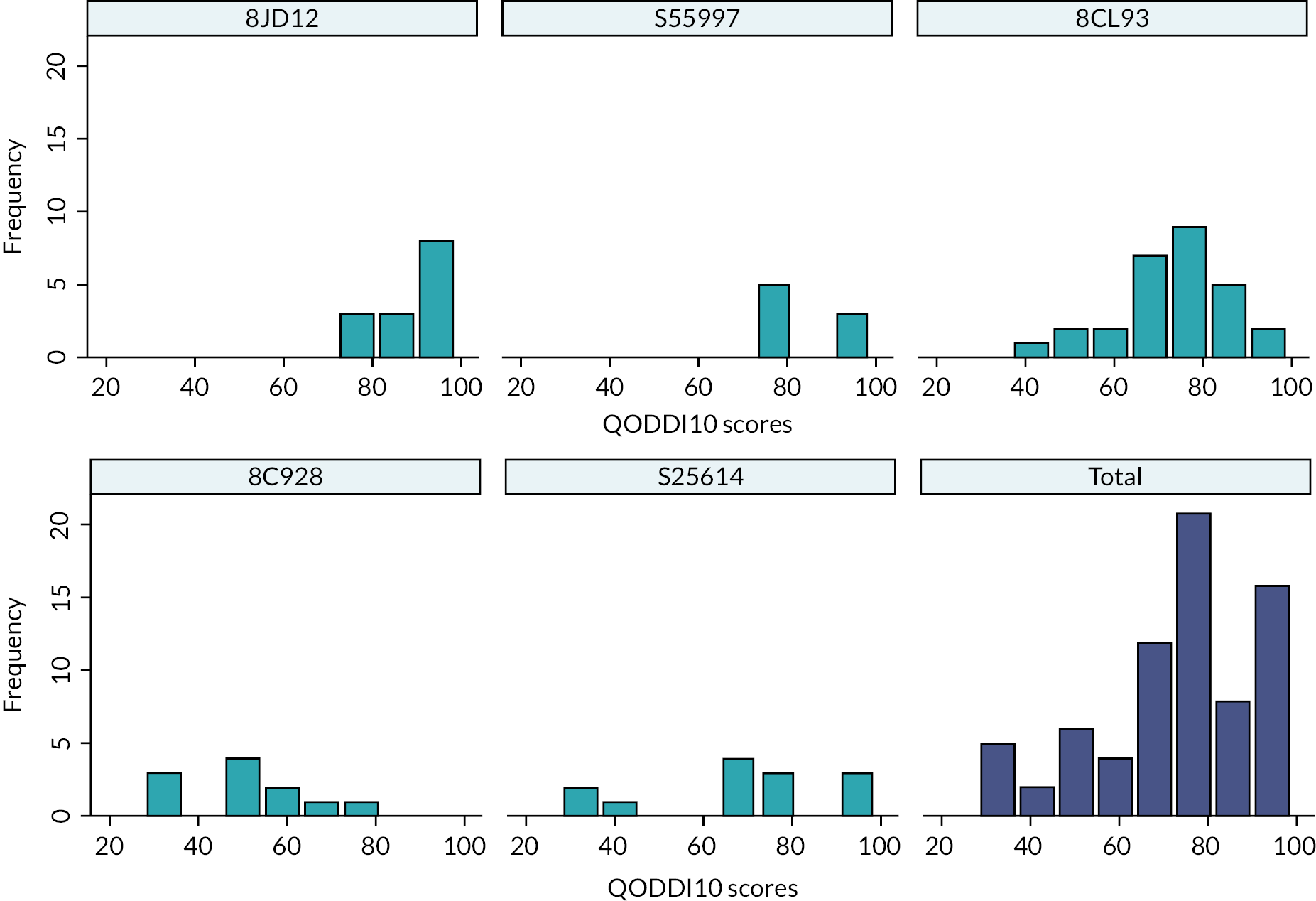

Quality of death and dying

As specified in Quality of death and dying, the item on euthanasia was removed, reducing the QODDI to 16 items. However, a large proportion of missing data was observed for some of the remaining items (see Quality of death and dying for further discussion on missing data), leaving only five complete QODDI responses using the 16-item survey. Thus, to optimise the sample size and facilitate analysis, subsets of the QODDI were calculated. Analysis was conducted using QODDI10, a subset of the QODDI questionnaire, which included 10 items. The QODDI10 was selected to preserve the largest proportion of the sample with complete responses (92.6%). Robustness checks were carried out by repeating the analysis with alternative subsets of the QODDI, including 12-item (QODDI12) and 14-item versions (QODDI14), which returned similar results. However, it is important to note that the validity of the QODDI as a shortened 10-item scale has not been rigorously tested, and thus, direct comparison should not be made with studies using the full version of the instrument. In Recommendations for future research, we recommend future research to validate shorter versions of the scales used in CH research to reduce burden on the staff. Scores for each of the QODDI items were coded from 0 to 10 and summed to give an overall QODDI score (ranging from 0 to 100 for the QODDI10), whereby higher scores indicate better quality of death. Data were analysed using linear regression models with robust standard errors. The outcome variable was total score on the QODDI10. Model 1 included only the main predictor variable, date of death; the relationship between date of death and QODDI score was important to examine to identify if deaths that occurred later in the Needs Rounds intervention were of better quality than those occurring early in the intervention period. In model 2, additional controls for size of CH and CH ownership were included to account for CH-related factors that might influence the quality of the decedent’s death. In the third model, staff role is controlled for to identify if certain staff groups were more likely to rate deaths as higher or lower quality, in addition to a variable which measured the time between the decedent’s death and when the QODDI survey was completed. Those who completed the QODDI survey closer to death may be more likely to accurately remember the details of the death, but there could be heightened psychological factors related to the reporting, whereas those reporting at a later date might have reduced accuracy in recalling the details. The final model included dummy variables created for five of the six hospices; 8A784 was dropped from the analyses as only one QODDI response was returned. The aim of this model was to identify any differences in quality of death between the hospice locations after accounting for all other relevant factors.

