Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as award number NIHR127367. The contractual start date was in August 2019. The draft manuscript began editorial review in July 2023 and was accepted for publication in March 2024. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Rhys et al. This work was produced by Rhys et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Rhys et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

This report presents the findings from a study funded by the UK National Institute for Health and Care Research Health and Social Care Delivery Research programme. Its purpose was to develop a qualitative understanding of the experience of making a complaint from the perspective of the NHS patient. The process of making a complaint within the healthcare system, including the final outcome, frequently fails to meet patient expectations. This has significant implications for the NHS, as dissatisfaction and the perception of an ineffective system can lead to legal action by patients. Litigation not only takes a toll on the health and well-being of both the complainants and the complained-about staff, but also imposes financial burdens both on the individuals and on the NHS budget.

The NHS as a public funded system of free healthcare has now existed for 75 years but is currently under huge threat from pressures on the services given tightened resources, increased demand, clinical complexity, and the fall-out from the COVID pandemic and its associated expense. In two recently published books marking the NHS’s 75th anniversary, Isabel Hardman1 and Andrew Seaton2 comment on its current existential crisis: ‘The NHS continues to operate at a pace and level of stress that it simply has not seen in its entire history’ and ‘patients are starting to lose faith with it in an unprecedented way’. 1 In our data, many of our complainants allude to the ‘crisis’ in the NHS, the sense that it is ‘on its knees’, in ‘utter chaos’, with wards ‘like a war zone’. It is therefore unsurprising that both the reasons to complain and the volume of complaints are increasing (e.g. written complaints to NHS England doubled to 208,626 between 2008 and 2018 and continue to grow, with 225,570 written complaints reported in 2021–23). Moreover, the complaints emerging from the current crisis are also more likely to lead to costly litigation for the NHS.

A significant body of research documents how dissatisfaction with complaint handling results from unmet expectations not only of the outcome of the complaint but also of the interpersonal conduct of NHS staff [both complaint handlers (CHs) and medical professionals]. 4 Moreover, the way in which a complaint is handled may be more consequential to a complainant’s decision to litigate than the gravity of the complained-about incident. For example, in an Australian incident, 11 patients received a contaminated solution during heart surgery, leading to 5 deaths. However, due to the Chief Executive’s genuine apology and his earnest commitment to investigate the issue, none of the affected families pursued legal action. 5 Similarly, a recent systematic review points to a recognised need for patient-centric ways of responding to complaints in order to improve complainant satisfaction. 6 One of the aims of this study therefore is to analyse whether and how good communication may contribute positively to the avoidance of a decision to pursue legal action.

While existing NHS guidance acknowledges the importance of communication in complaint handling, the current recommendations are broad and lack specific guidance on how to achieve effective communication. The current study was based on a pilot study conducted by Benwell, Rhys and McCreaddie7–12 on complaints calls to a Scottish NHS Health Board. The pilot highlighted contrasting patterns in the outcomes of the calls as an effect of the differing communication styles of the CH in the corpus. This pointed to the need for a more extensive observational study of the specific interactional practices influencing the outcomes of encounters between complainants and NHS staff. In addition, Friele et al. 13 demonstrated that complainants have nuanced expectations regarding the interpersonal conduct of CHs and clinical staff, with different expectations prioritised at different stages of the complaint process. These evolving expectations and shifting levels of satisfaction emphasise the need for a longitudinal approach to build knowledge of complainants’ lived experience of the complaints journey, understood as a series of communicative encounters (both spoken and written).

Our study thus investigated the following research question:

-

How can the power of language be harnessed to transform complainants’ experience of complaining in the NHS and reduce their recourse to litigation?

This was addressed through six research objectives:

-

to examine complainants’ lived experience of interacting with the ‘system’ through detailed micro-analysis of direct communications, both spoken and written, with NHS representatives

-

to audit patients’ perceptions of cultural bias in NHS contexts and show how this may create patterns of social relations that can help or hinder effective complaint resolution

-

to record self-reported expectations and experiences of the complaint's journey and its timeline, focusing on evolving perceptions of the complaints experience and the complained-about issue, and the impact of the process on complainant well-being and satisfaction

-

to identify and cross-reference moments of change and key drivers of change in complainants’ responses and intentions (including intentions to litigate) throughout their complaints journey

-

to develop an evidence-based ‘Real Complaints’ communication training resource to provide effective, evidence-based intervention that addresses the specific interactional and interpersonal challenges of NHS complaints handling

-

to disseminate good-practice recommendations to service users, NHS staff, local and national policy-makers and ombudsmen that will improve NHS complaint-handling processes and experiences.

The term ‘Real’ in the title of our training package (‘Real Complaints’) refers to the use of authentic recorded examples of complaints communication (written and spoken) to inform the identification of best practice and development of training, and foregrounds a significant contrast with the more common use of invented/role-played examples in existing training materials.

Structure of the report

Chapter 2 sets the context with key literature. Chapter 3 outlines our bespoke combination of observational and qualitative methods and our approach to developing the communication intervention as well as protocol changes made over the duration of the project. The subsequent analytic chapters detail the findings from our different data streams: the cultural audit (see Chapter 4), the longitudinal case studies (see Chapter 5), the written response letters (see Chapter 6) and finally the interactional findings (see Chapter 7). Chapter 8 discusses how our findings have been translated into Real Complaints Training and Guidance resources. Lastly, Chapter 9 presents our overall reflections and conclusions along with recommendations for further research.

Chapter 2 Literature review

Study context: complaining to the National Health Service

Patient satisfaction with the complaints-handling process in healthcare institutions, specifically the NHS, has been identified as an area of concern in the existing literature. Prior studies highlight that patient dissatisfaction is largely rooted in poor communication, leading to unmet service-user needs and, in extreme cases, litigation. 14,15 Although the actions of NHS staff managing complaints profoundly affect the outcomes, limited knowledge exists on this aspect. 4 Moreover, recent reports still highlight major failings with the current complaints system in the NHS. 16–18 This lack of insight underscores the need for comprehensive empirical research on the practices of responding to complaints.

The significance of effective communication in healthcare contexts is widely accepted, yet a troubling discrepancy persists between policy and practice. Even when strategies such as the ‘disclose and apologise’ policy were introduced, the expected reductions in litigation were not observed. 19,20 Mazor et al. 21 argued that this is due to a lack of understanding of how such disclosure should be executed. Similar gaps exist in the domain of complaints handling, where vague prescriptions for communication, such as adopting a non-judgemental, transparent and appropriate manner, provide insufficient guidance for actual implementation.

Healthwatch England has noted that previous improvements focused predominantly on systems rather than on understanding and enhancing the patient’s experience. 22 The preoccupation with system design and process optimisation has overshadowed the need for fostering trust and positive relationships between healthcare staff and complainants. The existing literature indicates a pressing requirement for adopting a relational, interpersonal view of the complaints process. 6,23,24

Certain principles, such as the ‘Power of Apology’ and ‘Duty of Candour’, have underpinned the complaints process in recent years. However, the assumptions that communicative events linked to these principles improve patient satisfaction require further empirical evidence. 25,26 While the ‘Power of Apology’ initiative outlines the components of a successful apology, understanding the precise timing and manner of apology delivery remains underexplored. 27–29 Furthermore, the complaints journey often involves a series of interactions, adding another layer of complexity. 30

According to Simmons and Brennan,31 the public expects the NHS to be responsive during their times of need. Both patients and complaint staff acknowledge the significance of communication quality in determining the outcome of the complaint journey. 8,23,27 Despite these insights, there is still a notable gap in the understanding of service users’ experience during the ‘complaints journey’ and the behaviour of staff managing patient complaints. 4

Complaint handling is a complex and sensitive social activity, significantly shaped by the social and institutional context. 32 The emotionally charged nature of the complaints topic, the potential defensive reactions of the clinical staff, and the varying needs and expectations of complainants all contribute to the intricacy of the complaints journey. 7,8,15,33 Hence, promoting empathy, reducing insensitivities, and avoiding alienation are essential for patient engagement and satisfaction, yet are often thwarted by institutional, procedural, and interpersonal factors. 31,34,35

Sociology and health services research on complaints

The expectations of complainants

A significant body of research indicates that complainants have diverse expectations and desired outcomes when initiating a complaint. Importantly, complainant expectations of responses to complaints or the accessibility/navigability of complaints systems have been shown to be important in terms of deciding whether or not actually to initiate a complaint in the first place. Complainants fear that they could potentially become victimised (with potential impacts on access to and quality of care) or that professionals will act defensively and ‘club together’ to undermine the complaint or complainant – thus may be reluctant to complain. 36 In this way, the types of expectations held by a potential complainant certainly feed into a very significant ‘moment’ in the complaints journey: where the decision is made about whether to make a complaint or not.

