Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 15/15/09. The contractual start date was in November 2016. The final report began editorial review in September 2021 and was accepted for publication in June 2022. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2022 Perkins et al. This work was produced by Perkins et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2022 Perkins et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Parts of this report have been reproduced from Eli et al. 1,2 These are Open Access articles distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced from Eli et al. 3 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) license, which permits others to copy and distribute this work, for non-commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

Background and study rationale

This study evaluated the use of the Recommended Summary Plan for Emergency Care and Treatment (ReSPECT) process during the early implementation phase (first 2 years) in acute NHS trusts in England. ReSPECT is an emergency care and treatment plan (ECTP) designed to address the shortcomings of standalone do not attempt cardiopulmonary resuscitation (DNACPR) decisions.

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) is a highly invasive medical treatment that is associated with potentially serious complications (e.g. rib fractures, sternal fractions, internal organ damage). 4 CPR attempts on someone with minimal comorbidities and a reversible cause of cardiac arrest can be life-saving. 5 Conversely, if CPR is attempted as someone approaches the end of their natural life, then it has little chance of success and deprives them of a dignified death. DNACPR decisions, introduced in the 1970s, provide a system through which CPR may be withheld in the event of cardiac arrest, which occurs as part of the process of natural death. 6 Current UK guidelines describe a DNACPR decision may be made:

-

at the request of a patient

-

if CPR has little chance of success

-

where the burdens of treatment outweigh the benefit.

Although DNACPR is a relatively straightforward concept, independent reviews7–10 identified the following substantial problems with the process of DNACPR decision-making and implementation:

-

A reluctance or fear in both patients and doctors to discuss CPR, leading to failures to involve patients in decision-making. 10–13

-

Poor communication with patients and people important to them (e.g. their family). 10,14–16

-

Variable levels of understanding of the incorporation of ethics issues in clinical decision-making. 10

-

CPR decisions being made in an ad hoc manner, with variation across different care settings, within similar care settings (e.g. hospitals, care homes, general practices) and among individual clinicians. 11,17

-

Unjustified DNACPR decisions being made for people with physical and mental disabilities. 8,18

-

Variation in the method of recording CPR decisions, and inconsistency in which methods of recording are accepted in different geographical regions and by different organisations within those regions, making good communication problematic. 19,20

-

People being subjected to CPR attempts that will be of no benefit or are contrary to their wishes. 7,10,15

-

Conflation of the term ‘DNACPR’ (which is meant only to apply to resuscitation) with limitations on other elements of care and treatment. 10,21,22

-

Evidence that patients with DNACPR decisions receive poorer care than patients with similar conditions and backgrounds without such decisions in place. 11,23,24

An ECTP is a patient-centred advance planning process for potential future emergency treatment situations. ECTPs seek to provide guidance on emergency treatments (including CPR) that should be considered in the event an emergency situation arises where the person does not have capacity to communicate their values and preferences or where there is insufficient time to consult. ECTP encompasses approaches variously described as limitation of treatment, limitation of care and treatment escalation plans (TEPs). Examples include the Universal Form of Treatment Options (UFTO), personal emergency plans and the Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment (POLST).

Evidence indicates that ECTPs may address care quality concerns associated with standalone DNACPR decisions. Evaluations of the POLST have shown that the system improved communication,25,26 implementation of end-of-life preferences and patient satisfaction. 27–31 In the UK, an evaluation of the UFTO found that UFTO was associated with a 23.3% [95% confidence interval (CI) 7.8% to 36.1%] reduction in harms (measured by the global trigger tool23) and that UFTO provided clarity of goals of care and reduced negative associations with resuscitation decisions. An internal evaluation of Gloucestershire Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust’s Unwell Patient escalation pathway found that the pathway reduced (from 17% to 5%) the proportion of resuscitation cases terminated for futility and increased (from 17% to 28%) overall cardiac arrest survival (David Gabbott, Gloucestershire Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, 2015, personal communication).

In October 2014, a stakeholder meeting for patients, clinicians and policy-makers to discuss findings of the DNACPR decisions evidence synthesis project10 identified the need for a national ECTP as a priority. Patients, clinicians and policy-makers recommended early evaluation following criticism by the independent enquiry into the Liverpool Care Pathway32 concerning absence of evaluation early in the national adoption process. The 2015 Health Select Committee report echoed the urgent need for such work. 9

Evidence and stakeholder recommendations prompted the Resuscitation Council UK (RCUK) (London, UK) and the Royal College of Nursing (London, UK) to establish a National Working Group to develop a national ECTP process, building on previous work. The National Working Group had representation from patients, professional organisations, regulatory bodies, the Care Quality Commission (CQC) (London, UK), acute, community and ambulance service NHS organisations, and patient and public members. Through an iterative development and usability testing process,33 an ECTP (i.e. the ReSPECT process) was produced. The ReSPECT process was adopted by the first acute NHS trusts in late 2016 and early 2017, and more widely from February 2017. The RCUK and the National Working Group provide support for organisations adopting the ReSPECT process and monitor its use. The ReSPECT process was designed for use with all patients

As noted earlier, ECTPs have been found to improve communication. Clinicians engaging with their patients to make a ReSPECT plan is central to the ReSPECT process. 33 Sharing the process of making the recommendations made on the ReSPECT plan has similarities with shared decision-making, which has been receiving increased policy, practice and research interest. The NHS Long Term Plan34 commits to giving people more control over their own health and more personalised care. The delivery plan for that objective of universal personalised care describes how the comprehensive model for personalised care should reach 2.5 million people by 2023/24. 35 A central component of the comprehensive model is the use of shared decision-making.

The ReSPECT process is a process that leads to recommendations about future clinical decisions in case an emergency arises, but it is not in itself a treatment decision. The ReSPECT process is designed for patients and families to share in the process of making ReSPECT recommendations and to agree them with their clinician. The responsibility for the recommendation stays with the clinician and responsibility for the eventual treatment decisions lies with the clinician caring for the patient at the time the emergency or urgent care is needed.

Understanding how, when and where the ReSPECT process was used in practice early during its adoption in UK NHS acute hospitals (1) allowed assessment of how far the ReSPECT process was going to address concerns associated with standalone DNACPR processes and (2) provided useful information about how clinicians approach making shared recommendations for future clinical treatment. We anticipated that the ReSPECT process would be used for all patients in acute settings as it was designed to be. The primary focus of this study was to evaluate how and where the ReSPECT process was used to support the DNACPR process in the acute care setting and its impact on patients. A wider evaluation of the process of implementation of ReSPECT was beyond the scope of this study.

Overview of research design, aims and objectives

This study focused on how, when and why ReSPECT process recommendations are made and what effects they have on patient outcomes in early adopting acute NHS hospitals. The rationale for focusing on acute settings was that (1) adoption was likely to occur initially in hospital settings, (2) 78% of incidents and complaints relating to DNACPR occurred in the hospital setting (with 90% of those incidents and complaints associated with severe harm or death),10 and (3) UK literature reports problems with communication, decision-making and implementation of DNACPR decisions in this setting. 10

We included some evaluation of adoption in the communities our six sites served through (1) evaluating the frequency, process and ethics basis of decisions in patients presenting to hospital with an ECTP decision initiated in the community and (2) conducting focus groups with community clinicians.

Design

Our mixed-methods evaluation comprised four work packages. The evaluation investigates different areas of practice and service organisation that the introduction of the ReSPECT process aims to affect and provides a narrative summary of key findings across the work packages. The work packages are reported in detail in subsequent chapters, as follows.

Work package 1 (see Chapter 2)

The first work package is a qualitative study of ReSPECT decision-making processes, using observations of ReSPECT conversations and interviews with clinicians and patients/family members, and an analysis of the quality of ReSPECT form completion. These data are combined with interviews and focus groups with general practitioners (GPs) and other community staff regarding their experiences of the ReSPECT process (note that this was originally part of work package 4 but is reported with work package 1).

Work package 2 (see Chapter 3)

