Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as award number 16/138/17. The contractual start date was in November 2020. The draft manuscript began editorial review in October 2023 and was accepted for publication in April 2024. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Sherlaw-Johnson et al. This work was produced by Sherlaw-Johnson et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Sherlaw-Johnson et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction and overview

Background and context

Introduction

The 2019 NHS Long Term Plan set out an ambitious programme to fundamentally redesign outpatient services in England. 1 This was in part a response to the steady rise in outpatient attendances in the UK over the previous decade, which outstripped population growth and was not matched with a commensurate increase in workforce or system capacity. 2 The number of outpatient appointments increased by two-thirds between 2008–09 and 2019–20 to 125 million a year. 3 This was the largest increase in activity of any hospital service and, given the context of chronic financial and workforce constraints and system pressures, long wait times, delayed appointments, and rushed consultations, have all become increasingly common, frustrating patients and staff alike. 4

After a drop during the COVID-19 (coronavirus disease discovered in 2019) pandemic, total volumes of outpatient activity have recovered to approximately where they were beforehand,5 but challenges have been exacerbated with the number of patients waiting for consultant-led elective care rising to 7.6 million by June 2023. 6,7

Traditional outpatient service models have relied on face-to-face consultations, which can require repeat hospital visits that prolong uncertainty and potentially waste patient and staff time. 2 As the number of appointments has grown, so too has the number of those that are unattended without prior cancellation [‘did not attend’ (DNA)] which account for nearly 8 million booked appointments each year, which is 6% of all appointments. 8 The high rate of missed appointments has led clinics to overbook, exacerbating problems of poor patient experience.

These inefficiencies have made improving the value of outpatient care a key priority for the NHS. In 2018, the Royal College of Physicians declared that the ‘traditional model of outpatient care is no longer fit for purpose’ and that the NHS must change how it commissions and delivers the service if it is to be sustainable over the long term. 2 It also aims to create a more ‘holistic’ service for patients who do not need to attend hospital, by making better use of primary, secondary and community services, and helping people to manage their own health. 9 As part of its outpatient redesign programme, the NHS Long Term Plan sought to avoid one-third of face-to-face outpatient appointments by 2024 – estimating that this would save the NHS £1.1bn per year (and patients 30 million visits to hospital) by streamlining service delivery through expanded technology at each stage of the pathway. Similar strategies have also been rolled out in Wales and Scotland to expand digital access and shift more care to community settings. 10,11 More recently, NHS England’s (NHSE) 2023–24 Operational Planning Guidance asked health systems to reduce follow-up outpatient attendances by 25% from 2019 to 2020 levels by March 2024. 12

Across the outpatient care pathway, a broad range of innovations have and are being pursued to better manage outpatient care and reduce unnecessary appointments.

Such innovations include referral optimisation (specialist triage of outpatient referrals), Advice and Guidance, Patient-Initiated Follow-Up (PIFU) and video consultation.

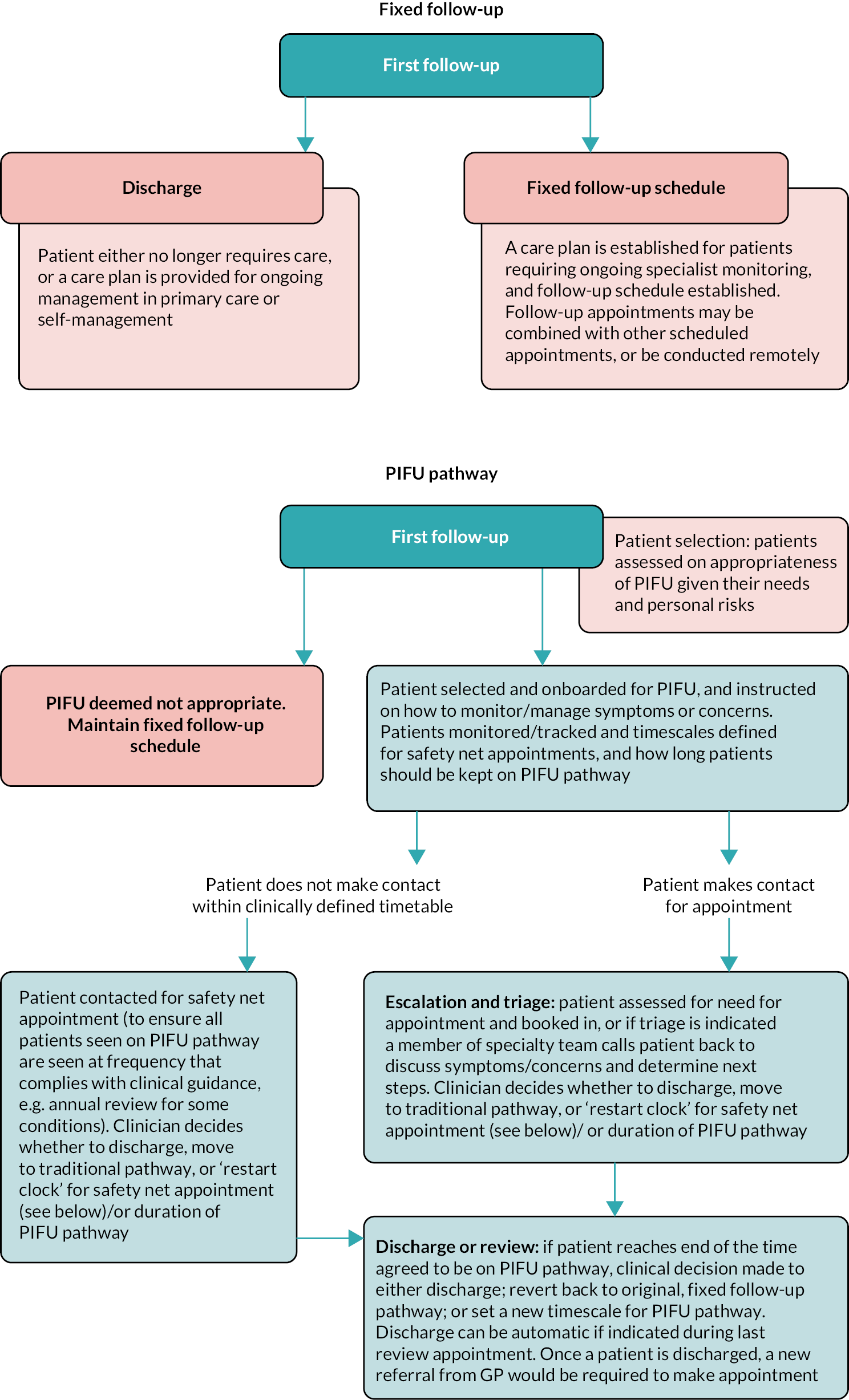

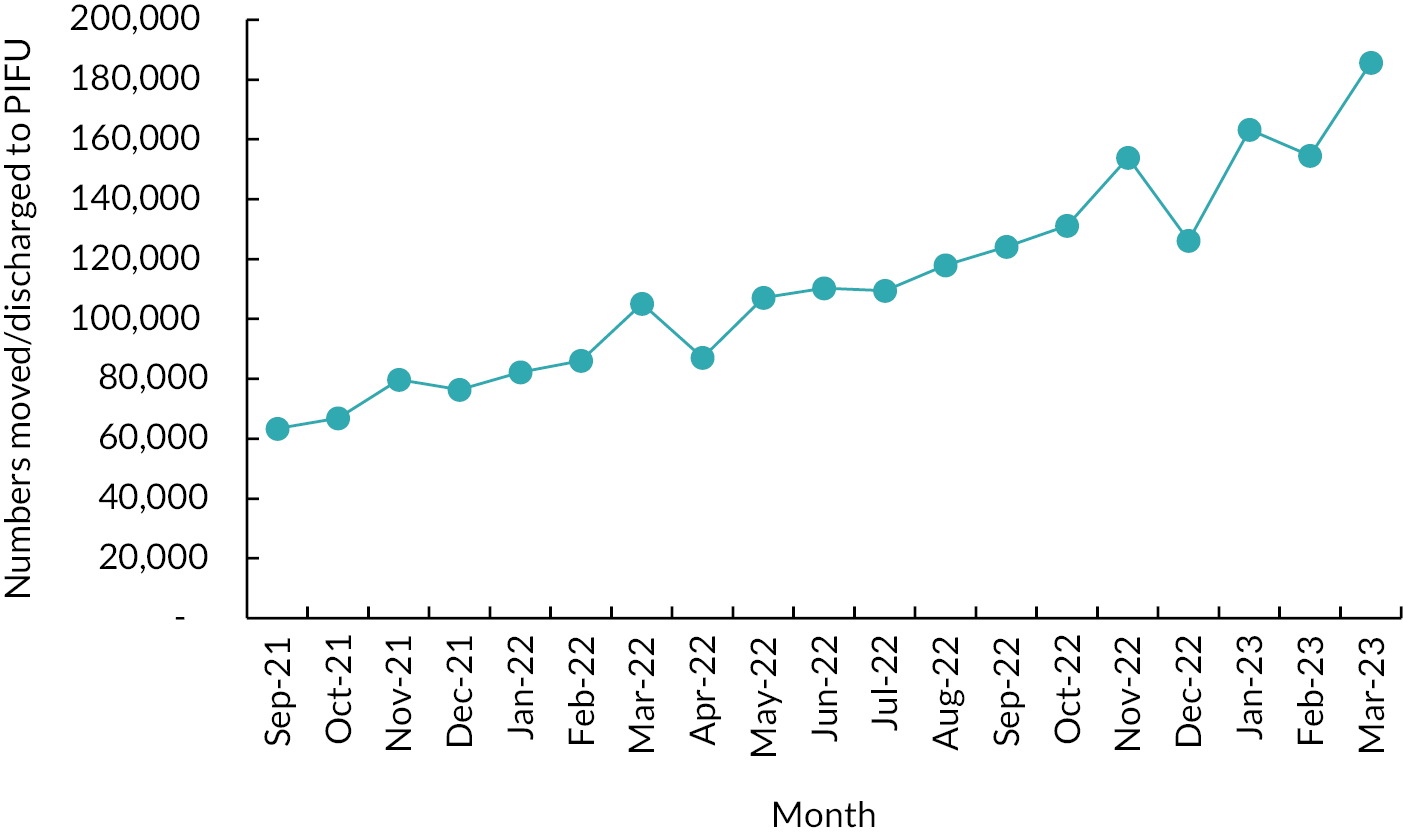

Through Advice and Guidance, general practitioners (GPs) can access specialist advice about a patient, thereby allowing a timely response to patients and reducing the need for referral to outpatient services. Expanding primary care access to specialist Advice and Guidance is a central part of NHSE’s delivery plan for tackling elective care backlog. Referral optimisation of outpatient referrals (e.g. rapid triage) involves GPs accessing specialist advice to discuss the most appropriate care with the aim to triage outpatient appointments more effectively, get the right support and reduce ‘unnecessary’ appointments. PIFU aims to give more flexibility and choice to patients over the timing of their care and allow them to book appointments as and when they need them, rather than follow a fixed or standard schedule (e.g. every 6 months).

Understanding which interventions are most effective and the factors that contribute to their success is limited by several factors: (1) innovations being delivered in conjunction with other service changes; (2) differences in delivery across specialties and conditions; (3) the precise components of the interventions often not being reported and (4) variation in the outcomes studied to judge effectiveness.

However, available evidence shows that digital innovations such as teleconsultations and virtual appointments can be effective in reducing missed appointments and lead to shorter consultation times. 13–15 Remote monitoring services have been found to be related to fewer outpatient visits across several specialties. 16–18 Innovations such as rapid triage services (e.g. telephone assessment clinics) have been found to reduce referral waiting times. 19,20 Similarly, direct or rapid access clinics have been shown to reduce waiting times and can alleviate requirement for face-to-face clinic attendances. 21–23 The introduction of non-specialist clinics and expanding of clinical support roles (e.g. advanced care practitioners, nurse practitioners) has also been linked to reduced waiting times24 and increased appointment availability. 25 Other innovations, such as clinic administration and scheduling systems, show variable outcomes, as these tend to be linked to the context in which they have been implemented.

The aims of outpatient transformation efforts have been varied but coalesce around several common themes, including:

-

Making better use of clinical space and staff time.

-

Making better use of wider professional teams.

-

Integrating primary, secondary and tertiary care.

-

Co-ordinating care for people with multiple health conditions.

-

Increasing patient satisfaction, empowerment and convenience.

-

Reducing unnecessary in-person appointments.

-

Increasing savings for the NHS and improving cost effectiveness.

-

Reducing greenhouse gases and other pollution through reduced travel.

-

Decreasing waiting times for patients and their carers.

Study aims

This study aimed to identify innovations in outpatient services implemented in recent years in the English NHS and to carry out a rapid evaluation of one of the most important but little studied recent innovations: PIFU. The identification of innovations included a review of published literature to understand the breadth of system innovations and their potential impacts. This was followed by detailed data analysis of national outpatient activity to identify hospital trusts or clinical specialties where there were notable and recent changes in activity. The evaluation of PIFU was a rapid mixed-methods study investigating its implementation and impact on the use of hospital services and on patients and staff.

The specific aims were:

-

To understand the scope and breadth of interventions being pursued to improve efficiency in outpatient service delivery, and to understand key evidence gaps and future research needs.

-

To identify trusts and/or specialties where there is quantitative evidence of a notable change to outpatient activity, for example, a reduction in the numbers of attendances, or a substitution between different modes of attendances (e.g. from face-to-face consultation to teleconsultation).

-

To undertake interviews of selected trusts and specialties thus identified, to investigate whether changes in their outpatient activity were the result of specific innovations in care management.

-

To conduct a mixed-methods evaluation of PIFU, considering its implementation, impact and the experiences of patients and staff.

Research questions

The evaluation included four workstreams associated with each of the four aims with the following research questions (RQs):

-

RQ1. What interventions to improve efficiency and effectiveness of outpatient care have been studied? Where are the greatest gaps in evidence? (workstream 1)

-

RQ2. Can we identify from routine NHS data any healthcare organisations or specialties that have exhibited significant and sustained changes in outpatient activity that might suggest the influence of service innovations? (workstream 2)

-

RQ3. Can any identified changes in outpatient activity be linked to specific service innovations? (workstream 3)

-

RQ4. What is the current evidence relating to the implementation and impact of PIFU? What is the impact of PIFU on measures of outpatient activity? What are the experiences of patients and staff? (workstream 4)

Further, more detailed RQs were developed for the PIFU evaluation in workstream 4, which are stated separately in Aims and objectives.

Motivation for the study

This study was carried out by members of the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR)-funded Rapid Service Evaluation Team (RSET) and arose following recommendations from the RSET Stakeholder Advisory Board (SAB). The initial aim for workstream 4 (RQ4) was to evaluate one of the promising innovations identified in workstreams 2 and 3. However, as the project progressed, we were approached independently by the Outpatient Transformation and Recovery Programme team at NHSE to undertake an evaluation of PIFU. Moreover, it was already becoming clear from the earlier workstreams that PIFU was the most prominent innovation in outpatient care within the English NHS. For these reasons we devoted workstream 4 to an evaluation of PIFU.

Report structure

This report has four main chapters. Chapter 1 is an overview of the clinical and policy context for outpatient services in the English NHS together with the project aims and a broad overview of the methods employed, including use of patient involvement and the approach to equality and diversity. Chapter 2 combines workstreams 1, 2 and 3, describing the work to identify innovations in outpatient care. Chapter 3 focuses on the methods and findings from the evaluation of PIFU (workstream 4), with an evaluation guide described in Chapter 4 and a discussion in Chapter 5. In Chapter 6 we outline recommendations for decision-makers and further research arising from all workstreams.

