Notes

Article history

The research reported here is the product of an HSDR Rapid Service Evaluation Team, contracted to undertake real time evaluations of innovations and development in health and care services, which will generate evidence of national relevance. Other evaluations by the HSDR Rapid Service Evaluation Teams are available in the HSDR journal.

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number NIHR131295. The contractual start date was in October 2018. The final report began editorial review in July 2020 and was accepted for publication in October 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2022 Sidhu et al. This work was produced by Sidhu et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2022 Sidhu et al.

Chapter 1 Background, context and objectives

Parts of this report have been reproduced with permission from Sidhu et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Summary of key points

-

The evaluation reported here is of instances where organisations running NHS acute hospitals have taken on the responsibility of also running some general practices.

-

This change in practice has been happening in several locations in England and Wales, with the first instances commencing in 2016, but it is not yet widespread practice.

-

An acute hospital taking responsibility for running general practices is an example of ‘vertical integration’, that is, integration between organisations operating at different stages along the patient pathway.

-

Vertical integration can occur in any area of the economy and can be seen as a way of attempting to reduce transaction costs and to reduce risks for the integrating entities. Vertical integration can make decision-making, monitoring and information-sharing more efficient. In health care, this might translate as better mutual understanding between general practitioners (GPs) and hospital specialists, better communication and flows of patient information between GPs and hospital specialists, and reduction of risks through better demand management.

-

The NHS across England and Wales is working towards systems of care that offer better co-ordination across the primary and secondary care interface. One innovative approach to achieving stronger integration of care is via vertically integrating primary care organisations with secondary care organisations (i.e. co-ordination within a single management entity of staff, infrastructure, functions and activities that contribute to different levels of patient care).

-

There has also been growing interest in extending the range of health-care services that are delivered in primary care settings. However, at the same time, in the face of growing patient demand combined with GP workforce constraints, the long-term sustainability of primary care has become an increasing focus of concern.

Background

This report presents a rapid evaluation of arrangements whereby NHS organisations operating acute hospitals have additionally taken over the running of general practices at scale in a few locations in the NHS in England and Wales (i.e. a new form of vertical integration). There is little systematic information on the rationale for, or desired impact of, such vertical integration in a UK NHS setting, or on why it is developing in some places despite not being an explicit part of current NHS policy in England or Wales. There is, correspondingly, limited understanding about how to implement vertical integration in a UK NHS setting (e.g. contractual/governance and commissioning issues) and the enablers of and barriers to its implementation. The number of examples of vertical integration is, nevertheless, growing and so it is timely to evaluate their implications.

The initial impetus for the evaluation of vertical integration was a desire to understand the logic of this form of integration in the provision of health care across primary and secondary care settings. However, as the study progressed, it became clear that a major driver of vertical integration is a response to difficulties with sustaining general practices and, therefore, local access for patients to primary health care.

In this chapter, we first describe the institutional context. We then locate the form of vertical integration that is the focus of this evaluation within the landscape of types of health-care integration, before going on to describe the current and recent past policy context relevant to such vertical integration. We finish the chapter by stating the aims of the evaluation reported here and outlining the structure of the rest of the report.

Institutional context

Within the NHS, acute hospitals do not usually run primary care services. Indeed, at the founding of the NHS in 1948, although hospital services were nationalised, GPs remained as independent practitioners. GPs were, and usually still are, contracted by the NHS to provide primary care medical services to the patients who register with them. GPs also have the responsibility of acting as ‘gatekeepers’ to other NHS services, including acute hospitals; however, GPs are not employees of the NHS. 2 This separation between primary and secondary care has been maintained through numerous NHS reforms, including the major reorganisations in 1974 and 1990. 3 Indeed, the 1990 reforms arguably deepened the divide by casting GPs in the role of fundholders and, therefore, ‘purchasers’ from secondary care providers (i.e. NHS trusts). In the past 20 years, the role of GPs as purchasers or commissioners of care for their patients from other NHS organisations, as individual practices, has reduced. However, as members of Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) and primary care networks (PCNs) in England, GPs’ involvement in purchasing hospital care remains strong. At the same time, the desirability of better integration of patient care across primary and secondary care settings has become firmly established as a policy objective, as described later in Policy-drivers for integration.

Acute hospitals are providers of hospital-based emergency and/or elective specialist health care. In England, acute hospitals are run by a publicly owned organisation known as an ‘NHS foundation trust’ or an ‘NHS trust’ (hereafter referred to collectively as trusts). There are 152 acute hospital trusts in England. 4 The institutional set-up of the NHS in Wales is different from that of the NHS in England. In Wales, NHS acute hospitals are run by seven territorially defined Local Health Boards (LHBs). The services of acute hospitals are contracted for by both national and local NHS ‘commissioners’ of care. In England, the commissioning organisations are NHS England (London, UK) (nationally) and CCGs (locally). In Wales, the commissioners are NHS Wales (Cardiff, UK) (nationally) and LHBs (locally).

Until the last few years, hospital trusts in England had no role in running general practices. Although it remains most often the case that hospital trusts do not run general practices, in recent years, a small number of departures from this have occurred (i.e. a few hospital trusts in England have started to run general practices). In Wales, the LHBs directly run hospitals and community health services. LHBs also contract with independent general practices, but LHBs do not usually operate general practices directly. However, in recent years, this has started to change in a few locations in Wales. It is these recent changes in England and Wales that provide the initial stimulus for the evaluation reported here. Our focus is on those cases where organisations running acute hospitals have taken on general practices at scale (i.e. more than just one or two practices). Such vertical integration at scale is a relatively new phenomenon in the NHS – occurring over the period since 2015 – and the number of examples is currently small and scattered geographically. Nevertheless, interest in vertical integration is growing and during the study we became aware of new examples starting up.

The arrangements for general practices are essentially the same in both England and Wales; they provide primary medical care to their registered populations, which are effectively the total national population in aggregate. General practices are staffed by GPs and, increasingly, other health-care professionals (e.g. nurses and pharmacists). In England, as of September 2019, there were around 7000 general practices with 34,586 GPs (headcount), of whom there were 26,958 full-time equivalent qualified permanent GPs (i.e. excluding locums and trainees). 5 In Wales, as of September 2018, there were 421 general practices6 with 1964 GPs (headcount). 7

There are, in both England and Wales, three types of contract by which the NHS buys the services of GPs: (1) General Medical Services (GMS), (2) Personal Medical Services (PMS) and (3) Alternative Provider Medical Services (APMS) (Box 1). GMS contracts are the most common and are between GP-owned practices and NHS England (in England) or their LHB (in Wales); PMS and APMS contracts, which resulted from primary care reforms in 1997,8 are less common. However, the traditional GMS contract, where GP partners own the practice, has been declining in popularity. The UK Government’s 2019 GP Partnership Review9 stated that ‘The numbers of GP partners are falling as a proportion of the general practice workforce’ (contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0) (although the report did not provide any relevant data).

The GMS contract is agreed nationally. This type of contract provides the contracting general practice with an income stream to pay for the staff, premises and other costs of providing a menu of compulsory ‘essential’ services. Under the GMS contract, a practice may also voluntarily provide, and be paid for, ‘additional services’ and ‘enhanced services’. Around 55% of general practices have GMS contracts.

Personal Medical ServicesPMS contracts are negotiated locally (with the local CCG in England or LHB in Wales). The GPs are paid to provide a defined service as agreed locally. Around 40% of general practices have PMS contracts.

Alternative Provider Medical ServicesAPMS contracts can be let to private-sector – both commercial and voluntary – organisations, as well as to traditional general practices. This type of contract tends to be used in areas where it is difficult to recruit and retain GPs. Around 5% of GP services are provided via APMS contracts.

Source: Healthcare Financial Management Association 2016, pp. 40–1.

In both England and Wales, there are many areas where recruitment and retention of GPs is a challenge. The number of GPs per 100,000 population has fallen in England since 2009 (from 66 then to 58 in 2018) and in Wales since 2013 (from 64 then to 63 in 2018) in a context, in both countries, of increasing demand from the population for health care, including primary care. 10

The evaluation reported here is of those instances where acute hospitals have taken on the responsibility for fulfilling GP contracts. This change in practice has been happening in several locations in England and Wales, with the first instances commencing in 2016; however, it is not yet widespread practice and so it is now timely to evaluate such arrangements.

Vertical integration

An acute hospital taking responsibility for these GP contracts and, therefore, for running general practices, is an example of ‘vertical integration’, that is, integration between organisations operating at different stages along the patient pathway. This kind of integration is distinct from ‘horizontal integration’, whereby organisations at similar stages along the patient pathway merge, such as when one acute hospital trust merges with another, or when one general practice merges with another or joins a network of general practices. 11,12 Vertical integration between acute hospitals and general practices in the NHS often entails an element of horizontal integration. When hospitals merge with more than one general practice, those practices are effectively integrated horizontally with one another, as well as vertically with the hospital. Our focus is on the vertical aspect of the integration. There are many other types of horizontal integration between general practices (Smith J and Sidhu M, University of Birmingham, 2020; Parkinson S and Harshfield A, RAND Europe, 2020; personal communication), but horizontal integration is not the focus of the evaluation reported here.

The concept and term ‘vertical integration’ has a long history in the economics literature13 and is seen as having three main aspects: (1) market power, (2) risk management and (3) transactions costs. Some associated perspectives on vertical integration have emerged in the context of competitive product markets; these perspectives are likely to be of limited relevance in an NHS context. For example, no UK NHS acute hospital has ever set up new general practices, as they might, in principle, were they in a competitive market where they were keen to channel patients to themselves rather than to rival hospitals. Nonetheless, the economic perspective does offer the following additional insights of potential relevance to the case of acute hospitals running general practices.

Vertical integration can be seen as a way of attempting to reduce transaction costs, as it can make decision-making, monitoring and information-sharing more efficient. 14 In the context of our evaluation, this might translate as better mutual understanding between GPs and hospital specialists, and better communication and flows of patient information between GPs and hospital specialists. A vertically integrated organisation can use more informal and less time-consuming procedures to resolve conflicts internally than would independent agents from separate organisations. 13

Vertical integration could also be a strategy to reduce risk. If risk grows over time, then the attractiveness of this strategy may increase correspondingly. In a competitive market, this may involve securing a segment of potential customers who might otherwise purchase from a rival, but it is also relevant in an NHS context, where the risk to be reduced may be that of demand growing faster than the capacity of the hospital and its sources of NHS funds to meet that demand. A hospital integrating with general practices from which patients are referred to it may offer the prospect of greater demand management. Less positively, vertical integration may mean that patients find themselves less able to exercise choice between alternative providers of hospital care because their GP is inclined to default to referring them to the hospital that employs them.