Family perceptions: CANHELP Lite

This questionnaire was analysed with descriptive statistics. Inferential analysis was not possible due to the low number of returns (n = 13).

Fidelity

Fidelity is concerned with the extent to which an intervention or programme is carried out in the way intended. It encapsulates the delivery, receipt and enactment of an innovation. 115 Various tools have been created to measure fidelity, focusing on both content and/or processes that impact implementation outcomes. Content focuses on the specific information to be conveyed, while process focuses on facilitation, including the skills of the practitioner, and the quality of delivery and engagement. 116 Given the centrality of i-PARIHS to this study, facilitation is reported in more detail (see Facilitation and facilitators).

Assessment of fidelity to the agreed approach to Needs Rounds was conducted based on the singular UK model developed and agreed in workshops. Fidelity was assessed against the published checklist,24 since Phase 1 determined that the UK approach would closely model the approach outlined in the checklist.

Fidelity was assessed through analysis of a random sample of 20% of all audio-recorded Needs Rounds. Fidelity is most often associated with positivist research paradigms; within this study, however, it was approached as a realist endeavour to map engagement with the agreed model. A three-tier scoring system, of 1 (high adherence), 2 (moderate) and 3 (low), was adopted. Operational definitions for these scores were developed to aid coding. For example, case-based learning is a core element of Needs Rounds meetings and was coded as high (relevant learning included for the majority of residents discussed), moderate (some relevant learning provided during the Needs Rounds, but not for most residents) and low (little or no relevant learning provided during the meeting). The fidelity schema was collaboratively developed by two researchers, with reference to the literature on fidelity, and coding was conducted by one researcher. The fidelity criteria are provided in Report Supplementary Material 14.

Estimating the treatment effect of the intervention on health service outcomes

Data on hospitalisations were requested from CHs across 5 months at baseline, between March and July 2021, and across a further 3 months at follow-up, from March to May 2022 (months 9–12 of the intervention).

At baseline, 11 CHs returned data for at least one of the months requested; however, there were a substantial number of missing and incomplete data. A minimum of 1 month’s complete data were obtained from nine of the 29 participating CHs; the average response rate was 3 months of data across those nine CHs, with only one site providing complete data for all five baseline months. At follow-up, six CHs returned at least 1 month of complete data; however, one had not provided adequate baseline data, and thus comparison could not be made.