Where a complaint does proceed, complainants expect the complaints procedure to be fair and impartial. 26 More specifically, Bouwman et al. 37 argue that what complainants expect to achieve when complaining can be divided into three categorie: (1) complaints to improve healthcare quality, (2) complaints for personal benefit and (3) complaints to provoke consequences for care providers. This typology is particularly useful because it captures complainant expectations and hopes as reported in a range of other empirical research.

In the first dimension, which was found to be the most significant for complainants, complaints are made to improve healthcare quality in terms of intending institutions to learn from complaints, to prevent similar events happening to others,34 or to improve healthcare safety or stop poor practice. 38,39 In the second, types of personal benefit expected include solutions to a specific problem, prevention of occurrence or recurrence, financial reparations, justice, an apology, expressions of regret, explanations or accounts of what happened26,40–42 or simply cathartic benefit found in vocalising a grievance. 39 Interestingly, research additionally highlights how, perhaps surprisingly, negative expectations exist amongst complainants about receiving sympathy from professionals and the hope for the revival of relationships with professionals. 26 In this respect, it seems that complainants see initiating a complaint as damaging significantly or terminating existing relationships with professionals. Finally, complainants’ expectations include punishment (including loss of ability to practise), regulatory scrutiny, organisational or department closures, and financial consequences for organisations. However, it is important not to overstate the expectation of punitive action. Bismark et al. ,34 in the Australian context, show that fewer than one in five complainants expected or hoped that sanctions would be taken against specific staff or organisations, indicating that punitive action is a relatively uncommon factor in complaints. Where complainants call for punishment of professionals, this is linked most clearly to the occurrence of a death. 43 Complaining in this instance can be interpreted as forming part of period of mourning39 and motivated by a sense of ‘owing’ it to the deceased. 26 It is also important to note that financial considerations (which can be argued to fit within both of the latter dimensions) have been shown to be of only limited significance to participants34,39,44 and, where complainants have held financial expectations, they are primarily related to costs incurred. 40

Complainant experiences and the ‘expectation gap’

Research shows that complainants are often left dissatisfied with the outcome of their complaint. 13,14,26,45 Indeed, complainants’ expectations and the subsequent experience of making a complaint are often significantly different. 13,34,37,40 It has been argued26 that complainants will not be satisfied with a complaints procedure unless it meets their expectations. As noted above, complainants expect corrective measures and improvements to be made relating to healthcare quality following their complaint. However, most complainants report feeling that no significant institutional changes or improvements were made following their complaint. 13 Research by Bismark et al. 34 clearly highlights an ‘expectations gap’, a mismatch between complainants’ initial desires and expectations and what they ultimately felt was achieved. In this research, 57% of complainants sought communication in the form of information about what had happened, an expression of responsibility, or an apology; 46% sought corrective action to reduce the risk of harm to future patients. Seventeen per cent of complainants sought sanctions (in the form of disciplinary action or other punitive measures) against specific individuals or organisations. While some form of communication-related remedy was nearly always offered to patients, only 1 in 5 complainants who sought correction were given assurance that changes had been or would be made to reduce the risk of others experiencing a similar issue, and fewer than 1 in 10 who sought sanctions experienced processes to achieve this outcome. 14 If correspondence during and/or at the end of the complaint journey does not clearly communicate steps taken or changes made, then this is potentially significant in the creation of the expectations gap. Many complainants are also left disappointed by the reactions of professionals involved in the complaint,13 particularly when there is no admission of error.

Conversation analysis research on complaints

Conversation analytic research examines complaints as a social action, and as an interactional activity, which can offer a window into how institutions function and how morality is produced in interaction through people’s attention to something as good/bad or right/wrong. Conversation analysis (CA), like other forms of ethnomethodological research, empirically examines what people do, and not what people think they do. CA specifically is an approach to understanding the organisations of interaction, and how those organisations fit within an understanding of social relations. 46

Conversation analytic research has examined both informal complaints in conversational settings and formal complaints in institutional settings. Researchers have noted that complaining is a delicate and accountable activity47 with negative social connotations. 48,49 Strategies used to manage complaints and enhance their legitimacy include expressing moral indignation, displaying anger through prosody and pitch, engaging in painful self-disclosure,48 using extreme case formulations50 and idiomatic expressions,51 and employing identity categories like ‘reasonable complainer’ and ‘normal person’ to manage accountability and strengthen the grievance. 52,53 Another observation is that complaining expects agreement or affiliation54 from the recipient,7,8 but that the provision and extent of affiliation can be influenced by the institutionality of the complaint encounter, potentially conflicting with patients’ expectations. 33

Designing a complaint as actionable

Across various environments, research has shown how service users design their trouble as relevant for the institution that they are contacting. To make a legitimate request for assistance, or a relevant complaint to the institution, the talk needs to have a sense of actionability,55 whereby something can be done about the trouble. Callers work to establish themselves as having a legitimate reason to call; it will be seen below how they craft themselves as reasonable users of the service and thus worthy of attention. In institutional contexts, that means presenting the problem as one for which seeking assistance or making a complaint is a reasonable action. 46 However, what is ‘actionable’ can be unknown, so it requires work by both the caller and call handler to jointly construct the request/complaint as something which can be solved. 56

The interactional environment of complaints to the NHS is a particular context where callers are not ‘just complaining’, but are calling to resolve some problem that they have encountered while using the service. 52,57–60 Building a case for help can thus be accomplished in a number of ways sensitive to local interactional environments; however, complainants must also consider how they can build their case genuinely without facing accusations of being someone who is simply ‘moaning’.

Legitimate complainant identities

Registering a complaint as legitimate is achieved using a variety of discursive devices. These focus on the construction of the complaint itself; however, a common feature of complaints is how people produce themselves as reasonable people who have a legitimate complaint. It should not be argued that these are divorced projects; rather, offers of personal information are contextually bound performances of the individual as part of impression management. 61

Complaining is considered face-threatening;62 indeed, the delivery of complaints typically attends to cultural acceptability of an act where complainants tread a line where they are directly speaking to how one should act and how one should not act,63 so they need to be heard as rational speakers. 49 Cultural values are indexed in how people produced themselves in complaints – it is common (certainly in British culture) for stoicism to be valued and complaining to be treated as ‘moaning’, ‘whingeing’, etc. 49 In institutional settings, complaining does not usually attract such negative judgements, but complainants nonetheless work to be taken seriously.

A large body of work on producing oneself as a legitimate complainer comes from discursive psychology on characterological formulations64 where the ‘type’ of person someone is gets worked up in and through the interaction. Alexander and Stokoe focused on the formulation ‘[positive description] person’, for example, ‘I am an extremely tolerant person’. 64 They argue that these formulations implicate the conduct of the complained-about person by rendering them responsible for the caller’s actions (i.e. calling to complain). Consequently, characterological formulations are a resource for action and for identity work. 65 Investigating how complainants produce themselves (and the object of complaint) can provide insights into complainants’ stance, attitude and disposition towards the world, their social reality, and ultimately the complainable matters. 66

Institutional perspectives: relationships and constraints

Building rapport

An overriding concern for institutions when interacting with service users is to establish and maintain a good relationship; in social relation terms this is commonly referred to as rapport. 55,67 Institutions clearly have a stake in rapport-building, which ostensibly means better outcomes and thus increased client satisfaction. Rapport is demonstrably useful for service users; as described above, it goes some way to lend credence to their complaint if they can be seen as working with the institution to solve a problem, and not against the institution to create new problems. Rapport is actively sought and tied up with how institutions manage their relationship with their users. 68

Gatekeeping

Gatekeeping is an action accompanying the interactional role of call handling;69–71 call handlers decide whether and how the complaint/request etc. progresses. Whether calls result in a complaint or request does not necessarily result from the actions of individual call handlers, as the institution will have its own frameworks and workflows; they are merely responsible for navigating these procedures and ensuring that the service user fulfils the remit of the service. Though gatekeeping is characterised by decisions made by the institution, it comprises a negotiation wherein service users are tasked with convincing the service provider of the legitimacy of their trouble/request/complaint. Examining gatekeeping thus provides a window into the frameworks, processes and culture of an institution.

Navigating and signposting

Calling an institution often requires some navigation of that institution, whether it be form-filling, answering questions, telling one’s story, etc. Part of the call handler’s role is to support the caller to navigate that system to make their complaint, such as by eliciting details or being empathetic to the complainant’s experience. One method of navigating is signposting. Alexander72 offers a detailed review of signposting as an interactional activity where direction is provided to service users. Interlocutors attend to a preference for helping and providing a service even when the request/complaint cannot be fulfilled. 72,73

Signposting is organised with respect to the goal-orientedness of these approaches to the services. 67 The ‘goal’ is often bound up with how service users make requests to service providers to fulfil a course of action,74 for example, whether a current problem such as the removal of stitches is formulated as a request for help (to remove the stitches) or as a complaint (their non-removal thus far). These constructions have implications for the trajectory and ultimate outcome of the encounter.