Laugesen and France15 reviewed the applicability of economic theories of integration to the health-care sector, with specific reference to the UK and the USA. Laugesen and France15 were particularly interested in the scope for risk management and transactions cost reduction via vertical integration. The study15 does not mention a specific example from primary care but vertical integration in the UK is such an example. Here, risk management might mean not only the risks to a hospital of insufficient or excessive demand, but also the financial risks faced by the owners of individual general practices that are facing difficulties in recruiting and retaining new partner GPs. In the US context, Laugesen and France15 highlighted Kaiser Permanente (Oakland, CA, USA) as a well-developed vertically integrated health-care organisation. Kaiser Permanente and other international examples of vertical integration in health care are briefly described in Chapter 2.

In the health-care context, vertical integration has been defined by Ramsay et al. 16 as being of six types: organisational integration (organisations merge into one or bind themselves together contractually), functional integration (non-clinical activities for multiple organisations are combined), service integration (clinical services are integrated within the same organisation), clinical integration (where patient care becomes a single integrated process both within professions and across them, e.g. by using shared guidelines), normative integration (the sharing of values in collaborating to deliver health care) and systemic integration (making rules and policies coherent across all organisational levels).

Conrad and Dowling17 have argued that vertical integration requires (1) the clinical integration of the processes involved in delivering patient care and (2) administrative (functional) integration at both inter- and intraorganisational levels. Therefore, strong administrative integration (e.g. management support, governance and strategy formation) is required to support clinical integration whereby patient care is improved over time. Subsequently, to achieve near-complete vertical integration of care across primary, community and secondary sectors, health care for patients should cut across health promotion and disease prevention all the way through to treating short-term episodic acute illness. Shortell et al. 18 identified a number of limiting factors that need to be considered prior to commencing vertical integration. These factors include (but are not limited to) the need to establish trust among clinicians and institutions, well-integrated information systems and non-clinical support services (i.e. back office functions) and consensus on practice and care delivery guidelines. Robinson and Casalino19 go further, suggesting that vertical integration needs to go beyond a physician’s desire for professional autonomy and a hospital’s desire for organisational co-ordination to show how services in primary care can be delivered through greater horizontal integration, achieving ‘integrated delivery systems’ (known as PCNs and primary care clusters in England and Wales, respectively). Theoretically, vertical integration between acute hospitals and integrated delivery systems can lead to efficient use of services across the care pathway (particularly post-acute care) and avoid duplication of administrative tasks; but, more importantly, vertical integration should lead to a single hierarchy of authority with shared goals and strategies.

Policy-drivers for integration

Despite the historical institutional separation between general practices and hospitals, integration between the multiple levels and providers of health and social care has increasingly been seen, in both England and Wales, as important for the effectiveness and efficiency of the NHS in the long term and to improving the care provided to patients. The NHS across England and Wales is working towards systems of care that offer better co-ordination across the primary and secondary care interface. One innovative approach to achieving stronger integration of care is vertically integrating primary care organisations with secondary care organisations (i.e. providing co-ordination within a single management entity of staff, infrastructure, functions and activities that contribute to different levels of patient care). 12,16,17 Such organisational integration can range from virtual integration that entails the formation of relatively flexible alliance arrangements to a fully integrated organisational model in which a single body holds contracts to deliver both secondary and primary care services. 20 In this evaluation, we are interested in the fully integrated model of vertical integration, specifically NHS acute hospitals taking over the management of general practices.

In England, the NHS Five Year Forward View21 described, among other options for stronger integration between primary and secondary care, what it termed primary and acute care systems (PACS), which would combine general practice and hospital services ‘for the first time’21 (contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0),21 although not yet within single vertically integrated organisations. There were nine PACS ‘vanguards’ at a variety of locations scattered across England. 22 In 2018, a report from The King’s Fund recommended that acute hospitals should play a greater role in primary care provision:

. . . acute hospitals will need to play a fundamentally different role within local health economies. This will involve: . . . working more closely with local partners, including primary care . . . developing integrated service models that span organisational boundaries . . .

Naylor et al. 23

Evaluations of the PACS ‘vanguards’ have found evidence of considerable change activity, but have not yet yielded clear conclusions on the outcomes achieved as a result. The National Audit Office (London, UK) has found early signs that PACS and other new models of care focused on integration are having a beneficial effect on emergency admissions to hospitals,22 and there have been ‘significant amounts of innovation in terms of both front-line services and wider structures supporting system-wide collaboration’. 20 However, data and findings are limited across the vanguard sites, with questions about the reliability of outcomes data and, consequently, uncertainty about the impact of PACS on key dimensions of health service delivery. 24,25

Five years on from the NHS Five Year Forward View,21 the 2019 NHS Long Term Plan26 announced the intention that all general practices in England should combine into PCNs covering populations of 30,000–50,000. 26 Since July 2019, all but a small number of practices have become horizontally integrated in that way with other practices, although remaining separate legal entities with separate contracts. Findings from a recent BRACE (Birmingham, RAND and Cambridge Evaluation Centre) rapid evaluation (Smith J, Parkinson S, Harshfield A, Sidhu M, personal communication) of PCNs show that there have been a number of facilitators of and challenges to horizontal integration achieving sustainable primary care, addressing growing workload issues and improving the availability and co-ordination of local primary care services. The evaluation (Smith J, Parkinson S, Harshfield A, Sidhu M, personal communication) revealed a tension between the desire for local autonomy and influence over PCNs, and the top-down nature of PCN policy (i.e. the need for effective leadership). Notably, rural case study sites from the evaluation felt that PCN policy had been developed with urban practices and collaborations in mind, and did not adequately account for the experience of primary care in rural areas. Vertical integration was not specifically mentioned in the NHS Long Term Plan,26 but is, nevertheless, happening in a few locations.

In 2015, the Welsh government published a plan for primary care services in Wales over the following 3 years. The plan set out a specific aim for the 64 ‘primary care clusters’ (i.e. collaborations between general practices) that had recently been set up in Wales, each covering a population of 30,000–50,000, to ‘play a significant role in planning the transfer of services and resources out of hospitals and into their local communities for the benefit of their local populations’ (© National Assembly for Wales Commission Copyright 2017. Inquiry into Primary Care: Clusters). 27 Reviewing progress with primary care clusters, the National Assembly for Wales Health, Social Care and Sport Committee reinforced the desirability of that form of integration. 27 The subsequent Strategic Programme for Primary Care in 2019 built further on these initiatives through an enhanced community-based model of primary care. 28 This model arose, in part, from the national Pacesetter Programme, in which LHBs received funding to support innovations within primary care. Research by University of Birmingham (Birmingham, UK) found that, although the Pacesetter Programme had enabled some positive developments, overall, it was hampered by a lack of clarity about its objectives, insufficient evaluation capacity and underdeveloped opportunities to share learning. 28 Similarly to the situation in England, vertical integration between acute hospitals and general practices is not currently being specifically advocated by NHS policy-makers in Wales, but it is happening spontaneously in a small number of places.

Alongside the push for better integrated care, there has been growing interest in extending the range of health-care services that are delivered in primary care settings. 21 However, at the same time, the long-term sustainability of primary care has become an increasing focus of concern in the face of growing patient demand combined with GP workforce constraints. 29,30

With this background of pressure to better integrate secondary and primary care services and to increase the range of services available in primary care settings, combined with concerns about the sustainability of general practices, there are a number of potential pragmatic reasons that might drive vertical integration between acute hospitals and general practices. Vertical integration brings the opportunity to redesign services; address problems with governance, funding, differing objectives and drivers; reduce transactions costs; enhance the ability to involve both primary care and secondary care clinicians in the design of effective and efficient clinical pathways; and, for patients, improve continuity of care and foster more seamless transitions between teams and services. Organisational vertical integration between hospitals and general practices might help to overcome co-ordination challenges that result from the discrete financial ‘silos’ in which primary care and secondary care otherwise find themselves (e.g. where investment in one sector yields cost savings in the other). Vertical integration, which entails practice staff becoming salaried employees of an acute hospital NHS trust (England) or LHB (Wales), may particularly suit younger GPs, many of whom are showing reluctance to buy into the traditional ‘partner model’ of general practice and are showing a preference to be sessional or salaried. 16,31

There are also potential downsides to the implementation of acute hospital and general practice vertical integration, including fears among some GPs of reduced GP autonomy and, therefore, damage to what they see as the entrepreneurialism and innovation of general practice;16,32 mistrust from local primary care stakeholders;33 and doubts over how much inappropriate health service utilisation can be reduced through vertical integration, especially compared with other models of integration. 34

Chapter 2 Scoping the evaluation

Summary of key points

-

The study team took a narrative-based descriptive thematic approach to synthesising findings drawn from a rapid scoping review guided by existing theory on vertical integration.

-

The reasons most commonly cited in the literature for integrating acute hospitals and primary care services (i.e. vertical integration) were concerned with expectations of providing better-quality, more effective health care, with better patient experiences of care being delivered at lower, or at least no higher, costs to the health-care system as a whole.

-

Vertical integration can be undertaken by recourse to different types of contractual and governance arrangements, but evidence as to which are more effective, and in which circumstances, is not yet available.

-

Core characteristics and enablers of vertical integration include establishing continuity of care; the management of finance, human resources (HR), information technology (IT) and planning being closely co-ordinated across the units being integrated; and building relationships with doctors who actively participate in management and are economically linked to their organisation.

-

Barriers to the successful implementation of vertical integration include professional silos, unlinked and differing information systems, difficulties sharing patient records between organisations and organisations’ different approaches to case management.

-

There is a lack of robust evidence on the impact and effectiveness of vertical integration in health care, particularly with respect to patient outcomes.

The first stage of the evaluation comprised a pragmatic rapid scoping review of the literature, supported by interviews with key informants, discussion with the members of the BRACE Steering Group (which includes experienced health services evaluators, commissioners and health-care practitioners) and a project design workshop with policy-makers and external researchers. This was a key stage in the evaluation to understand the existing evidence, develop research questions and identify potential case study sites. We obtained an overview of the evidence already reported on vertical integration of acute hospitals with general practices and identified knowledge gaps to be filled and propositions to be tested later through comparative case studies, following principles outlined by Munn et al. 35 In this chapter, we present our findings from the scoping of the literature and key learning from interviews with informants, and the research questions that subsequently emerged.