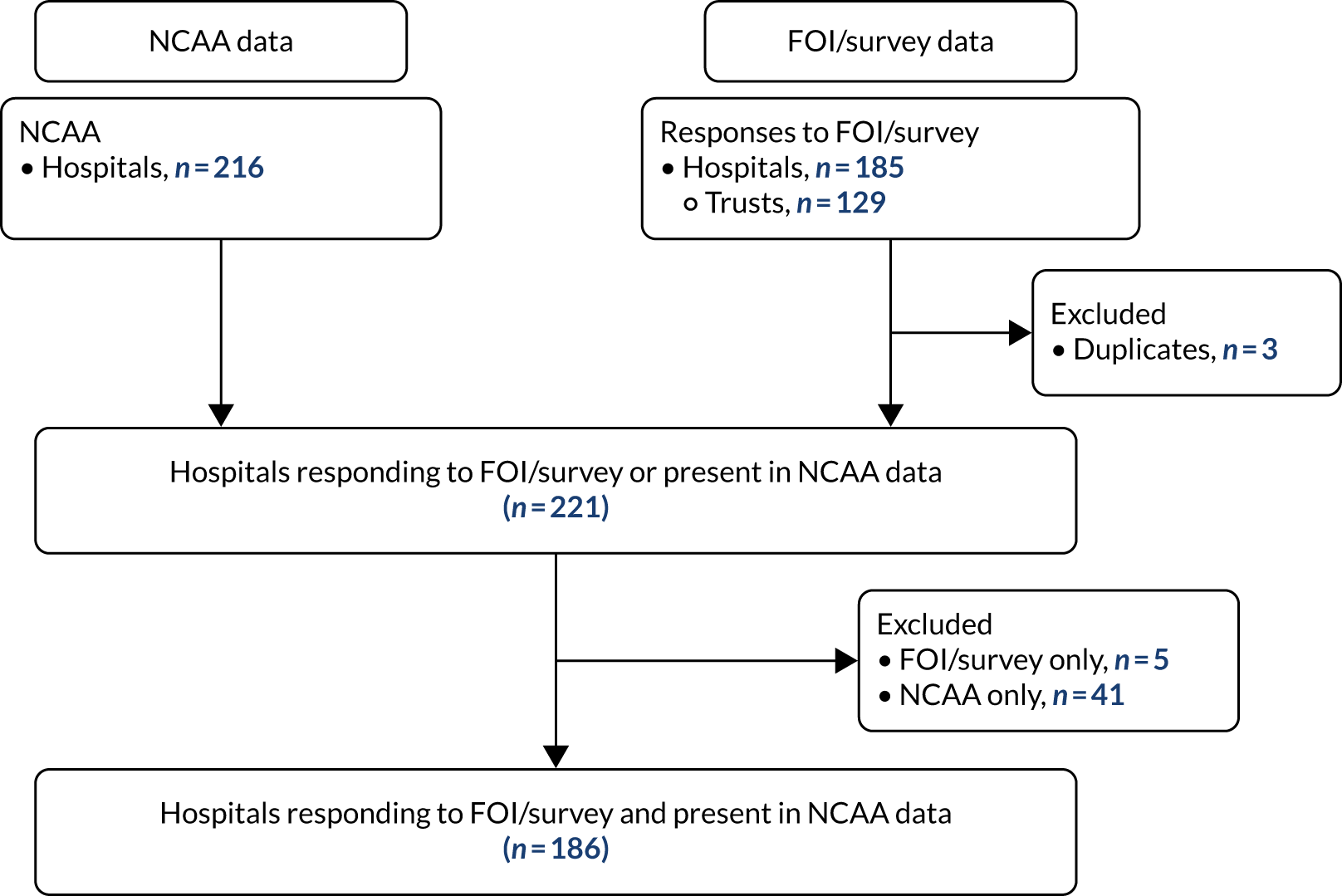

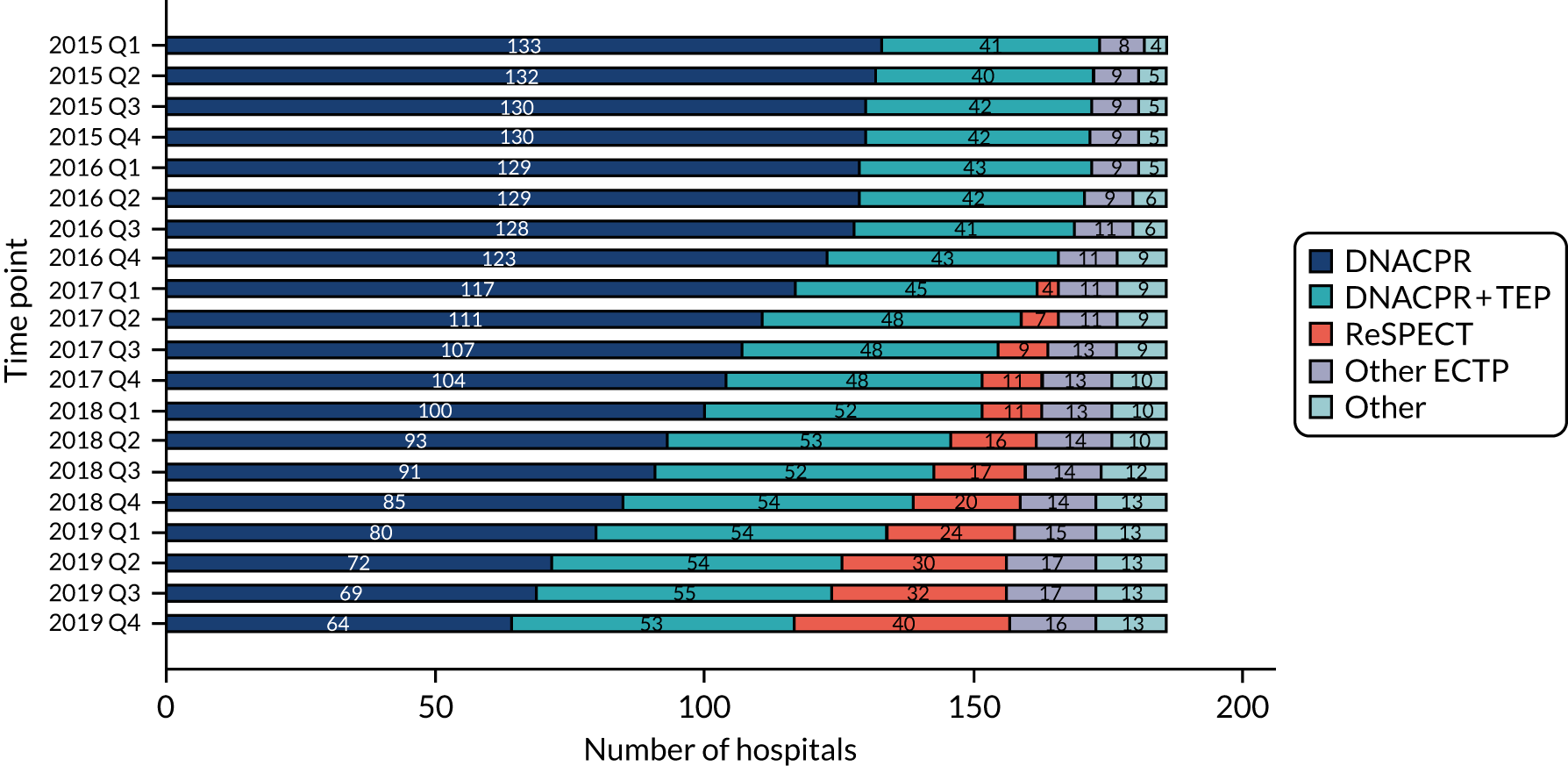

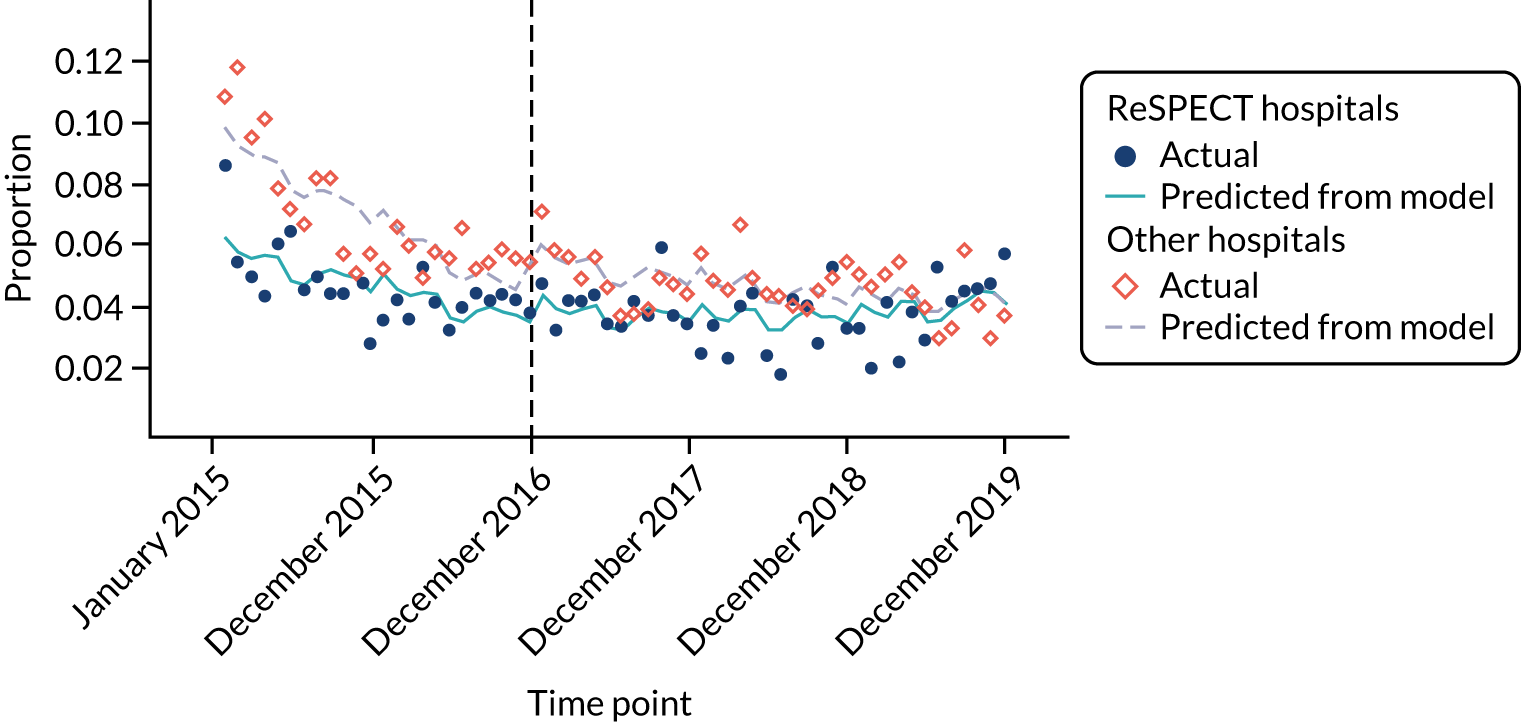

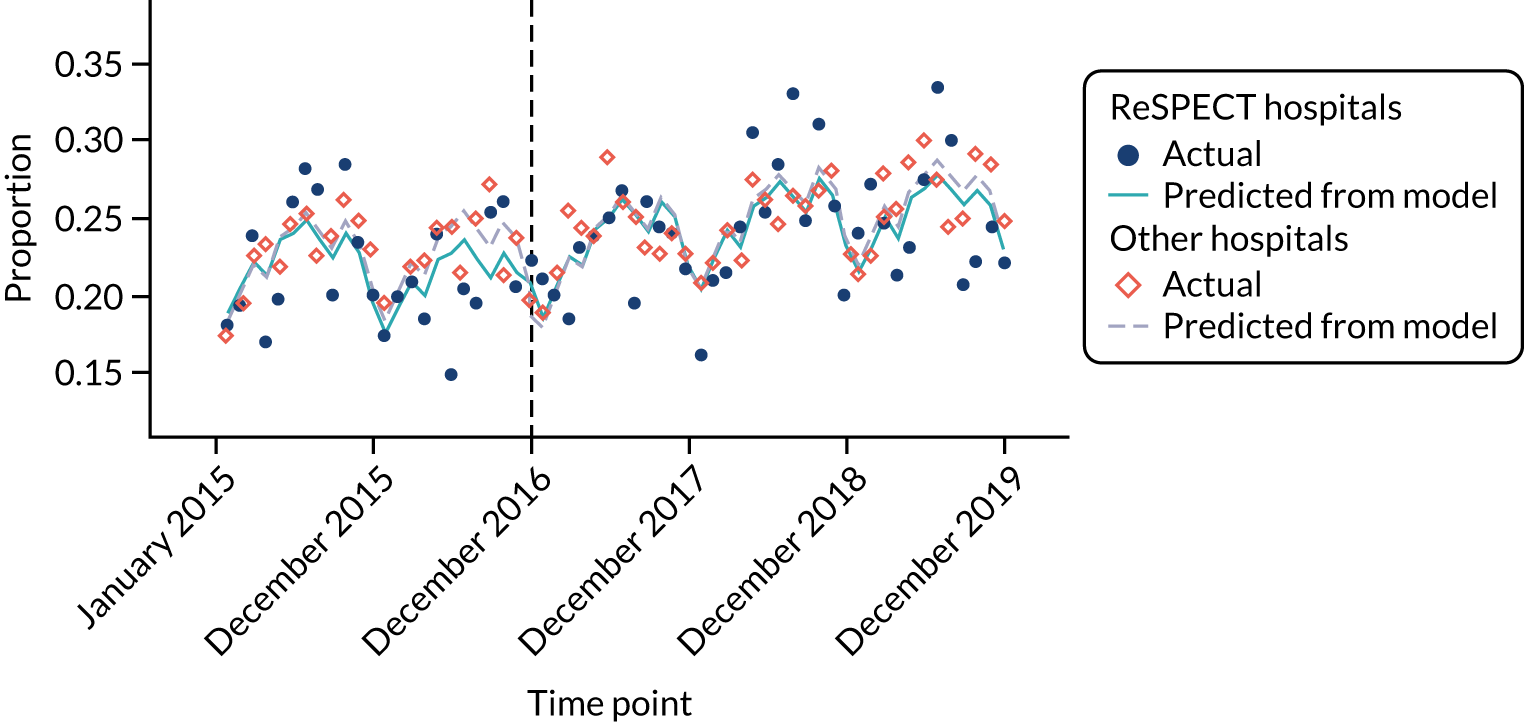

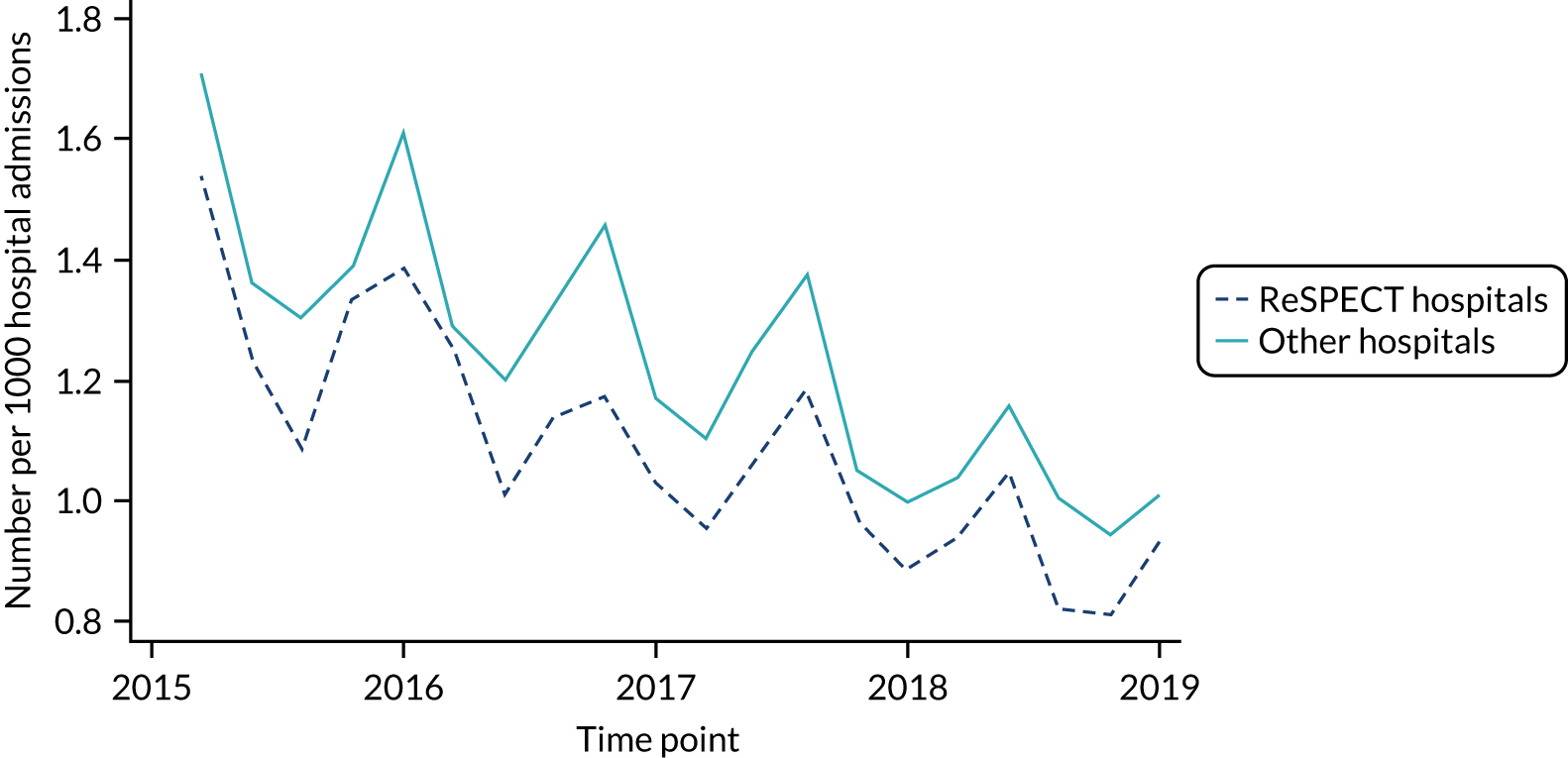

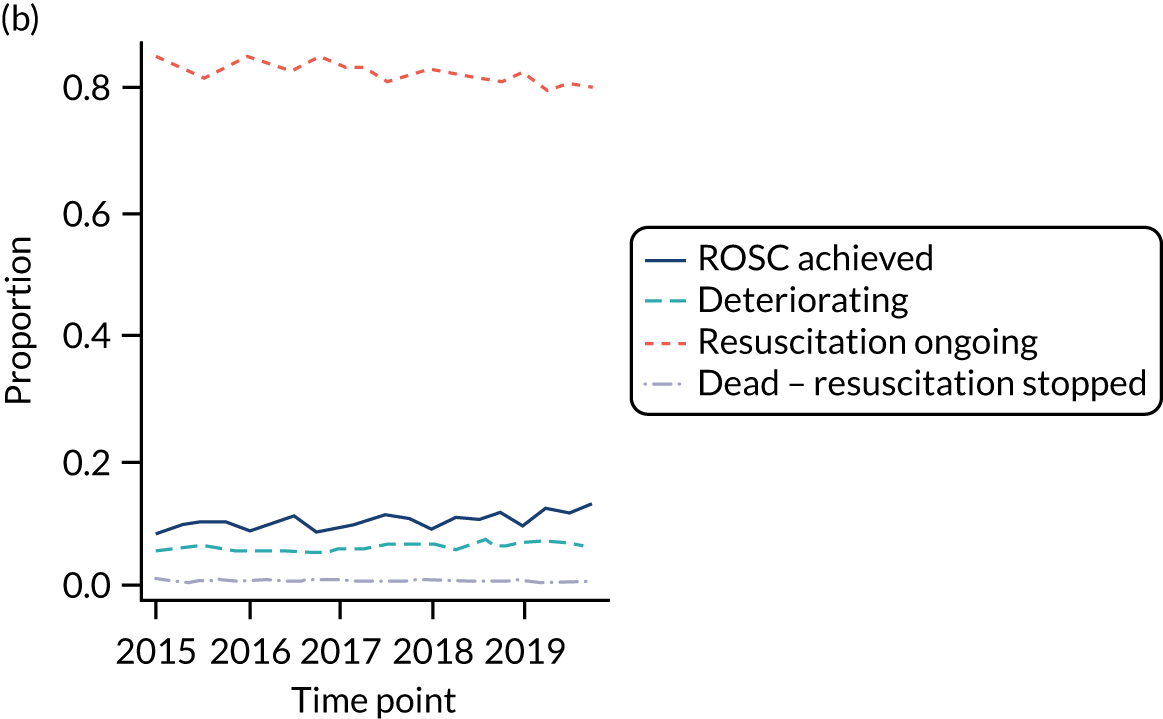

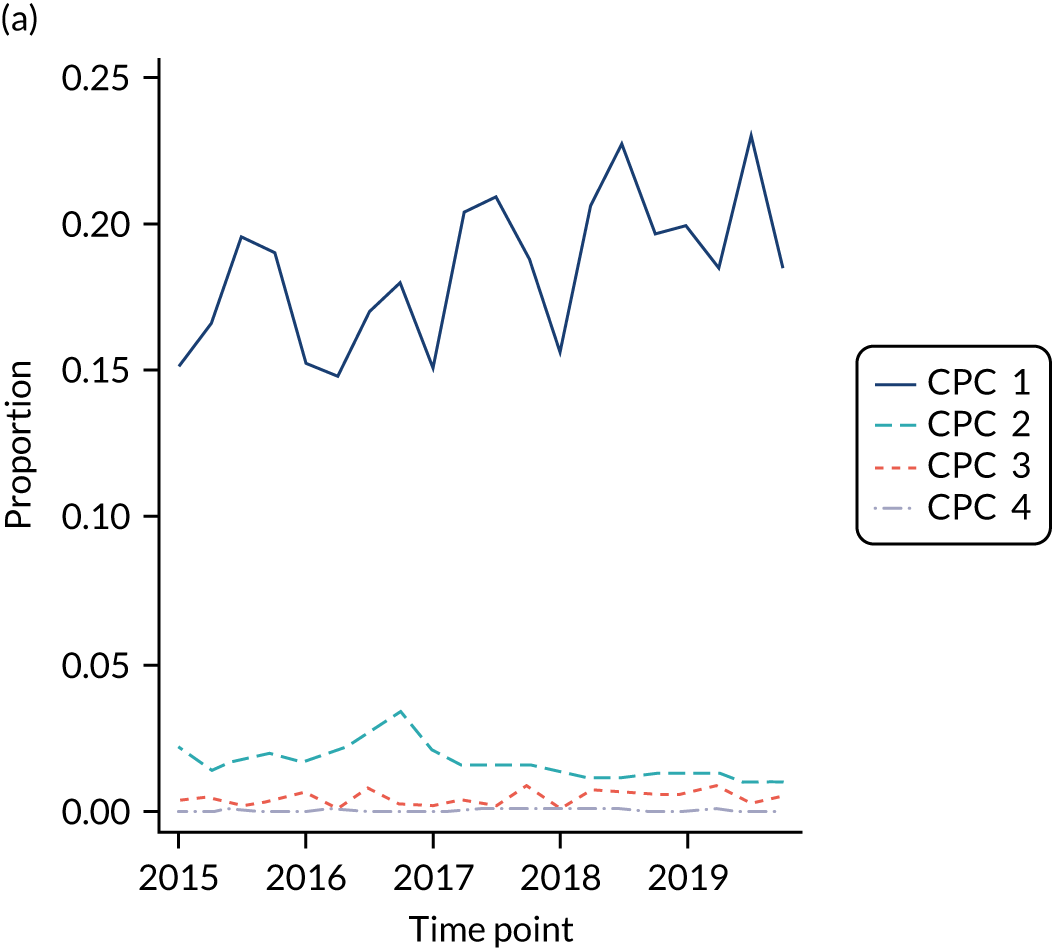

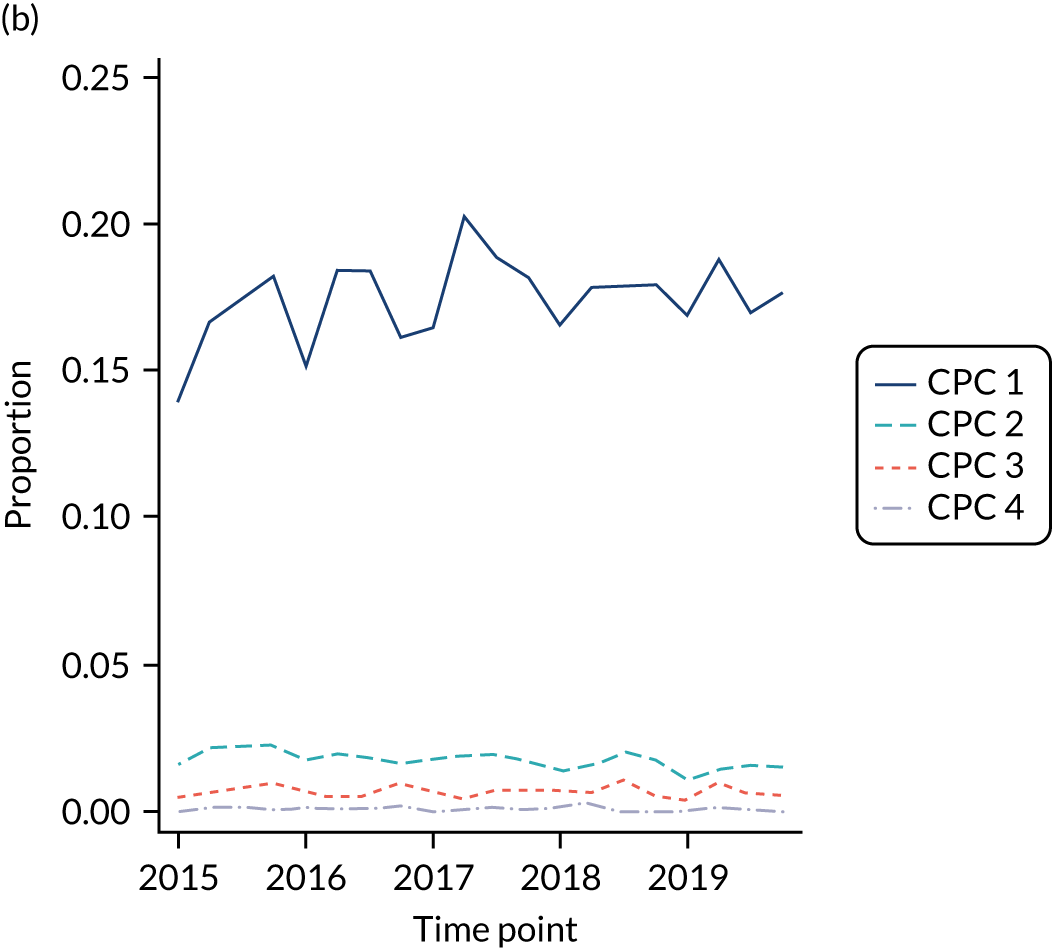

For work package 2, we carried out an interrupted time series (ITS) analysis using measures of process and survival outcomes for in-hospital cardiac arrests (IHCAs), using data from the National Cardiac Arrest Audit (NCAA), a survey and freedom of information request about use of DNACPR forms and other emergency planning approaches. The planned analysis covered 2 years before and 2 years after ReSPECT implementation.

Work package 3 (see Chapter 4)

Work package 3 was a retrospective observational study that comprised descriptive and regression analyses, using routinely collected data from adult acute patient medical records and the NHS Safety Thermometer audit.

Work package 4 (see Chapter 5)

The final work package (i.e. work package 4) provides a narrative summary of key findings from each previous work package (i.e. work packages 1–3).

Aim

We aimed to determine, in adults admitted to acute NHS hospitals, how, when and why ReSPECT plans are made, as well as what effects ReSPECT plans have on patient care.

Objectives

The overarching objectives of each work package were as follows.

Work package 1

-

To describe the clinician decision-making processes behind ReSPECT form completion, including how, when and why judgements are made, their ethics basis and patients’/families’ understanding and experiences of the process.

-

To explore the ethics basis and the experience of patients/families in the decision-making process.

-

To explore GPs’ experiences of the ReSPECT process, including uptake and attitudes to the ReSPECT process in the community, and how the ReSPECT process transfers across the acute/primary care boundary.

Work package 2

-

To quantify the effect of the introduction of the ReSPECT process on the frequency of, and outcomes from, in-hospital resuscitation attempts when compared with standalone DNACPR decisions.

Work package 3

-

To present a descriptive summary of patient characteristics according to ReSPECT treatment recommendation and to conduct an analysis of whether or not a DNACPR decision, made in the context of an overall treatment plan, is independently associated with risk of patient harm.

Work package 4

-

To synthesise the key findings from the study, to identify future research priorities from the patient, clinician and policy-maker perspective and to effectively disseminate findings, ensuring that key messages are integrated into future development work of the ReSPECT process.

A description of the context for implementation from regular meetings between sites, researchers and the ReSPECT National Working Group was planned as part of work package 4, on the recommendation of the Study Steering Committee. However, this work was discontinued because the ReSPECT National Working Group developed support and monitoring systems that would have duplicated this aspect of the study and this placed an undue burden on participants.

The ReSPECT process