Summary and opportunities for research

The central question explored in this literature review relates to complainant and professional expectations and experiences of complaining. Core findings include that complainants have three types of expectations when they make a complaint. They complain (1) to improve healthcare quality, (2) for personal benefit and (3) to provoke consequences for care providers. 37 However, very significantly, Bismark et al. 34 highlight an ‘expectations gap’ between expectations at the beginning of a complaint and what complainants ultimately felt was achieved – particularly relating to the expectation of corrective measures and improvements being undertaken.

Saliently, the sociological and health services research into complaints highlights the significance of poor communication and interpersonal problems as the cause of complaints. 75 Importantly for our purposes, however, only passing references are made about communication during the complaints journey, despite the evidence for the potential significance of poor communication for complainant (dis)satisfaction and the creation of the ‘expectations gap’ during the complaints process. It is clear that complainants expect certain communicative approaches and events, but, in the sociological and health services research literatures, little is said, for example, about what an effective apology or explanation would look like and how it might be received in an actual interaction. This provides scope for our project to attend to some of these gaps in the research field, specifically in engaging with longitudinal research. Such a longitudinal perspective offers the opportunity to identify whether certain forms or types of interaction with particular individuals or types of staff or, indeed, other specific moments during the complaints journey are especially important.

Chapter 3 Methodology

The aim of this project was to conduct primary research that would have implications for improving the patient experience of making a complaint. Our focus on communication stemmed from the existing research evidence indicating that the interpersonal conduct of NHS staff is a key factor in complainant dissatisfaction and that dissatisfaction with communication is the strongest predictor of litigation. 76,77 Our primary research therefore adopted a novel mixed-methods approach to provide a detailed, contextualised examination of the relationship between complainants’ observable, complaint-handling experiences and their personal, evolving perspective on both the complaint issue(s) and the complaints process.

Protocol history

In the course of this study, it became necessary to make certain changes to the protocol as originally designed. The original timeline called for data collection to begin early in 2020; however, the COVID-19 pandemic made it impossible to engage in face-to-face data collection until restrictions were relaxed, while the additional burdens placed on the NHS Trusts affected the ways in which they were able to participate. Some of the changes necessitated were on a relatively broad scale:

-

One Trust withdrew from the project completely, so the data sample consists of complaints journeys from two Trusts.

-

The remaining Trusts found that it was no longer feasible to involve clinical staff to document their role in the complaints process.

Other changes affected the nature of researchers’ interactions with complainants:

-

Face-to-face contacts with complainants were largely replaced with communication by telephone or online meeting.

-

Written communication by e-mail was offered as an alternative to post.

-

Complainants were not issued with recording devices to record their own telephone communication with the Trusts.

To compensate for some of the limitations imposed by these measures, other changes were made that increased the quantity of data available:

-

The number of longitudinal participants recruited was increased from 20 to 30.

-

Complainants were recruited even when their initial contact with the Trust regarding their complaint had occurred before the beginning of data collection, and as much information as possible on the earlier stages of their journey was obtained through interviews.

Despite these changes to the protocol, the data obtained are comparable in scope to what was envisaged in the original protocol design.

Patient and public involvement in project design

Three patient and public involvement (PPI) participants acted as consultants for the design of the data-collection tools. Of particular concern was the potential burden of longitudinal participation, particularly the diary method. All three participants were supportive of the use of diaries and recommended offering both ‘pen & paper’ and digital formats. The PPI members of the Project Management Group were consulted on the wording of the Participant Information Sheets and Consent forms.

Data sources

The project was conducted across three data-collection sites in Northern Ireland: two Health and Social Care Northern Ireland (HSCNI) Trust complaints services and one Patient Advocacy Service (PAS). Note that the health service in Northern Ireland is unique in the NHS in incorporating social care under the same organisational banner as healthcare. While clearly organisationally significant, this does not appear to be consequential for the communication phenomena in our analysis. The wider cultural context of these data-collection sites was examined via a quantitative cultural audit which explored the degree of congruence/dissonance between patient expectation and experience of the NHS in order to determine whether the patterns of social relations that matter most to patients are supported in the health service cultures they encounter.

The focus of the project was the observational microanalysis of language-in-use in both spoken and written communication between complainants and the NHS Trusts, complemented by a parallel analysis of participants’ subjective reflections on their complaint journey, both during and after the journey.

The observational data were structured in two key data sets: initial encounters (by telephone or e-mail) and longitudinal case studies following individual complainants through their entire complaint journey. The primary complaints data were either recorded phone calls, meetings or written correspondence (letters and e-mails). These observational data in the longitudinal case studies were complemented by a parallel qualitative data set of participant diaries and semistructured interviews with each of the longitudinal participants in order to cross-reference the findings of the observational analysis with participant appraisal of their complaints experience. Qualitative semistructured interviews with both complainants and complaint staff were conducted online with members of the research team and diaries were submitted online or by telephone with a researcher.

A total of 80 participants were recruited, of whom 23 ultimately became longitudinal participants. This yielded a final data set of 23 complaint journeys and a total of 86 phone calls (1155 minutes), 113 written communications and 6 recorded meetings as well as 36 participant diaries and 23 interviews. Both Trusts provided both spoken and written data, but there was a preponderance of written cases in Trust A and of spoken in Trust B. While our analysis was mindful of the differences between the Trusts, it was not the focus of the study. Both sites adhere to the same complaint-handling policy and our aim was to focus on commonalities in order to ensure the widest relevance of the training developed. The cultural audit yielded 115 cultural-audit responses.

Data on individual complaint journeys

A total of 30 longitudinal participants were recruited. Of these, 7 subsequently withdrew, leaving 23 longitudinal participants, 8 from Trust A and 15 from Trust B. Differences in practices in the two Trusts had a substantial effect on the nature of the longitudinal journey data available. All Trusts adhere to the standards for complaint handling set out by the Department of Health Social Services and Public Safety but operationalise those standards differently. Trust A has a telephone line for general enquiries but requires the complaint itself to be submitted in writing and issues written responses for all complaints. In Trust B, formal complaints may be logged by telephone and, in relatively simple cases, also resolved solely by telephone.

For Trust A, our data include all the written communication between the complainant and the Trust. Some complainants were also supported by the PAS and their journeys include recordings of telephone calls and face-to-face meetings between the complainant and a PAS representative.

For Trust B, we recorded all telephone calls between participating complainants and front-line CH made during the data-collection period. Two calls to complainants from complaints managers were also recorded. Where a complaint was closed by telephone, the Trust provided copies of the internal telephone resolution form (TRF). Where the final response to a complaint was in writing, these letters were also provided.

Complainants also provided diaries in the form of an online questionnaire (see Report Supplementary Material 1). Some participants preferred to update the research team by means of free-form e-mails or telephone calls from the researchers. In the latter case, the data that they provided have been treated as interview data.

A final interview was carried out with all complainants who consented and were available before the end of the data-collection period. These interviews were conducted using a semistructured format (see Report Supplementary Material 1); complainants were invited to reflect on their complaints journey as a whole, or, for those whose complaints were still ongoing at the end of the study, on their journey so far. These interview data are augmented by recordings of other contacts between complainants and researchers. It was found that many complainants wanted to discuss their complaints journey during the call to recruit them as longitudinal participants; as their comments were a potentially valuable source of data, some recordings of these calls were also made.

All data presented in this report and in related publications or presentations relating to the research have been anonymised in line with the project’s ethics protocol. Pseudonyms were used in place of real names (of people and places).

Complaint-handler interviews

Using a semistructured format (see Report Supplementary Material 1), three front-line CHs, two complaints managers (one from each Trust), and a PAS representative were interviewed, yielding 6.79 hours of data.

Cultural audit

The online cultural audit (see Chapter 4, Sample survey) was distributed through the mailing list of a PAS with a remit to engage the public in health research. Membership of this mailing list is open to the general public as service users of the NHS. One hundred and fifteen responses were obtained.