To scope the evaluation, we reviewed published literature, including grey literature (i.e. literature that is not formally published in sources such as books or journal articles such as NHS trust reports and/or working papers from policy groups or committees). We used a selective but systematic approach to searching and provided a descriptive summary of our findings.

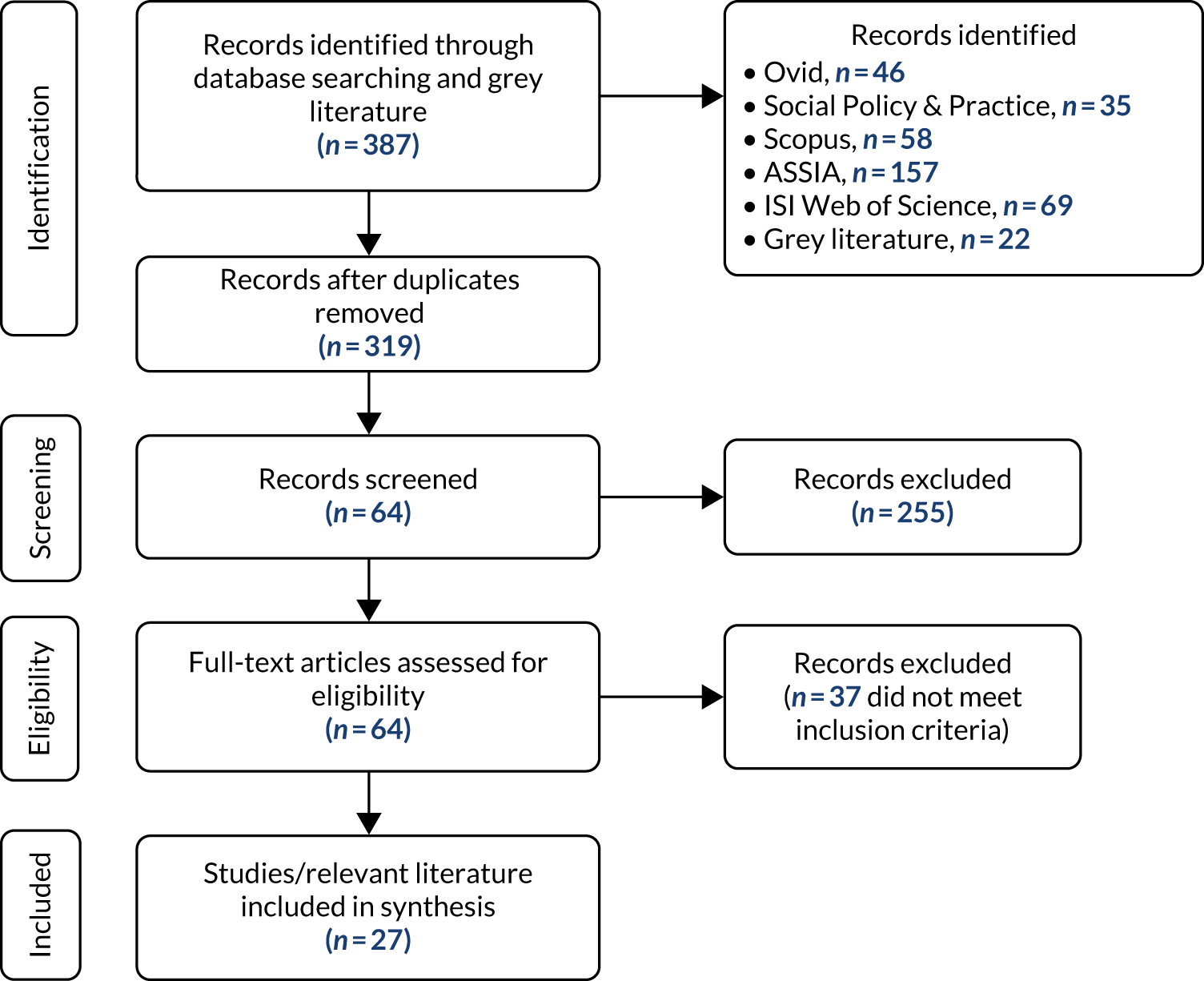

The study team took a narrative-based descriptive thematic approach to synthesising findings drawn from the rapid scoping review, guided by existing theory on vertical integration. 17 We thematically categorised literature according to differing models of vertical integration to aid the identification of core characteristics that act as enablers of successful implementation. We then sought to draw connections between core characteristics and desired outcomes for vertical integration within a UK NHS context. A more detailed description of our literature review method is provided in Appendix 1, along with our search terms (see Appendix 1, Box 2) and a PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) flow chart with regard to screening results (see Appendix 1, Figure 8).

Discussions with key experts

In parallel with the scoping review, members of the study team completed telephone interviews (using a structured topic guide informed by the literature; see Report Supplementary Material 1) and face-to-face meetings with academics, policy analysts and NHS staff involved in the implementation of vertical integration across different sites in the UK (total n = 13). The study team sought (1) their initial insights and perspectives on why vertical integration was introduced and (2) their views on which research questions should be prioritised in a rapid evaluation. The team also sought to better understand the current climate of primary and acute care working more closely together and what the possible advantages and disadvantages of vertical integration would be for acute trusts and general practices. Telephone interviews with NHS staff helped the research team to identify potential case study sites across the UK that would be eligible to partake in a rapid evaluation.

Following the review of the literature and the scoping interviews, the research team held a stakeholder project design workshop to consider the scope of an evaluation of vertical integration between acute hospitals and general practices, and to refine the research questions. 36 The workshop took place in Birmingham in March 2019. In addition to research team members, participants included an independent researcher expert in the field of integration in the NHS and employees of the Department of Health and Social Care (England) and NHS England.

Findings from the literature

Several examples of vertical integration between organisations involved at various stages of the care pathway were identified in the UK, some of which are examples of an NHS acute hospital taking responsibility for the delivery of GP services.

South Somerset’s Symphony Project (2016 to present)

-

The South Somerset’s Symphony Project involved integration between Yeovil District Hospital NHS Foundation Trust (Yeovil, UK) and local primary care providers through stronger partnerships, supporting practices and improving joint work between GPs and hospital services. 37

Southwark and Lambeth Integrated Care (2012–16)

-

Southwark and Lambeth Integrated Care was a 4-year integrated care programme across two adjacent south London boroughs, which attempted to integrate care across primary, acute, community, mental health and social care. 33

The Royal Wolverhampton NHS Trust primary care vertical integration (2016 to present)

-

Primary care vertical integration at the Royal Wolverhampton NHS Trust (Wolverhampton, UK) involved nine practices in the West Midlands being run by the Royal Wolverhampton NHS Trust. 38

Closer to Home (2006–7)

-

The Closer to Home project involved the moving of selected specialist services for less complex conditions from hospital into a community setting in five different sites across six specialties in each. 39

Northumbria Primary Care (2015 to present)

-

Six practices in Northumbria were run by the Northumbria Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust (Newcastle-upon-Tyne, UK). 40

The Willow Group (April 2017 to present)

-

The Willow Group comprised four practices in Gosport (Hampshire, UK) being run by the Southern Health NHS Foundation Trust (Southampton, UK). 41

Some international examples of specific relevance were also identified:

The Alzira model (1999–2018)

-

The Alzira model involved a single health-care provider receiving a fixed annual sum per inhabitant to supply free universal access to a range of primary, acute and specialist hospital services in Valencia, Spain. 42,43 It is worth noting that, in 2018, the contract with the private provider was terminated after nearly 20 years by Valencia’s health authority and the services then reverted to public ownership. According to Comendeiro-Maaløe et al. ,44 the termination was for a combination of reasons relating to ‘Financial concerns, governance failures and politics’.

The Kaiser Permanente Community Health Initiative (2003 to present)

-

The Kaiser Permanente Community Health Initiative is an integrated health-care delivery system that provides care for more than 12 million members in the USA. 45

Odense University Hospital co-operation model between the hospital and general practitioners, including co-location of primary and secondary services (2013–16)

-

The Odense University Hospital co-operation model involved an on-call GP facility located alongside the accident and emergency (A&E) department at a hospital in Odense, Denmark. 46

The remainder of this section draws on information from the literature on acute hospital/general practice vertical integration. The following themes emerged from the scoping of the literature and are used to organise the scoping results that are presented in the remainder of the chapter:

-

the rationale behind vertical integration schemes

-

contractual and governance arrangements

-

the core characteristics and enablers of vertical integration

-

concerns about and barriers to such programmes

-

the outcomes identified.

Rationale

As noted in Chapter 1, it is possible to hypothesise several reasons for integration between acute hospitals and general practices. It might bring the opportunity to redesign services; address problems with governance, funding, differing objectives and drivers; reduce transactions costs; enhance the involvement of both primary care and secondary care clinicians in the design of effective and efficient clinical pathways; and, for patients, improve continuity of care and foster more seamless transitions between teams and services.

Primary and acute care systems were a new model of care that was introduced in the hope that they would deliver on the ‘triple aim’ of the new care models programme as a whole (i.e. better patient experience, better population health and more efficient use of resources). 20 It is hoped that these aims will be met through better decision-making and a more sustainable use of resources, with a stronger focus on prevention and integrated community-based care and less reliance on hospital care. 21

The rationale for/drivers of integration in some UK examples from the literature are outlined in Table 1. The first of these – Southwark and Lambeth Integrated Care – is an example of where vertical integration stops short of the acute trusts concerned taking ownership of general practices. The Royal Wolverhampton NHS Trust has taken over a number of the general practices in its local area. Northumbria Primary Care is a not-for-profit company wholly owned by Northumbria Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust and is an example of where an organisation running acute hospitals (i.e. the trust) has taken over responsibility for running some general practices.

| Case study example | Description | Rationale/drivers |

|---|---|---|

| Southwark and Lambeth Integrated Care | Socioeconomically relatively deprived areas, with multiethnic populations, high burden of disease and fragmented health and social care services |

|

| The Royal Wolverhampton NHS Trust | Socioeconomically relatively deprived areas, with multiethnic populations, high burden of disease and fragmented health and social care services |

|

| Northumbria Primary Care | Socioeconomically relatively deprived areas, with an elderly white British population, high burden of disease and fragmented health and social care services |

|

With respect to the international examples, the institutional contexts in the respective health-care systems differ from England and Wales. However, the examples are interesting indications that the option of acute hospitals operating primary care practices has attracted interest beyond the UK. The rationales highlighted in the literature vary across the different vertical integration examples, but, in all cases, are potentially highly relevant in a UK context. The Alzira model was introduced with the expectation of efficiency improvements, leading to cost savings and, at the same time, providing services of a higher quality. 42,43 The Kaiser Permanente Community Health Initiative integrated health care at all levels to tackle local public health issues, such as reducing obesity in low-income communities. 45 In Denmark, the Odense scheme focused on improving co-ordination between hospital A&E services and GP services. 46

Overall, the rationales we found to be most commonly cited for integrating acute hospitals and primary care services were concerned with expectations, or hopes, of providing better quality and more effective health care, with better patient experiences of care being delivered at lower, or at least no higher, costs to the health-care system as a whole.