Methods overview

Study design

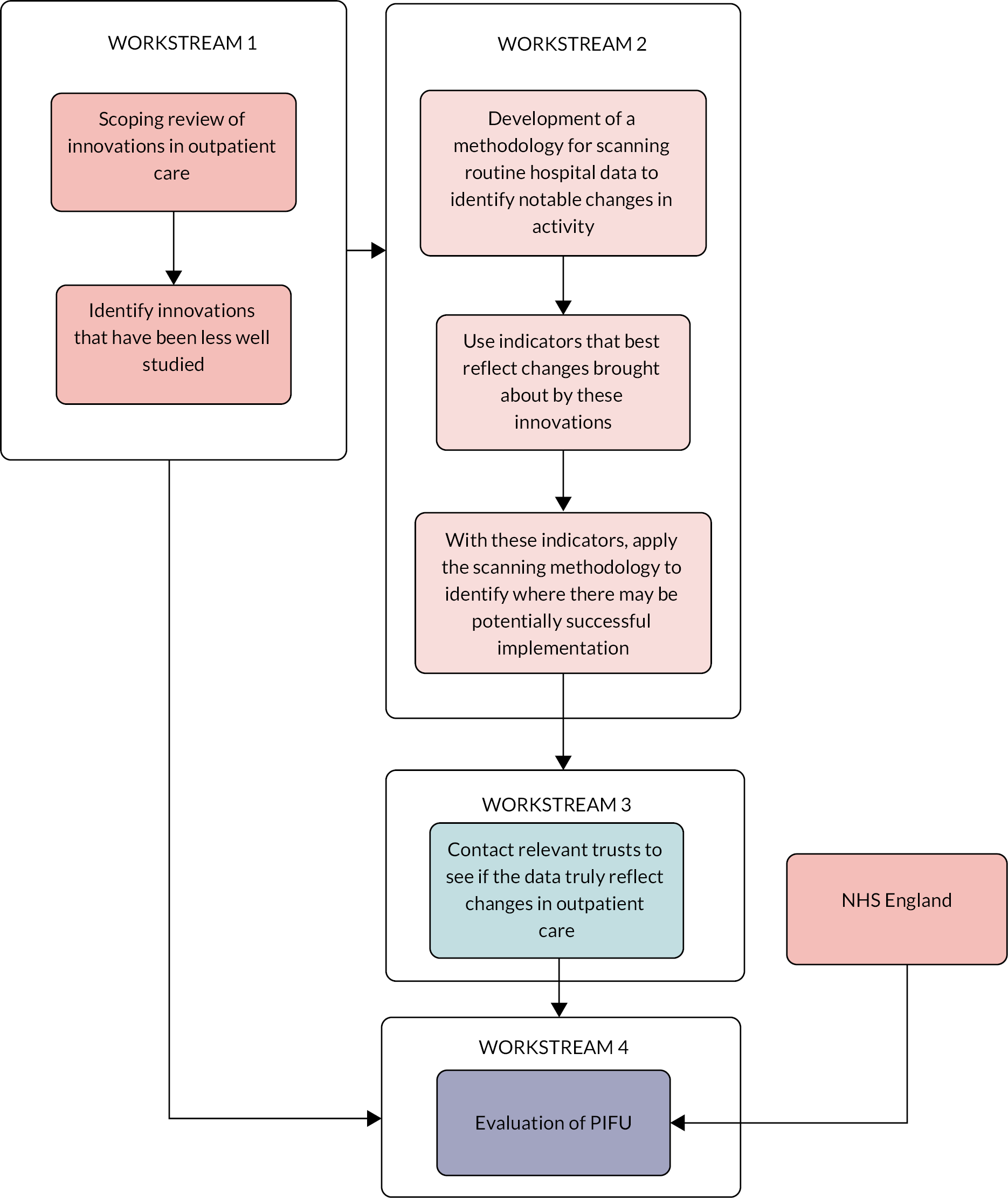

This study employed mixed methods and was divided into four workstreams (see Background and context). Workstream 1 was designed as a literature review to provide context for the rest of the study, workstream 2 was designed in parallel as a quantitative analysis of routine patient data. Findings from workstream 1 informed the final analysis in workstream 2 leading to engagement with healthcare providers in workstream 3. Workstream 4 arose from a combination of findings from workstreams 1 and 3, alongside engagement with external stakeholders. These links between the different workstreams are illustrated in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

How the different workstreams interact. The arrows represent the links between the different workstreams.

Workstream 4 was designed separately as a mixed-methods evaluation with an evidence review and two phases, with phase 1 providing interim findings that informed how we approached phase 2. For further details on the designs and methods for workstream 1, see Rapid scoping review of outpatient innovations. For workstreams 2 and 3, see The development and use of a methodology to detect, rank, and investigate positive changes in outpatient activity, and for workstream 4 see Methods for the evaluation of Patient-Initiated Follow-Up.

Contact with stakeholders and advisers

The initial idea for evaluating outpatient services was put forward by the NIHR RSET SAB. This group comprised health and social care professionals, patient representatives, data analysts, voluntary service representatives and service managers. The SAB reviewed progress at our annual board meetings and made suggestions for taking forward.

Distinct from the SAB, a formal Project Advisory Group (PAG) was established to oversee progress. This group reviewed the protocol (including amendments) and provided constructive feedback on all the outputs during the course of the project. They met by video conference once at the start of the project and then at intervals as appropriate, including at key points where decisions needed to be taken by the research team. Where meetings were not possible due to other commitments, we engaged with the group by e-mail.

The group included members with various types of experience and responsibilities, including clinical and academic expertise. The group also included one patient representative (see Patient and public involvement and engagement).

The responsibilities of the group included:

-

providing context, advice, and challenges to the research team, based on knowledge of outpatient service policy and delivery

-

helping the team to prioritise in addressing the RQs

-

advising on service issues around outpatient activity and related data collection

-

guiding the research team in seeking further expert advice

-

helping to interpret outputs, for example, activity patterns by specialty or the long list of trusts, with potential innovations from workstream 2

-

supporting the research team in scoping workstream 4.

Workstream 4 was shaped in partnership with the Outpatient Recovery and Transformation Policy and Strategy team at NHSE, with whom we had regular meetings to report ongoing findings. The team also provided advice, particularly about the data and engagement with the service.

The identity of the study sites was not revealed to any of the stakeholders or advisors.

Patient and public involvement and engagement

Patients and the public were actively involved in:

-

project design

-

project management

-

developing participant information resources

-

contributing to writing up and sharing findings.

Patient and public involvement and engagement (PPIE) benefited the project in the following ways:

-

ensuring the study focused on issues of importance to service users

-

ensuring that this focus was reflected in the aims, objectives and RQs

-

ensuring that these were operationalised suitably in the approach to data collection and analysis, and

-

ensuring that the findings were disseminated effectively and in a manner that is meaningful to patients, carers and the public.

Patient and public representatives reviewed the protocol and contributed to the design of this study. For example, two patient representatives from the NIHR RSET (PPIE) panel reviewed the initial protocol in November 2020 following a virtual meeting in which they were given an overview of the project and the opportunity to ask questions.

We recruited a patient representative with lived experience of outpatient care to be a member of the PAG to provide perspectives on their experiences of care and different system innovations to guide the work.

The patient representative [Jenny Negus (JN)] participated in all PAG meetings and commented on study documents, such as the protocol’s Plain language summary. They were offered appropriate training and support, for example, on how to effectively participate in meetings. The team budgeted to support them in all these activities. To support effective participation, the team ensured that documents relating to meetings and events were distributed in a timely fashion (e.g. a week in advance). Also, a member of the team [Pei Li Ng (PLN)] was identified as the primary contact with whom the patient representative could raise any issues or concerns.

Patient and public involvement and engagement feedback contributed significantly to several aspects of the project. This included the development of the patient interview materials (including the participant information sheet, consent form, and topic guide) which were submitted as part of the ethics application. We also conducted a mock patient interview with a member of the PPIE group, which informed the approach. Prior to publication, the PPIE representative reviewed and provided feedback on project outputs (e.g. PIFU evidence review and explainer,26 slide packs for NHSE).

Equality, diversity and inclusion

Many outpatient innovations would have important implications for equality, diversity and inclusion (EDI), for example, if they rely on engaging with technology or patient activation.

For the analysis in workstream 2 (see The development and use of a methodology to detect, rank, and investigate positive changes in outpatient activity), we were analysing changes in outcomes within providers over time, so we decided that corrections for patient characteristics between or within different populations did not need to be applied. Where notable changes in outcomes are driven by changes in population characteristics it is not appropriate to adjust for different patient groups, otherwise they would remain undetected.

The PIFU evidence review (see Rapid Patient-Initiated Follow-Up scoping review) sought to understand outcomes and experiences of PIFU across different patient groups, such as age, gender, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status; however, many studies did not report these findings. We identified further understanding of the impact of PIFU across different population groups as a crucial area for further research.

In phases 1 and 2 of the qualitative work in workstream 4, we aimed to sample sites based on several criteria in order to get a diverse sample. This included the levels of ethnic diversity and deprivation relative to the average population and other demographic factors such as age.

We identified staff interviewees primarily by role and aimed to include a variety of perspectives including clinical, operational, and administrative at different levels of the organisation (specialty and trust-wide). We considered the EDI implications for PIFU in the design of the topic guides and included questions which focused on understanding the opportunities and barriers for PIFU in access for different patient groups.

For the patient interviews, we intended to sample patients from a range of backgrounds to ensure we had a representative sample and to identify whether there were differences in experience depending on patient demographics. Initially we aimed to sample patients by age, gender, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status. We included optional demographic questions at the end of the patient interviews. Due to numerous challenges in setting up the patient interviews, the approach became more pragmatic and we sampled primarily based on specialty. Although we did capture demographic details of the interviewees we spoke to, given the low number of patient interviews (four) we were unable to comment on differences by patient background.

Methods for the evaluation of Patient-Initiated Follow-Up contains further details of how EDI influenced the selection of study sites and patient interviewees.

To evaluate EDI implications of PIFU in the quantitative analysis, we asked for specific data from local sites since the national data were not going to allow us to look at these aspects. Further details are provided in What is the impact of Patient-Initiated Follow-Up on health inequalities and how is this being measured?.

The research team consisted of researchers from two organisations [the Nuffield Trust and University College London (UCL)]. The team was multidisciplinary in nature and team members differed in seniority. The team comprised a mix of backgrounds in relation to gender and ethnicity. When members of the team had to leave, due to a variety of commitments, we ensured, as far as possible, they overlapped with their replacements so they could receive the necessary support during the handover.

Differences from the project protocol

Any changes from the original protocol were discussed with the advisory group.

The final conduct of workstream 1 differed from the project protocol in the following ways:

-

We stated that we would review studies published between 2010 and 2022. However, to manage scope and ensure we were focusing on more current innovations, we changed the start year to 2015. This is explained further in Methods overview.

-

We also stated we would summarise existing evidence of the impact of outpatient interventions, identify factors that might support or hinder the implementation and identify gaps in evidence. The final scope of the review did not include this. The revised aims and RQ are described in more detail in Rapid scoping review of outpatient innovations.

The final conduct of workstream 4 differed in the following ways:

-

We stated we would analyse local patient-level data from hospitals that can identify patients on PIFU pathways to compare their outcomes with patients from hospitals that have not applied PIFU within the same specialties. None of the hospitals we engaged with were able to supply such data, either because they could not identify PIFU patients within their electronic patient administration systems (PAS) or because of the local practicalities of preparing such data. We considered that a more practical way of using local data was to analyse differences in the use of and engagement with PIFU between different individual characteristics where we could use aggregated data that could be easily prepared by the local sites.

-

We stated that we would hold a workshop with three to four ‘late-adopter’ sites that show limited evidence of moving patients on to PIFU pathways. Due to challenges with engagement, the focus of the workshop was broadened to focus more generally on the barriers and facilitators to PIFU implementation. Sites represented at the workshop were therefore at varying stages of PIFU implementation. We considered this an advantage since focusing on late adopters assumes that these issues are specific to such organisations.

-

We stated that we would interview patient advocacy groups, such as Healthwatch and National Voices, but this did not take place as we thought it best, given the time available, to focus on interviewing individual patients who had a relationship with the services we had selected for staff interviews.

Chapter 2 Identifying innovations in outpatient care

Introduction

This section of the report describes the research into identifying innovations in outpatient care and covers project workstreams 1–3. The links between these workstreams are illustrated above in Methods overview (see Figure 1).

Rapid scoping review of outpatient innovations describes the scoping review of the literature to investigate what innovations have been previously studied and for what purpose. The development and use of a methodology to detect, rank, and investigate positive changes in outpatient activity describes the methods we used for scanning routine hospital outpatient data to identify changes in activity that might indicate innovations in service design and the subsequent follow-up with selected acute trusts with most notable changes.

Although the methods described in The development and use of a methodology to detect, rank, and investigate positive changes in outpatient activity are for more general application, we specifically applied them to an indicator that better reflects one of the innovations that we found from the scoping review to be less well studied.

Rapid scoping review of outpatient innovations

What this section adds

This section describes a rapid scoping review of the published literature on innovations in outpatient care that was carried out in the early stages of the project. Adopting an evidence-mapping approach, the review identified which innovations have been studied, their purposes and potential benefits. This has helped us identify where there were gaps in the evidence and inform the choice of innovation to study in workstream 4.

Introduction

In this scoping review we sought to address RQ1:

-

What interventions to improve efficiency and effectiveness of outpatient care have been studied? Where are the greatest gaps in evidence?

Across the outpatient care pathway, a broad range of innovations have and are being pursued to better manage outpatient care and reduce unnecessary appointments, but there is limited understanding of which interventions are most effective and what factors contribute to their success.

The purpose of this review was to provide context for the wider study of outpatient services and, in particular, help us to identify innovations that would be suitable to evaluate in workstream 4. Assessing the effectiveness of innovations in improving outpatient service delivery or examining outcomes were beyond its scope.

Methods

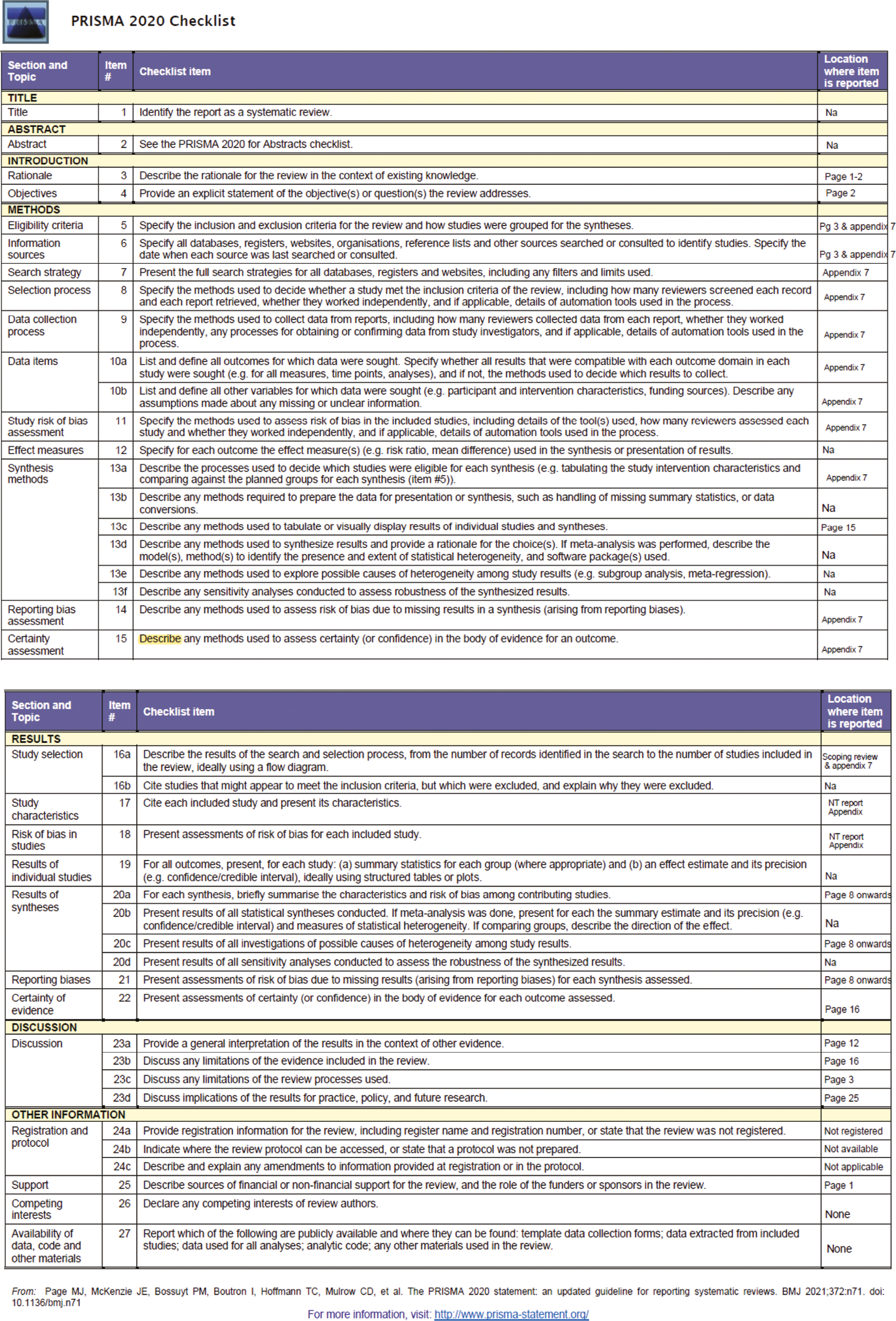

We adopted an evidence-mapping approach,27–29 followed a pre-defined protocol and, where applicable, have reported the methods and findings according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. 30

Eligibility criteria

The review included published studies conducted between January 2015 and July 2021 that evaluated the effect of an outpatient service innovation on outpatient or secondary care activity and resources (e.g. waiting times, referral rates, attendances, missed appointments, costs). Due to the rapid timescale, the review was limited to published articles (grey literature and commentaries were not included). See Appendix 1 for full details of the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Search strategy

We identified studies by searching the online databases MEDLINE, EMBASE, Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI) and Health Management Information Consortium (HMIC). To manage scope, and to capture innovations most relevant to current health services, we limited the review to papers published between January 2015 and July 2021 (search conducted August 2021) and from comparable health systems to the NHS.

Search terms were developed by conducting scoping work for relevant studies. Terms related to the setting, the innovation, and the outcome of interest (see Appendix 1).