Modes of analysis

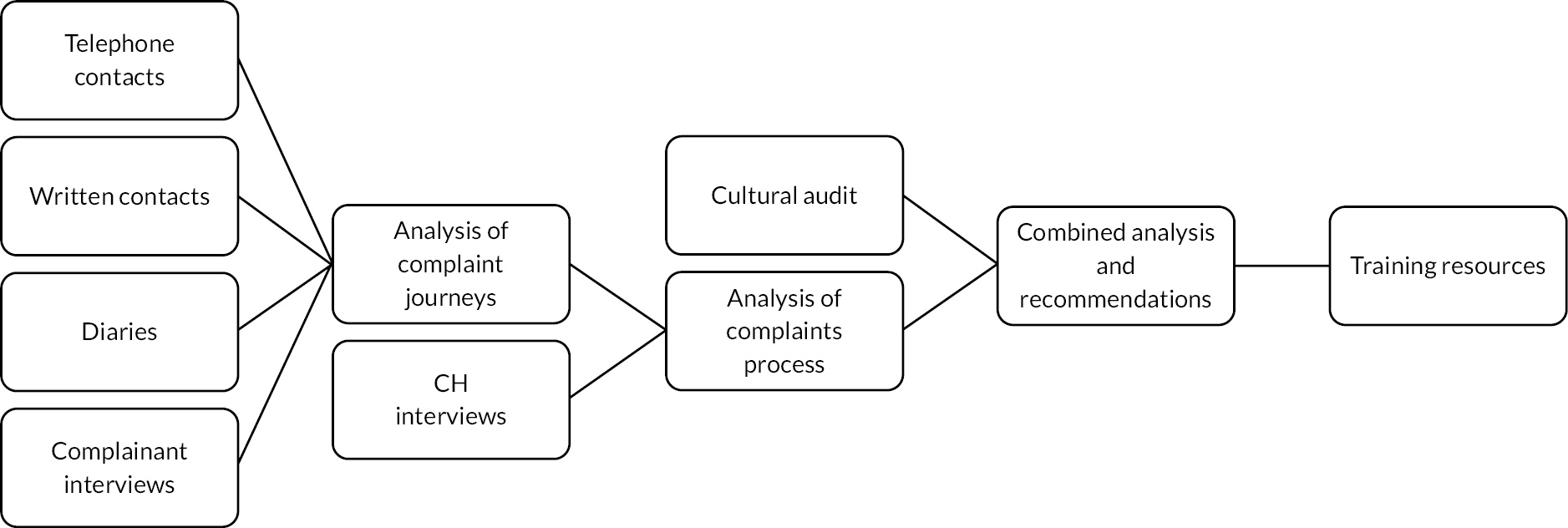

This study thus combines multiple modes of analysis to investigate the complaints process, as shown in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Research pathways.

At the heart of this project is the application of CA to the spoken (mostly telephone) interactions between complainants and CHs. CA is a form of observational research that studies in fine-grained detail how conversation participants methodically display their understanding of each other’s turns-at-talk and how those understandings are negotiated in interaction. CA involves turn-by-turn analysis of communication practices in context to understand what matters to speakers moment-by-moment in the interaction and to reveal the impact of particular language choices on the ongoing conversation. In this way, the ‘next turn proof procedure’ of CA78 provides robust evidence of the effectiveness (or otherwise) of individual interactional practices by examining participants’ own situated sense-making practices. While formal quantitative measurements of frequency are therefore not relevant to the CA approach, ‘informal quantification’, described by Schegloff79 as ‘an experience or grasp of frequency’, nonetheless informs the selection of analytic foci and of trainables (see Chapters 7 and 8). In presenting our findings in Chapter 7, we focus on the interactional patterns that recurred both within and across encounters.

Similarly, discourse analysis (DA) is a linguistic approach to the analysis of written texts, which focuses on the meanings, intentions, ideologies and consequences of particular language choices by the writer, and views discourse as a form of social action or practice. 80 The written communication in our observational data set was analysed focusing on choices in grammar, word choice and pragmatic meaning (what is implied or presupposed), to provide an empirically grounded account of good and poor written communication.

The analysis of the observational data in our longitudinal case studies was triangulated by thematic analysis of participant diaries and interview data for a holistic account of the key factors within and between cases. An iterative process of open coding, informed by the microanalysis of the observational data, was applied across all data sources for each individual journey to uncover central themes and detect inconsistencies across sources. These themes were subsequently categorised into two primary axes, ‘process’ and ‘c-concepts’ (causes, consequences, correlations, constraints), for the analysis of longitudinal case studies. The cumulative effects of multiple encounters in an overall complaint journey were examined to provide a deeper understanding of the relationship encounter-by-encounter between the personal and the systemic.

Finally, the themes from the longitudinal case studies were cross-referenced with insights from the cultural audit into the sociopolitical context of the patient–healthcare provider relationship within which these complaint journeys were taking place. The cultural audit applied a validated measurement tool81,82 to assess the relative influence of cultural perspectives on four key aspects of service users’ relational expectations and experiences within the NHS: ‘courtesy and respect’; ‘how knowledge is valued’; ‘how fairness and equity issues are resolved’; and ‘how voice is expressed’. Responses were analysed using descriptive and paired-sample statistics in SPSS 25 (IBM Corp. Released 2017. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 25.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.) to identify important gaps between expectations and experiences.

Communication skills training methodology

Communication skills training that draws on the outcomes of CA microanalysis of real recordings is well-established as delivering effective, evidence-based interventions. 76,83 The particular strengths of this approach are the authenticity and flexibility of the interactional skills identified using CA. 68,84 There are multiple benefits from the authenticity generated by inductive analysis of real recordings compared to, for example, role-play or simulation-based training approaches. To begin with, inductive analysis of real data reveals the tacit knowledge deployed in natural examples of good practice. This establishes an authentic evidence base for the targeted communication skills that clearly demonstrates their effectiveness in practice. This then also ensures the transferability of the communication behaviours from training to real-world experience. 85 In addition, the authenticity of using real examples has been shown to be particularly effective in encouraging reflection and learning about emotionally challenging communication. 86 The question of flexibility is tied to the evidence base for the training. At the heart of any CA is the recognition that turns at talk are context sensitive; each turn-at-talk both responds to the immediately prior talk and creates the context for the next turn-at-talk. 78 A key implication of this is that ‘trainables’, the communication practices targeted by a communication skills intervention, cannot be taught as standalone behaviours but as actions in a sequence of actions. Presenting trainables in their interactional context facilitates the development of reflective practice and enhanced awareness of how particular interactional strategies are not a priori effective but effective in particular interactional and sequential contexts. As our data analysis shows, this is particularly significant for some of the trainables in Real Complaints Training.

Presenting our findings

In the chapters to follow, the findings are presented from the macro to the micro. In Chapter 4, insights from the cultural audit provide the patient perspective on the sociopolitical/institutional backdrop against which individual complaints take place. Chapter 5 focuses on how the longitudinal case studies provide a nuanced understanding of patient complaints as a dynamic journey with evolving narratives and shifting expectations where each experience and encounter is shaped by preceding ones and, in turn, influences subsequent interactions and perceptions. Chapters 6 and 7 focus on the analysis of the language of first written and then spoken encounters, providing the microlevel analysis of the associations between communicative practices and outcomes that underpins the Real Complaints Training resources presented in Chapter 8.

Chapter 4 Cultural audit

Introduction

This chapter examines the influence of cultural–institutional factors in NHS/HSCNI which provide a context for the likely stance and expectations of patients/carers making a complaint. The ‘cultural audit’ tool developed by Simmons,81,82 based on Grid-Group Cultural Theory (CT), is used as part of a broader survey to structure the perceptions and opinions of service users of the NHS.

This analysis shows particular tensions between how patients think the service ‘should be’ and how they think the service ‘actually is’. Additional evidence from the survey is used to assess these findings: in particular, in the relationships between ‘good opportunities’ for patient/carer voice and the perceived quality of public service relationships and service performance.

This chapter thus addresses study objective 2.

Detailed background

The importance of relationships

The relationships between patients/carers and providers of NHS/HSCNI services are often an under-emphasised feature of public administration. Using CT as a way to structure the complexity of public service relationships, we examine whether the cultural–institutional arrangements in NHS/HSCNI services are congruent or dissonant with expectations of patients/carers.

Tensions persist in the realm of public service interactions. These arise from issues like bureaucratic paternalism, where agencies often disregard the perspectives of their users; target cultures, where relational aspects are seldom prioritised or quantified; and an emphasis on managerialism and public relations, leading to the technical handling or trivialising of relational concerns. This approach frequently results in users feeling impersonalised and powerless. 87,88 Consequently, there is a growing demand for a ‘relational state’ that emphasises meaningful service relationships over superficial transactions. 89,90

Patterns of social relations

This aspect of our study examines the extent to which the culture of NHS/HSCNI services is attuned to the patterns of social relations that matter most to patients/carers. Institutional theories offer insights into the behaviour of public service organisations and their responsiveness to user feedback. Yet, these theories fall short in clarifying the specific nature of what service users request or in identifying the initiatives that link these demands with their desired solutions. 91 The purpose of the ‘cultural audit’ is to establish the extent of compatibility between users’ perspectives about what patterns of social relations are present and what patterns are desired, as a way of setting the institutional context for the findings from this study’s microanalysis using CA.

Relational concerns, institutional work and cultural innovation

Relational concerns include aspects such as relational justice, relational satisfaction and relational morality. Notions of relational justice and relational fairness refer to the interpersonal treatment associated with decision-making. 92,93 As Waldron94 points out, people anticipate being heard, respected, taken seriously and having the chance to address any injustices in their relationships. Their sense of relational satisfaction partly stems from how well these unspoken agreements are adhered to. On the other hand, stories of relational betrayal are often told using vivid and resentful language, highlighting the strong emotions involved when expectations are not met.