Contractual and governance arrangements

Vertical integration can be undertaken by recourse to different types of contractual and governance arrangements, but evidence as to the advantages and disadvantages of different approaches is not available.

With respect to PACS, three contracting models are possible. 47

Virtual primary and acute care systems

Virtual PACS are when providers in different parts of the health-care system, including acute hospitals and general practices, are bound by an alliance agreement (i.e. where two or more independent entities agree to work together, without forming a jointly owned entity, to deliver care for the local population). PACS are not a new contractual model, but, instead, overlay an alliance agreement on top of the existing system of contracts by which acute hospital and primary care services are governed in the NHS (as described in Chapter 1). An alliance agreement could establish a shared vision and ways of working, and the role for each provider in the PACS.

Partially integrated primary and acute care systems

Partially integrated PACS go further than virtual PACS and require most providers, but excluding primary care practices, to have a single contract with the commissioner of health-care services, implying, in turn, that those other providers must have a contractual relationship with one another, but general practices are explicitly outside this. The single contract holder would be required to integrate directly with primary medical services delivered under GMS, PMS and APMS contracts (see Box 1).

Fully integrated primary and acute care systems

The PACS hold a single, whole-population budget for the full range of services in scope, including primary medical services. No fully integrated PACS yet exist.

Vertical integration between acute trusts and general practices would imply either partially integrated or fully integrated PACS. The Royal Wolverhampton NHS Trust and south Somerset’s Symphony Project have taken partially integrated PACS approaches. 37,38 Elsewhere, the evaluation of the Southwark and Lambeth Integrated Care programme, which adopted a ‘virtual’ approach rather than formal contracting, highlighted the importance of shared ownership and leadership among the stakeholders. 33

The health-care system in Spain is, like that in the UK, tax funded and largely provided by publicly owned organisations. With respect to the Alzira model, payment to the providers of the integrated services was made through a capitation system, whereby a budget is assigned according to population size and range of service provision. Furthermore, hospital doctors and many GPs were employed directly by the private organisation providing the integrated services. 43 Therefore, the Alzira model was equivalent to a fully integrated PACS approach.

Relatively little information was present about the governance of existing vertical integration programmes referred to in the literature. However, details were provided for the Southwark and Lambeth Integrated Care programme. The Southwark and Lambeth Integrated Care programme was set up as a partnership across local general practices, three NHS foundation hospital trusts, two CCGs, one mental health foundation trust and two local government authorities. 33 The Southwark and Lambeth Integrated Care programme was run by four main boards: (1) a sponsor board for strategic direction and high-level decision-making, (2) a provider group for turning strategy into action, which also acted as a programme board, (3) an operations board, which oversaw delivery, and (4) a citizens’ board, which gathered input from patients and local citizens. Importantly, citizens and primary care were also represented on the other three boards.

The Royal Wolverhampton NHS Trust employs a public health consultant and registrar to ensure that the general practices are up to date on ways to improve health in the area and reduce unnecessary demand for health-care services. Moreover, there is a ‘command centre’ that handles calls to all practices, which also employs social services staff. General practices run by the Royal Wolverhampton NHS Trust also have access to a live data set showing their patients’ contacts with acute, primary and community services, and the practices can book patients directly into hospital beds at the Royal Wolverhampton NHS Trust. 38

Core characteristics and enablers of vertical integration

The information found on core characteristics and enablers of vertical integration is drawn from the international literature, in particular relating to the USA, but many of the observations are relevant to a UK setting. Sheaff et al. 31 identified seven core characteristics of successful vertically integrated health-care organisations in the USA:

-

hierarchical governance or long-term relationships between organisations that vertically integrate

-

continuity of care and provision by teams, enabling less costly models of care

-

capitation payment, creating incentives for preventative care

-

competing with other providers on quality rather than price

-

good management and information systems, with ‘functional integration’ (i.e. support functions, such as the management of finance, HR, IT and planning, being closely co-ordinated across the units being integrated)

-

sufficiently large organisation and population served to ensure long-term stability of the organisation and enable the development of care pathways for common diseases

-

doctors who actively participate in management and are economically linked to their organisation.

Furthermore, Sheaff et al. 31 identified two strong enablers of vertical integration: (1) a ‘front-door’ triage of patients coming into hospital as emergencies and (2) an integrated electronic patient record system accessible by both hospital and primary care professionals. 31 Despite the major differences between the US health-care system and the systems in England and Wales, the characteristics and enablers of vertical integration identified by Sheaff et al. 31 are all relevant to the case of acute hospitals running general practices in the UK.

The Alzira model established a unified information system, becoming the first public hospital in Spain with a fully integrated computerised medical history system. 43 Moreover, the Alzira model introduced medical links between secondary and primary care, with a secondary care consultant physician associated with each primary care health centre and working with the same patients as the GP; integrated primary care centres with an increased scope of services provided (e.g. X-ray imaging); and integrated medical care pathways, from prevention through to palliative care, to enable the integration of primary and secondary care.

Concerns about, and barriers to, vertical integration

There is rather more evidence available on concerns about vertical integration and barriers to its success, particularly with respect to acute hospital integration with general practices. In their analysis, Sheaff et al. 31 found that obstacles to care co-ordination can remain within integrated organisations for reasons such as professional silos (with rivalries and self-imposed isolation of occupational groups from one another), discrepant IT systems for different divisions or care groups within one organisation, difficulties sharing patient records between organisations and organisations’ different approaches to case management. 31 All of these potential obstacles are familiar within the UK context too.

The impact of cultural barriers to integration across organisations and professions can be significant. Differences in practices, cultures and values may exist between different general practices being combined within a vertical integration arrangement, or between primary care staff and hospital staff; if so, such differences are likely to influence the extent and quality of joint working. (See Mannion et al. 48 for an example and a helpful summary of the meaning and use of organisational culture in health care.)

In their review of the evidence base for vertical integration for health care, Ramsay et al. 16 identified three major concerns:

-

integration that focuses mainly on bringing organisations together is unlikely to create improvements in care for patients

-

integrating providers in certain geographical areas may create a monopoly and, therefore, may restrict patient choice

-

top-down attempts to integrate (e.g. that impose mergers of service providers) often have less happy outcomes than those that are motivated from the bottom up.

The issues appear to be directly relevant to acute trust and general practice vertical integration because of the geographical proximity of the organisations, the natural focus it has on bringing different organisations together and the risk that it might be driven by top-down integration (i.e. instigated by the acute trust and, therefore, seen by general practices as being done ‘to’ them rather than ‘with’ them).

International literature on vertical integration schemes also points to various concerns and barriers. When considering the Alzira model in the context of the UK NHS, concerns raised by the NHS Confederation were that:43

-

commissioners of health services would have less control over how health care is provided, as more of the care process would be internal to an organisation and that organisation would be more powerful than individual unintegrated organisations would be

-

commissioners might even be subject to ‘regulatory capture’, meaning that the vertically integrated provider might control the local health economy to such an extent that independent oversight by the commissioner would cease to be effective

-

the vertically integrated model could squeeze out all other providers, such as social enterprises, charitable providers and other niche services, creating a local monopoly.

To some extent, these concerns stem from the involvement of a private sector organisation running the vertically integrated services for the publicly funded health-care system in that region of Spain. However, these concerns might, in principle, also apply to any vertically integrated group of health-care providers. The concept of regulatory capture of, and loss of control by, commissioners of/payers for health care appears not to have been a subject of much research in the NHS and comparable publicly run health-care systems.

With respect to the Odense University Hospital vertical integration in Denmark, the different incentives in primary care and secondary care around professional approach, culture and reimbursement made integration there challenging. 46 Such differences between primary and secondary care exist in the UK too. These difficulties are not necessarily removed by employing both primary care and secondary care staff in the same organisation.

Outcomes

There is a lack of robust evidence on the outcomes and effectiveness of vertical integration in health care, particularly with respect to patient outcomes. In the scoping review, all the evidence we found on the outcomes achieved by acute hospital integration with general practices was anecdotal. Caution is needed when interpreting the transferability and robustness of the data we collected, because (1) very little high-quality published evidence was available on the outcomes and impact of vertical integration and (2) in the evidence that was available, many of the findings demonstrated inconclusive or mixed results.

Ramsay et al. 16 concluded the following when considering the impact of vertical integration between different organisations on a care pathway:

-

Some evidence of strengthened partnerships [between the integrating organisations] . . .

-

Some reports of improved capacity, for example personnel, and improved focus on governance and adherence to guidelines

-

Little evidence of impact on health outcomes

-

Limited evidence of impact on cost. 16

The Southwark and Lambeth Integrated Care programme did not achieve the radical reductions in hospital and nursing home utilisation that were initially expected. 33 Although a reduction in admissions to nursing homes was observed and there was no increase in the rate of emergency admissions to hospital, this fell some way short of targets set at initiation. 34 Despite this lack of impact on health-care utilisation, other benefits did emerge. Effective efforts at integration took place between partners across health and social care, there was greater citizen engagement and co-production, and there was a reported shift in investment away from acute care towards community and primary care. 34

Similarly, the Closer to Home project saw a general improvement in patient-reported waiting times, quality of care, overall satisfaction and improved access compared with existing services. However, in this case, care co-ordination did not improve and neither did interpersonal quality of care. 39

Information on the outcomes of acute hospital vertical integration with general practices is largely limited at present, being drawn from providers’ own websites and/or online articles. However, the Royal Wolverhampton NHS Trust has conducted its own evaluation of the impact of vertical integration on A&E attendances, emergency admissions and emergency readmissions. This evaluation was published just as the current report was about to be submitted for publication. Yu et al. report a statistically significant 11% reduction in emergency admissions and a 2% reduction in emergency readmissions for patients of vertically integrated general practices compared with patients of equivalent non-vertically integrated practices in the same area. 49

According to the Northumbria Primary Care website, its vertical integration programme has seen the following results for its general practices: all of its practices had achieved > 98% in the Quality and Outcomes Framework for 2016/17, patient satisfaction was high (with more than 88% of patients likely or extremely likely to recommend their service to friends and family) and the Care Quality Commission (CQC) had rated all of its practices as ‘good’. 40

The Willow Group website41 states that its acute trust and general practice vertical integration programme has yielded positive outcomes in terms of improved access to care and the range of care provided, and has improved the integrated organisations’ resilience to respond to capacity challenges; however, no supporting data are provided.