The ReSPECT process involves discussion and is recorded on a two-sided form. During this study, versions 1 and 2 of the form were in use (see Report Supplementary Material 1). Both versions of the form were broadly similar, but with the second version clarifying how to record capacity and who was involved in the discussions during the process. The first page of the forms contains identifying information and relevant information about the patient’s medical history and condition, a section for recording patient preferences for care and treatment, a record of the focus of the clinicians’ recommendations for either life-sustaining or comfort care and then a space to record the individual clinical recommendations. The second page of the forms requires a record of the patient’s mental capacity, their own or their families’ involvement in making the plan and where in the medical records full details of the discussion are documented. When early adopting sites implemented the ReSPECT process, few supporting materials were available; however, these materials have been expanded during the course of the study and are available via the ReSPECT website [URL: www.resus.org.uk/respect (accessed 30 September 2022)].

Setting

Six acute NHS trusts and GPs from the areas of the trusts were purposefully selected for in-depth qualitative and quantitative evaluations. All acute hospital trusts that were participating in the NCAA were analysed in the ITS component.

Characteristics of sites

Of the six acute NHS trusts participating in work package 1, three implemented the ReSPECT process between December 2016 and December 2018. We used purposive sampling for diversity according to volume of admissions, performance according to CQC banding, social class and ethnic mix of populations served, and approach to ReSPECT implementation and its uptake.

Four sites were teaching hospitals with general and specialist regional and national services. One site comprised three district general hospitals. All sites provided some specialist services to national and international patients, although these services differed in number and specialties. The numbers of inpatient beds in participating hospitals ranged from 450 to 1300. Inpatient activity ranged from over 100,000 a year to over 200,000 inpatient and day case admissions. Trusts with more than one acute hospital chose which trust(s) would participate in the study. During the study, two of our sites merged to form one trust (but retained their different approaches to the ReSPECT process during the study) and one trust merged with another trust not participating in this study. Our participating trusts had CQC ratings of either ‘needing improvement’ or ‘good’ from inspections around the beginning of the project in 2016–17. One trust had recently improved from a CQC rating of ‘inadequate’.

Sites covered urban (n = 3), both rural and urban (n = 2) and mostly rural (n = 1) populations. Populations served by participating trusts ranged from approximately 500,000 to > 1,000,000 people. Two trusts served areas with a larger, than average, ethnic minority population. Two trusts served areas with a larger, than average, white population. One trust served a mixture of areas, with some areas having larger, than average, ethnic minority population and other areas having a larger, than average, white population. Based on the Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) figures,36 two trusts served areas in which the majority of the population was more affluent than the average in England, whereas four trusts served areas in which the populations were more deprived than average. Childhood poverty rates ranged from almost 15% to 33% in areas served by the different trusts. Compared with the average life expectancy in England, life expectancy was worse for some trusts’ populations, but better in other trusts’ populations.