Particular resonance for NHS/HSCNI services arises from further considerations of relational morality, whereby such factors as close proximity, forced interdependence and vulnerability to abuses of power may require users to develop with providers an unwritten code of relational ethics to supplement formal rules. 94 This requires institutional work,95 which may involve cultural innovation, or ‘a reprioritisation or rebalancing within organisational value systems that can help reframe the conceptual or emotional view of a situation, customize new strategies and promote new behaviours’. 96 Yet insufficient research has been directed toward the influence of broader cultural factors on how relational issues are constructed and negotiated within NHS/HSCNI services and organisations.

Understanding cultural diversity

Applying the Cultural Theory framework

Our initial discussion of cultural issues focuses on values such as relational justice, norms such as relational morality and practices that promote relational satisfaction. These are fundamental for understanding how institutional cultures preserve cultural values and norms, give them authority and provide a context for the practices of social interaction97,98 that are discussed in microanalytic detail in this study.

If we accept that patterns of social relations shape people’s preferences and justifications so that ‘everything human beings do or want is culturally biased’,99 CT, which distinguishes a limited number of cultural biases, provides a useful mechanism for simplifying system complexity in ways that are congruent with ‘real world’ processes. 100

The Cultural Theory framework and public services

Here we introduce the key elements of CT101–104 as a tool for understanding cultural diversity.

Cultural Theory has its roots in Durkheim’s105,106 two dimensions of social organisation: social regulation (‘grid’) and social integration (‘group’) (Figure 2). ‘High grid’ cultures are heavily constrained by rules and ascribed behaviour; ‘low grid’ cultures much less so. In ‘high group’ cultures, group membership is strong; in ‘low group’ cultures, much weaker. CT thus helps frame institutional analysis of the NHS/HSCNI service environment.

FIGURE 2.

The dimensions and cultural biases of CT.

The four cultural biases of Cultural Theory

Hood107 uses CT to describe four cultural biases describing ideal-typical patterns of relations in public administration:

-

Hierarchy (strong social regulation, strong social integration) sums up a bureau-professional relationship in which experts define users’ needs, and services are delivered according to strict rules of eligibility.

-

Individualism (weak social regulation, weak social integration) constructs service users as rational, utility-maximising individuals, negotiating the role to support their private needs and wants.

-

Egalitarianism (weak social regulation, strong social integration) is represented by ‘mutualistic’ forms of relationship, in which a sense of membership/ownership confers rights (but also responsibilities) on users to co-produce services through more collective processes.

-

Fatalism (strong social regulation, weak social integration) sees social relations as imposed by external structures. Fatalists consider the expression of voice as pointless, and therefore tend to feel isolated from the public service system.

Understanding cultural tensions

Cultural Theory includes two further theoretical propositions. First, the ‘requisite variety condition’ states that the four cultural biases need each other to be viable and define themselves against. 104 Elements of all four cultural biases should be expected to be present but exist with one another in a state of permanent disequilibrium, tension and flux. 104,108

Second, the ‘compatibility condition’ states that these different and mutually irreconcilable biases nevertheless need to be accommodated to maintain the viability of the system. 108 Hence, viable patterns arise when social relations and cultural biases are mutually supportive of each other. 104

Research methodology and operationalisation of Cultural Theory

General research approach

The survey tool was developed by Simmons,81,82 based on research in public service contexts which elicited four key themes in the patterns of social relations that mattered most to service users:

-

‘how fairness and equity issues are resolved’

-

‘how knowledge is valued’

-

‘courtesy and respect’

-

‘how rules are set and policed’

After review with staff at the PAS, the fourth theme was replaced with ‘expression of voice’ as more relevant in NHS settings.

Sample survey

The PAS membership list was contacted by e-mail and via the PAS newsletter, with a link to the survey on Jisc Online Surveys. Of 260 members receiving the link, there were 115 responses, a response rate of 44%. Cross-tabulation showed no significant mediating effects between survey responses and other basic differentiating sample characteristics (see Appendix 1, Table 10).

Operationalising Cultural Theory

The above thematic work defined the key elements of social relations in NHS/HSCNI services that could be evaluated using CT. Accordingly, these themes were applied in each corner of the CT framework to produce 2 sets of 16 attitude statements: first, about how NHS/HSCNI services actually are, then, in parallel, how these services should be (see Appendix 1, Table 11). Respondents used a five-point Likert-type scale (strongly agree, agree, neither agree nor disagree, disagree, strongly disagree). To avoid response bias, statements were mixed up by both theme and cultural bias, and respondents were unable to refer to their previous answers.

Findings from the cultural attitude statements

Visualising cultural characteristics

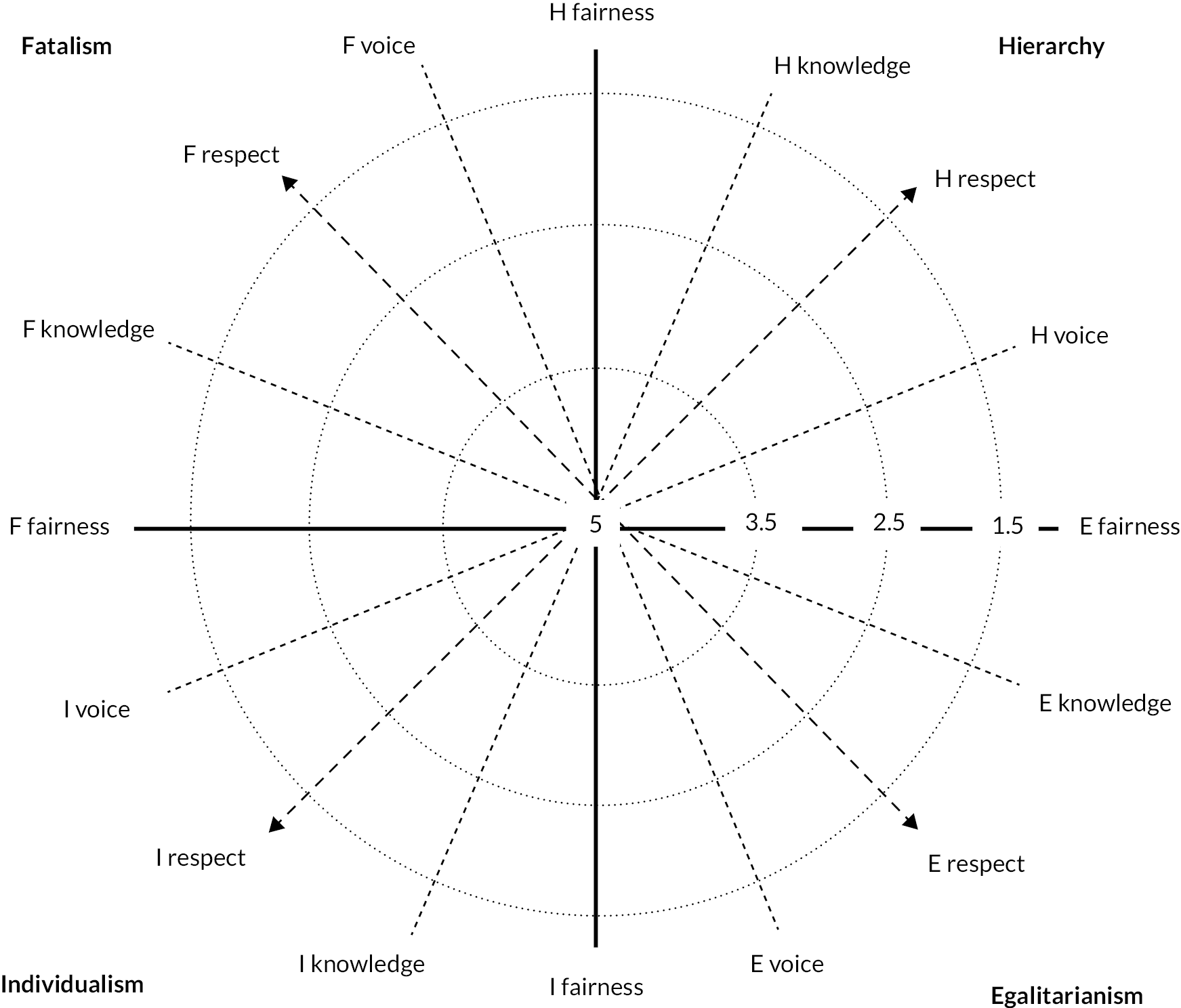

Patients’/carers’ scores against each of the attitude statements were combined to calculate a mean aggregate score for each statement. These scores were plotted on a concentric graph to represent the tension-bound nature of the cultural context in each case (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Template for radial plot showing dimensions and values. Note: lower scores represent greater agreement.