Data collection, extraction and synthesis

All references retrieved were exported into EndNote referencing software (v20) and duplicates removed. After removing duplicates, papers were screened in two stages by two researchers [Sarah Reed (SR) and Nadia Crellin (NC)], based firstly on the title and abstract and secondly on the full text. Papers were excluded at each stage if they did not meet the eligibility criteria. For those papers that did meet the eligibility criteria, data were extracted independently by two researchers (SR and NC). See Appendix 1 for details.

We conducted a narrative synthesis, organised by intervention and outcome using a framework that helped identify and classify interventions by type (e.g. virtual appointments, administrative/booking systems) and by their anticipated benefits (e.g. how they might affect outpatient activity or resource use), including optimising referral and booking, modernising consultations and personalising follow-up. See Appendix 1 and Table 1 for further details of the framework categories. The framework was developed in consultation with the PAG prior to undertaking the review. The focus of the review was to report the range of interventions and outcomes that have been explored but not to assess how well the different interventions worked.

| Intervention type | Total studies per intervention type | Potential benefits evaluated by each intervention within the studies | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Optimising referral and booking | Modernised consultations | Fewer and/or more personalised follow-up | ||||||

| Reduce referral volume and improve appropriateness of referrals | Book patients into all available time slots and reduce missed appointments | Using face-to-face only when it adds value | Optimising skill mix and staff mix | Reducing unnecessary administration, optimising clinical time per consultation | Appointments scheduled based on clinical need, streamlining number of appointments | Improving patient support and understanding of when to seek care | ||

| Teleconsultations/virtual appointments (incl. remote monitoring) | 42 | 2 | 1 | 39 | 4 | 4 | 10 | 14 |

| Management tools, administrative systems, and processes to support appointment scheduling (incl. patient reminders and pre-consultation communication) | 44 | 6 | 25 | 2 | 6 | 28 | 10 | 2 |

| New roles, non-specialist-led clinics, including task-shifting | 26 | 4 | 2 | 6 | 25 | 7 | 6 | 9 |

| Drop-in clinics, direct-access clinics, and rapid triage | 24 | 7 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 12 | 20 | 1 |

| Advice and Guidance, shared care models, and models that move care from secondary to primary care settings | 21 | 21 | 0 | 1 | 13 | 1 | 4 | 2 |

| Personalising follow-up and open booking | 7 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 7 | 6 |

| Other (e.g. intensive outpatient care clinic) | 9 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 1 |

Quality assessment

Due to the evidence mapping approach, rapid timescale and broad scope of the review, a quality assessment of included studies was not undertaken.

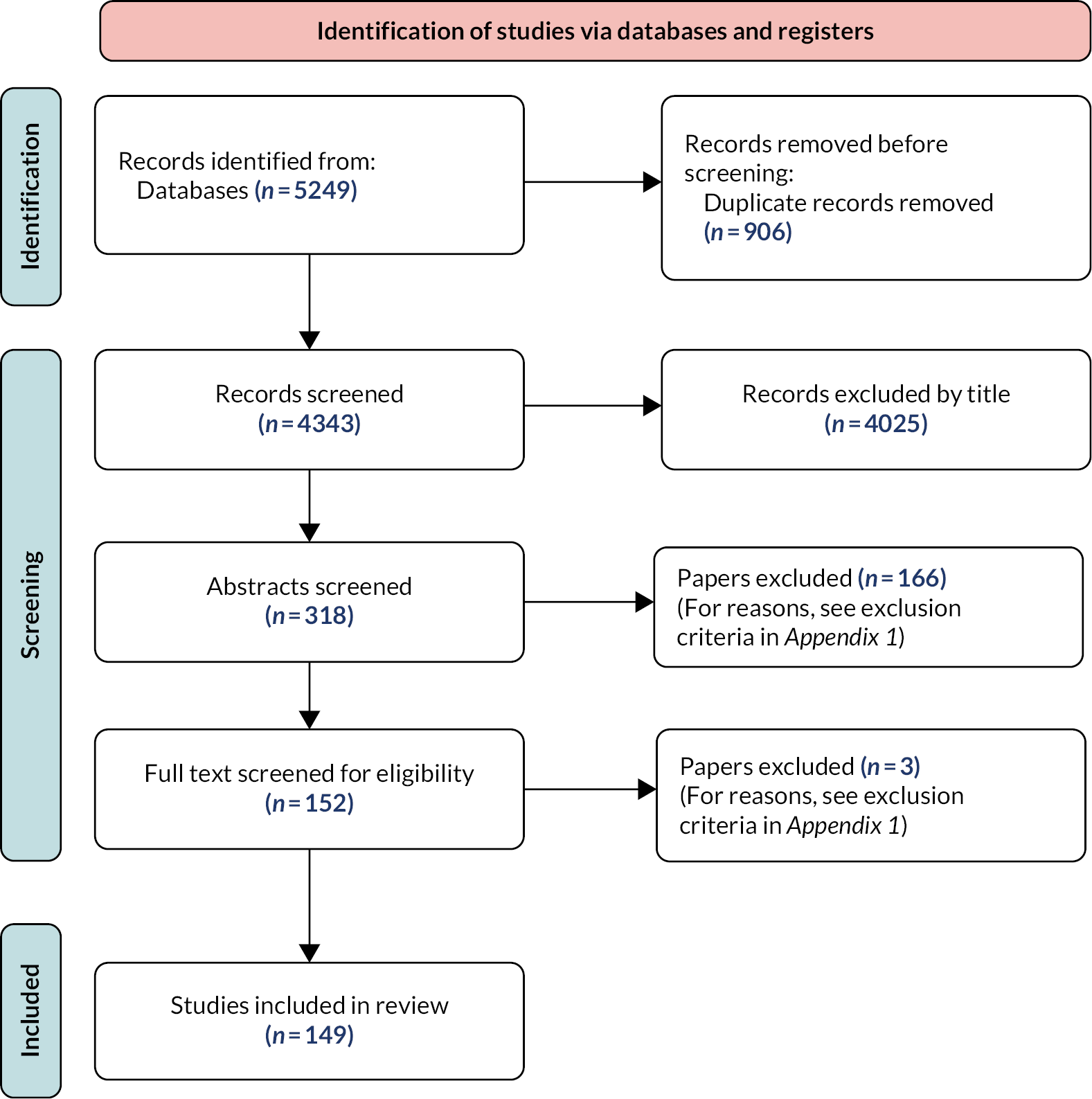

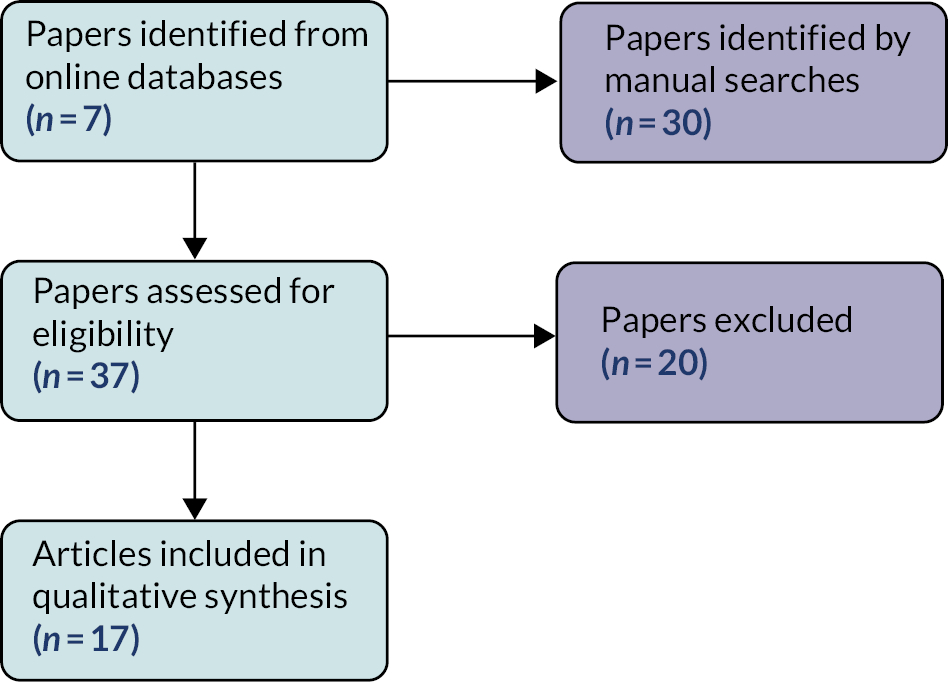

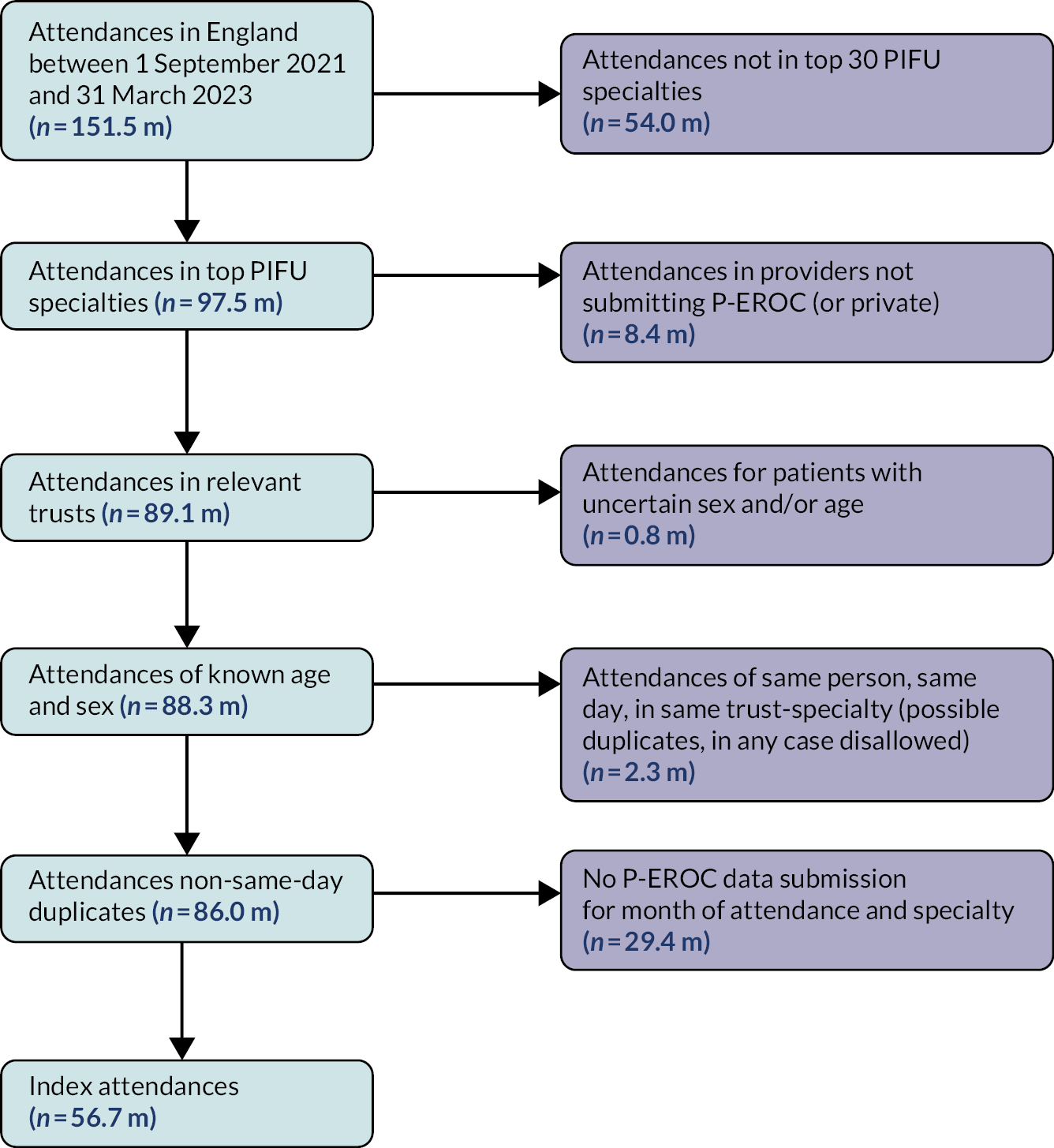

Findings

The initial searches identified 5249 papers, of which 149 were included for review (Figure 2). A summary of the characteristics of these studies is provided in Appendix 1, Table 13. A full list of studies is provided in Report Supplementary Material 1.

FIGURE 2.

Flowchart of study selection.

What innovations have been studied and what are the potential benefits?

We grouped the purposes of innovations into three main areas: (1) optimised referral and booking; (2) modernised consultations and (3) fewer and/or more personalised follow-ups. Within each of these we mapped the potential benefits evaluated by each of the 149 selected studies. This mapping is shown in Table 1 with the innovations specified in the second row and the mapped benefits in the third. For example, innovations with the purpose of modernising consultations could lead to the benefits of only using face-to-face where it adds value or optimising skill and staff mix. The number of studies that addressed each combination of innovation and benefit are also shown in Table 1. Further details on innovation purpose and benefits for each study are provided in Report Supplementary Material 1.

The most studied interventions were management tools or administrative processes to support appointment scheduling (n = 44) and teleconsultations and virtual appointments, including remote monitoring (n = 42). For the former, interventions included pre-consultation questionnaires,31 automated patient reminders (e.g. SMS or telephone),32 predictive models, and electronic booking systems,33 with the key aims of booking patients into all available slots and reducing missed appointments (n = 25) and reducing unnecessary administration to free up more time for appointments (n = 28). Teleconsultations and virtual appointments were most often aimed at modernising consultations, particularly only using face-to-face appointments when it added value (n = 39). 13,34,35

Only seven studies investigated different approaches to personalising follow-up, including more patient-directed or other forms of open access or open booking approaches. This represented the biggest gap in evidence in the existing literature. All seven of these studies evaluated whether personalising follow-up better matched appointment availability with clinical need and all but one evaluated whether it improved patient support and their ability to self-manage and know when to seek professional care.

Other studied innovations included those involving non-specialist-led clinics or expanding of clinical support roles, such as advanced care or nurse practitioners and advanced allied health practitioner roles,36 and patient navigator programmes. 37,38

Other interventions included direct access clinics,39 drop-in clinics and rapid triage services, such as telephone assessment clinics, active triage19 (i.e. referrals for advice only), and electronic triage. 40 Further interventions included shared care models (e.g. between primary and secondary care), for example, integrated, community-based primary-secondary shared care,41,42 and shared care models substituting hospital visits with primary care support. 43

Discussion

Key findings

There are a variety of innovations in outpatient care that have been implemented and evaluated within different health systems. These include changing how appointments are delivered, changing administration and support systems, better engagement with primary care and personalised follow-up. These meet several purposes, ranging from making booking systems more efficient, optimising use of resources to improving the clinical value of follow-up appointments. Virtual appointments and administration and scheduling systems are the most evaluated innovations and only a few studies investigated personalised follow-up.

Strengths and limitations

We are not aware of any previous studies that have reviewed the range and purpose of outpatient innovations implemented internationally. We have tried to be inclusive in the selection of studies, including many from other developed countries. We have also worked with external stakeholders to create a typology of innovations and purposes which was established before undertaking the review.

Because this was a rapid study and to capture innovations most relevant to current health services, we decided not to consider studies published before 2015, and so would have missed further evidence of specific innovations that may have been under-represented within the sample. Due to the scope of the review, we were not able to assess the quality of individual studies and are therefore not able to make any conclusions about the quality of evidence.

While the evidence-mapping approach has provided a good understanding of innovations that have been more or less well studied, it was beyond the final scope of the review to assess the relative effectiveness of the identified innovations to improve outpatient service delivery and summarise the evidence relating to outcomes, such as waiting times for outpatient care, the number of inappropriate appointments and patient health.

Implications and future research

There is currently a focus in the NHS in England and Wales on implementing PIFU, yet the scoping review has shown personalised follow-up and open booking has been little studied. This was one of the motivations for choosing to undertake an evaluation of PIFU within workstream 4 (see Chapters 3–5).

While the focus in the following workstreams is on PIFU, further work is needed to examine the effectiveness of the less well-studied outpatient innovations identified in the review (e.g. rapid triage, Advice and Guidance, models of shared care, direct access) to understand their potential impact. Work should also look to identify factors that might support or hinder the implementation and impact of these innovations, as well as whether and how such innovations might affect health inequalities.

Conclusions

The NHS has been facing significant problems in recent years, including a backlog of elective activity and waiting times for outpatient appointments. To meet these and similar challenges, in other countries health services have been reconsidering the value of outpatient appointments and how they could better meet the needs of patients while making more efficient use of available resources. A range of innovations have been tried out, the most commonly studied being virtual appointments and improved booking systems. Less frequent are studies of innovations that focus on personalised follow-up (e.g. PIFU), as well as rapid triage, Advice and Guidance, models of shared care, and direct access. Given that these innovations are an important component of outpatient transformation in the English NHS, we recommend further study of their impact.

The development and use of a methodology to detect, rank and investigate positive changes in outpatient activity

What this section adds

-

Indicator saturation (IS) methods can be successfully applied to large numbers of multiyear, clinical service-level time series derived from national-scale hospital data sets.