We were unable to select sites according to type of ReSPECT implementation, as planned, because of the small number of early adopting sites from which to recruit at the time. An overall summary of the implementation approaches used by sites follows.

Three sites changed from using a standalone paper-based DNACPR system to a paper-based ReSPECT system, and one of these sites also developed an electronic version during the study. One of the previous DNACPR systems was area wide (i.e. covering local acute trusts, community health-care organisations and the ambulance service). Another site used an area-wide DNACPR form and recorded escalation plans separately in the patient record. One site had its own electronic ECTP and changed to using an electronic ReSPECT form. One site has been using its own electronic ECTP for several years prior to implementing the ReSPECT process. Here, additional sections from the ReSPECT from were added to the site’s own ECTP on the electronic system and the site was piloting the actual ReSPECT form (paper version) on two wards. Adoption of the ReSPECT process in general practices in the areas served by our sites varied. In the two sites that had an area-wide DNACPR system and one other site, general practices across the area also adopted the ReSPECT process, but later than the acute trusts. At another site, the Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG) adopted the ReSPECT process a considerable time after the acute trust. At two sites, there was no area-wide plan to adopt the ReSPECT process at the time of the study.

All sites had a ReSPECT implementation lead. The professions of the ReSPECT implementation leads varied from resuscitation officers to medical or palliative care consultants. Working groups supported the lead at all sites to varying degrees, particularly when it came to running implementation activities. Some working groups included representation from community health-care providers and the ambulance service, and most working groups involved a range of clinicians from different acute specialties.

Five sites implemented the ReSPECT form on 1 day. At the sixth site, the adaptation to the site’s own ECTP was implemented on 1 day, and the pilot of the full ReSPECT form was conducted on two wards. The working groups carried out awareness-raising activities and conducted staff education for between 2 and 6 months before the implementation date. Most sites reported using e-mail, banners on trust intranets and attending meetings and giving presentations to raise awareness.

Staff education about the ReSPECT process included presentations, information tailored to different professions and, in some cases, advanced communication training for staff who would conduct ReSPECT conversations. One site emphasised the differences between its existing ECTP and ReSPECT as a focus for its training. Not many educational materials were available to the early adopting sites from the National Working Group and some sites reported developing their own. Some sites developed their own patient information leaflets. Some sites also used reminders and prompts to help embed the ReSPECT process. Audits were used to monitor progress and provide feedback.