Patterns in the way patients/carers felt the service relationship actually is are displayed in the visual ‘shape’ formed by these scores in Figure 4, which displays a greater degree of development or attenuation of particular ‘cultural biases’ (red line). The inconsistencies in these patterns stood in some contrast with the way patients/carers felt the service relationship should be (shaded area).

FIGURE 4.

Patient Advocacy Service members’ perceptions of how the service ‘is’ (red line) vs. how it ‘should be’ (shaded area). E, egalitarianism; F, fatalism; H, hierarchy; I, individualism.

Statistical comparison between ‘is’ and ‘should be’ statements

Such patterns indicate certain cultural ‘blind spots’; patients/carers tended to agree that their relationships with the service should be less hierarchical, much less fatalistic, more individualistic and much more egalitarian. Table 1 provides the results of a paired-samples t-test analysis comparing PAS members’ responses, showing the variations between patients’/carers’ perceptions of what ‘actually is’ and what ‘should be’ on each indicator. This analysis shows that work remains to close the gap on all four dimensions, with statistically significant differences between many of the ‘is’ and ‘should be’ statements.

| Ideal types and themes | t-test results | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| t | df | p | |

| Hierarchy | |||

| How fairness/equity issues are resolved | 3.760 | 114 | < 0.001*** |

| Whose knowledge is valued | 5.987 | 114 | < 0.001*** |

| Courtesy and respect | 1.106 | 114 | 0.136 |

| Expression of voice | 11.676 | 114 | < 0.001*** |

| Egalitarianism | |||

| How fairness/equity issues are resolved | 13.872 | 114 | < 0.001*** |

| Whose knowledge is valued | 12.625 | 114 | < 0.001*** |

| Courtesy and respect | 16.720 | 114 | < 0.001*** |

| Expression of voice | 2.496 | 114 | 0.014* |

| Individualism | |||

| How fairness/equity issues are resolved | 3.233 | 114 | 0.002** |

| Whose knowledge is valued | 7.819 | 114 | < 0.001*** |

| Courtesy and respect | 8.205 | 114 | < 0.001*** |

| Expression of voice | 2.271 | 114 | 0.013* |

| Fatalism | |||

| How fairness/equity issues are resolved | 14.528 | 114 | < 0.001*** |

| Whose knowledge is valued | 1.207 | 114 | 0.230 |

| Courtesy and respect | 10.673 | 114 | < 0.001*** |

| Expression of voice | 12.157 | 114 | < 0.001*** |

This is confirmed in Table 2, which uses a paired-samples t-test with the means of the ‘is’ and ‘should be’ scores for each cultural bias. This demonstrates both high levels of statistical significance and large effect sizes. These results appear to illuminate patients’/carers’ expectations and experiences on a range of factors, regarding patterns of social relations that would otherwise be hidden from view.

| t-test results | Effect size | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cultural bias | t | df | p | Cohen’s d | Effect size |

| Hierarchy | 9.824 | 114 | < 0.001*** | 0.916 | Large |

| Individualism | 7.984 | 114 | < 0.001*** | 0.745 | Medium |

| Egalitarianism | 15.594 | 114 | < 0.001*** | 1.454 | Large |

| Fatalism | 14.621 | 114 | < 0.001*** | 1.363 | Large |

Value of the cultural audit tool

Achieving ‘relational justice’

These findings display a level of cultural dissonance. As predicted by the ‘requisite variety’ and compatibility’ conditions of CT, the value of the cultural audit lies in showing how action can be taken, to work in a number of complementary ways in the pursuit of greater congruence (or ‘dissonance reduction’).

For this complaints study, where the patient/carer voice is relevant to achieving relational justice, factors in the culture of public service organisations are important in assessing the ‘possibility spaces’ or ‘opportunity structures’ they open up or close off. 109 Survey respondents were therefore asked: ‘Are there are good opportunities available to express your views about the service?’. Yet only 22% said ‘Yes’ – 49% said ‘No’ and 27% said ‘Don’t know’.

Links with service relationships and service performance

The expression of voice could also be cross-tabulated with two further variables (service relationships and service performance), where patients/carers were asked: ‘On balance, how good a service do you think you get?’, and ‘On balance, how positive or negative is your relationship with the people who deliver this NHS service?’. Chi-squared analysis confirmed clear relationships between these variables. Hence, the more likely patients/carers were to say there were ‘good voice opportunities’, the more positive their perceptions of both relational quality and service performance (Table 3). This confirms the findings of previous research and provides an important consideration for NHS/HSCNI service managers and staff.

| ‘Are there good opportunities available to express your views about the service?’ | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Relationship | Yes (%) | No (%) | Performance | Yes (%) | No (%) |

| Very good | 56.0 | 7.1 | Very good | 56.0 | 8.9 |

| Quite good | 36.0 | 32.1 | Quite good | 36.0 | 23.2 |

| Neither good nor poor | 4.0 | 33.9 | Neither good nor poor | 8.0 | 12.5 |

| Quite poor | 0.0 | 19.6 | Quite poor | 0.0 | 35.7 |

| Very poor | 4.0 | 7.1 | Very poor | 0.0 | 19.6 |

| χ2 value | 41.575 | χ2 value | 49.658 | ||

| df | 12 | df | 12 | ||

| sig. (two-sided) | < 0.001*** | sig. (two-sided) | < 0.001*** | ||

Tackling fatalism

Finally, we found that the more patients/carers/complainants felt unable to engage effectively in public service relationships, the more likely they were to feel isolated and fatalistic. Those who said ‘no’ to the ‘good opportunities to express your views’ question were significantly more likely to exhibit more fatalistic perceptions (Table 4).

| ‘Are there good opportunities available to express your views about the service?’ | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PAS members | ||||||

| Yes | N | No | N | Don’t know | N | |

| Fatalism mean score | 3.22 | 25 | 2.09 | 56 | 2.52 | 31 |

| χ2 value | 62.518 | |||||

| df | 32 | |||||

| sig. (two-sided) | < 0.001*** | |||||

As Hood107 observes, fatalist approaches arise in conditions where co-operation is rejected, distrust widespread, and apathy reigns. In promoting greater relational justice in public services, it is therefore important for greater efforts to be made to listen, engage and respond more carefully with patients/carers. 110

Conclusions

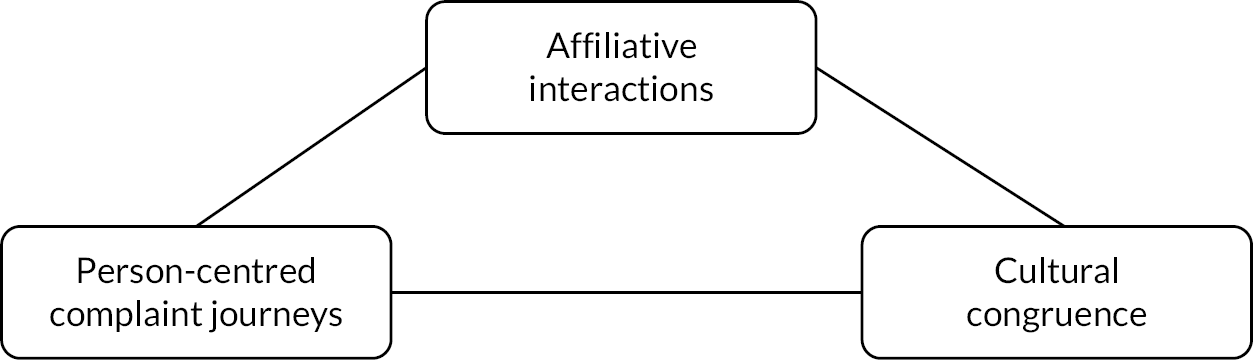

Four interconnected themes seem worthy of note in concluding this analysis.

The value of the cultural audit in understanding the cultural–institutional context

Cultural Theory analysis helps illuminate ways in which dissonance can be addressed and greater congruence promoted in NHS/HSCNI service cultures and service relationships. This added considerable value in triangulating, interpreting and assessing the microanalytical data at the analysis stage of this study.

Culture as context for complaining

Cultural dissonance between deontological (what should be) and ontological (what actually is) dimensions of service relationships constitutes a background against which a person makes a complaint. Participants’ answers portray the current relational condition in HSCNI as mostly fatalistic and hierarchical, meaning that these cultural predispositions create barriers and low expectations of the complaints process from the outset to the point of reluctance to complain. At the same time, the dissonance may encourage people to seek more congruent relationships with the service through systemic change, and the complaints procedure may be seen as an appropriate channel for such reform.