-

These methods simplify complex time series into relatively few best-fit lines and can identify change or break points: points in time where performance on an activity measure appeared to change.

-

The identification and prioritisation of exceptional potentially positive changes was more challenging, in part due to the wide scope of the aim.

-

We nevertheless found a small number of units where potentially positive changes in performance may have been tied to specific service changes.

-

Investigation with trusts raised questions about data quality and highlighted the importance of local data validation.

-

With more tightly focused study aims, IS methods could be more widely used to detect signals of changed performance within large health service data sets.

Introduction

National appointment-level outpatient data have been collected in England since 200344 and is made available for research and other secondary uses as Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) and Secondary Uses Service data (typically the latter for NHS organisations, the former for researchers and other users). After 20 years, while there are concerns about aspects of data quality,45,46 the data set has proven to be a substantial resource for service evaluation and research, although one which could be used more extensively.

One challenge comes from its size. In the most recent financial year 2022–3, it reported on 123.8 million appointments for 23.3 million people, in 170 clinical specialties, across 295 acute care providers (mostly NHS hospital trusts).

Rapid scoping review of outpatient innovations outlined approaches to reduce rates of unnecessary attendances, make better use of virtual consultations, and reduce the number of DNAs among other strategies to improve outpatient services. In 2019, the SAB recommended that we might prioritise evaluating innovations in outpatient service delivery as an important policy area with which secondary services were grappling.

One innovation of NIHR RSET has been the approved access to HES outpatient (HES OP) data collection for NIHR RSET programme work. This offered an opportunity to use data-led techniques to identify potential innovations that might benefit from evaluation.

In theory, where an innovative service change had been implemented, and the innovation had a direct or indirect positive effect on a measure of outpatient activity, it is possible that we might be able to detect the change retrospectively in HES OP data with an appropriate analytical methodology.

In this workstream we aimed to develop such a methodology. The anticipated outcome was a small list of clinical units with exceptional positive recent performance. We would then attempt to contact the relevant units to investigate potential reasons for the detected changes. Where innovative service changes were plausibly suggested as having caused or contributed to the detected changes, we would consider one or two units for more detailed mixed-methods evaluation work.

Hence, we aimed to implement the ‘positive deviance’ approach to improving quality of health care. This methodology, as described by Bradley et al. ,47 aims to identify exceptional performance that already exists within healthcare organisations, and follows this with detailed investigation, testing, and finally dissemination of evidence about best practice.

The aim was that the methodology should be able to prioritise between a potentially very large number of signals of positive change in HES OP data, covering different outpatient activity measures, and multiple clinical specialties within English NHS hospital trusts.

However, methods to achieve the above are not well defined. So, as well as being a potential prelude to evaluation, we hoped that this workstream would help to define new methods that might be applied perhaps not just to outpatient data, but more generally.

We took as a starting point the approach of Walker and colleagues. 48 In their 2019 paper, they outlined a novel approach to automatically detect the timing and magnitude of changes apparent in prescribing data. Noting that previous work to quantitatively assess implementation of new practices ‘has typically relied on measuring change at the level of a whole population, using techniques such as interrupted time series analysis or static measures of variation in care at one point in time’, they presented indicator saturation (IS) techniques as robust, systematic methods to find meaningful changes in data over many institutions, over any general time. These methods – adapted from econometric modelling – were able to detect ‘structural changes’ or ‘breaks’ in time series data ‘without imposing an intervention or change date a priori.’

Ultimately, in part due to the decision to focus the evaluation efforts on PIFU, we did not achieve all the aims. The analysis involved was complex, and we were not fully able to test the consequences of choices made within the context of a rapid evaluation study. However, we learnt several valuable lessons and discuss these at the conclusion of this section.

Aims

We aimed to develop a methodology to produce a ranked list of units (a unit being a clinical specialty at an English NHS hospital trust) where there was evidence of apparent exceptional positive improvement made in performance on an outpatient activity measure. We also aimed to identify whether positive changes identified may have been linked to specific service changes in trusts.

We addressed RQs 2 and 3 (see Background and context):

-

Can we identify from routine data any trusts or trust specialties that have exhibited significant and sustained changes in outpatient activity that might be indicative of the impact of innovations in service design? (RQ2)

-

Can any of these identified changes in outpatient activity be linked to specific innovations in care? (RQ3)

Methods

General approach

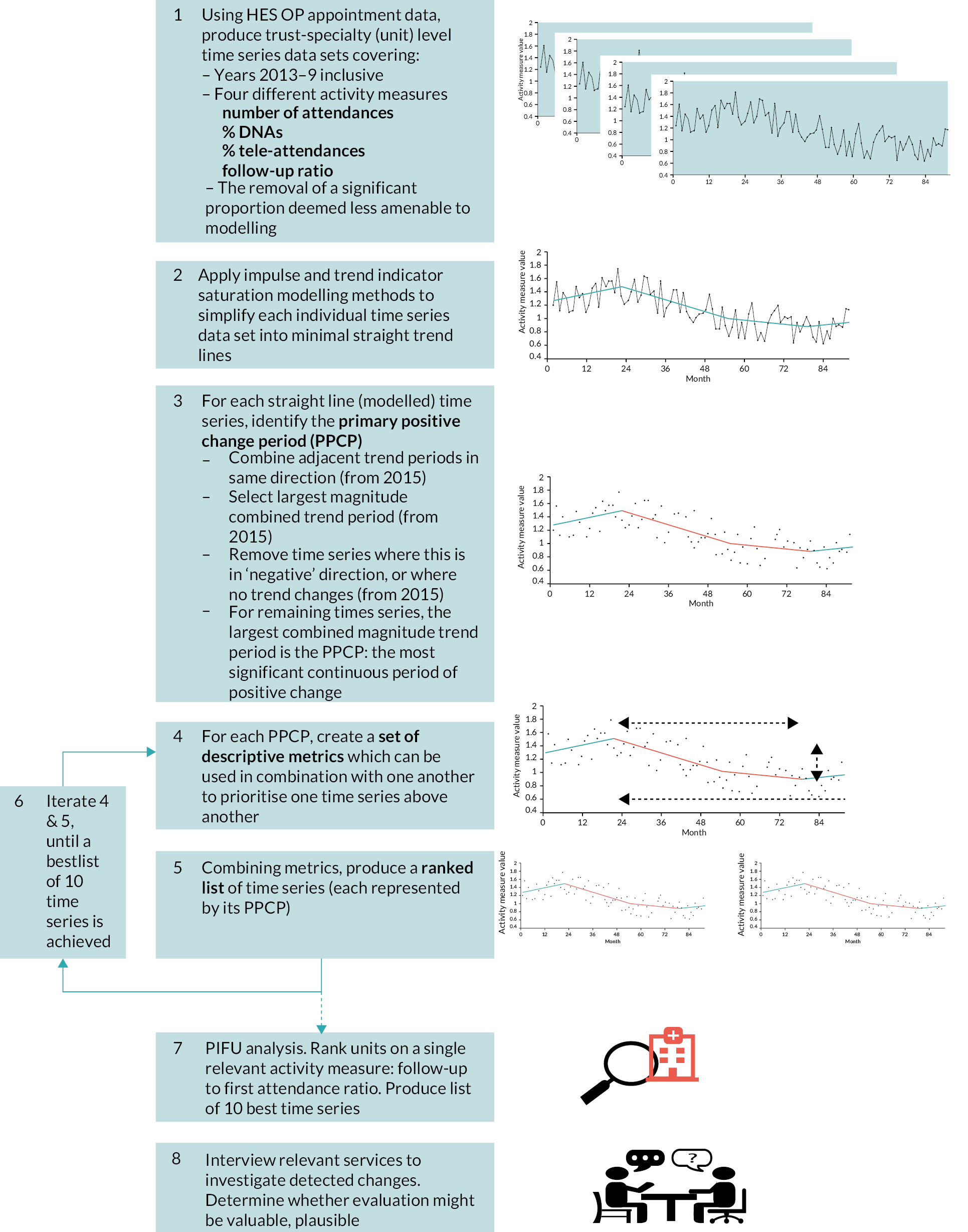

Figure 3 provides a summary of the approach. The analysis aimed to act as a filter and prioritisation tool to select approximately ten time series from upward of 20,000.

FIGURE 3.

Stages of analysis.

Data

For the main analysis, we used HES OP data from 12 December 2012 to 31 December 2019 (see below for explanation of the time periods used). Within this period, we searched for positive changes during the 5 years from 7 January 2015 to 31 December 2019 (referred to as the ‘search’ period), with the 2 earlier years 12 December 2012 to 6 January 2015 used to provide baseline information (referred to as the ‘baseline’ period).

We purposefully stopped the search period at the end of 2019, before the COVID-19 pandemic affected hospital services. The impacts of COVID-19 were significant and sudden, especially compared to pre-pandemic changes that might have reflected the impacts of innovations. 49 However, before the final selection of units at the latter stages of analysis, we used HES OP data to document follow-up and first attendance data to July 2021 (to test whether improvements had been sustained into the pandemic period).

Construction of time series of outpatient activity measures

From the appointment-level data, we created a large number of time series data sets (over 20,000 in total).

These included data describing four different measures of outpatient activity over time:

-

Attendances: count of all attendances.

-

DNAs: percentage of appointments not attended.

-

Tele-attendances: percentage of attendances that were tele-attendances/virtual consultations.

-

Follow-up to first attendance ratio: the number of follow-up attendances divided by the number of first attendances.

Each of these measures was simple to define, could be constructed with relatively few data quality concerns and was of a status whereby a change in the measure might plausibly have reflected positive impacts of active service change.

For attendances, DNAs, and the follow-up to first attendance ratio, a fall in measure values over time was considered to be broadly in line with the intended outcome of national strategies, while for tele-attendances, rising values were important.

Each activity measure was calculated for every English NHS hospital trust and clinical treatment specialty combination (each trust-specialty combination referred to in this section as a ‘unit’). For trusts which had closed or merged with another since 2012, we included historic activity against the relevant succeeding trust code reported in the NHS Organisation Data Service at May 2021. 50

In creating time series from appointment-level data, we aggregated into periods of 28 days, based on sets of 4 consecutive Wednesday to Tuesday weeks (ending Tuesday, 31 December 2019). This was a pragmatic choice: each time series would be constructed from a reasonable 92 points (there being 92 28-day periods between 12 December 2012 and 31 December 2019), and each time unit would contain the same number of days and the same number of working days (outpatient activity being relatively scarce on weekends). 49 We were not particularly interested in activity measure changes on scales shorter than 28 days. We focused development work on relatively high-volume units where it would be more likely that changes in activity would be found to reach statistical significance and also be of practical relevance. We made a series of exclusions of units where there were relatively few attendances and a further set of exclusions specific to DNA, tele-attendance, and follow-up ratio measures (see Appendix 2, Section 1).

Data extraction was carried out in Statistical Analysis System (SAS) v9.4 (SAS Institute, North Carolina, US). Time series construction and exclusions were carried out in R (tidyverse) (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). 51

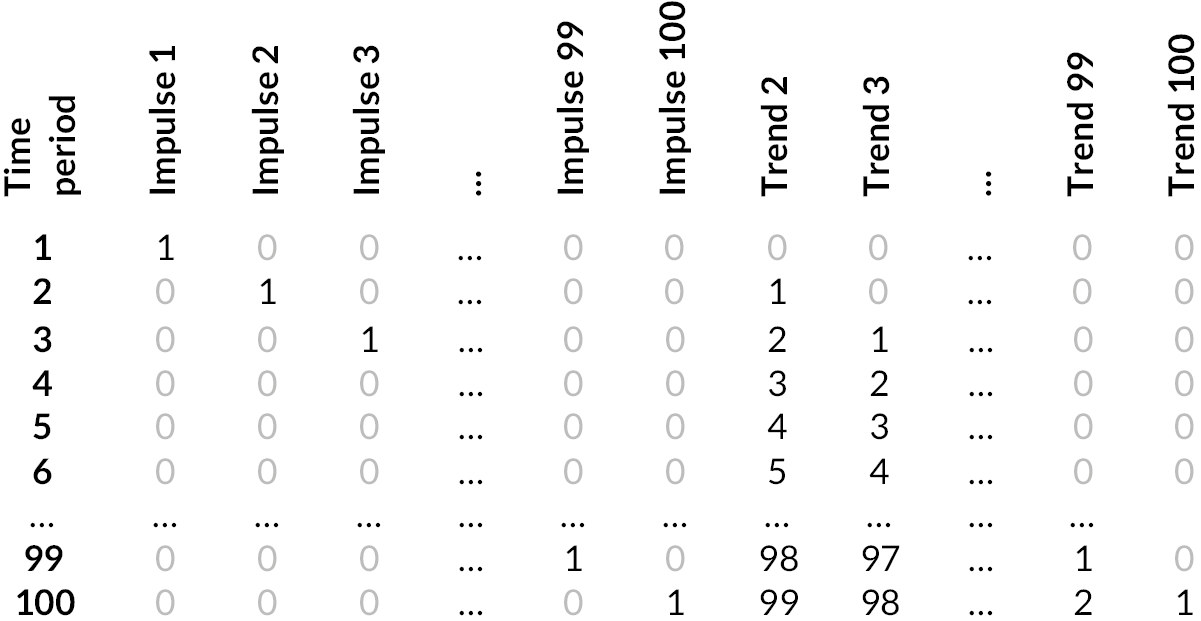

Application of indicator saturation to time series – detecting break points, and outliers

We applied impulse and trend IS modelling methods to all remaining time series (see Appendix 2, Section 2 and Appendix 2, Figures 21 and 22).

The trend-IS modelling had the effect of simplifying each time series into a relatively small number of best-fit trend lines, with break points between adjacent trend lines. The impulse-IS allowed for the handling of outlying data points.

Before applying to all time series, we needed to determine the specific implementation of impulse- and trend-IS appropriate to the four outpatient data measures, making choices about form of the models fitted and various modelling parameters. We started with attendances and expanded to the other measures. The approach – which took as its starting point the method used by Walker et al. 48 – was broadly as follows:

-

A ‘fully saturated’ model was set up (see Appendix 2, Section 2).

-

For attendances we added two dummy variables: one to signal 28-day periods containing Christmas Day, and another to count bank holidays. These were not necessary for the three other measures, which were ratios of activity.

-

The models specified in formulae (1) and (2), as appropriate, were estimated.

-

We chose a level of significance of p = 0.000001 to ensure a low false-positive rate and a ‘block size’ of 15, to ensure relatively few break periods per time series.

| Attendances | Yt= | μ | + βbh count + βchristmas | +∑j=1nγj1{t=j} | +∑j=1nδj1{t−j}(t−j) | +ut | (1) |

| DNAs Tele-attendances follow-up ratio |

yt= | μ | +∑j=1nγj1{t=j} | +∑j=1nδj1{t−j}(t−j) | +ut | (2) | |

| Explanation of terms >> | Rate | Intercept | Bank holiday and Christmas indicators (attendances only) | Impulse indicator | Trend indicator | Error term |

Given the large number of time series we were modelling, we were not looking to specify an approach that described every time series optimally, rather we required that the large majority of those we viewed had a reasonable fit when assessed empirically with relatively few, but practically significant, trend lines fitting the underlying data.

The modelling was carried out in R, with IS modelling applied using GETS package (version 0.21). 52

All subsequent analyses were carried out in R.

Selecting each time series’ primary positive change period

With IS methods applied, each time series was now represented by relatively few best-fit trend lines (typically fewer than four). From this point onward in the methodology, formal, well-defined statistical methods had relatively little part to play, and the approach was determined iteratively and pragmatically.

The first task was to define, for each time series, what we called the primary positive change period (PPCP) during the search period. This would be used to represent the time series in the subsequent ranking.

The PPCP would exist for time series where: (1) there was at least one break point (trend line change) in the search period and (2) where the largest magnitude trend period change (this might be a series of adjacent trend periods in the same direction, treated as one) was in the ‘positive’ direction. Where both conditions were true, the largest magnitude positive change was defined as the PPCP.

Time series without a PPCP were not eligible for subsequent ranking.

Classifying units via their primary positive change periods: creating summary metrics and ranking

Summary ranking metrics

For the remaining time series, the PPCP now primarily represented the unit/activity measure for the purpose of ranking.

We created a series of ‘summary metrics’ to describe each PPCP, and to help us to compare one unit with another, following the approach of Walker et al. 48 (Note: we use ‘metrics’ to refer to values used for ranking, vs. measures which are the underlying outpatient activity measures or data. See Glossary).

For example, two metrics we defined were the magnitude of change and the length of change. The former measured the total extent of the positive change in the activity measure during the PPCP (e.g. the total fall in attendances per 28-day period from the start of the PPCP to the end). The latter measured the time over which the change occurred (e.g. the PPCP might have been 56 days long, or 280 days or some other length).

The process we used to define summary metrics was iterative. We were guided by considering pairs of theoretical time series with small but realistic differences, in each case asking which we would prioritise above the other. Appendix 2, Section 3 and Appendix 2, Figure 23 give an example of the considerations.

It should be emphasised that these metrics were aimed at summarising and comparing, in general, different types of activity measure with one another (e.g. changes in attendance rates vs. changes in follow-up to first attendance ratios). This increased the complexity of the ranking approach development. This also meant that we used transformations for each metric, typically rescaling values on to a 0 (neutral/poor performance) to 1 (good performance) scale.