Sites developed their own policies for the ReSPECT process, including policies regarding who could conduct ReSPECT conversations and who should take responsibility for what was recorded on the form. At most sites, a consultant was the senior responsible clinician, but at several sites a senior specialist trainee could be too. At some sites, junior doctors and senior nurses could initiate ReSPECT conversations; however, senior doctors had to review the process and sign forms as the responsible clinician. In other sites, junior doctors could sign ReSPECT forms as long as they were reviewed by a senior doctor within a specified time frame.

Patient and public involvement

Grant application

We discussed and refined the study design and end points at a patient and public involvement (PPI) meeting. The PPI group felt that the overall design captured the key priorities from the October 2014 stakeholder meeting. The PPI group encouraged use of routinely available information. Observation of ReSPECT conversations was considered feasible provided that the process was handled sensitively. The team’s proposal to use patient experience questionnaires was rejected in favour of the richer perspectives that could be obtained from patient and relative interviews. The PPI group agreed to become the study’s PPI Advisory Group.

Strategic oversight

The Study Steering Committee had two PPI members. At their request, the PPI Advisory Group and the study team agreed that they could attend the PPI Advisory Group meetings throughout the study to facilitate communication between the groups and to contribute their insights and expertise to the PPI Advisory Group.

Management

Our funded PPI co-applicant’s contribution included development of the study proposal and subsequent protocol, discussion of consent processes, attendance at PPI Advisory Group meetings and review of patient information resources.

PPI Advisory Group

The PPI Advisory Group met approximately every 6 months or when there was a particular need for their advice. At all meetings, the study team updated the PPI Advisory Group on progress. Each meeting focused on areas where the study team needed PPI input. The first meeting involved a discussion of different consent models for different work packages that informed the Health Research Authority application for Research Ethics and Confidentiality Group approvals (details are reported in Report Supplementary Material 2).

Advice was sought on the direction of work package 1 qualitative data collection, based on early analysis of interview and observation data, to ensure that emerging issues of concern for PPI members would be explored in the remaining data collection. The group provided input for topics used in the GP focus groups. When the study was designed it was anticipated that the ReSPECT process would be used for a broad population; however, in practice, the ReSPECT process was used mostly with acutely unwell patients. The PPI group and the study team discussed their concerns about the difficulties in collecting interview data from patients and families/friends, and this discussion informed an amendment to include patients with a ReSPECT form who were not part of clinician observations (although this did not substantially increase patient recruitment) and to conduct informal observations on wards for further context. The PPI group advised that future research should consider how best to capture the patient voice (e.g. include interviews with patients when they are not so acutely ill).

The PPI group advised that our findings would be complex, covering difficult issues, and that we should use creative mediums and formats (e.g. plays, videos) that people could understand and respond to for dissemination.

Members of the PPI group commented on papers and provided input for the final report. Members of the PPI group have also advised on future research to evaluate the ReSPECT process in community settings.

We originally planned a meeting to present findings to stakeholders, including public and patient representation; however, owing to the COVID-19 pandemic, this event could not be held. Likewise, owing to the COVID-19 pandemic, we have had to modify our plans for a stakeholder meeting that would have included PPI representation. Instead we delivered a virtual dissemination event that included members of the PPI Advisory Group.

Members of the PPI Advisory Group and Study Steering Group were recruited through the University of Warwick’s (Coventry, UK) User Teaching and Research Action Partnership (UNTRAP) and co-applicants’ networks. UNTRAP provided initial advice and training for the study PPI members who needed it and Warwick Clinical Trials Unit (Coventry, UK) (WCTU) provided update training in 2019 for some members. All PPI study advisors were offered remuneration for their work.

Ethics approvals

We gained NHS ethics approval (reference 17/WM/0134) and Confidentiality Advisory Group (CAG) approvals (reference 17/CAG/0060) for the study. A summary table of the approvals, including amendments, is presented in Report Supplementary Material 2. The study sponsors were the University of Warwick (lead) and University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust (Birmingham, UK).

Ethics issues

The main ethics issues concerned consent and confidentiality. The degree of patient, relative and staff involvement and intrusiveness of the research varied between work packages. We gained approvals for different consent models that were proportionate, depending on what was being asked of research participants.

The research involved five main activities:

-

Interviewing clinicians, patients and families.

-

Observing clinicians engaged in ReSPECT conversations with patients and/or families.

-

Contextual observations and informal conversations about the ReSPECT process.

-

Accessing clinical records.

-

Use of anonymised data from the NCAA.

Interviewing clinicians, patients and families

We obtained written informed consent from clinician, patient and relative interview participants. Approaching patients and family members around the time a ReSPECT discussion occurred raised concerns about intrusion of privacy and causing further distress to patients and families who would already be anxious. The clinical team caring for the patient made the first approach and guided the researcher as to whether or not it was appropriate to approach the patient/family and, if it was appropriate, the timing of any approach. Interviews were tailored to individual patient and family member needs and could be brief. It was made clear that the interview could be stopped at any time if the participant wished to so.

To facilitate participation of people who did not speak English or who were deaf and able to use sign language, we made provision for a translator who was not a member of hospital staff.

Observation of clinicians engaged in making ReSPECT recommendations

We sought written informed consent from clinicians for observing their involvement in developing ReSPECT recommendations. The focus of the researcher’s observation was the clinician. However, the researcher was present when the clinician interacted with a patient or member of the patient’s family. At the start of any such interaction, the clinician introduced the researcher to the patient/family member and sought their permission for the researcher to remain, explaining that the researcher was there to observe the clinician. If the patient/family member did not want the researcher to be present, then the researcher would withdraw. The patient/family member could change their mind at any point without giving a reason and without prejudice. Verbal consent was sought from other staff present during observations.

For logistical reasons, it was not possible to obtain written consent from all patients and their families for the presence of a researcher conducting observations within a particular clinical area (e.g. hospital ward/emergency department). However, information about the study was displayed in these clinical areas and the researchers were clearly identified by their attire (i.e. a top with the word ‘researcher’ printed on the front and back).

Clinicians with whom the researcher had informal conversations regarding the ReSPECT process gave verbal consent. The researcher used pseudonyms to anonymise all participants in fieldnotes.

Accessing clinical records

The study required the research team to access relevant information from the patients’ clinical records and NHS Safety Thermometer audit data. Our approach sought to balance (1) respect for the patient’s right to information in their medical record being treated confidentially, (2) the risk to the validity and public interest in the research being harmed by a biased sample, and (3) consideration of practicable alternatives to obtaining consent.

This part of the data collection was the subject of our CAG approvals. CAG approvals allowed us to collect pseudoanonymised data on all eligible patients on participating wards from patient records without the patient’s consent. We provided study information leaflets that detailed how patients could inform study staff that they did not want their data collected or that they wanted their data removed after collection and before the end of the study data collection period. The rationale for CAG approvals is outlined in Report Supplementary Material 3.

Use of anonymised data from the National Cardiac Arrest Audit

Anonymous data from the NCAA were transferred in accordance with appropriate regulations and WCTU standard operation procedures on data security to the University of Warwick study team. The data were accessed by the study statisticians only and contained aggregated data with no individual patient-level data. The NCAA hold this information under CAG approval [reference ECC 2–06(n)/2009]. The NCAA Management Committee gave permission to access the data required for this study.

We planned repeated annual surveys to understand what systems were in place to record DNACPR decisions; however, after a poor response to the first survey, we gained additional approval to conduct freedom of information requests to NCAA participating sites. We needed a much higher response rate to conduct a robust analysis.

Outline of report content

In Chapters 2–4 we report each work package in more detail, and this is followed by a narrative synthesis of findings from all work packages in Chapter 5 and a discussion of overall findings, assessment of future research needs and conclusions in Chapter 6.

Chapter 2 Qualitative study of decision-making processes

Introduction

Although DNACPR processes have been widely used in hospital practice, increasing evidence shows that these processes are ethically fraught. In particular, audits and evaluations of DNACPR forms have shown that these forms are interpreted inconsistently by health-care staff, potentially carrying unintended consequences for patients, such as the denial of other types of treatment. 24,37–39 DNACPR decisions are often not accompanied by transparent documentation of decision-making processes and do not contextualise this decision within the patient’s preferences and wider treatment. 16,40,41 As DNACPR forms tend to be institution specific, the forms cannot be transferred across medical settings. 19,41 Historically, DNACPR decisions were often made without involving or informing patients and their families. 11,21,38 Following the Court of Appeal judgment in R (Tracey) versus Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust and others in 2014,42 it is a legal requirement in the UK for clinicians to consult with patients, or families of patients who lack capacity, about these DNACPR decisions. Few recent studies have investigated CPR discussions or decision-making post the Tracey judgment.

The ReSPECT process aims to place CPR recommendations within broader treatment considerations. 43 The goal of ReSPECT conversations are that patients and clinicians develop a shared understanding of the patient’s condition and preferences, agree on a direction of emergency care and treatment, and make shared recommendations about treatment options, including CPR. 44 Previous research on DNACPR and advance care planning (ACP) conversations found that patient involvement in decision-making is often inconsistent, with variations in the extent to which clinicians seek patient input or engage with patient values. 21,45 An integrative review noted that patients expect CPR-related conversations to elicit their values and preferences for shared understanding and decision-making. 46 However, a systematic review of ACP processes found that doctors use conversation scripts to overcome unpredictability and prompt their preferred medical decision. 45 Doctors hold differing views over whether or not patients should decide for themselves about resuscitation and treatment escalation, with decisions reliant on either patient preference or medical opinion,38 and this either/or approach runs counter to the ReSPECT process, which is designed for shared understanding. 43

Research suggests that ECTP forms facilitate conversations between clinicians and patients. 47 The ReSPECT process is supported by the ReSPECT form, which, in the community, is a patient-held document that is completed by clinicians. 43 The ReSPECT form is designed to prompt clinicians to discuss emergency treatment options with patients to (1) structure the documentation of decision-making for greater transparency and (2) be carried by patients across medical settings. 43 Through successive open-text boxes, the ReSPECT form facilitates a stepwise summary of discussions and decision-making. Taken together, the sections of the ReSPECT form are aimed at promoting the consistency, transparency and ethics justifiability of clinical decision-making.

Objectives

Our objectives were as follows:

-

To describe the decision-making process, including how, when and why judgements are made, their ethics basis and patients’/families’ understanding and experiences of the process, through a case study evaluation of ReSPECT decisions in clinical practice and a review of written records.

-

To establish uptake and attitudes to the ReSPECT process in the community through (1) focus groups with GPs, (2) collection of contextual data on ReSPECT implementation at sites, (3) a synthesis of findings and (4) identification of areas for improvement and further work.