Exposure was calculated by examining the reported data on the number of beds within each of the five CHs, the number of empty beds reported each month and the number of days of data that were reported (i.e. if data were returned for March and April, the number of baseline days equalled 61).

Using data reported from the CHs about the number of hospital admissions over the baseline period and the resulting number of nights spent in hospital, calculations were made to create ratios for admissions per 1000 exposure and nights in hospital per 1000 exposure for analysis.

Only five CHs returned data at both baseline and follow-up, which severely restricted the possibilities for analysis and interpretation. Our analysis therefore reports descriptive statistics in Chapter 5 for the estimated treatment effect on the two outcomes above (number of admissions and number of hospital days) for each of the CHs, as well as an average treatment effect. The sample size is too small to conduct an inferential test for statistical significance on the average treatment effect.

Care must be taken in interpreting both the site-specific treatment effects and the average treatment effect both due to the low power of the analysis and the confounding effect of COVID-19 on estimating a casual effect using a pre/post research design.

Estimating the cost effectiveness of the intervention on health service outcomes

A cost–benefit analysis of the intervention was planned from a health and social services perspective. The health economic analysis plan was described in the original funding bid. The intervention cost was to be derived from both direct and indirect costs to both NHS and CHs of delivering the intervention. Calculations were to include the change in NHS costs incurred following the intervention, including both primary and secondary care, by valuing the reduction in hospital stays, hospital days as a result of the intervention, ambulance usage, GP callouts and visits by specialists.

As described above, due to insufficient data, this analysis was not possible, both as a result of the small samples of data returned by CHs and the compromised validity of the primary treatment effect estimation due to COVID-19. There was insufficient detail in the data collected to accurately estimate the costs of hospitalisations or the wider health service costs. To augment the sparse quantitative data, in Chapter 5 we also provide qualitative data on costs gathered in the study.

Care home participation

To examine which, if any, factors related to the involved CHs were associated with greater participation in the study, analyses were conducted to examine different areas of participation.

Four binary variables were created: whether the CHs provided baseline data, whether the CHs provided follow-up data, whether the CHs returned any QODDI surveys and whether the CHs returned any CAPA surveys. These were scored as zero for no data returned and one for some data returned. A fifth overall participation score was calculated by summing four variables representing participation in different areas of the study (Table 3), including the number of QODDI and CAPA surveys returned and the number of months CHs returned data on hospitalisations and assessments and interventions triggered by Needs Rounds (see Resident data).

| Overall participation | Scoring (range) |

|---|---|

| Number of QODDI surveys returned | 0–15 |

| Number of CAPA surveys returned | 0–24 |

| Number of months of hospitalisations data returned | 0–8 |

| Number of months of assessments and interventions triggered by Needs Rounds data returned | 2–13 |

Descriptive data were compared for all aforementioned participation variables across the following predictor variables: CH size, ownership, country, location and types of care provided (see Descriptive analysis).

Some variables were derived using data that CHs provided. For example, CHs were categorised as either medium or large based on the number of beds they reported against CQC categories (see Staff capability: CAPA), and each site reported their ownership as either private or not for profit. The CHs were located either in England or Scotland, so a simple binary variable was created to reflect this and draw comparison between the two countries.

To determine whether location impacted CH participation, a binary rural–urban variable was created. Using the Office for National Statistics postcode directory,117 the postcode for each CH was used to find the 2011 output area (OA11) code. For the English CHs, the OA11 codes were cross-referenced in the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, 2011 Rural–Urban Classification lookup tables for small area geographies118 to determine which CHs were in rural areas and which were urban. This process differed slightly for the Scottish CHs, in that the OA11 codes were used to obtain sixfold urban or rural codes from the Scottish Postcode Directory Files. 119 The sixfold codes were collapsed into the twofold (binary) rural urban classification using the Scottish Government Urban Rural Classification. 120