With respect to the international examples, Caballer-Tarazona et al. 50 found that the Alzira model performed better than average, compared with the rest of the national health service in Spain, in terms of costs and efficiencies between 2009 and 2010, but was outperformed by some public provision models. López-Casasnovas and Del Llano51 found no difference in clinical or economic indicators when comparing the Alzira model with other public provision models from 2012 to 2015. Moreover, Comendeiro-Maaløe et al. 42 found that, generally, the Alzira model did not outperform other (public provision) models in respect of 15 out of 26 performance indicators (e.g. low-value care, potentially avoidable hospitalisation, hospital case fatalities and technical efficiency and expenditure), although in some areas of care its developments were outstanding (e.g. lower mortality after percutaneous coronary intervention).

Summary of findings from the literature

The evidence on vertical integration of health services from the literature found by the scoping review is relatively sparse and highlights the need for many questions to be addressed empirically. The reasons offered for vertical integration between acute hospitals and general practices are wide-ranging, from the desire to share expertise and knowledge, to the expectation of improved health outcomes. However, evidence on the advantages and disadvantages of different contractual and governance arrangements for implementing vertical integration was not apparent. Concerns about some effects of vertical integration are evident, as well as expectations of beneficial outcomes. However, evidence to either support or refute the stated rationale for vertical integration is largely lacking. There are reports that vertical integration can lead to stronger partnerships and greater collaboration across a wider range of stakeholders, but robust evidence on the impact on quality of care and patient experience is so far absent. We concluded, therefore, that evaluation of vertical integration of hospital care with primary care was necessary to fill an identified evidence gap.

Findings from discussions with key experts

Policy experts and academics expressed their concerns about the rationale given for vertical integration, as it appeared to be driven more by structural/organisational integration than better co-ordination of care delivery. Policy experts and academics perceived a paucity of evidence for vertical integration between acute hospitals and general practices, noting that some of the impetus was from international examples, which may not be transferable to UK settings, and they were keen to hear more about primary care-related outcomes and patient views, as distinct from the hospital perspective. In addition, NHS staff were concerned about the impact that vertical integration might have on general practices working in the same area but outside the vertically integrated arrangement and, therefore, having to compete with acute hospital-managed practices, which would have a greater pool of resources (e.g. finance, clinical staff and administrative capacity) to rely on. All stakeholders raised a number of questions with regard to the impact of vertical integration on the wider health economy, specifically how the delivery of community care services might change as a direct result of integration.