The extent to which National Health Service/Health and Social Care Northern Ireland services are attuned to relational aspects with patients/carers

This study suggests that less positive and productive contexts are created under conditions of relative dissonance. This supports calls for a more relational system that prioritises ‘deeper’, more person-centred service relationships,90 which links a need for a relational competence that goes beyond simple technical competence to the pursuit of more ‘person-centred’ approaches to public services,111,112 with concomitant prescriptions for changes in service systems, values and practices. 113,114

Whether cultural innovation can help manage emergent contradictions and incongruences within the service system

As stated above, cultural innovation involves a reprioritisation, recombination or rebalancing within organisational value systems to help reframe the conceptual or emotional view of a situation, customise new strategies and promote new behaviours. 96 In the context of this study, cultural innovation and the emergence of more congruent relational conditions may encourage patients/carers to contribute more often and more productively to the health of NHS/HSCNI services through their engagement with providers, harnessing the productive energy of emergent cultural conflict to build more harmonious relationships.

Chapter 5 The complaint as journey: longitudinal analysis

Introduction

Understanding the complaint as a journey

One of the main insights of our study is that the complaint should be understood as a journey. The concept ‘complaints journey’ captures the entire process of filing, handling, and resolving a complaint, including all the interactions and experiences that occur from the moment the complainant initiates the complaint until its resolution. This concept goes beyond just procedural elements and incorporates interpersonal elements such as the behaviour, expectations, thoughts and emotions of the complainants at each stage.

Studying complaints as journeys allows for a nuanced understanding of complainants’ expectations and satisfaction levels, which can vary at different stages of the process. Moreover, a journey-focused approach facilitates the discovery of interactional patterns and how one instance of interaction may lead to the next. This helps to understand how complainants build their future actions and understandings based on past interactions.

This chapter examines complainant evaluations of complaints journeys and thus addresses study objectives 1, 3, 4.

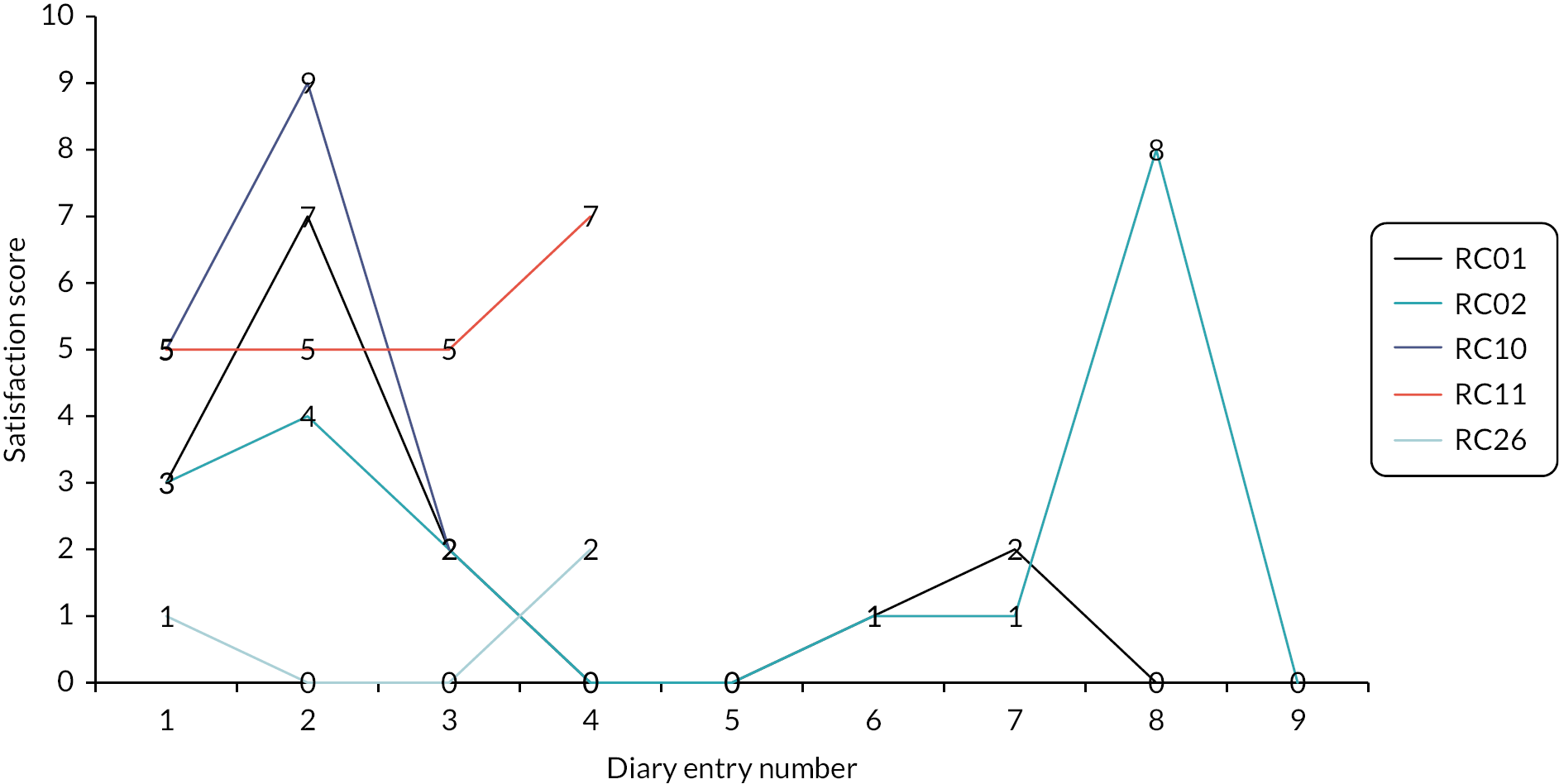

Data and methods

The analysis in this chapter relies on 21 full complaints journeys, 8 from Trust A and 13 from Trust B. RC18 and RC27 contributed to the recruitment quota for longitudinal participants, but their journeys provided too little data for inclusion in this chapter. (See the ‘List of abbreviations’ for the notation used to refer to participants and data sources.) Complaint journeys were varied in duration, ranging from 5 days to over 2 years (and ongoing). Figure 5 provides information on the communicative modalities used by the Trusts across the journeys.

FIGURE 5.

Communication methods across complaints journeys in two Trusts (excluding acknowledgement and holding letters).

Open coding was employed on all data sources associated with each individual journey to uncover themes and detect inconsistencies across sources (see Report Supplementary Material 2 for a coding template). The themes identified were subsequently categorised into two primary axes: ‘process’ and ‘c-concepts’ (causes, consequences, correlations, constraints). 115 This categorisation formed the foundation for the analysis that follows.

Survey data and qualitative appraisal data (diaries, interviews) capture complainants’ perceptions and expectations. Consequently, analysing these different data sources using multiple methods is expected to produce findings that reinforce and enrich one another. Meanwhile, the analysis of observational data (written correspondence, calls and meetings) offers an additional dimension. The insights from this type of data can either converge or diverge from the findings revealed by the survey and qualitative data.

Complaints journeys as processes

The complaints journey, as a temporal sequence, begins with certain negative events concerning medical care and treatment. Across our longitudinal data we see common themes uniting the patient experience in a number of cases. In addition, complainants’ broader reflections on the state of the NHS constitute a context to their complaint.

Entering the complaints process

Prior to the initiation of the complaints process, the complainant already carries a set of assumptions and expectations. In this section, we analyse how pre-existing beliefs and expectations influence the perception of the complaint journey.

Context of complaining

First, we explore how the cultural predispositions, identified in the cultural audit, are manifested in the qualitative data sources from the longitudinal journeys.

Cultural predispositions

The NHS is a revered public service to which the British public feel a strong sense of emotional attachment116 but this arguably coexists with the implicit expectation that the service should be delivered to a high standard. 7,109,117 A majority of longitudinal participants (15/21) make reference at some point in their complaint journey to a loss of confidence in the NHS as a system of healthcare. These reflections tend to emerge out of their individual experiences as they seek to understand the local failings leading to their complaint within a wider context of policy, management and funding decisions:

... there’s no such thing as the NHS anymore because they’re not providing the healthcare, they’re not providing it to the public. Because [daughter]’s not receiving any care.

RC21[Rc]

[S]omething went badly wrong with the nursing aftercare this time which made me feel afraid and lacking confidence in NHS.

RC28[D]

This perception of the NHS as a ‘failing’ institution, combined with a sense of regret at this development, is a strong theme threading through our participants’ descriptions of circumstances and motivations that lead people to complain. Sometimes the loss of faith is framed in terms of a more existential evaluation of the NHS as a whole institution:

I think the NHS is finished […]. I think the NHS is on its knees as it is.

RC28[I]

The system is just broken and the system is abused […]. The whole infrastructure, the whole environment doesn’t work.

RC30[I]

The relationships with healthcare are frequently characterised as hierarchical, and the NHS is framed as a faceless, bureaucratic and anonymous ‘system’ by our participants. In this context, individuals can feel ‘lost’, leading to negative experiences with healthcare that ultimately trigger complaints:

[S]he was just caught in the system and it was a vicious circle and nobody was, no one was there to help her.