Combining metrics: ranking

The ranking process started simply – we calculated an overall ranking score for each unit by summing the transformed descriptive metrics, weighted for the perceived importance of each metric. We were not overly concerned about starting weights as we intended for there to be multiple iterations.

Two researchers [Jonathan Spencer (JS) and Theo Georghiou (TG)] reviewed a selection of units at the top, in the middle and at the bottom of the ordered list of all ranked units. We reflected on factors including the mix of measures (did the ranking seem to be penalising or promoting one measure above others?) and understanding units which, for example, had been promoted to the top on the basis of changes that were clearly not likely to be related to service changes (e.g. where large changes were most likely to be data errors). Specific additional metrics were developed in the context of ranking iterations to solve some of the problems identified.

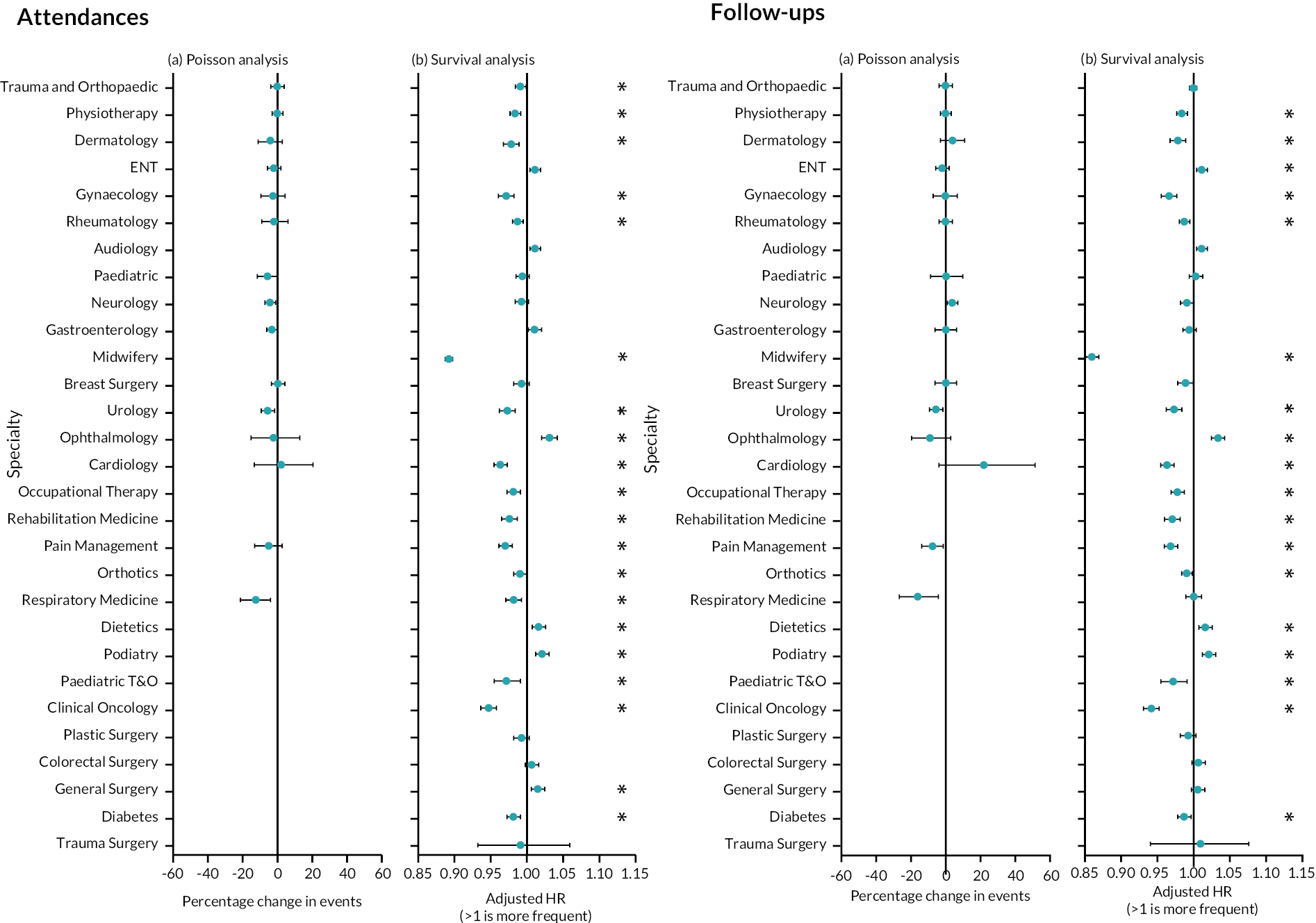

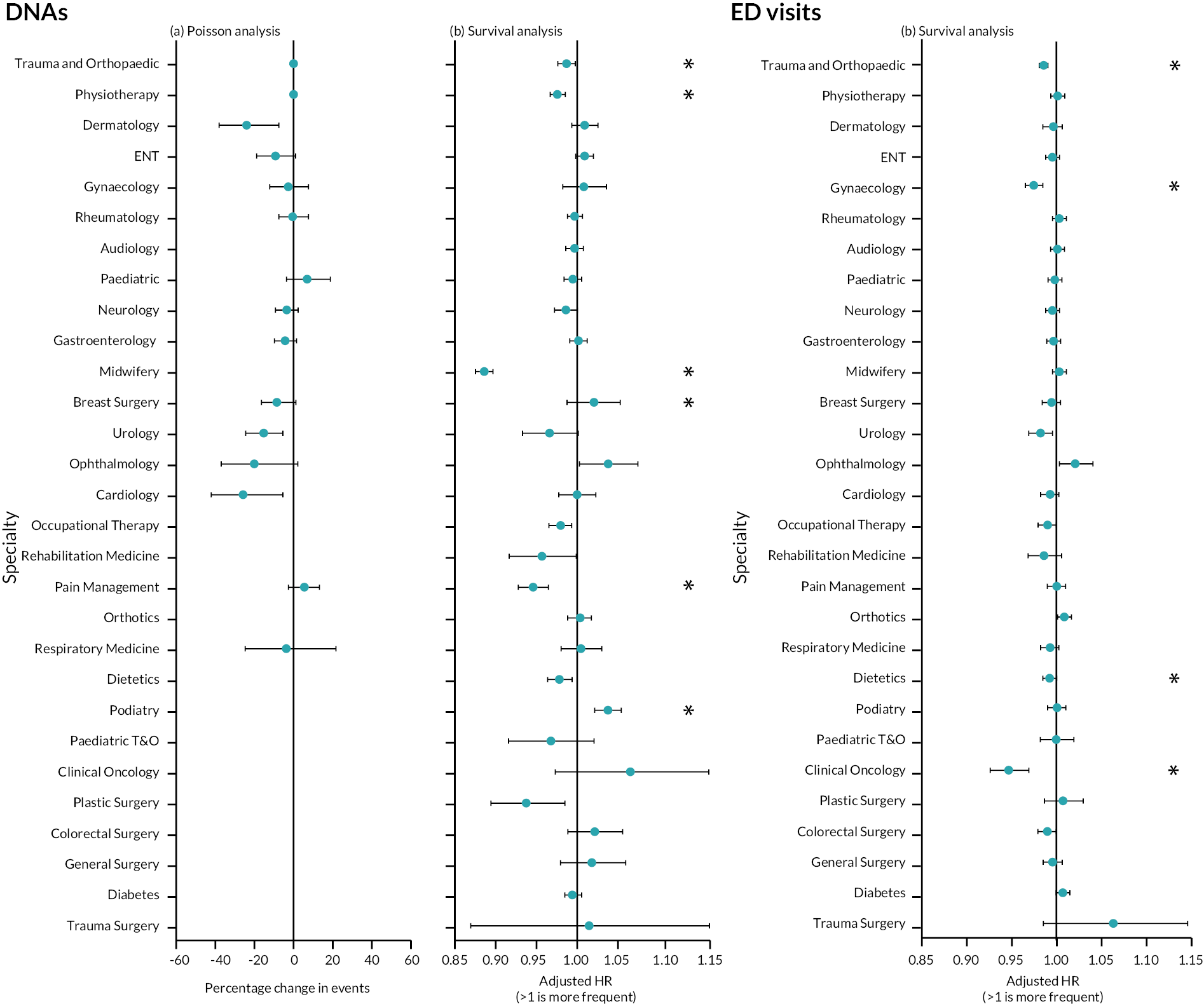

Focus on Patient-Initiated Follow-Up

Selecting time series for a single activity measure: follow-up to first attendance ratio

As the study’s focus shifted to the implementation of PIFU, the task became analytically simpler. We aimed to identify 10 or so units with reductions in numbers of follow-up attendance relative to first attendances. This was considered to be a plausible and desired impact of effective implementation of PIFU. 53

We used modelled time series and descriptive metrics produced up to this point rather than designing and carrying out a new analysis, and the process for final unit selection relied on a significant amount of manual researcher input, rather than a purely numerical ranking. This was driven by the research schedule, but it was enabled by the significant reduction in the number of time series being considered and the removal of the need to balance across different activity measures.

We first imposed new sets of filters to exclude a large proportion of follow-up to first attendance ratio time series. Two researchers (JS and TG) subjectively ranked several hundred remaining time series.

The top-rated 36 were then reduced to nine priority candidates by three researchers [JS, TG and John Appleby (JA)]. To prioritise these final units, we considered the trends prior to the PPCP, what had happened to the other activity measures (including the volume of activity) for the trust/specialty and we additionally considered whether the improvements had been sustained into the pandemic period (to summer 2021).

Service interviews

We contacted the nine selected hospital trusts by e-mail, in each case targeting chief executives and directors or managers of service transformation. The e-mail informed the recipient that an analysis of national data had identified that their trust – in a specific-named specialty – had been found to have made significant reductions in numbers of follow-up attendances relative to first attendances, starting at a specific year. We requested a meeting to present findings and to ask questions about how the service might have changed in the relevant period. Where we received no reply, we followed up with up to two e-mails.

Three trusts welcomed a meeting. To these we sent a brief (three-page) data pack, succinctly outlining trust- and clinical specialty-specific findings on the ratio of follow-up to first attendances over time, and we also included performance against national trends. We posed three questions in preparation for the discussion:

With respect to the reduction in follow-up to first attendance ratios between 2015 and 2020 [and with a special focus on changes from (specific year)]:

-

To what extent has this reduction been recognised by clinical and managerial leaders in the specialty and trust? If yes, in which forums and with whom was it discussed? What actions did it lead to, if any?

-

Does this reflect something you tried to achieve?

-

Are you able to identify specific initiatives or activities that might have contributed to these reductions? What are these?

Semistructured interviews were held virtually in January and February 2022 and were 45 minutes in length, each attended by two researchers. Interviews were carried out with a prepared topic guide outlining pre-set questions about the interviewee, the service and reflections on the trends, including questions around whether any specific initiatives or innovations might have contributed to the trend.

Results

Summary of implementation of approach

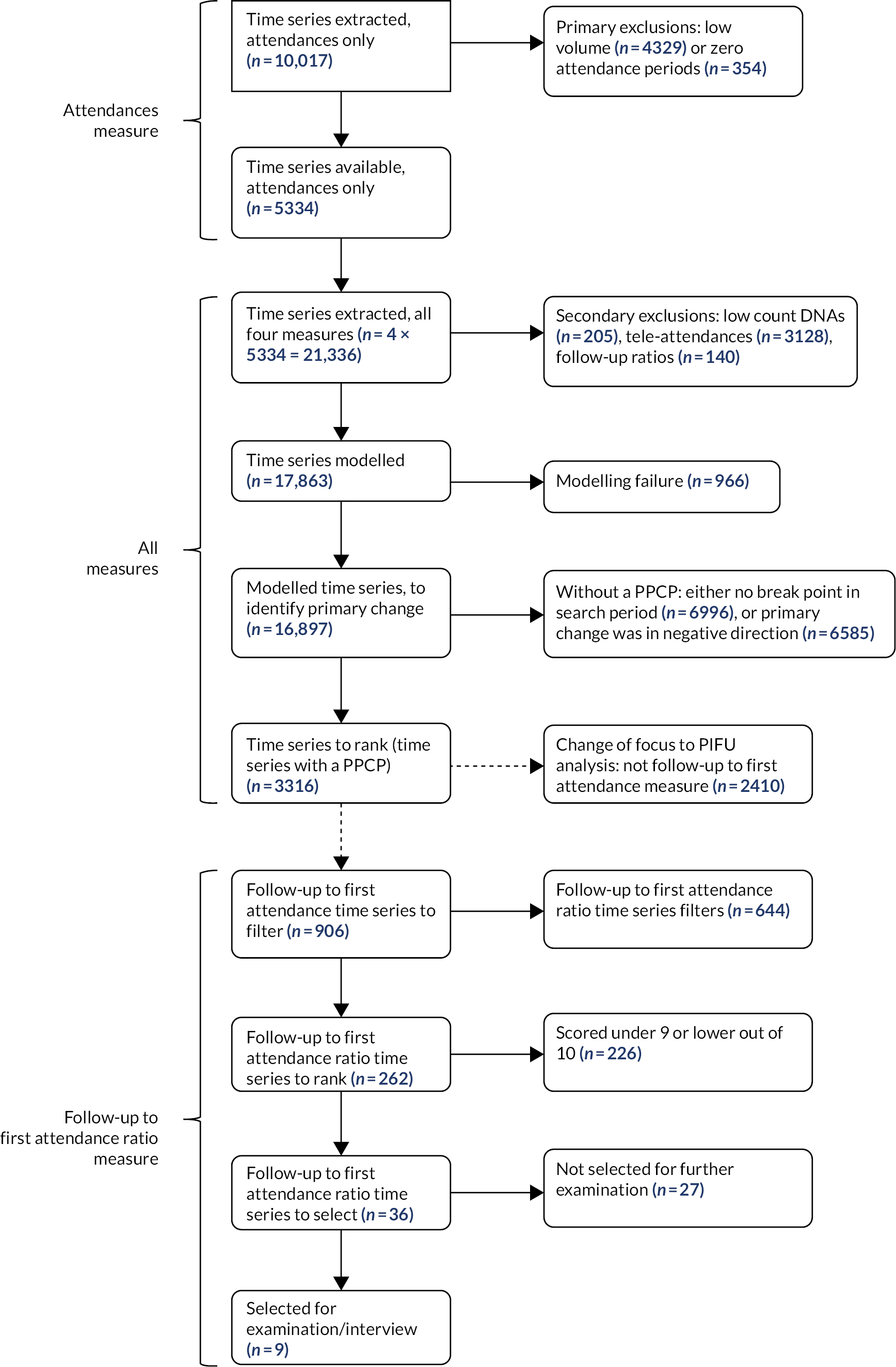

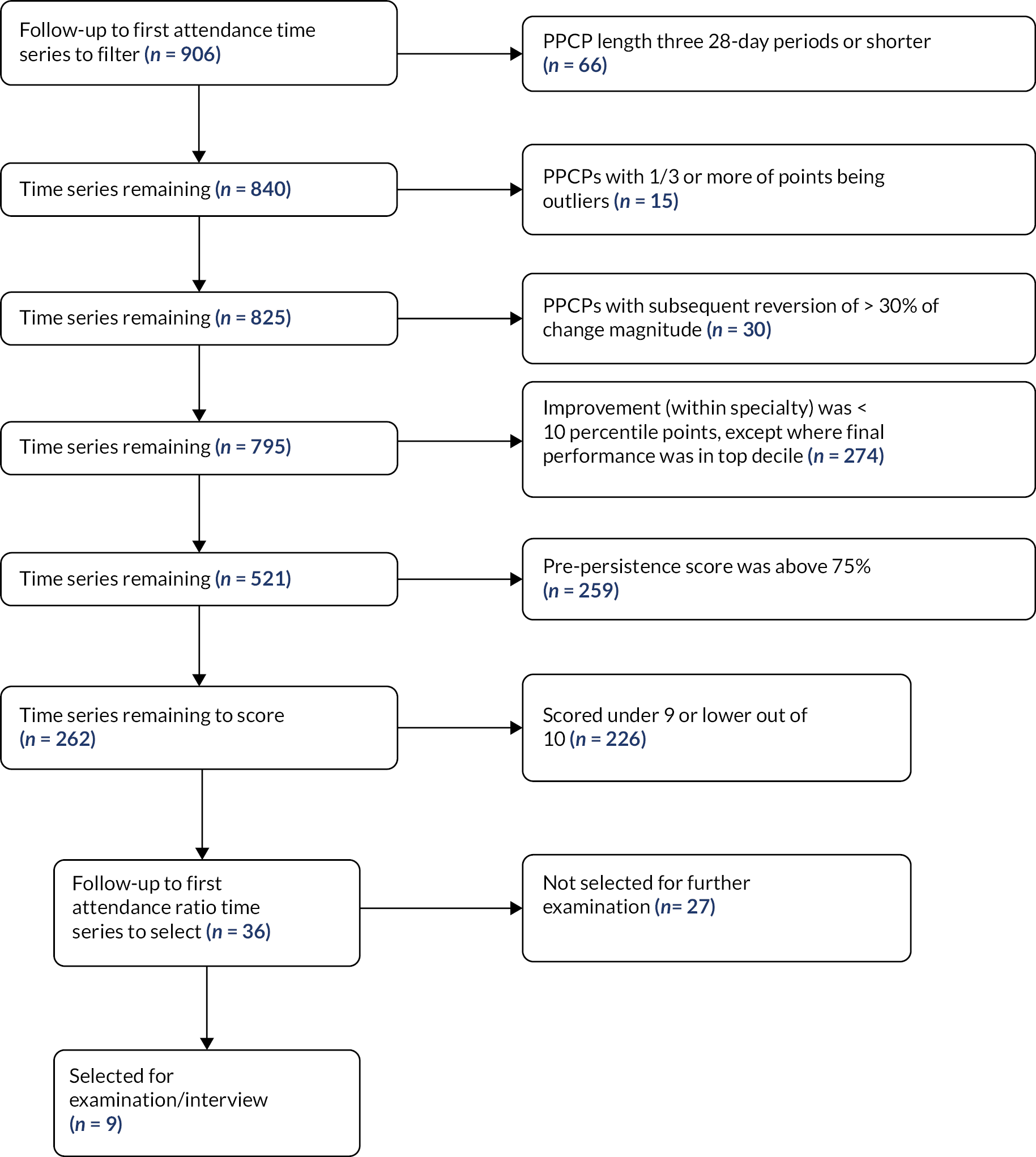

The flow chart in Figure 4 summarises the implementation approach of the analysis, through numbers excluded at each stage.