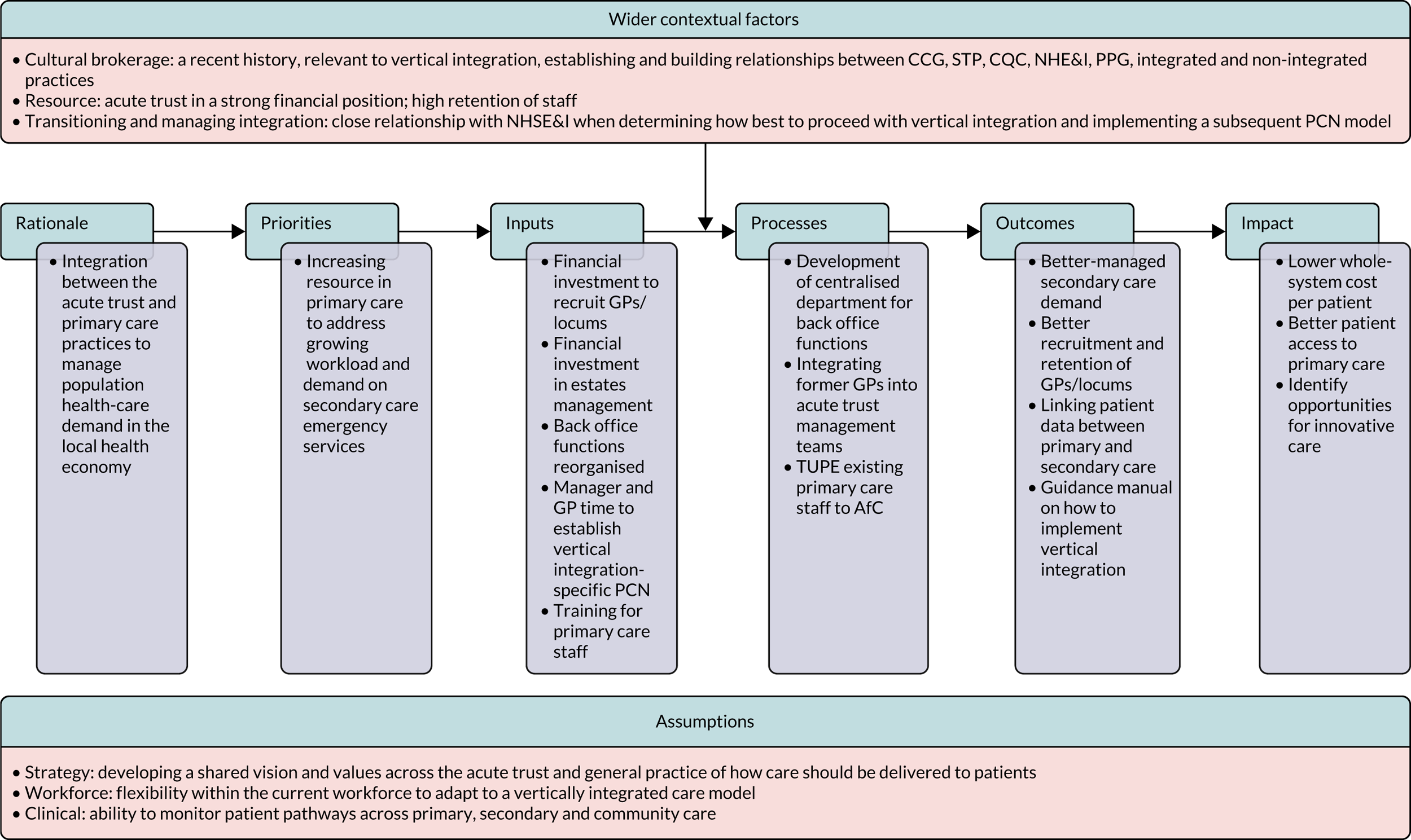

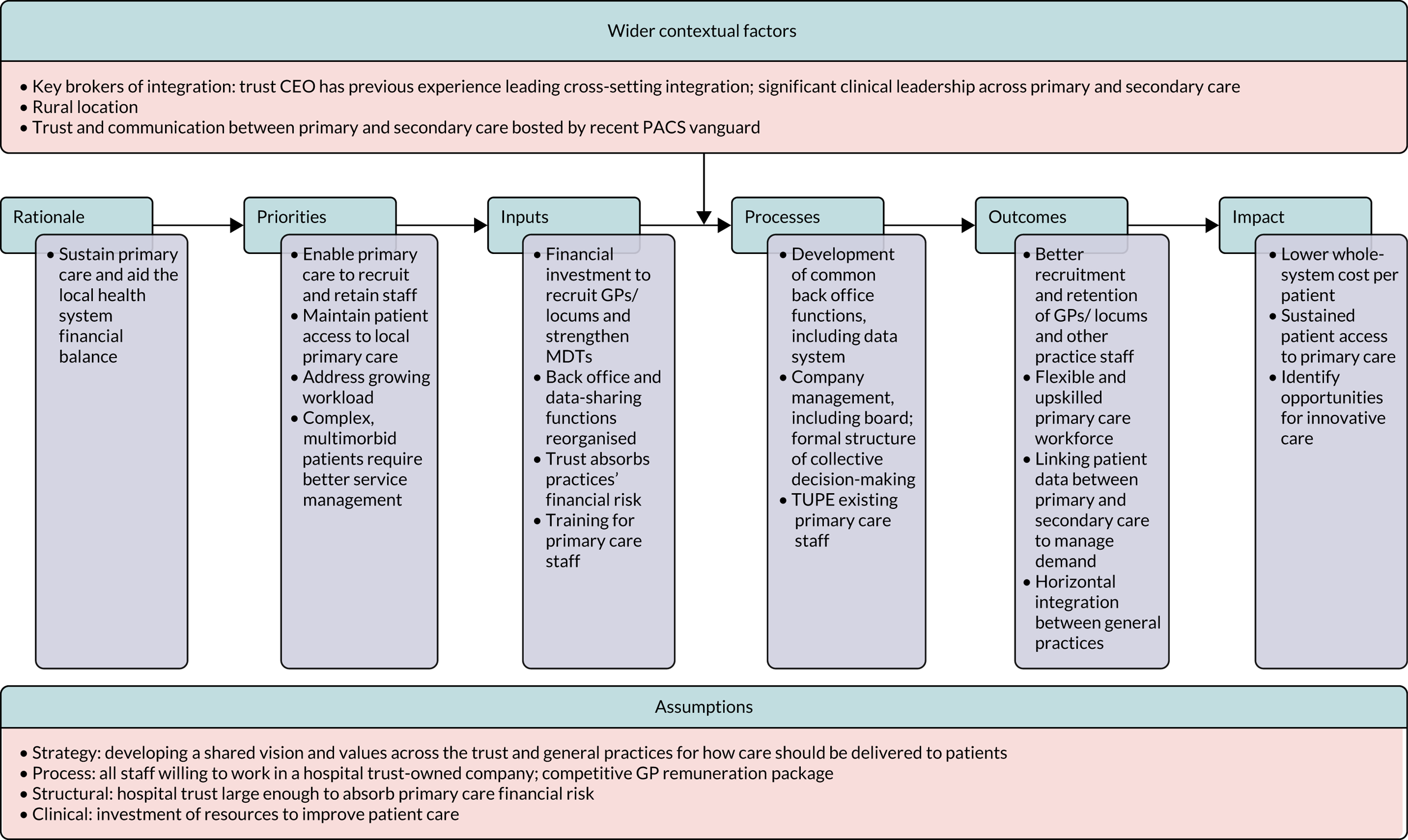

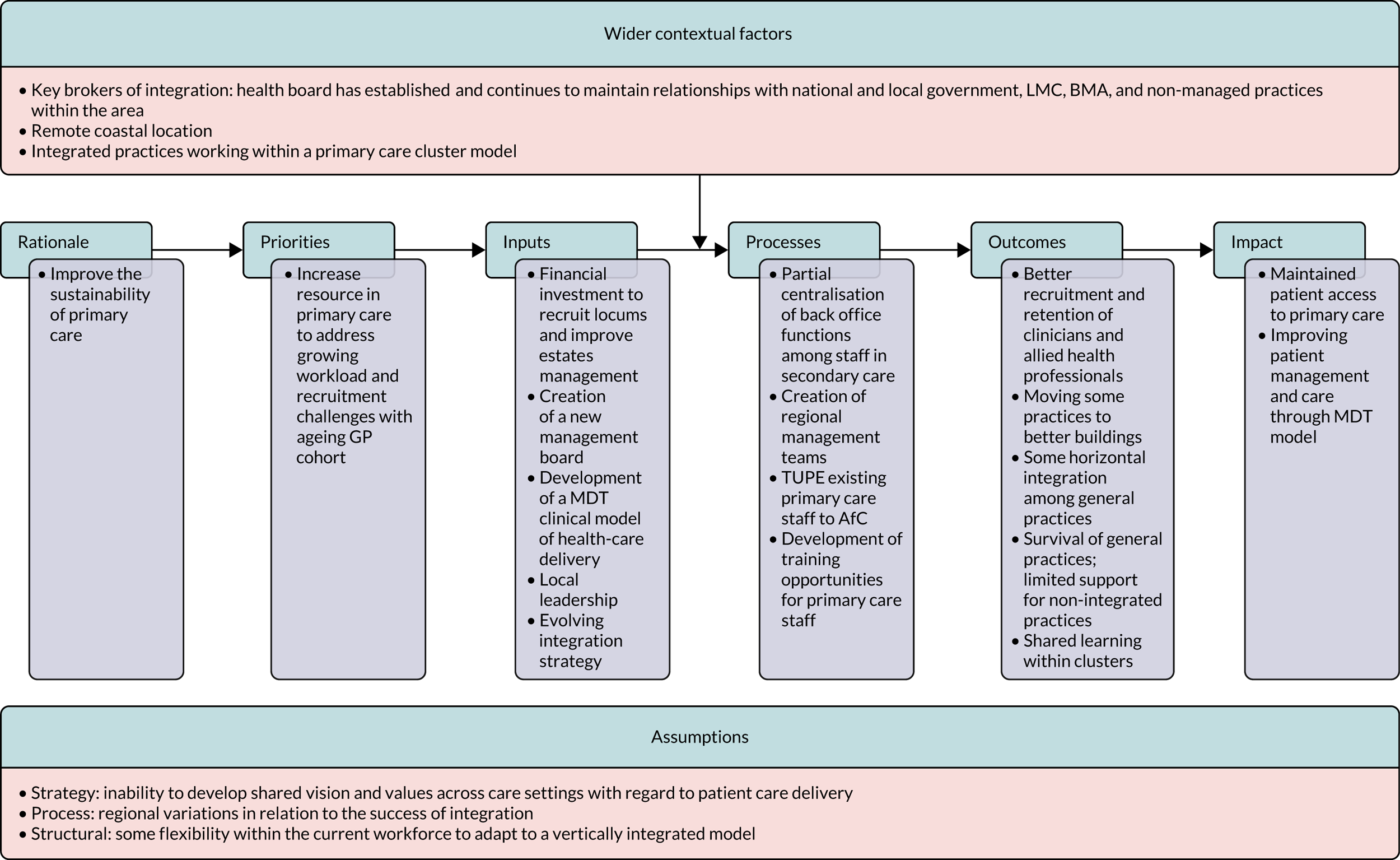

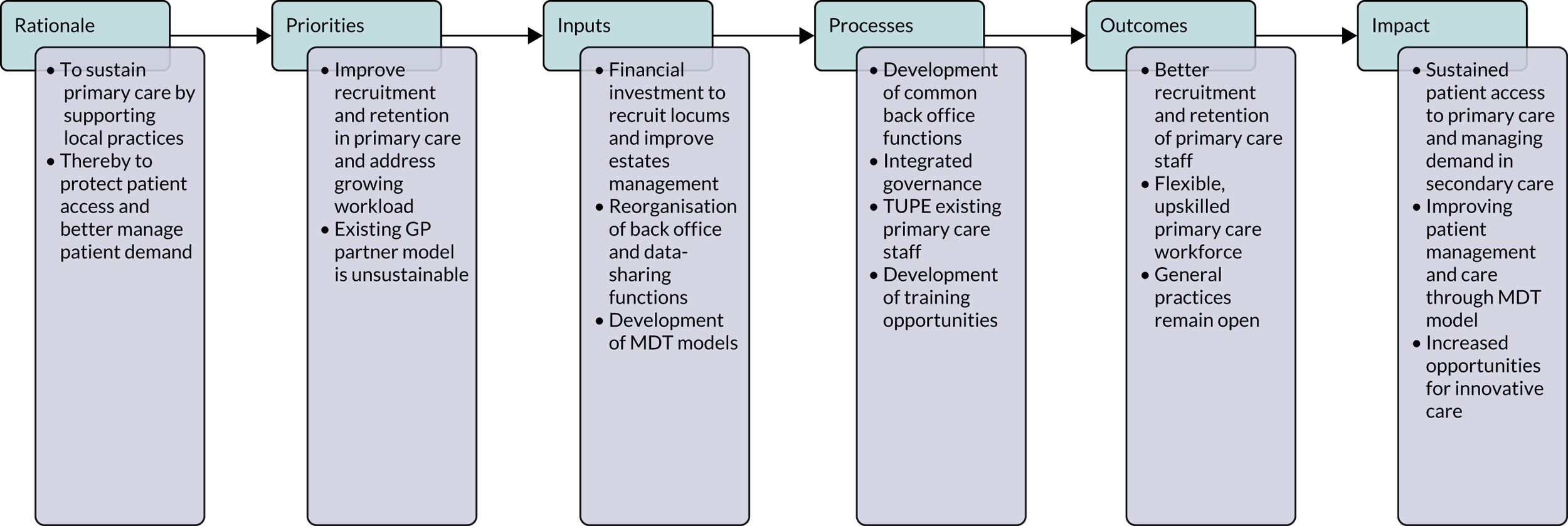

During scoping interviews, NHS staff and policy experts recognised benefits of vertical integration, especially for younger GPs, as younger GPs could be given greater opportunities to acquire specialist training across the primary and secondary interface and would be more likely to have a set/defined workload and greater back office support (e.g. legal, indemnity, procurement), creating more time for clinical contribution. This relates strongly to the current shift in primary care working among GPs, where almost half of GPs in the NHS in England are employed on a salaried or sessional basis (as opposed to having equity ownership of the practice) and a majority are women (many of whom work part-time and/or wish to have portfolio careers, as do some of their male colleagues). 52 However, a number of academics were cautious that there would be a marked difference of leadership styles between salaried GPs and GPs as partners. The closer integration of primary and secondary care might also lead to increased data-sharing aligned with improved management in primary care of high-risk patients who are more likely to access emergency secondary care. Policy experts also expressed a desire to understand how the ‘success’ of vertical integration would be measured. Would success be measured by general practice sustainability, by understanding the ‘right’ professional mix of multidisciplinary teams (MDTs) in primary care or by improved financial and outcomes-based performance by the acute trust? As a result, one academic interviewee felt that it would be appropriate for the study team to develop individual programme theories for each vertically integrated organisation so as to better understand the rationale for, and consequences of, vertical integration in a variety of approaches.

The project design workshop was an opportunity to consider, as a whole, the material gathered from the scoping interviews and literature review, and to identify and prioritise, in discussion with policy and academic stakeholders in the area, which questions to pursue for evaluation of vertical integration between acute hospitals and general practices. These discussions led the team to identify the following six research questions for an initial evaluation:

-

What are the drivers of and rationale for acute hospitals taking over the management and governance of general practices? What does this type of vertical integration aim to achieve?

-

What models/arrangements exist for acute hospital organisations to manage general practices (including different contractual/legal/organisational arrangements across primary, secondary and community health services)?

-

What is the experience of implementing this model of vertical integration, including barriers to and enablers of vertical integration, as well as the lessons learnt?

-

In what ways, if any, has this model of vertical integration influenced the extent and type of health service provision delivered in primary care?

-

What are the views of the primary and secondary care workforces about working together in this way across the care interface?

-

In what ways, if any, has this model of vertical integration had impact so far? What are the expected longer-term impacts? How is progress being measured?

Addressing these questions informs the development of a theory of change for vertical integration between acute hospitals and general practices, describing its desired outcomes and the mechanisms by which these are expected to be achieved.

A conclusion of the discussion at the workshop was that a rapid evaluation could not address all of the main knowledge gaps and that it would be better to adopt a phased approach. This phased approach would comprise an initial evaluation (which is the subject of the present paper) followed by a second phase evaluation somewhat later. The second phase would start from the theory of change and then more fully assess the impact of vertical integration, in particular on patients and on the efficiency and effectiveness of the health-care system.

The method adopted for the initial rapid evaluation is described in the next chapter.

Chapter 3 Methods

Summary of key points

-

This rapid evaluation had two distinct aims.

-

Aim 1: to understand the early impact of vertical integration, including its objectives, how it is being implemented, if and how vertical integration can underpin and drive the redesigning of care pathways, if and how services offered in primary care settings change as a result, and the impact on the general practice and hospital workforces.

-

Aim 2: to develop a theory of change for vertical integration, including identifying what outcomes this model of vertical integration is expected to achieve in the short, medium and long terms, and under what circumstances.

-

-

We completed a qualitative cross-comparative case study evaluation that comprised three work packages (WPs).

-

WP1: rapid review of the literature, telephone scoping interviews and a stakeholder workshop.

-

WP2: comparative case studies of three vertical integration sites with interviews with key staff involved in the conceptual design, implementation and analysis of this model of vertical integration; analysis of key documentation (both internal and publicly shared and that related to patient experience); and non-participant observation of strategic meetings.

-

WP3: development of a theory of change for each case study site and an overall theory of change for vertical integration.