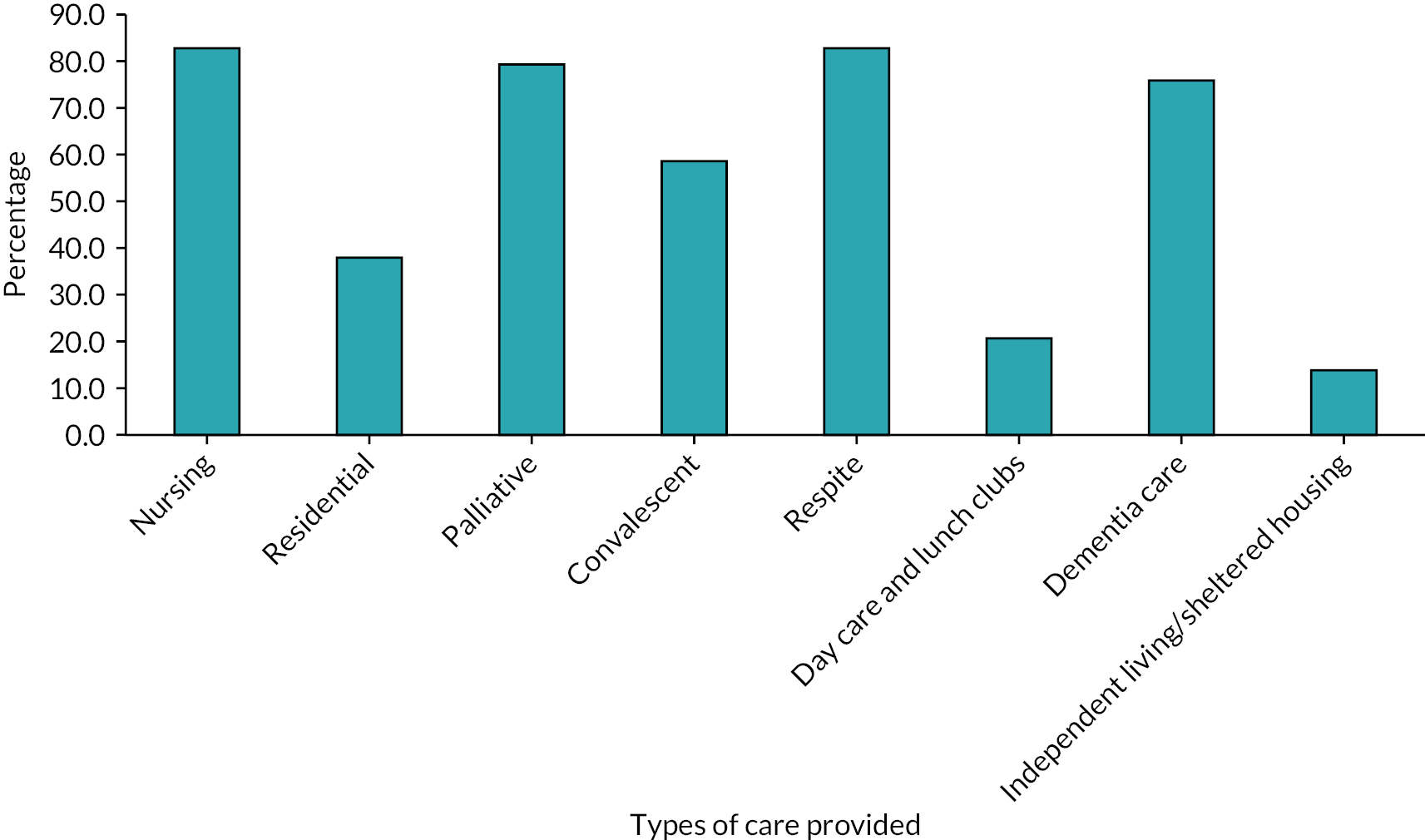

Finally, using the carehome.co.uk profile for each site, data were collected on the types of care provided at each home. Types of care included nursing, residential, convalescent, respite, day or lunch clubs, specialist care, dementia care and care to adults under 65 years.