FIGURE 4.

Flow chart summarising numbers of time series and exclusions. The stages are grouped under three categories, depending on which outpatient activity measures were relevant (left-hand side).

We extracted outpatient activity attendance time series data for 10,017 units covering 190 trusts and 153 treatment specialties (Table 2). We excluded 4329 (43.2%) units with low activity volumes (fewer than 100 mean attendances per 28-day period in the most recent calendar year 2019). A further 354 units (3.5%) were excluded as they had one or more 28-day periods (between 2017 and 2019) with zero attendances.

| Summary of stage of time series and exclusions | Units excluded | % | Units remaining | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total units initially extracted | – | – | 10,017 | (100%) |

| Primary exclusions (based on attendances) | ||||

| Low recent volumes (< 100 per 28-day period) | 4329 | (43.2%) | 5688 | (56.8%) |

| Zero attendance 28-day period | 354 | (3.5%) | 5334 | (53.2%) |

| Total after primary exclusions | 4683 | (46.8%) | 5334 | (53.2%) |

| Secondary exclusions (measure-specific) | ||||

| Attendances: (no further exclusions) | 0 | (0%) | 5334 | (100%) |

| DNAs: < 5 per 28-day period | 205 | (3.8%) | 5129 | (96.2%) |

| Tele-attendance: < 5 per 28-day period | 3128 | (58.6%) | 2206 | (41.4%) |

| Follow-up to first attendance ratio: <5 per 28-day period | 140 | (2.6%) | 5194 | (97.4%) |

| After primary and secondary exclusions: sum of four measures for modelling | – | – | 17,863 | – |

There were 5334 units (53.2%) remaining for potential modelling. For each of these units we constructed three additional time series, one for each of the other outpatient activity measures (DNA, tele-attendance, follow-up to first attendance ratio).

Secondary exclusions were made, such that 17,863 time series were finally taken forward for modelling. The tele-attendance time series were the most likely to be removed at this point: only 2206 time series were taken forward for modelling (vs. over 5000 each for each of the other three time series).

Application of indicator saturation to time series – detecting break points and outliers

Indicator saturation modelling was successfully applied to 16,897 of 17,863 time series. This was the case for 100% of attendance, 95.7% of DNA, 97.4% tele-attendance and 86.8% of the follow-up ratio time series.

Table 3 summarises characteristics of the resulting IS-modelled time series. DNA rates generally fell over the 7-year period. The opposite was the case for tele-attendances, and follow-up to first attendance ratios were stable.

| Activity measure | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attendances | DNA | Tele-attendance | Follow-up to first attendance ratio | ||

| Number time series, modelling attempted | 5334 | 5129 | 2206 | 5194 | |

| Number time series, successfully modelled (% of attempted) | 5334 (100%) | 4908 (95.7%) | 2148 (97.4%) | 4507 (86.8%) | |

| Mean value start baseline period (12 December 2012) (interquartile range) | 746 (133–919) | 8.6% (5.3–11.1%) | 2.5% (0–9.0%) | 3.7 (1.3–3.8) | |

| Mean value start search period (7 January 2015) (interquartile range) | 1145 (246–1370) | 7.9% (4.9–10.0%) | 3.6% (0.0–3.3%) | 3.5 (1.3–3.7) | |

| Mean value end search period (31 December 2019) (interquartile range) | 1077 (244–1300) | 7.2% (4.4–9.0%) | 10.1% (1.8–14.7%) | 3.6 (1.2–3.7) | |

| Mean number of changes (break points) during baseline and search period (12 December 2012 to 31 December 2019) | 2.14 | 1.83 | 1.68 | 1.72 | |

| Mean number of changes (break points) during search period (7 January 2015 to 31 December 2019) | 1.46 | 1.27 | 1.46 | 1.18 | |

| Number of series (%) with N changes (break points) during search period (7 January 2015 to 31 December 2019) | N = 0 | 1955 (36.7%) | 2160 (44.0%) | 696 (32.4%) | 2185 (48.5%) |

| N = 1 | 1010 (18.9%) | 683 (13.9%) | 433 (20.2%) | 638 (14.2%) | |

| N = 2 | 1440 (27.0%) | 1330 (27.1%) | 676 (31.5%) | 1072 (23.8%) | |

| N = 3 | 452 (8.5%) | 426 (8.7%) | 174 (8.1%) | 288 (6.4%) | |

| N = 4 | 200 (3.7%) | 137 (2.8%) | 98 (4.6%) | 157 (3.5%) | |

| N = 5 + | 277 (5.2%) | 172 (3.5%) | 71 (3.3%) | 167 (3.7%) | |

| Number with any outliers during search period (2015–9) (%) | 168 (3.1%) | 177 (3.6%) | 329 (15.3%) | 345 (7.7%) | |

| Mean number of outliers during search period (2015–9) for time series with any outliers | 4.0 | 2.9 | 3.5 | 2.8 | |

The IS modelling resulted in 1.7–2.1 break points on average (depending on activity measure) during the 7 years of the entire period, and 1.2-1.5 break points during the 5 years of the search period.

During the 5-year search period many time series (up to almost half, depending on activity measure) had no modelled breaks (and so were modelled as a single trend line). The next most likely outcome was two breaks (three trend lines). A minority of time series (3.3―5.2%) had five or more break points (six or more trend lines).

Modelled outlying points were common for tele-attendance time series (15.3% had at least one), but less so for the other activity measures (e.g. only 3.1% of attendance time series had at least one).

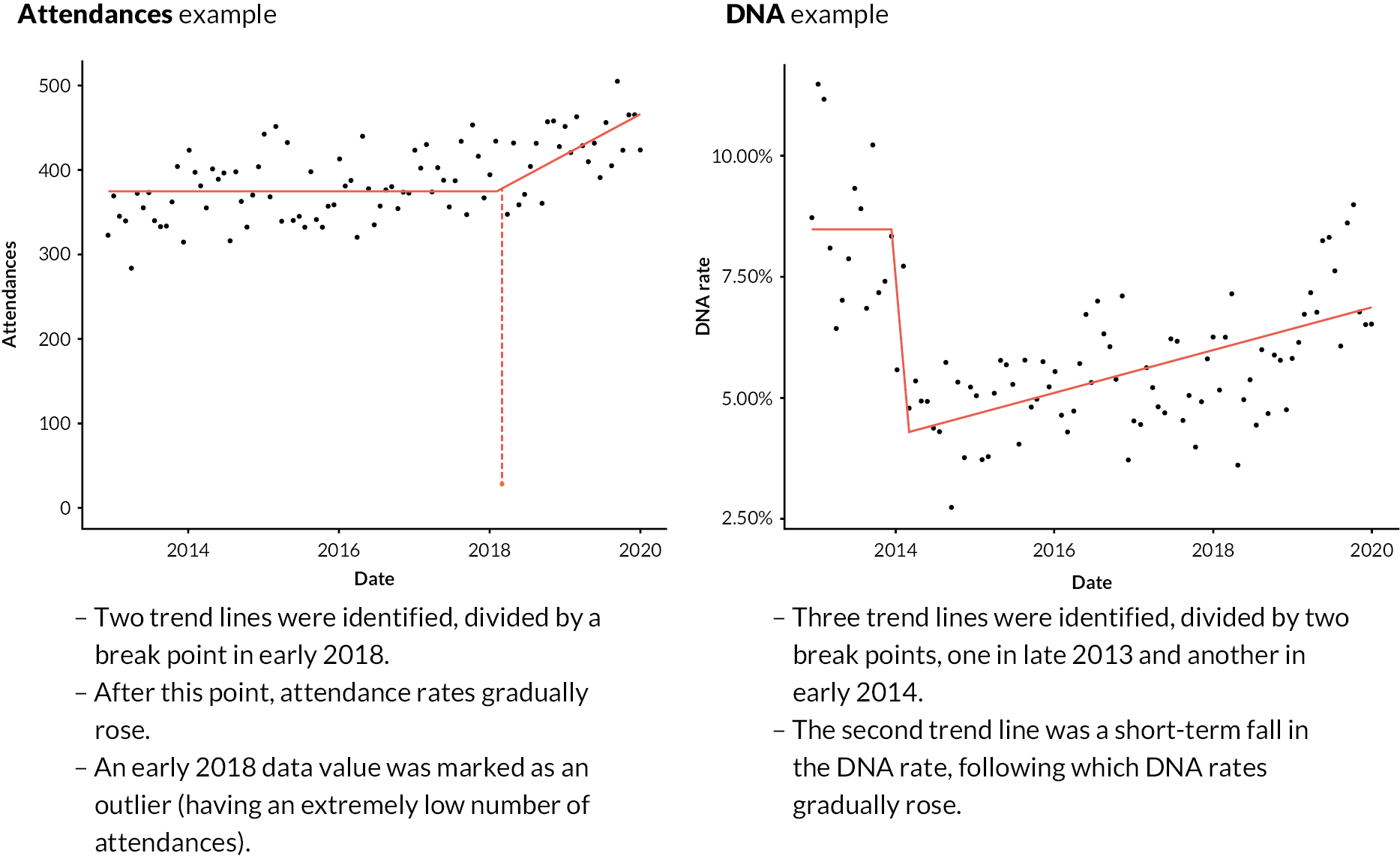

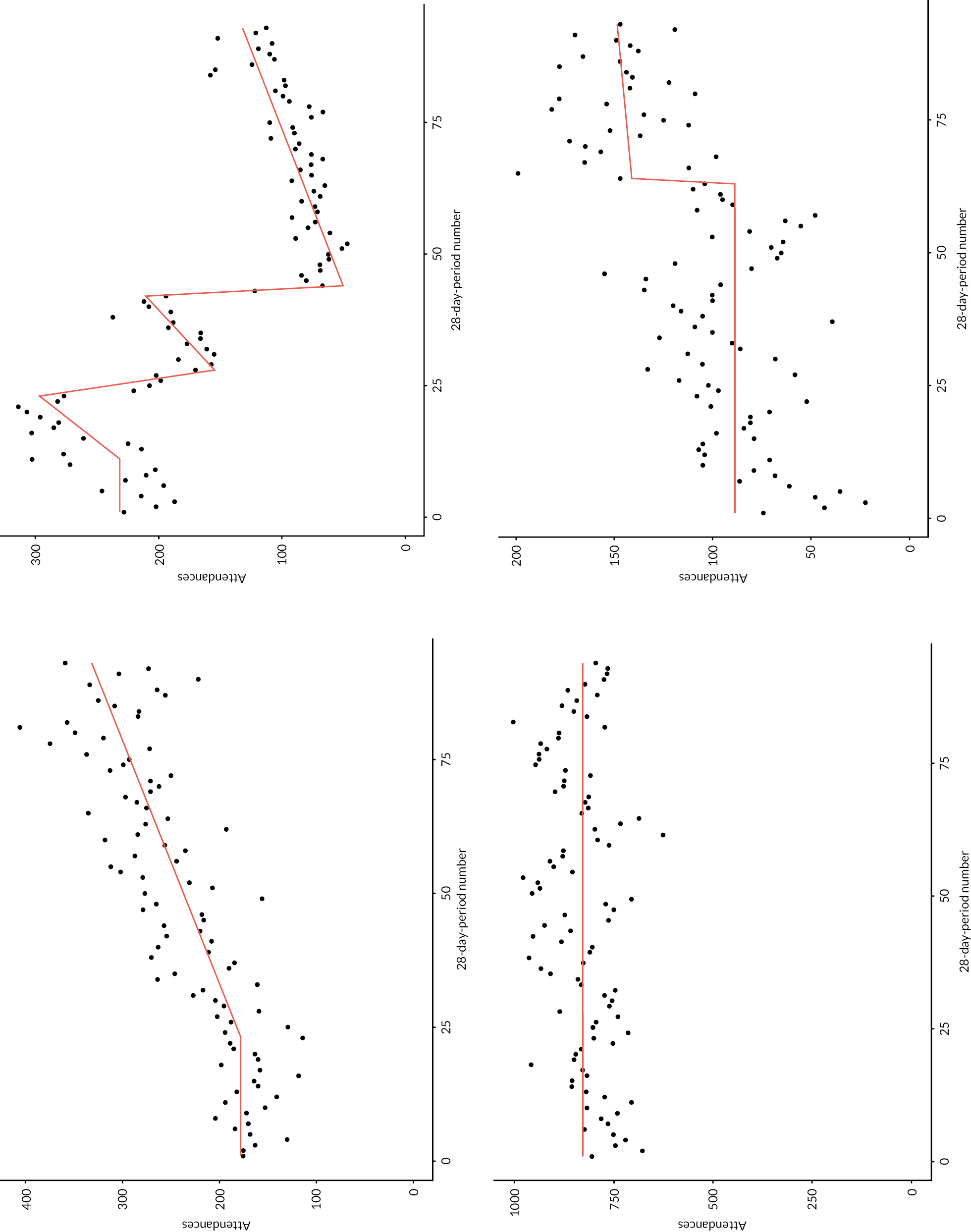

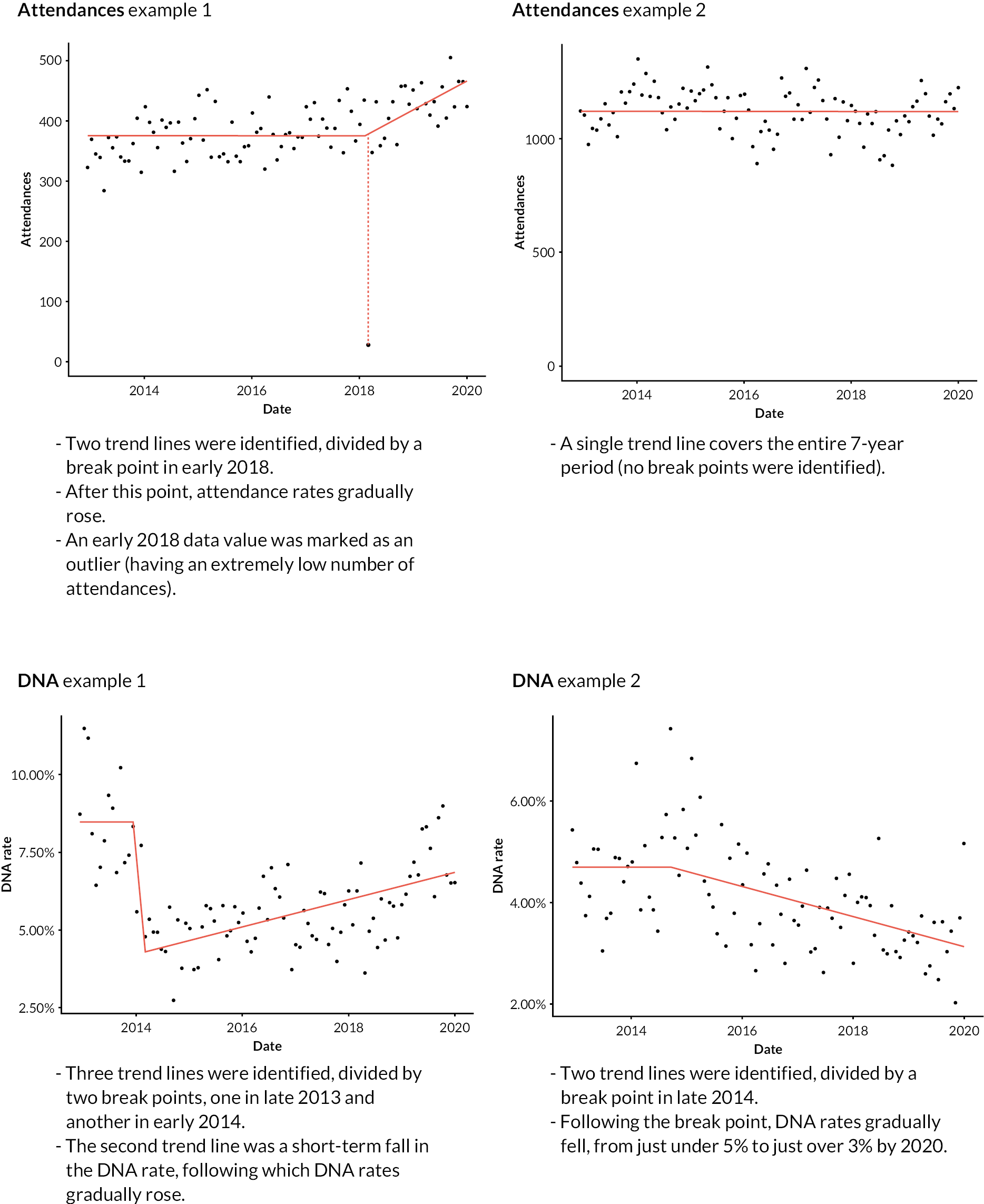

Figure 5 shows trend lines for two example time series (one for attendances, the other DNAs), overlaid on the data points, including a brief description of the key features of each. Appendix 2, Figure 24 includes further examples (two for each activity measure).