RC02[I]

But somewhere in the great bureaucracy in the sky, this letter has gone missing, and I was left with not belonging to anyone.

RC24[I]

You’re in a system. You put up with it. You think, ‘Oh well, this is the way it is’.

RC26[I]

This perception primarily originates from the system’s perceived failure to effectively communicate and provide adequate healthcare and aftercare. The examples of RC20, RC22, RC24 and RC29 illustrate this theme vividly.

RC20, reliant on ‘extension kits’ for her nutrition, is stuck in an endless cycle of promises for the kits’ delivery, raising doubts about the truthfulness of what she is told. Similarly, RC22 recounts his father’s experience, who was negligently discharged from the Emergency Department (ED) without proper arrangements. He describes his father as being ‘pushed out of the door’ with ‘absolutely nothing’, characterising the situation as a ‘let-down’. RC24’s missing referral, despite significant numbness in her legs, left her feeling abandoned and ‘in limbo’, resulting in her complaint as a final resort. This sentiment is mirrored in RC29’s experience of continuous surgical delays for her daughter due to overlooked referrals and unreturned calls, leaving them feeling stranded and uncertain about their next steps: ‘You’re just left with that “what the heck do we do?”’

These four cases underscore the problematic anonymity of a system which is too large and under-resourced to properly care for its patients. It is clear from these examples that the system’s impersonal nature fails to address the individual needs and unique circumstances of patients. This perception of the inhuman bureaucracy of the NHS leads many complainants to feel cynical and fatalistic about the possibilities of complaints being dealt with adequately:

[D]ealing with the bureaucracy of the NHS even at the higher levels can be a waste of time.

RC09[D]

[T]he reality of how difficult it is to implement change in such a large organisation.

RC11[I]

With many of the participants expressing their disappointment in the healthcare system, we see two polar consequences. On the downside, this loss of confidence creates a pessimistic outlook on the system from the outset of the complaints journey. Complainants embark on this journey already frustrated, disillusioned and cynical about the outcomes. As a result, they may perceive the complaints process not as a channel for resolution but as a part of a system that is fundamentally flawed. On a positive side, the disillusionment with the system’s failings motivates complainants to seek changes. The drive to ‘fix’ the system becomes one of the main reasons to lodge complaints, signifying a hope to bring about meaningful reform.

These findings offer a more detailed understanding of individuals’ cultural predispositions at the beginning of their complaints journey, as identified through the cultural audit: the reverence for the NHS juxtaposed with an expectation of high-quality service leads to significant dissonance when these expectations are not met. This cultural dissonance is further exacerbated by a perceived hierarchical and bureaucratic healthcare system, resulting in a sense of alienation and fatalism. It is against this cultural backdrop of lost confidence and the desire for change that the complaints journey commences.

Drivers of complaints

Certain issues leading to the initiation of a complaint can be seen to be repeated across our corpus of longitudinal participants (Table 5).

| Complainable issue | Count |

|---|---|

| Failure to communicate/provide adequate healthcare/aftercare | 10 |

| Attitudes of and communication with staff (healthcare and receptionists) | 8 |

| Problems caused by being passed back and forth between different departments | 7 |

| Chaotic state of ward/admissions | 5 |

| Concerns regarding patient dignity | 4 |

| Clinical error/medical negligence | 4 |

| Operation waiting times | 4 |

| Seemingly minor conditions with more serious impact on patient’s life | 3 |

| COVID (and other safety) concerns | 2 |

The most frequent problems stem from communication shortcomings, reaffirming the significance of this study. Although the issues outlined probably reflect real problems with healthcare, some narrative elements are frequently emphasised or magnified. They bring to the table the work of identity construction performed by complainants, which is often used in the service of framing the initiation of a complaint as ‘reasonable’.

Reasonable complaint/complainant identity

Across our data we find frequent general references to ‘reasonable’, ‘thoughtful’, ‘normal’ person identities, often in descriptions of themselves as patients or carers, for example, ‘I can imagine a lot of people a lot of parents kicking off and like we didn’t kick off’ (RC21). RC23 defends her ‘reasonable patient’ identity in the way she describes her own behaviour (compared to the ‘rude’ doctor) as beyond reproach:

I wouldn’t even lower myself to be cheeky back to him to give him a reason to say anything about me like I don’t drink alcohol or take drugs or anything I’m genuinely sick.

RC23[T]

RC28 constructs herself as a ‘good patient’:118

I am a very independent person as my records the last time will show that at 12 week check up my recovery was brilliant as surgeon couldn’t get over work I had put in.

RC28[D]

Complainants also regularly appeal to membership of the implicit category ‘reasonable complainant’ by distancing from the activity of complaining and stressing that complaining is exceptional or not something the caller usually does (e.g. ‘we’re not really complaining people’; ‘I don’t usually complain’) or through the announcement of explicit membership of particular kinds of ‘reasonable’ identity categories (e.g. ‘I’m not an ignorant man’; ‘I’m sort of the type that doesn’t like to bother anyone’), or through attributes or activities tied to the category ‘reasonable person’ (e.g. ‘don’t want anybody getting into trouble’; ‘it’s not about punishing the system … it’s trying to make a change’).

The moral accountability of complaining sets a threshold of ‘tolerance’ before initiating or progressing complaints. RC23 (a long-term and frequent patient at the hospital) states that her perception of poor staff attitudes began at a much earlier stage but it is only now that she has decided to complain formally: ‘over the course of the twelve years … it’s just getting worse and worse and worse’. Similarly, RC29, calling on behalf of her daughter, emphasises the period of waiting prior to making the complaint; RC21 also implicitly refers to his reasonableness and patience in waiting before ‘taking a stand’:

I’ve let this go on for seven weeks now. And I feel, it’s got to the stage now where I feel like I’m letting my daughter down and I’m neglecting her because I’m her father and I’m letting her suffer. So that’s why I have now taken this stand. I’ve had enough.

RC21[Rc]

Complaining is portrayed as a ‘last resort’, only taken when extraordinary circumstances demand it. Thus, the potential social disapproval associated with the act of complaining might deter some individuals from lodging a complaint at an earlier stage. It also influences how complainants present their motives in the decision and justification to complain.

Motivation to effect change for others (‘altruistic’ reasons)

One of the most common motives voiced by our participants is the hope that the complaints process may lead to positive change for others in the future:

I don’t want anything else it’s not for financial benefit … it’s just about getting my child home and helping any other kids in the same position that we’re in.

RC21[I]

This notion of giving a ‘voice’ to or leaving a legacy for future patients through the act of complaining is a strong theme characterising patients’ motivations for complaining, a finding previously observed by other researchers. 24 RC30 expresses this perspective repeatedly in her interview, and RC02 (complaining on behalf of her sister, who is a vulnerable adult) expresses the explicit objective for her complaint to lead to the development of a protocol for dealing with hospital admissions of brain-injured adults:

If there is any learning to come out of this investigation, I would like this to benefit Brain Injured adults who require treatment.

RC02[CW]

[T]here are people like him [her father] there who couldn’t speak for themselves and had no relative with them, but I’m making this complaint. I’m making it for every single person.

RC30[I]

Similarly, RC11 sets out her motivation for complaining in the outset of her letter:

I am writing this letter in the hope that another patient does not have to endure these issues in the future.

RC11[CW]

The nature of complaining makes the will for systemic change a fundamental driving force.

Pursuing/gaining validation of complaint as legitimate

Much of the work around the construction of a reasonable complainant identity indirectly pursues a validation of the complaint as valid, legitimate and reasonable, which we observe in different strategies complainants use to justify their concerns.

Adding to the rhetorical devices reviewed above, another means of presenting a complaint as reasonable is to emphasise the exceptional status of the events leading to the complaint and the lifeworld impact of these medical circumstances. Complainants may focus on explaining the details that show that they have grounds for complaining, such as the impact of the complained-of events on their daily lives:

I was so annoyed because I was in so much pain.

RC16[T]

This exceptional poorness of care and communication is used to underpin the justification for the complaint being made:

I don’t normally complain but this individual’s behaviour was so bad and uncalled for I felt I had to highlight it.

RC09[CW]

A complainant may also mitigate the negative connotations of a complaint by bestowing praise on another aspect of their healthcare experience. They laud elements such as the excellence of staff, their exceptional workloads, or the high-quality care received in a different setting or occasion. These positive remarks serve to demonstrate their reasonableness, showing that their complaints are not blanket criticism but rather targeted at specific issues, separate from the overall competence of the healthcare system.

In the service of a reasonable complainant identity, participants also show an explicit awareness of the potential negative impact and inconvenience of their complaint, as well as an appreciation of the resource constraints on the NHS, while regretting the necessity of complaining. They appreciate the substantial demands on the healthcare system and acknowledge the pressures and challenges staff face. This self-awareness underpins their commitment to being reasonable, with complainants distancing their grievances from systemic issues like long waiting times, staff shortages or the under-resourcing of services.