For the case study evaluation, we sought to determine the following:

-

How, when and why are clinicians making ReSPECT decisions in the acute hospital setting?

-

What happens when a patient brings a ReSPECT form or a similar document from the community to hospital?

-

How is the ReSPECT system used within the process of decision-making?

-

To what extent is the patient, and where appropriate family members, involved in the decisions? (Note that by ‘decision’ we mean the decision to make a ReSPECT recommendation, and our focus is on patient/family involvement in the process of thinking through and making this recommendation.)

-

How do patients/family members experience the decision-making process and their subsequent care?

-

What influences the ReSPECT decision-making process, including considerations of ethics (or not), and why?

-

From the clinician perspective, what are the perceived effects of the ECTP process on clinical decision-making and patient care, including their ethics dimensions, and what changes are needed to improve ReSPECT decision-making?

-

From the perspective of clinicians working with acute admissions, what changes are needed to improve ReSPECT decision-making, including the ethics dimensions of the decisions?

Key findings from this work package have been previously published. 1,48,49

Methods

Sampling and recruitment

ReSPECT conversations were observed in hospitals within six acute NHS trusts. In each study site, observations were designed to include five ward areas (i.e. three medical areas, one surgical area and one orthopaedic area). Ward areas were selected by the local principal investigator in each of the study sites. The local site principal investigators connected the researcher with physicians or surgeons working in the selected ward areas. In two sites, the ReSPECT process had been digitised and incorporated into the hospital’s digital patient note system. In one site, doctors were prompted to issue patients with a ReSPECT form within 48 hours of admission, whereas in the other five sites ReSPECT forms were optional.

Data collection methods

Between August and December 2017, data collection took place in two hospitals. Cynthia Ochieng (a qualitative researcher with a PhD in public health) shadowed consultant clinicians during ward rounds to observe ReSPECT conversations. Through analysing these initial data, we recognised that ReSPECT conversations also took place outside ward rounds. We, therefore, reviewed recruitment processes and changed our approach to an expanded observation framework, which included ReSPECT conversations throughout the day, alongside contextual observations of ward practices and informal conversations with clinical staff about the ReSPECT process. Between April 2019 and January 2020, Karin Eli (a medical anthropologist experienced in fieldwork research with a focus on narrative and lived experience) used this expanded observation framework to collect data in the remaining four NHS trusts.

Observations and interviews took place between 10 and 28 months after implementation of the ReSPECT process at each hospital site. For both Cynthia Ochieng and Karin Eli, this was their first research study involving ReSPECT or other ACP processes. Cynthia Ochieng and Karin Eli worked as part of a wider research team [which included FG (a GP and medical sociologist), CH (a health services researcher with nursing background) and A-MS (a clinical ethicist with general practice background)] that designed the qualitative aspects of the study. Both Frances Griffiths and Anne-Marie Slowther had clinical experience of DNACPR and ACP, and Claire A Hawkes was involved in the development of the ReSPECT process. Anne-Marie Slowther, Frances Griffiths and Claire A Hawkes were also involved in a previous National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR)-funded research study on DNACPR. 38

Most clinicians were interviewed within 72 hours of the observation(s). Interviews explored clinicians’ reflections on ReSPECT conversations and on conversations they chose not to hold, and clinicians’ broader experiences with the ReSPECT process. When possible, Cynthia Ochieng and Karin Eli interviewed patients and/or their families. However, most patients who had ReSPECT conversations were elderly and acutely unwell, and this limited the number of interviews that could be conducted with patients and/or their families.

To contextualise the findings, Karin Eli interviewed ReSPECT implementation leads in five of the study sites (in the sixth site, the implementation lead was unavailable for interview, but earlier implementation data from a telephone interview were available to contextualise the findings). The interviews focused on local implementation processes, challenges, lessons learned and future directions.

Analysis

The analysis of the observations and interviews was adapted to each research question, as follows.

How, when and why are clinicians making ReSPECT decisions in the acute hospital setting?

Karin Eli extracted data from observed ReSPECT conversations, capturing categories relating to the site and ward area, the content and outcome of conversations, timing and setting of conversations, reasons for holding ReSPECT conversations, and patient and clinician characteristics. Karin Eli then used inductive thematic analysis to open-code 21 observed conversations. Based on this, Karin Eli developed codes that focused on how each actor (i.e. clinician, patient and/or relative) framed the ReSPECT conversation and contributed to the flow of the conversation. Karin Eli then reanalysed the conversations according to these codes. Using the coded conversations, Karin Eli, Claire A Hawkes, Frances Griffiths and Anne-Marie Slowther decided on a key set of attributes, according to which a ReSPECT conversation typology would be developed:

-

Central purpose: confirm ReSPECT recommendation, establish resuscitation and/or treatment escalation recommendation, deliver bad news, make palliative care decisions or establish consensus among colleagues about limitations of treatment.

-

Extent of detail: limited (i.e. focus on CPR and/or intensive care admission only) or detailed (i.e. discussion of additional treatment options and plans).

-

Outcomes: complete (i.e. leading to a ReSPECT form) or incomplete (i.e. ending inconclusively, or leading to an interim, partially completed ReSPECT form).

-

Directionality of conversation: closed ended (i.e. with the clinician employing persuasive or directive speech) or open ended (i.e. with the clinician opening the conversation to patient/relative wishes and preferences).

-

Conversation prompts: patient’s condition, hospital or ward initiative, patient’s or relative’s expressed wishes, or unstated/unclear. 1

Karin Eli used these key attributes to develop a set of conversation types, which Claire A Hawkes, Frances Griffiths and Anne-Marie Slowther reviewed. After agreeing on the conversation types, Karin Eli applied the typology to all observed conversations and analysed extracts of the clinician interviews that applied to these conversations to explore relationships between conversation types and the research question ‘why, when and how do secondary care clinicians enact the ReSPECT process?’.

What happens when a patient brings a ReSPECT form or a similar document from the community to hospital?

Interview excerpts where clinicians and patients reflected on their experiences with community ReSPECT forms or similar documents were extracted and analysed thematically.

How is the ReSPECT system used within the process of decision-making?

Observed ReSPECT conversations were analysed to ascertain whether or not the ReSPECT form was used in the conversation, and whether or not key patient-facing elements of the form (e.g. questions about patient preferences/wishes, clarifications of which treatments will and will not be provided) were mentioned in the conversations.

To what extent is the patient and, where appropriate, family members involved in the decisions?

Observed ReSPECT conversations were analysed to ascertain whether they were open ended (i.e. exploratory) or closed ended (i.e. persuasive). Clinician interviews were analysed thematically to ascertain attitudes towards patient and relative involvement.

How do patients/family members experience the decision-making process and their subsequent care?

Patient and relative interviews were analysed thematically to explore the patient’s/family member’s experiences of the ReSPECT conversation, including the decision-making process involved and their subsequent care.

What influences the ReSPECT decision-making process (ethics and clinician perspectives)

The clinician interviews were reanalysed thematically. The analysis investigated the potential role of ethics considerations in prompting ReSPECT conversations, the role of ethics dimensions (e.g. a weighing of burdens and benefits) in the making of ReSPECT decisions, and the extent to which patients’ wishes and preferences are included in the decision-making process. In addition, the analysis examined clinicians’ attitudes towards the ReSPECT process and form, with particular attention to how ReSPECT influences (or does not influence) decision-making compared with previous systems, the perceived flaws in the ReSPECT process and how clinicians would like these flaws to be addressed.

Ethics considerations

Patients and families provided verbal assent before each ReSPECT conversation was observed. Written informed consent was provided by clinicians who were formally observed and/or interviewed, by patients and families who were interviewed and by ward managers (in the last four sites) to state their agreement to contextual observations on their ward. Verbal consent was provided by clinicians who participated in informal conversations with the researcher during contextual observations. Families were interviewed if the patient lacked capacity, or with the patient’s consent if they did have capacity. All participant quotes presented in this report have been screened for identifying details. Participant identifications (IDs) indicate study site number and a random participant number, and cannot be traced to the participants.

Findings

As described in our publication,1 across the six study sites, 49 ReSPECT conversations were observed in 12 ward types (i.e. acute geriatrics, acute medicine, acute stroke, critical care, emergency medicine, gastroenterology and general medicine, geriatrics/gerontology, hepatobiliary surgery, orthogeriatric, orthopaedics, renal and respiratory). Most conversations (n = 30) were observed during ward rounds. Observations were also conducted in colorectal surgery, emergency surgical admissions, haematology and frailty assessment wards, but no ReSPECT conversations were observed in these wards.

Thirty-four doctors (consultant-level doctor, n = 22; middle grade-level doctor, n = 6; junior doctor, n = 6) conducted the conversations. Most (n = 26) doctors conducted one conversation, three doctors conducted two conversations, two doctors conducted three conversations, one doctor conducted four conversations and one doctor conducted five conversations. Although most patients (n = 32) were aged ≥ 80 years, the ages of patients ranged widely, with the youngest patient aged 22 years. Twenty-three conversations were held with the patient, 19 conversations were held with the patient and their relative(s), six conversations were held with the relative(s) and one conversation was a conversation between colleagues.

Interviews were conducted with 47 clinicians (including 31 clinicians who were observed conducting ReSPECT conversations), 13 patients and 19 family members (note that there were seven group interviews with families or with patients and families combined).

The findings are presented with respect to each of the research questions.

How, when and why are clinicians making ReSPECT decisions in the acute hospital setting?

Descriptive findings

Based on a thematic analysis of observed ReSPECT conversations, the following conversation typology was developed (adapted from Eli et al. 1):

-

Resuscitation and escalation (n = 31). Conversations in which the key aim is to record a recommendation about CPR and/or other elements of escalation of treatment [e.g. ventilation, intensive treatment unit (ITU) admission]. These conversations could be either open ended (i.e. exploratory; n = 13) or closed ended (i.e. persuasive; n = 18).

-

Confirmation of decision (n = 8). Conversations in which the key aim is to confirm with a patient and/or their family members whether they still agree with or would like to revise a previous ReSPECT or DNACPR recommendation.

-

Bad news (n = 4). Conversations focused on delivering devastating prognostic news. Although DNACPR and other escalation decisions are discussed, the prognosis is central.

-

Palliative/future care (n = 5). Conversations in which the focus is on decision-making regarding future hospital admissions, care in the community and transitioning to comfort care.

-

Clinical decision (n = 1). Conversations between colleagues, where only clinicians are involved.

Thematic findings

Working with the conversation types, we developed three themes corresponding to the research question ‘how, when and why are clinicians making ReSPECT decisions in the acute hospital setting?’:

-

why: planning for the possible and the inevitable

-

when: responding to hospital-based, clinical and patient/relative prompts

-

how: engaging with treatment options, patients and families.