FIGURE 5.

Two examples of IS-modelled time series, with key features noted. Points are 28-day period values during the baseline and search periods (late 2012 to end-2019). Red lines are IS-modelled trend lines. Outlying data points are shown in orange, attached to a hashed vertical line (attendances example).

Selecting each time series’ primary positive change period

Across the four activity measures, 16,897 time series were successfully IS-modelled. During the search period, 6996 (41.4%) had no change and were excluded from ranking. This left 9901 (58.6%) time series with at least one change in the search period. For these, where adjacent trend periods were in the same direction, we effectively merged trend lines and treated them as a single trend line.

We calculated the largest magnitude trend change for each time series as the ‘primary change period’. This was done over the merged sets of trend lines and only from the start of the search period 7 January 2015 if the trend started in the baseline period. Of these time series, 3316 (19.6% of the original 16,897 time series) had primary changes in the ‘positive’ direction; these were those that were eligible for subsequent ranking, with the primary change period redefined as the PPCP. Table 4 gives numbers of these time series by measure.

| Attendances | DNA | Tele-attendance | Follow-up to first attendance ratio | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number with a PPCP (% of all with a PPCP) | 660 (19.9%) | 772 (23.3%) | 978 (29.5%) | 906 (27.3%) |

The remaining 5188 had primary changes in the negative direction; these were not eligible for ranking but were used to calculate some ranking metrics.

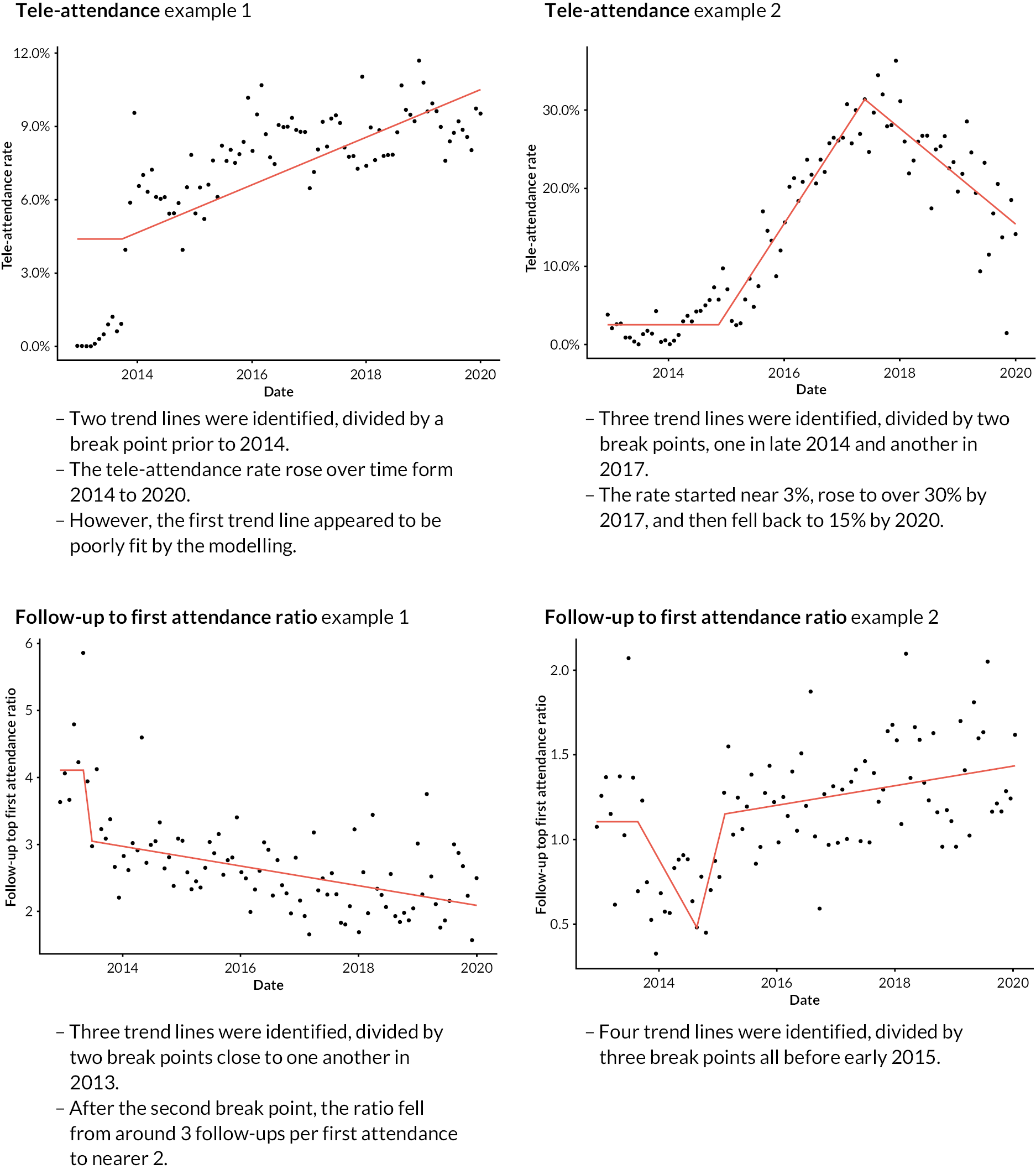

Appendix 2, Section 5 and Appendix 2, Figure 25 outline with example time series the choices we made about selecting PPCPs.

Classifying units via their primary positive change periods – creating summary metrics and ranking

Summary ranking metrics

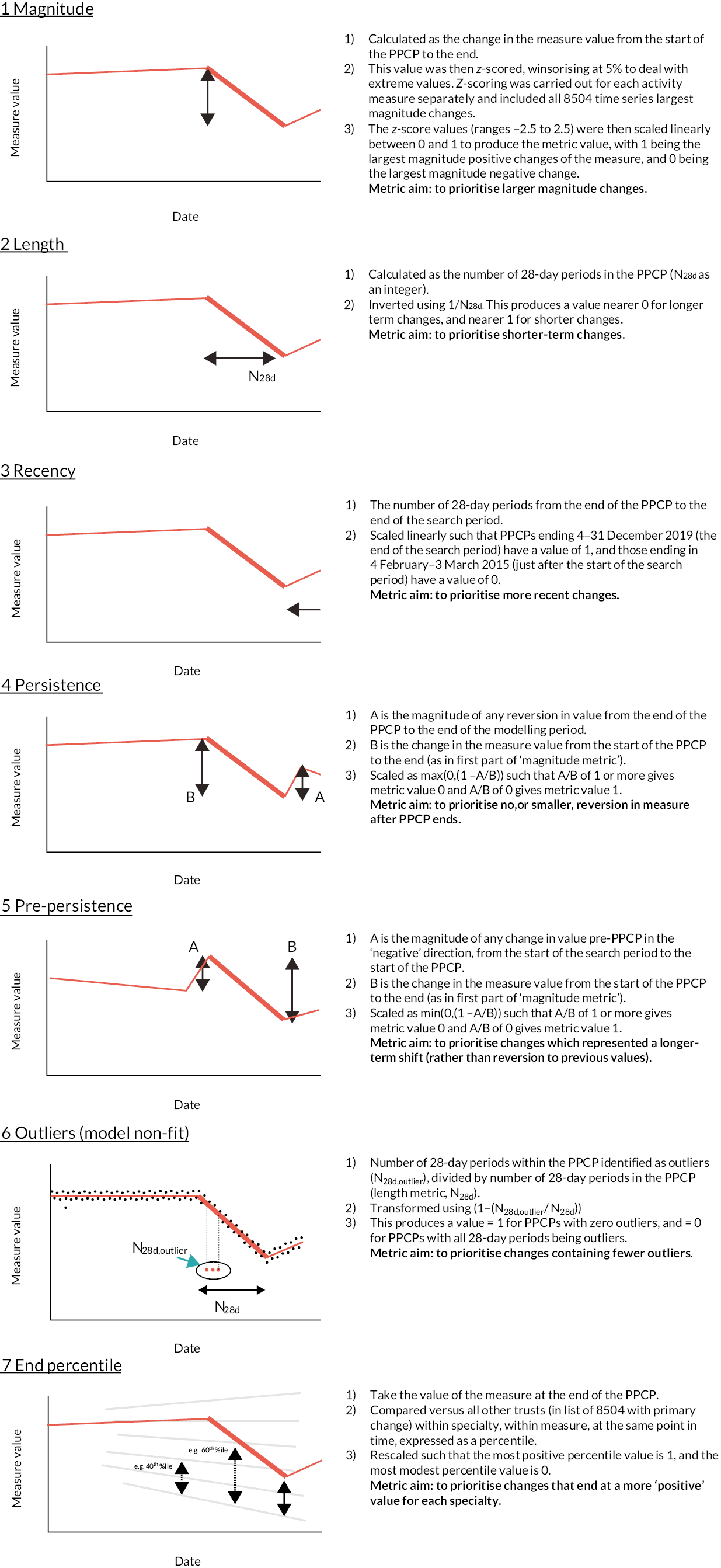

There were 3316 time series to rank, based on each series’ PPCP. Figure 6 summarises the ranking metrics we developed. The figure includes for each metric a description of transformations made and the aims for each.

FIGURE 6.

Summary of ranking metrics developed. Examples are given with respect to a measure where a fall in value is ‘positive’. PPCPs are shown as bold lines.

Many of the metrics we created included linear transformations (i.e. linearly scaling minima to maxima – or vice versa – on to a 0-to-1 scale), but for the length metric we used an inverse function and this risked overpromoting very short length changes. The implications of this are visible in the following section but is mentioned here to make the point that the metrics outlined in this section were a work in progress, and may have been changed in subsequent iterations.

Combining metrics: ranking

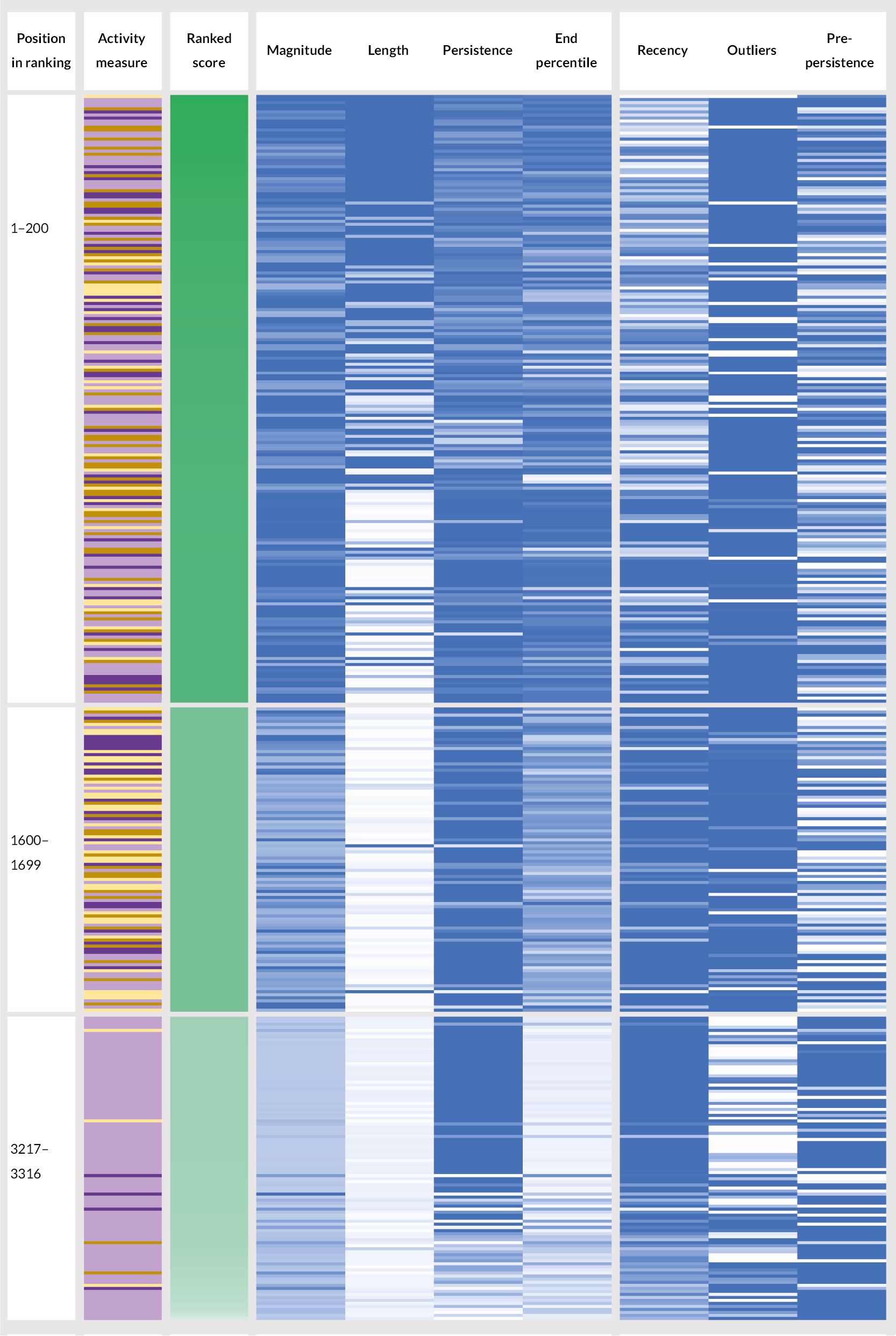

We ranked time series by combining sets of metrics. Appendix 2, Section 6 outlines a series of iterations of ranking attempts we made. At the time the study’s focus moved to the evaluation of PIFU, we were testing a relatively simple ranking approach, combining four metrics (magnitude, length, persistence, and end percentile) as a simple sum, with equal weights. Development of the general approach to ranking stopped at this point. Figure 7, however, shows a representation of the ranking outcome at this point. It shows 400 (of 3316) units as ranked by the third approach: 200 from the top of the list, 100 from the middle, and 100 from the very bottom.

FIGURE 7.

Representation of a subset (400 of 3316) unit time series from top, middle and bottom of ranked list (based on third-attempt method). Key included for activity measure and ranking and for metric score colour scales (deeper colours being better). The first four metrics listed were those used in the final approach ranking.

One observation is that there was not an equal distribution of the four activity measures across the ranking. For example, while making up 27% of all time series being ranked, only 14% of the top 200 were follow-up to first attendance ratio time series, and 42% in the top 200 were tele-attendance time series (which made up 29.5% overall). At the bottom of the ranking, 91 out of 100 time series were for tele-attendance measures. We would not necessarily expect a completely even distribution of activity measures throughout the ranking, but we might have investigated these discrepancies before the next iteration had there been one.

Briefly, other observations include:

-

The impact of having a non-linear length metric transformation is clear. Length contributed relatively little to the ranking for the majority of time series, except for the very shortest lengths (these were one or two 28-day periods), which were typically to be found promoted to the top of the ranking.

-

The correlations between recency and persistence are visible, with similar patterns of light/dark occurring in each.

Focus on Patient-Initiated Follow-Up

Selecting time series for a single activity measure: follow-up to first attendance ratio

The starting point was 906 time series describing the follow-up to first attendance ratio activity measure and their metrics, developed for the general ranking approach. The focus on a single activity measure greatly simplified the process of finding a small number of specially performing units.

We decided to implement a specific set of filters to reduce the number of time series further. These are outlined in the flow chart Figure 8. The reason for these filters was to prioritise more sustained improvements, better modelling performance and better relative performance versus other trusts in the clinical specialty. Applying these filters left us with 262 follow-up to first attendance ratio time series.

FIGURE 8.

Numbers of follow-up to first attendance ratio time series available and excluded in filtering and final time series selection.

With the number reduced so considerably, we manually ranked the subjective quality of the identified change on a scale of 1–10, and were left with 36 time series that scored 10.