A binary logistic regression was conducted to model participation, by means of completing baseline data, as a function of potential predictors of participation. The same models were applied in a linear regression analysis with overall participation score as the outcome. In model 1, location variables were included to identify how participation varied in England compared to Scotland and in urban versus rural CHs. In model 2, factors relating to the CH such as the size and the ownership were added. Ownership was dropped from this model for the baseline data analysis because, as shown in Descriptive analysis, 100% of the voluntary, not-for-profit CHs in the sample provided baseline data. In model 3, we controlled for the type of care provided. Residential was selected as it is one of the two main types of CH (i.e. CH with nursing – referred to in this section as nursing, or CH without nursing – referred to in this section as residential). When considering types of care provided, 24 (82.8%) provided some form of nursing care and 11 provided residential care (37.95). All CHs that provided nursing care also provided residential care, but not all CHs that provided residential care also provided nursing care (Table 4). Therefore, by including a dichotomous variable for the provision of residential care, we are comparing CHs that provide residential or residential and nursing care with those that solely provide nursing care. Due to small cell counts, it was not possible to include all care type variables in the analyses.

| Provides residential care | Provides nursing care | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | |||

| n | % | n | % | |

| No | 0 | 0.0 | 18 | 100.0 |

| Yes | 5 | 45.5 | 6 | 54.5 |

| Total | 5 | 17.2 | 24 | 82.8 |

Patient and public involvement and engagement

This is described more fully in Chapter 6 and in Equality, diversity and inclusion. However, in brief, the PPIE approach was informed by the National Standards and INVOLVE guidelines (49) and aimed to ensure the study was focused on improving services for residents and families. Terms of reference were developed to guide involvement and engagement (see Report Supplementary Material 15).

Lived experience is central to decision-making121 and has led to a proliferation of more collaborative approaches. 122,123 As a reflection of this position, research methodologies that privilege engagement with the communities or populations studied are increasingly used. 122,123 The language of coproduction and co-design has become more commonplace and adopted as an ethical approach to research. 124,125

The study had three PPIE members, defined as people who could speak about their lived experience of CHs/palliative care, or as a community member who might use a CH. One PPIE had an uncle living in a CH (not one of the study sites), who died towards the end of the implementation phase. A second PPIE member had undertaken lay inspections in CHs. The third PPIE member did not have direct experience of CHs and spoke from the position of a community member.

Patient and public involvement and engagement representatives were involved from the outset as co-applicants to ensure the research questions and aims were informed by people with non-academic/non-clinical experiences of CHs. Patient and public involvement and engagement members informed the choice of family outcome measures (focusing on a measure which would be least burdensome and most meaningful to relatives), devised interview questions, participated in recruitment of the research fellow (RF), contributed to ethical approval documentation and attended the research ethics committee (REC) meeting.

Patient and public involvement and engagement members attended monthly investigator meetings and provided advice on all aspects of the study. After each monthly meeting, they were invited to a debrief where further thoughts, reflections and questions could be raised with a member of the academic team. Patient and public involvement and engagement members participated in the workshops to coproduce UK Palliative Care Needs Rounds, data collection and data analysis.

As noted in Patient public involvement and engagement interviews, the PPIE work was evaluated via one-to-one interviews with a researcher external to the core Needs Rounds team. The interviews focused on all members of the teams’ experiences and reflections on PPIE. Furthermore, throughout the study, data were collected on PPIE resources/costs and evidence of impact.

It was intended to combine face-to-face involvement with online working. However, due to ongoing COVID-19 restrictions, ability to travel and greater familiarity with online platforms, all PPIE was conducted online.

Facilitators

Facilitation and facilitators are critical for successful implementation and a core element of i-PARIHS. Facilitators are agents of change who lead or champion an innovation. Facilitators for each site were identified during Phase 1 data collection.

A role description and person specification were developed, to ensure core skills, experiences and expertise of these facilitators. Although being a registered nurse (RN) was not a prerequisite, all six clinicians were RNs. The person specification listed the following:

-

registered health practitioner

-

minimum 3 years of postgraduate experience in palliative care

-

demonstrated advanced clinical knowledge, skills, experience and practice in the clinical assessment, diagnosis, investigation, treatment and referral as well as follow-up care of patients requiring SPC

-

understanding of multiple morbidities of CH population

-

demonstrated high-level communication, liaison, interpersonal and negotiation skills and an ability to form relationships with internal and external stakeholders

-

proven ability to prioritise and undertake timely comprehensive assessments of patients using evidence-based practice

-

proven ability to work within a risk management framework to ensure a high standard of safe clinical practice.