-

-

We undertook a purposive sampling to select three case study sites, based on identifying appropriate sites where vertical integration was happening at scale.

-

A content analysis approach to documentary reviews and observations was undertaken. Data analysis for interviews was informed by a framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multidisciplinary health research. Our analysis was guided by theoretical literature on vertical integration between acute trusts and general practices.

General approach

This rapid evaluation had two distinct aims.

Aim 1

To understand the early impact of vertical integration, including its objectives, how it is being implemented, if and how vertical integration can underpin and drive the redesigning of care pathways, if and how services offered in primary care settings change as a result, and the impact on the general practice and hospital workforces.

Aim 2

To develop a theory of change for vertical integration, including identifying what outcomes this model of vertical integration is expected to achieve in the short, medium and long terms, and under what circumstances.

As a result of the scoping work, we identified six research questions by which to address these aims(see Chapter 2, Findings from discussions with key experts).

Our general approach to meeting the aims and answering the research questions was a cross-comparative case study qualitative evaluation, comprising three WPs: (1) a rapid review of the literature, telephone scoping interviews and a stakeholder workshop, (2) interviews with key stakeholders across three case study sites, alongside observations of strategic meetings and analysis of key documents, and (3) development of a theory of change for each case study site, as well as an overall theory of change for this model of vertical integration (Table 2). 5

| WP | Description |

|---|---|

| WP1: rapid review of the literature, telephone scoping interviews and a stakeholder workshop | An overview of the evidence already reported on vertical integration of secondary and primary care services to inform the development of propositions to be tested through comparative case studies |

| WP2: comparative case studies of three vertical integration sites | Interviews with those involved in the conceptual design, implementation and analysis of this model of vertical integration at their respective sites; analysis of key documentation (both internal and publicly shared and that related to patient experience); non-participant observation of strategic meetings; and interpretation of existing metrics and cost information being collected by, and any quantitative analyses undertaken at, the case study sites |

| WP3: development of theory of change | A workshop meeting of the full research team plus other senior qualitative researchers from University of Birmingham and RAND Europe to develop a theory of change for each case study site, as well as an overall theory of change for this model of vertical integration |

The original project design additionally included a stakeholder workshop at each case study site and a further workshop with stakeholders from the Department of Health and Social Care and NHS England plus peer policy analysts active in the field of care integration. The workshops were intended to refine the theories of change and to contribute to the dissemination of evaluation findings. However, as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic and associated research-related restrictions from March 2020, the study team followed National Institute for Health and Care Research guidance on suspending research activity with NHS staff and temporarily omitted the workshops prior to report submission so as not to delay reporting for an indefinite, and likely protracted, period. Workshops were subsequently completed in August and September 2020.

Protocol sign-off

The study topic was identified and prioritised for rapid evaluation through BRACE’s approach of identifying innovations through horizon scanning. An initial topic specification (first-stage protocol) was prepared (February 2019) and, once approved, was used as the basis for writing the full research protocol (May 2019), which drew on the findings of the initial scoping review and workshop (WP1).

Ethics approval

An application for ethics review to the University of Birmingham’s Research Ethics Committee was made by the project team and approval was gained in July 2019 (reference ERN_13-1085AP35). The project team received confirmation from the Health Research Authority (London, UK) that this study was to be categorised as a service evaluation and, therefore, approval by the Health Research Authority or an NHS Research Ethics Committee was not required. At each case study site, we approached relevant local research and development offices to register our service evaluation and received confirmation that all were content for the evaluation to proceed in their local area.

The method and findings from WP1 are presented in the preceding chapter (see Chapter 2). The second and third WPs are described in the following paragraphs.

Comparative case studies of three vertical integration sites

In January 2019, through grey literature searching (of Pulse, the Health Service Journal and GPonline), during the scoping of the evaluation, the research team identified five sites (Table 3) across England and Wales where vertical integration between an acute hospital and general practices was already being delivered at scale (i.e. four practices or more integrated with the local trust/LHB). Members of the study team sent e-mail correspondence to vertical integration organisational strategic and/or clinical leads (or their equivalent) on behalf of the principal investigator (JS).