Three researchers (JS, TG and JA) further considered the top 36, and manually selected 9 of these that we considered to be most promising as potentially being the result of a service change or innovation. We considered, among other things:

-

The pattern of activity before the PPCP (whether the time series had been flat, rising or jumped upwards).

-

The volume of activity in the service, compared to others.

-

The context in terms of the other activity measures for the unit.

-

How sustained the changes had been into 2020 and 2021.

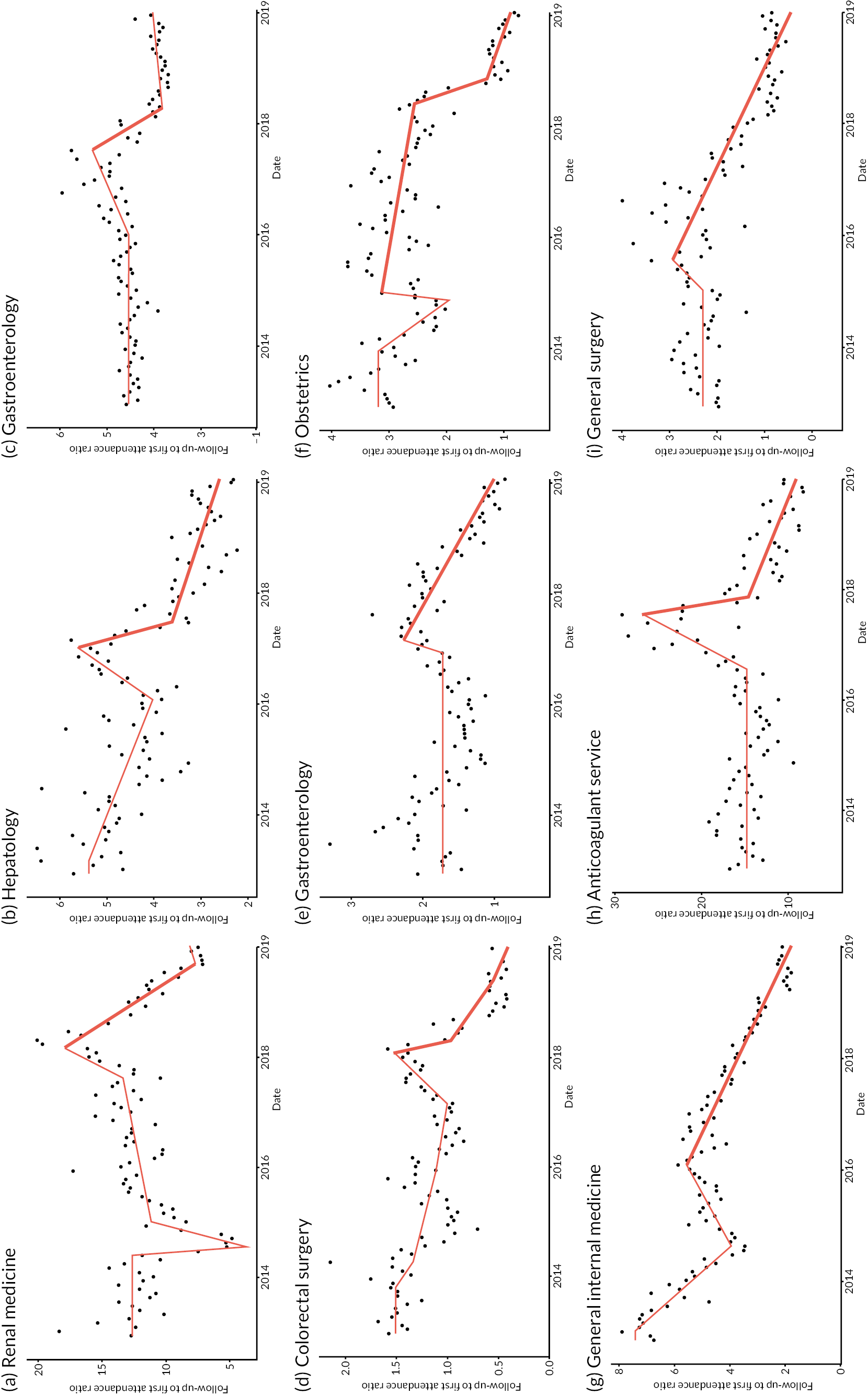

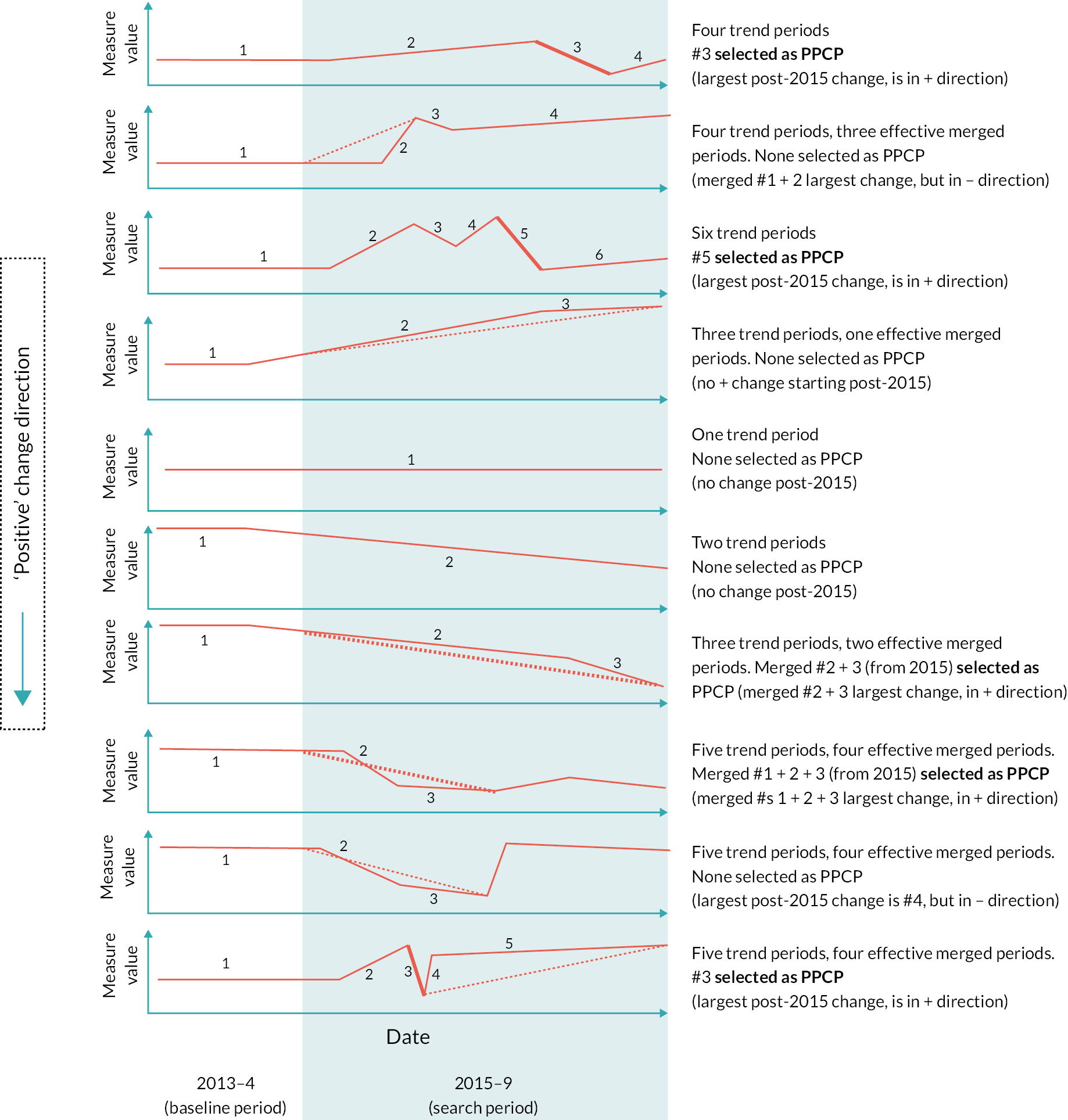

Figure 9 shows the time series of the nine services that we identified. All services were from different NHS trusts.

FIGURE 9.

The selected nine services with significant falls in follow-up to first attendance ratios [each from a different NHS trust, labelled (a)–(i)]. Red lines are IS-modelled trend lines. The PPCP is shown in bold.

Service interviews

We received five responses from nine hospital trusts contacted. One trust was unable to participate due to pandemic-related service pressures. A second – an anticoagulation service – responded that the finding had been recognised and understood locally and was likely due to a change to anticoagulant drugs which no longer needed regular blood test monitoring. This change had taken place in 2017, broadly matching the start of the changes identified but was out of scope as an innovation for further study. Note that we had been made aware of this change by one of the advisory group members, and we had made specific attempts to reduce the relative ranking of anticoagulant services in the earlier general ranking methodology (see Appendix 2, Section 6).

Three trusts welcomed a call and suggested one or more relevant members of staff who would be able to talk with us.

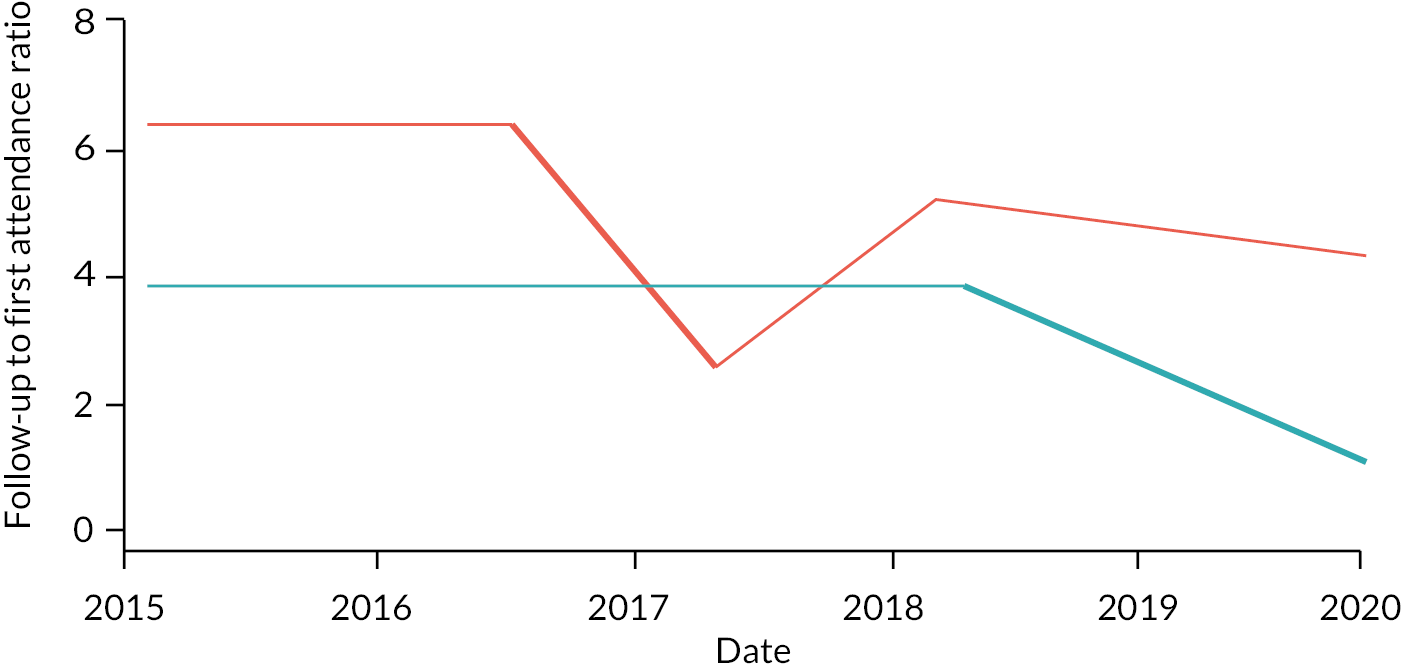

The outcome of the interviews was mixed. Table 5 summarises key reflections from the three unit interviews.

| Unit 1 | Unit 2 | Unit 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Unit clinical specialty | Gastroenterology | Obstetrics | General internal medicine |

| Organisation type, location | Teaching hospital trust, Midlands | Multi-hospital trust, South East | Teaching hospital trust, London |

| Interviewee role | Consultant gastroenterologist (in position > 8 years) |

|

Head of transformation (in position < 3 years) |

| Change in follow-up to first attendance ratio found and discussed | Reduction from 2.3 to 1, from 2017 to 2020 (Figure 9e) | Reduction from 3.1 to 1, from 2015 to 2020 (with accelerated fall in 2018) (Figure 9f) | Reduction from 5.5 to 2, from 2016 to 2020 (Figure 9g) |

| Trend recognised at trust? | Yes, and reflects a change in practice | Not picked up at the trust | No. Did not reflect trust’s own data; no such large falls known in any medical service |

| Suggested main cause of change | Clinical assessment service, introduced in 2017. Aimed to refer patients directly to tests without initial consultation. A modest trial had shown a large fall in consultations before discharge to general practice | No clear explanation identified. Suggestion of possible recording artefact, especially given declining birth rate (and yet first attendances more than doubling according to HES OP) | N/A |

| Additional notes | Other initiatives also noted:

|

In only one of the three units, a gastroenterology service, did the interviewee recognise the finding we presented of falling numbers of follow-up attendances compared to first attendances over time. This was cautiously attributed to a clinical assessment service that started in 2017 (and which a local trial had shown to reduce numbers of consultations before discharge).

Interviewees of the other two units were more surprised by the findings; indeed one (from a general internal medicine service) consulted internal trust data during the call and could find no such large fall in ratios in any medical specialty during the relevant period. This remains unexplained. The other unit interviewees (from an obstetric service) suggested that there were data recording problems, given that locally declining birth rates were at odds with rising numbers of first attendances as recorded in HES OP data.

No unit discussed PIFU as an intervention, and the investigation into these sites ended.

Discussion

The aim of this section’s work was twofold. Firstly, to develop a quantitative methodology to apply to national hospital outpatient data, the output of which would be a small, ranked list of clinical units where there was evidence of outstanding improvements in an aspect of outpatient activity data, potentially indicating the impact of a service change. Secondly, to investigate a small number of the detected improvements, with a view to identifying one or two potentially innovative service changes that we might evaluate.

The wider study changed course as the analytical work was in progress, and as a result we did not achieve all the aims. The work changed to support an evaluation of the implementation of PIFU, and this halted work on a generalised quantitative methodology for identifying positive changes in outpatient data. The final process had more manual – and subjective – input than was envisaged, and arguably might have been better supported with more well-established quantitative and statistical methods, given the increased simplicity of the analytical aim.

Of a small number of clinical units, we identified as having unusually large falls in numbers of follow-up attendances versus first attendances (an impact we expected to be connected to successful implementation of PIFU), we were able to interview three. Two did not recognise the data findings and had no explanation for the apparent improvements we found. The third recognised the changes and attributed them to a non-PIFU-related service change. A fourth (not interviewed) identified the fall as having been connected to a change in medication use. While these results are a potential measure of success for half of the units from which we received further information, numbers are too small to generalise, and we cannot exclude the possibility that there was no direct connection between data findings and the suggested causes.

Nevertheless, this work did not therefore feed into the PIFU evaluation.

We reflect below on the analytical work in the context of other studies, and its strengths and limitations within the setting of a rapid evaluation study.

How this work relates to previous research

Walker and colleagues successfully implemented methods to detect meaningful changes in prescribing practice in English general practices. 48 The scale of their work was not dissimilar in one respect to the present study; they analysed upward of 8000 practices over 5 + years, compared to 10,000 hospital ‘units’ over 7 years. However, their analysis was more focused. They aimed to study changes in practice with respect to two common medication treatments, at the time of a patent expiry, and new guidance and financial incentives. The same group has subsequently adapted similar methods for analysis of changes in statin prescribing connected with changes in national guidance54 and to analyse impacts of new policies to reduce opioid over-prescribing. 55 In the latter study, there was an element of ranking based on practices’ and commissioning groups’ changes in prescribing rates, however this was on a single measure of activity.

The present analysis lacked the tight focus of these studies. The aim was more ambitious: to cover multiple different aspects of activity data for an entire health service type – outpatient services – and to define methods to not only find meaningful changes, but importantly – given the potentially vast amount of data – to prioritise between these changes. It is perhaps not surprising that we have been less successful at achieving the full aims.

With the exception of the above-noted studies and a COVID-19 modelling study,56 limited use appears to have been made of these methods within research relevant to health services.

The present work had clear parallels with ‘positive deviance’ methodologies. Bradley et al. 47 defined these as having two goals: the identification of units that have had exceptional performance followed by promotion of good practice derived from these units. A 2015 systematic review of positive deviance approaches within healthcare organisations57 analysed studies against Bradley et al. ’s four-stage process for adopting positive deviance approaches in healthcare organisations. The four stages were: identification of positive deviants using routinely collected data; qualitative study of the positive deviants to generate hypotheses about the strategies used to succeed; quantitative testing of these hypotheses in larger samples of units; and dissemination of evidence of positive strategies. They found that research quality was generally low, that there was wide variation in how positive deviants were identified (some appearing to lack validity/replicability) and that the final two stages were often absent.