Specialist palliative care staff facilitating Needs Rounds should therefore be experienced clinicians. Core skills include diagnosing deterioration/dying, understanding of anatomy and physiology associated with ageing, frailty and life-limiting conditions, knowledge of medicines and equipment frequently used in palliative care contexts (such as syringe drivers), ability to communicate effectively with patients, family members and members of a broad MDT.

Training and skills of people facilitating Needs Rounds

Training was provided on Needs Round for all CH staff and hospice staff who would be delivering the intervention located in six geographically disparate areas.

The fourth videoconference-based workshop session in Phase 1 encompassed several facilitated examples of a Needs Round case discussion with some participants taking the role of SPC clinician and others in the role of CH staff. Other clinicians adopted the role of observer, with a task of reflecting on key learning regarding how to participate in Needs Rounds and actions they would need to undertake to be ready at their site for implementation. Observers therefore had the opportunity to act as a reflecting team to identify strengths and areas for development.

The Needs Round simulation exercise made use of the videoconference platform’s ‘chat’ function, allowing the verbal exchanges in the Needs Round to be accompanied by synchronous written commentary on the techniques used. Supplying this written commentary within the chat facility allowed the trainers to demonstrate links between theory and practice without the need to stop the simulation.

The platform’s breakout room structure was then used to form small groups to discuss the learning and run further bespoke simulations to allow participants to change roles and engage as both observers and active members. These smaller groups enabled deepening relationships between participants who would be delivering the intervention in each of the case study sites.

Action learning sets

To aid the SPC facilitators and gain coherence around the process of facilitation, action learning sets126 were adopted for monthly discussions with the SPC nurses delivering the Needs Rounds. The action learning sets offered a regular time for online video meetings of peer-to-peer learning, to share difficulties and solutions, in a collaborative relationship, facilitated by a member of the research team. Action learning sets provided opportunity to reflect on issues prospectively and develop learning and insights into the implementation across Scotland and England and enabled SPC staff to:

-

focus on their role within the Needs Round project

-

provide an opportunity to discuss emergent issues with each other and engage in problem-solving

-

give space for each SPC clinician to describe their situation and learning

-

provide a context which values being open, reflexive, practical and shared

-

not be overly structured, to allow for maximum scope of issues and topics to be within the remit of the action learning set

-

be non-hierarchical

-

be attentive to individuals’ contexts and hence complementary to the importance of context in implementation science.

Reflections within these monthly meetings fed into development of the programme theory. Due to the geographic spread of the sites, these action learning sets were always anticipated to run online. However, due to pandemic restrictions, the SPC clinicians did not get the opportunity to augment their online relationships with face-to-face meetings at workshops.

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was granted by Frenchay REC [287447] for the study.

Participants were provided with a participant information sheet (PIS). Easy read PIS and posters summarising the study were used to inform residents of the research and encourage participation in the Phase 1 interviews/workshops.

Informed consent was taken for participation in interviews, questionnaires and Needs Rounds recordings. Informed consent was not required for resident data as this was summary data to ensure anonymity, collated by routine care staff. A ‘no surprises’ approach was adopted, whereby posters were displayed within CHs to ensure that residents, relatives and staff members would be aware of the study and data being collected.

All resident demographic data were captured at CH level, not individual level, to ensure that data were anonymous and could not be traced to any individual. ID numbers are used throughout this report in place of organisations’ names.

All PISs, interview topic guides and questionnaires were examined by our PPIE representatives for appropriateness, and amendments made where requested.

Changes to data collection procedures (with researchers not involved in collecting demographic data), noted in the modified protocol, were introduced to minimise risk to CH staff and residents, as well as the research team. CHs were excluded if their size would preclude anonymity of residents.

Study management and sponsorship

A project steering group oversaw the study. It was chaired by an academic with expertise in CH research and had membership from individuals with expertise in implementation science, health economics, healthcare commissioning, palliative care and lay members providing the perspective of patients/public. The steering group was only able to meet online, due to ongoing COVID-19 restrictions and increased familiarity and desire to use video conferencing platforms. The research sponsor was the University of Stirling.

Summary of changes to protocol

Following study funding approval, several changes were made to the protocol:

-

CH data were collected and reported by routine care staff, rather than academic researchers. This was to minimise the potential for COVID-19 spreading and to ensure that only routine care staff had access to identifiable personal data.

-