The findings presented in this subsection have been adapted from Eli et al. 1 The adaptation retains the data and interpretations presented in the primary publication, but presents different illustrative participant quotes to avoid replication.

Why: planning for the possible and the inevitable

Depending on their key aim, as outlined in the conversation typology above, ReSPECT conversations implicated either a patient’s possible future deterioration or a response to a patient’s deterioration in the present.

Most resuscitation and escalation conversations were held with patients who were identified as at risk of imminent physiological deterioration. Most patients were elderly and suffered from multiple comorbidities. Doctors explained that these patients needed CPR decisions during the current admission both to prevent harm to the patients and to ensure that the medical team had a clearly documented plan in case of deterioration:

It’s making sure that the patient doesn’t have something that they shouldn’t have because it’s going to cause them harm. So it’s a benefit to them. And you also realise that the ward’s not going to be chaos.

Site 5, C01

To verify that patients agreed with a ReSPECT recommendation recorded when they had been acutely unwell, clinicians sometimes held confirmation of decision conversations with patients who had resuscitation and escalation conversations. These conversations also employed a possible future framework.

Bad news conversations responded to a clinically observed or diagnosed deterioration in a patient’s condition, and were concerned with present-tense changes:

The patient was deteriorating significantly . . . the aim of the discussion was to make quite sure that he was aware of the critical nature of the, of his wife’s illness . . . it was a fact-finding conversation as well to determine what the patient’s previously expressed wishes may have been.

Site 4, C02

Palliative care conversations also responded to deterioration in a patient’s condition; however, unlike bad news conversations, this deterioration was an expected part of a longer disease process, such that the ReSPECT conversation focused on planning for the patient’s end-of-life care, rather than providing information and ascertaining wishes about escalation of treatment.

When: responding to hospital-based, clinical and patient/relative prompts

Specific prompts guided clinicians in deciding when (during an admission and during the day) to hold a ReSPECT conversation.

Some conversations were prompted by a patient’s looming transfer to another ward, nursing home or hospice, which made treatment planning more urgent, and this was particularly the case for palliative care conversations. Hospital- or ward-based initiatives prompted some resuscitation and escalation conversations. In one hospital, a reminder to hold ReSPECT conversations appeared on all patients’ digitised notes, and doctors said that they incorporated the ReSPECT process into their ‘mental checklist’ (site 6, C02) during ward rounds. However, this meant that doctors prioritised CPR-related conversations to optimise their time and complete the task set by the digitised reminder.

Patients’ conditions prompted the majority of ReSPECT conversations. However, clinicians varied in their interpretation of which conditions necessitated the ReSPECT process. Some clinicians reserved these conversations for patients at risk for deterioration during the current admission or for patients who had experienced a substantial change during the admission:

. . . and now the situation changed and he, this person is very poorly . . . , we have to review it because now we know that ICU [intensive care unit] admission will not probably be appropriate for this person . . .

Site 4, C01

However, clinicians sometimes held ReSPECT conversations with patients who were not expected to deteriorate in the near future, but whose terminal diagnosis meant that they could benefit from a ReSPECT conversation.

In some cases, doctors conducted palliative care ReSPECT conversations when families requested that these conversations be held or after patients expressed their wishes to avoid or end life-saving treatment:

[My colleague] had seen him yesterday and it was reported to me that he said he was fed up; that he just wants to go home to die; so I wanted to explore that with him and make sure that was still his wish.

Site 3, C07

How: engaging with treatment options, and with patients and their families

Doctors varied in their engagement with treatment options beyond CPR, and in their engagement with patients’ and families’ wishes and questions during ReSPECT conversations.

Although some resuscitation and escalation conversations mentioned treatment options beyond CPR, many conversations were limited to CPR discussions, especially conversations conducted quickly during a ward round. Doctors explained that they did not want to ‘overwhelm’ (site 4, C03) patients with information about various treatment options when these options were likely irrelevant to their patients. In some cases, doctors felt that patients were not well informed enough to imagine treatment options beyond CPR:

. . . once you get down to the fine detail, ‘Would you want antibiotics if you had pneumonia? Would you want fluids if you weren’t able to swallow? . . . ‘ It’s, I just think that is really, really difficult to imagine being in that situation.

Site 3, C05

Doctors spoke about treatments beyond CPR and intensive care in all bad news and palliative care conversations. Doctors also did so in some confirmation conversations and in resuscitation and escalation conversations. In the palliative care context, detailed conversations focused on decision-making about comfort care and re-admission. In the resuscitation and escalation context, detailed conversations outlined which treatments the patient would and would not want (or be offered).

Most resuscitation and escalation conversations aimed at recording the treatment recommendation deemed most medically appropriate. Therefore, doctors often used persuasive language during these conversations. For example, one doctor (site 4, C06) asked an elderly patient for her views on CPR, but immediately explained that they had observed only one case in which CPR was successful and that the patient was aged 18 years.

Doctors sometimes took a persuasive stance in bad news conversations. In two observed conversations, doctors attempted to persuade the patient’s family that a DNACPR decision was essential.

In palliative care conversations, doctors emphasised the need to understand what a patient values and to plan accordingly:

And so, the process of ReSPECT is, is the all-important question: ‘what’s important to that patient right now?’.

Site 3, C07

Doctors also encouraged patients to express preferences and wishes in some resuscitation and escalation conversations and in some bad news conversations, in which doctors asked open-ended questions. This approach sometimes led doctors to recommend treatment plans that they had not considered before:

There’s been the odd one where having the conversation has changed what we’ve done. So even people who we thought were medically treatable but their priority was to get home. So we’ve compromised and got them home, because that’s what they wanted. And they were probably in the last year of life. There have been people who have found it quite empowering.

Site 2, C04

Thirteen conversations remained incomplete, leading to no or partial ReSPECT decisions, and this usually happened when there were disagreements between doctors and patients/families, or when patients felt that they needed more time to think about their treatment options. One doctor explained that they chose not to complete a digital ReSPECT form for an elderly patient who expressed conflicting CPR wishes:

. . . this is where maybe ReSPECT becomes tricky and where maybe it does fall down a bit. Because it’s, it is quite black or white, it, although there are sections where you can write free text and responses, the difficulty with him for example is you have to click on one of two things, is he for resuscitation or is he not for resuscitation? Now, at the moment he, kind of, is for resuscitation, but at the same time he’s also saying he doesn’t really think he wants to be or should be . . .

What happens when a patient brings a ReSPECT form or a similar document from the community to hospital?

Clinicians are most likely to see community-issued ReSPECT forms come in with elderly patients

Clinicians were aware that ReSPECT conversations often take place when people move into care homes. Clinicians said that many of their patients with a community-issued ReSPECT form were admitted to hospital from care homes, and these patients tended to be ‘elderly with comorbidities’ (site 4, C07) or with ‘severe disability or advanced dementia’ (site 3, C05). Community-issued ReSPECT forms ‘almost always’ (site 4, C09) recordeDNACPR decisions for these patients.

Community-issued ReSPECT forms are generally useful, but recommendations may be questioned

When a patient arrives on a ward with a pre-existing ReSPECT form, the clinician first checks that the form is appropriate and valid, and this often involves a short conversation with the patient or their family to confirm that they are happy with the existing recommendations. Some clinicians reported that they have ‘to confirm that it still applies, every time the patient comes in’ (site 3, C07). Knowing the date that the ReSPECT form was issued was considered important, as a patient’s health can deteriorate rapidly:

. . . it’s good to know when they were written . . . the situation might be completely different now.

Site 4, C09

Forms issued in community settings were generally considered useful. Knowing that the patient had already had a discussion about possible treatments and expressed their values and preferences was said to be particularly useful for patients admitted into critical care, where intervention could carry significant burdens. Clinicians also reported that they find it useful to have information about ‘treatment escalation decisions beyond resuscitation’ (site 3, C04) and reasons for certain treatment decisions.

Two clinicians commented that community-issued ReSPECT forms are not useful. One clinician reported that only CPR decisions are useful and the other clinician said that they would ‘always have the discussion again’ (site 4, C04). Another clinician expressed concern that community-issued ReSPECT forms might include recommendations for treatment that they do not think clinically appropriate, which could create tension with patients’ expectations:

. . . as long as the form didn’t then ask me to give treatment that I didn’t think was going to be in their best interests, that’s my concern . . . I just would hate to have patient families’ expectations built even higher than they already are about having treatment that’s not likely to be in their best interests.

Site 3, C05

Clinicians said that they do not always adhere to the recommendations recorded on community-based ReSPECT forms. Clinicians said that they would question recommendations against certain treatments if they felt that these treatments would be beneficial:

. . . if it is actually going to benefit . . . and only will go on for a very short period of time then, yes, I would consider it.

Site 3, C06

ReSPECT decisions are not questioned if the patient was admitted to hospital because of the condition that the ReSPECT form addresses. DNACPR decisions are also not questioned:

. . . the resuscitation part, it is saying ‘do not resuscitate’, I would almost always appreciate that decision.

Site 3, C06

There are advantages to initiating the ReSPECT process in the community

Hospital doctors felt that GPs would be good at holding ReSPECT conversations, as GPs know their patients well and can ‘appreciate the [patient’s] medical comorbidity, the psychological support, the social infrastructure’ (site 6, C06). Some hospital doctors also thought that holding these conversations while patients were relatively well and comfortable [as opposed to in hospital when ‘they feel vulnerable’ (site 1, C03)] is better for patients. Other hospital doctors said that community-issued ReSPECT forms indicate ‘what is important for the . . . patient in terms of symptomatic versus curative intent’ (site 4, C02) and provided a prompt for discussions about ceilings of care:

. . . it won’t have detailed ceilings for all hospital treatments, but it will be enough to allow me to elaborate upon that . . .

Site 2, C04

However, one participant pointed out that, when people are healthy, they do not consider emergency situations:

. . . you don’t sit at home watching TV at night thinking, ‘You know, I only want to have resuscitation in such and such circumstances’. It’s not, it’s not what people think about.

Site 1, C02

There needs to be better sharing of ReSPECT recommendations across primary and secondary care

Participants agreed that all health-care professionals involved in treating a patient should have the same ReSPECT information. However, participants expressed confusion about whether or not community-issued forms apply when patients are admitted to hospital. The original format of the ReSPECT form (i.e. a hard copy held by patients) was criticised as being impracticable in emergencies, as ‘a lot of people don’t bring the ReSPECT form with them, they are in a rush to come to the hospital and they don’t remember’ (site 2, C01), and, likewise, for patients who frequently transition between primary and secondary care:

. . . we’ve got dialysis patients who’ve got ReSPECT forms in place. The recommendation is that they should carry that with them at all times. That’s not practical. What we need is something that is available to the community based health services and ambulance service, and the hospital.