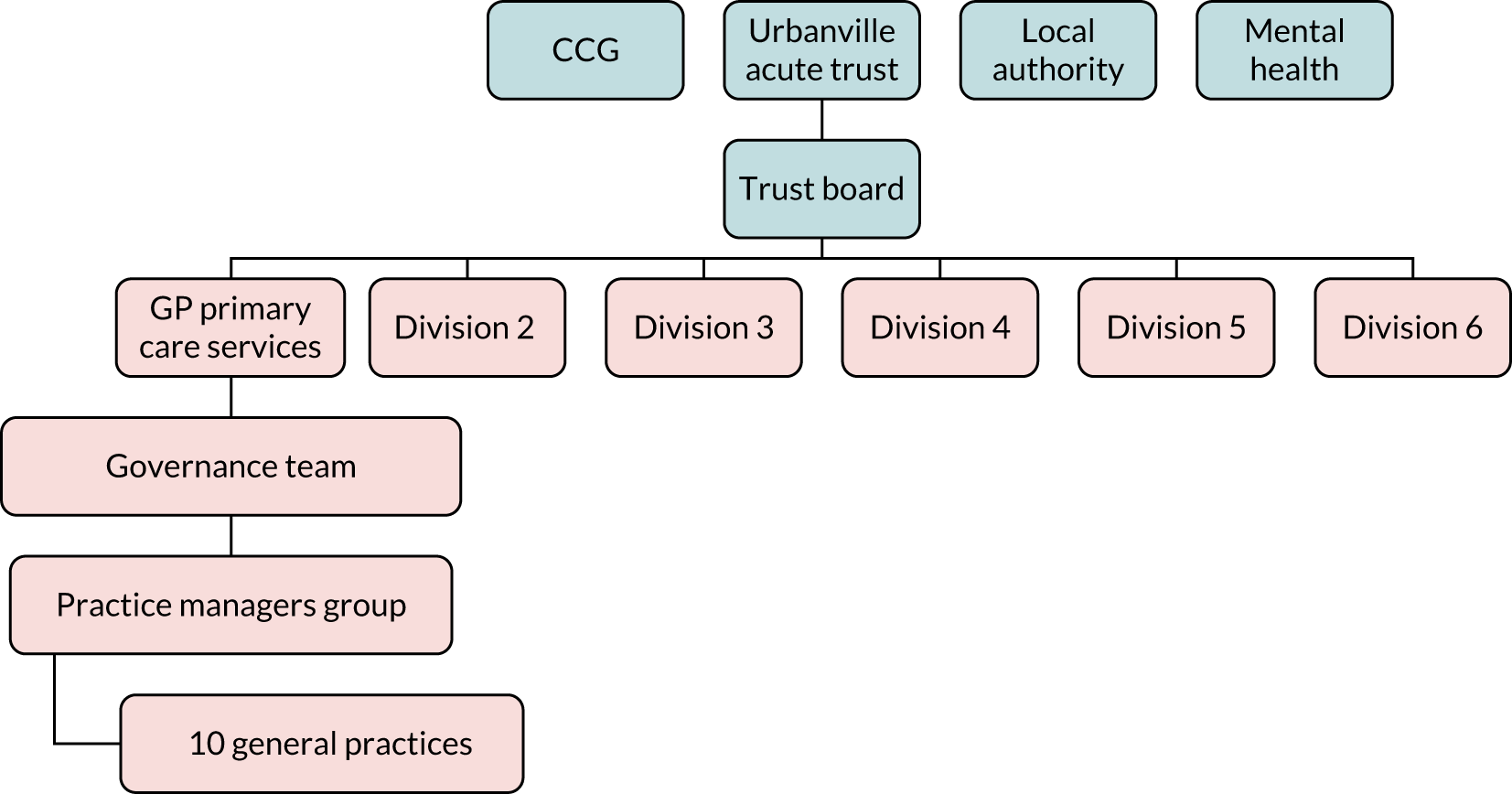

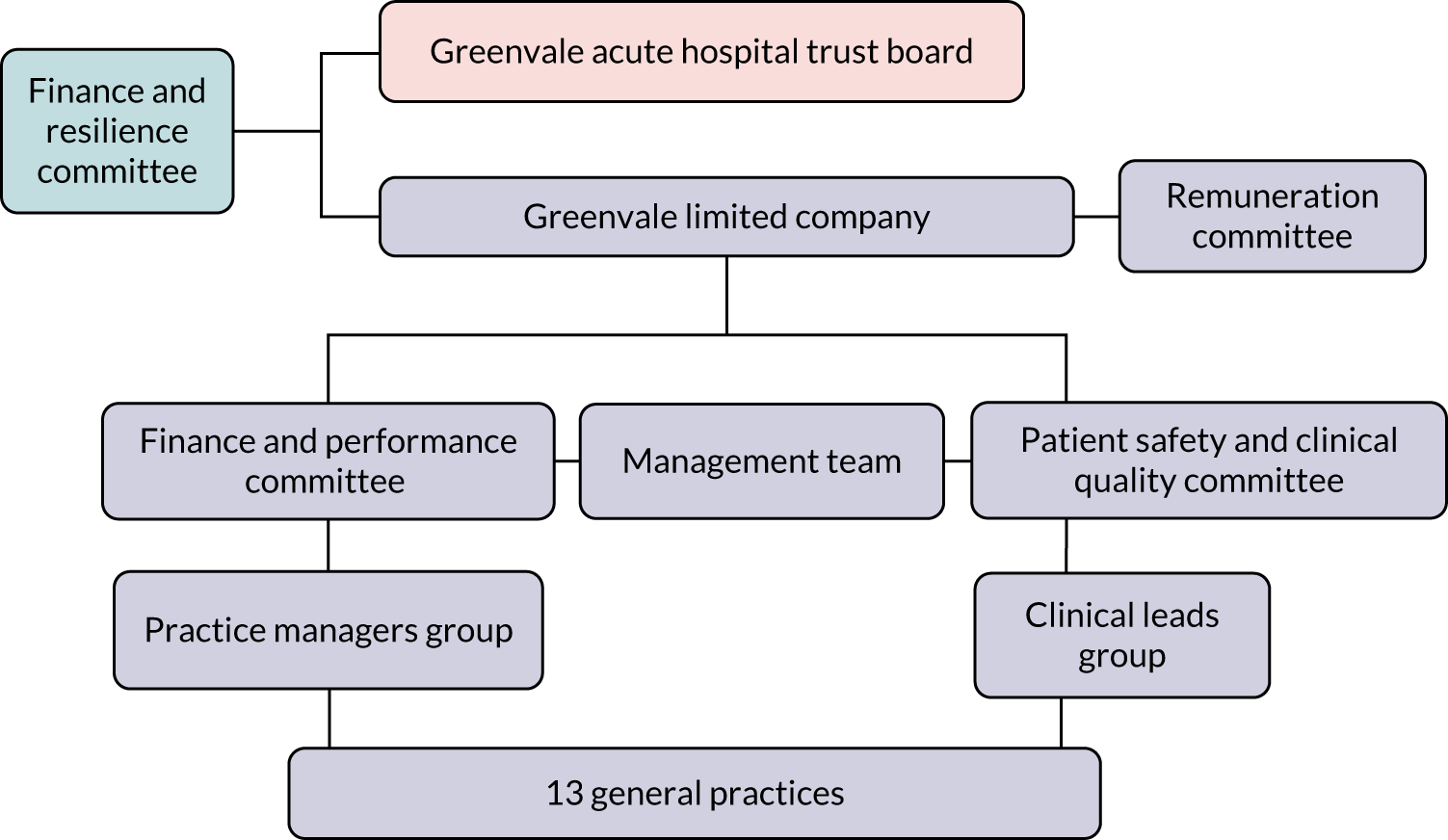

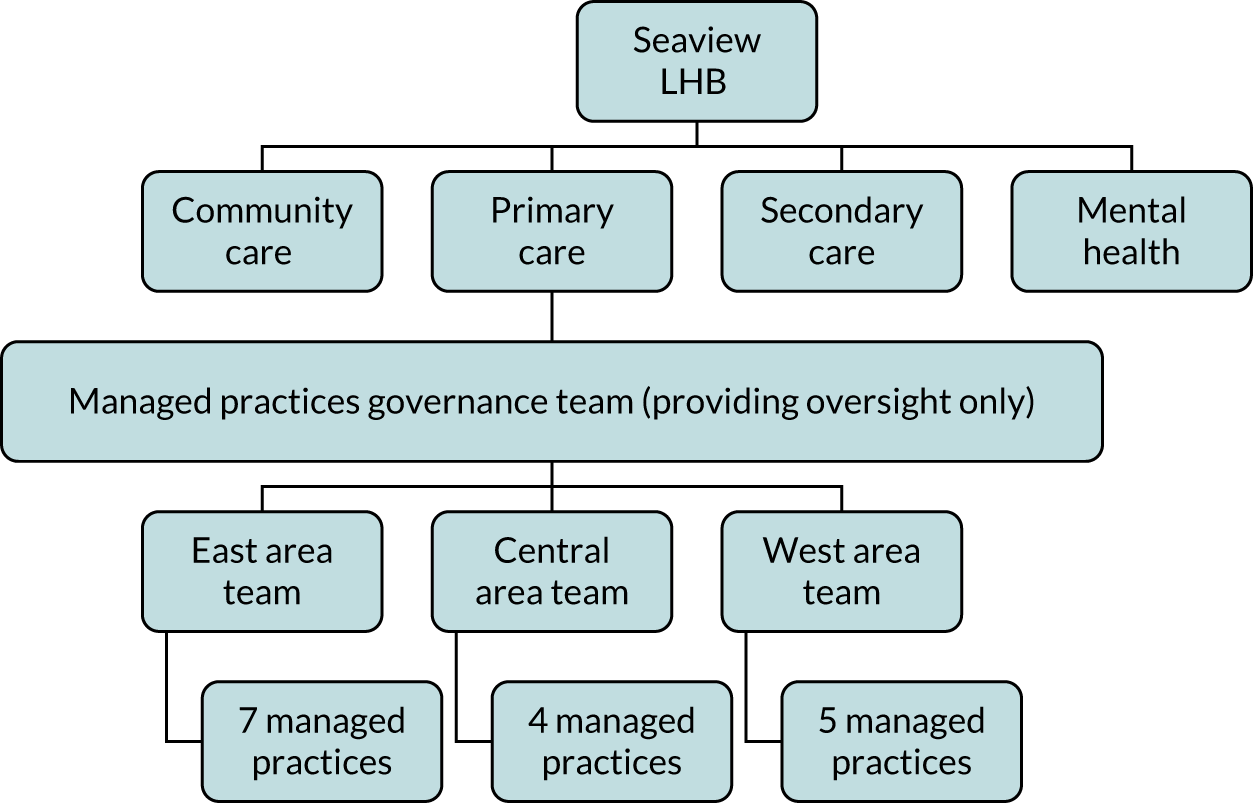

| Case study site | Rationale | Location | Legal framework | Date of commencement | Number of general practices |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Better management of secondary demand | England | Subcontracting GMS contract | June 2016 | 10 |

| 2 | Primary care stability and sustainability | Wales | Health board control over primary and secondary care | March 2016 | 22a |

| 3 | Primary care sustainability | England | Creation of a subsidiary limited company managed by local trust | April 2016 | 13 |

| 4 | Primary care stability | England | Subcontracting GMS contract | April 2017 | 4 |

| 5 | Primary care sustainability | England | Creation of non-profit limited company | April 2015 | 6 |

The selection of case study sites was purposive, with the aim of seeking variation across three sites in terms of (1) their rationale for implementing vertical integration and intentions for growth (i.e. management of more general practices operating under this model in future), (2) their geographical location and population served (i.e. a mix of rural and urban locations), (3) their legal and governance working frameworks and (4) the amount of time that has elapsed since vertical integration was introduced. One site declined to participate as it was already taking part in another research study, whereas another site was addressing pertinent local challenges to health-care delivery. Three sites were selected and approached to seek their agreement to participate in the study through face-to-face meetings at each respective site. All three sites agreed by sending formal confirmation of participation letters/e-mails.

Stakeholder interviews

The aim of completing interviews with stakeholders was to understand the rationale for, drivers of and challenges involved in the conceptualisation and implementation of vertical integration and interpret the experiences of primary and secondary care staff working together across the interface. The evaluation team planned to complete 15–20 interviews across each case study site or until data saturation (i.e. once data were triangulated, no new information was being discovered during data analysis, with the data confirming only existing themes and conclusions). The point of saturation was agreed by all members of the study team. Fieldwork was completed in parallel across all three case study sites (August–December 2019) by three members of the research team with experience of undertaking interviews and qualitative data analysis (led by MS). Manbinder Sidhu was responsible for all communication and data collection at two sites, and Jon Sussex and Jack Pollard were responsible for communication and data collection at the third site. A small number of interviews (n = 3) were conducted with both Jon Sussex and Jack Pollard present, at a single site, as the principal investigator wished to embed himself appropriately within the data collection process to better inform data analysis.

Participants for interview were purposively sampled and were approached through each case study site’s contact person/gatekeeper. 53 A gatekeeper was defined as a person based at our case study sites who could act as an intermediary between a researcher and potential participants, with the authority to deny or grant permission for access to potential research participants. 54 The gatekeeper facilitated the identification of key individuals (informants) involved in the design, implementation, governance and analysis of the model of vertical integration at the levels of strategic decision-making and delivering patient care. Informants included LHB and acute hospital chief executives, directors (clinical and non-clinical) and other NHS managerial-level staff (related to integration and strategy, delivery of health care services, as well as financial and governance-related management); staff and board members (from CCGs); GPs/general practice cluster leads and primary care staff who had, and some who had not, implemented the vertical integration model in each area; and members of patient participation groups.

The study team followed Johl and Renganathan’s55 phased framework for responsible engagement with organisations and gatekeepers to build their trust and support for the project, starting with formal e-mail requests for invitation, including a participant information sheet (see Project management information). Individuals participated in a semistructured interview with either one or two members of the study team, completed at their place of employment, at any other suitable location convenient to the interviewee or via telephone. Each participant was provided with the participant information sheet at least 48 hours in advance to enable them to make an informed decision regarding whether or not to participate. Interviewees had the opportunity to ask questions about the study and/or wider BRACE-related work. Participants signed a consent form (see Project management information) prior to participating in the interview. This included giving consent or not to the recording of the interview. Participants were informed that they were entitled to withdraw from the study at any time and were given information about how to find out more about the study and how to raise any concerns about its conduct. In total, the study team approached 67 potential participants to complete an interview across all three sites, with 52 participants agreeing to take part. Salient characteristics of stakeholders interviewed across our three case study sites are given in Table 4.

| Area of specialism | Generic description of role | Number of participants (participant identifiers) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary care | Clinical | 12 (A03, A12, A15, B12, B13, B17, C04, C07, C09, C15, C16, C17) |

| Organisational management | 9 (A17, A18, B01, B05, B08, B09, B10, B11, C08) | |

| Professional representation | 2 (B02, B04) | |

| Clinical and managerial | 1 (B03) | |

| Patient participation group | 2 (A08, B16) | |

| Primary and secondary care | Clinical | 1 (A07) |

| Clinical and managerial | 1 (B06) | |

| Organisational management | 3 (B14, C03, C11) | |

| Primary care commissioning | Organisational management | 1 (B15) |

| Secondary care | Clinical | 2 (A16, C10) |

| Organisational management | 15 (A01, A02, A06, A09, A10, A11, A13, A14, B07, C01, C02, C05, C06, C12, C14) | |

| Senior management | 3 (A04, A05, C13) | |

| Total | 52 |

A topic guide was developed and used by researchers as an aide-memoire during the interviews (see Report Supplementary Material 2). The main themes the topic guide covered were understanding the rationale behind the implementation of vertical integration, the clinical/legal/governance arrangements to facilitate this model, understanding the experiences of primary care and secondary care staff involved with the implementation of this model, and the outcomes the vertical integration model is expected to deliver in the short, medium and long term.

Interviews were audio-recorded (subject to consent being given), transcribed verbatim by a professional transcription service, anonymised and kept in compliance with the General Data Protection Regulation 201856 and the Data Protection Act 2018. 57

Non-participant observation of meetings

We observed meetings (at an executive and managerial level at the acute trust and at the general practice level among senior staff) between key stakeholders at case study sites to develop a better understanding of how decisions regarding implementation and delivery of vertical integration are made at local and executive board level. Non-participant observation provided the opportunity to gather data with regard to the ongoing challenges of sustaining the vertical integration model across a number of general practices, with input from stakeholders ranging from those who were more concerned with strategic decision-making to GPs and other practice staff who were familiar with the everyday effects of vertical integration on their work.