Site 1, C07

Participants felt that a standardised electronic copy of the ReSPECT form that could be ‘attached to the patient’s electronic record and visible across all health care’ (site 1, C04) would more seamlessly transfer ReSPECT decisions.

How is the ReSPECT system used within the process of decision-making?

The ReSPECT form is rarely used during conversations with patients and/or families

A paper ReSPECT form was used to engage with patients/families in only six conversations. In one conversation, the doctor showed a relative a blank ReSPECT form on a smartphone screen. In the two sites where digitised ReSPECT forms were used, patients/families had no interaction with the ReSPECT form during the conversation. Several clinicians at these two sites mentioned this as a downside of the digitisation of the ReSPECT process.

Most ReSPECT conversations elicit patients’ views on cardiopulmonary resuscitation and/or other treatment options

In most ReSPECT conversations the clinician asked the patient/relative about the patient’s wishes and preferences for CPR and/or other treatment options, including intensive care escalation and re-admission. However, in eight conversations, clinicians did not ask about patients’ preferences and, instead, informed them about the decisions the clinicians had already made about CPR and/or intensive care escalation. Clinicians took this approach when they were certain that these interventions would be futile, as one clinician explained:

. . . it was pointless to have a discussion knowing that you would not be able to offer the patient the options they might want.

Fieldnotes, site 1, C09

When clinicians asked about the patient’s wishes and preferences, the approach taken was either persuasive or exploratory. In persuasive conversations, although clinicians asked patients or their families what they would want, clinicians would also voice their own recommendation, explaining that CPR and/or intensive care escalation would be futile, sometimes using emotionally evocative language (e.g. telling patients that CPR would be undignified or would distress their families). In exploratory conversations, clinicians explored patients’ and families’ wishes openly, allowing these wishes to guide the rest of the conversation and the development of treatment recommendations. For example, after breaking bad news to a patient’s partner, an intensive care consultant said ‘I’m sorry to have to warn you about this but in this circumstance we do ask you as the person closest to her if you would know what her wishes would be in this situation’ (fieldnotes, site 4, C02). The patient’s partner asked for resuscitation, but not at the expense of patient’s quality of life, and the consultant responded with ‘we will resuscitate her’, but ‘there is a possibility it would not be successful . . . after repeated attempts we will step back and allow things to take their course’ (fieldnotes, site 4, C02).

In several cases, exploratory conversations resulted in no recommendations, as patients found it difficult to engage in the conversation, expressed ambivalence or asked for more time. In these cases, clinicians explained that they would either revisit the conversation later or leave the conversation where it was, hoping that it would encourage the patient to consider treatment escalation and have future conversations about this in community settings or with their families.

During ReSPECT conversations, many clinicians explain what treatments would and would not be provided

Clinicians spoke about what treatments (other than CPR) would and would not be provided in more than half of the observed ReSPECT conversations. The level of detail, however, was variable. In conversations conducted during ward rounds, treatments were typically mentioned in the context of the patient’s general management, rather than directly linked to what clinicians conceptualised as the ReSPECT conversation, which focused on CPR and/or intensive care. In conversations conducted outside ward round contexts, treatments were typically mentioned in the context of the ReSPECT process. In these cases, clinicians employed a reassuring tone, explaining to patients that they will still be treated regardless of a DNACPR decision, and this could be framed broadly [e.g. ‘it’s doesn’t mean we’ll stop treating you’ (fieldnotes, site 4, C09)] or specifically {‘[the doctor] said they will give her i.v. [intravenous] antibiotics and fluids, and fluid resuscitation, but ‘won’t bring you down to ICU [intensive care unit]’ (fieldnotes, site 4, C08)}.

However, in many (n = 21) of the observed ReSPECT conversations, clinicians did not speak about treatments other than CPR and/or intensive care escalation.

To what extent is the patient, and where appropriate family members, involved in the decisions?

Patients and families are involved in ReSPECT conversations, but not always in decision-making

Of the 49 ReSPECT conversations observed, 48 conversations involved patients and/or their families and one conversation was a discussion between clinical colleagues for a patient who lacked capacity, had no next of kin and no friends, and for whom an independent mental capacity advocate could not be located. Conversations varied in the extent to which patients/families were involved in the decision-making process. Twenty conversations were open ended, with clinicians actively eliciting the patients’ wishes and preferences, and taking these into account in decision-making. However, in 20 other conversations, clinicians took a persuasive stance, using conversational scripts to sway the conversation towards a decision aligned with medical opinion or simply informing the patient/relative about a medical decision that had already been made. For example, a doctor was observed saying ‘should the situation worsen, we will not put [the patient] on a machine’ (site 4, C07) to a relative. The remaining conversations were confirmatory, with clinicians asking patients/families if they agreed with a previously issued ReSPECT decision or community DNACPR.

Clarity and uncertainty about patients’ trajectories affect whether or not patients/families are informed or involved in decision-making

As reported in our earlier publication,2 using clinician interview data, a clinician’s clarity or uncertainty about a patient’s trajectory often determined the extent to which the patient/family was included in ReSPECT conversations. When clinicians were uncertain about a patient’s trajectory, the ReSPECT conversation emphasised patient preferences to a greater extent:

. . . the greyer . . . the decision then the more and more you allow the patient’s own perspective to sort of sway the ultimate outcome.

Site 1, C09

Similarly, although clinicians were certain that palliative patients were nearing the end of their lives, ReSPECT conversations acknowledged clinicians’ uncertainty about how patients wished to spend their last weeks or months, thereby emphasising patient preferences in certain aspects of care:

. . . my only main aim was, to get out what she wants from the rest of her life, and how she wants to be treated and how she wants to be, like, managed in all her, including her end-of-life care and everything, so . . .

Site 6, C07

By contrast, when a patient’s illness and treatment trajectory seemed clear, then clinicians tended to take a persuasive approach to ReSPECT conversations:

What I don’t think’s particularly helpful is having a discussion with a patient where it’s very clear from a medical objective point of view that it would be futile to escalate treatment to give them the impression that you’re giving an option of escalating treatment. Because again, I don’t think that’s, that’s fair. So if it’s very clear then I think our job is to explain why we’re making these decisions carefully and sensitively.

Site 3, C05

Accordingly, some clinicians said that ReSPECT conversations were mainly focused on informing patients/families about what was possible medically, rather than seeking their involvement in decision-making. Several clinicians stated that it was important to clarify to patients and, in particular, families that clinicians were not asking them to make medical decisions:

. . . you don’t want the family to feel that they have decided . . . that’s the last thing you want, the last thing you want is for them to feel responsible for having made that decision.

Site 4, C10

Some clinicians advocated a middle ground approach. Although clinicians did not ask patients/families to participate in medical decision-making, clinicians used ReSPECT conversations to contextualise the eventual clinical decision:

It’s a shared decision . . . we give the medical information. We take on board the family’s values and preferences, and we issue a recommendation based on that. And I think that’s important rather than feeling, letting the family feel either that they’ve got to make the decision, and we’re washing our hands of it, or that we’re making the decision for them doesn’t matter what they think.

Site 5, C08

The ReSPECT decision-making process is shaped by the patient’s autonomy

Many of our patient and family interviewees expressed their preferences after their doctor had explained CPR to them, and believed that their doctor respected their wishes. One patient reported disagreeing with their doctor who suggested a particular treatment, and some family members felt that the doctor would have implemented their wishes, even if they disagreed with the clinical recommendations:

I think she would have listened to us, and done everything she could have to have implemented any other action that we insisted upon.

Site 6, F02

In contrast, other patients and families felt that their doctor simply informed them about the ReSPECT decision without discussion or explanation, as one patient said:

The doctor told me . . . ‘I hope you know we won’t, won’t resuscitate you’.

Site 2, P03

This patient went on to say that they agreed with the doctor’s decision, but also felt unable to disagree:

I’m quite prepared to go along with that. Well, I can’t do anything else, can I?

Site 2, P03

Several patients commented that they trusted the doctor to make the right decision on their behalf, as doctors are experienced, highly trained and will do whatever is in the patient’s best interests:

. . . to be honest, I always say, ‘I’ll leave it in your hands’. You know, they know best.

Site 1, P05

Many ReSPECT discussions were held while the patient’s family were present. Patients said that their family provided emotional support, but that the decision was theirs alone to make:

. . . my daughter . . . she says, ‘It’s your decision, mum. I’m here to support you, whatever you decide’.

Site 2, P06

One patient, who felt shaken by the ReSPECT discussion, said they did not want to make any decisions without their children, but was worried about upsetting them.

If a patient lacked capacity to make their own decisions, then their family was responsible for expressing their wishes. These family members said that the ReSPECT process should reflect the patient’s wishes:

. . . you do have to stop and think actually what that individual wants, not actually what you want.

Site 2, F02

A few patients had discussed their preferences with their family prior to their hospital admission, and this made the ReSPECT conversation easier for their families:

. . . my dad’s always, sort of, you know, very open about what happens, you know, when his time comes, . . . I know exactly what they want the end of their life, so, yeah, so, you know, we have talked about things like that.

Site 2, P02

How do patients/family members experience the decision-making process and their subsequent care?

Patients and families do not always recall or understand their ReSPECT conversation

Although some patients had good recall of the conversation, several patients could not clearly remember what was discussed. For example, one patient said there had been no discussion of resuscitation:

It hasn’t been spoken about. That word ‘resuscitation’ has never come into it.

Site 1, P01

Lack of recall could be due to the confusion of being in hospital, or being very ill or in pain at the time of the conversation [e.g. ‘I was in a bit of pain anyway, you know’ (site 1, P04)]. Family members too described having the conversation while feeling anxious and upset [e.g. ‘we were all a bit uptight, you know, because we’d . . . had the ambulance journey’ (site 6, F01)] or in the time of crisis:

. . . when you come in [to hospital] so much is going on, it’s something’s happened all of a sudden . . . you’re trying to focus on your [relative] . . . you’re trying to work out what’s going to happen to them.

Site 2, F02

Having ReSPECT conversations with ill patients or in an emergency was criticised by one person, who thought that this timing was inappropriate:

. . . when you’re really poorly, you know, it’s not a good time. ’Cause then you feel like giving up. So you need to be well for such conversations.

Site 2, P01

Some patients, and most families, felt they had understood the ReSPECT conversation, and that the purpose of ReSPECT had been clearly explained to them. There were some misunderstandings, however. One patient initially thought that the conversation was related to organ donation, then assumed that much of the conversation was to prevent litigation if the patient received treatment they did not want, and this patient’s doctor ‘made it clear that it wasn’t’ (site 1, P04).

Patients and families are unprepared for the conversation